Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/91/36. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in March 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Aveyard has done ad hoc consultancy and research for the pharmaceutical industry on smoking cessation.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Blyth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and objectives

Smoking remains the leading preventable cause of premature deaths in the world. 1 Cigarette smokers lose about 10 years of lifespan compared with people who never smoke, although the risk of excess mortality can be considerably reduced by stopping smoking. 2 It is estimated that tobacco use was responsible for about 100 million deaths globally in the 20th century,3 and it kills about 6 million people each year in the 21st century. 1

Among adults (aged ≥ 16 years) in England, the prevalence of smoking was 20% in 2010, which was considerably lower than in 2000 (27%), and much lower than in 1980 (39%). 4,5 Two-thirds of current smokers in England report wanting to quit smoking and three-quarters have tried to do so in the past. Compared with many other countries, the percentage of former smokers among ever-smokers (former or current) in adults is relatively high in England, about 57% for men and 51% for women. 4–6

Pharmacotherapy and behavioural support are effective in helping motivated smokers to stop smoking,7–10 although relapse rates following these interventions are high. 11 Since 2001, a national network of NHS Stop Smoking Services has been established in England to provide behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to smokers who would like to quit. The English Stop Smoking Services were overseen by primary care trusts until April 2013, and have been overseen by local authorities since then. In 2010/11, 787,527 people (8% of all smokers) used NHS Stop Smoking Services, which generated 269,293 biochemically validated quitters (34% of those who set a quit date) at 4 weeks after the quit date. 12 However, about 75% of 4-week quitters go back to regular smoking after between 4 and 52 weeks. 13 The long-term success rates still make these interventions highly cost-effective14 but there is a need to find effective interventions to reduce relapse rates after the initial treatment episode.

Interventions for smoking relapse prevention

Interventions for smoking relapse prevention are generally based on the cognitive–behavioural approach to coping skills training15 and may be considered as complex health-care interventions with multiple interacting components. 16,17 For the development and evaluation of complex interventions, we need a good theoretical understanding about how the intervention causes change. 17 With the coping skill training approach, quitters are trained to anticipate situations associated with high risks of smoking relapse (such as going out with friends or feeling frustrated), and to develop skills to cope with such situations and urges to smoke again. Therefore, the effectiveness of coping skills training for relapse prevention will depend on (1) the delivery and receipt of interventions, (2) the acquiring of coping skills by quitters and (3) the use of such skills in high-risk situations. To benefit from coping skills training, quitters need to learn, practise and implement coping skills when required. 18

A Cochrane systematic review of trials of smoking relapse prevention found insufficient evidence to support the use of any specific intervention for preventing smoking relapse in short-term quitters. 19 The current smoking cessation guidelines do not recommend any specific interventions for smoking relapse prevention. 20,21 According to findings from a survey of smoking cessation professionals, the uncertain evidence base about effectiveness was an important barrier to the use of relapse prevention interventions in stop smoking practice. 22

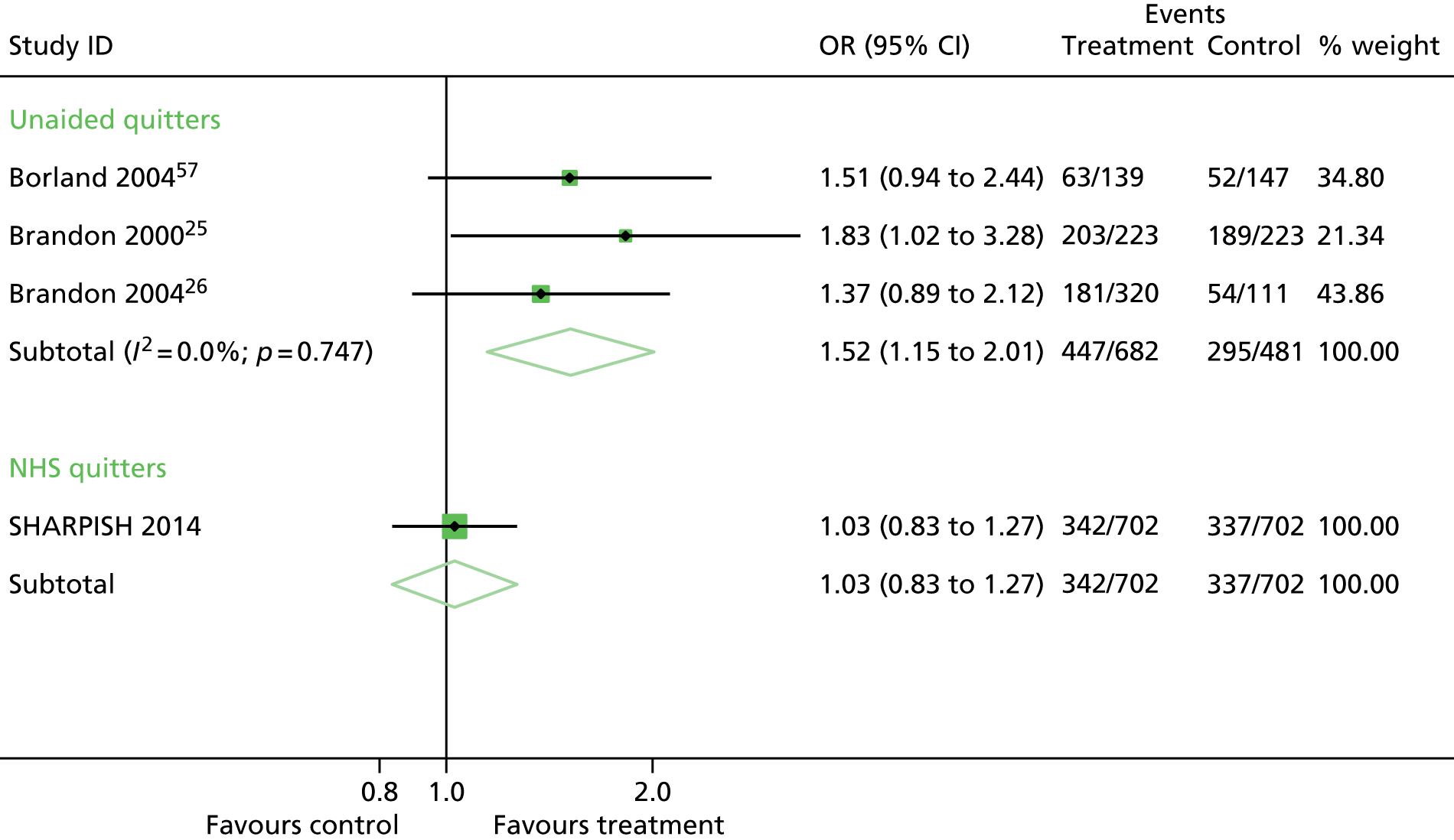

We conducted an exploratory meta-analysis in 2009 using data from 49 trials on psychoeducational interventions for smoking relapse prevention. 23 The meta-analysis showed that coping skills training interventions significantly reduced smoking relapse in community quitters who had stopped smoking for at least 1 week at baseline [odds ratio (OR) 1.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.14 to 1.81], although it was ineffective for current smokers, pregnant or postpartum quitters, hospitalised ex-smokers, forced short-term quitters and smokers with mental illness or drug abusers. 23 Therefore, it seemed that coping skills training may be effective in secured quitters who are highly motivated to remain abstinent. In addition, available evidence indicated that self-help educational materials may be as effective as interventions based on individual or group counselling for smoking relapse prevention. The pooled OR of relapse prevention associated with coping skills training was 1.46 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.05) for self-help material trials and 1.41 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.94) for counselling trials. 23 A systematic review conducted by an independent team also found that written self-help materials were efficacious for preventing smoking relapse in unaided quitters. 24

Forever Free booklets

Brandon and colleagues developed a series of eight booklets to be used as self-help materials for smoking relapse prevention and have evaluated the booklets in two randomised controlled trials in the USA. 25,26 Volunteers who had quit smoking unaided were randomised to receive either all eight booklets or only the introductory booklet. Participants who received all eight booklets had a lower rate of smoking relapse than participants who received only a single booklet (the introduction booklet). One of the two randomised studies of Forever Free booklets found that repeated mailing (high contact) was no more effective than massed mailing (low contact) of the eight booklets. 26 It has been suggested that the true effectiveness of Forever Free booklets might have been underestimated because participants in the control group received the introduction booklet that provided a summary of all relevant skills. The use of the Forever Free booklets for smoking relapse prevention was likely to be highly cost-effective [US$83–US$160 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained]. 26

Objective

Existing trials on coping skills training for smoking relapse prevention in community quitters recruited unaided quitters mainly by advertisement in newspapers and were mostly conducted in the USA. It is uncertain whether or not the results of meta-analysis23 and randomised controlled studies in the USA25,26 are generalisable to 4-week quitters who used the NHS Stop Smoking Services. A Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report recommended further research on the effectiveness of self-help interventions for smoking relapse prevention. 27

The objective of this randomised controlled study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-help materials (Forever Free booklets) in preventing smoking relapse in 4-week quitters who have used NHS Stop Smoking Services.

Chapter 2 Methods and design

The study design was a parallel-arm pragmatic individually randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of self-help educational material (Forever Free booklets) in preventing smoking relapse, compared with a smoking cessation booklet used currently. The trial protocol was published in an open access journal. 28

This was an open trial, without attempts to blind investigators and patients after randomisation. Because the outcome assessor and trial participants know the allocated intervention, bias may be introduced into the results. However, evidence suggested that the risk of bias may be much reduced in trials with objectively assessed outcomes. 29 In this trial, the primary outcome was biochemically verified abstinence at 12 months, which can be considered an objectively assessed outcome.

Setting

We planned to recruit 4-week quitters in NHS Stop Smoking Clinics in Norfolk, using specialist stop smoking advisors (these are specially trained stop smoking advisors who work exclusively in delivering smoking cessation advice and support). In comparison with all of England, Norfolk has a relatively high percentage of people aged 65 years and above (21.4% vs. 16.5% in 2010) and has a higher percentage of European white people (94.3% vs. 87.5% in 2009). Of those who set a quit date in 2010/11, the percentage of self-reported successful quitters was 52%, compared with an average of 49% in England. 30

After 7 months of recruitment, the number of participants recruited was under target and it was clear that we would not be able to achieve the study recruitment target from the specialist advisors in Norfolk alone. Consequently, recruitment was extended to include level 2 advisors (these are health-care professionals such as pharmacists, practice nurses or health-care assistants who are also trained in administering smoking cessation advice and support) in general practice and/or community pharmacies in Norfolk that had recruited 12 or more carbon monoxide (CO)-verified quitters in 2010/11. Participant recruitment was later further extended to include 4-week quitters from Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Lincolnshire, and Great Yarmouth and Waveney.

The investigated self-help educational materials were posted to trial participants for their use at home. At the final follow-up (12 months after quit date), participants who reported that they had not smoked during the previous 7 days were invited to have a breath CO test to confirm the self-reported status of non-smoking. The test was carried out by a researcher from the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich. Study participants came to a clinic at the UEA, or a researcher visited them at home for this test.

Participant recruitment

Smokers who are motivated to quit are referred to the NHS Stop Smoking Clinics from various sources, such as by general practitioners (GPs), or are self-referred. Clients who contact the Stop Smoking Service are given an appointment for assessment with a stop smoking advisor, either individually or in group sessions. Following assessment, the client typically receives weekly behavioural support, focused on withdrawal-oriented therapy, with medication to reduce craving and withdrawal. The total contact time for each client is at least 1.5 hours from pre-quit preparation to 4 weeks after quitting. The self-reported abstinence at 4 weeks after the quit date is about 50%, and the biochemically verified abstinence ranges from 31% to 36%. 12 However, most (75%) self-reported 4-week quitters will relapse by 12 months. 13

The target population for this trial was CO-verified, 4-week quitters treated in NHS Stop Smoking Clinics who can read English and could give informed consent. According to NHS Stop Smoking Services guidance,31 the biochemically verified 4-week quitter is defined as ‘a treated smoker whose CO reading is assessed 28 days from their quit date (–3 or +14 days) and whose CO reading is less than 10 ppm (parts per million)’. That is, a face-to-face follow-up interview should be normally conducted 4 weeks from the quit date. Where a follow-up at 4 weeks is impossible, it should be conducted 25–42 days after the quit date (the Russell Standard). 31

Inclusion criteria

-

Carbon monoxide-verified 4-week quitters in the NHS Stop Smoking Service clinic who sign the consent form were eligible to participate in the trial.

