Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/134/01. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Craig Ramsay and Miriam Brazzelli declare grants from the UK Department of Health during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Sharma et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Introduction

Surgical repair (herniorrhaphy) is undertaken in most people presenting with inguinal hernia in order to close the defect, alleviate symptoms of discomfort and prevent serious complications. Inguinal hernia repair is the most frequent and resource-consuming surgical intervention in the UK. 1,2 It is also the most common general surgical intervention performed in Europe1,3,4 and the USA. 5 Various surgical techniques and approaches are available for inguinal hernia. These can be classified in three main categories: open repair with suture (e.g. Bassini and Shouldice repair), open repair with mesh (e.g. Liechtenstein repair or preperitoneal repair) and laparoscopic repair with mesh [e.g. totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair or transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair].

Open and laparoscopic ‘tension-free’ repairs, which are based on the use of ‘mesh’ (prosthetic and biological), are widely performed and considered superior to the traditional ‘tissue-suture’ repairs, such as the Bassini or Shouldice techniques. 6,7 Compared with the traditional sutured techniques, a reduction in the risk of recurrence between 50% and 75% has been demonstrated after mesh repair. 8,9 However, the laparoscopic mesh repair has a longer learning curve and higher resource cost compared with the open mesh repair. 2,7,10–12 Different open repairs with mesh, such as the Lichtenstein repair and the preperitoneal repair, have shown similar results and very low recurrence rates, ranging from 2% to 5%. 13,14 The preperitoneal mesh repair has demonstrated similar or better outcomes compared with the laparoscopic mesh repair. 15

Considering the low recurrence rate reported in the literature after surgical repair of inguinal hernia, the current key outcomes on which to measure the clinical success of hernia recovery include chronic pain, complications, time to return to normal activities and quality of life (QoL). 16,17 Published evidence assessing the effects of common mesh techniques (including open preperitoneal repair, Lichtenstein repair and laparoscopic repair) in lowering chronic pain and improving major clinical outcomes have produced inconsistent results. 3,15,18–20 The aim of this assessment was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of open preperitoneal repair compared with Lichtenstein repair in adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia.

Aetiology, pathophysiology and clinical presentation

An inguinal hernia is a protrusion of the contents of the abdominal cavity through a defect in the inguinal canal. It manifests as a lump or swelling in the groin that may cause discomfort and pain, and impact on daily activities and ability to work. Unilateral hernias occur on one side of the lower abdominal wall, whereas bilateral hernias occur on both sides of the lower abdomen wall. Symptoms of inguinal hernia include swelling, pain or aching sensation in the groin, which develops gradually over time. Pain worsens with prolonged activities. 21 The bulge of the hernia increases in size with activities that cause intra-abdominal pressure, such as coughing, lifting or straining. Occasionally the hernia sac contents may get incarcerated causing obstruction or strangulation of the intestine, leading to ischaemia, necrosis and even perforation of the intestine. Rarely, inguinal hernias are asymptomatic.

Inguinal hernia is commonly diagnosed by clinical physical examination. Physical examination involves careful inspection of inguinal areas for bulges or impulses while the patient is standing and during a Valsalva manoeuvre (i.e. forceful attempted exhalation while keeping the mouth and nose closed). The sensitivity and specificity of physical examination for the diagnosis of inguinal hernia have been reported to be 75% and 96%, respectively. 22 In specific clinical situations such as recurrent hernia, hernia in female patients, surgical complications with chronic pain or uncertain aetiology, diagnosis of inguinal hernia can be improved by various imaging techniques (e.g. ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging or computerised tomography). 21 In particular, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography have shown high sensitivity and specificity estimates (> 80% and > 90%, respectively) for the diagnosis of groin hernia. 22

The classification of hernia is a prerequisite to describe the anatomy or size of inguinal hernia and to choose the best management. 3,23 Many classifications of inguinal hernia have been proposed and they are all based on the presence of indirect hernia (occurs because of the natural weakness in the internal inguinal ring), direct hernia (caused by the weakness in the floor of inguinal canal) and femoral hernia (less common groin hernia occurring mostly in women). 23 Table 1 illustrates a number of different classifications currently available.

| Type of classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Gilbert | Based on anatomical and functional defects described during open (anterior) operation; includes five types [1, 2, 3 (indirect); and, 4 and 5 (direct)]. Modified by Rutkow and Robbins23 |

| Nyhus | Describes the status of the fascia transversalis in the posterior wall of the inguinal and femoral canal; includes four types [I, II, IIIb (indirect); IIIa, IV (direct); IIIc (femoral)] |

| Stoppa | Derived from the Nyhus classification, with special attention to the aggravating factors; includes four types [1, 2 (indirect); and, 3 and 4 (direct)] |

| Bendavid TSD | An elaborate and complex system with 20 different subtypes, including typing, staging and measuring the dimensions of the hernia to classify them [I (indirect); II and V (direct); and III and IV (femoral)] |

| Aachen (Schumpelick) | Based on the more traditional European anatomical classification (direct or indirect inguinal, and femoral) combined with measurement of the hernia orifice (< 1.5 cm, 1.5–3.0 cm, > 3.0 cm); recommended simple method |

| Corcione | Includes three types [1 (indirect); 2 (direct); and 3 (femoral)] |

| Cost | Includes three types each for indirect and direct hernias (1, 2 and 3) |

| Porrero | Includes five types [1, 2, 3 (indirect); and, 4 and 5 (direct)] |

| European Hernia Society | Modification of Aachen classification; clear description of combined or femoral hernias, primary or recurrent hernia, the largest diameter to be used for quantification of hernia orifice size as 1 (≤ 1 finger), 2 (1–2 fingers) and 3 (≥ 3 fingers) |

Epidemiology and prevalence

A large population-based prospective study conducted in the USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1971–5) reported a 20-year cumulative incidence of hospitalisation with inguinal hernia of 6.3%. 24 The condition is observed more frequently in males and incidence increases with age. 24 The lifetime chance of getting inguinal hernia is estimated to be 27% in men and 3% in women. 25 Most inguinal hernias are found in men because of the vulnerability of the male anatomy to the formation of hernias in this region. 26 The average age group for the manifestation of inguinal hernia has been reported to be 10 years older in women (60–79 years) than in men (50–69 years). 27

A register-based 5-year study conducted in Denmark found that 97% of all groin hernia repairs (n = 46,717) were inguinal hernias. 4 In the Netherlands, approximately 30,000 inguinal hernia repairs are carried out annually. In the USA, data from the National Centre for Health Statistics suggest that approximately 800,000 groin hernia repairs were performed in 2003, with over 90% of these surgeries performed on an outpatient basis. 5

Impact of health problem: significance for the NHS and burden of disease

Symptomatic patients often present with pain and discomfort. Patients may experience a localised pain or aching (burning or gurgling) sensation at the site of hernia defect or a heavy or dragging sensation in the groin. There are various factors that may contribute to pain, including stretching or tearing of the tissue around the hernia defect, prolonged activity or Valsalva manoeuvres. 21 A prospective study by Hair and colleagues,28 evaluated the association between hernia symptoms and time from hernia presentation in 699 patients. About 65% (457) of patients complained of pain and discomfort at the hernia site on presentation, with the cumulative probability of pain increasing to almost 90% at 10 years, whereas more than one-third of patients (267/699) were asymptomatic. Patients with inguinal hernia are at risk of bowel strangulation, which requires emergency resection. A retrospective study,29 reported a cumulative probability of strangulation for inguinal hernias of 2.8% at 3 months and 4.5% after 2 years.

Severe chronic pain, wound infection and recurrence are among the postoperative complications that are reported after inguinal hernia repair. 16,17 With incidence rates ranging from 10% to 54%, chronic pain is undoubtedly the dominant complication after inguinal hernia repair. 16,30,31 The reason for long-term postoperative pain is complex and often related to intraoperative nerve damage, which is often associated with technical aspects of the surgical procedures as well as with surgeon’s dexterity and expertise. 32 The position of the mesh is likely to be another crucial factor.

Management of condition and current service provision

Conservative management

Asymptomatic inguinal hernias, which do not cause symptoms, can be managed through watchful waiting. However, asymptomatic patients need to be monitored over time for occurrence of symptoms, especially those indicating strangulation or incarceration, which require immediate medical attention. 7,21

Trusses are often recommended for the temporary management of hernia while patients are waiting for an operation. A truss is a type of surgical appliance that provides support for the herniated area during daily and working activities. 3 However, the benefit achieved through the use of a truss is debatable, as up to 64% of the patients have declared that they find it uncomfortable. 33 Nevertheless, in the UK, 40,000 trusses are issued every year with the rate of supply being very high as compared with other industrialised countries. 3

Surgical management

Inguinal hernias are commonly repaired using surgery, where the abdominal bulge is pushed back into place and the weakness in the abdominal wall is strengthened. Most hernia repairs are undertaken as elective procedures. 34 Surgical procedures for inguinal hernia include open repair with suture (e.g. Shouldice or McVay), open repair with mesh (e.g. Liechtenstein repair or preperitoneal repair) and laparoscopic repair with mesh. 34

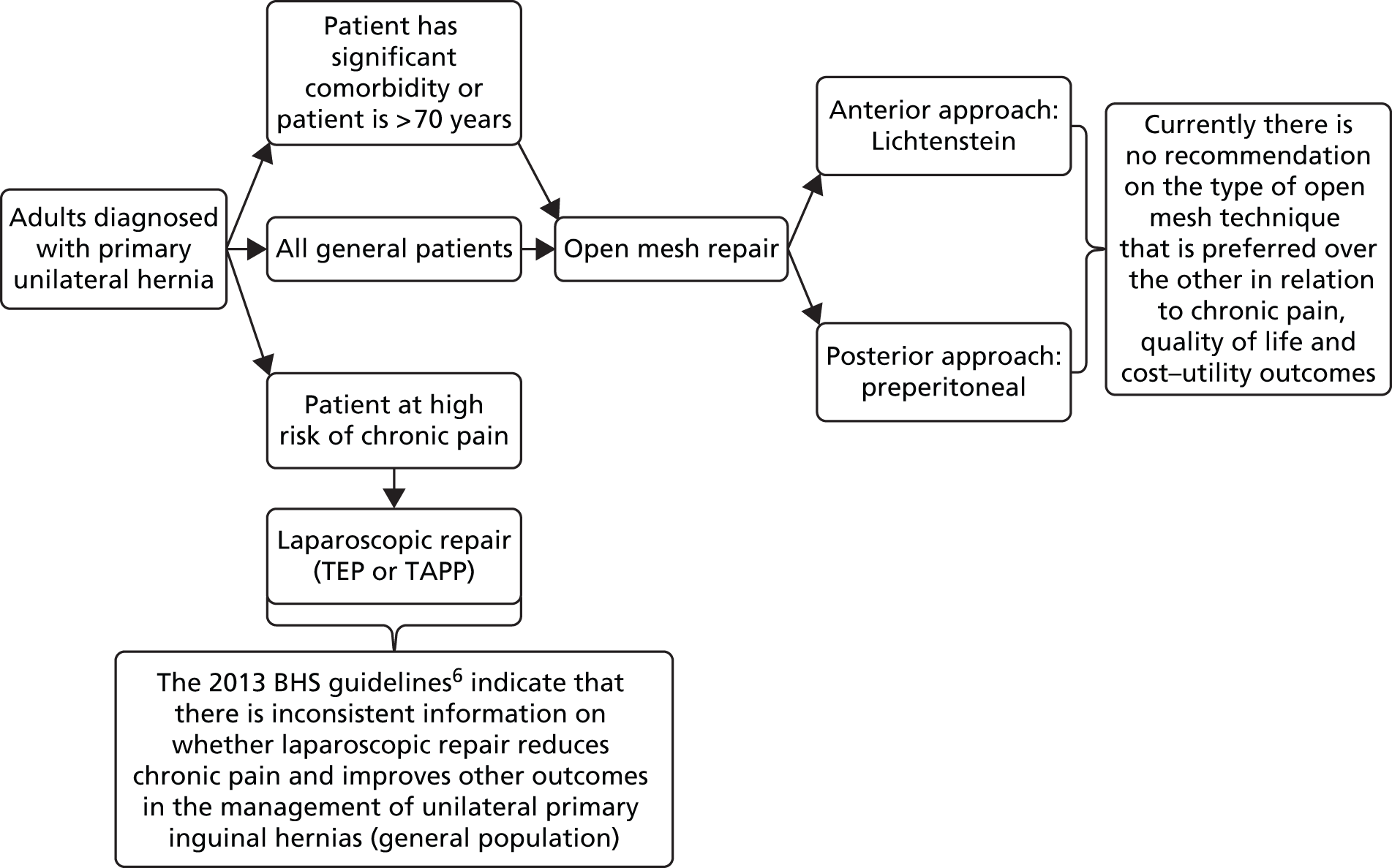

Open mesh repair is recommended for the management of primary unilateral inguinal hernia6,7 because of its low recurrence rates. Laparoscopic mesh repair is restricted to bilateral inguinal hernias, recurrent hernias, younger patients, patients with other chronic pain problems and those with severe groin pain. 3,6,35 When a mesh approach is not affordable or suitable (e.g. in older patients with significant comorbidity), a non-mesh repair is usually considered. 6,7

