Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/80/01. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Caroline Fairhurst, Sarah Cockayne, Sara Rodgers and David Torgerson all report other grants from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Clark et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Heart failure

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome that arises when the heart fails to pump in a manner adequate to meet the body’s needs. It is increasingly common and affects between 1% and 2% of the UK population. Its incidence and prevalence rise markedly with age. 1 The most common cause of heart failure is myocardial infarction and, as more people survive acute myocardial infarction with modern therapy, so the population of patients with damaged heart muscles grows. 2

Heart failure is the single most common cause for admission to hospital in England and Wales and, following admission to hospital, there is a 25% chance of readmission or death within 12 weeks. By 1 month after an index admission, 15% of patients have died, either as an inpatient or during the days following discharge. 3 The prognosis of heart failure is bleak if it is not well treated. However, one of the greatest success stories of modern medicine is the dramatic improvement in prognosis for patients with chronic heart failure (CHF). Good medical management largely consists of medicines designed to block the adverse consequences of neuroendocrine activation such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. In selected patients, treatment with cardiac resynchronisation therapy also improves prognosis and, taken together, these treatments approximately double life expectancy. 4

Chronic heart failure has been recognised for many years as having the greatest symptomatic burden of any chronic medical condition. 5 The cardinal symptoms of heart failure are breathlessness and fatigue, particularly on exertion. Worsening breathlessness is part of the cause of most admissions to hospital with heart failure, although many patients also complain of ankle swelling due to fluid retention. Drug therapy is very successful in controlling symptoms, and can induce ‘remission’ in a number of patients; that is, their symptoms can remit almost entirely. However, the clinical course for most patients with heart failure tends to be one of gradual decline, often punctuated with episodes of severe deterioration resulting in hospitalisation.

Symptom severity is most commonly measured using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification of symptoms (Table 1).

| NYHA class | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| I | Breathless on severe exertion (normal) |

| II | Breathless and/or fatigue on moderate exertion |

| III | Breathless and/or fatigue on mild exertion |

| IV | Breathless and/or fatigue at rest |

Towards the end of their lives, many patients with CHF become very symptomatic, with limiting breathlessness on minimal exertion (class III) and even at rest (class IV). Once they have reached this stage, although patients need continued treatment with drugs known to improve prognosis, the emphasis of treatment becomes the relief of symptoms, that is, palliative care. However, although drug treatment with diuretics (which relieve fluid congestion), other drugs and pacing devices may relieve symptoms, for many the last few months and even years of life can be miserable, with persisting severe breathlessness on minimal exertion and episodic hospitalisation.

Although there is some evidence that opioids may relieve breathlessness in patients with chronic airways disease and cancer,6–8 the evidence is mixed in heart failure,9–11 and there is no specific intervention for the intractable breathlessness of severe CHF. Another frequently encountered group with severe breathlessness is those patients with chronic airways disease. In patients with chronic airways disease who also have hypoxia, there is reasonably robust evidence that long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) can improve prognosis as well as symptoms (see Pulmonary disease and oxygen). By extension from these data, physicians often use home oxygen therapy (HOT) for patients with severely symptomatic heart failure. There is, however, no evidence that LTOT is helpful in CHF, either for the relief of symptoms or to improve prognosis.

Pulmonary disease and oxygen

For many years, patients with chronic airways disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been treated with LTOT, particularly if they have evidence of hypoxia at rest. Treatment is given for at least 15 hours a day (including overnight). The evidence for the benefit of oxygen therapy comes from randomised clinical trials; the Medical Research Council’s (MRC’s) oxygen trial12 and the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy (NOT) trial13 are perhaps the best known. A Cochrane review of oxygen therapy for patients with chronic airways disease suggests that ‘long[-]term home oxygen therapy improved survival in . . . COPD patients with severe hypoxaemia (PaO2 [partial pressure of arterial oxygen] less than 55 mmHg (8.0 kPa))’. 14 In the MRC’s oxygen trial,12 treating five patients with severe hypoxaemic COPD with LTOT saved one life over the 5-year study period. 14 The prognostic benefits were not apparent until after more than 1 year of therapy.

Although it does not affect prognosis in people with more modest hypoxaemia, LTOT does appear to help by reducing the severity of breathlessness. 15 There is no evidence that NOT alone (in other words, giving oxygen only at night) improves prognosis. 14 The authors of the systematic review and meta-analysis observed significant heterogeneity in most of their analyses and pointed out that most studies were either single blinded or not blinded at all. They therefore recommended an individual approach to care until data from large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are available.

Data on the effects of oxygen therapy on quality of life (QoL) in patients with chronic airways disease are not clear-cut. Although the MRC reported that symptoms improved, few data were given. In patients with moderate hypoxaemia, the Cochrane meta-analysis reported a reasonably robust improvement in breathlessness equivalent to a reduction of 0.78 cm on a 10-cm visual analogue scale. 15

It is difficult to estimate adherence to LTOT in people with airways disease. Using the oxygen delivery system for 15 hours per day is clearly burdensome, and most studies suggest that adherence to this demand is less than 50%. 16 The summary figure of 45–70% is commonly quoted,17 but the studies from which the figures are derived are now quite old (see Chapter 9 for discussion). The only recent study suggests that adherence remains poor. 18

Although the original studies demonstrated a positive relationship between benefit and duration of oxygen, the mechanism is not clear. People who used oxygen for a longer period of time would have been more likely to have prevented worse desaturations during sleep or exertion, and the same benefit could have been achieved by supplemental oxygen at night only, or during exertion. Furthermore, if the prevention of exertion-induced desaturation helped exercise tolerance, then increased physical activity and reconditioning over time could have been the mechanism of improved symptoms and prognosis. 19 However, given that the only studies to show an improvement in prognosis had a target of oxygen use for long periods of time during the 24 hours, 15 hours per day remains the recommended prescription for prognostic benefit.

Heart disease and oxygen

Oxygen is commonly prescribed for patients with heart disease. There is a widespread perception that oxygen therapy can do no harm and may possibly be helpful and, thus, patients are often given high concentrations of inspired oxygen immediately following acute myocardial infarction or when they are admitted with acute pulmonary oedema. It is also commonly used during an admission for CHF.

Patients with severe (or even end-stage) CHF can appear very similar to patients with severe chronic airways disease. They are breathless at rest or on minimal exertion despite maximal medical therapy. A consequence is that HOT is often prescribed for severely breathless patients with heart failure, even in the absence of hypoxia, particularly towards the end of life.

There is only very limited evidence for the use of oxygen in heart disease, and much of the evidence suggests that oxygen might be harmful. In a study of patients with acute myocardial infarction, oxygen was given at as near to 100% as possible. Oxygen therapy was associated with a fall in cardiac output and stroke volume, together with a rise in heart rate. 20

The failing heart requires a higher filling pressure. The higher the filling pressure, the worse the cardiac function; hence an intervention causing a rise in filling pressure is deleterious. In a study of 10 patients with CHF,21 100% oxygen caused a rise in cardiac filling pressure, a fall in cardiac output and an increase in systemic vascular resistance (SVR). The SVR represents the load against which the heart has to work: the higher the SVR, the greater the work required of the heart. In another study of 12 patients with CHF,22 high-dose oxygen was associated with an increase in left ventricular (LV) filling pressure.

In contrast, in a study of patients with CHF given lower doses of oxygen (50%), exercise capacity increased and patients were less breathless and had a lower level of ventilation during exercise than during exercise with room air. 23 Findings from studies are inconsistent; another study has suggested that supplementary oxygen has little effect on exercise performance. 24 There is little evidence of the effect of oxygen when given to patients with heart failure at the much more modest levels used for treating chronic airways disease.

There is no evidence on whether or not the low-dose oxygen delivered by home oxygen concentrators is safe in patients with heart failure. There is no evidence about the effects of low-dose oxygen on haemodynamics in patients with severe heart failure.

The equivocal findings are perhaps not surprising. Oxygen is perhaps likely to be helpful only to people who are hypoxic (i.e. have low levels of arterial oxygen). Where it has been measured, oxygen has been found to be normal, or even high, during exercise in patients with CHF. 25 When patients with CHF are found to be hypoxic, there is usually an alternative explanation, such as coincident lung disease or congenital heart disease. 26 Thus, although patients with CHF may resemble patients with chronic airways disease clinically, they are much less likely to be hypoxic, and so might be thought, a priori, to be less likely to gain benefit from oxygen treatment.

Sleep apnoea

One complicating issue in patients with heart failure is the possible contribution of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Depending on the population studied, approximately one-third of patients with heart failure have SDB. 27 SDB happens when breathing stops during sleep. There are two kinds of SDB: obstructive and central sleep apnoea. In obstructive sleep apnoea, there is upper airways obstruction from soft tissues; respiratory efforts continue but there is no movement of air into the lungs. The patient usually wakes and breathing restarts. In central sleep apnoea, the central drive to breathe stops, usually in a cyclical manner alternating with periods of hyperventilation.

Patients with SDB, of either kind, become hypoxic during periods of apnoea. It thus might be that patients with heart failure might benefit from oxygen therapy even in the absence of daytime hypoxia, because it may relieve hypoxia at night.

Oxygen therapy might be helpful for periodic respiration. 28 There are some studies in a small number of patients investigating the effects of short-term overnight oxygen therapy which suggest that there may be some beneficial effect. For example, Toyama et al. 29 studied 20 patients and found improvements in exercise capacity and cardiac function in the 10 patients randomised to overnight oxygen. Other small studies have found similar beneficial effects, but there is no systematic review available.

In the largest available study, Sasayama et al. 30 reported on 52 patients with CHF and a positive overnight sleep test randomised to receive NOT or conventional therapy for 1 year. The group with NOT had better sleep patterns and a slight improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and daytime activity level but no reduction in cardiac events.

Home oxygen therapy for breathlessness

There is surprisingly little evidence that oxygen is effective in treating breathlessness per se. A large observational study of patients with a variety of causes of breathlessness suggested that oxygen therapy was of no benefit,31 and apart from the review and a meta-analysis in people with COPD discussed in Pulmonary disease and oxygen,15 other systematic reviews identified no evidence that supplemental oxygen helped in the relief of breathlessness in patients with heart failure or patients with breathlessness from other causes in the absence of hypoxia. 32–35

A subsequent RCT compared LTOT via concentrator with a sham concentrator for refractory breathlessness due to a mixture of aetiologies (mainly COPD or cancer). Although breathlessness improved over 7 days in both groups, neither was superior. The authors suggested that it was simply airflow over the nasal mucosa, and not oxygen, that might have been the therapeutic intervention. 36

Despite the absence of any evidence in favour of using oxygen, HOT is commonly prescribed for severely symptomatic patients with end-stage heart disease: indeed, HOT in the UK is most commonly prescribed for conditions other than COPD (Department of Health, 2011, unpublished data).

