Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a project commissioned/managed by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC–NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’.

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high-quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HTA journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Charles Abraham acknowledges funding from the UK National Institute for Health Research and the Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Michie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 General introduction

Behaviour change interventions: purpose and reporting

Preventable behaviours, such as smoking, physical inactivity, eating unhealthy diets and excessive alcohol consumption, have been identified as leading causes of morbidity and mortality. 1–4 Behaviour change interventions (BCIs) are typically complex, involving many interacting components. 5 This can make them challenging to replicate in research, to implement in practical settings and to synthesise in systematic literature reviews.

Behaviour change interventions are ‘Coordinated sets of activities designed to change specified behaviour patterns’. 6 The development, implementation and evaluation of effective BCIs are fundamental for advancing behavioural science and its application. 7,8 However, both science and practice depend on having a good understanding of the nature and content of interventions. This includes knowing what was delivered in the intervention [i.e. the ‘active ingredients’ or behaviour change techniques (BCTs)] and how it was delivered (i.e. who delivered, to whom, how often, for how long, in what format, and in what context). 9–11 Poorly described interventions in research protocols and published reports mean that the precise content of interventions is difficult to establish, with the possibility of the same labels (e.g. behavioural counselling) meaning different things to different researchers/implementers and different labels being used to describe the same BCTs. As a result, the content delivered in practice often deviates from that specified in the intervention protocol12 presenting a barrier to scientific progress and effective translation.

Guidance documents have been published aimed at improving methods of specifying and reporting interventions. For example, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines for reporting randomised controlled trials (RCTs)13 advise researchers to report the ‘precise details’ of the intervention as ‘actually administered’, and the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs statement for reporting non-randomised trials14 emphasises the reporting of content and context and full description of comparison and intervention conditions. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions calls for the specification of the active ingredients as a necessary step for investigating how interventions exert their effect and, therefore, for designing more effective interventions and applying them appropriately across target population group and setting. 5 The Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research group has had some success in encouraging journal editors to ensure that transparent and accessible intervention descriptions are available before publication of intervention outcomes. 15 The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)16 provides a checklist of the minimum data required to report interventions, including surgical, pharmacological, psychotherapeutic as well as behavioural interventions. Although progress has been made in improving how intervention content is reported, if descriptions of BCIs are to be communicated effectively and successfully replicated, a shared and standardised method of classifying intervention content is needed. 17

Behaviour change techniques

A BCT is defined as an observable and replicable component designed to change behaviour. It is the smallest component compatible with retaining the postulated active ingredients and can be used alone or in combination with other BCTs. To enable interventions to be evaluated and effective interventions (i.e. those which bring about the desired change in the target behaviour or behaviours) to be implemented, a BCT should be well specified. BCTs are descriptors and vary in the extent to which they have been empirically investigated and the extent to which they bring about the desired change to behaviour(s) in different situations. BCT definitions used for coding have to be practical, non-overlapping and useful in the reliable reporting of interventions.

Specification of interventions according to component BCTs is beneficial for conducting primary research, implementing effective interventions and for conducting evidence syntheses. A comprehensive list of BCTs facilitates primary research, as intervention developers can draw on a wider range of BCTs than is likely to be considered without such a list. Specification of intervention and control conditions using BCTs can increase accurate replication of interventions found to be efficacious in RCTs. BCT methodology is also useful in assessing the fidelity of implementation of interventions. For systematic reviewers, BCTs provide a reliable method for extracting and coding information about intervention content. Reviewers can identify and synthesise discrete, replicable, potentially active ingredients associated with efficacy and multivariate statistical analysis can then be used to identify BCTs and BCT combinations associated with efficacy. By linking BCTs with theories of behaviour change, researchers and reviewers can investigate possible effect modifiers and/or mechanisms of action. There are some intervention components that can be thought of as ‘modifier BCTs’ in that they add value to BCTs but do not in themselves change behaviour, for example, tailoring, giving choice and homework tasks. Specifying intervention content with this degree of precision helps to maximise scientific as well as practical benefits of research investment into the development and evaluation of complex interventions.

Behaviour change technique taxonomies

To provide a more rigorous methodology for characterising intervention content, methods have been developed for specifying the potentially active ingredients in terms of BCTs. 18–20 Abraham and Michie’s20 taxonomy of 22 BCTs and four BCT packages observed in BCIs was demonstrated to have good intercoder reliability (i.e. the extent to which coders agreed on the presence/absence of BCTs) among the taxonomy developers and trained coders across 221 intervention descriptions in papers and manuals. This, and subsequent taxonomies developed for specific behavioural domains, have been widely used internationally to report interventions, synthesise evidence21–24 and design interventions. 25,26 BCT taxonomies have been developed in relation to smoking,27 physical activity and healthy eating,28 excessive alcohol use29 and condom use. 30 Taxonomies of BCTs have also been used to assess the extent to which published reports reflect intervention protocols12 and to assess fidelity of delivery. 31 They have enabled the specification of professional competences for delivering BCTs32,33 and as a basis for a national training programme. 34,35 Guidance has also been developed for incorporating BCTs in text-based interventions. 36

Previous classification systems have either been in the form of an unstructured list or have been linked to, or structured, according to theories and/or theoretical mechanisms19,20,32,33 judged to be the most appropriate by the authors.

A hierarchically structured list provides the advantage of making it more coherent to, and useable by, those applying it. 37 There are at least five potential benefits of developing a cross-domain, hierarchically structured and internationally supported taxonomy for specifying intervention content:

-

To promote the accurate replication of interventions and control conditions in comparative efficacy research, a key activity in accumulating scientific knowledge and investigating generalisability across behaviours, populations and settings.

-

To specify intervention content to facilitate faithful implementation of intervention protocols in research and, in practice, of interventions found to be effective.

-

To extract and synthesise information about intervention content in systematic reviews. BCT taxonomies, combined with the statistical technique of meta-regression or classification and regression tree (CART), have allowed reviewers to synthesise evidence from complex, heterogeneous interventions to identify effective component BCTs and BCT combinations. 21,23,24,38,39

-

To draw on a comprehensive list of BCTs in developing interventions (rather than relying on the limited set that can be brought to mind).

-

To investigate possible mechanisms of action by linking BCTs with theories of behaviour change and component theoretical constructs. 8,19,21,23

In this monograph, we present the development and evaluation of Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1): a cross-domain, hierarchically structured taxonomy based on interdisciplinary consensus as a method for the accurate and reliable reporting of interventions to change behaviour. 40

Phase 1: development

Chapter 2 Developing a comprehensive list of behaviour change techniques (study 1)

Abstract

Objectives: To develop an extensive, consensually agreed taxonomy of BCTs used in BCIs.

Methods: In a Delphi-type exercise, 14 experts rated labels and definitions of 124 BCTs from six published classification systems. 20,23,27,29,33,36 The resulting list was refined based on the feedback from group discussions of 16 members of the International Advisory Board (IAB).

Results: This resulting BCTTv1 comprised 93 distinct, non-redundant and non-overlapping BCTs.

Conclusions: BCTTv1 offers a step change in methods for specifying interventions using shared concepts and language. When sufficient data have been collected about its implementation and an international, interdisciplinary consortium established, v1 will be reviewed and v2 released as and when the need is judged by consensus.

Introduction

Literature reviews find that even essential elements of interventions are frequently omitted from intervention descriptions; an analysis of trials and reviews found that 67% of pharmacological intervention descriptions were adequate, compared with only 29% of non-pharmacological intervention descriptions. 41 While this occurs in descriptions of all types of intervention, it is an even more common problem in BCIs. Titles and abstracts of published interventions (i.e. the materials screened for inclusion in systematic reviews) have been found to mention the active components of the intervention in only 56% of published descriptions compared with over 90% in pharmacological interventions. 42 The TIDieR checklist and guide for reporting all types of interventions was developed using consensus methods with international participants from several disciplines and proposes a minimum set of information: brief name, why (rationale), what materials, what procedure, who provided, how, where, when and how much, tailoring, changes, how well monitored and how well delivered. 16 However, for BCIs, further information is required to specify the active ingredients, that is ‘components within an intervention that can be specifically linked to its effect on outcomes such that, if they were omitted, the intervention would be ineffective’. 42

The content, or active components, of BCIs are often described in intervention protocols and published reports with different labels (e.g. ‘self-monitoring’ may be labelled ‘daily diaries’) and the same labels may be applied to different techniques (e.g. ‘behavioural counselling’ may involve ‘educating patients’ or ‘feedback, self-monitoring, and reinforcement’). 43 This may lead to uncertainty, confusion and difficulties in determining the efficacy of specific change approaches; for example, Morton et al. 44 had considerable difficulty in identifying the necessary components of motivational interviewing and as a result found it difficult to synthesise evidence of efficacy. Further, behavioural medicine researchers and practitioners have reported low confidence in their ability to replicate highly effective behavioural interventions for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. 45 The absence of standardised definitions and labels for intervention components means that systematic reviewers develop their own systems for classifying behavioural interventions and synthesising study findings [e.g. Hardeman et al. ,18 Albarracín et al. ,19 Mischel (Presidential address given at the Association for Psychological Science Annual Convention, Washington, DC; 2012) and West et al. 46]. This proliferation of systems leads to duplication of effort and undermines the potential to accumulate evidence across reviews. It also points to the urgent need for consensus. Consequently, the UK MRC guidance5 for developing and evaluating complex interventions called for improved methods of specifying and reporting intervention content in order to address the problems of lack of consistency and consensus.

