Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/70/01. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The draft report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

this report contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Cooper et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Overview of cannabis use

Cannabis use may be defined as acute (occasional) or chronic, with chronic use often defined as use on most days over a period of years. 1 Cannabis dependence can develop from chronic use and is characterised by impaired control over use and difficulty in ceasing use. 1 Cannabis dependence is a recognised psychiatric diagnosis, often diagnosed via the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). 2,3

Cannabis use has been found to exacerbate the symptoms of psychiatric disorders. 4 In one study, individuals who used cannabis regularly were found to be six times more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder. 5 The term ‘dual diagnosis’ is used to describe individuals who have a mental health problem and also are dependent on drugs (or alcohol). 6

Epidemiology and prevalence

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug worldwide. 7 In one study reporting cannabis use in European countries, use for 20 or more days per month ranged from 3.5% to 44.1%, with the figure for the UK being 3.9%. 8 In Australia, the prevalence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)-defined cannabis abuse in the general population over a 12-month period has been estimated at 2.3%, whereas a national survey undertaken in the USA found that 6% of individuals who used cannabis within a 1-year period met the DSM-IV criteria for cannabis dependence. 9,10 This figure, as would be expected, varies by country. In Australia, 31.7% of individuals who used cannabis more than five times in the past year met the criteria for a cannabis use disorder. 11,12

Estimates for the prevalence of patients with a ‘dual diagnosis’ (substance abuse disorder and mental health problems) vary across sources, but it is frequently reported that over 50% of patients with mental health problems also have a substance abuse problem. 6

Impact of health problem and prognosis

The impact of cannabis use on the individual can be classed as acute or chronic. Acute effects include hyperemesis syndrome (recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain), impaired co-ordination and performance, anxiety, suicidal ideations/tendencies, impaired attention and memory and psychotic symptoms. 2,13 Chronic effects include development of cannabis dependence, cognitive impairment, pulmonary disease and malignancy of the oropharynx. 2,13 There is increasing evidence to suggest the presence of a cannabis withdrawal syndrome, with symptoms (such as dysphoric mood, disturbed sleep and gastrointestinal symptoms) beginning during the first week and continuing for several weeks following the start of abstinence. 4 In a study by Budney et al. ,14 47% of participants withdrawing from cannabis reported four or more severe symptoms, including irritability, craving and nervousness; other symptoms were less severe and included depression, restlessness and headaches.

In a cohort study comparing those seeking treatment with non-treatment seekers, those seeking treatment reported increased cannabis use and more symptoms of dependence but a more positive attitude to treatment. 15 Even when an individual has sought treatment, recovery from substance dependence is hampered by poor adherence to psychological and psychosocial treatments, with factors such as cognitive defects, personality disorder and younger age predicting low treatment adherence. 16

Measurement of disease

Cannabis abuse and dependence is diagnosed using one or more assessment criteria, the most widely used being DSM-IV and ICD-10. There are DSM-IV criteria for both substance dependence and abuse. 3 Dependence is defined as tolerance (a need for increased amounts of the substance to achieve the desired effect), withdrawal (either having withdrawal symptoms or taking another substance to avoid withdrawal symptoms), taking substance in larger amounts than intended, and having persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down use. Substance abuse is characterised by recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfil obligations, recurrent use in hazardous situations, recurrent substance-related legal problems and continued use despite recurrent social or interpersonal problems. For both sets of criteria, individuals meeting three or more criteria within a 12-month period meet the diagnosis. In 2013, the updated Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria were released. 17 In the revised criteria, there is no distinction between abuse and dependence, but a spectrum of substance use disorders. 18

Current service provision

Relevant national guidelines

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that pharmacological interventions for chronic cannabis users are not well developed, so psychosocial interventions are the mainstay of effective treatment. 19 UK Department of Health guidelines for the treatment of chronic users recommend that clinicians should consider motivational interventions in mild cases and structured treatment with key working (when a health professional works with the individual to ensure delivery and ongoing review of care being received) in more heavy users, whereas cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is recommended in cases with comorbid depression and anxiety. 20 European best practice guidance, produced by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, recommends the use of multidimensional family therapy for regular cannabis users, while individual sessions of CBT are stated to be possibly advantageous. 21

Management of the condition

Providing treatment to chronic users of cannabis to reduce or cease their use is a relatively recent occurrence. Until the 1980s, it was thought that chronic cannabis use did not lead to dependence and treatment was, therefore, not required. 22 Since then, research has looked into evaluating the use of a wide variety of psychological and psychosocial interventions, such as motivational interviewing (MI), CBT and contingency management (voucher incentives). 12 There is limited evidence to suggest which of the many psychological and psychosocial interventions are the most effective at reducing cannabis use.

A number of systematic reviews have been undertaken to assess the benefits of such interventions for regular cannabis users, many of which included meta-analyses. However, they all had limited scope and, therefore, did not assess all the available evidence, and several further studies have been published since. A review by Denis et al. 12 that excluded studies in populations dependent on drugs other than cannabis analysed six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) via narrative synthesis, involving interventions such as CBT and motivational enhancement therapy (MET), finding that CBT provided improved outcomes over brief interventions, whereas voucher incentives were found to enhance treatment when used in combination with other therapies. Dutra et al. 23 undertook a meta-analysis, identifying five studies assessing the use of psychological treatments (including case management, CBT and relapse prevention), finding a significant difference between outcomes for cannabis use, with a mean effect size of 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25 to 1.36] when comparing intervention treatments with control [which consisted of motivational enhancement, wait list control and treatment as usual (TAU)]. Other reviews have focused on specific interventions to treat regular users of cannabis. Tait et al. 24 assessed the use of internet-delivered interventions, finding that such interventions provided a significant decrease in cannabis use at post treatment [g (Hedges’ bias-corrected effect size) = 0.16, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.22; p-value < 0.001].

Previous reviews have also sought to investigate the effectiveness of such interventions across the spectrum of substance misuse, including alcohol and opioids. The review by Dutra et al. 23 reported that treatments incorporating both CBT and contingency management had the greatest effect sizes on substance use across a range of substances including cocaine, opiates and cannabis (Cohen’s d 1.02), whereas the two treatments alone had smaller effect sizes on the same group of substances (contingency management, Cohen’s d 0.58, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.90; CBT, Cohen’s d 0.28, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.51). In contrast, a review by Hunt et al. 6 included RCTs of patients with a severe mental illness and substance dependence, finding no compelling evidence to suggest a significant decrease in substance use when comparing CBT over TAU [two studies, risk ratio (RR) 1.12, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.86] or of CBT plus MI over TAU (one study, mean difference 0.19, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.60). The use of MI alone compared with usual treatment had positive effects on abstinence from alcohol (one study, RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.75) but no effect on other substances (one study, RR –0.07, 95% CI –0.56 to 0.42). 6 Other reviews have focused on specific interventions for ‘general’ substance misuse. Magill et al. 25 analysed 52 studies assessing the use of CBT (plus pharmacological treatments in a number of studies) on a range of substance dependences (including alcohol, cannabis, opiates and cocaine), reporting a small effect on the reduction of substance use for those studies reporting relevant outcomes (34 studies, g = 0.108, 95% CI 0.051 to 0.165; p-value < 0.005). Wood et al. 26 assessed the use of computer-delivered interventions, finding that drug prevention programmes were effective at reducing use in the mid-term (12 months) but not at post treatment. Mindfulness-based interventions have also been found to be effective for substance abuse. 27

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of interventions

This review assesses the clinical effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions aimed at assisting regular cannabis users to reduce or cease their use. Only interventions delivered in an outpatient or community setting are included. A full list is provided in Chapter 3, Methods for reviewing effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The aim of this assessment was to systematically review the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions for cannabis cessation in adults who use cannabis regularly.

Population and setting

The relevant population included individuals ≥ 18 years of age who were regular users of cannabis and had participated in a study providing treatment(s) for cannabis use in a community or outpatient setting. Studies focusing specifically on treating cannabis users within prisons or the criminal justice system or in inpatient settings were excluded. Inclusion was not restricted according to level of cannabis use at baseline.

Interventions

Studies involving psychological and psychosocial interventions were included.

Relevant comparators

Comparators included other psychological and psychosocial interventions, waiting list control, TAU or no treatment (comparisons with drug treatments were excluded).

