Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 02/06/02. The contractual start date was in November 2004. The draft report began editorial review in February 2015 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Janesh K Gupta reports personal fees and non-financial support from training workshops for Ethicon, personal fees and non-financial support from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Joe Kai reports personal fees from Bayer Group for a postgraduate lecture outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Gupta et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Definition and diagnosis

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), also called menorrhagia, is a common problem that can significantly impact on women’s lives and burden individuals and health-care systems. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that ‘for clinical purposes, HMB should be defined as excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality of life (QoL), and which can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms’. 1 In many previous studies, attempts were made to define HMB using an objective measure of blood loss, by weighing sanitary products or using the alkaline haematin method, with a loss of more than 80 ml of blood per cycle being considered excessive. Menstruation changes over a woman’s reproductive lifespan, with cycle length decreasing and the duration and heaviness of the period increasing with age. Heaviness is thus subjective, defined relative to what a woman considers normal and is influenced by sociocultural and psychological well-being factors. QoL and actual menstrual blood are not closely linked,2,3 so any interventions should aim to reduce the burden of the symptoms for the woman.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is generally considered to be heavy cyclical menstrual blood loss over a minimum of three consecutive cycles without any intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding. Where no organic pathology is present, the term dysfunctional uterine bleeding is used, whereas abnormal uterine bleeding includes that caused by uterine pathology, for example fibroids or genetic factors (e.g. von Willebrand disease). 4–6 The majority of women with HMB have no pathology that can be attributed as the cause of their symptoms, while approximately 30% will have uterine fibroids and 10% uterine polyps, with malignant causes being rare in the pre-menopausal population. 7

With a subjective definition, diagnosis of HMB is made through careful history taking, with any suggestion of pathology such as intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding prompting further investigation, including physical examination, ultrasound and biopsy if endometrial hyperplasia or cancer is suspected. Objective measures are inconvenient and impractical, and indirect measures of menstrual blood loss, such as pictorial diaries, are not consistently accurate and these too fail to reflect women’s experience of what is burdensome for them. 8 A full blood count is recommended by the NICE guidelines,1 but serum ferritin and oestradiol measurement are not considered worthwhile. Further testing for coagulation or thyroid disorders are dependent on symptoms and personal history.

Epidemiology

In various cohorts studies, reported prevalence has ranged from 4% to 51%, although it is acknowledged that differences in definition, measurement (objective vs. subjective), clinical and cultural setting will undoubtedly influence reporting. 1 A UK survey of women aged 18–54 years indicated an annual community incidence HMB of 25% and prevalence of 52%, with a slight increase with increasing age. 9

Heavy menstrual bleeding accounts for 19% of gynaecologist office consultations in the USA10 and 20% in the UK,11 and each year around 6% of women in the USA consult their general practitioner (GP). 12 Another survey found that while 22% of menstruating women over 35 years considered their periods heavy and interfering with their lives, only 7% had consulted their GP in the preceding 6 months. 13 Despite the many factors influencing women’s decisions not to seek help,14 the number and cost of consultations and treatments impose substantial demands on the NHS. In 2004–5, there were 7179 hysterectomies and 9701 endometrial ablations performed; compared with 1989–90 this represents a 69% decrease and an 11-fold increase in the number of procedures for HMB, respectively. 15 Rates of surgical procedures for HMB are 17.8 per 10,000 women aged 25–44 years in the USA,16 and 14.3 per 10,000 women in the UK. 17

Management of heavy menstrual bleeding

There are many treatments used for HMB, including medical therapies and surgical procedures. At the commencement of the ECLIPSE (clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in primary care against standard treatment for menorrhagia) trial, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines18 stated that the initial management should be usually medical, using the combined oral contraceptive (COC), tranexamic acid or mefenamic acid or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena®, Bayer) for women not specifically requiring contraception, but prepared to accept hormonal treatments. For those women requiring contraception, the options are COCs and the LNG-IUS.

In early 2007, NICE produced clinical guidelines for the management of HMB. 1 In these guidelines, pharmaceutical treatments were recommended as the first line of therapy, regardless of whether the women presents in primary or secondary care. Endometrial ablation may be considered as initial therapy, although only after full discussion of the risks and benefits of this and other treatments. Hysterectomy should not be offered as first-line treatment. The RCOG guidelines18 at the time considered the evidence for the effectiveness of other drug therapies as limited, and advised that high-dose norethisterone and long-acting injectable progestogens be used only if all other medical treatments are unsuitable or unacceptable. NICE, however, included these hormonal options in the guidelines to be considered after the LNG-IUS, tranexamic acid, mefenamic acid and COCs.

Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid is a plasminogen activator inhibitor that exerts an antifibrinolytic effect on the endometrium, reducing menstrual blood loss by 50%. 19 It is taken in high doses, of up to 1 g four times per day, during the first 5 days of the menstrual cycle. Initial concerns regarding a potential increase in adverse thrombogenic events has been refuted by long-term studies showing no excess risk. 20

Mefenamic acid

Mefenamic acid is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), which can reduce the formation of prostaglandins, implicated in the abnormal clotting in the endometrium by inhibiting the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase. It is also taken on days 1–5 days of the menstrual cycle, at a dose of 500 mg three times per day, but it is contraindicated in women with bleeding disorders. In terms of reducing menstrual blood loss, mefenamic acid substantially reduces objectively measured loss, but not to the same extent as tranexamic acid. 21

Combined oral contraceptive pill

Combined oral contraceptives of any formulation reduce the thickness of the endometrium and inhibit ovulation, with a resultant reduction in menstrual blood loss of 43%. 22 There is no evidence of any relative difference with other medical treatments. COCs are not suitable for everyone. They are contraindicated for those with a personal history or risk factors for thromboembolism, a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 35kg/m2 or migraine with aura, and are advised to be used with caution in women over 35 years who smoke or who are overweight or obese. 23

Norethisterone

Norethisterone is a synthetic progesterone which can reduce menstrual blood loss in ovulatory women if 10–15 mg is taken daily from day 5 to day 26 of the cycle, but is ineffective if taken only during the late luteal phase, from day 19 to day 26 of the menstrual cycle. Compared with tranexamic acid or the LNG-IUS, norethisterone is not as effective at reducing objectively measured menstrual blood loss. 21,24

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

The LNG-IUS is a highly effective long-acting reversal contraceptive. Since 2009 in the USA, and earlier in Europe, the LNG-IUS has been available for HMB. 23 The LNG-IUS is a T-shaped plastic frame containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which is released at a rate of approximately 20 µg per day and is licensed for 5 years’ use, after which it should be removed and replaced if desired. Fertility is quickly restored after removal. The LNG-IUS is contraindicated in women with a congenital uterine anomaly or who have fibroids that distort the uterine cavity, in women with a uterine or pelvic infection, and in those with a history of gynaecological cancers. The adverse events of interest fall into two categories: those related to an intrauterine device, such as dysmenorrhoea, irregular bleeding, ectopic pregnancy and expulsion of the device; and those related to progestogens, such as bloating, weight gain and breast tenderness. The main disadvantage of the LNG-IUS is the disruption to the menstrual cycle, particularly in the first 6 months, with the number of bleeding and spotting days increasing to a median of 18 days and the cycle becoming irregular in approximately 20% of women, before reducing in duration and severity. 25 The proportion of women who are amenorrhoeic a year following insertion has been reported at around 12%. 26,27

Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for heavy menstrual bleeding

Clinical effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system compared with medical treatments

Prior to the initiation of the ECLIPSE trial, the most comprehensive summary of the data for the LNG-IUS came from a systematic review which identified 10 studies of the LNG-IUS for women with heavy menstrual blood loss (≥ 80 ml per cycle). 28 Of these, only five studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs),20,24,29–31 and only four reported menstrual blood loss reduction in those with the LNG-IUS in place for 3–12 months, in whom the reduction in blood loss ranged from 79% to 96%.

In 2007, the NICE guidance1 considered all pharmaceutical treatments for HMB. In comparing the LNG-IUS with non-surgical options, NICE referred to the Cochrane review,27 which cited three small randomised trials comparing the LNG-IUS with norethisterone,24,32 mefenamic acid32,33 or danazol32 (Danol®, Sanofi-aventis), although the trial reported by Cameron et al. 32 used a now discontinued formulation of the LNG-IUS. From this review, the odds ratio for amenorrhoea (> 3 months) was 8.67 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.52 to 49.35] in favour of the LNG-IUS. The odds ratio for the proportion of women unwilling to continue with treatment was 0.27 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.67) and for the proportion of women satisfied with treatment the odds ratio was 2.13 (95% CI 0.62 to 7.33), both in favour of the LNG-IUS.

For COCs, only one small RCT of four treatments existed at the time of the NICE guidelines,34 suggesting that COCs reduce menstrual blood loss to a greater extent than the NSAID naproxen, but less than mefenamic acid or the gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist danazol. However, the COC used was a first-generation formulation and no data exist for the lower oestrogen doses now available.

There was sufficient evidence in three systematic reviews for NICE to conclude that a tranexamic acid causes a clinically significant reduction in menstrual blood loss for women with HMB, ranging from 29% to 58% in studies lasting up to 1 year, although long-term data are missing. 11,21,27,35 NSAIDs (mefenamic acid or naproxen) were also found to produce clinically important reductions in menstrual blood loss, ranging from 20% to 49%, but were inferior to danazol and tranexamic acid, although NSAIDs have fewer adverse effects than danazol. 36,37

The NICE guidelines development group stated that, in its interpretation of the evidence for pharmaceutical treatments for HMB, a high value was placed on reduction of menstrual blood loss and minimising adverse effects. The guidelines development group based its assessment first on the clinical effectiveness of treatments and, second, on the cost-effectiveness of treatments. The results of the systematic review showed that the LNG-IUS, mefenamic acid, tranexamic acid and COCs could be considered equivalent in terms of clinical effectiveness. However, the guidelines went on to state that, if both hormonal and non-hormonal treatments are acceptable, then the order in which treatment should be considered should be the LNG-IUS, then tranexamic acid, a NSAID or COC, then norethisterone on days 5–26 of the cycle.

