Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/05/05. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The draft report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Deborah Christie has received funding from the pharmaceutical industry for consultancy and lecturing.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aggressive behaviours among young people: a public health priority

The prevalence, harms and costs of aggressive behaviours, such as bullying and violence, among young people make addressing them a public health priority. 1–4 The World Health Organization considers bullying to be a major adolescent health problem, defining it as the intentional and repetitive use of physical or psychological force against another individual or group. 5 This includes verbal and relational aggression that aims to harm the victim or their social relations, such as through spreading rumours or purposely excluding them. 6,7 The prevalence of bullying among British youth is above the European average,8 with approximately 25% of young people stating that they have been subjected to serious peer bullying. 9

Being a victim of peer bullying is associated with an increased risk of physical health problems;10 engaging in health risk behaviours such as substance use;11–13 long-term emotional, behavioural and mental health problems;14–16 self-harm and suicide;17 and poorer educational attainment. 18,19 Students who experience physical, verbal and relational bullying on a regular basis tend to experience the most adverse health outcomes. 20 There is also emerging evidence suggesting that childhood exposure to bullying and aggression may also influence lifelong health through biological mechanisms, for example through reduced telomere length. 21 The perpetrators of peer bullying are also at a greater risk of a range of adverse emotional and mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety. 8,22

Although bullying is different from youth violence, which involves the intention of physical force, bullying is often a precursor to more serious violent behaviours commonly reported by British youth. For example, one UK study of 14,000 students found that 1 in 10 young people aged 11–12 years reported carrying a weapon and 8% of this age group admitted they had attacked another with the intention to hurt them seriously. 23 By age 15–16 years, 24% of students report that they have carried a weapon and 19% report attacking someone with the intention of hurting them seriously. 23 Interpersonal violence can cause physical injury and disability, and is also associated with long-term emotional and mental health problems. There are also links between aggression and antisocial behaviours in youth and violent crime in adulthood. 24,25 Although all bullying does not necessarily involve or lead to violence, and youth violence may emerge in isolation from bullying or victimisation, these different aggressive behaviours share common determinants which make common universal approaches to address aggressive behaviours appropriate. 14,22,23,25

Although a universal problem, the prevalence of aggressive behaviours varies significantly between schools, both in the UK22,26 and internationally. 27,28 For example, among 11- to 14-year-olds in London, the frequency of reporting being bullied at school has been found to vary from 21% to 47% across different schools, and the frequency of reporting being recently involved in physical violence from 22% to 52%. 26 There are also marked social gradients in bullying and violence among young people, with both family deprivation and school-level deprivation increasing the risk of experiencing bullying. 29 As well as leading to further health inequalities, the economic costs to society as a whole of youth aggression, bullying and violence are extremely high. For example, the total cost of crime attributable to conduct problems in childhood has been estimated at about £60B a year in England and Wales. 30

Policy responses to aggression and bullying among young people

Reducing aggression, bullying and violence in British schools has been a consistent priority within recent public health and education policies. 31–33 Schools are at the ‘epicentre’ of peer bullying, as the site where it most often begins, and where children and young people are most concerned about bullying and victimisation. 34 The Home Office has found that assaults against 10- to 15-year-olds are more likely to happen at secondary school than anywhere else, with 95% of victims likely to know the perpetrator. 35 There is also increasing educational concern regarding low-level provoking and aggressive behaviours in secondary schools, which are educationally disruptive and emotionally harmful and can lead to more overt physical aggression over time. 36–38

In 2009, the Steer Review concluded that schools’ approaches to discipline, behaviour management and bullying prevention vary widely and have little or no evidence base, and further resources and research are urgently needed to combat aggressive behaviours and other conduct problems. 38 The award of National Healthy Schools status, and its equivalents in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, had previously required that schools foster a ‘supportive’ and ‘positive’ school environment, although there has been no evidence-based guidance on how to achieve this39 and it is no longer a statutory requirement in England. Furthermore, the national schools inspectorate, Ofsted, is no longer required to inspect schools on how they promote students’ health and well-being. 40 There is, therefore, an urgent need to determine which interventions are effective in addressing bullying and aggression in schools, and to scale up such interventions across local and national school networks.

The current British government has stated its commitment to greater intersectoral, joined-up action to promote youth development in its ‘Positive for Youth’ strategy, including through work in schools and reducing bullying and aggression among adolescents. 41 There is also an increasing recognition that bullying and aggression can be serious barriers to academic attainment, and therefore schools must address these if they are to fulfil their core mission. 18 Most recently, the cross-government response to the 2011 riots included a commitment to assess existing school-based interventions focused on youth violence and ensure schools know how to access the most effective methods and approaches. 42

Effective school-based interventions to address bullying and aggression

A number of reviews identify school-based interventions to address bullying and aggression that are effective. The effects of curriculum-only interventions are patchy and often not sustained. 43–49 Although several reviews find insufficient studies to assess the effects of whole-school interventions, two report on the particular effectiveness of such approaches. First, Vreeman and Carroll’s review concluded that whole-school interventions addressing different levels of school organisation were more often effective in reducing victimisation and bullying than curriculum interventions. 46 The authors suggest this might be because these interventions address bullying as a systemic problem meriting an ‘environmental solution’. Smith and colleague’s review draws similar conclusions and suggests that whole-school interventions are likely to be universal in reach and a cost-effective and non-stigmatising approach to preventing bullying. 43

This is in keeping with other evidence from the UK and internationally, which shows that schools promote health most effectively when they are not treated merely as sites for health education but also as physical and social environments which can actively support healthy behaviours and outcomes. 50,51 These new school environment interventions thus take a ‘socioecological’52 or ‘structural’53 approach to promoting health, whereby behaviours are understood to be influenced not only by individual characteristics, but also the wider social context. A recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded systematic review of the health effects of the school environment found evidence from observational and experimental studies that modifying the way in which schools manage their ‘core business’ of teaching, pastoral care and discipline can promote student health and potentially reduce health inequalities across a range of outcomes, including reductions in violence and other aggressive behaviours, as well as improvements in various measures of mental health and physical activity and reductions in alcohol, tobacco and drug use. 51

Two recent studies report on randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies of interventions that aim to enable schools to improve aspects of their core business in order to reduce aggression and other health risk behaviours. First, the Aban Aya Youth Project (AAYP) is a multicomponent intervention that enables schools to modify their social environment as well as deliver a social skills curriculum. This approach is designed to increase social inclusion by ‘rebuilding the village’ within schools serving disadvantaged, African-American communities. To promote whole-school institutional change at each school, teacher training was provided and an action group was established (comprising both staff and students) to review policies and prioritise actions needed to foster a more inclusive school climate. For boys, the intervention was associated with significant reductions in the growth of violence (47%) and aggressive behaviour (59%). 54 The intervention also brought benefits in terms of reductions in sexual risk behaviours and drug use, as well as provoking behaviour and school delinquency. Second, the Gatehouse Project in Australia also aimed to reduce health problems through changing the school climate and promoting security, positive regard and communication among students and school staff. As with the AAYP, an action group was convened in each school, facilitated by an external ‘critical friend’ and informed by data from a student survey, alongside a social and emotional skills curriculum. A cluster RCT found consistent reductions in a composite measure of health risk behaviours, which included violence and antisocial behaviour. 55,56

School environment interventions that impact on a range of health risk behaviours including aggression are likely to be one of the most efficient ways of addressing multiple health harms in adolescence because of their potential for modifying population-level risk, as well as their reach and sustainability. 51 Multiple risk behaviours in adolescence are subject to socioeconomic stratification, and strongly associated with poor health outcomes, social exclusion, educational failure and poor mental health in adult life. 57 A recent King’s Fund report on the Clustering of Unhealthy Behaviours Over Time emphasised the association of multiple risk behaviours with mortality and health across the life-course, and the policy importance of reducing multiple risk behaviours among young people through new interventions that address their common determinants. 58

