Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 13/111/01. The protocol was agreed in December 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Aileen Clarke is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board and the Warwick Medical School receive payment for this work. Aileen Clarke and Sian Taylor-Phillips are partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Freeman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Overview

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a chemotherapy drug used to treat several cancers including those of the head and neck (H&N), pancreas, stomach and especially bowel (colorectal) cancer. 5-FU is usually given orally or by continuous intravenous (i.v.) infusion into the blood circulation and is often accompanied by additional chemotherapies. 5-FU is administered in a series of cycles usually over 3–6 months. 5-FU is cleared from patients’ blood at rates which vary between patients, and the dose that reaches cancer cells can therefore vary between individuals. As a result, some patients may receive doses which are too low to be fully effective, whereas others may experience toxicity because the circulating dose is too high.

The My5-FU test kit (Saladax Biomedical Inc., PA, USA; previously known as OnDose) is designed to measure the amount of 5-FU circulating in the blood using a small blood sample taken during the 5-FU infusion. Knowing the individual patient s level of 5-FU in the blood allows doctors to adjust the dose to be used at the next cycle of treatment so that it is more appropriate for that individual. The My5-FU assay can be used with patients who have various types of cancer. However, thus far most attention has been focussed on colorectal cancer (CRC), which is the third most common cancer in the UK, with around 40,000 new cases each year.

The current report was undertaken for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Diagnostics Assessment Programme (DAP). We aimed to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 5-FU plasma monitoring with the My5-FU assay for guiding dose adjustment in patients receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous infusion in the NHS in England and Wales.

Conditions and aetiologies

Therapeutic drug monitoring in cancer treatment aims to personalise chemotherapy to improve treatment efficacy, avoid severe toxicity and reduce health-care costs by using individual dosing schedules. It takes into account the interindividual variation in drug metabolism to bring drug exposure into the optimum therapeutic range. This is especially important for cytotoxic anticancer drugs which can have a narrow therapeutic window. 5-FU (or 5-fluoro-2,4-pyrimidinedione) is one of the most widely used cytotoxic drugs.

Descriptions of the health problem

The following sections will focus on the conditions of most relevance to the current report: CRC and H&N cancer. Additional, less detailed information will be provided for stomach cancer and pancreatic cancer, two other conditions which are also referred to in the report.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in the Western world and is the second most common cancer-related cause of death in combined male and female populations in the UK. 1 In 2010, there were 15,708 deaths from bowel cancer in the UK (62% from colon cancer, 38% from rectal cancer, including the anus), with 8574 (55%) in men and 7134 (45%) in women. 2–4 Around half of people diagnosed with CRC survive for at least 5 years after diagnosis. 5

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Colorectal cancer (also known as large bowel cancer) can affect both males and females equally at any age; however, it is most common in people aged > 65 years. 6–8

Studies have reported that a diet high in fat (especially animal fat), red meats and low in fibre can be associated with CRC. Other possible causes include lack of exercise, smoking and alcohol. 8–10 Two inherited conditions, familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer, account for 1% and 5% of all CRC respectively. 11,12 Those with a history of inflammatory bowel disease has a six times greater risk of developing CRC than the general population. 13

The majority of CRCs (90%) are adenocarcinomas which originate from epithelial cells of the colorectal mucosa. 14 Adenomas or adenomatous polyps are benign in most cases, but around 10% of adenomas will change into cancer over time. 7,15 Tumours with a villous histology, larger in size and with severe dysplasia have a higher chance of converting to cancer and these are indicators for progression. 15,16

Spread of the disease and diagnosis determines the prognosis of patients. Around half of people diagnosed with CRC survive for at least 5 years after diagnosis. 5

In the UK there are inequalities in cancer survival following a diagnosis of CRC, in that patients who are more socioeconomically deprived are more likely to have both poorer cancer-specific and overall survival (OS). 17 Approximately 80% of patients with CRC undergo surgical treatment for the cancer with/without adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy (including 5-FU). Recurrence has been reported in between 11% and 54% of patients. 7 More advanced cancers that have invaded other tissues or progressed to metastatic cancers tend to be treated with multiple chemotherapy drugs.

Advances in treatment and survival are likely to increase lifetime costs of managing CRC. 18 Cost-of-illness studies are key building blocks in economic evaluations of interventions and comparative effectiveness research. However, the methodological heterogeneity and lack of transparency of studies in this area have made it challenging to compare CRC costs between studies or over time. 18

Incidence and/or prevalence

In 2010 it was estimated that 42,747 cases of CRC were diagnosed in the UK of which 23,582 and 19,165 cases of CRC were diagnosed in men and women respectively. 19 Incidence rates of CRC have increased dramatically in both genders between 1999–2001 and 2008–10. Between 2001–3 and 2008–10, incidence rates increased by 6% in men and 7% in females. The incidence rate of CRC increases with increasing age (i.e. the highest rate is among those aged ≥ 85 years). 5 Around 73% of CRC cases diagnosed in the UK between 2008 and 2010 were among people aged > 65 years.

Significance for patients in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

According to one study by Jayatilleke et al. ,20 CRC accounted for approximately 9% and 7% of all cancer disability-adjusted life-years in England and Wales among men and women respectively.

Significance for the NHS

In 2006, the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme introduced faecal occult blood testing for both genders at age 60–69 years. The test is undertaken by taking small stool sample which is tested for the presence of blood. 21 The benefit of faecal occult blood testing in terms of reducing mortality was estimated from a systematic review of trials to be 16% and 23% for allocated and screened people respectively. 22 In addition, the test was cost-effective. 22

In addition, flexible sigmoidoscopy (NHS bowel scope screening) is a programme which has been introduced across England from 2013, for the prevention of CRC in high-risk patients by identifying and removing adenomatous polyps in the rectum and colon. This involves one-off flexible sigmoidoscopy around 55 years of age for both men and women. 23

Measurement of disease and/or response to treatment

In the UK, CRC causes around 16,000 deaths annually. The cancer mortality rates is 16,000 deaths over the time; however, it has been estimated that the overall 5-year relative survival is 50%. 24,25 A study by Coleman et al. reported that in the UK cancer survival rates are low in comparison with other Western countries. 26

Disease measurements are usually based on colonoscopy and histology for diagnosis and a range of other investigations including computerised tomography (CT) scans are undertaken for disease staging. Similarly, response to treatment is assessed by clinical consultation, with a range of tests including CT scans and regular serum antigen tests. Colonoscopy is also undertaken at annual and subsequent 5-yearly follow-up.

Diagnosis and management

The symptoms of CRC include rectal bleeding, a change in bowel habit (e.g. diarrhoea or loose stools), abdominal pain and weight loss. These symptoms become more prominent when the disease is in an advanced stage, although symptoms depend on location and size of the cancer. 27,28

Treatment options and prognosis depend on staging of the CRC. Staging is defined by how deeply the cancer has grown into the intestinal mucosa, whether or not it has spread to lymph nodes and other organs, and if the tumour node metastasis (TNM) classification system is most commonly used (see Box 1 and Table 1 with modified Dukes’ staging with 5-year survival). 29,30 Dukes’ classification of staging is:

-

Dukes’ A means the cancer is only in the innermost lining of the colon or rectum or slightly growing into the muscle layer

-

Dukes’ B means the cancer has grown through the muscle layer of the colon or rectum

-

Dukes’ C means the cancer has spread to at least one lymph node in the area close to the bowel

-

Dukes’ D means the cancer has spread elsewhere in the body such as the liver or lung.

TX: primary cannot be assessed.

T0: no evidence of primary carcinoma in situ (Tis) – intraepithelial or lamina propria only.

T1: invades submucosa.

T2: invades muscularis propria.

T3: invades subserosa or non-peritonealised pericolic tissues.

T4: directly invades other tissues and/or penetrates visceral peritoneum.

Lymph nodesNX: regional nodes cannot be assessed.

N0: no regional nodes involved.

N1: one to three regional nodes involved.

N2: four or more regional nodes involved.

MetastasisMX: distant metastasis cannot be assessed.

M0: no distant metastasis.

M1: distant metastasis present (may be transcoelomic spread).

Tis, tumour in situ.

| Stage (TNM status) | 5-year OS, % | Modified Dukes’ |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 (T in situ, N0, M0) | – | – |

| Stage I (T1, N0, M0) | 75 | A |

| Stage I (T2, N0, M0) | 57 | B1 |

| Stage II (T3, N0, M0) | – | B2 |

| Stage II (T4, N0, M0) | – | B3 |

| Stage III (T2, N1, M0/T2, N2, M0) | 35 | C1 |

| Stage III (T3, N1, M0/T3, N2, M0) | – | C2 |

| Stage III (T4, N1, M0) | – | C3 |

| Stage IV (any T, any N, M1) | 12 | D |

This brief account is based on NICE guideline CG1317 and advice of clinical experts.

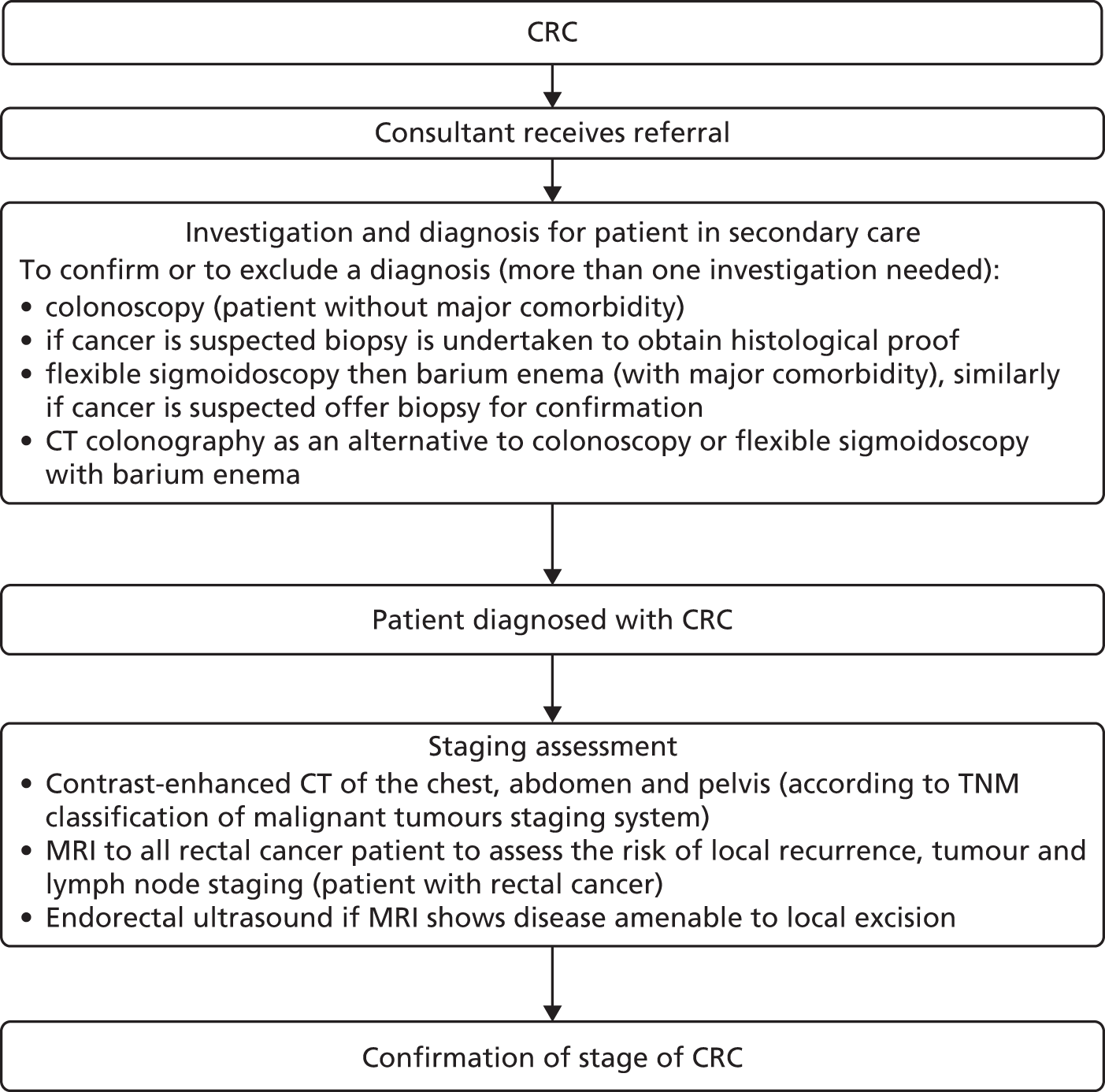

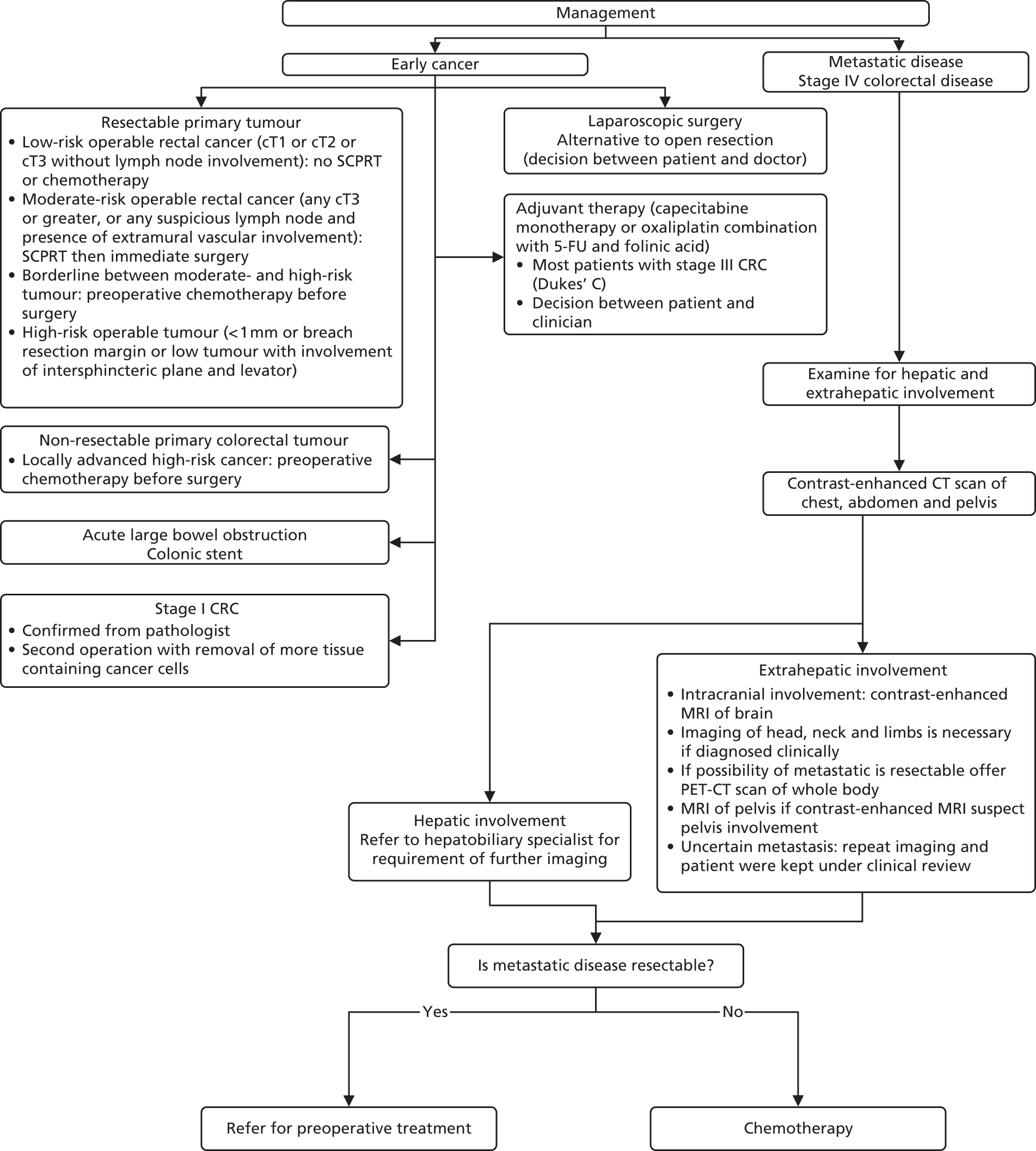

Figures 1–3 summarise the clinical pathways for patients with CRC.

FIGURE 1.

Colorectal cancer diagnosis pathway. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

FIGURE 2.

Colorectal cancer management pathway. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET-CT, positron emission tomography fused with computed tomography; SCPRT, short-course preoperative radiotherapy.

FIGURE 3.

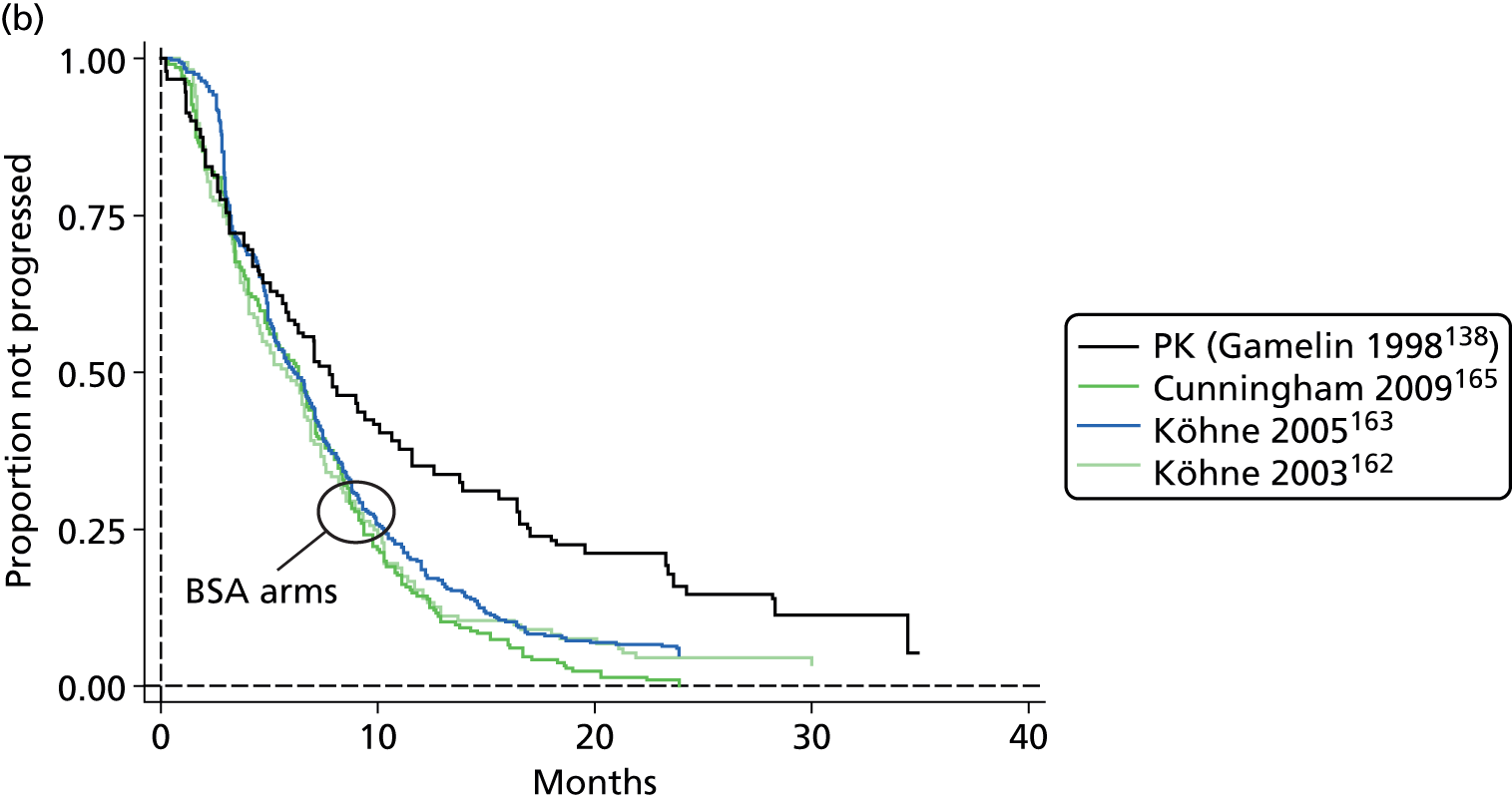

Illustrative role of pharmacokinetic adjustment of 5-FU regimens in treatment of metastatic CRC in standard practice (in theory pharmacokinetic adjustment could be applied in any treatment regimen that includes 5FU). a, The FOLFOX4 regimen (oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-FU): oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2); leucovorin (200 mg/m2); 5-FU loading dose (400 mg/m2); i.v. bolus; then 5-FU (600 mg/m2) for a period of 22 hours. FOLFOX6 regimen (folinic acid, 5-FU and irinotecan): oxaliplatin (85–100 mg/m2); leucovorin (400 mg/m2); 5-FU loading dose (400 mg/m2); i.v. bolus; then 5-FU (2400–3000 mg/m2) for a period of 46 hours. BSA, body surface area; FOLFIRI, irinotecan in combination with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin in combination with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid; FU, fluorouracil; FUFA, 5-FU + folinate; PK, pharmacokinetic.

There are various options for treatment of early-stage CRC including:

-

surgery (i.e. tumour resection if the tumour is resectable)

-

preoperative chemotherapy (this may be considered before surgery in patients with non-resectable primary colorectal tumours or borderline resectable tumours)

-

colonic stent in acute large bowel obstruction

-

further tumour resection in stage I CRC

-

laparoscopic surgery as an alternative surgery to open resection based on patient’s and doctor’s decision

-

adjuvant therapy: monotherapy capecitabine or a combination of oxaliplatin with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (FA) (FOLFOX) are recommended in most patients with stage III CRC based on patient’s and doctor’s decision.

According to NICE guideline CG1317 one of the following combinations of first- and second-line chemotherapies is used depending on side effects experienced and patient’s preferences:

-

FOLFOX as first-line treatment then single-agent irinotecan as second-line treatment; or

-

FOLFOX as first-line treatment then irinotecan in combination with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (FOLFIRI) as second-line treatment; or

-

oxaliplatin in combination with capecitabine (XELOX) as first-line treatment then FOLFIRI as second-line treatment.

In standard practice choice between 5-FU regimens, such as fluorouracil (FU) alone, FU + FA, FOLFOX (FOLFOX4 and FOLFOX6), is made with clinician’s advice. These regimens are administered for up to 12 cycles, one cycle every 2 weeks.

-

FU

-

FU + FA

-

FOLFOX4: oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2); FA (200 mg/m2); 5-FU loading dose (400 mg/m2); i.v. bolus; then 5-FU (600 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory for a period of 22 hours31

-

FOLFOX6: oxaliplatin (85–100 mg/m2); FA (400 mg/m2); 5-FU loading dose (400 mg/m2); i.v. bolus; then 5-FU (2400–3000 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory for a period of 46 hours. 31

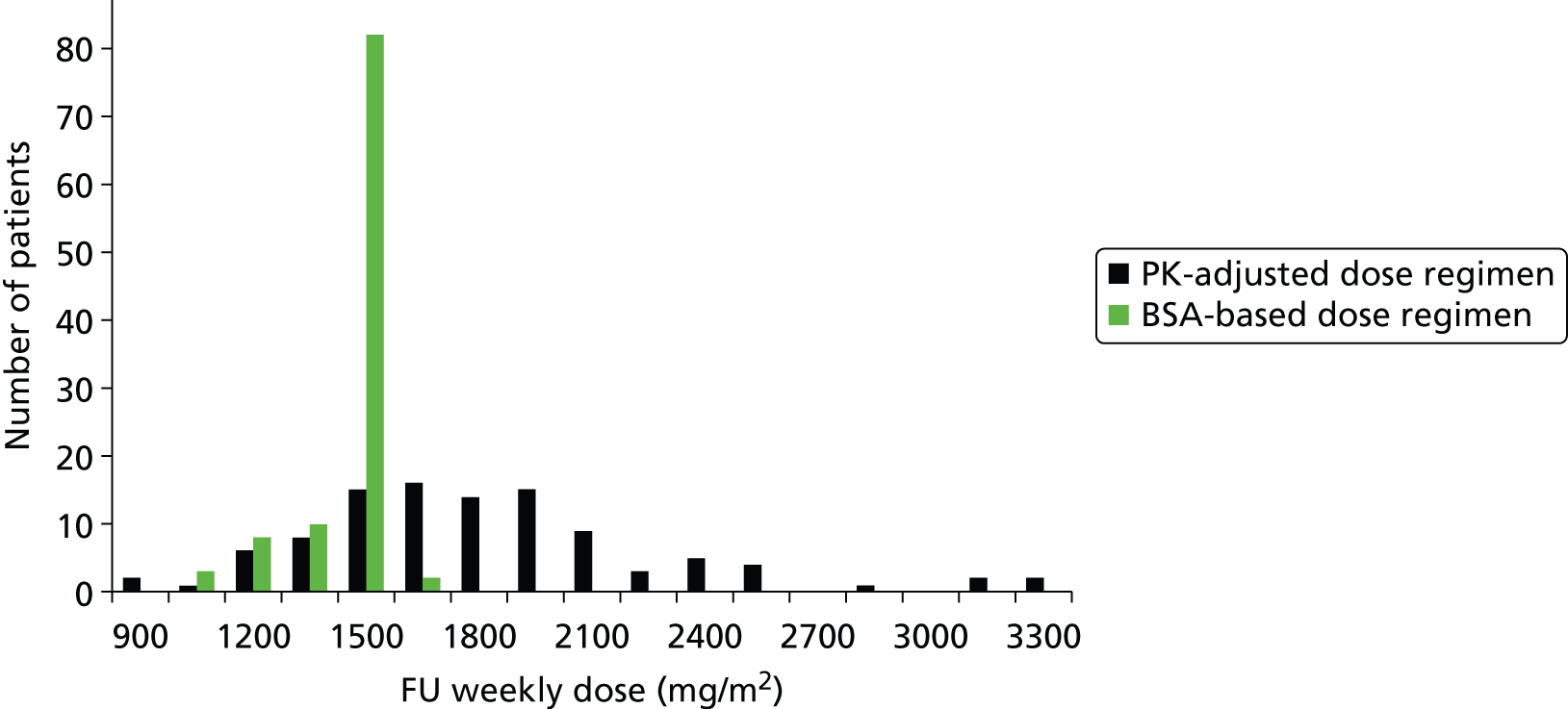

In standard practice the 5-FU dosage administered is based on patient body surface area (BSA). BSA is calculated using the Du Bois method:32 BSA (m2) = weight (kg) 0.425 × height (cm) 0.725 × 0.007184. Currently FOLFIRI and FOLFOX6 regimens recommend a 5-FU dose of 2400 mg/m2 administered by continuous infusion over 46 hours. It remains unclear how to dose cap, although dose capping is usually undertaken for large individuals because they may be overdosed using the BSA-based dosage and experience toxicity and adverse events (AEs). AEs range in severity and include diarrhoea, hand and foot syndrome, mucositis/stomatitis, neutropenia, anaemia, nausea/vomiting and cardiac toxicity. Dose capping is implemented at BSA > 2 m2 or > 2.25 m2. In practice, larger patients may be capped up to a BSA of 2.4 m2 (NICE committee assessment subgroup, 5 June 2014, personal communication). Dose may be reduced for patients judged at higher risk of toxicity (e.g. those heavily pre-treated with chemotherapy; those with poor performance status particularly 2 and above; those with impaired renal or hepatic function; and those with co-morbidities). In such instances dose of chemotherapy may be started low and cautiously increased while the patient is able to tolerate treatment.