The National Service Framework for coronary disease specifically recommends considering the potential benefit from ‘palliative care services and palliation aids (e.g. home oxygen)’. A Canadian study demonstrated that nearly 30% of oxygen prescribing costs were a result of palliative oxygen prescription (i.e. the patients did not meet the formal criteria for oxygen prescription for respiratory disease). 37 In another survey, 77% palliative physicians gave ‘intractable dyspnoea’ as the most common reason for prescription of home oxygen. 38 Fifty per cent of heart failure patients have breathlessness that markedly limits exercise in their last year of life,35 and in an Australian study between 10% and 20% of patients receiving palliative care were treated with HOT. 39 A small UK study found that 25% of patients receiving HOT had heart failure as their underlying pathology. 40 Finally, it is important to note that data from the Department of Health suggest that between 24% and 43% of the home oxygen prescribed to approximately 85,000 patients in England is not used or leads to no clinical benefit (Department of Health, 2011, unpublished data).

The home oxygen therapy trial rationale

Home oxygen therapy is potentially burdensome for patients and their carers. The concentrator has to be fitted to the home, usually requiring some drilling through walls. The device consumes electricity, although the costs are met by the NHS. The patient is encumbered to a degree by the oxygen. It is delivered through a nasal cannula, usually via a long length of piping, which limits movement. For some, oxygen cylinders to supply oxygen when the patient leaves the house are needed. The oxygen can leave the nose and throat feeling very dry. In addition, the stream of oxygen-enriched air is a potential fire hazard, particularly for patients who continue to smoke.

Home oxygen therapy is thus expensive to the health service and burdensome to the patient, and there is little evidence of its effectiveness. In the absence of any evidence-based guidance on the use of oxygen therapy for patients with CHF despite its widespread use, there is a need for a trial of HOT to find out if patients gain any benefit from its use.

Therefore, the HOT trial was designed to address the question of whether or not there is a role for HOT in patients with severely symptomatic heart failure, in terms of its effect on the symptoms for which it is usually prescribed (e.g. breathlessness), QoL and prognosis. We also planned to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis.

The study consisted of three parts. The main study was designed to measure the impact of HOT on QoL in severely symptomatic patients. A qualitative substudy was designed to assess the burden on patients and their carers, and an acute oxygen substudy was designed to study whether or not there was any effect on haemodynamics of oxygen given in the same concentration as used by concentrators at home.

Chapter 2 Synopsis of trial evolution

Trial structure and protocol

The trial was designed in response to a call from the NHS research and development Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (HTA number 06/80; see Appendix 1). The grant for the trial was originally awarded in March 2008.

Stage 1: the North East Oxygen Network trial

The HOT trial was originally named the North East Oxygen Network (NEON) trial. The original conception of the trial was an attempt to provide evidence from a double-blind trial of the effectiveness of HOT in patients with severely symptomatic CHF. Four centres in the UK were involved: Hull, Leeds, Darlington and Leicester.

In the absence of any data from adequately powered studies, it was impossible to know what duration of oxygen therapy might be useful. Whether long-term therapy, following the example of successful treatment for patients with chronic airways disease, or shorter-term overnight oxygen therapy alone was the better treatment was unknown.

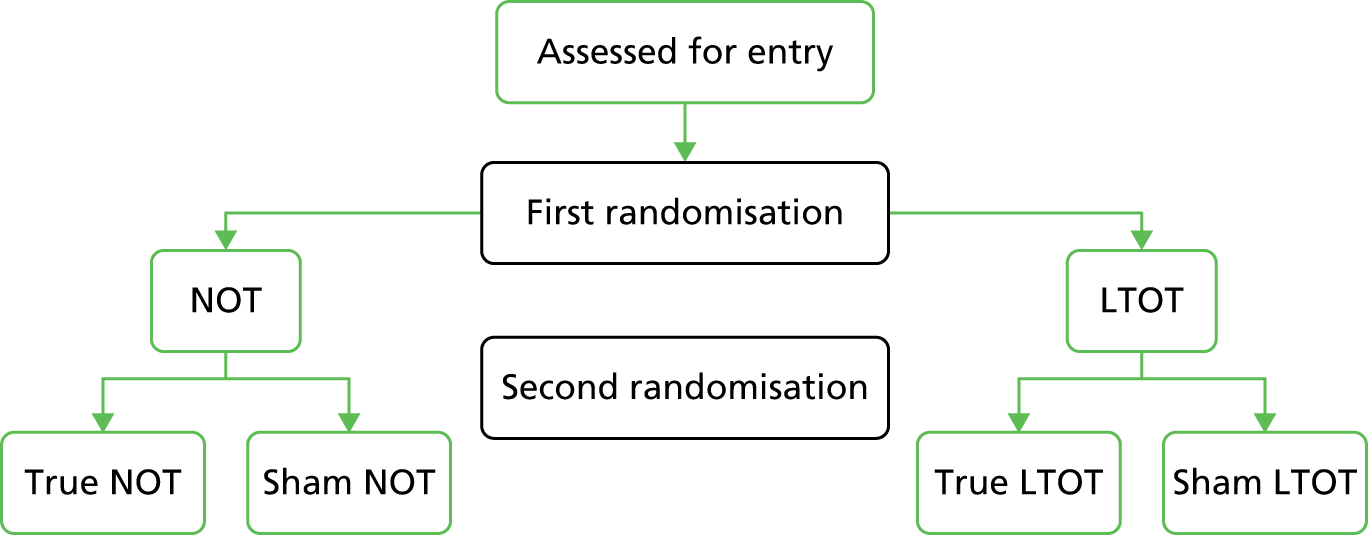

The study was thus designed in two phases. In the first phase (Figure 1), patients were to be randomised to receive either NOT overnight, assumed to be around 8 hours per night, or LTOT, aiming for at least 15 hours per day. A second randomisation would allocate patients within the two arms to receive either a true or a sham oxygen concentrator. The design of the second phase depended on the results of the first; whichever of NOT or LTOT appeared the better in phase 1 would then be formally tested in the second phase.

FIGURE 1.

The original design for the NEON trial.

There was discussion among the research group about the optimum design. Some felt that an open pragmatic trial was best, as this would estimate treatment effectiveness rather than efficacy, which is an important question for the NHS. On the other hand, a placebo or sham trial would estimate the true treatment efficacy of oxygen and ensure blinded assessment of outcomes. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that the symptom of breathlessness is partially relieved by air blowing over the face. 36,41 Consequently, the original trial design was to use sham concentrators for the control treatment. HOT was to be delivered in the trial using oxygen concentrators rather than oxygen cylinders. A concentrator uses room air and removes a fraction of the nitrogen catalytically, so that the resulting inhaled gas is room air with some nitrogen removed; the concentration of inspired oxygen thus increases from 20.9% to approximately 28%. The sham machines would have delivered only room air.

The aim of the pilot was to recruit 120 patients, 30 in each of the four potential arms (see Figure 1). The results of the initial pilot study were then to inform the second phase study. Whichever of the two oxygen delivery schedules was the more successful would be used in a three-way comparison of oxygen therapy, sham therapy and open-label best medical therapy (BMT).

The investigators negotiated with Air Products Healthcare (Air Products and Chemicals, Inc., Allentown, PA, USA), which was able to manufacture sham machines which delivered room air. At this stage, recruiting sites were thus restricted to those whose contract for home oxygen supplies was with Air Products Healthcare. Plans were developed for the two-stage randomisation.

The original grant application to the HTA programme was with this study design.

Problems with the North East Oxygen Network trial

Trial management

The University of Hull initially agreed to sponsor the trial; however, after a period of some months it decided not to sponsor the study because of the potential issue with indemnity which could arise if a sham oxygen concentrator machine was accidentally given to a patient outside the trial. In addition, a full-time trial manager had not been included in the original submission to the HTA programme.

These problems were rectified by the Hull and East Yorkshire NHS Hospitals Trust agreeing to sponsor the study and through the establishment of a trial management function.

Sham machines

A crucial component of the trial, as originally conceived, was the use of sham machines to deliver room air. However, although it was relatively straightforward for Air Products Healthcare to deliver the sham machines, their use led to two insuperable logistical problems.

As the sham machines had to look as similar to the real devices as possible, it was felt by the company and the sponsor to be a substantial problem that the sham machines might not be kept out of the general pool of machines intended for use in delivering HOT to non-trial patients.

In addition, as the sham machines had to have their alarm functions disabled, there was a risk that they would not detect electrical faults that could potentially be a fire hazard. Specific trial insurance for their use was required, but was too costly to allow the trial to proceed.

Eventually, the trial management group accepted that the problems being raised made the trial as originally conceived impossible to run. Following a HTA site monitoring visit by Professor Jenny Hewison and Dr Vaughan Thomas on 24 September 2010, the group redesigned the study and approached the HTA programme to approve an alternative trial design.

Stage 2: the three-arm home oxygen therapy trial

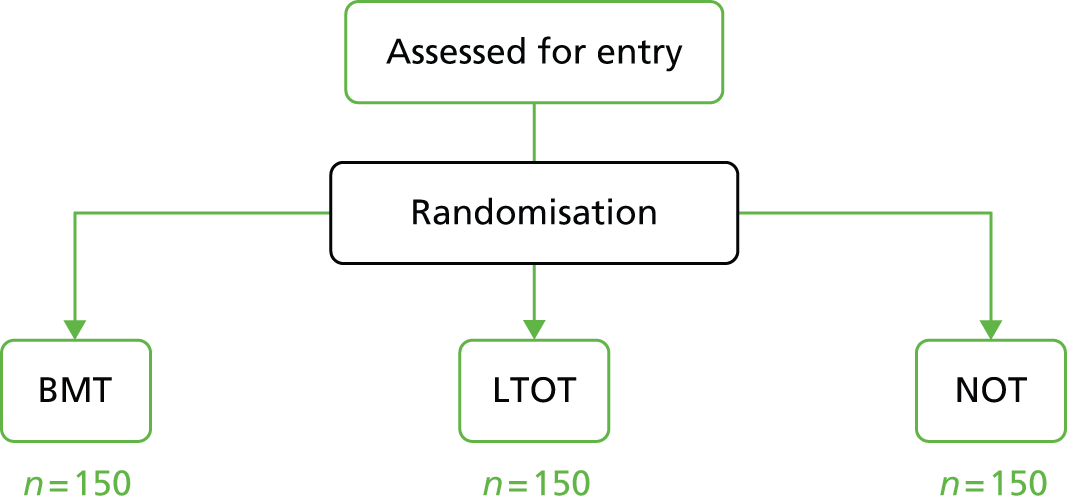

The redesigned trial was named the HOT trial. We chose a pragmatic study design avoiding blinding and did not include a sham oxygen arm. In turn, this meant that more oxygen supply companies could be used and the number of recruiting centres could be expanded. An additional benefit was to avoid the need for special insurance related to dummy devices. Furthermore, the answer to a pragmatic trial is arguably of more relevance to patients and clinicians than the original study design. The original research question, however, remained unchanged: to assess the effects of HOT on QoL in patients with CHF (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The original design for the three-arm HOT trial.

