Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 13/38/01. The protocol was agreed in August 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Whiting et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Objective

The overall objective of this project was to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of viscoelastic (VE) devices to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis disorders during and after cardiac surgery, trauma-induced coagulopathy or post-partum haemorrhage (PPH). We defined the following research questions to address the review objective:

-

How do clinical outcomes differ among patients who are tested with VE devices during or after cardiac surgery compared with those who are not tested?

-

Where there were no data on one of more of the VE devices we evaluated the accuracy of that or those VE device(s) for the prediction of relevant clinical outcomes (e.g. transfusion requirement) during or after cardiac surgery.

-

-

How do clinical outcomes differ among patients with coagulopathy induced by trauma who are tested with VE devices compared with those who are not tested?

-

Where there were no data on one of more of the VE devices we evaluated the accuracy of that or those VE device(s) for the prediction of relevant clinical outcomes (e.g. transfusion requirement) in patients with trauma-induced coagulopathy.

-

-

How do clinical outcomes differ among patients with PPH who are tested with VE devices compared with those who are not tested?

-

Where there were no data on one of more of the VE devices we evaluated the accuracy of that or those VE device(s) for the prediction of relevant clinical outcomes (e.g. transfusion requirement) in patients with PPH.

-

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of VE devices during or after cardiac surgery?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of VE devices in patients with trauma-induced coagulopathy?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of VE devices in patients with trauma-induced PPH?

Chapter 2 Background and definition of the decision problem(s)

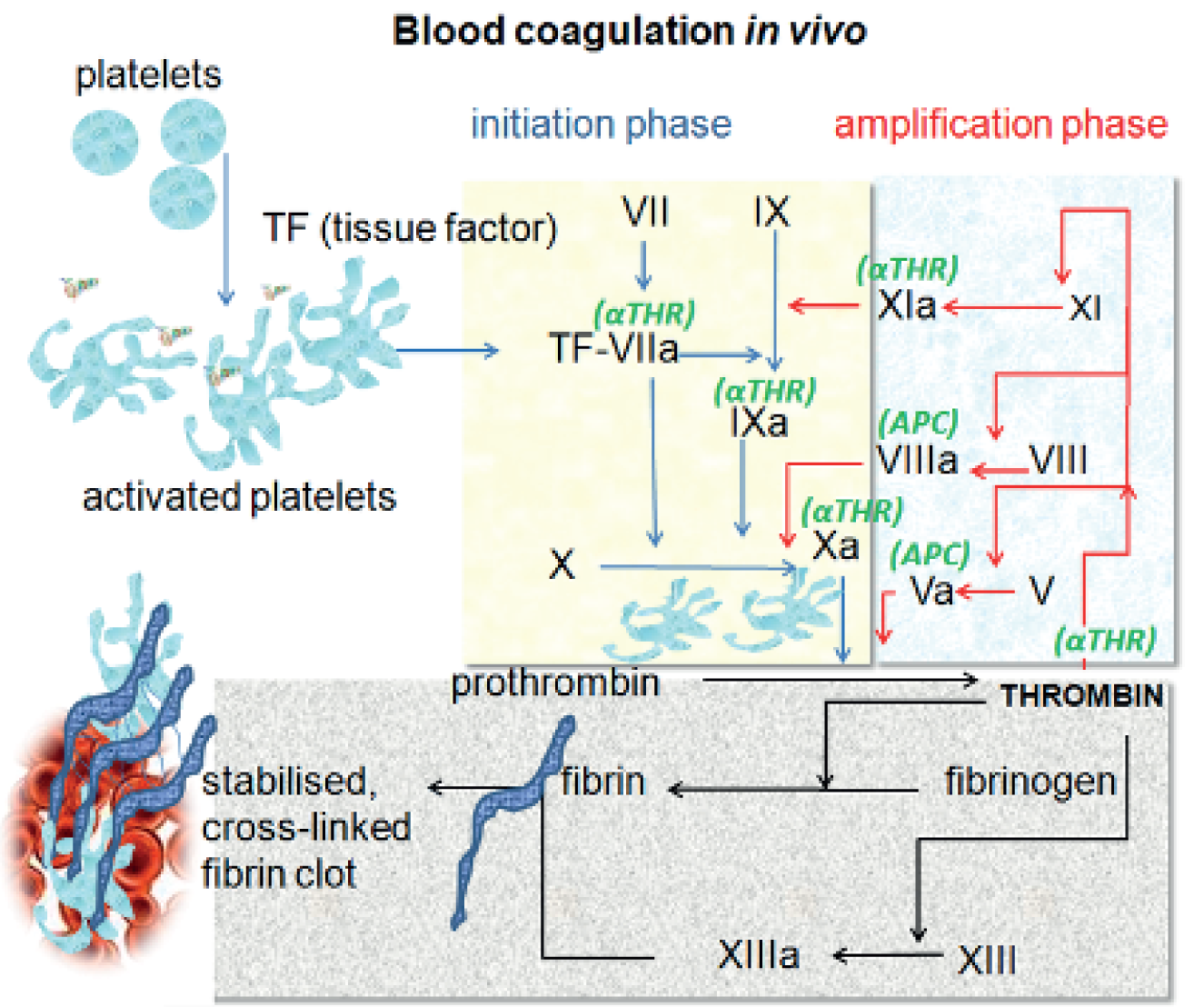

Population

This assessment focuses on three patient groups at high risk of bleeding identified by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as clinical priority areas: those undergoing cardiac surgery, those who have experienced trauma, and women with PPH. Patients undergoing cardiac surgery commonly present with bleeding complications, which can have a negative impact on their clinical outcome in terms of increased perioperative and post-operative morbidity and mortality. Bleeding can occur either as a result of the surgery/injury itself or because of acquired coagulation abnormalities as a result of the surgery, trauma or PPH. Coagulopathy occurs when the normal clotting mechanism (haemostasis) is interrupted, impairing the blood’s ability to clot. The normal clotting process starts with platelets which, combined with a number of clotting proteins, go through a series of steps to produce a solid fibrin clot (Figure 1). If any of these steps are interrupted this may result in prolonged or excessive bleeding. Although coagulopathy can be caused by genetic disorders such as haemophilia, it can also occur following injury, as occurs in perioperative or trauma-induced coagulopathy. The underlying mechanism of coagulopathy can include hyperfibrinolysis (markedly enhanced fibrinolytic activity), hypofibrinogenaemia [fibrogen (FIB) deficiency], thrombocytopenia (low levels of platelets), factor deficiency and heparin effect. 1 There are several factors that increase the risk of coagulopathy during surgery. In cardiac surgery, the use of heparin to prevent clotting while on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), pre-operative anticoagulation medication, the dilution, activation and consumption of coagulation factors, and the use of CPB machines – which may result in acquired platelet dysfunction, hypothermia (body temperature < 35 °C) – and hyperfibrinolysis are all associated with an increased risk of coagulopathy. 2 In major trauma, the following are associated with an increased risk of coagulopathy: consumption of coagulation factors and platelets during clot formation in an attempt to prevent loss of blood through damaged vessels; dilution of whole blood as a consequence of red cell transfusion; hormonal and cytokine-induced changes; hypoxia, acidosis and hypothermia, which predispose to further bleeding; and ongoing bleeding. 3 During pregnancy there are marked changes in haemostasis, with FIB deficiency thought to be the major coagulation abnormality associated with bleeding in PPH. 4

FIGURE 1.

Blood coagulation in vivo (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coagulation_in_vivo.png). APC, activated protein C; αTHR, antithrombin; TF, tissue factor.

The populations at risk of bleeding for the patient groups considered in this assessment present a significant burden to the UK NHS. There were 36,702 cardiac surgery cases (based on Specialised Services National Definitions Set),5 based on Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data. 6 There are approximately 20,000 major trauma cases in England every year,7 and injuries account for > 700,000 hospital admissions each year. 8 The incidence of major obstetric haemorrhage is 3.7/1000 births in the UK. 9

Patients with substantial bleeding usually require transfusion and/or re-operation. Cardiothoracic surgery (i.e. cardiac and thoracic surgery) uses 5% of all donated blood in the UK,10 and the proportion of patients requiring re-operation for bleeding is estimated at 2–8% of cardiac surgery patients. 11 Table 1 summarises the number of patients undergoing various cardiac surgeries in Scotland over a 2-year period, and shows the proportion of these patients who received a blood transfusion and the number of red blood cell (RBC) units per episode transfused. 12 The increased morbidity and mortality associated with bleeding following surgery has been shown to be related to both blood transfusion and re-operation for bleeding. 11 Patients with a diagnosis of trauma-induced coagulopathy on admission to hospital have a three- to fourfold greater mortality risk and it is independently associated with increased transfusion requirements, organ injury, septic complications and longer critical care stays. 3 Trauma is the leading cause of death and disability in adults aged < 36 years around the world,13 and haemorrhage is the cause of 40% of all trauma deaths in the UK. 14 PPH is one of the major causes of maternal mortality. There were 14 direct deaths from obstetric haemorrhage (nine from PPH) from 2006 to 2008, accounting for 9% of all maternal deaths in this period. 9

| Procedure | No. of episodes | % episodes transfused | RBC units/episode transfused |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary replacement operations (minus revisions) | 2359 | 47.9 | 1.6 |

| Heart and lung transplant | 8 | 75.0 | 11.3 |

| Revision coronary replacement operations | 29 | 44.8 | 2.1 |

| Valves and adjacent structures | 758 | 54.5 | 2.5 |

Red blood cell transfusion is independently associated with a greater risk of both infection (respiratory, wound infection or septicaemia) and ischaemic post-operative morbidity, hospital stay, increased early (30-day post operative) and late mortality (up to and > 1 year post operative) and hospital costs. 15 It is therefore important to appropriately treat the coagulopathy and reduce the blood loss thus reducing the requirement for blood transfusion and reducing the risks of transfusion-related adverse events and saving costs. 2 Knowledge of the exact cause of the bleed allows treatment to be tailored to the cause of the coagulopathy rather than replacing blood loss with transfusion. For example, if thrombocytopenia is identified as the cause of the bleed this can be treated by platelet transfusion. 16 Furthermore, the cost of donor blood has increased and availability has reduced and there is also the risk of blood-borne infection. 10

Intervention technologies

ROTEM delta point-of-care analyser

The ROTEM® Delta (TEM International GmbH, Munich, Germany; www.rotem.de) is a point-of-care (POC) analyser, which uses thromboelastometry, a VE method, to test for haemostasis in whole blood. It was previously known as rotational TEG or ROTEG. 6 It is performed near the patient during surgery or when admitted following trauma. It is used to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis disorders, during and after surgery, which are associated with high blood loss. It is an integrated all-in-one system and analyses the coagulation status of a blood sample to differentiate between surgical bleeding and a haemostasis disorder. 17 It uses a combination of five assays to characterise the coagulation profile of a citrated whole blood sample (Table 2). Initial screening is performed using the INTEM and EXTEM assays; if these are normal then it is an indication that surgical bleeding rather than coagulopathy is present. The use of different assays allows for rapid differential diagnosis between different haemostasis defects and anticoagulant drug effects. 17 Training in how to use the technology is required but specialist laboratory staff are not needed.

| Assay | Activator/inhibitor | Role |

|---|---|---|

| INTEM | Ellagic acid (contact activator) | Assessment of clot formation, fibrin polymerisation and fibrinolysis via the intrinsic pathway |

| EXTEM | Tissue factor | Assessment of clot formation, fibrin polymerisation and fibrinolysis via the extrinsic pathway. Not influenced by heparin. EXTEM is also the base activator for FIBTEM and ABTEM |

| HEPTEM | Ellagic acid + heparinase | Assessment of clot formation in heparinased patients. INTEM assay performed in the presence of heparinase; the difference between HEPTEM and INTEM confirms the presence of heparin |

| FIBTEM | Tissue factor + platelet antagonist | Assessment of FIB status allows detection of FIB deficiency or fibrin polymerisation disorders |

| APTEM | Tissue factor + fibrinolysis inhibitor (aprotonin) | In vitro fibrinolysis inhibition: fast detection of lysis when compared with EXTEM |

| Na-TEM | None | Non-activated assay. Can be used to run custom haemostasis tests |

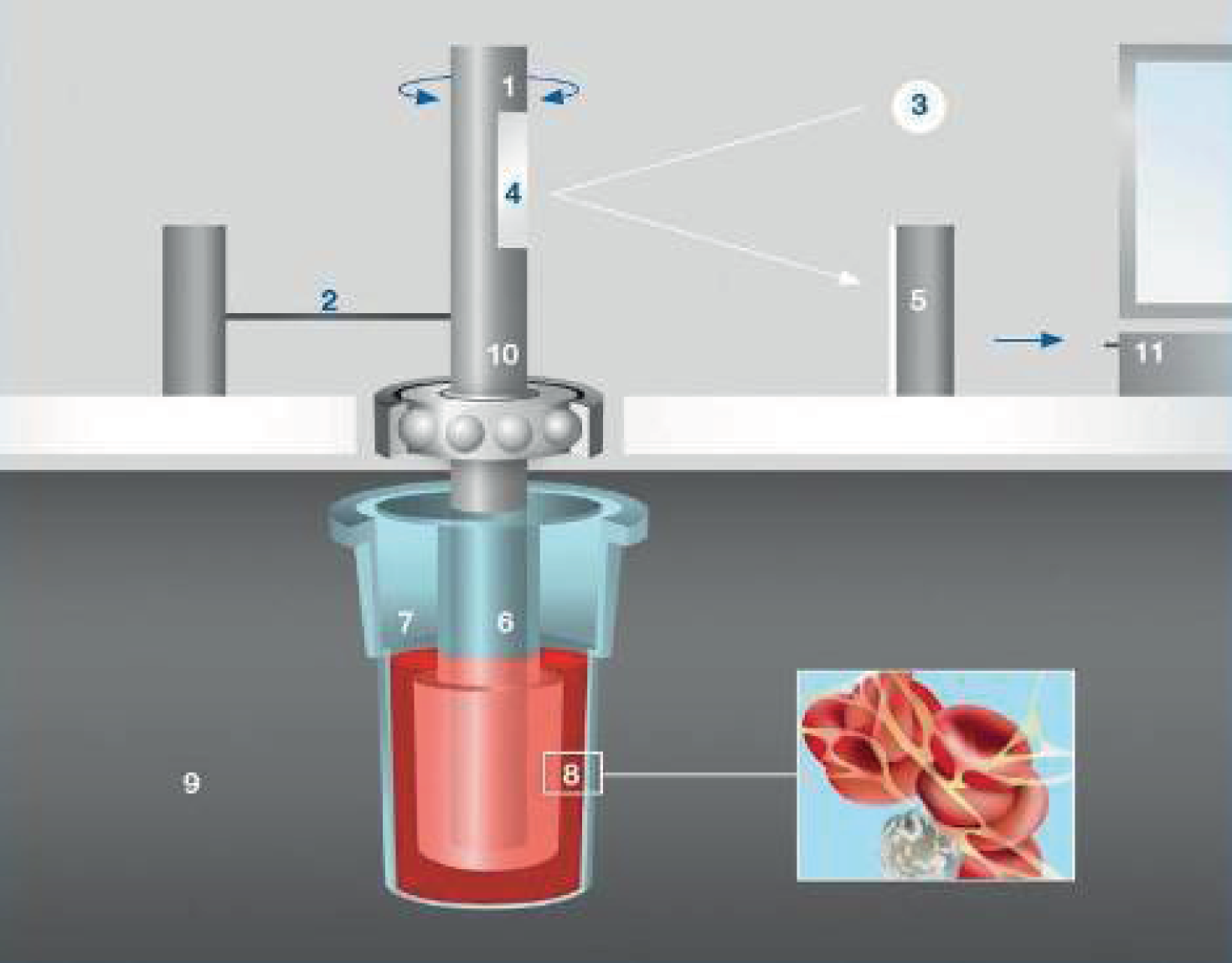

Figure 2 shows the ROTEM system. A 340-µl blood sample, which has been anticoagulated with citrate, is placed into the disposable cuvette (sample cup) (7), using an electronic pipette. A disposable sensor pin (6) is attached to the shaft, which is connected with a thin spring (2), and slowly oscillates back and forth (1), suspended in the blood sample. The signal from the pin is transmitted via an optical detector system (3–5). The test is started by adding the reagents described above. Although the typical test temperature is 37 °C, different temperatures can be selected, for example for patients with hypothermia. Although the blood remains liquid the movement is unrestricted, as the blood starts clotting, the clot restricts the rotation of the pin with increasing resistance as the firmness of the clot increases. This is measured by the ROTEM system and translated to the output, which consist of graphical displays and numerical parameters.