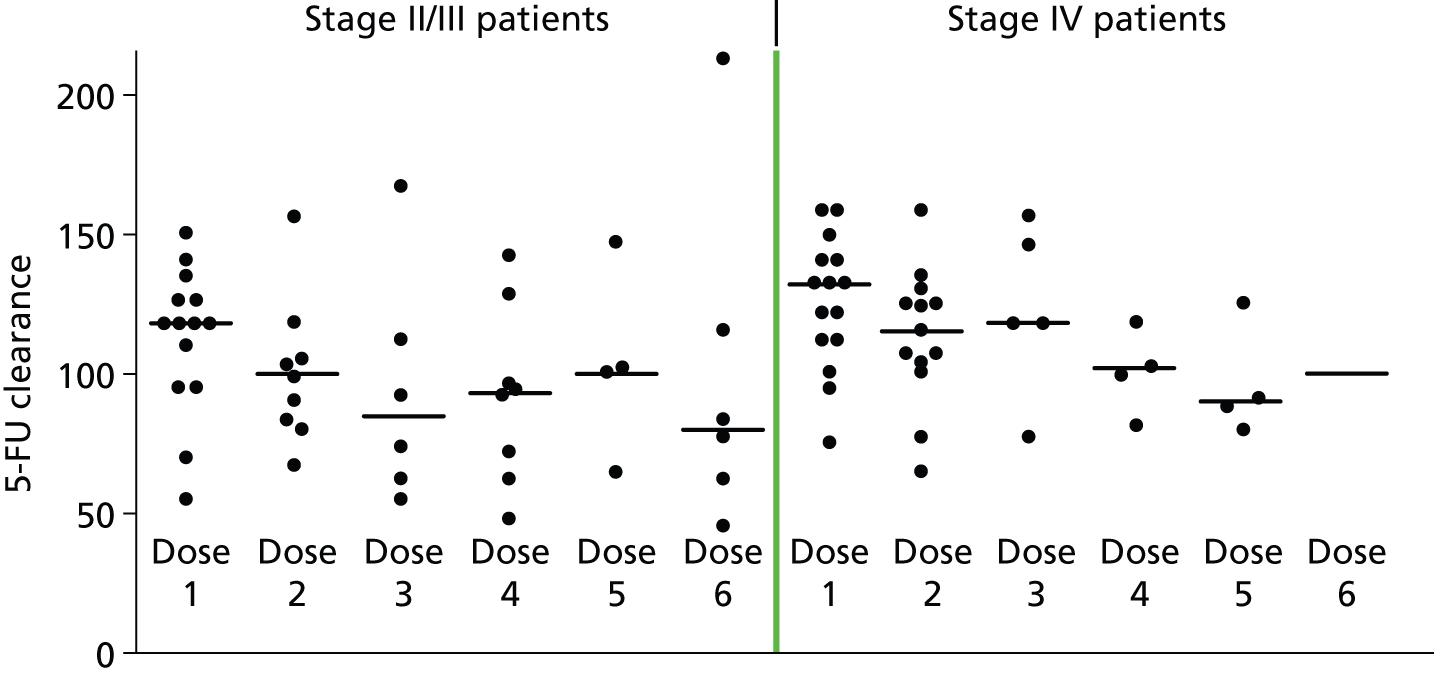

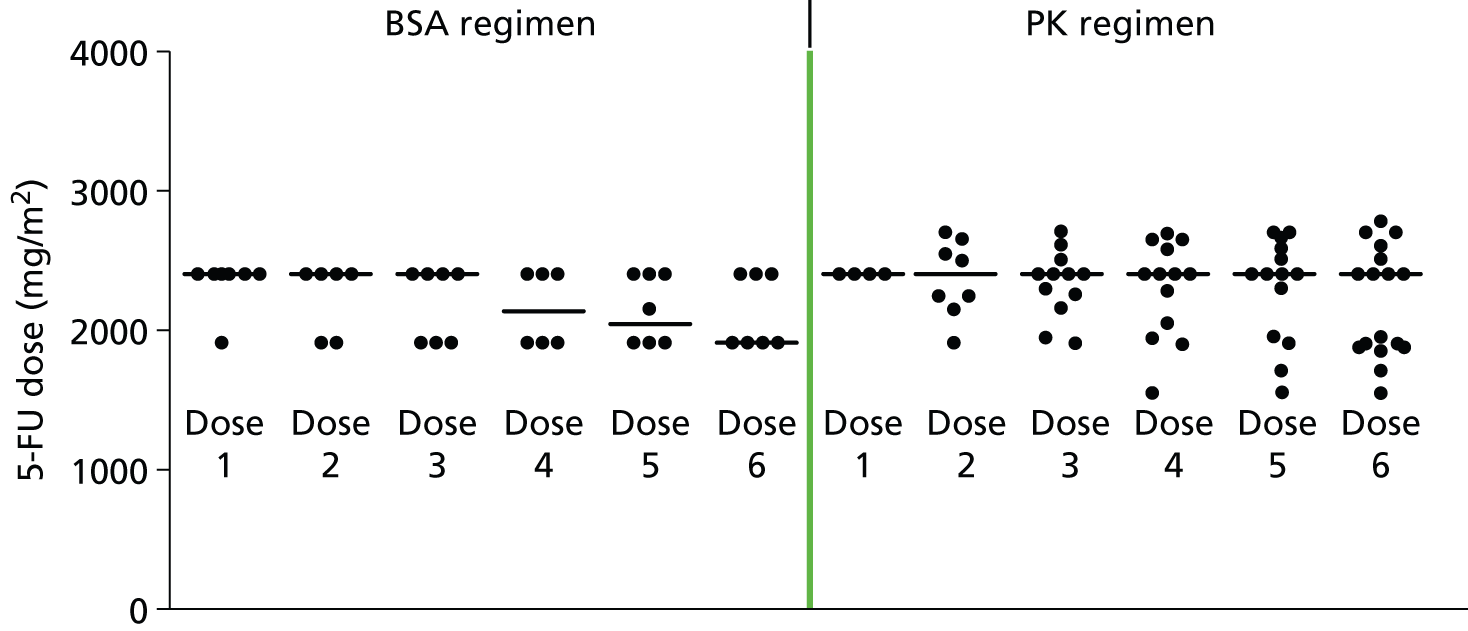

It is well documented that the plasma concentrations of 5-FU vary greatly between individuals who have received ‘standard’ dosage calculated from their BSA. 33 In advanced CRC, treatment focuses on both length and palliation of symptoms (e.g. pain, obstruction). Individualised pharmacokinetic (PK) adjustment of 5-FU dosage, which tailors an individual’s dosage to achieve the required plasma 5-FU level, might optimise time without toxic effects, while not compromising therapeutic benefit. The potential position of PK dose adjustment in the clinical pathway is illustrated in Figure 3.

In PK-adjusted regimens when the dose at the first cycle is based on patient BSA, a steady state plasma sample is taken (e.g. after 40 hours of a 46-hour infusion). The plasma 5-FU estimate is used to calculate the PK ‘area under the curve’ (AUC = mg × hour/l; where mg/l is the steady state plasma 5-FU concentration and hour the total infusion time in hours). An algorithm that relates AUC to dose adjustment is then used to calculate the dosage required for the next cycle of treatment. 33

In both standard and PK regimes, if toxicity occurs, treatment is stopped and/or the dose is reduced after which treatment is resumed. If there is progression of the disease, it may be reasonable to switch treatment (e.g. from FOLFOX to FOLFIRI). If patients are tolerating treatment even after 12 cycles, the treatment is continued until progression, or at the discretion of the medical team, but should be reviewed every 12 weeks.

A recent UK randomised clinical trial has investigated if there is a clinical advantage from treatment holidays between successive 12-week cycles. 34 Figures 1–3 illustrate the CRC diagnosis pathway.

NICE CG1317 makes recommendations for diagnosis and management of CRC and for management of locally advanced and metastatic disease.

An economic evaluation was undertaken using a decision tree. The FOLFOX–irinotecan sequence was taken as a reference for comparisons. All the combinations except FOLFOX–FOLFIRI were found to be dominated by FOLFOX–irinotecan (i.e. the latter was less effective and more costly). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of FOLFOX–FOLFIRI was found to be £109,604 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gain. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken discounting the price of drug. The resulting ICER of FOLFOX–FOLFIRI was £47,801 per QALY gain. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that three combination regimens, namely FOLFOX–irinotecan, FOLFOX–FOLFIRI and XELOX–FOLFIRI, had the highest probability of falling between £20,000 and £50,000 per QALY. Based on these findings, the Guideline Development Group made the following recommendation:

-

If there are no contraindications, then the three combination sequence namely FOLFOX–irinotecan, FOLFOX–FOLFIRI and XELOX–FOLFIRI should be considered as treatment options for treating patients with advanced and metastatic CRC (mCRC).

Head and neck cancer

Cancer of the H&N includes cancer of the mouth (i.e. oral cancer), throat and other rare cancers of the nose, sinuses, salivary glands and middle ear. Mouth cancer can be subdivided according to its location, such as lip cancer or cancer of the oral cavity. Similarly, throat cancer can be divided into nasopharyngeal cancer (the affected area is at the highest part of the throat behind the nose), oropharyngeal cancer (tonsils and the base of the tongue), cancer of larynx and thyroid cancer (thyroid gland). 35

The most common type of H&N cancer is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which comprises 90% of all H&N cancers. 36

Head and neck cancer begins with a non-invasive lesion in the squamous mucosa that lies in the inner part of the H&N (mouth, the nose and the throat). Following exposure to common carcinogens, a series of changes occurs (i.e. hyperplasia and dysplasia), this causes the cancer to finally become invasive. 36

The definitive cause for H&N cancer is still unknown; however, it has been thought that disease is associated with various factors. Cancer of the H&N is associated with risk factors such as active use tobacco and habitual drinking of alcohol. Dietary factors thought to be associated with increased risk include high intake of red meat, processed meat, fried food and poor diet. Other risk factors include a history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease for laryngeal and pharyngeal cancer. 37 Human papillomavirus infection is also an important risk factor for some H&N cancer (oropharynx and oral cavity). 24,38

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Head and neck SCC is the sixth most common cancer and the one of the leading causes of cancer death in the world. 39 In 2011, around 49,260 new cases of H&N cancer were diagnosed in the USA and there were 11,480 cancer deaths in the same year. 40 In England and Wales, around 8100 new H&N cancer cases are diagnosed annually. 41 In the UK there were 6539 new cases of H&N cancer, 66% in male and 34% in female, in 2010. 42

Incidence and/or prevalence

The disease incidence increases with age. In the UK, 85% of cases are seen in people who are aged > 50 years. However, the incidence has been found to be increasing in younger men and women. 37 In the UK, in the period 2008–10, approximately 44% of oral cancers were diagnosed in both genders in people aged ≥ 65 years, and 50% were diagnosed in those aged between 45 and 64 years. 42

Significance for patients in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

In England and Wales between 1995 and 1999 the age-adjusted mortality rate for oral cancer was 2.7 per 100,000 for males and 1.05 per 100,000 for females. Likewise, in Scotland, the age-adjusted mortality rate was 4.6 per 100,000 for males and 1.6 per 100,000 for females between years 1995 and 1999. In around 30–40% cases H&N SCCs present at an early stage which is potentially managed by surgery or adjuvant radiotherapy with an intention to cure the disease. In contrast, advanced diseases with unresectable H&N SCCs are treated by concurrent chemoradiotherapy as a palliative therapy mainly to improve survival. 43

Costs of treatment for (only surgical resection) and caring for H&N SCCs after surgery are substantial. Kim et al. 43 have reported the total cost of post-operative health-care utilisation over the 5-year follow-up. The cost was approximately £255.5M for 11,403 patients in the UK.

Measurement of disease and/or response to treatment

In the UK, about 7000 new cases of H&N cancer occur annually. At least 45% of cases survive ≥ 5 years. 44 Younger populations have better survival than older populations. 42 Within the UK there has been an increment of between 5% and 14% in 5-year survival for most cancers (e.g. oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx and salivary glands). Epidemiological evidence that covered about 10% of the US population suggested an improvement in survival from 55% to 66% in people with H&N cancer between 1992–6 and 2002–6. 44

Similar to CRC cancer, disease progression and response to treatment are measured by a multidisciplinary team. After treatment, there are regular examinations in the first 2 years and routine follow-up after 5 years. The identification of recurrent tumours or new primary tumours are made by professionals during follow-up visits. Patients are also helped with complications of the disease and AEs due to treatment. Patients are also given help with functional and psychosocial problems. 45

Diagnosis and management

Signs and symptoms of H&N cancer depend on the location of the primary tumour and also on the extent of the disease. Common signs and symptoms of H&N cancer include hoarseness or change of voice, difficulty in swallowing, lump/swelling in the neck and non-healing mouth ulcers. 46

Tumour staging is necessary to determine the treatment and also to know the prognosis of the condition. Pathological or histological diagnosis is usually done according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification from biopsy taken from surgery. Clinical staging of the H&N are done according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification and TNM. The AJCC classification divides T4 tumours into two categories – T4a for moderately advanced cancer; and T4b for very advanced cancer. Stage IV cancers are divided into three categories: IVA, IVB and IVC. The latter indicates metastatic disease. The TNM classification of the Union International Contre Le Cancer (UICC, i.e. International Union Against Cancer) and AJCC are designed for staging/classifying SCC and minor salivary cancers47–49 (Tables 2 and 3).

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T1, T2, T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage IVA | T1, T2, T3 | N2 | M0 |

| T4a | N0, N1, N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IVB | Tb | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| Stage IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

| Primary tumour (T) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| T1: tumour confined to the nasopharynx, or extends to oropharynx and/or nasal cavity without parapharyngeal extension T2: tumour with parapharyngeal extension T3: tumour involves bony structures of skull base and/or paranasal sinuses T4: tumour with intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves, hypopharynx, orbit, or with extension to the infratemporal fossa/masticator space |

|||

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||

| N1: unilateral metastasis in cervical lymph node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, above the supraclavicular fossa, and/or unilateral or bilateral, retropharyngeal lymph nodes, ≤ 6 cm, in greatest dimension N2: bilateral metastasis in cervical lymph node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, above the supraclavicular fossa N3: metastasis in a lymph node(s) > 6 cm and/or to supraclavicular fossa N3a: > 6 cm in dimension N3b: extension to the supraclavicular fossa |

|||

| Distant metastasis (M) | |||

| M0: no distant metastasis M1: distant metastasis |

|||

| Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T1 | N1 | M0 |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage III | T1 | N2 | M0 |

| T2 | N2 | M0 | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IVA | T4 | N0 | |

| T4 | N1 | M0 | |

| T4 | N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IVB | Any T | N3 | M0 |

| Stage IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

According to Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines,37 tumours are broadly subdivided into (a) early disease (stage I and II following the UICC/TNM classification of malignant tumour); and (b) locally advanced disease stages III and IV.

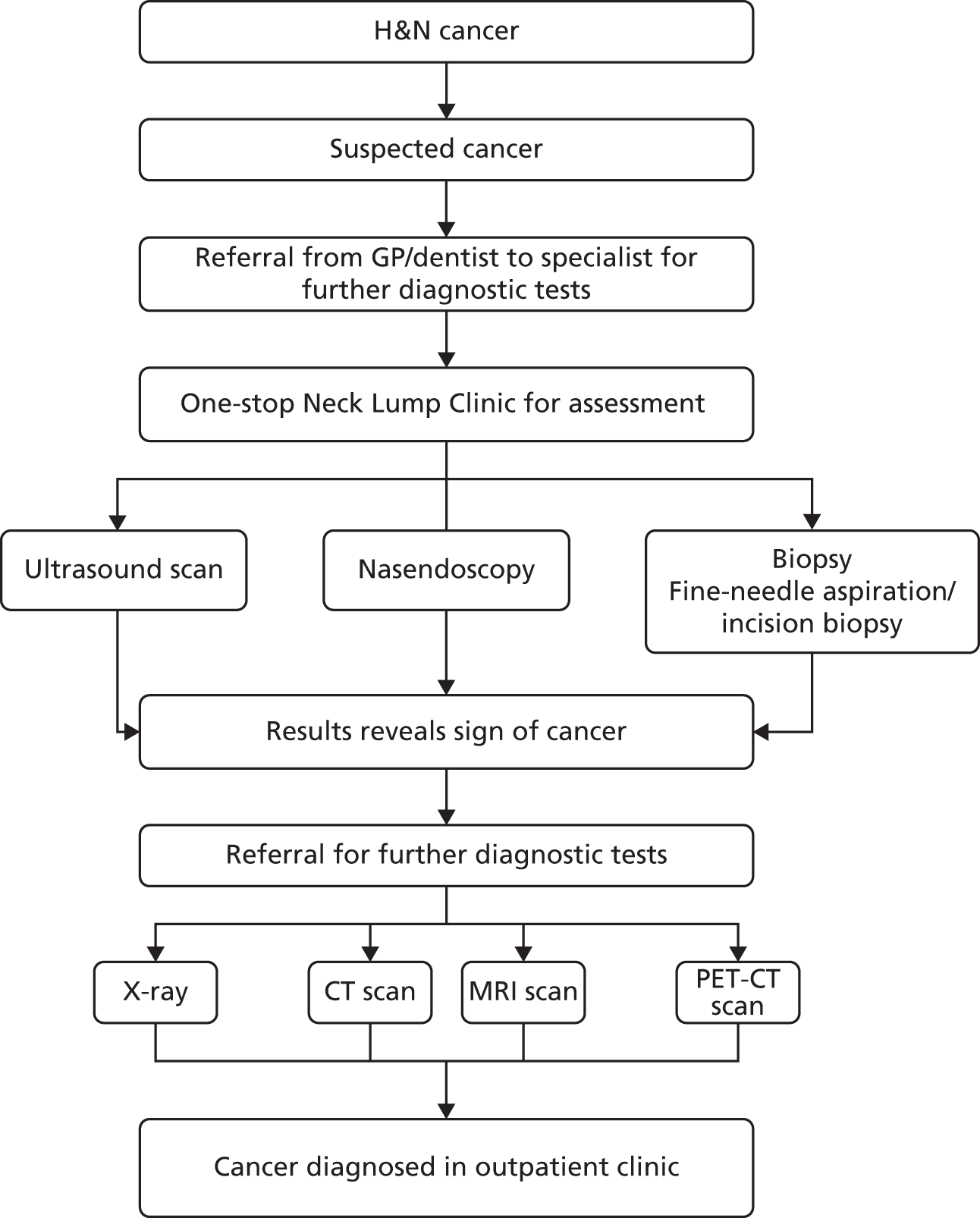

The management of H&N cancer falls into two broad categories: (1) management of early-stage cancer; and (2) management of locally advanced cancer (Figures 4 and 5).

FIGURE 4.

Head and neck diagnosis pathway. GP, general practice; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET-CT, positron emission tomography fused with computed tomography.

FIGURE 5.

Head and neck management pathway. a, Days 1, 22 and 43: i.v. cisplatin 100 mg/m2 + radiotherapy; b, day 1, i.v. docetaxel 75 mg/m2 + i.v. cisplatin 75 mg/m2 + days 1–5, 5-FU 750 mg/m2 continuous i.v. infusion. Repeat cycle every 3 weeks for four cycles. TPF, docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil.

Most (60–70%) patients present with locally advanced disease. The standard of care for this group is various combinations of surgery, radiotherapy and systemic treatments. Chemotherapy may be used prior to radiotherapy (induction) or combined with definitive or post-operative radiotherapy (synchronous).

Docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil (TPF) regimens are commonly used in the UK to treat locally advanced cancer (T3/4, N2/3). These regimens are also used as induction chemotherapy (prior to radiotherapy), for example to preserve the larynx, or in chemoradiation (concurrent radiation and cisplatin) followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin + continuous infusion 5-FU) for nasopharynx cancer. Meta-analysis evidence supports the addition of docetaxel to cisplatin plus 5-FU doublet. 50

For nasopharyngeal cancer the use of neoadjuvant TPF rather than cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (PF) is not as well established (clinical expert). The standard synchronous chemotherapy regimen (concurrent radiation + chemotherapy) is single-agent cisplatin 100 mg/m2, which is administered three weekly. 51 There are reports of severe side effects from 5-FU including diarrhoea; hand and foot syndrome; mucosities/stomatitis; neutropenia; anaemia; nausea and vomiting; and cardiotoxicity.

Stomach cancer

Stomach cancer refers to any malignant neoplasm occurring in the region between the gastro-oesophageal junction and the pylorus. 52 Stomach cancer also represents a major cause of cancer mortality worldwide. The most common cancer of the stomach is called adenocarcinoma. 53 This cancer starts in cells which line the innermost layer of the stomach, the mucosa. Stomach cancer spreads locally within the gastric wall and then to adjacent lymph nodes. 54 On reaching the serosa, it might spread into the peritoneal cavity, then distantly.

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

The aetiology of gastric cancer is complex. More than 80% of new diagnoses are attributed to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. 52 Lifestyle, diet, genetics, socioeconomic and a range of other factors appear to contribute to gastric carcinogenesis, despite a decline in the prevalence of H. pylori infection (a major cause of stomach cancer). 55,56

The incidence and mortality rates of stomach cancer appear to increase in socially and economically deprived groups. 57

The prognosis for patients with stomach cancer appears to depend on age, general health and how far the cancer has spread before it was diagnosed. No consensus has been reached on the best treatment option. 58

Incidence and/or prevalence

A total of 7610 new cases of stomach cancer were diagnosed in 2008 in the UK,59 with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 18%. 60 Currently, stomach cancer is the 15th most common cancer among adults in the UK. 59 In the UK approximately 13,400 people were still alive at the end of 2006, up to 10 years after being diagnosed with stomach cancer. 61 In the UK between 2009 and 2011, around 51% of cases of stomach cancer were diagnosed in people aged ≥ 75 years and stomach cancer incidence was strongly related to age, with the highest incidence rates in older men and women. 59 Overall, around 15% of people with stomach cancer will live at least 5 years after diagnosis and about 11% will live at least 10 years. Around 5000 people die from stomach cancer each year in the UK. 62

Significance for the NHS

Early-stage stomach cancer is often treated with surgery, with neo-adjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy offered where appropriate. The main chemotherapy drugs used to treat stomach cancer include 5-FU, cisplatin and epirubicin. Advanced stomach cancer is treated with chemotherapy. NICE technology appraisal (TA) 19163 recommends capecitabine in conjunction with a platinum-based regimen for the treatment of inoperable advanced gastric cancer.

Measurement of disease and/or response to treatment

A 2013 Cochrane study-level meta-analysis, reviewing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of post-surgical chemotherapy versus surgery alone for gastric cancer, reported a significant improvement in OS in 34 studies [hazard ratio (HR) 0.85, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.80 to 0.90] and in disease-free survival in 15 studies (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.87) as a result of adjuvant chemotherapy. 64 A recent meta-analysis concluded that D2 lymphadenectomy with spleen and pancreas preservation offers the most survival benefit for patients with gastric cancer when done safety. 65

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer refers to a malignant epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatic cancer, sometimes referred to as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, is the eighth and fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the world and Europe respectively. 66,67 It has very few symptoms in its early stage so is often diagnosed when the disease is advanced. The primary symptoms of pancreatic cancer include weight loss, stomach pain and jaundice, and these symptoms are associated with a number of conditions. 62

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

About 65% of pancreatic tumours starts in the head of the pancreas, 30% in the body and tail, and 5% can involve the whole pancreas. 68 The most common form of cancer occurs in the exocrine cells of the pancreas. These tumours account for over 95% of all pancreatic cancers.

Genetic factors, smoking and previous radiotherapy treatment for another cancer have been associated with an increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer. 69–71 Similarly, consumption of red and processed meat increased the risk of pancreatic cancer,72 and patients with chronic hepatitis B infection have an approximately 20–60% increased risk of pancreatic cancer. 73

Pancreatic cancer continues to be one of the most aggressive forms of tumour with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% and a median survival of 6 months after diagnosis; as a result it has a poor prognosis of all solid tumours. 74,75

Incidence and/or prevalence

In the UK a total of 8085 people were newly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2008. In 2009 a total of 8047 people died from this cancer. 76 In 2011 approximately 3600 men (2.6% of all newly-diagnosed male cancers) and 3700 women (2.7% of all newly-diagnosed female cancers) were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in England. 2 Pancreatic cancer is more common in men than women but this has started to change.

Impact of health problem

Pancreatic cancer in England has a crude incidence rate of 13.6 per 100,000 population and similar rates are seen in both sexes. Survival is poor with 1-year relative survival estimates of around 19% for both sexes. In many patients, the clinical diagnosis is fairly straightforward, although there are no clear clinical features which identify a patient with curable form of pancreatic cancer. 77

Significance for the NHS

Currently, treatment focuses on palliative surgery to relieve symptoms, resectional surgery with intent to cure, and endoscopic or percutaneous biliary stenting to relieve jaundice. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are often used, both as palliative treatments as well as in an adjuvant setting in conjunction with surgery. 78

The main chemotherapy drugs recommended to treat pancreatic cancer are 5-FU, gemcitabine and capecitabine. If surgery is possible, adjuvant treatment with 5-FU can reduce the risk of recurrence. NICE TA2579 recommends that gemcitabine may be considered as a treatment option for patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and a Karnofsky Performance Status score ≥ 50, where first-line chemotherapy is to be used. The guidance also states that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of gemcitabine as a second-line treatment in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Measurement of disease and/or response to treatment

The current management of pancreatic cancer is guided by tumour stage, comorbidities and performance status of the patients. In addition to gemcitabine and capecitabine FU, chemoradiation, and chemoradiation plus FU or gemcitabine are also used. 80 Surgical resection followed by a 6-month course of adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy is considered the standard care for early-stage disease. 81 Patients with metastatic disease can be considered for systemic palliative chemotherapy. In contrast, for patients with locally advanced disease without evidence of metastasis, optimal treatment remains unclear, with chemotherapy alone and chemoradiation both being an option for consideration. 82

Description of technology under assessment

5-fluorouracil

5-fluorouracil (5-FU or 5-fluoro-2,4-pyrimidinedione) is an antimetabolite of the pyrimidine analogue type, with a broad spectrum of activity against solid tumours (of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas, ovary, breast, brain, etc.), alone or in combination chemotherapy regimens. 83 5-FU has been used in daily clinical oncology practice for almost 50 years and continues to be the cornerstone of all major CRC treatment regimens for adjuvant therapy and for advanced metastatic disease. 84 The method of administration of 5-FU varies according to the type, location and stage of cancer, as well as the circumstances and preferences of the individual. 5-FU can be administered by infusion, injection, or orally as a pro-drug (e.g. capecitabine) and prescribed as either a single agent or in conjunction with other chemotherapy drugs.

Approximately ≥ 85% of administered 5-FU is inactivated and eliminated through the catabolic pathway; the remainder is metabolised through the anabolic pathway. 85 The enzyme dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) has a major role in clearance of 5-FU and the rate of clearance (inactivation) varies considerably from patient to patient. 5-FU chemotherapy typically lasts 3–6 months and usually for up to 12 cycles. Each cycle includes a period of 5-FU administration followed by a break to allow for recovery before the next cycle. Administration via continuous infusions usually lasts approximately 22–48 hours and requires patients to have a central venous access device such as a Hickman line or peripherally inserted central catheter line. Some patients have their 5-FU infusion via a portable pump which allows return to home during treatment.

When 5-FU was first developed in the USA, 5-FU monotherapy was usually administered via a bolus schedule; however, more recently these have been replaced by infusional regimens based on the work of de Gramont et al. 86,87

Intervention technology

My5-FU assay

The My5-FU assay is a nanoparticle immunoassay that measures levels of 5-FU in plasma samples. 88

As previously reported in the protocol to this work, the My5-FU assay is used with patients receiving 5-FU by continuous infusion to facilitate PK dose adjustment at the next cycle and drug monitoring to achieve an optimal plasma level of the drug. The assay uses two reagents: reagent 1 consists of a ‘5-FU conjugate’ which is a 5-FU-like molecule linked to a long spacer arm; reagent 2 consists of antibodies covalently bound to nanoparticles, these antibodies are able to bind either 5-FU or the 5-FU conjugate. When reagents 1 and 2 are mixed the nanoparticles aggregate together. In the presence of free 5-FU some of the antibodies bind 5-FU rather than 5-FU conjugate, the amount of aggregation of nanoparticles is reduced and this alters the light absorbing properties of the mixture (that is 5-FU and ‘5-FU conjugate’ compete for nanoparticle-bound antibodies). The light absorbance of the mixture is measured and can be compared against a calibrated standard curve in which light absorbance is compared with known concentrations of free 5-FU in the mixture. In short, photometric detection (changes in absorbance) of nanoparticle aggregation allows for determination of 5-FU concentration in plasma samples. 89 This assay can be performed on automated clinical chemistry analysers present in standard clinical laboratories. The assay requires a peripheral venous blood sample which is taken towards the end of each 5-FU infusion cycle using an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or a heparin tube. 90

Drug monitoring is potentially important for 5-FU because it has a narrow therapeutic index, with doses below the therapeutic window potentially limiting treatment efficacy and doses above the window more likely to cause side effects and toxicity. Commonly reported side effects of 5-FU chemotherapy include anaemia, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, mucositis and hand and foot syndrome,91 all of which can be dose limiting when severe. Other consequences of 5-FU toxicity can include neuropathy, severe damage to organs, cardiotoxicity, neutropenia, sepsis and septic shock. 92 Patients with DPD deficiency are at significantly increased risk of developing severe and potentially fatal neutropenia, mucositis and diarrhoea when treated with 5-FU. 93,94

Results are reported in nanograms 5-FU/millilitre plasma and are converted to an AUC value by multiplying the concentration of 5-FU in a steady state by the time of the infusion (in hours). This is then compared with a pre-defined optimal therapeutic range and the results, reported as mg × hour/l, are used to guide the dose of 5-FU given in the next cycles. Outlier results > 50 mg × hour/l are assumed to indicate that the blood sample has been taken too close to the infusion port and these results are disregarded. The My5-FU assay has been validated against liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)89,95 and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) laboratory techniques commonly used in PK studies.