Patients were randomised to receive BMT, BMT plus NOT or BMT plus LTOT for 15 hours per day. The primary end point was QoL at 12 months as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLwHF) questionnaire.

The trial started recruitment in April 2012. However, recruitment to the trial was much slower than expected and recruitment targets were not met. There were two major reasons.

First, it is a particular challenge to recruit patients to studies of palliative care,42–44 and the patients being recruited into the HOT study were necessarily very unwell and reaching the end of their lives. Some centres found it difficult to approach such patients and, in some centres, the patients being recruited were predominantly cared for by other groups of health-care workers in their area, commonly in the areas of palliative care, elderly care and primary care. Simply put, frail patients characterised by instability needed to be sufficiently fit and stable to participate in the trial.

The second, and more intractable, problem was the time it took to recruit centres to the trial. Multiple individual site approvals were needed, as for any clinical study, but the peculiar problem for HOT was the need for approval of HOT. Many sites took the view that this should be an NHS excess treatment cost. Hospital trust research and development departments naturally needed approval to prescribe HOT from the relevant primary care providers, leading in many instances to prolonged delays. During the trial set-up period of HOT, there were major upheavals in NHS structures. The replacement of primary care trusts with clinical commissioning groups made it extremely challenging to identify who was responsible for HOT. In some instances, clinical commissioning groups refused permission for the study to go ahead, and sometimes it proved impossible to find the responsible party with whom to negotiate. The median length of time taken from a centre expressing interest in the study to final approval was 9 months.

Stage 3: the two-arm home oxygen therapy trial

The trial management group realised that, with the difficulties in recruiting both patients and centres, it would prove impossible to complete the study within a reasonable time frame and budget. We again approached the HTA programme to ask permission for a modestly redesigned study. We removed the NOT arm, reducing the study from a three- to a two-armed trial comparing BMT with BMT plus LTOT (15 hours per day). LTOT was chosen over NOT as being the only form of oxygen therapy shown to improve prognosis, albeit in patients with COPD. The simplification of the study design allowed the sample size to be greatly reduced (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The final design for the two-arm HOT trial.

In addition, we brought forward the timing of the primary end point from 12 to 6 months. This had the effect of reducing the time required to follow up patients and increasing the time available for analysing the data and writing the report for the HTA. After discussion with the HTA programme, it was agreed that the cost-effectiveness analysis for the trial was not to be included.

Chapter 3 The home oxygen therapy trial: methods

The HOT trial was a Phase III, prospective, open, pragmatic, multicentred, randomised controlled parallel-group trial with equal randomisation. The study was designed after extensive consultations with patients in the Department of Academic Cardiology in Hull. Patients gave very helpful advice about (1) the design of the study and (2) the format and wording of the patient information leaflet. This was particularly useful, as we were aware of the need to be clear about the requirements of the study, but did not want to cause alarm (particularly about fire risk). The patients also advised about the number and type of study measures with regard to what was an acceptable participant burden.

We particularly acknowledge the help and advice we received in designing the study from Mr Patrick Foulk, who generously agreed to take part in the trial steering committee. Mr Patrick Foulk is an experienced patient representative who has been part of many trial management and trial steering groups. He has been particularly helpful in ensuring that the trial maintained patient relevance, was not afraid to ask the pertinent, and sometimes difficult, questions during meetings, and gave useful ongoing advice about recruitment from the patients’ viewpoint.

The aim of the study was to determine whether or not the addition of long-term HOT (given for at least 15 hours per day) improved the QoL for patients with stable, severely symptomatic CHF who were already receiving BMT. Such patients are usually thought of as being in need of palliative care: their outlook is limited and they are severely symptomatic. Any intervention which can relieve symptoms is to be welcomed; conversely, if a treatment is simply burdensome, its use should be abandoned.

Participants with NYHA class III or IV LV systolic dysfunction receiving optimal medical therapy were randomised to receive either:

-

BMT plus at least 15 hours’ LTOT or

-

BMT.

The original trial had a third arm with patients allocated to a NOT-only group. Twenty-five patients were randomised into the NOT arm before the decision was made to drop the arm in April 2013.

Approvals obtained

The Northern and Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee [the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC)] approved the study originally known as the NEON trial on 24 August 2009. Further approvals were received on 18 May 2011 and 2 April 2013 for changes to the design of the study that were implemented to improve recruitment.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency reviewed the trial protocol and on 28 June 2008 confirmed that oxygen concentrators were medical devices and not medicines. The study, therefore, did not fall under the Clinical Trials Directives and so a clinical trial authorisation was not required.

The details of MREC and research and development department approvals are provided in Appendix 2.

Patient study group

To make the findings of the study as widely applicable as possible, the inclusion criteria were very broad, with few exclusions.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the study, patients had to:

-

be willing to provide written informed consent and be able to complete patient assessments

-

be aged 18 years or over

-

have heart failure from any aetiology

-

have severe symptoms of heart failure (NYHA class III/IV)

-

have LV systolic dysfunction confirmed by echocardiography, with LVEF less than 40% or graded as at least ‘moderately’ impaired on visual inspection if an accurate ejection fraction could not be calculated

-

be receiving maximally tolerated medical management of their heart failure as

-

reached target dose of (or be on maximally tolerated dose of, or be intolerant of) an inhibitor of the renin–angiotensin system shown to improve prognosis

-

reached target dose of (or be on maximally tolerated dose of, or be intolerant of) a beta-adrenoceptor antagonist shown to improve prognosis

-

reached target dose of (or be on maximally tolerated dose of, or be intolerant of) an aldosterone antagonist.

-

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if they:

-

were unable to provide written informed consent

-

had had a cardiac resynchronisation therapy device implanted within the previous 3 months

-

had coexisting malignant disease if this would affect the study in the investigators’ opinion

-

had interstitial lung disease

-

had COPD likely to fulfil criteria for LTOT; forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 70% and FEV1 < 40% predicted and hypoxia [partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) < 7.3kPa or saturations < 90%]

-

were using any device or medication that would impede their ability to use LTOT or NOT, such as continuous positive airway pressure

-

were unwilling or unable to comply with safety regulations regarding oxygen use, particularly smoking

-

were unable to complete patient-related information on entry.

Randomisation

Allocations were centrally generated by the York Trials Unit. Patients were initially randomised into the trial on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis using block randomisation, with randomly permuted block sizes of three, six and nine. Subsequently, after the NOT arm was dropped, 1 : 1 allocation was used, with randomly permuted block sizes of four, six and eight. Patients were randomised by a member of the research team at the recruiting site using the secure, telephone-based randomisation service at the York Trials Unit.

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the total score from the MLwHF questionnaire at 6 months from baseline. As the patient group is highly symptomatic and has a limited prognosis, the 6-month primary outcome is highly clinically meaningful.

The MLwHF questionnaire is a validated, disease-specific QoL instrument widely used in heart failure research to assess both symptom severity and response to treatment. 45,46 It consists of 21 questions focusing on the impact of heart failure on QoL. Patients are asked to rate the extent to which their heart failure has prevented them from living as they wanted during the past month using questions rated on a scale of 0 (no effect) to 5 (very much). The questionnaire is scored by summing the responses to all 21 questions, thus resulting in a score from 0 to 105, with a higher score reflecting poorer QoL. The MLwHF questionnaire-validated QoL score, version 2, is easy to complete and has been shown to be especially effective in older patients with comorbidities. 47

An improvement in the score of 5 is sometimes taken to be a minimum clinically important difference,48 but others have suggested that a change of 1 standard error (SE) around the mean score is needed (around 6 or 7, depending on the population studied). 49 There are no studies of LTOT to help guide us. The MIRACLE (Multicenter InSync RAndomized CLinical Evaluation) trial of biventricular pacing was powered for a 13-point improvement in MLwHF questionnaire score and found a score difference of 9 between treatment groups. 50 The CARE-HF (CArdiac REsynchronization-Heart Failure) study of biventricular pacing found a score improvement of 10.6 with intervention. 51 In the absence of data on which to base study size, we took a MLwHF questionnaire score of 10 as an arbitrary indicator of the minimum improvement necessary to justify the cost and inconvenience of oxygen therapy for patients.

Power calculation

To detect a difference in MLwHF questionnaire score between the two groups of 10 points, with a standard deviation (SD) of 25, at 80% power and 5% significance, we required 100 patients per group. Assuming 10% attrition at 6 months, this equated to 111 per group, a total sample size of 222 patients.

Secondary outcomes

Other indices of QoL, exercise performance and severity of heart failure were also measured as part of the study.

Measures of quality of life

Health status as measured by the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions instrument

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a self-administered, validated measure of health status and consists of a five-question multiattribute questionnaire and a visual analogue self-rating scale. 52,53 Respondents are asked to rate severity of their current problems (level 1, no problems; level 2, some/moderate problems; level 3, severe/extreme problems) for five dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Patients can be classified into 243 health states plus two further additional states (unconscious and dead).

Numerical Rating Scale for breathlessness

The severity of and distress caused by breathlessness was measured by the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for breathlessness (average and worse over past 24 hours and global change in breathlessness). Patient satisfaction was also measured by the NRS (in addition to a qualitative substudy to assess patient experience). The NRS measures symptoms and satisfaction on a 10-point scale, anchored at 0 and 10. It is highly correlated with visual analogue scale scores, but is more repeatable. 31,54 Average and worst breathlessness over the past 24 hours were anchored with ‘not breathless’ and ‘worst breathlessness imaginable’. 55 Distress due to breathlessness was anchored with ‘no distress at all’ and ‘the worst imaginable distress’. The minimum clinically important difference in the scale is 1 point. 56,57 How well a patient had coped with their breathlessness over the past 24 hours was anchored on ‘not coping at all’ and ‘coping very well’. Satisfaction with treatment for breathlessness was anchored on ‘not at all satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale score to assess daytime somnolence

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a standard scale for screening for, and assessing the severity of, daytime sleepiness as part of the SDB syndrome. Patients are asked to rate their chance of dozing in eight different scenarios, such as being a passenger in a car or watching TV. Each is measured on a Likert-type scale from 0, would never doze, to 3, high chance of dozing, and a total score is obtained from summing the 8 items out of 24.

