Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/161/01. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Shahab has received grants and honoraria from Pfizer, a manufacturer of smoking cessation products. In the last 3 years, Professor Aveyard has received a consultancy fee for 1 day of consultancy with Pfizer, a manufacturer of smoking cessation products. Professor Coleman was paid an honorarium and travel expenses for speaking at Paris Smoking Cessation Practitioners’ Conference in January 2014. He was also reimbursed for attending two expert meetings hosted by Pierre Fabre Laboratories (PFL, France), a company that manufactures nicotine replacement therapy (2008 and 2012). Dr McRobbie has received research grants, honoraria and travel expenses from Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, manufacturers of smoking cessation products. Dr McEwen is a trustee and board member for Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), but received no financial reimbursement for this. He has received travel funding, honorariums and consultancy payments from manufacturers of smoking cessation products (Pfizer Ltd, Novartis UK and GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Ltd) and hospitality from North 51 that provide online and database services. He also has a shared patent on a novel nicotine device but has received no payment for, or relating to, this patent.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Dobbie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Tobacco use is one of the leading causes of preventable death in the world. Each year an estimated 5.1 million people die from smoking and another 600,000 die from second-hand smoke exposure. 1,2 As nearly 80% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries,3 tobacco causes over 90,000 deaths in the UK each year, reflecting decades of high smoking prevalence. Although smoking rates have reduced from 51% of men and 41% women in 1974 to 19% today (21.1% of men and 16.5% of women)4 they still remain high in the UK compared with countries such as Australia, Canada and Sweden. In addition, smoking rates in Britain are strongly socially patterned, with 29% of adults in routine and manual occupations smoking compared with 13% in managerial and professional groups. 4

Countries such as the UK have made concerted efforts to reduce smoking rates over several decades. Many of the policies and interventions that have been put in place form part of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the world’s first global public health treaty that was adopted by the World Health Assembly under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO). There are now 178 countries parties to the convention, including the UK. 5 The treaty seeks to reduce the burden of tobacco use through key supply and demand measures, which are laid out in its articles. Demand measures are highlighted in WHO’s ‘MPOWER’ report including ‘Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies’, ‘Protecting people from tobacco smoke’, ‘Offering help to quit tobacco use’, ‘Warning about the dangers of tobacco’, ‘Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship’, and ‘Raising taxes on tobacco’. 6 Guidance on ‘offering help to quit’, including the provision of services to support smokers to stop, offering counselling and effective smoking cessation medications, is contained in article 14 of the FCTC. 5 This is an important element of efforts to reduce smoking rates, as the success of unaided quit attempts is generally extremely low (around 5%). The chances of successfully stopping can be significantly raised if effective aids to quitting are made available. 7

The UK has played a significant role in developing the evidence to underpin effective interventions for smoking cessation as set out in article 14 of the FCTC. 5 This has its origins in early studies on smoking and health, to research on nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and behavioural support, through to real-world evidence on how a national treatment service for smoking can be developed and established. To introduce this study, we set out some of this historical background here, before outlining how the current study helps to bring this evidence base up to date and should inform the design of future services.

Early research on smoking cessation in the UK

The first evidence of clear links between tobacco smoking and ill-health emerged in the 1950s when Doll and Hill published the first paper showing that smoking caused lung cancer. 8 This, and other evidence, led to the production of two important reports – one in the UK and one in the USA – on smoking and health. In the UK the Royal College of Physicians report of 1962 outlined the need for a comprehensive approach to reduce smoking rates. 9 This described a series of needed policy measures including tobacco taxes, restricting advertising and availability, education on the risks of smoking and, importantly, support for smokers wanting to quit. In the end, it would take almost 50 years for all the recommendations in Smoking and Health to be implemented, but in the meantime a range of important studies were conducted that provided better evidence on smoking as an addiction, rather than a ‘habit’, and consequently how it should be treated. 10 A number of early studies on nicotine and NRT were conducted by Professor Michael Russell and colleagues at the Addiction Research Unit at the University of London. These contributed to the licensing of the first pharmacological treatment for smoking cessation in 1981 – nicotine gum. From that period onwards a number of important research and policy developments on smoking cessation took place in the UK. Members of our team summarised these in an earlier study and we reproduce these here, outlined in Table 1. 10

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| The 1950s | |

| 1950 | Doll and Hill paper published in the BMJ8 |

| 1951 | British doctors’ study commences |

| 1959 | First smoking dependence treatment clinic opens in Salford, Greater Manchester, UK |

| The 1960s | |

| 1962 | First RCP report, Smoking and Health9 |

| 1962 | Tobacco Practitioners Council (representing the tobacco industry) agreed to implement a code of advertising practice for cigarettes |

| 1965 | Television cigarette advertising ban |

| 1967 | Creation of Health Education Council |

| The 1970s | |

| 1970 | Mike Russell starts building a smoking research team at the Addiction Research Unit |

| 1971 | Second RCP report, Smoking and Health Now11 |

| 1971 | Voluntary agreements on advertising began |

| 1971 | Creation of ASH |

| Voluntary agreements on health warnings | |

| 1977 | Third RCP report, Smoking or Health12 |

| 1977 | Government health circular expressed need for smoking policies on all health premises |

| The 1980s | |

| 1981 | NRTs ‘blacklisted’ |

| 1983 | Fourth RCP report, Health or Smoking?13 |

| Voluntary agreements on product modification | |

| Excise duties on tobacco begin to rise significantly | |

| 1986 | British Medical Association join campaign against tobacco industry |

| The 1990s and 2000s | |

| 1991 | Illegal sales law strengthened |

| 1992 | Fifth RCP report, A Review of Your People Smoking in England14 |

| 1993 | Government commits to 3% above inflation tax increase on cigarettes |

| 1993 | Ban on oral snuff throughout European Union |

| 1997 | Government commits to 5% above inflation tax increase on cigarettes |

| 1998 | White Paper, Smoking Kills15 |

| 1998 | First English evidence-based guidelines on smoking cessation16 |

| 1999 | First smoking cessation treatment services established in the English NHS |

| 2000 | NHS smoking cessation treatment services established nationally |

| 2013 | SSSs transferred from NHS to local authorities |

NHS Stop Smoking Services

The NHS Stop Smoking Services (SSSs) were established following the publication of the 1998 White Paper, Smoking Kills. 15 Initially piloted in deprived areas of England in 1999, they were rolled-out across the UK from 2000. The services were developed on the basis of national guidance issued by the Department of Health (DH) that built on a review of the evidence of the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions published in the journal Thorax. 16 This evidence emphasised the efficacy of intensive behavioural support (in groups or one to one) plus pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Services were established by primary care trusts (PCTs) and operated primarily in primary care settings delivering behavioural support and providing access to NRT and bupropion (Zyban®, GlaxoSmithKline). From 2000–4, a national evaluation of the services in England was conducted by members of our team. The evaluation found that the services were effective in supporting smokers to quit in the short term (at 4 weeks)17 and the longer term (at 1 year),18 and were reaching smokers from more deprived groups. 19 A subsequent analysis by our team also found that they were making a contribution to reducing inequalities in health caused by smoking. 20 However, since these studies were conducted, NHS SSSs have continued to evolve, attempted to adapt to meet local needs and encountered various financial and structural challenges. National developments, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guidance on services (published in 2008),21 have influenced what is available and smoking cessation medications have also diversified, with new NRT products and the medication varenicline (Champix®, Pfizer) providing additional options for smokers trying to stop.

One element that has changed in the past decade is the type and variety of behavioural support options available to smokers using the services. In particular, a heavier reliance on one-to-one support options in a far wider range of settings. The existing evidence base from systematic reviews of trials would suggest that there is no significant difference in outcomes for smokers receiving group or one-to-one behavioural support. In a review of 50 randomised controlled trials22 and another review of 23 studies since January 2000,23 a group format for a behavioural intervention was not found to be significantly different from an individual format; yet real-world evidence may be different from trials in this respect. Findings from our earlier studies with NHS SSSs suggest that group interventions may be more effective in practice24 but that smokers, given a choice, will choose one-to-one support. Issues of perceived preference may have led to the dominance of one-to-one support in today’s services although new forms of group counselling (such as ‘rolling groups’ where clients can join without having to wait for a new group to start) have emerged.

Another element that has evolved is who provides support to stop smoking. Before the services existed, this was primarily doctors and nurses in primary care or hospitals with a few examples of specialist clinics. Today, a wider variety of professionals are involved in delivering support. In some cases this is described as different ‘levels’ of support. We describe these levels here.

-

Level 1 practitioners are typically primary care professionals who deliver ‘brief interventions’, which usually involves opportunistic advice, discussion, awareness raising and/or referral to SSSs.

-

Level 2 practitioners (known elsewhere as community practitioners) do not work exclusively as stop smoking specialists but instead work in other health and social care roles and deliver stop smoking support as one of a number of job tasks. The majority of level 2 service provision takes place in general practitioner (GP) practices (usually delivered by nurses and health-care assistants) and pharmacies (delivered by practitioners with a variety of posts from pharmacists to pharmacy assistants). Generally one-to-one support is offered.

-

Level 3 practitioners’ sole remit is to deliver smoking cessation working as smoking cessation ‘specialists’. They offer a wider variety of behavioural support which can include: open and closed groups, one to ones, drop-in services, text and telephone support,25 and work in various locations such as community centres, GP practices and workplaces.

For clarity, throughout this report we will differentiate between level 2 and level 3 service providers by using the terms ‘level 2′ and ‘specialist’ practitioners. Data on level 1 support are not collected by the SSS and is not part of the study.

