Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/122. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Latthe has received financial support from Pfizer and Astellas to attend international urogynaecology conferences.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Rachaneni et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overactive bladder

Definition and prevalence

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the International Continence Society and the International Urogynaecology Association1 as a symptom complex of urinary urgency (an intense, sudden desire to void) with or without incontinence, usually with increased urinary frequency or nocturia, but in the absence of infection or other proven pathology. Increased urinary frequency and urgency seem to be more common symptoms of OAB than urinary incontinence (UI). Incontinence may be the most distressing symptom of OAB, but affects only one-third of patients. 2

Overactive bladder affects millions of people worldwide. In the epiLUTS study, OAB prevalence was found to be 12.8%. 3,4 Prevalence and severity of OAB are known to increase with age from 14.9% in the 18- to 29-year group, to 21.3% in the 30- to 39-year group, 32.9% in the 40- to 49-year group, 35.8% in the 50- to 59-year group and up to 39.8% in the 60- to 69-year group. 5 With the increase in longevity owing to advances in health care and the population growth, the burden of OAB is going to increase in the next few decades, with a 9% increase anticipated from 500 million globally in 2013 to 546 million by 2018. 6 Two-thirds of a predominantly female sample of people with OAB had sought treatment in the 6 months prior to a multinational survey. 7

Moderate-to-severe symptoms may have an adverse impact on lifestyle. Affected women tend to cope by restricting fluid intake and ‘toilet mapping’ to control urgency and frequency. 8 Women may avoid sexual contact because of the risk of coital incontinence. 9 These coping strategies can have a deleterious effect on physical, social and emotional health. Low mood and depression due to social restriction and fear of embarrassment are also associated with OAB in women (with and without urgency incontinence), while OAB also has significant financial implications (e.g. cost of pads, prescriptions, time off work, job losses, effects on the family, etc.). 10,11 Urgency or nocturia in the elderly have been linked to a higher risk of falls and fractures. 12

Mixed urinary incontinence

The International Continence Society and International Urogynecology Association describe mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) as a complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also with effort or physical exertion, or on sneezing or coughing. 1 MUI may be urgency-predominant or stress-predominant and accounts for 49% of UI in women. 13 In a study on the prevalence of individual symptoms of MUI, 29% of participants had stress-predominant MUI, 15% of participants had urgency-predominant MUI and 56% (912/1626) of participants had equal severity of urgency- and stress-related MUI. 13 Appropriate categorisation of women into urgency-predominant or stress-predominant MUI has been a matter of great debate. Previous studies have used the Medical, Epidemiological, and Social Aspects of Ageing (MESA) Questionnaire,14 the Urogenital Distress (UI) Inventory15 and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores alongside 7-day bladder diaries to categorise women with mixed incontinence based on the predominant symptom (stress or urgency). 16 However, in routine clinical practice, women are categorised based on which symptoms they consider are more bothersome.

Underlying pathology of overactive bladder

The pathology behind OAB symptoms has been found to be detrusor overactivity (DO) in 54–58% of the cases. The remaining 42–46% of the patients may have other pathologies causing OAB symptoms17 (Table 1).

| Lower urinary tract conditions | Mechanism of affect |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic DO | Involuntary detrusor contractions associated with urgency during filling cystometry when there is no other cause |

| Urinary tract infection | Inflammatory markers trigger activation of sensory afferent signalling pathways |

| Obstruction including prolapse | Detrusor muscle hypertrophy and urinary stagnation leading to DO |

| Impaired bladder contractility | Urinary retention from reduced contractility, causing frequency and urgency incontinence |

| Bladder abnormalities or inflammation | Intravesical abnormalities may precipitate urgency and urgency incontinence |

| Neurological conditions: cerebrovascular accidents, Alzheimer’s disease, multi-infarct dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, normal pressure hydrocephalus, benign tumours or secondaries in the spine | Higher cortical inhibition of the bladder is impaired, causing neurogenic DO |

| Oestrogen deficiency | Inflammation from bladder mucosal atrophy, atrophic vaginitis and urethritis (e.g. local irritation and risk of urinary tract infections) |

The pathophysiology of the DO and other causes of OAB have not been understood completely. Enhanced afferent activity generated by the detrusor smooth muscle and the urothelium/lamina propria may be the main mechanism. 18 In vitro studies have shown that spontaneous contractile activity was seen more often in muscle strips from overactive than from normal bladders. 19

According to the myogenic theory, DO may be caused by an intrinsic abnormality of the detrusor muscle rather than a disturbance of its neural control. Detrusor smooth muscle cells may become hyperexcitable, react to minor stimuli and result in untimely bladder contractions resulting in urgency. In isolated bladder preparations from patients with DO, there seems to be increased co-ordination leading to larger amplitude contractions, possibly reflecting changes in intercellular communication. 20

In OAB patients, increase in intravesical pressure secondary to detrusor contractions may cause the symptom of urgency and prompt the woman to increase her urethral closure pressure using her urethral sphincter and pelvic floor musculature. Such isometric contractions against a closed bladder neck and competent sphincter may lead to the hypertrophy of the detrusor. A thickened bladder wall is suggestive of detrusor hypertrophy. 21

Clinical history

Clinical history taking for urinary symptoms includes the type of incontinence (provoked by urgency or activity), duration and severity of symptoms, impact of symptoms on quality of life (QoL), exacerbating factors including diet, fluid and medications, co-existing medical, surgical or gynaecological conditions and the person’s strategies for coping with symptoms. In a semisystematic review, mean sensitivity and specificity of clinical history compared with a reference standard diagnosis made by urodynamics (UDS) was 69% (range 35–96%) and 60% (range 21–97%), respectively, for OAB, and 51% (range 38–84%) and 66% (range 43–96%), respectively, for women with MUI. 22 Mean sensitivity for predicting DO in women with clinical symptoms of OAB was 76%, but the specificity was only 57%. 22 Meta-analytical averages were not presented.

However, in a more methodologically thorough review, Martin et al. 23 reported the pooled sensitivity of clinical history assessment of urgency symptoms, compared with a UDS diagnosis of DO, to be lower at 61% [95% confidence interval (CI) 57% to 65%], and the specificity to be higher at 87% (95% CI 85% to 89%).

History of urinary symptoms alone may not help in the differentiation of the underlying pathology. 24,25 Women go through a thorough clinical assessment to rule out other causes of OAB, for example urogenital atrophy, significant pelvic organ prolapse (POP), and should undergo post-void residual (PVR) ultrasonography to rule out incomplete bladder emptying.

Bladder diaries in the assessment of overactive bladder

Bladder diaries are useful tools in the investigation of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)3 and also to assess treatment response. 26 Episodes of urgency and sensation may also be recorded, along with the activities performed during or immediately preceding the involuntary loss of urine. Severity of incontinence in terms of leakage episodes and pad use may also be reported in bladder diaries. On evaluation of accuracy of bladder diaries in OAB patients against the urodynamic diagnosis of DO, sensitivity and specificity were found to be 0.88 and 0.83, respectively. 27 A high subjective score of urgency, frequent voiding and urgency incontinence episodes (over a 3-day diary period) were strongly associated with urodynamic DO in a multivariate analysis. 28

Urodynamics

Urodynamics are used to assess the neuromuscular function of the urinary tract and understand its storage and evacuation. 29 There are two basic aims of the UDS test: (1) to reproduce the patient’s symptoms and (2) to provide a pathophysiological explanation for the patient’s problems. 2 At present, laboratory UDS remain the gold standard test for assessment of OAB. Multiple diagnoses can be given following UDS tests, which include DO, urodynamic stress incontinence (USI), a combination of DO and USI and voiding dysfunction (VD).

Urodynamics consists of uroflowmetry, which measures the flow rate during voiding, and multichannel cystometry, which evaluates the pressure–volume relationship in the bladder during both filling and voiding phases. It is usually performed in the sitting or supine position and takes approximately 30 minutes to perform. Ambulatory UDS utilises natural filling and provides a more physiological technique for continuous monitoring of bladder function under nearly natural conditions, but does require a longer period of observation and for the patient to carry a data storage device while catheterised. Standard multichannel UDS has a NHS tariff of £401. 30 There were approximately 39,792 UDS attendances in England and Wales in 2013,31 although there is a 23-fold variation in uptake between localities. 32

Detrusor overactivity and low compliance are urodynamic diagnoses. DO is the occurrence of involuntary detrusor contractions during the filling phase of UDS. These contractions, which may be spontaneous or provoked, produce a wave form on the cystometrogram of variable duration and amplitude. 33 Neurogenic DO is where there is DO and there is evidence of a relevant neurological disorder. 33 In a normal compliant bladder, the bladder accommodates large volumes without a significant rise in detrusor pressure, but if the elasticity of the bladder is reduced, pressure rises with filling and the bladder is said to have low compliance.

In women with OAB symptoms, 45% do not have a diagnosis DO on UDS. UDS may miss DO if DO is not present at all times during the filling phase, or because UDS is not a test mimicking normal physiology and hence is not able to capture DO at its occurrence. 34 In a study of 2737 women with UI symptoms, 1626 (59%) reported mixed UI, of whom 42% had USI, 25% had pure DO, 18% had both DO and USI and 15% had normal UDS. 35 In those with stress-predominant MUI, 64% had pure USI and in those with urgency-predominant MUI, only 47% had solely DO. 35

Clinical use of urodynamics

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (CG 171)36 advise against the use of multichannel, ambulatory UDS or video UDS prior to commencing conservative management for OABs. However, there are recommendations to perform UDS before proceeding to invasive treatments for DO, for example botulinum toxin serotype A (BTX-A) (Onabotulinum A, Botox™, Allergan Ltd.) or neurostimulation.

Standardisation of the urodynamic assessment

Urodynamics is a skilled procedure, which requires training in setting up the UDS equipment, calibration of the machine, interpreting the pressure/flow recordings and counselling patients. One of the difficulties often encountered during UDS is the ability to identify artefacts and interpret the results. 5 One of the key aspects of maintaining the accuracy of UDS is to ensure that the initial resting pressures are correct and recognised. 8 Previous studies showed that even under ideal test–retest conditions, reliability can be poor for many urodynamic parameters. 9,10 In clinical settings in which UDS is performed, this can be further compromised by inconsistencies in practice. The site-to-site variation in UDS procedure may have resulted from difference in equipment and training of staff. 3 Quality control is a process through which procedure quality is maintained or improved, errors reduced or eliminated and is a crucial element of the good urodynamic practice (GUP) guidelines, which were developed following poor quality control observed during review of UDS traces from multicentre trials by the International Continence Society in 2002. 6

Acceptability of urodynamics

Women experience significant emotional distress in relation to diagnostic evaluation. 37 UDS is an intimate and invasive test13 involving the catheterisation of the bladder and rectum/vagina and some provocative manoeuvres. 13 A significant number of people who undergo UDS find it embarrassing, painful or distressing. 38,39 These feelings can be relieved by appropriate interpersonal skills, communication skills, maintenance of privacy and confidence in the technical ability of the health-care professional. 40 Younger women and those with a history of anxiety or depression, and those receiving a diagnosis of OAB and painful bladder syndrome have been reported to have more negative experiences during UDS. 41 Female patients found that UDS was more embarrassing when carried out by a male examiner, although they felt it less painful than their male counterparts. Patients with higher ‘bother’ scores may not tolerate UDS as well as a patient who has a lower bother score. 38

Bladder ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has been claimed to be a potentially accurate and reliable test of DO and definitely is a less invasive method of diagnosis of DO through direct measurement of bladder wall thickness (BWT), an increase of which has been shown to be associated with DO. 21,42 The bladder can be visualised by transabdominal, transperineal and transvaginal scanning. Transvaginal scanning is considered the optimal method of measuring BWT in women as the probe is closest to the bladder and captures high-quality images. Ultrasonographic measurement of BWT or detrusor wall thickness (DWT) both visualise and quantify bladder wall hypertrophy, but differ in their extent of measurement. BWT includes the detrusor, the mucosa and the adventitia of the bladder wall, while DWT includes only the detrusor. BWT values thus always exceed DWT values in the same patient, rendering them incomparable. 43

In one study, female adults with normal UDS pressure patterns had a mean BWT of 3.9 mm [interquartile range (IQR) 3.4–4.5 mm]. 44 Another study of 166 women without urinary symptoms found a mean BWT 3.04 mm [standard deviation (SD) 0.77 mm; range 1.2–7.6 mm] and a small positive correlation between the increase in age and BWT. The small increase in BWT with age could be related to detrusor hypertrophy or secondary to increased interstitial collagen deposition. 45 As the age-related increase in the thickness is small, and smaller than the likely measurement error of ultrasonography, correction with respect to age may not be required. 46

The optimum bladder volume to measure BWT is still a matter of debate. In our clinical practice, we measured BWT at a bladder volume < 30 ml. BWT is known to be fairly constant when bladder volumes are measured in the range from 0 to 50 ml. 44 Bladder outline is difficult to visualise at higher bladder volumes. Transabdominal measurement of BWT needs higher bladder volumes of around 250 ml, leading to more stretching of the bladder wall. BWT decreases rapidly between 50 ml and 250 ml of bladder filling (or until 50% of bladder capacity) but reaches a plateau with only minor changes thereafter. 43

Evidence for the accuracy of ultrasonographic measurement of bladder wall thickness in diagnosis of detrusor overactivity

There has been conflicting evidence in the literature on the diagnostic accuracy of BWT in diagnosing DO. 47,48 A systematic review identified five studies49–53 of women with OAB symptoms, three of these studies49,52,53 used transvaginal bladder ultrasonography but different UDS methods. 48 In one study of transvaginal bladder ultrasonography from which accuracy data could be extracted, a BWT cut-off point of 5 mm gave a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 76% to 89%) and specificity of 89% (95% CI 90% to 96%) for identifying DO, compared with video cystourethrography and ambulatory UDS. 49 In another study, BWT varied significantly between UDS-defined lower urinary tract conditions – the mean BWT was 3.78 mm (SD 0.39 mm) for USI, 4.97 mm (SD 0.63 mm) for DO and 6.01 mm (SD 0.73 mm) for bladder outflow obstruction; p < 0.0001. 54 This study reported an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.94 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.99) for the differentiation between USI and DO or bladder outflow obstruction and 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.97) to differentiate DO and bladder outflow obstruction, suggesting thresholds of 4.1 mm and 5.6 mm, respectively, for maximal diagnostic accuracy. 54 A subsequent update to the review identified seven further studies that have shown a significantly increased BWT in patients with DO than in patients without DO. 27,50,55–59 However, the heterogeneity in the methods, including the standardisation of bladder ultrasonography and of UDS, and poor reporting of the proportions of DO cases identified as well as missed, precludes a formal diagnostic meta-analysis. Other methodological weaknesses of prior studies include unclear description of how bladder ultrasonography and UDS results were blinded to each other, recruitment mainly from a single centre and retrospective design.

