Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/27. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

James Raftery is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Editorial Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Williamson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Definition

The term otitis media with effusion (OME) is often used synonymously with ‘glue ear’. 1 The descriptive definition is based on the intraoperative findings of sticky mucinous secretions behind the eardrum that can hamper the free movement of the ossicles in the middle ear. The viscosity of the middle ear fluid has been found to vary and the fluid is sometimes described as serous or secretory. 1,2 Effusions are associated with notional conductive hearing losses of about 15–45 dB owing to damping effects on sound transmission to the inner ear. OME occurs usually in one ear, but frequently in both ears. 3 Probably the earliest and most relevant description of the condition from a primary care perspective was made by Dr John Fry, who wrote about the ‘catarrhal child’: a syndrome of coughs, colds, catarrh and subhealth, in which OME and frequent or persistent upper respiratory infections are the predominant features, and which presents most commonly in young children of early school age. 4

Natural history and scale of the problem

As many as 80% of children of all ages develop OME. 3 Most such episodes are anticipated to resolve naturally, with an average duration of 6–10 weeks, and with just 10% of episodes lasting ≥ 1 year. 5,6 The problem with such a common condition is that it is often regarded as normal. The prevalence rises to 46% (a secondary peak) in the early school years,6 when recurrent ear-related symptoms and broader developmental concerns most often bring the condition to light,7,8 and not infrequently results in surgical referral for grommets. 1,9,10 Time to resolution of effusions remains clinically unpredictable; many last ≥ 3 months and 30% are recurrent. 3,11 In the UK, about 200,000 children are seen every year with this problem in primary and community care. 1,12 The full scale of the total health burden is only partly reflected in high international rates for grommet surgery,13–15 but with falling rates observed in the UK. 16 In the USA, in 2004, as many as 2.2 million people were diagnosed, at an estimated cost of US$4B. 17

The impact of this very common condition on child physical health, hearing, speech, behaviour, development and mapped quality of life (QoL) has been found to be just as great in a primary care sample as in hospital samples. 9,18–21

Clinical management

Diagnostic evaluation in primary care

Initial temporising management in primary care is often pragmatic, ad hoc and influenced mainly by parental concerns. 1,4 Research about diagnosis of OME suggests that more could be done in this setting to improve diagnostic accuracy. 22–25

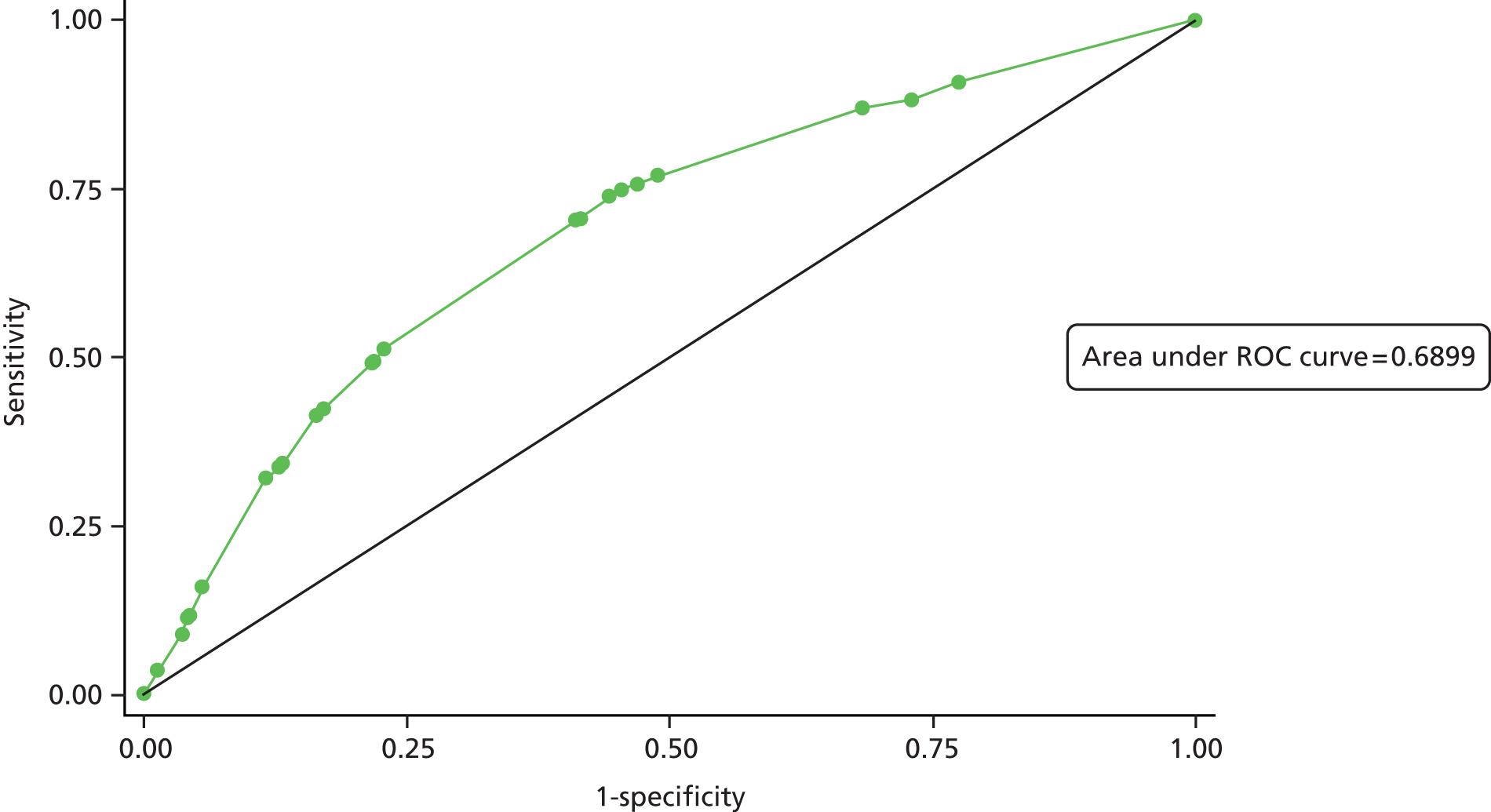

Although the history alone has moderate specificity, it is not particularly sensitive for how a child is likely to function, for example in a noisy learning environment. 26,27 OME has been described as a chronic ‘invisible’ illness that can be relapsing and frustrating for both the parent and child. It has been clinically noted that uncertainties are often expressed by families regarding whether the root cause is a behavioural issue or a genuine hearing problem. Concerns about school achievement have also been suggested as an important driver for surgical intervention. 28 Case ascertainment for treatment poses several dilemmas, caused not just by (a) the current lack of available ‘proportionate and cost-effective’ treatments (see The evidence for non-surgical interventions), but also by (b) lack of agreement within the profession about what one is treating: whether a disease or condition, a disorder, a disability or a global qualitative impact, as one moves from the more biomedical to a patient-centred model of the condition. 19,29 In general practice, evaluating this multidimensional aspect of OME appears to approximate to a simple formula or rule of thumb as: history of persistence (reported duration) × perceived severity (number of related surgery attendances and/or level of concern about salient markers in different domains, e.g. hearing-/speech-/ear-related physical health/behaviour and development). Symptoms and concerns are reasonable but variable predictors of the state of the child’s ears in terms of current effusion status,30 reinforcing the case for improving clinical assessment in primary care both at the point of treatment and to improve accuracy of referrals.

A careful clinical history is of central importance for case recognition and appears reasonably good for purpose; UK ear, nose and throat (ENT) referrals, although variable, are fairly conservative: about 15% referred in the General practice Nasal steroid trial of Otitis Media with Effusion (GNOME) trial, and with ≈50% of children nationally who are referred on, but who are subsequently found not to meet the strict criteria for grommets (after a period of waiting conducted in hospital, which will necessarily include natural resolution effects). 9,10,30,31 The majority of all affected children will initially undergo observation in primary care or in the community. 1 The more frequently that parents report ear-related episodes in their child in the previous 12 months, the greater the predictive values for the finding of an effusion on screening tympanometry [two or more episodes have an odds ratio (OR) of 2.9, and five or more have an OR of 4.3]. 32 However, it is probable that children with OME-related impacts remain under-recognised. 33 The intermittent history is problematic, and the spectrum of need is wide. 1,34 In this context, the current markedly limited range of evidence-based treatments both on offer and capable of informing policy requires strengthening.

A detailed history, for example finding evidence of reported hearing difficulty with other typical symptoms/concerns associated with OME, may be supplemented by good-quality otoscopy (using a halogen light) or, better still, by using tympanometry. 1 There are no studies of symptom predictors of effusions from primary care, but the sensitivity of history is thought to be around 70%. 1 Both otoscopy and tympanometry are more objective measures in pinpointing the current status of effusion(s) than parent report alone, and have some potential to improve case recognition and clarify those requiring treatment. Tuning fork tests are unfortunately unreliable for the vast majority of children when age at presentation is considered. Relevant audiological tests that improve precision include free-field voice testing done by specialists, and this is probably the most reliable evaluation of hearing for the presenting age group. 1 Accurate pure-tone audiography is not really feasible and is seldom valid in primary care settings.

However, all currently used tests and assessments, irrespective of setting, remain only weakly predictive of the QoL experienced by children and their families. 21 Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can capture such information and are relatively new for the condition of OME. They are moving from the research to clinical audit stage in secondary care, but remain at the research stage in primary care. 9,18,29 Such outcomes are intrinsically holistic and both child and family centred, and thus well suited to primary care use in their shortest available pragmatic form(s). They are endorsed as an important part of the battery of assessments by Cochrane, and are also seen to be of high priority by other experts. 35

Prognosis

Prognostic factors for likely persistence have been extensively reviewed, and nearly all have ORs below 2, curtailing their usefulness somewhat in clinical settings. 31,32,36 Age appears to be the best available predictor of population outcome, with fewer children aged > 6–7 years ‘troubled’ by OME. There is also a clear effect of season, with fewer cases found in the summer months (some of these may be allergy rather than infection related). 3,31,32

Birthweight and skull size have been mooted to have prognostic relevance as have genetic factors,8,31 but such variables have not found any clinical application. There appears to be little, if any, effect of sex at the level of disease/condition, although it is known that boys are slower to read than girls, and so sex may be a confounding factor in presentation and by contributing to outcome severity. This illustrates the importance of cofactors that may either heighten (or reduce) the impact of the OME, such as poor communicating styles at home or school, or reduced ability to lip read because of uncorrected poor visual acuities. 37

Sharing age-related natural history-based prognosis with families is very important, but generally it is difficult on the individual level to predict which children will persist with effusions for 3 months, thus partly justifying a watch-and-wait period.

The evidence for non-surgical interventions (available for use in primary care)

Published systematic reviews have evaluated many studies across a wide selection of non-surgical interventions that are currently used in the treatment of OME. The selected interventions considered here have been made with multidisciplinary input from (a) the current British Medical Journal Clinical Evidence team;34 (b) ENT colleagues editing the Scott-Brown Otolaryngology series;31 and (c) the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s 2009 grommets review. 1 The original (trial protocol) searches were based on a MEDLINE search from 1966 to March 2010, EMBASE from 1980 to March 2010, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from inception to 2010. All searches have since been updated using MEDLINE and EMBASE for systematic reviews to include individual randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and all publications using the key terms ‘otitis media’ and/or ‘OME’ that have been published between January 2006 up to August 2014. The main interventions of interest and summarised below are antibiotics, steroids, antihistamines/decongestants and autoinflation. Cochrane has underlined the importance of OME as a condition of considerable importance, with nine current published reviews on the topic and one protocol on its website (www.cochrane.org), with several of these reviews updated over the study period.