A method developed for this purpose is the reliable specification of interventions in terms of BCTs. 20 Previous classification systems have mainly been developed for particular behavioural domains (e.g. physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption or safer sex). Abraham and Michie20 developed the first cross-behaviour BCT taxonomy, building on previous intervention content analyses. 18,19 The taxonomy demonstrated reliability in identifying 22 BCTs (e.g. ‘self-monitoring’) and four BCT packages (e.g. ‘relapse prevention’). Identifying the presence of BCTs in intervention descriptions included in systematic reviews and national datasets of outcomes has allowed the identification of BCTs associated with effective interventions. 46,47 Effective BCTs have been identified for interventions to increase physical activity and healthy eating,23,48 and to support smoking cessation,27,46 reduce excessive alcohol consumption,29 prevent sexually transmitted infections19,30 and change professional behaviour. 49

Although the subsequent development of classification systems of defined and reliably identifiable BCTs has been accompanied by a progressive increase in their comprehensiveness and clarity, this work has been conducted by only a few research groups, but with each developing their own methodology. For this method to maximise scientific advance, collaborative work was needed to develop agreed labels and definitions and reliable procedures for their identification and application across behaviours, disciplines and countries. Therefore, the aim of study 1 was to develop a taxonomy that comprises an extensive list of clearly labelled, well defined BCTs that (1) are proposed as the active components of BCIs, (2) are distinct (non-overlapping, non-redundant) and precise, (3) can be used with confidence to describe interventions, and (4) have a breadth of international and disciplinary agreement.

Method

This study is also published as Michie et al. 40

Participants

Participants were international behaviour change experts (i.e. active in their field and engaged in investigating, designing and/or delivering BCIs) who had agreed to take part in one or more of the project phases or were members of the IAB50 or of the study team (which included a ‘lay’ person). All board members, as leaders in their field, were eligible to take part as a behaviour change expert. However, in light of their advisory role commitments, members were not routinely approached for further participation except to help widen participation in terms of country, discipline and behavioural expertise.

For the Delphi exercise, 19 international behaviour change experts were invited to take part. Experts were identified from a range of scientific networks on the basis of breadth of knowledge of BCTs, experience of designing and/or delivering BCIs, and of being able to complete the study task in the allotted time. Recruitment was by e-mail, with an offer of an honorarium of £140 (approximately US$230; conversion as of March 2014) on completing the task. Of the 19 originally approached, 14 agreed to take part (response rate of 74%). Ten participants were female, with an age range of 37–62 years [mean = 50.57 years; standard deviation (SD) = 7.74 years]. Expert participants were from the UK (8), Australia (2), the Netherlands (2), Canada (1) and New Zealand (1). Eleven were psychologists (six health psychologists, one clinical psychologist, three clinical and health psychologists and one educational psychologist); one was a cognitive–behaviour therapist and two had backgrounds in health sciences or community health. Eleven were active practitioners in their discipline. Eleven had research or professional doctorates and two had registered psychologist status. There was a wide range of experience of using BCTs, with all having used at least six BCTs, more than half having used more than 30 BCTs and four having used more than 50 BCTs for intervention design, delivery and training.

For the international feedback phase, 16 out of the 30 IAB members took part in discussions to comment on a prototype BCT classification system. IAB members were identified by the study team as being leaders in their field within the key domains of interest (e.g. types of health-related behaviours, major disease types, disciplines such as behavioural medicine) following consultation of websites, journals, and scientific and professional organisations. IAB members were from the USA, Canada, Australia, UK, the Netherlands, Finland and Germany (see Appendix 2). Feedback was also provided by members of the study team, who had backgrounds in psychology and/or implementation science and a ‘lay’ person with a Bachelor of Arts with Honours [BA (Hons)] in English but no background in psychology or behaviour change.

Procedure

Participants provided written consent and were assured that their responses would remain confidential. All participants were asked to provide demographic information (i.e. age, sex and nationality). Delphi participants were also asked to provide their professional background (i.e. qualifications, registrations, job title and area of work) and how many BCTs they had used professionally in intervention design, face-to-face delivery and training (reported in increments of 5 up to 50 +).

A prototype classification system was developed by the study team based on all known published classifications of BCTs following a literature review37 (step 1). An online Delphi-type exercise51 with two ‘rounds’ was used for initial evaluation and development of the classification system. Participants worked independently and rated the prototype BCT labels and definitions on a series of questions designed to assess omission, overlap and redundancy (step 2). The results of step 2 subsequently informed the development of an improved BCT list. The BCTs identified as requiring further clarification were sent to the Delphi participants for the second round. They were asked to rate BCTs for clarity, precision, distinctiveness and confidence of use (step 3). The resulting list of BCTs was then scrutinised by the IAB, who submitted verbal and written feedback (step 4), and was assessed by the lay and expert members of the study team (step 5). Following each of steps 2–4, the results were synthesised by SM and MJ in preparation for the next step.

Step 1: developing the prototype classification system

The labels and definitions of distinct BCTs were extracted from six BCT classification systems identified by a literature search (the relevant papers are marked with an asterisk in the reference section). For BCTs with two or more labels (n = 24) and/or definitions (n = 37), five study team members rated their preferred labels and definitions. Where there was complete or majority agreement, the preferred label and/or definition was retained. Where there was some, little or no agreement, new labels and definitions were developed by synthesising the existing labels and definitions across classification systems. Definition wording was modified to include active verbs and to be non-directional (i.e. applicable to both the adoption of a new wanted behaviour and the removal of an unwanted behaviour).

Step 2: Delphi exercise first round

Participants were provided with the study definition of a BCT,8 that is having the following characteristics: (1) aim to change behaviour, (2) are proposed ‘active ingredients’ of interventions, (3) are the smallest components compatible with retaining the proposed active ingredients, (4) can be used alone or in combination with other BCTs, (5) are observable and replicable, (6) can have a measurable effect on a specified behaviour(s), and (7) may or may not have an established empirical evidence base. It was explained that BCTs could be delivered by someone else or self-delivered.

The BCTs (labels and definitions) from step 1 were presented in a random order and participants were asked five questions about each of them:

-

Does the definition contain what you would consider to be potentially active ingredients that could be tested empirically? Participants were asked to respond to this question using a 5-point scale (‘definitely no’, ‘probably no’, ‘not sure’, ‘probably yes’ and ‘definitely yes’).

-

Please indicate whether you are satisfied that the BCT is conceptually unique or whether you consider that it is redundant or overlapping with other BCTs. (With forced choice as to ‘whether it was conceptually unique, redundant, or overlapping’.)

-

If participants indicated that the BCT was ‘redundant’, they were asked to state why they had come to this conclusion.

-

If they indicated that the BCT was ‘overlapping’, they were asked to state: (1) with which BCT(s) and (2) whether or not they can be separated (‘yes’ or ‘no’)’.

-

If the BCTs were considered to be separate, participants were asked how the label or definition could be rephrased to reduce the amount of overlap or, if not separate, which label and which definition was better.

Participants were given an opportunity to make comments on the exercise and to detail any BCTs not included on the list. They were asked, ‘does the definition and/or label contain unnecessary characteristics and/or omitted characteristics?’ with an open-ended response format. The exercise was designed to take 2 hours, follow-up reminders were sent to participants after 2 weeks and all responses were submitted within 1 month of the initial request.