FIGURE 2.

ROTEM system. 18 1, Oscillating axis; 2, counterforce spring; 3, light beam from LED; 4, mirror; 5, detector (electronic camera); 6, sensor pin; 7, cuvette with blood sample; 8, fibrin strands and platelet aggregates; 9, heated cuvette holder; 10, ball bearing; and 11, data processing unit. Reproduced with permission from ROTEM®.

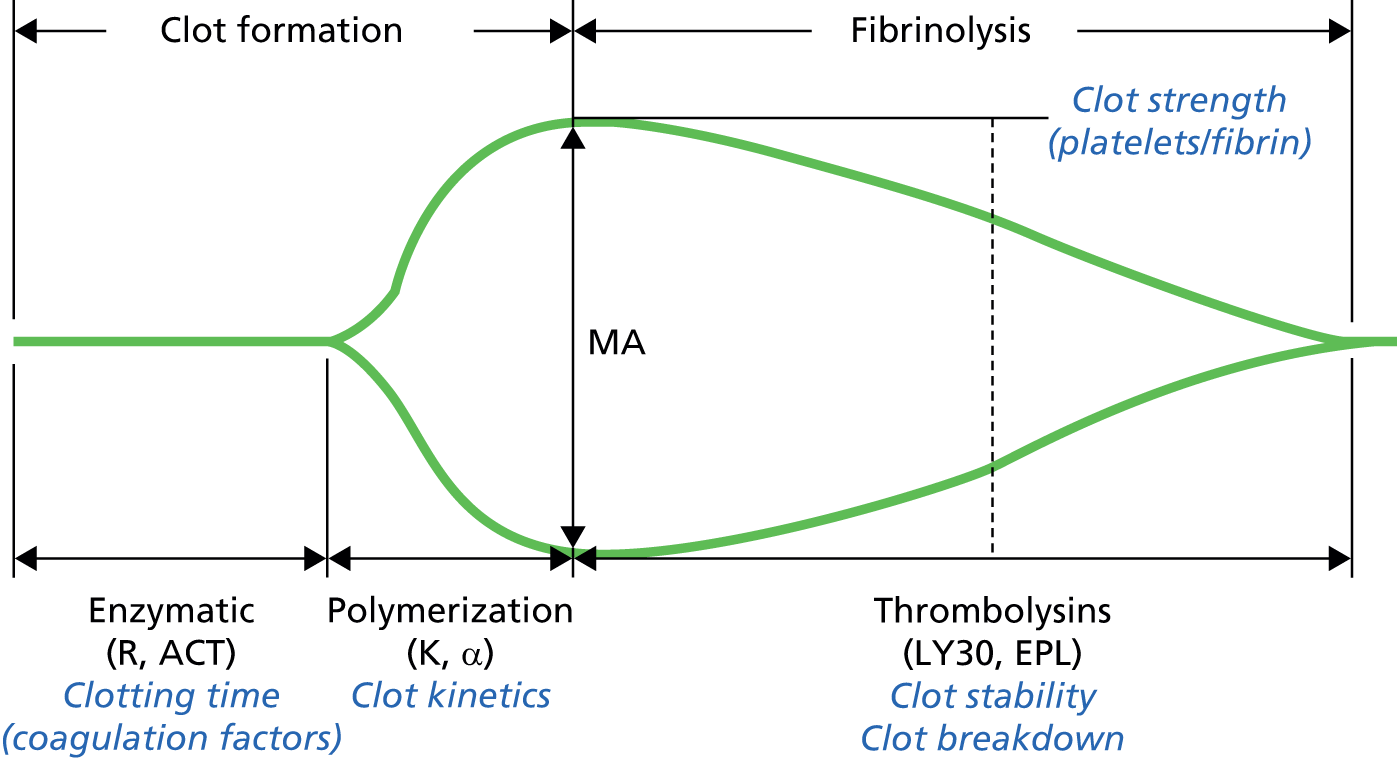

The graphical output of results produced by the ROTEM system is shown in Figure 3. A separate graphical display is produced for each reagent by an integrated computer. Numerical values for each of the following are also calculated and presented below the graph. Initial results are available within 5–10 minutes and full qualitative results are available in 20 minutes:

Clotting time (CT) – time from adding the start reagent until the blood starts to clot. A prolonged CT indicates abnormal clot formation.

Clot formation time (CFT) – time from CT until a clot firmness of 20-mm point has been reached and an α-angle, which is the angle of tangent between 2 and the curve. These measures indicate the speed at which the clot is forming and are mainly influenced by platelet function but are also affected by FIB and coagulation factors.

Amplitude 10 minutes after CT (A10) – used to predict maximum clot firmness (MCF) at an earlier stage and so allows earlier therapeutic decisions.

Maximum clot firmness – the greatest vertical amplitude of the trace. A low MCF value suggests decreased platelet numbers or function, decreased FIB levels of fibrin polymerisation disorders or low factor XIII activity.

Maximum lysis (ML) – fibrinolysis is detected by ML of > 15% or by better clot formation in APTEM compared with EXTEM.

Thromboelastography

The ROTEM system is a variant of the traditional thromboelastography (TEG) method developed by Hartert in 1948. 20 The two techniques are very similar, and other recent reviews have evaluated them as a single intervention class. 12,21,22 Like ROTEM, TEG is a VE method and provides a graphical representation of the clotting process. TEG is used in the TEG® 5000 analyser (Haemonetics Corporation, Niles, IL, USA; www.haemonetics.com). The rate of fibrin polymerisation and the overall clot strength is assessed. 1 Like ROTEM, TEG is able to provide an analysis of platelet function, coagulation proteases and inhibitors, and the fibrinolytic system within 30 minutes, or within 15 minutes if the rapid assay is used (Figure 4). The nomenclature used in TEG differs from that used in ROTEM; differences are summarised in Table 3. The practical differences between TEG and ROTEM are that TEG uses a torsion wire rather than the optical detector used in ROTEM to measure the clot formation, and, although the movement in ROTEM is initiated with the pin, with TEG it is initiated from the cuvette. 1 The assays used in TEG also differ (see Table 3). 24,25 The platelet mapping function means that TEG is able to measure platelet function, which cannot be assessed using ROTEM. Sample size requirements do not differ substantially between TEG and ROTEM; TEG uses a 360-µl blood sample compared with the 340-µl sample used in ROTEM. 25

| Assay | Activator/inhibitor | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Kaolin | Assessment of clot formation, fibrin polymerisation and fibrinolysis via the intrinsic pathway |

| Heparinase | Kaolin + heparinase | Assessment of clot formation in heparinased patients (both unfractionated and low molecular weight) |

| Platelet mapping | ADP arachidonic acid | To assess platelet function and monitor antiplatelet therapy (e.g. aspirin) |

| Rapid TEG | Kaolin + tissue factor | Extrinsic pathway test. Provides more rapid results than standard kaolin assay (mean 20 minutes vs. 30 minutes for standard TEG with initial results in < 1 minute) |

| Functional FIB assay | Lyophilised tissue factor + platelet inhibitor | Partitions clot strength (MA) into contributions from platelets and contribution from fibrin |

| Native | None | Non-activated assay. Can be used to run custom haemostasis tests |

FIGURE 4.

Thromboelastography: analysis and interpretation of results. 23 ACT, activated clotting time; EPL, estimated per cent lysis; LY30, lysis at 30 minutes; MA, maximum altitude; R, clotting time. Reproduced with permission from TEG®.

Sonoclot coagulation and platelet function analyser

Another method that uses viscoelastometry to measure coagulation is the Sonoclot® coagulation and platelet function analyser (Sienco Inc., Arvada, CO, USA). This analyser was first introduced in 1975 by von Kualla et al. 26 It provides information on the haemostasis process, including coagulation, fibrin gel formation, fibrinolysis, and, like TEG, is also able to assess platelet function. The Sonoclot process is similar to ROTEM and TEG; although Sonoclot is able to use either a whole blood or plasma sample, citrated blood samples can be used but are not required. 27 A hollow, open-ended disposable plastic probe is mounted on the transducer head. The test sample (blood or plasma) is added to the cuvette containing the reagents. A similar volume to ROTEM and TEG is used: 330–360 µl. As with ROTEM, it is the probe that moves within the sample; however, rather than moving horizontally the probe moves up and down along the vertical axis. As the sample starts to clot, changes in impedance to movement are measured. Like TEG and ROTEM, Sonoclot produces a qualitative graphical display of the clotting process and also produces quantitative results of activated clotting time (ACT), the clot rate and the platelet function (Figure 5 and Table 4). 24 However, the measure of ACT produced by Sonoclot reflects initial fibrin formation whereas the equivalent measures produced by TEG and ROTEM reflects a more developed and later stage of initial clot formation. 24 Most information on clot formation is available after 15 minutes. If details on platelet function are required this may take up to 20–30 minutes. 27

| Assay | Activator/inhibitor | Role |

|---|---|---|

| SonACT | Celite | Large-dose heparin management without aprotonin |

| kACT | Kaolin | Large-dose heparin management with/without aprotonin |

| aiACT | Celite + clay | Large-dose heparin management with aprotonin |

| gbACT+ | Glass beads | Overall coagulation and platelet function assessment for use on non-heparinased patients |

| H-gbACT+ | Glass beads + heparinase | Overall coagulation and platelet function assessment in presence of heparin |

| Native | None | Non-activated assay. Can be used to run custom haemostasis tests |

FIGURE 5.

Sonoclot analysis and interpretation of results.

Comparison of viscoelastic testing devices

This report refers to the three technologies – ROTEM, TEG and Sonoclot – as a class as ‘viscoelastic testing POC coagulation testing devices’ or ‘VE devices’; however, data from each device are analysed separately. Table 5 provides an overview of the different terms used by each device to refer to the different test outputs. This table also summarises the factors affecting clot formation at each stage and the different therapeutic options.

| Development of clot | Factors affecting clot28 | Therapeutic options | ROTEM | TEG | Sonoclot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement period | NA | NA | RT | – | – |

| Initial clot/fibrin formation | Factor XII and XI activity; reflective of intrinsic pathway if activators not used | Administration of plasma, coagulation factors, FIB or platelets | CT | R or ACT | ACT |

| Development of clot or rapidity of clot formation | Factor II and VIII activity; PLT and function, thrombin, FIB, HCT | CFT and α-angle (α) | Kinetics (k) and α-angle (α) | CR | |

| Maximum clot strength | FIB, platelet count and function, thrombin, factor XIII activity, HCT | MCF | MA | PEAK (peak amplitude) | |

| Time to maximum clot strength | MCF-t | TMA | Time to shoulder (P1); time to peak (P2); time from shoulder to peak (P2–P1) | ||

| Amplitude (at set time) | A5, A10 . . . | A (A5, A10 . . .) | |||

| Clot elasticity | MCE | G | – | ||

| ML | Fibrinolysis | Antifibrinolytic drugs and additional measures, such as administration of FIB or platelets | ML | – | R1, R2, R3 |

| CLR | – | ||||

| Lysis at fixed time | Lysis in 30, 45, 60 minutes (LY30, LY45, LY60) | Lysis in 30, 60 minutes (LY30, LY60) | |||

| Time to lysis | CLT (10% from MCF) | CLT ‘(2-mm drop from MA)’ instead of ‘TTL (2-mm drop from MA)’ | |||

| Platelet function | Platelet function | Platelets | _ | Platelet function | PF |

Platelet function tests

Viscoelastic tests are often performed in combination with platelet function tests in patients receiving antiplatelet drugs, such as aspirin and clopidogrel (Plavix®, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Sanofi-aventis). Although light transmission aggregometry in platelet-rich plasma is the gold standard test for platelet function, a number of rapid near-patient tests are available. 29 One of the most commonly used is the platelet function analyser (PFA) 100 (Dade-Behring, Marburg, Germany). 30 A more recently developed test, which is commonly used in combination with ROTEM, is the Multiplate® analyser (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), a near-patient test designed to detect platelet dysfunction. 31 It uses whole blood and is based on the principle of impedance platelet aggregometry. It has a turnaround time of 10 minutes and can process up to 30 tests per hour. As mentioned above, both TEG and Sonoclot can run specific platelet mapping assays – the TEG platelet mapping assay and glass bead-activated test (gbACT)+ assay for Sonoclot. However, some centres prefer to use a separate platelet function test, such as the Multiplate analyser instead of these assays. Tem International GmbH, the manufacturer of ROTEM, has recently introduced a new platelet module that is run in conjunction with the ROTEM delta. It measures platelet aggregation in whole blood samples using impedance aggregometry.

Comparator: standard laboratory tests for coagulopathy

The comparator for this technology appraisal is a combination of clinical judgement and standard laboratory tests (SLTs). Standard laboratory coagulation analyses include the following:

Prothrombin time (PT) – also used to derive the measures prothrombin ratio (PR) and international normalised ratio (INR). A measure of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. The PT is the time it takes plasma to clot after the addition of tissue factor. The PR is the PT for a patient, divided by the result for control plasma. The INR is the ratio of a patient’s PT to a normal (control sample) raised to the power of the international sensitivity index (ISI) value for the analytical system used. The ISI value indicates how a particular batch of tissue factor compares to an international reference tissue factor.

