Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/151/03. The contractual start date was in August 2013. The draft report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in March 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Pamela Enderby undertakes advisory work for the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Baxter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Stuttering is a complex disorder that may encompass social and emotional elements. It may comprise overt stuttering behaviours that may be apparent to a listener (such as the repetition of the beginning sound of a word or blocking in which a word appears to get stuck while being articulated). Stuttering also may encompass covert behaviours that may be undetectable to a listener, such as avoidance of particular words or situations. Despite many years of research, there is no certainty regarding the cause of stuttering, although differences in brain structure and functioning in people who stutter have been identified. Over time, those who stutter often develop a salient fear of speaking that becomes a deep-rooted obstacle impeding a person’s social and vocational opportunities. 1

Treatments for stuttering (which is more often known as stammering in the UK) have been available for children and adults since the 1950s. These treatments have encompassed diverse techniques from the use of carbon dioxide, or pharmacological interventions, to those that are behaviourally based. Recent interventions have begun to place a growing emphasis on negative cognitions and related anxiety with regard to stuttering in adults, and on related temperament issues in children and young people. Although many treatments exist, there remains little agreement as to which should be used and when. 2 In children, there is also a lack of consensus regarding when an intervention should begin as there is the complication of a high percentage of young children described as having transient stuttering recovering spontaneously. 3

In young children, treatment may involve combinations of indirect approaches that aim to modify the environment via parents and thereby have an impact on fluency, attitudes, feelings, fears and language, or direct approaches that involve working with the child to change individual speech behaviours. The use of indirect rather than direct approaches distinguishes treatment for stuttering in young children from those used for older children and adult interventions. Historically, there have been two broad philosophies within the field, with a distinction between stuttering modification approaches (stutter more fluently), which aim to reduce avoidance behaviours and negative attitudes and thereby modify stuttering episodes, and fluency-shaping approaches (speak more fluently), which teach new and controlled speech production patterns. These more fluent patterns are learned in formal practice sessions before gradually being generalised to normal conversational settings with these interventions seeking to achieve complete fluency for the people who stutter. These approaches to intervention may have become less defined in current practice, with interventions commonly drawing on a range of influences.

A number of new approaches for treating stuttering have become available in recent years, including the Lidcombe Program (LP), the McGuire Program, the Camperdown Program and also the use of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) based approaches. These interventions may be offered by a growing range of private providers in addition to interventions available via state-funded therapy services. A range of criticisms of these interventions for people who stutter have been voiced. Fluency-shaping approaches have been criticised for leading to unnatural sounding speech with difficulty implementing the techniques in certain situations, and methods that aim to modify stuttering episodes have been criticised for offering only short-term benefit. Both of these approaches have been criticised as offering limited effectiveness owing to the propensity for relapse among people who have completed programmes. 1 In addition to these programmes, the use of mechanical delayed auditory feedback (DAF) devices has been reported to have some success in reducing stuttering. However, there are concerns that these positive outcomes may occur predominantly when reading aloud, rather than in normal conversational interactions. 4

Although there has been a considerable growth in the range of interventions available to people who stutter, it has been highlighted that there is a need for greater use of evidence-based approaches. 3 A recent review of interventions for adults who stutter concluded that, although there was some evidence that fluency-shaping approaches may have the most robust outcomes, no single treatment is able to achieve successful outcomes with all participants. 5 Much of the review evidence to date has evaluated only behavioural programmes, which may be because they tend to have objective measures of effectiveness (i.e. reduction in overt stuttering episodes). There has been less examination of treatments that use outcome measures other than stuttering frequency. Primary research using a broader range of outcome measures is likely to use non-controlled study designs and, thus, be excluded from many systematic reviews.

The growing range of available treatment options for children and adults who stutter presents a challenge for clinicians, service managers and commissioners who need to have access to the best available treatment evidence to guide them in providing the most appropriate interventions. 2 Core outcomes for stuttering have not been established and there is considerable debate within the field regarding what a ‘good’ outcome from intervention should be. Proponents of fluency-shaping approaches use measures such as the number of stutters occurring per sentence, or the percentage of words spoken fluently. However, there are increasing calls to consider the outcome from the perspective of the person who stutters, with use of measures of self-perception, satisfaction with the intervention and well-being. These approaches consider effectiveness in terms of psychological change rather than solely greater spoken fluency.

Research questions

Specific aims of the study were:

-

To systematically identify, appraise and synthesise international evidence on the clinical effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to treat stuttering in pre-school children, school aged children, adolescents and adults.

-

To determine how applicable this evidence might be to the UK context, including identifying perceptions of staff and people who stutter regarding potential obstacles to successful outcomes following intervention.

The objective was to present a synthesis which outlines international evidence on interventions for stuttering including recommendations regarding which are most likely to be effective and produce a broad and long-term impact.

The review addressed the following research questions:

-

What are the effects of non-pharmacological interventions for developmental stuttering on communication and/or the well-being of children, adolescents and adults who stutter?

-

What are the factors that may enhance or militate against successful outcomes following intervention?

The patient group

The patient group considered in this review is people who have a stutter (and/or clutter) of developmental origin. The patient group included any age.

The intervention

The interventions defined in this review were any interventions that have the stated purpose of having beneficial outcomes for people who stutter.

Comparator

Interventions that have any comparator group of participants, or those interventions that have no comparator, were included.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were any outcomes that were considered to be of benefit for people who stutter in enhancing their communicative interactions or well-being.

How this study has changed from protocol

The study was completed with two very minor changes to the protocol. First, the original protocol had stated that we would exclude support group interventions. Although we found no studies that met our inclusion criteria and reported this type of intervention in isolation, we found literature that included this element as part of a programme of intervention. The patient and public members of our steering group also emphasised the potentially important role of support groups for people who stutter; therefore, this exclusion criterion was removed from the protocol. The second change related to consideration of outcomes that were eligible for inclusion. The original protocol placed no exclusions on the types of outcome that would be considered in the review. However, during the identification phase we identified a small quantity of literature carried out in laboratory conditions that reported stuttering behaviours only when reading aloud, with no measure of spoken interaction. As these data did not relate to functional speech (speech for the purposes of communication) we clarified the inclusion criteria for the review as being studies reporting beneficial outcome for communicative interaction or well-being.

Chapter 2 Methods

A number of reviews of interventions for specific populations or a specific type of intervention have been carried out in the field of stuttering; however, a broad-based systematic review across all forms of intervention for adults and children was needed. We adopted a review method that was able to combine multiple data types to produce a broad evidence synthesis. We believe that this approach was required to best examine the international evidence on interventions and ascertain whether or not, and how, these interventions would be best applied in a UK context in order to inform future guidelines and the implementation of effective treatments in the NHS.

Development of the review protocol

A review protocol was developed prior to beginning the study. The protocol outlined the research questions and detailed methods for carrying out the review in line with guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 6 The protocol encompassed methods for identifying research evidence; the method for selecting studies; the method of data extraction; the process of assessing the methodological rigour of included studies; and synthesis methods. The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database number CRD42013004861.

Involvement of patients and the public

People who stutter, a charity for stuttering and also health professionals working in the field were involved in development of the review protocol. The advisory group for the project also had representation from these groups in order to provide advice regarding potential sources of data during the searching phase of the work and later in the process in order to assist the team in understanding and interpreting the review findings. The representation on the advisory group of patient and public members was also valuable in terms of identifying avenues for dissemination and translating the key messages of the work for a lay audience.

Identification of studies

Search strategies

A systematic and comprehensive literature search of key health, medical and linguistic databases was undertaken in August 2013 to February 2014. The searching process aimed to identify studies that reported the clinical effectiveness of interventions for people who stutter and also studies that reported the views and perceptions of people who stutter and staff regarding interventions. Searching was carried out for both reviews in parallel, with allocation to either effectiveness or qualitative reviews at the point of identification and selection of studies for potential inclusion. The search process was recorded in detail with lists of databases searched, date search run, limits applied, number of hits and duplication as per PRISMA guidelines. 7 The search strategy is presented in Appendix 1.

The search involved combining terms for the population (stuttering) with terms for the interventions of interest, that is, non-pharmacological interventions. This highly sensitive search strategy (i.e. not using terms for comparators, outcomes or study design) was possible because scoping searches retrieved relatively small and manageable numbers of citations. The aim of the strategy was to identify all studies on non-pharmacological interventions for stuttering.

The search strategy was developed by the information specialist on the team (Anna Cantrell) who undertook electronic searching using iterative methods to create a database of citations using Reference Manager version 12 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). The search followed a process whereby search terms were developed initially from scrutinising relevant review articles, followed by scrutinising retrieved papers to inform further searching.