Exclusion criteria

-

Pregnant quitters were excluded. The process of relapse in pregnant women is very different from non-pregnant smokers. According to the available research evidence,23 smoking relapse prevention intervention by coping skills training is ineffective for women who have stopped smoking during pregnancy.

-

We excluded quitters who were not able to read the educational material in English because the revised booklets are available in English only.

-

We excluded quitters from families at the same address, as a family member has already been included in the trial.

-

Quitters younger than 18 years were not included.

Training of stop smoking advisors for participant recruitment

For participant recruitment, stop smoking advisors introduced the study, gained consent for participation from their clients and collected baseline data. For this role, they received a half-day’s training. This consisted of:

-

outline of study, including flow diagram

-

baseline questionnaire, including group activity: completing baseline questionnaire

-

informed consent

-

spot the mistakes: demonstration by co-ordinators of how not to consent participation

-

group activity role-play: undertaking informed consent

-

distribution of study materials.

The recruitment period was 24 months, so it was important to sustain the recruiters’ interest for the duration of this period and engender their ownership of the project. Consequently, training continued throughout the whole study. Co-ordinators regularly attended the stop smoking advisors’ team meetings, where ongoing training was given to reinforce the study procedures, along with reporting of study updates. In addition, two evening refresher sessions were held, which consisted of:

-

smoking cessation research evidence

-

study updates

-

role-play demonstrating recruitment techniques

-

quiz about targeted study procedures

-

opportunity for suggestions from recruiters about how to optimise recruitment.

When recruitment was extended to include level 2 advisors, and other counties, initial training was delivered by the co-ordinators to small groups or one to one; sometimes this was then cascaded down to other advisors at the recruitment sites. All recruiters signed a training record on completion of the initial training.

Trial procedures and randomisation

Stop smoking advisors completed a study screening form for each of their clients, and introduced the study to them, by giving them a participant information sheet, containing information on the trial. Then, at the final session in the Stop Smoking Clinic (4-week post quit, when all self-reported quitters undergo a breath CO test), the advisor again explained the nature of the trial to CO-verified quitters only, answered questions from them, and invited them to participate in the trial by signing the consent form. Clients who had failed to quit were not invited to participate in the study.

After eligible quitters had signed the consent form, stop smoking advisors asked participants to complete the baseline questionnaire, which they sent to the trial co-ordinator at the UEA, along with the screening form and a copy of the consent form. On receipt of these documents, the trial co-ordinator or trial administrator randomly allocated participants to two groups (the treatment and control group), using a computerised allocation system provided by the Norwich Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). We adopted a simple randomisation process, without attempts to stratify by participant characteristics. This allocation of trial participants was concealed because the recruitment of quitters occurred before the random allocation.

As it was necessary to avoid possible information contamination across the trial arms and non-independence between members of the same family or household, we screened all eligible participants and checked their address against recruited participants to ensure that no two people from the same household were recruited. Where two people of the same family or household were found eligible and willing to participate at the same time, we randomly selected only one of them to participate in the trial. If the members of the same family used the NHS Stop Smoking Service at different times during the trial recruitment period, we included only the first family member.

We expected that many people would make repeated attempts to quit using the Stop Smoking Service during the trial period, so, to ensure that clients participated in the study only once, stop smoking advisors checked if the ‘new’ quitter had already been included in the trial. In addition, the trial co-ordinators and/or administrator also checked this to make sure a quitter was not already recruited onto the study.

Interventions investigated

The experimental intervention tested in the trial was the full pack of eight Forever Free booklets. Findings from an exploratory meta-analysis suggested that coping skills training may be effective for smoking relapse prevention in motivated quitters. 23 The results of two clinical trials in the USA suggested that a cheap intervention using Forever Free booklets25,26 may be as effective as more expensive counselling for coping skills training. Forever Free booklets include a series of eight booklets (Table 1). Booklet 1 (with 17 pages) is a brief summary of all relevant issues, including an introduction of nicotine dependence, the stages of smoking cessation, situations that are high risk for relapse, ways of coping with urges to smoke, the abstinence violation effect and ways to handle an initial slip. The remaining seven booklets provide more extensive information on important issues for relapse prevention, entitled Smoking Urges; Smoking and Weight; What if You Have a Cigarette?; Your Health; Smoking, Stress, and Mood; Lifestyle Balance; and Life without Cigarettes. The booklets can be understood by people with a reading level of fifth to sixth grade in the USA (expected reading level for children aged 10–12 years).

| Material | Contents (booklets) or headings (leaflet) |

|---|---|

| Experimental intervention: Forever Free: A Guide to Remaining Smoke Free | |

| Booklet 1: An Overview (16 pages) | About Forever Free; Seven facts about smoking and quitting; The stages of quitting; ‘Risky’ situations for ex-smokers; How to handle urges to smoke; A non-smoking lifestyle; What if you DO smoke; The most important messages |

| Booklet 2: Smoking Urges (11 pages) | What are urges?; Different types of urges; How to deal with urges to smoke; When will the urges end?; Exercises; Remember . . . ; Notes |

| Booklet 3: Smoking and Weight (15 pages) | Why a booklet on weight control after quitting?; Who gains weight?; Why do ex-smokers gain weight?; Do I have to gain weight?; Effects of smoking and weight gain on health and looks; Weight control after quitting; Exercise; Make exercise part of your day; Summary |

| Booklet 4: What if I Have a Cigarette? (7 pages) | Can’t I have just one cigarette? Be prepared for a slip; Watch out for the effects of a slip; Keep a slip from turning into a full relapse; Summary |

| Booklet 5: Your Health (11 pages) | Why this booklet?; How harmful is smoking?; What makes smoking so harmful?; What happens when you quit smoking?; Quitting smoking helps others, too; How can this information help you stay quit?; If you are smoking again |

| Booklet 6: Smoking, Stress and Mood (11 pages) | What causes stress?; What is stress?; How is stress related to smoking?; What leads up to a cigarette; So, why not smoke when stressed?; Better ways to deal with stress and negative moods |

| Booklet 7: Lifestyle Balance (15 pages) | Stress; ‘Shoulds’ versus ‘Wants’; Your daily hassles; Your ‘Shoulds’; Your ‘Wants’; Positive addictions; Summary; Pleasant events list |

| Booklet 8: Life without Cigarettes (11 pages) | Urges; Benefits of quitting; But what about my weight; If you do smoke; In closing |

| Control leaflet: Learning to Stay Stopped | |

| Learning to Stay Stopped (including covers, eight pages; recommended 10 minutes to read through) | Congratulations on stopping smoking!; Learning to stay stopped; Nicotine withdrawal; Psychological dependence; Having doubts about quitting?; Constantly thinking about smoking?; Worried about weight gain?; Bored with quitting?; Over reacting to things?; Strong cravings?; Tempting triggers?; Tired of dealing with triggers?; Smoked a cigarette? (Note: provided a short list about ‘What you can do!’ following each of the above problems) |

The original Forever Free Booklets were prepared for users in the USA. We revised and updated the booklets in places where it was judged necessary or helpful, to make the material more suitable to British users and the UK NHS. We obtained permission from the copyright holders (H Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA). Members of the Trial Steering Committee, and of the project team and three lay representatives reviewed and commented on the revised booklets. During their modification, we ensured the acceptability and understanding of the booklets to as wide a range of users as possible. The revised booklets are currently available only in English because of the considerable cost implications of translating the booklets into other languages.

After randomisation, the research team sent the corresponding self-help material by post to participants’ homes. Participants in the intervention group received a letter and all eight Forever Free booklets, which were posted by normal delivery. The first 10 intervention packages were posted by special delivery to confirm that the booklets could be posted through participants’ letter boxes; no delivery was returned, confirming that the booklets were successfully delivered. Participants in the control group received a letter and a booklet about smoking cessation, Learning to Stay Stopped. 32 The leaflet (with eight pages in total) used in the control group contains brief but comprehensive information on issues related to smoking relapse and also provides brief recommendations on how to cope with cravings and tempting triggers (see Table 1). It is commonly used in NHS Stop Smoking Services.

Sample size calculation

Without smoking relapse prevention, about 75% of CO-validated 4-week quitters would go back to regular smoking between 4 and 52 weeks. 13 An exploratory meta-analysis indicated that coping skills training interventions may reduce smoking relapse in community quitters who had stopped smoking for at least 1 week (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.81). 23 Therefore, the abstinence rate of 4-week quitters at 12 months was estimated to be 25.0% in the control and 32.4% in the intervention group (based on an OR of 1.44). Assuming α = 0.05 (type 1 error) and 1 – β = 0.8 (statistical power), about 590 participants were required in each arm. 33 Assuming a dropout rate of 15%, about 700 participants were required in each arm (1400 in total).

Outcomes and data collection

At the session about 4 weeks (or 25–42 days)31 after the quit date, stop smoking advisors gathered baseline information from participants who had consented to participate in the trial. The information collected included participants’ demographic characteristics, smoking and quitting history, and level of determination and confidence to remain abstinent.

The specified primary outcome was prolonged, CO-verified smoking abstinence from months 4 to 12, with no more than five cigarettes being smoked during this period. This is in keeping with the consensus statement of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, and the Russell Standard. 34,35 The usual definition of prolonged abstinence allows a 2-week grace period following quit day, in which lapses do not invalidate abstinence, to assess the outcome of aid to cessation trials. However, a relapse prevention intervention might prevent lapses (occasional smoking) becoming relapses (regular smoking and abandonment of the attempt to keep abstinent). Therefore, we used a 2-month grace period during which lapses to smoking do not count against achieving abstinence. As participants on enrolment were abstinent at 4 weeks after quit date, this equated to the primary outcome being prolonged abstinence from 4 months to 12 months after quit date. Following the Russell Standard, the primary outcome was prolonged abstinence from months 4 to 12, with smoking of no more than five cigarettes in total, and confirmed by CO < 10 p.p.m. at the 12-month follow-up.

The secondary outcomes were 7-day self-report abstinence at 3 months, 7-day self-report and CO-validated abstinence at 12 months post quit date. We did not specify continuous abstinence from 2 to 12 months post quit date as a secondary outcome in the trial protocol. Because continuous abstinence from 2 to 12 months was used in previous studies, we added it as an outcome measure in the stage of data analysis, in order to compare results between different studies. The continuous abstinence was defined as CO-verified smoking abstinence at 12 months and no more than five cigarettes from 2 to 12 months after the quit date.

We assessed cost-effectiveness from an NHS perspective. We collected data on the resource use associated with self-help materials (including intellectual property, adaptation, printing and postage), any additional Stop Smoking Services and cessation products at follow-up interviews. Our hypothesis was that the intervention, if effective, would improve abstinence rates, would reduce repeated use of Stop Smoking Services and might reduce use of other health care. Other resources which might be affected by the intervention were also monitored, including GP visits and hospital admissions. The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L)36 was used to estimate the benefits in terms of the QALY gain associated with each intervention during the study period.

Study participants were followed up by a researcher from the UEA 2 months after recruitment (which was 3 months after quit date) and again 11 months following recruitment (12 months after quit date). The follow-up interviews were conducted by phone and involved the researcher administering a questionnaire which asked questions about the participant’s smoking status, process variables and the use of stop smoking and other NHS services.

At 3 months after quit day (2 months after enrolment), a researcher from the UEA telephoned participants primarily to assess process measures, that is receipt, liking and use of the booklets, and to assess key skills; the booklets were intended to teach in both the intervention and the control groups. If the intervention was ineffective, this would help us to assess whether the intervention was used but people did not acquire the skills or applying the skills was ineffective in preventing relapse. This early follow-up contact was important because of the high risk of relapse during the first few months.

