Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/45/01. The contractual start date was in July 2013. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Campbell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

There is a considerable body of evidence demonstrating the benefits of physical activity, in terms of both treating and preventing diseases including coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic back pain, osteoporosis, cancers, depression and dementia. 1,2 Current recommendations from the Department of Health1 suggest that adults should undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity each week (in the form of at least 30 minutes of activity on at least 5 days a week, which can be split into three 10 minutes bouts in the same day); however, according to the 2008 Health Survey for England, only 39% of men and 29% of women achieved these levels. 3

Interventions to promote increased levels of physical activity require a wide variety of approaches, with each facilitating small increments in behaviour change. 4 These may include interventions targeted at the population level, such as changes in the environment, as well as interventions targeted at the individual level, such as brief advice delivered in primary care. Over the past 10 years or so, there has been a shift in focus from promoting vigorous exercise to promoting moderate exercise, with more emphasis on lifestyle activity, because of the expanding body of evidence suggesting that there may be greater population gains through the least active becoming more active rather than moderately active people engaging in more vigorous forms of activity. 4

Description of technology under assessment

Primary care has been recognised as a potentially valuable setting for the promotion of physical activity in those who might benefit most. 5 One commonly used method to increase physical activity is the use of exercise referral schemes (ERSs). ERSs have seen considerable growth and are now the most common form of physical activity intervention in primary care. 6

Exercise referral is the practice of referring a person from primary care to a qualified exercise professional who uses relevant medical information about the person to develop a tailored programme of physical activity usually lasting from 10 to 12 weeks. In so doing, opportunities for exercise are provided and there is an expectation that levels of physical activity will increase, leading to positive changes in health behaviours over the long term. These types of schemes usually rely on a partnership between the local authority, primary care trust and private leisure service providers.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Since the early 1990s there has been a considerable growth in the number of ERSs in the UK. 5 By 2005, 89% of primary care organisations in England ran an ERS, making it one of the most common forms of physical activity intervention in primary care. 6

Five previous systematic reviews7–11 have been undertaken in this area exploring the effectiveness of ERSs. There was a lack of consistency in the included studies in each of these reviews, revealing a different understanding and interpretation of ERSs between authors. Despite these varying definitions, these previous systematic reviews conclude that ERSs have a small effect in increasing physical activity in the short term, with little or no evidence of long-term sustainability (i.e. 12 months or longer). There was also evidence of a reduced level of depression for participants given exercise referral compared with usual care. 11 However, owing to the considerable uncertainty surrounding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ERS, in 2006, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Public Health Intervention programme determined that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the use of ERSs as an intervention, other than as part of research studies in which their effectiveness could be evaluated.

The NICE guidance Four commonly used methods to increase physical activity: brief interventions in primary care, exercise referral schemes, pedometers and community-based walking and cycling,9 which included guidance for ERSs, drew on a review of evidence which included four randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 12–15 An additional four studies have been included in a more recent review11 and its update,33 three of which have been published since 2006. 16–18

Physical activity can be promoted in primary care in different ways, including through delivery of advice, provision of written materials and referral to an exercise programme. The UK has seen an expansion in ERSs since 1990,5 but there are concerns that this might not produce sustained change in physical activity beyond the typical programme length of 12 weeks. 19 In 2006, NICE20 advised that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the use of ERSs to promote physical activity other than as part of research studies where their effectiveness can be evaluated. Despite this recommendation, the schemes are still widely used.

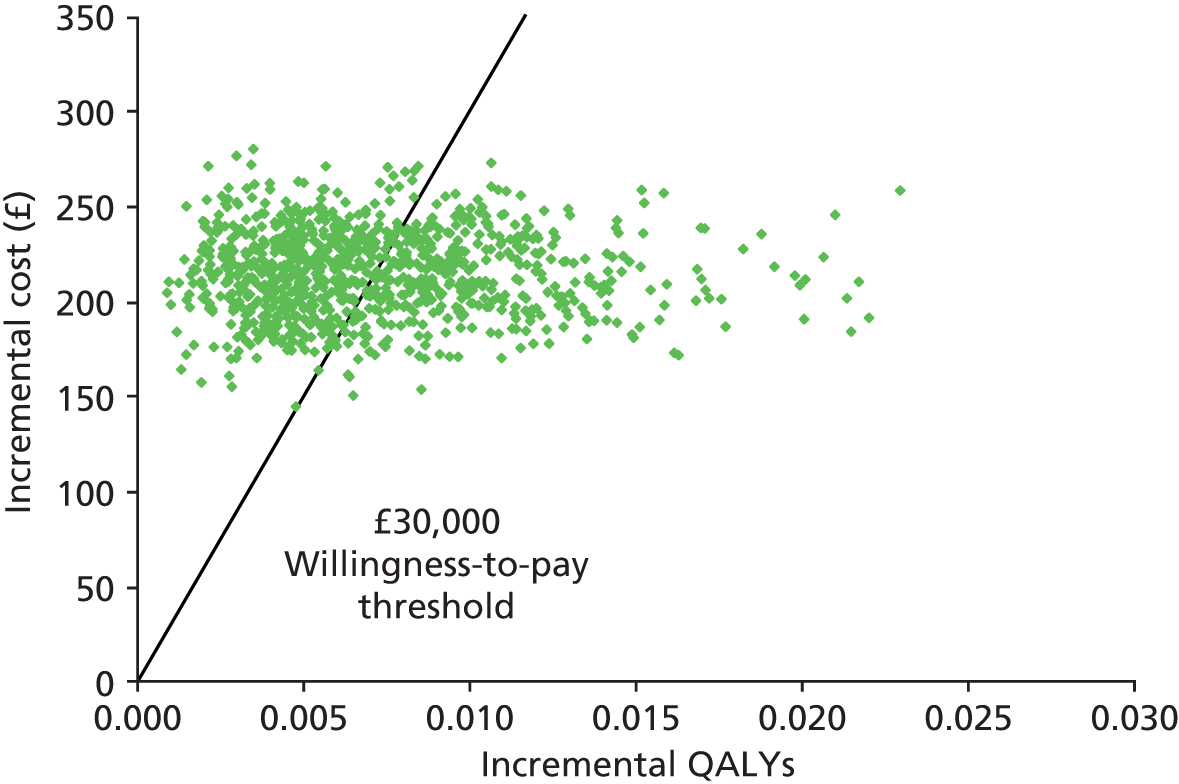

A model-based economic evaluation of ERSs concluded that the cost-effectiveness of an ERS is highly sensitive to small changes in the effectiveness and cost of an ERS and is subject to significant uncertainty, mainly as a result of limitations in the clinical effectiveness evidence base. 21

Given the considerable public health benefits of increasing levels of physical activity, it is important that any initiatives for its promotion are kept under consideration and review. Within this short report, newly available effectiveness evidence will be used to update the existing knowledge base and inform NICE guidance for ERSs referred from primary care. The report will address the question ‘what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ERS to promote physical activity?’ Key factors that will be addressed will include an analysis of effects for those referred for particular clinical conditions, and an exploration of subgroups for whom intervention effectiveness might have a greater effect than for others, including differences between sexes and age groups. We shall also explore where there may be differences in outcomes that relate to key elements of the intervention, such as frequency of contact with the exercise service. The economic evaluation will also build on previous work to explore whether or not the cost-effectiveness of ERSs differs for those referred for particular clinical conditions (hypertension, obesity and depression).

Report methods for synthesis of evidence of clinical effectiveness

This report will be an update of the Pavey et al. 11 systematic review of the evidence; updated searches will be carried out in order to identify new evidence. Any new evidence that is identified will be reviewed systematically and the findings integrated with those of the existing review. The scope of the review will be more limited than in Pavey et al. ,11 owing to the time and resource constraints of this project. We will only include RCTs and systematic reviews of RCTs to analyse effectiveness. We will use only the included RCTs to explore issues of adherence and uptake further. We will do this in two ways: (1) we shall explore adherence and uptake in the trials and (2) we shall examine explanations given within the papers by the authors. This will be done by qualitatively analysing the discussion and conclusion sections of the included trials as well as by extracting data on the numbers of participants who were included in the trials and the drop-out rates. In addition, using the included RCTs, we shall identify qualitative studies undertaken as part of a mixed-methods analysis of exercise referral.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

-

To identify any new research evidence that has become available since 2009 to inform the review of effectiveness of ERSs.

-

To update the Pavey et al. 11 review with any additional evidence.

-

To qualitatively analyse the discussion and conclusion sections of the included studies to identify potential barriers and facilitators to the implementation, uptake and adherence to ERSs.

-

To explore, where data allow, any characteristics of the intervention or the population that might influence the effectiveness of the intervention.

-

To update the cost-effectiveness evaluation with any new evidence that has become available.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Identification of studies

The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic databases

-

contact with experts in the field

-

scrutiny of bibliographies of retrieved papers.

The search strategies used in the Pavey et al. 11 systematic review of the evidence were used in this review. These consisted of two search strategies (stage 1 and stage 2), details of which are included in Appendix 1 of this report. The stage 1 search was a focused phrase search, with stage 2 being a more sensitive search combining the terms for exercise referral with study type and setting terms (primary care). Searches were limited by English language and a publication date of October 2009 to current (8 May 2013 for stage 1 and 17 June 2014 for stage 2). SPORTDiscus was not available to the research team; therefore, Scopus via Elsevier was used, and the stage 1 search was conducted in this data source. Key sports and exercise science journals such as Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise and International Journal of Sports Psychology have been covered, as they are indexed in one or more of the databases listed below. The Journal of Aging and Physical Activity was found not to be indexed in the databases searched, hence this journal was hand-searched by scanning the electronic table of contents available at http://journals.humankinetics.com/japa-contents (2009–current and in-press articles as of September 2013).

Sibling studies

In order to identify any sibling studies (qualitative studies conducted as part of a mixed-method evaluation of the intervention), two searches were undertaken. First, the names of authors and project names of the included trials papers were searched for in Google Scholar (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). To augment this search, citation searches of the included trials were undertaken in the Science Citation Index and proceedings and Social Science Citation Index and proceedings [via Web of Science Thomson Institute for Scientific Information (ISI)].

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid); EMBASE (via OvidSP); PsycINFO (via OvidSP); Scopus (via Elsevier); The Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); Science Citation Index and proceedings and Social Science Citation Index and proceedings (via Web of Science Thomson ISI), UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (UKCRN) portfolio database; Current Controlled Trials; and ClinicalTrials.gov.

An example of the stage 1 and 2 search strategies is shown in Appendix 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Population

The population included any adult (aged 18 years or over) with or without a medical diagnosis and deemed appropriate for ERSs.

