Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/06/07. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The draft report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Guthrie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme is a research funding programme that supports research that is tailored to the needs of UK NHS decision-makers, patients and clinicians. The programme is part of the wider National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and funds UK researchers to conduct a mix of primary research and evidence syntheses that address the needs of the NHS.

Hanney et al. (2007)1 described how the first formal NHS research and development (R&D) strategy, launched in 1991, led directly to the establishment of the HTA programme in 1993. 2 The R&D strategy Assessing the Effects of Health Technologies2 highlighted the importance of health technology assessment. In this section of the report, we outline the policy developments and changes that have affected the programme over the last 10 years, describe the programme’s current structure and approach, provide an overview of previous work reviewing the impact of the programme and set out the aims of this study.

Policy developments affecting the Health Technology Assessment programme from 2003 to 2013

One of the key developments over the last 10 years was the publication of the 2006 national health research strategy Best Research for Best Health. 3 The strategy changed the way that health research is funded in the UK and led, among other things, to the creation of the NIHR. The Best Research for Best Health strategy3 explicitly refers to the HTA programme, which was to be included within the remit of the newly created NIHR, stating that the HTA programme’s purpose is to ‘ensure that high-quality research information on the costs, effectiveness and broader impact of health technologies is produced in the most effective way for those who use, manage and provide care in the NHS’ (p. 22). The report also reaffirms the HTA programme’s links to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and suggests that alongside addressing questions of importance to the NHS and its users, it should provide ‘dedicated support for the work of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) by commissioning both primary research and Technology Assessment Reviews’ (p. 22). A key outcome of the Best Research for Best Health strategy3 was the introduction for a major new programme of pragmatic clinical trials. These pragmatic trials were intended to address topics of direct relevance to the NHS and to operate largely in response mode. By this point, the HTA programme had already started to work with the UK Clinical Research Network to identify and support relevant trials that were thought to have value for the NHS, but the formation of a new programme for pragmatic clinical trials formalised the shift in focus of the HTA programme to fund a wider range of clinical trials. The HTA programme also continued to support clinical trials and evidence syntheses (initially the primary focus of the programme) through its established commissioning routes, based on the research priorities identified through engagement with specialist groups, the NHS and researchers.

Over the period from 2003 to 2013 the size of the HTA programme grew significantly, as did the profile of its research. According to the Best Research for Best Health HTA implementation report,4 by 2009, 54 project grants had been awarded through the new clinical trials funding stream, which had been renamed the HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials. The new health strategy also led to an increase in funding for the programme, with its annual budget planned to grow by ‘a further £29m as a result of the Best Research for Best Health Research Strategy; and a further £48m following the Comprehensive Spending Review and the increase in the Joint Health Research Fund, both by 2012/13 compared to 2005/06 levels’ (p. 2). 4 The overall budget of £88M by 2012–13 was intended to fund more HTA trials through all commissioning routes. The Best Research for Best Health implementation report4 also referenced the quality of HTA research, noting that the roughly 50 monographs were published each year in the ‘internationally acclaimed’ Health Technology Assessment (HTA) journal, which had an impact factor (a measure of the level of citation of articles within the journal) of 3.87 in 2007, ranking it among the top 10% of health and medical-related journal titles.

Prior to the publication of the Best Research for Best Health report,4 there had already been some changes to the HTA programme in response to the public health White Paper Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier5 and the 2004 Wanless Report Securing Good Health for the Whole Population. 6 A new HTA panel on public health was established in 2005 and supported by £9.2M in funding. According to the Best Research for Best Health implementation plan,4 the panel was ‘developing close and complementary links with the recently established NIHR Public Health Research programme, which evaluates non-NHS public health interventions’ (p. 2) by 2009.

The Cooksey Review,7 A Review of UK Health Research Funding, also had implications for the strategy and focus of the HTA programme. A key recommendation of the Cooksey Review7 was the establishment of the Office for Strategic Coordination of Health Research to determine the government’s health research strategy, set the budget for health research, and distribute the budget for health research between the NIHR and Medical Research Council (MRC). The Cooksey Review7 also recommended the establishment of NIHR as a real, rather than a virtual, institute, and clarification of the roles of the NIHR and MRC, which had implications for the HTA programme. HTA research had previously been funded by both the MRC and the NIHR, but health technology assessment, along with health services research and applied public health research, was brought exclusively within the remit of the NIHR in response to these recommendations. The Cooksey Review7 explicitly stated that the HTA programme should benefit from these new arrangements by receiving a greater proportion of the financial support for this type of research within the overall UK funding portfolio. The report also praised the HTA programme as ‘very successful in its role of Knowledge Production, by providing NHS decision-makers with a high-quality evidence base, in meeting needs created by “R&D market failure” and for its innovation and flexibility’ (p. 85) and as ‘a global leader in this area’ (p. 99). The review recommended that the HTA programme be expanded to meet the increasing information needs of the NHS. Specific areas recommended for expansion included strengthening the commissioned workstreams for primary research, clinical trials and themed calls, following up on research recommendations from NICE and funding research of HTA methodologies. It is interesting to note that the Cooksey Review7 recommended that a set of metrics should be developed to evaluate the impact of the expansion of the HTA programme to inform future spending decisions.

More recent changes in the NHS, outlined in the 2011 document Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS,8 have been less closely focused on research and have had a less substantial impact on the HTA programme. Although the Equity and Excellence document8 does not refer to the HTA programme specifically, it reinforces the core role of research in the NHS. The document states that ‘the Government is committed to the promotion and conduct of research as a core NHS role’ (paragraph 3.16). The Equity and Excellence document8 also highlights the importance of the NIHR and clinical research, describing how the NHS has ‘an increasingly strong focus on evidence-based medicine, supported by internationally respected clinical researchers with funding from the National Institute for Health Research’ (paragraph 1.6). It also notes the importance of patient involvement in research, and states that to support the development of quality standards NICE will advise the NIHR (including the HTA programme) on research priorities.

Current structure and approach of the Health Technology Assessment programme

Aims

Recent NIHR briefing documents state the aim of the HTA programme as to ‘research information about the effectiveness, costs and broader impact of health-care treatments and tests for those who plan, provide or receive care in the NHS’ (p. 2),9,10 demonstrating that although the specific strategy of the programme has changed over time, the overarching aims of the programme have remained consistent.

Research funding

The HTA programme commissions and funds research via four routes:

-

Commissioned workstream This stream funds research on specific topics identified by a range of stakeholders, from patients to professional bodies, and prioritised by the six advisory panels (described below). Typically, the HTA programme advertises three calls per year, which consist of a set of specified research questions that are described in commissioning briefs. Responses from applicants to each commissioning brief are reviewed based on their scientific merit, feasibility and value for money by the HTA Commissioning Board.

-

Researcher-led workstream This stream funds research questions put forward by researchers. The Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board assesses proposals based on their relevance to clinical practice in the NHS and the importance of the outcomes to patients.

-

Themed calls Themed calls aim to increase the evidence base for key health priorities through funding a number of projects across the NIHR in a particular area. They are evaluated separately by independent review boards set up for that purpose. Previous calls include obesity, medicines for children, diagnostic tests, dementia and primary care.

-

Technology Assessment Reports (TARs) These provide evidence to support NICE’s technology appraisal and diagnostic assessment programmes (TARs are described in detail below).

Six advisory panels and the prioritisation group support the review boards across all of these programmes. The prioritisation group balances the relative priority of research topics for the commissioned research workstream and applications received from the researcher-led funding stream. The six advisory panels are as follows: Diagnostic Technologies & Screening Programmes; Elective and Emergency Specialist Care; Interventional Procedures; Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health; Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health; Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions. The role and remit of each of these advisory panels is described in more detail below (see Priority setting).

The programme supports both evidence syntheses and primary research across all six panels and across all the funding streams. Over the last 10 years, there has been a relative increase in both response mode-funded research and primary research, which is in line with the recommendations set out in Best Research for Best Health3 and the Cooksey review7 (see Policy developments affecting the Health Technology Assessment programme from 2003 to 2013, above). In 2001, the HTA programme had published only five clinical trials,11 whereas by April 2014 the programme had supported 530 primary research studies, 260 of them completed and published in the HTA journal. An overview of the HTA programme’s portfolio, by type of study and status of the project, is provided in Table 1.

| Type of study | Complete | Waiting to publish | In progress | Waiting to start | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NICE TARs | 157 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 171 |

| NICE diagnostic assessments | 12 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 21 |

| NICE ERG report | 152 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 186 |

| HTA TARs | 130 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 147 |

| Methodology reports | 121 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 122 |

| Evidence synthesis | 205 | 29 | 14 | 4 | 252 |

| Primary research | 260 | 65 | 198 | 7 | 530 |

Relationship with policy-making organisations

An important part of the HTA programme’s strategy is the way it engages and influences NICE, the National Screening Committee (NSC) and other policy-makers. The HTA programme has direct links with NICE through its commissioning of TARs to inform NICE guidance. However, HTA programme-funded research also feeds in to other aspects of NICE’s work. For example, HTA programme-funded research is often cited in NICE guidelines, but the links between the HTA programme and the guideline-producing parts of NICE are less strong than the links between the TAR programme and NICE. The HTA programme also has direct links with the NSC, which are less formalised than the programme’s links with NICE. In addition to its well-established links with NICE and the NSC, the HTA programme also has informal links with other policy-makers (e.g. NHS England). The remainder of this subsection discusses the links between the HTA programme and each of those organisations.

The HTA programme commissions independent TARs to meet the urgent needs of NICE and other users of TARs. 12 Nine TAR centres, based in universities and academic centres across the country and contracted by the Department of Health (DH), conduct all of the TARs for NICE. TARs provide evidence to support NICE’s technology appraisal and diagnostic assessment programmes. There are three types of TARs:

-

Single Technology Appraisal Reports (STAs) aim to ‘assess the strength and quality of the research evidence submitted by manufacturers to NICE as part of the evaluation of a single new drug or device close to when they are first licensed’ (p. 3)12 and are produced within 8 weeks.

-

Multiple Technology Appraisal Reports (MTAs) aim to ‘identify, assess and synthesise the research evidence (including data submissions) from across a number of interventions in a given healthcare area’ (p. 3). 12 MTAs typically provide estimates of the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different interventions. They are larger research reviews than the STAs and take 26–28 weeks to produce.

-

Diagnostic Assessment Reports aim to ‘identify, assess clinical outcomes and synthesise the research evidence for single or multiple diagnostic technologies in a given pathway’ (p. 3). 12 Diagnostic Assessment Reports typically provide estimates of the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different diagnostic technologies. Diagnostic Assessment Reports are also relatively large reviews and take 24 weeks to produce.

Recent users of TARs also include the Chief Medical Officer, the National Specialised Commissioning Team, and the Policy Research Programme. TARs produced for other policy-makers may take different forms, and their content is tailored to meet the needs of the particular policy-making organisation. However, they typically include a systematic review of evidence in a particular area and economic modelling.

The NICE Guidelines Programme also uses HTA programme-funded research, but the link between the policy impact and the HTA programme is less direct. The HTA programme also has direct links with the NSC, which relies heavily on HTA programme-funded research for formulating evidence-based advice for government. According to interviewees, the HTA programme sends research related to screening directly to the NSC. The HTA programme and the NSC also have regular meetings to discuss both ongoing and recently published HTA programme-funded research related to screening. The NSC also submits research topics directly to the HTA programme. However, the links between the HTA programme and the NSC seem to rely primarily on relationships between individuals rather than formal links between the two organisations.

Research budget

‘The research budget of the HTA programme has now grown considerably from the initial £1M in 1993/4 to £8M in 2003/4 and £60M in 2012/13’ [NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC), 3 April 2014, personal communication, reproduced with permission]. Adjusting for inflation, that growth is equivalent to an increase of more than 400%, in real terms, over the last 10 years. This funding increase reflects the growth in scope of the programme over that time period, particularly the expansion of the clinical trials element of the programme because clinical trials are typically much more costly than evidence syntheses.

Priority setting

The HTA programme identifies potential research topics from a number of sources. It engages key stakeholders in the NHS and the NIHR, in part through the NIHR horizon scanning centre. The programme also sources research topics from the James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnerships and from research recommendations in published research, particularly systematic reviews, and guidelines. The programme also elicits research suggestions from policy-makers (notably NICE and the NSC) and other health-care-related organisations (e.g. the Royal Colleges and patient groups). Research topics can also be submitted by members of the public through the HTA website.

The initial prioritisation process consists of a number of steps. First, potential research topics are reviewed to assess whether or not they fall within the remit of the programme and to determine whether or not the research questions are sufficiently different from existing or ongoing research. Research topics that do not fall within the remit of the HTA programme are passed on to other NIHR research programmes.

The remaining research topics are then reviewed by one of the six Topic Identification, Development and Evaluation (TIDE) panels. These panels comprise a range of professional, public and patient members who act to advise the HTA programme on the importance of the research topic to patients and the NHS. There are six such panels in the following areas:

-

Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions Covers interventions that are delivered in primary care or the community.

-

Elective and Emergency Specialist Care Focuses on interventions delivered in hospitals or by specialists.

-

Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Examines interventions related to obstetrics, paediatrics and specific maternal health issues.

-

Interventional Procedures Covers all surgical interventions, drugs used for interventional procedures and interventional radiology.

-

Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Covers rehabilitation, learning difficulties, mental health, cognitive deficits and occupational health.

-

Diagnostic Technologies & Screening Programmes Covers all tests used to diagnose, monitor or select patients for treatment; or to monitor a disease or the effect of its treatment.

The members of each panel consist primarily of clinicians and health-care professionals working in the front-line NHS but also include public and patient representatives. At panel meetings, the members discuss and refine research suggestions. The members of the panel then vote on the relative importance of the topics to the NHS. The most important topics are then developed into vignettes that guide ongoing work on the selected topics. The vignettes are discussed at the panel’s Methods Group, which provides advice on the proposed research design and methodology. After the panel finalises the vignettes, they send them to the HTA Prioritisation Group.

For researcher-led work, the TIDE panel reviews anonymised extracts from proposals against the ‘criteria to guide the setting of HTA Priorities’. They evaluate the importance of the research question and produce a ranked list of proposals for the HTA Prioritisation Group.

After the six advisory panels have completed the vignettes and the TIDE panel has reviewed researcher-led proposals, the HTA Prioritisation Group then determines which research should be funded. The HTA Prioritisation Group consists of the Programme Director of the NIHR HTA programme, the chairs from each of the six HTA panels and the two funding boards, and senior representatives from NETSCC. The role of the Prioritisation Group is to develop a portfolio of research that reflects the needs of the NHS, fits within the available programme budget and provides good value for money. The group reviews and prioritises topics from the panels based on the vignettes prepared, and decides which should be developed into commissioning briefs. The HTA Prioritisation Group also reviews researcher-led proposals and prioritises them for consideration at the Clinical Evaluations and Trials Board. Finally, the Group reviews funding recommendations from the HTA commissioning boards and prepares a final list for approval by the DH.

The Health Technology Assessment journal

The HTA programme has its own journal, Health Technology Assessment, which is part of the wider NIHR journals library. The HTA programme endeavours to publish all HTA programme-funded research in the HTA journal as a monograph, and includes a full description of the methods, results and conclusions of the research. The monographs include an abstract, scientific summary and plain English summary. Although the programme aims to publish all HTA programme-funded research in the HTA journal, the research must be of sufficiently high scientific quality, as assessed by external peer reviewers and the journal’s editors, to be published in the journal. The purpose of the journal is to ensure that the full results of all studies are publicly available. However, the HTA programme also encourages the publication of results in other peer-reviewed journals. Prior publication of HTA programme-funded research results in other journals is not a limitation to the publication of a monograph in the HTA journal. Typically, the HTA journal article is one of the final outputs of any project.

