Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/44/04. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Hill is an advisor for Slimming World on psychological issues related to weight management.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Simpson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Obesity: the problem

Poor diet, physical inactivity and high body mass index (BMI) have been identified as among the top 10 risk factors for the global burden of non-communicable disease. 1 Worldwide obesity has become a key public health concern, with the prevalence of obesity doubling since the 1980s. 2 Over one-quarter of adults in the UK are obese, and over 63% are either overweight or obese. 3 In 2010, 35% of men and 44% of women were at high or very high risk of health problems based on their BMI and waist circumference. 3 Obesity is associated with a reduced life expectancy of up to 14 years. 4 Obese and overweight individuals are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, osteoarthritis, depression, hypertension and certain cancers. 2 Although in some countries rates of obesity have stabilised, in others obesity rates are projected to continue increasing. 5 Despite efforts taken by many governments to tackle obesity, embracing increasingly comprehensive strategies and involving communities and key stakeholders, little progress has been made in successfully addressing ‘the obesity problem’.

The causes of obesity are complex and include biological, social, environmental and psychological influences. The Foresight report Tackling Obesities: Future Choices6 details the complex multidimensional array of influences affecting weight and concludes that tackling the obesity problem will require interventions at multiple levels of influence. Although obesity is associated with a number of potentially important genes, the effect that the genotype has on the development of obesity is strongly influenced by non-genetic factors. 7 Modern lifestyles tend to include low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary behaviours, resulting in reduced daily energy expenditure. Recent data, based on self-report, suggest that only 29% of women and 39% of men achieve government recommendations for physical activity in England. When this is based on objective measures, these rates are reduced to only 4% of women and 6% of men reaching government targets. 3 Many occupations have become more sedentary in nature, and easy access to different modes of transportation as well as concerns about safety negatively impact on walking and cycling. 8 Diet in developed countries has moved towards high-fat, energy-dense foods and large portions. 8 In the UK, and many other countries, the balance between energy intake and energy output has tipped in favour of weight gain.

Obesity-related illness represents a significant cost to the NHS, society and individuals. It is estimated that the NHS spends £5B per year9 treating obesity-related health problems. By 2050, if obesity continues to rise, the combined cost to the NHS and society has been estimated to be almost £50B per year. 6 In primary care, there are limited treatment options with proven effectiveness for weight management. Practice staff are often inadequately trained, and issues such as shortage of referral options, the large number of obese patients, the apparent lack of motivation of patients to change and time constraints compound the problem. 10

There is evidence that, in overweight or obese individuals, reductions in weight of 2–5 kg can lead to clinically important reductions in key cardiovascular risk factors and prevent progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus. 11–14 Evidence indicates that through various means, including lifestyle interventions and medication, this level of weight loss (and possibly more) can be achieved. 12,13,15–18 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance emphasises the importance of interventions that tackle both physical activity and diet and include behaviour change strategies. 19 Systematic reviews have shown that combining diet and physical activity is likely to be more effective than either alone. 20,21

Studies testing lifestyle interventions for weight loss have been successful in the short term; however, weight regain is common. 13,16 Weight loss interventions will ultimately be cost-effective and have a longer-term impact on health only if weight loss is maintained. Effective interventions that can help people successfully manage their weight in the longer term are therefore needed. Although there is some evidence that indicates maintenance interventions are associated with smaller weight gains than no contact, the prevention of weight regain remains a challenge. 20,22 Differences between intervention and controls tend to be small, and around one-third of weight is regained in the year following the intervention,23 with return to baseline weight within 5–6 years. 16 Helping individuals achieve long-term weight loss or maintenance has proven to be challenging. The skills and techniques used to maintain weight loss may be somewhat different to those required to lose weight. To date, research has provided limited insight into how this can be achieved;24 however, lifestyle and behavioural interventions are likely to be key to long-term weight loss.

The following two sections explore approaches to weight loss as well as weight loss maintenance (WLM). Evidence related to bariatric surgery was not considered because this group of patients are likely to require different support in terms of the strategies and psychological approaches. Bariatric surgery was also a specific exclusion criterion in the study. As there are few systematic reviews looking specifically at WLM interventions, we have included reviews that examine long-term weight loss (and, therefore, maintenance), with at least 1-year follow-up, as well as those in which the interventions being tested have a distinct focus on maintenance of weight already lost.

Weight loss interventions

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 randomised controlled trials (RCTs)25 of weight loss strategies, most of which included behavioural plus other approaches (13 diet alone, four diet and exercise, four exercise alone, seven meal replacement and two very low-energy diets) found that diet alone, diet and exercise, and meal replacements led to weight loss at 12 months of between 4.8% and 8%, and at 24, 36 and 48 months of between 3% and 4.3%. At 48 months, no groups regained weight to baseline levels. Only two of the studies of meal replacements went beyond a 1-year follow-up, and exercise alone did not appear to lead to successful WLM. When large weight losses were achieved using very low-energy diets, weight regain was rapid, but 5% loss could be maintained at 36 months. 25 A systematic review of six RCTs evaluating diet, exercise, or diet and exercise together indicated some advantage of combined diet and exercise interventions, which achieved a 20% greater sustained weight loss at 1 year than diet alone. 20 There is heterogeneity in the results of trials exploring type of diet and its relation to weight loss. A meta-analysis of five trials found no differences between low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets at 12 months. 26 A systematic review of 14 RCTs found that low-fat, 600 calorie deficit, or low-calorie diets were associated with weight loss at 12, 24 and 36 months. 13

Obesity medication has also been used to target long-term weight loss. A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs indicated that orlistat (Xenical®, Roche) conferred an advantage above diet alone of 3.1 kg weight loss [standard deviation (SD) 10.5 kg] at 24 months. 25 Another systematic review of 12 clinical trials found that orlistat plus dietary or lifestyle intervention resulted in a 3–10-kg loss after 12–24 months and increased the odds of attaining 5% weight loss or greater at 24 months. 27 However, the included studies suffered from high attrition rates, on average between 30% and 50%, highly selected patient populations, inadequate description of randomisation and few used intention-to-treat analyses.

Weight loss maintenance interventions

In terms of interventions specifically for WLM, there are limited data on diets suitable for WLM. However, evidence from the US Weight Control Registry indicates that those who maintain weight loss in the longer term generally follow low-fat, low-calorie diets, eat breakfast and have consistent eating patterns over weekdays and weekends. 28 A conceptual review of factors associated with WLM also found that eating breakfast and a regular meal pattern are important, as is having a healthier low-fat diet. 29

Although physical activity is important for maintenance of weight loss,30 limited evidence exists regarding the type or amount of physical activity required. A systematic review comprising 11 RCTs and 35 prospective or non-randomised studies suggested that higher levels of physical activity may be associated with WLM. 31 Secondary analyses of one well-designed trial found that individuals reporting higher levels of physical activity (275 minutes per week) were better able to maintain 10% weight loss at 24 months. 32 Another review identified that 60–90 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per day is needed to prevent weight regain. 33 The 2008 US Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Report34 identified that the currently available evidence has a number of limitations; nevertheless, the report suggests that ‘more is better’. The studies included in the report indicated that, to prevent weight regain, individuals should walk for 60 minutes or jog for 30 minutes daily. However, many individuals find this difficult to maintain in the longer term.

A recent systematic review of trials of interventions to maintain weight loss found that behavioural interventions focusing on diet and physical activity led to an average weight difference of –1.56 kg in weight regain in intervention participants relative to controls at 12 months. 35 Orlistat plus behavioural treatment led to a –1.80 kg difference between intervention and control. 35 In addition, a review of RCTs of WLM interventions found that treatment with orlistat or sibutramine (Reductil®, Knoll Abbott) alongside a dietary intervention, caffeine or protein supplementation, physical activity, low-fat diet, ongoing contact, problem-solving therapy, or acupressure was helpful in minimising weight regain. 36 A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of extended care on maintenance of weight loss in the longer term found that extended care could lead to an additional maintenance of 3.2 kg at 17.6 months compared with control. 37

There is some evidence that web- or computer-based interventions may be useful for WLM,38,39 and they are likely to cost less to deliver. One review suggested that web-based interventions are about as effective as face-to-face interventions and higher website use may be associated with WLM. 40 Another recent review found that computer-based interventions were more successful for WLM than no intervention or minimal intervention. 39 When computer-based interventions were compared with in-person interventions, the weight loss was smaller and weight maintenance was of shorter duration. 39 A recent telephone- and mail-based intervention found that, at the 24-month follow-up, the odds of weight maintenance was 1.37 times greater in the guided telephone intervention than in the self-guided arm. 41 This approach is likely to be more feasible and cost-effective to deliver.

Further research is needed, as the evidence base is limited, because most trials included in reviews are of poor or moderate quality. Many trials of longer-term weight loss or WLM are inconclusive. They are heterogeneous in terms of setting, length of follow-up, type and duration of intervention, many have methodological flaws, including inadequate reporting of randomisation processes or blinding and paucity of intention-to-treat analyses, and findings are often contradictory. High levels of attrition are evident and this is probably associated with WLM failure. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions about what works in WLM. There is a need to develop and rigorously test interventions that are based on evidenced behaviour change techniques which also take contextual factors into account, that can help people with long-term weight loss or maintenance of weight loss. Although there is a lack of research evidence for interventions that can effectively support longer-term weight loss, there have been some notable successes, for example the Finnish Diabetes Prevention programme, in which participants maintained an average weight loss of 3.5 kg at 3-year follow-up. 42 Conducting trials in this area is challenging for a number of reasons: difficulties achieving blinding owing to the nature of the intervention; the difficulty of retaining participants over long-term follow-up; and the cost of running such long-term studies, which makes the production of the required evidence time-consuming and expensive.

Psychological/behavioural therapeutic approaches

Trials of interventions for long-term weight loss or maintenance of weight loss usually include some aspect of behaviour therapy or counselling as part of the intervention, alongside other elements such as dietary change. Counselling or psychotherapeutic approaches that have been successfully used for weight loss include cognitive–behavioural therapy43 and motivational interviewing (MI). 44 As well as these particular counselling approaches, many interventions have employed specific behaviour change techniques and, in many cases, the effects of these elements are not teased out. Behavioural techniques that have been specifically assessed in high-quality RCTs and shown to offer significant benefit for WLM include goal-setting,38 problem-solving,22,38 relapse prevention,38 self-monitoring22,38 and daily self-weighing. 22 Peer or social support21,22 and frequent continued professional support have also been shown to be important. 22,38

As noted above, the psychological processes, skills and strategies which are likely to be effective for WLM are potentially different from those needed to lose weight. 22,24,45,46 Research examining 5000 people on the US National Weight Control Registry suggests that the only factor those losing weight have in common is that they combined diet and exercise to do so. However, when examining the maintenance phase, a number of common factors were identified, including low-fat diet, eating breakfast, self-monitoring and high levels of physical activity. 28 Losing weight requires a negative energy balance, whereas weight maintenance requires continued energy balance. This balance needs to be sustained by behaviours that can be continued over the longer term. In reviews of factors associated with WLM, a number of issues stand out: higher levels of physical activity,32 consumption of low-calorie and low-fat foods, individual tailoring of advice, self-regulation/monitoring, social support, internal motivation and self-efficacy. 28,29

The WeIght Loss Maintenance in Adults (WILMA) trial tested an intervention that incorporated many of the evidence-based behavioural techniques described above alongside three main components: MI (incorporating action-planning and implementation intentions47,48), social support and self-monitoring. These three main elements and evidence for them will be considered briefly in Motivational interviewing, Social support and Self-monitoring. The intervention elements and theoretical approach are described in more detail in Chapter 2.