Interventions

The ERS exercise/physical activity programme is required to be more intensive than simple advice and needs to include one or a combination of: counselling (face to face or via telephone), written materials and supervised exercise training. Programmes or systems of exercise referral initiated in secondary or tertiary care, such as conventional comprehensive cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation programmes, were excluded. We will exclude trials of exercise programmes for which individuals will be recruited from primary care, but there was no clear statement of referral by a member of the primary care team.

Comparators

Comparators included any control, for example usual (brief) physical activity advice, no intervention, attention control or alternative forms of ERSs.

Outcomes

Outcomes included physical activity (self-reported or objectively monitored), physical fitness [e.g. maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), health outcomes (e.g. blood pressure), adverse events (e.g. musculoskeletal injury)] and uptake and adherence to ERSs. We will also explore how patient characteristics, (age, sex and diagnosis) and programme factors (e.g. length and intensity of the exercise programme) might influence the outcome of ERSs.

Study design

We included any new RCT evidence, identified in searches of electronic databases published from October 2009 to May/June 2013 (see Appendix 1). Data were extracted and the data extraction tool was modelled on that used in the Pavey et al. 11 review. We also searched for any systematic reviews of ERSs published from 2009 to May/June 2013. Their lists of included studies were hand-searched to identify any further relevant studies.

For any new RCTs that we identified, any qualitative data that have been reported as part of a mixed-methods evaluation an ERS intervention were also included.

Any ongoing studies that we identify will also be reported. These would offer the most relevant insights into the particular factors influencing the adherence and uptake of that particular ERS intervention.

Titles and abstracts were examined for inclusion by two reviewers independently. Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Exclusion criteria

-

Animal models.

-

Pre-clinical and biological studies.

-

Narrative reviews, editorials, opinions.

-

Non-English-language papers.

-

Reports published as meeting abstracts only, in which insufficient methodological details are reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

Quality assessment strategy

The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used to assess study quality. 19 Consideration of study quality included assessment of the following trials characteristics:

-

method of randomisation

-

allocation concealment

-

blinding

-

numbers of participants randomised, excluded and lost to follow-up.

-

whether or not intention-to-treat analysis has been performed

-

methods for handling missing data

-

baseline comparability between groups.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Data from new studies published since 2009 were tabulated and discussed in a narrative review. The data from studies already identified and analysed by Pavey et al. 11 were used as published and data from new studies were integrated with them.

Meta-analyses were used to estimate a summary measure of effect on relevant outcomes based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. These meta-analyses used data published in the Pavey et al. 11 review and new data were added.

Meta-analysis was carried out using fixed- and random-effects models, using Review Manager 12 software (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, ON, Canada). Heterogeneity will be explored through consideration of the study populations, methods and interventions, by visualisation of results and, in statistical terms, by the chi-squared test for homogeneity and the I2 statistic.

In order to extend our understanding of the factors that predict uptake and adherence, we undertook a qualitative thematic analysis of the discussion and conclusion sections of the included RCTs. This yielded insights into the factors identified by the triallists that influenced variations in uptake or adherence. The results will be described in a narrative, and a logic model used to explore and explain associations between multiple and varied barriers and facilitators to uptake and adherence of ERSs.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

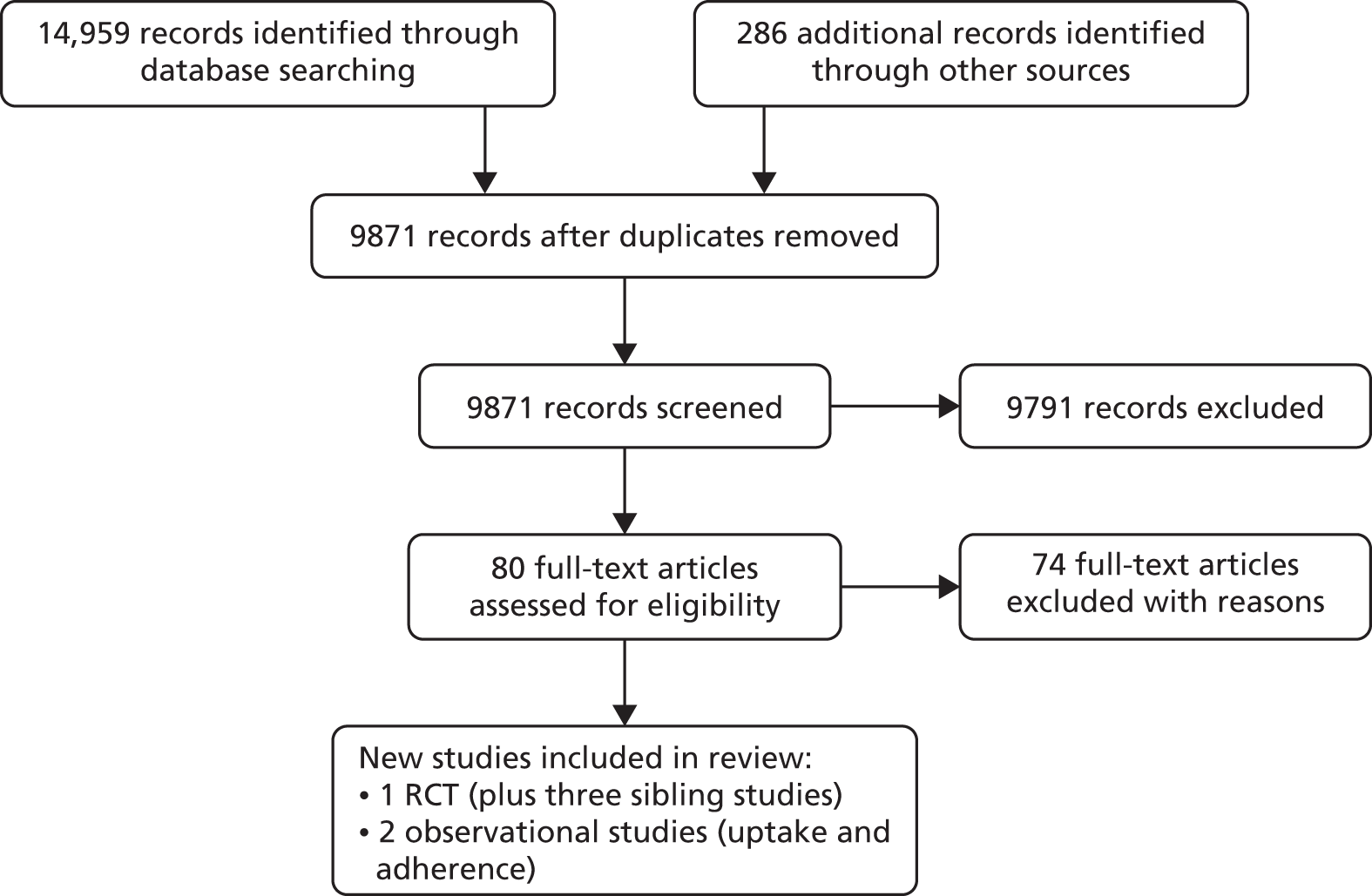

Our search of electronic databases and relevant journals yielded 9627 titles, of which one primary study was judged to meet the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 summarises the process of identifying the inclusion and exclusion process. In two studies,22,23 additional data were supplied by the authors. One study,24 identified in bibliographic searching, could not be retrieved. The main reasons for excluding studies included non-RCT design (n = 44), participants recruited from primary care for inclusion in an exercise programme but without referral from a health-care professional (n = 20), the intervention was a prescription to undertake exercise but not a referral to a third-party exercise provider (n = 5), the population was not appropriate (n = 1), participants were already part of an intervention prior to randomisation (n = 1) or randomisation occurred prior to the baseline assessment (n = 1). Appendix 2 provides the full list of excluded studies. The included studies are summarised in Table 1, which includes the studies incorporated in the Pavey et al. review. 11 The new evidence is highlighted in bold type within the tables.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating the process of identifying new studies for inclusion in the review.

| Study | Country | Number of GP practices | Date study conducted | RCT design | Overall (n) | Randomised (n) | Follow-up periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aTaylor et al.12,25 | UK | 3 | January to December 1994 | Individual | 142 | 97 ERS/45 control | 8, 16, 26 and 37 weeks |

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | 1 | Not stated | Individual | 714 | 363 ERS/351 control | 8 months |

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | 46 | March 2000 to December 2001 | Individual | 545 | 275 ERS/270 control | 6, 9 and 12 months |

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | 88 | October 1998 to April 2002 | Individual | 943 | 317 leisure centre/315 walking/311 control | 10 weeks, 6 and 12 months |

| aSorensen et al.27 | Denmark | 14 | 2005 to 2006 | Individual | 52 | 28 ERS/24 control | 4 and 10 months |

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | 4 | Not stated | Cluster | 287 | 127 ERS/160 control | 6 months |

| Duda et al.17 | UK | Not reported (13 leisure-centre sites) | November 2007 to July 2008 | Cluster | 347 | 184 ERS/163 control | 3 and 6 months |

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | 12 local health boards | Not stated. National ERS rolled out in 2007 | Individual | 2160 | 1080 ERS/1080 control | 6 and 12 months |

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included ERS studies are summarised in Table 2. All of the included studies were RCTs. The Pavey et al. 11 review included seven trials. 12,15,18,26–28,31 The data from these studies are included in the tables of this review, with new data emboldened. One additional study was identified (four publications). 23,25,26,32 This study was a mixed-methods evaluation, incorporating RCT and qualitative evidence, undertaken in Wales. It was larger than previous studies, with 2160 participants. The earlier studies ranged in size from 52 to 943 participants. The total number of participants in all eight studies was 5190.

| Study | Country | Age range of patients (years) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Inclusion/exclusion criteria determined/evaluated by | Number of participants excluded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | 40–70 | Smokers, hypertension (140/90 mmHg), overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2) | SBP > 200 mmHg, history of MI or angina pectoris, diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal condition preventing PA, previous ERS referral | Research team and GP determined and evaluated | 44 |

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | > 18 | Sedentary – < 20 × 30 minutes of moderate-intensity PA or < 12 × 20 vigorous-intensity PA in the past 4 weeks | Medical reasons for exclusion (e.g. registered disabled, diagnosis of heart disease) | Research team determined and evaluated | 113 |

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | > 18 | Sedentary, participating in < 90 minutes of moderate/vigorous PA a week, additional CHD risk factors; obesity, previous MI, on practice CHD risk management register, diabetes mellitus | GP identified contradiction to PA, SBP > 200 mmHg, not sedentary, only one family member (to avoid contamination – research team criterion) | GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | 285 |

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | 40–74 | Not active (no definition reported), raised cholesterol, controlled mild/moderate hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes mellitus, family history of MI at early age | Pre-existing overt CVD, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled insulin-dependent diabetes, psychiatric or physical conditions preventing PA, conditions requiring specialist programme | GP evaluation using criteria determined by an existing ERS | Not reported |

| Sorensen et al.27 | Denmark | > 18 | Patients must meet all criteria:

|

Not meeting the inclusion criteria | GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | Not reported |