When using the My5-FU assay in clinical practice, the initial dose of 5-FU is based on a patient’s BSA. A blood sample is taken towards the end of the infusion cycle. For an infusion > 40 hours sampling is recommended at least 18 hours after starting infusion. 96 The sample should also be taken during a steady state period of the infusion which is usually about 4 hours before the end of the infusion using a non-battery operated device (which is commonly used in the UK). Depending on practice, it may require an additional visit by a district nurse or an additional outpatient attendance. Subsequent doses of 5-FU are calculated using the AUC result, according to a pre-determined dose adjustment algorithm. An example of a dose adjustment algorithm for patients with mCRC recommends an optimal therapeutic range of 20–30 mg × hour/l with adjustments of no more than 30% of the dose for each infusion. 96 Patients typically require three or four PK-directed dose adjustments to reach an optimal therapeutic range.

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase is the rate-limiting enzyme involved in the catabolism of 5-FU. Up to 80–85% of an administered dose of 5-FU is broken down by this enzyme to inactive metabolites. DPD converts endogenous uracil into 5,6-dihydrouracil, and analogously, 5-FU into 5-fluoro-5,6-dihydrouracil. The presence of DPD deficiency results in a reduced ability to metabolise and clear 5-FU, and the half-life of the drug, which is normally approximately 10–15 minutes, can be markedly prolonged (to up to 159 minutes). 97–100 Response to 5-FU treatment is inconsistent with approximately 10–30% of patients displaying serious toxicity partly explained by reduced activity of DPD. 95

In the following section the key principles of the My5-FU assay procedure are provided; the majority of this information has been taken from the Saladax kit instructions. 90

Handling and storage instructions

Store reagents, calibrators and controls should be refrigerated at 2–8 °C (35–46 °F). Before use, the nanoparticle reagent (R2) should be mixed by gently inverting the R2 reagent vial three to five times, avoiding the formation of bubbles.

Sample collection

Plasma (EDTA or heparin) specimens may be used with the My5-FU assay. The sample is drawn towards the end of the infusion, preferably 2 hours before the end, ensuring that the pump still contains solution during the sample draw. The start time of continuous infusion and actual sampling time is recorded. A minimum of 2 ml of blood is collected into an EDTA or heparin tube. The blood sample is collected by venepuncture or through a peripheral i.v. line to avoid contamination by the infusing drug.

The sample stabiliser is available in Europe which negates the need for ice and immediate access to a centrifuge. The stabiliser maintains 5-FU levels in whole blood for up to 24 hours after collection.

Calibration

The My5-FU assay produces a calibration curve with a 0–1800 ng/ml range using the My5-FU calibrator kit. The minimum detectable concentration of 5-FU in plasma for the My5-FU assay is 52 ng/ml.

Quality control

The My5-FU control kit contains three levels of controls at low, medium and high concentrations of 5-FU. A laboratory should establish its own control ranges and frequency. At least two concentrations of quality control should be tested each day as patient samples are assayed and each time calibration is performed. It is important to reassess control targets and ranges following a change of reagent (kit) or control lot.

Limitations of the procedure

Performance characteristics for the My5-FU assay have not been established for body fluids other than human plasma containing EDTA or heparin.

High-performance liquid chromatography/liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

During the last 40 years, several methods for the quantitation of 5-FU levels have been developed and evaluated, these include gas chromatography, tachophoresis, HPLC, or thin layer chromatography as separating modalities, and radioactivity, mass spectrometer (MS), fluorescence, ultraviolet absorption, or flame ionisation as detection techniques. 101 The majority of these assays have been useful in pre-clinical and clinical pharmacological studies. Drug monitoring combined with early detection of patients at risk enables timely dose adaptation and maintain drug concentrations within a therapeutic window; however, the most effective method to identify such patients is unclear. 102

High-performance LC-MS methodology comprises an HPLC column attached, via a suitable interface, to a MS and is capable of analysing a wide range of components. Compounds are separated on the relative interaction with the chemical coating of these particles and the solvent eluting through the column. Components eluting from the chromatographic column are introduced to the MS via a specialised interface. Two most common interfaces used for HPLC/MS are the electrospray ionisation and the atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation interfaces. 103 For more details on a HPLC method please refer to a paper by Gamelin et al. 104

A popular method involves LC-MS/MS. 105–107 Despite LC-MS/MS methods being found to be sensitive and robust, the instrumentation is not in standard use in routine clinical laboratories in the UK. For more details on a LC-MS/MS method please refer to a paper by Kosovec et al. 101

Current usage of the My5-FU assay in the NHS

The My5-FU assay is currently not in clinical use in the UK, other than for research purposes. Several ongoing clinical trials are taking place. As part of the current report a detailed consultation was made with the NICE committee assessment subgroup expert advisors and other clinical experts. The responses to a large range of questions relevant to this work have been used as part of the health economic modelling detailed in Chapter 6.

Comparators

Currently in most clinical practice in the UK the 5-FU dose administered is calculated according to patients BSA. As described in Diagnosis and management, BSA is calculated using the Du Bois method:32 BSA (m2) = weight (kg) 0.425 × height (cm) 0.725 × 0.007184. Currently, FOLFIRI and FOLFOX6 regimens recommend a 5-FU dose of 2500 mg/m2 administered by continuous infusion over 46 hours.

It is well documented that the plasma concentrations of 5-FU vary greatly between individuals who have received ‘standard’ dosage calculated from their BSA and this dose remains unadjusted at subsequent cycles unless the patient experiences sufficient toxic effects to mandate dose reduction. Such dose reductions are guided by clinical judgement. The dose is not increased above an evidence-based (trial) maximum dose even if there is no toxicity.

Associations have been reported between 5-FU plasma levels and the biological effects of 5-FU treatment, both in terms of toxicity and clinical efficacy. 108–111 Although this method is commonly used with many anticancer drugs, its use has been questioned112,113 and clinical investigations have also failed to show a association between 5-FU plasma clearance and BSA. 114

Pharmacokinetic-guided studies have identified an optimal target therapeutic range for 5-FU and have recommended dose adjustment algorithms to bring plasma concentrations into the optimal range. 84 However, 5-FU monitoring has not been widely used. Any advances in testing based on LC-MS/MS or nanoparticle antibody-based immunoassay, might facilitate monitoring of 5-FU in routine daily clinical practice. 101,102

Chapter 2 Definition of decision problem

The current report being undertaken for the NICE DAP examines the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 5-FU plasma monitoring with the My5-FU assay for guiding dose adjustment in patients receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous infusion. The report will allow NICE to make recommendations about how well the My5-FU assay works and whether or not the benefits are worth the cost of the tests for use in the NHS in England and Wales. The test allows a more tailored dosing of 5-FU which may lead to improved clinical outcomes and less side effects. The assessment will consider both clinical improvement in patients symptoms and the cost of the test used to measure the amount of 5-FU.

The decision question taken from the NICE scope for this project is:

What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the My5-FU assay for the PK dose adjustment of continuous infusion 5-FU chemotherapy?

Overall aim of the assessment

The overall aim of this report was to present the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the My5-FU assay for guiding dose adjustment in patients receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous infusion.

Objectives

In the current report we:

-

(1) Provide a review of the studies which examine the accuracy of the My5-FU assay when tested against gold standard methods of estimation of 5-FU. HPLC and LC-MS are considered the gold standard for the purpose of assessing the accuracy of 5-FU plasma level measurements.

(2) Provide a review of the studies which have developed a treatment algorithm based on plasma 5-FU measures.

-

Systematically review the literature on the use of My5-FU to achieve adjusted dose regimen(s) to compare it with BSA-based dose estimation for patients receiving 5-FU administered by continuous infusion. Variations in current BSA-based dose regimens are considered where appropriate.

-

Systematically review the literature on the use of HPLC and/or LC-MS to achieve dose adjustment to compare it with BSA-based dose regimens for patients receiving 5-FU. This is undertaken for the purpose of performing a linked evidence analysis which incorporates estimates of comparability of assay performance [in terms of OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and AEs] of My5-FU relative to the gold standards (HPLC, LC-MS) as outlined in (a).

-

Provide an overview of systematic reviews of clinical outcomes in studies of 5-FU cancer therapies administered by continuous infusion in order to assess the generalisability of outcomes reported in the control arms of studies included in (b) and (c) above. Outcomes of interest include incidence of side effects and 5-FU toxicity; treatment response rates; PFS; OS; and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

-

Identify evidence relevant to the costs of using My5-FU. Illustrative clinical pathways have been constructed; for this, we have used information provided by the manufacturer, advice from specialist committee members and other clinical experts, data collected from an identified UK clinical laboratory and analysis of the published literature. We have collected information on the following:

-

– cost of My5-FU testing

-

– cost of delivering 5-FU by infusion

-

– cost of side effects and 5-FU toxicity and their associated treatment or hospitalisation.

-

These will be considered from an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness methods

Identification and selection of studies

Search strategies for clinical effectiveness

Scoping searches were undertaken to inform the development of the search strategies and to assess the volume and type of literature relating to the assessment questions. An iterative procedure was used, with input from clinical advisors and the NICE Diagnostic Assessment Programme Manual. 115 One search strategy was developed for objectives A–C and another two were developed for objective D (see Searches for objective D). Search strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

Searches for objectives A–C

This search strategy focused on My5-FU/gold standard technologies, FU, PKs and dose adjustment, with a limit to English language. No study type or date limits were applied. This search strategy developed for EMBASE was adapted as appropriate for other databases. The bibliographic database searches were undertaken in January 2014. Other searches were undertaken between February and April 2014. All retrieved papers were screened for potential inclusion.

The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic bibliographic databases

-

contact with experts in the field

-

scrutiny of references of included studies

-

screening of manufacturers and other relevant organisations websites for relevant publications.

The following bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE; MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; EMBASE; The Cochrane Library [including Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, NHS Economic Evaluation Database and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases]; Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings (Web of Science); National Institute for HTA programme; and PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews).

The following trial databases were also searched in April 2014: Current Controlled Trials; ClinicalTrials.gov; UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database; WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

The following specific conference proceedings, selected with input from clinical experts, were checked for the last 5 years. These websites accessed between 24 and 31 March 2014:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology (main and American Society of Clinical Oncology – Gastrointestinal Cancer) – URL: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/site/misc/meetings_archive.xhtml

-

American Association for Cancer Research – URL: www.aacr.org/home/scientists/meetings--workshops/aacr-annual-meeting-2014/previous-annual-meetings.aspx

-

European Society for Medical Oncology Congress – URL: www.esmo.org/Conferences/Past-Conferences

-

European Cancer Organisation – URL: www.ecco-org.eu/Events/Past-conferences.aspx

-

World Congress of Gastrointestinal Cancer – URL: http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/content/supplemental

The following websites were consulted via the internet between 24 and 31 March 2014:

-

Saladax – URL: www.saladax.com/

-

International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment – URL: www.inahta.org/

-

The Association of Cancer Physicians – URL: www.cancerphysicians.org.uk/

-

Royal College of Physicians: Oncology – URL: www.rcplondon.ac.uk/specialty/medical-oncology

-

UK Oncology Nursing Society – URL: www.ukons.org/

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology – URL: www.asco.org/

-

Oncology Nursing Society – URL: www.ons.org/

-

European Society for Medical Oncology – URL: www.esmo.org/

-

European Oncology Nursing Society – URL: www.cancernurse.eu/

-

The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland – URL: www.acpgbi.org.uk/

-

British Society of Gastroenterology – URL: www.bsg.org.uk/

The reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were checked. Identified references were downloaded into EndNote X7 software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

Searches for objective D

Several UK guidelines and evidence updates based on systematic reviews were identified via searches7,37,116 or personal communication (NICE 2010 Head and Neck Cancer Annual Evidence Update) (Fran Wilkie, NICE, 23 April 2014, personal communication). Two search strategies were then developed focussing on finding systematic reviews on the use of FU in mCRC and H&N cancer (see Appendix 1). H&N cancer was not considered further in objective D. The searches were limited to English language and to articles published in or after 2011 (the year the searches were run for the NICE mCRC guideline7 and most recent H&N evidence update116). A focussed search filter for systematic reviews developed in house was used. This search filter was developed to miss less well-reported reviews (e.g. where the terms systematic or meta-analysis are not included in the title or abstract), but recent initiatives, such as Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), mean that this is less of a concern than in the past. 117 The search strategies developed for MEDLINE were adapted as appropriate for other databases. The searches were undertaken in April 2014.

The following bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE; MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and HTA databases)

The following website was consulted via the internet:

-

Saladax – URL: www.saladax.com/

Identified references were downloaded into EndNote X7 software.

The searches, inclusion and exclusion criteria for objective E will be considered separately in Chapter 5, Methods.

Inclusion and exclusion of relevant studies

Objective A: inclusion criteria

Population:

-

cancer patients (CRC, H&N, stomach, pancreatic) receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous venous infusion.

Intervention:

-

PK monitoring using My5-FU.

Comparator:

-

HPLC, LC-MS/MS.

Outcome:

-

performance of My5-FU (e.g. correlation between My5-FU and ‘gold standard’).

Setting:

-

care services for cancer patients.

Objective A: exclusion criteria

Population:

-

animal studies

-

no patients, samples or cell lines only

-

patient group unclear

-

studies of cancer patients with cancers other than CRC, H&N, stomach, pancreatic

-

studies with < 80% of included cancers (CRC, H&N, pancreatic and gastric cancer).

Treatment:

-

treatment not containing 5-FU

-

non-included treatment (e.g. 5-FU + interferon alpha, chemotherapy + radiotherapy)

-

bolus only

-

oral 5-FU.

Intervention:

-

method for PK monitoring unclear

-

no PK monitoring

-

validation of other technology than My5-FU

-

tumour samples analysed.

Study type:

-

narrative reviews (but reference lists checked)

-

editorials/letters without original data

-

case studies

-

non-English-language papers.

Objectives B and C: inclusion criteria

Population:

-

cancer patients (CRC, H&N, stomach, pancreatic) receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous venous infusion.

Intervention:

-

PK monitoring using HPLC or My5-FU.

Comparator:

-

BSA or no comparator.

Outcome:

-

intermediate measures for consideration:

-

proportion of patients with 5-FU plasma levels in the optimal target range

-

AUC measurements

-

incidence of over and underdosing

-

frequency of dose adjustment

-

test failure rates

-

-

clinical outcomes related to intermediate measures of 5-FU exposure:

-

treatment response rates

-

PFS

-

OS

-

HRQoL

-

incidence of side effects and 5-FU toxicity.

-

Setting:

-

care services for cancer patients.

Objectives B and C: exclusion criteria

Population:

-

animal studies

-

no patients; samples or cell lines only

-

patient group unclear

-

population with non-included cancers)

-

studies with < 80% of included cancers (CRC, H&N, pancreatic and gastric cancer).

Treatment:

-

not 5-FU

-

wrong treatment (e.g. 5-FU + interferon alpha, chemotherapy + radiotherapy)

-

bolus only

-

oral 5-FU.

Intervention:

-

method for PK monitoring unclear

-

no PK monitoring

-

tumour samples analysed.

Outcome:

-

AUC or 5-FU plasma concentration not related to outcomes.

Study type:

-

narrative reviews (but reference lists checked)

-

editorials/letters without original data

-

case studies

-

abstracts without dose adjustment following My5-FU measurement

-

Non-English-language papers.

Objective D: inclusion criteria

Population:

-

CRC patients receiving 5-FU chemotherapy by continuous venous infusion.

Intervention:

-

5-FU therapy as folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (FUFOL) (Gamelin et al. 118) or FOLFOX6 (Capitain et al. 119) regimen.

Comparator:

-

none or any.

Outcome:

-

PFS, OS, AEs/toxicity.

Setting:

-

care services for cancer patients.

Study type:

-

systematic review or meta-analysis.

Objective D: exclusion criteria

Population:

-

cancers other than CRC.

Treatment:

-

treatment regimens other than FUFOL or FOLFOX6.

Study type:

-

non-English-language papers.

Review strategy

The general principles recommended in the PRISMA statement were used. 117 Records rejected at full-text stage and reasons for exclusion were documented. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all records identified by the searches and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Disagreement was resolved by retrieval of the full publication and consensus agreement. Full copies of all studies deemed potentially relevant were obtained and two reviewers independently assessed these for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer, using a piloted, data extraction form (see Appendices 2–4). A second reviewer checked the extracted data and any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer. Further details about data extraction are provided for objective A(1) below.

Data extraction for objective A(1)

A data extraction sheet (see Appendix 2) was developed combining basic study information, results and fields from the data extraction sheets for the other objectives so these data can be linked. The key measure for whether or not My5-FU can be considered equivalent to LC-MS/MS and HPLC is if both the upper and lower limits of agreement [mean difference ± 2 standard deviation (s.d.)] on the Bland–Altman plot are sufficiently small that in the context of a cautious dose adjustment algorithm they could be considered of little clinical concern. Additionally, if the 95% CI of the mean difference (bias) does not intersect zero then an adjustment should be made when converting from one measuring instrument to the other. 120 We also extracted data on the regression between the index test and reference standard, but this can only give information on the correlation between the two measures, and is not informative to the question of whether or not the two measures can be considered equivalent. Significant correlation cannot be considered evidence for significant equivalence. 120

Quality assessment strategy

Adapting the revised quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies checklist for objective A(1)

Where appropriate, the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies was assessed using the revised quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS-2). 121 For reasons explained below, QUADAS-2 was adapted for objective A(1) (see Appendix 5).

The QUADAS-2 is a broad tool used to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies. For this part of the review we were interested in analytic validity of the test only (i.e. its accuracy and reliability in measuring 5-FU plasma levels). Whether or not the test can accurately predict patients’ response to and side effects of treatment (its clinical validity) and be implemented to improve patient outcomes (its clinical utility) are considered in objectives B–D. We adapted the signalling questions in the QUADAS-2 tool for use with laboratory analytical studies. This was informed by the Analytic validity, Clinical validity, Clinical utility and Ethical guidance for assessing analytic validity for genetic tests. 122

In domain 1 (patient selection), one signalling question, ‘Was a case–control design avoided?’, was removed. In this measure of analytic validity the outcome of interest (5-FU plasma level) is continuous, and therefore by definition there were no cases or controls. The focus of concerns regarding applicability was adapted from relating entirely to patients to also including to plasma sample concentrations.

In domain 2 (index tests), the signalling question ‘Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard?’ was removed because the index test is objective. The signalling question ‘If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified?‘ was removed as we were interested in agreement between two continuous measure without a threshold. An additional signalling question was added to account for the potential bias in under-reporting or not including failed tests: ‘Were the number of failed results and measurement repeats reported?’. Under applicability we added ‘Describe the preparation and storage of the sample before the index test was applied’ to check whether or not sample preparation was similar to potential NHS practice.

In domain 3 (reference standard), the signalling question ‘Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?’ was removed because the reference standard is objective.

In domain 4 (flow and timing), exclusions from the ‘2 × 2 table’ and ‘analysis’ were replaced with exclusions from the ‘Bland–Altman plot’ because there will be no thresholds used and therefore no 2 × 2 tables produced, and the outcome of most interest is the Bland–Altman plot (see Data extraction strategy). Additionally, ‘Did all patients receive a reference standard?’ was replaced with ‘Were both index test and reference standard conducted on all samples?’

Quality assessment strategy for objectives B and C

For objectives B and C, as a broad range of study designs were identified in the scoping searches, the use of a single checklist, in contrast to individual checklists for each study design, was considered appropriate. The Downs and Black checklist123 was therefore used to assess the quality of papers meeting the inclusion criteria (see Appendix 6). This 27-item checklist enabled an assessment of randomised and non-randomised studies and provides both an overall score for study quality and a profile of scores not only for the quality of reporting, internal validity (bias and confounding) and power, but also for external validity. However, as some questions were not appropriate for single-arm studies, the overall score was not considered useful or appropriate and was therefore not used. The results of the quality assessment provide an overall description of the quality of the included studies and provide a transparent method of recommendation for design of any future studies. Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer through discussion.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Diagnostic accuracy studies (My5-FU vs. high-performance liquid chromatography/liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) [objective A(1)]

The My5-FU assay delivers an estimate of plasma 5-FU concentration. For a study population this may potentially allow discrimination of study populations into categories: overdosed, optimally dosed and underdosed. Where results from a gold standard were available, a 2 × 2 table was constructed allowing diagnostic accuracy to be estimated using standard statistics (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, positive and negative predictive values).

Diagnostic accuracy studies (My5-FU vs. HPLC/LC-MS) are considered to be those where patient samples are assayed for 5-FU concentration but patient outcomes may not be reported. Those studies that aimed to test the internal and/or external validity of the My5-FU assay were identified and their findings were summarised and appraised. Studies that do not report test failure rates were noted; where available, test failure rates were tabulated.

Patient-based studies (objectives B and C)

Analyses was stratified according to cancer type, 5-FU delivery mode and cancer stage (e.g. metastatic).

Study, treatment, population and outcome characteristics were summarised and compared qualitatively and, where possible, quantitatively in text, graphically and in evidence tables. Pooling studies results by meta-analysis was considered. Where meta-analysis was considered unsuitable for some or all of the data identified (e.g. due to the heterogeneity and/or small numbers of studies), we employed a narrative synthesis. This involved the use of text and tables to summarise data allowing the reader to consider any outcomes in the light of differences in study designs and potential sources of bias for each of the studies being reviewed. Studies were organised by research objective addressed. A commentary on the major methodological problems or biases that affected the studies was included, together with a description of how this may have affected the individual study results.

For objectives B and C we aimed to identify studies which compared BSA-based dose regimens of 5-FU with continuous infusion in which measures of plasma 5-FU are not undertaken to inform dose changes with dose regimens in which dose adjustment is informed by the My5-FU assay results applied to a stated dose adjustment algorithm. These studies would best report the following outcomes: incidence and severity of side effects of 5-FU; OS; and PFS, as stated in the inclusion criteria. We considered using a linked evidence approach124 in which studies report dose adjustment informed by plasma 5-FU measured by other methods (e.g. HPLC, LC-MS); this required a narrative linking of evidence of comparable performance of My5-FU with such assay methods.

In studies where My5-FU had been used but there was no comparator arm, or the comparator arm was a convenience sample (retrospective/historical population), outcomes were listed and appraised. Outcomes reported for non-randomised comparator arms (i.e. historical controls) were assessed for their representativeness in the light of information gained from systematic reviews (objective D). Relevant clinical outcomes from single-arm studies were considered for pooling should they be reported in sufficient detail and be considered relevant to the objectives.

