Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/45/04. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

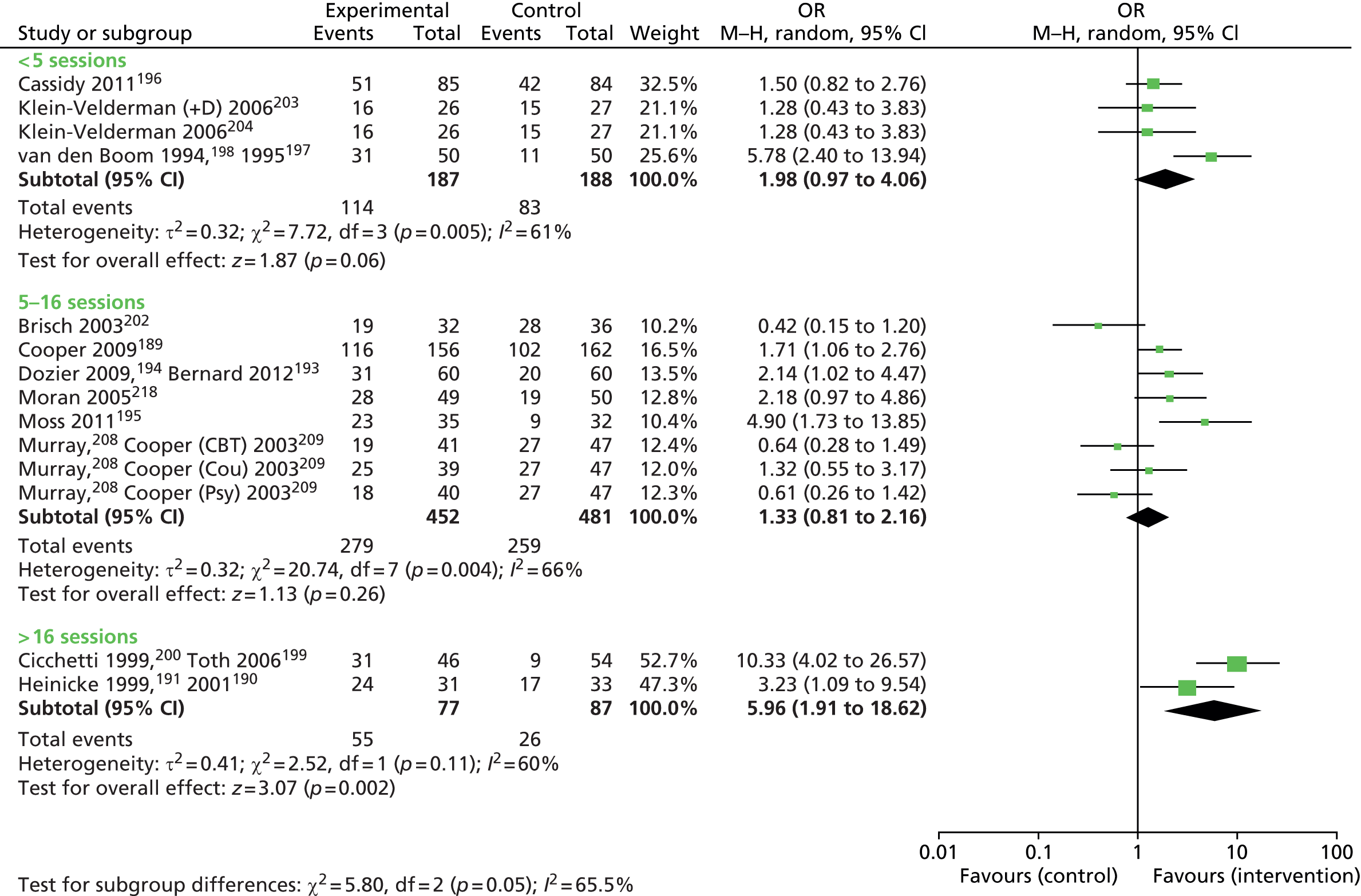

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

What is attachment?

The importance of the relationship between a child and his or her main caregivers has been recognised for some time and was captured most notably in the work of John Bowlby. 1 It is inherently linked to the promotion of survival by increasing the safety of the child. Attachment is a biological instinct whereby the child seeks proximity to the caregiver when feeling alarmed or sensing threat, in the expectation that the caregiver will provide protection for the child and reduce the child’s arousal. The child’s signals are designed to elicit the caregiver’s protective response. This response was termed by Bowlby as caregiving. 1 Attachment is the child’s bond to the caregiver and caregiving is the caregiver’s bond to the child; together, these bonds form an important aspect of the parent–child relationship. Attachment and caregiving allow the developing child to explore the environment safely and learn how to cope with the challenges and anxieties presented in the environment. 2

Attachment is thought to be important in social competence and emotion regulation. 3 It dynamically influences interactions as well as proactive and reactive responses to the environment. All of these influence brain development. 4 On the basis of repeated caregiving experiences, the infant develops internal working models which are representations of self and others that are used in the development of templates for relationships. 5 Such relationships are characterised by caregiving and care-seeking behaviours that have been experienced and rehearsed in infancy. Bowlby defined attachment as ‘the lasting psychological connectedness between human beings’. 1

Attachment patterns and their antecedents

There are different attachment patterns (sometimes referred to as attachment styles or classifications, or attachment organisation). Although each of these terms has its supporters and its merits, for the purposes of this review we will be using the term ‘attachment patterns’. It is the quality or nature of the attachments, not their intensity, which is at issue.

Differences in the behaviour of children towards their caregivers when the children are stressed have been noted over time. Early studies of attachment behaviours by Ainsworth and Wittig2 sought to operationalise and better understand these differences using the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) (see The Strange Situation Procedure), which they pioneered and which has been further developed. The patterns refer to the children’s strategies, when alarmed or feeling threatened, for gaining proximity to the caregiver in order to be protected. On the basis of earlier experiences, secure children (B pattern) are confident in the availability, and benign and consistent response of their caregivers to their display or distress, accept their caregiver’s comfort, return to equilibrium and resume play or exploration. By contrast, an insecure avoidant child (A pattern) has experienced the caregiver’s rejection, anger or unresponsiveness to his or her attachment needs. Consequently, while sensing distress, the child’s organised strategy will be not to show his or her distress to the caregiver. An insecure ambivalent/resistant child (C pattern) has experienced his or her caregiver as inconsistent and unpredictable. Consequently, these children’s organised strategy will be to show their distress or fear and cling to the caregiver, but resist the caregiver’s attempts to soothe them. According to the ‘mainstream’ ABC + D classification,6 infants and young children who have been emotionally and physically abused or neglected, and whose caregivers have been frightening or frightened, show a lack of organised strategy to gain their caregiver’s response when alarmed (D pattern). An alternative, Dynamic Maturational Model (DMM) developed by Crittenden7 regards those children termed disorganised as not, in fact, lacking a strategy, but using both an A strategy in which they maximise cognition and suppress genuine emotion, and a C strategy in which they express anger and coyness while minimising use of cognition.

It is known that different types of parenting practice are related to infant attachment patterns. Ainsworth and colleagues8 found that parental ways of carrying infants, responsiveness to crying, levels of interference and ignoring or rejecting behaviours all showed significant associations with different attachment patterns. A meta-analysis of over 4000 mother–infant dyads9 found only a small association between infant attachment classification and maternal sensitivity. This ‘transmission gap’ might be explained by the maternal sensitivity and actual behaviour towards the child being conceived as global, rather than attachment-specific maternal sensitivity. What has been shown is that child attachment patterns are related to reflective functioning of the caregiver,10 parental mental states11 and the ability of the mother to make appropriate mind-related comments about the child’s mental state. 12 Moreover, a significant correlation has been found between the attachment patterns of mother and father respectively, measured pre birth, and the attachment patterns of the infant to his or her parents, at age 1 year with the mother and 18 months with the father. 13

Further influences on attachment patterns have been proposed, including genetic factors, which have thus far evaded attempts at replication. 14 Gene–environment interactions and differential susceptibility are theories that continue to be explored. 15 Temperamental reactivity between monozygotic twins shows higher levels of correlation (r = 0.77) than that between dizygotic twins (r = 0.44),16 but no significant association has been shown between temperamental reactivity and infant attachment classification. Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van IJzendoorn15 give a good account of the relationship between temperament and attachment and the thorny issues in trying to unravel these complex relationships. When considering these issues, other authors have reminded us of the importance of potential transgenerational factors. 17

Natural history

Stability

The term natural history here refers to the progression, evolution and stability of early patterns of attachment. As a rule of thumb, providing there is no change in caregiving pattern (by either the same or different caregivers) and with secure attachment, there is evidence of overall stability of the pattern. 18 Insecure and, more so, disorganised attachment are associated with caregiver and caregiving difficulties, which are more likely to undergo change over a child’s development, both because of their likely inherent instability and because they are more liable to interventions which may influence them. 19 These factors are likely to be associated with a change in the child’s attachment pattern. However, Bowlby20 referred to ‘defensive exclusion’, by which he meant the child excluding new information about relationships which did not accord with his or her existing internal working models. This would suggest that there would need to be a sustained and perceptible change in caregiving to exert a meaningful effect on the child’s attachment pattern.

Evolution within disorganised pattern

There is some evidence21,22 that the behavioural pattern described as disorganised in infancy and early childhood evolves into coercive controlling or compulsive caregiving patterns in preschool and middle childhood, even in low-risk settings. 23 However, there may be continuing disorganisation at the representational level, as shown in narrative stem completion tasks19,24 and family drawings. 25

Change of assessed manifestation of attachment

With development, presumed manifestations of attachment, and therefore ways of assessing attachment, change. Thus, in infancy and early childhood, attention is given to the distressed child’s behaviour in relation to his or her caregiver, classically in separation and reunion procedures. In middle childhood, it becomes increasingly difficult to create sufficiently stressful situations in order to activate and then assess attachment behaviour. The solution has been to devise assessments of representation of attachment26 using narrative completions and pictures. In adolescence, there has been a further progression using linguistic representation of state of mind with respect to attachment, that is, coherence of accounts, by ‘surprising the unconscious’ (Ammaniti M, Candelori C, Dazzi N, De Coro A, Muscetta S, Ortu F, et al. University of Rome, 1990, unpublished protocol). The question then arises regarding how closely related the putative age-related manifestations or expressions of attachment are and how well they are measured by various proposed instruments used at different ages. This suggests that it might be preferable to refer to predictability rather than stability.