A growing proportion of clients now receive support from level 2 practitioners. Large differences have now been identified between the quit rates achieved by services in different locations, which may be partly because of the quality of behavioural support delivered by the practitioner who offers it. 26–28

The organisational context within which SSSs operate has also changed since our earlier studies. Some of these changes preceded the Evaluating Long-term Outcomes of NHS Stop Smoking Services (ELONS) study (e.g. reorganisation of PCTs in England) but possibly the most significant change occurred in April 2013, just after the fieldwork was completed, when commissioning of local SSSs moved from NHS to local authority control. This resulted in change to the funding and delivery structure of local SSSs, with some areas either reducing funding for the specialist service in favour of a greater reliance on level 2 providers or tendering out previously in-house services which has sometimes led to SSSs being run by private and voluntary sector companies. This structural change poses challenges for the services and preparation for the move also, to some extent, affected study recruitment, which is discussed further in Chapter 4.

As a result of all these changes, current research is needed to examine the longer-term efficacy of the different methods employed by NHS SSSs to deliver support to smokers trying to stop. Current evidence is also required to explore the effectiveness of services with different groups of smokers, particularly those from more disadvantaged groups. This report sets out findings from a study designed to examine these issues.

Structure of this report

This is a detailed report of a complex study with a number of different elements. Chapter 2 presents an overview of the research including aims and objectives, study design and settings. It was also describes the ethical approval and local research permissions process.

Chapters 3 and 4 present the methods and main findings of the secondary analysis element of the ELONS study respectively. Chapters 5 and 6 describe the methods and analysis (see Chapter 5) and the results and key findings (see Chapter 6) for the second (and main) part of our study. This was a prospective cohort study of smokers using the services who were followed up in the short (4 weeks post quit date) and longer term (at 1 year).

The subsequent three chapters present findings from elements that were added to the ELONS prospective study. For ease and clarity, they are presented as standalone chapters including the methods and results for each. The focus of Chapter 7 is an exploration of client satisfaction with the support received from their local SSS. Chapter 8 examines the relationship between well-being and smoking status of ELONS study participants. Chapter 9 outlines findings from a study of longer-term NRT use that was made possible by additional funding from the UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies [now the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS) – www.ukctas.ac.uk]. The remaining two chapters include the discussion (see Chapter 10) with conclusions presented in Chapter 11.

Chapter 2 Evaluating Long-term Outcomes of NHS Stop Smoking Services overview

This purpose of this chapter is to present an overview of the ELONS study including aims and objectives, study design, setting and the rationale for the methods used. It also describes the ethical approval and the local research permissions process.

Aim and objectives

The principal aim of the study was to explore the factors that determine longer-term abstinence from smoking following intervention by SSSs in England.

The study objectives were to:

-

examine the effectiveness of SSSs by PCT and intervention type using routine data

-

explore the reach of services by identifying what proportion of the local population set a quit date with services using routine data

-

describe the factors that determine longer-term abstinence from smoking or relapse to smoking among clients who set a quit date with services in a sample of PCTs in England

-

examine the relationship between client characteristics [in particular socioeconomic status (SES), age, gender, disability and ethnicity], adherence to treatment, intervention type received and longer-term abstinence

-

create an evidence base to guide delivery of interventions by SSSs so that these interventions will have maximal effect on smoking cessation and population health.

Overview of study design

The ELONS study was an observational study with two main stages:

-

secondary analysis of routine data collected by SSSs

-

a prospective cohort study of SSS clients with three additional elements (which are presented as standalone chapters on the report):

-

a client satisfaction survey (CSS)

-

a well-being survey

-

a study of longer-term NRT use.

-

The overall aim of the prospective element of the ELONS study was to collect long-term follow-up data at 52 weeks. A subsidiary aim was to collect detailed information about clients and the treatment they received in a consistent manner. Data were collected at three key stages: baseline (i.e. when a client registered with the SSS), 4-week follow-up and 52 weeks post quit date. The 52-week follow-up data were collected by a research company, TNS BMRB (Taylor Nelson Sofres, British Market Research Bureau), that had worked with the academic team on a previous study. 29 Table 2 describes the data collected at each time point and also summarises the data collected for the three additional elements (client satisfaction, well-being and long-term NRT). Further detail of the data collected at each stage and data collection tools can be found in Appendix 1. A flow chart depicting sample sizes and sampling frames is also available (Figure 1).

| Collection time point | Normal SSS practice | Prospective study | Client satisfaction | Well-being evaluation | Long-term NRT evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (client registers with service) |

|

|

WHO-5 Well-being Index scale added to enhanced monitoring data | Clients asked by practitioner to provide two saliva samples | |

| 4 weeks post quit date |

|

Client satisfaction and well-being postal survey to all clients administered by research team | |||

| Period that client is in contact with the services |

|

|

|||

| When client leaves |

|

||||

| 12 months post quit date | TNS BMRB collect:

|

Well-being postal survey to all clients administered by research team |

|

||

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for the ELONS prospective study. a, n refers to quit attempts at the SSS from March/April 2012 to March 2013; b, more detail is available in Chapters 5 and 6; c, providers’ employees provide smoking cessation support rather than specialists employed directly by SSSs; d, this is an overestimate because level 2 providers who did recruit did not usually recruit for the level 2 recruitment period at each site; and e, CSS.

Definitions of smoking cessation

Smoking cessation, or ‘quitting’, was defined in the following ways for this study.

Short-term (4 weeks after quit date) self-reported quitting

In normal SSS treatment, 4 weeks after their quit date, advisors ask their clients (either in person at a session or, if they have stopped attending treatment, by telephone) whether or not they have smoked a cigarette in the last 2 weeks. Clients who indicate that they have not smoked in this period are classified as a ‘self-report’ quitter at 4 weeks.

Short-term (4 weeks after quit date) carbon monoxide-validated quitting

During treatment sessions clients are asked to breathe into a carbon monoxide (CO) monitor, which records the CO parts per million (p.p.m.). If clients reduce the number of cigarettes smoked their CO level falls. This can be motivating as it provides a visual representation of how stopping smoking reduces exposure to CO, which is a harmful chemical. If a client has not been smoking for the past 24 hours then the level usually falls below 10 p.p.m. 30 Thus, at 4 weeks if a client has self-reported that they have stopped smoking and their CO level is < 10 p.p.m. then they are said to be a CO-validated quitter at 4 weeks. In this report, we refer to CO-validated quitting and in places also as ‘biochemically validated’ quitting or abstinence. Where we state biochemical validation, we mean CO validation.

If the client refuses to take a CO test then they are classified as a self-report quitter only. In a minority of cases, clients may self-report that they have stopped smoking but their CO level will be ≥ 10 p.p.m. In this case they are said to be a ‘self-reported quitter who has been refuted by CO validation’. For this study, this small minority were classified as non-quitters in quit rate and regression analysis.

Longer-term (52 weeks after quit date) self-reported quitting

The research team (in this case TNS BMRB) contacted clients who self-reported quitting at 4 weeks by telephone 12 months after their quit date and asked if they had smoked within the last 7 days. Those that had not smoked in this period were then asked if they had smoked since their quit date. If they had smoked up to but not more than five cigarettes they were classified as achieving ‘self-reported continuous abstinence’, as consistent with the Russell standard30 (the recognised standard for smoking cessation studies and also validating cessation in clinical practice). If they had smoked more cigarettes they were classified as achieving ‘self-reported point prevalence abstinence’. For the analysis outlined here, only those achieving continuous abstinence and whose self-report was not refuted by the CO breath test were classified as 52-weeks self-report quitters.

Longer-term (52 weeks after quit date) carbon monoxide-validated quitting

All clients who had achieved point prevalence self-report abstinence were asked if a researcher could make a home visit and carry out a CO breath test. For the analysis reported here clients with a CO level of < 10 p.p.m. and who had also self-reported that they were continuously abstinent since their quit date were classified as 52 week CO-validated quitters. Biochemically (CO-validated) abstinence from smoking at 52 weeks was the primary outcome for this study.

Setting

The setting for the study was SSSs in England. For the secondary analysis, routine data from 49 services were obtained. For the prospective study, nine services were involved. These were Bristol, County Durham and Darlington, Hull and East Riding, Leicestershire County and Rutland, North and North East Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Oldham, Rotherham, and South East Essex. The target population was clients of these services. The health technologies that the ELONS study assessed were the treatment provided by SSSs – a combination of behavioural support and medication intended to increase the chance of a successful quit attempt. A key focus was to evaluate outcomes for smokers who received one of the five main forms of behavioural support (also called intervention types) provided by the services:

-

closed groups (scheduled group sessions of around 1–2 hours dependent on the number of clients, normally delivered once per week and facilitated by a specialist practitioner

-

open/rolling groups (drop-in groups run at a variety of times of day and in a variety of locations where clients can attend without an appointment and for as many weeks as they wish)

-

one-to-one drop-in (a clinic hosted at a regular time where clients can attend without an appointment for one-to-one support)

-

one-to-one sessions with a specialist practitioner (scheduled one-to-one sessions with a practitioner whose main role it is to help people stop smoking)

-

one-to-one sessions with a level 2 practitioner.

Ethics and local permissions

Ethical approval for the ELONS study was obtained from NHS Lothian (South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee) in June 2011. During the recruitment phase of the prospective study a total of four substantial amendments were made for alternations to the study protocol and consent process. In addition to ethical approval, we also obtained local research and development (R&D) approval for each SSS. For three SSSs, single R&D office approvals were required but for the remainder two sets of approvals were required owing to the location of the SSSs and the NHS trusts involved. All the necessary local approvals were obtained before data collection began. It was also a requirement that the research team obtain NHS research passports and, for one site, it was necessary to obtain Caldicott Guardian approval.