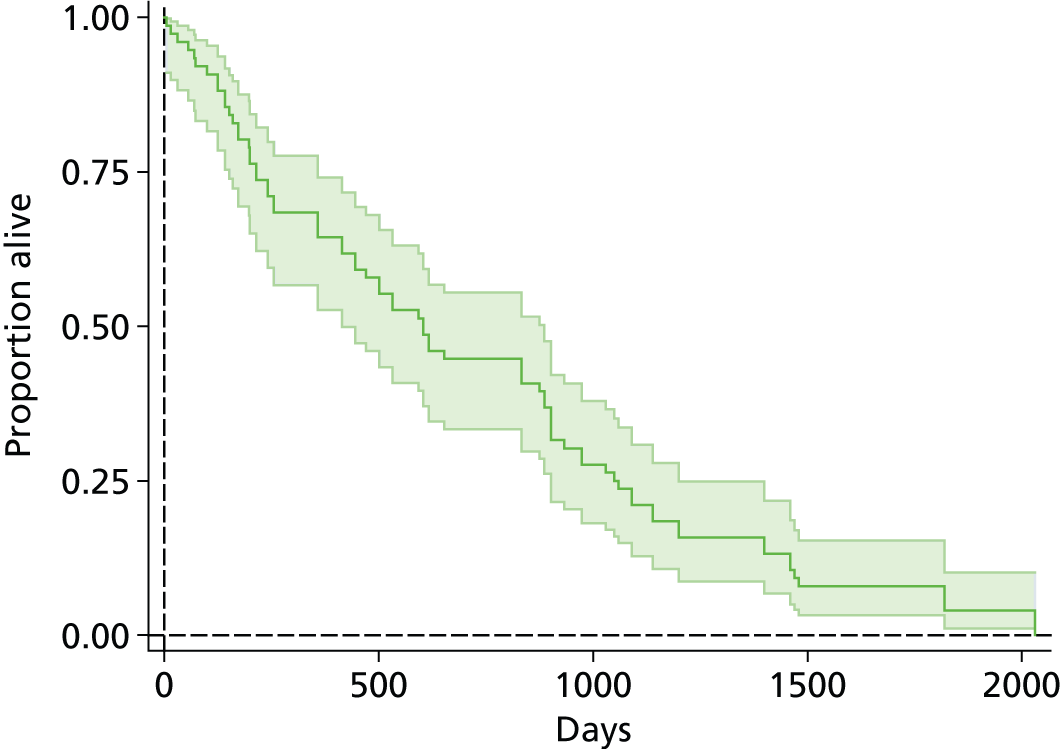

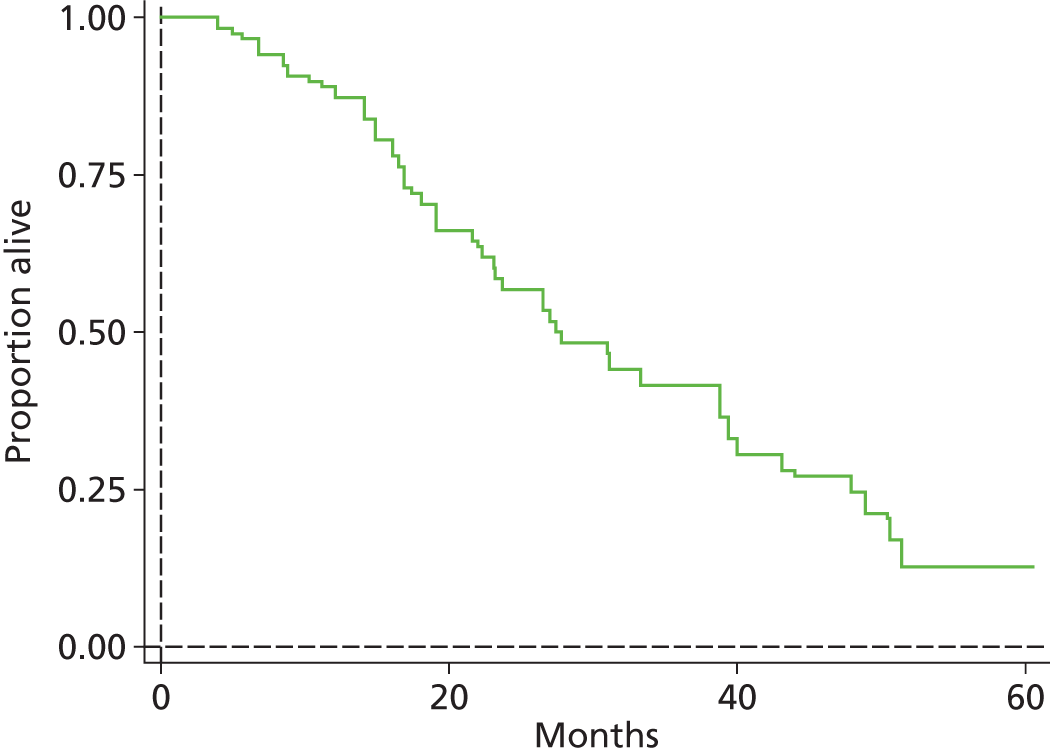

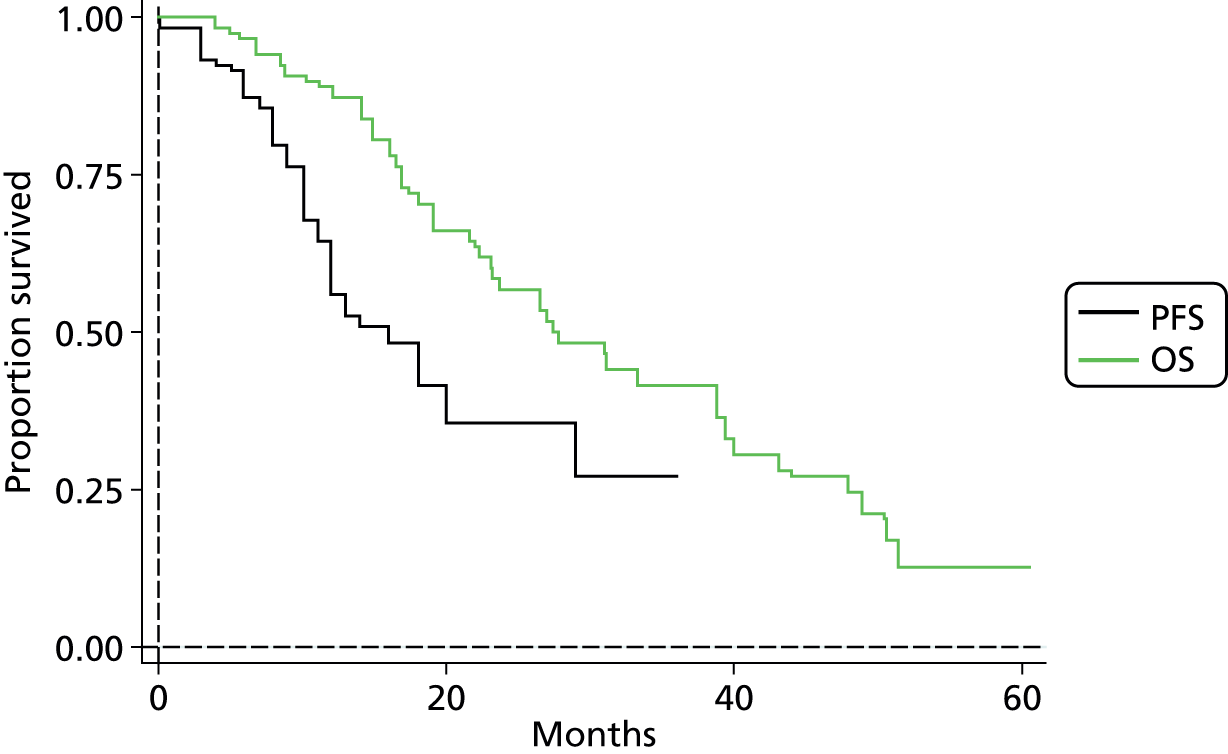

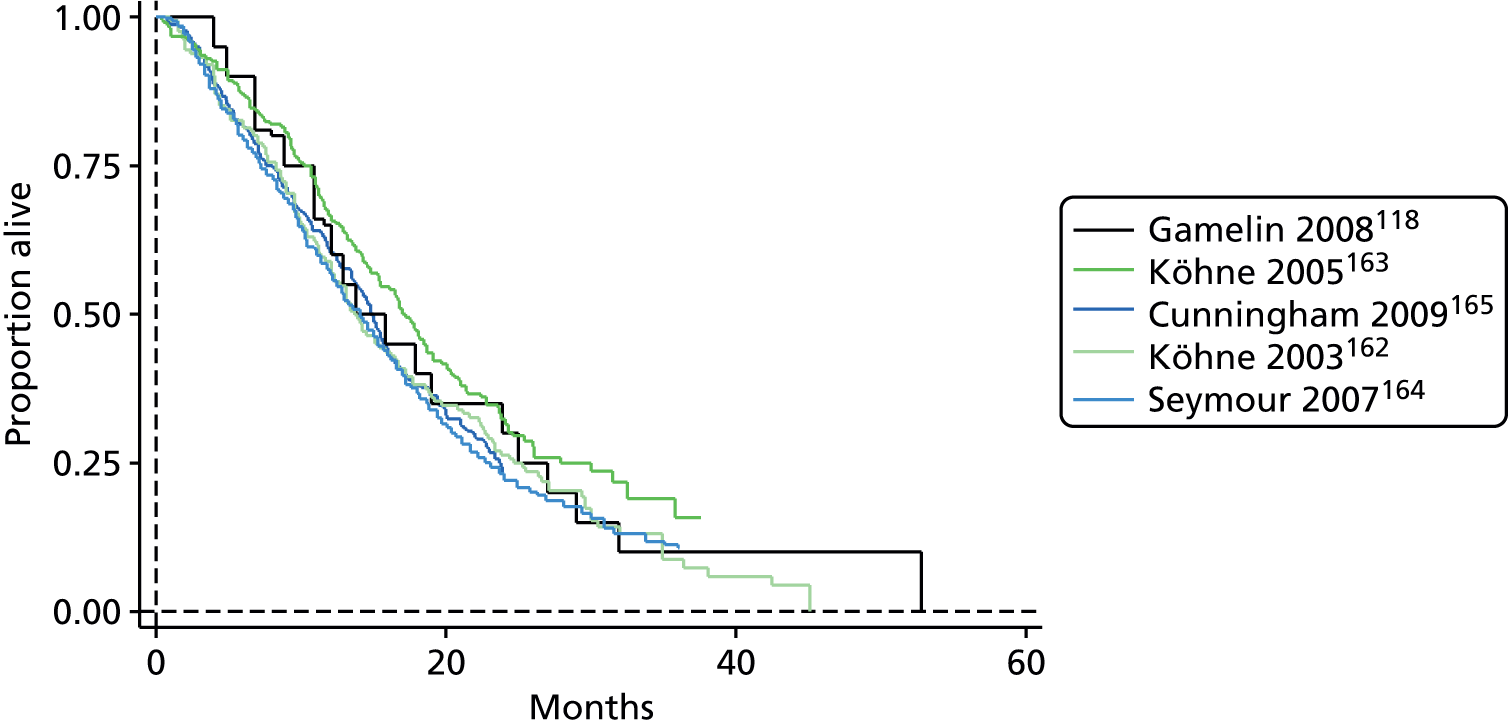

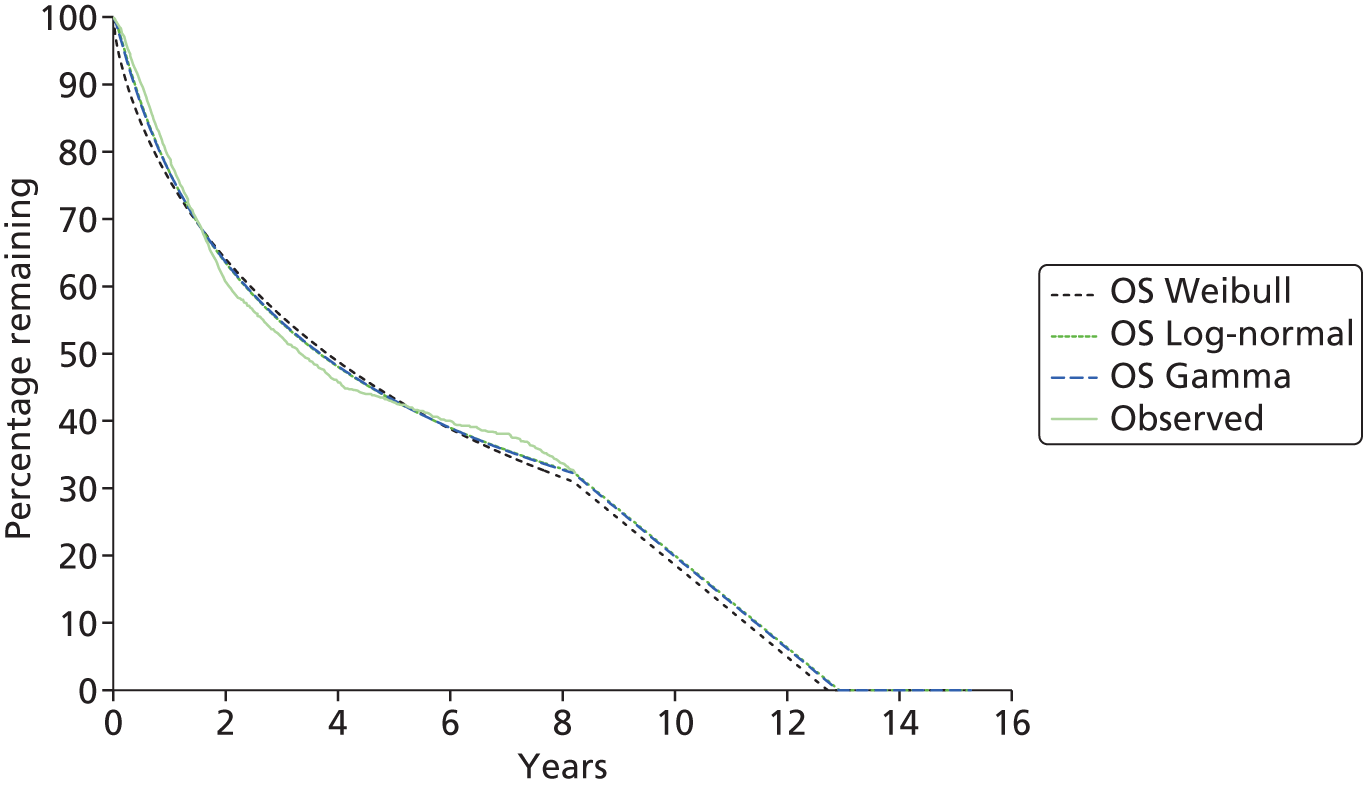

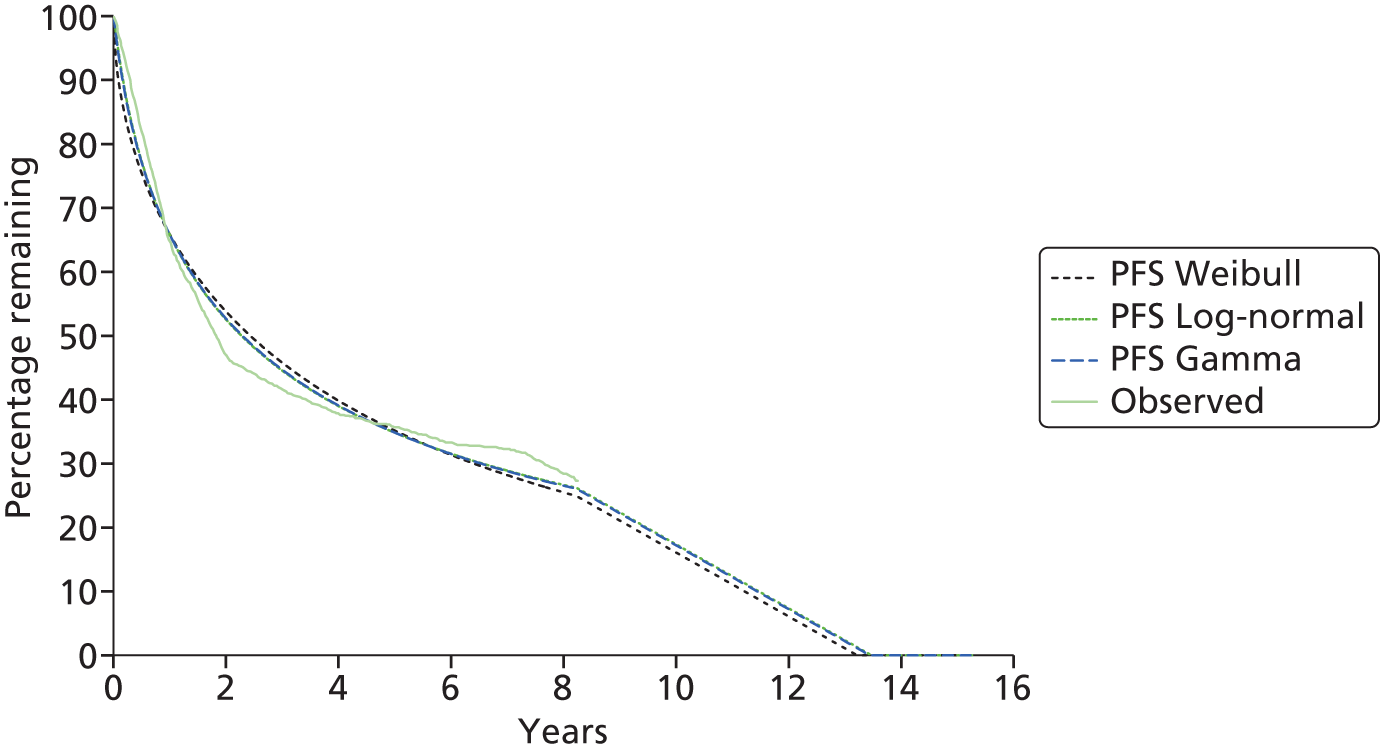

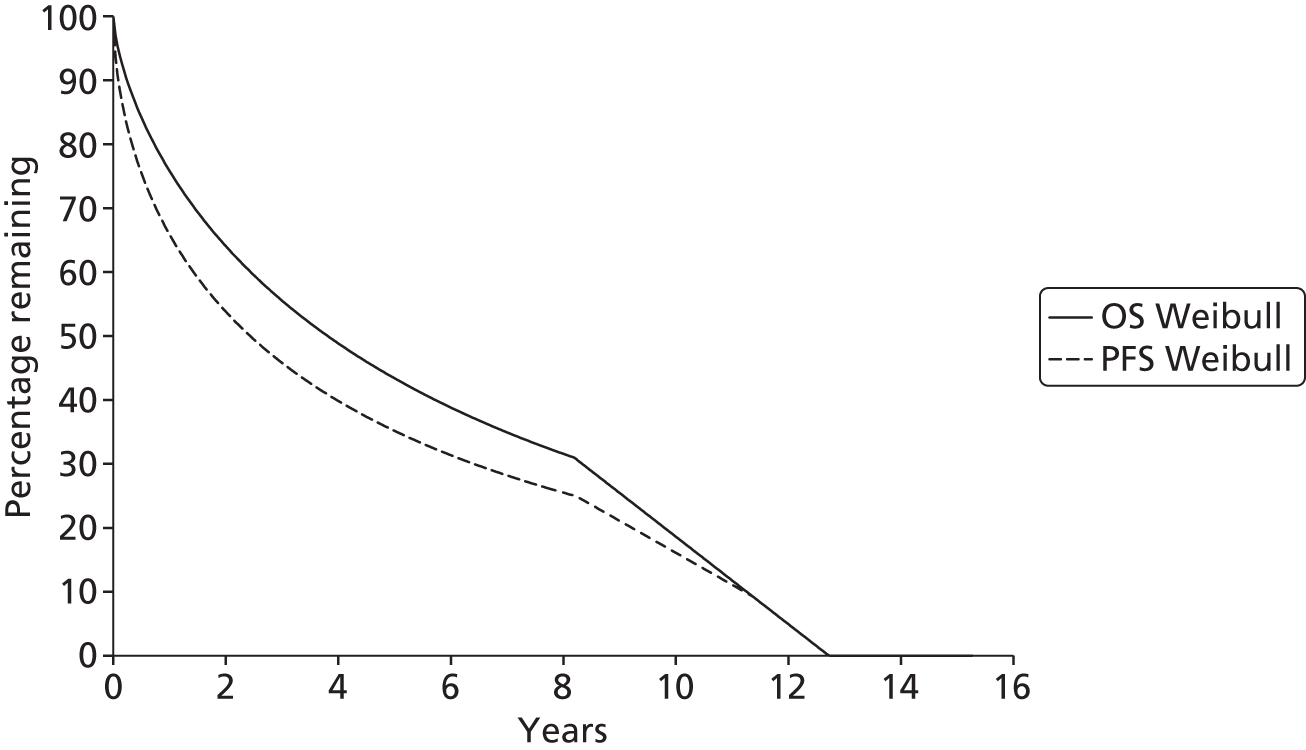

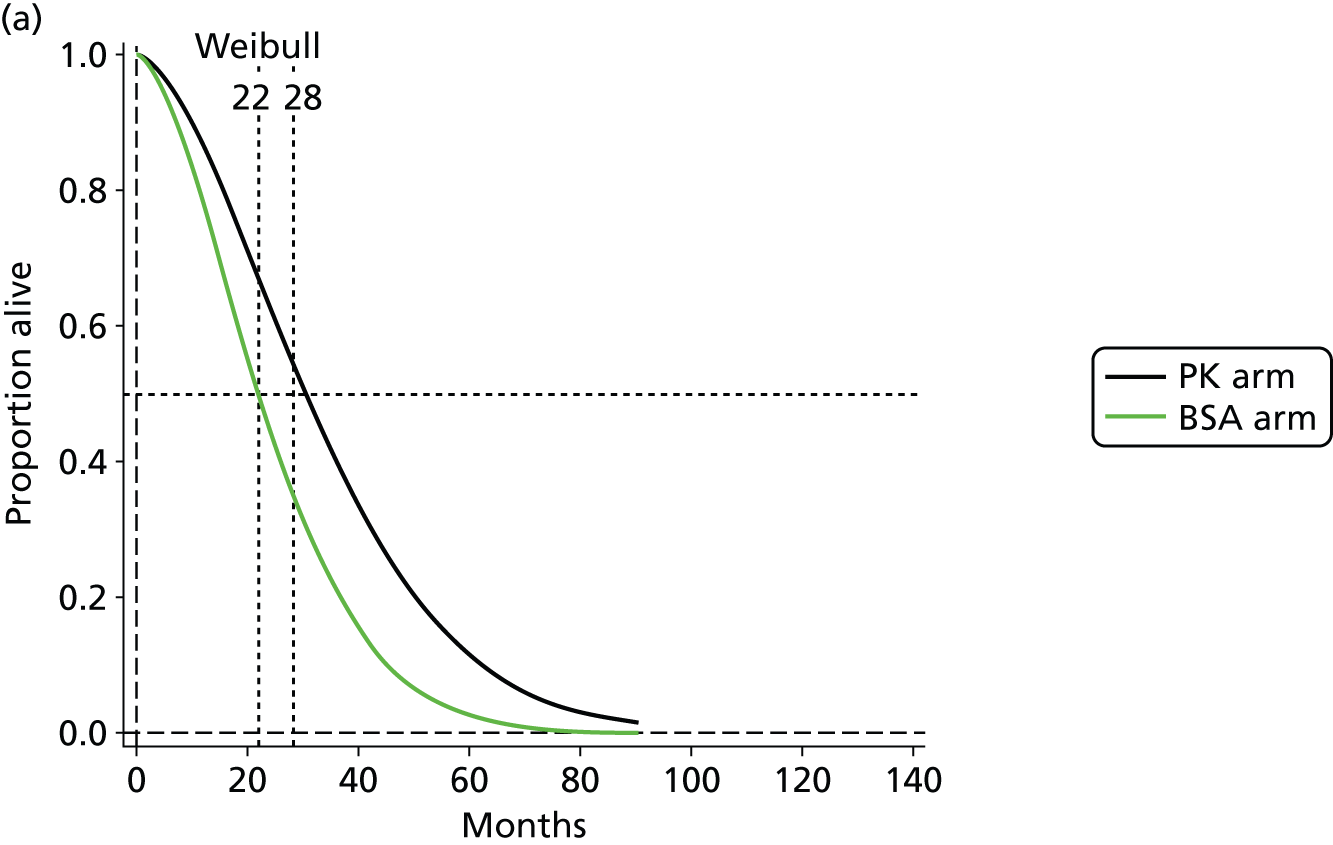

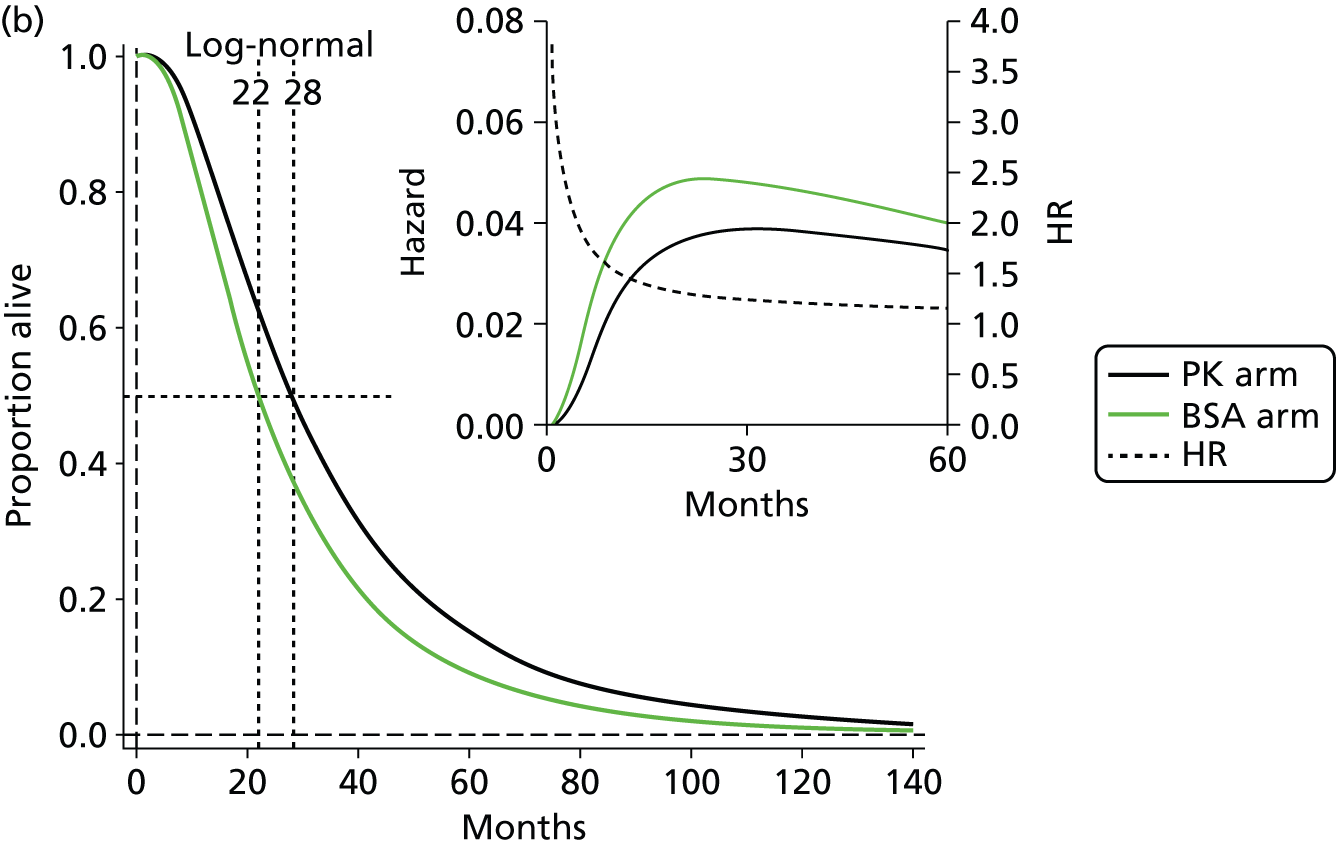

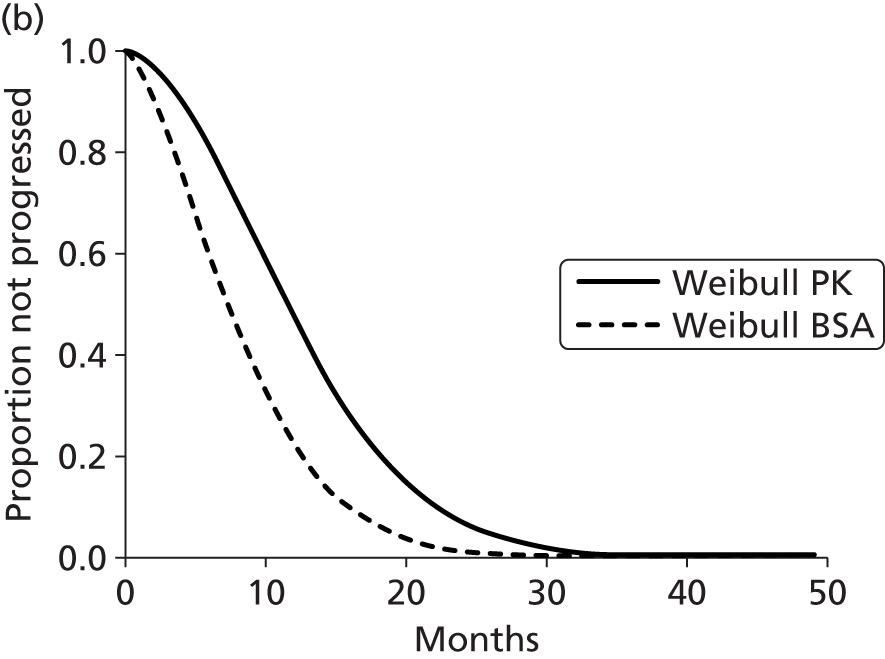

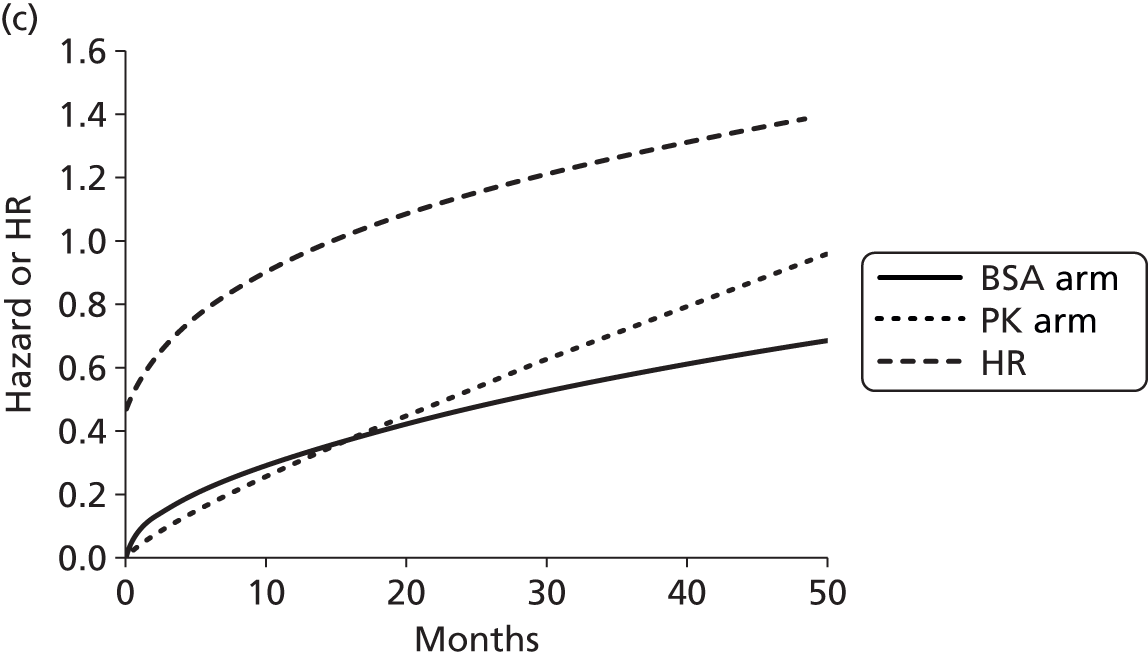

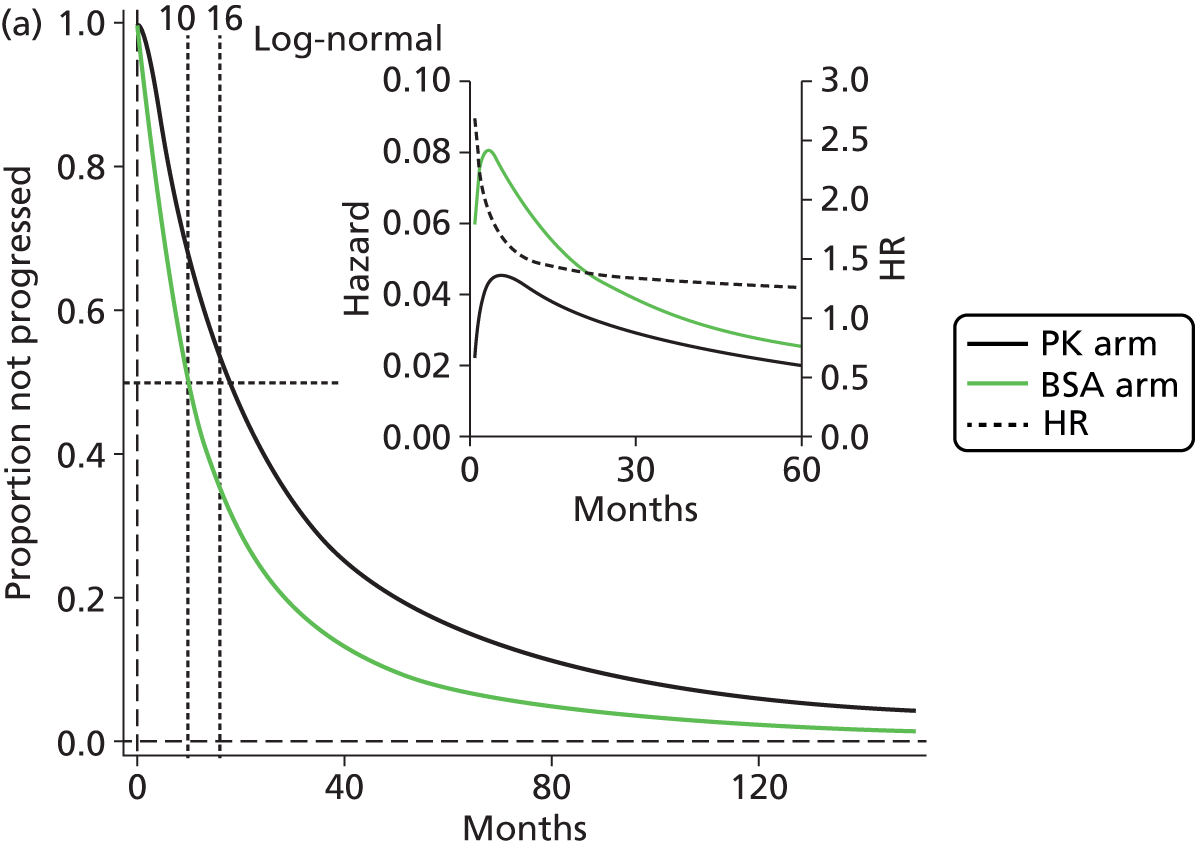

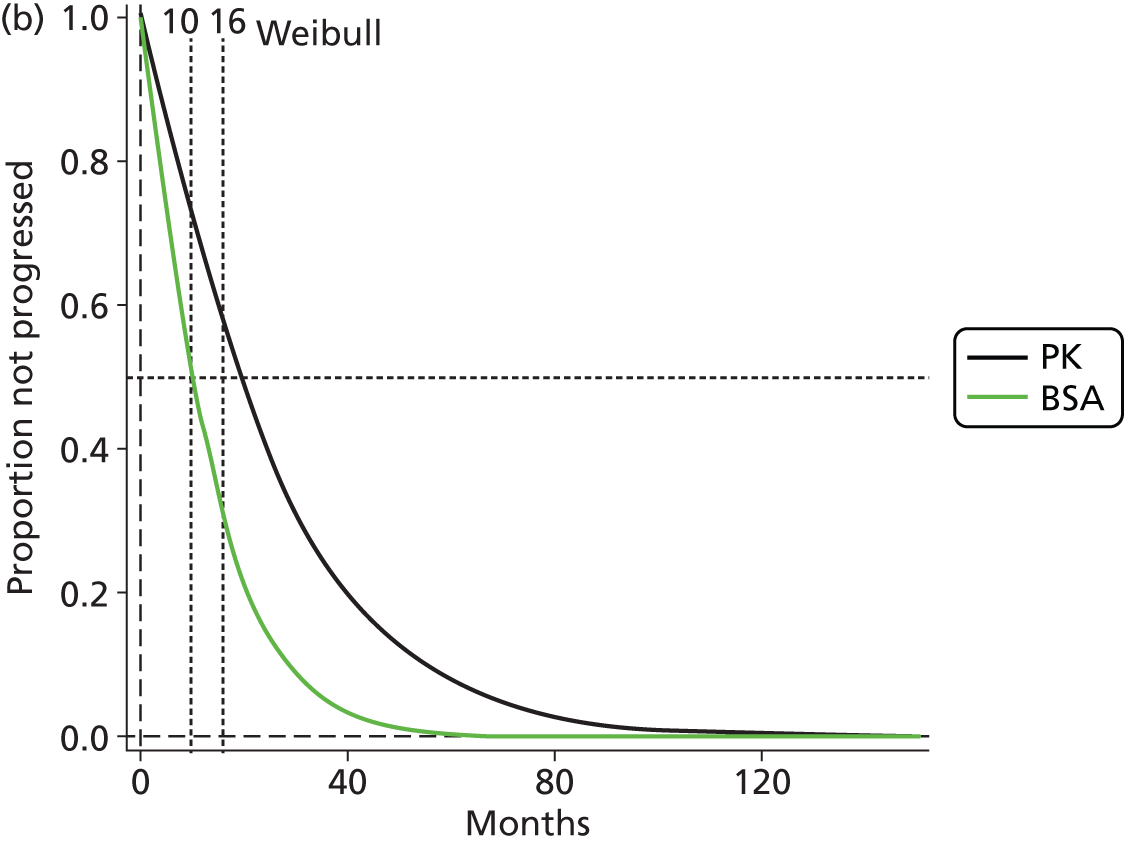

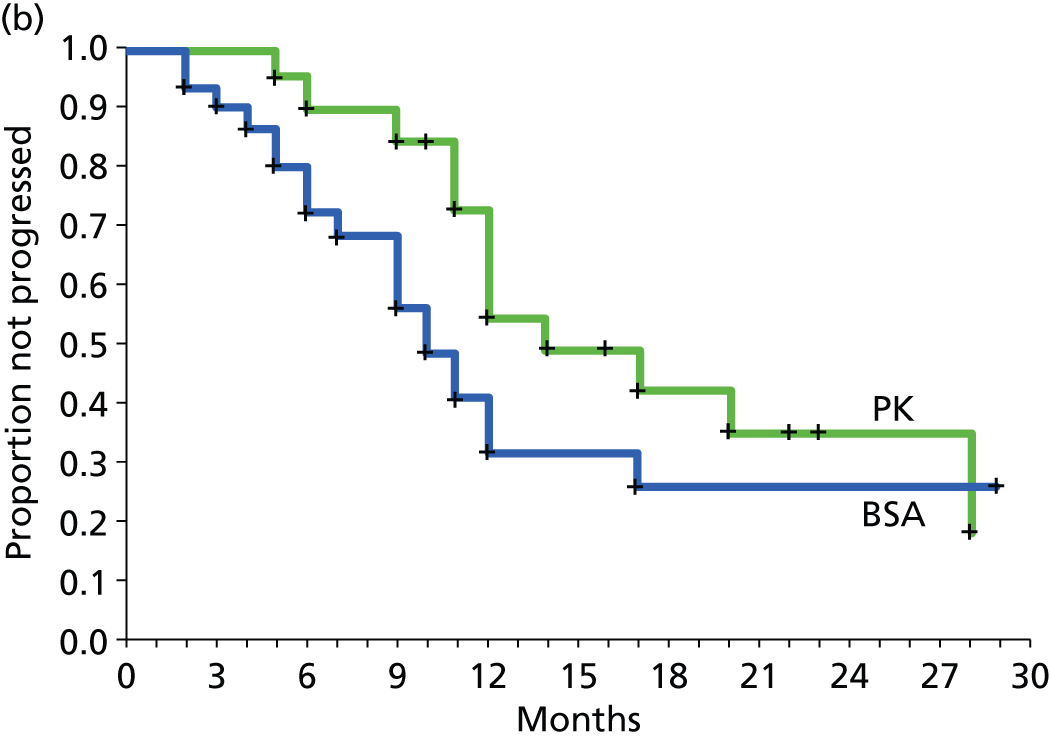

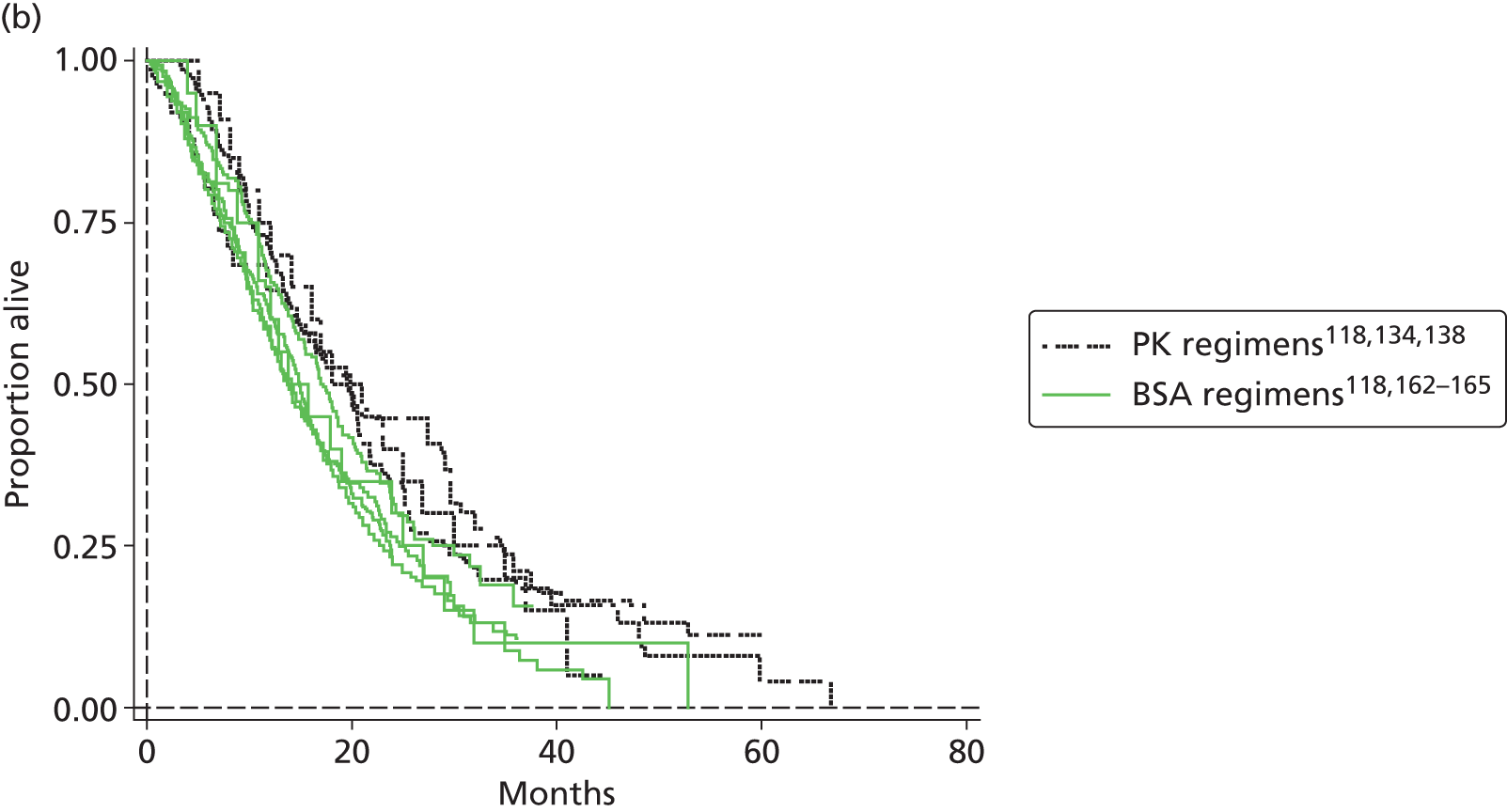

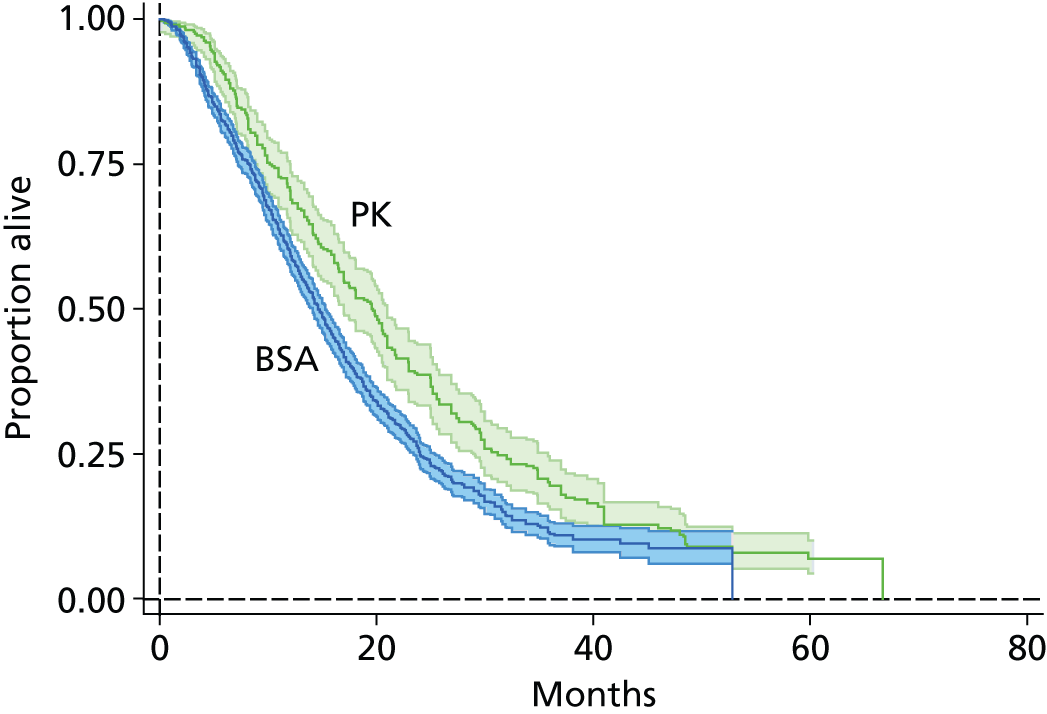

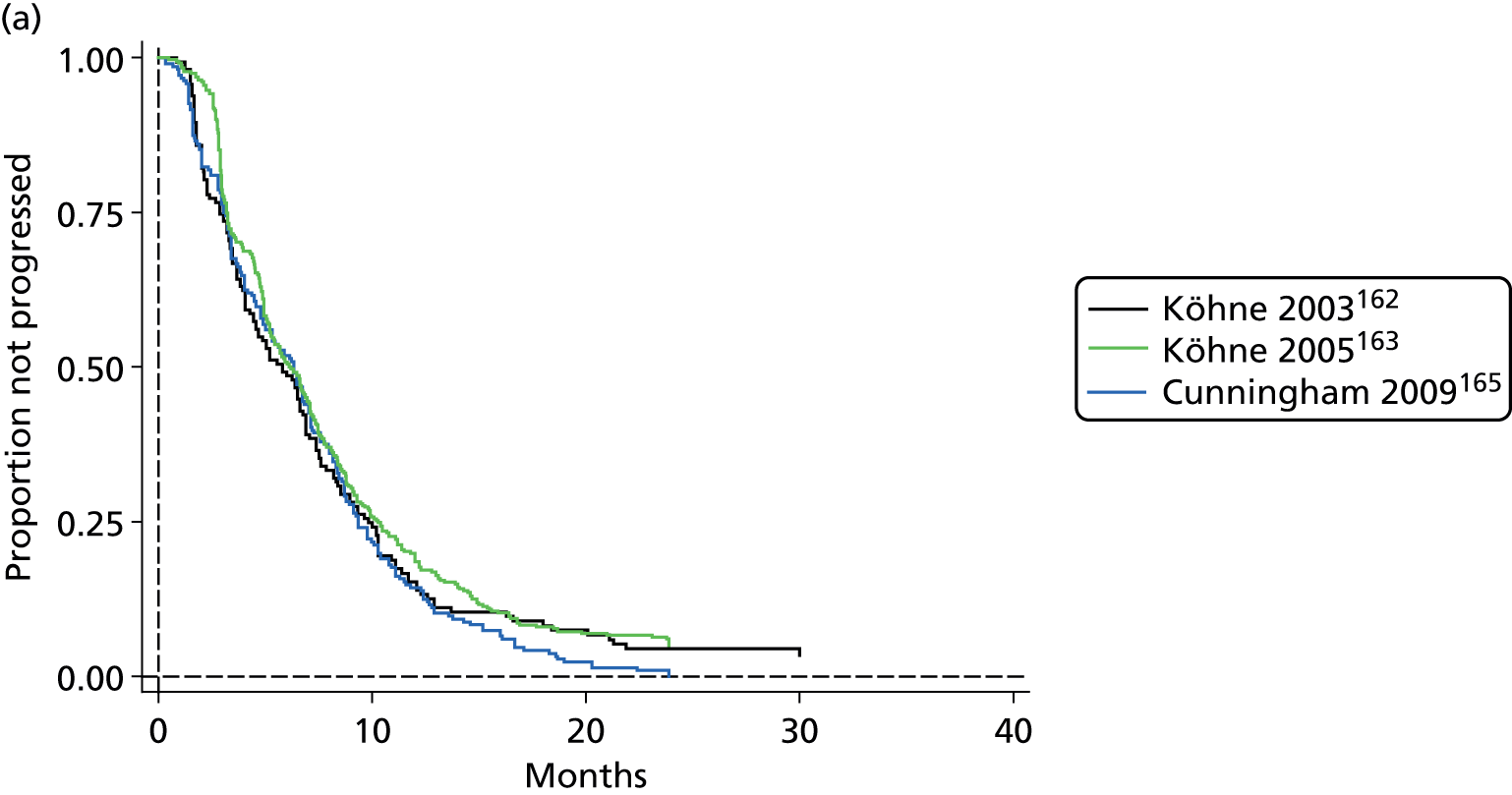

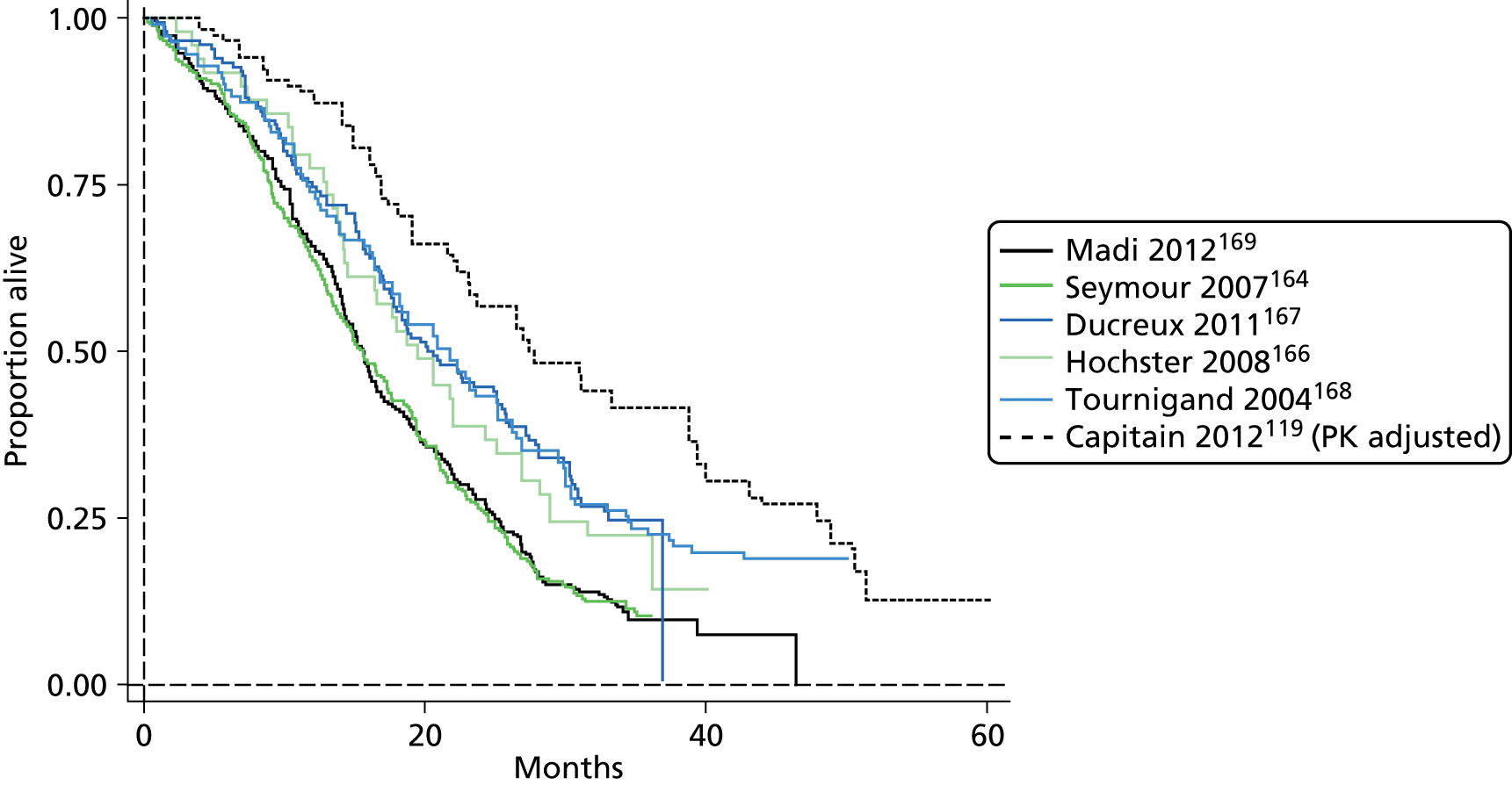

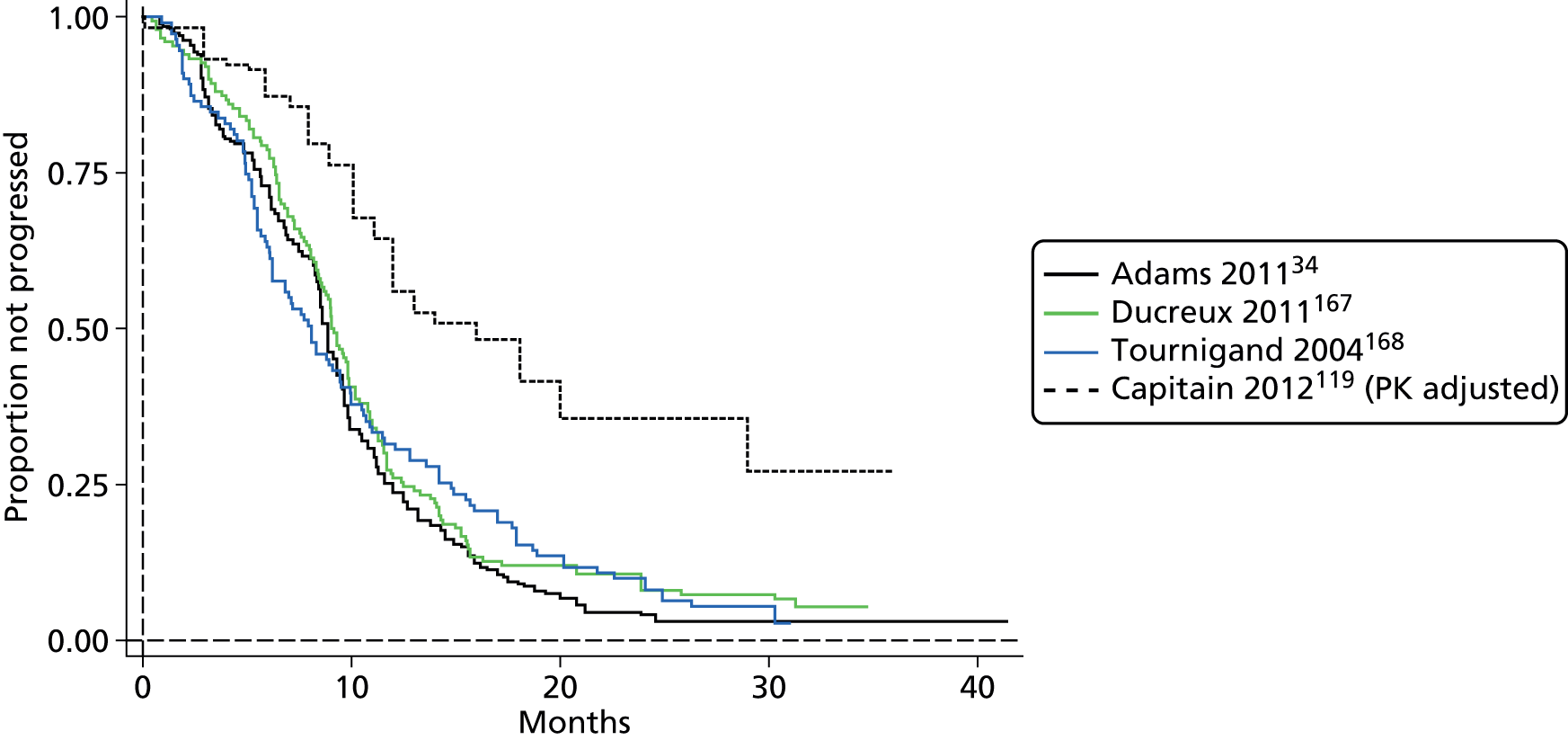

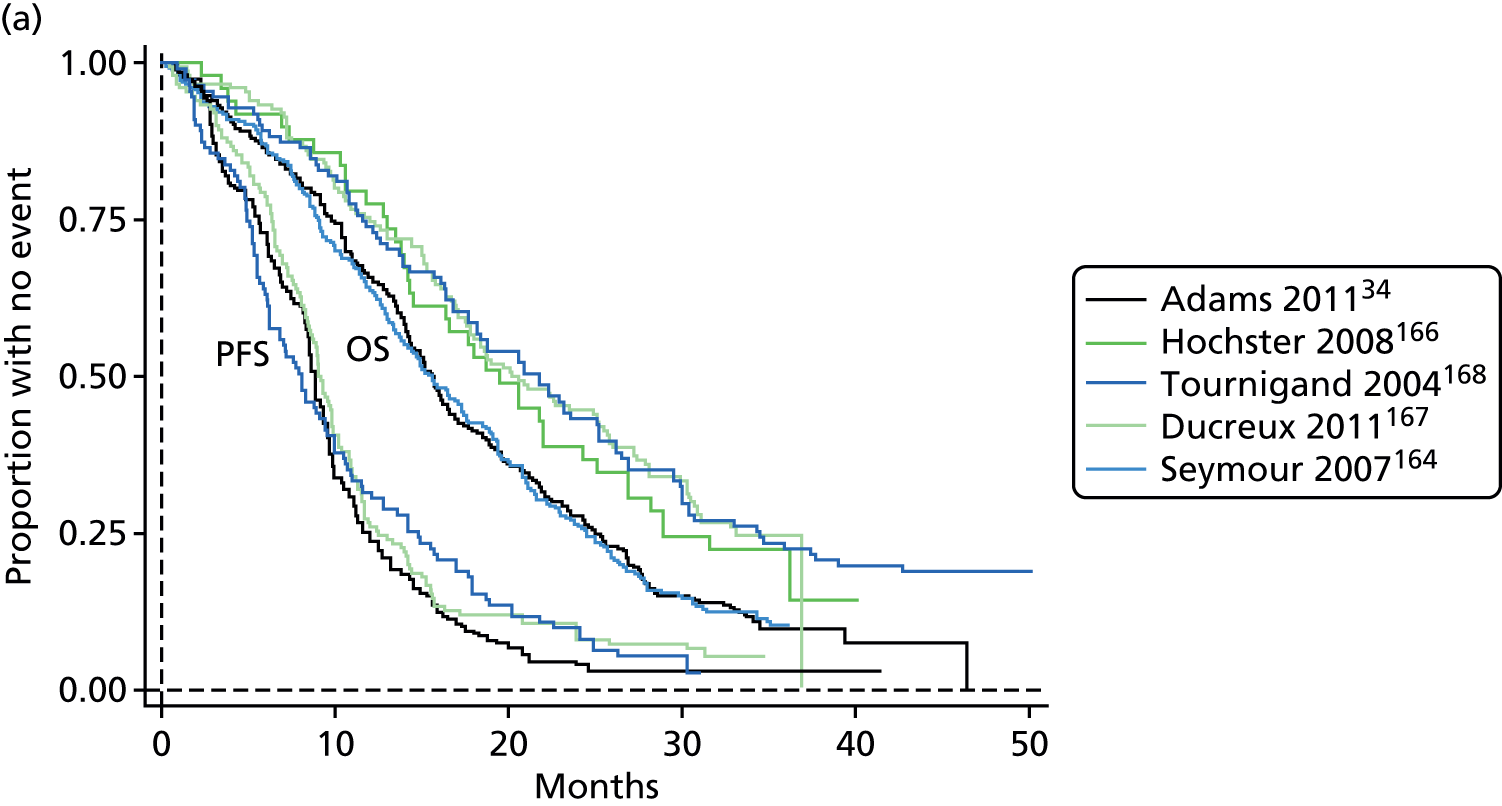

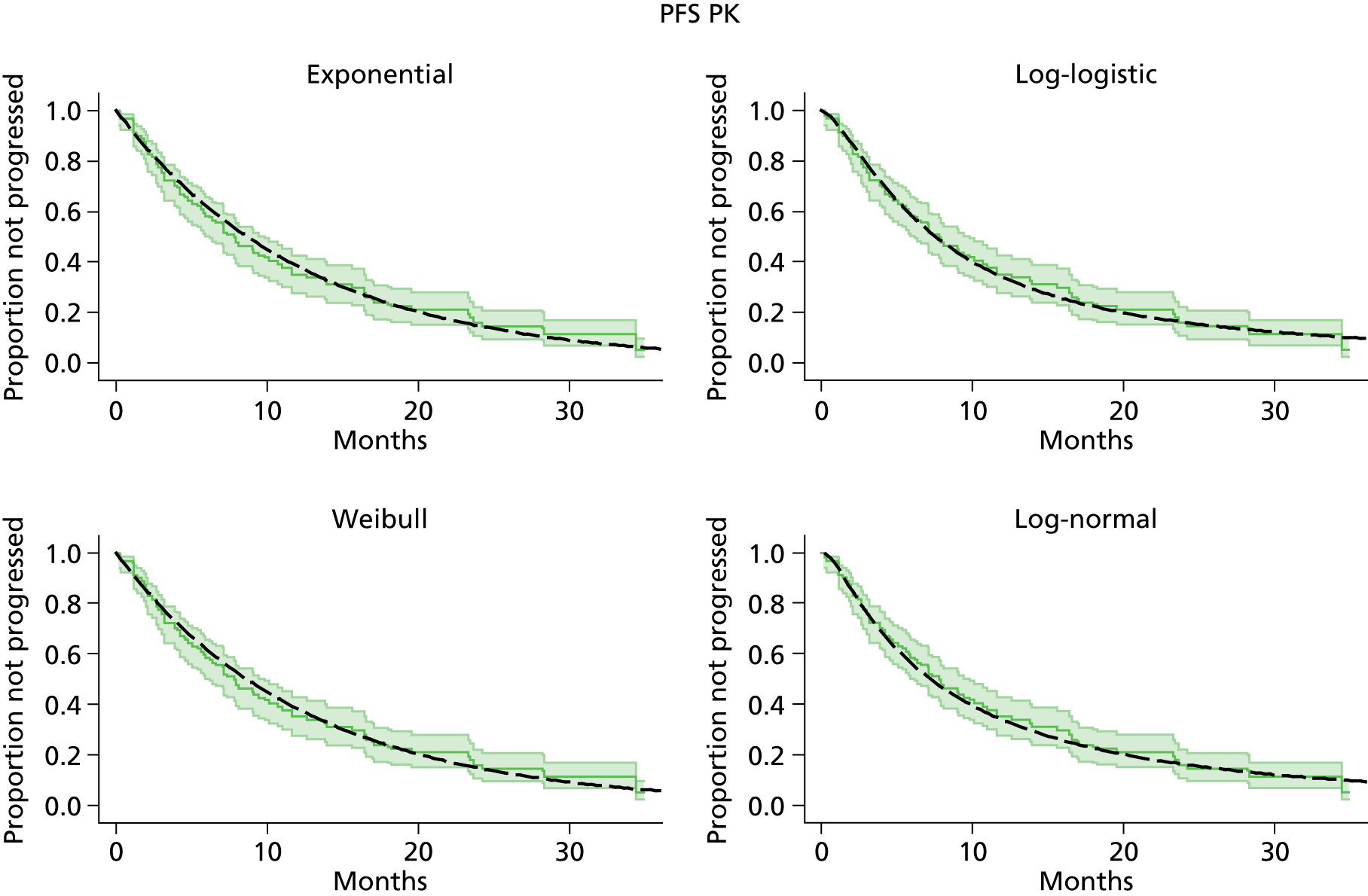

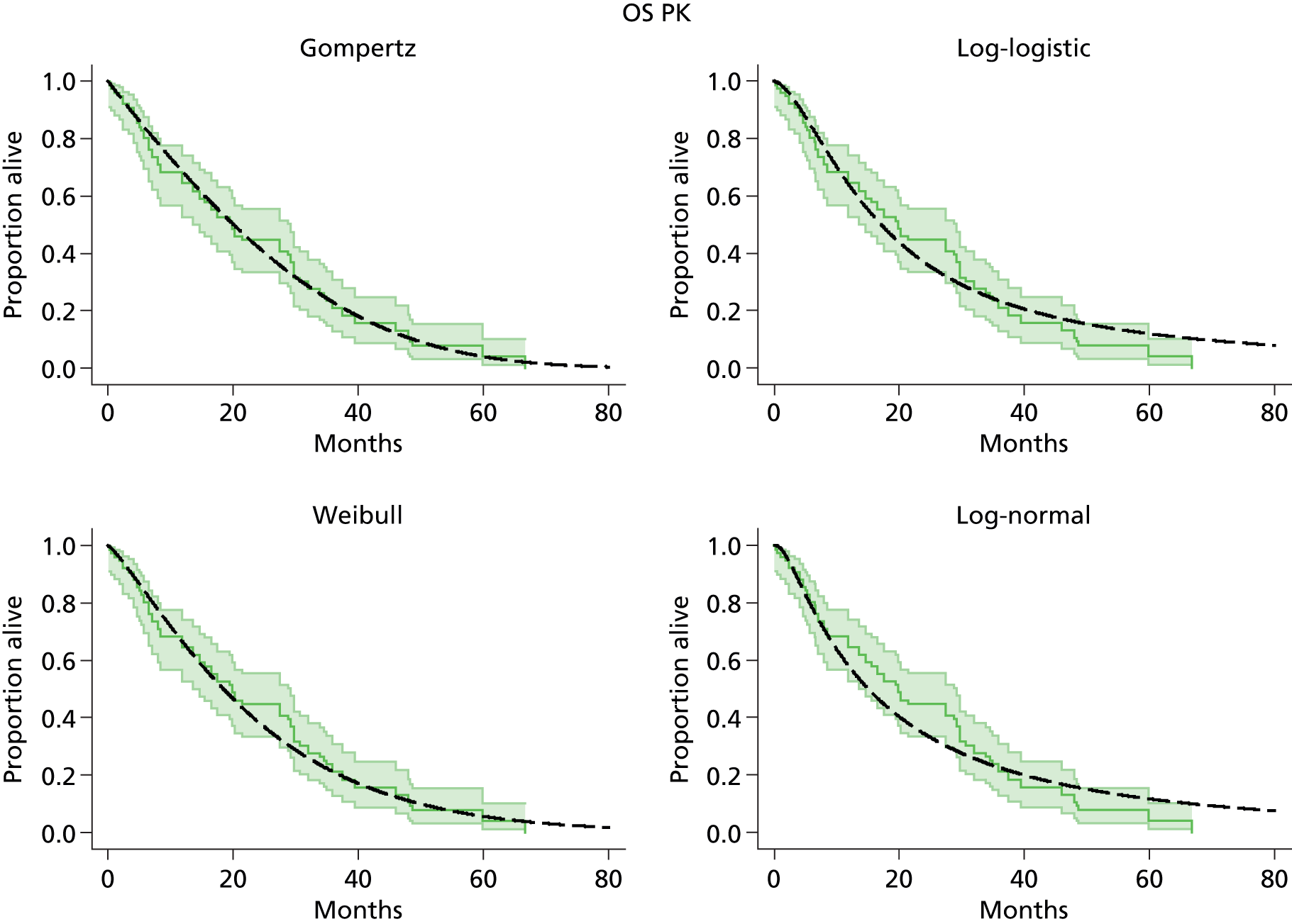

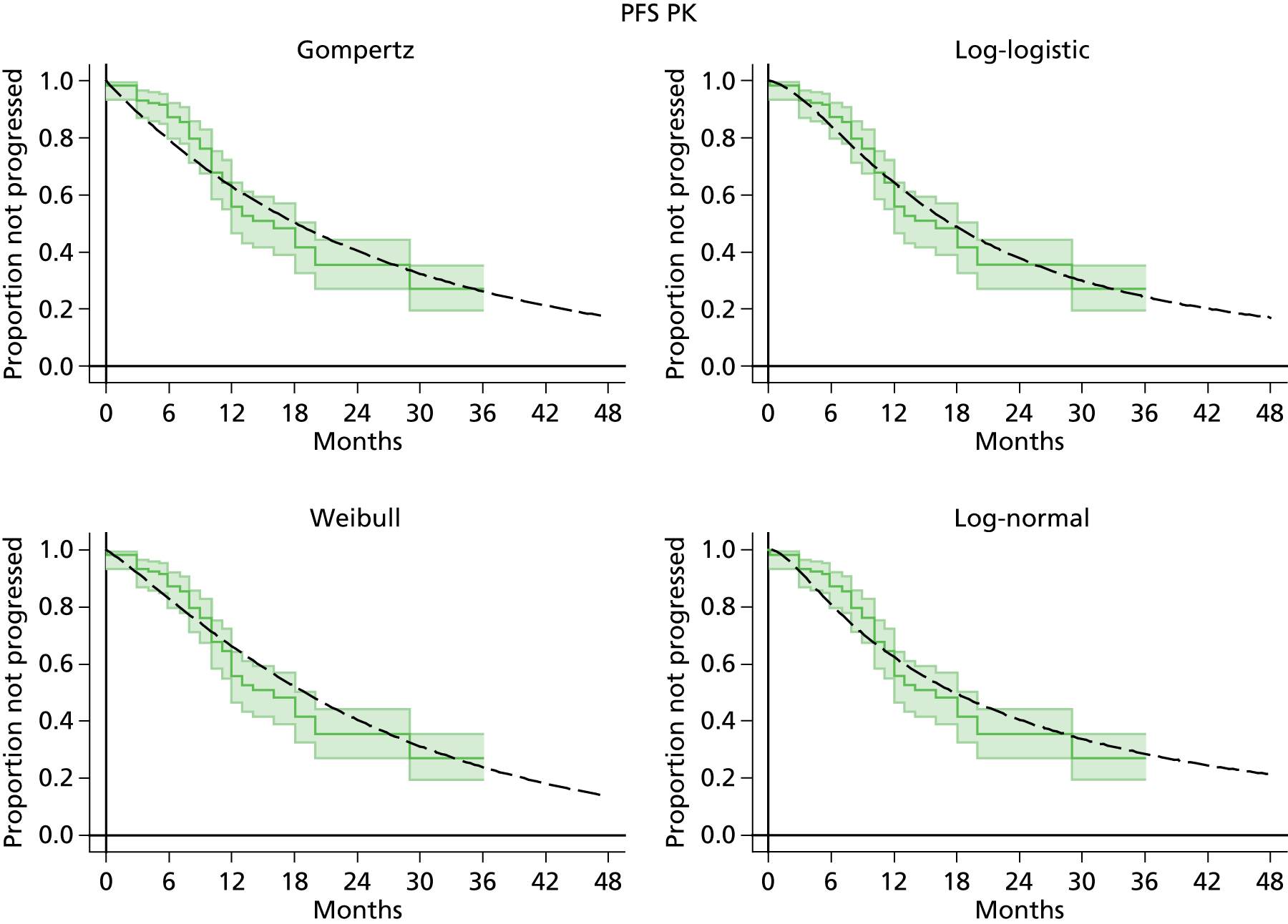

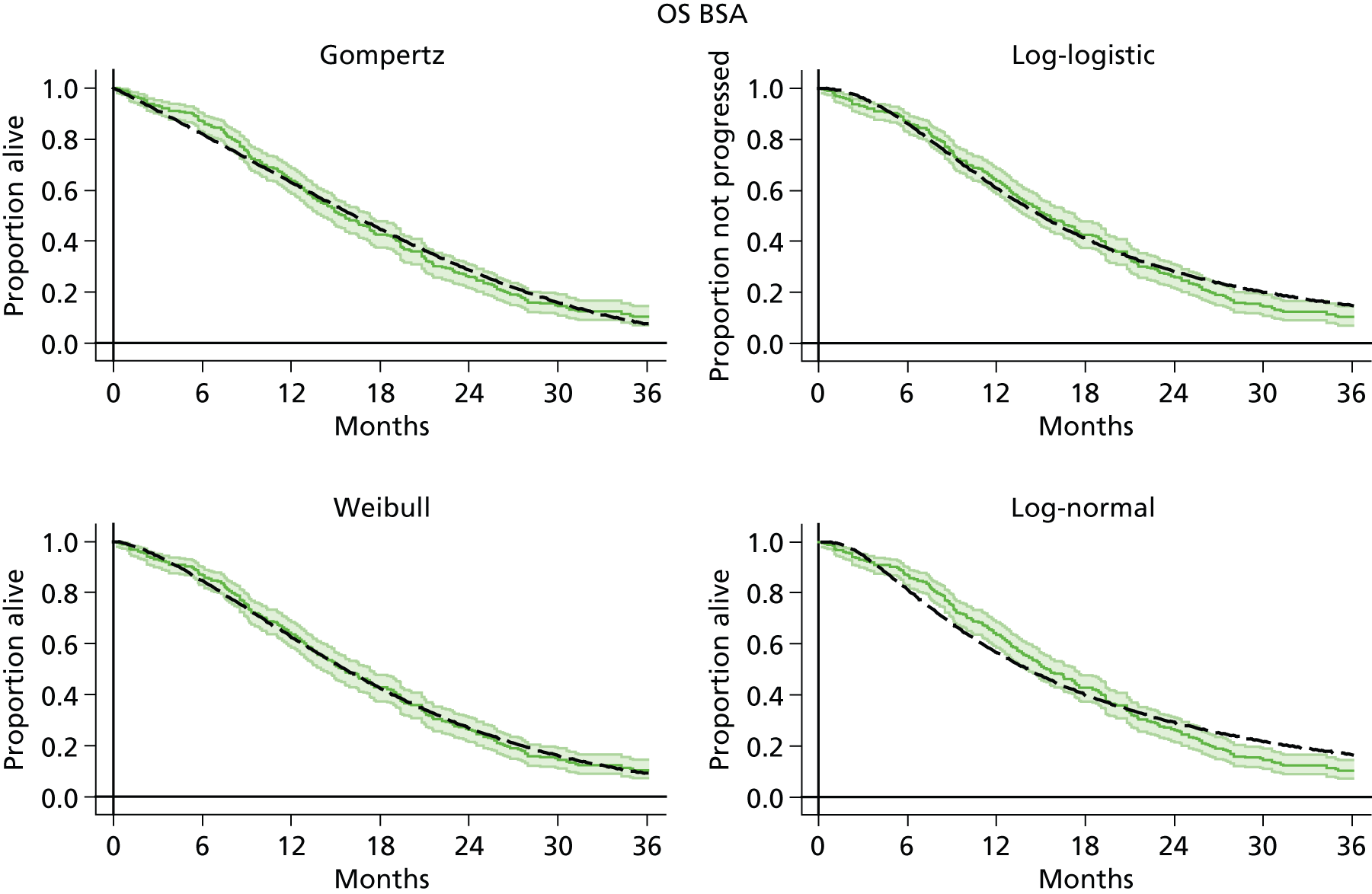

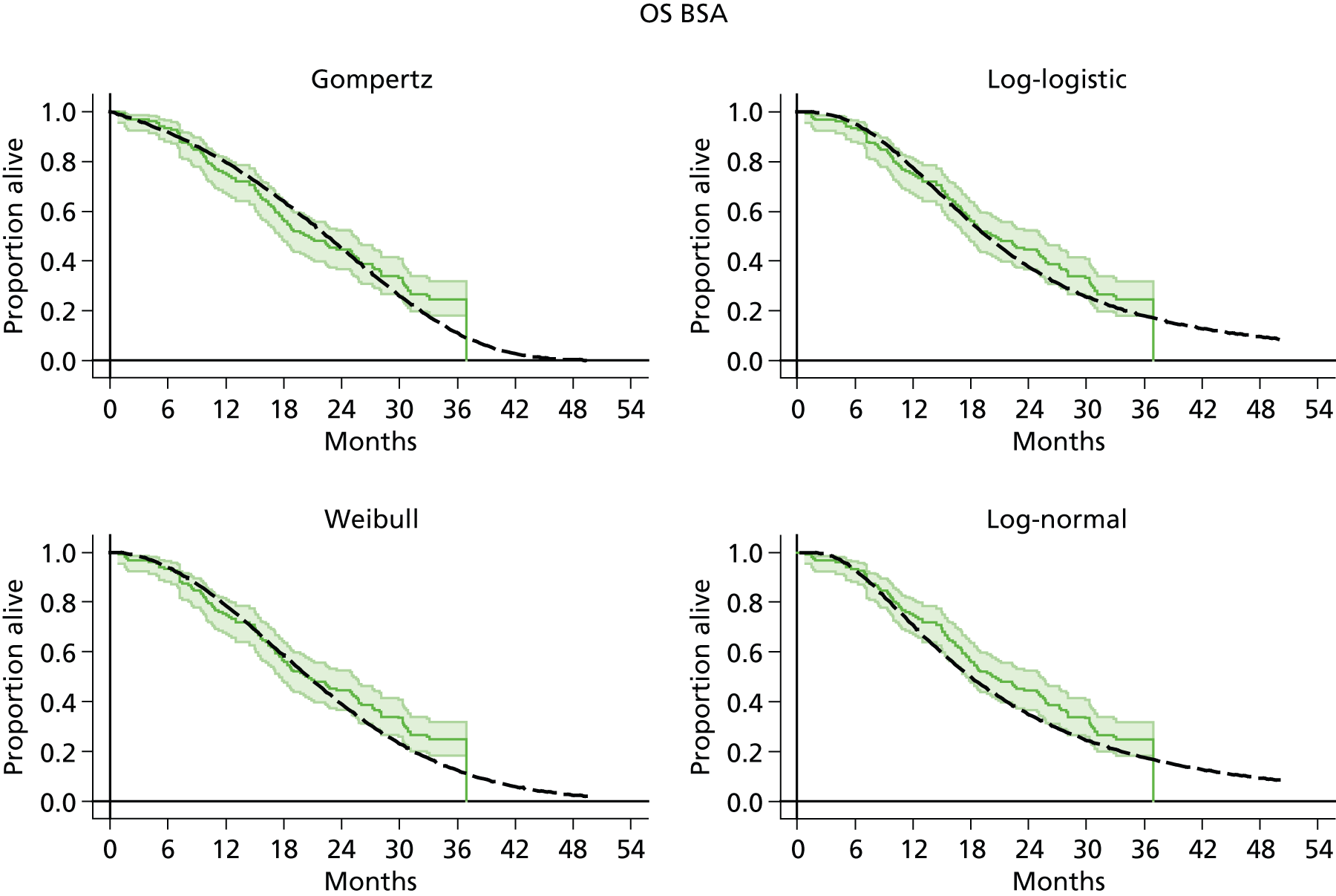

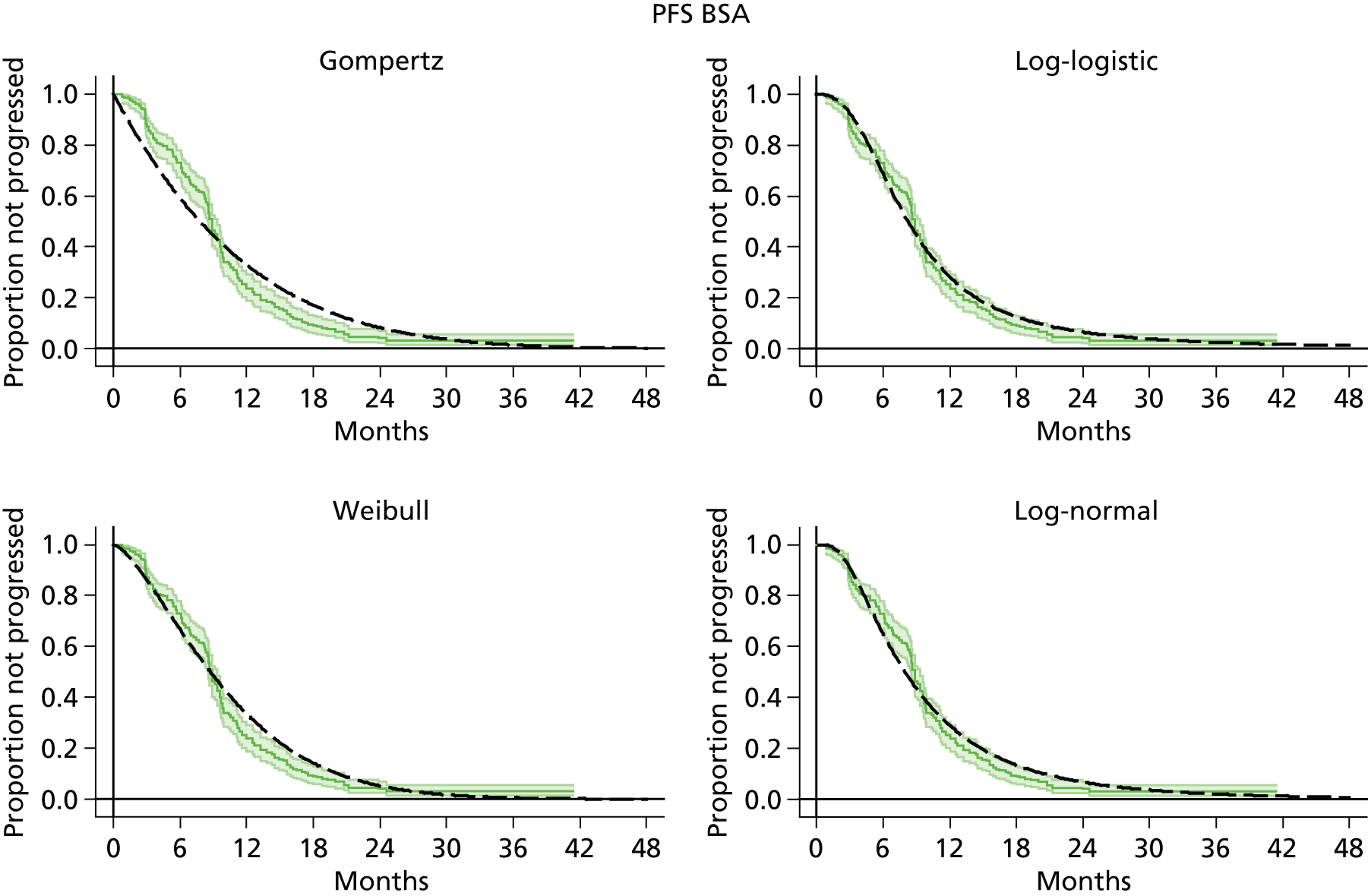

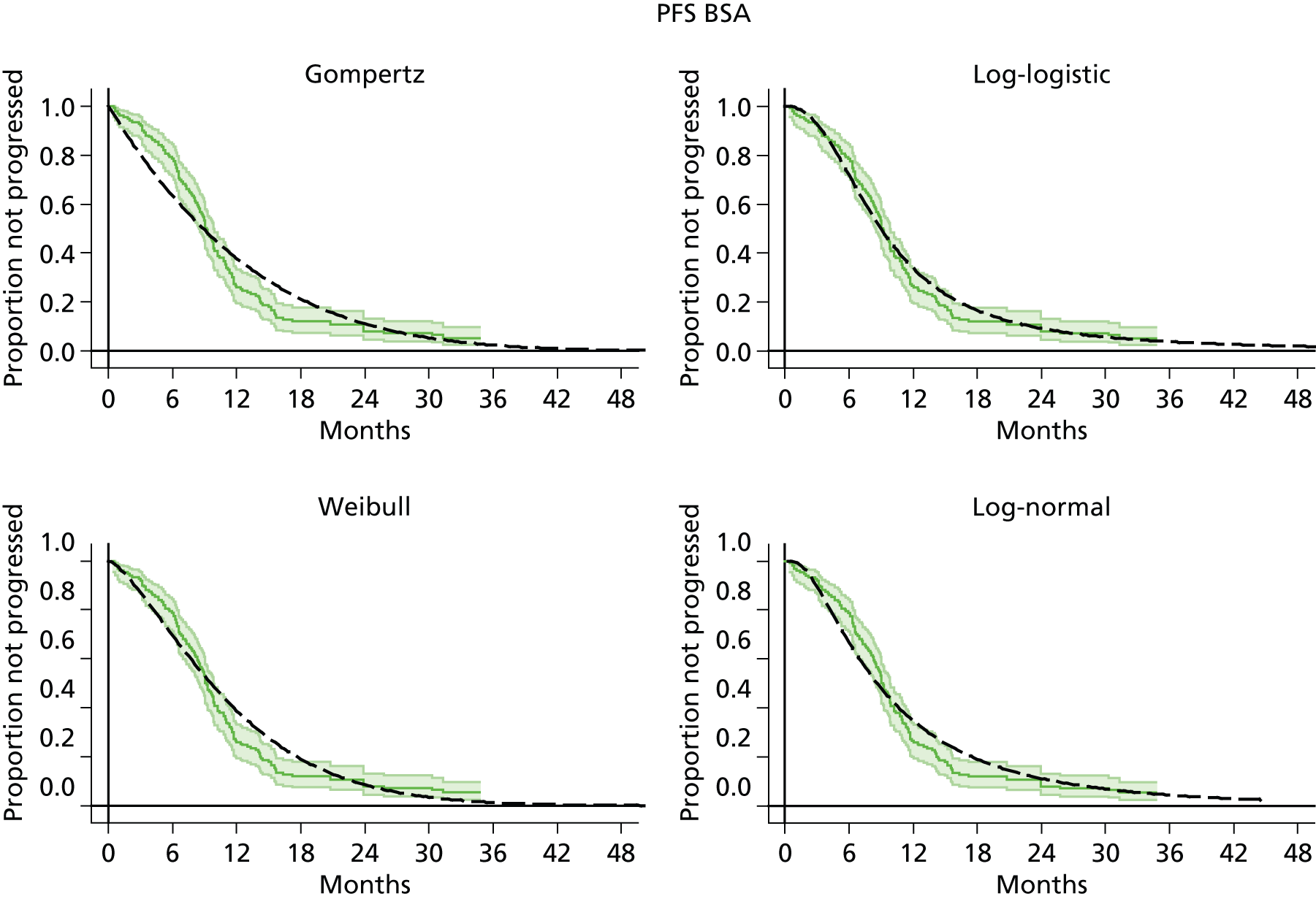

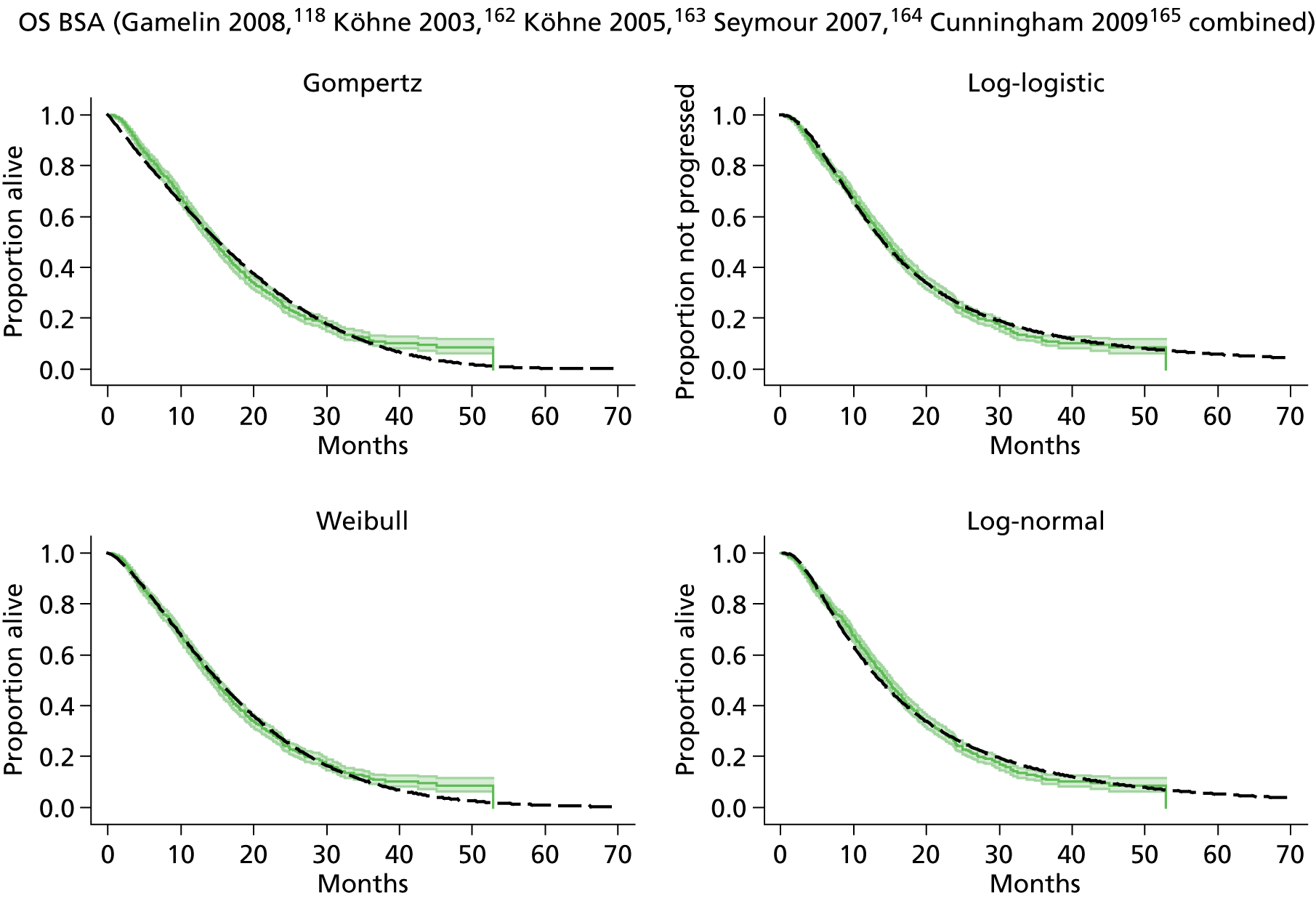

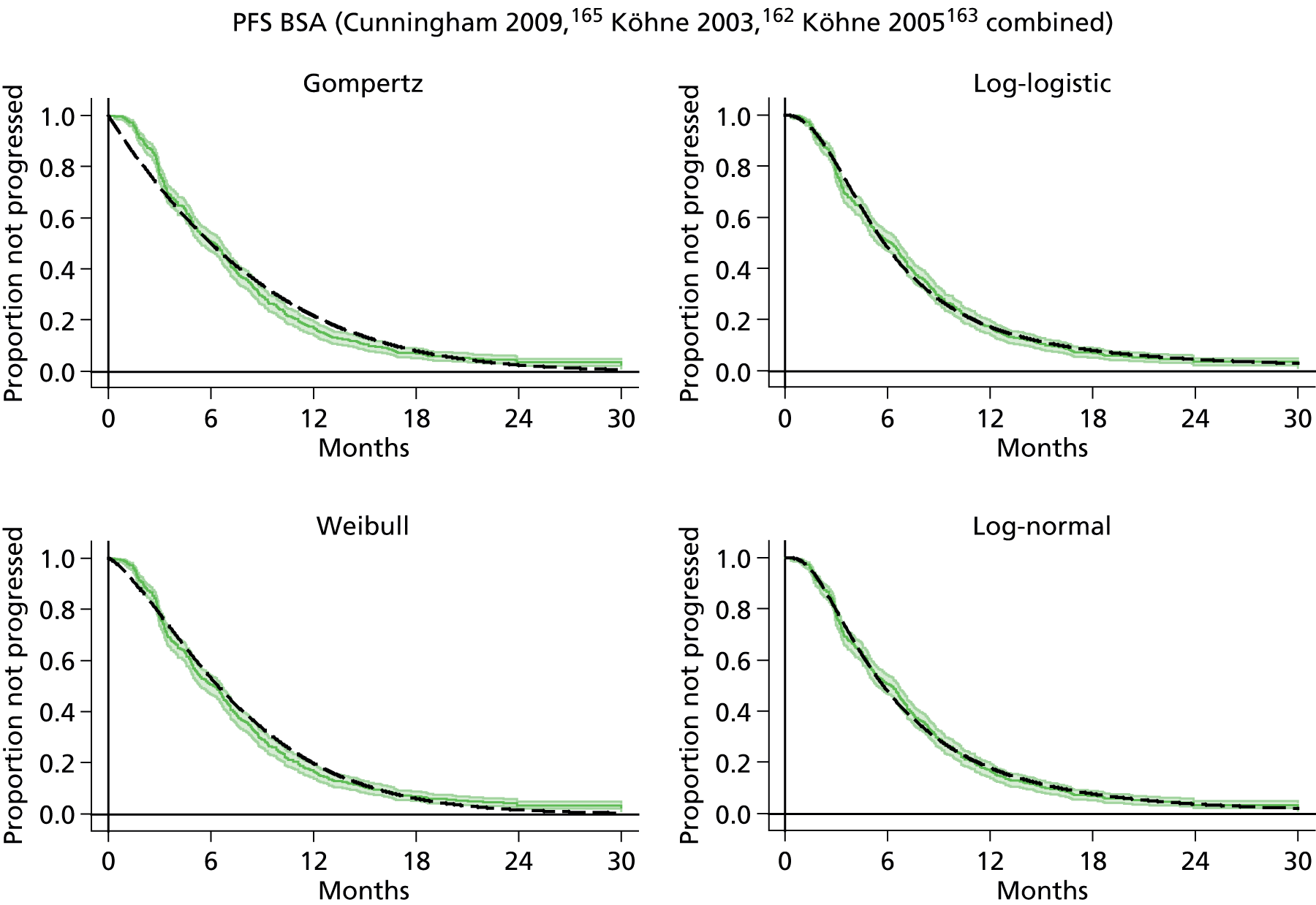

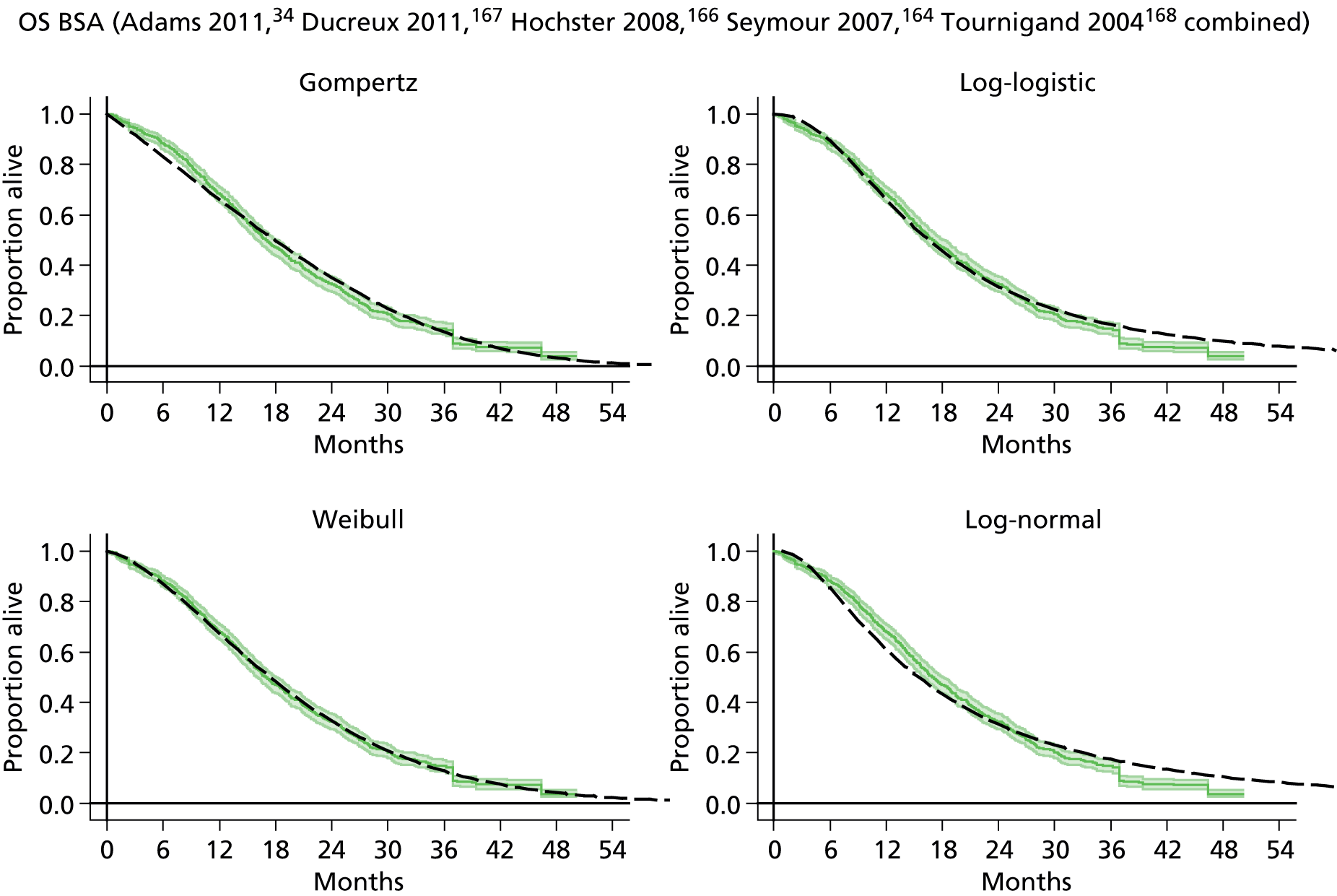

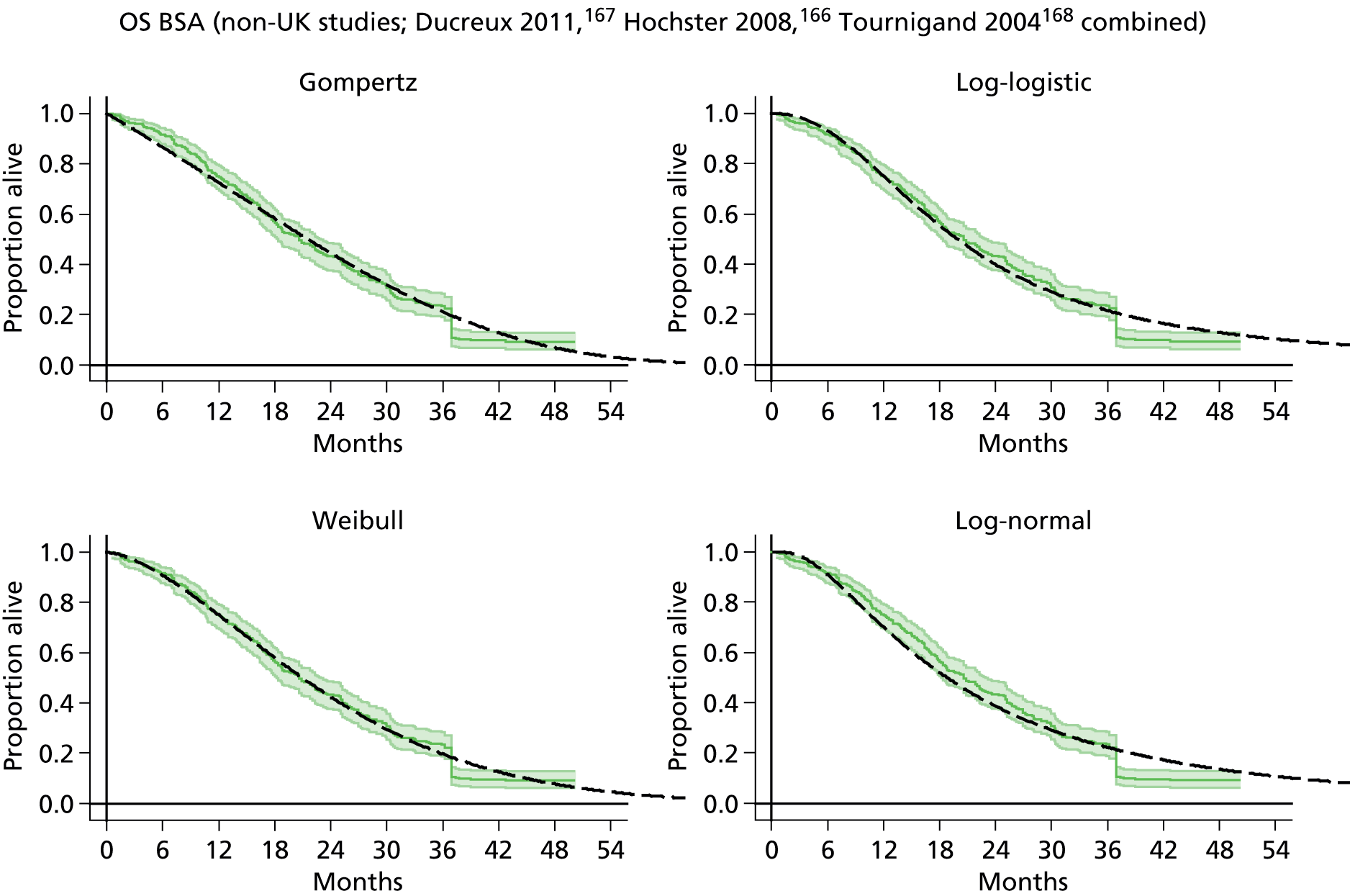

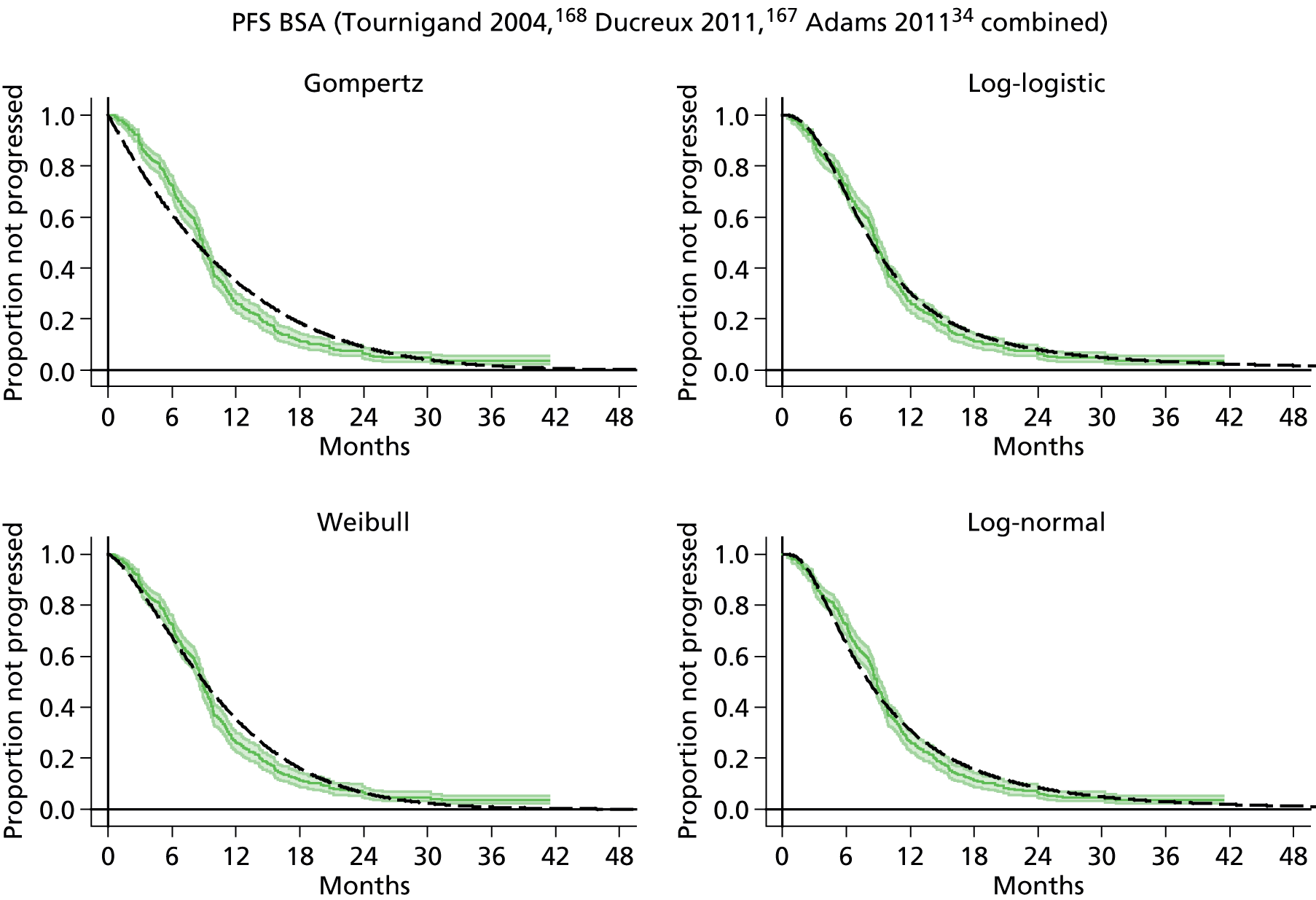

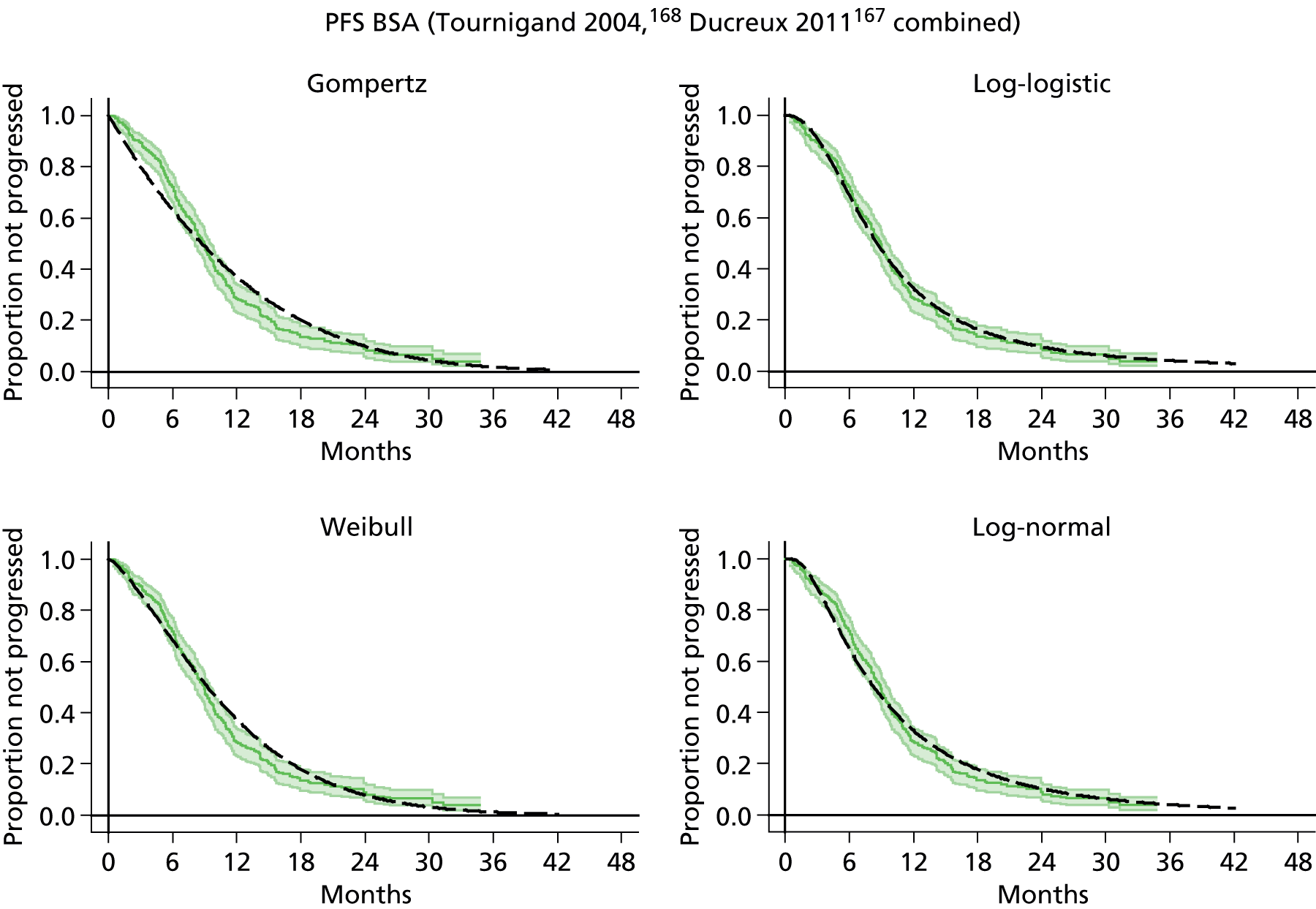

Time-to-event outcomes

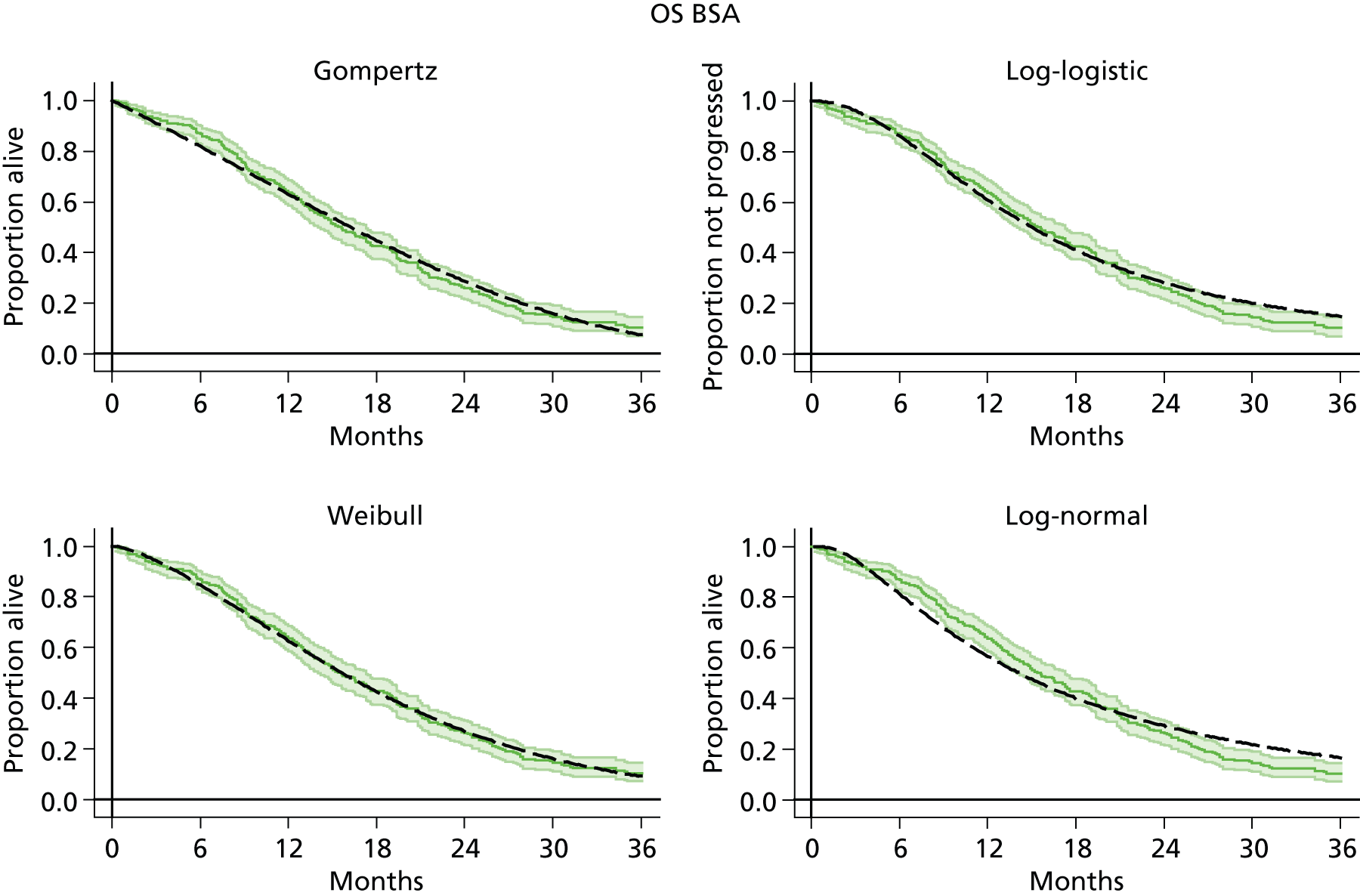

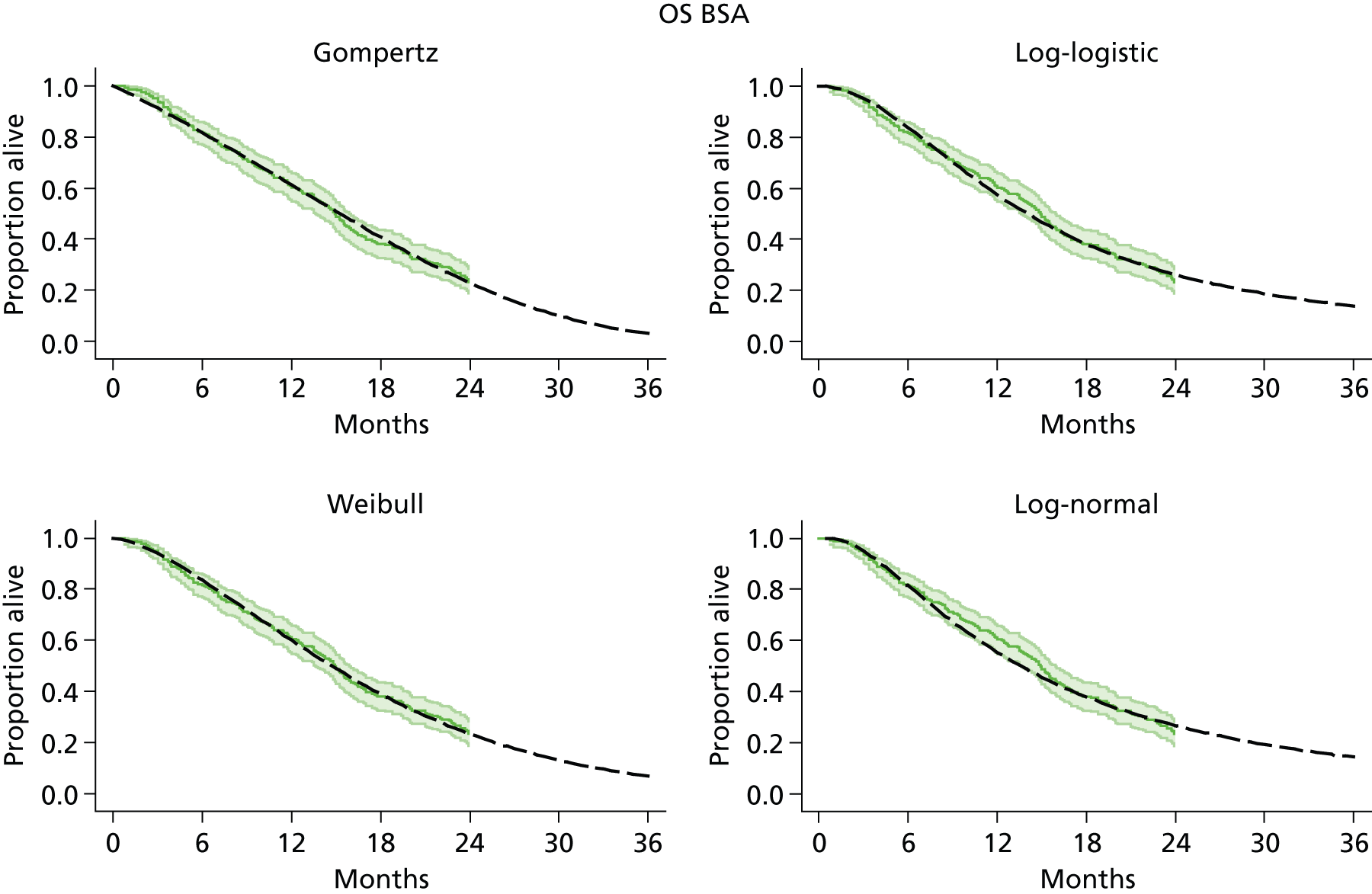

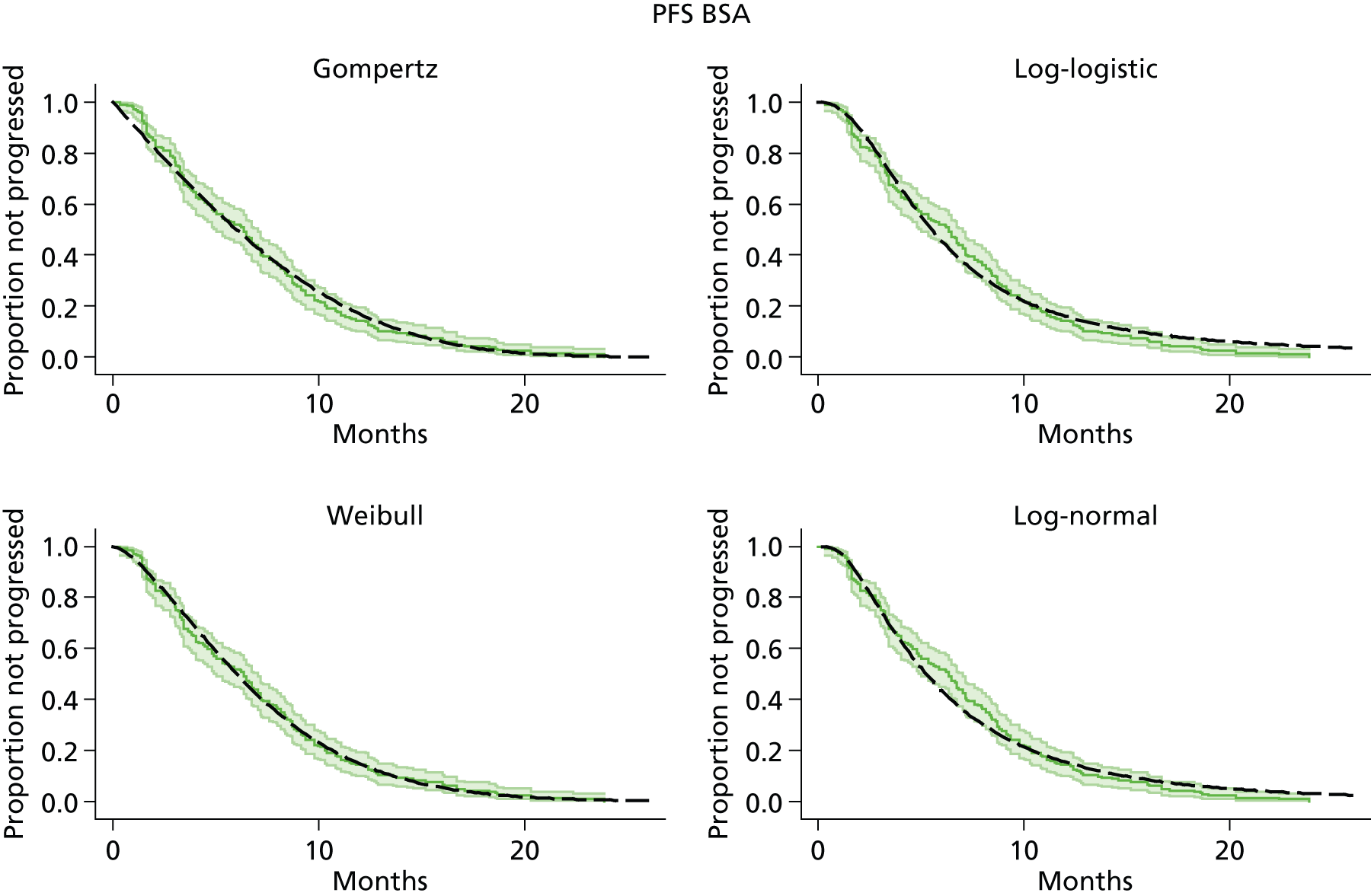

