Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/167/02. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The draft report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none.

Disclaimer

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Bruce et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate

Cleft lip and palate are among the most common congenital malformations, with an overall incidence of around 1 in 700 individuals. 1,2 Approximately 90% of children with cleft palate (CP) have a history of non-trivial otitis media with effusion (OME). 1–3 OME (also known as ‘glue ear’) is the accumulation within the middle-ear space of a mucoid or serous fluid. Although the exact mechanism for the development of OME is not fully understood, dysfunction of the Eustachian tube connecting the middle-ear space to the postnasal space is thought to be of fundamental importance. The function of the Eustachian tube is to equalise pressure either side of the tympanic membrane, avoiding the development of negative pressure in the middle ear. In children, the Eustachian tube does not work as efficiently, with the resultant tendency towards the development of negative middle-ear pressure and the accumulation of fluid within the middle-ear space (OME). This tendency towards Eustachian tube dysfunction is further increased in children with CP as a result of dysfunction of the muscles originating from the palate which act to open the Eustachian tube orifice. 4,5

A prospective longitudinal study following children between the ages of 1 and 5 years demonstrated that the overall prevalence of OME was 75% in children with cleft lip and palate compared with 19% in children without clefts. 2 This difference in prevalence of OME between children with and without clefts was also significant at individual time points throughout the study period. As well as being more common in children with CP, OME is likely to persist longer in children with CP. A retrospective longitudinal study of adolescents with various types of CP has demonstrated a decrease in prevalence of abnormal middle ears over time, with the decline in OME in patients with isolated CP occurring between 13 and 16 years of age. 6 Other studies have shown a similar decline in the prevalence of OME in late adolescence. 7,8 A questionnaire-based study of the natural history and outcome of middle-ear disease in children with CP reported that ear problems (ear infections and/or hearing loss) were most prevalent in the age range 4–6 years, only settling in adolescence, with 26% of the 13- to 15-years age group reported to have experienced ear problems in the preceding year. 9 However, 24% were still reported to have below-normal hearing when reaching early adulthood (16 years and above). Therefore, the prevalence of OME from early childhood into adolescence is an important factor when considering the optimum treatment strategy for OME in children with CP.

Otitis media with effusion commonly presents with hearing loss, but may also cause language delay, poor educational progress, recurrent ear infections, otalgia, behavioural deterioration, imbalance, tinnitus and hyperacusis. OME may also have a negative impact on quality of life (QoL) in affected children, with hearing being considered important at key stages in the development of language and behavioural and social relationships. 10

Management options for otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate

The diagnosis of OME requires a focused history, including information on the clinical features of OME and the general health and developmental status of the child. Clinical examination should include otoscopy, examination of the upper respiratory tract, tympanometry and an age-appropriate hearing test.

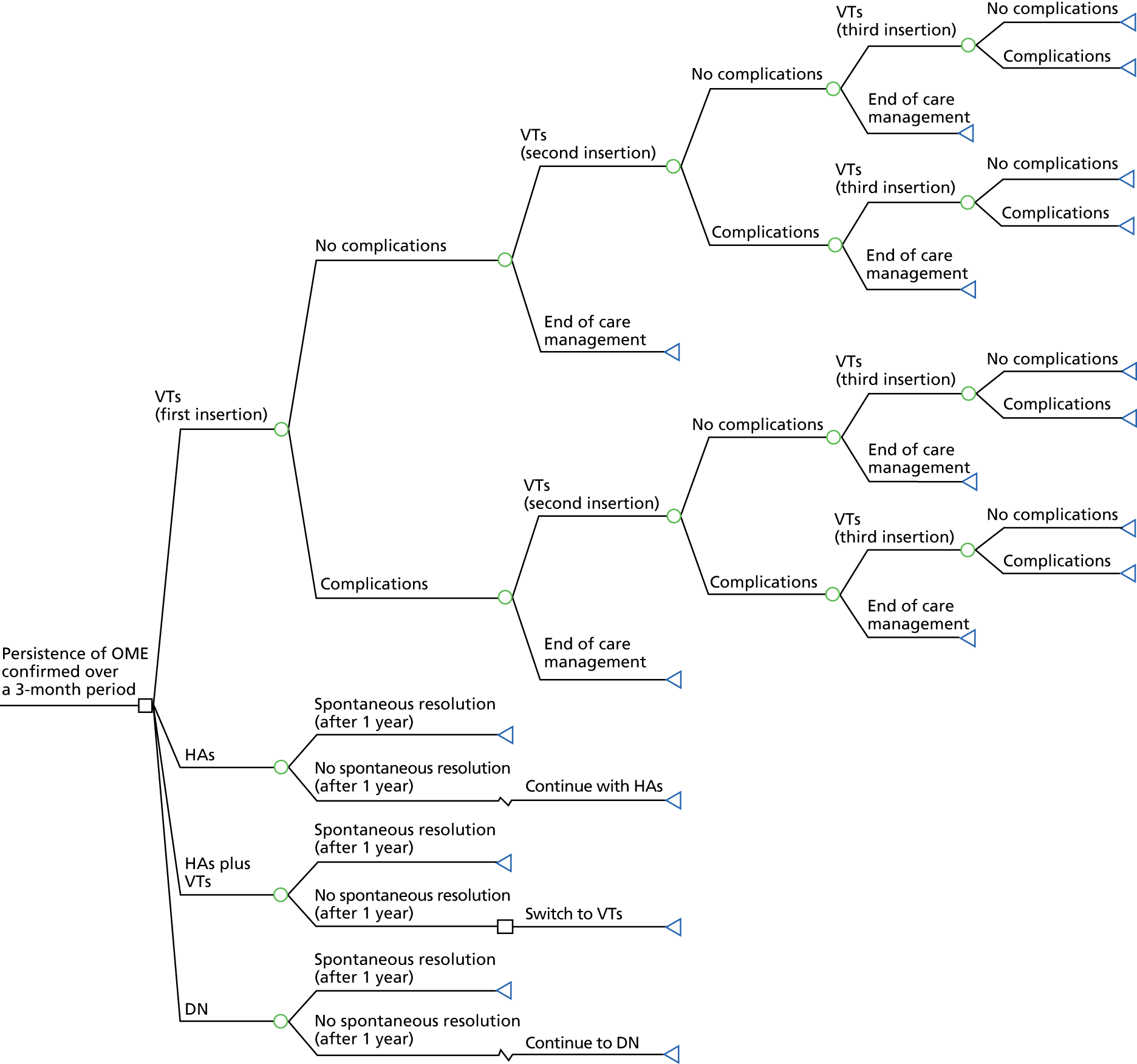

There are several possible approaches to the management of persistent OME in children with CP, which can be broadly divided into surgical, non-surgical and combination treatment. 4 The surgical treatment of persistent OME consists of the insertion of ventilation tubes (VTs, also known as grommets) into the tympanic membrane, which, while patent and in situ, prevent the development of the differential pressure between the surrounding environment and the middle-ear space, thought to be an important factor in the pathogenesis of OME. VTs have recognised complications, which include persistent tympanic membrane perforation, ear infections and early extrusion. 1 Adjuvant adenoidectomy is not recommended in children with CP owing to the risk of velopharyngeal competence. Hearing aids (HAs) provide an alternative non-surgical treatment option for OME, with the aim of amplifying the sound delivered to the middle ear, compensating for the ‘dampening’ of the sound signal as it crosses the middle-ear space to reach the cochlea. HAs may also lead to ear infections and may not be considered cosmetically acceptable by a proportion of children and parents. Compliance with HAs in children with CP with or without cleft lip and OME has been reported to be only 52% (16/31 patients). 4 However, the same study reported otological complications in 5% (2/44) of children managed non-surgically and 38% of those treated with VTs, with the authors subsequently advocating VTs only in children not compliant with HAs or those who develop recurrent ear infections. 4 Combination treatment describes the scenario in which the chosen treatment strategy changes between surgical and non-surgical (or vice versa) owing to persistence or recurrence of symptoms.

In a systematic review directed at the early routine insertion of VTs for the management of OME in children with CP, the authors identified 18 eligible studies (case series, retrospective cohorts, prospective cohorts and randomised studies), but only one of these was a randomised clinical trial. This randomised trial had several significant methodological limitations which critically limited interpretation. The authors concluded that the majority of studies were small or of poor quality, with many having no formal sample size calculation, with the resultant risk of being underpowered to demonstrate a clinically important effect of treatment. 1

When we consider outcomes, we see that studies have used diverse measures, mostly selected from clinicians’ point of view and with limited consistency between studies. As OME can impair hearing at stages thought to be important in the development of language and behavioural and social relationships before the start of school, it could be suggested that outcomes relevant to these issues should be used in future studies. It is clear, therefore, that if further research into this treatment is to be commissioned, those outcomes relevant to parents and patients should be considered.

Guidelines for the management of otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate

In 2008, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published clinical guideline 60 (CG60), entitled Surgical Management of Otitis Media With Effusion in Children, which included a section specific to children with CP. 11 The guideline highlighted the particular problems posed by OME in children with CP, which included early onset, prolonged clinical course and higher rate of recurrence. For children in general, the guideline recommends that

Children with persistent bilateral OME documented over a period of 3 months with a hearing level in the better ear of 25–30 dBHL or worse averaged at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz (or equivalent dBA where dBHL not available) should be considered for surgical intervention.

The recommendations for children with OME and CP were:

1.8.1 The care of children with cleft palate who are suspected of having OME should be undertaken by the local otological and audiological services with expertise in assessing and treating these children in liaison with the regional multidisciplinary cleft lip and palate team.

1.8.2 Insertion of ventilation tubes at primary closure of the cleft palate should be performed only after careful otological and audiological assessment.

1.8.3 Insertion of ventilation tubes should be offered as an alternative to hearing aids in children with cleft palate who have OME and persistent hearing loss.

The guideline also concluded that the evidence for a benefit of VT insertion in CP was lacking and that the optimal treatment for OME in children with CP had not been determined. In the absence of strong evidence, clinicians were recommended to base the management of OME in children with CP on the needs of the individual. Although the needs of each patient should be central to the decision-making process, there clearly remains a need to determine which treatment strategy is the most appropriate for these children.

Commissioning brief and objectives

The management of Otitis Media with Effusion in children with cleft palate (mOMEnt) study has been funded through a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-commissioned call (project number 09/167/02) to address the uncertainty in the treatment of OME and to address the question ‘What is the most appropriate way to manage OME in children with CP?’ by completing a feasibility study.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provide the highest level of evidence in the evaluation of health care. However, trials are expensive and require considerable additional effort from health-care staff and patients, which may create particularly high barriers to recruitment and successful completion of a study. From evaluating previous surgical trials, it appears that there are several challenges for a potential trial of care of OME in children with CP. 12 These concern feasibility, choice of comparator treatment, selection of relevant outcomes, and surgical compliance and skill. Furthermore, from the patient’s point of view there may be difficulties with equipoise as surgical and non-surgical treatments have different risks.

The aim of our research was to provide information on the feasibility of carrying out a RCT or strong prospective cohort studies of the management of OME in children with CP. The project involved a set of studies and a value of information (VOI) study with the aim of identifying the optimum study design to add to knowledge of the treatment of OME in children with CP.

The study had the following components:

-

Study Advisory Group (SAG) We formed a SAG comprising clinical and methodological experts with nominations from the Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and Ireland. This included audiologists, speech and language therapists, and ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeons. The SAG had the following specific roles: (i) to regularly provide advice for the study; (ii) to have an input into the design of the clinical survey and Delphi study; (iii) to advise on key parameters to explore the VOI analysis; and (iv) to have full input into the final exercise on feasibility.

-

Clinician surveys Surveys of clinicians were carried out to (i) identify the current UK practice for the treatment of OME in children with CP; and (ii) evaluate the feasibility of performing a RCT, or other relevant type of study, of VTs in comparison with ‘usual methods’ for the treatment of OME in children with CP.

-

A qualitative project The qualitative research project was designed to capture patient and parent opinions on willingness to take part in the trial, and to identify their needs for the content and form of information required to provide or withhold informed consent. Opinions on outcomes were also explored and data collected contributed to the core outcome set (COS) development.

-

The development of a COS A COS for a potential trial was developed. This would reflect the values of both providers and consumers of care.

-

VOI analysis This component was a VOI analysis that provided information on whether or not the extent of existing decision uncertainty about OME care for children with CP justifies the costs of the proposed research.

-

Evaluation The final part of the project was an evaluation of the data collected in the above components, in order to make recommendations on the feasibility of a potential study design.

Chapter 2 Clinician survey

Aim and objectives

The aim of the clinician survey was to collect data on the current clinical practice in cleft lip and palate centres in the UK, using a survey.

The main objective of the clinician survey was to collect information that would enable a decision to be taken on the feasibility of carrying out a trial or cohort investigation. As a result, within this report we are only including information on the following:

-

clinical provision and practice

-

method of delivery of care (centralised or ‘hub and spoke’)

-

caseload of the centres of children with non-syndromic CP.

A copy of the survey form is provided in Appendix 1.

Methods

We developed a survey form with the input of the SAG. This involved the preparation of drafts and a face-to-face discussion with the group, followed by development of the final form by e-mail ‘discussion’. The form was piloted in two cleft lip and palate units and further changes were made. The survey form is included in Appendix 1.

We then approached the clinical directors of each of the cleft lip and palate networks and asked them to identify the lead ENT/audiology clinicians who could complete the forms. They were sent the survey electronically. We utilised several methods to obtain a high response rate to the survey. These included:

-

encouraging the clinical directors to discuss the study with the lead clinicians

-

contacting the clinicians by e-mail several times

-

telephone contact with the clinicians to discuss the form and the study.

When centres were unable to provide the full data set requested, we subsequently asked them to provide information on the three most important questions that were relevant to the decision regarding the potential study design (Table 1).

| Question number in survey | Question text |

|---|---|

| 2.5 | What tests do you routinely use to diagnose and guide the subsequent management of OME? |

| 2.13 | What is your view on the optimum age for inserting VTs? |

| 3.1 | Do children attend cleft clinics outside your trust? |

Information on the caseload of the centres of children with non-syndromic CP was collected from two sources. Firstly, the cleft network co-ordinators were approached and asked to provide data for their centre; secondly, the Craniofacial Anomalies Network (CRANE) database, a national database that includes data on the caseload and treatment outcomes of cleft centres in England and Wales, was consulted.

Results

The response rate for the survey is provided in Table 2.

| Number of centres invited to complete the survey | 16 |

| Number of full responses received | 10 |

| Number of partial responses to an abbreviated questionnaire | 14 |

The full data are included in Appendix 2.

The key responses received from each centre are outlined below for the associated survey questions.

Clinical provision and practice

2.1 Does your cleft service have dedicated audiology input based at your centre?

The majority of centres (9/10) completing this question indicated that they had access to a named health-care professional who undertook age-appropriate hearing testing in children with CP.

2.4 How often do children with cleft palate receive routine audiological assessment at your cleft centre? If assessment varies by age please give frequency of routine audiological assessment and age ranges

Details received would suggest that although testing regimes vary, most children undergo at least four hearing assessments by the age of 5 years (in addition to Universal Newborn Hearing Screening). Children may be seen more regularly, depending on clinical need.

2.6 At primary cleft palate repair, how is the decision made to insert ventilation tubes or not, and who is involved in the decision-making process?

The responses received indicate that it is not standard practice in the centres surveyed to sanction the insertion of VTs at primary cleft repair.

2.8 After what period of time would a conductive hearing loss (> 25–30 dBHL) trigger ‘active’ intervention (referral for/decision to insert ventilation tubes or prescribe hearing aids) at your centre?

Most centres would need evidence of persistence of OME over at least a 3-month period to recommend HAs or VTs. The response to this question would suggest adherence to the recommendations contained in NICE CG6011 regarding a 3-month period of ‘watchful waiting’ prior to making a decision to recommend an intervention for OME.

2.9 Please describe the decision-making process to provide hearing aids or to insert/refer to ear, nose and throat for consideration of ventilation tubes as the first-line treatment for persistent otitis media with effusion. Please include any involvement of parents and/or the child

The responses indicated that patient choice is an important factor in the decision-making process, again adhering to NICE CG60,11 which recommends that ‘treatment and care should take into account children’s needs and preferences together with those of their parents or carers’.

2.5 What tests do you routinely use to diagnose and guide the subsequent management of otitis media with effusion?

All centres had access to a comprehensive set of audiological tests that would enable accurate assessment of frequency-specific hearing thresholds from approximately 6 months of age (visual reinforced audiometry 6 months to 3 years) through to adulthood (play audiometry 3–5 years, pure tone audiometry 4–5 years+). Tests were also available in certain centres that would enable threshold assessment in children < 6 months of age (auditory brainstem response) and assessment of other aspects of hearing, including the perception of speech.

This would indicate that all of the centres replying to the clinician survey were in a position to participate in a subsequent study to determine the most effective treatment for OME in children with CP.

2.13 What is your view on the optimum age for inserting ventilation tubes?

There was a spread of ages given in the responses received, with several centres indicating that clinical need was the more important determinant (Table 3).

| Age | Number of centres (n = 13) |

|---|---|

| Under 1 year (at palatal repair) | 2/13 (15%) |

| 1–4 years | 4/13 (31%) |

| 5 years and above | 1/13 (8%) |

| No optimum age/when clinical need dictates | 6/13 (46%) |

The results for this question should be interpreted cautiously, as the wording of some answers suggested that the question asked for a minimum age for inserting VTs, as opposed to an optimum age. Although there was variance in practice, the majority of centres considered that the decision to insert VTs was either influenced by clinical need and not age (6/13 centres), or 1–4 years (4/13 centres). Only 3 out of 13 centres stated that the optimum age to insert VTs was under 1 year or over 5 years. It is likely that a subsequent study would include children (> 1 year old) of nursery, pre-school and school age. Therefore, with respect to age at VT insertion, the majority of centres would not be required to agree to a significant change in clinical practice.

Method of delivery of care: centralised or ‘hub and spoke’?

Most centres (12/13) have a ‘hub-and-spoke’ clinics infrastructure, with the number of ‘spoke’ clinics ranging from 2 to 14. It should be noted that the one centre that stated it did not have any spoke sites indicated in response to a later question that it makes recommendations to clinics outside its cleft service.

The response to this question regarding structure of service was particularly relevant to the design and management of a future study, indicating that the majority of centres (12/13) had a hub-and-spoke infrastructure model. The number of spoke/outreach clinics varied and would have implications for any study design, especially randomisation, as well as standardisation of hearing testing and the need to obtain trust research and development (R&D) approval for multiple sites.

Caseload of the centres of children with non-syndromic cleft palate

Centres were unable to provide specific data on the number of non-syndromic patients only, and instead provided information on the total new referrals. This, unfortunately, appeared inaccurate according to the SAG. As a result, we have based our figures on yearly caseload on the data derived from the CRANE database. The advice from the CRANE database co-ordinator was that the caseload of non-syndromic CP/cleft lip and palate is approximately 75–80% of all registered cases. In generating these data, they assumed that this proportion was uniform across centres (Table 4).

| Centre | Number of new referrals (number of children with CP with or without cleft lip) | Estimate of numbers who would be recruited into a trial |

|---|---|---|

| Newcastle | 65 (49) | 6 |

| Leeds | 65 (49) | 6 |

| Liverpool | 64 (48) | 6 |

| Manchester | 69 (52) | 7 |

| Nottingham | 93 (70) | 8 |

| Birmingham | 121 (91) | 10 |

| Cambridge | 87 (65) | 8 |

| North Thames | 173 (130) | 14 |

| Oxford | 45 (34) | 4 |

| Salisbury | 53 (40) | 5 |

| Swansea | 51 (38) | 5 |

| Bristol | 65 (49) | 6 |

| South Thames | 145 (109) | 12 |

| Belfast | 31 (23) | 3 |

| Edinburgh | 29 (22) | 3 |

| Glasgow | 46 (35) | 4 |

| Total | 1202 (902) | 107 |

CRANE does not collect information for Scottish centres and so we have used the data directly from the centres, as this seemed logical to the SAG. We have calculated an estimation of the number of patients per year who would enter a trial based on the number of patients who are likely to have OME (90%), then taking a conservative estimate of those who would meet trial eligibility criteria (50%), and finally factoring in the predicted consent rate, estimated from the qualitative research described in Chapter 3 (25%).

Discussion

The survey has provided useful information for the potential study design. However, the response rate was disappointing in that only 10 out of the 16 centres provided us with a full response. We made multiple efforts to engage with the clinicians; this included liaising with the clinical director of each network/centre, multiple e-mail contacts and reminder telephone calls. In spite of these efforts, our data set is not complete for all networks/centres.

The low response rate may be due to variation between centres in the method of delivery of care and structure of the service. For example, although 90% of those responding had access to an audiologist within their cleft team, this was not the case for all centres. Importantly, in those centres where there is no dedicated audiologist/ENT surgeon, the patients are referred to a general paediatric clinic. This made it difficult to identify the appropriate clinician to respond to the survey. We did make efforts to identify if these issues were relevant to centres that did not respond completely, but we found that information was very limited.

It is therefore clear that when designing a future study, the structure of the clinical team at each centre/network and the engagement with the current study are important considerations when identifying sites to participate. One option would be to only approach those sites that provided a good response to the present study.

The clinician survey has highlighted several key factors for the design and delivery of a subsequent study, and has suggested that UK cleft centres are in a position to participate in a study to determine the most effective treatment for OME in children with CP. The results indicate that centres would be able to nominate a lead ENT/audiologist for a study to act as local primary investigator and that the centres are able to perform age-appropriate hearing tests from 1 year of age through to adolescence. The survey also suggested that centres adhered to the 3-month ‘watchful waiting’ period prior to considering an intervention for OME, as recommended by NICE CG60,11 and children were seen regularly for audiological assessment up to the age of 5 years. The majority of centres considered either the period from 1 to 4 years of age or any age based on clinical need to be the appropriate time for insertion of VTs. Therefore, a subsequent study is likely to be more readily acceptable to centres if it uses the criteria for intervention as recommended by NICE CG60, recruits patients within the first 5 years of life and concentrates testing within the same period to minimise additional clinic visits. The importance of parental opinion in the decision-making process regarding OME management was emphasised, and this has implications for the information provision contained in any study design.

The method of delivery of care was important for potential study design. It is clear that most of the cleft networks operated a hub-and-spoke infrastructure for clinics, in that the patients were seen at the centres, but their audiological/ENT care was provided in local clinics and hospitals. This has several important implications. Firstly, it would be difficult to engage peripheral clinicians with the random allocation of care as they may not be in equipoise, and the probability of protocol deviations would be high. Furthermore, obtaining trust R&D approval for multiple sites with potentially low caseloads would be problematic and inefficient. Finally, there will be the additional problem of standardising both audiological assessment and treatment away from the hub clinic. The potential numbers of eligible patients for recruitment were provided in Table 4, with the recruitment rate and required recruitment period being influenced by the study design and sample size.

Chapter 3 Qualitative interviews with parents and children with cleft palate

Background

There has been very little qualitative research on treatment or living with CP from the perspective of either parents13 or children,14 and none related to OME.

Aims

The aims of the qualitative interviews were to explore in depth (a) parents’ views about their willingness for a child to take part in a potential trial comparing VTs and HAs, and (b) outcomes of the management of OME considered important by parents and children.

Methods

A qualitative methodology was adopted to enable individuals to recount experiences in their own words, highlighting what is important to them. 15 We focused initially on descriptions provided by participants, but, as the study progressed, took a more interpretive approach to data, in line with the principles of framework analysis. 16

Participants

Parents were recruited from two cleft centres in northern England. They were eligible to take part if they had a non-syndromic child with CP (including cleft lip and palate) between 0 and 11 years of age, who had a current or past diagnosis of OME. This age range was selected because it is the common time period for children to experience OME, as reflected by the NICE17 guideline on management of this condition, which is specific to the care of those aged under 12 years. Families with particularly difficult social circumstances (e.g. domestic violence, recent bereavement) were not approached. Children aged 6–11 years were interviewed, if they were happy to talk to the researcher. We felt that children younger than this would have difficulty expressing their thoughts on the research topic. Participants had to be able to converse in English. The interviewer was a researcher who did not have a clinical background and was not involved in participants’ care.

A purposive approach to sampling was taken to ensure variation in terms of children’s age, treatment experiences for OME and gender. A sampling matrix was developed for this purpose18 to guide recruitment as it progressed. We intended to recruit parents of approximately 30 children with a range of treatment experiences, including VTs only, HAs only, both VTs and HAs, and neither VTs nor HAs (the watchful waiting group). Initially, any parent meeting the inclusion criteria was invited to take part. As recruitment progressed, practitioners were asked to identify specific individuals to ensure variation in the sample. Data collection continued until the sample was diverse in terms of children’s age, gender and treatment experiences, and it was judged that data saturation had been reached.

Procedures

In unit A, a designated member of the cleft team screened clinic lists and medical notes on a regular basis for potential participants due to attend. Children who had a CP and a clinical history of OME but no concurrent syndrome were identified. The researcher was informed in advance when eligible participants had an appointment, and visited the unit on these dates. A member of the cleft team talked to the identified parent and asked if he or she was happy to meet the researcher. If he or she agreed, the researcher introduced herself and gave the parent a copy of the participant information sheet. She also took a telephone number and called a day or two later to see if the parent was willing to be interviewed. As recruitment progressed, the clinic lists were not screened; rather, the researcher would attend on days when she might capture individuals missing from quota matrices (e.g. clinics for 10-year-olds).

In unit B, a designated member of the team screened clinic lists and patient notes to see whether or not eligible parents were due for an appointment, using the same criteria as for unit A. These individuals were sent a participant information sheet in the post. The researcher would visit clinic on dates when people identified as possible participants were attending. A member of the cleft team checked that parents were happy to talk to the researcher. If this was the case, she introduced herself and asked if they had received information in the post. When parents stated that they had and were happy to take part, a time and date were arranged for the interview. Sometimes parents said that they had not received information through the post or had not had time to read it. The researcher would give these parents a copy of the information sheet, taking a telephone number so that she could call them a day or two later to see if they were willing to be interviewed. As recruitment progressed, the practitioner screening clinic lists was advised to identify individuals who contributed to cells of the quota matrix that were lacking in numbers. For example, over time patients who had received HAs only were targeted.

Modified versions of information sheets, with simpler language and less text, were developed for children aged 6–7 years and a slightly more detailed version for 8- to 11-year-olds. These were given out at clinic in unit A or sent in the post for unit B along with study invitations to parents. Information sheets were piloted with families attending unit A in advance of data collection, and revised in light of their comments.

Data collection

In line with the qualitative methodology, semistructured interviews were conducted to gather data on views and experiences. Interviews took place at a time and place convenient to participants (mostly in their home, see Results) between March and August 2012. They were recorded with parents’ consent and transcribed verbatim for analysis, with identifying features removed during this process (including names of health-care professionals).

A topic guide was developed for parents, based on relevant literature and discussion among the research team in relation to the project’s aims (see Appendix 3). Interviews took the form of a conversation in which parents initially told the story of their child’s OME, prompted by questions including:

-

When did you first notice a problem with your child’s ears? What alerted you?

-

What information did you receive about different treatments for glue ear?

-

What made you choose [treatment] for your child?

-

How satisfied were you with treatment your child received?

-

What would you advise other parents about treatment for glue ear?

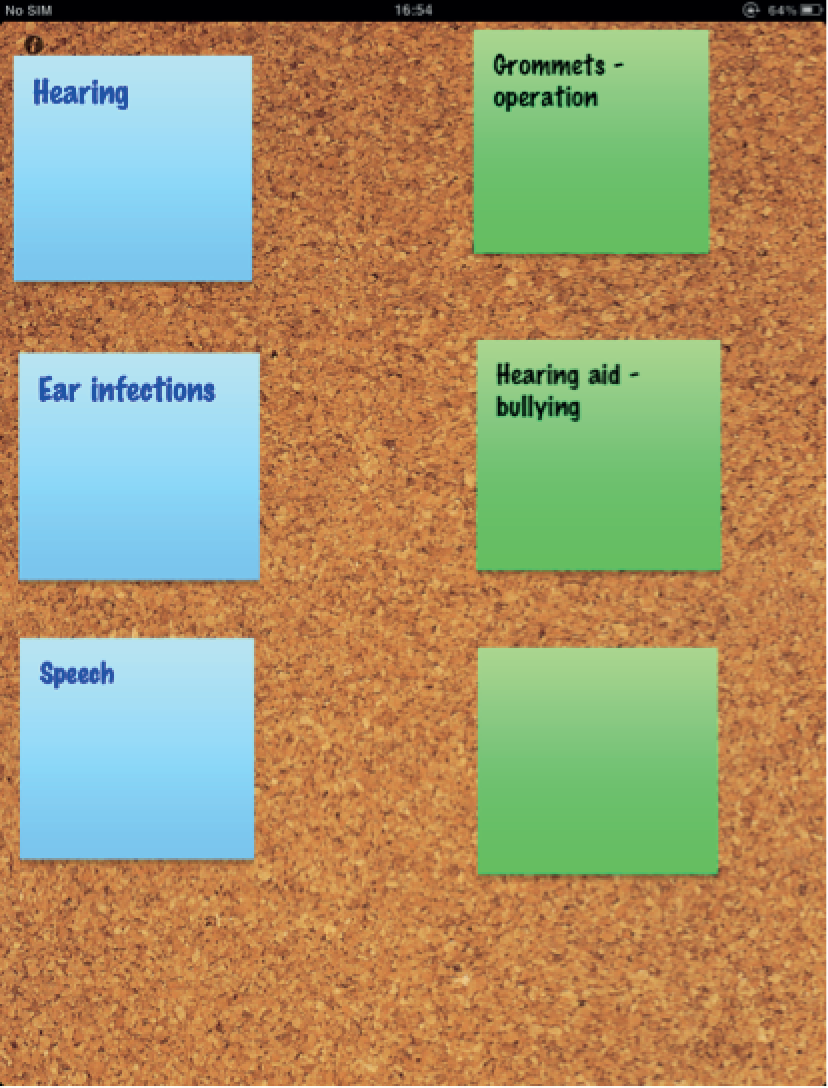

About midway through an interview, parents were invited to reflect on important results (outcomes) of treatment for OME, which were recorded on electronic ‘sticky notes’ on a tablet computer. Parents were able to move these around to demonstrate their importance; they were encouraged to elaborate on reasons for items they had listed and the order they placed them in. Towards the end of an interview, parents were introduced to the concept of a RCT comparing treatments for OME and asked for their thoughts on whether or not they would allow their child to be part of such a study.

The topic guide was revised as data collection progressed to incorporate additional topics raised during interviews. For example, parent 1 talked about the difficulties she found with obtaining a regular supply of batteries for her child’s HA; hence, subsequent parents of children who had HAs were asked specifically about battery supplies. Likewise, parent 2 mentioned struggling to understand feedback she received from audiology after her child’s hearing tests; this was added to the topic guide as an area for exploration in other interviews.

The first child to be interviewed was given the option of whether he wanted to talk to the researcher before or after his parent. He opted to go first. However, after interviewing his mother, the researcher had a better understanding of the child’s condition and a greater awareness of his character, interests and likes. Therefore, subsequent interviews with children tended to be carried out after data collection with their parent(s). This approach had specific advantages; as well as allowing more details to be gathered about the condition’s history, it enabled the child to (a) see their parent(s) interacting with the researcher, (b) become familiar with the researcher’s presence and (c) observe the conversational tone and format of the interview.

Children were interviewed separately from parents to avoid the difficulty of disentangling individual perceptions in joint interviews and the potential for children to sense that they should agree with parents. 19 Parents were in the same room or an adjacent one when a child’s interview was being conducted. Overall, children responded well to questions posed, but sometimes parents added comments to statements made or elaborated when a son or daughter struggled to verbalise his or her thoughts; this is something that others have noted to be helpful when gathering qualitative data from children. 20

Interviewing parents and children separately was necessary because a different approach to data collection was used with the latter. There is a wealth of literature on how to conduct investigations with children that aims to offer an in-depth understanding of their experiences or views. Within such work, a recurring theme is the need for participatory techniques, including songs, drawings and stories, because children are said to communicate better through such media,21 and the need for creativity in how data are collected. 22 We prepared a range of activities to engage children and to maintain interest among those with limited concentration. 23 Most were carried out on a tablet computer. For example, interviewees were shown a picture of a child and informed that this individual had just been told that he/she had glue ear. This indirect approach reduced the need for personal disclosure from the child straight away. They were then asked questions about how the child in the picture might feel about different treatments and to complete speech bubbles on the tablet computer to show what this child might be thinking. Activities were used as a starting point for discussion on areas relevant to the study’s aims. They were piloted with a group of children without clefts on the topic of healthy eating, to see which appeared best at facilitating conversation with the researcher. Interviewees enjoyed playing on the tablet computer, which made data collection a fun event. All the children could use this device, even if they had not seen one before. Questions asked when carrying out activities included:

-

Can you tell me about any problems you’ve had with your ears?

-

How do you feel when you have to go and see the doctor about your ears?

-

What’s the good thing about having grommets/HAs?

-

What’s not so good about having grommets/HAs?

Analysis

Framework analysis was applied to interview data. 24 This allows for the sharing of information within a team, by summarising data into charts. It is suited to applied qualitative research that has specific questions and objectives,25 and provides a clear record of how ideas moved from participants’ words to final findings. 26 Framework analysis is divided into five stages: (1) familiarisation with the data (becoming immersed in material collected); (2) development of a thematic framework (identifying key issues in the transcripts), which involved constantly comparing emerging codes and categories with original data, across all cases; (3) indexing data (labelling key issues that emerge across cases); (4) devising a series of thematic charts (allowing the full pattern across cases to be explored and reviewed); and (5) mapping and interpreting data (looking for associations, providing explanations, highlighting key characteristics and ideas). It facilitates either theme-based or case-based analysis, or a combination of the two, through the development of charts that can be read across rows (cases) or down columns (categories). It also allowed us to explore data based on specific interviewee characteristics, such as the child’s treatment experience or age.

Three researchers and three clinicians (surgeon, consultant in audiovestibular medicine, orthodontist) formed the analysis team. PC and ST led the process, meeting approximately once a week during data collection to discuss what participants were saying, consider areas to follow up in later interviews and debate emerging ideas. The analysis team came together halfway through data collection. Before this meeting, each member was given four to six interview transcripts to review and identify potential codes, which were discussed as a team. ST used ideas from this meeting, and her knowledge of the entire data set, to develop a thematic framework in consultation with PC. This was shared with the team for their comments via e-mail before being used to index all interview data within the qualitative computer package NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). At the descriptive stage of analysis, separate thematic frameworks were developed for parents and children, to ensure that children’s views were not lost among those of parents, whose more articulate expression could have dominated a single thematic framework for the entire data set.

Once all transcripts had been indexed using the thematic frameworks, ST charted data, again in NVivo 9. This involved summarising what participants had said in relevant cells of a chart (Table 5). PC checked 10% of transcripts and agreed how ST had indexed data overall; any disagreements were resolved through discussion between ST and PC. Charted data were sent to the analysis team in advance of a second meeting to talk about these summaries and to start interpreting data, a process that ST and PC continued in follow-up analysis sessions. To illustrate aspects of the analysis, we have included direct quotations from participants in this chapter. We have not used names, to avoid identification. Numbers are employed when referring to the sample, reflecting the order of data collection, with ‘C’ denoting a child interviewee, ‘P’ a parent, (m) a mother and (f) a father.

| Sequence of care | Glue ear vs. other aspects of cleft care | Hearing tests | GP’s role in treating glue ear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25 4-year-old child Male Unilateral CLP VTs and HA Centre A |

Tests when born suggested hearing was fine. Then at 18 months diagnosed with glue ear. Told from early on hearing could be problem but hard to take everything in then – focus on feeding. Happy when first tests came back OK – felt one less thing to worry about. Did not realise hearing could become a problem later on. Felt ‘devastated’ when told son had hearing problems. With HAs can hear as long as are in. So in bed and in morning cannot hear until put in | Had to make decision whether to have second set VTs or HAs. With cleft no decision to make – just go with what doctors advise | Just went for routine hearing test – did not think there was a problem but told there was. ‘Devastated’ with the news because thought would interfere with his speech | |

| P12 4-year-old child Male Unilateral CLP Watchful waiting Centre B |

Aware a number of problems associated with cleft, including hearing, even before the birth. Told at time about VTs that it was just a little operation that could help with this | Child went through so much with palate operations – at start did not really see ears as major, especially since everyone gets ear infections. But now is having ear infections all time and been through all major palate operations, mum’s concerned with ears and how these might affect child at school | Not had a hearing test for about 1 year. At last test, clinicians were impressed with child’s hearing and could not see a problem but since then he has had a number of ear infections. Coped well with hearing tests because some play involved | Goes to doctors as soon as child seems to have ear infection. GP gives antibiotics. Tends to clear up but then returns. Feels nothing else has been offered to stop infections recurring. Going to speak to GP next time child has infection to see if VTs would help with this as it has affected child’s sleep. But not had an infection for about 4 months |

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the qualitative interviews with parents and children was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service North East Committee – Greater Manchester East (reference 11/NW/0586). Approval was also obtained to further contact participants with an invitation to take part in the final consensus meeting described in Chapter 4.