Public involvement

Members of the public were involved in the ELONS study in a number of ways. Within the prospective study, the public were research participants and the study was designed to provide feedback on an important public service for the benefit of future users. However, more direct forms of involvement were also included in the research.

First, the study principal investigator, Professor Bauld, serves as the public engagement lead for UKCTAS, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration Centre for Public Health Excellence that covers 13 universities (the co-investigators for the study are also UKCTAS members). In this role she convenes a panel of continuing smokers and recent quitters who meet in Bath. The original design for the ELONS study was discussed with the panel at meetings in 2010 and again in 2011, and feedback sought. Initial results were also circulated to panel members at a meeting in 2013. One of the panel members, Robert Graham, was asked to join the study steering group as a lay adviser and did so. Although he was not able to attend all steering group meetings, he maintained contact with Professor Bauld and, having used NHS SSSs himself in the past, provided very useful input.

In addition to panel contributions and Mr Graham’s involvement, we had the participant information leaflets and consent forms for the study reviewed by a patient representative. This was organised through the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) Patient and Public Involvement Manager, and we are grateful to them for facilitating this process.

We also prepared the ELONS study newsletters for all the participating services in the prospective study. There were three of these during the study. These were intended to be available to service clients as well as staff and we sent these to each site for distribution.

Finally, tailored feedback from the study was prepared for each study site and for one site an event was held that involved a varied audience and presentations on study findings. Dissemination at a number of academic and practitioner conferences is currently under way.

Chapter 3 Secondary analysis of routine data: methods and analysis

This chapter outlines the rational, sample and analytical approach for the secondary analysis element of the ELONS study, with results presented in Chapter 4.

Rationale for secondary analysis

All SSSs in England are required to submit routine monitoring data to the Health and Social Care Information Centre. 31 These data include basic information on client characteristics and the types of treatment received. They also include self-reported smoking status at 4 weeks post quit date. These monitoring data are supplied as aggregated summary returns and so cannot be used to analyse which factors are associated with individual-level smoking cessation outcomes.

Increasingly, however, SSS outsource management of these data to private companies. The most commonly used is QuitManager (North 51, Nottingham, UK). 7,27 QuitManager provides a framework for SSSs to collect the minimum data set required by the DH, plus any additional client and service information thought to be useful locally. The research team includes the Director of the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT), who has good links with North 51 and has been able to access their data for previous research and training activities. We were therefore able to obtain QuitManager data for the ELONS study in an anonymised form. This was important as by having access to these data made it possible to examine individual-level information not available from the Health and Social Care Information Centre returns. Data were available from 49 services in England. These data were analysed to fulfil objectives 1 and 2, to examine the effectiveness and reach of services. Results from this first stage also informed the selection of SSSs for the prospective cohort study.

The secondary analysis had two aims:

-

to explore the reach of services by identifying the proportion of the local population who set a quit date with services using routine data

-

to examine the effectiveness of NHS SSSs by PCT and intervention type using routine data.

Sample

QuitManager32 is an online database for recording information on NHS SSS clients, including sociodemographic and treatment characteristics, in accordance with the DH’s standard SSS monitoring requirements. Collection of data starts at baseline (first contact with the SSS) and should be updated at each contact point. The data are collected by the stop smoking practitioner and entered onto QuitManager in ‘real time’ (via the computer software) or recorded on a paper form and entered at a later date. PCTs may elect not to ask clients questions, and clients themselves may not answer every question, leading to missing data. Within PCTs clients whose data are collected on paper forms may answer a slightly different set of questions to those whose data are entered electronically.

At 4 weeks post quit date clients are asked whether or not they have quit smoking for the past 14 days (self-report quit) and clients may also perform a CO breath test. Clients who have self-reported as quit and have CO readings of < 10 p.p.m. are said to be CO validated as quit. The DH guidelines suggest 85% of clients should be CO validated. 33

More than 60 out of the ≈ 150 English PCTs use QuitManager and 49 of these gave permission to the NCSCT for their data to be used for research purposes. Thus, data from these 49 PCTs were included in the analysis.

Data on clients who set quit dates from July to December 2010 were downloaded from QuitManager in January 2012 and data on clients with quit dates between January and June 2011 were downloaded in July 2011. In total there were 202,804 client records included in the database. Each record is a ‘treatment episode’ where the client sets a quit data and receives treatment. It is possible for clients who relapse to have more than one treatment episode in a year. 33

Measures

Outcomes

Efficacy of services: quit rates and carbon monoxide-validation rate

There were three dependent variables explored: self-report quit, CO-validated quit and CO validation. CO validation is the proportion of self-report quit who were also CO validated. We included CO-validated quit because some clients may state they have quit when they have not quit. We included self-report quit because some CO-validation rates vary so by using both of these outcomes, the results are rendered more robust.

The DH considers clients to be quitters only if self-report data are collected between 25 and 42 days after the quit date. 33 Inspection of the QuitManager database suggested that this narrow range may be underestimating the number of quitters, so all clients who self-reported as quit were included in the analysis.

As outlined above, we adhered to the Russell Standard for smoking cessation analysis by taking an intention-to-treat approach where clients with missing quit data were categorised as not quit. 30 Clients setting quit dates in December 2010 and June 2011 were therefore excluded from the analysis as they would not have reached 4 weeks post quit date (when self-report quit and CO validation occurs) when the data were downloaded. Thus, the months included were July–November 2010 and January–May 2011 (n = 19,481). Cases were also excluded from the main analysis if they were missing age (n = 201) and gender (n = 43) because too few were missing to include as a separate category. Additionally, cases were excluded if the practitioner who provided behavioural support was missing (n = 5573) because of the multilevel structure of the data. Thus, the number of cases used in the bi-variable and multilevel multivariable analysis of the efficacy of the services was 177,291.

Uptake: distribution of client groups and reach of services

In order to assess uptake we looked first at whether or not clients from all sociodemographic groups were accessing the services and which service options clients were accessing.

To understand the reach of services it is necessary to know the target population: the number of smokers in the PCT. Smoking is not asked in the UK census thus estimates have to be made from smoking rates collected by government surveys and populations that have been updated from 2001 census data. The most recent estimation of adult (≥ 16 years) smoking rates for PCTs was for 2003–5. 34 These were based on the Health Survey for England. Between 2004 and 2009 the smoking rate for Great Britain fell from 25% to 21%, thus PCT smoking rate estimates were reduced by 4% to estimate more recent smoking rates. Mid-year adult (≥ 16 years) population estimates of PCTs were available for 2010. The population multiplied by the smoking rate gave an estimate of the number of smokers in the PCT. These numbers were compared with the number of QuitManager clients aged ≥ 16 years between July 2010 and June 2011.

There were some PCTs where this formula was not suitable. First, a few PCTs started using QuitManager or gave permission for their data to be used after July 2010 so these PCTs were included only in the second data download in July 2011. For these PCTs the number of clients was doubled to provide an estimate of the annual number of clients. Second, one PCT had to a large extent merged with another and a population estimate was available only for the overall area and a smoking rate estimate for the overall estimate was calculated by taking the average of the two constituent PCTs. Third, a PCT was known to include only clients who saw practitioners through the specialist service in QuitManager. Thus it was not possible to provide an estimate of reach for this PCT. It is possible that other PCTs may not include all their clients on QuitManager. So far, however, none of the other PCTs contacted regarding the prospective study have raised this as an issue.

Predictors

The data have a multilevel structure: clients received behavioural support interventions from practitioners and practitioners are employed through SSSs. Originally each PCT had its own SSS although now some PCTs have a joint SSS so a few practitioners worked for more than one PCT, usually where both PCTs had a joint SSS.

The independent variables used cover client characteristics: age (divided into quartiles); gender (not pregnant women, pregnant woman, men); ethnicity (white, black, Asian, mixed, other, unknown); SES (eligibility for free prescriptions exempt, pays, unknown); National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NSSEC)35 (routine and manual occupation, intermediate occupation, managerial or professional occupation, retired or caring for the home, sick or disabled and unable to work, never worked or long-term unemployed, in prison, other); Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)36 (at PCT level) divided into quintiles of all English PCTs and quit attempt related characteristics [month set quit date, treatment episode number (first, second, third, fourth or more)]; medication (NRT alone, combination NRT, buproprion, varenicline, mixed medications, and other or no medication); intervention type (one to one, drop-in, open/rolling group, closed group, other); and practitioner type (specialist SSS practitioner employed by SSSs, practitioner who does cessation advice work as part of their role divided into GP, nurse, health-care practitioner, pharmacy employee, and other and unknown).

Impact: throughput and quitters per 100,000 population

Colleagues from University College London and the UK NCSCT have developed the methodology for measuring impact. Impact is calculated as ‘throughput’ (number of treated smokers per 100,000 adult population) × [percentage successfully quit at 4 weeks – 25 (if CO-verified quit or – 35 if self-report quit)]/100. The number of quitters is expressed per 100,000 of the population, not per 100,000 of the smoking population. The reason for CO-verified quit minus 25 being used in the calculation is that 25% of smokers trying to quit are estimated to be CO-verified quit at 4 weeks unaided or by use of medication alone without behavioural support. For self-reported quits minus 35 is used because of average differences between SSS self-report and CO-validated quit rates.