The second and final follow-up telephone call (conducted by a researcher from the UEA) took place at 12 months after quit day (11 months after enrolment), to assess the primary and secondary outcomes and to assess coping skills acquired. Participants who met the self-report criteria for at least 7-day abstinence were invited to attend a local centre to prove this by exhaled CO. People came to a clinic at the UEA or a researcher visited them at home for this test. To optimise CO test rates, we offered a shopping voucher (valued at £20) to each of the participants who attended the CO test at 12 months. If participants found it difficult to travel to the UEA, then researchers arranged to visit them at home, at a time convenient to the participant, including at evenings and weekends (46% of Norfolk CO tests were undertaken at participants’ homes). At non-Norfolk sites, local testing was arranged for the CO tests: at stop smoking shops in Lincolnshire, in participants’ homes in Suffolk and by local primary care research network nurses in Hertfordshire.

When arranging CO tests, if participants were willing but unable to commit to a time during the follow-up phone call, researchers phoned participants at a later date. If contact was not successfully made by phone, researchers sent a letter to participants inviting them to phone the research team to make a CO test appointment. When an appointment was successfully booked, participants were sent a letter confirming the appointment arrangements. To minimise non-attendance at CO test appointments, participants were sent a postcard a few days before the appointment and then phoned on the morning of the appointment. Travelling expenses were reimbursed to participants and a £20 ‘Love2shop’ shopping voucher (for use in many high-street shops) was given, in recognition of their time.

To optimise follow-up, researchers recorded all phone call attempts to participants (ranged from one to seven phone calls), and tried different days and varying times of days to be able to talk to participants, including evenings and Saturdays. Researchers also sent text messages to participants to arrange follow-ups, which also helped to increase follow-up response. If researchers were unsuccessful in contacting a participant by phone, they would then post the questionnaire, with a stamped addressed envelope, to the participant’s home. If there was no response within 2 weeks, then a second questionnaire would be posted; 5.3% of 3-month questionnaires were received by post and 6.8% of 12-month questionnaires. When completed postal questionnaires were received, the participants were posted a brief letter of thanks from the research team.

Data management and analysis methods

Paper data were held in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 37 The questionnaire data were identified by a unique study number, securely held in a locked filing cabinet, in a locked research office, in a corridor of research/academic offices with restricted swipe access; participants’ personal information was kept in a separate locked filing cabinet. Two Microsoft Excel® databases (2013; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) were created for the study by the Norwich CTU, one containing participants’ personal information and the other questionnaire data. Data entry was carried out by the UEA research team, and a 10% data entry check was undertaken. Data analyses were conducted using Stata software (Stata/IC for Windows, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The comparison of smoking abstinence rates (and any other binary outcomes) between the two trial groups was carried out using OR and its 95% CI as the measure of treatment effect, although estimated risk ratio was also reported for the primary end point. Participants who declined biochemical verification or who did not respond to follow-up were classified as smokers. However, participants who died or were known to have moved away were excluded from the numerator and denominator. Because there were no significant differences in missing data between the groups, we did not use imputation methods to assess the robustness of primary analyses. 38

We planned to compare survival curves of the intervention and control arm, by using data on time to the first event of smoking relapse. This secondary analysis was not conducted because of inadequate reporting of time the first relapse occurred by a large proportion of relapse participants.

We used exploratory subgroup analyses and logistic regression analyses with interaction terms to investigate possible effect-modifying variables, including age, gender, socioeconomic status, level of nicotine dependence, number of prior quit attempts and use of pharmacological interventions.

The analysis of mediating variables examined hypothesised mechanisms of the intervention. The effectiveness of coping skills training for relapse prevention depends on (1) the adequate delivery and receipt of the booklets, (2) the acquisition of coping skills by quitters and (3) the application of such skills in high-risk situations. This intervention mechanism suggests certain important process variables that should be investigated in the trial. At the follow-up interviews, we asked trial participants if they had received the booklets and if they had read the booklets (and how much time spent and how many booklets looked at). We then investigated whether or not the use of booklets helped the acquisition of coping skills by the participants, in terms of improved capability to identify risky situations and to know more appropriate ways of handling urges to smoke again. We then asked the trial participants whether or not they had actually applied the skills learnt from the booklets. Finally, we invited the trial participants to give an overall assessment of the usefulness of the booklets. We also planned to use more complex methods for the exploratory mediation analysis according to MacKinnon and Fairchild39 but did not because there were no differences in the primary or any secondary outcomes between the treatment and control group.

Qualitative process evaluation

We conducted a qualitative process evaluation using data collected as part of the trial telephone follow-up interviews and a further qualitative substudy of in-depth data collection. Methods used for the qualitative process evaluation are described in Chapter 6.

Economic evaluation methods

Using data from the trial, we calculated the mean incremental cost for those in the intervention arm (Forever Free booklets), compared with the control arm. As part of a cost–utility analysis, the incremental QALY gain associated with the intervention was estimated, based on EQ-5D data collected in the trial. Chapter 7 provides more details about the economic evaluation methods used in the trial.

Ethical arrangements

No adverse effects or harm on target population or society was expected from the intervention. We provided sufficient information for 4-week quitters to consider whether or not they would like to participate in the trial and recruited only those who signed the consent form. Data on individual participants remained strictly confidential. Only the project researchers directly involved in the trial had access to participants’ personal data during the study. Research ethical approval was granted by East of England Research Ethics Committee (11/EE/0091, approval received on 20 April 2011), and any protocol amendments were approved by the Research Ethics Committee.

Project management

A Trial Steering Committee was established to provide overall supervision for the study on behalf of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme. The trial was overseen by a trial management group, based at the UEA, including all co-investigators. The trial management group met every 3 months to monitor and manage the trial and to review an ongoing Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement (including data on recruitment, intervention and follow-up). The trial project team, consisting of the trial co-ordinators, project administrator and chief investigator, met weekly to monitor the day-to-day progress and management of the trial.

No adverse effects were expected to be associated with the educational booklets for smoking relapse prevention. This trial posed no substantial risks to participants and there would be no cause to propose stopping rules for premature closure of the trial. In addition, this trial is open and unblinded. After a discussion with the NIHR HTA programme, we decided not to have a separate data monitoring committee.

Three members of the public contributed to the revision of the Forever Free booklets, and one lay representative was on the trial steering committee.

Chapter 3 Main results

Participant flow

The study started in June 2011. We used 2 months to revise and print the Forever Free booklets, and to arrange trainings for stop smoking advisors who were involved in the recruitment of 4-week quitters. Participant recruitment started in August 2011. We initially recruited CO-validated 4-week quitters from the core Stop Smoking Clinics (level 3 stop smoking advisors) in Norfolk. By January 2012, we realised that the recruitment rate was slower than expected. From May 2012, the participant recruitment was expanded to level 2 stop smoking advisors and to new sites in Norfolk, Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Lincolnshire, and Great Yarmouth and Waveney. By June 2013, the recruitment target was achieved and the trial included a total of 1416 short-term quitters. The follow-up of participants, including CO test, was completed by July 2014.

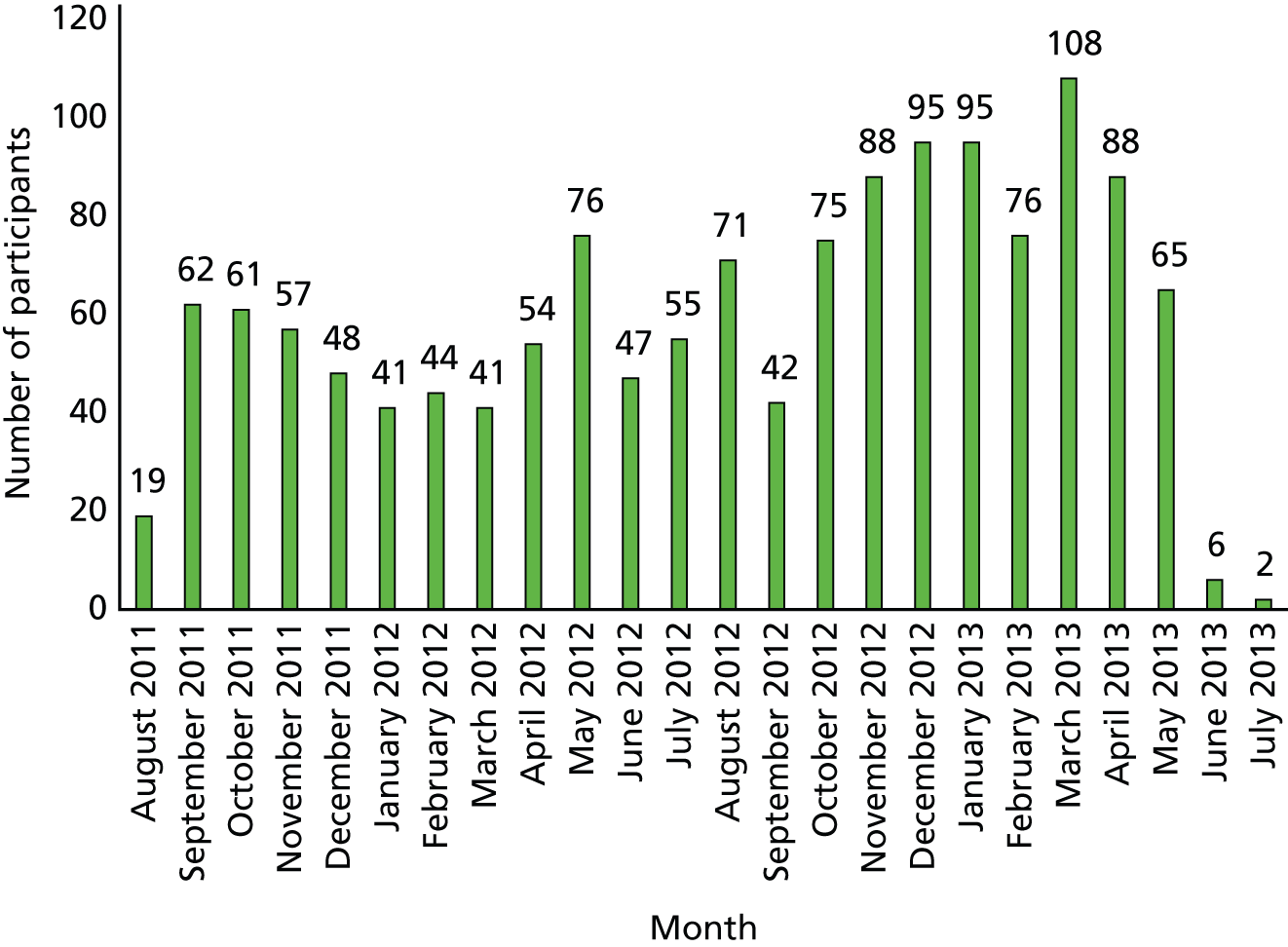

Table 2 shows the number of participants by area and service type, and Figure 1 shows the number of participants recruited by month.

| Area | Specialist service | General practice | Health trainer | Pharmacy | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfolk | 1040 | 97 | 57 | 14 | 1208 |

| Suffolk | – | 57 | – | 18 | 75 |

| Hertfordshire | – | 68 | – | 7 | 75 |

| Lincolnshire | 51 | – | – | – | 51 |

| Great Yarmouth and Waveney | 7 | – | – | – | 7 |

| Total | 1098 | 222 | 57 | 39 | 1416 |

FIGURE 1.

Number of participants recruited by month.

