Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/06. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Aimee Spector reports personal fees from NHS trusts, outside the submitted work. Professor Alistair Burns reports personal fees from the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, personal fees from NHS England, non-financial support from King’s College London and non-financial support from the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, outside the submitted work. Professor Robert Woods reports royalties for group cognitive stimulation therapy manuals paid to Dementia Services Development Centre Wales, Bangor University (Hawker Publication and Freiberg Press, USA) outside the submitted work. Professor Ian Russell reports grants from University College London, both for the submitted work and outside the submitted work. Lauren Yates, Professor Martin Orrell, Phuong Leung, Dr Aimee Spector, Professor Robert Woods and Dr Vasiliki Orgeta have a patent on the individual cognitive stimulation therapy manual.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Orgeta et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to the individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy trial

Background

Cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia

Developing and evaluating psychosocial interventions for people with dementia and their family carers is becoming increasingly important both in the UK and internationally. In fact, recent evidence indicates that psychosocial interventions are useful and may therefore be utilised either as standalone treatments or in addition to pharmacological treatments for dementia. Although a large number of non-pharmacological interventions are available, there is now consistent evidence of at least moderate quality that those interventions incorporating psychosocial1,2 or psychological approaches3 can benefit people with dementia.

Given the growing development and application of cognitive-based interventions in dementia care, it has been emphasised that each of the different approaches should be clearly defined, in order to avoid confusion in relation to the various interventions used. 4 For example, cognitive stimulation approaches allow opportunities for general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning through a range of activities, usually in a group setting, that differ from cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation techniques. 2

Cognitive stimulation approaches originate from reality orientation (RO),5 a theoretical tradition postulating that provision of intellectual and social stimulation for people with dementia can positively affect their well-being. Cognitive stimulation interventions are, in fact, those that have been researched most frequently and have been associated with benefits for people with dementia. A recent Cochrane review, for example, has concluded that cognitive stimulation programmes can benefit cognition in people with mild to moderate dementia and may have a potential beneficial effect for self-reported quality of life. 2

Among cognitive stimulation approaches used, cognitive stimulation therapy (CST)6 is an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for people with mild to moderate dementia, consisting of structured sessions of stimulating activities delivered in a group setting. Being one of the few manualised approaches and designed to be facilitated by health and social care professionals, the original CST programme was evaluated in a single-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial (RCT), which reported benefits in cognition and quality of life for people with dementia living in residential care. 6 CST compares favourably with trials of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and economic analysis has demonstrated that CST is cost-effective. 7

Participation in cognitive stimulation approaches for people with dementia has been recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)8 and the 2011 World Alzheimer’s Report,9 which concluded that CST interventions are among the few associated with evidence of efficacy in comparison to other psychosocial interventions currently available and should be made available to people with mild to moderate dementia. The recent Cochrane review2 suggested that, although cognitive stimulation interventions can benefit cognition, further randomised controlled studies are needed to evaluate effects of modality of delivery, such as carer-led, home-based approaches. The Cochrane review also suggested that there is currently minimal evidence in relation to in-depth qualitative studies of these approaches.

Individual cognitive stimulation approaches are likely to increase access to this intervention, specifically for those people with dementia who are unable to participate in groups owing to local service constraints, personal preference, or health or mobility issues. The justification of evaluating individual carer-led programmes stems from promising findings from studies that have applied home-based cognitive interventions. A carer-led, home-based programme of active training in memory management including cognitive stimulation, orientation and family carer counselling10 reported long-term benefits for cognition for people with dementia, reduced care home admissions and improved carer well-being. Home-based cognitive stimulation has also been associated with improvements in problem solving and memory, and a reduction in carers’ depressive symptoms,11 whereas the first RCT evaluating a home-based RO/cognitive stimulation intervention demonstrated improvements in cognition for the person with dementia. 12

Costs of dementia and use of cognitive stimulation interventions

Dementia is a health and social care priority for many countries worldwide. It is currently estimated that population ageing is likely to exert an enormous impact on the dementia epidemic, with rapid increases in the number of people affected in many countries. 13 Over 700,000 older people currently living in the UK have dementia, leading to high costs of treatment, care and support, with the current overall annual cost of dementia exceeding £26B. 14 Given that a high proportion of this overall economic impact is the value of unpaid care and support by family and other carers,14 it is important to find interventions that make good use of society’s limited resources, including the substantial inputs from carers. Cognitive stimulation approaches have been shown to be promising in this regard, being among the few post-diagnostic support interventions demonstrated to be cost-effective. 7 Moreover, given the high proportion of cost carried by unpaid carers, it is important that interventions targeting well-being in people with dementia also accommodate any associated effects on family carers and support them in their caring roles.

Aims and objectives

This report presents data on the development and evaluation of a home-based individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) programme for people with dementia and their family carers. The intervention was evaluated using a pragmatic, single-blind, RCT design comparing the effectiveness of iCST to treatment as usual (TAU). The objectives of the study were the following:

-

to develop an individual, home-based programme of CST for people with dementia and their family carers

-

to assess the effectiveness of iCST in improving cognition and quality of life for people with dementia, mental and physical health in carers, and other outcomes in conjunction with TAU

-

to assess the cost-effectiveness of iCST in comparison with TAU.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Development of individual cognitive stimulation therapy: overview and framework of development studies

The development of the iCST programme involved three separate components that informed the key characteristics of the intervention and its delivery in the main trial. We followed guidelines of the Medical Research Council15 for the development and evaluation of complex interventions characterised by multiple interacting components. 16 Following these guidelines, we used the best available evidence on group CST,2,6 appropriate theories5,17 and a series of development studies in order to develop the individual CST programme. The key objectives of the development phase were: (1) to ensure that the therapeutic materials were easy to use, clear and appropriately tailored to the needs of people with dementia and their carers; (2) to collect professional expertise data on the development of iCST; and (3) to gather data in relation to feasibility, appropriateness of materials and factors influencing fidelity. 18

Development study 1: service users’ views about the intervention

This component of the development phase involved assessing the appropriateness and acceptability of the intervention, by consulting people with dementia and their family carers using individual interviews and focus groups. During initial consultations of manual development, two family carers and two health and social care professionals were consulted. Carers’ and professionals’ feedback was sought in relation to the adaptation of group CST approaches6,19 and the key characteristics of previous individual cognitive-based interventions involving carers. 10,12 These consultations concluded that a carer-led manual should adapt similar layouts to those used in previous literature (i.e. group CST) but overall length should be reduced, academic terms should be simplified and simple instructions should be incorporated. At this stage, carers and professionals also identified the need to emphasise the dyadic nature of the intervention and to ensure that the manual is engaging. Data gathered from these first consultations resulted in the first draft of the iCST manual (and associated workbook). People with dementia and family carers taking part in the individual interviews and focus groups were recruited from local NHS and voluntary organisations in the North East London Foundation Trust. First drafts of the iCST manual and activity workbook were presented to service users for appraisal in a series of 10 individual interviews and six focus groups. Demographic characteristics of the sample taking part in Development study 1 can be seen in Appendix 1.

Ten caregiving dyads were recruited to participate in the individual interviews. People with dementia and their carers were interviewed separately, using a discussion guide that was applied to direct the content of the interviews, with each interview typically lasting 30–45 minutes. The interview with the person with dementia started with an appreciation of the concept of mental stimulation and involved completing a sample of iCST activities and collecting feedback about participants’ enjoyment and the level of difficulty. A general discussion about perceptions of, and needs for, a home-based programme of mentally stimulating activities followed. The aims of the carer interviews were similar, focusing primarily on collecting data about the quality and appropriateness of iCST, and identifying any practical issues that might affect the delivery of the programme and areas of support for carers.

Six focus groups were conducted with people with dementia and family carers. Thirty-two people participated in the groups, which aimed to identify key characteristics of mentally stimulating activities, to assess the feasibility of a home-based activity programme and to obtain feedback about the quality of materials presented. Two groups were held with carers, three groups were held with people with dementia and one group was held with both carers and people with dementia. Group discussions were conducted in a semistructured style guided by a series of pre-determined focus points. Details of the discussion points of the individual interviews and focus groups are presented in Appendix 1.