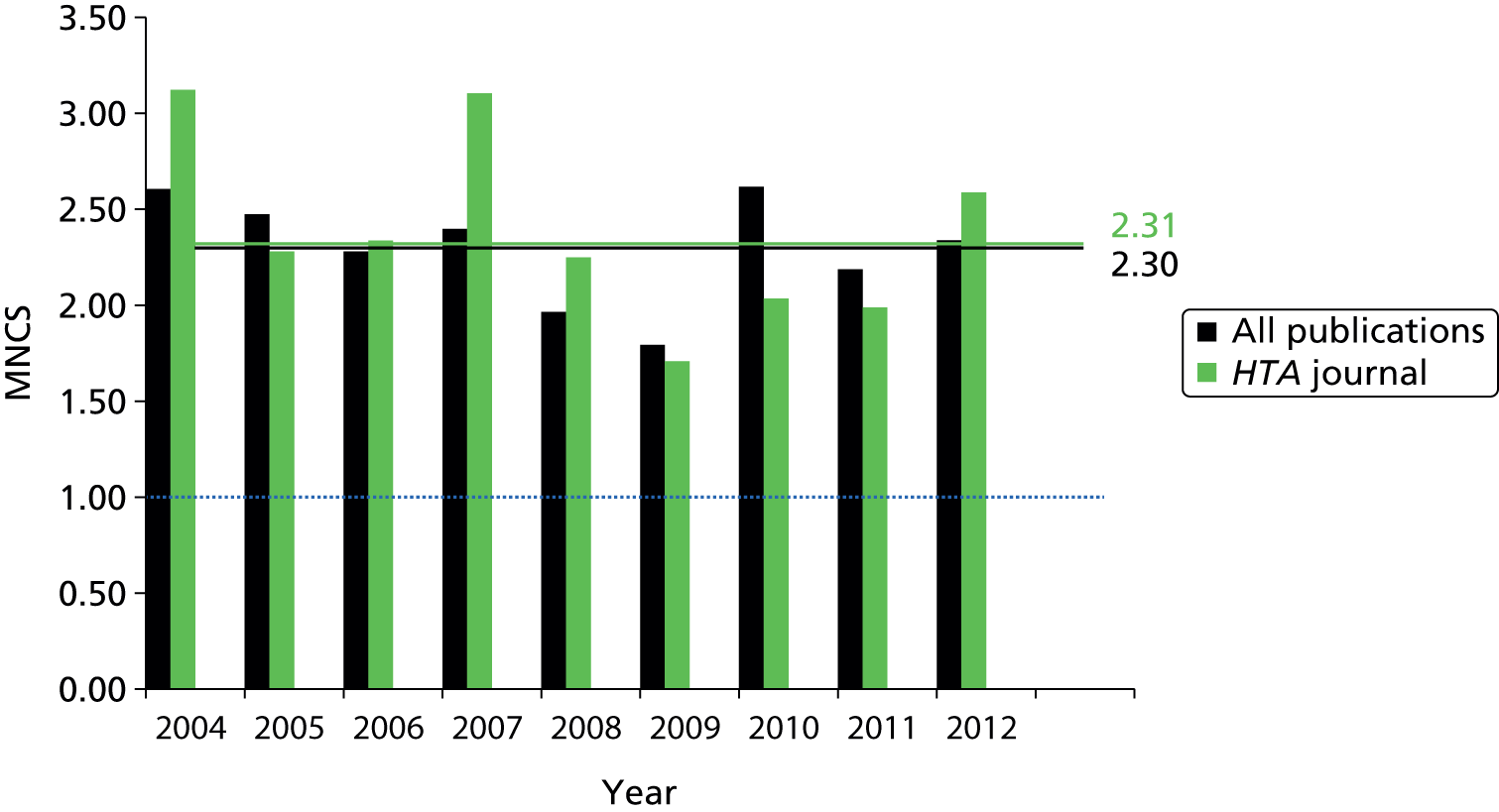

However, not all HTA programme-funded research is published in the HTA journal. For example, STAs are typically not published in the HTA journal (with a limited number of exceptions) because they are usually based on commercial data that were provided in confidence, and they primarily review manufacturers’ evidence rather than present original research. Despite the growth in the size of the HTA programme, there is evidence that the programme has maintained its academic quality, with the HTA journal’s 5-year impact factor of 5.595 ranking it fourth among all journals in the Health Care Sciences and Services category. 13

Adding value in research

The HTA programme has also been influenced by the work of Chalmers and Glasziou (2009)14 on research waste and, more recently, by the same authors and others in a series of publications on research waste in The Lancet in January 2014. The five papers15–19 published in The Lancet each expand on one of the key themes identified in the earlier paper by Chalmers and Glasziou (2009):14

-

decisions about which research to fund based on issues relevant to users of research15

-

appropriate research design, methods and analysis16

-

efficient research regulation and management17

-

fully accessible research information18

-

unbiased and usable research reports. 19

The HTA programme and the NIHR have used these themes to develop the Adding Value in Research framework. 20 The aim of the framework is to ensure that NIHR-funded research ‘answers questions relevant to clinicians, patients and the public; uses appropriate design and methods; is delivered efficiently; results in accessible full publication; and produces unbiased and usable reports’ (p. 1). 21 In fact, the HTA programme has been considered an exemplar of good practice in many of these areas. For example, Chalmers and Glasziou (2009)14 note:

Some elements of these recommendations reflect policies already implemented by some research funders in some countries. For example, the NIHR’s Health Technology Assessment Programme routinely requires or commissions systematic reviews before funding primary studies, publishes all research as web-accessible monographs, and, since 2006, has made all new protocols freely available.

p. 8814

The HTA programme’s perceived success in adding value in research contrasts with the evidence that shows that researchers more widely are not making sufficient use of existing evidence in the design and execution of their research. For example, the study by Clark et al. (2013)22 showed that of 446 trials submitted to research ethics committees in the UK, only 4% used meta-analyses of data from relevant previous studies to plan target sample sizes. Similarly, an analysis of clinical trials by Robinson et al. (2011)23 found that less than one-quarter of previous trials were cited in reports. This evidence suggests that not all research funders adhere to the UK policy on research governance in the biomedical research sector. According to the DH’s advice on research governance ‘all existing sources of evidence, especially systematic review, must be considered carefully before undertaking research. Research which duplicates other work unnecessarily, or which is not of sufficient quality to contribute something useful to exiting knowledge, is unethical’. 24

The Adding Value in Research framework is used by the HTA programme and the NIHR more widely for self-assessment and ongoing improvement. Through the Research on Research programme that was established in 2007, the NIHR funds studies on how they manage their research programmes and the projects they fund. Adding Value in Research is one of three core strategic areas of the Research on Research programme. Recent work funded through the programme has shown that the HTA programme is performing well against several of the elements of the framework. Wright et al. (2014)25 provided evidence that the programme is supporting research of clinical relevance. Turner et al. (2013)26 found that 95.7% of all HTA studies either have published, or will publish, a monograph in the HTA journal, and that that percentage increases to 98% for studies commissioned after 2002. Chinnery et al. (2013)27 showed that these publications were available promptly. They also found that the median time to publication for a HTA monograph was 9 months shorter than an external journal article.

However, published evidence suggests that the HTA programme could improve the value that it adds. Work by Douet et al. (2014)28 showed that not all the reports published in the HTA journal provide sufficient information to replicate the work, with components missing in 69.4% of the 98 reports analysed. In particular, only 58.2% of reports had complete patient information. Jones et al. (2013)29 looked at the use of systematic reviews in planning a sample of randomised trials and found that although the majority of HTA programme-funded research referenced the systematic review in their application, only half used the systematic review to inform the design of the study. Turner et al. (2010)30 found that, in one particular research area, eight similar HTA studies had been funded by different international HTA organisations. Although the studies looked at the issue within different contexts, the similarity between studies suggests that potential duplication of effort and research waste may have taken place. The authors suggest that such resource wastage could be minimised by the use of a toolkit designed to help adapt HTA reports between different contexts.

Complementary to the Adding Value in Research framework is the ‘needs-led, science-added’ approach, which is a set of principles used across the NIHR, including the HTA programme, which aims to maximise the utility of research for decision-makers. The underpinning principle is that research should be ‘needs led’ in that it should reflect the key information needs of decision-makers, while also being of high quality. To this end, the NIHR undertakes a range of activities, such as involving stakeholders – including policy-makers, patients and the public – in topic identification and prioritisation (as described above); conducting peer review of proposals and making the funding decisions via expert panels; ongoing monitoring and contact with projects in process; and comprehensive publication of findings in the NIHR journals library.

Patient and public involvement in research

Both the Adding Value in Research framework and the ‘needs-led, science-added’ approach advocate the involvement of patients and the public in the design and conduct of research. The NIHR defines involvement of patients and the public as:

. . . an active partnership between the public and researchers,

research done with or by members of the public, not to or about them,

the public getting involved in the research process itself.

p. 231

Health Technology Assessment programme-funded studies are expected to demonstrate that they will involve patients and the public, and this forms part of the assessment of proposals submitted for funding. The NIHR provides guidance to researchers on what that involvement could consist of, suggesting that patients and the public could be involved in:

-

designing questionnaires and patient information sheets

-

helping to find participants and designing the best way to approach them

-

participating in advisory or steering groups

-

undertaking aspects of the research

-

contributing to or commenting on the final report.

One of the main support mechanisms that the NIHR provides support for researchers is the Research Design Service, which can give researchers access to relevant patients or members of the public that they have recruited into their patient and public involvement (PPI) panels. In a study of a sample of HTA programme-funded projects, 85% of proposals described PPI representation in their application. However, only 41% of reviewer comments across the trials commented on the PPI plan, which suggests that more guidance could be provided for reviewers on this process. 32

Previous work assessing the impact of the Health Technology Assessment programme

Several previous studies have been conducted to assess the impact of the HTA programme. Hanney et al. (2007)1 undertook an assessment of the impact of the first 10 years of the HTA programme, which was commissioned by the NIHR. Using payback case studies, Hanney et al. (2007)1 identified a range of impacts results from the HTA programme and the mechanism through which those impacts arose. Hanney et al. (2007)1 found that the HTA programme primarily has an impact on knowledge generation, but that it also has a perceived impact on health policy and, to some extent, clinical practice. Hanney et al. (2007)1 suggested that the policy relevance of the funded studies contributed to the observed high impact of the programme. Hanney et al. (2007)1 also reported that the methodological rigour and strict peer review facilitated the publication of HTA programme-funded research in high-quality, peer-reviewed journals.

A second study examining the impact of the HTA programme was carried out by RAND Europe on the impact of a small sample of clinical trials funded by the HTA programme. 33 The study33 attempted to monetise the potential benefits to the NHS and patients of the findings of a small sample of HTA studies and compared these benefits to the cost of the HTA programme. The study33 provides quantitative evidence of the impact of the HTA programme in a limited number of cases, and demonstrates that a small subset of the work of the HTA programme has potential returns that would be greater than the total costs of the HTA programme if the findings of those studies were fully implemented and delivered the expected long-run returns. However, the approach has several limitations. First, only a limited range of types of benefit were captured. As well as providing evidence that new treatments could be effective and cost-effective (potentially influencing health policy, clinical practice, health outcomes and the economy), the programme also identifies new technologies that are no better than the existing standard of care, which prevents new, potentially less effective or more expensive technologies, being adopted by the health service. Similarly, the approach does not capture wider impacts of the HTA programme, such as its impact on the research system. In addition, the approach focused only on clinical trials, whereas part of the value of the HTA programme comes from its systematic reviews and evidence syntheses.

A recent paper by Raftery and Powell (2013)11 looked at the impact of the HTA programme over the last 20 years. They describe examples of when HTA programme-funded research has had an impact on health policy and clinical practice, and the impact of the programme at a wider level. Raftery and Powell (2013)11 see the programme as a provider of evidence to NICE and the NSC, and as an exemplar of good practice in the promotion of full, open access publication of all results, the registration of trial protocols at the outset of research and the insistence on systematic review before funding primary research. The study11 concludes by identifying key challenges for the HTA programme, which include ensuring that funding and publication of research is timely, addressing the methodological challenges around the research that it funds, ensuring that trials are incorporated into updated meta-analyses, and maintaining their independence from government. Another key challenge that Raftery and Powell (2013)11 identified is maintaining funding for the HTA programme from the NHS in the current economic climate. Raftery and Powell (2013)11 suggest that the HTA programme needs to demonstrate that it is cost-effective through the effect that it has on health service resources and public health. The authors recommended that the HTA programme funds more ‘research on research’, including work looking at the HTA programme. As well as considering other approaches, including the issues of adding value in research and the contribution of trials to subsequent systematic review, Raftery and Powell (2013)11 recommended the application of the payback framework to look at the second decade of the programme.

The present study is intended to be complementary to the previous studies on the HTA programme and, in particular, to provide an assessment of the impact of the HTA programme over the last 10 years, as recommended by Raftery and Powell (2013). 11

Aim of this study

The aim of this study is to review the impact of the NIHR HTA programme from 2003 to 2013. This study considers a broad range of potential impacts, spanning academic, health policy, clinical practice, and health and economic outcomes. Although the study’s approach was largely retrospective, reviewing impact from 2003 to 2013, it also included a forward-looking component, which considered how the HTA could increase its impact in the future, based on the evidence collected for the retrospective analysis.

Considering the objectives of the programme, and taking into account the different ways in which the HTA programme can have an impact, through the HTA programme-funded research and the programme itself, we identify three key research questions:

-

What has been the impact of HTA programme-funded research on the NHS, patients, clinicians, health policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy from 2003 to 2013?

-

What has been the impact of the HTA programme on the NHS, patients, clinicians, health policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy from 2003 to 2013?

-

What actions can the HTA programme take to increase its impact on the NHS, patients, clinicians, health policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy?

Chapter 2 Methodology

We have taken a broad approach to assessing the impact of the HTA programme, aiming to explore the full range of impacts resulting from HTA research across the programme, including the impacts resulting from the programme itself, not just as a body of individual projects. Therefore, the work presented in this report consists of two elements:

-

Analysis of impact across the HTA programme To do this, we have:

-

conducted 20 interviews with key stakeholders, spanning a range of viewpoints, to understand the impact of the HTA programme in different contexts

-

conducted a bibliometric analyses of the HTA programme

-

analysed all available survey data from Researchfish® (Cambridge, UK; www.researchfish.com) for HTA programme-funded research over the period. Researchfish is an online system that is designed to capture research outcomes for researchers and funding organisations through questions on a series of types of outcomes and impacts.

-

-

Analysis of the impact of a sample of individual HTA projects To do this, we have conducted 12 detailed payback case studies.

These tasks are mapped against the key study questions in Table 2.

| Question | Source |

|---|---|

| What broad impacts on the NHS and patients, policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy have resulted from the HTA at a programme level over the period 2003–13? | Interviews with stakeholders Bibliometrics Survey data |

| What is the impact on the NHS and patients, policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy of the HTA programme at a project level over the period 2003–13? | Interviews with stakeholders Bibliometrics Survey data Payback case studies |

| What actions can the HTA programme take to help increase its impact on the NHS and patients, policy, academia, the research system, industry and the economy in the future? | Cross-cutting analysis across all tasks |

Our methodology is based on the payback framework developed by Buxton and Hanney (1996). 34 This approach was specified by the commissioning brief and was selected because it is a useful way to collect information on the impact of research systematically and, comparably, allowing useful comparisons to be drawn across data sources to generate wider insights. In addition, it is well established and has been widely used as a method to investigate and catalogue the impacts of health research,35–38 and was used previously to assess the impact of the first 10 years of the HTA programme, following an assessment of potential approaches that could be used. 1 Using this approach allows us to make direct comparisons of our findings to those of the previous assessment.