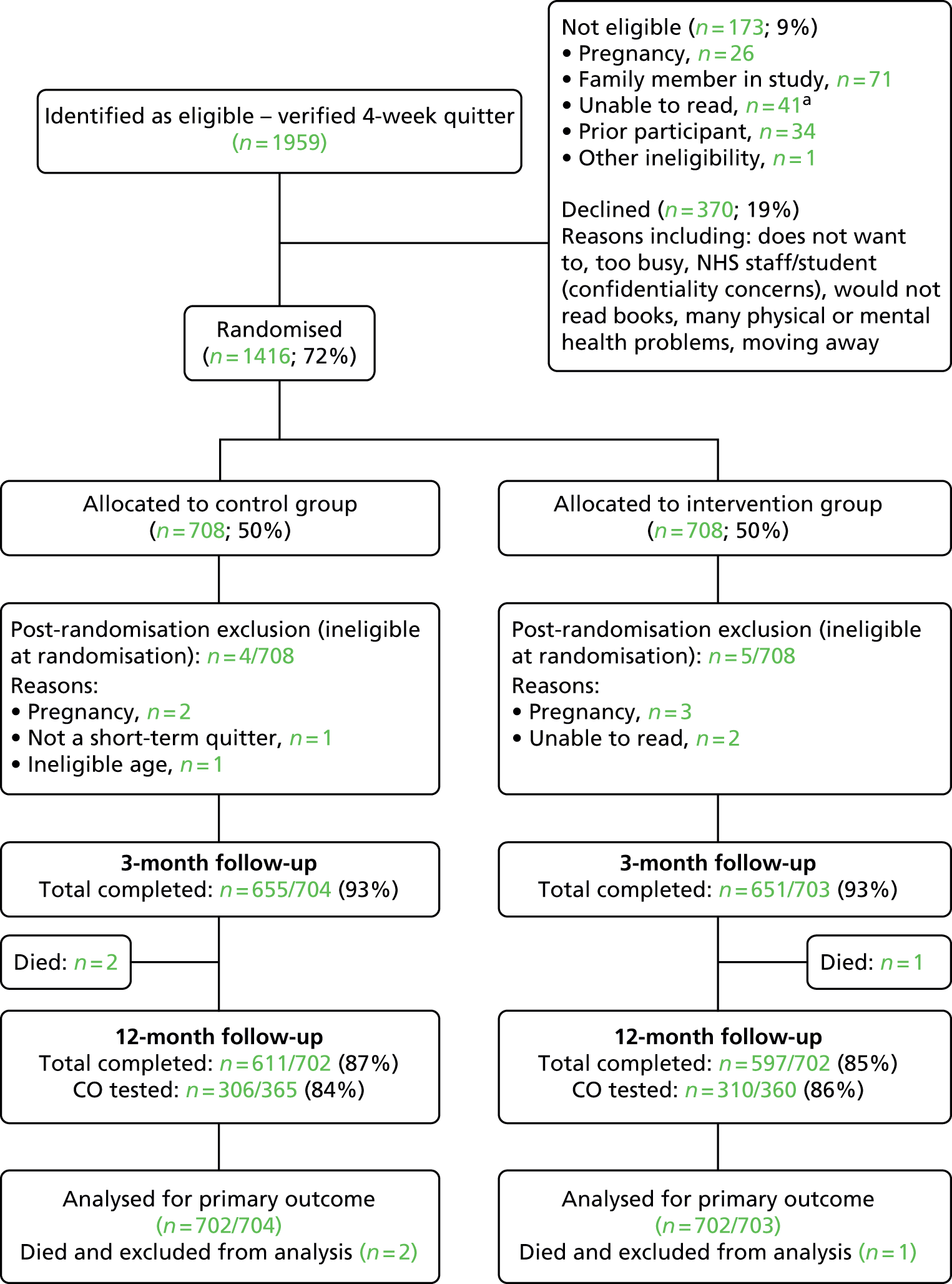

The participant flow diagram is shown in Figure 2. From August 2011 to June 2013, there were a total of 1959 short-term quitters who were considered potentially eligible by stop smoking advisors. The number of eligible quitters who declined to participant in the studies was 370 (19%), for various reasons. Before randomisation, 173 (9%) were excluded for the following reasons: pregnancy (n = 26), family member in study (n = 71), unable to read (n = 41), prior participant (n = 34) and other (n = 1).

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram. a, unable to read – literacy or disability (including dyslexia, learning difficulties and poor eyesight) = 20, limited English = 19, no further details = 2.

We randomly allocated 1416 short-term quitters to the intervention and the control group. After randomisation, four participants in the control group and five in the intervention group were found to be ineligible because of pregnancy at baseline, inability to read or ineligible age at randomisation. In addition, three participants in the intervention group and none in the control group withdrew from the study because of illness or other reasons (these three participants were included in analysis, with the assumption that they had started smoking again).

The follow-up rate was 93% in both the intervention (651 out of 703) and the control group (655 out of 704), at the 3-month follow-up. Two participants in the control group and one in the intervention group died before the 12-month follow-up, and these three participants were excluded from further analyses. The follow-up rate was 85% (597 out of 702) in the intervention group and 87% (611 out of 702) in the control group at the final 12-month follow-up (11 months after randomisation). The median interval between the CO verification before randomisation and the 3-month follow-up was 60 days [mean 60.6 days, standard deviation (SD) 7.6 days], and the mean interval between the CO test before randomisation and the 12-month follow-up was 334 days (mean 335.6 days, SD 11.4 days).

At the final follow-up, 360 participants in the intervention group and 365 in the control group reported abstinence in the previous 7 days and eligibility for a CO test. Verification tests were carried out for 616 of these participants, 86% in the intervention and 84% in the control group, while 109 participants declined or were unable to have the test.

The baseline characteristics of participants

The main demographic characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 3. The participants in the two groups were comparable at baseline in terms of age, sex, marital status, ethnic origin, education, employment status, English being the first language and receipt of free prescriptions. The percentage of participants who were unemployed was 10% and more than half (56%) were in receipt of free prescriptions.

| Demographic characteristic | Intervention (n = 703) | Control (n = 704) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47.8 (14.1) | 47.9 (13.6) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 381 (54.2) | 360 (51.1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married/living with partner | 444 (63.2) | 423 (60.1) |

| Separated/divorced | 110 (15.6) | 114 (16.2) |

| Single | 118 (16.8) | 138 (19.6) |

| Other/unknown | 31 (4.4) | 29 (4.1) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | ||

| European white | 690 (98.2) | 695 (98.7) |

| Other | 11 (1.6) | 8 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| English the first language, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 681 (96.9) | 674 (95.7) |

| No | 11 (1.6) | 16 (2.3) |

| Unknown | 11 (1.6) | 14 (2.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| In paid employment | 372 (52.9) | 368 (52.3) |

| Unemployed | 70 (10.0) | 71 (10.1) |

| Looking after the home | 53 (7.5) | 51 (7.2) |

| Retired | 144 (20.5) | 142 (20.2) |

| Full-time student | 9 (1.2) | 8 (1.1) |

| Other | 55 (7.8) | 64 (9.1) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| Degree or equivalent | 109 (15.5) | 105 (14.9) |

| A level or equivalent | 123 (17.5) | 115 (16.3) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 246 (35.0) | 234 (33.2) |

| Other | 89 (12.7) | 86 (12.2) |

| None | 129 (18.3) | 153 (21.7) |

| Unknown | 10 (1.4) | 8 (1.1) |

| Free prescription, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 400 (56.9) | 392 (55.7) |

| No | 298 (42.4) | 299 (42.5) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.7) | 13 (1.8) |

Table 4 shows smoking behaviours before the latest quit attempt. Denominators used for categorical variables were the number of participants who responded to these questions. The percentage of participants living with a smoking partner was slightly higher in the control group (29.7%) than in the intervention group (25.9%). Participants in the intervention and the control group were comparable in terms of cigarettes per day before quitting, first cigarette after waking up and previous quit attempts. Most of the participants (89%) had previously attempted to quit smoking at least once and many (27%) had attempted to quit at least four times. About 80% of participants had managed to sustain at least 4 weeks’ abstinence in their previous longest abstinence attempts and more than 40% had been abstinent for at least 6 months in their longest attempt (see Table 4).

| Smoking history variable | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes per day before quitting, mean (SD) | 19.9 (9.5) | 20.4 (10.2) |

| First cigarette after waking up, n (%) | n = 702 | n = 703 |

| Within 5 minutes | 295 (42.0) | 298 (42.4) |

| 6–30 minutes | 306 (43.6) | 292 (41.5) |

| > 30 minutes | 101 (14.4) | 113 (16.1) |

| Living with a smoking partner | 114 of 440 (25.9) | 124 of 418 (29.7) |

| Any previous quit attempts | 625 of 702 (89.0) | 629 of 704 (89.4) |

| Number of previous quit attempts, n (%) | n = 610 | n = 612 |

| One | 187 (30.7) | 173 (28.3) |

| Two | 171 (28.0) | 154 (25.2) |

| Three | 94 (15.4) | 112 (18.3) |

| Four or more | 158 (25.9) | 173 (28.3) |

| Longest time managed to stay quit before, n (%) | n = 603 | n = 603 |

| < 1 week | 40 (6.6) | 46 (7.6) |

| 1–4 weeks | 80 (13.3) | 68 (11.3) |

| > 4 weeks to 6 months | 224 (37.2) | 225 (37.3) |

| > 6 months to 12 months | 96 (15.9) | 111 (18.4) |

| > 12 months | 163 (27.0) | 153 (25.4) |

The reasons given for quitting were similar in the two groups (Table 5). Participants were allowed to select more than one reason. Health concern was the most common reason for quitting, including worry about participants’ own future health (70%), already affected health (55%) or family’s health (33%). Cost consideration was also a common reason given by participants (48%). Other reasons included ‘smoking sets a bad example to children’ (37%), ‘because I don’t like being addicted’ (32%) and ‘smoking is antisocial’ (21%).

| Quitting variable | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for quitting (multiple reasons allowed), n (%) | n = 703 | n = 704 |

| Because my health is already suffering | 380 (54.1) | 393 (55.8) |

| Because smoking costs too much | 341 (48.5) | 331 (47.0) |

| For my family’s health | 240 (34.1) | 223 (31.7) |

| Smoking is antisocial | 147 (20.9) | 145 (20.6) |

| I am worried about my future health | 491 (69.8) | 495 (70.3) |

| Other people are pressurising me to | 91 (12.9) | 69 (9.8) |

| Because I don’t like being addicted | 228 (32.4) | 222 (31.5) |

| Smoking sets a bad example to children | 265 (36.8) | 259 (36.8) |

| Importance of giving up smoking at this attempt, n (%) | n = 701 | n = 699 |

| Desperately important | 344 (49.1) | 343 (49.1) |

| Very important | 322 (45.9) | 327 (46.8) |

| Quite important | 34 (4.9) | 28 (4.0) |

| Not all that important | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Determination to give up smoking at this attempt, n (%) | n = 700 | n = 700 |

| Extremely determined | 483 (69.0) | 470 (67.1) |

| Very determined | 193 (27.6) | 214 (30.6) |

| Quite determined | 24 (3.4) | 16 (2.3) |

| Not all that determined | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chances of quitting for good at this attempt, n (%) | n = 701 | n = 699 |

| Extremely high | 273 (38.9) | 271 (38.8) |

| Very high | 305 (43.5) | 309 (44.2) |

| Quite high | 117 (16.7) | 115 (16.5) |

| Not very high | 5 (0.7) | 4 (0.6) |

| Low | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Very low | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Most participants considered that it was extremely or very important to give up smoking (95%) and were extremely or very determined to give up smoking at this attempt (97%). The majority of participants (83%) considered that they had an extremely or very high chance of giving up smoking forever at this attempt. There were no noticeable differences in the perceived importance, stated determination and perceived chances of giving up smoking between the two groups (Table 5).