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | > 60 | Moderately depressed (6–9 points on the Geriatric Depression Scale), overweight (BMI 25–39.9 kg/m2), capable of walking for more than 25 minutes | Severe obesity, major depression, debilitating medical condition, known unstable cardiac condition, attention or comprehension problems | Research team determined, GP evaluation | 32 |

| Duda et al.17 | UK | > 18 | Two or more risk factors for CHD; people with chronic medical conditions, such as asthma, bronchitis, diabetes mellitus, mild anxiety or depression; people for whom regular activity might delay the onset of osteoporosis, people with borderline hypertension and those perceived by the GP or practice nurse to possess motivation to change People suffering from well-controlled chronic medical conditions: mild or controlled asthma, chronic bronchitis, controlled diabetes mellitus, mild to moderate depression and/or anxiety, people for whom the onset of osteoporosis may be delayed through regular exercise (i.e. post-menopausal women, borderline hypertensive patients with a blood pressure no higher than 160/102 mmHg prior to medication, people exhibiting motivation to change) |

Angina pectoris, moderate-to-high (or unstable) hypertension ≥ 160/102 mmHg Poorly controlled insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, history of MI within the last 6 months – unless the patient has completed stage III cardiac rehabilitation, established cerebrovascular disease, severe chronic obstructive airways disease, uncontrolled asthma |

GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | Not reported |

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | > 16 | The patient must be sedentary (defined as not moderately active for > 3 times per week or deconditioned through age or inactivity) and have at least one of the following medical conditions: CHD risk factors (raised BP, BMI > 28 kg/m 2 , controlled diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance, raised cholesterol, family history of heart disease or diabetes mellitus, referral from cardiac rehab schemes); mental health (mild anxiety, depression or stress); musculoskeletal (at risk of osteoporosis, arthritis, poor mobility, musculoskeletal pain); respiratory/pulmonary (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mild/well-controlled asthma, bronchitis, emphysema); neurological conditions (multiple sclerosis); other (smoking, chronic fatigue) | Aged ≤ 16 years, unstable angina, blood pressure uncontrolled or above 180/100 mmHg, cardiomyopathy, uncontrolled tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, unexplained dizzy spells, excessive or unexplained breathlessness on exertion, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled epilepsy, history of falls or dizzy spells in previous 12 months, uncontrolled asthma, first 12 weeks of pregnancy, awaiting medical investigation, aneurysms, history of cerebrovascular disease, unstable or newly diagnosed angina, established CHD, any other uncontrolled condition | Clinicians in normal practice referred to evaluation team | 1493 |

The studies of Duda et al. 17 and Gusi et al. 28 used cluster allocation, with the other studies using individual-level randomisation. Follow-up duration ranged from 2 to 12 months. The general practitioner (GP) was the main referrer, usually using a bespoke referral form to a fitness or exercise instructor/officer. The Murphy et al. 23 study included referrals by health professionals working in a range of health-care settings.

Five studies12,15,26,23,28 compared ERSs with a usual-care group, which consisted of no exercise intervention or simple advice on physical activity. Sorensen et al. 27 compared ERSs with motivational counselling aimed at increasing daily physical activity. The Isaacs et al. study18 also included an instructor-led walking programme. The Duda et al. study17 compared two forms of ERSs, that is, standard ERS versus a combined ERS plus self-determination theory (SDT)-based intervention.

Characteristics of participants

A total of 5190 participants were included in the eight trials. 12,15,17,18,23,26–28 A summary of the characteristics of participants is presented in Table 3. All of the studies recruited participants who were sedentary or who were believed by their GP to be able to improve health by an increased physical activity level. They all also excluded individuals who had poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes mellitus or heart disease. Gusi et al. 28 also excluded those with severe obesity or major depression. Sorensen et al. 27 included participants who were willing to pay 750 Danish krone for the intervention.

| Study | Country | Mean age (years) | Sex (% male) | Ethnicity (%) | Reported diagnosed conditions for risk factors (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | ||

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | 54.1 | 54.4 | 37 | 38 | Not reported | Not reported | Smokers: 43 | Smokers: 40 |

| Overweight: 77 | Overweight: 71 | ||||||||

| Hypertensive: 46 | Hypertensive: 58 | ||||||||

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | 59.1 | 59.2 | 40 | 44 | White: 87 | White: 83 | BMI > 25 kg/m2: 46 | BMI > 25 kg/m2: 42 |

| Black: 5 | Black: 4 | Smoker: 18 | Smoker: 17 | ||||||

| Asian: 4 | Asian: 6 | ||||||||

| Other: 4 | Other: 5 | ||||||||

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | 18–44 (n = 111) | 18–44 (n = 107) | 33 | 34 | White: 71.9 | White: 74.1 | Smoker: 24.4 | Smoker: 20.7 |

| 45–59 (n = 101) | 45–59 (n = 98) | ||||||||

| > 60 (n = 63) | > 60 (n = 65) | At least one CHD risk factor: 75.3 | At least one CHD risk factor: 75.2 | ||||||

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | 57.1 | Usual care: 57 | ERS: 35 | Control: 32 | White: 75.7 | White (control/walking): 76.5/75.9 | Raised cholesterol (exercise/walking): 24.0 | Raised cholesterol (control/walking): 17.1/21.5 |

| Hypertension (exercise/walking): 44.5 | Hypertension (control/walking): 43.5/46.3 | ||||||||

| Obesity (exercise/walking): 65.9 | Obesity (control/walking): 63.5/58.5 | ||||||||

| Smoking (exercise/walking): 10.4 | Smoking (control/walking): 8.3/12.2 | ||||||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (exercise/walking): 12.3/11.3 | Diabetes mellitus (control/walking): 15.6/11.3 | ||||||||

| Walk: 56.9 | Walk: 31 | Asian: 16.7 | Asian (control/walking): 14/12.2 | Family history of MI (exercise/walking): 13.9 | Family history of MI (control/walking): 16.2/12.9 | ||||

| Sorensen et al.27 | Denmark | 53.9 | 52.9 | 43 | 37 | Not reported | Not reported | Metabolic syndrome: 36 | Metabolic syndrome: 25 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus: 18 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus: 21 | ||||||||

| CVD: 32 | Heart disease: 42 | ||||||||

| Other diseases: 14 | Other diseases: 13 | ||||||||

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | 71 | 74 | 0 | 0 | Not reported | Not reported | Overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2): 80 | Overweight: 86 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus: 39 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus: 37 | ||||||||

| Moderate depression: 34 | Moderate depression: 38 | ||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | UK | < 30 (n = 19) | < 30 (n = 11) | 24 | 30 | White: 74.9 | White: 67.5 | Smoker: 22.1 | Smoker: 23.1 |

| Hypertension: 38 | Hypertensive: 37.5 | ||||||||

| Overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2): 25.3 | Overweight: 26.3 | ||||||||

| Obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2): 52.3 | Obese: 51.9 | ||||||||

| 30–49 (n = 76) | 30–49 (n = 77) | Black: 10.6 | Black: 14.9 | Morbidly obese (BMI > 40 kg/m2): 12.1 | Morbidly obese: 13.5 | ||||

| 50–64 (n = 64) | 50–64 (n = 50) | Asian: 9.5 | Asian: 14.9 | Probable anxiety: 34.2 | Probable anxiety: 31.9 | ||||

| > 65 (n = 25) | > 65 (n = 25) | Other: 5 | Other: 2.6 | Probable depression: 21.9 | Probable depression: 15.3 | ||||

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | 52 (SD 14.7) | – | 44% | – | White: 96 | – | CHD risk factors: 72 | – |

| Mental health issues: 24 | |||||||||

The participants included in the Murphy et al. study23 shared a similar profile to those already included in earlier studies. Most of those recruited were middle-aged white adults, with at least one medical condition, who might benefit from an increased level of physical activity (Table 4). In the Murphy et al. study,23 72% of participants had CHD risk factors and 24% had mental health problems.

| Study | Country | Referrer | Format of referral | Referred to where | Participant cost | Referred to who |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | GP | Signed prescription card | Leisure centre | Half-price admission | Fitness instructor |

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | GP | Letter | Leisure centre | Not reported | Exercise development officer |

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | GP | Faxed referral form | Leisure centre | ‘Subsidised‘ | Exercise officer |

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | GP or practice nurse | Specially prepared ‘prescription pad’ – referral form | Leisure centre | Free | Fitness instructor |

| Sorensen et al.27 | Denmark | GP | Not reported | Clinic | Pay €100 | Physiotherapist |

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | GP | Not reported | Supervised walks in a public park or forest tracks | Not reported | Qualified exercise leaders |

| Duda et al.17 | UK | Member of the primary-care team | Not reported | Leisure centre | Not reported | Health and fitness adviser |

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | Clinician | Form | Evaluation team | Access to one-to-one exercise instruction and/or group exercise classes. Discounted rate for exercise activities, £1 per session | Evaluation team |

Characteristics of interventions

The characteristics of the interventions are summarised in Table 5. Interventions ran for between 10 weeks14,21,33 and 6 months28 and included instructor-led exercise classes or walks,28 some form of consultation aimed at increasing activity22,33 or a combination of the two. 14,17,21,23,34 The intervention by Sorensen et al. 27 was based on the transtheoretical model of behaviour change, which categorises people into stages of readiness for change and postulates 10 experiential and behavioural processes of change, pro and con beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs (beliefs in personal ability to carry out the behaviour in question). 22 The Duda et al. intervention17 was based on SDT, which emphasises the determinants and consequences of different reasons for behavioural engagement, which vary in their degree of self-determination. 23 The intervention aimed to promote autonomy support, which is assumed to foster participants’ feelings of competence, autonomy and relatedness and, as a result, enhance autonomous motivation for physical activity and associated mental health outcomes. 17 The only study added since the Pavey HTA,11 by Murphy et al. ,23 was also the only study to explicitly use motivational interviewing. However, fidelity to this intervention method during consultations was considered to be low. Motivational interviewing is ‘a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change’. 35 In those studies that held supervised exercise sessions or walks, the number of sessions per week varied between one32 and three,28 with the most common being two sessions per week,14,17,21 although one study27 held two sessions per week for the first 2 months and then one session per week for the following 2 months. Supervised exercise sessions or walks lasted between 30–40 minutes12 and 1 hour. 17,34 Two interventions were group interventions28,34 and four were at group and/or individual levels. 14,17,22,23

| Study | Country | Initial screen/assessment | Scheme duration | Provider | Exercise sessions per week | Exercise session intensity | Group or individual | Duration of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 30–40 minutes | Moderate intensity | Group and/or individual | 37 weeks |

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 8 months |

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | Yes | 12 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 1 hour | Individually based | Group and/or individual | 6 months |