The evidence for antibiotics

The most recent updated Cochrane review suggests that antibiotics are unlikely to be beneficial. The research was extensive and included 23 trials and 3027 subjects. 38 The author’s main conclusion was that there is no statistically significant evidence that antibiotics produce resolution of OME in the short term. Six studies39–44 (n = 738 children) were combined and show slight benefit of long-term antibiotics at 6 months, but none of these was from primary care. Unwanted effects of antibiotics reported in the literature include rashes, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and anaphylaxis. Unnecessary use of antibiotics also promotes the development of antibiotic resistance and the medicalisation of minor illness. 45–50 A few uncertainties remain for targeted, well-considered and selective use of antibiotics. 46 Speculatively, this may include secondary care subgroups as an alternative to surgery, or for any antibiotic-sensitive biofilm infection, or where recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) rather than OME is deemed to be the predominant underlying pathology. 51

To conclude, with inadequate evidence for routine use of antibiotics from primary care, a number needed to treat (NNT) was estimated to be over 20,52 and with the escalating level of threat from antibiotic resistance, antibiotics should not be recommended for routine use.

The evidence for steroids

A Cochrane systematic review,53 search date August 2010, which included 12 studies and 945 patients, found some evidence for improved short-term resolution of OME in those treated in secondary care with oral steroids, either alone or combined with antibiotics. However, there is insufficient evidence to date to determine their effect on resolution of OME-related symptoms or on longer-term outcomes. The systematic review also included several trials, and a UK primary care study of topical intranasal corticosteroids, and concluded that there was sufficient evidence to make the statement that there was ‘no benefit from topical intranasal steroids’. 18,53 Oral steroids have, however, been mooted as a simple, cheap treatment with the advantage that they could be used for a wide age range of selected affected children. However, better evidence of their effectiveness in clearing effusions, in improving patient-centred outcomes in the short and longer term, evidence for their cost-effectiveness and, importantly, a comprehensive evaluation of any associated harms is still required. There are concerns from both parents and professionals about the appropriateness and safety of courses of oral steroids for very young children in this clinical context, that is, a chronic intermittent condition of variable severity that eventually self-limits. These important issues and desired outcomes are being addressed in an ongoing trial funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (project number 11/01/26), with selected patients being recruited from hospital settings.

The evidence for autoinflation

Autoinflation is a promising technique, with some preliminary efficacy and effectiveness demonstrated in several small hospital-based trials reported in two meta-analyses. 35,54 In total, seven clinical trials were found suitable to be included in Cochrane. 55–61 Subsequently, a literature search (search date November 2013), which is an update of the original Cochrane systematic review, was performed using the standard Cochrane search method, as described in full elswehere. 35 Two additional references to clinical trials were found, one of which was a completed RCT carried out on a total sample of 40 children. 62 Different methods of autoinflation using Valsalva manoeuvre techniques, party blowers and face masks, as well as purpose-manufactured devices, were considered in both meta-analyses. The nasal balloon technique using Otovent (ABIGO Medical, Askim, Sweden), which was developed by Professor Stangerup (see Chapter 3, Trial intervention for a full description), and essentially consists in inflating a purpose-manufactured balloon through the nose, and the EarPopper® (Micromedics, St Paul, MN, USA) (a device operating to give a steady flow of air to the nose, which needs to be co-ordinated with the act of swallowing, which opens up the Eustachian tubes) are the only two purpose-manufactured standardised delivery devices, and appear also to yield the most promising results so far in terms of beneficial ORs. 35 Four small studies54–56,62 (one unpublished except in a review) that used the balloon intervention (Otovent) as the method for autoinflation were the basis of our power calculation. Combining these trials gives a potentially homogeneous total of 336 children and is completely dominated by secondary care studies. For the tympanometric outcomes at 1 month, the OR based on all four relevant studies was 2.4, but was not significant. The Cochrane authors, although finding a large aggregate effect size for the autoinflation method with a relative risk (RR) of improvement of 2.47 for tympanometric outcomes, reported wide confidence intervals (CIs) going through 1 (95% CI 0.93 to 6.8). The authors recognised that evidence to recommend widespread use of autoinflation in general practice was missing (a view echoed in subsequent NICE guidance),1 and highlighted the need for a large-scale pragmatic trial in primary care with a longer follow-up term of > 1 month. 35

The most recent updated MEDLINE search in August 2014 revealed one further autoinflation study. 63 This small pilot study involved a modified face mask with an external counter-pressure system intended for use in very young children. One must conclude that the clinical efficacy and effectiveness of autoinflation in a primary care population remains completely untested and requires full evaluation before wide-scale use in the NHS. Primary care is the best setting to evaluate effectiveness of autoinflation, because most children with OME are seen in primary care and in the community, and it is increasingly clear that there are, as yet, no evidence-based treatments that work in this setting. 1,31,34,35,52,53 Lack of a good non-surgical intervention is arguably a major factor fuelling the substantial rates of inappropriate early referral for consideration of surgery, which is thus far the only proven effective treatment. 16,37

There are no known or reported harms associated with nasal autoinflation to date, with higher respiratory tract infection (RTI) rates (including AOM) noted in the control groups in two studies, making it unlikely that the increased pressure in the nose during autoinflation can spread infections, or that it acts as an object that produces cross-infection. 55,56 Patent details outline advantages of controlled air flow and non-damaging pressures inside the nose (the latest patent was filed in September 2008, patent reference US 20100071707A1).

Perhaps compliance is the major potential weakness with this technique,31 and it can probably reliably be performed only in school-aged children (4–5 years and older). Nasal balloon autoinflation using Otovent (≈£5) has the advantage of being considerably less costly than using the EarPopper (≈US$200). Otovent also has better preliminary evidence than the single manufacturer randomised study of just 94 children for the EarPopper,57 thus making the nasal balloon method the intervention of choice for further evaluation.

In summary, the current best, but very limited, evidence from three small homogeneous moderate-quality studies combined at 1 month in the Cochrane review35 suggests there may be a higher rate of short-term tympanometric resolution in children using a purpose-manufactured balloon device (Otovent) than in control subjects. 55,56,61 All the meta-analysed studies, however, failed to provide a definitive answer; many lacked intermediate follow-up and all lacked any long-term follow-up. The Cochrane 3-month meta-analysis, although reporting statistically significant results, used combined (audiometric and tympanometric) outcomes. Furthermore, no relevant important patient-centred outcomes were included in the review, and all identified studies were conducted entirely in highly selected secondary care/specialist populations.

The evidence for other interventions

A British Medical Journal clinical evidence review34 found that mucolytics are unlikely to be beneficial, and that antihistamines and/or oral decongestants are likely to be ineffective and have unwanted side effects. 64 Hearing aids have not as yet been properly evaluated, with no good comparator studies available. 1

The evidence for surgery

For the sake of completeness, and context, a brief synopsis of the evidence for surgery is included here to help bring out some of the issues with current management. Surgery is demonstrably and clearly effective for a carefully selected minority of children, that is those with more severe histories and/or intractable presentations. 1,37 OME/glue ear remains consistently one of the commonest reasons for childhood surgery (inserting grommets/removing adenoids). 15–17,65

However, surgery is known to have a number of significant disadvantages, ranging from high costs and child-and-family preference for a non-surgical option to risks from anaesthetic (with post-operative adverse events that include otorrhoea,66 perforation, tympanosclerosis, residual hearing loss1,14,31 and significant re-insertion rates8). But arguably the most significant limitation of surgery is that, although effective, it is a treatment that is selectively applied post hoc, allowing many children to remain disadvantaged by their hearing loss and other clinically and socially significant OME impacts over a wait of approximately 9 months, rather than in a more timely fashion. This observation has been labelled the treatment paradox.

Conclusion

Temporising medical management is frequently given in general practice, and often includes prescribing antibiotics, decongestants and antihistamines, all of which have been shown to be clinically ineffective, and, worse still, have significant harms. 1,12,34,38,64 Furthermore, these interventions are associated with substantial NHS costs. Antibiotic prescription in primary care is rising progressively again, and has now exceeded the peak in the late 1990s, further driving the development of antibiotic resistance, which may lead to serious infections becoming untreatable. 47,50 The high prevalence of OME, and the fact that it is estimated that one-third of all cases of otitis media are primarily OME related,2,12 means that estimated rates of 80% antibiotic prescribing for all types of otitis media episodes in primary care are potentially reducible by a further 20–30%. 12 Finding an appropriate, feasible and low-cost management option for primary care for the majority of affected children must therefore be seen as an urgent priority, with the status quo of ‘watch and wait’ sometimes interpreted by parents as ‘doing nothing’ or as a form of demand suppression. 67

Autoinflation has been identified by a systematic search through the evidence as the best potential option for primary care. If found to be the case from research, a low-cost, safe and clinically effective treatment might resolve effusions and related symptoms, concerns and global impact on the child’s life and development. There is thus potential to improve child and parent QoL, increase satisfaction and adherence to a recommended watch-and-wait strategy, and also to reduce the harms of overprescribing antibiotics and other presently misapplied treatments.

A simple autoinflation method (Otovent) used for 1–3 months is proposed here in a pragmatic, open, randomised two-arm controlled trial in UK primary care, in which both arms receive usual (routine or standard) management, in order, primarily, to evaluate both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Health economic outcomes are proposed to be collected up to 12 months post randomisation.

Primary aim and objectives

The primary aim of the study is to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of autoinflation in resolving OME at 1 and 3 months by assessing the proportions of children showing rigorously defined improvement as accepted by Cochrane, that is, tympanometric resolution in at least one ear per child of a type B tympanogram (fluid) to normal, type A/C1, tympanograms. 35

Secondary aims and objectives

-

Tympanometric: assessment of the proportions of ears showing resolution from B to A/C1 types at 1 and 3 months. 35

-

Clinical outcomes: evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of the intervention on total symptoms (e.g. hearing difficulty, earache and difficulty concentrating) using a total diary score. We also used a total ear problem (mapped) QoL measure using a PROM [a 14-point questionnaire on the impact of OME (OMQ-14), which is a subset of the Medical Research Council-developed 30-point questionnaire on the impact of OME (OM8-30)].

