Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/71/01. The contractual start date was in August 2013. The draft report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in March 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Royle et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The commissioning brief notes that diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the major cause of sight loss in the working age population in the UK, and that people with diabetes are 25 times more likely than the general population to go blind. Pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) by laser treatment is the standard intervention for patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), and it has been shown to reduce the risk of severe vision loss by 50%.

In some areas, such as Newcastle District, diabetes may no longer be the leading cause of blindness in the population of working age, because of the success of the screening and treatment programmes. 1 A review by Wong et al. (2009)2 concluded that rates of progression to PDR have fallen over recent times because of earlier identification and treatment of retinopathy, and improved control of blood glucose and blood pressure (BP). This is supported by a recent paper from Wisconsin. 3

Nevertheless, DR remains common. A Liverpool study by Younis et al. (2003)4 reported prevalences of any DR and PDR to be 46% and 4%, respectively in type 1 diabetes, and 25% and 0.5% in type 2 diabetes, although the prevalence will vary with mean duration of diabetes, with higher proportions of those with longer duration having DR. Conversely, an increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes would reduce the overall proportion with DR because more people with short duration would be entering the pool.

Introduction to diabetic retinopathy

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) guidelines define DR as:5

Diabetic retinopathy is a chronic progressive, potentially sight-threatening disease of the retinal microvasculature associated with the prolonged hyperglycaemia and other conditions linked to diabetes mellitus such as hypertension.

And continues:

Diabetic retinopathy is a potentially blinding disease in which the threat to sight comes through two main routes: growth of new vessels leading to intraocular haemorrhage and possible retinal detachment with profound global sight loss, and localised damage to the macula/fovea of the eye with loss of central visual acuity.

Reproduced with permission from The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guidelines for Diabetic Retinopathy. 2012. URL: www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=451§ionTitle=Clinical+Guidelines (accessed 24 September 2013). 5

Diabetic retinopathy is due to damage to the retina, particularly to its blood vessels, caused by raised blood glucose levels. The earliest changes tend to affect the capillaries, starting with dilatation.

The next stage is closure of some capillaries leading to loss of blood flow (non-perfusion) to part of the retina. If large areas of the retina are deprived of their blood supply they may be seen as paler areas. Smaller areas of ischaemia may be detected only by fluorescein angiography (FA). In this investigation, a dye is injected into a vein and passes through the blood vessels which can then be seen, thereby revealing areas without blood flow.

Non-perfusion due to capillary occlusions is the most important feature of DR, as it leads to other changes.

Capillary closure is associated with two other features: cotton wool spots and blot haemorrhages.

Cotton wool spots are so called because they appear as greyish white patches in the retina instead of the usual red colour. They are areas where blood flow has ceased. There are usually only a few, but if many (more than 6–10 in one eye) develop, it may be a sign of rapidly developing serious retinopathy.

Haemorrhages come in different sizes and shapes, referred to as ‘dot and blot’. Multiple large haemorrhages are a bad sign and indicate large areas of non-perfusion. They may herald proliferative retinopathy.

Microaneurysms appear as small red dots in the retina. These are due to dilated capillaries. Small ones may not be visible with the ophthalmoscope but are revealed by FA. With ophthalmoscopy, it may not be possible to distinguish microaneurysms from small haemorrhages.

Damage to arteries also occurs, with thickening of the walls of the artery and narrowing of the lumen, and sometimes blockage (occlusion) of the artery, thereby reducing blood flow to parts of the retina.

There are also changes in the retinal veins, such as dilatation, and sometimes looping. Loops are usually related to areas of capillary non-perfusion. Venous beading can occur and is one of the signs of severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). The walls of the veins may be thickened. Retinal vein thrombosis may follow – this is known as retinal vein occlusion.

Abnormal new retinal blood vessels may develop and are the most serious manifestation of DR. This is called ‘neovascularisation’. Because these vessels are new, their presence is referred to as indicating ‘proliferative’ retinopathy. The new abnormal vessels are fragile and are more liable to bleed, causing haemorrhages. If they bleed into the vitreous, a gel-like structure that fills the eye, the result is called vitreous haemorrhage. They may also lead to the formation of fibrous scar tissue that can put traction on the retina, leading to tractional retinal detachments. Rarely, they may regress spontaneously.

Exudates are yellowish white patches, initially small specks but may later form larger plaques. They are usually near the macula, the most sensitive part of the eye, and are associated with areas of oedema. They contain lipid deposits.

Retinopathy takes years to develop. It is not seen at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. If seen at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, it is an indication that the patient had undiagnosed diabetes for years.

Retinopathy may go through several stages. The first stage is called non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), previously known as background DR. It is very common and most people with long-standing diabetes will have it. The features include microaneurysms, haemorrhages, hard exudates and occasional cotton wool spots. Progression is variable and the changes may regress. The prognosis for mild NPDR is good, but some patients will progress to the more serious forms of NPDR, macular oedema (MO) (maculopathy) and proliferative retinopathy. The presence of multiple cotton wool spots and widespread retinal haemorrhages may indicate that proliferative retinopathy is developing. Large blot haemorrhages are usually followed by new vessels within a few months.

Maculopathy refers to visual loss due to MO (fluid leaking out of blood vessels into the macula, making it swell). It can occur in the absence of proliferative retinopathy, especially in type 2 diabetes. Maculopathy can lead to gradual visual deterioration from increasing oedema, although it can also resolve spontaneously.

About half of the people with proliferative retinopathy also have MO, but it can occur at earlier stages without PDR.

For a useful description, see www.nei.nih.gov/health/diabetic/retinopathy.asp.

Classification of diabetic retinopathy

Classification and severity grading of DR have historically been based on ophthalmoscopically visible signs of increasing severity, ranked into a stepwise scale from no retinopathy through various stages of non-proliferative or pre-proliferative disease to advanced proliferative disease.

Two different approaches to classification have emerged: (1) those used in ophthalmology, covering the full range of retinopathy, based on the Airlie House/Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) classification and (2) those used in population screening.

There are various methods of classifying DR. As one protocol referee noted, no grading system is ideal for all purposes. Older studies used the ETDRS modification of the Airlie House classification and this is said to be the gold standard for classifying DR. 6

The commissioning brief refers to R2, which comes from the classification used by the English National Diabetic Retinal Screening Programme:7

-

R0 No retinopathy.

-

R1 Background – microaneurysms, retinal haemorrhages, with/without any exudate. This is broadly equivalent to the ETDRS mild NPDR stage.

-

R2 Pre-proliferative – multiple blot haemorrhages, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs). Moderate NPDR, referable to Ophthalmology.

-

R3 PDR.

The Scottish Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Service classification is shown in Table 1, and is slightly more detailed. 8

| Stage | Description | Action required |

|---|---|---|

| Retinopathy | ||

| R0 | No retinopathy anywhere | Routine rescreening at 12 months |

| R1 | Mild background retinopathy | Rescreen at 12 months |

| R2 | Background retinopathy requiring monitoring for progression | Rescreen at 6 months |

| R3 | Background retinopathy sufficient to require referral | Refer to Ophthalmology, probably for surveillance rather than laser treatment |

| R4 | Proliferative retinopathy | Refer to Ophthalmology, probably for laser treatment |

| Maculopathy | ||

| M0 | No features predictive of maculopathy | Rescreen 12 months |

| M1 | Any hard exudates within one to two DDs of the centre of the macula | Rescreen in 6 months |

| M2 | Any hard exudates or blot haemorrhages within one disc radius of the centre of the macula | Refer to Ophthalmology, probably for surveillance rather than laser treatment |

One problem with these classifications is that, for our purposes, the key category (R2 England or R3 Scotland), is too broad, as we are interested in the groups with severe NPDR or very severe NPDR. Another problem is that the term ‘pre-proliferative’ is sometimes used as synonymous with non-proliferative, but this usage implies that all NPDR progress to PDR, which is not the case.

There are problems with published studies because some authors talk simply of ‘moderate’ or ‘mild’ DR and do not provide sufficient data to determine the more detailed grading – as used by ETDRS. In this review, when studies have not used an accepted classification such as ETDRS, we have tried to extract enough details to allocate patients or studies to a classification as below, so that results can be expressed in terms of defined risk and features.

-

Mild to moderate NPDR:

-

intraretinal haemorrhage in fewer than four quadrants

-

microaneurysms

-

hard exudation

-

MO

-

abnormalities in the foveal avascular zone

-

-

moderate to severe NPDR:

-

mild/moderate intraretinal haemorrhage in four quadrants

-

cotton wool spots

-

venous beading

-

IRMAs

-

-

severe NPDR (4–2–1 rule) (one of the following):

-

severe intraretinal haemorrhage in four quadrants

-

venous beading in two quadrants

-

IRMA in one quadrant

-

-

very severe NPDR (two of the above)

-

proliferative diabetic retinopathy with or without high-risk characteristics (HRCs) (any three of the following):

-

presence of neovessels

-

location of the neovessels (at the optic nerve)

-

size of the neovessels: if at the optic nerve [neovascularisation of the disc (NVD)] ≥ ¼–⅓ disc area if elsewhere in the retina [neovascularisation of the retina elsewhere (outside the disc) (NVE) ≥ ½ of the disc area (if both NVD and NVE present, classified based on neovessels at the disc)

-

presence of pre-retinal haemorrhage or vitreous haemorrhage.

-

About half of patients with severe or very severe NPDR will progress to PDR within a year.

The descriptions used in the ETDRS9 are attached as Appendix 1.

Treatment of diabetic retinopathy

Laser treatment is not usually administered to people with NPDR. However, the commissioning brief from the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme poses the question whether:

intervention with pan-retinal laser treatment earlier in the disease, during the pre-proliferative stage (Level R2), may be more beneficial in terms of preventing loss of vision, given the detrimental and potentially irreversible effects of PDR if treatment is not obtained or is delayed.

Pan-retinal photocoagulation is sometimes referred to as scatter photocoagulation.

In considering treatment for retinopathy, three issues need to be considered:

-

The risk of visual loss without treatment.

-

The risk of visual loss with treatment.

-

The adverse effects of treatment. Laser treatment is a destructive process that can cause loss of peripheral vision in order to preserve the more important central vision.

Laser photocoagulation has been of great benefit to many people with PDR but in most cases has been better for preserving vision than restoring it, though it can improve vision, for example in eyes that have vitreous haemorrhages.

Two key studies of PRP were published in the 1980s: the ETDRS9 and the Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS). 10 The ETDRS9 recruited people with NPDR and people with PDR but without HRCs, and one aim was to determine when PRP should be used. In the EDTRS,9 laser treatment reduced the risk of moderate visual loss (a loss of three ETDRS lines) by 50%, but visual acuity (VA) improved in only 3% of patients. These studies9,10 are described in Chapter 2.

Laser has adverse side effects. Foveal burns, visual field defects, retinal fibrosis and laser scars have been reported. Ability to drive can be affected. Hence laser treatment is not undertaken lightly, and to extend it to people with NPDR would require careful consideration.

Treatment of DR has been based largely on the results of the ETDRS9 and DRS. 10 A small non-randomised study reported that laser treatment in people with type 1 diabetes at the severe NPDR stage reduced visual loss, compared with waiting to treat at the PDR stage, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. 11 A Swedish study by Stenkula (using xenon arc photocoagulation) also reported benefit from treating severe NPDR in a trial of PRP with one eye randomised to treatment. 12

One consideration is that if PDR is being detected earlier and treated more effectively than at the time of the landmark trials, notably ETDRS9 in the early 1980s, then any marginal benefit of treating at the NPDR stage may now be less.

