Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/08. The contractual start date was in February 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Crawford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The ageing population, widespread obesity and improved survival all mean that the prevalence of diabetes will more than double between 2000 and 2030. 1 Consequently, the serious complications of the disease are also anticipated to escalate and thus place an increasing demand on health-care resources. These complications are observed in the lower limb as peripheral vascular disease, foot ulceration, osteomyelitis (infection), gangrene and lower-extremity amputations (LEAs), and all are more likely to be experienced by those with diabetes than by the general population. 2

Published studies have reported variation in the incidence of diabetes-related foot ulceration between < 2% in UK primary care and community settings and 18% in hospital-based populations globally. 3–5 Routinely collected data from Scotland indicate that 13,789 (5.2%) people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes experienced a foot ulcer in 2013. 6 These foot ulcers give rise to considerable morbidity and generate a high monetary cost for health- and social-care systems2,7 and, importantly, 80% of diabetes-related foot amputations are preceded by a foot ulcer. 8 For those who experience diabetes-related amputations, the 5-year survival is poor, with mortality estimates of between 25% and 50% in 1985 in UK populations. 9,10

Changes in diabetes-related LEAs have been reported in parts of the UK. In common with some European countries and the USA, major LEA rates in Scotland have been reported to fall. A statistically significant reduction of 40% in LEA rates occurred between 2004 and 2008. 11 However, the 2013 Scottish Diabetes Survey shows that the absolute numbers and percentages of diabetes-related foot ulcerations and LEA have increased, although this is attributed to better recording procedures. In England, an analysis of national hospital activity data from 1996 to 2005 found that, although LEAs in people with type 1 diabetes fell, type 2 LEAs increased. 12 High levels of variation in diabetes-related LEAs are known to exist between primary care trusts (PCTs) across England, which may be explained by variation in the delivery of care. 13

The optimal clinical management of people with diabetes includes annual foot risk assessment, as recommended in national and international clinical guidelines and the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) of the General Medical Contract (GMC) in the UK. 14–17 Risk classifications of three or four levels (low, moderate, high and active) are increasingly being recommended. At present, the evidence underpinning these classifications is not from randomised trials and does not include the totality of evidence (i.e. data from all cohort studies), and the effect of such surveillance and the use of interventions thought to prevent the development of a foot ulcer in the at-risk population lack clear evidence of clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness. 18

Clinically effective and cost-effective health care requires the careful measurement of health outcomes, and the need for an evidence-based approach to foot care services in diabetes has been documented. 19,20 Two systematic reviews highlight the gaps in the knowledge about the best way to identify those at risk.

The first systematic review evaluated the independent contribution of predictive factors for foot ulceration based on meta-analyses of aggregate data. It found that the duration of diabetes, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), peak plantar pressure (PPP) and vibration perception threshold (VPT) distinguish between those people who will develop a foot ulcer and those who will not. However, there was significant heterogeneity between studies, possibly owing to differences in lengths of follow-up, methods of ascertaining the presence of ulcers and the use of different cut-off points (thresholds) for some of the tests. Furthermore, some tests that are commonly believed to be predictive of risk, such as the absence of a pedal pulse, were not found to be so and data for other common tests such as monofilaments were not amenable to meta-analysis.

A second systematic review of clinical prediction rules (CPRs) used for risk assessment of developing diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) identified five different risk stratification tools derived from consensus among clinical experts, literature reviews and prospective studies using logistic regression methods. 21 The predictive factors in these five CPRs were foot deformity; peripheral neuropathy; peripheral vascular disease [absent pulses and/or positive ankle–brachial index (ABI) test] and previous amputation; the presence of callus; HbA1c; tinea pedis; and onychomychosis. The review authors concluded that it was unclear which CPR possessed the greatest accuracy in the assessment of risk.

These two systematic reviews found marked variation between the incidences of foot ulcers across different study populations. The predictive factors and CPRs derived from high-risk populations may not be of value in predicting risk in the general ‘low-risk’ diabetes population. It is a matter of some concern that the accuracy of recommended foot risk assessment procedures has not been fully explored in different groups of people with diabetes and that little validation of derivative cohort studies has taken place. 22,23

These two systematic reviews of aggregate data represent the best attempts to integrate evidence about the independent contribution of risk factors and CPRs in the assessment of the foot in diabetes to date. These findings are compromised, however, because the authors of primary included studies approached their analyses in different ways: some present adjusted estimates, whereas others are unadjusted, and it is sometimes unclear which confounders or effect modifiers were used. Conventional meta-analytic techniques use aggregate data that are averaged across all individuals in a study and these do not permit adjustments for confounding to be performed. The best way to reliably analyse data from several cohort studies using a standard approach is to use individual patient data (IPD). 24,25

The success of IPD systematic reviews depends on a high level of collaboration, trust and commitment between multidisciplinary researchers and the authors of the primary studies. 25 The ownership of data from primary studies by the pharmaceutical industry can represent an obstacle to IPD analysis being accomplished. However, our background work found that none of the cohort studies included in the systematic reviews had industry sponsorship. The authors who possess the data from the cohort studies identified in the published systematic reviews agreed to take part in an IPD systematic review and to contribute anonymised data from their primary studies for reanalysis.

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis of IPD is to clarify the best risk assessment procedures for foot ulcers in people with diabetes. The international nature of these data, which are from more than 16,000 patients worldwide, should ensure a balanced interpretation. Given the increased worldwide prevalence in diabetes, the identification of the most predictive risk factors could lead to reduced costs for health-care providers.

Chapter 2 Hypotheses

Our research focused on the questions outlined below.

Review questions

-

What are the most highly prognostic factors for foot ulceration (i.e. symptoms, signs, diagnostic tests) in people with diabetes?

-

Can the data from each study be adjusted for a consistent set of adjustment factors?

-

Does the model accuracy change when patient populations are stratified according to demographic and/or clinical characteristics?

-

How predictive are the risk assessment recommendations in UK national clinical guidelines?

Research objectives

-

To systematically review IPD from cohort studies in a meta-analysis to estimate the predictive value of clinical characteristics (signs and symptoms) and diagnostic tests for DFU.

-

To develop a prognostic model of the risk factors for DFU based on data collected worldwide.

-

To test the robustness of the model in different demographic profiles, for example, age, duration of diabetes, control of diabetes (insulin, diet or oral medication), type of diabetes (type 1, type 2).

-

To create prognostic models of the risk factors for DFU contained in national and international clinical guidelines.

Chapter 3 Methods

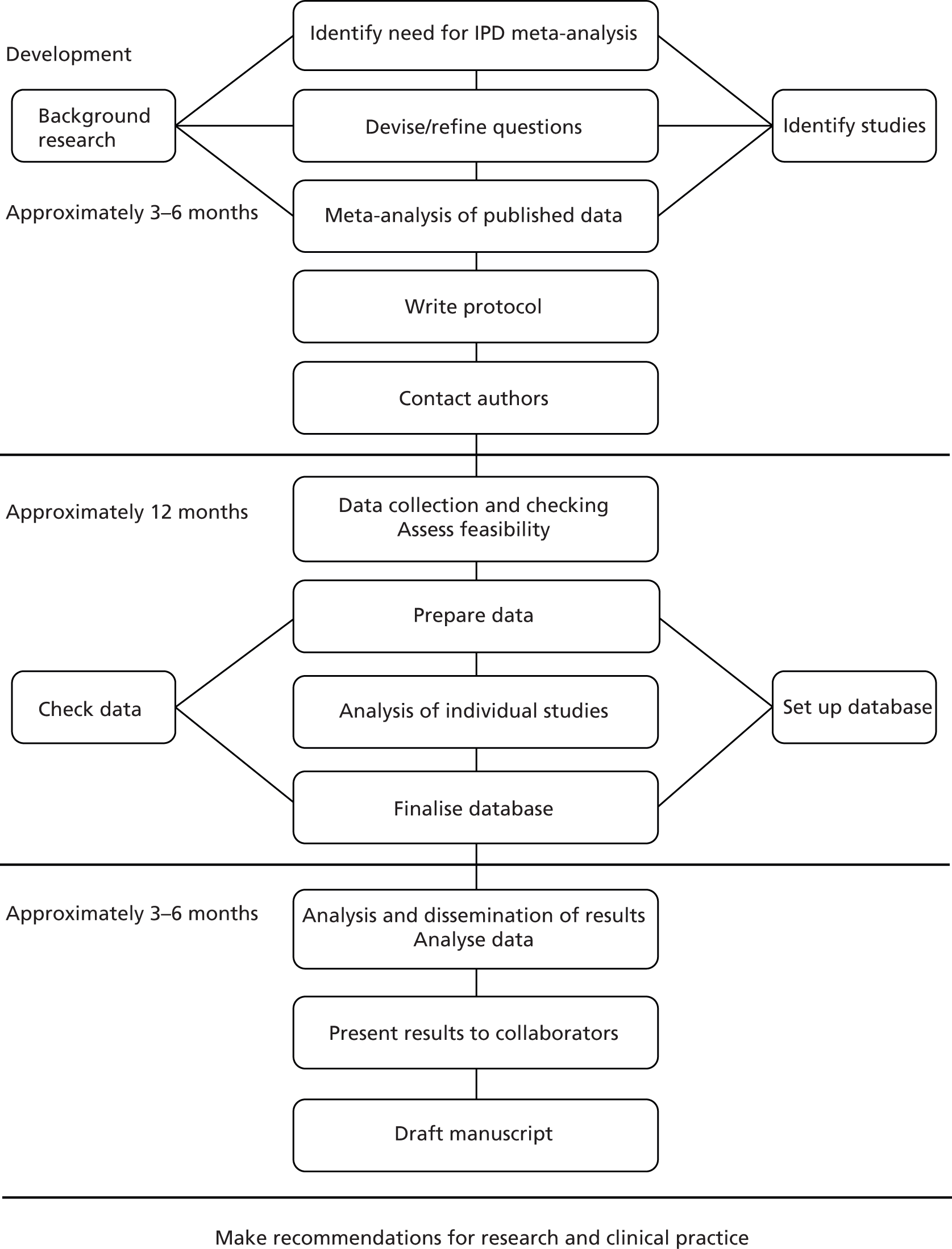

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of IPD use ‘raw’ data obtained from the authors of individual studies instead of mean or aggregate data extracted from published reports. These complex reviews are more time-consuming and expensive than aggregate systematic reviews because obtaining study data and data dictionaries and undertaking data checking and cleaning takes more time than the extraction of data from a published report (Figure 1). 25

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram: stages of an individual patient-based meta-analysis. Reproduced from the original25 with kind permission from John Wiley & Sons.

Individual patient data systematic reviews are useful for both randomised controlled trial (RCT) and observational data and enhance the main purpose of meta-analysis – the augmentation of statistical power – by permitting the conduct of complex statistical techniques, including multivariable analyses in which interactions between interventions and patient-level characteristics can be explored. 26 In the case of observational study designs, IPD is the best way to pool observational study data to allow adjustments and a standard statistical approach to be conducted.

This review method also confers an advantage on the process of quality assessment because the necessary communication between the review team and those contributing the data means that potential biases arising from the conduct, rather than the report, of the study can be investigated. However, although the opportunity to discuss the manner in which the study was conducted with the author means the reviewer is not required to interpret possible biases, IPD reviews do not avoid flaws in the original studies arising from conduct or design. 27

Ethics and governance

The ethics of obtaining data collected from a number of sources that cross international boundaries and different legal systems was carefully considered and informed by ethics advice issued by the Medical Research Council (UK). 28 This study did not require separate ethics committee approval for the following reasons:

-

Investigators of each of the original studies obtained local ethics committee approval and written, informed patient consent prior to each of the cohorts included in the review.

-

The data from each of the studies were already in the public domain.

-

The project uses anonymised data from individuals recruited to the original studies who cannot be identified.

Obtaining data

The aggregate systematic review of predictive factors for foot ulceration in diabetes led by the chief investigator (FC) identified 11 cohort studies that met the eligibility criteria. 4 During the review process requests were made to the corresponding author of each primary study for points of clarity, as per conventional systematic review methods. All those contacted provided additional information about their study, and there was strong encouragement for the aggregate review and enthusiasm for an IPD review to create a statistical model exploring the independent contribution of predicative factors for use in foot risk assessment procedures. A key factor in deciding to undertake the IPD meta-analysis was the total absence of industry sponsorship and the ownership of original study data by the corresponding authors who were prepared to contribute them if funding from a suitable source could be found to support the research.

The value of the IPD analysis lies in the production of a global data set. Anonymised data from each of the collaborators of the primary cohort studies were accepted in the way deemed most convenient to original study investigators.

Data were stored in password-protected files on a secure University of Edinburgh computer (University of Edinburgh data protection registration number Z6426984) during the conduct of the review and were only accessible to members of the Data Management Committee, membership of which can be found in the appendices (see Appendix 1).

Our published protocol29 incorporated a data confidentiality agreement making clear the need for the data provided to de-identify individual patients. It also included an assurance that the original investigators were in possession of local ethical approval for their study. A copy of this agreement can be found in the appendices (see Appendix 2).

Review Committee structure

A three-committee structure was created to manage the review:

-

The Data Management Committee developed the methods for the review and ensured the attainment of project milestones. They also took responsibility for reporting the progress to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme within the standard reporting mechanisms required by the Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board. Only these individuals had access to the data from individual cohort studies.

-

The research committee included a group of epidemiologists, health services researchers, clinicians and statisticians who advised the Data Management Committee about methodological and clinically relevant aspects.

-

An international steering committee comprising all principal investigators/corresponding authors of the included studies was strengthened with methodological input from five additional members with expertise in diabetic medicine, foot care provision in primary and community settings, methodological expertise in CPRs and IPD meta-analysis.

A list of members of each of these committees can be found in Appendix 1.

Identifying studies

Electronic search strategy

We searched for relevant studies using the highest methodological standards. 30 The electronic search strategies created during the aggregate systematic review of predictive factors for foot ulceration in diabetes were updated and rerun to January 2013. 4 Copies of the EMBASE and MEDLINE search strategies can be found in Appendix 3.

Selection criteria

One reviewer applied the IPD review eligibility criteria to the full-text articles of the studies identified in our literature search and also all studies excluded from our aggregate systematic review to ensure that we did not miss eligible IPD. A second reviewer applied the eligibility criteria to a 10% random sample of the search yield to ensure that no relevant material was missed.

Eligibility criteria

Types of participants

The review includes only data from individuals who were free of foot ulceration at the time of study entry and who had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (either type 1 or type 2). When we identified studies with patients who had prevalent foot ulcers at the time of recruitment, we ascertained whether or not IPD were available for patients who were free of ulcers at time of entry. The corresponding authors of all identified cohort studies were contacted and invited to share their data.

Types of exposure variables

All elements from the patient history, symptoms, signs and diagnostic test results were considered for inclusion in the prognostic model. These were collected variously as continuous, binary and multicategorical data.

Type of outcome variable

The outcome variables were incident foot ulceration (present/absent) and time to ulceration from initial diagnosis of diabetes as well as from the time of screening.

Types of studies

We included studies that used a cohort design and did not distinguish between those that planned the analysis before or after data collections. We excluded studies using all other study designs, including case–control designs. Our previous research indicated that data collected in older studies could be difficult to obtain and that some investigators were no longer in possession of their study data (David Armstrong, Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance, University of Arizona, 2012, and Lawrence Lavery, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Texas, 2012, personal communication).

Risk of bias

The assessment of methodological quality is an important component of an IPD systematic review, but there is complexity in assessing potential threats to the validity of primary studies for this research genre. No widely agreed criteria exist for assessing the risk of bias in aggregate systematic reviews of prognostic studies,31 and, currently, there is a complete absence of established guidelines for prognostic IPD reviews (Douglas Altman, University of Oxford; Richard Riley, Research Institute of Primary Care and Health, Keele University, 2012, personal communication). Although flaws in the recruitment of patients or the manner of data collection can influence systematic review findings, some quality domains usually assessed by systematic reviewers of published reports are irrelevant in IPD reviews (e.g. those pertinent to the analysis performed by the primary authors). We compiled a list of items relevant to our IPD review question which were judged likely to identify studies with data compromised by threats of validity. This checklist of items can be found in Appendix 4;22,32–42 this has been refined during a pilot phase by two researchers working independently.

Data extraction was undertaken by two reviewers working independently, and disagreements were resolved by discussion. For quality assessment, a two-stage process was used; two reviewers worked independently using items available from the published report first of all, then supplementing this with additional details obtained from authors of the primary studies.

Plan for analysis and handling missing data

The methodology of IPD meta-analyses of observational studies is relatively undeveloped compared with that for RCTs and reviewers undertaking IPD meta-analyses of observational studies need to proceed with caution as guidance is not always available and the methodology is untested. 43

There were, therefore, difficult methodological issues regarding the analysis for this review, some of which were particular to IPD meta-analysis methodology, and others which were more general:

-

method of meta-analysis (one step vs. two step)

-

method of meta-analysis (random vs. fixed effects)

-

assessment and handling of heterogeneity

-

handling of missing data, where data are missing for some but not all patients in a given data set (ordinarily missing data)

-

handling of missing data, where data are missing for a given variable for all patients in a given data set (systematically missing data)

-

choice of predictors

-

choice of effect size

-

validating the model.

Method of meta-analysis: one-step versus two-step methods

The two main methods of meta-analysis are commonly known as one-step and two-step methods. 44 Both these methods have pros and cons.

The one-step method uses just one model fitted to all the studies, with a term to indicate which patient belongs to which study. The model can be sophisticated and used to explore common structures in the data sets that would otherwise be undetectable. For this reason, it is the preferred method of meta-analysis for some statisticians. 43 However, it does require that all the data sets be available at the same time to the meta-analysts in order to fit one model to all the data sets. This was not the case for this project. It is also a relatively new development of meta-analysis methods; although IPD meta-analyses have been used for some time, they have most often been used for RCT data, where the recommendation is to use a two-step method to avoid comparison of patient groups that were not randomised together. 45

Two large data sets were contributed to this project but access to one was constrained,46,47 with around 3412 patients’ data only available to the authors via a safe haven facility. The safe haven facility allowed the analyses of data to obtain an estimate of effect but not to remove or copy the data. Another data set48,49 with 1489 patients was not permitted to be shared by the US Institutional Review Board governing its use. However, specific analyses could be requested and estimates of effect obtained from the original study authors.

Use of the one-step method of meta-analysis would mean that neither of these large data sets could be used, although it is straightforward to include them in a two-step meta-analysis. The two-step method is also simpler and more transparent as it uses methods that have been much used and are well understood by systematic reviewers.

For the two-step method, each data set is analysed in turn by the meta-analysts, using ordinary methods of analysis such as logistic regression, and then the estimates from each analyses are combined using established meta-analysis methods. The advantage of the two-step method over a meta-analysis of published studies is that the statistician has some flexibility in the estimates they can obtain from each study. If, for example, they require all estimates to be adjusted for age, and all the data sets have the patients’ ages, it is simple to get age-adjusted estimates.

We did consider a refinement to the one-step method that, in theory, would have enabled us to perform a one-step meta-analysis and incorporate the aggregate results from the two data sets not directly available to us. 50 However, like much of the methodology of IPD meta-analysis of observational studies, it is a new and therefore relatively untested development, and we did not consider it for this project.

