Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/16. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Barbara Gregson and A David Mendelow received a grant from the Medical Research Council and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme to undertake Surgical Trial In spontaneous lobar intraCerebral Haemorrhage (STICH II). A David Mendelow also reports grants from Newcastle Neurosurgery Foundation Ltd for sponsorship of meetings outwith this study and personal fees from Stryker Ltd for consultancy work. Elaine McColl is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library Editorial Group, but had no role in editorial decisions concerning this publication. Newcastle University is reimbursed for the time devoted to editorial work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Gregson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Much of this text is reproduced from Gregson BA, Rowan EN, Mitchell PM, Unterberg A, McColl EM, Chambers IR, et al. Surgical trial in traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (STITCH(Trauma)): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:193. © 2012 Gregson et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

In the UK there are 1.4 million presentations of head injury at emergency departments each year. 1 The mortality rate for severe isolated traumatic brain injury varies between 16% and 40%. 2 More than 150,000 of those who present to emergency departments with head injury are admitted to hospital each year. Of these, about 20,000 injuries are serious. One year after a serious head injury, 35% of patients are dead or severely disabled. Intracranial haemorrhage occurs in more than 60% of serious head injuries in one or more of three types: extradural haematomas (EDH), subdural haematomas (SDH) and intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). Prompt surgical removal of significant SDH and EDH is of established and widely accepted value. Intraparenchymal haemorrhage is more common than both the other types put together and is found in more than 40% of severe head injuries. It is clearly associated with a worse outcome, but the role of surgical removal of the clot remains undefined. Several terms are used to describe the condition, including traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage (TICH), traumatic intraparenchymal haemorrhage and contusion. Prospectively collected data in over 7000 head-injured patients in Newcastle upon Tyne showed that contusions are more common in older head-injured patients and occurred in patients with less severe injury.

Surgical practice in the treatment of TICH differs widely. Several issues inform the debate:

-

Contused brain does not recover but appears as encephalomalacic brain tissue loss on convalescent phase imaging. This suggests that removing TICH does not increase tissue loss.

-

Extravasated blood is believed to be neurotoxic, leading to secondary injury that may be avoided by surgical removal.

-

Larger TICHs may be associated with an ischaemic penumbra of brain tissue that could be salvaged.

-

Some TICHs expand to the point at which they cause mass effect with high intracranial pressure (ICP), resulting in secondary brain injury.

The aim of early surgical TICH removal is to prevent secondary brain injury from these mechanisms. A detailed description of the pathophysiology of ICH was published in 1993. 3 This information translated into the initial hypothesis that led to the Surgical Trial In spontaneous intraCerebral Haemorrhage (STICH), which began in 1993. 4 This was the justification for a trial of surgical intervention. However, use of the operation varies around the world. It is more frequently done in the Far East than in Europe or the USA.

Traditional neurosurgical care of patients with severe head injury is frequently based on ICP measurement. Patients with high ICP (> 30 mmHg) and TICH would undergo craniotomy and those with low ICP (< 20 mmHg) would be managed conservatively. Patients with ICP between 20 and 30 mmHg would be observed with ongoing ICP monitoring and undergo craniotomy if the ICP rises. 5 This ICP-based approach has been recommended by the Brain Trauma Foundation6 but its authority has recently been challenged in the Trial of Intracranial Pressure Monitoring in Traumatic Brain Injury (BEST TRIP) published by Chesnut et al. 7 from Latin America. In the light of this controversy, the early management of patients with TICH needs evaluation to determine if Early Surgery should become part of the standard of care in the same way it is for significant EDH8 and SDH. 9

There have been trials of surgery for spontaneous ICH (SICH),4,10 but none so far of surgery for TICH. The Cochrane Review (2nd edition) has shown benefit from surgical evacuation for SICH. 11 There are differences in the pathogenesis, clinical behaviour and outcome of the two conditions (SICH and TICH). 12 Patients suffering a TICH tend to be younger, by about 15 years on average, than patients suffering SICH and, therefore, the level of disability may have a larger effect on their ability to return to work and their economic output. TICHs are more likely to be lobar, to be superficial and to have a medium-sized volume (25–65 cc). These differences between the conditions mean that we cannot derive the role of surgery for TICH from results of the 15 published trials of surgery for spontaneous ICH; however, the STICH trials4,10 showed a trend towards better outcome with surgery for the group of spontaneous supratentorial ICH that are most like TICH: superficial haematomas with no intraventricular bleed.

We already know that surgery is effective in patients with traumatic EDH and SDH and that Early Surgery produces more favourable outcomes than delayed surgery. This is not known for TICH. If Early Surgery is of benefit to these patients, then implementation of early referral and diagnosis with immediate treatment may reduce death and disability in this specific group of head-injured patients.

Several authors13–15 have compared surgery with conservative treatment in single-centre retrospective series and recommended surgery for larger TICHs even if patients were in an apparently good clinical state initially. Matheisen et al. 13 found that patients with an admission Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of at least 6 and a lesion volume of at least 20 ml who had surgery without previous neurological deterioration had significantly better outcomes than those who did not have surgery or had surgery after deterioration. None of the patients who had surgery before any deterioration died or was vegetative, as opposed to 39% of those who had surgery after deterioration and 50% of those who did not have surgery. Choksey et al. 14 found that 38% of patients with a low GCS and a volume of the TICH > 16 ml who had surgery had a poor outcome, compared with 56% of those who did not have surgery. Zumkeller et al. 15 found that the poor-outcome rate in the operated patients was 29%, compared with 59% in the non-operated group.

Boto et al. 16 evaluated the characteristics of severely head-injured patients with basal ganglia TICHs and found that the TICH tended to enlarge in the acute post-traumatic period. They found that patients with a TICH of > 25 ml and those in whom TICH enlargement or raised ICP had occurred had the worst outcomes. They suggested that these patients might benefit from more aggressive surgical treatment.

D’Avella et al. 17 published a series and suggested that non-comatose patients with smaller TICHs may be treated conservatively but that surgery is indicated for patients with larger TICHs. Most of their comatose patients who were severely injured had a poor outcome whatever treatment was used.

None of these studies involved randomisation into surgical and non-surgical groups. They also differed in the characteristics of the parenchymal blood. Such uncontrolled observational studies may be potentially misleading and a randomised controlled trial was needed.

Guidelines for the surgical management of traumatic brain injury were published in 2006. 18 These confirmed that studies in this area have been observational and that there is a lack of evidence from well-designed randomised controlled trials. Those studies that attempt to compare outcome between surgical and non-surgical groups cannot adequately control for known prognostic variables.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended in the Clinical Guidelines CG56 Head Injury: Triage, Assessment, Investigation and Early Management of Head Injury in Infants, Children and Adults19 that research is needed to develop a consensus on criteria for lesions not currently considered to be surgically significant, namely TICH. This trial, Surgical Trial in Traumatic intraCerebral Haemorrhage [STITCH(TRAUMA)], was recommended by that NICE Head Injury Guideline Development Group.

Chapter 2 Methods

Much of this text is reproduced from Gregson BA, Rowan EN, Mitchell PM, Unterberg A, McColl EM, Chambers IR, et al. Surgical trial in traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (STITCH(Trauma)): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:193. © 2012 Gregson et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Trial objectives

The principal aim of the trial was to determine whether or not a policy of Early Surgery in patients with TICH improves outcome compared with a policy of Initial Conservative Treatment.

In addition, we wanted to assess the relative costs and consequences of Early Surgery versus Initial Conservative Treatment in UK patients and those in a subgroup of countries covering the likely highest-recruiting centres. (Following the trial being halted by the funding agency this objective was changed and reference to a UK-specific analysis removed.)

Finally, we hoped to confirm appropriate thresholds for ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) for clinical management in the subgroup of head-injured patients with TICH who undergo such monitoring. (Following the trial being halted by the funding agency this objective was changed to: to investigate the use of ICP monitoring for clinical management of head-injured patients with TICH and its effect on treatment decisions.)

Trial design

STITCH(TRAUMA) was an international, multicentre, pragmatic, patient-randomised, parallel-group trial comparing early surgical evacuation of TICH with Initial Conservative Treatment. Only patients for whom the treating neurosurgeon was in equipoise about the benefits of early surgical evacuation compared with Initial Conservative Treatment were eligible for the trial. An independent 24-hour telephone randomisation service based in the Aberdeen Clinical Trials Unit was used and backed by 24-hour availability of trial investigators who could advise on patient eligibility. Minimisation with a random component was used to ensure that the two groups were balanced within country, age and severity. Outcome was measured at 6 and 12 months via a postal questionnaire using the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE).

Additional data were collected in those centres that practised invasive brain monitoring to see if there was evidence that such monitoring techniques added value to clinical decision-making. The aim was to obtain an unbiased assessment of the effect of clot removal or not on ICP/CPP and to evaluate if monitoring ICP/CPP provided additional information that informed improved clinical management (the third objective). Such monitoring was not mandatory for a patient to be enrolled in the trial.

It was planned that relevant health-care costs be assessed in the UK, including length of hospital stay and the costs associated with surgical treatment (theatre time, consumables, overheads); health-care resource use outside hospital (e.g. district nurse, physiotherapy) together with productivity costs arising from absence from work; and additional costs for family members through extra caring responsibilities. Consequences were to be measured by combining data on quality of life, measured using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), with survival to generate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Existing questionnaires were adapted for use with TICH patients where appropriate, and they formed an additional 3-month postal questionnaire and part of the 6-month and 12-month postal questionnaires for patients.

The trial protocol was published in Trials. 20

Pilot study

An internal pilot phase21 was conducted with criteria for stopping the trial early if the recruitment of centres and/or patients was slower than projected or if unexpected difficulties arose in signing up collaborating centres.

The target was not fewer than 12 centres signed up at the end of year 1. If this target was met, then the pilot was to continue until a second point when the trial had a total of 12 recruiting centre-years. If at this point the average recruitment rate was less than 2 per centre-year, the trial was to be terminated.

Screening logs

Screening logs were to be maintained by each centre to record the patients admitted to the neurosurgical unit with any traumatic ICH; whether or not they were eligible for the trial and whether or not they were recruited (and, if not, why not, if the reason could be ascertained). These were to be used to provide a context for the study, to monitor recruitment rates and as the basis for constructing the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for reporting the trial.

