Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/03. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The draft report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests relevant to the submitted work except that Covidien Ltd (Mansfield, MA, USA) provided free supplies of its intermittent pneumatic compression devices and sleeves to hospitals participating in the trial. Neither Covidien Ltd nor the funders of the study had any role in data collection, data storage, data analysis, drafting of reports or the decision to publish, although we did allow Covidien Ltd to comment on the draft manuscripts prior to final submission to ensure that we described and used trademarks, etc., appropriately for their products.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Dennis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2005, a House of Commons Health Committee highlighted the very large number of patients dying in UK hospitals from venous thromboembolism (VTE) and called for more effective prophylaxis. 1 Studies reported since 1985 have shown that deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is particularly common in patients who have suffered a recent stroke. 2 Patients with a history of VTE and significant weakness of the leg and who are immobile appear to be at the greatest risk. 3 Studies with magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated DVT in 40% of stroke patients and above-knee DVT in 18% of patients within 3 weeks of stroke. 4 Studies using less sensitive screening techniques, such as compression duplex ultrasound (CDU), suggest a lower frequency of above-knee DVT (about 10%), although the types of patients included and the duration and timing of follow-up influences these estimates. 5 Clinically apparent DVT, confirmed on investigation, is less common than DVT identified through screening; however, DVT may not be recognised and may cause important complications including pulmonary embolism (PE), sudden death and, in the longer term, post-phlebitis leg syndrome. PE is an important cause of preventable death after stroke. 2 Clinically evident PE has been variably estimated to affect 1–16% of patients in prospective trials6 and 3–30% of patients in observational studies. 7 In the Clots in Legs Or sTockings after Stroke (CLOTS) 1 trial, about 5% of patients developed symptomatic DVT and 1.5% had a confirmed PE in the first month after stroke. 8 The rate of PE is likely to be underestimated because PEs are not routinely screened for and autopsies are rarely performed. Many patients who have pneumonia or unexplained fever may actually have PEs. 9 Fifty per cent of patients who die after an acute stroke showed evidence of PE on autopsy. 10 Studies, such as the CLOTS 1 trial, which screen for DVT may underestimate the clinical importance of VTE because patients are usually treated while still asymptomatic and so their risk of developing symptomatic DVT and PE is reduced.

A number of interventions have been used to reduce the risk of DVT, as summarised in the following sections.

Anticoagulants

A Cochrane systematic review showed that both low- and medium-dose subcutaneous heparin reduces the risk of DVT, and probably PE, in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. 6 However, evidence from the International Stroke Trial11 showed that even low-dose heparin (5000 units twice daily) is associated with a significant excess of symptomatic intracranial and extracranial bleeds which offset any other benefits heparin may have on recurrent ischaemic stroke and fatal PE. A systematic review of randomised trials testing anticoagulation for VTE prophylaxis in stroke patients focused on only symptomatic events: deaths, DVT, PE, fatal PE and bleeds. 12 The estimates of treatment effect, expressed as events avoided or caused per 1000 patients treated, are shown in Table 1. This review also compared the effect of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) with the effect of unfractionated heparin. The LMWH was associated with fewer DVTs, but no significant differences in other clinical outcomes.

| Outcome | Number of trials | Number of outcomes/number treated | Outcomes avoided (–) or caused (+) per 1000 patients treated | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparin | No heparin | ||||

| Death | 8 | 496/5276 | 990/10,129 | –9 | –29 to 18 |

| PE | 5 | 39/5015 | 95/9847 | –3 | –5 to 0 |

| Symptomatic DVT | 1 | 0/101 | 1/105 | –9 | –10 to 57 |

| Major bleeding | 8 | 79/5276 | 89/10,129 | +6 | 2 to 12 |

Graduated compression stockings

Although graduated compression stockings (GCSs) seem to reduce the risk of DVT in patients undergoing surgery,13,14 the CLOTS 1 trial showed that thigh-length GCSs were not associated with a clinically useful reduction in the risk of post-stroke DVT [absolute reduction in risk of proximal DVT 0.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –1.9% to 2.9%]. 8 Moreover, use of GCSs was associated with an increase in the risk of skin breaks on the legs. A Cochrane review of the effectiveness of physical means of reducing the risk of VTE after stroke identified only one other trial of GCSs. 15,16 The two trials included a total of 2615 patients with stroke. The use of GCSs was not associated with any significant effect on DVT [odds ratio (OR) 0.88, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.08] or death (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.47).

Intermittent pneumatic compression

Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) is achieved by means of a pair of inflatable sleeves which are wrapped around the legs and are secured by hoop-and-loop fastener and attached via flexible tubing to a small bedside electric pump. Different manufacturers produce systems with different characteristics, but it is unclear whether or not these influence the effect on risk of VTE. 17 The sleeves may be short (or below knee), wrapping around just the lower leg, or long (thigh length) to wrap around the thigh as well. Some types provide compression to the foot only. They are inflated one side at a time to compress the legs at intervals. Some types inflate sequentially, first around the lower leg and then the upper, to ‘milk’ the blood from the leg and increase venous flow. Others compress along the length of the sleeves at the same time (so-called single compression). Some inflate rapidly, others slowly. The frequency of inflation can be fixed or may vary depending upon the rate of venous refill. IPC is thought to reduce the risk of venous thrombosis by:

-

increasing the flow of venous blood through the deep veins of the leg to reduce the likelihood of thrombosis

-

stimulating release of intrinsic fibrinolytic substances. 18

Intermittent pneumatic compression has mainly been used in surgical patients during and immediately after operations. One systematic review identified 22 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of IPC, which included a total of 2779 patients. 13 Use of IPC was associated with a 64% reduction in the odds of DVT (p < 0.00001). This review concluded that a priority for future research was trials of ‘prevention of venous thromboembolism with mechanical methods among high-risk medical patients (such as those with stroke)’. 13 Another, more recently published, systematic review identified 40 RCTs comparing IPC with No IPC. 19 These trials included a total of 7252 patients, were of very variable quality and included mostly surgical patients. IPC was more effective than no-IPC prophylaxis in reducing DVT [7.3% vs. 16.7%; absolute risk reduction (ARR) 9.4%, 95% CI 7.9% to 10.9%; relative risk 0.43, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.52; p < 0.01; I2 = 34%] and PE (1.2% vs. 2.8%; ARR 1.6%; 95% CI 0.9% to 2.3%; relative risk 0.48; 95% CI 0.33 to 0.69; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%). This review also showed that IPC was also more effective than GCS in reducing DVT and appeared to be as effective as pharmacological thromboprophylaxis but with a reduced risk of bleeding (relative risk 0.41, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.65; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%). Adding pharmacological thromboprophylaxis to IPC further reduced the risk of DVT (relative risk 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.91; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%) compared with IPC alone.

The Cochrane systematic review of the effectiveness of physical means of reducing the risk of VTE after stroke identified only two small RCTs of IPC including just 177 patients in total. 15 IPC was associated with a non-significant trend towards a lower risk of DVTs (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.10) with no evidence of an effect on deaths (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.89).

Thus, the available evidence confirmed that after stroke, even applying current prophylactic strategies, the risk of VTE was substantial. The available data suggested that IPC is a promising but unproven and rarely used intervention in the UK. The CLOTS 3 trial aimed to:

-

establish whether or not the routine application of IPC to the legs of immobile stroke patients reduces their risk of DVT and PE

-

determine whether or not IPC adds to the benefits of routine care, which often includes good hydration, early use of aspirin and mobilisation

-

quantify any risks of IPC when applied to stroke patients

-

estimate the cost-effectiveness of IPC which would help health service planners decide whether or not IPC should be offered routinely in the UK NHS

-

provide robust estimates of the effectiveness of IPC in stroke patients which might be extrapolated to other groups of medical (rather than surgical) patients at high risk of VTE.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design overview

The CLOTS 3 trial was a multicentre, parallel-group trial with a centralised randomisation system to allocate treatment in a 1 : 1 ratio, which ensured allocation concealment. Its methods were very similar to those of CLOTS trials 1 and 2. 3,20 We aimed to blind the ultrasonographers who carried out the imaging to detect DVTs but were unable to blind the patients and their caregivers to allocation group because of the nature of the intervention. The multicentre research ethics committees in the UK and the local ethics committees in all contributing centres approved our protocol. We obtained written informed consent from all patients or, for patients lacking mental capacity, from the patients’ personal legal representatives. The trial was registered as [International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 93529999].

Setting

Our collaborators in 105 centres in the UK aimed to enrol and/or follow up at least 2800 patients. To participate, hospitals had to have a local principal investigator who took responsibility for the trial governance; a well-organised inpatient stroke service; nursing staff trained in the use of IPC; and a diagnostic ultrasound department which routinely performed CDU.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Any patient admitted to hospital within 3 days of a clinical stroke fulfilling the World Health Organization criteria and who was not able to get up from a chair/out of bed and walk to the toilet without the help of another person.

Patients could be randomised from day 0 (day of admission) to day 3 of hospital admission. Any patient who had a stroke during hospital admission was eligible until day 3 from the stroke onset (day 0). Stroke should have been the most likely clinical diagnosis, but it was not necessary for a visible infarction to be seen on a brain scan.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients under 16 years of age.

-

Patients with stroke due to subarachnoid haemorrhage.

-

Patients who, in the opinion of the responsible clinician/nurse, were unlikely to benefit from IPC – for instance, this would include patients who were expected to mobilise or die within the next day.

-

Patients with contraindications to the use of IPC. Contraindications included:

-

local leg conditions with which the IPC sleeves would interfere such as leg ulcers or dermatitis

-

severe arteriosclerosis, as indicated by absence of pedal pulses or history of definite intermittent claudication

-

massive leg oedema or pulmonary oedema from congestive heart failure.

