Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/01/14. The contractual start date was in February 2009. The draft report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The following coauthors have undertaken research or consultancy for companies that develop and manufacture smoking cessation medications: Robert West (Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer), Tim Coleman (Pierre Fabre Laboratories) and Paul Aveyard (Pfizer).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Ussher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem of smoking in pregnancy

Maternal smoking in pregnancy is the main preventable cause of morbidity and death among women and infants. Smoking is associated with adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, including miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, low birthweight, congenital abnormalities, and neonatal or sudden infant death. 1–3 Smoking also presents immediate risks for the mother, including placental abruption,4 as well as the longer-term risks reported for smokers in general. In addition, the children of mothers who smoke are twice as likely to become smokers. 5 Smoking in pregnancy is a global public health problem. In high-income countries the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy is typically between 10% and 25% and it appears to be reducing. 6–10 However, rates seem to be rapidly increasing in low- and middle-income countries. 11 In the UK it is estimated that 12% of women smoke during pregnancy7 and, as in other high-income countries, rates of smoking in pregnancy remain highest among younger women and those who are more socially disadvantaged. 7 Smoking cessation during pregnancy improves maternal and birth outcomes,12 yet only approximately 25% of pregnant smokers stop for at least part of their pregnancy and around two-thirds of these relapse after giving birth. 13

Treatments to aid smoking cessation in pregnancy

Face-to-face and ‘self-help’ behavioural support are the only two interventions that have been shown to help pregnant women to stop smoking. 12,14 Regular sessions of face-to-face behavioural support can increase smoking cessation rates in pregnancy by approximately 6%15 and there is a need to identify other interventions that are effective during pregnancy when combined with this support. The most effective therapy in non-pregnant smokers is a combination of behavioural support plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion or varenicline. 16–18 However, the efficacy of NRT during pregnancy is not known,19 and thus many pregnant women are reluctant to use it,20 and other smoking cessation medications are contraindicated during pregnancy. 19 There is a need to identify other non-pharmacological interventions that are effective for smoking cessation during pregnancy.

Evidence for physical activity aiding smoking cessation

Effective pharmaceutical aids for quitting are thought to work mainly through reducing cigarette cravings18 and there is good evidence from a meta-analysis21 to show that physical activity (PA) reduces these cravings, particularly at a moderate or vigorous intensity. Therefore, PA interventions could aid smoking cessation. For non-pregnant smokers, a Cochrane systematic review22 has considered the evidence for PA aiding cessation. The majority of the 15 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) reviewed had low statistical power to detect a meaningful difference between the treatment groups, with seven trials having < 25 participants in each treatment arm. Six adequately powered trials compared a group receiving a PA intervention combined with behavioural support with a group receiving behavioural support alone. Three of these studies showed significantly higher smoking abstinence rates in the PA group than in the control group at the end of treatment. 23–25 One of these studies also showed that a PA intervention increased abstinence compared with a control group at the 3-month follow-up and there was a benefit of exercise of borderline significance [relative risk (RR) 2.19, 95% CI 0.97 to 4.96; p = 0.05] at the 12-month follow-up. 23 A further study showed significantly higher abstinence rates for the exercise group than for the control group at the 3-month follow-up, but not at the end of treatment or at the 12-month follow-up. 26 The study with the most intensive PA intervention, entailing thrice-weekly sessions of supervised vigorous-intensity exercise, showed the strongest effect on abstinence. 23 The other studies involved PA interventions that were relatively less intense, particularly in terms of the extent of supervised exercise, and it is possible that supervised exercise is needed for efficacy. Adequately powered trials are needed that involve moderate-intensity exercise, which is likely to be more acceptable than vigorous exercise for most individuals. 27 Moderate-intensity PA (e.g. brisk walking) is recommended for pregnancy28 and has been shown to reduce cigarette cravings during pregnancy,29 and pilot work suggests that pregnant smokers are likely to be receptive to a PA intervention. 30

The effects of physical activity on maternal depression and weight gain

Important secondary outcomes included changes in maternal depression and weight. Antenatal and postnatal depression are important because they are common and are associated with harmful consequences for the mother and child. 31–38 Interventions are needed for preventing and treating these types of depression. Moreover, pregnant smokers are at a heightened risk of depression during and after pregnancy, and women who quit smoking during pregnancy are more likely to relapse if they experience depressive symptoms. 12,39,40 Thus, it is important that pregnant women who smoke or who are attempting to quit are offered effective interventions for depression. The London Exercise And Pregnant smokers (LEAP) trial was the first study to assess the effectiveness of a PA intervention for symptoms of antenatal and postnatal depression specifically among smokers.

Excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including large-for-gestational-age infants and caesarean section. 41,42 In addition, smoking cessation is associated with GWG. 43 Interventions for managing GWG are needed, especially among women attempting to quit smoking, and PA has potential in this regard. Observational studies have demonstrated an association between participation in PA and reduced risk of excessive GWG,44–46 whereas a recent meta-analysis using data from 10 RCTs showed an overall benefit of participation in PA compared with a control condition in terms of reducing GWG. 47 We are not aware of any studies that have examined the effect of a PA intervention on GWG in pregnant smokers. Among non-pregnant smokers, there is some evidence that PA interventions can limit post-smoking cessation weight gain. 48 The LEAP trial was the first large RCT to examine the effect of a PA intervention on preventing excessive GWG and postnatal weight retention.

Summary

In summary, smoking in pregnancy is extremely harmful for mother and baby and is an enduring global public health problem. Behavioural support is the only smoking cessation intervention shown to be effective in pregnancy. The evidence for PA programmes aiding smoking cessation is mixed and pregnancy provides a compelling rationale for their use because medication is contraindicated or ineffective. We conducted the LEAP RCT to assess the effectiveness of a PA intervention for smoking cessation during pregnancy.

Main objective

The main objective of the study was to investigate whether or not standard behavioural support for smoking cessation in pregnancy plus a PA intervention is more effective than behavioural support alone in achieving biochemically validated smoking cessation between a quit date and the end of pregnancy for women between 10 and 24 weeks’ gestation who currently smoke one or more cigarettes daily and who smoked at least five cigarettes daily before pregnancy. A further objective was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention for achieving smoking cessation at the end of pregnancy.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The LEAP trial was a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled, parallel-group trial of a PA intervention. Participants were monitored from their recruitment at between 10 and 24 weeks’ gestation until the end of pregnancy and were then followed up by telephone at 6 months after the birth. The trial protocol has been published. 49

Participants and recruitment

Eligibility criteria

Eligible participants were aged 16–50 years, were between 10 and 24 weeks’ gestation (subject to confirmation that they had a scan to show a viable pregnancy), were currently smoking at least one cigarette per day, were smoking at least five cigarettes per day before pregnancy, were prepared to quit smoking 1 week after enrolment and could confirm that they were able to walk continuously for at least 15 minutes. Women were excluded if they were unable to complete self-administered questionnaires in English (because of a lack of resources for translators) or if they reported any medical condition that might be exacerbated by exercise. There are no documented contraindications to moderate-intensity exercise but if a woman had been advised by her doctor or midwife not to take exercise during pregnancy, if she had any complications during her pregnancy or if she had been cautioned against taking exercise,28,50 a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at her hospital were consulted to check that it was safe for her to participate. Participants joining the trial were monitored at each treatment session for cautions to exercise and adverse events (AEs). Those with drug or alcohol dependence were excluded as the intervention described was not comprehensive enough to address these issues.

Although NRT is licensed for use in pregnancy, there is no evidence for its effectiveness at this time19 and many pregnant smokers prefer not to use it. 20 Allowing study participants to use NRT might create confounding; therefore, women who indicated that they wished to use NRT on commencing their quit attempt were excluded. Following guidelines,51 those women who were unable to stop smoking after their quit day and who expressed a wish to receive NRT were prescribed NRT by their general practitioner (GP). The participants’ GPs, midwives and obstetricians were informed of their patients’ participation in the trial.

Recruiting centres

Participants were recruited from 13 hospital antenatal clinics in England. Initially these were at hospitals in the Greater London area: St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust (St George’s Hospital), Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Chelsea and Westminster Hospital), Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (St Thomas’ Hospital), Croydon Health Services NHS Trust (Croydon University Hospital, previously known as Mayday Hospital), Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital and St Mary’s Hospital), Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust (Epsom Hospital) and Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Kingston Hospital). Five further sites around England were later added to improve recruitment rates: Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust (Crawley Hospital), West Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust (West Middlesex University Hospital), Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Leighton Hospital), King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (King’s College Hospital) and Medway Foundation Trust (Medway Maritime Hospital).

Researchers

At each centre a dedicated research midwife, research nurse or research psychologist undertook all trial-related procedures, including delivering all of the interventions and administering all of the outcome measures. Researchers were trained by the chief investigator/trial manager (Professor Ussher) in research procedures, including screening, enrolment and consent procedures. They also attended certified Good Clinical Practice training. Researchers were trained to national standards to provide behavioural support for smoking cessation and PA. 52

Recruitment and consent

The smoking status of all pregnant women is routinely recorded in the hospital computerised patient administration system (PAS) at the first antenatal booking visit, which is typically at 9–14 weeks of gestation. At this time, the hospital midwife informs all women recorded as smokers that it is hospital policy to telephone them to offer smoking cessation support. This support would usually be offered by their local NHS Stop Smoking Service but during the period of recruitment to the study a trial researcher telephoned the women. The following methods of recruitment were used:

-

On recording women as smokers, hospital midwives routinely passed referral forms to the researcher. In some cases these referral forms would be available before the smoking status of the women was recorded in the PAS and in these cases the researcher extracted the women’s contact details from the referral forms rather than from the PAS.

-

In cases in which a woman’s smoking status appeared in the PAS before a midwife referral form was received, the researcher extracted the woman’s contact details from the PAS and telephoned her. Following our consultation with the Patient Information Advisory Group, the ethics committee gave us permission to contact all pregnant women recorded as smokers. This is because during the trial the researchers were considered as part of the clinical care team and it is routine practice to contact women in this way.

-

A flyer containing brief information about the trial was included in women’s packs for their first antenatal booking appointment and women were invited to call a researcher if they were interested in finding out more about the study.

-

Women who had seen posters advertising the study in hospitals or children’s centres could contact a researcher directly.

-

We had initially planned to distribute a questionnaire at the first ultrasound visit inviting women to take part. This approach was piloted at several sites in the first month of the study; however, it had a low response rate and was labour intensive and, therefore, was abandoned.

Those who were interested in receiving help with quitting were invited to join the trial or were offered referral to the primary care trust (PCT), as per usual practice. Those women expressing an interest in volunteering were screened for eligibility by the researcher by telephone (see Appendix 1) and eligible women were sent a participant information sheet.

After having the chance to consider the participant information sheet for at least 24 hours and to discuss the study with the researcher, women who volunteered were offered an appointment at a community-based children’s centre or at their local hospital. At the first appointment they gave their written informed consent before trial data were collected. In addition to trial participation, women were asked to give consent for researchers to have access to their and their child’s medical records, for information held by the NHS to be used to keep in touch with them and to follow their health status, and for the researcher to inform their GP, midwife and obstetrician about their participation in the study.

Interventions

The interventions followed Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for non-pharmacological interventions. 53,54 Delivery of the interventions was standardised by training and by the therapists following manuals (see Appendices 2 and 3). The initial competence of the therapists was assessed by the trial manager/chief investigator by observing role-play scenarios during training. The fidelity of the interventions was monitored during the first 6 months by regular observations (at least five intervention sessions) by the trial manager/chief investigator, with the tasks listed in Appendices 2 and 3 used as a checklist. All sessions were face to face and one to one and were delivered in a private room at the hospital or in a community health centre/children’s centre. Social cognitive (learning) theory55 was the theoretical basis for the interventions. This theory recognises the interplay of individual factors (e.g. self-efficacy to quit smoking or increase PA) and social/environmental factors (e.g. social support) in health behaviour change. For each session that they attended, the women were paid £7 for their travel expenses.