Smoking relapse results

Prolonged carbon monoxide-verified smoking abstinence

The primary outcome was prolonged smoking abstinence (with no more than five cigarettes) from months 4 to 12, and CO-verified at the 12-month follow-up. The proportion of prolonged abstinence was 36.9% in the intervention group and 38.6% in the control group (Table 6). There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.15).

| End point | Intervention, n/N (%) | Control, n/N (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking abstinence | |||

| Primary outcome: prolonged abstinence from 4 to 12 months (CO-validated at 12 months) | 259 of 702 (36.9) | 271 of 702 (38.6) | 0.930 (0.749 to 1.154); p = 0.509 |

| Continuous abstinence from 2 to 12 months (CO-validated at 12 months) | 217 of 702 (30.9) | 238 of 702 (33.9) | 0.872 (0.697 to 1.091); p = 0.231 |

| CO-validated 7-day smoking abstinence at 12 months | 309 of 702 (44.0) | 305 of 702 (43.4) | 1.023 (0.829 to 1.264); p = 0.830 |

| Smoking relapse | |||

| 7-day self-reported smoking at 3 months | 145 of 703 (20.6) | 147 of 704 (20.9) | 0.985 (0.761 to 1.274); p = 0.906 |

| 7-day self-reported smoking at 12 months | 342 of 702 (48.7) | 337 of 702 (48.0) | 1.029 (0.835 to 1.269); p = 0.789 |

Secondary smoking outcomes

The 7-day self-report point prevalence of smoking was, on average, 21% at 3 months and 48% at 12 months, and there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups (see Table 6). CO-verified smoking abstinence at 12 months included participants who self-reported smoking abstinence that was validated by CO tests. The CO-verified smoking abstinence at 12 months was 44%, and again there was no difference between the two groups. We also calculated continuous CO-validated smoking abstinence from months 2 to 12, after excluding any self-reported smoking (even only a puff). The continuous smoking abstinence was 31% in the treatment group and 34% in the control group, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (see Table 6).

Interactions between treatment effect and patient-level variables

We explored the association between treatment effect and patient-level variables by logistic regression analysis with interaction terms. Ratio of ORs were used to indicate whether or not the effect of the treatment was modified by participant characteristics. The treatment effect was not statistically significantly associated with participant characteristics at baseline (Table 7).

| Baseline variable | Ratio of ORs (95% CI); p-value of interaction |

|---|---|

| Age | 0.994 (0.978 to 1.010); p = 0.448 |

| Sex (1, female; 0, male) | 1.364 (0.885 to 2.103); p = 0.160 |

| Education (1, none or GCSE; 0, A level/degree) | 1.017 (0.629 to 1.646); p = 0.944 |

| Marital status (1, yes; 0, other) | |

| Married or living with a partner | 0.912 (0.581 to 1.433); p = 0.690 |

| Single | 1.221 (0.688 to 2.169); p = 0.495 |

| Separated or divorced | 1.385 (0.744 to 2.579); p = 0.304 |

| Employment status (1, yes; 0, other) | |

| In paid employment | 0.925 (0.600 to 1.426); p = 0.724 |

| Looking after the home | 2.127 (0.907 to 4.989); p = 0.083 |

| Retired | 1.011 (0.593 to 1.722); p = 0.969 |

| Unemployed | 1.533 (0.693 to 3.391); p = 0.291 |

| Free prescription (1, yes; 0, no) | 1.052 (0.686 to 1.615); p = 0.816 |

| Stop smoking advisor who recruited quitters: core services vs. other | 0.663 (0.390 to 1.128); p = 0.130 |

| Living with a smoking partner (1, yes; 0, no) if married or living with a partner | 0.555 (0.297 to 1.039); p = 0.066 |

| Number of cigarettes per day before quitting | 0.991 (0.969 to 1.014); p = 0.436 |

| Time of smoking the first cigarette after waking (1, within 5 minutes; 0, ≥ 5 minutes) | 1.082 (0.696 to 1.683); p = 0.726 |

| Any previous quit attempt (1, yes; 0, no) | 0.868 (0.441 to 1.707); p = 0.681 |

| Longest time managed to stay quit before (1, < 4 weeks; 0, ≥ 4 weeks), among those with previous attempts | 1.243 (0.688 to 2.245); p = 0.471 |

Association between smoking abstinence and baseline variables

Smoking abstinence and demographic variables at baseline

The results of logistic regression analysis between smoking abstinence at 12 months (the primary end point) and demographic variables are shown in Table 8. The smoking abstinence was not statistically significantly associated with sex, education and receipt of free prescription. However, age was statistically significantly associated with smoking abstinence at 12 months (p = 0.011). For example, the prevalence of smoking abstinence was 42% in participants aged ≥ 50 years and 35% in those aged < 50 years. Marital status was also significantly associated with smoking relapse (p = 0.003). The prevalence of smoking abstinence was 33% in participants who were single, 30% in those separated or divorced and 41% in people who cohabited. There was also a strong association with employment status (p < 0.001). Of participants in paid employment, 38% remained smoking free, compared with 35% of participants looking after the home, 41% of retired people, 26% of unemployed participants and only 18% of full-time students.

| Baseline demographic characteristic | n | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1404 | 1.010 (1.002 to 1.0183) | p = 0.011 |

| Sex (1, female; 0, male) | 1404 | 0.960 (0.774 to 1.192) | p = 0.712 |

| Free prescription (1, yes; 0, no) | 1387 | 0.861 (0.692 to 1.071) | p = 0.179 |

| Educational level | |||

| None | 1211 | 1.00 | p = 0.744a |

| GCSE | 1.010 (0.744 to 1.372) | ||

| A level | 1.012 (0.707 to 1.450) | ||

| Degree | 1.172 (0.813 to 1.691) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1402 | 1.00 | p = 0.003a |

| Married or living with a partner | 1.412 (1.052 to 1.894) | ||

| Separated or divorced | 0.861 (0.584 to 1.269) | ||

| Employment status | |||

| In paid employment | 1404 | 1.00 | p< 0.001a |

| Looking after the home | 0.880 (0.572 to 1.353) | ||

| Retired | 1.138 (0.860 to 1.505) | ||

| Unemployed | 0.570 (0.379 to 0.886) | ||

| Full-time student | 0.356 (0.101 to 1.250) | ||

Smoking abstinence at 12 months and smoking-related variables at baseline

Table 9 shows the results of logistic regression analyses to investigate the association between smoking abstinence at 12 months (the primary end point) and smoking-related variables at baseline. Smoking abstinence at 12 months was not associated with stated reasons for quitting, stated importance, stated determinations or perceived chances of staying off cigarette for good (see Table 9).

| Smoking-related variable | n | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stop smoking advisor: core services vs. other | 1404 | 1.361 (1.043 to 1.774) | p = 0.023 |

| Living with a smoking partner (1, yes; 0, no) | 856 | 0.730 (0.536 to 0.995) | p = 0.046 |

| Number of cigarettes per day before quitting | 1403 | 0.993 (0.982 to 1.005) | p = 0.246 |

| Number of cigarettes per day before quitting (0, < 10; 1, ≥ 10) | 1403 | 0.606 (0.447 to 0.820) | p = 0.001 |

| Time of first cigarette after waking up | |||

| Within 5 minutes | 1403 | 1.00 | p = 0.005a |

| 6–30 minutes | 1.320 (1.042 to 1.673) | ||

| > 30 minutes | 1.631 (1.186 to 2.244) | ||

| Any previous quit attempt (1, yes; 0, no) | 1403 | 0.570 (0.406 to 0.799) | p = 0.001 |

| Number of previous quit attempts | |||

| None | 1371 | 1.00 | p = 0.001a |

| One | 0.701 (0.479 to 1.027) | ||

| Two | 0.593 (0.402 to 0.876) | ||

| Three | 0.581 (0.379 to 0.891) | ||

| Four or more | 0.445 (0.300 to 0.661) | ||

| Longest time managed to stay quit before | |||

| None | 1355 | 1.00 | p < 0.001a |

| < 1 week | 0.720 (0.422 to 1.228) | ||

| 1–4 weeks | 0.542 (0.341 to 0.861) | ||

| > 4 weeks to 6 months | 0.406 (0.278 to 0.592) | ||

| > 6 months to 12 months | 0.702 (0.461 to 1.071) | ||

| > 12 months | 0.765 (0.519 to 1.128) | ||

| Stated important of quitting (from 1, desperately important, to 4, not all that important) | 1397 | 0.932 (0.775 to 1.122) | p = 0.459 |

| Stated determination to quit (from 1, extremely determined, to 4, not all that determined) | 1397 | 0.878 (0.715 to 1.077) | p = 0.212 |

| Perceived chance of successfully quitting (from 1, extremely high, to 6, very low) | 1404 | 1.000 (0.998 to 1.001) | p = 0.765 |

| Stated reasons for quitting | |||

| Because my health is already suffering | 1404 | 1.042 (0.838 to 1.294) | p = 0.713 |

| Because smoking costs too much | 0.882 (0.711 to 1.095) | p = 0.256 | |

| For my family’s health | 0.981 (0.780 to 1.234) | p = 0.870 | |

| Smoking is antisocial | 1.293 (0.995 to 1.681) | p = 0.055 | |

| I am worried about my future health | 1.032 (0.815 to 1.307) | p = 0.794 | |

| Other people are pressurising me to | 1.093 (0.780 to 1.533) | p = 0.605 | |

| Because I don’t like being addicted | 1.141 (0.906 to 1.436) | p = 0.262 | |

| Smoking sets a bad example to children | 0.994 (0.795 to 1.243) | p = 0.961 |

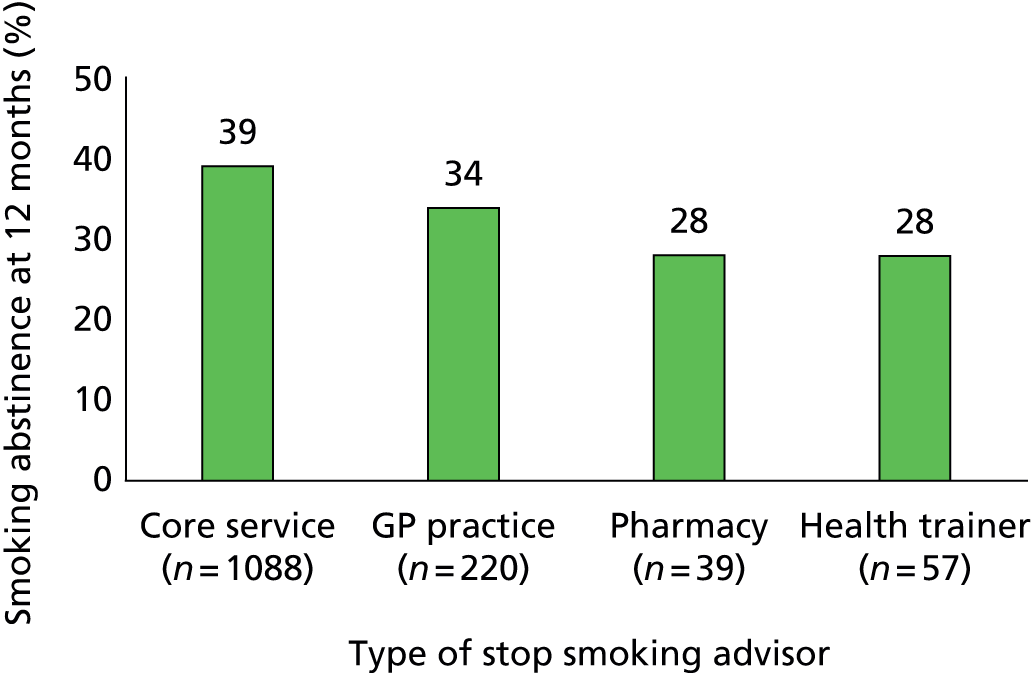

Quitters who were treated by specialist level 3 advisors were less likely to return to smoking than those recruited from other types of Stop Smoking Services (p = 0.023). The prevalence of smoking abstinence was 39% in quitters from core services, 34% from GP practice and 28% from pharmacies and health trainers (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months by type of stop smoking advisors who recruited quitters.

Although smoking abstinence at 12 months was positively associated with cohabitating with a partner (see Table 8), the percentage of smoking abstinence was lower for people living with a partner who smoked than for those who did not (see Table 9). The percentage of smoking abstinence at 12 months was 36% for participants living with a smoking partner and 43% for participants living with non-smokers (p = 0.046).