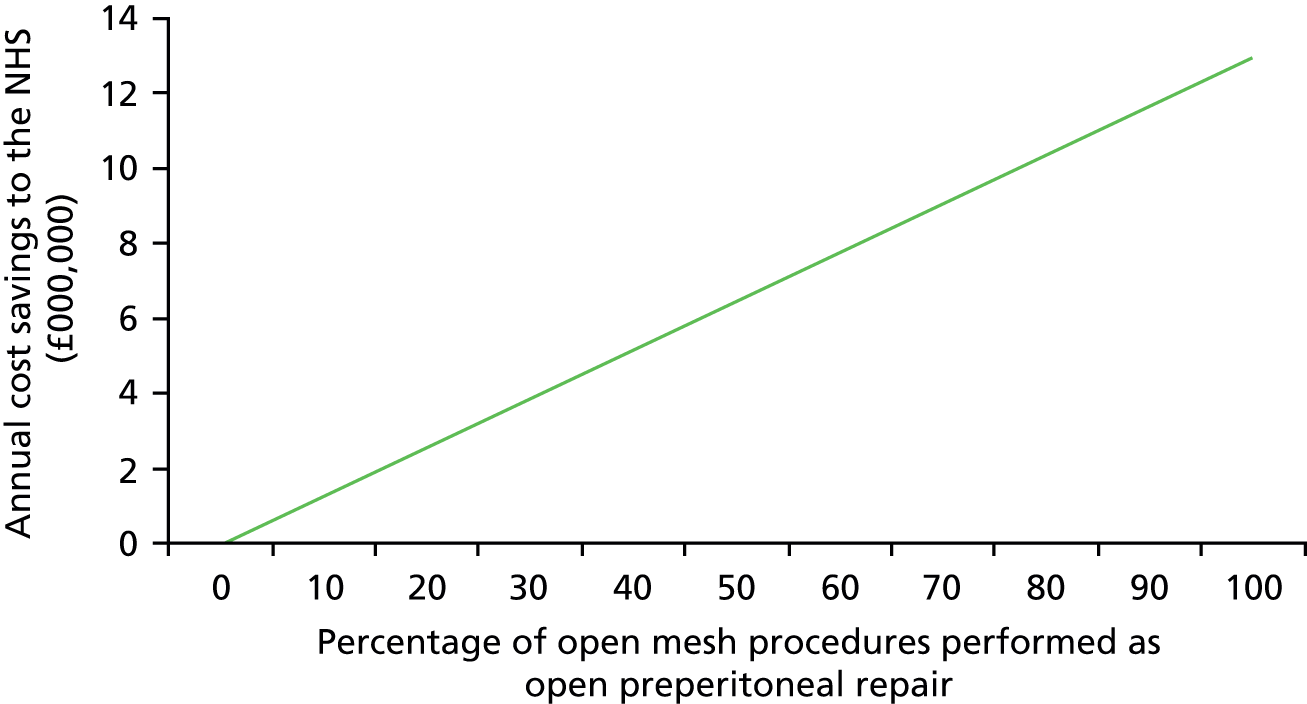

Current service cost

An increasing trend of primary inguinal hernia repairs performed as day-case procedures has been observed in England over the last decade. 2 In 2012/13, 41,384 out of 61,280 (68%) finished consultant episodes for primary inguinal hernia were performed as day-case procedures. 1 Based on national average reference costs, the costs for elective inpatient and day-case procedures are £2041 and £1471, respectively [see Appendix 1 for a derivation of the unit costs from Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) activity code FZ18]. The total annual cost to the NHS in England for primary hernia repair is estimated to be in the region of £114M per year, representing a substantial cost burden to the NHS. An implementation and uptake report completed by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 201035 indicates an increasing proportion of procedures performed as laparoscopic repair (16% of all primary inguinal hernia repairs in 2008/9). Therefore, assuming a similar breakdown of elective inpatient and day-case procedures for laparoscopic repair, the total cost to the NHS of open mesh hernia repairs is likely to be around £95M per annum.

Earlier studies show that the most important cost parameters for economic evaluation of inguinal hernia include the time patients spent in the operating room and recovery room, and the length of overall hospital stay. 5 The resources required for open surgery are less than those required for laparoscopic surgery. 6,10,11,13 Although there is little evidence comparing the costs of different types of open mesh repair, it can be assumed that operative costs are similar owing to the fact that open mesh procedures are technically comparable. Recent studies indicate that because of the observed low recurrence rates, one of the most important components for total NHS cost is that related to the management of chronic pain after surgery. 36 Evidence shows that laparoscopic repair may reduce postoperative chronic pain, but with the trade-off of additional resources required to perform the surgical mesh procedure. 13 There is no evidence comparing the total costs (including surgical and postoperative costs) or cost-effectiveness of different open preperitoneal mesh repairs from the perspective of health-care providers in the UK.

Variation in services and/or uncertainty about best practice

The relevant mesh techniques commonly used for the treatment of primary inguinal hernia in the UK are open mesh repairs (e.g. Lichtenstein repair and preperitoneal repair) and laparoscopic mesh repairs (TAPP repairs and TEP repairs). The choice of open versus laparoscopic repair, as well as the choice of specific mesh material, is usually based on surgeons’ preference and patients’ characteristics. There is a considerable variation (more than a twofold variation) in the rate of inguinal hernia repair across the NHS. 2 Figure 1 illustrates the number of inguinal hernia repair procedures per 100,000 population per clinical commissioning group across England. Of the 67.2% of inguinal hernia repairs performed in 2011/12 as day cases, the rate varied from 32% to 100% across providers. Owing to the lack of a national audit and of an established follow-up system, and taking into consideration the current low recurrence rate after inguinal hernia repair, it is difficult to rule out with certainty which technique is best.

FIGURE 1.

National variation plot by clinical commissioning group for inguinal hernia repair (from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014) (Emma Fernandez, The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2015, personal communication; permission gained from The Royal College of Surgeons of England for reproduction). The bubbles represent each clinical commissioning group and the size of the bubble represents the number of procedure undertaken.

Relevant national guidelines, including National Service Framework

The recent guidance from the British Hernia Society6 indicates that all adult inguinal hernias should be repaired using a flat mesh technique (or a non-mesh Shouldice technique, if experience is available). For the management of primary unilateral inguinal hernia, the British Hernia Society guidance suggests that an open technique under local anaesthesia should be regarded as an acceptable and cost-effective approach in suitable patients, that is those with significant comorbidity, those without other chronic pain problems and, in particular, older patients. A laparoscopic approach may be considered in bilateral inguinal hernias, groin hernias in women, younger patients, patients with other chronic pain problems or those with a severe groin pain even in the presence of a small hernia. The guidance concludes that at present there is conflicting information on whether or not laparoscopic repairs are better than open mesh repairs in terms of lowering the incidence and severity of pain. 6

Guidance from NICE on laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair suggests that laparoscopic repair should be considered one of the treatment options for inguinal hernia. 34 A shared decision-making model should be used for the choice of surgery by fully informing patients about the risks and benefits of open and laparoscopic repairs. Only trained and experienced surgeons should perform laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair. NICE guidance also provides recommendations for bilateral and recurrent hernias. 34

Description of interventions under assessment

The concept of ‘tension-free’ repair using a ‘mesh’ (prosthetic and biological) was introduced initially in the 1960s to overcome the drawbacks of tissue-suture techniques, which resulted in serious complications including ischaemia, pain, necrosis and recurrent hernia. A mesh technique repairs a defect in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal by blocking it with a plug or by placing the flat mesh prosthesis over the fascia transversalis to strengthen the inguinal wall. Meshes can be placed into the defect either anteriorly through open inguinal incision (i.e. Lichtenstein technique) or posteriorly in the peritoneal space through open (i.e. preperitoneal repair) or laparoscopic surgery.

Anterior Lichtenstein repair (open mesh)

Irving Lichtenstein developed the anterior open tension-free approach in 1984. 37 It is a very common and reproducible approach, and is relatively easy to perform. 7 The technique involves the placement of flat mesh (polypropylene) on top of the hernia defect through anterior dissection of the inguinal wall under local or general anaesthesia. Mesh is positioned between the internal and external oblique muscle and is sutured to the inguinal ligament such that there is adequate overlap of the posterior wall. At present, the Lichtenstein repair is considered the gold standard among open inguinal hernia procedures. Since its advent, the incidence of hernia recurrence has reduced up to 2%. 14

Different meshes and/or devices used for anterior open approach have been developed, including the mesh plug, the Prolene Hernia System (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) and the Hertra sutureless mesh (Herniamesh, Chivasso, Italy). Systematic reviews6,15,38,39 and clinical guidelines have assessed the effect of mesh plug repair and the Prolene Hernia System compared with Lichtenstein mesh repair. The Groin Hernia Guidelines published in 2013 included a meta-analysis of eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with a total of 2912 patients assessing the effects of mesh plug repair versus Lichtenstein repair. Meta-analyses results were similar with regard to postoperative complications and return to daily activities. 6 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 10 RCTs with a total of 2708 patients did not find significant differences in the number of recurrences between the Lichtenstein mesh repair, mesh plug repair and the Prolene Hernia System. 38 Another meta-analysis of six RCTs and a total of 1313 patients, which assessed the effects of the Prolene Hernia System versus the Lichtenstein repair, showed that the Prolene Hernia System was associated with a higher rate of perioperative complications. However, no significant differences were observed between the two techniques with regard to duration of operation, time to return to work, chronic groin pain or incidence of recurrences. 39 A more recent report commissioned by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), assessed the effectiveness of Lichtenstein open mesh with various mesh plug techniques. 15 Based on the findings of 21 studies (20 RCTs and one non-RCT), the report concluded that return to work was shorter after Lichtenstein mesh repair. No other significant differences were observed between the surgical procedures. In conclusion, current evidence seems to indicate that the standard Lichtenstein mesh repair performs better than mesh plug repairs and the Prolene Hernia System.