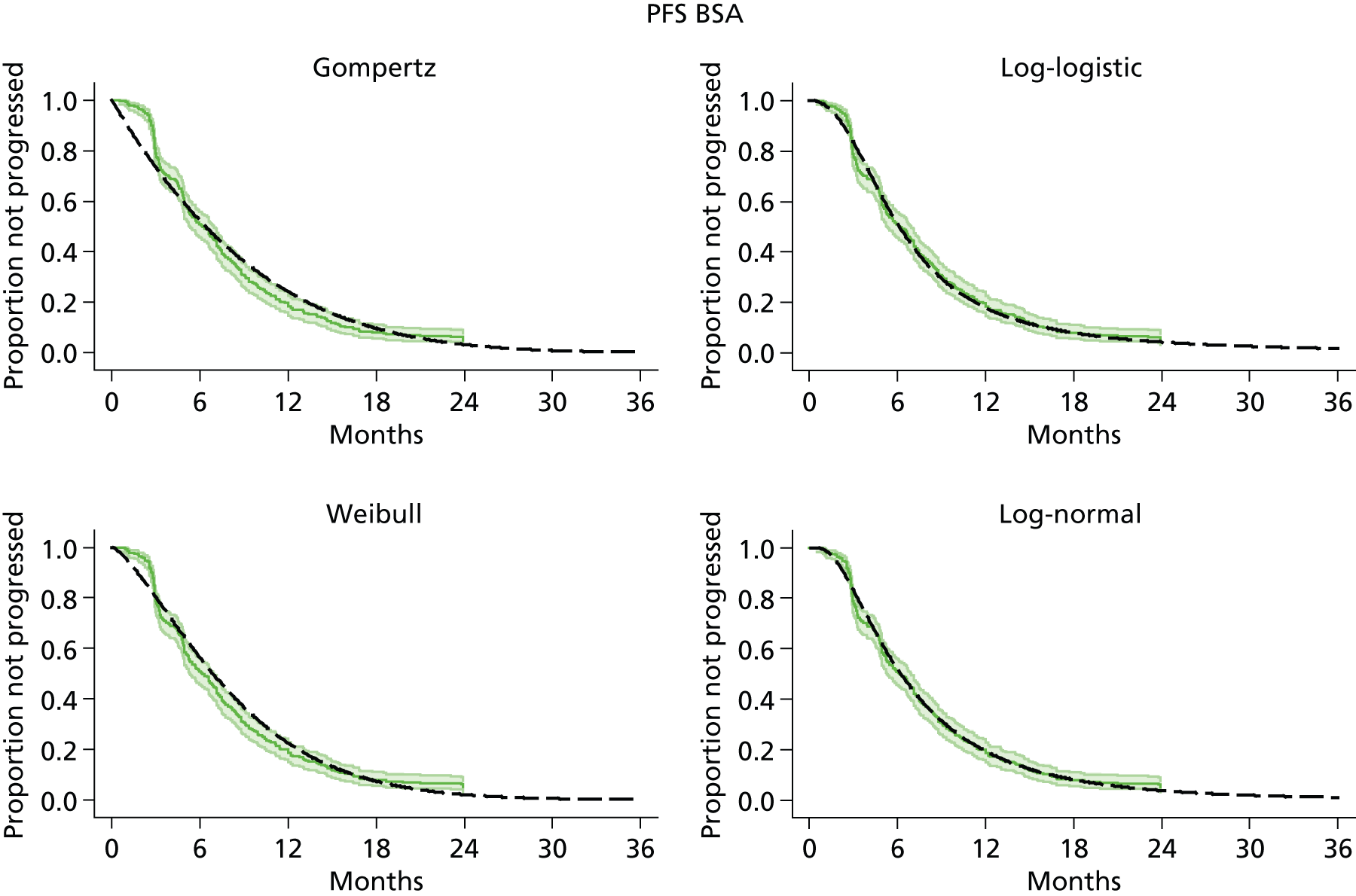

The protocol plan for the current report was to request individual patient data (IPD) from authors of important included papers, so as to inform parameterisation of OS, PFS and other relevant outcomes. In practice, efforts to obtain IPD were not successful. Therefore the method of Guyot et al. 125 was used for reconstruction of Kaplan–Meier plots and of IPD. For this the published Kaplan–Meier graphs were scanned using standard software (Digitizelt; Braunschweig, Germany). Reconstructed Kaplan–Meier plots were implemented from the IPD estimates using Stata version 11 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). As a visual test of faithful reconstruction the reconstructed plots were superimposed on the published originals (available on request from authors). Parametric fits using the estimated IPD were obtained for exponential, log-normal, Weibull, log-logistic and Gompertz distributions implemented with the ‘streg’ command with Stata version 11. Goodness of fit was judged visually and according to information criteria [Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC)]. Simple least squares method, implemented with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) with the solver add-in, was used to obtain parameters for distributions when only median survival values were available.