Acceptability of bladder ultrasonography

Transvaginal bladder ultrasonography is a less invasive technique than UDS. The acceptability and psychological impact of transvaginal scanning has been extensively studied. In a study of 755 pregnant women undergoing transvaginal scanning, 272 (36%) experienced some pain or physical discomfort,60 the majority (92%) describing it as ‘mild’ or ‘discomforting’, but a small minority found the scan ‘distressing’ (5%), ‘horrible’ (3%) or ‘excruciating’ (1%). The level of psychological trauma, measured by the impact of event score (with ratings of symptoms of avoidance and intrusion) was low, with a mean of 4.3 out of a possible maximum score of 40. The majority of the women (86%) said they would definitely or probably have a repeat scan in the future.

Rationale for the study

Urinary symptoms alone can be unreliable in establishing the diagnosis of DO in women with symptoms of OAB, so clinical guidelines recommend UDS. UDS is invasive, poorly tolerated by patients and costly with an associated risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). The mean BWT, as determined by bladder ultrasonography, appears to be higher in women with UDS defined DO and, therefore, may have a potential discriminatory role. Existing studies were small and of variable quality and further research into the role of bladder ultrasonography in diagnosis of DO in women with OAB symptoms is required. 48 If shown to be accurate, reproducible and cost-effective, bladder ultrasonography would reduce the need for UDS.

In the absence of comprehensive evidence on the accuracy of UDS and its role in influencing the appropriate treatment pathway, the necessity of UDS has increasingly started to be questioned. In women with uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI), evidence suggests that UDS is not a necessary or cost-effective component in the treatment pathway. 61–65 However, for women with predominant symptoms of OAB, the evidence is still inconclusive. On the one hand, studies conclude that urodynamic evaluation is essential in the management of women with symptoms of OAB,29 which is not a reliable indicator of DO in women. 17 On the other hand, others conclude that an urodynamic observation of DO is not a good predictor of the outcome of a variety of treatments for OAB. 66 NICE recommends the use of UDS prior to invasive treatments for OAB,36 but there has also been a call for further studies examining the role of bladder ultrasonography. 36

Overview of the research

The Bladder Ultrasound study (BUS) was a prospective multicentre diagnostic accuracy study to evaluate the accuracy of BWT in diagnosing DO. The study compared BWT measurement derived from transvaginal bladder ultrasonography with a reference standard of multichannel UDS used to verify the presence or absence of DO and other UDS defined diagnoses. Consecutive women with OAB symptoms who satisfied the eligibility criteria were approached. Consenting women with OAB symptoms were characterised by their clinical history and frequency, severity and ‘bother’ of their symptoms using a bladder diary and validated questionnaire International Consultation on Incontinence modular Questionnaire Overactive Bladder (short form) (ICIQ-OAB). 67 The interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility of bladder ultrasonography was assessed in substudies (see Chapter 4). Pain, embarrassment and acceptability of the two tests were assessed. An economic evaluation would compare different diagnostic strategies and treatments, using study and published data (see Chapter 7), to determine the most cost-effective diagnostic route. Women were also followed for 12 months following the investigations and the relationships between UDS diagnosis and bladder ultrasonographic measurement with treatments and symptoms were assessed.

Methodology for determination of the accuracy of bladder ultrasonography

Evaluation of the accuracy of a diagnostic test involves comparing the findings a new test with a reference standard diagnosis, which may be based on one or several pieces of test information. Accuracy focuses on estimating rates of test errors: false negatives – those who have the condition but who wrongly receive a negative test result; and false positives – those who do not have the condition but wrongly receive a positive test result. Sensitivity describes the ability of the test to correctly identify the disease (i.e. not give false-negative results) and specificity the ability to identify those without the disease (i.e. to not give false-positive results). For the evaluation of bladder ultrasonography, the findings of UDS are used for the reference standard as it is the best test for diagnosing DO. For bladder ultrasonography to be considered as a test to replace UDS, it is necessary for the rates of false negatives and false positives to be low (i.e. sensitivity and specificity to be high).

There are many possible sources of bias in accuracy studies68 and we report our study in accordance with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy statement to ensure that the risk of bias can be assessed. 69 There are three main domains of bias: (1) selection of the sample, (2) verification of the reference standard and (3) completeness of the data. Selection bias may arise if the sample is not suitably representative of the population. This is likely to occur with use of non-consecutive or convenience sampling. The BUS sought to approach all consecutive eligible women. A related issue is that of spectrum bias whereby the accuracy of tests varies among study samples with differences in disease severity (a measurable characteristic). We planned subgroup analysis to explore the variation in test accuracy owing to spectrum composition.

Empirical studies have shown that studies with differential verification, whereby the reference standard use is dependent on the index test result, produce more biased estimates of accuracy than studies with complete verification by the preferred reference standard. 70 Some of the studies of bladder ultrasonography have mixed reference standards according to the results of the index test, which can lead to bias. 44,49,52 This has occurred through using ambulatory UDS in selected subsets of patients selected according to the results of bladder ultrasonography. Although ambulatory UDS is probably a more accurate reference standard than standard UDS, it was available in only a single recruiting centre, and is costly and inconvenient, and thus we could not use it in all centres. We did aim to include a subset of patients in whom ambulatory UDS had been carried out on and use this enhanced reference standard in a sensitivity analysis, but the primary analysis is based on standard UDS assessments. We mandated that both tests were completed to ensure that we had complete data to enable the accuracy assessment to see if bladder ultrasonography can replace UDS. 71

Reproducibility of a test

The accuracy of a diagnostic test relates to its ability to detect differences in measurements between individuals related to disease state (the signal) against a background of variability in measurements caused by measurement error (the noise or analytical variability). Tests may fail when there is little signal or when the magnitude of the noise is high compared with the size of the signal. Studies of reliability and reproducibility provide estimates of analytical variability and allow assessment of the ability of a test to detect real differences of varying magnitude. For imaging studies, there are two core sources of analytical variability: first, relating to the interpretation of images, with variability caused by measurement error within an observer (intraobserver) and between observers (interobserver); and second, relating to the imaging technique.

Any newer diagnostic test developed to assess bladder function accurately should ideally be reliable and reproducible and easy to interpret. Reproducibility of BWT is of particular importance given the fact that the bladder is a distensible organ and its thickness is known to inversely correlate with the amount of urine present in the bladder. 46 Intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility is demonstrated by studying the difference between blinded observers/measurements when exposing the same patient to the technique independently at different points of time. Transabdominal and transperineal measurement of BWT was shown to have higher interobserver variation than transvaginal measurement in a study by Panayi et al. 72 Hence we chose transvaginal measurement of BWT to evaluate diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing DO.

Assessing the acceptability of bladder ultrasonography and urodynamics

Extreme anxiety disrupts and unsettles behaviour by lowering the individual’s concentration and affecting their self-confidence and muscular control. Unsettled behaviour during intimate and invasive tests such as UDS and bladder ultrasonography may have an impact on the level of co-operation gained from the patient, the ability to complete the test and may have an adverse effect on interpretation of test results. 73,74

There is no reported literature on the explicit quantification of the anxiety levels elicited by UDS and very little attention has been paid to the psychological impact of invasive diagnostic testing of lower urinary tract conditions. 26 We aimed to assess state anxiety, defined as a mood state associated with preparation for possible upcoming negative events75 and consider this alongside pain during and shortly after each test.

Effect of tests on subsequent treatment pathway

Pharmacotherapy is considered first-line treatment of OAB, with or without the use of conservative interventions like bladder retraining, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) (with or without biofeedback), weight loss and fluid management. The motor nerve supply to the bladder is via the parasympathetic nervous system (via sacral nerves S2, S3, S4),76–78 which stimulates detrusor muscle contraction. This is mediated by acetylcholine acting on muscarinic receptors at the level of the bladder. Cholinergic blockade may abolish or reduce the intensity of detrusor muscle contraction. 79 Various anticholinergic medications differ with respect to efficacy, tolerability and side effect profile. Women taking anticholinergic medications frequently experience adverse effects such as dry mouth, headache, constipation, dizziness, decreased visual acuity and tachycardia. A pharmacological classification of bladder agents used in OAB is:

-

Non-selective anticholinergics: tolterodine tartrate, trospium chloride, oxybutynin hydrochloride, propiverine hydrochloride, propantheline bromide.

-

M2–M3 selective anticholinergic: solifenacin succinate (Vesicare®, Astellas).

-

M3 selective antagonist: darifenacin hydrobromide (Emselex®, Merus).

-

Beta3 receptor agonist: mirabegron (Betmiga®, Astellas).

In patients who are refractory to conservative management of OAB (because of either a lack of efficacy or troublesome adverse effects), BTX-A has been used for over a decade with successful outcomes. The majority of patients who commence treatment with BTX-A may require long-term repeat treatments. 80 There is evidence of sustained reductions in UI episodes and increase in volume/void as well as QoL in patients with neurogenic DO81 on repeat (up to five) injections with BTX-A.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) involves stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve in the ankle using a fine-gauge needle, given weekly for 12 weeks and topped up as required. Improvement in OAB symptoms using PTNS is comparable to the effect of antimuscarinics but with a better side effect profile. 82 The studies included in the published systematic review considered only short-term outcomes after initial treatment. 82 In order to recommend PTNS as a practical treatment option, long-term data and health economic analysis are needed. 82 The NICE guideline on UI recommends that PTNS for OAB can be offered only if there has been a multidisciplinary team review, conservative management including OAB drug treatment has not worked adequately and the woman does not want BTX-A or percutaneous sacral nerve stimulation (SNS). 36

Sacral neuromodulation involves implantation of a permanent sacral nerve root stimulator, which is designed to stimulate the third sacral nerve root. It is recommended to patients with refractory OAB who have failed conservative measures (including drugs), who have not responded to BTX-A treatment and have voiding difficulties. 36,83 The surgical treatment for SUI is offered if the PFMT has been unsuccessful or declined and mainly consists of a mid-urethral sling. 36

The impact of a test is whether or not it ultimately improves patient outcomes, by identifying those that need treatment, or differentiating between alternative diagnoses and directing an appropriate treatment. There are widely held concerns that although a UDS DO diagnosis is accurate, it is not clear that it leads to different patient management or predicts patient outcome. There are some studies to suggest that patient-related outcomes are similar whether or not there is an urodynamic diagnosis of DO in patients with OAB, following a variety of treatment options. 84–87

A comparable situation exists for stress incontinence, whereupon non-invasive assessments alone were found to be not inferior to UDS for outcomes at 1 year in a randomised controlled trial (RCT). 61 A meta-analysis has concluded that pre-operative UDS does not influence the likelihood of subjective cure or post-operative complications in women without VD undergoing primary surgery for uncomplicated SUI and so should not be carried out. 88 In a RCT, urodynamic status could not predict treatment outcomes between patients treated with extended-release tolterodine tartrate or placebo. 84

There is a necessity, therefore, to establish the role of UDS and its impact on treatment and patient outcomes in OAB as at present its role is unclear. The BUS provided a unique opportunity to address this question and so, midway through, we proposed an extension to the study. The extension aimed to establish if treatment pathways differed following confirmation of DO based on UDS. Moreover, we sought to assess if the UDS diagnosis had an effect on patient-reported severity and improvement at 6 and 12 months after testing, and whether or not receiving the most appropriate treatment according to the UDS diagnosis improved symptoms.