Centre recruitment

Suitable centres were recruited from those already collaborating successfully with the team in other studies [STICH, Surgical Trial In spontaneous lobar intraCerebral Haemorrhage (STICH II), RESCUEicp] plus those identified by the various networks: TARN (Trauma Audit and Research Network), EBIC (European Brain Injury Consortium) and EMN (Euroacademia Multidisciplinaria Neurotraumatologica), BrainIT, EANS (European Association of Neurosurgical Societies), GNAMED (Glasgow, Newcastle, Aberdeen, Middlesbrough, Edinburgh, Dundee; Scottish and Newcastle Neurosurgery Research Group), SBNS (Society of British Neurological Surgeons), BNRG (British Neurosurgery Research Group), ICRAN (International Conference on Recent Advances in Neurotraumatology) and WFNS (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies) Neurotrauma Committee.

Centres were required to demonstrate effective trial experience and previous adherence to trial guidelines with high follow-up rates. In order to be eligible, centres should have been able to recruit a minimum of one patient per year. They had to be able to communicate with the research team. (At least one member of the local team had to be proficient in English and provide contact details where they could be reached easily to support the local centre and respond to the trial management team in Newcastle.) They had to be able to provide computed tomography (CT) images of sufficient quality to the study centre in Newcastle and be able to arrange follow-up for patients with limited literacy.

Each centre was required to obtain ethics approval and other permissions as needed to conform with local and national legislation and governance frameworks and to provide documentary evidence to the trial management team that these permissions were in place, prior to site registration and initiation. Each site was also required to sign an agreement with the sponsor (Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) and the contractor (Newcastle University). Applications by the lead collaborator in each centre for ethical approval (or Site-Specific Assessment in the UK) were supported by the trial manager and the clinical lead for the centre and country in which the centre was located. Also within the UK, research and development approval was sought in respect of all participating centres and the study was open to audit (‘for cause’ or as part of the routine 10% check) by the appropriate research governance teams in the participating Trusts. A member of the STITCH(TRAUMA) study team visited centres with high volume recruitment or where there were concerns about patient eligibility (identified by central monitoring) to confirm patient existence and monitor adherence to the trial protocol.

Multicentre Research Ethics Committee approval for the study was obtained from Southampton Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 09/H0502/68) on 15 June 2009 and the trial was registered (ISRCTN19321911).

Patient recruitment

To be considered for STITCH(TRAUMA), patients had to have had CT to confirm the diagnosis and the size and location of the haematoma. Any clotting or coagulation problems had to be corrected prior to randomisation in line with standard local clinical practice.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults aged 14 years or over.

-

Evidence of a TICH on CT with a confluent volume of attenuation significantly raised above that of the background white and grey matter that has a total volume greater than 10 ml calculated by (length × width × height)/2 in cm. 22

-

Within 24 hours of head injury. This criterion was later increased to 48 hours following discussion at an investigators’ meeting in order to increase the number of patients eligible, allowing more time for patients to reach the neurosurgery department and for the TICH to develop.

-

Clinical equipoise. Only patients for whom the responsible neurosurgeon was uncertain about the benefits of either treatment were eligible.

Exclusion criteria

-

A significant surface haematoma (EDH or SDH) requiring surgery. (The indications for intervention for these patients were already very well defined.)

-

Three or more separate haematomas fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

-

If surgery could not be performed within 12 hours of randomisation.

-

Severe pre-existing physical or mental disability or severe comorbidity which would lead to a poor outcome even if the patient made a full recovery from the head injury. (Examples would be a high level of dependence before the injury or severe irreversible associated injury such as complete spinal cord injury.)

-

Permanent residence outside a study country preventing follow-up.

-

Patient and/or relative having a strong preference for one treatment modality.

There was no specified upper age limit. The need for clinical equipoise and explicit exclusion of patients with severe pre-existing physical or mental disability or severe comorbidity which might lead to a poor outcome even if the patient made a good recovery from the head injury excluded the less able older patient while allowing a fit older person to be included. Haematoma rates were known to be more common in the older head-injured patient.

Recruitment was encouraged by quarterly glossy newsletters sent to each centre expressing interest, monthly e-mail newsletters to the site co-ordinators and investigators, regular attendance and presentations at national and international meetings, having stands at national and international meetings, sending an e-mail to the investigators and co-ordinators whenever a patient was recruited and awarding certificates to every surgeon who recruited a patient so that they would be able to demonstrate their involvement in clinical trials.

Consent procedure

Written witnessed informed consent of the patient or relative was obtained by trained neurosurgical staff prior to randomisation. The member of neurosurgical staff provided a written information sheet and allowed as much time as possible to discuss the options. One copy of the consent form was given to the patient, one was filed in the patient notes and one was filed with the trial documentation. If the patient was unable to give consent him- or herself because of the nature of the haemorrhage, a personal representative was approached to give consent on behalf of the patient. The personal representative was described as someone with a close personal relationship with the patient who was capable and willing to consent on behalf of the patient. (If the patient was unable to consent and the closest relative was not available the patient could not be included in the study. This study did not permit a professional legal representative to give consent because of the need to establish a relationship with potential carers to facilitate complete follow-up by postal questionnaire.)

Randomisation (treatment allocation)

Randomisation was achieved via the independent 24-hour randomisation service based in the Aberdeen Clinical Trials Unit either by telephone or by using the web-based version. The randomisation information was entered and at the end of the phone call or the web entry the neurosurgeon was informed of the patient identifier number for the trial and the treatment group the patient was allocated to. The neurosurgeon recorded this information on the randomisation form and then faxed the form to the STITCH(TRAUMA) office.

The data manager checked the form against the information received from the randomisation centre and entered the data into an anonymised password-protected database.

The 24-hour randomisation service was backed by 24-hour availability of the project team, who could advise on patient eligibility. If the site had problems contacting the randomisation service a member of the project team undertook the randomisation for them.

Allocation was stratified by geographic region, with a minimisation algorithm based on age group (< 50 years, 50 years to < 70 years, ≥ 70 years) and severity (as measured by whether the pupils are equal and reacting or not) and with a random component (i.e. with probability of 80%).

Trial interventions

The two trial interventions were early evacuation of the haematoma by a method of the surgeon’s choice (within 12 hours of randomisation), combined with appropriate best medical treatment versus best medical treatment combined with delayed (more than 12 hours after randomisation) evacuation if it became appropriate later. Both groups were monitored according to standard local neurosurgical practice.

Best medical treatment included (depending on the practices within the centre) monitoring of ICP or other modalities and management of metabolism, sodium osmotic pressure, temperature and blood gases.

All patients also had an additional CT at 5 days (± 2 days) to assess changes in the haematoma size with and without surgery.

Compliance

Patients or their relatives could withdraw consent for an operation, or, conversely, request an operation, after randomisation, thereby leading to crossover between the arms. In surgical trials it is common for the patient’s condition to change over time and a patient randomised to Initial Conservative Treatment might deteriorate and require surgery later. Such crossovers and the reasons for them were documented.

Information was collected about the status (GCS and focal signs) of patients through the first 5 days of their trial progress and ICP/CPP measures in invasively monitored patients in order to be able to describe the change in status that might lead to a change in equipoise for the treating neurosurgeon, and subsequent surgery in patients initially randomised to conservative treatment.

Compliance with treatment allocation was monitored by the data manager. In surgical trials, patients allocated to the non-surgical arm of the trial may later deteriorate and surgeons may intervene. This was the case in the Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded STICH4 and STICH II,10 in trials of cardiac surgery compared with angioplasty, in the MRC-funded back pain trial23 and in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). 24 These crossover rates to surgery were 26%, 21%, 28%, 28% and 30% respectively. While surgical trials will always have such crossovers when surgeons perceive that there is value in operating on patients who deteriorate after initial randomisation into the conservative limb of the trial, it is important to understand, monitor and report the rates of such crossovers. During the recruitment of centres and at investigator meetings the importance of clinical equipoise and minimising crossovers was emphasised and all crossovers were investigated. Centres exhibiting high crossover rates could be withdrawn from the study.

Data collection

To preserve confidentiality all patients were allocated a unique study identifier during the randomisation process, which was used on all data collection forms and questionnaires. Only a limited number of members of the research team were able to link this identifier to patient identifiable details; this was necessary in order to carry out centralised follow-up.

Baseline

Before randomisation, a one-page baseline form was completed by the responsible neurosurgeon recording demographic (age, gender) and clot characteristics [site, side, length (A), width (B) and height (C) measures to define volume] and status at randomisation (GCS, pupils equal and reacting or not). This information was required in order to randomise the patient.

Two week/discharge

At 2 weeks after randomisation or at discharge or death (whichever occurred first) the discharge/2-week form was completed. This form recorded the date, the event that triggered the form and the patient’s status at that time, whether or not the patient had had surgery and when (and why if randomised to Initial Conservative Treatment or why not if randomised to Early Surgery), the patient’s GCS and localising features for the 5 days following randomisation, the occurrence of any adverse events (including death, pulmonary embolism, deep-vein thrombosis, surgical site infection) following randomisation, past medical history and status prior to the head injury. This form, together with copies of the randomisation CT image and the 5-day post-randomisation CT image, was sent to the STITCH office within 2 weeks. The data manager entered the data into the anonymised password-protected database.

Computed tomography

Copies of two CT images were required: the diagnostic CT image prior to randomisation and a 5-day image. All patients had undergone a diagnostic CT imaging as standard practice. The 5-day image was due between 3 and 7 days after randomisation. Many patients received this as part of standard treatment and the study accepted and used any CT taken for clinical purposes during this period. Only patients who did not receive such a CT during this period required additional imaging.

The preferred scanning technique was CT with volume acquisition 32 × 0.5 mm (or equivalent), 120 kV, 400 mA (or equivalent) and 220 mm field of view. The preferred angle was parallel with the anterior cranial fossa, coverage from base of skull to vertex, reconstruct 5 mm whole head, soft tissue filter.

The preferred method of sending CT images was in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine)-compatible format, on separate CDs for the two time points, anonymised by use of a patient identifier. They were checked by the data manager initially on receipt at the STITCH(TRAUMA) office to ensure that the haematoma characteristics at randomisation conformed to the required inclusion criteria. Where protocol deviations were suspected, the data manager arranged for the image to be viewed by a trained reader to check whether or not the centre needed to be contacted immediately to prevent repetitions.