We are aware that PRP is usually used when people reach the proliferative stage, but also that there is some variation in how it is applied. Some ophthalmologists may start with sparse very scattered PRP, with further lasering if the retinopathy progresses. Others may start with full mid-peripheral PRP. A third approach might be to laser only areas of mid-peripheral ischaemia as seen on FA.

It may be used when patients have high-risk features, such as new vessels, or earlier, at severe NPDR stage. There are also different stages of PDR, with some patients being classified as ‘high-risk PDR’ (HR-PDR), and one protocol referee argued that laser was mainly of benefit in PDR with high-risk characteristics (HRC-PDR) and not all PDR.

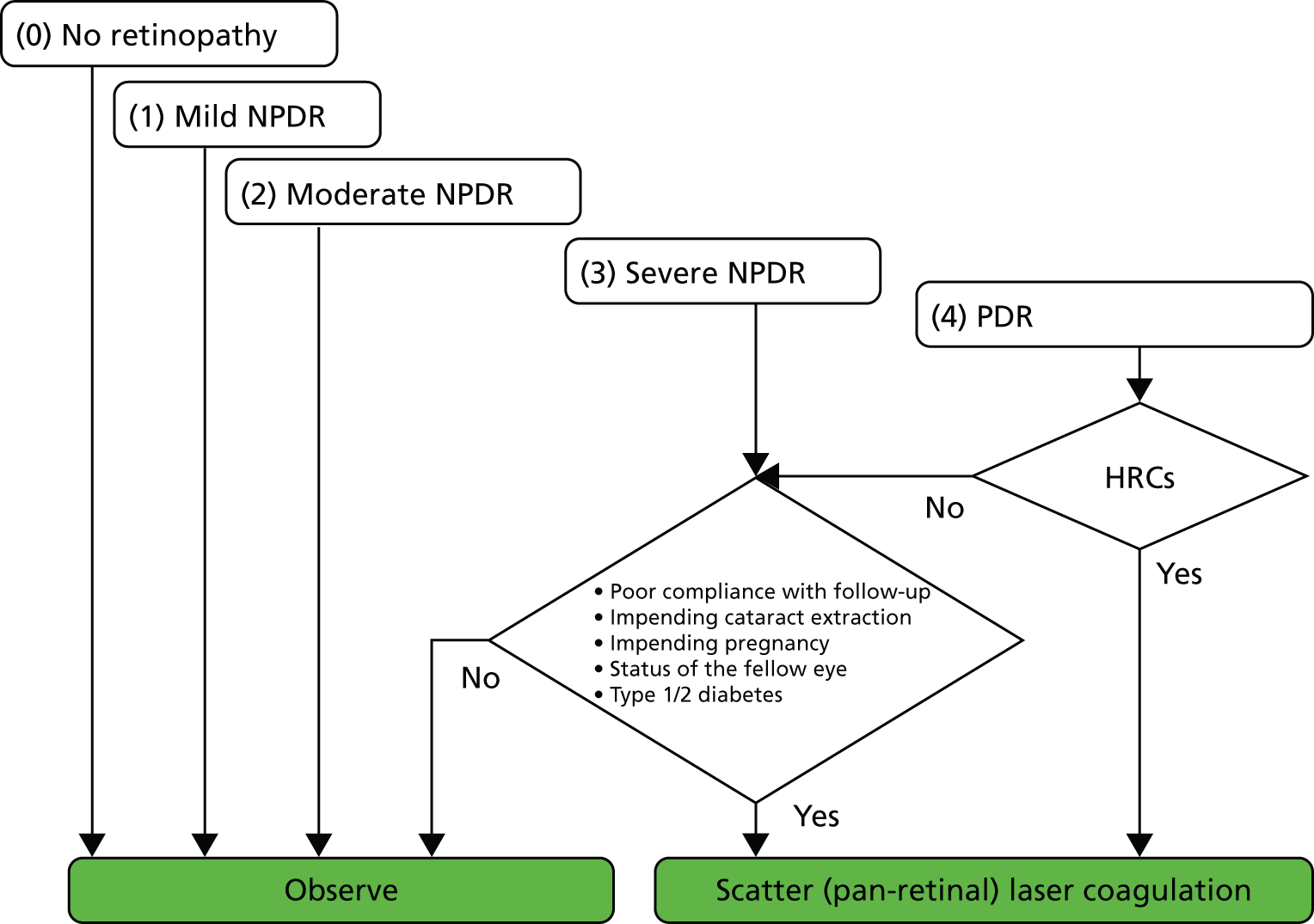

Figure 1 (reproduced with permission) from a review by Neubauer and Ulbig (2007)13 outlines current practice. Since the landmark studies DRS10 and ETDRS,9 new laser devices have been introduced.

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for pan-retinal scatter coagulation of the retina. Reproduced from Neubauer and Ulbig13 with permission from S. Karger AG, Basel.

Argon and krypton lasers use ionised gas as the lasing medium, while the tunable dye laser uses a liquid solution. Neodynium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) and diode lasers are both solid-state lasers that utilise crystals and semiconductors, respectively. The solid-state lasers are becoming the preferred option owing to their portability and ability to deliver laser in continuous and pulse mode.

Most people now use the pattern scan (PSC) or multi-spot lasers, rather than the argon laser, because they are faster and less painful. Some centres still use argon. With the traditional single-spot laser, treatment of large areas of the retina is time-consuming, can be uncomfortable for patients because of the length of time required, and there is a risk that, if the patient moves, laser may be mis-directed. With the pattern lasers, a number of spots can be applied simultaneously with one press of the foot pedal. In theory, this could be up to 56 with the PAtterned SCAnner Laser (PASCAL) system (developed by OptiMedica Corp, Santa Clara, CA, but now marketed by Topcon Corporation – Topcon UK, Newbury, Berkshire) but in practice smaller numbers are often used.

Other multi-spot lasers include the Valon TT (Valon Lasers, Vantaa, Finland), the Array LaserLink (Lumenis, Yokneam, Israel), the Navilas (OD-OS GmbH, Teltow, Germany) and the Quantel Supraspot (Quantel Medical, Cedex, France). However, most studies published used the PASCAL system. 14

The multi-spot system is much more comfortable for patients, and may reduce the number of sessions required.

The sub-threshold diode laser has been introduced though mainly for diabetic macular oedema (DMO)15,16 but has not spread much into use in PDR, possibly because for PRP it requires more sessions and more burns. It allows very short [millisecond (ms)] pulses of laser, shorter than conventional laser, sometimes called ‘micro-pulsed’. The sub-threshold refers to the visibility of burn spots. Photocoagulation is started with very low parameters, increased till a laser spot is seen, after which the power is reduced until the spot is just not seen – sub-threshold – and then the whole treatment is done at that level. But it is important to note that this is for treating the macula where the power used is much lower than that used in PRP.

We also note that in Japan a more selective approach to laser therapy is used, with targeting based on FA, so that only ischaemic areas are lasered. 17 This is a more restrictive approach than traditional PRP. Hence this review will need to classify methods of laser treatment.

Guidelines

Current guidelines from the RCOphth5 state that:

Mild and moderate DR does not require treatment, but patients should be monitored annually and advised to maintain as good diabetes control as possible.

Severe NPDR requires closer monitoring, usually every 6 months, in ophthalmology clinics, by clinical examination and digital photography. The aim is to detect progression to PDR.

In patients with very severe NPDR, PRP is considered in order to reduce progression in the following groups:

in older patients with type 2 diabetes

where monitoring of DR is difficult because of poor attendance or obscured retinal view

before cataract surgery, because that may be associated with progression

if vision has been lost in the other eye.

Reproduced with permission from The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guidelines for Diabetic Retinopathy. 2012. URL: www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=451§ionTitle=Clinical+Guidelines (accessed 24 September 2013). 5

In patients with PDR, urgent PRP is recommended.

The guidelines note that some ophthalmologists treat at NPDR stages:

10.3.1 Earlier treatment: Recognition that earlier laser prevents progression to high risk retinopathy, and that PDR has higher risk of blindness was reported in both DRS and ETDRS (LEVEL 1). However the balance of risks with laser modalities available at that time meant that laser intervention was recommended only when retinopathy approached high risk PDR. With modern laser techniques, PRP is often done before the development of PDR.

The RCOphth include, in the guidelines, a useful table (Table 2) comparing the different classifications.

| ETDRS | NSC | SDRGS | AAO International | RCOphth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 none | R0 none | R0 none | No apparent retinopathy | None |

| 20 microaneurysms only | R1 background | R1 mild background | Mild NPDR | Low risk |

| 35 mild NPDR | Moderate NPDR | |||

| 43 moderate NPDR | R2 pre-proliferative | R2 moderate BDR | High risk | |

| 47 moderately severe NPDR | ||||

| 53A–D severe NPDR | R3 severe BDR | Severe NPDR | ||

| 61 mild PDR | R3 proliferative | R4 PDR | PDR | PDR |

| 65 moderate PDR | ||||

| 71, 75 HR-PDR | ||||

| 81, 85 advanced PDR |

The SIGN diabetes guideline18 recommends that ‘Patients with severe or very severe NPDR should receive close follow-up or laser photocoagulation’.

Neither the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) diabetes guideline on type 1 diabetes19 nor on type 2 diabetes20 covers laser therapy.

Other treatment options

Control of blood glucose and blood pressure

Good control of blood glucose [aiming at glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) no greater than 7% (53 mmol/mol)], BP (aiming at 130/80 mmHg) and blood triglycerides reduces the risk of retinopathy, though in those who have some retinopathy and poor glycaemic control, too rapid restoration of good control may worsen retinopathy, usually temporarily.

Intravitreal drugs

In recent years, two groups of drugs for intravitreal use have become available. These are:

-

Steroids, including triamcinolone, the long-acting dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) and the longer-acting fluocinolone implant (Iluvien, Alimera).

-

The ‘anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)’ drugs, bevacizumab, pegaptanib, ranibizumab and aflibercept. These inhibit the action of VEGF or bind it. Aflibercept also blocks placental growth factor. VEGF increases vascular permeability and promote the growth of abnormal new vessels (neovascularisation).

The long-acting steroids have significant adverse effects, notably causation or acceleration of cataracts in the eye, and also raised intraocular pressure (IOP) that can lead to glaucoma. They are unlikely to be much used at such an early stage as NPDR because of the risk of cataract formation, but may have a role in pseudophakic patients, or in patients with DMO that does not respond to anti-VEGF treatment. The short-acting steroid, triamcinolone, is not licensed for use in the eye, but has been widely used.

The rationale for using the anti-VEGF drugs in PDR and NPDR has been summarised by the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCRN). 21 First, they note reports of raised VEGF in ocular fluid from patients with active new vessel formation compared with no rise in patients with NPDR or inactive PDR, suggesting that VEGF stimulates neovascularisation. 22 Second, they report a number of observational studies which report that anti-VEGF drugs cause regression of PDR, albeit temporarily because the effects last only a few weeks, making repeat injection necessary, as has been shown in the treatment of DMO.

