Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 13/48/01. The protocol was agreed in November 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Edwards et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Description of health problem

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is defined as a resting heart rate below 60 beats per minute (b.p.m.). A slow heart rate can occur naturally under various circumstances and is not necessarily associated with a medical condition. For example, some highly trained athletes have bradycardia. However, there is also pathological bradycardia, which is caused by conditions that affect the electrical conduction system of the heart, including sick sinus syndrome (SSS) and/or atrioventricular (AV) block. 1 Bradycardia does not necessarily require treatment unless it causes symptoms. People suffering from symptomatic bradycardia can present with dizziness, confusion, palpitations, breathlessness, exercise intolerance and syncope (blackout or fainting). However, bradycardia, and symptoms related to it, may be intermittent or may be non-specific, particularly in the elderly.

Sick sinus syndrome

Sick sinus syndrome is caused by dysfunction of the sinus node, the heart’s natural pacemaker. The sinus node consists of a cluster of cells that is situated in the upper part of the right atrium (the right upper chamber of the heart). The sinus node generates the electrical impulses that are conducted through the heart and stimulate it to contract. SSS covers a spectrum of arrhythmias with different underlying mechanisms, manifested as bradycardia, tachycardia (fast heart rate) or a mix of the two, but also as chronotropic incompetence (the inability of the heart to increase its rate appropriately with increased activity, leading to exercise intolerance). SSS manifesting as bradyarrhythmias includes sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest, sinoatrial (SA) exit block and alternating bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias such as bradycardia–tachycardia syndrome (BTS). 1,2

In sinus arrest or sinus pause, the sinus node transiently ceases to generate electrical impulses. 3 The pause can last from a couple of seconds to several minutes. The sinus pause usually allows escape beats or rhythms to occur, when other pacemakers in the heart initiate contraction of the ventricles. In SA exit block, the sinus node depolarises normally, but the signal is blocked before it leaves the sinus node, leading to intermittent delay (first-degree SA block) or failure (second-degree SA block) of atrial depolarisation.

Atrioventricular block

Atrioventricular block can occur independently from SSS, and so patients suffering from symptomatic bradycardia due to SSS may also have or develop AV block. In AV block, the electrical impulses from the sinus node in the right atrium to the ventricular chambers are slowed or blocked at the AV node or within the His–Purkinje system, which conducts electrical impulses between the atria and ventricular chambers. Although heart block can be present at birth (congenital), people are more likely to develop the condition, with the risk increasing with age along with the incidence of heart disease. As in SA block, there are several degrees of AV block. 4 First-degree AV block is usually asymptomatic and occurs when the electrical impulses slow as they pass through the AV node, but all impulses reach the ventricles. In second-degree AV block, some of the electrical impulses from the sinus node are unable to reach the ventricles, a condition that is more likely to present with symptoms such as syncope. In third-degree AV block (complete heart block), there are no electrical impulses between the atrial and ventricular chambers. In the absence of any electrical impulses from the atria, the ventricles produce escape beats, which are usually slow.

Aetiology and pathology

The resting heart rate in healthy people does not change with increasing age;5 however, bradycardia due to SSS becomes more common in older people because of idiopathic degeneration or development of scarring of the sinus node, both of which occur with ageing. 2 However, SSS can also be caused by extrinsic factors that can mimic or exacerbate SSS, such as some types of medication (e.g. calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers), electrolyte disturbances, hypothyroidism, hypothermia and toxins. SSS has also been linked with diseases and conditions that cause scarring or damage to the heart’s electrical system, such as atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF). 1,2

Atrioventricular block can also be either congenital or acquired. Acquired AV block is associated with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, heart surgery and with the use of many antiarrhythmic agents.

Incidence and prevalence

Sick sinus syndrome usually occurs in older adults, but it can affect persons of all ages, and it affects men and women equally. 2 The incidence of AV conduction abnormalities also increases with advancing age. 6 However, the prevalence of bradyarrhythmias due to SSS requiring permanent pacemaker implant is unknown,7 as is the breakdown of the prevalence of SSS with and without a concurrent AV block. Hospital Episode Statistics data from October 2012 to September 2013 included 2490 patients with a primary diagnosis of SSS in NHS hospitals in England.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SSS is made by considering a patient’s medical history and symptoms and through the use of electrocardiography (ECG). Diagnosis sometimes proves difficult because symptoms and electrocardiographic abnormalities are intermittent. When 12-lead ECG does not yield a diagnosis, prolonged ECG monitoring, such as Holter monitoring (ECG monitoring for 24–48 hours) or longer-duration cardiac monitoring either with event ECG recorders for weeks at a time or with an implantable loop recorder for months at a time, may help accurate diagnosis. 2,8 SSS manifested as chronotropic incompetence is usually assessed through various exhaustive and symptom-limited exercise tests; however, there are no well-validated standards for diagnosing SSS in this setting. 5

Atrioventricular conduction is also assessed by ECG. Adequate AV conduction, that is, absence of AV block, has been defined as presence of 1 : 1 conduction at rates of 140 b.p.m. 9

Prognosis and impact of health problem

The prognosis of bradycardia due to SSS depends on the aetiology. If the underlying cause is, for example, medication, hypothyroidism or electrolyte imbalance, then the bradycardia may resolve if the triggering cause is treated or removed. However, for most people, SSS is idiopathic and progressive, with a highly variable development of the disease. People with asymptomatic SSS do not require therapy. The only effective treatment for patients suffering from symptoms is implantation of a permanent pacemaker. 2 However, pacemaker implantation does not cure or affect the prognosis of SSS, and pacemakers are implanted with the aim of alleviating symptoms and improving the patient’s quality of life (QoL). Pacemaker implantation is associated with considerable risk for the patient, and therefore careful consideration must be given to the balance between potential benefits and adverse effects of treatment. Although pacemaker implantation has been shown to improve QoL for patients with bradycardia and sinus node dysfunction,10,11 it has been noted that women and older adults may achieve lower levels of improvement in QoL than other groups. 12 Additionally, research suggests that there may be differences between the sexes at pacemaker implantation, with less favourable outcomes for women in terms of complications. 13

Patients with SSS are at risk of developing a complete AV block, with considerable variation in the estimates of risk of AV block (from < 1% up to 4.5% per year). 4,14 A patient with SSS who develops AV block will require ventricular pacing (VP) and, consequently, an upgrade to a dual-chamber pacemaker if they already have a single-chamber atrial pacemaker. People with SSS may also develop BTS with AF as the tachyarrhythmia, which in turn leads to an increased risk of stroke. 2

Measurements of disease

Symptomatic bradycardia, and implantation of permanent pacemakers to relieve the symptoms, can have a significant impact on a patient’s QoL. 4 QoL has been measured using many different generic and disease/treatment-specific measures in pacemaker trials. Recommended generic measures include the Short Form Questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), a health questionnaire with 36 questions, which looks at functional health, general well-being and physical and mental health. 15

The Karolinska Questionnaire,16 which has been validated in patients paced for bradyarrhythmia, contains 16 questions on cardiovascular symptoms relevant to pacemaker patients. The Specific Activity Scale (SAS)17 is another disease-specific questionnaire for the functional classification of patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD). Based on physical capacity, patients are divided into class I (unlimited exercise capacity) to class IV (very low exercise tolerance). Many pacemaker trials also use the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional scale, which is used to classify patients’ cardiac disease according to the severity of their symptoms. Similar to the SAS, patients can fall into four categories based on the limitations on physical activity, from class I (no limitation of physical activity) to class IV (symptoms of HF at rest and inability to carry out any physical activity without discomfort).

Current service provision

Current guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s technology appraisal (TA) number 88,18 which was published in 2005, recommends dual-chamber pacemakers for patients with symptomatic bradycardia that is due to SSS, AV block or a combination of the two. 18 However, in a few exceptional cases single-chamber atrial or ventricular pacemakers are preferred:

-

single-chamber atrial pacemakers for patients with SSS in whom, after full evaluation, there is no evidence of impaired AV conduction

-

single-chamber ventricular pacemakers for patients with AV block with continuous AF

-

single-chamber ventricular pacemakers for patients with AV block alone, or in combination with SSS, when patient-specific factors, such as frailty or the presence of comorbidities, influence the balance of risks and benefits in favour of single-chamber VP.

Similarly, guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA), published in 2008, recommend dual-chamber pacemakers for AV block and for SSS if there is a suspected abnormality of AV conduction or increased risk of future AV block. 4 Single-chamber ventricular pacemakers are recommended for patients with AV block and chronic AF or other atrial tachyarrhythmias, and single-chamber atrial pacemakers are recommended for patients with SSS with no suspected abnormality of AV conduction and who are not considered to be at increased risk of future AV block.

In 2013, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published its guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronisation therapy. 7 ESC recommends dual-chamber pacemakers as a first choice for patients with SSS and/or AV block, with the exception of patients with a persistent AV block and continuous AF, for whom a single-chamber ventricular pacemaker is recommended.

The differences in recommendations between the more recent ESC guidelines and those of NICE and the ACC/AHA are linked to the completion and publication of the DANPACE trial,19 which has provided new evidence on the comparison of single-chamber atrial pacing with dual-chamber pacing in SSS with no evidence of AV block. The objectives for this multiple technology appraisal (MTA) were to evaluate formally the data from DANPACE1 study and to identify any other evidence in this area.