Method of meta-analysis: random versus fixed-effects meta-analysis

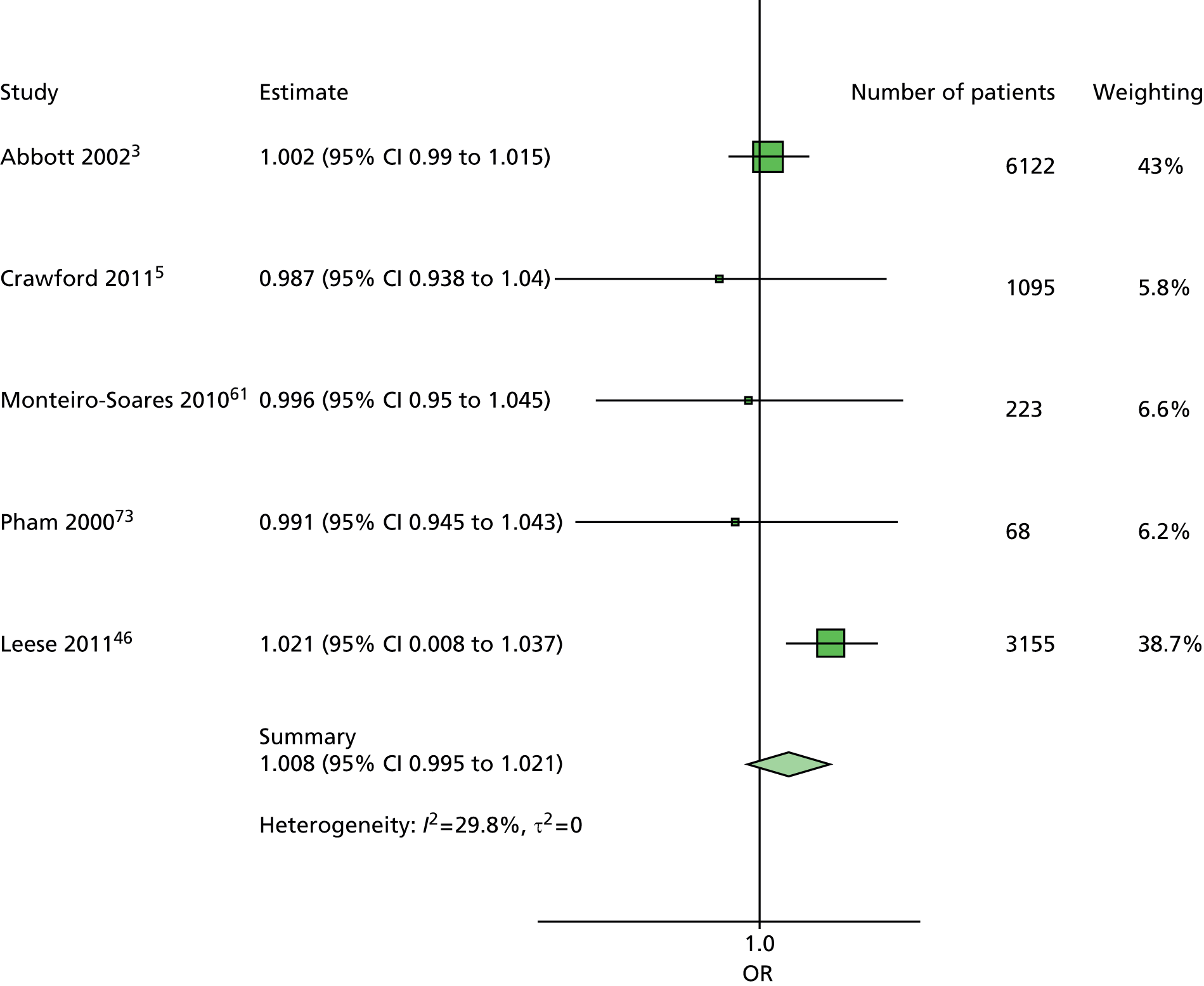

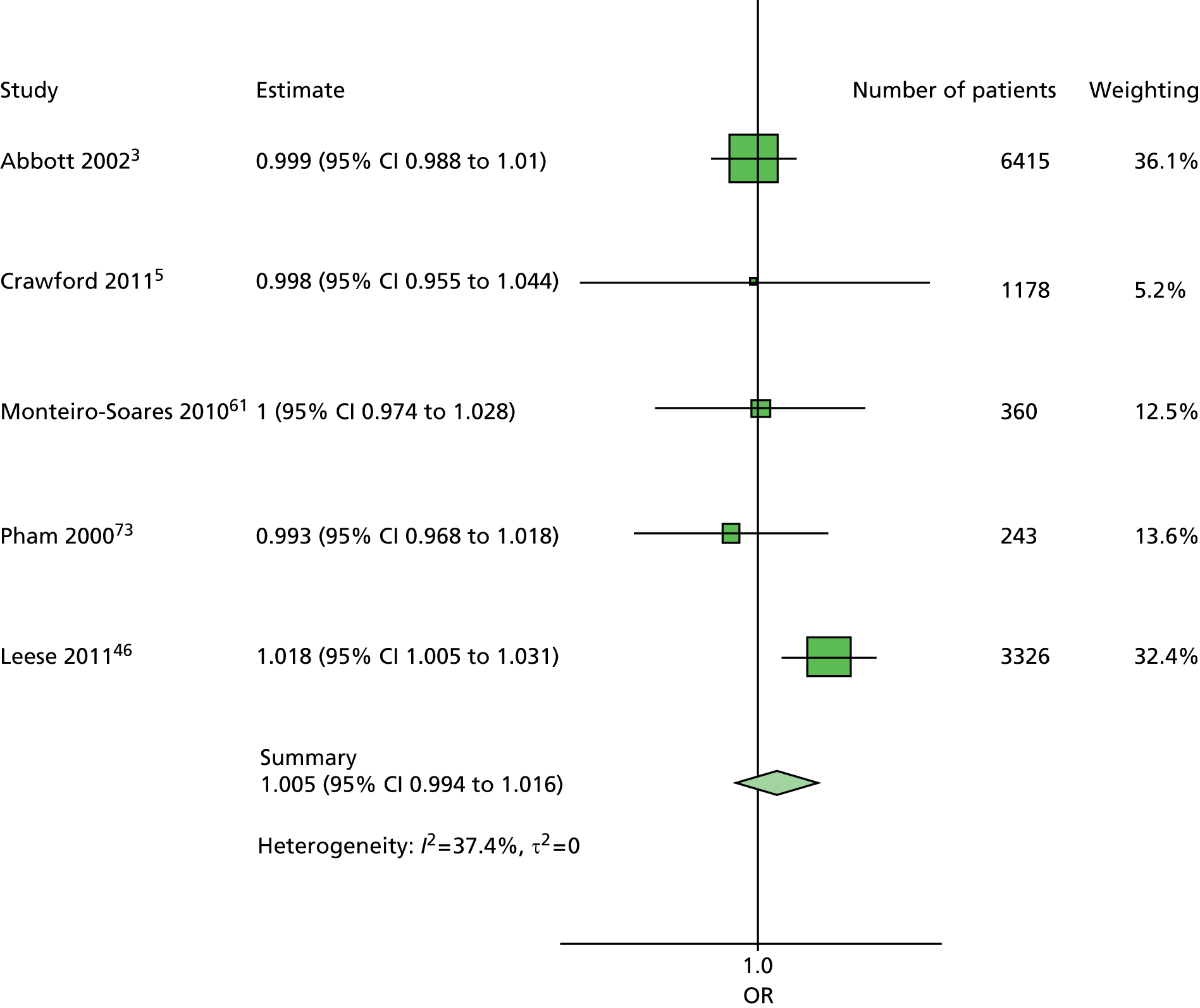

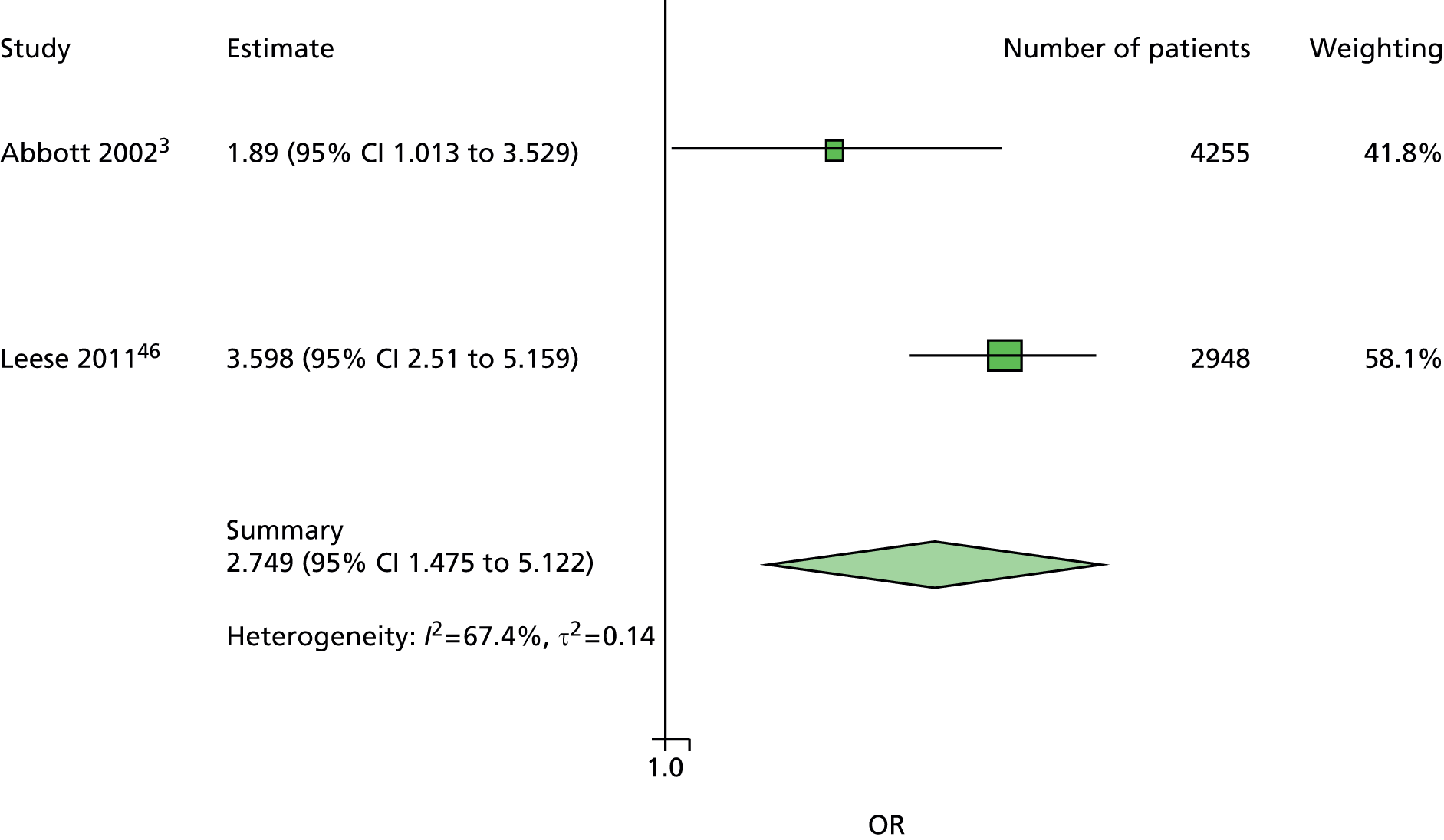

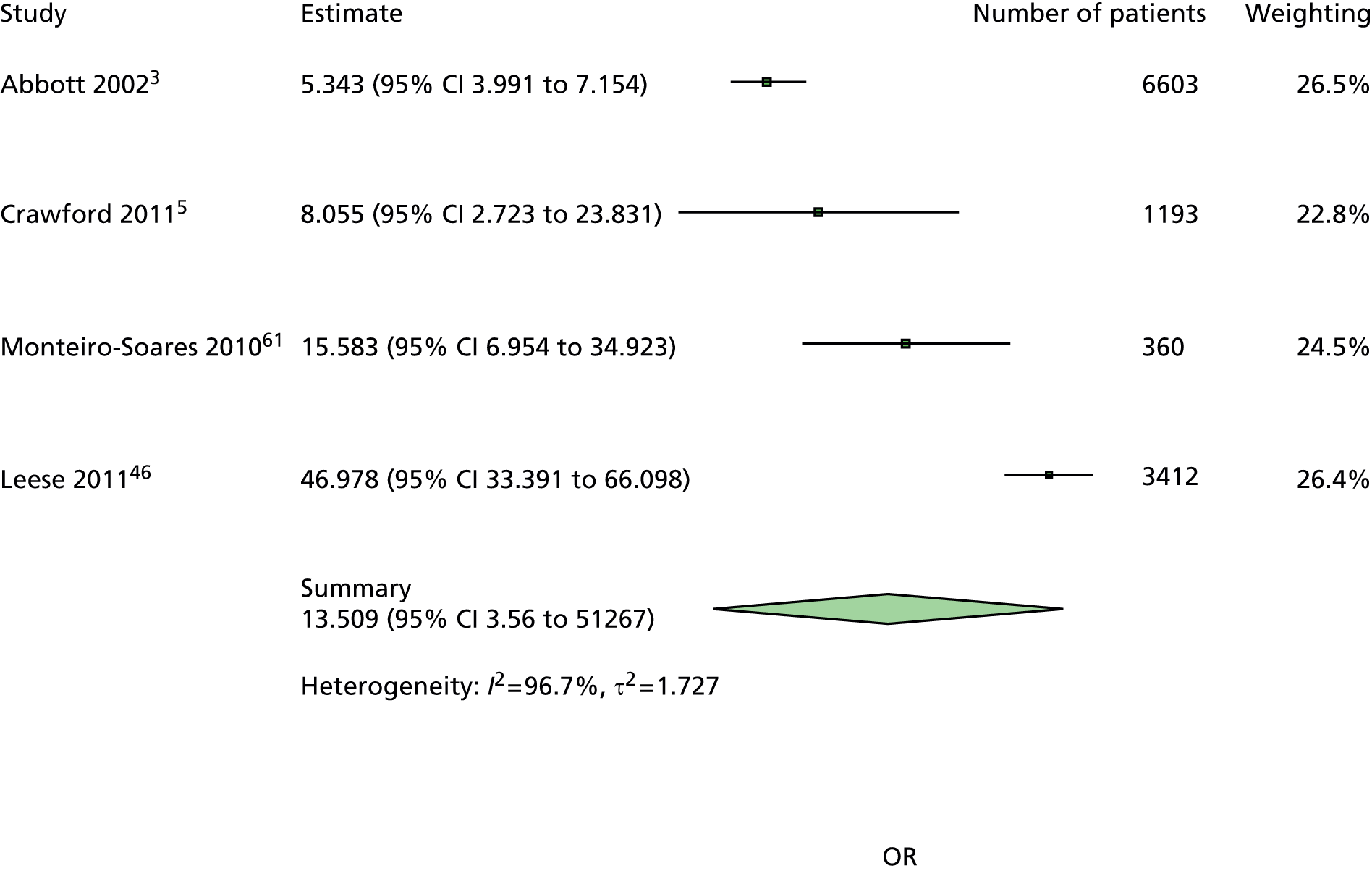

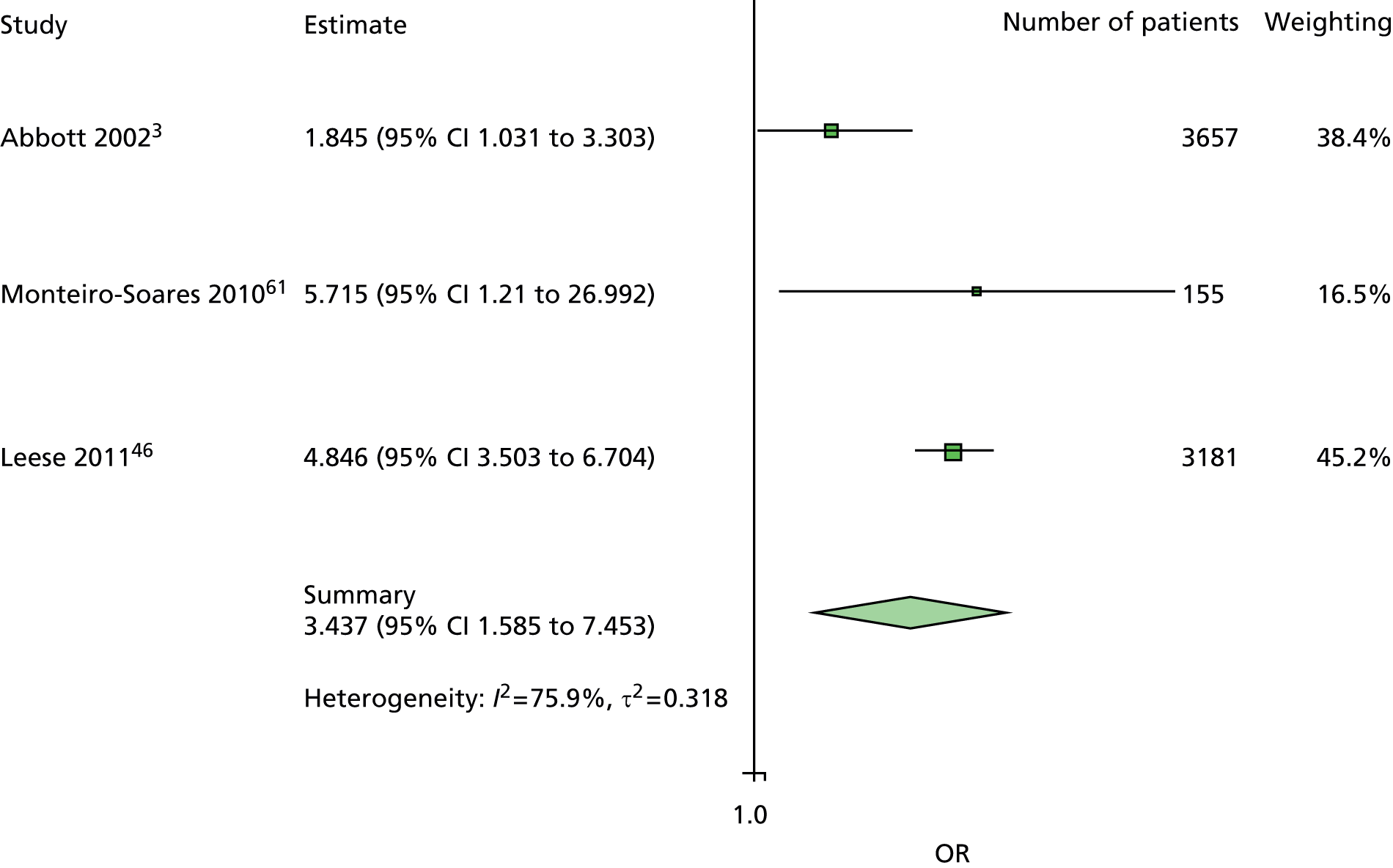

The data sets contributing IPD covered a range of temporal, geographical and clinical settings. It is therefore reasonable to expect some degree of heterogeneity between the studies. The data sets also varied in size from a few hundred to a few thousand patients. There has been much discussion among experts in the field about standard meta-analytic methods for examining the difference between random- and fixed-effects meta-analyses. 51 We have chosen to use random-effects meta-analysis, which does not assume that all the estimates from each study are estimates of the same underlying true value, but rather that the estimates belong to the same distribution. It has been argued that random-effects methods more appropriately weight the contribution of smaller versus larger studies. 52 Moreover, as the estimates will be adjusted odds ratios (ORs) (note that the same is true for hazard ratios), the appropriate method of meta-analysis is the generic inverse method. 52

Assessment and handling of heterogeneity

Before undertaking any meta-analysis we assessed the extent of heterogeneity. We employed the standard methods of assessing heterogeneity, by examining forest plots of estimates and calculating I2- and τ-statistics. However, we also conducted a thorough examination of heterogeneity, by visual comparison of histograms of continuous variables and bar charts of categorical variables. We also produced summary statistics for each continuous variable (mean, standard deviation, median, 25th and 75th percentile, minimum and maximum) and proportions with confidence intervals (CIs) for each categorical variable.

The assessment of heterogeneity for any meta-analysis was a matter of judgement, covering both statistical and clinical aspects. Therefore, the decision on whether or not a particular variable and/or study should be included in the meta-analyses was made in discussion between methodological and clinical authors, with due consideration of any possible bias or loss of precision in the estimate as a result of inclusion or exclusion. Specifically, we did not define any particular I2 percentage as representing an acceptable level of heterogeneity.

Handling of ordinarily missing data

Ordinarily missing data in epidemiological cohort studies occur when a variable is not recorded, completed or collected for one patient. For example, one patient may not want to provide personal information or test results may not be performed, available or readable. Handling missing data by analysing complete cases leads only to loss of information (exclusion of a portion of the original data) and bias. Methods to address missing data assume specific patterns of missingness and allow patients with incomplete data to be included in the analysis.

Our method of handling missing data depends on the extent of the missingness and if the mechanism causing the missingness is known, specifically if they are missing at random (MAR) or missing not at random. Under the MAR assumption, we planned to use the multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) developed in R [R 2.13.1, Murray Hill, NJ, USA; see (http://cran.r-project.org/)],53,54 which is a flexible and practical approach to handling missing data. To account for all patients’ data available and to help predict missing data for the risk factors of interest, we applied multiple imputations on the set of variables selected in our final model of predictors where the percentage of missing value did not exceed 15% and included the outcome variable. 55 We created m = 20 imputed data sets, where missing values were replaced by imputed values using imputation techniques specific to each type of variable (logistic regression for binary variables and Bayesian linear regression for continuous variables). The final model estimators were calculated for each imputed data set and differed owing to the variation introduced by the imputed set of missing values. Estimators were averaged and standard errors calculated using Rubin’s rules, which take into account the variability between imputed sets. To discuss the potential bias attributable to missing data, the results of the final model after imputation procedure were interpreted and compared with the complete case analysis.

Handling of systematically missing data

A systematically missing variable is a variable that has not been collected at all in a given data set. For example, not all the studies contributing IPD collected HbA1c, as it has not always been part of routine care. Therefore, if we wanted to adjust ORs of ulceration in patients with and without positive monofilament tests for HbA1c, then our analysis choices are:

-

to use only ORs from studies that collected HbA1c data, with resulting loss of data from not using all the studies (i.e. complete case analysis)

-

to use all studies by treating all ORs as if they have been adjusted for HbA1c, with resulting possible bias in the summary estimate

-

to use multiple imputation for the systematically missing data.

Given that all of the studies have not collected at least one of the variables of interest, we had systematically missing data. The methodology of handling systematically missing data in IPD meta-analysis is still very much in development and key papers were published after the start of this project. 56 We therefore felt that it would be useful to present the results of a complete case, as complete case analyses are known not to be biased, providing the missing data are MAR. 57 However, the loss of power by not using all the data results in wide CIs and large p-values. To overcome the loss of power, we could have used either the second or third method listed above. However, the second method was not chosen because it produces possibly biased estimates. The third method was another relatively new and untested method, and statistical methodological contributions also fell outside the scope of this project.

Choice of predictors

The studies contributing data to this IPD analysis collected data on hundreds of variables. It would not have been statistically rigorous or clinically relevant to meta-analyse all these variables. We therefore needed a method to select candidate variables for meta-analysis. We used the following criteria:

-

Variables had to have been collected in at least three studies, with < 60% missing.

-

Variables needed to have been coded in such a way to allow standardisation across data sets. For example, we were unable to use eye data, because in some data sets this had been defined as retinopathy and in others as requiring glasses.

We did not use a common method of variable selection, namely choosing variables for a multivariable model on the basis of univariate results, as we believe this to be a flawed method. 58,59

We also had the aim of producing a model with easily collectable or readily available data, and therefore had a preference for such variables.

Choice of effect size

Initially, we had hoped to use time-to-ulceration data to perform survival analyses and so obtain hazard ratios for a meta-analysis. Unfortunately, not all the data sets had time-to-event data and we therefore decided to use a binary outcome (ulcer vs. no ulcer) and use logistic regression to obtain ORs. Neither of the two largest data sets, with a combined total of over 9000 patients, had time-to-event data. Logistic regression is considered a less statistically powerful method than survival analysis, but we thought the loss of more than half of the data that would occur with a survival analysis would not compensate for the method’s increased power.

Chapter 4 Development of the model

The criteria for consideration for inclusion in the primary meta-analysis were:

-

variables had to have been collected in at least three data sets

-

variables had to have been consistently defined across data sets (or could be recoded so)

-

the extent of heterogeneity should not invalidate the results of meta-analysis.