The first main project search was run on MEDLINE (via Ovid) and PsycINFO (via Ovid) in August 2013. Following minor amendments to the search terms, a further iteration of the search was then conducted on a larger range of databases in October to November 2013. Topic experts and clinicians in the field were consulted for additional search terms and for suggestions of additional relevant studies or interventions at regular advisory group meetings and at a clinician workshop session.

In addition to standard electronic database searching, later in the project (February 2014) citation searching was undertaken for all included qualitative citations and searches were conducted for additional papers by the first authors of all included qualitative studies. In order to ensure that the most up-to-date literature was not missed, we also conducted hand screening of journals in April 2014 to identify any work published since the main searches had been carried out. The journals that we searched by hand were International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders; Journal of Speech and Hearing Research; Journal of Communication Disorders; Asia Pacific Journal of Speech Language and Hearing; Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics; Journal of Fluency Disorders; and International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology.

Sources searched

The following electronic databases were searched for published and unpublished research evidence from 1990 onwards.

First search iteration

-

MEDLINE (via OvidSP).

-

PsycINFO (via OvidSP).

Second search iteration

-

EMBASE (via OvidSP).

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCOhost).

-

The Cochrane Library (Wiley) including the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment and NHS Economic Evaluation Database databases.

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest).

-

Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts LLBA (ProQuest).

-

Science Citation Index (Web of Science).

-

Social Science Citation Index (Web of Science).

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Web of Science).

-

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest).

-

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre databases.

All citations were imported into Reference Manager and duplicates deleted prior to scrutiny by members of the team.

Search restrictions

Searches were limited by date (1990 to present) as the advent of new programmes may have led to changed practice and the review was aiming to synthesise the most up-to-date evidence. This date criterion was set as it marked a major change in interventions for stuttering associated with publication of the first papers reporting the Lidcombe Approach, with the field from this date forward addressing the need for more public evidence for effectiveness. The review thus encompassed nearly 25 years of research.

The searches did not set an English-language restriction. Although we intended that the review would be predominantly limited to work published in English to ensure that papers were relevant to the UK context, we aimed to search for and include any additional key international papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

-

The population eligible for inclusion was a person who stutters of any age. This included those with overt stuttering behaviours such as repetition of syllables or blocking, those with covert behaviours such as word avoidance and also those diagnosed with any other disorder of developmental fluency such as cluttering.

-

The review excluded people with a fluency disorder which had been acquired rather than developmental, such as non-fluency associated with an identified neurological impairment (such as head injury, stroke or Parkinson’s disease).

-

We included studies whose participants were described as being clutterers. Although cluttering is considered a distinct disorder from stuttering, it is recognised in the field that it may be challenging to differentially diagnose, and can also co-occur with stuttering. Therefore, we took the decision to search for and include any literature meeting our criteria, which examined interventions for this population. However, this work would be highlighted in the results as a separate population group.

-

The review excluded papers reporting interventions for children who have been defined as having normal non-fluency by the authors of the source study.

-

The qualitative review considered studies reporting the views and perceptions of interventions for stuttering. The population was people who stutter, their relatives, friends or significant others, together with the views of staff delivering interventions.

Interventions

-

The review included any intervention that had the stated aim of being of benefit to people who stutter. This could be by either reducing the frequency of occurrence of behaviours (overt and/or covert), or by aiming to address communication and/or social restrictions.

-

Non-pharmacological interventions were included.

-

Interventions delivered in any setting by any agent were included. This encompassed treatments provided as part of state-funded health service provision, those offered by private providers and interventions delivered by charitable or voluntary organisations.

-

The review excluded interventions that are pharmacological.

-

The review excluded interventions that do not have the stated aim of improving fluency outcomes, for example general relaxation or massage sessions, or the provision of information about stuttering.

Comparators

-

Studies with any comparator including an alternative intervention, no intervention or usual practice were eligible for inclusion. This included studies that compared pharmacological to non-pharmacological intervention.

-

Studies comparing pharmacological intervention to no intervention were excluded.

Outcomes

-

Any outcome relating to a positive effect on the communication or emotional well-being of people who stutter was included.

-

Relevant outcome measures included test scores on a standardised assessment such as frequency of non-fluent words; patient self-report of covert stuttering; patient experience; report of frequency of stuttering from a significant other such as a teacher or employer; and patient or staff views and perceptions of obstacles to intervention effectiveness.

-

Outcomes related to reading aloud only, rather than any measure of communicative interaction were excluded.

Study design

-

The review included designs which may be termed randomised controlled trials (RCTs), randomised cross-over trials, cluster randomised trials, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, before-and-after/longitudinal studies, case–control studies and non-survey cross-sectional studies.

-

Case reports (a single participant), case series (defined as reporting data from two or three participants) and survey (questionnaire) study designs were excluded.

-

The qualitative review examined studies that reported the views of people who stutter or staff perceptions. Any qualitative method was eligible for inclusion (such as interviews and focus groups). Non-qualitative data collection methods such as questionnaire/survey designs were excluded.

Other inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

The review included studies from any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country, thus studies from non-OECD countries were excluded.

-

Studies published in English and key studies published in other languages were included. Studies published in languages other than English without an English abstract were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English which had English abstracts were considered; however, only those considered to be key studies that may add significantly to the review (based on the information in the abstract) were eligible for translation and inclusion.

-

Grey literature (unpublished evaluations) from the UK was eligible for inclusion.

Selection of papers

Citations retrieved via the searching process were uploaded to a Reference Manager database. This database of study titles and abstracts was independently screened by two reviewers and disputes resolved by consulting other team members. This screening process entailed the systematic coding of each citation according to its content. Codes were applied to each paper based on a categorisation developed by the team from previous systematic review work. The coding included categorising papers falling outside of the inclusion criteria (e.g. excluded population, excluded design, excluded intervention) and citations potentially relevant to the clinical effectiveness review and those potentially relevant to the qualitative review.

Full-paper copies of all citations coded as potentially relevant were then retrieved for systematic screening. Papers excluded at this full paper screening stage were recorded and detail regarding the reason for exclusion was provided.

Data extraction strategy

Studies that meet the inclusion criteria following the selection process above were read in detail and data extracted. An extraction form was developed using the previous expertise of the review team, to ensure consistency in data retrieved from each study. The data extraction form recorded authors, date, study design, study aim, study population, comparator (if any) and details of the intervention (including who provided the intervention, type of intervention and dosage). Three members of the research team carried out the data extraction. Data for each individual study were extracted by one reviewer and in order to ensure rigour, each extraction was checked against the paper by a second member of the team.

Quality appraisal strategy

Quality assessment is a key aspect of systematic reviews in order to ensure that poorly designed studies are not given too much weight, so as not to bias the conclusions of a review. As the review included a wide range of study designs, this had an impact on the tool that we selected. Quality assessment of the clinical effectiveness studies was based on the Cochrane criteria for judging risk of bias. 8 This evaluation method classifies studies in terms of sources of potential bias within studies: selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias and reporting bias. As the assessment tool used within this approach is designed for randomised controlled study designs, we adapted the criteria to make them suitable for use across wider study designs, including observational as well as experimental designs. We anticipated that using controlled designs would be challenging for this literature (particularly owing to the ethical issue of withholding treatment).

Therefore, we aimed to use an appraisal tool that would provide a detailed examination of quality elements across the literature, which would enable the study conclusions to go beyond reporting that higher-quality controlled research designs were needed. In order to focus our evaluation, we also identified aspects within the risk of bias criteria that related particularly to the stuttering literature. These included the use of in-clinic versus real-life situation speech data and the process of collecting and evaluating the speech sample data (Table 1).

| Potential risk of bias | Bias present? | Detail of concerns |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Selection bias Method used to generate the allocation sequence, method used to conceal the allocation sequence, characteristics of participant group/s Consider: sample size (> or < 10), recruitment process, any issues with participants |

Yes/no/unclear | |

| 2. Performance bias Measures used to blind participants and personnel and outcome assessors, presence of other potential threats to validity Consider: blinding of assessment of speech data, any other concerns |

Yes/no/unclear | |

| 3. Attrition bias Incomplete outcome data, high level of withdrawals from the study |

Yes/no/unclear | |

| 4. Detection bias Accuracy of measurement of outcomes, length of follow-up Consider: clinic vs. outside clinic measures, process of collection of speech data |

Yes/no/unclear | |

| 5. Reporting bias Selective reporting, accuracy of reporting Consider: use of descriptive vs. inferential statistics, pooling of data vs. individual reporting |

Yes/no/unclear |

The summarising of quality appraisal scoring within and across clinical effectiveness studies is a source of debate in the field of systematic reviews, with the calculation of overall scores for each study discouraged. 8 Following assessment of the study against each criterion, we considered the overall categorisation of studies as having either higher risk of bias or lower risk of bias. ‘Higher-risk’ studies were those assessed as having bias such that it is likely to affect the interpretation of the results and ‘lower-risk’ studies were those for which bias is unlikely to have affected the results. The final categorisation was influenced by an aggregate approach (how many areas were of concern), but also by considering whether or not the study contained any particular potential bias that jeopardised the whole study findings. Thus, although the number of ‘yes’ responses was used as an indicator of a higher/lower bias rating of quality, it formed only part of the overall rating decision. In order to produce an inclusive review, no quality requirements were set for inclusion; however, the risk of bias was fully considered and detailed in reporting the results of the review. It is important to note that we deliberately used the comparative categorisation of higher/lower to provide an indication of stronger or weaker studies across the literature included in this review. However, a ‘lower’-risk study should not be assumed to be ‘low risk’ (to be outlined in Chapter 3, Quality of the evidence available) as few studies used comparator groups and even fewer used full randomisation; therefore, even the better-quality papers in the review may be subject to bias. See Appendix 2 for detail of the rating for each included study.