All parents gave informed written consent to their participation and the use of quotations from their interviews for dissemination purposes. They also consented to the involvement of children aged ≥ 6 years. Assent was obtained from children, who were made aware from the outset that there were no wrong or right answers, that data collection was a confidential process and that the researcher was not coming to provide treatment, but just to ask about their views and experiences. They were given the option of saying ‘no’ to taking part, even if their parents had consented to their involvement. To put children at ease, at the start of the interview the researcher showed them the digital recorder. She gave them the chance to take on the role of interviewer, inviting them to ask her any question they wanted or to choose a question from a selection she had prepared. This gave them the opportunity to understand how the recorder worked and introduced them to the conversational tone and form of the interview. Participants (parents and children) had the opportunity to ask questions prior to starting data collection and at the end of the interview. When the interview finished, children were asked to indicate how they felt by selecting one of a range of cartoon faces showing different emotions (e.g. happy, sad, angry, confused). There was a general sense of happiness at being listened to and being able to possibly help other children.

Rigour

Based on guidelines for producing good-quality qualitative research, we employed the following strategies. 27,28

-

Reflexive notes were made during data collection by ST. In these, she recorded contextual information relating to where interviews took place and emerging ideas relating to analysis.

-

Data were sought from a diverse group of individuals, in terms of factors thought to be pertinent to experiences of OME (e.g. age, type of treatment).

-

More than one person was involved in the analysis; the analysis team comprised members with different experiences in terms of the care of children with CP.

-

We looked for disconfirming data while developing themes to deepen the analysis and to ensure all aspects of transcripts were considered.

Results

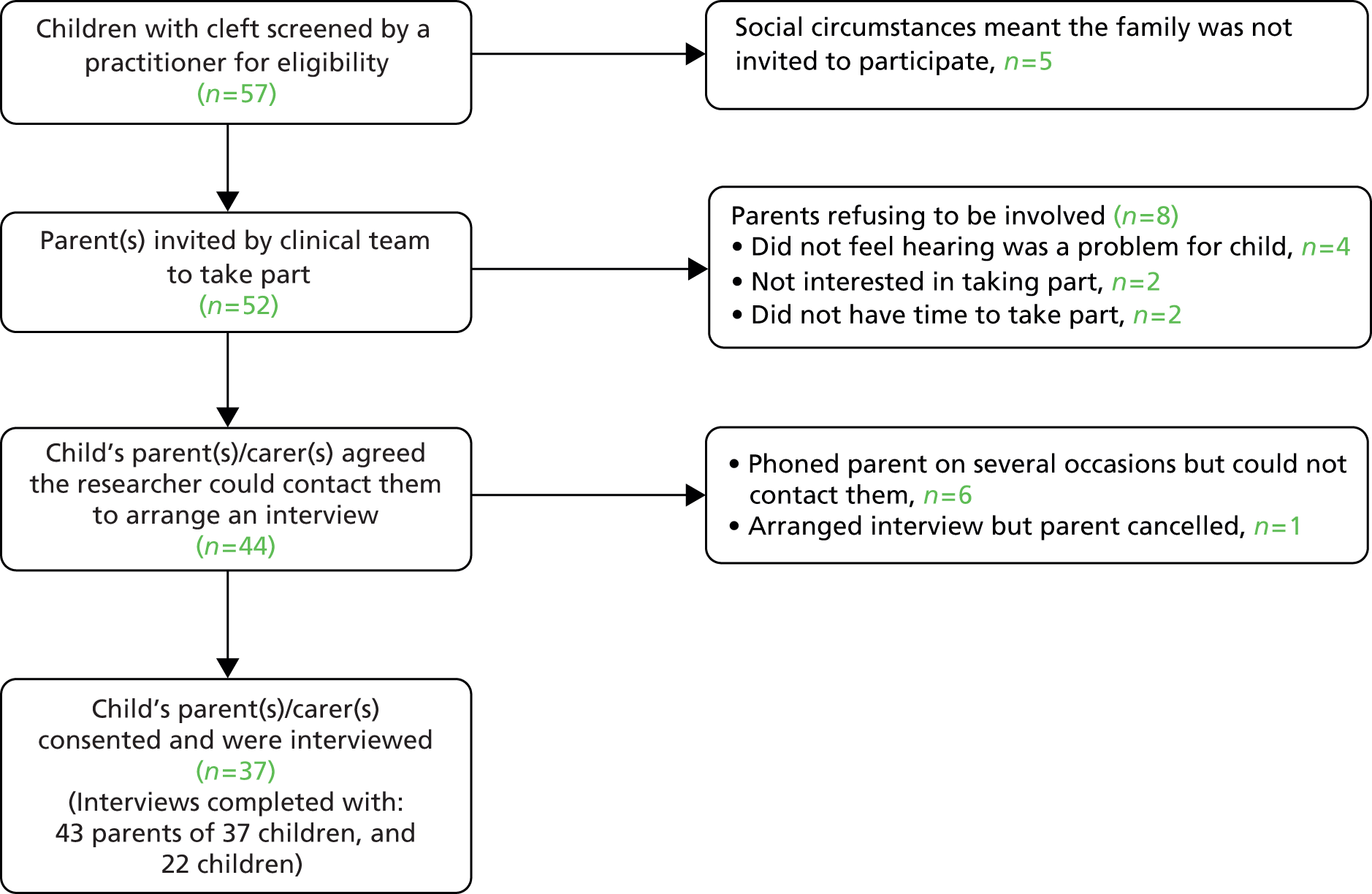

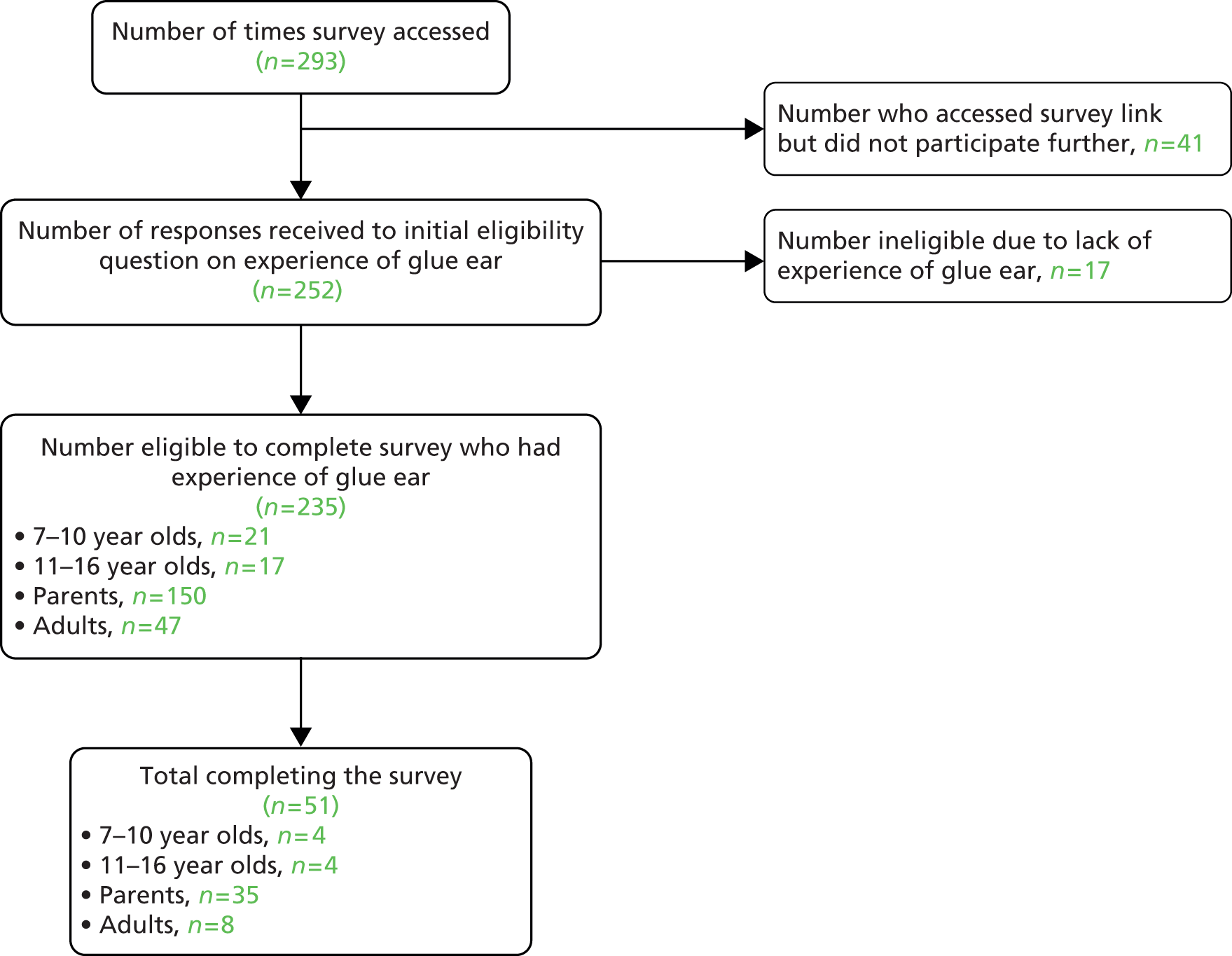

Interviews were conducted with 37 families (five from minority ethnic groups). Twenty-eight were recruited from unit A and nine from unit B. This represented a 71% response rate among those invited to participate, as shown in the flowchart in Figure 1. After comparing narratives from those in units A and B, no obvious differences were identified. Therefore, data from both sets of interviewees were combined within the analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment to the study.

Twelve parents were interviewed as couples, while one father and 30 mothers were interviewed on their own. The mean age of parents was 34.9 years [standard deviation (SD) 6.7 years]. Data were collected from 22 children, comprising 13 boys and 9 girls; two children aged 6–11 years did not want to take part, so only their mothers were interviewed. The mean age of children interviewed was 8.8 years (SD 1.3 years). The type of treatment and cleft experienced by children is illustrated in Tables 6 and 7. The most difficult group to identify was children with experience of HAs only, especially those in the younger age group. It appeared that VTs had often been inserted at a young age during an anaesthetic for another cleft procedure. In addition, children who had received HAs only were often syndromic and, therefore, not eligible to participate.

| Interview number | Parent(s) interviewed | Cleft type | Treatment experience | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | UCLP | BCLP | CP | VTs | HAs | Both | WW | |

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Child number | Parent(s) interviewed | Cleft type | Treatment experience | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | UCLP | BCLP | CP | VTs | HAs | Both | WW | |

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 27 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 28 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 31 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 32 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 33 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 35 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 37 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

Interviews with parents lasted between 20 and 65 minutes (average 40 minutes). Those with children ranged from 10 to 40 minutes (average 20 minutes). Most were conducted at a participant’s home but five interviews with parents and three with children were conducted in clinic, at the parents’ request. All but one interview was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim; one mother requested that her interview was not recorded but was happy for the researcher to take written notes.

For parent interviews, the team identified 139 initial codes through the familiarisation stage of analysis. These were clustered into 10 categories (service provision, family and social life, VTs, HAs, ear infections, communication, child’s education, parents’ involvement, outcomes from treatment, views of being part of a trial), each of which had subcategories. For child interviews, 54 initial codes were collapsed into six categories (everyday life and hearing, VTs, HAs, ear infections, clinical encounters, school); again, each of these had subcategories. Table 8 shows how data from initial codes relating to parents’ views of HAs were combined to create four subcategories. Categories and subcategories formed the indexing scheme that structured the summarising of data into charts. These charts were then used to describe and interpret interviewees’ words.

| Initial codes | Subcategories | Examples from transcripts |

|---|---|---|

|

Impact on hearing (to include impact on speech) | . . . when she put them in his ears for the first time and turned them on his face he was like that [pulls a face] and it was only about a year ago I think, maybe 18 months ago that he heard a microwave ping for the very first time ’cause obviously it’s all trial and error with hearing aids, getting the right frequencies . . .P1 (m)As soon as we got that [HA] it did, it did improve his speech. It has improved his speech since we got it ’cause he was hardly talking. He’s still not, I wouldn’t say he’s at the age of a 3-year-old speech-wise cause his little friends in school are all talking a lot better and are a lot more clearer as well.P15 (m) |

|

Visibility | I know a lot of parents who wouldn’t have hearing aids because of social reasons, people pick up on oh he’s deaf or whatever, whereas grommets they’re not seen, nobody has a clue.P2 (m)She was the only one with hearing aids so everybody loved them and we sent books in to school so she could read them with her friends to show them that this is what I’m going to get and everybody was dead excited and all of her friends keep saying ‘I want hearing aids’.P13 (m) |

|

Parents’ beliefs about HAs | . . . it [HA] looks like she’s relying on something, yeah rather than trying hard like for herself but obviously if it does affect her hearing during the class and she does need one then as I said you can’t see it from outside, I think it’s just for us as her parents, we were worried that it may not be comfortable for her, that’s all.P11 (m). . . if you put a grommet in it’s opening the tube so the tube, the fluid can drain, whereas these [HAs] are just, well it’s just making the hearing a little bit better. It’s not, so it’s still bunged up. It’s still, the eardrum is still as flat as anything. It’s not solving anything . . . it’s just assisting.P27 (m) |

|

Getting child to wear | It was just whether he would tolerate them, you know, for a long time because he’s a wee bit of a fussy wee boy [laughs]. He doesn’t like anything really that interferes with him and I just was worried that perhaps maybe he wouldn’t wear them or maybe he would just wear them for a week and then decide that these weren’t for him.P4 (m). . . he only wears the one, he only wears it at school. He doesn’t wear it at home or anything, he doesn’t really need it at home, he can manage watching the telly or listening to us. So I’ve never made him wear it at home.P33 (m) |

|

Supplies and maintenance | I soak them twice a week in warm water and . . . we have to make sure there’s not water in the tubes, so it’s using a puffer and puffing the water out. It’s not too bad.P3 (m)He doesn’t bother about the hearing aids ’cause they’re snazzy aren’t they. At the minute he’s got like red and yellow in and last time he had stickers in them and so he can do what he wants with them really . . . The batteries, through no fault of anyone, you just forget and you’d think oh I need to get batteries. They’re so tight. You think well, you go in and say can I have some batteries, for instance, [child] has school, here and his dad’s. So we leave them at all places but they’ll give you like one packet and you’re like oh great [sarcastic tone], you know, but no getting them is fine.P37 (m) |

As mentioned above, two main areas were explored during the interviews: willingness to enter a child into a RCT and outcomes of importance for children and parents following management of OME. Given that these are distinct topics, results and a discussion of what was found relating to involvement in a trial is followed by results and a discussion of what was found about perceptions of outcomes.

Analysis strand 1: parents’ views about their child’s participation in a potential trial

This section describes parents’ comments about whether or not they would allow their child to be part of a trial comparing VTs and HAs, and factors influencing their decision. It covers views of randomisation and explores possible barriers to recruitment. We focus on the opinions of mothers and fathers rather than those of children because they would make the ultimate decision of whether or not to participate. In addition, it was felt that children would struggle to understand the concepts of randomisation and equipoise. Parents were asked to state whether or not they would allow their child to take part in a trial to test the best method of treating OME. However, one mother (P9) was not asked because she expressed negative views about VTs with such emotion that it was inappropriate to explore if she would enter her son into a study where there was a 50% chance of receiving this treatment. An outline of how the topic was approached within the interview is shown in Box 1.

At the moment it’s not clear what treatment is best for glue ear. We would like to do a trial comparing two different treatments. The best way to do a fair test between two types of treatments is for there to be an equal chance of children receiving treatment A or treatment B. This could be done by a computer programme or by rolling a dice – for example, if an even number comes up the child receives treatment A and if an odd number comes up they receive treatment B. If a parent agreed to let their child be part of this type of trial it wouldn’t be a doctor who decided what treatment they received or the parent, and the child would have an equal chance of receiving treatment A or B. What they did receive would be down to chance. What are your views of letting your child be part of such a trial if [child’s name] got either treatment A or treatment B by chance?

(Invariably parents would ask which treatments at this point, so the researcher mentioned VTs vs. HAs.)

Follow-up questions: (a) What made you say [yes, no, unsure]?; (b) Is there anything that would change your view?; (c) What would you want to know before you decided?

Parents’ willingness to enter their child into a trial comparing ventilation tubes and hearing aids

In nine parent interviews, participants stated that they would allow their child to be part of the trial, whereas in 19 the answer was negative, and in eight, participants were unsure what they would do. Table 9 groups interviewees based on their response to taking part in a trial (‘no’, ‘unsure’, ‘yes’) and summarises key factors influencing their decision-making as recorded in interview transcripts. Patterns which emerged on how individuals responded are shown in Table 10.

| Reason for response | Parents saying ‘yes’ | Parents saying ‘no’ | Parents who were ‘unsure’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee identifier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 12 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 31 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 36 | 37 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 24 | 25 | 29 | 35 | |

| Trust in medical professionals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Benefits to child of being in trial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Altruism/advance knowledge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Want control/choice/optionsa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Child not getting best treatment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preference stated for VTs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preference stated for HAs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drawbacks related to VTs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drawbacks related to HAsb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

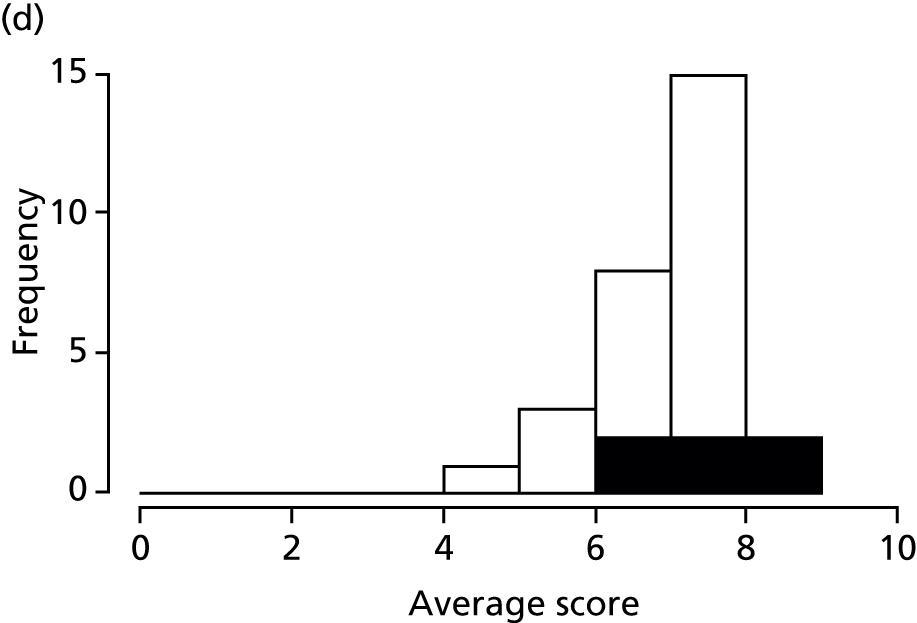

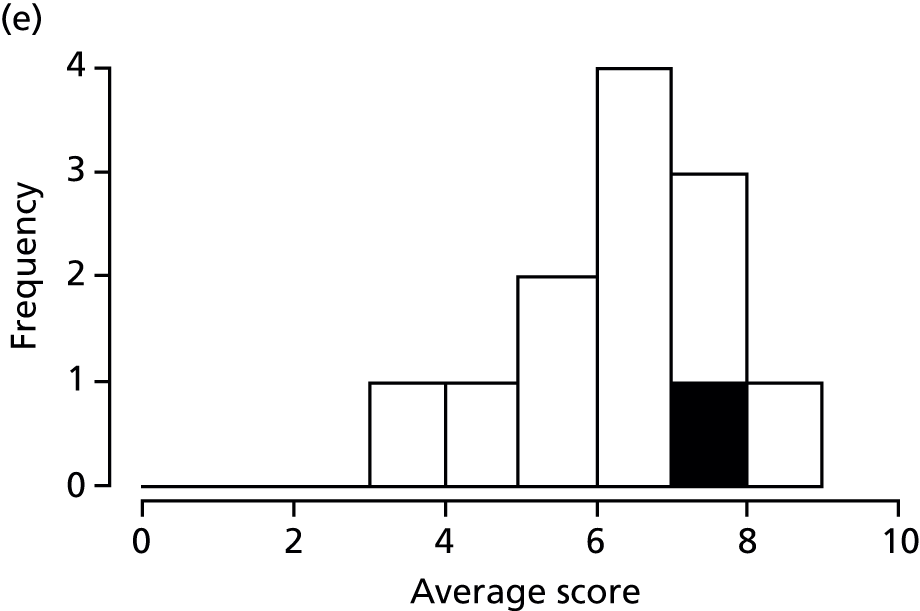

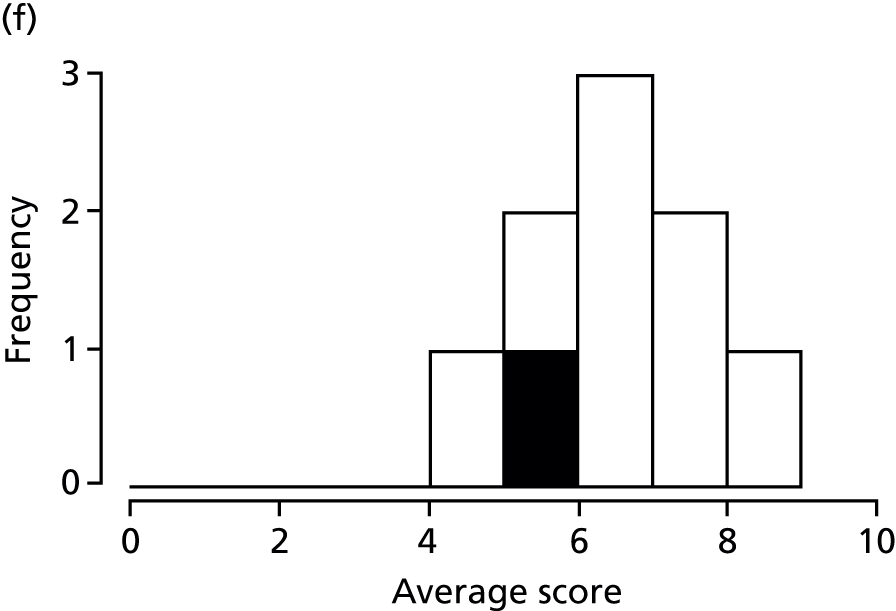

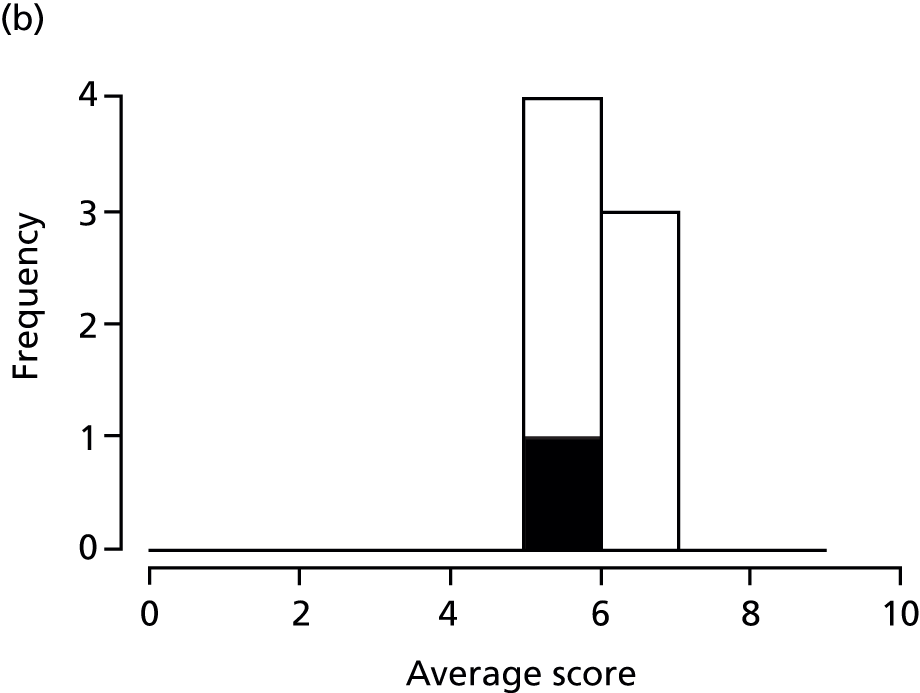

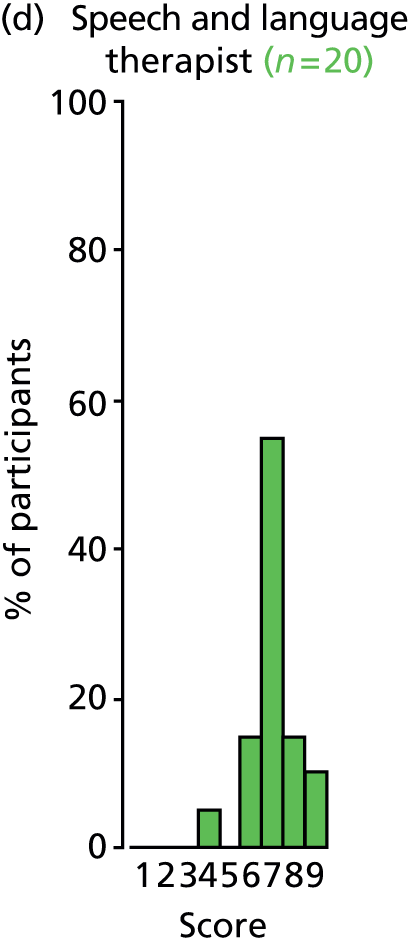

| Those saying ‘no’ | Those who were ‘unsure’ | Those saying ‘yes’ |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Most interviewees were reticent about entering their child into the proposed trial, although they recognised the need to advance scientific knowledge. Some of their reluctance stemmed from concerns about not being able to choose treatment and a risk of their child not being allocated to the most effective arm. Furthermore, several parents had pre-existing views about the benefits or drawbacks of VTs or HAs, as suggested in the following interview extracts:

Urm, possibly not, just because if she then fell in the grommets group, she would have to have an operation and I wouldn’t want her to go under general again just for grommets. So probably not.

P7 (m)

I’ve had the results and I’ve witnessed it and he was a changed child. He could hear perfectly well. I mean he went for his hearing test after his grommets and he was passing them with flying colours . . . So no I wouldn’t be happy with that and I wouldn’t want a hearing aid because it’s there, it’s on view, children will poke at it and say ‘what’s that in your ear?’ and it’s the sheer embarrassment for a child, I would say no, absolutely no way.

P8 (m)

Hence, interviewees saying ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ did not see the two treatments as sufficiently equivalent to accept randomisation and did not appear to feel that risks associated with one intervention were warranted. Some parents expressed fears that there could be social consequences of HAs, including the potential for bullying:

Just the stigma, the stigma with hearing aids isn’t it. It’s, you don’t want anything that anyone can say to, to the chances of your child being bullied, being picked on and you know yourself it’s like kids and it’s just one more that they can, he’s not a very confident child, you know you worry that he, that’s why we were concerned whether his speech, would that cause bullying and stuff like that. It’s just a stigma isn’t it really, it’s like anything.

P16 (m)

Others had strong views about physical risks that they associated with VTs (e.g. causing damage to the ear or infections):

I think she was about 1 when she had her first set of grommets that they said would help sort out the glue ear and that unfortunately made things worse . . . I think the hearing aids have actually helped more than the grommets ever did because we haven’t had an ear infection for over a year . . . They [VTs] never worked. She’d be ill, she’d be off school. We’d get phone calls saying she wasn’t in but it wasn’t our fault.

P24 (m)

Participants were divided in terms of their favoured treatment, including parents of children in the watchful waiting group (Table 11). Hence, even when interviewees had no personal experience of VTs or HAs, they could still hold strong opinions about these approaches, informed by conversations with friends or relatives, media outlets or social norms. Parents with children who had received VTs only tended to prefer this approach. Just one person in this group expressed a preference for HAs; P29 did not think it was fair to put her child under anaesthetic when the VTs kept falling out. Most parents with a child who had experienced HAs only described being encouraged to try them by a health-care professional. They expressed a preference for these devices in part because they eliminated the need for anaesthetic, which they worried could be required on several occasions if VTs fell out. These parents talked about their own struggles witnessing their son or daughter being anaesthetised. They also mentioned their child’s difficulties with surgery:

. . . he had a bad reaction . . . he was being sick . . . it was just horrible . . . I didn’t want to put him through another operation no matter how big or small.

P33 (m)

. . . we’ve had a lot of battles with her going for surgery . . . she goes to the play specialist a couple of months before surgery . . . cannulas . . . they are the major issue with her.

P34 (m)

| Interviewee | Prefer VTs | Prefer HAs | No preference | Not clear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child had VTs | ||||

| P4 | ✓ | |||

| P6 | ✓ | |||

| P8 | ✓ | |||

| P14 | ✓ | |||

| P17 | ✓ | |||

| P21 | ✓ | |||

| P22 | ✓ | |||

| P26 | ✓ | |||

| P28 | ✓ | |||

| P29 | ✓ | |||

| P31 | ✓ | |||

| P32 | ✓ | |||

| P36 | ✓ | |||

| Child had HAs | ||||

| P27 | ✓ | |||

| P30 | ✓ | |||

| P33 | ✓ | |||

| P34 | ✓ | |||

| P37 | ✓ | |||

| Child had VTs and HAs | ||||

| P1 | ✓ | |||

| P3 | ✓ | |||

| P5 | ✓ | |||

| P7 | ✓ | |||

| P9 | ✓ | |||

| P10 | ✓ | |||

| P13 | ✓ | |||

| P15 | ✓ | |||

| P18 | ✓ | |||

| P24 | ✓ | |||

| P25 | ✓ | |||

| Child in watchful waiting | ||||

| P2 | ✓ | |||

| P11 | ✓ | |||

| P12 | ✓ | |||

| P16 | ✓ | |||

| P19 | ✓ | |||

| P20 | ✓ | |||

| P23 | ✓ | |||

| P35 | ✓ | |||

It was notable that though interviewees with children who wore HAs said they had been worried about teasing, these fears had not been realised; most stated that their child coped better wearing HAs than they had expected. As for those whose children had tried both treatments, HAs tended to be preferred as a result of poor previous experiences with VTs (e.g. falling out, repeated insertions, ear infections that parents attributed to VTs). Of those receiving both, most children had received VTs followed by HAs; just C13 and C18 had HAs first. Only P25 in this group of parents preferred VTs because, unlike HAs, they allowed for a constant improvement in hearing while in place:

So sort of when you go to bed they’re not in and when you get up on a morning they’re not in so obviously you’ve got that lull of whereas it’s like putting contact lenses in, you can constantly see rather than put your glasses on you know that type of thing, that was the only thing in my head to compare it to . . . the grommets give you a more rounded hearing cause it’s always there as opposed to just when they’re in.

P25 (m)

Views on the presentation of information about trial participation

Interviewees stated that prior to deciding whether or not to allow their child to be part of the proposed trial, they would like to talk to a researcher about it and wanted written information which they could take home and reflect on with family members. They also suggested that information should be provided to children if they were old enough. Participants stated that the information they would like to help make a decision included:

-

General That neither treatment would make the child’s situation worse, potential benefits and drawbacks of each treatment and what might happen if either did not work.

-

HAs What this would involve for parents and how often they would have to take their child to get new moulds fitted.

-

VTs What might go wrong, how many sets would be inserted, the chances of them falling out and any after effects.

Some parents were clear that how the idea of randomisation was presented could affect their willingness to contemplate their child’s involvement:

I don’t know if kind of like, I know it’s, to me kind of like roll of a dice sounds a bit like a board game . . . you’re thinking about kind of like your child’s kind of like welfare and to think of a dice, you’re thinking I don’t know whether or not I like the idea of that, whereas if you’ve got kind of like a computer generated list . . . then that’s fine.

P5 (m)

This is consistent with previous research, which has noted that explaining randomisation in terms of pulling names out of a hat or coin tossing may influence willingness to be part of a trial, leaving individuals feeling as if the approach is haphazard. 29

Conditions for agreeing to participation

This section moves on from the description of beliefs, experiences and knowledge to consider how individuals could be clustered based on factors influencing their willingness to allow their child to be part of a trial comparing VTs and HAs. By reflecting on participants’ responses, we grouped them according to key factors shaping their decision-making:

-

‘protecting’: not wanting to put their child at undue risk of harm (physical or psychosocial)

-

‘fixing’: believing that one treatment was more appropriate and/or convenient

-

‘following’: being persuaded by the views of professionals

-

‘helping’: wanting to advance knowledge and assist patients in the future.

The response of those characterised as ‘protecting’ was influenced mainly by previous experience, either direct or vicarious. These individuals were concerned about perceived physical or social risks associated with either VTs or HAs. Some had witnessed their child having several sets of VTs and some believed that these had caused permanent damage inside the ear. Others were reluctant to agree to the possibility of HAs, seeing these devices as an additional burden on top of scars from surgery and speech difficulties:

Just because urm I think I had so many other things, so many other problems as well then to sort of . . . be picked out for grommets or hearing aids and think it’s going back to the hearing aids issue for us, I think we would say no.

P36 (m)

Whereas parents classed as ‘protecting’ rejected either HAs or VTs, those defined as ‘fixing’ articulated a preference for one of these treatments and a sense of knowing what was best for their son or daughter. Some valued the opportunity to capitalise on their child undergoing an anaesthetic for a palatal closure to have VTs inserted at the same time. Others felt that HAs were preferable because they could avoid the need for repeated VT insertions.

Data from parents whose response was shaped predominantly by a wish to protect or fix implied that accepting uncertainty about which option is most effective (clinical equipoise) was a necessary but not sufficient condition. Agreement to trial participation could also require what we refer to as ‘parental equipoise’. This relates to the wider impact a treatment may have on everyday life. For example, those defined as ‘fixing’ felt that one approach to managing OME was more suitable in terms of its bearing on their child’s psychosocial well-being. This could be expressed as a preference for the expedient solution of inserting VTs while the child was anaesthetised for another procedure. Alternatively, HAs could be preferred as an acceptable solution to hearing loss that avoided the need for surgery. Those classed as ‘protecting’ were not in parental equipoise because they had significant beliefs about potential adverse consequences of either VTs or HAs.

If parents expressed concerns or preferences for VTs or HAs, they were unable to agree to participation. When these were not overriding factors influencing decision-making, some individuals agreed to their child participating in a trial because they trusted practitioners. We have described this as ‘following’. Alternatively, those we designated as ‘helping’ talked about being motivated mainly by a wish to progress knowledge and assist others in a similar situation. These interviewees did not voice strong views about VTs or HAs and, in that sense, appeared to accept there was sufficient clinical and parental equipoise to allow their child to take part in a trial. In their narratives they reflected on the widespread benefits of participation for future generations of patients.