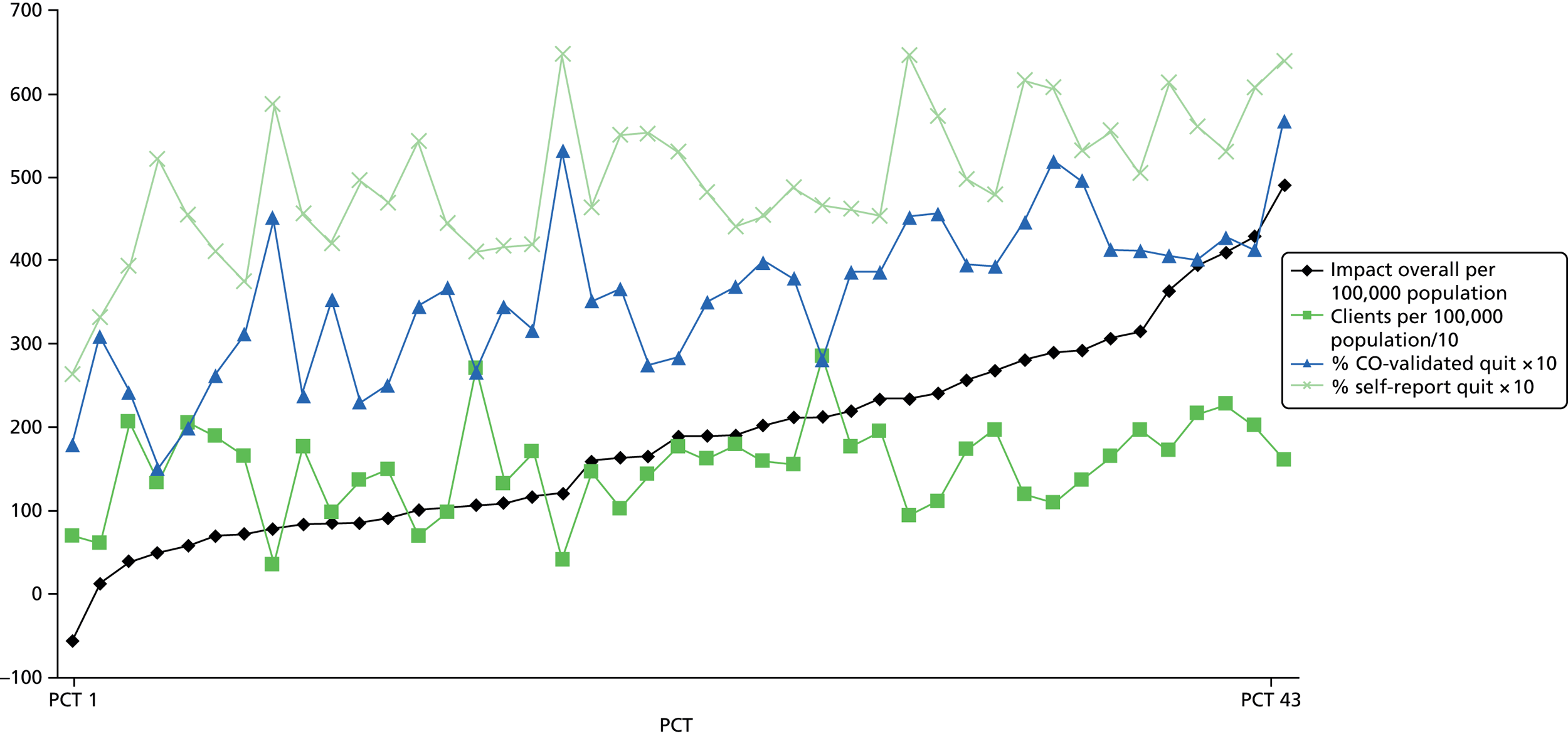

Owing to first to marked differences between CO-validation rates of PCTs and second to different services having a negative impact depending on whether or not the CO-validated or the self-report quit rate was used in the calculation, for this report an overall impact score was calculated. The overall impact score was the average of the CO-validated impact score and the self-report impact score.

To estimate impact on the population, unique clients were used rather than client records. The client records were aggregated so that for clients who had more than one record their age and quit status at their most recent episode at the SSS was used.

It was not possible to calculate impact for some PCTs and for others there were caveats, generally this was where there were issues in calculating uptake. Additionally, the unique patient identifier was of poor quality for four PCTs. For a further three PCTs, clients were included only in the second data download so to estimate impact the number of client records was doubled. This may be an overestimate of client records and it would be expected that some clients from the first 6 months would have revisited the services in the second 6 months so it may also be an overestimate of unique clients. Thus, these three PCTs were excluded from statistical summaries of impact data although impact data was calculated for them.

Analytic approach

The analyses were carried out using SPSS [SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) and PASW version 18.0.3 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)]; Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA); Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and MlwiN version (MLwiN, Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Bristol, UK) as follows.

See Table 3 for overall quit rates and validation rates for all clients and then for clients where their age, gender and practitioner were identified. Uptake (distribution), quit rates and CO-validation rates for subgroups of these clients with various client and quit attempt-related characteristics are presented. Chi-squared was used to assess significance.

Second, a descriptive table (see Table 4) provides further information about the PCTs. Each row represents a different PCT. It includes the number of practitioners within each PCT, the number of clients per PCT (throughout the year) and the average number of clients per practitioner (clients/practitioner) in addition to estimates of the smoking rate, population, clients aged over 16 years and reach of services of each PCT.

The analysis included a large number of predictors and three measures of SES, so in order to assess potential multicollinearity in multivariable models, the variance inflation factor (vif) and corresponding tolerance were calculated from a logistic regression using interaction expansion (part of the Stata xi suite). In this xi suite analysis, PCT was entered as a cluster variable and practitioner was entered as an explanatory variable as only one cluster variable is allowed.

Multilevel modelling (see Tables 5 and 6) allows PCT and practitioner to be treated as separate levels in the analysis – otherwise known as random effects. Thus there were three levels in the models: client (level 1), practitioner (level 2) and PCT (level 3). Other independent variables were entered as fixed effects. Practitioner types were entered as a level 2 fixed effects, IMD quintiles of the PCT entered as level 3 fixed effects and all other fixed effects were at client level. MLwiN second order penalised quasi-likelihood iterative generalised least squares (IGLS) estimation was used for the analysis.

Odds ratios (ORs) are reported for self-report quit, CO-validated quit and CO validation. Some changes were made to the predictors for the multilevel analysis. So that practitioner should completely nest within a PCT, PCTs that shared practitioners were merged. There were 63 practitioners who worked in more than one PCT. The IMD score was then recoded for the new merged PCTs so that it was the average of both PCTs taking into account the number of clients contributed by each PCT.

In preliminary analysis (not shown) MLwiN IGLS multilevel models were compared with Stata Survey Suite models. Anomalous results were explored further using SPSS crosstabulations, Stata xt and MLwiN Markov chain Monte Carlo. Full models did not converge in either Stata xt or MLwiN Markov chain Monte Carlo. However, the results that were produced tended to support IGLS results; thus only MLwiN IGLS models are presented here.

Ideally we would look at how much variance of the higher levels was explained by the fixed variables; however, when a binary outcome is modelled and there is more than one higher level, it is not possible to calculate because the level 1 variance is always constrained to be 3.29. 37 Thus the impact observed on the higher-level variances from adding a fixed-effect variable to the model may be because of the overall variance changing to allow for the addition of the variable since the level 1 variance cannot change, rather than because the new variable in the model has explained the higher-level variance. 38,39 It is not currently possible to accurately estimate how much of the change is caused by real changes in variance and how much is caused by the constrained level 1 variance (Yang M, University of Nottingham, 2012, personal communication).

The higher-level variance is shown later in the report (see Table 7). The first and second columns show higher-level variance in the CO-validated modelling. The first column displays PCT-level variance and the second column displays practitioner-level variance. The next two columns show variance for the self-report modelling and the other columns show higher-level variance for the CO-validation modelling with or without exclusions of extreme PCTs (see Table 4). The first row displays variance in null models with no fixed effects entered. The subsequent rows display variance when fixed effects are entered one at a time so there is only one fixed effect in a model. The final row displays variance for the multivariable model when all fixed effects are entered. PCTs with significantly below and above average residuals were identified.

Residuals for the PCTs were calculated and graphed using caterpillar plots.

For measures of impact by PCT, see Table 8. Each row represents a different PCT. Throughput (numbers setting a quit date per 100,000 population), CO-validated and self-report quit rates for all unique clients age 16 years or over, impact (numbers of 4-week quitters per 100,000 population) calculated using CO-validated quits only, all self-report quits and overall (average of previous two impacts) are shown and the results are also presented in a graphical format. Summary measures of unique patients, quit rates, throughput and impact, and correlations between them are provided (see Table 9).

Chapter 4 Secondary analysis of routine data: findings

As described in Chapter 3, the first part of the ELONS study involved secondary analysis of data from clients who had used SSSs in 49 of 150 PCTs in England. These PCTs’ SSSs used the QuitManager database to record and report on their routine data.

The results are ordered by topic: uptake, quitting and CO validation. Under uptake we consider client distribution of client characteristics and estimates of the percentage of each PCT’s smoking population that were using the service. Under quitting we discuss self-report quit and CO-validated quit in bivariable and multivariable multilevel models, and finally we explore the proportion of self-reported quit who were CO validated (CO validation) in bivariable and multivariable multilevel models. Please note that in addition, we have already published a paper based on this work,26 which had a particular focus on the relationship between SES and the types of behavioural support offered by the services.