An updated review identified seven further randomised trials,38–44 involving only 718 women in total, which compared the LNG-IUS with non-hormonal and hormonal treatments. In an industry-sponsored review,45 reduction in menstrual blood loss was achieved in only 230 women, from five studies,33,38,43,44,46 in which the LNG-IUS was administered. Reported median blood loss had decreased by 85% by 3 months, and had further decreased, by a total of 94%, by 12 months, remaining constant thereafter to 5 years.

The emphasis of all the previous trials has been on the reduction in menstrual blood loss. Very few trials collected data on QoL or impact of the symptoms. A small study of the LNG-IUS compared with norethisterone found no difference in the proportion of women in whom menstrual blood loss interfered with their QoL after treatment. 24

The trial by Lahteenmaki et al. 31 did report on QoL, measured using visual analogue scales (VASs) rather than any validated scale. The study selected women awaiting a hysterectomy and offered them the option of randomisation between continuing their existing treatment and the LNG-IUS. The lack of blinding and the control group remaining on an unsatisfactory treatment is likely to have influenced the women’s attitude to treatment and subjective assessment of QoL, therefore, is inherently biased against existing therapy. 31

Clinical effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system compared with surgery

Prior to the start of the ECLIPSE trial, there were six RCTs comparing the effectiveness of the LNG-IUS with surgery, two using first-generation ablation methods,29,30 three comparing the LNG-IUS with second-generation thermal balloon ablation47–49 and one comparing the LNG-IUS with hysterectomy. 50 No difference in the rates of amenorrhoea or satisfaction rates were seen compared with endometrial ablation, although menstrual blood loss was reduced to a greater extent with ablation. 29,48

In a subsequent Cochrane review of medical versus surgical treatments for HMB,51 an additional six trials, four49,52–54 comparing the LNG-IUS with thermal balloon ablation, one55 comparing the LNG-IUS with hysterectomy and two38,56 comparing the LNG-IUS with first-generation ablation, were included. There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction rates up to 2 years or in most domains of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) measure of QoL. As before, endometrial ablation was significantly more effective than the LNG-IUS in controlling bleeding at 1 year (relative risk 1.19, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.32; p = 0.001). Hysterectomy stopped all bleeding and provided greater satisfaction, but caused serious complications for some women. This review considered the long-term data to be weak.

This review was extended by obtaining individual patient data in order to be able to standardise outcome data, such as satisfaction or, the corollary, dissatisfaction. 57 Rates of dissatisfaction with the LNG-IUS and non-hysteroscopic endometrial destruction were similar (18% vs. 23%; odds ratio 0.8, 95% CI 0.4 to 1.5; p = 0.4). Lack of data from individual patients prohibited any further investigation of subgroups or first-generation ablative methods. There was weak evidence to suggest hysterectomy is preferable to the LNG-IUS (dissatisfaction 5% vs. 17%; odds ratio 2.2, 95% CI 0.9 to 5.3; p = 0.07).

As might be anticipated, women having surgical treatment were significantly less likely to require further surgery within 1 year than women who had a LNG-IUS (relative risk 0.13, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.33; p = 0.00002). None of the hysterectomy group required additional surgery, while about 3% of women who had endometrial ablation required extra surgery during the first year, compared with about 15% of women who were allocated the LNG-IUS. One study38 reported that 14% (4/29) of the surgical group underwent repeat ablation within 3 years (with two having subsequent hysterectomy), while 30% (9/30) of women allocated to the LNG-IUS group discontinued its use and ‘were offered’ endometrial resection. In a Finnish trial58 of 117 women with a LNG-IUS, 60 women no longer had it in situ 5 years after randomisation; 50 of these women had had a hysterectomy (42% of those randomised to the LNG-IUS) and one had had endometrial ablation.

The NICE guidelines1 highlighted the high level of subsequent surgery associated with the LNG-IUS and recommend that endometrial ablation may be offered as an initial treatment for HMB after full discussion with the woman of the risks and benefits and of other treatment options, while hysterectomy should not be used as a first-line treatment solely for HMB.

Cost-effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system compared with other treatments

The first trial to incorporate a cost-effectiveness analysis was the Finnish trial cited above. 50,58 There was no statistically significant difference in QoL scores between the two treatment groups at 5 years, as measured by the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) instrument. Mean direct costs remained significantly lower in the LNG-IUS arm (US$1892) than in the hysterectomy arm (US$2787), despite 42% of women in the LNG-IUS arm going on to have a hysterectomy. This trial, however, compared the LNG-IUS with hysterectomy in women referred to hospital. No economic analysis relevant to the use of the LNG-IUS in a UK primary care setting is available, nor had the relative cost-effectiveness of the LNG-IUS relative to medical treatment been assessed at the start of the ECLIPSE trial.

The health economic assessment performed in the process of developing the NICE guidelines populated a decision model with data predominantly from the Finnish study, and made significant assumptions regarding the effectiveness and discontinuation rates of COCs, tranexamic acid and mefenamic acid. The results showed that the LNG-IUS is the more effective treatment option when long-term use of a treatment is required, as the LNG-IUS generated more quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), at a lower cost, than any other pharmaceutical treatment strategy. The base-case result was £840 per QALY gained. 1 The uncertainty in this result was not explored at all and so the result could be highly misleading.

Rationale for the ECLIPSE trial

An early systematic review highlighted the lack of evidence on the relative benefits of the LNG-IUS compared with medical treatment and recommended large pragmatic trials. 28 This was reiterated by the NICE guidelines. 1 The LNG-IUS is an effective, relatively safe, treatment for HMB, at least in the short term, although it is less effective than endometrial ablation. However, women with HMB often have additional concerns, which may be altered by treatment. These include the presence or absence of pain, risk of sexually transmitted disease and reproductive function. Short-term reduction in menstrual blood loss may not translate into an improvement in a woman’s overall QoL or her need to seek further treatment, particularly as the LNG-IUS discontinuation rates are high.

Moreover, the consequences of HMB and its treatment extend for many years, and so a treatment that appears to be effective at 1 year may merely delay, not prevent, a definitive solution such as surgical intervention. None of the early trials measured the effect of HMB on women’s lives or followed women for longer than 1 year. In relation to the LNG-IUS, there may be ‘phase shifting’ of the patient’s journey. For example, once the device is removed, some patients’ symptoms may recur, resulting in later surgery. If a woman discontinues any medical treatment, it could be because the HMB has resolved, or it could be that the treatment does not produce sustained benefit. This means that it is essential to determine and compare the long-term consequences of different treatments over a prolonged period of time appropriate to the long natural history of HMB.

It is also unclear whether or not women presenting in primary care with HMB are best treated with a LNG-IUS. The LNG-IUS is slightly more difficult to insert than standard contraceptive coils and specific training for GPs is required. 1 A LNG-IUS is occasionally associated with troublesome menstrual irregularities, especially in the first few months, and is often removed for this reason. Given the potential complications, better evidence to establish the effectiveness of the LNG-IUS as a first-line therapy is needed before it becomes widely used in primary care.

It is apparent that a RCT of the LNG-IUS should take into account a range of patient needs and preferences. These include:

-

women’s preferences for contraception: some desire the maintenance of fertility, some require contraception contemporaneously with relief from HMB, while some others may want to be sterilised

-

long-term assessment of the treatment ‘pathway’, with different initial policies

-

self-reported outcome measures that identify the impact of treatment on overall QoL and further treatment decisions

-

the initial management of HMB in primary care

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and acceptability of treatment policies.

The choice of comparator needs to reflect current practice. The treatment objective in HMB is to alleviate heavy menstrual flow and, consequently, to improve QoL. Iron-deficiency anaemia must also be prevented. Both the superseded RCOG18 and NICE guidelines supported the use of COCs, tranexamic acid, mefenamic acid, injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-ProveraTM, Pfizer Ltd) and norethisterone, with the choice dependent on the woman’s preferences for hormonal or non-hormonal treatments and contraceptive needs. The comparison group was defined as usual medical treatment, with the choice specific drug being a joint decision between the GP and patient.

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the clinical effectiveness of the LNG-IUS compared with standard medical treatment for women seeking treatment for HMB in primary care in the short term (2 years following randomisation).

Secondary objective

-

To assess the clinical effectiveness of initial treatment with the LNG-IUS compared with standard medical treatment for women seeking treatment for HMB in primary care in the medium term (5 years following randomisation).

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of the LNG-IUS compared with standard medical treatment in the short and medium term.

-

To explore the perspectives of trial participants or women with HMB who declined to be randomised in a longitudinal qualitative study.

-

To measure the reliability and validity properties of the Menorrhagia Multi-Attribute Scale (MMAS).

Chapter 2 Outcome measures for the evaluation of treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding

Introduction

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a common gynaecological condition in the UK that has a significant impact on many women’s well-being. The principal driver for treatment of HMB is women’s experience of its impact on their lives. Women are mainly treated on the basis of symptoms, and therefore assessment of the condition and of the effectiveness of treatment has a large subjective component. There is poor correlation between quasi-objective measures of HMB, for example self-reports of blood loss, so a woman’s subjective assessment of the perceived impact on her QoL is increasingly used to assess treatment success. As the aim of treatment is to improve women’s well-being and QoL, it is necessary to have valid and reliable instruments to measure this.

A systematic review of research published before the ECLIPSE trial,59 which assessed the quality of QoL instruments from 19 studies of HMB, was used to select the most appropriate instruments to use for the trial. Studies for the review were identified through MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and PsycLIT, and the references of primary and review articles. Search terms included menorrhagia, questionnaires, psychometry, psychometrics, psychological(al) tests and QoL. Studies were selected if they measured QoL in women with HMB as either an outcome measure or as part of the development of the QoL instrument itself. They were assessed using a checklist of items for clinical face validity (i.e. issues relevant to patients’ expectations and concerns) and items for measurement properties (including reliability, responsiveness, criterion or construct validity and acceptability). 60

In terms of quality, although 90% of studies complied with more than half of the criteria for measurement properties, only 37% of studies complied with more than half the criteria for face validity. Only two studies61,62 used a condition-specific QoL instrument for HMB, which considered the most appropriate measure to assess the effect of treatment; these were instrument development studies rather than studies using the instrument as an outcome measure. The generic SF-36 was the most commonly used (63% of studies). This generic instrument has been validated in HMB60 and seems to be reliable and responsive;60,63 however, it is designed to assess QoL on a continuum from full health to death over the previous 4 weeks. Therefore, the SF-36 is not entirely appropriate for women with HMB because the symptoms of HMB are cyclical and the condition is distressing, but not life-threatening. This makes using the SF-36 on its own an inappropriate instrument for a patient-based outcome measure in HMB.

