Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 12/69/01. The protocol was agreed in September 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Picot et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in England, with 41,523 new diagnoses in 2011. 1 It accounts for about one-third of all cancers in women2 but is rare in men, accounting for < 0.25% of cancers in 2011 (303 new diagnoses in England in 2011). 1 Consequently, the primary focus of this report is breast cancer in women and, when data are presented for men, this is clearly indicated.

Breast cancer aetiology

Breast cancer, in common with all other cancers, is caused by deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) mutations that disrupt the normal maintenance of cellular identity, growth and differentiation. 3 The majority of breast and other cancers develop from somatic mutations3,4 resulting from errors in processes such as DNA replication, DNA modification or DNA repair,4,5 which in turn may be influenced by environmental and/or dietary factors. 6 A small proportion of cancer types arise from inheritable single-gene disorders,3 for example BRCA1 (breast cancer 1) and BRCA2 (breast cancer 2) are genes associated with inheritable breast cancer. 4,7–9

There are two main forms of breast cancer: non-invasive, in which the cancer cells have not spread; and invasive, in which the breast cancer cells can potentially spread to the surrounding breast tissue or beyond. Approximately 10% of newly diagnosed breast cancer cases are non-invasive, the majority (approximately 90%) being ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). 10 In DCIS, cancer cells have developed inside milk ducts but have not yet developed the ability to spread beyond the ducts. DCIS is usually identified by mammography as it rarely presents as a lump. The remaining 90% of newly diagnosed breast cancer cases are various types of invasive breast cancer.

When breast cancer is diagnosed, information is gathered to describe and classify it according to a variety of characteristics. Much of the information required can be obtained only from samples taken during surgical removal of the primary tumour. Key aspects include:11

-

histological type (e.g. invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma)

-

histological grade, ranging from low (generally slow growing) to high (generally fast growing)

-

stage, based on the tumour node metastasis (TNM) classification (Tables 1 and 2)

-

oestrogen receptor (ER) alpha status

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) status

-

DNA profile.

| STAGE | TNM (see Table 2) |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Tisa N0 M0 |

| Stage I | T1 N0 M0 |

| Stage IIa | T1 N1 M0 or T2 N0 M0 |

| Stage IIb | T2 N1 M0 or T3 N0 M0 |

| Stage IIIa | T2 N2 M0 or T3 N1 M0 or T3 N2 M0 |

| Stage IIIb | T4 N0 M0 or T4 N1 M0 or T4 N2 M0 |

| Stage IIIc | Any T N3 M0 |

| Stage IV | Any T any N M1 |

| Tumour stage | Nodal stage | Distant metastasis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tisa | Tumour in situ | N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | M0 | No distant metastasis |

| T1 | Tumour < 2 cm in diameter | N1 | Mobile regional lymph node metastasis | M1 | Distant metastasis |

| T2 | Tumour 2–5 cm in diameter | N2 | Fixed regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| T3 | Tumour > 5 cm in diameter | N3 | Supraclavicular lymph node metastasis | ||

| T4 | Tumour fixed to skin/chest wall or inflammatory cancer | ||||

This information is essential for deciding what local and systemic treatments may be required and provides information about prognosis. The focus of this assessment is the treatment of early breast cancer; however, it should be noted that there is no internationally agreed single definition of early breast cancer (e.g. in terms of TNM stage). Typically, however, early breast cancer would be classified as TNM stage I or II (either IIa or IIb), with potentially some stage III tumours (those for which treatment could be curative).

The aim of treatment for early breast cancer is to provide a cure. As already stated, there are two major categories of early breast cancer: non-invasive (in situ) disease (predominantly in the form of DCIS) and invasive cancer. 11 For invasive cancer to be categorised as early breast cancer, the tumour should not have spread beyond the breast or the lymph nodes (which remain mobile) in the armpit ipsilateral to (on the same side as) the affected breast. 13 Once an invasive cancer has spread to distant sites (which may occur after initial treatment with curative intent), it is no longer curable, but can be treated to control symptoms.

Breast cancer epidemiology

In England, in 2011, the age-standardised rates of breast cancer incidence per 100,000 of the population were 124.8 for women and 0.9 for men. 1 For the period 2008–10 the age-standardised rate for women in England was 125.7 [95% confidence interval (CI) 125.0 to 126.4]. 14 The strongest risk factor for breast cancer is increasing age and, consequently, over 80% of new diagnoses of breast cancer in England are in women aged > 50 years1 and in men aged > 60 years. 1 Other important risk factors include obesity, alcohol consumption and lack of physical activity, which are estimated to be linked to about 18.5% of UK female breast cancer cases. 15

There were 9702 deaths of women and 64 deaths of men from breast cancer in England in 2011. 16 The UK age-standardised mortality rate from breast cancer per 100,000 women in 2008–10 was 25.3 (95% CI 25.0 to 25.6 per 100,000 women). 14 For women diagnosed with breast cancer during 2004–6 and followed up to 2011, the age-standardised 1-year survival rate for all breast cancers was 94.7% and the 5-year survival was 83.3%. 17 Between 2002 and 2006, a statistically significant annual increase in 1-year survival of 0.3% and in 5-year survival of 0.9% was observed. 17 The rise in survival estimates has been due to earlier detection and improved treatment of breast cancer in women. 2 An analysis of survival by stage at diagnosis for women in the UK diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (DCIS was excluded) during 2000–718 reported 1-year and 3-year net survival as shown in Table 3.

| TNM stage | 1-year net survival (%) (95% CI) | 3-year net survival (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| TNM stage 1 | 100 (100 to 100) | 99.3 (99.2 to 99.4) |

| TNM stage 2 | 99.2 (99.2 to 99.3) | 92.4 (92.2 to 92.7) |

| TNM stage 3 | 90.9 (90.5 to 91.4) | 70.7 (69.9 to 71.5) |

| TNM stage 4 | 53.0 (52.0 to 54.0) | 27.9 (26.9 to 28.9) |

Breast cancer diagnosis

In England, the main routes to diagnosis for the majority of breast cancer cases are via the NHS Breast Cancer Screening Programme or urgent (2-week wait) referrals from a general practitioner (GP) due to a suspicion of cancer. The Breast Cancer Screening Programme targets women aged 50–69 years (with extension from 47 years to 73 years ongoing, and expected to be completed after 2016). In 2006–8, just over 50% of breast cancer cases in the 50–69 years age group were diagnosed through screening, whereas, in other age groups (< 50 years and ≥ 70 years), over 50% of cases were diagnosed through the urgent GP referral route. 19 Breast cancer screening aims to detect cancers at an early stage when they are too small to cause changes to the breast that can be observed or felt. In England in 2011–12, 40.7% (6403) of all the breast cancers detected by screening were invasive but small (< 15 mm in diameter). 20 In the case of breast cancers detected via routes other than screening, there are no regularly published data on stage of breast cancer at diagnosis;21 however, evidence suggests that the majority (at least 80%) of women are diagnosed with early disease (stage I or stage II) whatever their route to diagnosis. 22

The 2009 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment11 provides recommendations for breast cancer diagnosis. Diagnosis is made after triple assessment consisting of a clinical assessment, mammography and/or ultrasound imaging, and core biopsy and/or fine-needle aspiration cytology. 11 A multidisciplinary team should review and discuss the test results and, if a cancer diagnosis is pathologically confirmed, suggest a treatment plan.

Breast cancer natural history and prognosis

The natural history of breast cancer is variable and incompletely understood. 23 If left untreated, a typical invasive breast cancer might progress in the following manner. Initially, the breast cancer cells multiply, thereby increasing the size of the tumour;24 as the tumour proliferates, the risk that metastatic cells will be generated increases. 25 A key route for metastatic spread of breast cancer cells is via the lymphatic system. If a breast cancer spreads, the first place it spreads to is often the first lymph node (or nodes) receiving direct lymphatic drainage from the tumour;24,25 this lymph node is called the sentinel lymph node. 26 The tumour can also spread to more distant lymph nodes and to systemic sites via the bloodstream (e.g. bone, lung, liver, brain). It is also possible for tumour cells to metastasise via the vascular system directly to systemic sites;25 however, not all breast cancers metastasise. Evidence from screening studies suggests that some screen-detected breast cancers may regress spontaneously27 and natural history may vary according to a variety of factors, for example genotype,28 hormone receptor status29 and race. 30

The heterogeneous nature of breast cancer natural history has an impact when trying to provide a prognosis and tools have been developed which aim to predict invasive breast cancer outcome. For example, the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI)31 (Table 4) is a tool that combines information on the size of the tumour, the number of lymph nodes involved and the histological grade to produce an overall score, with a higher score indicating a worse prognosis. Other models have been developed which aim to more accurately predict outcome by including alternative indicators and/or more explanatory factors, for example Predict33 and the Galway Index of Survival. 34 The program Adjuvant! enables prognostic estimates of outcome either with or without therapy to be produced based on estimates of individual patient prognosis and data on the efficacy of a range of adjuvant therapy options and is available online (www.adjuvantonline.com/index.jsp). 35

| NPI = (T × 0.2) + L + G | ||

|---|---|---|

| Score | Prognostic group | 10-year survivala |

| 2.08–2.4 | Excellent | 96% |

| 2.42 to ≤ 3.4 | Good | 93% |

| 3.42 to ≤ 4.4 | Moderate I | 81% |

| 4.42 to ≤ 5.4 | Moderate II | 74% |

| 5.42 to ≤ 6.4 | Poor | 50% |

| 6.5 to 6.8 | Very poor | 38% |

Impact of breast cancer

Psychological distress, chiefly in the form of anxiety, may be experienced by women from the initial diagnostic procedures for a suspected breast cancer36 through all stages of treatment and beyond. 37,38 In addition to psychological aspects, women may experience a range of physical problems, for example arm and breast symptoms and/or lymphoedema39,40 and fatigue. 40

An analysis of patients’ free-text comments from the Cancer Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Survey in England41 identified a range of issues that may affect patients diagnosed with breast cancer. These included poor body image following breast surgery, ongoing problems following surgery such as pain and lymphoedema and problems associated with other non-surgical treatments, for example hot flushes related to hormone treatments, burns following radiotherapy and neuropathy during and following chemotherapy. In addition, some patients found that existing comorbidities such as arthritis and osteoporosis were exacerbated by their treatment. Some survey respondents highlighted that, during and/or following treatment, a lack of energy affected their everyday life, and some found that they had cognitive problems and memory loss. Both during and after treatment some patients suffered from feelings of depression, loneliness and isolation. A continuing fear of recurrence was also an issue for some. Other problems highlighted by the survey were social and financial issues, for example relating to employment and obtaining insurance.

The impact of breast cancer for the NHS is likely to increase across all facets of the breast cancer care pathway in the future. This is because the population of England is growing in both size and age, which will lead to increasing rates of breast cancer given that the strongest risk factor for breast cancer is age.