The anti-VEGF drugs have fewer adverse effects, and would probably be more acceptable at early stages than the steroids. They do have to be given by injection into the eye. In DMO, these injections are given monthly initially, but reducing in frequency thereafter. Nevertheless, anti-VEGF treatment places a significant burden on both patients and the NHS. In addition, it is, at least in DMO, only successful in about 30–50% of patients (defining success as a gain of 10 or more letters in VA). 23 Lastly, as experience is gained on the use of anti-VEGF in DR it is possible that initially unrecognised side effects may be apparent, as it was the case in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), where accumulating evidence suggests a possible effect of anti-VEGF on the development of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy. 24

The anti-VEGF drugs are now being used in combination with PRP, and we review the evidence on that in Chapter 4.

Fenofibrate

The Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) trial was primarily a study to see if the lipid-lowering agent fenofibrate could reduce macrovascular and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes. 25 However, a sub-study within FIELD25 recruited 1012 patients to a retinopathy study. The primary outcome in the main study was need for laser therapy (3.4% on fenofibrate vs. 4.9% on placebo) but the sub-study used retinal photography to assess progression of retinopathy or development of MO. The hazard ratio at 6 years for MO was 0.69 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.87] in the fenofibrate group compared with placebo. The effect of fenofibrate did not seem related to changes in blood lipid levels.

The ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) Eye Study reported a reduction of 40% in the risk of progression of retinopathy over a 4-year follow-up in patients on fenofibrate and a statin compared with those on a statin alone. 26 This was associated with a decrease in serum triglycerides. Lowering cholesterol does not appear to affect progression, as shown in the CARDS (Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study) trial of atorvastatin. 27

Preliminary searches have identified some evidence on the use of fenofibrate eye drops but such use appears to be at an early stage. The drops seem to have been patented and piloted, but not yet trialled in humans, though some work in rats suggests efficacy in arresting neovascularisation. 28 In Australia, oral fenofibrate has been approved for slowing the progression of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. 29

Fenofibrate seems to be little used in the UK for retinopathy.

This review includes only drugs that are administered directly into the eye.

What do clinical guidelines say?

This section outlines the recommendations from five clinical guidelines, from England, Scotland, Canada, Australia and the USA, on laser photocoagulation on the treatment of NPDR and PDR.

England, Canada, USA and Australia produced separate guidelines for DR, whereas Scotland devoted one section in the Management of Diabetes guideline to the management of DR. Table 3 summarises the recommendations.

| Guideline | Mild to moderate NPDR | Severe/very severe NPDR | Non-HR-PDR | High-risk/proliferative PDR | Advanced/severe PDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCOphth [RCOphth UK (England)]5 | No treatment indicated | Early PRP if retinopathy approaches the proliferative stage in specific patient groups (see text above) | Not covered in guidelines | Full scatter PRP | Vitrectomy with intravitreal anti-VEGF injection is recommended if PRP seems ineffective |

| SIGN (Scotland)18 | Not covered in guidelines | Close follow-up or PRP | Not covered in guidelines | PRP | With VH too severe for PRP consider vitrectomy |

| COS (Canada)30 | Not covered in guidelines | Not covered in guidelines | Not covered in guidelines | PRP | With VH consider vitrectomy and anti-VEGF |

| AAO (USA)31 | No treatment indicated | Early PRP in specific patient groups (see text above) | Early PRP in specific patient groups (see text above) | PRP | Consider vitrectomy |

| NHMRC Australia32 | Not covered in guidelines | Early PRP in specific patient groups (see text above) | Not covered in guidelines | PRP | Consider vitrectomy if unresponsive to PRP |

As recommended in the ETDRS, laser treatment is not considered in any of the guidelines for patients with DR at stages up to and including moderate NPDR. However, only the RCOphth UK and the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) guidelines actually state this in their guidelines.

Consideration of early PRP in conjunction with close follow-up at the severe stage of NPDR is recommended in England, Scotland, America and Australia but not in Canada, where the guidelines consider only the treatment of PDR. While the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines18 very generally recommend the consideration of PRP in patients with severe or very severe NPDR, the RCOphth UK reserved the treatment to patients approaching the proliferative stage and only in certain patient groups, i.e. older patients with type 2 diabetes, in patients in whom retinal view is difficult or examination is difficult, in patients who cannot be followed up closely, in patients in whom one eye has already been lost to PDR, and, generally, before cataract surgery. The AAO31 and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Australia32 do not seem to subcategorise the severe NPDR stage but list the same patient groups for consideration. They further include pregnancy (AAO31) and renal disease (NHMRC32) under the medical conditions for consideration. The AAO31 states further that partial PRP is not recommended and that, consequently, if PRP is indicated, full PRP should be performed. The AAO31 also includes the non-HR-PDR stage into this recommendation.

Pan-retinal photocoagulation is recommended for PDR with HRCs (AAO,31 NHMRC,32 COS30) and PDR with any new vessels (RCOphth UK and SIGN). The AAO,31 RCOphth UK5 and the Australian NHMRC32 stress the urgency of such treatment in their guidelines.

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor and steroids

None of the guidelines includes anti-VEGF as a treatment option for NPDR/PDR either alone or in combination with laser photocoagulation. However, three out of the five guidelines recommend anti-VEGF for the treatment of DMO. The RCOphth UK and the AAO recommend consideration of anti-VEGF either with or without combination laser therapy, and the RCOphth classes it as ‘the new gold standard of therapy . . .’ for DMO. The Canadian guidelines, however, recommend anti-VEGF prior to PRP only for PDR with DMO. They further recommend anti-VEGF treatment before vitrectomy. The Australian guidelines recognise that anti-VEGF treatment for the management of PDR with DMO is already widely in use but say that anti-VEGF for PDR prior to laser treatment or vitrectomy lacks evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Although anti-VEGF drugs need to be administered frequently, slow-release steroid implants have the advantage of lasting longer. The American guidelines state that intravitreal steroids might be considered in combination with PRP in patients with combined moderate NPDR and DMO. Similarly, the Australian guidelines suggest consideration of steroids in PDR with DMO in certain patient groups. Overall, recommendations to use steroids are very cautious and the Canadian Ophthalmological Society (COS), which does not include intravitreal steroids in their guidelines, reports that studies investigating the use of steroids produced conflicting results. The SIGN guidelines do not recommend any pharmacological treatment for the management of any form of PDR owing to lack of convincing evidence.

Decision problem

The commissioning brief gave the background to the topic as follows:

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the major cause of sight loss in the working age population in the UK and people with diabetes are 25 times more likely than the general population to go blind. Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) by laser treatment is the standard intervention for patients with high risk progressive* diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and it has been shown to reduce the risk of severe vision loss for eyes at risk by 50%. However, an intervention with pan-retinal laser treatment earlier in the disease, during the preproliferative stage, may be more beneficial in terms of preventing loss of vision, given the detrimental and potentially irreversible effects of PDR if treatment is not obtained or is delayed.

*The term used in the brief, but presumed to mean proliferative.

The key question for this review is about the timing of PRP – would there be advantages in PRP at the severe NPDR stage, rather than waiting till PDR develops?

Population: people with NPDR.

Interventions: PRP at the NPDR stage. All variants of PRP will be included. Drug–laser combinations using an anti-VEGF drug or an injected steroid will be included.

Comparator: PRP delayed till PDR develops. This may be at the HR-PDR stage but may be used in early PDR.

Outcomes: the primary outcome is visual loss with central and peripheral loss described separately when data permit.

Secondary outcomes include the need for further treatment, and adverse effects such as the development of DMO after PRP, peripheral visual loss, quality of life (QoL), ability to drive, colour vision.

Chapter 2 The landmark trials: Diabetic Retinopathy Study and Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Methods

Literature searches and study selection

The search question posed in the commissioning brief was:

What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of pan-retinal laser treatment in the management of non-proliferative (pre-proliferative) diabetic retinopathy (NPDR)?

The patient groups specified were those with early stages of NPDR (Level R2) versus the control or comparator treatment of PRP at PDR (Level R3), in any appropriate setting.

Our scoping searches gave a very low retrieval of studies that would be relevant to this search question, but did show that there were recent developments in types of laser and in the use of laser and drug combinations. Therefore, in the draft protocol we proposed a wider scope for this Technology Assessment Report than had been envisaged in the commissioning brief. This was approved by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) after being supported by the external referees. The decision problem was subsequently expanded to become:

Treatment of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a review of pan-retinal photocoagulation, other forms of laser treatment, and combinations of photocoagulation and anti-VEGF drugs or inject steroids.

However, the broader searches revealed that there were no RCTs that compared patients at the NPDR level to those at later stages of PRP. Indeed, the most relevant and largest study done addressing the timing of PRP laser in the treatment of DR, the ETDRS, grouped together patients with moderate to severe NPDR and early PDR, and did not report outcomes on these groups separately.

Therefore, it seemed likely that a trial to address the original research question was needed, and, in order to inform a future study on PRP treatment of patients at the NPDR stage, we decided to further broaden the searches to capture all forms of current laser and topical drug treatment of DR at any stage, and explore if these newer treatments could be applied to patients at the NPDR stage.