The payback framework consists of two elements: a classification system to capture and categorise the outputs and outcomes of research, and a logic model which helps to break down the research and translation process. As such, the payback framework helps not only to evaluate the range and nature of outputs from research, but also to conceptualise the process through which these outputs are generated. Although the logic model is linear in format, which is a simplification of the research process, it also explicitly includes feedback between different stages of the process.

The payback framework has five categories of impact to capture the range of impacts resulting from research. We used these to structure our data collection – primarily for the case studies (described in Case studies) but also for our other streams of evidence.

-

Knowledge production This category covers the knowledge produced as a result of the research conducted, and this knowledge is in general captured in publications. Peer-reviewed articles are generally the most common measure, but editorials, meeting abstracts, reviews and patent filings are other examples of knowledge production. Citation analysis is one approach to understanding and measuring the output in this category.

-

Research targeting and capacity building This category captures benefits for future research created by the research conducted both in terms of the direction of research and research priorities, and the building of research capacity in terms of infrastructure, skills and staff development.

-

Informing policy and product development This category captures the impact of research on health policy (illustrated by such things as citation on clinical guidelines) and on product development as findings are taken up by the private sector for commercialisation (possible measures are licensing intellectual property, contract research work and public–private joint ventures, along with new start-ups).

-

Health and health sector benefit This category covers health benefits and other benefits for the health sector (such as improved efficiency or cost savings) resulting from the findings of the research being put into practice. This typically occurs via the uptake of the policy, products or processes outlined in the previous category.

-

Broader economic benefit This final category covers the wider socioeconomic benefits resulting from the research. They might be the outcome of the increased productivity of a healthier workforce resulting from the health benefits described, or might result from increased employment or the development of new markets, stemming from the development of new products or processes. This can be very challenging to measure owing to the challenges of attributing such change to a particular piece of research.

Although we used the payback approach to structure our data collection, in our analysis of the impacts of the programme we categorised the impacts slightly differently to better reflect the aims and priorities of the HTA programme, particularly its focus on the UK, and the NHS and patients. Although our categorisation does not explicitly mention every potential impact of the programme (and indeed, it is not possible to identify and capture every possible impact), we felt that it was appropriate to focus primarily on assessing the impact of the programme against its own aims, while remaining open to other types of impact that may also be identified. The categories used, as defined below, are intended to be broad enough to capture the full range of impact identified, but also focused primarily on the key aims of programme. We used the following categories:

-

Impact on the NHS and patients This captures impacts on health and the health sector, and those socioeconomic benefits that relate to the improved health of patients.

-

Impact on UK policy Impact on health policy in the UK only. Part of what is captured under improving policy and product development.

-

Academic impact The equivalent of ‘Knowledge production’.

-

Impact on the research system The equivalent of ‘Research targeting and capacity building’.

-

Impact on industry and the economy This covers parts of what is captured under improving policy and product development, focusing on the product development side, but also takes in economic impacts when they do not relate to the NHS or patient health.

-

International impact This captures impacts across all categories outside the UK, with the exception of academic impact, which is hard to separate in this way. In particular, this category covers impacts on policy and practice outside the UK, and influences on wider research systems and structures.

These categories were used to structure the analysis of the results across the various data collection methods used, combining the broad findings across the programme from the interviews, bibliometrics and survey data with the in-depth examples provided by the case studies. The qualitative data from the interviews and case studies were coded and analysed by impact type and stakeholder group. Within the impact categories, we conducted a thematic analysis of the data coded in each impact grouping to identify key messages. The same categories were used to analyse the quantitative data from the bibliometric analyses and the Researchfish survey. The rationale for using the same impact categories to analyse all of the different data sources was to allow the identification of key messages and themes that were supported by the data.

In the following sections, we describe each of the methods used in more detail.

Interviews

The purpose of the interviews was to understand the broad impact of the HTA programme on the medical research funding, practice and policy landscape. Potential interview candidates were identified from the following sources:

-

analysis of key policy documents to identify important perspectives and, where possible, relevant individuals

-

suggestions of the advisory board

-

when a relevant perspective was identified, but not an individual, we looked at the structure of relevant organisation(s) to identify the appropriate contact point

-

snowballing based on suggestions from previous interviews.

Through the sample of interviewees chosen, we aimed to cover a wide range of perspectives, but the final sample of interviewees was ultimately pragmatic, based on our ability to identify appropriate, informed informants who were available and willing to participate in an interview over the relevant time frame. A total of 20 interviews were conducted with informants, covering a range of perspectives. A full list of the interviews conducted and the perspectives covered is provided in Table 3.

| Interview | Academic | Patient and public | NICE | NSC | SIGN | Cochrane | NHS | DH/political | International | HTA expert | MRC/other funder | Internal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (I1) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| 2 (I2) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 3 (I3) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| 4 (I4) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| 5 (I5) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 6 (I6) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 7 (I7) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 8 (I8) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| 9 (I9) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 10 (I10) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 11 (I11) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 12 (I12) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 13 (I13) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 14 (I14) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 15 (I15) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 16 (I16) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 17 (I17) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 18 (I18) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| 19 (I19) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| 20 (I20) | ✗ | |||||||||||

| Total | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

An important limitation to note is the potential inherent bias in using key informant interviews to collect information on the HTA programme. For interviews to be productive, it is necessary that the individuals interviewed are informed about the programme. However, informed individuals are typically (although not exclusively) in some way involved with the programme and, as such, will potentially be biased, with the most likely risk being that the perspectives offered are likely to be supportive of the programme. However, those that were previously involved in the programme (and are no longer) may be critical of the programme, and indeed critical from an informed perspective. In either case, it is important to note that those who are informed enough to provide information on the programme are likely to have had some direct engagement with the programme and, as such, are likely to bring their own personal perspective to the information provided. As such, analysis of the data provided need to be conducted in the context of those personal views and experiences.

Interviews were conducted by one of two researchers on the project team by telephone and took between 30 minutes and 1 hour. For the first few interviews, both interviewers joined the interview so that they could ensure that they were taking a similar approach and had a shared understanding of the protocol and how it should be applied. The remaining interviews were undertaken by one interviewer only. Interviews were recorded, but the recordings were kept for internal use only and were destroyed after completion of the analysis.

The interview questions were open ended and the protocol was flexible to allow the interviewer to focus on the most relevant questions for that particular stakeholder. A semistructured approach ensured that interviewers covered a consistent range of issues in each interview, but also allowed the particular context and circumstances relevant to the different groups to be discussed. The protocol consisted of three main sections. The first section was of a set of introductory questions to explore the informants’ backgrounds and engagement with the HTA programme. This information, together with our prior knowledge and research on the key informants, allowed us to select the relevant subsets of questions to ask in the second section, which was a set of focused questions relevant to particular perspectives (e.g. questions on policy impact, international impact or academic impact). The final section covered some overview questions about the impact of the programme at a high level, which could be used as required to pick up any issues not covered in the second section. The full protocol, including the detailed questions for all three sections, is provided in Appendix 1.

Interview notes were written up by the team member who carried out the interviews. These notes were intended to be comprehensive in capturing the points made by the interviewee, and were compiled with reference to the interview recording but were not word-for-word transcriptions. However, when the interviewers identified particular quotes of interest, the interviewers transcribed those quotes verbatim from the interview recordings. These notes were coded in NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), a qualitative analysis software package, against a common codebook. Initially interviews were double coded by both interviewers to ensure consistency in coding and a common understanding of the codebook. Subsequently, the interviews were coded by one interviewer (the person who had conducted the interview). The initial codebook was generated based on previous experience and a review of the study aims and questions, but was developed iteratively over the coding process, with new codes added as required, and regular meetings taking place between the two coders to ensure that all interviews were coded consistently and that any new codes added were applied to all interviews, and that there was a common understanding of the meaning of the codes used. The same codebook was also used for the analysis of the case studies to allow cross-comparisons across both data sets to be made. A full version of the final codebook is provided in Appendix 2.

Bibliometrics

Bibliometrics is the study of scientific publications and their dissemination and use in the scientific community. It offers a powerful set of methods and measures for studying the structure and process of scholarly communication, and has become a standard tool of science policy and research management. Bibliometrics utilises quantitative methods to analyse patterns of scientific publications and their citation, based on the reference lists of scientific journal articles. Citation analysis, a component of bibliometrics, is used extensively to measure the impact and quality of scientific work, as well as the intellectual influence of scientists and scholars. Primarily, it is based on the assumption that new papers will cite other articles that are perceived as useful for informing new research. In this regard, a citation is viewed as a measure of the ‘utility’ and ‘visibility’ of a piece of research. If a researcher or a piece of research has more utility as shown by a larger number of citations, it is assumed that the research is of higher quality. Therefore, a citation is perceived as a proxy for research quality and a measure for research achievement and excellence.

Benefits, drawbacks and common pitfalls of bibliometrics

The advantages of bibliometric methods are straightforward: they provide a quasi-objective and quantitative method of evaluating the performance of research, researchers, institutions and research systems. However, caution is needed when interpreting bibliometric results, as a number of caveats and drawbacks exist.

First, and foremost, citations are not a complete representation of research quality and are only ever a proxy. Bibliometric analysis provides a quantitative reflection of research performance and does not take into account the nuance that can be achieved with a more in-depth, qualitative analysis. Although it is generally accepted that there is a strong correlation between citations and scientific quality at the article, individual researcher and national levels, it does not necessarily follow that an article with a low number of citations is of low scientific value. Furthermore, ‘impact’ as demonstrated by a high level of citation should be considered in a narrow sense as impact within academia, and does not necessarily imply that the research will go on to impact on policy, practice or society more widely. 39 In order to build a more complete picture of research quality and impact, bibliometric indicators should be considered alongside other research evaluation methods, as we have done in this study. It is also important to use a variety of bibliometric indicators, as each has its own particular strengths and weaknesses, for example in relation to sensitivity to skewed distributions or small sample sizes. The specific indicators used in this study are explained further below.

Another issue to be aware of is that different research fields exhibit different citation patterns, with some fields attracting a larger number of citations than others. This can be attributed to a number of factors, including the size of the field; the number of journals and the number of times per year these journals are published; the number of journals indexed in Web of Science (WoS); and the publication norms of the field (e.g. the publication of research as book chapters rather than journal articles is more common in the humanities than the fields of natural and social sciences). These factors contribute to research in some fields having a higher probability of being published and/or cited. Additionally, assessment can be distorted by ‘fashions’ in particular fields; areas seen as particularly topical may attract large amounts of funding, more researchers and more citations. It is possible to control for these differences between fields, to some extent, and further detail on how this was achieved in this study is provided below.

Citations can also sometimes be manipulated by researchers and research organisations to unfairly represent the value of their scientific output. Citation counts can be enhanced by researchers citing their own work (self-citations) as well as researchers publishing flawed or controversial work that is likely to gain a number of citations in other articles that criticise the original research. These types of ‘negative citations’ are not easily recognised using bibliometric analysis, as all citations are assumed to be equal. Identification of negative citations requires a more in-depth, qualitative analysis, which is resource intensive and outside the scope of the current study.

Finally, bibliometric analysis tends to under-represent the research output of non-English speaking countries. The majority of journals indexed in citation databases, such as WoS, are English-language journals and the small number of non-English-language journals indexed may unfairly represent the value of research published in other languages. This issue should not prove particularly problematic in evaluating the HTA programme’s research, as it can reasonably be assumed that all project outputs are published in English.