Time until the first cigarette after waking was statistically significantly associated with smoking relapse (p = 0.001). The percentage of smoking abstinence was 33% in participants who smoked the first cigarette within 5 minutes after waking up, 40% in participants who had the first cigarette between 6 and 30 minutes after waking up and 45% in those who had the first cigarette more than 30 minutes after waking up. When the absolute number of cigarettes smoked per day before the current attempt was examined, there was no statistically significant association between the number of cigarettes per day and the smoking abstinence at 12 months (p = 0.246). However, smoking abstinence was statistically significantly higher in participants who smoked fewer than 10 cigarettes per day before quitting (48%) than in those who smoked 10 or more cigarettes (36%) (p = 0.001).

Previous quit attempt was associated with increased smoking relapse (see Table 9). The smoking abstinence prevalence at 12 months was 36% in participants with any previous quit attempt and 50% in participants for whom the current quit attempt was the first quit attempt (p = 0.001). In addition, there was a tendency that the more previous quit attempts, the higher the risk of smoking relapse at the current attempts. The percentage of smoking abstinence was 41% in participants who had only one previous quit attempt, 37% in participants who had two or three previous quit attempts and 31% for those with four or more previous quit attempts (Figure 4). Among participants who had previous attempts, there was a clear linear association between smoking abstinence at 12 months and the longest time they had previously managed to stay quit (see Table 9).

FIGURE 4.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months and number of previous quit attempts.

Chapter 4 Process and mediating variables

Educational booklets-related variables

Table 10 shows whether or not participants still had and had read the booklets. At the 3-month follow-up, 89% of the intervention group and 79% of the control group reported receiving the booklets or leaflet. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The percentage of participants who reported that they still possessed the booklets was statistically significantly higher in the treatment group than in the control group at the 3-month (83% vs. 62%) and 12-month follow-ups (49% vs. 35%).

| Booklet-related variable | Intervention group | Control group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Booklets received at 3 months | 628/703 (89.3) | 554/704 (78.7) | p < 0.001 |

| Still had booklets at follow-up, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 580/703 (82.5) | 437/704 (62.1) | p < 0.001 |

| At 12 months | 343/702 (48.9) | 242/702 (34.5) | |

| Had read the booklets (reported at follow-up), n/N (%) | |||

| 2–3 months | 495/703 (70.4) | 485/704 (68.9) | p = 0.535 |

| 4–12 months | 189/702 (26.9) | 144/702 (20.5) | p = 0.005 |

| How helpful was the booklet, n/N (%) | |||

| Reported at 3 months | N = 703 | N = 704 | |

| Unhelpful/missing | 299 (42.5) | 304 (43.2) | p = 0.805 |

| Somewhat helpful | 203 (28.9) | 250 (35.5) | |

| Very helpful | 201 (28.6) | 150 (21.3) | |

| Reported at 12 months | N = 702 | N = 702 | |

| Unhelpful/missing | 290 (41.3) | 294 (41.9) | p = 0.829 |

| Somewhat helpful | 215 (30.6) | 259 (36.9) | |

| Very helpful | 197 (28.1) | 149 (21.2) | |

At the 3-month follow-up, about 70% of the participants reported that they had read the booklets (or the leaflet) and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.535). By 12 months, only 27% in the treatment group and 21% in the control group reported having read the booklets or leaflet between 4 and 12 months, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.005).