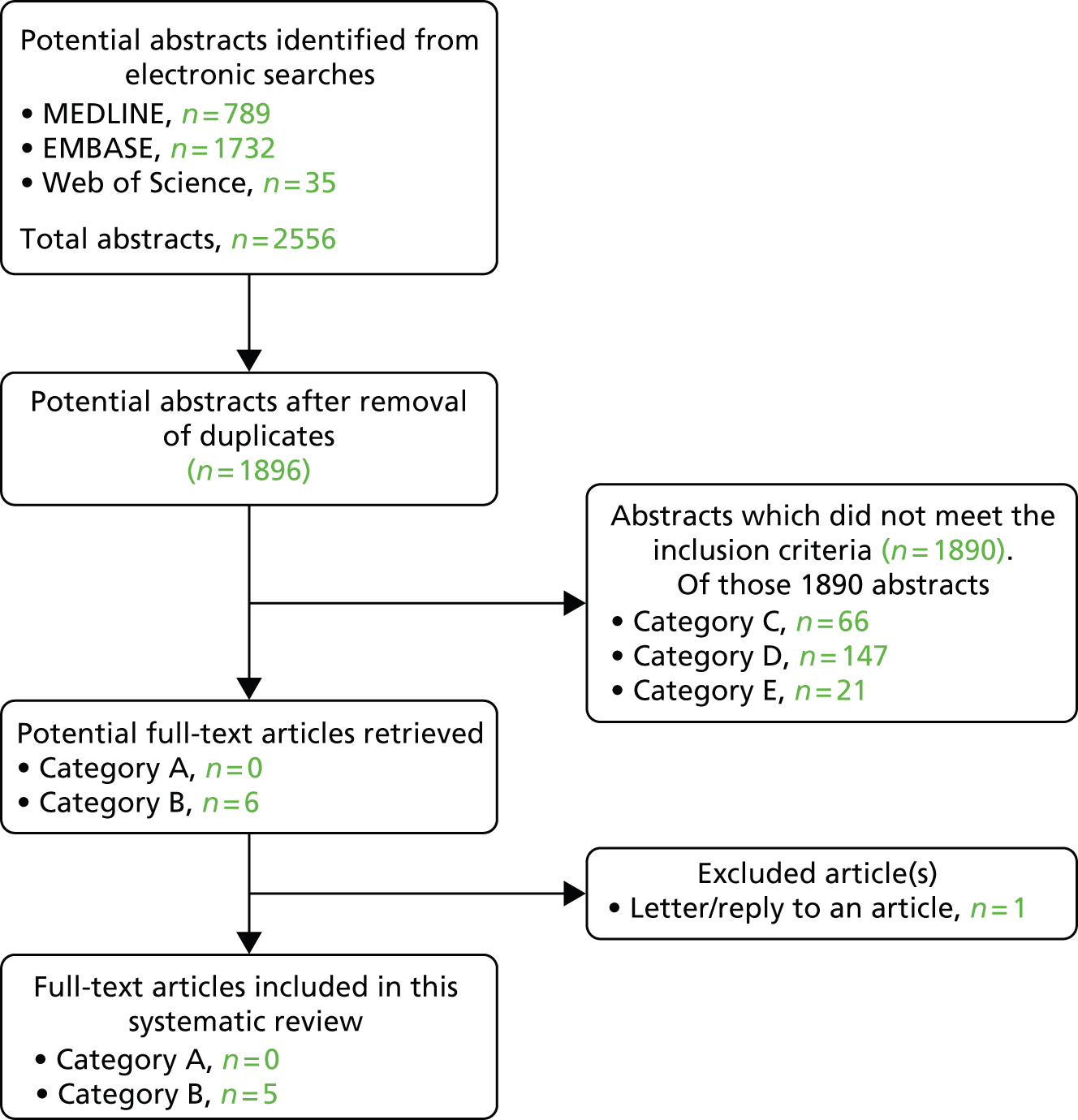

The databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library were searched for previous systematic reviews or meta-analyses relevant to our search question (see Appendix 2 for search strategies). There were 94 potentially relevant records downloaded and the full text of five articles was examined by two reviewers (PR, NW). The most relevant review was one by Mohamed et al. (2007). 33 Although this was a useful review, its objective was to review the best evidence for primary and secondary intervention in the management of DR, including DMO, which was a lot broader than our review, so did not address our specific research question. Also, the searches were performed in May 2007, so it was several years out of date.

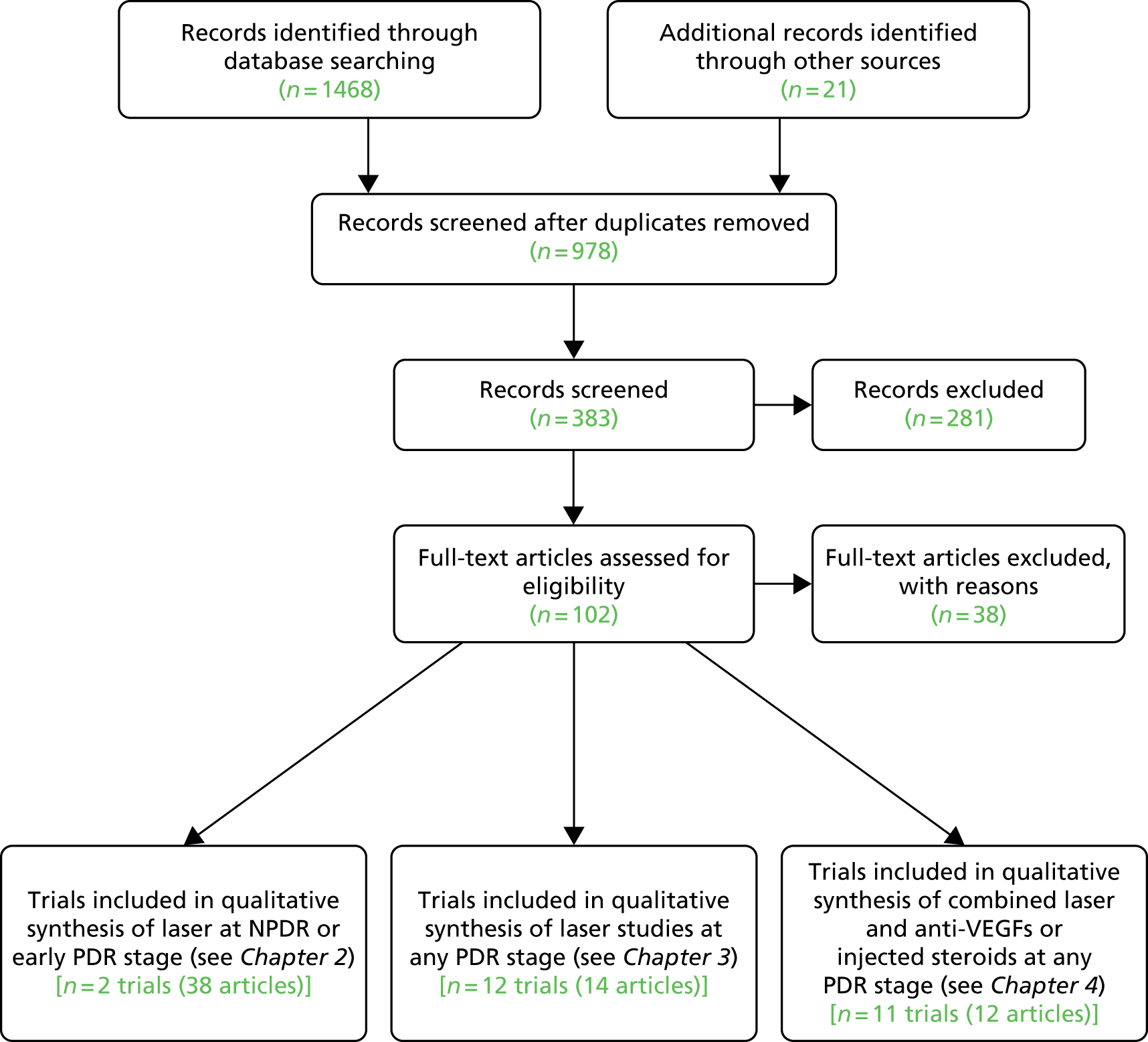

We searched for RCTs for the treatment of DR. We separated the results into three categories in order to provide evidence for each of the different aspects of our decision problem (Appendix 2 shows the details of the search strategies and Figure 2 shows the flow diagram for RCTs searches).

-

Trials of:

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for identifying RCTs included in Chapters 2–4.

From the 102 full-text papers assessed, independently checked against the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (PR/NW), 22 references relevant to category 1 above were identified. Upon reading the full text of these references, it became evident that all were papers arising from two large RCTs, the DRS and the ETDRS, each producing many papers. Further searches were done to search specifically for publications arising from the DRS and ETDRS, and reference lists were checked, in order to obtain all the relevant papers from these two trials; this resulted in an additional 18 articles.

The excluded papers were retained and were assessed for inclusion criteria relevant to category 2 and 3 searches above, and are reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extractions, and quality assessments (based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool34), of the two trials were carried out by one reviewer (PR) and checked by a second (NW). The final number of papers reviewed was 14 from the DRS and 24 from the ETDRS.

The flow of studies is shown in Figure 2.

The Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Background

Laser photocoagulation had become widely used in the management of DR by the early 1970s in the USA. However, there was a lack of good-quality evidence supporting the risk and benefits of this procedure. Therefore, in 1971, the National Eye Institute (NEI) funded the DRS35 to evaluate photocoagulation treatment for PDR.

Study design

The DRS was a randomised, controlled clinical trial involving 15 clinical centres. A total of 1758 patients were enrolled between 1972 and 1975. Patient follow-up was completed in 1979.

The main aim of the DRS was to determine whether photocoagulation helps prevent severe visual loss (SVL) from PDR, and whether a difference exists in the efficacy and safety of argon versus xenon photocoagulation for PDR. Another objective was to obtain information on the natural history and clinical course of proliferative retinopathy.

Patients were eligible if they had best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/100 or better in each eye, and the presence of PDR in at least one eye or severe non-proliferative retinopathy in both eyes. Both eyes had to be suitable for photocoagulation. The eye to be treated was chosen randomly.

The baseline VA of the enrolled patients was equal to or better than 20/20 in approximately half of the eyes. Patients were predominantly white and had a mean age of 42.6 years; approximately 45% were classified as juvenile-onset diabetics, and there were slightly more men than women.

The principal end point was SVL, which was considered to have occurred if VA was less than 5/200 at two or more consecutively completed 4-month follow-up visits.

Quality assessment

The DRS was a high-quality trial with a low risk of bias, as shown in Table 4. The details of the design, methods and baseline results of the DRS were extensively reported in DRS report no. 6 (DRS #6). 36

| Adequate sequence generation | Adequate allocation concealment | Adequate masking | Incomplete outcome data assessed | Free of selective outcome reporting | Free of other biases (e.g. similarity at baseline, power assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (randomisation schedules were created by the co-ordinating centre for each clinical centre and were designed to balance both the number of right and left eyes assigned to treatment and the number assigned to argon and xenon) | Yes (the co-ordinating centre sent the treatment allocation form to each clinic in a sealed envelopes) | Yes [the protocol specified that the individual who measured VA should be unaware of (‘masked’ with regard to) the identity of the eye assigned to treatment and VA at previous visits] | Yes (the number of patients who completed specified visits up to 5 years was reported in table 3 of DRS #810) | Yes (all prespecified outcomes reported) | Yes (percentage of patients with specified baseline characteristics for 14 different variables, and yielded no significant difference at 5% level. Sample size calculations set recruitment goal at 800 patients in each treatment group) |

Treatment

One eye of each patient was randomly assigned to immediate photocoagulation and the other to follow-up without treatment, regardless of the course followed by either eye. The eye chosen for photocoagulation was randomly assigned to argon laser or to xenon arc photocoagulation. Treatment was usually completed in one or two sittings. Both treatment techniques included extensive scatter photocoagulation (PRP) and focal treatment of new vessels on the surface of the retina.

The argon treatment technique specified 800–1600 scatter burns, 500 µm in size, 0.1-second duration and direct treatment of new vessels whether on or within one disc diameter (DD) of the optic disc (NVD) or outside this area (NVE). The xenon technique was similar, but scatter burns were fewer in number, generally of longer duration, and stronger, and direct treatment was applied only to NVE on the surface of the retina. Focal treatment was also applied to microaneurysms or NVE lesions thought to be causing MO. Those treated with argon could have flat or elevated NVE treated.

Follow-up visits were planned at 4-month intervals for a minimum follow-up of 5 years, where follow-up treatment was applied as needed. BCVA was measured in both eyes by masked techniques before treatment and at 4-month intervals after treatment.

The DRS data were reviewed every 3 months by the Data Monitoring Committee for evidence of adverse and beneficial treatment effects.

Results (before protocol change)

In 1975 after an average of only 15 months of follow-up (range 0–38 months), the 2-year incidence of blindness was 16.3% in untreated eyes but only 6.4% in treated eyes. 37 Therefore, photocoagulation had reduced the 2-year risk of blindness by about 60%. This finding was unexpected and highly statistically significant. These beneficial effects were noted to some degree in all stages of DR included in the study.

Protocol change

On the basis of these results a decision was made in 1976 (more than 3 years before the planned termination of the study) to consider photocoagulation treatment for the initially untreated eyes, which now, or in the future, would fulfil any one of the following criteria, referred to as eyes with HRCs:

-

Moderate or severe new vessels on or within one DD of the optic disc.