Assessment of quality for the qualitative papers was carried out using an 8-item tool adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for qualitative studies (Table 2). 9 The quality scoring for each study is presented in tabular form across each of the eight items (see Appendix 3). We also present a narrative summary of the issues arising from quality assessment across the set of included papers, with categorising of studies by the research team as having either higher risk (for which weaknesses in reporting or carrying out a study could affect the reliable interpretation of the conclusions) versus lower risk of bias.

| Quality item | Assessment |

|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aim of the research? | Yes/no |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes/no |

| 3. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Yes/no/unclear |

| 4. Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Yes/no/unclear |

| 5. Has the relationship between researcher and participant been adequately considered? | Yes/no |

| 6. Have ethical issues been taken into account? | Yes/no/unclear |

| 7. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes/no |

| 8. Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes/no |

Data analysis and synthesis strategy

Effectiveness studies

Data were synthesised in a form appropriate to the data type. It was proposed that meta-analysis calculating summary statistics would be used if heterogeneity permitted, with use of graphs, frequency distributions and forest plots. It was anticipated that subgroups including age of participants, learning disability, intervention content and delivery agent would be examined if numbers permitted. However, the heterogeneity of the included work precluded summarising the studies via meta-analysis.

Clinical effectiveness review findings were reported using narrative synthesis methods. We tabulated characteristics of the included studies and examined outcomes by typologies, outcome measurement, intervention dosage and length of follow-up. Relationships between studies and outcomes within these typologies were scrutinised.

Qualitative studies

Qualitative data were synthesised using thematic synthesis methods10 in order to develop an overview of recurring perceptions of potential obstacles to successful outcomes within the data. This method comprises familiarisation with each paper and coding of the finding sections (which constitute the ‘data’ for the synthesis), according to key concepts within the findings. Although some data may directly address the research question, sometimes information such as barriers and facilitators to implementation has to be inferred from the findings, as the original study may not have been designed to have the same focus as the review question. 10

Metasynthesis

The third element of the review comprised an overarching synthesis of the clinical effectiveness and qualitative elements, to describe how the results of each section of evidence may contribute to our understanding of implementation and outcomes for stuttering interventions. The aim was to produce a ‘state of the art’ review11 that would provide information for researchers, policy-makers and practitioners. New methods to review and synthesise different types of data have been suggested, including the use of grouping data by subquestions (one for qualitative studies and one for quantitative studies) and the use of a synthesis matrix to compare features of interventions with barriers and facilitators reported by intervention participants. 12,13 The use of both qualitative and quantitative data in a single review has been recommended as having the potential to shed light on negative trial results, to identify social factors, as a means of examining issues of implementation, and potentially having a key role in assisting in the interpretation of significance and applicability for practitioners and service planners. 14

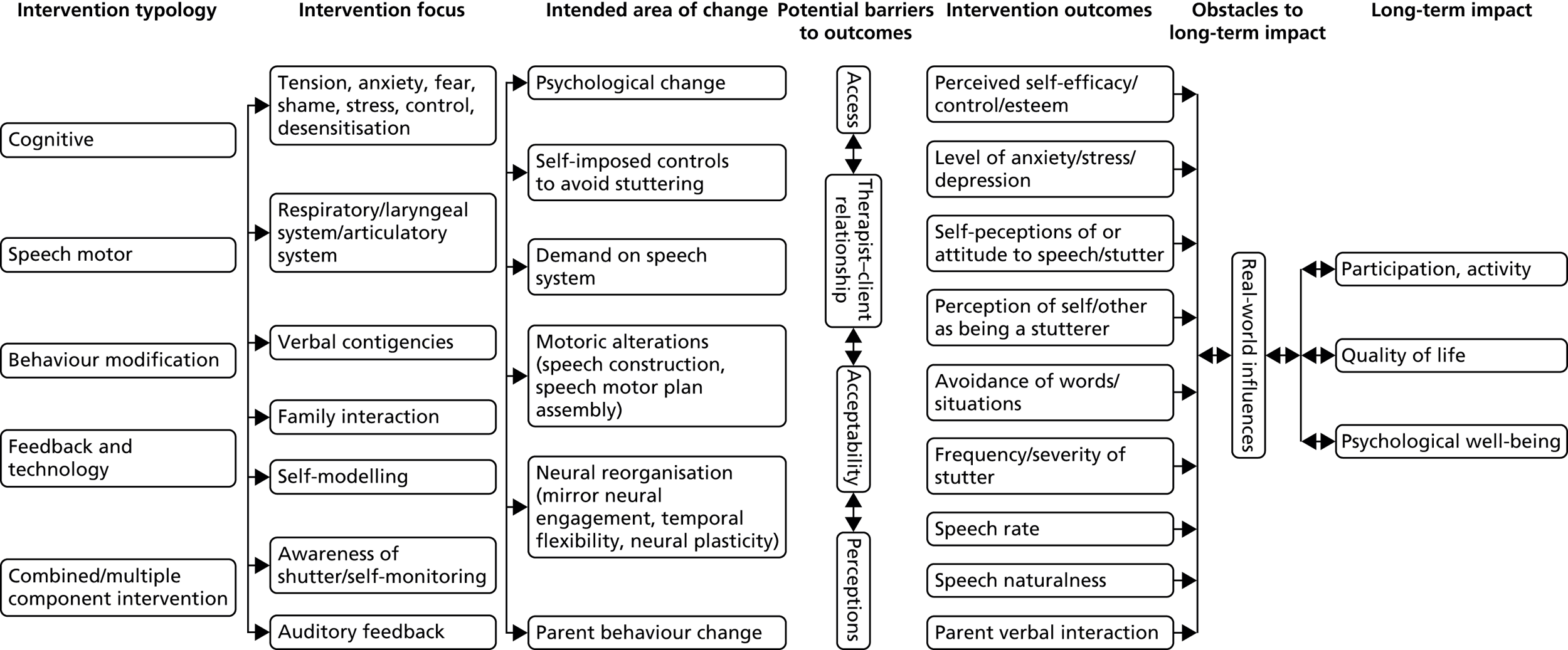

We had planned to metasynthesise findings from the two reviews via a tabular comparison of intervention outcomes and views and perceptions. However, the body of literature contained only limited data reporting perceptions of intervention and only one mixed-methods study examining both outcomes and views. In place of a tabular metasynthesis we have therefore combined the clinical effectiveness and qualitative review findings by developing a conceptual framework. This framework draws on logic model methods to metasynthesise the intervention typologies and content of interventions, with potential barriers and facilitators to intended outcomes from the qualitative review. 15 It also details outcome measures reported in the clinical effectiveness literature, together with factors influencing longer-term impact and types of impact from the qualitative studies. This method of synthesis using a logic model approach aims to assist in the communication and understanding of the complex pathway between interventions and long-term outcomes for people who stutter.

Chapter 3 Results of the effectiveness review

Quantity of the evidence available

The initial electronic database searches identified 4578 citations following deduplication. From this database of citations, 215 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for further scrutiny. Detailed examination of these articles resulted in 109 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review of clinical effectiveness. Two further papers relating to the review of effectiveness were identified from additional searching strategies (hand-searching of journals). Six further papers were identified from scrutinising reference lists or hand-searching (all qualitative). One paper used a mixed-methods design and, therefore, contributed to both reviews. Figure 1 provides a detailed illustration of the process of study selection.

FIGURE 1.

The process of study selection and exclusion.

