Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/11/01. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Pickett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the underlying health problem

Chronic inflammatory skin diseases are commonly encountered conditions in dermatology. They include commonly reported conditions, such as eczema, psoriasis and acne, which are associated with skin inflammation. This inflammation can range in severity from mild to severe and, in some patients, can have associated health complications. The focus of this report is on chronic inflammatory skin diseases that have lasted for at least 12 weeks and may have caused significant tissue destruction and, potentially, impacted the individual significantly. Our initial scoping of this project identified a number of conditions that come under the term chronic inflammatory skin diseases; however, only the most commonly studied in educational intervention studies are discussed in the background of this report.

Classification of disease

Dermatologists in the UK use a disease classification based on aetiology and anatomical site which has been developed by the British Association of Dermatologists. 1 This is a very detailed and comprehensive system used to obtain information about skin diseases and, as such, has not been described here. Common types of chronic inflammatory skin conditions include eczema (a general term covering a range of conditions, which may or may not be atopic), psoriasis and acne vulgaris (commonly known as acne). There is also a wide range of other types of skin condition such as rosacea, lichen planus, hidradenitis suppurativa, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, lichen sclerosus and seborroeic dermatitis. The working definitions, causes and epidemiology for the three most common conditions are summarised below.

Eczema

Eczema (of which atopic dermatitis eczema is the most common type) is a common skin condition that presents as red, dry, itchy skin, often on the elbow, knee or face, but sometimes all over the body. 2,3 Often associated with atopy (a predisposition to developing hypersensitivity reactions), the predominant symptom is itching. 4 In some people, the skin can weep or blister and become thickened. In the chronic form of the condition there can also be altered skin pigmentation and exaggerated surface markings. 2 Eczema can start at any age, but is most common in children. It is considered to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. 2 Concurrent illness and psychological factors such as stress can also function as a trigger. 5 For the purpose of this report, we refer to the general term ‘eczema’ unless an individual study specifies that the condition is atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a skin disease that is typically characterised by pink or red lesions which are covered with scales. 6 These lesions are well delineated and can vary in extent and shape, and the severity of psoriasis typically follows a relapsing and remitting course. 6,7 The most common form, plaque psoriasis, occurs in approximately 90% of people with the condition. Other types include guttate psoriasis and pustular forms. 7 The cause of psoriasis is thought to be a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors, with the immune system having an important role in the disease process. 8

Acne vulgaris

Acne vulgaris (commonly known as acne) is a common inflammatory skin disease, which usually starts during puberty. It is characterised by a combination of comedones (blackheads and whiteheads), papules, pustules, nodules and scarring. 9 Genetic and hormonal causes are some of the key factors that trigger the condition. 10

Epidemiology

Scholfied and colleagues1 undertook a health-care needs assessment in 2009 and reported that 55% of the overall population in the UK have had some form of skin disease, and that in previous studies 23–33% of people have had a skin problem that could benefit from medical care (i.e. a moderate or severe condition). This section presents a brief overview of the incidence and prevalence across the different inflammatory skin conditions discussed above.

Eczema

A recent review noted that, although there are several studies considering the epidemiology of atopic eczema in children, a wide range of prevalence estimates are available given differences in study populations, the definitions used and the survey methods applied. 5 It is generally estimated that atopic eczema affects one in every five children in the UK at some stage3 and it is the most commonly diagnosed dermatological disorder in children and adolescents. 11 The prevalence of atopic eczema appears to be increasing, although the reasons for this are unclear. 2,5

A recent guideline5 reported an increasing trend in point prevalence of the skin disease in the 1990s and early 2000s. Numerous studies, mostly of low-level evidence, were reviewed. In this overview, we have focused on those from the UK where available. The point prevalence rates differed between the studies; in five UK-based studies, the guideline reports that this ranged from 5.9% in 3- to 11-year olds to 14.2% in 4-year olds. Trends in point prevalence for those who had ever had eczema increased. 5

One-year period prevalence was reported in two studies; this was reported as 11.5% in 3- to 11-year olds12 and 16.5% in 1- to 5-year olds. 13 In a birth cohort study that followed children until the age of 10 years, it was reported that the period prevalence of atopic eczema was 9.6% at 1 year of age, which increased up to 10.3% at 2 years of age; 11.9% at 4 years and 14.3% at 10 years. 14 In one UK study, period prevalence rates were also reported; these were highest, at 25.6%, for children aged 6–18 months, followed by those aged 18–23 months at 23.2%, those aged between 0–6 months at 21%, and those aged 30–42 months at 19.9%. 5,15

The prevalence of atopic eczema varies across the world. A recent systematic review of incidence and prevalence studies published between 1990 and 2010 included 69 studies. Evidence suggested that the prevalence is increasing in many regions of the world, including the UK. 16

In one UK study reviewed in the recent guideline, the incidence of atopic eczema in children aged up to 2.5 years born in 1991 and 1992 was found to be highest at 21% during the first 6 months of life, declining to 11.2% by the age of 6–18 months, and to 3.8% by the age of 30 months. 15 In another birth cohort study set up in 1982–4 to monitor the natural history of allergic diseases for 23 years, eczema usually remitted between 1 and 7 years of age; the prevalence of eczema was more likely to persist if a child was atopic, especially in girls. 4

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is estimated to affect around 1.3–2.2% of the population in the UK. It occurs equally in men and women, at any age, although it is uncommon in children, and can persist for up to 50 years. 6,7,17

Gelfand and colleagues18 estimated the overall prevalence of psoriasis in the UK from 1987 to 2002 to be 1.5%, with the prevalence increasing more rapidly in young female patients compared with their male counterparts. As the population ages, the prevalence is similar between sexes. Furthermore, the prevalence declines significantly in people aged 70 years and above, regardless of sex. In studies reviewed in a recent systematic review,17 similar trends were noted. Another study by Seminara and colleagues19 showed an overall prevalence of 1.9% based on the electronic records of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database, which contained medical records of around 4.6% of the UK’s total population. The database presented prevalence data based on age groups and sex. Females had a slightly higher prevalence rate compared with males (1.9% vs. 1.8%). 19 Table 1 presents the UK-based prevalence rates reported by Gelfand and colleagues18 and Seminara and colleagues. 19

| GPRD by age group and sex (1987–2002) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence/10,000 | Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| 0–9 | 10–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | ≥ 90 | Total | |

| Male | 48.6 | 118.6 | 149.1 | 186.6 | 219.1 | 232.3 | 226.3 | 168.4 | 89.6 | 46.4 | 152.7 |

| Female | 61.8 | 154.8 | 152.6 | 169.8 | 187.9 | 213.7 | 225.7 | 156.6 | 87.9 | 47.6 | 151.4 |

| Total | 55.0 | 137.4 | 151.0 | 178.0 | 203.4 | 222.8 | 226.0 | 161.4 | 88.4 | 47.3 | 152.0 |

| THIN database by age19 | |||||||||||

| Prevalence (%) | Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| < 10 | 10–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | > 90 | ||

| 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 1.4 | ||

Recent estimates from a 2013 systematic review of global epidemiology of psoriasis17 found that the UK had a prevalence of between 1% and 3% (three studies) in adults. The review authors state that these rates were lower than estimates from other countries. 17 No UK-specific studies were identified in children, but the European prevalence rates were reported to be up to 0.71%. 17 A recent Norwegian population-based cohort study, following patients for 30 years, showed that the self-reported lifetime prevalence rose from 4.8% in 1979–80 to 11.4% in 2007–8. 20