Control group

Those in the control group received behavioural support for smoking cessation, which is generally provided by the NHS Stop Smoking Service to pregnant women as part of ‘usual care’. By extracting the elements of the intervention from written manuals and materials provided by the programme (see Appendix 2), the contents of the intervention were classified in accordance with the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) described by Michie and colleagues56 and used in individual behavioural support for smoking cessation (Table 1). Participants were offered six weekly sessions of 20 minutes of behavioural support for smoking cessation, commencing 1 week before the quit date and ending 4 weeks afterwards. The intervention (see Table 1) incorporated all 43 BCTs for smoking cessation defined by Michie and colleagues,56 except for the BCT ‘provide rewards contingent on successfully stopping smoking’, although financial rewards were offered to increase compliance (Table 2). Continued support was offered to women who failed to quit or who relapsed to smoking.

| Week | Session number | Session content | BCTs used (Michie categoriesa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Session 1 (1 week before quit day) | Explain the treatment, including the timing of quit | RC4, BS4 |

| Measure expired CO level and explain purpose | RC3 | ||

| Assess and discuss current and past smoking behaviour | RI1 | ||

| Identify reasons for wanting and not wanting to quit | BM9 | ||

| Assess current motivation/confidence for quitting | RI2 | ||

| Discuss past attempts at quitting | RI3 | ||

| Prepare for the quit attempt | BM6, BS3 | ||

| Discuss use of social support | A2 | ||

| Advise on reducing smoking cues | BS8 | ||

| Advise subject to note the times when they are likely to relapse | BS6 | ||

| Facilitate relapse prevention planning and coping | BS2 | ||

| Identify barriers to quitting and address these barriers | BS1 | ||

| Emphasise choice (e.g. when they take their final smoke) | RD2 | ||

| Provide information about the consequences of smoking during pregnancy | BM1, RC5 | ||

| Explain about quitting abruptly, rather than cutting down | BM10 | ||

| For all sessions: | |||

| Allow time for questions | RC2 | ||

| Summarise | RC9 | ||

| Use reflective listening | RC7 | ||

| Elicit participant’s views | RC8 | ||

| Build a general rapport | RC1 | ||

| Give praise for progress | BM7 | ||

| Tailor the interactions | RD1 | ||

| 2 | Session 2 (quit day) | Look for reasons why the woman is a good prospect | BM2, BM3 |

| Explain about cigarette withdrawal symptoms and strategies for dealing with them | RC6 | ||

| Identify barriers to quitting and address these barriers | BS1 | ||

| Advise on avoiding social cues for smoking | BS11 | ||

| Advise on changing routine | BS7 | ||

| Advise on conserving mental resources | BS10 | ||

| Set graded tasks (e.g. take 1 hour/day at a time) | BS9 | ||

| 3 | Session 3 (1 week after quit day) | Check smoking status | BS5 |

| Assess withdrawal symptoms | RI4 | ||

| Reassure about the norms for these symptoms | RC10, BM5 | ||

| Advise subjects to monitor when they want to smoke | BS6 | ||

| Assess CO level and give feedback about whether or not reading has reduced | BM11, BM3 | ||

| Discuss planning and coping strategies to prevent relapse | BS2 | ||

| If they have relapsed ask them to commit to a new quit date | BM6 | ||

| Advise about use of NRT | A1 | ||

| Liaise with PCT about obtaining NRT | A3 | ||

| Encourage subject to see themselves as a non-smoker | BM8 | ||

| Remind them of lottery prize for attending all sessions | BM7 | ||

| 4 | Session 4 (2 weeks after quit day) onwards | Assess CO level | BM11 |

| Check smoking status | BS5 | ||

| If they are struggling offer further support from PCT | A5 | ||

| Discuss relapse prevention planning and coping strategies for after birth | BS2, BM8 | ||

| Emphasise importance of not having a single puff | BM6 | ||

| If subject has relapsed, set a new quit date and review use of NRT | A4 | ||

| Incentive occasion | Maximum financial incentive (£) | |

|---|---|---|

| PA group | Control group | |

| Annual lottery with three prizes of £100 for attending at least 80% of the treatment sessions | 100a | 100a |

| Travel expenses (£7) for each session attended | 98b (14 sessions) | 42b (six sessions) |

| Follow-up at end of pregnancy | 10a | 10a |

| Follow-up at 6 months after birth | 10a | 10a |

| ≥ 5 days of accelerometer data recorded | 25a | NA |

| Total | 243 | 162 |

Treatment group

In addition to behavioural support for smoking cessation, those in the PA group received a PA intervention, combining PA consultations and supervised exercise. By extracting the elements of the PA consultation from the written manuals and materials of the PA programme (Table 3), the contents of the PA consultation have been classified in accordance with the taxonomy of Michie and colleagues57 of BCTs used to help people change their PA behaviours. There were 14 sessions of supervised exercise, twice a week for 6 weeks (one session with behavioural support for smoking cessation) and then weekly for 2 weeks. Following a familiarisation session at the first visit, participants were advised to aim for 30 minutes of continuous treadmill walking during each session. Following guidelines,58 moderate-intensity exercise was prescribed according to age and current activity levels and was monitored using a polar heart-rate monitor. The intensity of exercise was also guided by a rating of perceived exertion59 (‘fairly light’ to ‘somewhat hard’) and by the ‘talk test’, which indicates that the intensity of activity is too high if it is not possible to hold a conversation.

| Week | Session number | Session content | BCTs used (Michie categoriesa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Session 1 (1 week before quit day) | Review current PA and discuss PA benefits | 1, 2 |

| Explain and demonstrate use of treadmill and pedometer | 7, 21, 22, 26 | ||

| Check PA confidence levels using scaling questions | 16 | ||

| All sessions: | |||

| Agree PA goals | 10 | ||

| Provide weekly PA and step-count diaries | 16 | ||

| Allow time for questions, summarise, use reflective listening, elicit participant’s views, build a general rapport | NA | ||

| Give praise for effort and for achieving PA goals | 12, 13 | ||

| 1 | Session 2 | Review PA goals and effect of PA on cravings | 7, 9, 10 |

| Complete cost–benefit analysis for increasing PA | 2 | ||

| Identify PA barriers and problem solve | 8 | ||

| Explain and demonstrate exercises in booklet | 21, 22, 26 | ||

| Provide information on places to exercise | 20 | ||

| Discuss time management and exercise habits | 23, 38 | ||

| Plan social support | 29 | ||

| Provide weekly PA diary and step-count diary | 16 | ||

| 2 | Session 3 (quit day) | Review PA goals, set heart-rate targets on treadmill | 10 |

| Identify PA barriers and problem solve | 8 | ||

| Provide weekly PA diary and step-count diary | 16 | ||

| Check PA confidence levels with scaling questions | 8 | ||

| 3 | Session 4 (1 week after quit day) onwards | Review PA goals, set heart-rate targets on treadmill | 10 |

| Plan for relapse prevention/coping | 35 | ||

| Review exercises in booklet | 21, 22, 26 | ||

| Review social support | 29 | ||

| Use imagery to encourage identity as an ‘exerciser’ | 34 | ||

| Provide weekly PA diary and step-count diary | 16 | ||

| Reminder that sessions reduce to once per week for the last 2 weeks of the programme | 27 | ||

| Check PA confidence levels with scaling questions | 8 | ||

At the first two treadmill sessions and then on every other occasion women were offered a 20-minute PA consultation (total of nine sessions) on increasing their additional ‘home-based’ PA. The researcher worked through a booklet with each participant (see Appendix 4), which the participant retained. The intervention (see Table 3) incorporates 19 of 40 BCTs for increasing PA as defined by Michie and colleagues. 57 In general, the consultations aimed to identify opportunities to incorporate PA into women’s lives, to motivate them to use PA to aid smoking cessation and to help them use behavioural strategies to improve adherence to these plans. These consultations were tailored towards the women’s preferences for PA and their environment, including preference for type of PA, level of support from family or friends and availability of time and facilities for exercise. The participants were encouraged to view PA as a self-control strategy for reducing cigarette cravings and withdrawal60 and to maintain any increases in PA after their pregnancy. Following recommendations for pregnancy,28,61 the women were advised to be active for continuous periods of at least 10 minutes at a time, progressing towards accumulating 30 minutes of activity on at least 5 days of the week. The emphasis was on brisk walking, which is popular among pregnant smokers. 62 As a further option, a home-based antenatal exercise digital versatile disc (DVD) and booklet were provided. In addition, participants were given a pedometer for monitoring their daily steps (Digi-Walker SW-200; Great Performance Ltd, London, UK). Pedometers have been shown to increase activity levels in women63 and are acceptable during pregnancy64 and among pregnant smokers. 30 Participants were asked to log their daily steps, with the researcher calculating a 10% increment every 2 weeks, gradually progressing towards 10,000 steps a day. 65

Randomisation and blinding

An independent statistician generated a randomisation list using Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with random permuted blocks of random size stratified by recruitment centre. At enrolment the sequence was concealed from researchers, who had to confirm consent and eligibility on an online database before allocation was revealed. The online database was created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) and held on a secure server in accordance with their standard operating procedures. Allocation was concealed from the participant until all baseline assessments had been completed. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until interventions had all been assigned and recruitment, data collection and laboratory analyses were complete. Thus, neither participants nor researchers were blinded to treatment allocation during intervention delivery or during outcome assessment.

Data collection

At baseline, researchers recorded demographic characteristics (including age, marital status, number of children, highest educational qualification, ethnicity, occupation, weeks of gestation and history of premature births) and smoking characteristics [including cigarettes smoked per day (now and before pregnancy), weekly urge to smoke (combining ratings of strength and frequency of urges),66,67 cigarette withdrawal symptoms,66,67 Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) score68,69 and partner’s smoking status]. Depression was assessed with the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). 70 PA levels in the previous week (bouts of ≥ 10 minutes) were assessed for both groups using the 7-day PA interview (see Appendix 5). 71 Confidence levels with regard to taking up regular PA72 and stopping smoking73 were also recorded. Clothed weight (without shoes) was measured on a digital scale at the first antenatal booking visit by the midwife. The questionnaire showing assessments at baseline, including assessments repeated at further time points, is provided in Appendix 6. The timing of data collection is provided in Outcome measures.

Recording of adverse events

During all contacts, participants were asked about AEs. Medical records were examined monthly by research midwives for AEs and after delivery for maternal and infant outcome data. Researchers then summarised the descriptions in the case report forms and in the online study database. Descriptions were used to code the AEs according to standard terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities [see www.meddra.org (accessed 25 August 2015)]. Fetal deaths were recorded including miscarriage (non-live birth before 24 weeks’ gestation), stillbirth (non-live birth at ≥ 24 weeks’ gestation) and neonatal death (i.e. from live birth to 28 days).

Outcome measures

Timing of outcome measures

During the intervention period, the main assessment points were at 1 week, 4 weeks and 6 weeks after the quit day. The assessment at 1 week, when the vast majority of the sample was retained, was to assess the early impact of the intervention on cigarette withdrawal symptoms, urges to smoke, confidence for quitting and participating in PA and reports of PA. The 4-week assessment is a standard time for measuring short-term abstinence and is when the NHS Stop Smoking Service assesses abstinence. The 6-week assessment was timed to coincide with the end of the stop smoking programme. There were also follow-ups at the end of pregnancy and 6 months after the birth.

Primary outcome to end of pregnancy

The primary outcome was self-reported continuous abstinence from smoking between the quit date and the end of pregnancy, validated by exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) (Smokerlyzer; Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Maidstone, UK) or salivary cotinine (Salimetrics Europe Ltd, Newmarket, UK). Expired CO levels were assessed weekly up to 4 weeks after the quit day and at the end of pregnancy. Saliva cotinine levels were measured at 4 weeks after the quit day and at the end of pregnancy only among those who self-reported having smoked less than five cigarettes in total (on up to five occasions) since the quit day.

The primary outcome was operationalised as follows. Continuous abstinence was defined as having smoked less than five cigarettes in total (on up to five occasions) since the quit day. 74 Following an attempt to stop smoking, it is common for smokers to lapse on several occasions before finally succeeding in maintaining long-term abstinence; therefore, within the definition of continuous smoking abstinence it has become standard to allow five such lapses. With regard to exhaled CO, the criterion for confirming abstinence was a reading of < 8 parts per million (p.p.m.). 75 CO was assessed weekly up to 4 weeks after the quit day and at the end of pregnancy. With regard to salivary cotinine, the criterion for confirming abstinence was a value of < 10 ng/ml. 76 Cotinine was measured at 4 weeks post quit day and at the end of pregnancy.