Type of evidence available

Study design

Table 3 details the included effectiveness papers categorised by study design. We have provided a definition of each category in order to ensure clarity. The reporting of study design used by authors encompassed a variety of terminology, with terms in some instances not accurately representing the true design. Fourteen papers16–29 reported studies with a comparator, of these four17,18,24,25 randomly allocated participants to each arm of the study, six16,19–23 allocated participants using quasi-randomisation methods (such as consecutive randomising) and one29 was a controlled before-and-after study with no allocation. Of these 14 papers, three reported data from the same study16,20,21 with the greatest proportion of included empirical work using a before-and-after design (pre- to post measure).

| Design | Study |

|---|---|

| RCT, quasi-RCT, controlled before and after (participants in more than one study arm) (14) | Craig et al. 1996 (quasi-RCT),16 Cream et al. 2010,17 De Veer et al. 2009,18 Franklin et al. 2008 (quasi-RCT),19 Hancock and Craig 1998 (quasi-RCT),20 Hancock et al. 1998 (quasi-RCT),21 Harris et al. 2002 (quasi-RCT),22 Hewat et al. 2006 (quasi-RCT),23 Jones et al. 2005,24 Jones et al. 2008,25 Lattermann et al. 2008,26 Lewis et al. 2008,27 Menzies et al. 2008,28 Onslow et al. 199429 (controlled before and after) |

| Before and after (reported pre-intervention and post-intervention data with no comparator group) (86) | Amster and Klein 2007,30 Andrews et al. 2012,31 Baumeister et al. 2003,32 Beilby et al. 2012,33 Berkowitz et al. 1994,34 Block et al. 1996,35 Block et al. 2004,36 Block et al. 2005,37 Block et al. 2006,38 Blomgren et al. 2005,39 Blood 1995,40 Boberg and Kully 1994,41 Bonelli et al. 2000,42 Bray and James 2009,43 Bray and Kehle 1998,44 Carey et al. 2010,45 Cocomazzo et al. 2012,46 Craig et al. 2002,47 Cream et al. 2009,48 Druce and Debney 1997,49 Elliott et al. 1998,50 Femrell et al. 2012,51 Foundas et al. 2013,52 Franken et al. 1992,53 Franken et al. 2005,54 Gagnon and Ladouceur 1992,55 Gallop and Runyan 2012,56 Hancock and Craig 2002,57 Harrison et al. 2004,58 Hasbrouck 1992,59 Hudock and Kalinowski 2014,60 Huinck et al. 2006,61 Ingham et al. 2013,62 Ingham et al. 2001,63 Iverach et al. 2009,64 Jones et al. 2000,65 Kaya and Alladin 2012,66 Kaya 2011,67 Kingston et al. 2003,68 Koushik et al. 2009,69 Laiho and Klippi 2007,70 Langevin and Boberg 1993,71 Langevin and Boberg 1996,72 Langevin et al. 2006,73 Langevin et al. 2010,74 Lawson et al. 1993,75 Leahy and Collins 1991,76 Lincoln et al. 1996,77 Lutz 2009,78 Mallard 1998,79 Millard et al. 2008,80 Millard et al. 2009,81 Miller and Guitar 2009,82 Nilsen and Ramberg 1999,83 O’Brian et al. 2003,84 O’Brian et al. 2008,85 O’Brian et al. 2013,86 O’Donnell et al. 2008,87 Onslow et al. 1990,88 Onslow et al. 1992,89 Onslow et al. 1996,90 Pape-Neumann 2004,91 Pollard et al. 2009,92 Reddy et al. 2010,93 Riley and Ingham 2000,94 Rosenberger et al. 2007,95 Rousseau et al. 2007,96 Ryan and Van Kirk 1995,97 Sicotte et al. 2003,98 Smits-Bandstra and Yovetich 2003,99 Stewart 1996,100 Stidham et al. 2006,101 Stuart et al. 2004,102 Stuart et al. 2006,103 Trajkovski et al. 2011,104 Van Borsel et al. 2003,105 von Gudenberg 2006,106 von Gudenberg et al. 2006,107 Wagaman et al. 1993,108 Wagaman et al. 1995,109 Ward 1992,110 Wille 1999,111 Wilson et al. 2004,112 Woods et al. 2002,113 Yairi and Ambrose 1992,114 Yaruss et al. 2006115 |

| Mixed methods (used both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection) (1) | Irani et al. 2012116 |

| Cross-sectional (data from a single time point only) (11) | Allen 2011,117 Antipova et al. 2008,118 Armson and Stuart 1998,119 Armson and Kiefte 2008,120 Armson et al. 2006,4 Koushik et al. 2011,121 Lincoln and Onslow 1997 (follow-up data only),122 Onslow et al. 2002,123 Ratynska et al. 2012,124 Unger et al. 2012,125 Zimmerman et al. 1997126 |

Although 26 studies carried out outcome assessment immediately following the intervention,4,19,22,26,34,35,42,43,48,52,54,60,65,67–69,83,93,111,118–120,123–126 there were 51 papers reporting follow-up periods of 12 months or more16,20,21,25,27–29,37,38,40,41,45–47,49,51,56,57,59,61,63,66,69,71–74,77,79–82,84,90,91,96,97,100,103,104,106–110,112,114–117,122 (Table 4).

| Length of follow-up | Study |

|---|---|

| Immediate (26) | Antipova et al. 2008,118 Armson and Stuart 1998,119 Armson and Kiefte 2008,120 Armson et al. 2006,4 Berkowitz et al. 1994,34 Block et al. 1996,35 Bonelli et al. 2000,42 Bray and James 2009,43 Cream et al. 2009,48 Foundas et al. 2013,52 Franken et al. 2005,54 Franklin et al. 2008,19 Harris et al. 2002,22 Hudock and Kalinowski 2014,60 Jones et al. 2000,65 Kaya 2011,67 Kingston et al. 2003,68 Koushik et al. 2011,69 Lattermann et al. 2008,26 Nilsen and Ramberg 1999,83 Onslow et al. 2002,123 Ratynska et al. 2012,124 Reddy et al. 2010,93 Unger et al. 2012,125 Wille 1999,111 Zimmerman et al. 1997126 |

| ≤ 4 weeks (4) | De Veer et al. 2009,18 Harrison et al. 2004,58 Lawson et al. 1993,75 Onslow et al. 199289 |

| 1–2 months (6) | Baumeister et al. 2003,32 Bray and Kehle 1998,44 Riley and Ingham 2000,94 Smits-Bandstra and Yovetich 2003,99 Stidham et al. 2006,101 Woods et al. 2002113 |

| 3–4 months (8) | Amster and Klein 2007,30 Beilby et al. 2012,33 Block et al. 2004,36 Lutz 2009,78 O’Donnell et al. 2008,87 Pollard et al. 2009,92 Stuart et al. 2004,102 Van Borsel et al. 2003105 |

| 5–6 months (9) | Blomgren et al. 2005,39 Cream et al. 2010,17 Franken et al. 1992,53 Gagnon and Ladouceur 1992,55 Hewat et al. 2006,23 Iverach et al. 2009,64 Leahy and Collins 1991,76 O’Brian et al. 2008,85 Sicotte et al. 200398 |

| 9 months (8) | Andrews et al. 2012,31 Elliott et al. 1998,50 Ingham et al. 2013,62 Jones 2005,24 Laiho and Klippi 2007,70 O’Brian et al. 2013,86 Onslow et al. 1990,88 Rosenberger et al. 200795 |

| 12–18 months (26) | Allen 2011,117 Blood 1995,40 Carey et al. 2010,45 Cocomazzo et al. 2012,46 Craig et al. 1996,16 Druce and Debney 1997,49 Hancock and Craig 1998,20 Hancock et al. 1998,21 Kaya and Alladin 2012,66 Langevin and Boberg 1993,71 Langevin and Boberg 1996,72 Lewis et al. 2008,27 Mallard 1998,79 Menzies et al. 2008,28 Millard et al. 2008,80 Millard et al. 2009,81 Miller and Guitar 2009,82 O’Brian et al. 2003,84 Onslow et al. 1994,29 Ryan and Van Kirk 1995,97 Stuart et al. 2006,103 Trajkovski et al. 2011,104 von Gudenberg 2006,106 Wagaman et al. 1993,108 Ward 1992,110 Wilson et al. 2004112 |

| 2 years (12) | Boberg and Kully 1994,41 Craig et al. 2002,47 Femrell et al. 2012,51 Hancock and Craig 2002,57 Huinck et al. 2006,61 Ingham et al. 2001,63 Langevin et al. 2006,73 Lincoln et al. 1996,77 Pape-Neumann 2004,91 Rousseau et al. 2007,96 Stewart 1996,100 Yairi and Ambrose 1992114 |

| 3 years (3) | Hasbrouck 1992,59 Onslow et al. 1996,90 Yaruss et al. 2006115 |

| Up to 5 years (6) | Block et al. 2005,37 Block et al. 2006,38 Gallop and Runyan 2012,56 Langevin et al. 2010,74 von Gudenberg et al. 2006,107 Wagaman et al. 1995109 |

| > 5 years (4) | Lincoln and Onslow 1997,122 Irani et al. 2012,116 Jones et al. 2008,25 Koushik et al. 200969 |