This review concluded that there is a need for methodologically sound condition-specific QoL instruments in HMB with clinical face validity to assess treatment outcomes. One condition-specific instrument identified as having high face validity is the MMAS, developed by Shaw et al. 61 This was developed in collaboration with women with HMB using a multi-attribute utility method. 64 It was decided that this scale should be the principal outcome measure for the ECLIPSE trial. However, although the MMAS was designed to have good face and content validity, other psychometric properties of this instrument, such as reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and floor and ceiling effects, could not be evaluated in the original study. One study reported a small advantage for the MMAS over the SF-36 in predicting management outcome for HMB,65 but otherwise the measurement properties of the questionnaire when used in a treatment or observational study had not been reported before. These properties of the MMAS were assessed at the beginning of the ECLIPSE trial.

The disadvantage of the MMAS is that, as a condition-specific measure, it is anchored by full health and the worst possible state for the condition, rather than full health and death, as in generic measures. This is important in the economic evaluation of treatments, which is recommended by NICE. 66 Since economic evaluation is used by decision-making bodies such as NICE to help with decisions about resource allocation, it is important in the context of treatment trials. NICE endorses the use of generic instruments in economic evaluation of treatments in order to calculate the QALY. 66 The QALY reflects changes in both the quantity of life and the QoL, where quality is measured on a scale from 0 (death) to 1 (full health).

In order to undertake an economic evaluation in the ECLIPSE trial, it was therefore necessary to include generic measures in addition to the condition-specific MMAS. In the systematic review cited above,59 the SF-36 health survey questionnaire was the most commonly used generic instrument. However, NICE recommend the use of the EQ-5D,66 which can more straightforwardly be converted to QALYs. Clark et al. 59 suggest that, in order to ensure that a trial has an appropriate set of outcome measures, a condition-specific instrument could be used in combination with a generic instrument. It was therefore decided to combine the MMAS with a generic instrument. There was better evidence for the use of the SF-36 in HMB, but given the recommendation from NICE to use the EQ-5D and its relative brevity it was decided to use both generic instruments in the ECLIPSE trial. In addition to the QoL instruments, it was decided to include a measure of sexual well-being. Clinical experience has shown that sexual activity is an important dimension of women’s lives which may be specifically affected by HMB. The outcome measures used are described below. 61

Outcome measures used in the ECLIPSE trial

Menorrhagia Multi-Attribute Scale

The MMAS questionnaire captures the subjective consequences of HMB on six domains: practical difficulties, social life, psychological well-being, physical health, work routine and family life. Each of the six domains has four statements which represent four levels of response. Respondents indicate the statement which best matches their feelings for each domain. The statement scores derive from a weighting of the domains and a weighting of the statements in level of severity by women in the origin study. Scores range from 0 (worst possible state in all domains) to 100 (best possible state in all domains).

Medical outcomes study: Short Form questionnaire-36 items

The SF-36 version 2 is a 36-item short-form survey that measures general health-related QoL. The SF-36 is a practical and reliable way to obtain important health outcomes data in a variety of settings, measuring eight domains of health: physical functioning, role limitations owing to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations owing to emotional problems and mental health. Respondents are asked to recall how they have felt over the previous 4 weeks. It is commonly used in studies of HMB. 65

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

The EQ-5D is a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome and is widely used in economic evaluations of medical interventions. Applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments, it provides a simple descriptive profile and also a single-index value for health status measured on a VAS.

The Sexual Activity Questionnaire

The Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ) was developed as a self-report questionnaire, for use in gynaecological clinical trials, which would be quick to complete and acceptable to the majority of women. 67 Three dimensions of perceptions of sexual activity are measured: pleasure, discomfort and habit.

Measurement of reliability and validity properties of the menorrhagia multi-attribute quality-of-life scale

Method

Participants

Data from the first 431 women enrolled in the ECLIPSE trial were analysed for this study.

Procedure

Participants completed the MMAS, SF-36 version 2, EQ-5D and the SAQ as part of the baseline measures for the trial before randomisation, but before treatment. Fifty women were also invited to participate in a test–retest study of the MMAS and completed the questionnaires again within 2 weeks of the baseline measurement, but before treatment commenced.

Psychometric analysis

The measurement properties of the MMAS were assessed using traditional psychometric procedures. Estimates of reliability and validity were made using intra- and inter-test correlations, with additional comparison of means for the subscales of the questionnaire. Floor and ceiling effects were also assessed using frequency data on high and low scores.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 41.25 years [standard deviation (SD) 5.3 years]. The ethnic mix of the sample was representative of the patient population for the area and the trial as a whole, with 93% of women categorising themselves as from the two main ethnic groups, white British (83%) and South Asian (10%).

Reliability

Of the 50 women asked to take the questionnaire again within 2 weeks, 49 returned completed questionnaires. The test–retest correlation for the total MMAS score was acceptable (r = 0.836), suggesting that it is stable over time. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency of the six items of the MMAS. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.82 and lies within the range 0.7 and 0.9, suggesting that the items are all measuring aspects of the same construct. 68 Evidence of the homogeneity of the MMAS was also provided by the item total correlations (the correlation between each item and the total score minus that item) which range between 0.44 and 0.68. Only one such correlation fell below 0.6, that for ‘practical difficulties’ caused by HMB.

Validity

The MMAS has already been shown to have good face validity, so this analysis concentrated on construct validity, that is the extent to which the instrument measures what it is intended to measure. An important method of demonstrating construct validity is by showing that an instrument correlates with other instruments measuring similar constructs, for example generic QoL scales (convergent validity), and does not correlate with measures of different constructs, for example age and BMI (discriminant validity).

Convergent validity

To show convergent validity, correlations between test scores should be moderate to high, that is 0.4 or higher. Table 1 shows the correlations between the MMAS total score, the subscales of the SF-36 and the EQ-5D. These show moderate correlations for most components of the SF-36, but weaker correlations for physical functioning, general health perception and for the EQ-5D standardised score.

| Questionnaire and domains | MMAS total score | |

|---|---|---|

| r | n | |

| SF-36 subscales | ||

| Physical functioning | 0.33 | 420 |

| Physical role limitations | 0.45 | 422 |

| Emotional role limitations | 0.49 | 421 |

| Social functioning | 0.54 | 427 |

| Mental health | 0.40 | 426 |

| Energy/vitality | 0.42 | 426 |

| Pain | 0.38 | 428 |

| General health | 0.32 | 419 |

| EQ-5D summary score | 0.32 | 428 |

The individual domain scores of the MMAS were compared with the SF-36 subscales. With the exception of the practical difficulties domain on the MMAS, which did not significantly correlate with any SF-36 subscale, the highest correlations were between each of the MMAS domains and the SF-36 social functioning scale. The correlation between the psychological health scales of the two instruments is 0.39, and that between the MMAS relationships scale and the SF-36 emotional role limitations is 0.47. However, these correlations of subscales should be interpreted with caution as there are only 4 points on the MMAS subscales. In order to investigate these relationships further, respondents were divided into four groups for each MMAS domain and their scores on the SF-36 were compared using analysis of variance. The results for most subscales and domains were highly significant for each comparison, with high scores on the MMAS corresponding to high scores on the SF-36. Again, the exception was for comparisons in the practical difficulties domain. Here, three comparisons were not significant: mental health (F3,422 = 1.66; p = 0.175), pain (F3,424 = 0.62; p = 0.60) and general health (F3,415 = 2.21; p = 0.09).

There was a small non-significant difference in the total MMAS scores of women reporting that they were not engaging in sexual activity on the SAQ and those who were (38.86 and 41.49, respectively). It may be that the MMAS relationship domain reflects a particular problem with sexual relationships. To test this, comparisons were made between the scores on the pleasure, discomfort and habit scales of the SAQ for women scoring at the four different levels of the relationship domain. This revealed a statistically significant effect of level on the discomfort scale (F3,321 = 4.05; p = 0.008), but non-significant effects of pleasure (F3,321 = 1.71; p = 0.165) and habit (F3,326 = 2.54; p = 0.057).

Discriminant validity

The MMAS total score would not be expected to correlate with age or BMI. As expected, these correlations are very low for age (r = 0.086) and for BMI (r = –0.057). As well as providing evidence for the validity of the MMAS, it suggests that it can be used with all age groups.

Acceptability

All items in the MMAS were completed by all participants, indicating that the instrument was acceptable to them.

Floor and ceiling effects

In psychometric instruments, floor and ceiling effects have implications for the precision of the instrument and its responsiveness to change, as they reduce the likelihood that the instrument will measure further improvement or deterioration. In this sample, five (1.2%) women’s scores were the lowest possible and three (0.7%) were the highest possible. The overall distribution of scores was slightly positively skewed (skew = 0.41, standard error = 0.12), which is what might be expected in a sample of women just about to embark on treatment for HMB. These statistics indicate that there are no floor or ceiling effects.

Discussion

This study investigated further the psychometric properties of the MMAS. It has shown that, in addition to having high face validity, the MMAS has good convergent and discriminant validity, and test–retest reliability. It also has high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.82, which is further evidence of reliability and indicates that all the items are measuring different aspects of the same construct.

The overall MMAS score showed moderate correlation with most of the subscales of the SF-36. Lower correlations were found for physical functioning and general health perception. Rather than being a negative feature, these low correlations may reflect the inappropriateness of the SF-36 as the sole measure of QoL in women with HMB. The physical functioning subscale is heavily weighted to mobility and self-care, not likely to be affected by HMB. The general health subscale and the EQ-5D, which was also relatively poorly correlated with the MMAS, may not be precise enough to measure differences in this patient group, especially when women are asked to consider their general condition rather than that pertaining to their menstrual cycle.

Conversely, scores on the practical difficulties subscale of the MMAS were not related to other QoL measures. This domain of the MMAS is very specific to HMB, relating to sanitary protection and flooding and may pick up specific important issues not measured by generic scales.