Mood assessment using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a well-validated and easy-to-complete 14-item screening tool for depression and anxiety. 58 Each item is measured on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 3, and seven non-overlapping items make up each of the two subscales. For each of the two continuous subscales (anxiety and depression), patients are categorised as ‘normal’ (0–7), ‘borderline’ (8–10) or ‘clinically anxious/depressed’ (11–21).

Severity of heart failure

The severity of the patient’s heart failure was assessed by measuring LV dysfunction on echocardiography and the N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic hormone (NT-proBNP) levels.

Exercise capacity

The 6-minute walk test

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) followed a standardised protocol. 59–61 A flat, obstacle-free corridor with chairs placed at either end was used. Patients were instructed to walk as far as possible, turning 180° every 15 metres in the allotted time of 6 minutes. Patients were able to rest, if needed, and the time remaining called every second minute. Patients walked unaccompanied so as not to influence walking speed. After 6 minutes, patients were instructed to stop and the total distance covered was measured to the nearest metre.

Performance

Karnofsky Performance Status scale

This validated scale incorporates the components of physical activity, work and self-care of patients. 62,63 Patients are classified according to their functional impairment, with the status categories ranging from 0% (dead) to 100% (normal with no complaints and no evidence of disease) in steps of 10%. Although the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale is categorical, it is of an ordinal nature and was, therefore, treated as continuous data in our analysis. The scale can be further classified as ‘died’ (0); ‘unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; disease may be progressing rapidly’ (10–40); ‘unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed’ (50–70); and ‘able to carry on normal activity and to work; no special care needed’ (80–100).

Comorbidity

Charlson Comorbidity Index

This is a validated age–comorbidity index used to estimate relative risk of death from prognostic clinical covariates, and is useful in studies with 1 to 2 years’ follow-up. 64 [See also http://touchcalc.com/calculators/cci_js (accessed June 2015).]

Prevalence of hypoxia

The prevalence of hypoxia was assessed by measuring:

-

resting oxygen saturation

-

oxygen saturation at peak exercise during 6MWT

-

oxygen saturation 5 minutes after the end of the 6MWT

-

nocturnal oxygen saturation and the presence of SDB during an overnight sleep test using an Embletta (Natus Medical Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA).

Safety and adherence

We recorded the patients’ own report of their adherence with the oxygen concentrator, and the number of hours of oxygen used measured by the concentrator meter.

Participant death was recorded as a serious adverse event (SAE), with the date of death where possible.

The number of days the patient was alive and out of hospital was calculated.

Other measurements

Blood analysis

Standard biochemistry and full blood count were undertaken. Results from these tests undertaken within a month of baseline assessment could be used.

Electrocardiogram

A 12-lead electrocardiogram was undertaken to determine cardiac rhythm and electrocardiography intervals.

Echocardiogram

Routine echocardiographic assessment was performed including M-mode, 2-dimensional images and colour flow Doppler recordings by trained operators. Measurements were taken in accordance with American Echocardiography Society or European Association of Echocardiography guidelines. LV systolic function was assessed by attempted measurement of LVEF using Simpson’s biplane method in all subjects, and by estimation on a scale of LV systolic impairment as follows: normal, mild, mild to moderate, moderate, moderate to severe or severe systolic impairment. Results from echo assessments within 3 months of the baseline assessment were used.

New York Heart Association class

Assessment of NYHA grade was made using the following classification:

-

class I – breathless on severe exertion (normal)

-

class II – breathless and/or fatigue on moderate exertion

-

class III – breathless and/or fatigue on mild exertion

-

class IV – breathless and/or fatigue at rest.

Spirometry

Spirometry was undertaken to determine the FVC and forced expiratory volume in the first 3 seconds. Results from spirometry tests undertaken within 3 months of the baseline assessment were used.

Other assessments

Resting pulse rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate, peripheral oedema and lung crackles, if any, were measured and recorded.

Other data

Data recorded included height, weight and date of birth, which allowed age at recruitment to be calculated. Sex, aetiology of heart failure, current medication and adverse events were also recorded.

Cost-effectiveness

In addition to the EQ-5D instrument, the Health Service Use Questionnaire was used to measure the level of health resource use. Respondents were asked to recall the amount of use they had made of the specified services over the previous 6 months.

Adverse events

In this study an adverse event was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a patient which did not necessarily have a causal relationship with the study treatments or procedures.

Health-care professionals were asked to report any adverse event occurring in participants in both groups using either the SAE form or the adverse event form within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. A SAE was defined as an event that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect or was otherwise considered to be medically significant by the investigator. The reporting health-care professional was asked to indicate whether or not, in his or her opinion, the event was related to the treatment, to indicate if it was expected and to grade the intensity of the event. Further follow-up reports were completed if necessary or until the local principal investigator considered the event to be resolved or to have become a chronic ongoing condition.

Chapter 4 Statistical analysis

Analyses mainly compared the LTOT intervention group with the control (BMT) group on an intention-to-treat basis, including all randomised patients in the groups to which they were originally allocated. We performed exploratory analyses including contemporaneously recruited patients in the NOT arm for the primary outcome and survival analysis. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), using two-sided significance tests at the 5% significance level.

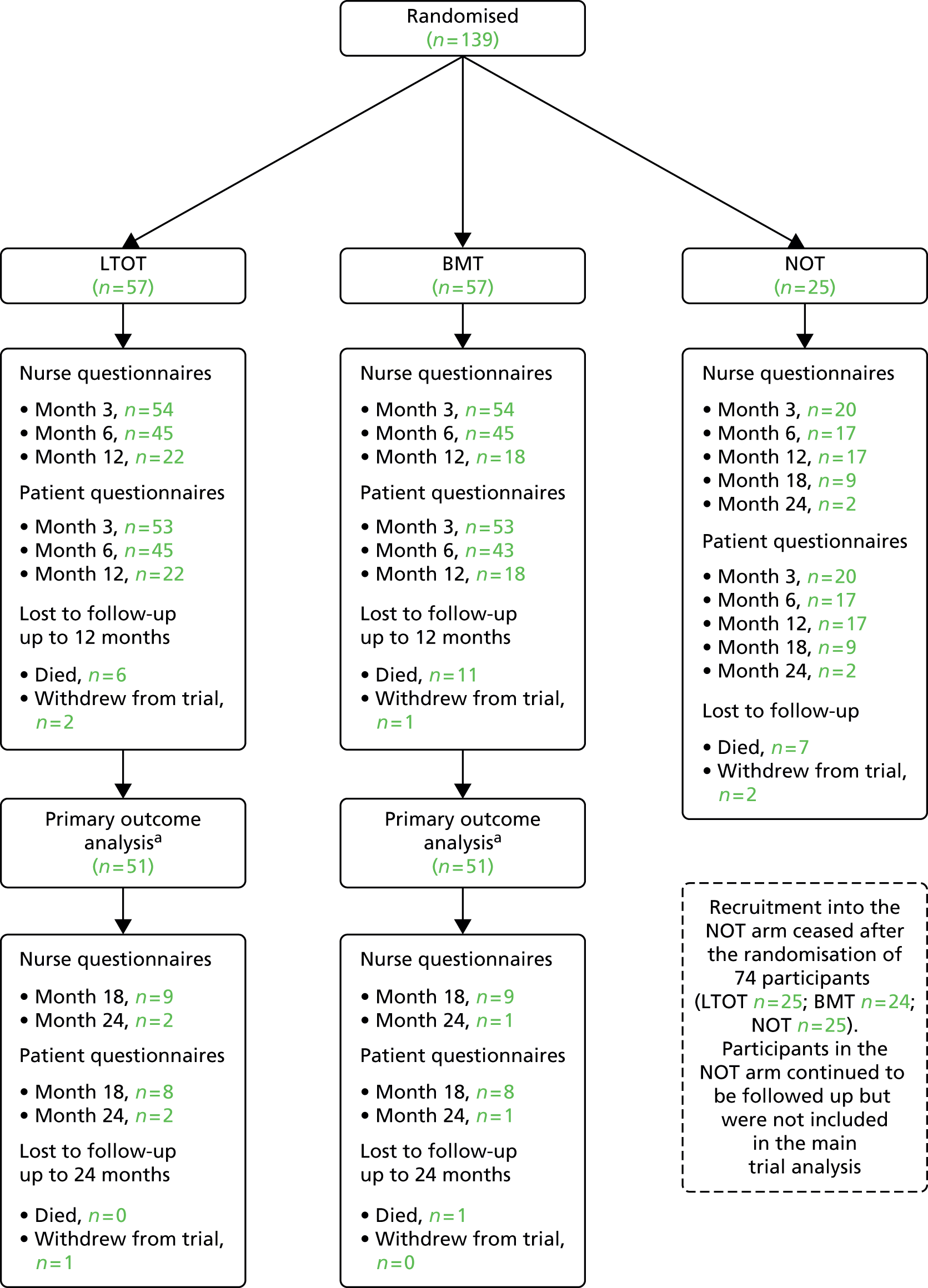

Trial completion

The flow of participants through the trial is presented in a CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram. The numbers of participants withdrawing from treatment and/or the trial are summarised with the reasons where applicable (see Figure 6).

Baseline data

All participant baseline data are summarised descriptively by treatment group. Continuous measures are reported using summary statistics (mean, SD, median, interquartile range, minimum, maximum) and categorical data are reported as counts and percentages. Comparisons were made between trial groups ‘as randomised’ and ‘as analysed’ in the primary analysis. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome was health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as measured by the MLwHF questionnaire scores at 6 months. A lower MLwHF questionnaire score indicates a better QoL. The MLwHF questionnaire consists of 21 items and a total score is obtained by summing the item scores, where all 21 items have a response. The number of missing MLwHF questionnaire responses was examined at each time point. Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to fill in missing questionnaire items, where there were fewer than four missing item responses, using other items in the questionnaire (http://178.23.156.107:8085/Instruments_files/USERS/mlhf.pdf). Linear regression was used to perform the imputation and five imputed data sets were created. The mean of the imputed values for each patient was used to replace the missing item. Where the mean was less than 0 or greater than 5 (the range of permitted scores for the MLwHF questionnaire) it was replaced with the nearest permitted value.

Our primary analysis compared MLwHF questionnaire scores between the LTOT and BMT treatment groups using a covariance pattern mixed model, where effects of interest and baseline covariates are specified as fixed effects, and the correlation of observations within patients is modelled by a covariance structure. The outcome modelled was total MLwHF questionnaire scores at 3, 6 and 12 months. The model included as fixed effects baseline MLwHF questionnaire score, age, log-NT-proBNP level, creatinine level, treatment group, time and a treatment group–time interaction term. Age, NT-proBNP levels and creatinine levels were all continuous variables as assessed at baseline. NT-proBNP data were found to be significantly positively skewed and so were log transformed.