Posterior open repair (open preperitoneal mesh)

The open preperitoneal mesh approach involves incision of the abdominal wall and implantation of the mesh in the space between the peritoneum and the muscle layers. The mesh is held in place with intra-abdominal pressure and requires less or no fixation. Implantation of the mesh can be achieved through (1) a transinguinal method (e.g. Rives), (2) a small incision (2–3 cm) made in broad abdominal muscles [e.g. Kugel repair (Davol, Warwick, RI, USA)] or (3) a lower midline abdominal incision (e.g. Stoppa repair). 40 Open preperitoneal mesh repairs are mostly performed under general anaesthesia. The first open preperitoneal technique was reported by Stoppa in 1980 (i.e. Stoppa repair). 7 Since then a number of different techniques have been developed including the Kugel patch, the Nyhus repair, the Read–Rives repair and the transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) technique. There is a lack of robust evaluations comparing the clinical efficacy of each of these techniques. Kugel, using a specially designed hernia patch, observed only five recurrences out of 808 hernia repairs. 41 A retrospective study found similar results between the participants who underwent TIPP repair and those who underwent Lichtenstein mesh repair, with low incidence of chronic pain in both intervention groups. 11

The open preperitoneal technique with soft mesh has been reported to be a safe and potentially cost-effective approach with a short learning curve. 41–44 Irrespective of either open or laparoscopic techniques, the position of the mesh is considered an important factor in the interpretation of chronic pain because of the location of the nerves in the inguinal canal. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which assessed the effects of common open mesh techniques in lowering chronic pain and improving major clinical outcomes, have failed to provide definite conclusions. 15,18–20 A Cochrane review20 based on the findings of three RCTs showed some potential benefits of the open preperitoneal mesh repair compared with the Lichtenstein mesh repair in terms of incidence of acute and chronic pain and recurrence rate. However, the evidence base of this review was limited. A recent meta-analysis of 12 RCTs19 found that open preperitoneal mesh repair was associated with a lower risk of developing chronic groin pain than the Lichtenstein mesh repair, and the two techniques were comparable with regard to rate of recurrences and complications. It is worth noting that this meta-analysis did not focus exclusively on people with primary unilateral inguinal hernia but included people with recurrent and incarcerated hernias. Two further systematic reviews in the literature15,18 confirmed that various open repair procedures yielded similar results with further potential benefits for the open preperitoneal mesh techniques. The results of these systematic reviews were, however, inconclusive as both included trials assessing the Prolene Hernia System versus the Lichtenstein mesh repair.

Ralph Ger first introduced the use of a laparoscopic approach in 1982. 45 Laparoscopic repairs are minimally invasive and are performed under general anaesthesia. Small incisions are made for the insertion of the operating instruments and prosthetic mesh is placed to close the hernia defect. Mesh is placed in the preperitoneal plane by using one of the two approaches:

-

TAPP repair: the abdominal cavity is entered and a flap of the peritoneum is deflected to expose the preperitoneal plane. A mesh is inserted to cover the hernia defect in the inguinal region. The peritoneum is then closed over the mesh.

-

TEP repair: the mesh is inserted via the preperitoneal plane without entering the peritoneal cavity to cover hernia defects while remaining outside the peritoneum.

The effects of open versus laparoscopic techniques have been assessed in a considerable number of RCTs. A UK Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report published in 200513 identified 37 RCTs that compared open mesh repairs with laparoscopic mesh repairs. A more recent report by the AHRQ, published in 2012, assessed the effectiveness and adverse effects of various surgical interventions for inguinal hernia in both adults and children. 15 The report identified 123 RCTs, two clinical registries and 26 non-randomised studies published between January 1990 and November 2011. 15 Thirty-six of the included 123 RCTs compared open mesh repairs versus laparoscopic mesh repairs for primary inguinal hernia (indicating that the size of the evidence base for this comparison has not significantly changed since 2003), while 20 RCTs assessed various open mesh repairs (some of which no longer reflect the repairs commonly performed in clinical practice). Both these reports concluded that people who underwent laparoscopic mesh repair had faster return to normal activities, less chronic pain and numbness, and fewer postoperative complications (infection and haematoma), while those patients who underwent open mesh repair had lower rates of serious complications (especially visceral injuries). The AHRQ showed a lower risk of recurrence after open surgery (2.49%) than after laparoscopic surgery (4.46%) for the treatment of painful primary hernias in adults,15 while the UK HTA report observed similar recurrence rates between laparoscopic (2.47%, 26/1052) and open procedures (2.07%, 22/1062). 13 However, there is conflicting information on whether or not laparoscopic repair is better than open mesh repair in terms of lowering the incidence and severity of pain outcomes. 6,21,34 The uptake of laparoscopic technique by surgeons is very low (16% in the UK, ≈ 10% in the USA), probably owing to the complexity of the procedure, potential serious complications, long learning curve and high cost. 3,35

Current usage in the NHS

Inguinal hernia repair is the most common general surgical intervention performed in the UK. In England, 71,490 inguinal hernia procedures were carried out in 2012/13, with over 100,000 NHS bed-days of hospital resources utilised. 1,2 Of these procedures, 65,759 repairs (92%) were for the repair of primary hernias and 5731 repairs (8%) were for the repair of recurrent hernias. 1 Out of 65,759 procedures for primary inguinal hernia, 61,280 (93%) were procedures involving the use of a mesh. Of 71,427 admissions for unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia, 6.8% (4867) were emergency admissions while almost 90% (64,017) were on a waiting list, with a mean waiting time of 62.5 days. In 86% of cases (61,169), primary repair of inguinal hernia was performed using mesh techniques (i.e. biological/prosthetic). The majority of inguinal hernia repairs were performed as day surgery procedures (> 80%) to overcome the demand of hospital bed requirement in the NHS. 2

The Lichtenstein open mesh repair is the most commonly performed procedure for hernia repair in the UK (performed by 96% of surgeons). 16 A NICE uptake report published in 201035 indicates that of all surgical repairs of inguinal hernia performed in 2008/9 in England, approximately 16% were performed using laparoscopic techniques. 35 In Scotland, the uptake of laparoscopic surgery in 2007/8 was lower, with only 13% of inguinal hernia repairs performed using a laparoscopic approach. 46

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Purpose of the decision to be made

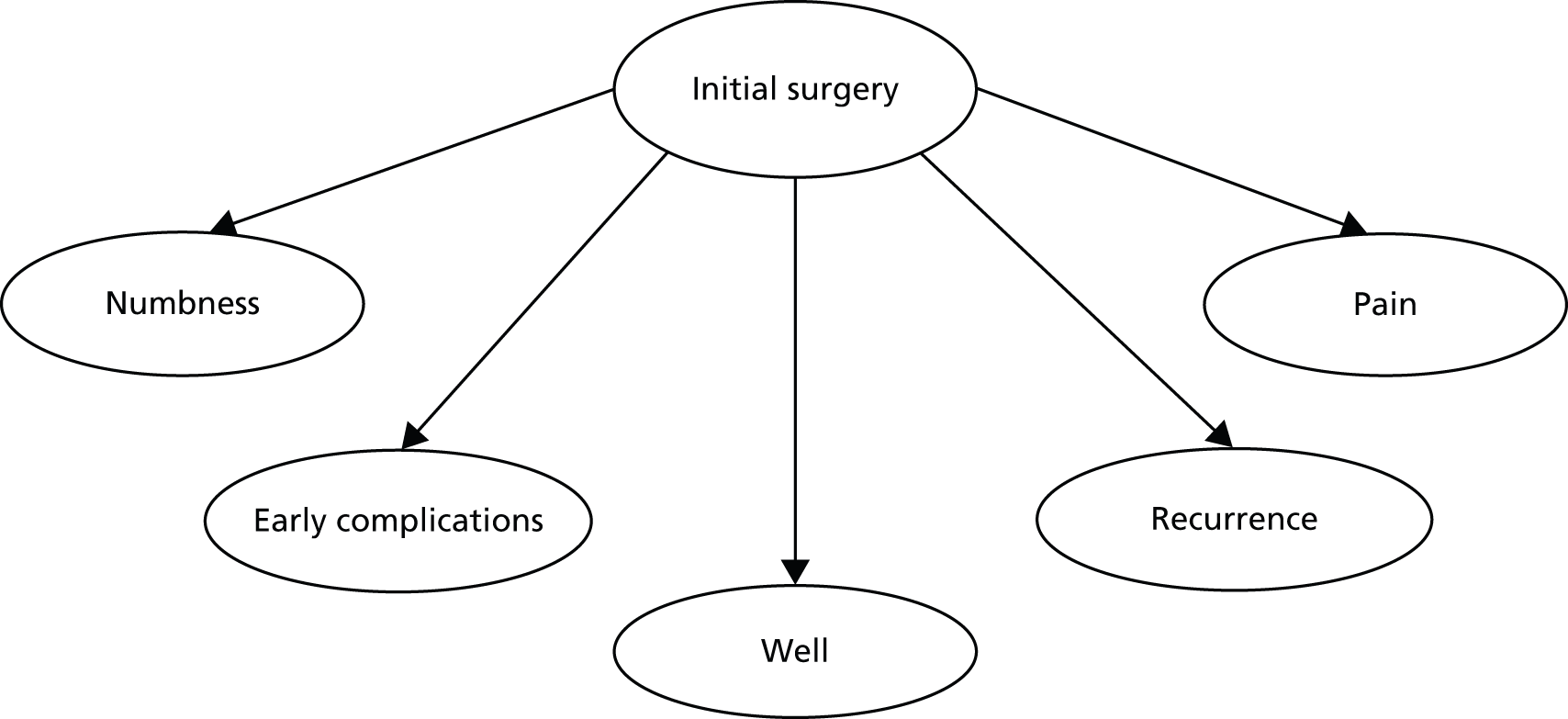

The general purpose of this assessment is to evaluate the current evidence on the effects of open mesh techniques for the treatment of unilateral, primary inguinal hernia. Figure 2 shows the care pathway for the management of adults diagnosed with primary unilateral inguinal hernia based on the current British Hernia Society guidelines. 6

FIGURE 2.

Framework of the care pathway for the management of patients diagnosed with primary unilateral inguinal hernia. BHS, British Hernia Society.

Population

The population considered for this assessment was adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in an elective setting. No relevant subgroups were identified. Recurrent or bilateral inguinal hernia will not be considered in this assessment.

Clinical diagnosis of inguinal hernia is usually established by physical examination. Imaging techniques such as ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging or computerised tomography may be used to confirm uncertain or challenging diagnoses. In particular, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography are considered highly accurate techniques for the diagnosis of groin hernias. 22

Intervention

Surgical repair with ‘mesh’ is the recommended treatment for inguinal hernia. 2,7 Mesh repair methods include those involving mesh to strengthen the inguinal wall (e.g. Liechtenstein open mesh repair, open preperitoneal mesh repair and laparoscopic mesh repair). The Lichtenstein mesh repair is the most commonly performed procedure for hernia repair in the UK. 16 The laparoscopic mesh repair is technically more complex and requires longer operation time, special equipment and high surgeon’s experience and, therefore, is not routinely used in the UK. 46 The open preperitoneal mesh repair has shown similar or better outcomes compared with the laparoscopic approach. 15 Open preperitoneal techniques with soft mesh have been reported to be safer and potentially cost-effective with a short learning curve. 42–44 Published evidence comparing open preperitoneal mesh repair with Lichtenstein mesh repair with regard to relevant clinical outcomes, such as chronic pain and QoL, have produced conflicting and inconclusive results. 15,19,20

The following open mesh repairs of inguinal hernia are considered in this assessment:

-

Anterior Lichtenstein mesh repair: Lichtenstein mesh repair is a very common approach that involves the placement of flat mesh on top of the hernia defect through anterior dissection of the inguinal wall under local or general anaesthesia.

-

Open preperitoneal mesh repair: the open preperitoneal mesh approach involves incision of the abdominal wall and implantation of the mesh in the space between the peritoneum and the muscle layers. The mesh is held in place with intra-abdominal pressure and requires less or no fixation. Open preperitoneal repair can be performed using various methods including the Kugel patch, the Nyhus repair, the Read–Rives repair, the TIPP repair and the Stoppa repair.