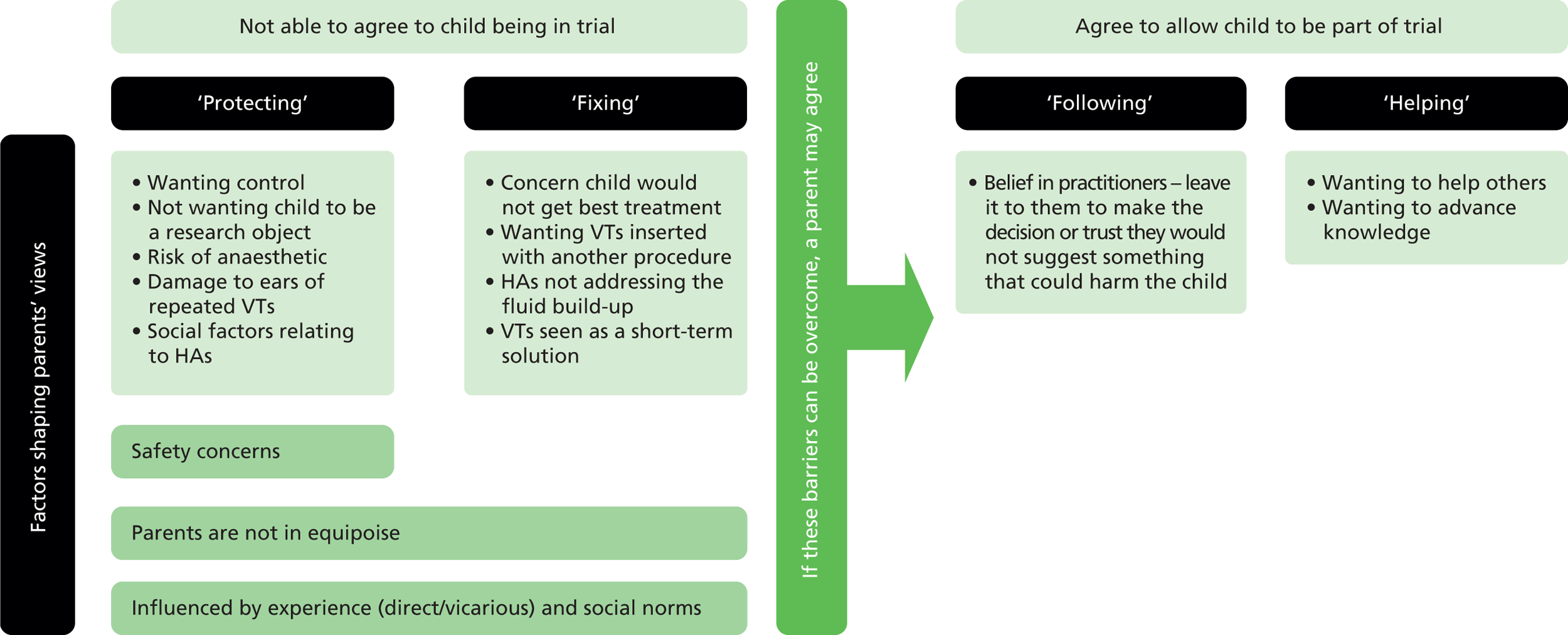

Figure 2 summarises conditions associated with agreeing to be in the proposed trial, which were derived from interview data. It highlights that those saying ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ expressed views associated with ‘protecting’ or ‘fixing’ which were not articulated by those saying ‘yes’, who were willing to follow a practitioner’s suggestion or to help advance knowledge. It also underlines differing moral drivers shaping people’s decisions. Those characterised as ‘protecting’ exhibited the socially expected role of safeguarding their child. Likewise, interviewees described as ‘fixing’ demonstrated parental authority by suggesting a need to improve their child’s circumstances in what they felt was the most efficient way possible. ‘Following’ could result from a sense of loyalty to staff involved in patient care, if they are the people asking parents to take part. ‘Helping’ suggested a wish to assist others in a similar position in the future.

FIGURE 2.

Conditions associated with agreeing to be part of a trial.

These different conditions associated with decision-making (‘protecting’, ‘fixing’, ‘following’, ‘helping’) highlight possible barriers to and enablers of recruitment. They suggest that allaying concerns around a perceived need to protect children from risks, and/or addressing beliefs that one treatment has particular benefits making it more suitable for the child, might be essential prior to recruitment. If parents can be reassured about the safety of interventions proposed, and that there is no definite advantage to either, they may be more likely to move on to ‘following’ or ‘helping’ and, therefore, saying ‘yes’ to randomisation. Further research could test how these drivers of decision-making relate to recruitment, which could allow for individualised approaches to trial presentation based on whether a parent’s view, at recruitment, was most reflective of ‘protecting’, ‘fixing’, ‘following’ or ‘helping’.

Nature of the two interventions being compared

We have described how most interviewees were resistant to the idea of entering their child into the proposed trial because they did not regard it as a fair comparison. As noted by P20:

I don’t think I’d be too happy . . . because they’re two extremes, you’ve got the grommets, which is an operation, or the hearing aid, which isn’t an operation and to me it’s, I’d be, you’d be scared to be put in the grommets group . . .

P20 (m)

To test the influence this perceived lack of equivalence had on parents’ response to our question about trial participation, after 10 interviews we explored participants’ views of their child being involved in a study of a hypothetical medication for OME. As shown in Table 12, they appeared much more receptive to this treatment route. Those whose initial response was characterised by a drive to protect agreed if convinced that the medication was safe, as did parents classed as ‘fixing’, if they saw it as an attractive solution to the child’s hearing problem. In general, participants described medication as a treatment that was easier to accept than surgery or HAs. They talked about taking medication being a ‘normal’ activity compared with the possibility of social stigma associated with HAs or the invasive nature of VTs. In addition, this option was seen as being more in parents’ control, with any side effects rectified by stopping the medication:

. . . you have to try new things because we’re never gonna learn are we and we’re never gonna progress, we’ve got to try new things and it’s a medicine. If he was ill from it, it would either come out of his bottom or through his mouth and I’d stop giving it him.

P37 (m)

| Willingness to consent to trial of surgical or medical intervention | Parent identifiera | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 37 | |

| Yes to trial comparing VTs and HAs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Yes to a study of medication for OME | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

The main hurdle that parents saw with this type of treatment was how the medication tasted, which might put the child off taking it.

Only one person agreeing to a child’s participation in a trial comparing VTs and HAs would not allow her son to be part of a study examining medication for OME. Her rationale related to a concern about potential side effects, and in that sense ‘protecting’ came to dominate her decision-making:

. . . the grommets will go in his ear but they come out after so long and . . . they’re not gonna damage him, you know, there’s nothing major that that’s gonna do to his body but obviously him taking a medication, I don’t know whether he could be allergic to something that’s in the medication . . . I wouldn’t really want to put him through that if there was no real, ’cause obviously they couldn’t promise me that something wasn’t gonna happen to [child].

P12 (m)

Two parents who said ‘no’ to the trial of VTs and HAs also said ‘no’ to a study of a hypothetical medication for OME. Their reasons related to a concern about side effects and not wanting to try a new treatment route for this condition.

Discussion: strand 1

Interviewees diverged in their opinions of VTs and HAs, with some favouring the former while others preferred the latter. They often held strong opinions about treatment, but also reflected the uncertainty that surrounds best practice in managing OME in those with CP. Our data show that recruitment could be difficult in research comparing VTs and HAs, a common obstacle with trials30 and a key reason for their failure. 31 Only one-quarter of those interviewed said that they would enter their child into such a study, although parents’ explanations for their responses are potentially more useful than this figure because they identify concerns that, if addressed, might facilitate a higher rate of recruitment.

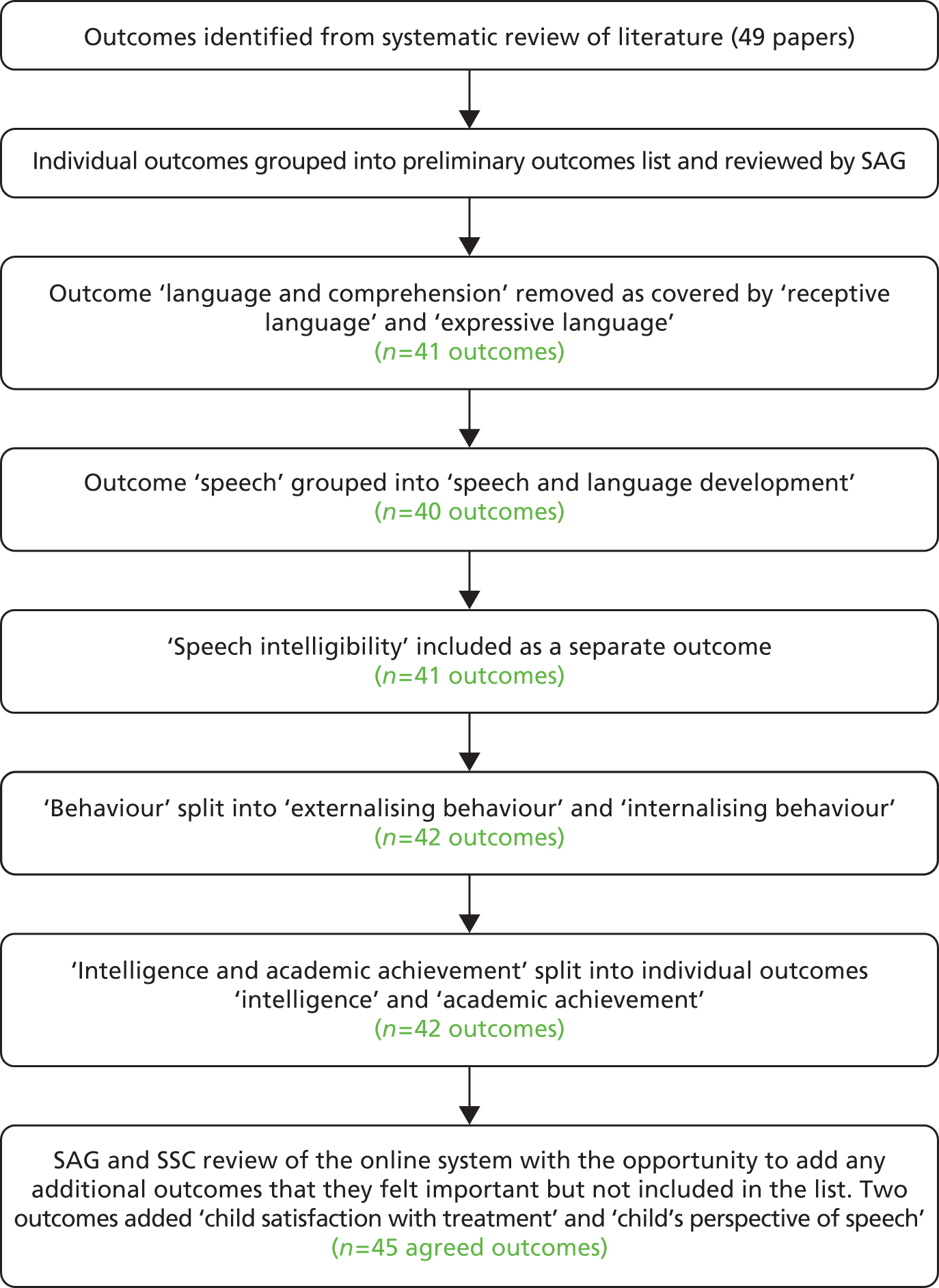

Other authors have talked about ‘individual’ or ‘patient’ as opposed to ‘collective’ equipoise. 32 We used the term ‘parental equipoise’ to highlight that interviewees thought more broadly than a treatment’s clinical effectiveness, considering its impact on a child’s and the family’s psychosocial well-being. Most participants were not in parental equipoise, a condition that is necessary, we suggest, before agreeing to enter a child into a trial comparing VTs and HAs. Individuals were distributed across a continuum that included phases of decision-making shaped primarily by a need to protect, fix, follow or help. Data suggested that a lack of parental equipoise would need to be addressed if it were not to be a significant hurdle to trial recruitment.

Parents whose responses we have described as ‘protecting’ were not in equipoise because of the risks they associated with treatments. Some were particularly concerned to avoid their child having general anaesthetics. Negative views about VTs could also be based on personal or vicarious experience of multiple insertions, ear infections and/or concerns about long-term damage inside the ear. Therefore, HAs were preferred in some cases because they were non-invasive. Alternatively, parents might worry about their child’s or others’ responses to HAs, owing to social norms with regard to visible difference and disability. The response of interviewees indicates how a range of parental concerns may need to be addressed in order to recruit to a trial, including social experiences as well as clinical benefits and risks.