The data manager loaded the images into a specialised password-protected image management program. They were allocated a separate randomly created identifier by the data manager, so that it would not be possible for the reader to identify the before-and-after images of the same patient. A separate list identifying patient identifier and scan identifier was kept by the data manager.

The CT images were to be analysed subsequently by trained readers using the image management program and a defined protocol. Their passwords gave access only to scans blinded to treatment group and patient identity.

Follow-up

Postal questionnaires had previously been designed for the STICH4 and STICH II10 studies and were translated into most of the languages required. Where new countries with different languages were recruited, the National Investigator was asked to arrange translation and another principal investigator from the country was asked to check the translation. Postal follow-up was due at 6 months and 12 months. The patient’s general practitioner (in the UK) or consultant (outside the UK) was contacted at 4.5 months and 10 months to check that the patient was alive and to confirm his/her place of residence. At that time the clinician was also requested to complete a major adverse events form to include death, pulmonary embolism, deep-vein thrombosis, stroke or any other serious adverse event. The 6-month outcome questionnaire was mailed to the patient at 5 months for completion by the patient or relative if the patient was unable to complete it him- or herself. If necessary, a reminder was sent at 6 months and telephone follow-up was carried out by ‘blinded’ clerical or nursing staff at 7 months to enhance response rates. Similarly, the 12-month questionnaire was mailed at 11 months with reminders at 12 and 13 months. In countries where the postal system was poor, patients were requested to attend a follow-up clinic at which the questionnaire was distributed and collected. In countries where literacy or language/dialect was a problem, a ‘blinded’ interviewer administered the questionnaire. This methodology had been developed for use and applied to good effect in STICH and STICH II.

Costs

The costs associated with surgical treatment (theatre time, consumables, overheads) were collected from published resources and local cost surveys undertaken by the study health economist. Length of stay, health-care resource use outside hospital, together with productivity costs arising from absence from work, and additional costs for family members through extra caring responsibilities were collected using the additional 3-month postal questionnaire and extended 6-month and 12-month postal questionnaires in the UK. Data were to be combined on quality of life with survival to generate QALYs. This included measurement of health-care costs, quality of life [EQ-5D-3 level (EQ-5D-3L)] work absence [World Health Organization (WHO) Health and Performance Questionnaire – Clinical Trial Version] and carer activities (measured by the discrete choice experiment developed by the Health Economics Research Unit). EQ-5D-3L and survival were collected for all patients by the postal outcome questionnaires in order to generate QALYS for the whole study and for a UK-only analysis.

Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events were recorded on the Major Adverse Events form. Serious adverse events were defined as an adverse experience that resulted in any of the following outcomes:

-

death

-

life-threatening

-

inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

persistent or significant disability or incapacity.

All serious adverse events were to be reported to the STITCH Office within 7 days of the local investigator becoming aware of the event and to the local ethics committee or other regulatory bodies as required.

Outcome measures

-

Primary: unfavourable outcome was defined as death or severe disability on the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), which was recorded using a self-completed structured questionnaire based on the 8-point GOS. 25

-

Secondary: Rankin, EQ-5D-3L, Mortality, Survival, Major Adverse Events (death, pulmonary embolism or deep-vein thrombosis, infection, rebleeding), QALYs, total health-care costs, social costs.

Structured postal questionnaires were used to collect follow-up data. They contained the GOSE, Rankin Scale and EQ-5D-3L and were translated into the necessary languages. GOSE and Rankin Scale had been translated by a national investigator for a previous study and were back-translated to check them. EQ-5D-3L was obtained in the necessary validated translated versions.

The GOS is the specific measure for head injury and the 8-point scale provides more sensitivity than the 5-point scale. Initially the plan had been to use a prognosis-based26,27 outcome measure such that for patients with a very poor prognosis an outcome of good recovery, moderate disability or upper severe disability would be regarded as a favourable outcome, while for patients with a better prognosis a favourable outcome would be good recovery or moderate disability. Following the withdrawal of funding, the analysis plan was altered to a simple dichotomised split for all patients. The Rankin Scale is widely used as a functional outcome measure in stroke and allows comparison of results between this study of patients with traumatic ICH and studies of patients with spontaneous ICH. EQ-5D-3L is the standard measure of quality of life incorporating a utility value and has been developed in many languages.

Sample size

Previous studies had suggested a favourable outcome in the non-operated group of about 40% and a favourable outcome in the surgical group of about 60–70%. However, this was in observational studies. Given that many randomised controlled trials observe a more favourable outcome than seen in observational data it was assumed that the favourable outcome (good recovery or moderate disability on the GOS) in the conservative treatment group would be 50% in order to calculate sample size. A total sample size of 776 would therefore be required to show a 10% benefit (i.e. 50% vs. 60%) from surgery (2p < 0.05) with 80% power. A safety margin of 9.5% was built in to allow for loss to follow-up, making a total sample size of 840 to be recruited and randomised (420 per arm).

In order to achieve this sample size in a reasonable time span and to provide robust evidence, it was necessary to recruit patients from outside the UK. In England and Wales there are only 30 neurosurgical units, and only one-third of these participate in randomised controlled trials. Experience with interested neurosurgical centres in previous studies had shown that about 25% of recruited centres fail to recruit any patients and a further 25% only recruit one or two patients. The best recruiting centres will recruit about 10 patients per year; therefore, to complete patient recruitment within the time scale, we estimated that we would need to approach at least 150 centres.

Loss to follow-up was reduced as much as possible. In the previous STICH study, the loss was about 5%. In STITCH(TRAUMA), the patient population was younger and likely to be more mobile; however, we implemented procedures that we had developed to minimise loss to follow-up. Methods of follow-up were adapted to those most likely to be successful within each country and centre according to local population and care characteristics. Residence in any study country was an eligibility criterion so patients who suffered a head injury while on holiday would be able to be followed up.

Following the decision by the funding agency to halt the trial, the power of the trial was recalculated. Using the uncorrected chi-squared test and assuming equal sample sizes in the two groups, and given an average favourable outcome of 60% (as observed after the recruitment and follow-up of 96 patients), there would be 26.4% power to detect a 10% difference. The achieved sample size of 170 gave 80% power to detect a 21% difference.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind either patients or treating surgeons to whether or not the patient had surgery or when. To minimise possible sources of bias, randomisation was undertaken centrally, thus ensuring concealment of allocation from the enrolling clinician, patient and relatives. The multidisciplinary team in the co-ordinating centre and the principal investigators were blinded to the results until after the data set was locked following receipt of the final outcome questionnaire. Only the data manager and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) had access to unblinded data.

Statistical analysis

Initially the primary analysis was planned to be a simple categorical frequency comparison using the uncorrected chi-squared test for prognosis-based26,27 favourable and unfavourable outcomes at 6 months. Patients with a good prognosis would be categorised as having a favourable outcome if they achieved good recovery or moderate disability on the GOS. Patients with a poor prognosis would be categorised as having a favourable outcome if they achieved good recovery, moderate disability or upper severe disability on the GOSE. Secondary outcomes were also to be analysed using the prognosis-based method as specified in STICH. 28

However, STITCH(TRAUMA) was halted early by the funding agency for failure to recruit in the UK. The achieved sample size, at the point when recruitment was halted on instruction from the funding agency, was 170 patients, with 4% from the UK. The analysis plan was, therefore, adapted from the original analysis statement published in the protocol20 in the light of this much reduced sample size. The new plan was developed and published on the study website without access to treatment allocation prior to unblinding the data.

Primary outcome

Analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis. The primary analysis was a simple categorical frequency comparison using the uncorrected chi-squared test for favourable and unfavourable outcomes at 6 months. Patients were categorised as having a favourable outcome if they achieved good recovery or moderate disability on the GOS. Patients were categorised as having an unfavourable outcome if they had severe disability on the GOS, were vegetative or had died. A sensitivity analysis using logistic regression was undertaken to adjust for age, volume of haematoma and GCS.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome analyses included the proportional odds model analysis of GOS, GOSE and Rankin Scale scores at 6 months, Kaplan–Meier survival curve with log-rank test, mortality at 6 months and dichotomised Rankin Scale score (0–2, 3–6) at 6 months (comparing patients able to look after their own affairs with patients who need help). For dichotomised outcomes, absolute differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Secondary outcomes were also collected at 12 months but were not required by the funding agency.