All individual interviews and focus groups were transcribed. Inductive thematic analysis techniques were employed in the coding and analysis of data,20 with meaningful excerpts of text extracted and used for categories emerging (i.e. ‘perceived barriers’). Two researchers independently reviewed all excerpts and additionally examined whether or not any could be coded to more than one category, reaching consensus over their category placement. Data from all focus groups were collated, then examined further by source (carers and people with dementia) to identify any variations in views. Individual interview data were also grouped by source and compared with data gathered from the focus groups.

The response to the first draft of the iCST manual and activity workbook was positive overall, with carers commenting that materials were clearly laid out and written in a way that was easy for people with dementia and carers to understand. Recommended changes to the manual included editorial changes to improve the clarity of instructions provided and alterations to the size of text and images. ‘Monitoring progress’ forms of overall enjoyment of activities underwent significant adjustments at this stage in response to feedback from carers that appraisal sessions should be informal in order to avoid the person with dementia feeling that their performance on the activities is being scrutinised. Appendix 1 provides a summary of the qualitative results of both the individual interview and focus group data.

Development study 2: expert feedback

The main purpose of Development study 2 was to gather ‘expert data’ on the suitability of the iCST manual and associated workbook. We used consensus methods guidelines to collect ‘expert data’ from dementia care professionals. 21 Additional objectives were to address and identify key components of the intervention in order to inform its final development. This study comprised an online survey evaluating the draft of the iCST manual and associated workbook, followed by a consensus conference. Health-care professionals, academics, service users, and private and voluntary sector professionals were invited to participate in an online survey and were asked to provide their opinions on the suitability of the iCST manual and workbook. We also sought input from European experts in dementia care.

Experts evaluated the iCST manual and activity workbook on the following domains: overall quality and layout; language used; font size; amount of information presented; clarity and variety of activities; and level of engagement. Statements were evaluated on a 5-point scale as follows: ‘strongly disagree’ (1); ‘disagree’ (2); ‘neutral’ (3); ‘agree’ (4); and ‘strongly agree’ (5). Very high agreement was defined as a median of 5, an interquartile range of 0 and ≥ 80% of participants scoring 4 or 5. High agreement was defined by a median of 5, an interquartile range of ≤ 1 and ≥ 80% scoring a 4 or 5. Moderate agreement was defined by a median value of 4–5, an interquartile range of ≤ 2 and ≥ 60% of participants scoring a 4 or 5. 22 For overall quality a 4-point scale was used: ‘poor’ (1); ‘fair’ (2); ‘good’ (3); ‘excellent’ (4).

A total of 25 dementia experts took part in the online consensus survey, of which two were family carers (8%), 11 (44%) were working in the NHS or social services, three (12%) were working in the private sector, seven (28%) were academics in dementia care and two (8%) were professionals working in the voluntary sector. Of these experts, 16 (64%) attended the consensus conference and additional workshops. Results of the online survey for the iCST manual and associated workbook appear in Appendix 2.

Additional qualitative comments from the online survey data were subjected to a thematic analysis. Analyses of these data emerged in the following key domains:

-

Person-centred focus: the activities and key principles of iCST should be more person-centred; there should be an emphasis on positive emotions and pleasurable experiences for both the person with dementia and family carer, and the manual should emphasise the dyadic nature of the intervention.

-

iCST activities: for each activity the level of difficulty of the session should be clearly separated and additional activities for people with mobility issues or compromised hearing should be accommodated. It was emphasised that activities should be accessible to all demographics and that all iCST sessions should be ‘collaborative’, highlighting that people with dementia and carers ‘work together’.

-

Layout and clarity of intervention: the manual should provide key information about the intervention only; it should incorporate a smaller and more manageable number of key principles and should emphasise that discussion is one of the key purposes of iCST by including open-ended questions.

Consensus workshops

An additional component of Development study 2 was consensus workshops inviting experts to comment on specific components of the development of the intervention, with a total of 16 experts taking part. Themes discussed were: Getting started with iCST, iCST toolkit of resources, Overview of iCST manual and associated workbook, Support for carers and Home-based training in iCST. A thematic analysis was used to analyse data in each of the four workshops. In the Getting started with iCST theme, results indicated that this aspect of the intervention would need to be tailored to individual needs and that carers should be encouraged to identify their own style, with the use of warm-up activities that incorporate person-centred interests. In relation to the iCST toolkit of resources theme, experts commented that physical games should be adapted for indoors use and have an increased cognitive component, and that maps of counties will be a useful relevant resource. In the workshop discussing the Overview of iCST manual and associated workbook theme, it was discussed that principles of iCST should avoid replication and should be shortened to a more manageable key list.

In the remaining two consensus expert workshops, issues of support for carers and set-up of home-based training for iCST were discussed. Analyses indicated emphasis by experts on the importance of empowering carers by providing extra information and help if requested, encouraging the involvement of other family members and inclusion of a Carers Diary providing easy access and navigation to sessions completed. Experts advised that a digital versatile disc (DVD) could be used for problem solving but that it should not become a barrier for carers adopting their own style.

Development study 3: field testing for final refinement prior to the main trial

The main aim of the third development study was to assess further key elements and components of adaptation of the intervention through field testing. Twenty-six people with dementia and their carers took part in this study. The majority of carers were family members of the person with dementia and were recruited either from the voluntary sector or from memory services in the North East London Foundation Trust. A small proportion of carers taking part were paid carers (n = 6), who were recruited from a private home care agency. People with dementia were screened for eligibility using the inclusion criteria of the main trial. Family carers were usually approached about the research study first by dementia care professionals (consultant old age psychiatrist) and then by the research team. A senior member of staff at the home care agency contacted potential carers working with people with mild to moderate dementia. If the dyad consented to participate, a set-up visit was arranged by local researchers. Written consent was provided by both the carer and the person with dementia at the beginning of the set-up visit. Demographic characteristics of the sample can be seen in Appendix 3.

For the purposes of the field testing, the 75-session programme was divided into six draft manuals and accompanying workbooks. Manuals 1–5 comprised a total of 60 sessions and manual 6 contained the remaining 15 sessions. Carers were asked to deliver up to 3 sessions per week. Participants were asked to complete a total of 24 sessions on average.

Training and support

Family carers were trained by a member of the research team in their own home. Paid carers were trained as a group, with training sessions lasting 1–1.5 hours. Carers were provided with materials including the iCST manual and associated workbook and additional toolkit items (such as dominoes and playing cards). The first part of the session focused on describing the programme, familiarising carers with the iCST materials and explaining key principles of the intervention. A clip of a DVD developed in the recent maintenance group CST trial19 was shown in order to demonstrate principles and examples of activities. The second part of the session focused on practising an iCST session with support from the researcher. In all set-up visits, carers were invited to participate in a session with their relative with dementia. At the group training session for paid carers, staff were divided into pairs in order to practise iCST. The guided session aimed to help carers understand the key principles of iCST and how these can be implemented in the delivery of the sessions.

Carers completed a short evaluation questionnaire at the end of the training session rating knowledge and confidence in delivering iCST, alongside information about the anticipated amount of support needed. An evaluation questionnaire was also completed by the researcher in order to assess the success of the carer’s training session and to measure additional fidelity-related components. Researchers contacted carers weekly to provide support and to gather feedback about the dyads’ experiences with the iCST programme. Carers provided additional feedback about each activity on ‘monitoring progress’ forms, rating the person with dementia’s interest, communication, enjoyment and level of difficulty of each session using a 5-point Likert scale.

Final visit

Debriefing visits were arranged with dyads who completed their allocated sessions. The purpose of the visit was to collect written feedback about the sessions and to interview the dyad about their experience in using iCST. Carers completed a modified version of the training visit evaluation questionnaire, assessing knowledge and confidence in delivering iCST, the quality of support received and their perceived success in engaging with the person with dementia. Similar data were also completed by the researcher at the end of the visit.

Appendix 3 shows number of sessions completed for dyads taking part in the field-testing phase. The average number of sessions completed was 12 out of 24, indicating that most dyads were able to complete approximately half of the sessions, as opposed to 3 sessions per week. For a total of nine dyads, additional information for each of the sessions was collected in the areas of enjoyment, communication and interest by the person with dementia. Information related to the difficulty level for each of the sessions was also collected, as well as fidelity parameters (see Appendix 3). Pre–post evaluations of the field-testing phase showed that carers’ knowledge of [before: mean = 2.78, standard deviation (SD) = 0.97; after: mean = 3.11, SD = 0.93] and confidence in iCST (before: mean = 3.78, SD = 0.83; after: mean = 4.11, SD = 0.78) increased.