No studies on the UK incidence of psoriasis specifically in children or adults were identified in the 2013 systematic review. 17 One UK study was identified that reported the combined incidence in all ages. The reported incidence rate was 140/100,000 person years. 21 A retrospective cohort study from the UK conducted in 2008 has since reported results that indicate an incidence of psoriasis in adults of 28/100,000 person years. 22

Acne

Epidemiological studies of acne show broad ranges of incidence and prevalence. 23 Acne affects up to 80% of people at some point in their lives, predominantly between the ages of 15 and 17 years. 24 Chronic acne can persist, however, into adulthood,24 and approximately 14% of people with acne are thought to consult their general practitioner (GP) (3.5 million visits annually). 9 A study suggests that this condition is prevalent in up to 50% of 14- to 16-year-olds in a community sample, and up to 30% of these teenagers had acne of sufficient severity to require medical treatment. 25 The prevalence of moderate-to-severe acne is likely to increase with age during puberty. 23 The incidence of the condition is similar in both men and women, with the numbers peaking in adults up to 25 years of age. 25

Other conditions

Other chronic inflammatory skin conditions include rosacea, lichen planus, hidradenitis suppurativa, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, lichen sclerosus and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Rosacea may affect up to 1 in 10 people; however, epidemiological data are scarce and controversial. The reported prevalence rates have ranged from 0.09% to 22% in the UK. 26 Lichen planus is reported to affect 1–2% of the population. Although the condition can occur at any age, it typically arises in females of middle age. A study reported that the condition primarily occurred in women aged over 45 years, with an annual incidence of 27/100,000 people in 2003. Hidradenitis suppurativa may have a prevalence of approximately 1% in the UK and is more prevalent in females than males. 27 Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is an uncommon autoimmune disorder, which has a variety of types. Those most commonly affected are women aged 20 to 50 years, although children, the elderly and males may also be affected. 28 Lichen sclerosus is a lymphocyte-mediated dermatosis that occurs in the genital skin and affects both sexes. The incidence is thought to be higher in females (peak ages of presentation are in prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women) than males. 29 Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common form of dermatitis affecting areas rich in sebaceous glands such as the face, scalp and centre of the chest. 30 It is thought to affect between 3% and 5% of the global population and is more common in younger adults.

Impact of the diseases

People with inflammatory skin conditions can experience symptoms including itching (and sometimes pain), dry skin and changes in skin appearance, to varying degrees of severity and bodily involvement. 5,7,29 The symptoms can be distressing for patients and their carers31,32 and, in some cases, can lead to functional impairments, particularly when conditions affect the face, genitalia, hands and feet. 7 In adults, reduced levels of employment and income have been noted in psoriasis7 and more severe acne vulgaris. 9 Patients can feel stigmatised by their condition owing to visible skin symptoms and changes in appearance,31,33,34 which may contribute to distress35 and impact on their social interactions,33,34,36 normal activities (e.g. going to a public swimming pool or to the hairdressers) and relationships with people, including sexual relationships. 34 Sleep quality can also be affected owing to itching and scratching which can be particularly intense at night, and the sleep of carers can also be disrupted through dealing with symptoms at night. 31

Chronic inflammatory skin conditions are associated with high levels of psychological comorbidities, including depression and anxiety,31,35,37–39 and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL),9,33,39,40 which does not always correlate with disease severity. 41–43 Psychological difficulties and stress, along with symptoms (such as itching), undergoing treatment and concerns about appearance may negatively impact patients’ HRQoL. 33,39,40 Self-managing a long-term skin condition, with a relapsing and remitting course, is demanding for patients and their carers, and patients may feel that they lack control owing to the unpredictability of the disease on a weekly, or even daily, basis. 31 Poor psychological health can lead to a vicious cycle in patients where symptoms can be exacerbated by stress44 and reduced HRQoL may lead to less adherence to treatment regimens, reducing the effectiveness of treatment and resulting in greater use of health-care resources. 45

HRQoL is a commonly used outcome measure in health care to evaluate the impact of disease on patients’ lives. It is defined as a person’s subjective experience and perception of the impact that their health status has on their physical, psychological and social functioning. 46,47 HRQoL instruments measure various dimensions of these three domains, including physical symptoms, social activity, mental health, ability to carry out normal activities, life satisfaction and perceived health status,34,46,48 although the specific dimensions measured vary according to the instrument used. 48 HRQoL is a distinct concept from psychological distress (e.g. depression or anxiety), although, as described above, experiencing psychological distress is associated with poorer HRQoL in chronic inflammatory skin conditions.

Measurement of disease

A wide range of validated instruments are used to measure HRQoL and disease severity in patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is one of the most frequently used instruments in studies in dermatology. It has been used extensively in studies of over 40 different skin conditions, although the most common conditions it has been used for are psoriasis, atopic eczema and acne. 49 Other common measures include the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQoL), which is aimed at children aged 0–4 years old,50 the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), which is aimed at children aged 4–16 years, the Quality of life in Primary Caregivers of children with Atopic Dermatitis (QPCAD), and the World Health Organization Quality of Life-26 items (WHOQOL-26). These instruments cover a range of dimensions of HRQoL, including the severity of the condition, quality of sleep, coping, adherence with treatment, satisfaction and the impacts on family members, partners or carers. Some of the instruments that have been developed specifically for use in children (such as CDLQI and Quality of Life in Children Aged 14–16 Years) use proxy judgements made by someone else, such as a parent or carer.

Some of the common measures of disease severity include the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), the Self-Administered Psoriasis Area Severity Index (SAPASI), the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) and the Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI).

Appendix 1 gives an overview of some of these common instruments, including definitions of clinically meaningful changes where this is known (that is, the degree of change that is considered to be of benefit to the patient and their disease management, regardless of whether the change is statistically significant46).

Impact on the NHS

The need to improve patients’ HRQoL and for clinicians to take a holistic approach to managing patients’ skin conditions has been advocated in the research literature34 and clinical guidelines. 5,7 This might benefit both patients and the NHS through reduced use of health-care resources. It was estimated (using 2005/6 data) that 2.23% of the total NHS expenditure (£140M) was spent on diseases of the skin and subcutaneous diseases. 1 This included prescribing costs, outpatient and inpatient costs, but not primary care consultations, which could add another £395M. 1 In a national statistical report published by the Health and Social Care Information Centre51 on prescriptions dispensed in the community in England from 2003–13, the costs of emollient prescriptions in the year 2013 were estimated at £105,000, although these were prescribed for a range of conditions and not just for inflammatory skin diseases.

A UK-based study1 estimated the direct costs of skin diseases to the individual and to the NHS. It reported a year-on-year increase in over-the-counter (OTC) sales of the skin disease treatments in the UK from 2001 to 2007. The OTC sales for such conditions were £413.9M in 2007; this was 18% of the total OTC sales. Of the total prescribing budget, 2.85% (£237.7M) was for prescribing costs for skin disease in England in 2007. The study reported an estimated cost of about £395M per year, or 4.4% of the General Medical Services budget for GP consultations in England and Wales. In the year 2005/6, the overall direct costs (including medical care and products) of providing care for people with skin diseases was reported as about £1819M in England and Wales. It was observed that the direct cost of skin disease to the NHS was relatively low despite the conditions being very common. 1

Current service provision

A brief overview of the management of different chronic inflammatory skin diseases with relevance to the UK is discussed in the context of the relevant national guidelines as outlined below, including the role of education in the treatment of these conditions. Educational interventions are typically defined as providing patients with information about, and training in, skills for managing their condition. 52 In its simplest sense, education can be thought of as the provision of information that is intended to influence a specified outcome. In general, educational interventions involve encounters between teachers and learners for one or more of the following purposes: to raise awareness, to enhance or improve knowledge, or to change behaviour. 53

Relevant national guidelines

Of all the chronic inflammatory skin diseases prevalent in the UK, national guidelines have been published on only two of the conditions: atopic eczema5,54 and psoriasis. 7 In addition, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standards for psoriasis and atopic eczema are available and these provide quality statements describing best clinical practice, including pathways for assessment and treatment. The details of the guidelines are presented below.