Restorative approaches

The Steer Review called for English schools to consider adopting more ‘restorative’ approaches to prevent bullying and other aggressive behaviour, and to minimise the harms associated with such problems. 38 These approaches have been developed and used widely in the criminal justice system. Their central tenet is to repair the harms caused to relationships and communities rather than merely assign blame and enact punishment. Such approaches have now been adapted for use in schools and can operate at a whole-school level, informing changes to disciplinary policies, behaviour management practices and how staff communicate with students in order to improve relationships, reduce conflict and repair harm. An example of such restorative practices currently employed in schools is the use of circle time to develop and maintain good communication and relationships. 59 Restorative ‘conferencing’ can also be used in schools to deal with more serious incidents. 59

Restorative approaches have been evaluated only using non-random designs, although such studies do suggest that the restorative approach is a promising one in the UK60–62 and internationally. 63–65 For example, in England and Wales, the Youth Justice Board evaluated the use of restorative approaches at 20 secondary schools and six primary schools, and reported significant improvements regarding students’ attitudes to bullying and reduced offending and victimisation in schools that adopted a whole-school approach to restorative practice. The study concluded that, when embedded in institutional cultural change, restorative principles and practices have the greatest potential. Similarly, a 2-year evaluation of restorative practices in Scottish schools found that the schools that reported the greatest success were those that focused on addressing the school culture and promoting supportive relationships throughout the whole school community. 61 A study carried out in Bristol, England, also concluded that when restorative approaches are implemented on a whole-school basis they can transform the institutional climate. 62

Restorative approaches thus appear to have the potential to complement school environment interventions such as the AAYP and the Gatehouse Project. They thus offer a highly promising way forward for reducing aggressive behaviours among British youth. A recent Cochrane review found no randomised trials of interventions employing restorative approaches to reduce bullying in schools and recommended that this should be a priority for future research. 49 If trialled and found to be effective, such a universal school-based approach could be scaled up to reach very large numbers of young people and deliver significant population-level health improvements. The Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on complex interventions recommends that interventions are piloted to assess feasibility and acceptability, when these are uncertain, prior to Phase III randomised trials. 66 This is the case with health improvement interventions in British secondary schools, which can be particularly challenging because of schools’ increasingly narrow focus on educational attainment and an inspection framework which largely ignores student well-being. 67,68

Health Technology Assessment commission

To address the public health problems and key research gaps outlined above, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) research programme at the NIHR commissioned a phased evaluation of a universal school-based intervention to reduce aggression and bullying among British secondary school students in 2011.

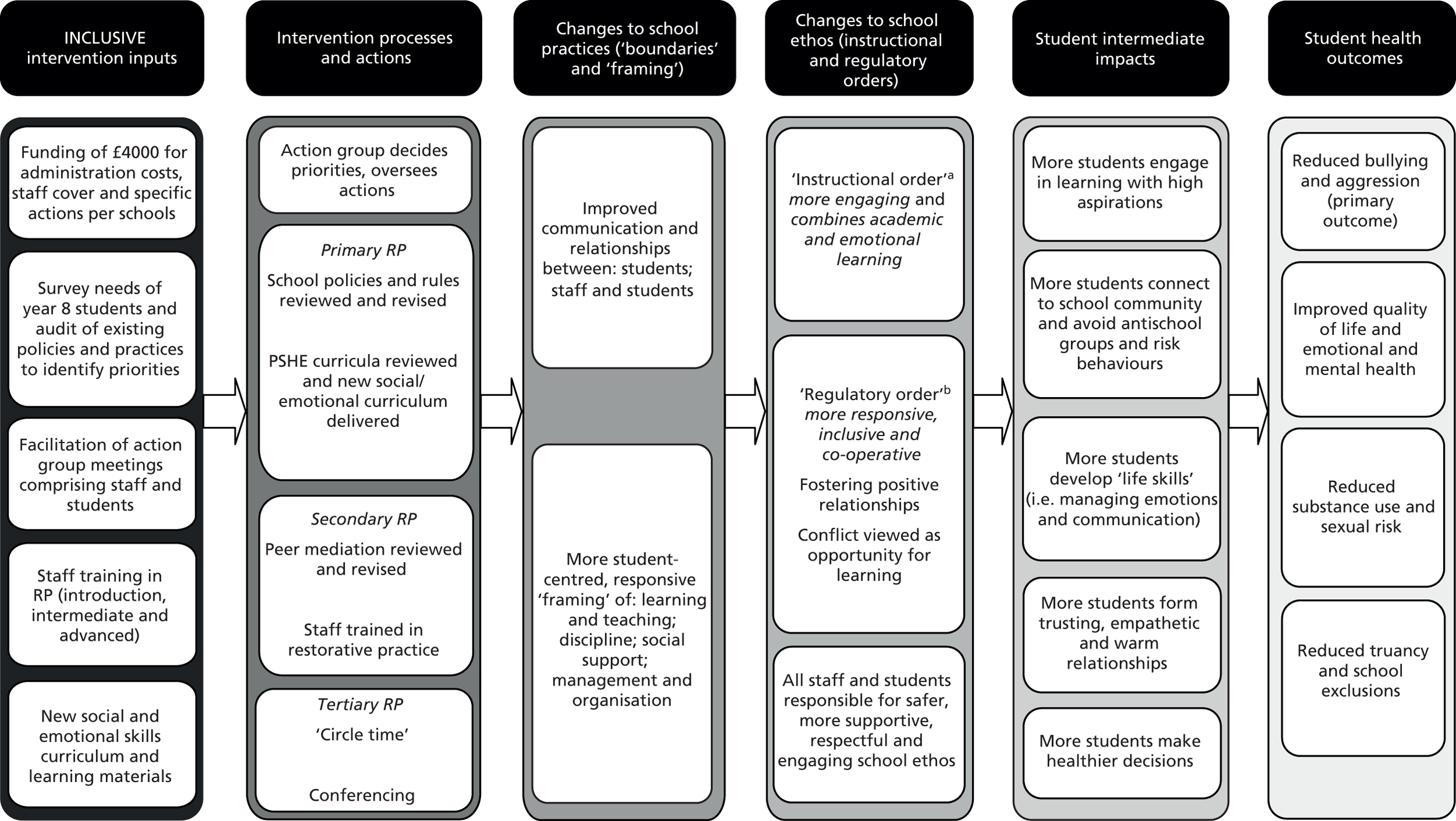

The INCLUSIVE (initiating change locally in bullying and aggression through the school environment) intervention is a new school environment intervention that is informed by AAYP54 and the Gatehouse Project,55 as well as the Healthy School Ethos (HSE) project that was piloted in two English schools in 2007–8. 69 These interventions offer a systematic and scalable process by which schools are enabled not only to deliver a health promotion curriculum but also to modify how they manage their ‘core business’ of teaching, pastoral care and discipline in order to encourage a more health-promoting school environment. We modified these previous interventions and combined them with a restorative approach to school management, teaching practices and conflict resolution (Figure 1). The intervention logic model is informed by Markham and Aveyard’s theory of human functioning and school organisation. 70 Although primarily focused on reducing aggression and bullying, our intervention is also hypothesised to promote student health more generally, including through reduced alcohol consumption and drug and tobacco use, reduced sexual risk behaviour and improved psychological well-being.

FIGURE 1.

The INCLUSIVE logic model. PSHE, personal, social and health education; RP, restorative practice. a, i.e. learning and teaching in school; b, i.e. discipline, social support and sense of community in school.

The HTA programme provided funding for 20 months for a pilot trial to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the INCLUSIVE intervention and trial methods over one academic year. Criteria were agreed for progression to a full trial, with further funding for a Phase III trial of a 3-year intervention being dependent on a new funding application. Research costs were provided by the HTA programme. As NHS support costs for the intervention were not available, because the intervention was being undertaken in schools, intervention funding was provided by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, the Big Lottery Fund and the Coutts Charitable Trust. The research was funded for 20 months from July 2011 until February 2013. The project was planned to begin in April 2011; however, funding was not confirmed by the HTA programme and by our intervention funders until March 2011. Subsequent contracting issues meant that the official start of the research project was delayed until July 2011.