-

-

Patients who already had swelling or other signs of an existing DVT. Such patients could be recruited once a DVT had been excluded by normal D-dimers or CDU. There was a concern that the application of IPC to patients who may already have a DVT might displace the thrombus and increase the risk of PE. However, this potential risk has not been documented in the RCTs so far. We have not identified any case reports that provide convincing evidence that this has occurred.

Inclusion in another research study, including another RCT, did not automatically exclude a patient from participating in CLOTS 3. As long as inclusion in the other study would not confound the results of CLOTS 3, co-enrolment was permissible. In addition, local researchers had to avoid overburdening their patients. Patients were not co-enrolled in another research study that aimed to test an intervention intended to reduce the risk of VTE.

We did not require local research teams to maintain a screening log, although many did because it was required by the UK National Institute for Health Research stroke research networks. First, our view is that maintenance of a screening log diverts valuable resource away from enrolment, data collection and other important aspects of the trial procedures. Second, given that almost inevitably only a small proportion of potentially eligible patients are enrolled, screening logs do not provide useful data on which to judge the generalisability (external validity) of trial results. Finally, if screening logs are to be robust they need to include patient identifiers, to avoid double counting; the legality of collecting and storing this personal and sensitive information (patient identifier and name of trial is enough to indicate the patient’s medical diagnosis) without obtaining informed consent is questionable.

Consent

The patients, or their legal representatives, were approached by a member of the clinical team looking after that patient to ascertain their interest in participating in the CLOTS 3 trial or to obtain their permission to pass their details onto any research staff involved. Written informed consent was sought wherever possible. If this was not possible, the randomising clinician or nurse could obtain witnessed verbal consent. Patients or legal representatives were given enough time to consider the trial fully and ask any questions they may have had about the implications of the trial.

Randomisation

Having obtained consent, the clinician entered the patient’s baseline data onto a randomisation form (see Appendix 2) and then into a computerised central randomisation service via a secure web interface or a touch-tone telephone system. We encouraged clinicians to enrol patients as early as possible, as prophylaxis for DVT is likely to have a greater effect if started early. Once the computer program had checked these baseline data for completeness and consistency, it generated that patient’s treatment allocation to either ‘routine care plus IPC‘ or ‘routine care alone’. The system applied a minimisation program to achieve balance for four prognostic factors:

-

delay since stroke onset (day 0 or 1 vs. days 2–7)

-

stroke severity (using a validated prognostic model21 which includes the following factors: age; prestroke dependency in activities of daily living; living with another person prior to stroke; able to talk and orientated in time, place and person; and able to lift both arms to horizontal position against gravity)

-

severity of leg paresis (able or not to lift leg off the bed)

-

use of heparin, warfarin or thrombolysis at the time of enrolment.

As simple minimisation can theoretically lead to alternation of treatment allocation, our system also incorporated a degree of random allocation, that is it allocated patients to the treatment group that minimises the difference between the groups with a probability of 0.8 rather than 1.0. 22 This helped to guarantee allocation concealment.

The interventions

In the IPC group we applied the Kendall SCD™ Express system (Covidien Ltd, Mansfield, MA, USA) using thigh-length sleeves only (Figure 1). Initially, we used the standard sleeves, but during the study we switched to the Comfort™ sleeves (Covidien Ltd, Mansfield, MA, USA), which were designed to improve adherence while delivering the same pattern of compression. These devices deliver sequential compression, first around the distal calf, then proximal calf and then the thigh. Compression is circumferential (i.e. around the whole circumference of the leg) and sleeve inflation is gradual compared with some types of IPC. The maximum pressure is 45 mmHg. The compression is delivered to one leg at a time at a frequency which depends on the ‘venous refill time’. When the leg is compressed, its volume is reduced. Between compressions the veins refill and the volume of the leg increases. The changes in volume are detected by the IPC controller, which detects movement of air between the sleeves and the controller. The frequency of compression is higher if venous refill is faster, such as when the legs are dependent. This system aims to maximise venous flow.

FIGURE 1.

The Kendall SCD™ Express system used in the trial. This patient is wearing thigh-length Comfort™ sleeves.

If allocated IPC, nursing staff sized, fitted and applied the sleeves, based on the manufacturer’s instructions, to both legs as soon as possible after the randomisation telephone call. The IPC sleeves were meant to be worn both day and night, while the patient was in the bed or chair for 30 days from randomisation, or until a second-screening CDU had been performed (if after 30 days). They could be removed earlier for any of the following reasons:

-

The patient was independently mobile around the ward (i.e. could get up from a chair/out of bed and walk to the toilet without the help of another person).

-

The patient was discharged from the participating hospital. If the patient was transferred to a rehabilitation unit where it was practical to continue the IPC and monitor its use appropriately, then IPC could be continued until the patient was independently mobile, or declined to continue or until an adverse effect of IPC occurred. If IPC could not be continued after transfer to a rehabilitation unit, a discharge form was completed at the time of transfer to the rehabilitation unit.

-

The patient declined to continue to have IPC applied.

-

Health-care staff identified any adverse effect of the IPC (such as pressure ulcers on the legs, falls due to the IPC) which they judged made continued application of the IPC unwise.

If the IPC was removed for any other reason, for example to check the legs, or for bathing or for screening CDU, then the IPC was to be re-applied as soon as possible. If the sleeves became soiled, they were to be replaced with new sleeves as soon as possible. If a reason to remove the IPC sleeve from one leg developed, treatment to the other leg could continue; however, information on how often this occurred was not captured systematically.

Our recruitment co-ordinator (CW) and representatives of Covidien Ltd provided onsite training to nursing staff in the correct sizing, fitting and monitoring of IPC. This was supplemented by a training video and web-based training. We asked nursing staff to record their use of IPC on the medication chart to increase compliance and to aid monitoring. We stipulated that both treatment groups should receive the same medical care, which could include, depending on local protocols, early mobilisation, hydration and antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs. The local co-ordinator, who was not blinded to treatment allocation, extracted information from the medication charts on the compliance with IPC and use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs during the admission and recorded this on our hospital discharge form (see Appendix 2); therefore, we could check that these aspects of medical care were used equally in the treatment groups.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the occurrence of either a symptomatic or asymptomatic DVT in the popliteal or femoral veins (detected on the first or second CDU performed as part of the trial protocol) or a symptomatic DVT in the popliteal or femoral veins, confirmed on imaging (either CDU or venography) within 30 days of randomisation. We focused on proximal DVTs because they are much more reliably detected by ultrasound and are generally regarded as clinically more important. 23–25

Secondary outcomes

In hospital or within 30 days:

-

death within 30 days

-

presence of definite or probable DVT in the popliteal or femoral veins detected on a screening CDU scan which had not been suspected clinically before the scan

-

definite (i.e. excluding probable DVTs) symptomatic or asymptomatic DVT in the popliteal or femoral veins detected on either a CDU scan or contrast venography or magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging within 30 days of randomisation

-

any definite or probable symptomatic or asymptomatic DVT (i.e. including DVTs which only involve the calf veins)

-

confirmed fatal or non-fatal PE

-

adherence to allocated treatment

-

adverse events related to IPC within 30 days of randomisation.

At 6 months:

-

death from any cause

-

any confirmed symptomatic or asymptomatic DVT or PE occurring between randomisation and final follow-up

-

any symptomatic DVT or PE occurring between randomisation and final follow-up

-

functional status (as measured by the Oxford Handicap Scale)26

-

place of residence

-

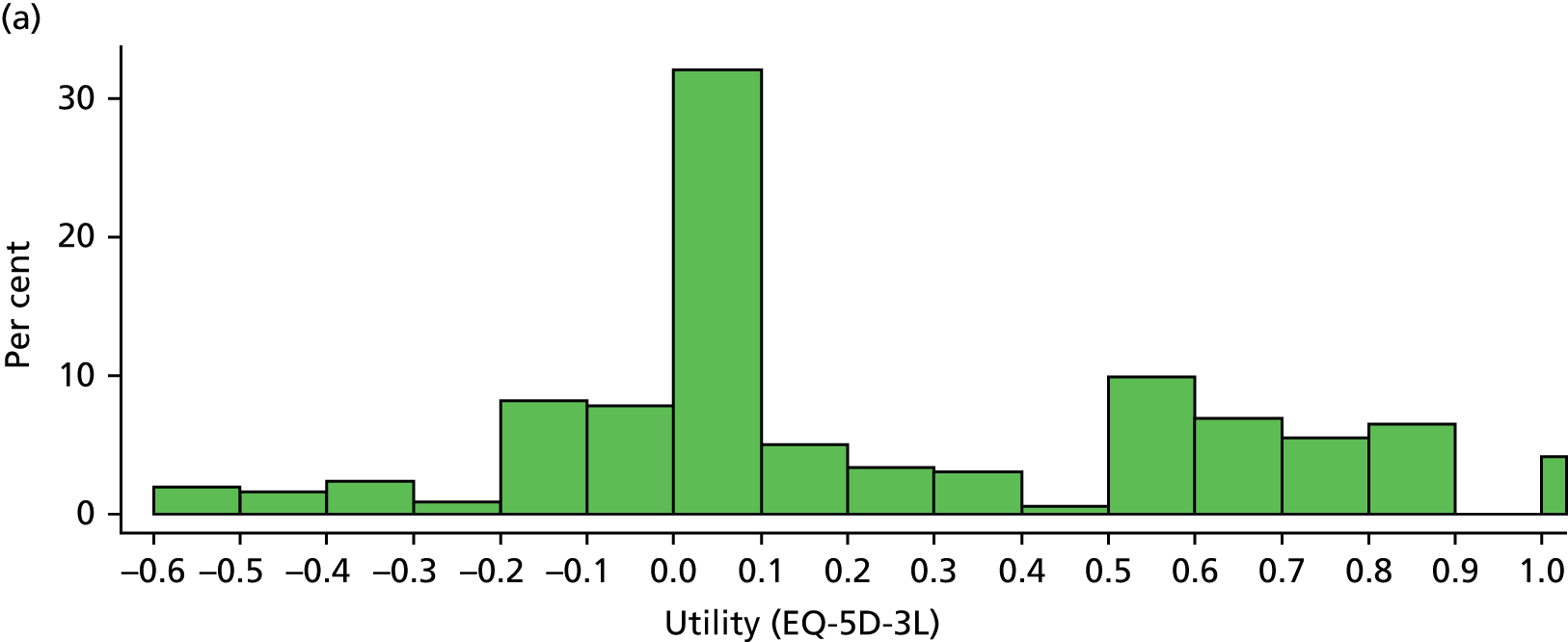

health-related quality of life [European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions 3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire]. 27,28

Adverse events

Stroke is a serious medical condition. About 20% of hospitalised patients are expected to die. Serious medical complications are common. The CLOTS 3 trial evaluated IPC, a non-drug intervention which has a CE mark and has been approved for the purpose of reducing the risks of VTE. The risks associated with IPC and participation in the trial were judged to be very small and generally predictable, for example skin problems on legs or falls resulting in injury. It would be relatively straightforward to attribute any serious adverse event to the IPC. In this trial we therefore did not require routine reporting of any adverse events, as this was unlikely to be informative and would have placed an unnecessary burden on the local researchers, which would have compromised the practicality of the trial. We did require prompt reporting of primary and secondary outcomes on the radiology report form (within 2 working days), discharge form (within 10 working days), general practitioner (GP) questionnaire and hospital follow-up forms (see Appendix 2).