Motivational interviewing

Motivation is a key precursor for behaviour change, and ongoing motivation is important in terms of maintaining behaviour change. 49 As ongoing intervention contacts have been shown to help maintain weight loss,38 and attrition from longer-term programmes is a problem,22 motivation is likely to be important. Many people are able to lose weight by dieting and/or exercise. 45 However, sustaining these behaviours seems to be challenging and, therefore, enhancing motivation is likely to be important in terms of maintaining healthy behaviours. MI is therefore the key ingredient of the intervention. MI is defined as:

a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change. It is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion. 50

The effectiveness of MI has been demonstrated in a wide range of behaviour change contexts including modification of drug use51 or alcohol consumption51 and smoking cessation. 52 Weight loss and WLM is a relatively new area for MI, and few studies have been completed. 53 MI has been shown to be effective as an adjunct to a behavioural weight control programme. 53 It can be useful in maintaining behaviour change as well as initiating change and supports participants in an ongoing, tailored way. 53,54

Brief interventions using MI have been effective in different areas of behaviour change including diet and physical activity. RCTs and systematic reviews of MI approaches have shown that it can be used successfully in interventions to change both diet and exercise. 55–59 It can also effectively be delivered by telephone, which provides a clear cost advantage over face-to-face delivery. 60,61 There is some evidence that MI can be effective when delivered in just one session62 and even when sessions are as short as 15 minutes. 57,63 One meta-analysis examining MI in different areas of disease showed a combined effect of MI on decreasing BMI by 0.72 kg/m2 (p < 0.0001) and found that longer follow-up increased the chance of an effect from 36% at 3 months to 81% at 12 months or longer. 57

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 11 RCTs examining the effect of MI on weight loss. 64 It found that participants who received MI lost more weight than controls [weighted mean difference −1.47 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) −2.05 kg to −0.88 kg]. The pooled effect size was 0.51. When weight loss was the primary outcome, treatment was more than 6 months and a treatment fidelity measure was used and the effect of MI on BMI increased. However, most of these studies had a follow-up period of less than 12 months. 64

No studies have tested MI as a WLM intervention, although a few have investigated longer-term WLM following an MI-based weight loss intervention. 53,54 West et al. 53 tested a weight loss intervention consisting of MI (plus a group-based weight control programme) in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. They found that women in the MI group lost significantly more weight by the 18-month follow-up assessment than those in the control group (3.5 kg ± 6.8 kg loss in MI and 1.7 kg ± 5.7 kg in control subjects, p = 0.04). Hoy et al. 54 conducted a study with a 5-year follow-up period. They evaluated a dietary intervention with MI techniques and found that, after 1 year, body weight was lower in the intervention group and at 5 years women in the intervention group weighed significantly less than controls [6.1 lb mean weight difference between groups (p = 0.005) at 5 years].

Social support

As environmental factors can encourage or impede behaviour change and maintenance, social support has a key role. Social support may operate in a number of ways to promote healthy behaviours, for example through reinforcement, encouragement, motivation, feedback, empathy, role-modelling, increased self-efficacy, instrumental support (help), appraisal (e.g. affirmation), peer pressure for healthy behaviours or access to health information. There is evidence indicating that social support and health are related65 and that social support can promote better health behaviours when employed alongside goal-setting and self-monitoring. Ferranti et al. 66 found that social support is positively correlated with a good diet and increased physical activity. 67,68 Social support can improve WLM,69 encourage health-promoting behaviours and promote well-being. 70 Conversely, there is also evidence that unhealthy behaviours are correlated with less social support. The current NICE behaviour change draft guidance notes that, across a range of health behaviours (including diet, alcohol and physical activity), social support was present in most of the effective interventions. 71

Social support tends to be employed and theorised as one of several key elements in behaviour change interventions72 and has been identified in reviews as one contributing factor to effectiveness, alongside goal-setting and self-monitoring. 21,73 Common intervention elements thought to operate in conjunction with social support are self-efficacy,74 perceived control68,74 and social norms. 75 A trial of diet change and weight loss with the inclusion of group-based social support found that those who received social support regardless of the diet they followed lost more weight at years 1 and 2 than those who did not receive support. 76 Other studies also report that participants who received interventions which included social support lost more weight by the end of the study than did controls. 69,77 Continued professional support is also related to better WLM. 21,22,38

Self-monitoring

Self-monitoring is important for successful behaviour change. 78 In a meta-analysis of behaviour change interventions of physical activity and healthy eating, more effective interventions were shown to combine self-monitoring with at least one other technique derived from control theory (e.g. intention formation, specific goal-setting). 73 Regular self-monitoring is associated with WLM and is recommended by NICE. 19 Self-monitoring in this context consists of regular self-weighing and monitoring of diet and physical activity. 57 A systematic review found a consistent association between self-monitoring and weight loss, although the authors suggest caution as the quality of the evidence is weak. 78 One good-quality study found that daily self-weighing was associated with a decreased risk of regaining weight at the 18-month follow-up. 22 Another study exploring WLM among participants in the National Weight Control Registry found that WLM for longer than 5 years was associated with regular self-monitoring of weight. 28

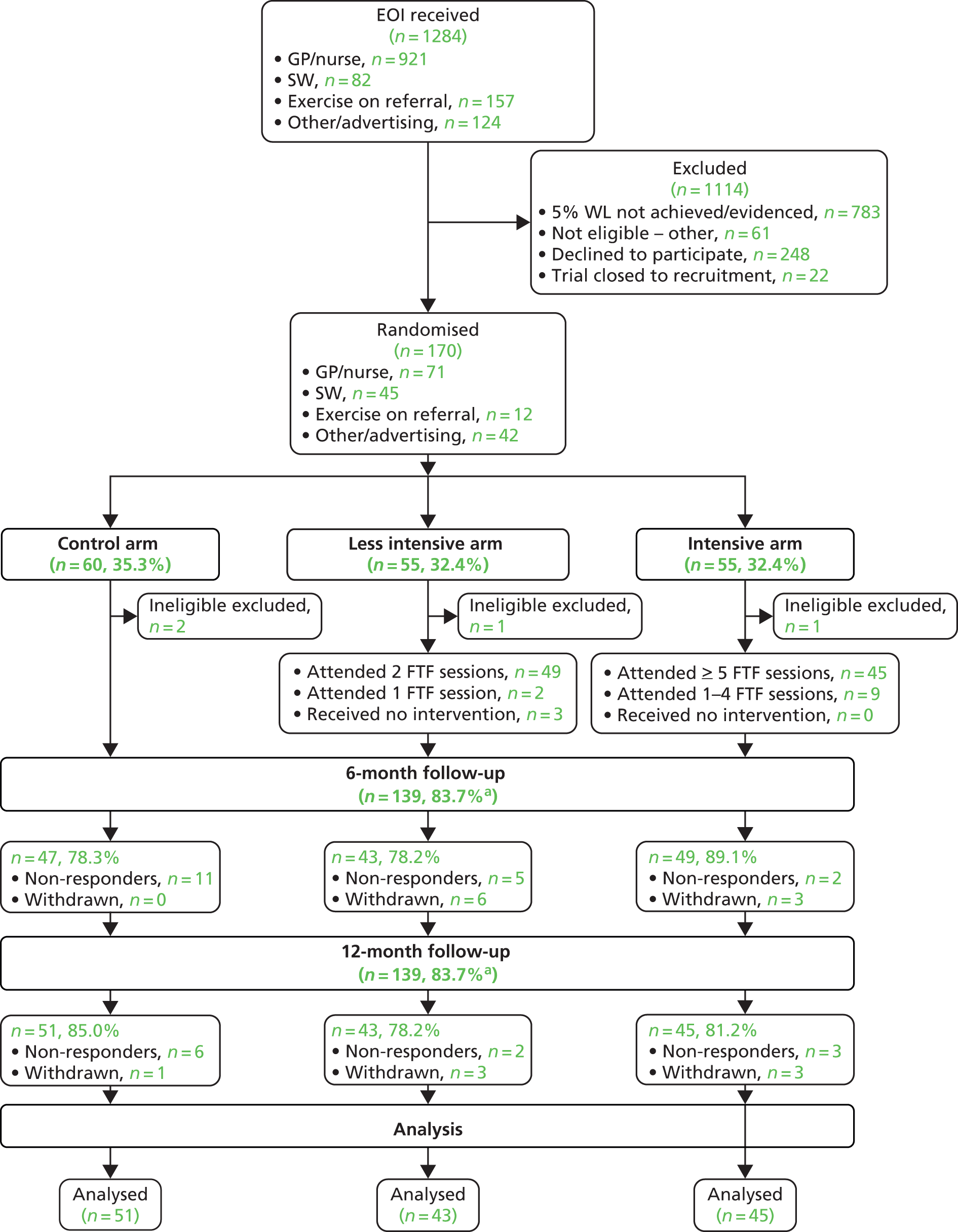

The trial

The present study evaluated a 12-month, individually tailored intervention based on MI incorporating implementation intentions/action-planning, peer support and self-monitoring. The trial comprised three arms: (1) an intensive intervention arm, (2) a less intensive intervention arm and (3) a control arm. The intervention, which is described in detail in Chapter 2, was initially delivered face to face and incorporated follow-on sessions delivered by telephone as well as group-based peer support sessions. The focus of the intervention was on maintaining gains already made. It is envisaged that this intervention, if successful and cost-effective, could be rolled out to a wide variety of people who have lost weight using different methods; therefore, the participants were recruited from a variety of settings.

The original aim of the study was to evaluate the impact of a 12-month multicomponent intervention, or a less intensive version, with a control intervention on participant BMI with follow-up at 3 years from randomisation. However, set-up and recruitment challenges meant that the trial design was changed to a feasibility study. The main objectives of the feasibility study were to assess the feasibility, acceptability, compliance and delivery of a 12-month multicomponent intervention, as well as recruitment and retention, which were assessed as part of the process evaluation. The process evaluation also examined the views of participants and intervention staff. To give an indication of effect sizes for a larger trial, we evaluated the impact of the intensive or less intensive intervention on participants’ BMI (primary effectiveness outcome) at 12 months from randomisation.

