Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/47/02. The contractual start date was in July 2007. The draft report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Carr et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report describes the results of the UK Rotator Cuff Surgery (UKUFF) trial assessing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic compared with open rotator cuff repair for people with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. This comparison was commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The trial began in 2007 and initially also included a non-operative comparator of a rest-then-exercise programme. However, because of high crossover from the rest-then-exercise group to surgery, the trial was reconfigured in 2010 to a comparison of arthroscopic and open repair only.

Rotator cuff tear

The prevalence of shoulder complaints in the UK is estimated to be 14%, with 1–2% of adults consulting their general practitioner (GP) annually regarding new-onset shoulder pain. 1 Rotator cuff pathology, including tendonitis, calcific tendonitis and rotator cuff tears, reportedly accounts for up to 70% of shoulder pain problems. 2 Painful shoulders pose a substantial socioeconomic burden. Disability of the shoulder can impair the ability to work or perform household tasks and can result in time off work. 3,4 Shoulder problems account for 2.4% of all GP consultations in the UK and 4.5 million visits to physicians annually in the USA. 5,6 More than 300,000 surgical repairs for rotator cuff pathologies are performed annually in the USA, where the annual financial burden of shoulder pain management has been estimated to be US$3B. 7

Rotator cuff pathology is associated with progressive change in the shape of the acromion, with ‘spurs’ forming at its anteroinferior margin. Some reports suggest that these spurs narrow the subacromial space, thereby making physical contact more likely in certain positions of the arm. This is most notable in abduction and elevation of the arm and is sometimes referred to as ‘painful arc’ or impingement because pain is maximal in the mid-range of movement. This process is argued to result in inflammation of the rotator cuff tendons (particularly the supraspinatus tendon) and the overlying subacromial bursa. A conflicting theory suggests that such mechanisms are not causative and that intrinsic age-related degeneration of the tendon is the main determinant of inflammation and symptoms. 8,9

Rotator cuff tear refers to structural failure in one or more of the four muscles and tendons that form the rotator cuff. Any tear that does not extend all the way through the tendon is termed a partial-thickness tear. Asymptomatic full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff are very common in the general population. It is estimated that the overall prevalence of tears is 34% and that risk increases significantly with age. 10 Partial tears are more prevalent than full-thickness tears. 11

Conservative management

Conservative treatment may include rest, exercise, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral corticosteroids, oral paracetamol, opioid analgesics, physiotherapy, activity modification, acupuncture, platelet-rich plasma injections, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, suprascapular nerve block, laser treatment, autologous blood injections, intra-articular NSAID injections, subacromial corticosteroid injections, electrical stimulation, ice and ultrasound.

A search of MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library up to August 2009 for treatment of shoulder pain was undertaken. 12 Harm alerts from relevant organisations, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), were included. The review found 71 systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies that met the inclusion criteria. Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) of the quality of evidence for interventions was performed. 2 It is not known whether topical NSAIDs, oral corticosteroids, oral paracetamol or opioid analgesics improve shoulder pain, although oral NSAIDs may be effective in the short term in people with acute tendonitis/subacromial bursitis. If pain control fails, the diagnosis should be reviewed and other interventions considered. Physiotherapy may improve pain and function in people with mixed shoulder disorders compared with placebo. Platelet-rich plasma injections may improve the speed of recovery in terms of pain and function in people having open subacromial decompression for rotator cuff impingement, but further evidence is needed. Acupuncture may not improve pain or function in people with rotator cuff impingement compared with placebo or ultrasound. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy may improve pain in calcific tendonitis. There is some evidence that suprascapular nerve block, laser treatment, arthroscopic subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair may be effective in some people with shoulder pain. There is no evidence to support the use of autologous blood injections, intra-articular NSAID injections, subacromial corticosteroid injections, electrical stimulation, ice or ultrasound. Concern exists regarding the potential longer-term damaging consequences of corticosteroid injection. 13

Role of imaging

Imaging is most useful in directing treatment in secondary care if conservative care has failed. A large proportion of the general population will demonstrate abnormalities on imaging of the rotator cuff. 14 Imaging findings need to be interpreted in the context of symptoms, disability and response to treatment. A high proportion of patients with rotator cuff pain will respond to conservative treatment. 15 The only reliable non-interventional method of determining if a rotator cuff tear has healed is use of postoperative imaging, either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography.

Surgical management

The most frequent indications for surgery are persistent and severe pain combined with functional restrictions that are resistant to conservative measures. Symptoms of pain and weakness typically disrupt daily activities and night pain affects sleep. Symptoms of a minimum of 3 months’ duration that are sufficiently severe to disrupt daily activities and rest or sleep and failure of standard conservative care (analgesics, rest and physiotherapy and cortisone injection) are usually required before surgery is considered. Surgical repair may be advised in cases of full-thickness rotator cuff tear with persistent pain and weakness after conservative treatment. A rotator cuff repair operation aims to reattach the torn tendons to the humeral bone. In general, two approaches are available for surgical repair. Open surgery involves the rotator cuff being repaired under direct vision through an incision in the skin. Arthroscopic surgery is keyhole surgery and involves the repair being performed through arthroscopic portals into the shoulder. A subacromial decompression (SAD) or acromioplasty to create space around the repaired tendon is usually performed in association with the tendon repair. Reports of the outcome of such surgery are conflicting and evidence for effectiveness is unclear. 16–18 An assessment of the treatment cost of impingement suggests that the addition of surgery, in comparison with exercise treatment alone, is not cost-effective. 19

Comparative studies of subacromial decompression and non-operative treatment options such as physiotherapy have not shown any significant difference in outcome between the two treatment modalities. 20–23 A growing number of studies have tried to assess the effectiveness of subacromial decompression against a control. Three studies of patients undergoing rotator cuff repair, including or excluding subacromial decompression in their operative treatment, did not demonstrate any difference in outcome between the groups. 24–26 A RCT of subacromial decompression plus subacromial bursectomy compared with bursectomy alone reported no significant difference in clinical outcome between the two groups. This finding suggests that removing acromial spurs might not be necessary. 27

The management of partial tears is particularly controversial and patients with such tears have commonly been treated conservatively. Favourable results have been reported following debridement of partial tears in association with subacromial decompression. 28 Higher rates of re-rupture are associated with repairs of larger tears, increased patient age and increased fatty degeneration of the cuff muscles. 29–32 Partial tears are most commonly managed without repair, but some authors advocate repair to prevent progression to full-thickness tears. The evidence supporting this approach is weak. 11 There is also uncertainty regarding the relative value of conservative care, repair surgery and debridement surgery for large and massive tears. 33–36 High failure rates of 13–68% have been reported for surgical repair of rotator cuff tears, irrespective of the surgical technique employed. 37–39 Some studies have suggested that re-rupture rates are associated with poorer outcomes. 40 Surgical decision-making in the management of rotator cuff tears was reviewed by Dunn et al. 41 They surveyed surgeons in the USA and found considerable variation in decision-making. This included the type of surgery, the surgical techniques employed and the type and duration of conservative treatment, including cortisone injections, physiotherapy, rest, analgesia and home exercises. Rates of medical visits for rotator cuff pathology in the USA were reviewed between 1996 and 2006. The volume of rotator cuff repairs had increased by 141% and the unadjusted number of arthroscopic repairs increased by 600% compared with a 34% increase in open repairs. 42 The volume of arthroscopic subacromial decompressions has also increased significantly over time. Recent figures from the USA report a 240% increase (from 30.0 to 101.9 per 100,000 people per year) in use of the procedure in New York state between 1996 and 2006. 43 This compares to a 78.3% increase in ambulatory orthopaedic surgery overall. Similar increases have recently been reported in the UK. 44 The introduction of less invasive arthroscopic techniques accounts for some of the overall increased rate of surgery, but does not explain regional variation. Patient and disease characteristics have not changed over time and there is a growing concern that this procedure is being overused. Observational studies of subacromial decompression surgery show positive results in terms of pain reduction and functional outcome, with high patient satisfaction rates. However, equally good outcomes have been noted in two studies following patients who had arthroscopic rotator cuff debridement or open rotator cuff repair in the absence of a subacromial decompression.

Rationale for the study design

The objective of the original commissioned call was to conduct a pragmatic multicentre randomised clinical trial to obtain good-quality evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of conservative care compared with arthroscopic surgical repair compared with open surgical repair for the treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tears. Because of high crossover from the conservative arm to surgery the study was reconfigured to a comparison of the two surgical techniques only. There is conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of open and arthroscopic repair. 12,45–47 Proponents of arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery suggest that the procedure may have advantages over standard open techniques by causing less trauma to the deltoid muscle and overlying soft tissue. Arguably, this causes less postoperative patient discomfort together with earlier return of movement. However, the success of the repair depends partly on the ability of the surgeon to achieve a secure attachment of tendon to bone. This may be more easily and reliably achieved by open/mini-open surgery. Other potential disadvantages of the arthroscopic approach include increased technical difficulty and longer time in theatre. There is a need to compare the outcomes of the two surgical techniques.

Literature update since the call

A review updating the literature published since the original commissioned call was undertaken to inform this report and set the results in context. Only reports of RCTs were included. Quasi-RCTs, which use methods of allocating participants to a treatment that are not strictly random, for example date of birth, hospital record number or alternation, were excluded.

Types of participants

Randomised controlled trials of adults aged ≥ 18 years with a degenerative rotator cuff tear as reported in the primary studies (e.g. confirmed by physical examination, MRI, ultrasound or MRI arthrogram) were included. RCTs of adults undergoing surgery for other types of rotator cuff disease, shoulder instability, joint replacement or fractures were excluded.

Types of interventions

All randomised comparisons between a surgical procedure (e.g. open or arthroscopic) and another surgical procedure for treating rotator cuff tear were included. Randomised comparisons between a surgical procedure and a non-surgical procedure (e.g. physiotherapy, drug therapy) were also included. RCTs in which the primary aim was to compare different types of surgical technique (e.g. different suturing techniques) as part of the surgical repair of the rotator cuff were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome for each RCT and time point when measured, as reported by the authors, was recorded. When reported by the authors, the primary outcome was that used for the calculation of the sample size. Primary outcomes included pain, disability or function measured using shoulder-specific instruments such as the Constant score,48 American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Shoulder Score49 or the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score. 50

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched Ovid MEDLINE from 2006 to March 2014 for possible reports of RCTs. The search strategy used was based on one developed by Coghlan et al. 16 for a Cochrane review of surgery for rotator cuff disease. This search strategy was modified to account for changes to the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms since the original search was conducted in 2006, the addition of free-text terms and the replacement of the original RCT filter used with the Cochrane sensitivity- and precision-maximising version RCT filter [2008 version; see http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_6/box_6_4_b_cochrane_hsss_2008_sensprec_pubmed.htm (accessed 23 August 2015)] (see Appendix 4 for search strategy). We also searched the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform51 to identify reports of any ongoing RCTs. One author screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved records. Full articles were then obtained for any potentially eligible studies and assessed using the predefined eligibly criteria described earlier.

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy identified 477 potentially eligible studies. Of these, eligible studies were identified as those comparing a surgical intervention with another surgical intervention and those comparing a surgical intervention with a non-surgical intervention.