Different covariance structures for the repeated measurements, which are available as part of Stata version 13, were explored and the most appropriate pattern used for the final model. Diagnostics including Akaike’s information criterion65 were compared for each model (smaller values are preferred).

Participants were naturally included in the model only if they had full data for the baseline covariates and outcome data for at least one post-randomisation time point (3, 6 or 12 months).

Estimates of the adjusted mean difference (AMD) between treatment groups in MLwHF questionnaire scores were extracted from the model for all time points with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. The primary end point is the treatment effect estimate at 6 months. Estimates for the other time points serve as secondary outcomes. An overall effect of the intervention across all included time points was not extracted.

Sensitivity analyses

Patients were recruited from multiple centres. To investigate whether or not centre affected the outcome, centre was included as a random effect in the primary analysis model. 66

Secondary analysis

Comparisons with the nocturnal oxygen therapy subgroup

Initially, the HOT trial recruited patients to three trial arms: BMT, LTOT and NOT. In April 2013, the decision was made to stop recruitment to the NOT arm, although patients in this group continued to be followed up. We conducted an exploratory analysis on the primary outcome including all three treatment arms, which included only contemporaneously recruited patients, that is only patients in any arm randomised up to the date at which the randomisation to the NOT arm was closed. This was to ensure comparability of the treatment groups. A covariance pattern mixed model was used similar to that described for the primary analysis including a variable for treatment with the three levels.

A non-significant difference was observed between the NOT and LTOT arms in a pairwise comparison from this model; therefore, these arms were combined and compared against the BMT arm on the primary outcome using a similar analysis, and including only patients randomised up to the time that the NOT arm was dropped from the study.

Secondary outcomes

The following outcomes were analysed using the same method as the primary outcome but just adjusting for the baseline value of the dependent variable: the six questions (separately) of the NRS for breathlessness; ESS; HADS scores for anxiety and depression; KPS of physical activity; metres walked as part of the 6MWT; the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI); and NT-proBNP levels.

Scoring of the secondary outcomes

-

A total score for the ESS was calculated only when all items had a valid response, in accordance with the scoring instructions detailed at http://epworthsleepinessscale.com/about-epworth-sleepiness/.

-

For the HADS, as is recommended, the score for a single missing item from a subscale was inferred using the mean of the remaining six items. If more than one item was missing, then the subscale was judged as invalid (www.gl-assessment.co.uk/products/hospital-anxiety-and-depression-scale/hospital-anxiety-and-depression-scale-faqs#FAQ4).

-

A total score for the CCI was computed by applying a certain number of points for each comorbidity present and adding a score for age (≤ 40 years, 0 points; 41–50 years, 1 point; 51–60 years, 2 points; 61–70 years, 3 points; and 71–80 years, 4 points) as detailed at http://touchcalc.com/calculators/cci_js (accessed June 2015).

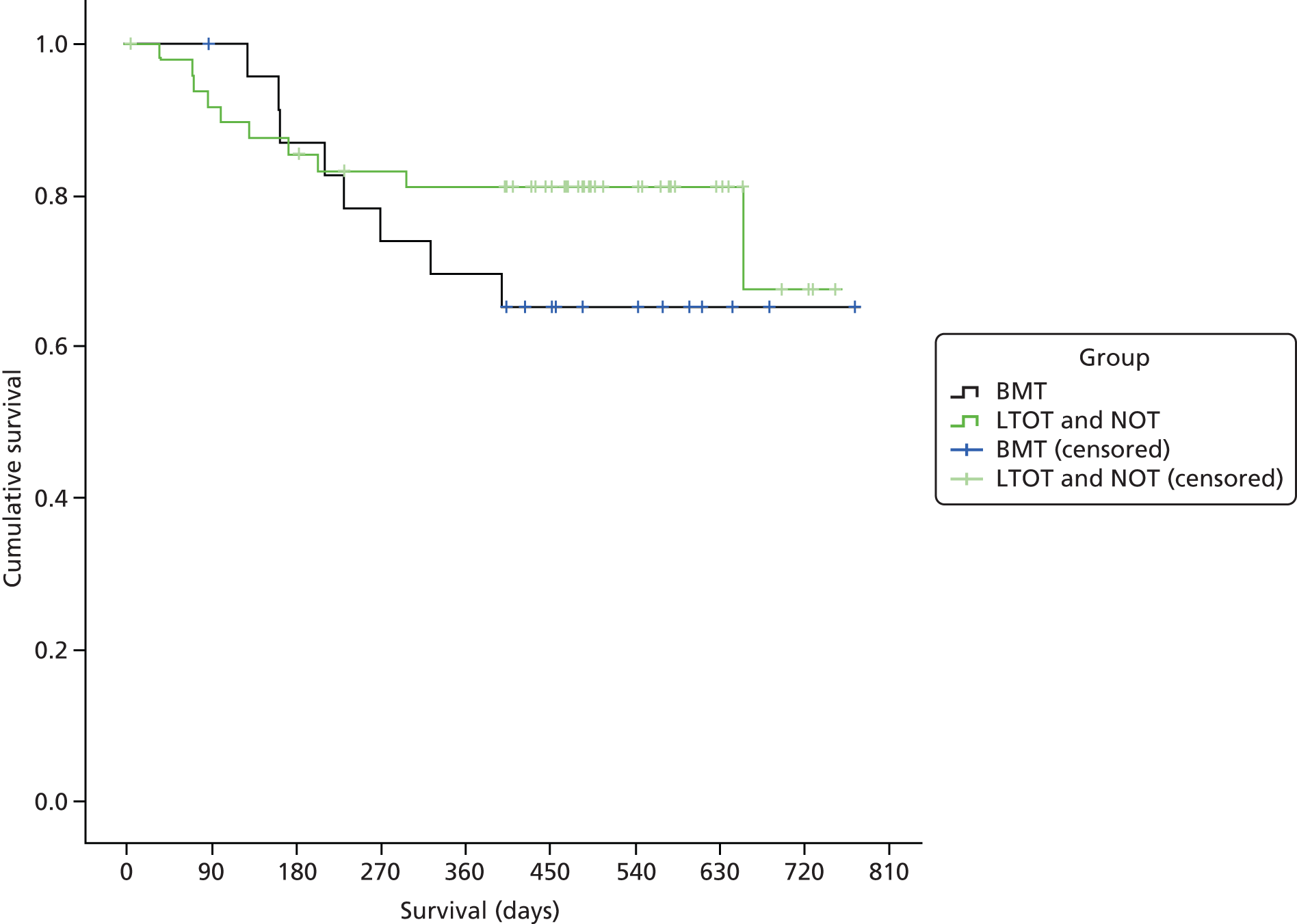

Mortality

Mortality was analysed as a time-to-event outcome. For each group, the distribution of time from randomisation to death was described using Kaplan–Meier survival estimates. Kaplan–Meier survival curves are presented for the two groups. The statistical equivalence of the two curves was tested using the log-rank test. Right censoring occurred if the patient was still alive at the end of follow-up or if they withdrew or were lost to follow-up.

We compared the survival of the LTOT and the BMT groups using a Cox proportional hazards regression model adjusting for baseline CCI score. Hazard ratios (HRs) are presented with p-values and 95% CIs.

Similar survival analyses were also conducted by combining the LTOT and NOT arms, and comparing them with the BMT arm, including only those patients contemporaneously recruited.

Number of days alive and out of hospital

The number of days alive and out of hospital (DAOH) was calculated for each patient as follows:67 the total potential follow-up time was determined as the number of days from randomisation until the date of the final follow-up time point (if alive) or the end of study date, 30 May 2014, if the patient had died. Patients who were lost to follow-up had a censoring date of 30 May 2014 to determine potential follow-up time. The number of nights spent in hospital over the previous 6 months was captured on the patient questionnaire at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. The total time spent in hospital was computed by adding the durations of each individual hospital stay. If a patient died, the number of days from their death to the end of the study was assigned as days dead. Days in hospital and days dead were then subtracted from the total potential follow-up time to arrive at DAOH for each patient. Summaries of the number and percentage of days the patients in the two groups are alive and out of hospital are presented.

Health-related quality of life as measured by the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

Data are summarised for the two treatment groups and a simple analysis of variance was used to compare each treatment at each time point. In addition, an unadjusted t-test compared baseline scores at each time point for each treatment group.

Prevalence of hypoxia

The prevalence of saturation at the thresholds of 90% and 95% are summarised for O2 saturation at rest, at peak and at 5 minutes after the 6MWT.

Patient-reported adherence

Patient-reported adherence to the oxygen machine is summarised at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months in the LTOT arm and NOT subgroup.

Number of hours of oxygen used measured by concentrator meter

Summary statistics for the mean number of hours that the machine was used per day by patients in the LTOT arm and NOT subgroup are reported.

Adverse events

The number of adverse events experienced by each participant and total number of events overall are summarised for each treatment group. The severity of the event and whether or not it was considered related to treatment is summarised.

Chapter 5 Study procedures

Members of the research team participating in the study received good clinical practice training as well as training in all aspects of the trial. Training included participant recruitment, eligibility criteria, trial protocol, adverse event reporting procedures and trial documentation. In order to standardise the study prior to commencement, each study site also received a trial handbook.

Potential participants for the trial were identified from NHS heart failure, cardiology or general medical clinics. Existing lists of likely eligible patients held within the NHS hospitals were also reviewed. The study was introduced to patients by the clinician responsible for their treatment (usually a consultant cardiologist). Patients then had the opportunity to discuss study participation with the research nurse. In order to aid recruitment some sites used patient identification centres. Potential participants were sent an introduction letter with an invitation to contact the study team if they were interested in taking part in the study. Alternatively, the research nurse could contact the patient directly by telephone.

Each potential participant was informed of the aims, methods, expected benefits, potential hazards and discomforts of the study verbally and through a patient information sheet (see Appendix 3). Participants were given at least 24 hours to consider participation in the study. Participants who wished to take part in the study provided written informed consent (see Appendix 4). Baseline data were then collected. Each participant’s general practitioner was notified of the patient’s involvement in the HOT trial and their group allocation after recruitment. The flow of participants through the trial is presented in a CONSORT68 diagram (see Figure 6).

Baseline and follow-up assessments

After written informed consent had been obtained, baseline data were collected using the nurse and patient baseline questionnaires.