We requested IPD of key included papers from authors, to enable parameterisation of OS and PFS implemented using standard parametric distributions. Goodness of fit to the observed data was judged visually and according to information criteria (AIC, BIC). In the absence of IPD becoming available, we digitised published Kaplan–Meier (or competing risks) analyses using standard software (e.g. DigitizeIt software). The digitised product was used to construct curve fits using methods developed by Guyot et al. 125 or Hoyle and Henley. 126

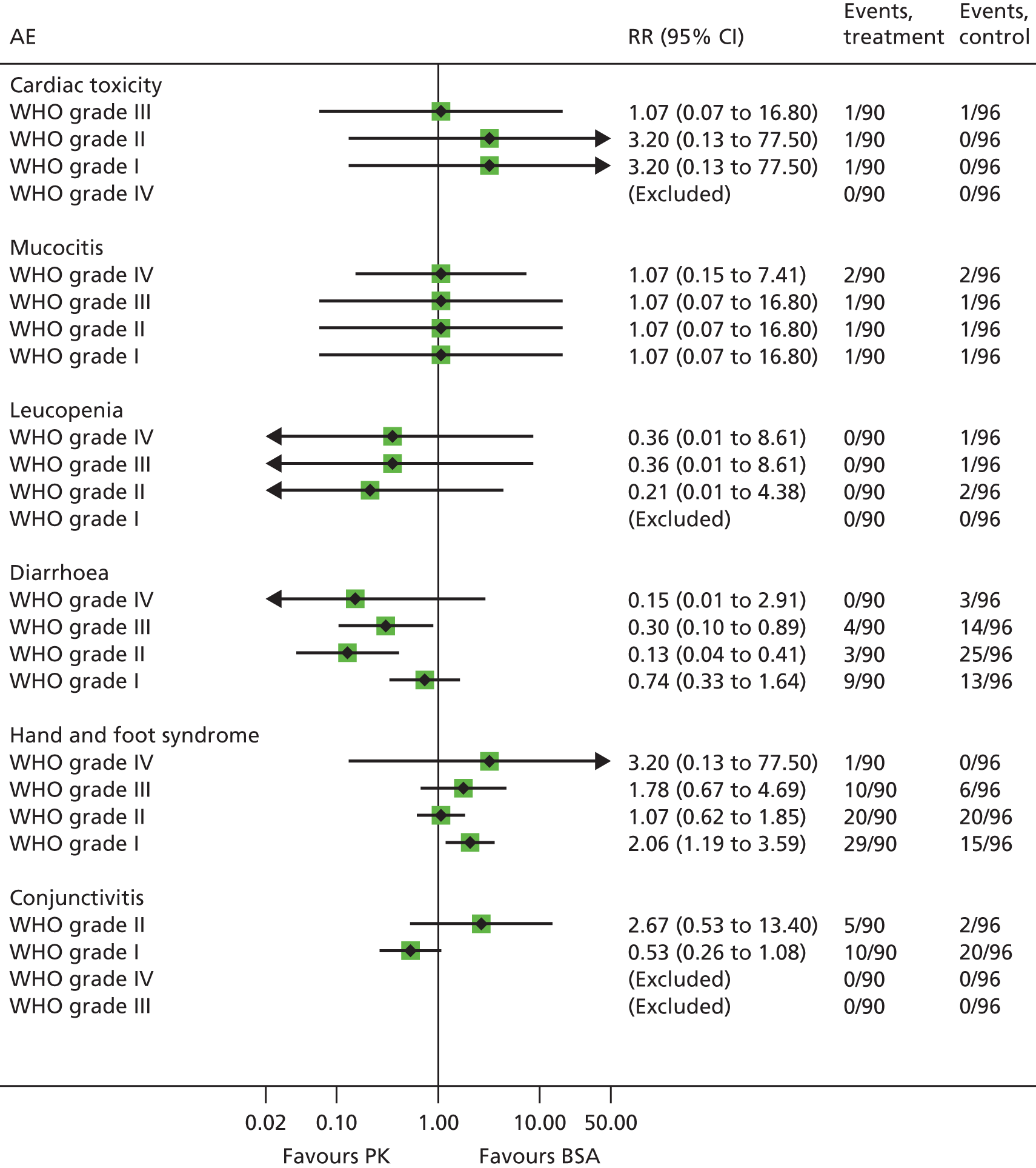

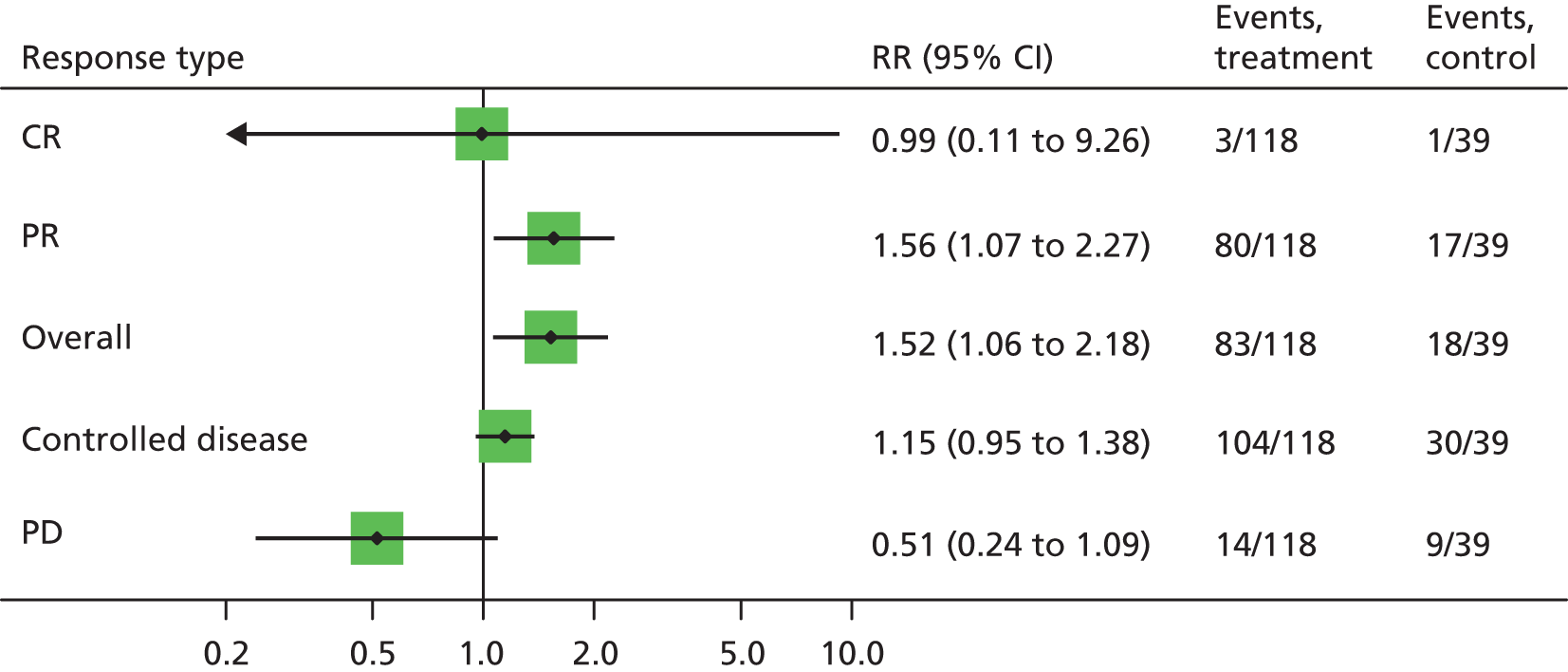

Outcomes reported as proportions

Reported percentages were converted to the nearest whole number of patients and the 95% CIs around proportions were estimated using the binomial distribution. Relative risks and associated 95% CIs were estimated in Stata version 11 using the ‘metan’ package. Pooling of relative risks was not undertaken because of differences in treatments and populations between studies.

Indirect- and mixed-treatment comparison

The methods outlined in the protocol anticipated the existence of several RCTs or comparative studies that would be appropriate for formal meta-analysis or network meta-analysis (NMA); the evidence was insufficient to support this approach.

The authors of the NICE guideline for advanced CRC (CG131)7 undertook NMAs of OS and of PFS using RCT data for 5-FU treatment regimens, and this offered a potential template approach for the present project. The CG131 authors were constrained by the lack of full data and their analyses required assumptions of constant hazard (i.e. fitting of exponential survival curves) and of proportional