Surgery compared with surgery

Six RCTs26,52–56 comparing a surgical intervention with another surgical intervention were identified (Table 1). Of these six trials, one RCT56 is ongoing, with completed recruitment but final results awaiting publication. Two other trials57,58 were identified comparing two different types of surgical intervention; however, these were excluded as the patients were not randomised.

| Study ID | Study designa | Blinding | Sample size | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcomeb | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included studies | ||||||||

| Abrams 201452 | RCT, single centre | Outcome assessor blinded | 114 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear – mean age 59 years | Arthroscopic with acromioplasty repair | Arthroscopic without acromioplasty repair | ASES score at 2 years | No statistically significant difference |

| van der Zwaal 201353 | RCT, single centre | Not blinded | 100 | Small to medium rotator cuff tear – mean age 57 years | Arthroscopic repair | Mini-open repair | DASH score at 1 year | No statistically significant difference; mean difference –3.4 (95% CI –10.2 to 3.4) |

| MacDonald 201154 | RCT, multicentre | Subject and outcome assessor blinded | 86 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear – mean age 57 years | Arthroscopic repair with acromioplasty | Arthroscopic repair without acromioplasty | Quality of life specific to rotator cuff disease (WORC) at 2 years | No statistically significant difference; mean difference –6.8 (95% CI –15.7 to 2.1) |

| Mohtadi 200855 | RCT, multicentre | Outcome assessor blinded | 73 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear – mean age 57 years | Arthroscopic acromioplasty with mini-open repair | Open surgical repair | Rotator cuff quality-of-life score (RC-QOL) at 2 years | No statistically significant difference; p = 0.943 |

| Gartsman 200426 | RCT, single centre | Outcome assessor blinded | 93 | Full-thickness supraspinatus tear – mean age 60 years | Arthroscopic with acromioplasty repair | Arthroscopic without acromioplasty repair | ASES score at 1 year | No statistically significant difference; p = 0.363 |

| Ongoing study | ||||||||

| MacDermid 200656 | RCT, multicentre | Subject and outcome assessor blinded | 225 | Small (≤ 1 cm) to medium (1–3 cm) rotator cuff tear – age 18–75 years | Arthroscopic repair | Mini-open repair | Quality of life specific to rotator cuff disease (WORC index) within 2 years | |

| Excluded studies | ||||||||

| Cho 201257 | Quasi-RCT, single centre | Not reported | 60 | Small (< 3 cm) supraspinatus tear – mean age 56 years | Arthroscopic repair | Mini-open repair | Pain score (VAS) at 6 months | No statistically significant difference; p = 0.98 |

| Kasten 201158 | Quasi-RCT, single centre | Not reported | 34 | Supraspinatus tear – mean age 60 years | Arthroscopic repair | Mini-open repair | Pain score (VAS) at 3 months | No statistically significant difference |

Of the five completed RCTs,26,52–55 three were single-centre studies and all were relatively small, ranging from 73 to 114 participants per trial, with a mean participant age between 57 and 60 years. Four RCTs included participants with full-thickness rotator cuff tears26,52,54,55 and one included participants with small and medium rotator cuff tears. 53 The type of surgical interventions differed between trials, with one RCT comparing arthroscopic repair with mini-open repair,53 one comparing mini-open repair arthroscopic acromioplasty with open surgical repair55 and three comparing arthroscopic with acromioplasty repair with arthroscopic without acromioplasty repair. 26,52,54 The choice of primary outcome also varied across studies and included pain, disability or function measured using shoulder-specific instruments. Four26,52,54,55 of the five completed RCTs reported blinded assessment of these outcomes. Overall, no RCT showed a statistically significant difference between the two types of surgical intervention being compared.

Surgery compared with non-surgery

Three RCTs59–61 comparing a surgical intervention with a non-surgical intervention were identified, of which one61 is ongoing, having completed recruitment but with final results awaiting publication (Table 2). Of the two completed RCTs, one59 was a multicentre study and both were relatively small, ranging from 103 to 173 participants per trial, with a participant age of between 60 and 65 years. One RCT59 was a three-arm trial comparing open surgical repair, acromioplasty and physiotherapy with acromioplasty and physiotherapy and physiotherapy alone. This trial found no statistically significant difference between the interventions being compared at 1 year based on the Constant shoulder score. 48 The other RCT60 compared open surgical repair (or mini-open repair) with physiotherapy and found a statistically significant difference in favour of surgery at 1 year based on the Constant shoulder score. 48

| Study ID | Study design | Blinding | Sample size | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcomea | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included studies | ||||||||

| Kukkonen 201459 | RCT, multicentre | Outcome assessor blinded | 173 (180 shoulders) | Atraumatic symptomatic supraspinatus tendon tear – mean age 65 years | Open surgical repair, acromioplasty and physiotherapy | Acromioplasty and physiotherapy or physiotherapy | Constant score at 1 year | No statistically significant difference; p = 0.34 |

| Moosmayer 201060 | RCT, single centre | Outcome assessor blinded | 103 | Small (≤ 1 cm) to medium (1–3 cm) rotator cuff tear – mean age 60 years | Open surgical repair (n = 42) or mini-open repair (n = 9) | Physiotherapy | Constant score at 1 year | Statistically significant difference in favour of surgery; mean difference 13 (95% CI. 4.9 to 21.1) |

| Ongoing study | ||||||||

| Lambers Heerspink 201161 | RCT, multicentre | Not reported | 108 | Atraumatic rotator cuff tear – age 45–75 years | Open surgical repair with acromioplasty | Physiotherapy, NSAIDs (if indicated), subacromial infiltration with corticosteroids | Constant score at 1 year | |

Chapter 2 Methods

At the outset (July 2007) the UKUFF study had two complementary components [UKUFF original Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 07/Q1606/49]:

-

a multicentre, pragmatic RCT comparing open and arthroscopic surgical treatments with a non-operative programme of rest then exercise to assess their relative clinical effectiveness

-

an economic evaluation of the treatments to compare the cost-effectiveness of the management streams, identify the most efficient provision of future care and describe the resource impact that various policies for surgical rotator cuff repair would have on the NHS.

Eligible patients who consented to participate in the study were randomly allocated to arthroscopic surgery, open surgery or a programme of rest then exercise. Participants completed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) at baseline and then at 8, 12 and 24 months post randomisation. Questionnaires were also completed by telephone at 2 and 8 weeks post treatment. For those patients randomised to surgery, who had a complete repair of the rotator cuff, MRI or an ultrasound scan was also performed 12 months after their surgery.

Randomisation in the original study design was organised within three strata depending on surgeons’ stated preparedness to randomise. A detailed survey of the members of the British Elbow & Shoulder Society (BESS) was conducted in preparation for this study. This survey showed that, at the time, only around 15% of surgeons regularly undertook arthroscopic surgery. Of the surgeons who regularly performed arthroscopic surgery, only 8% indicated that they would be prepared to randomise between surgical treatments. The remainder were happy to randomise between arthroscopic surgery and the rest-then-exercise programme. The majority of surgeons indicated that they performed only open surgery. Surgeons who performed only open surgery did not appear to have equipoise for open surgery compared with arthroscopic surgery.

Reflecting this lack of individual uncertainty around certain comparisons, the trial was designed such that surgeons could randomise between:

-

stratum A – arthroscopic surgery compared with open surgery compared with rest then exercise

-

stratum B – arthroscopic surgery compared with rest then exercise

-

stratum C – open surgery compared with rest then exercise.

Reconfigured study design

A high rate of crossover (77%) of the 214 patients in the rest-then-exercise programme to surgery was observed and so the trial was adapted and reconfigured on the instruction of the funder in 2009 after consultation with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). Crossover did not occur at a consistent or predictable time point. The reconfigured design was a two-way parallel-group RCT of open compared with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (UKUFF reconfigured REC reference number 10/H0402/24, April 2010). At the time of reconfiguration there were 131 participants in stratum A (n = 43, arthroscopic surgery; n = 44, open surgery; and n = 44, rest then exercise), 181 in stratum B (n = 91, arthroscopic surgery; and n = 90, rest then exercise) and 162 in stratum C (n = 82, open surgery; and n = 80, rest then exercise). The 87 patients already randomised between arthroscopic and open surgery (stratum A) were carried through to the subsequent reconfigured trial. After the reconfiguration it was calculated that a further 180 patients should be recruited and followed up for 2 years as per the original protocol, leading to a total of 267 patients treated with surgery.

During the period between 2007 and 2010, surgical opinion had changed and an increased number of surgeons were in equipoise between open and arthroscopic surgery. The UKUFF trial was reconfigured as a pragmatic multicentre study involving 20 surgeons from 16 UK centres; 15 of these surgeons had originally recruited to stratum A.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

From the outset patients were involved and engaged in the design of the trial. A patient representative (D Farrar-Hockley) was a member of the group designing the trial. He subsequently became a member of the TSC.

Interventions

Conservative care

For the original study a conservative regime of rest then exercise was developed. In view of the lack of evidence for type or dose of exercise therapy, a consensus approach was adopted with input from five physiotherapists, all with expertise and publications in shoulder physiotherapy. It was anticipated that most patients would have already undergone physiotherapy before referral to a surgeon and therefore further similar treatment would not be appropriate. In addition, there was a need for standardisation across a large geographical area and number of locations over a considerable period of time. It was decided to deliver, by post, a high-quality booklet to patients in their own home with an accompanying compact disc (CD) showing moving images. Information was given regarding rotator cuff tears and general and specific exercise options. The package included a sling, with advice to start with relative shoulder rest, using the sling if necessary, and to then start exercising. A free telephone helpline was available with physiotherapy expertise. However, because of the high crossover rate to surgery (77%), this treatment arm was discontinued in the reconfigured trial.

Surgery and surgeons

Surgery was either arthroscopic (fixation of tendon to bone using only arthroscopic techniques) or open (fixation to bone under direct vision through a surgically created opening in the deltoid muscle). The precise technique and method of fixation were not prescribed and surgeons used their preferred and usual technique. Details of the surgical technique used, including the method of repair and theatre equipment used (e.g. types of anchor), were recorded on a standard form (see Appendix 5), as well as the size of the tear, the ease of repair and the completeness of the repair. If circumstances dictated that the allocated surgical technique could not be carried out then any alternative procedure was recorded.

Participating surgeons required a ‘minimum level of expertise’ for the types of surgery undertaken. Only consultant orthopaedic shoulder surgeons with a minimum of 2 years’ experience in consultant practice could participate. Surgeons had to perform a minimum of five cases per year. The participating surgeons represented a cross-section of high-, medium- and low-volume practitioners from both general hospitals and teaching hospitals. Because of the nature of the study’s NHS setting, some patients recruited to the UKUFF study had their surgery performed by non-UKUFF surgeons. The trial accepted data from patients who were recruited by a UKUFF surgeon but who went on to have their surgery performed by a colleague of the same or similar experience and position or by a supervised senior trainee. An assessment of the surgeons’ position and experience was made by the chief investigator. NIHR local research networks provided help with patient identification, recruitment and obtaining any required data from patient notes. Patient eligibility was confirmed by the local consultant orthopaedic surgeons.

Study population

Eligible patients were those for whom care had been provided by a participating surgeon and who were deemed suitable for rotator cuff repair surgery, with the surgeon uncertain which surgical procedure was better. In addition, patients had to be aged ≥ 50 years, have symptoms from a degenerative full-thickness rotator cuff tear and be able to give informed consent.

Study registration/consent to randomise

Recruitment of patients occurred through a two-step process. A patient’s eligibility was assessed by the local consultant orthopaedic surgeon, who introduced the trial to the patient using a prompt sheet and a patient assessment form. If the patient was interested in participating, the surgeon then provided the patient with a copy of the patient information sheet (see Appendix 6), which summarised what the study involved and answered any questions the patient might have.

If the patient was willing to enter the trial then an initial consent form was signed, which allowed the patient’s details to be forwarded to the central study office in Oxford. The office then issued to the participant, by post, an invitation letter, the comprehensive patient information sheet (see Appendix 6), a consent form and a baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 7) with a prepaid return envelope. Patients were encouraged to contact the office or their surgeon if they had any further questions or concerns. Patients who had not returned their questionnaire and consent form within a week were telephoned by a member of the study team in Oxford. This contact allowed the patient to ask questions about the study and permitted the team to assess whether the patient was still willing to participate. When the full consent form and baseline questionnaire had been returned to the Oxford office the patient then officially entered the trial and was randomised to one of the surgical options. A copy of the signed consent form was returned to the patient.