Information from the field-testing phase was incorporated into the main trial, by revising sessions that were rated either low on items of interest, communication and enjoyment for the person with dementia, or rated high in levels of difficulty. Qualitative data were also collected during Development study 3 via standard telephone interviews. Carers delivering iCST were asked to comment on parameters such as barriers to being able to complete the sessions, and on the content of the manual and activity workbook. An overview of these findings appears in Appendix 3. The most common barrier in iCST was lack of time and availability for delivering the sessions followed by issues around the health of the person with dementia or the carer. An additional barrier noted by both family and paid carers was experiencing difficulties in motivating and engaging people with dementia in the sessions. When discussing potential gains, a high percentage of carers mentioned that iCST provided opportunities to spend more time with their relative and assisted in improving the caregiving relationship.

Patient and public involvement

We held initial meetings with two members of the public as part of our public and patient involvement for the iCST study. Both were family carers of people with dementia and were asked to read all previous group CST manuals and comment on their content and suitability for carer use. During the development phase of iCST and the main trial, we invited two additional family carers to be consultants on the project to comment on carer training issues and support around iCST. They both took part in meetings held to provide peer supervision to unblinded researchers supporting carers and people with dementia with iCST. Their feedback emphasised the need for paying attention to the needs of both people with dementia and family carers as well as the importance of focusing on positive aspects of the intervention during carer support.

Chapter 3 Final intervention tested in the main trial

The iCST intervention was developed primarily as a home-based programme of structured iCST for people with dementia to be delivered by carers. Dyads completed up to 3 30-minute sessions per week over 25 weeks. The programme consisted of a total of 75 themed activity sessions, including being creative, number games and art discussion (Box 1), which were intended to provide opportunities for general cognitive stimulation via a choice of specific activities. In order to accommodate personal interests, dyads were encouraged to adapt the materials provided and to take a flexible approach in relation to choosing sessions, such as omitting any activities not suited to their interests, or revisiting activities that were particularly enjoyable. Each iCST session followed a consistent structure, where the first few minutes involved engaging in discussions of orientation information prompted by family carers (i.e. day, date, weather, time, location), followed by discussion of current events (i.e. a news story, a community event or family occasion) and the main iCST activity (15–20 minutes).

-

My life.

-

Current affairs.

-

Food.

-

Being creative.

-

Number games.

-

Quizzes.

-

Sounds.

-

Physical games.

-

Categorising objects.

-

Household treasures.

-

Useful tips.

-

Thinking cards.

-

Visual clips discussion.

-

Art discussion.

-

Faces/scenes.

-

Word games.

-

Slogans.

-

Associated words.

-

Orientation.

-

Childhood.

We used recent guidelines23 aimed at improving the description of interventions evaluated in RCTs consistent with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statements, which enables replication of the specific intervention tested. An overview of the iCST intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist and guide is presented in Table 1.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | iCST for people with dementia |

| Why | iCST is based on theoretical principles of RO and uses the same structure and principles of the group CST approach. Carer-led iCST adapts a person-centred approach, in which the person is engaging in home-based cognitive stimulation activities. iCST activities focus more on opportunities to express opinions and less on discussing factual information, and place an emphasis on the person with dementia and their family carer spending enjoyable time together, using a specific framework of discussion |

| What | Materials |

| iCST manual (guidance for carers) | |

| iCST activity workbook (activities materials) | |

| iCST carer diary (reporting and evaluating activities) | |

| iCST toolkit (boules, playing cards, dominoes, magnifying card, sound activity compact discs, coloured pencils, and world and UK map) | |

| iCST training pack (iCST role-play exercises) | |

| Procedure | |

| Carers trained at their home, using a standardised training package aimed at demonstrating key principles of iCST. Additional support provided over the phone and additional home support visits | |

| Provider | iCST was provided by family carers. Carer training and support was provided by the research team of unblinded researchers who were either mental health nurses, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists or research assistants. All unblinded researchers received standardised training in supporting family carers in iCST |

| How | iCST was delivered by carers. iCST carer training was delivered by unblinded researchers. Unblinded researchers received training in a group. Support on iCST was provided as an additional home visit and over the phone by unblinded researchers |

| Where | iCST was delivered at the dyad’s home |

| When and how much | iCST consisted of 75 sessions delivered by the family carer for 30 minutes, three times a week, over 25 weeks |

| Tailoring | Tailoring included additional home visits or telephone support, or provision of additional resources related to the intervention (i.e. books, DVD player) |

| Modifications | No modifications occurred during the intervention |

| How well | Planned: intervention compliance was assessed by self-reported questionnaires completed by carers and researchers |

| Actual: mean compliance was 31.6 (SD = 26.8) sessions, where 22% completed 0 sessions, 13% completed 1–10 sessions and 51% completed more than 30 sessions |

Contents of individual cognitive stimulation therapy

Dyads were provided with the iCST manual, the iCST activity workbook, two carer diaries and the iCST toolkit. The iCST manual provides guidance on how to run the iCST sessions, the key principles of iCST (Box 2) and guidance on activities. This manual was disseminated at the ninth UK Dementia Congress and has been published. 24 The iCST activity workbook contains paper-based resources for activities suggested in the manual, such as word puzzles and images to stimulate discussion.

iCST should:

-

be ‘person-centred’

-

offer people with dementia choice in a range of home-based CST activities

-

focus on opinions rather than facts

-

use reminiscence

-

always use a focus such as senses, stimuli or objects

-

aim at maximising potential

-

recognise that enjoyment and fun are key for both the person with dementia and their family carer

-

provide opportunities to stimulate language

-

provide opportunities to strengthen the caregiving relationship.

Carer training

Carers were trained in their home by an unblinded researcher. A standardised training package was developed with interactive features, including a role-play exercise and the opportunity to see clips of group CST activities. The first part of the training session introduces the dyad to the iCST materials (manual, activity workbook, toolkit and carer diaries) and explains the session structure and key principles. Carers were encouraged to take part in a role-play exercise with the researcher, developed to demonstrate ‘good’ and ‘bad’ practice in iCST. In the final part of iCST training, family carers were invited to deliver their first iCST session with support from the unblinded researcher, who provided feedback afterwards. Where multiple family carers were involved in delivering the programme, the researcher invited them to be trained with the main carer.

Individual cognitive stimulation therapy support for carers

An unblinded researcher provided dyads with telephone support throughout their participation, providing weekly, fortnightly or monthly telephone support depending on carer needs and preference. Additional monitoring visits took place at 12 weeks and 25 weeks, which were aimed at collecting the iCST carer diaries, providing further support if necessary and completing measures of compliance. There were a total of 21 unblinded researchers supporting carers, of whom 81% were qualified professionals working in the local NHS trusts. Among qualified professionals, the majority were nurses (n = 13) or clinical psychologists (n = 3), with one member of staff being a qualified occupational therapist. The remaining staff were clinical studies officers (n = 2) or research assistants (n = 2). All unblinded researchers supporting carers received training in iCST.

Individual cognitive stimulation therapy fidelity

To ensure that psychosocial interventions can be replicated, and to ensure that the treatment delivered was indeed the treatment intended (known as ‘treatment integrity’),25 iCST components were described in detail in a treatment protocol. This protocol formed the basis of training of all unblinded researchers supporting and training family carers in delivering iCST. iCST diaries provided a method of tracking compliance to the programme, whereby in each theme, carers were required to record whether or not the session had been completed, the date of completion and their relative’s interest, enjoyment and communication. Space was provided for dyads to provide any additional comments related to the sessions. The progress of dyads and compliance to the programme was also measured during support activities via treatment questionnaires during both the telephone support and visits. A telephone support questionnaire was used to gather data on the average number of sessions completed per week, average duration of sessions, average time spent preparing and any difficulties encountered. Carers completed a self-report measure of confidence and knowledge in the delivery of iCST, level of engagement of the person with dementia, use of iCST principles and satisfaction with the support provided in treatment visits.

Chapter 4 Trial phase methods

Design

A multicentre, pragmatic, single-blind, two-treatment arm (iCST vs. TAU), randomised, controlled, clinical trial was conducted over 26 weeks. Participants were randomised to the two groups using a dynamic adaptive randomisation stratified for site and whether or not the person with dementia was taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors at baseline. Data collection was at baseline, 13 weeks and 26 weeks after completion of the intervention. The primary outcomes were assessed at both time points, with the primary hypothesis examining outcomes at 26 weeks.