Current service provision

Surgery is usually the first treatment option for early breast cancer (DCIS and invasive breast cancer). Pre-operative assessment of the breast and axilla determines the size of the primary tumour relevant to the volume of breast and this information is used to decide whether or not wide local excision (WLE) of the tumour (‘lumpectomy’) is possible, allowing breast-conserving surgery (BCS) instead of mastectomy (removal of the breast). Patients who have a mastectomy can have immediate breast reconstruction (carried out at the same time as the mastectomy) or delayed breast reconstruction.

Pre-operative assessment of the axilla includes ultrasound to determine whether or not morphologically abnormal lymph nodes are present. If abnormal lymph nodes are identified, ultrasound-guided needle biopsy is offered to obtain a tissue sample for testing. If there is no evidence of lymph node involvement on ultrasound, or the ultrasound-guided needle biopsy outcome is negative, lymph node clearance is not performed during BCS. The NICE guideline Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment11 recommends, instead, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as the preferred technique (SLNB was undertaken for 84% of invasive breast cancers identified during breast cancer screening between April 2011 and March 201242). The tissue from SLNB has typically been analysed using post-operative histopathology with a 5–15-day wait for results. If macrometastases (tumour deposits with at least one dimension over 2 mm) are identified, a second operation takes place to remove the remaining axillary lymph nodes (axillary lymph node dissection). 43 In August 2013, NICE recommended whole lymph node analysis using the RD-100i one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) system as an option for detecting sentinel lymph node metastases. This analysis is carried out during breast surgery, takes approximately 30 to 45 minutes and means that, if the result is positive for metastases (cytokeratin-19 gene expression identified which is a marker associated with breast cancer), axillary lymph node dissection can be completed during the initial surgery, removing the need for a second operation. 43 The advisory group for this assessment indicated that there are 22 RD-100i OSNA systems currently in use in the UK and use is increasing.

After surgical removal of the primary tumour (and axillary lymph nodes if indicated), the information on prognostic and predictive factors obtained by histological examination, the outcome of tests for ER and HER-2 status, and other patient and tumour characteristics are used by the breast cancer multidisciplinary team to consider options for adjuvant therapy for all patients with early breast cancer. Decisions regarding adjuvant therapy are made following discussion with the patient. 44 Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy should start as soon as clinically possibly and within 31 days of being ‘fit to treat’ after surgery. 45,46

Data from the NHS Breast Screening Programme Audit 2011–1242 indicate that, in practice, some trusts are struggling to meet this 31-day standard for radiotherapy. Overall, 57% of women received radiotherapy within 60 days and 92% within 90 days of their final surgery. 42 Advice from the advisory group for this assessment suggested that the figures for symptomatic cancer (i.e. not screen detected) were likely to be similar and that meeting the 31-day goal for adjuvant chemotherapy may also be difficult.

The range of recommended breast cancer treatment options described by the 2009 NICE guideline Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment11 are summarised in Table 5.

| Adjuvant treatment | Treatment options | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy | Whole-breast radiotherapy following BCS | |

| Post-mastectomy radiotherapy to chest wall | For example, if at high risk of local recurrence | |

| Boost to tumour bed following BCS | For example, if at high risk of local recurrence | |

| Radiotherapy to nodal areas | For example, if four or more involved axillary lymph nodes | |

| Systemic therapy for metastatic disease | Endocrine therapy | For example, tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor for ER-positive tumours only |

| Chemotherapy | For example, anthracycline-containing regimens, docetaxel | |

| Biological therapy | For example, trastuzumab (Herceptin®, Roche) | |

| May need assessment and treatment for bone loss | ||

| Primary systemic therapy | ||

| Chemotherapy | Before surgery, e.g. to shrink tumour before surgery, to observe response in the primary tumour before its surgical removal | |

| Endocrine therapy | ||

After BCS, whole-breast external beam radiotherapy (WB-EBRT) substantially reduces the risk of recurrence (15.7% absolute reduction in 10-year risk of any first recurrence) and moderately reduces the risk of breast cancer death (3.8% absolute reduction in 15-year risk of breast cancer death) for patients with early invasive breast cancer. 47 Therefore, post-operative WB-EBRT is the standard of care for all patients with early invasive breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy (as per the 2009 NICE guideline11). WB-EBRT works by directing a beam, or multiple beams, of radiation through the skin directly at the tumour and surrounding cancer cells to destroy them. The radiation beam is generated by an instrument, known as a linear accelerator, which is capable of producing high-energy X-rays or electrons. The most common types of external radiotherapy use photon beams (as X-rays). 48 From the patient’s perspective, external radiotherapy is similar to having an X-ray, only the radiation is more intense. In the UK, a hypofractionated regimen is standard practice, with NICE guidelines recommending that patients with early invasive breast cancer who have undergone BCS receive 40 Gy in 15 fractions. 11 The 15 fractions are typically delivered to patients by hospital radiotherapy departments at short (10–15-minute) treatment sessions each day, Monday to Friday, with a rest at the weekends. The course is usually given for 3 weeks, but may last longer. This course of radiotherapy can be followed by a ‘boost’ dose (e.g. 12 Gy in four fractions, 10 Gy in five fractions or 16 Gy in eight fractions) to the tumour bed over a further 1–2 weeks in patients considered to be at a higher risk of local recurrence (e.g. aged < 40 years, grade 3 disease and lymph node positive). 11 In many other parts of the world standard practice for whole-breast radiotherapy is 50 Gy in 25 fractions given daily (Monday to Friday) over 5 weeks. 49 For patients with apparently localised DCIS treated with BCS, there is a 25% risk of a local recurrence over 10 years if there is no further therapy and half of the recurrences will be of invasive cancer. 11 Unfortunately, there is no reliable way to identify the patients who will not be at risk of local recurrence. 50 Therefore, adjuvant radiotherapy should be offered to all patients with DCIS following BCS alongside a discussion of the potential benefits and risks. 11

The treatment schedule described above can be difficult for some women to undertake (e.g. if they live a long way from their nearest treatment centre, if they have caring responsibilities, if they are elderly and/or disabled). Whole-breast radiotherapy may also be associated with short-term adverse effects (e.g. skin soreness/redness, tiredness, nausea) as well as long-term adverse effects (e.g. changes to breast size and texture/feel, lung or heart problems), and can be impossible to deliver effectively in patients who are unable to lie flat or in those unable to raise the shoulder on the side receiving treatment.

When chemotherapy is indicated, WB-EBRT is nearly always given when chemotherapy has been completed and after a gap of 2–3 weeks that minimises overlapping and/or enhancing toxicities. For patients who require biological therapy or endocrine therapy, this is typically administered concurrently with WB-EBRT.

Radiotherapy is viewed as a cost-effective treatment. The total spend on radiotherapy (not limited to breast cancer) has been estimated to constitute just 5% of the estimated total NHS spend on cancer care. 45

Description of technology under assessment

The INTRABEAM® Photon Radiotherapy System (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) has a miniature, electronic, high-dose-rate, and low-energy X-ray source (XRS) which is used to deposit high-dose radiation directly to a tumour or tumour bed. 51 In the USA, INTRABEAM gained US Food and Drug Administration approval in 1997, and in Europe it was awarded Conformité Européenne (CE) certification in 1999. 52 As INTRABEAM uses a low-energy XRS, the system does not have to be contained within the kind of specially designed room that is required for high-energy radiation sources (e.g. linear accelerators). 51 This means that INTRABEAM can be used to deliver intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in an ordinary operating theatre at the same time as surgery. In addition, the system is mobile so it can be moved with care between different operating theatres.

The XRS component of the device has a 10-cm-long probe51 and one of a variety of applicators of different shapes and sizes can be attached to this depending on the anatomical site being treated. For breast cancer, a set of eight reusable spherical applicators is available with diameters from 1.5 to 5.0 cm. 52 An applicator is chosen for irradiating the tumour bed after lumpectomy depending on the size of the resection cavity. The INTRABEAM technical specifications state that the dose is usually entered by one person (usually a physicist) and must be checked by a doctor, who verifies the dose planning and confirms it by entering a password. 52 The tissue adjacent to the resection cavity is then irradiated by the INTRABEAM device for typically 20–30 minutes. 51 A characteristic of the low-energy X-rays produced by the INTRABEAM device is that the maximum dose of radiotherapy is delivered to the tissues at the surface of the cavity, but, because the dose attenuates steeply as tissue depth increases, peripheral healthy tissue is spared. 53 As a result, the surface of the tumour bed typically receives 20 Gy in this single-fraction treatment. 53 After this treatment the incision is closed. The design of the INTRABEAM equipment ensures that the tissue most at risk of developing a local recurrence, that is, comprising the wall of the resection cavity adjacent to the resected tumour, receives the largest dose of irradiation.

The INTRABEAM device has been used in patients with early breast cancer to deliver IORT to the cavity wall resulting from lumpectomy for treatment of the primary tumour. Patients at low risk of recurrence do not receive any further local treatment. Patients with a higher risk of recurrence (e.g. histopathology showing invasive lobular carcinoma, extensive intraductal component, grade 3, node involvement, close margins) may go on to receive an additional course of WB-EBRT to the whole breast but without a tumour bed boost because the INTRABEAM device has already delivered therapy directly to the tumour bed. Other adjuvant treatments, for example endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, biological therapy, will also be given if indicated.

Six centres in the UK (four in London, one in Winchester and one in Dundee) are known to have used the INTRABEAM device to treat breast cancer but in the absence of NICE guidance, the equipment has not entered into routine use. In addition to these six centres, information received from the advisory group for this assessment suggests that Liverpool and Harlow have purchased the equipment for neurosurgical and breast use, respectively. Ten other NHS trusts have expressed an interest in purchasing the device and private providers may also have or be intending to purchase the INTRABEAM device.

The device manufacturer has indicated that the cost of the INTRABEAM device in the UK is £435,000. This cost includes a set of spherical applicators, each of which would need to be replaced, at a cost of £3170 per applicator, after 100 treatments. A fully inclusive service contract for maintenance of the device would cost £35,000 annually. Additionally, there are associated consumable costs, for example radiation protection shields (pack of 10 costs £1041, sufficient for five treatments), and sterile plastic drapes (pack of five £95.00, sufficient for five treatments).

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

In line with the scope54 of the NICE appraisal, this assessment will consider the intraoperative use of the INTRABEAM Radiotherapy System as an alternative to post-operative WB-EBRT to the whole breast, and as a boost during BCS before WB-EBRT is provided. Its use for local recurrence will not be considered.

The comparator for this review is WB-EBRT delivered by linear accelerator. As already noted, post-operative WB-EBRT is the standard of care for all patients with early invasive breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy (as per the 2009 NICE guideline11).

The population of patients included within this assessment is people with early operable breast cancer who are eligible for WLE of the tumour followed by whole-breast radiotherapy. If the cancer has spread to the regional lymph nodes, the metastasis remains mobile (not fixed to other structures). Although there is no single definition of early breast cancer, a common definition is disease that is confined to the breast and draining nodes for which treatment could be curative. The majority of people with early breast cancer are, therefore, likely to have tumours classified as TNM stage I or II (either IIa or IIb) but some with stage III tumours could also be considered to have early breast cancer using this definition. People with a local recurrence are excluded from the assessment. The NICE scope that underpins this assessment did not identify any relevant subgroups for consideration.