The following were reported on the radiology report form, discharge form or GP questionnaire (if patient had been discharged) or hospital 6-month follow-up form (if the patient was still in hospital):

-

any confirmed DVT

-

any confirmed PE

-

any fall associated with significant injury occurring within 30 days of enrolment (when IPC might still be applied); an injury requiring investigation or specific treatment, which prolongs hospitalisation, or which leads to death, temporary or permanent disability

-

any damage to the skin of the legs including necrosis or ulcers occurring within 30 days of enrolment

-

reason(s) for prematurely stopping the IPC.

The following were expected complications of stroke and its comorbidities and did not need to be reported as adverse events:

-

deaths, which were reported as outcome events on the discharge or 6-month follow-up forms

-

infections other than those affecting the skin of the legs

-

further vascular events (including recurrent strokes, myocardial infarction and bowel ischaemia)

-

cardiac, renal or liver problems

-

epileptic seizures

-

spasticity or contractures

-

painful shoulder and other joint problems

-

mood disturbances.

Any other adverse events which the investigator felt might be a result of either the treatment or participation in the trial were to be reported within 10 working days to the co-ordinating centre. A serious adverse event (i.e. one resulting in death, is life-threatening or which results in significant disability or incapacity or prolongation of hospitalisation) was to be reported immediately on a serious adverse events form online or by fax. Serious adverse events attributed to the trial treatment or participation in the trial were reported to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), trial sponsors and ethics committees.

Follow-up

Detection of deep vein thrombosis

Patients should have had a CDU of the veins in both legs between day 7 and day 10 and usually between day 25 and day 30. We defined minimum acceptable technical standards for ultrasound equipment and stipulated that the trial ultrasonographers should have performed CDU to diagnose DVTs as part of a clinical service. We asked them to visualise the popliteal and femoral veins in both legs but did not insist that they routinely visualised the six deep veins in the calf, as detecting thrombosis in these is far less reliable. In addition, insisting on scanning of calf veins increases the time required for scanning, which might have impacted on the ability of centres to participate. We obtained a hard copy of scans in those patients with our primary outcome in order to enable our trial radiologist (JR), who was blinded to group allocation, to verify each primary outcome. We did not perform central verification of negative scans because, with ultrasound techniques, meaningful verification of static images is difficult. If no image was available we verified the scan result by obtaining a local radiologist’s clinical report. If the second ultrasound was delayed to more than 30 days and showed a popliteal or femoral DVT, it was included in the primary outcome. However, we did not include in our primary outcome a proximal DVT that came to attention only because symptoms started more than 30 days after enrolment, as this might have introduced bias because researchers unblinded to treatment allocation might theoretically include later clinical outcomes in one group preferentially.

Where the randomising person judged that it was likely to be impractical to perform a CDU between day 25 and day 30, he or she could, prior to randomisation, stipulate that a CDU would be performed only between day 7 and day 10. This might have been the case if the patient was likely to be discharged home to another region or transferred to a rehabilitation facility that did not have use of CDU facilities and was remote from the randomising centre. This was done to minimise losses to follow-up which, if unequal between the two treatment groups, could bias the trial results.

If a definite above-knee DVT was detected on the first screening CDU, that is the patient had our primary outcome, then the second screening CDU was no longer required.

Intermittent pneumatic compression was removed completely before the patient left the ward to undergo CDU, to ensure optimal blinding of the primary outcome measure. The CDU operator was asked to guess which treatment group the patient was in prior to the examination to estimate the effectiveness of blinding. In those allocated IPC, the sleeves were immediately re-applied on the patient’s return to the ward after the screening CDU.

In-hospital follow-up

The local co-ordinators completed a discharge form (see Appendix 2) for all randomised patients on discharge from the randomising centres or in the event of earlier death. We could not blind the local co-ordinators to group allocation. If a patient was transferred to a rehabilitation unit on a different site to the randomising centre, and it was impractical to continue the allocated treatment or its monitoring while the patient was in that unit, a discharge form was completed on transfer to that unit.

The data collected at hospital discharge by the unblinded local co-ordinator included:

-

Use of heparin, LMWHs, warfarin and antiplatelet drugs during admission to monitor the components of routine care and to ensure equal use in the two treatment arms. However, an imbalance of heparin or LMWH and warfarin might occur if IPC is effective as more patients in the control arm would receive these drugs to treat the excess of VTE. The indications for their use were therefore recorded. The timing of starting and duration of anticoagulation were not recorded.

-

Use of full-length or below-knee GCSs to monitor the components of routine care and to ensure equal use in the two treatment arms. Again the timing of initiation and duration of use were not recorded.

-

Adherence to treatment allocation and use of IPC. We captured the date any IPC was first applied and the date it was last applied. We also asked the local researcher to record the number of days between these dates when the IPC was not applied at all. We did not systematically record whether or not the IPC was applied to one or both legs and how many hours per day it was worn.

-

Any clinical DVT or PE requiring treatment.

-

Any complications of treatments, in particular skin problems on the legs and falls resulting in injuries and fractures occurring within the first 30 days after randomisation. Local researchers were asked to provide the date that each event occurred, and whether or not it was thought likely to be because of the IPC on the basis of the type of event and its timing.

The discharge form included checkboxes to record these secondary outcomes and adverse events (see Appendix 2). The date of occurrence of any secondary outcome was recorded along with a free-text description of the problem. The chief investigator (MD) reviewed these data centrally and coded the events as far as possible blind to the group allocation.

Later outcomes

The co-ordinating centre telephoned and sent a postal questionnaire to the GPs of all patients who survived to discharge from hospital about 24 weeks after randomisation. This established that the patient was alive prior to sending out a follow-up form and to ascertain whether he or she had had any DVT or PE since discharge from the randomising centre.

Six-month follow-up

The co-ordinating centre sent a postal questionnaire (and one postal reminder and then a telephone follow-up for non-responders) to those surviving patients who had been discharged. The 6-month questionnaire (see Appendix 2) aimed to establish:

-

the place of residence (own home, with relatives, residential care or nursing home) (as a guide to resource use)

-

their functional status [as measured by the Oxford Handicap Scale (OHS)]

-

their current antithrombotic medication regimen

-

presence of leg swelling or ulcers which might reflect post-DVT syndrome.

The questionnaire was completed by the patient or, in the case of those who had difficulties which prevented them doing it themselves, it could be completed by someone close to them. If there was a delay in completing the questionnaire, no attempt was made to judge retrospectively what the patient’s status had been at 6 months.

If the patient was still in hospital when the 6-month follow-up was due, the randomising clinician/nurse was sent a 6-month ‘in-hospital’ follow-up form, which was completed through consultation with the patient. We checked data centrally for completeness and consistency and sent monthly reports to each centre with data queries.

Management of deep vein thrombosis in the trial

If the clinician was satisfied that the patient had a proximal DVT (with or without a confirmatory venogram), the patient was anticoagulated using subcutaneous heparin/LMWH according to local protocols as long as there was no contraindication. If only calf vein thrombus was detected (by screening CDU and/or venography), the responsible clinician could anticoagulate the patient according to local protocols or, alternatively, arrange follow-up CDU approximately 7 days later to identify any propagation into the popliteal vein. If definite popliteal or femoral vein thrombus was detected, the patient was anticoagulated unless contraindicated. Any patient who developed symptoms or signs suggestive of DVT during their admission was investigated by either CDU and/or venography or magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging and treated in accordance with local protocols if the diagnosis was confirmed. Use of heparin, LMWHs and warfarin to treat DVT and/or PE during admission was recorded on the discharge form. Timing of any use of anticoagulants during admission but after randomisation was not recorded. Continued use of IPC in patients with DVT was at the discretion of the responsible clinician.

Sample size

We originally planned to enrol at least 2000 patients. This aimed to give the trial a > 90% power (α = 0.05) to identify an absolute reduction in risk of our primary outcome of 4% (i.e. a reduction in risk of our primary outcome from 10% in the no IPC group to 6% in the IPC group). The frequency of our primary outcome was estimated from the CLOTS trials 1 and 2. We aimed to enrol at least 75% of patients from day 0 to day 2 after stroke onset. If the proportion enrolled after day 2 exceeded 25% of the total, then the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) could consider raising the overall target. This aimed to ensure that we did not miss a real treatment effect because of delays in recruitment.