Bibliometrics in this study

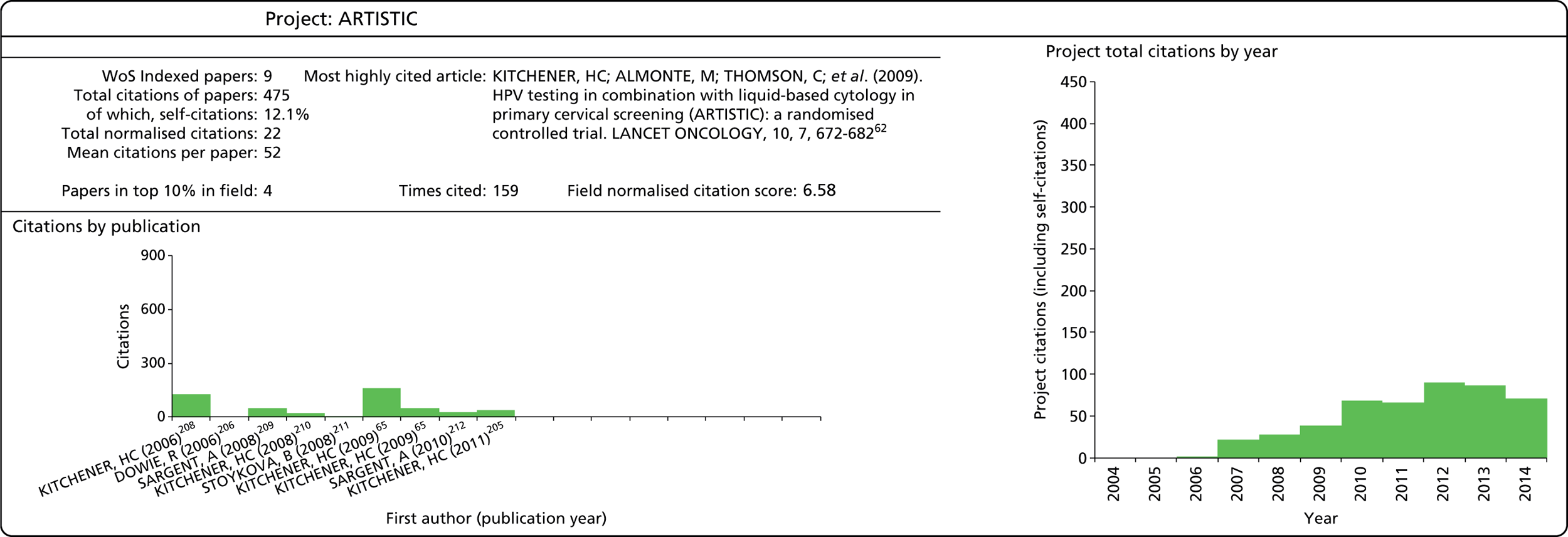

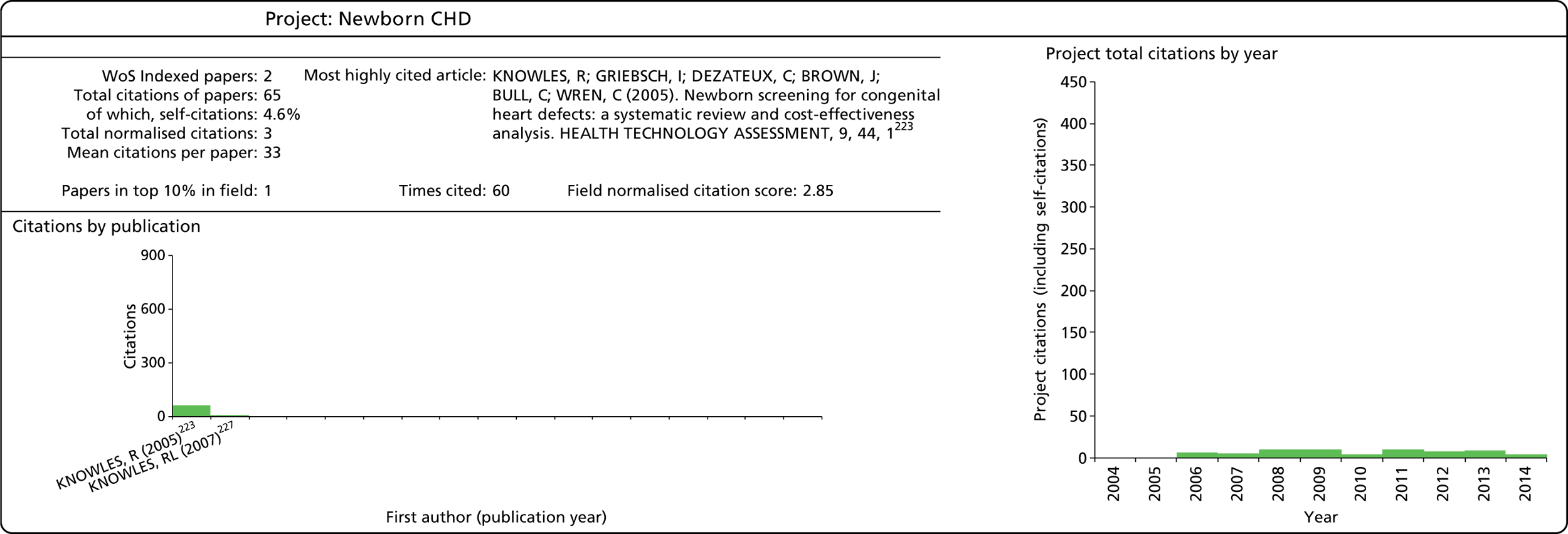

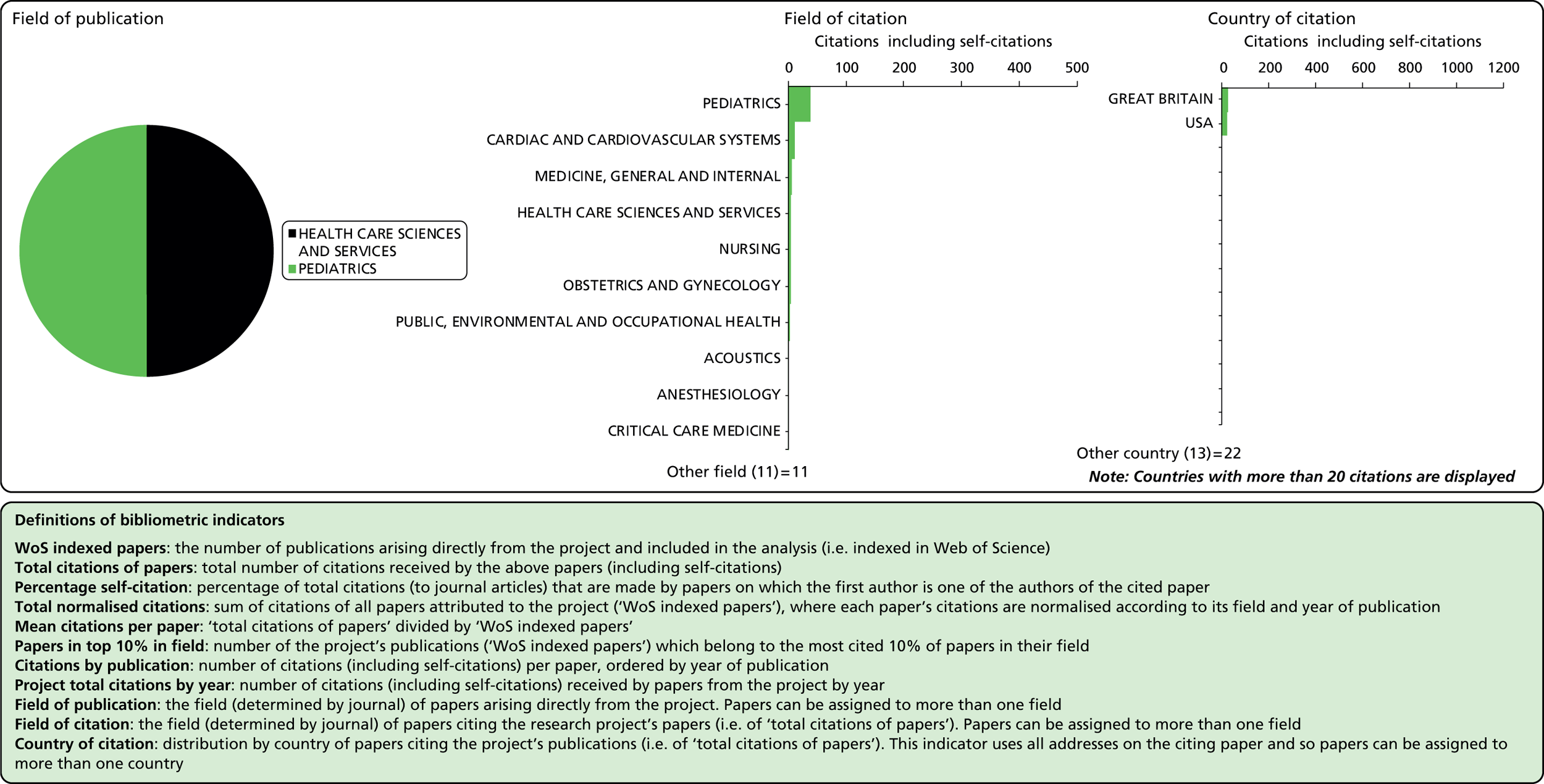

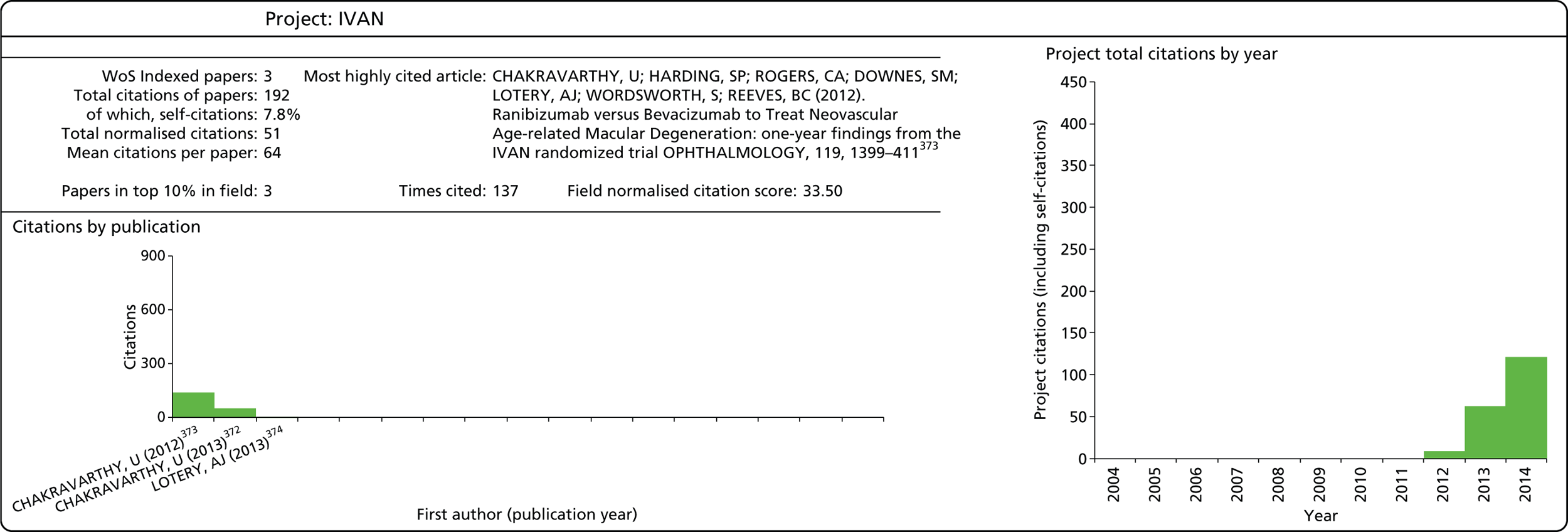

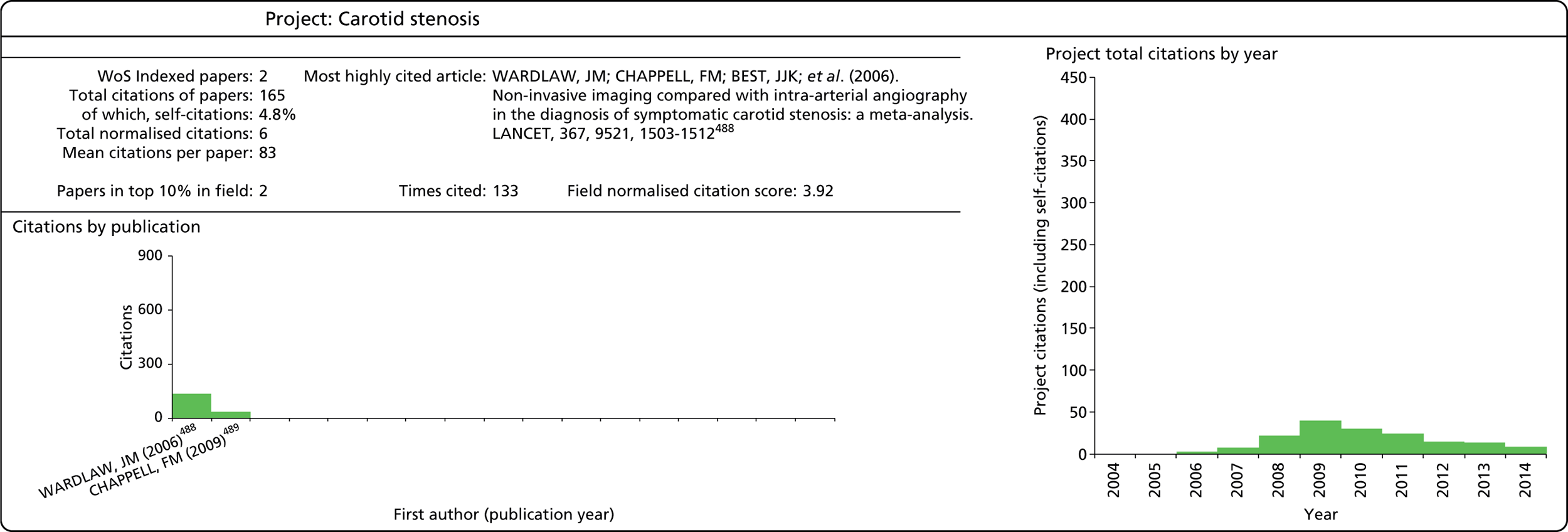

Bibliometric analysis was used in this study to provide a quantitative analysis of the academic output and impact of HTA programme-funded projects. It was carried out at two levels: an overall assessment of the entire HTA portfolio and specific project-level profiles of the studies selected as case studies. Although many of the indicators were the same for these two purposes, there were differences in the methods used, particularly in compiling the relevant data. Each of these is described below, in turn (see Identifying the Outputs of Health Technology Assessment programme-funded research).

Bibliometric data source

The Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) was contracted by RAND Europe to provide the bibliometric analysis for this project. CWTS is an interdisciplinary research institute housed within the Faculty of Social Sciences at Leiden University in the Netherlands, which specialises in advanced quantitative analysis of scientific research and its connections to technology, innovation and society.

The CWTS maintains a bibliometric database of scientific publications for the period 1980 to the present, generated from the Thomson Reuters WoS database. WoS is a bibliographic database that covers the publications of about 12,000 journals in the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the arts and humanities. Each journal in WoS is assigned to one or more subject categories representing different fields of research. The CWTS in-house database makes a number of improvements to the original WoS data, most importantly by using a more advanced citation-matching algorithm and an extensive system for address unification. The database is based on the journals and serials of the Science Citation Index and associated citation indices: the Science Citation Index, the Social Science Citation Index, and the Arts & Humanities Citation Index, extended with six so-called specialty Citation Indices (Chemistry, Compumath, Materials Science, Biotechnology, Biochemistry & Biophysics, and Neuroscience).

Identifying the outputs of Health Technology Assessment programme-funded research

Programme level

The programme-level analysis required two different types of publication to be identified: papers published in the HTA journal and outputs from HTA programme-funded projects published in other WoS indexed journals. Three different data sources were used to compile the complete publication list:

-

All articles and reviews published in the HTA journal during the period 2004–12. This list comprised 512 papers.

-

Papers listed on all HTA project pages of the NETSCC website (data provided by NETSCC). More than 80% of these papers were matched to the CWTS database, resulting in a list of 474 papers to be included in the analysis.

-

Papers reported by researchers in Researchfish. Matching this list to the CWTS database resulted in 331 unique papers (excluding those published in the HTA journal).

Papers that were not matched to WoS in lists (2) and (3) tended either to have been published too recently to have been indexed in the database or be editorial material (our analysis included only articles and reviews, as other document types do not usually contribute substantially to scientific knowledge). Once duplicates were removed from lists (2) and (3), the final data set comprised 1087 papers.

Although we are confident that this data set covers the majority, and likely the most visible/cited portion, of HTA programme-funded outputs, there will inevitably be publications that are not included. A number of other methods of verifying our data set and identifying missing papers were tested to explore how comprehensive our list was:

-

A review of the NETSCC and Researchfish data revealed that although the NETSCC data appeared to be more complete, Researchfish often provided additional publications for currently active projects, suggesting that it may be particularly useful in identifying more recent publications and that both sources were valuable in building a robust data set for this study.

-

An alternative approach to identifying HTA programme-funded publications would have been to build the data set up from individual papers that acknowledge the HTA programme as their source of funding. Since 2008, WoS has systematically recorded this information, when available, from papers. A brief search revealed more than 20 valid variants of the HTA programme’s name (e.g. UK HTA, HTA programme, NIHR HTA), and these variants retrieved around two-thirds of the number of papers in our existing data files for the covered time period, suggesting that many publications do not acknowledge the HTA programme in an easily recognisable form. Given this variation, and the fact that the acknowledgement data in WoS are available from only mid-2008 onwards, this approach was not considered a reliable and efficient method for contributing to the set of publications for this study.

-

For a small sample of projects we searched WoS for the associated grant number, for which there is also a specific field. However, grant numbers are not always provided in a consistent format in publications and this approach also proved unreliable.

Project level

Publication lists for individual case study projects were initially compiled from the sources used at the programme level and a review of the CI’s publication record in WoS. The resulting list was then shared with the CI for verification.

Indicators

As noted above, it is useful to use a variety of bibliometric indicators to reflect different aspects of the HTA programme’s research output. A summary of these is provided in Table 4. A more in-depth discussion of the meaning and use of these indicators follows below.

| Indicator | Description |

|---|---|

| Number of publications | Number of individual publications produced |

| Field of publication | The field of the journal in which a paper appears, based on WoS subject categories; journals can be categorised to more than one field |

| Number of citations | Total number of citations |

| Field of citation | The field of the journal of a citing paper, based on WoS subject categories; journals can be categorised to more than one field |

| MNCS | Average number of citations, normalised according to each paper’s field and year of publication, relative to the world average |

| MNJS | The average number of citations received by articles in a journal in a field, relative to the world average |

| Papers in top 10% in field | Percentage (or number) of publications that belong to the most cited 10% of papers in their field |

| Collaboration | Articles including authors from more than one institution (based on all author addresses) |

| International collaboration | Articles with at least one author with an address outside the UK |

Number of publications

This indicator is calculated simply by counting the total number of publications attributable to the HTA programme or to a particular project. Only publications classified as an article or review in WoS are taken into account. Publications of other document types usually do not make a significant scientific contribution and are commonly excluded from bibliometric analysis.