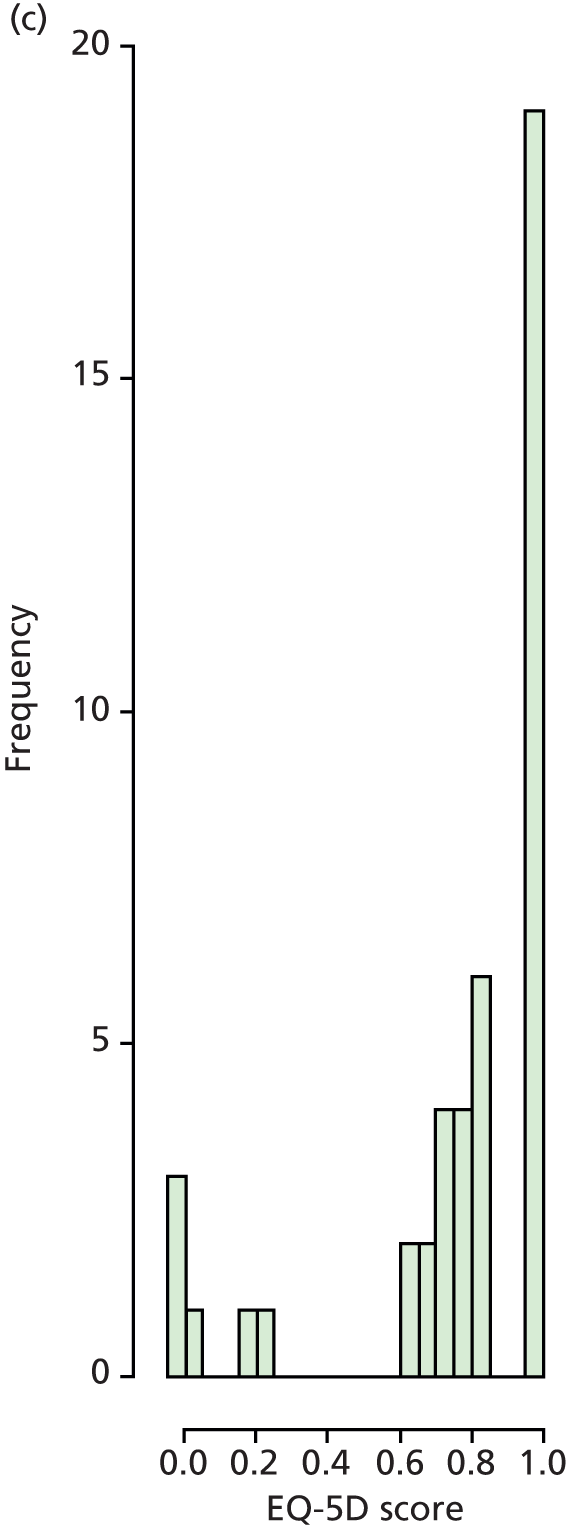

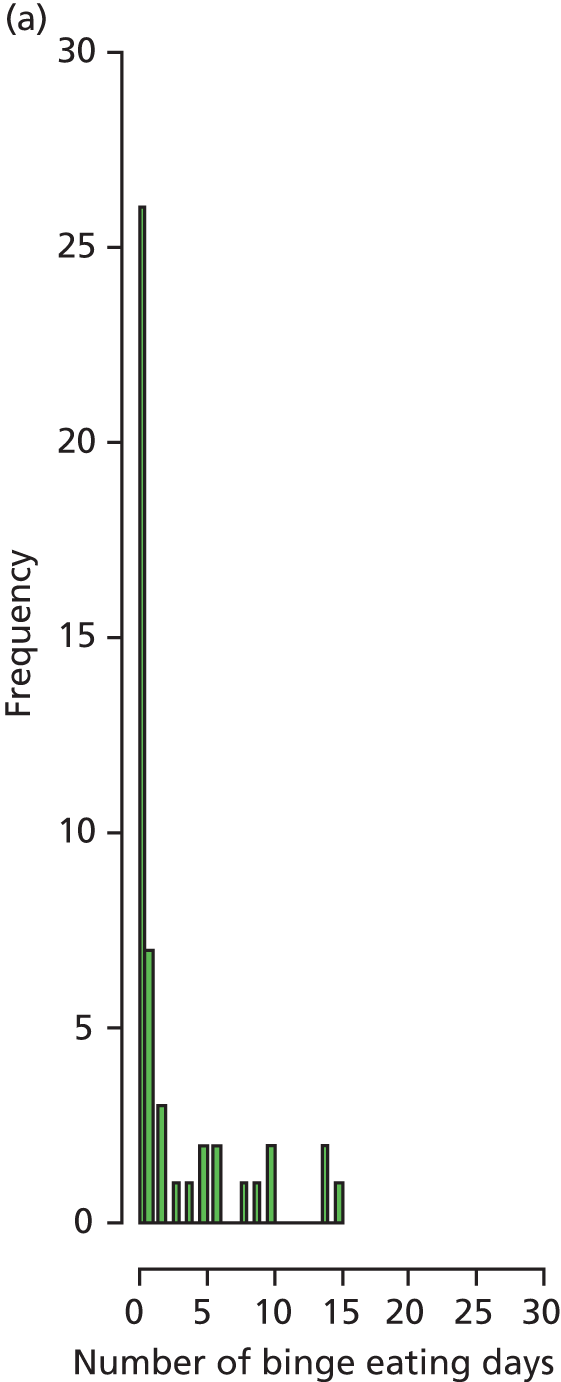

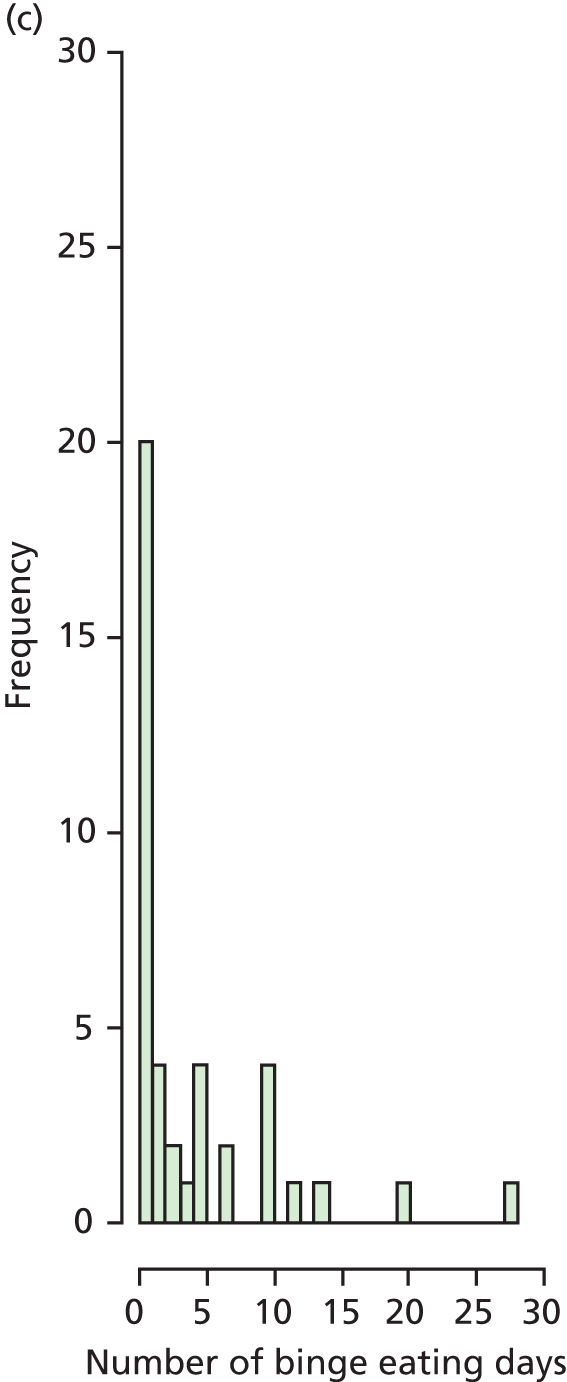

We examined the effect of the intervention on physical activity, diet, health-related quality of life, binge eating, psychological well-being and health resource use. We also examined the proportion of participants maintaining their baseline weight at the 1-year follow-up (defined as having a weight at follow-up the same as or lower than their baseline weight). To assess abdominal obesity, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were included as outcomes. This is important because visceral fat is independently associated with all-cause mortality79 and many of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including type 2 diabetes mellitus. 80 As the direct measurement of visceral fat relies on sophisticated imaging technology, most large-scale, community-based studies have relied on anthropometric measurements of the waist and hip circumference to determine abdominal obesity. Although the findings of these studies are not completely consistent, evidence suggests that a measurement of abdominal obesity (waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio) provides explanatory information in addition to that provided by BMI. 81

We assessed mediators associated with change and hypothesised mediators include self-efficacy, social support, self-monitoring, implementation intentions, habit formation and intrinsic motivation. Analyses sought to identify the extent to which the intervention was successful at changing these mediators and the extent to which mediator change was associated with WLM (see Chapter 5). See Table 2 for a full description of mediators.

Data on key moderators were collected to examine factors associated with success in WLM. These include demographics (age, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity and employment status), binge eating, quality of life, source of recruitment, psychological well-being, gender and socioeconomic status. Although a number of studies have found no differential effects of gender on weight management interventions,38 some have found that the male physiological response to physical activity does impact on weight management interventions, although further work is needed. 82–84 The effects of age are also unclear, but older participants have been reported to be more successful in WLM programmes. 85 Prevalence of obesity is higher in some ethnic minority groups, and ethnicity has also been associated with better WLM in some American studies. 86,87 This may be confounded by lower socioeconomic status, which impacts on food choices resulting from environmental factors and sociocultural attitudes. 87 Finally, a cost-effectiveness evaluation was also undertaken.

Chapter 2 The WeIght Loss Maintenance in Adults trial intervention

Background

There has been a significant focus in recent years on developing behaviour change interventions with a strong theoretical foundation that are clearly described and consequently replicable. 88–92 Furthermore, there are a number of suggested frameworks and taxonomies of behaviour change techniques88,90–92 which provide a method for defining intervention components and a set of accompanying definitions that facilitate accurate description and replication of these components. Researchers have also indicated which psychological theories some of these techniques map onto, for example goal-setting and social cognitive and control theories. 88 However, there remains a significant amount of uncertainty regarding how best to match behaviour change techniques to theoretical constructs. 90 Based on these recommendations and observations, the approach taken here was to develop a well-described, theory-based intervention and to explicitly test the theorised mechanisms of effect.

Intervention components and theory

As outlined in Chapter 1, the WILMA trial intervention was based on three main components: MI (incorporating implementation intentions),47 social support and self-regulation (self-monitoring).

Motivational interviewing

Motivation is central to many theories seeking to explain behaviour change. Motivation is unlikely to be static and is a product of both internal and external factors related to the individual. 49 As highlighted in Chapter 1, motivation is likely to be critical in minimising attrition,22 which is important as sustained intervention contact is associated with better weight outcomes. 38 For this reason, MI is the key ingredient of the intervention.

Four key processes have been identified as occurring during MI counselling sessions: engaging, guiding, evoking and planning. 50 Engaging is the process whereby the counsellor develops rapport and a collaborative working alliance with the client. Guiding occurs after engagement and is the process in which the counsellor helps guide the client along a particular course in relation to change. Evoking involves prompting the client to think about and describe his or her motivations for change, and this is a key aspect of MI. Planning involves the client developing a plan in order to achieve the change that he or she desires. These processes are ongoing and may need to be revisited at different time points.

The effectiveness of MI has been demonstrated in a wide range of behaviour change contexts51,52 (see Chapter 1). MI in relation to weight loss and maintenance is a relatively new area, although MI appears to be effective as an adjunct to a behavioural weight control programme. 51 MI may facilitate maintenance of behaviour as well as behaviour change. In the context of the WILMA trial intervention, MI supports participants in an ongoing and tailored way. 53,54

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding MI. 93 SDT characterises motivation as either intrinsic or extrinsic, with intrinsic motivation being linked to more sustained behaviour change. 94 According to SDT, intrinsic motivation for a behaviour is enhanced when the behaviour is associated with feelings of competence (i.e. confidence or belief that one can accomplish the behaviour), autonomy (i.e. that the behaviour is the individual’s choice) and relatedness (i.e. feeling understood and valued by significant others). MI supports feelings of competence, autonomy and relatedness and is therefore thought to help promote intrinsic motivation for behaviour change. It achieves this using a variety of techniques such as developing discrepancy, providing information, helping the client develop goals, supporting autonomy and self-efficacy, being non-directive, exploring pros and cons and avoiding blaming or judgement. 49,50 These are central to the WILMA trial intervention.

Motivational interviewing can also be said to draw on cognitive dissonance theory (CDT). 95 This states that when an individual holds conflicting cognitions it produces a state of tension or discomfort. The individual is motivated to reduce this discomfort, usually by rejecting one set of beliefs in favour of the other. MI creates cognitive dissonance by developing discrepancy, that is helping individuals see a mismatch between where they are and where they want to be.