Current pacemaker usage in the NHS

During 2012–13 in England, more than 20,000 people had a single- or a dual-chamber pacemaker implanted and just over 8000 people had an implanted pacemaker renewed. 20 The median length of hospital stay was 2 days for implantation of both single- and dual-chamber pacemaker systems, resulting in 82,000 bed-days in the UK in 2012–13. Of the newly implanted single and dual pacemakers, SSS was the fourth most prevalent primary diagnosis (9.5%), after AF and flutter (22.5%), complete AV block (18.8%) and second-degree AV block (10.6%). 8 Among patients with a primary diagnosis of SSS (2490 patients), 67.5% had a dual-chamber pacemaker implanted, 14.8% had a single-chamber pacemaker and 2.2% had a reoperation on an existing implanted pacemaker. 8

The target for the implantation rate of new pacemakers in England and Wales is 700 pacemakers per million people. In 2012, the total implant rate in England and Wales fell short of this target, reaching 559 per million of the population. 21 In England, implantation rates varied between 379 and 638 new pacemaker implants per million people in different parts of the country, although a decrease in variability was noticed across the country from 2010 to 2012. 21

Description of technology under assessment

Pacemakers

Pacemakers are small battery-driven devices which regulate abnormal heart rhythms. A pacemaker consists of a generator and one or more leads, which are connected to the heart. The leads will sense the heart’s electrical activity and, when it becomes too slow, an electrical impulse from the generator will initiate contraction of the heart.

Single-chamber pacemakers have one lead which is attached to either the atrium (atrial pacing) or the ventricle (VP). Dual-chamber pacemakers have two leads: one lead is attached to the atrium and the second to the ventricle.

The North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (NASPE) and the British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group (BPEG) have established nomenclature to describe the different pacing modes of pacemakers, which is a four-letter combination (Table 1). 22 The first letter indicates which chamber or chambers are paced, and the second letter specifies which chamber(s) are sensed. Letters I and II are usually, but not necessarily, the same. The third letter describes the mode of response to sensing. The pacemaker can be inhibited (I), if it senses a spontaneous depolarisation; triggered (T), if it senses that no depolarisation has occurred (uncommon); or both inhibited and triggered (D).

| Position | I | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Chamber paced | Chamber sensed | Response to sensing | Rate modulation |

| Codes |

|

|

|

|

In an AAI or VVI pacemaker, the pacemaker senses an atrial or ventricular event and withholds its signal. DDI pacemakers will inhibit the output of the device in either chamber where it senses a signal. The most common example of the letter D in the third position is in DDD pacemakers, which have dual functionality. On sensing an atrial signal, the DDD pacemaker initially inhibits the atrial output, which triggers a timer that, after a set time interval (AV delay), initiates a ventricular output. If the DDD device senses a ventricular signal during the triggering interval, the pacemaker also inhibits the ventricular output. The fourth letter specifies whether or not the pacemaker is programmed to sense and increase the heart rate in response to physical, mental or emotional activity. This is termed rate response.

Modern pacemakers have numerous programmable features that can be altered to optimise pacemaker function. Programming is a complex and rapidly evolving technical area, and a detailed description of pacemaker programming is beyond the scope of this report; thus, a few key parameters are summarised:

-

Rate responsiveness As mentioned previously, some pacemakers can be programmed to vary the pacing rate in response to the patient’s activity level. Rate-responsive pacemakers control heart rate by sensing body movement or breathing or by closed-loop stimulation. Closed-loop stimulation determines the appropriate heart rate based on intracardiac impedance measurements, which reflect information from the autonomic nervous system.

-

AV delay The AV delay is the time interval between an atrial paced or sensed event and the delivery of a VP stimulus in dual-chamber pacemakers. If intrinsic conduction is more rapid than the duration of the programmed AV delay, the intrinsic signal will inhibit VP.

-

Mode switching Dual-chamber pacemakers may have an additional feature called mode switching. 23 Mode-switch algorithms track tachyarrhythmias, such as AF, and when these occur trigger a non-tracking mode, or VP to avoid tachycardia. Atrial arrhythmias would otherwise cause sustained high ventricular rates. When the atrial rate falls below the rate programmed for mode switch, the pacemaker changes back to a tracking mode. 23

Implant procedure and follow-up

Pacemakers are usually implanted under local anaesthetic. An incision is made below the collarbone to facilitate lead implantation and a pocket is created under the skin to hold the pacemaker device. The pacing lead is inserted into the heart through a major vein. One end of the lead is securely lodged in the tissue of the heart and the other end is connected to the pacemaker. The position of the lead is checked using radiographic imaging. Testing and programming of the pacemaker may sometimes be done wirelessly and can be changed at any time. The hospital stay is usually brief and the implant procedure could be carried out as day surgery or might require a single overnight stay in hospital. Implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker may take longer than implantation of a single-chamber pacemaker, because dual-chamber pacemakers require the insertion and placement of two leads. The requirement for an additional lead in dual- versus single-chamber pacemakers might result in an associated increased risk of complications, such as lead displacement. 24

People with permanently implanted pacemakers require regular follow-up to check the function of the pacemaker leads, the frequency of utilisation and the battery life of the pacemaker, and for abnormal heart rhythm. 25 The battery life of a pacemaker is about 5–8 years; after this time, replacement of the pacemaker will be required. Replacement of the pacemaker involves making an incision over the previous site of insertion, removing the old pacemaker generator, checking the lead(s), and, if satisfactory, attaching a new generator to the existing lead(s). Problems with pacemaker leads, such as loss of contact between the lead and the heart, require reoperation. Where repair of a fault with a lead is necessary, the old lead may be left in place but disconnected from the pacemaker and a new lead implanted. Removal of old leads can be complicated by the formation of scar tissue connecting the lead to the vein and/or the heart.

Complications

Most complications occur during or soon after implantation of a pacemaker. Some of the more common complications are lead displacement (1.4–2.1%) and puncture of the lung when placing the leads, which can lead to a pneumothorax (1.9%) or haemothorax. 26,27 One of the most serious, but rarer, complications that can arise during the implant procedure is cardiac perforation. There is also the risk of infection of the pacemaker pocket or the leads. 27,28 Complications occurring at a later date mainly involve dysfunction of the pacemaker or of the leads, that is, failure to pace or sense appropriately. Other late complications include infection or erosion of the pacemaker site or its leads. 28

Reoperation may be required as a result of a complication, such as lead displacement, infection or pacemaker erosion, but it can also be because of a need for pacemaker upgrade (single to dual) or pacemaker replacement as a result of changed clinical needs or end of battery life. 24 The complication rate associated with a reoperation is substantially higher than that associated with initial implantation. 29

Costs associated with intervention

The cost of pacemaker implantation comprises several elements:

-

price of the generator and leads

-

implant procedure (setting and personnel)

-

personnel involved prior to and following implantation

-

regular routine follow-up

-

management of perioperative complications

-

management of late complications

-

replacement or upgrade at the end of the life of the pacemaker or in response to changing clinical need.

Further details on the costs associated with pacemaker implantation are given in Chapter 4, Costs.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Population

The population of interest to this review is people with symptomatic bradycardia due to SSS without AV block, that is, with intact AV conduction, and who required permanent pacemaker implantation.

Intervention and comparator

The review considered permanent implantable dual-chamber pacemakers programmed to dual-chamber pacing compared with permanent implantable pacemakers (single or dual) programmed to atrial pacing.

All programmable features, such as rate responsiveness, mode switch and VP-minimising features, were allowed.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest considered for this review included:

-

mortality (all-cause)

-

HF

-

AF

-

stroke

-

exercise capacity

-

cognitive function

-

requirement for further surgery

-

adverse effects of pacemaker implantation (including peri- and post-operative complications, AF and device replacement)

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aims of this MTA were to appraise the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dual-chamber pacemakers for treating symptomatic bradycardia in people with SSS in whom there is no evidence of impaired AV conduction and to update the recommendations of NICE’s TA8818 in relation to this indication.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

The clinical effectiveness of single-chamber atrial and dual-chamber pacemakers for the treatment of symptomatic bradycardia due to SSS without AV block was assessed by conducting a systematic review of published research evidence. The review was undertaken following the general principles published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and the Cochrane Collaboration. 30,31 The protocol for the systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42013006708).

Identification of studies

To identify relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs), multiple electronic databases were searched, including MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library [including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database]. Bibliographies of retrieved studies identified as relevant were manually reviewed for potentially eligible studies. In addition, experts in the field were contacted with a request for details of published and unpublished studies of which they may have knowledge. Furthermore, submissions submitted to NICE were assessed for unpublished data.

The search terms included medical subject heading (MeSH) and text terms for the interventions: artificial pacemakers and pacing; dual-chamber pacemakers/pacing; and single-chamber atrial pacemakers/pacing. As the scoping search using this search strategy identified all relevant trials known from the previous MTA, search terms for the condition (i.e. bradycardia and SSS) were not used. To keep in line with the original MTA, which focused on RCT evidence, the search strategy included a RCT filter developed and validated by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 32 No language or date restriction was applied to the searches. Electronic databases were initially searched on 7 January 2014 and results uploaded into Reference Manager Version 11.0 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) and deduplicated. An update search was carried out on 12 May 2014. Full details of the terms used in the searches are presented in Appendix 1, Literature search strategies.

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts according to the inclusion criteria (see Table 2). Full paper manuscripts of any titles/abstracts of potential relevance were obtained and assessed independently by two reviewers. If a study was only reported as a meeting abstract or if full-paper manuscripts could not be obtained, the study authors were contacted to gain further details. Studies for which insufficient methodological details were available to allow critical appraisal of study quality were excluded. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for the review of effectiveness were based on the decision problem outlined in Table 2. The review included RCTs of parallel and crossover design. Systematic reviews and non-randomised studies were excluded.

| Domain | Inclusion criterion |

|---|---|

| Study design | RCTs of parallel or crossover design |

| Intervention | Permanent implantable dual-chamber pacemakers |

| Population | People with symptomatic bradyarrhythmias due to SSS without AV block |

| Comparator | Permanent implantable single-chamber atrial pacemakers |

| Outcomes | Mortality (all-cause) |

| HF | |

| AF | |

| Stroke | |

| Exercise capacity | |

| Cognitive function | |

| Requirement for further surgery | |

| Adverse effects of pacemaker implantation (including peri- and post-operative complications, AF and device replacement) | |

| HRQoL |

The intervention was permanent implantable dual-chamber pacemakers compared with single-chamber atrial pacemakers or dual-chamber pacemakers programmed primarily to atrial pacing. Studies were not excluded based on programming of the pacemakers; both rate-responsive and non-rate-responsive programming were included. The review also allowed other programmable features, such as prolonging or eliminating the AV interval in order to minimise VP.