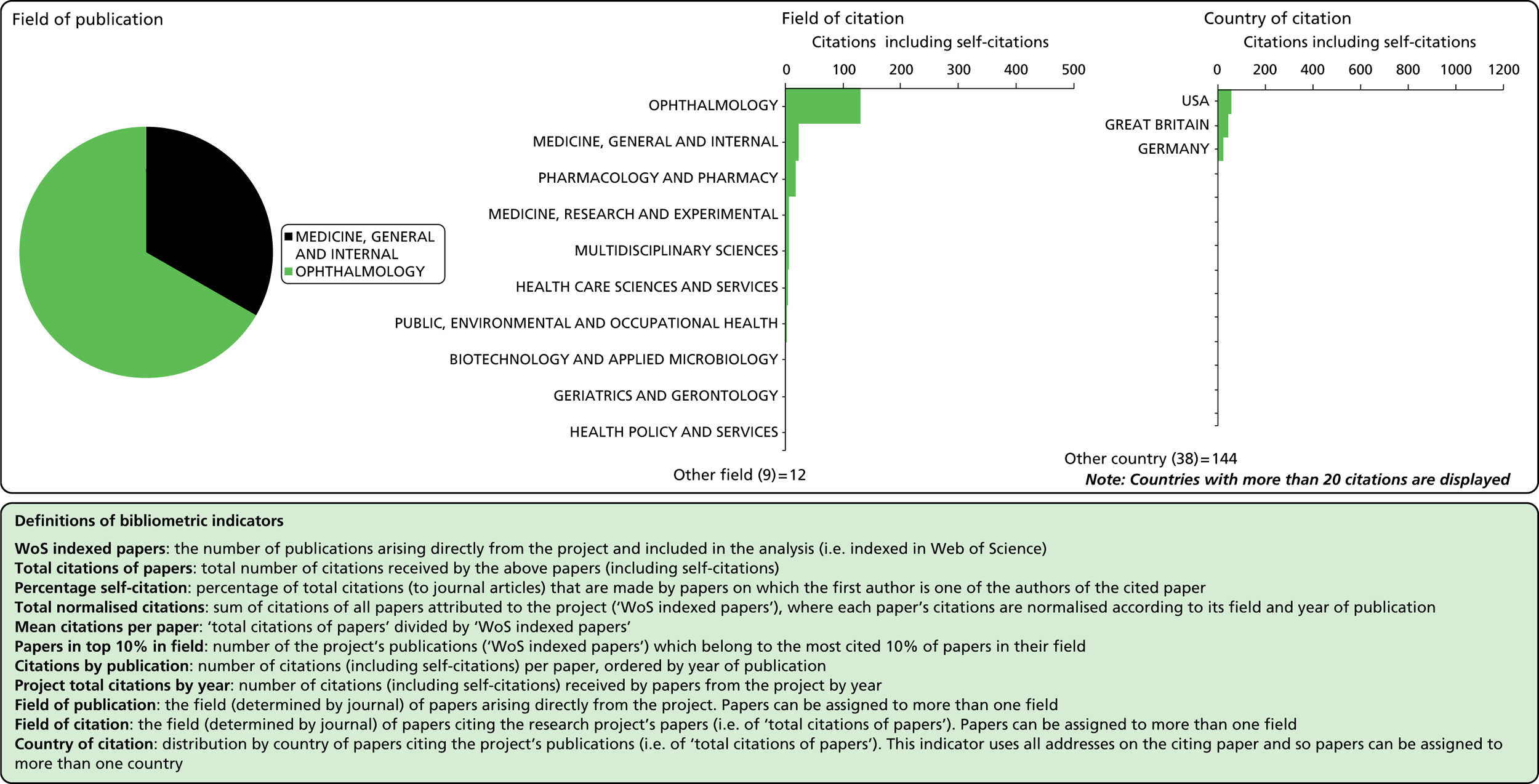

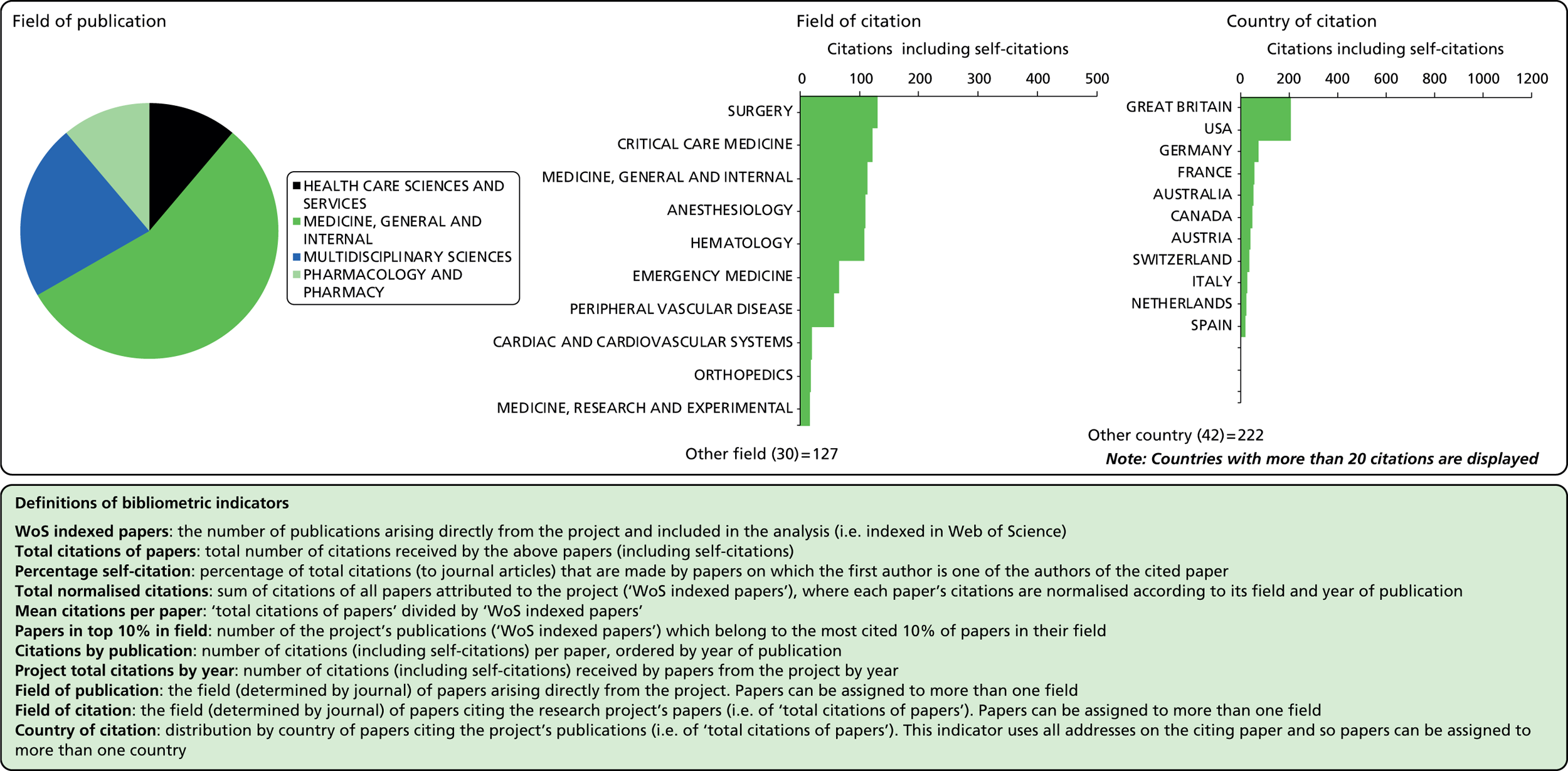

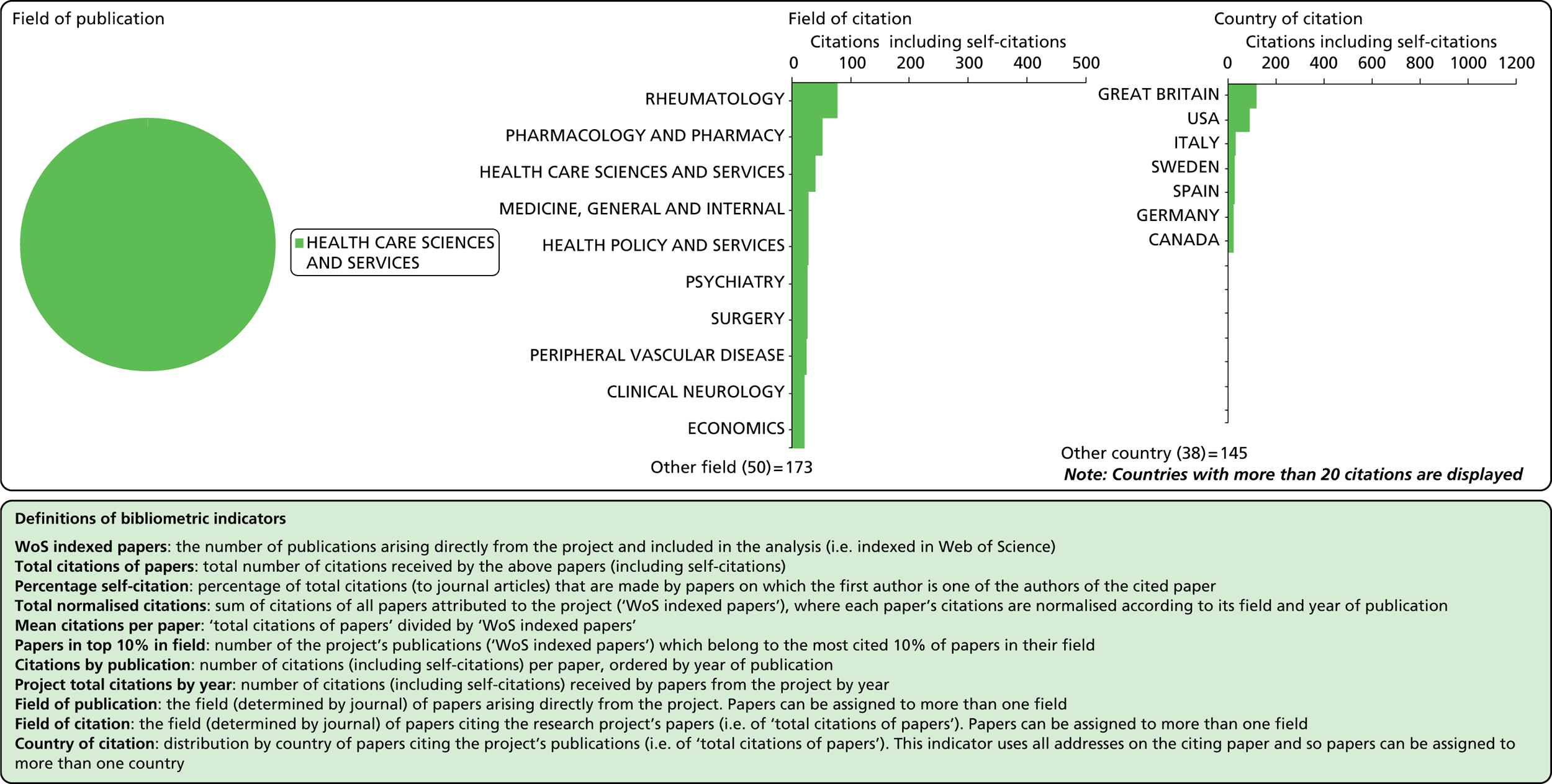

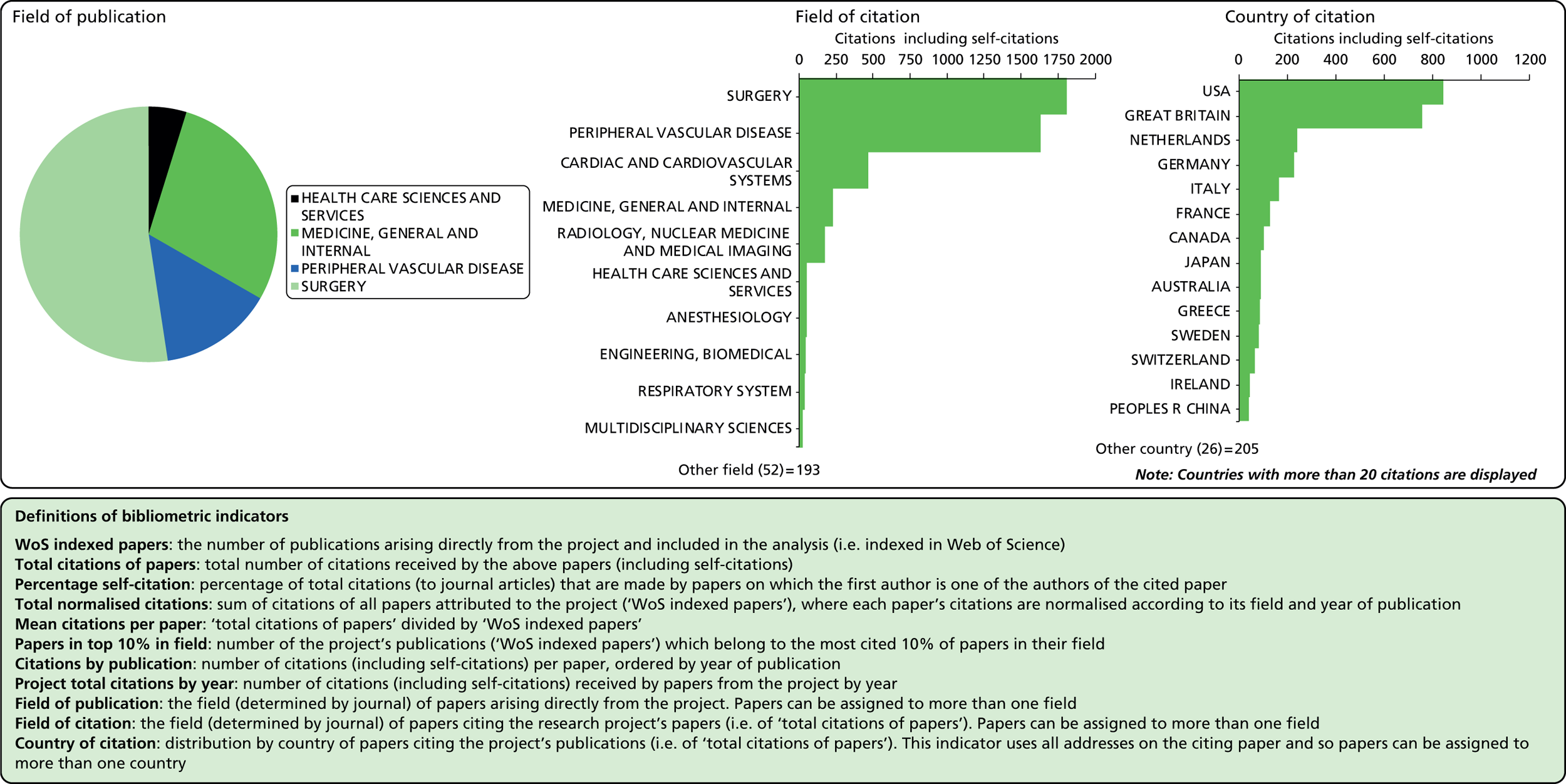

Field of publication

Each journal in WoS is assigned to one or more subject categories, of which there are approximately 250. These subject categories can be interpreted as scientific fields, and thus the field to which a paper belongs is determined by the journal in which it is published. Publications in multidisciplinary journals such as Nature, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and Science are individually allocated, if possible, to subject fields on the basis of their references.