-

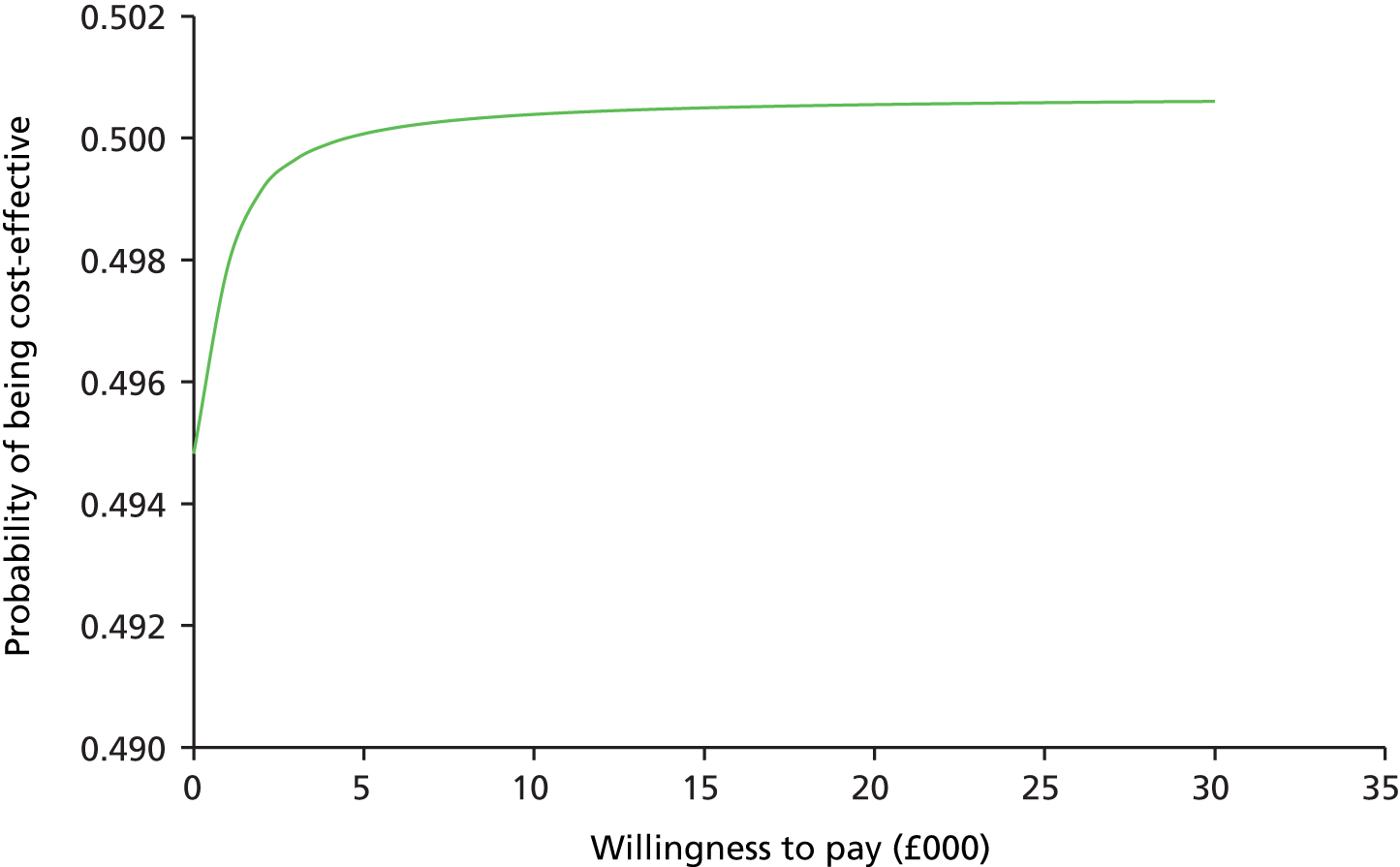

Health economic (HE) assessment of the cost-effectiveness of autoinflation in terms of the cost per additional child achieving resolution of OME at 1 and 3 months, and also in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Evaluation by notes audit30 of the 12-month HE outcomes.

-

Qualitative: to describe the experience of using autoinflation, including nurse-observed competence and reported compliance, and develop an easy-to-use training package for everyday practice.

Chapter 2 Pilot study

Introduction

A pilot study was proposed in advance of a main trial of autoinflation to test the feasibility of recruitment rates, randomisation procedures, training of practice staff, acceptability to patients and compliance with the autoinflation device. The pilot also improved costing estimates for the main trial.

Methods

Aims and objectives

The principal aims of the pilot study were to test the feasibility of conducting a trial of autoinflation in a primary care setting and, in particular, to evaluate children’s compliance in using the device. Other benefits of piloting are as indicated above. 68

Setting

The pilot study was set in four general practitioner (GP) practices recruited through the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) (in Hampshire, Wiltshire, Buckinghamshire and West Berkshire).

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the pilot and main study was awarded by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) on 10 August 2009, reference number 09/H0504/75 (see Appendix 1). Research governance approval was obtained from four primary care trusts (PCTs) (in Hampshire, Wiltshire, Buckinghamshire and West Berkshire).

Recruitment of practices and research nurses

Four practices participated in the study. All nurses had current good clinical practice (GCP) training and attended a structured study training day held at their practices and delivered by the research team. On-site training of the nurses included identifying and inviting potential participants, informed consent process, performing each assessment and use of the specific study equipment (otoscope, tympanometer and autoinflation device). In addition, a prototype study manual was given to each research nurse (RN) for reference purposes, and provided preliminary support.

Recruitment of children

School-aged children (aged 4–11 years) were identified for the study either by initial computer searches or by opportunistic case finding within the practices. Children were eligible for inclusion if they displayed symptoms typical of OME in the previous 3 months or their notes recorded a history of ear problems in the previous 12 months or a relevant presenting problem. Full details are presented in Chapter 3, Recruitment of children. The youngest children (aged 4–6 years) attending school were deemed to have highest base level of risk for OME, so were selected for screening provided they had recent symptoms irrespective of notes history.

Eligibility and informed consent

Children were assessed for eligibility according to the criteria in Box 1. Prior to tympanometry, all parents gave written, informed consent for screening and children were also invited to give written assent wherever deemed applicable by the RN.

-

Children aged 4–11 years and attending school.

-

At least one ear with a type B tympanogram (using the modified Jerger classification). 69–71

PLUS

-

(a) For children (aged 4–6 years) identified from the practice age/sex register, parental concern with report of at least one relevant symptom/concern associated with OME in the previous 3 months from the following symptom/concern checklist:1,2,8,30,72

-

a prolonged or bad cold, cough or chest infection

-

an earache

-

appears to mishearing what is said

-

hearing loss has been suspected by anyone

-

says ‘eh what?’ or ‘pardon’ a lot

-

needs the television turned up

-

may be irritable or withdrawn

-

appears to be lip reading

-

not doing so well at school as you or the teacher think, e.g. with reading

-

has noises in the ear or is dizzy

-

snores, blocked nose or poor sleep

-

speech seems behind other children’s

-

any suspected ear problem.

OR

-

(b) For children identified in the targeted attendance screen (aged 7–11 years), a history of recent and/or recurrent otitis media or OME in the previous 12 months recorded in the child’s medical records OR ear-related problems in the previous year including suspected hearing loss, snoring, concerns about child’s behaviour, speech or educational development. 30

OR

-

(c) For children newly presenting, relevant expressed clinical concern from the health team about OME as a cause. 30

-

Children with a grommet already in the eardrum, or who have been referred or listed for ear surgery.

-

Children with a latex allergy (owing to use of latex nasal balloons).

-

Children with uncommon conditions and syndromes at high risk of recurrent disease including cleft palate, Down syndrome, Kartagener syndrome, primary ciliary dyskinesia and immunodeficiency states for whom early referral is indicated.

Randomisation and concealment of allocation

Eligible children were individually randomised to autoinflation plus routine care or routine care alone via a telephone dial-in service to the Primary Care and Vaccines Collaborative Clinical Trials Unit (PCVC-CTU) at the University of Oxford.

The randomisation method used an algorithm with minimisation based on three previously found key variables: age, sex and baseline severity of OME. 18,30 Owing to the nature of the intervention use of placebo was not possible, and therefore nurses, children and families were unable to be masked to treatment allocation.

Intervention

The intervention in the pilot involved the autoinflation method using a nasal balloon (Otovent) three times per day through each nostril for 1–3 months plus routine care compared with routine care alone.

Assessments

The primary outcomes assessed were tympanometric, resolution of type B (effusions) at 1 and 3 months. Tympanometric outcomes were assessed blind to intervention group by the chief investigator.

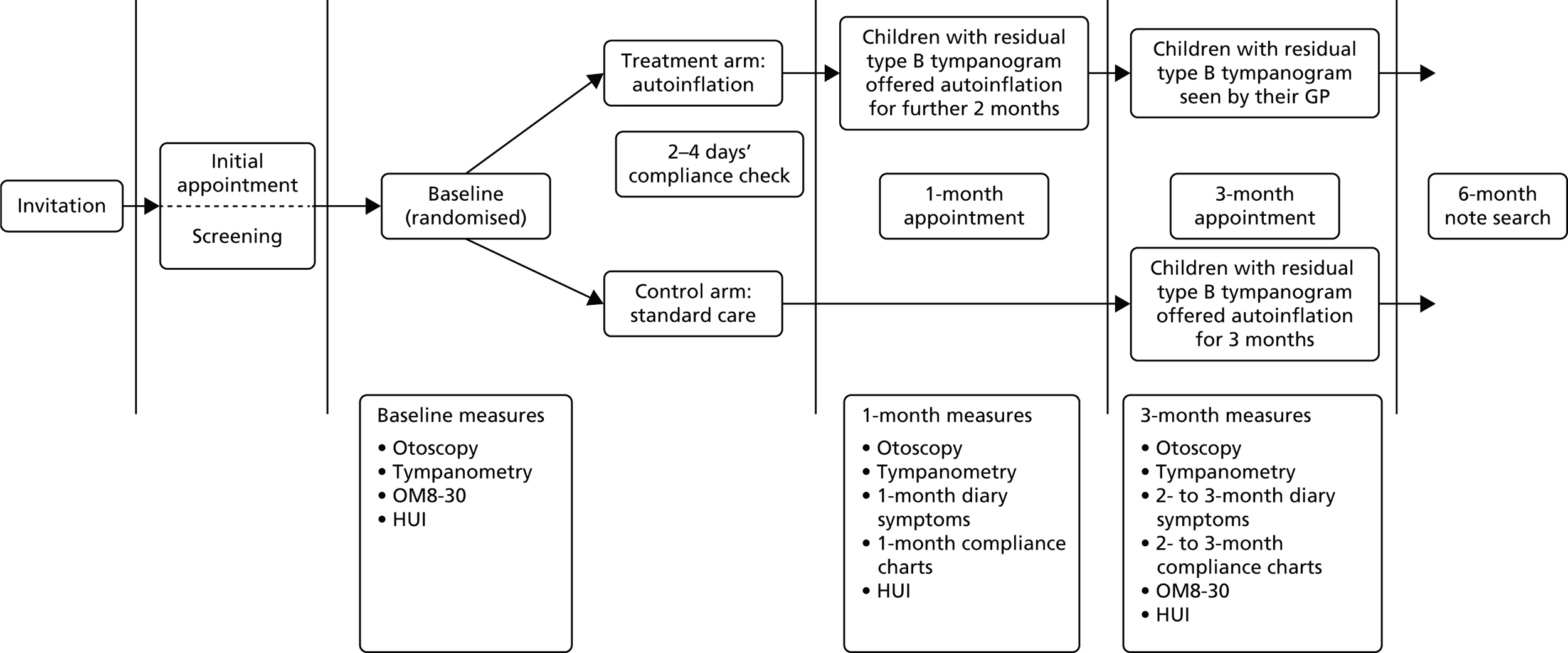

Compliance with the autoinflation device over the study period was recorded using a daily sticker reward chart completed by the child and was also parent reported (as use of autoinflation on a 4-point Likert scale and number of times per day). The ear-related QoL questionnaire (OM8-30) and Health Utilities Index (HUI) were also evaluated in the pilot study (Figure 1). 30

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants through the pilot study.

Results

Patient recruitment

Practices commenced their computer searches in November 2009, with 357 children invited for screening from four practices between January 2010 and May 2010. Fifty-eight children were consequently screened for eligibility and 21 were randomised into the pilot.

