Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/38/03. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jeremy Fairbank reports non-financial support from Integrated Shape Imaging System (ISIS) scanner during the conduct of the study. Adrian Gardner reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Medtronic Spine, Dublin, Ireland, and personal fees from Depuy Synthesis Spine, Leeds, UK, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Williams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Rationale for a feasibility study

Feasibility studies are used to estimate important parameters that are needed to design a definitive trial. They are not designed to estimate the effect on the outcome of interest, and, consequently, a primary outcome is not usually defined and a typical power calculation is not normally undertaken. Instead, the sample size should be adequate to estimate the critical parameters (e.g. recruitment rate, baseline variability) to the necessary degree of precision (see www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/glossary).

The brief for the Active Treatment for Idiopathic Adolescent Scoliosis (ACTIvATeS) feasibility study stipulated that two interventions should be compared: standard NHS care and a defined package of scoliosis-specific exercise (SSE) therapy for patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). The following conditions were also specified:

-

The patient group investigated should be children or adolescents, aged 10–16 years, with mild/primary AIS and a Cobb angle < 50° (i.e. conservatively managed).

-

The setting should be an outpatient clinic or community setting.

-

The control group would receive standard NHS care.

-

The acceptability and adherence of intervention should be assessed.

-

A survey of orthopaedic surgeons should be conducted to identify the available number of participants and surgeons willing to participate.

-

Training requirements of therapists should be assessed and described.

In order to achieve these specifications the ACTIvATeS study team proposed the following methods:

-

a national survey of current practice and opinion for the management of AIS

-

a systematic review of the literature regarding exercise interventions for AIS

-

development of both exercise and control interventions involving key stakeholders

-

a randomised feasibility study at multiple NHS trusts

-

a qualitative study involving patients, parents and physiotherapists.

Condition

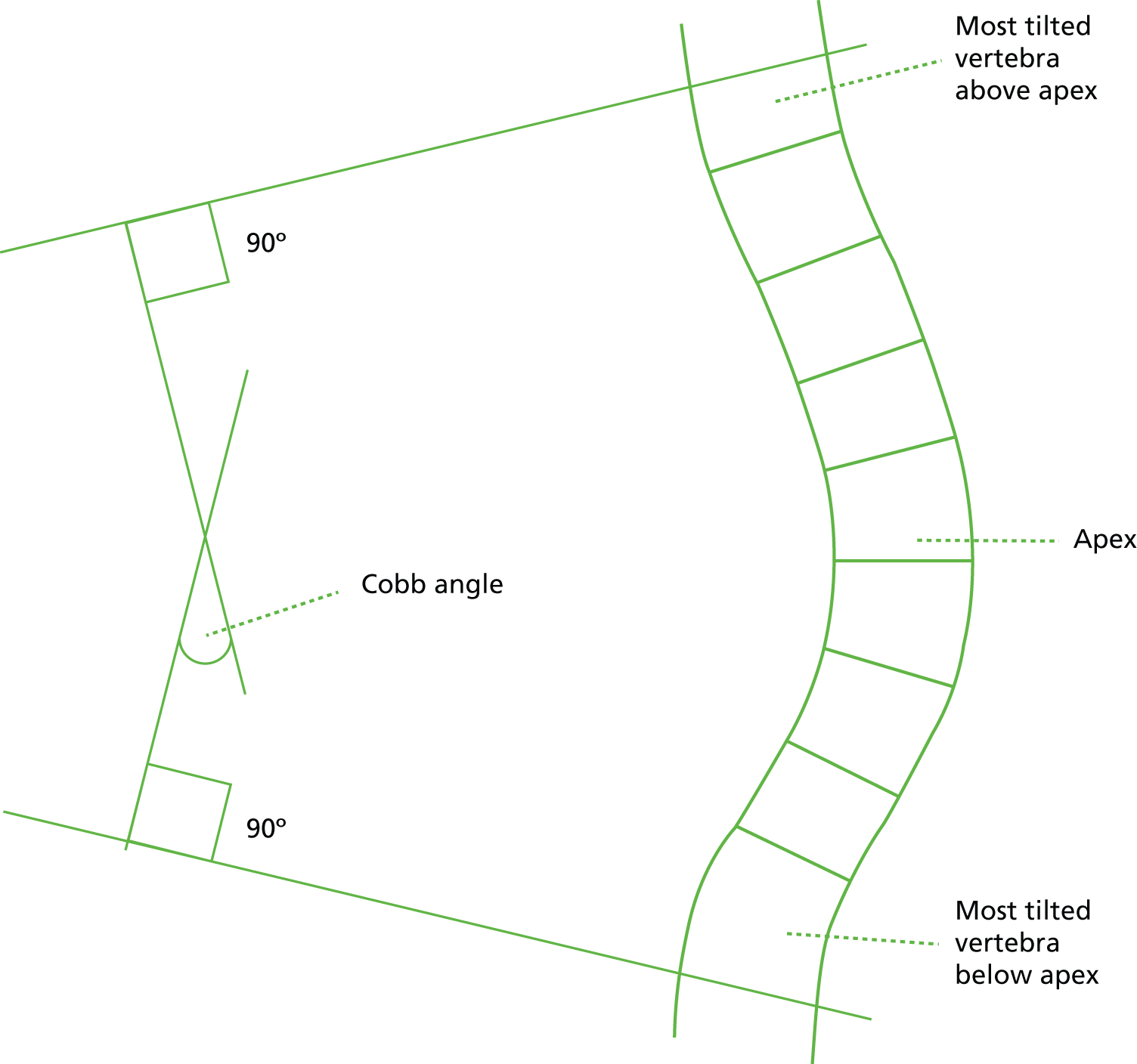

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is often referred to as a structural lateral curvature of the spine, although it is actually a three-dimensional spinal deformity that results in lateral deviation, rotation and flexion/extension of the vertebrae. It is of unknown cause and occurs at or near the onset of puberty. 1 AIS is usually diagnosed by radiography using the Cobb angle (see Figure 2 for detail) and, to meet the definition, the lateral curvature must have a Cobb angle of > 10°.

In the UK, the prevalence of AIS in children aged 10–16 years is 1–3%,2,3 suggesting that there are 50,000–150,000 sufferers. 4 The effects of AIS include pain, cosmetic concerns, functional limitations, cardiorespiratory problems and possible further curve progression in adulthood. 5 About 10% of AIS patients require surgical or conservative management. 6 Current UK management includes monitoring, bracing for some and, for the most progressive and serious patients, surgery. Surgery is generally undertaken only when spinal curvature reaches a Cobb angle of > 45–50°. 7 Surgery is a very extensive procedure, with exposure of large segments of the spine and substantial fixation which, although reducing curve progression, also permanently limits mobility in the affected part of the spine. Surgery also comes with a risk of complications, which are estimated to occur in approximately 6% of patients undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis and include pulmonary complications, wound infection and neurological damage. 8

The risk of curve progression is not completely understood but is thought to be dependent on the size of curve, stage of growth and skeletal maturity.

Existing research

Current treatments

In the UK, surveys of current surgical practice9 and advice information provided at initial diagnosis have previously been conducted;10 however, a survey of current conservative treatments provided in the NHS has not been undertaken. Currently, it is thought that the main components of conservative management of scoliosis in the UK are monitoring and a limited use of bracing.

Rationale for treatments

Braces are an intrusive and uncomfortable intervention. Two publications reported bracing protocols that lasted up to 4 years and required the brace to be worn for 23 hours per day. 11,12 The effectiveness of bracing protocols is unclear,13 although a recent trial reported by Weinstein et al. 14 suggests that there is promise of efficacy.

Exercise is a promising intervention for which there is an emerging, although low-quality, evidence base. 15,16 The rationale is to use exercises that promote spinal realignment and thus either improve or halt progression of the curvature. Exercise is, potentially, a low-cost intervention and, even if not effective in all patients, it may be of substantial benefit if the relative risk reduction in progression to curvature of > 45° or requirement for surgery was reduced in a modest proportion of those participating. It is thought that exercise should be applied as early in the disease process as possible.

Exercise therapy is not commonly provided in the UK and the USA, although it is routinely provided in parts of Europe. 17 Within continental Europe, there are various schools of exercise therapy for AIS. The Schroth method (originating in Germany), Scientific Exercises Approach to Scoliosis (SEAS; Italy), the Lyon method (France) and the DoboMed method (Poland) are among the most well-known and reported in the literature. However, there is little evidence to support the choice of one form of therapy over another or evidence of their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The rationale for exercise to manage AIS is that a number of underlying impairments in spinal muscular function and postural ability contribute to or accompany the development of curvature and are potentially reversible. Electromyography (EMG) of trunk muscles in AIS patients indicates disrupted patterns of muscle recruitment under static and dynamic conditions, in a broad range of postures. These asymmetries extend to the paraspinal lumbar and abdominal oblique muscles and are associated with a disparity in trunk isometric rotation strength between sides. 18–21 In keeping with differential muscle activity, there are differences in muscle fibre type distribution on the convex and the concave sides of the curve. AIS patients exhibit greater balance control problems and proprioceptive impairments. 22,23 AIS may be associated with distorted body schema, resulting in a mismatch between actual body alignment and patients’ internal bodily representation of the body. 24

Hence, to improve function and reduce or stabilise curvature, exercise programmes must include strengthening of all affected muscle groups; exercises to encourage the appropriate magnitude and timing of muscle activation; proprioceptive elements; and postural/body awareness components. These programmes will require careful tailoring to each individual. There is evidence that such approaches can remediate underlying impairments in EMG activation and strength, although effects may well be limited to curves with a Cobb angle of < 50°. 19–21,25,26

Although there is a theoretical basis for exercise in AIS, there is little robust evidence that it has a significant effect on curve progression. There are relatively few studies investigating this important outcome,15 and only one randomised controlled trial (RCT)27 had been published at the time of the application (March 2011). A small number of prospective cohort studies have attempted to evaluate the European schools of exercise including SEAS and Schroth. 15 Although these studies show a favourable outcome in support of exercises, the research is problematic for a variety of reasons. These include a lack of control group, failure to randomise, the reporting of very small statistically significant but not necessarily clinically important differences in Cobb angle, poor statistical analysis, limited descriptions of baseline characteristics of participants, and no reporting or poor adherence to treatment and the exercise programmes evaluated. 28 Clear evidence that these approaches are beneficial is lacking.