All women completed the whole of MMAS, which suggests that it is acceptable to women and seen to be relevant. It could be argued that this sample was more highly motivated than women with HMB more generally because they had already agreed to take part in the ECLIPSE trial. However, there were missing data in other questionnaires administered at the same time. These results suggest that the MMAS has good measurement properties and is, therefore, an appropriate condition-specific instrument to measure the outcome of treatment for HMB.

General discussion

In this chapter we have discussed some of the challenges in assessing the outcome of treatment trials for HMB. We have demonstrated that the MMAS is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the impact of HMB, and its treatment, on women. However, although the MMAS appears to be the most suitable measure, owing to its condition-specific nature it cannot produce QALYs and is therefore not appropriate for economic evaluation.

A more recent systematic review of the QoL instruments used in HMB by Sanghera et al. 69 found no consensus on the most appropriate economic measure to use when valuing outcomes in HMB, with both the SF-36 and EQ-5D lacking face validity. Evidence suggests that women do not consider HMB to be solely a health-related condition, so purely generic health-related QoL measures are unsuitable. This is supported by the analysis, which showed that the practical difficulties question in the MMAS did not correlate with any of the components of the health-related generic instruments.

A different approach that Sanghera et al. 69 explored in their review is willingness to pay (WTP). WTP considers a broader range of QoL than that related to health. Many studies have successfully elicited WTP values in other disease areas,70 so perhaps WTP could prove to be the most suitable economic measure in HMB in future trials. However, even at the time of this later review there was insufficient evidence for its use, with only one study reviewed assessing the reliability of WTP. 69

Conclusions

At the beginning of the ECLIPSE trial the evidence suggested that while the primary outcome of the trial, that is, the impact of treatment on women with HMB, should be measured by a condition-specific instrument, economic evaluation of the trial required generic instruments. In addition, clinical experience suggested that sexual well-being was an aspect of women’s lives particularly affect by HMB, so it was decided to investigate this in more detail using the SAQ. Consequently, four self-report instruments were chosen to measure the outcomes of the ECLIPSE trial, MMAS as the primary outcome measure with the SF-36 version 2, the EQ-5D (both the profile and VAS scores) and the SAQ as secondary outcome measures.

Chapter 3 Methods and results of the randomised controlled trial up to 2 years’ follow-up

Objectives

The study rationale is presented in Chapter 1. The objectives of the RCT presented in this chapter were to assess the clinical effectiveness of the LNG-IUS compared with standard medical treatment for women seeking treatment for HMB in primary care, with up to 2 years’ follow-up.

Methods

Population

Women between 25 and 50 years of age who presented to their GP with HMB involving at least three consecutive menstrual cycles were eligible to participate. Women were excluded if they intended to become pregnant over the next 5 years, were taking hormone replacement therapy or tamoxifen (SoltamoxTM, Rosemount Pharmaceuticals), had intermenstrual bleeding (between expected periods) or post-coital bleeding or findings suggestive of fibroids (abdominally palpable uterus equivalent in size to that at 10–12 weeks’ gestation) or other disorders, or had contraindications to or a preference for either the LNG-IUS or usual medical treatments. Women with heavy, irregular bleeding were ineligible unless the results of endometrial biopsy were reported to be normal; no further investigations were mandated by the protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

Randomisation

Patients were assigned to a study group by telephone or a web-based central randomisation service at the University of Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit. A computerised, minimised randomisation procedure was used to achieve balance between the groups with respect to age (< 35 years or ≥ 35 years), BMI (≤ 25 kg/m2 or > 25 kg/m2), duration of symptoms (< 1 year or ≥ 1 year), need for contraception (yes or no) and heavy HMB alone or HMB accompanied by menstrual pain. GP practice was not included as a minimisation variable to avoid any chance of the allocation becoming too predictable.

Study interventions and compliance

Eligible women who provided written informed consent were randomly assigned to either the LNG-IUS or usual medical treatment. Usual treatment options included mefenamic acid, tranexamic acid, norethisterone, a combined oestrogen–progestogen or progesterone-only oral contraceptive pill (any formulation), or medroxyprogesterone acetate injection and were chosen by the physician and patient on the basis of contraceptive needs or the desire to avoid hormonal treatment. 1,18 The particular medical treatment to be used was specified before randomisation. Subsequently, treatments could be changed (from one medical treatment to another, from the LNG-IUS to medical treatment, or from medical treatment to the LNG-IUS) or could be discontinued because of a perceived lack of benefit, side effects, a change in the need for contraception, referral for endometrial ablation or hysterectomy, or other reasons, according to usual practice. 1,18 Treatment changes reported by patients were confirmed with the GP.

Outcome measures and follow-up

The primary outcome measure was the condition-specific MMAS,61,71 which is designed to measure the effect of HMB on six domains of daily life (practical difficulties, social life, psychological health, physical health, work and daily routine, and family life and relationships). Summary scores, which range from 0 (severely affected) to 100 (not affected), were assessed at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after randomisation. Details on how summary scores are calculated can be found elsewhere. 61 The MMAS has a high degree of reliability and internal consistency,71 has good content and construct validity,61,71 is responsive65,72 and is acceptable to respondents. 61,65,71,72 Secondary outcome measures included general health-related QoL and sexual activity. To assess QoL, we used three instruments: the SF-36 version 2 [with scores ranging from 0 (severely affected) to 100 (not affected)], the EQ-5D [with scores ranging from −0.59 (health state worse than death) to 100 (perfect health state)] and the EQ-5D VAS [with scores ranging from 0 (worst health state imaginable) to 100 (most perfect health state imaginable)]. The validated SAQ measures pleasure [with scores ranging from 0 (lowest level) to 18 (highest level)], discomfort [with scores ranging from 0 (greatest) to 6 (none)] and frequency (assessed relative to perceived usual activity as an ordinal response). 73 Scores were obtained before randomisation and by mail at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after randomisation. Data were collected from participating clinicians regarding all serious adverse events, defined as adverse events that resulted in death, disability or hospitalisation. Patients were also asked to report any hospitalisations and adverse events leading to discontinuation of the study drug.

Study oversight

The study sponsor was the University of Birmingham. Study oversight was provided by an independent steering committee and an independent data and safety monitoring committee, whose three reviews of interim data provided no reason to modify the trial protocol on the basis of pragmatic stopping criteria,74 other than to support revision of the recruitment target, which is described in Statistical considerations. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, which is available at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/020602. Approval of the study was obtained from the South-West England Multicentre Research Ethics Committee, and clinical trial authorisation was received from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority. All medications and devices were prescribed by providers through the NHS. The manufacturers of the LNG-IUS and other therapeutic agents used in the study were not involved in any aspect of the trial.

Statistical analysis

The study was originally designed to have 95% power at p < 0.01 to detect small to moderate (0.3 SD) differences in mean MMAS score between groups at any one time point. 75 Following interim review of recruitment rates, in consultation with the independent data monitoring committee, the power and type 1 error parameters were revised to more conventional levels of 90% and p = 0.05, to allow timely completion of the study. This required an enrolment of 470 patients; we increased the sample size to 570 to allow for up to 20% loss to follow-up.

Analyses was by intention to treat with continuous measures compared using multilevel repeated-measures models,76 including parameters allowing for participant, treatment, time and baseline score. Responses including all three time points were considered in the primary analysis. Differences between slopes were assessed by including treatment-by-time interaction parameters in the models. If these were not significant (p > 0.05), then they were dropped from models and constant treatment differences over time were assumed. In a similar fashion, treatment-by-subgroup interaction parameters were included in the above model to test for the importance of the prespecified subgroup parameters (same as the minimisation variables, see Randomisation). Treatment effect estimates within subgroups are presented where interaction parameters were statistically important. Differences between groups at each assessment time point were also examined by analysis of covariance (adjusting for baseline score). Changes from baseline score within groups were examined using paired t-tests.

A number of sensitivity analyses were performed on the primary outcome to test the robustness of the results. 77,78 Analyses were performed excluding data received subsequent to a crossover to the alternative treatment group and also once study treatment was ceased altogether. Further sensitivity analyses included assigning the best possible score (100) to those women who indicated that they were no longer experiencing bleeding and did not complete the MMAS, and a carried forward (pre-intervention) score for those undergoing hysterectomy or endometrial ablation. Further analyses included the exclusion of MMAS data from late returned booklets (defined as more than 3 months past the due date) and an analysis assuming all missing responses were the worst possible score (0). Missing MMAS responses were also simulated using a multiple imputation approach with analysis performed on the resulting 20 simulated data sets. 78

Kaplan–Meier plots were constructed for time to first treatment change with women censored at date of last follow-up or, if appropriate, date of death, withdrawal or loss to follow-up. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to construct hazard ratios. Standard statistical methods were used to test the statistical significance of other responses (chi-squared tests for dichotomous data, Cochrane–Armitage test for trend and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for ordinal data). Effect sizes are presented with 95% CIs and two-sided p-values for all. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for analyses.