Ethics approval

A protocol was submitted for ethical review to the East London 3 Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 10/H0701/71) in January 2010, with provisional approval being granted in July 2010. The following information was identified by the Committee as needing further clarification and amendment:

-

Participant Information Sheet to be modified to cover video-recordings and information about the control/usual care group and minor editing changes (i.e. language use)

-

consideration of a cross-over or add-on scheme and whether or not participants will be given a copy of a DVD and manual

-

provision of additional information about the interviews in both consent and participant forms and further clarification over whether or not recruitment posters and leaflets would be used.

Final approval was granted in September 2010. Participating centres obtained approval from the appropriate local REC and relevant NHS research and development departments.

Intervention and control conditions

Participants randomised to the intervention group received iCST at their own home. The control condition was TAU, with participants in this group receiving no additional intervention. The services and interventions available to people with dementia and family carers randomised to receive TAU varied between and within the iCST centres and may have changed over time. We recorded the use of drugs and services across the two groups and any changes that occurred. In general, services offered to the TAU group were also available to those in the active treatment group condition.

It is very unlikely that any comparable (or even any other) individual cognitive stimulation intervention for the person with dementia would have been available, as these types of therapies are generally unavailable in the UK. We followed standard best-practice methods around pragmatic trials involving an intervention group compared with usual care. Outside the iCST intervention, both groups, in general, would have access to the same kinds of mentally stimulating activities. It is possible that some participants in the TAU group may have engaged in some form of mentally stimulating activities in day-centres; however, this is unlikely to have been as structured as iCST. We asked sites to note instances in which the person with dementia may have been engaged in cognitive stimulation groups by their local services. Those participants who have engaged in such activities during the 3 months prior to recruitment were considered to be ineligible.

Study population

Eight centres in England and Wales were involved in the study: London, Bangor, Hull, Manchester, Norfolk and Suffolk, Dorset, Lincolnshire and Devon (covering Devon North and Devon South), which comprised 12 recruitment sites in total. Researchers in three centres (London, Bangor and Manchester) were based in universities, whereas those in Hull, Norfolk and Suffolk, Dorset, Lincolnshire and Devon were based in NHS mental health services (Table 2). Recruitment commenced in April 2012 and was completed in July 2013.

| iCST centre | iCST recruitment site |

|---|---|

| London | North East London NHS Foundation Trust |

| Barnet Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust | |

| Bangor | Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board |

| Hull | Hull Humber NHS Foundation Trust |

| Manchester | Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust |

| Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust Site A | |

| Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust Site B | |

| Dorset | Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust |

| Lincolnshire | Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust |

| Norfolk and Suffolk | Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust |

| Devon | Devon Partnership NHS Trust |

| Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust |

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

All participants were people with dementia who:

-

met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition criteria for dementia of any type (Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body type and mixed)

-

scored 10 or above on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)

-

had some ability to communicate and understand communication, indicated by a score of 1 or 0 on the relevant items of the Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly – Behaviour Rating Scale

-

could see/hear well enough to participate in the programme activities

-

had no major physical illness or disability affecting their participation

-

lived in the community at baseline, had regular contact with a relative or other unpaid carer who could act as an informant and could participate in the intervention.

Exclusion

People with dementia were excluded if:

-

they were not living in the community (i.e. living in a care home)

-

they had no available family carer to deliver the sessions and act as an informant.

Sample size

The main analysis was based on intention to treat for the primary outcome of cognition [Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog)]. Our group CST study6 had an effect size of 0.32. Our Cochrane review of RO26 found a standardised mean difference (SMD) of 0.58, whereas the individual RO/CST study12 found a SMD of 0.41. Taking a conservative approach, we estimated the SMD relative to TAU to be 0.35. A sample size of 260 will have to yield 80% power to detect a SMD of 0.35 using a two-group t-test with a 0.05 (two-sided) significance level comparing the iCST and the TAU groups. Assuming 15% attrition, we originally proposed to recruit 306 people with dementia. During the course of the trial the observed attrition rate was nearer to 25% than the 15% accounted for in the sample size calculation and, therefore, the target recruitment was revised to account for this. The final recruited sample size was 356.

Recruitment procedures

In each iCST centre, people with dementia and their family carers were recruited through mental health services for older people, such as Memory Clinics and Community Mental Health Teams, through dementia care professionals, including psychiatrists, and through local voluntary sector organisations, such as the Alzheimer’s Society (see www.alzheimers.org.uk). The centres in London, Bangor and Manchester were supported by clinical studies officers accessed through the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research Clinical Research Centre in Wales and the Dementias and Neurodegenerative Disease Research Network (DeNDRoN) in England. In Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire, all patients and carers referred with dementia (and their general practitioners who currently have additional DeNDRoN support to assist with recruitment to dementia trials) were automatically provided with ‘opt-in information’ on current NHS portfolio studies in dementia care, via a centralised clinical academic unit, The Hull Memory Clinical Resource Centre.

The aim of the project was briefly described to potential participants by members of the research and clinical team, and permission for them to be contacted by local researchers was obtained prior to further contact. Research assistants discussed the project and provided full details to participants, answered any questions related to the project and, if participants agreed, undertook informed consent.

Informed consent

Participants enrolled to the study only after providing informed consent in line with guidelines set by the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 27 Participants were in the mild to moderate stages of dementia and were therefore expected to be competent to give informed consent for participation, provided that appropriate care was taken in explaining the research and sufficient time was allowed for them to reach a decision. It was helpful for a family member to be involved, and we aimed to ensure that this was done wherever possible. Both people with dementia and family carers were informed that no disadvantage would accrue if they chose not to participate, and all participants were provided with at least 24 hours to review information about the study prior to making a decision. In seeking consent, we followed current guidance from the British Psychological Society28 on the evaluation of capacity. In this context, consent is regarded as a continual process rather than a one-off decision, and willingness to continue participating was continually checked through discussion with participants during the assessments. If, at any point, the person with dementia or family carer became uncomfortable with the assessments, these were discontinued.

Ethical arrangements

The study was approved through the appropriate REC. All researchers received training in Good Clinical Practice guidelines. 29 There appear to be no documented harmful side effects from participating in CST interventions or other types of cognitive-based interventions. Regular monitoring by, and support from, the key local unblinded researchers in each centre was undertaken during the intervention to ensure that people with dementia participating in the iCST sessions did not feel deskilled or undervalued.

Prospective participants were fully informed of the potential risks and benefits of the project. A reporting procedure was put in place to ensure that serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the Chief Investigator (see Appendix 8). On becoming aware of an adverse event involving people with dementia or their carers, a member of the research team assessed whether or not it was ‘serious’. A SAE was defined as any untoward occurrence experienced by either a person with dementia or carer that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator

-

came within the scope of the Protection of Vulnerable Adults protocol,30 which was in place to ensure that suspected cases of abuse or neglect were followed up in an appropriate manner.

A reporting form was submitted to the Chief Investigator who assessed whether or not the SAE reported was:

-

related to the conduct of the trial

-

unexpected.

Serious adverse events that were judged to be related and unexpected were to be reported to the REC and the trial Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) within 15 days of occurrence.

Randomisation

Remote randomisation of participant allocation treatment was undertaken via a web-based randomisation service managed by the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH) clinical trials unit, after baseline assessment and informed consent. Randomisation was completed using a dynamic adapative allocation method,31 with an overall allocation ratio of 1 : 1. Random allocation was stratified by site and receipt of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs). For each participant randomised, the likelihood of their allocation to each treatment group is recalculated based on the participants already recruited and allocated. This recalculation is done at the overall allocation level, within stratification variables and within stratum level (the relevant combination of stratification levels). By undertaking this recalculation, the algorithm ensures that balance is maintained within acceptable limits of the assigned allocation ratio while maintaining unpredictability.

Allocation concealment

The randomisation database was held at NWORTH, and the analysts involved in the trial did not have access to the database. The dynamic adaptive algorithm is tuned using weighting parameters. These parameters are chosen by simulation modelling to ensure that the balance is maintained at an acceptable level, while ensuring that the sequence of allocations does not become predictable. Strong parameters would make the randomisation algorithm behave in a deterministic way, thus making allocation concealment difficult. Unblinded researchers were the only staff who were informed at each of the iCST centres of participants’ allocation.

Implementation

A web-based randomisation system was set up at NWORTH. Unblinded researchers could log into the system, enter participants’ details and receive randomisation results on screen and by confirmation e-mail. The system ensured that each entry had a unique trial identification number.