In October 2010, the frequency of the primary outcome in both groups combined was 12.2%, rather than the expected 8%. The TSC therefore revised the sample size to 2800 to ensure that the trial maintained power to detect a 4% absolute difference in proximal DVT (i.e. a reduction from 14% in the routine care group to 10% in the routine care plus IPC group). The TSC was not aware of any results split by treatment group.

Statistical analyses

The trial statistician (CG) prepared analyses of the accumulating data which the independent DMC reviewed in strict confidence at least once per year. No other members of the trial team, TSC or participants had access to these analyses.

A detailed analysis plan was prepared by the members of the TSC and then published prior to the completion of enrolment without input from the trial statistician or reference to the unblinded data. 29,30 For the purposes of all primary analyses, we retained participants in the treatment group to which they were originally assigned irrespective of the treatment they actually received. We strived to obtain full follow-up data on every patient to allow a full intention-to-treat analysis. Inevitably, some patients were lost to follow-up. If data were unavailable, we excluded these patients from the analyses and conducted sensitivity analyses to see the effect of these exclusions on our conclusions. For binary outcomes (e.g. occurrence of a primary or secondary outcome or not), outcomes are presented as ORs and 95% CIs, adjusted using logistic regression for the factors used in the minimisation algorithm. We calculated absolute reductions in risk from these values. We converted ORs into relative risks using a standard method. 31 We analysed survival with Cox regression, adjusting for baseline variables included in our minimisation algorithm. We analysed the OHS in two ways: dichotomised into OHS score of 0–2 versus 3–6 (by logistic regression) and as an ordinal scale (by ordinal regression). The utility based on the EQ-5D-3L score was compared by a two-sample Wilcoxon test given the non-normal distribution of the data.

Preplanned subgroup analyses

Preplanned subgroup analyses included the effect of treatment allocation on the primary outcome subdivided by key baseline variables:

-

Time from stroke onset to randomisation (day 0 or day 1 vs. days 2–7, and days 0–2 vs. days 3–7). As DVT may develop very soon after stroke onset and IPC may not influence propagation of thrombus which has already started, it is plausible that IPC would be more effective if started earlier after stroke.

-

Paralysis of leg (able to lift both legs or not?).

-

Stroke severity [using a validated prognostic model. Probability of independent survival (OHS score of < 3) = 0–0.15 vs. > 0.15 (simple six-variable model21)].

-

High or low risk of DVT based on the presence of any one or more of the following indicators of a higher risk of DVT: dependent in activities of daily living (ADL) prior to stroke; prior history of DVT; unable to lift both arms or unable to lift both legs. 3

-

Use of heparin, LMWHs, warfarin or thrombolysis at the time of enrolment.

-

Haemorrhagic stroke versus ischaemic or unknown pathology.

-

Standard versus Comfort™ sleeves.

Subgroup analyses were performed by observing the change in log-likelihood when the interaction between the treatment and the subgroup was added into a logistic regression model.

Secondary analyses

Intermittent pneumatic compression has usually been used for a relatively short time on perioperative patients and patients in high-dependency units. In the CLOTS 3 trial, we aimed to maintain the IPC treatment for up to 30 days, if the patient remained in hospital and was still immobile. However, for a variety of reasons, the IPC was often terminated earlier than this or it was not applied continuously. In the CLOTS 1 and 2 trials, 79% of proximal DVTs were detected on the first CDU scan. 5 The risk of DVT seemed to be highest early on, and therefore any prophylaxis might be more effective during this period. We carried out additional analyses (including all those subgroups identified in the primary outcome) of the effect of allocation to IPC on the primary outcome occurring within 14 days of randomisation, rather than 30 days. This would, we hoped, to some extent, reduce the impact of patients who required IPC for only a few days before becoming mobile or adhered to IPC for only a short time. In addition, it would reflect the practice in many places where acute hospital admission for stroke is short and prophylaxis is applied for only the first few days. However, it is also possible that prophylaxis for the first 7, 14 or 30 days may simply defer the onset of DVT. We therefore analysed whether or not there is a difference in frequency of any symptomatic and/or asymptomatic DVT or PE within 6 months between patients allocated to IPC and those not.

These statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Research governance

The principal investigator in each centre was responsible for:

-

discussing the trial with medical and nursing staff who see stroke patients and ensure that they remained aware of the state of the current knowledge, the most recent trial protocol and its procedures

-

delegating roles to those with appropriate knowledge and skills

-

ensuring that patients admitted with stroke were considered promptly for the trial

-

ensuring that the randomisation forms, radiology report forms and discharge forms were completed and either entered on line or sent to the co-ordinating centre promptly and that copies were kept in a site file and patient notes

-

ensuring that the trial was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice and fulfilled all national and local regulatory requirements

-

ensuring that the patients’ confidentiality was not breached

-

allowing access to source data for audit and verification.

The co-ordinating centre was responsible for:

-

providing study materials, a 24-hour randomisation service and helpline

-

giving collaborators regular information about the progress of the study

-

helping ensure complete data collection at discharge

-

responding to any questions (e.g. from collaborators) about the trial

-

assuring data security and quality in accordance with good clinical practice and local guidelines

-

ensuring trial was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice.

Monitoring

Intermittent pneumatic compression devices carry a CE mark and are licensed for use as prophylaxis for VTE. In surgical practice, use appears to be associated with a low risk of adverse effects. The trial procedures were relatively simple and placed only a small burden on the patients. No significant financial inducements were offered to collaborating centres to encourage their active participation or to reward high recruitment rates. Central follow-up of all patients at about 6 months after enrolment provided confirmation of the trial participants identity (hence avoided the need for detailed on-site source data verification of patient identity, a very resource-intensive activity). After an appropriate risk assessment process, the Trial Management Group and the trial sponsors judged that the risks of patients being harmed by the trial interventions were small, any hazard associated with participation in the trial was very small and the risk of research misconduct was also small. The intensity of on-site monitoring which we undertook was based on this risk assessment. The co-ordinating centre monitored the completeness, internal consistency and validity of the data from all trial sites. We used the trial data collected to monitor adherence to the trial protocol. Our study monitor carried out source data verification in a small random sample of patients during site visits. If concerns arose as a result of the routine central statistical monitoring, a more detailed investigation including on-site verification of source data was carried out. 32

The trial was jointly sponsored by NHS Lothian and the University of Edinburgh [ACCORD (Academic and Clinical Central Office for Research and Development)].

Patient and public involvement

Two patient representatives on the TSC provided feedback on our trial materials, procedures and results. Both had had a stroke and both had worked in nursing in the past; therefore, both were familiar with the problem of VTE. One worked for the NHS in procurement and was very knowledgeable about NHS purchasing of GCSs and IPC devices. This proved very valuable to us. She had been eligible for the CLOTS 1 trial but had declined to be enrolled, although she had then agreed to work with us on the TSC of each of the CLOTS trials. The other had been enrolled in the CLOTS 3 trial during the start-up phase and could therefore provide personal experience of being a trial participant.

Chapter 3 Trial conduct

Between 8 December 2008 and 6 September 2012, 2876 patients were enrolled in 94 centres in the UK, and an additional 11 centres took responsibility for delivering the allocated treatment and follow-up for patients who were transferred from the randomising hospital (see Appendix 1).

Recruitment

Funded by the Chief Scientist Office in Scotland, recruitment at the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, started in the start-up phase once the CLOTS 1 trial had completed recruitment (in September 2008), although recruitment into the CLOTS 2 trial continued in other hospitals. The CLOTS 2 trial completed recruitment in May 2009, after which many centres switched to recruiting into the CLOTS 3 trial. The CLOTS 3 collaboration was expanded after funding from the Health Technology Assessment programme was secured in April 2010. The rate of recruitment over time is shown in Figure 2. The recruiting hospitals, and the number each recruited, are listed in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment in the CLOTS 3 trial over time.

The rate of recruitment exceeded our expectations; therefore, we reached our revised target of 2800 approximately 1 year before we had expected to reach our original target of 2000 patients.

Baseline characteristics of patients recruited

The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2 and were well balanced between treatment groups. The patients’ progress through the trial is shown in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram (Figure 3).

| Baseline variable | IPC (n = 1438) | No IPC (n = 1438) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age,a years (IQR) | 76 (67–83) | 77 (68–84) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 74.2 (12.3) | 74.9 (11.9) |

| Males, n (%) | 695 (48.3) | 688 (47.8) |

| Final diagnosis at hospital discharge | ||

| Stroke/TIA (definite/probably ischaemic), n (%) | 1211 (84.2) | 1217 (84.6) |

| Confirmed haemorrhagic stroke, n (%) | 187 (13.0) | 189 (13.1) |

| Unknown type, n (%) | 19 (1.3) | 14 (1.0) |

| Non-strokes (included in primary analysis), n (%) | 19 (1.3) | 18 (1.3) |

| Missing (no discharge form), n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Past history and risk factors | ||

| Previous DVT or PE, n (%) | 66 (4.6) | 74 (5.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 256 (17.8) | 247 (17.2) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 24 (1.7) | 31 (2.2) |

| Overweight, n (%) | 417 (29.0) | 457 (31.8) |

| Current cigarette smoker, n (%) | 250 (17.4) | 228 (15.9) |

| Independent before stroke,a n (%) | 1301 (90.5) | 1295 (90.1) |

| Lives alone before stroke,a n (%) | 500 (34.8) | 503 (35.0) |

| Indicators of stroke severity | ||

| Able to lift both arms off bed,a n (%) | 499 (34.7) | 502 (34.9) |

| Able to talk and orientated,a n (%) | 886 (61.6) | 845 (58.8) |

| Able to lift both legs off bed, n (%) | 494 (34.4) | 493 (34.3) |

| Able to walk without help,a n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Stroke severity – probability of being alive and independent = 0 to 0.15), n (%) | 898 (62.4) | 892 (62.0) |

| Stroke severity – median (IQR) probability of being alive and independent | 0.09 (0.02–0.31) | 0.09 (0.01–0.31) |

| On warfarin at recruitment, n (%) | 25 (1.7) | 29 (2.2) |

| On heparin or LMWHs at recruitment, n (%) | 86 (6.0) | 78 (5.4) |

| Taken antiplatelet drug in the last 24 hours, n (%) | 970 (67.5) | 971 (67.5) |

| Received thrombolysis since admission, n (%) | 249 (17.3) | 255 (17.7) |

| On heparin or LMWH or warfarin at recruitment or received thrombolysis since admission, n (%) | 347 (24.1) | 352 (24.5) |

| Delay from stroke to randomisation | ||

| 0 to 1 day, n (%) | 624 (43.4) | 620 (43.1) |

| 2 days, n (%) | 478 (33.2) | 457 (31.8) |

| ≥ 3 days, n (%) | 336 (23.4) | 361 (25.1) |

| Second CDU considered unlikely to be practical at time of randomisation, n (%) | 225 (15.6) | 215 (15.0) |

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT diagram (the number screened for eligibility was not collected). a, The number of patients who withdrew consent is less than the number published in The Lancet. 33 The figure includes data only up to the point at which permission to follow up the patients or to use data was explicitly withdrawn. F/u, follow-up.