Randomisation was by computer allocation using the service provided by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen. Allocation was minimised using surgeon, age and size of tear. After randomisation the participant was considered irrevocably part of the trial for the purpose of the research, irrespective of what occurred subsequently.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS)62 completed at 24 months after randomisation. The OSS is a 12-item shoulder-specific PROM that was developed, with patients, for the assessment of shoulder pain and function in the context of shoulder surgery, particularly in trials. Items refer to the past 4 weeks and each offers five ordinal response options. Originally, these were scored from 1 to 5 (5 = most severe) and then summed to produce a summary score ranging from 12 to 60. Subsequently, the recommended method of scoring was changed. 63 Under the new system, each item on the OSS is scored from 0 to 4, with 4 representing the best outcome (i.e. the opposite direction from the original method of scoring). When the 12 items are summed, this produces an overall score ranging from 0 to 48, with 48 being the best outcome. The OSS has been demonstrated to be reliable, valid, responsive and very acceptable to patients.

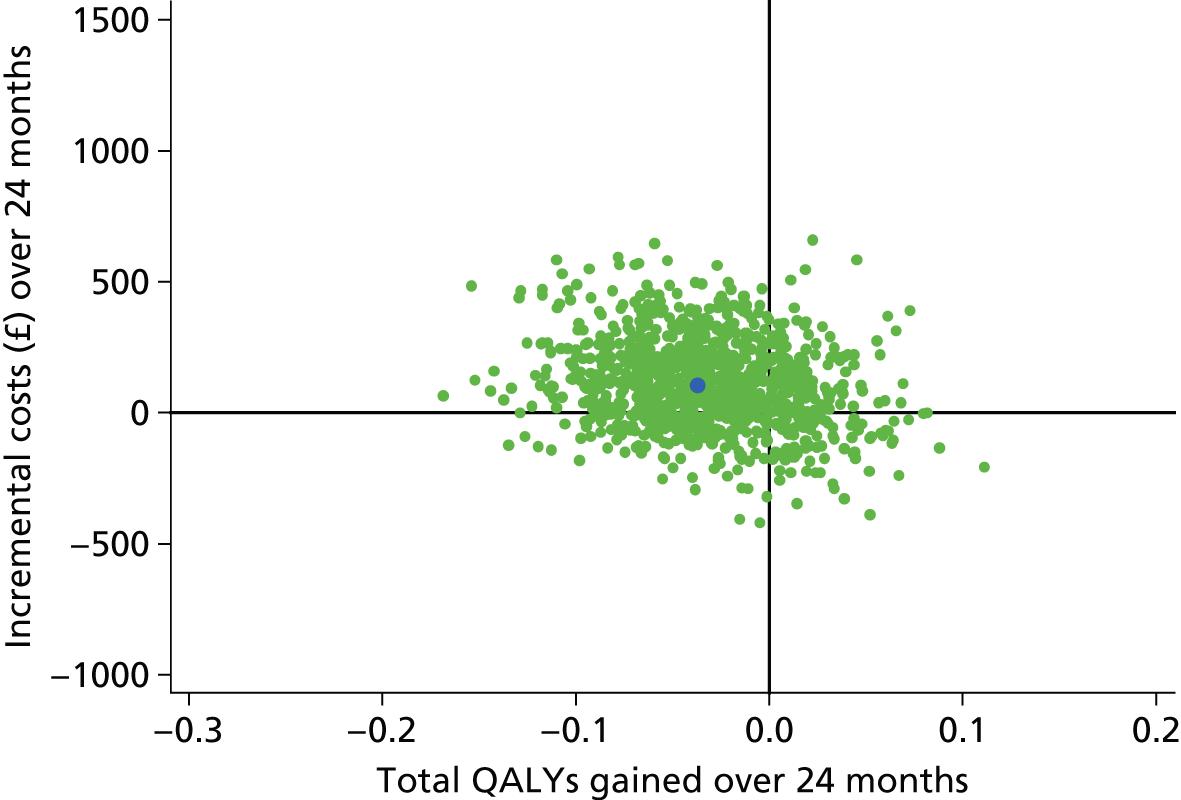

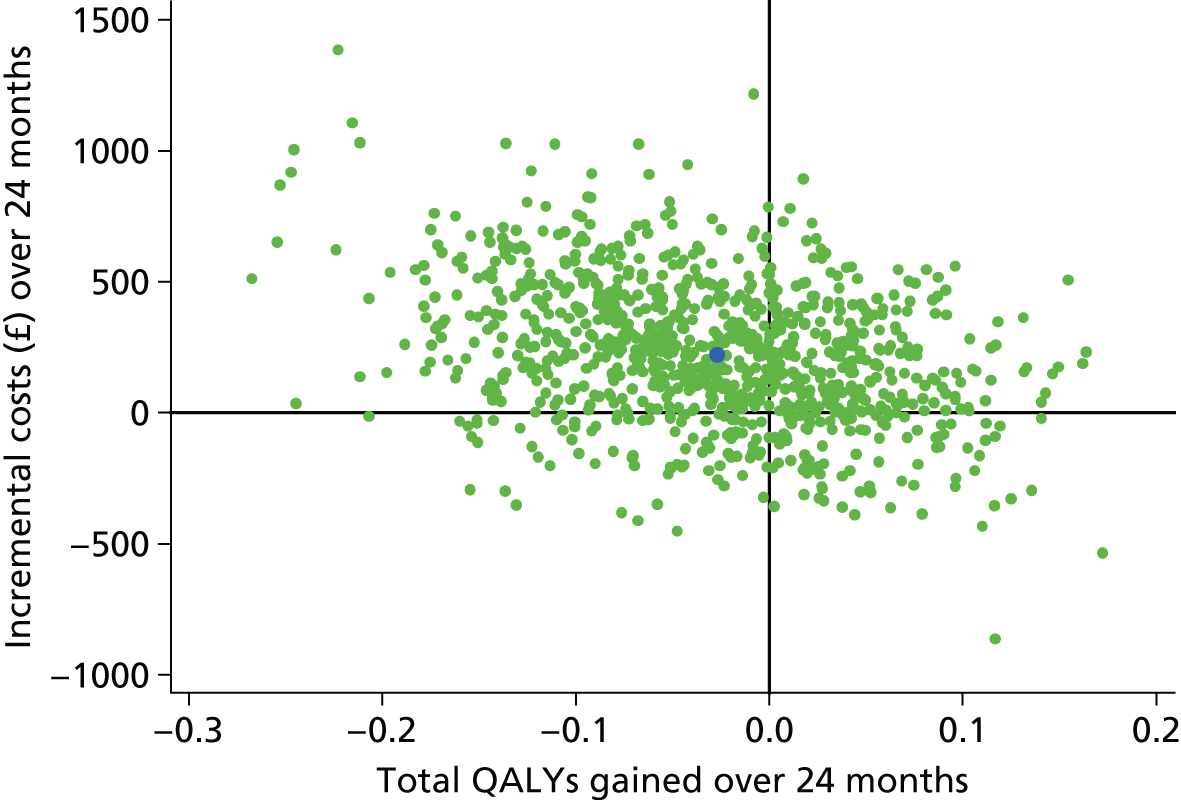

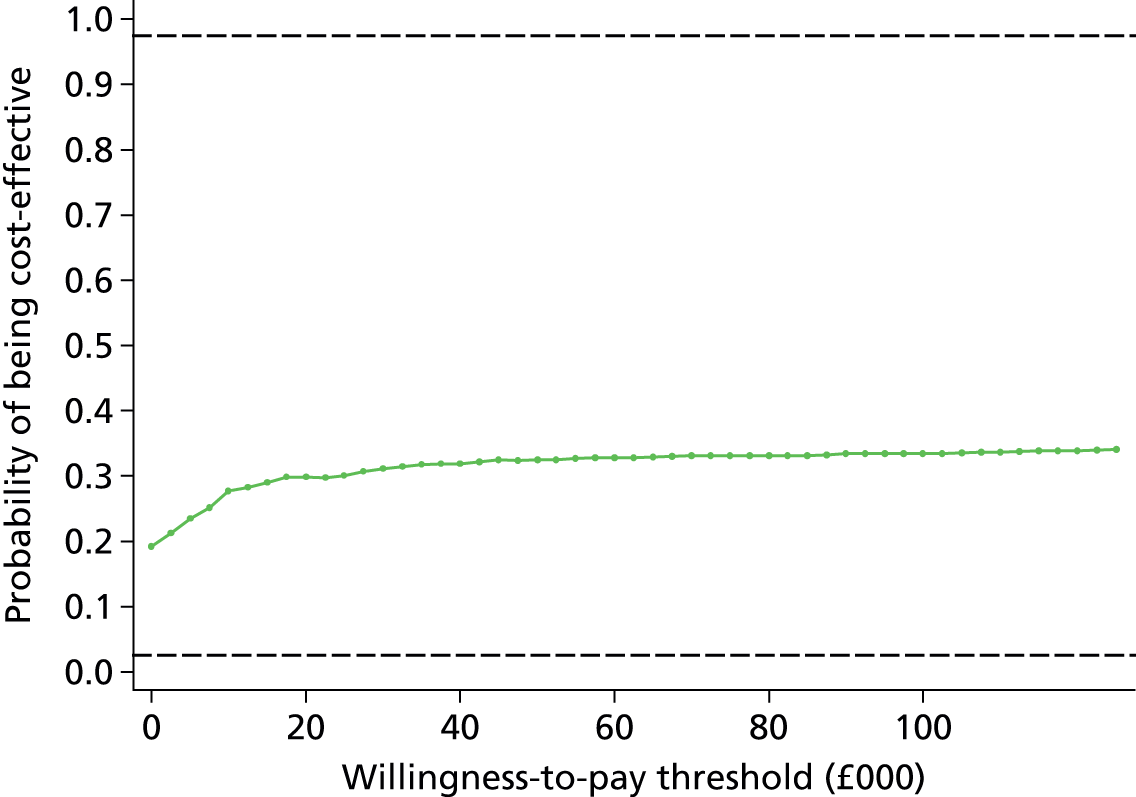

The primary measure of cost-effectiveness was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