Number of citations

This refers to the total number of citations that an article has received during the period 2004–13. In this analysis, a variable citation window has been used, i.e. the time period over which citations are counted varies according to the year of publication (papers published nearer the start of our study period have had more time to accumulate citations). Given this, it is important to also consider a normalised indicator that takes account of the variable citation window, as described below.

Field of citation

Considering the fields in which a particular paper has been cited can provide some indication of the diffusion of knowledge to different scientific fields. As noted above, the field of a paper is determined by the WoS subject category (or categories) to which the journal in which it appears has been assigned.

Mean Normalised Citation Score

Normalisation is applied to correct for differences in citation characteristics between publications from different scientific fields and between publications of different ages (in the case of a variable-length citation window). The normalised citation score of a publication is the ratio of the actual and the expected number of citations of the publication, for which the expected number of citations is defined as the average number of citations of all publications in WoS belonging to the same field and having the same publication year. The Mean Normalised Citation Score (MNCS) indicator is then obtained by taking the average of the normalised scores of all papers produced by a programme, researcher, institution, or other unit of analysis. If the MNCS has a value of ‘1’, it means that, on average, those publications have been cited as frequently as the world average for papers in their field and of similar age. Similarly, a score of ‘2’ would indicate that, on average, the papers are cited twice as often as would be expected for that field and publication year. A score of ‘< 1’ indicates a citation level that is below the world average.

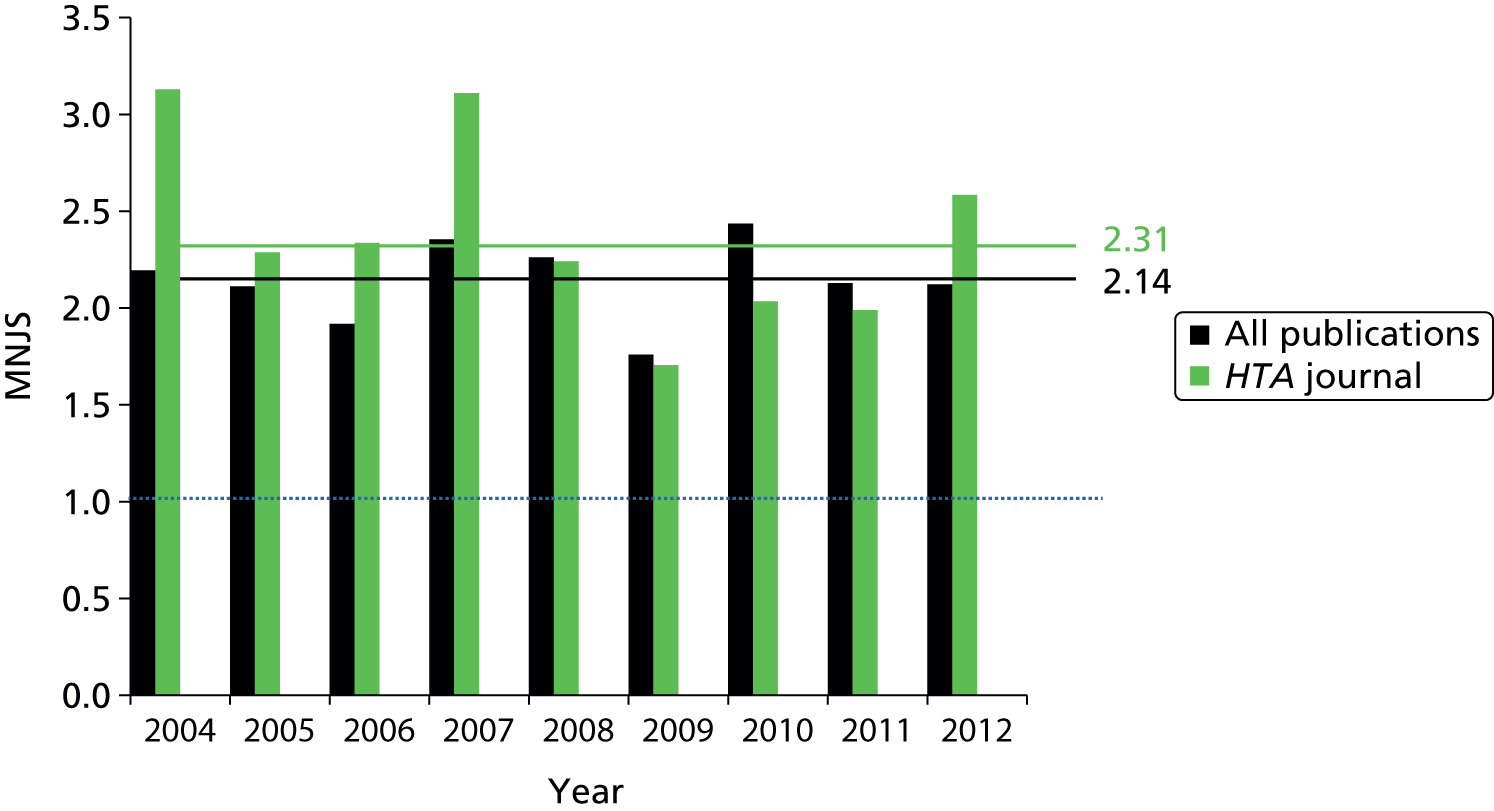

Mean Normalised Journal Score

This indicator, closely related to the MNCS, is a measure of the visibility of the journals in which the papers of a researcher, institution, programme or other unit are published. The difference is that rather than using the actual number of citations of a paper, as in the MNCS, it uses the average number of citations of all articles published in a journal in a specified year. The interpretation of the Mean Normalised Journal Score (MNJS) indicator is analogous to the interpretation of the MNCS indicator. If a unit has a MNJS indicator of ‘1’, this means that, on average, papers appear in journals that are cited as frequently as would be expected based on the field to which they belong.

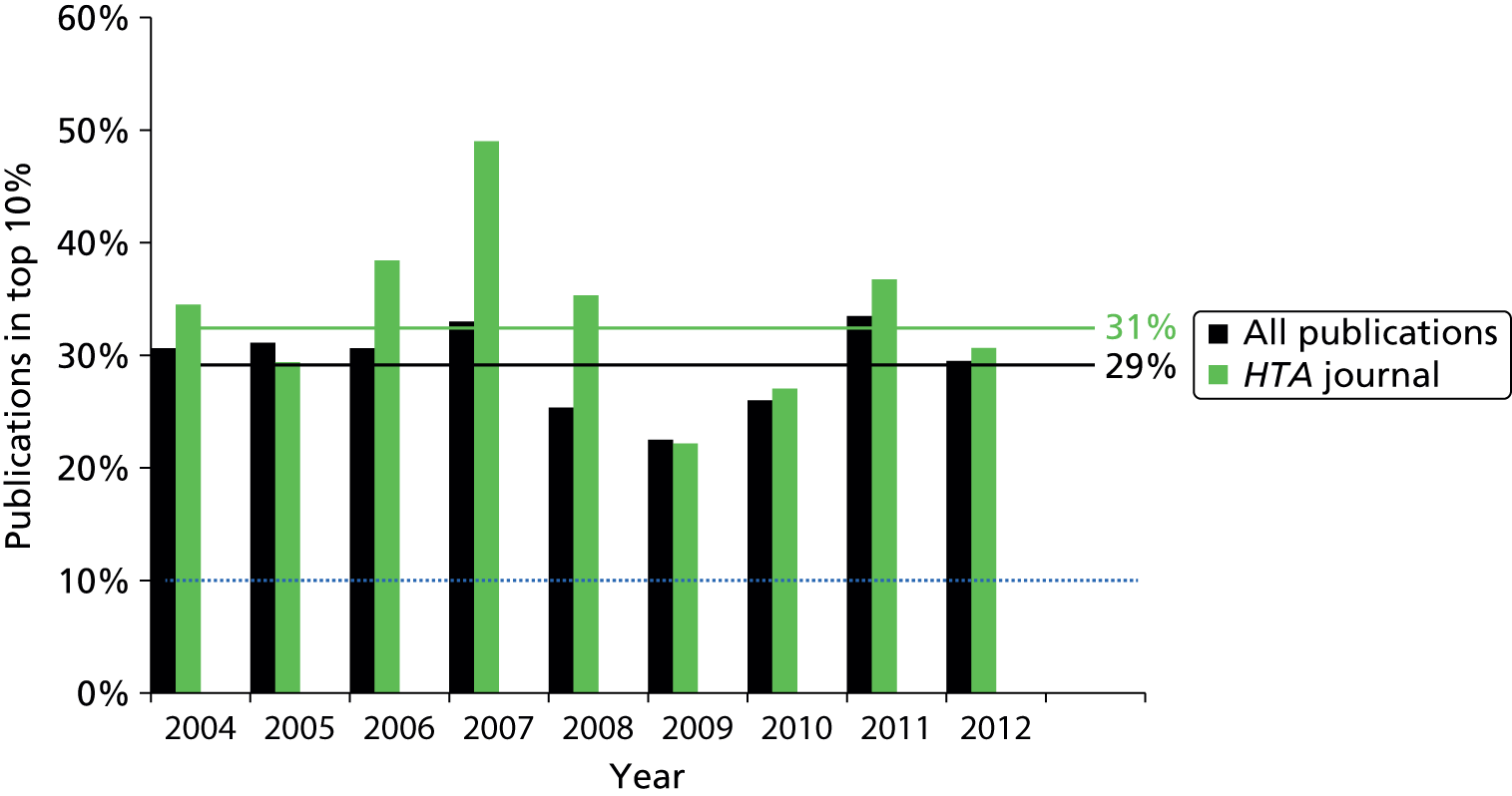

Papers in top 10% of field

Alongside the MNCS, we also look at this indicator as a measure of citation impact. It is the percentage of publications (of a programme, researcher, etc.) that belong to the most cited 10% of papers in their field published in the same year. For example, a research programme with 20% of its papers in the top 10% for its field would be doing twice as well as an average programme. This indicator is complementary to the MNCS, in that although both are measures of utility or impact, they are sensitive to different aspects of the distribution of the sample of papers. One of the weaknesses of the MNCS indicator is that it is sensitive to extreme outliers in the data; one very highly cited paper can skew the mean dramatically. However, a paper belongs to the top 10% if it is cited more frequently than 90% of similar papers, regardless of the actual number of citations. The weakness of this indicator is that there is a somewhat false dichotomy created between the top 10% and other papers, whereas at the boundary the actual difference in citation level can be very small. Considering it alongside the MNCS provides a more complete picture of the distribution of publications.

Indicators of collaboration

Indicators of scientific collaboration are based on an analysis of addresses listed in the publications produced by the research unit. Collaboration exists when authors are from more than one institution, and international collaboration exits when at least one of these institutions is outside the UK.

Analysis of Researchfish data

All HTA awards that were active from June 2003 onwards were taken as a sample for the portfolio of work funded by the HTA scheme. TARs are excluded from Researchfish, because the nature of the TARs, for which researchers often move therapeutic area with each piece of work, means that it would be very difficult for researchers to track the impact of any one piece of work. In addition, researchers will have involvement with many TARs, so it would be particularly burdensome to report on. We were able, however, to collect evidence about the impact of TARs through a case study.

Researchfish is an online questionnaire that enables research funders and research institutions to track the impacts of their investments, and researchers to log the outputs, outcomes and impacts of their work (www.researchfish.com). It is currently used by more than 90 funders in the UK and internationally to gather information from researchers about the outcomes from their work. The question set descends from the Arthritis Research UK’s RAND/ARC Impact Scoring System and MRC’s e-Val. 39

The project team used Researchfish, rather than a bespoke survey, because the NIHR already held data on the impact of HTA awards since 2009. This allowed us to reduce the burden on the HTA researchers by reducing the duplication of information requests. Similarly to other questionnaire-based data collection, Researchfish data have various limitations – which is why it was used in concert with other forms of evidence. The data are self-reported and therefore could be biased towards the categories of impact that the researcher deems most valuable. For researchers who are unfamiliar with the Researchfish interface, limited time may mean that they put in only a selection of their impacts. The project team were not aware of any research on the accuracy and completeness of Researchfish data.

The request for data went out to a total of 619 awards. The submission period in Researchfish was open for 5 weeks, between 6 August and 10 September 2014. The chief investigator (CI) for each award was sent a request to complete the survey, and two reminders while the survey was live. Overall, 109 awards responded to the request for data. Data – submitted for the annual NIHR submission in November 2013 – were already held on an additional 269 awards, and, subsequently, these were combined with data collected for the annual NIHR submission in November 2014, providing data on an additional 44 awards. Therefore, combining the sources, we had data on 68% (422/619 awards). A consequence of this data collection method, which builds on a precollected data set, is that our sample is likely to be biased towards more recent grants because they are required to report through Researchfish on an ongoing basis.