The aim was to follow up women within 2 weeks of birth; however, it was acceptable for the primary outcome to be taken at any time between 36 weeks’ gestation and 10 weeks after the birth.

The primary outcome was dichotomous, that is, abstinent or non-abstinent. For a participant to be classed as abstinent from smoking at the end of pregnancy (i.e. positive primary outcome), the following criteria had to be satisfied:

-

At 4 weeks post quit (it was acceptable for this measure to be taken between 25 days and 6 weeks post quit):

-

‘Have you smoked at all since your quit day?’ = ‘no not even a puff’ or ‘yes just a few puffs’ or ‘yes, between one and five cigarettes’ or ‘missing’ (i.e. any response other than ‘yes, more than five cigarettes’) and CO is < 8 p.p.m. and/or cotinine is < 10 ng/ml or CO or cotinine is missing.

-

-

At the end of pregnancy:

-

‘Have you smoked at all since your quit day?’ = ‘no not even a puff’ or ‘yes just a few puffs’ or ‘yes, between one and five cigarettes’ (i.e. any response other than ‘yes, more than five cigarettes’) and CO is < 8 p.p.m. and/or cotinine is < 10 ng/ml.

-

The concentration of either exhaled CO or salivary cotinine was used to validate abstinence; if both measures were available both were required. Some women will not have data for self-report of smoking or biochemical validation at 4 weeks. If these women are confirmed as abstinent at the end of pregnancy it will be considered as a positive primary outcome.

For a participant to be considered as non-abstinent from smoking at the end of pregnancy (i.e. negative primary outcome), the following criteria had to be satisfied:

-

At 4 weeks or the end of pregnancy:

-

‘Have you smoked at all since your quit day?’ = ‘yes, more than five cigarettes’

-

CO or salivary cotinine values do not confirm abstinence

-

has withdrawn from the study (i.e. refuses follow-up)

-

fails to set a quit date that the follow-up assessment can be referenced against.

-

-

At the end of pregnancy:

-

refuses to allow biochemical validation

-

refuses to self-report number of cigarettes smoked

-

unable to contact to confirm smoking status (i.e. lost to follow-up).

-

Secondary outcomes

Biochemically validated continuous smoking abstinence was also assessed at 4 weeks after the quit day and 6 months after the birth. In addition, we assessed biochemically validated continuous smoking abstinence using a stricter criterion whereby no cigarettes were allowed after the quit day, at 4 weeks after the quit date, at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months postnatally. Self-reported smoking status at 6 months after the birth was reported by telephone and was not biochemically validated. Many women report that, rather than stopping smoking, they reduce their smoking during pregnancy77,78 and there is some evidence to suggest that a reduction in smoking of ≥ 50% is associated with an increased infant birthweight. 79 Therefore, levels of smoking reduction were assessed for those women who relapsed.

Other secondary outcome measures were changes in urge to smoke, tobacco withdrawal symptoms and confidence for stopping smoking and maintaining regular PA between baseline and 1 week after the quit day. We also assessed changes in depression between baseline, the end of pregnancy and 6 months after the birth, as well as changes in maternal weight between baseline, 4 weeks after the quit date and the end of pregnancy (the women were weighed again at the end of pregnancy by a researcher using the same method as used by the midwife at the first antenatal booking visit).

Further self-reports of PA levels were collected at weeks 1, 4 and 6 after the quit date and at both follow-ups (i.e. the end of pregnancy and 6 months postnatally). To validate self-reported PA levels, a 10% random subsample of participants had their PA levels objectively measured using an accelerometer (Model GT1M or GT3X; Actigraph, Pensacola, FL, USA). Only 90 women were asked to wear an accelerometer as our pilot work showed that most women would not tolerate waist-worn devices and at the start of the study validated wrist-worn accelerometers were not commercially available; therefore, as the only practicable alternative, we used self-reported PA levels in the primary analysis of PA. During the fourth week after the quit date, the accelerometer was worn over the right hip for 7 consecutive days, recording non-water-based activities during waking hours at 1-minute epochs. The Actigraph has been shown to be practicable and valid during pregnancy. 80–82

The duration of treadmill exercise and attendance rates were also recorded and use of NRT was monitored throughout the intervention period. At the end of pregnancy, follow-up participants were asked if they had received any face-to-face support to stop smoking during their pregnancy beyond that provided in the study.

Finally, the following birth and maternal outcomes were extracted from participants’ hospital records:

-

birthweight

-

gestational age at delivery

-

preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestation)

-

Apgar score

-

cord blood pH

-

neonatal intensive care unit admission

-

elective termination

-

maternal mortality

-

mode of delivery.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis plan, which is presented in Appendix 7, was finalised before any analyses started. The analysis for the primary outcome was conducted by an independent statistician, with allocation to the two study groups concealed until the analysis was completed. Analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Throughout, a p-value of < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Sample size

We anticipated a cessation rate of 15% in the control group on the basis that 9% of pregnant women who are smokers stop smoking with usual care after their first antenatal visit and that with behavioural support another 6–7% quit. 15 Based on pilot work,30 a cessation rate of 23% was anticipated in the treatment group. We calculated that 866 participants would provide 83% power at a 5% significance level (two-sided) to detect an absolute difference of 8 percentage points in the rate of the primary outcome between the two groups, corresponding to an odds ratio (OR) of 1.69 or a RR of 1.53.

The prime aim of assisting smoking cessation in pregnancy is to improve the outcome of the pregnancy. The latest version of the Cochrane review of psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy showed evidence that such interventions were effective in helping women stop smoking and improving perinatal outcome. 12 For example, the main subgroup in the review consisting of counselling compared with usual care showed a RR of 1.44 for achieving abstinence in late pregnancy, the same outcome that we used. No individual trial of smoking cessation in pregnancy detected differences in perinatal outcomes by intervention status, but the meta-analysis of all trials in the review showed evidence of this. When pooled together, these interventions produced the following RRs for the intervention compared with the control condition: low birthweight RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.94); preterm birth RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.96); increased mean birthweight 41 g (95% CI 18 g to 63 g). Thus, relative increases in the rate of cessation of a similar size to the one that we were aiming to detect have led to meaningful improvements in perinatal outcomes and would be expected to do so in this trial. A power of 80% is generally considered the minimum power for a trial. Based on available evidence, anticipated recruitment rates and budgeting constraints, we increased the power from the minimum of 80% to 83%. The trial as designed had adequate power for a plausible effect size.

Analysis for the primary outcome at the end of pregnancy

Analysis was on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis; participants with missing outcome data were assumed to be smoking. 74 The proportion of women reporting continuous smoking abstinence at the end of pregnancy was compared between study groups using logistic regression, with adjustment for recruitment centre using fixed effects. Statistical significance was assessed with the likelihood ratio test, with the estimate of effect given as the OR and 95% CI. A secondary analysis adjusted for centre, nicotine dependence, age, depression, maternal educational level and partner’s smoking status, as potentially important prognostic baseline factors. 83 In addition, as it was observed that the vast majority of participants reported high levels of PA at baseline, we tested for an interaction between baseline PA [< 150 minutes per week of moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA (MVPA) vs. ≥ 150 minutes per week of MVPA] and the treatment effect for the primary outcome. For the primary outcome, to assess the influence of the assumption that missing data equals ‘smoking’ on the effect size, we used the Hedeker method to test various scenarios of the association between smoking and having missing data. 84 Other outcomes for smoking cessation were analysed in a similar way.

Analysis for secondary outcomes

For ratings of withdrawal symptoms, urge to smoke, confidence for quitting smoking and confidence for participating in PA we conducted a series of linear regressions with scores at 1 week post quit as the dependent variable and the two groups, recruitment centre and baseline scores as independent variables. We compared the use of NRT and behavioural support between the two groups using chi-squared tests.

Physical activity outcomes

Self-reported weekly minutes of MVPA were log-transformed (log base 10) to normality and the difference in self-reported PA between the groups over time was analysed using a mixed-effects model to account for within-person correlations over time. In this model, the difference between treatment groups at each time point was estimated with adjustment for visit time, baseline minutes of MVPA, the interaction of visit time and baseline minutes of MVPA, and recruitment centre. The accelerometer data were analysed using KineSoft software (version 3.3.76; Loughborough, UK). Files with at least 10 hours of valid wear time on ≥ 1 day were retained in the analyses. Standard cut-points were used to determine MVPA. 85 Consistent with the self-report data, only MVPA sustained for at least 10 minutes was included in the assessment of validity using correlational analysis. The validity of the self-reports was also assessed by examining the difference between the self-report data and the accelerometer data using a Bland–Altman plot. 86 The two study groups were compared (Mann–Whitney U-tests) for accelerometer reports of MVPA, both when restricting the analysis to bouts of > 10 minutes (to allow comparison with the self-report data) and when including all MVPA, irrespective of duration.

Fetal and maternal birth outcomes

For binary outcomes, fetal and maternal birth outcomes were compared using logistic regression adjusted for recruitment centre. For continuous outcomes we compared study group means using multiple linear regression, again with adjustment for recruitment centre. For fetal outcomes, the primary analysis was of singleton births. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis including multiple births, with clustering of outcomes accounted for using an approach previously published. 87 This adapts methodology previously created for use with cluster RCTs, assuming that each woman is regarded as the ‘cluster’ and her number of offspring as the cluster size. A chi-squared test was used to compare the total number of women or their infants who had at least one AE or serious adverse event (SAE).

Depression outcome

One participant was randomised but withdrew consent without reason before providing any data. Thus, the sample for the depression analysis consisted of 784 women. All 784 participants provided EPDS data at baseline, with 383 (48.9%) and 279 (35.6%) participants providing data at the end of pregnancy and 6 months postnatally, respectively. First, we checked whether or not those with EPDS data at the two follow-up points (end of pregnancy, 6 months postnatally) had similar baseline characteristics, quit rate at the end of pregnancy and amount of PA reported as those from the total trial sample. Then, we examined whether or not the baseline characteristics of the PA and control participants were similar in the subsamples with EPDS data at the two follow-up points.

To maximise statistical power, the EPDS data were treated as a continuous variable. We used a mixed-effect linear model, adjusted for visit time, baseline EPDS score, the interaction of visit time and baseline EPDS score, and recruitment centre, and presented the estimated difference in score at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months’ follow-up for the PA group compared with the control group. This model allows for correlation between the repeated measurements at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months. In a final linear mixed-effect model, analysis was further adjusted for the following potential predictors of postnatal depression: marital status, age at leaving full-time education (as a proxy for socioeconomic status), body mass index (BMI) and young age (i.e. age ≤ 20 years). At the end of pregnancy, as some of the women provided EPDS data before the birth and some after the birth, we used t-tests to explore whether or not EPDS scores were similar at these two times.

Maternal weight outcome

First, we compared the subsample providing maternal weight at the end of pregnancy (n = 271) with the main LEAP trial sample (n = 785) for baseline characteristics and key end-of-pregnancy outcomes that might be associated with weight gain (i.e. quit rates, PA levels and depression scores). As we are conducting separate analyses for those providing an end of pregnancy weight before the birth (GWG) and those providing an end of pregnancy weight after the birth (postnatal weight retention), we performed the latter comparison separately for the subsamples before and after birth. Second, in the combined sample at the end of pregnancy and in the subsamples providing an end of pregnancy weight before and after delivery we compared baseline characteristics between the two randomisation groups. Subsequent analysis adjusted for any baseline differences between groups that might affect weight.

For all analyses the main outcome was the mean change in maternal weight (i.e. weight in early pregnancy minus weight at the end of pregnancy), computed separately for the subsamples providing an end of pregnancy weight before and after birth. Weight change was first compared between the two randomisation groups using linear regression analyses, with adjustment for baseline weight and recruitment centre. All of the regression analyses were then further adjusted for the following potential prognostic factors for weight change during pregnancy: age and number of previous pregnancies. In a sensitivity analysis we further adjusted the results for baby’s weight, which is important because women who quit may have bigger babies than those who do not quit, and continuous rate of smoking abstinence at the end of pregnancy. For the subsamples providing an end of pregnancy weight before and after birth, the sensitivity analyses were limited to 140 and 131 participants, respectively, because of missing data for baby’s weight and because three sets of twins were excluded.