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 45 minutes | Not reported | Group and/or individual | 6 months |

| Sorensen et al.27 | Denmark | Yes (and motivational counselling) | 4 months | Clinic | First 2 months: 2 sessions × 1 hour; second 2 months: 1 session × 1 hour | More than 50% of heart rate reserve for a minimum of 20 minutes | Group | 10 months |

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | Not reported | 6 months | Walking scheme | 3 × 50 minutes | Not reported | Group | 6 months |

| Duda et al.17 | UK | Yes | 12 weeks | Leisure centre | Individually based | Individually based | Group and/or individual | 6 months |

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | With exercise professional on entry: lifestyle questionnaire, health check (resting heart rate, blood pressure, BMI and waist circumference), introduction to leisure-centre facilities, motivation interview and goal-setting | 16 weeks | Exercise professionals | Access to one-to-one exercise instruction and/or group exercise classes |

4-week telephone contact with exercise professional: review of goals, motivational interview, relapse prevention

16-week consultation with exercise professional: review of goals, motivation interview, health check, lifestyle questionnaire, service evaluation questionnaire and advice on continuing with exercise after the programme 8-month telephone contact by exercise professional to ask about their exercise behaviour and relapse prevention |

Individual | 12 months review including repeat of health check carried out at entry and Chester fitness step test |

Risk of bias

Table 6 summarises the risk of bias for each of the included studies. Most included a power calculation and allocated participants using an appropriately generated random number sequence. However, the reporting of concealment of trial group allocation was poor, although there was good evidence of participant characteristics of intervention and control groups at baseline. Although blinding of participants and intervention providers in these studies was not feasible, blinding of outcome assessment was possible. Outcome blinding is particularly important in preventing assessment bias in the case of outcomes that require observer judgement or involvement (e.g. blood pressure measurement or exercise testing). Two studies17,23 reported outcome blinding. Recall Questionnaire was assessed via telephone to maintain blinding. The reporting and handling of missing data were detailed for most studies, and all studies, except one,12 reported the use of ITT analysis. The level of missing data at follow-up ranged across studies from 16.5% to 50%. Most studies used imputation methods (last observation carried forward or complete case average values) to replace missing data values at follow-up. Overall, three studies12,15,26 were judged to be at moderate overall risk of bias and five17,18,23,27,28 to be at low overall risk of bias.

| Risk-of-bias criterion | Study and country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.,12 UK | Stevens et al.,26 UK | Harrison et al.,15 UK | Isaacs et al.,18 UK | Sorensen et al.,27 Denmark | Gusi et al.,28 Spain | Duda et al.,17 UK | Murphy et al.,23 UK | |

| Power calculation reported? | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Method of random sequence generation described? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes a | Yes |

| Method of allocation concealment described? | Yesa | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Method of outcome (assessment) blinding described? | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Were groups similar at baseline? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was ITT analysis used? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was there any statistical handling of missing data? | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were missing data (dropout and loss to follow-up) reported? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Exercise referral scheme eligibility, uptake and adherence

There was a considerable range in the proportion of individuals randomised compared with those deemed eligible (Table 7). In both the Sorensen et al. 27 and Duda et al. 17 studies, of those deemed eligible for ERSs, a substantial number refused participation in the trial. In the Sorensen et al. 27 study this low number may be reflective of the 750 Danish krone payment by patients as part of a standard Danish Exercise on Prescription. In the Duda et al. 17 study, this may be related to the workload and training needs of the health and fitness advisors at the time of recruitment.

| Study | Country | Number deemed eligible (n) | Total n randomised (%) | ERS (n) | Control (n) | ERS uptake, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | 345 | 142 (41) | 97 | 45 | 85 (88) |

| Stevens et al.26 | UK | 827 | 714 (86) | 363 | 351 | 126 (35) |

| Harrison et al.15 | UK | 830 | 545 (66) | 275 | 270 | 232 (84) |

| Isaacs et al.18 | UK | 1305 | 949 (73) | 317 leisure centre, 315 walking | 311 | 293 (92) |

| Sorensen et al.27 | Denmark | 327 | 52 (16) | 28 | 24 | 28 (100) |

| Gusi et al.28 | Spain | 160 | 127 (79) | 64 | 63 | Not reported |

| Duda et al.17 | UK | 1683 | 347 (21) | 184 | 163 | Not reported |

| Murphy et al. 23 | UK | 3286 | 2160 (66) | 1080 | 1080 | n = 919 (85) |

The terms ‘adherence’ and ‘uptake’ can be used variably within the literature. ‘Uptake’ refers to initial attendance, take-up or enrolment. ‘Adherence’ describes the level and duration of participation, and the threshold for determining adherence may vary in different studies. 34

Rates of uptake varied in the included studies. Taylor et al. ,12 Isaacs et al. ,18 Sorensen et al. 27 and Murphy et al. 23 reported uptake rates in excess of 85%, and in the Stevens et al. study26 only 126 (35%) of the 363 randomised to ERSs attended the first consultation. Stevens et al. 26 discussed how the low uptake they experienced may have been reflective of the nature of the invitation letter sent to participants and the point of randomisation (pre-invitation letter). Furthermore, they hypothesise that a change in the format of the letter (e.g. including a specific appointment date for the first ERS appointment) would have improved participation. Uptake was not reported by Duda et al. 17 or Gusi et al. 28

Adherence was assessed differently between the trials, and levels of adherence also varied. Stevens et al. 26 and Gusi et al. 28 reported ERS programme completion rates of 25% and 86%, respectively. However, these rates do not reflect the number of sessions attended, only those who attended a second consultation26 or follow-up assessment. 28

Sorensen et al. 27 reported that an average of 18 out of a total of 24 ERS exercise sessions were attended and 68% and 75% of participants attended the counselling sessions at 4 and 10 months, respectively. Both Taylor et al. 12 and Isaacs et al. 18 provide a detailed description of ERS programme adherence. Taylor et al. 12 reported 13% attending no exercise sessions and 28% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions, with an average of 9.1 out of 20 prescribed exercise sessions attended. Isaacs et al. 18 reported 7.6% attending no exercise sessions and 42% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions in the leisure centre group. In the walking group, 23.5% attended no exercise sessions, with 21.5% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions. As shown in Table 8, there was no consistent difference in attendance rates between those in at-risk groups and the overall study population in the studies of Taylor et al. 12 and Isaacs et al. 18 In the Isaacs et al. study,18 the 60–69 years age group had the highest adherence in both the ERS (53.3%) and the walking (24.2%) groups. There were no significant differences in attendance rate based on employment status, educational level, socioeconomic status, ethnicity or relationship status. However, Murphy et al. 23 did find differences in uptake and adherence between participants from deprived and less-deprived areas. Adherence was lower for those without access to private transport in both the ERS and walking groups. Harrison et al. 15 and Duda et al. 17 did not provide information on participants’ adherence to the ERS intervention.

| Study | Country | Smoking (%) | Obesity (%) | Hypertension (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.12 | UK | 12 | 28 | 23 | 28 |

| Isaacs et al.,18 ERS group | UK | 45.5 | 38.8 | 46.1 | 42 |

| Isaacs et al.,18 control walking group | UK | 26.3 | 18.7 | 22.9 | 21.5 |

Murphy et al. 23 found that participants already active at baseline were the most likely to enter the ERS, but that they were also most likely to partially attend a programme. Men and younger participants were slightly less likely to enter the scheme, and women were less likely to complete the programme. Participants in the least-deprived areas were more likely to take up the scheme, although the differences in adherence between the most- and least-deprived areas were smaller. Non-car owners were less likely to take up the scheme or to adhere to it if they joined. Those referred for mental health reasons were more likely not to enter the ERS, and only one in three mental health patients completed the programme.

In a univariate regression analysis of predictors of uptake and adherence, the only significant correlates of uptake in the Murphy et al. study23 were car ownership and deprivation. Those in moderately deprived areas were less likely to enter the ERS than those in the least-deprived areas. Car owners were significantly more likely to enter the ERS than non-car owners. Older participants, those referred for non-weight-related CHD risk factors, non-mental health patients and those already moderately active at baseline were most likely to complete the programme.

In a multivariable regression analysis, the significant difference between low and medium deprivation areas remains and car ownership remains predictive of uptake. Associations of CHD risk factors with adherence become non-significant and associations of age and mental health status remain significant. Associations of baseline activity with adherence are strengthened in the multivariable analysis, with the contrast between inactive and moderately inactive participants becoming more significant (see Barriers and facilitators of referral, uptake and adherence to exercise referral schemes for further discussion of factors influencing uptake and adherence).

Assessment of effectiveness

Only Isaacs et al. 18 reported all outcome domains applicable to this systematic review (Table 9). New data added to the Pavey et al. 11 review are emboldened within the tables.

| Study | PA | PA measure | Physical fitness | Clinical outcomes | Psychological well-being | HRQoL | Patient satisfaction | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al.,12 UK | Yes | Self-report, 7 day-PAR | Yes, submax. HR | Yes, BP, BMI, BF%, waist to hip | Yes, PSW | No | No | No |

| Stevens et al.,26 UK | Yes | Self-report, 7 day-PAR | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Harrison et al.,15 UK | Yes | Self-report, 7 day-PAR | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Isaacs et al.,18 UK | Yes | Self-report, Minnesota LTPAQ | Yes, submax. bike test, submax. walking test | Yes, BP, cholesterol, lipoproteins, triglycerides, weight, BMI, BF%, waist-to-hip ratio, FEV, PEF | Yes, anxiety, depression | Yes, SF-36 mental | Yes | Yes, GP records |

| Sorensen et al.,27 Denmark | Yes | Self-report, unspecified | Yes, submax. bike test | Yes, weight, BMI | No | Yes, SF-12 mental, physical | No | No |

| Gusi et al.,28 Spain | Not reported | N/A | No | Yes, BMI | Yes, anxiety, depression | Yes, EQ-5D | No | No |

| Duda et al.,17 UK | Yes | Self-report, 7 day-PAR | No | Yes, BMI | Yes, anxiety, depression | Yes, Dartmouth QoL | No | No |

| Murphy et al.,23 UK | Yes | Self-report, 7 day-PAR | No | Measured at baseline | Yes, HADs | Yes, EQ-5D | Yes, Client Service Receipt Inventory | No |

Physical activity

All studies, with the exception of Gusi et al. ,28 provided a measure of self-reported physical activity. Self-reported measures included the validated 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-Day PAR) questionnaire12,23,26,27 and the validated Minnesota Leisure Time Activity questionnaire. 18 None of the studies reported methods of measuring physical activity using an objective method of measurement, and all relied on self-report tools.