Atopic eczema

Atopic eczema in children: management of atopic eczema in children from birth up to the age of 12 years. NICE Clinical guidelines, CG57. Issue date: December 2007. 5 In addition to covering the management of atopic eczema in children from birth up to 12 years, this guideline provides guidance on diagnosis and assessment, management, and providing information and education for children and their parents and carers.

Management of atopic eczema in primary care: a national clinical guideline. March 2011. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline for atopic eczema. 54 Similarly to the NICE clinical guideline, the SIGN guideline also provides recommendations based on current evidence for the management of atopic eczema in children as well as adults in primary care in Scotland.

Psoriasis

The assessment and management of psoriasis. NICE Clinical guidelines, CG153. Issue date: October 2012. 7 This guideline provides evidence-based advice on the assessment and management of psoriasis in adults, young people and children.

Management of disease

A range of treatment options are available for inflammatory skin diseases and current recommendations for best practice are summarised here. Although these vary from condition to condition, they typically fall into topical treatments, which are applied directly to the skin; systemic pharmacological treatments (intravenous, subcutaneous or oral); bandaging techniques; and, for some conditions, phototherapy. 5,7 In addition, patients are encouraged to practise self-care (such as using emollients as indicated, avoiding known triggers) to minimise environmental triggers of their disease, to monitor their condition, maintain adherence to treatments, and to seek support groups. Education is an important way to help individuals manage the symptoms of chronic diseases55 and, in recent years, educational interventions for people with inflammatory skin disease have been seen as a useful adjunct to usual medical care with topical and pharmacological therapies.

Atopic eczema

The NICE clinical guideline on atopic eczema5 provides guidance on management of the condition during and between flares, in children from birth up to the age of 12 years. The guideline suggests that a holistic approach should be adopted by health-care professionals (HCPs) when assessing a child’s atopic eczema. Potential trigger factors, such as irritants (e.g. soaps and detergents), skin infections, contact allergens, food allergens and inhalant allergens should be sought by the HCPs while clinically assessing children with the condition. With respect to treatment of the condition, NICE recommend the use of a stepped approach whereby the treatment step was tailored to the severity of the atopic eczema. Emollients are recommended to form the basis of atopic eczema management.

The current NICE guideline5 states that parents and carers, along with the children with atopic eczema, should be offered information on how to recognise the symptoms and signs of bacterial infection and how to access appropriate treatment when a child’s atopic eczema becomes infected. Furthermore, children, along with their parents and/or carers, should be educated about the health condition and its treatment. In addition, HCPs should provide both verbal and written information, along with practical demonstrations on quantity and frequency of the treatment to use. NICE recommends that the information should be tailored to suit an individual child’s cultural practice relating to skin and the way they bathe. The NICE guideline acknowledges the impact that the disease can have on a patient’s HRQoL and makes a recommendation that the effect of the condition on HRQoL should be taken into account at consultations and treatment decisions. 5 Future research recommendations were advocated by NICE to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of educational programmes in the management of atopic eczema in children, as lack of education about therapy could lead to poor adherence, thereby leading to treatment failure.

In addition to the above guideline, NICE Quality Standards 4456 include a reference to the provision of education in Statement 2, that children with atopic eczema should be treated using a stepped-care plan on the basis of the recorded disease severity and that this care plan should be supported by education. The NICE pathways for atopic eczema state that quality of life (QoL) should be assessed by practitioners when making treatment decisions.

The SIGN guideline54 identifies a Cochrane review that examined the effect of parent educational interventions on severity of eczema in children. This review showed heterogeneity with respect to the format, content and settings of the interventions and, although two of the four included studies found the intervention to be effective in reducing clinical severity scores, no recommendations in the SIGN guideline were made owing to the lack of consistency seen in the trials included. 54

The SIGN guideline provides a checklist of information that patients and carers should have access to at the different stages of diagnosis and treatment. These largely focus on explanation of the condition, what treatment options there are, how to self-manage their conditions and look for changes in their condition. There is some limited reference to providing patients and carers with the contact details of organisations that may be able to provide advice and support. There is no specific advice regarding any educational interventions. 54

There are no published audits of how well the national guidelines are being adhered to in clinical practice with regard to education. The general impression of our Advisory Group was that this is variable.

From a patient and carer perspective, the need to establish which is the most effective route to manage eczema has been identified by the James Lind Alliance Eczema Priority Setting Partnership. 57 One of the top research priorities for HCPs identified by the group is to establish which of the following management approaches is the most effective: education programmes, GP care, nurse-led care, dermatologist-led care or multidisciplinary care.

Psoriasis

The NICE guideline on psoriasis7,58 provides recommendations on the management of all types of psoriasis across all age groups: children aged up to 12 years, young people and adults aged 18 years and above.

The NICE guideline7 recommends that for people with any type of psoriasis, disease severity should be assessed, along with the impact of disease on physical, psychological and social well-being, and whether they have psoriatic arthritis or presence of comorbidities. The guideline states reasons for referral to a dermatology specialist for a number of reasons, including uncertainty over the diagnosis, severe psoriasis, psoriasis that cannot be controlled with topical therapy or psoriasis that has a major impact on a person’s physical, psychological or social well-being.

It was recommended to discuss risk factors for cardiovascular comorbidities with people who have any type of psoriasis and with their families and/or carers.

With regard to treatment, practical support and advice about the use and application of topical treatments should be provided by trained and competent HCPs. For adults with trunk or limb psoriasis, NICE recommends the use of a potent corticosteroid applied once daily plus vitamin D or a vitamin D analogue applied once daily for up to 4 weeks as initial treatment. However, people with plaque or guttate-pattern psoriasis that cannot be treated with topical treatments alone should be offered narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy two or three times a week depending on patient preference. Systemic non-biological therapy should be offered to people with any type of psoriasis if the disease cannot be controlled with topical therapies, if it has a significant impact on the patient in terms of physical, psychological or social well-being, or if it is associated with significant functional impairment. 7

In citing the principles of care for patients with the condition and their families or carers, the guideline recommends the provision of support and information to be provided to meet the requirements of each individual. Areas of focus for information should be an understanding of their diagnosis, the available treatments (including their safe and effective use), what the associated risk factors are, when and how to seek support, and information on strategies to deal with the impact on physical, psychological and social well-being. 7 The NICE guideline also recognises the potential impact on a patient’s HRQoL and notes that HRQoL should be taken into account during patient consultations and when making treatment decisions. The NICE pathways for psoriasis state that psychological well-being should be assessed by practitioners at diagnosis and when assessing response to treatments.

Similarly to the situation with eczema guidelines, there are no published audits of how well the NICE psoriasis guideline is adhered to in clinical practice with regard to education. The Advisory Group to this review believed that adherence is currently variable.

Overall, although these guidelines for eczema and psoriasis outline to some extent where patient education, information and advice sit in clinical practice, the guidance tends to focus on education relating to patients’ use of treatments, self-care and understanding of the disease. It is not currently clear where educational interventions that more directly address HRQoL could be placed in the clinical pathway, including which patient groups should be targeted for these kinds of interventions. The guidance also does not currently clearly state how any type of education is best provided in primary or secondary care, such as whether it should be provided in a structured, planned way or more informally by practitioners during routine medical consultations.