Economic considerations

There is no information on the cost-effectiveness of the various exercise approaches and whether or not they offer a viable alternative to surgery and bracing. Many patients with similar spine deformities report lower scores in physical functioning than the general population. 29 The impact of treatment of illness on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) can be measured with ‘utility’ scores that represent people’s preferences towards a particular health state. The current study used two preference-based HRQoL instruments, namely the Health Utilities Index (HUI) and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). These systems employ multidomain health status questionnaires completed by individuals to obtain information on self-assessed health status. Preference-based scores for those health states are then calculated using published scoring functions for the two systems. The published scoring functions are based on preferences obtained from random samples of the general population; the Canadian and UK adult populations for the Health Utilities Index Mark 2 (HUI2), the Canadian adult population for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) and the UK adult population for the EQ-5D. These multiattribute preference-based instruments are significantly less resource- and time-consuming than direct utility or preference elicitation approaches, such as the standard gamble and time-trade-off approaches, which can directly measure the utility that patients attach to their health states. HUI and EQ-5D measures have been shown to be valid, reliable and responsive to changes in health status over time. 30–32

There is no evidence in the literature with respect to comparisons of the EQ-5D and the HUI in patients with AIS. One study by Adobor et al. 33 evaluated the repeatability, reliability, internal consistency and concurrent validity between the Scoliosis Research Society-22 patient questionnaire (SRS-22) and EQ-5D in AIS. Their results showed a moderate correlation between these two instruments. The authors claimed that one of the reasons for this was that the EQ-5D has been validated for use in adult populations with back pain, but not in adolescents with spine deformity (as in the ACTIvATeS study). The advantage of preference-based measures such as the HUI and EQ-5D is that they can generate health utility scores for comparative economic evaluation purposes. In addition, the HUI has been widely used in the literature to describe the self-rated health of youths and young adults. 29,34–36

Relevant evidence with regards to head-to-head comparison of the HUI and EQ-5D measures in adolescents is provided by a recent study by Oluboyede et al. ,37 which attempted to understand the practicality, validity and reliability of using these two measures for adolescents who have experienced a self-harm episode. Their results showed that the HUI had a higher rate of missing data, and adolescents had difficulties interpreting some of its questions. No missing data were observed for any questions in the EQ-5D in the population of 49 adolescents. In a study of children with meningitis38 there was evidence that, although the EQ-5D may be preferable because it has been used in many different patient populations and is the preferred measure of HRQoL in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) health technology assessments, the HUI classifications are more precise and discriminative. This study also indicated that both instruments would produce the same HRQoL weights or utility scores in the meningitis context.

Following structured literature searches we have found no evidence to indicate the cost of AIS in the UK. A study conducted in the USA suggested the overall national cost of AIS to be around US$1.13B (based on 2006–7 prices). 39 Earlier evidence from the World Health Organization suggests that the cost from musculoskeletal diseases in general stems mainly from hospital admissions, physician visits, nursing home services, medications and non-health-related sources. The contribution of these different health-care services to economic costs may vary by musculoskeletal disease, age and sex. Treatment of AIS is often a lengthy process and, therefore, requires considerable contributions from different providers within the health-care system.

Qualitative study

Understanding why patients and their families make the decisions they do about their health care can help us to provide the appropriate treatments. Although parents are often used in research to elicit young people’s experiences, we believed that we needed to seek information directly from the young people in order to determine the feasibility of the proposed intervention. 40 An adult may not give such a useful account of the young person’s experience. 41 This is the first qualitative study to explore the experiences of young people with AIS undergoing an exercise programme. Previous research has focused on young people’s experiences with scoliosis surgery and bracing. 42–45

Study aim

The aim of this feasibility study was to assess the feasibility of conducting a large, definitive, multicentre trial of SSE treatment for patients with AIS, in comparison with standard care. Specific objectives are listed within each of the reported sections.

Chapter 2 Systematic review update

Objective

To conduct an up-to-date systematic review of the literature evaluating the efficacy or effectiveness of SSE for patients with AIS.

This would inform the development of the interventions to be evaluated in the ACTIvATeS randomised feasibility trial and would also indicate whether or not further research is warranted at the end of the feasibility phase.

Methods

A systematic literature review published by Cochrane included publications up to 30 March 2011. 17 We have followed the methods, including the search strategy, published in the original Cochrane review to carry periodic updates of this review.

Identification of new eligible studies

We have rerun the published search strategies to identify new eligible trials and searched databases up to 12 February 2014. A further study was also identified from an e-mail alert of new research from a journal publisher (see Table 1). We attempted to source grey literature using the OpenGrey database (OpenGrey V1.0, Institut de l’Information Scientifique et Technique, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France).

Full articles of studies that seemed eligible from the abstract were examined independently by two assessors and checked for eligibility based on the original criteria for inclusion.

According to the original Cochrane review criteria, studies were eligible for the review if they were RCTs, quasi-RCTs or observational studies that included participants diagnosed with AIS (defined as at least a 10° Cobb angle) who were older than 10 years but had not reached the end of bone growth.

Studies were excluded if participants had any type of secondary scoliosis (congenital, neurological, metabolic, post-traumatic, etc.). The experimental interventions in this review included all types of SSE that are considered to be ‘specific movements performed with a therapeutic aim of reducing the deformity’. Sports, active recreational activities and generalised physiotherapy were not considered to be specific exercises for the treatment of scoliosis, and studies including these types of activities were excluded.

Control interventions included no treatment, different types of SSE, usual therapy, different doses or schedules of exercises or other non-surgical treatments. Comparison could include exercises versus no treatment; another treatment versus that treatment plus exercises; exercises versus another conservative treatment; exercises versus usual physiotherapy; and comparisons between different types of exercises or different doses/schedules of exercises.

Risk of bias assessment

After identifying eligible studies, a risk of bias assessment was carried out using the criteria published in the original review (see Table 6). This was done independently by two reviewers who then compared findings. Any differences were resolved through discussion.

Each study was then classified as at high or low risk of bias using the same criteria as the previous review. 17 A study was considered to be at low risk of bias if it fulfilled the three key criteria related to randomisation, allocation concealment and outcome assessor blinding, as well as any three of the other criteria.

Data synthesis

Data extraction was carried out independently by two assessors using a standardised form. Data were compared and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two assessors.

Meta-analysis was not performed owing to lack of homogeneity between studies. The variability between exercise approaches assessed, outcome measures used and timings of follow-up was too great to allow us to combine study findings. We assessed the overall quality of evidence for each outcome using an adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach as used in the original Cochrane review of exercises for AIS17 and as recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group. 46

In accordance with the GRADE approach:

-

High-quality evidence was defined as consistent findings among at least two RCTs with low risk of bias that are generalisable to the population in question (consistency is defined as 75% or more of the studies with similar results); sufficient data, with narrow confidence intervals; no known or suspected reporting biases; further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect.

-

Moderate-quality evidence was defined as failure to meet one of the factors described in the high-quality definition. Further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

-

Low-quality evidence was defined as failure to meet two of the factors described in the high-quality definition. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

-

Very low-quality evidence was defined as failure to meet three of the factors described in the high-quality definition. Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

-

No evidence was defined as complete lack of evidence from RCTs.

Results

Five new eligible studies were identified (Table 1), which, in addition to the two studies previously included in the Cochrane review,15,27 brought the total number of studies eligible for inclusion in the review to seven.

| Databases searched using search strategies from Cochrane review17 limited to March 2011 to February 2014 | Hits | Number of studies after screening of abstracts | Retrieved full articles (duplicates removed) | Eligibility after review of full article |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | 302 | 1 | 8 | Eligible = 5 Ineligible = 3 |

| EMBASE | 4 | 0 | ||

| CINAHL | 392 | 3 | ||

| Cochrane | 41 | 3 | ||

| PEDro | 5 | 1 | ||

| PsycINFO | 4 | 1 | ||

| Index to Chiropractic Literature | 3 | 0 | ||

| Other sources | 1 | 1 |

With a substantial increase in the number of eligible randomised studies it was decided that the justification for inclusion of non-randomised studies provided in the original Cochrane review was no longer valid, and, therefore, we separated the synthesis and evaluation of randomised and non-randomised studies and primarily consider evidence from randomised studies in line with best Cochrane practice. 47 This resulted in two non-randomised studies15,48 being isolated for secondary evaluation.