Subgroup analysis

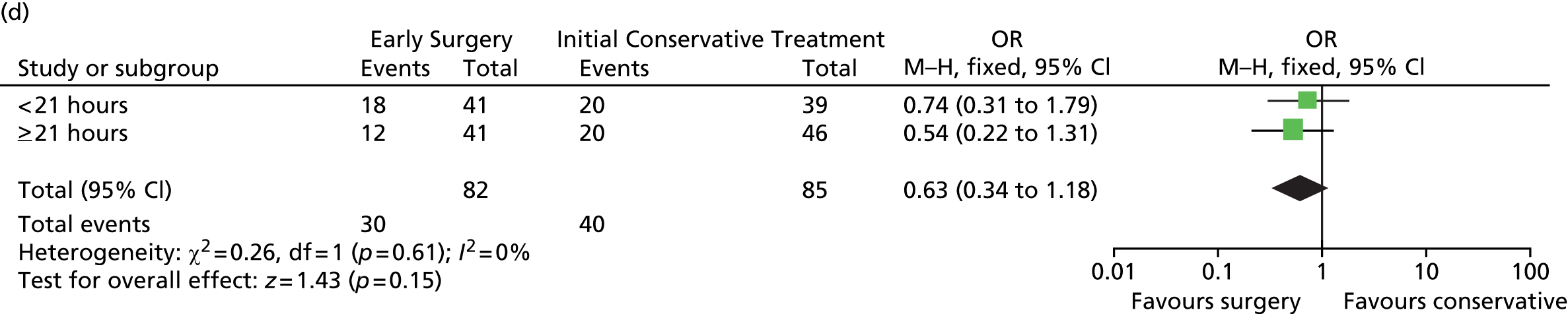

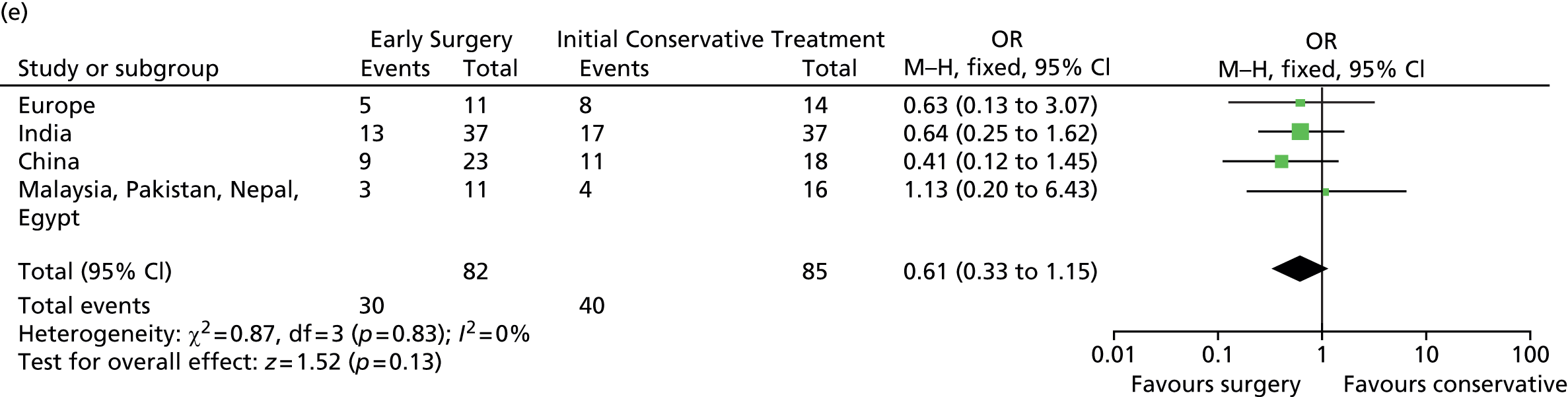

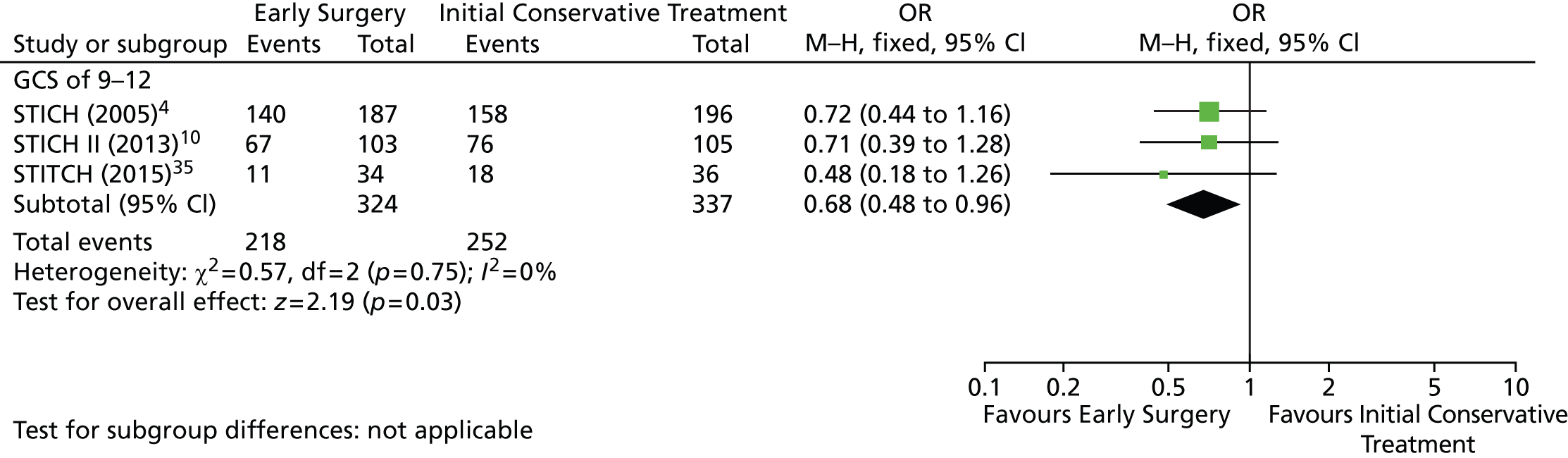

Minimal subgroup analysis was undertaken and regarded as exploratory. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were reported for the following subgroups: age (two bands using randomisation strata: < 50 years and ≥ 50 years – there were very few patients aged over 70 years so the two upper age bands were combined), volume of haematoma (using median split: ≤ 23 ml, > 23 ml), GCS (using standard classification of head injury severe, moderate, minor: 3–8, 9–12, 13–15), time from ictus to randomisation (using median split < 21 hours, ≥ 21 hours) and geographical region (four bands: Europe, India, China, other). Interaction tests (chi-squared test for heterogeneity) were undertaken and relevant p-values reported.

Protocol violations

There were two cases of major protocol violation in that the treatment decision was taken prior to randomisation. One patient randomised to surgery had already had a decision made for no surgery to take place and one case randomised to Initial Conservative Treatment had already had surgery. These two cases will be excluded from all analyses.

Health economics analysis

A cost–utility analysis was conducted from a health service perspective and based on an intention-to-treat principle.

Health-care resource use data were sourced from individual case report forms and participant questionnaires and supplemented using additional questionnaires administered to a sample of trial recruiting centres. Standard unit cost estimates were applied to resource use data for intervention delivery, hospital length of stay and rehospitalisation. Where standard unit costs were not available, supplemental information was collected from the additional questionnaire (e.g. cost of an hour of a surgeon’s time) and WHO choice data for the cost per night in hospital. Intervention and follow-up costs were summed to generate total costs to the health services for each individual within the trial. Costing followed recommended procedures for international studies29,30 and costs were transformed into 2013 international dollars. 31 Standard general linear regression methods were used to estimate the impact of treatment group (conservative or Early Surgery) on costs. Estimates were calculated for all countries as well as country subgroups classified according World Bank classifications32 based on gross national income (GNI) per capita as follows: low income (GNI ≤ Int$1005, e.g. Nepal), lower middle income (GNI Int$1006–3975, e.g. India), upper middle income (GNI Int$3976–12,275, e.g. China), and high income (GNI ≥ Int$12,276, e.g. Western Europe, USA). Owing to small sample sizes, regression analyses were not undertaken.

Reporting statistics

For categorical variables, the number and percentage in each group are reported. Percentages are reported to no decimal places. For continuous variables, the median, quartiles, maximum and minimum are reported. Where p-values are reported, these are given to three decimal places or to one significant figure if four decimal places are required and then < 0.0001 if smaller still. The absence of data is reported. Outcomes are reported as ORs with 95% CIs and to two decimal places and p-values to three decimal places. Absolute benefits with 95% CIs to one decimal place are also reported.

Research governance

To conform with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care, the role of sponsor for this study was taken on by the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust. All study-attached staff were appropriately qualified and trained in Good Clinical Practice appropriate to their role in the study.

Trial Steering Committee

Independent oversight of the study was provided by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The TSC met at 6-monthly intervals during the study. It provided overall supervision of the trial on behalf of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. It considered progress of the trial (in particular, success in site and patient recruitment), adherence to the protocol, patient safety and consideration of new information. The trial was conducted according to the standards set out in the MRC Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Data Monitoring Committee

In order to monitor accumulating data on patient safety and treatment benefit, a DMC was established. The DMC considered data from interim analyses after 50, 100 and 150 patients had been recruited. It reported to the TSC. Interim analyses were strictly confidential and the committee would recommend stopping the trial early only if one or other treatment showed an advantage at a very high significance level or if the recruitment rates were unexpectedly low. The DMC recommended at each review that the trial should continue.

Management committee

This group met weekly to monitor progress and compliance. On a quarterly basis, funnel plots showing the proportion of patients who had died by the number recruited per site and the proportion of crossovers were reported to the group.

National Investigators

In countries with multiple centres, one centre investigator was required to fulfil the role of National Investigator and be responsible for obtaining national ethics approval and other permissions as required, for ensuring that documentation was translated from English as required, for identifying suitable centres within their country, for encouraging recruitment and for acting as a liaison person between the management team and the centres if required.

Centre investigators

Each centre had a centre investigator responsible for the conduct of the trial in that centre.

Patient and public involvement

There are two main charities involved with head injury research in the UK: Headway and UK Acquired Brain Injury Forum. Both organisations were invited to propose representatives to sit on the TSC. These representatives supported the study, providing advice on all aspects of the trial including design of the questionnaires, changes in the protocol and recruitment to the study.

Chapter 3 Results

Timelines

Funding was activated on 1 September 2009 and the first site opened to recruitment on 1 October 2009. The first patient was recruited in December 2009. In March 2012, the HTA programme announced that it would be withdrawing funding because of the low UK recruitment. It felt that the study was not viable in the UK and that there was no realistic chance of that changing in the near future. It did agree to a managed process of withdrawal, particularly for non-UK centres, to enable the project team to investigate the possibility of support from another funder in order to continue the trial and to fulfil the ethical responsibility for follow-up of current study participants and maximise data available for future meta-analyses. Despite considerable efforts to identify further funding both in the UK and abroad, the project team were unsuccessful in achieving this in the short time available and the final patient was recruited by 30 September 2012.

Centre recruitment

Interest in the study was expressed by 139 centres, and 59 of these completed all the regulatory requirements to become registered centres. The registered centres were located in 20 countries: the UK (n = 9), Armenia (n = 1), Bulgaria (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), the People’s Republic of China (n = 3), the Czech Republic (n = 1), Egypt (n = 2), Germany (n = 6), Hungary (n = 1), India (n = 14), Italy (n = 1), Latvia (n = 1), Lithuania (n = 2), Malaysia (n = 2), Nepal (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Romania (n = 3), Russia (n = 1), Spain (n = 2) and the USA (n = 6). A further 13 centres had obtained ethical approval but were unable to complete the regulatory processes prior to the study being halted. Figure 1 shows the accumulation of centres through the trial. Regulatory processes are difficult and time-consuming and the difficulties in recruiting centres to surgical trials have been reported previously. 33 The times to recruitment for individual centres are shown in Figure 2 and the variability within countries in Figure 3.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment of centres over time.

FIGURE 2.

Time to achieve regulatory approval.

FIGURE 3.

Time to approval by country.