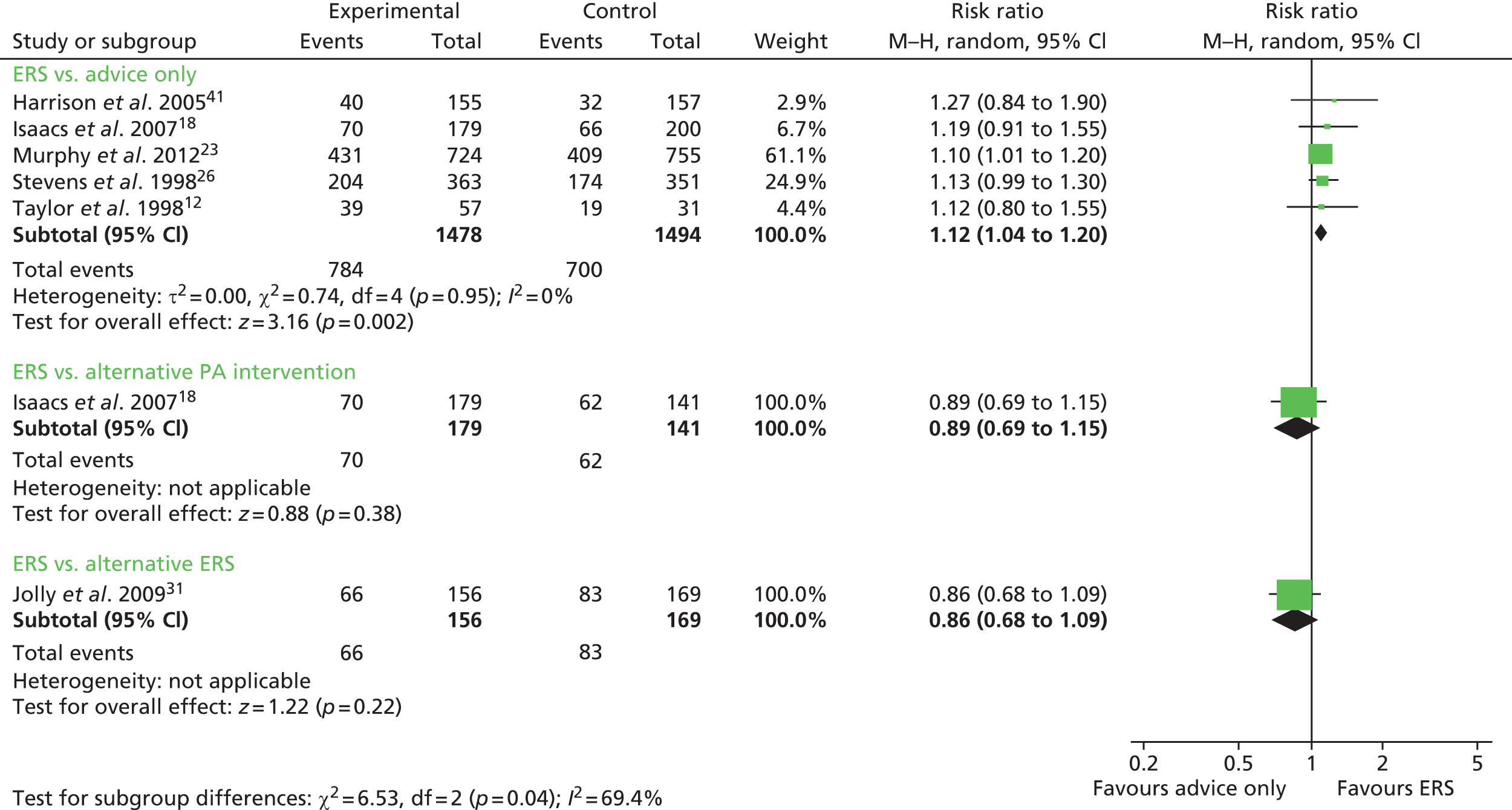

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care/advice only

The most consistently reported physical activity outcome across studies was the proportion of individuals achieving 90–150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity activity per week. Data for this outcome in the Murphy et al. study23 were supplied by the author (Professor Simon Murphy, Cardiff University, 2013, personal communication). When pooled across studies the relative risk (RR) was 1.12 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 1.20] of achieving this outcome with ERS compared with usual care at 6–12 months’ follow-up (Figure 2). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in this analysis (I2 0%). This analysis draws on data published by Pavey et al. 11 Three studies12,15,23 reported this outcome based on the number of individuals who were available at follow-up. These results show a decrease in the RR found by Pavey et al. 11 (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.30). In order to assess the potential (attrition) bias in using completers, the denominators of these three studies were adjusted to all individuals randomised in order to perform an ITT analysis (Figure 3). It was assumed that all missing cases did not meet the physical activity threshold. In the pooled ITT analyses, the proportion achieving the physical activity threshold in the ERS group compared with usual care was RR 1.08 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.17). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in this analysis (I2 0%). This is also a reduction on the RR found by Pavey et al. 11 (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.25).

FIGURE 2.

Number achieving 90–150 minutes physical activity/week (updated meta-analysis). df, degrees of freedom; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; PA, physical activity.

FIGURE 3.

Number achieving 90–150 minutes physical activity/week (ITT analysis) (updated meta-analysis). df, degrees of freedom; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; PA, physical activity.

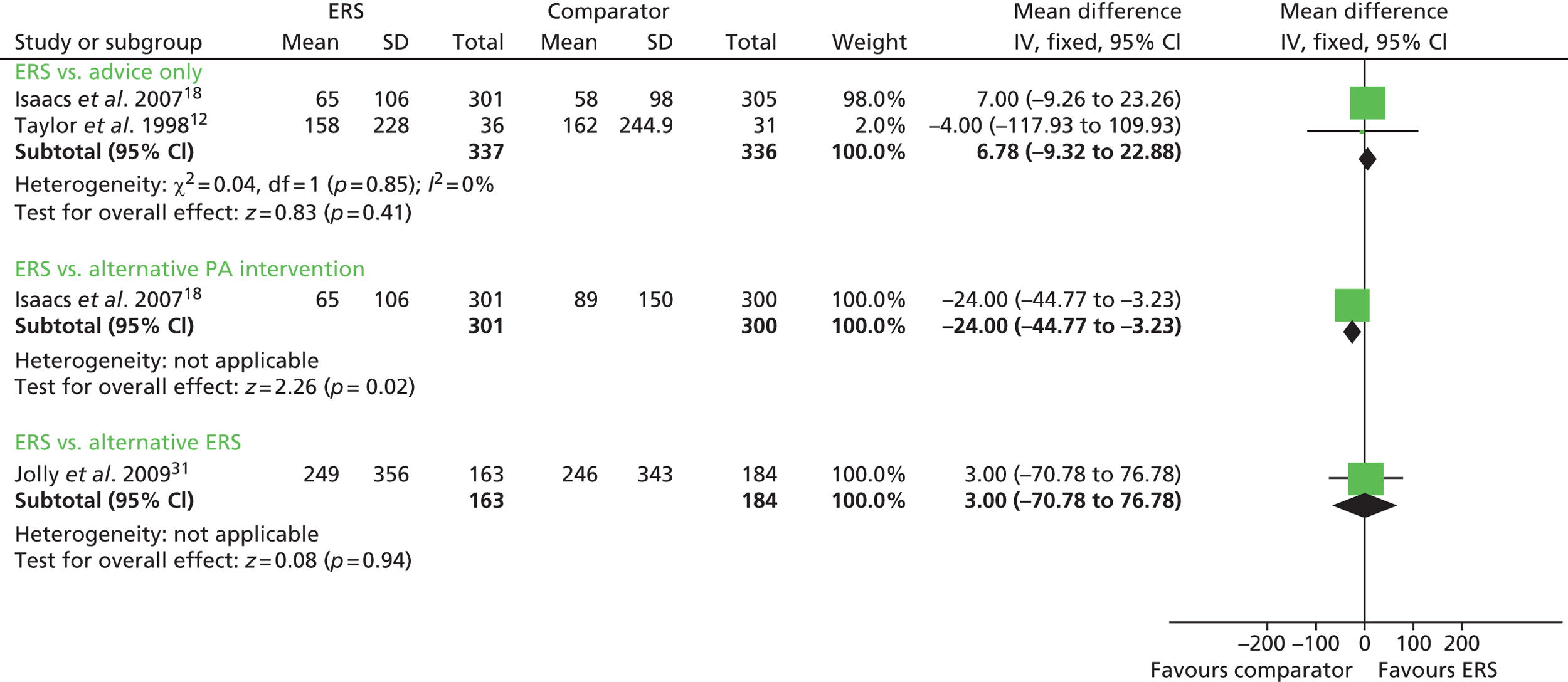

Total minutes of physical activity were reported by Isaacs et al. 18 and Murphy et al. 23 When these data were pooled, there was a significant increase in the number of minutes of physical activity per week in the ERS group; mean difference 55.10 minutes (95% CI 18.47 to 91.73 minutes) (Figures 4–6).

FIGURE 4.

Minutes spent in at least moderate-intensity physical activity per week at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 5.

Minutes of total physical activity/week at 6–12 months’ follow-up ERS vs. advice only (updated meta-analysis). df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 6.

Minutes of total physical activity/week at 6–12 months’ follow-up ERS vs. alternative physical activity. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

Sorensen et al. 27 reported a higher level of energy expenditure with ERS than with physical activity counselling. In contrast, the study by Isaacs et al. 18 observed a higher level of physical activity (minutes of total and moderate-intensity activity, energy expenditure) in those in the walking programme than in the ERS group. When pooled across studies, there was no significant difference in the total amount of physical or energy expenditure between ERSs and alternative physical activity interventions (Figures 7 and 8).

FIGURE 7.

Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day) ERSs vs. usual care at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 8.