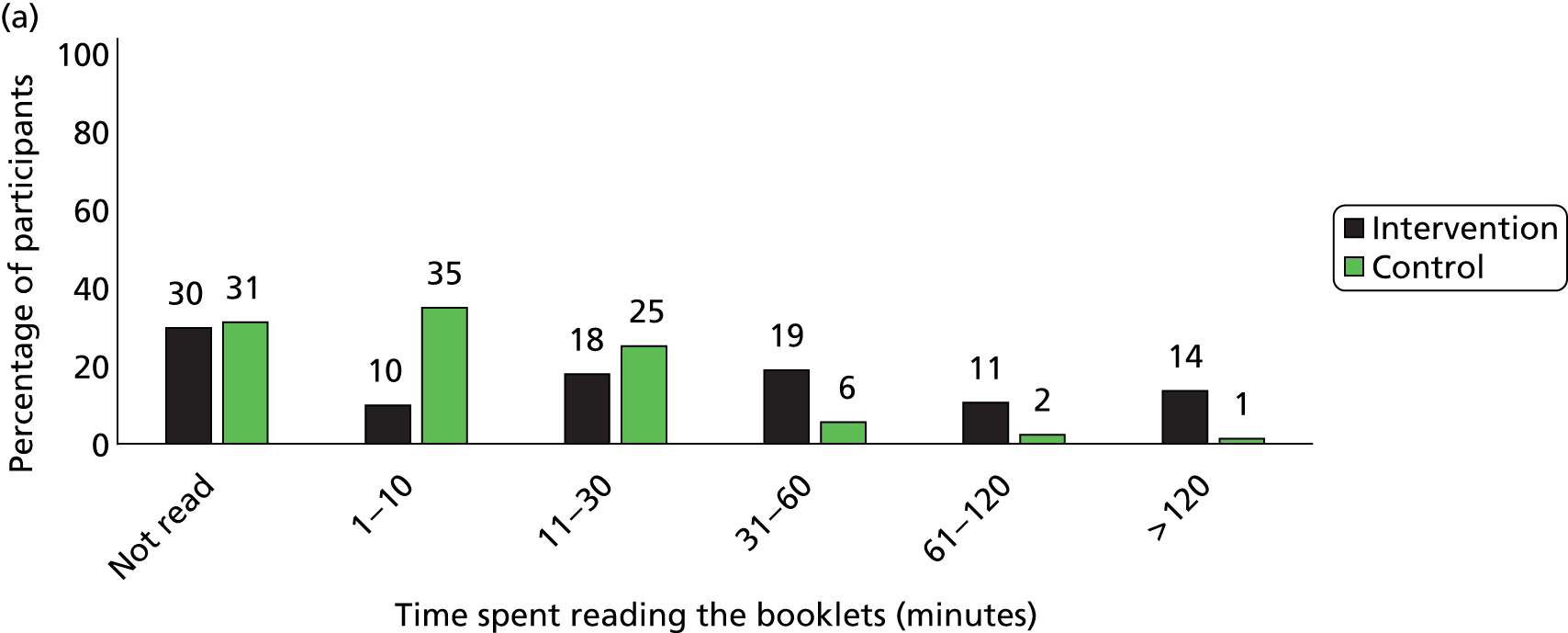

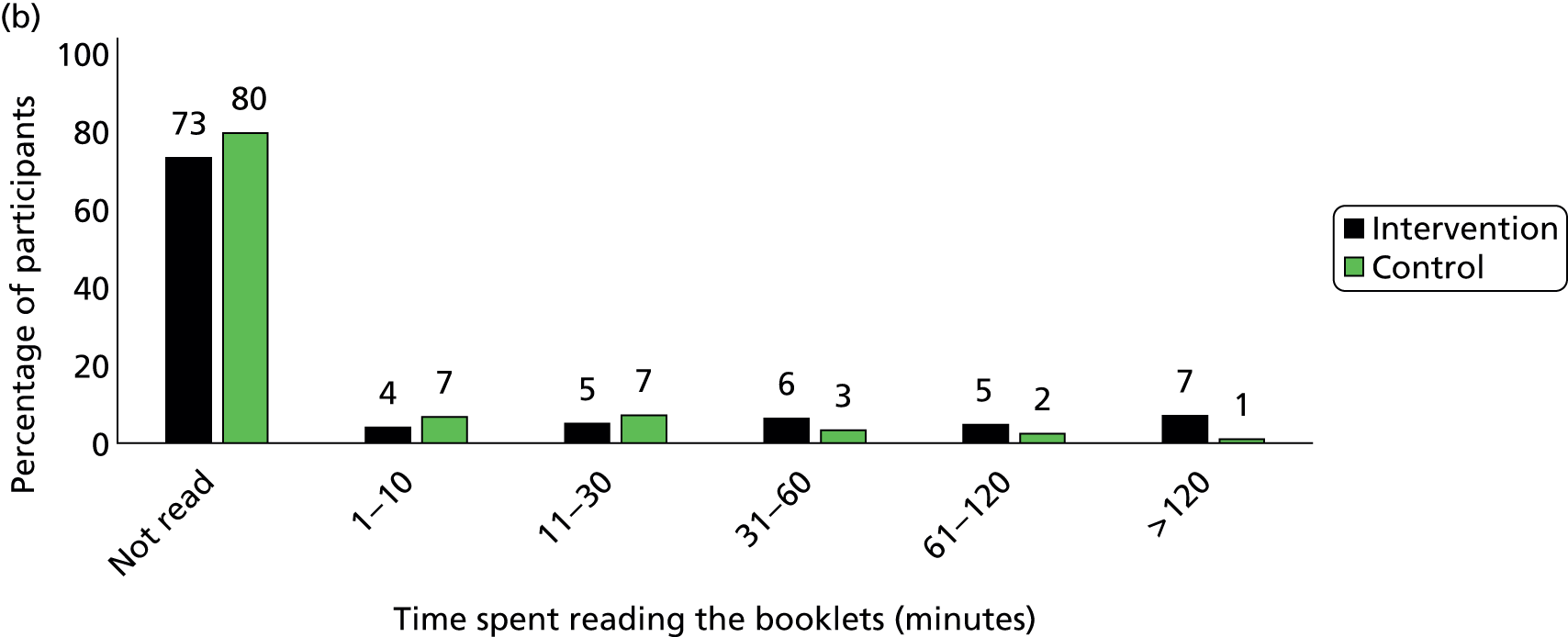

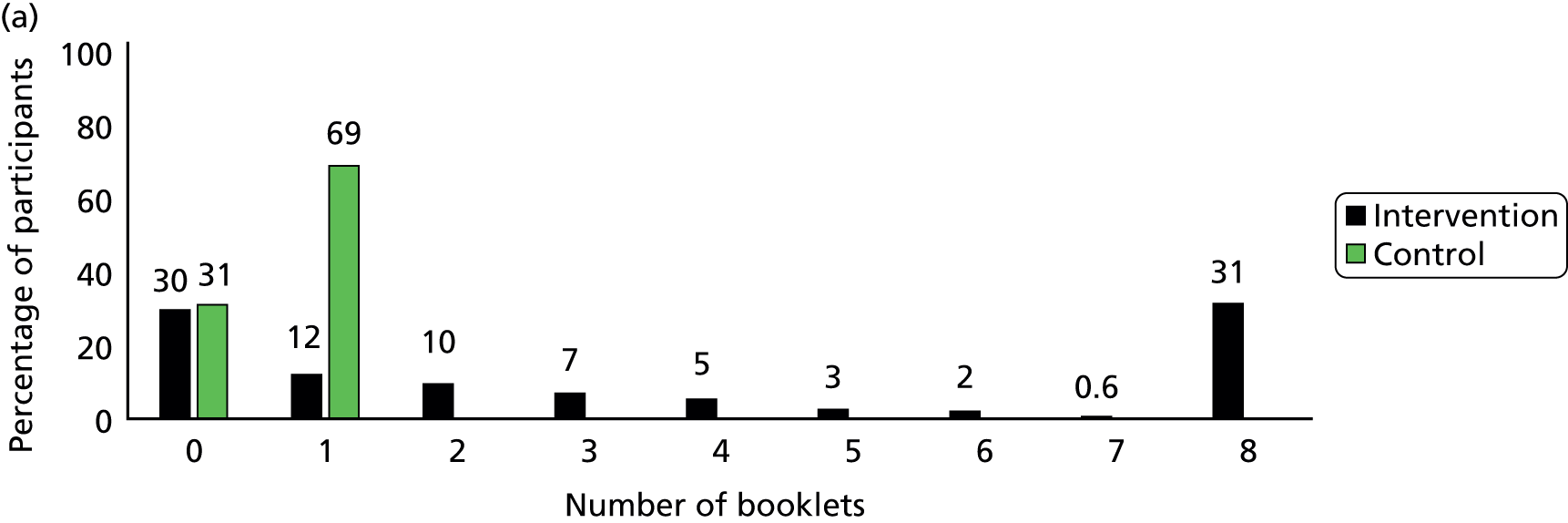

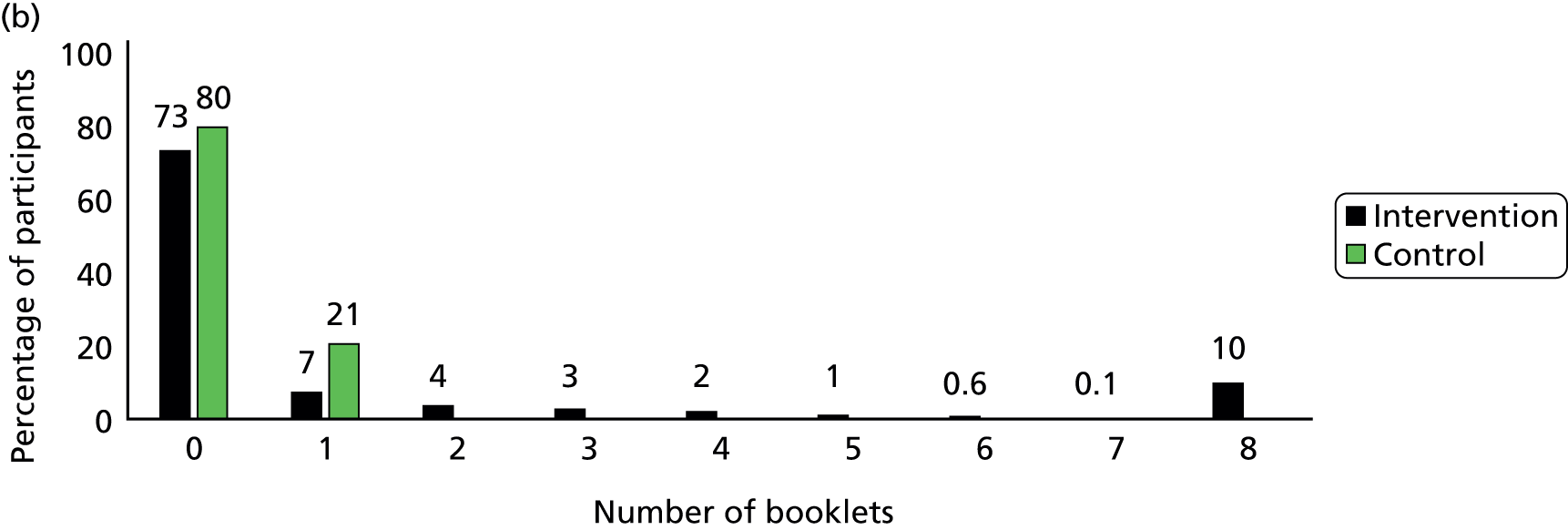

Participants in the intervention group reported spending more time reading the booklets than did control group participants (Figure 5). The percentage of participants who spent more than 30 minutes on reading the booklets was 43% in the intervention group and only 9% in the control group by the 3-month follow-up, and it was 18% and 7% respectively between 4 and 12 months. In the intervention group, 58% of participants reported they had read more than one of the eight booklets by 3 months and only 20% had done so between 4 and 12 months (Figure 6). The percentage of participants who read all eight booklets in the intervention group was 31% by 3 months and 10% between 4 and 12 months.

FIGURE 5.

Time spent on reading the educational booklets. (a) Between 2 and 3 months; (b) between 4 and 12 months. Note, percentages have been rounded.

FIGURE 6.

Number of booklets that participants had read. (a) Between 2 and 3 months; (b) between 4 and 12 months.

The percentage of participants who considered the booklets unhelpful (or unclear) was similar between the treatment and control group (see Table 10). Compared with the control group, the percentage of participants who considered the booklets very helpful was somewhat higher in the intervention group (28% vs. 21% at 12 months), while the percentage of those who considered the booklets somewhat helpful was slightly lower in the intervention group (31% vs. 37% at 12 months).

We asked the participants if reading the booklets meant that they were more able to identify situations in which the risk of relapse was higher. The proportion of participants reporting that they knew much more about which situations might lead to relapse was 26% in the intervention group and 18% in the control group at the 3-month follow-up, and 25% and 21% respectively at the 12-month follow-up. The proportion of participants who reported that reading the booklets taught them no more than they knew already was lower in the treatment group at the 3-month follow-up (48% vs. 53%; p = 0.04), but there was no difference between the groups at the 12-month follow-up (Table 11). Between the treatment and control group, there were no significant differences in the proportion of participants who reported that reading the booklets taught them more about ways to handle urges to smoke at 3 and 12 months (see Table 11).

| Knowledge about risky situations and ways of handling urges | Intervention group | Control group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knew more about relapse risky situations, n (%) | |||

| Reported at 3 months | N = 703 | N = 704 | |

| No/not sure | 335 (47.7) | 374 (53.1) | p = 0.040 |

| A little more | 187 (26.6) | 204 (29.0) | |

| Much more | 181 (25.8) | 126 (17.9) | |

| Reported at 12 months | N = 702 | N = 702 | |

| No/not sure | 340 (48.4) | 341 (48.6) | p = 0.957 |

| A little more | 180 (25.6) | 212 (30.2) | |

| Much more | 182 (25.9) | 149 (21.2) | |

| Knew more about ways of handling urges, n/N (%) | |||

| Reported at 3 months | N = 703 | N = 704 | |

| No/not sure | 342 (48.7) | 373 (53.0) | p = 0.104 |

| A little more | 193 (27.5) | 193 (27.4) | |

| Much more | 168 (23.9) | 138 (19.6) | |

| Reported at 12 months | N = 702 | N = 702 | |

| No/not sure | 344 (49.0) | 346 (49.3) | p = 0.915 |

| A little more | 190 (27.1) | 220 (31.3) | |

| Much more | 168 (23.9) | 136 (19.4) | |

Coping strategies and activities

When participants were asked what things they knew they could do to cope with urges to smoke, the percentage of all participants who reported one or more strategies was 87% at the 3-month follow-up and 66% at the 12-month follow-up, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (Table 12). The number of coping strategies that participants reported they knew is shown in Figure 7, which reveals no significant difference between the groups at both the 3-month follow-up (p = 0.798) and the 12-month follow-up (p = 0.453).

| Coping strategy | Intervention group | Control group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knew at least one thing that could be done to handle urges, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 608/703 (86.5) | 611/704 (86.8) | p = 0.867 |

| At 12 months | 447/702 (63.7) | 460/702 (65.5) | p = 0.468 |

| Knew at least one behavioural activity that could be used to handle urges, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 465/703 (66.2) | 470/704 (66.8) | p = 0.807 |

| At 12 months | 325/702 (46.3) | 339/702 (48.3) | p = 0.454 |

| Knew at least one mental exercise that could be used to handle urges, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 303/703 (43.1) | 275/704 (39.1) | p = 0.124 |

| At 12 months | 201/702 (28.6) | 194/702 (27.6) | p = 0.678 |

| Knew both behavioural and mental things that could be used to handle urges, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 160/703 (22.8) | 134/704 (19.0) | p = 0.086 |

| At 12 months | 79/702 (11.3) | 73/702 (10.4) | p = 0.606 |

| Ever attempted to do something to cope with urges, n/N (%) | |||

| At 3 months | 580/703 (82.5) | 585/704 (83.1) | p = 0.768 |

| At 12 months | 420/702 (59.8) | 431/702 (61.4) | p = 0.548 |

FIGURE 7.

Percentage (%) of participants who reported things they knew to handle urges, by number of things reported and treatment group. (a) At 3 months; (b) at 12 months.

Behavioural coping strategies were more frequently reported than mental scoping skills. At the 3-month follow-up, the percentage of participants who reported at least one behavioural coping strategy was 67%, compared with 41% who reported at least one mental coping strategy. Only 21% of participants reported both behavioural and mental coping strategies at the 3-month follow-up (see Table 12).

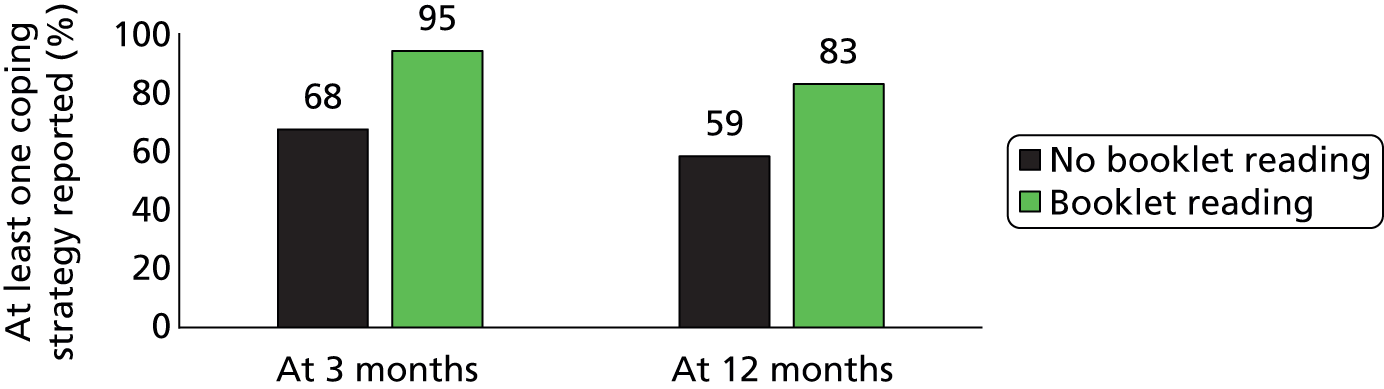

People who reported reading the booklets tended to report knowing more strategies to cope with urges (Figure 8). For example, at the 12-month follow-up, the percentage of participants who knew one or more coping strategy was 83% in those who had read the booklets and 59% in those who had not.

FIGURE 8.

Reporting of coping strategies and booklet reading.

About 83% of all participants by 3 months and 61% between 4 and 12 months reported enacting a strategy to handle urges to smoke, with no significant differences between groups (see Table 12). The percentage of participants who tried to do something was positively associated with any booklet reading, knowing more about risky situations and knowing more about ways of handling urges (Figure 9). However, there were no significant differences in attempts to do something to handle urges between reading of one and more booklets, and between knowing little more and much more about risky situations and ways of handling urges (see Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Ever tried to do something to handle urges and booklet reading, and changes in knowledge on risky situations and ways of handling urges.