Screening logs

Screening logs were returned by 32 centres from 15 countries, covering 251 centre-months out of a potential 1028 centre-months. The logs reported 1735 patients screened, of whom 1542 were reported to be ineligible, 134 eligible but not included and 59 recruited. The main reasons for ineligibility were that the ICH was too small (49%) or that the patient had an EDH or SDH that required surgery (20%). Reasons for not recruiting eligible patients included no consent (77%) and failure to randomise (23%). Further descriptions of these data are given in Francis et al. 34

Patient recruitment

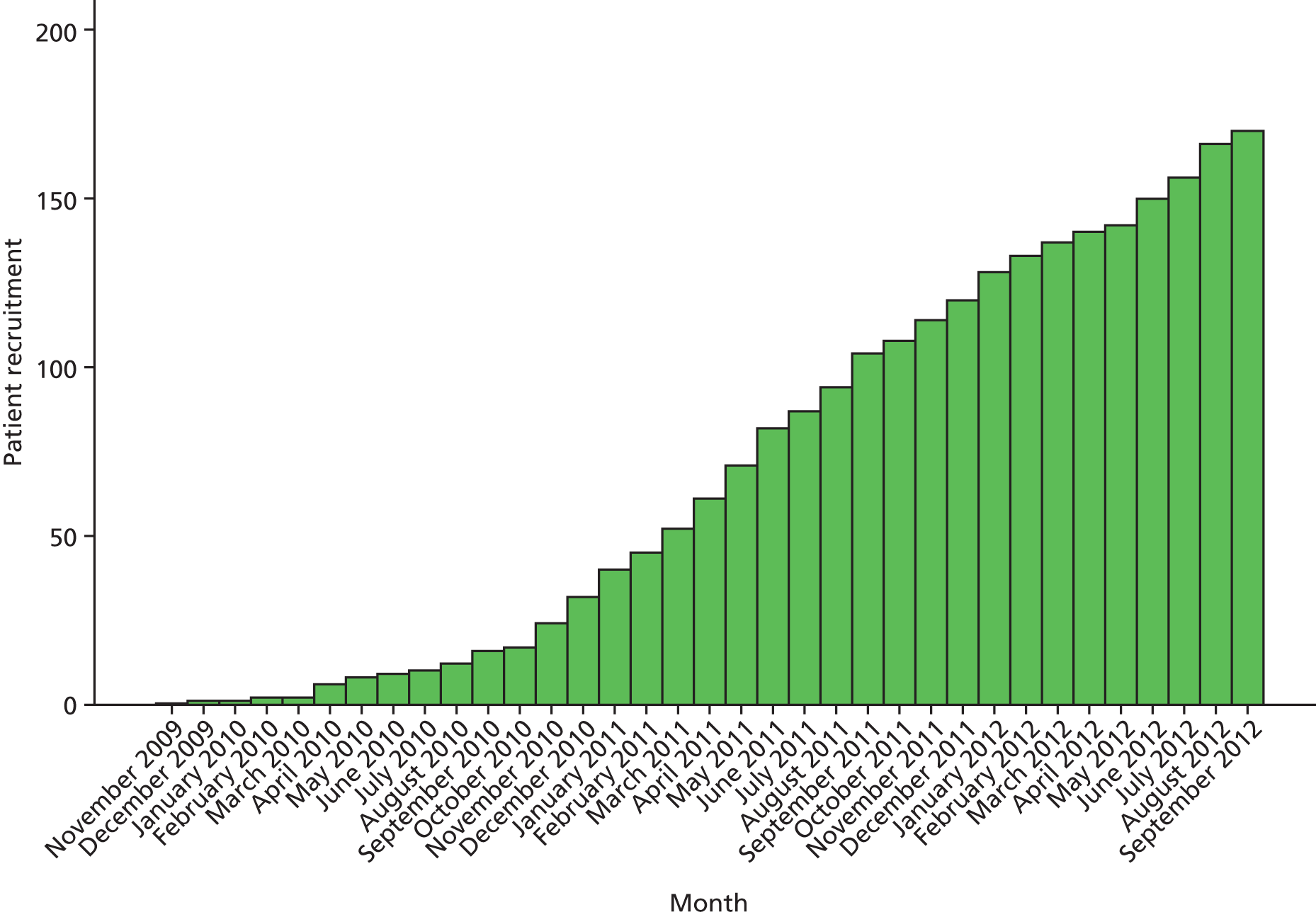

Between December 2009 and September 2012, 170 patients were recruited from 31 centres in 13 countries and randomly assigned to treatment groups: 83 to Early Surgery and 87 to Initial Conservative Treatment (Figure 4). After an initial slow recruitment phase, when the number of centres recruiting was low, the rate of recruitment picked up and in fact matched the recruitment seen in a previous SICH study. However, announcement of the plan to withdraw funding resulted in a slowdown in recruitment even though it continued for a further 6 months. This was probably a result of trial fatigue and a decision by the trial team not to encourage further centre recruitment until attempts to obtain further funding had been exhausted.

FIGURE 4.

Patient recruitment over time.

Figure 5 shows recruitment by centre and country. India was the highest-recruiting country, with a total of 74 patients, followed by China with 43. There were 27 patients recruited in Europe, including six in the UK, and 26 in the other countries (Pakistan, Malaysia, Nepal and Egypt).

FIGURE 5.

Recruitment by centre and country. (a) Centre; and (b) country. NIMHANS, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences.

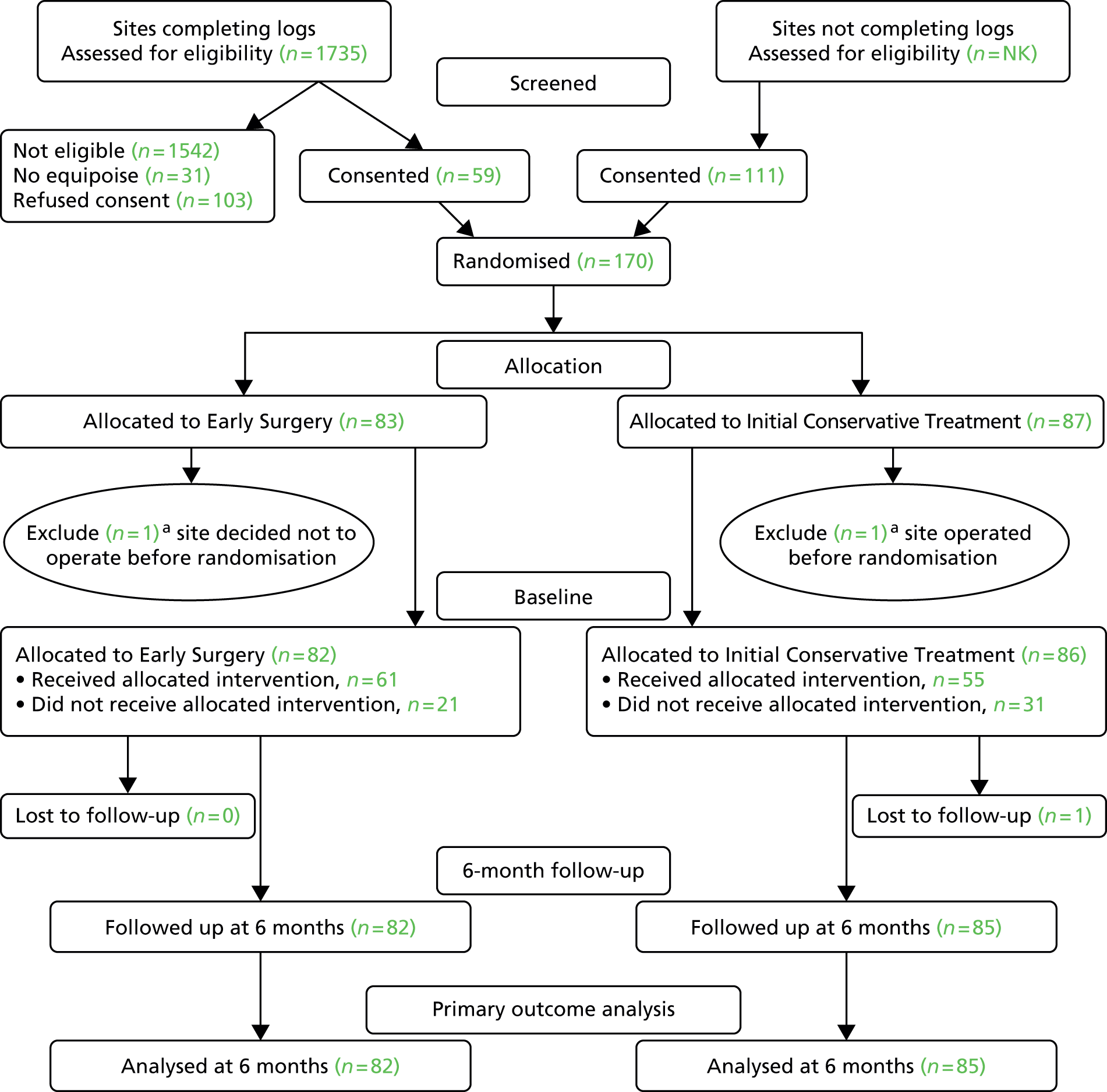

Figure 6 shows the CONSORT diagram for the trial. Two patients were excluded because the treatment decision was made prior to randomisation: in one case the patient was operated on prior to randomisation and in the other a decision was made not to operate prior to randomisation. These were serious protocol violations. All other patients were included in the analysis. Only one patient was lost to 6-month follow-up. This report therefore reports baseline measures for 168 patients and results for 167 patients, 82 patients assigned to Early Surgery and 85 patients assigned to Initial Conservative Treatment.