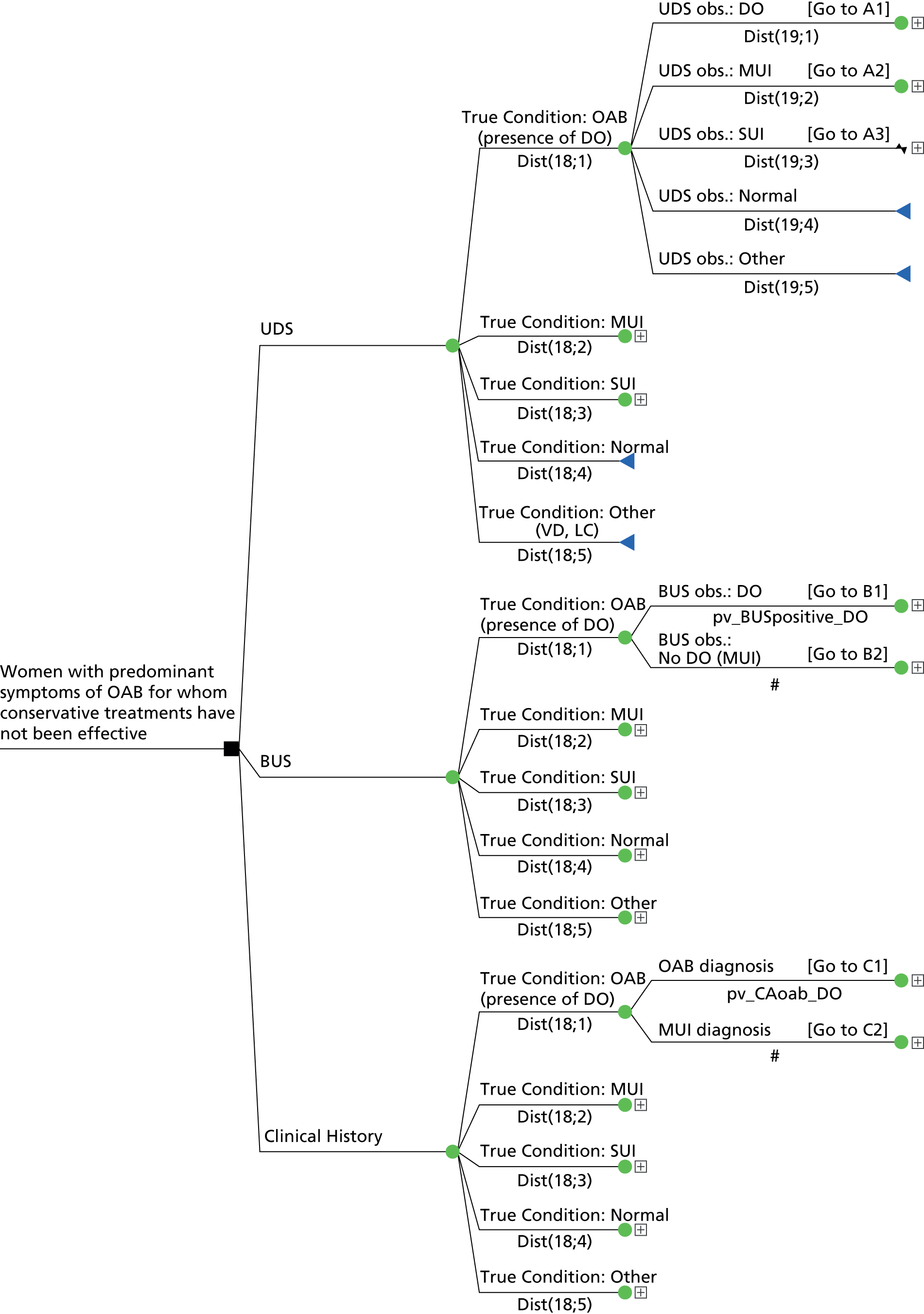

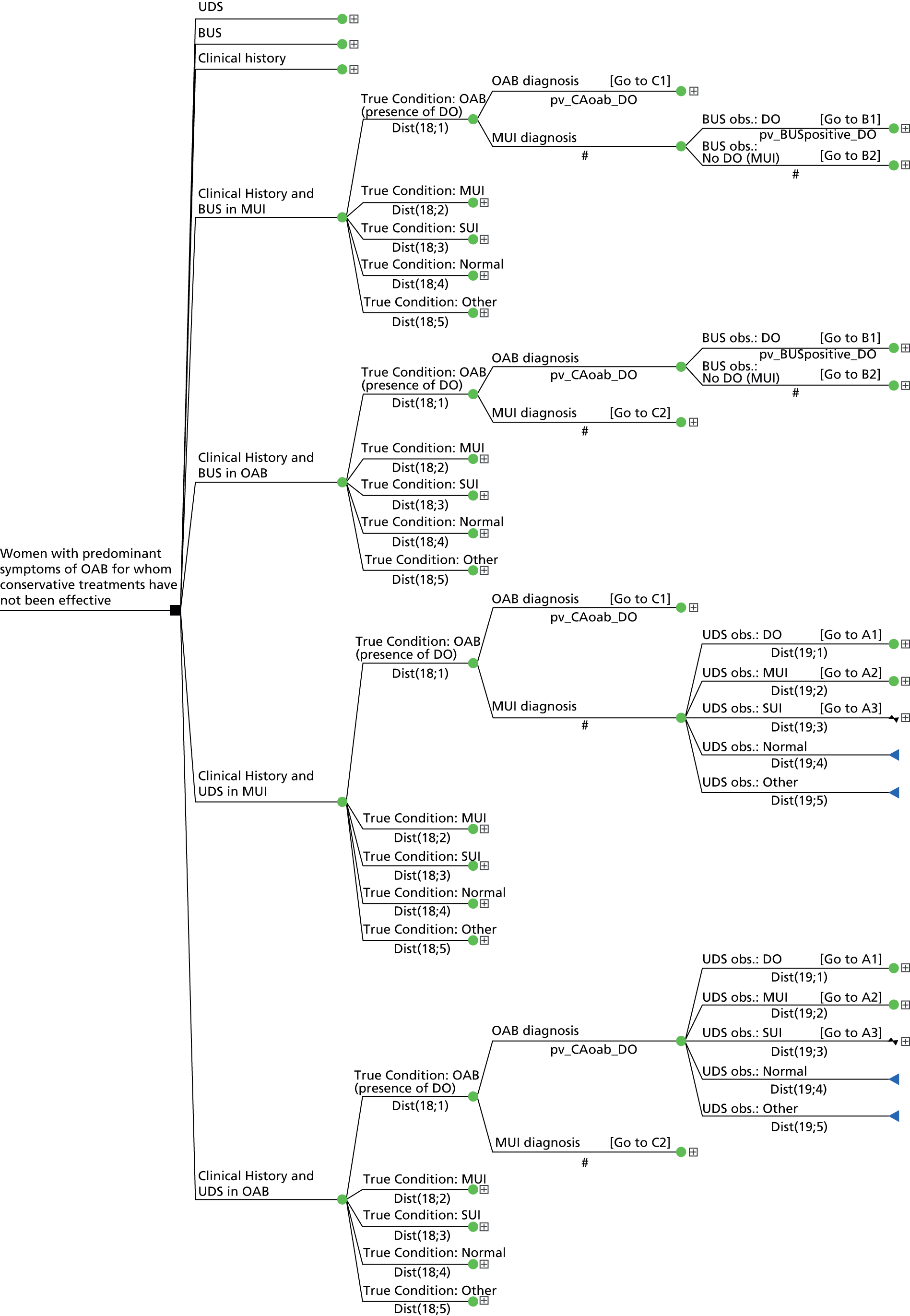

Economic evaluation of the alternative diagnostic strategies

In addition to evaluating the reproducibility, accuracy and acceptability of bladder ultrasonography, it is important to assess the cost-effectiveness of testing strategies involving bladder ultrasonography, UDS and based on the primary presenting symptom in clinical history alone. The BUS would enable comprehensive primary resource utilisation for bladder ultrasonography and UDS to be collected as part of the study and the extension provided the opportunity to collect outcome data for all women who having reported bladder problems, and the treatment they received, whether or not they had a UDS diagnosis of DO. These data, together with other estimates obtained from the literature,89–92 were used to clarify whether or not the UDS test itself represents an appropriate and justifiable use of health service resources, given the doubt over its predictive ability.

Aims and objectives of the Bladder Ultrasound Study

The original primary research objective was to estimate the diagnostic accuracy of BWT, measured by transvaginal bladder ultrasonography, in the diagnosis of DO.

The original secondary research objectives were:

-

to conduct a decision-analytical model-based economic evaluation comparing the cost-effectiveness of various care pathways (including pathways that incorporate bladder ultrasonography)

-

to investigate the acceptability of UDS and bladder ultrasonography

-

to assess whether or not measurements of BWT made using transvaginal ultrasonography have adequate reliability and reproducibility to be likely to detect differences in BWT potentially indicative of disease.

We also aimed to investigate the value added by bladder ultrasonography to information already obtained from routinely used initial non-invasive tests (history, bladder diary, disease-specific QoL questionnaire), but this became redundant when the accuracy of bladder ultrasonography was found to be poor. Subsequently, a fifth objective was added to the BUS, namely to establish the role of UDS and its impact on treatment and patient outcomes in OAB and MUI. There were six key questions:

-

Does the UDS diagnosis affect treatment pathways?

-

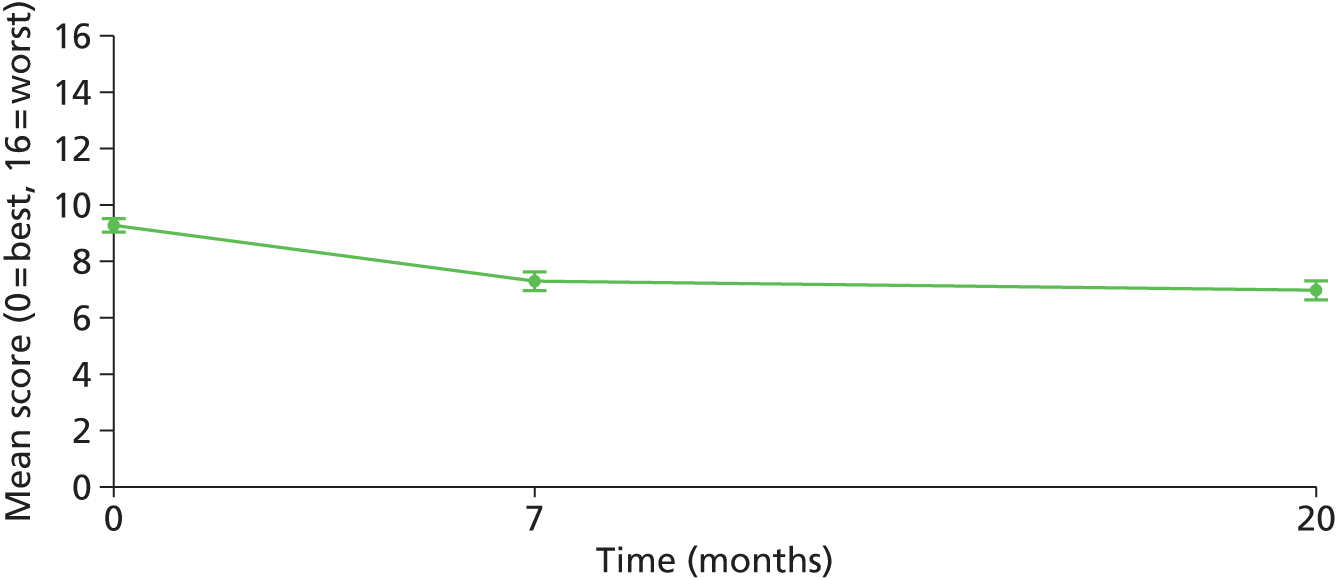

What were the patient-reported outcomes in the cohort of women recruited in the BUS at 6 and 12 months after testing?

-

Does the diagnosis by UDS have any effect on symptoms after 6 and 12 months, that is, can UDS predict improvement in different patient groups?

-

Does receiving treatment concordant with the urodynamic diagnosis improve patients’ symptoms, compared with not receiving a concordant treatment?

-

Are presenting symptoms related to outcomes at 6 and 12 months?

-

Does ultrasonographic measurement of BWT have any prognostic value?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of UDS in the diagnosis of DO?

Chapter 2 Diagnostic accuracy of bladder wall thickness via bladder ultrasonography in the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity

Introduction

A cross-sectional test accuracy study was undertaken to assess the accuracy of BWT in diagnosing DO in women with OAB symptoms. Women were recruited with OAB or urgency-predominant MUI and BWT was measured from transvaginal ultrasound scans. DO status was judged from findings obtained from multichannel UDS, which was undertaken blind to the findings from the transvaginal ultrasonography. Test accuracy was estimated by comparing BWT measures (the index test) against diagnosis of DO (the target condition) obtained from UDS (the reference standard).

Oversight

The study plan was detailed in a protocol which received a favourable ethical opinion from the Nottingham Research ethics committee (MREC 10/H0408/57). NHS trust research governance approval was obtained for 22 recruiting hospitals in the UK, with the Birmingham Women’s Hospital and University of Birmingham acting as sponsors. A detailed description of the independent oversight of the study is given in Appendix 1.