After giving consent and completing baseline assessments, patients were randomised by a member of the research team at the recruiting site using the secure, telephone-based randomisation service at the York Trials Unit.

In the event that the local clinical team felt that a patient needed to be assessed for obstructive sleep apnoea, the patient was not randomised until a clinical decision was made.

Home oxygen therapy

If the patient was randomised to receive HOT, a clinical prescription was completed and sent to the local oxygen supply company holding the standard NHS contract within that particular region. These were Air Liquide UK (Birmingham, UK), Dolby Vivisol (Stirling, UK), BOC Healthcare (Manchester, UK) and Air Products (Crewe, UK). Concentrators were delivered to the patient’s home by the recruiting hospital’s usual oxygen supplier, in accordance with existing NHS agreements. The oxygen supply company typically installed the equipment within 3 days of the prescription being issued. The installing engineer instructed the participant about the safety requirements of using the machines and gave details of how to claim for the electricity costs of running the machine. In accordance with NHS agreements, the concentrators should have been serviced approximately every 6 months.

At the end of an individual patient’s trial participation, oxygen concentrators were removed from the patients’ homes unless they wished to continue treatment.

Best medical therapy

Patients allocated to this arm received the BMT currently available. Patients received the maximally tolerated medical management for their heart failure and reached their target dose of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system, a beta-adrenoceptor antagonist and an aldosterone antagonist.

Follow-up

Patients with CHF usually attend clinic every 6 months and follow-up in the study was arranged around standard attendances to prevent patients being unduly burdened with additional hospital visits. At the conclusion of the trial, final clinical data were collected using existing hospital records, including admission and mortality. The data collected are summarised in Table 2, together with the schedule for data collection.

| Assessment | Months after recruitment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline: clinic | 3: home or clinic | 6: clinic | 12: clinic | 18: clinic | 24: clinic | |

| Clinical | ||||||

| Age, sex, aetiology, height | ✗ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Weight | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Current medication | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Resting pulse rate and blood pressure, respiratory rate | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Assessment of peripheral oedema and lung crackles | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ECG | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Blood test – BCP, FBC (standard biochemistry and haematology) | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Blood test – NT-proBNP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Spirometry | ✗ | – | – | ✗ | – | ✗ |

| Echocardiogram | ✗ | – | – | ✗ | – | ✗ |

| 6MWT and pre/post O2 saturation | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Overnight sleep test (if locally accessible) | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CCI | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| KPS score | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| QoL | ||||||

| MLwHF questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| NRS – breathlessness | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HADS | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ESS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health economics | ||||||

| EQ-5D | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health Service Use Questionnaire (not all questions) | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Trial completion

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when:

-

they had been in the trial for 24 months or 6 months if there was insufficient time to follow the patient further

-

they wished to withdraw from the trial

-

their treating physician or medical researcher withdrew them from the trial

-

they were lost to follow-up

-

they died.

As well as withdrawing fully from the trial, participants had the option of:

-

withdrawing from receiving oxygen (if that had been their allocation)

-

withdrawing from the collection of data via patient questionnaires

-

withdrawing from the collection of data via nurse questionnaires.

Chapter 6 Results

Trial recruitment

The HOT study was stopped early by the funders because of poor patient adherence to the oxygen prescription. Recruitment began in April 2012 and stopped in February 2014. Randomisation to the NOT arm was stopped in April 2013. In total, 139 patients were randomised, 57 to each of the LTOT and BMT arms and 25 to the NOT arm. The overall rate of recruitment is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The overall rate of recruitment in the HOT trial.

The original sample size for the three-arm trial was 450 patients. The aim was to recruit these patients in 12 months; however, recruitment was slower than expected and, by the end of April 2013, 74 patients had been recruited into the trial (25 to each of the LTOT and NOT arms and 24 to the BMT arm). The decision was made to drop the NOT arm and continue the trial with two arms with a revised sample size of 222 patients. The recruitment period was extended to August 2014. When the trial was closed at the end of February 2014, a total of 139 participants had been randomised.

Over the course of the trial, a total of 15 participating sites joined, all in the UK (Table 3). Recruitment was staggered, with sites joining over the course of the trial. At least one trial participant was recruited in 13 out of the 15 sites (Figure 5 and Table 3). The median number of participants recruited per site was 4 (range 1–76). Over half of the participants (n = 76) were recruited from the Hull site, where the chief investigator was based.

| Site | Principal investigator | Started recruiting | LTOT (n = 57) | NOT (n = 25) | BMT (n = 57) | Total (n = 139) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hull | Professor Andrew Clark | April 2012 | 26 (45.6) | 18 (72.0) | 32 (56.1) | 76 (54.7) |

| Chesterfield | Dr Justin Cooke | October 2012 | 7 (12.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.8) | 12 (8.6) |

| Oldham | Dr Jolanta Sobolewska | January 2013 | 6 (10.5) | 3 (12.0) | 3 (5.3) | 12 (8.6) |

| Darlington | Professor Jerry Murphy | September 2012 | 4 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.0) | 8 (5.8) |

| Dundee | Dr Miles Witham | November 2012 | 6 (10.5) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.0) |

| Leicester | Professor Iain Squire | November 2012 | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.8) | 7 (5.0) |

| Barnet | Dr Ameet Bakhai | October 2012 | 1 (1.7) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) |

| Durham | Dr Mohamed El-Harari | January 2013 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (5.3) | 4 (2.9) |

| Bradford | Dr Paul Smith | January 2013 | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (2.2) |

| Ealing | Dr Stuart Rosen | May 2013 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (1.4) |

| Sunderland | Dr John Baxter | June 2013 | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (1.4) |

| Pinderfields | Dr Paul Brooksby | July 2013 | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Plymoutha | Dr Andrew Stone | June 2013 | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

FIGURE 5.

Participant recruitment by site (two sites did not recruit any patients).

Two sites did not recruit any patients. Significant attempts were made to recruit a patient in Aneurin Bevan University Health Board but no eligible, consenting patients were identified; East Cheshire NHS Trust was granted research and development approval only shortly before recruitment ceased and, therefore, did not have time to recruit a patient.

Figure 6 shows the CONSORT flow diagram of participants through the trial.

FIGURE 6.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Based on patients who provided full covariate data for the primary analysis model and primary outcome data at at least one of the 3-, 6- or 12-month time points.

Withdrawals

A greater proportion of patients in the LTOT arm (n = 8, 14%) than the NOT arm (n = 2, 8%) formally withdrew from their allocated trial treatment. One patient in the NOT arm withdrew from completing the postal patient questionnaires and one patient in each of the NOT and BMT arms withdrew from completing the nurse questionnaires. A total of four patients (one LTOT, one BMT and two NOT) requested full trial withdrawal and two further patients (one LTOT, one NOT) were withdrawn by a health professional. The reasons given for each of the change of circumstances are shown in Table 4. There were 25 recorded deaths during the course of the trial (LTOT, 6; BMT, 12; and NOT, 7).

| Reason | LTOT, n (%) | NOT, n (%) | BMT, n (%) | Overall, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrew from treatment | n = 8 | n = 2 | – | n = 10 |

| Did not feel oxygen was helping | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | – | 3 (30) |

| Was not using oxygen | 2 (25.0) | 1 (50) | – | 3 (30) |

| Problems sleeping/at night | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | – | 1 (10) |

| Worried about tripping over tubing | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | – | 1 (10) |

| Cannula and mask uncomfortable | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | – | 1 (10) |

| No reason given | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | – | 1 (10) |

| Withdrew from patient questionnaires | n = 0 | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 1 |

| No reason given | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Withdrew from nurse questionnaires | n = 0 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 2 |

| Did not wish to attend hospital for visits | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Withdrew from trial | n = 1 | n = 2 | n = 1 | n = 4 |

| Did not feel study was beneficial | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Did not want assessments/site visits | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (25) |

| Had not used oxygen at all as was afraid of it, and did not want to be followed up | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| No reason given | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Withdrawn by health-care professional | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 2 |

| Patient in hospice and unwell | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

| Patient incapacitated due to stroke | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

Baseline participant characteristics

Completed baseline questionnaires were received from 139 (100%) randomised participants. Participant baseline characteristics are summarised by treatment group (LTOT and BMT arms only) in Tables 5 and 6.

| Characteristic | LTOT (n = 57) | BMT (n = 57) | Total (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 40 (70.2) | 40 (70.2) | 80 (70.2) |

| Female | 17 (29.8) | 17 (29.8) | 34 (29.8) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 73.1 (10.6) | 71.4 (11.9) | 72.3 (11.3) |

| Median (min., max.) | 74.7 (51.7, 94.0) | 74.4 (38.9, 87.4) | 74.7 (38.9, 94.0) |

| Height (m) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.68 (0.10) | 1.68 (0.08) | 1.68 (0.09) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.67 (1.43, 1.85) | 1.67 (1.48, 1.90) | 1.67 (1.43, 1.90) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83.0 (20.7) | 84.1 (21.8) | 83.5 (21.2) |

| Median (min., max.) | 83.2 (41.5, 165.1) | 82.0 (50.0, 140.0) | 82.1 (41.5, 165.1) |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |||

| IHD | 51 (89.5) | 45 (79.0) | 96 (84.2) |

| Arrhythmia | 15 (26.3) | 21 (36.8) | 36 (31.6) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 4 (7.0) | 10 (17.5) | 14 (12.3) |

| Valvular heart disease | 2 (3.5) | 3 (5.3) | 5 (4.4) |

| Amyloidosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| NYHA class, n (%) | |||

| III | 57 (100.0) | 51 (89.5) | 108 (94.7) |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.5) | 6 (5.3) |

| NT-proBNP (ng/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5463.2 (8402.0) | 3558.4 (4026.7) | 4510.8 (6627.3) |

| Median (min., max.) | 2243 (118, 35,000) | 1931 (82, 15,594) | 2202.5 (82, 35,000) |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 126.0 (44.1) | 132.0 (50.2) | 129.0 (47.1) |

| Median (min., max.) | 113 (66, 252) | 117.5 (63, 235) | 114 (63, 252) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.0 (7.7) | 28.2 (8.1) | 28.1 (7.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 29 (7, 39) | 28 (11, 50) | 28 (7, 50) |

| LV impairment, n (%) | |||

| Mild to moderate | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Moderate | 11 (19.3) | 9 (15.8) | 20 (17.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 10 (17.6) | 12 (21.1) | 22 (19.3) |

| Severe | 35 (61.4) | 36 (63.2) | 71 (62.3) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs, n (%) | 50 (87.7) | 48 (84.2) | 98 (86.0) |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 53 (93.0) | 49 (86.0) | 102 (89.5) |

| Aldosterone antagonists, n (%) | 47 (82.5) | 38 (66.7) | 85 (74.6) |

| Characteristic | LTOT (n = 57) | BMT (n = 57) | Total (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse rate (beats per minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 68.7 (13.0) | 70.5 (12.8) | 69.6 (12.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 69 (18, 99) | 72 (15, 97) | 70 (15, 99) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 120.1 (20.8) | 116.6 (20.8) | 118.3 (20.8) |

| Median (min., max.) | 117 (78, 180) | 114 (65, 194) | 115 (65, 194) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.1 (9.8) | 65.1 (13.3) | 65.1 (11.6) |

| Median (min., max.) | 63 (46, 100) | 63 (25, 111) | 63 (25, 111) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.6 (4.7) | 15.6 (3.4) | 16.1 (4.1) |

| Median (min., max.) | 16 (10, 36) | 16 (9, 24) | 16 (9, 36) |

| FVC (l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 2.34 (0.89, 4.42) | 2.48 (0.73, 5.28) | 2.37 (0.73, 5.28) |

| FEV1 (l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.7) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.65 (0.55, 3.49) | 1.78 (0.45, 3.80) | 1.74 (0.45, 3.80) |

| Rhythm, n (%) | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 29 (50.9) | 25 (43.9) | 54 (47.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (24.6) | 16 (28.1) | 30 (26.3) |

| Atrial flutter | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Biventricular pacing synchronous | 12 (21.1) | 12 (21.1) | 24 (21.1) |

| Biventricular pacing asynchronous | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| RV pacing synchronous | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| RV pacing asynchronous | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 7 (12.3) | 3 (5.3) | 10 (8.8) |