FIGURE 6.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart for STITCH(TRAUMA) patients. NK, not known. a, One site recruited one patient but had undertaken surgery prior to randomisation; the patient was allocated to Initial Conservative Treatment. Another site recruited one patient for whom a treatment decision not to operate was made before the patient was randomised; this patient was allocated to Early Surgery. Because of the severe breach of protocol, these patients were excluded. Reproduced from Mendelow et al. 35 © A. David Mendelow, Barbara A. Gregson, Elise N. Rowan, Richard Francis, Elaine McColl, Paul McNamee, Iain R. Chambers, Andreas Unterberg, Dwayne Boyers, and Patrick M. Mitchell 2015; Published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

Baseline measures

Tables 1–6 show the distribution of baseline variables between the two treatment groups. Patients ranged in age from 16 to 83 years, with a median age of 50 years, and 122 (73%) were male (Table 1). Despite 13% of patients being over the age of 70 years, only 7% were on any anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication. Prior to the head injury, 164 patients (98%) scored 0 or 1 on the Rankin Scale, and 22 (13%) had a medical history of cardiovascular disease (Table 2). The main causes of the head injury were road traffic accidents (113, 67%) and falls (47, 28%) (Table 3). Most of those who were in a road traffic accidents were motorbike riders (n = 45, 40%) or pedestrians (n = 29, 26%). Patients from Europe were most likely to have suffered a fall (74%) while patients from Asia were most likely to have had a road traffic accident (76%) either on a motorbike or as a pedestrian.

| Variable | Early Surgery (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 51 (32–63) | 50 (33–61) |

| Range | 18–83 | 16–77 |

| Mean (SD) | 48 (17.7) | 48 (16.9) |

| Age band (years), n (%) | ||

| < 50 | 37 (45) | 42 (49) |

| 50–69 | 34 (42) | 33 (38) |

| ≥ 70 | 11 (13) | 11 (13) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 57 (70) | 65 (76) |

| Female | 25 (30) | 21 (24) |

| Pre-ICH Rankin Scale score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 74 (90) | 78 (91) |

| 1 | 6 (7) | 6 (7) |

| 2 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Pre-ICH mobility, n (%) | ||

| Able to walk 200 m | 80 (98) | 82 (95) |

| Able to walk indoors | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Unable to walk | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Handedness,a n (%) | ||

| Right | 80 (98) | 84 (99) |

| Left | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Variable | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Significant medical history | ||

| Cardiovascular | 10 (12) | 12 (14) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Musculoskeletal | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Oncological | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Renal | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Epilepsy | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Endocrine | 4 (5) | 5 (6) |

| Haematological | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Neurological | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| Pulmonary | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Social history | 3 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Antiepileptics | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| ENT | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Hepatic | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Previous TBI | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Psychiatric | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Developmental | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Prior to ICH anticoagulant | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Prior to ICH antiplatelet | 3 (4) | 7 (8) |

| Prior to ICH thrombolytic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Variable | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Cause of injury | ||

| Road traffic accident | 54 (66) | 59 (69) |

| Fall domestic | 15 (18) | 15 (17) |

| Fall outside home | 8 (10) | 9 (10) |

| Work | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Violence/assault | 3 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Animal attack | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Mechanism of injurya | ||

| Acceleration/deceleration | 13 (16) | 23 (28) |

| Direct impact | 38 (47) | 25 (30) |

| Crush | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Fall from ground | 18 (22) | 26 (31) |

| Fall from height | 8 (10) | 8 (10) |

| Fall (details unknown) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

Sixty-eight (40%) patients were admitted to another hospital prior to their transfer to the neurosurgical unit, and the time from injury to randomisation varied between 3 and 48 hours with a median of 22 hours (Table 4). Two-thirds (n = 111; 66%) had an initial loss of consciousness, 25 (15%) pretraumatic amnesia and 41 (24%) post-traumatic amnesia.

| Variable | Early Surgery (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to randomisation (hours) | ||

| Median (IQR), range | 21 (13–31), 3–48 | 22 (14–28), 4–48 |

| Mean (SD) | 22 (11.7) | 22 (10.6) |

| Emergency services provided for the airway, n (%) | ||

| None | 28 (34) | 21 (24) |

| Oxygen | 45 (55) | 56 (65) |

| Intubation | 6 (7) | 8 (9) |

| Oxygen and intubation | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Site of additional injuries, n (%) | ||

| Skin | 35 (43) | 46 (53) |

| Head and neck | 63 (77) | 67 (78) |

| Face | 34 (41) | 37 (43) |

| Chest | 11 (13) | 11 (13) |

| Abdomen | 7 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Extremities | 17 (21) | 11 (13) |

| Spine | 3 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Initial loss of consciousness, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 57 (70) | 54 (63) |

| No | 15 (18) | 20 (23) |

| Unknown | 10 (12) | 12 (14) |

| Pre-traumatic amnesia, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (20) | 9 (10) |

| No | 33 (40) | 40 (47) |

| Unknown | 33 (40) | 37 (43) |

| Post-traumatic amnesia, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 22 (27) | 19 (22) |

| No | 27 (33) | 34 (40) |

| Unknown | 33 (40) | 33 (38) |

| Secondary insults, n (%) | ||

| Hypoxic | 3 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Hypotensive | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Hypothermic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Referral details, n (%) | ||

| Primary admission | 45 (55) | 55 (64) |

| Secondary admission | 37 (45) | 31 (36) |

The volume of the largest haematoma varied between 10 ml and 97 ml, with a median of 23 ml, and 61 (36%) patients had a second haematoma between 0 ml and 26 ml, with a median of 3 ml (Table 5). All of the reported haematomas were located in the lobar regions of the brain, particularly in the frontal or temporal areas. The distribution of baseline variables between the two groups was very similar. At the time of randomisation, 70 (42%) patients had a GCS of 13–15, 78 (46%) a GCS of 8–12 and 20 (12%) a GCS of < 8 (Table 6). More than 85% of patients had a motor score on the GCS of 5 or more.

| Variable | Early Surgery (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Volume of largest haematoma (ml) | ||

| Median (IQR), range | 25 (18–37), 11–96 | 23 (15–32), 10–97 |

| Mean (SD) | 31 (18.0) | 27 (16.8) |

| Location of largest haemorrhage, n (%) | ||

| Frontal | 36 (44) | 43 (50) |

| Temporal | 39 (48) | 37 (43) |

| Parietal | 4 (5) | 5 (6) |

| Occipital | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Second haematoma present, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 28 (34) | 33 (38) |

| No | 54 (66) | 53 (62) |

| Volume of second haematoma if applicable (ml) | ||

| Median (IQR), range | 3 (1–10), 0–20 | 4 (2–8), 0–26 |

| Mean (SD) | 6 (6.3) | 6 (6.6) |

| Location of second haemorrhage, n (%) | ||

| Frontal | 20 (24) | 15 (17) |

| Temporal | 6 (7) | 12 (14) |

| Parietal | 1 (1) | 6 (7) |

| Occipital | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| No second haemorrhage | 54 (66) | 53 (62) |

| Variable | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| GCS: eye | ||

| 1 | 7 (9) | 12 (14) |

| 2 | 21 (26) | 17 (20) |

| 3 | 23 (28) | 25 (29) |

| 4 | 31 (38) | 32 (37) |

| GCS: verbal | ||

| 1 | 12 (15) | 15 (17) |

| 2 | 21 (26) | 19 (22) |

| 3 | 8 (10) | 14 (16) |

| 4 | 23 (28) | 20 (23) |

| 5 | 18 (22) | 18 (21) |

| GCS: motor | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 2 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 4 (5) | 5 (6) |

| 4 | 6 (7) | 4 (5) |

| 5 | 32 (39) | 33 (38) |

| 6 | 38 (46) | 42 (49) |

| GCS: total | ||

| 3 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| 6 | 6 (7) | 3 (3) |

| 7 | 4 (5) | 3 (3) |

| 8 | 1 (1) | 6 (7) |

| 9 | 11 (13) | 8 (9) |

| 10 | 11 (13) | 14 (16) |

| 11 | 6 (7) | 8 (9) |

| 12 | 6 (7) | 7 (8) |

| 13 | 10 (12) | 8 (9) |

| 14 | 14 (17) | 13 (15) |

| 15 | 12 (15) | 13 (15) |

| Pupils | ||

| Both reactive | 77 (94) | 79 (92) |

| One reactive | 3 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Both unreactive | 2 (2) | 4 (5) |

Surgery

Of the 82 patients in the Early Surgery group, only 61 (74%) had surgery, 57 (93%) of these within 12 hours of randomisation (Table 7). The reasons for not having surgery were patient or relative refusal (n = 15), improvement (n = 1), deterioration (n = 2), seizures (n = 1), anaesthetic risk (n = 1) and change of history suggesting spontaneous rather than traumatic ICH (n = 1). Although informed consent was obtained prior to randomisation, patients often had more than one relative and further discussion could lead to a change of opinion.

| Variable | Early Surgery: surgical cases only, N = 61 (74%) | Initial Conservative Treatment: surgical cases only, N = 31 (36%) |

|---|---|---|

| Method, n (%) | ||

| Craniotomy | 59 (97) | 25 (81) |

| Other | 2 (3) | 6 (19) |

| Other surgical details | ||

| Bone flap replaced | 47 (77) | 13 (42) |

| Other cranial surgery | 1 (2) | 3 (10) |

| Paralysed and sedated | 17 (28) | 12 (39) |

| Any non-cranial surgery | 1 (2) | 2 (7) |

| Pre-operative GCS: eye, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 5 (8) | 15 (48) |

| 2 | 18 (30) | 8 (26) |

| 3 | 19 (31) | 5 (16) |

| 4 | 19 (31) | 3 (10) |

| Pre-operative GCS: verbal, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 13 (21) | 16 (52) |

| 2 | 15 (25) | 7 (23) |

| 3 | 6 (10) | 5 (16) |

| 4 | 18 (30) | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 9 (15) | 3 (10) |

| Pre-operative GCS: motor, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 4 (13) |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| 3 | 6 (10) | 3 (10) |

| 4 | 4 (7) | 6 (19) |

| 5 | 26 (43) | 14 (45) |

| 6 | 23 (38) | 3 (10) |

| Time randomisation to surgery (hours) | ||

| Median (IQR), range | 3 (1–6), < 1–24 | 25 (6–79), < 1–318 |

| Mean (SD) | 4 (4.5) | 58 (75.6) |

| Surgery within 12 hours of randomisation, n (%) | 57 (93) | 10 (32) |

| Time injury to surgery (hours) | ||

| Median (IQR), range | 23 (16–36), 4–69 | 45 (26–99), 9–332 |

| Mean (SD) | 26 (13.8) | 78 (79.0) |

| Surgery within 12 hours of injury, n (%) | 9 (15) | 3 (10) |

Of the 86 patients randomised to Initial Conservative Treatment, 31 (36%) had surgery within 14 days of randomisation, 10 (32%) of these within 12 hours. The reasons for having surgery were neurological deterioration (n = 29), no shrinkage in haematoma size (n = 1) and rise in ICP (n = 1). Neurological deterioration was identified by a drop in GCS, enlargement of the haematoma or increase in midline shift, increase in weakness or change in pupil size or reactivity.