-

Mild new vessels on or within one DD of the optic disc if fresh vitreous or pre-retinal haemorrhage is present.

-

Moderate or severe new vessels elsewhere (NVE), if fresh vitreous or pre-retinal haemorrhage is present, and if the area of new vessels was half the disc area or more.

Photocoagulation techniques were modified when treatment was carried out in eyes initially assigned to the untreated control groups after the 1976 protocol change. Argon treatment was preferred, and to decrease the risk of VA loss, many DRS investigators divided scatter treatment into two or more episodes, days or weeks apart.

Evidence of recovery before protocol change

Although the principal goal of photocoagulation treatment is to prevent visual loss, not to improve vision, there were eyes with some evidence of recovery, defined as VA ≥ 5/200 at any subsequent visit at 1, 2 or 3 consecutively completed follow-up visits. The percentage of eyes with some evidence of recovery at each visit were 28.6%, 12.2% and 7.7% in untreated eyes compared with 48.8%, 28.6% and 20.8% in treated eyes, respectively. Therefore, it appeared that recovery of VA was more frequent in treated than untreated eyes.

Harms

Some harmful effects of treatment were also found, including moderate losses of VA and constriction of peripheral visual field, which were greater in the xenon treated group than the argon group. The loss in sharp, central vision was temporary in some patients but persisted in others. However, DRS physicians believed that these harmful effects of photocoagulation in eyes with moderate or severe retinopathy were outweighed by the reduced risk of SVL without treatment at these stages.

Results after the protocol change

Additional follow-up after the DRS protocol change confirmed previous reports that, by 24 months, photocoagulation reduces the risk of SVL by 50% or more.

Cumulative rates of SVL for argon and xenon groups combined up to 72 months’ follow-up are shown in Table 5 (adapted from table 2, DRS #810). Although the risk of SVL in untreated eyes increases from 14% at 24 months to 36.7% at 72 months, it can be seen that over this time period the treatment effect was consistent (ranging between 56% and 59%).

| Follow-up (months) | Treated | Untreated | Reduction of SVL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 41.7 |

| 24 | 6.2 | 14.0 | 55.7 |

| 36 | 9.0 | 21.7 | 58.5 |

| 48 | 11.6 | 27.8 | 58.3 |

| 60 | 13.9 | 33.0 | 57.9 |

| 72 | 16.6 | 36.7 | 54.8 |

The 24-month data in Table 5 differ slightly from that presented earlier (prior to the protocol change), as 43% of the 2-year visits and all of the 4-year visits included were carried out after the 1976 protocol change. All eyes are classified in the group to which they were originally randomly assigned, ignoring treatment of control eyes.

The treatment effect was somewhat greater in the xenon group than in the argon group (data not shown), but its statistical significance was borderline, and its clinical importance was outweighed by the greater harmful treatment effects observed with the xenon technique used in the DRS.

Occurrence of severe visual loss in eyes classified according to baseline severity

As patients enrolled in DRS had a broad range of severity of DR, it was important to evaluate results for different stages. Table 6 (taken from table 2, DRS #1438) shows the cumulative 2- and 4-year rates of SVL by eyes grouped by their severity of retinopathy at baseline and treatment assignment.

| Severity of retinopathy | Rate | Treated | Untreated | Reduction of SVL (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVL (%) | No. at risk | SVL (%) | No. at risk | |||

| NPDR | 2 year | 2.8 | 303 | 3.2 | 297 | 12.5 |

| 4 year | 4.3 | 188 | 12.8 | 183 | 66.4 | |

| Proliferative without HRCs | 2 year | 3.2 | 615 | 7.0 | 603 | 54.3 |

| 4 year | 7.4 | 390 | 20.9 | 332 | 64.6 | |

| Proliferative with HRCs | 2 year | 10.9 | 570 | 26.2 | 473 | 58.4 |

| 4 year | 20.4 | 324 | 44.0 | 238 | 53.6 | |

| All eyes | 2 year | 6.2 | 1489 | 14.0 | 1378 | 55.7 |

| 4 year | 12.0 | 903 | 28.5 | 754 | 57.9 | |

It can be seen that the treatment effect in Table 6 is substantial (except for the group without PDR at 2 years) and fairly uniform across all subgroups at both 2 and 4 years, with reductions of SVL by from 54% to 65%.

The rate of SVL for untreated eyes with proliferative retinopathy with HRCs after 24 months of follow-up is about 26% and is reduced to 11% in treated eyes. However, in eyes with proliferative retinopathy without HRCs, the untreated rate at 2 years is much lower (7.0%), and although the beneficial treatment effects are substantial (a 54% reduction in SVL), the risks without treatment are smaller, and so the harmful effects of treatment need to be given more weight than for eyes with a higher risk.

In eyes with severe NPDR the risk of SVL without photocoagulation treatment at 2 years is low (3.2%) and reduces to 2.8% (a reduction of 12.5%) only with treatment, so the risks of treatment become even more important.

Harms: argon and xenon

Decreases of VA of one or more lines and constriction of peripheral visual field due to treatment were also observed in some eyes. These changes were sometimes due to an increase in MO, and sometimes the reduction in VA was temporary. In others, the changes persisted. The changes in visual field are important because they may mean that patients can no longer meet the requirements for driving.

Visual fields were measured using the Goldman method, wherein normal fields range from 50° (superiorly) to 90° (temporally). The DRS group defined modest visual field loss as a reduction from over 30° up to 45°, and 30° or less as severe.

The UK legal requirement is VA of 6/12 (measured in metres) or better (this is equivalent to 20/40 using measurements in feet) and with regards to visual field, to have a binocular visual field of 120 ° horizontally (in the horizontal axis) and no significant defect within the central 20 °, horizontally or vertically (above or below the horizontal meridian).

These harmful effects were more frequent and more severe following the DRS xenon technique; 50% of xenon-treated eyes suffered some loss of visual field compared with 5% of the argon-treated eyes. It was also estimated that a persistent VA decrease of one line was attributable to treatment in 19% of xenon-treated eyes and a persistent decrease of two or more lines in an additional 11%. Comparable estimates for the argon group were 11% and 3%, respectively.

Xenon photocoagulation has been discontinued.

Macular oedema in the Diabetic Retinopathy Study patients (DRS #12)

The DRS39 was not designed to evaluate the effect of photocoagulation in eyes with MO. Although focal treatment was carried out in those eyes with MO assessment, its direct effect cannot be determined because it was always combined with scatter treatment.

The loss of VA associated with scatter photocoagulation observed soon after treatment was especially prominent in eyes with pre-existing MO. It was also associated with the intensity of treatment. It was suggested that reducing MO by focal photocoagulation before initiating scatter treatment and dividing scatter treatment into multiple sessions with less-intense burns may decrease the risk of the visual loss associated with photocoagulation. 39

Summary

Results of the DRS showed that photocoagulation reduced the 2-year incidence of SVL by more than half in eyes with PDR, both with and without HRCs. However, in eyes with NPDR, where the 2-year risk of SVL in the untreated control group was low at 3.2%, photocoagulation only reduced the risk to 2.8%. Therefore, in patients with NPDR the harmful effects of photocoagulation assume more importance. Some of the harmful effects of treatment for some patients included a moderate loss of VA and a narrowing of the visual field.

Implications of Diabetic Retinopathy Study findings for treatment of early proliferative or severe non-proliferative retinopathy

The DRS concluded that in the eyes with PDR and HRCs the risk of SVL without treatment substantially outweighs the risks of photocoagulation, and prompt treatment is usually advisable. However, as the DRS findings result from a comparison between prompt treatment versus no treatment, they did not provide evidence on the relative value of prompt treatment versus deferral of treatment in the earlier stages of DR. They recommended careful follow-up for changes with DR and when non-proliferative changes are present, the follow-up visits should be at frequent intervals. 37

Finally, their conclusions stated:

Demonstration that prompt treatment of eyes with early proliferative or severe nonproliferative retinopathy is better than no treatment does not mean that prompt treatment is superior to deferral of treatment until progression occurs. 37

They called for a randomised trial to examine when best to apply PRP.

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Background

The ETDRS was a multicentre, randomised clinical trial designed to evaluate argon laser photocoagulation in the management of patients with non-proliferative or early PDR. It was supported by the NEI and arose from results of the DRS, which had shown that laser photocoagulation was effective in reducing the rate of SVL from an advanced stage of DR. 9,40

Purpose and aims

The three principal clinical questions of ETDRS were:

-

When in the course of DR is it most effective to initiate photocoagulation therapy?

-

Is photocoagulation effective in the treatment of MO?

-

Is aspirin effective in altering the course of DR?

This summary will focus on the first of these questions. Our main interest is between early scatter treatment of eyes with moderate to severe NPDR or PDR without HRCs and deferral of scatter treatment unless PDR with HRCs develops.

Initially, patients were also assigned randomly to aspirin (650 mg per day) or placebo. However, aspirin was not found to have an effect on retinopathy progression, so patients assigned to aspirin were pooled with those assigned to placebo.

Quality assessment

The ETDRS was a high-quality trial with a low risk of bias as shown in Table 7.

| Adequate sequence generation | Adequate allocation concealment | Maskinga | Incomplete outcome data assessed | Free of selective outcome reporting | Free of other biases (e.g. similarity at baseline, power assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (co-ordinating centre staff assigned patients randomly) | Yes (sealed mailer from the central co-ordinating centre) | Partial/unclear? (masking of outcome assessors ‘Fundus Photograph Reading Center Staff did not have knowledge of the assigned photo-coagulation strategy’, ‘Visual acuity examiners were masked from treatment assignment’) | Yes (90–95% of expected follow-up visits were completed for first 3 years; 80–90% completed for follow-up longer than 3 years Of the 130,908 expected VA scores, all but 1.5% were available) |

Yes (all prespecified outcomes reported) | Yes (groups were well balanced for all characteristics, except a significantly greater proportion in the full scatter group had higher diastolic BP; power calculations performed) |

Patient recruitment

Recruitment of eligible patients began in December 1979 and was completed in July 1985. The 3711 patients accepted for the study, from 22 clinical centres in the USA, were followed through to 1989. Recruitment ended with 98% of the goal of 4000 patients enrolled. By study end, 706 patients had died, and, of the 2971 patients known to be alive, 164 did not have a final eye examination but all but 11 had some sort of final check.

Patient eligibility

To be eligible for the ETDRS, patients had to be aged between 18 and 70 years and to have DR in both eyes. Each eye had to meet either of the following eligibility criteria:

-

No MO, VA of 20/40 or better and moderate or severe non-proliferative or early proliferative retinopathy, or

-

MO, VA of 20/200 or better and mild, moderate or severe non-proliferative retinopathy or early proliferative retinopathy.

Methods for assessing outcome variables

Best corrected visual acuity was measured with logarithmic VA charts at baseline and each subsequent follow-up visit, scheduled at 4-month intervals. A standardised protocol for the collection of VA measurements was used in all clinical centres.

Stereoscopic 30° colour photographs were taken of seven standard fields at baseline, 4 months, 1 year after entry and yearly thereafter. All fundus photographs were graded according to a standardised procedure by the Fundus Photograph Reading Center staff, who had no knowledge of treatment assignments and clinical data.