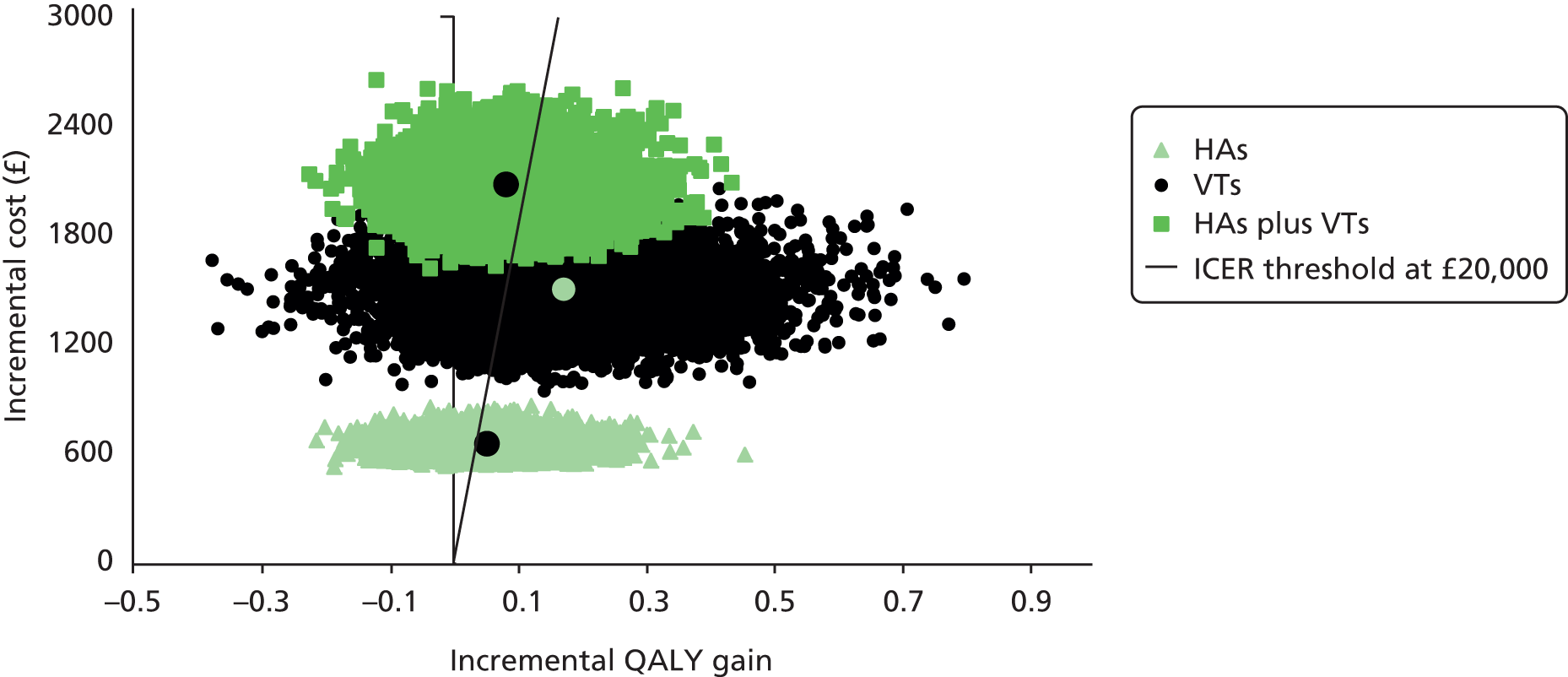

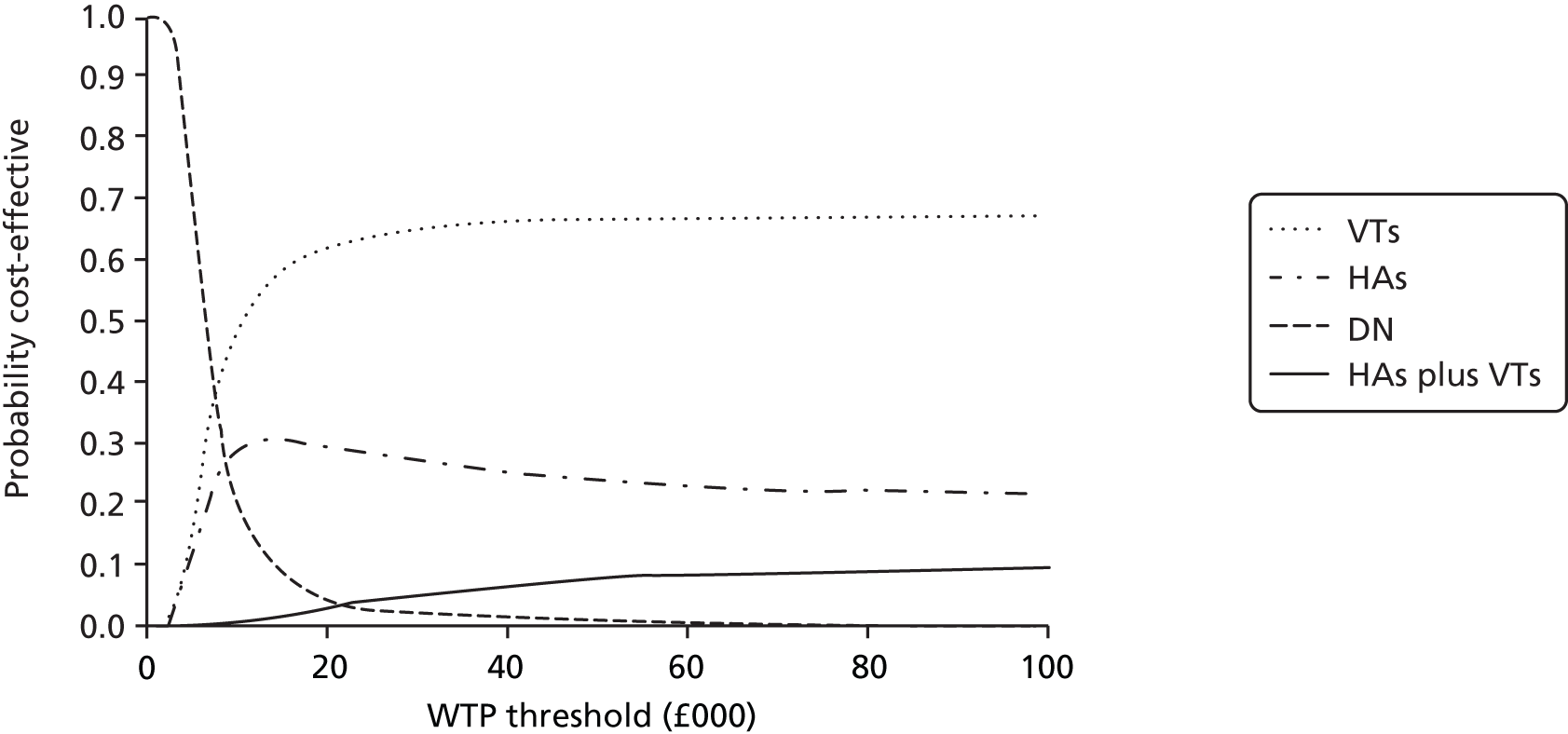

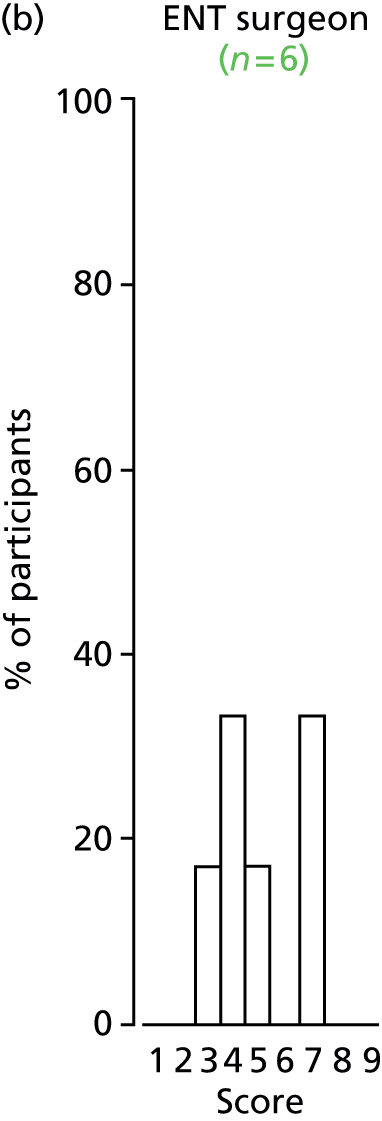

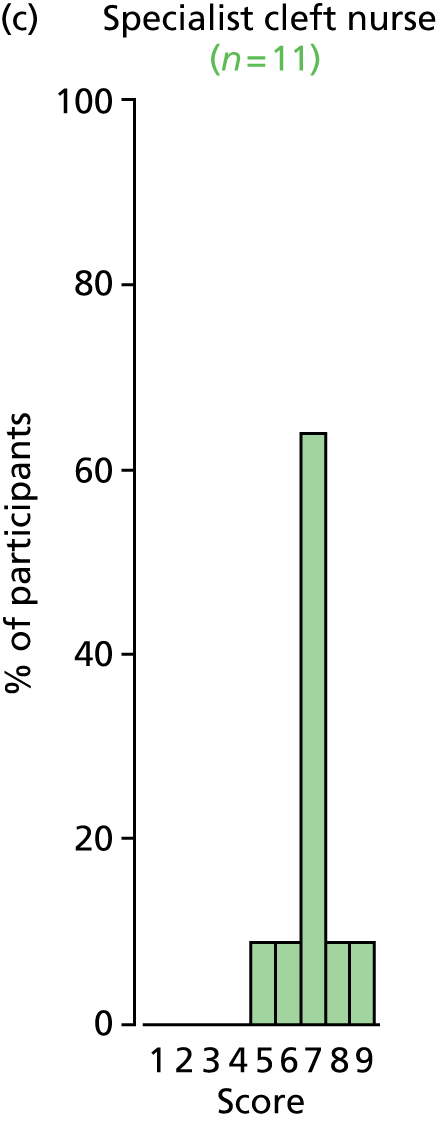

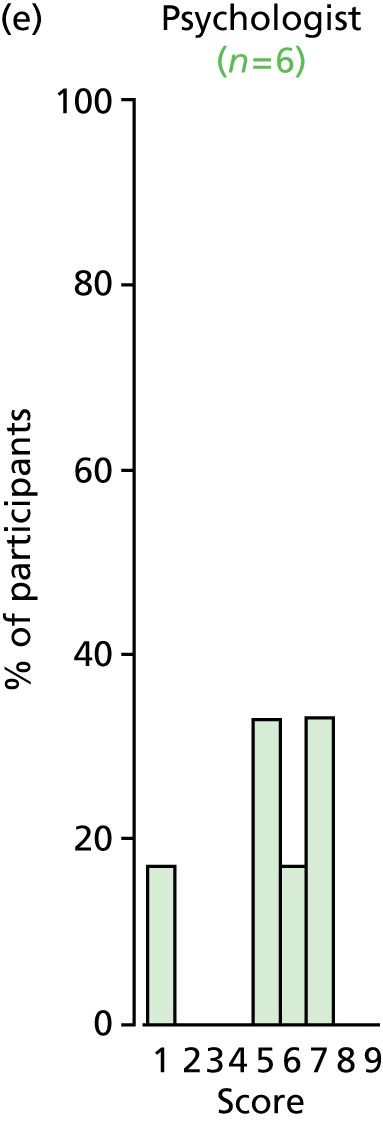

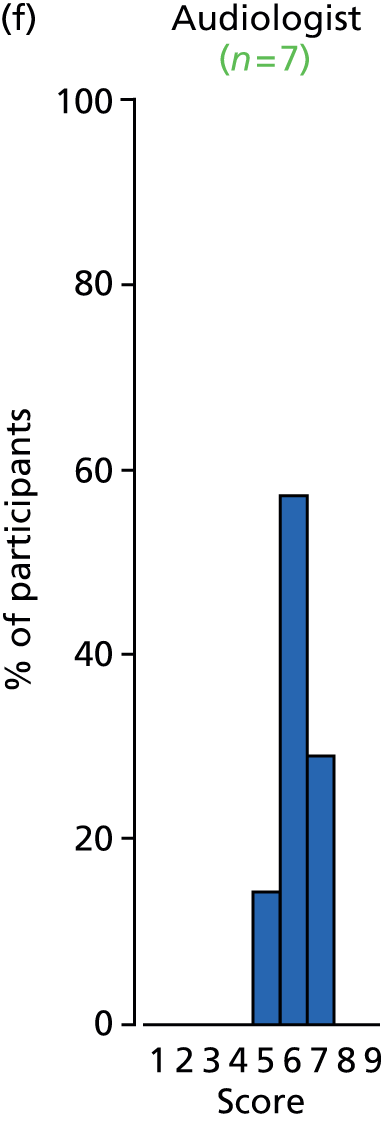

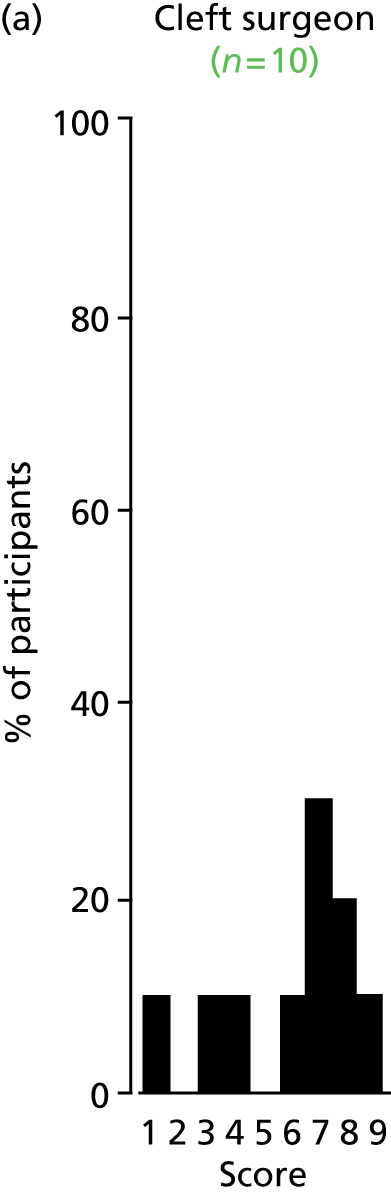

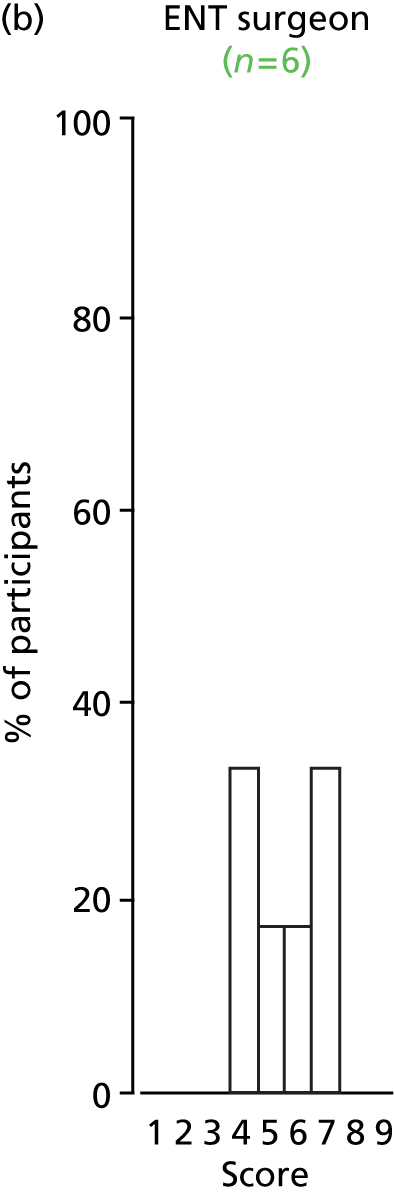

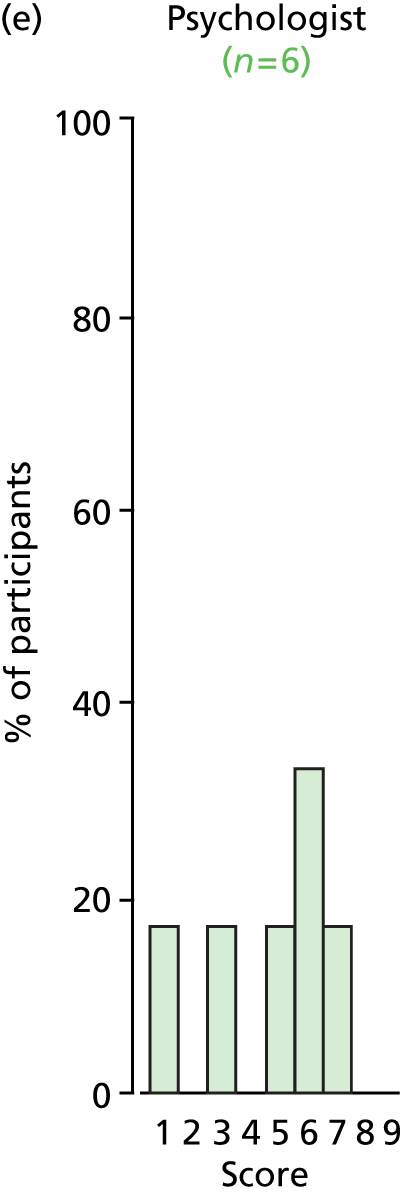

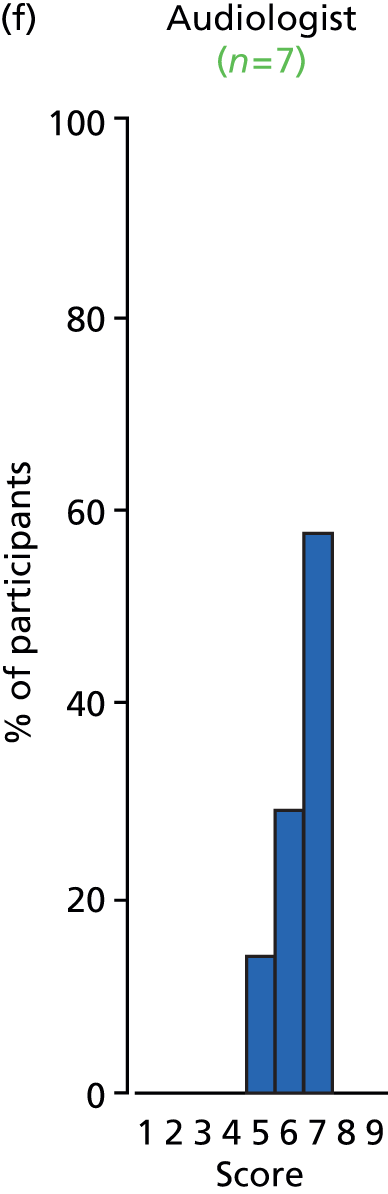

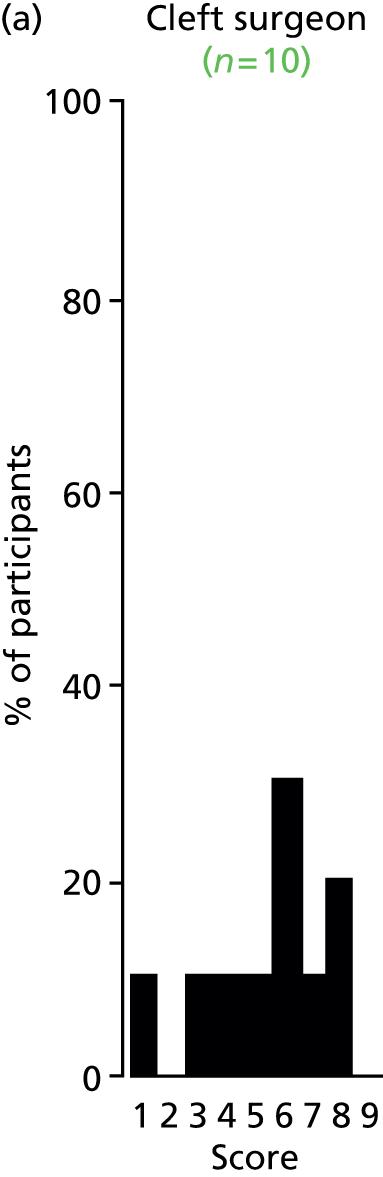

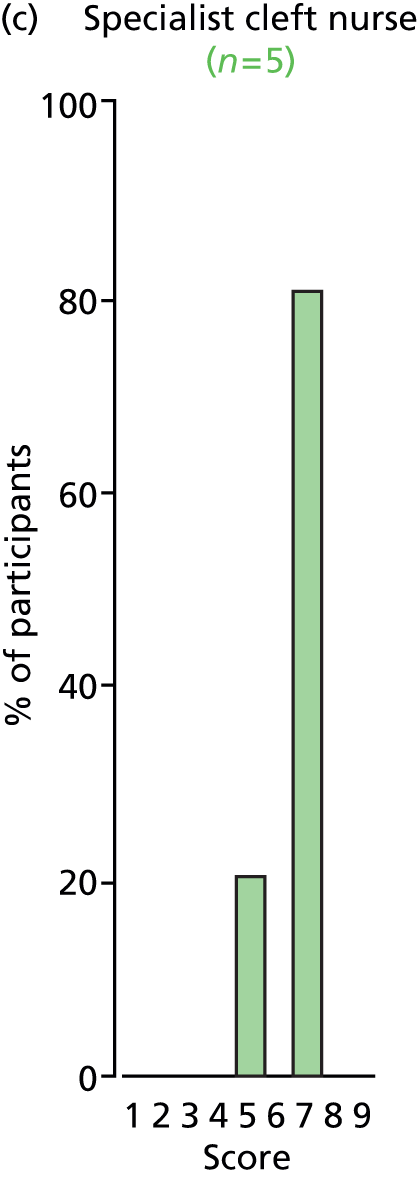

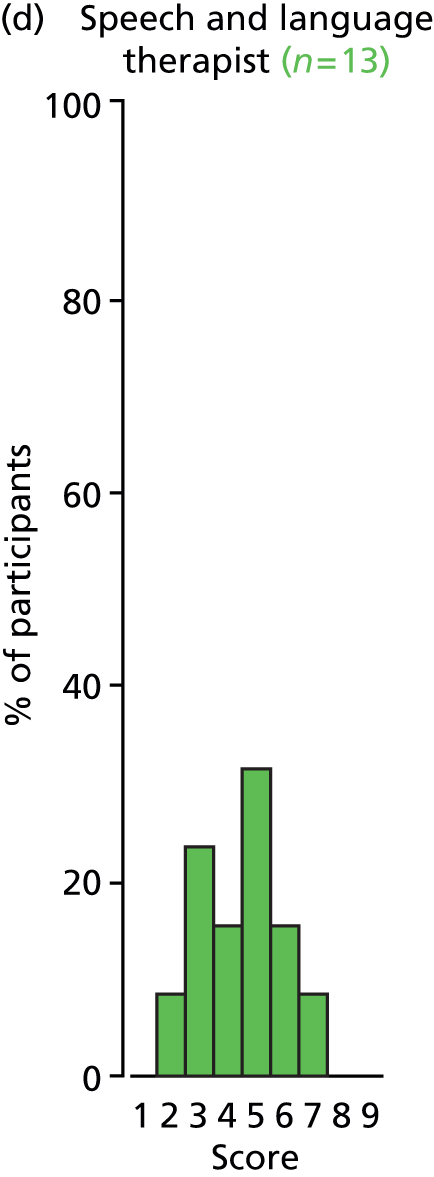

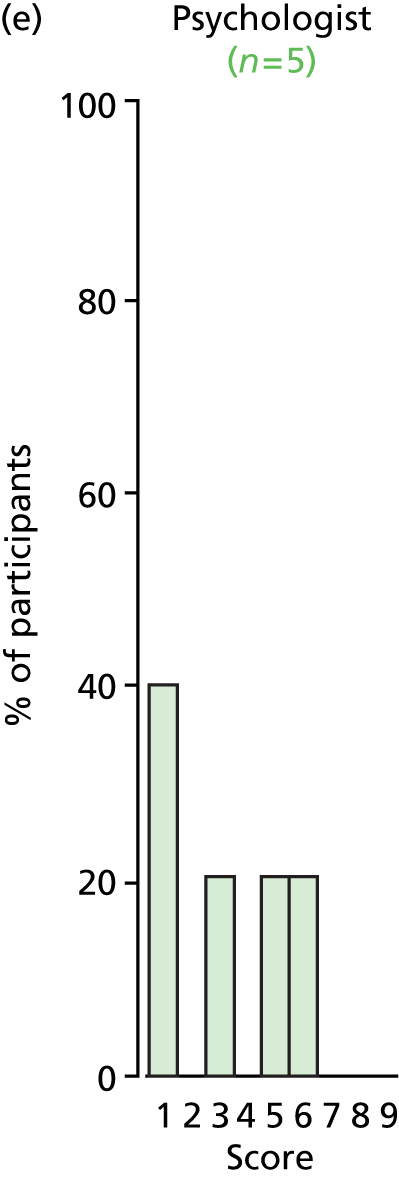

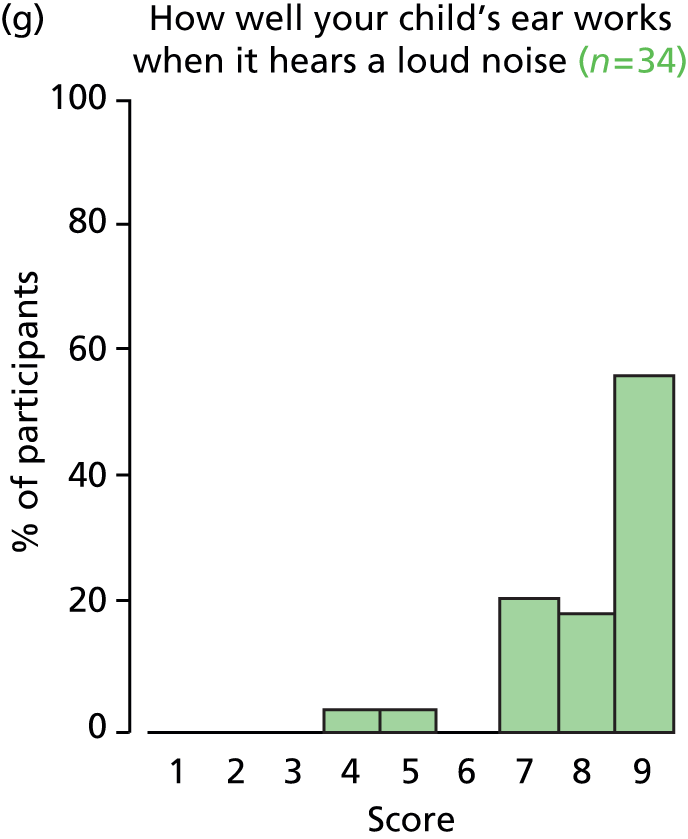

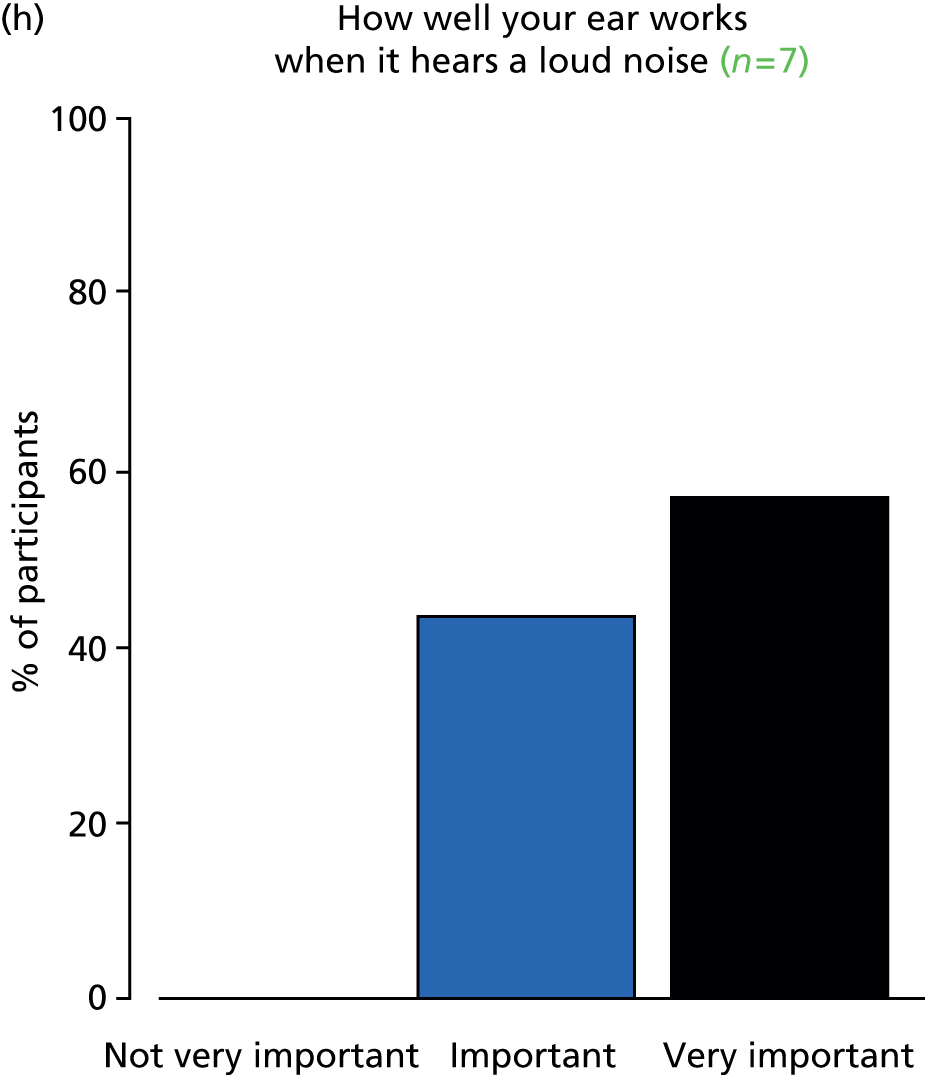

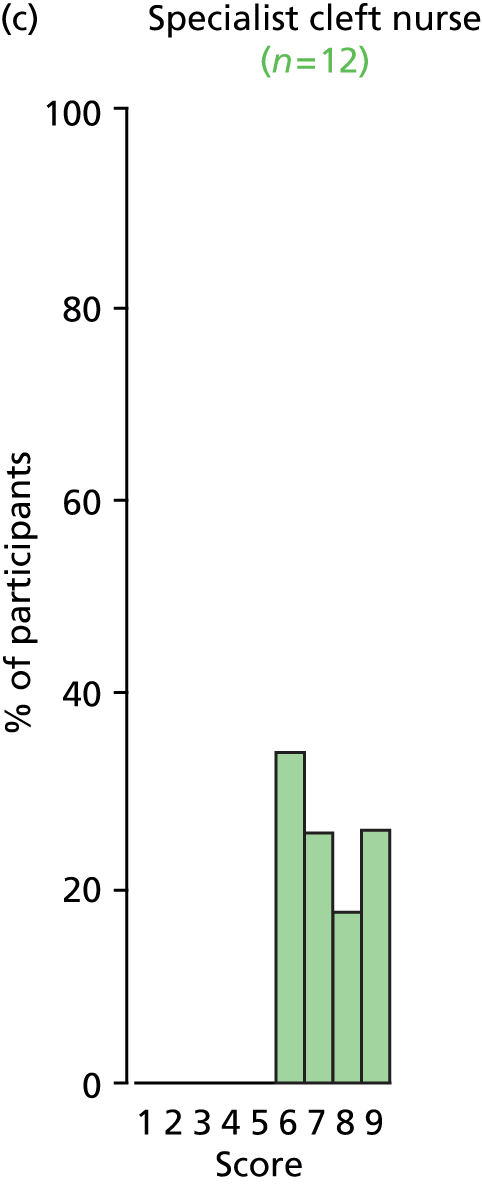

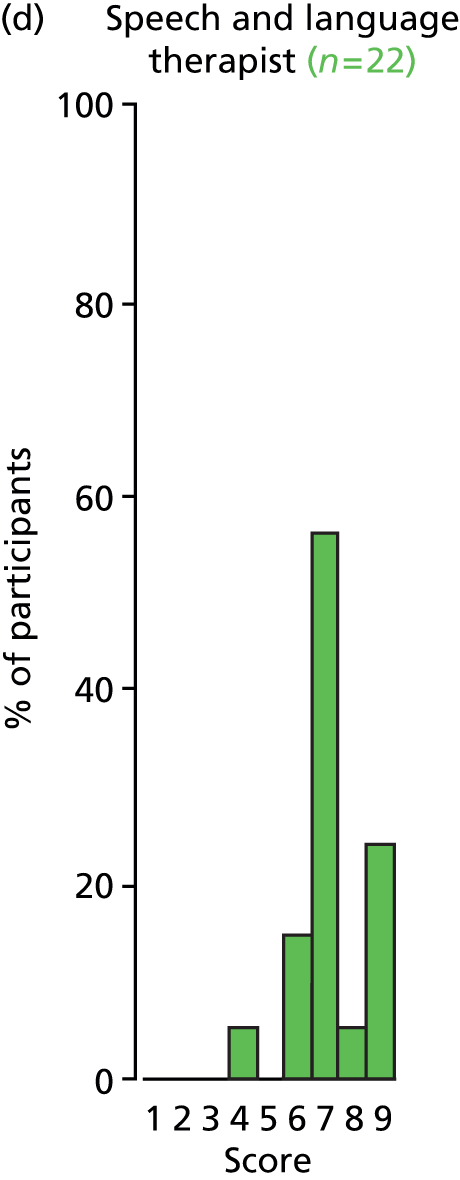

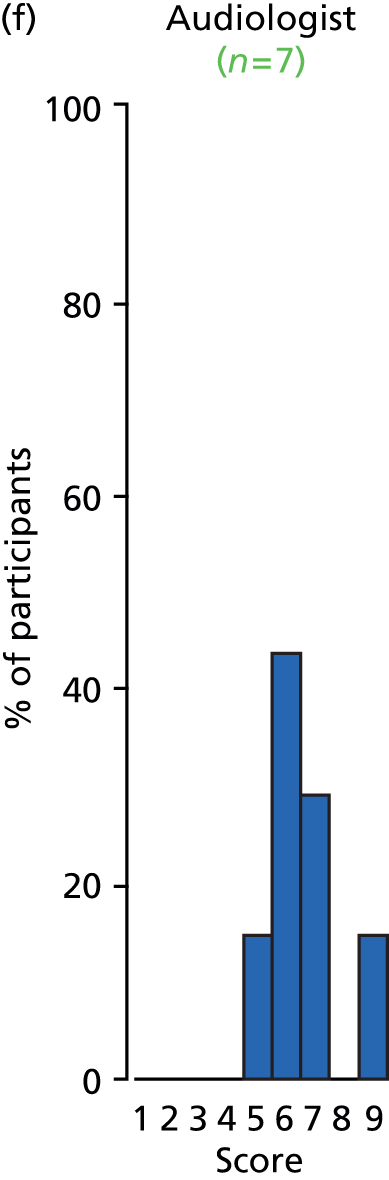

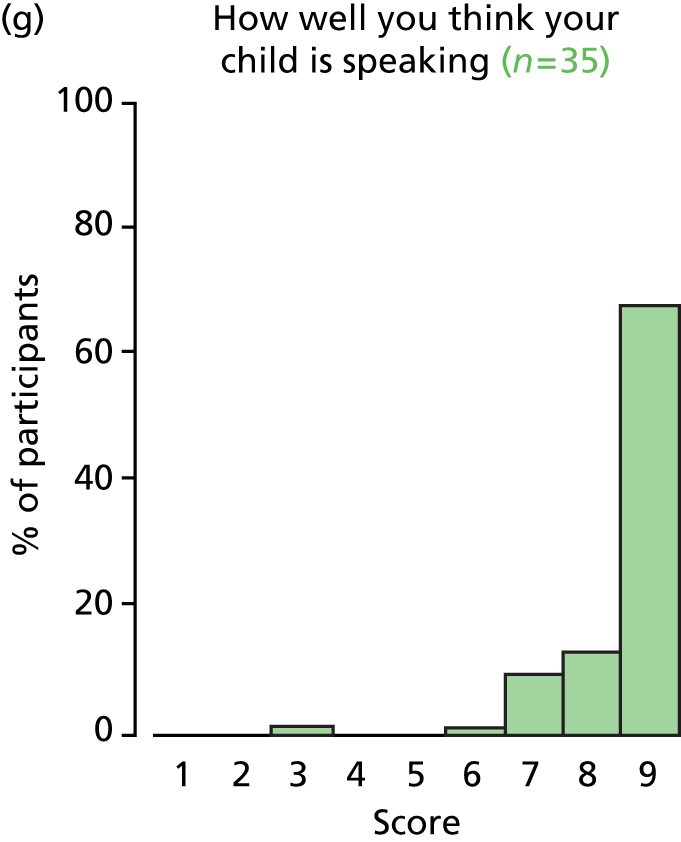

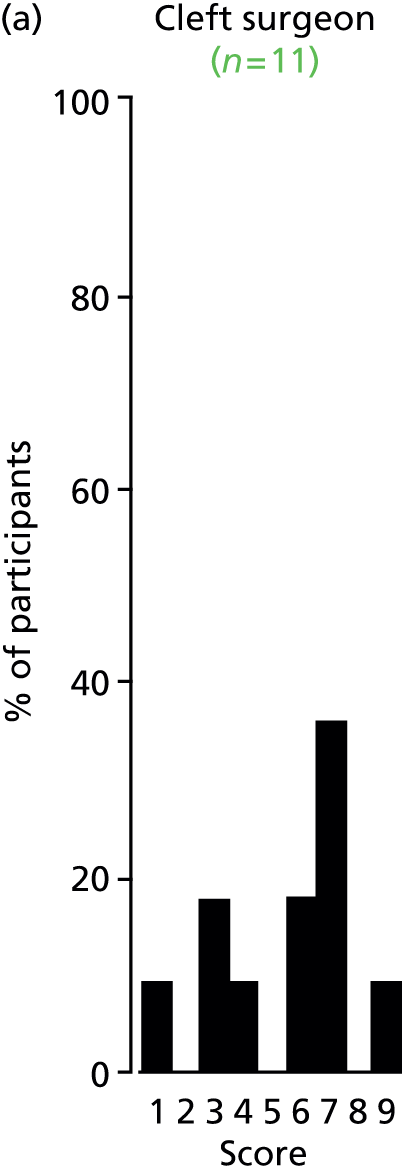

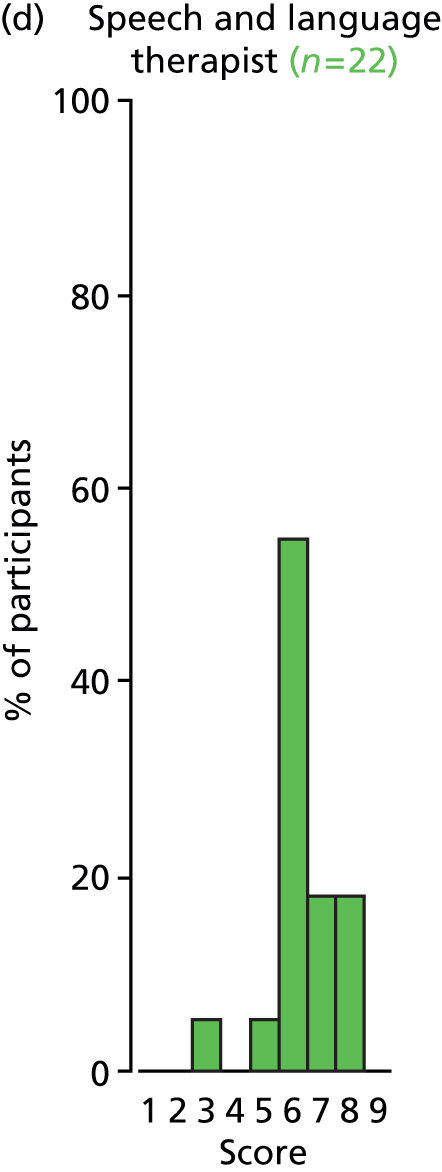

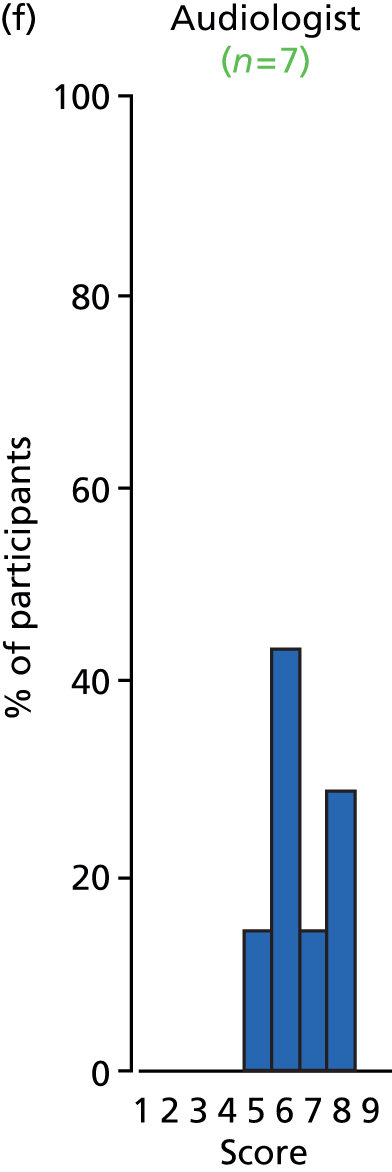

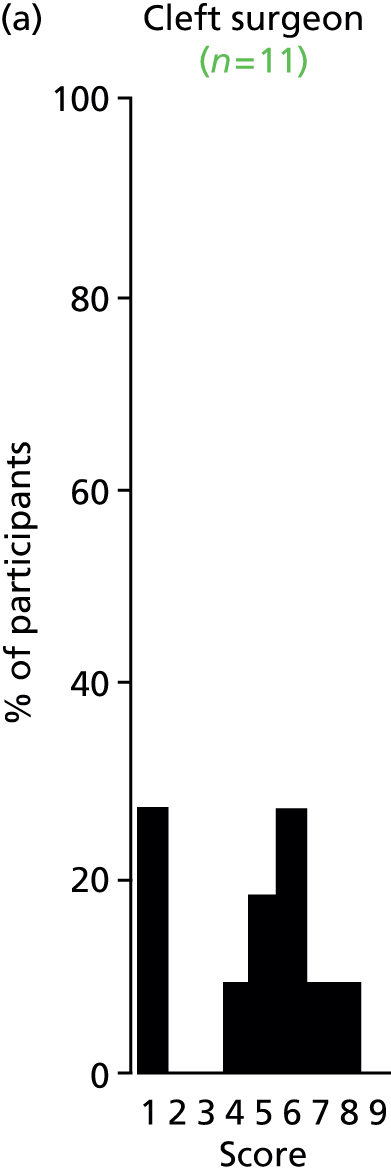

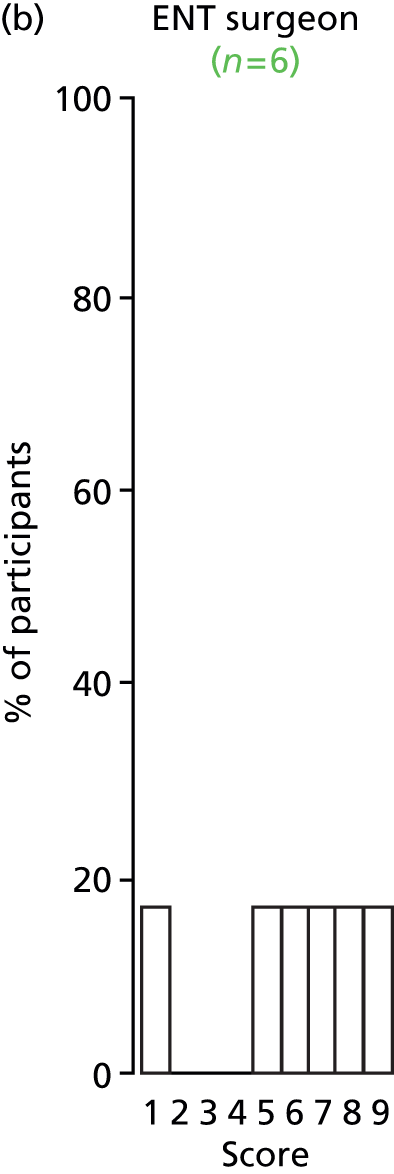

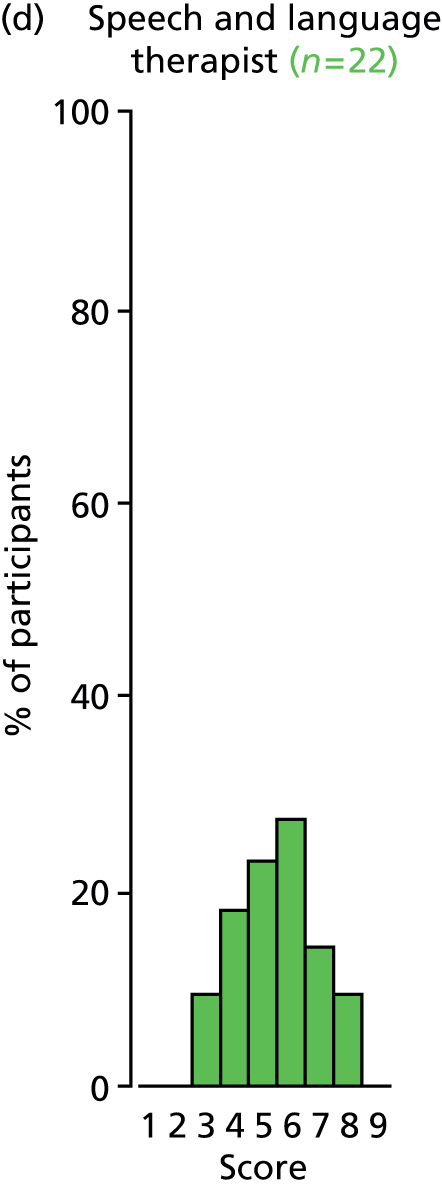

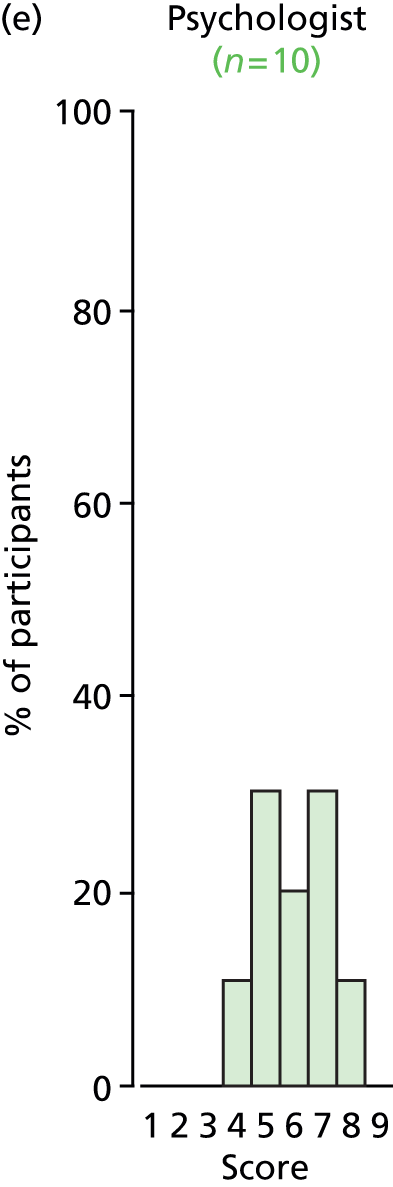

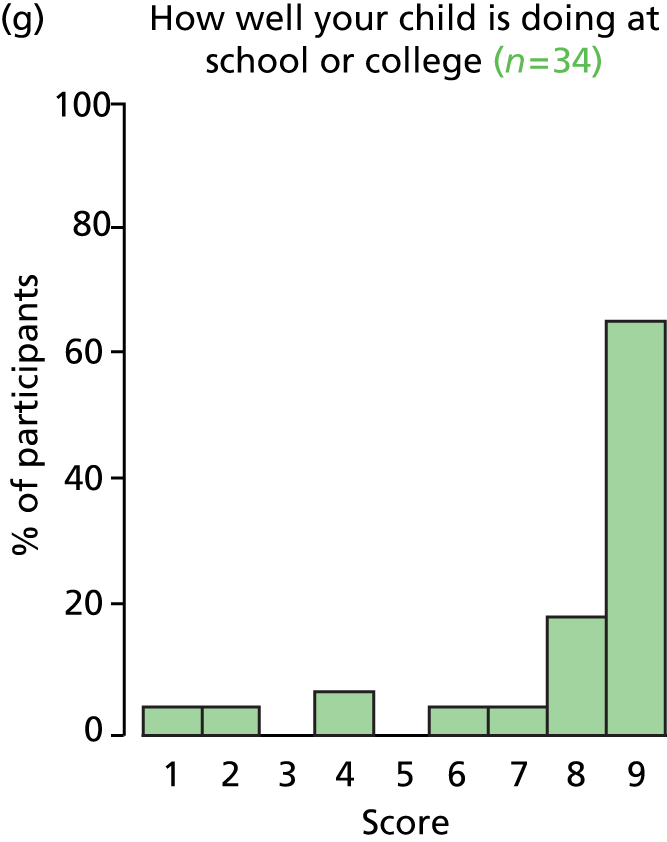

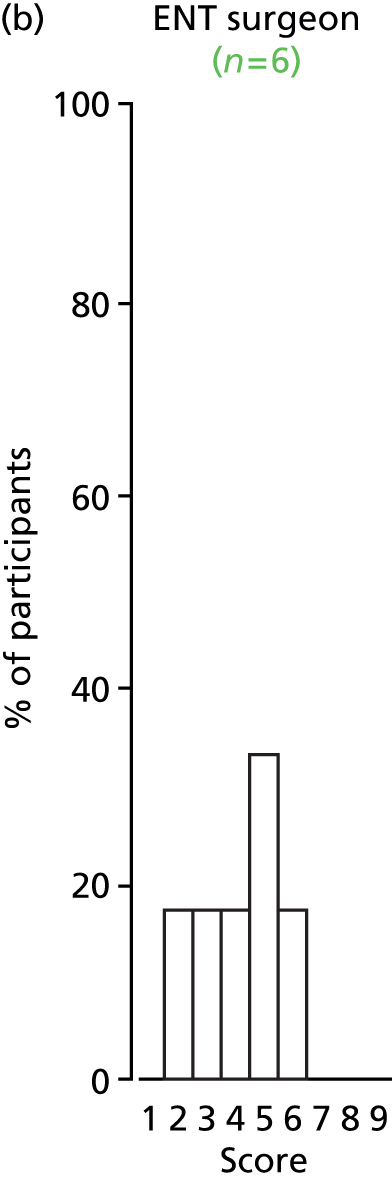

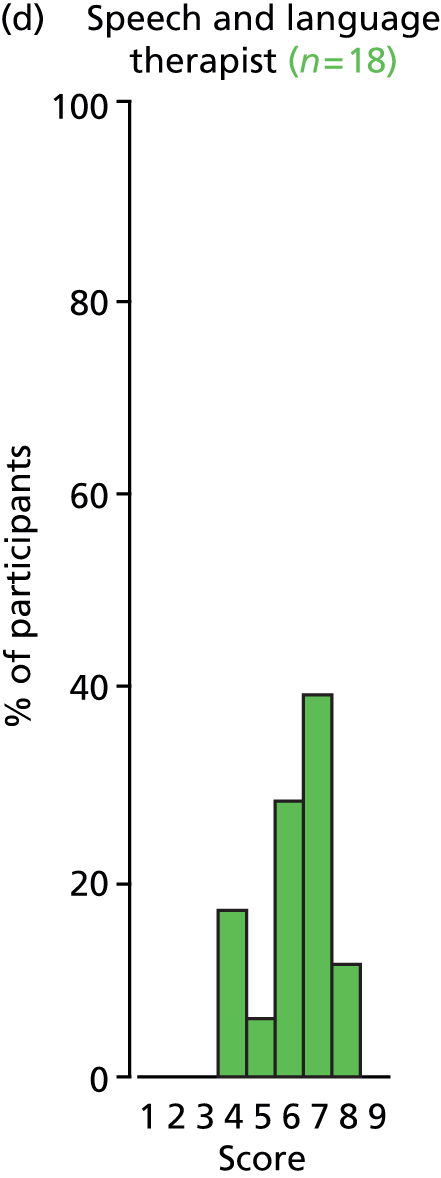

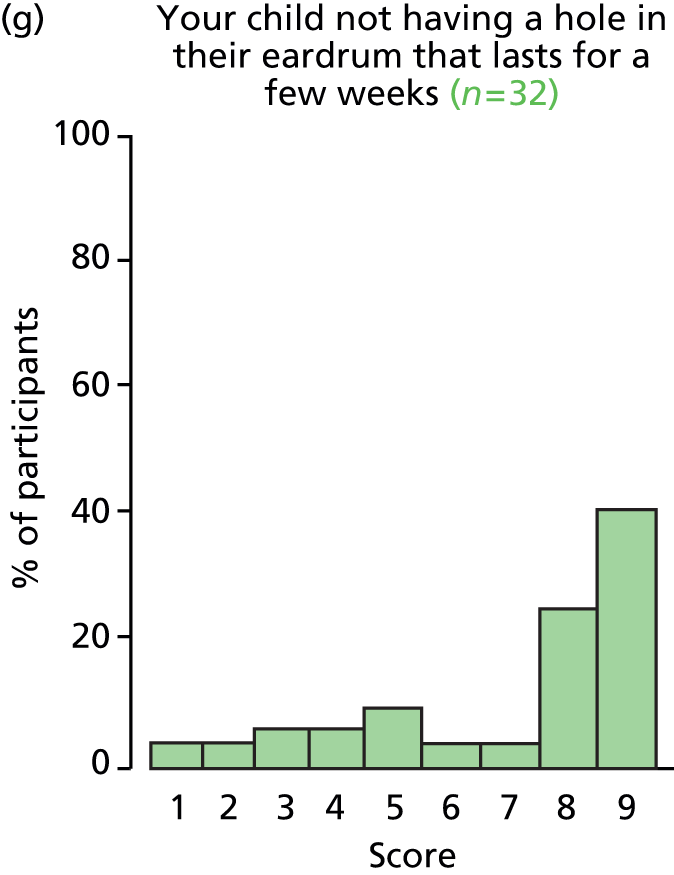