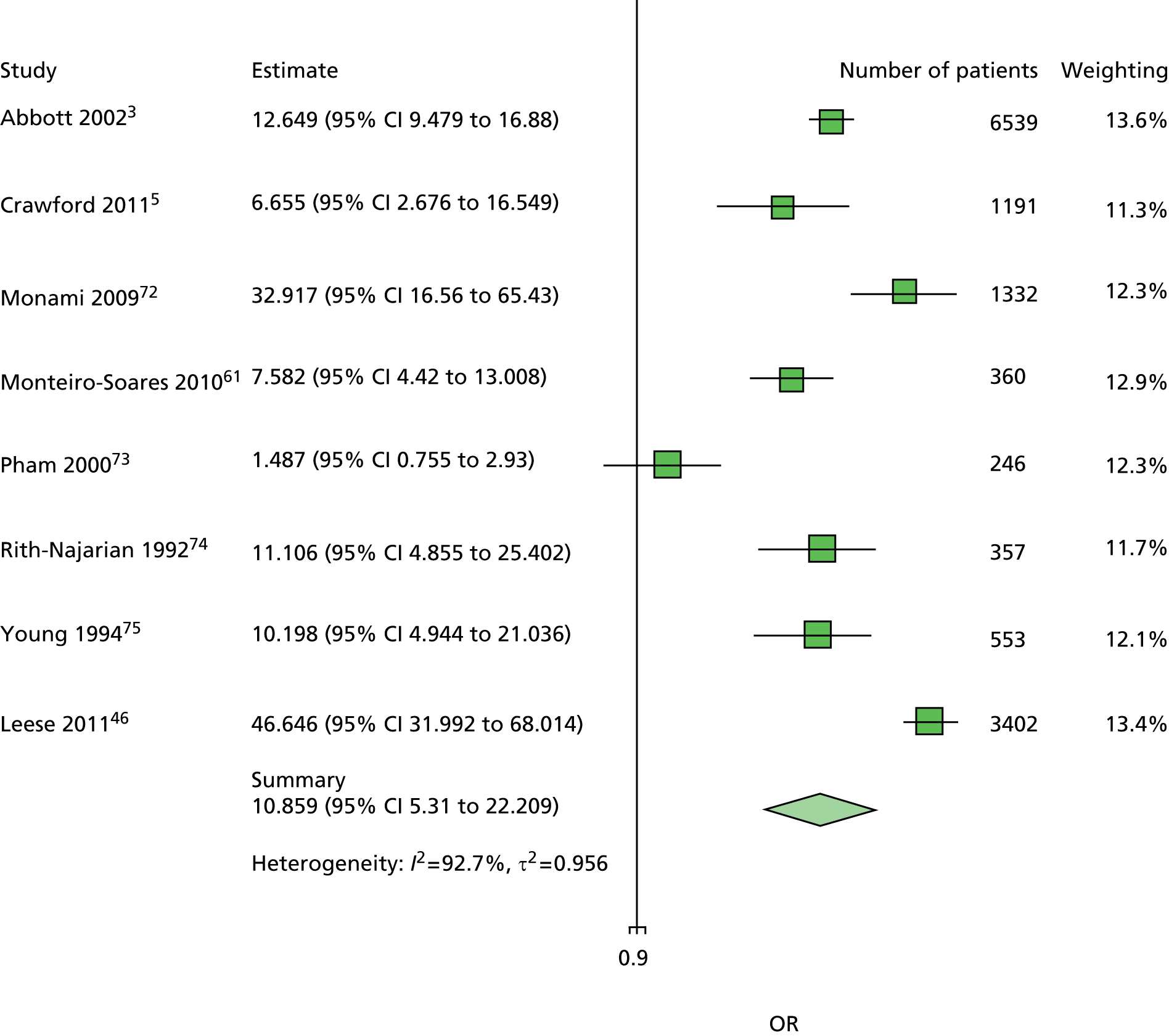

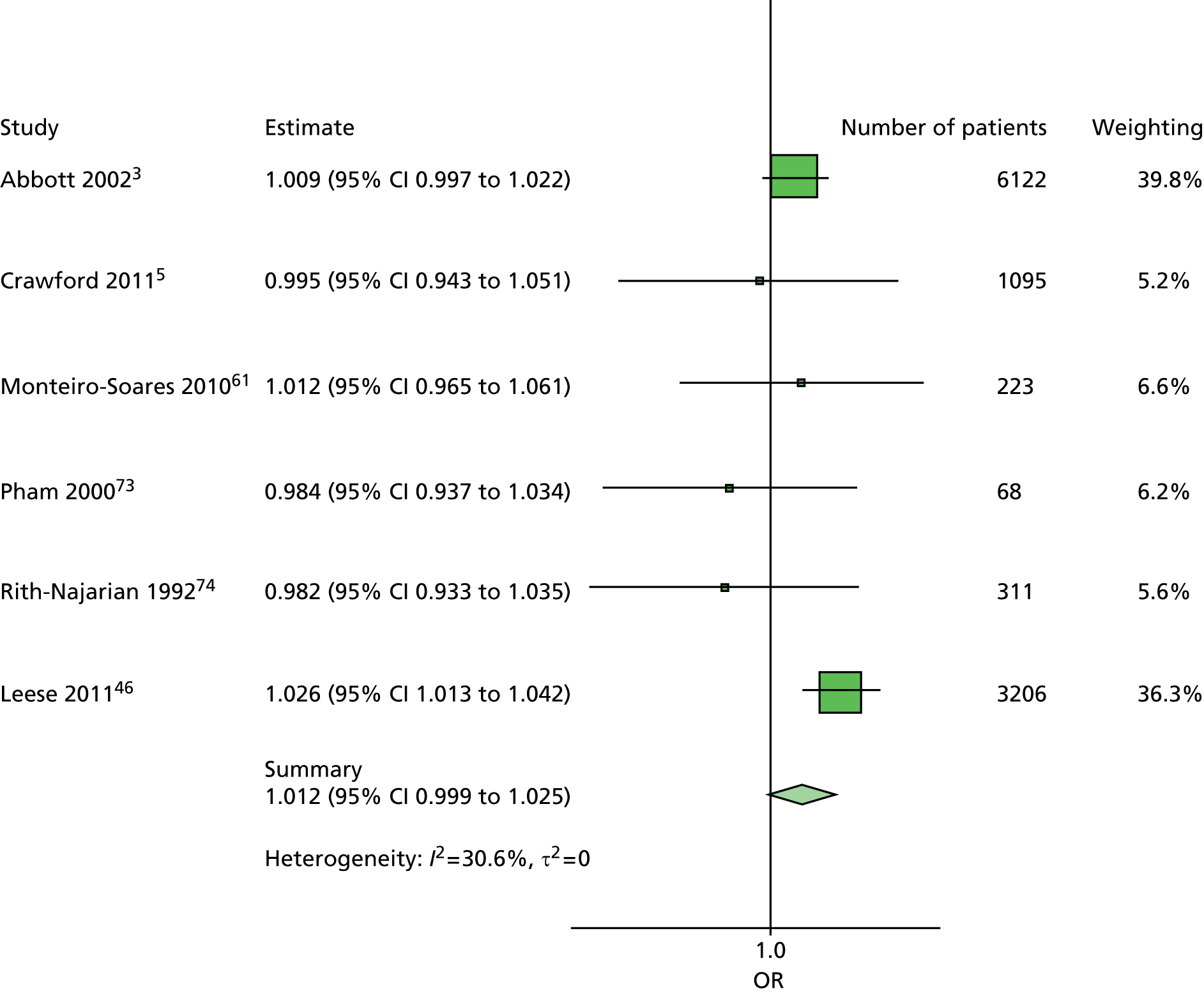

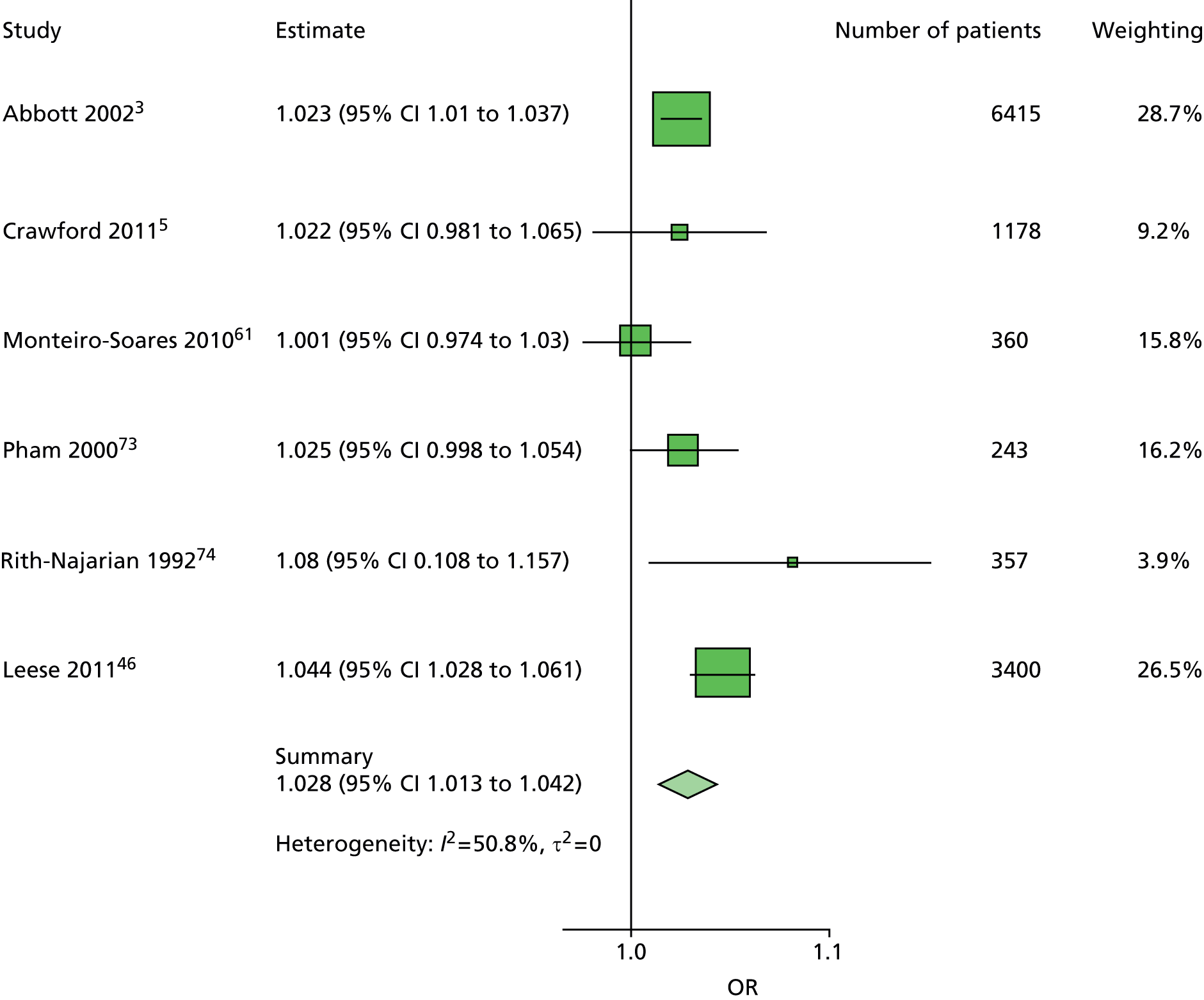

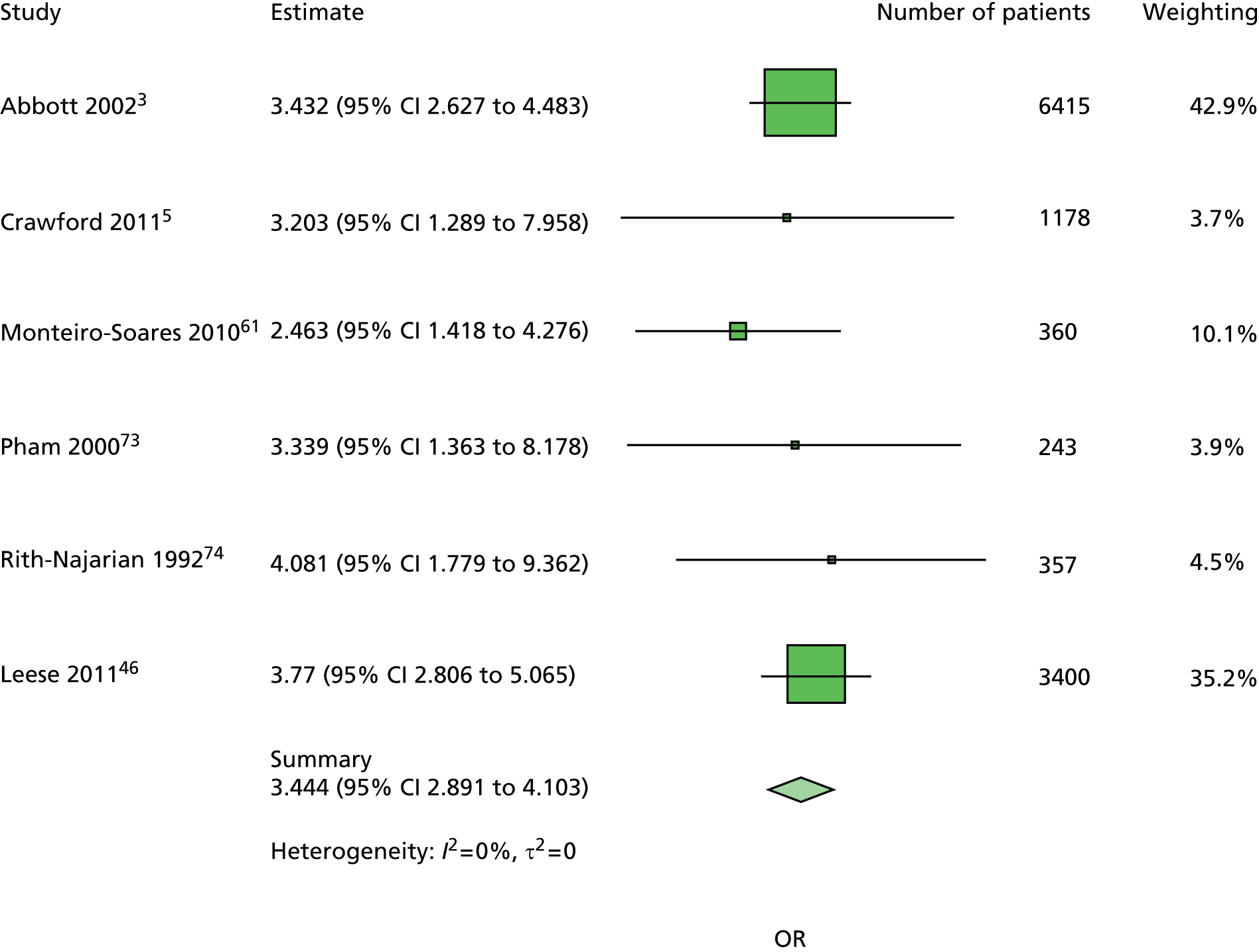

The majority of the variables collected were not suitable for the primary meta-analysis, because often they had been collected in only one or two studies. Also, in some cases, there was some variation in the definition of the variable across all the data sets, and it was a matter of judgement to decide if the degree of inconsistency was acceptable or not. However, variables that met the first two criteria were used in univariate logistic regression to obtain ORs. The ORs were plotted in forest plots so that heterogeneity could be assessed.

As the assessment of heterogeneity includes both clinical and statistical aspects, it cannot be designed solely on methodological grounds. Therefore, to ensure that all important clinical considerations were fully addressed, all the variables considered to be potential candidates were presented to the clinical and methodological co-authors at our international meeting.

All authors of the original studies presented details of the study design and conduct, with particular emphasis on the characteristics of the patient cohort and the particular risk factors studied. Univariate analyses of common variables were presented on forest plots to display the degree of heterogeneity between studies. Because the co-authors were also involved in the original studies producing the data sets, there was ample opportunity to discuss reasons for heterogeneity, encompassing inconsistency in the definitions, and what variables were felt to be clinically important.

The variables that met the first two criteria (collected in at least three data sets and consistently defined) were:

-

age

-

sex

-

body mass index (BMI)

-

smoking

-

height

-

weight

-

alcohol

-

HbA1c

-

insulin regime

-

duration of diabetes

-

eye problems

-

kidney problems

-

monofilament

-

pulses

-

tuning fork

-

biothesiometer

-

ankle reflexes

-

ABI

-

PPP

-

prior ulcer

-

prior amputation

-

foot deformity.

We chose not to present height and weight. BMI, height and weight are all obviously highly correlated. Using variables that are highly correlated in a statistical model can lead to collinearity problems, which are unstable estimates, as well as incorrect CIs and p-values. To avoid using a model with high collinearity, we decided to use BMI rather than height or weight. BMI is very commonly used as a measure of body size, and there were six studies with BMI data but only four each for height and weight.

The following variables, which did not meet the criteria, were also presented to demonstrate explicitly why we were unable to include them in any meta-analyses, despite their potential as predictors of foot ulceration: ethnicity, living alone, pinprick test, temperature test (i.e. possibly important demographic and foot sensation variables).

After a discussion of each variable in turn, the members of the group were asked to select a few variables to be examined for inclusion in the primary analysis to ensure that the final model was simple and easy to implement in a clinical environment; widely used CPRs tend not to have many predictors. In addition, for a study to be included, it must have collected data on all the relevant variables, which means that there is an inevitable trade-off between the number of variables and the number of studies to be included. For example, a model with just age and sex could use data from all the studies, but a model with age, sex and ABI could include only four studies. Therefore, limiting the number of predictors also maximises the number of studies that can be included.

The variables chosen at the international meeting for possible inclusion in the primary analysis were age, sex, duration of diabetes, prior ulceration or amputation and monofilament results. In addition, insulin use and kidney problems were to be added to the primary model to assess their impact on prediction of ulcer. E-mail was used to continue the discussion of the predictors after the meeting, resulting in some significant changes.

Patients with a known history of ulcer or amputation are already known to be at high risk of a further ulcer or amputation. These patients therefore have a different risk profile from patients with no history of ulceration or amputation, who may generally be at low risk. From a clinical view, it was regarded as important to be able to identify those patients without history who are nonetheless at high risk of ulceration to allow targeted treatment. Therefore, it was decided on clinical grounds to construct two models, one for all patients and the other for those patients with no history of ulceration or amputation, and, consequently, to drop history as a predictor from the model for patients with no previous ulceration or amputation.

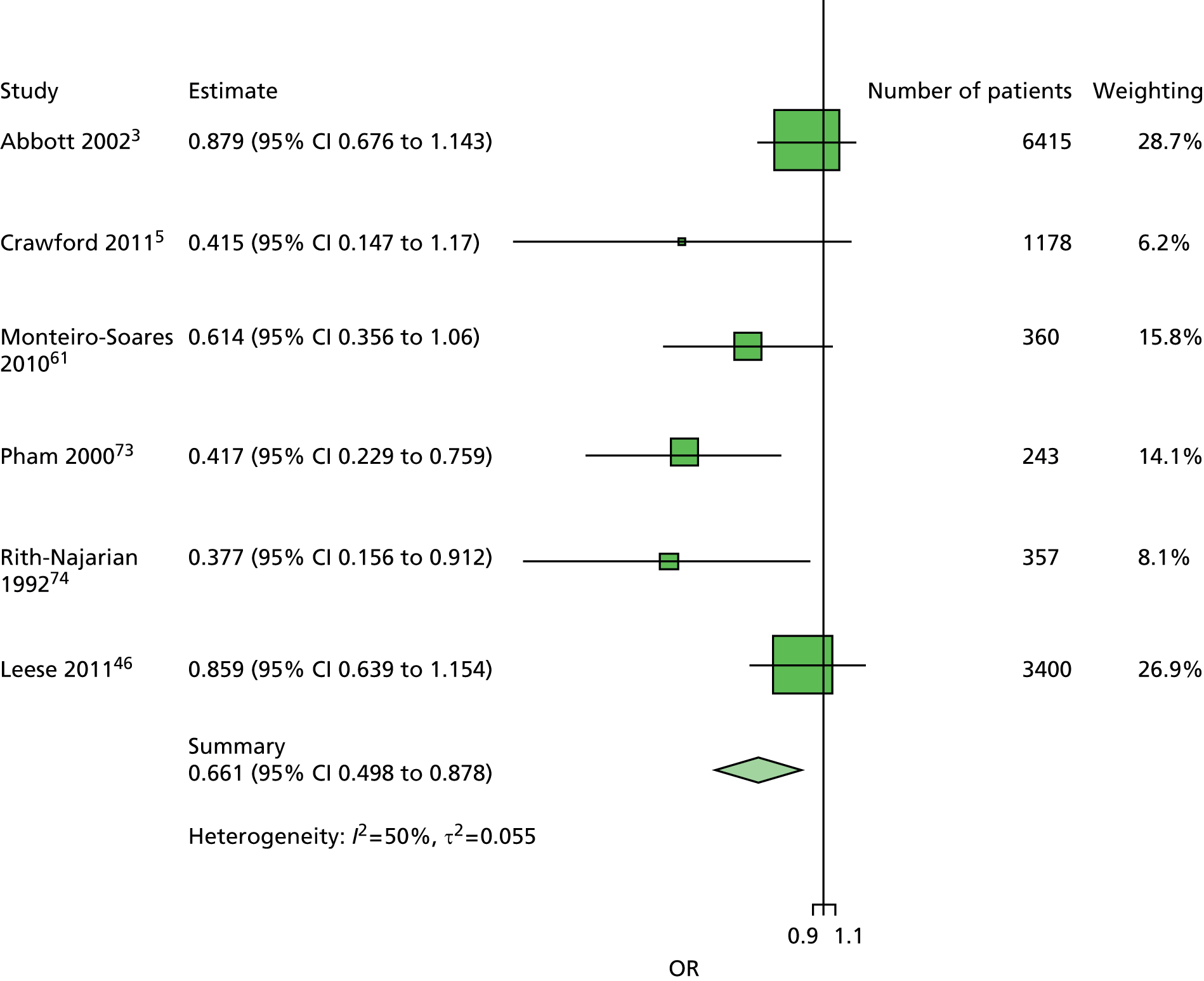

Another predictor dropped from the primary analysis was insulin use. Discussion at the international meeting covered the difficulties of interpreting the use of insulin as a predictor. A patient may simply be using insulin because he or she has type 1 diabetes. However, it is also possible that a patient is using insulin because he or she has poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. A further complication is that some patients with type 2 diabetes achieve good control with insulin. Moreover, the definition of insulin use varied from insulin use at any time prior to the study to current insulin use at the time of recruitment to the study. This was given as a possible explanation for inconsistency and a high degree of heterogeneity among the ORs for insulin use. It was therefore decided to drop insulin use from the primary analysis and retain it for secondary analyses only.

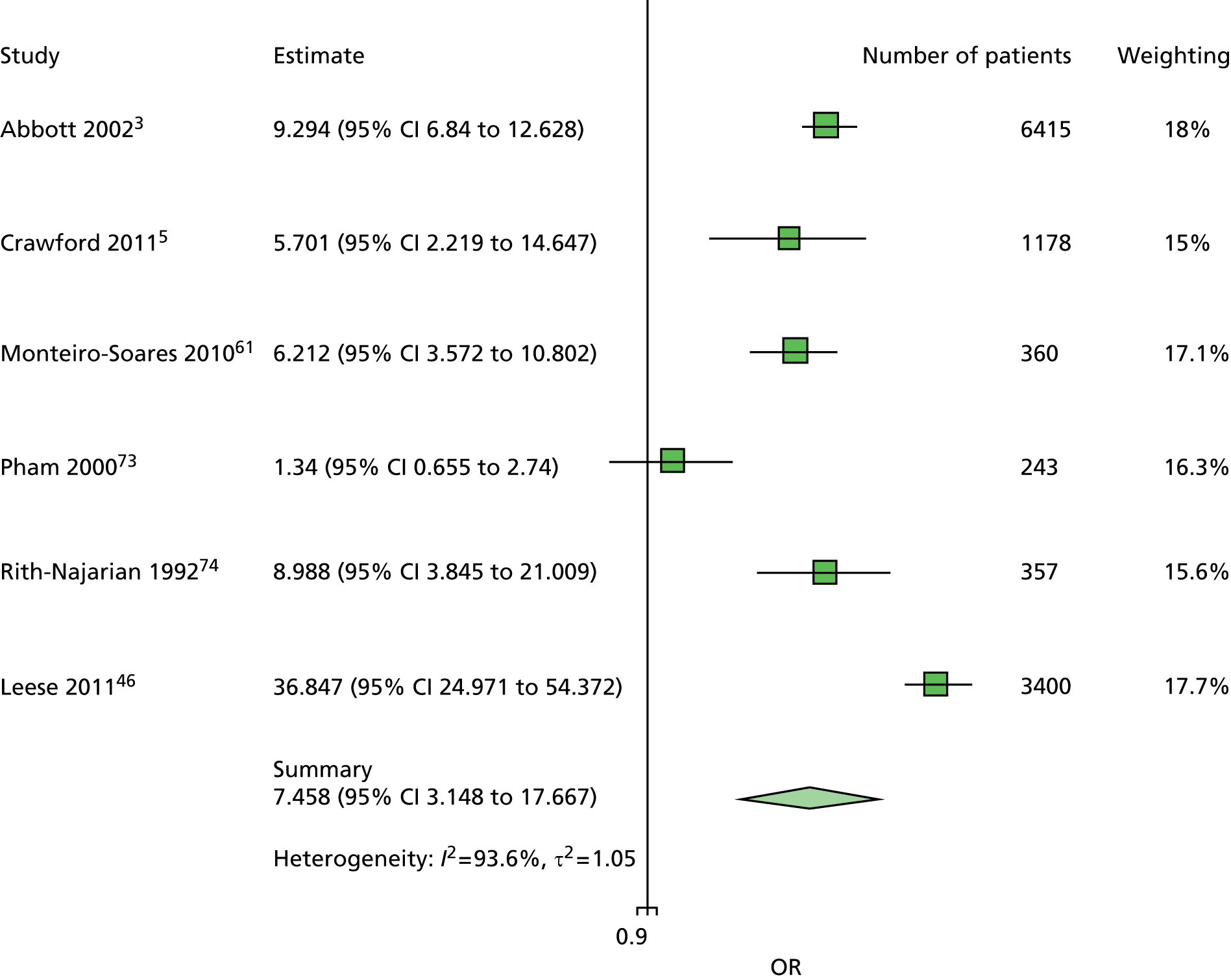

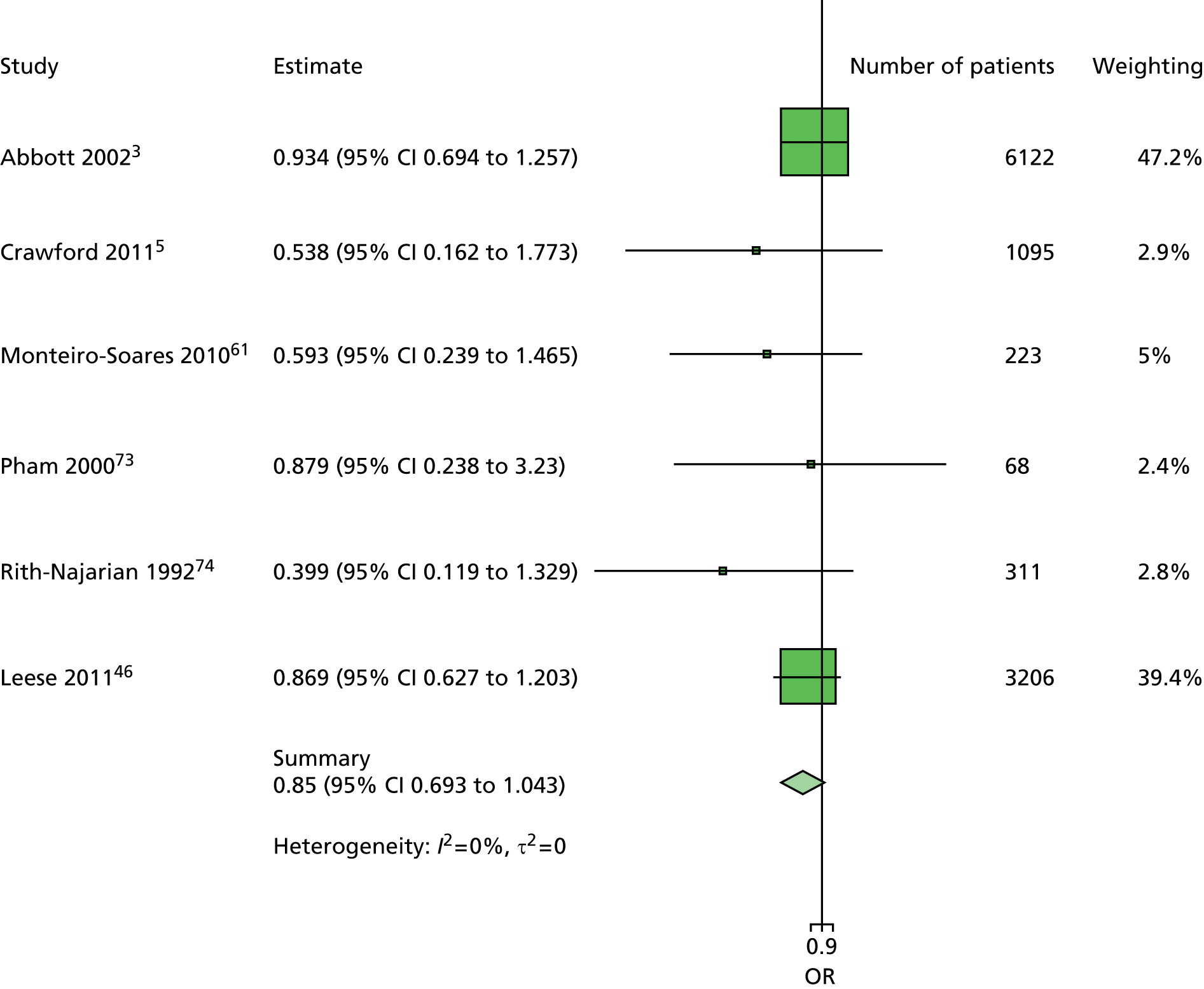

A similar line of reasoning was followed for the predictor kidney problems. These had been defined as outright nephropathy in some data sets and were derived from estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in others, which may or may not always be an adequate proxy. 60 In multivariate models, the effect of kidney problems was not consistent, being apparently protective against ulceration in some cases5,61 but predictive in others, for example. 3,46,47,62 Again, it was decided to drop kidney problems from the primary model but retain it for secondary analyses.

Dropping three predictors from the primary model meant that other potential predictors could be considered. We added pulses to the primary model. The argument in favour of use of pulses is that it is a test of the vascular integrity of the foot. The model already included monofilaments, a neurological test. Therefore, by including both a vascular and a neurological test of the foot, the model would encompass the major mechanisms by which foot ulceration occurs in diabetes.

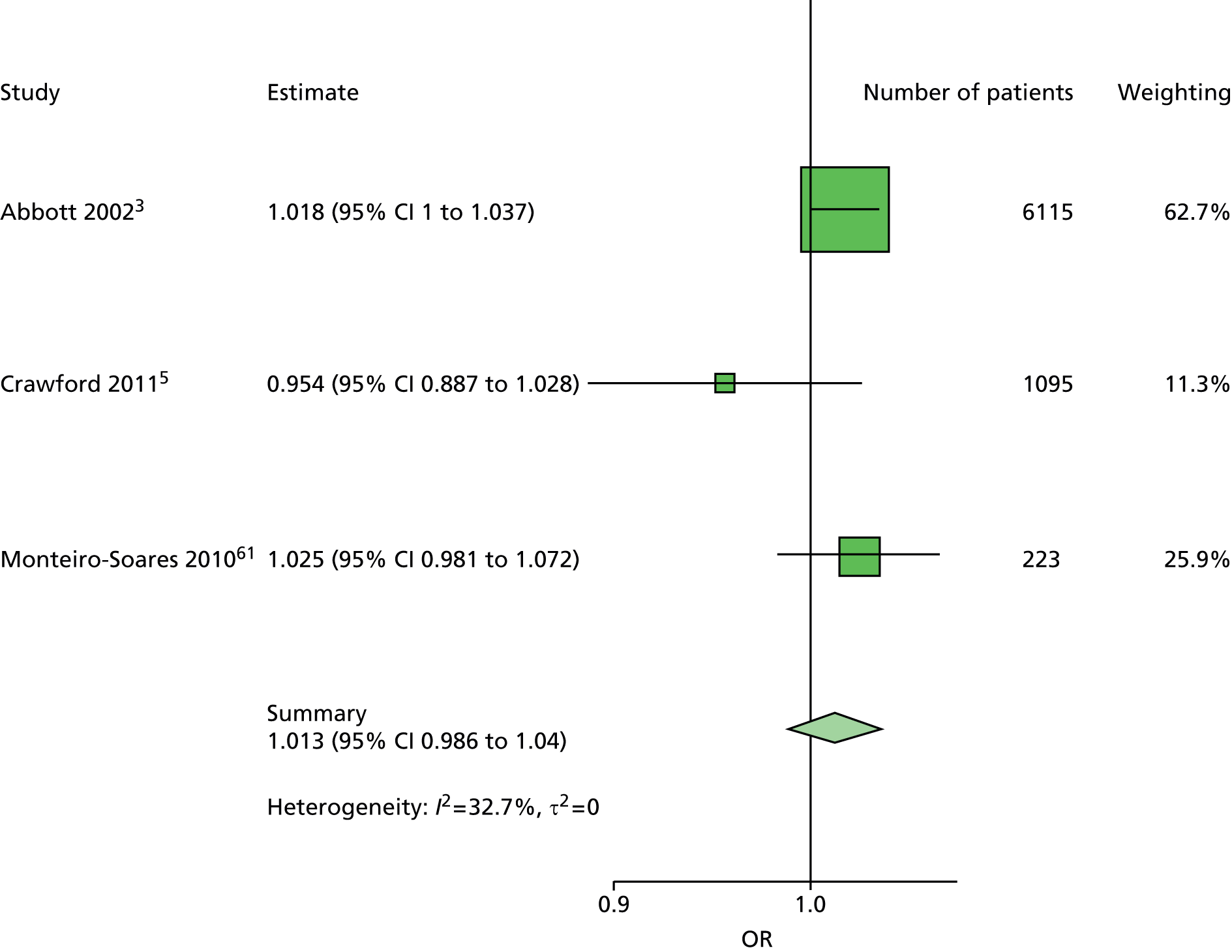

It was decided to include HbA1c in a secondary analysis in order to include a predictor in the model that could be influenced by patients themselves. The only variables in the list of potential predictors that could be influenced by patients were BMI, smoking, alcohol and HbA1c. However, discussion of BMI at the international meeting suggested that it would not be a good predictor, because a BMI in the low range could be indicative of two opposing states, either the patient does not gain weight through appropriate diet and exercise or the patient is unable to maintain weight owing to advanced diabetic illness. The univariate forest plot for BMI showed that a low BMI was protective of ulceration in some studies but predictive of ulceration in others. Furthermore, the data on the effect of smoking and alcohol were also not clear, with both smoking and drinking being protective against ulceration in some data sets and predictive of ulceration in others. These results were discussed, with some speculation on the vasodilation properties of nicotine and the possible benefits of moderate alcohol intake. Therefore, HbA1c was chosen for use in a secondary analysis. It is also the only patient-modifiable predictor directly related to diabetes. Two further tests, namely VPT by either tuning fork or biothesiometer and the ABI, were also retained for secondary analyses, as these were of particular interest to the clinical co-authors.