Model of action phases

According to the model of action phases (MAP), behaviour change consists of a motivational phase, in which an individual decides to change his or her behaviour, and a volitional phase, during which the individual decides how to implement the change. 96 As such, action-planning/implementation intentions were incorporated into the MI sessions in order to target the volitional phase of behaviour change. Implementation intentions have been shown to be very effective at helping individuals achieve their goals47,97,98 and, in keeping with MAP, have been shown to be particularly useful in promoting behaviour change when combined with motivational interventions. 99,100 Implementation intentions specify a plan of when, where and how a person is going to, for example, start exercising. This is believed to result in the behaviour being elicited automatically by the relevant environmental cue rather than by a more effortful decision-making process. It also helps ensure that good opportunities to perform the target behaviour are not missed. 101 If the behaviour is repeated over time it may become increasingly automatic or habitual. Turning healthy behaviours into habits is critical if they are to be maintained over the long term as habits tend to be very resistant to change. 102 The promotion of healthy habits is therefore a key aim of the proposed intervention.

Social cognitive theory

Development of the intervention was also strongly influenced by social cognitive theory (SCT),103 which states that individuals have to believe that they possess the necessary skills to change their behaviour (self-efficacy) and also that their actions will produce certain consequences, for example improved health (outcome expectancies). Furthermore, these beliefs can be modified though observing the behaviour of others (modelling) and/or as a result of positive reinforcement.

Social support

As outlined in the previous chapter, social support can help promote healthy behaviours (e.g. through reinforcement, encouragement, motivation, feedback, empathy, role-modelling and increased self-efficacy), particularly in combination with goal-setting and self-monitoring,65 and has been identified as a component of the majority of effective behaviour change interventions. 71 Additionally, continued professional support is related to better WLM. 21,22,38

Self-monitoring

Self-monitoring is a key aspect of self-regulation and is important for successful behaviour change. 78 Regular self-monitoring is associated with both WLM22,28 and weight loss,78 and is recommended by NICE. 19 Self-monitoring allows people to track their eating, physical activity and weight, and observe links between patterns of behaviour and changes in body weight. Monitoring weight also allows individuals to identify smaller changes before these escalate and they can then take steps to prevent further weight gain.

The WeIght Loss Maintenance in Adults trial intervention model

The WILMA trial intervention model is detailed in Figure 1. The main component of the WILMA trial intervention is MI, incorporating self-monitoring and social support. The intervention utilises a number of techniques and processes central to MI, such as promoting intrinsic motivation using a collaborative and curious style (engaging, evoking), providing tailored support (guiding) and encouraging goal-setting (action-planning). Providing feedback and positive reinforcement and enabling clients to develop discrepancy between behaviours and desired outcomes are also techniques that are key to MI and the current intervention. The concept of self-monitoring was generally encouraged during MI sessions: participants were also asked to record their weight weekly and submit these weekly weights to the study team. An optional component of self-monitoring and behavioural regulation was also provided, in the form of an online and/or paper diary; these data were not collected by the study team. MI practitioners (MIPs) provided professional support and encouraged peer support; additionally the group session component described here (see Peer group support sessions) was intended to provide peer support and encourage information sharing and modelling of behaviour.

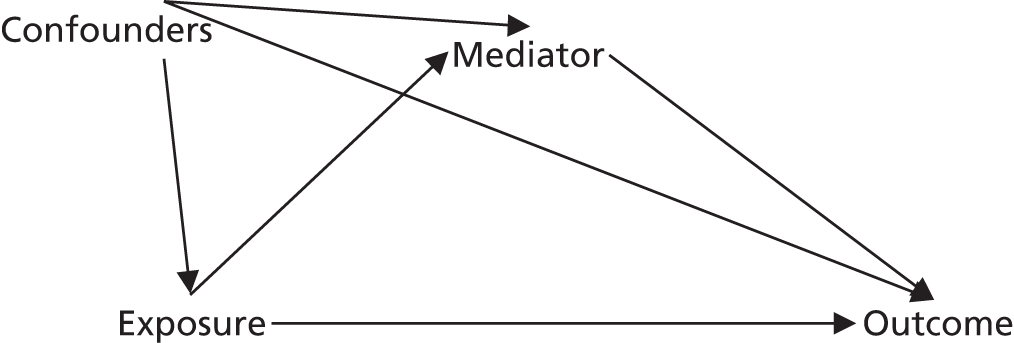

FIGURE 1.

The WILMA trial intervention model. a, MI style/technique; and b, theorised mediators.

It was hypothesised that the intervention components detailed in Figure 1 would be associated with specific variables and that these, in turn, may mediate relationships between the intervention and outcomes. Specifically, it was hypothesised that the intervention would increase intrinsic motivation, action-planning, self-efficacy, self-monitoring behaviours and boost/provide a source of social support. These variables were theorised to increase physical activity and healthy diet behaviours that would eventually become habitual, ultimately leading to successful WLM and, in some cases, further weight loss.

The components of the WILMA trial intervention and their suggested theoretical links are outlined in Table 1.

| Intervention component/outputs | Relevant theory |

|---|---|

| Promoting intrinsic motivation | SDT93 |

| Providing positive feedback/reinforcement | SDT, SCT103 |

| Developing discrepancy between current behaviours/weight and ideal behaviours/weight | CDT95 |

| Goal-setting/forming implementation intentions/action-planning | SCT (GS), MAP (II)96 |

| Self-monitoring | SCT (self-regulation) |

| Encouraging/providing social support | SCT, SDT |

| Encouraging problem-solving | SCT |

| Promoting self-efficacy | SCT, SDT |

The WeIght Loss Maintenance in Adults trial intervention

The WILMA trial comprised an individually tailored intervention based on MI, incorporating implementation intentions, social support and self-monitoring. The main part of the intervention was concentrated in the first 2 (less intensive) to 6 months (intensive), tapering down to less regular support. It was felt that this longer-term support, although not resource intensive, would be important for the effectiveness of the intervention. Previous studies that have had success with WLM have had longer-term interventions and support. 22,38,104 The trial comprised three arms: (1) an intensive intervention arm, (2) a less intensive intervention arm and (3) a control arm. We hypothesised that the intensive intervention would be effective and that the less intensive intervention would have an effect somewhere between the control and intensive intervention. This less intensive arm is important because, although some studies have emphasised the importance of long-term intervention and follow-up, it remains unclear how intensive this should be and how it is best delivered. This has important implications for cost and the feasibility of rolling out the intervention should it be successful. Effectiveness in this trial refers to maintenance of initial weight loss rather than additional weight loss, although the latter may occur for many participants.

Individual motivational interviewing sessions

Participants in the intensive intervention group had six one-to-one individually tailored MI sessions. Sessions were delivered by experienced MIPs and were delivered approximately fortnightly for 3 months, lasting around 1 hour. For the final 9 months of the intervention participants received monthly MI telephone calls lasting approximately 20 minutes. This level of monthly contact in the intensive intervention group is based on evidence from previous trials. 38 Participants in the less intensive intervention group received two face-to-face tailored MI sessions 2 weeks apart. This was based on experience from clinical practice as well as evidence from reviews and meta-analyses. 57,63 Participants also received two MI-based telephone calls at 6 and 12 months lasting around 20 minutes.

Motivational interviewing session content

Motivational interviewing practitioners were given a handbook to guide the sessions (see Appendix 1). This comprised the following information: a summary of the client group and their challenges, MI within the context of the WLM trial and intervention ‘hot topics’. Hot topics comprised self-monitoring, goal-setting and implementation intentions, habits, emotional eating and coping with relapse, diet, physical activity, barriers to maintenance, social support and self-efficacy. The purpose of this section of the handbook was to summarise, in non-expert language, the key research evidence suggesting that these components are likely to be effective for WLM. Information on each topic was provided in the following format: (1) description of the topic (‘what is it?’), (2) summary of research evidence (‘why is it important?’) and (3) suggestions on how to use the information during individual sessions in an MI-consistent (i.e. non-directive) way (‘what do I need to do?’). MIPs were also provided with summary information relating to each of these intervention hot topics on laminated sheets. This summary information covered key components of the detail provided in the practitioners’ handbook in lay language, for them to use as a reference and share with participants as required during MI sessions.

Diet and physical activity were discussed in the MI sessions in line with current government guidance. Participants were encouraged to reflect on their values, goals and current behaviour and to develop their own goals and techniques for implementing and maintaining behaviours. Participants in the intervention groups were encouraged by researchers at their baseline assessments to self-monitor by weighing themselves weekly and MIPs encouraged the concept of self-monitoring generally. Participants were able to record all self-monitoring activity, including diet, physical activity, other markers of successful maintenance (e.g. clothes fitting better), goals set at sessions and implementation intentions, in a diary provided by the study team (paper-based and brief online version); however, completion was optional. Diaries provided to participants were intended for their personal use only and were not collected by the study team for outcome assessment. However, participants were asked to record their weekly weight and send this information to the study team via the study website or by text, e-mail or telephone. MIPs kept a written record of each face-to-face and telephone session (including goal-setting and implementation intentions) using the appropriate case report form (CRF) and this information was collected by the study team. MIPs also completed a brief written summary of the session for the participant to take away.

Information on study-specific procedures [reporting serious adverse events (SAEs), lone working, actual/risk of self-harm to participants and administrative processes] was also included in the handbook.

Peer group support sessions

Professional-led peer group support sessions were planned to take place monthly, lasting 1.5 hours, for 4 months, to follow on from the face-to-face MI sessions. The group sessions were the same for both intervention arms. The number of sessions chosen was felt to provide a cost-effective method of reinforcing the main messages of the intervention as well as allowing people to share their experiences and increasing their social support. The group sessions were to be led by a facilitator with the aim of providing participants with the opportunity to share problems, techniques and tips with peers. The sessions were designed around four themes: (1) barriers to maintenance, emotional eating and coping with relapse, (2) diet, (3) physical activity and (4) intervention-related tasks and activities such as self-monitoring, goal-setting and implementation intentions, social support and habit formation. Each session was structured around a series of interactive tasks, intended to provide an opportunity to share tips and increase knowledge in these key areas. Participants were to be given a summary sheet at the end of each session to take away with them and asked to complete a brief feedback sheet aimed at gauging the extent of knowledge of topics prior to sessions and what they found most useful.

A handbook was also prepared for group facilitators (GFs) (see Appendix 2) to guide the content of sessions. Information covered the following: a summary of the study, intervention and client group, WLM issues, key intervention components (self-monitoring, goal-setting, habits, social support, self-efficacy), group facilitation skills, overview of group sessions, individual session structure and content. Information on study-specific procedures was also included.

Motivational interviewing practitioner and group facilitator training and ongoing support

Training packages were developed for both the MIPs and GFs to cover and expand on key information detailed in the handbooks. For MIPs, specific guidance was developed regarding the challenges of delivering MI in just two sessions and over the telephone. Guidance was developed in consultation with MIPs during training. Both the MIPs and GFs were given training on issues around obesity as well as diet and physical activity recommendations. We discussed with them the challenges of WLM and weight loss and how we might best support participants in this process. The GFs were additionally given training on group facilitation skills. Training was delivered face to face over 2 days by experienced MIPs and key members of the study team involved in intervention development. Training for GFs comprised a 1-day face-to-face session and was delivered by the study team. All MIPs were required to have experience of delivering individual MI in health-care settings. All GFs were required to have experience of group facilitation. The GFs were trained to deliver sessions in a MI-consistent manner and many had experience of delivering face-to-face MI counselling; however, the group sessions were not group MI sessions.

We planned to run four peer support sessions for MIPs in which they would get together in small groups to share their experiences, listen to recordings of sessions and discuss any challenges or issues in MI delivery. These sessions were designed to give WILMA trial intervention-specific support in addition to that which the MIPs arranged as part of their own supervision. We also planned to run four workshops on specific WILMA trial intervention-related topics spaced out across the intervention delivery period, to support the MIPs and discuss difficulties.