Results

Patients and follow-up

Between February 2005 and July 2009, a total of 571 women with HMB from 63 UK centres (median centre recruitment was three, interquartile range one to seven) were randomly assigned to either the LNG-IUS (285 women) or usual medical treatment (286 women). Baseline characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Usual medical treatment (n = 286) | LNG-IUS (n = 285) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ≥ 35a | 255 (89%) | 257 (90%) |

| Mean (SD) | 41.8 (5.5) | 42.1 (5.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| ≥ 25a | 200 (70%) | 200 (70%) |

| Mean (SD) | 29.3 (6.7) | 29.1 (6.1) |

| Ethnic groupb | ||

| White | 246 (86%) | 225 (79%) |

| Asian | 23 (8%) | 28 (10%) |

| Black | 12 (4%) | 18 (6%) |

| Mixed | 4 (1%) | 9 (3%) |

| Other | 1 (< 1%) | 4 (1%) |

| Duration of HMB ≥ 1 yeara | 229 (80%) | 231 (81%) |

| Presence of menstrual paina | 211 (74%) | 213 (75%) |

| Contraceptive requirementa | 55 (19%) | 55 (19%) |

| Copper or non-hormonal coil in place | 10 (3%) | 9 (3%) |

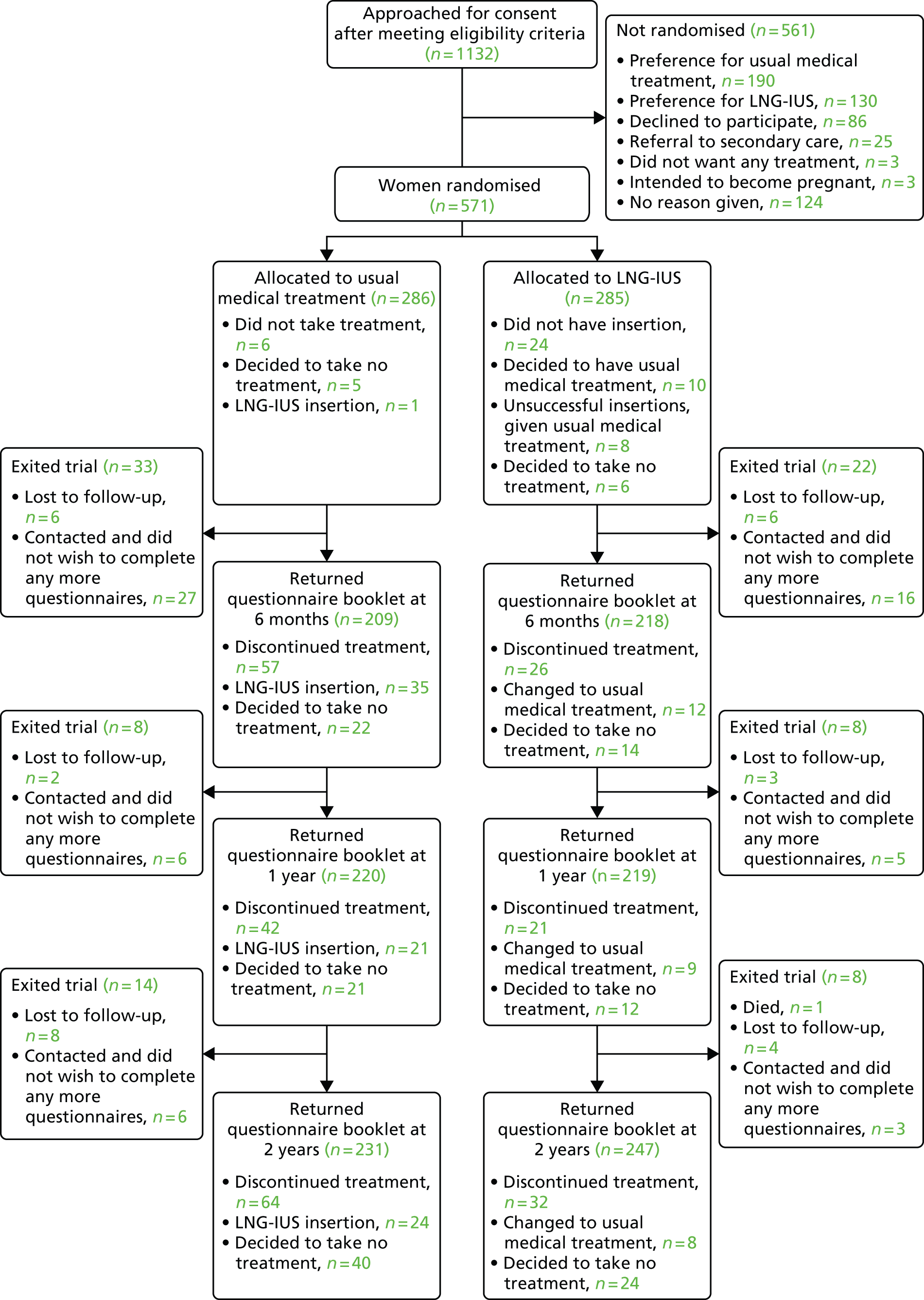

For 215 (75%) of the women assigned to usual medical treatment, the initial prescription, decided prior to randomisation, was for mefenamic acid, tranexamic acid or a combination of the two drugs (Table 3); 55 (19%) of the women in the usual treatment group required contraception. Study questionnaire booklets were returned by 478 (84%) of the patients at the 2-year time point (see Figure 1);38 of these women, 45 (9%) could not complete the MMAS appropriately because their menstrual bleeding had ceased, but they completed other parts of the booklet and this information was used to inform the sensitivity analysis.

| Intended prescriptions | Usual medical treatment (n = 286) | LNG-IUS (n = 285) |

|---|---|---|

| Mefenamic acid and tranexamic acid | 134 (47%) | 123 (43%) |

| Tranexamic acid alone | 50 (17%) | 66 (23%) |

| Mefenamic acid alone | 31 (11%) | 23 (8%) |

| High-dose norethisterone alone | 20 (7%) | 23 (8%) |

| COC alone | 16 (6%) | 22 (8%) |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate injection only | 14 (5%) | 1 (< 1%) |

| Mefenamic acid, tranexamic acid and COC | 9 (3%) | 14 (5%) |

| Other combinationa,b | 12 (4%) | 13 (5%) |

Of the 285 women randomly assigned to the LNG-IUS, 24 (8%) did not have the intrauterine system (IUS) inserted: 10 chose usual medical treatment, six chose no treatment and, in eight, insertion of the system was unsuccessful and, therefore, usual medical treatment was subsequently instituted (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Enrolment, randomisation and follow-up to 2 years of the study patients. See Appendices 1 and 2 for reasons for discontinuation of treatment.

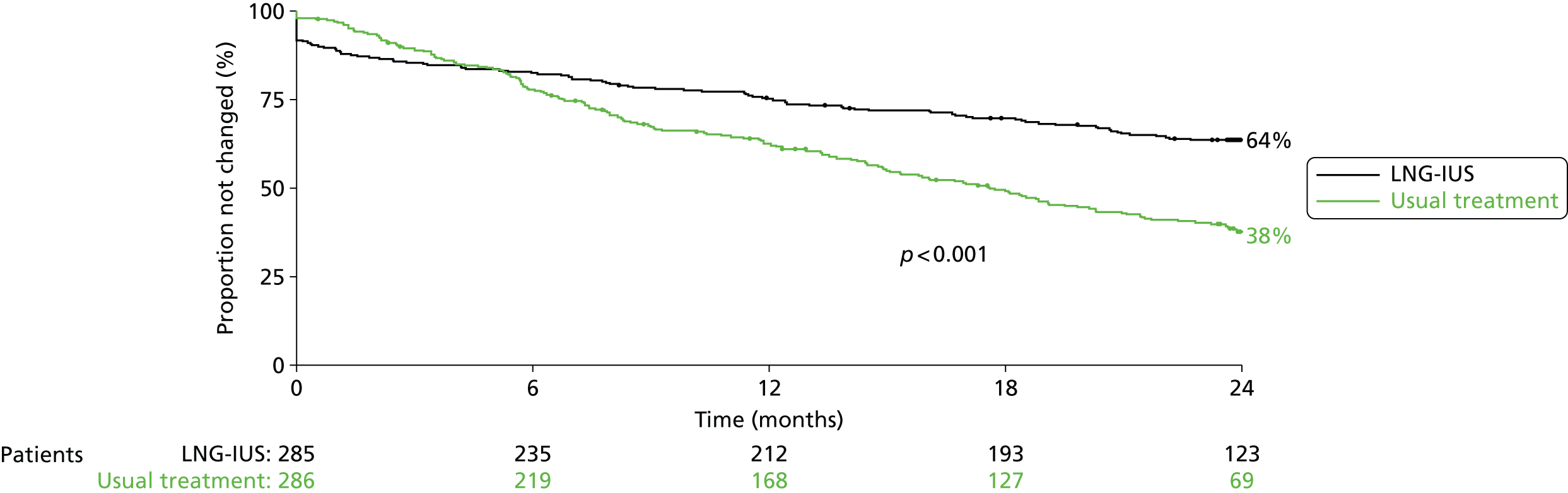

Women in the LNG-IUS group were almost twice as likely as those in the usual treatment group to still be receiving their assigned treatment at 2 years (64% vs. 38%; p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The most common reasons cited for discontinuation of the LNG-IUS were lack of effectiveness (37%) and irregular or prolonged bleeding (28%). Of the 163 women who discontinued usual medical treatment, 80 (49%) switched to the LNG-IUS. The most common reason for discontinuation of usual medical therapy was lack of effectiveness (53%). Reasons for discontinuing therapy are summarised in Appendices 1 and 2.

FIGURE 2.

Time to first treatment change during 2 years’ follow-up. Data are for women who crossed over from the assigned study treatment to the other study treatment and for those who discontinued treatment.

Primary outcome: Menorrhagia Multi-Attribute Scale

In both groups, total scores on the MMAS were significantly improved, compared with baseline scores, at 6 months, and this improvement was maintained at 1 and 2 years (Figure 3 and Table 4) However, improvements in scores were significantly greater among women assigned to the LNG-IUS than among those assigned to usual treatment over the course of the 2 years (mean difference in scores 13.4 points, 95% CI 9.9 to 16.9 points; p < 0.001). This difference was apparent by 6 months and maintained thereafter.

FIGURE 3.