Uptake

Table 3 shows which groups of clients were more or less common among service users and the service options that they were more or less likely to use.

| Client characteristics | 4-week quit rates | CO-validation rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Self-report quit, % (p-value) | CO-validated quit, % (p-value) | Self-report quit, n | Self-reports CO-validated, % (p-value) | |

| Total: intention-to-treat quit available (December and June starts excluded) | 182,603 | 100.0 | 44.1 | 30.7 | 89,085 | 73.9 |

| Total: intention-to-treat quit and age, gender, practitioner identifieda | 177,291 | 100.0 | 48.8 | 34.1 | 86,512 | 74.3 |

| Age quartiles (years) | ||||||

| < 30 | 44,968 | 25.4 | 39.2 | 24.9 | 17,647 | 68.2 |

| 31–42 | 47,719 | 26.9 | 49.6 | 34.4 | 23,651 | 73.6 |

| 45–53 | 40,410 | 22.8 | 50.7 | 36.2 | 20,485 | 75.8 |

| ≥ 54 | 44,194 | 24.9 | 56.0 | 41.4 | 24,729 | 78.1 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (not pregnant) | 88,246 | 49.8 | 48.1 | 33.9 | 42,451 | 74.9 |

| Female (pregnant) | 5650 | 3.2 | 45.8 | 26.5 | 2585 | 62.0 |

| Male | 83,395 | 47.0 | 49.7 | 34.9 | 41,476 | 74.5 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||

| White | 158,377 | 89.3 | 49.3 | 34.6 | 5237 | 74.0 |

| Black, Asian, mixed, other | 12,165 | 6.9 | 43.1 | 30.9 | 78,149 | 74.6 |

| Unknown | 6749 | 3.8 | 46.3 | 28.4 | 3126 | 67.1 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Routine and manual | 43,741 | 24.7 | 51.7 | 36.1 | 22,621 | 74.0 |

| Intermediate | 13,376 | 7.5 | 54.2 | 36.6 | 7251 | 70.7 |

| Managerial and professional | 23,661 | 13.4 | 56.6 | 39.6 | 13,400 | 75.0 |

| Retired or home care | 32,388 | 18.3 | 54.4 | 39.7 | 17,627 | 77.5 |

| Sick or disabled and unable to work | 11,852 | 6.7 | 41.7 | 28.5 | 4943 | 73.2 |

| Never worked or long-term unemployed | 24,512 | 13.8 | 38.8 | 27.0 | 9520 | 73.6 |

| In prison | 2223 | 1.3 | 48.0 | 42.4 | 1066 | 90.0 |

| Other | 25,538 | 14.4 | 39.5 | 26.0 | 10,084 | 70.6 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 86,512 | < 0.001 |

| Prescription charges | ||||||

| Exempt | 104,304 | 58.8 | 46.2 | 33.0 | 48,194 | 75.8 |

| Pays | 56,903 | 32.1 | 54.2 | 38.1 | 30,843 | 74.5 |

| Unknown | 16,084 | 9.1 | 46.5 | 27.2 | 7475 | 63.8 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Average IMD 2010 score (PCT) | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | 49,101 | 27.7 | 44.3 | 30.1 | 21,757 | 72.7 |

| 31–60 | 25,695 | 14.5 | 48.5 | 37.0 | 12,457 | 80.7 |

| 61–90 | 22,123 | 12.5 | 49.9 | 35.8 | 11,031 | 72.8 |

| 91–120 | 40,793 | 23.0 | 50.4 | 36.9 | 20,539 | 76.8 |

| ≥ 121 | 39,579 | 22.3 | 52.4 | 33.5 | 20,728 | 70.5 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Month set quit date | ||||||

| July 2010 | 15,244 | 8.6 | 46.4 | 31.4 | 7066 | 72.9 |

| August 2010 | 13,892 | 7.8 | 48.0 | 32.8 | 6670 | 73.7 |

| September 2010 | 14,765 | 8.3 | 49.5 | 33.8 | 7314 | 73.6 |

| October 2010 | 15,535 | 8.8 | 49.3 | 33.7 | 7654 | 74.1 |

| November 2010 | 13,901 | 7.8 | 48.2 | 30.3 | 6694 | 69.8 |

| January 2011 | 26,924 | 15.2 | 52.9 | 38.8 | 14,242 | 76.4 |

| February 2011 | 22,565 | 12.7 | 51.4 | 36.9 | 11,595 | 75.0 |

| March 2011 | 22,490 | 12.7 | 47.8 | 33.7 | 10,740 | 73.8 |

| April 2011 | 17,221 | 9.7 | 47.4 | 33.6 | 8161 | 75.6 |

| May 2011 | 14,754 | 8.3 | 43.2 | 31.2 | 6376 | 75.5 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Treatment episode | ||||||

| Episode 1 | 114,369 | 64.5 | 48.5 | 34.3 | 55,420 | 75.0 |

| Episode 2 | 36,154 | 20.4 | 49.1 | 33.5 | 17,748 | 72.7 |

| Episode 3 | 14,391 | 8.1 | 49.6 | 33.9 | 7134 | 73.6 |

| Episode 4 or more | 12,377 | 7.0 | 50.2 | 34.9 | 6210 | 74.0 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | 0.0 | – | 0.003 |

| Medication used | ||||||

| Single NRT | 40,607 | 22.9 | 37.5 | 25.4 | 15,222 | 74.0 |

| Combination NRT | 67,703 | 38.2 | 49.7 | 37.0 | 33,646 | 78.1 |

| Bupropion only | 1129 | 0.6 | 52.1 | 32.9 | 588 | 69.7 |

| Varenicline only | 45,149 | 25.5 | 60.2 | 43.0 | 27,167 | 75.8 |

| Mixed NRT/bupropion/varenicline | 4479 | 2.5 | 46.6 | 34.3 | 2085 | 76.6 |

| No medication or missing | 18,224 | 10.3 | 42.8 | 21.0 | 7804 | 52.9 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Intervention type | ||||||

| One to one | 140,119 | 79.0 | 47.6 | 33.8 | 66,621 | 74.5 |

| Drop-in clinic | 24,736 | 14.0 | 50.7 | 33.3 | 12,550 | 74.8 |

| Open (rolling) group | 4780 | 2.7 | 65.5 | 52.1 | 3130 | 85.3 |

| Closed group | 2512 | 1.4 | 63.5 | 50.1 | 1595 | 80.9 |

| Other or missing | 5144 | 2.9 | 50.9 | 23.3 | 2616 | 49.8 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Practitioner type | ||||||

| Specialist | 55,603 | 31.4 | 55.6 | 37.7 | 30,902 | 74.6 |

| GP | 3535 | 2.0 | 45.1 | 34.9 | 1593 | 78.7 |

| Nurse | 18,091 | 10.2 | 42.3 | 28.3 | 7660 | 69.5 |

| Health-care assistant | 7070 | 4.0 | 45.4 | 35.2 | 3206 | 80.4 |

| Pharmacy | 18,890 | 10.7 | 40.6 | 29.7 | 7670 | 76.5 |

| Other or unknown | 74,102 | 41.8 | 47.9 | 33.9 | 35,481 | 73.9 |

| p-value | – | – | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 |

| Total | 177,291 | 100.0 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 86,512 | < 0.001 |

Client characteristics

There were slightly more women setting quit dates than men, with 3.2% of clients pregnant at the time of data entry. Seven per cent of clients were from ethnic minorities, although 4% of client ethnicities are unknown. One-quarter of the clients were under 30 years and one-quarter were aged ≥ 54 years. A large proportion was exempt from paying prescription charges (58.8%), and for 9% this information was unavailable. The largest category of occupation in the sample was routine and manual (24.4%), with the second largest being retired or home carer (18.1%). There were over 2000 prisoners who set quit dates.

Service type characteristics

Between 13,000 and 27,000 clients set quit dates each month. The highest numbers of clients set quit dates in January to March and the lowest numbers were in August and November. The PCTs providing client data were fairly evenly divided by disadvantage. The majority of clients (64.5%) had not used the SSS previously (treatment episode 1). Combination NRT (more than one type of NRT) was the most commonly used medication (38.2%). Less than 1% used bupropion alone. Among intervention types, one-to-one behavioural support was by far the most common (79%) whereas only 14% took part in drop-ins, 2.7% took part in open/rolling groups and 1.4% were members of closed groups. Practitioner type had a large proportion of missing values (41.8%), so it was not possible to assess how accurately the proportions of the other categories reflect the distribution of practitioner types, however, the largest category displayed was specialist practitioner at 31.4%.

Each row in Table 4 displays information about a different PCT. For each of these, the first column displays information on the number of practitioners within each PCT (ranging from 14–334). The subsequent column shows the number of clients seen in each PCT with practitioner identified and this is followed by an average of clients per practitioners for each PCT (ranging from 8–310). There was variation in the number of practitioners recorded by the PCTs (from 20–300). In some PCTs it appeared that practitioners saw over 250 clients on average whereas in others practitioners saw fewer than 10 clients each.