Methods

Study sample

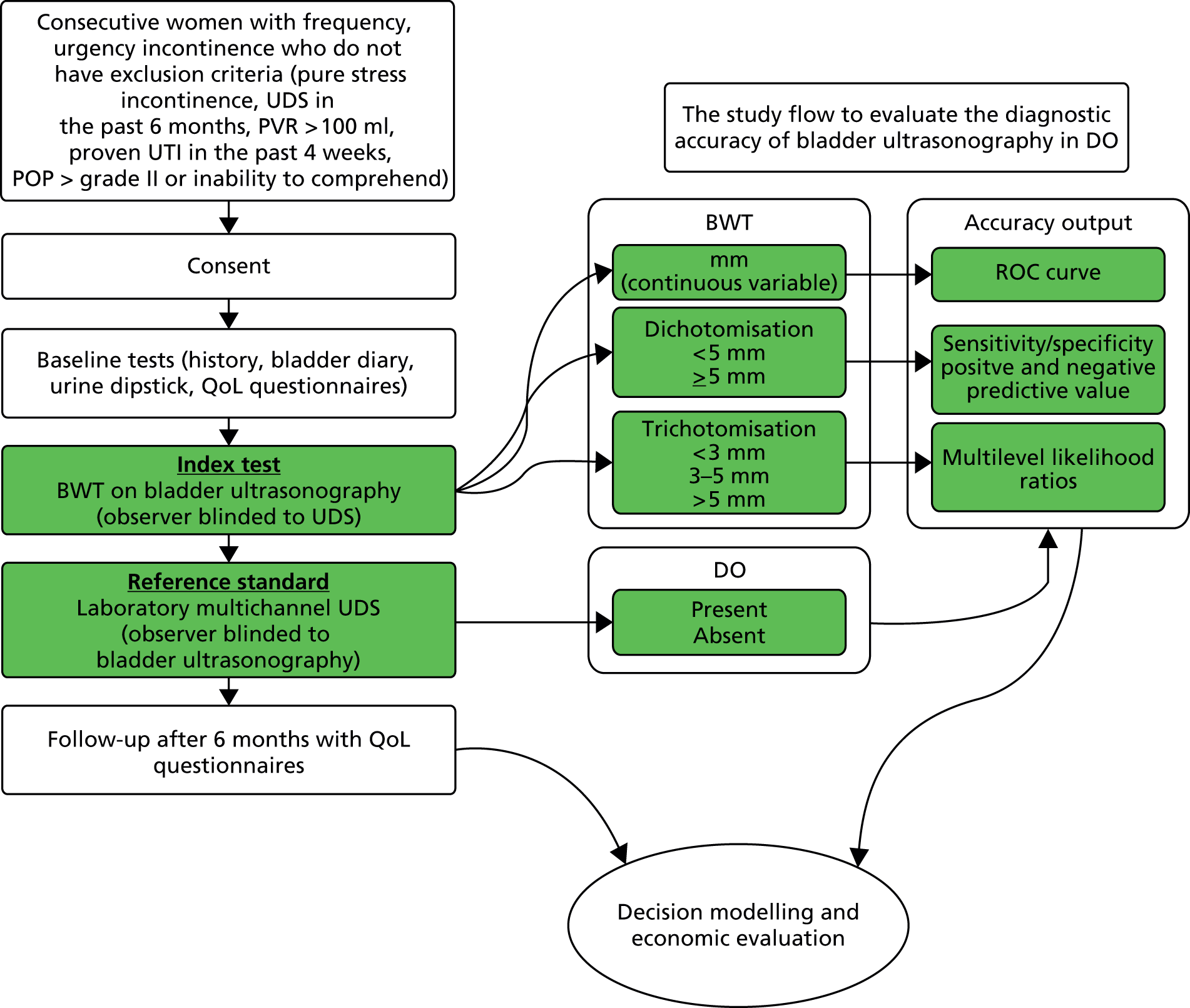

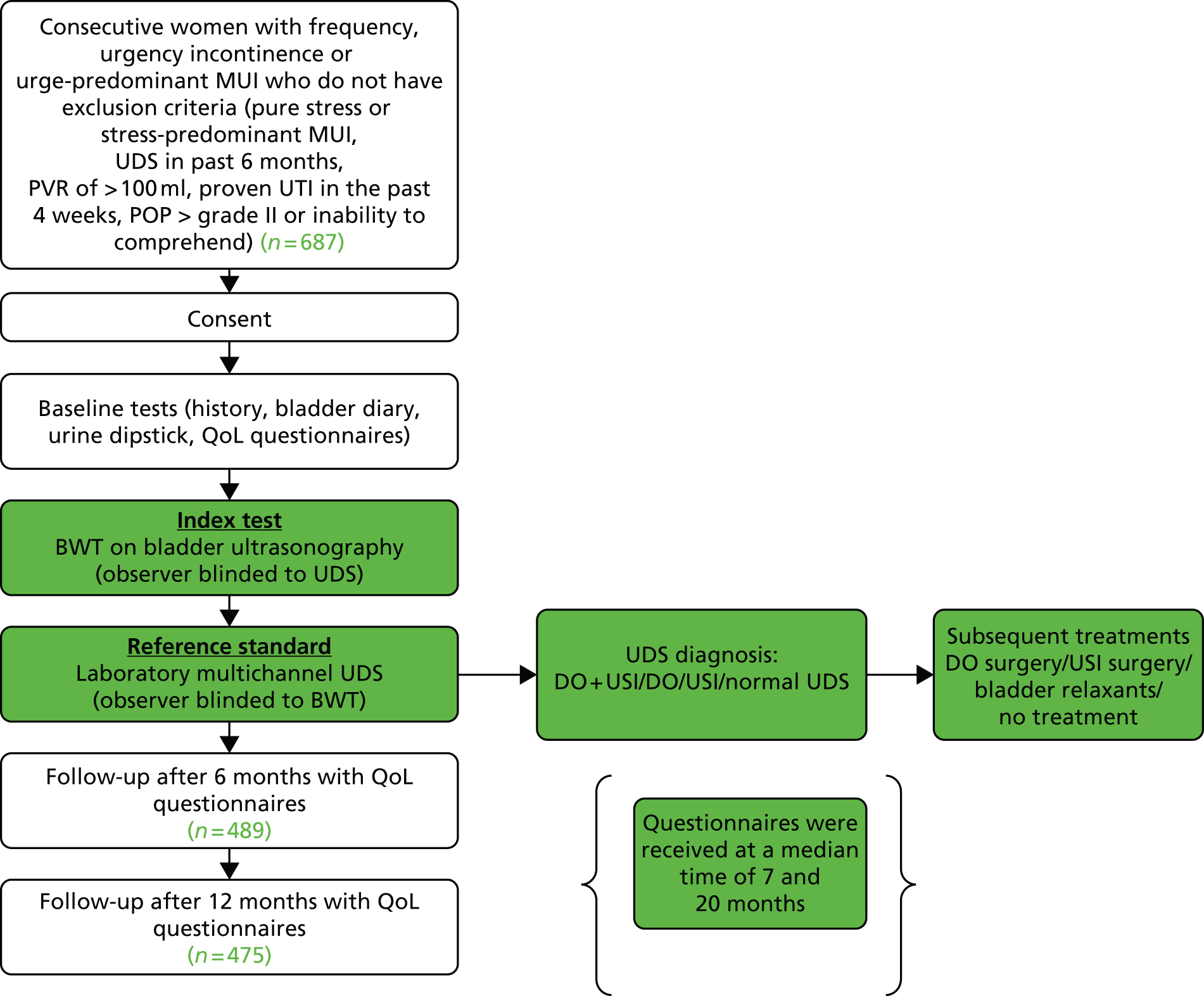

Consecutive women attending urogynaecology or urology clinics at either specialised referral centres or district general hospitals were approached for consent to the study. They were eligible for inclusion in the study (Figure 1) if they satisfied the following criteria:

-

Frequency of nine or more voids in 24 hours as reported in a 3-day bladder diary (on at least on one of the days).

-

Urgency (cannot defer the urge to void) recorded on at least two occasions in the 3-day bladder diary.

-

PVR volume ≤ 100 ml on the screening bladder scan.

-

No stress incontinence surgery and/or BTX-A in the past 6 months.

-

Provided written informed consent.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

Exclusion criteria were:

-

Current pregnancy or up to 6 weeks post partum.

-

Pure symptoms of stress incontinence or stress-predominant mixed incontinence.

-

Evidence of cystitis (dipstick positive for leucocytes/nitrites).

-

Voiding difficulties (e.g. PVR of > 100 ml).

-

Prolapse > grade II (any compartment, as defined by the Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) Quantification system). 93

-

Previous UDS assessment in the past 6 months.

-

Use of antimuscarinics for more than 6 months continuously.

-

Current use of antimuscarinics (e.g. tolterodine, solifenacin, oxybutynin). If the woman was taking antimuscarinics at the point of consent, she was eligible if the medication was ceased immediately and there was a delay of at least 2 weeks before the index and reference tests were carried out.

Given the need to fully inform each woman about the study (to provide time for her to consider participation and to avoid burdening her with information at the time of recruitment), a two-stage informed consent strategy was employed. The study information leaflets along with a sample consent form and bladder diaries were posted to all prospective participants with their clinic appointment letter. Research nurses and principal investigators in the recruiting hospitals were trained to reinforce the information provided and answer any questions that the women may have had. The collaborating teams approached patients for recruitment and consent at the time of consultation. We advised the recruiting centres to maintain a screening log of the eligible and ineligible participants was (identification and demographic details and any exclusion criteria).

Demographic and clinical history of the participants was collected prior to testing. This included medical and surgical history, previous treatments, if any, for bladder, bladder diary results and incontinence pad use. The ICIQ-OAB questionnaire67 was also administered prior to testing and then at 6 and 12 months post-testing for use in the long-term follow-up study (see Chapter 6). A generic and preference-based health-related QoL questionnaire, the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),94 was administered at the same time points. The Investigating Choice Experiments CAPability measure for Adults (ICECAP-A) was given at baseline and 6 months only. Questionnaires on the acceptability of the testing were given immediately post-testing (see Chapter 5 for output).

Setting of tests

Urodynamics was carried out by health-care professionals (doctors or nurses) who routinely carry out the procedure in clinical practice. The standard operating procedures (SOPs) (see Appendix 5) and quality assurance processes are described in Chapter 3. For bladder ultrasonography (see Appendix 6), hands-on training was delivered on site at each of the recruiting sites for the clinicians (doctors or sonographers) and two training workshops were carried out at the Birmingham Women’s Hospital.

At centres where ultrasonography was undertaken in the UDS suite, the scan was performed at the same clinic visit but by an independent trained observer blinded to the UDS result. At centres where the scan was to be performed in the radiology department, both diagnostic tests were carried out within 4 weeks of each other. Clinicians performing each of the tests were blinded to the results of the other. The operator performing the UDS recorded the findings and the diagnosis in the UDS test pro forma and the operator performing bladder ultrasonography recorded the BWT measurements in the bladder ultrasonography test. The index test (bladder ultrasonography) was carried out in a scan suite and the UDS carried out in the UDS suite in the majority of the centres. Both data collection forms were then collected by a research nurse/research fellow co-ordinating the recruitment at each centre and were sent to the bladder ultrasonography trial office (Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit) in a sealed envelope.