Key outcomes

The key outcomes for this review were frequency and amount of cannabis use; severity of dependence; motivation to change; level of cannabis-related problems (including medical and other); and attendance, retention and dropout rates. The results of the review were also used to formulate recommendations for future research.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aims and objectives of this assessment were to systematically review the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions for cannabis cessation in people who use cannabis regularly.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

A systematic review was undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions for cannabis cessation in adults who use cannabis regularly. The review was undertaken in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org/). 28 The completed PRISMA checklist is presented in Appendix 1.

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched to February 2014 for published and unpublished research evidence: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, PsycINFO and Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index. This included reference searching within relevant systematic reviews and included studies, contact with experts and searching clinical trials databases (https://ClinicalTrials.gov and www.controlled-trials.com) and relevant websites, including United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (www.unodc.org), DrugScope (www.drugscope.org.uk), American Society of Addiction Medicine (www.asam.org), National Institute on Drug Abuse (www.drugabuse.gov), Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (www.ccsa.ca), and Canadian Society of Addiction Medicine (www.csam-smca.org).

The protocol for this review is available on request from the authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population and setting

The relevant population included participants aged ≥ 18 years, who were regular users of cannabis. Inclusion was not restricted according to level of cannabis use at baseline. The review focused on studies in a community or outpatient setting.

Studies focusing on the following subpopulations were excluded:

-

Studies in the setting of the criminal justice system, that is prisons, following release (on parole) or within the court system.

-

Studies for which the majority of participants were young people (< 18 years of age). In studies of mixed age groups, data for subgroups aged ≥ 18 years were extracted if available or, if not, then the study was included if ≥ 80% of participants were aged ≥ 18 years or, if these data were not available, where the mean age of participants was ≥ 18 years, at baseline.

-

Studies for which participants were treated in an inpatient setting, that is, the patient received treatment for regular cannabis use while occupying a hospital ward, drug rehabilitation centre or within an emergency department. Studies for which a subset of the participants were residing in inpatient psychological treatment centres were included, provided that the cannabis intervention was delivered as a standalone therapy rather than as an integrated part of psychological treatment.

-

Studies in which the intervention, or a component of the intervention, was provided to participants other than the cannabis user (e.g. parents or partners). An example of such an intervention is Multidimensional Family Therapy.

-

Studies in very specific subpopulations (such as indigenous communities or human immunodeficiency virus patients).

For studies covering abuse of more than one substance (i.e. poly-substance abuse, involving other drugs or alcohol), the following approach was taken:

-

Studies were included only if they reported cannabis-use outcomes (rather than any drug use) for the subpopulation who were cannabis users.

-

Studies were excluded if the entire study population was dependent on alcohol, cocaine, opiates, amphetamines or receiving methadone maintenance (as these are quite specific populations and less relevant to cannabis cessation).

Included interventions

Relevant interventions included a range of psychological and psychosocial interventions aiming to reduce or cease cannabis use. Combinations of therapies were included. All possible modes of delivery were included, including individual face-to-face or group sessions, plus interventions provided via the internet or telephone. Relevant interventions included:

-

CBT – an approach aiming to manage cannabis use by changing the way the participant thinks or behaves29

-

MI – a person-centred approach that aims to improve motivation to change and resolve ambivalence to change30

-

MET – a variant of MI that is manual based31

-

relapse prevention therapy – based on CBT, enables clients to cope with high-risk situations that may lead to drug taking32

-

contingency management – providing patients with tangible rewards (such as monetary vouchers) in return for a reduction or cessation in drug taking20

-

case management – a strategy to improve the co-ordination and continuity of the delivery of services to a patient33

-

mutual aid therapy – therapy in which people with similar experiences assist each other to overcome or manage their issues (e.g. Self-Management and Recovery Training)

-

other psychological and psychosocial interventions as identified within the review process.

Comparators

Comparators included other psychological and psychosocial interventions, waiting list control, TAU or no treatment. Studies comparing a psychosocial intervention with a drug treatment were excluded.

Outcomes

The key outcomes for this review were:

-

frequency and intensity of cannabis use, via self-report, with or without confirmation by biological analysis (urinalysis, hair/saliva analysis)

-

number (%) of days used, time periods of use per day, amount per day

-

number (%) reporting abstinence following intervention

-

-

severity of drug-related problems [measured via the Addiction Severity Index (ASI)]34

-

severity of dependence [measured via the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS)]11

-

stage of change or motivation/contemplation to change [e.g. as measured by the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RCQ)]31

-

level of cannabis-related problems – medical problems, legal problems, social and family relations, employment and support [assessed via questionnaires such as the Cannabis Problems Questionnaire (CPQ)]35

-

attendance, retention and dropout rates, measured as number of sessions attended or number (%) completing whole treatment period

-

recommendations for future research.

Included study types

Only RCTs were included in this review.

Excluded study types

The following study types were excluded:

-

non-randomised studies

-

narrative reviews, editorials, opinion pieces

-

reports written in a language other than English or published as meeting abstracts, if insufficient methodological details are reported in the abstract to allow critical appraisal of study quality and extraction of study characteristics and key outcomes.

Data extraction strategy

Titles and abstracts of citations identified by the searches were screened for potentially relevant studies by one reviewer and a 10% sample checked by a second reviewer (and a check for consistency undertaken). Full texts were screened by two reviewers. One reviewer performed data extraction for each included study. All numerical data were checked against the original article by a second reviewer and any disagreements were resolved through discussion. When studies comprised duplicate reports (parallel publications), the most recent and relevant report was used as the main source and additional reports checked for extra information. Excluded studies were tabulated (see Appendix 3).

Methods of data synthesis

Data were analysed via a narrative synthesis. As described by Popay et al. ,36 this method is based around grouping and tabulating the data in meaningful clusters, allowing results to be summarised (in the form of text and tables) to provide an overview of the direction of effect for each relevant subgroup. Within this review, studies were first divided into two main population subgroups (general cannabis users and those with a major psychiatric condition). Second, studies were categorised according to their intervention and comparison groups (e.g. CBT vs. wait list, CBT vs. MI, etc.). Third, results were tabulated for two key time points (post treatment and later follow-up). Within each study, outcomes at each time point were categorised according to whether or not they were significantly different between groups or between baseline and follow-up. Finally, summary tables were populated for each intervention/comparison. Outcomes across studies at each time point were summarised as being mainly significant, mainly not significant or mixed.

There was substantial heterogeneity between studies in terms of populations, interventions, comparators, outcome measures reported and statistics reported. To increase clarity, the main results of this review are presented in the form of an overview of the outcomes reported per study and how many showed a significant difference, as described above. Detailed numerical results per study group are not presented in the main results section, but are provided in Appendix 4 for reference. Meta-analysis was not undertaken, as this would have required restricting each analysis to studies reporting the same outcome in a consistent format with full data and it was felt that the broad results picture might have been lost.

Subgroup analyses were undertaken with regard to number of treatment sessions, group/individual treatment, high/low cannabis use at baseline, recruitment method (referral vs. voluntary), participant age and use of other substances (tobacco and alcohol) at baseline.

Quality assessment of included studies

Methodological quality of included RCTs was assessed using an adapted version of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment criteria. This tool addresses specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. 37 Outcome assessment was considered to be blinded if the person assessing or interviewing the participants was blinded to group allocation (although participants were not blinded and many of the data were self-reported). We made two adaptations to these criteria in order to aid quality assessment. First, we utilised the ‘5-and-20 rule’ for incomplete outcome data, as proposed by Schulz and Grimes. 38 Schulz and Grimes38 state that a lower than 5% loss in participants probably leads to little bias, while a greater than 20% loss potentially poses serious threats to validity. We therefore defined < 5% attrition as ‘low risk’, between 5% and 20% attrition as ‘intermediate risk’ and > 20% attrition as ‘high risk’. Attrition was defined as the percentage of patients not followed up at the final time point reported. The second adaptation we made to the Cochrane criteria was to add an ‘overall risk’ criterion, aiming to summarise the overall risk of studies. We categorised studies as low risk, high risk or unclear risk, determined using the following criteria. Low risk was allocated to studies where randomisation, allocation concealment, blinded outcome assessment and incomplete data were all determined to be low risk. High risk was allocated to studies deemed to have undertaken inadequate randomisation (self-selection, sequential patients, odd and even), and/or when allocation was not concealed, and/or when incomplete data were deemed to be high risk. Unclear risk was allocated to all other studies.