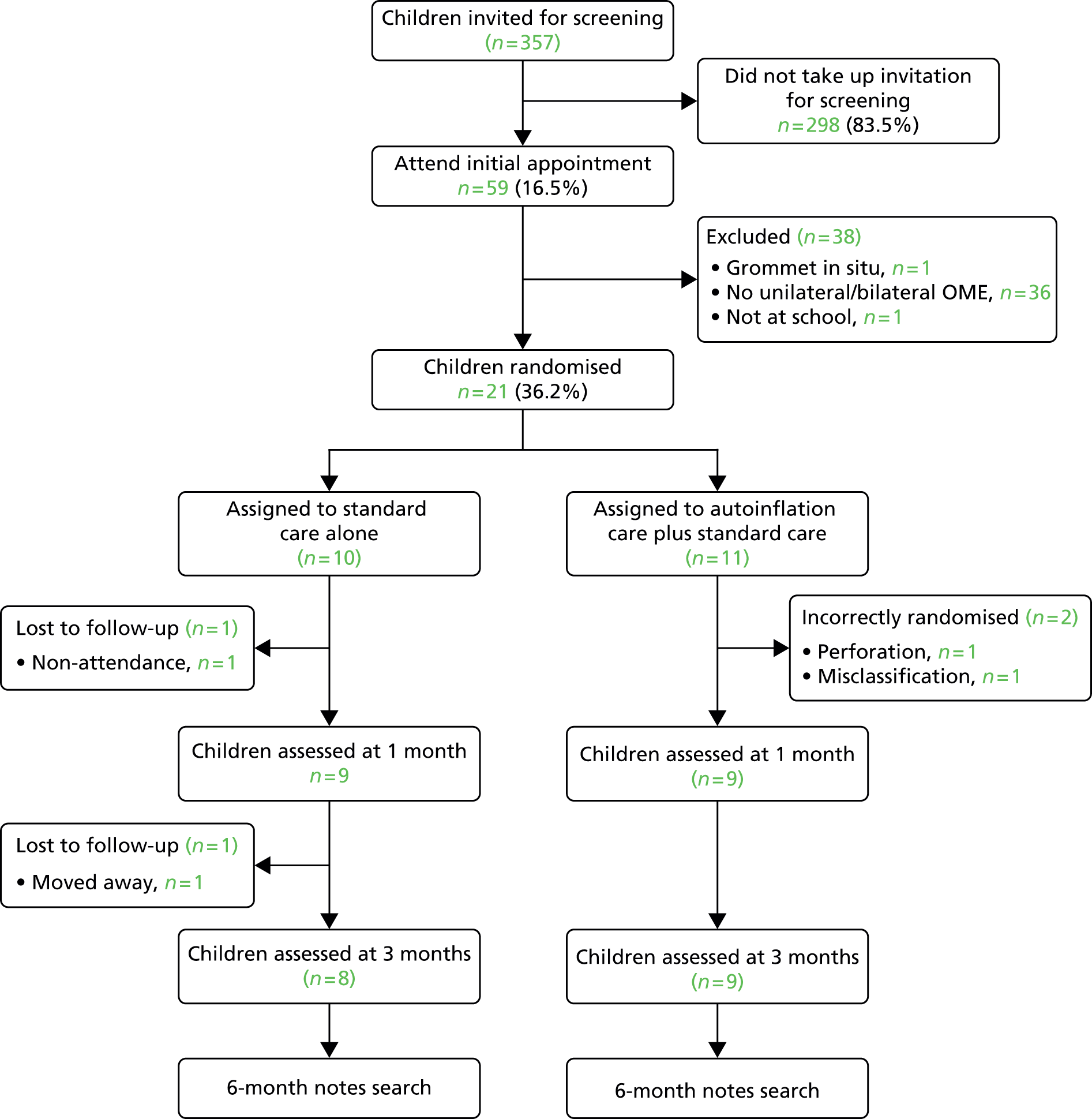

The pilot Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram, illustrated in Figure 2, details the numbers of children that progressed or otherwise through the study. Two children had to be excluded after randomisation, both in the autoinflation group, one because of an existing perforation of the eardrum and the second because of a tympanometric misclassification error, leaving 19 patients who were correctly randomised into the pilot.

FIGURE 2.

The pilot CONSORT diagram.

The baseline characteristics of children screened for the study are presented in Table 1 and all correctly randomised children are presented in Table 2.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at screening (years) | |

| 4–5 | 12 (21) |

| 5–6 | 32 (55) |

| 6–7 | 4 (7) |

| 7–11 | 10 (17) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 30 (52) |

| Female | 28 (48) |

| Variable | Autoinflation (n = 9), n (%) | Standard care (n = 10), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 5 (56) | 5 (50) |

| Male | 4 (44) | 5 (50) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 4–5 | 3 (33) | 2 (20) |

| 5–6 | 4 (45) | 8 (80) |

| 6–7 | – | – |

| 7–11 | 2 (22) | – |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 8 (89) | 9 (90) |

| Oriental | – | – |

| Afro-Caribbean | – | – |

| Bangladeshi/Indian | – | 1 (10) |

| Mixed | – | – |

| Other | 1 (11) | – |

Outcome measures

Objective resolution was defined by ear as change from at least one type B (fluid) to A/C1 (clear) tympanogram. Intermediate negative-pressure C2 tympanograms were considered insufficient evidence of clearance of fluid.

The main effects of autoinflation were estimated using the difference in proportions of children with fluid resolved between the two treatment arms at both 1 and 3 months.

The estimated difference between groups at 1 month based on the by-child results from Table 3 is 11.1% (95% CI –36.0% to 58.2%), which is equivalent to an OR of 1.75 (95% CI 0.20 to 14.20).

| Severity | Resolution | 1 month | 3 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoinflation | Standard care | Autoinflation | Standard care | ||

| Bilateral | Both ears resolved | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| One ear resolved | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Neither resolved | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Unilateral | Resolved | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Not resolved | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| % of children resolved (n/N) | 33.3% (3/9) | 22.2% (2/9) | 57.1% (4/7) | 44.4% (4/9) | |

The estimated difference at 3 months is 12.7% (95% CI –44.6% to 70.0%), which is equivalent to an OR of 1.7 (95% CI 0.2 to 12.2). This is comparable to the effect found in the meta-analysis from the Cochrane systematic review35 for full resolution (an OR of 2.4). The power calculation estimates for the main study were considered not to require revision by our statistician.

Compliance and use of the autoinflation device

Reported compliance was very high and consistent across both reward charts and parent-reported usage (Table 4). However, prospective use of a reward sticker chart was considered to be the most reliable method.

| Group | n | Reward chart (mean times per day) | Parent-reported frequency at 1 month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Mean number of times per day | |||

| Improved | 6 | 2.95 | All of the time, n = 5 | 3 |

| Most of the time, n = 1 | ||||

| Not improved | 3 | 2.70 | All of the time, n = 3 | 3 |

| Most of the time, n = 0 | ||||

Discussion

The pilot study under-recruited compared with the target set of 15 children per group. The main reasons for under-recruitment were twofold. First, delays in obtaining necessary ethics, governance and site permissions resulted in a late recruitment start date of January 2010, leaving only half the anticipated recruitment time frame (OME is a seasonal condition that substantially tails off around April). Second, the lowest recruiting of the four practices involved an enthusiastic GP who, because of time pressures, started recruitment extremely late.

A previous primary care trial estimated the need for 2940 children to be invited, in order to screen 1176 (40%), of whom 294 (25%) would be randomised. 30 Using the pilot CONSORT figures for a revision of the estimates, it was predicted that, of 5570 invitations for screening, 891 (16%) would respond and 294 (33%) would be randomised. This enabled a more precise estimate of practice recruitment and costs for the main study. More 4- to 6-year-olds than anticipated were identified, and approximately half of all those with symptoms who were screened were eligible and subsequently randomised. No parent/guardian of an eligible child refused consent for screening or to participate in the pilot, revealing very high acceptance rates for the study, and overall retention was good.

Web-based randomisation was the preferred option for site staff, and considered a more robust and inclusive system for randomisation, and was therefore implemented in the main study.

Children randomised to autoinflation were noted to be fully compliant with the method of autoinflation. No withdrawals occurred once children had started using the device. Feedback obtained from both parents and children about using the device was incorporated into subsequent training days for the main trial. Feedback included what to expect from the technique; the importance of prior stretching of new balloons; the need to involve the parents in demonstrating the method; and the need for persistence, especially over the first few days.

One child did experience nosebleeds while using autoinflation. The parent reported that the child had suffered from previous recurrent nosebleeds, but chose to continue with the study anyway. Dr Stangerup (Otovent inventor) told us that there had been no previous reports of nosebleeds as a complication of nasal balloon inflation (Professor Sven Eric Stangerup, University of Copenhagen, 2011, personal communication). However, it was decided on review that it would be best to avoid any such prior histories based on a degree of hypothetical risk. A new exclusion criterion was therefore added (Box 2).

-

Change in method of randomisation: a continuously available web-based randomisation, instead of telephone randomisation, would be employed for the main study.

-

Additional exclusion criterion: an additional exclusion criterion would be added to the main study as follows: ‘A recent nosebleed in the previous 3 weeks, or more than one episode of nosebleeds in the preceding 6 months’.

-

Web-based hearing test [Two Alternative Auditory Disability and Speech Reception Test (TADAST)]:27 the TADAST forced-choice hearing disability test (previously evaluated in primary care) would be used as a baseline and 1-month measure. It was agreed that this would be optional in the main study and used in secondary analyses.

-

An improved, pragmatic version of the OM8-30 questionnaire (OMQ-14):20,21,30 the OMQ-14 became available courtesy of Professor Mark Haggard and was used in the main study. Database analyses showed that the OMQ-14 retained the validity, sensitivity and reliability for the most important symptoms and concerns of relevance for primary care, and was anticipated to have better completion rates that the longer OM8-30 and would be more amenable to primary care use.

The trial materials and operating manual were deemed satisfactory and were well accepted. The pilot study highlighted that not all nurses were confident with tympanometry, and three nurses would have liked additional training in use of the machine and interpretation (Box 3).

-

Trial management: the trial management group suggested revising the research management structure to allow for recruitment to be co-ordinated from Southampton with close supervision from the chief investigator once the trial design had been finalised and data collection tools and other trial materials had been finalised. The PCVC-CTU would continue to provide Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) supervision and expertise in data management and statistics.

-

Improved support for nurses: regional training days with an audiologist and the Otovent suppliers, and improved tympanometric support by the management team (fax and telephone) for screening and recruitment purposes were recommended for the main study.

-

Recruitment: more precise recruitment logistics and costing were made for the main study. It was agreed to use trained RNs rather than GPs (for whom time pressures were considered to be greater). Owing to the seasonal nature of OME, it was agreed to push for recruitment before the Christmas period to increase uptake.

Conclusion

This small-scale study, once under way, was successful in recruiting patients, compliance was excellent and no major protocol changes were needed for the main study and costing was improved. A great number of useful and practical points were learned from the study, in both a systematic and informal way, from parents and nurses. The overall performance of the pilot was encouraging and appeared sufficient in terms of recruitment and in answering what was felt to be the major unknown issue about whether or not children were able perform the technique and achieve sufficient compliance over 1 month in a primary care setting. 35

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design

We conducted an open, pragmatic RCT in primary care. We examined the difference in effectiveness between regular autoinflation with standard care and standard care alone.