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) – measures the ‘intrinsic’ or contact activation pathway and the common coagulation pathway. An activated matrix (e.g. silica, celite, kaolin, ellagic acid) and calcium are mixed into the plasma sample, and the time the sample takes to clot is measured.

Activated clotting/coagulation time – based on ability of whole blood to form a visible fibrin monomer in a glass tube. Used to measure heparin anticoagulation.

Platelet count (PLT) – in general, a low PLT is associated with an increased risk of bleeding. It is a purely quantitative measure and cannot detect pre-existing, drug-induced or perioperatively acquired platelet dysfunction. 2

Plasma FIB concentration – a number of assays are available to assess plasma FIB levels. The Clauss fibrinogen assay is the most common and is based on the thrombin CT. Diluted plasma is clotted with a high concentration of thrombin at 37 °C and the CT is measured. The result is compared with a calibration curve prepared by clotting a series of dilutions of a reference plasma sample of known FIB concentration to give a result in grams per litre. Most laboratories use an automated method in which clot formation is considered to have occurred when the optical density of the mixture has exceeded a certain threshold. 32

These tests have a number of limitations for prediction and detection of perioperative coagulopathy, as they were not developed to predict bleeding or guide coagulation management in a surgical setting. They are performed at a standardised temperature of 37 °C, which limits the detection of coagulopathies induced by hypothermia. 1 The aPTT and INR tests affect only the initial formation of thrombin in plasma without the presence of platelets or other blood cells. These tests are also not able to provide any information regarding clot formation over time or on fibrinolysis and so they cannot detect hyperfibrinolysis. They generally take between 40 and 90 minutes from taking the blood sample to give a result; this turnaround time may be so long that it does not reflect the current state of the coagulation system when the results are reported. 2

Care pathway

Current care pathway

The exact care pathway and use of SLTs before, during and after surgery will vary according to the specific type of surgery. Some centres routinely screen all patients pre operatively for coagulation disorders using SLTs, such as the PT and aPTT tests. 33 However, UK guidelines published in 200834 do not recommend routine coagulation tests to predict perioperative bleeding risk in unselected patients before surgery. Instead, pre-operative testing should only be considered in patients at risk of a bleeding disorder, for example those with liver disease, family history of inherited bleeding disorder, sepsis, diffuse intravascular coagulation, pre-eclampsia, cholestasis and those at risk of vitamin K deficiency. 33

It is generally recommended that patients stop taking anticoagulant medications (clopidogrel warfarin and aspirin) a number of days before surgery to reduce the risk of bleeding during surgery. 10,35 In the event of emergency surgery, this may not be possible, in which case coagulation testing should be performed. 33 If the surgery involves CPB then heparin may be administered prophylactically to reduce the risk of clotting while on CPB. 35 It is essential to monitor heparin anticoagulation if this has been administered. An initial ACT test should be performed after the first surgical incision and be repeated at regular intervals during surgery. 36 Standard coagulation tests (PLT, FIB concentration, PT, aPTT) are most commonly used to assess the coagulation status of patients who are experiencing high blood loss during surgery. However, these generally take too long to give a result that can inform treatment decisions. Instead, decisions on how to treat the bleed have to be based largely on clinical judgement. The same tests are used after surgery to monitor coagulation status.

If bleeding occurs, surgical intervention may be needed or packed RBCs are transfused if required. This is generally to maintain a haemoglobin concentration of > 6 g/dl during CPB and 8 g/dl after CPB or according to other requirements as indicated by national guidelines. Other therapeutic options depending on laboratory test results include FIB concentrate (bleeding patients with abnormal FIB), fresh frozen plasma (FFP) (if after transfusion of packed erythrocytes new laboratory results were not available and/or bleeding did not stop after FIB administration), prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) (abnormal aPTT), antithrombin concentrate (when ACT analyses not controlled by heparin alone), desmopressin (suspected platelet dysfunction), platelet concentrates (low PLT),35 cryoprecipitate, antifibrinolytic drugs and tranexamic acid. If bleeding continues despite these treatments then additional treatment options include factor XIII concentrate and activated recombinant factor VII or factor VIIa, although not licensed for use in the UK. 10,35 Heparin dose adjustments may be made to try and control the bleeding.

Role of viscoelastic testing in the care pathway

Viscoelastic testing can be repeatedly performed during and after surgery and so can provide a dynamic picture of the coagulation process during these periods. The role of VE testing in the care pathway is unclear. It could be used either as an add-on test, in which case it would be performed as well as SLTs, or it could be as replacement test in which case SLTs would no longer be needed.

If VE testing does not prevent the need for SLTs and provides complementary findings then it should be performed in addition to any laboratory coagulation tests already recommended for specific populations. However, if the SLTs do not offer any supplementary information to that provided by VE testing then there should no longer be a need for standard tests and VE testing should replace some or all of the SLTs. VE tests offer two key potential benefits over SLTs: the shorter timescale in which they are able to provide results and the additional information on the clotting process that they offer compared with standard tests. It is hypothesised that by providing additional information and quicker results requirements for blood components/products could be targeted and so the patient is not subjected to risks associated with unnecessary transfusion. Time in theatre, resource use, length of stay (LoS) in a critical care unit, length of hospital stay, blood component/product usage and the associated costs may therefore be reduced.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

A systematic review was conducted to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of VE POC testing to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis. Systematic review methods followed the principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in health care37 and NICE Diagnostic Assessment Programme manual. 38 We developed a protocol for the review and the protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42013005623).

Systematic review methods

Search strategy

Search strategies were based on index test (ROTEM delta, TEG and Sonoclot), as recommended in the CRD guidance for undertaking reviews in health care37 and the Cochrane Handbook for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Reviews. 39

Candidate search terms were identified from target references, browsing database thesauri [e.g. MEDLINE (MeSH) and EMBASE (EMTREE)], existing reviews identified during the rapid appraisal process and initial scoping searches. These scoping searches were used to generate test sets of target references, which informed text mining analysis of high-frequency subject-indexing terms using EndNote X4 reference management software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Strategy development involved an iterative approach testing candidate text and indexing terms across a sample of bibliographic databases and aimed to reach a satisfactory balance of sensitivity and specificity.

Search strategies were developed specifically for each database, and the keywords associated with ROTEM, TEG, thromboelastometry and Sonoclot were adapted according to the configuration of each database.

Primary clinical effectiveness searches

Primary searches were undertaken for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in TEG, thromboelastometry and Sonoclot, and these searches were limited with an objectively derived study design filter, where appropriate.

The following databases were searched for relevant studies from inception to December 2013:

-

MEDLINE (OvidSP): 1946–September week 3 2013

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily Update (OvidSP): up to 26 September 2013

-

EMBASE (OvidSP): 1974–30 September 2013

-

BIOSIS Previews (Web of Knowledge): 1956–26 September 2013

-

Science Citation Index (SCI) (Web of Science): 1970–26 September 2013

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI-S) (Web of Science): 1990–26 September 2013

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Internet): Issue 10, October 2013

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Internet): Issue 10, October 2013

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Internet): Issue 4, October 2013

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (Internet): Issue 4, October 2013

-

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) (Internet): http://regional.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=en

-

International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA): up to 27 September 2013, www.inahta.org/

-

NIHR HTA Programme (Internet): up to 27 September 2013

-

Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility (ARIF) (Internet): 1996–27 September 2013, www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/mds/projects/HaPS/PHEB/ARIF/index.aspx

-

Medion (Internet): up to 27 September 2013, www.mediondatabase.nl/

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Internet): up to 27 September 2013, www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/

Completed and ongoing trials were identified by searches of the following resources:

-

National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov (Internet): up to 27 September 2013, www.clinicaltrials.gov/

-

metaRegister of Current Controlled Trials (mRCT) (Internet): up to 27 September 2013, www.controlled-trials.com/

-

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (Internet): up to 26 September 2013, www.who.int/ictrp/en/

Electronic searches were undertaken for the following conference abstracts:

-

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) (Internet): 2009, 2011, www.isth.org/?PastMeetings

-

American Society of Anesthetists (ASA) (Internet): 2009–13, www.asaabstracts.com/strands/asaabstracts/search.htm;jsessionid=FF1E2F6EA4FF34468F5594FA255F3423

-

European Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesiologists (EACTA) (Internet): 2009–13

-

2013: www.applied-cardiopulmonary-pathophysiology.com/acp-2–2013.html

-

2012: www.applied-cardiopulmonary-pathophysiology.com/acp-supp1–2012.html

-

2011: Searched via publisher’s website

-

2010: www.applied-cardiopulmonary-pathophysiology.com/fileadmin/downloads/acp-2010–1/10_abstracts.pdf

-

Viscoelastic testing in post-partum haemorrhage and trauma

A second series of focused searches were undertaken without a study design filter to identify relevant references reporting TEG, thromboelastometry and Sonoclot in PPH or trauma response.

The following databases were searched for relevant studies from inception to December 2013:

-

MEDLINE (OvidSP): 1946–September 2013 week 3

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily Update (OvidSP): up to 26 September 2013

-

EMBASE (OvidSP): 1974–5 November 2013.

No restrictions on language or publication status were applied. All search strategies are presented in Appendix 1. The main EMBASE strategy for each search was independently peer reviewed by a second information specialist, using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies (CADTH) Peer Review Checklist. 40 Identified references were downloaded in EndNote X4 software for further assessment and handling. References in retrieved articles and the websites set up by the manufacturers of ROTEM delta and Sonoclot were also screened for additional references. The manufacturers of ROTEM and Sonoclot, and clinical experts, submitted references of relevant publications for consideration for inclusion in the review. The final list of included papers was checked on PubMed for retractions, errata and related citations. 41–43

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for each of the three clinical review questions are summarised in Table 6. Studies that fulfilled these criteria were eligible for inclusion in the review.

| Question | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clinical outcomes in cardiac surgery | Prediction in cardiac surgery | 2. Clinical outcomes in trauma-induced coagulopathy | 2a. Prediction in trauma-induced coagulopathy | 3. Clinical outcomes in PPH | 3a. Prediction in PPH | |

| Participants | Adult (age ≥ 18 years) patients undergoing cardiac surgery | Adult (age ≥ 18 years) with clinically suspected coagulopathy induced by trauma | Women with PPH | |||

| Index test | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) alone or combined with platelet testing (e.g. Multiplate test) or SLTs | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) or SLTs | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) or SLTs | VE devices (ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot) |

| Comparators | No testing, SLTs or other VE device | Any other VE device or none | No testing, SLTs or other VE device | Any other VE device or none | No testing SLTs or other VE device | Any other VE device or none |

| Reference standard | NA | Patient-relevant outcomes, e.g. transfusion, bleeding | NA | Patient-relevant outcomes, e.g. transfusion, bleeding | NA | Patient-relevant outcomes, e.g. transfusion, bleeding |

| Outcomes | Any reported outcomes. We anticipate that outcomes will include post-operative mortality, bleeding and transfusion outcomes, complications and re-intervention outcomes | Sufficient data to construct a 2 × 2 table of test performance | Any reported outcomes. We anticipate that outcomes will include post-operative mortality, bleeding and transfusion outcomes, complications and re-intervention outcomes | Sufficient data to construct a 2 × 2 table of test performance or prediction model data | Any reported outcomes. We anticipate that outcomes will include post-operative mortality, bleeding and transfusion outcomes, complications and re-intervention outcomes | Sufficient data to construct a 2 × 2 table of test performance or prediction model data |

| Study design | RCTsa | Diagnostic cohort studies/prediction studies | RCTsa | Diagnostic cohort/prediction studies | RCTsa | Diagnostic cohort/prediction studies |

Inclusion screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (MW and PW) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by searches, and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Full copies of all studies that were deemed to be potentially relevant were obtained and the same two reviewers independently assessed these for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Details of studies excluded at the full-paper screening stage are presented in Appendix 4.

Studies cited in materials provided by the manufacturers of ROTEM, TEG or Sonoclot were first checked against the project reference database, in EndNote X4; any studies not already identified by our searches were screened for inclusion following the process described above.

Data were extracted on the following: participant characteristics; study design; inclusion and exclusion criteria; details of VE test and/or test parameters evaluated; details of SLTs, where applicable; details of outcomes assessed [main outcomes were bleeding outcomes, transfusion outcomes, hospital/intensive care unit (ICU) stay, re-operation and mortality]; results. Data were extracted by one reviewer, using a piloted, standard data extraction form and checked by a second (MW and PW); any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Full data extraction tables are provided in Appendix 2.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. 44 Prediction studies were assessed for methodological quality using QUADAS-2. 45 Risk of bias assessments were undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (MW and PW), and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The results of the risk of bias assessments are summarised and presented in tables and graphs in the results of the systematic review, and are presented in full, by study, in Appendix 3.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

We provided a narrative synthesis involving the use of text and tables to summarise data to show differences in study designs, population, VE device and potential sources of bias for each of the studies being reviewed. Studies were organised by research question addressed (study population), outcome and VE device. Where possible, meta-analysis was used to derive summary effect estimates. All meta-analyses were performed using the MetaExcel (Epigear International) add on for Microsoft Excel version 1997–2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Randomised controlled trials comparing viscoelastic testing with no testing

Meta-analysis was used to estimate summary effect sizes for outcomes evaluated in multiple studies for which sufficient data were reported. Data were reported only in an appropriate format to permit pooling for dichotomous data. Summary relative risks (RRs), together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models. Heterogeneity was investigated visually using forest plots and statistically using the I2- and Q-statistics. Data were pooled for all VE devices combined and stratified according to VE device; if no difference based on VE device was found then a summary estimate was calculated comparing VE testing irrespective of VE device to no testing. Where multiple sets of data were reported for the same outcome for a single study, for example pre-operative, post-operative and total number of patients transfused, a single data set was selected. The data set relating to the largest number of participants or latest time point was selected.

For continuous outcomes, data were not reported in a sufficiently similar format to permit pooling. Only a small number of studies reported data as means and standard deviations (SDs) or CIs, which would have allowed calculations of mean differences, and there were insufficient studies reporting data in this format to pool data. Most studies reported data as medians [some with interquartile ranges (IQRs)] and some reported p-values for comparisons of the differences between medians, usually estimated using the Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Some studies reported only medians, with no measure of distribution around the median or estimation of the significance of the difference between groups. We summarised the results for continuous outcomes in a table showing the measure of effect reported in the study (mean or median with associated SD, CI, IQR or range), the effect estimate in the VE testing and in the control group, and any reported p-value for the comparison between the two groups.