The significance of attachment and its relationship to psychopathology

In studying associations between attachment patterns and impaired functioning or psychopathology, the question arises about the nature of the association. If the impairment can be causally explained by prior or concurrent attachment difficulties, then the impairment can be properly considered as an aspect of the natural history. However, it is also possible that the antecedents of attachment difficulties – specifically, harmful parent–child interactions and their associated risk factors – could, independently of attachment, contribute to the functional impairment and psychopathology. In practice, it is difficult to disentangle these two mechanisms. 27 For this reason, discussion of the significance of attachment and its relationship to psychopathology is placed in its entirety under natural history.

There are various examples of studies that have attempted to link attachment patterns with subsequent disorders or outcomes. Studies have sought to show that behaviour problems in children can be predicted by attachment patterns. 28–30 These include both emotional and conduct problems. 30 For example, Speltz and colleagues31 found that only 20% of a sample of clinic-referred children with early-onset conduct problems were securely attached to their parents, whereas 72% of children in the control group were securely attached. Futh and colleagues32 examined how attachment representation related to social functioning and psychopathology in a sample of 113 children, 50% of whom were defined as high risk and 50% as low risk. Behaviour problems rated by teachers were linked to disorganised attachment patterns. Disorganised attachment was also predictive of poorer social functioning32 and poor school attendance, conduct disorder and academic underachievement. 33 Offenders are also more likely to report disturbed or insecure attachments, and separation from attachment figures in childhood is suggested as being associated with personality disorder in offenders. 34 Insecure attachment is also purportedly linked to increased reactivity to stress,35 notably in increased cortisol reactivity, which has itself been associated with a range of psychopathologies, including psychotic illness. 36 Longitudinal studies have linked disorganised attachment with hostility and hyperactivity, aggression and oppositional defiant disorder in children37 and with dissociative symptoms in 17- to 19-year-olds. 27 Furthermore, attachment disorders, as distinct from insecure attachment patterns, are purported to have increased comorbidity with conduct disorders, developmental delay, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. 38

One of the problems, however, is that much of this often-quoted research uses a range of methodologies, often in small or selected samples and often using bespoke or unvalidated instruments for measuring attachment. For us to be confident in these associations, this research needs to be carefully scrutinised using high-quality standards. Although insecure attachment patterns may represent risk factors for some future problems, approximately one-third of infants in normal populations show some form of insecure attachment. Thus, insecure patterns of attachment should not be considered as indicators of pathology, but rather, may be considered as potential risk factors for the child’s future functioning. 39 In this sense, although many people with psychopathology may be more likely to have had insecure attachments, many infants with attachment pattern difficulties may not go on to develop psychopathology. Indeed, some argue that measurements from the SSP are poor predictors of psychopathology in longitudinal studies. 40

Work that has sought to quantify these issues suggests that genetic influences for prosocial behaviours are strong and independent of attachment pattern. 41,42 The interaction between environment and genetics is complex, with different children varying in susceptibility to environmental influences on their subsequent attachment pattern. However, once a particular attachment pattern has developed, genetic influences appear to take a significantly less part in the development of those behaviours for which attachment patterns are seen as risk factors.

In summary, while, there is some evidence that disorganised attachment patterns are related to psychopathology, the link between insecure patterns and subsequent problems is not so clear. 39 This lends itself urgently for review, given that many clinicians use the paradigm of attachment in assessment and intervention, and there is a need to better understand the evidence that informs clinical practice. We have enough literature to consider that disorganised attachment is the most promising candidate. It is associated with poor outcomes and is a group to follow up, exploring systematically whether or not parental interventions are effective or cost-effective. Attachment disorders, to be discussed below (see Attachment disorders), could also be included in the overall term ‘severe attachment problems’.

Tools for assessing attachment patterns

For developmental reasons, there cannot be a single gold standard for the measure of attachment that is usable across ages of development and akin to the measurement of haemoglobin. As described above (see Change of assessed manifestation of attachment), there are, by necessity, different ways of assessing attachment. Moreover, whereas some tools use observation, others use self-reports, either by questionnaires or by interview, Q-sorts and parental questionnaires. 43 There are numerous tools, some of which vary in their coding of the same observational procedure (e.g. ABC + D and DMM).

Assessment of attachment behaviour

The Strange Situation Procedure

The first procedure, developed by Ainsworth and Wittig,2 was the SSP, also called the Strange Situation Test. This involved observing the child’s reactions in a situation where the child’s mother and a stranger (a safe adult unknown to the child) interact with the infant. In sequence, this involves the infant being with the mother, then a stranger entering; then the mother leaving and the infant being left with the stranger; then the mother returning and the stranger leaving; then the mother leaving the child alone; then the stranger returning; and finally, the mother returning and the stranger leaving. The stranger is included as a stressor, and the infant’s interaction with the stranger is not part of the assessment of security of attachment. Mary Ainsworth proposed that an attachment pattern can be observed and characterised by the child’s behaviour towards the mother at the two reunions. 2 She described three main attachment patterns within her work: secure attachment, ambivalent insecure attachment and avoidant insecure attachment. A fourth pattern of attachment, termed ‘disorganised insecure attachment’, was later added. 44 This addition was thought to be very significant in that, as described above, it was the greatest predictor of psychopathology. 45

The SSP was the first procedure for assessing and defining childhood attachment behaviours and has come to be the bedrock that defines attachment patterns in infancy and early childhood. The SSP is known to be cross-culturally valid but to have some cross-cultural differences. 46

For older children, there are modifications of the SSP to take account of the developmental changes relating to what is regarded as stressful. For preschool children, an adapted procedure extends the second separation to 5 minutes and the coding is modified to include controlling under disorganisation. 47 For 6-year-olds, the procedure extends the separation to 1 hour and there is no stranger. 22

Attachment Q-set

The attachment Q-set (AQS) can be used to describe secure base behaviour in a number of environments, either at home or in a public place, inside or outside. It is designed to cover the spectrum of attachment-relevant behaviours, with items concerning a broad range of secure base and exploratory behaviour, affective response and social cognition. The observer spends a set amount of time observing the child. 48

Representations of attachment

The two main procedures by which to assess the older child’s representations of attachment are narrative stem completion and the use of pictures, commencing from the age of 4 years. Variants include the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB),49 the Story Stem Assessment Profile (SSAP) (Hodges J, Steele M, Hillman S, Henderson K, 2002, unpublished data) and the Manchester Child Attachment Story Task (MCAST). 50 Drawings are used in the Separation Anxiety Test (SAT) and the School-age Assessment of Attachment. 51

Coherence of accounts

These assessments are based on semistructured interviews with the child, and what is rated is the linguistic representation of the child’s state of mind with respect to attachment. The two main tools are the Child Attachment Interview (CAI) for 7- to 11-year-olds, adapted from the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI),52 and the Friends and Family Interview. 53

Self-report attachment pattern questionnaires have also been used in 4- to 12-year-olds. 54

Meta-analysis evidence23 shows numerous subcatergorisations of attachment patterns, but does suggest that the measurement of disorganised attachment can be reliable.

Attachment disorders

Another group of attachment ‘problems’ has been defined in terms of psychopathology and these are ‘attachment disorders’. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),55 defines two main attachment disorders: reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited attachment disorder (DAD). According to the ICD-10,55 RAD is

characterized by persistent abnormalities in the child’s pattern of social relationships that are associated with emotional disturbance and are reactive to changes in environmental circumstances (e.g. fearfulness and hyper vigilance, poor social interaction with peers, aggression towards self and others, misery, and growth failure in some cases).

Disinhibited attachment disorder is described as55

a particular pattern of abnormal social functioning that arises during the first five years of life e.g. diffuse, nonselectively focussed attachment behaviour, attention-seeking and indiscriminately friendly behaviour, poorly modulated peer interactions; sometimes with associated emotional or behavioural disturbances. It tends to persist despite marked changes in environmental circumstances.

One issue with attachment disorders is that they extend beyond attachment relationships, and many of the difficulties included are not related to the central construct of attachment. There is a lack of clarity about the relationship between attachment disorganisation and attachment disorders, and the two may be conceptually different. There is widespread misconception about the meaning of the presumed diagnoses of attachment disorders. What is clear, however, is that children who acquire this ‘diagnosis’ are very troubled in terms of their behaviour and interpersonal relationships. Some very questionable interventions have been applied to them.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) classification system, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), refers to an inhibited and a disinhibited subtype, both requiring ‘pathogenic care’. 56 This attempts to integrate the literature on attachment patterns and disorders, although this has been criticised57 and some suggest that research evidence no longer supports the currently described defining features of attachment disorder.

The DSM-IV56 has now been updated to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-V). 58 In DSM-IV, RAD included an inhibited and a disinhibited subtype. In DSM-V, RAD no longer has a disinhibited subtype. RAD (emotionally withdrawn) remains, and a new diagnosis is created, called disinhibited social engagement disorder.

The WHO ICD-1055 system is being revised and is under consultation, with a new system being released in 2016. Other classification systems for developmental disorders have also been proposed. 59 It remains to be seen how these widespread changes in different classification systems will influence practice and research.

Is there a gold standard for measuring attachment?

As discussed, for developmental reasons there cannot be a single gold standard for the measure of attachment that can be used across ages of development and akin to the measurement of haemoglobin. Attachment is expressed by observable behaviour, providing there is an age-appropriate stressor. With development, it is possible to capture internal working models such as projective tests, as in the story stem procedures. 60 Later still, it is the coherence of the cognitive and emotional processing of childhood attachment experiences which appears to indicate security of attachment. 61 The research literature is peppered with instruments and tools that suggest they are measuring attachment with variable amounts of evidence. Although many of these may indeed be measuring attachment, there needs to be more caution and clarity on how they relate to each other. We cannot assume total stability in attachment patterns over time, and so concurrent administration of instruments will help us better understand concurrent validity. We have carried out a supplementary review to explore concurrent validity further.

The SSP will be our reference standard for this purpose, but we will also include other instruments compared concurrently with each other.

Alongside attachment patterns, research diagnostic criteria (RDC) for attachment disorders (such as RAD and DAD) have also been defined. They therefore also represent reference standards for systematic review.

The literature is ready, therefore, for a review that clarifies the current situation and subjects the vast literature on attachment to rigorous, high-quality standards. This will hopefully clarify our current knowledge, the quality of research that informs it and future potential research directions.