Mediating variables and smoking abstinence at 12 months

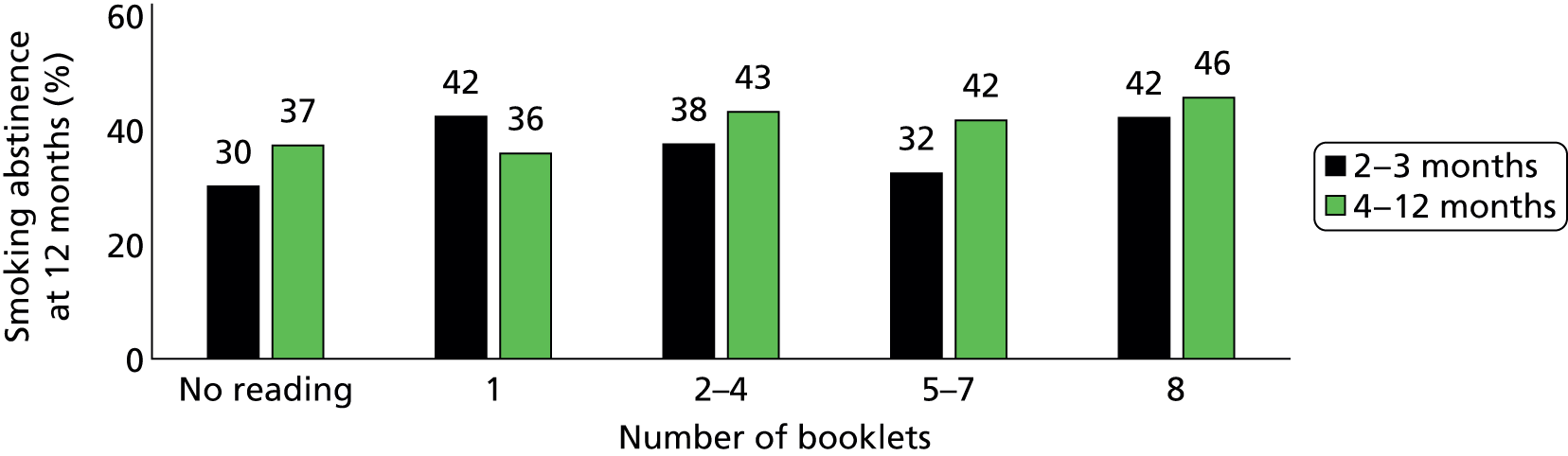

The mediating variables were not associated with the educational materials used in general, and the analyses of associations between mediating variables and the smoking outcome were therefore conducted without taking into account participants’ treatment group. The results of the logistic regression analyses to investigate the association between smoking abstinence at 12 months and mediating variables are presented in Table 13. Smoking abstinence at 12 months was less common in people who had not read booklets by 3 months than in those who did, although there was no significant association between smoking abstinence and booklet reading between 4 and 12 months (p = 0.493). The percentage of smoking abstinence at 12 months was 41% in participants who read the booklets, compared with 30% for those who did not, by the 3-month follow-up, and it was 39% and 37% respectively between 4 and 12 months (Figure 10).

| Mediating variable | OR (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| 2–3 months | 4–12 months | |

| Any reading of booklets | 1.625 (1.274 to 2.072); p < 0.001 | 1.092 (0.849 to 1.406); p = 0.493 |

| Time spent on reading booklets | 1.073 (1.001 to 1.151); p = 0.048 | 1.020 (0.943 to 1.104); p = 0.615 |

| Number of booklets being looked at | 1.035 (0.996 to 1.075); p = 0.080 | 1.047 (0.989 to 1.109); p = 0.117 |

| Know more about risky situations | 1.186 (1.037 to 1.356); p = 0.013 | 1.484 (1.299 to 1.696); p < 0.001 |

| Know more about ways of handling urges | 1.146 (1.002 to 1.310); p = 0.046 | 1.462 (1.276 to 1.675); p < 0.001 |

| No. of coping strategies reported | 1.076 (0.989 to 1.170); p = 0.088 | 1.375 (1.246 to 1.517); p < 0.001 |

| Ever tried to do something to handle urges | 1.730 (1.275 to 2.347); p < 0.001 | 3.109 (2.445 to 3.954); p < 0.001 |

FIGURE 10.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months by booklet reading status.

There was no clear dose–response relationship among participants who had read any booklets (Figures 11 and 12). The results of multiple logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 14. Smoking abstinence at 12 months was statistically significantly associated with booklet reading between 2 and 3 months (p < 0.001), but not with booklet reading between 4 and 12 months (p = 0.759), which indicated that the use of education materials at an early stage may be important. After including the variable of any booklet reading in analyses, there was no significant association between smoking abstinence and any reading of booklets during months 4–12, time spent on reading or the number of booklets read (see Table 14).

FIGURE 11.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months by time spent on reading booklets.

FIGURE 12.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months by number of booklets read.

| Booklet reading | OR (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| 2–3 months | 4–12 months | |

| Any reading (binary) | 1.850 (1.323 to 2.587); p < 0.001 | 1.083 (0.650 to 1.806); p = 0.759 |

| Time on reading (ordinal) | 0.931 (0.827 to 1.049); p = 0.240 | 0.927 (0.778 to 1.103); p = 0.392 |

| Number of booklets read | 1.012 (0.960 to 1.068); p = 0.650 | 1.077 (0.989 to 1.174); p = 0.088 |

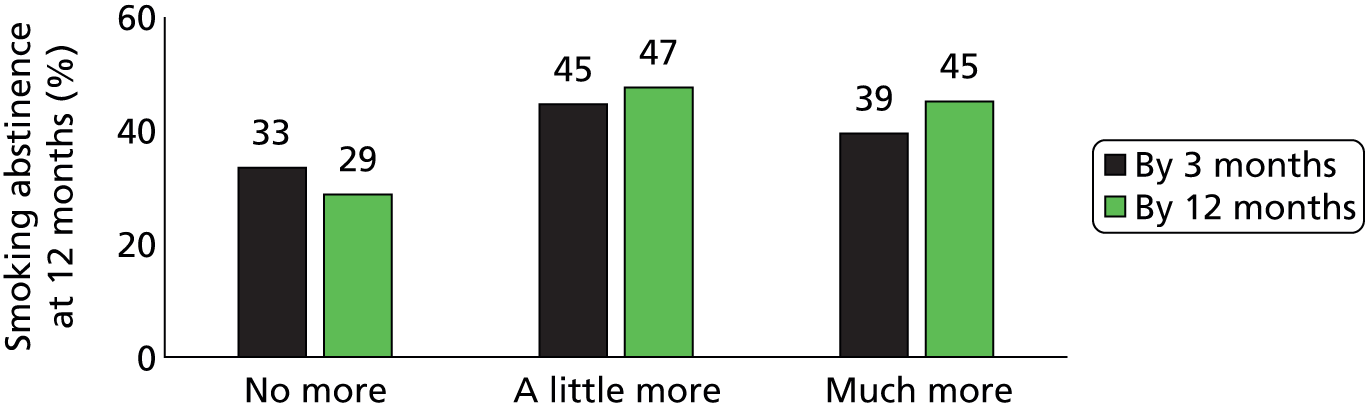

Smoking abstinence at 12 months was higher in participants who reported knowing more about risky situations or knowing more ways to handle urges because they had read the booklets (see Table 13). However, there was no significant difference in smoking abstinence at 12 months between knowing a little more and knowing much more (Figures 13 and 14). The proportion of smoking abstainers was higher in those who reported knowing more strategies to cope (see Table 13), although there was no clear dose–response relationship between knowing only one and knowing more than one strategy (Figure 15).

FIGURE 13.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months by knowing more about risky situations.

FIGURE 14.

Smoking relapse at 12 months by knowing more about ways of handling urges.

FIGURE 15.

The number of coping strategies known and smoking abstinence at 12 months.

Participants who reported doing something to handle urges to smoke were less likely to relapse by 12 months than were people who had no strategy to cope with urges (see Table 13). Of participants who reported that they had tried to handle urges between 4 and 12 months, 48% remained smoking free by 12 months, compared with 23% of those who did not report a strategy (Figure 16). The difference in smoking abstinence between no attempt and any attempts from 4 to 12 months (48% vs. 23%) was greater than between no attempt and any attempts from 2 to 3 months (40% vs. 28%).

FIGURE 16.

Smoking abstinence at 12 months and attempts to do something to handle urges.

Further analysis was conducted by using the following categories: participants who reported no strategy to handle urges, participants who reported using strategies only at the 3-month follow-up, participants who reported strategies only at the 12-month follow-up and participants who reported using strategies at both the 3-month and the 12-month follow-ups (Table 15). The proportion of smoking abstainers was lowest among participants who reported using no strategies or attempts to control urges at all (19%) and highest among participants who had attempted by the 3-month and 12-month follow-up (48%). Participants who reported any attempts by only the 3-month follow-up had a smoking relapse rate slightly higher than those who reported no attempts at all (24% vs. 19%). These results indicated that the prevention of smoking relapse needs continued efforts to do something to handle urges.

| Attempt | n/N | Smoking abstinence, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| No attempt at all | 30/159 | 18.9 (13.5 to 25.8) |

| Only by 3-month follow-up | 95/394 | 24.1 (20.1 to 28.6) |

| Only by 12-month follow-up | 37/83 | 44.6 (34.1 to 55.6) |

| At both 3- and 12-month follow-up | 368/768 | 47.9 (44.4 to 51.5) |

Chapter 5 Use of additional smoking cessation interventions

Any use of additional cessation interventions

At the 3- and 12-month follow-up interviews, participants were asked whether or not they had used smoking cessation aids following their initial use of the NHS Stop Smoking Service at baseline. There were no significant differences in the use of additional stop smoking interventions between the treatment and the control groups (Table 16).

| Additional stop smoking interventions | Treatment group | Control group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any contacts with Stop Smoking Clinics, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 406/703 (57.8) | 434/704 (61.7) | p = 0.136 |

| During 4–12 months | 105/702 (15.0) | 107/702 (15.2) | p = 0.881 |

| Any use of stop smoking medications, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 510/703 (72.6) | 532/704 (75.6) | p = 0.196 |

| During 4–12 months | 155/702 (22.1) | 180/702 (25.6) | p = 0.118 |

| Any use of varenicline (Champix®, Pfizer), n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 282/703 (40.1) | 275/704 (39.1) | p = 0.687 |

| During 4–12 months | 38/702 (5.4) | 41/702 (5.8) | p = 0.728 |

| Any use of bupropion (Zyban®, GSK), n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 1/703 | 4/704 | –a |

| During 4–12 months | 2/702 | 2/702 | –a |

| Any use of NRT products, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 244/703 (34.7) | 267/704 (37.9) | p = 0.210 |

| During 4–12 months | 122/702 (17.4) | 143/702 (20.4) | p = 0.152 |

| Use of other educational materials, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 124/703 (17.6) | 142/704 (20.2) | p = 0.225 |

| During 4–12 months | 68/702 (9.7) | 62/702 (8.8) | p = 0.581 |

| Any use of electronic cigarettes, n/N (%)b | |||

| During 2–3 months | 18/703 (2.6) | 19/704 (2.7) | p = 0.871 |

| During 4–12 months | 43/702 (6.1) | 56/702 (8.0) | p = 0.175 |

In total, 60% of participants contacted an NHS Stop Smoking Clinic in the 2 months after they were proven abstinent at week 4; 15% did so from months 4 to 12. Most people (74%) continued using cessation medication in the 2 months after randomisation; 24% did so between 4 and 12 months after randomisation. Specifically, 40% of participants used varenicline and 36% used nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) by the 3-month follow-up. Only 6% of participants used varenicline and 19% used NRT between 4 and 12 months after randomisation. In general, the use of cessation aids decreased over time. The exception is the use of electronic cigarettes, which increased from 2.6% between 2 and 3 months to 7.1% between 4 and 12 months.

Additional cessation treatments and smoking abstinence at 12 months

Table 17 compares the results of prolonged abstinence between 4 and 12 months by the use of additional cessation interventions. In general, the use of cessation interventions between 2 and 3 months was associated with increased smoking abstinence by 12 months, while the use of cessation treatments between 4 and 12 months was associated with a lower percentage of prolonged smoking abstinence. Of the participants who contacted stop smoking advisors, 42% achieved prolonged smoking abstinence during the first 2 months after randomisation, compared with 31% of those without such contact (p < 0.001). However, only 25% of participants who contacted stop smoking advisors remained abstinent between 4 and 12 months, compared with 40% of participants who did not have such contact (see Table 17). These results indicated that additional smoking cessation treatments were more likely to be used during months 4–12 by relapsed participants than by those who were still smoking free.

| Additional stop smoking interventions | Not used | Used | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any contacts of Stop Smoking Clinics, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 176/565 (31.2) | 354/839 (42.2) | p < 0.001 |

| During 4–12 months | 478/1192 (40.1) | 52/212 (24.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Any stop smoking medications, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 106/363 (29.2) | 424/1041 (40.7) | p < 0.001 |

| During 4–12 months | 440/1069 (41.2) | 90/335 (26.9) | p < 0.001 |

| Any use of varenicline, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 310/847 (36.6) | 220/557 (39.5) | p = 0.273 |

| During 4–12 months | 520/1325 (39.3) | 10/79 (12.7) | p < 0.001 |

| Any use of NRT, n/N (%) | |||

| During 2–3 months | 318/894 (35.6) | 212/510 (41.6) | p = 0.026 |

| During 4–12 months | 450/1139 (39.5) | 80/265 (30.2) | p = 0.005 |

| Any use of bupropion, n/N (%) | |||