Frequencies, means and/or modes of responses to questions (1) and (2) were considered for each BCT. Based on the distribution of responses, BCTs for which (a) more than one-quarter of participants doubted that they contained active ingredients and/or (b) more than one-third considered them to be overlapping or redundant were flagged as ‘requiring further consideration’. These data, along with the responses to questions (3) to (4), guided the rewording of BCT labels and definitions, and the identification of omitted BCTs. The BCTs for reconsideration and the newly identified BCTs were presented in the second Delphi exercise round.

Step 3: Delphi exercise second round

The BCTs identified as requiring further consideration were presented. The rest of the BCTs were included for reference only, to assist judgement about distinctiveness. For each BCT, participants were asked three questions and asked to respond using a 5-point scale (‘definitely no’, ‘probably no’, ‘not sure’, ‘probably yes’ and ‘definitely yes’).

-

If you were asked to describe a BCI in terms of its component BCTs, would you think the following BCT was (a) clear, (b) precise, (c) distinct?

-

Would you feel confident in using this BCT to describe the intervention?

-

Would you feel confident that two behaviour change researchers or practitioners would agree in identifying this BCT?

If participants responded ‘probably no’, ‘definitely no’, or ‘not sure’, to any question, they were asked to state their suggestions for improvement.

Frequencies, means and/or modes were calculated for all questions for each BCT. BCTs for which more than one-quarter of participants responded ‘probably no’, ‘definitely no’ or ‘not sure’ to any question were flagged as needing to be given special attention. Using information on the distribution of ratings, the modal scores and suggestions for improvement, SM and MJ amended the wording of definitions and labels. This included changes to make BCTs more distinct from each other when this had been identified as a problem and to standardise wording across BCTs. When it was not obvious how to amend the BCT from the second round responses, other sources (e.g. Vandenbos52) were consulted for definitions of particular words or descriptions of BCTs.

Step 4: feedback from the International Advisory Board

Sixteen out of the 30 members of the IAB took part in one of three, 2-hour long teleconferences to give advice to the study team, and the BCT list was refined based on their feedback.

Step 5: feedback from study team members

The BCT definitions were checked to ensure that they contained an active verb specifying the action required to deliver the intervention. 53 The ‘lay’ member of the study team (FR, see Acknowledgments) read through the list to ensure syntactic consistency and general comprehensibility to those outside the field of behavioural science. Subsequently, the study team members made a final check of the resulting BCT labels and definitions.

Results

All data tables for this chapter are reported elsewhere, please refer to Michie et al. 40 The evolution of the taxonomy at the different steps of the procedure is summarised in Michie et al. 40

Step 1: developing the prototype classification system

Demographic information about the experts involved is summarised in Michie et al. 40 Of the 124 BCTs in the prototype classification system, 31 were removed: five composite BCTs and 26 BCTs overlapping with others, which were rated to have better definitions. One additional BCT was identified by the study team, given a label and definition and added to the system. This produced a list of 94 BCTs.

Step 2: Delphi exercise first round

The means, modes and frequencies of responses to the Delphi exercise first-round questions are shown in Michie et al. 40 On the basis of these scores, 21 BCTs were judged to be ‘satisfactory’ and 73 ‘requiring further consideration’. Of the 73 reconsidered BCTs, four were removed, four were divided and one BCT was added, giving 74 BCTs. During this process, one reason for overlap became evident: there was a hierarchical structure meaning that deleting overlapping BCTs would end up with only the superordinate BCT and a loss of specific variation (e.g. adopting the higher order BCT ‘consequences’ would have deleted ‘reward’).

Step 3: Delphi exercise second round

The means, modes and frequencies of responses to the five Delphi exercise second round questions are shown in Michie et al. 40 On the basis of these scores, 38 BCTs were judged to be ‘satisfactory’ and 32 ‘requiring further consideration’. Of the 70 BCTs reconsidered, seven labels were amended, 35 definitions were rephrased and seven BCTs were removed, giving 63 BCTs. Together with the 21 BCTs judged to be ‘satisfactory’ in the first round, there were 84 BCTs at the end of the Delphi exercise. Some further standardisation of wording across all BCTs was made by study team members (e.g. specifying ‘unwanted’ or ‘wanted’ behaviours rather than the more generic ‘target’ behaviours and ensuring that all definitions included active verbs).

Step 4: feedback from the International Advisory Board

The IAB members made two general recommendations: first, to make the taxonomy more usable by empirically grouping the BCTs and second, to consider publishing a sequence of versions of the taxonomy (with each version clearly labelled) that would achieve a balance between stability/usability and change/evolution. Feedback from members led to the addition of two and the removal of four BCTs.

Step 5: feedback from study team members

Further refinement of labels and definitions by study team members resulted in a list of 93 clearly defined, non-redundant BCTs (see Appendix 2, Table 19). The full evolution of the taxonomy across the five steps is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram to show evolution of the taxonomy: labels and definitions of BCTs modified.

Discussion

An extensive list of 93 distinct, non-redundant BCTs was developed with labels and definitions refined to capture the smallest components compatible with retaining the proposed active ingredients with the minimum of overlap: BCTTv1 (see Appendix 2, Table 19). Development comprised a series of consensus exercises involving 35 experts in delivering and/or designing BCIs. These experts were drawn from a variety of disciplines including psychology, behavioural medicine and health promotion, and from seven countries (the USA, Canada, Australia, UK, the Netherlands, Finland and Germany). Therefore, the resulting BCTs have relevance among experts from varied behavioural domains, disciplines and countries, and potential relevance to the populations from which they were drawn. Evidence is already emerging to suggest that some BCTs from BCTTv1 occur more frequently than others in descriptions of BCIs. 40 These BCTs are marked with an asterisk in Table 19 (see Appendix 2).

The extent to which BCTTv1 is applicable without adaptation across behaviours, disciplines and countries is an important question for future monitoring and research. The process of building a shareable consensus language and methodology is necessarily collaborative and will be an ongoing cumulative and iterative process, involving an international network of advisors and collaborators. 50 The balance of stability to allow accumulation of knowledge and development to incorporate significant bodies of new knowledge and experience means that classificatory systems are updated at strategic intervals. 37 Examples where this has happened are Linnaeus’s classification of plants and systems based on consensus such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition54 or the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition. 55

There was no prior agreed methodology for this work and there are limitations to the methods we have used. The purpose of the Delphi exercise was to develop a prototype taxonomy on which to build. It was the first in a series of exercises adapted to develop the taxonomy. Our Delphi-type methods involved 14 individuals, an appropriate number for these methods,51 but a number that makes the choice of participants important. We attempted to ensure adequate coverage of behaviour change experts. Although we had some diversity of expertise, we acknowledge the predominance of European experts from a psychological background within our sample. At various stages we made arbitrary decisions such as the cut-offs for amending BCT labels and descriptions. In the absence of agreed standards for such decisions, we were guided by the urgent need to develop an initial taxonomy that was fit for purpose and would therefore form a basis for future development. Our amendments of the BCT labels and definitions also depend on the expertise available and, therefore, we based our amendments on a wide range of inputs – the data we collected from Delphi participants and coders, expert modification, international advice and lay user improvements.

The BCTTv1 encompasses a greater number of BCTs than previous taxonomies. Therefore, it requires structure to facilitate recall and access to the BCTs, and thus increase speed and accuracy of use. A true, that is hierarchically structured, taxonomy provides the advantage of making it more coherent to, and useable by, those applying it. 37 As the number of identified BCTs has increased, so also has the need for such a structure, to improve the usability of the taxonomy.

Simple, reliable grouping structures have previously been used by three groups of authors. Dixon and Johnston33 grouped BCTs according to ‘routes to behaviour change’, ‘motivation’, ‘action’ and ‘prompts/cues’; Michie et al. 27 grouped according to ‘function’ in changing behaviour, ‘motivation’, ‘self-regulation capacity/skills’, ‘adjuvant’ and ‘interaction’; and Abraham et al. 30 grouped according to ‘change target’, that is ‘knowledge’, ‘awareness of own behaviour’, ‘attitudes’, ‘social norms’, ‘self-efficacy’, ‘intention formation’, ‘action control’, ‘behavioural maintenance’ and ‘change facilitators’. In order to achieve our aim of a structured taxonomy that is acceptable and useable over diverse disciplines and theoretical orientations, we used a basic method of grouping that does not depend on a theoretical structure. In the next study, we therefore adopted an empirical, ‘bottom-up’ method to developing a consensus of BCT groupings.