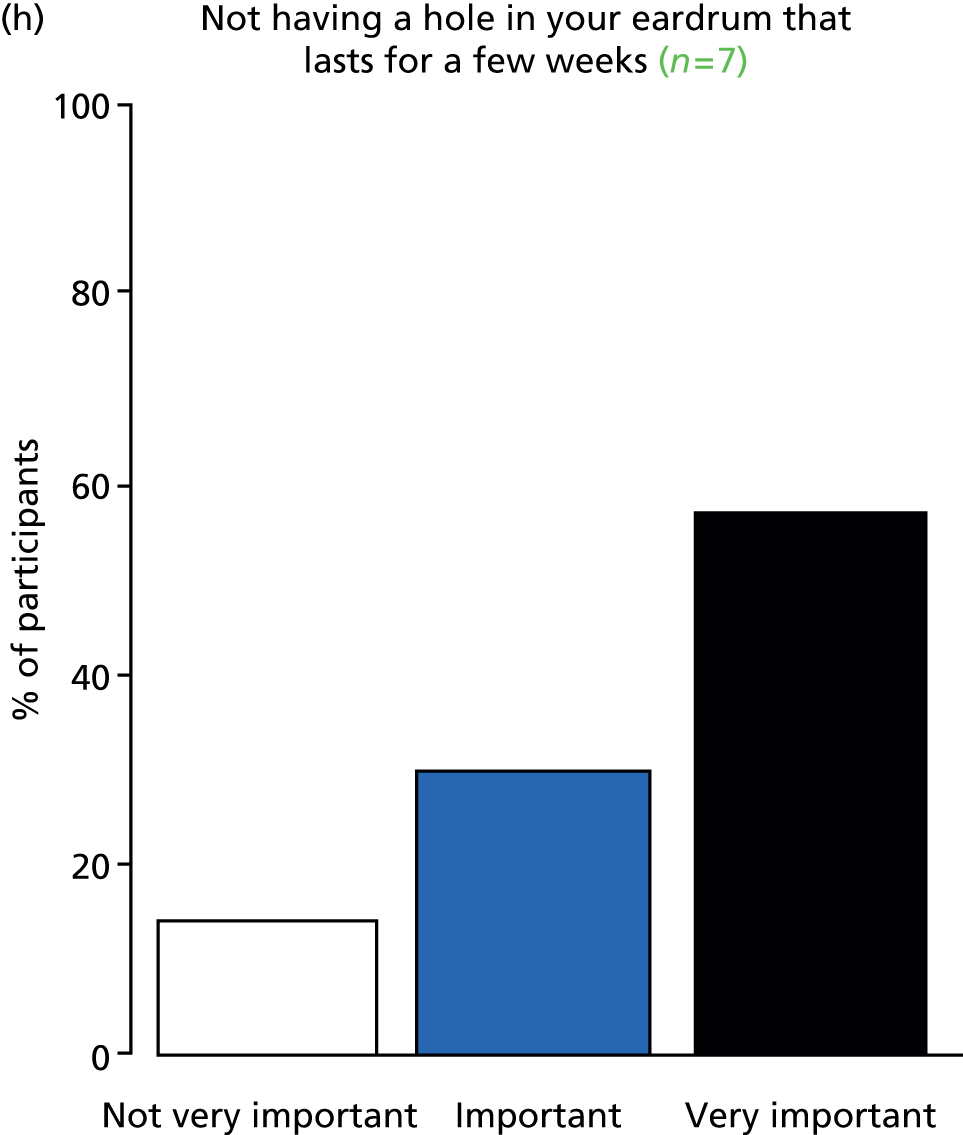

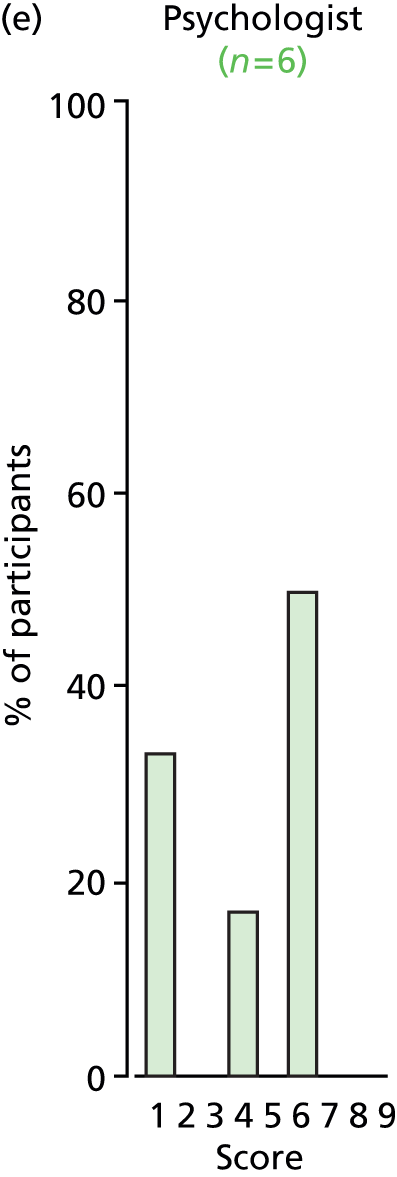

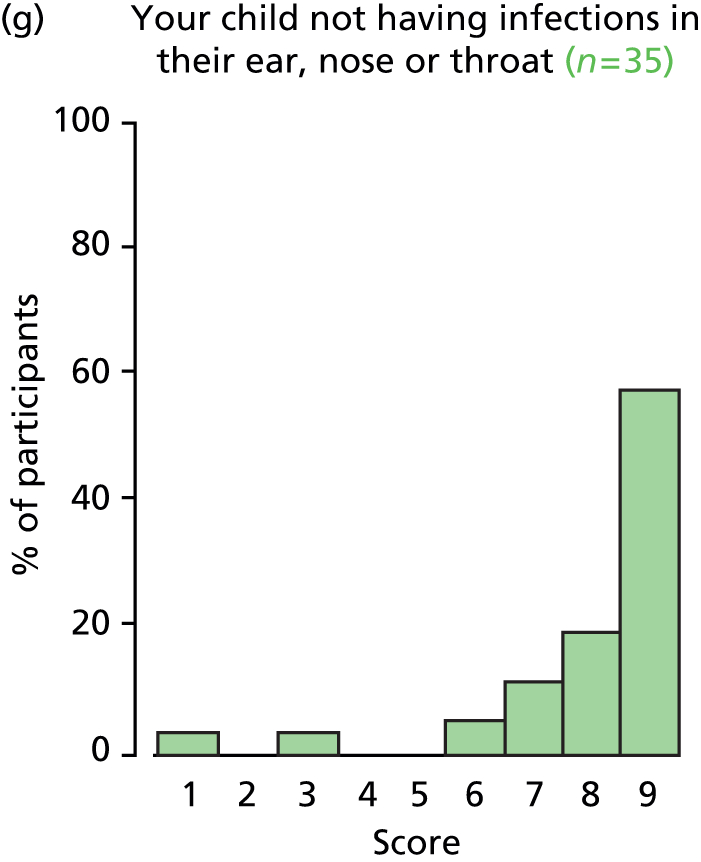

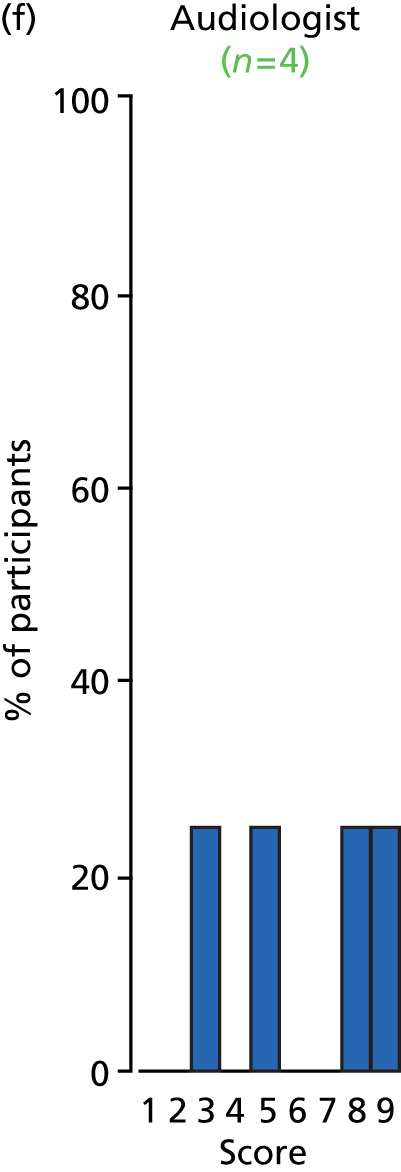

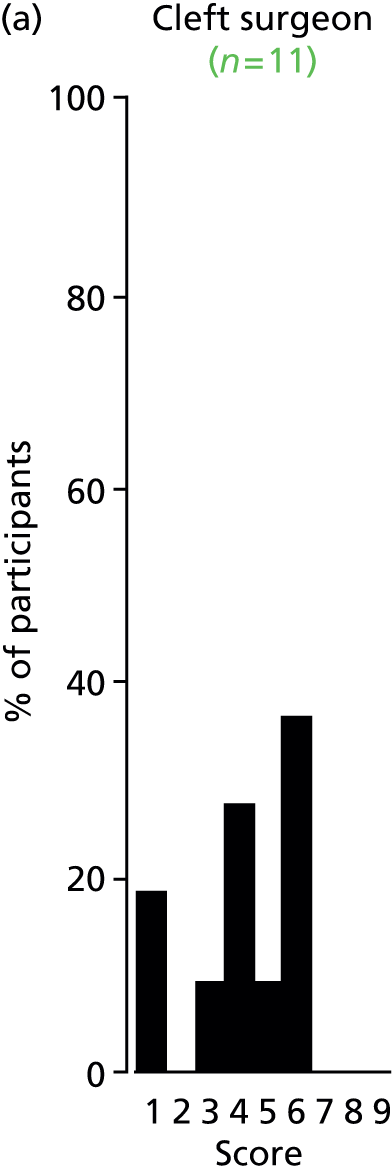

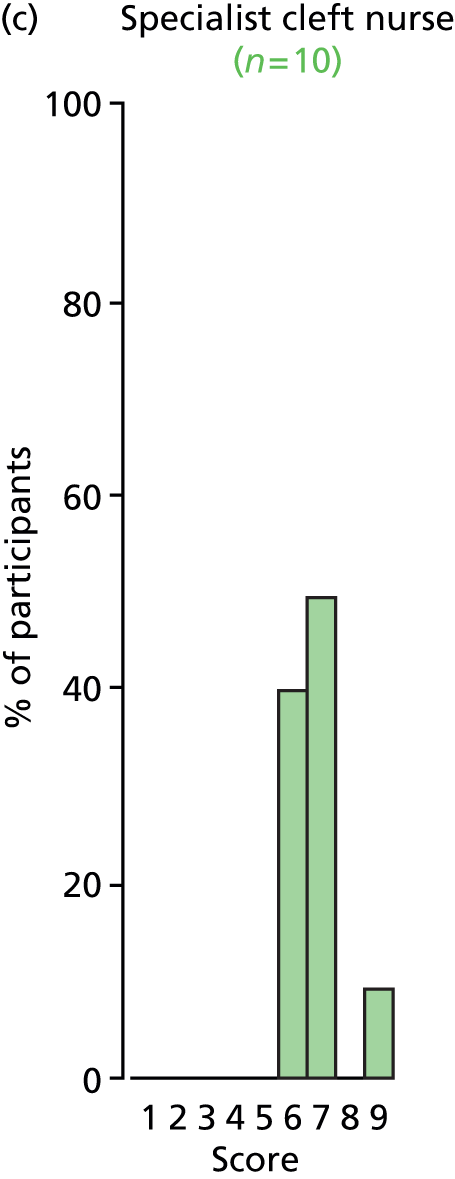

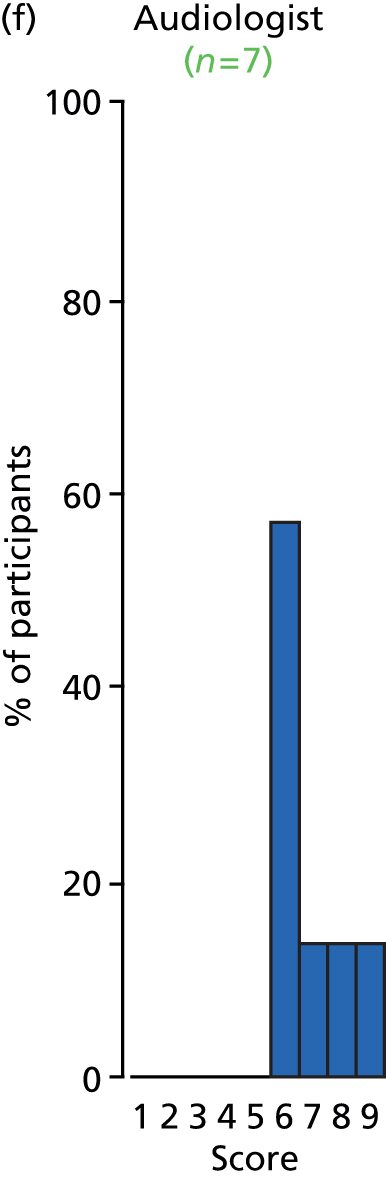

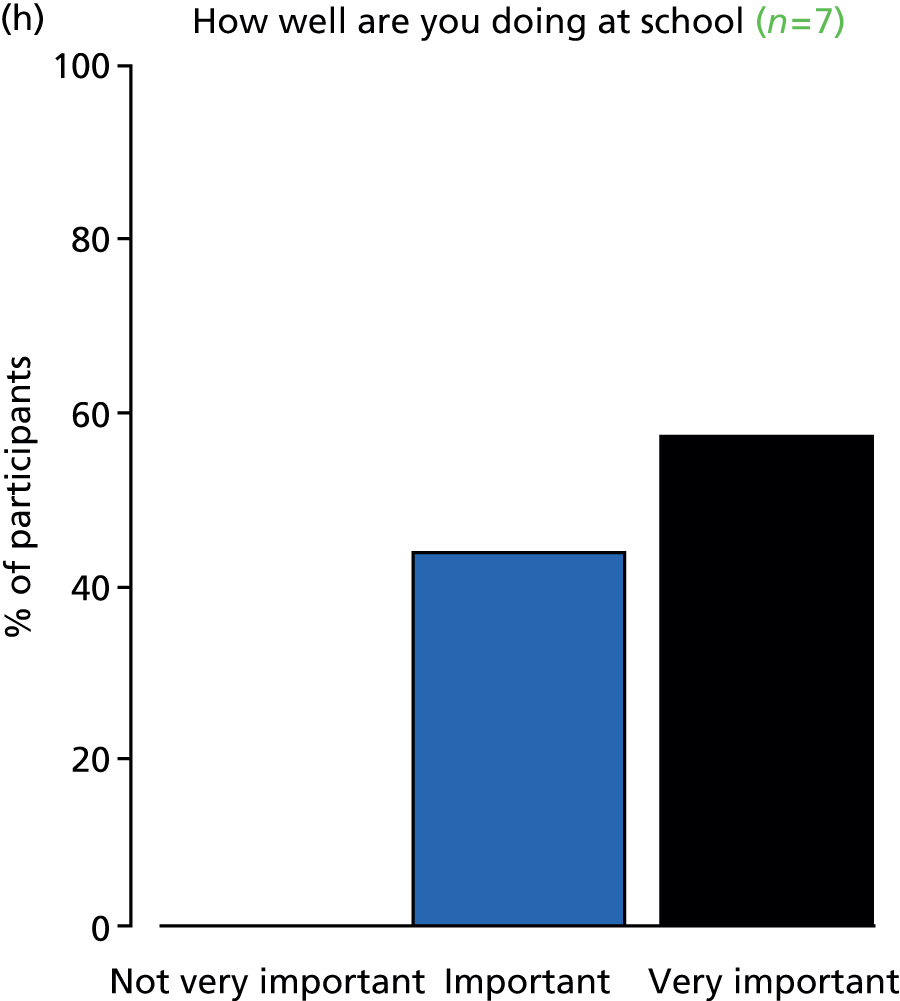

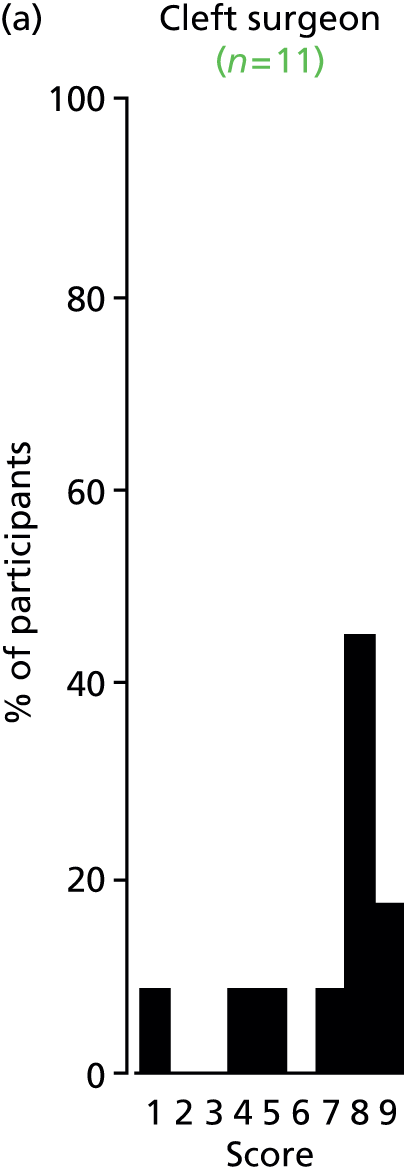

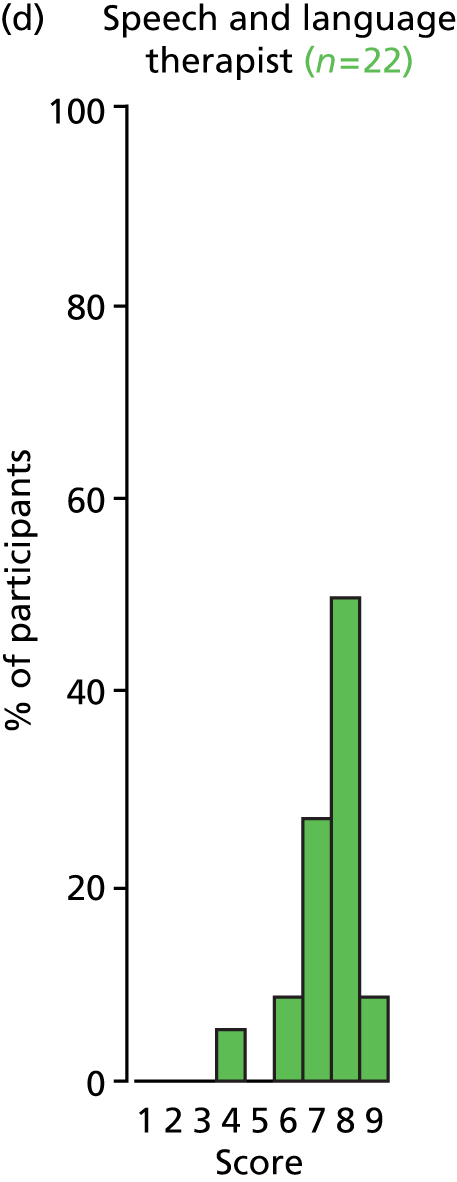

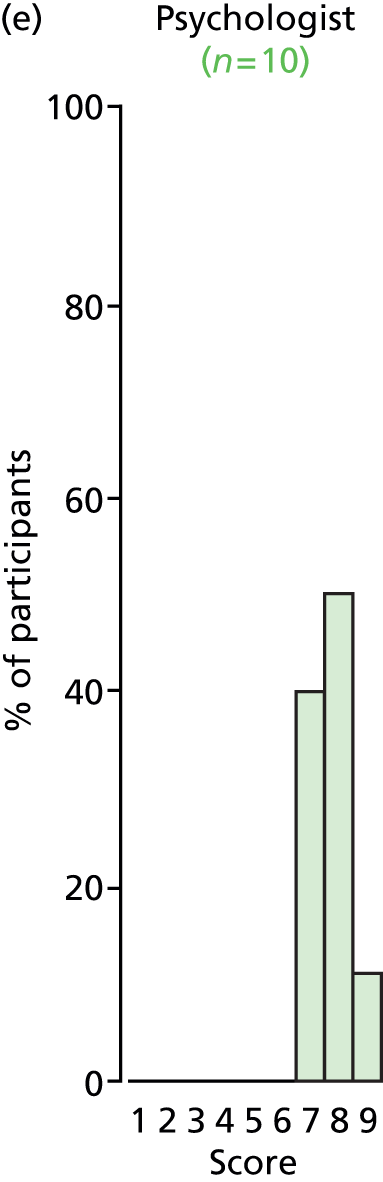

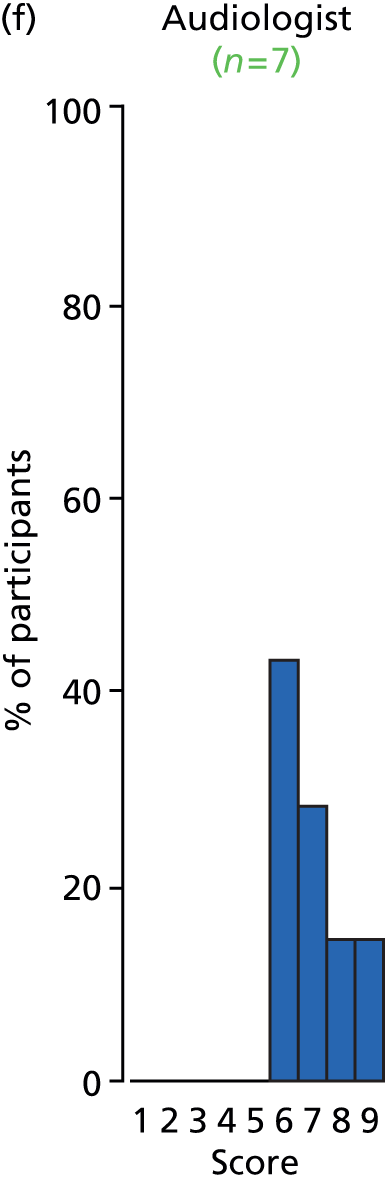

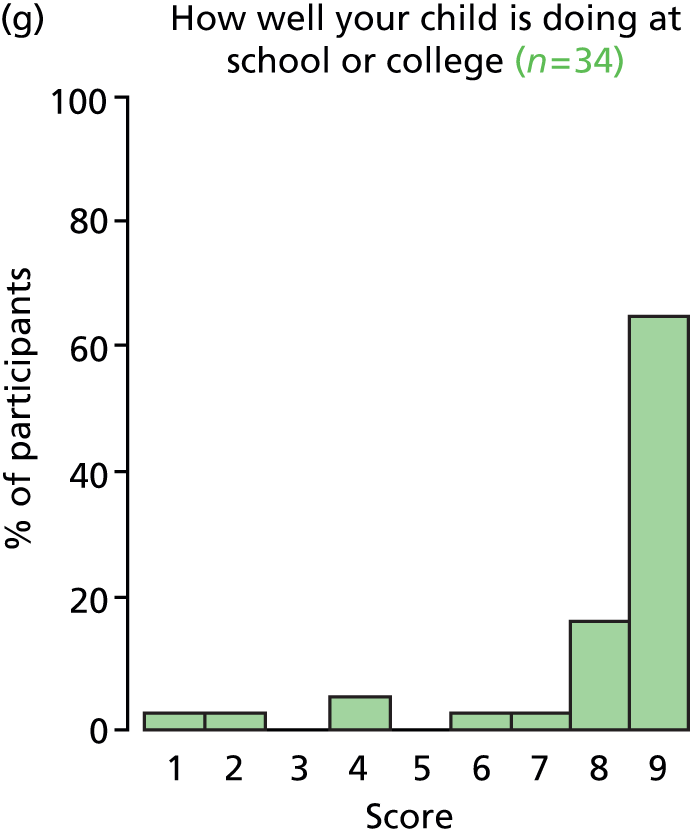

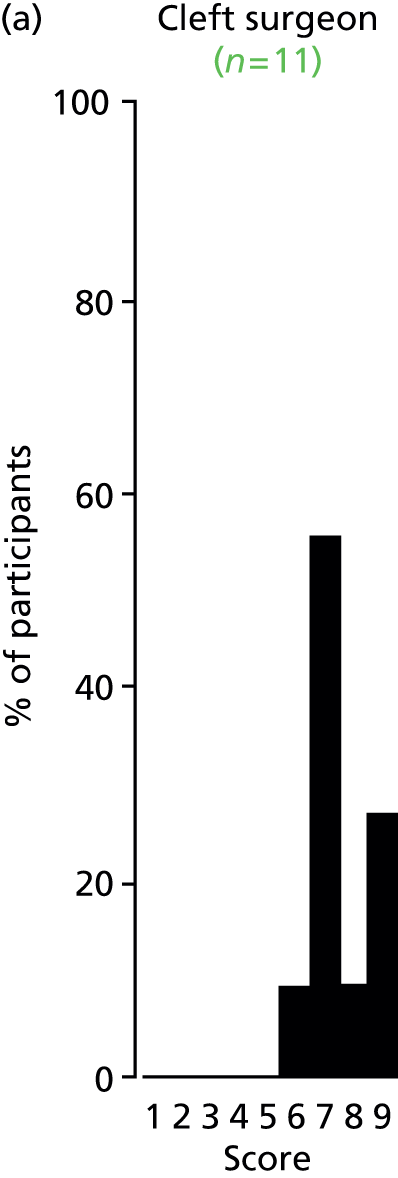

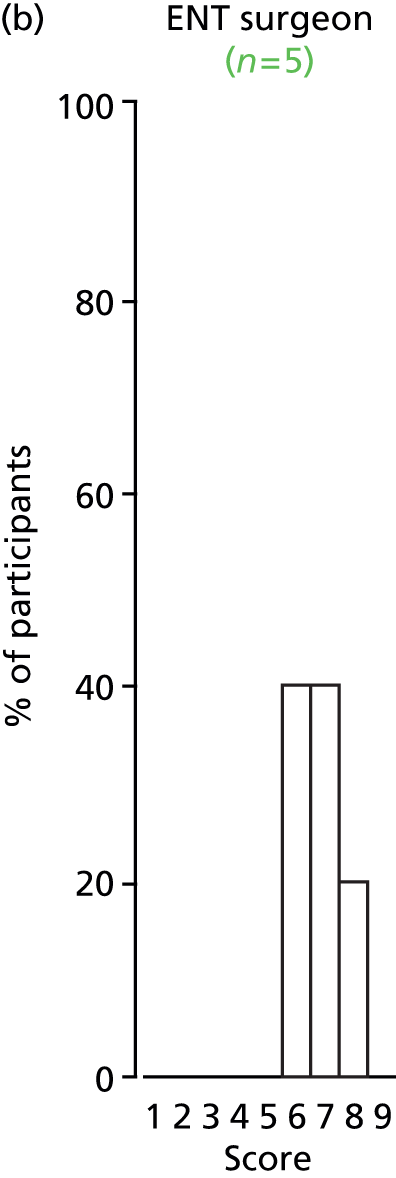

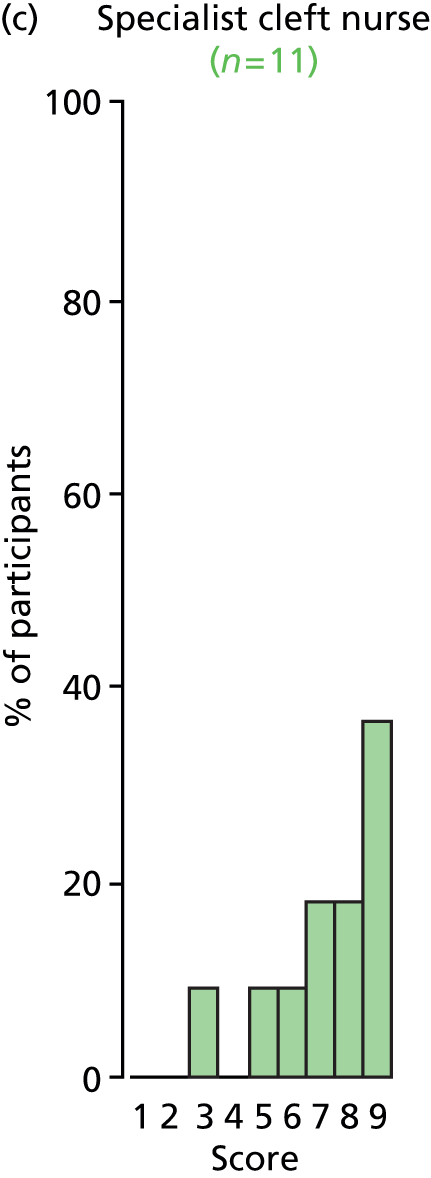

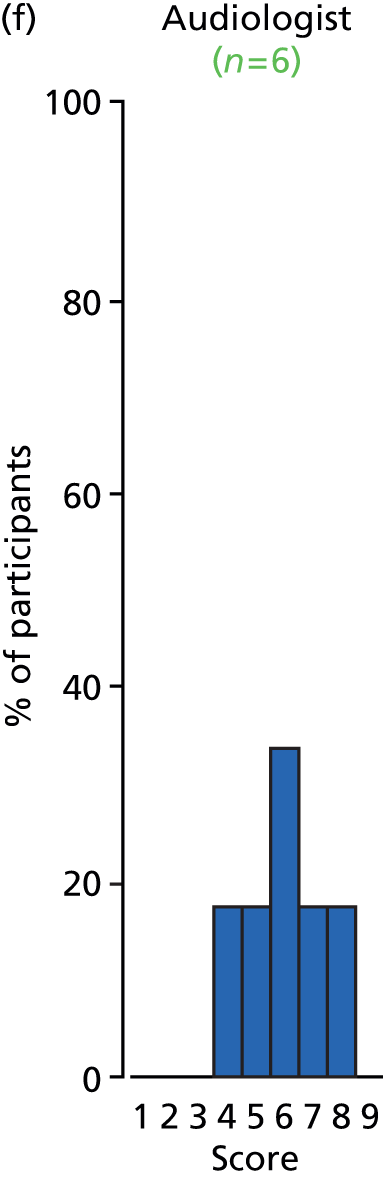

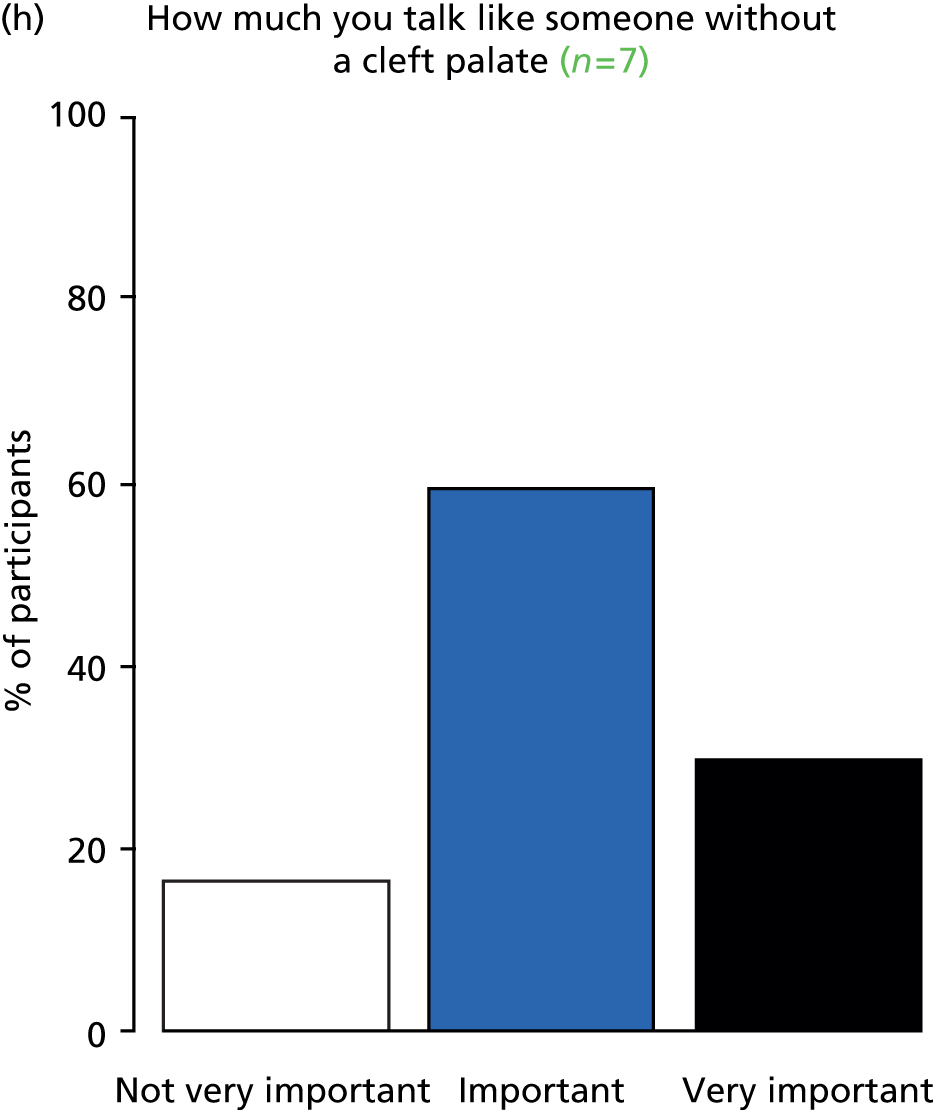

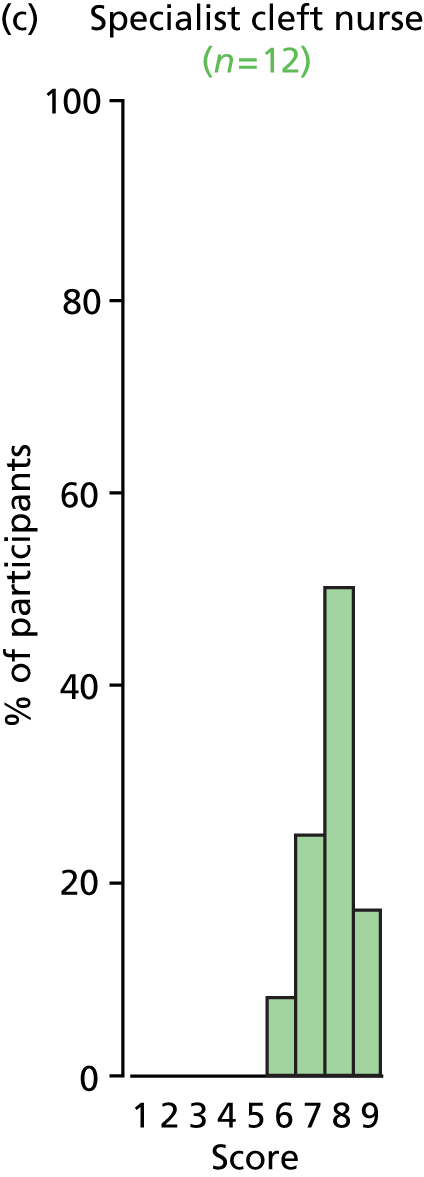

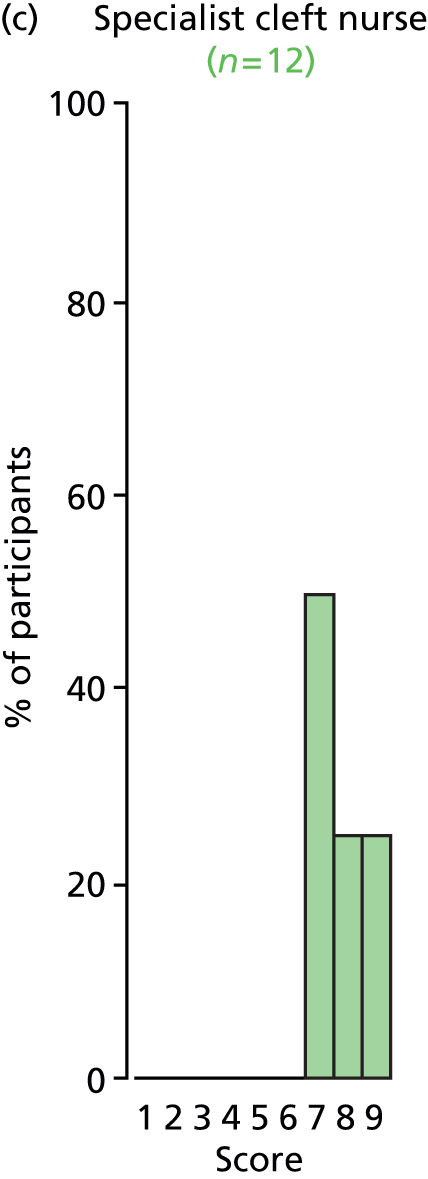

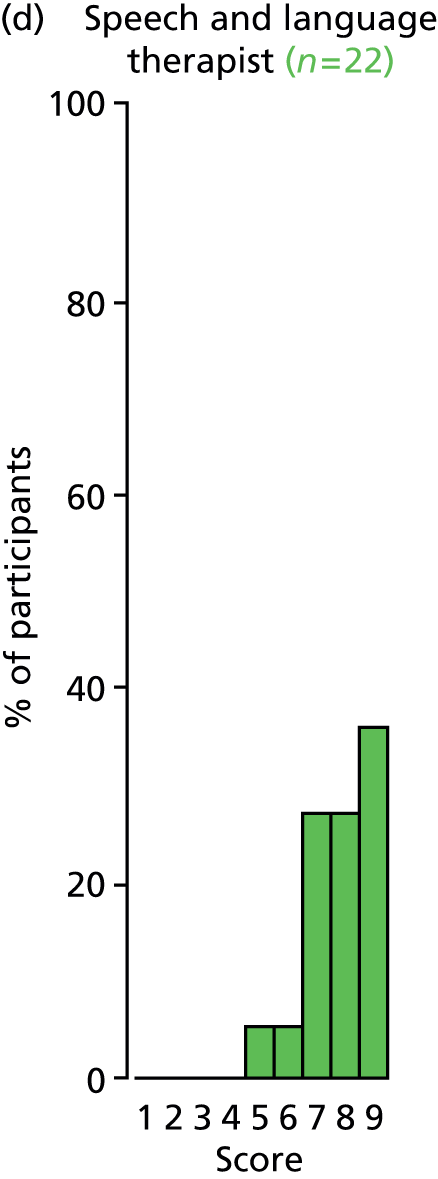

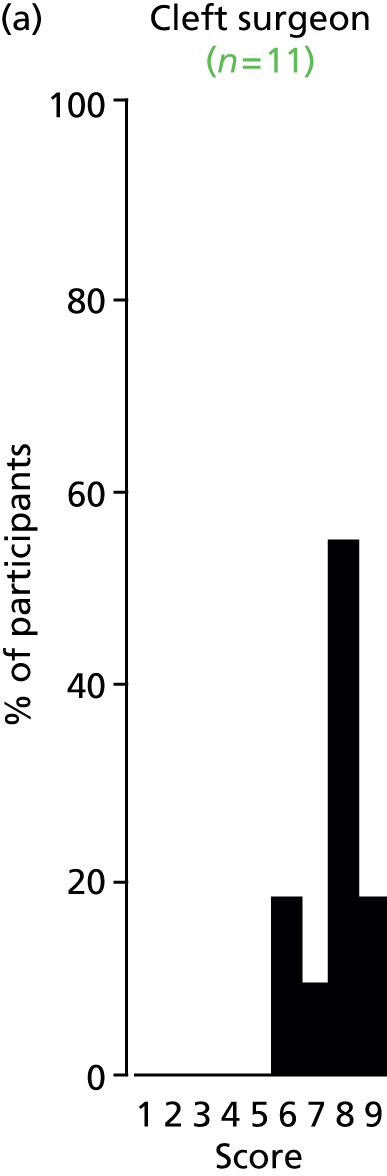

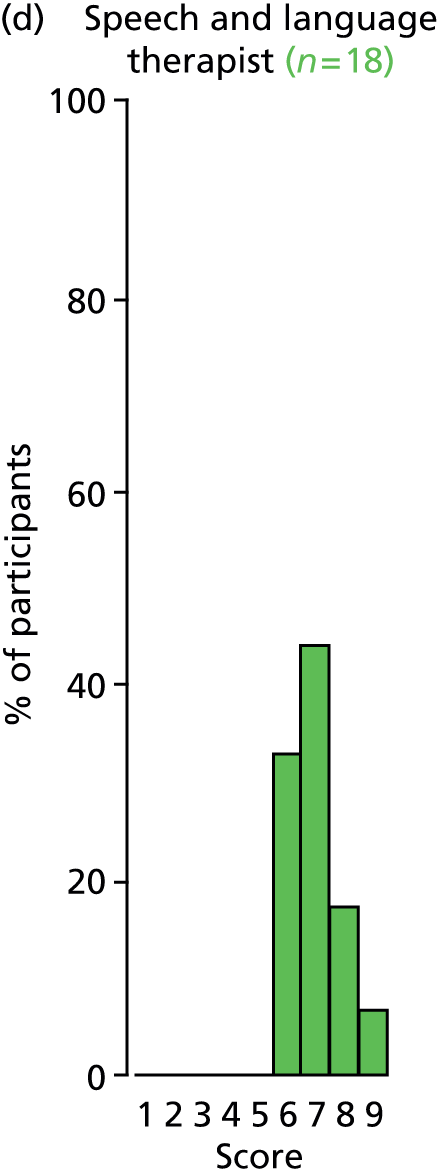

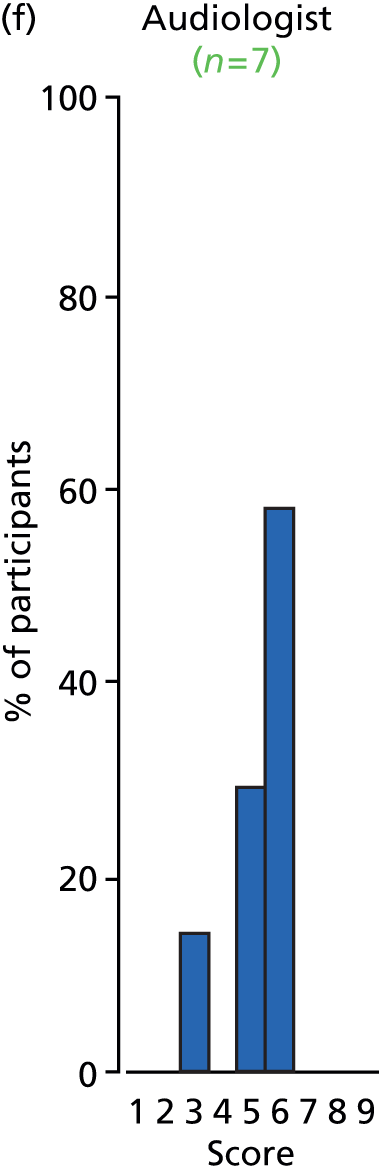

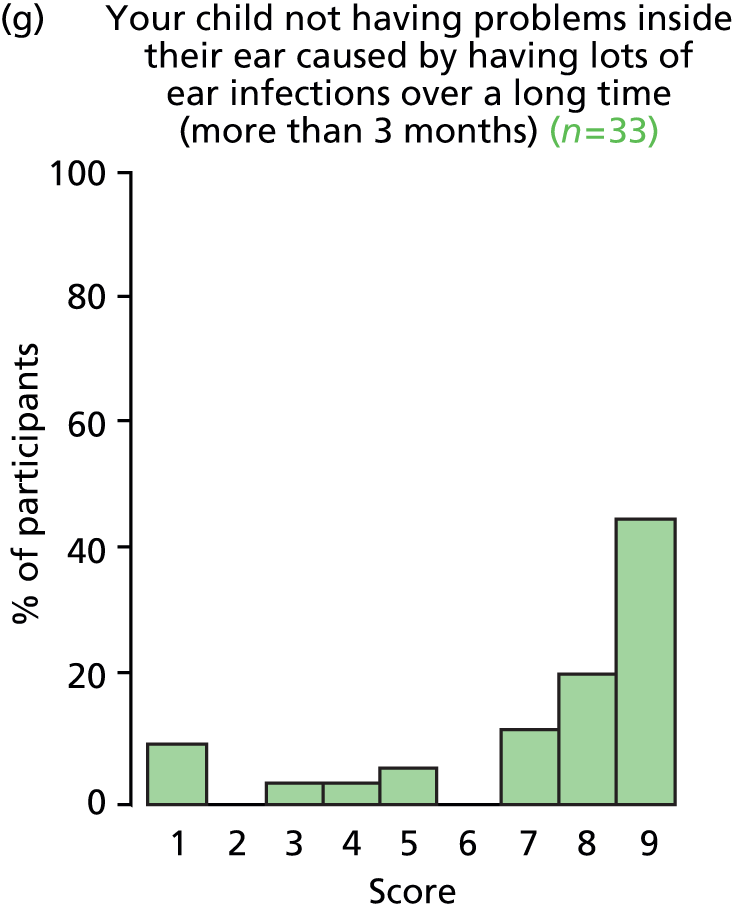

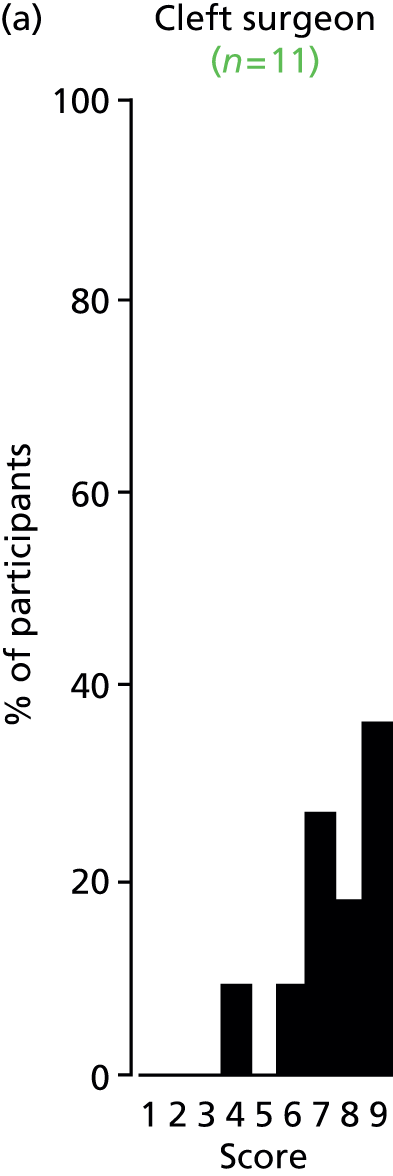

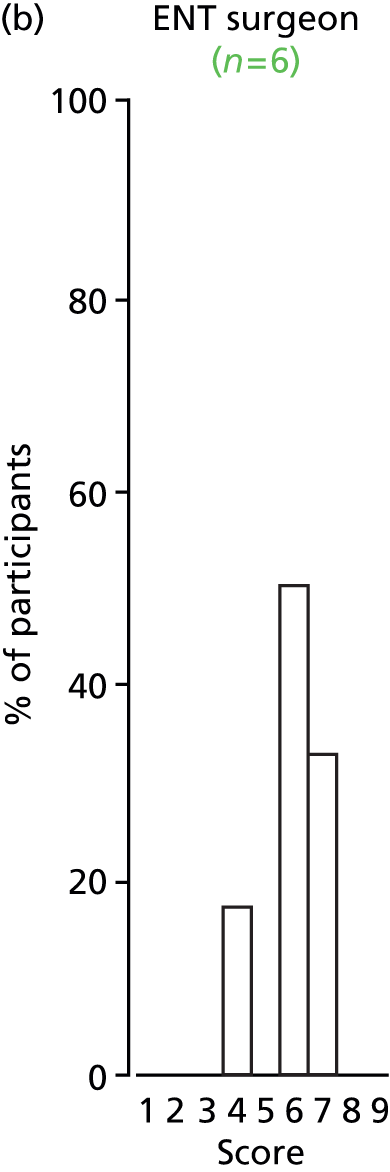

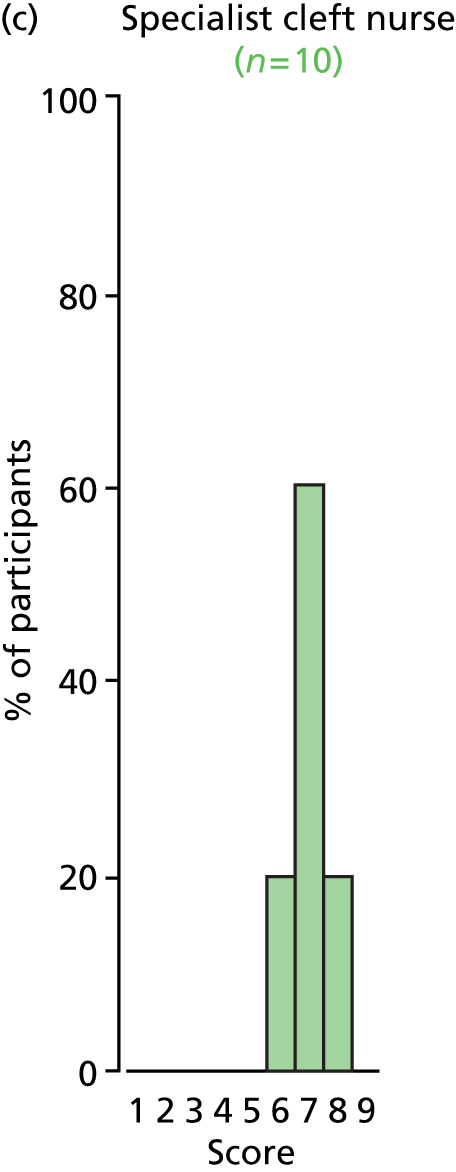

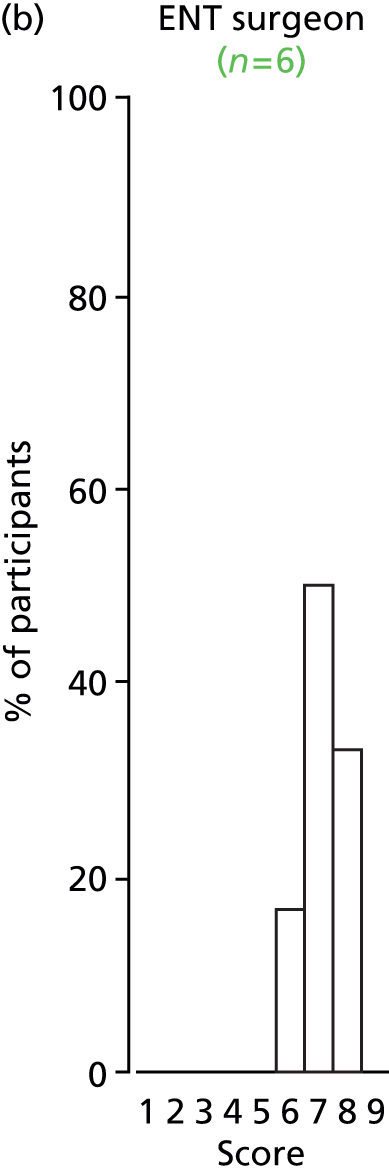

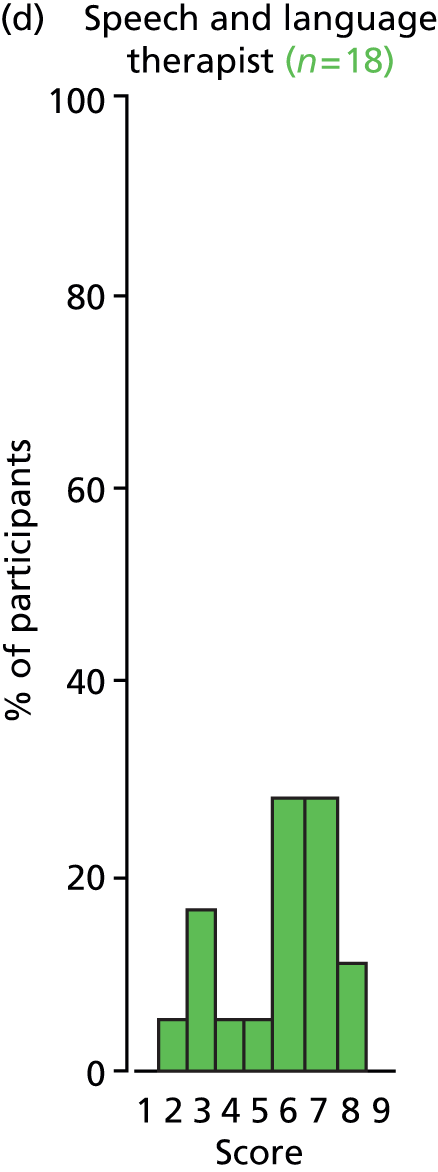