Blinding

As with all psychosocial interventions, participants cannot be blind to the allocation they receive. Within each iCST centre, there were nominated blinded and unblinded researchers; both were able to conduct baseline assessments and request randomisation. However, once participants were randomised, follow-up data were collected by the team of blinded researchers only, whereas the training and carer support in delivering iCST was run by unblinded researchers. Given that participants may occasionally and inadvertently inform researchers of the treatment they are receiving, we aimed to reduce this bias by use of self-report measures wherever feasible and brief reminders to participants. We asked all blinded researchers to record their impression of the group to which each participant was allocated and their confidence in that prediction. Statisticians remained blind to allocation for the main analysis, whereas compliance analysis incorporating compliance to the intervention was conducted after the main analyses only.

Data collection

Primary and secondary measures were completed at baseline, 13 weeks after baseline (week 13) and 26 weeks after baseline (week 26). Researchers were instructed to conduct all week-13 assessments within the 13-week period, but no later than 2 months from the scheduled first follow-up appointment (starting at date of baseline assessment), and to conduct all week-26 assessments by 26 weeks, but no later than 2 months from the scheduled second follow-up (starting at date of baseline assessment).

Most interviews were conducted in dyads’ homes. All questionnaire instruments were arranged in the form of booklets, with additional show cards of responses supporting the person with dementia during the assessment. If, at any point, the person with dementia felt uncomfortable with the assessment this was discontinued and was only rescheduled to take place during a second visit where appropriate.

Measures

Primary outcome measures for person with dementia

-

Cognition for the person with dementia, assessed by ADAS-Cog,32 measuring the severity of the most important cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). ADAS-Cog is the most popular cognitive testing instrument used in clinical trials of drug treatments for dementia consisting of 11 tasks assessing disturbances of memory, language, praxis, attention and other cognitive abilities, often referred to as the core symptoms of AD. This widely used test has good reliability and validity,33 and is scored from 0 to 70, with higher scores indicative of greater cognitive impairment.

-

Quality of life of the person with dementia, measured using the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (QoL-AD). 34 QoL-AD is a widely used, brief, self-report questionnaire, covering 13 domains of quality of life. The QoL-AD has good validity and reliability. 35 Both self and carer ratings were collected, in which higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Secondary outcome measures

-

Quality of life, assessed using the Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) measure,36 covering five domains of quality of life, including daily activities, health and well-being, cognitive functioning, social relationships and self-concept. The scale uses self-rated reports of quality of life administered to the person with dementia. The measure was also administered to the family carer in order to collect DEMQOL-proxy ratings.

-

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. 37 The Neuropsychiatric Inventory assesses 10 behavioural disturbances occurring in people with dementia, using a screening strategy to minimise administration time by examining and scoring only those behavioural domains with positive responses to screening questions. Both frequency and severity of each behaviour are determined, with both validity and reliability for the measure established. 37

-

Functional ability for the person with dementia, measured by the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS),38 a carer-rated instrument consisting of 20 daily-living abilities. The BADLS shows sensitivity to change in people with AD receiving anticholinesterase medication and significantly correlates with changes in the MMSE and the ADAS-Cog. 39

-

Depression, measured using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)-15,40 one of the most commonly used self-rating depression scales in geriatric populations. The shorter version of the scale comprises easy-to-use items, designed to exclude somatic symptoms of depression that are also seen in non-depressed elderly people. The GDS-15 has acceptable sensitivity and specificity when used with people with mild to moderate dementia. 41

-

Quality of the relationship, measured by the Quality of Caregiver–Patient Relationship (QCPR),42 applicable to both spousal and adult child carers, completed by both the person with dementia and family carer. The QCPR has good internal consistency and concurrent validity with other measures of relationship quality and carer distress. 42

-

Use of health and social care services provided by public or non-public bodies, as measured on the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI),43 adapted for use in this study. The CSRI was used to collect information on the identified carer’s costs and the participant’s use of health and social care services. Additional data collected included medications for mental health, the carer’s provision of unpaid care and employment status, and out-of-pocket costs to both participant and carer (travel expenses to health and social care appointments, payment for equipment and adaptations).

Primary outcome measures for carers

-

Mental and physical health, measured by the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). 44 The SF-12 measures health by scoring standardised responses, which are expressed in terms of two meta-scores: the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS).

Secondary outcome measures

-

Depression, measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),45 a self-completed measure, generating scores for generalised anxiety and depression, used widely to identify caseness for clinically significant depression and anxiety. 46

-

Health-related quality of life, measured using the three-level response version of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D™) (hereafter EQ-5D-3L),47 a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome. Applicable to a wide range of health conditions, the EQ-5D-3L provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status.

-

Resilience, measured by the Resilience Scale-14 items,48 in which responses are summed and higher scores indicate stronger resilience. The measure demonstrates high construct validity. 49

Data checking

A full data-management plan was written, encompassing data storage and processing, data filing, data sharing, data freezing and data archiving. Data were collected in questionnaire packs and entered into a data-management system (MACRO version 4.1.2.3750, InferMed, London), which was audited for data entry accuracy, before being exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) files. SPSS Predicative Analytics SoftWare version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all further data manipulations and analysis. In all SPSS files, cleaning processes were undertaken, including checks for consistency and out-of-range data. If applicable, questionnaire data were cross-checked with the SPSS data to explore any issues of inconsistency. CSRI data were cleaned and analysed in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), again checking for consistency. Adherence data were entered by unblinded researchers into the MACRO system and used in both outcomes and economic analyses.

Data analysis

Missing data for clinical effectiveness

Data were not imputed for participants who did not provide any information at a particular time point. However, standard statistical tests were employed to ensure that there were no significant differences in demographics or baseline outcome scores between those who completed at a time point and those who did not. There were two types of missing data: missing items within measures and missing measures at time points.

Missing items within measures: pro-rating

For items missing within measures, the rules for completing missing data for the relevant measure were applied. The missing data rules implemented for each measure are considered to be part of the validated tool and were therefore used as designed in line with the original validation.

Pro-rating within participant measures were undertaken at the 20% missing level (i.e. if there was one item missing for a 5-item score, this was completed with the mean of the other items).

Missing measures at time points: regression model using multiple imputation

A regression within the treatment group was applied to impute total scores in line with the trend seen in the group, as multiple imputations, allowing an assessment of the sensitivity of the data. The multiple imputation model included demographic variables such as sex, age, ethnicity, type of relationship and site. It also included the completed scores for the other outcome measures at each time point. At both follow-up time points, the model included the allocated treatment group. Scores at baseline were used to predict scores at week 13. Scores at baseline and week 13 were used to predict scores at week 26.

Baseline characteristics

No statistical tests were conducted for significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two treatment arms. 50

Interim analyses

No interim analyses were planned for the data. No additional analyses were requested or identified by the DMEC.

Primary effectiveness analyses

We used an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model to assess the differences between the two groups in the ADAS-Cog and the QoL-AD as the primary outcome measures for people with dementia. The dependent variable in the model was the outcome at week 26, with covariates being the baseline measurement, age of participants with dementia and relationship with the carer. The fitted fixed factors considered were sex, marital status and receipt of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Site was added as a random factor. Both stratification variables were included in the model (site and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors).

A similar ANCOVA model was fitted for the carer primary outcome. The dependent variable in the model was the outcome at week 26, with the covariates being the baseline measurement, age of carer and relationship with the person with dementia. The fitted fixed factors considered were sex and marital status. Site was fitted as a random factor.

Secondary effectiveness analyses

The ANCOVA model described above was used to assess the differences between the two groups on all secondary outcomes for people with dementia. A similar ANCOVA model was fitted for all carer secondary outcomes.

Additional analyses

A basic adherence analysis was undertaken. The number of iCST sessions completed was held as a continuous variable and added to the model of the main analysis. This would allow an insight into whether or not the number of sessions completed was important to the outcome.

Economic analyses

The economic evaluation was a cost-effectiveness analysis, conducted first from a health and social care perspective and, second, from a societal perspective. The primary outcome measures for the person with dementia were the incremental cost of achieving:

-

one SMD (taken to be 2.4 points on the scale) in the ADAS-Cog

-

one SMD (taken to be 1.7 points on the scale) in the QoL-AD.

The primary outcome measure for the carer was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) (derived using the EQ-5D-3L with societal weights).