For the subsample with GWG (i.e. weight measured before birth) it is important to consider that women will have delivered at different weeks of pregnancy; therefore, besides using the change in the crude measure of weight, we computed the change in mean kilograms per gestational week. This was calculated by dividing the total weight gain by the number of weeks of pregnancy. The regression models used for crude weight change were then repeated using weight change adjusted for gestational weeks as the dependent variable. To assess whether or not weight change is modified by the presence of obesity at baseline we also added an interaction between the effect of PA and whether or not the individual was obese at baseline. Weight at early pregnancy was not added to this model because of its colinearity with the assessment of whether individuals were obese or non-obese.

Next, using Institute of Medicine guidance,88 we investigated what proportion of women gained excessive gestational weight (coded ‘yes’ or ‘no’) relative to their early pregnancy BMI. A woman was considered to have gained excessive gestational weight if she was underweight according to her early pregnancy BMI and her GWG was > 18 kg, her weight was healthy and her GWG was > 16 kg, she was overweight and her GWG was > 11.5 kg or she was obese and her GWG was > 9 kg. We used logistic regression analyses to compute ORs of excessive GWG for each BMI category and for the randomised groups. In the final logistic regression model, the results were adjusted for all prognostic factors that were used in the above main analyses, except weight at early pregnancy.

Ethics and governance

An independent Trial Steering Committee met once or twice per year to monitor the conduct and progress of the trial and to address any safety issues. London Wandsworth Research Ethics Committee granted national research ethical approval (reference number 08/H0803/177), with additional local approvals for each recruitment centre.

Trial management

The trial was co-ordinated from a central trial office located within St George’s, University of London (SGUL), with the day-to-day running supervised and organised by the trial manager and administrator. The trial was sponsored by SGUL and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. 89 The chief investigator/trial manager and administrator received Good Clinical Practice training. Monthly research staff meetings were held at SGUL. There were no stopping rules or plans for interim analysis.

The NCTU provided a web-based database and randomisation system and data management reports. The system was held on a secure server in the NCTU, had a full electronic audit trail and full back-ups of the database were made every 24 hours. All of the outcome data were entered directly into the online forms by the participants or researchers. The database included validation checks whereby responses not meeting expected criteria would be flagged so that data entry errors were minimised.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Primary Care Research Network adopted the study. For public and patient involvement in the study see Appendix 8.

The protocol49 has been published and includes a description of approved amendments made to the original protocol after the start of recruitment; details of these amendments are given in the following section.

Protocol amendments

-

For the follow-up at the end of pregnancy, the valid period for assessment was originally defined as from 38 weeks’ gestation to 2 weeks after the birth. As there were a number of women who could not be contacted during this time frame, the valid period was extended to 36 weeks’ gestation to 4 weeks after the birth (approved by the research ethics committee on 18 May 2010). However, because there were still some women being followed up later than 4 weeks after the birth, the valid period was further revised to 36 weeks’ gestation to 10 weeks after the birth (approved 31 January 2012). The aim remained to attempt to follow up as many women as possible within 2 weeks of the birth.

-

To provide the women with an incentive to complete the follow-ups at the end of pregnancy and 6 months postnatally, all women who completed these follow-ups were given a £10 shopping voucher for each of the follow-up sessions attended (approved 18 May 2010).

-

Originally, to be eligible women had to report smoking at least 10 cigarettes a day before their pregnancy. We found that a good number of women reported smoking five to nine cigarettes a day at this time. Therefore, we extended the eligibility criteria to include women smoking at least five cigarettes a day before pregnancy (approved 15 September 2010). These women are still likely to be dependent on smoking as there is evidence that women who say they were smoking five to nine cigarettes before pregnancy are back to smoking 14 cigarettes a day at 18 months postnatally. 90

-

Initially, women had to be between 12 and 24 weeks’ gestation to be eligible for the trial. However, after the trial started most of the hospital trusts began offering earlier antenatal booking appointments (before 12 weeks’ gestation) and, because we wished to recruit women as early as possible in pregnancy, we revised this eligibility criterion to 10–24 weeks’ gestation (approved 31 January 2012).

-

‘Partner’s smoking status’ was adjusted for in the final model for all of the outcomes related to smoking abstinence; this amendment was approved after publication of the protocol.

Trial extension

The NIHR agreed a 12-month time extension to the trial. This was necessary as the rate of recruitment had been slower than anticipated and several additional recruitment sites had been established. Through careful budgeting, mostly as a result of the researchers working fewer hours and the chief investigator taking the role of trial manager, the majority of this extension was funded within the original budget. An addition to the budget was awarded to extend the contract of the trial administrator.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment of participants

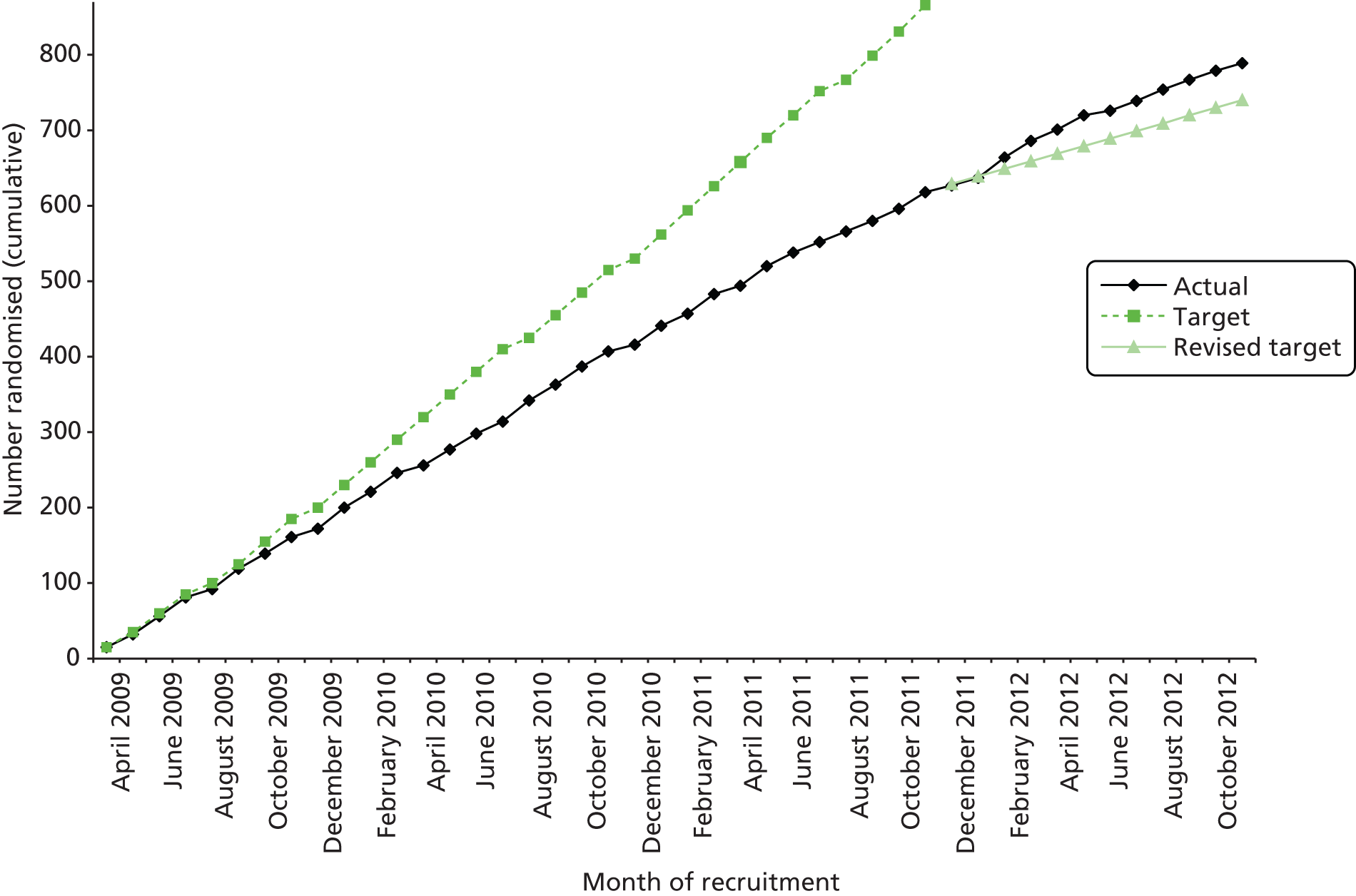

Recruitment took place between April 2009 and November 2012. Follow-up at 6 months after birth continued until January 2014. Figure 1 shows accrual for the original recruitment target of 866 participants, the revised target of 774 participants [agreed with the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme following approval of the trial extension] and the 789 participants who were actually randomised. Four women were excluded post randomisation. Two women (PA group) were enrolled twice in sequential pregnancies and their second enrolment was removed. The other two women (control group) were excluded because they were found to be ineligible at their baseline visit before any data were collected and had been randomised erroneously. When ineligible participants are mistakenly randomised into a trial it is acceptable, within an ITT approach, to exclude their data without risking bias. 91 Table 4 shows the recruitment numbers for each centre for the final sample size of 785 participants included in the analysis. As shown in Table 5, over two-thirds of participants were recruited through midwife referral and over one-quarter through direct calling, through extracting contact information from the PAS. Fewer than 4% of participants were recruited using the other methods combined.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative trial recruitment.

| Centre | PA group (n = 392), n | Control group (n = 393), n | Total (N = 785), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust (St George’s Hospital) | 44 | 44 | 88 (11.2) |

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Chelsea and Westminster Hospital) | 26 | 25 | 51 (6.5) |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital) | 78 | 76 | 154 (19.6) |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (St Mary’s Hospital) | 52 | 51 | 103 (13.1) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (St Thomas’ Hospital) | 21 | 22 | 43 (5.5) |

| Croydon Health Services NHS Trust (Croydon University Hospital) | 38 | 37 | 75 (9.6) |

| Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Kingston Hospital) | 40 | 41 | 81 (10.3) |

| Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust (Epsom Hospital) | 47 | 46 | 93 (11.8) |

| Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust (Crawley Hospital) | 20 | 20 | 40 (5.1) |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (King’s College Hospital) | 5 | 5 | 10 (1.3) |

| Medway Foundation Trust (Medway Maritime Hospital) | 6 | 7 | 13 (1.7) |

| West Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust (West Middlesex Hospital) | 8 | 10 | 18 (2.3) |

| Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Leighton Hospital) | 7 | 9 | 16 (2.0) |

| Recruitment method | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Midwife referral | 69.3 | 544 |

| Direct calling after consulting the PAS | 27.1 | 213 |

| Flyer/poster | 1.3 | 10 |

| Ultrasound questionnaire | 1.4 | 11 |

| Referral from PCT or other health professional | 0.9 | 7 |

| Total | 100 | 785 |

The CONSORT diagram (Figure 2) shows the flow of participants through the study to the primary end point at the end of pregnancy. Around 8100 women were recorded as smokers in the PAS. Of these, approximately one-quarter were uncontactable, just over one-quarter said that they were not interested in participating and just under one-third did not meet the inclusion criteria. A breakdown of the reasons for excluding participants is presented in Table 6. The main reason for exclusion was ‘reports smoking less than one cigarette a day’. Overall, of the 8096 women recorded as smokers at their first antenatal visit, 9.7% (785) were included in the ITT analysis. Of 785 pregnancies, 774 were singleton pregnancies, 10 were twin pregnancies and one was unknown as the woman withdrew consent.

FIGURE 2.