Patient and public involvement

In order to seek patient and public input into the review, we recruited a service user through liaison with the project’s clinical advisors, who was currently acting as a ‘service ambassador’ within their treatment service (an individual who has completed a treatment regime, ceased their primary substance use and is now involved in supporting patients at the treatment centre).

A short ‘briefing document’ using non-academic language was developed (see Appendix 5) in order to introduce the individual to the research. The briefing document included sections describing the basic principles of a systematic review, the general area in which the research is being undertaken (i.e. psychological/psychosocial treatments for regular users of cannabis) and the input required from the service user. The service user was compensated for the time spent at meetings and for travel expenses.

The review team met with the service user twice. The first meeting was scheduled once the protocol had been written. The service user provided valuable input into the following areas of the protocol:

-

an additional intervention not already identified in the protocol (mutual aid therapy)

-

two additional outcome measures that were felt to be important (daily time periods of cannabis use and contemplation to change)

-

general approval of the focus of the review.

The review team then met with the service user after the draft report had been written, when the service user had the following inputs:

-

suggested amendments to the plain English summary

-

reviewed the suggested research priorities

-

reviewed the section describing factors relevant to the NHS.

Results

Quantity of research available

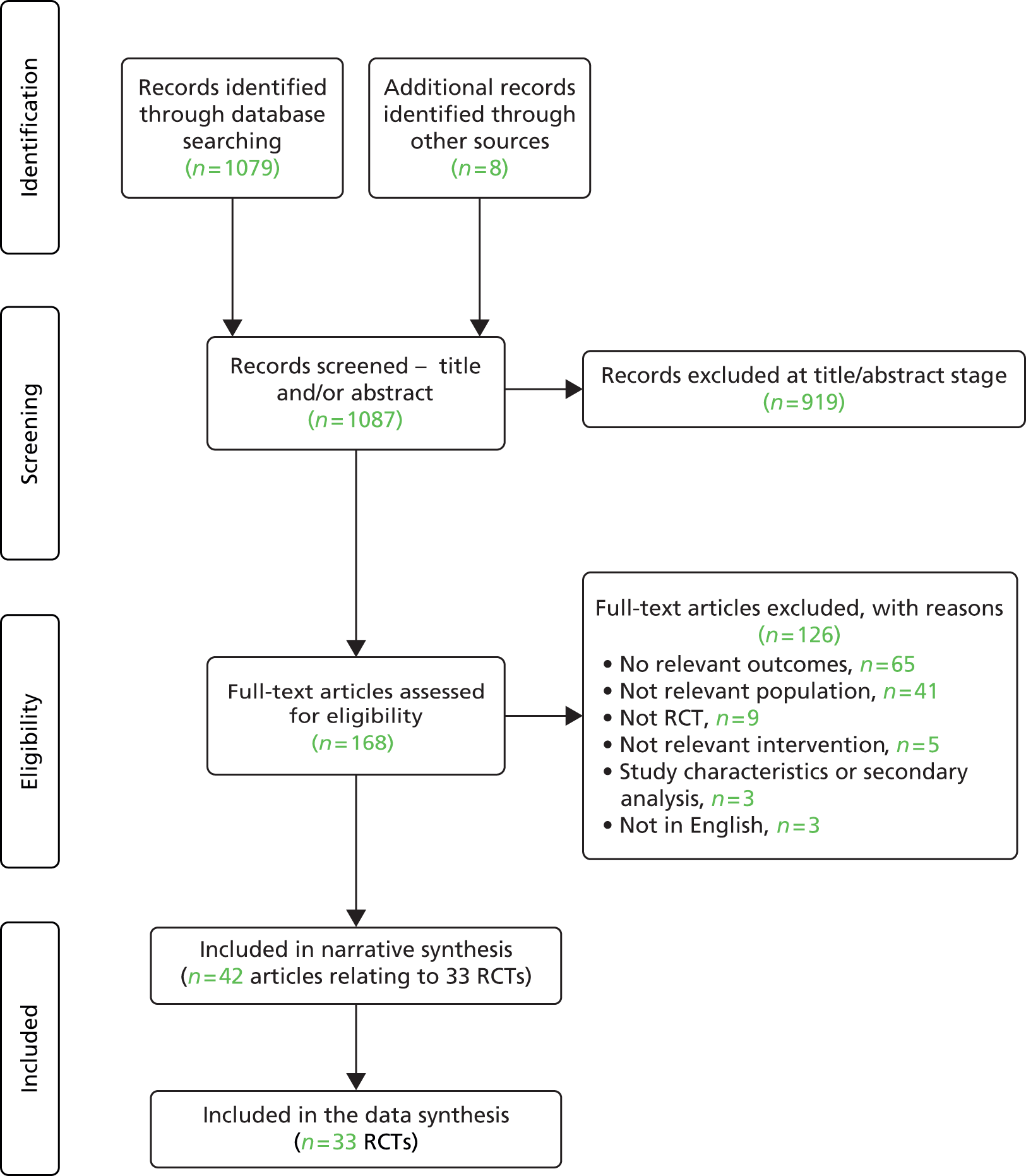

The searches identified 1087 citations (1079 via database searches and eight via other sources). Of these, 919 citations were excluded at the title/abstract stage and 168 full-text articles were screened. Of these, 126 were excluded: 65 did not include relevant outcomes, 41 evaluated irrelevant populations, nine were not RCTs, five did not involve a relevant intervention, three detailed a non-relevant secondary analysis or study characteristic and three were not in English (excluded studies are listed in Appendix 3). In total, 42 articles relating to 33 RCTs were included in this review. The PRISMA flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study selection process: PRISMA flow diagram.

All titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion by one reviewer and a check for consistency was undertaken. A second reviewer screened approximately 10% of the references (n = 100) during the initial screening stage. No discrepancies were found.

Characteristics of included studies

The 33 studies included in this review were undertaken in a range of countries: the USA (13 studies39–51), Australia (seven studies52–58), Germany (three studies59–61), Brazil (two studies62,63), Canada (two studies64,65), Switzerland (two studies66,67), Denmark (one study68), Ireland (one study69) and worldwide (two studies, one utilising internet-based interventions70 and the other undertaken in a number of locations worldwide71) (Tables 1 and 2).

| Study (country, mode of recruitment) | Interventions (number of sessions) | Number of cannabis users | Inclusion criteria: age (years) | Mean age at BL (years) (range) | Level of cannabis use/dependencea | Mean cannabis use at BL | Additional exclusion criteria | Mean alcohol and tobacco use at BL | Key outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis use | Severity of dependence | Cannabis-related problems | Session attendance | |||||||||

| Babor 200439 and Litt 200572 (USA, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MET/CaseM (9); MET (2); wait list | 450 | ≥ 18 | 36 (18–62) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence; cannabis used ≥ 40 out of 90 days | 27 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Total drinks in last 90 days: 47–59 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Budney 201142 and ClinicalTrials.gov 201373 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/MET/voucher (9); computer-delivered CBT/MET + brief therapist + voucher (9); MET (2) | 45 | 18–65 | 35 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis abuse or dependence and used cannabis ≥ 40 of previous 90 days | NR | Other drug use | NR | Yes | |||

| Budney 200641 (USA, voluntary and referral) | CBT (14); CBT/vouchers (14); vouchers | 60 | ≥ 18 | 33 (NR) | High use: MET DSM-IV cannabis dependence and used cannabis in past 30 days | 26 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Mean days alcohol use in past 30 days = 6–8 days | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Budney 200040 and Moore 200374 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/MET (14); MET (4); CBT/MET/vouchers (14) | 60 | ≥ 18 | 32 (NR) | High use: DSM-III-R classification for cannabis dependence; cannabis use in previous 30 days | 23 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Days of alcohol use past 30 days: 2.7–7.0 days | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Copeland 200153 (Australia, voluntary) | CBT (6); MI (1); wait list | 229 | ≥ 18 | 32 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence | NR | Other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| de Dios 201243 (USA, voluntary) | MI/meditation (2); AO | 39 | 18–29 | 23 (NR) | Low use: ≥ 3 times past month | 18 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Fernandes 201062 (Brazil, voluntary) | Tele-brief motivational intervention (1) written cannabis information | 1744 | NR | 25 (11–NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Yes | |||