Description of the technology under assessment

As stated, educational interventions are typically defined as providing patients with information about and training in skills for managing their condition (see Current service provision). 52 People with chronic skin conditions and their carers have several educational needs. These include an understanding of the condition (typically chronic and relapsing, with no cure at present, but in general manageable), an opportunity to try treatments to find those that suit them best, reassurance that many treatments are generally safe and effective, guidance on how best to apply topical treatments, and motivation to continue treatment when the disease is in remission. 59 Educational interventions have traditionally been based on what health-care experts believed patients need to know about their conditions rather than patients’ expressed needs. 60,61 Recently, however, there has been a movement in medicine towards greater patient involvement in treatment and patient-centred care. 62 A more patient-empowering subset of educational interventions are self-management educational interventions, which focus on enabling patients to develop problem-solving skills and teach patients actions that they can take to resolve issues (including emotional and psychosocial issues) relating to their condition when they arise. 52 Self-management educational interventions will often involve the creation of patient action plans52 and represent a collaborative approach between HCPs and patients. 60 Patient activation is also an important part of promoting self-management in chronic diseases. 63 Patient activation is defined as the extent to which patients believe and have confidence that they can play an active part in managing their health and the extent to which they carry out and maintain activities which can positively impact their condition and health more broadly. Patient activation is associated with better QoL in patients in general64 and potentially could be improved through patient education.

Educational interventions may be delivered in a variety of ways, may include a number of inter-related elements that either singly or together may bring about change in an outcome and some tailoring to individual patient or carers’ needs, and therefore could be considered ‘complex interventions’. 65 Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions emphasises the importance of early groundwork in developing an intervention. 65 This should include specification of a clear theoretical basis for the intervention that outlines its rationale and how it might bring about change in the outcomes of interest, drawing on available evidence and theoretical models. This is because theory-based interventions tend to be more effective than those that are not theory-based. The MRC guidance additionally recommends carrying out research, such as qualitative work, with potential users, deliverers or creators of the intervention to supplement existing theory and evidence, if needed, to further inform intervention development. The guidance also recommends that systematic reviews of current evidence for the effectiveness of the intervention and pilot studies (e.g. to evaluate feasibility) are carried out.

As another consideration in intervention development and delivery, it is also recommended in the wider literature that educational interventions in dermatology should be sensitive to and take account of patients’ social and cultural backgrounds, including their education level, literacy and preferred language, and their favoured learning methods. 66,67 Some degree of tailoring of the intervention to individual needs might also be beneficial, as it has been found in health care generally that tailored interventions result in better outcomes than more generic ones. 68 Consideration might also be given to the characteristics of the intervention deliverer, because it has been suggested that interventions delivered by people who have similar characteristics to the intervention participants (such as similar social and ethnic backgrounds) might be more effective than those delivered by people who differ to the participants. 70 Ideally, evaluations of complex interventions should include process evaluations to gain insight into contextual factors during intervention delivery that may impact its effectiveness. 65

Research studies have investigated a wide variety of approaches for educating patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases – mostly those with eczema and psoriasis, and, in some cases, their carers or families also. 2,36,55,70 The existing evidence for educational interventions in general shows variability in whether these interventions are effective in improving HRQoL, but some studies have shown positive effects. 55,60,71 A systematic review of educational interventions for children with eczema and their parents suggests that programmes for parents that are delivered by either a nurse or a multidisciplinary team may lead to improvements in infant and child HRQoL and disease severity. 71 However, there is currently little understanding overall about which elements of educational interventions make them effective in improving HRQoL and other outcomes. 60,61

Our project Advisory Group of patients, HCPs and researchers indicated that educational interventions are generally not widely used in UK clinical practice to supplement medical treatment for patients with chronic inflammatory skin conditions. The Group suggested that education in primary care is especially limited and will generally involve verbal instructions on medication use, provision of information leaflets and sign-posting to other information sources. The Group stated that educational interventions are more commonplace in secondary care and are often nurse-led and more likely to be planned and structured. These tend to involve information giving and advice, combined with paper- or web-based information. The Group stated that, overall, educational interventions are not sufficiently individualised and the creation of action plans is rare.

As part of educational interventions, patients with chronic inflammatory skin conditions are often provided with information about their condition and the use of treatments. However, it has been suggested that the impact of standard education in dermatology on HRQoL could be enhanced by the additional inclusion of elements that address issues related to HRQoL. This review focuses on these additional elements as per the commissioning brief. Our Advisory Group was aware of only two UK educational programmes that specifically aim to improve HRQoL. One is The Eczema Education Programme,72 which is a nurse-led programme delivered in the community and a specialised centre, which aims to improve parents’ and carers’ management of their child’s eczema and parents’ QoL. Elements covered in the programme include: understanding the disease, trigger factors and treatment; enhancing parental confidence in using treatments; action planning; and practical strategies for reducing itching and sleep problems. A before- and after- study evaluation of the programme73 found improvements in infant, child and parental HRQoL, indicating that this may be a potentially successful approach. The other programme is an online intervention delivered through the Supporting Parents and Carers of Children with Eczema (SPaCE) website for carers of children with eczema. 74

As with educational interventions in general, it is currently unclear which specific elements of these interventions may enhance HRQoL or what factors should be targeted to lead to improvements in HRQoL. Where complex educational interventions for chronic skin diseases involve multiple interacting components it may not be possible to identify which intervention components are responsible for observed effects on outcomes. 75,76 However, taxonomies of intervention techniques may be used, if appropriate, to map which intervention components may be related to improved outcomes. 69,77 In line with the MRC complex interventions guidance,65 authors of some studies evaluating educational interventions for childhood eczema aimed at improving HRQoL have provided information on the underlying theory of change. These studies have hypothesised that educational interventions may improve HRQoL through enhancing the ability to manage the disease,72,74,78 increasing self-efficacy72,78 (that is, patients’ or carers’ confidence in their ability to successfully manage the condition79), promoting positive outcome beliefs and behavioural capability78 and through the use of a number of other behaviour-change techniques. 74 As far as the authors of this review are aware, however, a clear theoretical basis for such interventions, including potential underlying mechanisms of change, has not been adequately outlined in the literature.

Based on opinion from our Advisory Group, addressing the following factors may differentiate educational interventions aimed at improving HRQoL from general educational interventions: unpredictability of the disease, interaction of multiple factors, impact of everyday life (e.g. family, tiredness and personal and work life) on the condition, mental well-being, negative thinking, coping skills (e.g. to cope with the disease or for managing psychological distress), problem-solving and action planning, and management of medication side effects. Additionally, the Group suggested that it may also be important to cover issues relating to parental guilt associated with passing on a genetic disease, and parents’ or carers’ empathy and appreciation of the impact of the disease. The Group also stated that educational interventions that improve condition management may also result in improvements in HRQoL and emphasised the potential importance of theory-based interventions in enhancing the effects of an intervention on this (e.g. through the incorporation of elements hypothesised to improve self-efficacy from social cognitive theory80). The literature shows that experiencing psychological difficulties, such as depression, is associated with poor HRQoL in chronic inflammatory skin diseases, among other factors,33,39,40 and patients experiencing a high psychosocial burden from their disease have been identified as a (psoriasis) subgroup requiring additional support. 81 Based on a model of delivery of psychosocial interventions for skin conditions generally,82 recommended nurse-delivered interventions for patients experiencing mild to moderate psychosocial distress include training in relaxation techniques, scratching habit reversal, problem solving and ways of camouflaging skin. It may be reasonable to assume that if these aspects are part of educational interventions, they may also help enhance HRQoL.