Numbers of participants who were enrolled in the study and included in the primary analysis. The participants lost to follow-up included some who had fetal or infant loss and were not assessed for smoking status.

| Reason for exclusion | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Reports smoking less than one cigarette a day now | 27.5 | 710 |

| Gestation > 24 weeks | 26.1 | 673 |

| Gestation < 10 weeks | 8.0 | 207 |

| Unable to attend all visits | 13.9 | 359 |

| Wants to use NRT from commencing quit attempt | 11.2 | 290 |

| Poor English | 5.8 | 149 |

| Drug or alcohol problem | 3.1 | 80 |

| Reports smoking < 10 cigarettes a day before pregnancy | 2.1 | 53 |

| Medical contraindication to exercise | 1.2 | 31 |

| Age < 16 years | 0.7 | 17 |

| Unable to walk for 15 minutes | 0.5 | 13 |

| No permission to contact GP/obstetrician | 0.04 | 1 |

| Total | 100 | 2583 |

Baseline characteristics

Participants in the two groups had similar baseline characteristics (Table 7). Women were recruited to the trial at a mean gestational age of 16 weeks and on average they were 27 years of age. Over half (53.6%) were smoking at least 10 cigarettes a day. By self-report, 70% were achieving the recommendation of 150 minutes a week of MVPA. 27,28

| Characteristic | PA group (n = 391a), n (%) | Control group (n = 393), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 27.2 (6.1) | 27.8 (6.5) |

| Age at leaving full-time education (years), mean (SD)b | 17.8 (3.0) | 18.0 (3.3) |

| Maternal weight at first antenatal booking appointment (kg), mean (SD)c | 68.3 (14.4) | 70.4 (15.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD)c | 25.6 (5.0) | 26.6 (5.6) |

| Gestational age (weeks), mean (SD) | 15.6 (3.3) | 15.6 (3.3) |

| Number of cigarettes smoked daily before pregnancy, median (IQR) | 20 (12–20) | 20 (12–20) |

| Number of cigarettes smoked daily at randomisation, median (IQR) | 10 (5–12) | 10 (5–15) |

| FTCD score, median (IQR)d | 4 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) |

| Expired CO level (p.p.m.), median (IQR)e | 10 (7–14) | 10 (6–14) |

| Self-report of weekly MVPA (minutes), median (IQR) | 210 (125–350) | 225 (130–360) |

| Married or living with partner | 230 (58.8) | 221 (56.2) |

| Women with partner who smokesf | 261 (66.8) | 250 (63.6) |

| Caucasiang | 308 (78.8) | 298 (75.8) |

| Professional/managerial occupation | 46 (11.8) | 53 (13.5) |

| Smoked in a previous pregnancyh | 186 (78.2) | 193 (77.5) |

| EPDS score of ≥ 13 | 68 (17.4) | 75 (19.1) |

| Self-report of > 150 minutes per week of MVPA | 275 (70.3) | 273 (69.5) |

| Self-report walking as main type of PA | 301 (77.0) | 313 (79.6) |

| Parityi | ||

| 0–1 | 317 (81.1) | 309 (78.6) |

| 2–3 | 67 (17.1) | 75 (19.1) |

| ≥ 4 | 7 (1.8) | 9 (2.3) |

| Previous preterm birthj | 68 (17.4) | 61 (15.5) |

| Very or extremely high confidence for quitting smoking | 89 (22.8) | 98 (24.9) |

| Very or extremely confident of doing 30 minutes of PA on at least 5 days a week during pregnancy | 274 (70.1) | 277 (70.5) |

| Drinks alcohol more than twice a week | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) |

| Consumes more than three alcoholic drinks on a drinking dayk | 14 (15.9) | 3 (3.8) |

Follow-up rates

At 4 weeks after the quit day, 316 (80.6%) women were successfully followed up in the PA group and 319 (81.2%) in the control group. At the end of pregnancy follow-up, 587 (74.8%) women were assessed before the birth and 198 (25.2%) were assessed after the birth. The overall follow-up rate for the primary outcome at the end of pregnancy (see Figure 2) was 88.8% (697 participants) and there was no evidence of a significant difference in the follow-up rate between study groups. Of the 88 participants (11.2%) who did not complete the assessments necessary for analysis of the primary outcome, 43 (48.9%) were known to have smoked from the follow-up assessments (PA group n = 19, control n = 24). In addition, of the remaining 45 participants (5.7% of total), 24 had a fetal or infant death and were not asked about smoking status, and one individual withdrew consent; all were assumed to be smoking at the end of pregnancy.

Rates of biochemical validation of smoking status

For the majority of participants who reported that they were not smoking, biochemical validation was obtained. At the end of pregnancy, validation rates for smoking status were 71.4% (30/42) in the PA group and 56.8% (25/44) in the control group (p = 0.158); at 4 weeks, the rates were 98.0% (50/51) and 100.0% (61/61) respectively (p = 0.272).

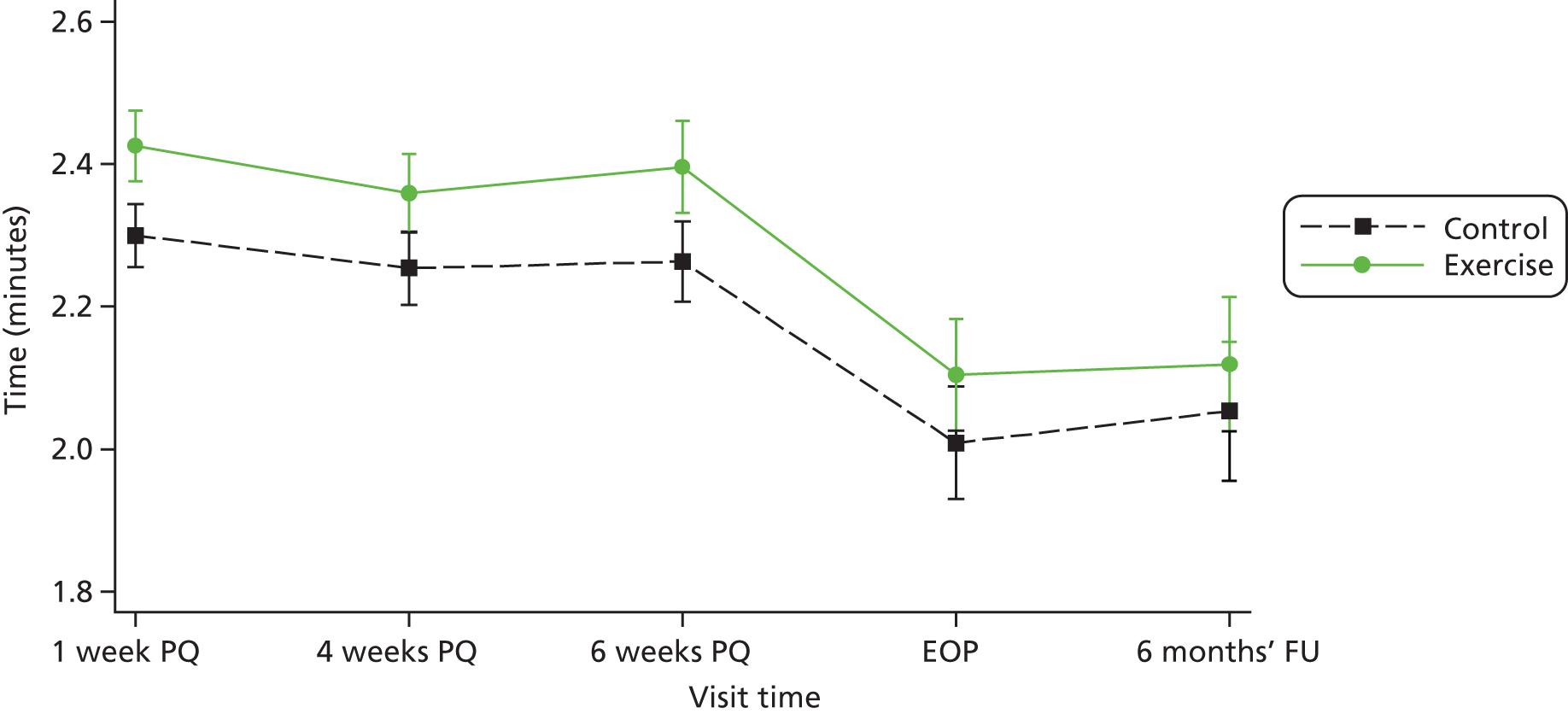

Attendance at treatment sessions and compliance with the physical activity intervention

Participants attended a median of four of 14 treatment sessions in the PA group and three of six in the control group (Table 8). For the PA group compared with the control group, there was a 33% (95% CI 14% to 56%), 28% (95% CI 7% to 52%) and 36% (95% CI 12% to 65%) significantly greater increase in self-reported minutes of MVPA from baseline to 1 week, 4 weeks and 6 weeks respectively (see Table 8 and Figure 3). There was a decrease in self-reported minutes of PA at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months relative to baseline for both groups.

| Variable | PA group | Control group | Relative change in PA (95% CI): mixed-effect model for the log of PA | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported weekly minutes of MVPA, n, median (IQR) | ||||

| Baseline | 391, 210 (125–350) | 393, 225 (130–360) | ||

| 1 week post quit | 162, 280 (190–425) | 206, 240 (140–420) | 1.33 (1.14 to 1.56) | < 0.001 |

| 4 weeks post quit | 135, 270 (180–420) | 157, 210 (120–340) | 1.28 (1.07 to 1.52) | 0.006 |

| 6 weeks post quit | 90, 277 (180–400) | 121, 220 (130–350) | 1.36 (1.12 to 1.65) | 0.002 |

| End of pregnancy | 188, 155 (100–240) | 187, 140 (60–240) | 1.25 (0.96 to 1.61) | 0.093 |

| 6-month follow-up | 147, 180 (80–330) | 136, 135 (60–285) | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.59) | 0.339 |

| Number of treatment sessions attended, n, median (IQR) | 391, 4 (2–8)a | 393, 3 (2–6) | NA | |

| Time walked on treadmill during supervised exercise (minutes), n, mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 390, 12.2 (7.5) | NA | NA | |

| 1 week post quit | 163, 19.0 (8.5) | |||

| 4 weeks post quit | 134, 15.2 (10.8) | |||

| 6 weeks post quit | 90, 17.7 (10.9) | |||

FIGURE 3.

Comparisona of predicted self-reported levels of MVPA on a log-scale in the trial groups at different time points (bars represent CIs). EOP, end of pregnancy, FU, follow-up; PQ, post quit. a, Prediction on log scale from the mixed-effect model.