Country of origin

A categorisation of included studies by country of origin is presented in Table 5. The greatest proportion of work was reported by authors based in Australia (39 papers), followed by the USA (26 papers). Eight papers were from the UK.

| Country of origin | Study |

|---|---|

| Australia (39) | Andrews et al. 2012,31 Beilby et al. 2012,33 Block et al. 1996,35 Block et al. 2004,36 Block et al. 2005,37 Block et al. 2006,38 Bonelli et al. 2000,42 Carey et al. 2010,45 Cocomazzo et al. 2012,46 Craig et al. 1996,16 Craig et al. 2002,47 Cream et al. 2009,48 Cream et al. 2010,17 Druce and Debney 1997,49 Franklin et al. 2008,19 Hancock and Craig 1998,20 Hancock and Craig 2002,57 Hancock et al. 1998,21 Harris et al. 2002,22 Harrison et al. 2004,58 Hewat et al. 2006,23 Iverach et al. 2009,64 Jones et al. 2000,65 Lewis et al. 2008,27 Lincoln et al. 1996,77 Lincoln and Onslow 1997,122 Menzies et al. 2008,28 O’Brian et al. 2003,84 O’Brian et al. 2008,85 O’Brian et al. 2013,86 Onslow et al. 1994,29 Onslow et al. 1990,88 Onslow et al. 1992,89 Onslow et al. 1996,90 Onslow et al. 2002,123 Rousseau et al. 2007,96 Trajkovski et al. 2011,104 Wilson et al. 2004,112 Woods et al. 2002113 |

| USA (26) | Amster and Klein 2007,30 Berkowitz et al. 1994,34 Blomgren et al. 2005,39 Blood 1995,40 Boberg and Kully 1994,41 Elliott et al. 1998,50 Foundas et al. 2013,52 Gallop and Runyan 2012,56 Hasbrouck 1992,59 Hudock and Kalinowski 2014,60 Ingham et al. 2013,62 Ingham et al. 2001,63 Irani et al. 2012,116 Mallard 1998,79 Miller and Guitar 2009,82 Pollard et al. 2009,92 Riley and Ingham 2000,94 Ryan and Van Kirk 1995,97 Stidham et al. 2006,101 Stuart et al. 2004,102 Stuart et al. 2006,103 Wagaman et al. 1993,108 Wagaman et al. 1995,109 Yairi and Ambrose 1992,114 Yaruss et al. 2006,115 Zimmerman et al. 1997126 |

| Canada (11) | Armson and Stuart 1998,119 Armson and Kiefte 2008,120 Armson et al. 2006,4 Gagnon and Ladouceur 1992,55 Koushik et al. 2009,69 Langevin and Boberg 1993,71 Langevin and Boberg 1996,72 Langevin et al. 2010,74 O’Donnell et al. 2008,87 Sicotte et al. 2003,98 Smits-Bandstra and Yovetich 200399 |

| Germany (9) | Baumeister et al. 2003,32 Lattermann et al. 2008,26 Lutz 2009,78 Pape-Neumann 2004,91 Rosenberger et al. 2007,95 Unger et al. 2012,125 von Gudenberg 2006,106 von Gudenberg et al. 2006,107 Wille 1999111 |

| UK (8) | Allen 2011,117 Bray and James 2009,43 Bray and Kehle 1998,44 Lawson et al. 1993,75 Millard et al. 2008,80 Millard et al. 2009,81 Stewart 1996,100 Ward 1992110 |

| The Netherlands (4) | De Veer et al. 2009,18 Franken et al. 1992,53 Franken et al. 2005,54 Huinck et al. 200661 |

| Sweden (2) | Femrell et al. 2012,51 Nilsen and Ramberg 199983 |

| Turkey (2) | Kaya and Alladin 2012,66 Kaya 201167 |

| New Zealand (2) | Antipova et al. 2008,118 Jones et al. 200524 |

| Finland (1) | Laiho and Klippi 200770 |

| Ireland (1) | Leahy and Collins 199176 |

| India (1) | Reddy et al. 201093 |

| Poland (1) | Ratynska et al. 2012124 |

| Belgium (1) | Van Borsel et al. 2003105 |

| Across countries (4) | Jones et al. 2008,25 Kingston et al. 2003,68 Koushik et al. 2011,121 Langevin et al. 200673 |

Intervention dosage

We endeavoured to identify from author report how many hours of intervention were provided in the included studies (Table 6). Papers varied considerably with regard to the level of detail provided and, therefore, the table below may not be completely accurate in representing intervention dosage, but is based on information we could glean. It can be seen that a sizeable proportion of the papers varied the number of hours of intervention according to individual need. This makes comparing effectiveness by dosage unfeasible. It can also be seen from the table that the contact time ranged from fewer than 10 hours to more than 75 hours, again making the drawing of comparisons between different interventions on the basis of dosage problematic. The interventions that had shorter contact times tended to be those which were based on the use of technology (such as DAF systems). The interventions with longer contact time (perhaps unsurprisingly) tended to be those with multiple elements.

| Intervention detail | Studies |

|---|---|

| Hours varied by individual participant. The range or mean is detailed if provided by authors (27) | Femrell et al. 201251 (9–46 visits), Franken et al. 200554 (mean 11.5 sessions), Gagnon and Ladouceur 1992,55 Ingham et al. 2013,62 Ingham et al. 2001,63 Jones et al. 2000,65 Jones et al. 2005,24 Jones et al. 2008,25 Kingston et al. 2003,68 Koushik et al. 200969 (6–10 visits), Koushik et al. 2011121 Lattermann et al. 200826 (average 13 sessions), Lewis et al. 200827 (mean 49 consultations), Lincoln and Onslow, 1997122 (mean 10.5 sessions), Lincoln et al. 199677 (median 12 sessions), Miller and Guitar 200982 (mean 19.8 sessions), O’Brian et al. 200384 (range 13–29 hours), O’Brian et al. 201386 (median 11 visits), O’Donnell et al. 2008,87 Onslow et al. 199429 (median 10.5 hours), Pape-Neumann 2004,91 Rousseau et al. 2007,96 Wagaman et al. 1993,108 Wagaman et al. 1995109 (average 10 sessions), Wilson et al. 2004112 (range 3–26 consultations), Woods et al. 2002,113 Yaruss et al. 2006115 |

| Individual < 10 hours (19) | Antipova et al. 2008,118 Block et al. 2006,39 Bray and Kehle 1998,44 Carey et al. 2010,45 Cream et al. 2009,48 Elliott et al. 1998,50 Foundas et al. 2013,52 Franklin et al. 2008,19 Gallop and Runyan 2012,56 Hudock and Kalinowski 2014,60 Millard et al. 2008,80 Millard et al. 2009,81 O’Brian et al. 2008,85 Pollard et al. 2009,92 Stuart et al. 2004,102 Stuart et al. 2006,103 Unger et al. 2012,125 Van Borsel et al. 2003,105 Zimmerman et al. 1997126 |

| Unclear (16) | Allen 2011,117 Andrews et al. 2012,31 Armson and Stuart 1998,119 Armson et al. 2006,4 Armson and Kiefte 2008,120 Bonelli et al. 2000,42 Bray and James 2009,43 Hewat et al. 2006,23 Langevin and Boberg 1996,72 Leahy and Collins 199176 Onslow et al. 1990,88 Onslow et al. 2002,123 Ratynska et al. 2012,124 Trajkovski et al. 2011,104 Wille 1999,111 Yairi and Ambrose 1992114 |

| Individual + group 30–75 hours (11) | Block et al. 2005,37 Block et al. 2006,38 Blomgren et al. 2005,39 Craig et al. 1996,16 Cream et al. 2010,17 Hancock et al. 1998,21 Irani et al. 2012,116 Iverach et al. 2009,64 Langevin and Boberg 1993,71 Lawson et al. 1993,75 Menzies et al. 200828 |

| Individual + group > 75 hours (9) | Boberg and Kully 1994,41 Huinck et al. 2006,61 Langevin et al. 2006,73 Langevin et al. 2010,74 Nilsen and Ramberg 1999,83 Onslow et al. 1992,89 Onslow et al. 1996,90 Rosenberger et al. 2007,95 Stewart 1996100 |