In summary, the primary model has the following predictors: age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament and pulses. The secondary models are:

-

age, sex and duration of diabetes

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes and monofilament

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament and insulin

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament and kidney problems

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament, pulses and VPT

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament, pulses and HbA1c

-

age, sex, duration of diabetes, monofilament and ABI.

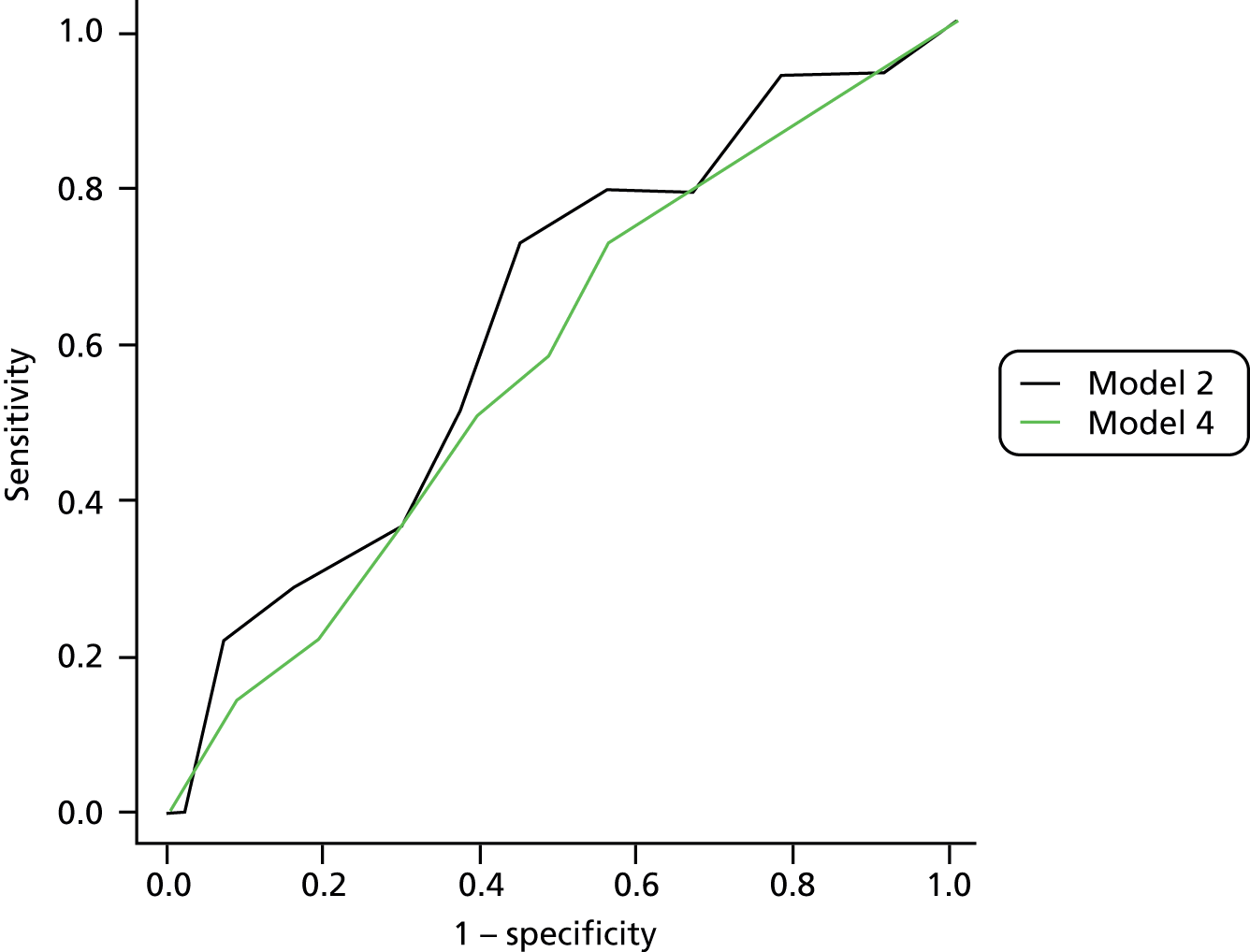

The primary model meets our aim of a parsimonious model of easily obtainable predictors. The purpose of the secondary models is to allow comparison with the primary model, for example to see what the value of HbA1c is as a predictor in addition to the predictors of the primary model. Prediction models are often assessed in terms of their discrimination (how well they distinguish between groups of patients) and calibration (how well the model’s estimated probability matches the actual probability of outcome for each patient).

Given two patients, one with an ulcer at follow-up and the other with no ulcer at follow-up, the area under the curve (AUC) is the probability that the model calculates a higher risk for the ulcer patient; thus, the AUC can be used to assess the discrimination of the model. The AUC takes a value between 0.5 (no discrimination) and 1 (perfect discrimination). Values between 0 and 0.5 are theoretically possible but would only occur if a model was worse than using a coin toss to predict outcome. The Brier score is an indication of how well the model is calibrated and takes a value between 0 and 1. A perfect model would have a Brier score of 0, and, as a rule of thumb, a prediction model should have a Brier score of 0.25 or under. 63

Chapter 5 Validation of the model

Validation is an essential part of assessing prediction models. For most studies that have access to only one data set, the emphasis is on internal validation. Internal validation is an assessment of model performance based on the data set used for development. Prediction models tend to perform best in the data set in which they were developed, and, therefore, one of the purposes of internal validation is to try and assess to what degree the estimates reflect true relationships between variables rather than the idiosyncrasies of the development data set. Teasing apart true and spurious relationships can be a problem when there are too many predictors and/or predictors are selected using a data-driven method such as stepwise regression.

The aim of our methodology was to avoid this problem by choosing a priori few predictors based on the criteria described above; see Chapter 3, Choice of predictors. These criteria do not use any information based on p-values or CIs and so avoid the problems of data-driven methods.

Internal validation methods generally consider the concepts of model discrimination and model calibration. In this context, discrimination is a reflection of how well the model differentiates between patients who do and do not ulcerate. Calibration is a reflection of how well the model assigns the relative proportions of risk categories; a poorly calibrated model would place many patients in the wrong risk category. A statistic that encompasses both these concepts is the two-component Brier score, which takes values between 0 and 1, with a perfectly calibrated model having a score of 0 and model with no calibration having a score of 1.

Given that we had several data sets, we also addressed external validation. External validation is the assessment of model performance in data sets other than the development data set and was arguably more important than internal validation because it related directly to the generalisability of our results. Performing external validation required two decisions to be made: how should it be done and which data should be used? There are six different methods of external validation for logistic regression models described by Steyerberg et al. 64 We chose one method for ease of implementation and interpretation, which was simply to re-estimate the ORs of our final model in a new data set not previously used in any analysis. We then compared the ORs from the meta-analyses with those from the validation data set. The validation data set had to fulfil one mandatory criterion, that is, it had to have all the variables used in the primary model, and more than one data set fulfilled this criterion. However, one data set in particular seemed to be the natural choice as the validation data set. The reasons for this were:

-

The validation data set was only available for analysis at a late stage. By using this data set for validation rather than model development, work on the meta-analyses could proceed in a timely manner.

-

The validation data set was not accessible to those performing the meta-analyses. Analyses could be requested and aggregate results supplied from the validation data set. This ensured that the persons conducting the meta-analyses were not influenced by any validation results, which were requested only after the meta-analyses had been completed.

-

The persons conducting the validation analyses were not informed of the results of any meta-analyses until after the validation analyses had been completed and supplied. This ensured that they were not influenced by any meta-analysis results.

Therefore, our methods allowed the validation process to be independent of the model development process and vice versa. It is also worth noting that the use of this particular data set, which was analysed by statisticians not otherwise involved in the project, meant that the method of external validation had to be simple, as the time available to conduct the validation by these statisticians was necessarily limited. To ensure that the time required was minimal, Statistical Analysis System [(SAS); SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA; see www.sas.com] programs (version 9.3) were supplied to produce all the required analyses.

Chapter 6 Results of the systematic review

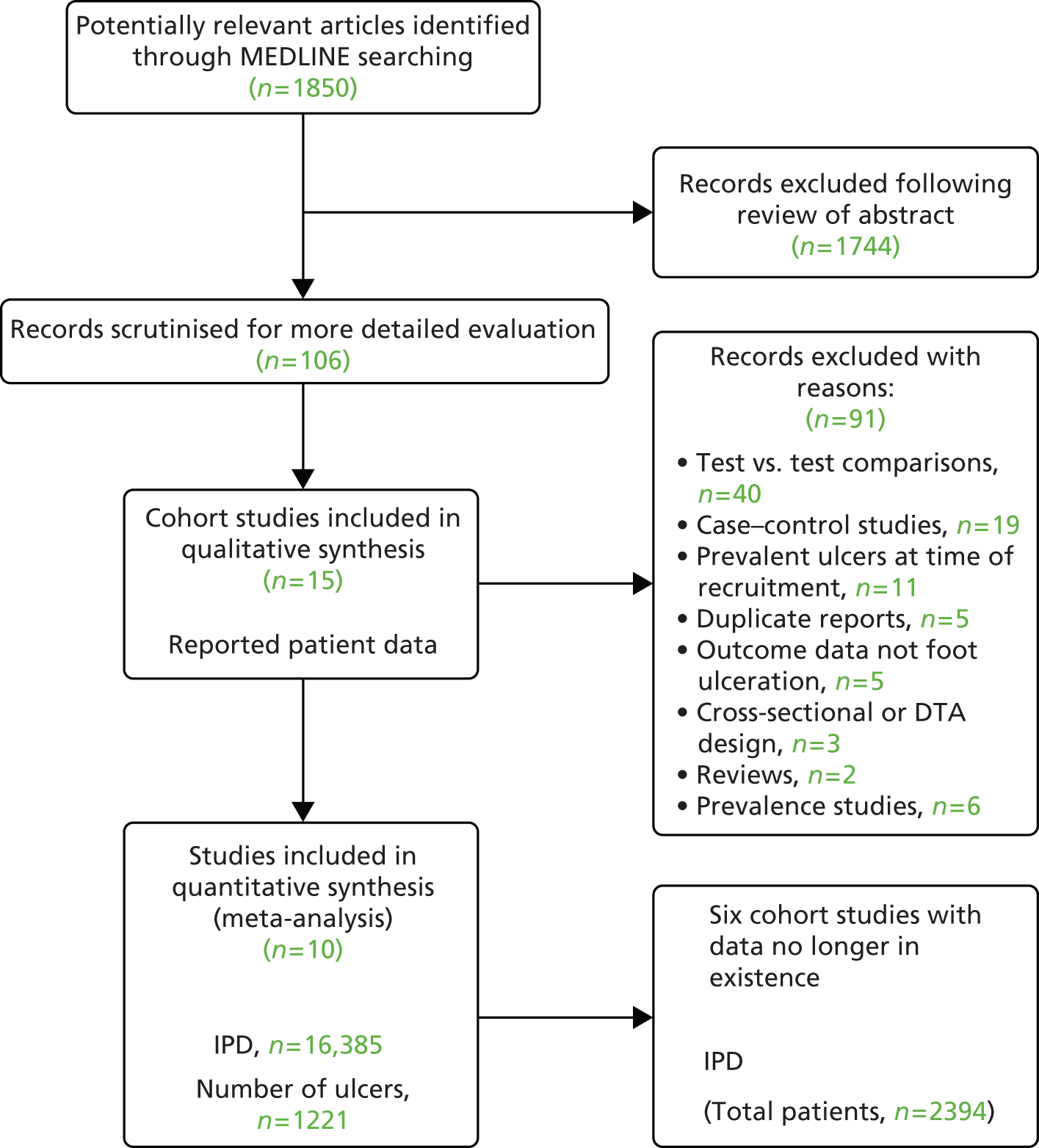

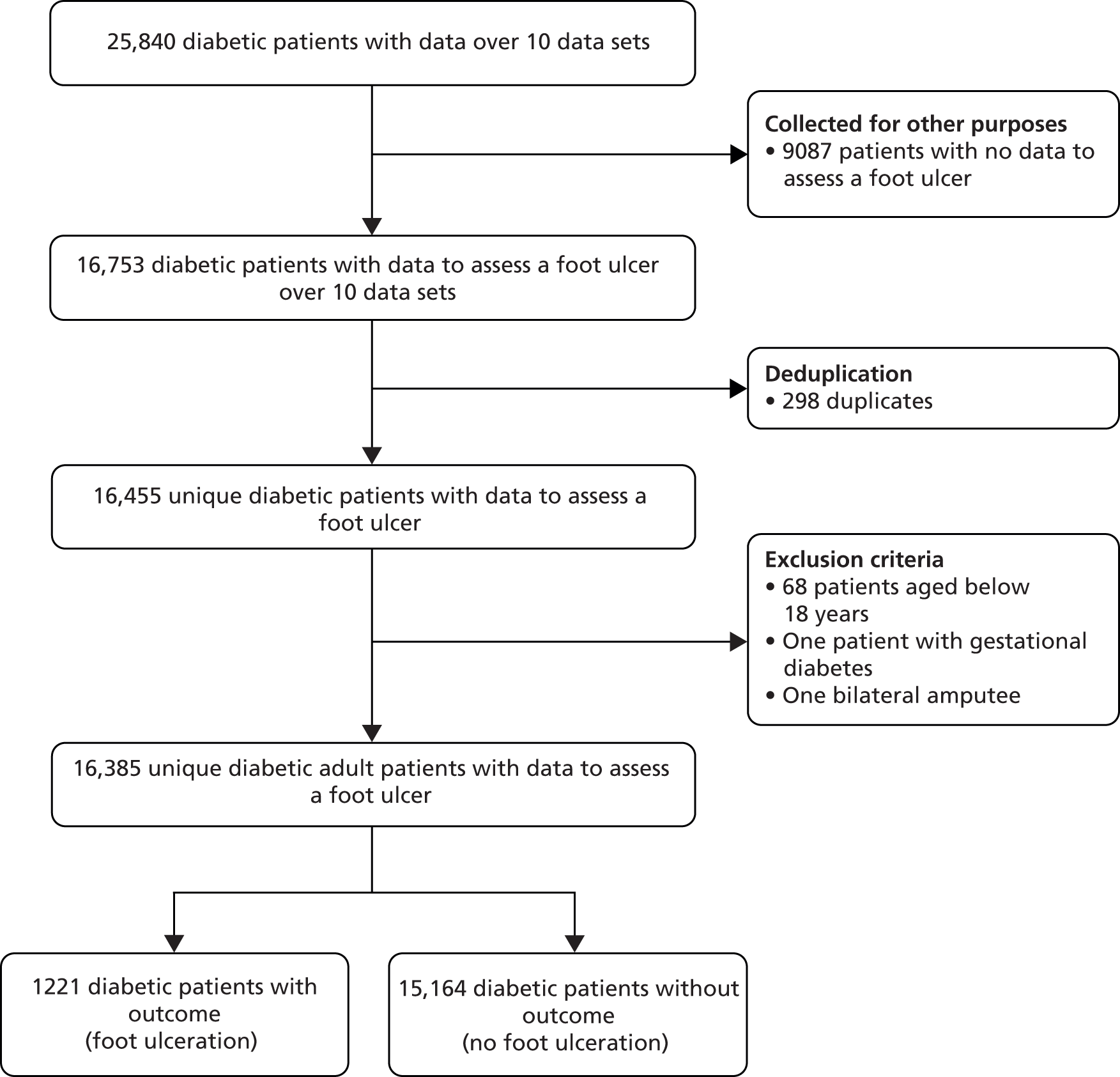

The flow diagram below (Figure 2) depicts the flow of literature during the review process.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of studies in the IPD systematic review, showing the studies included in the review and meta-analysis. 65 DTA, diagnostic test accuracy.

Chapter 7 Characteristics of included studies

There were 16 eligible studies identified from our search activities. We were unable to obtain IPD from six of these because either we could not make contact with the authors66–68 or the authors were no longer in possession of the data69–71 (Aristidis Veves, Harvard Medical School; Lawrence Lavery, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Texas, David Armstrong, Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance, University of Arizona, personal communication) (see Figure 2).

The corresponding authors of eight studies made raw data available to the Data Management Committee. 3,5,61,62,72–75 Data from a ninth study46,47 were made available to the Data Management Committee via Safe Haven, a data-management system. Finally, a 10th corresponding author was not granted permission to share the data from a cohort study by the Institutional Review Board48 but was able to contribute to the meta-analysis by subjecting the data to the same analytical procedures as all other studies to provide estimates of effect, which could be incorporated into the final (meta) analysis. Of these 10 studies, nine were derivation studies, and all are summarised in Table 1. Below, we briefly describe each.

| Author (date) | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Derivation/validation study; recruitment dates; duration of follow-up | Setting | Origin of the data | Who took the measurements | Types and number of events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott et al., 20023 | Type 1 or type 2 diabetes | Derivation study | GP practices Diabetes centres Hospital outpatients Podiatry clinics in north-west England, UK |

Consultation and examinations | Podiatrists and research nurses | Patients = 6603 Ulcers = 291 Amputations = 27 Deaths = 0 |

| April 1994–6 | ||||||

| 2 years | ||||||

| Boyko et al., 200649 | Inclusion: all general internal medicine clinic patients with diabetes Exclusion: current foot ulcer; bilateral foot amputations; wheelchair use or inability to ambulate; illness too severe to participate; psychiatric illness preventing informed consent |

Derivation study | The general internal medicine clinic of a single Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center | Consultations in specialised foot research clinic whose sole purpose was the collection of data for this research | Two nurse practitioners and two technicians who worked full-time for this research | Patients = 1489 Ulcers = 229 Amputations = 50 Deaths = 121 |

| Recruitment initiated in 1990 and continued until end of follow-up on 31 October 2012 | ||||||

| Mean duration of follow-up: 48.7 months | ||||||

| Crawford et al., 20115 | ≥ 18 years of age; diagnosis of diabetes mellitus; ambulant; free of foot ulceration; able to give informed consent | Derivation study | 32 podiatry clinics in primary care settings in Tayside, UK | Consultations and examinations Events ascertained from patient paper records by individuals blind to test results |

Eight podiatrists | Patients = 1193 Ulcers = 23 Amputations = 0 Deaths = 59 |

| March 2006–June 2007 | ||||||

| 11.4 months | ||||||

| Kästenbauer et al., 200162 | Inclusion: type 2 diabetes in men and women aged < 75 years old; normal gait pattern; plantar pressure could be reliably measured Exclusion: past or current foot ulcers; LEAs; severe peripheral arterial disease; severe neurological deficits attributable to diseases other than diabetes; Charcot foot |

Derivation study | Diabetes centre within a hospital in Vienna, Austria | Consultation and examinations | Two biologists working in the field of diabetes foot research, one diabetologist, who was responsible for the diabetic foot clinic | Patients = 187 Ulcers = 18/10 patients Amputations = 3 Deaths = 9 |

| January 1994–5 | ||||||

| Mean: 3.6 years | ||||||

| Leese et al., 201147 | Inclusion: all people with diabetes and on the diabetes register who had undergone foot risk assessment between 2004 and 2006 | Derivation study | Community and hospital diabetes foot clinics in Tayside, UK | Routinely collected clinical information (regional diabetes electronic register) Linked data Same electronic records The local multidisciplinary foot clinic and community and hospital podiatry paper records (for ascertaining events) |

Any GP, podiatrist nurse or specialist caring for diabetes mellitus patients | Patients = 3412 Ulcers = 322 Amputations = 55 Deaths = 575 |

| 2004–6 | ||||||

| 1.19 ± 0.91 | ||||||

| Monami et al., 200972 | Inclusion: type 2 diabetes outpatients referred the diabetes clinic of the geriatric unit | Derivation study | Diabetic clinic of the geriatric unit of a hospital, Florence, Italy | Consultation Ulcer ascertained by routinely collected data |

Diabetologists and research fellows | Patients = 1944 Ulcers = 91 Amputations = 0 Deaths = 321 |

| December 1995–December 2000 | ||||||

| 4.2 ± 2.2 years | ||||||

| Monteiro-Soares and Dinis-Ribeiro, 201061 | Diabetes mellitus Exclusion: unable to walk; data incomplete; fewer than three podiatry appointments |

Validation study | A public tertiary hospital, Portugal | Consultation (interview and foot examination) Medical records for both predictive and outcome variables |

Two podiatrists with 6 and 10 years’ experience in the management of the diabetic foot | Patients = 360 Ulcers = 94 Amputations = 0 Deaths = 0 |

| February 2002–October 2008 | ||||||

| 25 months (range 3–86) | ||||||

| Pham et al., 200073 | Diabetes mellitus who attended one of three large diabetic foot centres. Diabetes mellitus diagnosis confirmed by primary care provider | Derivation study | Three large diabetic foot centres, USA | Consultation interview and examination | Podiatrists | Patients = 248 Ulcers = 73 Amputations = 0 Deaths = 13 |

| January 1995–6 | ||||||

| Followed up for 30 months (range 6–40) | ||||||

| Rith-Najarian et al., 199274 | On diabetes register and had an annual foot examination | Derivation study | Primary care setting native American Indian reservation, USA | Consultation | Physical therapist and a physician | Patients = 358 Ulcers = 41 Amputations = 14 Deaths = 19 |

| July 1988–February 1991 | ||||||

| 32 months | ||||||

| Young et al., 199475 | At least one pedal pulse, no history of ulceration | Derivation study | Foot clinic in diabetes centre | Consultation Medical patient notes for ascertainment of ulcers |

A physician | Patients = 592 Ulcers = 47 Amputations = 0 Deaths = 8 |

| April 1988–March 1989 |

Derivation cohort studies

A total of 6603 people diagnosed with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus were recruited in the north-west of England, from several different settings, including general medical practices, diabetes specialist centres, hospital out-patient departments and podiatry clinics. Podiatrists and research nurses performed examinations and collected data for each of the exposure variables between April 1994 and April 1996. Ascertainment of the outcome variable (ulcer present/ulcer absent) was collected using a patient self-report postal questionnaire after an average follow-up period of 2 years. 76

A total of 1489 people with diabetes mellitus were recruited from a general internal medical clinic of a Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the USA. Patients were excluded if they had current foot ulcers or bilateral foot amputations, used a wheelchair, were too sick from illness to participate, or had psychiatric illness that prevented informed consent. Patients were recruited between 1990 and 2012 by two nurse practitioners and two technicians who performed all examinations and data collection. Ascertainment of the outcome variable (ulcer present/ulcer absent) was established by examination, and the average follow-up period was almost 49 months (4 years). 49

A total of 1193 people with diabetes mellitus were recruited from community podiatry clinics in Tayside, UK. Participants were free of foot ulceration at the time of recruitment, more than 18 years of age, ambulant and able to give informed consent. Recruitment took place between March 2006 and June 2007, and examinations were performed by eight NHS community podiatrists. Ascertainment of the outcome variable (ulcer present/ulcer absent) was collected from patients’ paper records by podiatrists who were unaware of the results of the patients’ examinations. The follow-up period was, on average, 11.4 months. 5

A total of 187 patients with diabetes mellitus were recruited from a hospital diabetes centre in Vienna, Austria. The study inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in men and women aged < 75 years, a normal gait pattern and a reliable measurement of plantar pressure. The study exclusion criteria were past or current foot ulcers, LEAs, severe peripheral arterial disease, severe neurological deficits attributable to diseases other than diabetes and Charcot foot. Patients were recruited between 1994 and 1995, and examinations and follow-ups were performed by two biologists, who worked in the field of diabetes foot research, and a diabetologist, who was responsible for the diabetic foot clinic. Ascertainment of the outcome variable (ulcer present/ulcer absent) was collected by the same individuals. The period of follow-up was, on average, 3.6 years. 62

Data from 3412 people with diabetes who had undergone a foot risk assessment between 2004 and 2006 were routinely collected from a regional diabetes electronic register. The data originated from patients being managed in community hospital diabetes foot clinics in Tayside, UK, and were entered into the electronic system by general practitioners (GPs), podiatrists and nurses providing patient care. Ascertainment of the outcome variable (ulcer present/ulcer absent) was performed using the same electronic register. 46,47

A total of 1944 patients with a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus were recruited from a diabetes outpatient clinic in a geriatric unit of an Italian hospital. The data were collected by diabetologists and research fellows between 1995 and 2000. Follow-up occurred, on average, 4.2 ± 2.2 years, and ascertainment of the outcome variable was achieved by accessing routinely collected data. 72

Two hundred and forty-eight people with diabetes were recruited from one of three large diabetic foot centres in the USA between January 1995 and January 1996. The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was confirmed by a primary care provider or from medical records. Podiatrists conducted data collection during interviews and examination consultations. Patients were followed up by the study podiatrists, who ascertained the presence or absence of a foot ulcer during a follow-up period, which was, on average, 30 months. 73

Three hundred and fifty-seven patients were recruited from a primary health-care facility on a native American reservation. All participants had diabetes mellitus, were on a diabetes register and had an annual foot examination by a physician or a physical therapist. The results were recorded on a paper form which was placed in the medical record. The date of the examination and risk category were logged into a clinic-based electronic diabetes registry of the community. At the conclusion of the study, the forms were abstracted from the form to the medical record and the data entered in to an Epi Info database (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). The study was conducted between July 1988 and February 1991, and follow-up was performed at 32 months on average. The ascertainment of the outcome variable was obtained from an Epi Info database by the study physician or physical therapist. 74

Five hundred and ninety-two patients with diabetes mellitus were recruited by a physician working in a specialist diabetes foot clinic in the UK. Patients were invited to take part in the research if they had at least one pedal pulse and no history of ulceration. The study was conducted between April 1988 and March 1989, and exposure data were collected during a consultation. The ascertainment of the outcome ulcers was performed from medical notes. 75

Validation cohort studies

One study validated the risk factors previously identified in a derivation cohort study by Boyko et al. 49 Three hundred and sixty people with diabetes mellitus were recruited from a public tertiary hospital in Portugal between February 2002 and October 2008. Patients were excluded if they could not walk, if they had had fewer than three podiatry appointments or if their data were incomplete. Two podiatrists collected data in interview and examination consultations and obtained routinely collected data for the exposure variables. Patients were followed up at 25 months, on average, and ascertainment of the outcome variable was achieved using routinely collected data. 61

Chapter 8 Risk of bias

The tabulated results of the quality assessment process can be found in Appendix 5. Of the four items used to assess the quality of the conduct of the studies, three indicated a low risk of bias. Patients were recruited consecutively in all but one study. 74 Follow-ups were conducted at least 1 month after the data collection of risk factors, allowing enough time for an ulcer to develop, and all reports provided enough detail for the tests to be replicated.