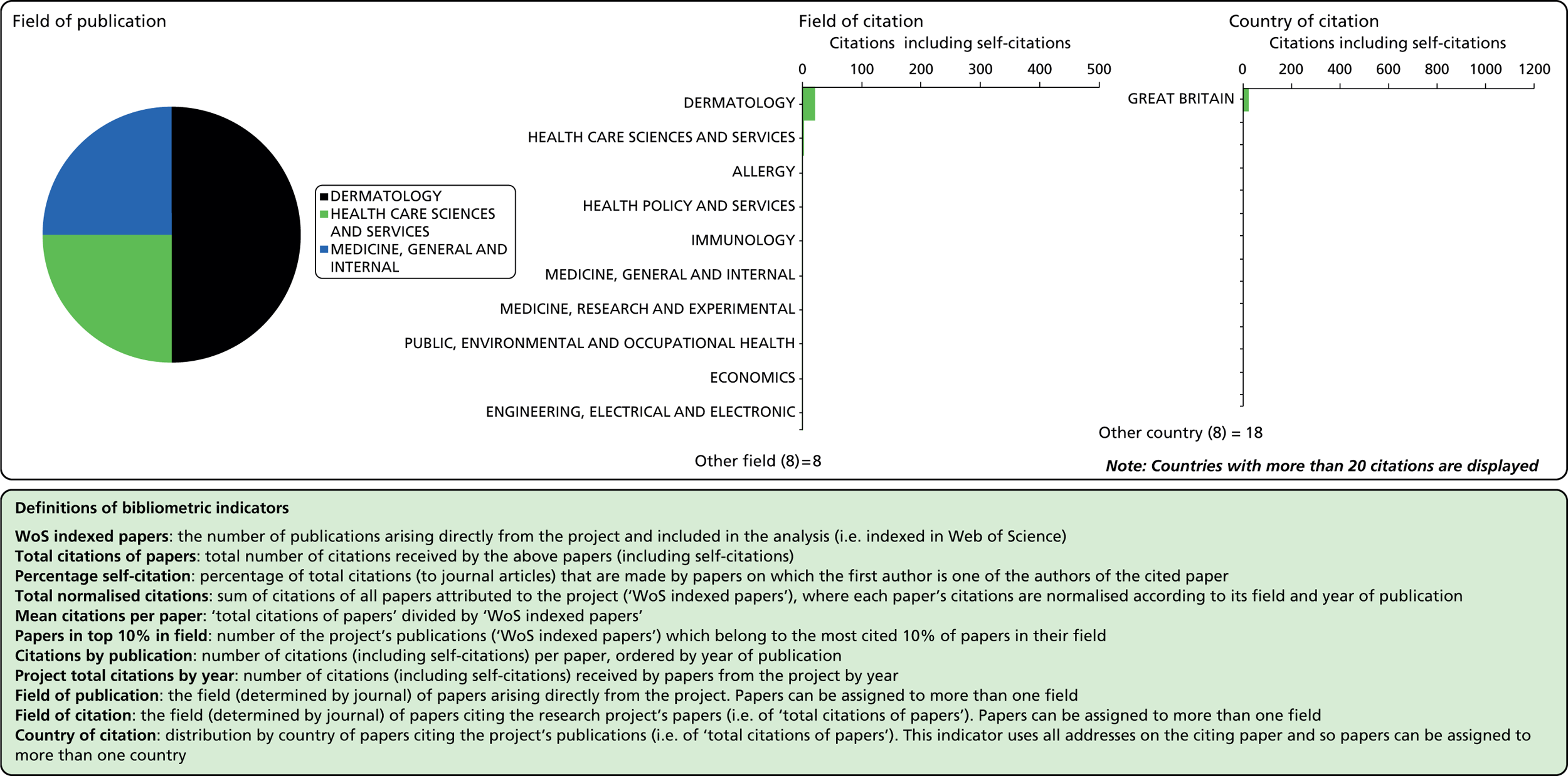

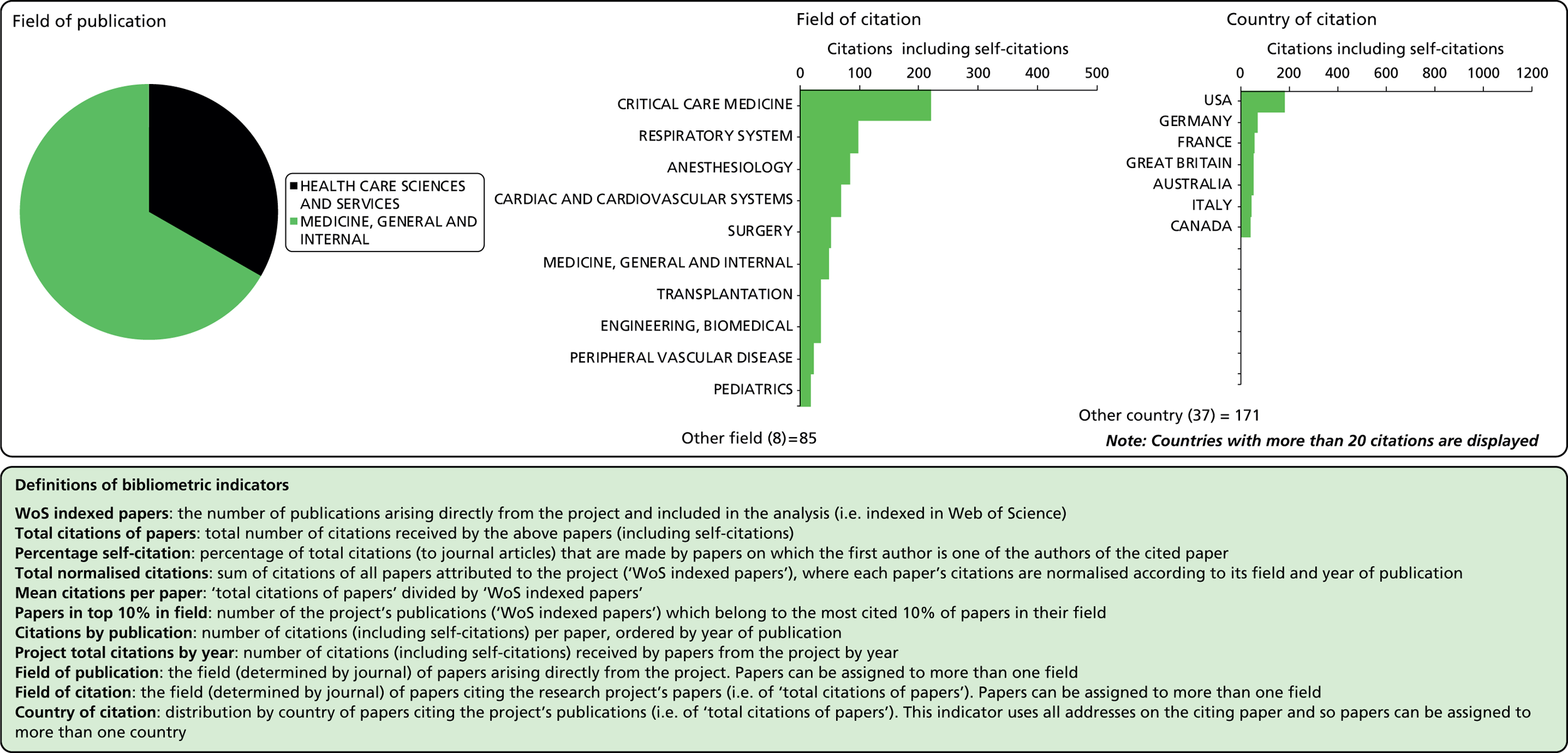

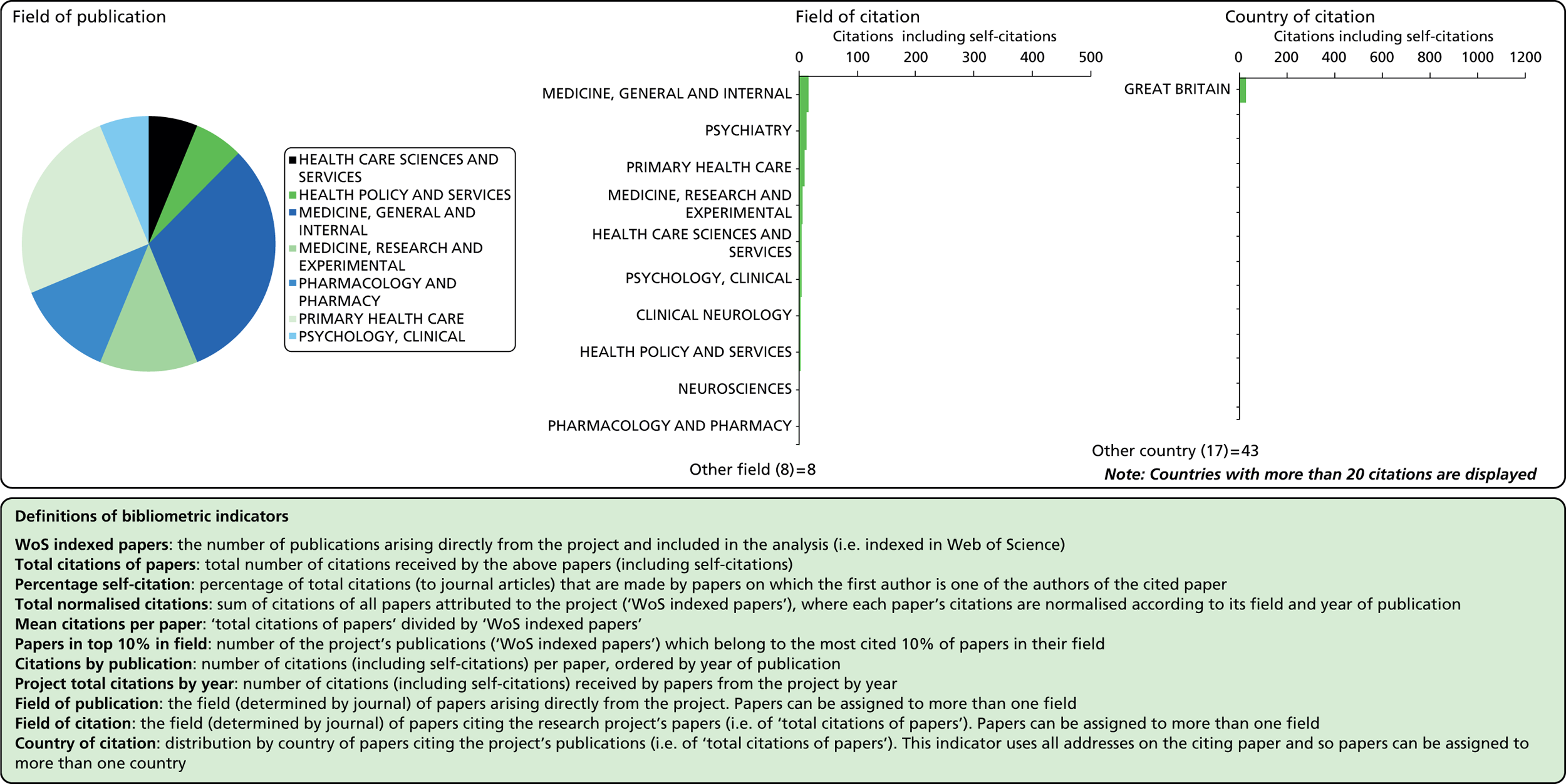

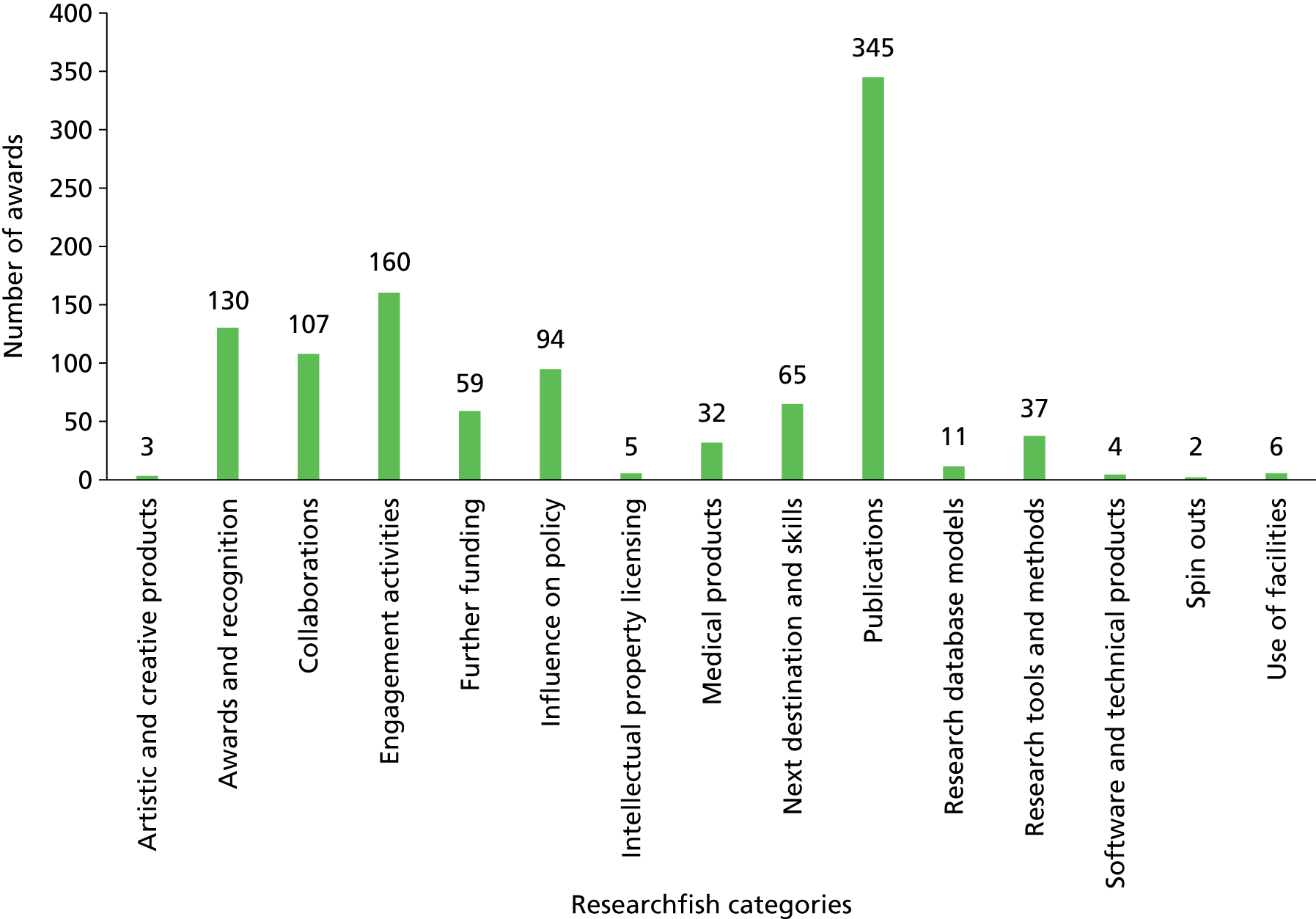

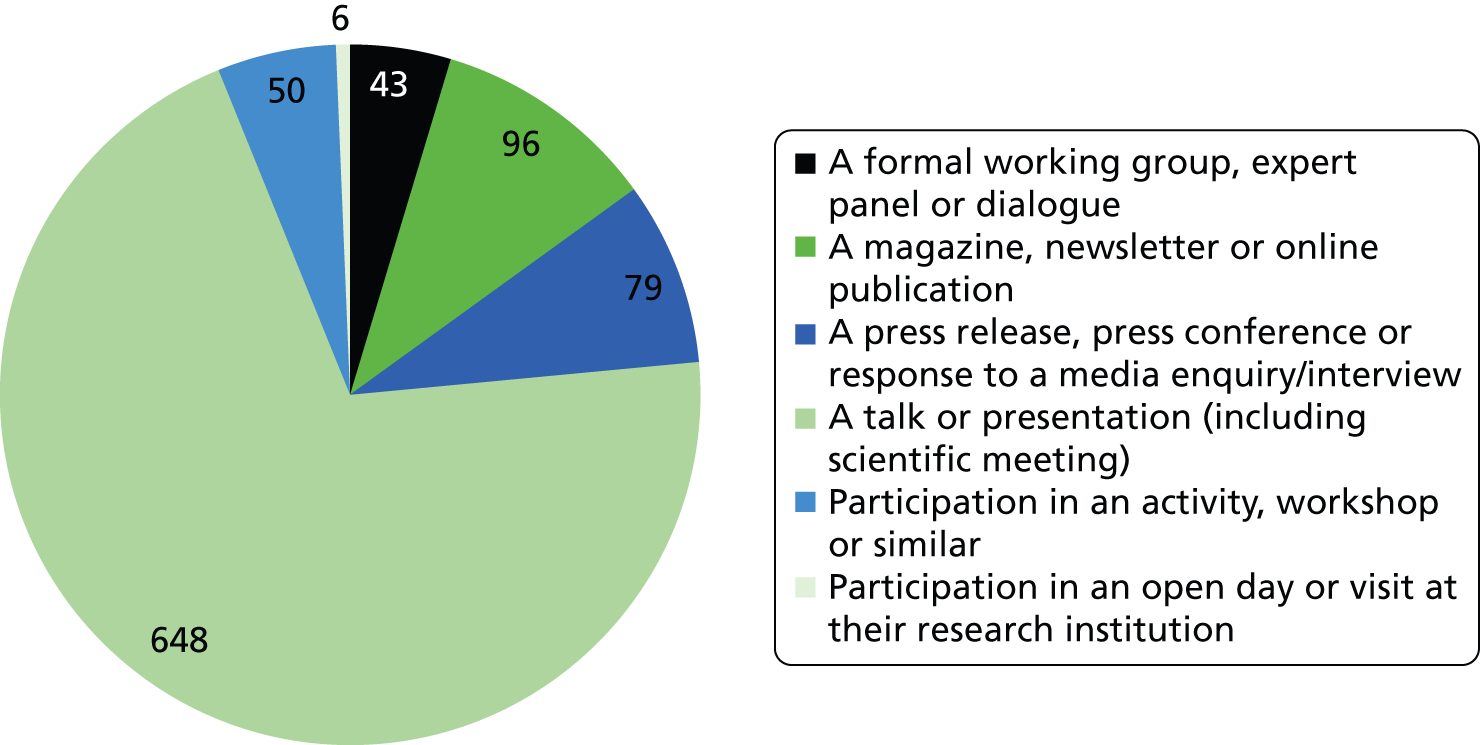

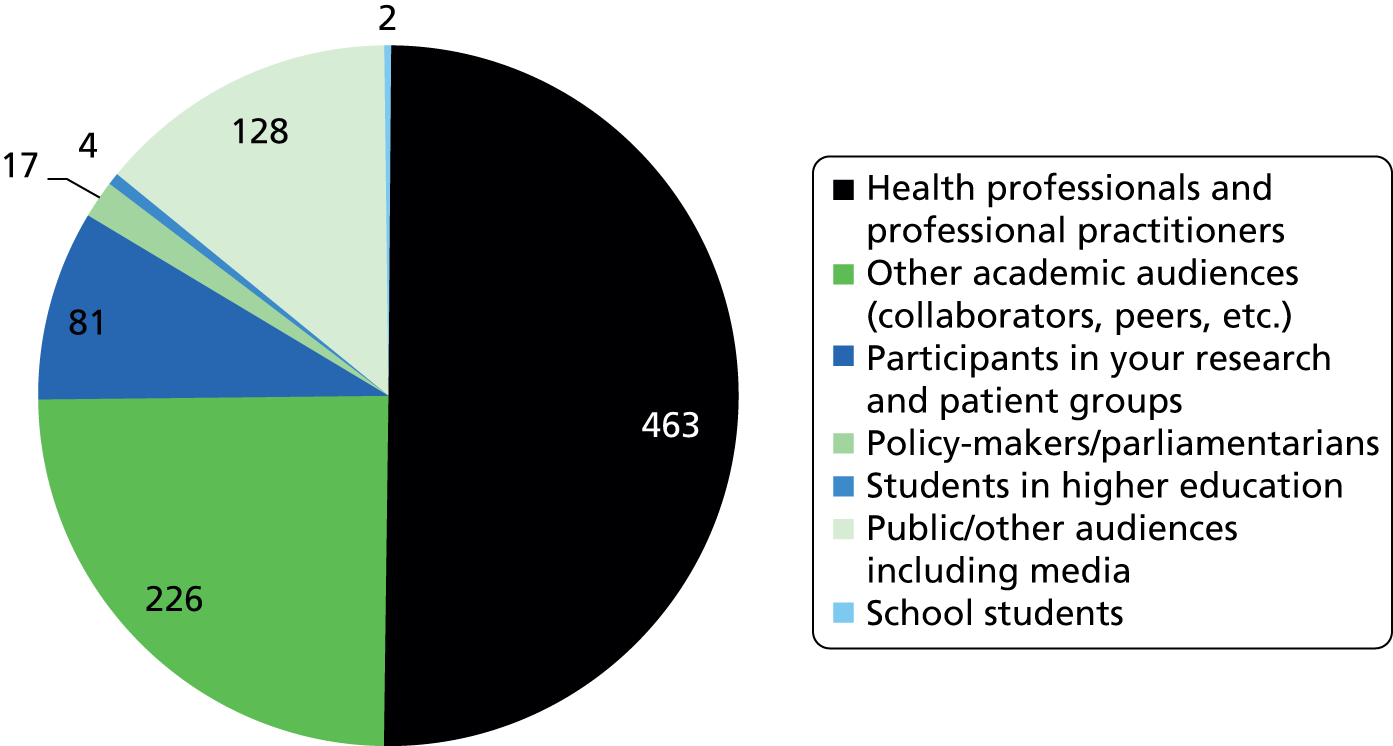

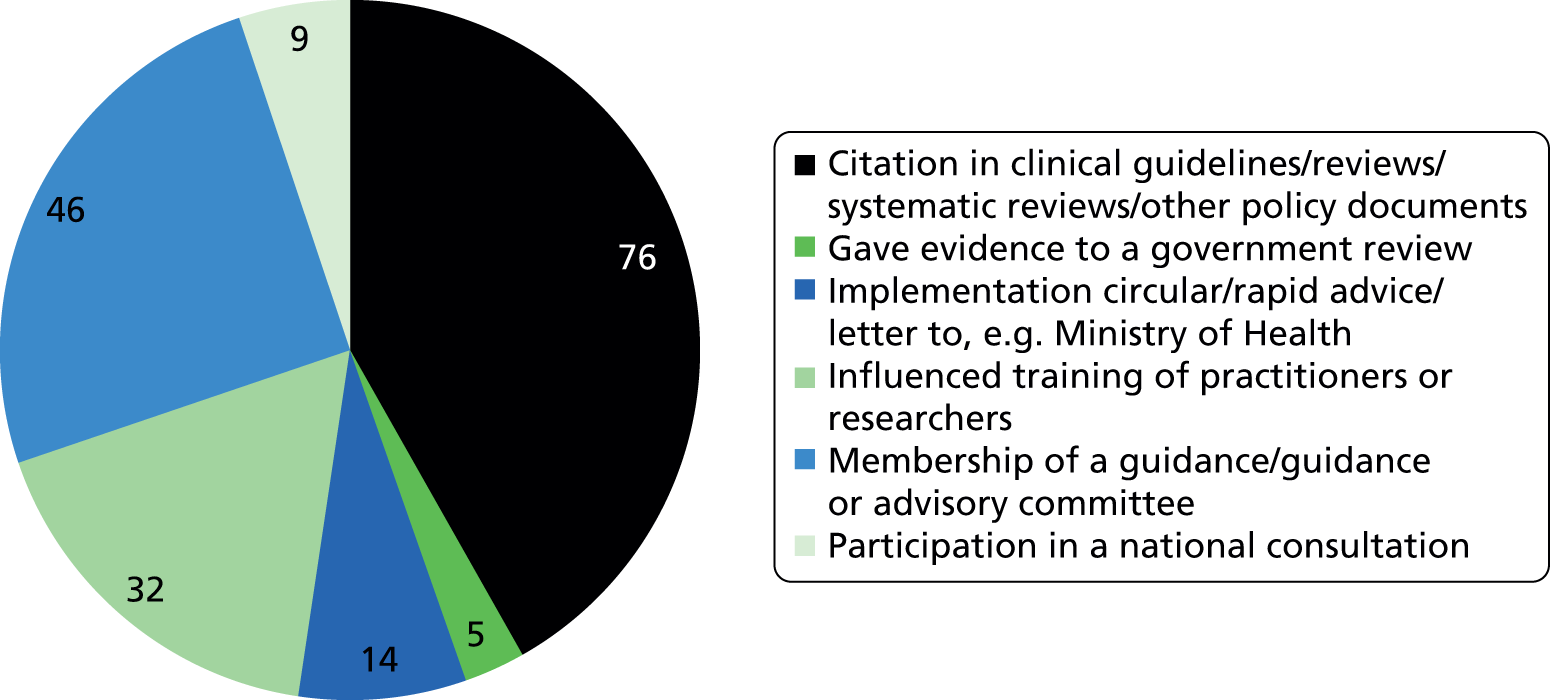

Researchfish is structured to allow researchers to provide data on a wide range of impacts (across all of the payback categories); however, there is no requirement for researchers to indicate ‘none’ in categories for which they have not had an impact. This means that it is not possible to calculate response rates for individual categories or questions. Overall, 2099 pieces of data were captured across the 13 categories of impact, as defined within Researchfish (Figures 1 and 2). We used Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to analyse the data on the impact of the portfolio. We also used the bibliometric information as a factor in the selection of case studies.

FIGURE 1.

Number of instances of each category of impact in Researchfish recorded for the NIHR HTA programme.

FIGURE 2.

Number of HTA awards reporting impacts in the Researchfish impact categories.

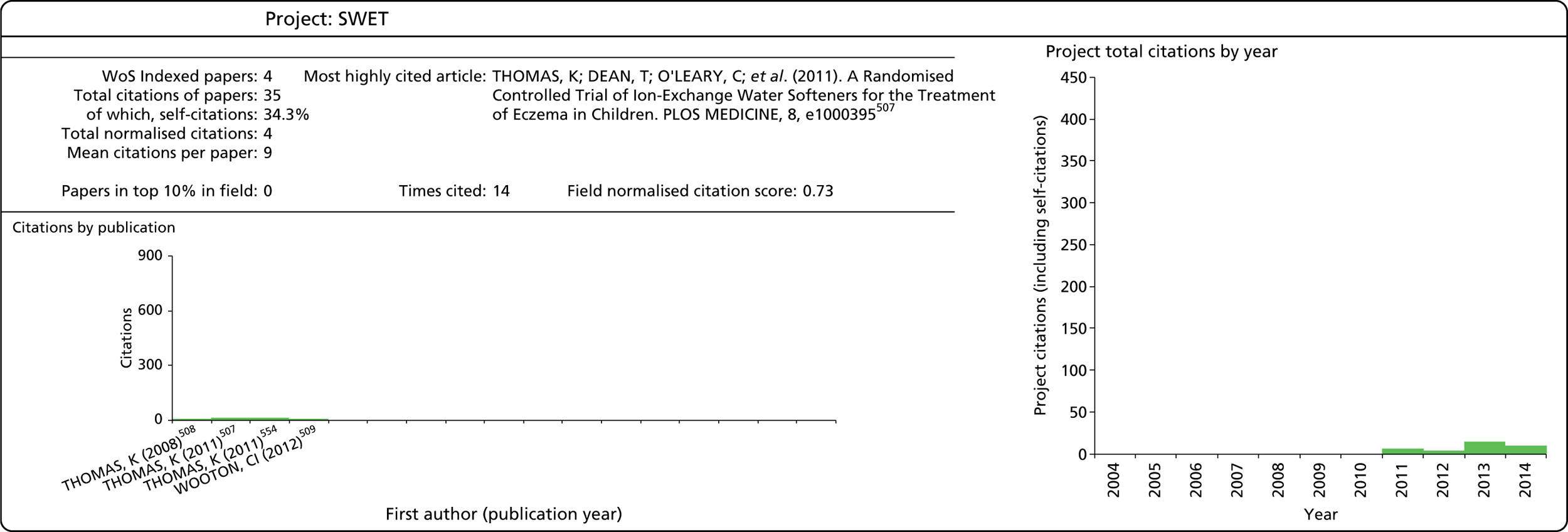

Case studies

Case study selection

We conducted 12 case studies with individual HTA projects as the unit of analysis for the case studies. As described at the start of the chapter, the case studies were conducted using a payback case study approach. Following the discussion with the advisory board, we decided to select a purposive sample of case studies of projects that we expected to have had high impacts across a range of different areas. The intention was that this would allow us to explore the range of impacts emerging from the HTA programme and the routes by which that impact occurred. One disadvantage of this selection approach was that it tells us less about cases in which research did not have an impact – to partially address this we examined the barriers to impact that our case studies had overcome. The selection approach also means that we cannot generalise from the case studies to extrapolate the overall impact of the HTA programme. In addition, case studies were chosen to reflect the diversity of the research funded through the programme. Overall, case study selection was based on four main criteria:

-

high impact

-

mix of primary research, evidence synthesis and TARs

-

mix of research areas

-

timing of the publication of final results.

Each of these is described in more detail below.

High impact

In order to identify relevant studies for inclusion, we compiled a long list of potential studies for inclusion from the following sources:

-

high-impact projects listed on the HTA website

-

projects highlighted at the NIHR HTA Conference 201340

-

projects highlighted by Raftery and Powell11

-

suggestions from our project advisory board

-

suggestions and examples from the key informant interviews

-

highly cited publications identified through the bibliometric analysis (among the top 15 most highly cited publications in the set of publications analysed, normalised for field)

-

projects with a range of impacts according to the Researchfish survey data.

We selected all of the case studies based on evidence that they have already had, or would likely have, a high level of impact in one or more of the following categories: knowledge production, capacity building, and policy and practice.

Mix of primary research, evidence synthesis and Technology Assessment Reports