Definitions of diabetic retinopathy

The ETDRS adopted the DRS definitions of severe NPDR and HR-PDR and defined moderate NPDR (see table in Appendix 1). Subsequently, the ETDRS developed a more detailed scale, which provided further subdivisions within both the NPDR and the PDR categories. 6

Assessment of severity of retinopathy and macular oedema

Fundus Photograph Reading Center staff, without knowledge of treatment assignments and clinical data, followed a standardised procedure to grade fundus photographs and fluorescein angiographs for individual lesions and DR.

Randomisation procedure

To obtain information on the appropriate timing of scatter photocoagulation, one eye of each patient in the ETDRS was assigned randomly to early photocoagulation (either mild or full scatter) and the other to deferral of photocoagulation, with follow-up scheduled every 4 months and photocoagulation to be performed promptly if HR-PDR developed.

All eyes chosen for early photocoagulation were further randomised to one of two scatter photocoagulation techniques (full or mild). Full scatter involved 1200–1600 burns in two sessions, mild scatter 400–650 burns in one session. Eyes also with MO were assigned randomly to one of two timing strategies for focal photocoagulation (immediate or delayed), so that for these eyes there were four strategies of early photocoagulation.

Three categories were defined on the basis of retinopathy severity and the presence or absence of MO at baseline, and the type of photocoagulation differed for each category.

Less severe retinopathy was defined as eyes with mild to moderate non-proliferative retinopathy, and more severe retinopathy as eyes with severe non-proliferative or early PDR.

-

Category 1: eyes without MO Eyes in this category had moderate to severe non-proliferative or early proliferative retinopathy.

Eyes randomised to immediate photocoagulation were further randomised to full or mild scatter.

In the deferred arm, eyes were followed up at 4-monthly intervals and received photocoagulation if PDR with HRC-PDR developed.

In both arms, delayed focal photocoagulation was initiated during follow-up if clinically significant macular oedema (CSMO) developed (i.e. MO that involved or threatened the centre of the macula).

Ideally, the trial would have separated NPDR from PDR, but this was not done.

-

Category 2: eyes with MO and less severe retinopathy Eyes in this category had MO and mild to moderate NPDR.

Early photocoagulation for these eyes consisted of (1) immediate focal photocoagulation to treat the MO, which was seen as a greater threat to vision than the retinopathy, with scatter photocoagulation (with further randomisation to mild or full) added if severe non-proliferative or early proliferative retinopathy developed during follow-up and (2) immediate scatter photocoagulation (with further randomisation to mild or full), with focal photocoagulation delayed for at least 4 months.

Eyes assigned to delayed focal photocoagulation received treatment at the 4-month visit if the oedema had not improved clinically and the VA score had not increased by five or more letters by that time. Focal photocoagulation was initiated at the 8-month visit if the oedema was not substantially improved, as demonstrated by either a return of an initially thickened macular centre to normal thickness or improvement in VA score by 10 or more letters. At and after the 12-month visit, initiation of focal photocoagulation was required for all eyes assigned to early PRP if they had CSMO and had not yet received focal photocoagulation. So focal was not given if the MO improved.

In the deferred arm, eyes were followed up at 4-monthly intervals and received scatter photocoagulation if HRC-PDR developed. They could receive focal photocoagulation if CSMO developed. Note that this group could only receive scatter PRP if HRC-PDR developed, whereas the early treatment arm could have PRP if they progressed to severe NPDR, early PDR or HRC-PDR.

-

Category 3: eyes with MO and more severe retinopathy Eyes in this category had MO and severe non-proliferative or early PDR.

Early photocoagulation for these eyes consisted of (1) immediate focal and scatter photocoagulation (with random allocation to mild or full) or (2) immediate scatter photocoagulation (randomisation to mild or full), with focal photocoagulation delayed for at least 4 months. The same procedure as described above for initiating focal photocoagulation at or after 4 months was used.

In the deferred arm, eyes were followed up at 4-monthly intervals and received photocoagulation if HRC-PDR developed.

Thus, in each of the three categories there are four different randomly allocated strategies for the timing and extent of early photocoagulation. All eyes received scatter (mild or full) originally, and if the retinopathy progressed to HRC-PDR, the mild scatter group received full scatter. Eyes that had MO, or developed it, received full focal photocoagulation treatment. (Approximately 85% of eyes with MO at baseline eventually received focal photocoagulation compared with only 40% of eyes without MO at baseline.)

In the deferred arms, the initial protocol specified that full scatter be given if HRC-PDR developed. The protocol was modified in 1985 to allow focal photocoagulation if CSMO was present. This was because the data had by then shown that focal photocoagulation reduced visual loss in eyes with CSMO.

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study photocoagulation technique

Argon laser was chosen for photocoagulation in the ETDRS. The photocoagulation treatment techniques used were based on those used in the DRS and on the clinical experience of the ETDRS investigators.

Major features of the scatter and focal photocoagulation techniques used in the ETDRS are shown in the table in Appendix 3.

Full scatter Full scatter treatment consisted of a spot size of 500 µm and exposure time of 0.1 second, used with power adjusted to obtain moderately intense white burns that do not spread to become appreciably larger than 500 µm. It was estimated that a total of 1200–1600 burns were required to complete the full scatter treatment. The protocol specified that division of scatter treatment be applied in two or more episodes, in the hope of reducing the incidence of adverse treatment effects. If applied in two episodes, these were to be no less than 2 weeks apart; if in three or more episodes, these must be at least 4 days apart. No more than 900 scatter burns were to be applied in a single episode, and the initial treatment session was to be completed within 5 weeks.

Mild scatter Mild scatter treatment involved a spot size, exposure time and intensity the same as for full scatter treatment, in order to produce burns of the same strength. Burns were placed at least one burn diameter apart and scattered uniformly across the same zone of retina as specified or full scatter, using 400–650 burns, usually applied at a single episode.

Focal photocoagulation Focal photocoagulation for MO consisted of the application of argon laser burns to focal lesions (such as leaking microaneurysms as determined by FA or areas of retinal ischaemia) located between 500 and 3000 µm from the centre of the macula.

Definition of terms used in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

A definition of the terms as used in the ETDRS studies is given in Table 8.

| SVL | VA < 5/200 at two consecutive follow-up visits (scheduled at 4-month intervals) |

| Moderate visual loss | Loss of 15 or more letters between baseline and follow-up visit, equivalent to a doubling of the visual angle (i.e. 20/20 to 20/40 or 20/50 to 20/100) |

| MO | Thickening of the retina within one DD of the centre of the macula: and/or hard exudates ≥ standard photograph 3 in a standard 30-degree photographic field centred on the macula (field 2), with some hard exudates within one DD of the centre of the macula |

| CSMO | Retinal thickening at or within 500 µm of the centre of the macula; and/or hard exudates at or within 500 µm of the centre of the macula, if associated with thickening of the adjacent retina. A zone or zones of retinal thickening one disc area or larger, any part of which is within one DD of the centre of the macula |

| NVD | New vessels on the disc or retina within one DD of the disc margin, or located in the vitreous any distance anterior to this area, determined by grading fundus photographs |

| NVE | New vessels ‘elsewhere’ (outside the area defined for NVD), determined by grading fundus photographs |

End points

The primary end point for assessment of early photocoagulation was the development of SVL. This was defined as VA < 5/200 at two consecutive follow-up visits (scheduled at 4-month intervals). BCVA was measured at 6 weeks and 4 months after randomisation. The procedure was repeated every 4 months thereafter.

Other end points evaluated included either severe visual loss or vitrectomy (SVLV), and change between baseline and follow-up visits in visual field, colour vision or retinopathy. Visual fields were assessed by Goldman perimetry and identification of scotomas.

Study power

Power calculations for the primary end point of SVL assumed that 10% of eyes assigned to deferral would develop SVL within 5 years. With 2000 eyes assigned to the deferral group and their 2000 fellow eyes assigned to early photocoagulation, a 40% reduction in the rate of SVL could be detected with 98% power.

Statistical methods

Comparisons of end points expressed as proportions of events were made with two-sample tests of equality of proportions. Comparisons of continuous variables were based on the two-sample z-test of equality of means.

Because multiple end points in the different groups were compared several times for the Data Monitoring Committee, a 0.01 level of probability was used for the primary end points rather than 0.05. Observed z-values of ± 2.58 or more extreme (corresponding to a 0.01 level for a single test of significance) were considered statistically significant. 9

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the ETDRS patients, by assignment of scatter photocoagulation are shown in Table 9.

| Characteristics | Mild scatter (n = 1868) | Full scatter (n = 1843) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age at entry (years) | < 30 | 300 | 16 | 326 | 18 |

| 30–49 | 611 | 33 | 557 | 30 | |

| ≥ 50 | 957 | 51 | 960 | 52 | |

| Sex (male) | 1063 | 57 | 1033 | 56 | |

| Race (white) | 1440 | 77 | 1394 | 76 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 558 | 30 | 572 | 31 | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | < 10 | 312 | 17 | 298 | 16 |

| 10–19 | 1085 | 58 | 1034 | 56 | |

| ≥ 20 | 471 | 25 | 511 | 28 | |

| Per cent desirable weight | ≥ 120 | 768 | 41 | 773 | 42 |

| SBP (mmHg) | ≥ 130 | 1215 | 65 | 1233 | 67 |

| ≥ 160 | 357 | 19 | 392 | 21 | |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | ≥ 85 | 691 | 37 | 760 | 41a |

| ≥ 90 | 478 | 26 | 583 | 32b | |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 884 | 47 | 928 | 50 | |

| Cigarettes/day ≥ 6 | 842 | 45 | 799 | 43 | |

| Severity of retinopathy | Level ≤ 35 (mild NPDR) | 316 | 17 | 288 | 16 |

| Level 43 (moderate NPDR) | 452 | 24 | 459 | 25 | |

| Level 47 (moderately severe NPDR) | 477 | 26 | 482 | 26 | |

| Level 53a–d (severe NPDR) | 245 | 13 | 231 | 13 | |

| Level 53e (very severe NPDR) | 50 | 3 | 53 | 3 | |

| Level 61 (mild PDR) | 169 | 9 | 169 | 9 | |

| Level 65 (moderate PDR) | 153 | 8 | 155 | 8 | |

| Level 71 (HR-PDR) | 6 | < 1 | 6 | < 1 | |

| For patients enrolled before September 1983 | HbA1c ≥ 10% | 566 | 42 | 556 | 42 |

| Serum cholesterol | ≥ 240 mg/100 ml (6.2 mmol/l) | 495 | 36 | 470 | 35 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | Cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/100 ml (4.1 mmol/l) | 318 | 25 | 346 | 27 |

Of the 3711 patients randomised, 56% were male, 52% were between 50 and 70 years of age, 57% had a duration of diabetes between 10 and 19 years, and 30% were classified as having type 1 diabetes.

By today’s standards, control of blood glucose, BP and cholesterol would not be considered satisfactory; 19% had systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 160 mmHg or more, and 42% had HbA1c of 10% or more; 36% had total cholesterol level over 6.2 mmol/l. The mean HbA1c was over 12%.

Groups were well balanced for all characteristics, except that a significantly greater proportion in the full scatter group had higher diastolic BP.