| Fischer 201275 and Fischer 201364 (Canada, voluntary) | Brief MI (1); written cannabis information; therapist general health MI (1); written general health information | 134 | 18–28 | 20 (NR) | Low use: used for > 1 year, at least 12 of past 30 days | 24 days/month | NR | NR | Yes | |||

| Gates 201255 (Australia, voluntary) | Tele-CBT/MI (4); wait list | 160 | ≥ 16 | 36 (NR) | Low use: ≥ 1 use cannabis in last month | NR | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Nicotine 90-day use: 57.6–59. Alcohol: 90-day use: 20.1–25.9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gmel 201367 (Switzerland, voluntary) | Brief MI (1); AO | 378 | 19–20 | 20 (19–20) | NR | 7–9 days/month | NR | NR | Yes | |||

| Grenyer 199756 (Australia, NR) | SEDP (16); MI (1) | 40 | NR | 34 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence | NR | Other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Hoch 201460 (Germany, referral) | CBT/MET/PPS (10); wait list | 385 | ≥ 16 | 27 (16–63) | Low use: ≥ 9 days/month | 20 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Alcohol: mean 0.2 litres/day. Tobacco: 78–82% used daily | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hoch 201259 and Hoch 200876 (Germany, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MET/PPS (10); wait list | 122 | ≥ 16 | 24 (16–44) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence/abuse 89% | NR | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Alcohol dependence: 30% | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Humeniuk 201271 (worldwide, referral) | Brief MI (1); wait list | 395 | 16–62 | 31 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Yes | |||

| Jungerman 200763 (Brazil, NR) | CBT/MI/RP (4) (3 months); CBT/MI/RP (4) (1 month); wait list | 160 | ≥ 18 | 32 (18–58) | Low use: ≥ 13 days/month | 26–28 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Alcohol: 10–11% of prior 90 days | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kadden 200744 and Litt 200877 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/MET (9); CaseM (9); CBT/MET/vouchers (9); vouchers | 240 | ≥ 18 | 33 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence | NR | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | ASI alcohol score 0.10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lee 201346 (USA, referral) | Brief MI (1); AO | 212 | 18–25 | 20 (NR) | Low use: ≥ 5 days/month | 16–17 days/month | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Lee 201045 (USA, referral) | Internet-based personalised feedback (1); AO | 341 | 17–19 | 18 (NR) | Low use: any use | 3 days/month | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Litt 201347 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/MET/vouchers (homework) (9); CBT/MET/vouchers (abstinence) (9); CaseM (9) | 215 | ≥ 18 | 33 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence | 24 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Rooke 201370 (worldwide, voluntary) | Internet-based CBT/MI (6); internet-based written cannabis information | 230 | ≥ 18 | 31 (NR) | Low use: ≥ 1 day/month | 21 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sobell 200965 (Canada, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MI (4) (group); CBT/MI (4) (individual) | 17 | ≥ 18 | 32 (NR) | Low use: ‘not severe dependence’ | 27 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | |||

| Stein 201148 (USA, voluntary) | MI (2); AO | 332 | 18–24 | 21 (NR) | Low use: ≥ 1 day/month | 17 days/month | Other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Stephens 200751 (USA, voluntary) | MI/personalised feedback (1); cannabis education (1); wait list | 188 | ≥ 18 | 32 (18–57) | High use: ≥ 15 days/month | 26 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | Alcohol use on 1.8 days per week | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stephens 2000,50 Lozano 200678 and DeMarce 200579 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/RP/social support (14); MI (2); wait list | 291 | ≥ 18 | 34 (NR) | High use: DSM-III-R cannabis dependence | 25 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stephens 199449 (USA, voluntary) | CBT/RP (10); social support group (10) | 212 | ≥ 18 | 32 (18–65) | High use: ≥ 17 days/month | 27 days/month | Psychiatric conditions; other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tossmann 201161 (Germany, voluntary) | Internet-based counselling; wait list | 1292 | NR | 25 (NR) | High use: ‘any use’, 92% DSM-IV cannabis dependent at BL | NR | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Study (country, mode of recruitment) | Interventions (number of sessions) | Number of cannabis users | Inclusion criteria: age (years) | Mean age at BL (years) (range) | Level of cannabis use/dependencea | Mean cannabis use at BL | Inclusion criteria: psychiatric condition | Additional exclusion criteria | Mean alcohol and tobacco use at BL | Key outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis use | Severity of dependence | Cannabis-related problems | Session attendance | ||||||||||

| Baker 200652 (Australia, referral) | CBT/MI + TAU (10); TAU | 73 | ≥ 15 | 29 (15–61) | Low use: ≥ 4 days/month | 5–8 days/month | ICD-10 psychotic disorder | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Bonsack 201166 (Switzerland, referral) | CBT/MI + TAU (6); TAU | 62 | 18–35 | 26 (18–35) | High use: 82% cannabis dependent | 23 days/month | ICD-10 psychotic disorder | Other drug use | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Edwards 200654 (Australia, referral) | CBT/MI + TAU (10); psychoeducation (non-cannabis) + TAU (10) | 47 | 15–29 | 21 (NR) | Low use: 49% DSM-IV cannabis dependent | 8 days/month | DSM-IV psychotic disorder | NR | 2.2% DSM-IV diagnosed alcohol dependence | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Hjorthoj 201368 and 201280 (Denmark, referral) | CBT/MI + TAU (24); TAU | 103 | 17–42 | 27 (NR) | High use: ICD-10 cannabis dependence/abuse | 15 days/month | ICD-10 schizophrenia | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Kay-Lambkin 201158 (Australia, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MI (10); computer-delivered CBT/MI + brief therapist (10); PCT (10) | 109 | ≥ 16 | 40 (17–70) | Low use: ≥ 4 days/month | NR | DSM-IV major depressive disorder, BDI-II ≥ 17 | Psychotic conditions | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Kay-Lambkin 200957 (Australia, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MI (10); computer-delivered CBT/MI + brief therapist (10); brief MI (1) | 43 | ≥ 16 | 35 (18–61) | Low use: ≥ 4 days/month | NR | DSM-IV major depressive disorder, BDI-II ≥ 17 | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

| Madigan 201369 (Ireland, voluntary and referral) | CBT/MI (group) (12); TAU | 88 | 16–65 | 28 (NR) | High use: DSM-IV cannabis dependence | NR | DSM-IV schizophrenia, psychosis, major depressive or bipolar disorder | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | ||

Population

General or psychiatric

The included studies can be broadly categorised into those that sought to treat the ‘general cannabis users population’ (26 studies;39–51,53,55,56,59–63,65,67,70,71,75 see Table 1) and those that sought to treat patients with a ‘dual diagnosis’ (patients with both a psychiatric condition and cannabis use, seven studies;52,54,57,58,66,68,69 see Table 2). Among the psychiatric studies, two studies52,66 included participants with schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder (via ICD-10 criteria), one study68 included those with schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis (via ICD-10 criteria), two studies54,69 included those with psychosis (via DSM-IV criteria) and two studies57,58 included those with major depressive disorder (via DSM-IV criteria and a score ≥ 17 on the Beck Depression Inventory II).

The included studies recruited a total of 8168 participants; 7643 were involved in general population studies, whereas 525 were recruited into the psychiatric studies (participant numbers were not reported in one study,52 in which the participant numbers at follow-up were used to calculate total number of participants). The studies of the former grouping tended to restrict the inclusion of patients, with 15 studies39–41,43,44,47,49–51,55,59,60,63,65,70 excluding patients with a psychiatric condition and other drug dependencies and four studies42,48,53,56 excluding only patients with other drug dependencies. One psychiatric study excluded participants who had other drug dependences. 66

Recruitment

In order to recruit participants, the studies treating the general population most frequently used voluntary recruitment methods, that is, participants responded to advertisements (16 studies40,42–44,47–51,53,55,61,62,67,70,75), with fewer studies employing a referral mechanism (four studies45,46,60,71) or a combination of voluntary recruitment and referrals (four studies39,41,59,65); recruitment methods could not be ascertained for two studies. 56,63 Conversely, the psychiatric studies all employed referral mechanisms (four studies52,54,66,68) or a combination of referral and voluntary recruitment methods (three studies57,58,69). Therefore, the ‘general population’ studies mostly involved self-selected participants who may have been more motivated to cease use than the average cannabis user.