| Number of practitioners in QuitManager database | Clients with practitioner identified, July 2010–June 2011 | Mean clients per practitioner | Estimated PCT smoking rate (%) in 2003–5 aged ≥ 16 years (95% CI)a | Estimated population 2010 aged ≥ 16 yearsb | SSS clients aged ≥ 16 years, July 2010–June 2011c | Estimate of PCT smokers reached (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77 | 2876 | 37.4 | 32.1 (28.0 to 36.5) | 135,000 | 2849 | 7.5 |

| 106 | 2673 | 25.2 | 27.8 (24.1 to 31.9) | 182,100 | 2659 | 6.1 |

| 15 | 4398 | 293.2 | 24.9 (22.1 to 28.0) | 315,500 | 6132 | 9.3 |

| 22 | 5441 | 247.3 | 24.9 (22.1 to 28.0) | 278,200 | 5400 | 9.3 |

| 137 | 6635 | 48.4 | 30.3 (27.4 to 33.4) | 114,300 | 6597 | 21.9 |

| 74 | 4000 | 54.1 | 20.1 (18.6 to 21.7) | 259,300 | 4000 | 9.6 |

| 256 | 5887 | 23.0 | 24.8 (22.0 to 27.7) | 368,300 | 5868 | 7.7 |

| 121 | 2546 | 21.0 | 21.9 (19.0 to 25.2) | 251,200 | 2584 | 5.7 |

| 95 | 6236 | 65.6 | 19.6 (18.5 to 20.8) | 373,100 | 6164 | 10.6 |

| 302 | 10,038 | 33.2 | 25.0 (23.6 to 26.5) | 422,400 | 10,083 | 11.3 |

| 58 | 1662 | 28.7 | 27.9 (24.7 to 31.5) | 81,400 | 1683 | 8.6 |

| 128 | 4573 | 35.7 | 26.8 (24.3 to 29.5) | 255,200 | 4576 | 7.9 |

| 276 | 3804 | 13.8 | 25.0 (22.4 to 27.8) | 199,700 | 3769 | 9.0 |

| 44 | 7229 | 164.3 | 23.5 (22.4 to 24.5) | 599,500 | 7097 | 6.1 |

| 177 | 3113 | 17.6 | 18.6 (16.5 to 20.9) | 256,600 | 3125 | 8.3 |

| 83 | 2862 | 34.5 | 21.2 (19.1 to 23.6) | 282,000 | 2834 | 5.8 |

| 87 | 1936 | 22.3 | 14.5 (11.9 to 17.5) | 185,400 | 1965 | 10.1 |

| 102 | 3573 | 35.0 | 24.9 (22.1 to 28.0) | 215,500 | 3718 | 8.2 |

| 332e | 8203 | 24.7 | 22.9 (21.8 to 24.1) | – | – | – |

| 334e | 6293 | 18.8 | 19.8 (18.7 to 21.0) | – | – | – |

| –e | – | – | 21.4 (20.3 to 22.6) | 886,500 | 14,512 | 8.8 |

| 188 | 3689 | 19.6 | 28.2 (25.8 to 30.7) | 161,600 | 3626 | 9.3 |

| 95 | 3861 | 40.6 | 22.0 (19.4 to 24.9) | 190,100 | 3942 | 11.5 |

| 73 | 4878 | 66.8 | 40.9 (36.4 to 45.5) | 217,100 | 4824 | 6.0 |

| 131 | 3432 | 26.2 | 27.5 (22.9 to 32.6) | 163,100 | 3708 | 9.7 |

| 81 | 1154 | 14.2 | 18.8 (14.4 to 24.2) | 141,800 | 1963 | 9.4 |

| 79 | 637 | 8.1 | 21.7 (18.7 to 24.9) | 138,400 | 619 | 2.5 |

| 142 | 4993 | 35.2 | 30.1 (26.1 to 34.4) | 243,300 | 4921 | 7.8 |

| 228 | 7400 | 32.5 | 21.9 (20.8 to 22.9) | 564,000 | 7286 | 7.2 |

| 100 | 2996 | 30.0 | 26.8 (24.1 to 29.7) | 212,600 | 2985 | 6.1 |

| 280 | 10,778 | 38.5 | 23.3 (22.2 to 24.5) | 583,300 | 10,634 | 9.4 |

| 43 | 1493 | 34.7 | 24.6 (22.0 to 27.3) | 128,100 | 1487 | 5.6 |

| 123 | 3111 | 25.3 | 18.4 (16.4 to 20.6) | 173,900 | 3115 | 12.4 |

| 21 | 6518 | 310.4 | 25.9 (24.6 to 27.1) | 550,800 | 12,920f | 10.7 |

| 36 | 2215 | 61.5 | 33.5 (29.7 to 37.4) | 128,400 | 2207 | 5.8 |

| 62 | 5060 | 81.6 | 36.2 (32.1 to 40.6) | 256,600 | 4994 | 6.0 |

| 27 | 5268 | 195.1 | 29.0 (26.4 to 31.8) | 171,100 | 5203 | 12.1 |

| 89 | 1273 | 14.3 | 17.6 (15.1 to 20.3) | 211,600 | 1532 | 5.3 |

| 63 | 582 | 9.2 | 19.3 (16.1 to 23.0) | 152,900 | 573 | 2.4 |

| 130 | 5105 | 39.3 | 25.3 (22.6 to 28.1) | 205,800 | 5013 | 11.5 |

| 14 | 459 | 32.8 | 29.0 (26.1 to 32.0) | 230,900 | 1754 | 3.0 |

| 113 | 4224 | 37.4 | 21.3 (20.2 to 22.5) | 241,500 | 4163 | 10.0 |

| 21 | 603 | 28.7 | 21.1 (20.0 to 22.2) | 429,700 | 1356f | NA |

| 268 | 4155 | 15.5 | 24.5 (22.9 to 26.2) | 275,500 | 8254f | 14.6 |

| 90 | 1774 | 19.7 | 27.7 (24.2 to 31.5) | 236,500 | 1772 | 3.2 |

| 75 | 3562 | 47.5 | 25.2 (22.7 to 27.9) | 129,500 | 3501 | 12.7 |

| 113 | 2100 | 18.6 | 25.8 (23.4 to 28.4) | 203,200 | 4140f | 9.3 |

| 293 | 3937 | 13.4 | 21.3 (20.2 to 22.5) | 438,000 | 7798f | 10.3 |

| 93 | 4099 | 44.1 | 21.7 (20.3 to 23.1) | 193,000 | 4061 | 11.9 |

| 6040 | 196,511 | 32.5 (average) | – | – | – | – |

Reach of services by primary care trust

Estimated smoking rates varied from 15% to 41%. PCT populations varied from 80,000 to nearly 900,000. Most services saw between 5% and 10% of their population of smokers between July 2010 and June 2011. Note that smoking estimates were accompanied by confidence intervals (CIs) of approximately 6% thus these should be treated with caution.

Cessation

Bivariable results

The overall quit rates of the entire database (see Table 3) without exclusions for missing data in the gender, age or practitioner type variables were 44.1% (self-report) and 30.7% (CO validated). The quit rates of the sample used in the analysis were 48.8% (self-report) and 34.1% (CO validated).

The SSSs target is at least 35% for self-report and CO-validated quit. 33 Overall, the self-report quit rate comfortably passed this level and the CO-validated quit rate almost reached this level. Three PCTs did not reach the 35% target for self-report quitting. Some subgroups met this target for CO-validated quitting, they were: clients who were working or who were retired or caring for the home, prisoners, clients who paid for prescriptions, clients in PCTs who were not particularly disadvantaged or affluent, clients who set quit dates in January or February, clients who took combination NRT or just varenicline, clients who attended groups and clients whose practitioner was a specialist or a health-care assistant. Of the 49 PCTs, 28 met this target for CO-validated quitting.

Multivariable results

Multivariable modelling in Stata indicated the extent of multicollinearity. All vifs were below 2.54 for self-reported and CO-validated models so there was no significant multicollinearity in the data (concerns are raised if a vif is ≥ 10). Multilevel multivariable ORs for client variables are presented in Table 5 and ORs of quit attempt-related variables are presented in Table 6.

| Outcome | Self-report quit, OR (95% CI) (n = 177,291) | CO-verified quit, OR (95% CI) (n = 177,291) | CO validation, OR (95% CI) (n = 86,512) | CO validation, OR (95% CI) (n = 80,002) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusions | – | – | – | Extreme PCTsa |

| Null model (constant) | 0.34 (0.27 to 0.43) | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.19) | 1.58 (0.77 to 3.25) | 1.69 (0.98 to 2.90) |

| Age (years) at quit date quartiles | ||||

| 10–30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 31–42 | 1.44 (1.40 to 1.48) | 1.53 (1.48 to 1.58) | 1.29 (1.22 to 1.35) | 1.34 (1.27 to 1.41) |

| 43–53 | 1.54 (1.49 to 1.59) | 1.73 (1.67 to 1.79) | 1.48 (1.40 to 1.57) | 1.60 (1.51 to 1.69) |

| 54–100 | 2.02 (1.96 to 2.09) | 2.28 (2.20 to 2.37) | 1.69 (1.60 to 1.80) | 1.87 (1.76 to 1.99) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (not pregnant) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female (pregnant) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.38) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.26) | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) | 0.87 (0.77 to 1.00) |

| Male | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.07) | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.00) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black, Asian, mixed, other | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| White | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.13) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) |

| Unknown | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.03) | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.02) | 0.89 (0.79 to 1.01) |

| NSSEC | ||||

| Routine and manual | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.19) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.03) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.03) |

| Managerial and professional | 1.19 (1.15 to 1.24) | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.18) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) |

| Retired or home carer | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) |

| Sick or disabled and unable to work | 0.70 (0.67 to 0.73) | 0.70 (0.67 to 0.74) | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.93) | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90) |

| Always/long-term unemployed | 0.75 (0.72 to 0.78) | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.79) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) |

| In prison | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.32) | 1.98 (1.71 to 2.29) | 3.82 (2.92 to 4.98) | 4.84 (3.61 to 6.47) |

| Other | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.85) | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.97) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.96) |

| Prescription payment | ||||

| Exempt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pays | 1.24 (1.21 to 1.27) | 1.18 (1.14 to 1.21) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) |

| Unknown | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.86) |

| Average IMD score 2010 (PCT) | ||||

| Ranked 1–30 (disadvantaged) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ranked 31–60 | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.69) | 1.58 (0.91 to 2.77) | 3.61 (1.14 to 11.47) | 1.67 (0.72 to 3.86) |

| Ranked 61–90 | 1.29 (0.88 to 1.89) | 1.34 (0.72 to 2.51) | 0.61 (0.17 to 2.19) | 0.60 (0.25 to 1.45) |