In light of limited existing evidence, there is uncertainty about best practice methods for educational interventions. Therefore, systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness as well as cost-effectiveness of educational interventions aimed at improving QoL in people with chronic inflammatory skin diseases are required.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this health technology assessment is to undertake systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of educational interventions for people with chronic inflammatory skin diseases.

The main objectives are:

-

to conduct systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of educational interventions for improving HRQoL in patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases

-

if data permit, to adapt an existing economic model or construct a de novo model from the perspective of the UK NHS to estimate the cost-effectiveness of educational programmes for chronic inflammatory skin diseases

-

to identify deficiencies in current knowledge and to generate recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were described in a research protocol which was sent to our expert Advisory Group for comment. Although helpful comments were received relating to the general content of the research protocol, none of the comments identified specific problems with the methodology of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

During data extraction, we made a modification to our protocol to exclude post hoc those papers that otherwise met our inclusion criteria, but which did not report a study’s results in sufficient detail to be informative in the review.

Identification of studies

A comprehensive search strategy was developed, tested and refined by an experienced information specialist. Separate searches were conducted to identify studies of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Sources of information and search terms are provided in Appendix 2. The most recent searches were undertaken in July 2014.

Literature was sourced from 12 electronic databases, the bibliographies of included articles and relevant systematic reviews, and our expert Advisory Group were contacted to identify any additional studies. All databases were searched from inception and limited to the English language. The following electronic databases were searched:

-

The Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (University of York) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database

-

MEDLINE (Ovid)

-

EMBASE (Ovid)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus with full text (EBSCOhost)

-

PsycINFO

-

Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI) (ISI Web of Knowledge)

-

Global Resource for Eczema Trials (GREAT) database (University of Nottingham).

A comprehensive database of relevant published and unpublished articles was constructed using Reference Manager (Thomson ReseachSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) software. Research-in-progress databases were searched for any ongoing studies of relevance.

Searches for ongoing studies were undertaken in the following databases: UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN), controlled-trials.com, clinicaltrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), Centre for Evidenced Based Dermatology (University of Nottingham), UK Clinical Trials Gateway (UKCTG).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic reviews if they met the criteria outline below.

Population

Adults, young people and children with a chronic inflammatory skin condition and/or their carers.

Intervention

Educational interventions that either specifically aimed to improve HRQoL or could improve HRQoL [e.g. by targeting patients’ ability to cope with the negative effects of chronic skin disease or by targeting compliance with therapy (with the aim of reducing the degree of skin affected)]. That is, to be included in the review, the educational interventions needed explicitly to state that the aim of the intervention was to improve HRQoL or, in the absence of this, the content of the intervention needed to focus on more than just information about the specific skin disease and its treatment, and needed to address patients’ ability to cope with the negative effects of the disease (e.g. by providing education on stress management, coping with itch or addressing the psychosocial effects of the disease, such as feelings of stigmatisation attributable to changes in skin appearance) or adherence to therapy.

Any type of educational technique was permitted provided that effects of education on outcomes could be isolated from effects of any non-educational intervention components that may also be present in the intervention. Therefore, any interventions that were purely psychological approaches (e.g. to manage distress) and did not seem to include an element of education were excluded.

Comparators

Any comparator was eligible. This could include treatment as usual, waiting-list controls, or other educational interventions.

Outcomes

-

HRQoL: only studies that measured HRQoL as an outcome, using a validated measure, were included.

The following outcomes, where reported in the included studies, were also included:

-

disease severity

-

disease control

-

scratching behaviour (where applicable)

-

health-care utilisation

-

depression

-

anxiety

-

patient or carer self-efficacy regarding disease management (self-efficacy is defined as a person’s level of confidence in their ability to perform particular behaviours to achieve desired outcomes,79 such as successful self-management of a condition)

-

process evaluations, including adherence to therapy, attitudes and knowledge.

Patient-reported outcome measures were included if assessed by validated tools. Reviewers considered that a measure was validated if the publication stated that it was or, where this information was not available, if a consultation of the wider literature determined that the measure fulfilled at least one validity criterion.

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness, studies reporting measures of cost-effectiveness [e.g. cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), cost per life-year saved] were eligible.

Study design

For each skin disease, relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were sought. If no RCT evidence existed for a given disease, prospective trials with concurrent control group(s) were eligible.

The identified systematic reviews were used as sources of references only.

Studies were included in the systematic review of cost-effectiveness if they were full economic evaluations (cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analyses) that reported both measures of costs and consequences or if they were cost–consequence or cost analyses.

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were only included if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

Study selection and data extraction strategy

Studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness through a two-stage process using the predefined and explicit criteria specified above. Titles and abstracts from the literature search results were independently screened by two reviewers to identify all citations that possibly met the inclusion criteria. Full papers of relevant studies were retrieved and assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer using a standardised eligibility form. As far as possible, full papers or abstracts describing the same study were linked together, with the article reporting key outcomes designated as the primary publication. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or if necessary by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness were assessed for potential eligibility by two reviewers using the predetermined inclusion criteria. Full papers were formally assessed for inclusion by one reviewer with respect to their potential relevance to the research question and this was checked by another reviewer. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or if necessary by discussion with a third reviewer.

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standard data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. At each stage, any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by arbitration by a third reviewer.

In the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, for each study, results for outcomes measured at the immediate end of the intervention and the longest follow-up time point (where this differed) were extracted and presented. That is, results for any intermediary time points were not extracted. During data extraction, a modified version of Schulz and colleagues’69 intervention taxonomy was used to structure how and which information was extracted about the educational interventions in the included studies. The taxonomy characterises the different elements of interventions. Based on this, the following intervention components were extracted for each study: where it was delivered; whether it was a form of self-help; whether it was individual- or group-based; mode; materials used; provider; duration and intensity; scripting (use of a protocol guiding interaction between the interventionist and participants); sensitivity to participant characteristics; interventionist characteristics and training; content and topics (including educational strategies used); tailoring; and theoretical basis. Reviewers additionally extracted the following: intervention overview and aims; stated target group; ongoing support provided; and whether individuals’ preferred learning styles were taken into account.

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality and the quality of reporting of the included clinical effectiveness studies were assessed using risk of bias criteria based on those recommended by Cochrane83 (see Appendix 3). Quality criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, with any differences in opinion resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Quality assessment for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness was based on a checklist for economic evaluation publications. 84

Method of data synthesis

Studies of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of results of included studies. In the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, studies were grouped according to the condition being considered and the general age group of the participants.

It was not considered appropriate to combine the studies in a meta-analysis owing to the heterogeneity between studies in patient characteristics (ages, conditions, duration of disease, severity of disease), the interventions and the comparators.

Advisory group

The Advisory Group informed the protocol and provided comments on the near complete draft report. In addition, members of the Advisory Group provided responses to specific questions around the current use of educational interventions for chronic inflammatory skin disease, which informed the background section of the report.