Summary

The WILMA trial intervention comprises a number of behaviour change techniques which have been shown to be effective in other domains,90 namely MI incorporating goal-setting and action-planning, self-monitoring and social support. The purpose of the current chapter and the intervention handbooks appended to this report is to describe the components and theoretical underpinnings of the WILMA trial intervention and provide sufficient detail about how it was operationalised to allow replication or modification. Chapters 5 and 8 will seek to explore and describe relationships between the behaviour change techniques used and associated intervention functions as well as outcome.

Chapter 3 Methods

As noted previously (see Chapter 1, The trial), this study was originally designed as an effectiveness trial of a multicomponent intervention, with the main outcome (BMI) assessed 3 years post randomisation. However, owing to significant problems in set-up and recruiting, the trial was closed early and is therefore reported as a feasibility study. We feel it is nonetheless important to detail the methods as originally designed (see Design through to Cost-effectiveness analysis), prior to describing changes made following conversion to a feasibility study. The changes to the trial design are described in detail in Feasibility study methods; however, the key changes were that primary outcomes were feasibility outcomes, the follow-up was shortened to 12 months and the group-based aspect of the intervention was no longer delivered because of feasibility issues.

Design

The study was a three-arm individually randomised controlled trial comprising an intensive intervention arm, a less intensive intervention arm and a control arm. The two experimental arms received a 12-month intervention based on three key elements – (1) MI, (2) self-monitoring and (3) social support – which differed only in amount of contact with the MIP. The control arm received an information pack and usual care. Follow-up was planned at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months post randomisation. The aim was to recruit 950 adults aged 18–70 years with a current or previous BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 who had lost a minimum 5% body weight during the previous 12 months. Ethics approval was given by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) for Wales.

Objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate the impact of the intervention on participant BMI 3 years post randomisation. Secondary objectives were to examine the effect of the intervention on waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, physical activity, diet, health-related quality of life, binge eating, psychological well-being and health resource use. Additionally, we planned to examine the proportion of participants maintaining their baseline weight and mediators and moderators associated with change (see Mediators and moderators). A process evaluation examined intervention delivery, participant and practitioner views, dropout, adherence and retention. A cost-effectiveness evaluation was also planned.

Participants

Participant Identification Centres selection

Participants were recruited from general practitioner (GP) practices, exercise referral schemes, a commercial weight loss programme (Slimming World) and the community. The aim was to recruit participants throughout South Wales, South West England and the East Midlands. A sample of research-active GP practices across four health boards in South Wales were approached to participate (approximately 15 practices per region in Cardiff and Vale, Cwm Taf, Aneurin Bevan and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards), with a view to recruiting 20–25 practices. All exercise referral and Slimming World schemes within these geographical areas, as well as within the boundaries of Derby City, Derby County and Nottingham Primary Care Trusts (PCTs), were identified and approached to act as Participant Identification Centres (PICs).

Identifying participants

Individuals were approached either face to face or via record searches from GP surgeries, exercise referral schemes and Slimming World, and provided with an information sheet and an expression of interest (EOI) form to return to the research team. Participants also self-referred from the community via poster and local media advertisements. Once an EOI form was received, two main routes for recruitment were employed.

-

Route 1: 5% weight loss achieved. Individuals able to provide independent verification of weight loss (e.g. from a referring practitioner) were invited to a baseline visit at which the researcher confirmed eligibility, provided further details about the study and took consent prior to completing assessments. Current and starting weight (i.e. pre-5% loss) were recorded on the EOI form by the referring practitioner or researcher. If it was not possible to verify weight loss, participants were referred to route 2.

-

Route 2: yet to achieve 5% weight loss. We contacted these individuals to either (1) attend a screening meeting with a researcher or (2) self-screen by providing documented evidence of starting weight and subsequent 5% loss (e.g. a printout from scales in their local chemist/supermarket, slimming club booklet, GP letter). At locally held screening appointments, participants were provided with a second information sheet outlining the screening procedure. They then consented to have their weight, height and contact details recorded and were asked to contact us once they had achieved the 5% target. If no contact was made after 2 months, potential participants were followed up by telephone at agreed time intervals. On reaching the 5% target, participants were invited to a baseline visit.

All participants referred by a GP/nurse, pharmacist, exercise referral professional or slimming club consultant were asked to confirm on the EOI form whether they had lost (route 1), or intended to lose (route 2), 5% body weight. Referring practitioners were asked to verify 5% weight loss for those approached during face-to-face consultations and who selected route 1. Participants approached by letter who returned an EOI form either sent verification directly to the research team or provided details as to how we could access verification, for example by contacting the referring practitioner. Participants approached by letter and unable to provide verification were recruited via route 2. Referring practitioners were asked to record how many patients were approached (face to face or via letter) as well as basic anonymised demographic data (age and gender).

Inclusion criteria

Adults aged 18–70 years with a current or previous BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 were eligible for inclusion if they had intentionally lost at least 5% body weight (by pharmacological, lifestyle and/or behavioural methods) during the previous 12 months and this weight loss had been independently verified.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were factors rendering potential participants unable to comply with the protocol, such as previous bariatric surgery (unless fully reversed, e.g. by removal of a gastric balloon), terminal illness, poor competence in English (i.e. inability to complete study materials), living with another study participant or, in the case of women, pregnancy (note: women who became pregnant after recruitment were not excluded, but given a leaflet on exercising safely during pregnancy).

Assessment of risk

Participants’ GPs were informed of their trial participation and sent a copy of the consent form. All initial contacts with participants were in public community venues. However, some face-to-face MI sessions and/or follow-up appointments were conducted in participants’ homes. Participants’ GPs were asked to contact the study team to give an assessment of the level of risk posed to individuals undertaking home visits and a study-specific lone worker policy was developed.

Withdrawal and loss to follow-up

Participants were free to withdraw at any time; however, consent to use data already collected was assumed unless otherwise notified. The following measures were taken to maximise retention:

-

The importance of obtaining follow-up data was emphasised to participants.

-

All assessments were conducted face to face (except at 6 months which was by post) and in locations convenient to participants.

-

Newsletters and birthday cards (including a change of address form) were sent to all participants.

-

Participants in the control group were offered £50 in high-street vouchers or free 12-week attendance at a local commercial weight loss programme at the end of follow-up to minimise unequal dropout.

-

Two reminders were sent to participants requesting that they return the postal questionnaire.

-

Follow-up appointments were rearranged for those who did not attend appointments.

-

Mobile telephone numbers were obtained in order to contact participants directly for follow-up.

-

Participants were asked for their GP’s address as an alternative contact.

-

Outcomes were carefully chosen to minimise respondent burden.

-

Key questionnaires were completed by telephone when possible for non-responders to ensure a minimum data set.

-

Although we did not offer travelling expenses, participants were offered vouchers for attending follow-up outcome assessments (£10 per time point on completion of assessment) and completing and returning the questionnaire at 6 months (£5 not conditional on completion).

Interventions

Intensive intervention arm

Participants received six one-to-one individually tailored MI sessions, delivered by experienced MIPs. These sessions were delivered face to face, approximately fortnightly for 3 months, and lasted about 60 minutes. During the final 9 months of the intervention, participants received monthly MI telephone calls lasting approximately 20 minutes.

Less intensive intervention arm

Participants received two face-to-face tailored MI sessions 2 weeks apart and two MI-based telephone calls at 6 and 12 months only. All other aspects of intervention delivery were as described for the intensive intervention arm (see Chapter 2).

Peer group sessions

Participants in both the intensive and the less intensive arms had the opportunity to attend four professional-led peer group support sessions which were planned to occur monthly lasting 1.5 hours for 4 months and following on from face-to-face MI sessions (see Chapter 2). Allocation to group sessions was on a rolling basis; participants did not necessarily attend sessions in the same order.

Control arm

The control group were given an information pack also sent to participants in both intervention arms. The content of the information pack was based on useful resources for weight loss and healthy lifestyle, and advice on WLM. Participants in all arms were able to access usual care, for example attending a slimming club.

Trial procedures

Adverse events and serious adverse events

No adverse effects or SAEs were expected as recommendations for physical activity were in line with current and widely publicised UK government guidelines. However, the possibility of cardiovascular/musculoskeletal events occurring related to increased physical activity was acknowledged in the protocol and the physical activity leaflet, and the main trial information sheet stated that any increase in physical activity should be gradual. Participants were advised to contact their GP if they felt unwell as a result of increased physical activity (e.g. experiencing severe breathlessness, chest pain, fainting or dizziness). Safety reporting procedures are outlined in Appendix 3.

Risk of harm

Motivational interviewing practitioners were asked to notify the study team directly if they became concerned that a participant had caused, or was likely to cause, significant harm to him- or herself. Provision was also made to inform participants’ GPs when appropriate. MIPs were asked to inform the appropriate authorities directly if concerned that a participant had caused, or was likely to cause, harm to others.

Training

All intervention staff (MIPs and GFs) were trained as per the appropriate manual (see Chapter 2). All staff undertaking randomisation and data collection visits were trained in study-specific procedures.