Interventions for attachment problems (disorganised attachment patterns and attachment disorders)

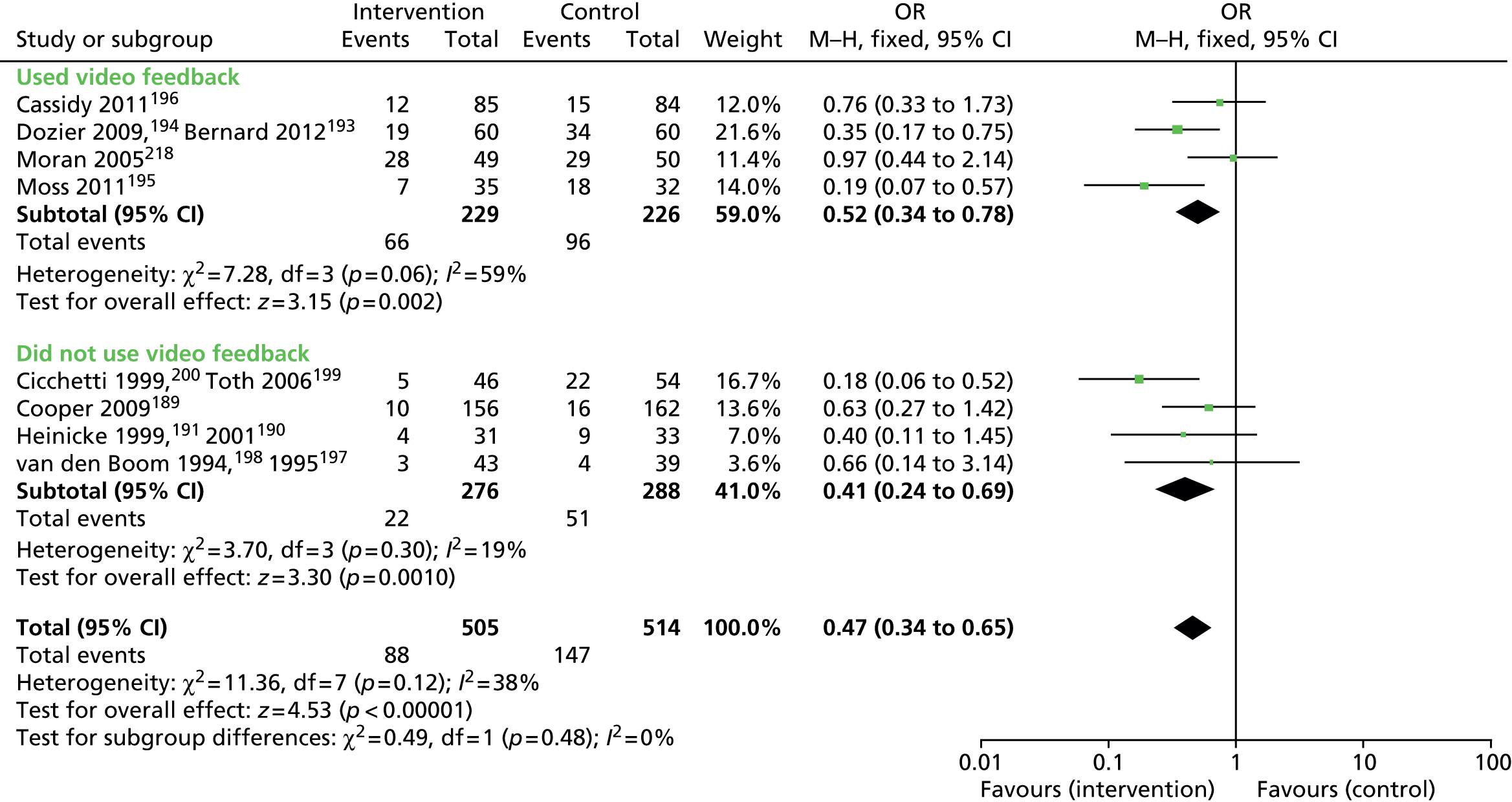

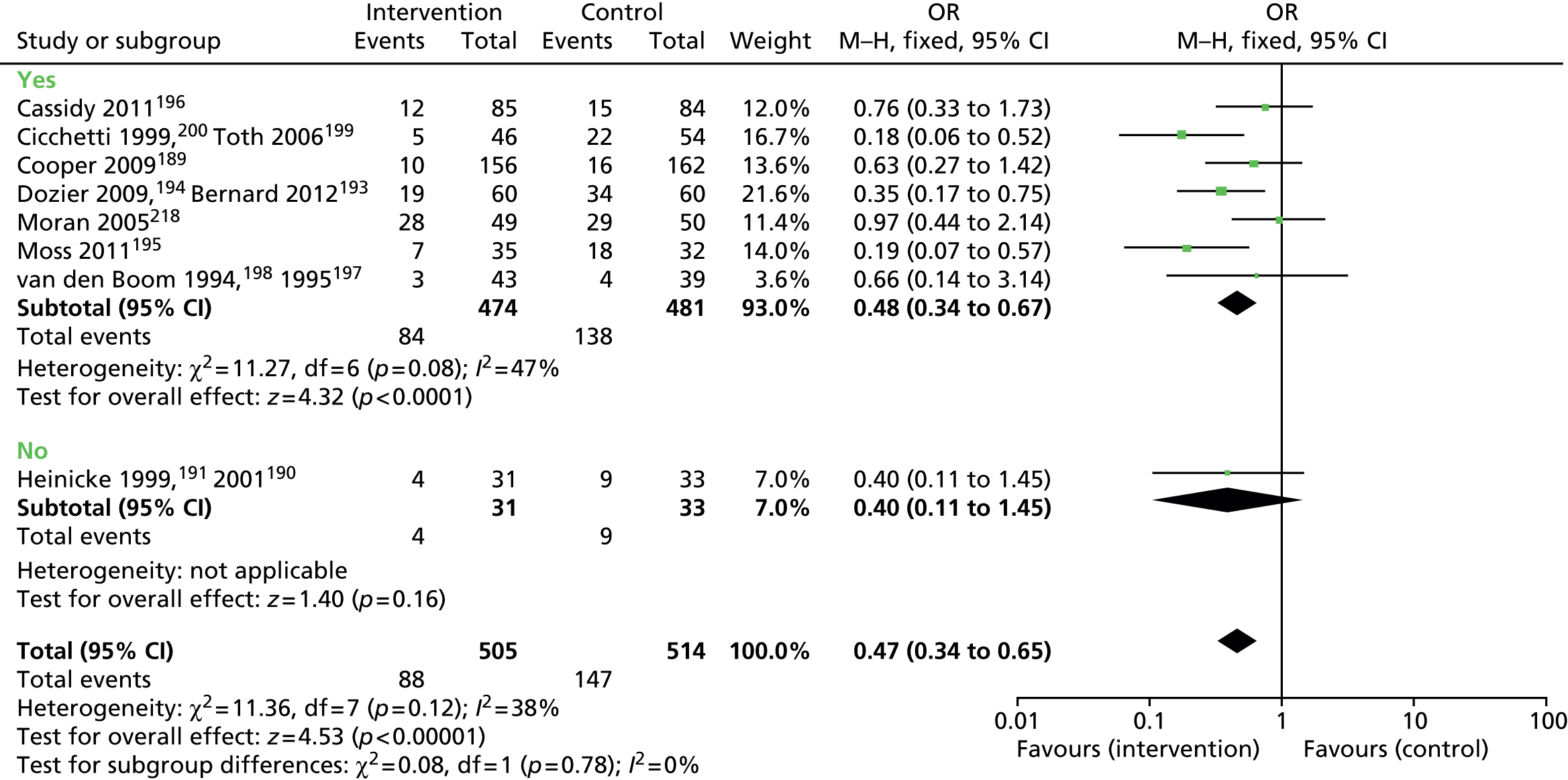

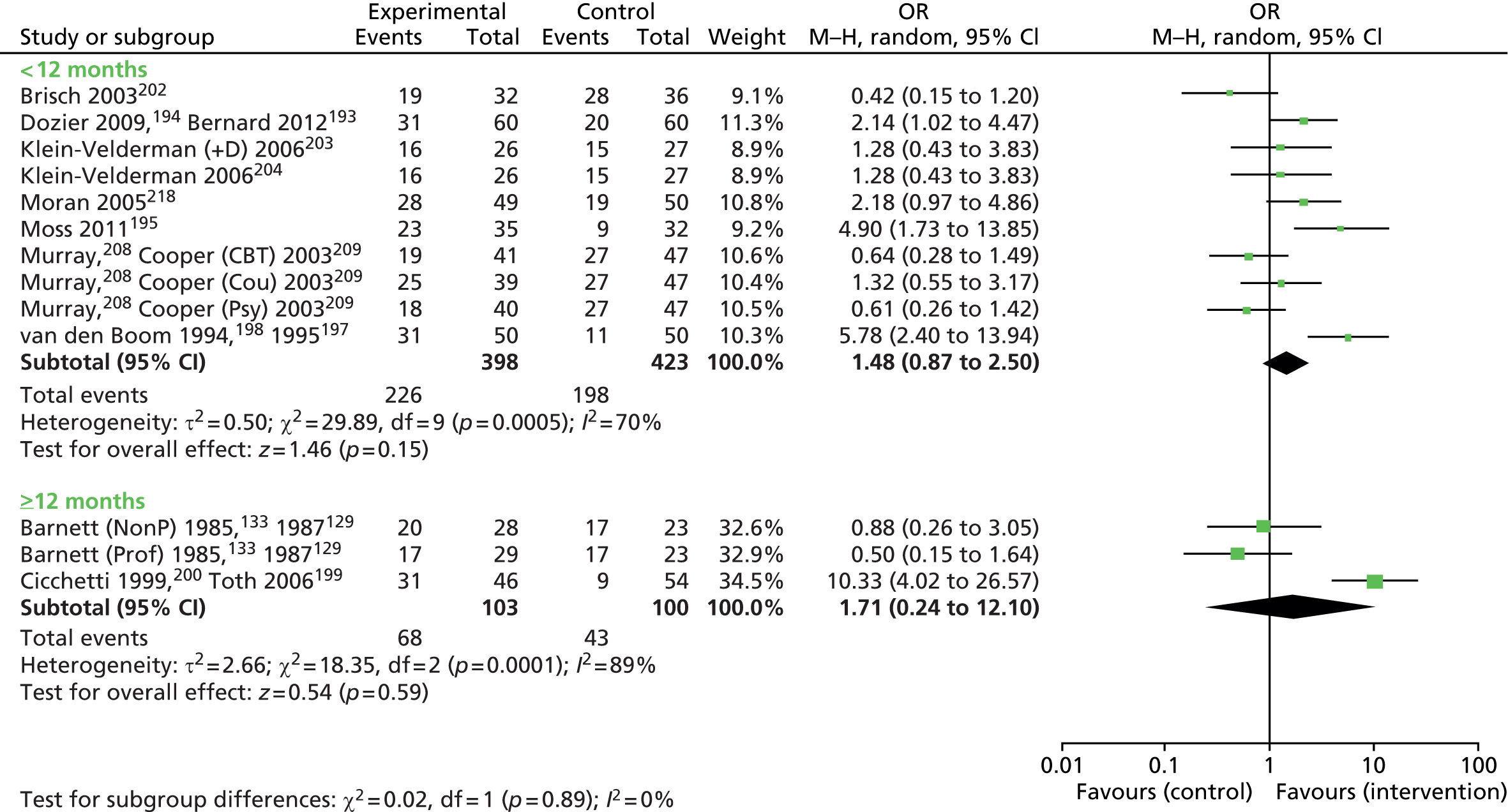

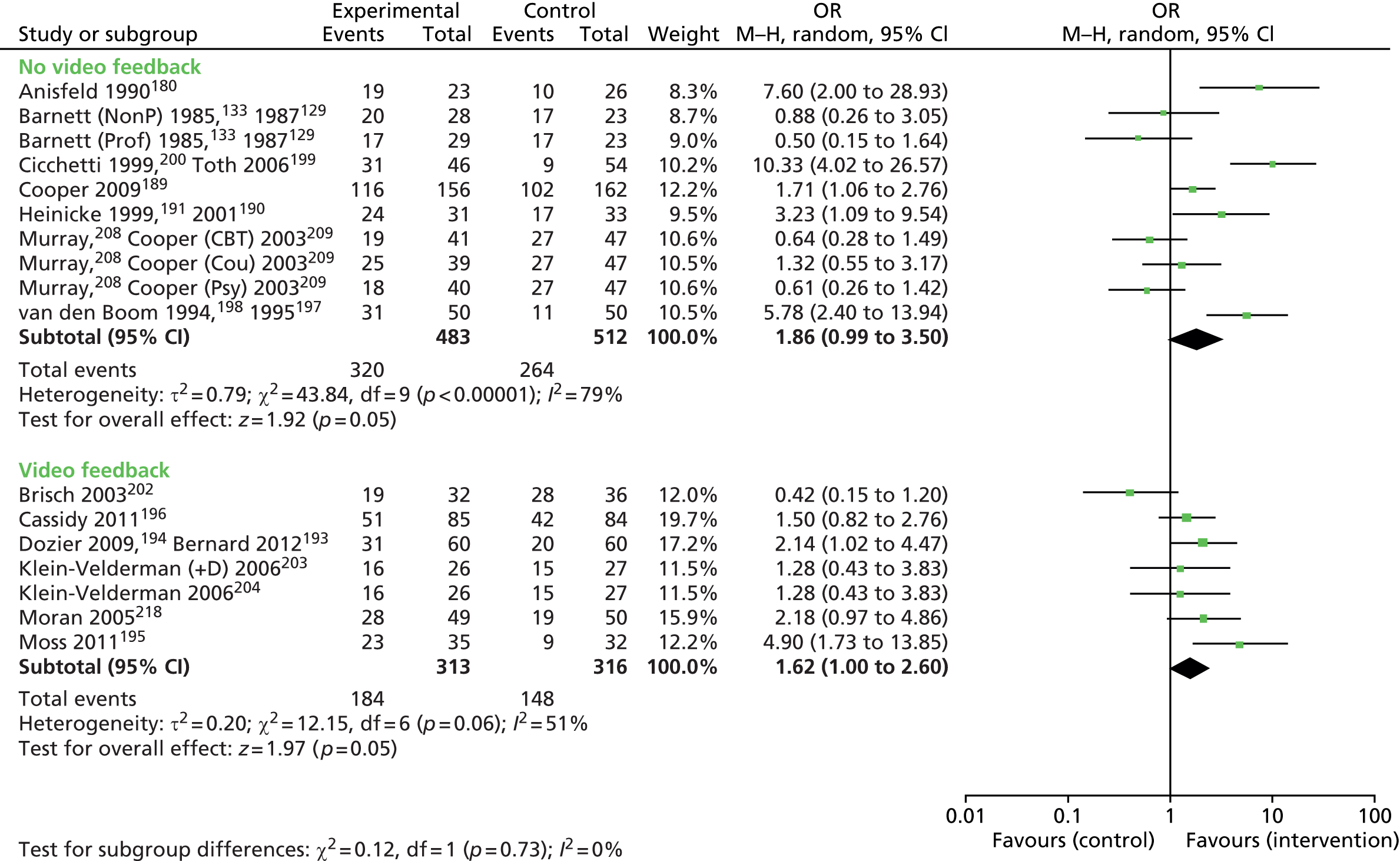

Juffer and colleagues62 undertook a meta-analysis of interventions aimed at increasing parental sensitivity, improving attachment or both. Seventy studies, including 88 interventions, were included within the analysis. The authors report that typically developing infants from middle-class families formed the basis of some samples. The most effective interventions were found to be those with a focused, behavioural approach which were aimed at increasing parental sensitivity. They were particularly effective when video feedback was used. Twenty-nine of the interventions investigated were specifically intended to improve attachment security. These showed a significant, although small effect size (d = 0.19). Again, those interventions which targeted parental sensitivity were the most effective at improving attachment relationships. Although this meta-analysis resulted in the development of a promising intervention,62 the interventions focused more widely than on children with severe attachment problems, including preventative interventions for children with no current attachment problems and at low risk for developing them. A more clinically based practitioner review highlights a range of current intervention options, and notes that many of these have maternal sensitivity and an improved understanding of the developmental needs of the child as central components of therapy. 63 More research systematically reviewing high-quality parental intervention studies in high risk groups will be a helpful addition to the literature.

Policy and practice

The introduction of the Every Child Matters agenda64 and the Children Act (2004)65 provided a framework for all services to work together holistically to support children’s development. The government has recognised that the early years of a child’s development are of vital importance. 66 This has been incorporated into the Children’s Plan,67 a 10-year strategy that aims to promote the development of social and emotional skills during the early years of a child’s life and onwards, including the promotion of attachment and bonding in the first years of life. The Early Years Foundation Stage68 was developed with a focus on learning, development and welfare standards, and looks at the whole range of a child’s cognitive and non-cognitive development.

An early years commission report, Breakthrough Britain: The Next Generation,69 published by The Centre for Social Justice, suggested that government policy was focusing on reducing economic poverty and improving educational achievement and not on the importance of relationships in young children’s development. It called for greater recognition of the role of attachment and family relationships in contributing to the well-being of children. The report argues that children who experience ‘relationship dysfunction’ are at a higher risk of later life difficulties than children exposed to economic or educational disadvantage.

The early years commission report68 highlights the importance of parent–child relationships during the earliest years of a child’s life and the need for effective intervention strategies aimed at parents in order to enhance children’s social and emotional health and well-being. The report acknowledges how emotional, environmental, physical, biological and social factors are all interrelated. It further concludes that parenting educational programmes are effective and recommends the use of parent management training. Such programmes include the Incredible Years programme70 and parent–child interaction therapy. 69