Prediction studies

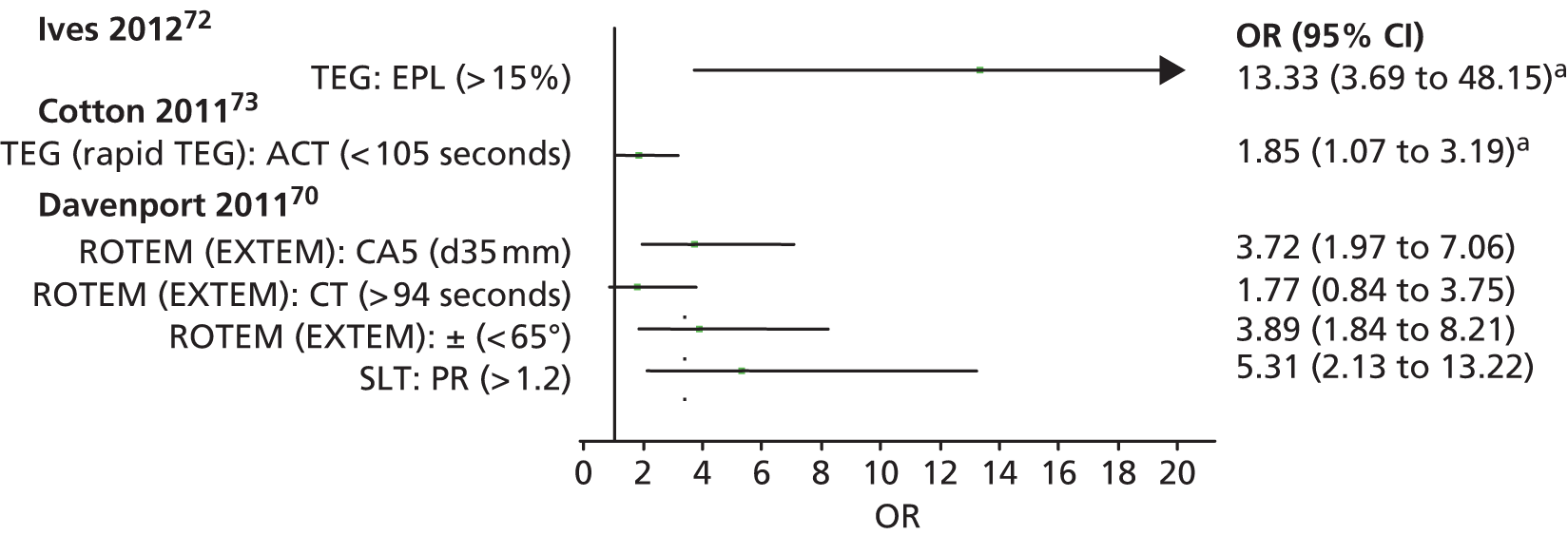

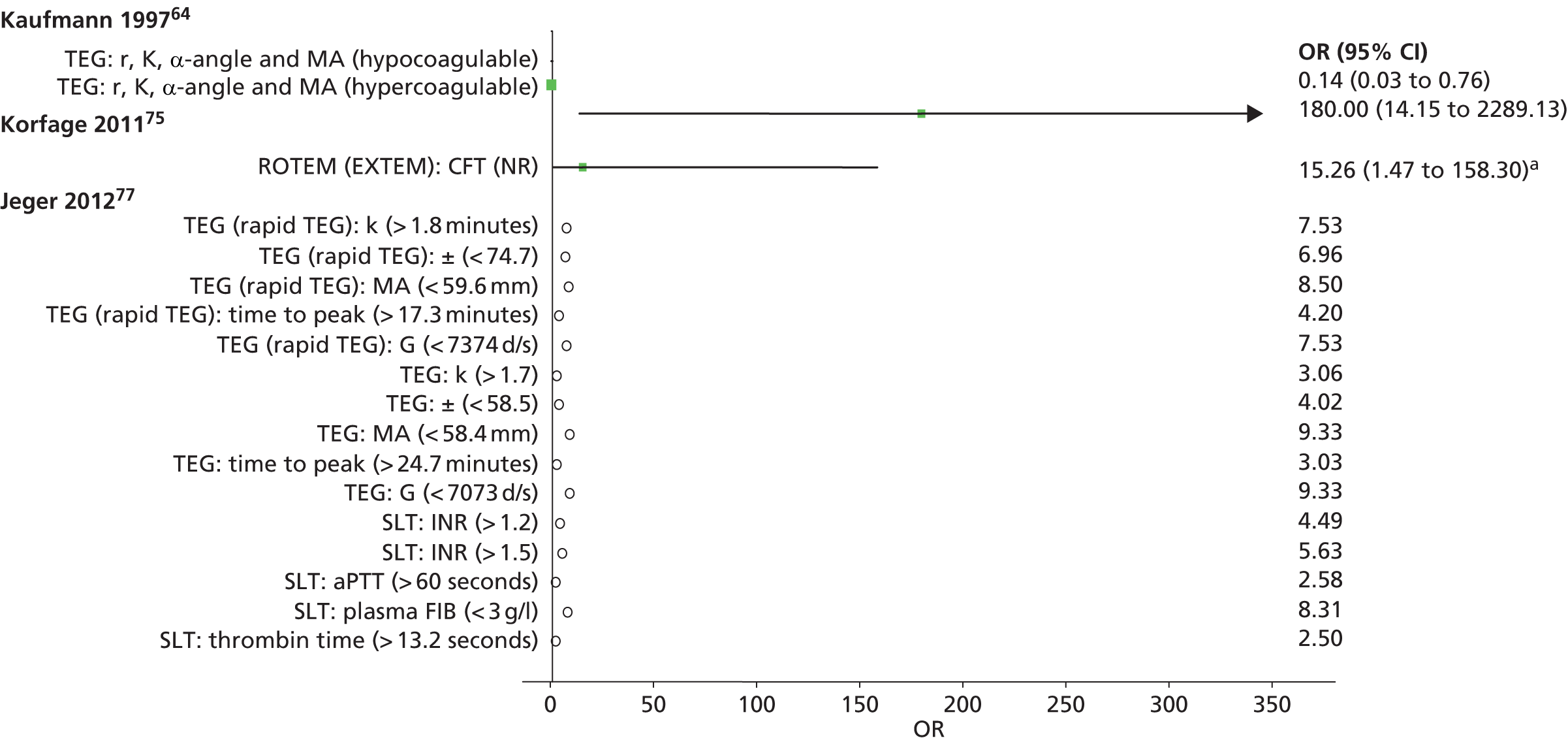

Prediction studies provided data in a variety of formats:

-

Logistic regression models for the association of the VE test parameter and the outcome (reference standard) under investigation, adjusted for a range of other variables. From these studies, we selected the adjusted odds ratio (OR) and associated 95% CI as the measure to use in the analysis.

-

Crude (unadjusted) ORs with associated 95% CIs for the association of the VE test parameter and the outcome (reference standard) under investigation. We selected these as the measure to use in the analysis.

-

Two-by-two data for the association of the VE test parameter (index test) with the outcome (reference standard) under investigation. We used these data to calculate crude ORs and associated 95% CIs.

-

Sensitivity and specificity data for the VE test parameter for the prediction of the outcome (reference standard) under investigation. If these studies also reported data on the number of participants with and without the outcome, these data were used to calculate a 2 × 2 table from which ORs were derived, as described above. If this information was not provided then sensitivity and specificity were used to calculate ORs; for these studies it was not possible to calculate associated CIs.

-

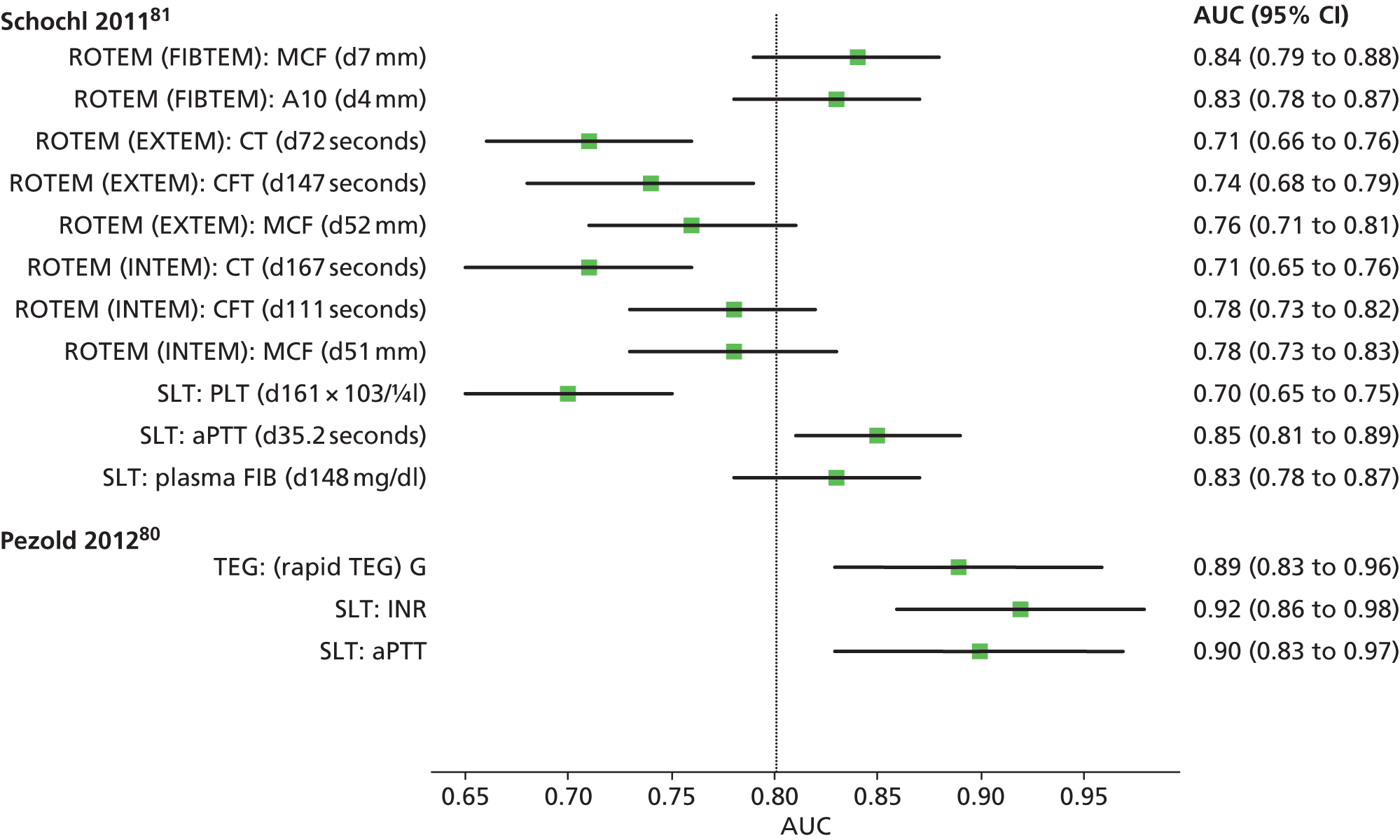

Area under the [receiver operating characteristic (ROC)] curve (AUC) for the VE test parameter for the prediction of the outcome (reference standard) under investigation. Some studies reported crude (unadjusted) AUCs; others used regression models to adjust the AUC for various other variables. If both were reported the adjusted values were selected, otherwise crude (unadjusted) AUCs together with 95% CIs were selected.

Data were not sufficiently similar to permit pooling for any of the outcomes for any of the population groups for the prediction studies; studies differed in the variables adjusted for in the regression models and the VE test parameters evaluated. For outcomes evaluated in more than two studies, forest plots were used to display adjusted and crude (unadjusted) ORs or AUCs, together with 95% CIs for individual studies. A narrative summary of the results was provided.

Investigation of heterogeneity

There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies included in the meta-analyses, and the numbers of studies included in most analyses were small. Formal statistical investigation of heterogeneity for these analyses was therefore not appropriate. The following variables were considered as possible explanations for differences between studies in the narrative synthesis: patient demographics (age, gender, surgery type), type of VE device (ROTEM, TEG, Sonoclot), time point of surgery (during surgery only, during and after surgery, and risk of bias domains).

Results of the assessment of clinical effectiveness

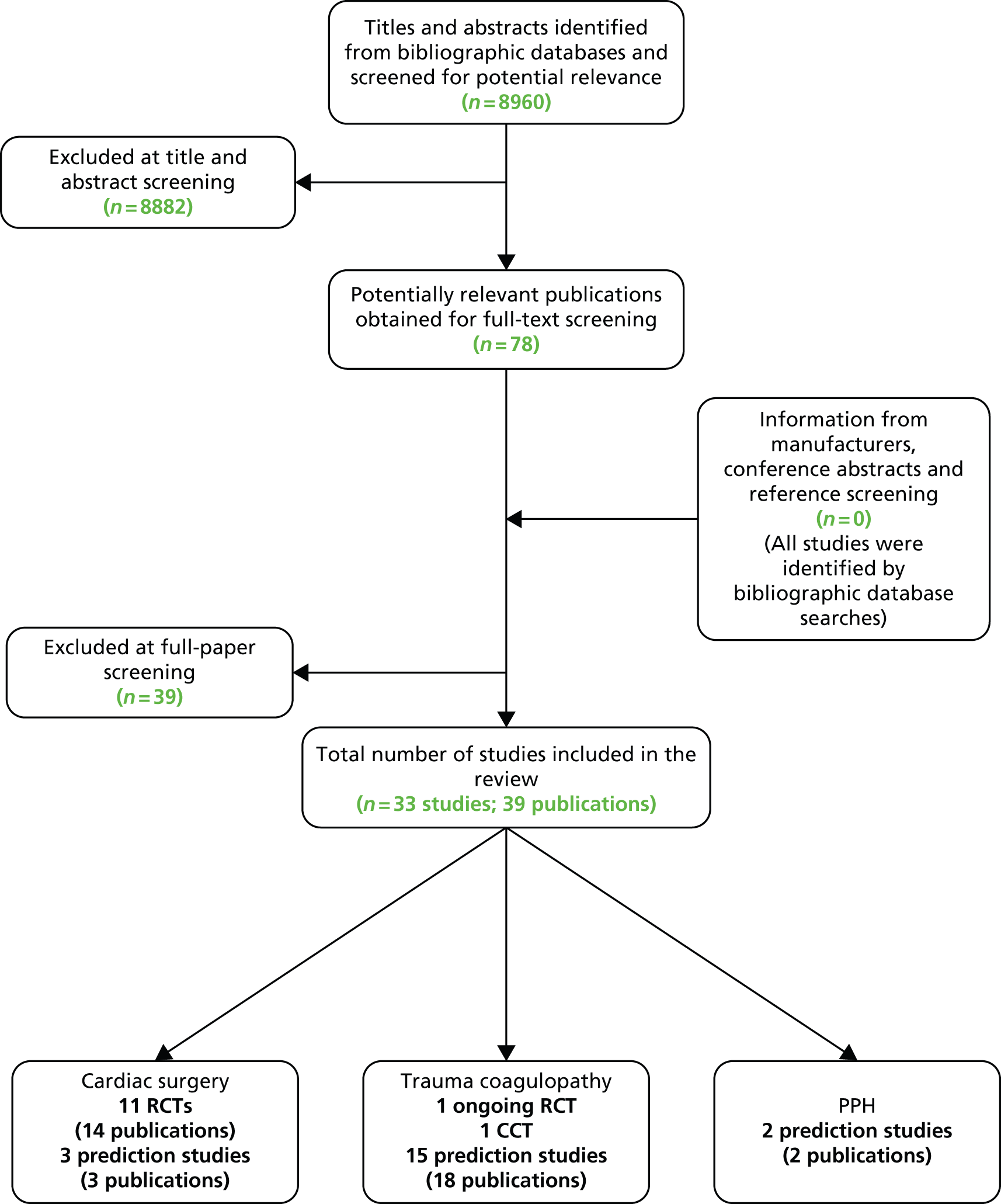

The literature searches of bibliographic databases identified 8960 references. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 78 were considered to be potentially relevant and ordered for full-paper screening. No additional papers were ordered, based on screening of papers provided by test manufacturers, conference abstract hand-searching or screening references of included studies; all studies cited in documents supplied by the test manufacturers, identified through reference screening or conference abstract screening, had already been identified by bibliographic database searches. Figure 6 shows the flow of studies through the review process, and Appendix 4 provides details, with reasons for exclusions, of all publications excluded at the full-paper screening stage.