Characteristics of included randomised studies

Characteristics of the five randomised studies and the outcomes they measured are described in Tables 2 and 3. 27,49–52 Characteristics of the two non-randomised studies are presented in Tables 4 and 5. 15,48

| Study | Number of participants at baseline/follow-up | Mean age in years (SD) | Sex, n (%) | Type of curve | Specifics of the intervention(s) | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wan et al. 200527 | 80/80 | Intervention and control: 15.0 (4.0) | Intervention and control: females, 43 (54); males, 37 (46) | S-shaped scoliosis excluding C-shaped scoliosis, with mean Cobb angles of 25° (13) and 23° (11) for the control, and 26° (12) and 24° (10) for the thoracic and lumbar segments, respectively | Intervention: electrostimulation + postural training + gymnastic exercise for correcting essential S-shaped scoliosis Control: electrostimulation on the lateral body surface by therapeutic apparatus + postural training |

Gradual increase over 6 months of therapy for both groups Intervention: exercise was once daily; repeating each step 10 times up to 30 times; holding the position for 30 seconds with 30-second rests, repeated two or three times. The exercise volume and intensity was increased by attaching 0.15–0.25-kg bags on the left leg Control: first day – three times per day for 30 minutes each; second day – twice for 1 hour each; third day – once for 3 hours Afterwards treatment was increased by 1 hour every day until it reached 8 hours per day with progression to traction therapy for 30 minutes |

| Toledo et al. 201151 | 20/20 | Intervention and control: 10 (3.0) | Intervention: females, 4 (40); male, 6 (60) Control: females, 5 (50); males, 5 (50) |

Structural thoracic scoliosis excluding patients without positive tests, with mean Cobb angles of 15.0° (10.0) and 14.0° (7.0) for the intervention and control, respectively | Intervention: RPG method Control: no treatment |

Intervention: 25–30 minutes per session with 2–3-minute rests, twice per week for 12 weeks Control: no treatment |

| Diab 201249 | 76/68 | Intervention: 13.2 (1.2) Control: 14.5 (1.3) |

Intervention: females, 18 (47); males, 20 (53) Control: females, 17 (45); males, 21 (55) |

All types of curves with Cobb angle of 10–30°; Risser grade: 0, 1 or 2 and Lenke scale of 1A | Intervention: corrective exercise programme; individually adapted forward head posture correction alongside conventional stretching and strengthening exercises Control: traditional exercise treatment – stretching of concave tightened structures and strengthening of trunk muscles |

Intervention: conventional treatment three times per week + three sets of 12 repetitions of the strengthening exercises; four times per week daily, for 10 weeks Stretching cervical flexors through a chin drop in sitting; unilateral and bilateral pectoralis stretches alternating each 2-week period. Three stretching exercises held for 30 seconds each Control: conventional treatment three times per week for 10 weeks |

| Schreiber et al. 201350 | 31/31 | Intervention (Schroth + standard care): 14.4 (2.1) Control: 13.7 (1.7) |

Intervention and control: NR | All types of curves with Cobb angles of 10–45° and Risser grade of 0–5 Mean Cobb values: 32.6° (7.0) and 28.8° (10.0) for the intervention and control, respectively |

Intervention: Schroth SSE – consists of three-dimensional exercises based on sensorimotor and kinaesthetic principles, teaching patients to maintain the correct posture in daily activities in order to improve the curve, pain and self-image using endurance and strength training Control: monitoring or bracing (based on Boston brace criteria) for 6 months |

Intervention: five individual visits to learn the exercises, followed by weekly supervised group sessions of 1 hour each (tailored) 30–45 minutes of daily training using algorithm, with daily home exercises for 6 months Control: 6 months |

| Monticone et al. 201452 | 110/98 | Intervention: 12.5 (1.1) Control: 12.4 (1.1) |

Intervention: females, 39 (71); males, 16 (29) Control: females, 41 (75); males, 14 (25) |

All types of curves with Cobb angles of 10–25° and Risser grades of < 2 Mean Cobb angle values: 19.30° (3.9) and 19.20° (2.5) for the intervention and control, respectively |

Intervention: ASC, with individually adapted exercises, cognitive–behavioural strategies and ergonomic education via booklet by three experienced physiotherapists Control: general exercises aimed at spinal mobilisation |

Intervention: 60-minute outpatient workout sessions. Once per week at the institute, 30 minutes of individualised sessions twice per week at home. Mean time on treatment = 42.8 months (SD 9.09) Control: 60-minute outpatient workout sessions. Once per week at the institute, and 30 minutes of individualised sessions twice per week at home |

| Study | Follow-up | Cobb angle measures in degrees (°) | Change in trunk balance | Flexibility and muscular strength | ATR | Quality of life | Psychological issues including cosmetic issues | Back pain and disability | Global rating of change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wan et al. 200527 | 6 months | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Toledo et al. 201151 | 6 months | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Diab 201249 | 10 weeks and 3 months | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Functional rating index | No |

| Schreiber et al. 201350 | 3 months | No | No | Muscle strength: Biering-Sørensen test | No | SRS-22 total score | SRS-22 self-perceived image subscale and self-efficacy questionnaire | SRS-22 function and pain subscale | Yes |

| Monticone et al. 201452 | Skeletal maturity (mean time = 42 months) and 12 months post maturity (mean time = 52 months) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | SRS-22 self-perceived image, mental health and satisfaction with management subscales | SRS-22 function and pain subscale | No |

| Study | Study design | Number of participants at baseline/follow-up | Mean age in years (SD) | Sex, n (%) | Type of curve | Specifics of the intervention(s) | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negrini et al. 200815 | Prospective controlled cohort study | 74/70 | Intervention: 12.7 (2.2) Control: 12.1 (2.1) |

Intervention: females, 25 (71); males, 10 (29) Control: females, 27 (69); males, 12 (31) |

All type of curves under proven radiograph, Cobb angle > 15° or 20° and Risser grade of 0–1 or 2–3, respectively Mean Cobb angle: 15° (SD 6°) Mean ATR: 7° (SD 2°) |

Intervention: ASC and individually adapted SEAS programme Control: different exercise activities as designed by attending physiotherapist |

Intervention: 1.5 hours of quarterly (2–3 months) supervised sessions. Additionally, 40 minutes of training, twice weekly, was carried out at a nearby institute + 5 minutes of daily home exercise training for 12 months Control: 45–90 minutes of semistructured exercises (supervised and individualised sessions), two or three times per week for 12 months |

| Choi et al. 201348 | Cluster quasi-controlled trial | 44/35 | Intervention: 13.30 (0.57) Control: 13.10 (0.46) |

Intervention: females, 28 (100); males, 0 Control: females, 16 (100); males: 0 |

All type of curves within Cobb angle ranges of > 10 and < 20°s Mean Cobb angles: 14.90° (3.09) and 14.08° (1.66) for the intervention and control, respectively |

Intervention: theory of planned behaviour for posture management Control: 30 minutes of posture management behaviour using written material with photographs |

Intervention: 60 minutes per session, twice per week + five times per week of home exercise for 6 weeks. 30 minutes were allocated for strengthening attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and behavioural intention towards posture management behaviour. The other 30 minutes were used for posture-management exercises Control: 30 minutes of daily practice of posture behavioural management for 6 weeks |

| Study | Follow-up | Cobb angle measures in degrees (°) | Change in trunk balance | Flexibility and muscular strength | ATR | Quality of life | Psychological issues including cosmetic issues | Back pain and disability | Global rating of change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negrini et al. 200815 | 12 months | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Choi et al. 201348 | 2 months | Yes | No | Range of movement and dynamometer measures of strength | No | No | No | No | No |

For randomised studies, samples sizes ranged from 20 participants to 110 participants, and all studies included males and females. The mean age of participants at baseline ranged from 1051 to 15 years. 27 Three studies included participants diagnosed with AIS irrespective of curve type, with the remaining two studies only including participants with specific curves: S-shaped or double curves27 and structural thoracic curves. 51

Most studies used criteria based on the Cobb angle to select patients and there was some variability here. The inclusion criteria in three studies included those patients with curves between 10° and 30°,49 those with curves from 10° to 25°52 and those with curves between 10° and 45°, respectively. 50 Two studies did not define inclusion criteria using the Cobb angle. 27,51

The mean Cobb angle of participants recruited to studies varied between approximately 15°,51 19°,52 25°27 and 30°. 50 One study did not report Cobb angles at baseline. 49

The most common lengths of follow-up were 3 months49,50 and 6 months post inclusion. 27,51 One study followed up participants to 12 months after skeletal maturity was reached (mean time to follow-up was 52 months). 52

Outcome measures varied across the studies (see Table 3). The Cobb angle was the only outcome measured in more than one study,27,51 whereas two other studies also collected additional physical measurements. 15,48 Only one study reported the Cobb angle alongside a patient-reported measure. 52 Two studies did not include the Cobb angle as an outcome. 49,50 One used postural parameters, including craniovertebral angle and spinal balance, along with a functional measure as outcomes,49 whereas the other evaluated back endurance, quality of life and self-efficacy. 50

The studies reported a variety of different approaches to exercises for scoliosis (see Table 2). No one study evaluated the same approach, although there are some similarities between the approaches used. The concept of active self-correction (ASC) underpinned the majority of the approaches,50–52 facilitated by varying degrees of assistive manual therapeutic techniques. Of the remaining studies, one included stretches of tightened structures on the concave side of the curve and strengthening of trunk muscles with and without the inclusion of exercises to correct adapted forward head posture,49 whereas the other evaluated a gymnastic-based exercise programme where participants exercised in asymmetrical postures to correct the S-shaped curve. 27