Among the studies selected for in-depth analysis41–52 through case studies were two case studies focused on TARs,45,52 two focused on evidence synthesis42,47 and eight focused on primary research. 41,43,44,46,48–51 This distribution of case studies among the different research types funded by the HTA programme was chosen to reflect the focus of the programme over the last 10 years.

Mix of research areas

The case studies were also selected to cover the main research areas of the HTA programme: screening and diagnostics, surgery, medical devices, pharmaceuticals and mental health interventions. We included at least one, and no more than three, case studies from each of these groupings.

Timing of the publication of final results

An additional selection criterion was the timing of the studies. We required that all projects selected for inclusion had published their full study results, ideally as a final HTA journal article, at the time we started to conduct the case studies (September 2014). Initially, we considered focusing on older studies (e.g. studies that had their final HTA journal article published in 2010 or earlier) because of the time needed for research to be translated into impact. However, we decided to loosen this selection criterion for a number of reasons. First, from our work in the earlier stages of the project looking at the impact of the programme overall, and through our discussions with the advisory board, it became apparent that, in some instances, HTA research can have an impact shortly after completion, as it is typically very close to practice. In addition, the findings of HTA programme-funded research are often published in other journals well before the monograph is published in the HTA journal. Second, it became apparent that selecting an earlier publication deadline as an inclusion criterion would significantly limit our sample and would prevent us from including more recent larger studies, the size of which were previously unprecedented in the HTA programme’s history. These more recent, large studies were also longer in duration because of their scale, and hence have published their findings only recently. Even this looser criterion – that the key study findings should have been published – meant that we had to exclude some high-profile and potentially high-impact studies, such as the ProtecT Trial (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment), which had been recommended to us by a number of sources. However, we felt that it was important that the full results of the trial were at least publicly available to conduct the case studies effectively.

The final sample of case studies selected is set out in Table 5, demonstrating the range of projects covered. More description of the individual projects selected is available in Chapter 3 (see Table 6).

| Case study | Project number | Primary | Evidence synthesis | MTA/STA | Screening/diagnostics | Pharmaceuticals | Surgery | Devices | Mental health | Other | Knowledge production | Capacity building | Policy/practice | Value of award (£) | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTISTIC41 | 98/04/64 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 1,187,000 | 2001–9 | |||||||||

| Newborn CHD42 | 99/45/01 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 60,000 | 2001–5 | |||||||||

| IVAN43 | 07/36/01 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 3,346,000 | 2007–14 | ||||||||

| CRASH-244 | 06/303/20 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 2,546,000 | 2007–13 | ||||||||

| RA45 | 04/26/01 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Unknowna | 2005–6 | |||||||||