INCLUSIVE intervention

The INCLUSIVE intervention involves the following inputs: £4000 of funding per school; a needs assessment survey; an external expert facilitator; staff training in restorative practices; and a social and emotional skills curriculum. (Box 1 has more details of each of these intervention inputs.) These inputs were intended to enable schools to convene an action group comprising students alongside staff and support that group in the processes of reviewing and revising school rules and policies relating to discipline, behaviour management and staff–student communication; reviewing and enhancing the school’s existing peer mediation and ‘buddying’ schemes via which they recruit and train students to assist their peers in resolving conflicts within the school environment before they escalate; implementing restorative practices; identifying local priorities; and delivering the six-module social and emotional skills curriculum. The action group comprised (at a minimum) six students and six staff, including at least one senior management team (SMT) member, and one member of each of the teaching, pastoral and support staff. Membership of specialist health staff, such as the school nurse and/or local child and adolescent mental health services staff, was desirable but optional. The action group was intended to meet at least six times over the school year (i.e. approximately once every half-term).

-

Funding: each school action group received £4000 to cover schools’ administrative costs, provide cover for staff involvement and fund specific actions to support change (e.g. training and equipment for peer mediators, convening student ‘away days’ to revise school rules, etc.). This funding was provided in addition to the costs of the external facilitator, whose services were provided to intervention schools free of charge as part of this intervention. Allocation of the £4000 of funding was determined by the school action group, with financial responsibility taken by a SMT member of the action group.

-

Needs assessment: we used our baseline survey of students in year 8 to examine students’ views of the school environment and their experiences of aggression and bullying (overall and by sex) and various known risk factors for aggression and bullying. Detailed reports were produced using these student survey data that presented tailored information for each intervention school on students’ reports of the following: school engagement and ‘connectedness’; perceptions of safety/risks; relationships, social support and social skills; and teaching and learning about social and emotional skills in personal, social and health education (PSHE) lessons. Data were ‘benchmarked’ against the average across all four intervention schools and these reports were used by school action groups to determine local priorities and inform decision-making regarding their actions to improve the school environment.

-

Facilitator: schools were supported by an expert facilitator (a freelance education consultant with previous secondary school leadership experience). This individual co-ordinated the intervention in each school and held preliminary meetings with the SMT, school staff and students to build interest, commitment and trust. The facilitator also supported the action group to ensure broad participation, critical reflection and effective delivery; organised the staff training (see below); assisted schools in integrating a restorative approach across existing school policies and practices; and worked with schools to adapt, and integrate the curriculum (see below) into, the school timetable and existing lesson plans; and provided school leaders with ongoing, informal support and feedback.

-

Staff training in restorative practices: the facilitator provided an introduction to restoratives approaches (approximately 30–60 minutes) to all staff in the school, and a further half-day of training were delivered by a specialist training provider and offered to all staff (a minimum of 20 staff in each school were required to attend). This initial half-day of training focused on introducing them to restorative practices, such as circle time. Circle time is a technique that can be used in schools to support the development of young people’s social and emotional literacy and communication skills to promote positive relationships. It typically involves students and teachers sitting together in a circle formation in order to share their ideas and feelings and to discuss other social, emotional or curricular issues. The central underlying principle of circle time is that all participants are treated as equals and valued for their unique contribution.

An enhanced 3-day training course in restorative practices for secondary schools was also provided by the specialist training provider for 5–10 staff at each school, including training in formal ‘conferencing’ to deal with more serious incidents, such as violent incidents or serious bullying within school, through bringing together students, parents and staff. The aim of these school-based restorative conferences is to provide a safe, inclusive environment in which all individuals involved in a serious aggressive incident feel able to constructively and fully participate in the process of resolution to repair any harm which has occurred to relationships, as well as to identify appropriate forms of punishment. Through the use of a safe, inclusive conference environment facilitated by trained staff both the victim(s) and perpetrator(s) can participate.

-

Curriculum: students in year 8 received 5–10 hours’ teaching on restorative practices, relationships, and social and emotional skills based on the Gatehouse Project curriculum. Our curriculum was devised as a set of learning modules which schools could address in locally decided ways, using either our teaching materials and methods or their own existing approaches if these aligned with our curriculum. The following modules were covered: establishing respectful relationships in the classroom and the wider school; managing emotions; understanding and building trusting relationships; exploring others’ needs and avoiding conflict; and maintaining and repairing relationships. Informed by the needs assessment data, schools tailored the curriculum to their own needs and could deliver modules as ‘stand-alone’ lessons, for example within PSHE, and/or integrated into various subject lessons (e.g. English).

The intervention was specifically designed to enable local tailoring, informed by the needs assessment report and other local data sources. These locally adaptable actions occurred within a standardised overall process with various core standardised intervention elements, such as the whole-school staff training in restorative practices; review and revision of school rules and policies; and a new social and emotional skills curriculum for year 8 students (aged 12–13 years). This balance of standardisation and flexibility, which is common practice in complex interventions,66,71 enables a balance between fidelity of the core components with local adaption,72 thus allowing schools to build on their current good practice, and also encouraging students and staff to develop ownership of the work, which may be a key factor in intervention effects. 69,73 The facilitator worked with schools to ensure all members of the action group were supported in identifying and undertaking locally determined actions to improve the school environment. 69

This study examined the feasibility and acceptability of planning and delivering the intervention over 1 academic year only, as this was deemed sufficient time to pilot a new whole-school restorative approach. It was anticipated that a subsequent Phase III trial of effectiveness would involve a 3-year intervention. The first 2 years would involve an externally facilitated intervention (i.e. schools being provided with additional funding, facilitation and training, etc.) and the third year would involve schools continuing with the intervention unassisted to assess its sustainability in the absence of facilitation.

Involvement of young people

Young people from the National Children’s Bureau’s (NCB) young researchers group (YRG) were involved both in the development of the intervention and in the research protocol for the pilot study. This is a group of approximately 15 young people who receive research training from the NCB. This group includes young people with medical conditions, who have a range of experiences of health services, as well as young people from a diversity of social backgrounds. Two meetings with the NCB young researchers were held: one on 16 July 2011 and the other on 3 November 2011.

The first meeting (July 2011) was held before the intervention commenced and focused on the design of the intervention and baseline survey, in particular which aspects of the school environment might influence bullying and how we might assess this, as well as seeking the YRG’s advice more generally on how to engage young people in the research and ensure high survey completion rates. The YRG provided important insights into which aspects of their school environment they felt might influence levels of aggression. The group had a range of suggestions which fell into four broad categories: staff, sports/extracurricular, school policies and common areas/break times. The group consistently reported that staff should also be available to discuss private matters and respect students’ views. These issues were fed into the intervention design, particularly through the needs assessment survey design and through facilitators, who worked with school action groups to focus on changing the school climate, and informed the baseline survey.

The second meeting (November 2011) coincided with the formation and initial meetings of the school action groups and, therefore, focused on exploring the young researchers’ views on how to encourage students to participate in these action groups (see Public involvement by young people during the intervention for further information).

Study aim, objectives and research questions

The long-term goal of the investigator team is to examine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the INCLUSIVE intervention for reducing bullying and other aggressive behaviours among young people in the UK. In line with current guidance concerning the evaluation of complex public health interventions,66 the aim of this pilot trial was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of implementing and trialling this intervention in English secondary schools. We chose to do so in a challenging purposive sample of schools rated by the Ofsted school inspectorate as either satisfactory or good/outstanding, and with moderate or high rates of student entitlement to free school meals (FSM). The study had three objectives.

The first objective was to assess whether prespecified feasibility and acceptability criteria were met, which were agreed with the NIHR HTA programme co-ordinating centre and deemed necessary conditions for progressing to a Phase III trial. In order to meet this objective, we collected and analysed data to address the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: was it feasible to implement the intervention in (at least) three out of four intervention schools? (This was assessed according to the following implementation criteria: the needs assessment survey had an ≥ 80% response rate; the action group met six or more times during the course of the school year and was always quorate; the action group reviewed and revised school policies; whole-school actions were a collaborative process involving staff and students from across the school; peer mediation and/or ‘buddying’ schemes were reviewed and enhanced; ≥ 20 staff completed restorative practice training; restorative practices were used; and the student curriculum was delivered to year 8 students.)

-

RQ2: was the intervention acceptable to a majority of school SMT members and a majority of action group members?

-

RQ3: did randomisation occur and was this acceptable to the school SMT?

-

RQ4: did (at least) three out of four schools from each of the intervention and comparison arms accept randomisation and continue to participate in the study?

-

RQ5: were the student survey response rates acceptable in (at least) three out of four comparison schools?

