Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/71/01. The contractual start date was in June 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor John Norrie is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board and a member of the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment Editorial Boards.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Pickard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2008, the UK Government Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme called for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to answer the following clinical care question: ‘What is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the use of calcium channel blockers and α-blockers to facilitate urinary stone passage in people with ureteric colic?’ This report describes the research [the SUSPEND (Spontaneous Urinary Stone Passage ENabled by Drugs) trial] that was subsequently commissioned.

The SUSPEND trial was a large, pragmatic, UK-based, multicentre RCT. It aimed to establish whether or not the use of either alpha-blockers or calcium channel blockers was clinically effective as medical expulsive therapy (MET) to facilitate spontaneous stone passage for people requiring emergency care for ureteric colic in comparison with placebo, and whether or not their use was cost-effective from the perspective of the UK NHS.

Background

Target population for trial

Ureteric colic describes the pain felt when a stone formed in the urine collection part of the kidney (usually resulting from the aggregation of calcium-based crystals) passes down the ureter, the urine drainage tube connecting the kidney to the bladder (Figure 1). The pain is typically severe and recurrent; each episode usually lasts for an hour or two and is interspersed with periods without pain. Female sufferers consider it to be more intense than the pain experienced during childbirth. 1 Repeated episodes have a detrimental influence on perception of quality of life. 2 Pain is usually felt in the abdomen but can go down into the groin and scrotum in males, and labia in females. Some people also get increased frequency and urgency of urination. The pain is likely to relate to direct contact of the stone with the epithelial cells lining the ureter and sustained contraction (spasm) of the smooth muscle surrounding the ureter in response to the obstruction of urine flow. 3 The severity of the pain leads to secondary symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and fever. Pain episodes generally continue until the stone passes into the bladder from where it can be freely voided by urination. Kidney stone disease is highly prevalent in most countries, where it affects 5% to 10% of the population,4 and, as there is no effective disease-modifying treatment, sufferers may have repeated episodes following the first bout of colic, with an approximate lifetime risk of recurrence of 50%. 5,6 The cause of kidney stone formation is multifactorial with genetic, environmental and dietary influences all playing a part. In epidemiological terms it is more common in people aged 15–60 years, in men and in those of Caucasian race, and there is a higher incidence during the summer months. 7

FIGURE 1.

Anatomy of urinary tract showing definition of ureteric segments. Reproduced, with permission, from Medindia. URL: www.medindia.net/news/michigan-hospitals-lead-the-way-in-preventing-common-and-costly-urinary-tract-infections-116433-1.htm (accessed July 2015).

Ureteric colic is one of the most common reasons for people to seek emergency health care, with an annual incidence of around 30 out of 100,000 in high-resource parts of the world. 8 In the UK, 83,000 people required emergency care for ureteric colic in 2009,9 and NHS England health episode statistics data for 2012–13 showed 31,000 hospital admissions with a 1-day median stay and a NHS tariff cost of £19.3M. 10 In the USA, there were 600,000 emergency room visits in 2000 at an estimated health-care cost of US$490M. 7 In both countries, the incidence of ureteric colic increased by over 50% during the previous decade. 7,9

Clinical assessment

The diagnosis of ureteric colic is usually straightforward from the characteristic history of pain, the lack of abdominal tenderness and, to some extent, the finding of non-visible haematuria on reagent strip testing of urine. 8 At this point the patient is given effective pain relief in the form of opiates or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alone or in combination. 11,12 Urine is then checked for infection by microscopy and culture, and renal function is estimated by measurement of serum creatinine. Once the patient is comfortable, the presence of a stone in the ureter can be reliably confirmed by imaging using computerised tomography scanning of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (CT KUB) without the use of intravascular contrast agents. Further analysis of the CT KUB images will localise the stone to the upper, mid or lower ureter (see Figure 1) and will estimate stone size defined by the maximum linear dimension in millimetres. Less commonly, patients may have evidence of severe urinary and bloodstream infection (urosepsis) as a result of the stone obstructing drainage from the affected kidney; they may have stones in both ureters; or they may have a single kidney, all of which cause marked impairment of renal function. Each of these situations will require resuscitation and urgent intervention and, therefore, such patients are not the focus of this trial.

Interventions for ureteric colic

Guidance on patient management options with summarised relative benefits and harms has been formulated under a joint initiative between the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association, and form the basis of clinical management for people with kidney and ureteric stones, particularly across Europe and North America. 13 The options for treatment fall under three headings – symptom management, MET and active treatment – and these are discussed below.

Symptom management

For the majority of patients (approximately 75%) without a reason for prompt intervention to drain the affected kidney, management consists of pain relief, antiemetics and encouragement of adequate oral fluid intake. Once the pain is controlled, care can continue at home with oral analgesics but with the facility for rapid readmission if there is deterioration, together with a planned reassessment at approximately 4 weeks to assess whether or not spontaneous stone passage has occurred. Reasons for changing to active management would include poor pain control, the onset of systemic infection or concerns regarding deterioration in kidney function.

Medical expulsive therapy

Patients with ureteric stones face the uncertainty of when spontaneous stone passage and associated episodic pain will occur. Simple adjunctive treatments that lessen stone symptoms, hasten stone passage and increase the likelihood of eventual passage, thus reducing the risk of requiring active treatment, would reduce this burden. After many years of different agents being trialled, recent meta-analyses of multiple RCTs have encouraged clinicians to prescribe MET. An alpha-blocker drug [typically tamsulosin hydrochloride (Petyme, TEVA UK Ltd) 400 µg once daily] or a calcium channel blocker [typically nifedipine (Coracten®, UCB Pharma Ltd) 30 mg once daily] is prescribed to patients who, following assessment and diagnosis, can be treated by symptom management while awaiting spontaneous stone passage. 14,15 The results of most individual trials, and the summarised effects in the meta-analyses, suggest that these two drug classes have efficacy for the three desired outcomes of reduced pain, quicker stone passage and higher rate of eventual stone passage. However, the small sample size and the single-centre nature of the individual trials included limits, certainty and generalisability of the treatment effect, hence the need for a large, more pragmatic, trial such as SUSPEND. Current status of the evidence basis for use of MET is discussed later in this introduction.

Active treatment

Definitive removal of the stone can be achieved in two ways. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) is an ambulatory treatment whereby acoustic waves that can be generated by a number of different energy sources are focused on the stone from outside the body. The physical characteristics of the stone allow it to be fragmented without significant damage to surrounding tissue. The treatment does require continued imaging of the stone by radiography or ultrasound, however, and the patient has to pass the fragments in the urine. Alternatively, stones can be directly visualised by passing a fine endoscope (ureteroscope) up from the bladder. The stone can then be extracted whole or fragmented in situ with a variety of energy sources and removed in pieces. This ureteroscopic technique gives greater certainty of stone removal but does involve a hospital admission and general anaesthetic. 16 Emergency drainage of an obstructed infected kidney can be achieved either by retrograde passage of a drainage tube (ureteric stent) up the ureter to the kidney from below or by direct insertion from above of a tube (nephrostomy) through the skin of the back into the urine collection part of the kidney.

Outcomes of interest

Cohort studies and observations from placebo or standard therapy groups of RCTs suggest that about 50–85% of people with ureteric colic will pass their stone unaided (spontaneous stone passage) within 4 weeks of diagnosis. Speedier passage of the stone would tend to reduce overall pain burden and thereby lessen the impact of any pain on the patient’s lifestyle, in terms of time off work and interference in day-to-day activities. From a clinical perspective, confirming stone passage is difficult. Patients are sometimes encouraged to sieve their urine (most stones are the size of a match head), but adherence is doubtful and small fragments can easily be missed. Simple imaging by plain single abdominal radiography or by ultrasound to confirm the absence of a stone has low diagnostic accuracy,17 whereas further definitive imaging by repeated CT KUB gives levels of radiation exposure that are generally considered to be unacceptable for this predominantly young patient group. 18 Clinical definition of stone passage is, therefore, the absence of pain or other relevant symptoms or signs. For the 30% of patients who continue to experience symptoms, further intervention (sometimes with MET if not previously used, but more usually with active stone removal by ESWL or ureteroscopy) will be required following repeat imaging. The urgency of any active intervention will depend on individual patient circumstances and resource availability in the particular health-care setting. There is an increased likelihood that active treatment will be required with larger stones (conventionally described as > 5 mm) and with stones located in the mid or upper ureter at the time of first presentation (Table 1). The need for further treatment is an important and routinely measurable outcome for both patients and providers of health care, as active intervention is associated with harm to patients and increased health-care costs. 13

Current evidence base for use of medical expulsive therapy

Background

Given that care for most patients with ureteric stones is delivered with the expectation of spontaneous stone passage, several strategies aimed at reducing pain, hastening stone passage and increasing the rate of stone passage have been proposed and trialled. Such strategies are termed MET. Agents that initially appeared to be useful but then failed to show efficacy in more robustly designed studies included diuretics and administration of high fluid load to increase urinary hydrostatic pressure above the stone;20 steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and NSAIDs to reduce ureteric oedema and inflammation around the stone;21,22 and antimuscarinic drugs to inhibit ureteric muscular contraction. 23 The two drug classes that appear to show efficacy in repeated small-scale RCTs and subsequent meta-analysis are calcium channel antagonists and alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonists. 24

Experiments using animal and human tissue models demonstrate that ureteric smooth muscle contraction can be stimulated by activation of adrenergic receptors, particularly the alpha-1D subtype. 25–28 Blockade of alpha-1 receptors by specific pharmacological antagonists (alpha-blockers) such as doxazosin,29 terazosin,30 alfuzosin31 and, most typically, tamsulosin32,33 results in ureteric smooth muscle relaxation. It was hypothesised that this would translate into clinical benefit for people with ureteric colic. Smooth muscle contraction is stimulated in part by the influx of calcium ions into the smooth muscle cell through specific channels in the cell membrane, which are opened and closed by changes in the degree of electrical polarisation. These channels can be blocked by specific pharmacological antagonists, such as nifedipine, resulting in less calcium influx and reduced smooth muscle contraction. Experimental work demonstrating this effect in vitro encouraged translation to the clinical care of people with ureteric colic. 34–38

Pharmacological characteristics of putative agents

Tamsulosin is a readily available alpha-blocker which is licensed by the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration at a dose of 400 µg in the form of a modified-release (MR) oral tablet to be taken daily for relief of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. 39,40 It is generally well tolerated but is associated with common (0.1–1%) risks of dizziness and retrograde ejaculation in men. The calcium channel blocker nifedipine is available in the form of MR tablets or capsules in varying doses, ranging from 20 mg to 60 mg, with 30 mg being most often used. 40 The drug is licensed for the treatment of hypertension, Raynaud’s phenomenon and prophylaxis of angina, although it has been largely superseded for these indications by more specific and effective calcium channel antagonists. The common side effects (0.1–1%) include headache, dizziness, flushing, constipation and oedema of the lower limbs.

Evidence review for efficacy of tamsulosin and nifedipine as medical expulsive therapy

Multiple RCTs have been carried out testing the efficacy of both alpha-blockers (typically tamsulosin 400 µg) and calcium channel blockers (typically nifedipine 30 mg) compared with placebo, standard care, which may include other interventions, and each other. The medications are prescribed for use either up until the time of spontaneous stone passage or for up to one per month without stone passage. The conduct, quality and results of these trials have been examined by a number of systematic reviews and the results combined in meta-analyses, the findings of which concerning the main outcomes of interest will now be summarised.