Randomised controlled trials were included if the relevant pacing modes were compared in a population with symptomatic bradycardia, documented SSS, BTS and normal AV conduction. Studies were excluded if none of the outcomes of interest was reported.

Data abstraction strategy

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a standardised data extraction form. Information extracted included details of the study’s design and methodology, baseline characteristics of participants and results, including clinical outcome efficacy and any adverse events reported. Where there was incomplete information, the study authors were contacted with a request for further details. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer if necessary. Data extraction forms for the included studies are provided in Appendix 2, Data abstraction.

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality of the clinical effectiveness studies was assessed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and if necessary a third reviewer was consulted. The study quality was assessed according to recommendations by the CRD30 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions31 and recorded using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. 31

Methods of data synthesis

Details of results on clinical effectiveness and quality assessment for each included study are presented in structured tables and as a narrative summary. The possible effects of study quality on the effectiveness data and review findings are discussed. Standard pairwise meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness for several outcomes based on intention-to-treat analysis. Intention-to-treat analysis was defined as analysis of patients in the trial arm to which they were allocated at randomisation regardless of whether or not they changed pacing mode, withdrew or were lost to follow-up.

Dichotomous outcomes data were meta-analysed using Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and a random-effects model. Individual trial data were analysed and presented in the same way as meta-analysed data for comparison where appropriate. In addition, if hazard ratios (HRs) were presented in the original publication of a trial, these have been reproduced in this report for comparison. Missing data were imputed and analysed as treatment failures.

For the dichotomous outcomes reported in this review (mortality, HF, AF, stroke, further surgery and adverse events), only RCTs with a parallel-group design have been considered, excluding RCTs with a crossover design. RCTs with a crossover design are most appropriate for symptomatic treatment of chronic or relatively stable conditions, such as symptomatic bradycardia treated by artificial pacing with a permanently implanted pacemaker. 33 However, crossover trials are appropriate only when looking at treatment effects that are likely to be reversible and short-lived, and inappropriate when studying outcomes where an outcome event may alter the baseline risk, that is, on entry to the second phase the patients systematically differ from their initial state. 33

Data for the continuous outcomes exercise capacity, cognitive functioning and QoL were primarily reported in included crossover trials. Data from parallel and crossover RCTs have been reported separately. It was planned a priori to analyse continuous outcome data from crossover studies using the mean difference (or the difference between the means) of dual-chamber and single-chamber atrial pacing and the standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE) for the within-person differences. However, the included crossover trials reported means and SDs for treatment-specific outcomes but did not report paired results. One crossover trial provided individual patient data (IPD) for exercise capacity34 and one for QoL35 from which the mean difference and SE for within-person difference could be obtained. However, because there was a lack of reporting of relevant data across the included crossover trials, a meta-analysis of data was not performed for these trials.

A meta-analysis was carried out for the parallel-group trials using Review Manager Version 11 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA), with the use of a random-effects model. Statistical heterogeneity between included studies was assessed using the I2 test. In the presence of heterogeneity (I2 > 30%), possible sources were investigated, including differences between individual studies’ populations, methods or interventions. The possibility of publication bias and/or small study effects was not investigated because of the low number of included studies.

Stakeholders’ submissions

A joint manufacturers’ submission from the Association of British Healthcare Industries (ABHI) was expected for this MTA; however, the only submission to NICE in relation to this MTA was from the British Cardiovascular Society. As such, this report does not contain confidential information from stakeholders. No data additional to the studies identified in the systematic review were presented in the submission.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

Database searches retrieved 492 records (post deduplication). One additional reference was identified through hand searching, giving a total of 493 references that were screened for inclusion (Figure 1). Full references were sought for 34 of these, which were potentially eligible for inclusion. Of the records identified as potentially relevant, only one reference was unobtainable. 36 However, this reference was identified in the original NICE MTA TA8818 and excluded because it was a pre-clinical study. Of the remaining 33 records, nine references describing six studies were included in the review. Characteristics of the studies included in the review are given in Table 3. A list of excluded references (with reason for exclusion) is presented in Appendix 4, Table of excluded studies.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporing Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the clinical effectiveness review.

| Study | Population | Intervention | Comparator 1 | Comparator 2 | Randomisation | Country | Number of patients | Follow-up | Supplementary publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel-group RCTs | |||||||||

| Albertsen et al.37 | Sinus arrest/SA block, BTS, sinus bradycardia | DDD(R) | AAI(R) | N/A | Device | Denmark | 50 | 12 months | None identified |

| DANPACE19 | SA block/sinus arrest, sinus bradycardia, BTS | DDDR | AAIR | N/A | Device | Denmark, UK, Canada | 1415 | Mean 5.4 years (SD 2.6 years) | Andersen et al.;38 Nielsen et al.;39 Riahi et al.40 |

| Nielsen et al.41 | Sinus bradycardia, SA block, BTS | DDDR-s | AAIR | DDDR-l | Device | Denmark | 177 | Mean 2.9 years (SD 1.1 years) | Kristensen et al.42 |

| Crossover RCTs | |||||||||

| Gallik et al.34 | Sinus node disease | DDDR | AAIR | N/A | Programming | NR | 12 | < 1 day | None identified |

| Lau et al.35 | SSS | DDDR | AAIR | N/A | Programming | NR | 15 | 4 weeks per treatment | None identified |

| Schwaab et al.43 | Sinus bradycardia | DDDR | AAIR | N/A | Programming | Germany | 21 | 3 months per treatment | None identified |

No additional studies were retrieved from submissions made to NICE as part of the appraisal of this technology.

Randomised controlled trial characteristics

A summary of study characteristics (populations, interventions, comparator and follow-up) is shown in Table 3.

Six RCTs described and reported in nine publications were included in the review. The review included one trial34 that was identified but excluded from the original MTA, NICE’s TA88. 18 In NICE’s TA88,18 studies of fewer than 48 hours’ duration, such as Gallik et al. ,34 were excluded, whereas no time limitation was specified for the purposes of this review. This review also includes two trials that have been completed and published since NICE’s TA88: Albertsen et al. 37 and DANPACE. 19

Information about and results from DANPACE19 have been published in three publications included in this review: the protocol, the primary publication and one publication focusing on subgroup analyses of HF data. 19,38,40 One other included trial was reported in a main publication41 and an additional paper focusing on AF and thromboembolism analyses. 42

Study design

Three RCTs with a parallel-group design19,37,41 and three crossover RCTs34,35,43 were identified as relevant and were included in this review.

The follow-up period varied greatly among the included studies. Of the parallel-group RCTs, Albertsen et al. had a set follow-up of 12 months,37 the DANPACE trial had a follow-up of up to 10 years with an average of 5.4 years (SD 2.6 years),19 and, in Nielsen et al. the follow-up ranged from 6 days to 5.3 years (mean 2.9 years, SD 1.1 years). 41

The follow-up in the crossover trials was shorter than in the parallel studies. In Lau et al. 35 and Schwaab et al. ,43 patients spent 4 weeks and 3 months, respectively, before crossing over to the other pacing mode. Gallik et al. 34 studied the immediate effects of pacing mode during exercise; haemodynamic effects were measured during bicycle exercise first in one pacing mode and after 0.5–1 hour’s rest, the exercise was repeated in the other pacing mode.

Intervention and comparator

The three parallel RCTs randomised patients to receive single- or dual-chamber pacemakers. 19,37,41 In the crossover trials, all patients were implanted with a dual-chamber pacemaker and then randomised to a pacing programme of dual-chamber or single-chamber atrial pacing, followed by the alternative pacing mode. 34,35,43

Most trials randomised patients before pacemaker implantation, including the trials randomising patients by device (parallel RCTs),19,37,41 and two of the studies randomising by pacing programme. 35,43 The remaining trial, by Gallik et al. ,34 randomised patients who had recently had a dual pacemaker implanted.

The single and dual pacemakers used in the included trials were from several different manufacturers including Medtronic (Minneapolis, MN, USA), ELA Medical Inc. (Arvada, CO, USA), Boston Scientific (Marlborough, MA, USA); St Jude Medical (St Paul, MN, USA), Guidant (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Pacesetter (St Jude Medical; St Paul, MN, USA); Cardiac Pacemakers Inc. (St Paul, MN, USA), Telectronics Pacing Systems (Englewood, CO, USA) and Intermedics Inc. (Angleton, TX, USA).

The included trials compared DDD(R) with AAI(R) pacing. However, Nielsen et al. 41 included two DDDR trial arms with different programmed AV delay: DDDR-s with a short AV delay (< 150 milliseconds) and DDDR-l with a fixed long AV delay (300 milliseconds). Data for these two study arms have been combined in analyses in this review. However, for each outcome, either the impact of combining the study arms has been explored in a sensitivity analysis or data from each study arm have been presented separately.

The DANPACE19 study was the only trial that specifically stated that programmable features prolonging or eliminating the AV interval, in order to minimise VP, were not permitted in the trial.

In all the included studies, all or the majority of patients within each study received pacemakers programmed with the rate-adaptive function activated. The rate-adaptive function was activated in all patients in Albertsen et al. ,37 DANPACE,19 Gallik et al. ,34 Lau et al. 35 and Schwaab et al. 43 In Nielsen et al. ,41 all but two patients had the rate-adaptive function active.