FIGURE 6.

Flow of studies through the review process. CCT, controlled clinical trial.

Based on the searches and inclusion screening described above, 39 publications of 33 studies were included in the review. We included 11 RCTs (13 publications)35,46–57 evaluating ROTEM and TEG in cardiac surgery patients; as no RCTs evaluating Sonoclot were identified, we also included three prediction studies58–60 that evaluated Sonoclot. We included one ongoing RCT,61,62 one controlled clinical trial (CCT)63 and 15 prediction studies (18 publications)64–81 in trauma patients, and two prediction studies82,83 in women with PPH.

Full details of the characteristics of study participants, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, VE test used and results are reported in the data extraction tables presented in Appendix 2. The results of the risk of bias assessments are presented in Appendix 3.

How do clinical outcomes differ among patients who are tested with viscoelastic devices during or after cardiac surgery compared with those who are not tested?

We included 11 RCTs (n = 1089, range 22–228) (13 publications)35,46–57 for the assessment of VE devices in patients undergoing cardiac surgery; six assessed TEG,46–51 four assessed ROTEM35,53–55 and one52 assessed ROTEG. ROTEG was an early name for ROTEM and so the study assessing ROTEG52 was grouped with the ROTEM studies in the analyses. Two RCTs53,55 were available only as abstracts.

Study details

The RCTs were conducted in Australia, Austria, Germany, Spain, Turkey, UK and the USA. Most included patients undergoing surgery irrespective of whether or not they had a bleeding event; however, two RCTs35,53 assessing ROTEM were restricted to patients who had experienced bleeding above a certain level (≥ 300 ml in first post-operative hour53 or bleeding from capillary beds requiring haemostatic therapy or blood loss exceeding 250 ml/hour or 50 ml/10 minutes35). A further RCT51 of TEG was restricted to patients at moderate to high risk for transfusion procedures. One RCT54 was restricted to patients undergoing aortic surgery, two RCTs46,48 included patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and the remainder included patients undergoing mixed cardiac surgery. One study48 excluded patients with abnormal pre-operative conventional coagulation tests, another study46 excluded patients with pre-operative haemodynamic instability or a history of bleeding diathesis, and one study54 excluded patients with known (inherited) coagulation disorders. The majority of studies did not place any restriction on entry based on anticoagulation use, but one study48 excluded patients who had used low-molecular-weight heparin up to the day of operation. One study51 excluded patients with pre-existing hepatic or severe renal disease. Mean or median age, where reported, ranged from 53 to 72 years. The proportion of men ranged from 56% to 90%.

The ROTEM/TEG algorithms varied across studies. Six studies35,46,48,50,51,55 used an algorithm based on TEG or ROTEM alone. Two studies combined TEG with SLTs,50,51 two combined ROTEM with platelet function testing (POC in one),35 one of these also used Hepcon® (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to monitor heparin and protamine dosage,48 and one55 combined ROTEM with clinical evaluation. The timing of the VE test varied across studies. All except one study,50 which performed TEG on arrival at the ICU, administered multiple VE tests. Timing included baseline/before bypass/before anaesthesia, after CPB, after protamine administration, on admission to ICU and up to 24 hours post CPB in one study. 46 Four studies35,47,48,54 performed VE testing post surgery only on patients who were continuing to bleed. Four studies35,46,48,53 used an algorithm based on SLTs in the control group; all other studies stated that control groups included combinations of clinical judgements and SLTs. Further details are summarised in Table 7.

| Study details | n | Patient category | Entry restricted to excessive bleeding? | Entry restriction based on anticoagulation? | VE testing algorithm | Control | Timing of VE test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ak (2009)46 | 228 | CABG | No | No | TEG | Clinician judgement including SLTs | Before anaesthesia, after CPB, 15 minutes after protamine, admission to ICU, 6 and 24 hours post CPB |

| Avidan (2004)48 | 102 | CABG | No | Yes – no coagulation medication < 72 hours of surgery | TEG combined with Hepcon platelet function testing and ACT | SLTs algorithm | Five minutes and 1 hour post CPB, 20 minutes post protamine, 2 hours post surgery if bleeding |

| Girdauskas (2010)54 | 56 | Aortic surgery | No | No | ROTEM | Clinician judgement including SLTs | Rewarming phase of CPB, before chest closure, on ICU in case of increased bleeding. Repeat ROTEM also performed 15 minutes after administration of coagulation products |

| Kultufan Turan (2006)52 | 40 | CABG or valve surgery | No | Unclear | ROTEG | Routine transfusion therapy and SLTs | Pre operation, 1 hour post operation |

| Nuttall (2001)50 | 92 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | No | TEG combined with PT, aPTT, PLTs and FIB concentration | Clinician judgement with or without SLTs | On arrival in ICU |

| aPaniagua (2011)53 | 22 | Mixed cardiac surgery | Yes (≥ 300 ml in first post-operative hour) | NR | ROTEM | SLTs | NR |

| aRauter (2007)55 | 213 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | NR | ROTEM + clinical signs | Routine management including SLTs | NR |

| Royston (2001)49 | 60 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | No | TEG | Clinician judgement including SLTs | Prior to surgery, at bypass 10–15 minutes after protamine |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999)51 | 107 | Mixed cardiac surgery | Moderate to high risk for transfusion procedures | No | TEG + PLT + FIB | SLTs algorithm | Baseline, during rewarming on CPB, after protamine |

| Weber (2012)35 | 100 | Mixed cardiac surgery | Yes – bleeding from capillary beds or blood loss > 250 ml/hour or 50 ml/10 minutes | Yes – pre-operative antiplatelet therapy stopped > 6 days before surgery | ROTEM + POC testing for platelet function | SLTs algorithm | Unclear; appears to be before weaning off CPB, after protamine, for ongoing bleeding |

| Westbrook (2009)47 | 69 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | No | TEG | Clinician judgement including SLTs | Prior to surgery, at bypass, 10–15 minutes after protamine |

Risk of bias assessment

There were a number of methodological issues with the RCTs included in this assessment. Only three35,51,54 of the 11 RCTs35,46–55 were rated as ‘low’ risk of bias with respect to their randomisation procedures. The trials were generally poorly reported; all were rated as ‘unclear’ or ‘high’ risk of bias on at least 50% of the assessed criteria. Allocation concealment and blinding were particularly poorly reported. Only one study50 reported sufficient information to assess risk of bias in relation to allocation concealment and this study was considered to have a ‘high’ risk of bias on this criterion. This study50 moved four patients initially randomised to the algorithm group to the control group, and so allocation was not concealed for these patients.

Five of the 11 RCTs46–48,52,55 reported details of blinding of study participants and personnel; only three46,47,52 of these were rated as ‘low’ risk of bias. In one of these studies46 the anaesthesiologist who performed the transfusion was blinded to the patient’s group assignments, in one47 the surgeons were blinded to the method of haemostasis assessment, and in the third52 the physician in charge of ROTEG and ICU physician were blinded. The other two studies48,55 explicitly stated that they were unblinded. Only three RCTs48,50,55 reported details on blinding of outcome assessors. Two RCTs48,50 were rated as ‘low’ risk of bias: one48 reported that outcomes were recorded by staff in the recovery unit who were unaware of group allocation; the other50 stated that surgeons and anaesthesiologists were not aware of group allocation at the time the decision on whether or not to transfuse was made. The third RCT55 reported that it was unblinded.

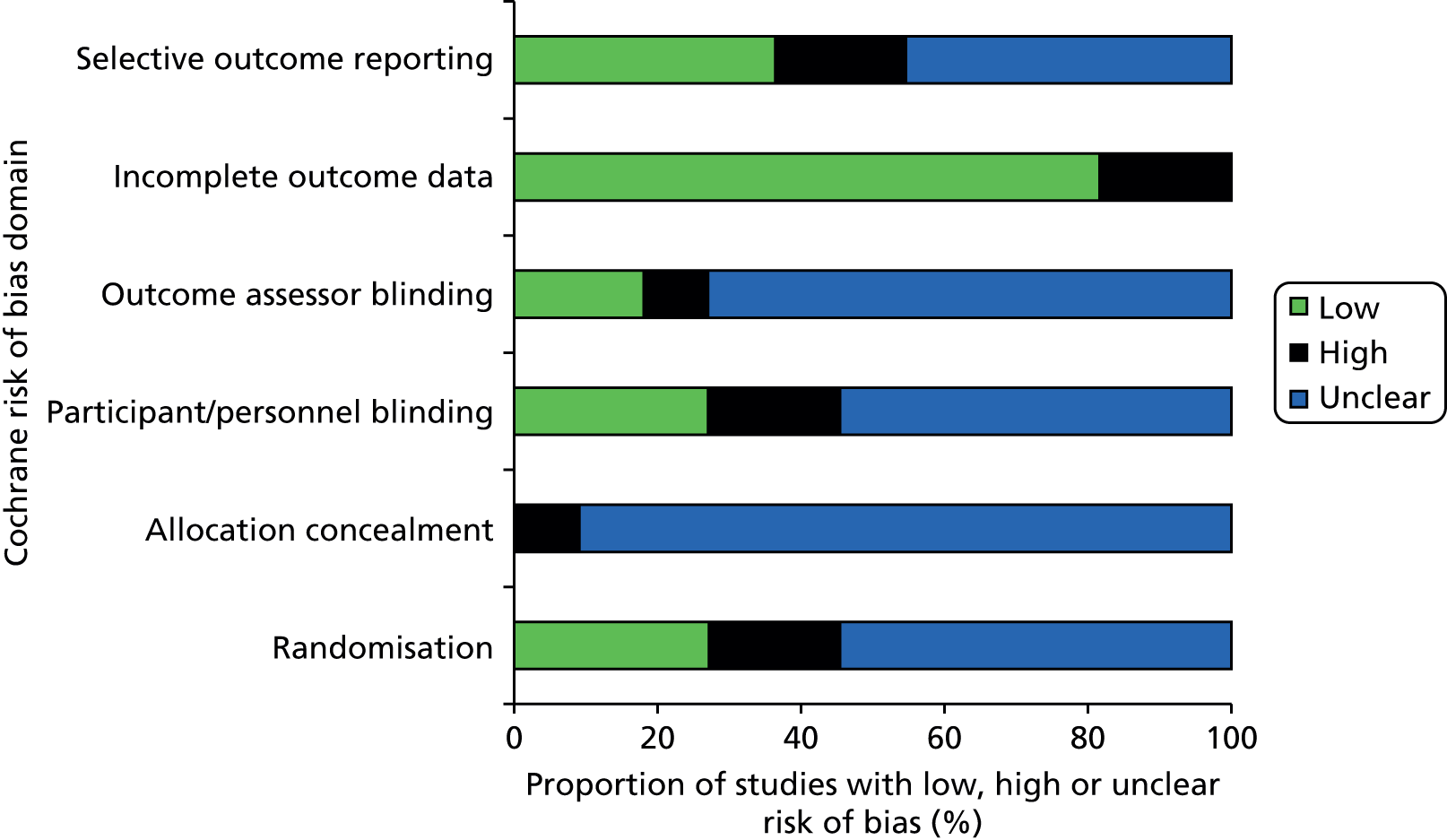

Inclusion of all study participants in analyses was the only notable area of methodological strength, with all but three trials rated as ‘low’ risk of bias for the completeness of outcome data criteria. 35,46,48,50–54 The results of risk of bias assessments are summarised in Table 8 and Figure 7; full risk of bias assessments for each study are provided in Appendix 3.

| Study | Risk of bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Participant and personnel blinding | Outcome assessor blinding | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | |

| Ak (2009)46 | ? | ? | ☺ | ? | ☺ | ☺ |

| Avidan (2004)48 | ? | ? | ☹ | ☺ | ☺ | ? |

| Girdauskas (2010)54 | ☺ | ? | ? | ? | ☺ | ☺ |

| Kultufan Turan (2006)52 | ? | ? | ☺ | ? | ☺ | ☺ |

| Nuttall (2001)50 | ☹ | ☹ | ? | ☺ | ☺ | ? |

| Paniagua (2011)53 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ☺ | ☹ |

| Rauter (2007)55 | ? | ? | ☹ | ☹ | ☹ | ☹ |

| Royston (2001)49 | ☹ | ? | ? | ? | ☹ | ? |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999)51 | ☺ | ? | ? | ? | ☺ | ? |

| Weber (2012)35 | ☺ | ? | ? | ? | ☺ | ☺ |

| Westbrook (2009)47 | ? | ? | ☺ | ? | ☹ | ? |

FIGURE 7.

Proportion of studies fulfilling each risk of bias criteria for RCTs evaluating VE devices in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Results

Red blood cell transfusion

All but one49 of the included RCTs evaluated RBC transfusion as either a continuous or dichotomous outcome. Eight RCTs35,46,47,50,51,53–55 evaluated RBC transfusion within 24–48 hours as a continuous outcome (Table 9). All RCTs35,46–55 reported less volume of RBC transfusion in the VE algorithm group than in the control group but this was statistically significant in only three35,50,55 (two of ROTEM35,55 and one of TEG50); one RCT53 did not report on the statistical significance of the difference.