As specified in the NICE scope,54 the following outcome measures are included in the decision problem:

-

overall survival

-

disease-free survival

-

ipsilateral local recurrence

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this assessment is to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the INTRABEAM Photon Radiotherapy System for the adjuvant treatment of early breast cancer during surgical removal of the tumour.

Other intraoperative techniques were not included as comparators in the NICE scope because they are not currently in use in clinical practice. These techniques were also not included as interventions alongside the INTRABEAM Photon Radiotherapy System because their use was not considered sufficiently comparable.

Chapter 3 Methods

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol, which was sent to our expert advisory group for comment. None of the comments we received identified specific problems with the methods of the review which has been undertaken following the general principles outlined in Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance For Undertaking Reviews In Health Care. 55 The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Identification of studies

The search strategies were developed and tested by an experienced information scientist. The strategies were designed to identify all relevant clinical effectiveness studies of the INTRABEAM Photon Radiotherapy System for people with early operable breast cancer. Separate searches were conducted for the economic evaluation to identify studies of cost-effectiveness and HRQoL.

The following databases were searched for published studies and ongoing research from inception to March 2014: The Cochrane Library [including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (University of York) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database], MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), Web of Science with Conference Proceedings, Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI) – Science (ISI Web of Knowledge), Bioscience Information Service (BIOSIS) Previews (ISI Web of Knowledge), Zetoc (Mimas), National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – Clinical Research Network Portfolio, ClinicalTrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials, and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP). Searches were limited to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) for the assessment of clinical effectiveness. Although searches were not restricted by language, only full texts of English-language articles were retrieved during the study selection process.

Bibliographies of included articles, systematic reviews and clinical guidelines were also searched. The manufacturer’s submission (MS) to NICE was searched for any additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. Members of our advisory group were asked to identify additional published and unpublished evidence. Further details including search dates for each database and an example search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were derived from the final scope54 issued by NICE.

Study design

-

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, RCTs were eligible for inclusion. If the data from available RCTs were incomplete (e.g. absence of data on outcomes of interest), evidence from good-quality CCTs was eligible for consideration.

-

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness, full economic evaluations (cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analyses) reporting on measures of both costs and consequences were eligible for inclusion.

-

For the systematic review of HRQoL, primary research studies based in the UK, Europe, North America and Australasia were eligible for inclusion.

-

Abstracts or conference presentations of studies were eligible for inclusion only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

-

Case series, case studies, narrative reviews, editorials and opinions were excluded, as were non-English-language studies. Systematic reviews and clinical guidelines were used only as a source of references.

Intervention(s)

-

INTRABEAM Photon Radiotherapy System with or without post-operative WB-EBRT.

Comparator(s)

-

External beam radiotherapy delivered by a linear accelerator.

Population

-

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, people with early operable breast cancer (as defined by the trials).

-

For the systematic review of HRQoL, people with breast cancer (not limited to early-stage breast cancer).

-

People with a local recurrence were excluded.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported on one or more of the following outcomes:

-

overall survival

-

disease-free survival

-

ipsilateral local recurrence

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL

-

cost-effectiveness [expressed in natural units such as life-years gained (cost-effectiveness analysis), quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (cost–utility analysis), or in monetary units (cost–benefit analysis)].

Inclusion screening process

Studies were selected for inclusion through a two-stage process. Literature search results (titles and, if present, abstracts) identified by the search strategy were screened independently by two reviewers to identify all citations that potentially met the inclusion/exclusion criteria detailed above. Full manuscripts of selected citations that appeared potentially relevant were obtained. These were assessed by one reviewer against the inclusion/exclusion criteria using a flow chart and checked independently by a second reviewer before a final decision regarding inclusion was agreed. At each stage any disagreements were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Data extraction process

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and each data extraction was checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Critical appraisal strategy

The risk of bias of the included clinical effectiveness studies was assessed using criteria devised by the Cochrane Collaboration. 56 Criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer with any disagreements resolved by consensus and involvement of a third reviewer where necessary. The methodological quality of included cost-effectiveness studies was assessed using criteria adapted by the review authors from checklists for appraising economic evaluations by Drummond et al. 57 The economic evaluation included in the MS [Multiple Technology Appraisal (MTA) INTRABEAM Photon Radiosurgery System for the Adjuvant Treatment of Early Breast Cancer. Carl Zeiss, UK. 2014] to NICE was assessed using criteria adapted by the review authors from checklists for appraising economic evaluations by Drummond et al. ,57 supplemented with additional criteria for critical appraisal of model-based evaluations by Philips et al. 58 For the systematic review of HRQoL, the included studies were assessed against a critical appraisal checklist adapted by the review authors from common themes found in other published assessment forms for HRQoL studies. 59–62

Method of data synthesis

Clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and HRQoL data were synthesised through narrative reviews that included critical appraisal of study methods, critical assessment of data used in any economic models and tabulation of the results of included studies.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

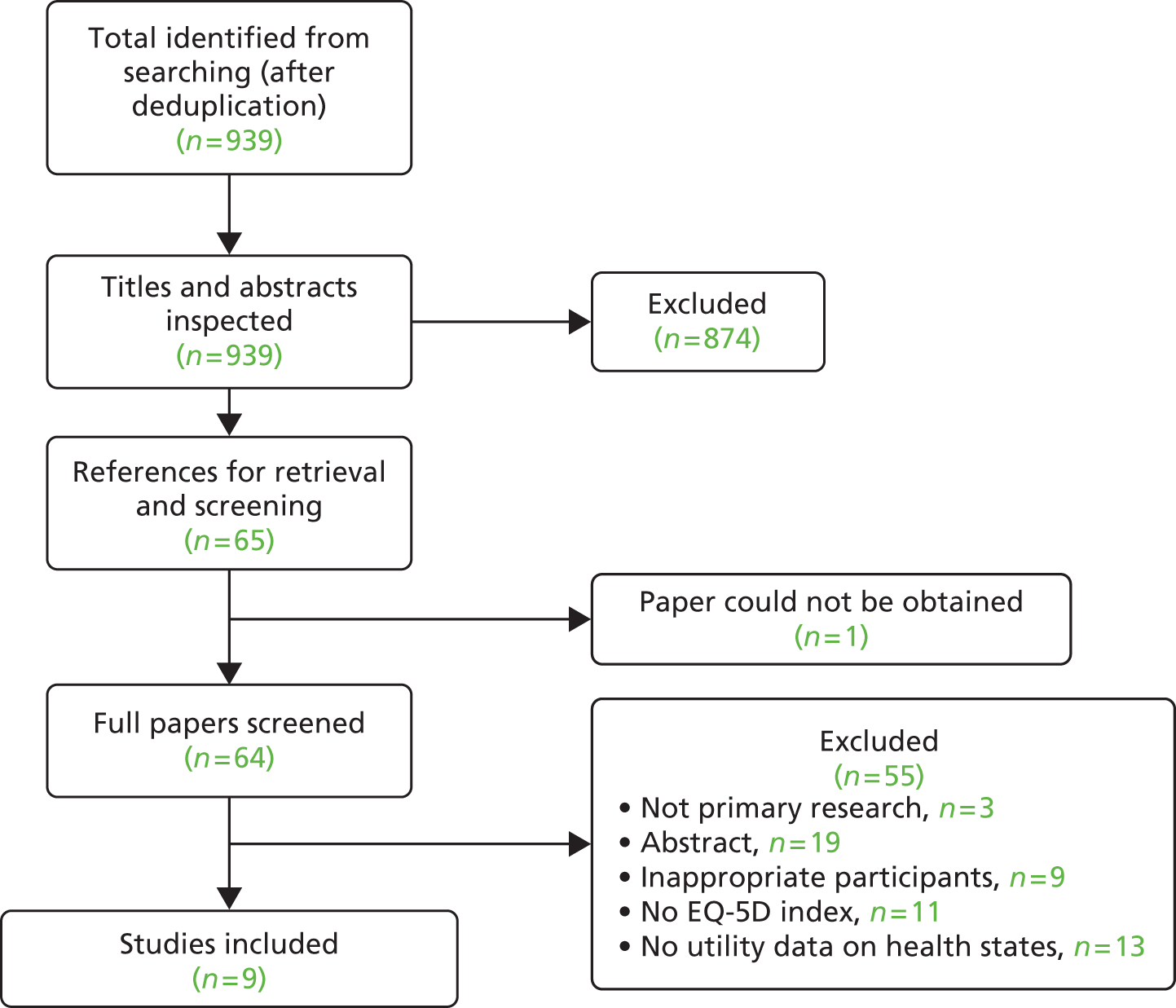

Titles and, where available, abstracts of a total of 655 citations were screened and full copies of 44 references were obtained. Of these, 38 were excluded after inspection of the full article (see Appendix 2). The most common primary reason for exclusion was that the reference was an abstract containing insufficient details to allow appraisal of methodology and/or results (n = 25); a further eight records were excluded chiefly because the outcome was not relevant to the review, three records were excluded chiefly because of an incorrect intervention, one record was excluded on the basis of study design and one record was excluded because it related to an ongoing study (see Chapter 4, Ongoing studies). One RCT, the TARGeted Intraoperative radioTherapy Alone (TARGIT-A) trial, met the inclusion criteria for the review (Figure 1). The primary and secondary outcomes for the whole trial population were described by two full papers and three linked abstracts. Five substudies of the TARGIT-A trial which report outcome data from participants at just one or two centres were identified. Four of these substudies were excluded from this systematic review on the grounds of outcome (see Appendix 2). One substudy has been included which reports data on HRQoL from patients at one TARGIT-A trial centre. 63 Table 6 provides a summary description of the TARGIT-A study publications included in the clinical effectiveness systematic review.

| Author | Study | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Vaidya et al., 201064 | TARGIT-A trial | Initial results of local recurrence and complications, n = 2232 |

| Vaidya et al., 201465 | TARGIT-A trial | Updated longer-term results of local recurrence, complications and survival, n = 3451 |

| Welzel et al., 201363 | TARGIT-A trial substudy, one centre (Germany) | QoL outcome, n = 88 |

Overview of the TARGIT-A trial

The key characteristics of the TARGIT-A trial64,65 are shown in Table 7 with further details in the data extraction form (see Appendix 3). The TARGIT-A trial is the pivotal trial evaluating the concept of delivering a single dose of targeted IORT at the time of surgery using the mobile INTRABEAM Photon Radiotherapy System.

| Study | Methods | Key inclusion/exclusion criteria | Key participant characteristicsa | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaidya et al., 201064 and 201465 TARGIT-A trial Number of centres: 33 (six in UK) Countries: 11 (Europe, USA, Canada and Australia) |

Design: international, multicentre, non-inferiority RCT Intervention: TARGIT (INTRABEAM device) Dose: typically 20 Gy to surface of tumour bed attenuating to 5–7 Gy at a depth of 1 cm Comparator: WB-EBRT |

Inclusion criteria:

|

Reported in updated 2014 paper (n = 3451):65 Age (years):

|

Primary outcome:Secondary outcomes:

|

| Sponsor: academic and government bodies | Dose: typically 40–56 Gy ± boost of 10–16 Gy Other interventions used: adjuvant systemic treatment as appropriate. Participants in the INTRABEAM group with unfavourable pathological features found subsequently (e.g. lobular carcinoma) received WB-EBRT in addition after INTRABEAM Number of participants: n = 3451:65

Follow-up: median 2 years and 5 months (IQR 12–52 months) |

Nodes involved:

|

||

PgR status:

|

||||

Additional characteristics reported only in 2010 paper (n = 2232):64

|

||||

DCIS:

|

||||

Adjuvant therapy:

|

Design

The TARGIT-A trial is an international, multicentre, non-inferiority RCT that recruited participants in 33 centres in 11 countries including the UK (six centres), Europe (17 centres in six countries), the USA (seven centres), Canada (one centre) and Australia (two centres). The trial evaluated IORT using the INTRABEAM device compared with conventional WB-EBRT. The planned follow-up for trial participants was at least 10 years. 69 Median follow-up achieved for the most recent 2014 publication65 is 2 years 5 months.