Withdrawal

Patients, or their proxies, were informed at the time they gave consent that they could stop the allocated treatment at any time, and without giving a reason. They were also told that they could withdraw completely from the study, although the data collected up to that point would be used in analyses. Unfortunately, local research teams did not always clearly establish the precise wishes of the patient or proxy. For instance, if the patient wished to stop receiving the allocated treatment, then this was sometimes interpreted as wishing to withdraw from the trial completely (implying that the patient would not be followed up). In addition, even when a patient expressed a wish not to be contacted directly by mail or telephone for follow-up, this did not necessarily preclude us from establishing their follow-up status through their GP or routine data sources. As a result, in some cases there was some uncertainty about whether or not we could use certain data items, such as date of death. In general, we included patients in the analysis unless it was clear from the correspondence that they did not want anything more to do with the trial. Based on this experience, it is clearly important that trials are rigorous in defining exactly what the patient wishes to do when they stop the intervention and whether or not they are also refusing any further contact for follow-up.

Background treatment

The use of antiplatelet medications, prophylactic- and treatment-dose heparin or LMWHs, oral anticoagulants and GCSs was recorded in both treatment groups on the discharge form by the local co-ordinator. However, we did not collect the dates that these treatments were given; therefore, we cannot tell if they were given concomitantly with IPC, if they followed IPC and if any anticoagulation was used in response to the diagnosis of a DVT or PE. We did not record timing of mobilisation, use of parenteral fluids or any measure of hydration.

Background treatment with antiplatelet medications, anticoagulants and GCSs is shown in Table 3. Use of prophylactic-dose heparin or LMWHs after randomisation was very similar in the treatment arms (IPC 17.2% vs. no IPC 16.7%). There was a small excess of treatment-dose heparin or LMWHs in the control arm, probably because DVTs occurred more commonly in that group. The low overall use of GCSs suggests that most centres were aware of, and accepted, the evidence from the CLOTS 1 trial that GCS use is not associated with lower risk of DVT. There was a small excess of GCS use in the IPC group, perhaps because the manufacturer of IPC previously recommended using IPC and GCSs in combination. However, it is possible that the GCSs were applied after the IPC had been removed or to prevent post-phlebitis leg syndrome.

| Background treatment prescribed | IPC (n = 1438) | No IPC (n = 1438) |

|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelet medication, n (%) | ||

| Aspirin | 1039 (72.4) | 1033 (71.8) |

| Dipyridamole | 152 (10.6) | 155 (10.8) |

| Clopidogrel | 526 (36.6) | 524 (36.4) |

| Anticoagulation, n (%) | ||

| Prophylactic-dose heparin/LMWHs | 248 (17.2) | 240 (16.7) |

| Treatment-dose heparin/LMWHs | 182 (12.7) | 219 (15.2) |

| Warfarin | 292 (20.3) | 294 (20.5) |

| Other oral anticoagulant | 10 (0.7) | 8 (0.6) |

| GCSs, n (%) | ||

| GCSs worn (any length) | 118 (8.2) | 42 (2.9) |

| Thigh-length GCSs worn only | 90 (6.3) | 22 (1.5) |

| Below-knee GCSs worn only | 17 (1.2) | 19 (1.3) |

| Both thigh-length and below-knee GCSs worn | 10 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) |

| GCSs of unknown length | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

Adherence

The measurement of adherence to IPC was based on data provided on the hospital discharge form by the local co-ordinators. In most cases it was based on the recording of IPC use on medication charts completed by the nurses on the stroke unit. It was not always complete. We attempted to collect the date the IPC was first applied, the date it was permanently taken off, the number of days between when it was not worn at all, and the reason why the IPC was stopped, especially if it was stopped prematurely.

In total, 1424 (99.2%) patients were allocated to the IPC group and were treated with IPC at some point in the first 30 days after randomisation. In the group allocated to no IPC, four patients received IPC at some point in the first 30 days. Three patients received IPC having been transferred to an intensive care or high-dependency unit where IPC was standard care, and one received IPC for 3 days because of a mistake in recording the allocated treatment.

Ideally, we would have defined 100% adherence as wearing IPC sleeves every day (i.e. no days on which they were not worn) from randomisation until the patient regained mobility, was discharged from a participating hospital or died or until 30 days or until a delayed second screening CDU. However, the number of days on which the IPC sleeves were not worn was not well recorded and was sometimes inconsistent with other data items. We therefore defined 100% adherence as wearing IPC sleeves from randomisation until the patient regained mobility, was discharged from a participating hospital or died, or until 30 days, or until a delayed second screening CDU, ignoring the likelihood that some patients would have had the sleeves removed for some intervening days and may not have worn them on both legs day and night. One hundred per cent adherence was achieved in 378 (26.3%) of patients in the IPC group. The distribution of percentage adherence is shown in Figure 4. The median adherence was 55.7% [interquartile range (IQR) 16.7–100%]. The adherence to the standard and Comfort™ sleeves are compared in Table 4.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of percentage adherence.

| Adherence measure | Standard sleeves (n = 834) | Comfort™ sleeves (n = 604) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration IPC applied (stop date–start date), n (%) | ||

| Missing | – | – |

| ≤ 1 day | 140 (16.8) | 96 (15.9) |

| 2–5 days | 180 (21.6) | 145 (24.0) |

| 6–10 days | 169 (20.3) | 104 (17.2) |

| 11–20 days | 138 (16.5) | 109 (18.0) |

| 21–30 days | 172 (20.6) | 138 (22.8) |

| > 30 days | 35 (4.2) | 12 (2.0) |

| Mean duration of IPC use (SD) in days | 11.6 (10.7) | 11.7 (10.4) |

| Median duration of IPC use (IQR) in days | 8 (3–20) | 8 (3–20) |

| Wore IPC sleeves until death/discharge/mobile/30 days or later second CDU (i.e. 100% adherence) | 222 (26.6) | 156 (25.8) |

| Mean adherence (SD), % of days applied per protocol | 55.5 (39.0) | 55.9 (37.9) |

| Median adherence (IQR) | 54.4 (16.7–100.0) | 55.9 (16.9–100.0) |

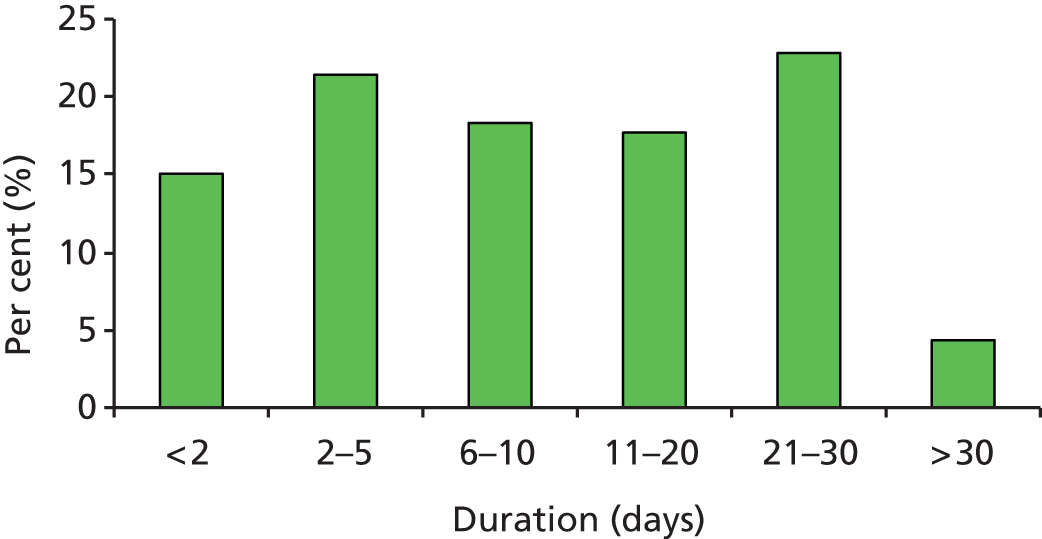

The distribution of duration of use in the IPC group is shown in Figure 5. The mean and median duration of IPC use was 11.7 days [standard deviation (SD) 10.6 days] and 8 days (IQR 3–20 days) respectively.

FIGURE 5.

The distribution of duration of use of IPC in the group allocated IPC.