| Individual 20–50 hours (8) | Block et al. 2004,36 Cocomazzo et al. 2012,46 De Veer et al. 2009,18 Reddy et al. 2010,93 Riley and Ingham 2000,94 Sicotte et al. 2003,98 Stidham et al. 2006,101 Ward 1992110 |

| Individual 10–19 hours (6) | Beilby et al. 2012,33 Harris et al. 2002,22 Harrison et al. 2004,58 Kaya and Alladin 2012,66 Kaya 2011,67 Ryan and Van Kirk 199597 |

| Individual > 75 hours (4) | Blood 1995,40 Franken et al. 1992,53 von Gudenberg 2006,106 von Gudenberg et al. 2006107 |

| Child group + parent group 10–19 hours (3) | Craig et al. 2002,47 Hancock and Craig 2002,57 Hancock and Craig 199820 |

| Child group + parent group 20–50 hours (3) | Druce and Debney 199749 (six sessions of 5 hours each for parents and children during a 1-week intensive course), Mallard 199879 (2-week intensive), Smits-Bandstra and Yovetich 200399 (3-week semi-intensive) |

| Individual + parent group (2) | Berkowitz et al. 199434 (8 hours for parents, not clear for children), Laiho and Klippi 200770 (at least 30 hours) |

| Individual + group 10–20 hours contact time (2) | Amster and Klein 2007,30 Hasbrouck 199259 |

| Parent group (1) | Lutz 200978 (12 hours) |

| Reported by length of treatment time only (1) | Baumeister et al. 200332 (3 weeks) |

Intervention provider

In terms of the person delivering the intervention, 51 studies reported that clinicians provided the therapy. In all except three cases these clinicians were speech and language pathologists/therapists (two interventions were delivered by clinical psychologists and one jointly by a therapist and psychologist). Fifty papers16–36,51–54,56–60,65–72,79,82–90,100–102 were unclear with regards to who delivered the sessions; it was presumed that in most cases this was the author/s. Eleven studies reported that student clinicians had been used to provide therapy, with supervision by qualified staff.

Number and type of studies excluded

As can be seen from Figure 1, a large number of citations were excluded at initial screening of title and abstract. Many of these retrieved citations were excluded as not relating to stuttering. A large number of these had been retrieved by our searches as they included reference to fluency (e.g. reading fluency, fluency of movement). In addition, the term ‘clutter’ resulted in papers relating to untidiness in the home. In addition, we found reference to a number of medical conditions not related to communication which include the term ‘stutter’. Other factors that underpinned large numbers of exclusions were papers consisting of general discussion rather than reporting data; articles relating to diagnosis and causation; and studies reporting the development or discussion of outcome measures.

Appendix 4 lists the studies initially identified as being potentially relevant but which were subsequently excluded at full-paper stage. The rationale for the exclusion of each is provided.

Quality of the evidence available

Quality assessment of the included papers using the tool previously described resulted in 35 studies16,17,20–28,33,37–39,45,46,54,57,58,61,64,65,69,72–74,82,86,92,96,97,104,108,113 being categorised as being at lower risk of bias and 77 studies4,21,29–32,34–36,40–44,47–53,55,56,59,60,62,63,66–68,70,71,75–81,83–85,87–91,93–95,98–103,105–107,109–112,114–126 were categorised as being at higher risk of bias. Note our earlier discussion regarding the use of higher/lower categorisation rather than high/low. Few studies used controlled designs and, of these, the allocation process was frequently carried out by pseudo rather than completely randomised procedures. The areas which tended to distinguish studies rated as having higher potential for bias were (1) having samples of fewer than 10 participants; (2) reporting data by individual rather than pooling findings; (3) using only descriptive statistics [means and standard deviation (SDs)]; (4) failing to blind assessors to the time point of data collection; (5) limited length of speech data samples; and (6) concerns regarding the process of data collection. See Appendix 2 for details of the completed assessment for each study. In many of the smaller before-and-after studies (and some of those with larger samples) the process of selection of individuals whose data would be reported was unclear. It seemed likely (and was sometimes mentioned) that interventions had been delivered to larger numbers of people who stutter with only a sample of these being presented. The possibility that those recruited and reported may differ from those who were not recruited and reported must be considered a potential significant source of bias in interpretation of the data for these studies (see Quality of the evidence available).

Population

Table 7 presents the included studies categorised by the type of participants. As can be seen, the greatest number of studies reported findings from interventions carried out with adults who stutter, followed by school age and then pre-school children. Nine studies delivered interventions to mixed age groups of participants.

| Participant type | Study |

|---|---|

| Pre-school (including children and parents) (15) | Bonelli et al. 2000,42 Femrell et al. 2012,51 Franken et al. 2005,54 Harrison et al. 2004,58 Jones et al. 2005,24 Kingston et al. 2003,68 Lewis et al. 2008,27 Millard et al. 2008,80 Millard et al. 2009,81 Miller and Guitar 2009,82 Onslow et al. 1994,29 Onslow et al. 1990,88 Trajkovski et al. 2011,104 Yairi and Ambrose 1992,114 Yaruss et al. 2006115 |

| Parents only (1) | Lutz 200978 |

| Predominantly school age (greatest proportion of participants aged 4–11 years) (26) | Andrews et al. 2012,31 Berkowitz et al. 1994,34 Bray and Kehle 1998,44 Druce and Debney 1997,49 Elliott et al. 1998,50 Gagnon and Ladouceur 1992,55 Harris et al. 2002,22 Jones et al. 2008,25 Jones et al. 2000,65 Koushik et al. 2009,69 Koushik et al. 2011,121 Laiho and Klippi 2007,70 Lattermann et al. 2008,26 Lincoln et al. 1996,77 Lincoln and Onslow 1997,122 Mallard 1998,79 O’Brian et al. 2013,86 Onslow et al. 2002,123 Riley and Ingham 2000,94 Rousseau et al. 2007,96 Smits-Bandstra and Yovetich 2003,99 von Gudenberg 2006,106 Wagaman et al. 1993,108 Wagaman et al. 1995,109 Wilson et al. 2004,112 Woods et al. 2002113 |

| School age and adolescents (8) | Baumeister et al. 2003;32 Block et al. 2004,36 Craig et al. 1996,16 Hancock et al. 1998,21 Rosenberger et al. 2007,95 Ryan and Van Kirk 1995,97 Sicotte et al. 2003,98 Wille 1999111 |

| Adolescents (aged > 11 years) (5) | Craig et al. 2002,47 Hancock and Craig 2002,57 Hancock and Craig 1998,20 Lawson et al. 1993,75 Nilsen and Ramberg 199983 |

| Adults (47) | Allen 2011,117 Amster and Klein 2007,30 Antipova et al. 2008,118 Armson and Stuart 1998,119 Armson and Kiefte 2008,120 Armson et al. 2006,4 Beilby et al. 2012,33 Block et al. 1996,35 Block et al. 2005,37 Block et al. 2006,38 Blomgren et al. 2005,39 Blood 1995,40 Bray and James 2009,43 Carey et al. 2010,45 Cocomazzo et al. 2012,46 Cream et al. 2009,48 Cream et al. 2010,17 De Veer et al. 2009,18 Foundas et al. 2013,52 Franken et al. 1992,53 Franklin et al. 2008,19 Hasbrouck 1992,59 Hudock and Kalinowski 2014,60 Huinck et al. 2006,61 Ingham et al. 2013,62 Ingham et al. 2001,63 Irani et al. 2012,116 Iverach et al. 2009,64 Kaya and Alladin 2012,66 Kaya 2011,67 Langevin and Boberg 1993,71 Langevin and Boberg 1996,72 Langevin et al. 2010,74 Langevin et al. 2006,73 Leahy and Collins 1991,76 Menzies et al. 2008,28 O’Brian et al. 2003,84 O’Brian et al. 2008,85 O’Donnell et al. 2008,87 Onslow et al. 1996,90 Pollard et al. 2009,92 Reddy et al. 2010,93 Stewart 1996,100 Stidham et al. 2006,101 Unger et al. 2012,125 Van Borsel et al. 2003,105 Zimmerman et al. 1997126 |

| Mixed age (9) | Boberg and Kully 1994,41 Gallop and Runyan 2012,56 Hewat et al. 2006,23 Onslow et al. 1992,89 Pape-Neumann 2004,91 Ratynska et al. 2012,124 Stuart et al. 2004,102 Stuart et al. 2006,103 von Gudenberg et al. 2006107 |

| Unclear (1) | Ward 1992110 |

Cluttering

As outlined earlier, we took the decision to search for and include any work that examined interventions for people who clutter – a related speech fluency difficulty. We found only one paper which met our inclusion criteria and identified some of the participants as people who clutter. 72