Outcomes

Primary and secondary outcomes

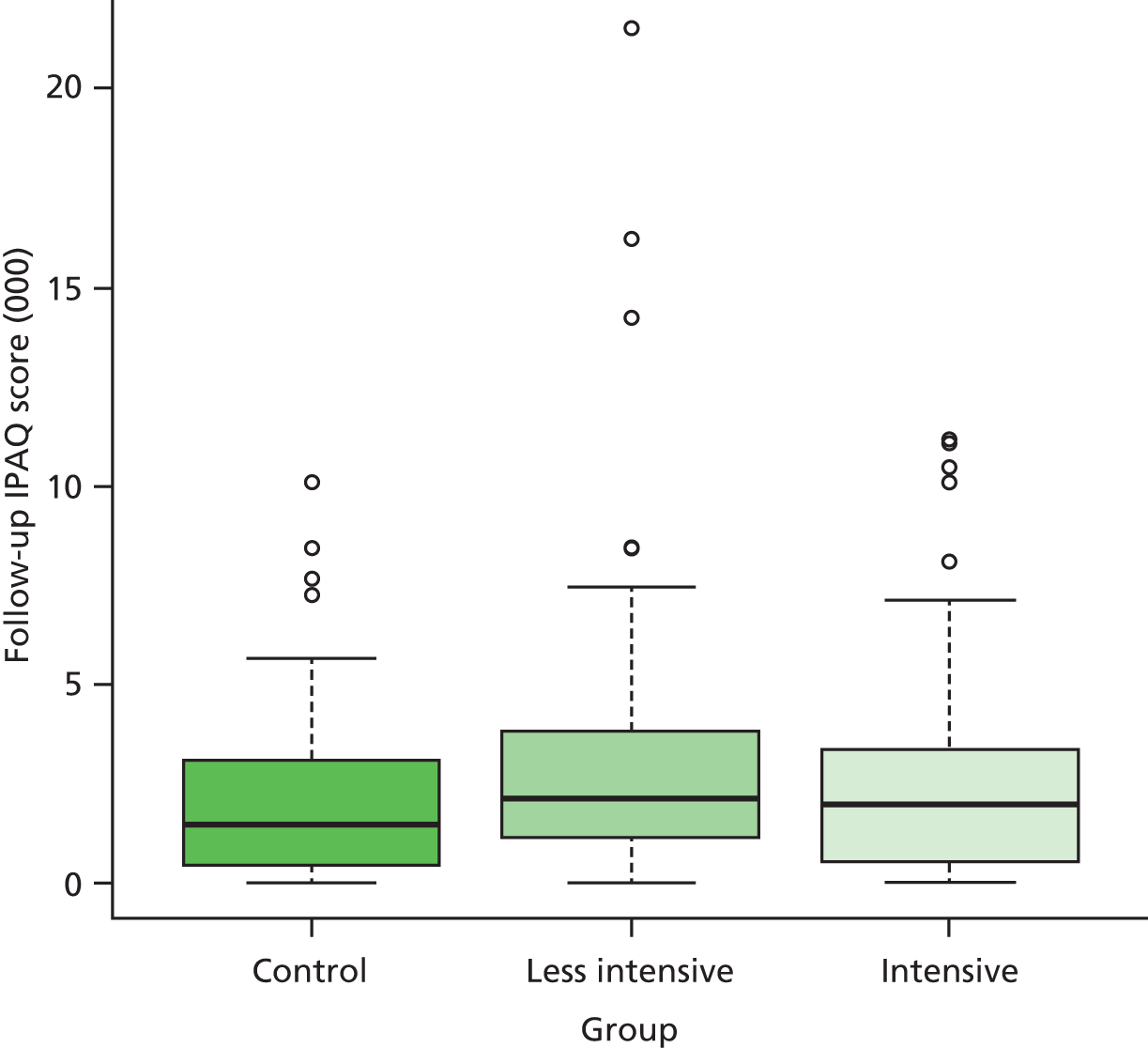

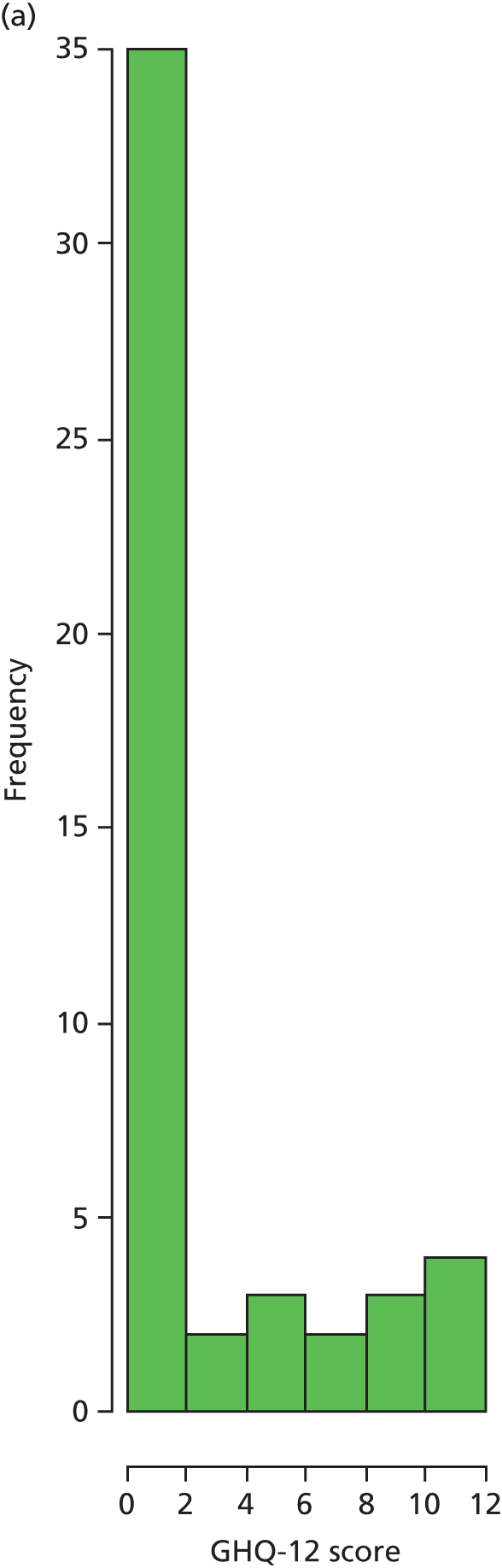

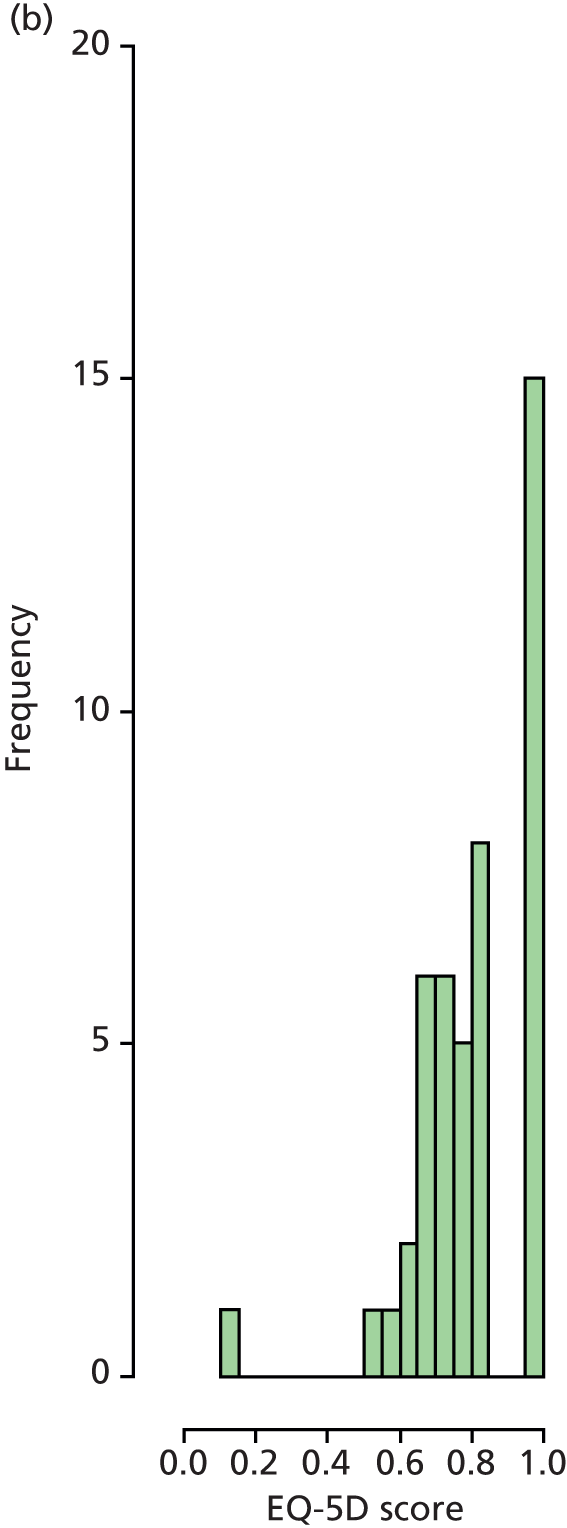

Outcome measures were self-reported with the exception of height, weight and waist and hip measurements, which were measured by the researcher at each visit. Outcome assessors were given video training in measuring weight, height, waist and hip circumference to ensure consistency. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Seca 213 stadiometer (Seca, CA, USA). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with calibrated Seca 877 weighing scales (Seca, CA, USA). Participants were weighed wearing a single layer of clothing (having removed shoes, belts, heavy items). Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the superior iliac crest and the lowest rib at the end of a normal expiration; hip circumference was measured at the maximal level of the maximal circumference around the buttocks with a Seca 201 measuring tape (Seca, CA, USA). A number of secondary outcomes were also assessed (Table 2): physical activity, diet, waist-to-hip ratio, health-related quality of life, health and other resource use, binge eating, psychological well-being, health-related behaviours and proportion maintaining weight loss. Maintenance of weight loss is defined as successful when the participant’s weight at the end of the trial is less than or equal to their weight at baseline. All outcomes were recorded on study-specific CRFs (see Appendix 4). For both height and hip measurements, the average across both time points was used. If a follow-up height or hip measurement was missing, then the baseline measurement alone was used.

| Outcome | Measure | Type | Time point | Modifications | Number of items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric measures | |||||

| BMI (weight, height) | Calibrated digital scales, stadiometer | Primary | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | N/A | – |

| Waist and hip circumferences | Tape | Secondary | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | N/A | – |

| Secondary outcomes/moderators | |||||

| Physical activity | IPAQ105 | Secondary | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | Wording change to reflect UK population (‘house and yard work’ changed to ‘housework and gardening’) | Seven |

| Diet | DINE106 | Secondary | Baseline, 12-month follow-up |

|

39 |

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D107 | Secondary | Baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up | None | Six |

| Proportion maintaining weight loss | Participants whose weight at 1 year is less than or equal to their weight at baseline were defined as maintainers | Secondary | 12-month follow-up | N/A | N/A |

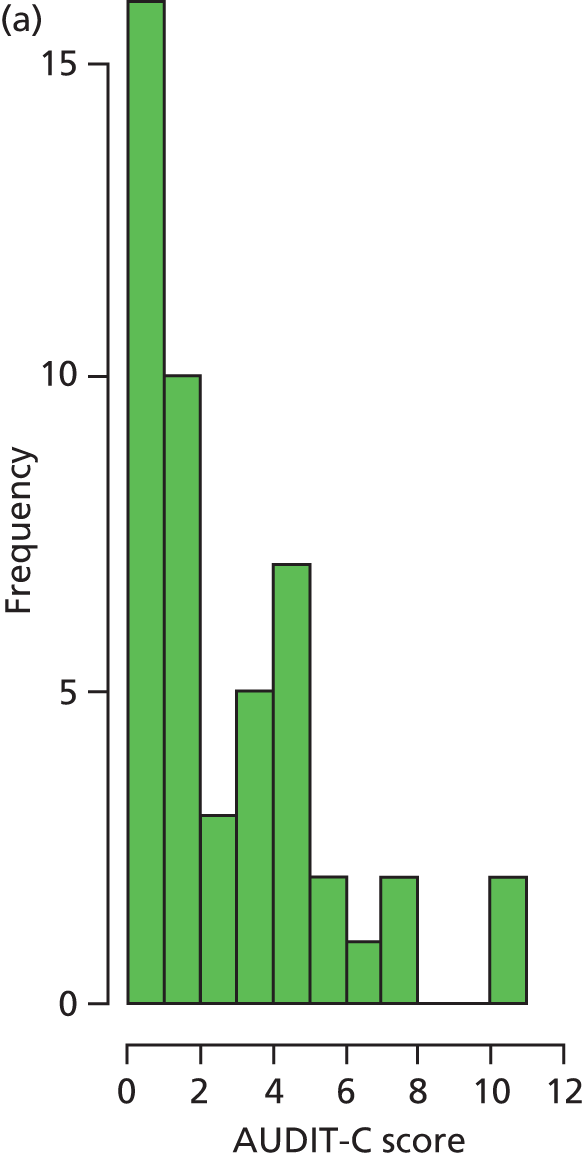

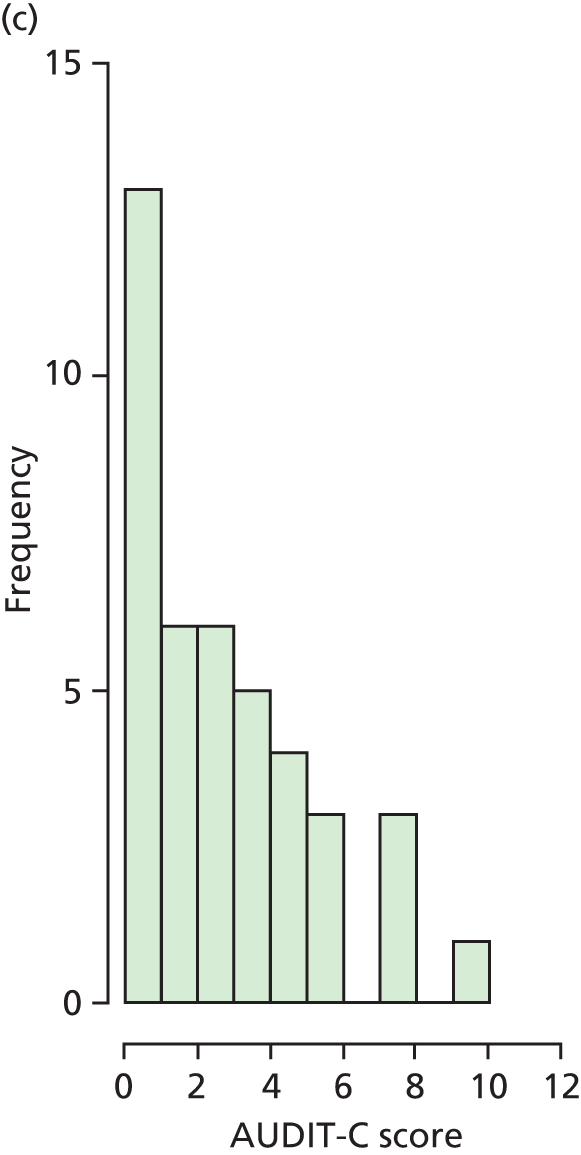

| Alcohol and smoking status | AUDIT-C108 and HSI109 | Secondary | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | None | Three per scale |

| Health and other resource usage | Medication, health service contacts, other weight control resources used | Secondary | Baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | 16 |

| Binge eating | EDE-Q110 | Secondary; moderator | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | None | Six |

| Psychological well-being | GHQ-12111 | Secondary; moderator | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | None | 12 |

| Demographics | Age, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, employment status | Moderators | Baseline | N/A | 10 |

| Mediators | |||||

| Social support | SSEH and SSEX112 | Mediator | Baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up | Eating: shortened from 10 items to three on two themes – encouragement (two items) and discouragement (one item) Exercise: shortened from 10 items to three on two themes – family and friend participation (one item) and family rewards and punishments (one reward item; one punishment) |