As a non-inferiority trial, the RCT sought to determine whether or not INTRABEAM treatment was no worse than WB-EBRT. The pre-stated non-inferiority margin was an absolute difference of 2.5% in the primary end point (local recurrence) between groups. The 2.5% non-inferiority margin was chosen at the trial outset because it seemed clinically acceptable to both clinicians and patients. 64 However, it should be noted that, when the non-inferiority margin was chosen, the estimated local recurrence rate (LRR) (based on the literature available in 1999)70,71 was 6%, and since then recurrence rates have fallen. Two patient preference studies72,73 suggest that patients would be willing to accept an increase in the risk of local recurrence for the convenience of INTRABEAM treatment but it should be noted that these studies were conducted in countries in which WB-EBRT is typically delivered over 5–6 weeks and it is not known whether or not patient preference would be similar in England where WB-EBRT is typically delivered over 3 weeks.

The trial randomised participants in three strata: pre pathology, post pathology and contralateral breast cancer. In the initial 2010 publication,64 pre-pathology entry accounted for two-thirds of patients, post pathology approximately 30% and contralateral breast cancer patients < 4%. It is not clear if these proportions were maintained in the additional patient numbers reported in the updated 2014 publication. 65 The baseline stratification data show differences between centres in the number of patients entering the trial according to the three timings of delivery strata, particularly pre and post pathology (see Appendix 3 for further details). Patients who entered the trial in the pre-pathology stratum were randomised to either INTRABEAM or WB-EBRT prior to WLE of the primary tumour (Figure 2a). The trial was pragmatic in that if participants randomised to INTRABEAM were subsequently found to have unfavourable pathological features (unexpected lobular carcinoma, extensive intraductal component, positive margins at first excision), and hence were at high risk of recurrence elsewhere in the breast, they received WB-EBRT in addition (i.e. INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT, approximately 15% of INTRABEAM patients). The protocol also allowed for post-pathology entry of patients whereby patients underwent initial surgery and then, providing no unfavourable pathological features were identified, were randomised in a second stratum to receive INTRABEAM delivered as a second procedure or WB-EBRT (Figure 2b). Post-pathology entrants to the trial were randomised within 30 days after lumpectomy and the median time between initial lumpectomy and post-pathology INTRABEAM treatment was 37 days. The timing of INTRABEAM delivery was not specified in the intervention description within the NICE scope and, therefore, the post-pathology participants are included in this systematic review. Additionally, patients with a history of previous contralateral breast cancer were also included and randomised in a third stratum. Treatment for breast cancer in the contralateral breast is not an exclusion criterion for this review and, therefore, these participants are also judged to meet the criteria for inclusion.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram for the two main trial strata. (a) Pre pathology; and (b) post pathology.

Participants

The TARGIT-A trial was a moderately large trial, recruiting 3451 women with early breast cancer eligible for BCS (2298 to the pre-pathology stratum, 1153 to the post-pathology stratum, as noted above final proportion of contralateral breast cancer patients not reported). 65 Participants had to be ≥ 45 years of age and have invasive ductal carcinoma that was unifocal on conventional examination and imaging. The trial protocol specifically defined early invasive breast cancer as T1 and small T2, N0–1, M0. 69 The initial trial publication64 stipulated the pre-operative diagnosis of lobular carcinoma as a single exclusion criterion, although the trial protocol specified additional exclusion criteria. 69 Furthermore, because the trial was pragmatic, each participating centre had the option to predefine more restrictive entry criteria than in the core protocol (e.g. age, tumour size, grade, node) and to stipulate local policy for the delivery of WB-EBRT.

The majority of women (77%) were aged between 51 and 70 years. Approximately one-third of participants had a grade 1 tumour and around half had grade 2 tumour, while only 15% had a grade 3 tumour. The publications64,65 did not specify the grading system used, but it is likely to have been the standard Bloom–Richardson system74 or the Nottingham system,75 which is modification of the Bloom–Richardson system. In the majority of women, tumour sizes were small (87% < 2 cm) and were associated with a good prognosis – nodes were uninvolved (84%) and ER status and progesterone receptor (PgR) status were positive (93% and 82%, respectively). 65 Two-thirds of women were receiving hormone therapy as adjuvant systemic treatment, while around 12% were receiving chemotherapy. 64

Intervention

The INTRABEAM patients received a typical dose of 20 Gy to the surface of the tumour bed (attenuating to 5–7 Gy at a 1 cm depth).

Comparator

External beam radiotherapy patients received a typical dose of 40–56 Gy with/without an additional boost to the tumour bed of 10–16 Gy. Trial centres were allowed to stipulate local policy for the delivery of WB-EBRT and, therefore, there would have been some differences between WB-EBRT delivered at different centres. It is presumed that, in UK centres, 40 Gy in 15 fractions would have been the likely treatment schedule, whereas in some other centres local policy was an alternative schedule, for example 56 Gy in 28 fractions. 63

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the trial was pathologically confirmed local recurrence in the conserved breast. In the initial 2010 paper,64 survival free of recurrence (i.e. disease-free survival) was reported, but, in the 201465 paper, the data on recurrence are not presented in that format. Secondary outcomes were rates of local toxicity or morbidity, which were assessed using a complications form that contained a pre-specified checklist. The timing of the data collection for complications was unclear in the trial publications, being described as ‘early’ in the 2010 paper64 and ‘arising 6 months after randomisation’ in the 2014 paper. 65 Complications recorded on the pre-specified checklist were haematoma, seroma, wound infection, skin breakdown, delayed wound healing and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) toxicity grade 3 or 4 (for dermatitis, telangiectasia, pain in irradiated field, or other). Overall survival was reported as a secondary outcome measure in the 2014 updated publication. 65 No data on HRQoL have been published for the whole trial population; however, one small substudy63 is included in this systematic review which reports on HRQoL for 88 participants enrolled at one centre in Mannheim, Germany. HRQoL was assessed by two validated questionnaires of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the quality of life (QoL) questionnaire – C30 (QLQ-C30, version 3; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels, Belgium) and the QoL questionnaire – Breast Cancer Module (QLQ-BR23). Data presented in the initial TARGIT-A trial publication64 suggest that all the participants enrolled at this centre were randomised to the pre-pathology stratum.

For most outcomes, analyses were by intention to treat (ITT), one exception being local recurrence in the conserved breast which, because of the nature of the outcome, could not include women who had undergone a mastectomy (approximately 2%). For a superiority trial, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement76 states that analysis should be by ITT. However, the TARGIT-A trial is a non-inferiority trial. An extension to the CONSORT statement77 for non-inferiority trials indicates that non-ITT analyses might be desirable and that there would be greater confidence in the results if these were consistent between ITT and non-ITT analyses. Therefore, an analysis by treatment received in addition to the ITT analyses presented for the TARGIT-A trial would have been welcome. Outcomes of local recurrence and overall survival were reported for the whole trial population and separately for the pre- and post-pathology strata. Data from participants who received INTRABEAM only and from those who received INTRABEAM with WB-EBRT in addition were analysed together for most outcomes. Median length of follow-up for participants in the initial 2010 publication was not reported, although it was stated that maximum follow-up was 10 years. 64 The more recent 2014 publication65 reported an overall median follow-up of 2 years 5 months, with 2020 (59%) participants reaching a median 4 years and 1222 (35%) reaching a median 5 years.

Quality assessment of TARGIT-A trial

Overall, the methodological quality of the TARGIT-A trial was judged to be good with a low risk of bias. Table 8 shows the judgements of risk of bias in the various domains. For the HRQoL substudy, the assessment of selection bias and reporting bias for the main trial was judged to apply. For the remaining criteria it was judged that the HRQoL substudy could potentially differ from the main trial and, therefore, separate assessments were conducted (see Table 8). Overall, the substudy was judged to be at a high risk of bias owing to the lack of blinding and it is not clear how representative the results are for the total trial population because the substudy represents only about 2.5% of the overall trial population. Therefore, the substudy results should be interpreted with caution.

| Cochrane criteria for assessment of risk of bias in RCTs56 | Judgementa | Support for judgement |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | ||

| Random sequence generation | Low risk | Computer-generated randomisation schedules |

| Allocation concealment | Low risk | Central allocation |

| Performance bias | ||

| Blinding of participants and personnel in the TARGIT-A trial | Low risk | Neither patients nor investigators were blinded. However, outcomes of mortality and recurrence were unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Blinding of participants and personnel in the HRQoL substudy | High risk | As part of the TARGIT-A trial neither patients nor investigators were blinded and the outcome could potentially be influenced by the lack of blinding |

| Detection bias | ||

| Blinding of outcome assessment in the TARGIT-A trial | Low risk | Some investigators and teams were not blinded and it is not clear whether or not all the analyses were performed unblinded. However, outcomes of mortality and recurrence are objective measures and hence unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment in the HRQoL substudy | Unclear risk | No information reported for this substudy |

| Attrition bias | ||

| Incomplete outcome data addressed in the TARGIT-A trial | Low risk | Low proportion of withdrawals and participants not receiving allocated treatment (reasons similar between groups). Analyses by ITT |

| HRQoL sub-study | Low risk | Reason for loss of one participant given |

| Reporting bias | ||

| Selective reporting | Low risk | The protocol is available online (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/51892/PRO-07-60-49.pdf)69 and specifies all outcomes including relapse-free survival and overall survival (as secondary outcomes) |

| Other bias | ||

| Other sources of bias in the TARGIT-A trial | Low risk | None evident |

| Other sources of bias in the HRQoL substudy | Unclear risk | Retrospective questionnaire with no baseline QoL measurement |

Randomisation schedules that were generated by computer and held securely in two centres, with requests for randomisation made by telephone or fax, meant that the risk of selection bias was low.

Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not feasible to blind the patients or investigators in the trial, which could potentially introduce performance bias. However, given that the main trial outcomes (recurrence and survival) were objective measures, it was deemed unlikely that patients or investigators were influenced by the lack of blinding and thus performance bias was judged to be low. Similarly, for the main trial, although not all outcome assessors were blinded, the risk of detection bias was judged to be low because the main trial outcomes (recurrence and survival) were objective measures. For the substudy,63 the lack of patient and investigator blinding led to a judgement of a high risk of performance bias, and detection bias was judged as unclear owing to a lack of information.

The risk of attrition bias (differences between groups in withdrawals from the study) was deemed to be low in the TARGIT-A trial. There was a low proportion of withdrawals, and the rate appeared similar between treatment groups (0.5% INTRABEAM, 1.6% WB-EBRT). 65 Similar numbers of patients in the two treatment groups received their allocated treatment (91% INTRABEAM, 92% WB-EBRT)65 and all randomised patients were included in an ITT analysis for most outcomes. However, as noted above (see Overview of the TARGIT-A trial, Outcomes), an additional analysis by treatment received would have been desirable. The substudy63 was deemed to be at low risk of attrition bias because only one patient was reported as lost to follow-up.

The risk of bias due to selective reporting was deemed low as all outcomes specified in the trial protocol69 were reported in either the original or updated publication. 64,65 No other sources of bias in the total trial population were identified. The substudy63 used a retrospective questionnaire without reporting baseline measurements and was therefore deemed to be at unclear risk of other sources of bias.

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The majority of the results presented in the following section are the most recent data for the TARGIT-A trial reported in the updated publication by Vaidya et al. 65 Results are presented for ipsilateral local recurrence, overall survival, and morbidity and toxicity. The main trial outcome data are supplemented with some morbidity data from the initial trial publication (see Vaidya et al. 64). The TARGIT-A trial presented outcomes of recurrence and survival for the whole trial population, and separately for the pre- and post-pathology strata. The separate analysis of these two strata was pre-specified. No data were presented from the third stratum (participants with a history of previous contralateral breast cancer) and no data on HRQoL have been published for the whole trial population. However, limited data on the secondary outcome of QoL are provided by a substudy at one trial centre. 63

Ipsilateral local recurrence

Local recurrence in the conserved breast was the primary outcome in the TARGIT-A trial. Recurrence was defined as a recurrent tumour in the ipsilateral breast and was confirmed pathologically by clinical examination and cytology or biopsy. 69 The most recent data from the 201465 publication are shown, which were not expressed in terms of disease-free survival. Results are presented in Tables 9 and 10 and show data for the whole cohort and for the two pre-specified randomisation strata (pre pathology and post pathology) representing the different timings in delivery of INTRABEAM therapy. The trial authors also report results separately for the mature cohort (participants previously reported in the initial publication in 201064) and the earliest cohort (which excludes participants enrolled in the last 4 years of the study) in order to ‘assess stability over time’65 (see Table 10). However, there has been criticism of this approach78 because all patients included in the earliest cohort are also included in, and account for, just over half of the mature cohort and are included again in the whole cohort representing approximately one-third of this. The assessment team and the advisory group for this assessment also have concerns about the approach taken. For the INTRABEAM arm, data from participants who received INTRABEAM only and from those who received INTRABEAM and WB-EBRT were analysed together.

| Local recurrence | INTRABEAM events/n; 5-year cumulative risk (%) (95% CI)65 | WB-EBRT events/n; 5-year cumulative risk (%) (95% CI)65 | Absolute difference in Kaplan–Meier estimate at 5 years; p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole group (n = 3375)a | 23/1679; 3.3 (2.1 to 5.1) | 11/1696; 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 12 (2.0%); p = 0.042 |

| Pre-pathology stratum (n = 2234)a | 10/1107; 2.1 (1.1 to 4.2) | 6/1127; 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) | 4 (1.0%); p = 0.31 |

| Post-pathology stratum (n = 1141)a | 13/572; 5.4 (3.0 to 9.7) | 5/569; 1.7 (0.6 to 4.9) | 8 (3.7%); p = 0.069 |

| Local recurrence65 | Median follow-up | Events, n | Absolute difference (%) (90% CI) in the binomial proportionsa of ipsilateral local recurrence (INTRABEAM minus WB-EBRT) | z-value | p non-inferiority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole trial | |||||

| All patients | 2 years 5 months | 34 | 0.72 (0.2 to 1.3) | –5.168 | < 0.0001 |

| Mature cohortb | 3 years 7 months | 32 | 1.13 (0.3 to 2.0) | –2.652 | 0.0040 |

| Earliest cohortc | 5 years | 23 | 1.14 (–0.1 to 2.4) | –1.750 | 0.0400 |

| Pre pathology | |||||

| All patients | 2 years 4 months | 16 | 0.37 (–0.2 to 1.0) | –5.954 | < 0.0001 |

| Mature cohortb | 3 years 8 months | 14 | 0.60 (–0.3 to 1.5) | –3.552 | 0.0002 |

| Earliest cohortc | 5 years | 9 | 0.76 (–0.4 to 2.0) | –2.360 | 0.0091 |

| Post pathology | |||||

| All patients | 2 years 4 months | 18 | 1.39 (0.2 to 2.6) | –1.503 | 0.0664 |

| Mature cohortb | 3 years 7 months | 18 | 2.04 (0.3 to 3.8) | –0.429 | 0.3339 |

| Earliest cohortc | 5 years | 14 | 1.80 (–1.2 to 4.8) | –0.382 | 0.3511 |

By nature of the outcome, the recurrence data do not include women who underwent mastectomy (n = 76). Statistical significance levels were set at p < 0.01 for recurrence. The rationale for setting p < 0.01 for recurrence but p < 0.05 for survival (see Overall survival) is not provided.

As can be seen in Table 9, the 5-year risk of local recurrence in the conserved breast in the whole cohort of patients was higher in patients receiving INTRABEAM than in those treated with WB-EBRT, but the absolute difference did not exceed the pre-stated non-inferiority margin of 2.5% (3.3% vs. 1.3%, respectively; absolute difference 2.0%; p = 0.042). With the statistical significance level set at p < 0.01 for recurrence, the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Similarly, in the pre-pathology stratum (INTRABEAM delivered at the time of BCS), the absolute difference in recurrence did not exceed the 2.5% non-inferiority margin (2.1% INTRABEAM vs. 1.1% WB-EBRT, absolute difference 1.0%; p = 0.31) and the difference between groups was not statistically significant. However, in the post-pathology stratum (INTRABEAM delivered after BCS as a secondary procedure), although the difference between groups was not statistically significant (and the analysis may not have been powered to detect a difference), the 5-year local recurrence was higher in INTRABEAM patients, with the difference being larger than the pre-defined non-inferiority margin of 2.5% (5.4% INTRABEAM vs. 1.7% WB-EBRT, absolute difference 3.7%; p = 0.069). Therefore, INTRABEAM has been shown to be non-inferior to WB-EBRT for the whole group and for the pre-pathology stratum but not for participants in the post-pathology stratum (based on a non-inferiority margin of 2.5%).

The data on recurrence were used to generate a non-inferiority statistic (pnon-inferiority) for the absolute difference in the binomial proportions of ipsilateral local recurrence (see Table 10). INTRABEAM was shown to be non-inferior to WB-EBRT for the whole cohort (absolute difference in binomial proportions 0.72%, 90% CI 0.2% to 1.3%; pnon-inferiority < 0.0001) and for all pre-pathology patients (absolute difference in binomial proportions 0.37%, 90% CI –0.2% to 1.0%; pnon-inferiority < 0.0001). However, non-inferiority was not established for the post-pathology patients (absolute difference in binomial proportions 1.39%, 90% CI 0.0% to 2.8%; pnon-inferiority = 0.0664).

The non-inferiority statistic was also reported separately for two cohorts of participants within the trial that had longer follow-up. As already noted, the stated aim of these analyses was to ‘assess stability over time’,65 but participants in the earliest cohort are also included in the mature cohort and whole trial population and there are concerns about this approach; therefore, the results should be interpreted cautiously. For the mature cohort, which comprised participants previously reported on in 2010,64 and the earliest cohort, which had a median follow-up of 5 years, results reflect those of the ‘all-patients’ analyses. It is worth noting that the number of local recurrence events in the earliest cohort (median follow-up 5 years) was 23 events for the whole trial, just nine of which occurred in pre-pathology participants.

The absolute differences in the 5-year Kaplan–Meier estimates of percentage with local recurrence in the conserved breast were calculated and presented as a figure in the trial publication65 for the pre-pathology stratum only. Data were estimated from the figure using Engauge digitising software (version 4.1, © Mark Mitchell) (see Appendix 3). The Kaplan–Meier estimates were consistent across the three cohorts with increasing median follow-up, with absolute differences in percentage with local recurrence in the conserved breast of 1.1 (whole cohort), 1.1 (mature cohort) and 1.0 (earliest cohort).

Overall survival

Overall survival was a secondary outcome in the TARGIT-A trial and was reported in the more recent 2014 publication. 65 Overall survival was defined as the time interval between randomisation and death69 and included breast cancer deaths and non-breast cancer deaths. Statistical significance levels were set at p < 0.05 for survival. As already noted, the rationale for setting p < 0.05 for survival but p < 0.01 for recurrence was not provided.

There were no statistically significant differences in overall mortality between women who received INTRABEAM compared with those who received WB-EBRT (3.9% vs. 5.3%, respectively; difference –1.4%; p = 0.099) (Table 11). When mortality was split into breast cancer and non-breast cancer deaths, rates of breast cancer death were similar between the two treatments (2.6% vs. 1.9%; p = 0.56), but there were significantly fewer non-breast cancer deaths in the INTRABEAM group than in the WB-EBRT group (1.4% vs. 3.5%, respectively; p = 0.0086).

| Mortality65 | INTRABEAM events/n; 5-year cumulative risk (%) (95% CI)65 | WB-EBRT events/n; 5-year cumulative risk (%) (95% CI)65 | Absolute difference; p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mortality | |||

| All patients (n = 3451) | 37/1721; 3.9 (2.7 to 5.8) | 51/1730; 5.3 (3.9 to 7.3) | –14 (–1.4%); p = 0.099 |

| Pre-pathology stratum (n = 2298) | 29/1140; 4.6 (1.8 to 6.0) | 42/1158; 6.9 (4.3 to 9.6) | –13 (–2.3%); p = NR |

| Post-pathology stratum (n = 1153) | 8/581; 2.8 (1.3 to 5.9) | 9/572; 2.3 (1.0 to 5.2) | –1 (0.5%); p = NR |

| Breast cancer mortality | |||

| All patients (n = 3451) | 20/1721; 2.6 (1.5 to 4.3) | 16/1730; 1.9 (1.1 to 3.2) | p = 0.56 |

| Pre-pathology stratum (n = 2298) | 17/1140; 3.3 (1.9 to 5.8) | 15/1158; 2.7 (1.5 to 4.6) | p = 0.72 |

| Post-pathology stratum (n = 1153) | 3/581; 1.2 (0.4 to 4.2) | 1/572; 0.5 (0.1 to 3.5) | p = 0.35 |

| Non-breast cancer mortality | |||

| All patients (n = 3451) | 17/1721; 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | 35/1730; 3.5 (2.3 to 5.2) | p = 0.0086 |

| Pre-pathology stratum (n = 2298) | 12/1140; 1.3 (0.7 to 2.8) | 27/1158; 4.4 (2.8 to 6.9) | p = 0.016 |

| Post-pathology stratum (n = 1153) | 5/581; 1.58 (0.62 to 3.97) | 8/572; 1.76 (0.7 to 4.4) | p = 0.32 |

In the pre-pathology stratum (INTRABEAM delivered at the time of BCS), overall mortality was slightly lower in the INTRABEAM group (4.6% vs. 6.9% for INTRABEAM and WB-EBRT, respectively; difference –2.3%; no p-value reported). When split into causes of death, the same pattern was observed as for the whole cohort for which deaths attributable to breast cancer were similar between the two treatments (3.3% vs. 2.7% for INTRABEAM and WB-EBRT, respectively; p = 0.72), but there were significantly fewer non-breast cancer deaths in the INTRABEAM group (1.3%) than in the WB-EBRT group (4.4%; p = 0.016). When INTRABEAM was delivered after BCS as a delayed procedure (post-pathology stratum), rates of overall mortality, breast cancer and non-breast cancer mortality were similar between treatment groups (see Table 11).