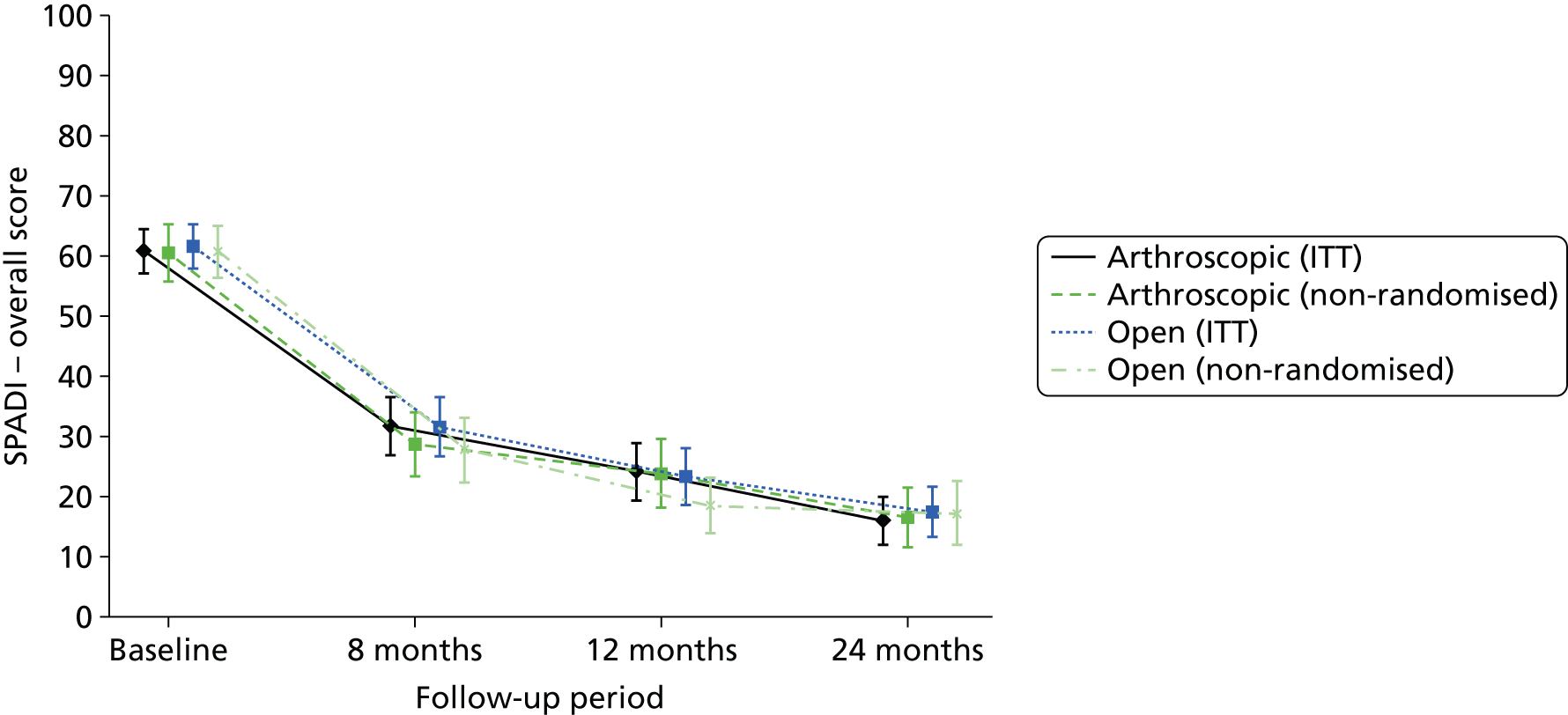

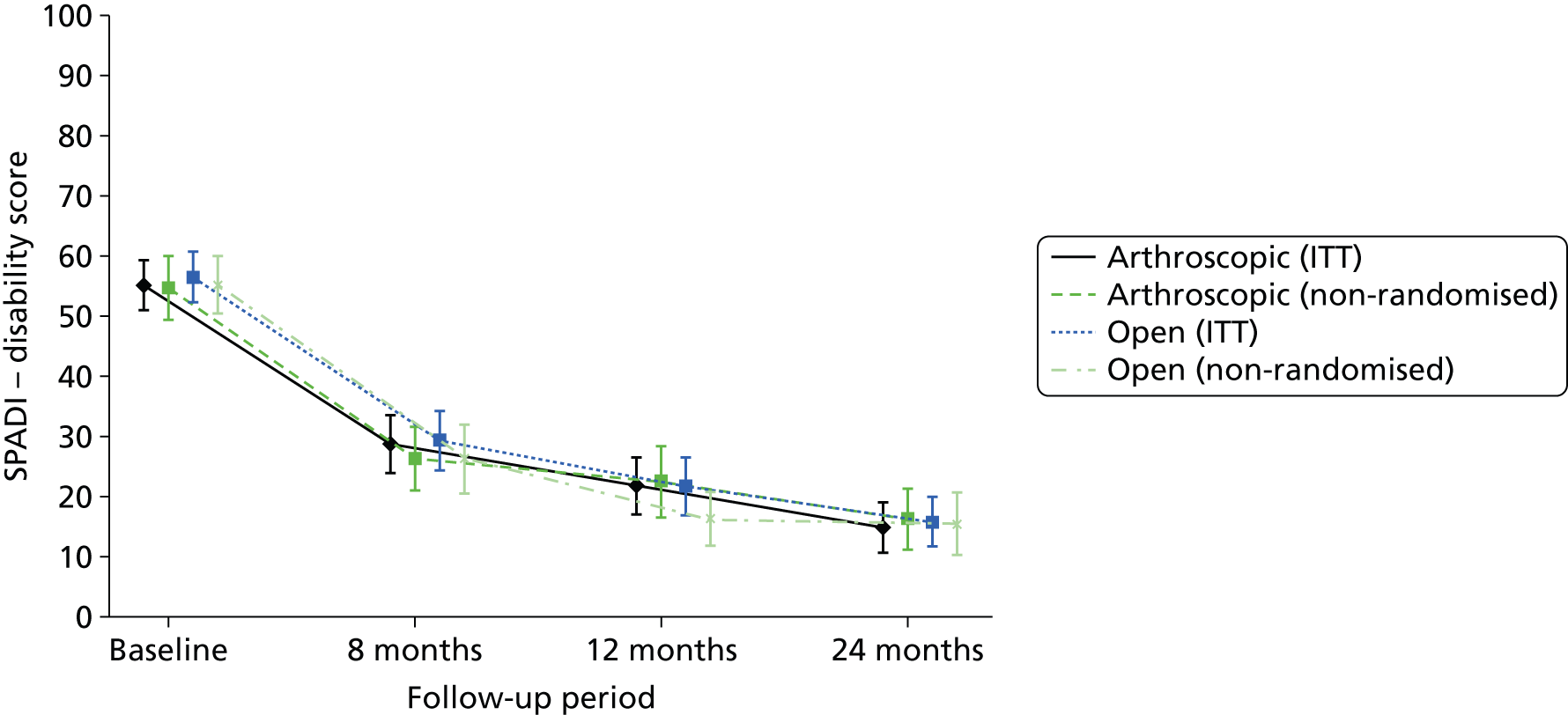

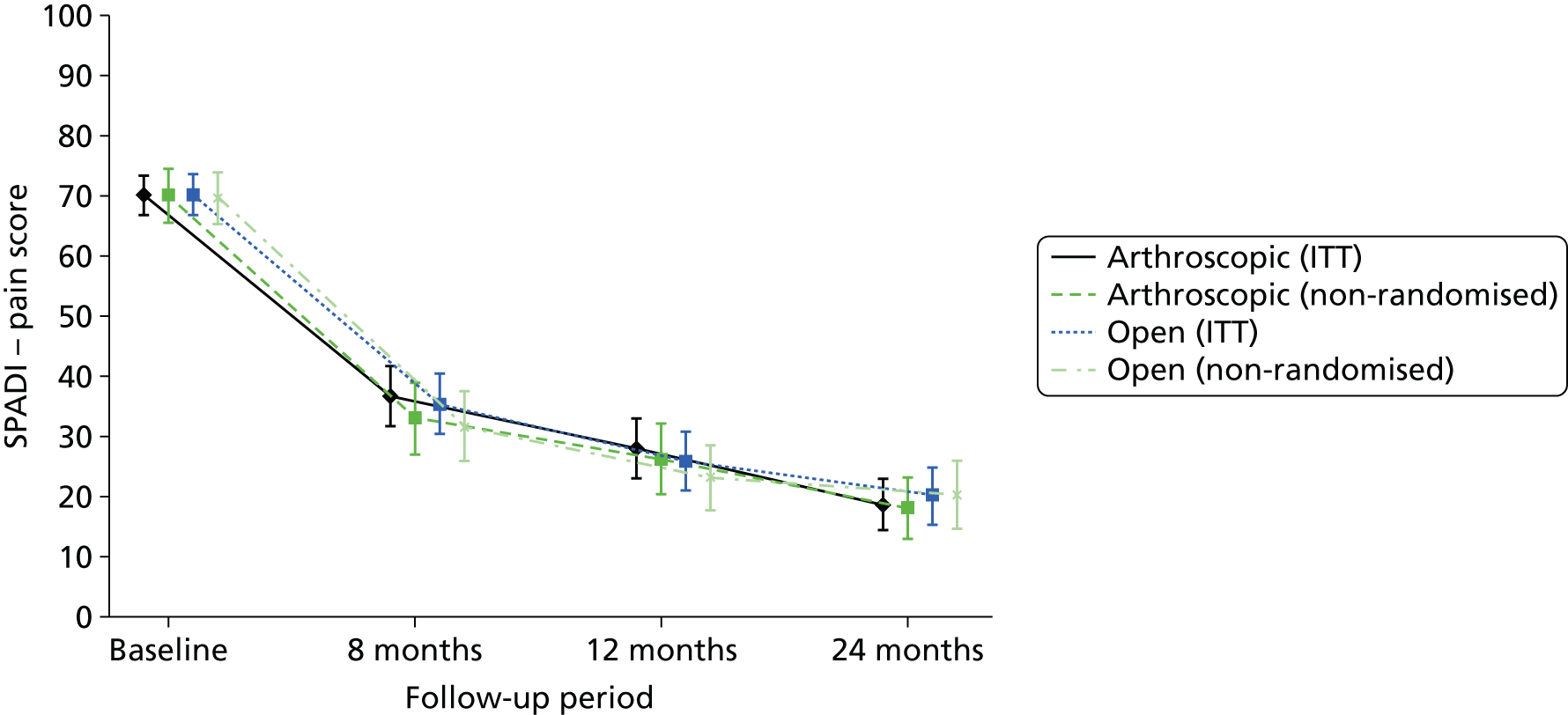

The secondary outcome measures were used to further assess functional outcome and patient health-related quality of life. These assessed a range of symptoms often experienced with rotator cuff tears, for example pain, weakness and loss of function. These included:

-

Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI)64 at 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation. The SPADI is a self-administered questionnaire, developed by a panel of rheumatologists and a physiotherapist, to measure shoulder pain and disability in an outpatient setting. 64 It contains 13 items that assess two domains: shoulder pain (five items) and disability (eight items), all with reference to the last week. The original version scored each item on a visual analogue scale (VAS). A second version, used in this trial, replaced the VAS with a 0–10 numerical rating scale. 65 Item responses within each subscale are summed and transformed to a score out of 100. A mean is taken of the two subscales to give a total score out of 100, with a higher score indicating greater impairment or disability. The SPADI is reliable, valid and responsive. 64

-

Mental Health Inventory 5 (MHI-5)66 at 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation. The MHI-5 is the mental health subscale of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) generic health status measure. 67 It contains five items that address anxiety, depression, loss of behavioural or emotional control and psychological well-being, all with reference to the past 4 weeks. Each item offers responses on a 6-point scale (ranging from ‘all of the time’ to ‘none of the time’). The total score is calculated by reversing the answers to two items (the third and fifth), summing the scores, and transforming the raw scores to a scale ranging from 0 to 100. A higher score indicates better mental health. The MHI-5 has been demonstrated to be good at detecting major depression, affective disorders generally and anxiety disorders. 66