Chapter 3 Results of the systematic review of clinical effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

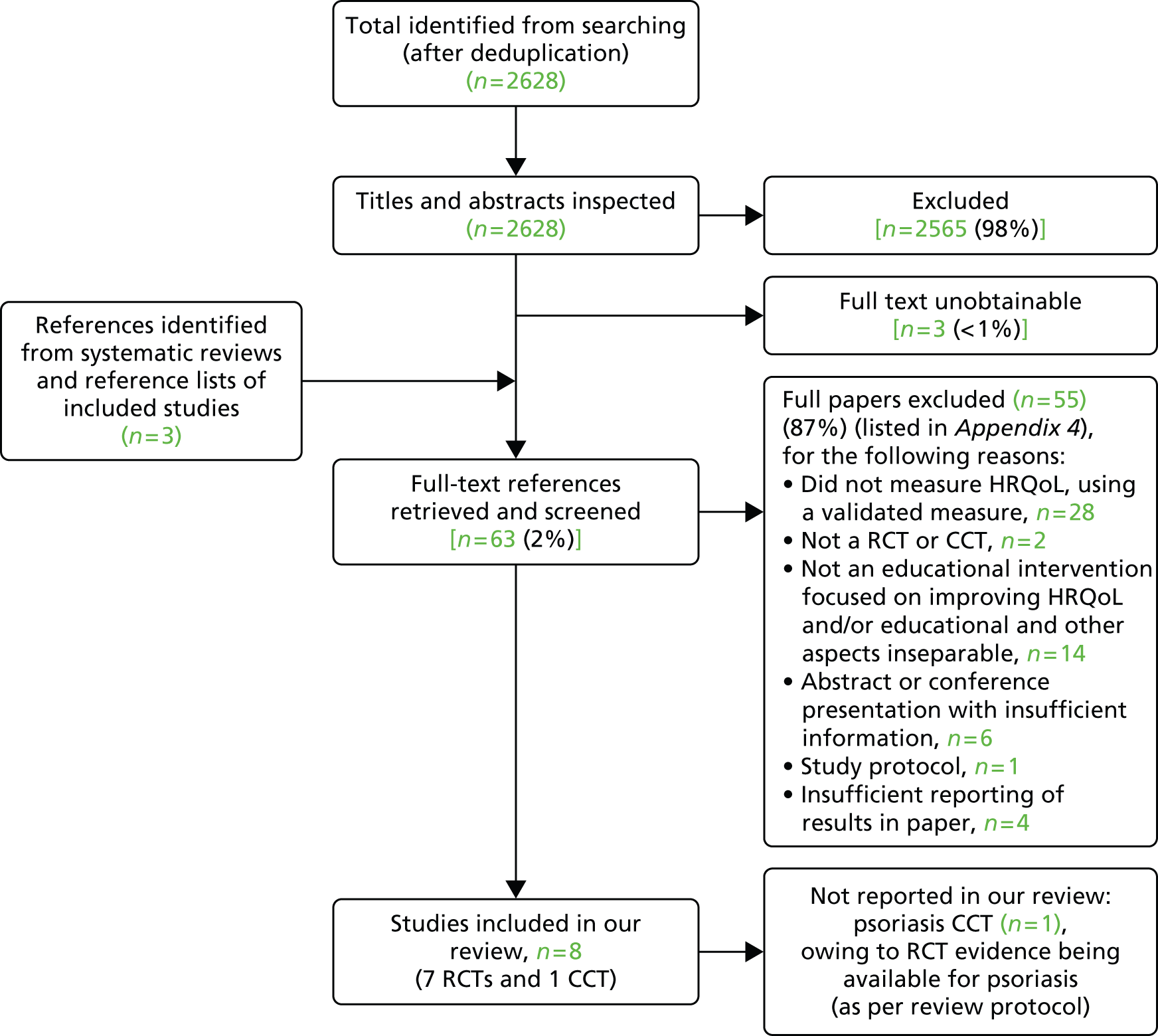

Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review. Eight studies74,76,85–90 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, seven were RCTs74,76,85–89 and one was a controlled clinical trial (CCT). 90 The CCT90 evaluated an educational intervention for psoriasis. In line with our review protocol, which pre-specified that CCTs would only be included if no RCT evidence existed for a particular condition, the CCT is not discussed further because RCT evidence was available for psoriasis.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for the identification of studies in the review of clinical effectiveness. CCT, controlled clinical trial.

Searches identified 2628 records, of which 2565 were excluded at title and abstract screening. At the full-text screening stage of the review, 63 references were reviewed and 55 were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were that studies did not measure HRQoL using a validated measure (n = 28) or that the intervention was not an educational intervention that aimed to, or could, improve HRQoL, and/or the effect of the educational component of the intervention on outcomes could not be isolated from the effect of other non-educational components of the intervention (n = 14) (see Appendix 5 for a full list of reasons for specific exclusions). Three studies, reported in four publications,78,91–93 were excluded for not reporting results in sufficient detail to be informative in the review. Of these, one reported in Staab and colleagues93 and Wenninger and colleagues78 was a RCT examining a theory-based programme called the ‘Berlin education programme’ for parents of children with atopic dermatitis, aimed at improving HRQoL and the disease course, which covered medical, nutritional and psychological issues. The authors reported limited numerical data in the results. For example, data were reported for only one of the five dimensions of a disease-specific HRQoL measure. The other two excluded studies were Jaspers and colleagues91 and Lora and colleagues,92 which were RCTs of a combined psychoeducational and dermatological treatment programme delivered by a multidisciplinary team for young adults with atopic dermatitis and a psychoeducation programme for patients with psoriasis, respectively. Jasper and colleagues91 provided numerical results for only one domain of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) (HRQoL measure) at 10 weeks post intervention and narratively reported changes for other domains at 10, 20 and 40 weeks post intervention as non-significant. Lora and colleagues92 presented no results for the HRQoL measure they used. Such exclusions as a result of poor quality reporting are important to note, because these studies otherwise met the review inclusion criteria and formed around one-third of the relevant evidence-base – this issue is considered further below (see Discussion).

Characteristics of the included trials

Table 2 provides an overview of the characteristics of the seven included RCTs. Detailed information about the educational intervention(s) evaluated in each RCT is provided in Table 3, with full details also provided in Appendix 6. The full data extraction forms are shown in Appendix 4. Two RCTs, by Balato and colleagues85 and Ersser and colleagues,86 assessed the effects of daily text message education over 12 weeks and a one-off nurse-delivered educational session for adults with psoriasis; one RCT by Matsuoka and colleagues88 focused on instructions in make-up use and skin care from a dermatologist to adult women with acne; and two RCTS, by Staab and colleagues87 and Santer and colleagues,74 focused on children (and adolescents in one trial87) with atopic dermatitis and their parents or carers, evaluating a 6-week educational programme delivered by a multidisciplinary team and an educational website (the ‘SPaCE website’), respectively. The educational interventions in the remaining two RCTs, by van Os-Medendorp and colleagues89 and Bostoen and colleagues,76 were delivered to people with a mixture of skin conditions. van Os-Medendorp and colleagues89 included people with chronic pruritic skin diseases (including eczema, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, prurigo, psoriasis and chronic urticaria) and evaluated a ‘Coping with itch’ programme, and Bostoen and colleagues76 included people with either psoriasis or atopic dermatitis in an evaluation of a 3-month programme delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

| Reference and design | Skin condition(s) | Population: patients (general age group), parents or carers | Intervention(s)/comparator(s) | Setting, country | Number of participants (randomised) | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balato et al., 201385 RCT (pilot study) |