The Department of Health has now developed the Healthy Child Programme (HCP),71 an early intervention and prevention public health strategy for children aged 0–5 years. 72 The HCP feeds directly into the Children’s Plan68 and contributes to the National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. 73 The HCP aims to improve the health and well-being of children by adopting an integrated approach to support for children and families. This was delivered by health professionals, particularly health visitors, and was a service provided within Sure Start Children’s Centres. 74 The Department of Health advocates that effective implementation of the HCP should lead to ‘strong parent–child attachment and positive parenting, resulting in better social and emotional well being among children’. 71

The National Academy of Parenting Practitioners (NAPP)75 was established in 2007 with the aim of training and supporting practitioners in evidence-based parenting skills, programmes and therapies. Building on the knowledge gained by HCP in ‘what works’, a key aim of NAPP is to evaluate high-quality evidence in order that commissioners can commission effective parenting programmes. A commissioning toolkit containing a database of parenting interventions, available for different situations, was developed by the Children’s Workforce Development Council in 2008. 76 The Department for Education and Skills set up the Parenting Fund in 2004. This funds projects to provide direct support to parenting services and to support nurturing relationships. More recently, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT)77 has been rolled out across the country, with robust monitoring of child outcomes and parenting programmes coming to the fore in a second wave of therapies being delivered.

Recent government policy on early years education proposes to improve access to nursery education for the most disadvantaged 2-year-olds. 78 Given that those children with severe attachment problems are likely to come from the most disadvantaged families in society,79 this is likely to have an impact and change the relationships, responsibilities and tasks of those caring for infants. This is as yet unevaluated in terms of attachment and other future outcomes.

In a strategic review of health inequalities in England, Professor Sir Michael Marmot80 highlighted the importance of acting in the early years. In reviewing the child protection system, Professor Eileen Munro81 also suggested that early intervention is important, with a need to understand the importance of preventative services and early support for children.

In written evidence submitted to Frank Field’s review of poverty and life chances,82 ‘many highlighted the importance of strong parent and child relationships’ (see sections 6.11 and 6.15 in Field82) including ‘the forming of strong attachments’ (see section 6.11) [© Crown copyright 2010, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0 (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/)]. It is not, however, specifically listed in this report as a strong predictor of children’s life chances (see section 6.36), suggesting that although attachment is widely accepted as being important, additional research would be helpful to strengthen the evidence base.

The UK government response to these various reviews of early intervention services,83 the prevention of poverty and its impact on children,82 health inequalities80 (including those affecting children) and the child protection system84 was published in 2011. 85 This included a number of commitments, including an intent to continue to build an effective evidence base (see Supporting Families in the Foundation Years,85 pp. 76–8); to improve systems to measure school readiness, for example through a revised Early Years Foundation Stage Profile84 (p. 8185); to continue a rolling review of effective and evidence-based early intervention programmes (p. 8285); to continue to develop a more highly qualified early-years workforce (p. 8385); to refocus local services, including children’s centres, on work to support the most disadvantaged children (p. 8485); to give parents and local communities more influence over local services they receive (p. 8585); and to explore a new foundation to champion early intervention (p. 8585). These both directly and indirectly require an improved evidence base on which to draw. The review published here provides additional evidence on what works and describes future research that is necessary.