Stone clearance

Comparison of the rate of spontaneous stone passage between MET and control is the primary outcome for the great majority of RCTs included in the meta-analyses. The absolute rates of stone passage are likely to vary according to trial eligibility criteria, such as type of diagnostic imaging used, stone location, stone size, the time point at which the outcome is censored and the protocol used to decide whether or not the stone has passed. Variation in these trial features is illustrated from 22 studies included in a Cochrane review14 that compared tamsulosin 400 µg with control (Table 2).

| Trial features | Option 1 (n) | Option 2 (n) | Option 3 (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic imaging | CT KUB (4) | Any imaging (15) | Unclear (3) |

| Stone size | ≤ 10 mm (10) | 4–10 mm (4) | Other (8) |

| Stone location | Distal (20) | Proximal (1) | Any (1) |

| Follow-up duration | < 4 weeks (11) | 4 weeks (10) | > 4 weeks (1) |

| Follow-up assessment | CT KUB (3) | Imaging (10) | Unclear (9) |

| Primary outcome | Rate of stone passage (20) | Time to stone passage (2) |

Despite these inconsistencies in trial design, the available meta-analyses all demonstrate an apparent beneficial effect of both tamsulosin and nifedipine as agents to increase the proportion of patients with ureteric colic who spontaneously pass their stone within a reasonable time frame (Table 3).

| Review | Comparators | Stone clearance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone free | RR (95% CI) | Number of studies | Number of participants | ||

| Hollingsworth et al., 200624 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | 72% vs. 47% | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 4 | 222 |

| EAU/AUA, 200713 | Tamsulosin vs. control | NA | 29% (20% to 37%)b | 5 | 280 |

| Singh et al., 200741 | Alpha-blocker vs. control | 80% vs. 52% | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 16c | 1235 |

| Seitz et al., 200915 | Tamsulosin vs. control | 82% vs. 59% | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 10 | 816 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Tamsulosin vs. placebo | 80% vs. 65% | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 6d | 629 |

| Lu et al., 201242 | Tamsulosin vs. standard caree | 75% vs. 50% | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 9 | 661 |

| Fan et al., 201343 | Tamsulosin vs. control | 80% vs. 52% | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) | 15 | 1593 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Alpha-blocker vs. control | 78% vs. 49% | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | 21f | 1565 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Tamsulosin vs. standard | 77% vs. 52% | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 24 | 1875 |

| EAU/AUA, 200713 | Tamsulosin vs. nifedipine | NA | 20% (–7% to 45%)b | 2 | Not stated |

| Lu et al., 201242 | Tamsulosin vs. nifedipine | 84% vs. 73% | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 6 | 597 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Tamsulosin vs. nifedipine | 94% vs. 73% | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 4 | 3486 |

| Hollingsworth et al., 200624 | Nifedipine vs. control | 71% vs. 47% | 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9) | 2 | 135 |

| EAU/AUA, 200713 | Nifedipine vs. control | NA | 9% (–7% to 25%)b | 4 | 160 |

| Singh et al., 200741 | Nifedipine vs. control | 78% vs. 52% | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 9 | 686 |

| Seitz et al., 200915 | Nifedipine vs. control | 79% vs. 53% | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 9 | 686 |

Regarding the effect of stone size, the meta-analysis by Seitz et al. 15 reported a relative risk (RR) in favour of tamsulosin versus control of 1.25 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12 to 1.40] for stones < 5 mm, and 1.62 (95% CI 1.50 to 1.74) for stones ≥ 5 mm. For nifedipine against control, the RR for stones < 5 mm was 1.49 (95% CI 1.17 to 1.88) and for stones ≥ 5 mm was 1.49 (95% CI 1.31 to 1.69). Similarly, Campschroer et al. 14 reported absolute rates of stone clearance for alpha-blocker against control for stones ≤ 5 mm of 83% versus 56%, with a RR of 1.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.7), and for stones > 5 mm of 67% versus 39%, with a RR of 1.7 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.1). Summarised results for the effect of stone location on clearance rates for tamsulosin against standard therapy were reported by Fan et al. ,43 with a RR of 1.55 for lower ureteral stones (95% CI 1.43 to 1.68) and a RR of 1.28 for upper ureteral stones (95% CI 1.04 to 1.57). Similarly, Campschroer et al. 14 reported absolute rates of stone clearance for alpha-blockers against control for stones in the lower (distal) ureter of 79% versus 55% (RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6) and for stones in the mid or upper ureter of 39% versus 27% (RR 1.5, 95% CI 0.9 to 2.4). The results of these meta-analyses should be interpreted with caution given the uncertainties associated with estimating effect size in subgroups of the overall trial population. Overall, it does appear that these drugs demonstrate efficacy for passage of larger stones and for stones in the upper section of the ureter that are considered to be less likely to pass without active intervention. 8

Time to stone passage

Shorter duration of stone episode is likely to be associated with less pain and less social inconvenience, such as time off work, which may be of benefit to patients. Most RCTs examined time to stone passage as a secondary outcome, although the degree to which this was reported varied, thus making meta-analysis difficult. However, the direction of effect was consistent in favouring tamsulosin or nifedipine (Table 4). It should also be noted that censoring of exact time of passage is reliant on precise patient report or timing of follow-up imaging leading to reporting inaccuracy.

| Review | Comparators | Time to stone passage (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute number of days | RR (95% CI) | Number of studies | Number of participants | ||

| Singh et al., 200741 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | 5 vs. 8 | – | 8 | 584 |

| Lu et al., 201242 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | – | –3 (–5 to –2) | 6 | 454 |

| Fan et al., 201343 | Tamsulosin vs. control | – | –3 (–5 to –3) | 7 | 555 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Alpha-blocker vs. placebo | – | –2 (–4 to 1) | 4b | 293 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Alpha-blocker vs. standardc | – | –3 (–4 to –1) | 18d | 1388 |

| Singh et al., 200741 | Nifedipine vs. controla | 8 vs. 13 | – | 9 | 686 |

Pain episodes/use of analgesia

Pain is likely to be the main reason for continued ill health in people with ureteric stones and it drives both transient quality-of-life detriment and the need for further intervention. However, it is difficult to measure in an ambulatory setting, particularly for conditions such as ureteric colic which are characterised by episodic pain of varying severity and frequency. The RCTs and subsequent meta-analyses reported this outcome, but the differences in definition make measurement of comparative effect uncertain (Table 5).

| Review | Comparators | Number of pain episodes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute rate | RR (95% CI) | Number of studies | Number of participants | ||

| Lu et al., 201242 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | – | –0.4 (–0.7 to –0.1) | 8 | 633 |

| Fan et al., 201343 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | 24% vs. 40% | – | 4 | 326 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Tamsulosin vs. placebo | – | –0.7 (–1.3 to –0.1) | 1 | 96 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Tamsulosin vs. standardb | – | –0.5 (–1.0 to –0.0) | 6 | 555 |

Need for hospitalisation

The final main outcome of interest is the proportion of patients that require further active management, which will mainly consist of stone removal using ESWL or ureteroscopy. Within the RCTs and subsequent meta-analyses this is mainly reported as the rate of further hospital admissions for treatment of a ureteric stone (Table 6).

| Review | Comparators | Need for active intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute rate | RR (95% CI) | Number of studies | Number of participants | ||

| Seitz et al., 200915 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | 5% vs. 25% | – | 5 | 480 |

| Fan et al., 201343 | Tamsulosin vs. controla | 12% vs. 34% | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 5 | 325 |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Alpha-blocker vs. standardb | 14% vs. 37% | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.0) | 4c | 313 |

| Seitz et al., 200915 | Nifedipine vs. controla | 20% vs. 34% | – | 1 | 140 |

Cost-effectiveness

A cost-minimisation study has been performed which assessed the potential health economic benefit of MET compared with observation alone. 44 A decision analytical model was used to predict comparative costs and resource use for a MET strategy using tamsulosin based on cost data obtained from the USA and four European countries, and efficacy data from existing meta-analyses. The costs of adverse events and other treatment-related complications were not included and a cost–utility analysis was not performed. The study found that use of tamsulosin for MET might lead to a saving of US$1132 over observation, with this conclusion being unchanged by sensitivity analyses. The cost-effectiveness of MET for different health-care systems remains unknown.

Summary

All seven meta-analyses using different selection criteria and reporting protocols appear to suggest that treatment with either tamsulosin or nifedipine at the time of presentation with acute ureteric colic increases the likelihood of eventual spontaneous stone passage, hastens the time to stone passage and reduces the risk of unwanted consequences such as pain and the need for an intervention to remove the stone. This leads the authors of these reviews to conclude that the balance of evidence supports routine use of these therapies, although with caveats regarding individual trial quality and trial size, with all but one trial having fewer than 100 participants in each group (Table 7). One large trial compared the use of tamsulosin (400 µg) against nifedipine (30 mg) as MET for stones sized 4–7 mm located in the very distal ureter (ureter course within the bladder wall) across 10 centres in China. 45 The trial randomised 3189 patients, and, at 4 weeks, the stone expulsion rate was 96% for tamsulosin and 74% for nifedipine with no further details given, although the Cochrane review14 gave a RR of 1.3 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.4) and found the trial to have low risk of bias. However, limited details given in the trial report makes quality assessment difficult; there was no sample size calculation to justify the large sample and diagnosis was by any imaging method, although follow-up and primary outcome assessment was by weekly CT KUB until stone passage or up to 4 weeks. Mean time to stone passage was given as 78.35 hours in the tamsulosin group and 137.93 hours in the nifedipine group. This duration of stone episode appears much shorter than that recorded in previous trials and may relate to the inclusion criteria and recruitment policies for this particular study. Additionally, the Jadad quality score was low (one) and the trial was supported by a manufacturer of tamsulosin.

| Review | Blinding | Overall quality | Ascertainment bias | Publication bias | Research recommendation | Recommendation for practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hollingsworth et al., 200624 | Majority unblinded | Not assessed | Mediterranean setting mainly | No | High-quality RCT | Viable option |

| Fan et al., 201343 | 27% low risk | Variable | Good | Unlikely | None | None |

| Lu et al., 201242 | Varied: potential source of bias | Varied | Varied | Yes | Large RCT | Tamsulosin recommended for distal stones of < 10 mm |

| Singh et al., 200741 | Majority unblinded | Poor | NA | No risk for nifedipine; small risk for tamsulosin | Large RCT | Promising but await large trial |

| Seitz et al., 200915 | Majority not blinded | NA | Varied imaging | Yes | Large study | MET for < 10 mm |

| Campschroer et al., 201414 | Noted lesser effect size in placebo studies | Variable | NA | Small risk | Large, multicentre RCT with CT for diagnosis | Alpha-blocker for distal < 10 mm |

The possibility that the conclusion from published meta-analyses regarding the benefits of MET is incorrect has to be borne in mind, as up to one-third of meta-analyses that show positive outcomes of a therapy are later altered by the inclusion of results from single, large, multicentre, robust, well-designed RCTs. 46 In the case of MET trials it is noted that use of less diagnostically accurate methods of imaging for participant inclusion prior to the widespread availability of CT KUB may lead to selection bias, because either smaller or radiolucent stones are missed, or people without a stone are included. Similarly, older, less accurate methods of imaging were widely used to decide if the stone had passed. This, together with lack of blinding in non-placebo-controlled studies, could lead to ascertainment bias in favour of the intervention group.

Need for a further trial and implications for design

The change of practice recommendations in some of the published meta-analyses has led to the adoption of MET for people with expectantly managed ureteric colic. The most widely used care guidance document gives a ‘Grade A’ recommendation for use of an alpha-blocker with follow-up within 14 days. 47 The extent of use of MET is hard to measure, but a survey of urologists in the USA suggests that 25% would recommend its use for stones in the mid and upper ureter and 32% would recommend its use for stones in the distal ureter. 48 The routine use of MET appears to be increasing, at least in the USA, with rates of 14% in 200949 rising to 64% in 2012. 50 In the UK, anecdotal discussion at the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS), Section of Endourology, meetings suggests that use is also widespread in response to the EAU guideline recommendation. Despite this practice recommendation and widespread adoption of MET, the uncertainties expressed by most meta-analyses and associated suggestions of the need for a large RCT should be borne in mind. This is of particular importance as the use of ineffective treatment is both wasteful and potentially harmful.