Table 5 shows the adherence and reason(s) for removal of IPC in the 1438 patients allocated to IPC (reasons given are not always mutually exclusive).

| Use of IPC | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients with a completed discharge form | 1436 (100) |

| Wore IPC sleeves at any time in the first 30 days after randomisation | 1424 (99.2) |

| Wore IPC sleeves every day was supposed to according to protocol | 378 (26.3) |

| Removed according to protocol | |

| Patient regained mobility | 142 (9.9) |

| Second CDU delayed after 30 days | 33 (2.3) |

| Completed 30 days of IPC | 66 (4.6) |

| Removed early | |

| Concerns about patient’s skin | 62 (4.3) |

| Patient refused to wear IPC any longer | 474 (33.0) |

| Patient complained of discomfort | 189 (13.2) |

| Other reasons specified by local researchers | 535 (37.3) |

| Change in view of staff | 142 (26.5) |

| Patient/family refused | 107 (20.0) |

| Intermediate-severity skin problems | 3 (0.6) |

| Low-severity skin problems | 18 (3.4) |

| Other leg problems | 4 (0.8) |

| Technical fault with IPC | 7 (1.3) |

| Fall | 1 (0.2) |

| Other events – fractures, stroke, palliative care | 3 (0.6) |

| Confirmed PE | 3 (0.6) |

| Symptomatic/confirmed DVT | 3 (0.6) |

| Change of use because of DVT | 41 (7.7) |

| Incontinence/diarrhoea | 18 (3.4) |

| Transferred/discharged to another unit | 79 (14.8) |

| Administrative error | 56 (10.5) |

| Other – including no reason | 50 (9.3) |

Screening compression duplex ultrasounds

The number and proportions of patients having a CDU in each treatment group are shown in the CONSORT diagram (see Figure 3). The reasons for a missing CDU are also given. Our protocol stated that CDU should be performed between day 7 and day 10 after randomisation and between day 25 and day 30. The median delay from randomisation to the first CDU was 8 days (IQR 7–10 days) in both treatment groups. The median delay from randomisation to the second CDU was 28 days (IQR 26–30 days) in both treatment groups. The actual timing of CDU is shown in Table 6.

| Delay from randomisation to CDU | IPC, n (%) | No IPC, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of first CDU | 1315 (100.0) | 1305 (100.0) |

| < 7 days | 17 (1.3) | 14 (1.1) |

| 7–10 days | 1091 (83.0) | 1060 (81.2) |

| > 10 days | 207 (15.7) | 231 (17.7) |

| Timing of second CDU | 955 (100.0) | 938 (100.0) |

| < 25 days | 9 (0.9) | 6 (0.6) |

| 25–30 days | 721 (75.5) | 737 (78.6) |

| > 30 days | 225 (23.6) | 195 (20.8) |

Compression duplex ultrasound scans were not available for all surviving randomised patients (see Figure 3). In addition, we did not stipulate in our protocol that all patients should undergo CDU of the calf veins. The minimum acceptable CDU image set was one scan visualising the popliteal and more proximal veins. Therefore, calf veins were not visualised fully in all patients. Among patients who underwent first CDU, we were unable to exclude an isolated calf DVT in 615 out of 1315 (46.8%) in the IPC group and in 596 out of 1305 (45.7%) in the non-IPC group. Among those who underwent second CDU, we were unable to exclude an isolated calf DVT in 453 out of 955 (47.4%) in the IPC group and in 451 out of 938 (48.1%) in the non-IPC group.

In the IPC arm, 117 of 1315 (8.9%) patients were wearing IPC sleeves when they attended for their first CDU and 37 of 995 (3.7%) were wearing IPC sleeves when they attended for their second CDU. Therefore, the technician was not blinded in 154 (6.7%) of these 2310 CDUs. In addition, among the remaining 1198 patients who did not attend their first CDU wearing IPC, the technician guessed correctly they were allocated to IPC in 48 of cases (4%), had no idea in 916 (76.5%) and guessed incorrectly in 219 (18.3%). Of the 918 patients who were not wearing IPC at their second CDU, the technician correctly guessed the treatment allocated in 33 (3.6%), had no idea in 702 (76.5%) and guessed incorrectly in 171 (18.6%).

In the no-IPC arm, 4 of 1305 (0.3%) patients were wearing IPC sleeves when they attended for their first CDU and 4 of 938 (0.4%) were wearing IPC sleeves when they attended for their second CDU. At the first CDU the technician correctly guessed IPC status in 296 (22.7%) patients, had no idea in 970 (74.3%) patients and guessed incorrectly in 22 (1.7%) patients. At the second CDU, the technician correctly guessed the treatment allocation in 167 of cases (17.8%), had no idea in 739 (78.8%) and guessed incorrectly in 17 (1.8%) cases.

These data suggest that, where centres followed the protocol which required that they remove any IPC device from the patient before sending them for CDU, blinding was reasonably effective, that is the vast majority of observers had little idea of the treatment allocation.

Confirmation of primary outcome

Our primary outcome was confirmed in 276 of 296 (93.2%) cases by central review of CDU images by our radiologist (JR). In the remaining 20 cases (6.8%), the centres were unable to provide an image for central review. In these cases, the presence of a proximal DVT was confirmed by obtaining the local radiology report produced for clinical purposes. In the case of some patients, the local co-ordinator or technician had recorded a proximal DVT on the CDU report form which was entered into our database. These were not counted as primary outcomes unless the central review or local clinical report confirmed it.

Six-month follow-up

We aimed to follow up all surviving patients at about 6 months after randomisation. The number and proportions of patients in whom this was achieved in each treatment group are shown in our CONSORT diagram (see Figure 3). Patients and GPs were initially followed up by postal questionnaire, with a repeat mailing for non-responders. If no response, or an incomplete response to the postal questionnaire was received, then the chief investigator (MD) telephoned the respondent to obtain as much information as possible. The method of follow-up is shown in Table 7.

| Method of follow-up | IPC (n = 1098), n (%) | No IPC, (n = 1058), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient completed postal questionnaire | 359 (32.7) | 336 (31.6) |

| Proxy completed postal questionnaire | 474 (43.2) | 440 (41.6) |

| Postal completer not recorded | 20 (1.8) | 24 (2.3) |

| Telephone interview with patient | 112 (10.2) | 115 (10.7) |

| Telephone interview with proxy | 108 (9.8) | 117 (11.1) |

| Telephone interview not recorded if patient or proxy | 15 (1.4) | 15 (1.4) |

The timings of the 6-month patient follow-ups are shown in Table 8. As, inevitably, many of the follow-up questionnaires were not obtained until much more than 6 months later, some patients had died in the period from 6 months to the time when a follow-up questionnaire was obtained. We did not try to retrospectively code the functional status in such cases. However, it does mean that the number of patients recorded as having an OHS score of 6 (i.e. dead) at their 6-month follow-up is greater than the number of deaths which had occurred by 6 months (based on an actuarial analysis).

| Delay since randomisation (days) | IPC, n (%) | No IPC, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| < 167 | 6 (0.5) | 14 (1.3) |

| 167–183 | 659 (60.0) | 588 (55.6) |

| 184–199 | 122 (11.1) | 119 (11.2) |

| 200–219 | 224 (20.4) | 237 (22.4) |

| 220–239 | 66 (6.0) | 79 (7.5) |

| ≥ 240 | 20 (1.8) | 21 (2.0) |

| Missing time | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Total received | 1098 | 1058 |

Causes of death

For patients who died during their initial hospital admission, the local researcher coded the cause of death on the discharge form. For patients who died after hospital discharge, we aimed to obtain a copy of their death certificate, supplemented, where possible, by their GP notes or relevant hospital notes. Whenever an autopsy was carried out we tried to obtain the report. Final cause of death was coded by the Chief Investigator, usually blind to the treatment allocation. However, attribution of cause of death is notoriously difficult unless autopsies are performed. These data are reported for completeness, but we do not believe that any robust conclusions can be drawn from them.

We attempted to detect post-phlebitic leg syndrome by asking about leg swelling and ulcers at the 6-months follow-up. However, these questions were not validated and unlikely to be specific given the high frequency of swelling in stroke-affected limbs and of leg ulcers of other types.

Close out

After the final follow-up questionnaire had been completed, we sent each principal investigator a close-out checklist (see Appendix 3) to complete and send back to us. This checklist had been approved by ACCORD, the sponsor of the trial. Completed checklists were received from 93 (99%) of the 94 randomising hospitals. The remaining hospital, which had withdrawn from the trial before its completion, had lost all documentation and has instigated an internal inquiry. The trial master file was archived.

Chapter 4 Results

Results: primary and secondary outcomes – effectiveness and safety

Primary outcomes

The patients’ outcomes, with respect to our primary outcome, within 30 days of enrolment are shown in Table 9. The primary outcome occurred in 122 of 1438 patients (8.5%) allocated to IPC and in 174 of 1438 (12.1%) allocated to no IPC, with an OR of 0.65 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.84; p = 0.001) after adjustment for baseline variables and an ARR of 3.6% (95% CI 1.4% to 5.8%). To allow for any observer bias in detecting symptomatic DVTs not detected on routine-screening CDU, we repeated the primary analysis excluding those primary outcomes where a DVT was suspected prior to the CDU (n = 22). The estimates of effect were unchanged.

| Outcome | IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | No IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (proximal DVT) | 122 (8.5) | 174 (12.1) | –3.6 (–5.8 to –1.4) | – | – |

| Alive and free of primary outcome | 1145 (79.6) | 1071 (74.5) | – | – | – |

| Died prior to any primary outcome | 147 (10.2) | 176 (12.2) | – | – | – |

| Missing | 24 (1.7) | 17 (1.2) | – | – | – |

| Dead and missing excluded (unadjusted) | 122/1267 (9.6) | 174/1245 (14.0) | –4.3 (–6.9 to –1.8) | 0.66 (0.51 to 0.84) | 0.001 |

| Primary analysis (dead and missing excluded) | – | – | – | 0.65 (0.51 to 0.84) | 0.001 |

| Dead included with DVT and missing included with no DVT (unadjusted) | 269/1438 (18.7) | 350/1438 (24.3) | –5.6 (–8.6 to –2.6) | 0.71 (0.60 to 0.86) | 0.0002 |

| Dead included with DVT and missing included with no DVT | – | – | – | 0.71 (0.59 to 0.85) | 0.0002 |