The collection of outcomes in a ‘blind’ manner to protect the data from investigator bias was a feature of only 50% of the studies included in our review. 3,5,61,73,75

All study reports provided sufficient details about the conduct of the tests to permit their replication.

Chapter 9 Data cleaning and pattern of missingness

Data preparation

All data sets were prepared the same way, following a list of rules, exclusion criteria and a selected number of variables. Few data sets contained more patients than presented in the corresponding manuscript owing to multipurpose collection. We focused on the data collected to assess an ulcer or amputation outcomes in diabetic patients.

Two sets of authors5,46,47 collected their data in the same geographical area; common patient encrypted identifiers were placed in a safe haven and merged with the data set of the Leese study in order to exclude duplicated patients.

The data preparation was performed using the SAS software in a uniform way across studies. The SAS code was structured in steps of data preparation for each study: importing the data set; including any additional relevant data; checking the data set content and each variable of interest for inconsistent values; cross-checking information; applying exclusion criteria; correcting errors and values by applying rules; formatting dates; and combining information in order to create all the variables for analysis in a consistent way across studies. A list of inconsistencies and queries were sent to each author when required to ensure that corrections were made appropriately. This allowed the validation of the data preparation. A harmonised data set was created for each study and subsequently merged with the other for validation of harmonisation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, a diagnosis of diabetes (type 1 or type 2), and having at least one foot. At the stage of data preparation, a total of 21 patients aged below 18 years, one patient with gestational diabetes and one bilateral amputee were excluded. The same inclusion criteria were used to exclude 47 patients in the Boyko et al. 49 data set (Table 2).

| Study | Abbott et al., 20023 | Leese et al., 201147 | Monami et al., 200972 | Crawford et al., 20115 | Young et al., 199475 | Monteiro-Soares and Dinis-Ribeiro, 201061 | Rith-Najarian et al., 199274 | Pham et al., 200073 | Kästenbauer et al., 200162 | Boyko et al., 200649 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data available | ||||||||||

| Number of patients with outcome | 6613 | 3712 | 1945 | 1196 | 598 | 360 | 358 | 248 | 187 | 1536 |

| Number of patients excluded | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| Number of duplicate patients | 295 | 3 | ||||||||

| Total patients for analysis | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 1193 | 592 | 360 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 1489 |

Rules for data cleaning

The rules were developed in order to include atypical but plausible values from an adult diabetic population. Extreme values were checked with authors for confirmation. Any irrelevant information was either corrected or removed prior to analysis.

-

Age and duration of diabetes were recorded in years. They were calculated from relevant dates and rounded to the lowest integer value when necessary.

-

Duration of follow-up was recorded in months. It was converted into months or calculated from relevant dates when available.

-

For anthropometrics, the following ranges were considered as possible and reasonable to include: weight between 35 kg and 180 kg; height between 120 and 210 cm; and BMI between 16 kg/m2 and 65 kg/m2. The measurements of three patients were confirmed as real and accurate: a weight of 27.3 kg for a small person75 (height 125 cm and BMI 17.5 kg/m2); a height of 211 cm for a tall person;73 and a weight and BMI of 230 kg and 71 kg/m2, respectively, for an extremely obese person. 73 Malignant obesity (BMI over 50 kg/m2) remains rare in the general population, but is considered possible in a person with diabetes.

-

Smoking was recorded as smoking history (yes/no) and as smoking status (never smoker/ex-smoker/current smoker). The possible number of cigarettes per day ranged between 1 and 60. A number of cigarettes per day higher than 60 was corrected by the maximum value of 60 and a value below 1 was considered as zero.

-

Alcohol was classified as current alcohol consumption (yes/no), with a very occasional alcohol intake being grouped with no alcohol. The possible number of alcoholic units per week was ranged from 1 to 100. A number of alcohol units per week higher than 100 was corrected by the maximum value of 100 and a value below 1 was considered as null.

-

HbA1c between 3% and 21% was considered possible. When multiple measurements were taken, the measure at the initial visit or the first measure available was used.

-

Kidney problems were identified as ‘nephropathy’ or ‘chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3–4–5 [glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2]’. In some cases, only a more advanced stage of the disease was available and was used, such as ‘end-stage renal disease’ or ‘kidney failure’ (CKD stage 5). CKD levels were calculated from GFR and creatinine levels.

-

The serum creatinine level (measured in µmol/l) was converted into eGFR using the Cockcroft–Gault formula:

-

(140 – age) × weight (in kg) × 1.04/creatinine, for women

-

(140 – age) × weight (in kg) × 1.23/creatinine, for men.

-

-

A wide inclusive range of creatinine levels between 20 and 300 was considered acceptable.

-

CKD stages were derived from the eGFR level (ml/minute/1.73 m2):

-

stage 1 ≥ 90

-

stage 2 60–89

-

stage 3 30–59

-

stage 4 15–29

-

stage 5 < 15.

-

-

eGFR can be recorded as 60+ ml/minute/1.73 m2, which does not allow the distinction between stages 0, 1 and 2. The moderate and severe stages of renal disease (stages 3, 4 and 5), which correspond to an eGfR below 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2, were considered to be a ‘kidney problem’ for the analysis.

-

-

The foot test results were combined, when available, for both feet. The measure used was from the worst outcome for any foot (at least one foot) at the initial visit or baseline.

-

A VPT value over 25 V in any foot, as measured by a biothesiometer, was considered an abnormal VPT.

-

An ABI of < 0.9 or > 1.3 was considered an abnormal value.

-

A dichotomised foot pressure with an abnormal result (high foot pressure > 6 kg/cm) was available in one study. This was applied in other studies to harmonise the results.

-

Pattern of missingness

Table 3 presents the numbers and percentages of missing values for each selected variable by study. It also identifies studies in which a variable is systematically missing with a percentage of 100. More than 10% missing data in available variables were identified in specific studies for the following potential predictors: height, weight, BMI, HbA1C, diabetes duration, kidney problems, VPT tuning fork, Achilles reflexes and ABI.

| Studies | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott et al., 20023 | Leese et al., 201147 | Monami et al., 200972 | Crawford et al., 20115 | Young et al., 199475 | Monteiro-Soares and Dinis-Ribeiro, 201061 | Rith-Najarian et al., 199274 | Pham et al., 200073 | Kästenbauer et al., 200162 | Boyko et al., 200649 | Total | ||

| Number of patients in data set | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 1193 | 592 | 360 | 358 | 248 | 187 | 1489 | 16,385 | |

| Variables | Statistics | |||||||||||

| Age | Number missing | 31 | 1 | 1 | 33 | |||||||

| % missing | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| Sex | Number missing | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| % missing | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Weight | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 33 | 170 | 360 | 358 | 52 | 21 | 12,952 | |

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2.76 | 28.72 | 100 | 100 | 20.97 | 1.41 | 79.05 | ||

| Height | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 68 | 122 | 360 | 358 | 86 | 12,952 | ||

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 5.69 | 20.61 | 100 | 100 | 5.78 | 79.05 | |||

| BMI | Number missing | 6603 | 217 | 293 | 113 | 239 | 360 | 358 | 52 | 89 | 8323 | |

| % missing | 100 | 6.36 | 15.07 | 9.47 | 40.37 | 100 | 100 | 20.97 | 5.98 | 50.80 | ||

| Lives alone | Number missing | 49 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 360 | 358 | 248 | 187 | 1498 | 8638 | |

| % missing | 0.74 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 52.72 | ||

| Smoking | Number missing | 14 | 59 | 1944 | 358 | 2374 | ||||||

| % missing | 0.21 | 1.73 | 100 | 100 | 14.49 | |||||||

| Alcohol | Number missing | 38 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 360 | 358 | 50 | 6753 | |||

| % missing | 0.58 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3.36 | 41.21 | ||||

| HbA1c | Number missing | 6603 | 48 | 166 | 128 | 227 | 357 | 248 | 18 | 7795 | ||

| % missing | 100 | 1.41 | 8.54 | 10.73 | 38.34 | 100 | 100 | 1.21 | 47.57 | |||

| Insulin treatment | Number missing | 10 | 357 | 248 | 1 | 616 | ||||||

| % missing | 0.15 | 100 | 100 | 0.07 | 3.76 | |||||||

| Diabetes type | Number missing | 52 | 3412 | 1193 | 19 | 4676 | ||||||

| % missing | 0.79 | 100 | 100 | 3.21 | 28.54 | |||||||

| Diabetes duration (full years) | Number missing | 33 | 10 | 612 | 2 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 689 | |||

| % missing | 0.50 | 0.29 | 31.48 | 0.17 | 6.59 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 4.26 | ||||

| Eye problems | Number missing | 57 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 20 | 6817 | ||

| % missing | 0.86 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.34 | 41.61 | |||

| Eye problems (retinopathy) | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1193 | 592 | 357 | 15 | 4 | 12,176 | |||

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 8.02 | 0.27 | 74.31 | ||||

| Kidney problems | Number missing | 109 | 1291 | 148 | 366 | 357 | 6 | 71 | 2348 | |||

| % missing | 1.65 | 37.84 | 12.41 | 61.82 | 100 | 3.21 | 4.77 | 14.33 | ||||

| Monofilament | Number missing | 125 | 2 | 1944 | 13 | 592 | 3 | 48 | 2727 | |||

| % missing | 1.89 | 0.06 | 100 | 1.09 | 100 | 1.21 | 3.22 | 16.64 | ||||

| Pulses | Number missing | 3 | 76 | 1944 | 357 | 2 | 187 | 115 | 2684 | |||

| % missing | 0.05 | 2.23 | 100 | 100 | 0.81 | 100 | 7.72 | 16.38 | ||||

| Pinprick | Number missing | 11 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 360 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 1489 | 8600 | |

| % missing | 0.17 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 52.49 | ||

| VPT: tuning fork | Number missing | 8 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 189 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 727 | 7664 | |

| % missing | 0.12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 52.50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 48.82 | 46.77 | ||

| VPT: biothesiometer | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1 | 360 | 357 | 2 | 1055 | 11,790 | |||

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 0.08 | 100 | 100 | 0.81 | 70.85 | 71.96 | ||||

| VPT: combined | Number missing | 8 | 3412 | 1944 | 1 | 0 | 189 | 357 | 2 | 187 | 293 | 4261 |

| % missing | 0.12 | 100 | 100 | 0.08 | 52.50 | 100 | 0.81 | 100 | 19.68 | 26.01 | ||

| Ankle reflexes (tendon hammer) | Number missing | 87 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 190 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 24 | 7041 | |

| % missing | 1.32 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 52.78 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.61 | 42.97 | ||

| Temperature sensation (hot, cold) | Number missing | 73 | 3412 | 1944 | 592 | 360 | 357 | 248 | 187 | 1489 | 8662 | |

| % missing | 1.11 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 52.87 | ||

| ABI | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 223 | 66 | 360 | 169 | 248 | 3 | 13,028 | |

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 18.69 | 11.15 | 100 | 47.34 | 100 | 1.60 | 79.51 | ||

| PPP | Number missing | 6603 | 3412 | 1944 | 109 | 592 | 360 | 357 | 9 | 2 | 1489 | 14,877 |

| % missing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 9.14 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3.63 | 1.07 | 100 | 90.80 | |

| Foot deformity | Number missing | 19 | 1944 | 592 | 248 | 2 | 2805 | |||||

| % missing | 0.29 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.13 | 17.12 | ||||||

Each author provided information about the reasons for the data being missing where possible. This information was essential to confirm the patterns of missing data. In most studies, the data were missing because they were not collected or recorded by clinicians or there were administrative problems in some period of collection. Our exploration of missing data found the pattern of ‘missingness’ to be MAR.

Chapter 10 Patients with diabetes: description

Demographics, anthropometrics and lifestyle

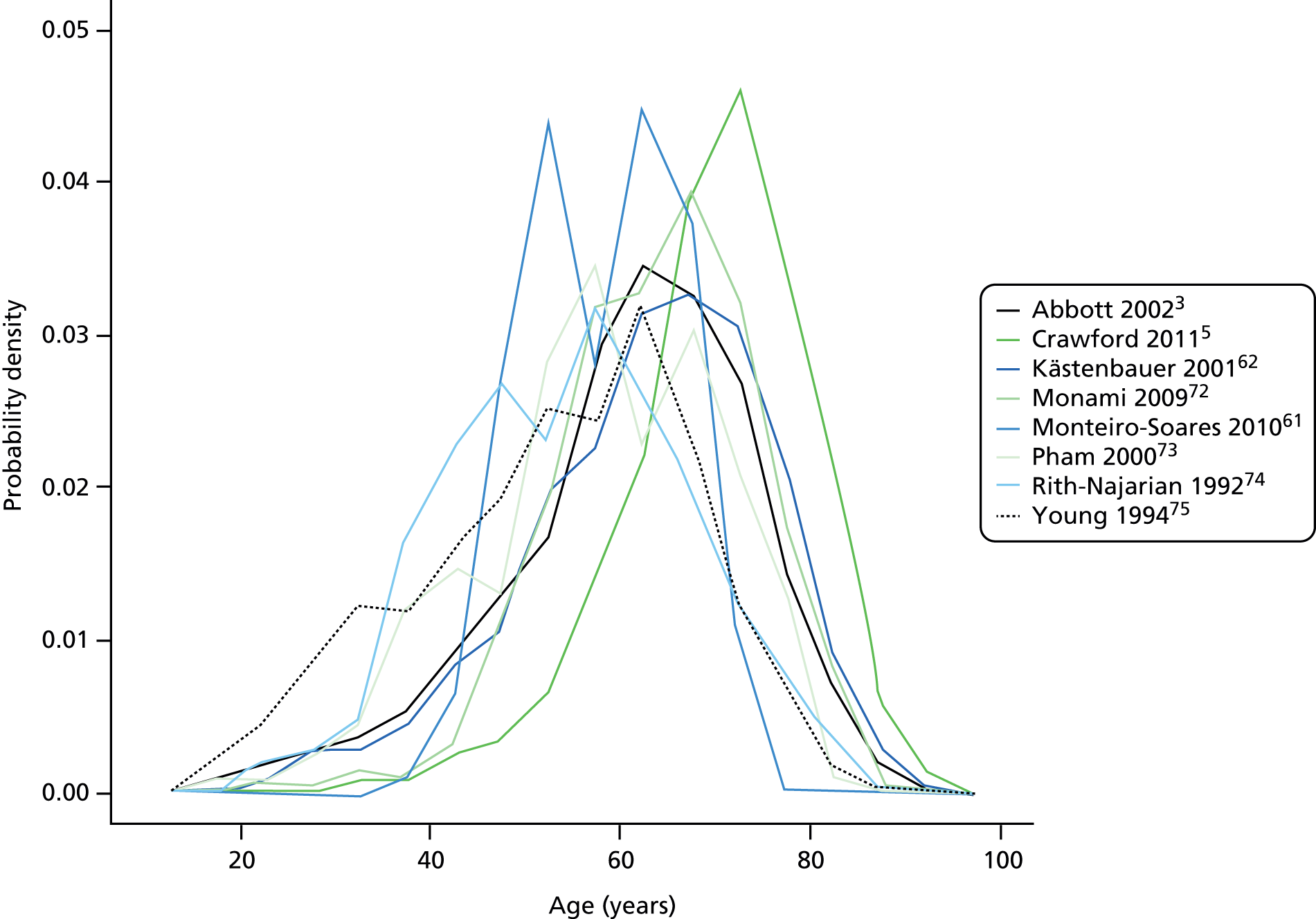

Appendix 6 shows the demographic, anthropometric and lifestyle profile of the diabetic population per study. The overall average age was 63 years, ranging from 54 and 55 years in the two earliest studies,74,75 to 71 years in the study by Crawford et al. 5 Figure 3 shows the similar distribution of age per study, with higher modes for the more recent studies by Monami72 and Crawford. 5 The overall percentage of men was 58% and varied from 44% to 57% for most studies, but was 98% in the study by Boyko et al. 49

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of age per study.

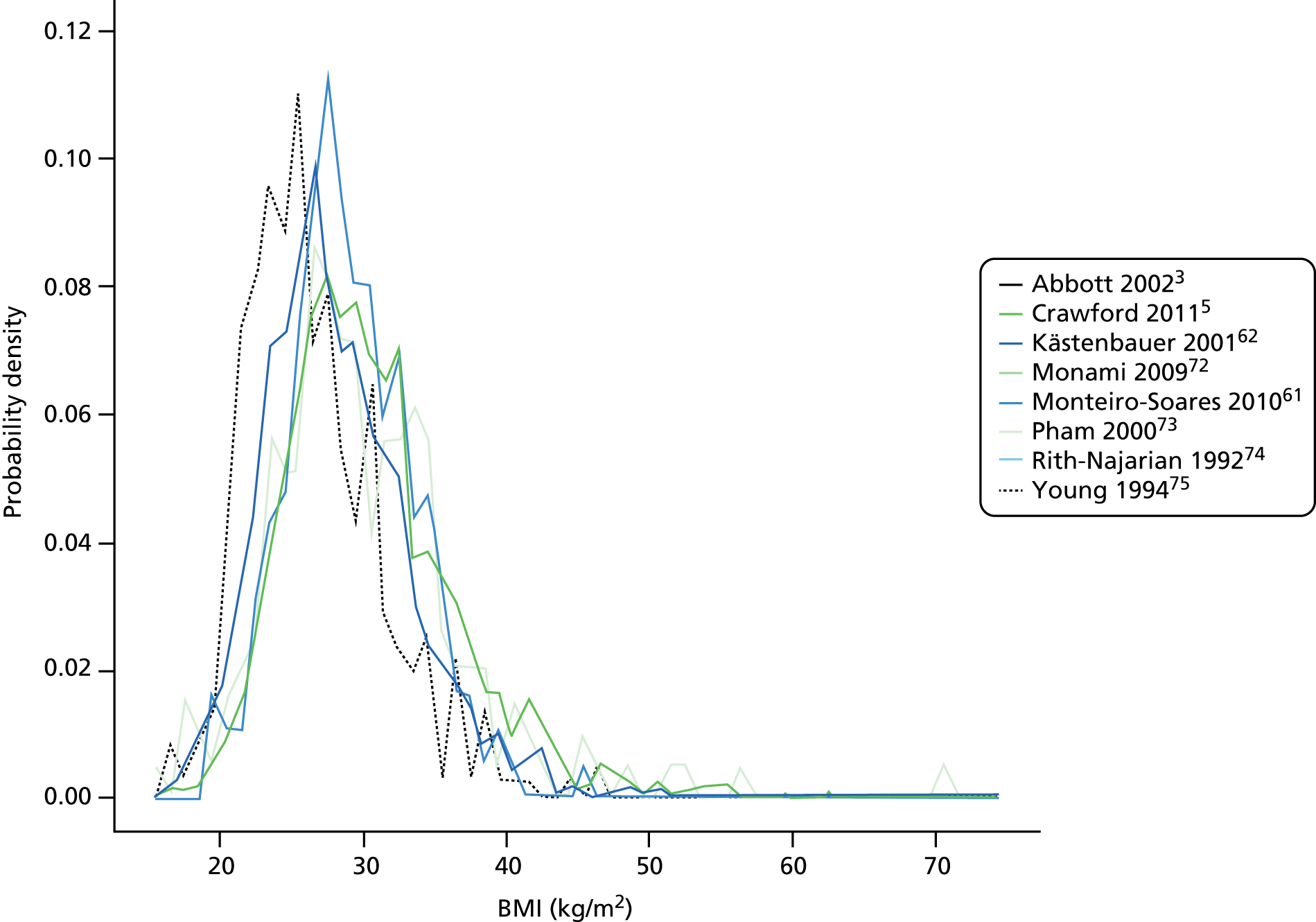

Average weight and height were recorded for only four studies, with BMI recorded more commonly. The overall mean weight and height were 89 kg and 171 cm, respectively. The distributions of weight and height were very similar across studies, although the patients in the study by Young et al. 75 were slightly lighter. Mean BMI ranged from 27 kg/m2 to 31 kg/m2, with an overall average of 30 kg/m2 just at the threshold for obesity. Figure 4 shows the similar distribution of BMI per study. Most patients had a BMI between 20 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2, with few cases of extreme and malignant obesity.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of BMI per study.

The studies by Abbott et al. 3 and Crawford et al. 5 observed the proportion of diabetic patients living alone to be 22% and 29%, respectively. Smoking and alcohol consumption were heterogeneous across studies; 19–81% of patients had ever smoked and 17–55% were consuming alcohol. For most studies, around 50% or more of the patients had a history of smoking, and the trends were similar for alcohol consumption.

Diabetes and comorbidities

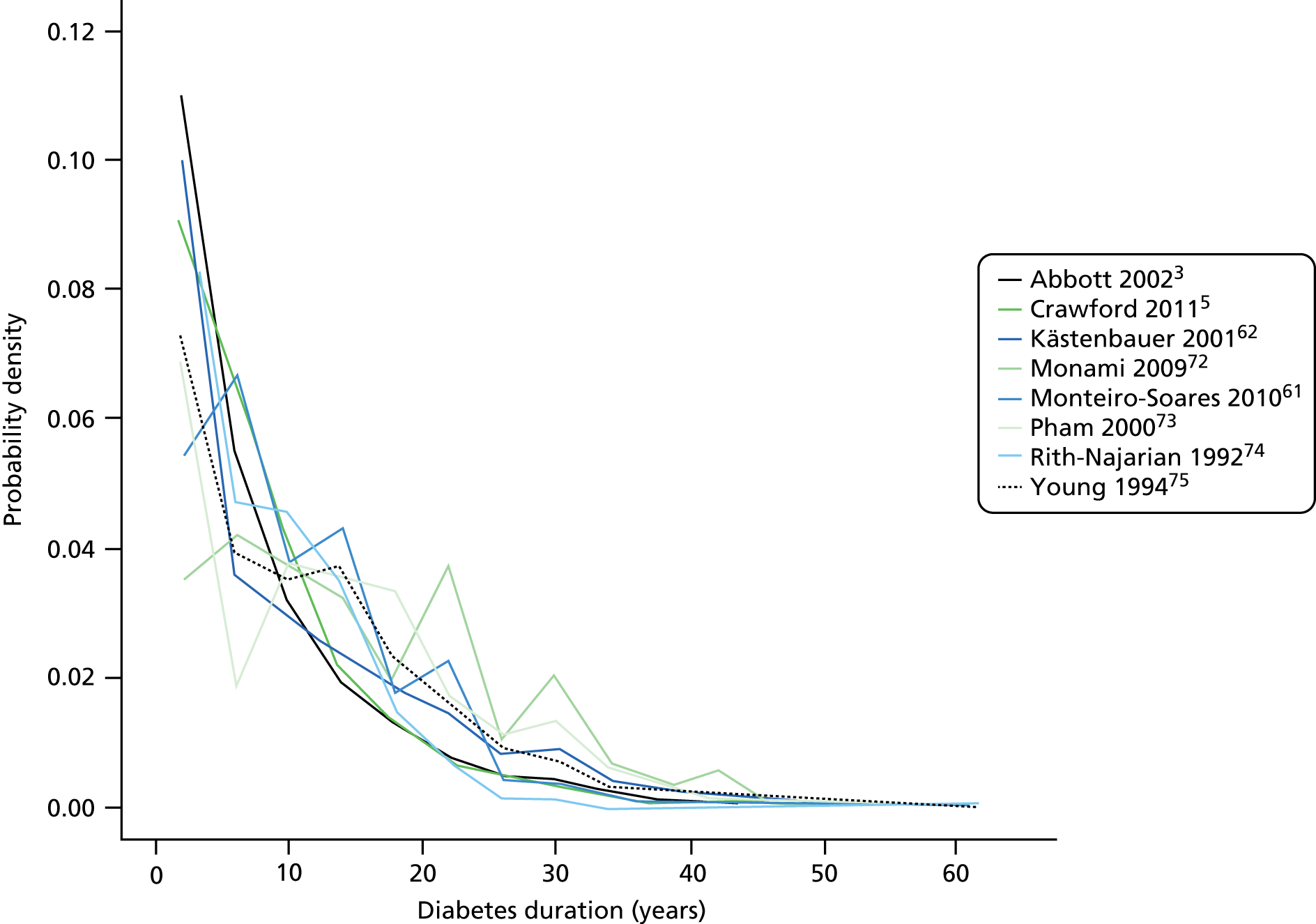

Appendix 7 shows the diabetic, eye and renal profile of the diabetic population per study. The majority of patients had type 2 diabetes. Three studies focused on patients with type 2 diabetes only; in the remaining studies the proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes was between 61% and 98% . Overall, type 1 diabetes accounted for about 9% of recorded types of diabetes. Insulin treatment accounted mostly for 20–40% of each diabetic population. Overall, the average diabetes duration was 9 years and was disparate across studies, average duration ranging from 7 to 16 years. Figure 5 shows that the distribution of diabetes duration per study was similar overall. HbA1c was, on average, 8% in each study apart from the studies by Young et al. 75 (11%), Kästenbauer et al. 62 (10%) and Boyko et al. 49 (10%).