The amount of time that participants were expected to carry out exercises was variable. Although descriptions of interventions were not always clear, it appears that three studies required participants to carry out daily exercise programmes, although the amount of time spent exercising varied between approaches. 27,49,50 For example, an exercise programme based on the Schroth programme required participants to carry out 30–45 minutes of training per day. 50

Those undergoing global postural re-education attended treatment sessions twice per week. 51 Participants taking part in an ASC programme were required to attend a weekly 1-hour workout session at the institution supplemented by two 30-minute exercise sessions at home per week. 52

The duration of exercise interventions also varied between studies. These varied from 10 weeks49 and 12 weeks,51 to 6 months. 27,50 One study required participants to exercise until they reached skeletal maturity, which resulted in a mean duration of exercise intervention of 42 months. 52

Risk of bias for randomised studies

One randomised study was considered to be at low risk of bias52 and the remaining studies were considered to be at high risk of bias (Tables 6 and 7). 27,49–51

| Wan et al., 200527 | Diab, 201249 | Monticone et al., 201452 | Schreiber et al., 201350 | Toledo et al., 201151 | Trial characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ? | Random sequence generation (selection bias) |

| ? | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ? | Allocation concealment |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Blinding (performance bias and detection bias): all outcomes – patients |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Blinding (performance bias and detection bias): all outcomes – providers |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Blinding (performance bias and detection bias): all outcomes – outcome assessors |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): were dropouts reported and equal between groups? |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): were all randomised participants analysed in the group to which they were allocated? |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ✓ | Selective reporting (reporting bias) |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Group similar at baseline |

| ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Co-interventions |

| ? | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | Adherence with interventions |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Similar outcome timing |

| Negrini et al., 200815 | Choi et al., 201348 | Observational study characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ✗ | ? | Representativeness of exposed cohort |

| ✗ | ✗ | Selection of the non-exposed cohort bias (population) |

| ✓ | ✓ | Ascertainment of exposure |

| ✗ | ✓ | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis |

| ✓ | ✓ | Complete follow-up (attrition bias) |

| ✗ | ✗ | Independent blind assessments (detection bias) |

Allocation

The majority of studies failed to report adequate methods of random sequence generation and concealment of allocation27,50,51 and this was the main reason that studies were considered to be at high risk of bias. Explicit methods were described in Diab49 (random permuted blocks generated by independent person, sealed in opaque envelopes) and Monticone et al. 52 (random blinded treatment codes and automatic concealed assignment).

Blinding

No study blinded participants or treatment providers, which is not unreasonable owing to the nature of the interventions. However, only two studies50,52 reported the use of blinded outcome assessors, which should be possible in these types of studies and was the other reason the majority of studies were classified as being at high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data were not an apparent source of bias in any of the studies. No dropouts were reported by three studies. 50,51,56 Loss to follow-up was reported to be approximately 20% in the remaining studies with dropouts balanced across both arms. 49,52

Selective reporting

The majority of studies reported outcome data fully, as described in the methods section of each study. There was one exception to this – the study by Schreiber et al. 50 Online information about this study (see http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01610908) indicated that Cobb angle was the primary outcome, but this is not reported as an outcome in the published report. The report does stipulate that this trial is ongoing, which may account for the fact that it is not reported, but this is unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

It appears that the intervention and control groups were similar at baseline and that the timing of outcome assessment was similar for both groups in all the studies.

All studies failed to report co-interventions and so it is unclear if co-inventions may have been a source of bias. Information on adherence with exercise programmes was unreported in the majority of studies27,49,51,52 so is it unknown if adherence may have introduced bias. A high level of adherence to exercise programmes, ranging between 81% and 88%, was reported Schreiber et al. 50

Risk of bias for non-randomised studies

Both observational studies were considered to be at high risk of bias. Both studies were rated as being at high or unclear risk of bias for at least three of the six criteria (see Table 7). Both studies were considered to be at low risk of bias for ascertainment of exposure and completeness of follow-up. The self-selection process used in Negrini et al. 15 is a source of bias because it was based on participant and physician choice; however, it is reported that there were no statistically significant differences between the groups at baseline for any scoliosis parameters, which suggests that risk of bias had been minimised.

Levels of evidence

Scoliosis-specific exercises versus no treatment or standard care

Toledo et al. 51 compared a programme of exercises based on the global postural re-education approach, with no treatment in a small group of 10-year-old participants (mean baseline Cobb angle ≈15°). Among those in the intervention arm there was a statistically significant improvement in Cobb angle (mean reduction in size of 35% compared with mean increase of 9.5% in the control group) at 12 weeks’ follow-up. Table 8 shows actual Cobb angles. No other outcomes were measured in this study.

| Study | Actual Cobb angles, degrees [mean (SD)] | Categorical outcomes, n/N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Wan et al., 200527 | Thoracic spine | Thoracic spine | ||

| 0 weeks: 26.0 (12.0) | 0 weeks: 25.0 (13.0) | |||

| 6 months: 10.0 (7.0)a | 6 months: 18.0 (9.0)a | |||

| Lumbar spine | Lumbar spine | |||

| 0 week: 24.0 (10.0) | 0 week: 23.0 (11.0) | |||

| 6 months: 9.0 (5.0)a | 6 months: 16.0 (8.0)a | |||

| Toledo et al., 201151 | Thoracic spine | Thoracic spine | ||

| 0 months: 15.10 (2.51) 6 months: 9.80 (2.90)a |

0 months: 14.70 (3.77) 6 months: 16.10 (3.75)a |

|||

| Diab, 201249 | ||||

| Monticone et al., 201452 | 0 months: 19.3 (3.9) | 0 months: 19.2 (2.5) | 42 months: | 42 months: |

| 42 months: 14.0 (2.4)a | 42 months: 20.9 (2.2)a | bNumber of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | bNumber of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | |

| 56 months: 14.3 (2.3)a | 56 months: 22.0 (1.6)a | Improved: 36/52 (69) | Improved: 3/51 (6) | |

| Worsened: 4/52 (8) | Worsened: 20/51 (39) | |||

| Same: 12/52 (23) | Same: 28/51 (55) | |||

| Subgroup analysis:b Age < 13 years (N = 32) |

Subgroup analysis:b Age < 13 years (N = 35) |

Subgroup analysis:b Age < 13 years |

Subgroup analysis:b Age < 13 years |

|

| 0 months: 18.9 (4.1) | 0 months: 19.3 (2.4) | Number of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | Number of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | |

| 42 months: 14.1 (2.5)a | 42 months: 20.7 (2.5)a | Improved: 22/31 (71.0) | Improved: 3/32 (9.4) | |

| 56 months: 14.2 (2.3)a | 56 months: 21.9 (1.6)a | Worsened: 3/31 (9.7) | Worsened: 10/32 (31.2) | |

| Same: 6/31 (19.3) | Same: 19/32 (59.4) | |||

| Age > 13 years | Age > 13 years | |||

| Age > 13 years (N = 23) | Age > 13 years (N = 20) | Number of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | Number of participants whose Cobb angle changed by > 3° | |

| 0 months: 19.9 (3.6) | 0 months: 19 (2.7) | Improved: 14/21 (66.7) | Improved: 0/19 (0) | |

| 42 months: 14.0 (2.4)a | 42 months: 21.4 (1.8)a | Worsened: 1/21 (4.8) | Worsened: 10/1 (31.2%) | |

| 56 months: 14.5 (2.4)a | 56 months: 22.1 (1.5)a | Same: 6/21 (19.3) | Same: 9/16 (59.4) | |

The RCT of exercises based on the Schroth method compared with standard care (monitoring or bracing) reported effect sizes at only 6-month follow-up. 50 The treatment effects reported demonstrated no effect on function and very small to small effects on pain, self-image, self-efficacy, overall SRS-22 scores and back extensor strength. The perceived mean global rating of change was greater in the intervention and was described as a moderate improvement, whereas those in the control group reported a small amount of deterioration. Cobb angle was not reported. From information available on the US Trials Register, this report includes data from only 31 out of the expected 100 study recruits, so this analysis was underpowered.

Level of evidence

There is very low-quality evidence that a SSE programme based on the global postural re-education approach improves Cobb angle compared with no treatment in the short term.

There is very low-quality evidence that a SSE programme based on the Schroth method is no different from usual care for improving function in the short term.

There is very low-quality evidence that a SSE programme based on the Schroth method results in small improvements in pain, self-image, HRQoL and back extensor strength compared with usual care in the short term.

Scoliosis-specific exercises plus other treatments versus other treatments only

One study compared the addition of an exercise programme to other treatments (traction and electrical stimulation). 27 The exercise group showed a statistically significant reduction in Cobb angle at 6-month follow-up compared with those who just received traction and electrical stimulation (mean baseline Cobb angle 23–26°). No other outcomes were measured.

Level of evidence

There is very low-quality evidence that a SSE programme added to traction and electrical stimulation improved Cobb angle compared with traction and electrical stimulation alone in the short term.

Scoliosis-specific exercises versus general exercises

The largest and best-conducted study reported that a programme of SSEs was superior to general exercises (mean baseline Cobb angle ≈19°). 52

Measurements of Cobb angle favoured the SSE group compared with general exercise on completion of the programme at skeletal maturity and 12 months later. The percentage of participants who showed improvement was higher in the SSE group than in the general exercise group, in which a greater proportion of participants either stayed the same or worsened. Stratification by age (< 13 years and ≥ 13 years) showed that the subgroup with the higher risk of progression (age < 13 years) exhibited less improvement than older participants, but differences were small and it was not reported if they had reached statistical significance or not.