Purpose of the present review

As highlighted in the brief literature review above, there are many gaps and ambiguities in the literature, and this confirms that ‘the area of attachment is ripe for greater synthesis of evidence-based practice that covers both intervention and assessment’. 43 A particular limitation is the need to investigate the effectiveness of interventions in a UK setting. 86 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is currently considering this issue. The main focus of this review is to systematically review the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parenting interventions for severe attachment problems (disorganised attachment patterns and attachment disorders). Chapter 2 will describe the aims, objectives and scope of this work and the decision problem that faces decision-makers in the context of a UK setting.

Chapter 2 Aims, objectives and scope

Many proposed parenting interventions are time-consuming and costly, utilising the time of experienced clinicians and therapists. The availability of such interventions in services is, therefore, limited. At present, services face uncertainty about who to prioritise for treatment. What is on offer, when and to whom varies largely from service to service, whether this be local authority provision, voluntary provision or services provided by child health or child mental health teams. As described in the opening chapter, there has been an increasing focus on the importance of attachment, parenting and early-life relationships in government policy.

Aims

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned a systematic review to provide more evidence, specifically around parenting interventions for parents of children likely to develop severe attachment problems. The main aim of the HTA call was to study:

The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of an early parenting intervention for parents whose children show signs of developing severe attachment problems

Technology: Interventions to support parents in modifying child behaviour to prevent, reduce and treat severe attachment problems.

Patient Group: Parents of children who show evidence of developing severe attachment problems.

Setting: Community.

Control or comparative treatment: Treatment as usual.

Current review definition

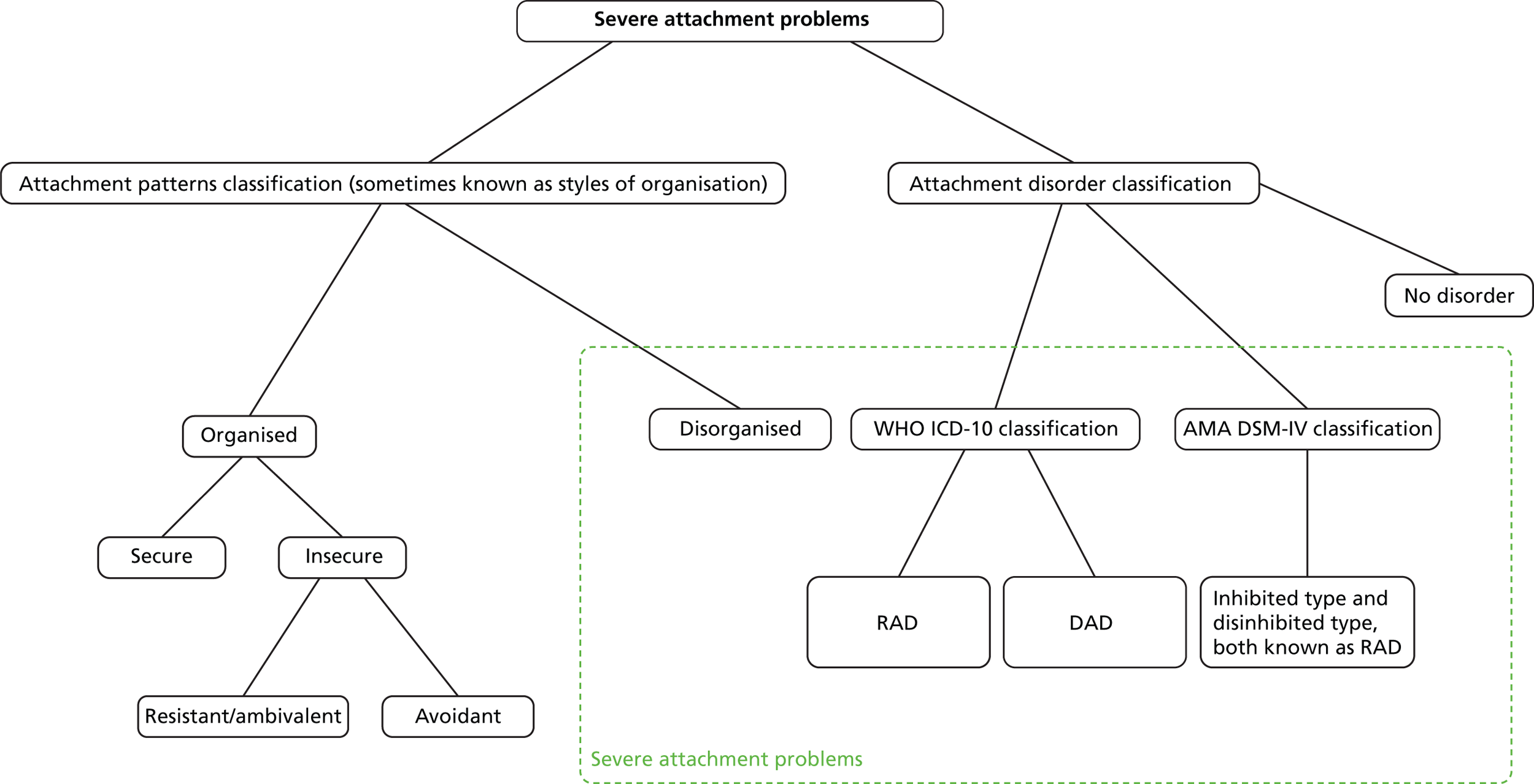

We need initially to define what is included within a definition of severe attachment problems. The extant literature discussed in Chapter 1 describes the best evidence to date linking both attachment disorders and disorganised attachment patterns with subsequent psychopathology. The use of insecure attachment as a predictor is less promising because of very high prevalence rates of insecure attachment (approximately 35%). 87 For the purposes of this review, therefore, we will consider severe attachment problems to be either attachment disorders, as defined using RDC (including RAD and DAD and the subtypes defined), or disorganised attachment patterns, using the SSP with the classification system that includes disorganised attachment pattern (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Severe attachment problems definition as defined by our review. AMA, American Medical Association.

Scope of the review

Resources for this review were focused around the specific NIHR HTA programme call to explore the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parental interventions for severe attachment problems. This is our main review. As the commissioned research has a focus around parental interventions, we have excluded studies that do not include parental interventions, where the focus may, for example, have been organisational, administrative or systemic. We include parenting/caregiver interventions working with a consistently available caregiver (alone or with caregiver and child, but not child alone). This would not, for example, include institutionalisation or multiple staff/child interactions as a parenting intervention. We are specifically examining the change in the child’s attachment patterns or disorder and any associated changes.

In order to carry out this work, it was necessary to carry out two supplementary reviews. The first supplementary review assessed the mechanisms for identifying severe attachment problems (see Chapter 4). We also carried out a second supplementary review to bolster evidence to the health economists about long-term follow-ups (see Chapter 5). This restricted itself to a review of 10-year follow-up or more of infants/children with severe attachment problems at baseline to enable us to explore outcomes of children at primary school age and above. We recognise that there is a huge literature on shorter-term outcomes which has been covered extensively in other systematic review work and is not the central focus of our main review of parental interventions.

Objectives

To achieve the overall aim of assessing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parenting interventions, we specified a series of objectives as follows:

-

to identify the range of intervention programmes that are designed for parents of children with severe attachment problems (see Chapter 6)

-

to examine the clinical effectiveness of intervention programmes designed for parents of children with severe attachment problems (see Chapter 6)

-

to examine the cost-effectiveness of intervention programmes designed for parents of children with severe attachment problems (see Chapter 7)

-

to identify research priorities for developing future intervention programmes for children with severe attachment disorders, from the perspective of the UK NHS (see Chapter 8)

-

to review the methods of assessment and/or diagnosis of attachment patterns and/or disorders (supplementary systematic review 1; see Chapter 4)

-

to examine the 10-year and longer outcomes among children with severe attachment problems and collect prevalence information from these studies (supplementary systematic review 2; see Chapter 5).

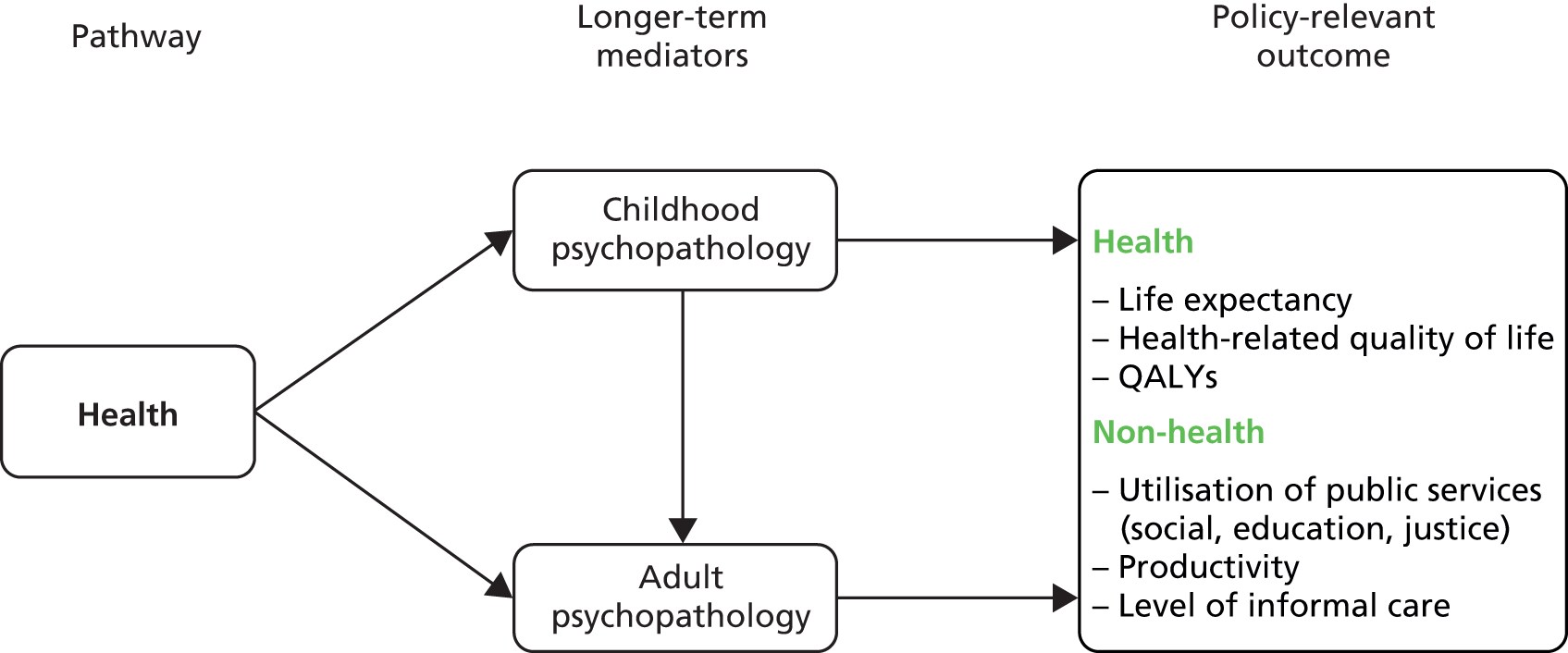

Description of the decision problem for the purposes of health economic analysis

How do we identify those who will benefit from interventions?