For non-breast cancer mortality, which was statistically significantly different between the INTRABEAM and WB-EBRT groups, Vaidya et al. 65 detailed the causes of death. These included other types of cancer, cardiovascular causes and other causes. Details can be found in the data extraction form in Appendix 3.

The absolute differences in the 5-year Kaplan–Meier estimates of percentage overall mortality were calculated and presented in the published paper65 for the pre-pathology stratum only (as with local recurrence, see Ipsilateral local recurrence) for the three cohorts with increasing median follow-up. As noted in section Ipsilateral local recurrence, there are concerns about the approach taken and, therefore, the results should be interpreted cautiously. The Kaplan–Meier estimates were similar across the three cohorts, with absolute differences in percentage mortality of –2.3 (whole cohort), –2.6 (mature cohort) and –2.2 (earliest cohort) (the data extracted from the published figure are available in Appendix 3). These data and the absolute differences in the 5-year Kaplan–Meier estimates of percentage with local recurrence in the conserved breast (see Ipsilateral local recurrence) were presented together in the 2014 trial publication65 to demonstrate the relationship between local recurrence and mortality whereby women receiving INTRABEAM experience more local recurrences but fewer deaths than those receiving WB-EBRT.

Morbidity and toxicity

Complications, in the form of local toxicity and morbidity, were reported as secondary outcomes. The initial publication by Vaidya et al. 201064 reported early complications but did not specifically define ‘early’, although the trial protocol69 stipulated that the period of serious adverse event observation extended from the time of registration onto the trial until 90 days after the completion of randomised treatment. The more recent TARGIT-A publication65 reported complications arising 6 months after randomisation.

As can be seen in Table 12, the incidence of any early complication was similar in the two treatment groups. Clinically significant complications were also similar between groups with the exception of two. Wound seroma requiring more than three aspirations occurred more frequently in women receiving INTRABEAM than in those receiving WB-EBRT (2.1% vs. 0.8%, respectively; p = 0.012), while, conversely, a RTOG toxicity score of grade 3 or 4 was less frequent in the INTRABEAM group than in the WB-EBRT group (0.5% vs. 2.1%; p = 0.002). 64 Separate data were not reported for the categories of dermatitis, telangiectasia, pain in irradiated field, or other that contributed to the RTOG toxicity grade 3 or 4 outcome. A member of the advisory group for this assessment indicated that the clinical impact for patients with grade 3 or 4 toxicity is much greater than for those with a seroma requiring several aspirations.

| Earlya complications | INTRABEAM (n = 1113) | WB-EBRT (n = 1119) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of complications per patient64 | |||

| 0 | 917/1113 (82.4%) | 946/1119 (84.5%) | NR |

| 1 | 151/1113 (13.6%) | 139/1119 (12.4%) | NR |

| 2 | 29/1113 (2.6%) | 27/1119 (2.4%) | NR |

| 3 | 11/1113 (1.0%) | 5/1119 (0.4%) | NR |

| 4 | 3/1113 (0.3%) | 0/1119 | NR |

| 5 | 2/1113 (0.2%) | 0/1119 | NR |

| 6 | 0/1113 | 3/1119 (0.3%) | NR |

| Any complicationa | 196/1113 (17.6%) | 174/1119 (15.5%) | χ2 1.74; p = 0.19b |

| aClinically significant complications64 | |||

| Haematoma needing surgical evacuation | 11/1113 (1.0%) | 7/1119 (0.6%) | 0.338 |

| Seroma needing > 3 aspirations | 23/1113 (2.1%) | 9/1119 (0.8%) | 0.012 |

| Infection needing i.v. antibiotics or surgical intervention | 20/1113 (1.8%) | 14/1119 (1.3%) | 0.292 |

| Skin breakdown or delayed wound healingc | 31/1113 (2.8%) | 21/1119 (1.9%) | 0.155 |

| RTOG toxicity grade 3 or 4d | 6/1113 (0.5%) | 23/1119 (2.1%) | 0.002 |

| Major toxicitye | 37/1113 (3.3%) | 44/1119 (3.9%) | 0.443 |

| Wound-related complications arising 6 months after randomisation65 | INTRABEAM (n = 1721) | WB-EBRT (n = 1730) | p-value |

| Haematoma/seroma needing > 3 aspirations | 4/1721 (0.2%)f | 2/1730 (0.1%)f | NR |

| Infection needing i.v. antibiotics or surgery | 12/1721 (0.7%)f | 9/1730 (0.5%)f | NR |

| Skin breakdown or delayed wound healing | 3/1721 (0.2%)f | 5/1730 (0.3%)f | NR |

| Total | 19/1721 (1.1%) | 16/1730 (0.9%) | 0.599 |

| Radiotherapy-related complications65 | |||

| RTOG toxicity grade 3 or 4 | 4/1721 (0.2%) | 13/1730 (0.8%) | 0.029 |

The incidence of complications arising 6 months after randomisation (reported by the 2014 publication65) was lower in both treatment groups, although it is not clear whether or not these complications occurred in any of the same patients who were reported in the 2010 publication64 as having clinically significant complications. There appeared to be no differences between treatment groups in any single defined wound-related complication (see Table 12) (p-values not reported), or in total complications (1.1% INTRABEAM vs. 0.9% WB-EBRT; p = 0.599). The incidence of radiotherapy-related complications (RTOG toxicity score of grade 3 or 4) remained higher in women receiving WB-EBRT (0.8%) than in those receiving INTRABEAM (0.2%), but the difference between the groups was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.29).

Substudy reporting quality of life for participants at one trial centre

No data on HRQoL have been published for the whole trial population; however, Welzel et al. 63 have assessed QoL retrospectively in one small substudy of 88 participants enrolled at one centre in Mannheim, Germany. The initial TARGIT-A trial publication64 indicates that all the participants enrolled at this centre were randomised to the pre-pathology stratum. QoL was assessed by using two validated questionnaires of the EORTC: the QLQ-C30 (version 3) and the QLQ-BR23. Participants (n = 88) were asked to report on their situation in the last week and these participants represent 2.5% of the total TARGIT-A trial population. The results of both an ITT analysis and an as-treated analysis (with a threshold for significance of p < 0.01 in both cases) are presented in Table 13. The as-treated analysis removes five participants from the INTRABEAM group and moves four of them to the WB-EBRT group because this was the treatment received, with the fifth (who refused WB-EBRT) not contributing data. The ITT analysis did not identify any statistically significant differences in QoL measures (global health status, restrictions in daily activities, general pain, breast or arm symptoms) reported by the INTRABEAM arm in comparison with the WB-EBRT arm. The as-treated analyses were not presented in the same way as the ITT analysis. For the as-treated analyses, the results for the INTRABEAM arm were reported separately for those who received INTRABEAM therapy only and those who received INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT with statistical comparisons of INTRABEAM only versus WB-EBRT, INTRAEAM only versus INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT, and WB-EBRT versus INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT being reported. Thus, a statistical comparison between the original randomised groups is not reported. For the comparison of the INTRABEAM-only group with the WB-EBRT-treated group the as-treated analyses showed a statistically significant benefit of INTRABEAM for restrictions in daily activities, general pain, breast symptoms and arm symptoms, but there was no statistically significant difference in the global health status subscale. When comparing the INTRABEAM-only group with the INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT group, the only statistically significant difference in the reported QoL measures was for breast symptoms. No statistically significant differences were reported for comparisons of QoL measures between the INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT and the WB-EBRT groups. These data should be interpreted cautiously owing to their non-randomised nature and the small numbers involved. The breast and arm symptoms most commonly reported by participants were moderate or severe pain in the arm or shoulder, difficulty in raising/moving arm sideways and pain in area of affected breast. No statistically significant differences between groups were reported for the as-treated analysis of frequency of symptoms.

| ITT analysis, QoL outcome, mean (SD) | INTRABEAM (N = 46; IORT n = 30, INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT n = 16) | WB-EBRT (n = 42) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health statusb | 61.6 (21.7), n = 46 | 54.8 (19.9), n = 40 | 0.183 | |

| Restrictions in daily activitiesb | 72.8 (32.3), n = 46 | 61.8 (29.2), n = 41 | 0.055 | |

| General painc | 29.3 (32.8), n = 46 | 42.5 (33.0), n = 42 | 0.048 | |

| Breast symptomsc | 17.0 (20.8), n = 45 | 18.1 (20.2), n = 42 | 0.629 | |

| Arm symptomsc | 24.4 (26.7), n = 45 | 31.1 (27.9), n = 40 | 0.279 | |

| As-treated analysis, QoL outcome, mean (SD) | INTRABEAM (n = 25) | INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT (n = 16) | WB-EBRT (n = 46) | p-value |

| Global health statusb | 63.6 (24.2) | 60.9 (19.9) | 52.4 (22.1) | > 0.01 |

| Restrictions in daily activitiesb | 78.7 (35.2) | NR | 60.5 (29.5) | 0.007d |

| General painc,e | 21.3 (95% CI NRf to 54.4) | 43.7 (95% CI 11.6 to 75.9) | 40.9 (95% CI 8.6 to 73.2) | 0.007d 0.018g |

| Breast symptomsc,e | 7.2 (95% CI NRf to 20.9) | 29.7 (95% CI 6.8 to 52.5) | 19.0 (95% CI NRf to 39.2) | 0.001d < 0.001g 0.021h |

| Arm symptomsc,e | 15.2 (95% CI NRf to 37.2) | 32.6 (95% CI 6.8 to 58.4) | 32.8 (95% CI 4.2 to 61.5) | 0.009d 0.011f |

| As-treated analysis, frequency breast/arm symptomsi | INTRABEAM (n = 25), % moderate/severe | INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT (n = 16), % moderate/severe | WB-EBRT (n = 46), % moderate/severe | p-value |

| Pain in area of affected breast | 4/0 | 25/13 | 11/4 | > 0.01 |

| Swelling in area of affected breast | 0/0 | 7/7 | 4/2 | |

| Oversensitivity in area of affected breast | 4/0 | 20/7 | 9/7 | |

| Skin problems on or in area of affected breast | 4/4 | 13/6 | 9/4 | |

| Pain in arm or shoulder | 8/8 | 33/20 | 18/23 | > 0.01 |

| Swelling in arm or hand | 8/4 | 6/6 | 9/7 | |

| Difficulty in raising or moving arm sideways | 20/0 | 13/7 | 24/12 | > 0.01 |

Summary of clinical effectiveness

-

One RCT64,65 met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review. It evaluated IORT using the INTRABEAM device compared with conventional WB-EBRT. In addition to the main trial,64,65 one substudy reported on participants from an individual trial centre for the outcome of QoL. 63 Other publications from TARGIT-A were not included.