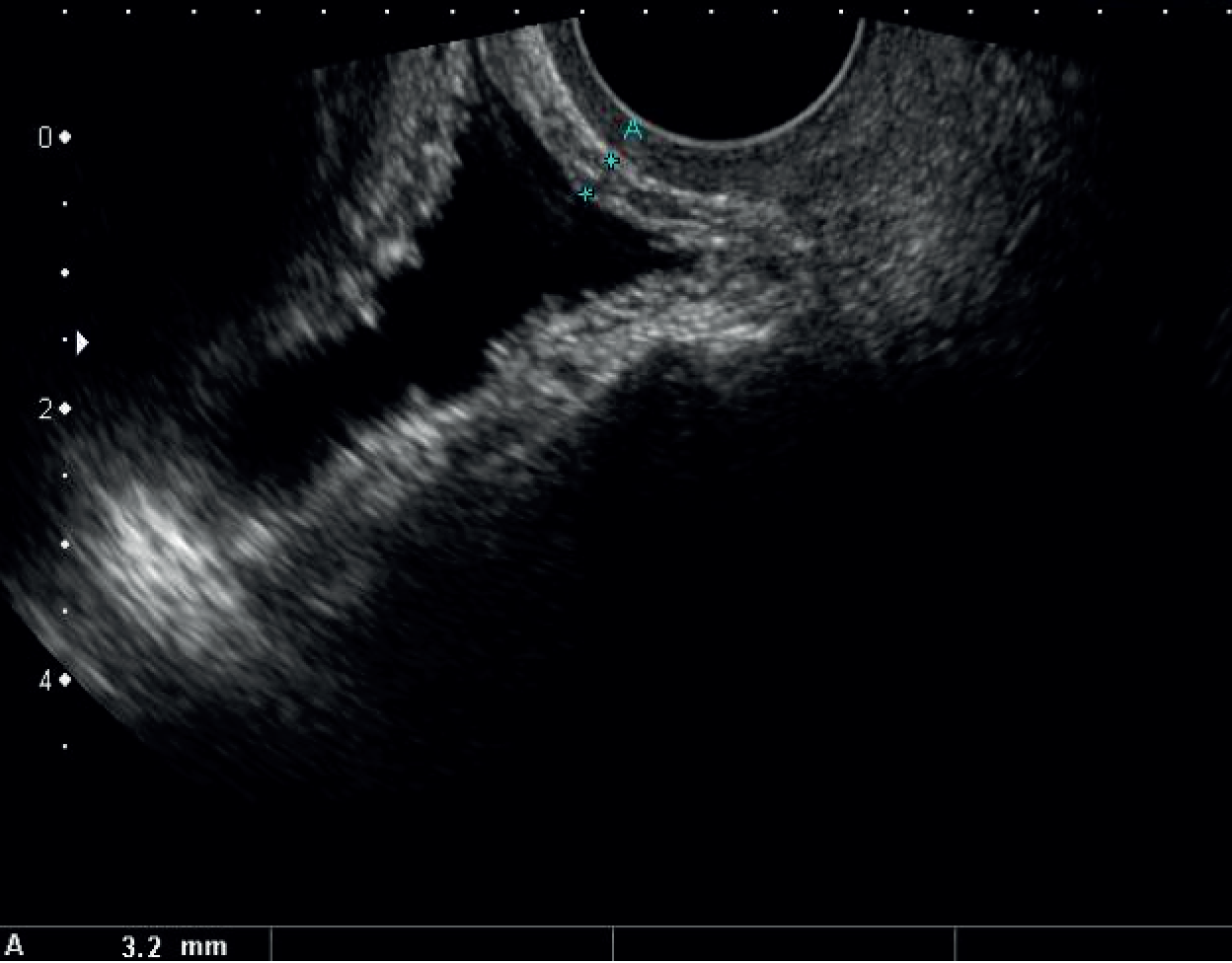

Index test: bladder wall thickness via ultrasonography

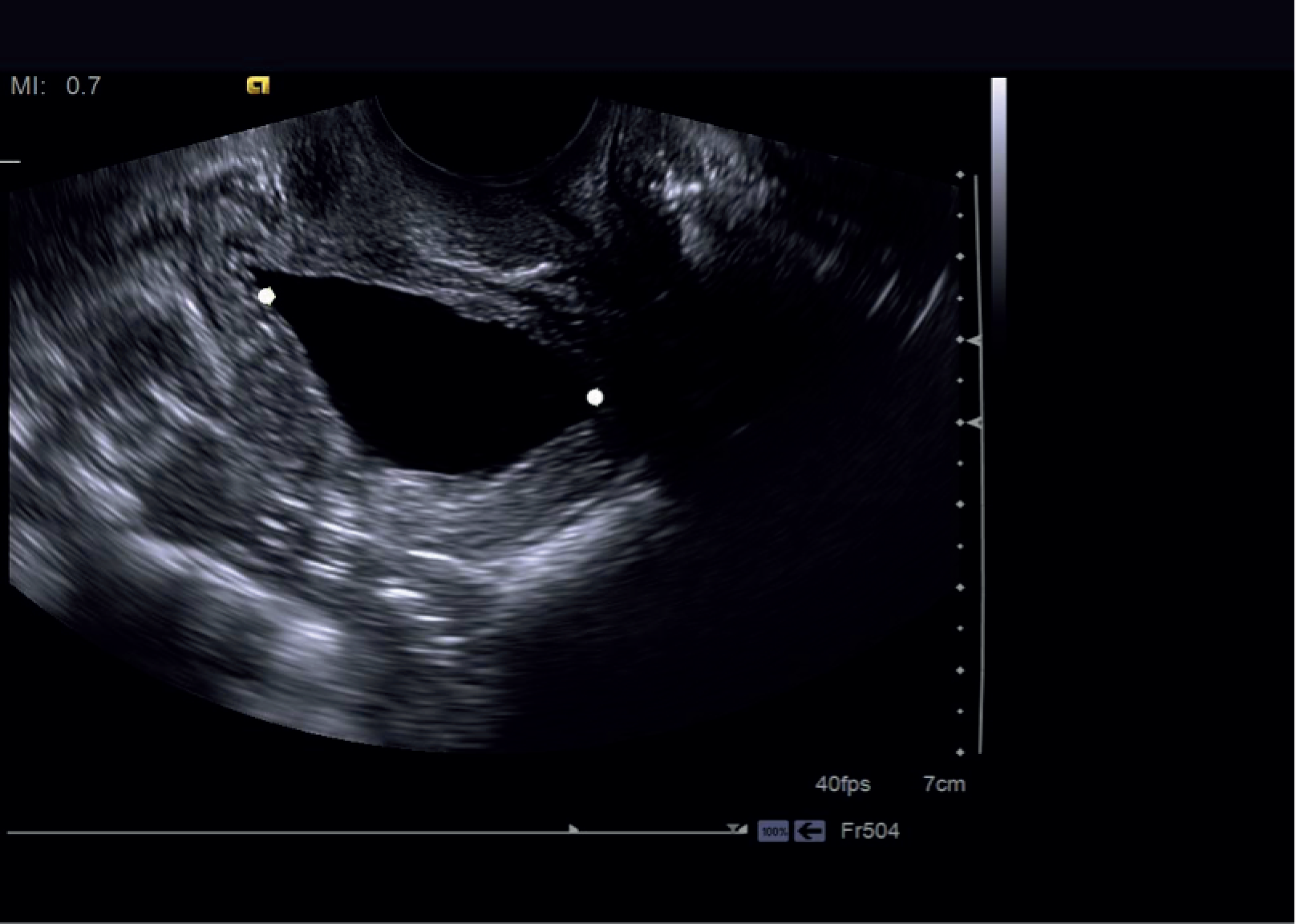

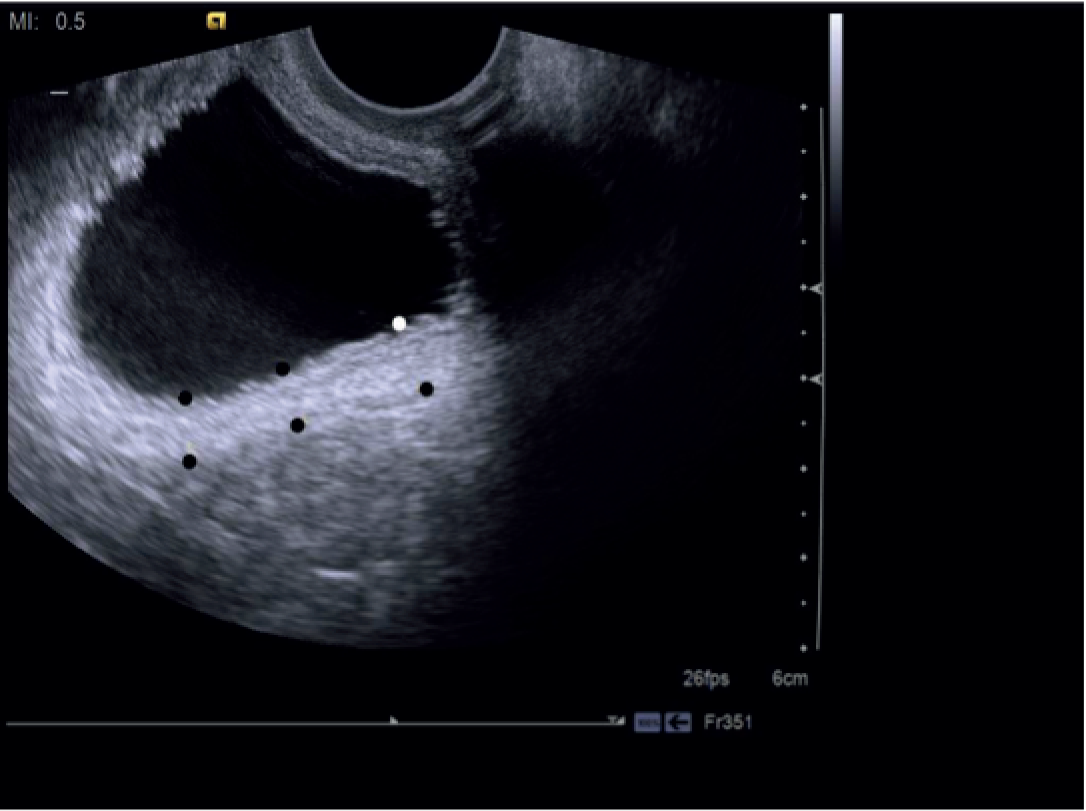

The BWT was measured from a transvaginal scan with the end-firing transvaginal probe in the sagittal plane (midline) introduced 1 cm beyond the vaginal introitus in the midline. BWT measurement involved measuring the inner and outer hyperechoic areas along with the hypoechoic detrusor sandwiched in the middle. 49,95 When the inner and outer hyperechoic areas are excluded and the inner hypoechoic area only is measured, it is classed as DWT. We measured BWT via the transvaginal approach at a volume < 30 ml. The echo-poor central area of the urethra was used as a landmark for BWT scanning. BWT was measured in millimetres using tools provided on the ultrasonography machine at the following three sites perpendicular to the luminal surface of the bladder (Figures 2 and 3):

-

The thickest part of the trigone.

-

The dome of the bladder in the midline.

-

The anterior wall of the bladder.

FIGURE 2.

Bladder wall thickness measurement at trigone.

FIGURE 3.

Dome midline and two lateral measurements on either side.

For the purposes of this study, BWT was to be calculated as the mean of these three measurements. In order to assess whether or not the mean of three values at the dome was similar to the value obtained on dome, anterior wall and trigone, two further measurements of DWT 1 cm on either side of the dome midline were also taken.

Reference standard: urodynamics

All women underwent UDS, using a standardised protocol in accordance with the GUP guidelines of the International Continence Society. 96 Participants attended the UDS clinic with a full bladder. Uroflowmetry was performed with the woman voiding in private and recorded on a gravimetric flow meter. Filling cystometry was then performed with the woman in sitting position. This was then followed by voiding cystometry with the pressure lines in situ (see Appendix 5).

Sample size

A target sample size of 600 participants was determined a priori. The computation was based on presuming a prevalence of 50% for DO,17 providing 300 women for the estimate of sensitivity and 300 for the estimate of specificity. This allows estimation of sensitivities and specificities with 95% CIs of width 10% for sensitivity and specificity values between 70% and 95%, and narrower for higher values.

Data analysis

The primary analysis involved calculations of sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios (LRs) using a BWT of 5 mm as a cut-off point (≥ 5 mm indicating presence of DO, < 5 mm indicating absence of DO). BWT of 5 mm was chosen as the cut-off point for discriminating DO based on the evidence from previous studies49,97 and was pre-specified in the protocol.

Likelihood ratios for the following three ordered categories of BWT were also pre-specified: < 3 mm, ≥ 3 mm to < 5mm, ≥ 5 mm. 98 95% CIs were calculated using binomial exact methods. A ROC curve was constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) computed (with 95% CI) to give an overall estimate of BWT accuracy across all thresholds. Statistical significance was tested by comparing against the uninformative model (i.e. for which AUC = 0.5) using a non-parametric approach. 99 The distributions of BWT measurements in groups with and without a DO diagnosis were depicted using box-and-whisker plots and mean values compared using a two-sample t-test.

A number of sensitivity analyses were performed on the primary population to test the robustness of the results to protocol deviations and missing data. ROC curves and associated AUC values were computed for each analysis. The analyses were:

-

Excluding those patients for whom it was revealed that the UDS test result was not blinded to the results of ultrasonography (to exclude any possible diagnostic review bias).

-

Excluding those patients for whom it was calculated to be more than 4 weeks between index and reference standard tests (to exclude any possible disease progression bias).

-

Including results of incomplete ultrasonographic measurements, that is when not all three components of BWT were recorded (in these cases, if one or two measurements were missing, the average of the remaining values was taken to be BWT; this was to exclude the impact of missing measures).

-

Replacing the original UDS diagnosis with that from the additional ambulatory UDS test when available (this happened only in 14 instances, all from one centre; this analysis was intended to assess the impact of this presumed more sensitive UDS than supine UDS).

-

Using the trigone measurement alone as BWT (to explore whether or not a single measurement was as accurate as the mean of three locations).

-

Excluding those who had ‘provoked DO’ (detrusor pressure rise on provocation testing – 187 cases; this was to assess the impact of iatrogenic DO).

-

Excluding those who had PVR of > 30 ml on BWT testing (34 cases; this was to explore the impact of those with minor degrees of incomplete emptying).

-

Taking the average of dome, 1 cm left of dome and 1 cm right of dome as BWT (to explore whether or not measurements at this location improve accuracy).

In addition, some unplanned exploratory analyses were also performed to gauge the effect of changing the population of interest and also to see which parameters were associated with DO diagnosis. The populations explored were:

-

Women with urgency alone on clinical history (i.e. excluding those with mixed stress/urgency incontinence).

-

Women with ‘pure’ DO only (i.e. not alongside another diagnosis from UDS).

-

Women with ‘wet’ DO only (i.e. not including those with ‘dry’ DO).

Pre-planned subgroup analyses were also performed to compare test accuracy between subgroups. ROC curves were created for each subgroup and associated AUC values compared using a large sample chi-squared test for independent curves. 100 The subgroups used here to dichotomise patient groups were:

-

Previous treatment with antimuscarinics.

-

A clinical history suggesting mixed incontinence.

-

Presence of a UTI in the previous 12 months.

-

Voiding difficulties.

-

Previous incontinence surgery.

-

Body mass index (BMI) (< 25 kg/m2, ≥ 25 kg/m2).

Exploratory analyses were undertaken to assess variables associated with a diagnosis of DO using logistic regression. The above six subgroup variables were included along with pre-test International Consultation on Incontinence modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) score, BWT, age, duration of symptoms, ethnicity, number of vaginal deliveries, menopausal status, parity and previous POP surgery. Covariates were considered individually and then in a multivariable analysis. Three multivariable models were constructed: one using all possible explanatory variables, another using all possible explanatory variables but using a multiple imputation approach to generate missing responses101 and another using a backward-step process to eliminate unimportant variables (a level of p = 0.1 was used here as criteria for staying in the model). We also examined whether or not BWT had any relationship with baseline ICIQ-OAB score using a simple linear regression model.