Setting

The study was set in primary care in three regions of England: the South West, Thames Valley and Cheshire regions. The main study recruited children from 43 family practices from 17 UK PCTs, between January 2012 and February 2013.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was awarded by the NRES on 10 August 2009, reference number 09/H0504/75 (see Appendix 1), and local research governance approval was obtained from all participating PCTs.

Recruitment and training of research nurses

Practices were recruited to the study by the PCRNs. At each practice a GP acting as principal investigator and a RN were assigned to the study. Practices were reimbursed for nurse time by the Department of Health service support costs.

Recruitment of practices

A total of 50 general practices were recruited to the study, of which 43 practices actively screened and randomised children during the study period (Tables 5 and 6). During winter 2011, 39 practices received training; seven did not continue to patient screening because of practice withdrawal (n = 3), slow start (n = 2), staff illness (n = 1) or research governance delay (n = 1). In order to maximise recruitment, an additional 11 practices were trained in autumn 2012 to replace nine low-/non-recruiting practices from the first season. Reasons for low recruitment included change in nursing staff (n = 3), practice withdrawal owing to other commitments (n = 2), recruitment problems (n = 1) and small practice list size that limited further recruitment (n = 1).

| PCRN/PCT | Number of practices (n = 43) |

|---|---|

| PCRN South West | 27 |

| Bath and North East Somerset | 4 |

| Bournemouth and Poole | 1 |

| Dorset | 1 |

| Gloucestershire | 2 |

| Hampshire | 9 |

| Somerset | 3 |

| Southampton City | 1 |

| Wiltshire (North, East and West) | 5 |

| Wiltshire (South) | 1 |

| PCRN Thames Valley | 13 |

| Berkshire East | 1 |

| Berkshire West | 3 |

| Milton Keynes | 1 |

| Oxfordshire | 8 |

| Cheshire CLRN | 3 |

| Central and Eastern Cheshire | 3 |

| Characteristics | Number of practices (n = 43) |

|---|---|

| Practice list size | |

| 1–4999 | 3 |

| 5000–14,999 | 32 |

| 15,000+ | 8 |

| Number of GP partners | |

| 0–5 | 15 |

| 6–10 | 21 |

| 11–15 | 6 |

| 16+ | 1 |

| Deprivation score | |

| High | 1 |

| Mid | 11 |

| Low | 31 |

| Main duties of participating research staff | |

| Practice nurse fitting in research around other duties | 24 |

| RN within GP practice | 13 |

| RN from outside GP practice | 3 |

| GP conducting research | 3 |

Training of research personnel

Five regional training days took place between November 2011 and January 2012 in Southampton (n = 2), Chippenham (n = 1), Oxford (n = 1) and Nantwich (n = 1). This provided convenient training locations for RNs and helped establish good and effective communication between RNs and the study team. One practice received on-site training and three practices requested additional pre-study visits from the study manager. One further training day took place in September 2012 (Oxford) for the 11 additional practices.

The training days involved the chief investigator, the trial co-ordinator, an audiologist, PCRN observers and a company representative. Study aims and methods were comprehensively covered. These included procedures for identifying and screening patients, taking consent, how to perform web-based randomisation, patient assessment and data management. A training manual was provided giving full details of the study methods and outcome assessments. Training in otoscopic examination and tympanometry was provided by the chief investigator and an audiologist from Starkey Laboratories Ltd, who gave detailed information and a practical demonstration of the technology and interpretation of the tympanometric results. This included classification of the four main types (A, C1, C2 and B) of tympanograms, recognition of obstructing wax, perforations, grommets and appropriate canal volumes for age, etc. Nurses had the opportunity to practise and refine their techniques during the training day. Brief training in the correct use of the autoinflation device (Otovent) was given by a representative from the suppliers (Kestrel Medical Ltd). All nurses or recruiting GPs had current training in GCP by the start of the trial.

As a means of additional support and training, nurses were invited to fax their initial screening tympanograms to the co-ordinating centre, where they were independently reviewed for categorisation based on all available parameters and observations. Any discrepancies in tympanometric classification were then fed back to nurses to help improve their precision of diagnosis in the field. Extra on-site training was offered by two experienced members of the study team where requested. Regional meetings were scheduled at the start of the second recruitment season to provide a study update and a further review of tympanometry and interpretation.

Recruitment of children

Participating practices were asked to invite 140 children as a target for screening. It was conservatively estimated from the pilot study that the proportion of invited children who would be recently symptomatic and/or whose parents would have concerns and who would, therefore, attend for screening would be 16%, and that one-third of these would be eligible for randomisation (140 children invited; 22 screened; and seven randomised in each participating practice, i.e. 1 in 20 children).

Children were identified by practice-based computer search or opportunistic case finding by practitioners, nurses and health visitors as follows.

Computer searches

-

High-risk children, that is those aged 4–6 years, were identified from practice age/sex registers and those with one or more OME-related symptoms or concerns in the previous 3 months were invited for screening.

-

An audit of the attendance records of 7- to 11-year-old children identified those with ear-related problems in the previous year.

Opportunistic case finding

-

General practitioners, nurses and health visitors identified children leading to an in-practice referral to the RN.

The parents of children identified for the study received an invitation letter and information sheet, and children received an age-appropriate information sheet (see Appendices 2 and 3). Parents gave written informed consent for screening and children were invited to give written assent if deemed appropriate by the RN (see Appendix 4). Table 7 shows features of study entry by practice and PCT.

| PCRN/PCTs | Participating practices | Number of children screened | Number of children randomised |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCRN South West | 27 | 843 | 212 |

| Bath and North East Somerset | 4 | 84 | 18 |

| Bournemouth and Poole | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Dorset | 1 | 66 | 11 |

| Gloucestershire | 2 | 92 | 22 |

| Hampshire | 9 | 316 | 81 |

| Somerset | 3 | 126 | 34 |

| Southampton City | 1 | 24 | 5 |

| Wiltshire (North, East and West) | 5 | 116 | 37 |

| Wiltshire South | 1 | 14 | 4 |

| PCRN Thames Valley | 13 | 253 | 77 |

| Berkshire East | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| Berkshire West | 3 | 23 | 6 |

| Milton Keynes | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| Oxfordshire | 8 | 211 | 67 |

| Cheshire CLRN | 3 | 139 | 31 |

| Central and East Cheshire | 3 | 139 | 31 |

| Total | 43 | 1235 | 320 |

At the screening visit, the RN checked both ears for any obstructing wax, perforations or grommets using otoscopy. If the ear canal was occluded with wax, olive oil ear drops were recommended to soften and disperse the wax, and rescreening was rescheduled. Tympanometric screening was performed to assess full eligibility for the study, that is, every symptomatic child had to have one or two type B tympanograms confirming the presence of uni- or bilateral OME (Table 8 shows details of tympanometric classification used). This examination was requested to be repeated wherever the interpretation was unsatisfactory or inconclusive. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Box 1.

| Tympanometric classification | Middle ear pressure | Tympanogram | Positive predictive value for OME |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | +200 to –99 | Peak | Normal |

| Type C1 | –100 to –199 | Peak | Normal |

| Type C2 | –200 to –399 | Peak | 54% |

| Type B | –400 | Flat trace | 88% |

Randomisation and masking

Eligible children were individually randomised to autoinflation plus routine care or routine care alone within 1 week of screening. An independent external agency provided a centralised web-based randomisation system (www.sealedenvelope.com) for nurses to access while recruiting children to the study. The Oxford Primary Care CTU independently managed, co-ordinated, analysed and checked the data validity. The randomisation used an algorithm with minimisation based on three potential effect modifiers/confounders: age (< 6.5 years vs. > 6.5 years), sex and baseline severity of OME (one vs. two baseline type B tympanograms). 18 Owing to the nature of the intervention, use of placebo was not possible and therefore nurses, children and families were not masked to treatment allocation.

Trial intervention

The simple autoinflation treatment used in this trial involved inflating a purpose-manufactured balloon (Otovent), by blowing through each nostril into a connecting nozzle three times per day for 1–3 months (Figure 3). 55,56,60,61,73 Children in the treatment arm were instructed by watching the nurse and/or parent demonstrate the procedure, starting with stretching the balloon (by hand or mouth blowing). A website, which included a short instruction video, was also available as a back-up for parents and children (www.gluear.co.uk). A sticker book was provided to encourage the child’s ongoing participation. Children still recording a type B tympanogram in either ear at 1 month were advised to continue with nasal balloon autoinflation for a further 2 months. All study children (both arms) received their usual/routine clinical care as normal. At the end of the 3-month clinical study period, children in the standard care arm with tympanometric evidence of glue ear were offered a 1-month supply of nasal balloons.

FIGURE 3.

Nasal balloon autoinflation (Otovent). Reproduced with permission from Kestrel Medical Ltd.

Assessments

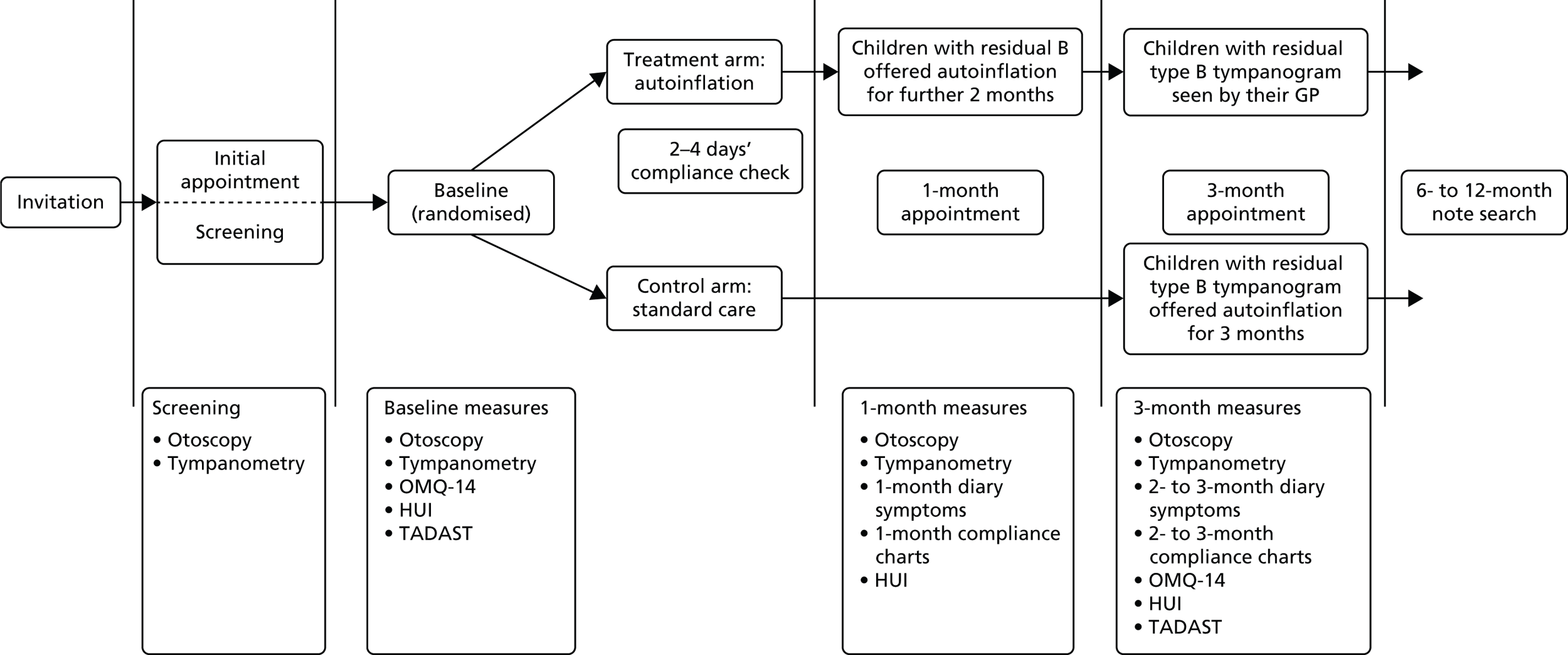

Baseline assessment was conducted within 1 week of screening. Parents of children in the intervention group were routinely contacted by telephone after 3 days to provide additional support for autoinflation, if required. All children were followed up at 1 and 3 months (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Flow of participants through the main study.