The programmed AV delay in the dual-chamber pacing mode differed greatly across the studies and between study arms, as shown in Table 4. The studies had, for each study arm with dual-chamber pacing, an AV delay that was set at a specific value,34,41 in a range19,35,37 or optimised according to a programmed algorithm. 43 Gallik et al. ,34 Lau et al. 35 and the DDDR-s arm in Nielsen et al. 41 employed relatively short AV delays, up to 150 milliseconds. By contrast, the DDDR-l arm in Nielsen et al. 41 had an AV delay of 300 milliseconds. The AV delay in Albertsen et al. 37 and the DANPACE trial19 was around 220 milliseconds.

| Study | Intervention | Rate adaptive | AV delay | Mode switch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel-group RCTs | ||||

| Albertsen et al.37 | DDDR | On | Maximum 220–225 milliseconds | On |

| DANPACE19 | DDDR | On in all but two patients | 140–220 milliseconds | On |

| Nielsen et al.41 | DDDR-s | On | 150 milliseconds | On |

| DDDR-l | On | 300 milliseconds | On | |

| Crossover RCTs | ||||

| Gallik et al.34 | DDDR | On | 100 milliseconds | NR |

| Lau et al.35 | DDDR | On | 96 milliseconds (SD 7 milliseconds) to 140 milliseconds (SD 5 milliseconds) | NR |

| Schwaab et al.43 | DDDR | On | AV delay was optimised based on the maximum time velocity integral of the aortic flow | On, but not in all patients |

The mode switch function was active in all three parallel-group RCTs. 19,37,41 In Schwaab et al. ,43 mode switch was activated in some patients, but the number of patients was not specified. Gallik et al. 34 and Lau et al. 35 did not report mode switch settings; however, mode switching may not have been available at the time of these trials.

Population

Most of the parallel and crossover RCTs included patients with symptomatic bradycardia or SSS in combination with certain ECG criteria, for example indicating normal AV conduction.

Schwaab et al. 43 had slightly different inclusion criteria: patients had to have chronotropic incompetence, have experienced at least two documented episodes of atrial tachyarrhythmia, be on antiarrhythmic medication for prevention of atrial flutter or AF, as well as being eligible for a dual-chamber pacemaker for symptomatic bradycardia.

The parallel RCTs19,37,41 had similar exclusion criteria, excluding patients if they had chronic AF, AV block, carotid sinus syndrome, vasovagal syncope, bundle branch block, surgery, a short life expectancy, dementia or cancer. Lau et al. 35 did not report specific exclusion criteria, and Gallik et al. 34 excluded patients with evidence of AV node disease or who were unable to exercise.

Summaries of the characteristics of the study populations in the included RCTs are presented in Table 5 (parallel RCTs) and Table 6 (crossover RCTs). More detailed baseline characteristics can be found in Appendix 2, Data abstraction.

| Patient characteristics | Albertsen et al.37 | DANPACE19 | Nielsen et al.41 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDDR, n (%) | AAIR, n (%) | DDDR, n (%) | AAIR, n (%) | DDDR-s, n (%) | DDDR-l, n (%) | AAIR, n (%) | |

| Number of participants | 26 | 24 | 708 | 707 | 60 | 63 | 54 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 73 (13) | 72 (10) | 72.4 (11.4) | 73.5 (11.2) | 74 (9) | 74 (9) | 74 (9) |

| Sex (male) | 8 (31) | 10 (42) | 267 (37.7) | 235 (33.2) | 23 (43) | 26 (43) | 24 (38) |

| Sinus arrest/sinoatrial block | 16 | 14 | NR | NR | 17 | 16 | 19 |

| BTS | 12 | 11 | NR | NR | 38 | 36 | 27 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 8 | 4 | NR | NR | 5 | 11 | 8 |

| Previous history of AF | NR | NR | 318 | 303 | NR | NR | NR |

| Previous stroke | 1 | 5 | 53 | 61 | NR | NR | NR |

| NYHA class, n | |||||||

| I | 18 | 19 | 522 | 503 | 38 | 46 | 32 |

| II | 8 | 3 | 158 | 172 | 22 | 14 | 18 |

| III | 0 | 2 | 24 | 29 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anticoagulant drugs | NR | NR | 89 | 108 | 5 | 11 | 5 |

| Beta-blockers | 11 | 6 | 132 | 159 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Diuretics | 11 | 14 | 263 | 304 | NR | NR | NR |

| Calcium channel blockers | 5 | 5 | 142 | 137 | 7 | 11 | 14 |

| ACE inhibitors | 10 | 11 | 170 | 160 | NR | NR | NR |

| Cardiac glycoside | NR | NR | 62 | 73 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| Sotalol | NR | NR | 44 | 43 | 8 | 10 | 7 |

| Amiodarone | NR | NR | 24 | 25 | NR | NR | NR |

| Aspirin | 14 | 20 | 361 | 369 | 40 | 36 | 35 |

| Class I antiarrhythmics | NR | NR | 20 | 14 | NR | NR | NR |

| Patient characteristics | Gallik et al.34 | Lau et al.35 | Schwaab et al.43 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number of participants | 12 | 15 | 21 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61 (SE 4) | 62 (2) | 70 (7) |

| Sex (male) | 8 (67) | 5 (42) | 11 (58) |

| Previous history of AF | NR | Some of the patients | NR |

| Previous stroke | NR | NR | NR |

| NYHA class | NR | NR | NR |

| Beta-blockers | 4 | 1 | NR |

| Class I antiarrhythmics | NR | NR | 2 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 4 | 2 | NR |

| ACE inhibitors | NR | 1 | NR |

| Cardiac glycoside | 3 | 3 | NR |

| Potassium channel blockers | NR | 1 | 18 |

| Aspirin | NR | 1 | NR |

| Nitrates | NR | 2 | NR |

The parallel RCTs19,37,41 varied in size from 50 to 1415 randomised patients. The crossover studies34,35,43 were smaller, with between 12 and 21 participants. The RCTs all included patients with SSS or sinus node dysfunction (SND). The parallel RCTs, Albertsen et al. 37 and Nielsen et al. ,41 reported the breakdown of pacing indication of the participants for sinus arrest/SA block BTS and sinus bradycardia, with some imbalances between the trial arms; most notably, there were more people with BTS in the two dual-chamber pacing arms than in the AAIR arm in Nielsen et al. 41

Mean age was similar across the three parallel RCTs,19,37,41 and between study arms (72–74 years). The participants in the crossover trials34,35,43 had a slightly lower mean age, of 61–70 years. Only the DANPACE trial1 reported previous history of AF, with around 44% of the participants having a history of AF in each trial arm. 3 Previous stroke was captured in Albertsen et al. and the DANPACE trial. In the smaller study by Albertsen et al. ,37 the number of patients with prior stroke was low but with a notable difference between groups in the proportion of people with prior stroke (5 out of 24 patients in the AAIR arm and only 1 out of 26 in the DDDR arm). In the DANPACE trial, there was no statistically significant difference between the trial arms in the percentage of patients having experienced a stroke at trial entry (7.5% and 8.6%, respectively). 19 In the parallel RCTs that reported NYHA class at baseline19,37,41 the majority of participants were NYHA class I or II (96%) with no or mild symptoms of HF.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest to this review that were reported in the included studies are listed in Table 7. For several of the outcomes, the trials had used different scales or measurements, which have been reported separately. These include HF, exercise capacity and HRQoL.

| Outcome | Parallel RCTs | Crossover RCTs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albertsen et al.37 | DANPACE19 | Nielsen et al.41 | Gallik et al.34 | Lau et al.35 | Schwaab et al.43 | |

| All-cause mortality | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CV mortality | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HF | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| AF | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Stroke | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Exercise capacity | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Cognitive functioning | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Further surgery | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Adverse events | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HRQoL | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

Randomised controlled trial quality

This section describes the trial designs and methodology employed in the trials, which may give rise to an increased risk of bias in terms of selection, detection, performance, and attrition bias. Additionally, other potential sources of bias, such as statistical methods used, are also assessed. Tables 8 and 9 summarise the results of critical appraisal of the included parallel and crossover RCTs, respectively. A more detailed description of the quality assessment of the trials can be found in Appendix 3, Quality assessment.

| Outcome | Potential source of bias | Albertsen et al.37 | DANPACE19 | Nielsen et al.41 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Random sequence generation | ?a | ? | ? |

| Allocation concealment | ? | ✓ | ? | |

| Selective reporting | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Mortality | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | ? | ✓ | |

| Stroke | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | ? | ✓ | |

| AF | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | ? | ? |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | ? | ? | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | ? | ✓ | |

| HF | Blinding of participants and personnel | ? | ? | ? |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | ✗ | ? | ? | |

| Incomplete outcome data | ✓ | ? | ✓ | |

| Requirement for further surgery | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | ? | N/A |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | ? | N/A | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | ✓ | N/A | |

| Exercise capacity | Blinding of participants and personnel | ? | N/A | N/A |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | ✗ | N/A | N/A | |

| Incomplete outcome data | ✓ | N/A | N/A | |

| Adverse events | Blinding of participants and personnel | ? | N/Ab | N/A |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | ? | N/Ab | N/A | |

| Incomplete outcome data | ✓ | N/Ab | N/A |

| Outcome | Potential source of bias | Gallik et al.34 | Lau et al.35 | Schwaab et al.43 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Random sequence generation | ?a | ? | ? |

| Allocation concealment | ? | ? | ✓ | |

| Selective reporting | ✓ | ? | ✗ | |

| Exercise capacity | Blinding of participants and personnel | ? | N/A | ✓ |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | ? | N/A | ✓ | |

| Incomplete outcome data | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | |

| Cognitive function | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | N/A | ✓ |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | N/A | ✓ | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | N/A | ✓ | |

| HRQoL | Blinding of participants and personnel | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Incomplete outcome data | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

Selection bias

None of the full publications of the included trials described how the randomisation sequence had been generated. However, based on correspondence with the researchers for Albertsen et al. ,37 randomisation was performed in a 1 : 1 ratio. 37 Each patient was asked to draw one envelope, containing the allocation, from a batch of 10. Albertsen et al. ,37 the DANPACE trial19 and Schwaab et al. 43 gave some details about how the allocation sequence had been concealed from staff involved in the enrolment and assignment of participants. In these studies, the allocation was performed using sealed envelopes before pacemaker implantation19,37 or programming of the first pacing mode. 43 Nielsen et al. ,41 Gallik et al. 34 and Lau et al. 35 did not describe allocation concealment.