hazards between treatments. CG1317 preceded publication of the Guyot et al. 125 procedure to estimate IPD from Kaplan–Meier plots. Our use of this method with available PK data revealed that the exponential distribution was the poorest performing of various parametric distributions tried in exploring reported Kaplan–Meier plots. We therefore considered the method described by Ouwens et al. 127 for NMA of Weibull parametric survival curves since this was reported to avoid proportional hazard assumptions. In practice, because of commercial considerations, the authors’ kept the published NMA code incomplete. There was insufficient time available to develop our own code and contact with the corresponding author failed to resolve the difficulty. A further problem confronting NMA approaches was the almost total lack of randomised evidence about PK dose adjustment and the heterogeneity of available studies. NMA was therefore not undertaken.

Face-to-face discussions and written questions

Information was extracted from face-to-face discussions and written questions undertaken with a relevant laboratory. Information was used within the model. Expert opinion from specialist committee members and other clinical experts was sought and appropriately accessed.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness results

This chapter provides the search results for the clinical effectiveness assessment including results of:

-

objective A(1) which considers the accurate estimation of plasma 5-FU when using the My5-FU assay; and objective A(2) which considers available information about treatment algorithms based on 5-FU measures

-

objectives B and C which consider the evidence on PK dosing compared with traditional BSA-based dosing

-

objective D which examines the comparability of BSA comparators used in the PK comparison compared with the generality of BSA regimens.

Search results for objectives A–C

Figure 6 provides the PRISMA flow diagram for objectives A–C. A total of 3751 records were identified through electronic searches. One additional record was identified from other sources. The removal of duplicates left 2565 records to be screened, of which 2362 were excluded at title/abstract level as these were irrelevant. The remaining 203 records were examined for full text, of which 35 were included in the clinical effectiveness review (see Appendix 7). The included 35 references represent:

-

29 studies in 30 papers for objectives B and C,118,119,130–156 of which three studies addressed both objective A(2) and objectives B and C. 130–132

FIGURE 6.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram: My5-FU clinical effectiveness objectives A–C. a, Three studies addressed both objective A(2) and objectives B and C.

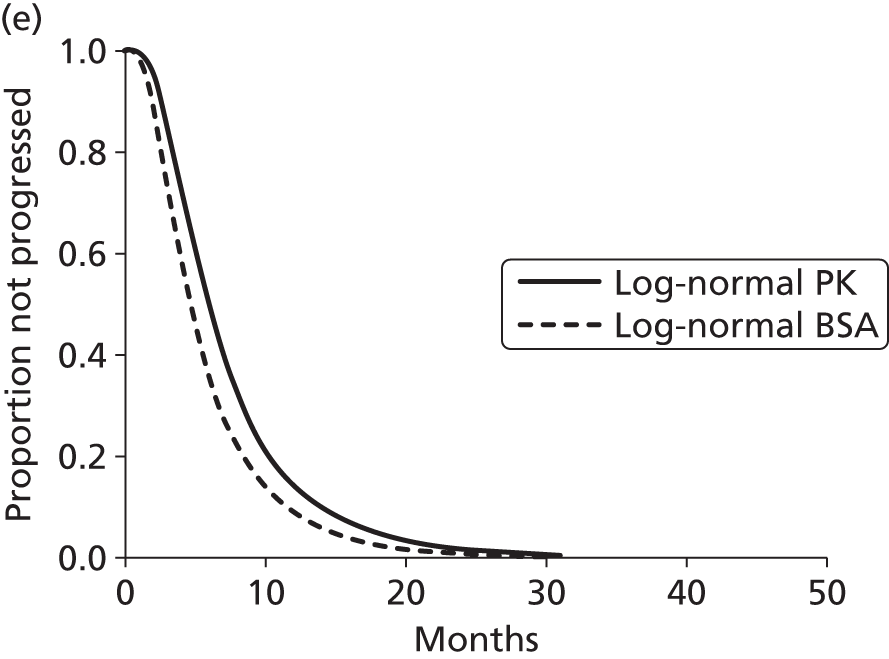

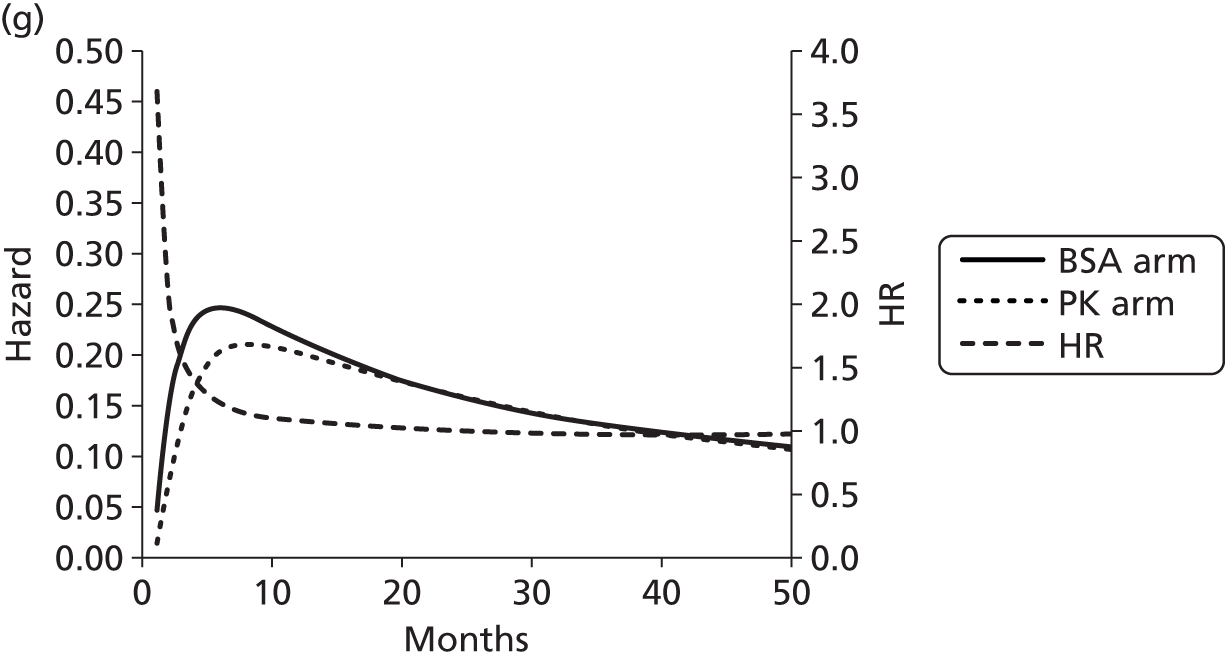

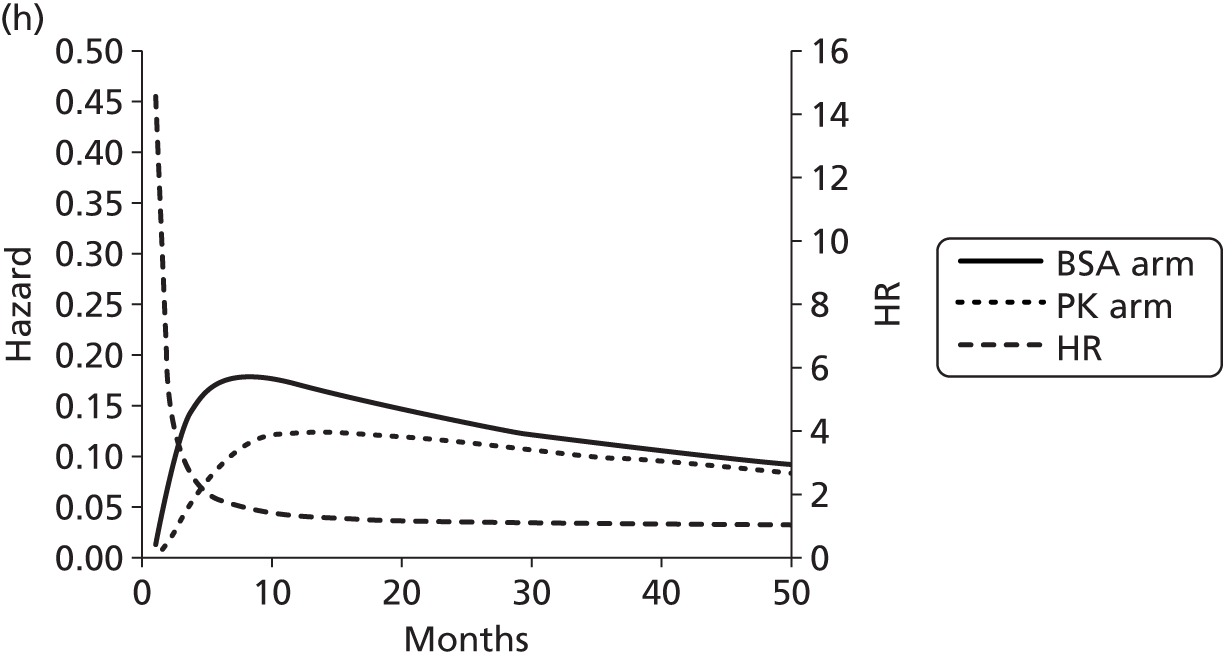

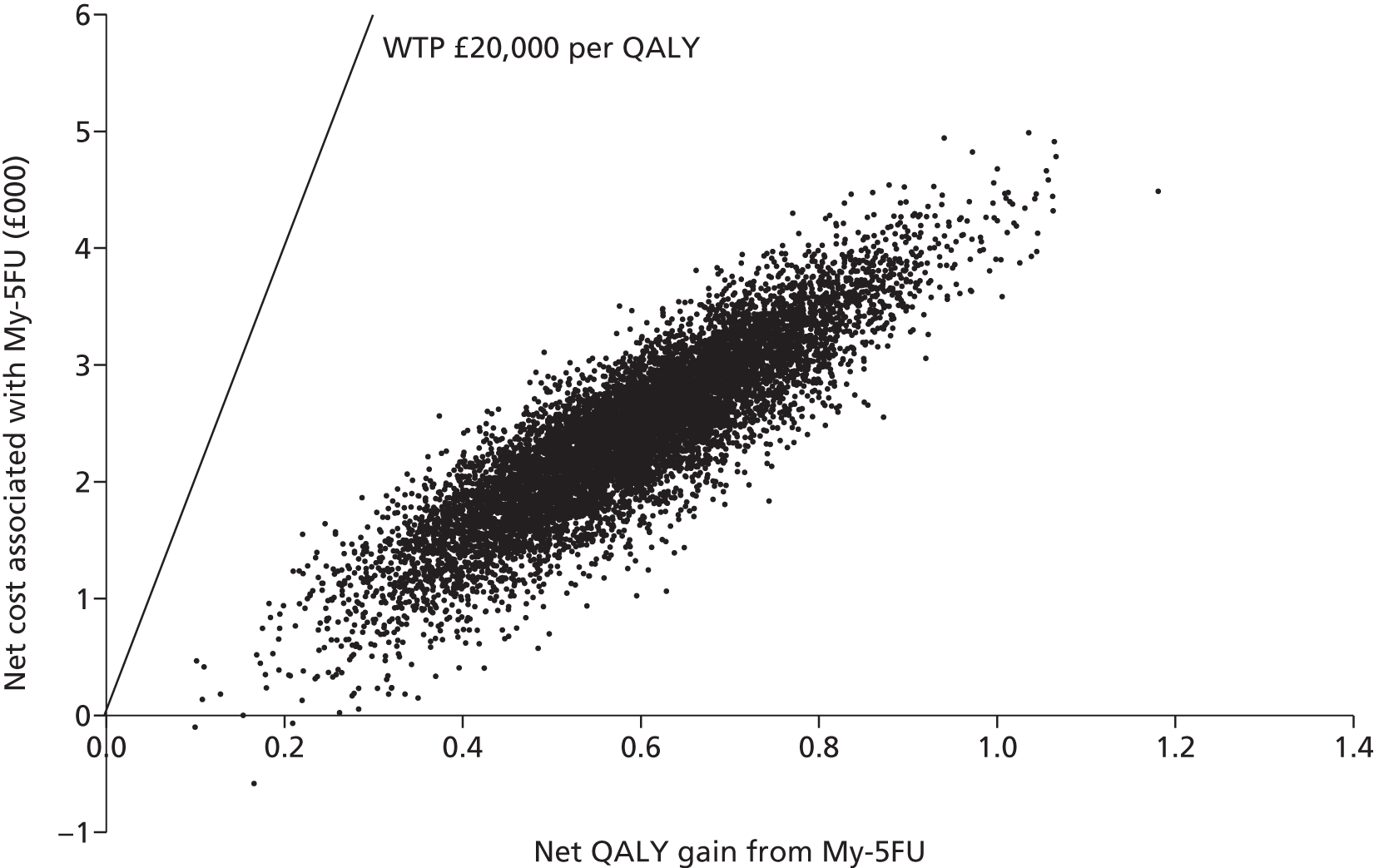

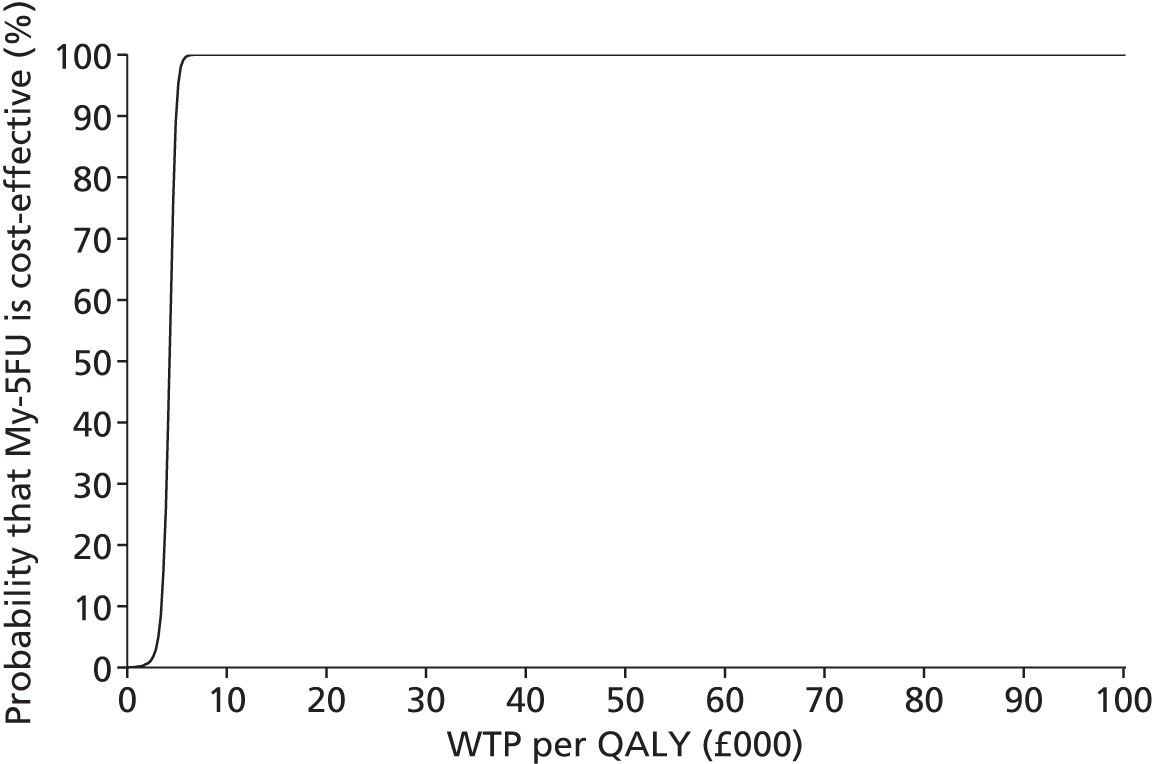

Full details on the reasons for excluding studies at full text can be found in Appendix 8.