Results

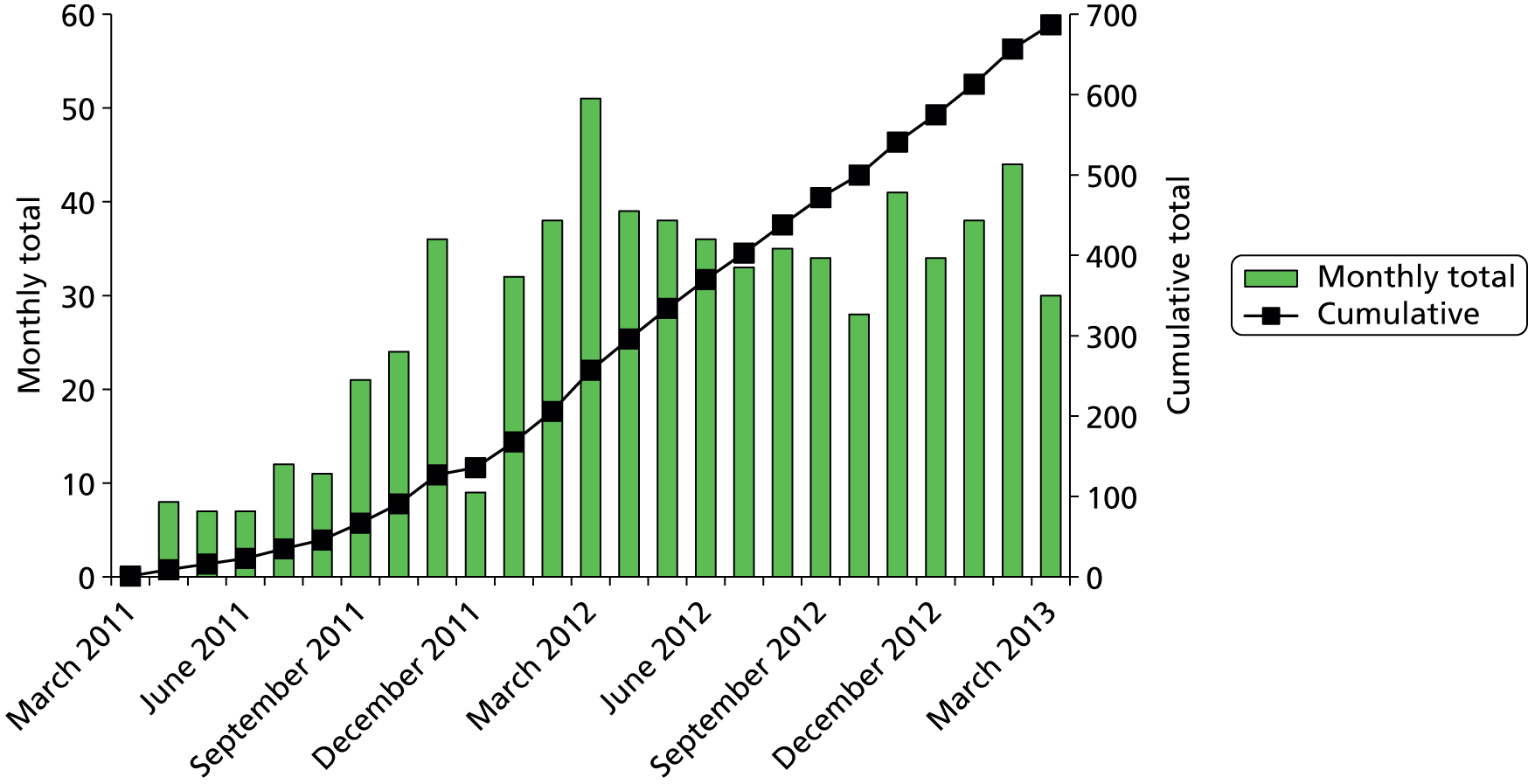

Recruitment

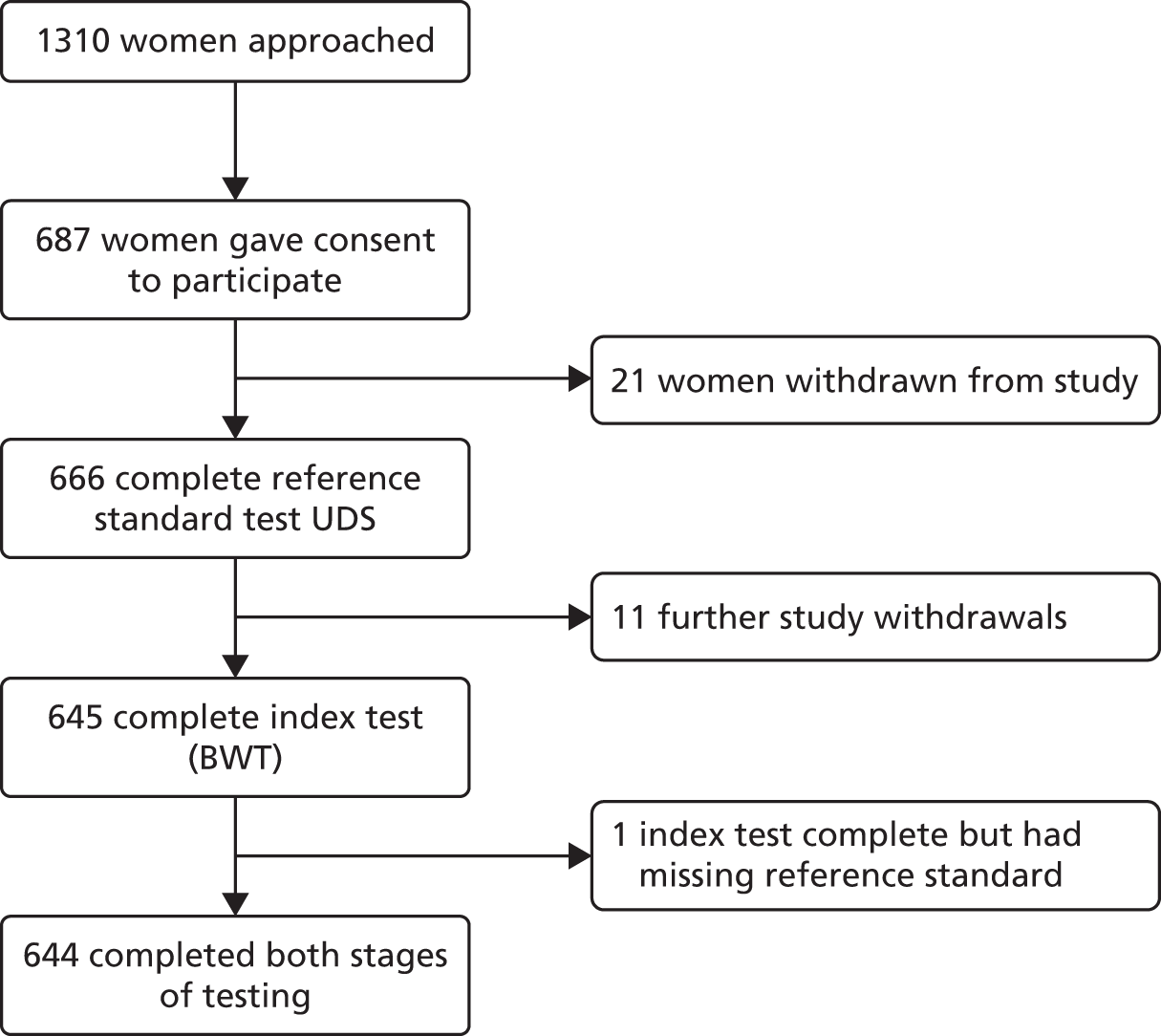

Recruitment of participants started in March 2011 and closed in March 2013. A total of 1310 women were approached. Six hundred and eighty seven women who were eligible and consented to participate were recruited into the study from 22 centres (Table 2 and see Figure 23). This number was slightly higher than the agreed sample size calculation to compensate for a small number of study withdrawals and women without complete index and reference standard test results (Figure 4).

| Recruiting centre | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Birmingham Women’s Hospital | 254 | 37 |

| Medway Maritime Hospital, Kent | 109 | 16 |

| Mayday University Hospital, Croydon | 92 | 13 |

| Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital | 30 | 4 |

| St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester | 26 | 4 |

| Staffordshire General Hospital | 26 | 4 |

| Stepping Hill Hospital | 25 | 4 |

| Ormskirk and District General Hospital | 19 | 3 |

| New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton | 16 | 2 |

| Royal Bournemouth General Hospital | 16 | 2 |

| The Alexandra Hospital, Redditch | 14 | 2 |

| City General Hospital (University Hospital of North Staffordshire) | 10 | 1 |

| Crosshouse Hospital, Ayrshire | 9 | 1 |

| Manor Hospital, Walsall | 8 | 1 |

| Northampton General Hospital | 6 | 1 |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield | 6 | 1 |

| Derriford Hospital, Plymouth | 5 | 1 |

| Pinderfields General Hospital | 4 | 1 |

| St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington | 4 | 1 |

| Southern General Hospital, Glasgow | 3 | < 1 |

| The Royal London Hospital | 3 | < 1 |

| Sandwell General Hospital, Birmingham | 2 | < 1 |

| Total | 687 | 100 |

FIGURE 4.

Participant flow diagram.

Characteristics of participants

Characteristics of women who consented to take part in the study are shown in Table 3. The mean age of women was 52.7 years (SD 13.9 years) and the average BMI was 30.6 kg/m2 (SD 12.2 kg/m2). A total of 55% (378/687) of the women were post menopausal. According to the clinical history, 33% (226/687) reported only urinary urgency without incontinence and 61% (419/687) had urgency-predominant MUI. The median duration of symptoms was 3.0 years (IQR 1.6–7.0 years).

| Characteristic | Category | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 52.7 (13.9) |

| Missing | 0 (–) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White British/Irish/other | 538 (78) |

| Asian Pakistani/Indian/Bangladeshi/other | 72 (10) | |

| Black Caribbean/African/other | 49 (7) | |

| Mixed/other | 18 (3) | |

| Not given/missing | 10 (1) | |

| Parity, n (%) | 0 | 69 (10) |

| 1 | 90 (13) | |

| 2 | 241 (35) | |

| 3 | 152 (22) | |

| 4 | 56 (8) | |

| > 4 | 63 (9) | |

| Missing | 16 (2) | |

| Post menopausal (last menstrual period > 1 year), n (%) | Yes | 378 (55) |

| No | 293 (43) | |

| Missing | 16 (2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean (SD) | 30.6 (12.2) |

| Missing | 28 | |

| Incontinence type, n (%) | MUI | 419 (61) |

| Urgency incontinence alone | 226 (33) | |

| Stress incontinence alone | 4 (1) | |

| Neither | 19 (3) | |

| Missing | 19 (3) | |

| If mixed, which started first, n (%) (N = 419) | Urgency | 226 (54) |

| Stress | 107 (26) | |

| Unsure | 54 (13) | |

| Missing | 32 (8) | |

| Current or previous treatment with antimuscarinics, n (%) | Yes | 226 (33) |

| No | 444 (65) | |

| Missing | 17 (2) | |

| Recurrent cystitis (three or more in last 12 months), n (%) | Yes | 50 (7) |

| No | 606 (88) | |

| Missing | 31 (5) | |

| Voiding difficulties, n (%) | Yes | 286 (42) |

| No | 374 (54) | |

| Missing | 27 (4) | |

| Vaginal birth, n (%) | Yes | 561 (82) |

| No | 95 (14) | |

| Missing | 31 (5) | |

| Previous incontinence surgery, n (%) | Yes | 36 (5) |

| No | 623 (91) | |

| Missing | 28 (4) | |

| Previous POP/UI surgery, n (%) | Yes | 56 (8) |

| No | 603 (88) | |

| Missing | 28 (4) |

The reference standard: urodynamics

The number of participants with a complete reference standard diagnosis was 666/687 (97%). The other 21 (3%) decided to withdraw from the study before any testing could take place (see Figure 4). Details of the findings in these tests are given in Table 4. Of these, 399 (60%) were diagnosed with DO (95% CI 56% to 64%) (Table 5). Of the 399, 245 were given further subdiagnosis of ‘wet’ DO (61%) and 154 as ‘dry’ DO (39%). The participants also had their DO diagnosis subcategorised as phasic ‘spontaneous’ DO (detrusor contraction during the filling phase: 182/369, 49%; 30 observations missing), provoked DO (if the detrusor contraction occurred during or after provocative measures such as cough, running water or immersion of hands in cold water: 56/369, 15%) or both spontaneous and provoked (131/369, 36%).

| Uroflowmetry | Number of women (%) for binary data, median (IQR) for continuous data, n values recorded |

|---|---|

| Patient had comfortably full bladder, yes, n/N (%) | 502/655 (77) |

| Volume voided (ml), n (IQR) | 129 (58 to 245), n = 627 |

| PVR volume (ml), n (IQR) | 10 (2 to 40), n = 619 |

| Maximum flow rate (ml/seconds) | 16 (9 to 25), n = 596 |

| Filling cystometry | |

| Patient in recommended sitting position for test, yes, n/N (%) | 457/664 (69) |

| Fill rate (ml/min), n (IQR) | 100 (70 to 100), n = 660 |

| First desire (ml), n (IQR) | 135 (84 to 197), n = 644 |

| Normal desire (ml), n (IQR) | 200 (140 to 268), n = 587 |

| Strong desire (ml), n (IQR) | 272 (199 to 357), n = 562 |

| Pain (if reported) (ml), n (IQR) | 300 (203 to 395), n = 154 |

| Leakage (if applicable) (ml), n (IQR) | 10 (0 to 100), n = 229 |

| Total volume in bladder at the end of filling (ml), n (IQR) | 421 (314 to 498), n = 639 |

| Rise in detrusor pressure upon filling, yes, n/N (%) | 350/598 (59) |

| Detrusor pressure at start (cm H2O), n (IQR) | 0 (–1 to 1), n = 638 |

| Detrusor pressure rise on filling to 500 ml (cm H2O), n (IQR) | 12 (6 to 21), n = 576 |

| Detrusor pressure rise when complaint of urgency (cm H2O), n (IQR) | 12 (5 to 21), n = 557 |

| Provocation test (when performed) | |

| Detrusor pressure rise with cough, yes, n/N (%) | 101/517 (20) |

| Detrusor pressure rise with running tap, yes, n/N (%) | 119/367 (32) |

| Detrusor pressure rise with exercise, n/N (%) | 39/124 (31) |

| Voiding cystometry | |

| Peak flow rate (ml/seconds), n (IQR) | 20 (15 to 28), n = 624 |

| Maximum voiding pressure (cm H2O), n (IQR) | 41 (29 to 60), n = 577 |

| Residual volume (ml), n (IQR) | 0 (0 to 20), n = 540 |

| Urodynamic diagnosis | Number of women (%), n = 666 |

|---|---|

| Including DO (n = 399) | |

| DO only | 258 (39) |

| DO/USI | 97 (15) |

| DO/VD | 18 (3) |

| DO/VD/USI | 12 (2) |

| DO/low compliance | 8 (1) |

| DO/USI/low compliance | 5 (1) |

| DO/VD/USI/low compliance | 1 (< 1) |

| Not including DO (n = 267) | |

| Normal | 124 (19) |

| USI only | 78 (12) |

| Low compliance only | 36 (5) |

| VD only | 14 (2) |

| VD/USI | 8 (1) |

| USI/low compliance | 6 (1) |

| VD/low compliance | 1 (< 1) |

The index test: bladder wall thickness

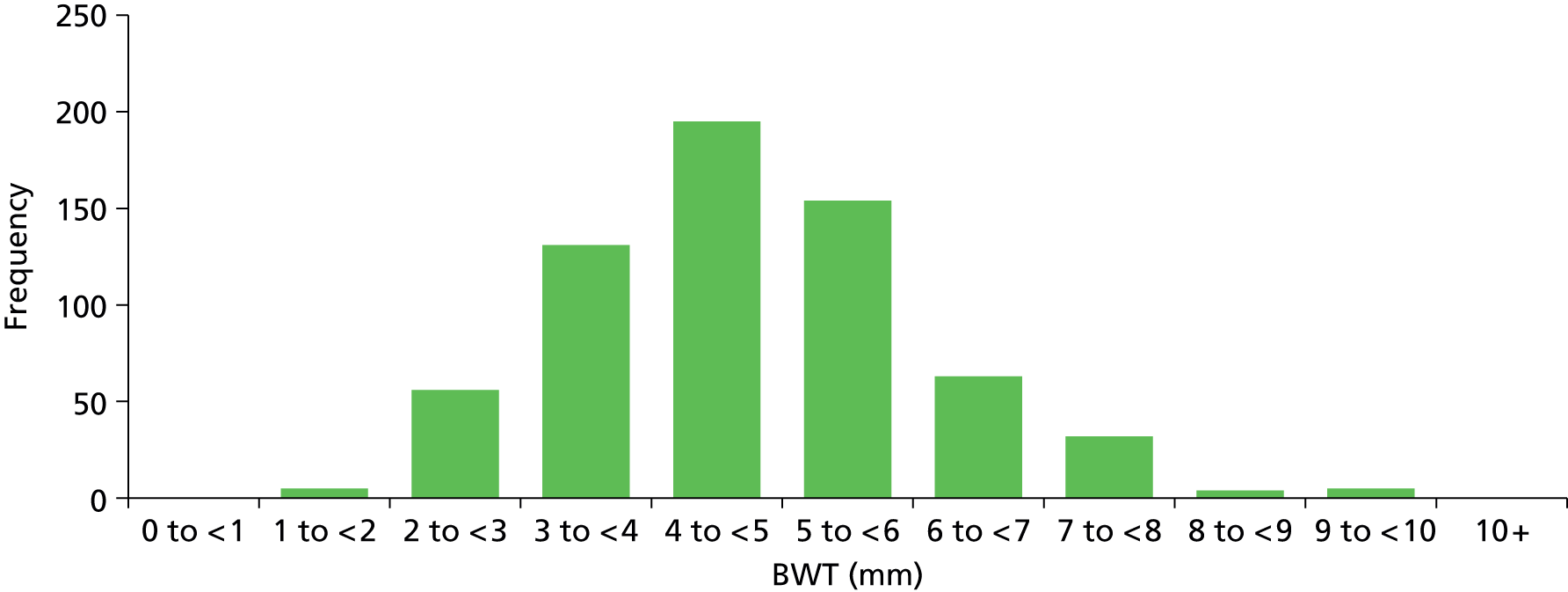

The number of participants with all three BWT measurements (trigone, dome midline, anterior wall midline) available was 645 (94%). Eleven patients had withdrawn after having UDS but prior to ultrasonography (see Figure 4) and a further 10 (1%) had partial measurements recorded (nine with two out of the three measurements and one with one of the three measurements). Summary statistics and distribution of BWT are provided in Table 6 and Figure 5.

| Measurement | Mean (SD), n | Minimum, maximum |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Trigone | 4.51 (1.50), 649 | 0.70, 9.90 |

| (b) Dome midline | 5.00 (1.67), 654 | 1.30, 11.90 |

| (c) Anterior wall midline | 4.85 (1.53), 651 | 1.00, 11.30 |

| Average (a, b, c) | 4.78 (1.34), 645 | 1.07, 9.60 |

| (d) Dome 1 cm left | 4.84 (1.69), 641 | 1.20, 12.10 |

| Average (a, d, c) | 4.73 (1.32), 631 | 0.97, 10.13 |

| (e) Dome 1 cm right | 5.00 (1.76), 639 | 1.10, 10.80 |

| Average (a, e, c) | 4.78 (1.36), 629 | 1.10, 10.50 |

FIGURE 5.