| Ranked 91–120 | 1.25 (0.92 to 1.70) | 1.43 (0.88 to 2.35) | 1.34 (0.49 to 3.67) | 1.19 (0.59 to 2.42) |

| Ranked ≥ 121 (affluent) | 1.36 (0.96 to 1.91) | 1.61 (0.92 to 2.81) | 1.06 (0.34 to 3.33) | 1.01 (0.45 to 2.22) |

| Outcome | Self-report quit, OR (95% CI) (n = 177,291) | CO-verified quit, OR (95% CI) (n = 177,291) | CO validation, OR (95% CI) (n = 86,512) | CO validation, OR (95% CI) (n = 80,002) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusions | – | – | – | Extreme PCTsa |

| Quit date month | ||||

| July 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| August 2010 | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.10) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) |

| September 2010 | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.20) | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) |

| October 2010 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.09) | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.09) |

| November 2010 | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07) | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.93) | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.89) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.85) |

| January 2011 | 1.33 (1.27 to 1.39) | 1.34 (1.28 to 1.41) | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.19) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.21) |

| February 2011 | 1.17 (1.12 to 1.22) | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.25) | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.15) | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.15) |

| March 2011 | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) |

| April 2011 | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.17) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) |

| May 2011 | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.89) | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.02) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.19) | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.21) |

| Episode | ||||

| Episode 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Episode 2 | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) |

| Episode 3 | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.03) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.07) |

| Episode 4 or more | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.13) | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) |

| Medication | ||||

| Single NRT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Combination NRT | 1.88 (1.83 to 1.94) | 2.06 (2.00 to 2.13) | 1.55 (1.47 to 1.65) | 1.66 (1.56 to 1.76) |

| Bupropion only | 1.79 (1.58 to 2.03) | 1.48 (1.29 to 1.69) | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.20) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.18) |

| Varenicline only | 2.57 (2.49 to 2.65) | 2.31 (2.24 to 2.40) | 1.31 (1.23 to 1.39) | 1.37 (1.29 to 1.45) |

| Mixed NRT/bupropion/varenicline | 1.46 (1.37 to 1.57) | 1.64 (1.53 to 1.76) | 1.46 (1.30 to 1.65) | 1.55 (1.37 to 1.76) |

| No medication or missing | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.18) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.84) | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.80) | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.74) |

| Intervention type | ||||

| One to one | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Drop-in clinic | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.07) | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.06) |

| Open (rolling) group | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 1.28 (1.15 to 1.41) | 1.39 (1.18 to 1.64) | 1.45 (1.23 to 1.73) |

| Closed group | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.26) | 1.11 (0.99 to 1.24) | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.37) | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.39) |

| Other or missing | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.21) | 0.62 (0.57 to 0.68) | 0.46 (0.40 to 0.51) | 0.41 (0.36 to 0.46) |

| SSS practitioner | ||||

| Specialist | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| GP | 0.46 (0.38 to 0.55) | 0.53 (0.42 to 0.66) | 1.15 (0.83 to 1.61) | 1.43 (0.97 to 2.10) |

| Nurse | 0.58 (0.52 to 0.64) | 0.70 (0.62 to 0.78) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.29) | 1.19 (0.99 to 1.43) |

| Health-care assistant | 0.69 (0.60 to 0.78) | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99) | 1.29 (1.05 to 1.58) | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.80) |

| Pharmacy | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.02) | 1.80 (1.55 to 2.10) | 2.20 (1.84 to 2.64) |

| Other or unknown | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.97) | 1.25 (1.10 to 1.41) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.55) |

The results for CO-validated quit and self-report quit are mostly similar so they are discussed simultaneously with differences alluded to. Generally unknown and other classifications were associated with less chance of quitting than reference groups.

Demography

The relationship between client-related characteristics and CO-validated or self-report quits were mostly similar. As age increased so did the chances of quitting. Clients aged over 53 years were twice as likely to quit as those age 30 years or under. Men and pregnant women were more likely to quit than non-pregnant women. In the bivariable results pregnant women had the lowest quit rate. Further exploration (not shown) suggested that the change in the multivariable results was attributed to pregnant women being less likely to take medication. Ethnicity was not significantly related to quitting.

Socioeconomic status

Compared with clients with routine and manual occupations, clients with intermediate, managerial and professional occupations, the retired, home carers and prisoners were more likely to quit. Those who paid for prescriptions were more likely to quit than those who were exempt. PCT deprivation was not significantly related to quitting.

Stop Smoking Service related

September, January and February appeared to be particularly successful months for setting a quit date with a SSS. Lower chances of quitting in May and November might partly be because of late quit information not being included in the database owing to cut off points at the end of December and June. However, differences between these months and the other months were not always significant, suggesting this had a minimal effect. Clients who had used the service once before were less likely to quit than those who had never used the service before and those who had used the service four or more times were more likely to quit. Taking any medication other than single NRT increased the chances of quitting. The highest ORs were for clients who took varenicline alone. These people were more than twice as likely to self-report and CO validate as quit.

For intervention type, the highest chances of quitting were among clients who took part in open/rolling groups. Closed-group clients were significantly more likely to self-report as quit than those who undertook one-to-one counselling but the difference did not quite reach significance for CO validation. Further analysis (not shown) suggested this was caused by a number of factors such as the practitioner, SES and medication.

Among the practitioner types, clients of specialist advisers were more likely to quit than clients of other (and unspecified) practitioner types. This difference was significant for all categories except for CO validation among practitioners who held pharmacy posts. ORs were surprisingly low for GPs given bivariable results. Further analysis (not shown) suggested this was because the majority of GPs worked in one PCT (Warwickshire) where quit rates were similar to other practitioner types, but in most other PCTs, with more than 20 clients seen by GPs, GPs were achieving fewer CO-validated quits than other practitioner types.

Primary care trust and practitioner

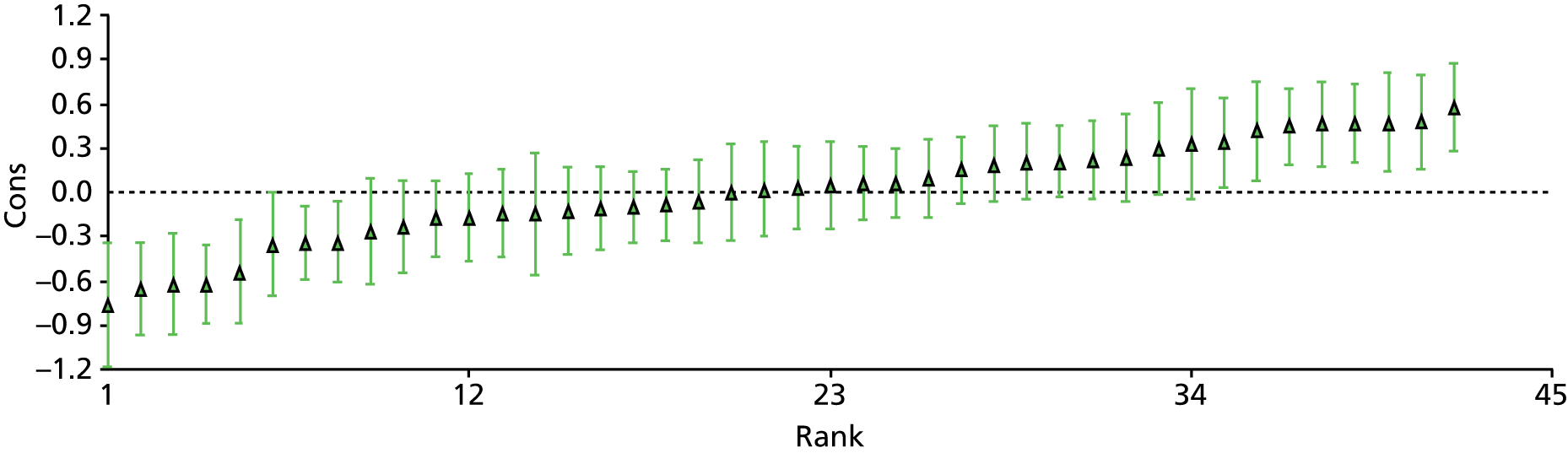

Figure 2 is a caterpillar plot of PCT residuals for the multilevel multivariable model of self-report quit. PCT CIs that do not overlap 0.0 represent significant departures from the average. The lowest chances of self-reported quitting were found in the PCT ranked 1.

FIGURE 2.

Residual caterpillar plot of PCTs for multivariable multilevel model of self-report quits.