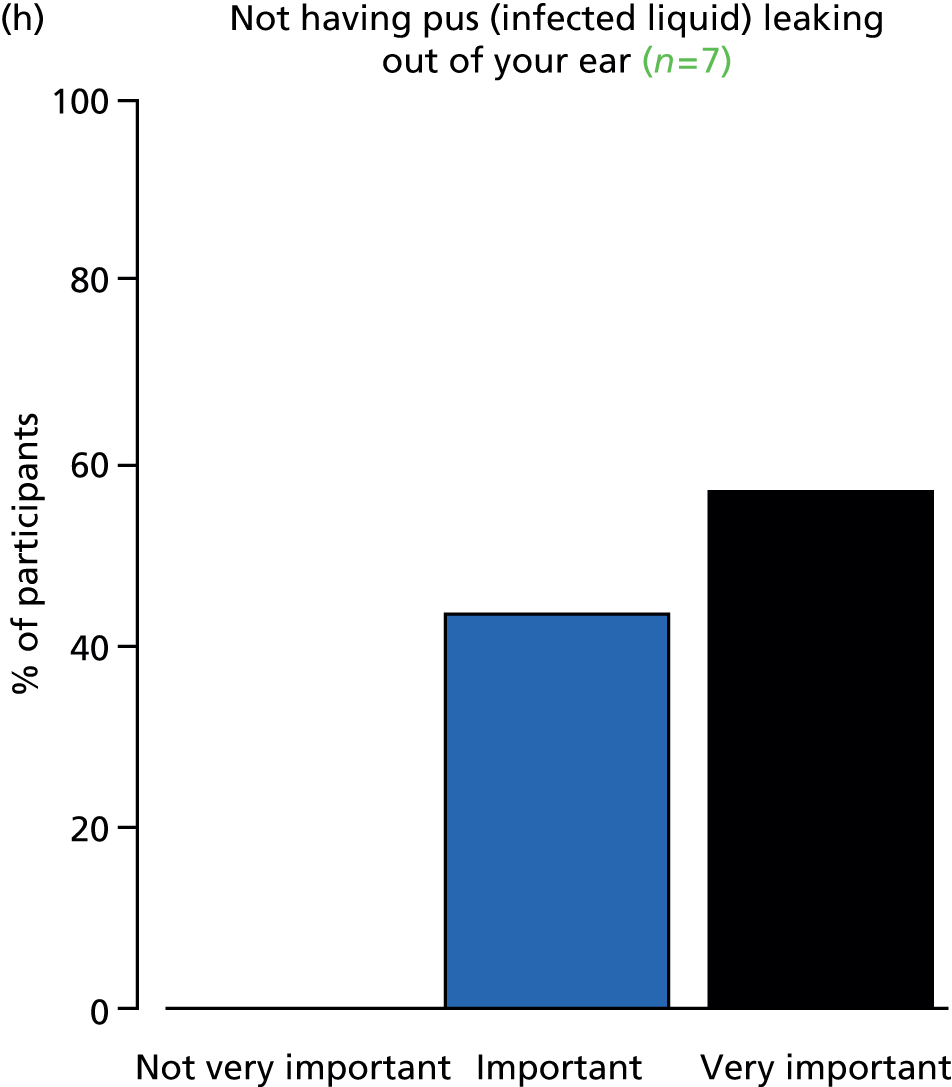

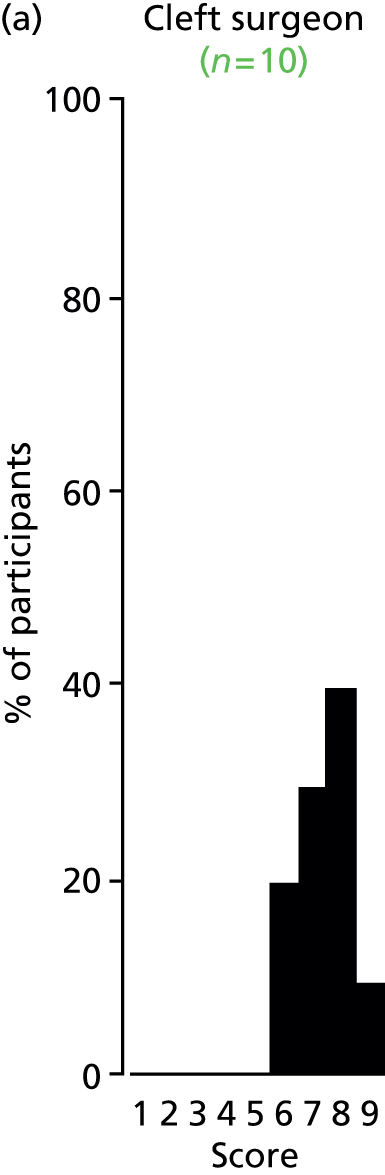

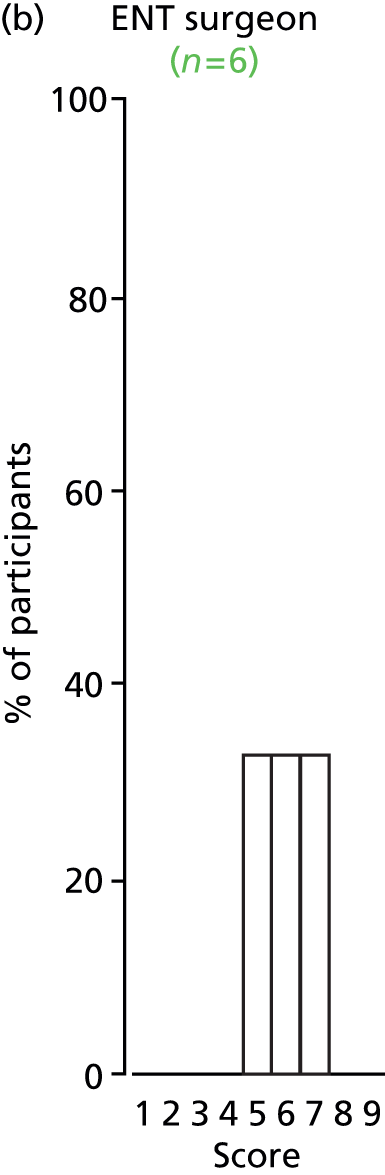

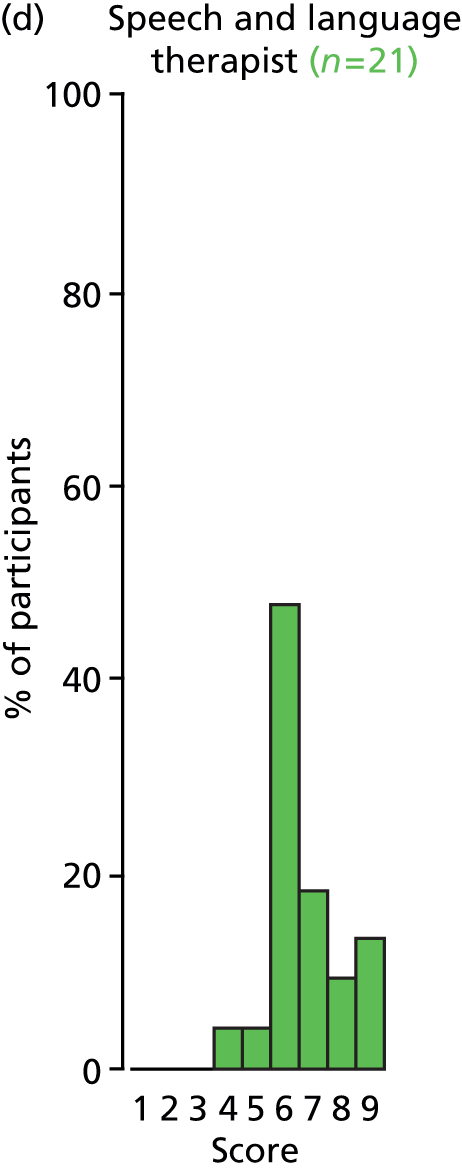

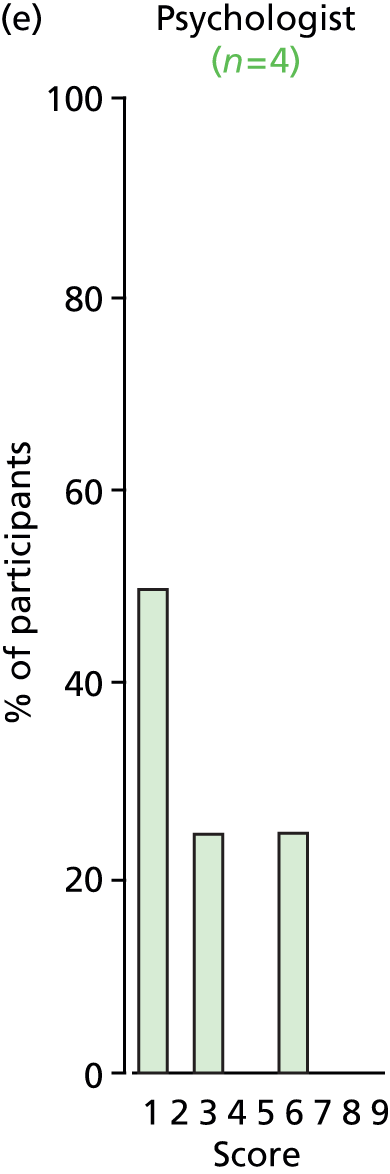

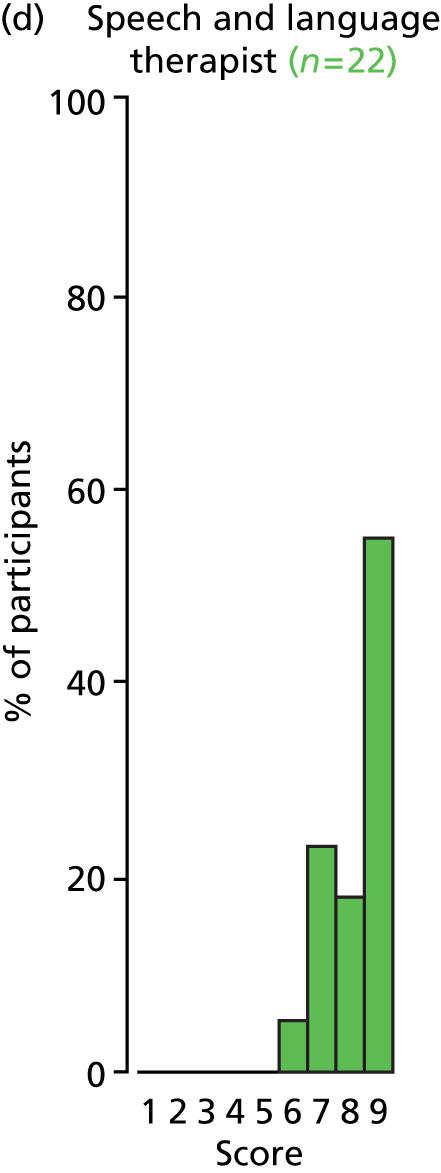

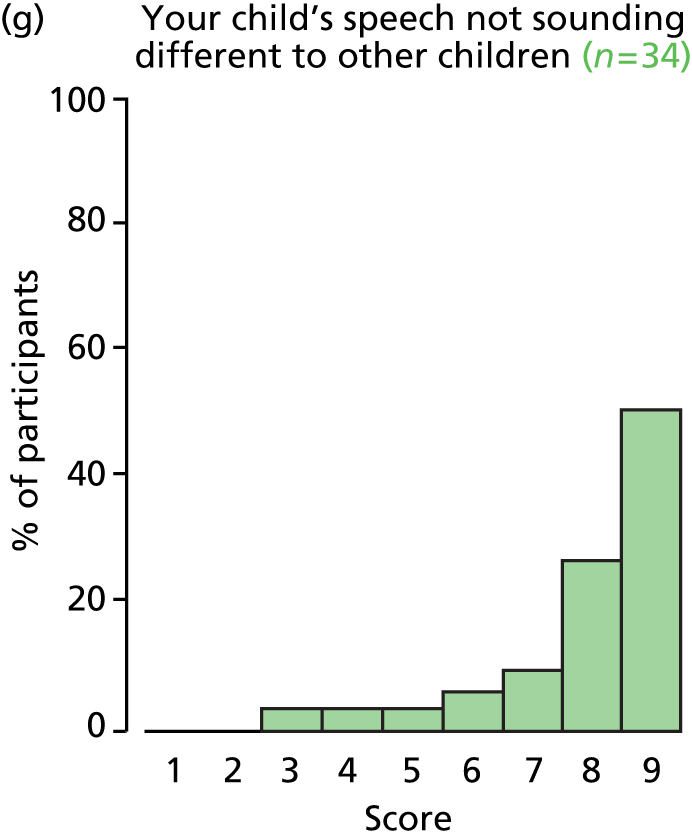

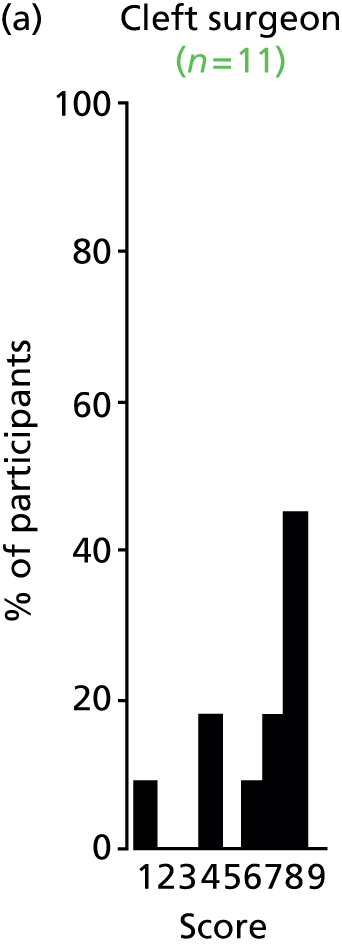

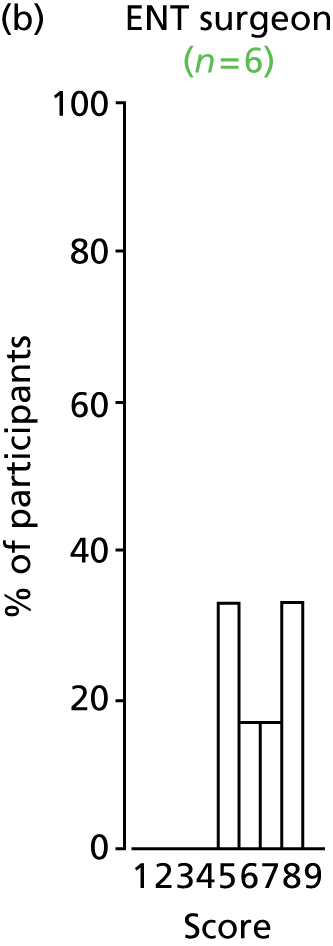

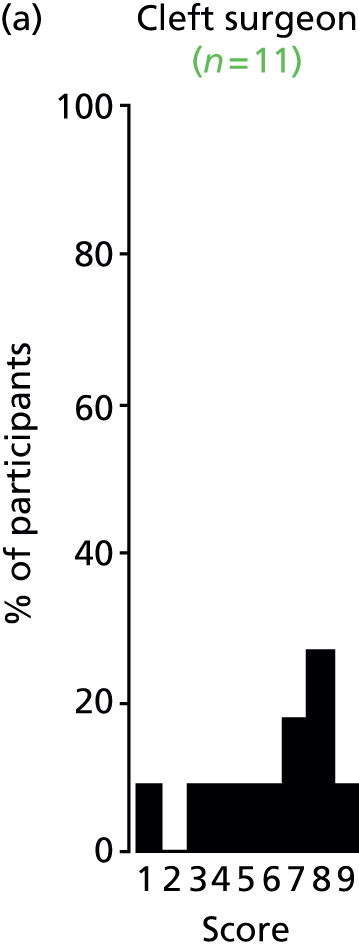

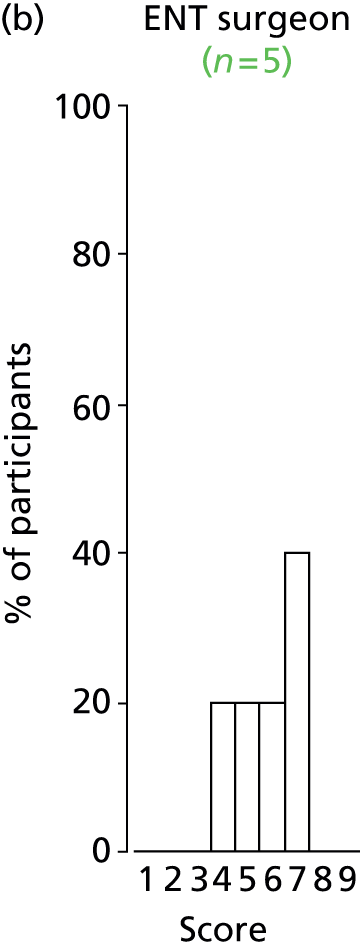

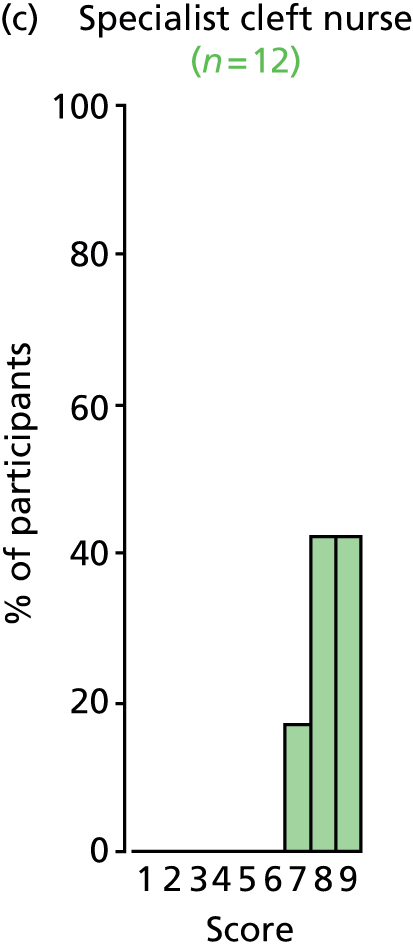

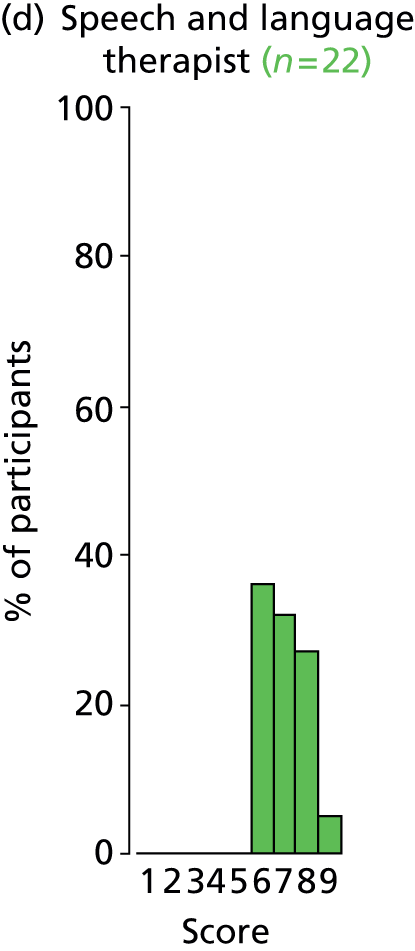

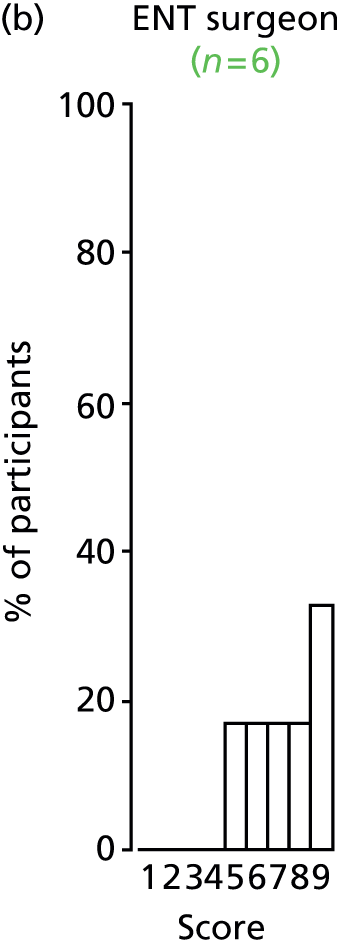

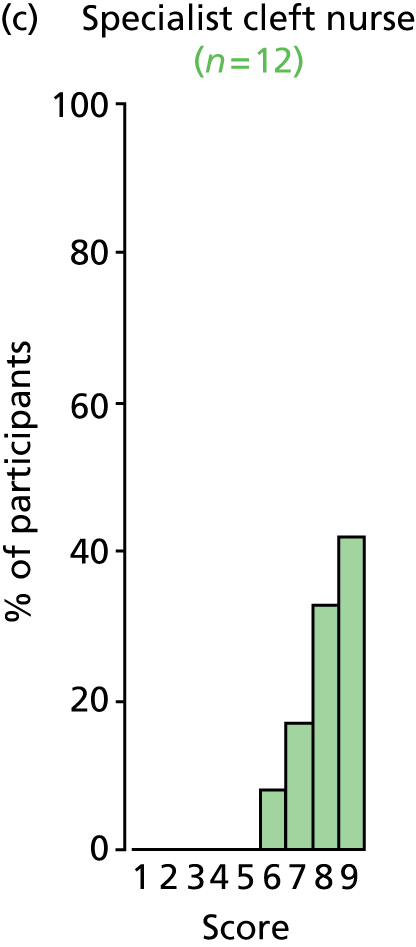

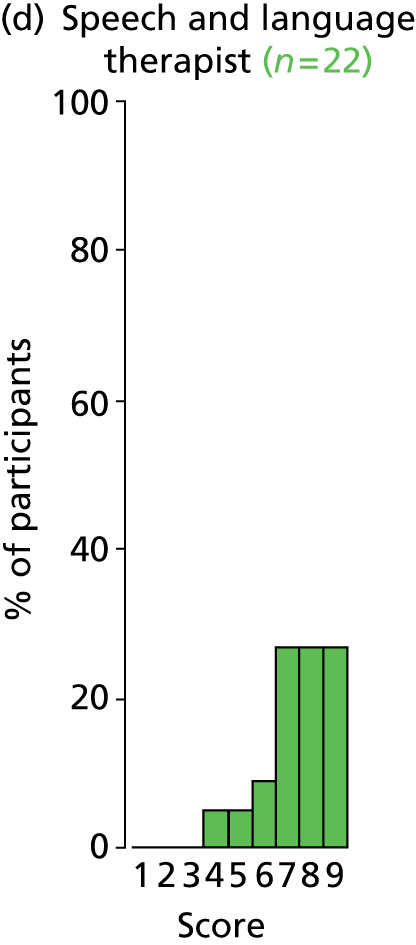

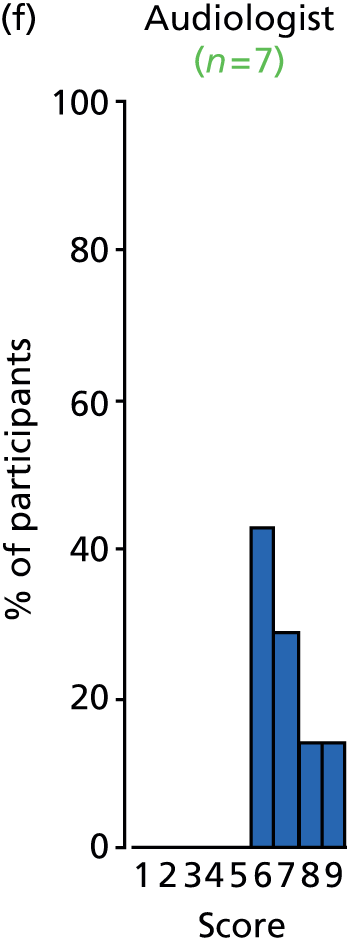

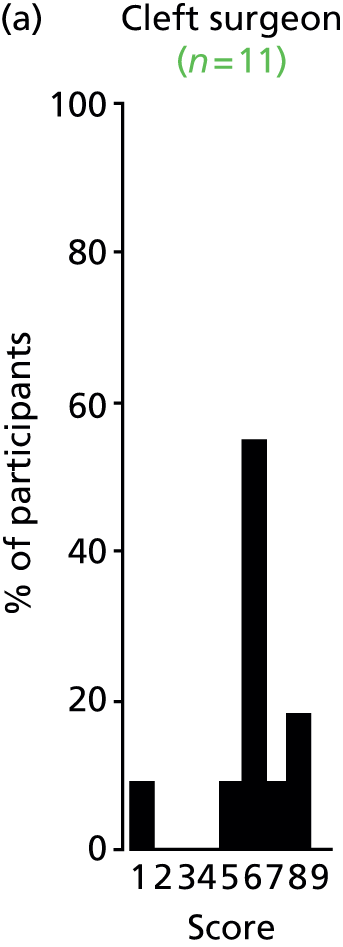

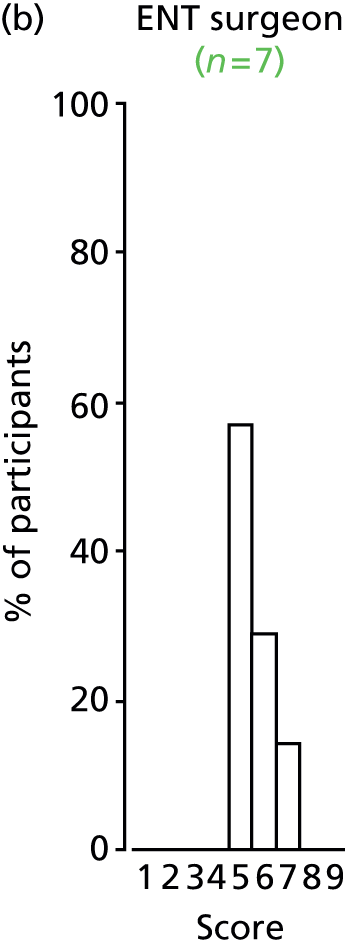

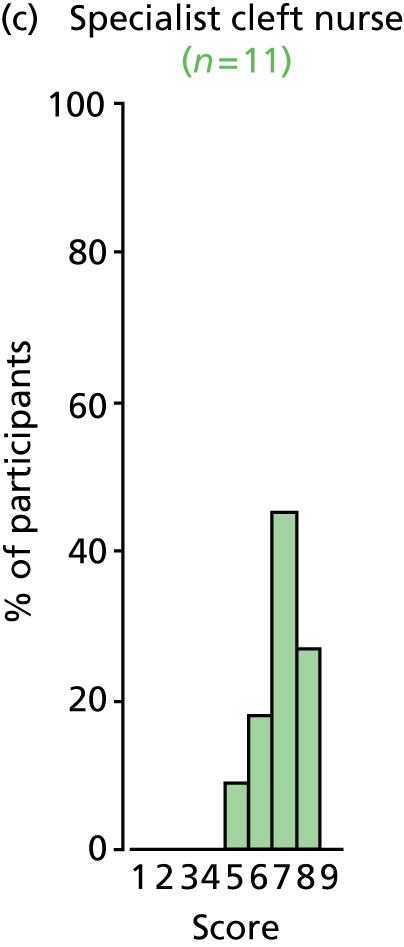

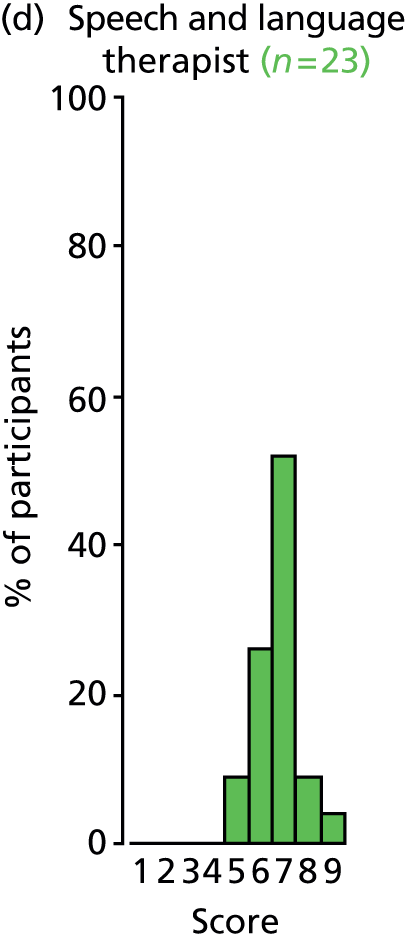

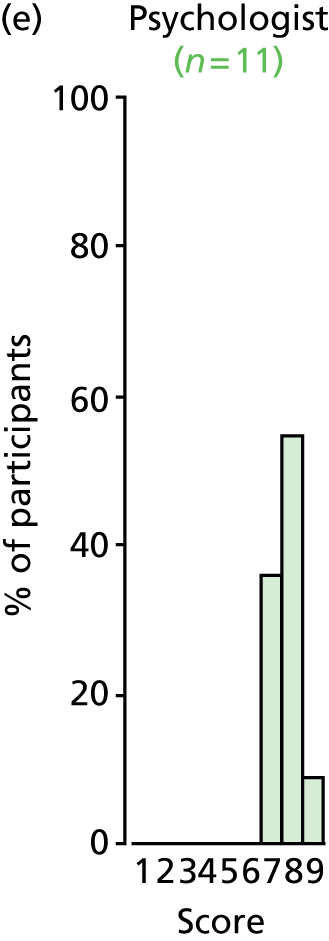

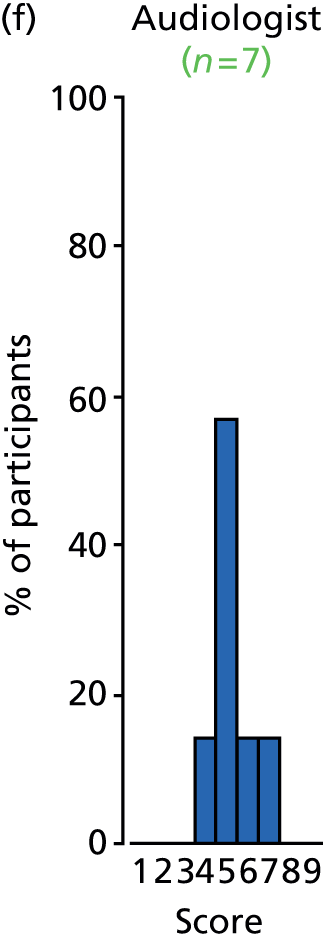

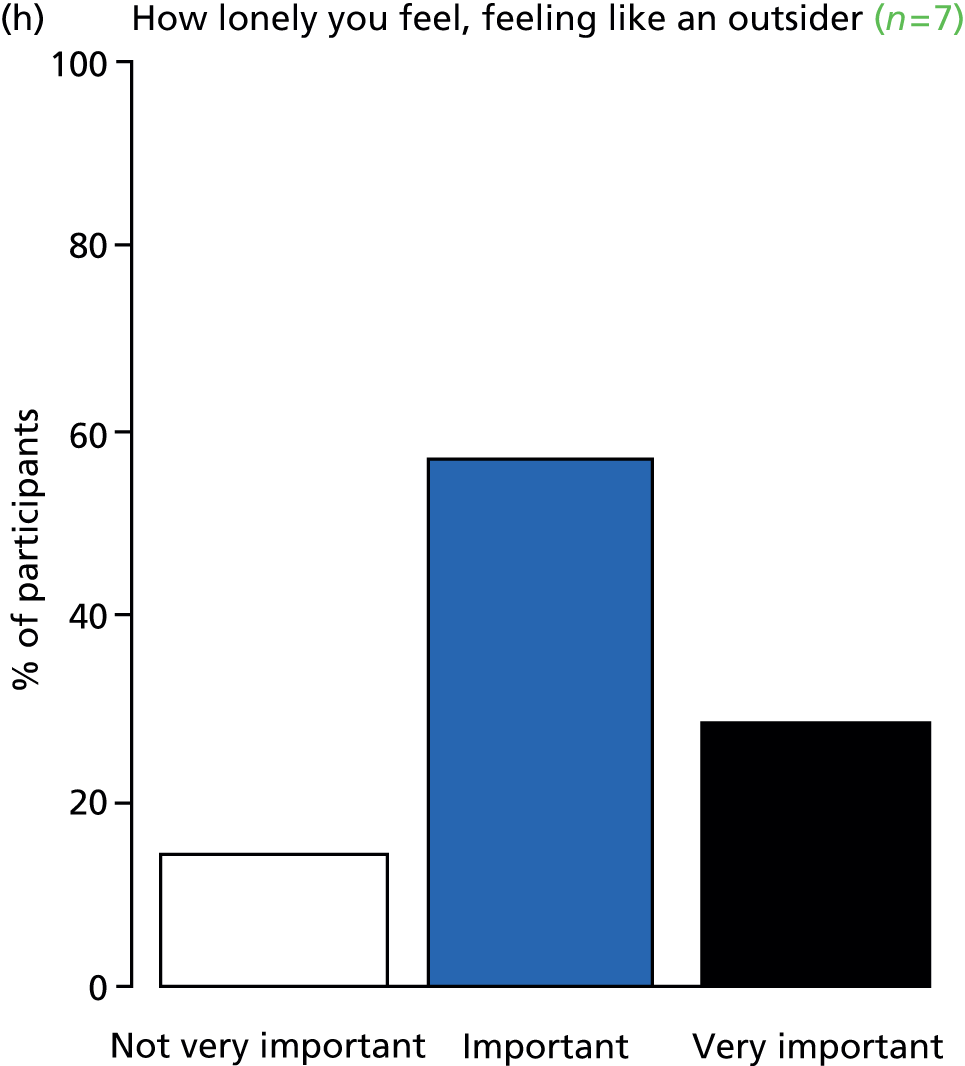

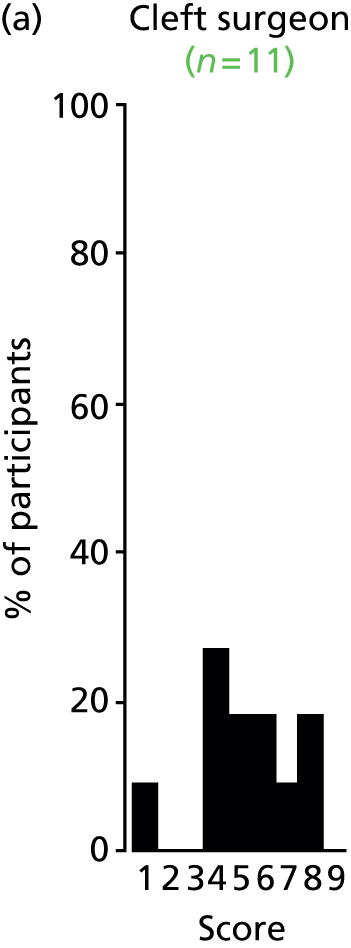

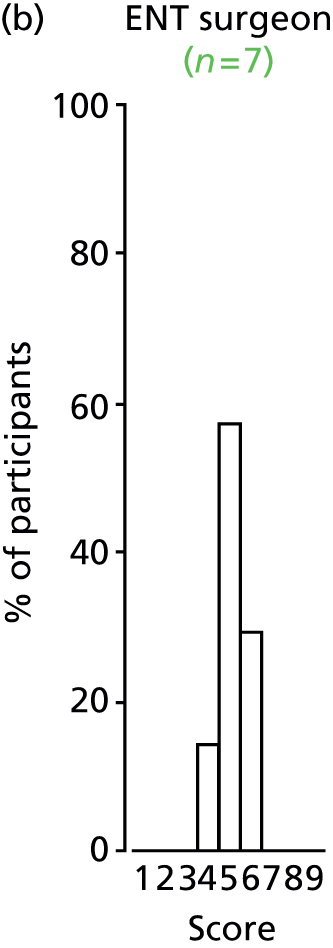

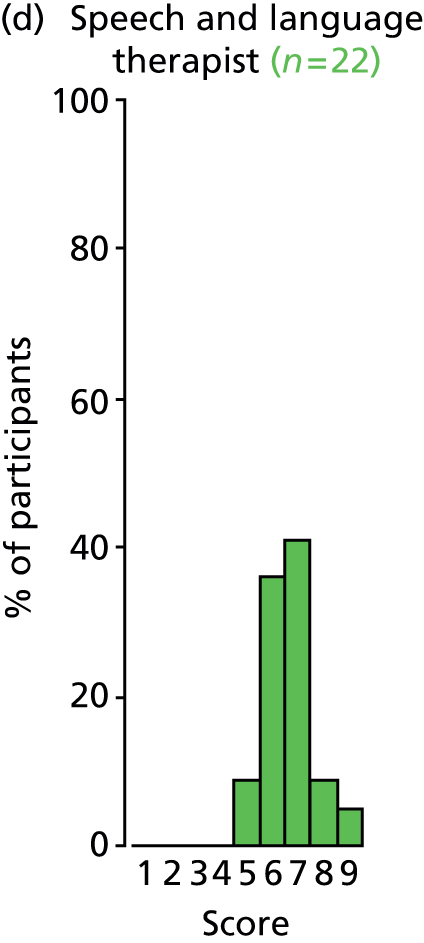

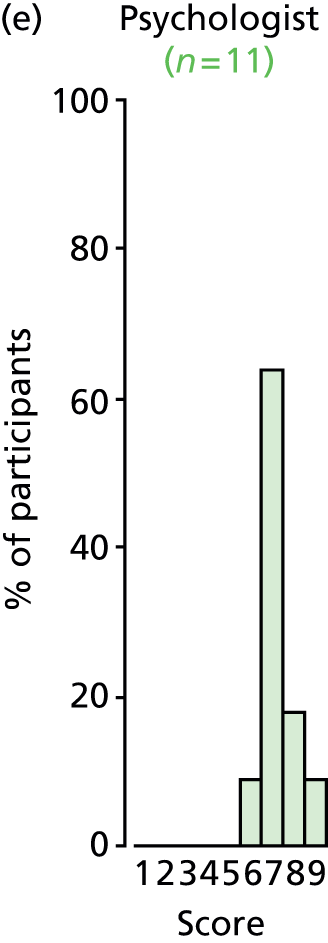

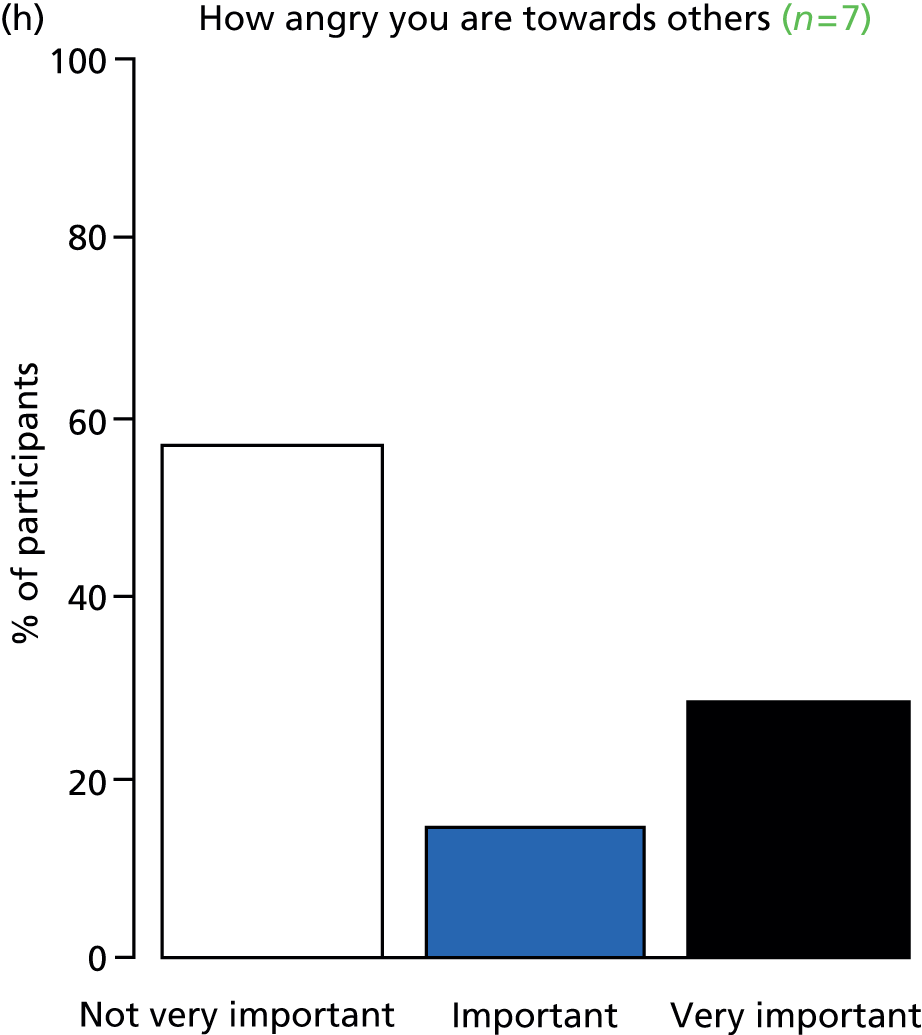

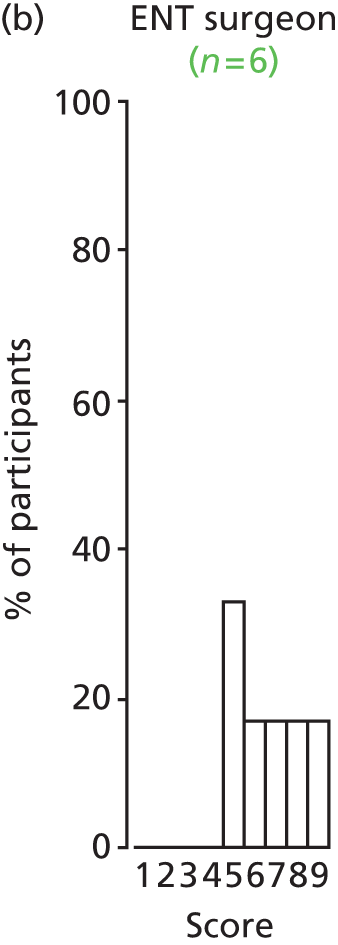

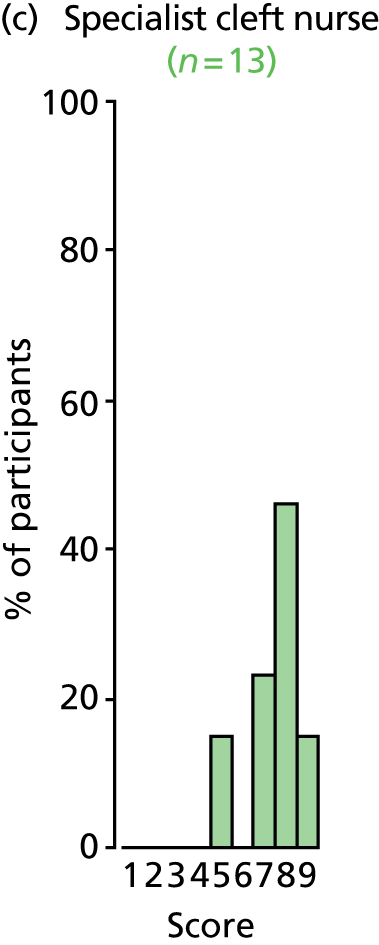