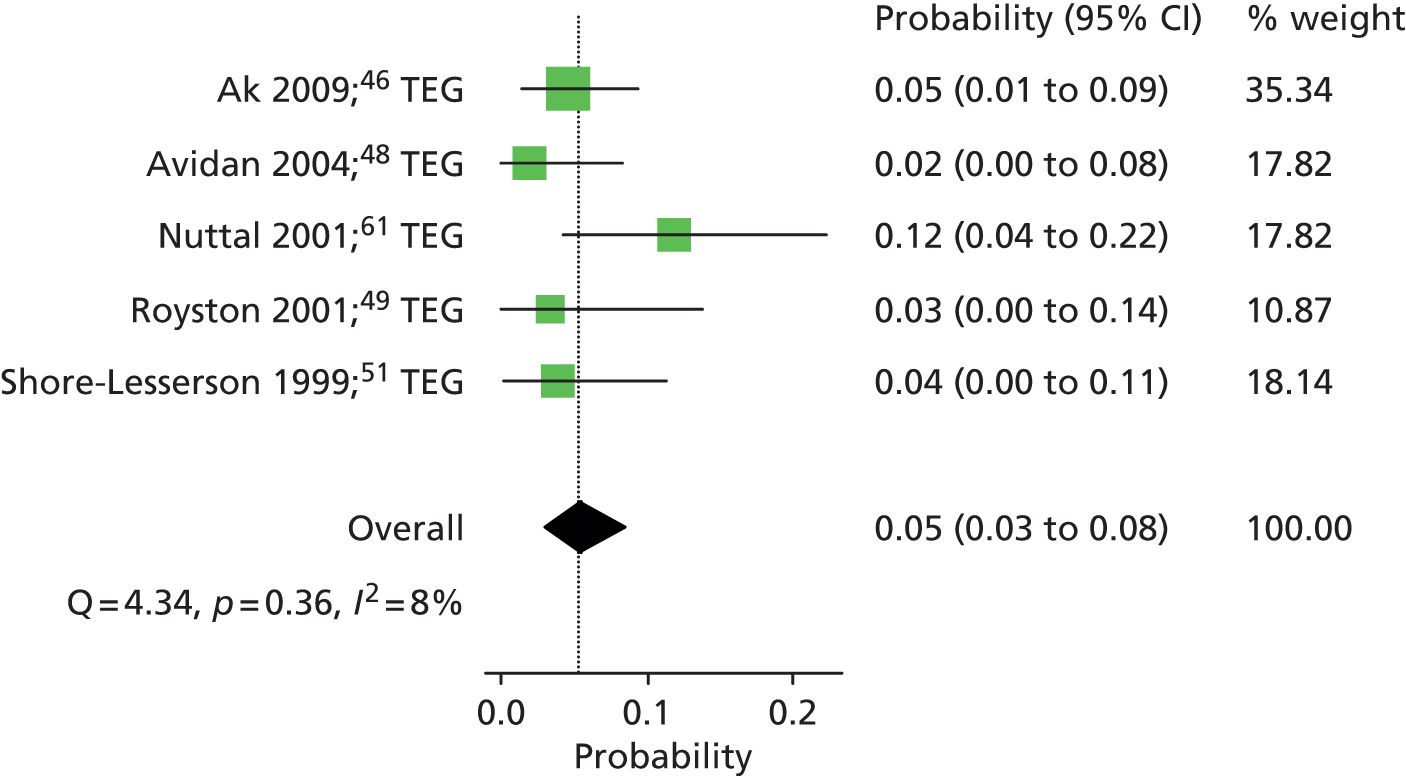

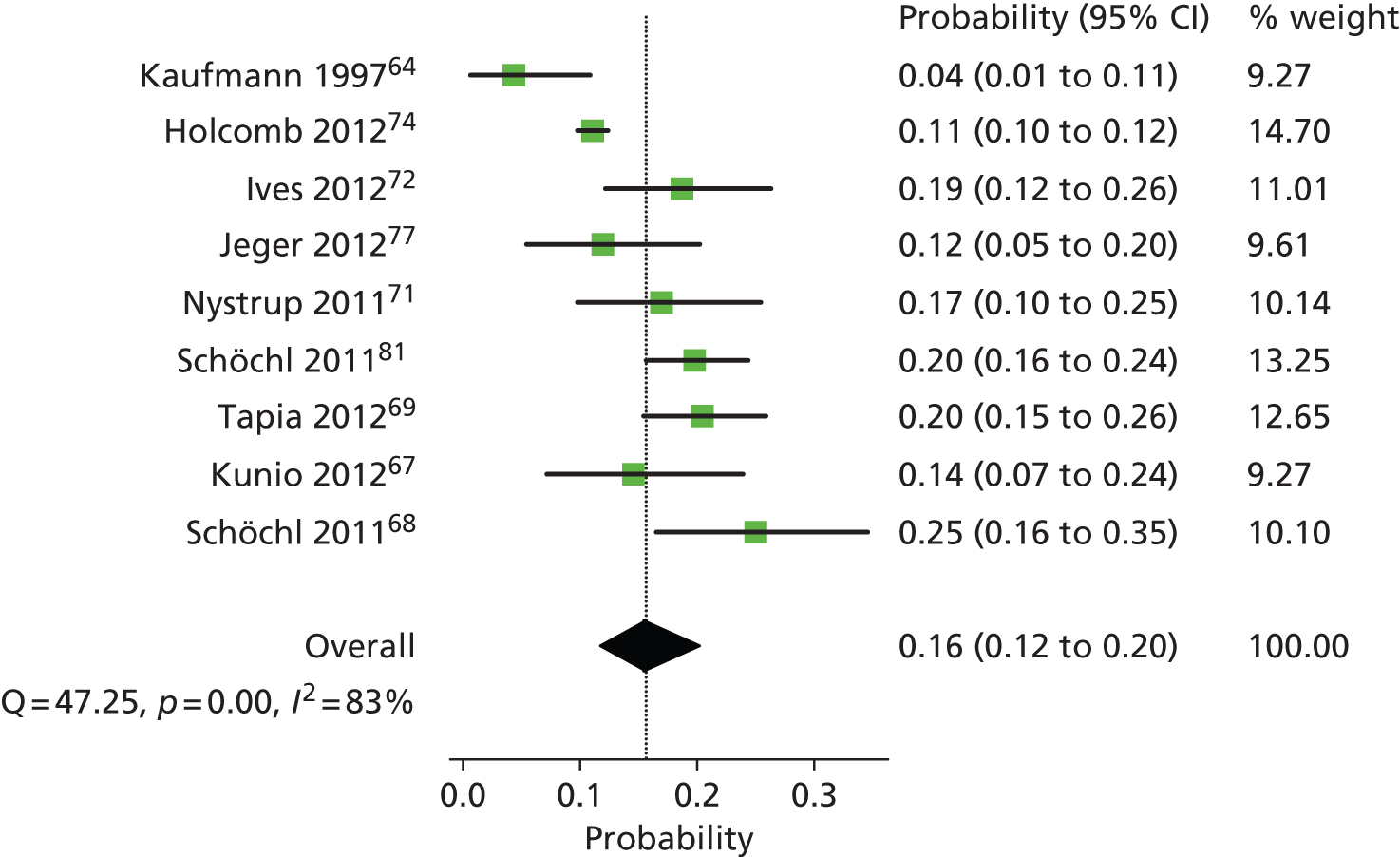

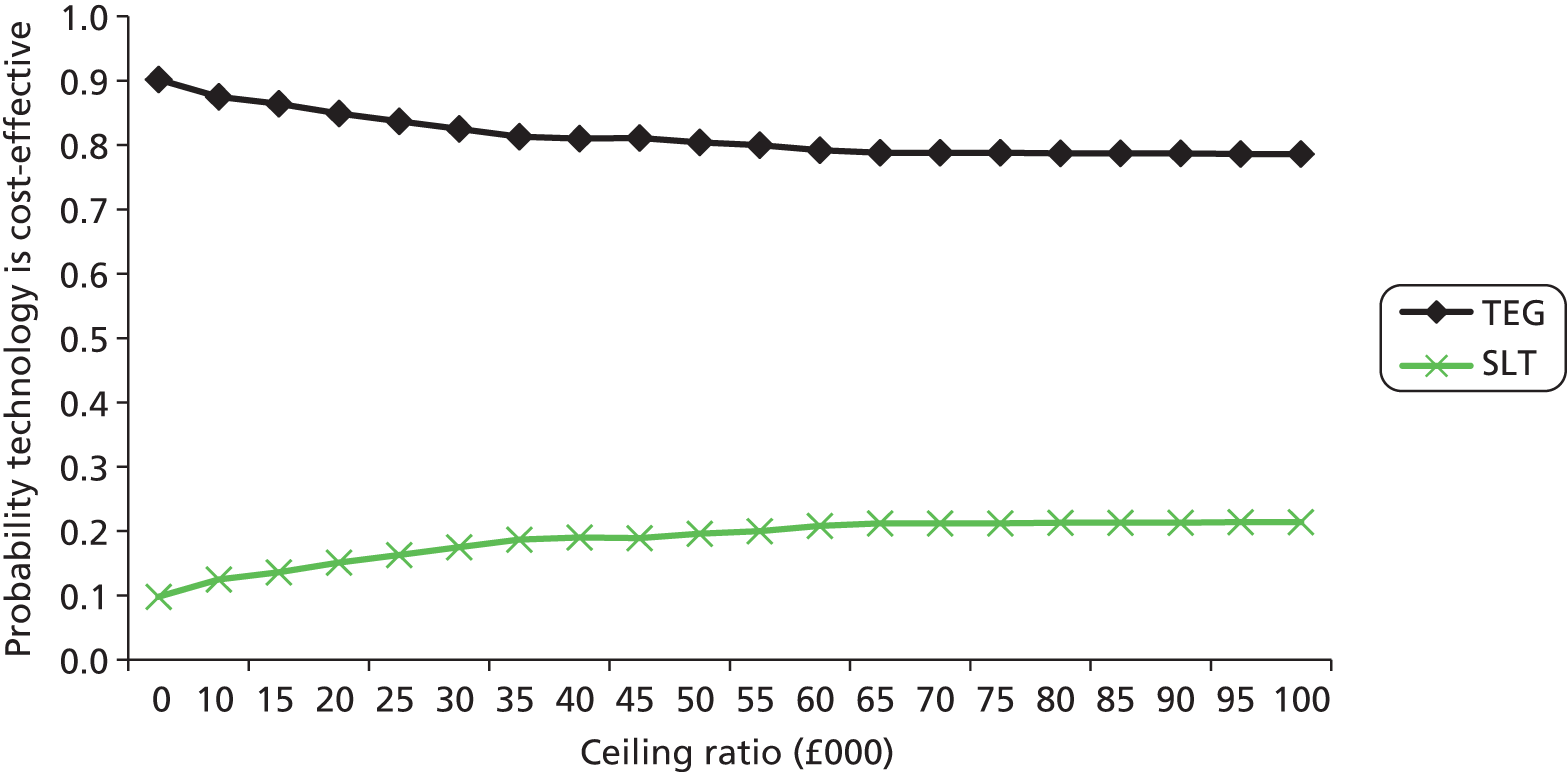

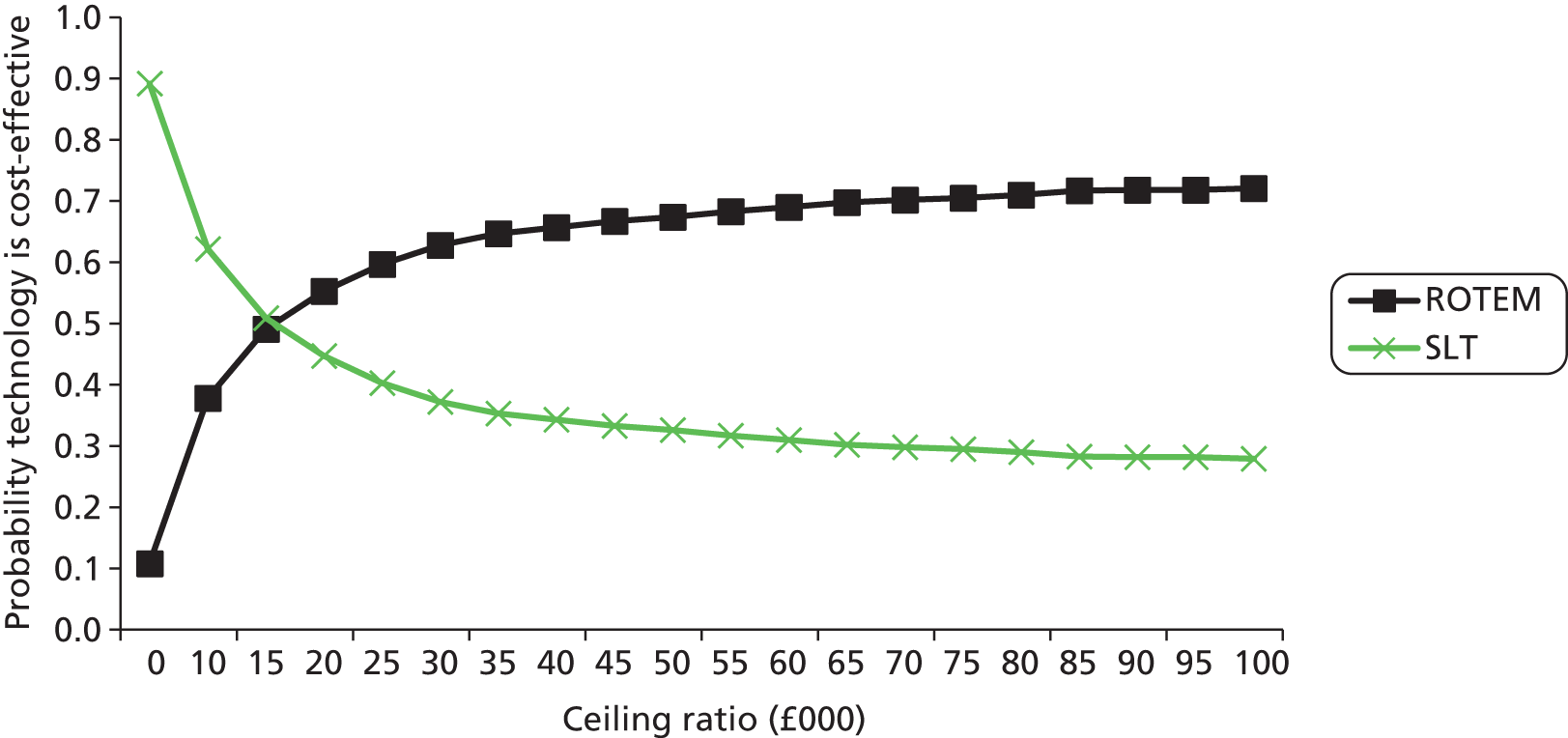

Six RCTs35,46,48,51,52,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received an RBC transfusion in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.88 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.96), suggesting a significant beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm in reducing the number of patients who received an RBC transfusion (Figure 8). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%). Summary estimates were similar when stratified according to VE device: RR 0.86 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.02) for the three RCTs that evaluated TEG46,48,51 and 0.88 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.00) for the three RCTs that evaluated ROTEM35,54 and ROTEG. 52