Performance and detections bias

Participants and investigators were blinded to the pacing mode in Lau et al. 35 and Schwaab et al. 43 Albertsen et al. ,37 Nielsen et al. 41 and Gallik et al. 34 did not describe the trial design regarding blinding. Based on correspondence with the researchers of the DANPACE trial,1 it was confirmed that this study was an open-label trial with participants, researchers and outcome assessors aware of the type of pacemaker and pacing mode in each patient. 19

In Nielsen et al. ,41 physical examinations and echocardiography were carried out unblinded, in contrast to the study by Albertsen et al. ,37 in which echocardiographic analyses were carried out blinded to the pacing mode. 37 However, blinding of echocardiography would have had only limited impact on the outcomes of interest captured in Albertsen et al. :37 HF, exercise capacity and adverse events. 37 In the DANPACE trial,19 a committee adjudicated stroke and thromboembolic events unaware of the assigned pacing mode. Gallik et al. 34 did not specify the blinding status of any outcome assessors.

Attrition bias

As mentioned previously, the DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. 41 study participants were followed up for a variable length of time. In both studies, patients were followed up from enrolment to death or end of study, with no loss to follow-up. In Albertsen et al. ,37 one patient randomised to single-chamber atrial pacing was lost to follow-up, which has been accounted for as a treatment failure in the Technology Assessment Group (TAG)’s analyses.

Despite the small number of patients lost to follow-up, the number of patients changing pacemaker or pacing mode from the one to which they were randomised was relatively high and uneven between the trial arms in all three parallel RCTs. 19,37,41 In all three trials, the number of patients in the single-chamber atrial pacing arm who switched to (predominantly) DDDR pacing was higher than the number of patients in the dual-chamber pacing arm who switched to another pacing mode.

Among the crossover trials, three patients in Lau et al. 35 and two patients in Schwaab et al. 43 were excluded from the trials. The reasons for exclusion in Lau et al. 35 were pacemaker failure (n = 2) and patient non-compliance (n = 1), and, in Schwaab et al. ,43 development of chronic AF (n = 1) and death (n = 1). As expected, the crossover trials had to exclude participants who did not complete both intervention periods.

Reporting bias

In an early publication of the DANPACE trial results,19 outlying the protocol for the study,38 one of the secondary end points listed was a QoL evaluation, comprising elements from the general health questionnaire SF-36. However, no result of this outcome was published in either of the identified references linked to this study. 1,40

All three crossover trials34,35,43 reported results for each pacing mode separately, with mean and SE or SD. Exact p-values were not provided for the within-patient difference for any of the outcomes: the p-value was not reported, was described as non-significant or was reported to be less than a certain value. Lau et al. 35 reported IPD for general well-being [as measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS)] and Gallik et al. 34 reported IPD for exercise time, which were used to calculate the within-patient difference for these outcomes. The lack of reporting of p-value for the paired t-test for other outcome data in the crossover trials rendered the data unsuitable for meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

Both the DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. 41 were suspended before reaching the target number of participants and are consequently underpowered to show a statistically significant difference in the primary outcome: all-cause mortality in the DANPACE trial19 and changes in left atrium size and left ventricle (LV) size and function in Nielsen et al. A total of 450 patients were to be included in Nielsen et al. ,41 but recruitment was stopped after randomisation of 177 patients because recruitment for the DANPACE trial19 had started. However, recruitment for the DANPACE trial19 was also stopped early, at 1415 randomised patients, compared with the target of 1900 patients. 1 This was as a result of the increasing use of dual-chamber pacemakers with features that prolong or eliminate the AV interval to minimise VP in patients with SSS, which were not permitted in the trial and which therefore led to a decrease in the recruitment rate. In addition, a planned interim analysis showed that no statistically significant difference could be reached with respect to the primary outcome of all-cause mortality even with the planned 1900 patients.

Overall trial quality

Overall trial design and methodology were appropriate in the included trials; however, detailed descriptions of randomisation and allocation concealment were sparse. The parallel RCTs were either open label or it was unclear if and how patients, trial personnel and outcome assessors were blinded to the pacing modes. Blinding is likely to have a limited effect on the result of objective outcomes such as mortality, stroke and adverse events; however, for more subjective outcomes, including patient-reported outcomes such as QoL and HF questionnaires and exercise capacity, there is an increased risk of introducing bias into the results. The two crossover RCTs reporting results on QoL were both described as double blind. The risk of attrition bias was generally low as few patients were lost to follow-up in the parallel RCTs and the crossover trials excluded a small number of patients from the analyses. However, the number of patients in the parallel RCTs who changed pacing mode during the follow-up period was uneven between the pacing modes, which may lead to a conservative estimate of the effect of pacing mode.

Assessment of effectiveness

Change in pacing mode

Several patients in the parallel RCTs19,37,41 changed pacing mode during the study from the one to which they were randomised. Among the 857 patients randomised to DDDR and 785 to AAIR in the three trials, significantly more people with single-chamber atrial pacing than with dual-chamber pacing changed pacemaker and pacing mode (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.67; Figure 2). There was no statistical heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of the three trials and only modest uncertainty; however, the result was mainly driven by the largest and longest trial, DANPACE.

FIGURE 2.

Results from analysis of change in pacing mode.

Most patients who changed from AAI(R) changed to DDD(R). The primary reasons for the implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker in patients with a single-chamber atrial pacemaker were development of a high-degree AV block, or Wenckebach block during implantation. However, there were also a small number of patients who switched from AAIR to VVI. Patients randomised to DDD(R) who changed pacing mode during implantation or during follow-up primarily changed to VVI pacing because of development of persistent AF. One patient was lost to follow-up in the AAIR arm of Albertsen et al. ,37 and has been included in this analysis as changing pacing mode.

Per cent atrial and ventricular pacing

The rate of atrial pacing and VP (%) varied greatly among the studies, study arms and pacing modes (Table 10). Differences between studies in the rate of paced atrial or ventricular beats may be associated with differences in other outcome measures. VP has been associated with an increased incidence of AF. 44

| Study | Pacing mode | AV delay | % VP | % atrial pacing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel RCTs | ||||

| Albertsen et al.37 | DDDR | Paced AV delay maximum 220–225 milliseconds | 66 | 62 |

| AAIR | N/A | Two patients, 3% and 99%, respectivelya | 53 | |

| DANPACE19 | DDDR | Mean maximum paced AV delay 225 (SD 39 milliseconds) | 65 (SD 33) | 59 (SD 31) |

| AAIR | N/A | 103/122 patients, 53 (SD 35)a | 58 (SD 29) | |

| Nielsen et al.41 | DDDR-s | 150 milliseconds | 90 | 57 |

| DDDR-l | 300 milliseconds | 17 | 67 | |

| AAIR | N/A | NRa | 69 | |

| Crossover RCTs | ||||

| Gallik et al.34 | DDDR | 100 milliseconds | NR | NR |

| AAIR | N/A | N/A | NR | |

| Lau et al.35 | DDDR | 96 milliseconds (SD 7 milliseconds) to 140 milliseconds (SD 5 milliseconds) | 64 (SD 11) | NR |

| AAIR | N/A | N/A | NR | |

| Schwaab et al.43 | DDDR | AV delay was optimised based on the maximum time velocity integral of the aortic flow | 99 (SD 2) | 95 (SD 5) |

| AAIR | N/A | N/A | 96 (SD 5) | |

In the DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. ,41 the percentages of atrial pacing and VP were calculated using the mean of the number of paced beats at each follow-up, which was captured by the pacemaker event counters. Schwaab et al. 43 used stored pacemaker histograms to capture the percentage of paced beats in the atrium and ventricle. Albertsen et al. 37 and Lau et al. 35 did not describe how the percentages of atrial pacing and VP were captured, and Gallik et al. 34 did not report data on the percentages of atrial pacing or VP.

Schwaab et al. 43 had the highest rate of atrial pacing and VP, with patients being paced in both the atrium and ventricle for almost every beat. The amount of atrial pacing was balanced between the trial arms in Schwaab et al. 43 (95–96%) and in the DANPACE trial19 (58–59%). By contrast, in Albertsen et al. 37 the percentage of atrial pacing was higher in the DDDR (62%) than in the AAIR group (53%), and in Nielsen et al. 41 there were similar amounts of atrial pacing in the AAIR (69%) and DDDR-l (67%) group but less in DDDR-s (57%). Lau et al. 35 did not report the percentage of atrial pacing.

The variation between the trials in percentage of VP was even greater than for atrial pacing. The VP in the dual-chamber pacing arm was 64–66% in Albertsen et al. ,37 the DANPACE trial1 and Lau et al. 35 However, the dual-chamber pacing arm with the long AV delay in Nielsen et al. 41 (DDDR-l) had only 17% VP compared with a VP percentage of above 90% in the dual-chamber pacing arm with short AV delay (DDDR-s) in the same trial. VP was also above 90% in Schwaab et al. 43 The programmed AV delay varied between the included studies, which may explain some of the variation in the percentage of VP.

All-cause mortality

The DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. 41 reported all-cause mortality. With 831 people randomised to DDDR pacing and 761 patients to AAIR pacing in total, there were fewer deaths among patients with dual-chamber pacing than single-chamber atrial pacing, but the difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.41; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Results from analysis of all-cause mortality.