-

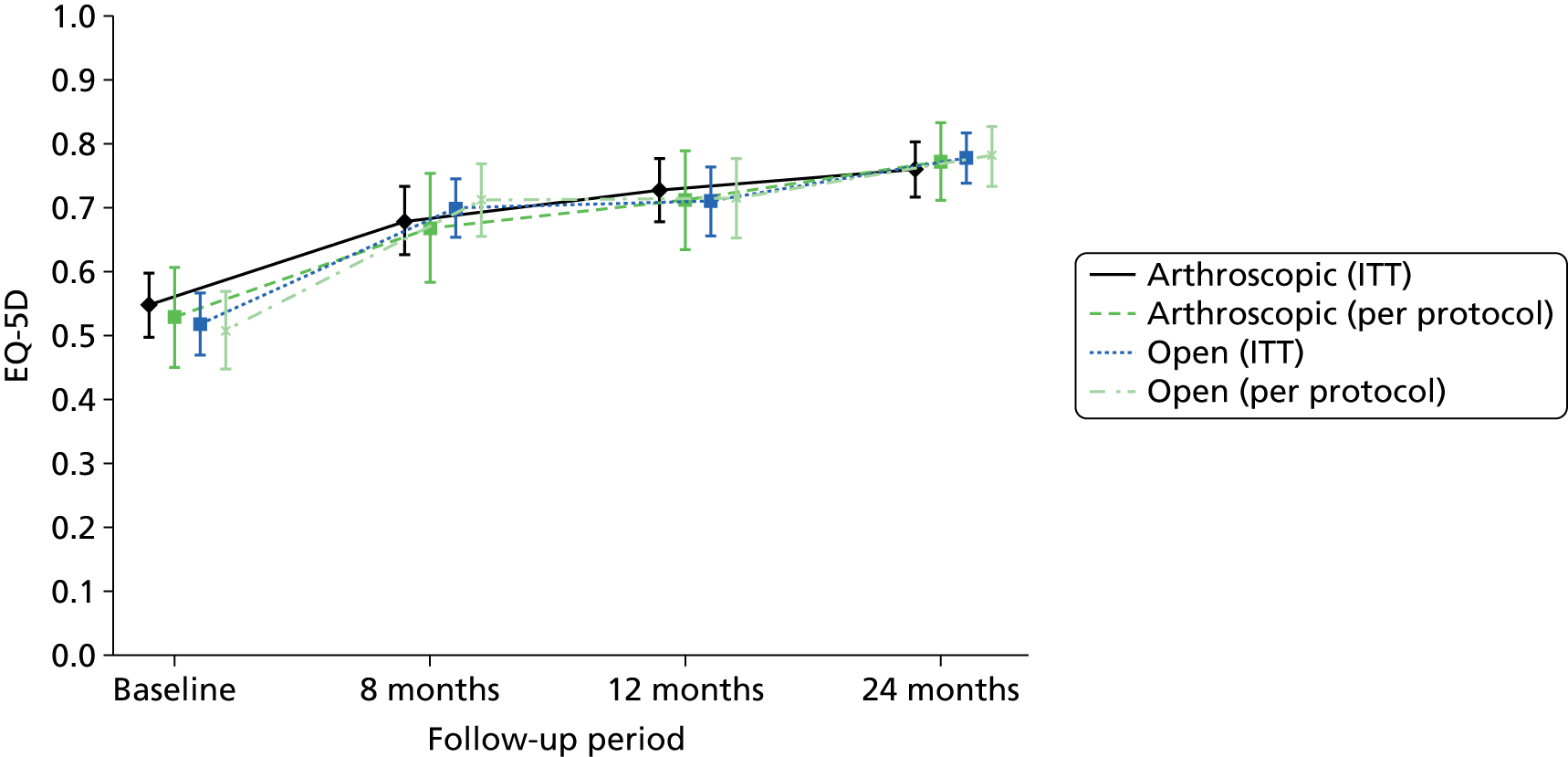

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three levels (EQ-5D-3L)65,68 at 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation. The EQ-5D-3L is a standardised generic instrument for use as a self-completed measure of health outcome. It provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status that can be used in the clinical and economic evaluation of health care, as well as population health surveys, and consists of five items on mobility, self-care, pain, usual activities and psychological status, with three possible answers for each item (1 = no problem, 2 = moderate problem, 3 = severe problem). The response for each item/domain is converted to a quality-of-life estimate using an algorithm (see Chapter 6 for further details) to produce an index score for each patient. Negative scores represent health states worse than death, 0 represents the state of worst health and 1.00 represents full health.

-

The OSS62 completed at 8 and 12 months after randomisation.

-

Participants’ view of the overall state of their shoulder compared with an earlier time point (‘transition item’) at 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation. There were five possible responses to this item: ‘much better’, ‘slightly better’, ‘no change’, ‘slightly worse’ or ‘much worse’.

-

Participants’ rating of how pleased they were with their shoulder symptoms at 12 and 24 months after randomisation. There were four possible responses to this item: ‘very pleased’, ‘fairly pleased’, ‘not very pleased’ or ‘very disappointed’.

-

Surgical complications (intra- and postoperative) at 2 and 8 weeks post surgery and at 12 and 24 months after randomisation.

-

12-month postoperative imaging.

Data collection

Outcome assessment was conducted using questionnaires that participants self-completed and, as such, interviewer bias and clinical rater bias were avoided. This form of outcome measurement has consistently performed well compared to clinician-based assessments and general health status measures. All participants, including those who had withdrawn from their allocated intervention but who still wished to be involved in the study, were followed up, with analysis based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle.

Participants received questionnaires at the following time points:

-

baseline (see Appendix 7) – questionnaire completed before randomisation

-

2 and 8 weeks post treatment (see Appendix 8) – questionnaire completed by telephone

-

8, 12 and 24 months post randomisation (see Appendix 9) – questionnaire completed by post.

The baseline and 12 and 24 months’ post-randomisation questionnaires also incorporated a section that measured cost-effectiveness. This included questions relating to primary care consultations, other consultations, out-of-pocket costs and the work impact of the intervention received.

The study team based at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, contacted participants whose questionnaires had not been returned. In the first instance this was through a reminder letter by post or e-mail, depending on participant preference. If a questionnaire had still not been returned within the specified time frame, the study team telephoned the participant and addressed any administrative issues that may have arisen, such as change of address or loss of questionnaire. If any clinical issues were identified, the study team in Oxford contacted participants, if appropriate, and addressed these issues. The time period allocated to the follow-up checks depended on which outcome assessment was involved.

Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound scans

Postoperative imaging was performed on patients who had undergone a repair. It was not performed if a repair was either impossible to perform or when no tear was found. Both the MRI and the ultrasound scans were undertaken locally to the participant and were arranged by the study office in Oxford, at a time agreed by the trust and the participant. The scans were collected centrally. The MRI scans were reported by an independent consultant radiologist who was blinded to the type of surgery that was performed. Because of the operator-dependent nature of the ultrasound scans, an independent report on these was not valid. The report obtained from the site was used to determine the tear status. Any re-tears were not reported to the participating surgeons, so that no deviation occurred from their normal practice.

Statistical analysis of outcomes

Statistical analyses were based on all people randomised, irrespective of subsequent compliance with the randomised intervention. The principal comparison was all those allocated arthroscopic surgery compared with all those allocated open surgery. When an effect size is shown for the intervention, a negative sign on the effect size indicates that an open procedure is favoured over an arthroscopic procedure.

Reflecting the possible clustering in the data, the outcomes were compared using repeated-measures mixed models with centre as a random effect and with adjustment for minimisation variables (size of tear and age) and participant baseline values (when available) as fixed effects. Statistical significance was at the 5% level, with corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) derived. All participants remained in their allocated group for analysis (ITT).

Preplanned subgroup analyses on the primary outcome included exploration of tear size (small/medium vs. large/massive) and age (≤ 65 years vs. > 65 years); these analyses were conducted by including a subgroup by treatment interaction term in the primary outcome model described above. Conservative levels of statistical significance (p < 0.01) were sought, reflecting the exploratory nature of these subgroup analyses.

Non-response analysis

Descriptive data comparing the baseline characteristics of participants who did and did not respond at 24 months were displayed. The t-test (continuous outcomes) and chi-squared test (dichotomous outcomes) were used to estimate the statistical significance of the differences between responders and non-responders.

Sensitivity analysis: treatment received (per protocol)

Reflecting the level of non-compliance, the effect on the primary outcome of those participants who actually received an arthroscopic or open repair was estimated. In an open trial design a per-protocol analysis can have substantial selection bias. To minimise the effects of selection bias we used the instrumental variable approach as described by Nagelkerke et al. 69 The method used a two-stage least-squares approach whereby treatment randomised was regressed onto treatment received and the residuals from that model were used as an independent variable in a second model, together with the treatment received, to estimate the effects on the primary outcome measure. As with the ITT analysis, the model also adjusted for centre, minimisation variables (age, size of tear) and baseline OSS score.

Learning curve

The main analyses adjusted for centre effects and therefore adjusted for the majority of differences between centres. Learning effects may, however, be present in the trial (i.e. the surgeon’s performance improves throughout the trial). To test for these effects a covariate for each surgeon was developed that indicates the increasing surgeon experience in the trial (e.g. first patient randomised = 1; second = 2, etc.). This covariate was used in subsequent adjusted analyses to measure the size of the trend in effects over time.

Health economics methods

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed. A simple patient cost-related questionnaire was sent out at baseline and at 12 and 24 months post randomisation to obtain information on primary care consultations, other consultations, out-of pocket costs, the work impact of the intervention received and return to work (when relevant). Although longer intervals between questionnaires may result in recall errors (in particular under-reporting of health-care use70) more frequent data collection can result in a higher proportion of missing responses, which introduces uncertainty. It has been argued that there is no optimal interval for self-reported data collection70 and as such the timing of questionnaire distribution was chosen to coincide with those for the clinical study outcomes. Unit costs came from national sources and participating hospitals. The patient questionnaire was also used to administer the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), which was obtained at baseline. The main health economic outcome was within-trial and extrapolated QALYs, estimated using the EQ-5D. 71

Incremental cost-effectiveness was calculated as the net cost per QALY gained for arthroscopic surgery compared with open surgery. Power calculations (see following section) were based on clinical effectiveness rather than cost-effectiveness outcomes, which were estimated rather than used in hypothesis testing. Cost-effectiveness ratios and acceptability curves were calculated.

An important component of this trial was the assessment of cost. Therefore, obtaining an accurate record of procedures at each of the proposed centres was essential. To evaluate the costs of each type of surgery, information was collected from the operating theatres. Resources used, equipment costs and standard procedures for rotator cuff repairs were examined. Per-case information was also analysed. A checklist of equipment, consumables, implants, time and staff utilised during each case was completed by theatre staff. Information from theatres was collected by the Oxford office and used in a cost comparison of the arthroscopic and open surgery approaches.

Sample size

In the original UKUFF trial, with three randomised strata, the sample size was constructed to detect a difference in the OSS 24-month postoperative score of 0.38 of a standard deviation (SD) for the comparison between arthroscopic surgery and open surgery at 80% power. We did not propose any amendment to that clinically important difference in the reconfigured study. This defined difference was based on our experience of developing the OSS score and using it in a variety of settings; a 3-point score difference (0.33 of a SD) was deemed a clinically important difference. In the original UKUFF trial, the detectable difference of 0.38 was constructed by combining evidence from a direct randomised comparison with indirect (non-randomised) comparison data from the other strata. Incorporating indirect effects is a suboptimal approach to measuring effectiveness because unmeasured confounders can bias the outcomes. The proposed change in this proposal was to achieve the detectable difference of 0.38 of a SD by direct randomised comparison data only at 85% power. As described earlier, such an approach was feasible by 2010 because of the increased number of surgeons in equipoise between the arthroscopic approach and the open approach.

Attrition was expected to be low (10%), as were the effects of clustering of outcomes by surgeon [intracluster correlation (ICC) < 0.03]. 72,73 Although we did not have a direct estimate from a shoulder trial, other orthopaedic data sets available to our team support this low ICC estimate. Both of these factors required the sample size to be inflated; however, the primary analysis adjusted for baseline OSS score, which conversely allowed the sample size to be decreased by a factor of (1 – correlation squared). 74 Our previous studies showed that the correlation in the OSS score pre surgery to 6 months post surgery in patients similar to the potential trial participants was 0.57. Assuming a conservative correlation of 0.5 implied that the sample size could be reduced by 25% and still maintain the same power. Therefore, a study with a total of 267 participants would still have 85% power to detect a clinically important difference in each comparison, assuming that attrition and clustering accounted for approximately 25% of variation in the data.