A statistically significant reduction in angle of trunk rotation (ATR) was observed in the group receiving SSEs compared with those receiving general exercises following completion of training and 12 months later (Table 9).

| Study | Change in trunk balance | ATR (°) | Trunk flexibility and strength | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Diab, 201249 | Trunk inclination (mm) 0 weeks: 5.8 (0.6) 10 weeks: 4.8 (0.7)a 3 months: 5.1 (0.8)a |

Trunk inclination (mm) 0 weeks: 6.6 (0.5) 10 weeks: 6.4 (0.6)a 3 months: 6.5 (0.5)a |

||||

| Thoracic kyphosis (˚) 0 weeks: 8.9 (0.9) 10 weeks: 10.4 (1.10)a 3 months: 10.0 (1.05)a |

Thoracic kyphosis (˚) 0 weeks: 8.8 (1.5) 10 weeks: 9.0 (1.8)a 3 months: 8.9 (1.7)a |

|||||

| Lumbar lordosis (˚) 0 weeks: 18.6 (5.4) 10 weeks: 21.6 (1.8)a 3 months: 20.9 (1.9)a |

Lumbar lordosis (˚) 0 weeks: 18.1 (5.5) 10 weeks: 20.0 (1.7)a 3 months: 19.2 (1.6)a |

|||||

| Trunk imbalance (mm) 0 weeks: 22.7 (1.3) 10 weeks: 16.7 (2.7)a 3 months: 16.6 (2.3)b |

Trunk imbalance (mm) 0 weeks: 21.8 (4.3) 10 weeks: 20.0 (1.7)a 3 months: 19.2 (1.6)b |

|||||

| Lateral deviation (mm) 0 weeks: 16.8 (2.3) 10 weeks: 14.3 (2.3)a 3 months:14.7 (2.4)a |

Lateral deviation (mm) 0 weeks: 15.1 (1.8) 10 weeks: 14.5 (1.6)a 3 months: 15.5 (1.7)a |

|||||

| Pelvic torsion (˚) 0 weeks: 3.5 (1.02) 10 weeks: 2.7 (0.8)a 3 months: 2.7 (0.8)b |

Pelvic torsion (˚) 0 weeks: 2.8 (0.8) 10 weeks: 2.4 (0.5)a 3 months: 2.5 (0.5)b |

|||||

| Surface rotation (˚) 0 weeks: 7.4 (1.2) 10 weeks: 6.08 (1.6)a 3 months: 6.20 (1.5) |

Surface rotation (˚) 0 weeks: 6.7 (0.9) 10 weeks: 6.5 (1.0)a 3 months: 7.08 (0.5)a |

|||||

| Craniovertebral angle (˚) 0 weeks: 33.5 (2.5) 10 weeks: 41.2 (5.2)a 3 months: 42.1 (5.1)a |

Craniovertebral angle (˚) 0 weeks: 38.1 (2.9) 10 weeks: 38.4 (3.6) 3 months: 37.5 (4.2) |

|||||

| Schreiber et al., 201350 | 6 months Effect size (Cohen’s d) Biering-Sørensen test (back extensor strength): 0.28 |

|||||

| Monticone et al., 201452 | 0 months: 7.1 (1.4) 42 months: 3.6 (1.1)b 56 months: 3.3 (1.1)b |

0 months: 6.9 (1.3) 42 months: 6.6 (1.2)b 56 months: 6.5 (1.1)b |

||||

At baseline the SRS-22 domains had high scores in both groups. Further significant post-training improvements of > 0.75 points were achieved for all domains in the experimental group, whereas none was noted in the control group (Table 10).

| Study | Measures of pain, function or disability, mean (SD) unless otherwise stated | Quality of life, mean (SD) unless otherwise stated | Psychological measures, mean (SD) unless otherwise stated | Global rating of change, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |||

| Diab, 201249 | Functional rating index 0 weeks: 13.9 (1.7) 10 weeks: 10.7 (0.9) 3 months: 10.0 (0.9)a |

Functional rating index 0 weeks: 16.1 (1.7) 10 weeks 11.9 (2.0) 3 months: 13.8 (1.9)a |

||||||

| Schreiber et al., 201350 | 6 months: effect size (Cohen’s d) SRS-22 function subscale: 0.00 SRS-22 pain subscale: 0.09 |

6 months: effect size (Cohen’s d) SRS-22 total score: 0.21 |

6 months: effect size (Cohen’s d) SRS-22 self-perceived image subscale: 0.09 Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: 0.18 | 6 months: 3.8 (2.2)b | 6 months: –0.3 (1.7)b | |||

| Monticone et al., 201452 | SRS-22 function subscale 0 months: 3.8 (0.5) 42 months: 4.7 (0.2)c 56 months: 4.8 (0.2)c |

SRS-22 function subscale 0 months: 3.9 (0.5) 42 months 4.0 (0.4)c 56 months: 3.9 (0.4)c |

SRS-22 self-perceived image subscale 0 months: 3.6 (0.6) 42 months: 4.4 (0.3)c 56 months: 4.6 (0.3)c |

SRS-22 self-perceived image subscale 0 months: 3.4 (0.6) 42 months: 3.7 (0.5)c 56 months: 3.6 (0.4)c |

||||

| SRS-22 mental health subscale 0 months: 3.8 (0.6) 42 months: 4.5 (0.3)c 56 months: 4.7 (0.2)c |

SRS-22 mental health subscale 0 months: 3.9 (0.6) 42 months: 3.9 (0.5)c 56 months: 3.8 (0.4)c |

|||||||

| SRS-22 pain subscale 0 months: 3.8 (0.4) 42 months: 4.6 (0.3)c 56 months: 4.7 (0.2)c |

SRS-22 pain subscale 0 months: 0.9 (0.5) 42 months: 4.3 (0.3) 56 months: 4.2 (0.4) |

SRS-22 satisfaction with management subscale 0 months: N/A 42 months: 4.8 (0.3)c 56 months: 4.9 (0.3)c |

SRS-22 satisfaction with management subscale 0 months: N/A 42 months: 4.0 (0.5)c 56 months: 4.2 (0.5)c |

|||||

Minor adverse events (AEs) of transient pain worsening were reported in each arm of the study (n = 11 in the SSE group; n = 14 in the general exercise group).

Level of evidence

There is moderate-level evidence that a long-term SSE programme improves Cobb angle, ATR and quality of life (including subscales of pain, function, mental health, self-image and satisfaction with treatment) compared with general exercise in the long term.

Traditional scoliosis exercise programme plus forward head posture correction exercises versus traditional scoliosis exercise programme only

The addition of forward head posture correction exercises to a traditional scoliosis exercise programme resulted in a statistically significant improvement in measures of trunk balance and craniovertebral angle at 10-week and 3-month follow-up compared with a traditional scoliosis exercise programme alone. 49 A statistically significant improvement in function was observed in the intervention group at 3-month follow-up compared with the control. Cobb angle was not measured.

Level of evidence

There is very low-quality evidence that the addition of forward head posture correction exercises improves trunk balance, craniovertebral angle and function compared with a traditional programme of scoliosis exercises alone in the short term.

Discussion

Five new studies were identified since the Cochrane review was published, but most of these were rated as having high risk of bias. They provide encouraging signals that exercise might be a beneficial approach, but the majority of evidence generated is of very low quality with small sample sizes (increasing the chance of false-positive findings). Follow-up was generally short term only and there are issues with generalisability. Two of the studies included participants with AIS with any type of curve, suggesting that these cohorts are generalisable to patients with AIS; however, three cohorts included only participants with small curves (mean Cobb angles < 25°). 49,50,52 Other studies had inclusion criteria that could further limit generalisability. First, in the study by Diab,49 participants were eligible if they had a Cobb angle between 10° and 30° but they also needed to have a craniovertebral angle of at least 50°. Two other studies only included participants with a specific type of curve – double curves27 or structural thoracic curves. 51

The study by Monticone et al. 52 was the only study to which the criticism of being of very low quality did not apply. This is the first study evaluating a SSE programme to be considered at low risk of bias. It also included participants with mild and moderate size curves, making it more generalisable to patients in clinical practice. This study provided moderate evidence of effectiveness of a long-term SSE programme compared with general exercises. A strength of this study is that follow-up data were collected at skeletal maturity and 12 months after, when further progression of the curve is unlikely. However, an important omission of this study was the lack of information regarding the impact of the SSEs on surgical rates and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Cost is important because participants attended treatment, on average, for 42 months, during which time they attended a weekly physiotherapy session. It is likely that a large study is required to be definitive for these additional outcomes. Participants were also required to exercise at home twice per week for the duration of the study. Cognitive–behavioural strategies formed part of the intervention to encourage adherence with the programme but no information was provided on adherence with treatment. The SSEs evaluated in this study do seem promising, but it is questionable that such an intensive intervention would be deliverable within the NHS. Further research should investigate whether a less intensive and/or shorter programme would provide similar benefit to patients.

In addition to the studies presented, searches identified a protocol for a randomised trial53 which is due to be undertaken. This is a three-arm study evaluating general exercise advice, general exercise advice plus night-time bracing and general exercise advice plus SSEs. The SSE programme description seems broadly similar to that being tested in ACTIvATeS. The authors are aiming to recruit 45 patients in each arm. According to trial registry this research will be completed in 2019.