Non-mesh techniques requiring suturing (e.g. Shouldice, Bassini, McVay, Maloney darn and plication darn techniques) will not be considered in this assessment as they have been proved to be inferior to current mesh techniques and hence no longer recommended. 7–9 Similarly, plug mesh repair and the Prolene Hernia System will not be included in this assessment as they have not demonstrated to be superior to the standard Lichtenstein method. 6,15,18,39 The effects of open versus laparoscopic mesh techniques have been assessed in a considerable number of RCTs. 13,15 In general, evidence has shown similar results with very low recurrence rates. 13–15,18 However, there is conflicting information on whether or not laparoscopic mesh repair is better than open mesh repair in terms of lowering the incidence and severity of pain. 2,21,34 Moreover, laparoscopic mesh repair is not commonly performed in the UK. Laparoscopic mesh techniques will not be considered in this assessment.

Overall aim and objectives of this assessment

This assessment will evaluate the current evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of open preperitoneal mesh repairs versus standard anterior Lichtenstein mesh repair, with particular attention to postoperative chronic pain.

The specific aims of this assessment will be the following:

-

systematically review the relative clinical effectiveness of surgical open preperitoneal mesh repairs compared with standard Lichtenstein mesh repair for the treatment of adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in an elective setting

-

systematically review existing economic evaluations on surgical open mesh techniques for the treatment of adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in an elective setting

-

develop a de novo economic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of surgical open mesh repairs for the treatment of adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in an elective setting.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness of open mesh repairs

This chapter reports the assessment of clinical effectiveness of open mesh repairs for primary inguinal hernia. The methods were prespecified in a protocol (PROSPERO database CRD42014013510).

Methods for assessing the outcomes arising from the use of the intervention

We conducted an objective synthesis of the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of relevant open mesh surgical procedures for the repair of primary unilateral inguinal hernia. The evidence synthesis was carried out according to the general principles of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance for undertaking reviews in health care,47 the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions48 and the NICE Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal,49 and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 50

Identification of studies

Comprehensive electronic searches were conducted to identify reports of published randomised trials. Highly sensitive search strategies were designed, including appropriate subject headings and text word terms, to combine the search facets for inguinal hernia repair, the surgical interventions under consideration and randomised trials. Final searches were carried out on 31 October and 1 November 2014 and were not restricted by year of publication or language. Full details of the search strategies are reported in Appendix 2. The databases searched were MEDLINE (1946 to October week 4 2014), MEDLINE in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (31 October 2014), EMBASE (1947 to 2014, week 44), Bioscience Information Service (BIOSIS; 1980 to 1981 November 2014), Science Citation Index (1980 to 1981 November 2014), Scopus Articles In Press (inception to 31 October 2014) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (inception to 2014). Evidence syntheses were sought by searching the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (inception to 2014), Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness (inception to 1 November 2014) and the HTA database (inception to 1 November 2014). Reference lists of all included studies were perused for further evidence. Members of our advisory group were contacted for details of additional reports.

Identification of other relevant information, including unpublished data

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched on 1 November 2014 for evidence of ongoing studies. Websites of relevant professional groups and HTA organisations were also checked for additional reports (see Appendix 2).

Eligibility criteria

The studies fulfilling the following criteria were included in the assessment.

Population

Adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in any appropriate elective setting. Adults presenting with recurrent, bilateral or strangulated inguinal hernias and children (< 18 years old) were not deemed suitable for inclusion.

Interventions

Open preperitoneal mesh repairs and standard anterior Lichtenstein mesh repair. Open preperitoneal mesh repairs can be performed using various techniques including Kugel patch repair, Read–Rives repair, TIPP repair, Nyhus repair and Stoppa repair. The relative clinical effectiveness of any of these techniques compared with the standard Lichtenstein mesh repair was assessed.

Open non-mesh techniques (including Shouldice, Bassini, McVay, Maloney darn and plication darn techniques) and mesh repairs performed using both an anterior approach and a posterior approach (such as the Prolene Hernia System and the mesh plug repair) were not considered suitable for inclusion (see Chapter 1 for further information).

Outcomes

Studies providing data on any of the following outcomes (using any measure) were included:

-

patient-reported outcomes:

-

chronic pain (≥ 3 months after repair)

-

chronic numbness (≥ 3 months after repair)

-

acute pain (< 3 months after repair)

-

acute numbness (< 3 months after repair)

-

QoL.

-

As definitions of acute and chronic pain vary considerably among studies, we have also taken into consideration the specific definitions used by individual study investigators:

-

clinical and surgical outcomes:

-

mortality

-

complications (such as haematoma, seroma, wound/superficial infection, mesh/deep infection, vascular injury, visceral injury, port site hernia, other serious complications)

-

recurrence/reoperation rate

-

length of hospital stay (days)

-

time to return to normal activities (days).

-

Study design

Randomised controlled trials or quasi-RCTs assessing the clinical effectiveness of open preperitoneal mesh repairs compared with Lichtenstein mesh repair were considered for inclusion. There was no restriction on the publication status (published or unpublished), the year or the language in which trials were reported. Well-conducted systematic reviews were included as sources of relevant data.

Exclusion criteria

Studies not fulfilling the prespecified criteria and the following type of reports were excluded:

-

biological studies

-

editorials and opinions

-

case reports

-

conference abstracts.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (PS and MC) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations identified by the search strategies. Full-text copies of all potentially relevant studies were retrieved and assessed independently by the two reviewers for eligibility using a screening form developed for this purpose (see Appendix 3, Table A). Full-text copies of non-English-language studies deemed to be potentially relevant were translated before they were assessed for eligibility. Any disagreements during study selection were resolved by discussion or in consultation with a third reviewer (MB or IA).

A data extraction form was specifically designed and piloted for the purpose of this assessment (see Appendix 3, Table B). Two well-conducted RCTs were used to pilot the data extraction form. Detailed information on study design, characteristics of participants, settings, characteristics of interventions and outcome measures were recorded. Three reviewers carried out data extraction (PS, MC and NS); one reviewer completed the data extraction form for all selected studies and two other reviewers cross-checked the details extracted by the first reviewer. There were no disagreements between reviewers.

Further information from the included studies (methodological details or outcomes data) was requested by written correspondence to the original investigators (using open-ended questions and outcome tables for missing outcome data). Principal investigators of relevant ongoing trials were contacted to obtain unpublished data. Any relevant information retrieved in such a manner was included in the review. We contacted eight trial investigators and received further information from three of them. Where trials reported more than two study arms, only data from the relevant arms were extracted.

Where possible, means and standard deviations (SDs) were extracted for continuous data. When SD values were not available, we attempted to (1) calculate SD values using other reported values and (2) contact the original trial investigators for further details. Only when these attempts proved unfeasible or unsuccessful, values were imputed using the average of the SDs from other trials reporting the same outcomes.

Quality assessment strategy

The potential risk of bias for included studies was assessed by a single reviewer (PS or MC) and cross-checked by a second reviewer (PS or MC). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration with a third reviewer (MB). Studies were not included or excluded on the basis of their methodological quality. The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias of all included RCTs48 (see Appendix 4). Critical judgements were made for all main domains: selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessor), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (free of selective reporting) and other sources of bias (e.g. bias related to the validity of the tools used for measuring outcomes and bias related to inappropriate source of funding). The domains ‘blinding of outcome assessment’ and ‘incomplete outcomes data’ were assessed for each outcome of interest. The blinding of personnel delivering the intervention was not considered relevant for this assessment, as in clinical practice it is not feasible to blind the surgeon who performs the operation.

Each included study was judged to be at ‘low risk of bias’, ‘high risk of bias ‘or ‘unclear risk of bias’ according to the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 48 Adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and blinding of outcome assessor were identified as key domains for the assessment of the risk of bias of the included trials. Studies were classified as follows: (1) high risk of bias, if one or more key domains were at high risk; (2) unclear risk of bias, if one or more key domains were judged to be at unclear risk; and (3) low risk of bias, if all key domains were judged to be at low risk.

Method of analysis/synthesis

For binary outcomes, the Mantel–Haenszel approach was used to pool risk ratios (RRs) derived from each study. However, because some adverse outcomes were expected to be relatively uncommon for outcomes with rare events (i.e. < 5%), the Peto odds ratio (OR) approach was considered the most appropriate meta-analysis approach. For continuous outcomes, mean differences between groups were pooled using the inverse variance method. For time-to-event outcomes (recurrence and time to return to normal activities) we planned to pool hazard ratios if suitable data were available.

The statistical heterogeneity across studies was explored using the Chi-squared and I-squared statistics. The primary analysis used a random-effects model to calculate the pooled estimates of effect. This was not possible when the Peto approach was used for binary outcomes with rare events.

If a sufficient number of trials were available, sensitivity analyses restricted to trials at low risk of bias were planned.

Results of the evidence synthesis

Quantity and source of the evidence

The original primary searches and the subsequent updates retrieved a total of 1204 records. After reviewing all titles and abstracts, 1122 records were subsequently excluded because they were not relevant. Full-text copies of 82 potentially relevant reports were obtained and screened for inclusion. Six non-English full-text articles published in Dutch (n = 1), German (n = 1), Italian (n = 1), Spanish (n = 2) and Persian (n = 1) were identified and assessed. Colleagues from the School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Aberdeen, who were native Dutch, German, Italian or Spanish speakers, translated five of these articles professionally. A full-text article, published in Persian, was initially translated using the Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) translator tool and subsequently checked by a colleague who could read Persian. After translation, only two non-English-language papers (published in Persian and Spanish) met the prespecified inclusion criteria and were included for further assessment.

Three systematic reviews of RCTs assessing open mesh repair versus Lichtenstein mesh repair were deemed suitable for inclusion (the Cochrane review by Willaert and colleagues,20 the meta-analysis by Sajid and colleagues,19 and the systematic review by Li and colleagues18). In line with the prespecified research protocol, these systematic reviews were used as a source of existing evidence but were not formally updated. Further methodological details and missing data from one included ongoing RCT51 were derived from the systematic review by Willaert and colleagues,20 which cited this RCT and was based on individual participant data, as we were not able to make contact with the principal investigator.

In total, 12 RCTs (11 RCTs published in 13 full-text papers and one ongoing RCT) met the inclusion criteria and were included for the clinical effectiveness assessment. 42,51–63 One of the included trials53 used a quasi-random method to allocate participants to interventions (i.e. order of admittance).

Figure 3 shows the flow diagram of the study selection process. Appendix 5 lists all the studies included in this assessment, together with the systematic reviews that were used as a source of relevant evidence.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Appendix 6 lists the studies excluded after full-text scrutiny together with the reasons for their exclusion. Sixty-six studies were excluded because they failed to meet one or more of the specified inclusion criteria with regard to study design, participants, intervention or outcomes. In particular, 45 studies were excluded because they were non-RCTs, one study because patients did not present with primary inguinal hernia, 15 studies because they did not include a relevant comparison and five studies, published in non-English languages, because they could not be obtained.