Age

The majority of studies employed participant age study inclusion criteria, bar three. 56,61,62 Participants were included if they were aged 18–19 years or over (19 studies39–44,46–51,53,63,65–67,70,75), aged 16–17 years or over (nine studies45,55,57–60,68,69,71) or aged 15 years or over (two studies52,54). Twelve studies also included an upper age limit; this was in the twenties (six studies43,46,48,54,67,75), thirties to forties (two studies66,68) or sixties (three studies42,69,71), while one study used an age range of 17–19 years45 and one used a range of 19–20 years. 67 At baseline, the mean age of participants across studies was 29 years (all studies, range for mean age 18–40 years, median 32 years; general population studies, range 18–36 years, median 32 years; psychiatric studies, range 21–40 years, median 28 years).

Cannabis use or dependence at baseline

Thirty of the included studies specified criteria for the level of cannabis use at study inclusion. 39–61,63,65,66,68,69,70,75 These criteria varied by study, with eight studies44,47,53,56,65,68,69,71 utilising dichotomous criteria [patients meeting the DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Three (Revised) (DSM-III-R) or ICD-10 criteria for cannabis dependence or cannabis abuse], 18 studies43,45,46,48–52,54,55,57–60,63,66,70,75 selecting an inclusion point on a continuous scale of cannabis use (ranging from 1 to 20 or more days of use of cannabis per month) and four studies39–42 using a combination of both. Therefore, we classified studies into those for which the inclusion criteria for cannabis use or dependence were deemed to be ‘low’ and those for which they were deemed to be ‘high’. ‘High use’ was defined as a study inclusion criterion or population baseline measurement in which ≥ 80% of participants met the DSM or International Classification of Diseases criteria for cannabis dependence or abuse, and/or an inclusion criterion specifying that all participants used cannabis on at least 50% of days over a specified time period. Thirteen studies treating the general population included participants with ‘high’ use39–42,44,47,49–51,53,56,59,61 and 10 with ‘low’ use,43,45,46,48,55,60,63,65,70,75 and baseline use could not be determined for three studies. 62,67,71 Of those treating the psychiatric population, three studies66,68,69 included only participants with high use, whereas four52,54,57,58 included low-use participants.

Other substance use

Participants’ use of other substances at baseline was seldom reported by the studies; studies that did report this did not do so in a consistent manner. Overall, 10 studies reported alcohol use at baseline39–41,44,51,54,55,59,60,63 and two also reported tobacco use;55,60 the remaining 23 studies did not report this baseline measurement. Of the studies reporting alcohol use, five reported the average proportion of participants’ drinking days over a specified period,40,41,55,63,66 two reported average drinks per day over a specified period,51,60 two reported the proportion of participants who were deemed to meet the DSM criteria for alcohol dependence54,59 and one reported participants’ ASI score. 39

Comparators

Of the 26 ‘general population’ studies, 11 tested two or more interventions (with no inactive control arm, although some included an active control such as education),40–42,44,47,49,56,62,65,70,75 10 tested a single intervention against an inactive control [wait list or assessment only (AO)]43,45,46,48,55,59–61,67,71 and five tested more than one active intervention against an inactive control. 39,50,51,53,63 The general population studies utilised wait list (10 studies50,51,53,55,59–61,63,71) or AO (five studies43,45,46,48,67) as inactive controls. Of the ‘psychiatric’ studies, four tested a single intervention against a TAU control52,66,68,69 and three tested two or more active interventions with no inactive control. 54,57,58 TAU consisted of antipsychotic medication and psychiatric condition monitoring, plus self-help material in one study and a psychosocial intervention in two studies.

Interventions

The included interventions varied considerably. Single interventions consisted of multiple and overlapping components. In the following summary, we have classed studies by their ‘main’ intervention, which we have defined as either CBT or MI or contingency management. If a study consists of multiple intervention arms or multicomponent interventions consisting of CBT or MI, we have classed the ‘main’ intervention as CBT. The majority of general population studies (15 studies39–42,44,47,49,50,53,55,59,60,63,65,70) evaluated CBT as their main intervention, or a variation thereof. Of the 15 studies, three studies55,59,60 compared CBT with a wait list control; eight40–42,44,47,49,65,70 compared CBT with MI, a variation of CBT or another intervention; and four39,50,53,63 compared CBT with both a wait list control arm and another arm consisting of MI, a variation of CBT or another intervention. Five of the 15 studies also assessed contingency management, alone and/or in combination with CBT. 40–42,44,47 Of the 15 studies, 12 assessed the use of therapist-delivered CBT, whereas three42,55,70 assessed the use of computer- or telephone-delivered treatment (one42 of which tested therapist-delivered CBT against computer-delivered). Duration of CBT treatment ranged considerably, from 4 weeks63 to 1850 weeks. The majority of interventions involved weekly (or near weekly) sessions, with the notable exceptions of Hoch et al. 59 (two sessions per week over 5 weeks), one treatment arm of Budney et al. 40 (four sessions over 14 weeks) and Babor et al. 39 (two arms: nine sessions over 12 weeks and two sessions over 5 weeks). Nine studies assessed the use of a motivational intervention but not CBT;43,45,46,48,51,62,67,71,75 two45,62 of these assessed computer- or telephone-delivered treatment. Two general population studies did not involve MI or CBT components; Tossman et al. 61 provided internet-based counselling, whereas Grenyer et al. 56 provided supportive–expressive dynamic psychotherapy.

The psychiatric population studies evaluated the use of CBT (seven studies). 52,54,57,58,66,68,69 Five studies utilised therapist-delivered interventions,52,54,66,68,69 the remainder (two studies)57,58 assessed the use of computer-delivered CBT compared with therapist-delivered CBT. Length of treatment varied: in four studies treatment lasted 10 weeks,52,54,57,58 in one study 12 weeks69 and in two studies 24 weeks. 66,68 All CBT sessions were delivered on a weekly basis, with the notable exception of Bonsack et al. 66 (four to six sessions over 24 weeks).

No studies were found that assessed the efficacy of mutual aid therapy.

Outcomes

All of the included RCTs measured the effect of the intervention(s) on participants’ cannabis use; however, the way in which this was measured varied greatly by study. For example, studies measured point abstinence rates, abstinence over a specified period, frequency of cannabis use per day over a specified period and number of cannabis-using days over a specified period. Thirteen studies39,40,44,50,51,53–56,59,60,63,70 measured participants’ severity of cannabis dependence (measured via self-report using various instruments, most frequently using the SDS or ASI). 11,34 Fifteen studies39–41,44–47,49–51,53,55,60,63,66 measured participants’ number of cannabis-related problems [measured using various instruments, most frequently the Marijuana Problems Scale (MPS)]. 35 Twenty-five studies measured participants’ use of the intervention or session attendance. 39–41,43,44,47–55,57–61,63,66,68,69,70,77

Risk of bias in included studies

Table 3 summarises the risk of bias for each of the included studies. Most studies used an appropriately generated randomisation sequence, with 21 studies being deemed ‘low risk’, 10 ‘unclear risk’ and two ‘high risk’. Allocation concealment followed a similar pattern. No studies blinded study participants to group allocation and we deemed this form of blinding to be impossible for the interventions under review. As many of the outcome measures were self-reported, outcomes were deemed to have been blinded if the outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation. This form of blinding was poorly reported; in 18 studies, blinding of outcome assessment was unclear or unreported. 40,44–46,49,50,52,55,56,58–63,66,75,81 Participant attrition was well reported but high, ranging from 6% to 79% (mean 30.2%, median 25.5%); 22 studies were rated as high risk for this attribute (with attrition of > 20% at the final follow-up time point). Regarding overall risk, 24 studies40,41,43,48,49,52–55,57–63,65,67–69,70,71,75,81 were deemed to be ‘high risk’, in nine studies39,44–47,50,51,56,66 the risk was unclear and no studies were deemed to be ‘low risk’. In the general population subgroup, 18 studies40,41,43,48,49,53,55,59–62,63,65,67,70,71,75,81 were deemed to be at high risk of bias, whereas in eight studies39,44–47,50,51,56 the risk was unclear. In the psychiatric population studies, six52,54,57,58,68,69 were deemed to be at high risk and in one study66 the risk was unclear. Twenty-one of the studies40,41,43,48,49,53–55,57–63,65,67–69,75,81 were deemed to be at high risk owing to incomplete outcome data (high level of attrition) and three studies52,70,71 were deemed to be at high risk owing to poor random sequence generation or allocation concealment.