The first step in providing clarity as to who should be prioritised for treatment is to clarify how we identify the children who will benefit from the available treatments in a valid and reliable way. As discussed in Chapter 1, a central problem facing this review on attachment is large differences between attachment patterns and attachment disorders. Furthermore, how do we identify severe attachment problems in infants or children when stability over time may vary? For example, a meta-analysis of 840 infants in nine samples, where assessments took place between 2 and 60 months apart, found a stability of r = 0.34 for disorganised attachment. 23 The concept of attachment may also be used by clinicians in many different ways, with some straying far from Bowlby’s original construct1 by using it to describe broad aspects of the quality of relationships between parent and child. These all lead to misunderstandings in interpreting the literature.

Many attachment instruments have not been well validated. There is currently no biological measure of attachment patterns. In regard to attachment disorders, the construct is under scrutiny and subject to revision, as is the case with both the APA (DSM-IV to DSM-V56,58) and WHO [ICD-1055 to International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Edition (ICD-11)88] definitions of attachment disorders. We can, however, review extant research diagnostic systems for attachment disorders from both groups.

Clinicians do not currently know which is the best assessment tool to use to identify severe attachment problems. Therefore, the aim of the first supplementary systematic review of the literature is to identify the valid and reliable assessments of attachment patterns and disorders. As this review has its focus on parenting interventions, we are interested in identifying severe attachment problems early in life. In order to better understand the relationship between attachment patterns and attachment disorders, we will also explore how they relate to one another by looking for any studies that have compared their use in the same children at the same time.

Who is at risk and who is it that we should be treating?

Once we have identified clear ways of measuring severe attachment problems that are reliable and valid, we need to know what this means in terms of outcomes for the child, whether they receive the intervention or not. We need to understand more clearly what it means to have different attachment patterns in infancy1,6,8 or attachment disorders57 in older infants and children. What happens to those children in the longer term? For health economic reasons, we are particularly interested in studies that look at follow-up that takes infants or children at least to the end of primary school education, and hopefully considerably beyond, to inform any health economic modelling work. Very short- or short-term studies, although important for many reasons, are less useful for this purpose.

Using the findings from the first systematic review on assessment and measurement, we seek to evaluate the longer-term outcomes for those identified that have been left untreated. This forms the second supplementary systematic review (see Chapter 5). This will look at the evidence from longitudinal studies that follow children up for 10 years or more. We will explore attachment outcomes and, where possible, whether or not other outcome information is of value in its current form. This is a small supplementary review to inform the main focus of this work, which centres on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parental interventions.

Which parenting interventions work and are they cost-effective?

Clinicians are often unsure about the best intervention or treatment options for the children (and their families) identified as having severe attachment problems. Resources for these interventions are limited. There are ambiguities surrounding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions provided to families, including whether or not any improvement in attachment would be associated with a change in other outcomes (educational attainment, psychological well-being, quality of life, future criminality, etc.), and how acceptable these interventions would be in terms of the practicalities of delivering them in busy services and their acceptability to service users.

The attachment literature investigating the efficacy of parenting interventions consists of a variety of research designs, from single case-study designs to randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We seek to systematically review this literature, selecting only RCT designs which illustrate the highest level of evidence for the clinical efficacy of treatment. Do the interventions work (see Chapter 6) and are they cost-effective (see Chapter 7) in a current environment where funding is tight?

By liaising with experts and service users in patient and public involvement (PPI) groups as we conduct our reviews, we hope to identify any gaps in the literature and the acceptability of interventions that are found to be clinically effective.

Overview of process

A single comprehensive literature search strategy was carried out to identify the evidence needed for the review (see Chapter 3). This was then passed to three teams of systematic reviewers. The first conducted the main review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness alongside the health economists. Two supplementary review teams carried out work on assessment tools and 10-year follow-up after baseline severe attachment problems. At each stage of the review and the production of the final report, we adhered to the relevant guidelines for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews [Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD),89 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)90 and Cochrane91 guidelines].

Chapter 3 Literature search

The main focus of the literature search was to identify studies about the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parental intervention programmes for children with severe attachment problems. However, we also wanted more broadly to identify studies about methods of assessment and diagnosis. In order to provide additional information for the health economics aspect of cost-effectiveness, we systematically reviewed 10-year follow-up studies and extracted any outcome data and prevalence estimates from within these studies. It was decided, following an initial scoping exercise, that a single comprehensive search, as opposed to a separate search for each phase of the review, would be the most effective and efficient means of identifying the relevant literature for each phase. A large single search encompassing five search strategies was designed (see Appendix 1) to identify studies about attachment disorder/patterns/problems from the following perspectives:

-

assessment/diagnosis

-

epidemiology/natural history

-

named intervention programmes

-

controlled trials

-

economics/costs.

At all stages, the CRD guidelines were followed.

Search strategy

A range of databases and organisational websites, covering both databases of predominantly peer-reviewed citations and grey literature sources, were searched to identify relevant clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness literature:

-

PsycINFO

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

EMBASE

-

Social Policy & Practice

-

Science Citation Index (SCI)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH)

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)

-

Social Services Abstracts

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

HTA database

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

The Campbell Library

-

Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED)

-

Social Care Online

-

Research Register for Social Care

-

Index to THESES

-

OAIster

-

OpenGrey

-

Zetoc

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

metaRegister of Current Controlled Trials (mRCT)

-

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

-

UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN)

-

Health Services Research Projects in Progress (HSRProj).

The following organisation websites were also searched:

-

APA (www.psych.org/)

-

Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health (www.acamh.org.uk/)

-

Mental Health Foundation (www.mentalhealth.org.uk/)

-

MIND (www.mind.org.uk/)

-

Royal College of Psychiatrists (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/)

-

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) (www.nccmh.org.uk/)

-

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (www.nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml)

-

Institute for Attachment & Child Development (www.instituteforattachment.org/)

-

Association for Treatment and Training in the Attachment of Children (www.attach.org/)

-

YoungMinds (www.youngminds.org.uk/)

-

British Association for Adoption and Fostering (www.baaf.org.uk/).

All searches were carried out between 6 and 12 January 2012.

Search terms

The literature searches involved searching a wide range of databases covering research in the fields of health, mental health, health economics, education and social care. The search strategies were devised using a combination of subject indexing terms (where available), such as medical subject headings (MeSH) in MEDLINE, and free-text search terms in the title and abstract. The search terms were identified through discussion in the research team, by scanning background literature and by browsing database thesauri. Appendix 1 provides the full list of search terms for each of the included databases.

In a number of resources it was possible to conduct generic searches for ‘attachment’, rather than undertake five separate targeted searches. For the ‘assessment’, ‘controlled trials’ and ‘economics’ searches we included methodological search filters identified from the InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group Search Filter Resource (www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/index.htm).

This approach still retrieved relatively large numbers of results, and so we introduced a further facet of search terms for ‘children’, ‘parents’, ‘fostering’, ‘adoption’, ‘child neglect’ and ‘child abuse’. The introduction of this facet made the results more precise by removing much of the adult-oriented literature about romantic/couple attachment, God/religion attachment, friendship problems and other similar attachment-related items in which we had no interest. A further limit was introduced to the search strategy which removed selected publication types (letters, editorials and book reviews).

No limitations were made in terms of publication status, publication date or language.

Screening of citations

The titles and abstracts of bibliographic records were downloaded and imported into EndNote bibliographic management software (version 5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicate records were removed using several algorithms. Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies produced from the literature search. Full papers for potentially eligible studies were obtained and assessed for inclusion independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus, or by a third party when necessary, at both the abstract and full-paper sift.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Detailed separate participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design (PICOS) criteria were developed for the different phases of the review (for further details see each individual relevant chapter). Reviewers were instructed to be inclusive at the first sift (titles and abstracts) if there was any uncertainty about a reference, but to apply the PICOS criteria rigorously at the second sift (full paper).

Additional search strategies

A manual search of the reference lists of included studies was conducted to ensure that all studies had been identified. Authors were subsequently contacted to clarify information or gain additional studies that might be unpublished or ongoing. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that contained potentially relevant references for inclusion in the review were flagged, to be searched and reference checked at the end of the screening.

Stakeholder involvement

A range of different stakeholders were contacted to help us frame some of our ideas and understanding about the associated problems of caring for and conducting research with young people with attachment patterns or disorders. This PPI was integral to the work and the stakeholders formed part of the wider research team. They were involved from the creation of the protocol, helping to identify what the issues were, how to contextualise the intervention findings and how to present information, and will be involved in determining how the findings should best be disseminated. Throughout the project we consulted with academics with methodological expertise in the conduct of systematic reviews and economic analysis and content expertise of attachment theory and disorders.

In addition to membership of a steering group, we held PPI/stakeholder workshops in February 2013 and September 2013. The workshops provided an outline of the research project and the group (consisting of parents and expert academics working in the field) were asked to take part in a series of focus groups. We were particularly interested in generating knowledge which might inform the economic decision modelling process, currently available parenting interventions and desirable treatment options and mechanisms to disseminate the research findings. Appendix 2 provides a list of the stakeholder and advisory group members.

Chapter 4 Supplementary systematic review 1: validity of methods to identify attachment patterns and disorders

Introduction

The research objective of our first supplementary review was to review the methods of assessment and/or diagnosis of attachment problems and/or disorders.

The literature referring to the concept of infant attachment is vast. Defined clinical and research paradigms, such as attachment patterns and disorders as discussed in Chapter 1, differ from each other in a number of significant ways. In order for research on potential parental interventions for severe attachment problems to progress, it is necessary to be clear about how we are defining and identifying severe attachment problems. For example, the attachment pattern literature seeks to identify risk factors and identifiable behaviours that give us important developmental information. By contrast, the attachment disorder literature sits within the context of diagnostic systems. They therefore come from very different traditions. This supplementary systematic review seeks to shine further light on the evidence base in this area to date.