Surgical patients in the Early Surgery group were more likely to undergo craniotomy than surgical patients in the Initial Conservative Treatment group (97% vs. 81%; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.016). One patient in the Initial Conservative Treatment group underwent burrhole surgery, but all other patients who did not have craniotomy underwent craniectomy. The bone flap was more likely to be replaced in the surgical patients in the Early Surgery group (77%) than in the Initial Conservative Treatment group (42%) (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.001). As Table 3 demonstrates, surgical patients in the Early Surgery group had significantly higher pre-operative GCS values on all the subscales than those requiring surgery in the Initial Conservative Treatment group. Comparison of the baseline characteristics of patients in the Initial Conservative Treatment group who had surgery with those who did not showed that patients who deteriorated and went on to have surgery had larger haematomas initially (Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.010) and were more likely to have at least one pupil unreactive (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0005) but did not differ on age, GCS at the time of randomisation or presence of a second haematoma.

Hospital stay

At 2 weeks post randomisation, similar proportions of patients in the two groups were still on the neurosurgical ward: 29 (35%) of the Early Surgery patients and 32 (37%) of the Initial Conservative Treatment patients. The proportions that had been transferred to another ward or hospital were also similar: three (4%) and four (5%) respectively. However, 43 (52%) Early Surgery patients had been discharged, compared with 33 (38%) Initial Conservative Treatment patients. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the percentage of patients who had died by 2 weeks: 7 (9%) Early Surgery patients compared with 17 (20%) Initial Conservative Treatment patients (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.047).

At some point in the first 2 weeks, ICP was monitored in seven (9%) Early Surgery patients, compared with 16 (19%) Initial Conservative Treatment patients (p = 0.073), and this affected management decisions in one Early Surgery patient, compared with 10 Initial Conservative Treatment patients (p = 0.069) (Table 8). Patients were less likely to be monitored in India, where the rate was 4% (3 out of 74), compared with 21% elsewhere (20 out of 94).

| Variables | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| ICP monitored | ||

| Yes | 7 (9) | 16 (19) |

| No | 75 (91) | 70 (81) |

| Monitor type (of ICP-monitored cases) | ||

| Intraventricular | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Camino | 3 (43) | 5 (31) |

| Codman | 2 (29) | 7 (44) |

| Spiegelberg | 2 (29) | 3 (19) |

| Monitoring affected management (of ICP-monitored cases) | ||

| Yes | 1 (14) | 10 (63) |

| No | 6 (86) | 6 (37) |

Very few postrandomisation events were recorded during the first 2 weeks of the hospital stay (Table 9). The most frequently reported was pneumonia, with eight Early Surgery patients and eight Initial Conservative Treatment patients.

| Variable | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 7 (9) | 17 (20) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pneumonia | 8 (10) | 8 (9) |

| Postoperative EDHa | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Septicaemia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Urinary tract infectiona | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Epilepsy | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 5 (6) | 1 (1) |

Primary outcome

Six-month outcome was available for 82 Early Surgery patients and 85 Initial Conservative Treatment patients; one patient from the Initial Conservative Treatment group was lost to follow-up. Fifty-two (63%) Early Surgery patients had a favourable outcome on the dichotomised GOS, compared with 45 (53%) Initial Conservative Treatment patients (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.21; p = 0.171): an absolute difference of 10.5% (95% CI –4.4% to 25.3%) (Table 10). Adjusting for age, volume and GCS gave an OR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.29 to 1.16; p = 0.122).

| Primary outcome (prognosis-based) | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 85) | Test and p-value, absolute difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavourable | 30 (37) | 40 (47) | Chi-squared test, p = 0.170, 10.5% (–4.4% to 25.3%) |

| Favourable | 52 (63) | 45 (53) |

Secondary outcomes

However, there was a highly significant difference in mortality at 6 months, with 12 (15%) Early Surgery patients dying compared with 28 (33%) Initial Conservative Treatment patients (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.75, p = 0.007): absolute difference 18.3% (95% CI 5.7% to 30.9%) (Table 11). Figure 7 shows the Kaplan–Meier plot of survival for the two groups of patients, illustrating the significant advantage of Early Surgery compared with Initial Conservative Treatment (p = 0.008).

| Variable | Early Surgery, n (%) (N = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment, n (%) (N = 85) | Test and p-value, absolute difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality at 6 months | |||

| Dead | 12 (15) | 28 (33) | Chi-squared test, p = 0.006,a 18.3 (5.7 to 30.9) |

| Alive | 70 (85) | 57 (67) | |

| GOS | |||

| Dead | 12 (15) | 28 (33) | Chi-squared test trend, p = 0.047,a POM, p = 0.153 |

| Vegetative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Severely disabled | 18 (22) | 12 (14) | |

| Moderately disabled | 26 (32) | 18 (21) | |

| Good recovery | 26 (32) | 27 (32) | |

| GOSE | |||

| Dead | 12 (15) | 28 (33) | Chi-squared test trend, p = 0.052, POM, p = 0.127 |

| Vegetative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Lower SD | 4 (5) | 8 (9) | |

| Upper SD | 14 (17) | 4 (5) | |

| Lower MD | 5 (6) | 3 (4) | |

| Upper MD | 21 (26) | 15 (18) | |

| Lower GR | 12 (15) | 12 (14) | |

| Upper GR | 14 (17) | 15 (18) | |

| Dichotomised Rankin Scale score | |||

| Unfavourable | 27 (33) | 37 (44) | Chi-squared test, p = 0.159, 10.6 (–4.0 to 25.3) |

| Favourable | 55 (67) | 48 (56) | |

| Rankin Scale score | |||

| 0 | 17 (21) | 18 (21) | Chi-squared test trend, p = 0.043,a POM, p = 0.147 |

| 1 | 27 (33) | 22 (26) | |

| 2 | 11 (13) | 8 (9) | |

| 3 | 8 (10) | 4 (5) | |

| 4 | 7 (9) | 3 (4) | |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | |

| Dead | 12 (15) | 28 (33) | |

| EQ-5D index | |||

| Median | 0.80 | 0.71 | Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.218 |

| IQR | 0.52–1.00 | 0.00–1.00 | |

| Range | –0.33 to 1.00 | –0.59 to 1.00 | |

| Limb movement | |||

| Worse-affected legb | |||

| Unaffected | 50 (72) | 47 (82) | Chi-squared test, p = 0.374 |

| Weak | 18 (26) | 9 (16) | |

| Paralysed | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Worse-affected armb | |||

| Unaffected | 48 (70) | 43 (75) | Chi-squared test, p = 0.464 |

| Weak | 21 (30) | 14 (25) | |

| Paralysed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

FIGURE 7.

Kaplan–Meier: survival analysis. Log-rank test, p = 0.0081. Reproduced from Mendelow et al. 35 © A. David Mendelow, Barbara A. Gregson, Elise N. Rowan, Richard Francis, Elaine McColl, Paul McNamee, Iain R. Chambers, Andreas Unterberg, Dwayne Boyers, and Patrick M. Mitchell 2015; Published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

The main causes of death were the initial head injury (Early Surgery 5 vs. Initial Conservative Treatment 14) and pneumonia (Early Surgery 4 vs. Initial Conservative Treatment 2). Other causes of death in the Initial Conservative Treatment group included cachexia (n = 2), ischaemic stroke (n = 2), meningitis (n = 1), pulmonary embolism (n = 2), renal injury (n = 1), head injury and surgery (n = 1), seizure (n = 1) and unknown – sudden death in the community (n = 1). In the Early Surgery group, the other causes were hypovolaemic shock (n = 1), pulmonary embolism (n = 1), head injury and surgery (n = 1) and unknown in the community (n = 1). Only eight non-death-related major adverse events were recorded (in eight patients): seizure (n = 3), new/enlarged haematoma (n = 2), infection (n = 2) and other (n = 1).