Risk-of-bias assessment of included studies

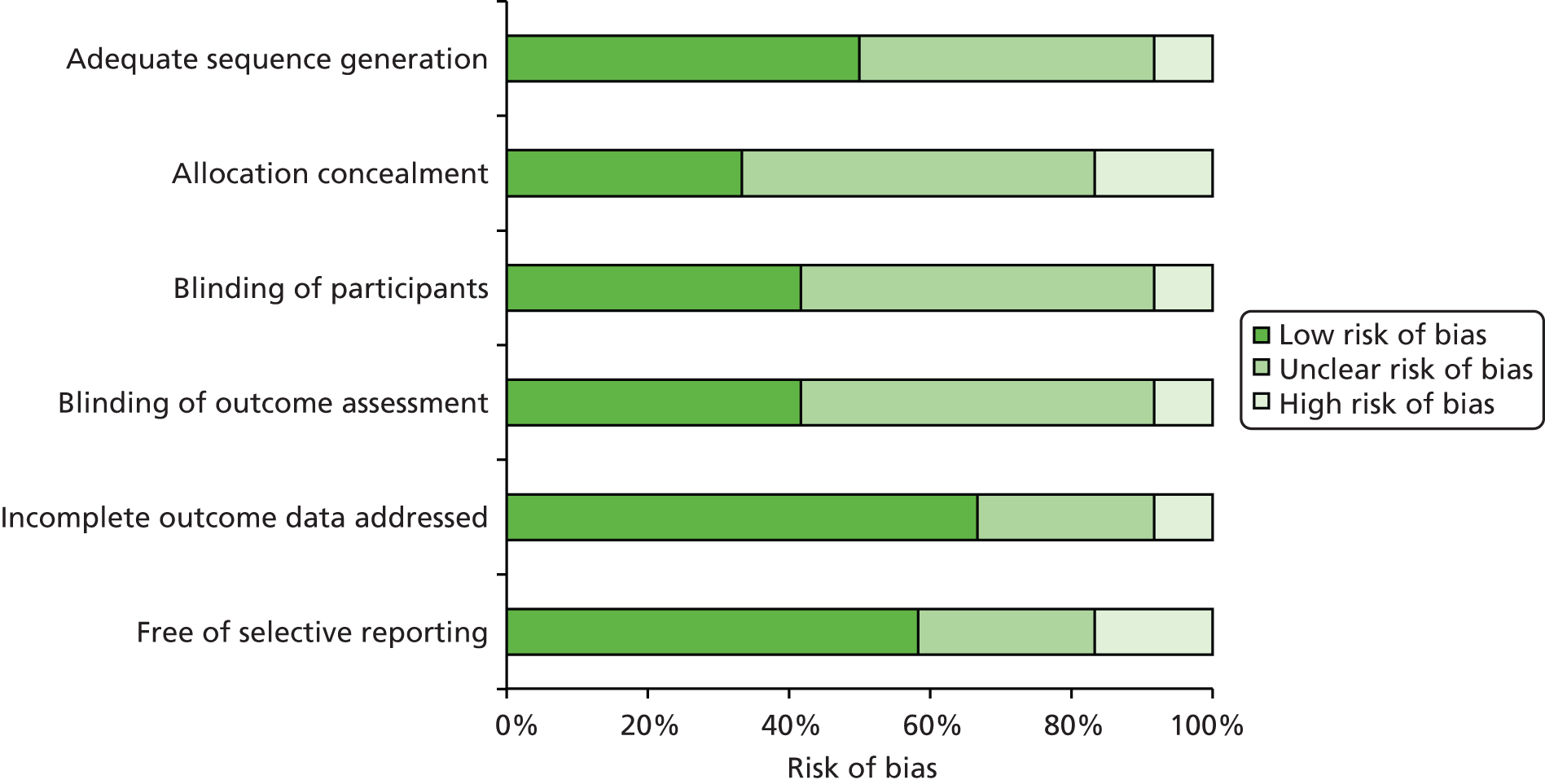

Figure 4 illustrates the summary of the risk-of-bias assessment for all 12 included studies. 42,51–63 Risk of bias of individual studies is detailed in Appendix 7, Tables 30 and 31.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of risk-of-bias assessment of included 12 studies.

Generally, trials were at high or unclear risk of bias. Only two trials were judged to be at low risk of bias, with adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and blinding of outcome assessor. 52,56 Two trials were judged at high risk of selection bias because of the inadequate randomisation process,53,59 whereas one trial was judged at unclear risk of selection bias because not enough information was provided on allocation concealment. 61 One trial51 did not blind participants or outcome assessors, and was considered at high risk of performance and detection biases. Six of the included trials,54,55,57,58,60,63 failed to provide sufficient information to formulate a reliable judgement about risk of bias and no additional details were obtained from the corresponding authors.

Selection bias (adequate sequence generation/allocation concealment)

Of the 12 included trials, four reported adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment. 51,52,56,58 Randomisation was performed using a computer-generated list and allocation of participants was concealed by means of sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes. Two trials used a computer-generated method59 and a random number table, respectively,61 but did not conceal participants’ allocation59 or failed to report information on concealment allocation. 61 Another trial had a high risk of selective enrolment of participants as randomisation was done according to order of admittance. 53 In the remaining trials, there was insufficient information on sequence generation and allocation to make a reliable judgement. 54,55,57,60,63

Performance and detection bias (blinding)

The blinding of personnel delivering the intervention was not assessed, as it is impossible to blind the surgeon performing the surgical operation. It was reported that participants were blinded to the specific type of surgical intervention in four trials. 52,56,59,61 Five trials reported that the main outcome assessor was blinded to the patients’ clinical reports and to the type of surgical procedure. 52,56,57,59,61

Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data)

Eight of the included trials were graded to be at low risk of attrition bias. 51,53,56–61 Missing data were adequately addressed in four trials53,56,58,59 and four other trials reported that there were no missing data. 51,57,60,61 One trial, conducted in Turkey, which did not address missing data adequately and had a 5% drop-out rate, was judged to be at high risk of attrition bias. 52 With regard to the remaining three trials,54,55,63 no information was provided on the number of participants enrolled, number of participants randomised or number of participants lost to follow-up.

Reporting bias (free of selective reporting)

In seven of the included trials, the outcomes assessed were either prespecified in a protocol or in the analysis section and there was no clear evidence of reporting bias. 51,52,56,58–61 Two other trials were judged to be at high risk of reporting bias as they failed to report all outcomes that were assessed. 53,63 Three other trials were graded to be at unclear risk of bias as they reported acute pain and/or patient satisfaction using a visual analogue scale (VAS), but did not report chronic pain. 54,55,57

Other sources of bias

One trial52 measured chronic pain using the Sheffield scale. We could not identify sufficient evidence to decide whether or not the Sheffield scale was a validated tool to measure pain in patients who underwent inguinal hernia repair. Therefore, this study was judged to be at unclear risk of other source of bias. None of the included trials was sponsored by industry. No other sources of bias were obvious in the published trials reports.

Study characteristics

Details of all included studies, including baseline characteristics of participants, description of surgical interventions (i.e. open preperitoneal mesh repair and Lichtenstein mesh repair) and clinical outcomes are tabulated in Appendix 8, Tables 32–34.

Included trials were conducted in Turkey (four studies),52–54,63 the Netherlands (two studies),56,59 Belgium (one study),51 Egypt (one study),55 Iran (one study),57 India (one study),60 the USA (one study)58 and Mexico (one study). 61 Four trials were sponsored by professional organisations. 51,55,56,61 In the remaining eight trials, the source of funding was not specified. 52–54,57–60,63

Among included studies, the lengths of follow-up ranged from 1 week63 to 110 months. 58 Only two trials had long follow-up assessments; the trial by Gunal and colleagues,54 conducted in Turkey, reported mean length of follow-up of 98 months and the trial by Muldoon and colleagues,58 conducted in the USA (224 participants in total), had a median length of follow-up of 82 months (range 24–110 months). In the remaining trials the mean length of follow-up was 17.3 months (range 0.25–54.5 months; median 12 months).

Participants

A total of 1568 participants with primary unilateral inguinal hernia were assessed among the 12 included trials. The characteristics of the participants’ hernia defects [classified according to either Nyhus classification or the American Society of Anaesthetists (ASA) grade] varied across trials. Four trials54–56,59 included low-risk participants such as those with ASA grade I–III or Nyhus type I–III defects, while two other trials57,58 included participants with large hernia defects (Nyhus type III–IV). The remaining trials did not specify the physical status of the hernia defect. 51–53,60,61,63

Table 2 summarises the baseline characteristics of all included trials and Appendix 8 describes the characteristics of each individual trial. The mean sample size among included trials was 130.7 ranging from 45 participants63 to 302 participants. 56 Apart from the TULIP (the Tilburg double-blind randomised controlled trial comparing inguinal hernia repair according to Lichtenstein with the TIPP technique) trial by Koning and colleagues,56 which was conducted in two large hospitals in the Netherlands, all trials were conducted in a single centre. The trial by Koning and colleagues,56 with a total of 302 participants, was also the largest included trial. The trial by Smolinski-Kurek,64 which originally planned to include 168 participants, reported only preliminary results based on a total of 90 participants. 61

The age of participants ranged from 18 to 85 years. Demographic characteristics of participants (age, sex and body mass index) were balanced between intervention groups (i.e. open preperitoneal mesh repair and Lichtenstein mesh repair).

| Baseline characteristics | Open preperitoneal | Lichtenstein | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total randomised, N | 771 | 797 | 1568 |

| Total analysed, N | 743 | 775 | 1518 |

| Number lost to follow-up, n (%) | 28 (3.8) | 22 (3) | 50 (3.5) |

| Number of men,a n (%) | 698 (90.5) | 726 (91.1) | 1424 (90.8) |

| Range of mean age (years), n | 23.85–60.7 | 22.76–63.3 | 22.76–63.3 |

| Range of mean BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2–26.36 | 24.34–26.82 | 22.2–26.82 |

| Hernia typeb | N = 611 | N = 641 | N = 1252 |

| Indirect, n (%) | 382 (62.5) | 388 (60.4) | 770 (61.5) |

| Direct, n (%) | 176 (28.8) | 203 (31.6) | 379 (30.3) |

| Others,c n (%) | 53 (8.7) | 50 (8.0) | 103 (8.2) |

Hernia repair (open preperitoneal mesh repair and Lichtenstein mesh repair)

In all included trials, participants were randomised to either Lichtenstein mesh repair or open preperitoneal mesh repair. Appendix 8, Table 34 describes the details of these techniques including type of incision, type of mesh, mesh fixation methods, duration of operation and surgeon’s level of experience.

All 12 included trials referred to a ‘standard’ Lichtenstein repair even though the procedure has technically evolved since its first introduction in 1984. The type of mesh used to repair the hernia defect varied among trials. Eight of the included trials opted for a polypropylene mesh. 52,53,57–61,63 The trials by Koning and colleagues56 reported the use of a soft mesh, whereas Berrevoet51 used a lightweight mesh.

Various open preperitoneal mesh techniques were utilised in the included trials. Three of the most recent trials compared TIPP repair with Lichtenstein mesh repair. 51,56,60 Two of these trials56,51 used a polysoft mesh (soft mesh with memory ring), whereas the other trial used a polypropylene mesh. The other three trials used a Kugel approach. 52,53,59 Two of these trials used a double-layer mesh patch as originally described by Kugel53,59 while one trial52 used a modification of the original Kugel technique (i.e. a single-layer polypropylene mesh patch), with the intent to reduce the occurrence of a foreign body reaction. Another trial61 used an elliptical domed mesh preperitoneal technique with polypropylene mesh. Of the remaining five trials, two compared standard Read–Rives repair with Lichtenstein repair;57,58 two compared Nyhus repair with Lichtenstein repair;54,63 and one did not specify the type of open preperitoneal technique. 55

Among the 12 included trials, three had multiple arms and, alongside the Lichtenstein mesh repair and the open preperitoneal mesh repair, included additional comparisons with various laparoscopic techniques (TAPP and TEP repairs)54,55,63 or with the Bassini open non-mesh technique. 63 Only data from the comparisons relevant to the purpose of this assessment were considered suitable for inclusion.

Mean duration of open preperitoneal surgery ranged from 34.1 minutes (SD 9.9 minutes)56 to 59 minutes (SD 11 minutes)61 and that of Lichtenstein repair ranged from 34.2 minutes (SD 23.5 minutes)55 to 58 minutes (SD 10 minutes). 61 Six trials52–54,56,59,63 reported that the Lichtenstein mesh repair took longer to perform than the open preperitoneal mesh repair, while four trials reported that the open preperitoneal mesh repair (performed using either the TIPP technique,60 the Read–Rives technique57,58 or an unspecified preperitoneal technique55,61) required more time.