Six |

| Self-efficacy | WEL113 | Mediator | Baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up | None | 20 weight, 10 exercise |

| Intrinsic motivation | TSRQ diet and exercise114 | Mediator | Baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up | None | 15 diet, 15 exercise |

| Automaticity/habits | Self-reported habit index (diet and exercise)115 | Mediator | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | None | 12 diet, 12 exercise |

| Self-monitoring/regulation | SREG116 | Mediator | Baseline, 12-month follow-up | Subset of eight questions comprising positive and negative statements selected from full SREG | Eight |

| Implementation intentions | From MI records and interviews | Mediator | All sessions | N/A | – |

Mediators and moderators

We measured a number of potential mediators and moderators associated with change. Mediators included self-efficacy, social support, self-monitoring, implementation intentions, habit formation and intrinsic motivation. Moderators included demographics, weight loss history, satisfaction with weight loss, current weight loss goals, binge eating and psychological well-being.

Statistical methods

Sample size

To give 90% power at the 5% significance level to detect a difference in mean BMI of 1.7 units (SD 5.5 units) between the primary contrast of the intensive intervention and control, 221 participants per group would be required. This assumes a baseline mean BMI of 32.5 kg/m2 and a mean of 34.2 kg/m2 prior to 5% weight loss. Allowing for 30% attrition,20,27,55 a total of 950 participants would be required.

Randomisation

Allocation to groups was by remote telephone randomisation, stratified by region and minimised by age, gender, ethnicity, source of recruitment (GP, exercise referral, slimming club, community), percentage weight loss and current BMI. The service was provided by the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration randomisation service. This used a bespoke system written in the programming language C++.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind participants to arm allocation given the complex procedural and interactive nature of the intervention. Outcome assessors were also involved in recruitment and randomisation and were therefore not blind to allocation.

Main analysis

The planned main analysis was intention to treat comparing the three groups on average BMI using a three-level linear regression model to account for clustering within MIP and groups. The main analysis was intended to examine the longest end point. A secondary analysis was planned to examine the three groups using the interim time point as the end point, with baseline BMI and previous weight loss as covariates. Both intervention groups were to be compared with the control (reduced to a one-level model if no evidence of clustering is observed). Secondary outcomes were to be analysed using linear or logistic regression or Poisson as appropriate. The analyses of BMI and weight were repeated including the self-reported weights as a sensitivity analysis. There is evidence that single-item measures are more likely to be biased than multiquestion measures. 117 We do not feel that the results for the other questionnaires are likely to be biased.

Exploratory analyses were proposed to consider the impact of demographic factors, original weight loss method and theoretical moderators on the intervention effect, using interaction terms included in main analysis models. Exploratory longitudinal analyses were proposed to explore the effect of theoretical mediators on subsequent outcomes and interactions with intervention groups. These were to be conducted in a similar manner to the primary analyses, with outcomes predicted using a hierarchical model and controlling for baseline randomisation variables and in accordance with the 1986 Baron and Kenny guidelines. 118 This analysis was used to check the postulated logic model produced by the WILMA trial team. Individuals who failed to respond would be compared with those who completed follow-up to identify potential biases. The planned sensitivity analysis assumed that those non-responders would return to weight levels prior to weight loss (i.e. not baseline, but previous BMI). A last observation carried forward assumption would not be conservative for WLM and so was not used. Self-report weight was added to objectively assessed weight to account for some loss to follow-up. A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was proposed, using multilevel mixture analysis119 to focus on estimating intervention effects in the presence of non-compliance.

Subgroup and interim analysis

Primary subgroup analyses were proposed to investigate associations between WLM and age, gender, method of weight loss and weight at entry. Exploratory subgroup analyses were planned to investigate associations between WLM and smokers, binge eaters, weight-affecting medications and ethnicity.

Process evaluation

We conducted a process evaluation, the aims of which were to:

-

assess delivery of the intervention to ensure it was provided in accordance with the protocol and delivered consistently

-

establish the level of participant adherence to the intervention

-

explore participants’ views of, and satisfaction with, the intervention

-

explore MIPs’ and GFs’ experiences of delivering the intervention

-

test the logic model.

Intervention delivery

Motivational interviewing practitioners were asked to audio-record as many sessions (face to face and telephone) as possible, with a view to collecting a minimum sample of six sessions per MIP over the course of the study. A random sample of recordings from face-to-face sessions was assessed using the motivational interviewing treatment integrity (MITI) coding scale. 120 A stratified sample included sessions delivered in both intervention arms and by all MIPs. Skill in MI delivery was assessed prior to study entry (via audio-recorded mock consultations with trained actors). In order to be recruited as a practitioner, individuals were required to reach the MITI proficiency threshold (see Chapter 6). We planned to observe group sessions to assess fidelity of intervention delivery.

Participant adherence

Data on intervention delivery and exposure to the intervention were examined. Overall attendance at intervention sessions and success of telephone contact were monitored (number of contact attempts and length of calls was recorded). MI CRFs from face-to-face and telephone sessions were examined for evidence of self-regulation, goal-setting and implementation intentions and analysed descriptively. Participant self-regulation was examined by the frequency of self-weighing records/reports of self-weighing.

Participants’ views of the intervention

Semistructured telephone interviews were carried out with participants in all arms, during the intervention (at approximately 6 months) and following the end of the intervention period (see Chapter 8). Participants were purposively sampled across key factors including trial arm, gender, age, recruitment route and attendance levels. In addition to assessing general views around intervention delivery, views on efficacy, barriers and facilitators, we also examined potential mediators not examined elsewhere such as the impact of life events on adherence; environmental influences; levels and importance of social support from family and friends as well as the professional support provided as part of the intervention; impact on their wider social network; WLM challenges; intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for WLM; health value; body image; and strategies, coping mechanisms and responses to relapses (see Appendix 5). In addition, we planned to interview a small sample of participants who dropped out of the intervention to establish their reasons for discontinuing. Interviews continued until themes were saturated. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and checked by the researcher.

Intervention staff’s views of the intervention

All MIPs, apart from one who took part in an interview, contributed to two focus groups designed to enable us to elicit their views of the intervention, the perceived challenges or barriers in implementing it and how they thought the intervention and training could be improved. Separate focus groups with GFs were also planned. The MIP focus groups and interview took place following recruitment closure. At this point the majority of MIPs had completed their face-to-face sessions and were mid-way through their telephone sessions. A focus group guide was developed to explore the MIPs’ experiences. This comprised 18 items and spanned four main topics (see Appendix 6). Up to three members of the research team were present during the focus groups, one of whom facilitated the session, and the interview was conducted by one member of the research team. The focus groups lasted around 2 hours, while the interview lasted 1 hour.

Qualitative analysis

All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Transcripts were checked and uploaded into QSR International NVivo10 software version 10 (QSR International, VIC, Australia) and analysed using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a systematic approach in which the data are initially coded and then collated into themes. 121 Themes are then analysed in more detail to map out the overall data and examine relationships between them. Finally, themes are refined to produce an overall story of participants’ views and experiences. 121,122 As outlined by Braun and Clark121 thematic analysis consists of five defining phases: (1) familiarisation, (2) initial coding, (3) creation of themes, (4) reviewing themes and (5) defining and naming themes. Our analysis followed each of these phases and is described in relation to these below. Data collection and analysis of interview data were conducted simultaneously and the analyses informed data collection in terms of changes to the interview schedule, for example adding new questions to probe particular areas of interest. Data collection continued until data saturation was reached. Analysis of the focus group data was conducted after data collection, but followed the same process.

Phase 1: familiarisation

During the familiarisation phase, a coding scheme was devised by the team to inform the coding procedures. Separate schemes were developed for the participant interview and MIP focus group (plus one interview) analysis, as they had differing aims and different questions were asked accordingly. Therefore, it was not appropriate to analyse all data across a common coding scheme. The coding schemes were developed by initially reading and rereading a few of the early transcripts. Codes were mapped out by three researchers (for the participant analysis: SS, YM and CS; for the MIP analysis: SS, YM and LC) during two face-to-face meetings (following independent coding of two interviews/focus groups) and these initial codes were pulled together into a coding scheme. Following development of the initial coding scheme, it was then applied to other interviews/focus groups independently by two coders. Each of the schemes was then further refined as new codes emerged from the data during the initial coding procedure.

Phase 2: initial coding

Following the coding scheme development, the initial coding of participant interviews was completed by CS and YM, while the focus group coding was completed by YM and LC. Transcripts were closely examined and indexed according to the coding scheme. During the coding phase, the coders had regular discussions concerning any new codes identified and sought common agreement on any further amendments needed to the scheme. This ensured consistency between coders. An analysis log was kept to record coders’ discussions and track any changes made to the coding scheme as well as to record further thoughts and developments of the analysis process. A total of 10% of the interview transcripts were double coded to ensure reliability of the coding scheme and any discrepancies discussed and resolved. Both MIP focus groups and interviews were read and reread by YM and LC in preparation for the scheme development and were therefore not double coded.

Phase 3: searching for themes

Once all transcripts were coded, codes were examined in detail and broken down further into subcodes where appropriate. Moreover, some extracts were recoded where necessary. This phase was both data driven (i.e. bottom up) and theory driven as we sought to answer specific process evaluation questions and look at mediators not measured elsewhere. Commonly expressed themes, as well as unusual cases, were identified. Relationships between codes were explored by carrying out queries to identify text common to two (or more) related codes. This analysis led to the development of overarching themes.

Phase 4: reviewing themes

The themes developed in the previous phase were reviewed by the coders, who remained in close contact to further discuss and develop their thoughts. During this phase, coders referred to the key questions identified in the process evaluation model to support the final analysis. The initial codes were examined for any instances that were inconsistent with the emerging themes. The themes were further examined across groups (arm/gender/age) to explore their differences and similarities. A thematic map was developed for both the participant interview and practitioner focus group analysis to further inform this phase.