The second objective was to explore students’, school staff members’ and facilitators’ experiences of implementing and trialling the INCLUSIVE intervention and how these varied across the different school contexts in order to refine the intervention/methods. In order to meet this objective, we collected and analysed data to address the following RQs:

-

RQ6: what are students’, school staff members’ and intervention facilitators’ experiences of the intervention, particularly in terms of whether it is feasible and acceptable?

-

RQ7: how successfully was each component implemented and did this vary according to school context?

-

RQ8: how acceptable were the research design and data collection methods to students and staff?

The third objective was to pilot and field test potential primary, secondary and intermediate outcome measures and economic methods prior to a Phase III trial. In order to meet this objective, we collected and analysed data to address the following RQs:

-

RQ9: which of the pilot indicative primary outcome measures of aggressive behaviour performs best according to completion rate, discrimination and reliability statistics?

-

RQ10: was it feasible and acceptable to collect data at baseline and follow-up on pilot indicative primary (aggressive behaviour), secondary (quality of life, psychological distress, psychological well-being, health-risk behaviours, NHS use, contact with the police, truancy and school exclusion) and intermediate outcome measures (students’ perception of the school environment and connection to the school)?

-

RQ11: is it feasible to measure year 8 students’ health utility status using the Child Health Utility 9D (CHU-9D) measure and to embed an economic evaluation within a Phase III trial?

Chapter 2 Pilot trial design

In this chapter of the report we describe the study design and methods used to assess the HTA ‘progression criteria’ (objective 1), explore participants’ experiences of the process of implementing and trialling the intervention (objective 2) and examine pilot trial outcomes and develop a framework for economic evaluation (objective 3), as well as provide details regarding trial registration, governance and ethics. The process of undertaking the trial and the methods of data collection are described in detail in Chapter 3.

Overview of study design

The intervention was piloted during the 2011–12 academic year (September 2011–July 2012). The study had a 1 : 1 allocation cluster RCT design, as recommended in the MRC complex intervention guidance for Phase II exploratory trials. 66 Following baseline surveys, four clusters (schools) were randomly allocated to the intervention arm and four to the comparison arm. The intervention was intended principally to augment, rather than to replace, existing activities (e.g. training, curricula, etc.) in intervention schools. However, it was intended to change existing non-restorative disciplinary school policies and practices when restorative approaches were deemed more appropriate. Comparison schools continued with their usual practices.

Quantitative and qualitative process evaluation data were collected and analysed to assess whether prespecified feasibility and acceptability criteria were met (see section Health Technology Assessment progression criteria below for more details). We also collected qualitative and quantitative process data to explore students’, school staff members’ and facilitators’ experiences of implementing and trialling the INCLUSIVE intervention and how these varied across the different school contexts in order to refine the intervention and trial methods (see Process evaluation: participants’ experiences below for more details). Although not intended to (and therefore not powered to) examine intervention effects, this study did provide the opportunity to pilot our primary, secondary and intermediate indicative outcome measures, and develop methods for a future economic evaluation (see sections Piloting of outcome measures and Economic evaluation below for more details).

Sampling and recruitment

Schools eligible to participate were mixed-sex, state secondary schools (including academies) in London and south-east England judged by the national schools inspectorate (Ofsted) as being ‘satisfactory’ or better and in which ≥ 6% of students are eligible for FSM. Independent schools, single-sex schools and schools with unsatisfactory Ofsted ratings and/or schools in which < 6% of students were eligible for FSM (which represent the least economically deprived 15% of British schools) were not eligible for inclusion. We excluded schools rated as unsatisfactory because we judged that such schools, being subject to special measures interventions, would not be able to implement our intervention. We excluded schools in which < 6% of students were eligible for FSM because we aimed to test the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in more challenging school contexts.

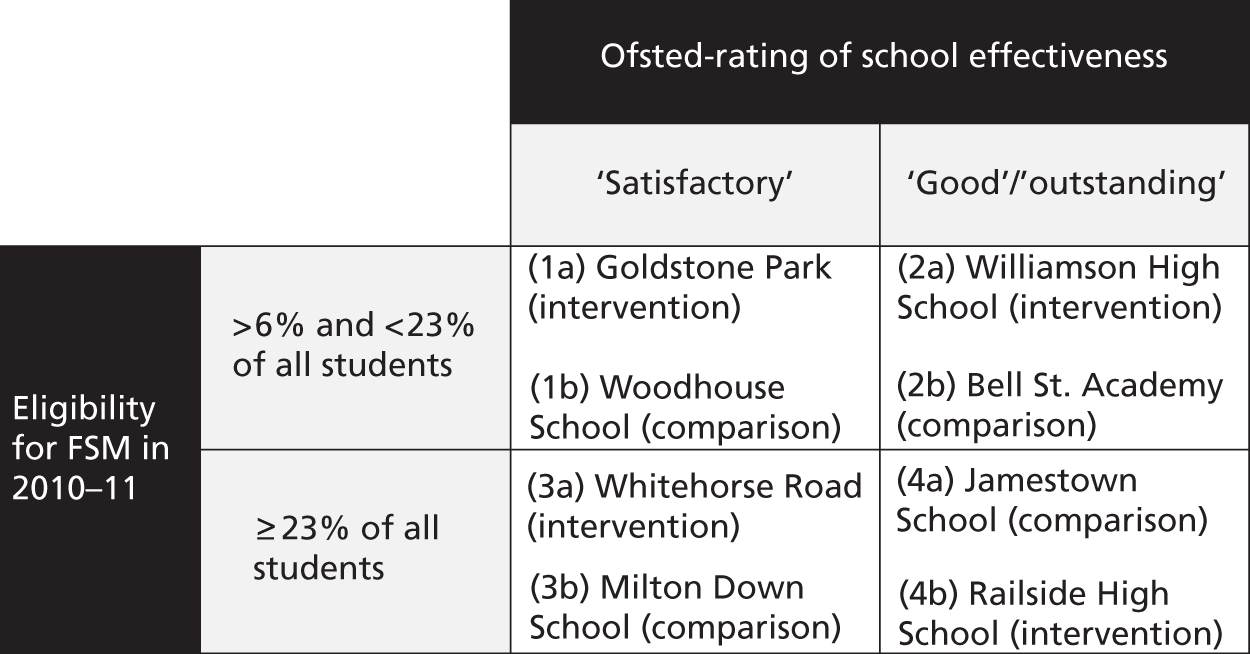

Eight schools were identified and recruited by the intervention facilitators between July and September 2011 (see Recruitment of schools for more detail). Figure 2 explains the final sampling and matching criteria for schools in the study. The initial aim (at the funding application stage) was to identify a mix of schools with Ofsted ratings ranging from satisfactory to outstanding and above or below the national average for the number of students eligible for FSM (approximately 15% of secondary-school students). However, FSM eligibility is considerably higher than the national average in London (approximately 23%). 40 As the majority of schools were recruited from London boroughs and nearby counties, we revised the final sampling and matching criteria so that schools were divided by Ofsted rating and between those with greater than or less than 23% student eligibility for FSM, as a benchmark of greater/lesser economic deprivation in this region.

FIGURE 2.

Sampling and matching criteria for schools (n = 8).

Recruiting and matching pairs of schools according to their FSM eligibility and Ofsted rating prior to randomisation was useful primarily because it allowed the intervention, trial methods and outcome measures to be piloted in a diverse and particularly challenging range of school contexts. It also enabled us to pilot our ability to use such techniques to increase baseline equivalence between arms within a Phase III trial, but we recognised that even with matching we were unlikely to achieve baseline equivalence in a small pilot study.

Although the intervention aimed to address the whole school, only students in year 8 (aged 12 and 13 years) at each participating school were recruited as the analytical sample, which participated in baseline and follow-up surveys. No other student inclusion or exclusion criteria operated. The sample size for the student baseline and follow-up surveys was estimated to be approximately 1200 students (approximately 150 year 8 students per school). No power calculation was performed, as this was a pilot study and the research objective was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methods, and not to estimate intervention effects. All teaching staff at the participating schools were also invited to participate in baseline and follow-up surveys. Non-teaching school staff were not eligible for inclusion in these surveys. Action team members were also invited to participate in surveys post intervention which focused on their experiences of the intervention. Although the surveys of teachers and action team members were not included in the funding application, they were considered useful to pilot in preparation for a Phase III trial and were therefore included in our trial protocol.