In 75% of ETDRS patients both eyes belonged to the same baseline category. Within each baseline category there were no large differences in mean VA scores between groups of eyes assigned to various strategies for early photocoagulation and eyes assigned to deferral of photocoagulation. Randomised treatment groups were comparable. Adherence to the assigned strategy for photocoagulation at the initial treatment session was reviewed and found to be over 98% for application of the assigned scatter and/or focal photocoagulation.

Results

Severe visual loss

All eyes in ETDRS had low rates of SVL, whether they received early photocoagulation (2.6%) or were in the deferral group (3.7%) at 5 years.

The relative risk (RR) of SVL for the entire period of follow-up in eyes assigned to early photocoagulation (including all strategies) compared with eyes assigned to deferral photocoagulation was 0.77 (99% CI 0.56 to 1.06), calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model with retinopathy severity and presence or absence of MO at baseline as covariates.

The RRs of SVL with photocoagulation compared with deferral for all baseline retinopathy categories when all photocoagulation strategies are compared are summarised in Table 10. It can be seen from the CIs that in none of the categories was the RR statistically significant.

| Baseline retinopathy category | RR |

|---|---|

| 1. Eyes without MO | 1.37 (99% CI 0.67 to 2.77) |

| 2. Eyes with MO and less severe retinopathy | 0.59 (99% CI 0.32 to 1.09) |

| 3. Eyes with MO and more severe retinopathy | 0.70 (99% CI 0.44 to 1.11) |

| All baseline categories combined | 0.77 (99% CI 0.56 to 1.06) |

Data for the development of SVL for all baseline categories are shown in Table 11, which gives estimates of RR in each of the categories. Analyses for the 5-year follow-up period demonstrated no statistically significant differences between any of the strategies for early photocoagulation and deferral within each category.

| Baseline retinopathy category | Photocoagulation treatment strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early full scatter | Early mild scatter | Deferral | |||

| Immediate focal | Delayed focal | Immediate focal | Delayed focal | ||

| 1. No MO | |||||

| 1-year rate (%) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||

| 3-year rate (%) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | ||

| 5-year rate (%) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.2 | ||

| No. of eyes | 583 | 590 | 1179 | ||

| RR (99% CI) | 1.24 (0.52 to 2.98) | 1.49 (0.65 to 3.39) | |||

| 2. MO and less severe retinopathy | |||||

| 1-year rate (%) | – | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| 3-year rate (%) | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1 |

| 5-year rate (%) | 1 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.9 |

| No. of eyes | 362 | 356 | 365 | 365 | 1429 |

| RR (99% CI) | 0.43 (0.13 to 1.44) | 0.43 (0.13 to 1.44) | 0.75 (0.29 to 1.91) | 0.74 (0.29 to 1.88) | |

| 3. MO and more severe retinopathy | |||||

| 1-year rate (%) | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| 3-year rate (%) | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 5-year rate (%) | 4.7 | 3.8 | 4 | 4.1 | 6.5 |

| No. of eyes | 272 | 270 | 276 | 272 | 1103 |

| RR (99% CI) | 0.78 (0.68 to 1.62) | 0.59 (0.26 to 1.34) | 0.74 (0.35 to 1.57) | 0.68 (0.31 to 1.46) | |

The eyes assigned to full scatter showed a trend towards a greater treatment effect than eyes assigned to mild scatter in the first two categories. The RR of SVL for the entire period of follow-up for all categories combined in eyes assigned to early full scatter compared with eyes assigned to deferral was 0.69 (99% CI 0.45 to 1.05); in eyes assigned to mild scatter the RR was 0.84 (99% CI 0.57 to 1.25); so neither early or full scatter showed a significant decrease in RR, but full was slightly better than mild at preventing SVL.

Both the severity of retinopathy and the presence of MO at baseline were both significantly associated with the development of SVL. The RR (adjusting for the presence of MO) for the development of SVL for eyes with more severe retinopathy compared with eyes with less severe retinopathy was 2.41 (99% CI 1.73 to 3.37). Similarly, the RR (adjusting for severity of retinopathy) for the development of SVL for eyes with MO compared with eyes without MO was 1.73 (99% CI 1.17 to 2.57).

Causes of severe visual loss in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Severe visual loss developed in 257 eyes (219 persons); however, 17 of these 257 eyes with SVL had insufficient follow-up and were not included in the analysis. Of the 240 eyes left for analysis, 149 eyes (127 persons) did not recover to 5/200 or better at any visit (persistent SVL) and VA improved in 91 eyes. 41

The most common cause of SVL was vitreous or pre-retinal haemorrhage, occurring in 125 (52.1%) of the 240 eyes included in the analysis. The second and third most common causes were MO (13.8%), and macular or retinal detachment (7.1%).

When patients with persistent SVL were compared with patients without persistent SVL, they were found to have higher mean levels of HbA1c (10.4% vs. 9.7%; p = 0.001) and higher levels of cholesterol (244.1 vs. 228.5 mg/dl; p = 0.0081) at baseline. 41

The low frequency of SVL in ETDRS is probably due to the use of PRP as soon as HR-PDR developed, and to vitrectomy when required.

Severe visual loss: subgroup analysis of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes

Patients were categorised into type 1 and type 2 diabetes in order to conduct a subgroup analysis of the ETDRS data to determine whether the effects of photocoagulation on SVL in patients differed by type of diabetes. 42

The benefit of early photocoagulation for SVL was statistically significantly greater in patients with type 2 diabetes than in those with type 1 diabetes. (Cox regression for SVL: interaction of early photocoagulation and type of diabetes; p = 0.0003). However, the reduction was small and the risk was low in the deferral group in which only 3.7% developed SVL. (Note that the definition used was truly severe – very low levels of vision). Also, because of the high correlation between age and type of diabetes, a subgroup analysis by age showed similar results. The results varied amongst the categories, and according to outcome. In patients with mild to moderate NPDR at baseline, a small benefit of laser in reducing SVLV was seen in both types of diabetes with no interaction between laser treatment and type of diabetes. In patients with more severe retinopathy (severe NPDR or early PDR) there was no difference in SVLV in type 1 diabetes between early and deferred laser, but a large difference in type 2, partly because they had much poorer outcomes than those with type 1. 42

If we use progression to HRC-PDR as the outcome, statistically significant benefit is seen in both types of diabetes. If we use reduction in VA, there is a large difference between early and deferred laser in patients with type 2 diabetes and clinically significant MO who had severe NPDR or early PDR at baseline but little in patients with type 1. If we look only at those who did not have CSMO at baseline, there is no difference in type 2 between early and deferred groups.

If we use legal blindness (defined in ETDRS as VA worse than 20/100), patients with type 2 diabetes again show a significant difference between early and deferred groups, whereas no difference is seen in type 1, but the frequency of this outcome was much higher in type 2.

The difference between the types of diabetes may be due to chance. As the ETDRS authors stated, many analyses were done and chance could lead to ‘statistically significant’ results. They show this quite neatly by doing a subgroup analysis on date of birth, which showed a statistically significant interaction. 42

Vitrectomy

The initial ETDRS protocol said that vitrectomy should be done after SVL had occurred, but this was changed after the results of the Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study appeared in 1985, and earlier vitrectomy was performed, either 1 month after detection or as soon as progressive retinal detachment occurred. 43 This meant that vitrectomy was performed in many ETDRS patients who had not developed SVL.

Vitrectomy was performed at least once in 208 (243 eyes) of the 3711 patients (the overall vitrectomy numbers suggest that about 18% of eyes had more than one vitrectomy.) At baseline, eyes undergoing vitrectomy were more likely to have severe non-proliferative or worse retinopathy. Also, there were no differences in the mean VA scores or percentages with clinically significant MO. It appears that all patients who had vitrectomy, did so after developing HRC-PDR, on average 21 months before vitrectomy. About 20% had SVL before vitrectomy. 44

The majority of patients undergoing vitrectomy had type 1 diabetes. The indications for vitrectomy were either vitreous haemorrhage (53.9%) or retinal detachment with or without vitreous haemorrhage (46.1%).

The cumulative rates of vitrectomy were 3.9% and 2.2% in the deferred and early groups, respectively, so this outcome was about as common as SVL.