Plaque psoriasis | Patients (adults) |

|

Home-based, Italy | 40 | 12 weeks (intervention end) |

| Ersser et al., 201186 Cluster RCT (pilot study) |

Psoriasis | Patients (adults) |

|

Primary care, UK | 64 | 6 weeksa |

| Bostoen et al., 201276 RCT |

Psoriasis or atopic dermatitis | Patients (adults) |

|

Setting not reported (reviewers inferred this as likely to be outpatients), Belgium | 50 | 9 months (from baseline) |

| Santer et al., 201474 RCT (pilot study) |

Eczema | Patients (children aged ≤ 5 years) and parents/carers |

|

Primary care, south-west England, UK | 149 | 3 months (from baseline) |

| Staab et al., 200687 RCT |

Atopic dermatitis | Patients (children and adolescents) and parents |

|

Setting not reported, Germany | 992 | 12 monthsa |

| Matsuoka et al., 200688 RCT |

Acne vulgaris | Patients (adults; women aged > 16 years) |

|

Outpatient clinic, Kagawa, Japan | 50 | 4 weeksa |

| van Os-Medendorp et al., 200789 RCT |

Chronic pruritic skin diseases | Patients (adults) |

|

Secondary care, The Netherlands | 120 | 9 months (from baseline) |

| Study | Balato et al., 201385 | Ersser et al., 201186 | Bostoen et al., 201276 | Santer et al., 201474 | Staab et al., 200687 (further information provided by Wenninger et al., 200078) | Matsuoka et al., 200688 | van Os-Medendorp et al., 200789 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin condition(s), population | Psoriasis, patients (adults) | Psoriasis, patients (adults) | Psoriasis or atopic dermatitis, patients (adults) | Eczema (children aged ≤ 5 years) and parents/carers | Atopic dermatitis, patients (children and adolescents) and parents | Acne, patients (adults; women aged > 16 years) | Chronic pruritic skin diseases, patients (adults) |

| Overview | Text message education | A theory-based self-management educational intervention | Educational programme for patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis | Two educational intervention groups:

|

Group-based educational programme, with different educational sessions for (a) parents of children aged 3 months to 7 years; (b) children aged 8–12 years and their parents; and (c) adolescents aged 13–18 years (parents optional for selected sessions) | Instructions on skin care and how to use make-up from a dermatologist | ‘Coping with itch’ programme – individual sessions with dermatology nurse, including educational and cognitive behavioural interventions |

| Intervention aim(s) | Not stated explicitly but implicit from the paper that aim was to use text messaging to improve treatment adherence and patient outcomes including HRQoL | To support self-management in psoriasis | Not explicitly stated. Study aimed to examine if the educational intervention ‘added value to medical therapy’ (p. 1025) and examine the effects on disease severity and QoL | Aimed to improve carers’ management of their child’s eczema by increasing regular use of emollients. Ultimate aim of intervention was to improve HRQoL through enhancing carers’ management of the condition | Not reported in primary publication, but the intervention for children aged 3 months to 7 years was based on one reported in Staab et al.,93 and Wenninger et al.,78 the aim of which was to improve parents’ ability to manage their child’s disease and thus improve disease course and families’ QoL | Not explicitly stated, but part of the aim of the study was to examine if instructions in make-up use from a dermatologist could affect female acne patients’ QoL | To reduce itch and to help patients cope with itch |

| Mode, including if individual- or group-based mode | Text messaging, individual-based | Face to face, written and audiovisual materials, individual telephone consultation. Group-based | Face-to-face workshop, group-based |

|

Face-to-face, group-based sessions | Face to face, with supporting videotape instructions and detailed leaflets/prescriptions. Not reported if individual- or group-based | Face to face, individual-based |

| Provider | Not reported | Nurse-led | Multidisciplinary team |

|

Multiprofessional team | Dermatologist | Dermatology nurse |

| Duration and intensity | One text message per day for a period of 12 weeks | Group session: one-off 2-hour session Telephone consultation: one-off 20-minute session |

3-month programme, with two, 2-hour sessions a week |

|

One 2-hour session a week, over 6 weeks | Not reported | Patients visited the itch clinic a mean of 2.9 times (median 3 times, range 1–6 times); duration of sessions not reported |

| Content and topics | Covered frequently asked questions about psoriasis drugs (e.g. administration and adverse effects) and general recommendations for taking care of overall health. Educational topics included daily care statements, healthy lifestyle statements, prompts about the use of treatments, and one statement about the psychosocial effects of psoriasis. Reminders reinforced many of the same principles | Practical element (no details provided), individual action planning, stress reduction (through provision of relaxation materials), feedback on action plans (through telephone consultation) | Information on specific skin disease and skin care sessions, healthy lifestyle and stress-reducing techniques, feedback sessions. Further details of the intervention provided in a separate publication94 |

|

Intervention for parents of 3-month- to 7-year-olds was based on the one reported in Staab et al.87 and Wenninger et al.78 Across the three groups, the educational sessions covered medical, nutritional and psychological issues. Participants were encouraged to share experiences and to put new skills into practice. A manual specified content | Patients received instructions on use of skin care and make-up products. Instructions included general skin care and how to use ‘point make-up’ (e.g. eyeliner and lipstick) | Education about: itch causes, consequences and treatment; patient advocacy groups; avoiding triggers; diet; interventions to relieve itching and scratching and their consequences. Cognitive behavioural therapy including diary-based awareness training, habit reversal to reduce scratching, and relaxation. Based on an initial itch medical history assessment taken by the nurse and structured according to an individual-based nursing care plan |

| Ongoing support | None reported | Nurse provided one 20-minute follow-up telephone consultation 1 month after the group session (based on outline script) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Individual counselling and ‘support’ (not defined) provided as required (no details given) |

Five of the included RCTs74,76,86,88,89 compared educational programmes with standard care for the skin condition. Balato and colleagues85 and Staab and colleagues87 compared the text message education and 3-month educational programme with a ‘control intervention’ and a ‘no education control’, respectively, but did not provide details about what, if any, treatment was given to the control conditions. In six RCTs74,76,85,86,88,89 the educational interventions were delivered as an adjunct to standard medical care, and it was unclear if it was an adjunct in the remaining trial evaluating the 6-week programme including children with atopic dermatitis and their carers. 82 Only one RCT74 compared two different approaches to the education delivery, in addition to comparing each educational approach with standard care. This trial compared education delivered through the SPaCE website only with education delivered through the same website, but with additional support through a one-off appointment with a HCP who promoted engagement with the website and supported participants in completing some of the modules.

Only two UK studies were identified. 74,86 One examined the effects of a one-off educational session for patients with psoriasis in primary care86 and the other was also set in primary care, but provided education mainly through the SPaCE website. 74 The other RCTs were conducted in a range of countries and settings, including secondary care in the Netherlands89 and Japan88 and home-based education in Italy. 85 In the remaining RCT,76 conducted in Belgium, the setting was unclear. The generalisability of these studies to the UK setting is, therefore, unclear.

No studies of any other chronic inflammatory skin diseases were identified in our searches.

All tables are ordered by condition and then by patient age group within condition.

The largest RCT was of 992 children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis and their parents. 87 One other RCT of mixed skin conditions had a sample size of 120 participants89 and another of children with eczema and their parents or carers had a sample size of 149. 74 Sample sizes in the four remaining trials,76,85,86,88 including all the RCTs of patients with psoriasis, ranged from 40 to 64 participants. One study measured outcomes at the end of the intervention only,85 with the other six74,76,86–89 employing various lengths of post-intervention follow-up, ranging from 4 weeks88 to 12 months. 87 Three studies76,87,89 had a follow-up of a reasonable duration to capture the clinical effects of the intervention (≥ 3 months post intervention; which the review Advisory Group suggested would be the minimum follow-up time necessary in studies to measure the effect and durability of patient benefits from an intervention).

Aims, content and structure of the educational interventions in the included trials

During data extraction, a modified version of a taxonomy of elements of interventions developed by Schulz and colleagues69 was used to structure how information about the interventions in each trial was recorded (see Methods for more information about this). Following this principle, an overview is provided here of the educational interventions in each trial, with summary details shown in Table 3. More detailed information about the interventions, covering all elements extracted, can be found in Appendix 6.