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of diabetes duration per study.

Four studies recorded visual impairment and/or blindness with heterogeneous results. Retinopathy was collected for four studies and recorded diagnoses ranged from 9% to 49% of the population. Renal problems were collected for most studies but in various ways. Nephropathy accounted for 2% and 17% of the population in two studies, stage 3–5 CKD accounted for 13–37% of the population in two studies, and end-stage renal failure for 2% and 4% of the population in another two studies.

Foot measurements by study

Appendix 8 presents the descriptive statistics of 10 foot measures per study. Insensitivity to monofilament, pulses, VPT and any kind of foot deformity were the most frequently collected variables. The proportion of abnormal results varied across studies; the proportion of patients insensitive to monofilament in any foot ranged from 7% to 76%. The proportion of patients with no pulses in any foot ranged from 3% to 30%, and the proportion with abnormal VPT ranged from 25% to 95%. The proportion of patients with abnormal ABI ranged from 25% to 78%, and the proportion with any foot deformity ranged from 4% to 80%. Abnormal temperature sensation accounted for 21% and 33% of the diabetic population in the studies by Abbott et al. 3 and Crawford et al. ,5 respectively. The same studies had 33% and 50% of patients, respectively, with abnormal pinprick test. Abnormal ankle reflexes were recorded in 50% or more of patients for three studies, and PPP was recorded in about half of the patients in the same studies.

Chapter 11 Common variables

The data dictionary relating to these tables can be found in Appendix 9. The variables common to the included studies can be found in Table 4.

| Abbott et al., 20023 | Leese et al., 201147 | Monami et al., 200972 | Crawford et al., 20115 | Young et al., 199475 | Monteiro-Soares and Dinis-Ribeiro, 201061 | Rith-Najarian et al., 199274 | Pham et al., 200073 | Kästenbauer et al., 200162 | Boyko et al., 200649 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication information | |||||||||||

| Year of publication | 2002 | 2011 | 2009 | 2011 | 1994 | 2010 | 1992 | 2000 | 2001 | 2006 | |

| Level of analysis | Patient | Visit | |||||||||

| Number of patients | 6613 | 3719 | 1945 | 1192 | 469 | 360 | 358 | 248 | 187 | 1536 | 16,627 |

| Demographics, anthropometrics, lifestyle | |||||||||||

| Age | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 |

| Sex | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 |

| Weight | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| Height | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| BMI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Lives alone | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| Smoking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Alcohol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| Diabetes | |||||||||||

| HbA1c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Insulin treatment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Diabetes type | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (type 2) | ✓ | ✓ (type 2) | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Diabetes duration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 |

| Eye problems | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Kidney problems | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |

| Foot measurements | |||||||||||

| Monofilament | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Pulses | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Pinprick | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| VPT: tuning fork | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| VPT: biothesiometer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| Ankle reflexes (tendon hammer) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||

| Temperature sensation | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| ABI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| PPP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||

| Foot deformity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| History and outcome | |||||||||||