Assessment of clinical effectiveness analysed by intervention type

We grouped the effectiveness papers according to the content of the intervention. The literature we identified used a variety of terms to describe the intervention reported (e.g. ‘speak more fluently’ vs. ‘stutter more fluently’, ‘indirect’ vs. ‘direct’, ‘speech restructuring’ treatment vs. ‘speech modification’ therapy). In order to avoid potential confusion between different authors’ use of terminology, we adopted the classification below which endeavours to categorise the approaches taken within the included studies. The categorisation consists of seven typologies: (1) feedback and technology interventions which aim to change auditory feedback systems (22 papers4,17,35,36,43,44,48,52,56,60,87,92,101–103,105,118–120,124–126); (2) cognitive interventions which aim to lead to psychological change (six papers18,30,66,67,76,93); (3) behavioural modification interventions which aim to change child or parental behaviour, or the behaviour of an adult who stutters (29 papers19,22–27,29,42,51,58,65,68,69,77–82,86,88,96,112,113,115,121–123); (4) speech motor interventions (18 papers31,37,38,45,46,49,53,62–64,84,85,89,90,104,106,107,114) which aim to impact on the mechanisms of speech production such as the respiratory, laryngeal or articulatory systems; (5) speech motor combined with cognitive interventions (18 papers32–34,39,41,61,70–75,83,95,99,100,110,116); (6) multiple component interventions (11 papers40,47,50,55,57,59,91,98,108,109,117); and (7) studies which compared interventions to each other (eight papers16,20,21,28,54,94,97,111).

Feedback and technology interventions

Twenty-two papers were included that described the effectiveness of a range of a technologies aiming to reduce the frequency or severity of stuttering in speech (Table 8). The earliest of these papers was published in 1996, and the most recent in 2014, with 13 of the papers from North America (see Table 8). The greatest proportion of the technologies described were devices that alter the way that a person who stutters hears their own speech [altered auditory feedback (AAF)] by changing the frequency [frequency altered feedback (FAF)] and/or by introducing a delay before the speech is heard (DAF). All but one of the included studies52 either compared stuttering level while using a device with stuttering level with no use of the device, or compared fluency level using different device settings. The other paper52 compared use of a device in people who stutter with use by non-stuttering speakers. All but one of the papers92 in this group was rated as being at higher risk of bias. The papers described the use of AAF under a variety of conditions including reading, monologue and conversation (either in person or via the telephone).

| Study detail | Design | Risk of bias | Country | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipova et al. 2008118 | Cross-sectional | Higher | New Zealand | Adults, n = 8 |

| Armson and Stuart 1998119 | Cross-sectional | Higher | Canada | Adults, n = 12 |

| Armson et al. 20064 | Cross-sectional | Higher | Canada | Adults, n = 13 |

| Armson and Kiefte 2008120 | Cross-sectional | Higher | Canada | Adults, n = 31 |

| Block et al. 200436 | Before and after | Higher | Australia | Aged 10–16 years, n = 12 |

| Block et al. 199635 | Before and after | Higher | Australia | Adults, n = 18 |

| Bray and James 200943 | Before and after | Higher | UK | Adults, n = 5 |

| Bray and Kehle 199844 | Before and after | Higher | UK | Aged 8–13 years, n = 4 |

| Cream et al. 200948 | Before and after | Higher | Australia | Adults, n = 12 |

| Cream et al. 201017 | RCT | Lower | Australia | Adults, n = 89 |

| Foundas et al. 201352 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adults, n = 24 |

| Gallop and Runyan 201256 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adults, n = 11 |

| Hudock and Kalinowski 201460 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adults, n = 9 |

| O’Donnell et al. 200887 | Before and after | Higher | Canada | Adults, n = 7 |

| Pollard et al. 200992 | Before and after | Lower | USA | Adults, n = 11 |

| Ratynska et al. 2012124 | Cross-sectional | Higher | Poland | Mixed, n = 335 |

| Stidham et al. 2006101 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adults, n = 10 |

| Stuart et al. 2004102 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adolescents and adults, n = 7 |

| Stuart et al. 2006103 | Before and after | Higher | USA | Adolescents and adults, n = 9 |

| Unger et al. 2012125 | Cross-sectional | Higher | Germany | Adults, n = 30 |

| Van Borsel et al. 2003105 | Before and after | Higher | Belgium | Adults, n = 9 |

| Zimmerman et al. 1997126 | Cross-sectional | Higher | USA | Adults, n = 9 |

This type of intervention alters the auditory feedback process in people who stutter with the aim of reducing the proportion of stuttered speech. Although the precise area of change and way that these interventions act to reduce stuttering is debated, it has been proposed that they may activate a ‘mirror neural system’ to link perception with production or, alternatively, that they have an impact on timing processes that control speaking rate. In the following synthesis we have detailed only the findings relating to conversational interaction (or monologue if no conversational measure was available). Many of the papers contained further detailed data regarding outcomes in terms of reading aloud. 4,17,35,36,48,52,56,60,87,92,102,103,105,118–120,124–126

Use of the SpeechEasy device (Janus Development Group, Inc., NC, USA) was reported in six papers. 4,52,56,87,92,120 These studies explored the use of the technology in laboratory, clinical and naturalistic contexts and examined follow-up for periods up to 59 months. Sample sizes ranged from seven to 31 individuals with no studies using a control group design. Five out of the six papers were assessed as being at higher risk of bias, with only one92 judged to have a lower risk of bias.

All studies reported some degree of effectiveness for this intervention. Armson et al. 4 found stuttering was significantly reduced having the device in place versus no device (p = 0.01) with a small effect size (ES) of 0.108. However, there was considerable individual variation in responses, with the suggestion that those having lower initial stuttering had better outcomes. A second paper by Armson and Kiefte120 also reported significant decreases in stuttering rate with SpeechEasy compared with stuttering rate without SpeechEasy for all but two of 31 participants (p < 0.001, ES 0.724). The mean stuttering frequency pre-device was 16.4 and with device the mean was 2.3, an average reduction during monologue of 60.7%. Participant self-rating of stuttering severity also improved during the device condition (from 5.95 to 3.29; p = 0.028, ES 0.658). The paper examined whether or not stuttering reduction was at the expense of reduction in speech naturalness or rate and concluded that participants had a slower than normal rate both with and without the device. Naturalness ratings increased to just below normal levels with the device. The Foundas et al. 52 paper echoes these findings, with a significant reduction in stuttering frequency with the SpeechEasy device in place and activated versus in place but not producing DAF or FAF (p = 0.014, a 36.7% reduction). The paper examined the effect of different device settings and concluded that the setting preferred by the participants was more effective than the default setting. In contrast to the findings above, individuals with more severe stuttering at baseline had a greater benefit.

Three papers examined longer-term outcomes of SpeechEasy intervention. 56,87,92 One56 followed up device users following initial fitting. Eight of the 11 participants were still using the device at a mean of 37 months’ follow-up. The study found that level of dysfluency (for the seven participants that data were available for) was not significantly different at long-term follow-up than it had been at first fitting (p = 943). However, there was significant variation with three having increased fluency, one was unchanged and three had worsened fluency since initial fitting. Analysis of data for all 11 people who stutter (those who continued to use the device and those who did not) found that all had significantly improved levels of fluency from before they were fitted with SpeechEasy to the current time point (p = 0.017). The authors suggested that this indicates carry over effect from the device even when use discontinues. However, an alternative interpretation may question the long-term value of using the device in that continued users did not differ from non-users. In support of this, the study reports that at time of follow-up there was no difference in fluency whether the device was worn or not worn (p = 0.92).

The second paper reporting longer-term follow-up data92 similarly casts some doubt on the long-term clinical effectiveness of SpeechEasy and this paper was judged to be at lower risk of bias. This study examining beyond-clinic data found a positive effect on the percentage of syllables that are stuttered in the shorter term following fitting (p = 0.02); however, no significant effect on the percentage of syllables that are stuttered at 4-month follow-up (p = 0.090). Self-report scores on the Stuttering Severity Index (SSI) and Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering Questionnaire (OASES) showed no difference pre- to post intervention; however, the Perceptions of Stuttering Inventory (PSI) scores had significantly improved (p < 0.05). Only 4 out of the 11 participants had purchased the device, eight reported they disliked the irritating background noise and five that they disliked being unable to hear self/others. Six reported that using the device had increased their confidence in speaking and six reported that they had an overall increase in fluency using it.