Chapter 3 Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 with hierarchical structure (study 2)

Abstract

Objectives: To enhance understanding and use of BCTs by investigating the hierarchical structure of BCTTv1.

Methods: Participants grouped BCTs according to similarity of active ingredients in an open-sort task. This structure was examined for higher-order groupings using a dendrogram derived from hierarchical cluster analysis. This ‘bottom-up’ sort method was compared with a theory-based ‘top-down’ method in which 18 experts sorted BCTs into 14 theoretical domains in a closed-sort task. Discriminant content validity (DCV) was used to identify groupings and chi-squared tests, and Pearson’s residual values were used to examine the overlap between groupings.

Results: Participants created an average of 15.11 groupings (SD = 6.11 groupings, range 5–24 groupings). BCTs relating to ‘Reward and Punishment’ and ‘Cues and Cue Responses’ were perceived as markedly different from other BCTs. Fifty nine of the BCTs were reliably allocated to 12 of the 14 theoretical domains; 47 were significant and 12 were of borderline significance. Two domains had no BCTs significantly assigned to them. An additional grouping of ‘No Domain’ was included to represent these cases. There was a significant association between the 16 ‘bottom-up’ groupings and the 13 ‘top-down’ groupings (χ2 = 437.80; p < 0.001). Thirty-six of the 208 ‘bottom-up’ × ‘top–down’ pairings (i.e. 16 × 13) showed greater overlap than expected by chance. However, only six combinations achieved satisfactory evidence of similarity.

Conclusions: The moderate overlap between the groupings indicates some tendency to implicitly conceptualise BCTs in terms of the same theoretical domains. Understanding the nature of the overlap will aid the conceptualisation of BCTs in terms of theory and application. Further research into different methods of developing a hierarchical taxonomic structure of BCTs for international, interdisciplinary work is now required.

Introduction

Study 1 presented the synthesis of existing BCT taxonomies into a single comprehensive, cross-context, overarching BCT taxonomy: BCTTv1. 8,17,40 Previous BCTs groupings have been based on judgements made by the study author. 20,27,32,33 Given the 93 items of BCTTv1, it is necessary to group the BCTs to make the taxonomy more memorable and useable. To achieve this, we need an agreed method for identifying links between particular BCTs and theoretical constructs.

Two methods were investigated: (1) a ‘bottom-up’ linkage and (2) a ‘top-down’, theoretically guided linkage. The ‘bottom-up’ approach allows each respondent to propose linkages inductively and then identifies which linkages are common across respondents. It makes no assumptions about underlying theory and, therefore, the results should be accessible to users from diverse theoretical and disciplinary backgrounds. Nevertheless, it may reflect commonalities in theoretical approaches. The ‘top-down’ approach prompts each respondent to deduce theoretical linkages based on underlying theory. Common linkages across respondents are then identified.

Theories of behaviour change summarise what is known about the mechanisms of behaviour change and the conditions in which behaviour change is most likely to occur. 8 The importance of understanding the theoretical underpinnings of BCTs has been highlighted in previous research. 10,21,56,57 However, a recent meta-analysis found that BCIs are often not designed on a clear theoretical foundation; for example, only 22.5% of 235 implementation studies explicitly used theories of behaviour change58,59 and the majority of those doing so gave no clear explanation for why the selected theories had been used. Therefore, there is a clear need for improving methods for applying theory to intervention design to increase our understanding of how BCTs exert their influences. Grouping BCTs by theory would help guide understanding of the functional relationships between BCTs, the underlying mechanisms through which they exert their effects and the most effective ways in which BCTs can be applied.

In light of the 93 BCTs of BCTTv1 and the large number of behaviour change theories and component constructs,60 grouping by individual theoretical constructs is impractical. An alternative is to group by broader domains of theoretical constructs (e.g. knowledge, skills, etc.) as has been done in the theoretical domains framework (TDF). 45,61 The TDF is an integrative framework of theoretical constructs of behaviour change that was originally developed by 18 psychological theorists in collaboration with 16 health service researchers and 30 health psychologists. 45 It was developed to make theory more accessible to, and usable by, a range of disciplines and theoretical orientations. The first version of the TDF contains 12 theoretical domains synthesised from 128 theoretical constructs related to behaviour change; the validated version61 suggested minor modifications, with 14 domains.

The TDF has been used by research teams across many countries and health-care systems to investigate implementation problems and inform interventions to change professional practice. 62–72 The TDF was validated using two sort tasks,61 producing a refined TDF containing 87 theoretical constructs relevant to behaviour change categorised across 14 domains: knowledge, skills, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, optimism, beliefs about consequences, reinforcement, intentions, goals, memory, attention and decision processes, environmental context and resources, social influences, and emotion and behavioural regulation. A previous study linking 35 BCTs to 11 theoretical domains from the original TDF showed good reliability across four researchers, with 71% agreement over the 385 possible links. 43 Building on this work, we aim to link BCTs from the more comprehensive BCTTv1 to the refined TDF, using a larger number of experts in behaviour change.

Study 2 aimed to:

-

investigate the hierarchical structure of the groupings of the taxonomy, which were obtained from an inductive ‘bottom-up’ method, using quantitative clustering methods

-

identify to what extent the taxonomy can be reliably grouped using a deductive, ‘top-down’ theory-based method into the 14 theory-based domains of the revised TDF

-

examine similarities and differences in the groupings that emerged using these two methods of developing a hierarchical structure.

Method

This study is also published as Cane et al. 73 Some text has been reproduced from Cane et al. 73 © 2014 The Authors. British Journal of Health Psychology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of the British Psychological Society. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Participants

For the ‘bottom-up’ method, participants were recruited from the pool of behaviour change experts used in study 1 (see Chapter 2) to take part in an online, open-sort grouping task. Eighteen of 19 participants approached from the pool of experts completed the task. Eight were women and 10 men, with an age range of 27–67 years (mean = 43.94 years); 16 were from the UK and two were from Australia.

For the ‘top-down’ method, 25 individuals were invited to take part in the closed-sort task. Participants were eligible to take part if they had (1) experience in designing interventions that specifically used BCTs, (2) experience in writing manuals or protocols of BCIs or (3) undertaken a narrative or systematic review of behaviour change literature. Participants were recruited via announcements through university networks and scientific societies’ mailing lists – the Society of Behavioural Medicine, the American Psychological Association Health Division and the Society for Academic Primary Care. Eighteen people (72%) met the eligibility criteria and all who were eligible consented to complete the task (Table 1 shows demographic information). There was no overlap in participants between the ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ sort tasks. The sample size for the closed-sort task was based on estimates given for content-validation exercises, with 2–24 participants being shown to be sufficient74–77 and more than five participants reducing the influence of rater outliers. 78

| Sort task | Open ‘bottom-up’ | Closed ‘top-down’ |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 43.94 | 40.83 |

| SD | 13.58 | 10.47 |

| Range | 27–67 | 24–63 |

| Gender – number of participants | ||

| Women | 8 | 15 |

| Men | 10 | 3 |

| Country – number of participants | ||

| Australia | 2 | |

| Italy | 1 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | |

| New Zealand | 1 | |

| UK | 16 | 5 |

| USA | 10 |

Procedure

Invitations included a brief overview of the study and participation consent form. Consenting participants were given detailed instructions on how to complete the task and were asked to provide demographic information (including age, sex and nationality) and to rate their expertise in behaviour change theory and in delivering BCIs on a 5-point scale (1 – ‘A great deal’, 2 – ‘quite a bit’, 3 – ‘some’, 4 – ‘a little’, 5 – ‘none’).

Open-sort task: the open-sort grouping task was delivered via an online computer program. Participants were asked to sort the list of BCTs into groupings (up to a maximum of 24) of their choice and label the groupings. Instructions guided the experts to ‘group together BCTs which have similar active ingredients i.e. by the mechanism of change, NOT the mode of delivery’. 73

Closed-sort task: participants sorted BCTs into the 14 domains specified in the revised version of the TDF:61 knowledge, skills, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, optimism, beliefs about consequences, reinforcement, intentions, goals, memory, attention and decision processes, environmental context and resources, social influences, and emotion and behavioural regulation. The closed-sort task was delivered via a Microsoft Word document 1997–2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), comprising labels and definitions of the 14 theoretical domains and of the 87 BCTs from BCTTv1, which were randomly ordered. 40 The closed-sort task was conducted on an earlier version of the taxonomy containing 87 BCTs and the open-sort task an even earlier version containing 85 BCTs. Both were conducted while BCTTv1 was in development. Participants were required to indicate which domain was most relevant for each BCT and give a confidence rating for their allocation. Participants were asked to allocate each of the 87 BCTs to one or more of the 14 theoretical domain(s), giving a confidence rating for each allocation (from 1 – ‘not at all confident’ to 10 – ‘extremely confident’). After assigning all BCTs, participants were asked to review their BCT allocations and to revise any allocations if they wanted to. There was no time limit for the tasks and participants were debriefed about the study on completion.