| Author and year | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data (% attrition)a | Selective reporting | Overall riskb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babor 200439 and Litt 200572 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | High risk | Intermediate risk (17) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Baker 200652 | High risk | High risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (20) | Low risk | High risk |

| Bonsack 201166 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (13) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Budney 201181 and ClinicalTrials.gov 201373 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (39) | Unclear risk | High risk |

| Budney 200641 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | High risk | High risk (28) | Low risk | High risk |

| Budney 200040 and Moore 200374 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (25) | Low risk | High risk |

| Copeland 200153 | Unclear risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (26) | Low risk | High risk |

| de Dios 201243 | Unclear risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (27) | Low risk | High risk |

| Edwards 200654 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (30) | Low risk | High risk |

| Fernandes 201062 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (70) | Low risk | High risk |

| Fischer 201275 and Fischer 201364 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (46) | Low risk | High risk |

| Gates 201255 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (31) | Low risk | High risk |

| Gmel 201367 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (21) | Low risk | High risk |

| Grenyer 199756 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unreported | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Hjorthoj 201368 and Hjorthoj 201280 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (34) | Low risk | High risk |

| Hoch 201460 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (79) | Low risk | High risk |

| Hoch 201259 and Hoch 200876 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (27) | High risk | High risk |

| Humeniuk 201271 | Low risk | High risk | Not possible | High risk | Intermediate risk (14) | Low risk | High risk |

| Jungerman 200763 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (38) | Low risk | High risk |

| Kadden 200744 and Litt 200877 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (17) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Kay-Lambkin 201158 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (41) | Low risk | High risk |

| Kay-Lambkin 200957 | Unclear risk | Low risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (24) | Low risk | High risk |

| Lee 201346 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (17) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Lee 201045 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (6) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Litt 201347 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | High risk | Intermediate risk (15) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Madigan 201369 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (42) | Low risk | High risk |

| Rooke 201370 | High risk | High risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (46) | Low risk | High risk |

| Sobell 200965 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (21) | Low risk | High risk |

| Stein 201148 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Low risk | High risk (21) | Low risk | High risk |

| Stephens 200751 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | High risk | Intermediate risk (17) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Stephens 2000,50 Lozano 200678 and DeMarce 200579 | Unclear risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | Intermediate risk (10) | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Stephens 199449 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (21) | Low risk | High risk |

| Tossmann 201161 | Low risk | Low risk | Not possible | Unclear risk | High risk (84) | Low risk | High risk |

Assessment of effectiveness

Overview of effectiveness section

Results are presented for each intervention/comparator category (e.g. CBT vs. wait list, CBT vs. brief MI, etc.). An overall summary of results is provided in Tables 4 and 5. This is followed by more detailed results for each intervention/comparator category (see Tables 6–23). Owing to the large number of studies and the variability in outcomes and data format, detailed numerical results are not presented here. Instead, this section provides an overview of the outcomes reported per study and how many showed a significant difference, both between intervention groups and in terms of changes from baseline, at different follow-up time points. Full extracted data per study are provided in Appendix 4.

| Comparison | Number of studies, number randomised (number of patients followed up), cannabis use categorisation high n, low n | Intervention (n sessions) | Computer (n sessions) | Individual or group, duration | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs. wait list | Six studies,39,50,53,59,60,63 n = 1265 (997), high 4, low 2 | CBT (4–14 sessions) | Wait list | Five individual/one group, 5–18 weeks | CBT (4–14) significantly better than wait list: post treatment (five of five studies with data39,50,59,60,63) and at 9 months (one of one study39). Significant change from baseline: CBT, post treatment (four of four studies39,50,59,60) and at 6–9 months (three of three studies39,59,60). Wait list, post treatment (two of two studies59,60) |

| CBT vs. brief MI | Four studies,39,40,50,53 n = 707 (581), high 4 | CBT (6–14 sessions) | MI/MET (1–4 sessions) | Three individual/one both, 6–18 weeks | CBT (6–14) vs. MI (one to four): mixed results. Of four studies, two studies40,50 showed CBT better on some outcomes while two studies39,53 showed few between-group differences (post treatment and at 9–16 months). Significant change from baseline: CBT and MI, post treatment (three studies39,40,50) and 9–16 months (two studies39,53) |

| SEDP vs. brief MI | One study,56 n = 40 (40), high 1 | SEDP (16 sessions) | MI (1 session) | NR, NR | SEDP (16 sessions) significantly better than MI (1 session): post treatment (one study,56 limited outcomes) |

| CBT vs. other | Four studies,44,49,63,65 n = 462 (365), high 2, low 2 | CBT (4–10 sessions) | Various | Two individual/one group/one both, 4–12 weeks | CBT vs. social support group or case management: no significant difference, post treatment or 14–15 months (two of two studies49,77). Significant change from baseline, all groups, post treatment and 14–15 months (two of two studies44,49). Group vs. individual: one small study65 favours individual vs. group CBT-4 (limited data) |

| Computer-/tele-CBT vs. other | Three studies,55,61,70 n = 1682 (481), high 1,61 low 2 | Computer-/tele-CBT (4–6 sessions) | Wait list or education | Three individual, 3–7 weeks | Tele-CBT significantly better than wait list: most outcomes, post treatment and at 3 months (one of one study55). Internet-delivered CBT/counselling significantly better than wait list/education: most outcomes at 3 months (two of two studies61,70). Significant change from baseline: all groups, post treatment and at 3 months (two of two studies55,70) |

| Brief MI vs. wait list or AO | 10 studies,39,43,45,46,48,50,51,53,67,71 n = 2437 (2288), high 4, low 6 | MET/MI (1 or 2 sessions) | Wait list or AO | Nine individual/one group, 1–5 weeks | Brief MI vs. wait list/AO: some significant differences. Brief MI significantly better on some outcomes but not all, post treatment (five of five studies39,43,48,50,51) and at 3–9 months (seven of seven studies43,45,46,48,53,67,71). Significant change from baseline: post treatment and at 3–6 months, brief MI (two of two studies39,48), wait list/AO (two of two studies48,71) |

| Brief MI vs. other | Three studies,51,62,75 n = 2002 (754), high 1, low 2 | MI or tele-MI (1 session) | Cannabis or health education | Three individual, 1 week | Brief MI vs. other: mixed results, limited data. Brief MI better than education control on some but not all outcomes, post treatment (one of one study51) and at 3–12 months (two51,62 of three studies51,62,70). Significant change from baseline: brief MI and education control at 3 months (one of one study75) |

| Contingency management vs. other | Five studies,40–42,44,47 n = 680 (581), high 5 | Voucher (abstinence), CBT + voucher | CBT (9–14 sessions), MET (2–4 sessions), other | Five individual, 8–14 weeks | Post treatment: CBT + voucher or voucher alone better than CBT or MET (three of three studies40,42,44). Maintained for CBT + voucher, not voucher alone: CBT + voucher better than CBT or voucher at 14–15 months (two of two studies41,44). Significant change from baseline: all groups post treatment and at 14–15 months (three of three studies41,44,47) |

| Comparison | Number of studies, number randomised (number of patients followed up), cannabis use categorisation high n, low n | Intervention (n sessions) | Computer (n sessions) | Individual or group, duration | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT + TAU vs. TAU | Four studies,52,66,68,69 n = 326 (254), high 3, low 1 | CBT (6–24 sessions) + TAU | TAU | Three individual/one group, 10–26 weeks | CBT + TAU vs. TAU: few significant differences post treatment. No significant difference at 10–12 months (four of four small studies,52,66,68,69 limited data). Little significant change from baseline: no change (two studies52,69), change on one outcome in both groups (one study66), post treatment and at 12 months |

| CBT vs. other | Three studies,54,57,58 n = 199 (197), low 3 | CBT or computer-delivered CBT (10 sessions) | Education (10 sessions), CBT (10 sessions), PCT (10 sessions), brief MI (1 session) | Three individual, 10–12 weeks | CBT vs. psychoeducation (10 sessions): no significant difference post treatment or at 9 months; both groups improved from baseline (one study,54 limited data). Computer-based CBT vs. CBT or PCT (10 sessions): no significant difference post treatment; (one study,58 limited data). Computer-based CBT or CBT (10 sessions) better than brief MI (1 session) at 12 months; all improved from baseline (one study,57 limited data) |

Outcomes reported

Outcomes reported in most studies could be classified into four main groups: cannabis use, severity of dependence, cannabis-related problems and level of attendance or compliance with the intervention(s). Cannabis use outcomes included point abstinence rates, abstinence over a specified period, number of days using cannabis or number of days abstinent (over a specified period), amount of cannabis use per day and number of periods of use per day (e.g. of four daily periods). For session attendance, seven studies41,44,47,49,54,57,58 reported significance levels between study groups; this was non-significant in all cases.