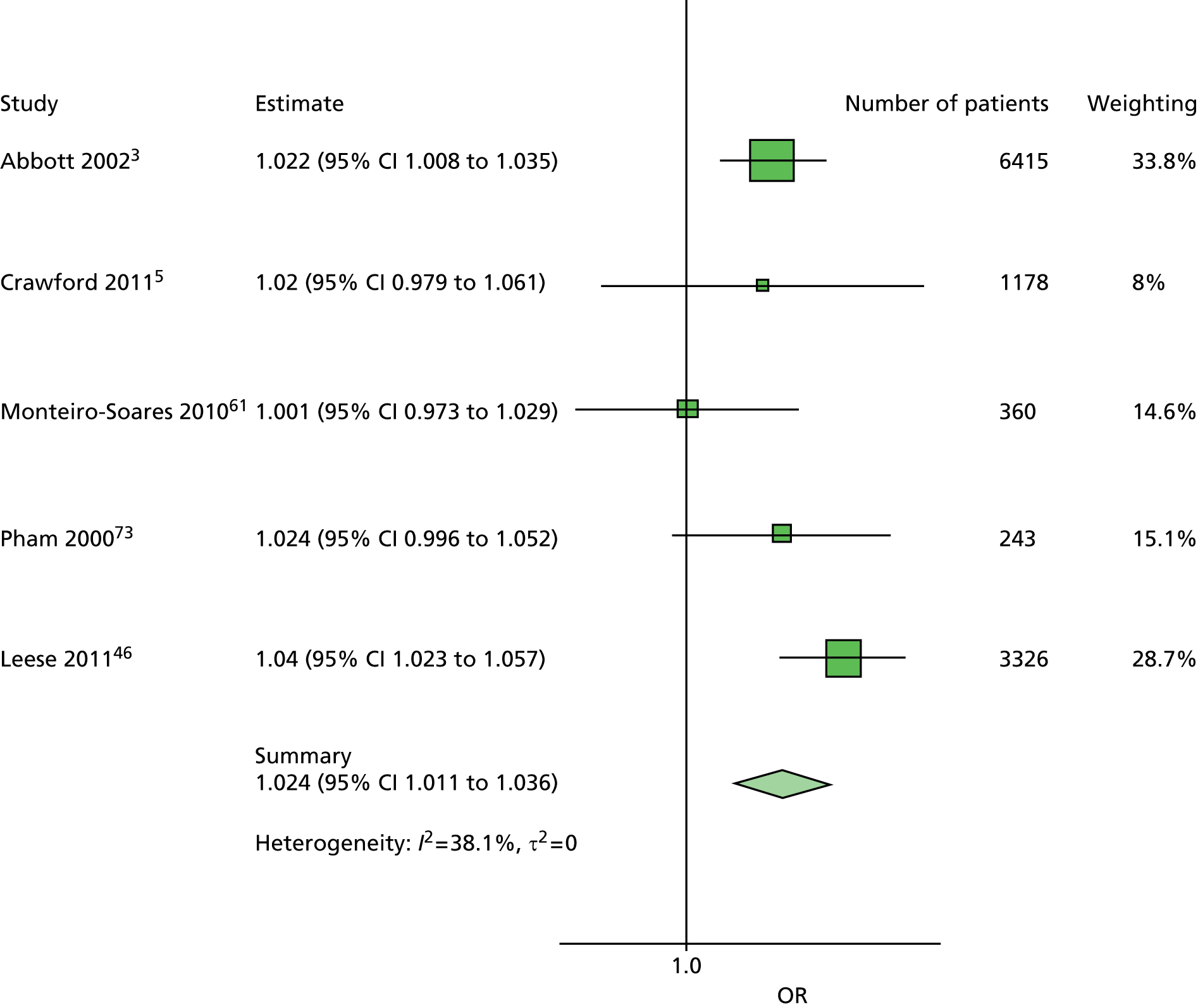

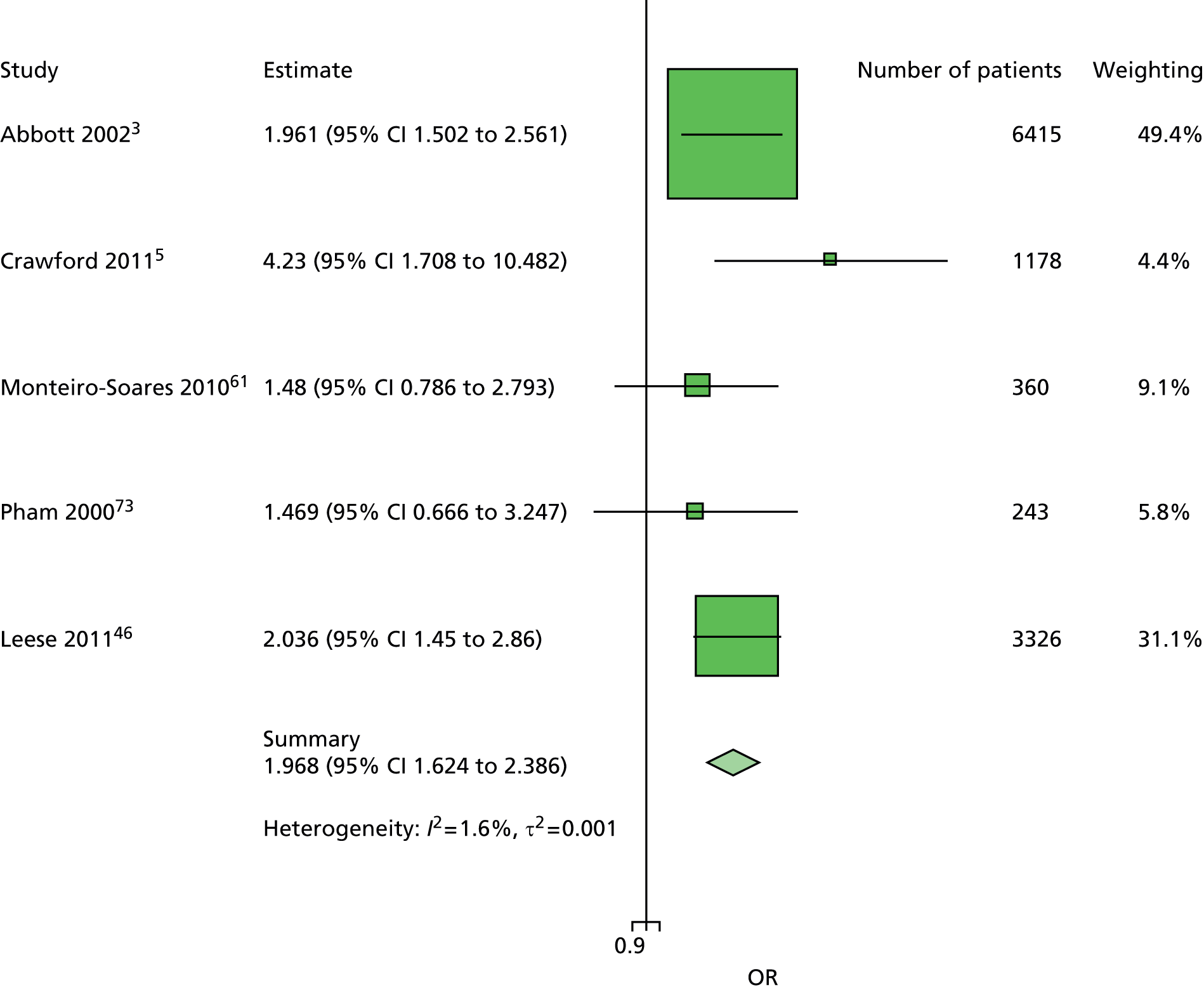

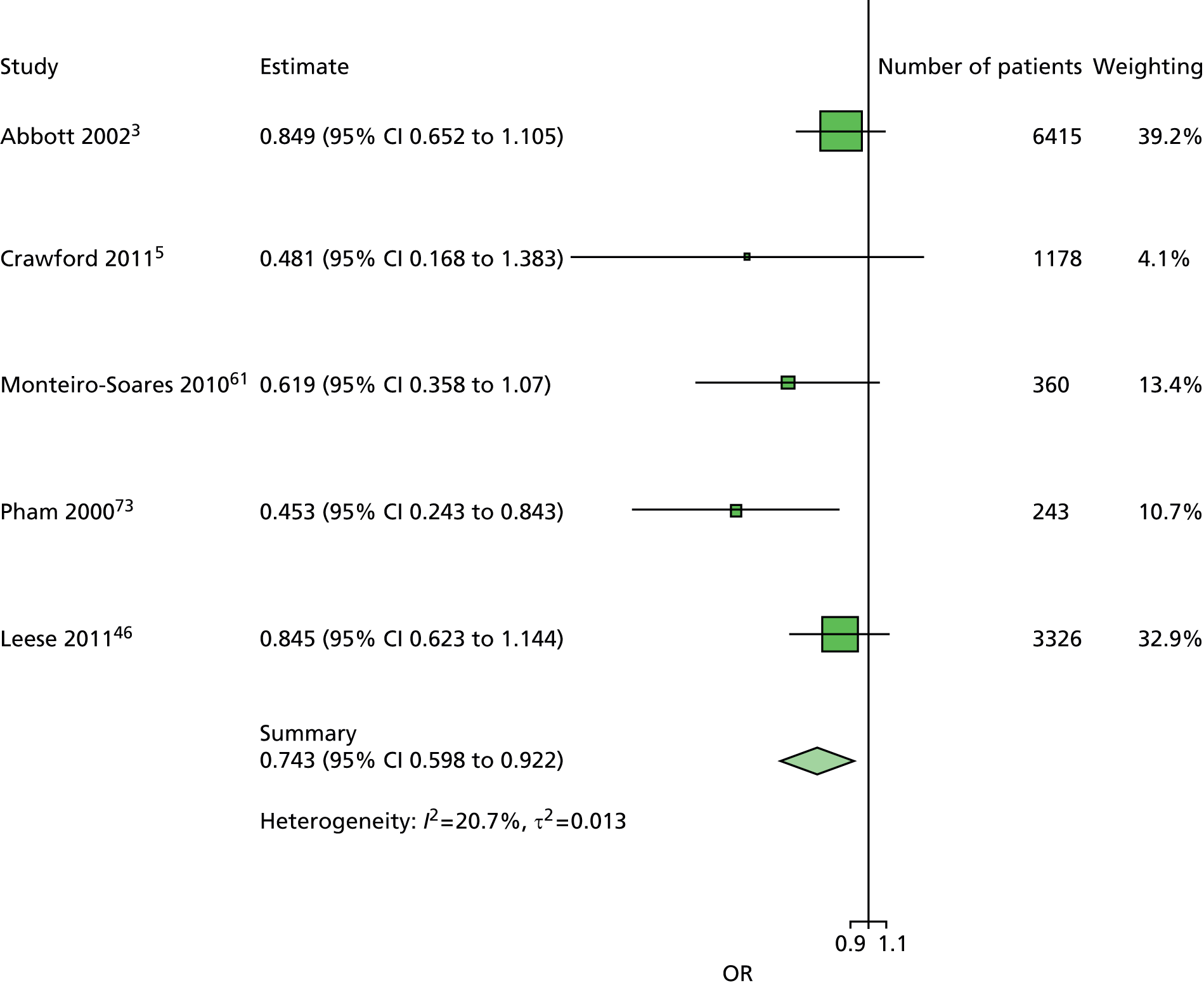

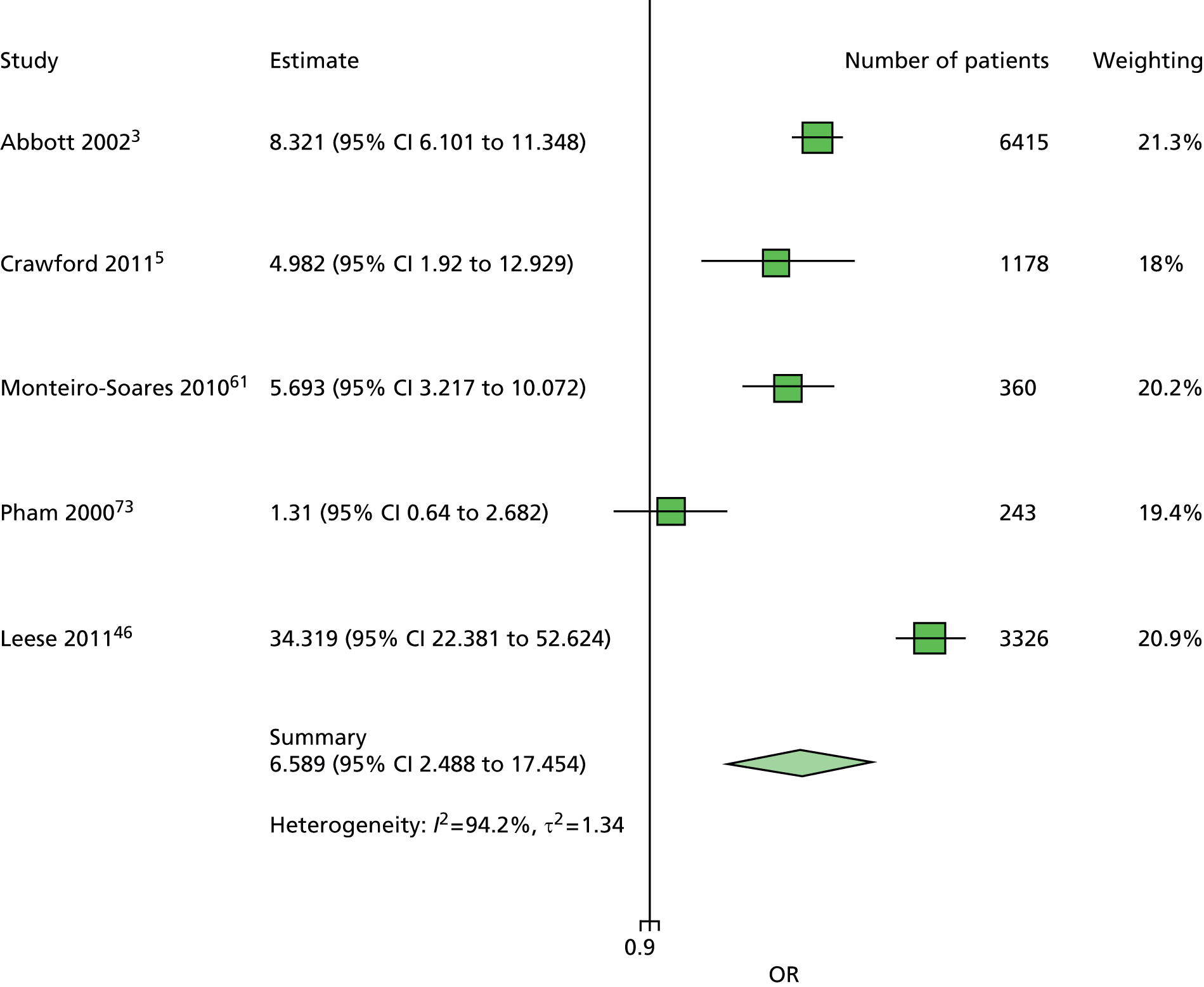

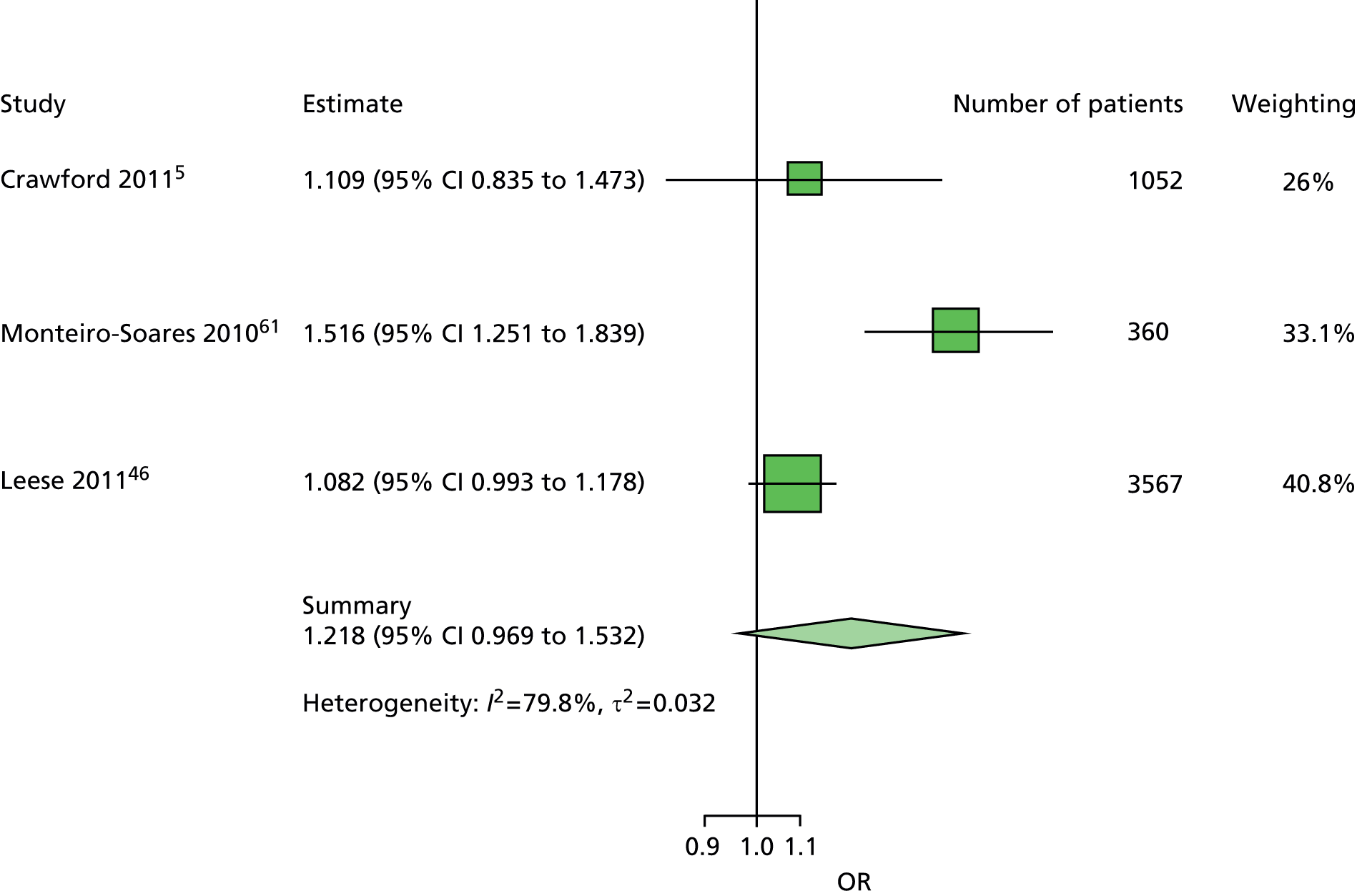

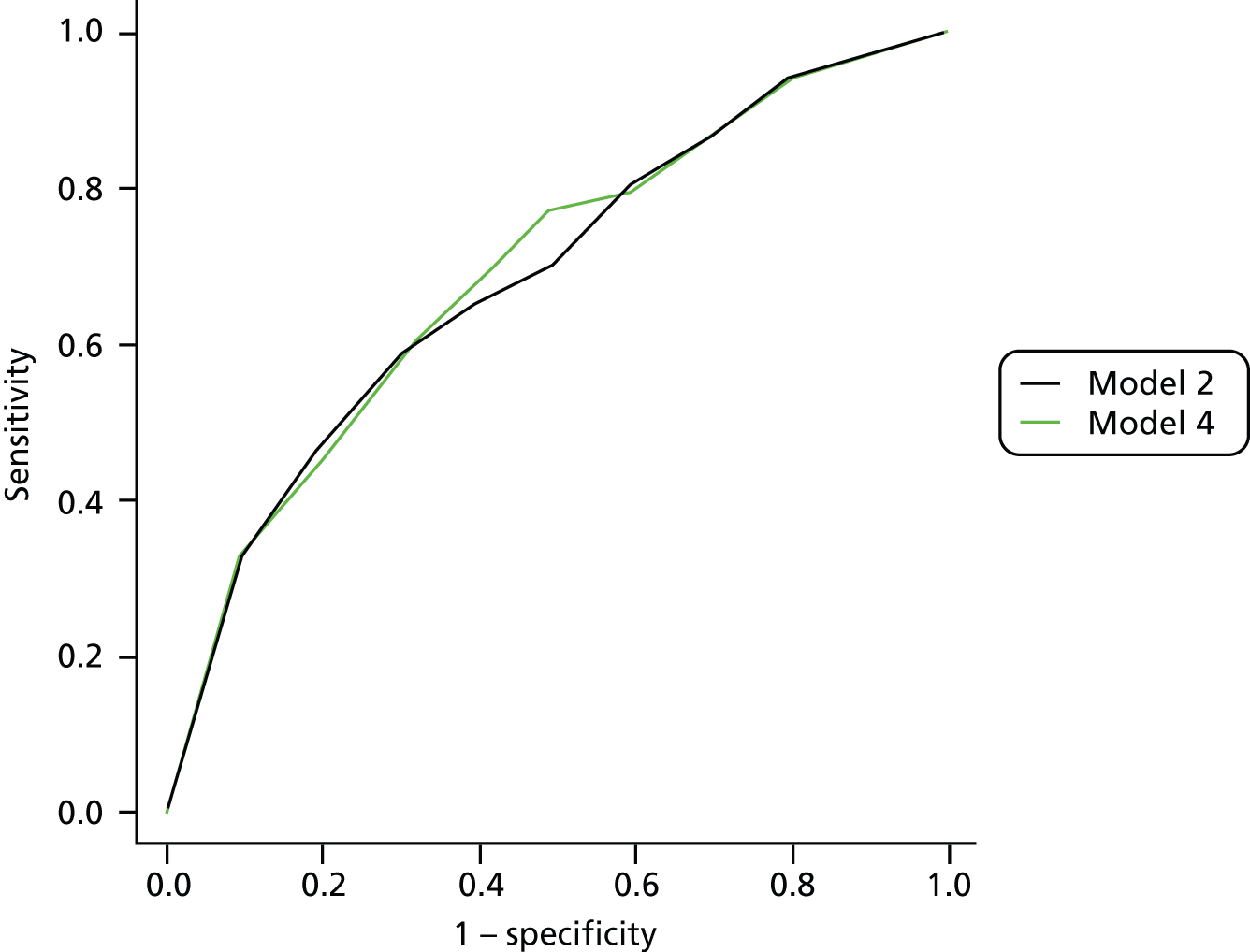

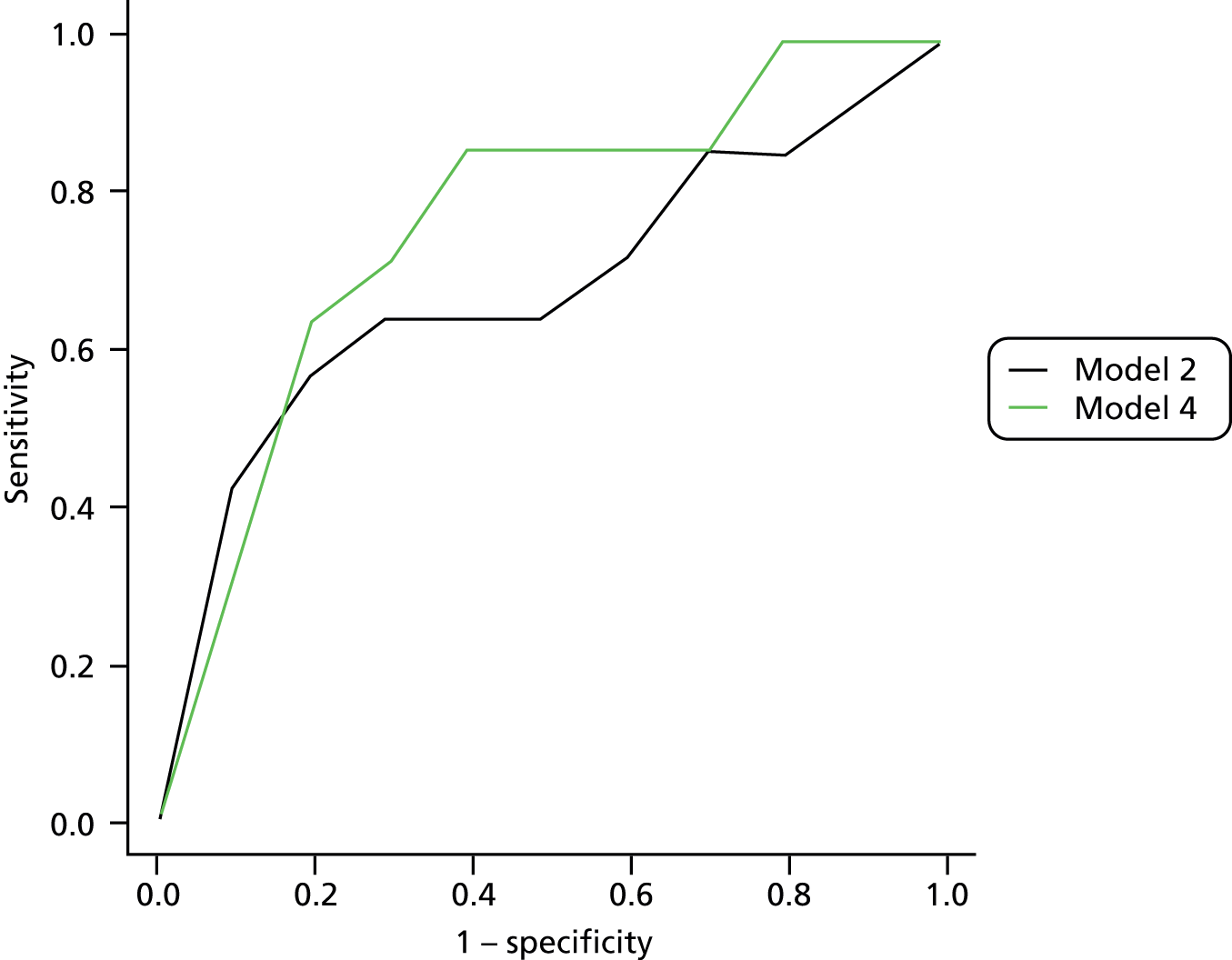

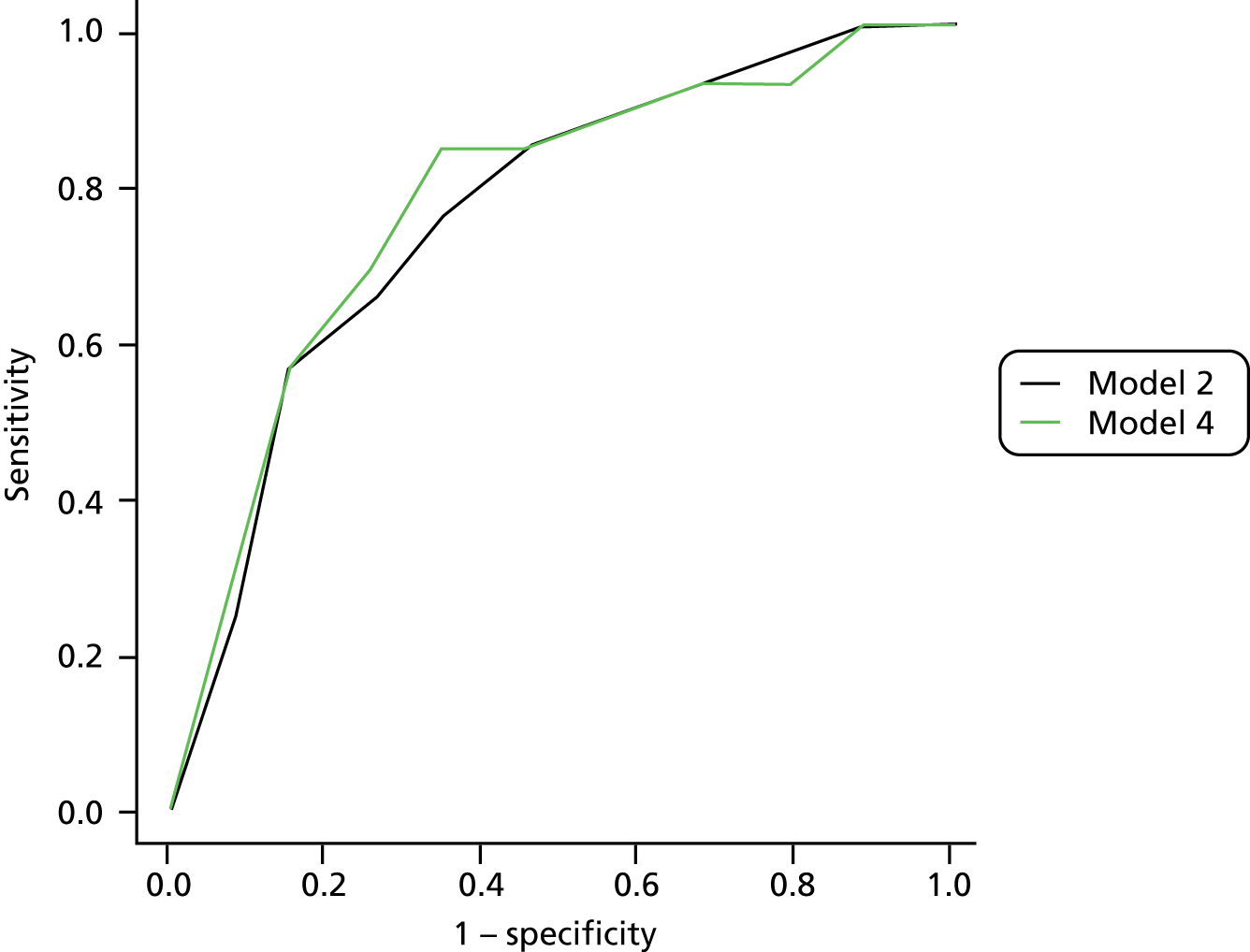

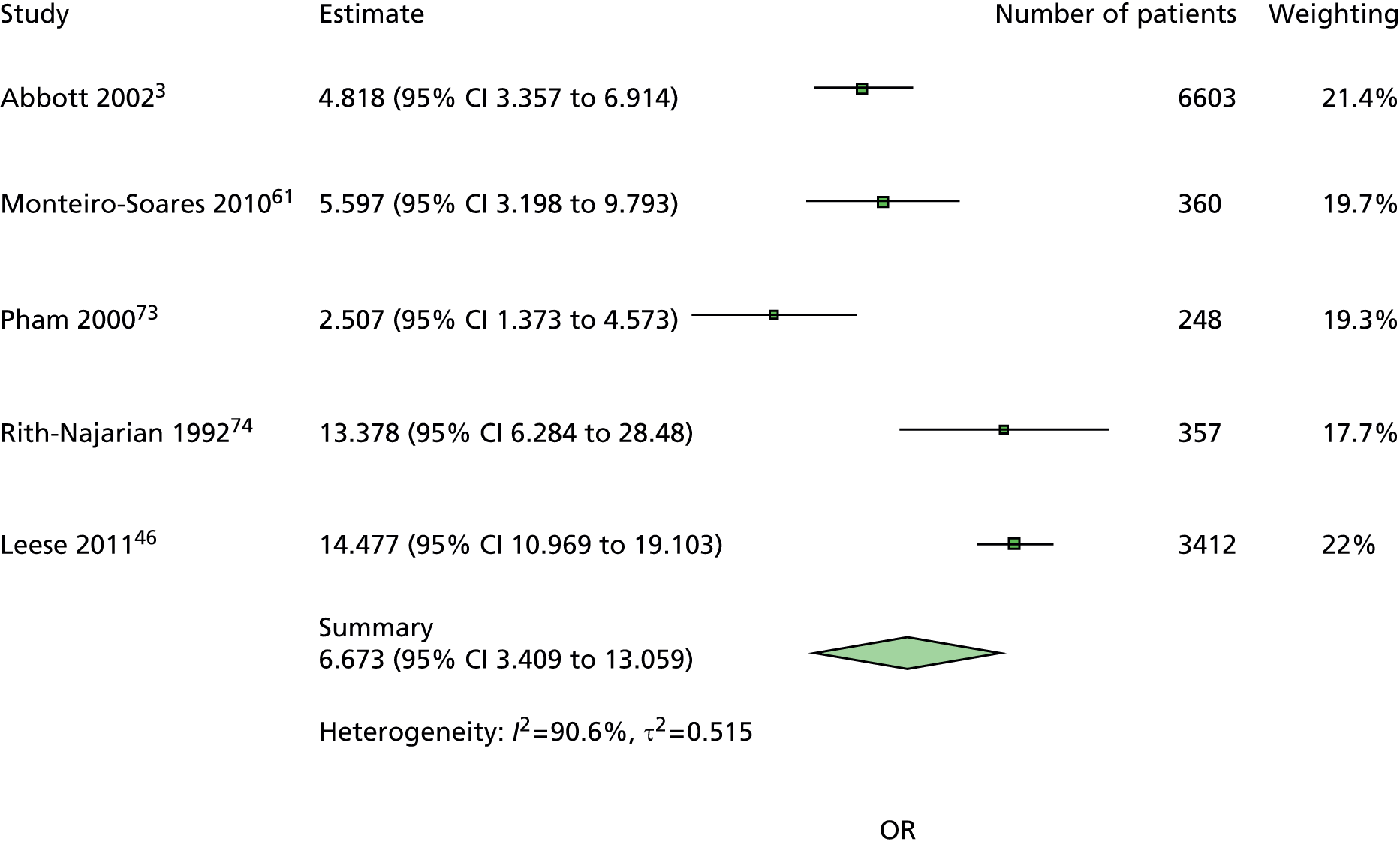

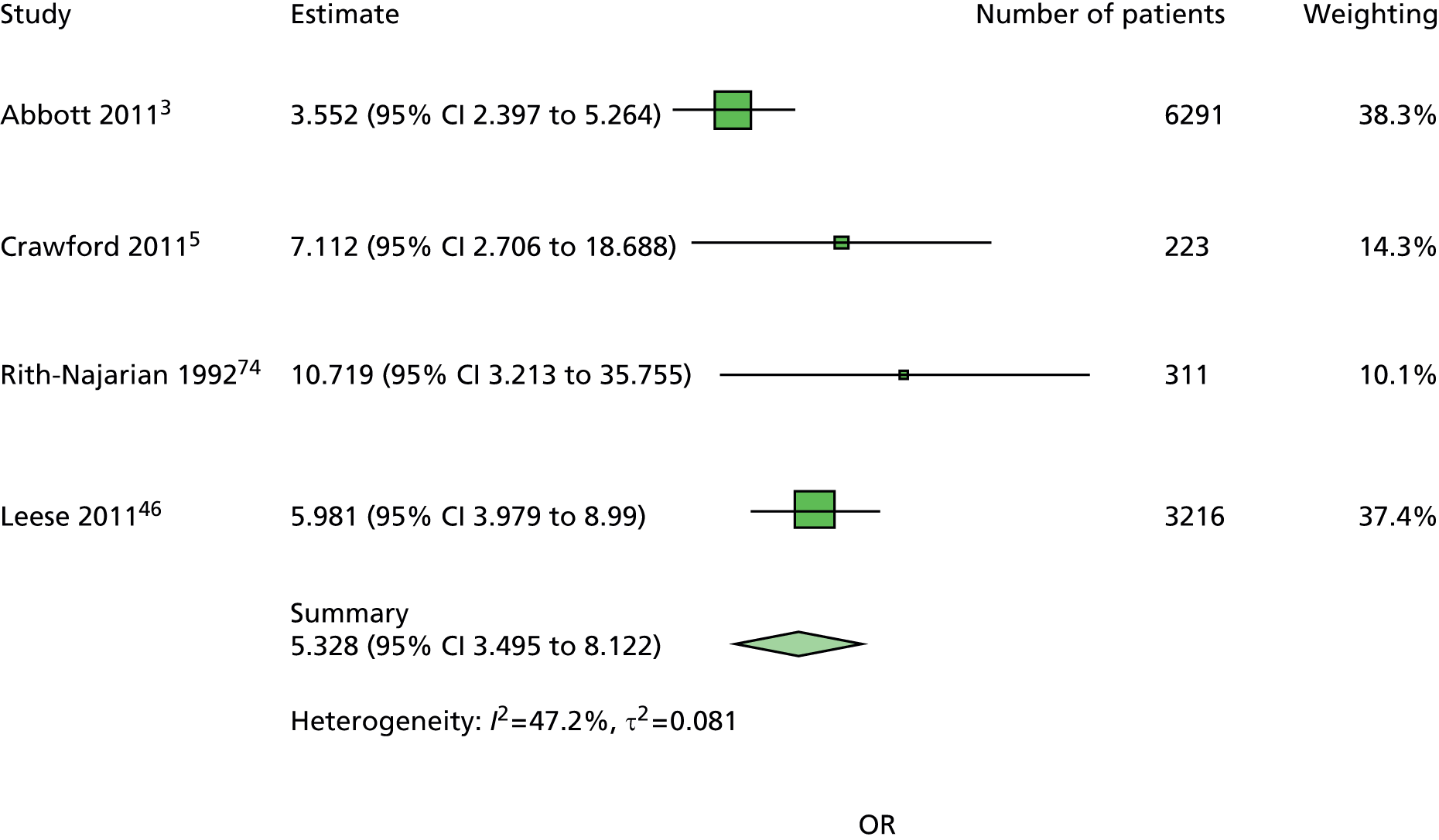

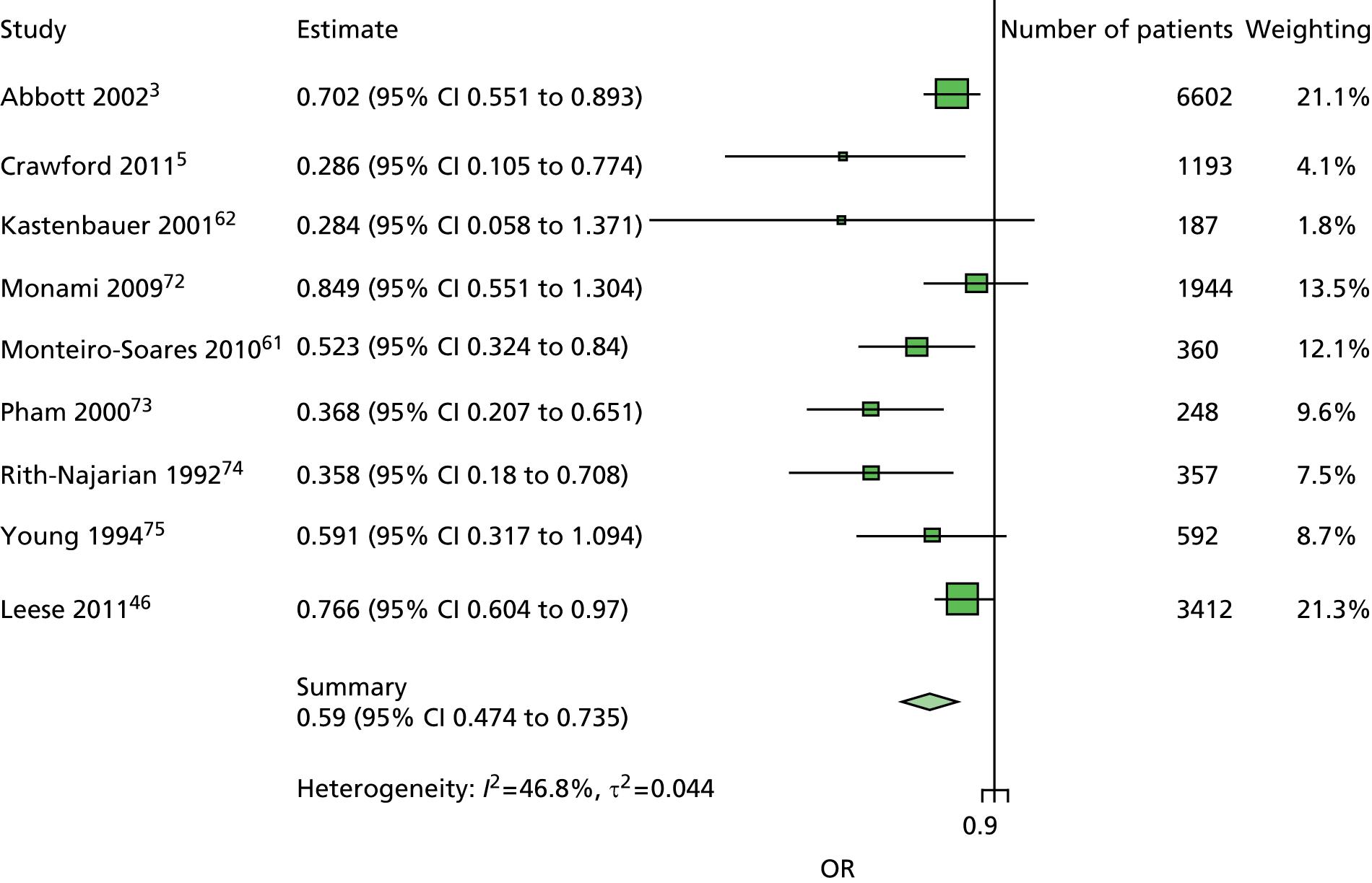