The aims, content and structure of the educational interventions were heterogeneous across the seven included RCTs. Only one of the included studies,74 of the SPaCE website intervention, explicitly reported that the aim of the intervention was to improve HRQoL (although another, by Staab and colleagues,87 was in part based on the ‘Berlin education programme’ reported in the excluded Staab and colleagues93 and Wenninger and colleagues78 publications, and these linked publications state that the aim of the intervention was to improve HRQoL; see Table 3 for more details). The other studies were included in the review because it was inferred from the content that the intervention could improve HRQoL (e.g. it included aspects that targeted compliance or patients’ ability to cope with the negative effects of their disease).

Three of the studies reported that the educational interventions were theory-based. The one-off educational session for patients with psoriasis in Ersser and colleagues86 and the 6-week programme for atopic dermatitis in Staab and colleagues87 were based on social cognitive theory. The SPaCE website intervention in the trial by Sanler and colleagues74 incorporated 20 of the 26 behaviour-change techniques listed in Abraham and Michie’s77 taxonomy of behaviour-change techniques. The design of the intervention in Ersser and colleagues86 was additionally informed by findings of previous qualitative research on the self-management needs of individuals with psoriasis. Similarly, the design and content of the SPaCE website in Santer and colleagues74 was based on qualitative interviews and input from a patient support group, as well as evidence-based patient information leaflets, ‘think-aloud’ interviews with users of a draft version of the website and feedback from other parents and HCPs.

The educational content and strategies used in the interventions varied across the studies. All the trials except one86 reported that participants were provided with information about the skin disease, its treatment, skin care, or the causes, consequences and treatment of itch. The interventions also commonly included education about stress-reducing or relaxation techniques (reported in five RCTs74,76,86,87,89) and living a healthy lifestyle and/or nutritional issues (reported in five RCTs74,76,85,87,89). Other psychosocial aspects included education on coping with the disease and managing itching, scratching and sleep,74,87,89 managing the psychosocial consequences of the disease,85 and provision of information about patient support groups. 89 The SPaCE website for carers of children aged 5 years or younger with eczema also contained information about how to involve their child in their treatment and guidance for carers on how to manage a consultation with their GP. 74 The intervention in the trial by Matsuoka and colleagues,88 in which patients with acne were provided with instructions on skin care and make-up use, could be considered to help patients manage appearance concerns and the feelings of stigma associated with their condition. As well as information provision, the reported education strategies used included encouraging participants to share experiences,87 discussion of difficulties in transferring newly learnt skills into their everyday lives,87 individual action planning or creation of (self-)management plans,74,86,87,89 feedback sessions,76 a 2-week challenge involving short message service (SMS) text alerts for setting goals, monitoring and rehearsing behaviours,74 and cognitive behavioural therapy, including habit reversal to reduce scratching. 89 Where reported, the duration and intensity of the educational interventions ranged from two 20-minute compulsory online modules (plus optional additional modules)74 to a 3-month programme consisting of two 3-hour sessions a week. 76

In all the RCTs except one,85 educational interventions were delivered at least in part through face-to-face sessions, and in three trials it was also delivered in groups. Group sizes across and within the studies ranged from 5 to 23 participants. 76,86,87 In the RCT by Santer and colleagues,74 the intervention was mainly delivered online (via the SPaCE website), but one group also received additional support from a HCP in a face-to-face appointment. Participants could also opt to take part in a 2-week challenge, which involved receiving behavioural prompts by text message. It is unclear if the instructions in skin care and using make-up were provided to patients individually or as part of groups in the RCT by Matsuoka and colleagues. 88 In one trial85 education was provided to individuals solely by daily text messages, over a period of 12 weeks. The educational interventions were delivered by a multidisciplinary team in two RCTs,76,87 a nurse in another two RCTs86,89 and a dermatologist in one RCT. 88 In the Santer and colleagues RCT,74 the SPaCE website, which had been developed by medical experts and informed by patient support groups, was the main delivery mechanism. The HCPs who provided support to one group varied across the general practices taking part and were the practice nurse in 11 practices, a health-care assistant in one practice and a GP in one practice. Only one of the HCPs was dermatology trained. In the remaining RCT, of text message education,88 it was unclear who provided the intervention. Three trials74,86,87 reported information about the interventionist characteristics, with all stating that the interventionists received training prior to delivering the programmes (although this was minimal in Santer and colleagues74 and consisted of 1 hour for the HCP to familiarise themselves with the SPaCE website). None of the RCTs provided information about whether the people delivering the educational interventions had similar characteristics to the patients taking part, such as similar social and ethnic backgrounds.

Ersser and colleagues,86 Bostoen and colleagues76 and Staab and colleagues87 reported that the interventionist was required to follow a protocol, syllabus or content manual, respectively, to standardise delivery. Delivery of the text message85 and website education74 was also standardised (but with some optional as well as compulsory modules on the website). In Ersser and colleagues,86 there was flexibility for the intervention to be tailored to participants’ needs. Another two RCTs74,89 also reported that, to some extent, the educational interventions were tailored to patients’ individual needs. The interventions in two trials85,87 were sensitive to participants’ characteristics to some extent, by providing parent and child education according to age group87 and ensuring that text messages were written in simple language. 85 None of the interventions took into account individuals’ preferred learning styles.

Outcomes assessed in the included trials

As per our inclusion criteria, all seven RCTs measured HRQoL using one or more validated measures. All seven trials also measured disease severity as an outcome. Other measured outcomes were: depression, stress, lifestyle (measured by a set of unvalidated questions in one trial76), health resource use, medication and ointment use, cost-effectiveness, itching behaviour, itch-related coping, skin-related psychosocial morbidity, general psychosocial morbidity, patient–physician relationship, attitudes and perceptions of ability to manage the condition, and treatment adherence. Only one trial88 measured adverse events. In line with our protocol, patient-reported outcome measures were extracted and included in the review only if assessed by validated tools. HRQoL was a primary outcome in four of the trials76,86,87,89 and a secondary outcome in one trial. 74 The remaining two trials85,88 did not specify if outcomes were primary or secondary. Three RCTs74,85,86 included process measures that could be regarded as ‘process evaluations’ (e.g. assessing patients’ perceptions of the usefulness of the intervention).

Four of the included trials76,85,86,88 measured HRQoL using the DLQI, which is a dermatology-specific, self-report measure. 95 van Os-Medendorp and colleagues89 measured HRQoL using the QoL subscale of the Adjustment to Chronic Skin Diseases Questionnaire (ACS), which measures skin-related psychosocial morbidity. Staab and colleagues87 measured parents’ HRQoL using the German questionnaire ‘Quality of life in parents of children with atopic dermatitis’. Santer and colleagues74 measured the impact of the website for carers on each family’s QoL using the Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) questionnaire and also measured the impact on the carers’ children’s HRQoL using the IDQoL (for children aged ≤ 4 years) and the CDLQI (for children aged ≥ 5 years). Other HRQoL measures used in the RCTs were: Skindex-29,76 PDI,76 Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD)76 and WHOQOL-26. 88 For more information about the most commonly used measures and how they are interpreted, please see Appendix 1.

Disease severity was assessed using a range of measures, including the PASI (used in all three trials that included patients with psoriasis76,85,86), the SCORAD (used in two studies including patients with atopic dermatitis76,87) and the POEM (used in a study of children with eczema and their carers74). Other measures used were the Plewig and Kligman’s grade measure of acne severity88 and a patient-reported measure of the frequency and intensity of itching. 89 For more information about the most commonly used measures and how they are interpreted, see Appendix 1.

Participants’ baseline characteristics