Data monitoring

An independent DMC met on four occasions and did not recommend any fundamental changes to the protocol. The decision in 2009 to reconfigure the trial was made by the NIHR HTA programme. The committee did not meet after recruitment was completed.

Chapter 3 Description of the study population

This chapter describes the derivation of the populations that took part in the UKUFF study, the characteristics of the participants at presurgical assessment and the baseline characteristics of included participants.

Recruitment to the study

Participants were recruited in 47 clinical centres, all within the UK (Table 3). Nineteen centres recruited to the randomised arthroscopic surgery and randomised open surgery comparison (referred to as the stratum A comparison). Thirteen of these centres also randomised participants to stratum A prior to reconfiguration of the study in December 2010 (see Chapter 2). Twenty centres recruited to stratum B (arthroscopic surgery vs. rest then exercise) and 18 to stratum C (open surgery vs. rest then exercise). A total of 660 participants were recruited to the study, with 317 in stratum A (n = 136, allocated to arthroscopic surgery; n = 137, allocated to open surgery; and n = 44, allocated to rest then exercise prior to reconfiguration), 181 in stratum B (n = 91, allocated to arthroscopic surgery; and n = 90, allocated to rest then exercise prior to reconfiguration) and 162 in stratum C (n = 82, allocated to open surgery; and n = 80, allocated to rest then exercise prior to reconfiguration). Table 3 shows recruitment by centre. No centre contributed more than 12% of participants to stratum A. Recruitment to the trial began on 9 November 2007 and continued until 28 February 2012, although not all centres enrolled over the total period because of the staggered introduction of centres and early closure for reconfiguration of the study (range 6 months to 39 months from first to last participant randomised in stratum A). Data were closed to follow-up on 31 December 2013.

| Centre | Stratum A, n (%) | Stratum B, n (%) | Stratum C, n (%) | Total (n = 660) | Randomised to stratum A prior to reconfiguration | Length of time randomising to stratum A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | ||||

| University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | 16 (11.8) | 17 (12.4) | 4 (9.1) | 4 (4.9) | 3 (3.8) | 44 (6.67) | Yes | 3 years 0 months | ||

| Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 16 (11.8) | 16 (11.7) | 4 (9.1) | 36 (5.45) | Yes | 2 years 8 months | ||||

| Gwent Healthcare NHS Trust | 13 (9.6) | 13 (9.5) | 5 (11.4) | 31 (4.70) | Yes | 3 years 3 months | ||||

| Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre | 15 (11.0) | 15 (10.9) | 18 (22.0) | 18 (22.5) | 66 (10.00) | No | 1 years 4 months | |||

| Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust | 12 (8.8) | 13 (9.5) | 4 (9.1) | 29 (4.39) | Yes | 2 years 11 months | ||||

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | 8 (5.9) | 9 (6.6) | 7 (15.9) | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.0) | 31 (4.70) | Yes | 2 years 11 months | ||

| South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 9 (6.6) | 8 (5.8) | 4 (9.1) | 21 (3.18) | Yes | 2 years 9 months | ||||

| Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic and District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 7 (5.1) | 6 (4.4) | 6 (13.6) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 23 (3.48) | Yes | 2 years 7 months | |

| Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | 8 (5.9) | 8 (5.8) | 2 (4.5) | 18 (2.73) | Yes | 2 years 2 months | ||||

| Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust | 8 (5.9) | 9 (6.6) | 11 (12.1) | 10 (11.1) | 38 (5.76) | No | 1 years 3 months | |||

| Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust | 7 (5.1) | 6 (4.4) | 3 (6.8) | 16 (2.42) | Yes | 2 years 5 months | ||||

| Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 4 (2.9) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (4.5) | 10 (1.52) | Yes | 2 years 8 months | ||||

| Swansea NHS Trust | 3 (2.2) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (4.5) | 10 (1.52) | Yes | 3 years 3 months | ||||

| University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust | 3 (2.2) | 4 (2.9) | 8 (9.8) | 8 (10.0) | 23 (3.48) | No | 0 years 2 months | |||

| North Bristol NHS Trust | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (0.61) | Yes | 0 years 11 months | ||||

| East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (0.61) | No | 1 years 2 months | ||||

| Barnet and Chase Farm NHS Trust | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (0.61) | No | 0 years 6 months | |||

| Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (0.45) | Yes | 1 years 1 months | ||||

| Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.15) | No | 0 years 1 months | ||||||

| Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 5 (6.1) | 4 (5.0) | 9 (1.36) | No | NA | |||||

| Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust | 6 (6.6) | 6 (6.7) | 12 (1.82) | No | NA | |||||

| Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 3 (3.3) | 5 (5.6) | 8 (1.21) | No | NA | |||||

| Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust | 15 (16.5) | 15 (16.7) | 30 (4.55) | No | NA | |||||

| Forth Valley Acute Operating Division | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) | 4 (0.61) | No | NA | |||||

| Frimley Park Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.30) | No | NA | |||||

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (0.45) | No | NA | |||||

| Heatherwood and Wexham Park Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) | 4 (0.61) | No | NA | |||||

| Hereford Hospitals NHS Trust | 5 (6.1) | 4 (5.0) | 9 (1.36) | No | NA | |||||

| Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.30) | No | NA | |||||

| Lothian University Hospitals Division | 8 (8.8) | 9 (10.0) | 17 (2.58) | No | NA | |||||

| Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (0.45) | No | NA | |||||

| Mid Staffordshire General Hospitals NHS Trust | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) | 4 (0.61) | No | NA | |||||

| Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust | 5 (5.5) | 5 (5.6) | 10 (1.52) | No | NA | |||||

| Milton Keynes Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (0.45) | No | NA | |||||

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 5 (6.1) | 6 (7.5) | 11 (1.67) | No | NA | |||||

| North Cumbria Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 4 (4.9) | 4 (5.0) | 8 (1.21) | No | NA | |||||

| Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | 6 (0.91) | No | NA | |||||

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital NHS Trust | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.15) | No | NA | ||||||

| Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust | 5 (5.5) | 4 (4.4) | 9 (1.36) | No | NA | |||||

| Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | 6 (0.91) | No | NA | |||||

| Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust | 4 (4.4) | 3 (3.3) | 7 (1.06) | No | NA | |||||

| Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust | 4 (4.4) | 4 (4.4) | 8 (1.21) | No | NA | |||||

| South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 8 (9.8) | 8 (10.0) | 16 (2.42) | No | NA | |||||

| St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust | 5 (5.5) | 4 (4.4) | 9 (1.36) | No | NA | |||||

| Stockport NHS Foundation Trust | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (0.61) | No | NA | |||||

| Trafford Healthcare NHS Trust | 16 (17.6) | 17 (18.9) | 33 (5.00) | No | NA | |||||

| Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 5 (6.1) | 5 (6.3) | 10 (1.52) | No | NA | |||||

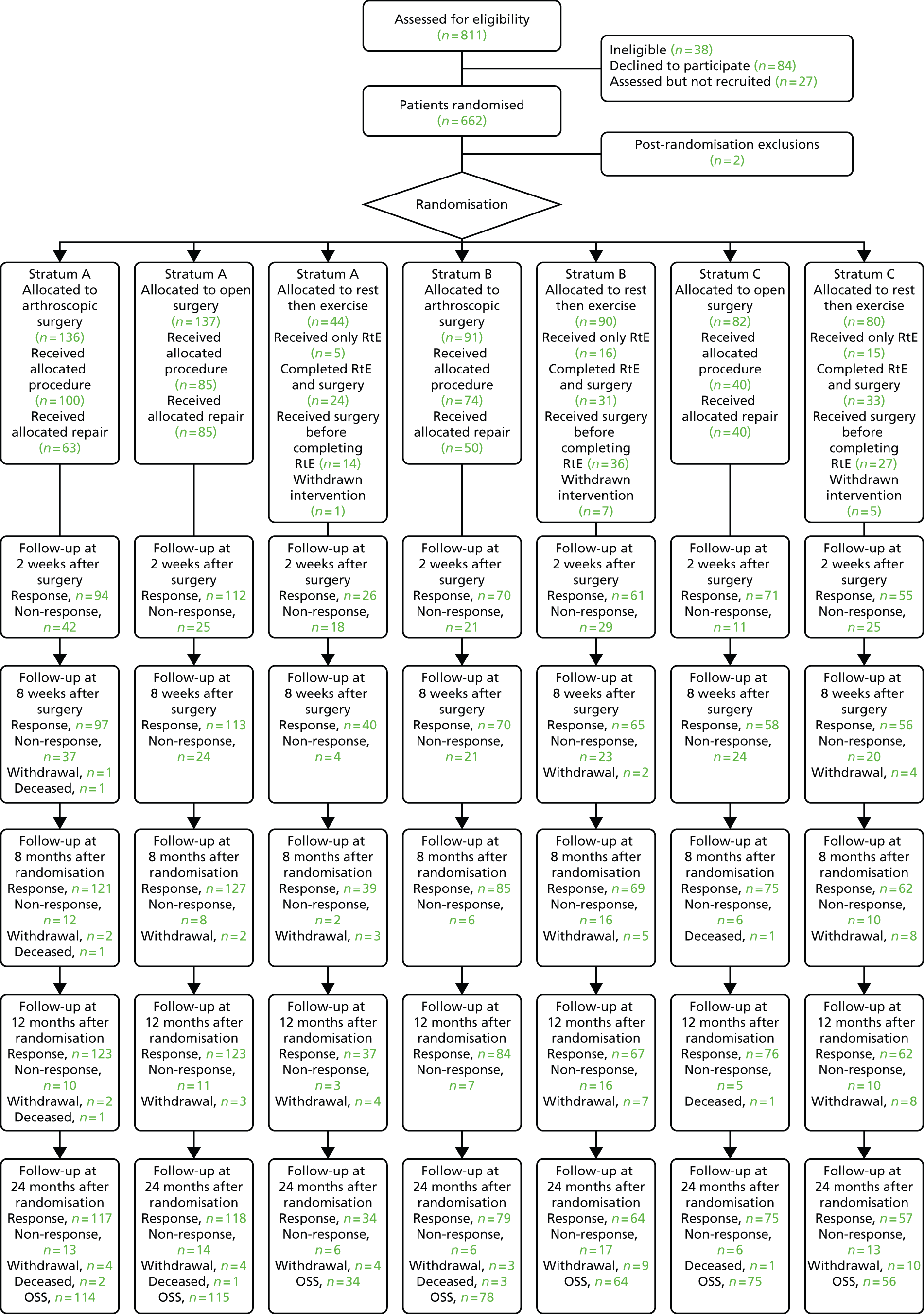

Study conduct

The derivation of the main study groups and their progress through the stages of follow-up in the trial is shown in Figure 1 This is in the form of a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. In total, 811 patients were considered for trial entry and 38 (5%) of these were found not to meet one or more of the eligibility criteria. Of the 111 patients eligible for the study but not recruited, 84 declined to participate and the remaining 27 could not be randomised while the study underwent reconfiguration (because of the requirement for new research ethics and research and development approvals). Two participants were excluded post randomisation because each had received previous surgery prior to randomisation. Details of the clinical management actually received are provided in Chapter 4. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] time intervals in days between randomisation by the trial office and each subsequent follow-up are shown in Table 4; all were similar between groups, as would be expected. The 2-week and 8-week follow-ups were timed to occur at 2 weeks and 8 weeks after surgery. Table 5 illustrates the success of this strategy in the subgroup of participants who did receive a surgical procedure.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. RtE, rest then exercise.

| Follow-up | Stratum A | Stratum B | Stratum C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | |

| 2 weeks | 99 (65–137) | 97 (65–134) | 93 (63–126) | 82 (62–108) | 99 (65–126) | 87 (60–129) | 101 (75–126) |

| 8 weeks | 135 (105–169) | 139 (102–178) | 149 (114–181) | 126 (106–152) | 134 (110–162) | 142 (107–177) | 141 (113–167) |

| 8 months | 231 (227–248) | 230 (227–236) | 232 (228–244) | 231 (227–248) | 232 (227–245) | 229 (227–239) | 234 (228–246) |

| 12 months | 374 (369–387) | 373 (369–383) | 371 (369–389) | 374 (370–383) | 375 (369–389) | 371 (368–378) | 372 (369–386) |

| 24 months | 737 (733–745) | 736 (733–745) | 740 (734–754) | 738 (734–754) | 739 (733–754) | 736 (734–752) | 736 (733–746) |

| Follow-up | Stratum A | Stratum B | Stratum C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 100) | Open (n = 114) | Arthroscopic (n = 74) | Open (n = 68) | |

| 2 weeks | 14 (14–16) | 14 (14–15) | 14 (14–16) | 14 (14–15) |

| 8 weeks | 56 (56–59) | 56 (56–58) | 57 (56–61) | 57 (56–60) |

| 8 months | 161 (117–194) | 155 (122–188) | 169 (147–201) | 164 (122–197) |

| 12 months | 307 (258–336) | 296 (262–335) | 316 (292–342) | 306 (259–333) |

| 24 months | 656 (620–693) | 654 (622–699) | 682 (647–708) | 672 (623–712) |

The overall rates of return of follow-up questionnaires at 8, 12 and 24 months were equivalent to > 85% of the study participants allocated to surgery (see Figure 1). There were no substantive differences in response rates between the surgery groups. Seven participants are known to have died by the end of the 2-year follow-up. There was no evidence that these deaths were linked to trial participation.