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results | p-value for difference between groupsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC transfusion (units unless otherwise stated) within 24–48 hours | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Median (IQR) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | 0.599 |

| Nuttall (2001);50 TEG | Median (range) | 2 (0–9) | 3 (0–70) | 0.039 |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999);51 TEG | Mean (SD) | 354 (487) ml | 475 (593) ml | 0.12 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Total | 14 | 33 | 0.12 |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 6 (2–13) | 9 (4–14) | 0.20 |

| Paniagua (2011);53 ROTEM | Mean | 3.8 | 6.4 | NR |

| Rauter (2007);55 ROTEM | Mean | 0.8 | 1.3 | < 0.05 |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 3 (2–6) | 5 (4–9) | < 0.001 |

| Any blood component transfusion (units) | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) | 0.001 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Total | 37 (NR) | 90 (NR) | NR |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 9 (2–30) | 16 (9–23) | 0.02 |

| FFP transfusion (units, unless stated) at 12–48 hours | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Median (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 0.001 |

| Nuttall (2001);50 TEG | Median (range) | 2 (0–10) | 4 (0–75) | 0.005 |

| Royston (2001);49 TEG | Total | 5 | 16 | < 0.05 |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999);51 TEG | Mean | 36 (142) ml | 217 (463) ml | < 0.04 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Total | 22 | 18 | NR |

| Kultufan Turan (2006);52 ROTEG | Mean (SD) | 2.80 (0.95) | 2.70 (1.46) | 0.403 |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 3 (0–12) | 8 (4–18) | 0.01 |

| Paniagua (2011);53 ROTEM | Total | 3.1 | 3.4 | NR |

| Rauter (2007);55 ROTEM | Total | 0 | 4 | NR |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | 5 (3–8) | < 0.001 |

| FIB (g) transfusion at 24–48 hours | ||||

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.70 |

| Rauter (2007);55 ROTEM | Total | 31 | 30 | NR |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 0.481 |

| Platelet transfusion (units, unless otherwise stated) transfusion at 12–48 hours | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Median (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 0.001 |

| Nuttall (2001);50 TEG | Median (range) | 6 (0–18) | 6 (0–144) | 0.0001 |

| Royston (2001);49 TEG | Total | 1 | 9 | < 0.05 |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999);51 TEG | Mean (SD) | 34 (94) ml | 83 (160) ml | 0.16 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Total | 5 | 15 | NR |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.70 |

| Paniagua (2011);53 ROTEM | Total | 0.50 | 1.57 | < 0.05 |

| Rauter (2007);55 ROTEM | Total | 0 | 0 | NR |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 2 (0–2) | 2 (0–5) | 0.010 |

| PCC (international units) transfusion at 24–48 hours | ||||

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 0 (0–2000) | 3000 (2000–3000) | < 0.001 |

| Rauter (2007);55 ROTEM | Total | 3000 | 13600 | NR |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 0 (0–1800) | 1200 (0–1800) | 0.155 |

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving RBC transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Any blood component transfusion

Three RCTs46,47,54 evaluated any blood component transfusion as a continuous outcome (see Table 9). All three46,47,54 reported less volume of any blood component transfusion in the VE algorithm group than in the control group. This was statistically significant in two (one ROTEM54 and one TEG46); the third RCT54 did not report on the statistical significance of the difference.

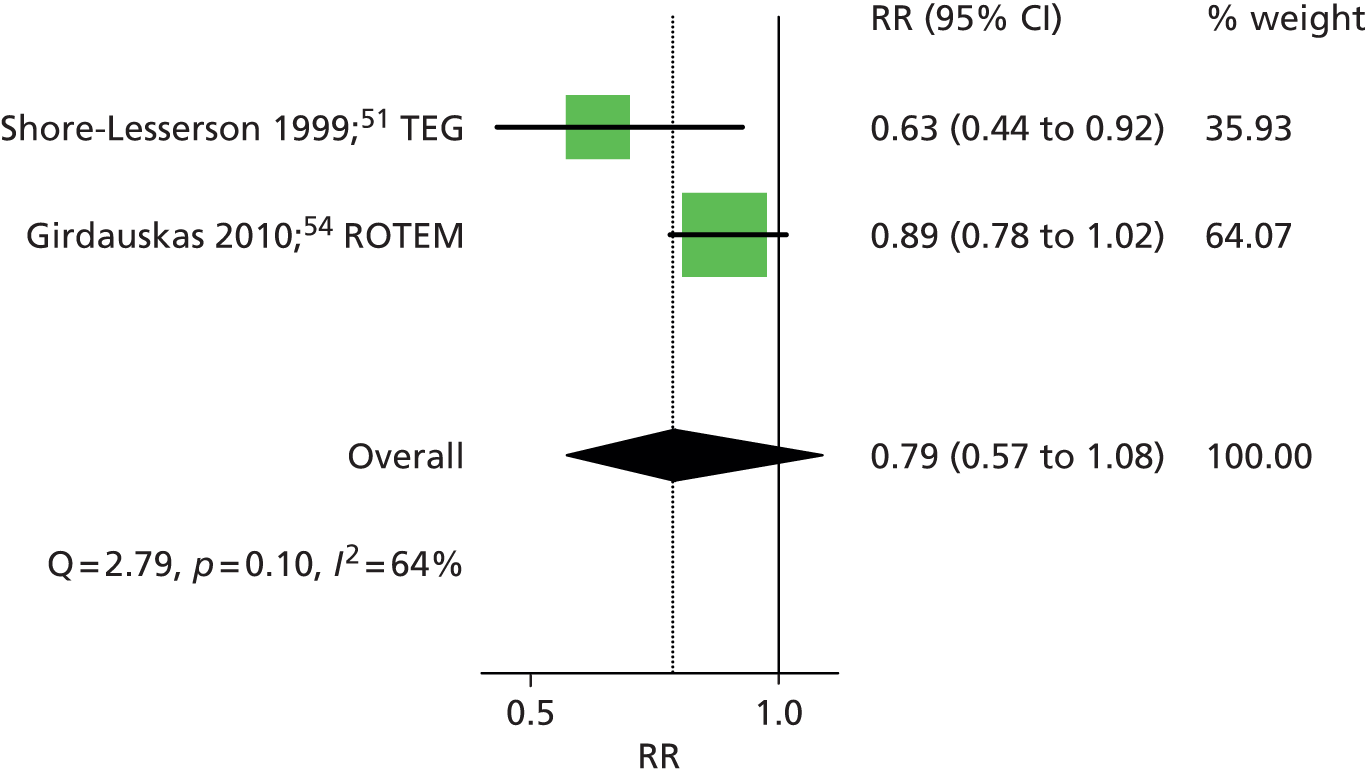

Two RCTs51,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received any blood component (defined as any blood component in one and allogeneic blood component in the other) transfusion in each intervention group. One54 assessed ROTEM (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.02) and the other51 assessed TEG (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.92). The summary RR was 0.79 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.08), suggesting a beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm in reducing the number of patients who received any blood component transfusion, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 9). There was some evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 64%).

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving any blood component transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Factor VIIa transfusion

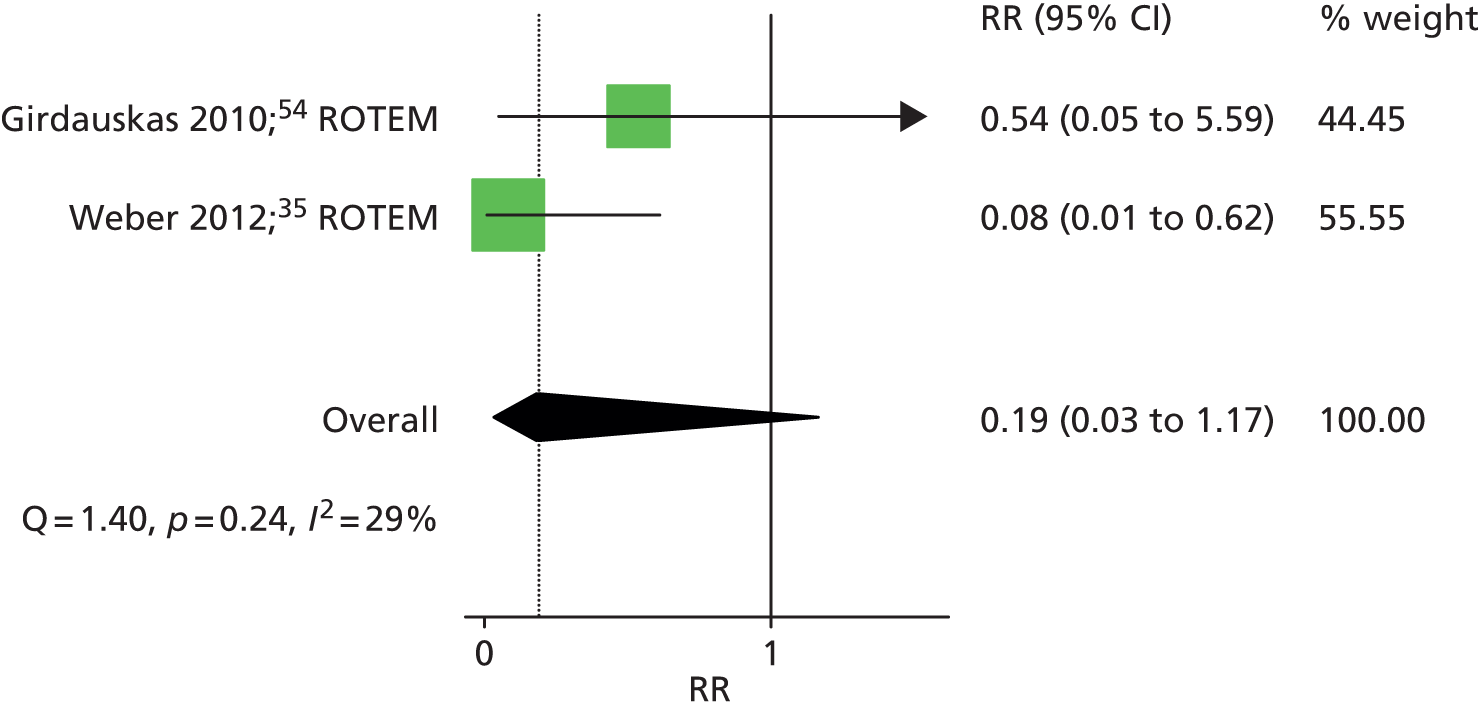

Two RCTs35,54 that assessed ROTEM provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received a factor VIIa transfusion in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.19 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.17), suggesting a beneficial effect of the ROTEM testing algorithm, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05) (Figure 10). There was little evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 29%).

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving any factor VIIa transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Fresh frozen plasmas transfusion

All of the included RCTs35,46–55 evaluated FFP transfusion as either a continuous or dichotomous outcome. Ten RCTs35,46,47,49–55 evaluated RBC transfusion within 24–48 hours as a continuous outcome (see Table 9). All but two RCTs47,52 reported less volume of FFP transfusion in the VE algorithm group than in the control group; this was statistically significant in six35,46,49–51,54 (two of ROTEM35,54 and four of TEG46,49–51); three RCTs47,53,55 did not report on the statistical significance of the difference.

Five RCTs35,46,48,51,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received an FFP transfusion in each intervention group, all but one48 of which also reported continuous data. The summary RR was 0.47 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.65), suggesting a significant beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm in reducing the number of patients who received an FFP transfusion (Figure 11). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%). However, the study by Avidan et al. 48 appeared to be an outlying result, with a RR of 5.0; however, the CI was very wide (95% CI 0.25 to 101.61). This was due to the very small number of events (two in the intervention arm and zero in the control arm). Removal of this study48 from the meta-analysis had very little impact on the summary estimate (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.61). Summary estimates were similar when stratified according to VE device: RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.20 to 1.35) for the three RCTs that evaluated TEG46,48,51 and 0.46 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.63) for the two RCTs35,54 that evaluated ROTEM.

FIGURE 11.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving FFP transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Fibrinogen transfusion

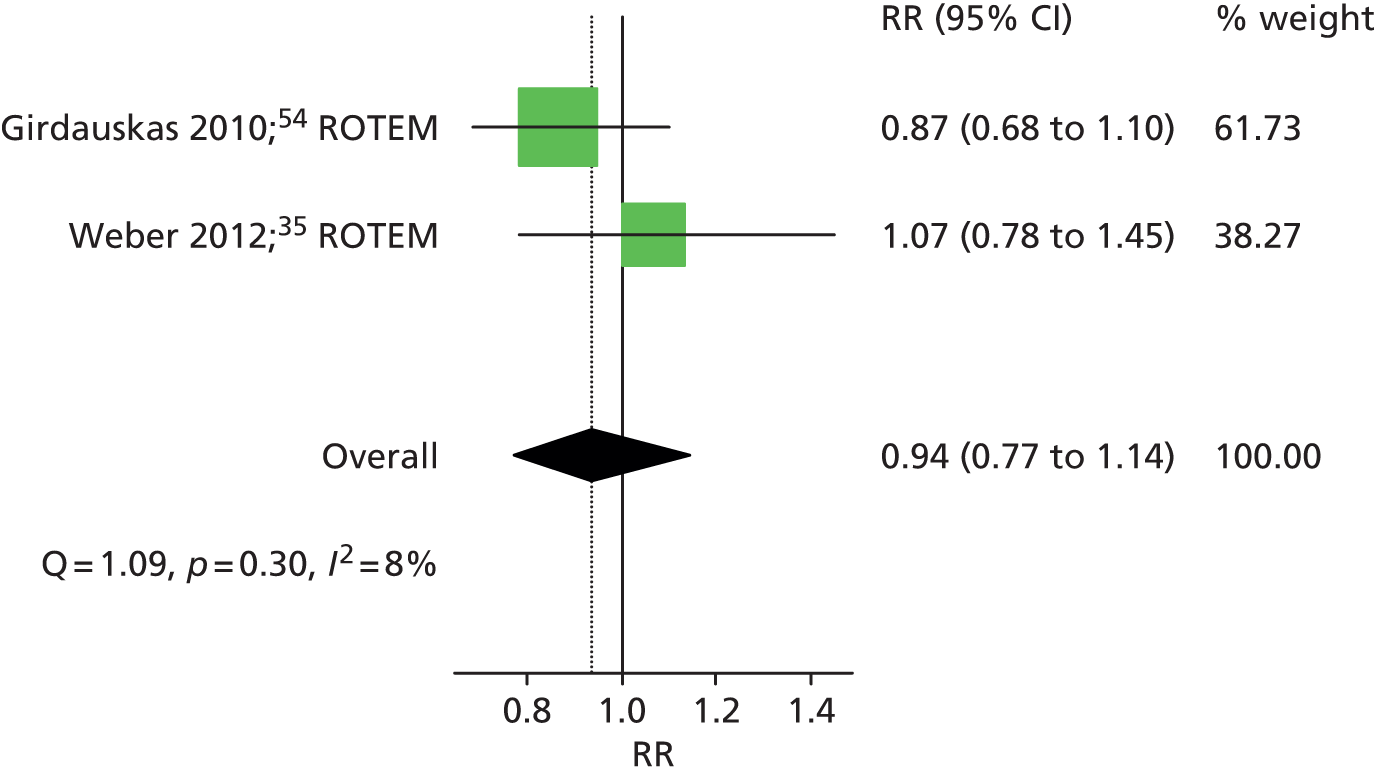

Three RCTs35,54,55 evaluated any FIB transfusion as a continuous outcome (see Table 9). All three35,54,55 reported no difference between the VE algorithm group compared with the control group in the volume of FIB transfused. Two of these RCTs35,54 also provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received a FIB transfusion in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.14), suggesting no difference between the treatment groups (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving FIB transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Platelet transfusion

All of the included RCTs35,46–55 evaluated platelet transfusion as either a continuous or dichotomous outcome. Nine RCTs35,46,47,49–51,53–55 evaluated platelet transfusion within 24–48 hours as a continuous outcome (see Table 9). All RCTs reported less volume of platelet transfusion in the VE algorithm group compared with the control group but this was statistically significant in only five RCTs35,46,49,50,54 (two of ROTEM35,54 and three of TEG46,49,50); two RCTs47,55 did not report on the statistical significance of the difference.