Energy expenditure ERSs vs. alternative physical activity intervention at 5–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

Exercise referral schemes versus a self-determination theory informed delivery of exercise on referral

In the Duda et al. study,17 the proportion of patients achieving at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week increased in the standard ERS group from 27% at baseline to 63% at 3 months and 46% at 6 months. There were no significant differences in these proportions between the standard ERS and a SDT-informed delivery of ERSs (Table 10).

| Study and time of follow-up | Patients achieving PA guidance (90–150 minutes/at least moderate intensity per week) | At least moderate intensity PA (minutes per week) | Total PA (minutes per week) | Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, n/N | Control, n/N | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | |||

| Moderate | Vigorous | Moderate | Vigorous | |||||||

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||||

| Taylor et al.12 | ||||||||||

| 8 weeksb | 51/63 | 20/31c,d | 247 (174) | 49 (60) | 145 (178)e | 21 (61)e | Not reported | Not reported | 34.6 (1.2) | 33.7 (1.7)e |

| 16 weeksb | 51/57 | 18/31d,e | 226 (252) | 59 (72) | 160 (262)c | 21 (72)e | Not reported | Not reported | 34.6 (1.2) | 33.9 (1.7)e |

| 26 weeksb | 39/47 | 18/31d,e | 183 (234) | 56 (108) | 206 (251)c | 34 (111)c | Not reported | Not reported | 34.4 (1.8) | 34.3 (1.2)c |

| 37 weeksb | 39/57 | 19/31c,d | 158 (228) | 42 (96) | 162 (245)c | 23 (106)c | Not reported | Not reported | 34.1 (2.4) | 33.9 (2.2)c |

| Stevens et al.26 | ||||||||||

| 8 monthsf | 204/363 | 174/351c,d | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Harrison et al.15 | ||||||||||

| 6 monthsb | 38/168 | 22/162d,e | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 9 monthsb | 36/149 | 31/140c | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 12 monthsb | 40/155 | 32/157c | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||

| 10 weeksg | 48/164 | 29/157d,e | 93 (115) | – | 79 (114)c | – | 584 (479) | 668 (555)c | 34 (26) | 36 (32)c |

| 6 monthsg | 70/179 | 66/200c,d | 65 (106) | – | 58 (98)c | – | 692 (496) | 647 (463)c | 38 (27) | 35 (27)c |

| Gusi et al.28 | ||||||||||

| 6 months | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Murphy et al. 23 | ||||||||||

| 12 months | 431/724 | 409/755 | – | – | – | – | 335.53 (442.47) | 277.42 (371.70) | – | – |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||||

| hSorensen et al.27 | ||||||||||

| 4 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | 63 (114) | 23 (107)c | 43 (2.4) | 41 (4.8) |

| 10 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | – | 20 (124) | 20 (152)c | 41 (2.1) | 40 (5) |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||

| 10 weeksg | 48/164 | 53/92d,e | 93 (115) | – | 113 (291)c | – | 584 (479) | 863 (1026)e | 34 (26) | 43 (38)e |

| 6 monthsg | 70/179 | 62/141c,d | 65 (106) | – | 89 (150)e | – | 692 (496) | 759 (539)c | 38 (27) | 42 (27)c |

| ERS vs. SDT-informed ERS | ||||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | ||||||||||

| 3 monthsg | Not reported | Not reported | 319 (338)c | – | 331 (336)c | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 6 monthsg | 66/156 | 83/169c,d | 249 (356)c | – | 246 (343)c | – | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

Subgroup analysis exploring the impact of patient variables on effects of exercise referral schemes on levels of physical activity

Pavey et al. 11 reported the following analysis of subgroups within seven studies: Harrison et al. 15 reported no statistical significant interaction effects between the ERS effect and pre-specified baseline variables (i.e. CHD risk factors, sex and age). Comparing high adherers (> 75% attendance at ERS) with low adherers (< 75% attendance at ERS) in the Isaacs et al. 18 study, 32 high adherers and 16 low adherers were achieving > 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week at 10 weeks. At 6 months, 41 high adherers and 29 low adherers were achieving > 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week. However, these proportions were not significantly different. In the Duda et al. study,17 age, sex, deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation score), ethnicity, depression at baseline and level of physical activity at baseline were assessed by regression methods as predictors of physical activity at 6 months. Only physical activity at baseline was associated with physical activity at 6 months’ follow-up (p < 0.001). Murphy et al. 23 also found that effectiveness was highly dependent on adherence, with significantly greater differences in all outcomes among those who completed the 16-week programme compared with those who attended only partially or not at all.

Murphy et al. 23 reported that referral and participation in ERSs increased physical activity significantly for those referred for CHD risk factors [odds ratio (OR) 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.60]. However, among those referred for mental health reasons, either solely or in combination with CHD, there was no difference in physical activity between the ERSs and normal-care participants at 12 months’ follow-up. The effect of being in the ERS group on all referrals was an increase in levels of physical activity at 12 months, but this finding was of borderline statistical significance (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.43).

Physical fitness

No additional data were available for this outcome; the following results are taken from Pavey et al. 11 The studies by Taylor et al. ,12 Isaacs et al. 18 and Sorensen et al. 27 reported physical fitness outcomes (Table 11).

| Study and time of follow-up | Mean predicted heart rate at a workload of 150 W | VO2max (ml/kg/minute) | Submaximal bike ergometer (minutes) | Submaximal shuttle walk (m) | Isometric knee strength (N) | Leg extension power (W) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||||||

| Taylor et al.12 | ||||||||||||

| 16 weeksa | 138.6 (23.0) | 147.2 (29.7)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 26 weeksa | 136.3 (22.6) | 142.3 (28.5)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 37 weeksa | 134.2 (19.0) | 146.0 (24.2)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||||

| 10 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 9.65 (1.5) | 8.87 (1.5)c | 456 (102) | 434 (104)b | 277 (54) | 265 (56)b | 174 (31) | 165 (31)b |

| 6 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 8.86 (1.7) | 9.08 (1.7)b | 445 (96) | 434 (97)b | 265 (58) | 267 (66)b | 173 (66) | 167 (68)b |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||||||

| Sorensen et al.27 | ||||||||||||

| 4 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | 23.8 (7.1) | 21.7 (11.0)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 10 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | 23.0 (8.2) | 22.4 (12.7)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||||

| 10 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 9.65 (1.5) | 8.92 (1.7)b | 456 (102) | 437 (100)b | 277 (54) | 275 (58)b | 174 (31) | 166 (32)b |

| 6 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 8.86 (1.7) | 8.92 (1.8)b | 445 (96) | 448 (95)b | 265 (58) | 264 (66)b | 173 (66) | 164 (68)b |

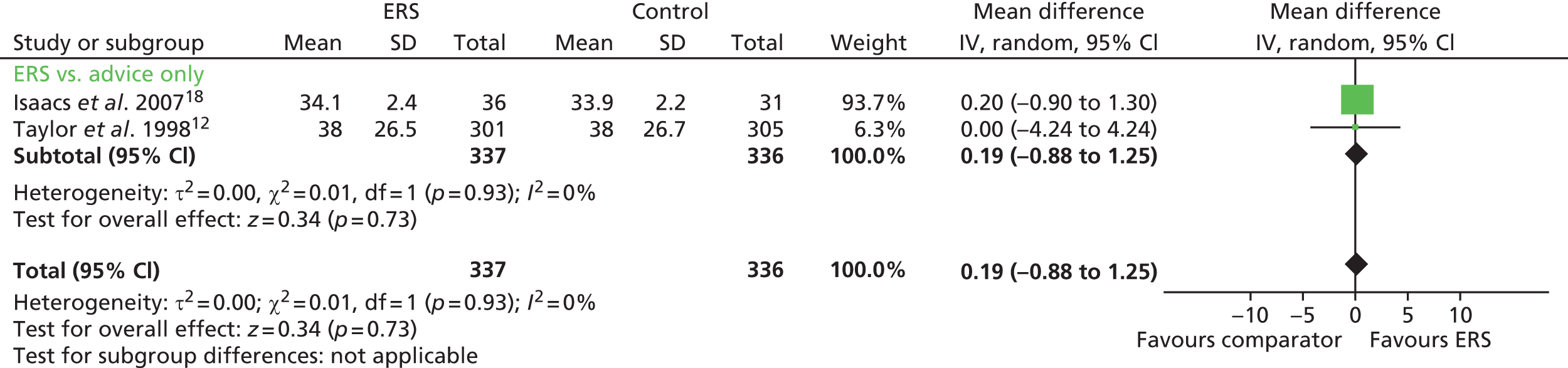

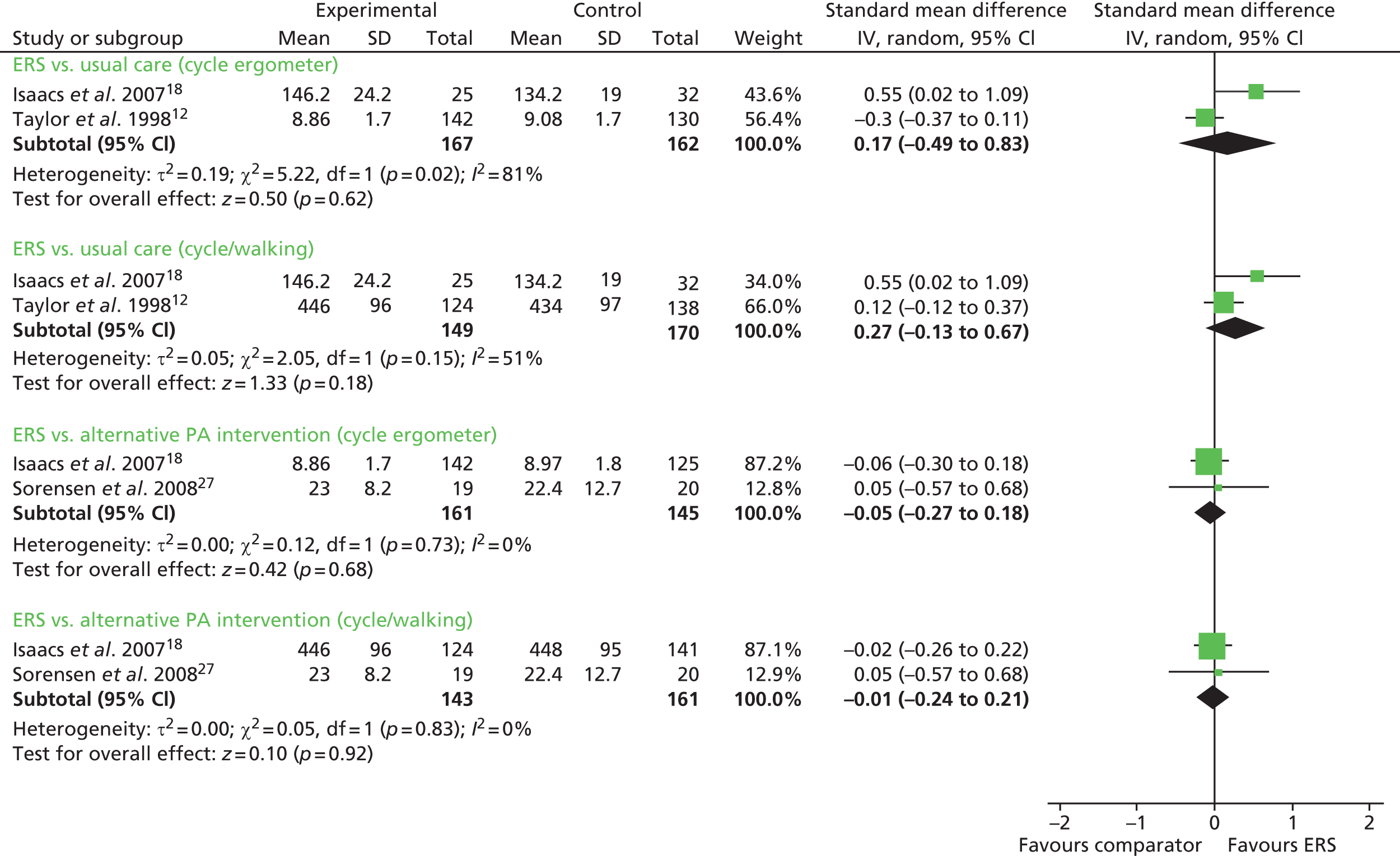

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care

Taylor et al. 12 reported a lower (more favourable) submaximal heart rate (at 150 W) for ERS compared with usual care. Isaacs et al. 18 reported no significant differences in any of the physical fitness measures (submaximal bike and shuttle walk, isometric knee strength, leg extension power) between the ERS and usual-care groups at follow-up, except at 10 weeks for the submaximal bike ergometer test. Pooling of the cardiorespiratory measures (mode: cycle ergometer or cycle/walking) showed no difference between ERSs and usual care (Figure 9). There was considerable evidence of statistical heterogeneity.