Description of the groups at trial entry

Clinical assessment at baseline

Table 6 displays the results of the presurgical assessment at recruitment. Approximately two-thirds of the tears were diagnosed using ultrasound. Tears were small or medium in about 75% of the participants in strata A and C and in 58% of participants in stratum B. Within the randomised groups there were no apparent imbalances. Around 10% of participants had received no previous treatment to their shoulder. Previous treatments primarily included physiotherapy and/or cortisone injections.

| Assessment | Stratum A, n (%) | Stratum B, n (%) | Stratum C, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | |

| Size of tear | |||||||

| Small/medium | 103 (75.7) | 103 (75.2) | 34 (77.3) | 53 (58.2) | 52 (57.8) | 62 (75.6) | 62 (77.5) |

| Large/massive | 33 (24.3) | 34 (24.8) | 10 (22.7) | 38 (41.8) | 38 (42.2) | 20 (24.4) | 18 (22.5) |

| Method of diagnosing tear | |||||||

| MRI | 41 (30.1) | 36 (26.3) | 9 (20.5) | 20 (22.0) | 20 (22.2) | 19 (23.2) | 12 (15.0) |

| Ultrasound | 87 (64.0) | 93 (67.9) | 32 (72.7) | 64 (70.3) | 60 (66.7) | 60 (73.2) | 56 (70.0) |

| Missing | 8 (5.9) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (6.8) | 7 (7.7) | 10 (11.1) | 3 (3.7) | 12 ( 15.0) |

| Received no treatment on shoulder in the last 5 years | 15 (11.0) | 10 (7.3) | 2 (4.5) | 9 (9.9) | 9 (10.0) | 3 (3.7) | 8 (10.0) |

| Received physiotherapy on affected shoulder in the last 5 years | |||||||

| Yes | 77 (56.6) | 83 (60.6) | 28 (63.6) | 54 (59.3) | 64 (71.1) | 59 (72.0) | 49 (61.3) |

| No | 41 (30.1) | 38 (27.7) | 10 (22.7) | 22 (24.2) | 21 (23.3) | 12 (14.6) | 23 (28.8) |

| Missing | 18 (13.2) | 16 (11.7) | 6 (13.6) | 15 (16.5) | 5 (5.6) | 11 (13.4) | 8 (10.0) |

| Duration of physiotherapy (weeks) | |||||||

| ≤ 4 | 17 (22.1) | 20 (24.1) | 7 (25.0) | 10 (11.0) | 13 (20.3) | 16 (27.1) | 10 (20.4) |

| 5–12 | 24 (31.2) | 22 (26.5) | 11 (39.3) | 15 (16.5) | 18 (28.1) | 17 (28.8) | 13 (26.5) |

| > 12 | 19 (24.7) | 21 (25.3) | 8 (28.6) | 21 (23.1) | 19 (29.7) | 16 (27.1) | 13 (26.5) |

| Missing | 17 (22.1) | 20 (24.1) | 2 (7.1) | 45 (49.5) | 14 (21.9) | 10 (16.9) | 13 (26.5) |

| Received an injection in affected shoulder in the last 5 years | |||||||

| Yes | 79 (58.1) | 83 (60.6) | 30 (68.2) | 52 (57.1) | 46 (51.1) | 59 (72.0) | 53 (66.3) |

| No | 40 (29.4) | 35 (25.5) | 9 (20.5) | 25 (27.5) | 34 (37.8) | 14 (17.1) | 21 (26.3) |

| Missing | 17 (12.5) | 19 (13.9) | 5 (11.4) | 14 (15.4) | 10 (11.1) | 9 (11.0) | 6 (7.5) |

| Number of injections | |||||||

| 1 | 34 (43.0) | 35 (42.2) | 14 (46.7) | 26 (50.0) | 24 (52.2) | 25 (42.4) | 21 (39.6) |

| 2 | 21 (26.6) | 29 (34.9) | 8 (26.7) | 13 (25.0) | 10 (21.7) | 17 (28.8) | 16 (30.2) |

| 3 | 10 (12.7) | 10 (12.0) | 4 (13.3) | 9 (17.3) | 5 (10.9) | 8 (13.6) | 6 (11.3) |

| 4 | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (3.4) | 3 (5.7) | |

| 5 | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| 6 | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| 7 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.9) | ||||

| 9 | 1 (1.7) | ||||||

| 10 | 1 (1.9) | ||||||

| Missing | 7 (8.9) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (8.7) | 3 (5.1) | 4 (7.5) |

| Received other treatment on the affected shoulder in the last 5 years | |||||||

| Yes | 18 (13.2) | 28 (20.4) | 5 (11.4) | 5 (5.5) | 2 (2.2) | 16 (19.5) | 13 (16.3) |

| No | 72 (52.9) | 61 (44.5) | 20 (45.5) | 43 (47.3) | 48 (53.3) | 36 (43.9) | 32 (40.0) |

| Missing | 46 (33.8) | 48 (35.0) | 19 (43.2) | 43 (47.3) | 40 (44.4) | 30 (36.6) | 35 (43.8) |

| Other treatment | |||||||

| Acupuncture | 2 (11.1) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | 5 (31.3) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Analgesics | 6 (33.3) | 13 (46.4) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (6.3) | |||

| Chiropractor | 3 (16.7) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (31.3) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Exercises | 2 (7.1) | 1 (50.0) | |||||

| Hydrotherapy | 2 (11.1) | ||||||

| Massage | 1 (6.3) | ||||||

| Nerve block | 1 (5.6) | ||||||

| Osteopathy | 1 (3.6) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (15.4) | |||

| TENS | 1 (5.6) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (6.3) | |||

| Ultrasound | 1 (3.6) | 3 (23.1) | |||||

| Missing | 3 (16.7) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Are there any problems with other shoulder? | |||||||

| No problems | 84 (61.8) | 86 (62.8) | 27 (61.4) | 49 (53.8) | 64 (71.1) | 47 (57.3) | 49 (61.3) |

| Mild problems | 32 (23.5) | 29 (21.2) | 9 (20.5) | 24 (26.4) | 11 (12.2) | 23 (28.0) | 22 (27.5) |

| Moderate problems | 11 (8.1) | 12 (8.8) | 3 (6.8) | 14 (15.4) | 11 (12.2) | 9 (11.0) | 7 (8.8) |

| Severe problems | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Missing | 5 (3.7) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (6.8) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) |

Participant and sociodemographic factors

Participant and sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 7. The average age of the participants was 63 years, 40% were female and 90% were right-handed. The mean period of time that the participants reported having the shoulder problem prior to surgery was approximately 2.5 years; however, the mean was driven by a few extreme values in each group relating to participants who had had shoulder problems for decades. The median (IQR) time that the participants had had the shoulder problem prior to recruitment was 1.2 (0.7–2.5) years. There were no substantive differences within or between strata on any of the sociodemographic factors.

| Characteristic | Stratum A, n (%) | Stratum B, n (%) | Stratum C, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | |

| Age (years), n, mean (SD) | 136, 62.9 (7.1) | 137, 62.9 (7.5) | 44, 62.9 (7.5) | 91, 65.7 (7.9) | 90, 64.7 (8.0) | 82, 61.9 (6.5) | 80, 61.3 (6.8) |

| Years with shoulder problem, n, mean (SD) | 136, 2.6 (5.3) | 137, 2.5 (4.1) | 43, 2.0 (2.7) | 90, 2.5 (3.4) | 87, 2.2 (3.3) | 82, 2.7 (4.7) | 79, 2.3 (2.6) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 81 (59.6) | 88 (64.2) | 28 (63.6) | 53 (58.2) | 63 (70.0) | 49 (59.8) | 51 (63.8) |

| Female | 55 (40.4) | 49 (35.8) | 16 (36.4) | 36 (39.6) | 27 (30.0) | 33 (40.2) | 29 (36.3) |

| Missing | 2 (2.2) | ||||||

| Handedness | |||||||

| Right-handed | 125 (91.9) | 115 (83.9) | 40 (90.9) | 83 (91.2) | 78 (86.7) | 66 (80.5) | 66 (82.5) |

| Left-handed | 7 (5.1) | 17 (12.4) | 1 (2.3) | 8 (8.8) | 9 (10.0) | 11 (13.4) | 8 (10.0) |

| Both | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| Highest qualification | |||||||

| None | 63 (46.3) | 59 (43.1) | 23 (52.3) | 39 (42.9) | 37 (41.1) | 34 (41.5) | 25 (31.3) |

| Secondary | 41 (30.1) | 49 (35.8) | 16 (36.4) | 37 (40.7) | 38 (42.2) | 33 (40.2) | 41 (51.3) |

| Higher | 32 (23.5) | 27 (19.7) | 5 (11.4) | 12 (13.2) | 12 (13.3) | 15 (18.3) | 12 (15.0) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Housing tenure | |||||||

| Home owner | 107 (78.7) | 119 (86.9) | 34 (77.3) | 78 (85.7) | 78 (86.7) | 69 (84.1) | 68 (85.0) |

| Private rent | 7 (5.1) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (6.8) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.2) | 5 (6.1) | 4 (5.0) |

| Council rent | 17 (12.5) | 9 (6.6) | 5 (11.4) | 7 (7.7) | 7 (7.8) | 5 (6.1) | 2 (2.5) |

| Other | 4 (2.9) | 8 (5.8) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (6.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | |||

| Lives alone | |||||||

| Yes | 23 (16.9) | 12 (8.8) | 6 (13.6) | 15 (16.5) | 19 ( 21.1) | 14 (17.1) | 12 (15.0) |

| No | 101 (74.3) | 118 (86.1) | 34 (77.3) | 74 (81.3) | 67 (74.4) | 66 (80.5) | 64 (80.0) |

| Missing | 12 (8.8) | 7 (5.1) | 4 (9.1) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (4.4) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (5.0) |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Full-time | 47 (34.6) | 58 (42.3) | 12 (27.3) | 22 (24.2) | 30 (33.3) | 28 (34.1) | 35 (43.8) |