Secondary outcomes within 30 days

The frequencies of deaths and other VTE outcomes within 30 days of randomisation are shown in Table 10. There were significant reductions in ‘any DVT’ (symptomatic or asymptomatic involving proximal or calf veins) (ARR 4.9%, 95% CI 2.1 to 7.8; p < 0.001) and symptomatic DVT (including proximal or calf) (ARR 1.7%, 95% CI 0.0 to 3.3; p = 0.045).

| Secondary outcomes by 30 days or later second CDU | IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | No IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead by 30 days | 156 (10.8) | 189 (13.1) | –2.3 (–4.7 to 0.1) | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01) | 0.057 |

| Symptomatic proximal DVT | 39 (2.7) | 49 (3.4) | –0.7 (–2.0 to 0.6) | 0.79 (0.51 to 1.21) | 0.269 |

| Asymptomatic proximal DVT | 83 (5.8) | 125 (8.7) | –2.9 (–4.8 to –1.0) | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.86) | 0.003 |

| Symptomatic DVT (proximal or calf) | 66 (4.6) | 90 (6.3) | –1.7 (–3.3 to –0.0) | 0.72 (0.52 to 0.99) | 0.045 |

| Any DVT (symptomatic or asymptomatic, proximal or calf) | 233 (16.2) | 304 (21.1) | –4.9 (–7.8 to –2.1) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.87) | 0.001 |

| All confirmed PE (imaging or autopsy) | 29 (2.0) | 35 (2.4) | –0.4 (–1.5 to 0.7) | 0.83 (0.50 to 1.36) | 0.453 |

| Any DVT or confirmed PE | 248 (17.2) | 325 (22.6) | –5.4 (–8.3 to –2.4) | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.86) | 0.00035 |

| Any DVT or dead | 377(26.2) | 472 (32.8) | –6.6 (–9.9 to –3.3) | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.85) | 0.00009 |

| Any DVT, PE or dead | 391 (27.2) | 491 (34.1) | –7.0 (–10.3 to –3.6) | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.84) | 0.00005 |

There were fewer deaths from all causes within 30 days among those allocated to IPC, but the difference was non-significant: IPC, 156 (10.8%), versus no IPC, 189 (13.1%; OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.01; ARR 2.3%, 95% CI to 0.1 to 4.7%; p = 0.057).

Table 11 shows the causes of death among the patients who died within 30 days of randomisation. This was based on the information provided by the local researchers. Autopsy to confirm the cause of death was carried out in only 10 (3%) of the patients who died within 30 days (three in the IPC group and seven in the no-IPC group).

| Cause of death | IPC, n (%) | No IPC, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial stroke | ||

| Neurological | 56 (36) | 64 (34) |

| Pneumonia | 43 (28) | 61 (32) |

| PE | 4 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Recurrent stroke | 18 (12) | 16 (8) |

| Coronary heart disease | 12 (8) | 8 (4) |

| Other vascular | ||

| Cerebrovascular | 10 (6) | 12 (6) |

| Bowel ischaemia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 7 (4) |

| Non-vascular | ||

| Fall | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Carcinoma | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Renal failure | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory failure | 2 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Sepsis | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

| Uncertain | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Total deaths | 156 (100) | 189 (100) |

Adverse events

Adverse events, including skins breaks, leg ischaemia, falls and fractures, which might have resulted from wearing IPC sleeves are shown in Table 12. There was a statistically significant excess of skin breaks on the legs of patients allocated to IPC [44 (3.1%) vs. 20 (1.4%), p = 0.002] but no significant differences in the risk of falls with injury or fractures within 30 days. Few of the skin breaks or falls with injury were attributed by the local researchers to the IPC. The majority of adverse events occurred either when IPC sleeves had been removed or when skin breaks affected the heels (which are not covered by the IPC sleeves); therefore, they were unlikely to be caused by the IPC. However, the reporting of secondary outcomes in hospital and adverse effects was based on case note review and was not blinded to treatment allocation. These adverse event data are therefore prone to ascertainment bias.

| Outcome | IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | No IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential adverse effects of IPC | |||||

| Skin breaks | 44 (3.1) | 20 (1.4) | 1.7 (0.6 to 2.7) | 2.23 (1.31 to 3.81) | 0.002 |

| Skin breaks attributed to IPC | 10 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) | – | – |

| Lower limb ischaemia/amputation | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | –0.1 (–0.3 to 0.1) | – | – |

| Falls with injury in 30 days | 33 (2.3) | 24 (1.7) | 0.6 (–0.4 to 1.6) | 1.39 (0.82 to 2.37) | 0.221 |

| Falls with injury in 30 days attributed to IPC | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 (–0.1 to 0.2) | – | – |

| Fractures within 30 days | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 0.0 (–0.4 to 0.4) | – | – |

Deaths and venous thromboembolism events up to six months

The deaths and VTE events up to 6 months, including those arising during the first 30 days, are shown in Table 13. There was no evidence of an excess of VTE events in the post-treatment period to indicate that IPC simply deferred VTE events.

| Outcome | IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | No IPC (n = 1438), n (%) | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead by 6 months | 320 (22.3) | 361 (25.1) | –2.9 (–6.0 to 0.3) | 0.85 (0.70 to 1.01) | 0.059 |

| Any DVT | 240 (16.7) | 312 (21.7) | –5.0 (–7.9 to –2.1) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.87) | 0.001 |

| Any symptomatic DVT | 77 (5.4) | 101 (7.0) | –1.7 (–3.4 to 0.1) | 0.75 (0.55 to 1.02) | 0.061 |

| Any confirmed PE | 42 (2.9) | 49 (3.4) | –0.5 (–1.8 to 0.8) | 0.86 (0.56 to 1.30) | 0.463 |

| Any death, DVT or PE | 526 (36.6) | 626 (43.5) | –7.0 (–10.5 to –3.4) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.86) | < 0.001 |

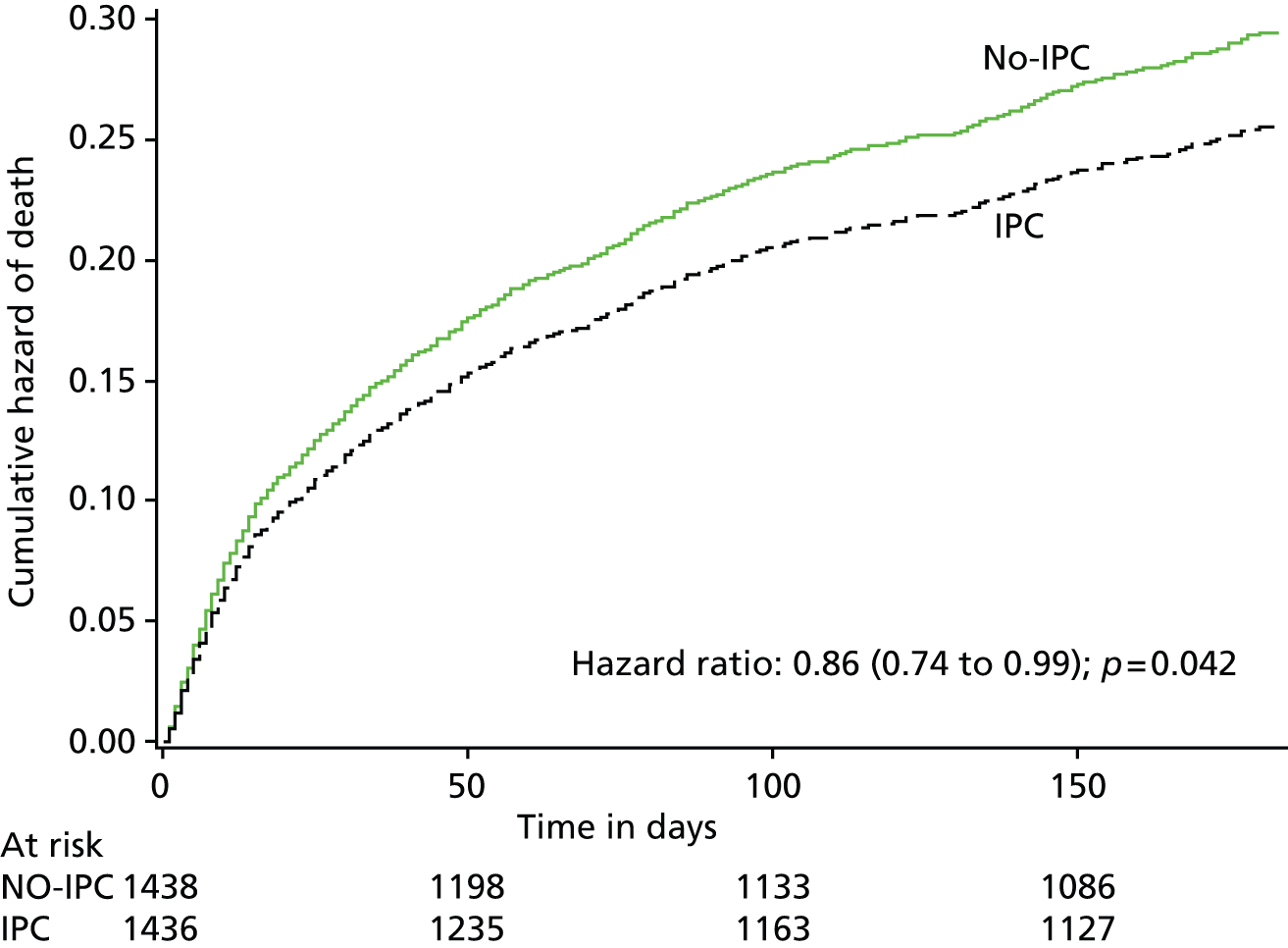

By 6 months from randomisation, there had been 320 deaths in the IPC group and 361 in the no-IPC group. The probability of death over the 6 months after randomisation in the two treatment groups is shown in Figure 6. The Cox model, adjusted for the factors included in our minimisation algorithm, showed a reduced hazard ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99; p = 0.042) for death up to 6 months after randomisation in those allocated IPC.