Analysis

To analyse open-sort data, a binary dissimilarity matrix containing all possible BCT × BCT combinations was produced for each participant, for whom a score of one indicated BCTs that were not sorted into the same grouping, and a score of 0 indicated items that were sorted into the same grouping. Individual matrices were aggregated to produce a single dissimilarity matrix, which could be used to identify the optimal grouping of BCTs using cluster analysis. Using hierarchical cluster analysis, the optimal number of groupings (2–20) were examined for suitability using measures of internal validity (Dunn’s Index) and stability (figure of merit). 79 Bootstrap methods were used in conjunction with the hierarchical cluster analysis, whereby data were resampled 10,000 times, to identify which groupings were strongly supported by the data. The approximately unbiased p-values yielded by this method indicated the extent to which groupings were strongly supported by the data with higher approximately unbiased values (e.g. 95%) indicating stronger support for the grouping. 80 The words and phrases used in the labels given by participants were analysed to identify any common themes and to help identify appropriate labels for the groupings. For each grouping, labels were created based on their content and, when applicable, based on the frequency of word labels given by participants. After the labels were assigned to relevant groupings, the fully labelled groupings with the word frequency analysis were sent out to a subset of five of the original participants for refinement.

To analyse closed-sort data, mean confidence ratings for each BCT × domain pairing were calculated and analysed using DCV methods. 74,77 BCT × domain pairings that had no confidence rating from individual participants (i.e. BCT was not allocated to that domain by that participant) were scored zero and entered into the mean score for that pairing. A series of one-sample t-tests compared the mean confidence ratings for the assignment of BCTs to a value of zero. This established the extent to which BCTs were related to each domain. In cases for which no experts allocated a BCT to a specific domain (i.e. all scores for a BCT × domain pairing were zero) the BCT × domain pairings was excluded from t-test analyses.

The BCTs were considered to be reliably allocated to a domain if their mean confidence ratings were significantly greater than zero (p < 0.05) after Hochberg’s correction81 [applied using the p.adjust function in R version 3.0.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)]. This was used to control for the family-wise error rate, given the large number of tests used, and provided a suitable criterion for inclusion and exclusion of BCTs to a particular domain, over and above the use of a subjective cut-off value. Hochberg’s correction also provides a conservative p-value that makes it less likely that a BCT × domain pairing achieving low confidence ratings across the majority of participants will achieve significance. The agreement of BCT allocation across participants was analysed using a two-way intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) within each domain.

To identify any overlap between groupings, two types of comparisons were made between the ‘bottom-up’ groupings and the ‘top-down’ TDF derived groupings – comparison between the theoretically derived ‘top-down’ groupings and, (1) the higher order strategy groupings found in the ‘bottom-up’ sort task, and (2) the final groupings of the ‘bottom-up’ sort task. To test the possibility of overlap between groupings derived from using ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ methods, Pearson’s chi-squared test was adopted. To adjust for potential inaccuracy of the p-value estimation (resulting from the number of cells that had expected frequencies < 1), Monte Carlo simulation (using 2000 replications) was used. Pearson’s residual values [(observed – expected)/sqrt (expected)] were used to quantify the extent of overlap between individual BCTTv1 grouping × TDF domain pairings resulting from the ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ methods. Positive values indicate that the observed overlap in BCT assignment between the BCT taxonomy and TDF domain pairings is greater than expected by chance whereas negative values indicate that it is less than expected.

Results

Participants for the closed-sort task reported moderately high levels of expertise in behaviour change theory (mean = 3.17, SD = 0.71) and in delivering BCIs (mean = 2.17, SD = 1.38) as measured on 5-point scales (scores are reversed so a higher score indicates more experience). This was not significantly different from the level of expertise reported by participants in the open-sort task: behaviour change theory, mean = 3.00, SD = 0.88, t(34) = 0.64; p > 0.10; BCIs, mean = 2.42, SD = 0.96, t(34) = 0.63; p > 0.10. Although the age of participants did not differ significantly between the two sort tasks [t(34) = 0.77; p > 0.10] the number of female and male participants did [χ2(1) = 4.33; p < 0.05] as did the country of residence (χ2 = 20.76; p < 0.001) (Monte-Carlo simulation using 2000 replicates was used to compute the p-value given that a number of the expected cell values were < 1). This was an artefact of the selection process as there was no duplication of participants across the two sort tasks.

Developing a basic hierarchical structure within Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 using an open-sort task (‘bottom-up’ method)

The BCTs were grouped using an inductive ‘bottom-up’ method based on the similarity of their active ingredients. This process yielded 16 distinct sets of BCTs, as follows (with number of BCTs in parentheses): scheduled consequences (10), reward/threat (7), repetition/replacement (7), antecedents (4), associations (8), covert learning (3), natural consequences (6), feedback and monitoring (5), goals and planning (9), social support (3), comparison of behaviour (3), self-belief (4), comparison of outcomes (3), identity (5), shaping knowledge (4) and adjunctive (4). The hierarchical structure is illustrated using a dendrogram (see Michie et al. 40). The distance between the groupings at each split is indicated by the ‘height’ on the y-axis of the dendrogram, with greater height values indicating greater distance and less similarity between the groupings, and lower height values indicating less distance and greater similarity between the groupings.

Within the reported 16-grouping open-sort solution of the taxonomy, there are six points at which groupings of BCTs split into groupings containing similar BCTs (creating seven split groupings, i.e. higher order strategy groupings). These groupings themselves contain more subtle distinct groupings as detailed in BCTTv1. The first split is at ‘split 1′ (height = 31.78), for which the body of BCTs split into two groupings, the grouping to the left containing the groupings of ‘scheduled consequences’ and ‘reward and threat’ that involve BCTs relating to the anticipation of a direct reward or punishment (e.g. social reward, negative reinforcement, extinction). The next split, ‘split 2’ (height = 14.16) reveals three groupings to the left of the remaining BCTs: ‘repetition and substitution’, ‘antecedents’ and ‘associations’ comprising BCTs relating to cues and cue responses. From split 3 onwards, the distance between the groupings is markedly smaller (height < 10), indicating that the groupings formed are less distinct from each other. At split 3 (height = 9.56) BCTs from the groupings ‘covert learning’ and ‘natural consequences’ are separated off from the remaining groupings. At split 4 (height = 7.69), the split includes the groupings ‘feedback and monitoring’, and ‘goals and planning’ and BCTs relating to goals, planning and feedback. At split 5 (height = 5.55), the split includes the groupings ‘social support’ and ‘comparison of behaviour’ and BCTs related to social factors. The final split occurs at split 6 (height = 4.18), where the groupings ‘self-belief’, ‘comparison of outcome’ and ‘identity’ (BCTs relating to the self and identity) are separated from the groupings of ‘shaping knowledge’ and ‘regulation’ (BCTs relating to knowledge and regulation).