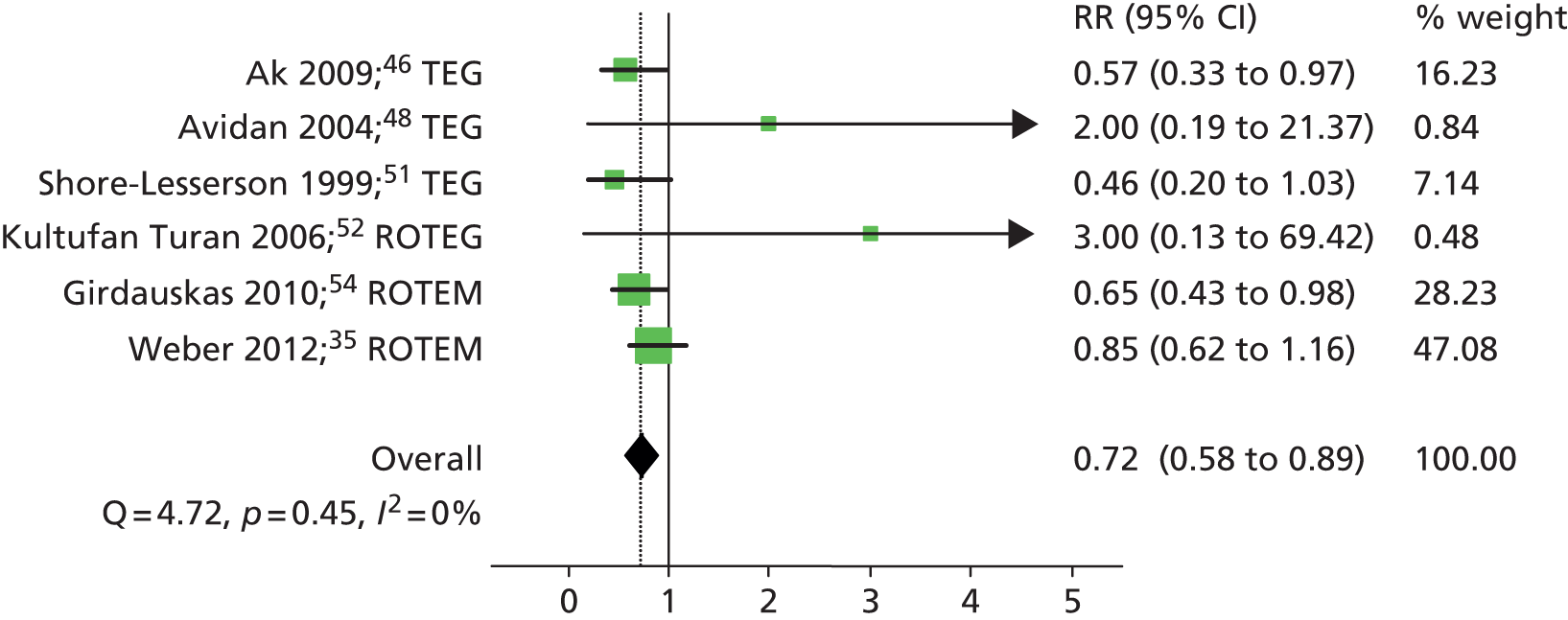

Six RCTs35,46,48,51,52,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received a platelet transfusion in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.72 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.89), suggesting a significant beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm in reducing the number of patients who received a platelet transfusion (Figure 13). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%). Summary estimates were similar when stratified according to VE device: RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.86) for the three RCTs46,48,51 that evaluated TEG and 0.78 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.00) for the three RCTs35,52,54 that evaluated ROTEM and ROTEG.

FIGURE 13.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving platelet transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Prothrombin complex concentrate transfusion

Three RCTs35,54,55 evaluated any PCC transfusion as a continuous outcome (see Table 9). All three RCTs35,54,55 reported less volume of PCC transfusion in the VE algorithm group than in the control group but this was statistically significant in only one RCT (p < 0.001);54 one RCT55 did not report on the statistical significance of the difference.

Two of these RCTs35,54 also provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who received a PCC transfusion in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.39 (95% CI 0.08 to 1.95), suggesting no difference between the treatment groups (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients receiving PCC transfusion in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Bleeding

Nine RCTs35,46–52,54 evaluated bleeding, generally measured as mediastinal tube drainage, as a continuous outcome (Table 10). The majority reported less bleeding in the VE intervention group; however, only two studies35,50 reported a statistically significant difference in bleeding between the two groups.

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results | p-value for difference between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding/mediastinal tub drainage (ml) at 12-/24-hour follow-up | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Mean (SD) | 480.5 (351.0) | 591.4 (339.2) | 0.087 |

| Avidan (2004);48 TEG | Median (IQR) | 755 (606–975) | 850 (688–1095) | > 0.05 |

| Nuttall (2001);50 TEG | Median (range) | 590 (240–2335) | 850 (290–10,190) | 0.019 |

| Royston (2001);49 TEG | Median (IQR) | 470 (295–820) | 390 (240–820) | NR |

| Shore-Lesserson (1999);51 TEG | Mean (SD) | 702 (500) | 901 (847) | 0.27 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Median (IQR) | 875 (755–1130) | 960 (820–1200) | 0.437 |

| Kultufan Turan (2006);52 ROTEG | Mean (SD) | 837.5 (494.1) | 711.10 (489.2) | 0.581 |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 890 (600–1250) | 950 (650–1400) | 0.50 |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 600 (263–875) | 900 (600–1288) | 0.021 |

| Length of ICU stay (hours) | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Mean (SD) | 23.3 (5.7) | 25.3 (11.2) | 0.099 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Median (IQR) | 29.4 (14.3–56.4) | 32.5 (22.0–74.5) | 0.369 |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Mean (SD) | 175.2 (218.4) | 194.4 (201.6) | 0.6 |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 21 (18–31) | 24 (20–87) | 0.019 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | ||||

| Ak (2009);46 TEG | Mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.4) | 0.552 |

| Westbrook (2009);47 TEG | Median (IQR) | 9 (7–13) | 8 (7–12) | > 0.05 |

| Girdauskas (2010);54 ROTEM | Mean (SD) | 16.6 (16.4) | 17.0 (14.8) | 0.80 |

| Weber (2012);35 ROTEM | Median (IQR) | 12 (9–22) | 12 (9–23) | 0.718 |

Re-operation

Seven RCTs35,46,48–51,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients who required re-operation to investigate bleeding in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.72 (95% CI 0.41 to 1.26), suggesting a beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm in reducing the number of patients requiring re-operation, however, this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 15). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%). Summary estimates were similar when stratified according to VE device: RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.83) for the five RCTs46,48–51 that evaluated TEG and 0.69 (95% CI 0.33 to 1.44) for the two RCTs35,54 that evaluated ROTEM.

FIGURE 15.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients requiring re-operation in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Surgical source of bleeding identified on re-operation

Four RCTs46,50,51,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of patients in whom a surgical source of bleeding was identified on re-operation in each intervention group. The summary RR was 1.04 (95% CI 0.42 to 2.57), suggesting no difference between the intervention groups (Figure 16). There was very little evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 3%). One RCT assessed ROTEM54 and reported a RR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.26 to 2.87); the summary estimate for the three RCTs assessing TEG50,51,54 was similar at 0.99 (95% CI 0.18 to 5.36).

FIGURE 16.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of patients in whom a surgical source of bleeding was identified on re-operation in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Length of intensive care unit stay

Four RCTs35,46,47,54 evaluated the length of ICU stay as a continuous outcome (see Table 10). All studies35,46,47,54 reported shorter stays in the VE group than in the control group but this difference was statistically significant in only one study. 35

Length of hospital stay

Four RCTs35,46,47,54 evaluated the length of hospital stay as a continuous outcome (see Table 10). All studies35,46,47,54 reported that durations of stay were similar in the two treatment groups; none reported a statistically significant difference between groups.

Adverse events

One study35 reported on adverse events, including acute renal failure, sepsis and thrombotic complications. All were reduced in the ROTEM group compared with SLTs but differences were not statistically significant for individual outcomes. When the compound outcome of any adverse event was considered this was found to be significantly reduced in the ROTEM group compared with SLTs (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.57).

Mortality

Four RCTs46,49,51,54 provided dichotomous data on the number of deaths (within 24 hours,51 48 hours,49 in hospital54 or ‘early mortality’46) in each intervention group. The summary RR was 0.87 (95% CI 0.35 to 2.18), suggesting no difference between the intervention groups (Figure 17). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%). One RCT assessed ROTEM54 and reported a RR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.26 to 2.87); the summary estimate for the three RCTs46,49,51 assessing TEG was similar at 0.88 (95% CI 0.21 to 3.66). An additional RCT35 provided data on 6-month mortality. This study35 reported significantly reduced mortality in the VE testing group at 6 months compared with the SLT group (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.87).

FIGURE 17.

Forest plot showing RRs (95% CI) for number of deaths in VE groups compared with control groups in cardiac patients.

Other reported outcomes

Data were also reported on the following outcomes but each were assessed in only one or two studies, and so are not discussed in detail here: cryoprecipitate use, desmopressin treatment, dialysis-dependent renal failure, duration of ventilation, factor VIIa, fresh blood transfusion, intubation time, need for additional protamine, non-RBC balance, post-operative confusion, reinfusion, reintubation, stroke, time to stop bleeding, total heparin dose, total protamine dose, total ventilation time, time to extubation and tranexamic acid use. Full results can be found in Appendix 2.

Summary

Pooled estimates from each of the meta-analyses are summarised in Table 11. Overall, there was a significant reduction in RBC transfusion, platelet transfusion and FFP transfusion in VE testing groups compared with control. There was no significant difference between groups in terms of any blood component transfusion, factor VIIa transfusion or PCC transfusion, although data suggested a beneficial effect of the VE testing algorithm but these outcomes were evaluated in only two studies. There was no difference between groups in terms of FIB transfusion. Continuous data on blood component/product use, although inconsistently reported across studies, supported these findings; the only blood component/product that was not associated with a reduced volume of use in the VE testing group was FIB. There was a suggestion that bleeding was reduced in the VE testing groups but this was statistically significant in only two of the nine RCTs that evaluated this outcome. Clinical outcomes (re-operation, surgical cause of bleed on re-operation and mortality) did not differ between groups. There was some evidence of reduced bleeding and ICU stay in the VE testing groups compared with control but this was not consistently reported across studies. There was no difference in length of hospital stay between groups. There was no apparent difference between ROTEM or TEG for any of the outcomes evaluated.

| Outcome | Summary RR (95% CI) | No. of studies | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood component/product use | |||

| RBC transfusion | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.96) | 6 | Q = 4.47, p = 0.48, I2 = 0% |

| Any blood component transfusion | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.08) | 2 | Q = 2.79, p = 0.10, I2 = 64% |

| Platelet transfusion | 0.72 (0.58 to 0.89) | 6 | Q = 4.47, p = 0.48, I2 = 0% |

| FFP transfusion | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.65) | 5 | Q = 4.72, p = 0.45, I2 = 0% |

| Factor VIIa transfusion | 0.19 (0.03 to 1.17) | 2 | Q = 1.40, p = 0.24, I2 = 29% |

| FIB transfusion | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.14) | 2 | Q = 1.09, p = 0.30, I2 = 8% |

| PCC transfusion | 0.39 (0.08 to 1.95) | 2 | Q = 10.23, p = 0.00, I2 = 90% |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| Re-operation | 0.72 (0.41 to 1.26) | 7 | Q = 3.49, p = 0.74, I2 = 0% |

| Surgical cause of bleed on re-operation | 1.04 (0.42 to 2.57) | 4 | Q = 3.09, p = 0.38, I2 = 3% |

| Mortality | 0.87 (0.35 to 2.18) | 4 | Q = 1.26, p = 0.74, I2 = 0% |

How well do viscoelastic devices predict relevant clinical outcomes during or after cardiac surgery?

As none of the RCTs evaluated the Sonoclot VE test, we included lower levels of evidence for this device. Three prediction studies58–60 that evaluated Sonoclot were included in the review; two of these studies59,60 also evaluated TEG and so provided a direct comparison between these two devices. Baseline data from these studies are summarised in Table 12; full details of the studies are provided in Appendix 2.

| Study details | n | Patient category | Entry restricted to excessive bleeding? | Entry restriction based on anticoagulation? | VE test | Conventional tests | Outcome/reference standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aBischof (2009)58 | 300 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | Yes – no anticoagulant medication | Sonoclot | None | Bleeding > 800 ml 4 hours after surgery |

| Nuttall (1997)59 | 82 | Mixed cardiac surgery | No | No | Sonoclot, TEG | Bleeding time, platelet MPV, plasma FIB concentration, PLT, PT, aPTT, platelet HCT | Bleeding; subjective evaluation by anaesthesiologist and surgeon 10 minutes after protamine administration |

| Tuman (1989)60 | 42 | Mixed cardiac patients | High risk for transfusion procedures | Yes – no anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications 7 days before surgery | Sonoclot, TEG | ACT, PT, PTT, PLT and FIB | Bleeding; chest tube drainage greater than 150 ml/hour for 2 consecutive hours or > 300 ml/hour in 1 hour during the first 8 hours after surgery |

Study details

The cardiac prediction studies were conducted in Switzerland and the USA. All included patients undergoing mixed cardiac surgery irrespective of whether or not they had a bleeding event. One study58 excluded patients with a known coagulopathy and another excluded patients with abnormal pre-operative coagulation studies;60 both of these studies58,60 excluded patients receiving anticoagulant medication and one study60 also excluded patients on antiplatelet medications. Mean or median age, where reported, ranged from 63 to 65 years. The proportion of men ranged from 61% to 69%.