FIGURE 9.

Physical fitness at 6–12 months’ follow-up. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

Isaacs et al. 18 and Sorensen et al. 27 reported no significant differences in any of the physical fitness measures between the ERS and the alternative physical activity intervention groups at follow-up (see Figure 9).

Exercise referral schemes versus exercise referral scheme plus self-determination theory

The study of Duda et al. 17 did not assess physical fitness.

Clinical factors

Five studies provided information on clinical outcomes, that is, CHD risk factors (Table 12), weight and obesity measures (Table 13) and respiratory function (Table 14).

| Study and time of follow-up | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | Cholesterol (mmol/l) | High-density lipoproteins (mmol/l) | Low-density lipoproteins (mmol/l) | Triglycerides (mmol/l) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||||||

| Taylor et al.12 | ||||||||||||

| 16 weeksa | 130 (14.5) | 130 (14)b | 84 (8) | 84 (8)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 26 weeksa | 130 (14) | 131 (14)b | 84 (8) | 84 (8)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 37 weeksa | 130 (17) | 131 (18)b | 85 (9) | 83 (9)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||||

| 10 weeksa | 133 (10) | 132 (10)b | 82 (6) | 83 (6)b | 5.68 (0.53) | 5.71 (0.42)b | 1.35 (0.18) | 1.35 (0.18)b | 3.41 (0.46) | 3.44 (0.47)b | 2.12 (0.71) | 2.14 (0.71)b |

| 6 monthsa | 133 (12) | 133 (12)b | 82 (6) | 82 (7)b | 5.65 (0.50) | 5.60 (0.50)b | 1.37 (0.25) | 1.38 (0.17)b | 3.40 (0.48) | 3.37 (0.50)b | 2.04 (0.74) | 2.00 (0.84)b |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||||||

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||||

| 10 weeksa | 133 (10) | 134 (10)b | 82 (6) | 84 (6)b | 5.68 (0.53) | 5.69 (0.53)b | 1.35 (0.18) | 1.33 (0.17)b | 3.41 (0.46) | 3.45 (0.46)b | 2.12 (0.71) | 2.05 (0.76)b |

| 6 monthsa | 133 (12) | 134 (12)b | 82 (6) | 83 (6)b | 5.65 (0.50) | 5.56 (0.57)b | 1.37 (0.25) | 1.37 (0.16)b | 3.40 (0.48) | 3.36 (0.48)b | 2.04 (0.74) | 1.95 (0.74)b |

| ERS vs. ERS plus SDT | ||||||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | ||||||||||||

| 6 monthsa | 130 (17) | 127 (16)b | 82 (11) | 79 (11)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Study and time of follow-up | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | Body fat (%) | Waist-to-hip ratio (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||

| Taylor et al.12 | ||||||||

| 16 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | 27.5 (0.6) | 27.6 (0.6)b | 70 (8) | 76 (8)c | 0.87 (0.08) | 0.83 (0.09)b |

| 26 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | 27.3 (1.3) | 27.5 (1.1)b | 70 (11) | 75 (11)c | 0.87 (0.08) | 0.83 (0.09)b |

| 37 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | 27.5 (1.3) | 27.6 (1.1)b | 71 (13) | 76 (13)c | 0.87 (0.08) | 0.84 (0.09)b |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||

| 10 weeksd | 81 (3) | 81 (3)b | 30.2 (0.8) | 30.1 (1.5)b | 37.4 (1.9) | 37.5 (1.9)b | 0.88 (0.06) | 0.89 (0)b |

| 6 monthsd | 82 (3) | 82 (3)b | 30.5 (1.1) | 30.4 (1.1)b | 37.8 (2.4) | 37.8 (2.4)b | 0.88 (0) | 0.88 (0)b |

| Gusi et al.28 | ||||||||

| 6 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | 29.7 (4.2) | 30.6 (4.3)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||

| fSorensen et al.27 | ||||||||

| 4 monthse | –1.1 (4) | –1.1 (4)b | –0.3 (1.3) | –0.04 (1.6)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 10 monthse | –0.3 (4.4) | –0.3 (4.4)b | –0.1 (1.9) | –0.6 (2.8)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||||||

| 10 weekse | 81 (3) | 81 (3)b | 30.2 (0.8) | 30.2 (1.6)b | 37.4 (1.9) | 37.1 (1.9)b | 0.88 (0.06) | 0.88 (0.06)b |

| 6 monthse | 82 (3) | 82 (3)b | 30.5 (1.1) | 30.5 (1.1)b | 37.8 (2.4) | 37.8 (1.1)b | 0.88 (0) | 0.88 (0)b |

| ERS vs. ERS plus SDT | ||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | ||||||||

| 6 monthse | Not reported | Not reported | 32.8 (6.9) | 32.8 (6.4)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Study and time of follow-up | FEV : FVC ratio | PEF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||

| 10 weeksa | 0.86 (0.0) | 0.86 (0.06)b | 417 (58) | 409 (58)b |

| 6 monthsa | 0.86 (0.09) | 0.86 (0.09)b | 407 (115) | 411 (117)b |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||