The large DANPACE trial,19 which stopped recruitment before reaching the planned 1900 patients, was not powered to detect a difference in mortality between the two pacing modes. However, from a planned interim analysis of the DANPACE trial results,19 it was calculated that no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality would have been observed even if all 1900 patients had been recruited. As the meta-analysis of the DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. considers only 1592 patients, it is unlikely to have sufficient power to identify a statistically significant difference. The breakdown of the number of deaths in the two DDD trial arms in Nielsen et al. is shown in Table 11. 41

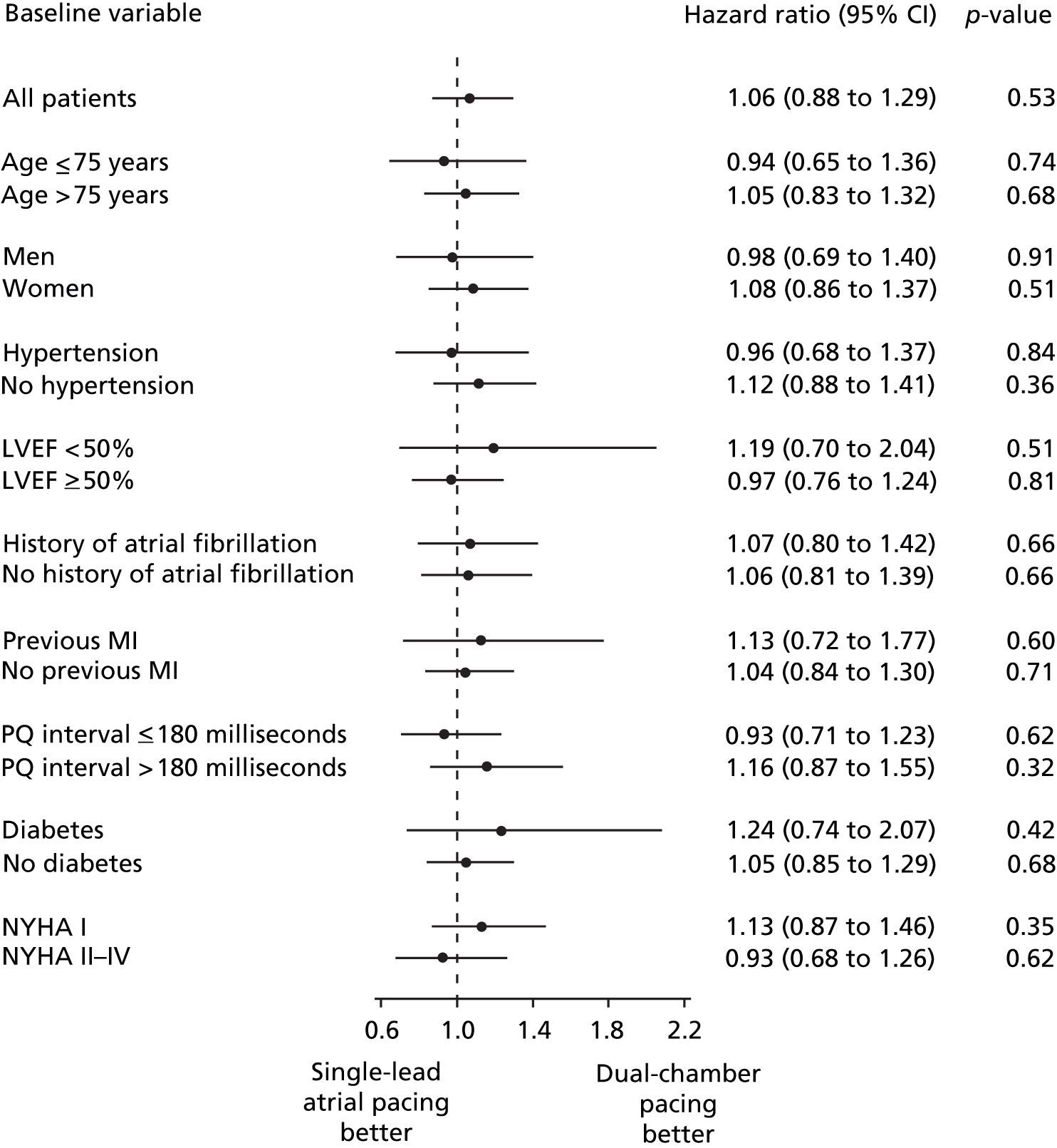

| Outcome | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDDR-s | DDDR-l | AAIR | |||||

| n | N | n | N | n | N | ||

| Mortality | 14 | 60 | 14 | 63 | 9 | 54 | 0.51 |

The DANPACE trial,19 in which the primary outcome was all-cause mortality, presented this outcome as a HR. The HR presented in the full publication was in line with the meta-analysis of mortality OR of the two included trials. The unadjusted HR for AAIR pacing compared with DDDR pacing was 1.06 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.29; p = 0.53). The HR after adjustment for baseline variables [age, sex, prior history of AF, prior myocardial infarction, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%, and hypertension] was 0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.14; p = 0.52) for AAIR pacing versus DDDR pacing. The all-cause mortality incidence was similar in all predefined subgroups (age > or ≤ 75 years; sex; hypertension; LVEF < or ≥ 50%; history of AF; previous myocardial infarction; PQ-interval > or ≤ 180 milliseconds; diabetes; NYHA class I or II–IV), with the smallest p-value for interaction of 0.45 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Subgroup analyses of all-cause mortality in the DANPACE trial. 1 MI, myocardial infarction.

In Albertsen et al. ,37 which did not report mortality as an outcome, one patient was lost to follow-up in the AAIR group, and may have died within the follow-up period.

Heart failure

Heart failure was reported in all three parallel RCTs. 19,37,41 However, the outcome measures varied between the studies (Table 12). In the three trials, HF was captured as NYHA class at the end of follow-up; number of patients taking diuretics; HF leading to hospitalisation; number of cases of new HF (defined as new NYHA class IV or new NYHA class III with the presence of oedema and/or dyspnoea); number of patients with an increase in consumption of diuretics; and number of patients with an increase of at least one NYHA class.

| Study | Time point | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | Estimate of effect | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | n | N | n | N | ||||

| Albertsen et al.37 | DDDR | AAIR | |||||||

| NYHA class | |||||||||

| I | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 18 | 26 | 19 | 24 | NR | NR |

| II | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 8 | 26 | 3 | 24 | NR | NR |

| III | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 0 | 26 | 2 | 24 | NR | NR |

| IV | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 0 | 26 | 0 | 24 | NR | NR |

| I | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 14 | 26 | 18 | 23a | NR | NR |

| II | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 10 | 26 | 5 | 23a | NR | NR |

| III | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 1 | 26 | 0 | 23a | NR | NR |

| IV | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 1 | 26 | 0 | 23a | NR | NR |

| DANPACE19 | DDDR | AAIR | AAIR vs. DDDR | ||||||

| NYHA class | |||||||||

| I | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 522 | 708 | 503 | 707 | NR | NR |

| II | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 158 | 708 | 172 | 707 | NR | NR |

| III | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 24 | 708 | 29 | 707 | NR | NR |

| IV | Baseline | N/A | N/A | 2 | 708 | 0 | 707 | NR | NR |

| NYHA class | |||||||||

| I | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 341 | 666 | 364 | 666 | NR | 0.43 |

| II | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 260 | 666 | 231 | 666 | NR | |

| III | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 61 | 666 | 67 | 666 | NR | |

| IV | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 4 | 666 | 4 | 666 | NR | |

| Patients on diuretics | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 328 | 708 | 324 | 707 | NR | 0.89 |

| HF (leading to hospitalisation) | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 28 | 708 | 27 | 707 | HR 1.06 | 0.84 |

| New HF (new NYHA IV or III + symptoms) | End of follow-up | N/A | N/A | 169 | 708 | 170 | 707 | Unadjusted | |

| HR 1.00 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| Adjusted | |||||||||

| HR 1.09 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Nielsen et al.41 | DDDR-s | DDDR-l | AAIR | ||||||

| Patients with increased consumption of diuretics | End of follow-up | 19 | 60 | 13 | 63 | 15 | 54 | NR | 0.34 |

| Patients with at least one NYHA class increase | End of follow-up | 18 | 60 | 29 | 63 | 17 | 54 | NR | 0.17 |

All the outcome measures for HF with a reported measure of uncertainty consistently showed no statistically significant difference between dual-chamber and single-chamber atrial pacing (see Table 12). However, because of low event rates or relatively small sample sizes the uncertainty was large around the HF outcome measures reported by Nielsen et al. 41 (patients with increased consumption of diuretics, patients with an increase of at least one NYHA class) and HF leading to hospitalisation reported by the DANPACE trial. 19

Pre-defined subgroup analyses in the DANPACE trial19 showed a statistically significant difference between single-chamber atrial pacing and dual-chamber pacing for patients aged ≤ 75 years and patients aged > 75 years in the number of patients developing new HF. In the younger subgroup (≤ 75 years), patients with AAIR were at a lower risk than those with DDDR of developing HF (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.00), and in the older subgroup (> 75 years) patients were at a higher risk when on AAIR (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.80). All other subgroup analyses were non-significant (sex; hypertension; LVEF < or ≥ 50%; previous myocardial infarction; PQ interval > or ≤ 180 milliseconds; NYHA class I or II–IV; diuretics, p > 0.31).