Primary outcome in the two treatment groups up to 2 years’ follow-up. The primary outcome was the score on the MMAS (scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater severity). Mean MMAS scores are shown for the two groups at 6, 12, and 24 months. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Overall, the average difference in scores between the women treated with the LNG-IUS and those treated with the usual medical therapy was 13.4 points (95% CI 9.9 to 16.9 points; p < 0.001).

| Treatment group and comparisons | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 2 years | Overalla |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual medical treatment, mean (SD, n) | 39.2 (21.3, 269) | 61.0 (25.1, 212) | 61.5 (26.3, 216) | 66.8 (28.5, 208) | – |

| Change within group (95% CI) | – | 21.4 (18.1 to 24.7; p < 0.001) | 21.1 (17.5 to 24.6; p < 0.001) | 26.8 (22.8 to 30.8; p < 0.001) | – |

| LNG-IUS, mean (SD, n) | 42.5 (20.5, 280) | 74.9 (22.5, 222) | 78.8 (25.0, 218) | 81.0 (23.2, 225) | – |

| Change within group (95% CI) | – | 32.7 (29.3 to 36.0; p < 0.001) | 35.0 (31.2 to 38.7; p < 0.001) | 39.0 (35.4 to 42.6; p < 0.001) | – |

| Difference between groups (95% CI) | – | 12.8 (8.6 to 17.0; p < 0.001) | 16.0 (11.4 to 20.7; p < 0.001) | 13.3 (8.6 to 18.1; p < 0.001) | 13.4 (9.9 to 16.9; p < 0.001) |

The effect in favour of the LNG-IUS was apparent in all six individual domains of the MMAS at every time point through examination of the frequencies of responses (Table 5).

| Domain and response | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 2 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual medical treatment (n = 269) | LNG-IUS (n = 280) | Usual medical treatment (n = 212) | LNG-IUS (n = 222) | Usual medical treatment (n = 216) | LNG-IUS (n = 218) | Usual medical treatment (n = 208) | LNG-IUS (n = 225) | |

| Practical difficulties | ||||||||

| 1. None | 6 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 48 (23%) | 131 (59%) | 61 (28%) | 142 (65%) | 82 (39%) | 152 (68%) |

| 2. Extra sanitary protection only | 86 (32%) | 100 (36%) | 115 (54%) | 71 (32%) | 100 (46%) | 50 (23%) | 71 (34%) | 54 (24%) |

| 3. Extra sanitary protection and clothes | 92 (34%) | 92 (33%) | 29 (14%) | 9 (4%) | 30 (14%) | 14 (6%) | 35 (17%) | 10 (4%) |

| 4. Severe problems | 85 (32%) | 81 (29%) | 20 (9%) | 11 (5%) | 25 (12%) | 12 (6%) | 20 (10%) | 9 (4%) |

| Social life during cycle | ||||||||

| 1. Unaffected | 16 (6%) | 26 (9%) | 57 (27%) | 126 (57%) | 68 (31%) | 145 (67%) | 86 (41%) | 157 (70%) |

| 2. Slightly affected | 122 (45%) | 139 (50%) | 106 (50%) | 78 (35%) | 98 (45%) | 53 (24%) | 77 (37%) | 51 (23%) |

| 3. Limited | 106 (39%) | 92 (33%) | 42 (20%) | 16 (7%) | 38 (18%) | 11 (5%) | 35 (17%) | 14 (6%) |

| 4. Devastated | 25 (9%) | 23 (8%) | 7 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 12 (6%) | 9 (4%) | 10 (5%) | 3 (1%) |

| Psychological health during cycle | ||||||||

| 1. No worries | 23 (9%) | 29 (10%) | 56 (26%) | 99 (45%) | 64 (30%) | 127 (58%) | 85 (41%) | 133 (59%) |

| 2. Some anxiety and worry | 119 (44%) | 129 (46%) | 107 (50%) | 99 (45%) | 105 (49%) | 62 (28%) | 79 (38%) | 66 (29%) |

| 3. Often feel down and worry | 100 (37%) | 100 (36%) | 36 (17%) | 19 (9%) | 37 (17%) | 20 (9%) | 35 (17%) | 18 (8%) |

| 4. Depressed and cannot cope | 27 (10%) | 22 (8%) | 13 (6%) | 5 (2%) | 10 (5%) | 9 (4%) | 9 (4%) | 8 (4%) |

| Physical health and well-being during cycle | ||||||||

| 1. Well and relaxed | 7 (3%) | 11 (4%) | 48 (23%) | 75 (34%) | 50 (23%) | 101 (46%) | 76 (37%) | 113 (50%) |

| 2. Well and relaxed most of the time | 55 (20%) | 55 (20%) | 72 (34%) | 84 (38%) | 75 (35%) | 73 (33%) | 57 (27%) | 75 (33%) |

| 3. Often tired and not especially well | 165 (61%) | 178 (64%) | 84 (40%) | 57 (26%) | 79 (37%) | 36 (17%) | 67 (32%) | 29 (13%) |

| 4. Very tired and not well at all | 42 (16%) | 36 (13%) | 8 (4%) | 6 (3%) | 12 (6%) | 8 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 8 (4%) |

| Work/daily routine during cycle | ||||||||

| 1. No disruptions | 22 (8%) | 19 (7%) | 57 (27%) | 121 (55%) | 67 (31%) | 140 (64%) | 81 (39%) | 146 (65%) |

| 2. Occasional disruptions | 92 (34%) | 127 (45%) | 107 (50%) | 80 (36%) | 90 (42%) | 54 (25%) | 79 (38%) | 55 (24%) |

| 3. Frequent disruptions | 125 (46%) | 104 (37%) | 39 (18%) | 16 (7%) | 50 (23%) | 17 (8%) | 41 (20%) | 16 (7%) |

| 4. Severe disruptions | 30 (11%) | 30 (11%) | 9 (4%) | 5 (2%) | 9 (4%) | 7 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 8 (4%) |

| Family life/relationships during cycle | ||||||||

| 1. Unaffected | 33 (12%) | 41 (15%) | 61 (29%) | 95 (43%) | 65 (30%) | 117 (54%) | 84 (40%) | 139 (62%) |

| 2. Suffer some strain | 120 (45%) | 140 (50%) | 105 (50%) | 108 (49%) | 104 (48%) | 83 (38%) | 84 (40%) | 67 (30%) |

| 3. Suffers quite a lot | 83 (31%) | 88 (31%) | 38 (18%) | 15 (7%) | 37 (17%) | 14 (6%) | 35 (17%) | 16 (7%) |

| 4. Severely disrupted | 33 (12%) | 11 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 4 (2%) | 10 (5%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (2%) | 3 (1%) |

In a sensitivity analysis that excluded women who crossed over from the assigned treatment to the other study treatments, improvement with the LNG-IUS, as compared with usual medical treatment, increased (mean difference in scores over the course of 2 years, 17.8 points, 95% CI 14.1 to 21.5 points; p < 0.001). Other sensitivity analyses yielded results that were not materially different from the results of the primary analysis (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (see Appendix 3).

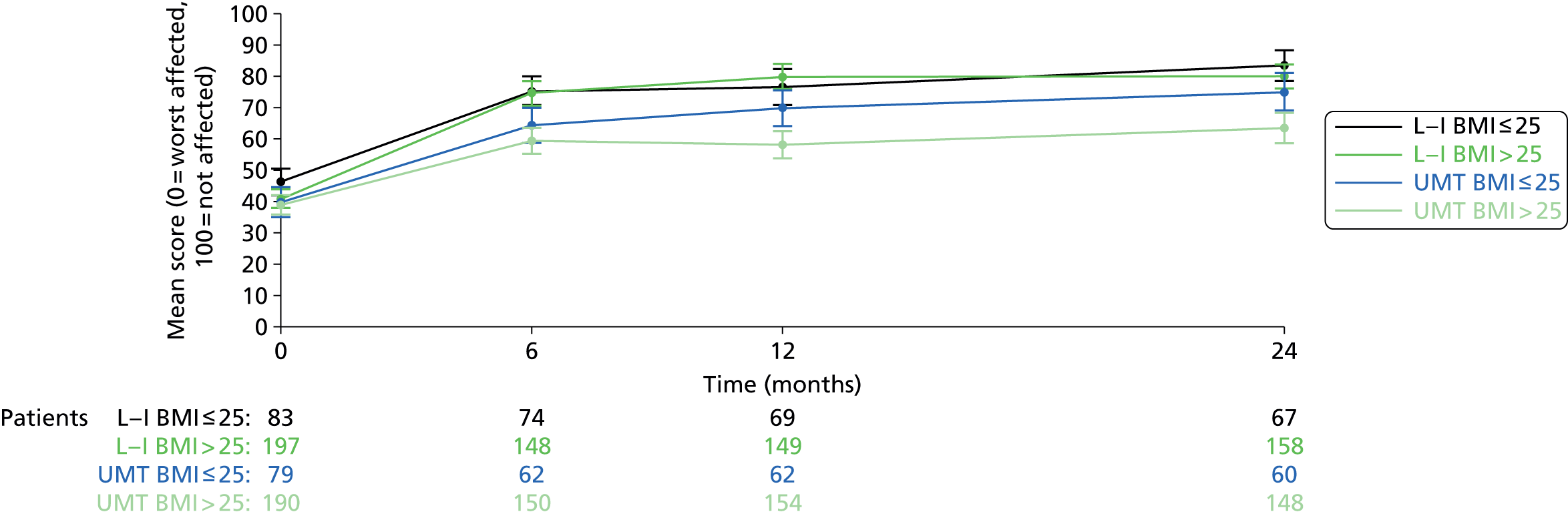

In subgroup analyses, there was a significant interaction between treatment and BMI (p = 0.004). The benefit of the LNG-IUS was greater in women with a BMI > 25 kg/m2 (16.7 MMAS points, 95% CI 12.6 to 20.9 MMAS points; p < 0.001) than in those with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 (5.4 MMAS points, 95% CI −1.0 to 11.8 MMAS points; p = 0.10). This finding appeared to be attributable to the superior outcome with usual medical treatment in leaner women (see Appendix 4). Improvements with the LNG-IUS were similar in both subgroups. None of the other tests for subgroup interaction was significant (p > 0.10).