-

The RCT was a non-inferiority trial that sought to determine whether or not INTRABEAM treatment was no worse than WB-EBRT. The pre-stated non-inferiority margin was an absolute difference of 2.5% in the primary end point (local recurrence) between groups. However, the choice of non-inferiority margin was based on an estimated 5-year LRR of 6%, but since then trial recurrence rates have reduced.

-

The RCT had two randomisation strata. Participants in the pre-pathology stratum were randomised to INTRABEAM or WB-EBRT prior to surgery to remove the tumour. Any participants in the INTRABEAM arm who were subsequently found to have unfavourable pathological features received WB-EBRT in addition (i.e. INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT). Participants in the post-pathology stratum received surgery to remove the tumour and were entered into the trial providing initial histopathology showed no adverse criteria. Participants in the INTRABEAM arm found to have unfavourable pathological features on final histopathology received INTRABEAM + WB-EBRT.

-

The quality of the RCT was judged to be good with a low risk of bias.

-

Local recurrence in the conserved breast was the primary outcome of the RCT, with the pre-stated non-inferiority margin being an absolute difference of 2.5% between groups. Overall survival was a secondary outcome. The median follow-up was 2 years 5 months, with 2020 (59%) of the total study population reaching a median follow-up of 4 years and 1222 (35%) reaching a median follow-up of 5 years. Results were presented for the whole trial population, the pre-pathology stratum and the post-pathology stratum.

Whole trial population

-

Local recurrence for the whole trial population was higher in the INTRABEAM group, but the absolute difference in 5-year risk of local recurrence did not exceed the 2.5% non-inferiority margin. Analysis of the non-inferiority statistic for local recurrence indicated that INTRABEAM was non-inferior to WB-EBRT.

-

The difference in overall survival for the whole trial population between women who received INTRABEAM and those who received WB-EBRT was not statistically significant. Analysis of breast cancer and non-breast cancer deaths showed that rates of breast cancer death were similar between the two treatments but there were significantly fewer non-breast cancer deaths in the INTRABEAM group than in the WB-EBRT group.