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 129.5 (16.7) | 129.5 (19.6) | 129.5 (18.2) |

| Median (min., max.) | 128 (96, 170) | 127 (92, 179) | 127.5 (92, 179) |

The majority of patients in the study were male (n = 80, 70%) and the mean age was 72 years (range 38–94 years). The most common cause of the participants’ heart failure was ischaemic or coronary heart disease (n = 96, 84%), and the vast majority of participants were in NHYA class III (n = 108, 95%).

To be eligible for the trial, participants had to have a LVEF < 40% or be graded as at least ‘moderately’ impaired on visual inspection. LVEF was not recorded in eight participants in the LTOT or BMT arm, and all of these participants had either ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ LV impairment. One participant with a LVEF > 40% was randomised as he or she was visually assessed as having ‘severe’ LV impairment. NT-proBNP level was not an entry criterion to the study, but the very high levels suggest that patients with severe heart failure were recruited.

In general, the two treatment groups were comparable across baseline participant characteristics; however, there was a slight imbalance in NT-proBNP level and proportion of patients taking aldosterone antagonists. The mean NT-proBNP level was higher in the LTOT arm than in the BMT arm, and the proportion of patients taking an aldosterone antagonist was greater in the LTOT arm. NT-proBNP level was pre-specified as a covariate in the primary analysis and so this imbalance was controlled for.

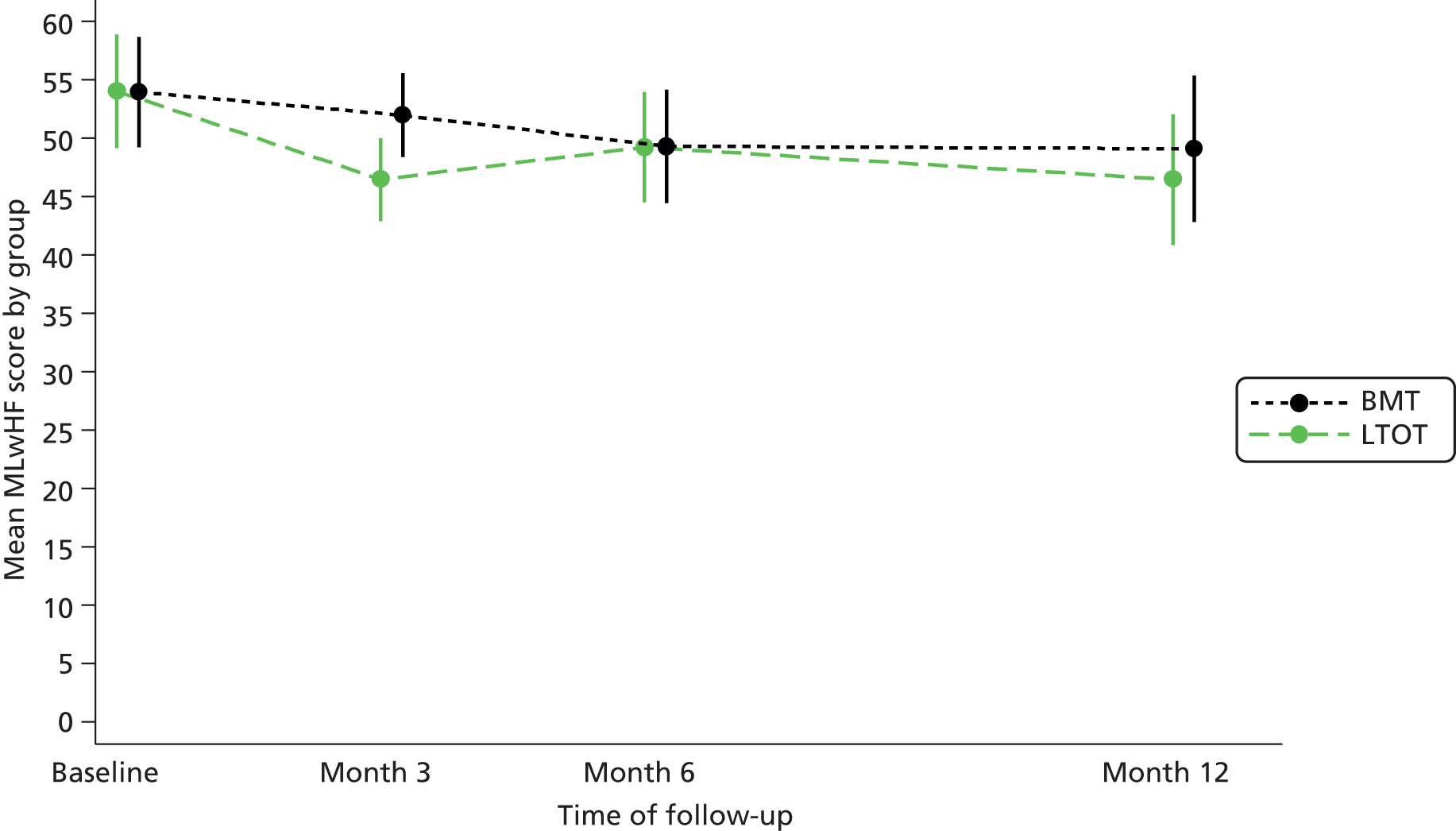

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was MLwHF questionnaire score at 6 months post randomisation. At baseline, a response to one item was missing in two patients and responses to two items were missing in two patients. At 3 months, among those for whom the MLwHF questionnaire was returned, there were no missing data. At 6 months, seven patients had a missing response to one item. At 12 months, one questionnaire was returned not completed, with a note to say that the patient was too unwell to complete the questionnaire; otherwise there were no missing data. At 12, 18 and 24 months, where patients returned a questionnaire, there were complete item data for the MLwHF questionnaire. Imputation of missing items was, therefore, necessary only on baseline and 6-month data. Summaries of the MLwHF questionnaire score (post imputation) by treatment group at each time point are presented in Table 7.

| Time point | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTOT (n = 57) | BMT (n = 57) | Total (n = 114) | LTOT | BMT | Mean difference (95% CI); p-value | |||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | Median (min., max.) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (min., max.) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (min., max.) | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | ||

| Baseline | 57 | 54.0 (18.4) | 52 (13, 95) | 57 | 54.0 (17.9) | 50 (20, 93) | 114 | 54.0 (18.1) | 52 (13, 95) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Month 3 | 53 | 45.3 (16.2) | 46 (7, 84) | 53 | 52.4 (18.2) | 52 (2, 99) | 106 | 48.5 (19.2) | 48 (2, 91) | 46.5 (1.8) | 42.9 to 50.1 | 52.0 (1.8) | 48.4 to 55.6 | –5.5 (–10.5 to –0.4); p = 0.03 |

| Month 6 | 45 | 48.1 (18.5) | 49 (2, 81) | 43 | 49.0 (20.2) | 47 (10, 91) | 88 | 48.5 (19.2) | 48 (2, 91) | 49.2 (2.4) | 44.5 to 54.0 | 49.3 (2.5) | 44.5 to 54.2 | –0.1 (–6.9 to 6.7); p = 0.98 |

| Month 12 | 21 | 48.0 (16.0) | 46 (20, 79) | 18 | 47.7 (18.8) | 51 (11, 77) | 39 | 47.8 (17.1) | 49 (11, 79) | 46.5 (2.8) | 40.9 to 52.1 | 49.1 (3.2) | 42.9 to 55.4 | –2.6 (–11.0 to 5.8); p = 0.54 |

| Month 18 | 8 | 43.4 (18.6) | 35.5 (25, 72) | 8 | 36.3 (20.4) | 30.5 (12, 72) | 16 | 39.8 (19.2) | 33 (12, 72) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Month 24 | 2 | 43.5 (13.4) | 43.5 (34, 53) | 1 | 51 | – | 3 | 46.0 (10.4) | 51 (34, 53) | – | – | – | – | – |

A covariance pattern model was used to compare MLwHF questionnaire score between the LTOT and BMT arms, adjusting for baseline MLwHF questionnaire score, age, log-NT-proBNP level, creatinine level, treatment group, time and a treatment group–time interaction. The model included all patients who provided full data for each of the included covariates, and MLwHF questionnaire outcome data at one or more post-baseline time points up to 12 months, and so was based on 102 out of 114 patients (89.5%): 51 (89.5%) in each group. Baseline characteristics of participants as included in primary analysis model are compared between the treatment arms in Table 8. It does not appear that the loss of the 12 patients for whom covariate or outcome data were missing significantly impacted on the balance between the treatment arms achieved at randomisation.