We have set out to explore studies in which tools available to screen, assess and/or diagnose attachment problems (both attachment patterns and attachment disorders) are compared with each other, and we are particularly interested in concurrent validity. This is to complement the fundamentally different work of Van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg,23 who empirically studied single measures of disorganised attachment but without comparison with other instruments. We provide information on the procedures surrounding each tool identified in the review, the psychometric properties and validity of the reported tools and the population studied. Where raw data are available in a comparison between a reference standard and another instrument concurrently used, we calculate sensitivity and specificity. We also carry out a quality assessment of each publication. Finally, for those instruments meeting the quality criteria and where comparison with a reference standard is available, we describe the instrument in more detail to form part of taxonomy.

By extracting this information, we can establish the variability in the assessment tools available and how they relate to the reference standards. This informed our choice of instruments to use in the second supplementary review, exploring outcomes of severe attachment problems at 10 years or more, and laid out the state of research in this field to inform future research directions.

Methods

The identified literature was dual screened according to the screening criteria specified in Inclusion criteria. Initially, titles and abstracts were reviewed independently, with disagreements discussed and resolved between reviewers and a third party when required. Complete copies of all potential ‘includes’ (papers to be included) were then obtained. When required, disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third party. Where a foreign language paper was identified, translation then screening was performed as above.

Inclusion criteria

All study designs were eligible in this stage of the review. For inclusion, studies had to provide sufficient data for extraction. Sensitivity and specificity analysis data were not a requirement, although this analysis was undertaken where possible (only where complete raw data were available).

The PICOS criteria were as follows:

-

Population and setting Children being assessed for attachment patterns or disorders where the research reports an average age of 13 years or below (we chose this in discussion with PPI and experts in the light of the overall aim of the review on early parental interventions). As discussed in Chapter 1, we refer to attachment patterns to mean any paper that explored attachment patterns, attachment styles or attachment organisation, recognising that different authors in the field use different terminology. We felt that it was important not to exclude any papers that were relevant but used different terminology.

-

Intervention Screening, assessment and/or diagnostic tools evaluating attachment patterns or disorders. The instrument must have been under development or evaluation, and must have been a completed tool or subscale on attachment rather than an individual item. Attachment pattern requires a primary caregiver (NB a member of staff in a child care institution is not considered a fair test).

-

Reference A comparison tool assessing attachment patterns or disorders identified by ICD-1055 or DSM criteria. 56

-

Outcomes Studies reporting on the psychometric properties and validity of the tools.

-

Study design Cross-sectional studies, case–control studies or prospective cohort studies incorporating any method of assessment (for example observation, semistructured interviews and questionnaires).

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed, piloted and adapted on the basis of this piloting. Subsequently, all studies were dual extracted and reviewers met to agree and discuss discrepancies in data items. Where studies had multiple publications, data were extracted as a single study. The following items were extracted from each study: study characteristics, population details, index and reference tool details, data for sensitivity and specificity analysis, economic resource information and psychometric properties of index and reference tools.

Diagnostic accuracy

Where possible, a sensitivity and specificity analysis was calculated.

Quality assessment strategy

Each study was assessed for methodological quality by two reviewers using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies – version 2 (QUADAS-2). 92 Discrepancies in quality assessment were discussed and resolved between reviewers. QUADAS-292 is a validated quality assessment tool for diagnostic studies. It consists of four key domains: domain 1, patient selection; domain 2, index test(s); domain 3, reference standard(s); and domain 4, flow and timing [flow of patients through the study and the timing of the index and reference test(s)]. To help reach a judgement on the risk of bias, signalling questions were included. These flagged aspects of study design related to the potential for bias and aimed to help reviewers make risk-of-bias judgements. A further three questions in the tool consider the applicability of the patient selection, index tool and reference tool. Each item was rated ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ according to the guidance provided.

Following quality assessment of the first few studies, it became apparent that the range of study designs made two questions irrelevant to some studies, as follows:

-

Domain 2. Question 2: if a threshold was used, was it prespecified?

-

Domain 3. Question 1: is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?

In order to avoid penalising studies where these aspects were not relevant, we agreed to enter a response of ‘not applicable’. The following circumstances led to an opinion of ‘not applicable’: in cases where screening was performed using observational opinion, question 2 is not applicable; in studies where diagnosis is not the objective and, therefore, a ‘cut-off’ is not specified, question 2 is not applicable; and finally, in case–control studies where only one tool is assessed, question 1 is not applicable.

Data synthesis

A meta-analysis was not conducted because it was not appropriate. A wide range of instruments were compared with the reference standards, most of which were not repeated in further study to enable comparison between studies. A descriptive summary of results is presented.

Results

The initial literature search identified 10,167 publications after the removal of duplications. Following title/abstract screening and additional reference checks, 454 publications were full-paper screened. Figure 2 (PRISMA diagram) details the flow of screened, included and excluded articles. A total of 35 publications24,25,47,50,52,93–122 met the inclusion criteria for this phase of the review, of which two109,112 duplicated data from other included reports.

FIGURE 2.

A PRISMA diagram illustrating the results of the screening process in the supplementary review.

Three studies were found that compared an attachment assessment procedure with the reference standard (SSP)93–95 (see Table 1 for a summary of the characteristics of these studies). Two of the studies were conducted in the USA93,94 and the third study was conducted in Romania. 95 The ages of the samples ranged from 17 to 25 months. There was no significant difference in the proportions of boys and girls in any of the studies.

Study characteristics

An overview of study characteristics is detailed in Table 1 and a taxonomy of the tools identified is presented in Tables 2 and 3. Thirty-three studies were published between 1988 and 2011, of which the majority were undertaken in the USA (n = 1824,47,93,94,96–100,102–104,106,111,113,115,116,118,121), with the rest spread across the UK (n = 450,52,107–109), Canada (n = 425,105,110,119), Germany (n = 2101,122), the Netherlands (n = 2117,120), Romania (n = 194) and Spain (n = 1114).

| Author, year and country of publication | Participant details: children | Participant details: parents | Test instrument(s) (classification)/tool description and administration | Comparison test(s) (classification)/tool description and administration | Coding classification key (see Box 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aber et al. (1990)96 USA |

n = 58 Age range 19–24 months 24 males Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | Modified SSP (summary scores derived) Scales of 0–3 and qualitative assessment on 18 behavioural variables. Time 30 minutes. Delivered by research assistant. Conducted in playgroup room |

Teacher-sorted Toddler AQS Adapted Waters and Deane (1985),48 92-item sort. Time 7–14 hours. Delivered by teacher. Conducted in playgroup room |

|

| Backman (2003)97 USA |

N = 37 Clinical: n = 20; ethnicity 10 mixed Normative: n = 17; ethnicity 10 white Age range 1–5 years Gender unknown |

Clinical group: mean age 28.30 years, age range 18–44 years; ethnicity seven white Normative group: mean age 33.24 years, age range 24–44 years; ethnicity 10 white |

MIMRS (summary scores derived) 7–10 task cards rated on 5-point scales. Time not reported. Delivered by mother and researcher. Location not reported |

AQS Waters (1987),123 90-item sort. Time 2–6 hours. Delivered by mother. Location not reported |

|

| Boris et al. (2004)98 USA |

n = 69 Age: mean/SD not reported, range 13–48 months Gender: 45–54.5% male Ethnicity unknown |

Age: mean/SD not reported, range 17–35 years Ethnicity: 9.1–55.0% white |

Clinical assessment (DSM-IV criteria for presence/absence of attachment disorders) Diagnostic manual. Time not reported. Delivered by experienced clinical assessor. Laboratory setting |

SSP: standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] and AQS: Waters and Deane (1985),48 90-item sort. Time: 2 hours. Delivered by trained observers. Conducted at home |

(CC5) |

| Bureau et al. (2009)99 USA |

n = 43 Age range 7.3–9.6 years Gender unknown Ethnicity 81% Caucasian |

Details unknown | MCDC scales (CC28) Behavioural rating scales from 1 to 9. Time 1 hour 5 minutes. Delivered by interviewer. Laboratory setting |

SAT (CC9) Six story drawings. Time not reported. Unclear who administered. Location not reported |

(CC9) (CC28) |

| Cassidy (1992)47 USA |

n = 52 Mean age 6.2 years, range 5.7–6.8 years 26 males Ethnicity unknown |

Mean age 35.2 years, range 28–44 years Ethnicity unknown |

Incomplete stories with doll family (CC21) Six stories rated on 5-point scales. Time not reported. Delivered by experimenter. Location not reported |

Separation–reunion episode (CC24) 9-point scales. Time not reported. Delivered by experimenter. Location not reported |

(CC24) (CC21) |

| Clarke-Stewart et al. (2001)93 USA |

n = 60 Age range unknown Mean age 16.6 months (SD 1.11 months) Gender unknown Ethnicity 79% white |

Average age 32 years Ethnicity unknown |

CAP (CC6) Three stressor stimuli under observation. Time 1 hour. Delivered by research assistant. Laboratory setting |

SSP (CC6) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1969),3 (1978)8] |

(CC6) |

| Crittenden et al. (2007)100 USA |

n = 51 Age: mean 39 months, (SD 5.2 months) range 2.5–4 years Gender: 57% males Ethnicity Caucasian |

Details not reported | SSP (CC11) SSP; Ainsworth extended method [Crittenden (1985)124]. Time: 20 minutes for procedure. Delivered by undergraduate coders. Laboratory setting |

SSP (CC26) Cassidy–Marvin classification method.47 Reclassification of Ainsworth extended method video. Delivered by trained graduate coders. Laboratory setting and SSP (CC22) PAA classification method. Reclassification of Ainsworth extended method video.8 Delivered by trained graduate coders. Laboratory setting |

(CC26) (CC11) (CC22) |

| Equit et al. (2011)101 Germany |

n = 299 Mean age 3.94 years, range 0–5 years 182 males Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | DC: 0–3R used to screen psychiatric referrals for any diagnosis Diagnostic manual. Time not reported. Delivered by psychiatrist and clinical psychologist. Location not reported |

ICD-1055 used to screen psychiatric referrals for any diagnosis Diagnostic manual. 3–4.5 hours. Delivered by child psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. Location not reported |

|

| Fagot et al. (1996)102 USA |

n = 175 (completed cases, n = 96) Aged 18 and 30 months at first and second visits, respectively Gender unknown Ethnicity 95% European American |

Details unknown | Modified SSP 30 months (CC12) Time not reported. Shortened Ainsworth procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] (only one reunion episode) |

SSP 18 months (CC7) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1969)3] |

(CC7) (CC12) |

| Finkel et al. (1998)94 USA |

n = 16 Age range 19–25 months Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | LTS (CC7) Similar to the SSP. Time 88 minutes. Delivered by researcher. Conducted at LTS facility |