Conclusion

All studies that used Cobb angle as an outcome measure showed evidence of favouring the SSEs over other treatments, different types of exercises and no treatment or standard care. Generally, the level of evidence available was very low apart from one study that demonstrated a moderate level of evidence of long-term benefit from a long-term SSE programme compared with general exercise in regard to outcomes based on the Cobb angle.

Generally, there are a lack of studies evaluating patient-reported measures such as pain, disability, quality of life and psychological factors, including cosmetic issues. Evidence favouring SSEs was primarily of very low quality, apart from one study that provided moderate evidence of long-term benefit from a long-term SSE programme compared with general exercises in regard to quality of life measured by the SRS-22 and its subscales, which included pain, function, self-image, mental health and satisfaction with treatment.

No studies evaluated the cost-effectiveness of SSEs compared with other interventions or if these exercises reduced the proportion of participants requiring surgery. Further research is needed to evaluate definitively both the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SSEs.

Chapter 3 Survey

Objectives

-

To gain an understanding of current conservative management approaches for AIS used within the NHS to allow us to standardise the control arm of the pilot RCT.

-

To estimate the number of potential participants who could take part in a definitive RCT.

-

To determine equipoise and willingness to randomise of clinicians involved in the care of patients with AIS.

-

To identify learning needs and training requirements for physiotherapists to deliver the interventions.

Design

An online questionnaire was developed by the clinical research fellows with the input of orthopaedic consultants and specialist physiotherapists at collaborating feasibility sites. Survey domains included patient population dealt with by the centre (sources and numbers of new referrals, numbers meeting the proposed inclusion and exclusion criteria), current management activities (proportions and details of surgical, bracing and therapy strategies and monitoring methods), attitudes to this research (willingness for patients to be randomised, attitudes towards conservative treatment, likely barriers to be encountered, trade-off questions), concerns and beliefs about the interventions and tips for maximising adherence. We used both closed- and open-format responses.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct the survey was granted by the Warwick Medical School Biological Research Ethics Committee (REC) and individual NHS trust research and development departments at each of the clinicians’ places of employment.

Informed consent

The clinician was provided with information about the survey in the contact e-mail. The clinician was deemed to have consented by completing the online survey and was informed of this in the information provided. If an individual did not wish to take part in the survey we asked them to contact the study manager stating this and did not contact them again. Approval was gained at each NHS research and development department.

Data collection

An online questionnaire was sent to orthopaedic clinicians (consultants and specialist nurses) at all NHS hospitals that manage patients with scoliosis. A list was obtained from Scoliosis Association UK (SAUK)/British Scoliosis Research Foundation, which detailed named consultants at 36 NHS trusts who managed patients with scoliosis. We then contacted physiotherapy departments to ascertain if the department was involved in managing patients with AIS and, if so, who the lead clinician was. We contacted individuals for verbal consent prior to e-mailing the survey link.

We used evidence synthesised by Edwards et al. 57 to maximise survey response. The approach e-mail was personalised, contained a brief introduction about the study and committed to providing details of results of the completed survey. If a response to the initial e-mail was not received, a telephone call was made to the clinician (or clinician’s secretary) and responses were collected over the telephone if possible.

Analysis

Questionnaire data were summarised as descriptive statistics or frequency counts for each question. Frequency counts are presented as one of three response options: (1) no or rare (< 10%) patients; (2) selected patients; or (3) most (> 90%) or all patients.

Results: survey of orthopaedic clinicians managing adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients

Respondents

Thirty-three trusts were approached, which involved 106 individual clinicians (three of the 36 trusts were covered by clinicians working at other trusts). A response was received from 19 trusts (78%) and 39 (37%) individual clinicians. Eleven questionnaires had incomplete data, leaving 28 complete questionnaires. All respondents were consultant spinal surgeons who stated that patients with AIS were managed in their department.

Consultants who responded were generally experienced, with the majority having been managing AIS patients for at least 6 years (22/28 respondents). A similar proportion had been performing surgery for at least 6 years (21/28). Approximately half of the respondents maintained a private list of patients (17/28). The median number of consultants providing treatment in departments was 3 [interquartile range (IQR) 3–4]. Results are shown in Table 11.

| Questionnaire item | Respondent response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No or rare (< 10%) patients (n) | Selected patients (n) | Most (> 90%) or all patients (n) | No response (n) | |

| Source of referral | ||||

| Primary care | 2 | 12 | 13 | 12 |

| Secondary care | 4 | 14 | 9 | 12 |

| Self-referral | 22 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Other | 10 | 2 | 0 | 27 |

| Methods for monitoring progress | ||||

| Symptoms: pre pubescence | 3 | 7 | 14 | 15 |

| Symptoms: post pubescence | 2 | 6 | 14 | 17 |

| Cobb angle: pre pubescence | 1 | 1 | 22 | 15 |

| Cobb angle: post pubescence | 0 | 2 | 24 | 13 |

| Scoliometer: pre pubescence | 8 | 3 | 8 | 20 |

| Scoliometer: post pubescence | 7 | 4 | 7 | 21 |

| Visual estimation: pre pubescence | 11 | 4 | 9 | 15 |

| Visual estimation: post pubescence | 10 | 3 | 10 | 16 |

| Surface topography: pre pubescence | 11 | 3 | 6 | 19 |

| Surface topography: post pubescence | 10 | 3 | 5 | 21 |

| MRI: pre pubescence | 12 | 7 | 3 | 17 |

| MRI: post pubescence | 13 | 4 | 3 | 19 |

| Respiratory function: pre pubescence | 14 | 7 | 0 | 18 |

| Respiratory function: post pubescence | 14 | 5 | 0 | 20 |

| Other: pre pubescence | 10 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

| Other: post pubescence | 11 | 1 | 2 | 25 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Proportion having surgery: pre pubescence | 1 | 24 | 2 | 12 |

| Proportion having surgery: post pubescence | 0 | 27 | 0 | 12 |

| Proportion braced: pre pubescence | 11 | 16 | 0 | 1 |

| Proportion braced: post pubescence | 25 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| Referrals to physiotherapy | 29 | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| Format of physiotherapy referred to | ||||

| NHS inpatient physiotherapy | 23 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| NHS outpatient physiotherapy | 20 | 7 | 0 | 12 |

| Private inpatient physiotherapy | 25 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Private outpatient physiotherapy | 22 | 4 | 0 | 13 |

| Reasons for patients referral to physiotherapy | ||||

| Surgery not indicated | 17 | 6 | 0 | 16 |

| Newly diagnosed | 15 | 5 | 0 | 19 |

| For bracing management/monitoring | 16 | 5 | 1 | 17 |

| General monitoring | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| For exercise prescription | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| For education | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| If body image issues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Curve has a particular presentation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| If patient is certain age | 17 | 5 | 0 | 17 |

| If patient is certain sex | 17 | 4 | 0 | 189 |

| Other | 13 | 5 | 0 | 21 |

| Beliefs about efficacy of treatments | ||||

| Proportion of patients for whom bracing is helpful: pre pubescence | 11 | 16 | 0 | 12 |

| Proportion of patients for whom bracing is helpful: post pubescence | 23 | 4 | 0 | 12 |

| Proportion of pre-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can limit curve progression | 25 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| Proportion of post-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can limit curve progression | 25 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| Proportion of pre-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can reverse curve progression | 27 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Proportion of post-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can reverse curve progression | 26 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

Patient population

Referrals were received equally from primary and secondary care. Consultants reported rarely taking self-referrals. There was a wide variation in the numbers of patients seen; the mean [standard deviation (SD)] number of new NHS patients with AIS per month was 10 [SD 6.2 (range 2–28) new NHS patients with AIS per month]. Similarly, there was a wide variation in the number of follow-up patients per month [mean 23 (SD 16, range 4–80) follow-up patients per month].

Patient management

A total of 92% (22/24) of respondents stated that most or all pre- and post-pubescent patients were monitored by Cobb angle. A total of 67% and 74% of consultants stated that respiratory function was monitored in no or rare cases in pre- and post-pubescent patients, respectively.

A majority of clinicians reported following-up pre-pubescent patients at 6-monthly intervals (74%), and post-pubescent patients at 12-monthly intervals (63%). Use of radiography mirrored this frequency of follow-up, with a majority of consultants radiographing pre-pubescent patients every 6 months (74%) and post-pubescent patients every 12 months (82%).

Most consultants stated that only selected pre- and post-pubescent patients would go on to have surgery (89% and 96% of respondents, respectively). A total of 60% of respondents said selected pre-pubescent patients were braced, whereas 93% said they either never or rarely braced post-pubescent patients. This was corroborated by reporting that 60% of consultants believed that bracing could help in selected patients, whereas 85% believed that bracing is never or rarely helpful in post-pubescent patients.

Use of physiotherapy for conservative management

A total of 78% of respondents rarely or never referred patients to NHS physiotherapy. The remainder of consultants only referred selected patients. When consultants do refer patients to physiotherapy, they report doing this mostly to NHS outpatient departments.

The majority of consultants believed that physiotherapy could not limit curve progression (65% and 73% of clinicians for pre- and post-pubescent patients, respectively). An even greater proportion of consultants believed that physiotherapy could not reverse curve progression. The remaining consultants believed it can only rarely have an effect.

Involvement in research

Approximately half of the respondents were involved in research for AIS (54%), and a majority were happy for their patients to be involved in a RCT that randomised to exercise or watchful waiting (78%).