Histogram of BWT measurements (average: trigone/dome midline/anterior wall).

Timing and safety of tests

Six hundred and forty-four participants had both complete index and reference standard results (one had a complete index test but was missing their reference standard, see Figure 4). Of these, 439/644 (68%) had both BWT and UDS performed on the same day. Only a small proportion (26/644, 4%) were performed more than 4 weeks apart. Ninety-seven per cent of reference tests (616/632, 12 observations missing) were confirmed as being blind to the index test. No serious adverse events were reported following either test, although 49/479 (10%) of those responding reported having a UTI within 2 weeks of testing at a 6-month follow-up. Seventy five per cent (36/48, one observation missing) of these were diagnosed by a general practitioner (GP) or in a hospital and resulted in antibiotic use in 83% of cases (39/47, two observations missing).

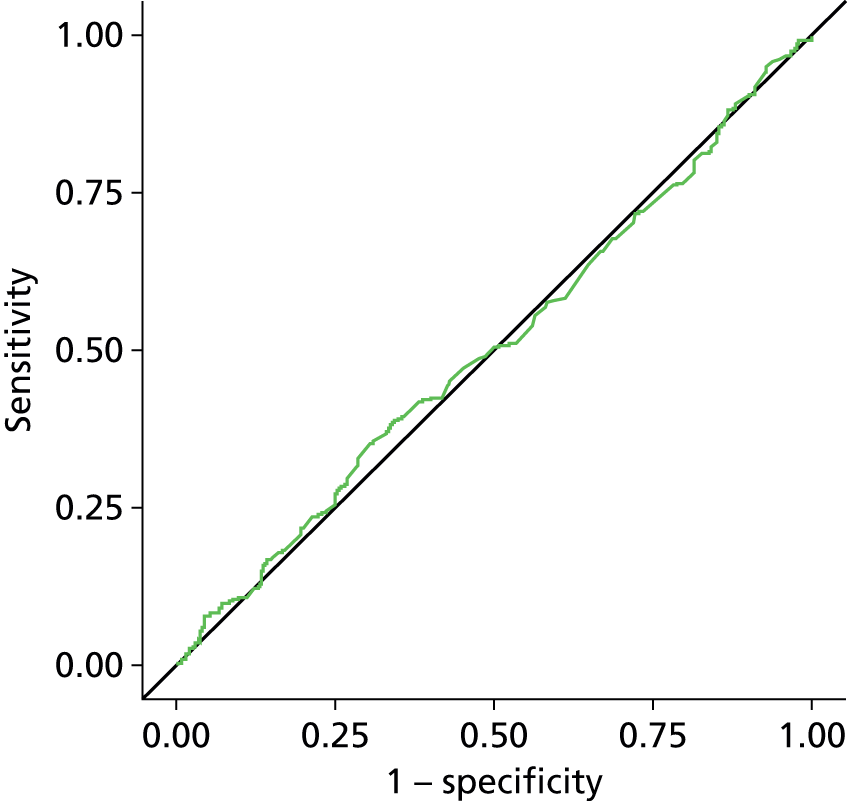

Estimates of test accuracy

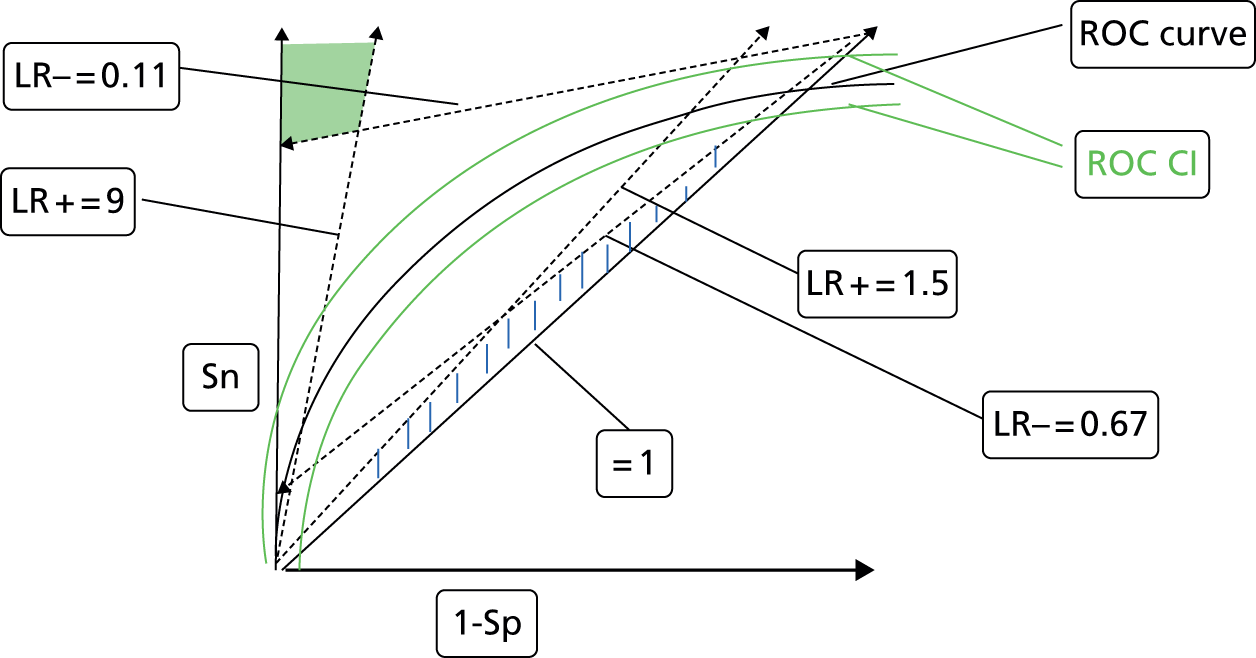

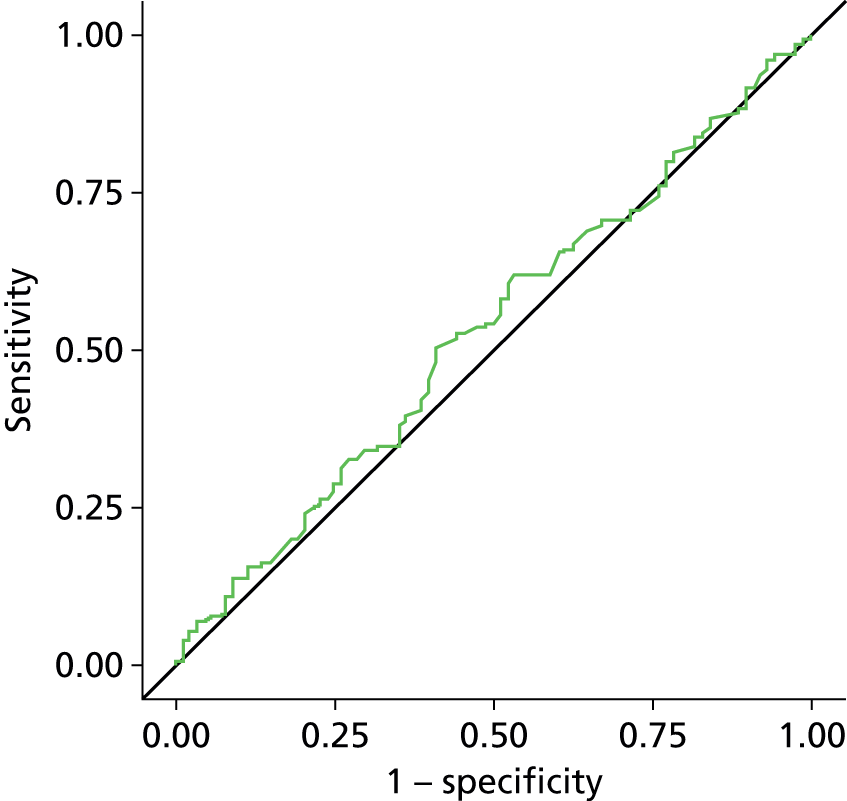

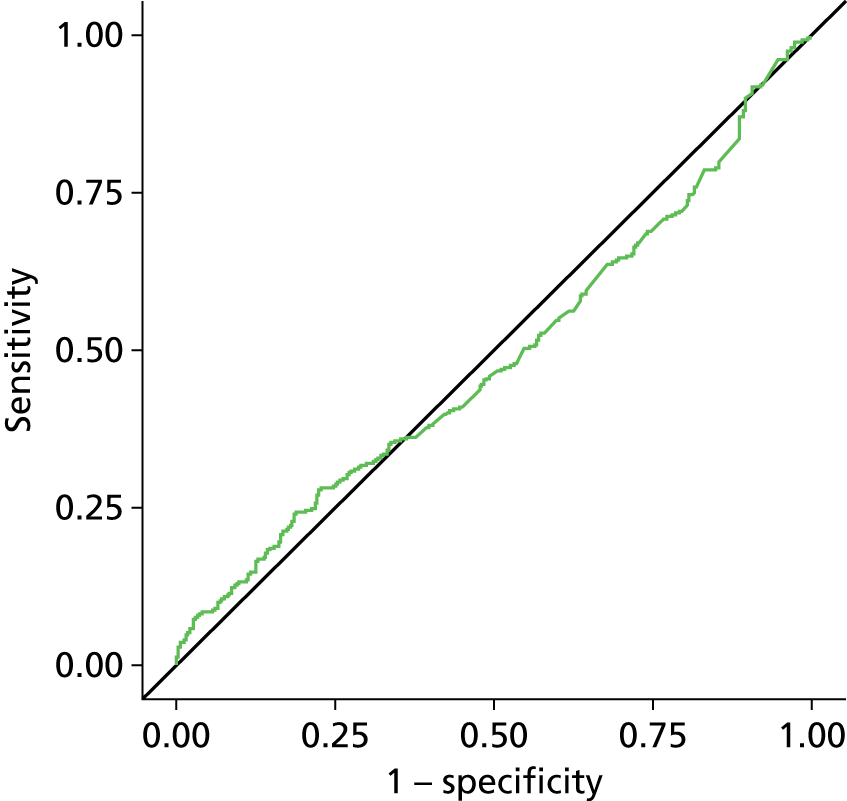

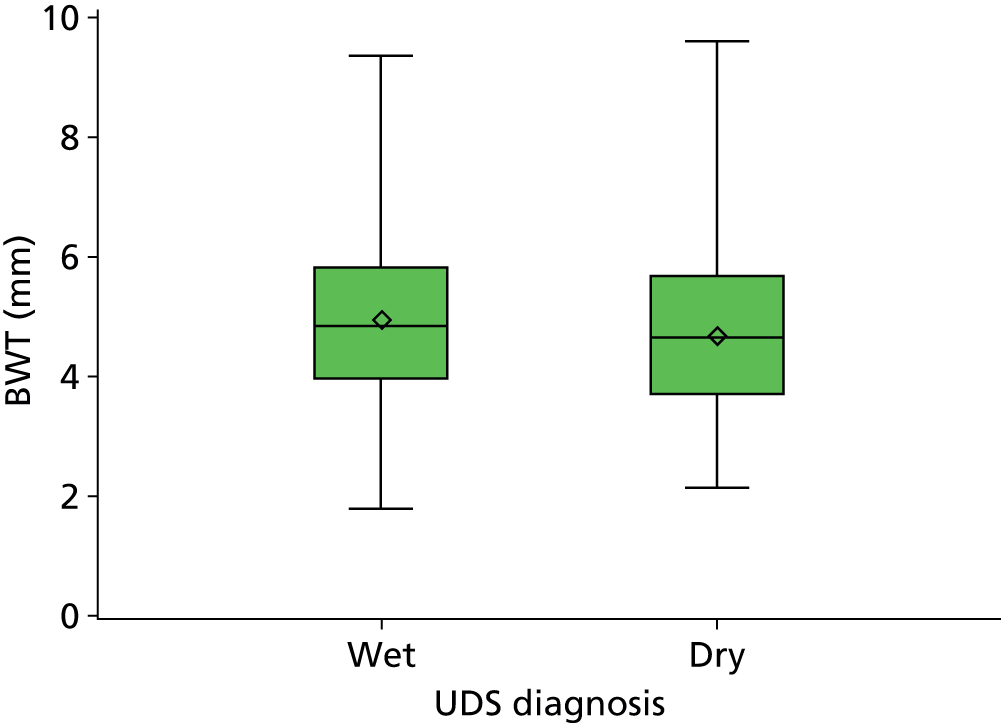

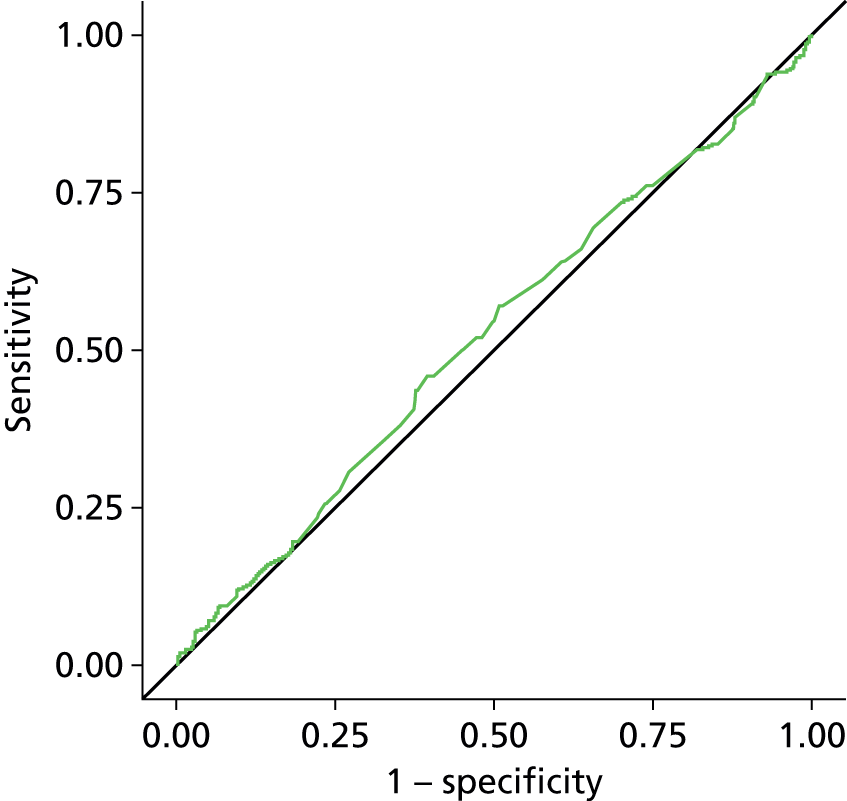

Estimation of the accuracy of BWT showed poor sensitivity, specificity and LRs at all pre-specified cut-off points of 5 mm, < 3 mm/3–5 mm/≥ 5 mm (Tables 7–9). The ROC curve (Figure 6) showed no evidence of discrimination at any threshold between those with and without DO (p = 0.25); the AUC was 0.53, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.57. Furthermore, there was no evidence that the mean BWT measurements were any higher in the DO-positive group than the DO-negative group: 4.85 mm (SD 1.36 mm) versus 4.70 mm (SD 1.29 mm); p = 0.19 (Figure 7) or that it had any relationship with ICIQ-OAB symptoms score when measured at presentation (r = –0.01; p = 0.88).