Assessment of outcomes and follow-up

Table 3 highlights the type of outcome measures that were assessed in the included trials. Pain was measured at different time points after surgery and during follow-up (see Appendix 8, Table 32). In total, seven trials assessed chronic pain (≥ 3 months),51,52,56,58–61 nine acute pain51,54–57,59–61,63 (< 3 months) and four chronic numbness56,58,59,61 (≥ 3 months).

| Outome reported | Study ID | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arslan et al. 201452 | Berrevoet51 | Dogru et al. 200653 | Gunal et al. 200754 | Hamza et al. 201055 | Koning et al. 201256 (Koning et al. 2013)42 | Moghaddam et al. 201157 | Muldoon et al. 200458 | Nienhuijs et al. 200759 (Staal et al. 2008)62 | Ray et al. 201460 | Smolinski-Kurek et al. 201261 | Vatansev et al. 200263 | |

| Chronic pain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Chronic numbness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Acute pain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Recurrence/reoperation rate | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Length of hospital stay | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Time to return to normal activities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Complications | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mortality | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

The definition of pain and time points when pain was measured varied among trials (see Appendix 9, Tables 35–40). Four trials used the VAS score to measure chronic pain. 51,56,59,61 The VAS is a validated instrument for measuring pain on a scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Three of these four trials51,56,59 defined chronic pain as ‘any VAS score above zero which lasts for more than three months as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain’ and reported chronic pain at 3 months,59 1 year56 and 2 years. 51 One trial61 defined chronic pain as ‘any VAS score between 3 and 10’ and reported chronic pain at 3 and 6 months. A different trial52 defined chronic pain as ‘a pain lasting for more than 6 months after surgery according to the Sheffield scale’. The Sheffield scale is a tool that measures pain using a score from 0 to 3, where 0 indicates no pain, 1 indicates no pain at rest but some pain during movement, 2 indicates temporary pain at rest and moderate pain during movement and 3 indicates constant pain at rest and severe pain during movement. The remaining two trials58,60 did not specify the instrument used to measure pain, but reported the number of participants suffering from ‘chronic pain’ at 6 months.

Of the nine trials that assessed acute pain51,54–57,59–61,63 (measured within 3 months after surgery), seven measured pain using the VAS score or reported the proportion of participants suffering from pain. 51,54–57,59,61 Follow-up measurements of acute pain varied among these seven trials (see Appendix 9, Tables 37–39). One trial assessed pain 1 month after surgery but did not specify how pain was measured60 and one trial reported postoperative pain levels by assessing the need for analgesia during the first 24 hours after surgery. 63

In five trials,51,52,56,59,61 chronic pain was the primary outcome. Four of these five trials52,56,59,61 were powered to detect differences in chronic postoperative pain.

Eleven of the 12 included trials51–61 assessed recurrences and complications,63 and five trials52,55–57,60 assessed length of hospital stay and time to return to normal activities.

None of the included trials specifically assessed QoL, but two of the trials reported health measures42 and patient satisfaction57 after open preperitoneal mesh repair and Lichtenstein mesh repair.

Results of the individual studies and data synthesis

The 12 trials identified included a total of 1568 participants; 771 randomised to open preperitoneal mesh repair and 797 to Lichtenstein mesh repair. Eleven trials with a total of 1523 participants provided suitable data for statistical analyses relevant to the comparisons and outcomes of interest. The main results are reported under two broad sections entitled Patient-reported outcomes and Clinical outcomes. See Tables 4–7 for the results and Appendix 9, Tables 35–44 for the results from individual studies.

Patient-reported outcomes

Table 4 displays the meta-analysis results for patient-reported outcomes (also see Figures 5–7).

| Outcomes | RR or WMD | 95% CI | p-value | Number of trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic pain | RR 0.50 | 0.20 to 1.27 | 0.15 | 7 |

| Chronic numbness | RR 0.48 | 0.15 to 1.56 | 0.23 | 4 |

| Acute pain | WMD –0.49 | –1.06 to 0.09 | 0.10 | 5 |

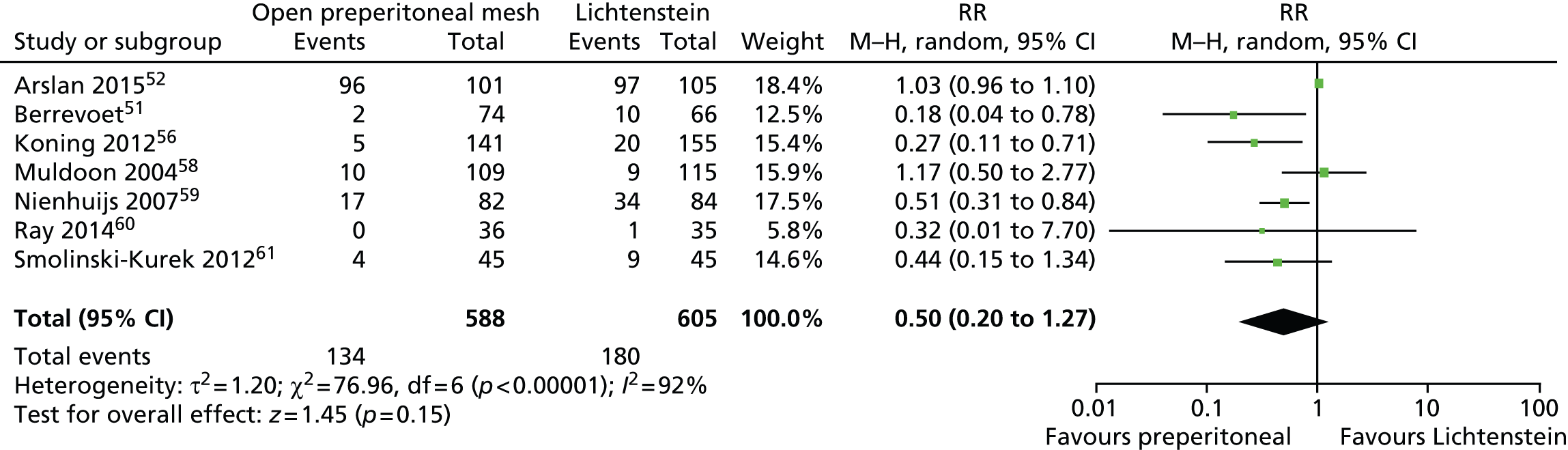

Chronic pain

Figure 5 shows the meta-analysis results for chronic pain. There was considerable variation in the definition of pain used (see Assessment of outcomes and follow-up) by the individual trial investigators and the reported rates of chronic pain (see Appendix 9, Table 35). With the exception Arslan and colleagues,52 who reported a high proportion of participants with chronic pain (90%) in both intervention groups, all the remaining trials reported relatively low rates of chronic pain.

FIGURE 5.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: chronic pain. df, degrees of freedom; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

The random-effects meta-analysis showed a RR of 0.50, indicating a 50% reduction in the risk of chronic pain among participants who underwent open preperitoneal mesh repair compared with those who underwent Lichtenstein mesh repair. The difference between intervention groups was not statistically significant [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20 to 1.27] and there was evidence of high statistical heterogeneity among trials (I2 = 92%). The observed variation in the rates of chronic pain between trials can be partly explained by the way trial investigators described chronic pain. ‘Chronic pain’ was (1) defined according to the definition of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), including a VAS score above 0 which lasts for more than 3 months; (2) defined by a VAS score between 3 and 10; or (3) was not defined at all. Other possible sources of heterogeneity include the position of the mesh and the type of mesh fixation, the type of techniques used for inguinal hernia repair and the surgeon’s clinical expertise.

Additional chronic pain outcomes

Two trials also reported the proportion of participants with ‘activity-related pain’,56,58 and two other trials reported ‘mean pain scores’52,59 (see Appendix 9, Table 36).

However, owing to the observed heterogeneity between trials, data were not combined to provide a single estimate of effect. Koning and colleagues56 reported that significantly fewer patients in the open preperitoneal group experienced pain during activity compared with those in the Lichtenstein group (8.5% vs. 38.5%; p = 0.001). In contrast, the trial by Muldoon and colleagues,58 with a follow-up period of more than 2 years, showed that the proportion of patients who experienced pain during activity was slightly higher in the open preperitoneal group (9.2%) than in the Lichtenstein group (6.1%). Mean pain scores, measured using either the VAS score or the Sheffield scale, were lower in the open preperitoneal group than in the Lichtenstein group (mean VAS score, 0.4 vs. 0.9;59 mean Sheffield score, 1.12 vs. 1.34). 52

Chronic numbness

Four trials reported the proportions of participants with chronic numbness. 56,58,59,61 There was evidence of high heterogeneity (I2 = 91%). Two trials58,61 reported considerably higher rates of numbness following Lichtenstein mesh repair but the other two trials56,59 reported similar rates in each group. The random-effects meta-analysis did not provide evidence of statistically significant differences between the intervention groups (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.56) (Figure 6). Potential sources of heterogeneity include the definition and measurements of numbness, the position of the mesh and the type of mesh fixation, the type of techniques used for inguinal hernia repair and the surgeon’s clinical expertise.

FIGURE 6.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: chronic numbness. df, degrees of freedom; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Acute pain

Five trials54–57,59 reported mean VAS scores (Figure 7) and were included in a random-effects meta-analysis. The trial by Gunal and colleagues54 reported unrealistically high standard error (SE) values. It was assumed that these values indicated SDs rather than SEs, even though no confirmation from the authors was obtained. It is worth noting, however, that the Cochrane review by Willaert and colleagues,20 which included individual participant data, also interpreted these values as SDs. The trial by Moghaddam and colleagues57 did not report any measure of variability and, therefore, SD values were estimated using a simple average of the measures reported in the other trials (excluding the trial by Gunal and colleagues54).

FIGURE 7.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: acute pain. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

The meta-analysis results showed no clear evidence of a difference between intervention groups (mean difference –0.49, 95% CI –1.06 to 0.09). Acute pain tended to be lower after open preperitoneal mesh repair, but moderate statistical heterogeneity was evident between trials (I2 = 53%).

Four trials51,57,60,61 reported the proportion of participants with acute pain assessed between 1 week and 1 month after surgery. In general, fewer participants suffered from acute pain after preperitoneal mesh repair than after Lichtenstein mesh repair at week 1 (62.2% vs. 84.4%),61 at week 2 (6.7% vs. 38.7%)51 and at 1 month (0–26.7% vs. 8.6–51.1%)57,60,61 (see Appendix 9, Table 38).

Two trials57,63 reported the postoperative need for analgesics. The use of analgesics during the first 24 hours after surgery was lower among participants who underwent Lichtenstein mesh repair than among those who underwent open preperitoneal mesh repair (see Appendix 9, Table 39).

Acute numbness

None of the included trials reported acute numbness.

Health status and patient satisfaction

The trial by Koning and colleagues42,56 examined the postoperative effects of the interventions using the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) health survey. The SF-36 is a validated short questionnaire with 36 items that comprises eight domains: physical functioning (10 items); social functioning (two items); role limitations owing to physical problems (four items); role limitations owing to emotional problems (three items); mental health (five items); energy and vitality (four items); pain (two items); and general perception of health (five items). Scale scores are transformed to a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates poorest health and 100 indicates best health. In the trial by Koning and colleagues,42,56 data on health status were prospectively collected after physical examination at scheduled follow-up visits. At 1 year, participants who underwent open preperitoneal mesh repair provided better mean responses to the physical functioning domain [94.9 (SD 12.0) vs. 91.4 (SD 14.9); p = 0.023] and to the pain domain [mean 91.6 (SD 16.4) vs. 85.5 (SD 17.0); p = 0.002] than those who underwent Lichtenstein mesh repair. For the remaining six domains no statistically significant differences were observed between intervention groups (Table 5).

| Health status domains | Open preperitoneal (n = 141) | Lichtenstein (n = 155) | Difference between groups (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| General health | 81.5 (18.0) | 82.5 (17.9) | –5.1 to 3.1 | 0.630 |

| Physical pain | 91.6 (16.4) | 85.5 (17.0) | 2.3 to 9.9 | 0.002 |

| Vitality | 77.6 (14.9) | 78.2 (15.1) | –4.1 to 2.7 | 0.696 |

| Mental health | 84.4 (14.7) | 86.5 (13.1) | –5.2 to 1.1 | 0.197 |

| Role emotional | 95.1 (18.5) | 93.9 (20.8) | –3.3 to 5.7 | 0.604 |

| Role physical | 93.5 (21.6) | 91.7 (22.1) | –3.2 to 6.8 | 0.474 |

| Social functioning | 94.1 (13.3) | 92.1 (15.4) | –1.3 to 5.3 | 0.230 |

| Physical functioning | 94.9 (12.0) | 91.4 (14.9) | 0.5 to 6.7 | 0.023 |

Moghaddam and colleagues57 measured patient satisfaction after surgery using a VAS score. A significantly higher mean score was observed among participants in the open preperitoneal group (9.6, SD 1.6) than among those in the Lichtenstein group (7.3, SD 3.1; p < 0.01).