Atrial fibrillation

The DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. 41 reported results on the incidence of AF. In both studies, DANPACE19 and Nielsen et al. ,41 AF was diagnosed by standard 12-lead ECG at planned follow-up visits. In the DANPACE trial,19 AF was defined as either paroxysmal (the first diagnosis of AF detected on ECG and verified by the pacemaker telemetry at a planned follow-up visit) or chronic (AF at two consecutive follow-up visits and at all subsequent follow-up visit). The results of paroxysmal and chronic AF have been combined to simplify the comparison with the results from Nielsen et al. (Table 13), but they are also reported separately (Table 14).

| Study | Outcome | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | Effect estimate DDDR vs. AAIRa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | n | N | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Nielsen et al.41 | AF | 25 | 123 | 4 | 54 | 3.19 | 1.05 to 9.67 |

| Sensitivity analysis | Subgroup | n | N | n | N | OR | 95% CI |

| Nielsen et al.41 | DDDR-l | 11 | 63 | 2 | 27 | 2.64 | 0.54 to 12.84 |

| DDDR-s | 14 | 60 | 2 | 27 | 3.80 | 0.80 to 18.10 | |

| Study | Outcome | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | Effect estimate DDDR vs. AAIRa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | n | N | OR | 95% CI | ||

| DANPACE19 | Paroxysmal AF | 163 | 708 | 201 | 707 | 0.75 | 0.59 to 0.96 |

| Chronic AF | 76 | 708 | 79 | 707 | 0.96 | 0.68 to 1.33 | |

Nielsen et al. found that the risk of developing AF with dual-chamber pacing was significantly higher than with single-chamber atrial pacing (OR 3.19, 95% CI 1.05 to 9.67; see Table 13). 41 A sensitivity analysis of the DDDR-l and DDDR-s trial arms analysed separately similarly shows a larger proportion of patients developing AF in either dual-chamber pacing arms than in the trial arm paced with a single-chamber atrial pacemaker (see Table 13). In the sensitivity analysis, the single-chamber atrial pacing group has been split in two, so as to avoid double counting of patients.

In contrast to the results in Nielsen et al. ,41 in the DANPACE trial,19 the risk of developing paroxysmal AF was significantly lower with dual-chamber pacing than with single-chamber atrial pacing (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.96; see Table 14). By contrast, no statistically significant difference between dual-chamber and single-chamber atrial pacing was identified when focusing on the number of patients who developed chronic AF (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.33; see Table 14); substantial uncertainty was identified in this analysis.

The HRs for paroxysmal and chronic AF reported in the DANPACE trial19 (unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, prior history of AF, prior myocardial infarction, LVEF < 50% and hypertension), comparing single-chamber atrial pacing with dual-chamber pacing, support the analyses (Table 15).

| Study | Outcome | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | Unadjusted effect estimate AAIR vs. DDDR | Adjusted effect estimate AAIR vs. DDDR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | n | N | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| DANPACE19 | Paroxysmal AF | 163 | 708 | 201 | 707 | 1.27 | 1.03 to 1.56 | 1.24 | 1.01 to 1.52 |

| Chronic AF | 76 | 708 | 79 | 707 | 1.02 | 0.74 to 1.39 | 1.01 | 0.74 to 1.39 | |

There are several possible reasons for the disparity in the result of AF between the DANPACE trial19 and Nielsen et al. ,41 including differences in baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the studies and differences in pacemaker programming. Various hypotheses have been put forward around factors that may have an effect on the incidence of AF:

-

Previous history of AF: in the DANPACE trial19 the strongest predictor of paroxysmal AF was prior history of AF (HR 3.23, 95% CI 2.59 to 4.03; p = 0.001). However, the DDDR and AAIR pacing arms were well balanced for previous AF at baseline. Nielsen et al. 41 did not report previous history of AF; however, they did report a breakdown of the underlying pacing indications including BTS, in which the tachyarrhythmia often is AF. In Nielsen et al. 41 there was an imbalance in the number of patients with BTS, with a larger proportion among patients in the two dual-chamber pacing arms than in the single-chamber pacing arm. Nielsen et al. 41 found a correlation between BTS at implantation and an increased risk of AF (relative risk 3.3, 95% CI 1.3 to 8.1; p = 0.01).

-

PQ-interval: the result of a subgroup analysis of 650 patients in the DDDR group in the DANPACE trial19 indicates that a longer baseline PQ-interval (> 180 milliseconds) is associated with an increased risk of AF (p < 0.001). There was a slight difference in PQ interval at baseline between the studies; however, the PQ interval was well balanced between the different trial arms within each study (Table 16). 1,41

-

Programmed AV interval and percentage VP: both DDDR and AAIR preserve AV synchrony. However, in AAIR normal ventricular activation pattern is preserved, whereas DDDR causes some degree of unnecessary VP with changes to the ventricular activation and contraction pattern, which has been associated with an increased risk of AF. 44,45 The programmed AV delay is closely linked to the resulting VP percentage; the DDDR-l arm in Nielsen et al. 41 had a programmed AV delay of 300 milliseconds and just 17% VP, whereas the DDDR-s arm had an AV delay of 150 milliseconds and 90% VP. In the DANPACE trial19 the patients in the DDDR arm had an AV delay and VP percentage in the middle of the range observed in Nielsen et al. 41 [225 milliseconds (SD 39 milliseconds) and 65% (SD 33%), respectively; see Table 10]. However, in Nielsen et al. ,41 there were significantly more patients with AF in both the DDDR-l and the DDDR-s arms than in the AAIR group, despite having low and high VP percentages, respectively. A subgroup analysis of 650 patients with a DDDR pacemaker in the DANPACE trial19 showed no statistically significant association between percentage VP or the length of the AV delay and risk of AF. 39

| Baseline characteristic | Nielsen et al.41 | DANPACE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDDR-s | DDDR-l | AAIR | DDDR | AAIR | |

| PQ baseline (millisecond), mean (SD) | 183 (28) | 184 (27) | 186 (27) | 179 (30) | 179 (29) |

Both studies, DANPACE19 and Nielsen et al. ,41 seem to be of good quality, although there are some differences in the methods (e.g. programmed AV interval) and in the baseline characteristics of the patients in the two studies. However, the DANPACE trial19 is almost 10 times the size of Nielsen et al. 41 and it has a longer mean follow-up [5.4 years (SD 2.6 years) compared with 2.9 years (SD 1.1 years), respectively]; thus, it is reasonable to have more confidence in the results from the DANPACE trial1 than from the Nielsen et al. study.