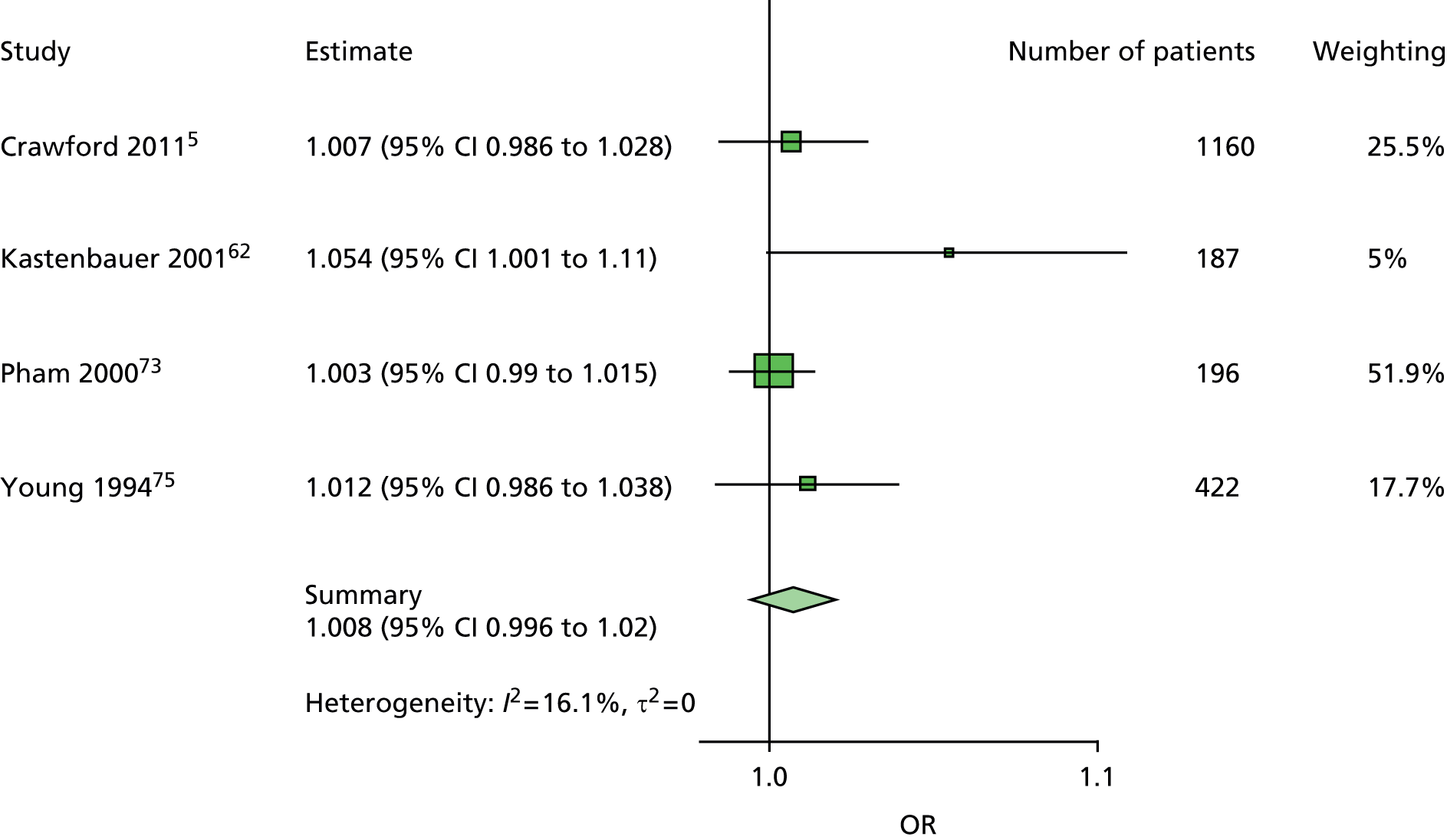

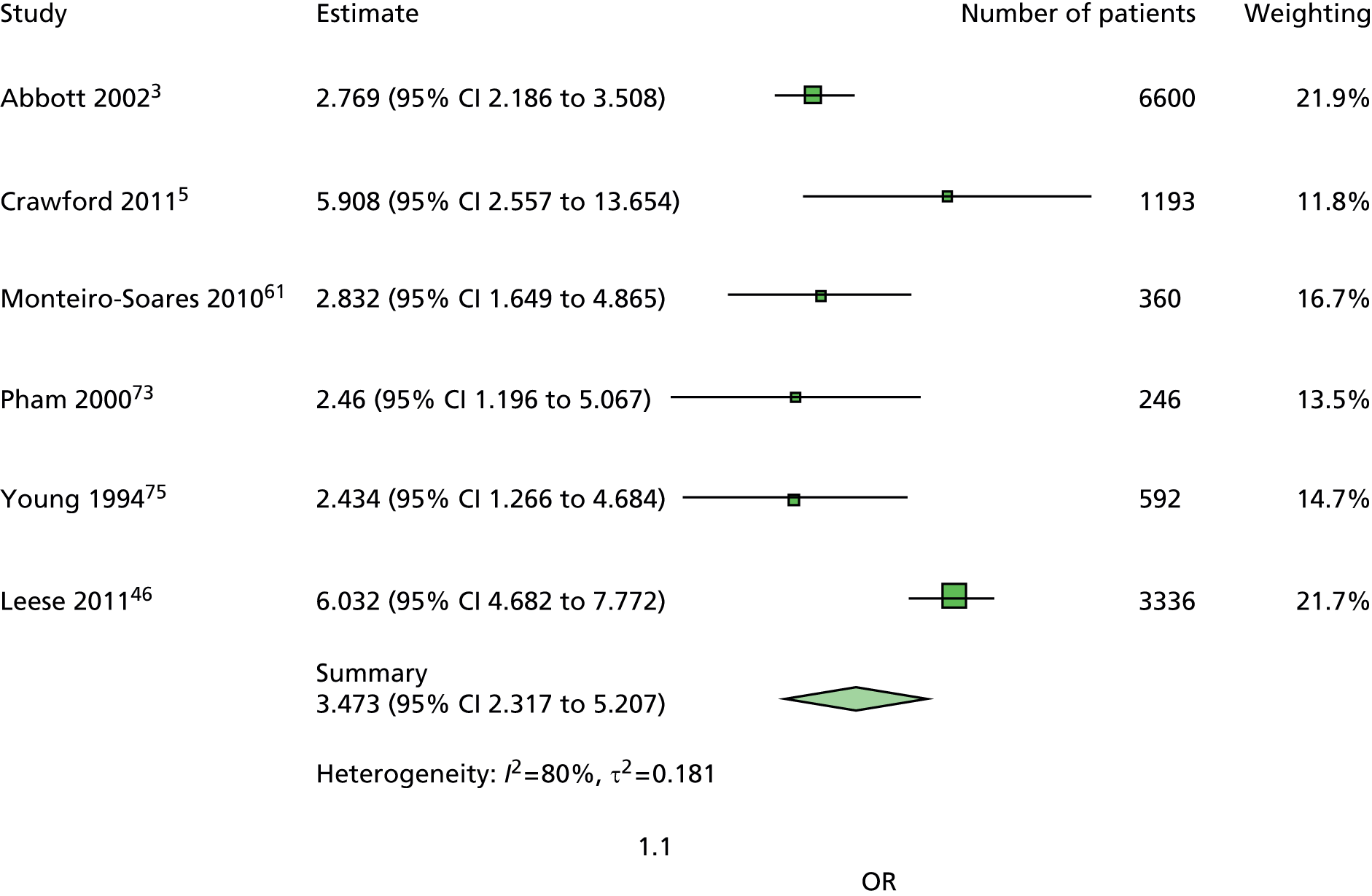

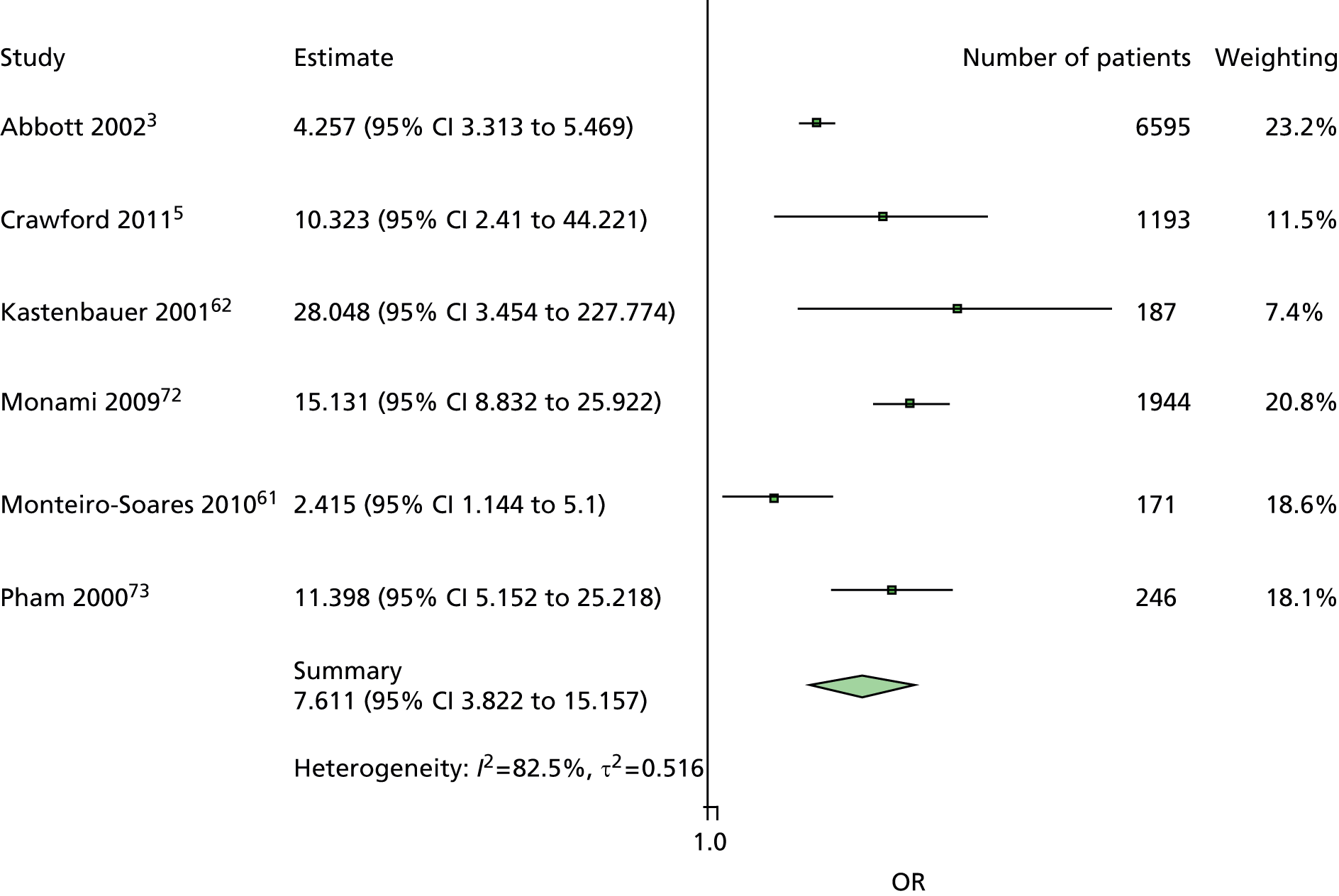

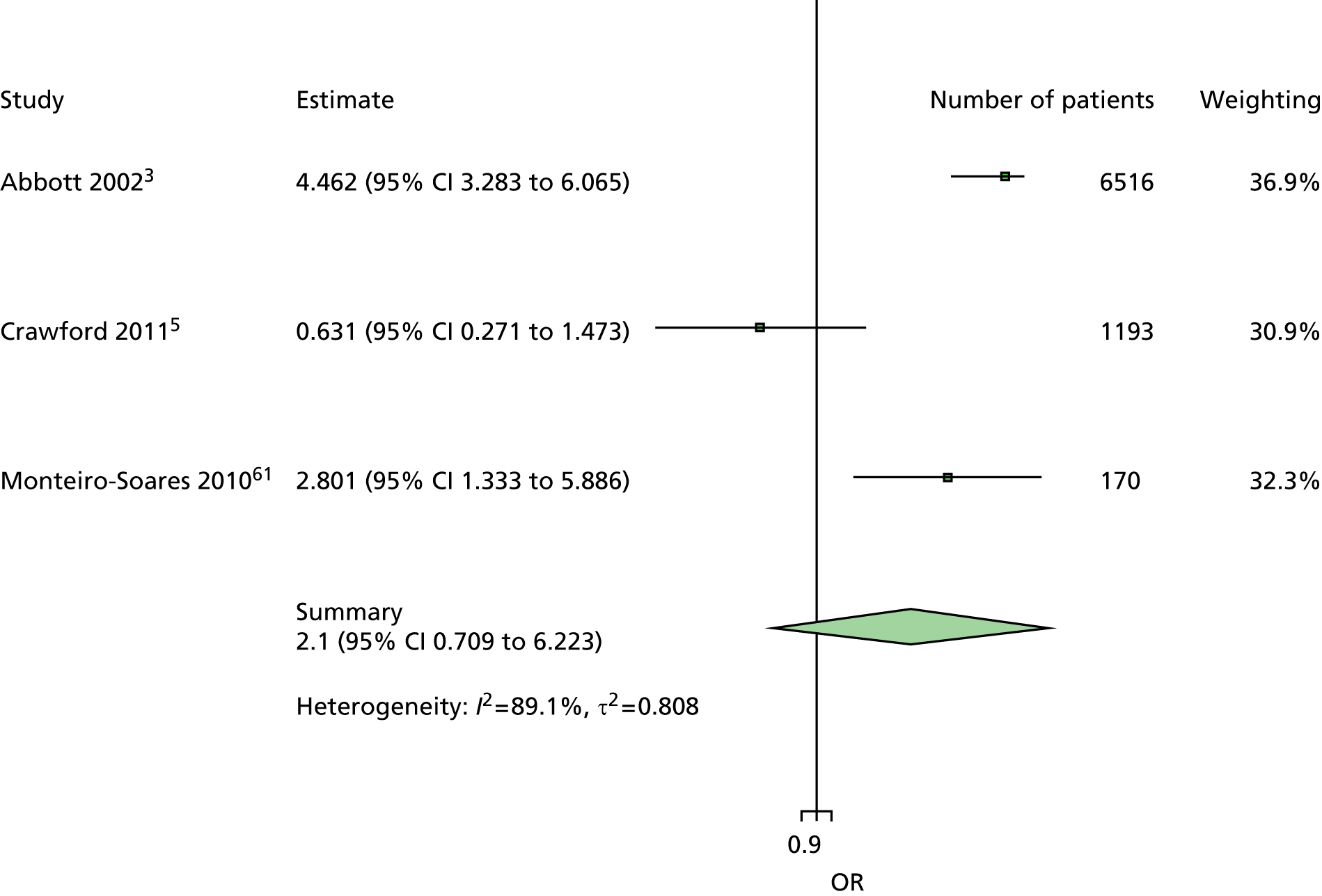

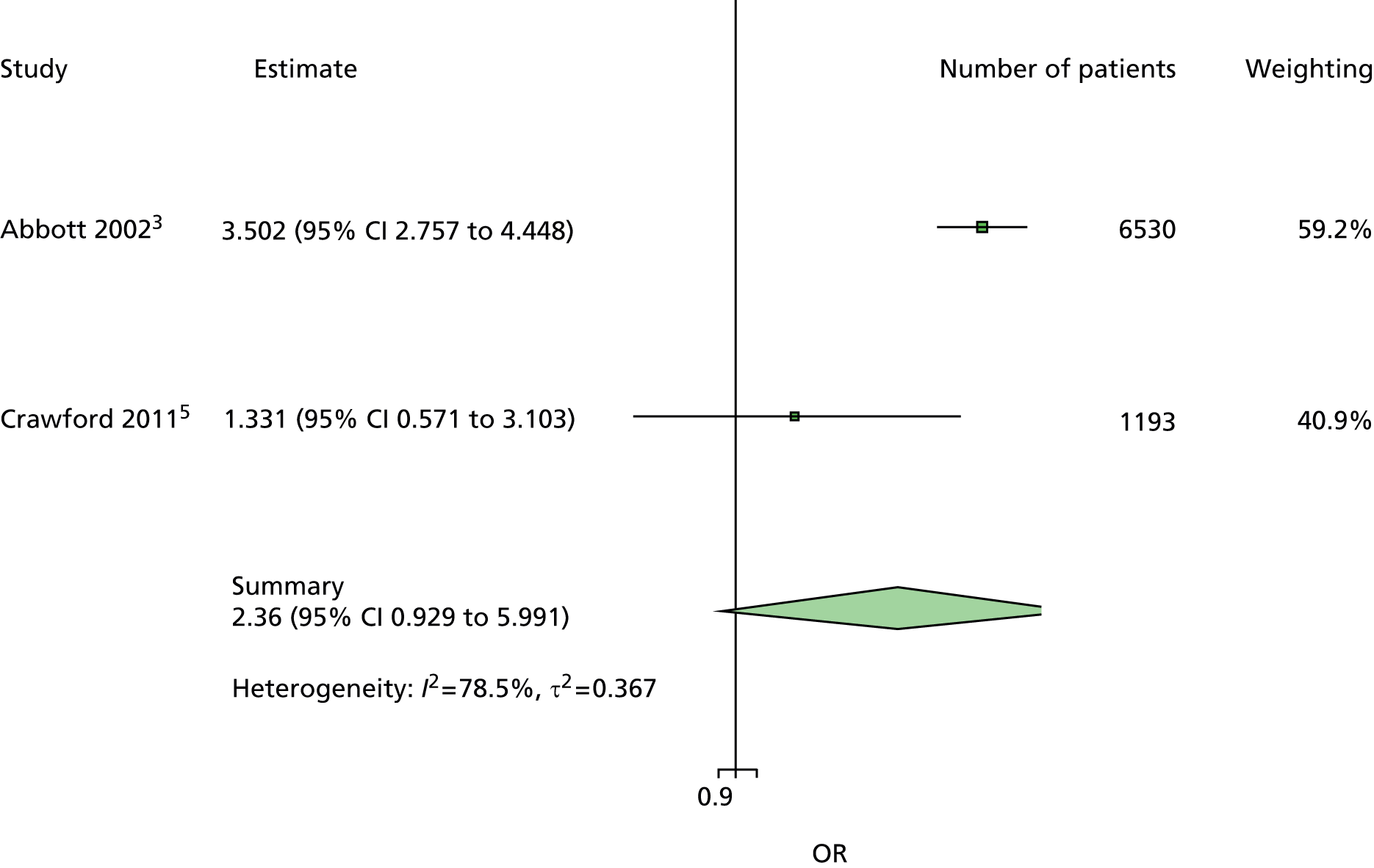

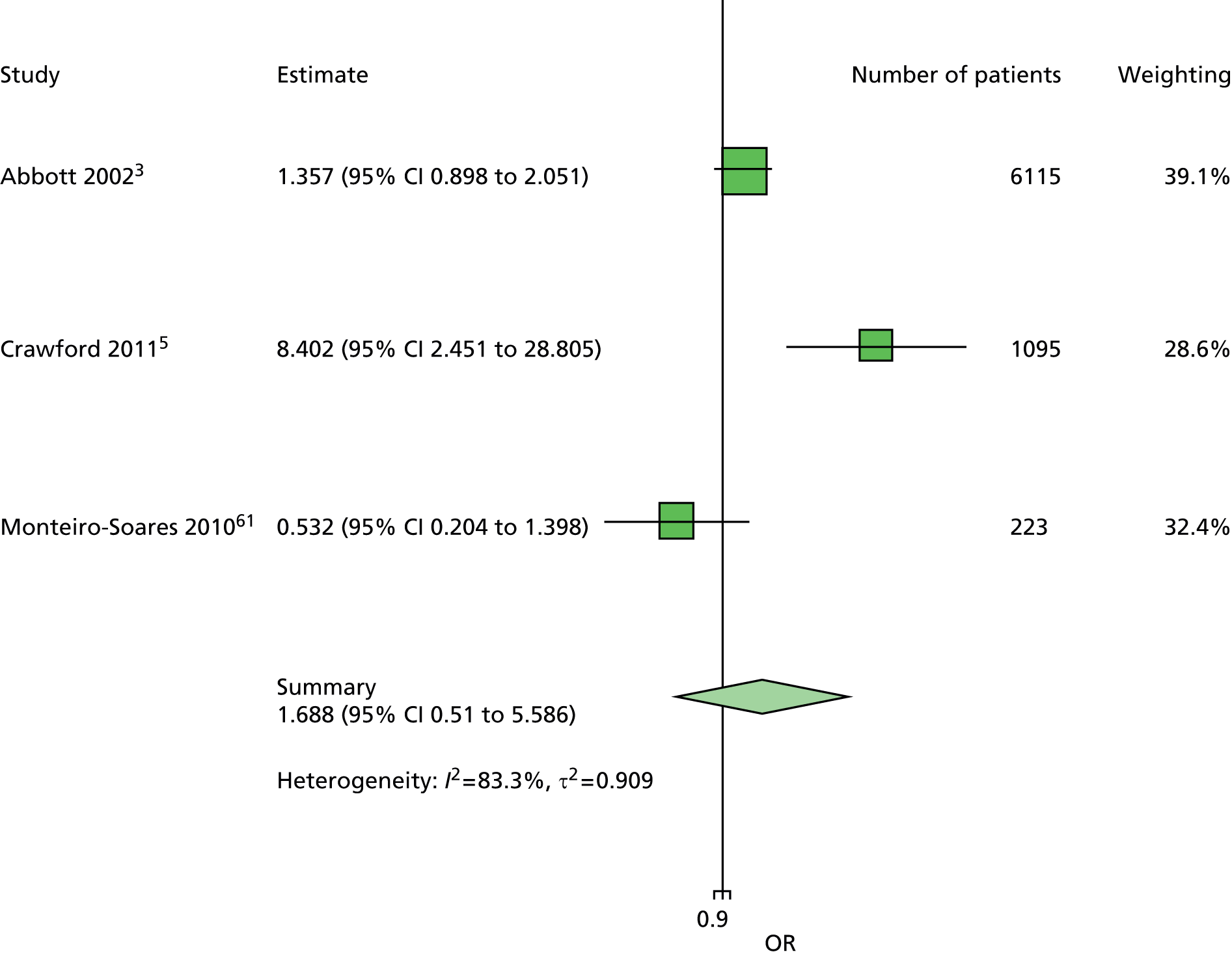

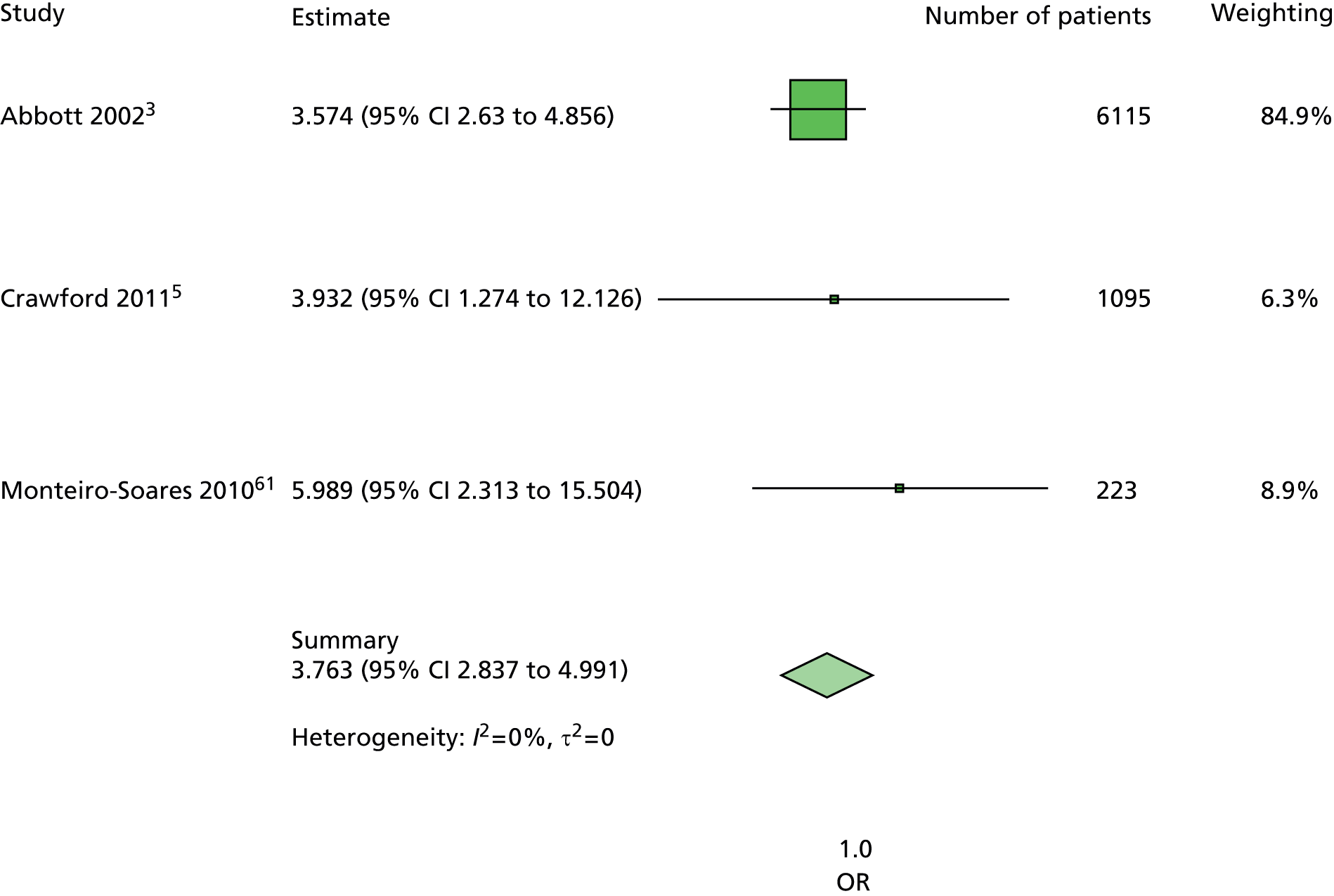

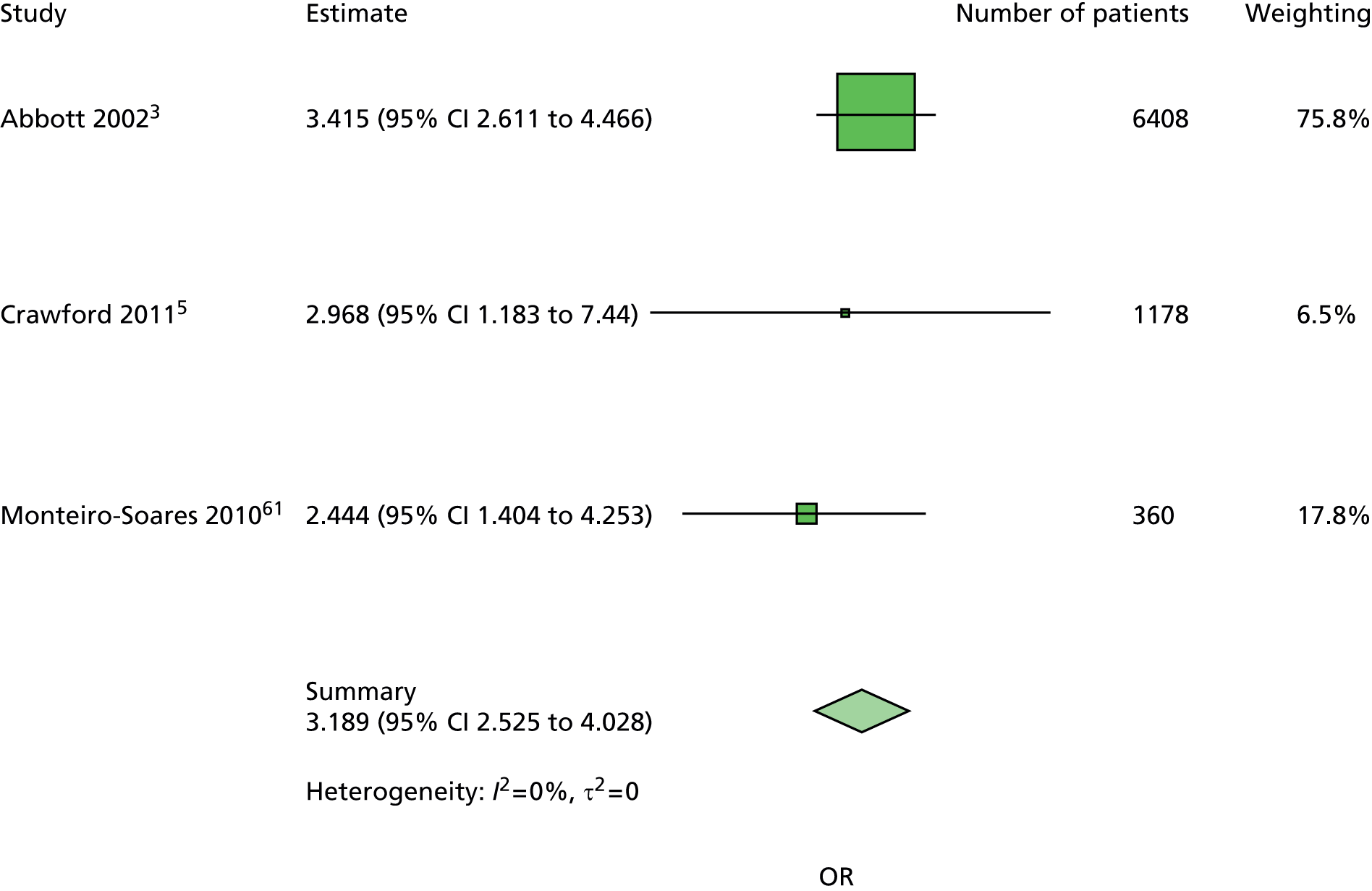

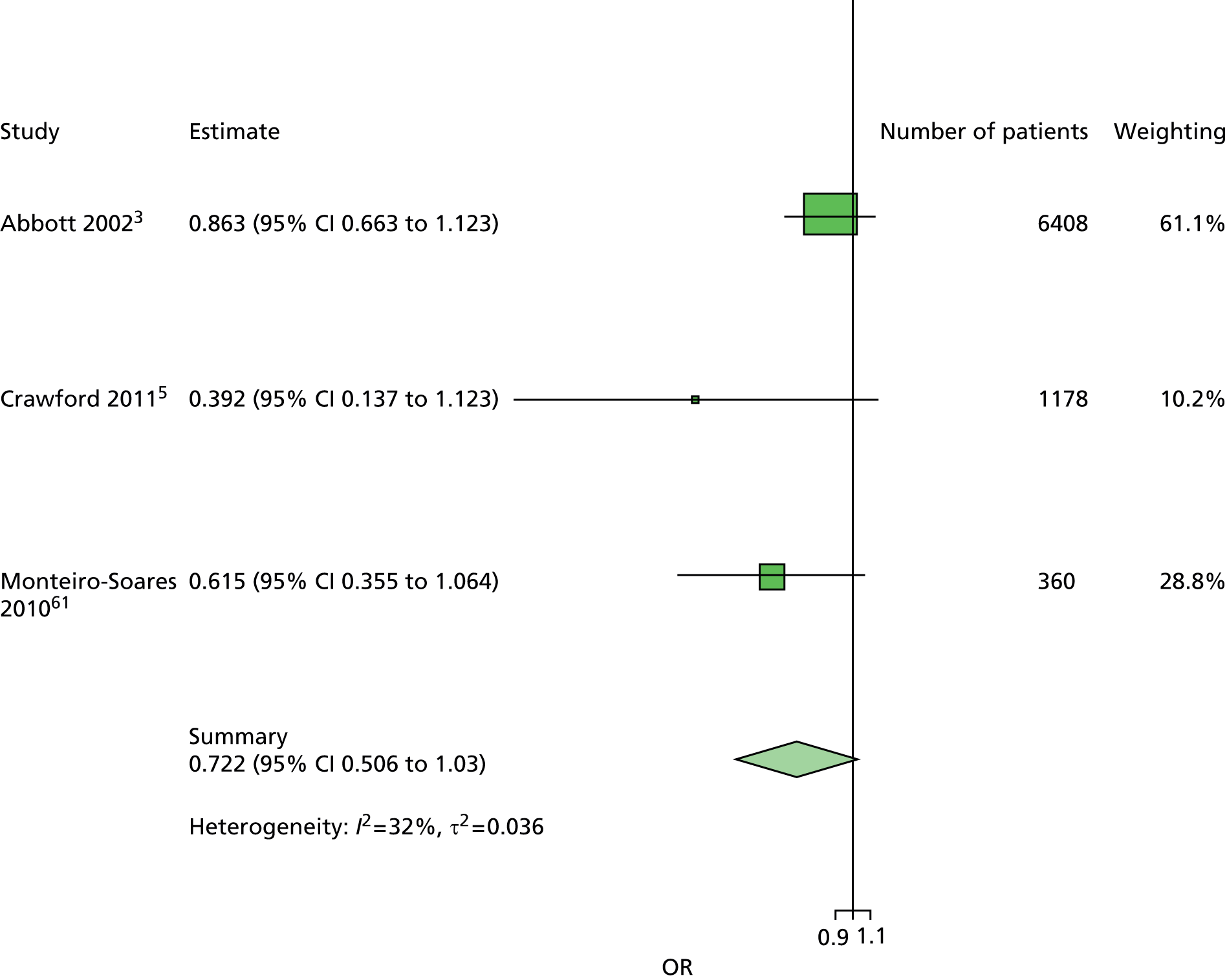

| Prior ulcer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0 | ✓ | 10 |