Subgroups of year 8 students and school staff were also recruited to take part in focus groups and individual interviews. At each of the four intervention schools, four groups of year 8 students and one group of school staff were recruited to participate in focus group discussions. Students were sampled purposively, and grouped with similar peers, according to their sex and level of school engagement (as reported by staff), to ensure a range of views and school experiences. School staff members were purposively sampled according to their sex, experience and role at the school to ensure a range of staff was represented. A maximum of 10 participants were recruited per focus group by researchers working with a member of the SMT. Intervention action group members (three to seven per school) and SMT staff (one or two per school) were also recruited to take part in semistructured interviews at the end of the school year. All INCLUSIVE facilitators working in schools (n = 3), one of whom co-ordinated the intervention, and the staff training provider (n = 1) were also recruited to take part in individual semistructured interviews after the intervention had been delivered.

Comparison group

Schools allocated to the comparison group continued with standard practice and received no additional input. Our experience from previous school trials was that retaining those schools allocated to the comparison group can be challenging. 74 We provided a payment of £500 at the end of the study as participation compensation to comparison schools (to cover administrative costs and/or provide cover for staff involvement in organising data collection). In addition, we offered feedback of survey data to comparison schools after completion of the study, if requested, because we know that schools highly value data that can be used to monitor and change policy and practice. 75

Health Technology Assessment progression criteria

Data collection during the pilot trial focused on assessing acceptability and feasibility and allowing us to judge progress against the agreed criteria for progression to a Phase III trial. The first objective was specifically to assess whether the criteria deemed necessary in order to progress to a Phase III trial were met (Box 2). These were agreed by the investigator team, the HTA co-ordinating centre and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) prior to commencing the pilot trial, being considered to represent evidence of feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methodology.

RQ1: was it feasible to implement the intervention in (at least) three out of four intervention schools? This was assessed according to the following implementation criteria:

-

The needs assessment survey had a ≥ 80% response rate.

-

The action group met six or more times during the course of the school year and was always quorate (i.e. minimum of two-thirds of members present).

-

The action group reviewed and revised school policies (e.g. relating to discipline, behaviour management and staff–student communication).

-

Whole-school actions (e.g. rewriting school rules) were a collaborative process involving staff and students from across the school.

-

Peer mediation and/or ‘buddying’ schemes were reviewed and enhanced if necessary.

-

≥ 20 staff completed restorative practice training.

-

Restorative practices (e.g. circle time, restorative conferencing, etc.) were used.

-

The student curriculum was delivered to year 8 students.

RQ2: was the intervention acceptable to the majority of school SMT members and a majority of action group members?

RQ3: did randomisation occur and was this acceptable to schools’ SMTs?

RQ4: did (at least) three out of four schools from each of the intervention and comparison arms accept randomisation and continue to participate in the study?

RQ5: were the student survey response rates acceptable at (at least) three out of four comparison schools?

Data sources

In order to answer RQ1 (see Box 2), multiple sources of quantitative and qualitative data were collected. To assess needs assessment response rates, student baseline survey response rates at each intervention school were examined. To examine the fidelity of action group implementation, documentary evidence was collected (intervention facilitators’ checklists, action group meeting minutes and school policies), and supplemented by observations of action group meetings and interviews with action group members at each school to cross-check the validity of the documentary evidence and provide additional data. To examine the reach of staff training and the uptake of restorative practices, documentary evidence was collected from training providers’ checklists and supplemented by observations of staff training sessions and focus groups with school staff to cross-check the validity of the documentary evidence and provide additional data. To examine the delivery of the student curriculum, documentary evidence from intervention facilitators’ checklists was collected and supplemented with focus groups with school staff and students to cross-check the validity of the documentary evidence and provide additional data.

In order to answer RQ2 (see Box 2), semistructured interviews with school SMT members at each participating school were undertaken to explore their views on the intervention’s acceptability and action group members at each intervention school were surveyed to examine their views on acceptability. A subsample of action group members was also interviewed to explore participants’ views in more depth and cross-check the validity of other data sources. To answer RQ3 (see Box 2), the acceptability of randomisation was explored in the semistructured interviews with school SMT members at each participating school. In order to answer RQ4 and RQ5 (see Box 2), the retention of schools was assessed, as were response rates to baseline and follow-up student surveys in intervention and comparison schools.

Data analysis methods

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and qualitative data entered into NVivo 10 software version 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Burlington, MA, USA) to aid data management and analysis. Documentary evidence and records of observations were also uploaded to support cross-checking and data triangulation. Codes were applied to transcripts to identify key themes and how these inter-relate in order to develop an analytical framework. Each transcript was coded to indicate the type of participant, the school and the date, allowing analytical themes to be explored in relation to different groups’ experiences and processes to be compared across schools. Quantitative data from the action group member survey were entered into and analysed using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

In order to assess whether the intervention was delivered as planned in at least three out of the four pilot schools (RQ1), the following analyses took place to examine each of the specific implementation criteria systematically:

-

Student needs assessment data reports were examined at each intervention school to assess whether the response rate was greater or lower than 80% of all year 8 students at the school at baseline.

-

Intervention facilitators’ checklists and action group meeting minutes were analysed to assess whether each intervention school action group met six or more times (with a minimum of two-thirds of members present), and were cross-checked against and supplemented by data from observations of action group meetings and thematic content analysis of action group member interviews.

-

Intervention facilitators’ checklists and school policy documents were analysed to assess whether each action group reviewed and revised school policies (e.g. relating to discipline, behaviour management and staff–student communication) and cross-checked with supplementary data from observations of action group meetings and thematic content analysis of action group member interviews.

-

Action group meeting minutes and thematic content analysis of qualitative data from interviews with action group members were examined to assess whether whole-school actions (e.g. rewriting school rules) were a collaborative process involving staff and students from across the school.

-

Action group meeting minutes and thematic content analysis of qualitative data from interviews with action group members were examined to assess whether peer mediation and/or ‘buddying’ schemes were reviewed and, if necessary, enhanced.

-

Documentary evidence from training providers’ checklists was examined to assess the attendance of staff restorative practices training, and cross-checked with supplementary data from observations of staff training sessions and thematic content analysis of data collected via focus groups with school staff.

-

Focus groups of school staff examined the uptake of restorative practices (e.g. circle time, restorative conferencing, etc.) in intervention schools.

-

Intervention facilitators’ checklists were examined to check the student curriculum was delivered to year 8 students in all intervention schools, and cross-checked via thematic content analysis of data collected via focus groups with school staff and students.

Semistructured interviews with school SMT and action group members were subjected to thematic content analysis and coded according to views on acceptability, and supplemented with analyses of the action group member survey data in order to examine how many action group members reported acceptability (RQ2). We monitored whether randomisation occurred, and thematic content analysis of qualitative data from semistructured interviews with school SMT members was also used to assess the acceptability of randomisation (RQ3). We also monitored how many schools from each of the intervention and comparison arms accepted randomisation and continued to participate in the study at follow-up (RQ4) and student response rates at follow-up at each comparison school (RQ5).

Process evaluation: participants’ experiences

In addition to examining intervention delivery according to prespecified criteria (objective 1), a second objective was to explore students’, school staff members’ and facilitators’ experiences of implementing and trialling the INCLUSIVE intervention, and how these varied in different school contexts in order to refine the intervention and trial methods. To answer RQ6–8, multiple sources of qualitative data collected via interviews, focus groups and observations and quantitative data from student and staff surveys were analysed. The qualitative process data allowed us to explore students’, school staff members’ and facilitators’ experiences in depth and see how these varied in different school contexts. In addition, surveys of students and teachers provided an overview of their experiences of intervention activities.