Results: survey of physiotherapists working at NHS trusts managing adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients

Respondents

Thirty-six trusts were approached, which involved 57 individual physiotherapists. A response was received from 28 of the 36 trusts (78%) and from 42 individual physiotherapists (74%).

Five (14%) physiotherapists reported that their trusts did not provide any physiotherapy treatment for AIS patients, despite being listed as a NHS trust that has a consultant providing care for patients with scoliosis.

Of the 37 physiotherapists who responded, eight provided pre- and post-operative care only, seven provided conservative physiotherapy management and 22 provided both.

Respondents were experienced, with the majority having at least 6 years’ experience managing AIS patients (0–5 years, n = 8; 6–10 years, n = 8; 10–15 years, n = 7; 16 + years, n = 5). The median number of physiotherapists providing treatment in departments was 3 (IQR 1–5). Results are shown in Table 12.

| Questionnaire item | Respondent response (N = 37) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No or rare (< 10%) patients (n) | Selected patients (n) | Most (> 90%) or all patients (n) | No response (n) | |

| Source of referral | ||||

| Primary care | 19 | 6 | 1 | 11 |

| Secondary care | 0 | 6 | 20 | 11 |

| Self-referral | 24 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Other | 26 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Reasons for patients referral to physiotherapy | ||||

| Surgery not indicated | 2 | 11 | 6 | 18 |

| Newly diagnosed | 7 | 8 | 3 | 19 |

| For bracing management/monitoring | 12 | 2 | 5 | 18 |

| General monitoring | 11 | 5 | 2 | 19 |

| For exercise prescription | 2 | 6 | 11 | 18 |

| For education | 7 | 6 | 6 | 18 |

| If body image issues | 10 | 6 | 3 | 18 |

| Curve has a particular presentation | 13 | 2 | 4 | 18 |

| If patient is certain age | 15 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| If patient is certain sex | 17 | 1 | 0 | 19 |

| Other | 15 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Bracing | ||||

| Proportion of patients presenting to physiotherapist with brace | 16 | 7 | 3 | 11 |

| Treatments used for conservative treatments of AIS | ||||

| Joint mobilisation | 15 | 6 | 4 | 12 |

| Joint manipulation | 22 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| Core stability exercises | 1 | 3 | 21 | 12 |

| Strengthening exercises | 2 | 3 | 20 | 12 |

| Stretching exercises | 2 | 6 | 17 | 12 |

| Postural correction exercises | 0 | 2 | 22 | 13 |

| Sensorimotor retraining (including balance/proprioception exercises) | 1 | 7 | 17 | 12 |

| Acupuncture | 22 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| Electrotherapy | 23 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Education | 0 | 3 | 22 | 12 |

| Other | 16 | 5 | 2 | 14 |

| Treatment formats | ||||

| Inpatient one-to-one sessions | 16 | 2 | 1 | 18 |

| Inpatient group sessions | 19 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Outpatient one-to-one sessions | 0 | 2 | 17 | 18 |

| Outpatient group sessions | 15 | 3 | 1 | 18 |

| Other | 16 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| Methods for monitoring progress | ||||

| Symptoms | 2 | 2 | 12 | 21 |

| Cobb angle | 3 | 0 | 16 | 18 |

| Scoliometer | 9 | 1 | 8 | 19 |

| Visual estimation | 5 | 5 | 7 | 20 |

| Surface topography | 12 | 3 | 2 | 20 |

| MRI | 7 | 8 | 4 | 18 |

| Respiratory function | 10 | 6 | 1 | 20 |

| Other | 14 | 0 | 1 | 22 |

| Beliefs about efficacy of treatments | ||||

| Proportion of pre-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can limit curve progression | 8 | 9 | 1 | 19 |

| Proportion of post-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can limit curve progression | 9 | 8 | 1 | 19 |

| Proportion of pre-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can reverse curve progression | 17 | 2 | 0 | 18 |

| Proportion of post-pubescent patients for whom physiotherapy can reverse curve progression | 18 | 1 | 0 | 18 |

| Proportion of patients for whom bracing is helpful | 1 | 10 | 5 | 21 |

Patient population

Physiotherapists reported that the most common referral source was secondary care (n = 20 for most or all patients). Only in rare cases were referrals received from primary care or self-referrals. On average, NHS departments managed three new AIS patients per month [mean 2.8 (SD 2.2) new AIS patients per month] and five follow-up patients per month [mean 5.4 (SD 5.0) follow-up patients per month]. For those departments that did provide outpatient care, a median of five (IQR 4–6) sessions were given, with respondents often specifying that this depended on individual patients. There was a wide variation in the length of time patients were kept on the caseload, ranging from a few weeks up to 4 years (or until skeletal maturity).

The reason for referral to physiotherapy was for exercise prescription. Referrals were unlikely to be received for a curve having a particular presentation (n = 12/19 said never or rarely) or for management/monitoring of bracing (n = 11/19 said no patients), and there seemed to be no discrimination of referrals owing to the age (n = 14/18 said no patients) or sex (n = 16/18 said no patients) of the patients. More than 50% of physiotherapists (16/37) reported that no or few patients were using a brace.

Patient management

In most or all cases, treatments consisted of core stability exercises, strengthening, stretching, postural correction and sensorimotor retraining. Manipulation, acupuncture and electrotherapy were never or rarely used. In most cases, conservative treatments of AIS (i.e. not pre- or post-operative physiotherapy) were provided at outpatient one-to-one appointments. Inpatient sessions or outpatient group sessions were never or rarely used.

Training

Eight (22%) physiotherapists had received training and used specialist scoliosis approaches.

Beliefs about the effectiveness of physiotherapy

Beliefs that physiotherapy and exercise can limit curve progression were mixed. Responses varied between ‘never’, ‘rarely’ and ‘in selected cases’, with no real difference for pre- and post-pubescent adolescents. Few physiotherapists believed that physiotherapy and exercise could reverse curve progression, and then only in selected patients. The most common response to the question of whether or not physiotherapists believed bracing was helpful was ‘only in selected patients’.

Involvement in research

Two physiotherapists (5%) were currently involved in research for AIS. A total of 16 (43%) respondents said they would be happy for patients to be involved in a RCT that randomised them to exercises or watchful waiting, with a number of comments about requiring consultant permission. Ten (27%) respondents were interested in their patients participating in a full trial.

Discussion

Current conservative management of AIS in the UK comprises monitoring by spinal consultants with periodic radiograph review (frequency dependent on maturity and risk of progression), with selected cases being referred for individual outpatient physiotherapy for exercise prescription. Referral for bracing occurs in a minority of selected cases.

There was a wide variation in the numbers of patients seen on a monthly basis at the different respondents’ NHS hospitals, owing to the fact that small and large centres were included in the study. An average of 10 new and 23 follow-up patients per month (equivalent to approximately 150 new and 350 follow-up patients per month from 15–20 centres) indicates that there is a sufficient pool of patients for a full-scale national trial.

A majority (78%) of the responding spinal consultants reported that they would be willing to have their patients involved in a RCT that randomised patients to either an exercise or control intervention. Interestingly, a smaller proportion of the surveyed physiotherapists reported willingness to randomise (43%), although there appeared to be a common free-text response that this would depend on the opinion of the spinal consultant in charge of the care of the patient. Physiotherapists were more optimistic about the ability of exercise to limit curve progression, with about 25% of respondents saying it could help in selected cases. Virtually all physiotherapists and consultants said that physiotherapy would reverse curve progression in no or rare cases. Overall, there appears to be favourable equipoise for the conduct of a full-scale national trial that would randomise patients to exercise or monitoring.

Evaluating training needs was limited by the necessity for a brief questionnaire to maximise response. From the findings of the survey it appears that a very small number of physiotherapists have undertaken extended training in approaches for SSEs. What is reassuring is that the average physiotherapy respondent managing patients with AIS has > 5 years’ experience working with the patient group.

The findings need to be interpreted with some caution for two reasons. First, the study is based on the reporting and opinions of consultants and physiotherapists and not on actual observed practices. Second, the response rate for the survey of orthopaedic clinicians was low at the individual level, although at a NHS trust level nearly 80% of the listed trusts were represented via the individual clinicians. Non-responders may be atypical, but the types of trusts represented varied from district generals to large university teaching hospitals.

In conclusion, NHS trusts involved in specialist management of patients with AIS are providing variable physiotherapy services.

Chapter 4 Intervention development and delivery

Objectives

-

To develop and document a best evidence intervention of SSE treatment for AIS.

-

To determine adherence to allocated treatment arm (> 60% of adolescents attended required exercise sessions).

-

To assess and finalise training requirements for the intervention.

Developing the interventions

A number of principles were taken into consideration in the development of the intervention package:

-

the need to design an intervention that was reflective of best practice

-

the need to ensure that the intervention was acceptable to the clinicians and patients (including their families)

-

the need to ensure that the intervention could be delivered within the context of the UK NHS in terms of staffing and time

-

the need to ensure that the intervention was documented to a standard that promoted consistency in delivery and that would enable replication.