Surrogate patient-reported outcome

The study by Staal and colleagues,62 which is a secondary report from the trial by Nienhuijs and colleagues,59 reported the Pain Disability Index (PDI) at 3 months. The PDI is a questionnaire that comprises seven subscales of activities: family and home duties (activities related to home and family); recreation (hobbies, sports and other leisure time activities); social functions (participation with friends and acquaintances other than family members); occupation (activities partly or directly related to working including housework or volunteering); sexual behaviour (frequency and quality of sex life); self-care (personal maintenance and independent daily living, such as bathing, dressing, etc.); and life-support functions (basic life-supporting behaviours, such as breathing, eating, sleeping, etc.). Impairment related to pain for each of the above items is rated on a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 indicates no impairment and 10 indicates maximum impairment. Scores for each of the seven subscales are summed to give a total PDI score (range 0–70). Nienhuijs and colleagues59 and Staal and colleagues62 reported that the mean PDI score was statistically significantly lower among participants in the open preperitoneal group (2.0, SD 6.2) than among those in the Lichtenstein group (4.1, SD 11.2; p = 0.006).

Clinical and surgical outcomes

Meta-analysis results for clinical and surgical outcomes are presented in below (see Figures 8–13). Table 6 shows the total number of early complications reported in the included studies while Table 7 summarises the meta-analyses results for the clinical and surgical outcomes.

| Study | Open preperitoneal | Lichtenstein | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events (n) | Total (N) | % | Number of events (n) | Total (N) | % | |

| Arslan et al. 201452 | 28 | 101 | 27.7 | 22 | 105 | 20.9 |

| Berrevoet51 | 2 | 75 | 2.7 | 14 | 75 | 18.7 |

| Dogru et al. 200653 | 3 | 69 | 4.3 | 1 | 70 | 1.4 |

| Gunal et al. 200754 | 2 | 39 | 5.1 | 9 | 42 | 21.4 |

| aHamza et al. 201055 | 2 | 25 | – | 1 | 25 | – |

| Koning et al. 201256 | 9 | 141 | 6.4 | 29 | 155 | 18.7 |

| aMoghaddam et al. 201157 | 3 | 62 | – | 6 | 64 | – |

| aMuldoon et al. 200458 | 17 | 109 | – | 18 | 115 | – |

| Ray et al. 201460 | 1 | 36 | 2.8 | 1 | 35 | 2.9 |

| Smolinski-Kurek et al. 201261 | 9 | 45 | 20 | 8 | 45 | 17.8 |

| Outcomes | WMD or OR | 95% CI | p-value | Number of trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence/reoperation | Peto OR 0.76 | 0.38 to 1.52 | 0.44 | 11 |

| Mortality | Peto OR 1.05 | 0.21 to 5.25 | 0.95 | 4 |

| Complications | ||||

| Wound infection | Peto OR 0.53 | 0.21 to 1.36 | 0.19 | 6 |

| Haematoma/seroma | Peto OR 1.29 | 0.75 to 2.20 | 0.35 | 8 |

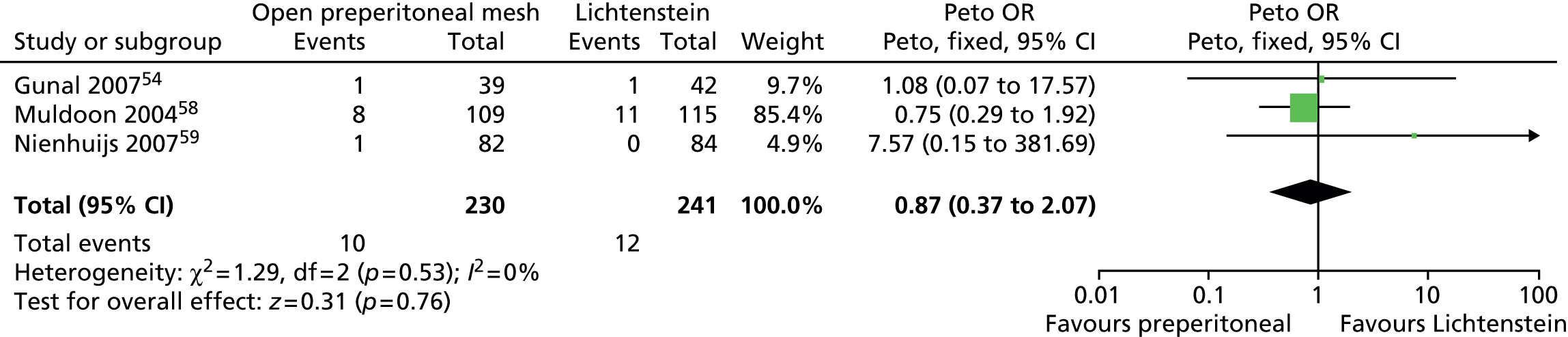

| Urinary complications | Peto OR 0.87 | 0.37 to 2.07 | 0.76 | 3 |

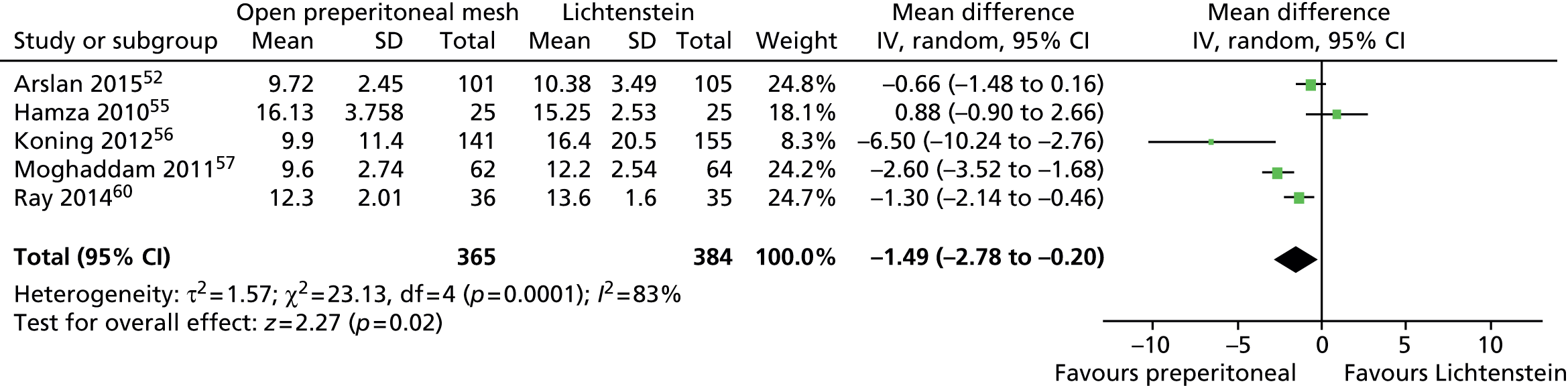

| Time to return to normal activities | WMD –1.49 | –2.78 to –0.20 | 0.02 | 5 |

Mortality

Four trials reported mortality data. 53,56,57,59 There were only six deaths in total and this was balanced between the intervention groups. Three deaths occurred after open preperitoneal mesh repair and three after Lichtenstein mesh repair (Peto OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.21 to 5.25) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: mortality. df, degrees of freedom.

Complications

Eleven trials51–61 reported postoperative complications (see Appendix 9, Table 41). There was a considerable variation across trials in the way type of complications and time of assessments were reported. In many trials, complications were categorised as ‘early or ‘late’ by the trial investigators. When an adequate definition was not provided, any complication reported after 6 months was classified as ‘late’. Where time points were not specified, we consulted with our clinical experts to classify the complication as late or early. Complications, such as haematoma, seroma or urinary complications, were assumed to occur soon after surgery and were categorised as ‘early’ complications.

Ten trials51–58,60,61 reported data on early complications (see Table 6), including wound infection, haematoma, seroma, cord oedema, scrotal oedema and urinary complications (urinary retention/urinary tract infection). One trial59 reported overall complications data (haematoma, dysejaculation and infection) without separating the results for open preperitoneal group and Lichtenstein group. This trial, however, reported one participant with higher urinary frequency in the open preperitoneal group. While some trials reported each type of complication separately, others reported broad categories of complications. For three trials55,57,58 it was unclear whether complications were presented as number of people with any complication or as a total number of events. Owing to the lack of consistency among trials and taking into account the potential risk of double-counting events, a formal meta-analysis for early complications is not presented. Separate meta-analyses were, however, conducted for the following complication categories: wound infection, haematoma/seroma and urinary complications.

There was no clear evidence of differences between intervention groups for the incidence of wound infection (Peto OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.36), haematoma/seroma (Peto OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.20) or urinary complications (Peto OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.07) (Figures 9–11).

FIGURE 9.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: incidence of wound infection. df, degrees of freedom.

FIGURE 10.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: incidence of haematoma/seroma. df, degrees of freedom.

FIGURE 11.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: urinary complications. df, degrees of freedom.

Three trials reported information on late complications, including testicular atrophy58 and mesh infection/reaction. 51,53 Overall, events were balanced between intervention groups: one case of testicular atrophy and two cases of mesh infection/reaction were reported in the open preperitoneal groups while three cases of testicular atrophy were reported in the Lichtenstein groups. No trials reported any vascular/visceral injury, port site hernia or any other serious complications.