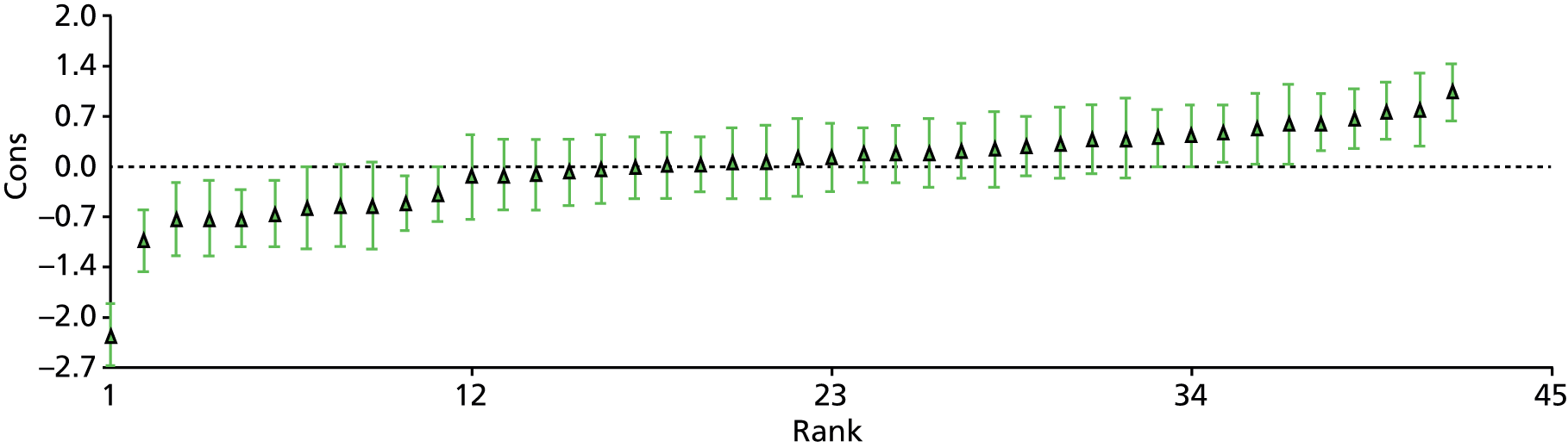

Figure 3 is a caterpillar plot of PCT residuals for CO-validated quit. PCT CIs that do not overlap 0.0 represent significant departures from the average. Further exploration (not shown) suggested that excluding clients from the lowest ranked PCT made little difference to the results.

FIGURE 3.

Residual caterpillar plot of PCTs for multivariable multilevel model of CO-validated quits.

There is little that can be said with certainty about the higher-level variance (Table 7), as it is not possible to tell how much of the change in variance between models is owing to fixed effects in the model and how much is the result of level one variance being constrained to 3.29, leading to inflated or deflated higher level variance.

| Models | CO validated | Self-report | CO validation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCT variance (95% CI) | Practitioner variance (95% CI) | PCT variance (95% CI) | Practitioner variance (95% CI) | PCT variance (95% CI) | Practitioner variance (95% CI) | |

| No fixed effects | ||||||

| Null model (constant) | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.58) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.41 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.83 (1.03 to 2.63) | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.42) |

| One fixed effect | ||||||

| Quit date month | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.52) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.58) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.41 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.83 (1.02 to 2.64) | 1.33 (1.23 to 1.42) |

| Age (years) at quit date quartiles | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.55) | 0.55 (0.51 to 0.58) | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.21) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.84 (1.03 to 2.65) | 1.35 (1.25 to 1.44) |

| Gender | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.41 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.82 (1.01 to 2.63) | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.41) |

| Ethnicity | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.83 (1.02 to 2.64) | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.42) |

| NSSEC | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.51) | 0.52 (0.49 to 0.56) | 0.12 (0.07 to 0.18) | 0.39 (0.36 to 0.41) | 1.83 (1.03 to 2.63) | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.40) |

| Prescription payment | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.52) | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.57) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.43) | 1.82 (1.02 to 2.63) | 1.30 (1.21 to 1.39) |

| IMD 2010 (PCT) | 0.30 (0.17 to 0.44) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.56) | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.16) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.40 (0.78 to 2.02) | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.80) |

| Episode | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.58) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.20) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 1.83 (1.02 to 2.63) | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.42) |

| Medication | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.55) | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.57) | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.23) | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.43) | 1.84 (1.02 to 2.65) | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.38) |

| Intervention type | 0.35 (0.20 to 0.51) | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.56) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.19) | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.42) | 1.80 (1.00 to 2.60) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.38) |

| SSS practitioner | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.57) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.19) | 0.38 (0.35 to 0.40) | 1.91 (1.07 to 2.75) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.38) |

| All fixed effects | ||||||

| Multivariable model | 0.34 (0.19 to 0.50) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.52) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.18) | 0.36 (0.33 to 0.38) | 1.47 (0.82 to 2.11) | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.76) |

| Multivariable MCMC model | 0.43 (0.22 to 0.65) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.57) | – | – | – | – |

| Multivariable model without extreme PCTs | – | – | – | – | 0.64 (0.34 to 0.94) | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.10) |

We can safely say that there was significant variance between practitioners and between PCTs even after all fixed effects had been included for both self-report and CO-validated quit. It is probably also safe to say that there was less variance between PCTs and between practitioners for self-report quits than CO-validated quits.

Carbon monoxide validation

The CO-validation rate (self-reports that were CO validated) of the database was 73.9% and was 74.3% among clients with gender, age and practitioner identified (see Table 3). The DH has recommended that SSSs should aim to CO validate 85% of clients. 33 Client groups where CO validation of 85% was achieved were prisoners and clients enrolled in open groups. Of the 49 PCTs, 13 achieved CO-validation rates of 85% or more.

Multivariable results

Odds ratios for IMD at PCT level and multilevel variance changes suggested that some PCTs were having a disproportionate effect on the results, as an intermediate quintile was most associated with quitting (see Table 4) and including this variable in the model was associated with a major reduction in PCT-level variance (see Table 7). Two PCTs, with very high CO-validation rates and one PCT with a particularly low validation rate were consequently excluded. Both models are shown (see Table 6). Multivariable modelling in Stata provided vifs and tols. All were below 3.20, so there was no significant multicollinearity in the data.

Demography

As age increased, CO validation was more likely. Non-pregnant women were more likely to be CO validated than men and pregnant women. Ethnicity had no effect on CO-validation rates.

Socioeconomic status

Prisoners were much more likely to be CO validated than other groups, approximately four times more likely than routine and manual workers. Eligibility for paying for prescriptions and PCT deprivation (once extreme PCTs were excluded) did not significantly affect CO-validation rates.

Stop Smoking Service related

Self-report quitters who set quit dates in January were most likely to be CO validated and November quitters were least likely. Clients who took varenicline, combination NRT or a mixture of medications were more likely to be CO validated than those who took single NRT. Self-report quitters who enrolled in open groups were more likely to be CO validated. CO-validation rates were lowest among specialist practitioners. Health-care assistants, pharmacy employees and unclassified practitioners were significantly more likely to CO validate clients than specialist practitioners (see Table 6).

Primary care trust and practitioner

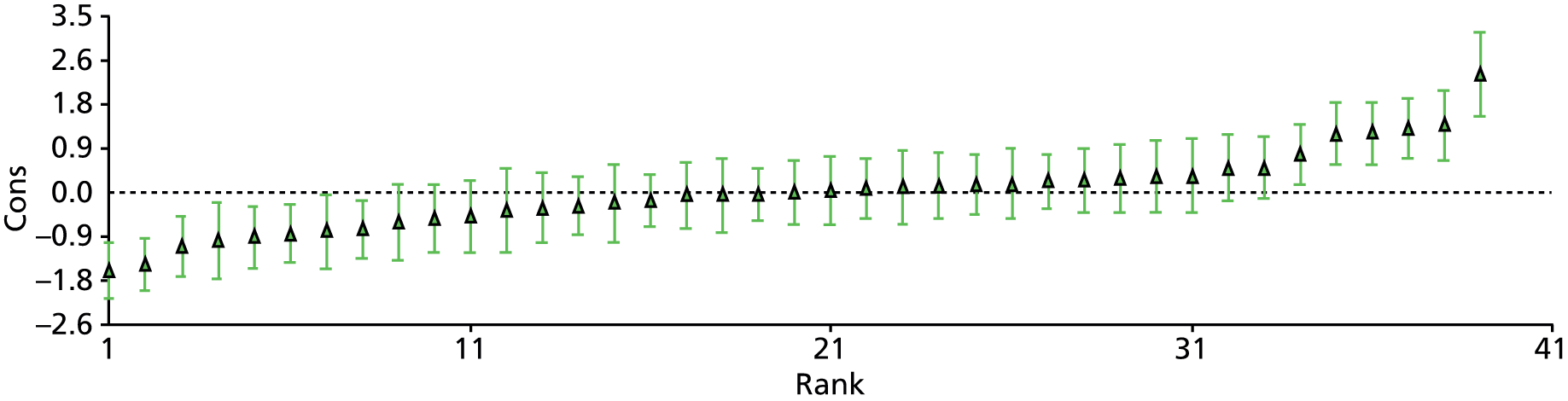

Residuals suggest (Figure 4) that, after taking other demographic- and service-related factors into account, there was significant variation in PCT validation rates.

FIGURE 4.

Caterpillar plot of residuals for multivariable multilevel model predicting CO validation (model excluding extreme PCTs).

There is little that can be said with certainty about the higher-level variance, as it is not possible to tell how much of the change in variance between models (see Table 7) is owing to fixed effects in the model and how much is the result of level one variance being constrained to 3.29 in binary outcome models.

The variance between PCTs appeared to halve when PCT deprivation was entered into the model. The fixed effects suggested that PCTs that were fairly, but not the most, disadvantaged were three times more likely to be CO validated. This suggested that idiosyncrasies were responsible rather than an effect of deprivation. When extreme PCTs were excluded the variance between PCTs halved and there was no longer significant variation between practitioners.

Impact

In general, the services had a positive impact over and above what would be expected from quitting spontaneously or with medication only. When the impact was calculated using all self-report quitters, two services were estimated to have a negative impact as did six services when only CO-validated quitters were included. However, only one service was judged to have a negative impact when both CO-validated quitting and all self-report quitting were taken into account. At the other end of the scale, two PCTs were estimated to have independently added over 400 ex-smokers per 100,000 population between mid-2010 and mid-2011 (Table 8).

| Unique clients aged ≥ 16 years | Clients per 100,000 PCT populationa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Impact (4-week quitters) calculated | ||||||

| n | Client records unique clients (%) | CO-validated quit (%)b | Self-report quit (%)b | From CO-validated quit | From self-report quit | Overall (average self-report and CO validated) | |