Conclusions

Ureteric stone disease is a significant health problem in the UK and worldwide in terms of its impact on patients and the use of resources. A large proportion of patients with a ureteric stone will ultimately experience spontaneous stone passage. However, any drug treatment that facilitates and increases the chance of this (i.e. MET) will bring added benefit in terms of reduced pain, a reduced need for active intervention and a quicker return to normal activity. Provided the drug is effective and safe, the benefits of use will probably lead to cost savings for the NHS and society as a whole. The available evidence from meta-analyses of a high number of predominantly small, underpowered studies with a high degree of clinical and statistical heterogeneity suggest that MET with either tamsulosin or nifedipine may have some of those advantages over standard therapy of observation and supportive therapy, which has led to increasing adoption as part of routine care. However, as a result of significant uncertainties and knowledge gaps within the evidence base, it was clear that a large, multicentre, well-designed trial was required. From an effectiveness perspective, any trial would also need to measure the impact on pain burden, quality of life and cost-effectiveness from the perspective of the NHS.

Trial objectives

The aim of the SUSPEND trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the use of tamsulosin and nifedipine in the management of people with symptomatic ureteric stones. The following question was addressed:

In patients with a symptomatic ureteric stone of ≤ 10 mm in maximum dimension, what is the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of using either tamsulosin 400 µg or nifedipine 30 mg once a day for up to 4 weeks over placebo?

In the context of a trial group receiving placebo, two pragmatic comparisons of equal importance were made in the evaluation of MET for facilitating ureteric stone passage:

-

tamsulosin 400 µg or nifedipine 30 mg once daily versus placebo

-

tamsulosin 400 µg once daily versus nifedipine 30 mg once daily.

The hypotheses being tested were:

-

The use of tamsulosin or nifedipine will result in an absolute increase in the spontaneous stone passage rate of at least 25% compared with placebo (from 50% to 75%).

-

The use of tamsulosin will result in an absolute increase of 10% in the spontaneous stone passage rate compared with nifedipine (from 75% to 85%).

Chapter 2 Trial design

The SUSPEND trial was a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the benefit of two drugs as MET, the alpha-blocker tamsulosin and the calcium channel blocker nifedipine to increase stone clearance rate for UK NHS patients with symptomatic ureteric stones.

The trial protocol has been published by McClinton et al. 51

Participants

Potential participants were adults presenting as an emergency with a diagnosis of ureteric colic at UK NHS hospitals and identified according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria specified below.

Inclusion criteria

-

Patients presenting acutely with ureteric colic.

-

Patients aged ≥ 18 years to ≤ 65 years.

-

Presence of stone confirmed by non-contrast CT KUB.

-

Stone within any segment of the ureter.

-

Unilateral ureteric stone.

-

Largest dimension of the stone ≤ 10 mm.

-

Female participants who were willing to use two of the listed methods of contraception prior to taking any trial medication until at least 28 days after receiving the last dose of trial medication, who were post menopausal (defined as 12 months with no menses and without an alternative medical cause) or who had undergone permanent sterilisation. Acceptable forms of contraception for trial purposes included:

-

Established use of hormonal methods of contraception.

-

Placement of an intrauterine device or intrauterine system.

-

Barrier methods of contraception: condom or occlusive cap (diaphragm or cervical/vault caps) plus a spermicidal foam/gel/film/cream/suppository.

-

Male partner was sterile (with the appropriate post-vasectomy documentation of the absence of sperm in the ejaculate) prior to a woman partner starting the trial and was the sole partner of the female participant.

-

True abstinence: when this was in line with the preferred and usual lifestyle of the person willing to take part in the trial. Periodic abstinence (e.g. calendar, ovulation, symptothermal, post-ovulation methods) and withdrawal were not acceptable methods of contraception for trial purposes.

-

-

Capable of giving written informed consent, which includes compliance with the requirements of the trial.

Exclusion criteria

-

Women who have a known or suspected pregnancy (confirmed by a pregnancy test).

-

Women who are breastfeeding.

-

Women intending to become pregnant during anticipated period of participation in trial.

-

Asymptomatic incidentally found ureteric stone.

-

Stone not previously confirmed by CT KUB.

-

Stone with any one dimension of > 10 mm on CT KUB.

-

Kidney stone without the presence of ureteric stone.

-

Multiple (i.e. ≥ 2) stones within one ureter.

-

Bilateral ureteric stones.

-

Stone in a ureter draining an either anatomically or functionally solitary kidney.

-

Patients with abnormal upper urinary tract anatomy (such as a duplex system, horseshoe kidney or ileal conduit).

-

Presence of urinary sepsis.

-

Chronic kidney disease stage 4 or worse (estimated glomerular filtration rate of < 30 ml/minute).

-

Patients currently taking an alpha-blocker.

-

Patients currently taking a calcium channel blocker.

-

Patients currently taking a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor.

-

Contraindication or allergy to tamsulosin or nifedipine.

-

Patients who are unable to understand or complete trial documentation.

Participants were randomised to one of the three trial groups on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis. The randomisation algorithm used trial centre (site), stone size (≤ 5 mm, > 5 mm) and stone location (upper, middle or lower ureter) as minimisation covariates. A remote telephone interactive voice response randomisation application hosted by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), Health Services Research Unit (HSRU) at the University of Aberdeen, UK, was used to perform randomisation.

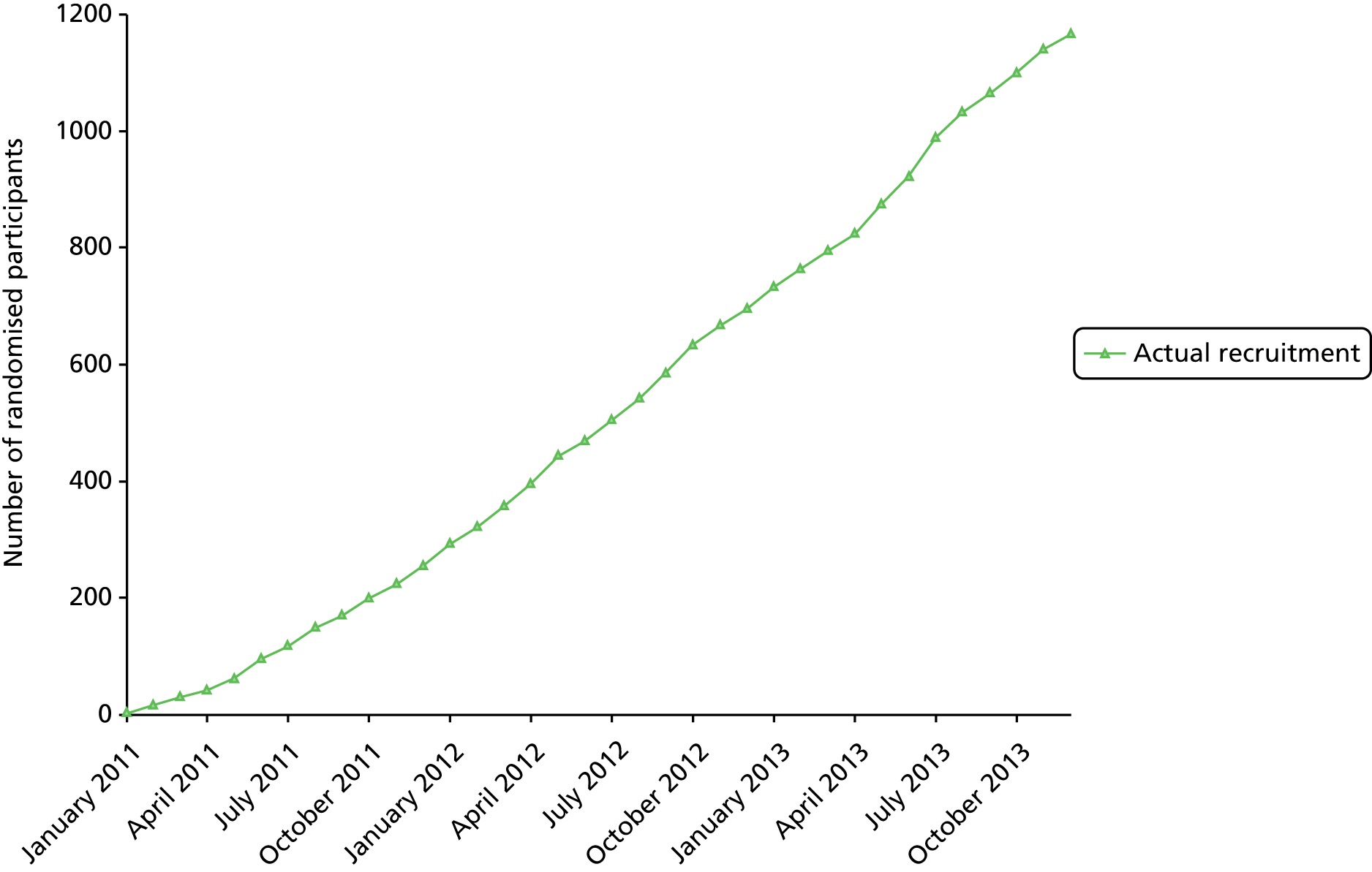

The main criterion for selection of UK NHS hospital sites where participant recruitment could take place was a high rate (> 15 per month) of patient emergency admissions owing to ureteric colic. Information on admission rates was obtained from a national audit of ureteric stone management undertaken by the BAUS Section of Endourology in 2007 (see www.BAUS.org.uk). A total of 24 UK NHS sites took part in the trial (Figure 2). These were Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen; Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge; Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol; Broadgreen Hospital, Liverpool; Cheltenham General Hospital, Cheltenham; Derriford Hospital, Plymouth; Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne; Guy’s Hospital, London; Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester; Morriston Hospital, Swansea; Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norwich; Pinderfields Hospital, Wakefield; Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham; Raigmore Hospital, Inverness; Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield; Southampton General Hospital, Southampton; Southmead Hospital, Bristol; St George’s Hospital, London; St James’s University Hospital, Leeds; Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland; The James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough; Torbay Hospital, Torquay; University Hospital of South Manchester, Manchester; and the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh.

FIGURE 2.

The UK location of the 24 SUSPEND trial sites.

Trial interventions

Two active treatments were being investigated and compared with a placebo group and each other:

-

tamsulosin hydrochloride 400 µg MR once daily up to a maximum of 28 days

-

nifedipine 30 mg MR once daily up to a maximum of 28 days

-

placebo [lactose-filled capsule (Tayside Pharmaceuticals)] once daily up to a maximum of 28 days.

Medication was overencapsulated to ensure that both participants and trial staff remained blinded to the identity of allocated medication.

Apart from allocated trial medication, all participants received the standard care for expectant management of people with ureteric colic. This included other medications to relieve symptoms, such as analgesics and antiemetics, advice on general measures, such as adequate fluid intake and resumption of normal activity, and appropriate review arrangements to detect stone passage, progressive symptoms or complications such as sepsis. No other adjunctive medications thought to promote stone passage, such as corticosteroids, are approved for use in the UK and clinical staff were asked to avoid use of such agents at site initiation visits.

Duration of interventions

Participants took one capsule of trial medication per day until stone passage occurred or further intervention was decided upon, up to a maximum of 28 days after randomisation.

Comparisons

Two pragmatic comparisons were made evaluating MET for facilitating ureteric stone passage:

-

tamsulosin (alpha-blocker) or nifedipine (calcium channel blocker) versus placebo

-

tamsulosin versus nifedipine.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Clinical effectiveness

The primary outcome was spontaneous passage of ureteric stones at 4 weeks after randomisation. This was defined as no further intervention planned or carried out to facilitate stone passage at up to 4 weeks. A further intervention was classified as any clinical record entry detailing actual interventions reported to have been carried out within 4 weeks or any further planned intervention. This information was reported on the 4- and 12-week case report form (CRF). Patients’ returned questionnaires at 4 weeks and 12 weeks were also assessed for additional interventions that may not have been captured by the CRF.