| 10 weeksa | 0.86 (0.0) | 0.85 (0.06)b | 417 (58) | 407 (61)b |

| 6 monthsa | 0.86 (0.09) | 0.85 (0.09)b | 407 (115) | 416 (117)b |

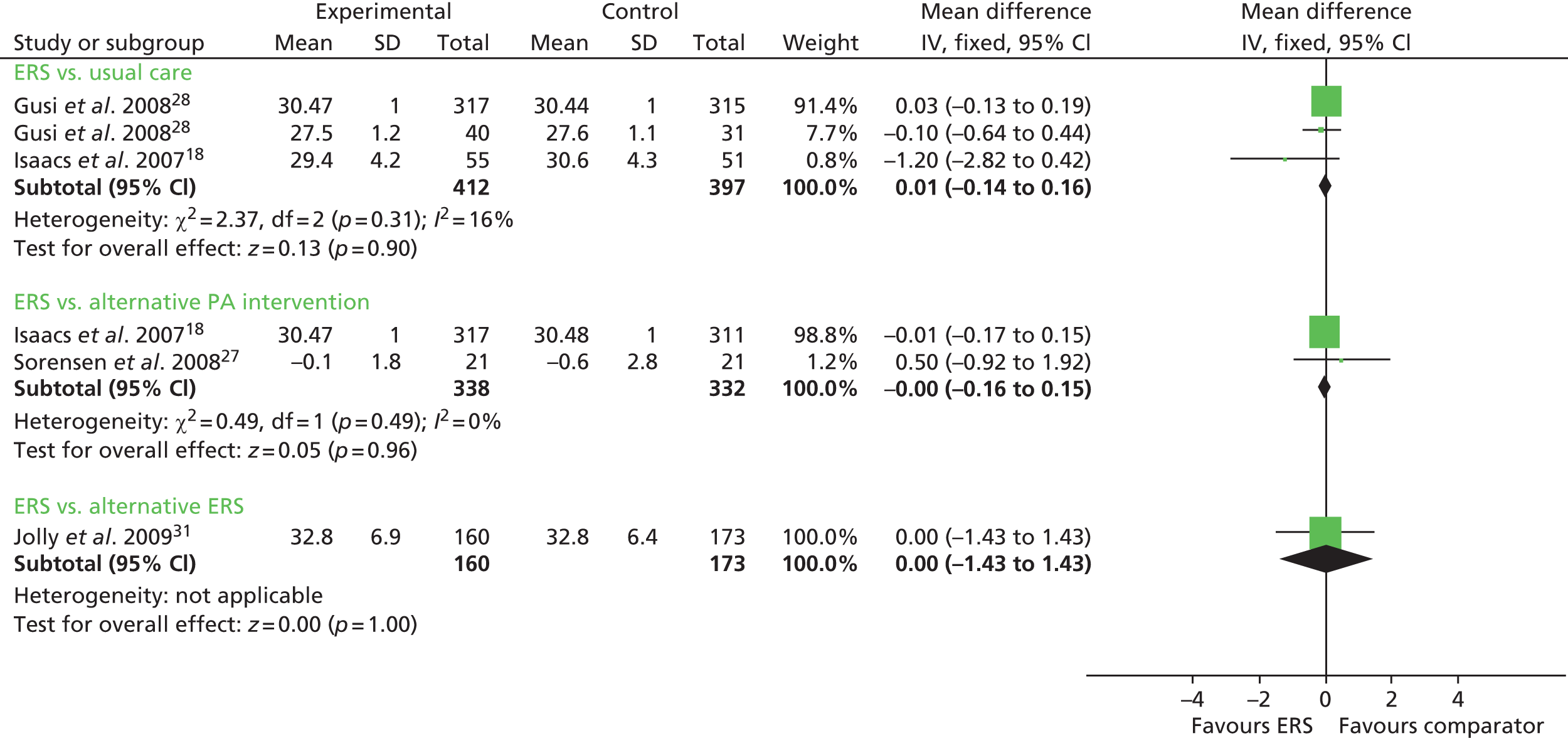

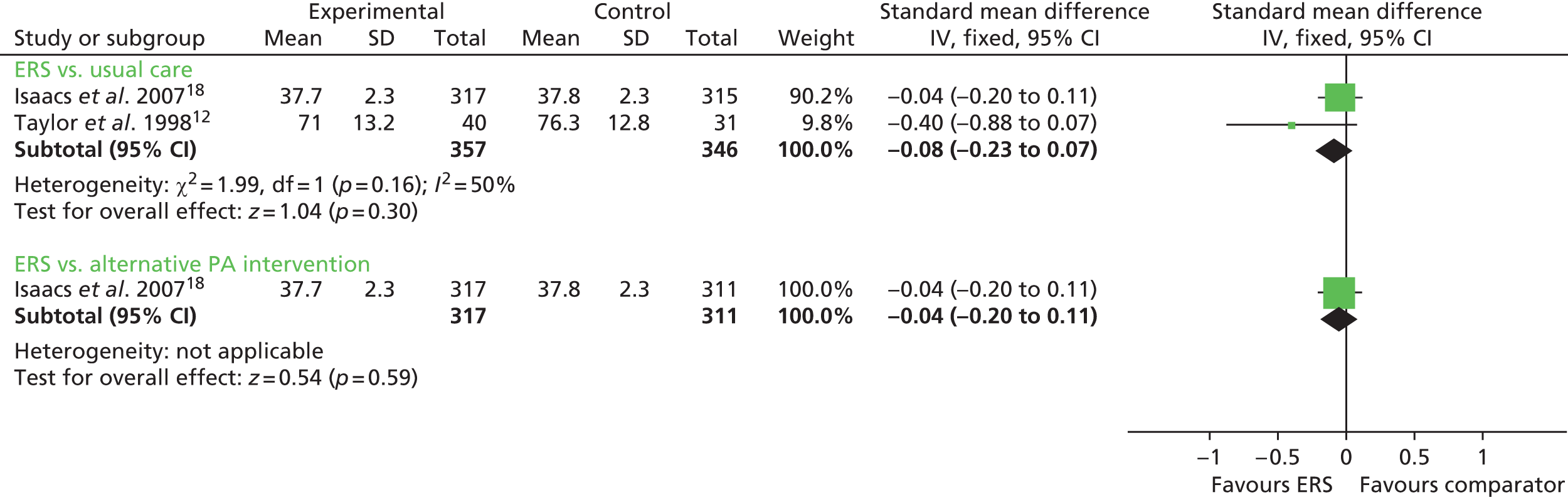

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care

Taylor et al. 12 reported percentage of body fat in ERS participants compared with usual care at follow-up and found no statistically significant difference between the groups. Gusi et al. 28 reported a lower body mass index (BMI), with no other between-group differences in weight and body fat outcomes for the other measured clinical factors (Figures 10 and 11). There was no significant difference in resting blood pressure, serum lipids or respiratory function between ERSs and usual care at follow-up (Figures 12 and 13).

FIGURE 10.

Systolic blood pressure at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 11.

Diastolic blood pressure at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 12.

Body mass index at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 13.

Body fat at 6–12 months’ follow-up. 11 df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

In both the studies by Isaacs et al. 18 and Sorensen et al. 27 there were no significant between-group differences at follow-up in resting blood pressure (see Figures 10 and 11), BMI (see Figure 12), body fat outcomes, serum lipids and respiratory function. The Sorensen et al. trial27 reported reduced levels of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in both the ERS group (mean –0.26%, 95% CI –0.79% to 0.27%) and the physical activity counselling group (mean –0.23%, 95% CI –0.47% to 0.02%) at 4 months’ follow-up, although there was no difference between groups.

Exercise referral schemes versus exercise referral scheme plus self-determination theory

Duda et al. 17 reported no significant difference between standard ERS and ERS plus SDT in BMI or resting blood pressure.

Psychological well-being

Four studies17,18,23,25,28 reported psychological well-being outcomes and the results are summarised in Table 15.

| Study | Psychological well-being | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety/depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||

| aTaylor and Fox25 | ||||||||

| 16 weeksb | 2.31 (0.79) | 2.31 (0.67)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 37 weeksb | 2.41 (0.79) | 2.42 (0.54)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| dIsaacs et al.18 | ||||||||

| 6 monthse | Not reported | Not reported | 6.9 | 7.1f | 4.8 | 4.9f | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gusi et al.28 | ||||||||

| 6 monthse | Not reported | Not reported | 14.1 (9) | 22.2 (9.8)c | 1.8 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.5)c | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.7)c |

| Murphy et al.23 | ||||||||

| 12 months | Not reported | Not reported | HADS 7.82 (95% CI 7.39 to 8.25) (n = 472) | HADS 8.35 (95% CI 7.92 to 8.77) (n = 502) | HADS 6.14 (95% CI 5.73 to 6.54) (n = 471) | HADS 6.93 (95% CI 6.53 to 7.32) (n = 506) | ||

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||

| dIsaacs et al.18 | ||||||||

| 6 monthse | Not reported | Not reported | 6.9 | 7.5f | 4.8 | 5.1f | Not reported | Not reported |

| ERS vs. ERS plus SDT | ||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | ||||||||

| 3 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | 7.7 (4.4)f | 8.89 (4.3) | 5.9 (4.2)f | 6.68 (4.1) | Not reported | Not reported |

| 6 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | 7.9 (4.8)f | 8.86 (4.7) | 6.1 (4.4)f | 6.65 (4.3) | Not reported | Not reported |

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care

Taylor and Fox25 reported physical self-perceptions measures, with improvements shown in physical self-worth, and perceptions of physical condition and physical health-collected physical self-perceptions data, and reported significant differences favouring the ERS group compared with usual-care group at 16 and 37 weeks. Isaacs et al. 18 reported no differences between the ERS and usual-care groups in the anxiety and depression scores using the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. In the Gusi et al. study,28 all measures [Geriatric Depression Scale, State Trait Anxiety Inventory and the anxiety/depression subscale of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)] at 6 months were found to favour ERS participants compared with those receiving the usual care. In the Murphy et al. study,23 in participants who were referred for mental health reason or in combination with CHD, there were significantly lower levels of anxiety (OR –1.56, 95% CI –2.75 to –0.38) and depression (OR –1.39, 95% CI –2.60 to –0.18) but no effect on physical activity. Murphy et al. 23 also found significant interactions with sex for both mental health outcomes, with the beneficial effect of the intervention apparent only among women. There was a suggestion that the intervention was more effective on mental health outcomes among the youngest age group (18–44 years), although this was not statistically significant. Effects did not vary significantly by deprivation status.

Pavey et al. 33 in a review updating his earlier review,11 pooled HADS score data from Murphy et al. 23 and Gusi et al. 28 (Figure 14). This showed a significant reduction in depression (standardised mean difference –0.82, 95% CI –1.28 to –0.35) but not in anxiety (standardised mean difference –4.12, 95% CI –11.52 to 3.28) for ERSs compared with usual care.

FIGURE 14.

Meta-analysis of depression and anxiety in patients, at 6–12 months’ follow-up: fixed-effects model used. (Pavey et al. 33 reproduced with permission, ©2011 BMJ). df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

Isaacs et al. 18 reported no differences between the ERS and walking programme in anxiety or depression outcomes at the 6-month follow-up.

Exercise referral schemes versus exercise referral scheme plus self-determination theory

Duda et al. 17 reported no difference between groups in anxiety or depression outcomes at either the 3- or 6-month follow-up.

Health-related quality of life

Five studies17,18,23,27,28 reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as summarised in Table 16.

| Study and time of follow-up | SF-36 mental | SF-12 mental | SF-12 physical | EQ-5D | Dartmouth QoL (overall QoL scale) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||||||||

| aIsaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||

| 6 monthsb | 54.2 | 54.3c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gusi et al.28 | ||||||||||

| 6 monthsc | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0.89 (0.18) | 0.51 (0.2)d | Not reported | Not reported |

| Murphy et al. 23 | ||||||||||

| 12 months | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0.64 (0.32) ( n = 395) | 0.61 (0.32) ( n = 391) | Not reported | Not reported |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||||||||

| Sorensen et al.27 | ||||||||||

| 4 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | 40 (10.7) | 37 (11.9)e | 49 (1017.6) | 46 (13.1)e | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 10 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | 41 (10.8) | 39 (10.9)e | 51 (11.6) | 45 (15.4)e | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| aIsaacs et al.18 | ||||||||||

| 6 monthsb | 54.3 | 53c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| ERS vs. ERS plus SDT | ||||||||||

| Duda et al.17 | ||||||||||

| 3 months | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 3.16 (0.8)e | 3.25 (0.7)c |

| 6 months | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 3.15 (0.8)e | 3.24 (0.8)c |

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care

Isaacs et al. 18 reported no differences between the ERS and usual-care groups at follow-up on the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) mental health scale. Gusi et al. 28 observed higher EQ-5D scores in the ERS group than in the usual-care group at 6 months. Murphy et al. 23 also observed higher EQ-5D scores in the ERS group than in the usual-care group at 12 months, but it was not statistically significant.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

Isaacs et al. 18 reported no differences between the ERS and walking groups at follow-up on the SF-36 mental health scale score. Similarly, Sorensen et al. 27 found no differences in scores between the groups at follow-up on the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) items mental and physical scales.

Exercise referral schemes versus exercise referral scheme plus self-determination theory

Duda et al. 17 reported no difference between groups in overall Dartmouth CO-OP (Primary Care Cooperative Information Project) chart score, although there was a difference for the feelings subscale at 6 months in favour of the alternative ERS group (not tabularised).

Patient satisfaction

Two studies15,18 reported patient satisfaction and results are summarised in Table 17.

| Study | Satisfied with received information (%) | Needed further information (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs. usual care | ||||

| Harrison et al.15 | ||||

| 3 months | 92 | 69a | 43 | 54a |

| ERS vs. alternative PA intervention | ||||

| Isaacs et al.18 | ||||

| 10 weeks | 97 | 96b | 15 | 17b |

Exercise referral schemes versus usual care

The Harrison et al. study15 reported that the ERS group participants were significantly more satisfied with the information they received and felt they needed less information about physical activity compared with the usual-care group. In the Taylor et al. study,12 comments about the concept of ERSs (measured at 8 weeks) identified that 50% of patients were positive, 35% had mixed feelings and 15% had only negative comments. Negative comments included a long waiting time before introductory session, lack of staff support, crowded facilities and inconvenient facility times.

Exercise referral schemes versus alternative physical activity intervention

In the Isaacs et al. 18 study, there was no between-group difference in participant satisfaction with received information or the need for additional information. In the ERS group, 97.8% felt better for taking part and enjoyed the programme compared with the walking group, in which 93.8% felt better for taking part and 95.2% enjoyed the programme.

Exercise referral schemes versus exercise referral scheme plus self-determination theory

Duda et al. 17 did not assess participant satisfaction.

Adverse events

Although participation in ERSs has the potential to lead to negative events (e.g. an increase in exercise-related musculoskeletal injuries or exercise-related cardiac complications), only the Isaacs et al. 18 study assessed such events. Using GP records, the authors assessed the change in consultations before and after ERSs. There was evidence of a small increase in GP visits for falls and fractures in the ERSs and walking groups compared with usual-care control after the start of the study (Table 18).

| Adverse events | Leisure centre | Walking control | Advice-only control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visits for chest pain | |||

| 12–6 months before start of study | 1 (%) | 3 | 7 |

| 6 months before start of study | 3 (%) | 4 | 7 |

| Start of study to 6 months | 2 (%) | 9 | 7 |

| 6–12 months after start of study | 10 (%) | 4 | – |

| Visits for aches/pains | |||

| 12–6 months before start of study | 64 | 48 | 56 |

| 6 months before start of study | 62 | 53 | 55 |

| Start of study to 6 months | 52 | 42 | 44 |

| 6–12 months after start of study | 63 | 44 | – |

| Visits for sprains | |||