Identifying whether or not behaviour change techniques can reliably be linked to theoretical domains using a closed-sort task (‘top-down’, theoretically driven method)

All TDF domains had BCTs allocated to them in the closed-sort task, with the number of BCTs allocated ranging from 15 for social/professional role and identity to 68 for behavioural regulation (Table 2). This allocation was reliable for 12 of the 14 domains, that is BCTs were allocated consistently with high confidence across experts, leading to p < 0.05 (see Table 2 for frequencies and see Table 4 for confidence ratings, ICC values and related p-values).

| Domain | Number of BCTs allocated | Number of BCTs allocated where p < 0.10 |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 40 | 4 |

| Skills | 44 | 5 |

| Social/professional role and identity | 15 | 0 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | 46 | 2 |

| Optimism | 24 | 1 |

| Beliefs about consequences | 46 | 10 |

| Reinforcement | 45 | 17 |

| Intentions | 27 | 2 |

| Goals | 29 | 5 |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | 49 | 0 |

| Environmental context and resources | 42 | 5 |

| Social influences | 42 | 10 |

| Emotion | 44 | 4 |

| Behavioural regulation | 68 | 1 |

Within these domains, 59 (68%) of the BCTs were considered to be reliably allocated, with a further 12 (14%) BCTs having borderline statistical significance (p > 0.05 but p < 0.1) and six being allocated to multiple domains (Table 3). The domains, in order of number of BCT allocations obtaining statistical or marginal statistical significance, were (numbers of BCTs in brackets): reinforcement (17), beliefs about consequences (10), social influences (10), goals (6), environmental context and resources (6), skills (5), emotion (5), knowledge (4), beliefs about capabilities (2), intentions (2), optimism (1) and behavioural regulation (1). Two domains, ‘social/professional role and identity’ and ‘memory, attention and decision processes’ had no BCTs significantly assigned to them. This indicates that, although both of these domains had BCTs allocated to them during the sort process (15 and 49, respectively), experts did not consistently allocate or rate highly any of the BCTs to these two domains.

| Domain label and associated BCTs | Mean confidence rating | Associated probability | 95% confidence intervals | ICC (p < 0.005) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Knowledge | |||||

| Health consequences | 6.06 | 0.001 | 3.80 | 8.32 | |

| Biofeedback | 3.78a | 0.066 | 1.66 | 5.90 | 0.15 |

| Antecedents | 3.72a | 0.051 | 1.71 | 5.74 | |

| Feedback on behaviour | 3.67a | 0.057 | 1.65 | 5.68 | |

| Skills | |||||

| Graded tasks | 4.89 | 0.014 | 2.62 | 7.16 | |

| Behavioural rehearsal/practice | 4.78 | 0.016 | 2.53 | 7.02 | 0.16 |

| Habit reversal | 4.33 | 0.018 | 2.27 | 6.40 | |

| Body changes | 4.06 | 0.020 | 2.08 | 6.03 | |

| Habit formation | 4.33a | 0.091 | 1.57 | 5.88 | |

| Social/professional role and identity | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.07 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | |||||

| Verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacyb | 5.11 | 0.015 | 2.72 | 7.50 | 0.11 |

| Focus on past success | 4.33 | 0.040 | 2.07 | 6.60 | |

| Optimism | |||||

| Verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacyb | 3.83 | 0.049 | 1.62 | 6.05 | 0.09 |

| Beliefs about consequences | |||||

| Emotional consequencesb | 6.39 | 0.0001 | 4.48 | 8.30 | |

| Salience of consequences | 5.67 | 0.005 | 3.33 | 8.01 | |

| Covert sensitisation | 4.56 | 0.016 | 2.43 | 6.68 | |

| Anticipated regret | 4.44 | 0.018 | 2.34 | 6.55 | |

| Social and environmental consequences | 4.28 | 0.041 | 2.05 | 6.51 | 0.22 |

| Comparative imagining of future outcomes | 4.17 | 0.041 | 1.99 | 6.34 | |

| Vicarious reinforcement | 4.00a | 0.092 | 1.69 | 6.31 | |

| Threatb | 4.06 | 0.023 | 2.08 | 6.03 | |

| Pros and cons | 3.67a | 0.078 | 1.60 | 5.73 | |

| Covert conditioning | 3.50 | 0.041 | 1.68 | 5.32 | |

| Reinforcement | |||||

| Threatb | 6.78 | 0.00006 | 4.86 | 8.70 | |

| Self – reward | 5.50 | 0.006 | 3.20 | 7.80 | |

| Differential reinforcement | 5.33 | 0.014 | 2.88 | 7.79 | |

| Incentive | 5.39 | 0.008 | 3.06 | 7.72 | |

| Thinning | 5.28 | 0.008 | 2.99 | 7.56 | |

| Negative reinforcement | 5.28 | 0.008 | 3.00 | 7.56 | |

| Shaping | 5.06 | 0.017 | 2.67 | 7.44 | |

| Counter conditioning | 5.17 | 0.010 | 2.89 | 7.44 | 0.28 |

| Discrimination training | 5.06 | 0.012 | 2.77 | 7.34 | |

| Material reward | 4.89 | 0.024 | 2.48 | 7.30 | |

| Social rewardb | 4.94 | 0.015 | 2.65 | 7.24 | |

| Non-specific reward | 4.89 | 0.019 | 2.55 | 7.23 | |

| Response cost | 4.94 | 0.011 | 2.74 | 7.15 | |

| Anticipation of future rewards or removal of punishment | 4.67 | 0.022 | 2.40 | 6.94 | |

| Punishment | 4.56 | 0.025 | 2.30 | 6.81 | |

| Extinction | 4.33 | 0.018 | 2.28 | 6.39 | |

| Classical conditioning | 3.89a | 0.078 | 1.69 | 6.09 | |

| Intentions | |||||

| Commitment | 4.44 | 0.022 | 2.14 | 6.75 | 0.13 |

| Behavioural contract | 3.56a | 0.064 | 1.45 | 5.66 | |

| Goals | |||||

| Goal-setting (outcome) | 6.50 | 0.0007 | 4.13 | 8.87 | |

| Goal-setting (behaviour) | 5.50 | 0.008 | 2.98 | 8.02 | |

| Review of outcome goal(s) | 5.06 | 0.011 | 2.67 | 7.44 | 0.23 |

| Review behaviour goals | 4.28a | 0.057 | 1.82 | 6.74 | |

| Action planning (including implementation intentions) | 4.39 | 0.026 | 2.10 | 6.68 | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.22 |

| Environmental context and resources | |||||

| Restructuring the physical environment | 6.33 | 0.001 | 4.03 | 8.64 | |

| Discriminative (learned) cue | 5.33 | 0.006 | 3.06 | 7.61 | |

| Prompts/cues | 5.17 | 0.005 | 2.97 | 7.36 | 0.04 |

| Restructuring the social environmentb | 4.33 | 0.037 | 2.08 | 6.59 | |

| Avoidance/changing exposure to cues for the behaviour | 3.67a | 0.076 | 1.58 | 5.75 | |

| Social influences | |||||

| Social comparison | 6.11 | 0.001 | 3.86 | 8.36 | |

| Social support or encouragement (general) | 6.11 | 0.001 | 3.88 | 8.34 | |

| Information about others’ approval | 5.72 | 0.005 | 3.35 | 8.097 | |

| Social support (emotional)b | 5.50 | 0.004 | 3.23 | 7.77 | |

| Social support (practical) | 5.00 | 0.013 | 2.68 | 7.32 | |

| Vicarious reinforcement | 4.89 | 0.013 | 2.63 | 7.15 | |

| Restructuring the social environmentb | 4.67 | 0.013 | 2.50 | 6.84 | 0.19 |

| Modelling or demonstrating the behaviour | 4.44 | 0.014 | 2.37 | 6.52 | |

| Identification of self as role model | 4.22 | 0.040 | 2.00 | 6.44 | |

| Social rewardb | 3.89a | 0.088 | 1.63 | 6.14 | |

| Emotion | |||||

| Reduce negative emotions | 5.06 | 0.014 | 2.71 | 7.40 | |

| Emotional consequencesb | 5.11 | 0.007 | 2.90 | 7.32 | |

| Self-assessment of affective consequences | 4.78 | 0.016 | 2.52 | 7.04 | 0.03 |

| Social support (emotional)b | 3.94a | 0.061 | 1.77 | 6.12 | |

| Behavioural regulation | |||||

| Self-monitoring of behaviour | 4.50 | 0.022 | 2.39 | 6.61 | 0.32 |

Of the 24 most commonly occurring BCTs (see Michie et al. 40), 18 (75%) were reliably linked to seven of the theory domains, with a further two (8%) obtaining borderline statistical significance. These domains were (with number of BCTs in brackets): goals (5), social influences (4), environmental context and resources (3), knowledge (2), reinforcement (2), skills (1), and behavioural regulation (1). The following commonly identified BCTs were not linked to any of the theoretical domains: problem-solving, credible source, discrepancy between current behaviour, self-monitoring of outcome of behaviour, monitoring of outcome behaviour by others without feedback and pharmacological support.

Identifying overlap between the ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ groupings

The chi-squared analyses used for the grouping comparisons did not allow us to include domains in which no BCTs were assigned (i.e. not linked to domains through the DCV process); therefore, the domains of memory, attention and decision processes, and social/professional identity were excluded from these analyses. An additional grouping of ‘No domain’ was included in the ‘top-down’ groupings and represented cases for which BCTs included in BCTTv1 were not assigned to any TDF domain. Therefore, the chi-squared analysis was conducted first on 91 (7 × 13) possible pairings for the seven higher-order ‘bottom-up’ sorting strategy groupings and the 13 ‘top-down’ groupings, and second on 208 (16 × 13) possible pairings derived from the original 16 BCTTv1 ‘bottom-up’ groupings and the 13 ‘top-down’ groupings.