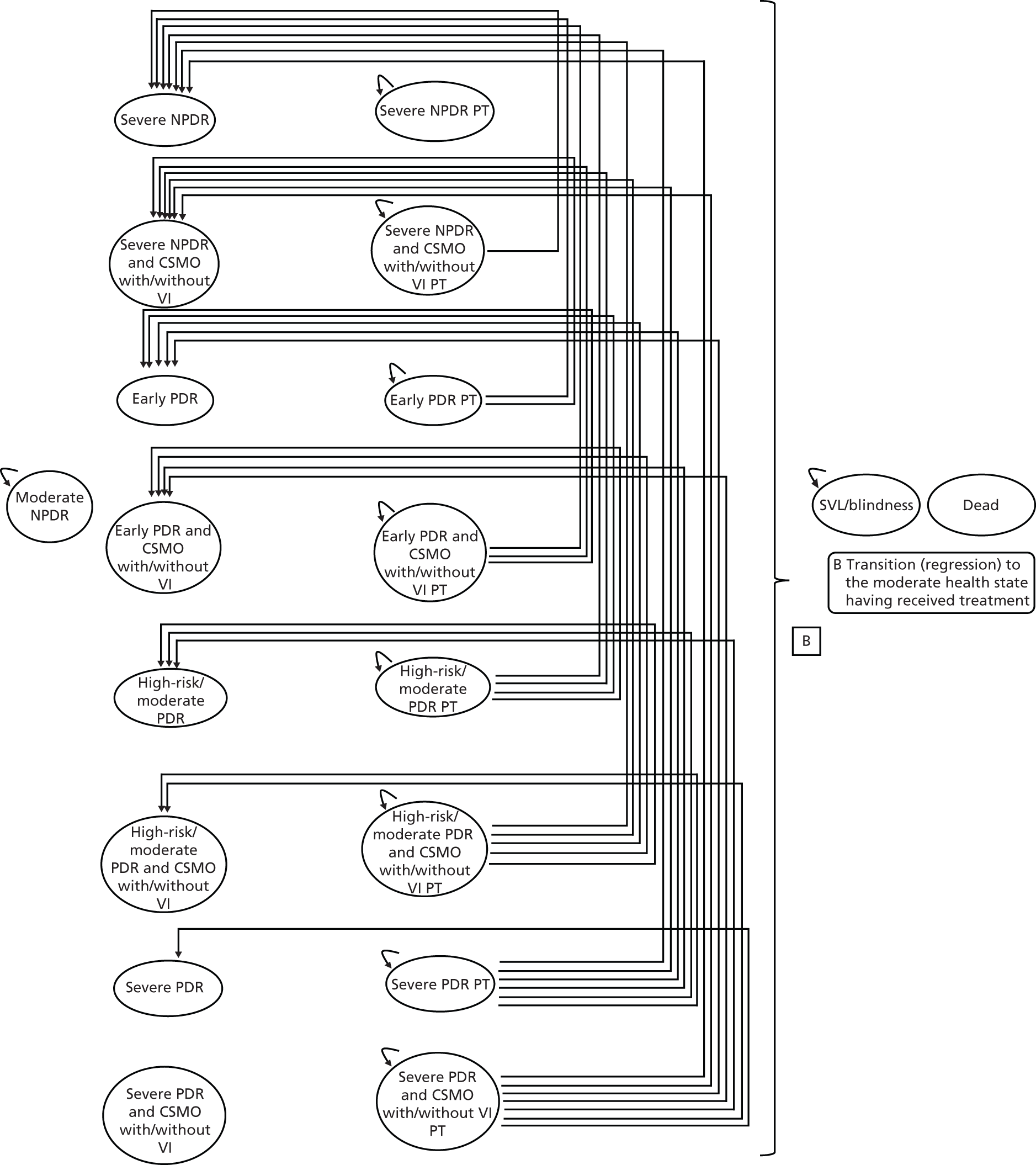

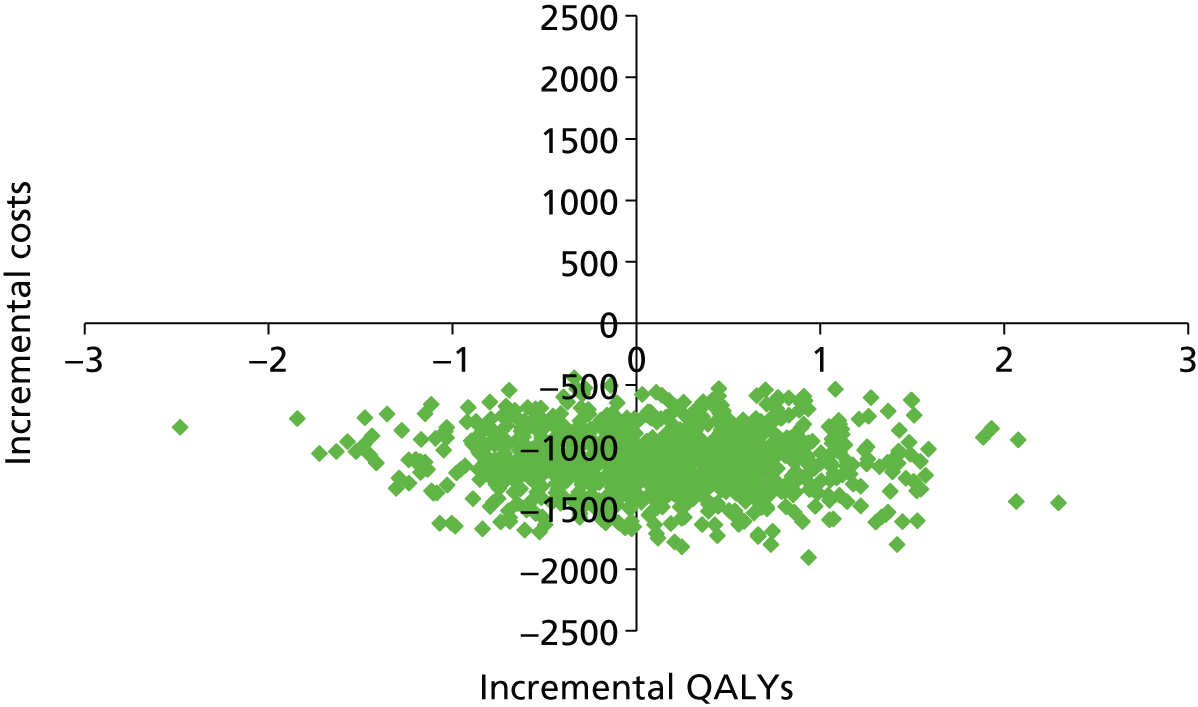

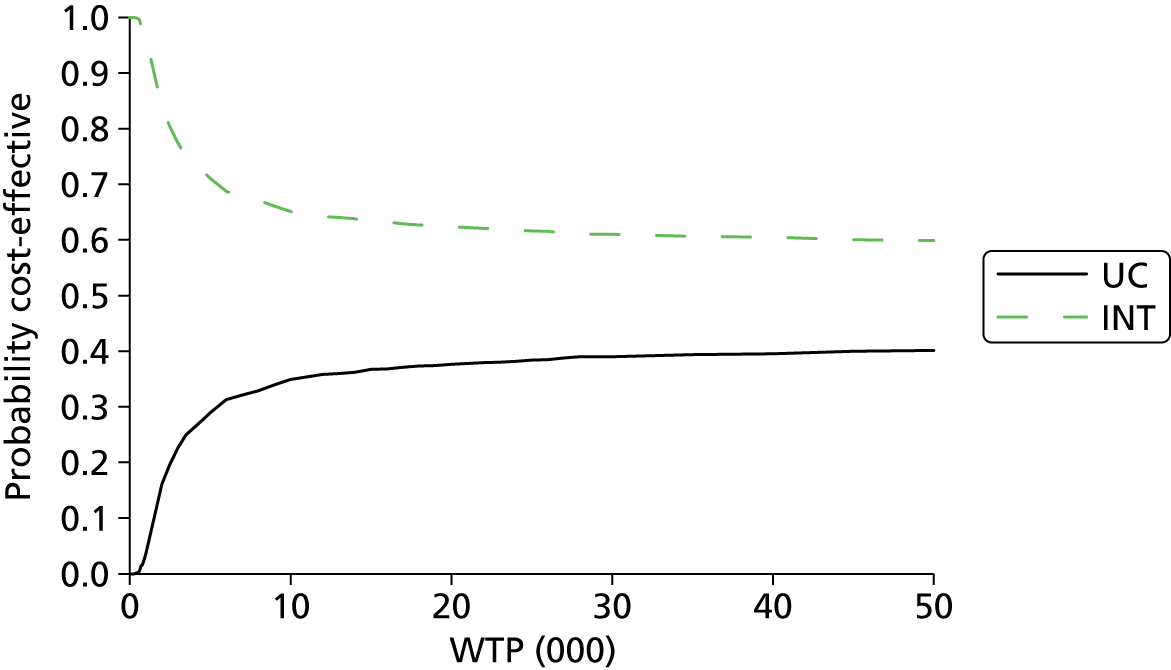

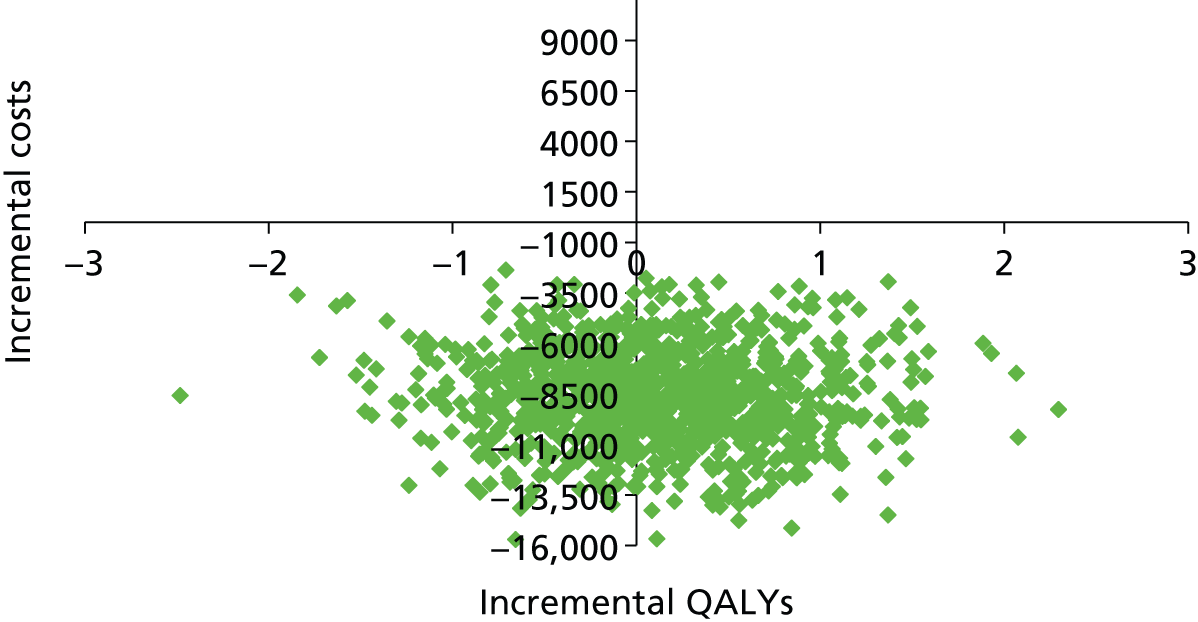

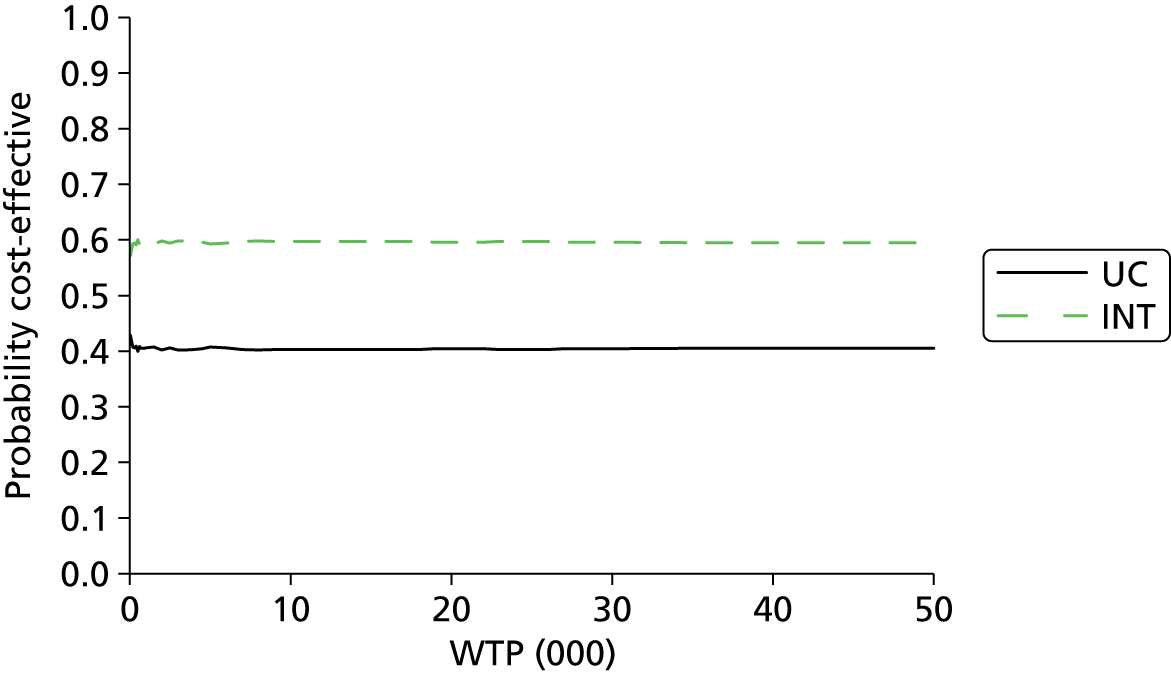

The 5-year vitrectomy rates for eyes grouped by their initial photocoagulation assignment were 2.1% of eyes assigned to early full scatter photocoagulation group, 2.5% of eyes assigned to the early mild scatter group, and 4.0% of eyes assigned to the deferral group (based on ETDRS #1744 – ETDRS #99 gives a figure of 3.9% for the deferred group).