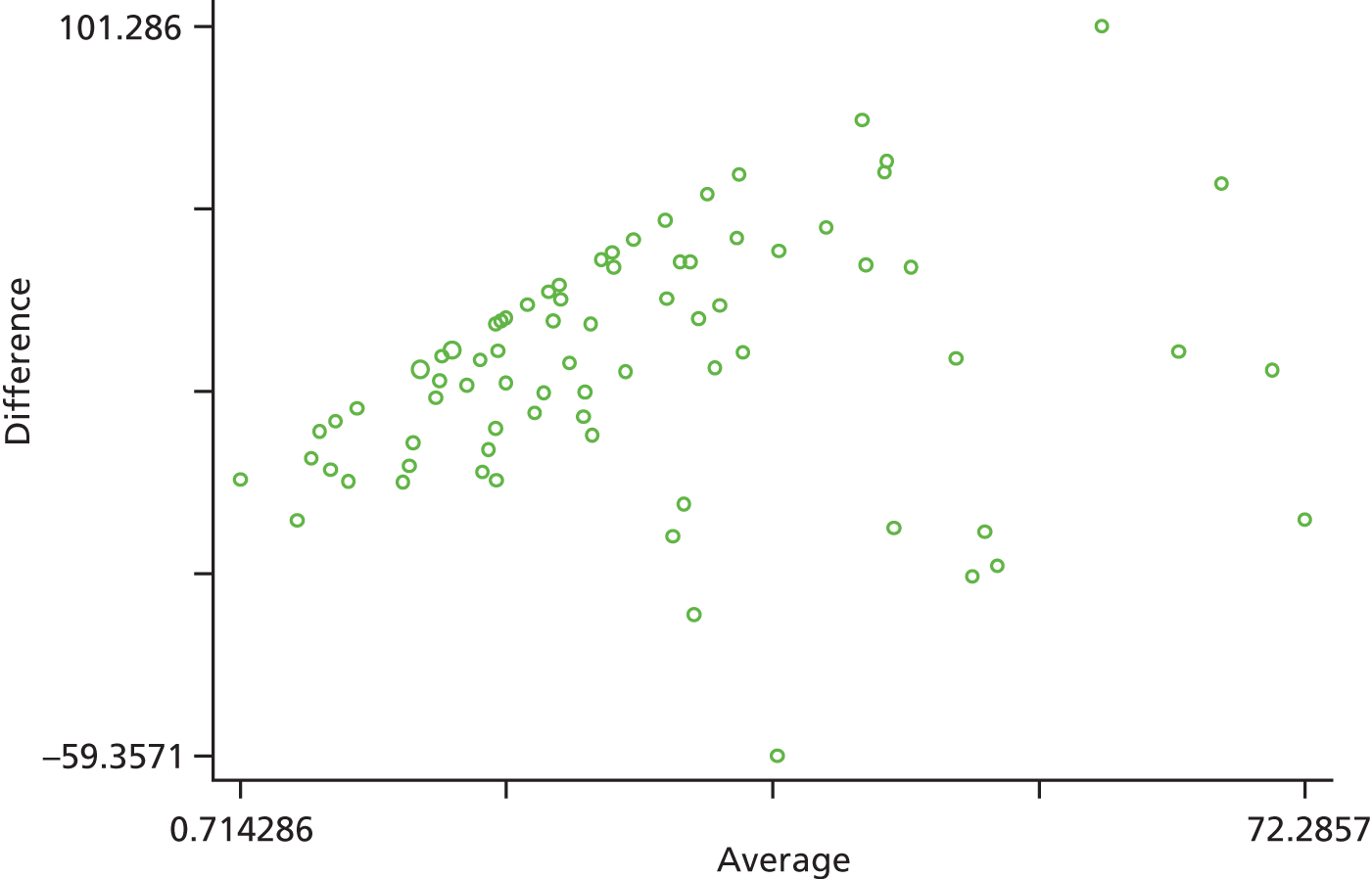

Of 90 participants asked to wear an accelerometer, 78 (86.7%) provided valid data (n = 37 PA group), 10 provided insufficient data and two were technical failures. Participants providing accelerometer data had similar baseline characteristics to those in the total sample. The majority (72%) had valid accelerometer data for at least 4 days. During the week of accelerometer wear, the median number of minutes of MVPA per day by self-report and according to accelerometer data was 38.2 [interquartile range (IQR) 25.4–54.5] and 7.8 (IQR 0–16.5) respectively. In total, 87% of participants self-reported higher levels of MVPA compared with the accelerometer data. Self-reports of minutes of MVPA per day were not significantly correlated with the accelerometer data (Spearman’s rho = 0.133, p = 0.247). Consistent with the correlation, using a Bland–Altman plot the mean difference between the self-report data and the accelerometer data for MVPA was 26.85 (95% CI 20.81 to 32.88) minutes (Figure 4). The median number of minutes of MVPA according to accelerometer data, when including only bouts of at least 10 minutes, was very similar for the PA group [7.5 (IQR 0–15.5)] and the control group [8.0 (IQR 0–16.2)] (p = 0.816). When including all MVPA, irrespective of duration, median activity levels per day tended to be higher for the PA group [38.00 (IQR 20.00–52.60)] than the control group [31.17 (IQR 19.00–44.10)], although this difference did not reach significance (p = 0.538).

FIGURE 4.

Bland–Altman plot of the difference between self-reported MVPA and accelerometer data for MVPA against the average of these measures (n = 78) showing the distribution of differences and how they relate to the average. Limits of agreement (reference range for difference) –26.698 to 80.390; range 0.714–72.286.

Only 28 women reported receiving face-to-face behavioural support for smoking cessation besides that offered in the trial and 60 women reported using NRT; the numbers reporting this support were similar in the two groups.

Smoking abstinence and reduction rates

There was no significant difference in smoking abstinence rates or smoking reduction rates between the two groups at follow-up (Table 9). The rate of validated continuous abstinence at the end of pregnancy (primary outcome) was 7.7% in the PA group and 6.4% in the control group (OR for PA group, adjusted for centre only, 1.21, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.10). At 4 weeks the validated abstinence rate was 12.8% in the PA group and 15.5% in the control group (OR, adjusted for centre only, 0.79, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.18). At 6 months postnatally the self-reported abstinence rate was 6.1% in the PA group and 4.1% in the control group (OR, adjusted for centre only, 1.55, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.97). Fully adjusted analyses yielded similar findings (at end of pregnancy: OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.41). The sensitivity analyses showed that the observed effect size and its statistical significance were independent of the influence of missing data for the primary outcome. There was no significant interaction between baseline self-reports of MVPA (< 150 vs. ≥ 150 minutes per week) and the treatment effect for the primary outcome [logistic regression model adjusted for site only: likelihood ratio test (LR chi-squared) = 2.31, p = 0.129; similar results were found for the fully adjusted model].

| Abstinence/reduction outcomesa | PA group (n = 392), n (%) | Control group (n = 393), n (%) | OR (95% CI)b | Adjusted OR (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||||

| Self-reported continuous abstinence at end of pregnancy with biochemical validationd | 30 (7.7) | 25 (6.4) | 1.21 (0.70 to 2.10) | 1.37 (0.78 to 2.41) |

| Secondary | ||||

| Self-reported continuous abstinence at 4 weeks after quit day with biochemical validatione | 50 (12.8) | 61 (15.5) | 0.79 (0.53 to 1.18) | 0.87 (0.57 to 1.31) |

| Self-reported continuous abstinence at 6 months after birth | 24 (6.1) | 16 (4.1) | 1.55 (0.81 to 2.97) | 1.66 (0.82 to 3.37) |

| Self-reported lapse-free abstinence with biochemical validation | ||||

| At 4 weeks after quit day | 17 (4.3) | 16 (4.1) | 0.68 (0.38 to 1.22) | 0.74 (0.41 to 1.34) |

| At end of pregnancy | 20 (5.1) | 29 (7.4) | 1.07 (0.53 to 2.14) | 1.22 (0.60 to 2.48) |

| At 6 months after birth | 10 (2.6) | 10 (2.5) | 1.04 (0.43 to 2.56) | 1.12 (0.45 to 2.78) |

| PA group, n, mean (SD) | Control group, n, mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| Self-reported reduction in no. of cigarettes smoked dailyf | ||||

| Between baseline and 4 weeks after quit day | 67, 4.3 (4.4) | 70, 4.0 (4.7) | 0.23 (–1.22 to 1.73) | 0.27 (–1.16 to 1.65) |

| Between baseline and end of pregnancy | 130, 4.0 (4.7) | 119, 2.9 (5.9) | 1.13 (–0.26 to 2.55) | 1.08 (–0.11 to 2.32) |

| Between baseline and 6 months after birth | 97, 1.4 (4.5) | 100, 1.0 (5.3) | 0.37 (–0.99 to 1.74) | 0.21 (–1.14 to 1.58) |

Withdrawal symptoms and urge to smoke

Tables 10 and 11 show the withdrawal symptom and urge to smoke scores, respectively, at baseline and 1 week post quit. When controlling for baseline score and treatment centre there was no significant group difference in total withdrawal score or urge to smoke score at 1 week post quit. When withdrawal symptoms were examined individually there were still no significant group differences.

| Follow-up | PA group, n, mean (SD) score | Control group, n, mean (SD) score | Linear regression: β (95% CI) for PA group vs. control group; p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Withdrawal symptoms scale total score (range 1–35) | 391, 16.3 (4.9) | 393, 16.4 (4.7) | |

| Symptoms | |||

| Restless | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | |

| Irritable | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.2) | |

| Depressed | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | |

| Hungry | 2.8 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.2) | |

| Poor concentration | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.1) | |

| Poor sleep at night | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | |

| Anxious | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.2) | |

| 1 week post quit | |||

| Withdrawal symptoms scale total score (range 1–35) | 163, 16.0 (4.6) | 206, 16.6 (4.6) | –0.56 (–1.45 to 0.33); 0.256 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Restless | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.1) | |

| Irritable | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.2) | |

| Depressed | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.0) | |

| Hungry | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.2) | |

| Poor concentration | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.1) | |

| Poor sleep at night | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | |

| Anxious | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | |

| Follow-up | PA group, n, mean (SD) score | Control group, n, mean (SD) score | Linear regression: β (95% CI) for PA group vs. control group; p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 391, 6.2 (2.0) | 393, 6.2 (1.9) | |

| 1 week post quit | 163, 5.3 (2.0) | 206, 5.5 (2.0) | –0.23 (–0.62 to 0.16); 0.242 |

Confidence for participating in physical activity and stopping smoking

Tables 12 and 13 present the scores for confidence for participating in PA and for stopping smoking, respectively, at baseline and 1 week post quit. When controlling for baseline score and treatment centre, ratings for confidence for participating in PA were significantly higher at 1 week post quit in the PA group than in the control group. When making the same adjustments, there was no significant group difference in confidence for quitting smoking at 1 week post quit.

| Follow-up | PA group, n, mean (SD) score | Control, n, mean (SD) score | Linear regression: β (95% CI) for PA group vs. control group; p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 391, 3.9 (1.1) | 393, 3.9 (1.0) | |

| 1 week post quit | 163, 3.9 (1.0) | 157, 3.7 (1.0) | 0.30 (0.10 to 0.49); 0.002 |

| Follow-up | PA group, n, mean (SD) score | Control group, n, mean (SD) score | Linear regression: β (95% CI) for PA group vs. control group; p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 391, 3.9 (0.9) | 393, 4.0 (1.0) | |

| 1 week post quit | 163, 4.4 (1.0) | 206, 4.3 (0.9) | 0.15 (–0.03 to 0.33); 0.097 |

Birth outcomes

Table 14 shows outcomes for singleton births. These outcomes were very similar between the two study groups except that there were significantly fewer deliveries by caesarean section in the PA group than in the control group (21.3% vs. 28.7%). Analyses that included twin births gave very similar findings.

| Fetal outcomes (singleton births only) | PA group (n = 384), n/N (%) | Control group (n = 391), n/N (%) | OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miscarriagec | 6/383 (1.6) | 10/389 (2.6) | 0.60 (0.22 to 1.67) |

| Stillbirthc | 2/377 (0.5) | 2/379 (0.5) | 1.01 (0.14 to 7.24) |

| Neonatal deathc | 0 | 1/391 (0.3) | Not calculated |

| Preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestation) | 35/356 (9.8) | 26/348 (7.5) | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.31) |

| Low birthweight (< 2.5 kg) | 38/353 (10.8) | 44/359 (12.3) | 0.87 (0.55 to 1.38) |

| NICU admission | 27/352 (7.7) | 36/356 (10.1) | 0.74 (0.44 to 1.25) |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes < 7 | 8/344 (2.3) | 11/351 (3.1) | 0.74 (0.29 to 1.85) |

| Cord blood arterial pH < 7 | 2/130 (1.5) | 0/125 | Not calculated |

| Congenital abnormalitiesd | 9/346 (2.6) | 6/348 (1.7) | 1.43 (0.50 to 4.12) |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 46/357 (12.9) | 32/359 (8.9) | 1.51 (0.94 to 2.43) |

| Caesarean delivery | 76/357 (21.3) | 103/359 (28.7) | 0.67 (0.48 to 0.95)e |

| PA group (n = 384), mean (SD) | Control group (n = 391), mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI)b | |

| Birthweight (kg) | (n = 354) 3.13 (0.58) | (n = 359) 3.15 (0.64) | –0.01 (−0.11 to 0.08) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | (n = 356) 39.24 (2.1) | (n = 348) 39.26 (2.1) | –0.02 (–0.36 to 0.31) |

Adverse events

There were similar numbers of AEs and SAEs in the two groups (Table 15). The total number of women or their infants who had at least one AE or SAE was 217 (55.4%) in the PA group and 219 (55.7%) in the control group (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.32). The full breakdown of the data for less frequent AEs is provided in Appendix 9.

| Event | PA group (n = 392), n (%) | Control group (n = 393), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SAEs | ||

| Maternal death | 0 | 0 |

| Other eventsb | 12 (3.1) | 13 (3.3) |

| Maternal AEs potentially related to treatmentc | 2 (0.5) | 0 |

| Maternal AEs as probable complications of pregnancy | ||

| Vaginal bleeding or haemorrhage | 37 (9.4) | 35 (8.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 79 (20.2) | 83 (21.1) |

| Infection in pregnancy | 61 (15.6) | 55 (14.0) |

| Premature rupture of membranes at < 37 weeks’ gestation | 19 (4.8) | 16 (4.1) |

| Gestational diabetes | 7 (1.8) | 8 (2.0) |

| Gestational hypertension | 13 (3.3) | 13 (3.3) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 4 (1.0) | 11 (2.8) |

| Other, less frequent eventsd | 105 (26.8) | 114 (29.0) |

| Fetal AEs as probable complications of pregnancy | ||

| Decreased fetal movement | 41 (10.5) | 49 (12.5) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 15 (3.8) | 18 (4.6) |

| Other, less frequent eventsd | 7 (1.8) | 6 (1.5) |

| Neonatal AEs | 15 (3.8) | 14 (3.6) |

| Total AEs | 417 | 435 |

Maternal depression

All 784 participants provided EPDS data at baseline, with 383 (48.9%) and 279 (35.6%) participants providing these data at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months postnatally, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the subsamples used for the EPDS analysis at the two follow-up points were similar to those for the total trial sample. The baseline characteristics of the two trial groups were also similar in the subsamples at the end of pregnancy and at 6 months postnatally.