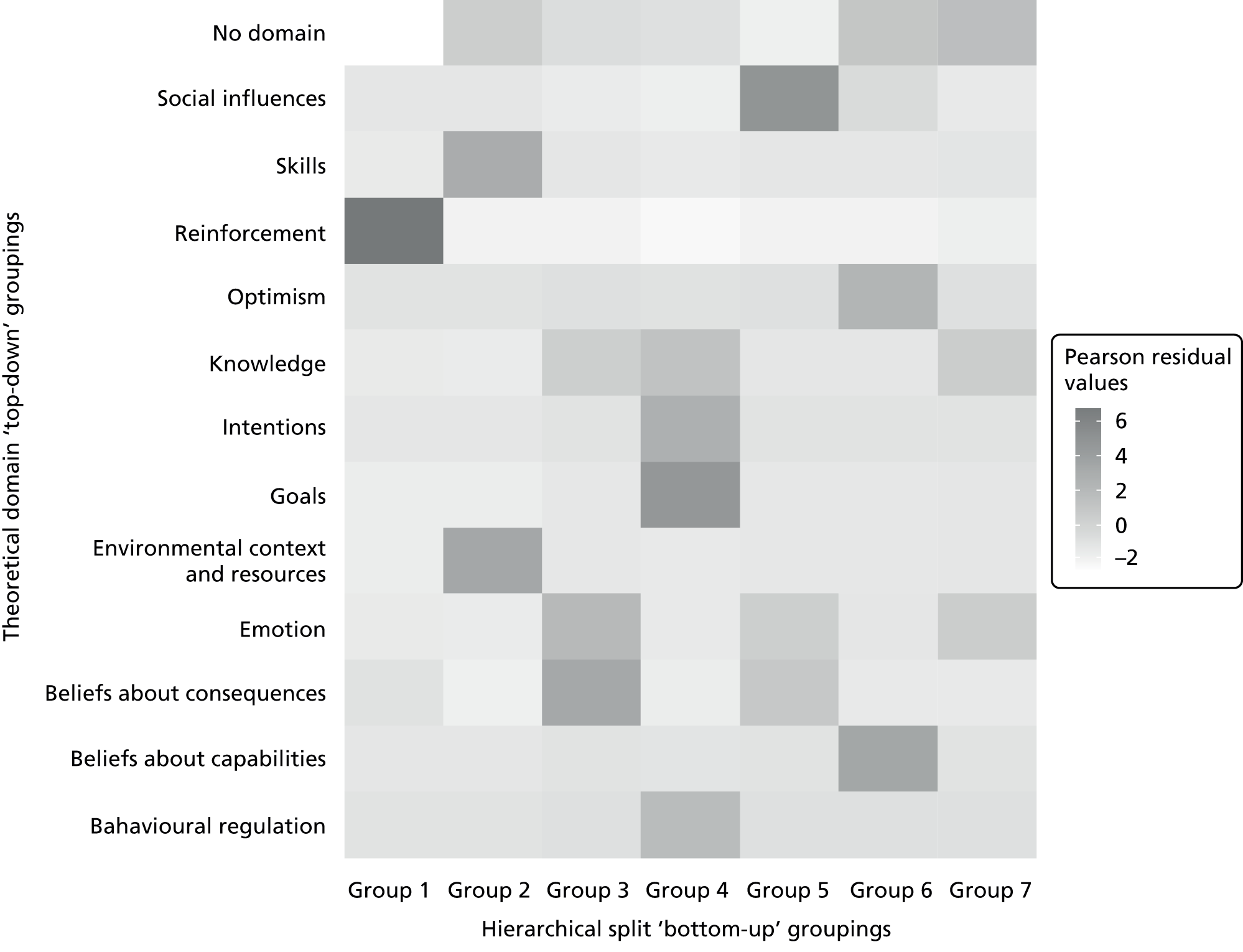

Comparison of the BCT groupings derived from the higher-order ‘bottom-up’ sorting strategies, shown in the dendrogram and the ‘top-down’ TDF derived groupings (see Table 3) revealed a significant association (χ2 = 236.13; p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the level of overlap between each of the grouping × TDF pairings within each cell (Pearson’s residual value range –2.10 to 6.61).

FIGURE 2.

Pearson’s residual values for the association between BCT allocation to ‘top-down’ theoretical domain groupings and the ‘bottom-up’ higher-order hierarchical split groupings. Note: ‘No domain’ indicates BCTs contained within a ‘bottom-up’ higher-order grouping not assigned to any TDF domain. Reproduced from Cane et al. 73 © 2014 The Authors. British Journal of Health Psychology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of the British Psychological Society. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Twenty one of the 91 ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ TDF domain combinations showed a greater than expected overlap with positive Pearson’s residual values (Table 4). Only two combinations achieved Pearson’s residual values > 5, which were: ‘grouping 1′ with ‘reinforcement’ (Pearson’s residual value = 6.61) and ‘grouping 5′ with ‘social influences’ (Pearson’s residual value = 5.04).

| Taxonomy grouping | TDF domain | Pearson’s residual value |

|---|---|---|

| Repetition and substitution | Skills | 6.66 |

| Goals and planning | Goals | 6.41 |

| Covert learning | Beliefs about consequences | 5.76 |

| Self-belief | Beliefs about capabilities | 5.70 |

| Scheduled consequences | Reinforcement | 5.22 |

| Antecedents | Environmental context and resources | 5.20 |

| Comparison of behaviour | Social influences | 4.96 |

| Social support | Social influences | 4.14 |

| Reward and threat | Reinforcement | 4.10 |

| Goals and planning | Intentions | 4.05 |

| Feedback and monitoring | Behavioural regulation | 4.03 |

| Self-belief | Optimism | 4.03 |

| Feedback and monitoring | Knowledge | 3.80 |

| Comparison of outcomes | Beliefs about consequences | 3.68 |

| Natural consequences | Emotion | 3.05 |

| Associations | Environmental context and resources | 2.35 |

| Regulation | Emotion | 1.97 |

| Shaping knowledge | Knowledge | 1.97 |

| Social support | Emotion | 1.97 |

| Identity | No domain | 1.83 |

| Regulation | No domain | 1.46 |

| Shaping knowledge | No domain | 1.46 |

| Associations | No domain | 1.45 |

| Natural consequences | Knowledge | 1.25 |

| Antecedents | Social influences | 0.72 |

| Identity | Social influences | 0.72 |

| Natural consequences | Beliefs about consequences | 0.63 |

| Natural consequences | No domain | 0.46 |

| Repetition and substitution | No domain | 0.46 |

| Reward and threat | Beliefs about consequences | 0.37 |

| Feedback and monitoring | No domain | 0.27 |

| Self-belief | No domain | 0.27 |

| Reward and threat | Social influences | 0.12 |

| Comparison of outcomes | No domain | 0.01 |

There was also an association between the 16 ‘bottom-up’ groupings and the 13 ‘top-down’ groupings (χ2 = 437.80; p < 0.001). Figure 3 shows the level of overlap between structures; Pearson’s residual values range from –1.72 to 6.66. Thirty six of the 208 combinations showed greater than expected overlap, achieving positive Pearson’s residual values (see Table 4). Six combinations achieved Pearson’s residual values > 5 indicating a comparatively high level of overlap and these combinations were ‘repetition and substitution’ and ‘skills’ (Pearson’s residual value = 6.66), ‘goals and planning’ and ‘goals’ (Pearson’s residual value = 6.41), ‘covert learning’ and ‘beliefs about consequences’ (Pearson’s residual value = 5.76), ‘self-belief’ and ‘beliefs about capabilities’ (Pearson’s residual value = 5.70), ‘scheduled consequences’ and ‘reinforcement’ (Pearson’s residual value = 5.22), and ‘antecedents’ and ‘environmental context and resources’ (Pearson’s residual value = 5.20).

FIGURE 3.