In the analysis plan, the secondary economic measures for the person with dementia were set out as: QALYs derived from the DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-Proxy-U, the MMSE, BADLS, GDS-15 and QCPR. Secondary economic measures for the carer were the HADS, MCS-12, PCS-12 and QCPR.

Valuation strategy for outcomes

Carers’ utility scores were calculated from the EQ-5D-3L, applying published societal weights. 51 We also derived utility scores for people with dementia based on self-ratings and carer proxy-ratings (the DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-Proxy-U indexes, respectively) from the DEMQOL and DEMQOL-Proxy instruments, using published societal weights. 52 All QALYs were calculated using the area-under-the-curve method with linear interpolation between the three assessment points and the last value carried forward from the final assessment to 12 months post-baseline.

The ADAS-Cog scores were reversed so that an increased score can be interpreted as a positive change for the purposes of deriving net benefit in order to plot cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). For the QCPR, an estimate of the points equivalent of the SMD was obtained by taking the baseline SD for the QCPR and multiplying by the effect size53 of 0.35 set for the study. This gave a difference of 3.1.

Costs

Perspective

Costs from the health and social care perspective covered services used by the person with dementia, including care/nursing home care, hospital care (inpatient, day, outpatient and accident and emergency services), primary and community health and social care. Costs from a societal perspective covered the aforesaid services, plus the costs of care and support provided by unpaid carers.

Time horizon

The economic analysis used the mean end point (week 26) outcome measure (as the primary outcome for people with dementia and secondary outcomes) and costs over the 26-week period. In the case of the ICER for the primary outcome for caregivers (cost per QALY), we calculated QALYs over the year from the baseline assessment; we likewise assumed that mean costs remained unchanged since the end of the intervention period and calculated annual equivalent costs by doubling the costs estimated for the 26-week period.

Cost data collections

Costs were calculated based on several collections:

-

data on services used by the person with dementia, as observed and reported by carers using the CSRI. 43 Service use items were collected and aggregated into cost categories

-

data on time spent by professionals (unblinded researchers) in supporting carers to deliver the training package, using one of a suite of ‘treatment adherence’ forms

-

data on professionals’ labour costs, using a pro-forma distributed to the unblinded researchers

-

data on time spent by carers to deliver the training package:

-

average time spent in preparing and in delivering the session: these data were collected by unblinded researchers during their telephone contacts, using one of a suite of ‘treatment adherence’ forms

-

number of sessions completed: this information was collected from carers who were asked to complete a workbook feedback form after every session. A manual count of sessions completed was conducted by unblinded researchers at each follow-up monitoring visit (one per follow-up period)

-

-

data on carer time spent on care and support activities, and lost employment and out-of-pocket costs, using the CSRI

-

costs of training materials (excluding costs of the initial development and testing of the package), supplied by the project management team.

Unit costs/valuation of health and social services and unpaid care

Unit costs were applied to units of resources in the estimation of per-participant costs. The base year for unit costs was 2012–13. Unit costs employed are summarised in Table 3 (unit costs and sources are given in further detail in Appendix 4). Costs of health and social care were calculated from service-use data by applying relevant, nationally generalisable unit costs [e.g. NHS reference costs54 and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) costs compendium55]. Costs of carers’ inputs were calculated using two methods: replacement costs and opportunity costs. 56–58 The primary analysis used opportunity costs, attaching a value equal to the national minimum wage to each hour of unpaid carer time spent on care and the cost of lost production; a replacement costs approach was employed in the sensitivity analyses (valuing time spent on care at the unit cost of a home care worker) (see Table 3). Certain out-of-pocket payments were also considered to be a cost to the dyad rather than to health and social care: the travel costs of accompanying the person with dementia to dementia-related appointments by car, public transport or taxi, and the private purchasing of equipment and adaptations.

| Service use item | Unit cost (£), 2012–13 |

|---|---|

| Inpatient bed-day, per specialty (range) | 344–1495 |

| Inpatient bed-day, weighted average across adult specialties | 577 |

| Day attendances, per specialty (range) | 540–817 |

| Day case, weighted average across specialties | 693 |

| Outpatient attendances (range) | 27–468 |

| A&E attendances, admitted and non-admitted (range) | 115–160 |

| Outpatient, weighted average of follow-up attendances across adult specialties | 98 |

| Primary, community and community mental health services, per contact (range) | 36–115 |

| Primary and community health services, per minute (range) | 0.5–3.6 |

| Residential care, per day (range) | 76–143 |

| Nursing home care, per day | 107 |

| Community-based social care, per minute (range) | 0.4–2.7 |

| Day services, per session/day (range) | 5–38 |

| Medications, standard quantity units (range) | 0.1–6.0 |

| Equipment and adaptations, cost over 3 months (range) | 0.1–104.0 |

| Carer hour, valued at replacement cost: home care worker, per hour | 19 |

| Carer hour, valued at opportunity cost: minimum wage, per hour | 6 |

Valuation strategy for intervention costs

The iCST intervention was produced from both professional and carer inputs. Unblinded researchers from the nursing and psychology disciplines worked to set up and train carers to deliver the sessions and then provided ongoing face-to-face and telephone support to carers throughout the study period.

In order to value the costs of professional time taken to deliver the intervention, we collated information on each researcher’s Agenda for Change band,59 on costs and full-time equivalents on the project. We estimated workers’ indirect and direct overheads using PSSRU unit costing methods;56 in estimating capital costs we assumed that workers were based in premises with a shared treatment space. A weighted hourly cost of professional support was then calculated based on the full-time equivalent contribution per Agenda for Change band. In addition, we calculated site-level average travel costs per visit, including professionals’ travel time and costs of mileage (unblinded researchers were asked to estimate their average travel time and miles driven in visiting participants on their iCST case load in each site). The costs of iCST training, including professional time and travel expenses and venue costs, were provided by the University College London project team. The project team also provided an estimate of the cost of the iCST training manual and materials (excluding the costs of developing the manual). We calculated an average training cost per participant and the average cost of manual materials per participant. The unit costs of professional support time and travel, training and materials costs of the intervention are summarised in Table 4. These unit costs were used to calculate a total cost of the package of materials and professional support in the cost-effectiveness analysis. We attached the weighted hourly cost of professional time to the reported telephone and face-to-face contact time for each participant, and a site average cost of mileage and travel time to reported face-to-face visits. We spread the per-participant manual and training costs, and the costs of professionals’ time spent in providing the set-up visit, across the two follow-up periods, allocating half the cost to each period.

| Costs of professional support (intervention) | Unit cost (£), 2012–13 |

|---|---|

| Total iCST training costs | 17,288 |

| Per participant (total divided by 180 intervention participants) | 96 |

| iCST manual and materials, per participant | 94 |

| Professional time, per hour | 49 |

| Mileage costs per one-way journey (per site) (range) | 4–32 |

Carers provided data on the number of iCST sessions completed over each follow-up period (see also Cost data collections); they were asked by the unblinded researchers to estimate the time spent in preparing for and delivering the sessions during scheduled telephone support calls. The average time spent in preparing and delivering sessions in each follow-up period was calculated and this estimate was used in turn to calculate the total hours spent in these activities in each period. This time was valued at the national minimum wage in the primary analysis and at the unit cost of a home care worker in the sensitivity analysis.

Missing data for cost-effectiveness

For missing service-use data (collected from the CSRI), the following rules were applied: when service use was indicated but frequency was missing, a suitable nationally applicable unit cost was used if available (e.g. cost per visit). If no suitable unit cost was available, the cost was calculated as follows: (1) establish the mean duration of use of those with frequency information; (2) assign that mean value to cases with missing duration data; (3) estimate the average cost by multiplying frequency by duration by unit cost and estimate the mean cost of those where any use of the service has been indicated; (4) assign the mean cost to cases where both frequency and duration of use information are missing. For each case, items in each cost category (see Trial results) were summed to give a total cost per category. Category-level costs were summed to give a total overall cost per case. If all costs in the category were missing, the category total (per case) was also calculated as missing; if some items were missing, these were treated as zeros and the case was assigned the cost of the sum of available costs in the category. Missing outcomes and costs data were multiply imputed separately for the person with dementia and the carer. We used the MI impute chained command in Stata 1360 to build a regression model, including demographic variables (site, whether or not acetylcholinesterase inhibitors were being taken, sex, relationship with the other member of the dyad, ethnicity, who the carer/person lived with, level of education), treatment allocation, cost categories and scale-level non-missing primary and secondary outcome measure variables as predictors. For the adherence data entered by unblinded researchers, the same procedure was followed; professional support costs were imputed within the model for imputing carers’ costs. The cost of carers’ time in delivering the intervention was imputed in cases where unblinded researchers had not recorded the time taken to prepare and deliver sessions within the adherence forms (so that the cost of the session time could not be estimated). Again, these costs were imputed within the model for imputing carers’ costs. The multiple imputation procedure was used to generate five complete data sets, to be combined according to Rubin’s rules. 60,61 Service use and intervention contact counts were not multiply imputed, only the costs. If the CSRI had not been completed (e.g. no questions or just one or two initial questions had been answered), these cases were considered wholly missing and were not included in the cost-effectiveness analyses.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

The iCST intervention was to be defined as cost-effective compared with TAU if it was:

-

less costly and more effective

-

more costly and more effective, and society is willing to pay the additional cost in order to achieve the gain in outcome

-

less costly and less effective, and society is willing to sacrifice some of the outcome difference in order to make a saving.