Qualitative process data

Semistructured interviews with a range of stakeholders were undertaken to explore in greater depth the processes of planning, delivering and receiving the intervention and undertaking the trial: semistructured interviews with school SMT members at each intervention school were undertaken to explore their experiences of planning, delivering and trialling the intervention, and how successfully each component was implemented; semistructured interviews with school SMT members at comparison schools provided insights regarding the feasibility and acceptability of our trial methods; and semistructured interviews with intervention facilitators and the training provider explored their experiences of planning and delivering the intervention, and how and why these may have varied across different school contexts. Further individual interviews with student and staff action group members at each intervention school explored in-depth how successfully action groups were implemented and their experiences of barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Focus group discussions, each with a maximum of 10 year 8 students, were undertaken at each of the four intervention schools, to explore the acceptability of the intervention to students in year 8, how benefits (or harms) may occur to students’ health via such an intervention and their experiences of the evaluation methods. A focus group comprising a maximum of six school staff members at each intervention school also explored how successfully each component was implemented, why fidelity may vary across schools and the acceptability of the intervention, as well as staff views on the trial methods. Unstructured observations of action group meetings, staff training and the school environments were also recorded to provide further contextual data on potential barriers and facilitators to implementation. Further details on the qualitative data collection process and the sample of participants recruited are provided in Chapter 3, Qualitative data collection.

Quantitative process data

Follow-up survey data also provided an overview of year 8 students’ and teachers’ experiences of intervention activities. Neither survey measured these factors at baseline, so it was not possible to adjust effect estimates for baseline differences in school practice. Items on students’ experiences of restorative practices (‘Do teachers at your school ever use circle time?’) and participation in decision-making (‘At this school do students have a say in writing the rules?’) were included in the student follow-up survey. Eight items on students’ experiences of PSHE were also included at follow-up, which were adapted from the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit’s Teenage Health in Schools item measures using a four-point response scale (Totally agree/I agree a bit with responses/I do not really agree/No, totally disagree). These eight items were as follows: PSHE helps me feel more confident; PSHE helps me understand other people’s feelings and problems; in PSHE I talk about how I feel; in PSHE students can be honest about how they feel; in PSHE we talk about how our words and actions affect other people; in PSHE we talk about strategies for working with others; and in PSHE we talk about how to be a good friend.

The teacher follow-up survey included two items on teachers’ use of restorative practices (‘Do teachers at your school ever use circle time to discuss how students feel about school?’ and ‘Do staff at this school ever use restorative conferences to deal with disputes and repair relationships?’), two measures of behaviour management practices (‘How well are teachers supported with behaviour management at this school by senior members of staff?’ and ‘How well are teachers supported with behaviour management at this school by all staff implementing consistent techniques across the school?’) and one question on PSHE (‘Do you think that PSHE lessons at this school help to promote students’ social and emotional well-being?’).

Data analysis

Qualitative data collected via interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo software to aid data management and analysis. Thematic content analysis of qualitative data was undertaken76 by two researchers (AF, the trial manager, and CB, the process evaluation manager for this study) via the following stages of analysis. First, each transcript was coded by AF to indicate the type of participant (e.g. female, student, etc.), the school and the date and then checked by the second researcher (CB). Second, one researcher (AF) coded all the interview and focus group transcripts to identify key themes, using an inductive framework based on our RQs as higher-level codes and memos to record inter-relationships across questions (e.g. to explore how implementation varied across different school contexts). Third, the second researcher (CB) cross-checked these codes. Finally, the two researchers compared their analyses, refined the coding framework and generated additional codes and memos in discussion, before coding the data a second time deductively to explore other analytical themes grounded in the data (e.g. unexpected barriers or facilitators to implementation).

Analyses of survey data examined how many students and teachers reported evidence of successful implementation at follow-up (see above for a full list of items). All quantitative data were analysed in Stata 12 and adjusted for clustering by school and, when possible, appropriate confounders: the analyses of students’ reports adjusted for sex, ethnicity and housing tenure at baseline, and the analyses of teachers’ responses adjusted for sex, ethnicity and teaching role at baseline. Adjustment for baseline differences in school practices was not possible, as these were not measured.

Piloting of outcome measures

The final objective of this study was to pilot and field test our indicative primary, secondary and intermediate outcome measures and economic methods prior to a Phase III trial (RQ9–11). The methods for piloting our economic measures and analyses are described in the section Economic evaluation. In this section, we provide details of the primary, secondary and intermediate outcome measures piloted in this study and describe the methods of statistical analysis used for assessing the performance of the indicative primary outcome measures (bullying and aggressive behaviour) and changes in our indicative primary outcomes at follow-up. Outcomes were measured in baseline and follow-up questionnaire surveys of year 8 students conducted in September 2011 and June/July 2012, respectively (described in more detail in Chapter 3).

Primary outcome measure development

In order to develop primary outcome measures of bullying and aggressive behaviour for a Phase III trial, we examined the properties (response rates, discrimination and reliability) of two variables pre-hypothesised as primary indicative outcome measures: (1) the bullying victimisation scale used in the Gatehouse Project trial78 and (2) the AAYP violence subscale for measuring aggressive behaviours used in the AAYP trial. 54 We also examined one additional pilot primary outcome: (3) the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime (ESYTC) school misbehaviour subscale. 77 Outcomes (1) and (2), respectively, assess student self-reports regarding bullying victimisation and perpetration of aggression within the last 3 months and are, therefore, potentially able to assess changes within a school year. Although they have been used previously in intervention studies, these were in Australia and the USA, respectively, and thus may not be appropriate to the UK. Outcome (3) might be more relevant to the UK context but has not previously been used in intervention research.

The Gatehouse Bullying Scale (GBS)78 consists of 12 items that assess overt and covert types of bullying victimisation. Students were asked whether they had been teased or called names, had rumours spread about them, been deliberately left out of things and/or recently been physically threatened or hurt. Each of the four types of bullying was defined as frequent if it occurred on most days, and upsetting if the student reported being quite upset. The resulting bullying score was on a scale from 0 to 3, where 0 indicated that the student had not been subjected to any of the four types of bullying, and scores of 1–3 denoted increasing intensity (frequency and level of upset) of one or more of the four types of bullying.

Four items from the AAYP violence scale54 were piloted. Questions concerning students’ self-reported perpetration of violent behaviours over the previous 3 months requested information regarding the frequency of the most common overt direct aggressive behaviours, including verbal aggression (threatening to beat up, cut or stab) and physical aggression (cutting, stabbing). The four items were scored on a scale of 0–3 (0 = never; 1 = yes but not in the last 3 months; 2 = once recently; 3 = more than once recently). The resulting violence score ranged from 0 to 12; higher average scores represented higher levels of violence.

The ESYTC school misbehaviour subscale79 measured several domains of violence and aggression at school. The ‘school misbehaviour’ scale piloted at baseline included 10 items relating to aggression towards students and teachers, which were coded according to four response categories: hardly ever or never; less than once a week; at least once a week; and most days. A further three items were added and piloted at follow-up regarding physical aggression in more detail using these response categories. The total score was a summed frequency of school misbehaviour with high scores indicating higher levels of self-reported school misbehaviour.

Consultation with young people on measures of bullying and aggression

We consulted with young people from the NCB YRG at a meeting held before the surveys were undertaken to explore young people’s views concerning how to define bullying and aggression within schools and assess whether the aggression items designed for INCLUSIVE were appropriate and acceptable (see Chapter 1, Involvement of young people). It was important to assess young people’s views on what constitutes aggressive behaviour both to inform the aims of the intervention and to inform our measures. The group identified a wide range of behaviours that could be perceived as bullying and aggression, including physical violence, verbal abuse, ‘jokes’, cyber bullying, pictures, drawings and websites, rumours, exclusion, peer pressure and theft. They concluded that bullying should be defined based on how often it occurs, arguing that repetitive and relentless behaviour is more likely to be experienced as aggressive.

We then asked the young researchers for their opinions on the scales we were testing as potential primary outcomes for a Phase III RCT. The group identified some concerns with both questionnaires. There were concerns about false reporting, which might be improved by ensuring confidentiality. Some items on the AAYP violence scale were thought of as possibly too ‘extreme’, leading to concerns that no British students would report these (e.g. stabbing someone). In contrast, other questions might assess experiences reported by almost everyone (e.g. using bad language). Some items were considered not to be well defined (e.g. verbal bullying), which may lead to variability in student responses. However, in general, the young researchers felt that the measures were likely to reflect students’ experiences of aggression and bullying and were appropriate to pilot.

Pilot secondary outcome measures

We also piloted and field tested pre-hypothesised secondary outcomes using the baseline and follow-up surveys of year 8 students. These pilot secondary outcome measures are described in detail below.