SSP (CC7) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1969)2] |

(CC7) |

| Fury et al. (1997)103 USA |

n = 171 Age range 8–8.9 years Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Age range 12–37 years at delivery Ethnicity 80% Caucasian |

Family drawing modified checklist (CC17) and Family Drawing Global Rating Scale (summary scores derived) 21-item checklist and eight 7-point scales. Time 20 minutes. Delivered by examiner. Conducted at home |

SSP (CC13) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

(CC13) (CC17) |

| Gleason et al. (2011)95 Romania |

n = 136 Age range unknown Mean age 22 months Gender unknown Ethnicity 53.9% Romanian |

Details unknown | DAI (diagnostic interview: indiscriminately social/disinhibited RAD or emotionally withdrawn/inhibited RAD) 8-item interview. Time not reported. Delivered by trained interviewer. Location not reported |

PAPA (diagnostic interview: RAD, ADHD, disruptive behaviour disorder, major depressive disorder and functional impairment) Diagnostic interview, details not reported. Time not reported. Unclear who administered. Location not reported |

|

| Goldwyn et al. (2000)50 UK |

n = 31 Age unknown Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | MCAST (CC9) Details not reported. Time not reported. Unknown who administered. Location not reported |

SAT (CC8) Details not reported |

(CC8) (CC9) |

| Gurganus (2002)104 USA |

n = 243 Age range 4–18 years Mean weighted age 8.6 years 122 males Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | CBRS (CC1) Fifty-two items rated on 4-point scales. Time not reported. Caregiver self-report questionnaire. Conducted at home |

RADQ (summary score derived) Questionnaire details not reported. Time not reported. Caregiver self-report questionnaire. Conducted at home |

(CC1) |

| Head (1997)105 Canada |

n = 42 Mean age 6 years, range 5–7 years 23 males Ethnicity unclear |

Details unknown | Revised PBAR (CC1) One to five drawings. Time 2 hours. Delivered by research assistant. Laboratory setting |

SSP (CC22) SSP (unclear method reference). Time 21 minutes. Laboratory setting |

(CC22) (CC1) |

| Madigan et al. (2003)25 Canada |

n = 123 Mean age 7.2 years 50 males Ethnicity unknown |

Reported based on infant’s previous attachment classification Mean maternal age: avoidant = 28.1 years; secure = 29.4 years; resistant = 30.7 years Ethnicity unknown |

Family Drawing clinical scheme (summary scores derived) and Family Drawing checklist (markers of attachment styles) and Family Drawing Global Rating Scale (CC17) and Family Drawing clinician’s opinion (CC3) 18-marker clinical scheme, 22-item checklist and 7 items rated on 7-point global rating scale. Time 30 minutes. Delivered by examiner. Location not reported |

SSP (CC3) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

(CC3) (CC17) |

| Mangelsdorf et al. (1996)106 USA |

N = 100 (complete data n = 74) Clinical: n = 34, 54.1% male, ethnicity 89.2% Caucasian Normative: n = 40, 40.5% male, ethnicity 95.1% Caucasian Aged 14 and 19 months at first and second visits |

Clinical group: mean maternal age 27.5 years Normative group: mean maternal age 28.9 years Ethnicity unknown |

SSP (CC11) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

AQS Waters (1995),125 90-item sort. Time 3 hours. Delivered by observers. Conducted at home |

(CC11) |

| Minnis et al. (2009);108 McLaughlin et al. (2010)109 UK |

N = 77 Age range unknown Clinical: n = 38, mean age 6.57 years, 66% males Normative: n = 39, mean age 6.44 years, 67% males Ethnicity 100% white British |

Details unknown | CAPA-RAD (screening tool for RAD and other diagnosis) Twenty-eight items. Time 15–30 minutes. Delivered by interviewer. Location not reported and WRO (screening tool for RAD) Yes/no rating on 20 items. Time 15 minutes. Delivered by observer. Location waiting room and RPQ (screening tool for RAD) Fourteen items rated on a scale of 0–3. Time not reported. Delivered by teacher. Location not reported |

MCAST (CC10) Four vignettes rated on a scale of 1–9. Time not reported. Delivered by researcher. Location not reported RAD children screened with ICD-10 vs. normative sample |

(CC10) |

| Minnis et al. (2010)107 UK |

N = 82 Complete data n = 55 (33 male) Clinical: n = 28; normative n = 27 Age range 5–8 years Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | CMCAST (CC10) Four stories. Time 22 minutes. Delivered by research assistant. Location not reported |

RAD children, screened with ICD-10 vs. normative sample and MCAST (CC10) Four stories. Time 17 minutes. Delivered by research assistant. Location not reported |

(CC10) |

| Ogilvie (2000)110 Canada |

N = 303 Complete data n = 285 Mean age 12.17 years, range 6–20 years. 151 males Ethnicity 53% Caucasian |

Age range 20–70 years (two unspecified) Ethnicity 59% Caucasian |

BERS + BAT (summary scores derived) Eighty-five items rated on scale of 0–3 Time estimated 15 minutes. Caregiver self-report questionnaire. Conducted at home |

RADQ (summary score derived) Thirty items rated on scale of 1–5. Time estimated 10 minutes. Caregiver self-report questionnaire. Conducted at home |

|

| Oppenheim (1990);111 Oppenheim (1997)112 USA |

n = 35 Mean age 44 months, range 35–58 months 19 males Ethnicity 100% Caucasian |

Details unknown | ADI (summary scores derived) Six vignettes rated on scales of 1–3 and 1–4. Time 20–40 minutes. Delivered by trained interviewer. Conducted at school |

AQS version 3.0 Waters (1987),123 90-item sort. Time 72 hours. Delivered by mother. Conducted at home and Bespoke separation–reunion observation (summary scores derived) Seven items rated on scales of 0–4 and 0–3. Time 25–48 minutes. Delivered by teachers and observers. Conducted at school |

|

| Posada (2006)113 USA |

n = 45 Age range 36–43 months 25 males Ethnicity 44 white |

Average maternal age 33.04 years, paternal age 35 years Ethnicity 44 white |

AQS Waters (1995),125 90-item sort and 4-scale scores. Time 5–6 hours. Delivered by researchers. Conducted at home |

SSP (CC16) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

(CC16) |

| Roman (2010)114 Spain |

N = 148 Age range unknown Adopted group: n = 40, average age 75.68 months, 72.5% male Care centre children: n = 50, average age 77.60 months, 48% male Normative: n = 58, average age 75.17 months, 50% male Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | SSAP (markers of attachment styles) Thirteen narrative story stems. Time not reported. Delivered by interviewer. Location not reported |

IMAS [shortened AQS, Chisholm et al. (1999)126] Twenty-three items. Time not reported. Delivered by interviewer. Location not reported and RPQ (summary scores derived) Ten items. Time not reported. Caregiver self-report questionnaire. Conducted at home or foster centre |

|

| Shmueli et al. (2008)52 UK |

N = 227 Age range unknown Clinical: n = 65, mean age 10.4 years, 58.5% male, ethnicity 82% white Normative: n = 161, mean age 10.9 years, 50.3% male, ethnicity 70% white |

Details unknown | CAI (CC20) Fifteen items rated on scales of 1–9. Time 20–80 minutes. Delivered by interviewer. Location not reported |

SAT (CC2) Nine pictures. Time not reported. Delivered by experienced interviewers. Location not reported |

(CC2) (CC20) |

| Silver (2005)115 USA |

N = 233 Complete data n = 140 Age range unknown Mean age 7 years 76 males Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | Family Drawing checklist (markers of attachment styles) and Family Drawing Global Rating Scales (summary scores derived) and Family Drawing principal investigator’s opinion (CC4) and Family Drawing clinician’s opinion (CC4) and Modified relatedness scales (CC29) Twenty-three-item checklist and six 5-point global scales and 15 items rated on 4-point scales. Time not reported. Delivered by researcher. Conducted at home |

SSP (CC4 and CC23) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1969)2] |

(CC4) (CC23) (CC29) |

| Sirl (1999)116 USA |

N = 69 Complete data n = 56 Mean age 6.57 years, range 5.77–7.25 years 25 males Ethnicity 100% African American |

Details unknown | Modified ASCT Four story stems coding on scale of 0–1 for over 30 socioemotional codes (modified Rochester Narrative coding system). Time not reported. Delivered by examiner. Laboratory setting |

SSP with separation–reunion procedure (CC26) Items rated on 7- and 9-point scales. Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] with separation–reunion procedure [Cassidy and Marvin (1989)47] |

(CC26) |

| Smeekens et al. (2009)117 the Netherlands |

n = 129 Complete data n = 111 Age range unknown Mean age 63.6 months 59 males Ethnicity unknown |

Age range 22–47 years Ethnicity unknown |

SSSP (CC4) Modified Ainsworth procedure [Ainsworth (1978)7] (only one separation lasting 4 minutes). Time 10 minutes |

AQS version 3.0 Waters (1995),125 90-item sort. Time 2 hours. Delivered by trained observer. Conducted at home |

(CC4) |

| Solomon et al. (1995)24 USA |

n = 69 Mean age 70.5 months, range 57–94 months Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Reported in groups based on method of recruitment: by telephone (n = 17) 18% non-white; by letter (n = 52) 21% non-white No further details |

Adapted separation–reunion story completion task (CC30) Five stories. Time 1 hour. Delivered by researcher. Laboratory setting |

Separation–reunion episode (A15) Details not reported. Time 65 minutes. Delivered by parent and researcher. Laboratory setting |

(CC15) (CC30) |

| Spieker and Crittenden (2010)118 USA |

n = 306 Aged 15 and 36 months at first and second visits Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Details unknown | Modified SSP (CC27 and CC19) Modified Ainsworth procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] (stranger reunion removed and second separation duration 5 minutes) |

SSP (CC4) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

(CC4) (CC27) (CC19) |

| Tarabulsy and Moran (1997)119 Canada |

n = 79 Aged 15 and 36 months at first and second visits Gender unknown Ethnicity unknown |

Pre-term mothers, mean age 29 years (SD 4.9). Full-term mothers, mean age 30 years (SD 4.9) Ethnicity unknown |

AQS Waters and Deane (1985),48 90-item sort. Time 2–3 hours. Delivered by observers and caregiver. Conducted at home |

SSP (CC8) Standard Ainsworth laboratory procedure [Ainsworth (1978)8] |

(CC8) |

| van Dam and Van IJzendoorn (1988)120 the Netherlands |

n = 39 Age range unknown Mean age 18 months 19 males Ethnicity unknown |