Pearson’s residual values for the association between BCT allocation in ‘top-down’ theoretical domain groupings and ‘bottom-up’ groupings. Note: ‘No domain’ indicates BCTs within a ‘bottom-up’ BCTTv1 grouping not assigned to any domain. Reproduced from Cane et al. 73 © 2014 The Authors. British Journal of Health Psychology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of the British Psychological Society. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Discussion

Examination of the hierarchical structure of BCTTv1 uncovered a ‘higher-order’ grouping strategy taken by the behaviour change experts in the ‘bottom-up’ task and the dendrogram indicates that some groupings of BCTs within the 16-grouping solution can be considered as more clearly distinct from others. The grouping of BCTs in the ‘top-down’ sort task has helped illuminate relationships between particular BCTs and theoretical domains and could aid the selection of BCTs in the construction of theory-based interventions. There was a moderate overlap between the 16 BCT groupings derived from the ‘bottom-up’ inductive approach and the 12 groupings from the ‘top-down’ theoretically driven approach, indicating some common conceptualisation of BCTs across these two approaches. These findings may help to further our understanding of the relationships between BCTs and enable researchers to use common BCT grouping labels to discuss individual, or groupings of, BCTs in behaviour change research.

The grouping methods employed in the ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ sort tasks improve on previous attempts to group BCTs using consensus approaches. First, use of an open-sort grouping task allowed for the individual groupings of BCTs defined by participants to hold equal weight within the final solution and be aggregated using empirical techniques (hierarchical cluster analysis in the ‘bottom-up’ sort task and DCV methods in the ‘top-down’ sort task). As a result, the groupings reported here are potentially more robust than those derived using consensus methods among a few people. 43

A second advance was that a comprehensive, cross-behavioural domain taxonomy of BCTs was used rather than BCTs relevant for a single behavioural domain (e.g. road safety,82 smoking cessation,32 weight management83). Third, the BCTs were grouped according to the perceived active ingredients underlying BCTs, rather than by categorisations that may not have reflected how people think about BCTs.

In addition to providing 16 groupings, the ‘bottom-up’ open-sort task yielded systematic empirical estimates of how distinct the groupings are. Examination of this hierarchical structure revealed that BCTs related to reward and threat, and those related to cues and cue responses, were conceptualised quite distinctly from the other BCTs. The least distinct groupings (i.e. ‘social support’, ‘comparison of behaviour’, ‘self-belief’, ‘comparison of outcome’ and ‘identity’) comprised BCTs relating to social support, social comparisons, and self and identity, suggesting that there is less clarity about the BCTs within these theoretical domains. Four further groupings of BCTs (‘covert learning’ and ‘natural consequences’, and ‘feedback and monitoring’ and ‘goals and planning’) lay between these most distinct and least distinct groupings. BCTs in distinct groupings are clearly perceived to share a common mode of action in changing behaviour whereas BCTs in less distinct groupings may be viewed as having less distinct or more than one mode of action.

This difference in distinctiveness not only has implications for understanding how BCTs are conceptualised by behaviour change experts but also has implications for the practical use of BCTTv1 in behaviour change research. For example, the groupings increase the practical use of BCTs by aiding recall. Distinct sets of individual items with semantic similarity can be more easily recalled than a single list of individual items both in the short term and long term, particularly when the semantic category is cued. 84–86 This is especially useful when quick reference to BCTs is necessary, for instance when coding descriptions of interventions or in choosing BCTs to develop or report a BCI. Therefore, in those cases where the groupings are less distinct, adopting additional strategies to aid recall the groupings may be of particular advantage.

The ‘top-down’ mapping of BCTs to theoretical domains advances the limited consensus methods used by Michie et al. 43 by using an improved BCT taxonomy, an empirically validated TDF and a larger number of respondents. In this ‘top-down’ task, 59 out of 87 BCTs were reliably allocated to one or more of the TDF domains with a further 12 BCTs having borderline statistical significance. Thirty-seven BCTs were allocated to three domains that also had high confidence ratings and ICCs: ‘beliefs about consequences’, ‘reinforcement’ and ‘social influences’. This suggests that these are the theoretical domains for which there is the greatest number of agreed methods for bringing about change. Other domains also showed high agreement but had fewer associated BCTs – ‘behavioural regulation’ had only one assigned BCT but achieved good agreement, while ‘goals’ had five BCTs assigned with good agreement. In designing interventions, it may be more important to have a few agreed BCTs than to have a large choice of BCTs available to target change in a given theoretical determinant of behaviour. Further evidence is required to ensure that these ‘agreed’ BCTs do in fact achieve behaviour change by changing the proposed theoretical domain. For the two theoretical domains for which no BCTs were reliably assigned, there would appear to be no shared, or recognised, way of changing them.

Most of the commonly used BCTs were associated with a theoretical domain. Of the 24 most frequently identified BCTs in Michie et al. ,40 18 were clearly grouped into one of the 14 domains and the remaining seven BCTs were not reliably allocated to any domain even though they could be identified reliably in the intervention descriptions. This finding suggests that these BCTs may have evolved from several different behavioural domains, theoretical approaches or disciplines and, therefore, may be less associated with a particular theoretical domain.

Comparison of open and closed-sort tasks

Six of the open-sort tasks groupings, ‘repetition and substitution, ‘goals and planning’, ‘covert learning’, ‘self-belief’, ‘scheduled consequences’ and ‘antecedents’, showed a high level of overlap with the BCTs assigned to the equivalent TDF domains, suggesting that experts may have sorted BCTs by theoretical constructs or domains (implicitly or explicitly) across both tasks. This is supported by the fact that both groups of experts reported high levels of expertise in relation to behaviour change theory. For the higher-order groupings created by the top-down task, there were only two similarly strong overlaps with the BCTs allocated to the equivalent TDF domains indicating that the relationship between higher-order sorting strategies and theoretically derived groupings is not strong. It would appear that the lower-level groupings are more in line with the TDF domains than the empirically higher-order groupings, suggesting that the higher-level grouping shared by respondents does not align as well with the theoretical domains. It may be that the higher-order groupings of BCTs depended on considerations other than theory, for example target populations or behaviours.

The next step for this line of research is to evaluate the extent to which these groupings facilitate the usability of the taxonomy, and to do this for larger sample sizes and a greater disciplinary and geographical spread. It may be that different groupings may be useful for different tasks (e.g. identifying BCTs in reports of interventions vs. designing interventions) and/or be beneficial to different users in different contexts. It may be that for those applying BCTs to designing or specifying interventions without reference to theory, the open-sort groupings may be of more benefit as all of the BCTs were grouped. On the other hand, the closed-sort grouping of BCTs is likely to be more useful for those who are seeking a theoretical base for coding and designing interventions. Further work will be necessary to investigate the replicability and utility of these groupings, as well as their theoretical basis. As more evidence is gained from the application of BCTTv1, it may be that the BCT groupings will be modified to incorporate links between BCTs that are commonly used together in research practice and/or to reflect the ‘common mechanisms of action.’

The hierarchical structure and grouping of BCTs within the taxonomy has practical use in that it is predicted to increase the speed by which BCTs can be recalled by users. It also has theoretical interest in that links between BCTs and theory can be used to inform the design and evaluation of BCIs. Although BCTTv1 represents an advance in methods for specifying BCIs, reliable and valid application of BCTTv1 will require skills and, therefore, training. To investigate how best to train the skills of using BCTTv1, two programmes of user training were developed (face-to-face workshops and distance group tutorials). The next study reports the development and evaluation of these training programmes.

Phase 2: evaluation

Chapter 4 Training to code intervention descriptions using Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 (study 3)

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate two programmes of user training in improving reliable, valid and confident application of BCTTv1 to code BCTs in descriptions of BCIs.

Methods: 161 trainees (109 in face-to-face workshops and 52 in distance group tutorials) were trained to code frequently occurring BCTs. Training was evaluated by comparing three measures before and after training: (1) intercoder agreement, (2) trainee agreement with expert consensus and (3) confidence ratings. Coding was assessed for 12 BCTs in workshops and for 17 BCTs in tutorials. Trainees also completed a course evaluation.

Results: Workshop and tutorial training improved trainee agreement with expert consensus [workshops: mean prevalence- and bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) before training = 0.39, after training = 0.50; tutorials: mean PABAK score = 0.57, after training = 0.72; both p < 0.05] but not intercoder agreement (p = 0.08 and p = 0.57, respectively) and increased confidence ratings for BCTs assessed in workshops (mean number of assessed BCTs, identified with high confidence before training = 8.38, after training = 9.56; p < 0.001). Training was evaluated positively by trainees; all components of both types of training were highly rated in terms of usefulness.