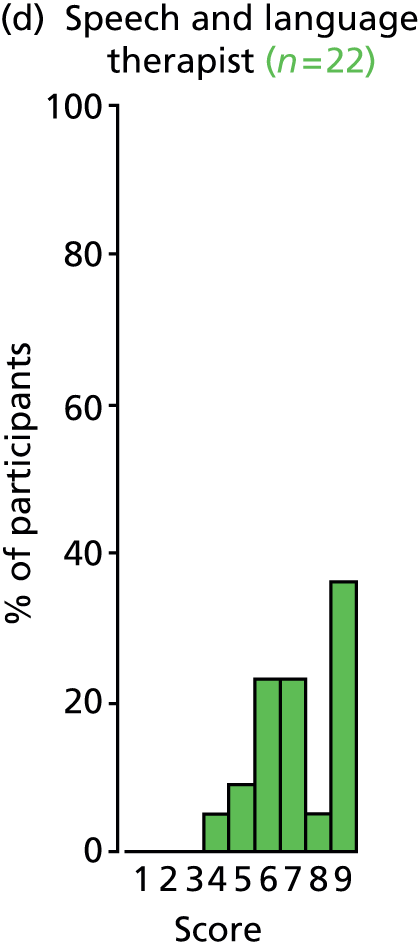

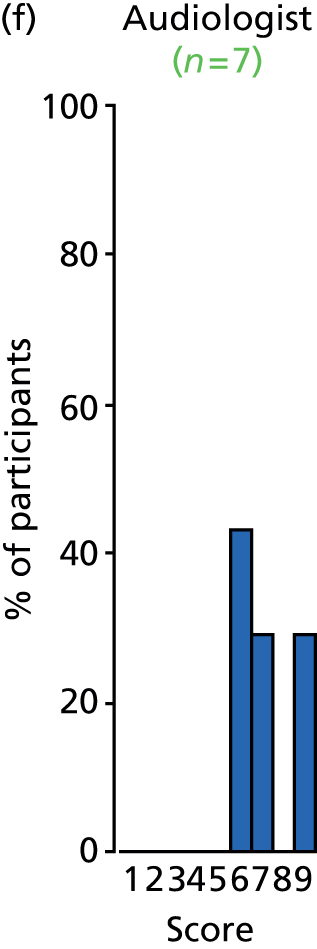

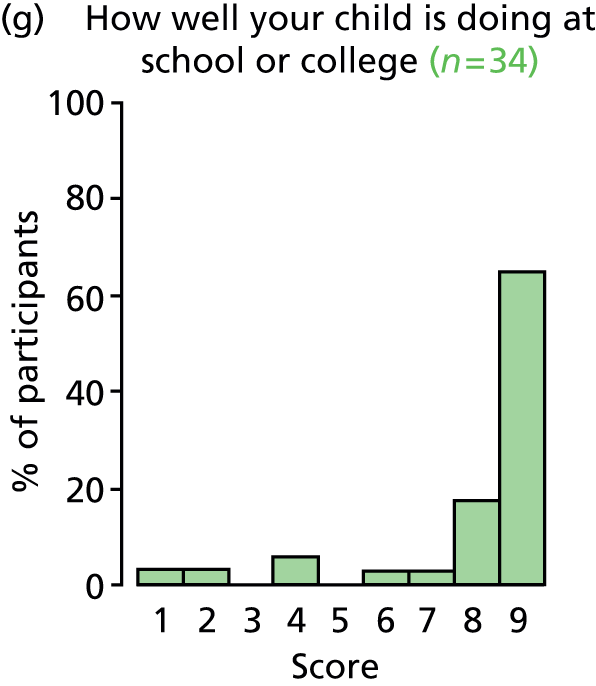

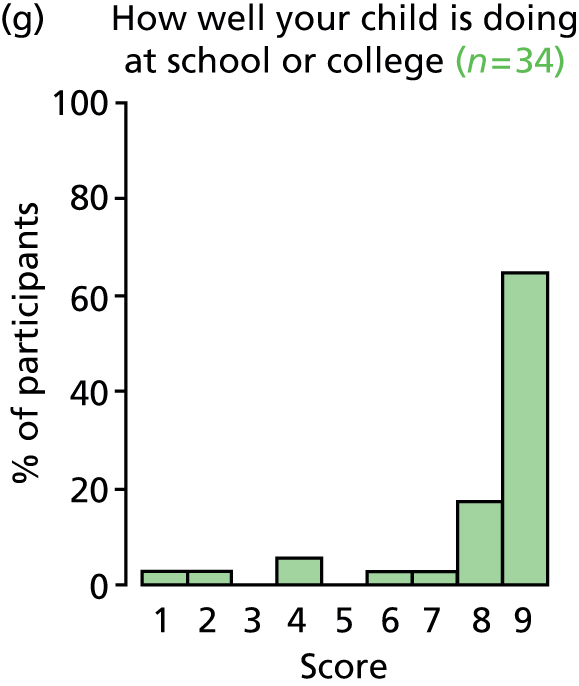

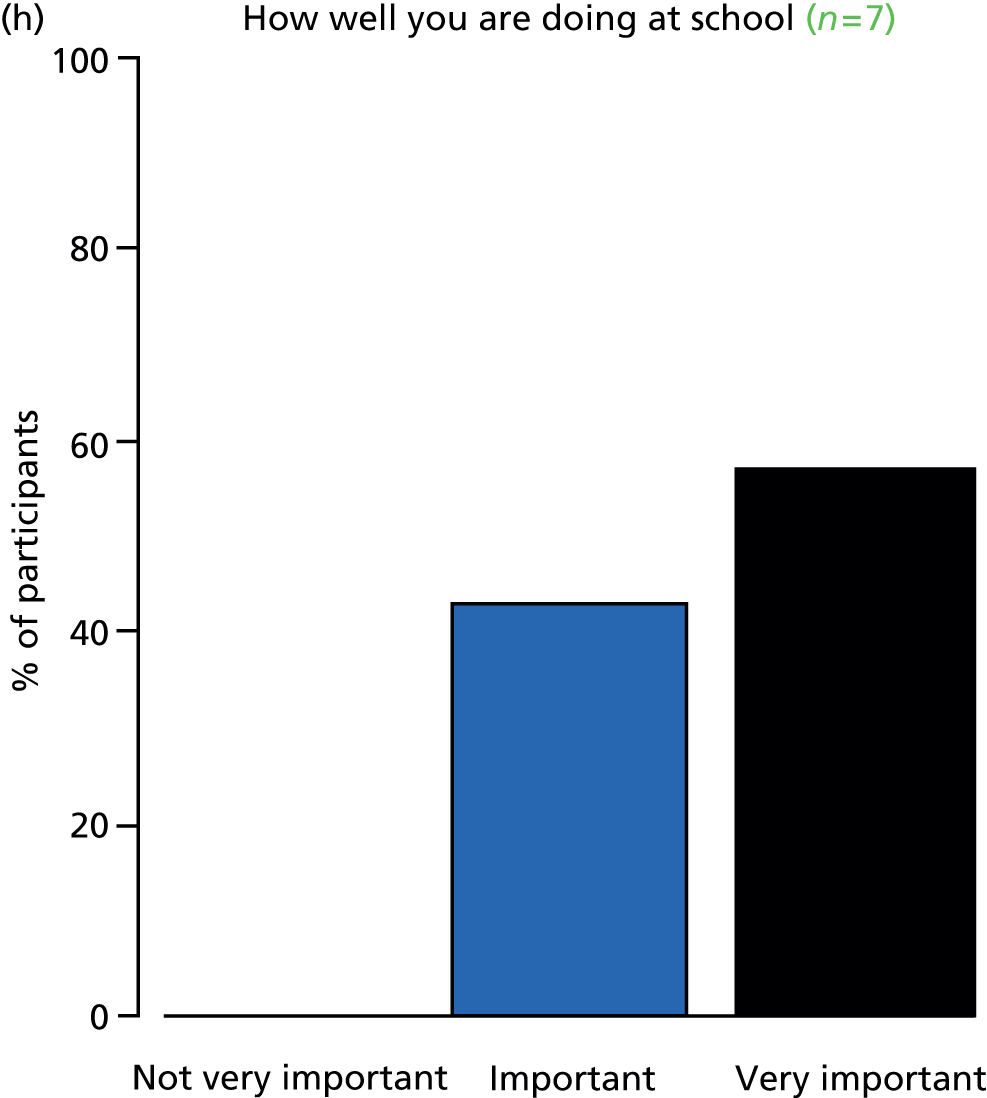

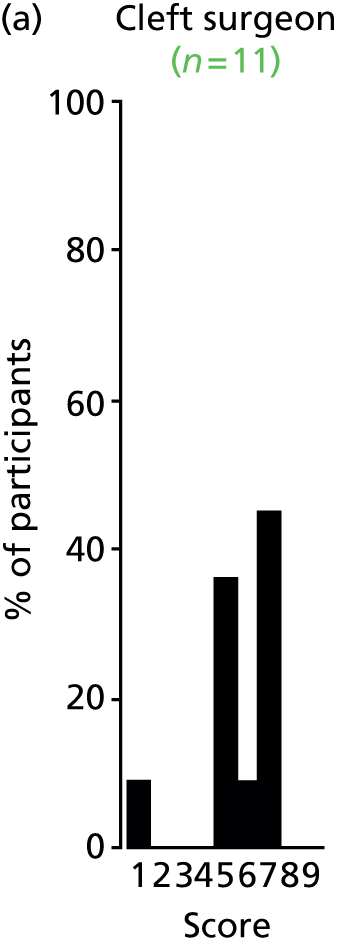

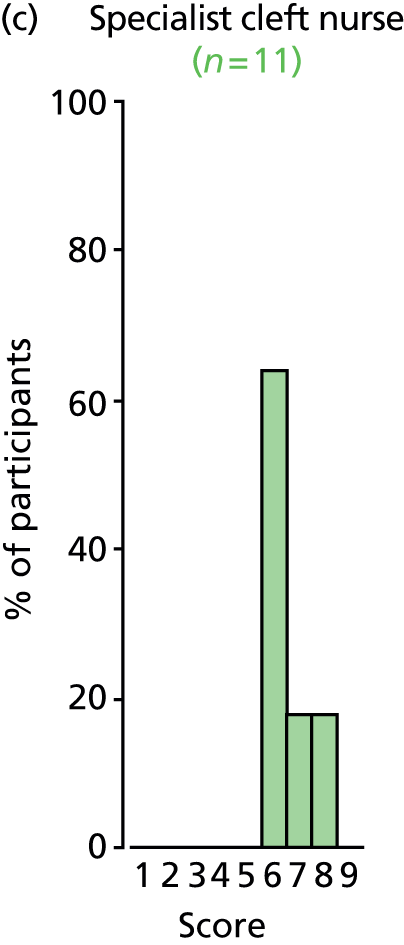

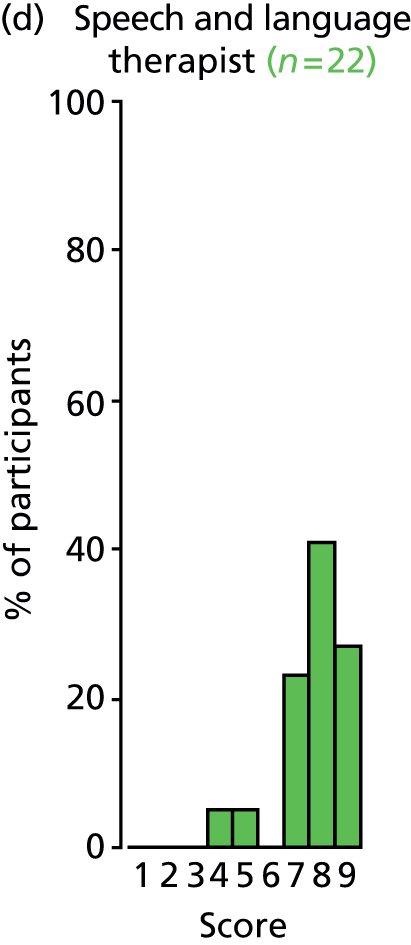

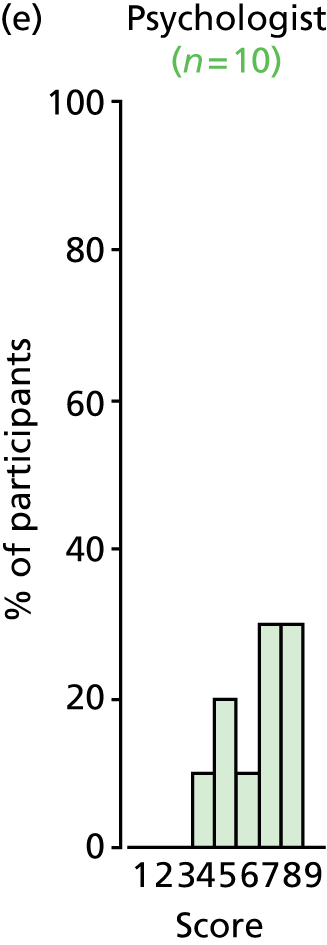

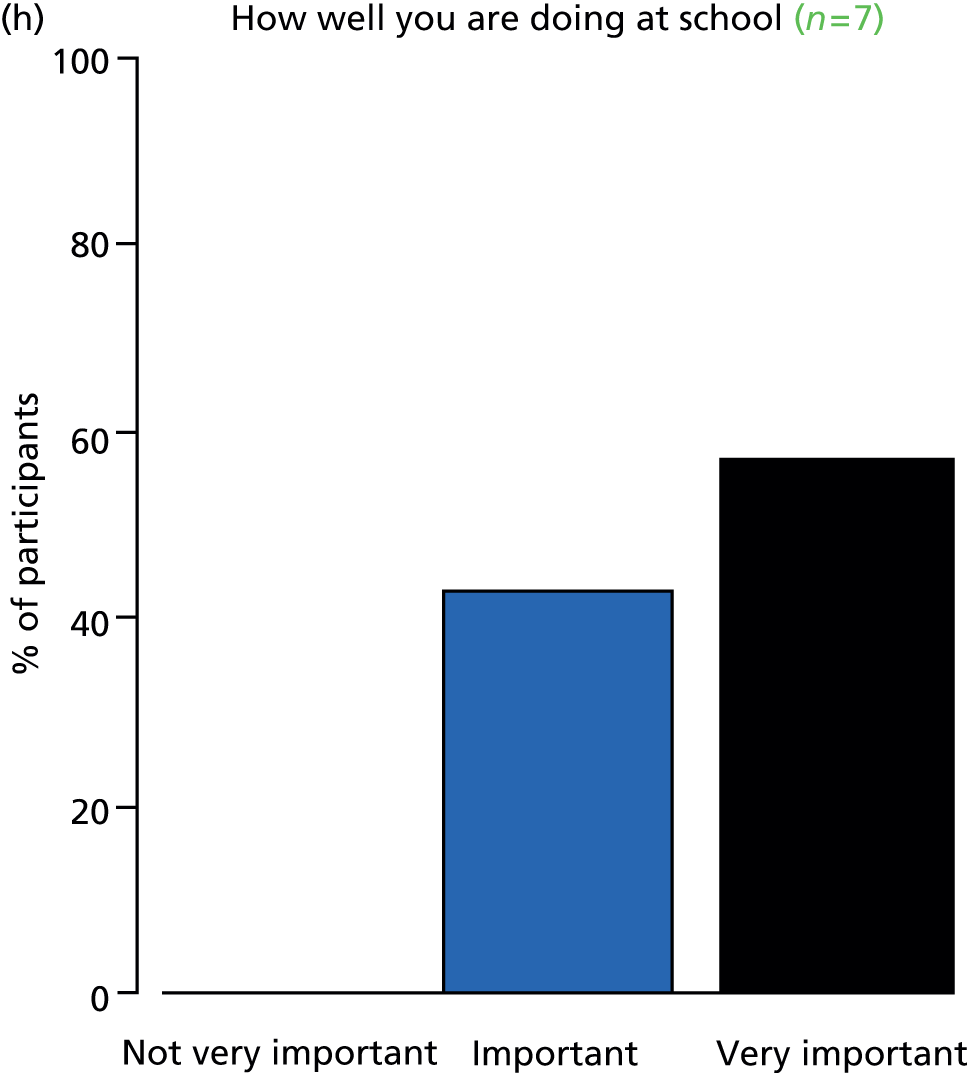

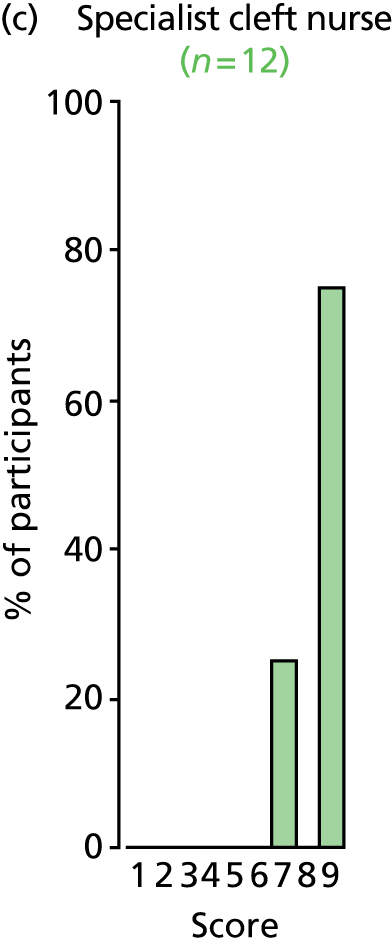

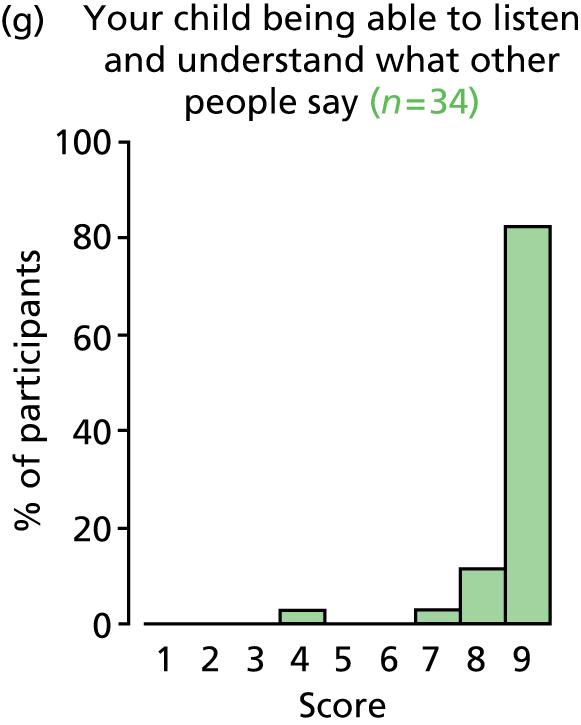

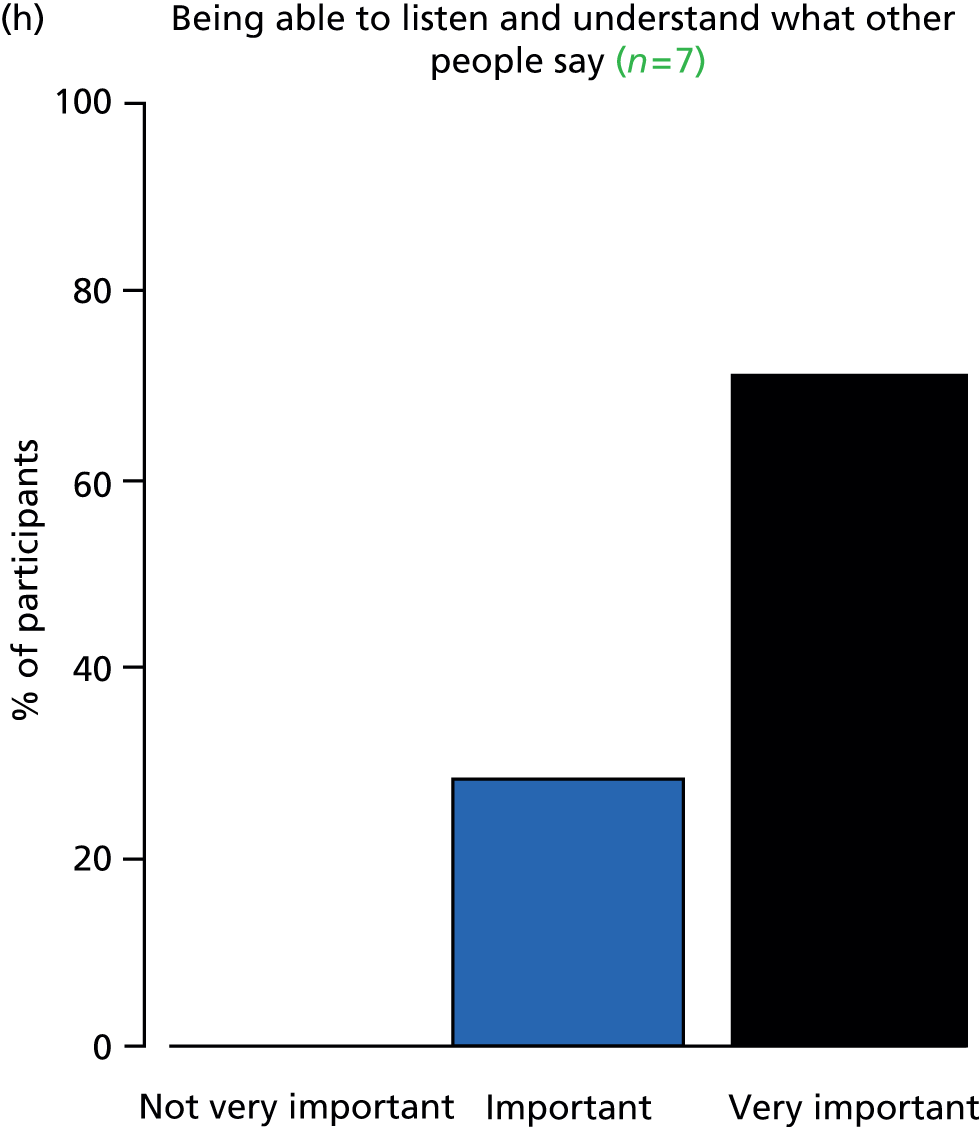

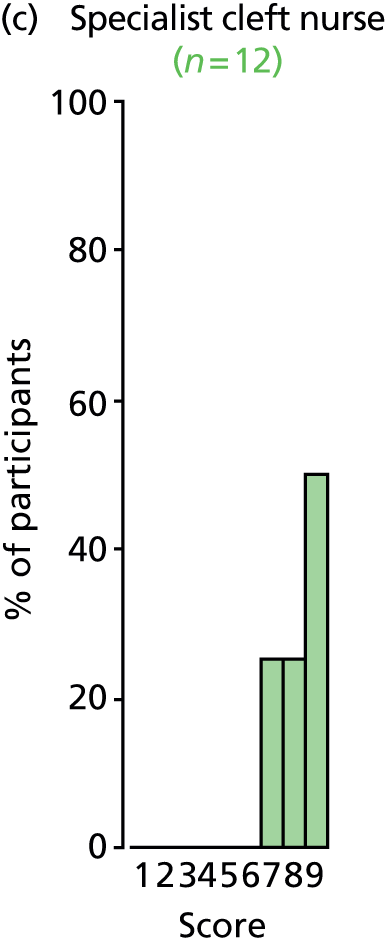

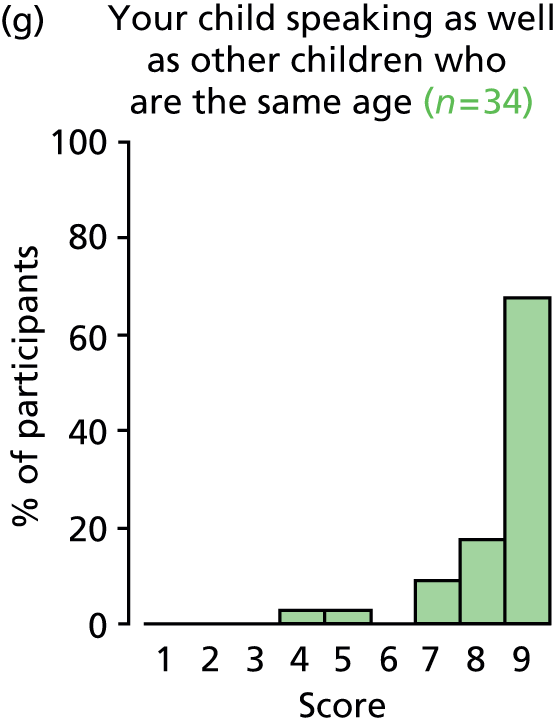

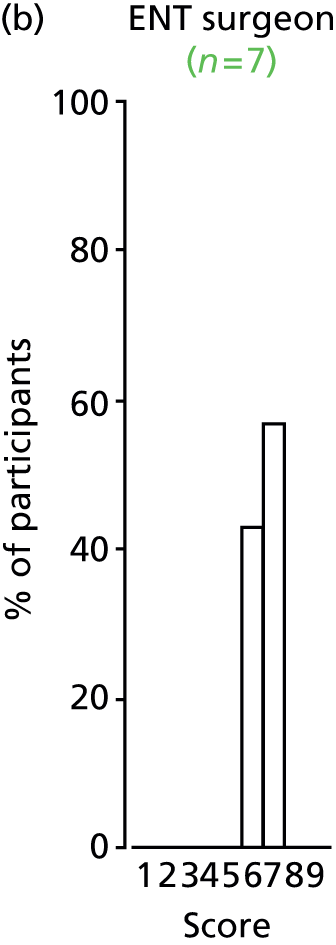

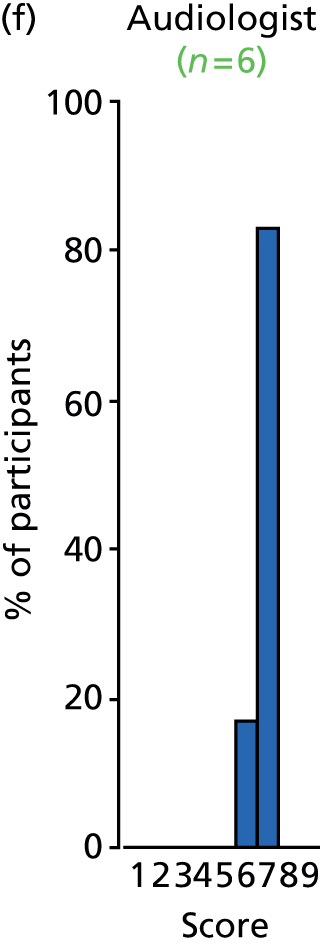

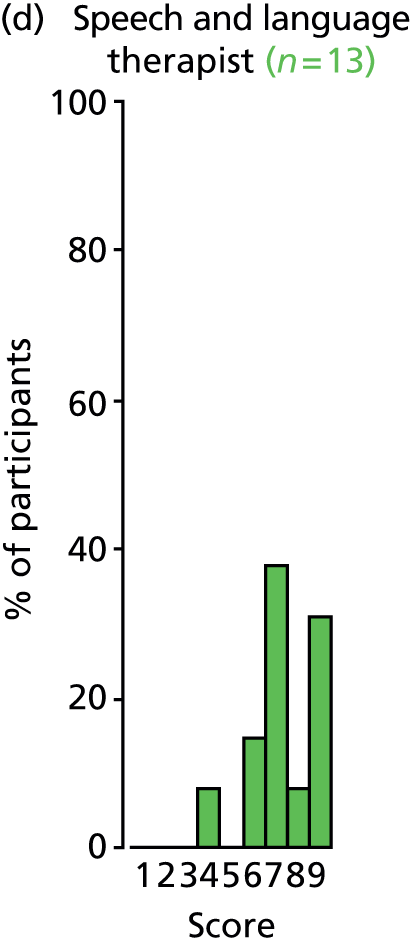

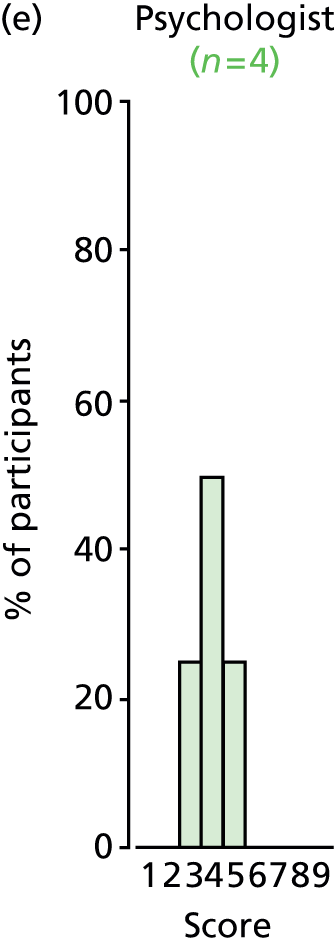

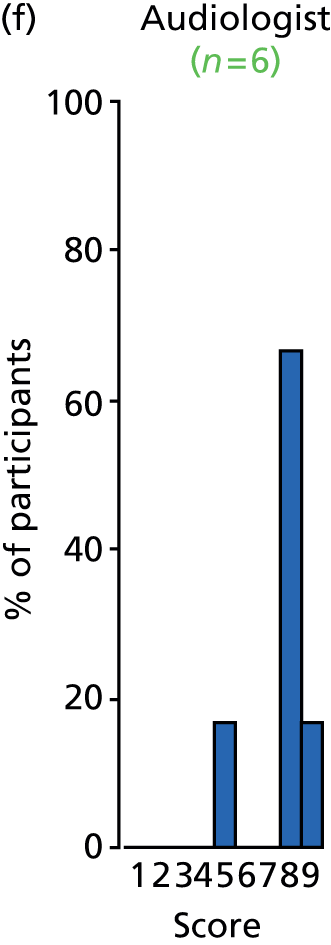

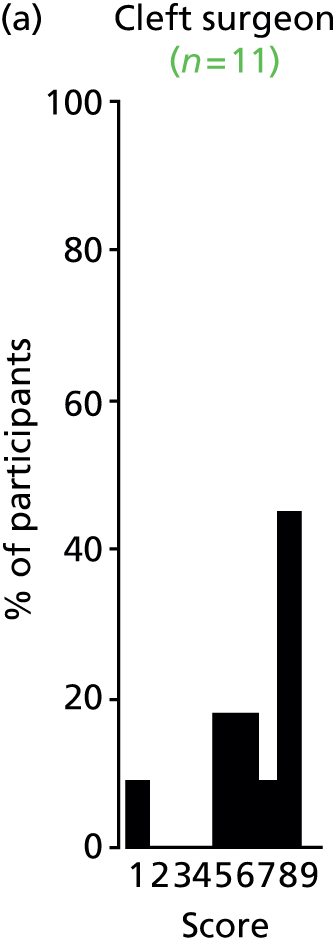

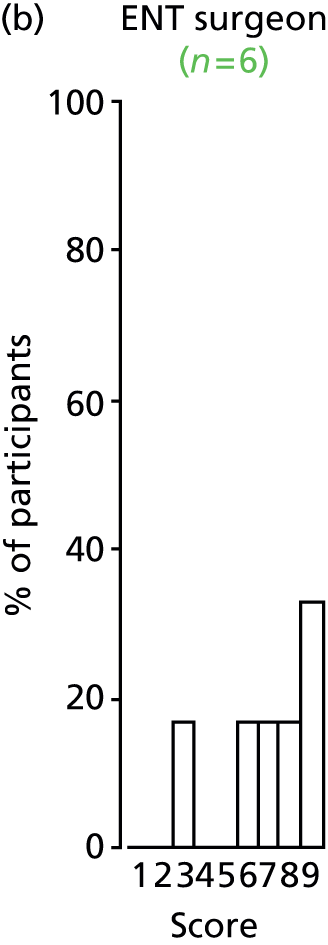

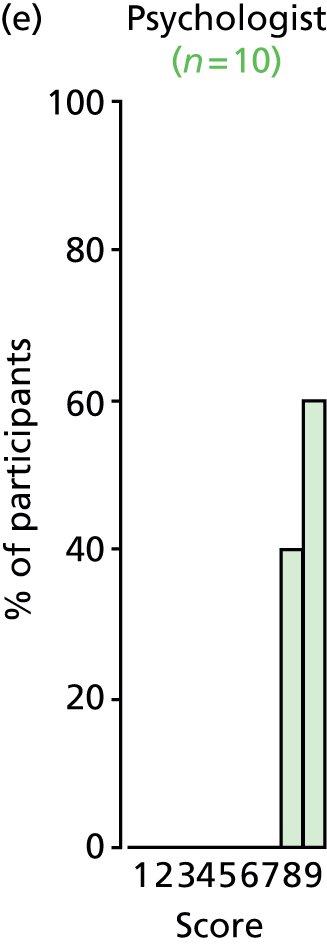

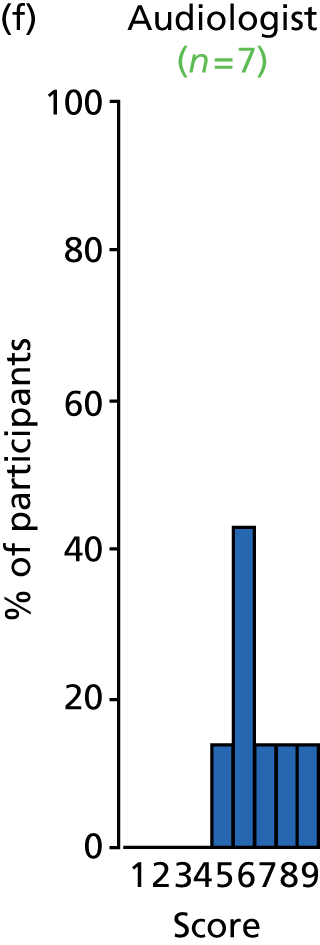

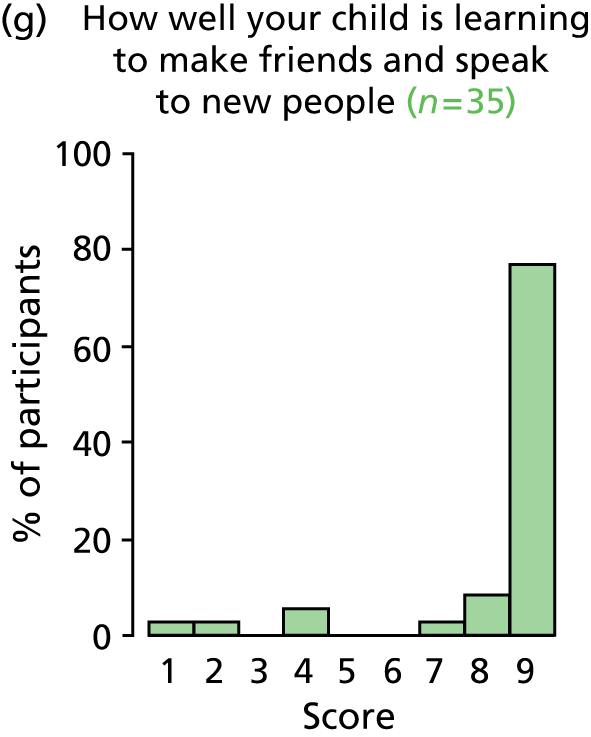

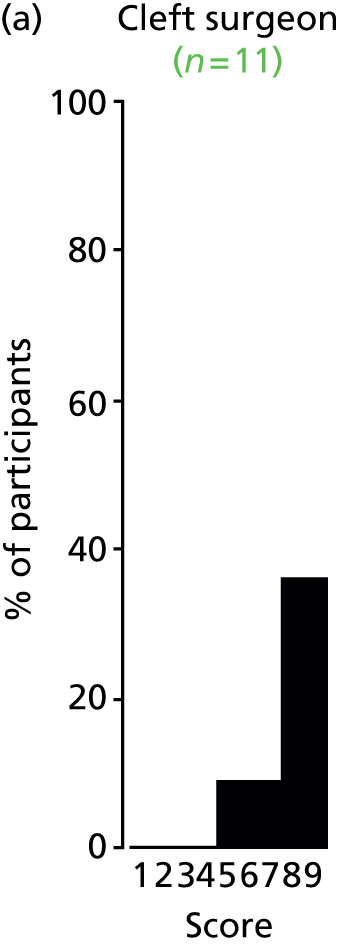

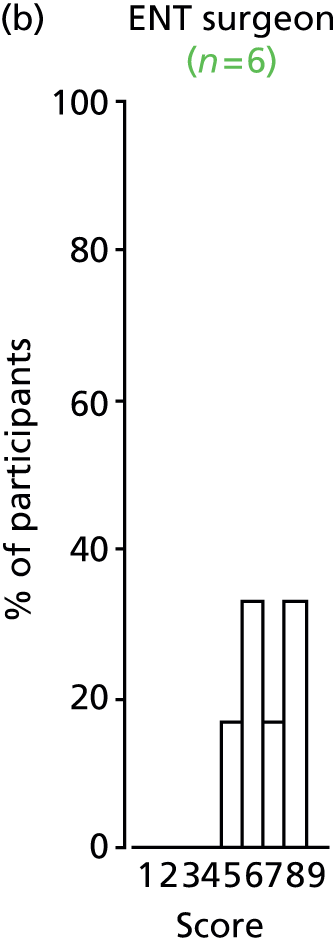

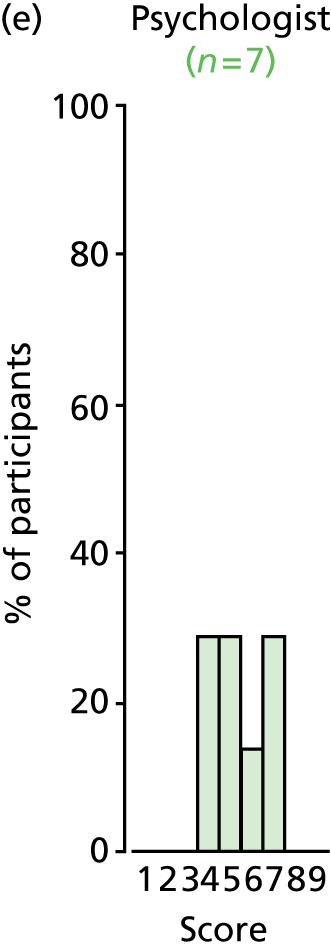

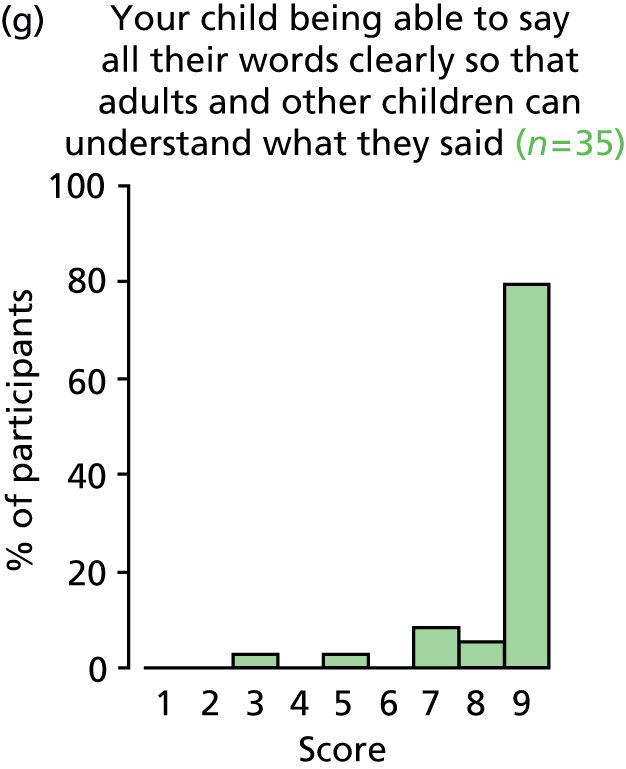

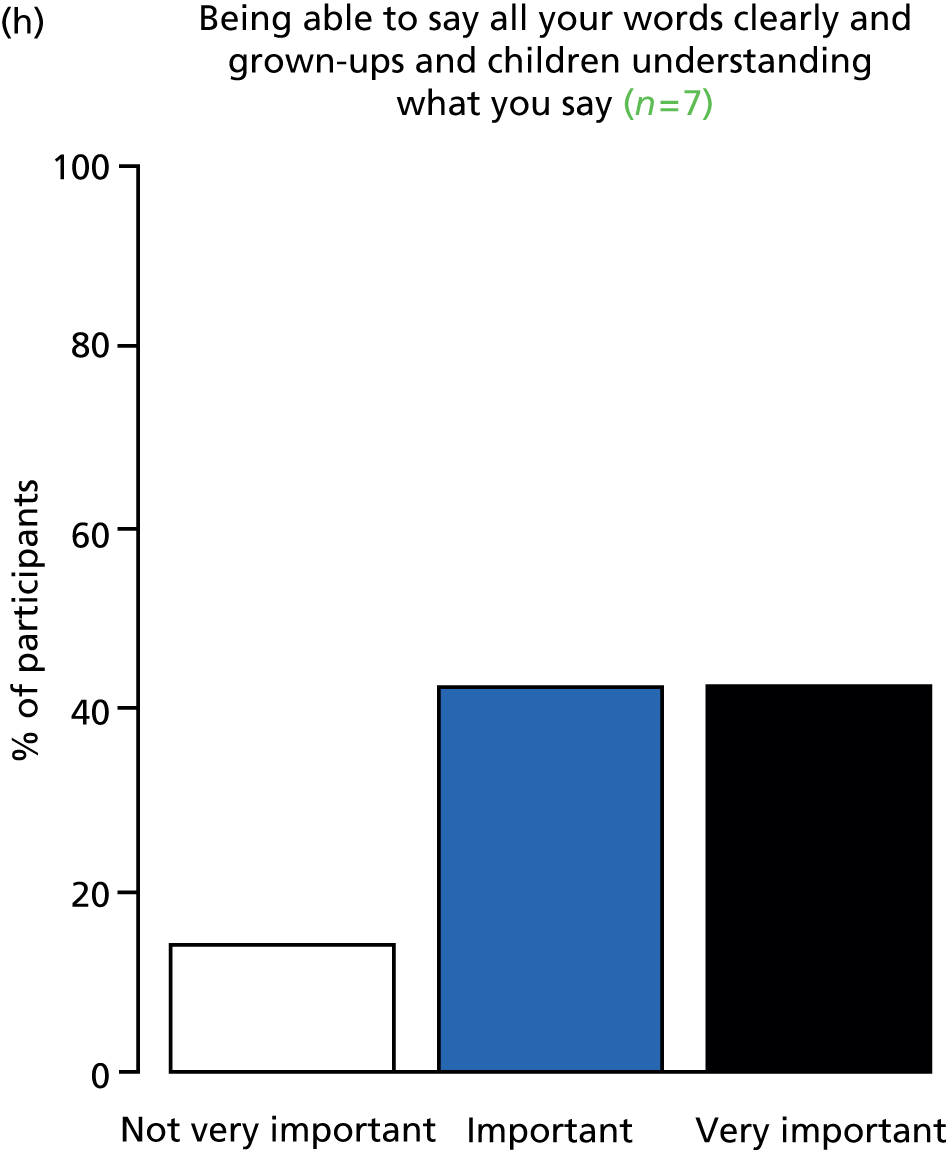

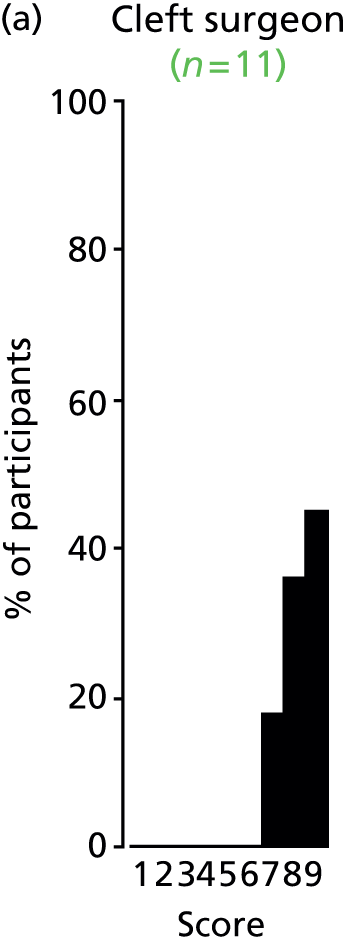