Advanced appointments were made for the next follow-up assessment at each visit and an appointment card given. A postcard reminder was sent 1 week before the next appointment to encourage attendance. In the case of non-attendance, the RN was asked to attempt contact twice by telephone and twice with a missed appointment card, after which the patient was considered lost to follow-up.

Withdrawals

In accordance with GCP, parents/guardians were free to withdraw their children from the study at any time without affecting their medical care. Children were withdrawn from the study in the event of incorrect diagnosis at the time of randomisation (no type B tympanogram confirmation).

Outcome measures

Children were assessed for the most important clinical outcomes at 1 and 3 months post randomisation over a recommended 3-month waiting or monitoring period, over which time natural resolution effects would be expected to occur in some children. 3,5,6 It was anticipated that, if the method was effective, it would most likely be at 1 month, when taking into account poor compliance reported in one secondary care study,58 and implied or suggested concerns for general use and durability of the method in primary care. 1,35,37,74 Health economic outcomes were collected for 1, 3 and 12 months. With the protocol indicating that routine care should not be affected in any way during the clinical phase (3 months) of the study, referrals in particular would be difficult to assess without longer-term follow-up (12 months). The flow diagram for the main study was essentially unchanged from the pilot except that (1) the OMQ-14 replaced the OM8-30 at baseline and 3 months; (2) the TADAST hearing performance test (see Two alternative auditory disability and speech reception tests hearing test) was added at baseline and 1 month; and (3) a notes audit for HE purposes was completed up to 12 months post randomisation.

Main outcomes

Primary outcomes in children at 1 and 3 months

-

The primary outcome was dichotomous: the difference in the proportion of children showing definite tympanometric resolution (from a type B tympanogram to a type A or C1 tympanogram, i.e. back to normal middle ear pressures) in at least one affected ear at 1 month. Intermediate negative-pressure C2 tympanograms were considered insufficient evidence of resolution of fluid, that is, not classified for analysis purposes as resolved (see Table 7). 69,71 Tympanometry has better test characteristics for the presence of effusion than history and/or simple otoscopy, and is thus a good choice for primary care studies, in which it has been shown to be a reliable diagnostic instrument. 1,18,24,31,36 It provides a reasonably objective outcome measure that can also be assessed blind to allocation arm. Two members of the trial team, trained in tympanometry, independently reviewed anonymised tympanometry printouts (for the main 1- and 3-month outcomes, see Tympanometric assessments). Cases of disagreement were settled by an independent audiologist. All MTP-10 micro-tympanometers (Interacoustics, Assens, Denmark), previously used in the GNOME study,18,30 were recalibrated by PC Werth Ltd prior to the start of the study and subsequently on an annual basis while in use.

-

The difference in the proportion of children showing definite tympanometric resolution (of a type B tympanogram to a type A or C1, i.e. back to normal middle ear pressures) in at least one affected ear at 3 months was considered a second main outcome and is justified as above and in accordance with guideline suggestions for the monitoring period duration. 1,2

Secondary outcomes

Tympanometric resolution based on ears as the unit of analysis

Differences in the proportions of ears by group that show resolution (from type B to A/C1) at 1 and 3 months was a secondary outcome. This is justified as a means of demonstrating efficacy that provides additional power by using the data from both ears. Ears are not independent variables and previous trials that have not taken into account the correlation between ears in the analysis, resulting in overly precise CIs, have been justifiably criticised. Such outcomes are included in the main Cochrane meta-analyses, with post-hoc adjustments to account for this correlation. 35 Generalised estimating equations can be used to adjust the analysis for the non-independence of ears in a pre-specified manner. Thus, these robust outcomes are useful to demonstrate efficacy of the method in actually clearing children’s ears of effusions. However, such, and indeed all, tympanometric outcomes require additional clinical confirmation of effectiveness to better inform a child-centred management model of OME. 19,34,35,75

Non-tympanometric clinical outcomes

Ear-related QoL was measured at 3 months using the OMQ-14 (see OMQ-14 impact measures). Parents completed weekly diaries to record symptoms, adverse events and compliance, and also HUI version 3 (HUI3),76,77 with resource use questionnaires at baseline, 1 and 3 months to inform a HE analysis. Pure-tone audiometry was not conducted, as it cannot be done with adequate precision in non-specialist and noisy settings, and correlates only weakly with child and family QoL.

OMQ-14 impact measure

The OMQ-14 is a 14-item PROM developed by a process of extensive statistical refinement and iteration from two large primary and secondary care UK trials on OME [GNOME/TARGET (Trial of Alternative Regimens of Glue Ear Treatment)]9,18 and further evaluated in ongoing cohort/audit data sets from across Europe (Eurotitis 2) (Professor Mark Haggard, University of Cambridge, 2010, personal communication). 21 It is a functional health status measure that is reported by proxy. As a shortened form of the OM8-30,18,19,21,30,75,78 the 14 items selected have been demonstrated to efficiently optimise item mapping on to the HUI. 20 As a questionnaire it is simpler to administer and has better completion rates with fewer missing data than the longer OM8-30 (cf. HTA report for GNOME, where the missing outcome data was disappointing). 30 Its brevity also makes it more suitable for primary care use. It measures three domains found to map on to QoL in primary care: reported hearing difficulty and speech concerns; behavioural and developmental impact; and ear-related physical ill health. 21 It was decided a priori in the statistical plan to use the total instrument score (the OMQ-14 score used here is not the total integer ‘quick score’ intended for rapid field use, but the more precise decimal QoL-weighted sum of the three factor scores mentioned; the used version is slightly more precise) as the single most useful measure for family practice (and to avoid data dredging). The OMQ-14 total score refers to the 3-month period prior to completion, and in this study was completed at baseline and at 3 months (see Appendix 5). A standard deviation (SD) change of ≈0.3 in score is considered a clinically important effect for the child and family in terms of ear-related QoL.

Parent-reported symptom diary

Parents were asked to complete a weekly diary recording the number of days (0–7) of their child’s main symptoms of hearing loss, earache, difficulty concentrating, pain relief, disturbed sleep and absence from school.

In addition, a second diary of items was included to systematically record a number of other symptoms including nosebleeds, clumsiness/off-balance, systemic illness, nasal discharge and nasal congestion/snoring. Symptoms considered potentially adverse were collected on an adverse event form and some of these overlapped with the diary symptoms.

Two alternative auditory disability and speech reception tests hearing test

Hearing disability was evaluated at baseline and at 1 month for all children using the TADAST web-based test. TADAST is a forced-choice test, originally developed in primary care, that evaluates hearing disability associated with glue ear, and which has shown good test–retest repeatability in 4- to 11-year-old children. 27,79 Parents received an instruction card with details to log on to the new website at home after the baseline and 1-month assessments.

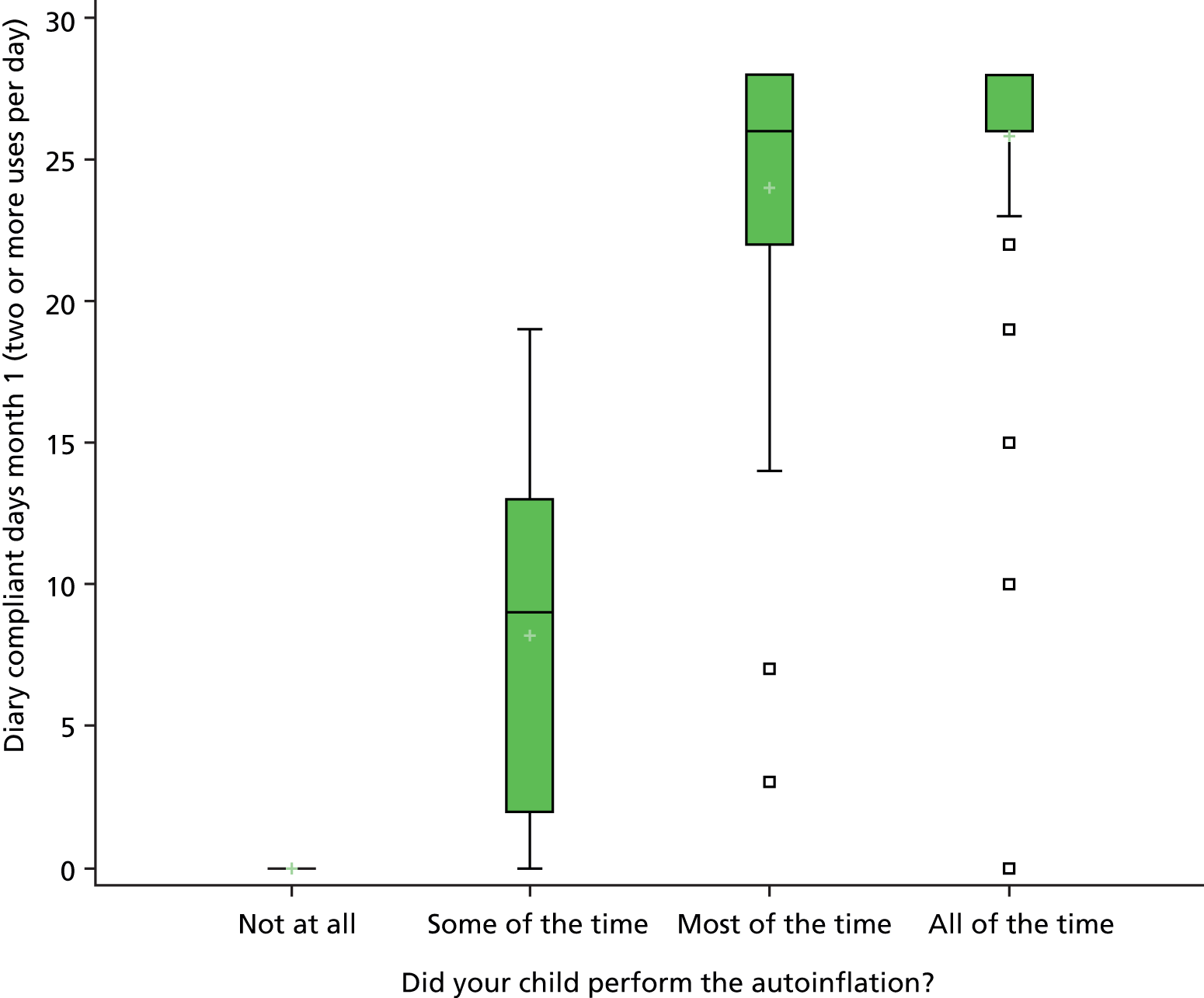

Compliance with the intervention

Compliance measures allow for the assessment of experiences of using the Otovent device (see Chapter 6), as concerns have been raised regarding what age autoinflation can be reliably performed. 80 All parents in the intervention group were contacted 2–4 days after the baseline visit primarily as a supportive measure but also to assess their compliance. If the parent reported problems with the autoinflation technique or adherence, a follow-up visit with the RN was offered so the parent/child could be given further specific tips and education about improving the technique, based directly on observation of use.