Subgroup analyses: effect of intervention and population characteristics

The effect of intervention and population characteristics on results was also examined to assess whether or not any patterns could be observed in terms of which studies showed positive results. Findings are described within each intervention/comparator category and an overview provided in Subgroup analyses: effect of intervention and population characteristic.

Studies in general population of cannabis users

Cognitive–behavioural therapy compared with wait list control

Description of studies

Six studies39,50,53,59,60,63 (n = 1265 randomised, 997 followed up) compared CBT (4–14 sessions) with wait list control (Tables 6 and 7). Session attendance ranged from 60% to 72% (not reported in three studies59,60,63). Five studies39,53,59,60,63 provided individual CBT sessions and one50 provided group sessions. CBT interventions also incorporated other strategies including case management (one study),39 psychosocial problem-solving (two studies)59,60 and a social support group (one study). 50 Participants were classified as having high baseline use/dependence in four studies39,50,53,59 and low use/dependence in two studies. 60,63 Two studies were conducted in the USA,39,50 two in Germany,59,60 one in Australia53 and one in Brazil. 63

| Comparison | Number of studies, number randomised (number followed up), categorisation high n, low n | Intervention (n sessions) | Computer (n sessions) | Individual or group, duration | Post-treatment difference between groups | Post-treatment change from baseline | Follow-up | Follow-up difference between groups | Follow-up change from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs. wait list | Six studies39,50,53,59,60,63 (see Table 7), n = 1265 (997), high 4,39,50,53,59 low 260,63 | CBT (4–14 sessions), some CBT included: CaseM (1), PPS (2), social support (1) | Wait list | Five individual, one group, 5–18 weeks | Significant difference: five studies:39,50,59,60,63 CBT significantly better than wait list on most outcomes: | Significant change: four studies:39,50,59,60 significant improvement baseline to post treatment on most outcomes, CBT group (two studies39,50) or both groups (two studies59,60) | 6–9 months | Significant difference: one study:53 CBT-6 significantly better than wait list on most outcomes at 9 months:

|

Significant change: three studies:39,59,60 significant improvements on most outcomes in CBT group from baseline to 6 months (two studies59,60) or to 9 months (one study39) |

| Study, country, cannabis use, recruitment, mean age (range) | Intervention (number of sessions) (mean number of sessions attended), number randomised (followed up) | Computer, number randomised (followed up) | Individual or group, duration | Post-treatment difference between groups | Post-treatment change from baseline | Follow-up | Follow-up difference between groups | Follow-up change from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babor 200439 and Litt 200572 (MTP), USA, high use (DSM-IV 100%), voluntary + referral, 36 years (18–62 years) | CBT/MET/CaseM (9) (6.5), n = 156 (133) | Wait list, n = 148 (137) | Individual, 12 weeks | Significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

9 months | Significant change:

|

|

| Copeland 2001,53 Australia, high use (DSM-IV 96%), voluntary, 32 years (≥ 18 years) | CBT (6) (4.2), n = 78 (58) | Wait list, n = 69 (51) | Individual, 6 weeks | 9 months | Significant difference:

|

|||

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

| Hoch 201460 (CANDIS-II), Germany, low use (ICD-10 56%), referral, 27 years (16–63 years) | CBT/MET/PPS (10) (NR), n = 255 (166) | Wait list, n = 130 (106) | Individual, 12 weeks | Significant difference:

(All p < 0.001) (d = –0.7, 95% CI –2.9 to 2.1) |

Significant change:

|

6 months | Significant change:

|

|

| (All groups except amount/week, CBT only) | (Data for CBT only) | |||||||

| Hoch 201259 and Hoch 200876 (CANDIS), Germany, high use (DSM-IV 89%), voluntary + referral, 24 years (16–44 years) | CBT/MET/PPS (10) (NR), n = 90 (79) | Wait list, n = 32 (31) | Individual, 5–8 weeks | Significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

6 months | Significant change:

|

|

| Jungerman 2007,63 Brazil, low use (≥ 13 day/month), NR, 32 years (18–58 years) | CBT/MI/RP (4) (NR), n = 52 (27) | Wait list, n = 52 (35) | Individual, 12 weeks | Significant difference:

|

||||

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

| Stephens 2000,50 Lozano 200678 and DeMarce 2005,79 USA, high use (DSM-III-R 98%), voluntary, 34 years (≥ 18 years) | CBT/RP/social support group (14) (8.4), n = 117 (95) | Wait list, n = 86 (79) | Group, 18 weeks | Significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

Main results

Five studies39,50,59,60,63 reported post-treatment (5–18 weeks) outcomes. All five reported significantly better results for CBT (4–14 sessions) than for wait list on most outcomes, including cannabis use (significant in all five studies), severity of dependence (significant in four39,50,59,60 out of five studies) and cannabis problems (significant in three39,50,60 out of four studies39,50,59,60 reporting this). In addition, four studies39,50,59,60 reported change from baseline to post treatment; all four reported significant improvements from baseline on most outcomes, for the CBT groups (two studies39,59) or for both the CBT and wait list groups (two studies50,60). Effect sizes at 12 weeks (based on data from two studies39,60) ranged from 0.4 to 1.1 for cannabis use outcomes and from 0.9 to 1.6 for severity of dependence.

Only one study53 reported between-group data at a later follow-up point than post treatment (because, in most studies with a wait list comparison, the wait list group began treatment when other groups completed theirs and so could not be followed for longer). This study reported significantly better results for CBT (6 sessions) than wait list on most outcomes at 9 months post baseline (7.5 months after end of treatment), including cannabis use, severity of dependence and cannabis problems. Three studies39,59,60 reported significant improvements from baseline to 6 months (two studies59,60) or 9 months (one study39), for the CBT group (wait list groups were not followed for this long).

Effects of intervention characteristics

All six studies reported mainly positive findings so there were no clear differences in results according to population or intervention differences. 39,50,53,59,60,63 All durations of CBT (4–14 sessions) appeared effective; there were slightly fewer significant effects in the study of four-session CBT,63 but this may have been owing to the smaller number of participants in this study. The one study of group CBT50 (14 sessions) had similar positive outcomes to the individual CBT studies.