FIGURE 6.

Cumulative hazard of death over the 6 months after randomisation.

The patients’ OHS scores are shown in Table 14. The numbers of deaths on the OHS were greater than the number of deaths by 6 months, because some patients died between 6 months and the completion of their OHS score.

| Outcomes | IPC, n (%) | No IPC, n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OHS score | |||

| 0 | 45 (3.1) | 45 (3.1) | 0.375a |

| 1 | 94 (6.5) | 92 (6.4) | |

| 2 | 156 (10.8) | 156 (10.8) | |

| 3 | 306 (21.3) | 320 (22.3) | |

| 4 | 181 (12.6) | 185 (12.9) | |

| 5 | 309 (21.5) | 255 (17.7) | |

| Deadb | 330 (22.9) | 367 (25.5) | |

| Missing | 17 (1.2) | 18 (1.3) |

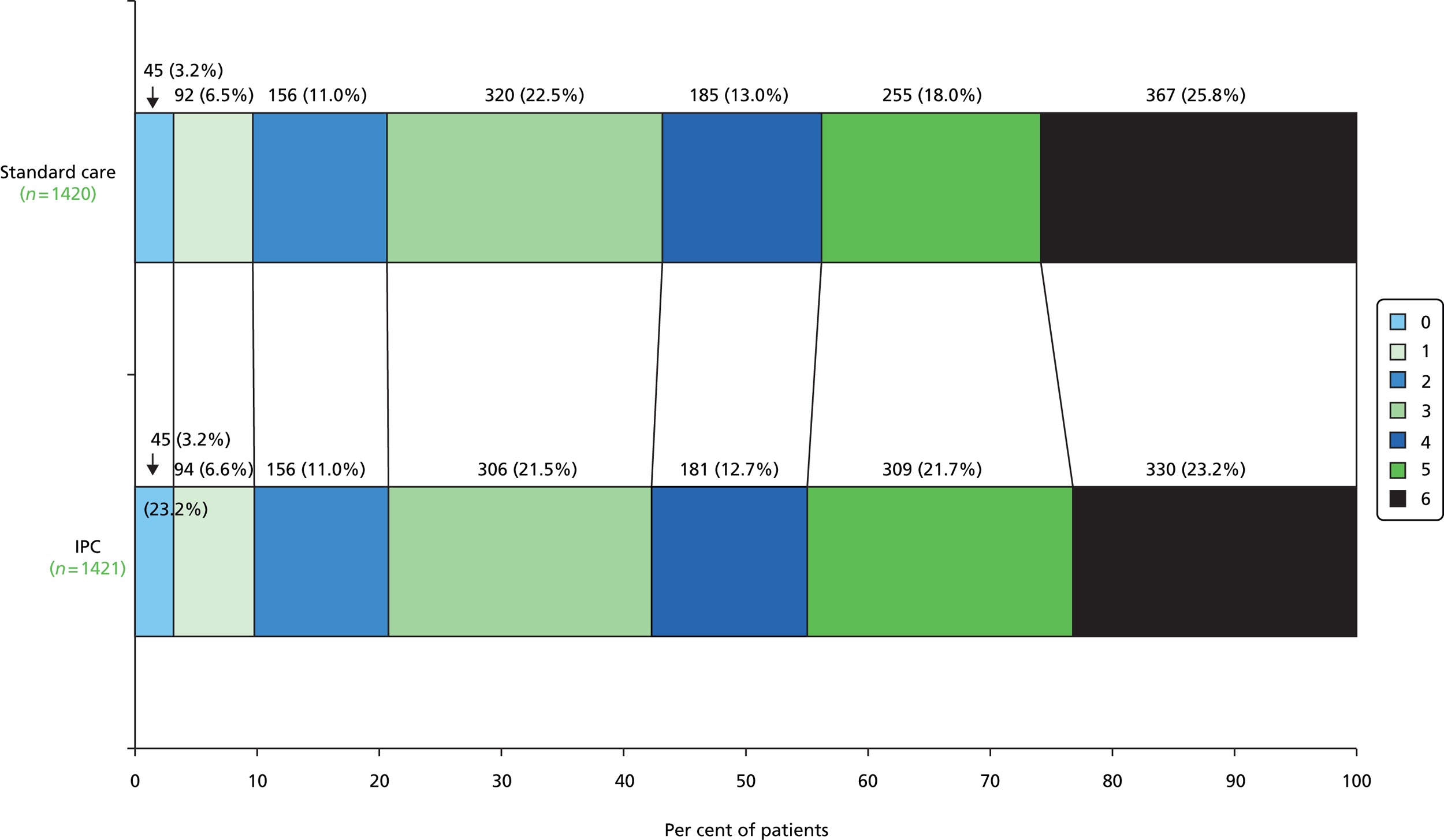

In total, 295 (20.5%) patients in the IPC group had an OHS score of 0–2, compared with 293 (20.4%) in the no-IPC group, an absolute risk difference of only 0.1% (95% CI –2.8% to 3.1%), a relative risk of 0.98 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.14) and an OR adjusted for baseline imbalance of 0.98 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.19; p = 0.83). Figure 7 illustrates the differences in functional outcomes in the two treatment groups at the final follow-up.

FIGURE 7.

The differences in functional outcomes (OHS) at 6 months between treatment groups (excluding the missing data so % values do not match those in Table 14).

We carried out an ordinal analysis of the OHS using ordinal regression (results in Table 15). Neither the adjusted nor the unadjusted analysis showed a difference in the common odds between those treated with IPC or standard care.

| Comparing standard care with IPC | OR for poor outcome | p-value | 95% CI lower limit | 95% CI upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | 0.97 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 1.11 |

| Unadjusted | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 1.12 |

Table 16 shows the individual dichotomies of the OHS scores. None of the differences between the treatment groups was statistically significant. However, a post-hoc exploratory analysis of the OHS scores shows that a 2.6% increase in the proportion of patients surviving at 6 months (p = 0.11) is more than offset by a 3.8% increase in the proportion of patients surviving with an OHS score of 5 (p = 0.013). However, this p-value needs to be interpreted with caution given that this analysis was not prespecified, was exploratory and might be spurious because of this.

| OHS score dichotomy | No IPC | IPC | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 45 | 45 | 1.00 | 0.70 to 1.64 |

| 1–6 | 1375 | 1376 | ||

| 0–1 | 137 | 139 | 0.98 | 0.77 to 1.26 |

| 2–6 | 1283 | 1282 | ||

| 0–2 | 293 | 295 | 0.99 | 0.83 to 1.19 |

| 3–6 | 1127 | 1126 | ||

| 0–3 | 613 | 601 | 1.04 | 0.89 to 1.20 |

| 4–6 | 807 | 820 | ||

| 0–4 | 798 | 782 | 1.05 | 0.90 to 1.22 |

| 5–6 | 622 | 639 | ||

| 0–5 | 1053 | 1091 | 0.87 | 0.73 to 1.03 |

| 6 | 367 | 330 | ||

| Total | 1420 | 1421 | – | – |

Living circumstances at 6 months

There were two questions on the 6-month follow-up form concerning patients’ living circumstances. Table 17 shows the cross-tabulation of the two variables where follow-up was completed.

| Where do you live now? | How do you live now? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not applicable | On my own | With partner or relative | Missing | Total | |

| In a nursing home | 120 | 48 | 6 | 171 | 345 |

| In a residential home | 32 | 34 | 10 | 43 | 119 |

| In my own home | 3 | 413 | 1101 | 0 | 1517 |

| In the home of a relative | 0 | 2 | 97 | 0 | 99 |

| Other | 28 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 37 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36a | 36 |

| Total | 185 | 502 | 1219 | 250 | 2156 |

To determine if there is a relationship between use of IPC and living circumstances at final follow-up, we dichotomised the location of the patients at follow-up as living at home (in my own home or in the home of a relative) or living in an institution/still in hospital (in a nursing home, in a residential home, in-hospital patient). Those whose living circumstances were classed as ‘other’ or ‘unknown’ were not included in this analysis. Of those allocated to IPC, 24.7% (266 out of 1076) were living in an institution or were still in hospital at 6 months, compared with 22.4% (233 out of 806) of those allocated to standard care.

A summary of the logistic regression models is shown in Table 18. In both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis the CI for the ORs indicate that treatment is not significantly related to location at 6 months in those who responded at 6 months.

| Comparing home with institution at 6 months (excluding dead and missing) | OR for poor outcome | p-value | 95% CI lower limit | 95% CI upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | 1.11 | 0.358 | 0.89 | 1.37 |

| Unadjusted | 1.14 | 0.214 | 0.93 | 1.39 |

Post-phlebitis leg syndrome

The reported frequency of leg swelling and leg ulcers at the 6-month follow-up is shown in Table 19. However, it is unclear whether or not these reported symptoms indicate the development of post-phlebitis leg syndrome, or if they simply reflect comorbidities such as heart failure or ulcers due to other causes.

| Completed 6-month follow-up form | IPC (n = 1098), n (%) | No IPC (n = 1058), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Leg swollen since stroke | 388 (35.3) | 396 (37.4) |

| Leg ulcer since stroke | 24 (2.2) | 19 (1.8) |

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed to determine if particular types of patients might gain more or less benefit from IPC. We estimated the effect of treatment allocation on our primary outcome subdivided by key baseline variables and adjusted for the other factors included in our minimisation algorithm. Subgroup analyses were performed by observing the change in log-likelihood when the interaction between the treatment and the subgroup is added into a logistic regression model. We determined whether or not there was any significant heterogeneity between these subgroups. The lack of any significant interaction between the subgroups and treatment effect has to be interpreted with caution, given that the trial was not large enough to identify small to moderate interactions.