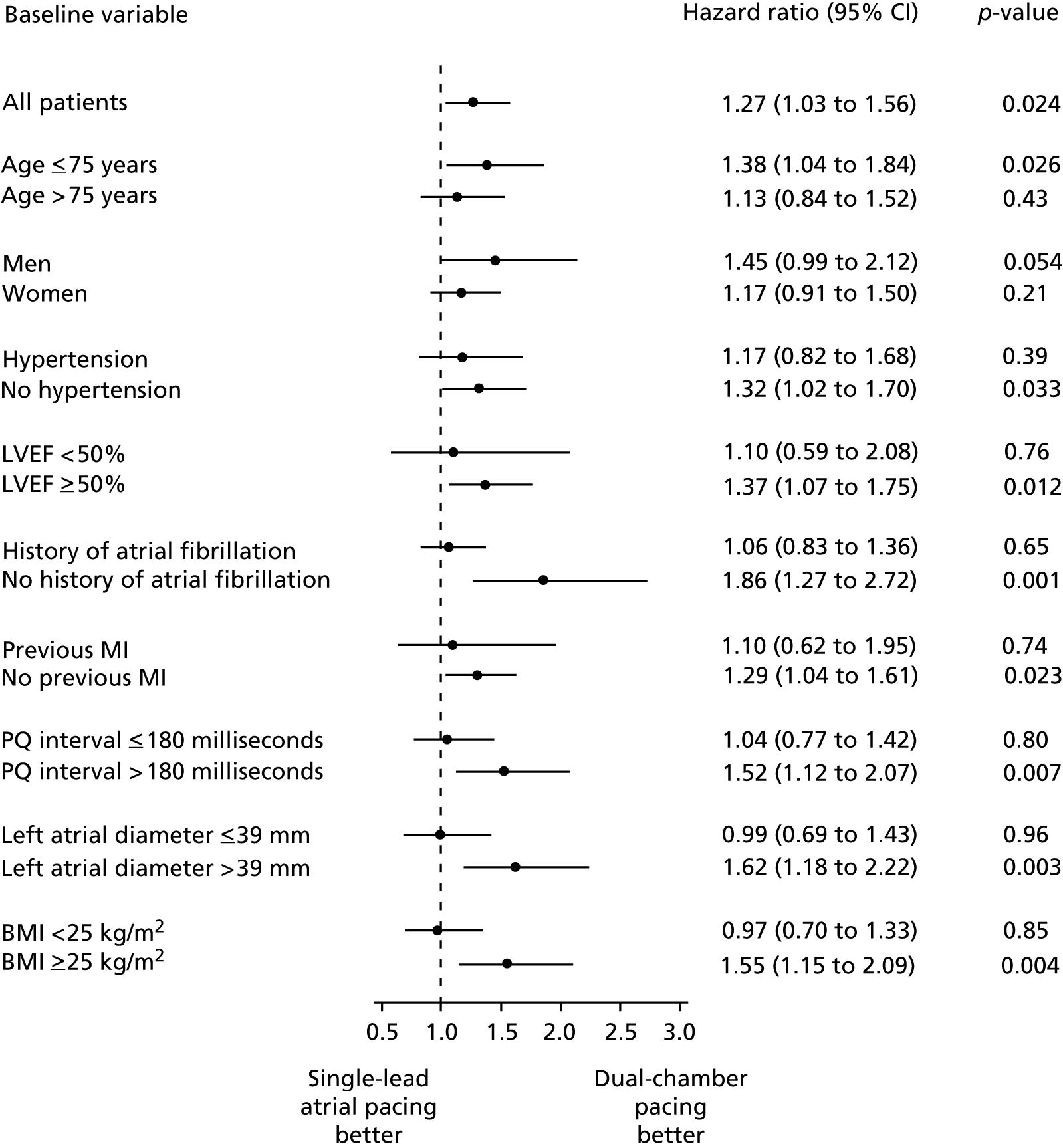

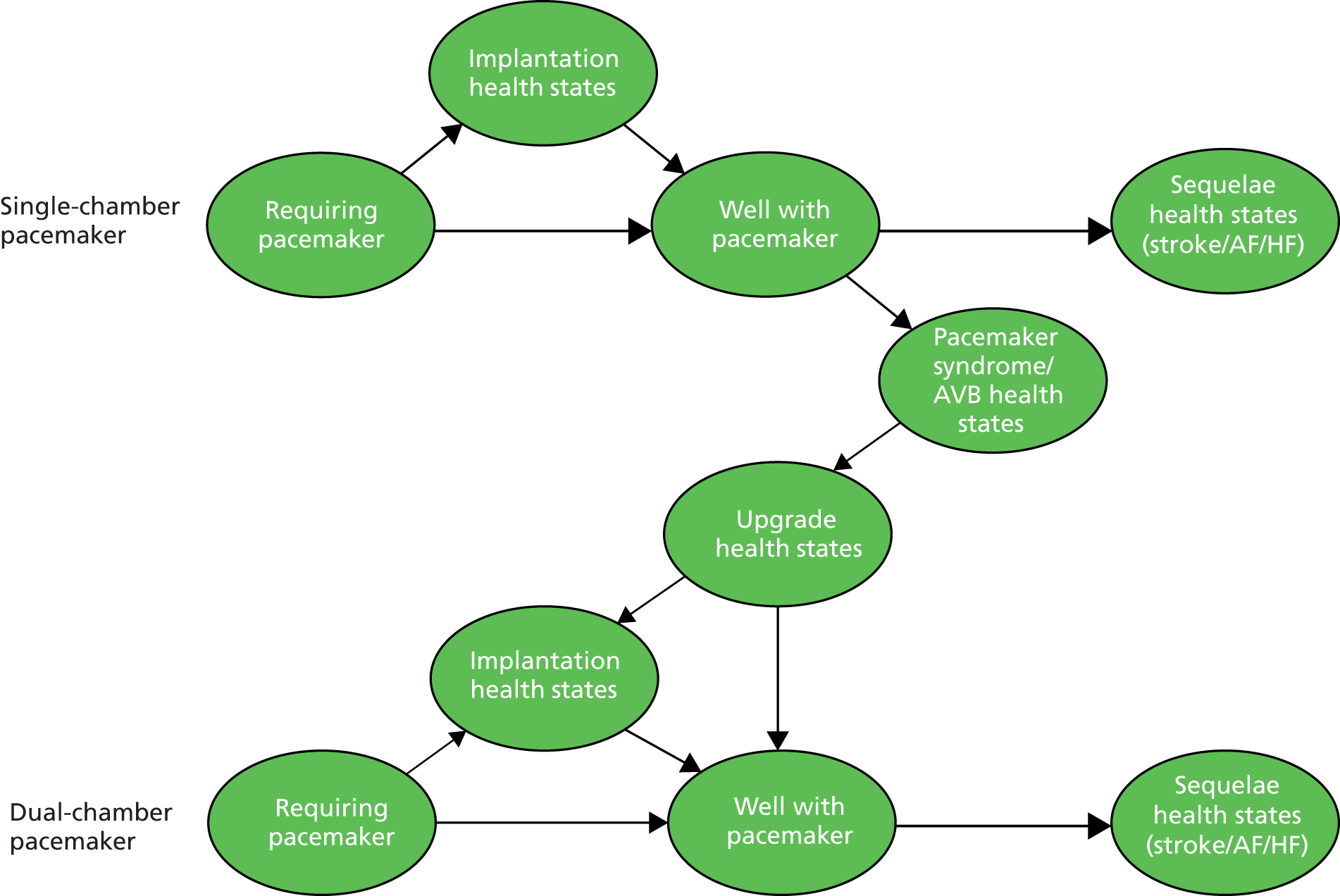

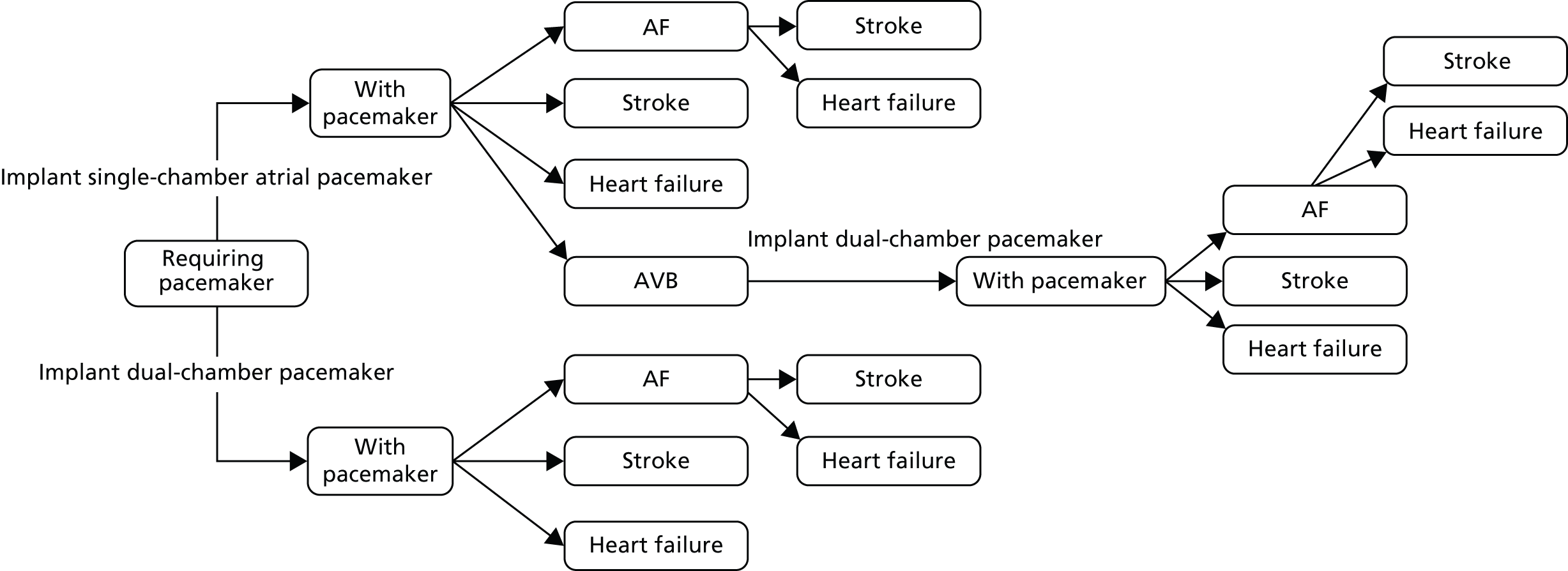

Subgroup analyses of paroxysmal AF in the DANPACE trial19 showed a statistically significant difference between the subgroups of patients with and without a prior history of AF, body mass index (BMI) ≥ or < 25 kg/m2, and a left atrial diameter > or ≤ 39 mm at baseline (Figure 5). 1 In these three subgroups the incidence of paroxysmal AF was lower with DDDR than with AAIR pacing in patients without a prior history of AF, a higher BMI and a dilated left atrium at baseline (p < 0.05). The subgroup analysis of patients with different PQ-interval > or ≤ 180 milliseconds indicated a lower risk of paroxysmal AF with DDDR than AAIR pacing in patients with a longer PQ-interval (p = 0.084). The p-values for all other interaction were > 0.34.

Stroke

The studies, DANPACE19 and Nielsen et al. ,41 captured the number of patients suffering a stroke as an outcome. In Nielsen et al. ,41 the diagnosis of stroke was given when neurological symptoms of presumably cerebral ischaemic origin persisted for more than 24 hours, or if patients died within 24 hours from an acute cerebrovascular event. The definition of stroke in the DANPACE trial19 was similar: the sudden development of focal neurological symptoms lasting more than 24 hours. As for several other outcomes, the number of events was low, the uncertainty considerable and no statistically significant difference was shown (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.45; Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Results from analysis of stroke.

The DANPACE trial19 reported an unadjusted HR for stroke of 1.13 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.80; p = 0.59) for patients with single-chamber atrial pacing compared with dual-chamber pacing. The HR when adjusted for age, sex, prior history of AF, hypertension and prior stroke was similar (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.77; p = 0.65).

The breakdown of the number of patients suffering a stroke in the trial arms in Nielsen et al. 41 is shown in Table 17.

| Outcome | Dual-chamber pacing | Atrial pacing | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDDR-s | DDDR-l | AAIR | |||||

| n | N | n | N | n | N | ||

| Stroke | 7 | 60 | 4 | 63 | 3 | 54 | 0.32 |

Exercise capacity

Exercise capacity was measured in the parallel RCT Albertsen et al. 37 and the crossover trials Gallik et al. 34 and Schwaab et al. 43 Albertsen et al. 37 used the 6-minute walking test (6MWT) to test exercise tolerance/capacity. 37 The 6MWT measures the distance an individual is able to walk over a total of 6 minutes on a hard, flat surface. In Gallik et al. ,34 exercise capacity was tested through an upright bicycle exercise. The initial workload was 200 kilopond metres (kpm), which was increased incrementally by 200 kpm every 3 minutes. The aim was to achieve a peak heart rate ≥ 85% predicted by age, and the outcome measure was exercise time. Schwaab et al. 43 used bicycle ergometry by incremental exercise test to exhaustion, using workload increments of 15 W/minute. 43 Outcome measures included total exercise duration and maximum workload.

Gallik et al. 34 presented IPD for exercise duration, whereas Schwaab et al. 43 presented only data for the individual treatment periods, but the results of paired t-tests of the within-patient difference for both studies were only reported as significant or not, without the numerical details of p-values.

In Albertsen et al. ,37 there was no statistically significant difference between the trial arms in the 6MWT at baseline, but, at 12 months’ follow-up, patients with a single-chamber atrial pacemaker walked significantly further than patients with a dual-chamber pacemaker (Table 18). 37 Although the result was statistically significant and the mean difference just reached the minimal clinically important difference of 54–80 m,46 there was substantial uncertainty around this value. One patient in the single-chamber atrial pacing group was lost to follow-up during the study, which may have had a small impact on the overall result.