A sticker book diary was used to record compliance with the intervention, with children placing a sticker in the diary each time they inflate the nasal balloon. Parent-reported adherence was also recorded at the 1- and 3-month assessments (when use of the device was recorded as not at all, some of the time, most of the time and all of the time) and compared with the sticker book diary.

Parents of children in the standard care group were asked if Otovent had been used independently either because of self-purchase or because it was inadvertently prescribed during the study period.

Adverse events

The RN specifically asked parents about the occurrence of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and nosebleeds at the 1- and 3-month assessments. In addition, the RN inspected the symptom diary for any further information. Serious adverse events were reported by fax to the co-ordinating centre within 24 hours of the practice being made aware of the event. The co-ordinating centre’s standard operating procedures were followed with respect to reporting to the sponsor, the Research Ethics Committee, the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC)/Trial Steering Committee and governance offices. Annual safety reports were submitted to the Research Ethics Committee.

Changes to the protocol

The majority of these were made as a result of the pilot study and are described in Chapter 2. During the main study a total of four substantial amendments were approved by the ethics committee and comprised minor changes to the study documentation, addition of a qualitative evaluation, a 12-month notes review (instead of 6 months post baseline) and a refinement to the study closure strategy, which allowed for a slight overshoot of recruitment. Full details are presented in Appendix 1.

Data management, cleaning and validation

All trial data were captured on paper case-report forms or participant-completed questionnaires. Trial data were tracked and managed using a clinical data management system [Open Clinica EnterpriseTM (OpenClinica LLC version 3.1, Waltham, MA, USA)]. Preliminary monitoring of received trial data was performed to assess completeness of forms, and compatibility and consistency of paperwork bundles in relation to participant identifiers. All trial data were double entered by two independent users. Self-evident modifications to captured data (correction of spelling errors, conversions, date formats, obvious updates based on supplementary data) were applied to reduce the number of data queries sent to the research sites. Responsible personnel at each research site reviewed and authorised a list of all prospective modifications. Validation of data was performed in three main ways:

-

On entry, programmed rules and range checks to highlight missing or inconsistent data would fire if predetermined conditions were met.

-

Listing checks were employed to identify potential discrepancies across participant visits/forms.

-

Review of the data set to identify discrepant, missing or outlying data was performed when participants completed their study schedule.

Requests for missing responses or clarification of inconsistent data (queries) were sent to the RNs at regular intervals to increase the likelihood of resolution.

Tympanometric assessments

Screening: finding cases

Tympanograms from 1104 of 1235 children screened (89%) were faxed to the co-ordinating centre soon after initial assessment as part of ongoing training in interpretation and to improve precision of diagnosis prior to randomisation. Only 55 of 2207 (2.5%) tympanograms (ears) were uninterpretable owing to poor technique or wax on expert review. All available data were used in the assessments, including otoscopic findings, shape of the curve, pressures, gradients and canal volume. The tympanogram classifications recorded in the database reflect the assessment made by the trial manager and/or chief investigator. Where these differed from the nurse classification, a data query was issued.

Outcome assessments

Tympanogram data captured from all follow-up assessments were retained as captured by the RN at the time of the patient assessment and a data query was issued only in the case of missing classifications. Tympanogram data collected during the follow-up assessments were reviewed in a separate fully anonymised process by the trial manager and chief investigator. For all tympanogram type classifications (A, C1, C2 and B), the expert inter-rater agreement was 89%. In all cases of disagreement, a blinded independent audiologist adjudicated. The reviewed outcome data were blinded to study identification number and treatment group. The final determined classifications for reviewed tympanogram data were entered into the clinical database using double data entry, consistent with all other data. These blinded agreed expert data assessments were the ones used in the final efficacy analyses at 1 and 3 months.

With regard to nurse interpretation of tympanometry and classification of all available ears, the summary level of agreement beyond chance between the nurse interpretation and the agreed blinded expert interpretation as the standard found substantial agreement that improved throughout the study (Table 9). 81

| Time point | n (ears) | Kappa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 548 | 0.706 (0.689 to 0.771) |

| 3 months | 497 | 0.792 (0.782 to 0.823) |

Once all the follow-up assessment data were received, a 100% critical item review was performed on all tympanogram data and any inconsistencies rectified, particularly in the case where multiple tympanogram readings were taken during one assessment. The entire data set was then reviewed for inconsistencies and any further missing data points, before conducting a final quality control check on all data received for 19 patients randomly selected from all those recruited to the study. The final error rate was calculated to be 0.00% for critical items (tympanogram data) and 0.04% across all data points.

Statistical validation

Validation of all results presented in this report was conducted by Ly-Mee Yu, Oxford CTU. All results/major end points/primary end points were validated by independent programming using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Statistical methods

A detailed statistical analysis plan was developed at the start of the study.

Definition of populations used

Screened population

The screened population comprises all children who attended for the initial appointment and gave written informed consent.

Intention-to-treat population

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population comprises all children, out of those randomised, for whom tympanometric readings are available.

Per-protocol population

The per-protocol (PP) population comprises those randomised who satisfied the study eligibility criteria, received their allocated intervention, who did not used any autoinflation devices other than those provided for the study purposes and who used autoinflation at least twice per day for at least 70% of their treatment period during the first month. Children who presented more than 7 days before or after the scheduled 1-month visit date were considered not to have complied with the trial protocol and were excluded from the PP population.

Safety population

The safety population comprises all randomised children.

Primary analyses

The primary analysis was based on the ITT population. The proportion of children in each group with tympanometric resolution in at least one affected ear at 1 month (primary outcome) was compared using a generalised linear model with log-link function. 82 Results are presented as adjusted RRs with 95% CIs. The regression model83 adjusts for pre-specified baseline covariates: tympanometric baseline severity (one or two type B tympanograms), age, sex and PCT. Sensitivity analyses are performed on ITT and PP populations.

Multiple imputation of all missing data was performed using baseline variables as per the statistical plan: use of antibiotics, eczema, hay fever, asthma, age, sex, baseline severity, baseline OMQ-14 and follow-up OMQ-14 weighted scores. Multiple imputed data sets were created using Stata version 13 and the ‘ice’ and ‘mim’ functions. 84

For the 1-month ear-based analysis of tympanometric resolution, the non-independence (correlation) of the ears was adjusted for using generalised estimating equations with an independent working correlation structure. 85,86

Secondary analyses

Subgroup analyses

Four subgroups were compared using interaction tests on the primary outcome of resolution in at least one ‘B’ ear by 1 month. The subgroups considered were those described in the protocol, namely:

-

age: < 6.5 years or ≥ 6.5 years

-

severity: one or two B-type ears at baseline

-

OMQ-14 standardised total score: < 0 or ≥ 0

-

sex.

No interaction tests were significant; thus, results are not presented according to subgroups. The p-values ranged from 0.25 to 0.50.

Tympanometric resolution at 3 months

The analysis of the 3-month secondary end points by both child and ear were analysed in the same way as the primary end point using a generalised linear model that adjusts for a limited number of pre-specified baseline covariates.

Other tympanometric outcomes were analysed as per the statistical plan. Tympanometric deteriorations in normal ears at baseline were evaluated for potential confounding of results. However, as very few deteriorations occurred, no further analyses of this end point were undertaken.

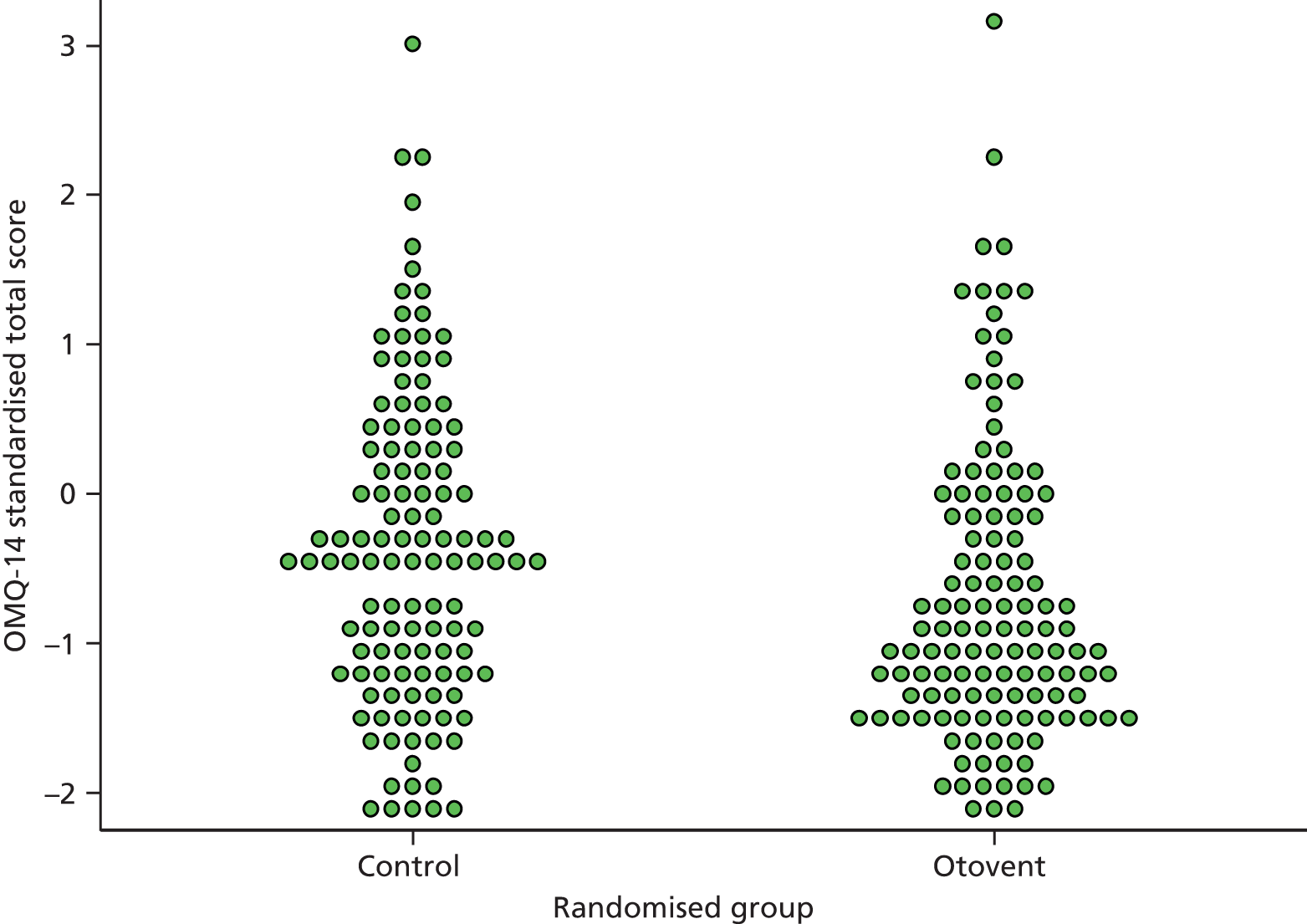

Quality of life (OMQ-14)

The OMQ-14 standardised total scores at baseline and 3 months were calculated based on weightings provided by Professor Mark Haggard and Helen Spencer of the Eurotitis-2 Study Group (Cambridge University, 2011, personal communication). Standardised OMQ-14 change from baseline scores were analysed using a linear mixed-effects model with PCT as a random effect, and age, sex, baseline severity and OMQ-14 baseline score as fixed effects. Summary statistics for baseline and follow-up (3-month) standardised OMQ-14 scores are presented. Higher scores represent worse outcomes. The average change from baseline score is compared between groups. Questionnaires with more than four missing items were pre-specified as indicating separate analysis; however, this applied to only one person so no sensitivity analysis was carried out.