Quality of life

This was measured using two instruments. First, the 30-item Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) version 4.080 was used to assess all-round quality of life (QoL). The PedsQL has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of QoL in normative adolescent populations. 80 It consists of 30 items representing five functional domains: physical, emotional, social, school and well-being. Items are rated on a series of five-point Likert scales ranging from 0, ‘never’, to 4, ‘almost always’. The PedsQL yields a total QoL score, two summary scores for ‘physical health’ and ‘psychosocial health’ and three subscale scores for ‘emotional’, ‘social’ and ‘school’ functioning. For the total QoL score, items are reverse-scored and linearly transformed to a scale of 0–100 (i.e. 0 = 100, 1 = 75, 2 = 50, 3 = 25 and 4 = 0); higher scores represented better QoL. Second, the CHU-9D measure81 was used to assess health-related QoL and piloted and examined prior to use in a subsequent economic analysis; the validation of the CHU-9D is described below in detail (see Validation of the Child Health Utility 9D questionnaire).

Psychological function

Psychological distress was measured using the child self-completion Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a validated measure of a range of behavioural and emotional problems in children and adolescents. 82 The SDQ consists of 25 items which assess difficulties in four domains (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems) and an additional measure of pro-social behaviour. Items are rated on a scale of 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true). A ‘total difficulties’ score is calculated by the summation of all scales, apart from pro-social behaviour, a high score being indicative of a higher level of emotional and behavioural difficulty. In this study, the total SDQ score and the emotional, conduct, hyperactivity and peer problem scores were treated as continuous variables.

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being was measured using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS), which consists of seven items designed to capture a broad concept of positive mental well-being, including psychological functioning, cognitive-evaluative dimensions and affective-emotional aspects. 83 Items were rated on a five-point scale: none of the time (score = 1), rarely (2), some of the time (3), often (4), all of the time (5). The responses are scored and aggregated to form a ‘well-being index’ (total score), which can range from a minimum of 7 (those who answered ‘rarely’ on every statement) to a maximum of 35 (those who answered ‘all of the time’ to all statements). Higher scores represent improved mental well-being. The SWEMWBS was piloted in this study because it potentially provides a brief (seven-item) measure of well-being, although it has not yet been validated with year 8 students in English schools.

Health risk behaviours

Measures of two key adolescent health risk behaviours were piloted as secondary outcome variables. Self-reported use of tobacco and consumption of alcohol were examined using the HSE pilot trial measures. 69 Students were asked if they had smoked in the past month (30 days) and if they had drunk alcohol, defined as ‘more than a sip’, in the past month (30 days).

Note that drug use and contraceptive use would also be secondary ‘health risk behaviour’ outcomes in a Phase III trial in which students would be followed up until the end of year 10 (aged 14 or 15 years), but they were deemed not appropriate for the pilot trial surveys of year 8 students (aged 12 or 13 years).

NHS use

Self-reported use of NHS services (primary care, accident and emergency, other) in the past year was scored as a dichotomous variable (i.e. those who reported that they had used NHS services in the last year were given a value of 1).

Contact with the police

Contact with the police was assessed using the Young People’s Development Programme evaluation measure. 84 Young people were asked if they had been stopped, told off or picked up by the police in the last 12 months. This was a dichotomous response variable (ever/never had contact).

Truancy and school exclusion

Self-reported truancy and school exclusion were measured using items from the ESYTC survey. 78 Self-reported truancy was a dichotomous variable (‘ever bunked/skipped school? yes/no’), as was self-reported school exclusion, which was assessed according to whether they had ever been permanently or temporarily excluded from school.

Pilot intermediate outcome measures

To examine the logic model (see Figure 1) via which the intervention is hypothesised to impact on students’ health and well-being, we piloted the following intermediate outcomes examining year 8 students’ perception of the school environment and antischool actions.

Student perceptions of school climate

The Beyond Blue School Climate Questionnaire (BBSCQ) scale was used to measure students’ perceptions of the school climate. The scale was originally developed in Australia,85 using items selected from the Quality of School Life,86 Patterns of Adaptive Learning87 and Psychological Sense of School Membership questionnaires. 88 It consists of 28 items, which produce an overall score and also assess four key domains of school climate (subscale): supportive teacher relationships, sense of belonging, participative school environment and student commitment to academic values. Each item was coded 1–4 on a four-point scale. Responses ranged from ‘Yes, totally agree’ to ‘No, totally disagree’. A total BBSQ score was calculated by the summation of all scales, reversing scores when necessary. The total BBSQ score and subscale scores were treated as continuous variables; higher scores represent a positive report of school climate.

Antischool actions

Students’ reports of antischool actions were derived from the ESYTC self-reported delinquency (SRD) subscale. 79 The total SRD score was a summed frequency based on six items, with high scores indicating higher levels of self-reported school delinquency.

Analysis plan for pilot outcome measures

All quantitative data analyses were carried out in Stata 12. In order to examine which of the pilot primary outcome measures performed best, according to their completion rate, discrimination and reliability (RQ9), and inform our choice of outcomes for a Phase III trial, multiple analyses were undertaken. First, the completion rate and prevalence for each outcome measure (total score and for each individual item) was examined overall and by sex. Second, mean scores, standard deviations and response distributions were calculated for all the pilot primary outcome measures at baseline to examine their discrimination and the potential for ‘floor effects’ (i.e. the scales may not be sensitive to low levels of reported bullying) with year 8 students (aged 12–13 years). Third, the intraclass correlation (ICC) for each score was calculated and used as an indication of the stability of the measure over time. Fourth, Cronbach’s alpha statistics were calculated at baseline and follow-up to provide an indication of each scale’s internal consistency, a measure of the extent to which items within the scale are measuring the same latent construct.

The pilot study did not aim to, and was not powered to, determine intervention effects. Nonetheless, we did carry out analyses of outcomes, purely in order to pilot our primary outcome measures and analysis methods. To estimate intervention effects on the indicative pilot primary outcome measures, multilevel modelling was carried out according to the principle of intention to treat. Appropriate multivariate regression models were used with a random effect at the school level to allow for clustering, fitting baseline measures of outcomes when possible. Cluster-adjusted mean differences were computed for each of the pilot primary outcomes, with odds ratios used as a measure of effect for analyses of dichotomous data. Results of unadjusted and adjusted analyses are presented with a 95% confidence interval. ‘Unadjusted’ analyses adjusted only for baseline measures of the outcome in question. Adjusted analyses additionally adjusted for other pre-hypothesised potential confounders (sex, ethnicity and housing tenure) as covariates. This strategy of adjustment was highly conservative, the study’s lack of statistical power rendering any more comprehensive approach to adjustment liable to generate highly unstable estimates of effect. All analyses were complete case analyses, as we had no reason to believe data were not missing at random.

We should stress that these quantitative analyses offer no guide to the intervention’s effectiveness. The lack of statistical power means that no value can be placed on the cross-sectional point estimates or on estimates of differences between arms in longitudinal analyses. Only 95% confidence intervals offer any indication of potential effect sizes. Furthermore, as expected, the random allocation of only eight units did not generate baseline equivalence and there were marked differences by arm in several measures of students’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as parental employment and family structure (see Chapter 4, Description of pilot trial sample) and prior experiences of bullying and aggression estimates (see Chapter 4, Development and piloting of indicative primary outcome measures), both of which suggested that the intervention group was notably more disadvantaged at baseline. Thus, the estimates of effects are subject not only to random error but also to confounding, which our conservative approach to adjustment could not control. Estimates of effect should therefore not be interpreted as reflecting the potential effectiveness of the intervention.

Economic evaluation

It is important that studies evaluating complex public health interventions include an economic component. 89,90 The aim of the economic component of this pilot study was not to perform an economic evaluation of the intervention per se, but rather to collect and collate evidence regarding the appropriate design of an economic evaluation in a Phase III trial. To do this, the analysis was divided into two tasks. The first task was to assess the feasibility and desirability of using the recently developed CHU-9D to measure changes in health. The second task was to define an appropriate economic evaluation framework based on the CHU-9D results, broader pilot trial data and consideration of the wider literature.