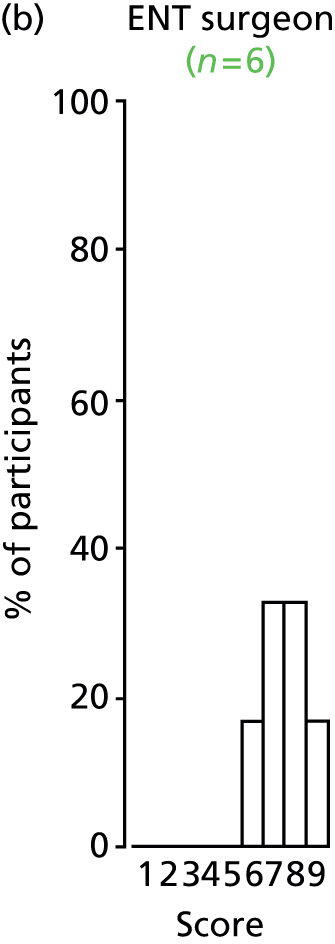

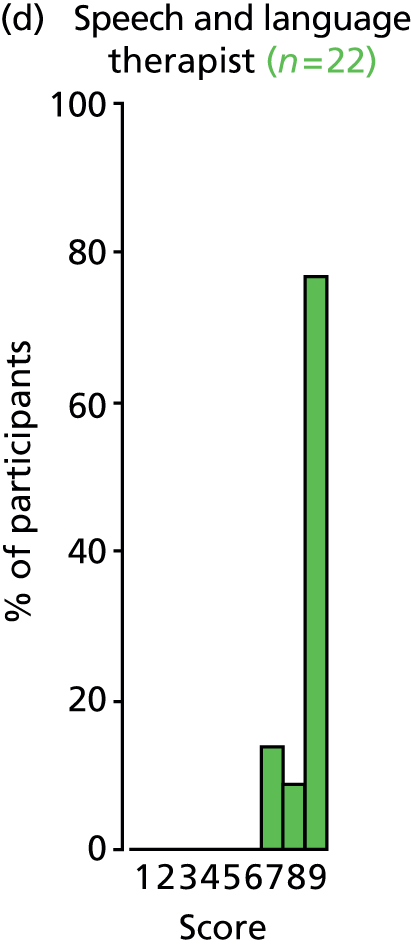

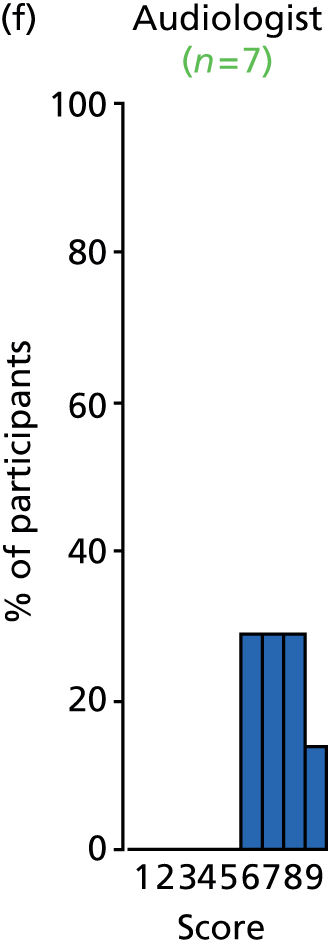

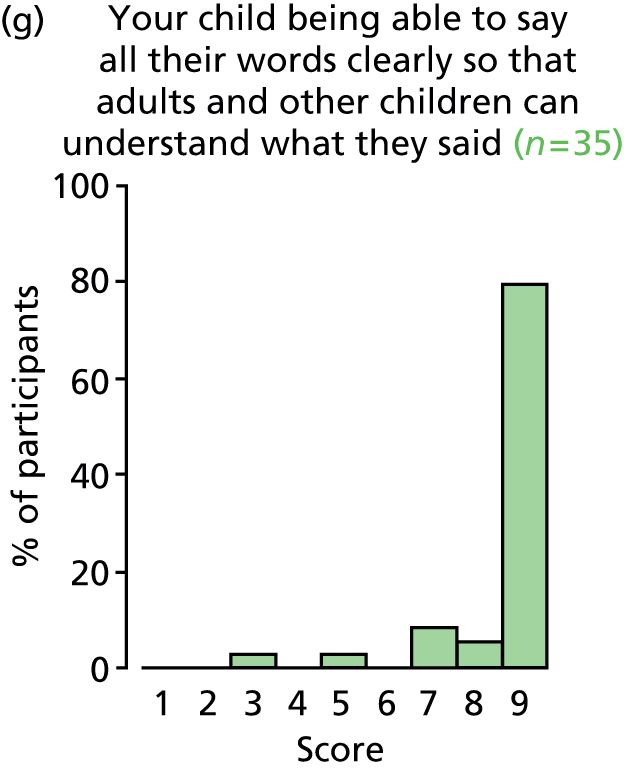

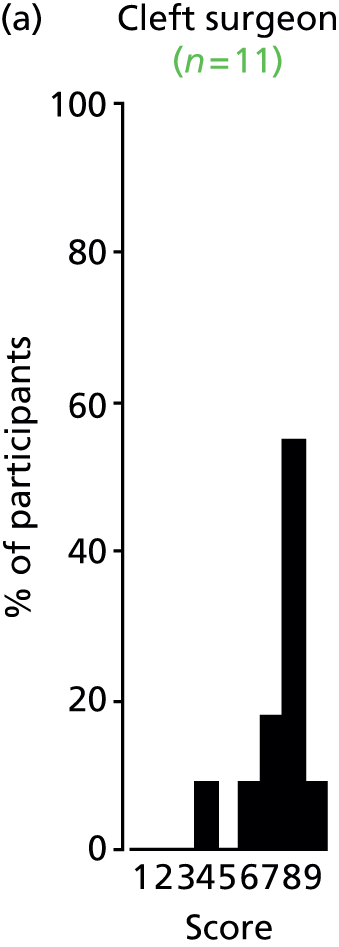

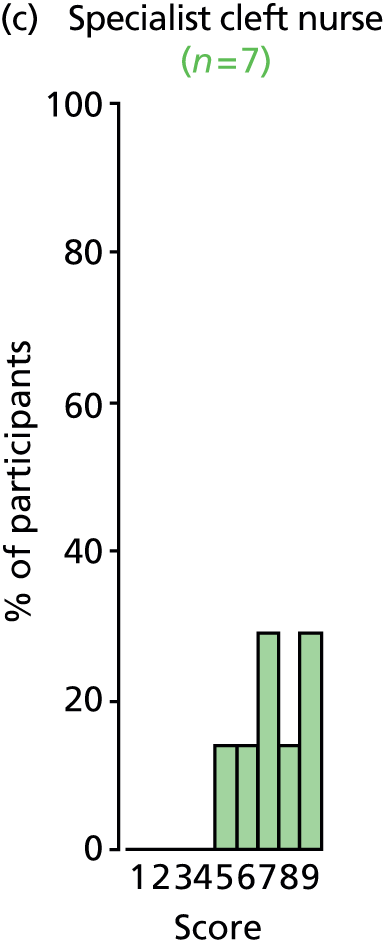

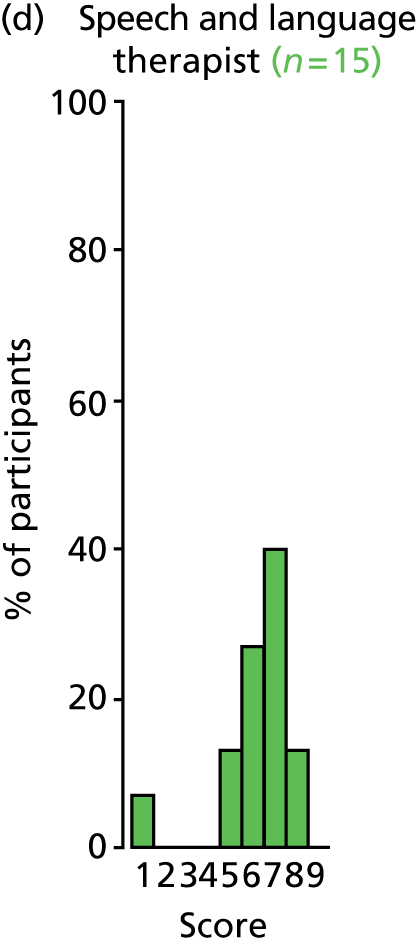

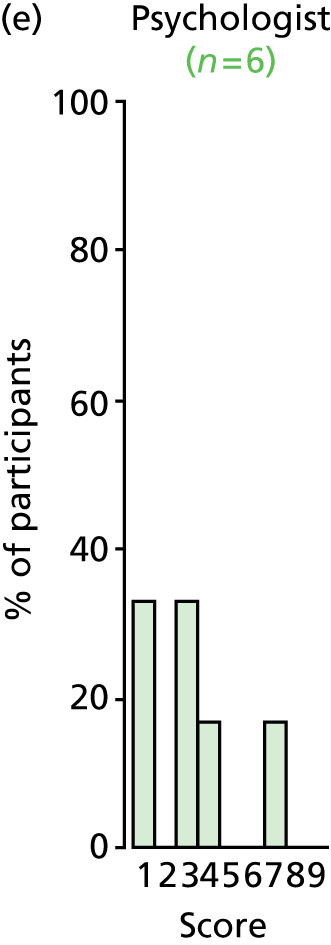

‘Protecting’ could be seen as focusing on perceived negative implications of a treatment, whereas ‘fixing’ suggested that individuals were making a positive choice of one way of managing OME over another. Parents described as ‘fixing’ believed that a particular treatment would be of greater benefit to a child and/or was more convenient than the alternative. Some considered the risks associated with VTs to be minimal, particularly if the insertion took place while a child was anaesthetised for another procedure. In contrast, HAs may be seen as requiring a longer commitment from parents, ensuring that children wore them, that batteries were replaced and that the HAs were not lost or broken. However, if VTs had not been an effective treatment, for example because they fell out soon after insertion, or if parents had seen the child flourish with HAs, they may believe this to be the most appropriate intervention for their son or daughter.