The O’Donnell et al. 87 paper includes beyond-clinic measures using data obtained via the telephone. This study followed participants at regular intervals for 16 weeks after fitting and included speech data and participant self-report. Use of the device varied from 2 hours per day to 15 hours per day. Stuttering reduced for all participants at the baseline evaluation point (by 75.5–97.9%); however, there was considerable variation in outcome between participants at the final follow-up. Four stuttered less with the device than those without it and three stuttered less without the device than those with it. Five of the seven stuttered more at follow-up than they had at baseline with the device in use (although all had reduced levels of stuttering when not using the device than they had previously). Analysis of the beyond-clinic telephone recordings indicated positive outcomes for five participants, with mean reduction in stuttering ranging from 20% to 94.4% when conversing with the experimenter while having the device in place, compared with not using it. On self-report measures, six participants described reduced struggle or avoidance behaviour with five participants identifying substantial benefit.

Six papers reported the use of other feedback devices combining DAF and FAF. All were considered to be at higher risk of bias. 35,103,104,118,124,125 Antipova et al. 118 used The Pocket Speech Lab (Casa Futura Technologies, CO, USA) with eight participants and found all reduced the percentage of words stuttered using the device by an average of 3–4%. The paper details individual response under eight different AAF conditions with a significant difference between these and the no-device condition (p = 0.049) in terms of the percentage of syllables that are stuttered. The authors report a trend for those with more severe stuttering to have a greater reduction; however, they highlighted the significant individual variability in response. Unger et al. 125 found a significant reduction in SSI severity rating (p = 0.000) for 30 participants using the VA 601i Fluency Enhancer (VoiceAmp Ltd , Middlesex, UK) or the SmallTalk devices (Casa Futura Technologies, CO, USA). Individual variability in outcome was also emphasised in this study. The Digital Speech Aid (Digital Recordings – Advanced R & D, Nova Scotia, NS, Canada) was evaluated in a study with a larger sample of 335 individuals. 124 Statistically significant improvement in the number of dysfluent syllables was observed using the device than non-use (p < 0.005). In dialogue, the odds ratio (OR) of exhibiting dysfluency without the device was 0.58 and with the device in use was 0.18. Although moderate or considerable improvement was found for 84.5% of participants, deterioration or lack of improvement was found for 15.5%.

Use of the Edinburgh Masker (Casa Futura Technologies, Boulder, CO, USA) in both clinic and home settings was evaluated by Block et al. 35 Results for the 18 participants showed a decrease in the percentage of syllables that are stuttered for all across all conditions (conversation with experimenter: 2.1% reduction of syllables that are stuttered, conversation familiar person: 2.6% reduction of syllables that are stuttered, telephone: 2.8% reduction of syllables that are stuttered). The authors reported that an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed which indicated a significant reduction in stuttering; however, the details of this are not provided. Some individual differences in response are described (eight participants increased stuttering on at least one task) and although speaking rate was found to be unaffected, speech naturalness appeared to be reduced using the device (p < 0.01).

Companion papers103,104 report 4-month and 12-month follow-up data from intervention using a self-contained in-the-ear prosthetic fluency device providing both FAF and DAF. The earlier paper103 describes three experiments using the equipment. The proportion of stuttered syllables was significantly reduced for the seven participants in experiment 1 when they used the device during monologue (p = 0.011, a 67% reduction of syllables that are stuttered). Similarly, for eight participants in experiment 2 there was a significant reduction in proportion of stuttered syllables (p = 0.0028). The third experiment focused on evaluating speech naturalness and found that speech while using the device was rated as more natural sounding than without (p < 0.0001), although scores were below that for normal speakers. The follow-up paper similarly outlines three experiments. The first found that initial reductions in stuttered syllables reported at initial fitting with the device in place compared with no device were repeated at 12 months (p < 0.0001), with a 75% reduction in percentage of syllables that are stuttered using the device during monologue. Experiment 2 details significantly improved PSI scores at 12 months compared with scores prior to receiving the device. Participants were asked to self-report current levels and recall previous, but this means the reliability of these data must be questioned. Experiment 3 examines speech naturalness and found an increased naturalness rating at 12 months compared with 4 months and that speech while using the device was rated as more natural than without (although as with the earlier paper was less natural than normal speakers).

Three papers focused on the use of AAF devices to reduce stuttering during use of the telephone. 44,60,126 The most recent paper60 examined the effectiveness of different combinations of DAF and FAF during scripted telephone conversations. Although this study could be perceived to be using a reading aloud only outcome and, therefore, falls within the exclusion criteria, the script was considered to be similar to notes that a person who stutters may make in everyday life when making a telephone call and so the study offered more functional outcomes. Stuttering frequencies in both AAF conditions for all nine participants were significantly lower than the non-altered feedback condition (p < 0.0001, an average of a 65% reduction). These findings are similar to an earlier paper126 which reported a reduction in stuttering frequency of 55–60% using AAF during scripted telephone conversations (p = 0.004) with a positive effect for all nine participants. Bray and James44 support the clinical effectiveness of using an AAF device when making telephone calls. The Telephone Assistive Device (VoiceAmp Ltd, Middlesex, UK) evaluated in this study reduced stuttering frequency for four out of five participants (group mean 8.28% pre-device and mean 4.82 using device). The authors suggested some improvement in self-reported feelings and attitude following use of the device, but there are limited data to support this.

One paper reported the use of FAF only,119 and another the use of DAF only. 105 Amson and Stuart119 found that although some improvement to reading using FAF was observed, there was no significant effect on the number of stuttering events during monologue, with 10 out of the 12 participants showing no benefit. Use of DAF over 3 months105 was found to significantly reduce the percentage of stuttered words (when using the device compared with not using it) for non-functional speech tasks and picture description (p = 0.050); however, not significantly for conversation (p = 0.066). Levels of stuttering without the device in place were significantly reduced from baseline levels for all but conversation (p = 0.0666). Overall levels of stuttering when using the device from baseline to 3-month follow-up had not significantly changed. Self-report perception of fluency (using median scores on the summary table provided) was that fluency using DAF was better than fluency without DAF for four out of nine participants (unchanged for four, worse for one).

Other types of technology evaluated in the literature were bone conduction stimulation and electromyography (EMG). Stidham et al. 101 reported the use of bone conduction stimulation with DAF which participants used for at least 4 hours a day for 4 weeks. Although baseline to immediate post provision of the device indicated a significant reduction in stuttering (p < 0.001), the effect had faded at 2- and 6-week follow-up. Of the nine participants, slightly more than half reported that their speech had improved using the device (56%) and 66% rated it as helpful to some degree. However, the headband element of the device was described as being uncomfortable and obtrusive.

Two papers examined the use of EMG feedback. One of these16 compared EMG with two other interventions and will be outlined in detail later (see Papers comparing interventions). In summary, this study found that for 6 out of the 10 children taking part, EMG reduced stuttering to less than 1% of syllables that are stuttered immediately post intervention, with four children remaining at this level at 1-year follow-up. The other paper36 used EMG with 12 children and adolescents daily over a 5-day period. There was a reduction of mean 36.7% in stuttering after treatment (pre-mean 4.9% of syllables are stuttered to post mean 4.4% of syllables are stuttered), however it was noted that rate of speech post intervention was only around half that of a non-stuttering population. One participant had a worse percentage of syllables that are stuttered following intervention.

The final papers included in this categorisation of feedback and technology interventions were three papers outlining the use video self-modelling (VSM) (participant viewing of videos of themselves which had been edited to remove stuttering). The self-modelling intervention tested by Bray and Kehle44 was carried out on seven occasions over 6 weeks. Results are reported descriptively by the four individual participants, with mean number of stuttered words ranging from 5.9 to 9.1 at baseline and 0.3 to 3.2 at the 8-week follow-up. A more recent paper48 evaluated the viewing of edited videos daily over a 1-month period. This study investigated the potential use of this intervention with people who stutter who had received previous interventions but had relapsed. Results indicated a significant reduction of 5.4% of syllables that are stuttered (p < 0.0001) post intervention, an ES of 1.1. Self-reported rating of severity also was significantly reduced (p < 0.0001, ES 1.4), with no significant adverse effect on speech naturalness found. A second paper from this research team17 evaluated VSM as part of the maintenance programme following a smooth speech/prolonged speech (PS) intervention. The study (which was judged as at lower risk of bias) compared standard maintenance with VSM over a 4-week post-intervention period. It found that there was no significant difference between standard maintenance and VSM outcomes in terms of percentage of syllables that are stuttered (p = 0.92), self-rated anxiety (p = 0.12) or avoidance (p = 0.69); however, self-reported rating of typical and worst severity were better in the VSM group (p = 0.062 and p = 0.012). Participants in this group rated their satisfaction with fluency as greater (p = 0.043) and quality-of-life scores were higher (p = 0.027).

Cognitive interventions