Generic quality of life and sexual activity

The SF-36 domains were generally significantly improved from baseline in both groups at all time points, although the scores for women in the LNG-IUS group were better than for those in the usual treatment group in seven of the eight domains in the analyses over all time points (Table 6); mental health was the only domain for which there were no significant between-group differences. The improvements appeared to be greatest at 6 months, but had lessened by the 2-year follow-up assessment (see Appendix 5). No significant differences were seen between treatments with respect to the EQ-5D instrument; scores were significantly improved from baseline in both groups at 2 years, but not at earlier assessments (see Appendix 6). The treatments did not differ significantly with respect to the scores for the pleasure, discomfort and frequency domains of the SAQ (see Appendix 7).

| Questionnaire and domain | Baseline score (SD) | Difference between groups over 2 years (95% CI)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual medical treatment | LNG-IUS | |||

| SF-36b | ||||

| Physical functioning | 77.8 (24.7) | 80.0 (20.4) | 2.7 (0.0 to 5.4) | 0.05 |

| Physical role | 68.9 (26.2) | 72.1 (24.7) | 5.9 (2.6 to 9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Emotional role | 69.8 (26.8) | 71.9 (25.1) | 4.6 (1.3 to 8.0) | 0.007 |

| Social functioning | 62.4 (25.9) | 64.3 (24.5) | 5.1 (2.0 to 8.1) | 0.001 |

| Mental health | 59.0 (19.8) | 60.3 (19.3) | 1.5 (–1.0 to 3.9) | 0.23 |

| Energy/vitality | 40.8 (21.7) | 40.7 (20.9) | 5.3 (2.5 to 8.2) | < 0.001 |

| Pain | 49.5 (24.9) | 54.2 (24.9) | 7.8 (4.5 to 11.0)c | < 0.001 |

| General health perception | 60.3 (21.9) | 61.8 (21.4) | 2.9 (0.3 to 5.4) | 0.03 |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| EQ-5D descriptive systemd | 0.714 (0.276) | 0.756 (0.243) | 0.013 (–0.016 to 0.042) | 0.38 |

| EQ-5D VASe | 69.7 (19.8) | 70.3 (19.1) | 2.0 (–0.5 to 4.6)c | 0.12 |

| SAQf | ||||

| Pleasure | 10.9 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.9) | 0.4 (–0.3 to 1.1) | 0.26 |

| Discomfort | 4.62 (1.69) | 4.65 (1.48) | –0.07 (–0.30 to 0.16) | 0.55 |

Adverse events

There were no serious adverse reactions attributable to study treatments. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the frequency of unrelated serious adverse events (58 in the usual treatment group and 49 in the LNG-IUS group; p = 0.59). There was one death in the LNG-IUS group; the cause of death was recorded by the coroner as inconclusive and the LNG-IUS was not in situ. Unrelated serious adverse events are summarised in Appendix 8.

Surgical interventions

The frequency of surgical interventions for HMB within 2 years did not differ significantly between the two groups. Hysterectomy was performed in 6% of the women in each group; endometrial ablations were performed in 4% of women in the LNG-IUS group and in 6% of those in the usual treatment group (p = 0.44).

Discussion

The results of this trial show that, compared with usual medical therapies for HMB, the LNG-IUS leads to greater improvement in women’s assessments of the effect of HMB on their daily routine, including work, social and family life, and psychological and physical well-being.

At baseline, the women were substantially affected by HMB, as assessed with the use of condition-specific (MMAS) and general (SF-36) health-related scales. The scores improved significantly over a period of 2 years in both the LNG-IUS group and the usual treatment group. However, improvements in average MMAS scores were greater in the LNG-IUS group than in the usual medical treatment group over the first 2 years, by an average of 13.4 points, in an intention-to-treat analysis. The greater improvement in the LNG-IUS group than in the usual treatment group was both statistically significant and clinically meaningful. The between-group difference was more than 0.5 SD, which is the minimum clinically important difference identified in a systematic review of studies reporting such data for health-related QoL measures. 79 A 13.4-point difference represents a change in two or three MMAS domains: from being substantially to minimally affected by HMB (e.g. from frequent to occasional disruptions of work and daily routine) or from being minimally affected to being unaffected (e.g. from experiencing some strain in family life to experiencing no strain in family life). The between-group difference reported here is also greater than that reported in an observational study comparing women who did and those who did not undergo surgery for HMB. 65 The differences seen in favour of the LNG-IUS on the SF-36 domains were generally highly statistically significant, but were on average small in magnitude (SD 0.2–0.3). 79 It is therefore debatable whether or not they are clinically important.

The strengths of our randomised trial include its size (larger than prior trials of treatments for HMB), the multicentre design, the inclusion of patients ethnically representative of the UK population, the relatively low rates of loss to follow-up, and the assessment of outcomes over a period of 2 years rather than 6 or 12 months, as in previous studies. 28,45 In addition, previous trials have focused on the reduction of menstrual blood loss, which does not reflect the full effect of HMB on women’s lives. 28,45 In contrast, our primary outcome measure was the patient-reported, psychometrically valid, condition-specific MMAS, which better reflects women’s personal experience of the burden of HMB. Interference with the QoL, rather than perceptions of HMB itself, appears to be the primary factor in women’s decision to seek treatment. 80

Some limitations of our study should be noted. The range of options available for medical treatment complicates any efforts to compare the LNG-IUS with individual agents. However, the choice among the various agents is representative of current clinical practice. In addition, substantial numbers of patients switched treatments over the course of the study; however, these crossovers would be expected to result in an underestimation of the benefits that might be achieved with perfect compliance. A range of sensitivity analyses did not change the conclusions. Although the interventions studied in this trial represent options available in primary care settings in the UK, insertion of intrauterine devices is not part of primary care in all health-care settings, and in some circumstances it requires consultation with a gynaecologist.

The 21.4-point improvement from baseline in the average MMAS score at 6 months in the usual treatment group, which was sustained throughout the 2 years of follow-up, was not explained by a switch in treatment, since similar improvements were noted when crossovers to the LNG-IUS were excluded from the analyses. The higher rate of discontinuation in the usual treatment group than in the LNG-IUS group could reflect greater symptom relief with the LNG-IUS, but another possible explanation is that discontinuation of usual medical treatment does not require consultation. Nonetheless, at 2 years, 36% of women in the LNG-IUS group had had the system removed, generally because of lack of effectiveness or irregular or prolonged bleeding, which are well-recognised reasons for discontinuing the LNG-IUS. 81,82 This proportion is consistent with the proportions of women who discontinued the LNG-IUS treatment in smaller trials that compared it with hysterectomy50 (31% of 117 women at 12 months) or with endometrial ablation (28% of 105 women at 2 years). 30,49,81 In subgroup analyses, the LNG-IUS appeared to be less beneficial in women with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or less than in those with a BMI of more than 25 kg/m2, an observation that was explained by an apparently greater efficacy of usual medical treatments in the leaner women. This analysis was one of several subgroup analyses and should be interpreted with caution, since the findings may be explained by chance and require confirmation.

We expected fewer surgical interventions in the LNG-IUS group, but rates were similarly low in the two groups. This finding may reflect the eligibility criteria for the trial, since women who had fibroids or other disorders were excluded.

Finally, given the long natural history of HMB, study outcomes need to be assessed over a period that is longer than 2 years; additional intention-to-treat analyses are reported for 5 years in Chapter 4 and planned for 10 years.

In conclusion, our study showed that both the LNG-IUS and usual medical treatments reduced the adverse effect of HMB on women’s lives over the course of 2 years, but the LNG-IUS was the more effective first choice, as assessed by the impact of bleeding on the women’s QoL.

Chapter 4 Methods and results of randomised controlled trial at 5 years’ follow-up

Objectives

The objectives of the RCT presented in this chapter were to assess the clinical effectiveness of the LNG-IUS compared with standard medical treatment for women seeking treatment for HMB in primary care in the medium to long term (5 years’ follow-up).

Methods

Trial methods

For details on the population, randomisation and outcome measures the reader should refer to Chapter 3.

Statistical considerations

The sample size assumptions for MMAS scores were the same as previously detailed in Chapter 3, Statistical consideration. Four hundred and seventy patients were required to have 90% power (p = 0.05) to detect 0.3 SD in MMAS score. We ultimately received 424 responses at 5 years’ follow-up. A post-hoc calculation suggests this many responses would provide 87% power (p = 0.05) to detect this same size of difference. For progression to surgical intervention (hysterectomy or endometrial ablation), using an assumed rate of 35% in the standard arm (a figure that was set out in the protocol), 424 women (the number followed up to 5 years; see Figure 4 for details) would provide 80% power (p = 0.05) to detect an absolute reduction of 12%, that is, 35% down to 23%.

The statistical methods used to analyse the data were similar to those set out in Chapter 3; however, given the long length of time between this and the previous assessment point at 2 years, we felt a repeated-measures analysis incorporating all accumulated responses to no longer be clinically meaningful and therefore this has not been included.