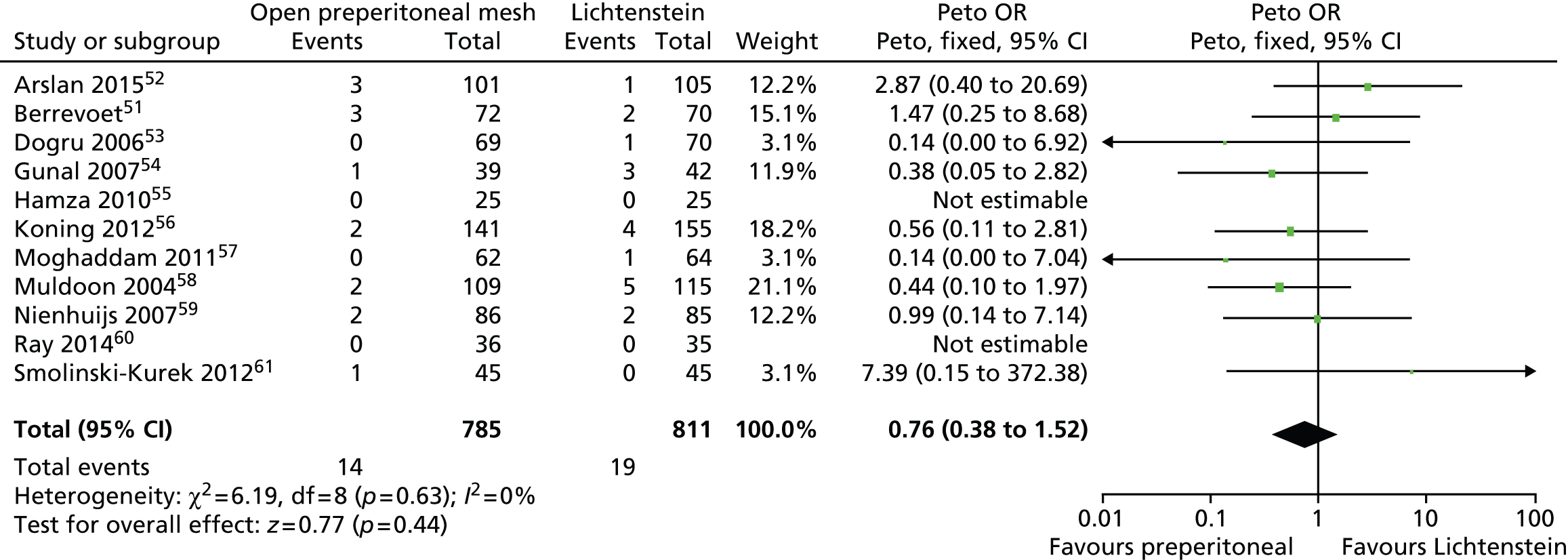

Recurrence/reoperation

Information on recurrence or reoperation was available in 11 trials. 51–61 Rates of hernia recurrence were generally low. Overall, there were 14 recurrences among participants who underwent open preperitoneal mesh repair and 19 among those who underwent Lichtenstein mesh repair. There was no clear evidence of a difference between the two surgical procedures (Peto OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.52) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

Open preperitoneal mesh repair vs. Lichtenstein mesh repair: rate of recurrence/reoperation. df, degrees of freedom.

Length of hospital stay

Owing to the observed heterogeneity between trial data, a statistical summary of length of hospital stay was deemed inappropriate. Some studies reported the mean number of days52,56,57,60 and others the proportion of patients with an overnight stay. 55,56 Appendix 9, Table 43 highlights the duration of hospital stay after surgery reported by five of the included trials. In each trial, no statistically significant differences were reported between intervention groups. Mean days of hospital stay ranged from 0.34 to 4.6 days in the preperitoneal groups and from 0.37 to 4.7 days in the Lichtenstein groups.

Time to return to normal activities

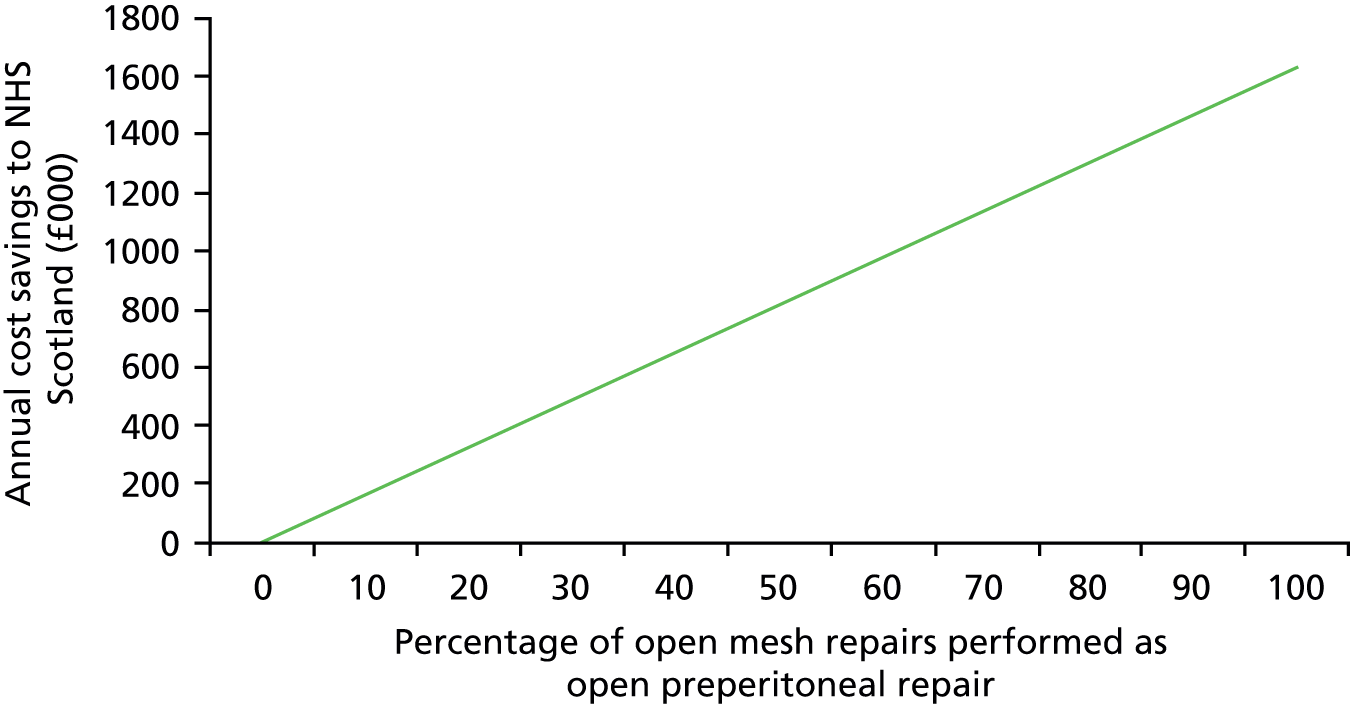

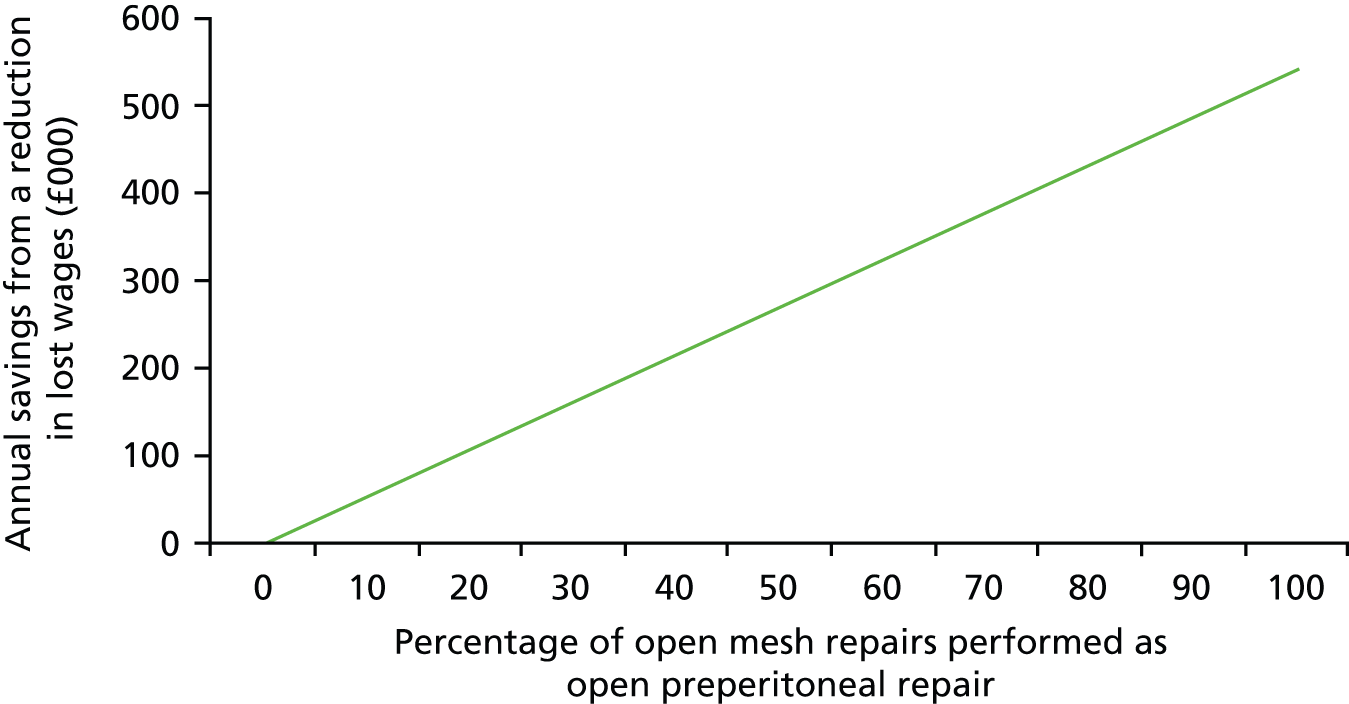

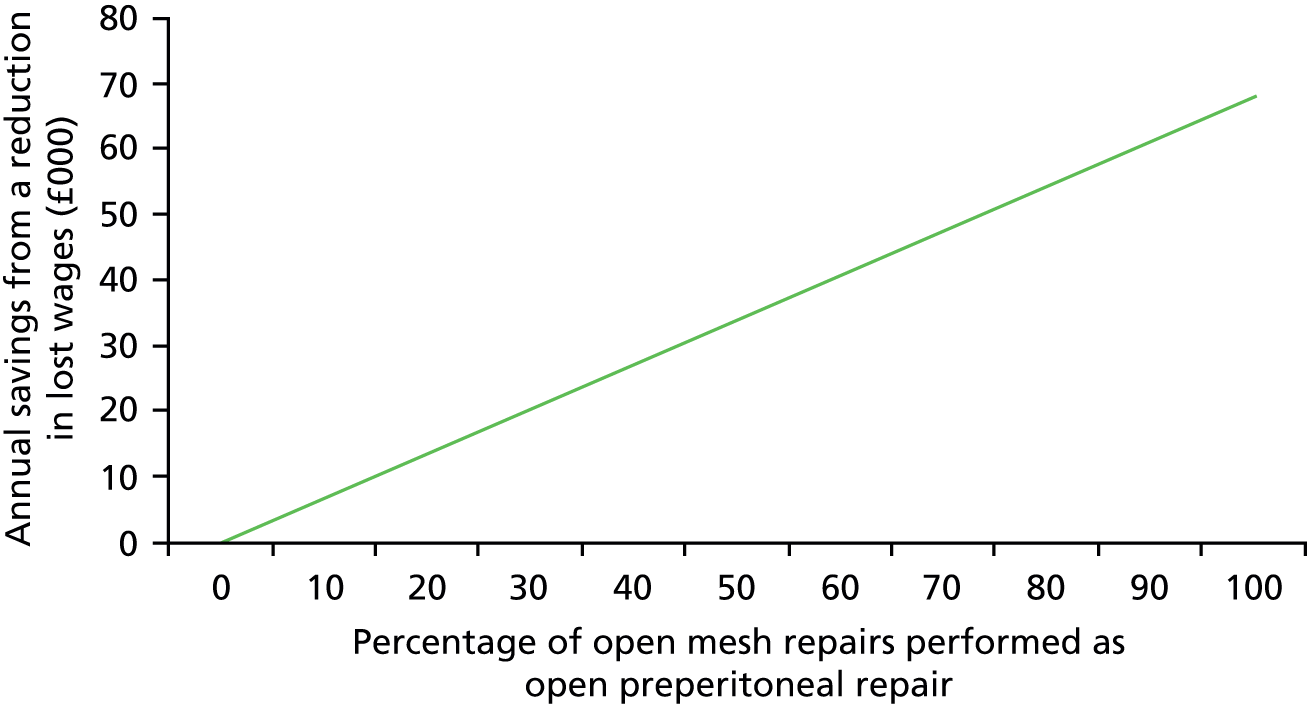

Five trials42,52,55–57 reported the time to return to work or to usual activities. There was considerable variation in the definition of the activities assessed but all of them included the word ‘work’ (see Appendix 9, Table 44). The SD values were not reported in one study;57 therefore, an average of the measures used in the other studies was imputed for the purposes of the meta-analysis.