Effects of population characteristics

In terms of baseline cannabis use/dependence, three studies classed as high use39,50,59 all showed significant effects post treatment, while of the two studies classed as low use, one60 showed significant effects on all outcomes and the other63 on some but not all outcomes. This may indicate slightly less effectiveness in participants with lower baseline use, or may be simply a result of the smaller number of participants in the latter study. 63 Two studies50,53 used voluntary recruitment, one60 used referrals, and two39,59 used a combination (for one63 this was not reported); all studies showed significant effects regardless of recruitment method. Mean age ranged from 24 years to 36 years and there were no clear differences in effects according to age.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy or psychotherapy compared with brief motivational interviewing

Description of studies

Four studies39,40,50,53 (n = 707 randomised, 581 followed up) compared CBT (6–14 sessions) with brief MI/MET (1–4 sessions) (Tables 8 and 9). Three studies39,40,53 provided individual CBT sessions, whereas one50 compared group CBT with individual MET. CBT interventions also included case management (one study)39 and a social support group (one study). 50 One further study, reported only in abstract form, compared supportive–expressive dynamic psychotherapy (16 sessions, not reported whether individual or group) with brief MI (1 session). 56 Attendance within the CBT or psychotherapy arm of the studies ranged from 60% to 72% (not reported in two studies40,56). Owing to the brief nature of the MI arms, only one study39 reported attendance for this intervention (mean 1.6 sessions attended from a total of 2). Participants were classified as having high baseline use in all five studies. Three studies were conducted in the USA39,40,50 and two in Australia. 53,56

| Comparison | Number of studies, number randomised (number followed up), categorisation high n, low n | Intervention (number of sessions) | Computer (number of sessions) | Individual or group, duration | Post-treatment difference between groups | Post-treatment change from baseline | Follow-up | Follow-up difference between groups | Follow-up change from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs. brief MI | Four studies39,40,50,53 (see Table 9), n = 707 (581), high 4 | CBT (6–14 sessions) | MI/MET (1–4 sessions) | Three individual, one group vs. individual, 6–18 weeks | Mixed results: one study:39 CBT-9 significantly better than MET-2 on most outcomes (one study).39 Two studies:40,50 no significant difference on most outcomes (CBT-14 vs. MET-2/4); one study40 had few participants | Significant change: three studies:39,40,50 significant improvement baseline to post treatment on most outcomes, CBT and MI groups | 9–16 months | Mixed results: two studies:39,53 CBT-6/9 significantly better than MET-1/2 on some outcomes but not others at 9 and 15 months. One study:50 no significant difference on most outcomes for CBT-14 vs. MET-2 at 16 months | Significant change: two studies:39,50 significant improvement from baseline on most outcomes in CBT and MI groups at 9–16 months |

| Supportive–expressive dynamic psychotherapy vs. brief MI | One study56 n = 40 (40), high | Supportive–expressive dynamic psychotherapy (16 sessions) | MI (1 session) | NR, NR | Significant difference (limited data): one study:56 psychotherapy-16 better than brief MI-1, limited outcomes |

| Study, country, cannabis use, recruitment, mean age (range) | Intervention (number of sessions) (mean number of sessions attended), number randomised (followed up) | Computer (number of sessions), number randomised (followed up) | Individual or group, duration | Post-treatment difference between groups | Post-treatment change from baseline | Follow-up | Follow-up difference between groups | Follow-up change from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babor 200439 and Litt 200572 (MTP), USA, high use (DSM-IV 100%), voluntary + referral, 36 years (18–62 years) | CBT/MET/CaseM (9) (6.5), n = 156 (133) | MET (2) (1.6), n = 146 (128) | Individual, 12 weeks | Significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

9 months, 15 months | Significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

| Mechanism: CBT-9 and MET-2 increased coping skills relative to wait list (no difference between CBT and MET). Increase in coping skills reduced cannabis use |

Significant difference:

|

|||||||

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

| Budney 2000,40 USA, high use (DSM-III-R 100%), voluntary, 32 years (≥ 18 years) | CBT/MET (14) (NR), n = 20 (15) | MET (4) (NR), n = 20 (16) | Individual, 14 weeks | No significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

|||

| Copeland 2001,53 Australia, high use (DSM-IV 96%), voluntary, 32 years (≥ 18 years) | CBT (6) (4.2), n = 78 (58) | MI (1), n = 82 (61) | Individual, 6 weeks | 9 months | Significant difference:

|

|||

No significant difference:

|

||||||||

| Grenyer 199756 (abstract), Australia, high use (DSM-IV 100%), NR, 34 years (NR) | SEDP (16) (NR), n = 20 (20) | MI (1), n = 20 (20) | NR, NR, 16 sessions | Significant difference:

|

||||

| Stephens 2000,50 Lozano 200678 and DeMarce 2005,79 USA high use (DSM-III-R 98%), voluntary, 34 years (≥ 18 years) | CBT/RP/social support (14) (8.4) (group), n = 117 (95) | MI (2) (NR) (individual), n = 88 (75) | Group vs. individual, 18 weeks | No significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

16 months | No significant difference:

|

Significant change:

|

Main results

Overall, the comparison of longer durations of CBT with brief MI/MET showed mixed results; however, both interventions provided improvements from baseline. Three CBT studies reported between-group data post treatment (at 12–18 weeks). 39,40,50 Of these, one study39 reported that nine-session CBT was significantly better than two-session MET on most outcomes (including cannabis use, dependence and problems). Conversely, two studies40,50 reported no significant difference on any outcomes between CBT (14 sessions) and MET (2 or 4 sessions), although one study40 involved few participants, which may impact on significance levels. Three CBT studies39,40,50 reported change from baseline to post treatment; all three reported significant improvements on most outcomes for both the CBT and MI groups. One study investigating possible mechanisms for changes in cannabis use reported that participants in both the 9-session CBT and 2-session MET groups increased their coping skills relative to wait list with no significant difference between CBT and MET, and that this increase in coping skills was associated with reduction in cannabis use. 39 Effect sizes at 12 weeks (based on data from one study39) ranged from 0.4 to 0.5 for both cannabis use and severity of dependence outcomes.

One further study56 reported that 16-session dynamic psychotherapy was significantly better than one-session MI; however, limited outcomes were reported (i.e. percentage abstinent, severity of symptoms).

Results for later follow-ups were again mixed. Three studies of CBT reported between-group data at later follow-ups. Two of these studies39,53 reported that CBT (6 or 9 sessions) was significantly better than MET (1 or 2 sessions) on some outcomes (some cannabis use, dependence) but not other outcomes (some cannabis use, cannabis problems) at 9 and 15 months’ follow-up. The third study50 reported no significant difference on most outcomes for CBT plus social support (14 group sessions) compared with MET (2 individual sessions) at 16 months’ follow-up. The study of dynamic psychotherapy did not report later follow-up data. Two studies39,50 reported change from baseline at follow-up (9–16 months), both finding significant improvements on most outcomes in both the CBT and brief MI groups. Effect sizes at 9 months (based on data from one study39) ranged from 0.3 to 0.5 for both cannabis use and severity of dependence outcomes.

Effects of intervention characteristics

In terms of number of sessions, this section compares four studies of CBT (6–14 sessions) with briefer MI/MET treatments (1–4 sessions). As described above, some studies showed better results for CBT than MI (one39 post treatment, two at later follow-ups39,53), whereas others showed no significant differences (two40,50 post treatment, one at later follow-ups50). When CBT gave better outcomes, this may be owing to the nature of the CBT treatment, or the fact that more sessions were provided, or a combination of the two. In terms of group compared with individual treatments, one study50 showed little difference between group CBT plus social support and individual MI (although both groups improved from baseline), whereas studies of individual CBT compared with MI showed mixed results, as described above. 39,40,53

Effects of population characteristics

It was not possible to assess the effects of baseline cannabis use/dependence, as all studies were classified as high use. In terms of recruitment method, three CBT studies used voluntary recruitment40,50,53 and showed mixed results, whereas the one study39 using a combination of voluntary recruitment and referrals showed mostly significant effects; however, no studies used referrals only, so the significance of this is not clear. It was not possible to assess effects of participant age, as all studies in this grouping had a similar mean age (32–36 years).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy compared with other interventions (or different cognitive–behavioural therapy format or duration)

Description of studies

Four studies44,49,63,65 (n = 462 randomised, 365 followed up) compared CBT (4–10 sessions) with another intervention (social support group,49 case management sessions44) or compared individual with group CBT65 or CBT over different durations (Tables 10 and 11). 63 Two studies44,49 reported overall session attendance (of both interventions), ranging from 58% to 76%, with both studies reporting no significant differences in attendance between the two interventions (session attendance not reported in two studies63,65). Participants were classified as having high baseline use in two studies44,49 and low use in two studies. 63,65 Two studies were conducted in the USA,44,49 one in Canada65 and one in Brazil. 63

| Comparison | Number of studies, number randomised (followed up), categorisation high n, low n | Intervention (number of sessions) | Computer (number of sessions) | Individual or group, duration | Post-treatment difference between groups | Post-treatment change from baseline | Follow-up | Follow-up difference between groups | Follow-up change from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|