The iCST intervention was to be defined as not cost-effective if it was both significantly more costly and less effective compared with TAU.

The criteria for this decision was based on the following rule:

where ΔC represents the additional cost, ΔE represents the gain in outcome associated with the treatment and λ represents the willingness to pay (WTP) for that outcome gain. 62 The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (ΔC : ΔE) must be below λ to be considered cost-effective.

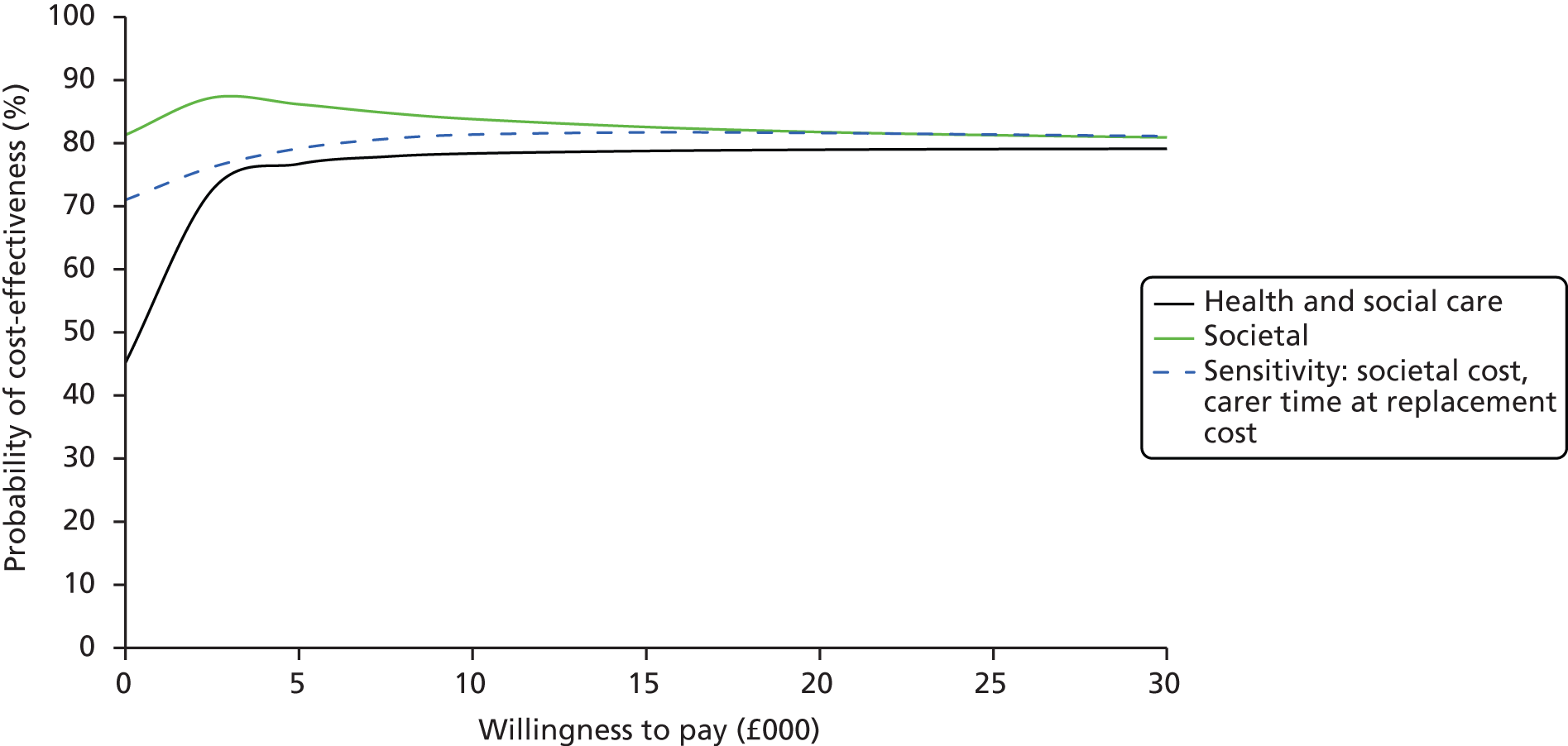

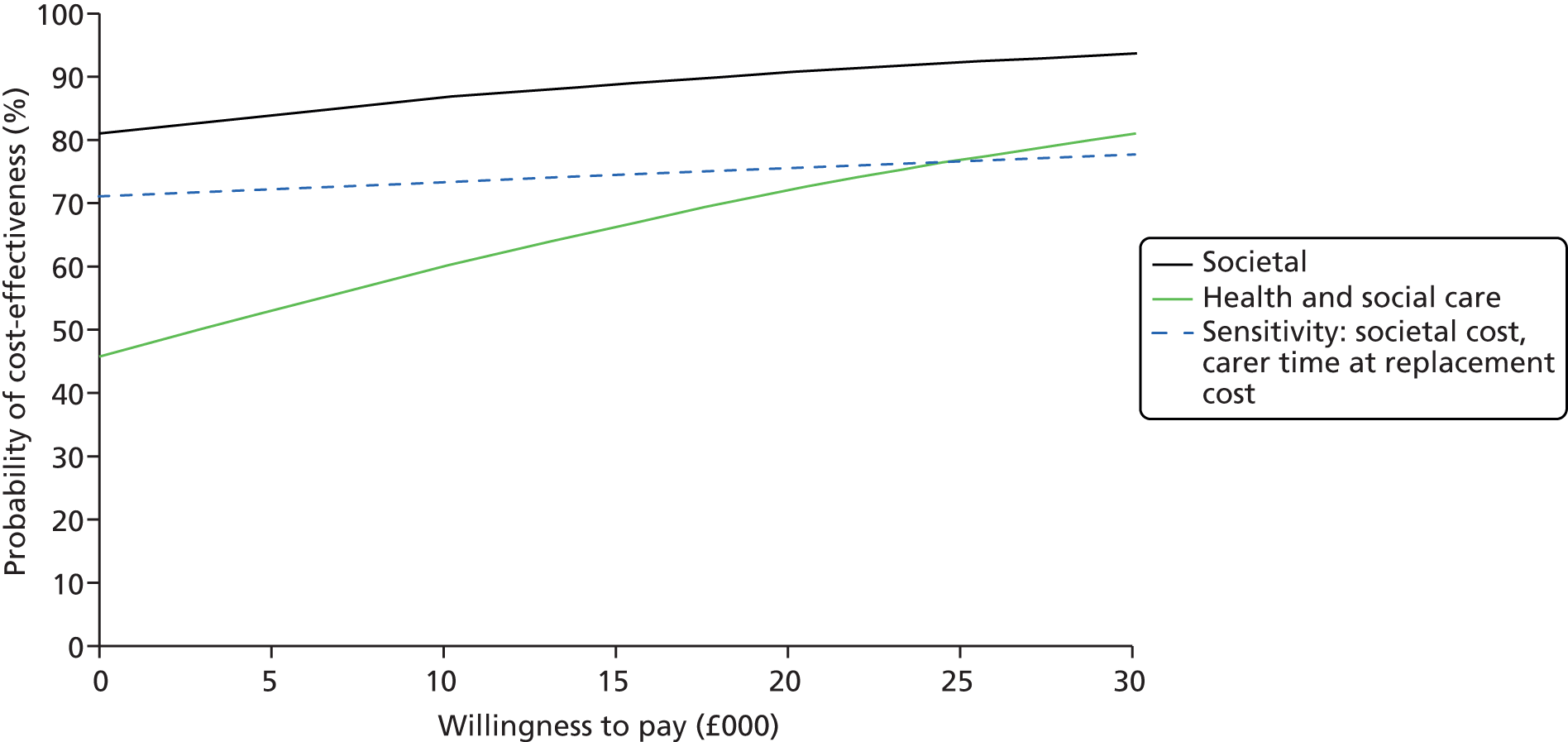

The ICER was defined as the difference in the mean costs of the iCST and TAU groups over the period of follow-up, divided by the difference in the mean end point outcome measure (primary outcome for people with dementia and secondary outcomes) between groups. In the case of the ratio of incremental costs and QALY, the denominator was the difference in the mean QALY over the year from the baseline assessment. The numerator was the difference between annualised costs, calculated by doubling the costs estimated over the full follow-up period. The decision rule can be rearranged to be expressed in terms of the net monetary benefit as λ × ΔE – ΔC > 0,62 the monetary value of gains in outcome associated with the treatment at a given WTP, net of the additional cost of the treatment. 62 CEACs were produced to represent graphically the uncertainty around the point estimate of the ICER.