Health economic

The health economic outcome was incremental costs per quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained at 12 weeks. QALYs were calculated from participant responses to the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions questionnaire 3 level response (EQ-5D-3L™)52 completed at baseline, 4 weeks and 12 weeks post randomisation, and costs from use of primary and secondary NHS health-care services from the responses to the 12-week participant questionnaire and the 4- and 12-week CRFs.

Secondary outcome measures

Patient reported

Patient-reported secondary outcomes were:

-

severity of pain

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

self-reported use of analgesics

-

time to stone passage

-

self-reported discontinuation of trial medication (and reasons).

Severity of pain related to the pain on the day of completion of the 4-week questionnaire as measured by the numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). 53,54 Analgesic use was measured using the self-reported number of days that pain medication was used up to the time of completion of the 4-week participant questionnaire. HRQoL was measured using the generic health profile measure Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36),55 and the generic health status measure European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D™),56 at baseline, 4 weeks and 12 weeks. Time to stone passage was derived from the 4-week CRF where there was passage of stone confirmed by imaging. Self-reported stone passage was not used to assess time to stone passage. Discontinuation of trial medication up to 4 weeks after randomisation was measured in the 4-week participant questionnaire.

Chapter 3 Methods

Research ethics and regulatory approvals

The SUSPEND trial was a clinical trial involving investigational medicinal products (CTIMPs). It was conducted under the European Union Clinical Trials Directive and was reviewed and approved by the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and allocated the EudraCT number 2010–019469–26. The trial was also given a favourable opinion prior to commencement by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service Research Ethics Committee 2 (reference 10/S0501/31). It was approved by the sponsors (NHS Grampian and University of Aberdeen) and by the research and development departments of the NHS organisations at each participating site prior to trial commencement at each site. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and was registered on the UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio (UKCRN Study ID 9184) and assigned an International Standard Randomised Clinical Trial number (ISRCTN69423238). Prior to starting recruitment at each site, a site initiation visit took place where central trial staff detailed and explained trial procedures to the local principal investigator and clinical research team, and provided a trial-specific site file.

Participants

Trial flow

The flow of participants through the trial is detailed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Flow of participants through the trial. GP, general practitioner.

Identification of patients (screening)

Patients were identified by clinicians working in the urology or accident and emergency departments of participating sites, who were supported by local clinical research teams. Approved trial publicity material in the form of posters was used to help alert staff that the trial was taking place at specific sites.

Recruitment process

Clinicians assessed patients presenting with suspected ureteric calculi in accordance with standard practice. A screening log was completed and included all patients assessed at participating sites to document the reasons for inclusion or non-inclusion in the trial. Following adequate pain relief and confirmation of a single ureteric stone by CT KUB, identified eligible patients were given a patient information leaflet (PIL; see Appendix 1) to inform them of the purpose and need for the trial as well as the uncertainties around the clinical usefulness of MET. The PIL was developed in conjunction with the BAUS Section of Endourology Patient Group. Following receipt of the PIL, a member of the local research team asked the patient if they were interested in the trial and ensured any questions that the patients had were answered appropriately. Further checking against eligibility criteria, particularly around the use of tamsulosin and nifedipine as MET, was performed by local research staff. When a patient was eligible and happy to take part in the trial they were asked to sign a trial consent form (see Appendix 2).

Randomisation and intervention allocation

Eligible and consenting participants were allocated using minimisation to one of the two intervention groups or the placebo group on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis using the telephone interactive voice response randomisation application hosted by the CHaRT, HSRU, at the University of Aberdeen. The minimisation algorithm used the trial centre (site), stone size (≤ 5 mm, > 5 mm) and stone location (upper, middle, lower ureter) as covariates.

Blinding

At randomisation, the participant was allocated a unique participant study number and assigned a numbered participant pack. The packs were provided by an independent supplier containing the overencapsulated trial medication to ensure that the participant, local investigator and trial personnel remained blinded to treatment allocation.

Unblinding

The treatment code was broken only in the case of a serious adverse event (SAE), when it was necessary for the principal investigator at site or treating health-care professional to know which intervention the participant was receiving to determine a management plan.

Each participant was given a card to carry with details of a contact telephone number at the site to be used in the event that unblinding was necessary. Contact information was also available in the participant’s hospital records. If unblinding was necessary, a member of the research team or a member of clinical staff at the local recruiting site telephoned the dedicated randomisation service at the CHaRT in Aberdeen on the number provided using the trial centre identification and the participant study number. In the unlikely event of the randomisation service not being able to field the query, the on-call pharmacist at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was contacted and the same procedure followed.

Following any unblinding via the telephone randomisation service, automatic e-mails were sent to the chief investigator, trial manager and members of the CHaRT management team. If an on-call pharmacist performed the unblinding they would e-mail the same list of people. These e-mails did not contain the treatment code, and the trial team remained blinded as far as was practicable. The chief investigator then ascertained why unblinding had taken place. If the patient was unblinded because of a SAE this was then reported.

Interventions

The trial interventions were:

-

tamsulosin hydrochloride in the form of 400-µg MR capsules

-

nifedipine in the form of 30-mg MR capsules

-

placebo (lactose-filled capsules).

A summary of product characteristics for each of the investigational medicinal products (tamsulosin hydrochloride and nifedipine) used in the trial is included in Appendix 3.

All the medicinal products were overencapsulated to maintain the blinding of the trial. Trial medication was presented as capsules in amber plastic containers with a childproof closure and labelled in accordance with Annex 13 of Volume 4 of The Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European Union: Good Manufacturing Practices. 57 All disguised drug packs were stored at site pharmacies under temperature-controlled conditions until dispensed to participants. The medicinal products and the placebo were overencapsulated, packaged and labelled by Tayside Pharmaceuticals, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, UK, in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practice.

Participants were instructed to store the medication in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Unused medication and/or empty packaging were returned to the site by the participant at the 4-week follow-up visit or returned directly to the pharmacy; alternatively, if participants did not attend the 4-week visit, they were instructed to dispose of surplus trial medication appropriately.

Data collection

Questionnaires were designed to obtain information on stone passage or further intervention, pain, HRQoL and resource use, including NHS and personal costs. Participants were asked to complete trial questionnaires at baseline, 4 weeks post randomisation and 12 weeks post randomisation. The baseline questionnaire was completed in hospital before randomisation. Further questionnaires were sent to each participant by post from the trial office (CHaRT, Aberdeen) with pre-paid envelopes at 4 weeks and 12 weeks post randomisation (see Appendix 4). If a participant did not return the questionnaire a reminder letter was sent out approximately 2 weeks later with a short form of the questionnaire containing the EQ-5D only (see Appendix 4).

In addition, CRFs were completed by the research team at the recruiting site at baseline and at the follow-up visit 4 weeks after randomisation (see Appendix 5). If the participant did not attend the follow-up visit, the CRF was completed from the participant’s health-care records. If participants indicated on their 12-week questionnaire that they had received further intervention for their stone since their 4-week questionnaire, or if they completed only a short form of the questionnaire, or if no 12-week questionnaire was returned, a further CRF was completed 12 weeks post randomisation from their health-care records (see Appendix 5). The outcome measures collected and their timings of measurement are described in Table 8.

| Outcome measure | Source | Timing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | 4 weeks post randomisation | 12 weeks post randomisation | ||

| Further intervention planned | CRF | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Pain (NRS) | PQ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Use of analgesics | PQ | ✓ | ||

| Further interventions received | PQ and/or CRF | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Health status: SF-36 and EQ-5D | PQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Adverse events | PQ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Time to passage of stone | PQ and CRF | ✓ | ✓ | |

| NHS primary and secondary health-care use | PQ and CRF | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Participant personal costs | PQ | ✓ | ||

Safety reporting

Non-serious adverse events were not collected or reported. Planned hospital visits for conditions other than those associated with the ureteric stone were not collected or reported. Hospital admissions (planned or unplanned) associated with the treatment of the ureteric stone diagnosed at the time of entry to the trial were expected to occur for a proportion of participants. These were recorded as an outcome measure, but were not recorded or reported as SAEs.

All suspected SAEs were assessed in respect of severity, potential relationship to trial medication and whether they were expected or unexpected. Confirmed SAEs were reported to the Trial Office and then to the chief investigator and sponsor, who subsequently provided their assessment and action plan.

Participants who had left hospital were advised to contact their general practitioner (GP) should they experience an adverse event. This is current standard clinical practice for participants receiving tamsulosin or nifedipine within the NHS. As part of their notification that one of their patients was participating in the trial, GPs were asked to inform the trial office of any SAEs or reactions. This provided a robust system for the notification of any serious adverse reactions or SAEs occurring outside hospital research sites.

Change of status/withdrawal

The trial status of some participants changed during the trial for a number of reasons. These included post-randomisation exclusion, participant withdrawal and medical withdrawal. Participants were free to withdraw from the trial at any time without giving a reason. If a participant withdrew from receiving the trial questionnaires, permission was sought for the research team to continue to collect outcome data from their hospital records. In the event that a participant was told to stop taking trial medication by clinical or trial staff for any reason, the participant continued in the trial and was asked to complete the trial documents unless he or she did not wish to do so.

Data management

Clinical data were entered into the electronic SUSPEND database through the trial web portal (https://viis.abdn.ac.uk/HSRU/suspend/), together with data from participant questionnaires, by the research team working at each hospital site. Questionnaires returned by post to the trial office were entered into the database by the central research team. Staff in the trial office worked closely with the local research teams to ensure that the data were complete and accurate. All trial staff and the statistician responsible for analysing the data remained blinded to allocation until completion of the trial and locking of the database.

Data collected during the course of the research were kept strictly confidential and accessed only by members of the trial team. Participants’ details were stored on a secure database under the guidelines of the Data Protection Act 1998, including encryption of any identifiable data. 58 Participants were allocated an individual specific trial number and all data, other than personal data, were identified only by this unique study number.

A random 10% sample of all trial data was generated by the database for re-entry by the trial office to validate correct data entry input. Any discrepancies between original data entry and the re-entered data were reviewed against the original paper copy and incorrect entries corrected accordingly. An initial data entry error rate of > 5% would have triggered a requirement to re-enter the entire data set from that questionnaire. This was not found to be necessary.

Trial oversight committees

The trial Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) comprised three independent individuals who met initially at the beginning of the trial when terms of reference and other committee procedures were agreed. The DMC then met a subsequent four times during the course of the trial to monitor unblinded trial baseline and outcome data provided by the trial statistician and details of SAEs. The DMC reported any recommendations to the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

The TSC was chaired by a clinician independent from the trial and consisted of two other independent members as well as the grant holders. The TSC met five times over the duration of the trial.

Patient and public involvement

A patient representative was involved in the study design and conduct, with input into production of the PIL and other trial documentation, and membership of both the trial management group and the TSC. The patient representative contributed to, and reviewed, the trial protocol and final report. Additionally, the PIL for the trial (see Appendix 1) was developed in conjunction with the BAUS Section of Endourology Patient Group.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

Serious adverse events

During the initial stages of the trial, a number of SAEs were reported and recorded which, on investigation, were found to be a result of readmissions for continuing treatment of the participant’s ureteric stone (i.e. the primary outcome). These were, therefore, being recorded as a SAE as well as an outcome. To ensure that such events were recorded only as an outcome, the wording regarding the collection of these events was clarified to state:

Hospital admissions (planned or unplanned) associated with the treatment of the ureteric stone diagnosed at the time of entry to the trial are expected. These will be recorded as an outcome measure, but will not be recorded or reported as serious adverse events.

Strategies to improve questionnaire return rate

A number of strategies were implemented during the trial to improve participant questionnaire return rate. A substudy investigating the use of text message notification to participants to inform them that their questionnaire would arrive shortly, combined with e-mail delivery of questionnaires with a link to complete an online version, did not affect response rate. A short version of the 4- and 12-week questionnaires designed to collect the information needed for the primary outcomes of the trial was sent instead of the full questionnaire as a reminder to encourage completion. 59 This did not have any effect on response rate.