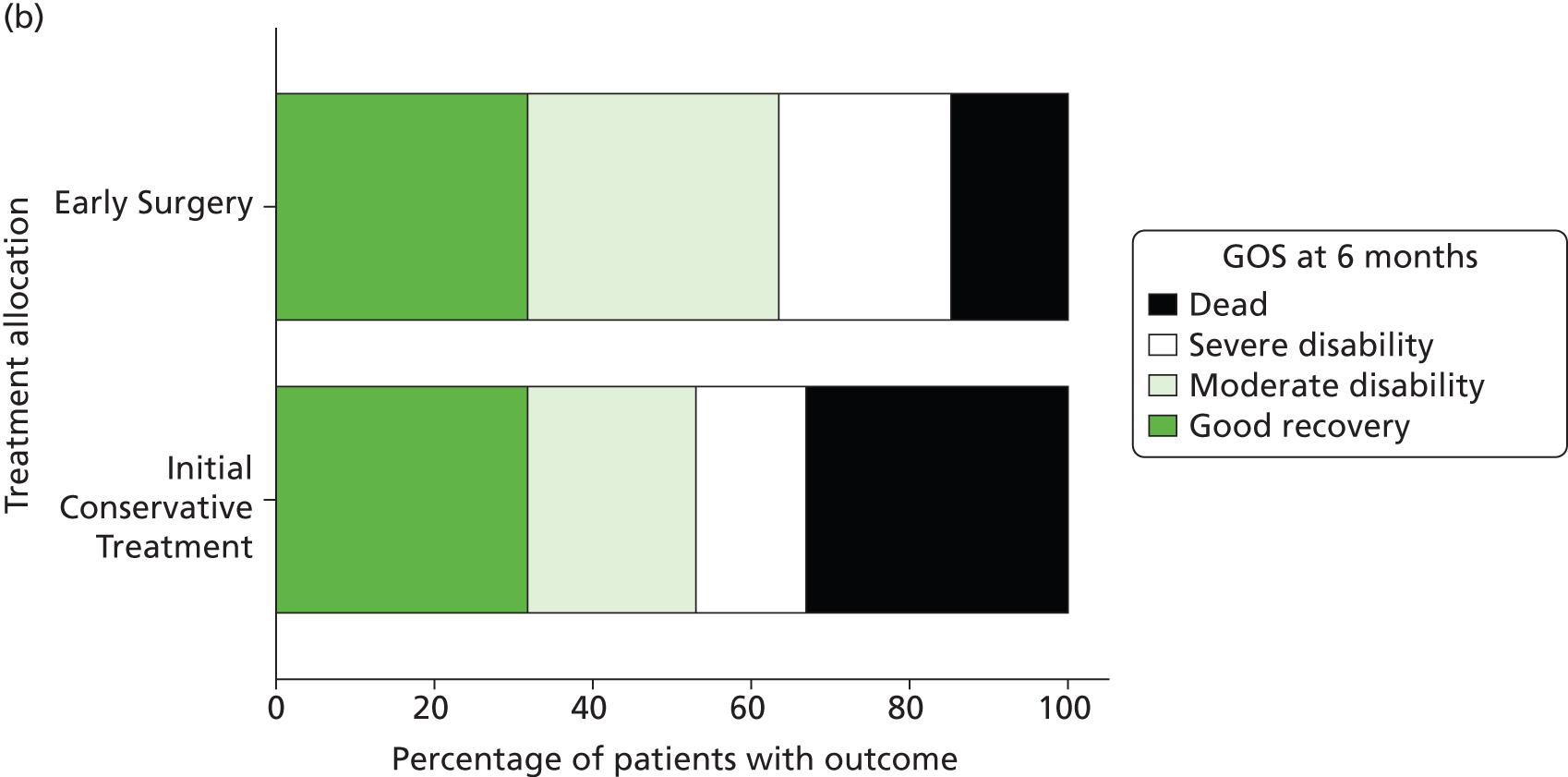

Table 11 and Figure 8 show the distribution of GOS, GOSE and Rankin Scale at 6 months by treatment group. For each of these secondary outcomes there is a significant trend towards better outcome in the Early Surgery group (p = 0.047, 0.052 and 0.043 respectively), although the proportional odds models did not reach statistical significance (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.16, p = 0.153; OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.13, p = 0.127; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.15, p = 0.147).

FIGURE 8.

(a) GOSE at 6 months; (b) GOS; and (c) Rankin Scale. Notes (a) proportional odds model, p = 0.127; chi-squared for trend, p = 0.052; (b) proportional odds model, p = 0.153; chi-squared for trend p = 0.047; and (c) proportional odds model, p = 0.147; chi-squared test for trend, p = 0.043. Reproduced from Mendelow et al. 35 © A. David Mendelow, Barbara A. Gregson, Elise N. Rowan, Richard Francis, Elaine McColl, Paul McNamee, Iain R. Chambers, Andreas Unterberg, Dwayne Boyers, and Patrick M. Mitchell 2015; Published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

There were also no significant differences in EQ-5D or limb movements between groups. Of 68 Early Surgery patients, 20 (29%) reported being employed at 6 months and, of 54 Initial Conservative Treatment patients, responding to the question 13 (24%) reported being employed.

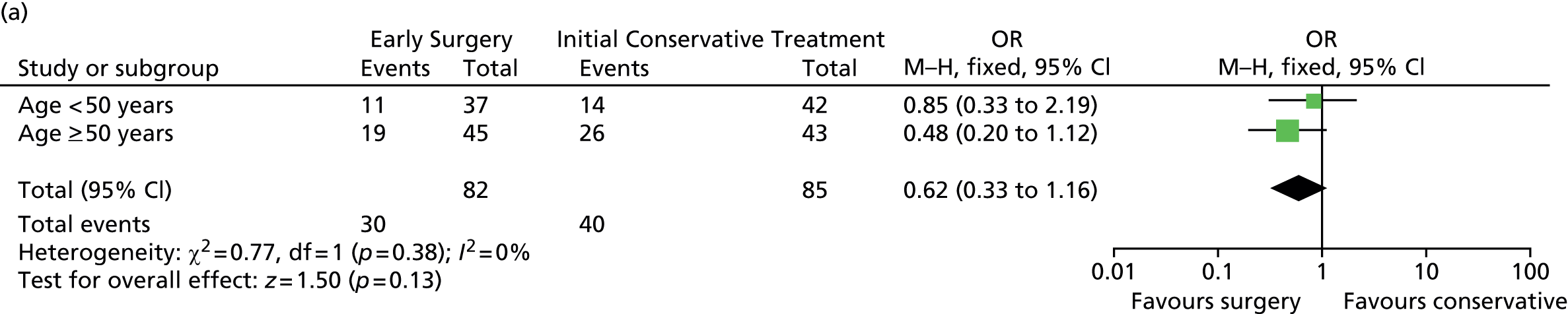

Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses are shown in Figure 9. None of the subgroups display any significant heterogeneity of treatment response, although the patients with a GCS of 9–12 had the best response to Early Surgery.

FIGURE 9.

Subgroup analysis. (a) Age; (b) GCS; (c) volume of haematoma; (d) time from injury to randomisation; and (e) geographical region. df, degrees of freedom; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel. Reproduced from Mendelow et al. 35 © A. David Mendelow, Barbara A. Gregson, Elise N. Rowan, Richard Francis, Elaine McColl, Paul McNamee, Iain R. Chambers, Andreas Unterberg, Dwayne Boyers, and Patrick M. Mitchell 2015; Published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

Outcome by treatment allocation and treatment received

Looking at outcome by allocated and received treatment, 33% (20 out of 61) of patients who were allocated to Early Surgery and had surgery had died or were severely disabled at 6 months. However, 65% (20 out of 31) of patients who were allocated to Initial Conservative Treatment and had delayed surgery had died or were severely disabled at 6 months, compared with 37% (20 out of 54) of the conservative patients who did not have surgery.

Costs outcome

An unadjusted comparison of raw mean costs showed that Early Surgery was, on average, Int$476 more costly than Initial Conservative Treatment (Table 12). Generalised linear model (GLM) regression analysis, adjusting for patient characteristics, showed Early Surgery to be Int$1774 more costly (95% CI –Int$284 to Int$3831) than Initial Conservative Treatment. Sensitivity analyses showed that overall conclusions were robust to the choice of regression model for the analysis. Results from subgroup analyses (Table 13) were highly uncertain based on small sample sizes (and too small to conduct regression analysis) and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

| Cost (Int$) | Early Surgery (n = 82) | Initial Conservative Treatment (n = 86) | Difference of means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Raw difference | Adjusted difference | |

| All countries | ||||||

| Cost surgery | – | 981 (1678) | – | 515 (1206) | ||

| Cost ICU | 4.18 (4.20) | 2808 (5762) | 4.06 (4.61) | 2988 (6131) | ||

| Cost HDU | 1.72 (2.55) | 385 (1053) | 1.76 (3.01) | 461 (1445) | ||

| Cost ward | 11.88 (15.95) | 3595 (10,206) | 14.24 (29.43) | 3997 (13,789) | ||

| Cost readmission | 4.23 (14.43) | 1145 (5775) | 2.42 (9.63) | 421 (1720) | ||

| Total cost | – | 8812 (18,032)a | – | 8336 (18,685)a | 476 | GLM model 1774 (95% CI –284 to 3831) |

| Cost (Int$) | Early Surgery (n = 6) | Initial Conservative Treatment (n = 10) | Difference of means | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | ||

| Low-income countries | |||||

| Cost surgery | – | 142 (0) | – | 14 (45) | |

| Cost ICU | 0.83 (1.60) | 203 (391) | 1.20 (2.70) | 293 (659) | |

| Cost HDU | 3.83 (0.75) | 468 (92) | 3.50 (2.12) | 427 (259) | |

| Cost ward | 5.33 (1.03) | 325 (63) | 6.30 (6.43) | 384 (392) | |

| Cost readmission | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | |

| Total cost | – | 1139 (418) | – | 1118 (614) | 20 |

| Cost (Int$) | Early Surgery (n = 40) | Initial Conservative Treatment (n = 39) | Difference of means | ||

| Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | ||

| Lower middle-income countries | |||||

| Cost surgery | – | 439 (511) | – | 176 (369) | |

| Cost ICU | 3.20 (3.78) | 580 (1449) | 2.38 (3.39) | 227 (314) | |

| Cost HDU | 1.93 (2.84) | 87 (128) | 1.97 (3.08) | 168 (513) | |

| Cost ward | 5.70 (5.84) | 64 (98) | 6.31 (5.29) | 125 (364) | |

| Cost readmission | 0.35 (2.21) | 3 (20) | 0.13 (0.59) | 1 (5) | |

| Total cost | – | 1174 (1583) | – | 697 (964) | 477 |

| Cost (Int$) | Early Surgery (n = 28) | Initial Conservative Treatment (n = 30) | Difference of means | ||

| Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | ||

| Upper middle-income countries | |||||

| Cost surgery | – | 1089 (1174) | – | 822 (1031) | |

| Cost ICU | 5.43 (3.79) | 4272 (4134) | 6.93 (4.49) | 6010 (5588) | |

| Cost HDU | 0.93 (1.84) | 643 (1261) | 1.17 (3.26) | 821 (2295) | |

| Cost ward | 16.86 (16.30) | 3603 (4132) | 14.27 (26.05) | 3080 (6267) | |

| Cost readmission | 8.39 (20.55) | 997 (2986) | 6.23 (15.48) | 805 (1881) | |

| Total cost | – | 10,603 (7517) | – | 11,538 (10,149) | –936 |

| Cost (Int$) | Early Surgery (n = 8) | Initial Conservative Treatment (n = 7) | Difference of means | ||

| Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | Resource use, mean (SD) | Costs, mean (SD) | ||

| High-income countries | |||||

| Cost surgery | – | 4927 (3617) | – | 2020 (3542) | |

| Cost ICU | 7.25 (5.95) | 13,432 (14,847) | 5.14 (6.72) | 10,310 (15,989) | |

| Cost HDU | 1.88 (3.18) | 1089 (2668) | 0.57 (0.98) | 622 (964) | |

| Cost ward | 30.25 (31.45) | 23,671 (24,462) | 69.71 (68.18) | 34,662 (35,806) | |

| Cost readmission | 12.27 (22.53) | 8233 (16,895) | 2.29 (6.05) | 1719 (4547) | |

| Total cost | – | 46,489 (38,880)a | – | 47,483 (46,221)a | –994 |