| Characteristic | LTOT (n = 51) | BMT (n = 51) | Total (n = 102) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 35 (68.6) | 36 (70.6) | 71 (69.6) |

| Female | 16 (31.4) | 15 (29.4) | 31 (30.4) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 72.0 (9.8) | 71.5 (11.9) | 71.8 (10.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 74.1 (51.7, 91.8) | 74.9 (38.9, 86.4) | 74.5 (38.9, 91.8) |

| Height (m) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.68 (0.10) | 1.68 (0.08) | 1.68 (0.09) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.68 (1.43, 1.85) | 1.67 (1.48, 1.90) | 1.67 (1.43, 1.90) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83.1 (20.9) | 83.8 (21.9) | 83.5 (21.3) |

| Median (min., max.) | 84.2 (41.5, 165.1) | 82.0 (50.0, 140.0) | 82.4 (41.5, 165.1) |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |||

| IHD | 47 (92.2) | 39 (76.5) | 86 (84.3) |

| Arrhythmia | 14 (27.5) | 17 (33.3) | 31 (30.4) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 4 (7.8) | 10 (19.6) | 14 (13.7) |

| Valvular heart disease | 1 (2.0) | 3 (5.9) | 4 (3.9) |

| Amyloidosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| NYHA class, n (%) | |||

| III | 51 (100.0) | 45 (88.2) | 96 (94.1) |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.8) | 6 (5.9) |

| NT-proBNP (ng/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4483.6 (7288.2) | 3476.7 (4081.2) | 3980.1 (5898.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 2198 (118, 35,000) | 1900 (82, 15,594) | 1915.5 (82, 35,000) |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 125.3 (46.1) | 134.7 (51.6) | 130.0 (48.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 112 (66, 252) | 127 (63, 235) | 113.5 (63, 252) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.5 (7.8) | 28.7 (8.3) | 28.6 (8.0) |

| Median (min., max.) | 30 (7, 39) | 29 (11, 50) | 29.5 (7, 50) |

| LV impairment, n (%) | |||

| Mild to moderate | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Moderate | 10 (19.6) | 9 (17.7) | 19 (18.6) |

| Moderate to severe | 10 (19.6) | 11 (21.6) | 21 (20.6) |

| Severe | 30 (58.8) | 31 (60.8) | 61 (59.8) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs, n (%) | 44 (86.3) | 43 (84.3) | 87 (85.3) |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 47 (92.2) | 43 (84.3) | 90 (88.2) |

| Aldosterone antagonists, n (%) | 41 (80.4) | 35 (68.6) | 76 (74.5) |

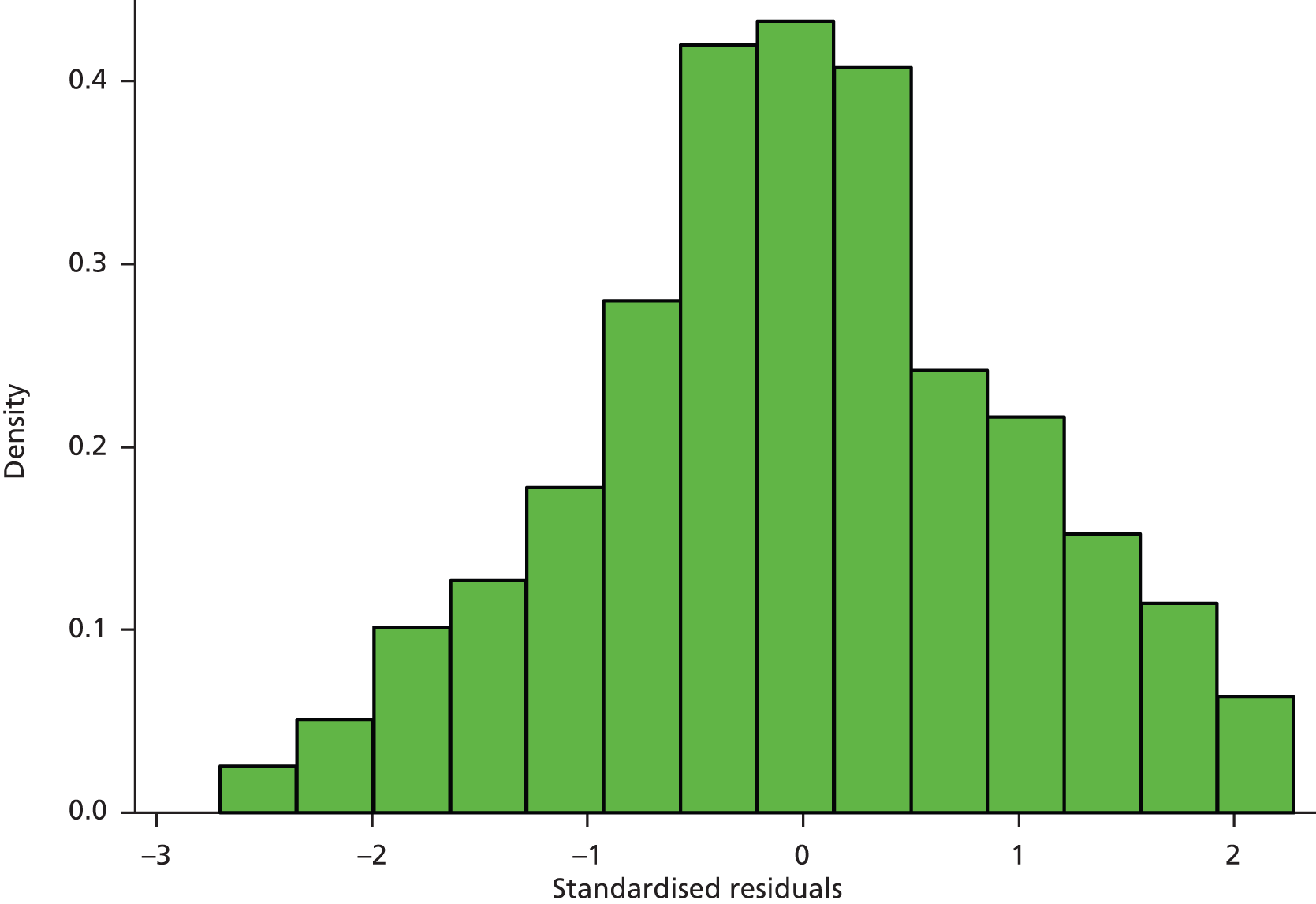

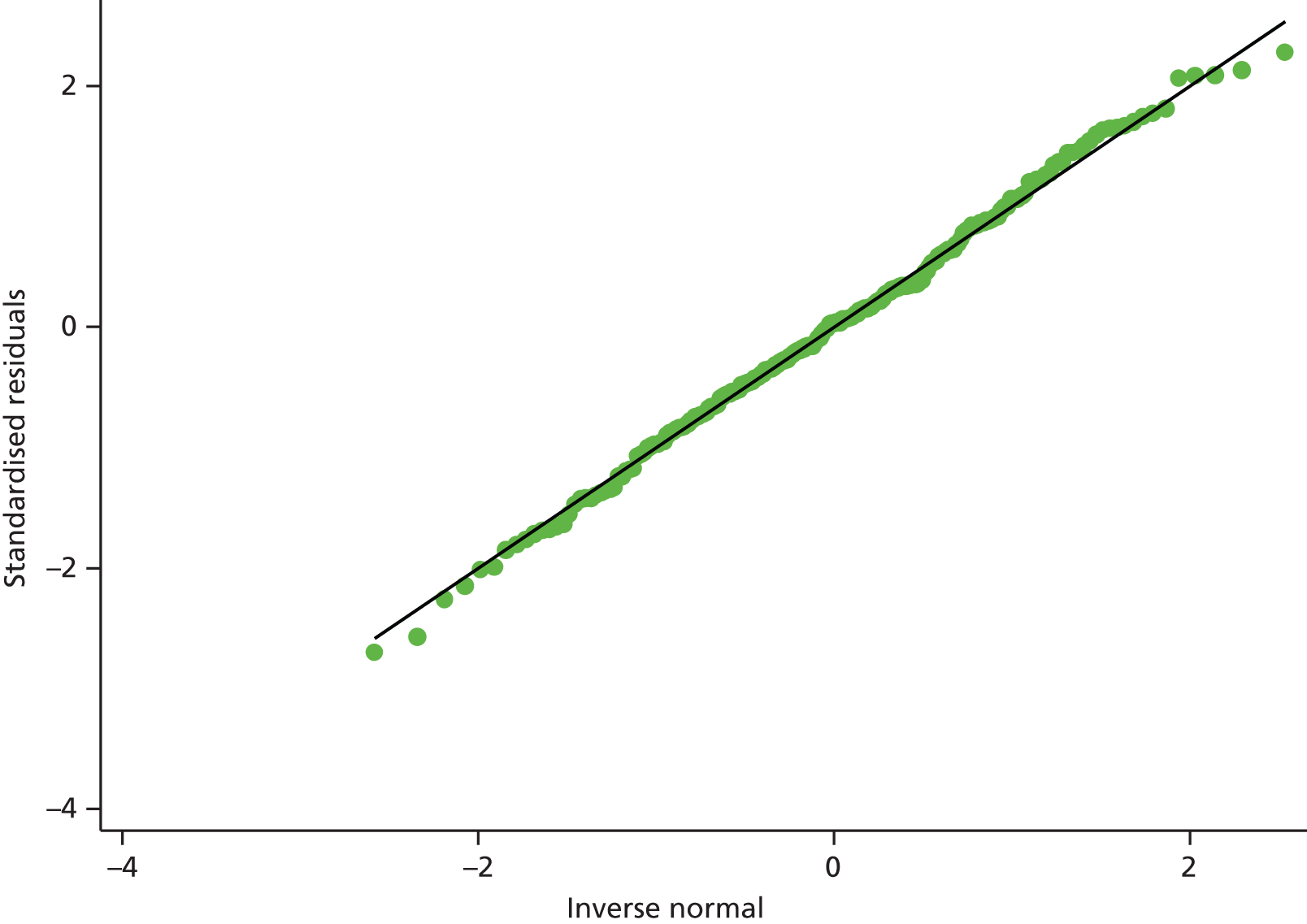

The assumptions of the linear model were checked visually. The normality of the standardised residuals was assessed via a histogram and Q–Q plot (see Appendix 5), and the homoscedasticity of the errors was checked by plotting the residuals against the fitted values. These plots gave no reason to be concerned about the validity of the assumptions.

In total, 88 participants provided valid MLwHF questionnaire data at 6 months (LTOT n = 45; BMT n = 43); however, five of these participants did not provide data for at least one of the included baseline covariates (MLwHF questionnaire score, age, NT-proBNP level, creatinine level) so they were not included in the model. A further 19 participants (LTOT n = 8; BMT n = 11) were included in the model, as they provided valid MLwHF questionnaire data at 3 and/or 12 months, resulting in an analysed sample of 102 participants. An estimate of the treatment effect at 6 months was extracted from the model. As well as the 85 participants in the model who provided primary outcome data at 6 months, participants who provided data at 3 and/or 12 months but not at 6 months are taken into account when the treatment effect at 6 months is estimated owing to the specification of the covariance pattern between the within-patient repeated measures.