A Cochrane review on strategies to improve retention in RCTs found monetary incentives to be one of the few approaches to be effective in increasing response rates to participant questionnaires. 60 Part-way through the trial, a £5 high-street voucher was sent out with the 12-week questionnaire to encourage response. This appeared effective, in that response rate increased from 46% to 57%, but influence from other confounders cannot be ruled out.

Statistical methods and trial analysis

Sample size and power calculation

We combined the data from two meta-analyses,24,41 which suggested a RR of approximately 1.50 comparing MET (either alpha-blocker or calcium channel blocker) against ‘standard care’ as the primary outcome. These reviews indicated that the percentage of spontaneous stone passage was approximately 50% in control groups of included RCTs. Only three of the included RCTs directly compared a calcium channel blocker and an alpha-blocker, and these suggested that alpha-blockers were potentially superior to calcium channel blockers. From an analysis of data from Singh et al. 41 and Hollingsworth et al. ,24 we estimated that proportions of stone passage in the alpha-blocker and calcium channel blocker groups were approximately 85% and 75%, respectively. The most conservative sample size was required to detect superiority between the two active treatments, and the trial was powered on this basis. To detect an increase of 10% in the primary outcome (spontaneous stone passage) from 75% in the calcium channel blocker group to 85% in the alpha-blocker group, with type I error rates of 5% and 90% power, required 354 participants per group (1062 in total); adjusting for 10% loss to follow-up inflated this to 400 per group. We aimed to recruit 1200 participants (randomising 400 to each of the three treatment groups: alpha-blocker, calcium channel blocker and placebo) to provide sufficient power (> 90%) for all other comparisons of interest, and allowing for an anticipated 10% loss to follow-up.

General methods

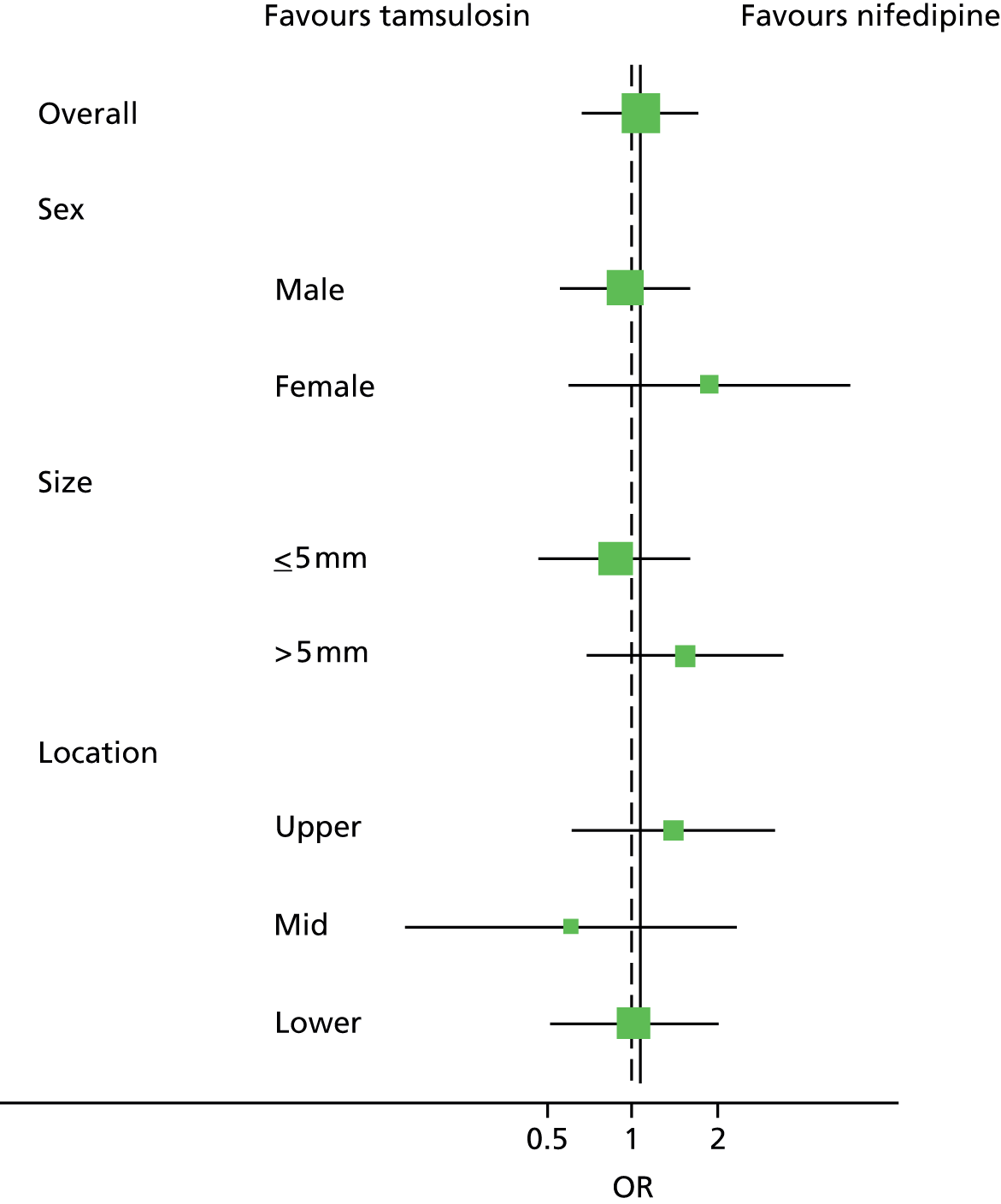

Treatment groups were described at baseline and follow-up using means [with standard deviations (SDs)], medians (with interquartile ranges) and numbers (with percentages) where relevant. Primary and secondary outcomes were compared using generalised linear models. Treatment effects were estimated from unadjusted and adjusted models. Adjusted models included the trial centre (random effect), stone size (≤ 5 mm, > 5 mm) and stone location (upper, middle or lower ureter). All estimates of treatment effect are presented with 95% CIs. The analysis strategy was by allocated group (intention to treat). Two a priori comparisons were considered for the primary trial analysis:

-

MET [an alpha-blocker (tamsulosin) or a calcium channel blocker (nifedipine)] versus placebo

-

an alpha-blocker (tamsulosin) versus a calcium channel blocker (nifedipine).

We also made two post-hoc comparisons between tamsulosin and placebo, and nifedipine versus placebo. All analyses were carried out using Stata® 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was analysed using logistic regression. We summarised treatment effects as odds ratios (ORs) and absolute percentage differences, from both adjusted and unadjusted models and presented with 95% CIs. Subgroup analyses (appropriately analysed by testing treatment by subgroup interaction) explored the possible effect modification of stone size (≤ 5 mm or > 5 mm to 10 mm), location in ureter, (upper, mid or lower) and sex, all using stricter levels of statistical significance (99% CIs; p-value < 0.01). 61 Subgroup analyses were also summarised visually using forest plots. 62 There was no correction for multiple testing. 63 During the planning of the SUSPEND trial it was anticipated that there would be few or no missing primary outcome data (owing to the algorithm specifying the primary outcome) and the primary outcome was analysed using complete-case analysis. The pragmatic nature of the trial made assessing the adherence unreliable, and no attempt was made to incorporate any analysis of treatment received.

Secondary outcomes

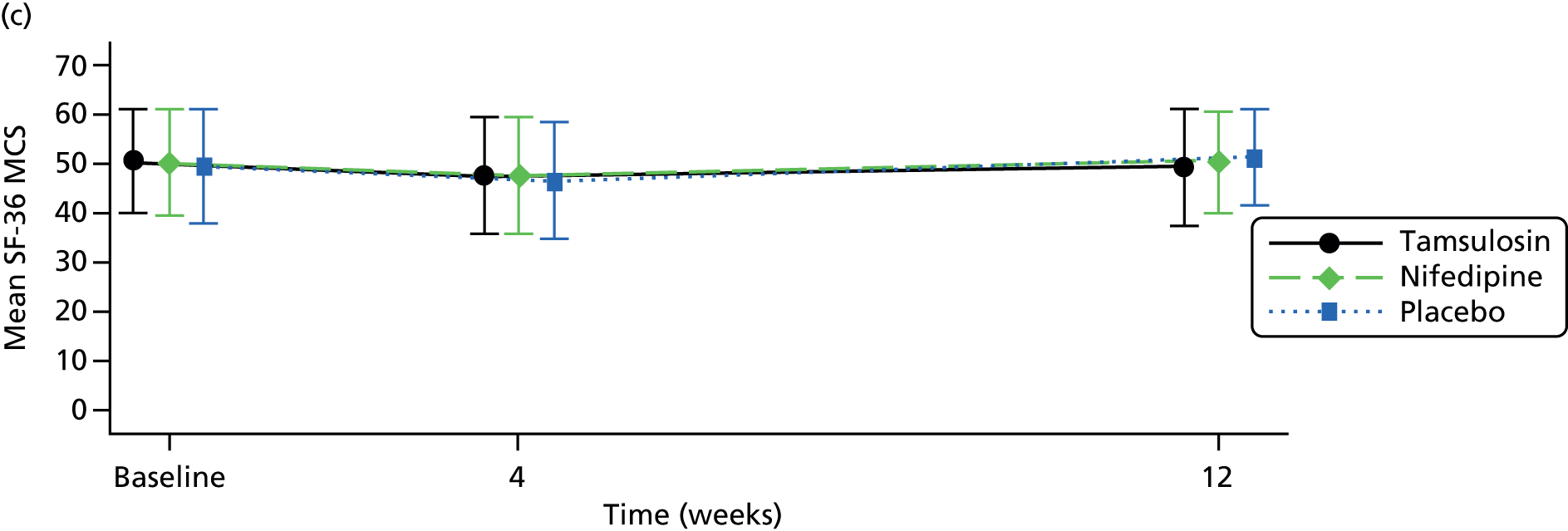

The secondary outcomes were analysed in a similar manner to the primary outcome using the appropriate link functions. Quality-of-life data were analysed using a mixed model that allowed treatment effects to vary at each time point.

Timings and frequency of analysis

The DMC considered interim inspection of the data on four occasions during the trial. The committee met to review and consider data on outcome measures and SAEs after randomisation of 300, 600 and 900 participants had occurred. Having seen and considered these data, the DMC did not make any recommendations to alter the progression of the trial on any of the occasions on which they met.

Algorithm for primary outcome

The primary clinical outcome is spontaneous passage of ureteric stones at 4 weeks (defined as no further intervention required to facilitate stone passage at up to 4 weeks). The algorithm to create this outcome can be found in Appendix 6.

Missing data

Baseline data were collected prior to randomisation. Where baseline data were missing, no imputation was undertaken for the reporting of the baseline covariates of the trial cohort. If there were missing data for covariates that were used in the analyses of the trial outcomes, single imputation was performed using the guidelines set out in White and Thompson64 (i.e. centre-specific means for continuous variables and an indicator for categorical variables). It was anticipated that the nature of the clinical condition and the algorithm to generate the final outcome would result in few cases of missing primary outcome data and, as such, no plan was made to impute missing primary outcome data. Participants with missing primary outcome data were excluded from analysis of the primary outcome. For other outcomes, participants were included where they provided data under a missing-at-random assumption. Sensitivity analyses were planned to follow guidelines laid out by White et al. 65 to assess the impact of any missing outcome data on quality-of-life data from patient questionnaires. The analysis of quality-of-life outcomes was repeated using multiple imputation models with predictions based on all baseline covariates collected. Results were combined across 10 imputed data sets. The robustness of the results was then tested using pattern mixture models, which imputed missing data across a range of potential values from minus half of the observed SD to plus half of the SD of the outcome being analysed.

Economic methods

Introduction

Given that the condition under study was anticipated to be a short-term resolving problem for patients and the NHS, the main planned economic analysis was a ‘within-trial’ economic evaluation using data collected during the 12 weeks of individual participation. The question addressed was: ‘What is the cost-effectiveness of medical expulsive therapy using either tamsulosin or nifedipine compared to no treatment (placebo)?’ The trial was set within the perspective of the NHS, although it included both the NHS costs as well as those health-care costs falling on the participants.