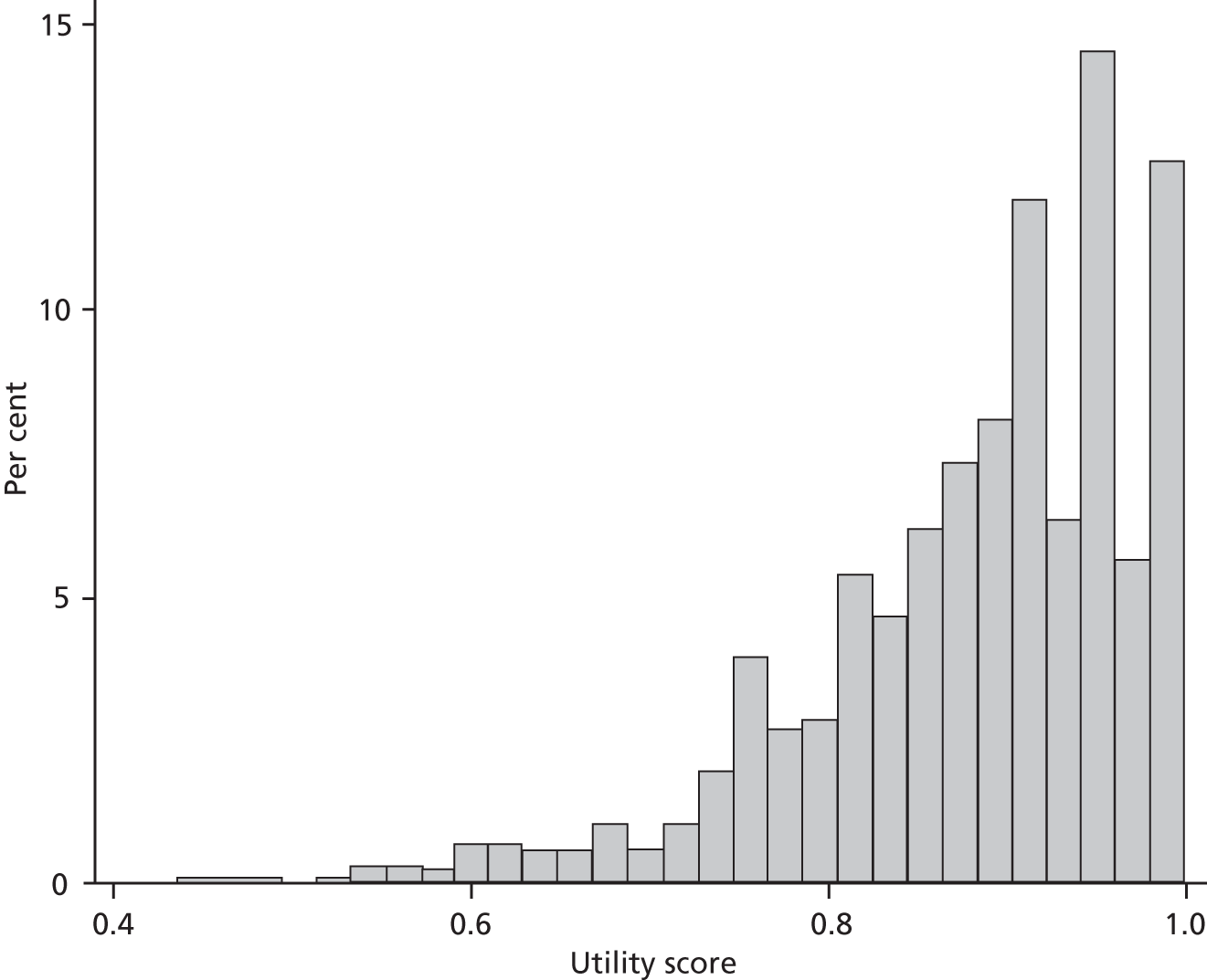

Validation of the Child Health Utility 9D questionnaire

We chose to use the CHU-9D rather than any other outcome measure for three reasons. First, although it was known at the time of the study’s conception that the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) health questionnaire was being developed for use with children and young people (the EQ-5D-Y), it was not clear how this process would evolve. Second, discussions regarding the face validity of the EQ-5D-Y and the CHU-9D among the investigation team strongly supported the use of the latter because of the items it contains: they were considered to be much more relevant given the target age group. Third, it was noted that the CHU-9D classification system has been specifically developed using children’s input, whereas the EQ-5D-Y simply involved changes to the wording of the original system in order to make it more ‘child friendly’. We discussed the appropriateness of including both questionnaires in the student survey in order to compare their results; however, it was agreed that the questionnaire was already approaching a maximum length and that concerns over the face validity of the EQ-5D-Y outweighed any potential benefits of including it in the pilot.

The feasibility and desirability of using the CHU-9D in a subsequent Phase III trial were assessed by determining its acceptability, construct validity and sensitivity. Acceptability was examined by analysing response rates, and basic psychometric properties were initially assessed by analysing the distribution of the calculated utility scores and exploring the potential for floor and ceiling effects. Construct validity was assessed using two approaches. First, the discriminant validity of the CHU-9D (i.e. its ability to differentiate between individuals in different states of ‘health’) was assessed by correlating baseline survey CHU-9D utility scores with the baseline PedsQL scores. Second, the convergent validity of the CHU-9D was examined by assessing the relationship between the CHU-9D subscales and subscales on other questionnaires that were believed to be measuring similar items. For example, it was hypothesised that the ‘sad’ CHU-9D scale would be positively related to the PedsQL psychosocial summary score, and that the CHU-9D ‘worried’ and ‘sad’ subscales would correlate with the SDQ and the SWEMWBS. As the data were either non-normally distributed or ordinal, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated in all instances (all statistical tests were two-tailed). Finally, sensitivity was assessed by calculating the change in utility score between the baseline and follow-up surveys, and correlating this change in score with the corresponding change in the PedsQL total score and the three pilot primary outcome measures, again using Spearman’s rank test. Correlations and tests for trend were also performed to assess the relationship between the CHU-9D utility score, the PedsQL total score and these outcomes.

Developing a framework for economic evaluation

At their most basic level, economic evaluations of cost-effectiveness compare the costs and consequences of a relevant set of alternative health-care programmes or interventions. It implicitly follows that, in order to maximise outcomes given a limited budget, resources should be allocated towards interventions that are considered to be cost-effective and away from those that are not. However, an economic evaluation of INCLUSIVE is likely to be complex for several reasons. First, no multiattribute health ‘utility’ status classification systems have been validated for use among young people in schools or for ‘antibullying’ interventions. Second, costs and benefits are likely to extend beyond traditional health boundaries and into a number of other sectors and policy domains (e.g. education and the criminal justice system). Third, it is possible that the intervention will not only impact on students but also potentially provide benefits for school staff. Fourth, a RCT will not capture the potential longer-term health incremental benefits and costs arising later in the life-course as a result of the intervention; the value of undertaking complementary decision modelling, which this would require, is unclear.

There are various different forms of economic evaluation. They are similar in the way that they measure and value costs but different in terms of how they measure and value health outcomes. For example, in a cost–benefit analysis, outcomes are expressed in monetary terms, whereas, in a cost–utility analysis (CUA), they are typically expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), where QALYs are calculated as the time spent in a state of health adjusted for the ‘quality’ or ‘utility’ of this time. These techniques contrast with a cost-effectiveness analysis approach, for which outcomes are expressed in ‘natural’ units, such as ‘life-years’ or perhaps ‘episodes of bullying’. The most appropriate form of economic evaluation to use typically depends on the level of efficiency that the evaluation is trying to address (e.g. within a health-care sector such as the NHS or at a broader public health level) and the type of intervention outcomes that are anticipated. For example, QALYs reflect changes only in ‘health’; they do not capture potential wider non-health benefits that might be valued by society, such as improved educational attainment.

A number of guidelines exist for performing economic evaluations on which to base a framework for INCLUSIVE. However, the practical approach we took, given that a Phase III RCT would be UK based and consist of a relatively ‘complex public health intervention’, was to follow the methodology outlined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE’s ) public health guidance. 91 More specifically, key design elements were abstracted from its methods guide, such as ‘the categories of cost to include’ (i.e. the cost perspective) and ‘the appropriate time horizon for the analysis’, in order to debate the appropriate design response. The overall analysis framework in which this choice rests was of equal importance; for example, the choice of time horizon, whether decision modelling is needed and which costs to include.