Results

Patients and follow-up

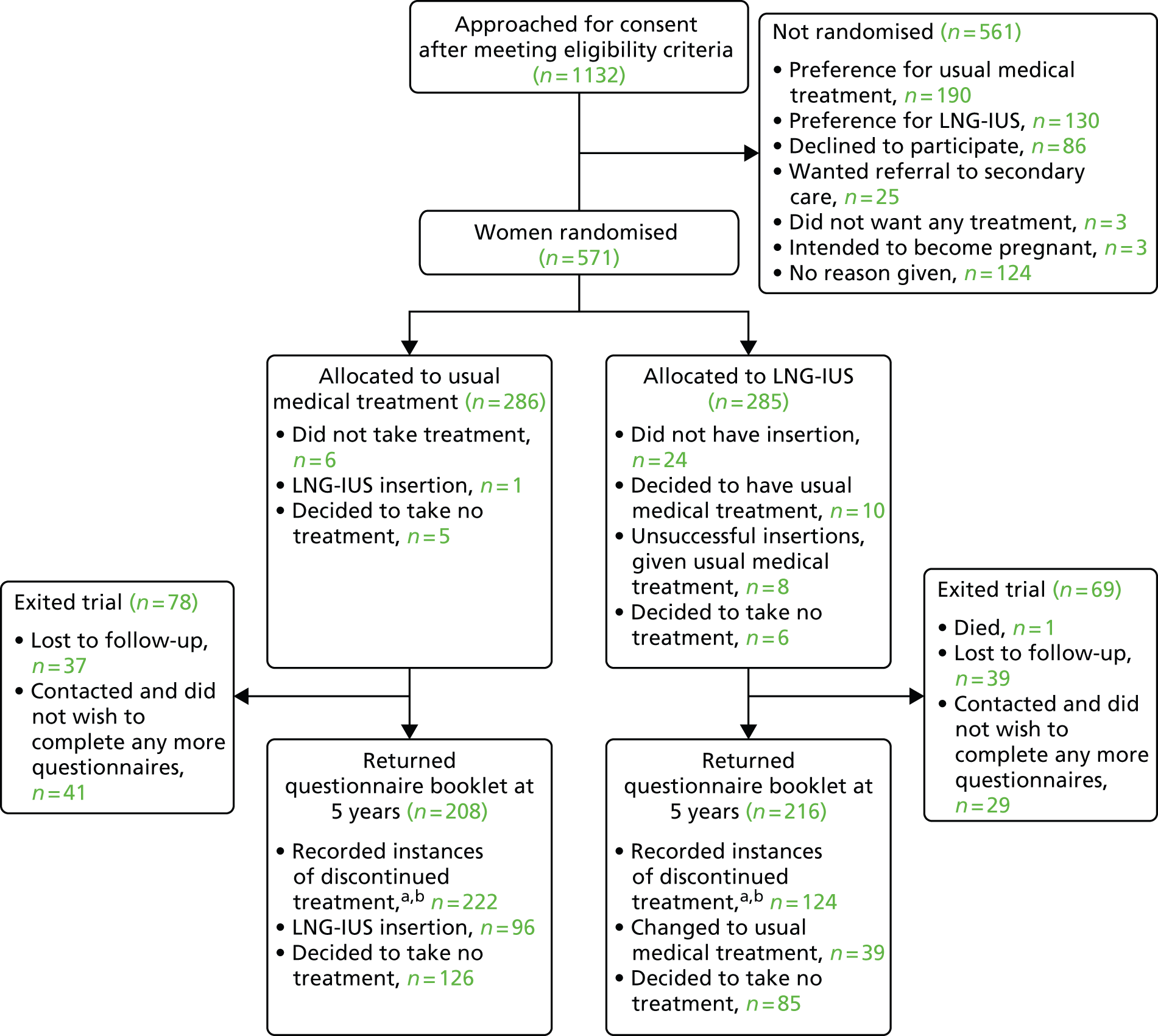

See Chapter 2 for details on the demographics and prescribed treatments of those randomised and Figure 4 for losses to follow-up. Study questionnaire booklets were returned by 424 (74%) of the participants. One hundred and fifteen of the women (27%) declined to complete the MMAS, but indicated on the form that they were no longer bleeding; their score was assumed to be the maximum achievable (100, ‘no problems’). These women completed other parts of the questionnaire booklet and a sensitivity analysis of MMAS responses without any assumption was also performed.

FIGURE 4.

Enrolment, randomisation and follow-up up to 5 years of the study patients. a, See Figure 5 for time to first treatment change survival estimates; b, see Appendices 9 and 10 for reason reported for discontinuing treatment.

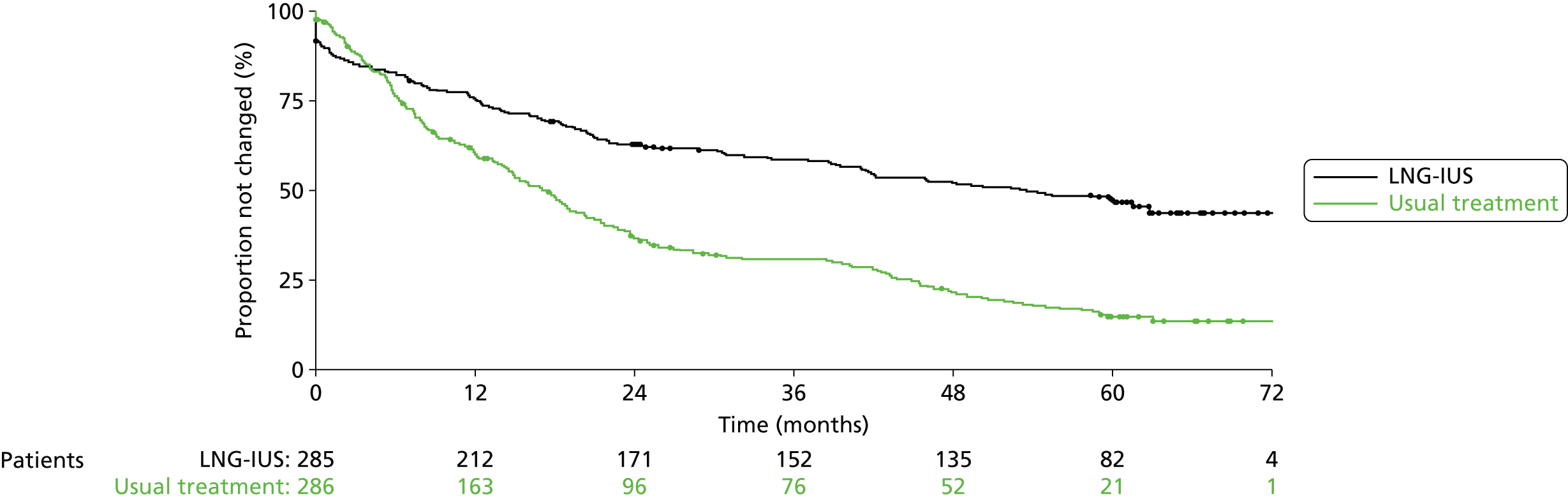

The 5-year allocated treatment retention rate was estimated to be 47% (95% CI 40% to 52%) in the LNG-IUS group and 15% (95% CI 11% to 20%) in the usual treatment group (Figure 5). Reported reasons for discontinuation of treatment are summarised in Appendices 9 and 10. Lack of efficacy was cited 41% (94/228) of the time in the usual treatment group and 24% (36/148) of the time in the LNG-IUS group. Of the 228 recorded instances of treatment change in women allocated usual medical treatment, 97 (43%) were to the LNG-IUS. In the LNG-IUS group, 39% (57/148) of treatment switches were to usual treatment. There was no significant difference between the groups in the total number of serious adverse events up to 5 years (see Appendix 11).

FIGURE 5.

Time to first treatment change over 5 years’ follow-up.

Menorrhagia Multi-Attribute Scale

After 5 years, scores on the MMAS were significantly improved compared with baseline in both groups (Table 7). This improvement was greater, on average, among women assigned to the LNG-IUS, but the difference was not statistically significant (3.9 points, 95% CI –0.6 to 8.3 points; p = 0.09). The same analysis without any assumption about MMAS scores where a blank form was returned and the woman indicated she was no longer bleeding returned a similar result (5.2 points difference in favour of the LNG-IUS, 95% CI –0.4 to 10.8 points; p = 0.07). Per-protocol analysis (excluding women who switched or stopped taking treatment) – limited to 28 responses in the usual treatment group and 88 in the LNG-IUS group – returned a 15.8-point difference in favour of the LNG-IUS (95% CI 7.4 to 24.2 points; p = 0.0003).

| Treatment group and comparisons | Baseline score | 5-year score |

|---|---|---|

| Usual medical treatment (SD, n) | 39.2 (21.3, 269) | 83.1 (24.4, 208) |

| Change within group (95% CI) | – | 43.4 (39.1 to 47.7; p < 0.0001) |

| LNG-IUS (SD, n) | 42.5 (20.5, 280) | 87.1 (22.1, 216) |

| Change within group (95% CI) | – | 44.9 (4.10 to 48.8; p < 0.0001) |

| Difference between groups (95% CI) | – | 3.9 (–0.6 to 8.3; p = 0.09) |

Surgical interventions

There were 53 surgical events (endometrial ablation or hysterectomy) in the LNG-IUS group, compared with 56 in the usual treatment group, that were included in the surgery-free survival analysis (109 events in total). This difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.31; p = 0.6) (Figure 6). Analysis excluding participants who crossed over from one group to another returned a similar result (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.52; p = 0.9). Five-year surgery-free survival rates were estimated to be 80% (95% CI 74% to 84%) in the LNG-IUS group compared with 77% (95% CI 71% to 82%) in the usual treatment group. In total, there were 24 ablations in the LNG-IUS group compared with 31 in the usual treatment group as well as 30 hysterectomies in both groups (115 operations in total; the extra six events coming from patients who had both types of surgery).

FIGURE 6.

Surgery-free (hysterectomy/endometrial ablation) survival analysis over 5 years’ follow-up.

Generic quality of life and sexual activity

Responses to the EQ-5D and SF-36 instruments were generally significantly improved from baseline in both groups (Table 8); the only statistically significant difference between groups was seen in the general health perception domain of the SF-36 and favoured the LNG-IUS (4.7 points, 95% CI 0.6 to 8.8 points; p = 0.02). The treatment groups did not differ significantly with respect to any of the domains of the SAQ.

| Questionnaire and domain | Baseline score (SD, n) | 5-year score (SD, n) | Difference between groups over 5 years (95% CI, p-value)a | Change within group (95% CI, p-value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual medical treatment | LNG-IUS | Usual medical treatment | LNG-IUS | Usual medical treatment | LNG-IUS | ||

| SF-36b | |||||||

| Physical functioning | 77.8 (24.7, 264) | 80.0 (20.4, 272) | 83.0 (26.3, 208) | 85.4 (23.5, 216) | 1.6 (–2.7 to 5.9; p = 0.5) | 5.6 (1.8 to 9.5; p = 0.004) | 5.9 (2.8 to 9.1; p = 0.0003) |

| Physical role | 68.9 (26.2, 264) | 72.1 (24.7, 276) | 80.6 (27.2, 208) | 83.9 (25.5, 217) | 2.7 (–2.1 to 7.5; p = 0.3) | 12.6 (7.9 to 17.2; p < 0.0001) | 13.3 (9.5 to 17.1; p < 0.0001) |

| Emotional role | 69.8 (26.8, 264) | 71.9 (25.1, 276) | 83.3 (25.3, 208) | 81.4 (26.9, 217) | –2.0 (–6.8 to 2.9; p = 0.4) | 13.1 (8.7 to 17.6; p < 0.0001) | 10.9 (6.7 to 15.1; p < 0.0001) |

| Social functioning | 62.4 (25.9, 268) | 64.3 (24.5, 277) | 76.9 (25.5, 207) | 79.5 (25.1, 214) | 2.2 (–2.5 to 6.9; p = 0.4) | 14.0 (9.4 to 18.5; p < 0.0001) | 15.6 (11.6 to 19.6; p < 0.0001) |

| Mental health | 59.0 (19.8, 267) | 60.3 (19.3, 277) | 72.6 (19.4, 206) | 71.4 (20.5, 214) | –1.6 (–5.2 to 2.0; p = 0.4) | 13.6 (10.5 to 16.7; p < 0.0001) | 11.4 (8.5 to 14.3; p < 0.0001) |