Measurement of resource utilisation

Resource use and costs were estimated for each participant. Resource data collected included the costs of the intervention drugs and simultaneous and consequent use of primary and secondary NHS services by participants. Personal health-care costs, such as purchase of medication, were also estimated.

At recruitment, data were collected on the intervention that the participants received, the diagnostic tests conducted and the medications prescribed at the admission. At 12 weeks post randomisation, participants were asked to provide information by questionnaire of their primary and secondary health-care service use. They were asked for details of medications purchased, the cost of these and whether or not they had any visits to non-NHS health-care providers.

The consequential use of health services was recorded prospectively for each participant in the trial. Resource utilisation data were based on responses to the participant questionnaires and the CRFs completed by the local research teams. The CRFs recorded information on non-protocol visits (protocol visits are those scheduled for the purposes of data collection), outpatient visits and readmissions relating to the use and consequences of drug treatment. Use of primary care services, such as prescription medications, and contacts with primary care practitioners (e.g. GPs and practice nurses) were collected via the health-care utilisation questions administered in the participant 12-week questionnaire. Details of the sources used to estimate resource utilisation are included in Table 9.

| Resource | Relevant variable | Source | Reported outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Drug (e.g. tamsulosin) | CRFa | Number |

| Diagnostic tests | CRFa | Number | |

| Analgesic/antibiotics | CRFa | Number | |

| Primary care visits | GP doctor visits | PQ | Number |

| GP nurse visits | PQ | Number | |

| Secondary care | Outpatient visit | CRFa and PQ | Number |

| Active further intervention (e.g. insertion of stent) | CRFa and PQ | Number | |

| Admissions days | CRFa and PQ | Number |

Identification of unit costs

Unit costs were obtained from published sources such as the British National Formulary (BNF)40 and NHS reference costs. 66 The unit cost data source year was 2012–13 and the currency was British pounds.

The cost of the trial intervention included the cost of the drug to which the participants were allocated, the costs of diagnostic tests performed to confirm ureteric stone and the cost of the medications or antibiotics prescribed at diagnosis. The unit costs of medications were obtained from the BNF40 and the diagnostic tests costs were obtained from NHS reference costs. 66 The unit costs of medicines given on admission were assumed to be those of the most commonly used drugs. The unit cost of NSAIDs was that of diclofenac (50 mg) given as a tablet, and the cost of opiates was based on the cost of morphine (10-mg injection). Antibiotic costs were based on the unit cost of a 3-day course of ciprofloxacin (500 mg). The initial secondary care attendances prior to and at recruitment were not included as costs because they were considered to be the same across all trial groups. The unit cost for the diagnostic test received was based on the average NHS reference cost for a computerised tomography (CT) scan ordered by the urology department.

The costs of subsequent resource use comprised costs to both the primary (GP appointments) and secondary (outpatient appointments and admissions) NHS care services. Unit costs for GP visits were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit costs of primary care. 67 Outpatient visit unit cost was based on the average NHS tariff for a urology department consultant-led outpatient appointment obtained from the reference costs. 66 A summary of the unit costs of the resources used is provided in Table 10.

| Resource | Unit cost | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | |||

| Alpha-blocker (tamsulosin) | £4.76 | BNF40 | The 28-day cost of the non-proprietary tamsulosin hydrochloride, daily cost of £0.17 |

| Calcium channel blocker (nifedipine) | £6.95 | BNF40 | The 28-day cost of the non-proprietary nifedipine, daily cost of £0.25 |

| Diagnostic test | £60.00 | Reference costs66 | RA08A CT scan, one area, no contrast, 19 years and over, diagnostic imaging: direct accessa |

| Analgesia | |||

| NSAID | £2.49 | BNF40 | Based on cost of diclofenac (Voltarol®, Novartis) |

| Opiate | £2.60 | BNF40 | Based on cost of morphine injection |

| Other | £2.55 | Average of above 2 | |

| Antibiotic used | £0.80 | BNF40 | Based on most frequently administered antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, non-proprietary) |

| Cost additional day in hospital | £264.00 | Reference costs66 | LB05G intermediate percutaneous kidney or ureter procedures, 19 years and over, with CC score of 0 [non-elective inpatient (long-stay) excess bed-days] |

| Percutaneous insertion of nephrostomy tube | £1207.00 | Reference costs66 | LB09D intermediate endoscopic ureter procedures, 19 years and over [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £691.00 | Day case | ||

| Antegrade insertion of stent into ureter | £647.00 | Reference costs66 | LB05G intermediate percutaneous kidney or ureter procedures, 19 years and over, with CC score of 0–2 [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £566.00 | Day case | ||

| Therapeutic ureteroscopic operations | £1458.00 | Reference costs66 | LB65E major endoscopic kidney or ureter procedures, 19 years and over with CC score 0–2 [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £1434.00 | Day case | ||

| Endoscopic insertion/removal of stent into ureter | £524.00 | Reference costs66 | LB72A diagnostic flexible cystoscopy, 19 years and over [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £402.00 | Day case | ||

| ESWL of calculus in ureter | £775.00 | Reference costs66 | LB36Z ESWL [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £504.00 | Day case | ||

| Hospital admission without procedure | £470.00 | Reference costs66 | LB40G urinary tract stone disease without interventions, with CC score of 0–2 [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| £456.00 | Day case | ||

| More than one intervention | £1719.00 | Reference costs66 | LB40D urinary tract stone disease with interventions, with CC score of 0–2 [non-elective inpatients (short stay)] |

| Outpatient visit | £101.00 | Reference costs66 | Based on the average unit cost of outpatient attendances (both consultant- and non-consultant-led) to urology department |

| Practice nurse visit | £15.50 | Based on cost per consultation | |

| GP visit | £44.46 | Per surgery consultation lasting 11.7 minutes | |

| Cost of visit to other health-care professionals | As indicated by participant | Based on information on PQ | |

| Medications | As indicated by participant | Based on information on PQ | |

| Visits to non-NHS providers | As indicated by participant | Based on information on PQ | |

Unit costs of further active intervention for the ureteric stone were derived from costs associated with different urology Healthcare Resource Group codes as detailed in Table 10. For occasions when a participant received two interventions on the same day, unit cost use was defined as the average cost of treatment of urinary tract stone disease with intervention. For those that had an admission with no intervention, the cost of urinary stone disease without intervention was used. As the median stay in the urology department was 1 day, any extra admissions days were costed using the long-stay excess days tariff. 66

The participant resource use data and unit cost were combined for each of the primary and secondary NHS care services to give an estimate of the total health-care cost per participant, as well as the average cost for each identified resource and the average total cost for each group of the trial.

Participant costs

Participant costs comprised self-purchased health care, such as prescription costs (for participants who pay prescription charges), over-the-counter medications and visits to non-NHS health-care providers. Information about participant resource use was collected using the 12-week health-care utilisation questionnaire (see Appendix 4).

Health status

Health-related quality-of-life measures were collected at baseline, 4 weeks and 12 weeks by participant completion of the EQ-5D and the SF-36 questionnaires. The EQ-5D divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each of these dimensions has three levels, so 243 possible health states exist. Responses on the participants’ EQ-5D questionnaires were transformed using a standard algorithm to produce a health-state utility at each time point for each participant. The utility scores obtained at baseline, 4 weeks and 12 weeks were used to estimate the mean QALY score for each group52 over the 12-week (approximately 0.25 years) period of observation.

Responses from the SF-36 questionnaire were also used as the basis of QALYs as a sensitivity analysis to validate the EQ-5D scores. They were mapped onto the existing Short Form questionnare-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) measure using a standard algorithm68 to allow utility values to be estimated for each time point. These utility scores were transformed to QALYs using the methods described above to provide an alternative measure of QALYs for each participant.

Data analysis

Resource use, cost and QALY data were summarised and analysed using Stata 13. As data were collected over a short (12-week) period, discounting was not carried out. The main cost-effectiveness analysis reports the results of participants with complete data. All the difference estimates are presented with 95% CIs. Data reported as mean costs for both active treatment groups and the placebo group were derived for each item of resource use and then compared using unpaired Student’s t-test and linear regression adjusted for baseline values. The mean incremental costs were estimated using general linear models, with adjustment for minimisation variables [centre at which participant was recruited, stone size (≤ 5 mm, > 5 mm), stone location at diagnosis (lower, mid or upper ureter) and sex]. The general linear model allowed for heteroscedasticity by specifying a distributional family which reflects the relationship between mean and variance. 69 A modified Park’s test was conducted to identify the appropriate family, which identified a gamma family. This allows for the skewness of cost data and assumes that variance is proportional to the square of the means as appropriate. A link function needs to be identified for the general linear model to specify the relationship between the set of regressors and the conditional mean. The link test recognised the identity link as the appropriate link function. The identity link leaves the interpretation of the coefficients unchanged from that of the ordinary least squares, as the covariates act additively to the mean. The mean incremental QALYs were estimated using ordinary least squares and were adjusted for minimisation factors, as well as for the baseline EQ-5D score.