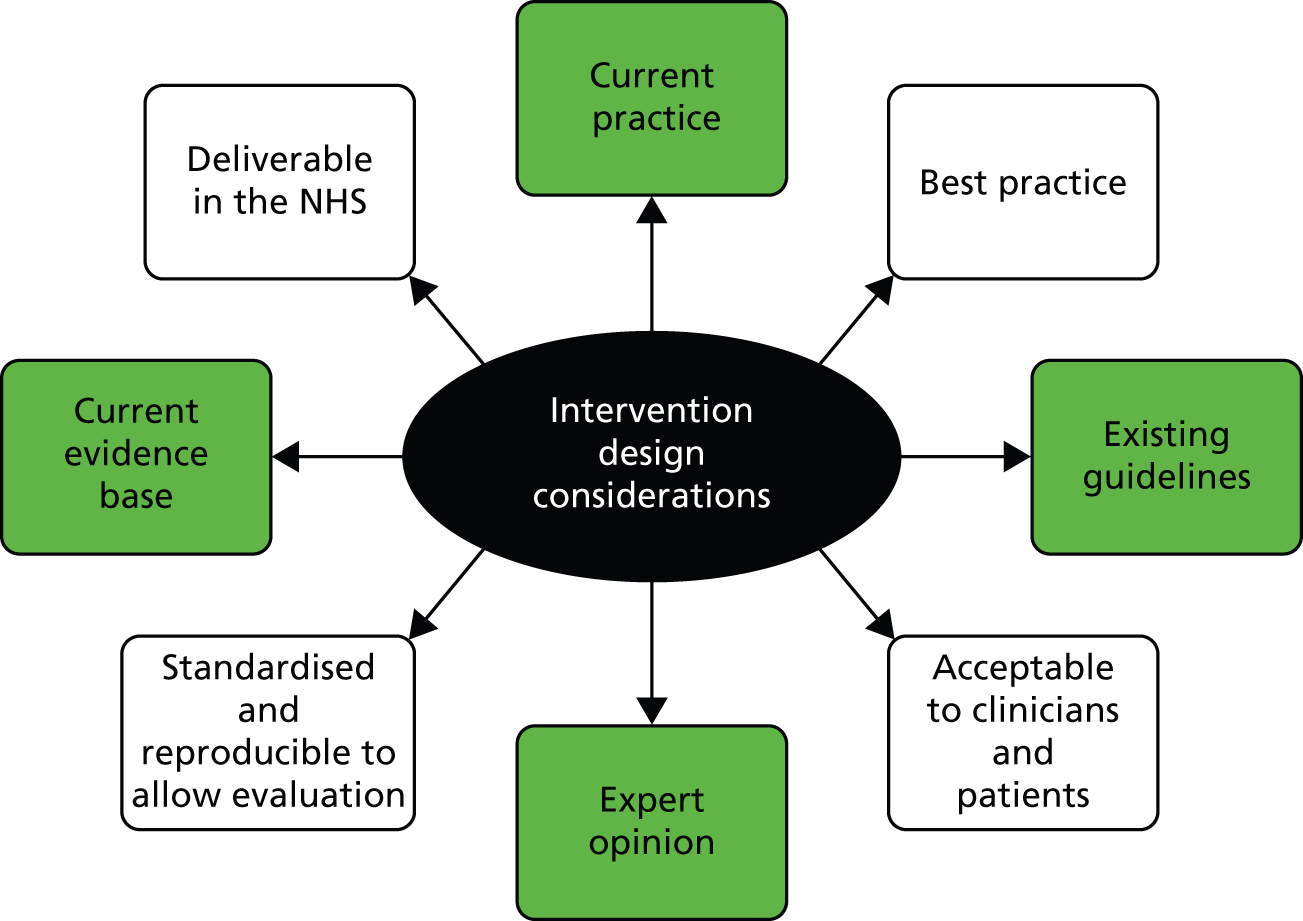

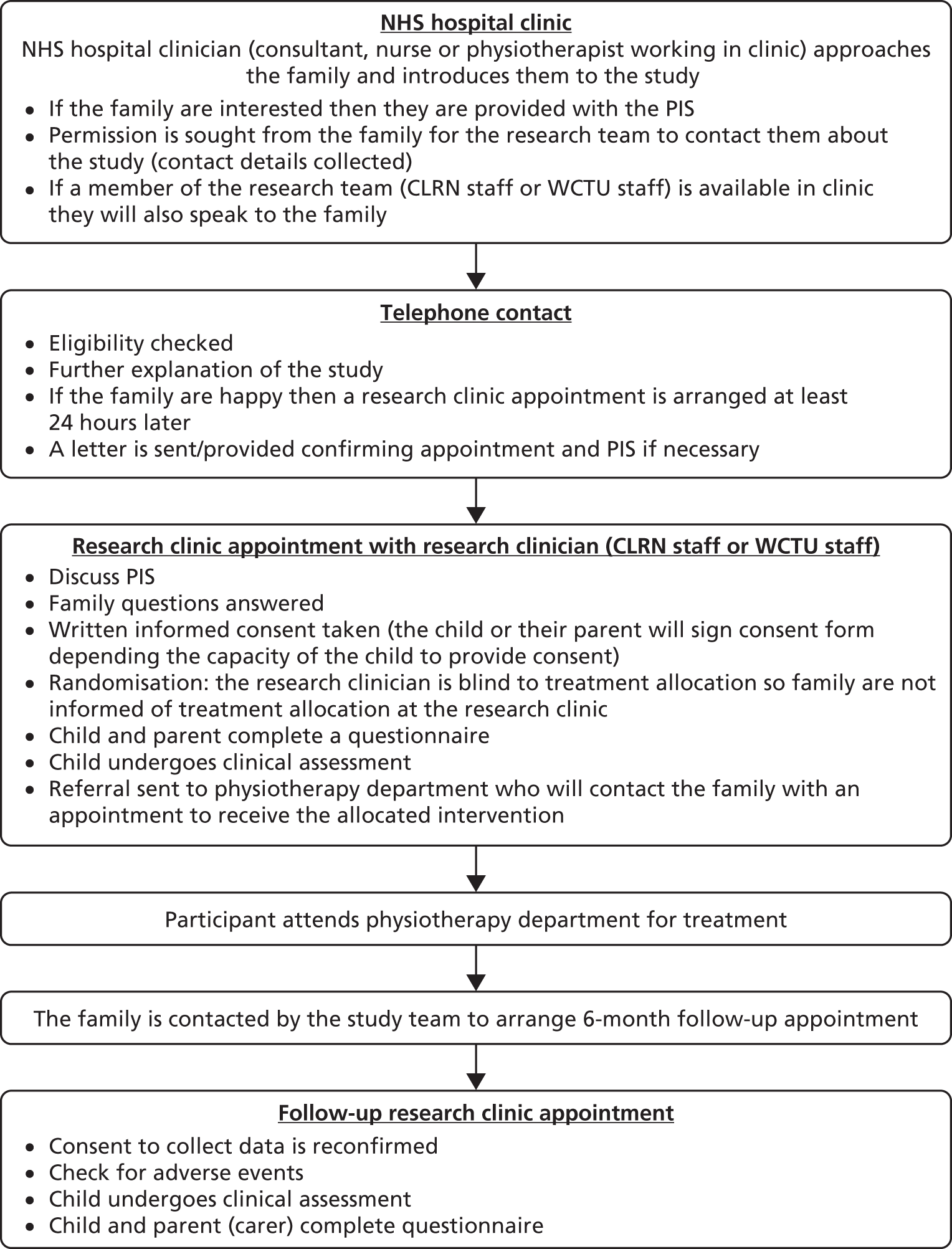

This was achieved by a triangulation of methods, including the survey of current practice, a review of existing guidelines, evidence from the literature and expert opinion (Figure 1), and following guidance on developing complex interventions. 58

FIGURE 1.

Intervention design methods and considerations.

Current practice

Current practice regarding conservative treatment for AIS was assessed as part of a nation-wide survey of orthopaedic consultants and specialist physiotherapists (see Chapter 3 for more details). The results indicate that the main components of conservative management of scoliosis in the UK are ‘watchful waiting’ and, in a minority of cases, bracing. Although some NHS trusts offer other services, including referral to physiotherapy for advice and/or exercises, these are not routinely offered within the NHS in the UK, and survey responses suggest that only a small percentage of patients are referred to physiotherapy. The majority of consultants at these centres rarely or never refer patients to physiotherapy for conservative management of AIS.

Once diagnosed with AIS, patients generally will come under the care of a specialist spinal consultant. Depending on the size of the curve and prognosis regarding potential progression, a monitoring plan will be instituted to maintain regular evaluation of the spinal deformity. Typically, this will occur every 6 or 12 months and will involve some form of imaging, although the timing will alter depending on prognosis and the speed of any changes. For 90% of patients with AIS, monitoring is the only ‘treatment’ they will receive.

Clinical guidelines

We searched for but did not find UK guidelines concerning conservative management of AIS. The Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment, an international group dedicated to scoliosis treatment and research, has produced a series of papers detailing the results of consensus exercises using Delphi techniques. They state the aims of conservative management to be stopping curve progression; preventing pulmonary dysfunction; treating any pain; and improving appearance via postural correction. 59 A series of recommendations regarding conservative treatment were also made. These include:

-

SSE programmes should be used and should include education, postural self-correction and integration of postural correction into activities of daily living (ADLs).

-

Exercise programmes should be individualised according to patients’ needs and curve type.

-

SSEs should be performed regularly.

No specific recommendations were provided regarding the type of exercises or their exact frequency or delivery method.

Evidence base

The majority of the studies included in the systematic review update described in Chapter 2 were not published when the ACTIvATeS trial intervention was developed. At that time, the evidence base for the effectiveness of exercise in AIS consisted of the Cochrane review published in August 2012,17 which included publication of studies up to 30 March 2011. This review included two studies (154 participants): the RCT by Wan et al. 27 and the prospective controlled cohort study by Negrini et al. 15