| Part-time | 18 (13.2) | 15 (10.9) | 7 (15.9) | 13 (14.3) | 10 (11.1) | 13 (15.9) | 8 (10.0) |

| Homemaker | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.4) | |||

| Retired | 59 (43.4) | 54 (39.4) | 22 (50.0) | 52 (57.1) | 45 (50.0) | 36 (43.9) | 32 (40.0) |

| Unemployed | 7 (5.1) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (5.6) | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| Type of work | |||||||

| Manual | 36 (55.4) | 41 (56.2) | 12 (63.2) | 22 (62.9) | 27 (67.5) | 24 (58.5) | 24 (55.8) |

| Non-manual | 26 (40.0) | 28 (38.4) | 6 (31.6) | 12 (34.3) | 11 (27.5) | 16 (39.0) | 15 (34.9) |

| Not sure | 3 (4.6) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (7.0) |

| Missing | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.3) | ||||

| Off sick or working reduced duties | |||||||

| Yes, off sick | 7 (10.8) | 6 (8.2) | 3 (15.8) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (12.5) | 3 (7.3) | 4 (9.3) |

| Yes, working reduced duties | 10 (15.4) | 7 (9.6) | 5 (26.3) | 5 (14.3) | 8 (20.0) | 9 (22.0) | 8 (18.6) |

| No | 45 (69.2) | 58 (79.5) | 11 (57.9) | 28 ( 80.0) | 27 (67.5) | 29 (70.7) | 31 (72.1) |

| Missing | 3 (4.6) | 2 (2.8) | |||||

| Would you be able to do your job or everyday activities with your arm in a sling? | |||||||

| No | 70 (51.5) | 76 (55.5) | 18 (40.9) | 51 (56.0) | 48 (53.3) | 41 (50.0) | 43 (53.8) |

| Yes, with difficulty | 62 (45.6) | 59 (43.1) | 19 (43.2) | 39 (42.9) | 35 (38.9) | 39 (47.6) | 31 (38.8) |

| Yes, no difficulty | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (9.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (6.8) | 5 (5.6) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.3) | |

Health status

The health-related quality-of-life measures are shown in Table 8. The mean OSS was approximately 26 across the groups. The EQ-5D, MHI-5 and SPADI measures were broadly similar across and within the strata.

| Measure | Stratum A, n, mean (SD) | Stratum B, n, mean (SD) | Stratum C, n, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | |

| OSS | 136, 26.2 (8.1) | 137, 25.2 (7.9) | 44, 23.7 (8.3) | 91, 25.3 (8.9) | 90, 23.5 (8.0) | 82, 25.9 (8.4) | 80, 26.2 (7.9) |

| SPADI | 136, 60.9 (22.0) | 136, 61.6 (22.0) | 44, 66.9 (22.1) | 91, 60.6 (23.1) | 90, 67.8 (20.4) | 82, 60.7 (20.1) | 79, 62.3 (20.1) |

| SPADI pain | 136, 70.0 (19.5) | 137, 70.1 (20.5) | 44, 73.0 (22.0) | 91, 70.0 (21.8) | 89, 73.1 (19.4) | 82, 69.6 (19.5) | 80, 69.4 (18.2) |

| SPADI disability | 136, 55.1 (25.0) | 135, 56.4 (24.7) | 44, 63.0 (23.7) | 91, 54.7 (25.9) | 90, 64.4 (22.1) | 82, 55.2 (21.9) | 77, 57.7 (23.3) |

| MHI-5 | 136, 22.5 (4.9) | 137, 22.9 (4.5) | 44, 21.5 (5.5) | 90, 22.4 (5.1) | 90, 22.7 (4.9) | 82, 22.1 (4.7) | 80, 22.9 (4.6) |

| EQ-5D | 135, 0.548 (0.299) | 136, 0.519 (0.291) | 43, 0.448 (0.332) | 91, 0.514 (0.326) | 89, 0.503 (0.287) | 81, 0.536 (0.287) | 79, 0.538 (0.298) |

Attitudes to surgery

As expected, there was variation in participants’ attitudes to undergoing surgery in general, but the variation was not different between groups (Table 9).

| Question | Stratum A, n (%) | Stratum B, n (%) | Stratum C, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Rest then exercise (n = 44) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Rest then exercise (n = 90) | Open (n = 82) | Rest then exercise (n = 80) | |

| To what extent do you agree that doctors rely on surgery too much? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 2 (2.2) | ||||||

| Agree | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (6.8) | 6 (6.6) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (1.2) | 5 (6.3) |

| Uncertain | 52 (38.2) | 51 (37.2) | 26 (59.1) | 40 (44.0) | 35 (38.9) | 26 (31.7) | 29 (36.3) |

| Disagree | 72 (52.9) | 76 (55.5) | 13 (29.5) | 35 (38.5) | 42 (46.7) | 52 (63.4) | 39 (48.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 7 (5.1) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (4.5) | 7 (7.7) | 7 (7.8) | 2 (2.4) | 5 (6.3) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | |

| To what extent do you agree that doctors place too much trust in surgery? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (2.2) | ||||

| Agree | 6 (4.4) | 4 (2.9) | 9 (20.5) | 9 (9.9) | 7 (7.8) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (10.0) |

| Uncertain | 66 (48.5) | 61 (44.5) | 22 (50.0) | 47 (51.6) | 35 (38.9) | 39 (47.6) | 33 (41.3) |

| Disagree | 54 (39.7) | 62 (45.3) | 11 (25.0) | 27 (29.7) | 43 (47.8) | 36 (43.9) | 33 (41.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (6.6) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (5.5) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | |

| To what extent do you agree that you worry about surgery risks? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 5 (3.7) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (6.8) | 13 (14.3) | 12 (13.3) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (5.0) |

| Agree | 58 (42.6) | 51 (37.2) | 20 (45.5) | 37 (40.7) | 35 (38.9) | 30 (36.6) | 33 (41.3) |

| Uncertain | 21 (15.4) | 18 (13.1) | 8 (18.2) | 13 (14.3) | 14 (15.6) | 22 (26.8) | 16 (20.0) |

| Disagree | 43 (31.6) | 49 (35.8) | 12 (27.3) | 23 (25.3) | 23 (25.6) | 22 (26.8) | 20 (25.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 8 (5.9) | 12 (8.8) | 1 (2.3) | (5.5) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | ||

| To what extent do you agree that surgery should be only a last resort? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 17 (12.5) | 19 (13.9) | 6 (13.6) | 20 (22.0) | 12 (13.3) | 11 (13.4) | 11 (13.8) |

| Agree | 75 (55.1) | 67 (48.9) | 17 (38.6) | 41 (45.1) | 48 (53.3) | 38 (46.3) | 36 (45.0) |

| Uncertain | 19 (14.0) | 24 (17.5) | 9 (20.5) | 14 (15.4) | 12 (13.3) | 16 (19.5) | 13 (16.3) |

| Disagree | 23 (16.9) | 22 (16.1) | 11 (25.0) | 9 (9.9) | 15 (16.7) | 13 (15.9) | 15 (18.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (7.7) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.8) | |||

Summary

There was no evidence of any important imbalances between the groups. With a mean OSS of around 26, the population was representative of those in other shoulder studies (see Chapter 1). Most participants had undergone some form of non-surgical intervention (such as physiotherapy) before the trial and had had symptoms for over a year. In Chapter 4, the results of the randomised trial of arthroscopic compared with open surgery will be reported. A description of the findings from the rest-then-exercise programme will be provided in Chapter 5.

Chapter 4 Results: arthroscopic surgery compared with open surgery

This chapter describes the comparison between arthroscopic surgery and open surgery and includes operative characteristics and outcomes at 2 and 8 weeks post surgery as well as 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation.

Analysis populations

Throughout the analyses presented in this chapter, the participants in the formal randomised comparison between arthroscopic surgery and open surgery (stratum A) are kept separate from those in the arthroscopic and open groups in strata B and C respectively. All 273 participants who joined the randomised arthroscopic compared with open surgery component in stratum A are referred to as the randomised ITT population; the 148 (n = 63 arthroscopic; n = 85 open) within this group who actually received a repair over the 2-year follow-up period are referred to as the per-protocol population. The non-randomised population refers to the 91 participants allocated to arthroscopic surgery from stratum B and the 82 participants allocated to open surgery in stratum C (included in this chapter for completeness and visual inspection of data). No statistical analysis is performed on the non-randomised population.

Surgical management

Randomised intention-to-treat population

Table 10 shows the types of procedure undertaken in each group. For the 136 participants randomised to receive arthroscopic surgical management, 63 (46.3%) underwent an arthroscopic repair of a tear, nine (6.6%) began as an arthroscopic procedure and converted to an open repair, 28 (20.6%) underwent an arthroscopic procedure (that did not involve a repair of a tear) and 36 (26.5%) withdrew and did not undergo any surgery. Of the arthroscopic procedures not involving a repair, a shoulder subacromial decompression was the most common procedure undertaken. Some 100 (73.5%) participants received the intended randomised arthroscopic surgical management, although only 63 (46.3%) received an arthroscopic repair.

| Surgical management | Randomised, n (%) | Non-randomised, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic (n = 136) | Open (n = 137) | Arthroscopic (n = 91) | Open (n = 82) | |

| Received an arthroscopic repair | 63 (46.3) | 5 (3.6) | 50 (54.9) | 2 (2.4) |

| Received a converted arthroscopic procedure | 9 (6.6) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Received an open repair | 85 (62.0) | 40 (48.8) | ||

| Received an arthroscopic procedure | 28 (20.6) | 24 (17.5) | 23 (25.3) | 26 (31.7) |

| Details of procedure | ||||

| SAD | 20 (14.7) | 16 (11.7) | 14 (15.4) | 18 (22.0) |

| SAD and ACJ resection | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 4 (4.4) | 6 (7.3) |

| Biceps tenotomy | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Capsular release | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.2) | |

| PTT repair | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Partial repair | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Type of procedure not documented | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) |

| Withdrawn from intervention | 36 (26.5) | 23 (16.8) | 15 (16.5) | 12 (14.6) |

| Awaiting surgery when study ended | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Cancelled because of other surgery | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Complete withdrawal from study | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Family commitments | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| No surgery on medical grounds | 11 (8.1) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.4) |

| Patient asymptomatic | 7 (5.1) | 7 (5.1) | 2 (2.2) | 5 (6.1) |

| Patient deceased | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Patient did not want surgery | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.4) |

| Patient not happy with hospital | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Patient withdrew from NHS waiting list | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Personal reasons | 2 (2.4) | |||

| Shoulder problem improved without surgery | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Work commitments | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Surgery type missing | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.4) | ||

Of the 137 participants randomised to receive open surgical management, 85 (62.0%) underwent an open repair of a tear and five (3.6%) an arthroscopic repair (see Table 10). Some 24 participants underwent an arthroscopic procedure and, as with the participants randomised to arthroscopic management, the most common procedure was a shoulder subacromial decompression. Twenty-three participants withdrew from any surgery. The principal reasons for participants withdrawing from surgery were related to medical conditions (primarily cardiac events) or participants being asymptomatic and not judged to be associated with either of the allocated procedures.

Non-randomised population

Similar proportions of non-randomised participants as randomised participants received the various management strategies, suggesting that the participants were broadly similar and their management was not biased by the surgeons’ preferred techniques.

Operative details

Procedural details are shown in Table 11 for those participants who received any surgery. The size of tear and surgical completeness were similar between the randomised groups. In the randomised group the ease of repair, although broadly similar, was reported to be easier for the open procedure (18% of arthroscopic operations were easy vs. 36% of open repairs). Such a difference was not observed in the non-randomised groups and therefore any difference must be interpreted with caution. However, the difference may be a proxy measure that the surgeons in the randomised comparison were more comfortable with the open than the arthroscopic approach.