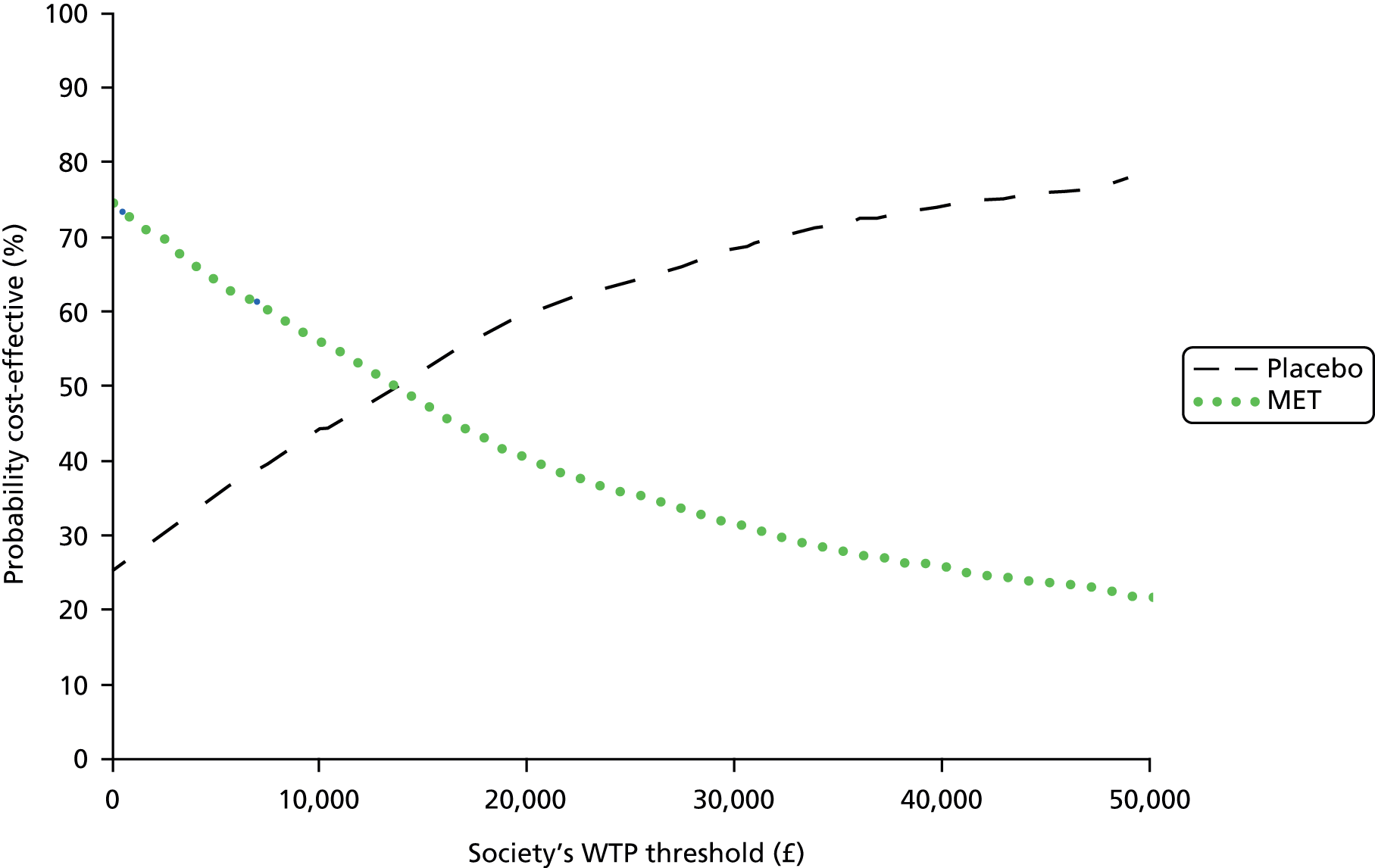

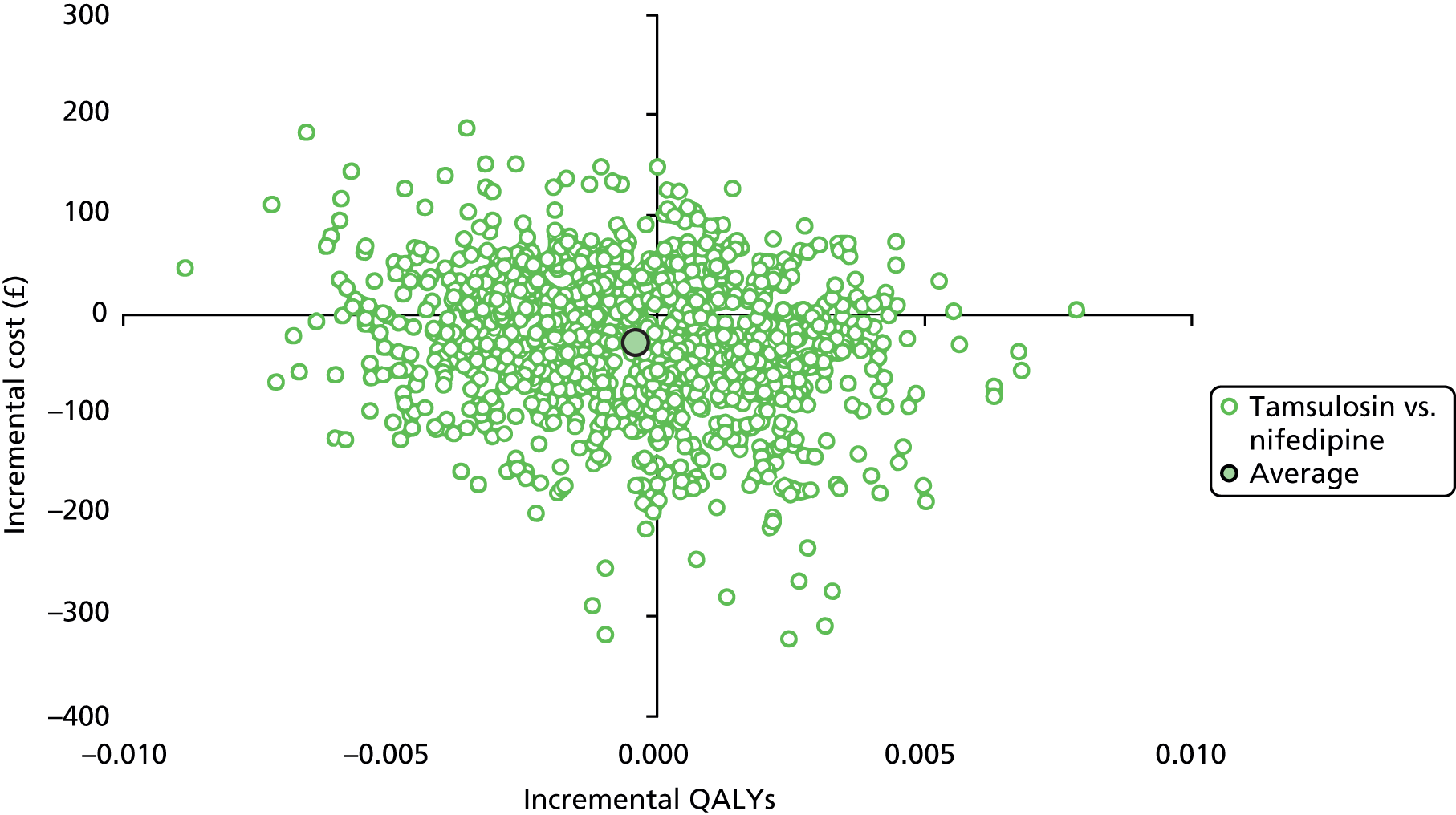

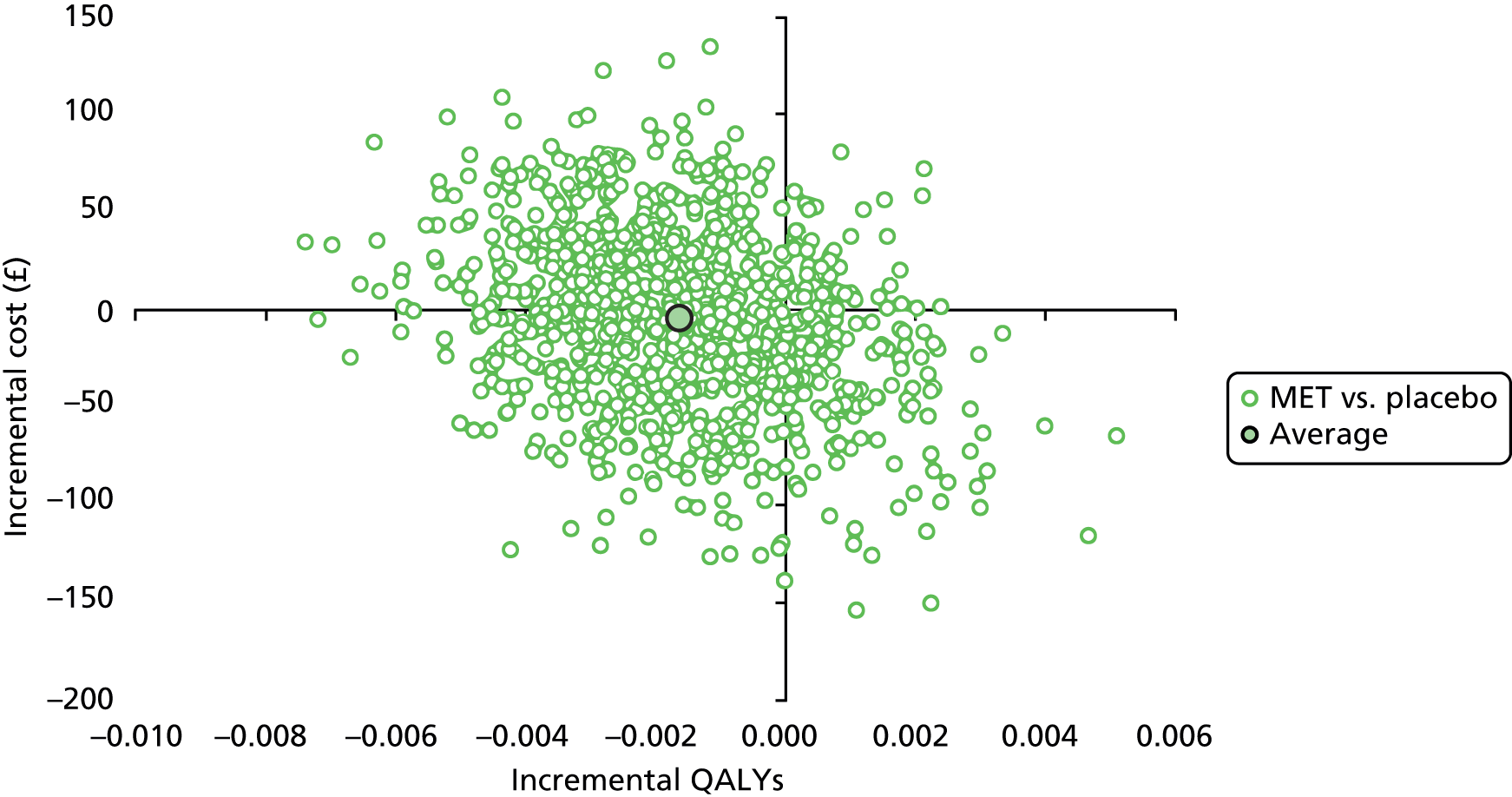

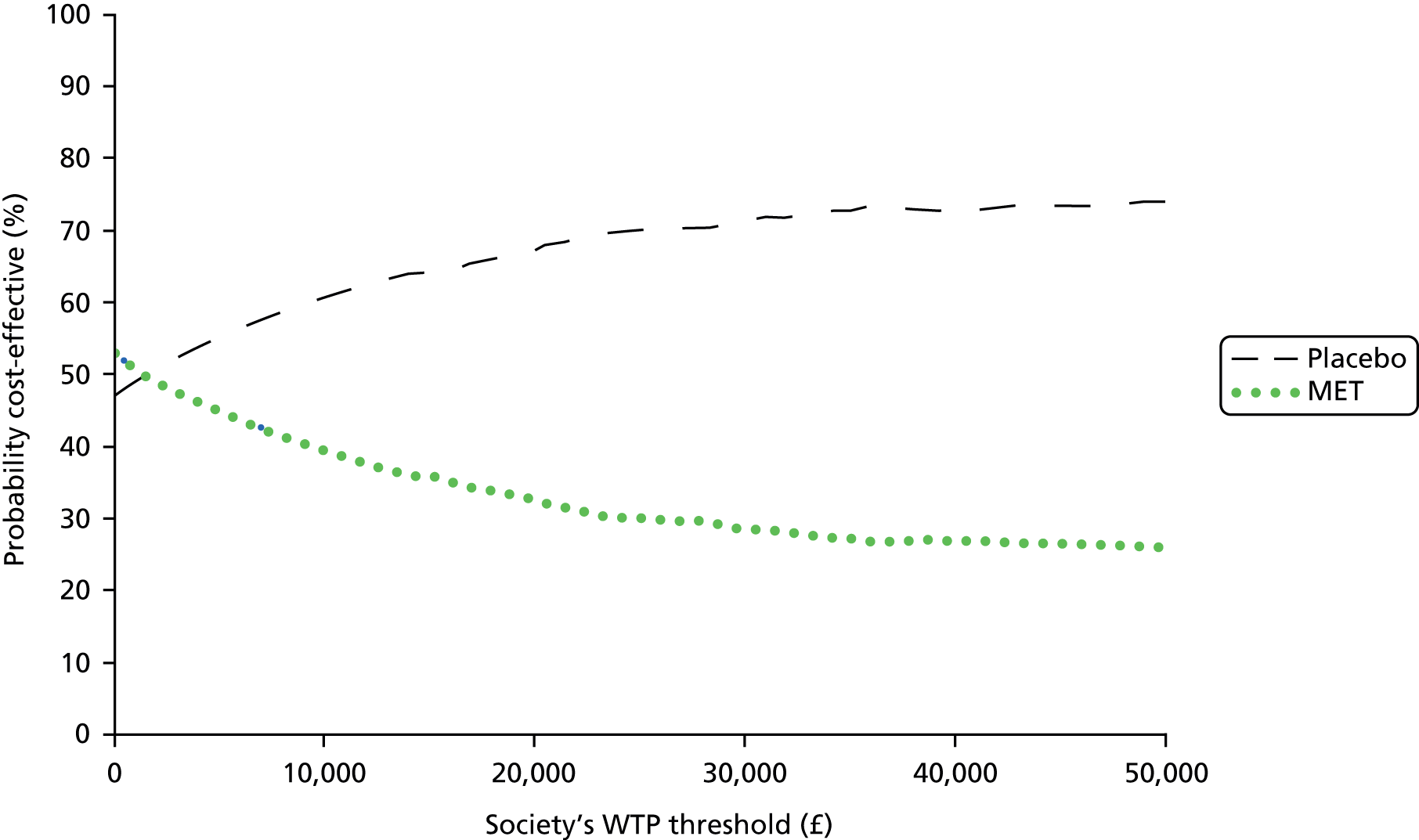

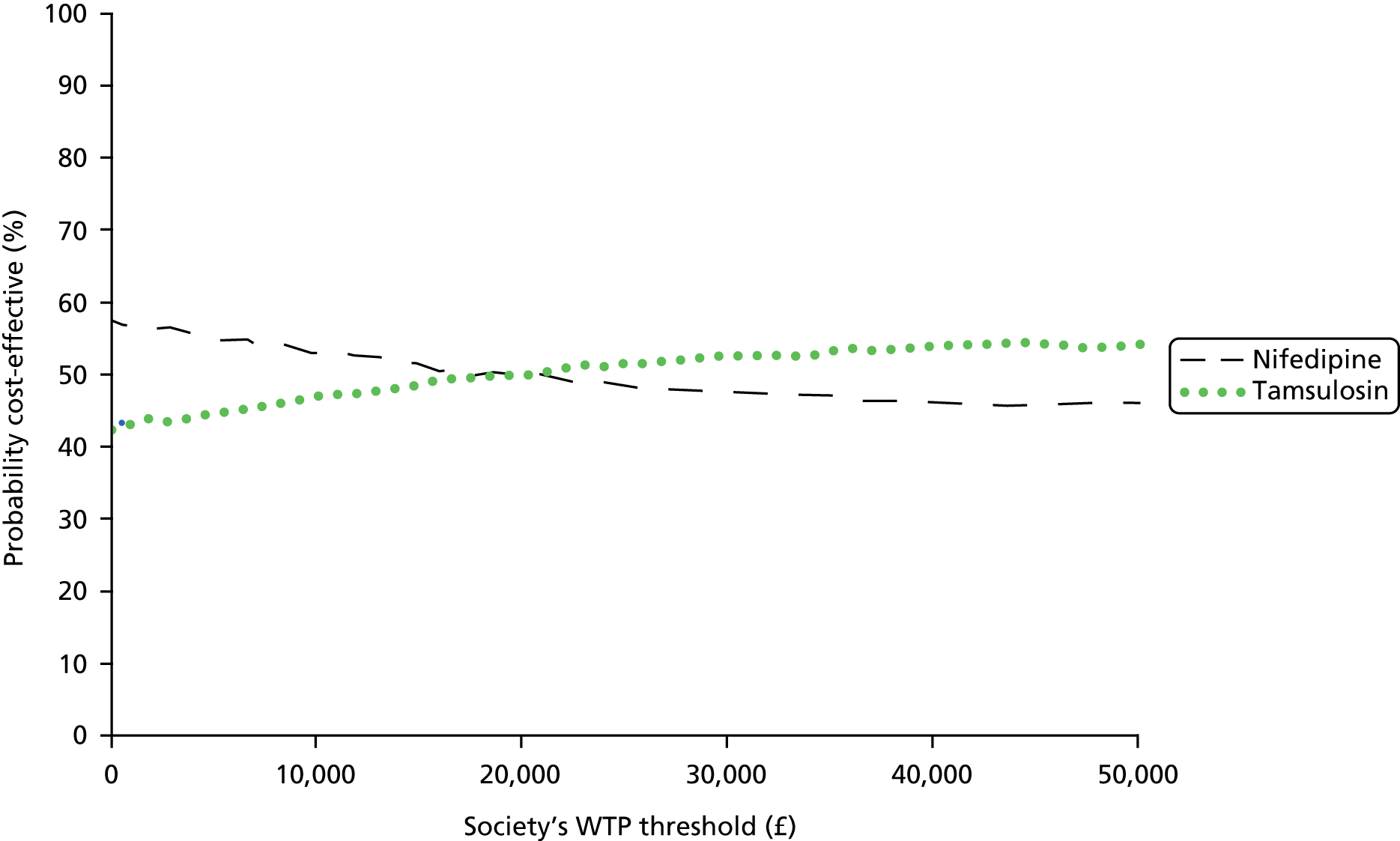

Incremental cost-effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness of the trial interventions from the perspective of the NHS during the period of observation was measured in terms of the number of participants needing further treatment within 12 weeks, and in terms of QALYs accrued by participants in each group at 12 weeks. The results are presented as point estimates of mean incremental costs, number of further treatments needed, QALYs, incremental cost per further treatment needed and incremental cost per QALY. Measures of variance for these outcomes required bootstrapping of the point estimates. Incremental cost-effectiveness data are presented by cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). Forms of uncertainty (e.g. concerning the unit cost of a resource from the different centres) are addressed using deterministic sensitivity analysis. As the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric bootstrapping was used to generate 1000 estimates of mean costs and QALYs for each treatment group. CEACs were generated using these 1000 estimates, using the net monetary benefit (NMB) approach. The NMB associated with a given treatment option is given by the formula:

where effects are measured in QALYs and Rc is the ceiling ratio of willingness to pay (WTP) per QALY. Using this formula, the strategy with greatest NMB is identified for each of the 1000 bootstrapped replicates of the analysis, for different ceiling ratios of WTP per QALY. Plotting the proportion of bootstrap iterations favouring each treatment option (in terms of the NMB) against increasing WTP per QALY produces the CEAC for each treatment option. These curves graphically present the probability of each treatment strategy being considered optimal at different levels of WTP per QALY gained.

The degree of missing data for the variables used in the derivation of costs was very low, and the data that were missing were considered to be missing completely at random. However, the number of participants with completely missing data for EQ-5D scores at 4 weeks and 12 weeks used for the derivation of QALYs was high (available data: tamsulosin group = 164/383; nifedipine group = 165/383; and placebo group = 157/384). Several methods of imputation were used as described in the sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

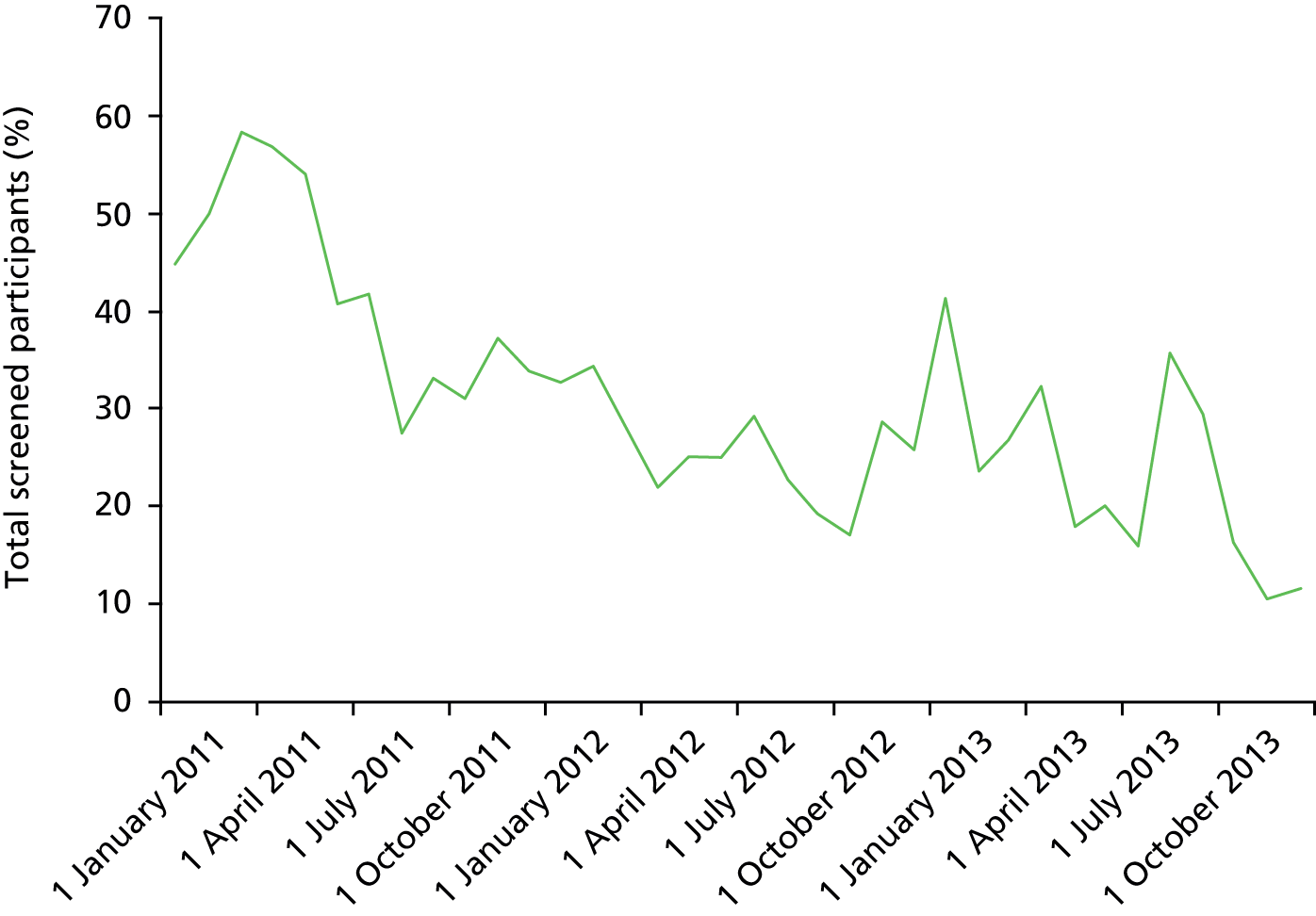

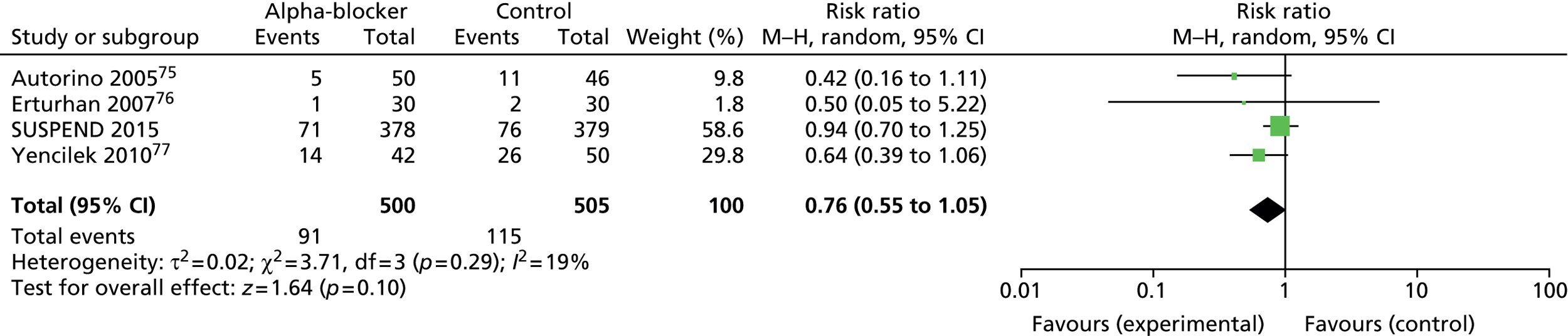

There are elements of uncertainty owing to the lack of available information; therefore, various sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the importance of such uncertainties. One-way sensitivity analyses using extreme values were performed around the QALY estimates. As the base-case analyses were performed using participants with complete cases, multiple imputation was carried out using chained equations in Stata 13 to replace missing cost and EQ-5D variables with a plausible value in 20 imputed data sets.