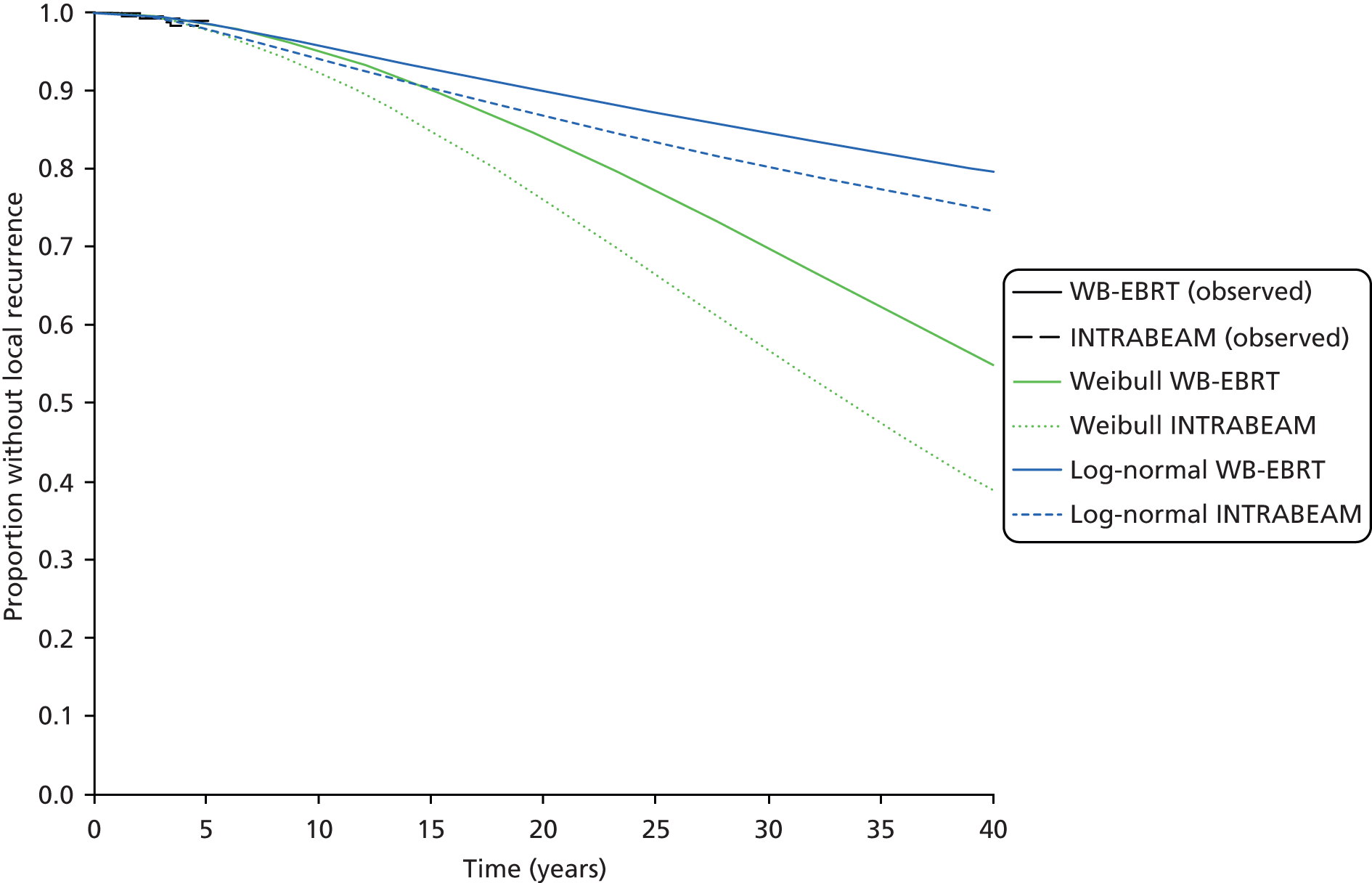

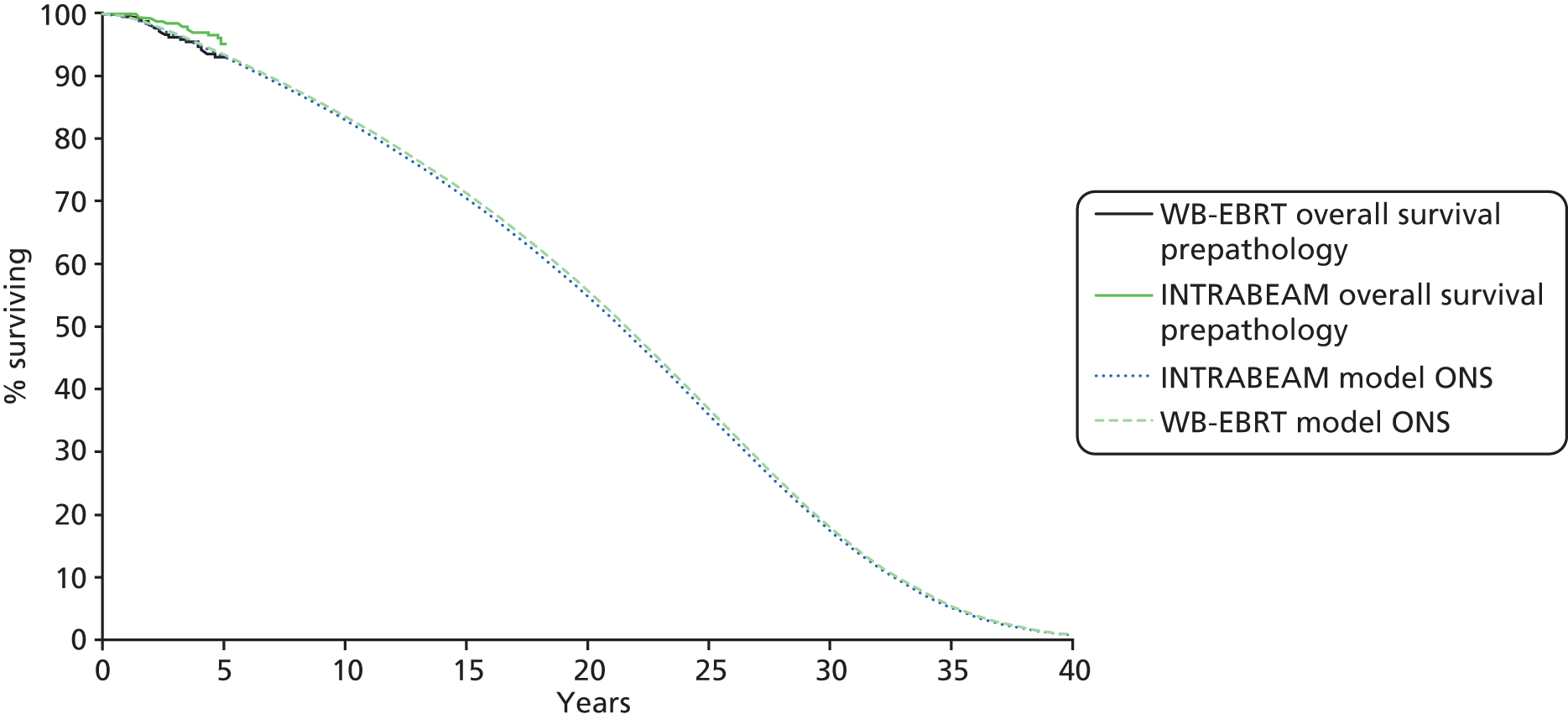

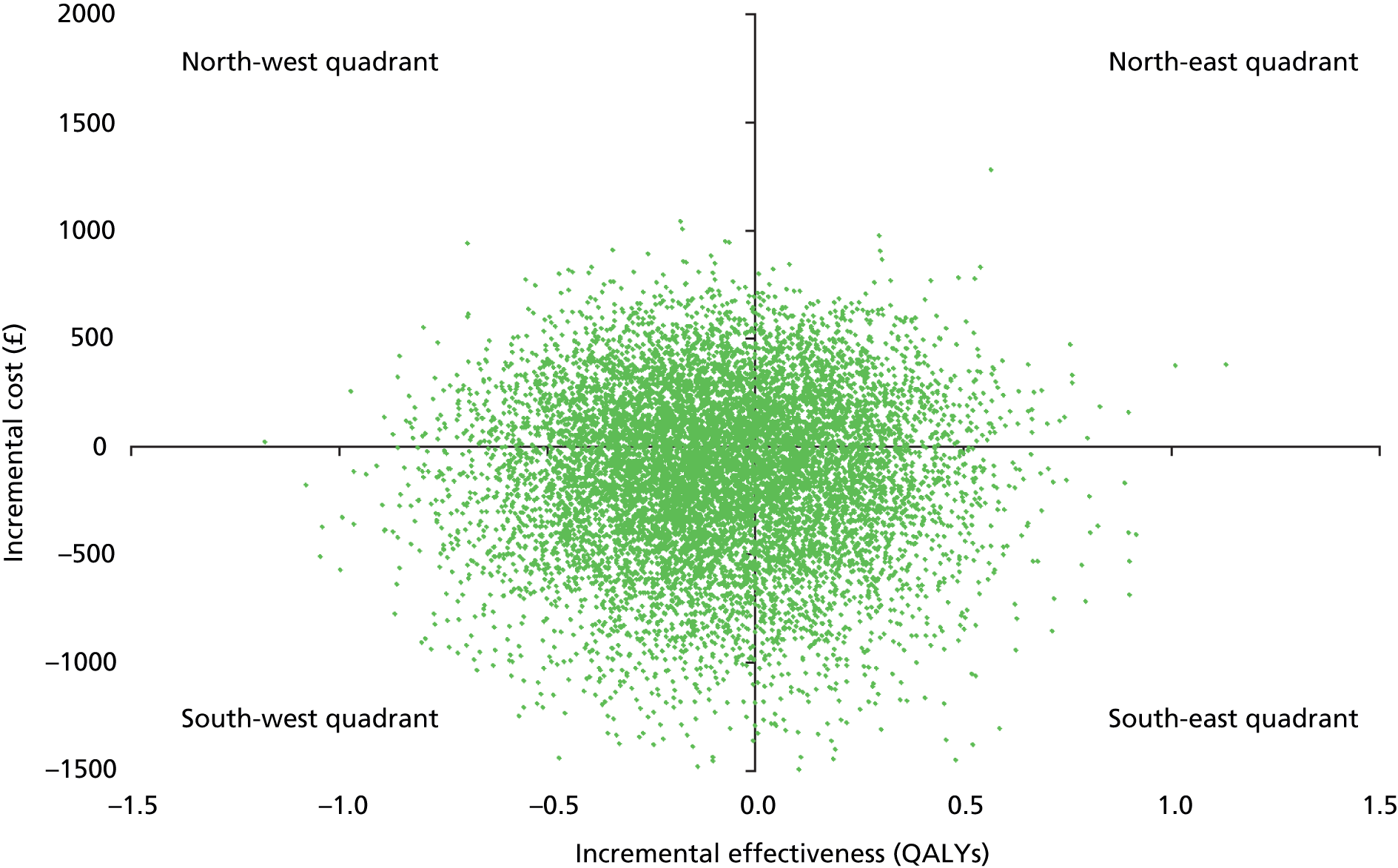

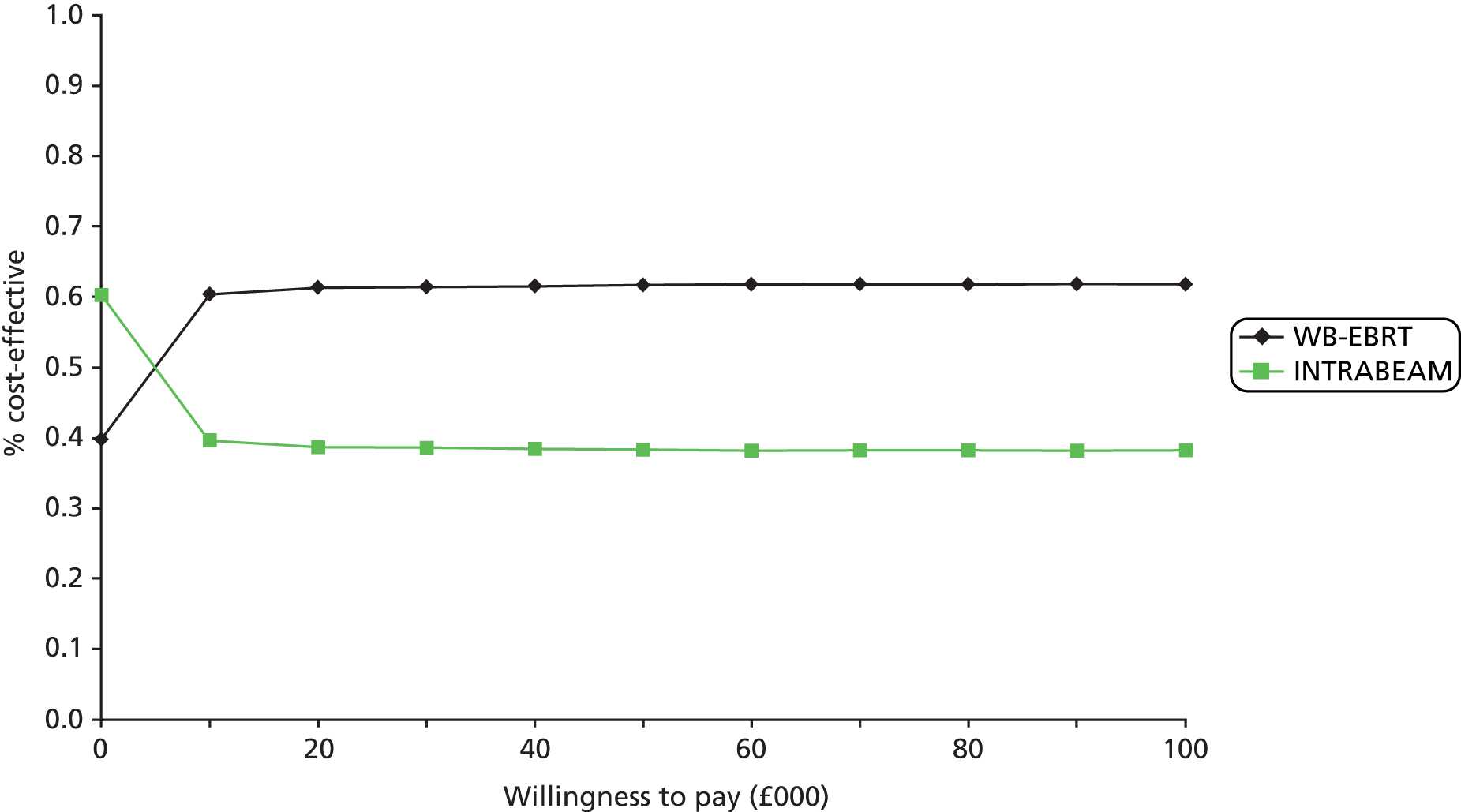

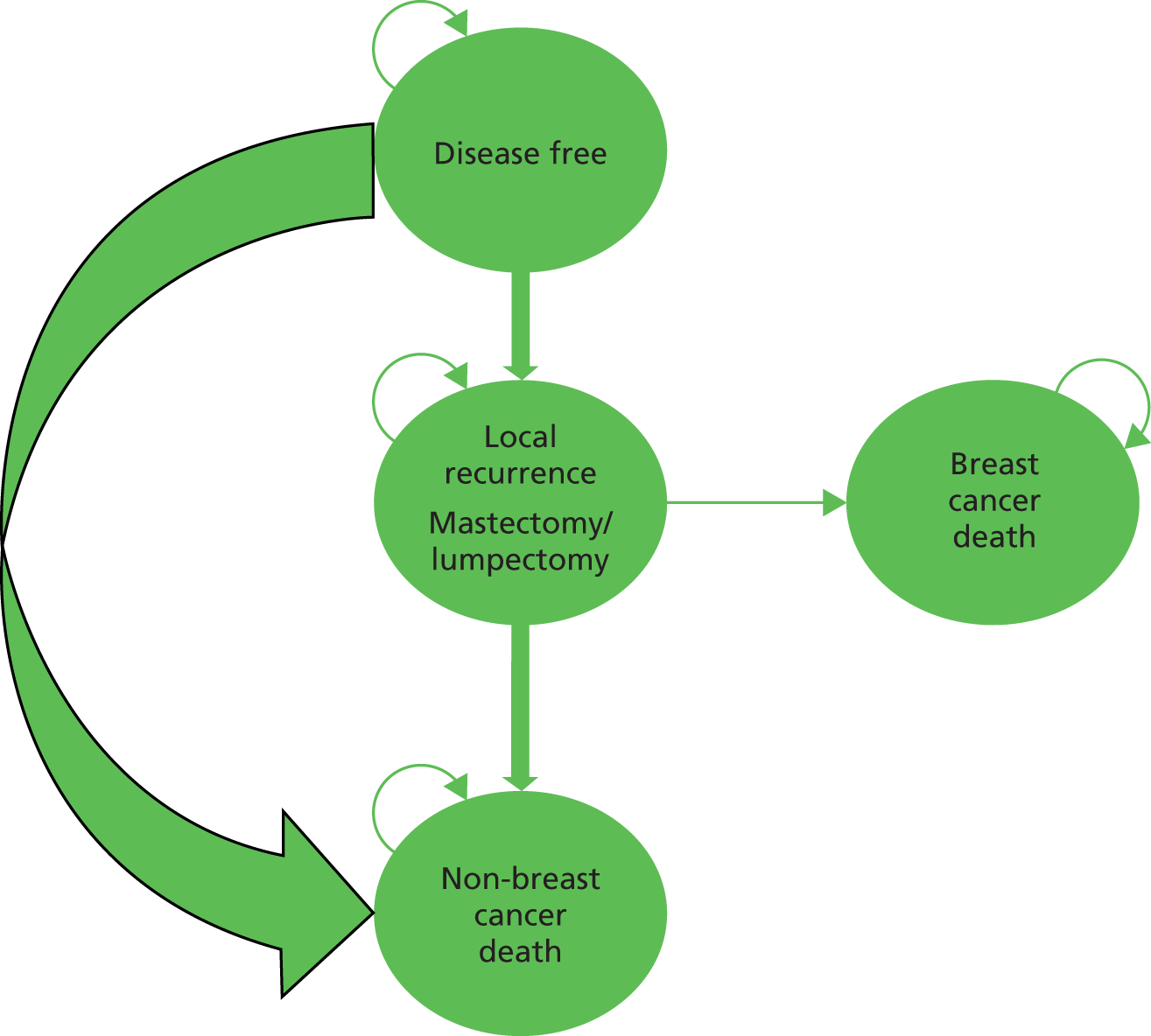

-