Phase 5: defining and naming themes

During the final phase, coders examined themes in detail ensuring they accurately represented the data and captured the overall story. Themes were mapped out in order to explore broader links and relationships within the overall data and analysis. As themes were explored, a detailed narrative was written for each, which provided the structure for the final reporting of results. The qualitative findings then fed into the overall process evaluation.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

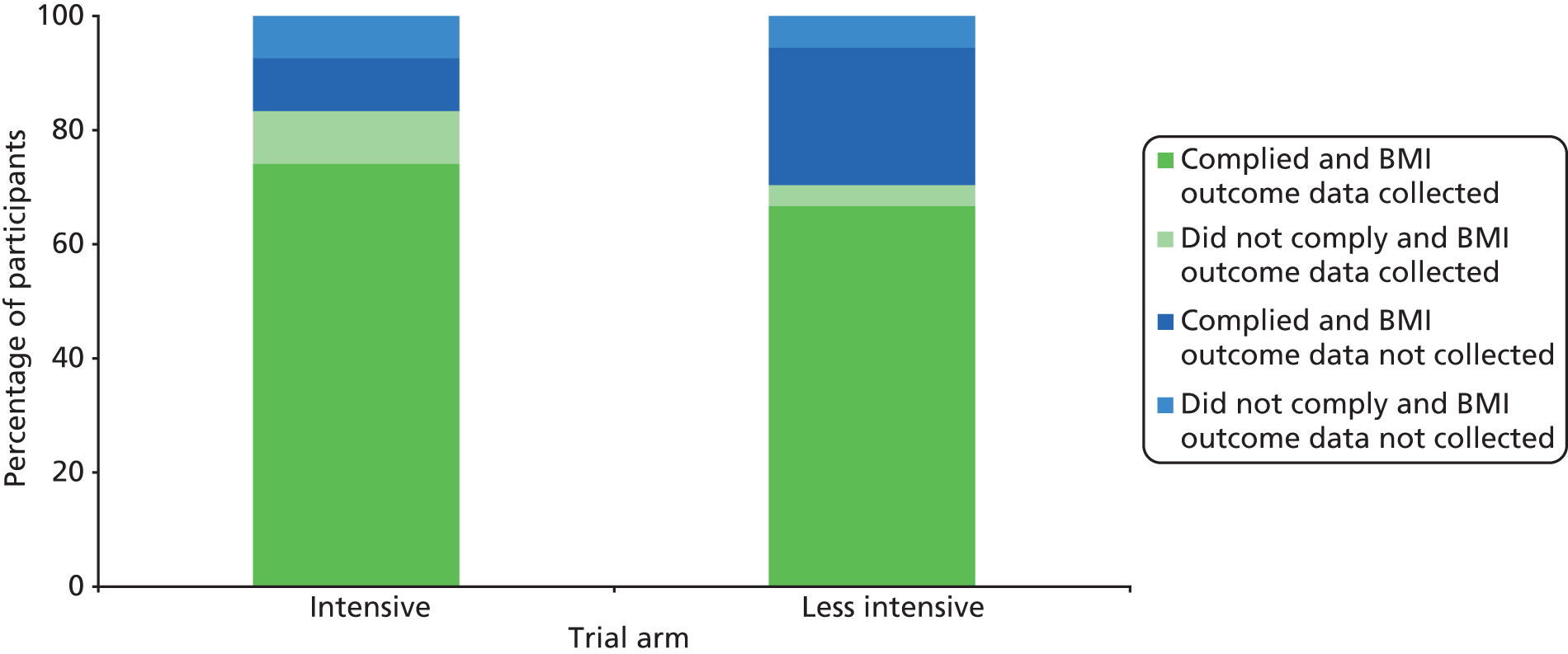

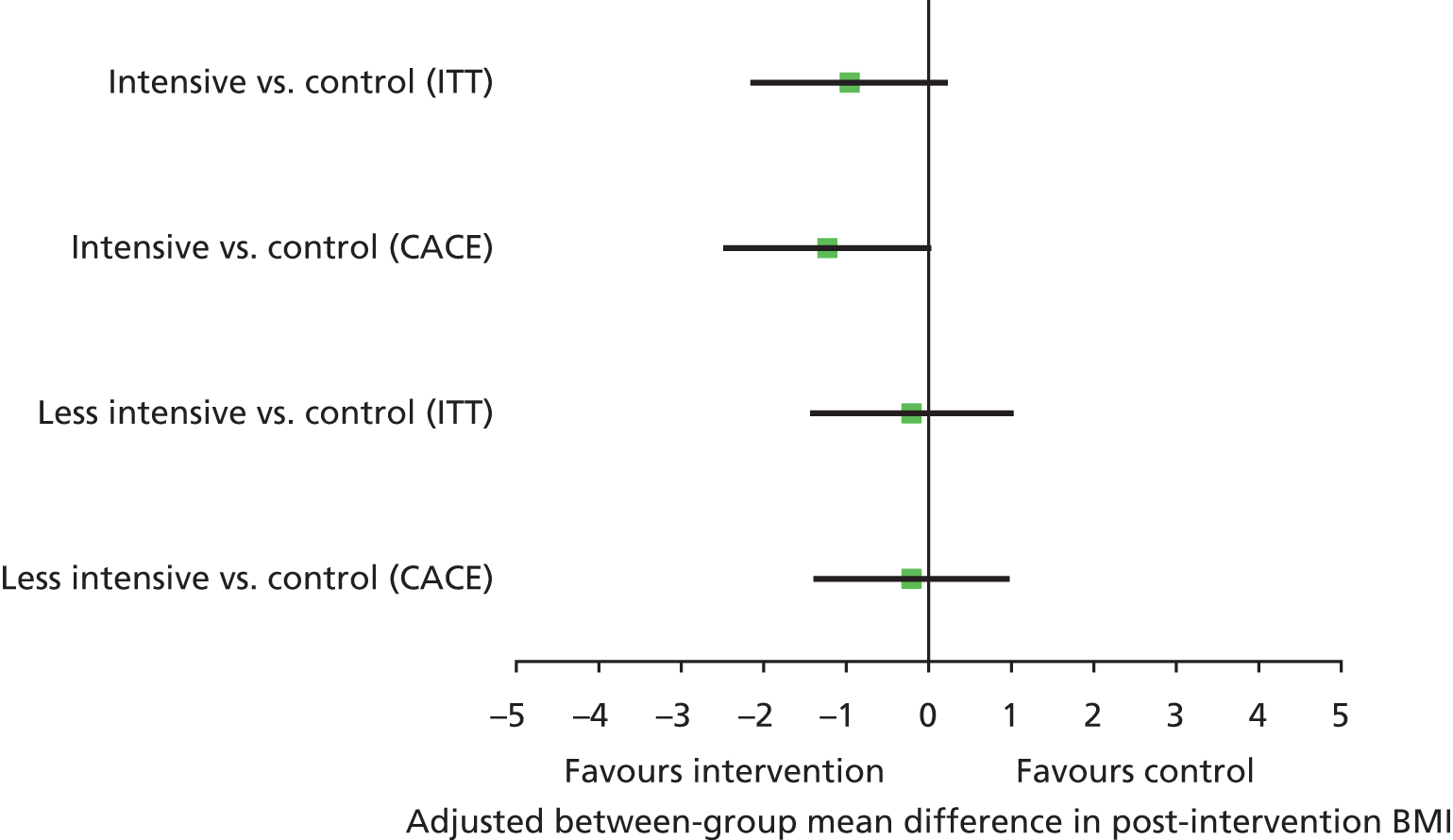

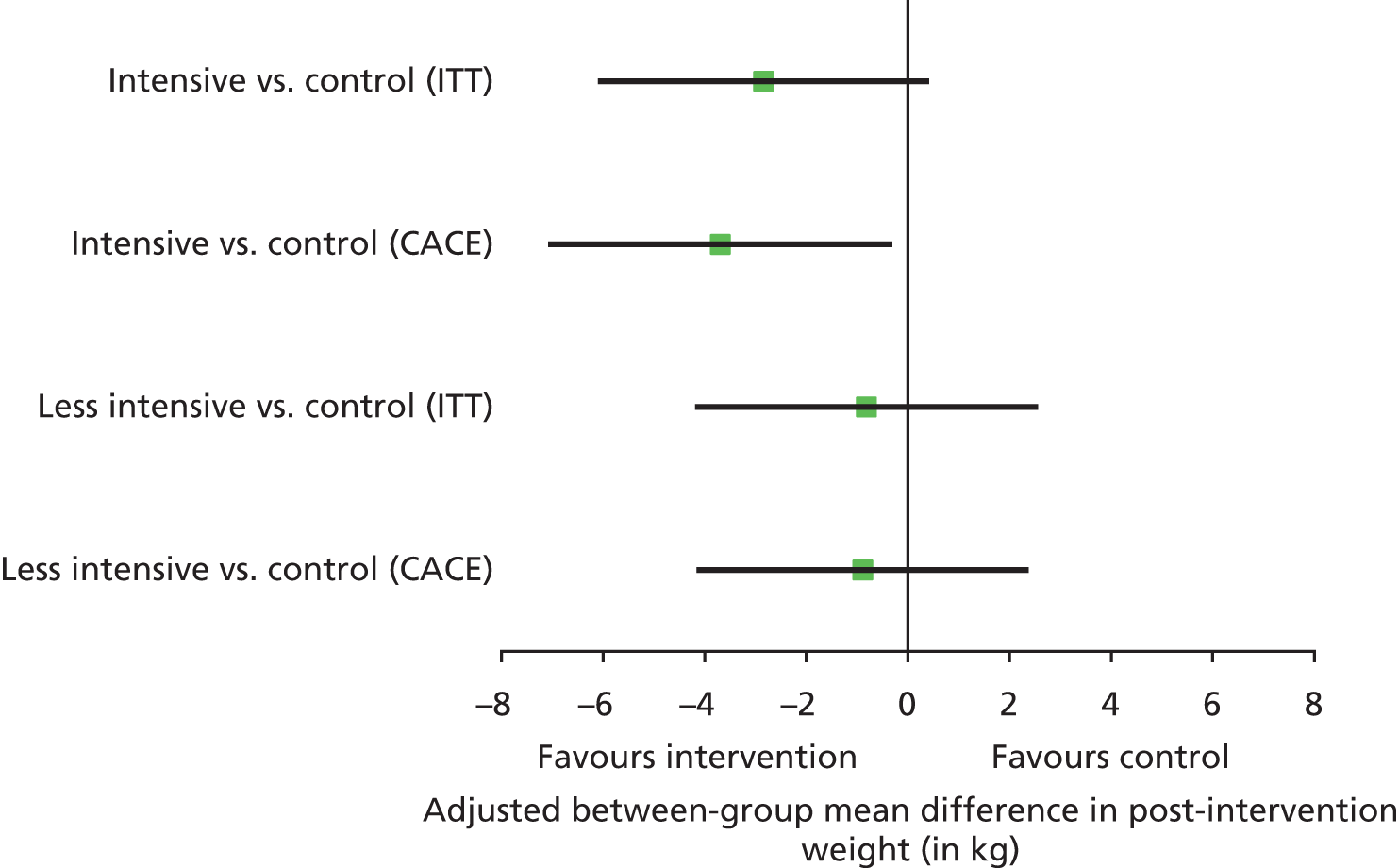

The original intention was to undertake (1) a within-trial cost–utility analysis assessing between-group differences over 3 years in total costs against differences in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) [derived from European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) quality-of-life data], (2) a lifetime cost–utility analysis using an economic Markov model and (3) a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) assessing between-group differences in total costs against differences in BMI at 3 years. All analyses were from a NHS perspective. In pursuit of this, all direct intervention costs were recorded prospectively in relevant units and valued using standard methods. 21 These included all resources used in intervention delivery (staff time, staff travel, materials, venues). All resources used in training professionals in MI skills were similarly prospectively recorded and valued. As training is a one-off investment producing a flow of benefits over time, training costs would be amortised similarly to equipment expenditures and expressed on an equivalent annual cost basis. Indirect costs would include differential use of health service resources from recruitment to end of follow-up.