Health economic modelling methods

Incremental costs and outcomes and their ratio (ΔC : ΔE) were estimated by seemingly unrelated regressions (SURs), with bootstrapped standard errors (SEs). This system of equations was used to obtain the cost/outcome difference between groups by estimating the coefficients on the intervention term in each (cost/outcome) equation. The SUR approach is useful for obtaining an estimator for the ICER and for net benefit for a given WTP, while also allowing for adjustment for a set of baseline covariates (which can differ between cost and outcome equations). 63 The analyses were performed on 300 bootstrapped replications from each complete data set (generated by the multiple imputation process), using the Stata command gsem, and the results combined. The estimates of costs and outcomes for the person with dementia were adjusted for the covariates: site, whether or not the person with dementia was taking AChEIs, who the person lived with, and baseline costs (cost equation only) or baseline outcome (outcome equation only). The estimates of costs and outcomes for the carer were adjusted for the covariates: site, whether or not the person with dementia was taking AChEls, baseline costs and who the person with dementia lived with (cost equation only), who the carer lived with, carer sex, carer age (outcome equation only) and baseline outcome (outcome equation only). This approach was used to calculate the net monetary benefit over a range of WTP values for incremental benefits (SMDs in the primary and secondary outcome measures, QALY gains), including the £20,000–30,000 NICE threshold range. 64

Summary of changes to the protocol

Approval was obtained from the REC for one substantial amendment to the protocol during the trial. This was related to the inclusion of additional questionnaires for both the person with dementia and their family carer. There was one non-substantial amendment notified to the study’s sponsor (University College London) representative, which was related to minor changes to the study protocol and inclusion of new sites and investigators. There was one protocol violation (this is described in detail in Appendix 9).

Chapter 5 Trial results

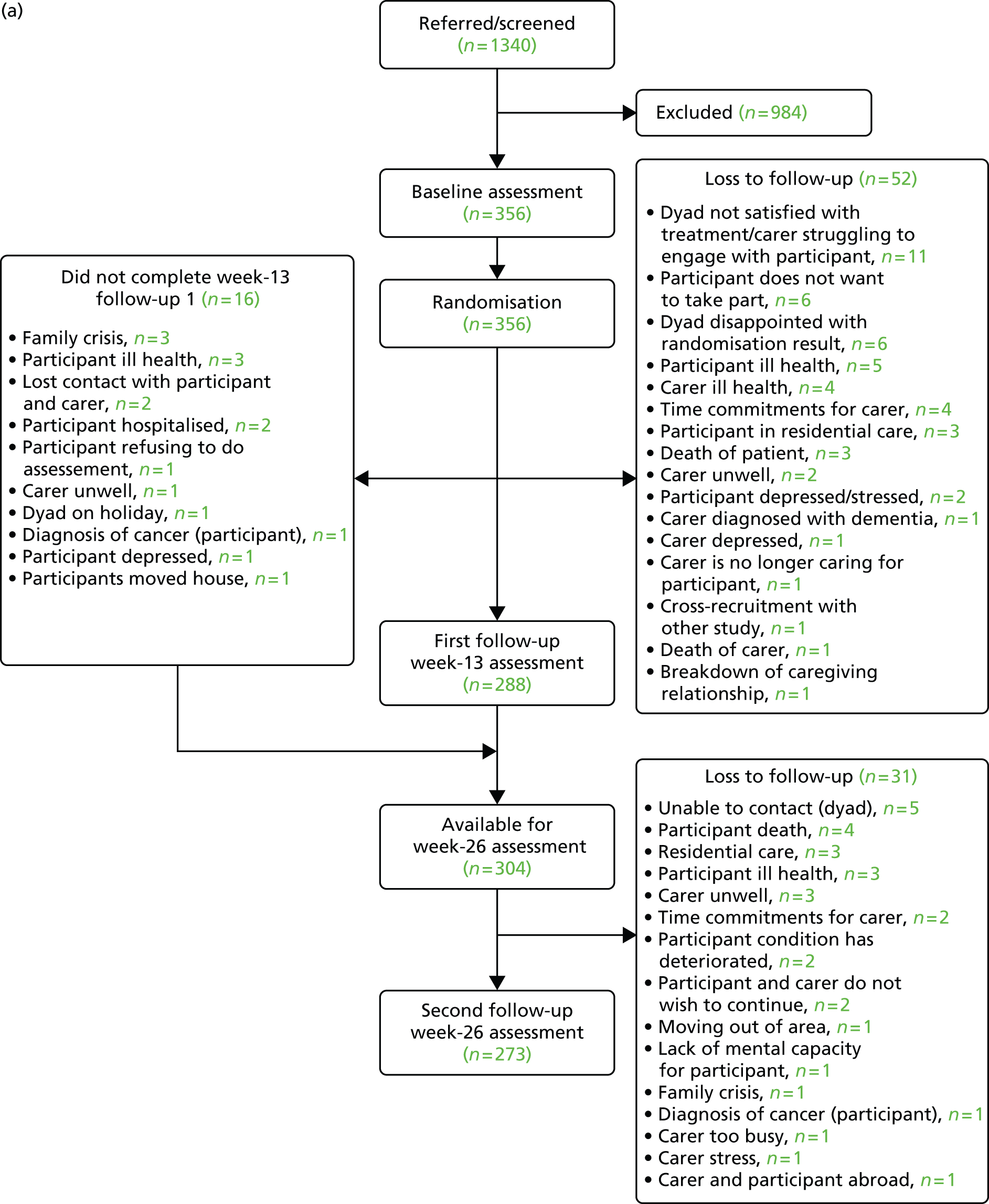

Figure 1 presents the details of the flow of participants through the trial. In total, 1340 people were considered for recruitment to the study. From these, 356 were randomised and together constituted the final sample for the study. The most common reason for loss between referral and randomisation was participants not wishing to take part in the study. Losses in 22% of cases were attributable to people with dementia not meeting the clinical criteria, indicating that this factor was, to some extent, a barrier to study recruitment (Table 5). Table 6 shows sources of referrals to the project, of which 45% came from Memory Clinics. Conversion of referrals to randomisation for each of the centres can be seen in Table 7. Variation between centres may be attributable to, in part, differences in recruitment methods (e.g. note screening vs. personal invitation by clinician).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Participant flow through trial; and (b) participant flow through trial indicating treatment allocation. DNC, did not complete.

| Reason | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Does not wish to take part | 320 (24) |

| iCST exclusion criteria apply | 295 (22) |

| Dyad has not responded | 215 (16) |

| Could not make contact/reason not known | 53 (4) |

| Not available owing to holiday/family/work commitments | 33 (2) |

| Health problems for dyad | 21 (2) |

| Subtotals | 937 (70) |

| Other | |

| Prefers group activities/does activities at home/considers intervention not suitable | 18 (1) |

| Already participating in similar study | 16 (1) |

| Distressed during interview | 4 (< 1) |

| Family not discussing diagnosis | 3 (< 1) |

| Moved out the area | 3 (< 1) |

| Person with dementia has died | 3 (< 1) |

| Subtotals | 47 (3) |

| Total lost between referral/screening and randomisation | 984 (73) |

| Total number randomised | 356 (27) |

| Total referred or screened | 1340 |

| Source | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|