Diary card

Diary card symptom counts were quite skewed, with fewer children/parents reporting multiple diary symptoms. For this reason standard linear models could not be used to analyse these data and they were instead classified into categories based on the total number of weeks with symptoms (0, 1–7, 8–28, 29 + days). Category boundaries were decided on prior to data lock and were detailed in the amendment to the statistical analysis plan.

Data were analysed using an ordinal logistic regression model. 87 The model is an extension of the standard logistic regression model used for binary data, but allows for more than two categories for the outcome. The OR from an ordered logistic regression expresses the odds of being in a higher ordered category (i.e. more days with symptoms) when in the autoinflation group compared with the standard care group. Models were adjusted for age and sex as before.

Outputs from the analyses are displayed alongside a summary of the data for the 1- and 3-month diary cards.

Two Alternative Auditory Disability and Speech Reception Test

The TADAST score was a continuous variable out of a total of 36, with a chance score of 16 out of 36 to be compared between groups. However, because of problems with the website and late ethics permission, insufficient numbers of children completed the follow-up test (seven children at 1 month and two children at 3 months), so results are not presentable.

Sample size calculation

A 45% control resolution (improvement) rate at 1 month was anticipated in the calculations, as found in the previous GNOME trial. 18 The best estimates for the expected difference at 1 month were based on a meta-analysis of four small secondary care trials that used Otovent, included in the update for Cochrane. 35 Thus, for resolution at 1 month, the most conservative evidence-based estimate of effect size was an OR of 2.4. Given this effect size, 250 children were required (125 in each group) for a standard α = 5% and power = 90%. With 15% lost to follow-up, 295 were needed in total (for power = 80%, 226 were needed in total). The sample was also powered to detect a ≈0.3 SD effect on continuous variables such as the OMQ-14 total score at 3 months, which was deemed clinically significant.

Changes to the statistical analysis plan

-

Analyses were not completed using Stata version 11.2 (which is now an old version) but rather SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

-

Twenty multiply imputed data sets were created for the sensitivity analysis of the primary end point rather than the five data sets specified, as more data sets result in more robust estimates.

Chapter 4 Results

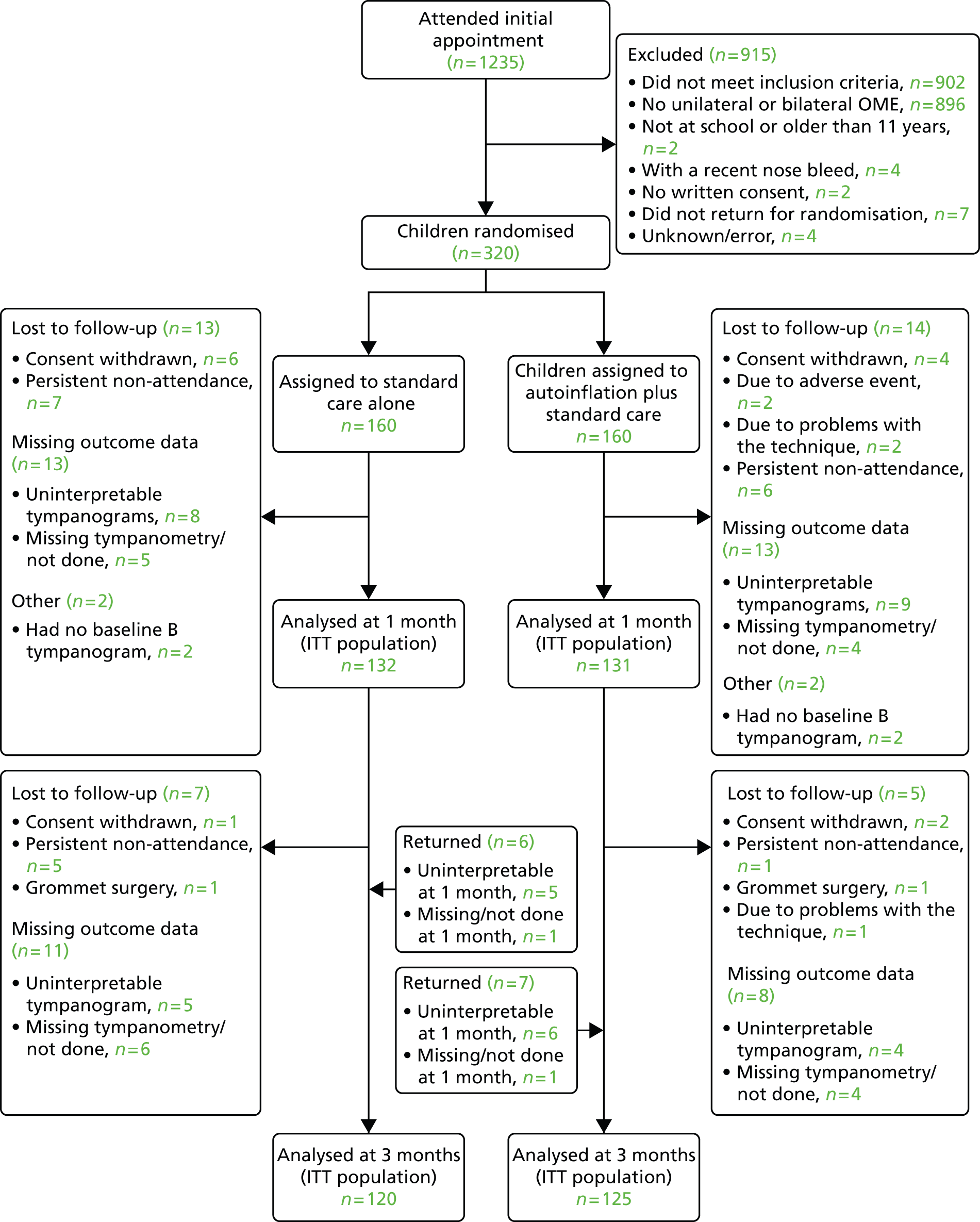

Recruitment and trial flow profile

Screening commenced in December 2011. The first patient was randomised in January 2012 and the last child was randomised in February 2013. A total of 1235 children were screened, with 320 children (26%) randomised into the study over a period of 13 months. Table 10 displays the characteristics of screened children. The main reasons for ineligibility were no type B tympanogram, not currently at school or a recent nosebleed. Ineligible children reported fewer symptoms associated with OME in the preceding 3 months, and had fewer consultations for otitis media and OME in the previous 12 months.

| Variable | Randomised, n (%) (N = 320) | Screened only, n (%) (N = 1235) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 153 (47.8) | 429 (46.9) |

| Male | 167 (52.2) | 485 (53.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 4 | 58 (18.1) | 158 (17.3) |

| 5 | 147 (45.9) | 370 (40.4) |

| 6 | 77 (24.1) | 250 (27.3) |

| 7 | 21 (6.6) | 53 (5.8) |

| 8 | 8 (2.5) | 23 (2.5) |

| 9 | 6 (1.9) | 29 (3.2) |

| 10 | 3 (0.9) | 13 (1.4) |

| 11 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (1.7) |

| 12 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Was this child recruited from: | ||

| 4- to 6-year-old list | 265 (82.8) | 758 (82.8) |

| 7- to 11-year-old list | 21 (6.6) | 103 (11.3) |

| GP/nurse/health visitor referral | 34 (10.6) | 50 (5.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) |

| A prolonged or bad cold, cough or chest infection | ||

| No | 37 (11.6) | 178 (19.5) |

| Yes | 262 (81.9) | 662 (72.3) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 75 (8.2) |

| Appears to be lip reading | ||

| No | 240 (75.0) | 756 (82.6) |

| Yes | 57 (17.8) | 84 (9.2) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 75 (8.2) |

| An earache | ||

| No | 124 (38.8) | 504 (55.1) |

| Yes | 175 (54.7) | 336 (36.7) |

| Missing | 23 (7.2) | 75 (8.2) |

| Not doing as well at school as you or the teacher reasonably think | ||

| No | 219 (68.4) | 680 (74.3) |

| Yes | 79 (24.7) | 157 (17.2) |

| Missing | 22 (6.9) | 78 (8.5) |

| Often mishears what is said | ||

| No | 61 (19.1) | 323 (35.3) |

| Yes | 238 (74.4) | 516 (56.4) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 76 (8.3) |

| Has noises in the ear or is dizzy | ||

| No | 225 (70.3) | 674 (73.7) |

| Yes | 73 (22.8) | 163 (17.8) |

| Missing | 22 (6.9) | 78 (8.5) |

| Hearing loss is suspected by anyone | ||

| No | 154 (48.1) | 606 (66.2) |

| Yes | 144 (45.0) | 232 (25.4) |

| Missing | 22 (6.9) | 77 (8.4) |

| Snores, blocked nose or poor sleep | ||

| No | 81 (25.3) | 318 (34.8) |

| Yes | 218 (68.1) | 522 (57.0) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 75 (8.2) |

| Says ‘eh what?’ or ‘pardon’ a lot | ||

| No | 50 (15.6) | 252 (27.5) |

| Yes | 249 (77.8) | 587 (64.2) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 76 (8.3) |

| Speech seems behind other children’s | ||

| No | 239 (74.7) | 689 (75.3) |

| Yes | 60 (18.8) | 152 (16.6) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 74 (8.1) |

| Needs the television turned up | ||

| No | 119 (37.2) | 505 (55.2) |

| Yes | 180 (56.3) | 333 (36.4) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 77 (8.4) |

| Any suspected ear problem | ||

| No | 177 (55.3) | 675 (73.8) |

| Yes | 122 (38.1) | 164 (17.9) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 76 (8.3) |

| May be irritable or withdrawn | ||

| No | 207 (64.7) | 633 (69.2) |

| Yes | 92 (28.8) | 205 (22.4) |

| Missing | 21 (6.6) | 77 (8.4) |

| Observational register – was the child recruited from: | ||

| Computer records | 284 (88.8) | 859 (93.9) |

| Referral | 36 (11.3) | 53 (5.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) |

| How many episodes of OME have they had in the last 12 months? | ||

| 0 | 234 (73.1) | 787 (86.0) |

| 1 | 42 (13.1) | 69 (7.5) |

| 2 | 17 (5.3) | 14 (1.5) |

| 3 | 3 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) |

| 4 | 6 (1.9) | 2 (0.2) |

| 6 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 7 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Missing | 17 (5.3) | 32 (3.5) |

| How many episodes of OM have they had in the last 12 months? | ||

| 0 | 195 (60.9) | 678 (74.1) |

| 1 | 67 (20.9) | 154 (16.8) |