In both models the EPDS score was significantly higher in the PA group than in the control group at the end of pregnancy (Table 16). At this time there was a mean increase in EPDS score of 0.4 in the PA group and a mean reduction in EPDS score of 0.5 in the control group (mean difference between groups in fully adjusted model 0.95, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.83). When examining the data separately for end of pregnancy outcomes before and after the birth the findings were very similar. There was no significant difference in EPDS score between the groups at 6 months’ follow-up (fully adjusted mean difference 0.37, 95% CI –0.59 to 1.33).

| Follow-up | EPDS score, n, mean (SD) | β (difference between PA and control group, adjusted for baseline EPDS and centre onlyb) (95% CI); p-value | β (difference between PA and control group, fully adjustedc) (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | PA group | |||

| Baseline | 393, 7.7 (5.0) | 391, 7.6 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| End of pregnancy | 194, 7.2 (5.0) | 189, 8.0 (4.9) | 1.06 (0.19 to 1.94); 0.017 | 0.95 (0.08 to 1.83); 0.033 |

| 6 months | 133, 6.6 (4.7) | 146, 6.8 (4.8) | 0.52 (–0.45 to 1.50); 0.293 | 0.37 (–0.59 to 1.33); 0.450 |

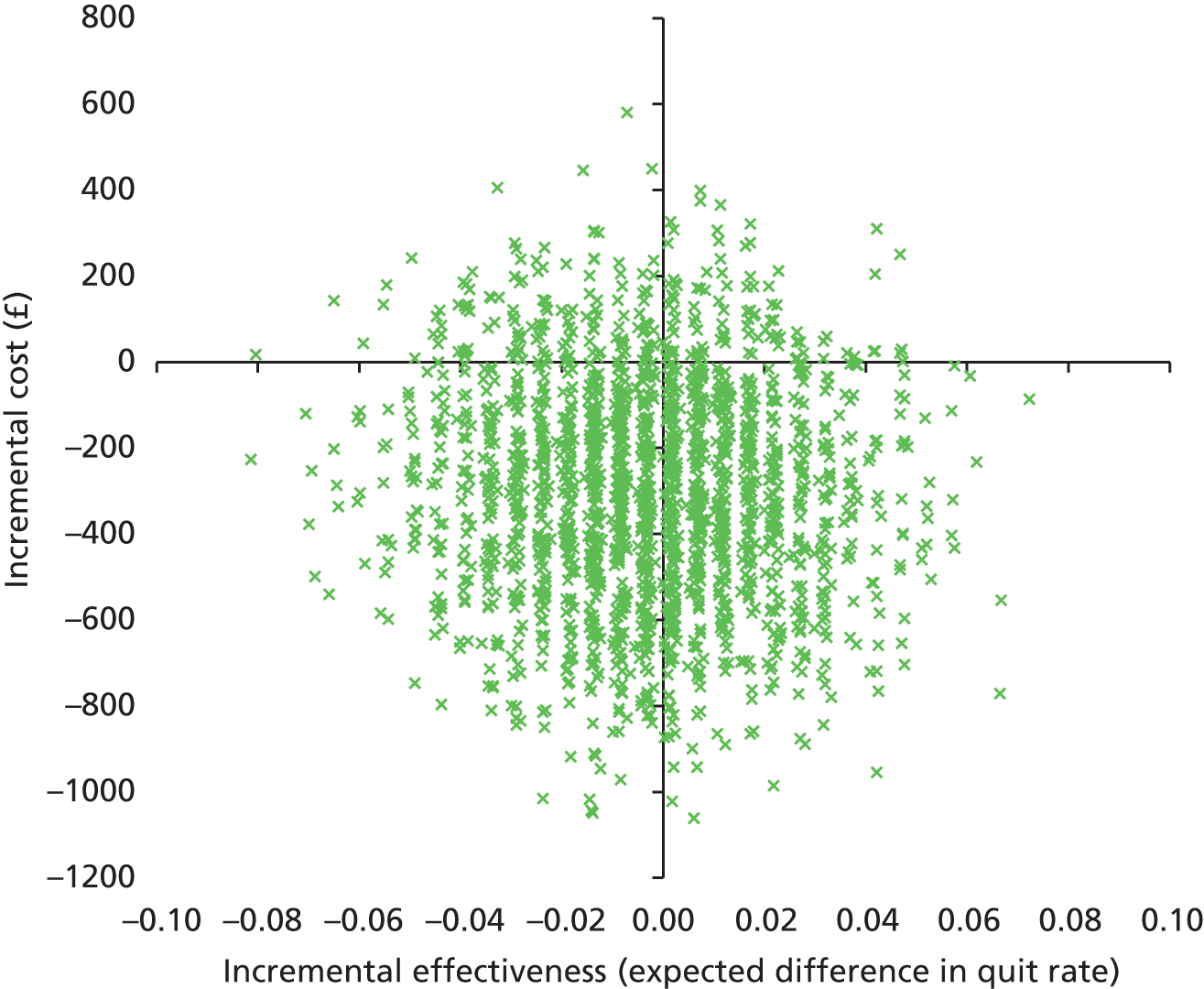

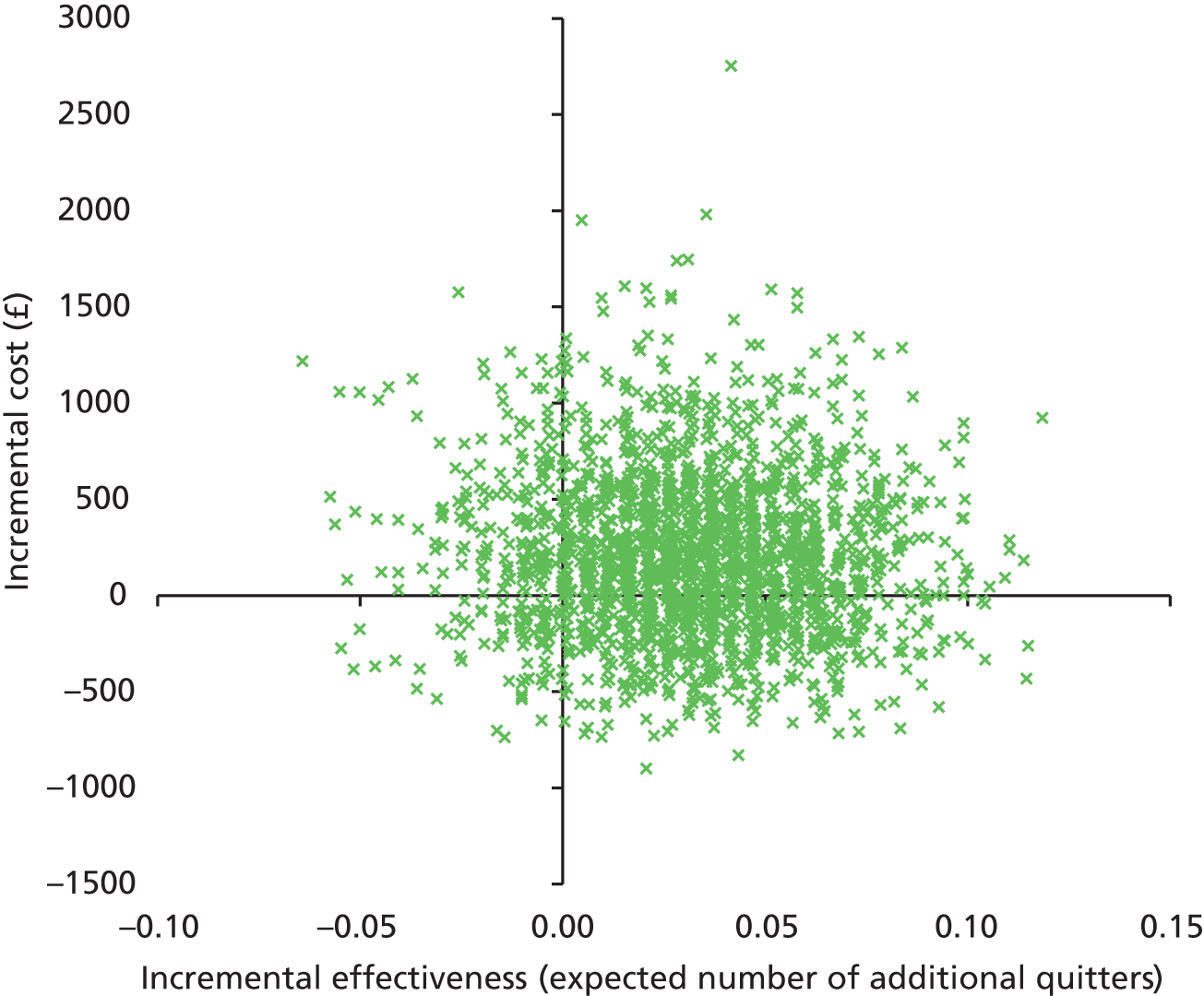

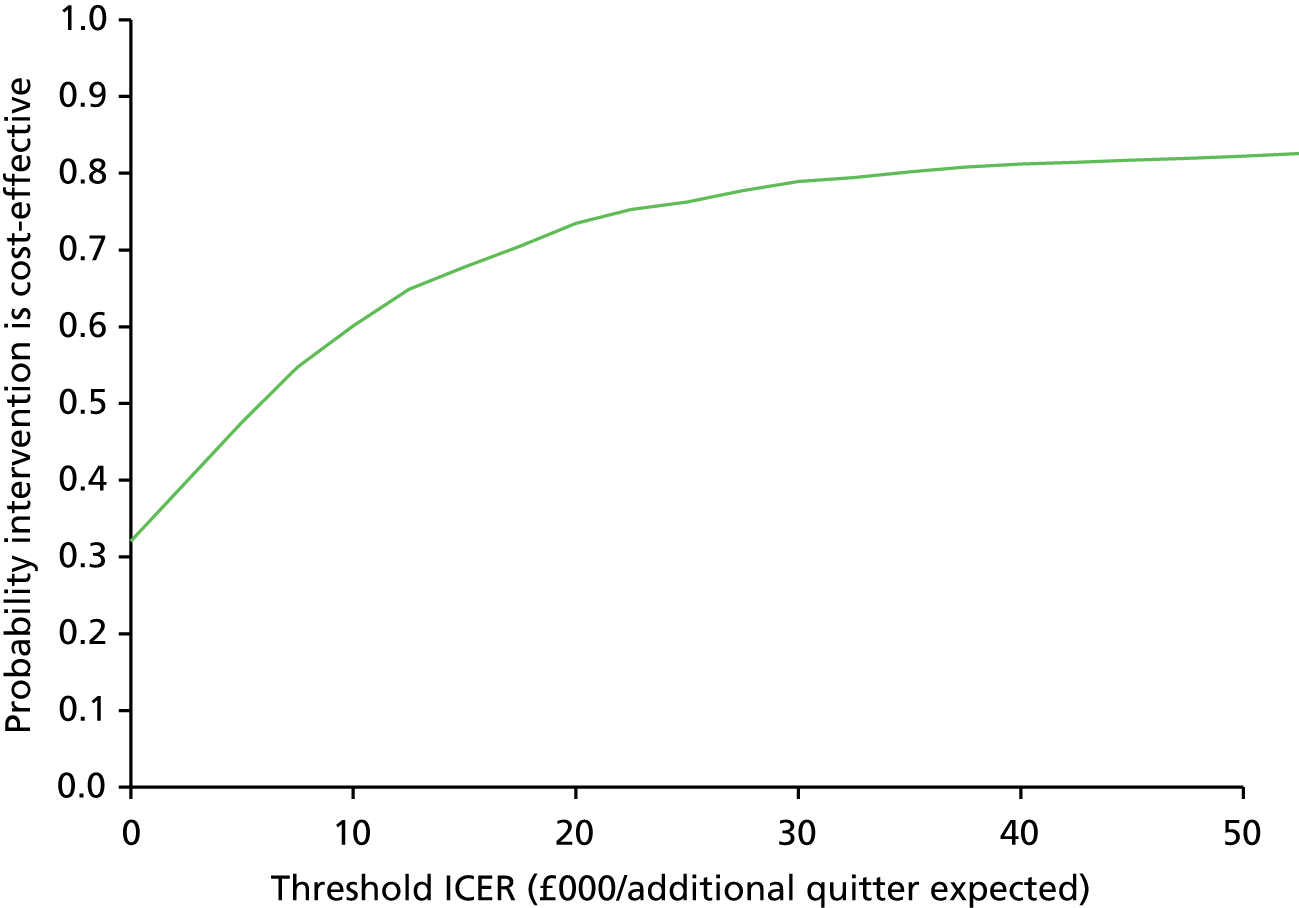

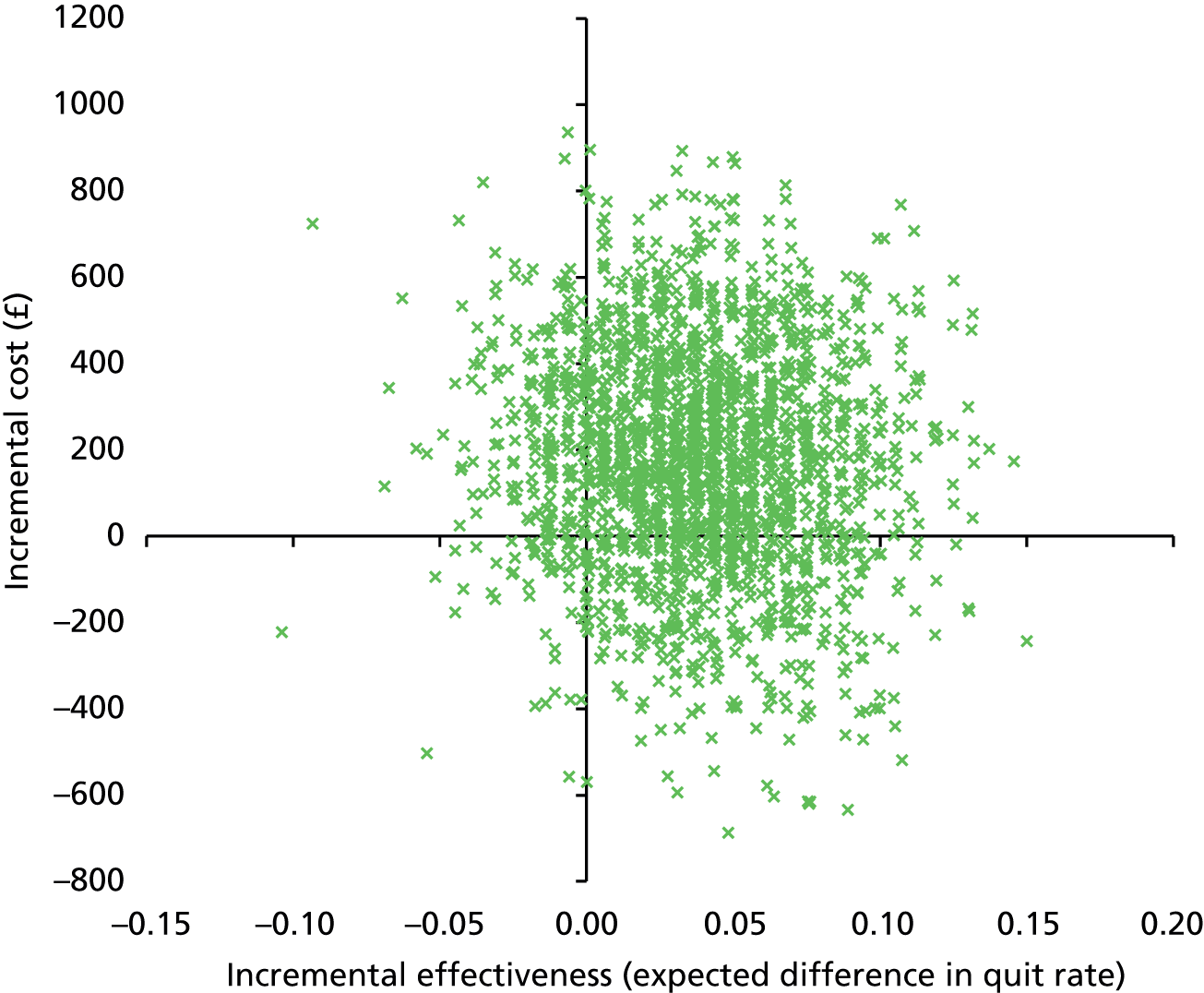

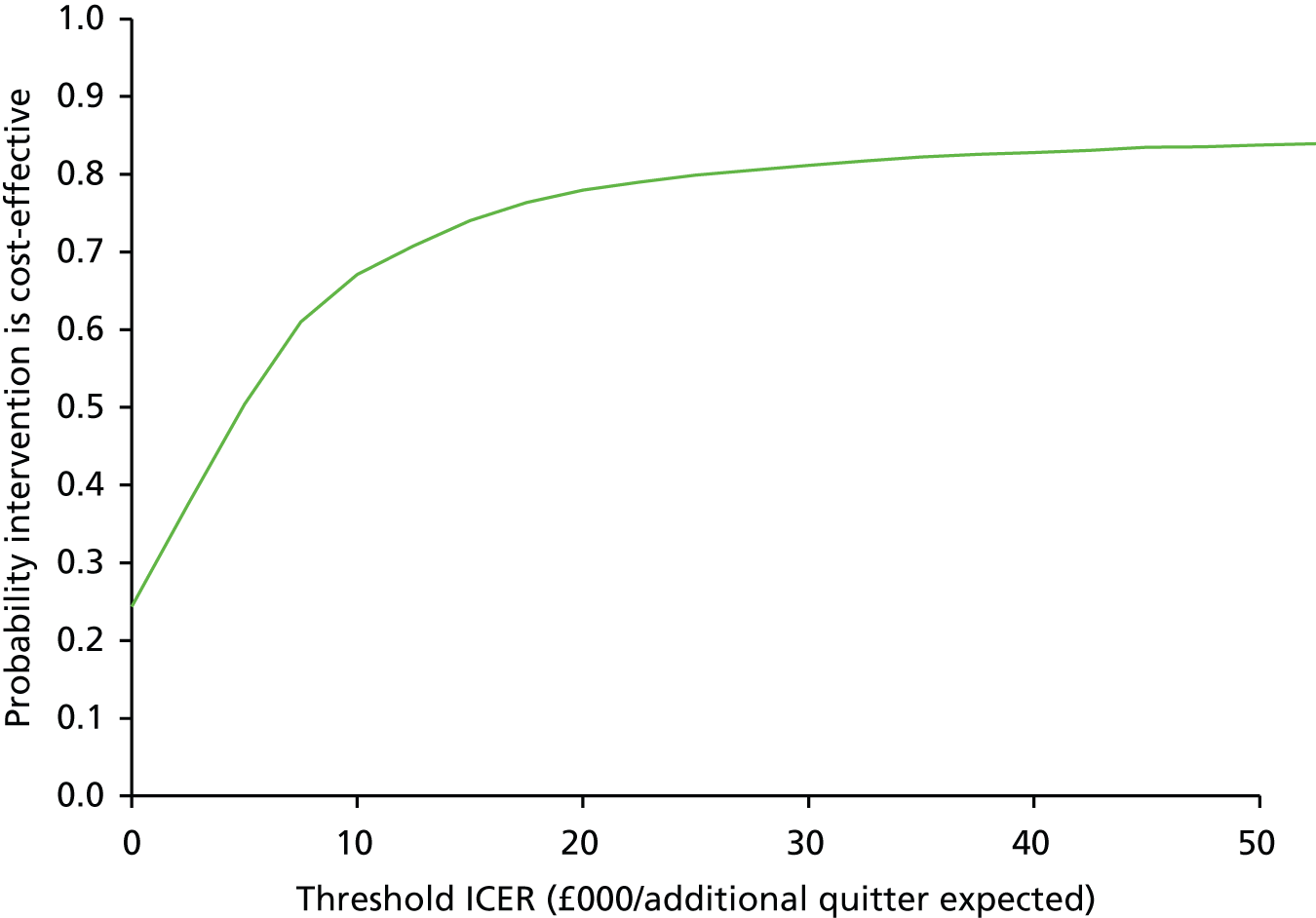

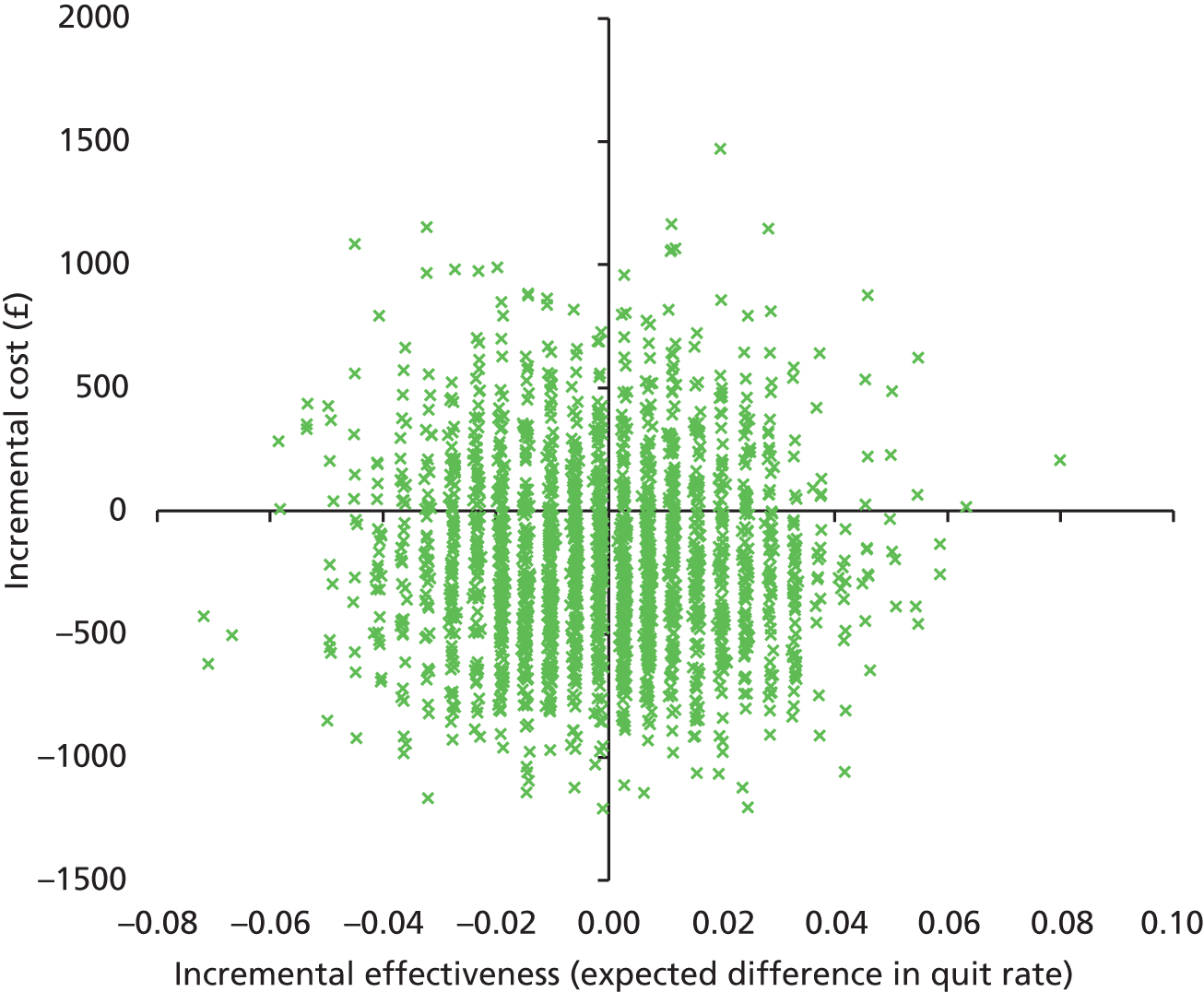

Maternal weight