| Reference standard (UDS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO | Non-DO | Total | ||

| Index test: BWT by ultrasonography | Positive result (≥ 5 mm) | 165 | 98 | 263 (41%) |

| Negative result (< 5 mm) | 223 | 158 | 381 (59%) | |

| Total | 388 (60%) | 256 (40%) | 644 | |

| Accuracy parameter | Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 43% | 38% to 48% |

| Specificity | 62% | 55% to 68% |

| PPV | 63% | 57% to 69% |

| NPV | 41% | 36% to 47% |

| LR+ | 1.11 | 0.92 to 1.35 |

| LR– | 0.93 | 0.82 to 1.06 |

| Reference standard (UDS) | LR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO | Non-DO | Total | ||||

| Index test: BWT by ultrasonography | Result > 5 mm | 165 | 98 | 263 | 1.11 | 0.92 to 1.35 |

| Result 3–5 mm | 193 | 132 | 325 | 0.96 | 0.83 to 1.13 | |

| Result < 3 mm | 30 | 26 | 56 | 0.76 | 0.46 to 1.26 | |

| Total | 388 (60%) | 256 (40%) | 644 | |||

FIGURE 6.

Receiver operating curve analysis for BWT. AUC = 0.5267.

FIGURE 7.

Box and whisker plot comparing BWT with DO diagnosis.

The planned and unplanned sensitivity analysis described above did not change the interpretation of these findings (see Appendix 2, Figure 23 and Appendix 3, Figures 24–36). There was some evidence, albeit weak, that those diagnosed with ‘wet’ DO had higher BWT than those with ‘dry’ DO (wet 4.94 mm vs. dry 4.69 mm; p = 0.08) (see Appendix 3, Figure 32). However, when the BWT for the wet DO group was analysed alone, the AUC was only 0.55, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.59. There was no evidence that BWT performed any differently in any of the pre-specified subgroups (see Table 45).

In the multivariable exploration of factors possibly associated with DO diagnosis, only higher baseline ICIQ score (i.e. worse symptoms) was associated with DO [odds ratio (OR) 1.21, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.29; p < 0.0001 from the model including all possible variables], that is, the odds of DO diagnosis were increased by 21% for every point increase in ICIQ score. Previous treatment with antimuscarinics and previous history of UTI in the previous 12 months also showed some relationship but these were of borderline statistical significance (see Tables 46 and 47). Despite the evidence of association between ICIQ score and DO diagnosis, ICIQ was not found to be an accurate predictor of DO with an AUC of 0.65 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.70).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

To date, BUS is the largest diagnostic accuracy study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of BWT to diagnose DO in women with symptoms of OAB and using transvaginal ultrasonography with a near empty bladder. We could not find any evidence that BWT was of any clinical benefit in women with DO, indeed it appeared to be no better than chance at making this diagnosis with an AUC of 0.53 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.57). Extensive sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses were carried out but did not alter the interpretation of these findings. Furthermore, BWT had no relationship to ICIQ score upon presentation, indicating that it has no relationship with symptom severity. ICIQ score was shown to have some relationship with DO diagnosis. Based on this evidence, we conclude that BWT is not a useful test in diagnosing DO.

Strengths and limitations of methods

The validity of our findings relied on the quality of the study. The protocol pre-specified key study methods and analyses and was peer reviewed. The study was undertaken with independent oversight with biannual meetings of independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and Study Steering Committees. Blinding of operators performing bladder ultrasonography and UDS was ensured for 97% of the women recruited into the study. Verification bias was minimised by incorporating a complete verification design. Disease progression bias was minimised by conducting BWT and UDS within a short time span of each other, often within the same day. The spectrum variation (recruiting women with varying degree of severity of OAB or urgency-predominant MUI) was a strength of the design, assuring the applicability of the findings to NHS practice.

The study was powered to ensure that estimates of sensitivity and specificity would be made with adequate precision to draw robust conclusions and we recruited beyond the target. Participants in the study were recruited from several centres (university teaching and district general hospitals). Women were of mixed ages, ethnicities and social background, and were recruited from various parts of the UK.

The prevalence of DO in our study was 60%, which was similar to other studies (48% of ‘OAB dry’ and 58% of ‘OAB wet’ women were found to have DO on UDS). 102 The adverse events in our study were UTI in 10% of the population following the UDS procedure. The post UDS rate of UTI was very similar to the other studies so far. 103

As bladder ultrasonography is a relatively new transvaginal scan technique, concerns may be raised on the quality of scan measurements in the study. However, the technique is straightforward to perform with the urinary bladder being an anterior and relatively superficial midline structure. To standardise the performance of bladder ultrasonography, we developed a SOP (see Appendix 5) for carrying out ultrasonography and provided hands-on training at individual recruitment sites to our co-investigators and organised two workshops on BWT measurements. The chief investigator and clinical research fellow were assessed by the main recruiting centre consultant radiologist of 14 years’ experience in the technique of BWT measurement. The collaborators had to be signed off as competent by the chief investigator or clinical research fellow once they had completed at least five scans before recruiting patients into the study.

Good site-to-site reliability is essential for multicentre clinical trials using UDS. With the use of continuous quality improvement and training on standardised urodynamic testing procedures and interpretation guidelines, the technical quality of urodynamic findings were improved. 104 To improve reliability of our gold standard test UDS, we used various proactive measures such as standard urodynamic testing protocols, standard interpretation guidelines and auditing the traces centrally every 6 months to ensure ongoing quality assurance. We are therefore confident of the methods and hence the results.

Concerns about the reference standard

Accuracy measures express how the results of the test under evaluation agree with the outcome of the reference standard. Estimates of diagnostic accuracy are directly influenced by the quality of the reference standard. 105 When the accuracy of the reference standard is unknown, or known to be imperfect, estimates of the sensitivity and specificity or AUC for new diagnostic tests will be biased as misclassifications in the reference standard diagnosis will have been misattributed to errors made by the index test. Our reference standard, UDS, has been shown to have less than perfect reproducibility in previous studies in patients with OAB106,107 and also in healthy women. 108,109 When estimating the test accuracy of BWT against an imperfect reference standard (UDS), the accuracy of BWT may have been biased to an unknown degree, or submerged in the ‘noise’ from the imperfect reference standard. However, the poor accuracy for BWT elicited in our study is unlikely to have been entirely caused by misclassifications made by UDS, as there was no significant relationship between BWT measurements and grades of DO severity or subsequent treatment responses (see Chapter 6). When the test values do not differ among those with varying grades of the target condition, it can be inferred that the lack of accuracy may be an inherent feature of the index test.

Evidence of the misclassification rates for UDS comes from several studies. 110,111 Homma et al. 107 undertook repeat UDS in DO patients within 2–4 weeks to study reproducibility. There was increase in the volume variables by 10–13% (p < 0.01), absence of involuntary contractions (10%) and a reduction in the maximum detrusor pressure by 18% during the repeat urodynamic test indicating poor reproducibility. 107 In a study of 59 healthy women without LUTS, UDS was repeated immediately after the initial test without removing the catheters and then again 1–5 months later. The mean difference was dispersed away from zero in both immediate and short-term reproducibility indicating poor reproducibility. 112

Placing the results in the context of other research

In an update of the systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of BWT in diagnosing DO (unpublished data: Suneetha Rachaneni, University of Birmingham, 2015) 21 studies28,49–59,72,97,113–119 have been identified that have investigated the relationship between BWT measured by ultrasonography and DO, results from which for the sensitivity, specificity and AUC for bladder ultrasonography vary from 37% to 91%, 61% to 97% and 0.61–0.91, respectively (see Appendix 7). The studies draw mixed conclusions, ranging from claims that bladder ultrasonography is highly diagnostic, to finding statistically significant but diagnostically weak relationships, to finding no relationship at all. 49,51,54,57,72,117 Our study is the most conclusively negative study of the diagnostic value of bladder ultrasonography to date.

Initial studies have shown transvaginal BWT to be an accurate diagnostic marker for DO. 44,49 For a mean BWT cut-off point of 5 mm, the specificity was calculated to be 89% (95% CI 78.8% to 96.11%) with a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 75.8% to 89.7%). 49 However, this study used ambulatory UDS (in patients who had normal video UDS) as a secondary diagnostic test in 25% of the study population and this introduced workup bias that might have resulted in inaccurate estimation of sensitivity and specificity of BWT.

Many of the other studies have differences in the tests used and the populations studied and methodological weaknesses, which may explain why their results vary and differ from the finding of this prospective study. Poor reporting renders it difficult to make comparisons with findings in 10 studies that did not report estimates of sensitivity, specificity or area under the ROC curve. These studies typically compared the mean BWT between diagnostic groups and did not interpret the findings against a positivity threshold.

Eight of the studies did not use transvaginal ultrasonography,28,50,51,56,57,114,116,119 but instead used transabdominal or translabial ultrasonography. Some transabdominal ultrasonography studies included men as well as women and usually were undertaken with a full bladder leading to much smaller measures of mean BWT. 116,119

Ten studies made comparisons with healthy controls,28,50,55–59,114–116 two others excluded patients with MUI54,117 and one other enriched with women with equivocal UDS findings. 52 One was undertaken in patients with spinal injuries. 119 It is known that altering the spectrum of patients from that encountered in practice will influence estimates of sensitivity and specificity. 120 Exclusion of the MUI cases and inclusion of healthy controls will lead to overestimation of test accuracy; enrichment of difficult to diagnose cases will underestimate test accuracy.

A key difference between the BUS and all others is the focus on the accuracy of ultrasonography in women who do not have signs of pure SUI. Women with SUI diagnosed by symptoms and diary usually proceed to treatment without further diagnostic investigation, including UDS. 36 Thus, ultrasonography has no role in this group. The BUS focused on identifying women with DO among those who have urgency or mixed incontinence, for which UDS currently is used, to assess whether or not ultrasonography can replace UDS in this context. Women in whom SUI is diagnosed clinically, by symptoms and bladder diary responses, usually proceed to treatment without further diagnostic investigation, including UDS. 36 Thus, ultrasonography has no role in this group. Studies that have assessed the value of ultrasonography to differentiate between pure SUI and OAB have addressed a question that is no longer relevant to clinical practice.

In summary, our study was the largest prospective study to date, it is the only study that recruited a representative sample of women presenting with an urgency-dominant complaint (others have recruited other wider groups), and used service-based (but trained and quality assured) ultrasonography services from across many centres (whereas other studies were all single centre and often tertiary centre based).

Variation in technique of transvaginal bladder wall scanning

Our technique of measuring BWT in the sagittal plane with a transvaginal probe placed at the introitus was easy to learn and perform with visualisation of the urethra as the landmark. Previous studies have described parasagittal measurements of BWT at three places on the bladder wall, with the calculation of an average BWT. 41,109 In one study, DWT instead of BWT was measured by transperineal scanning. 51 The rest of the studies have used transabdominal scanning at various bladder volumes, but we rejected this technique on account of the greater reported interobserver variation. 71

Interpretation of findings

Measuring BWT is not accurate enough to consistently identify those with DO and hence it will not be helpful in reducing the need for UDS. It is believed that spontaneous DO is secondary to pathology in detrusor muscle whereas provoked DO is caused by pathology in the bladder neck. Provoked DO, which was previously called urethral instability, could be caused by primary urethral aetiology or some unknown pathology. 121 As women with spontaneous DO are known to respond better to antimuscarinic treatment122 than those with provoked DO or urethral instability, we carried out sensitivity analyses to evaluate diagnostic accuracy of BWT excluding those with provoked DO. Similar to findings in the study by Serati,113 we did not find any difference in BWT in spontaneous and provoked DO groups. 113

Implications for practice

Given the poor performance for BWT as tool for diagnosing DO, BWT cannot be recommended as a replacement test for UDS.

Recommendations for research

There is some emerging evidence in the literature that the response to invasive therapies may be similar in patients with frequency and urgency with or without urgency incontinence, with or without the observation of DO on UDS. 123–125 The necessity to diagnose DO on UDS and its role in improving patient-related outcome measures needs to be evaluated in future diagnostic RCTs.

Chapter 3 Quality control of the urodynamics

Introduction

Objectives

The objectives of this part of the study were as follows:

-

To audit the quality of UDS traces submitted to the study office at the University of Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit as the reference standard for the patients in the BUS.

-

To assess whether or not recommended changes in UDS practice had been implemented following an initial audit among the recruiting centres for the BUS.

Methods

Urodynamic studies

Urodynamic studies were to be performed in a standardised manner as per the GUP guidelines from the International Continence Society6 and a SOP that had been produced for the study based on this (see Chapter 2, The reference standard: urodynamics). For patients at the main centre (Birmingham Women’s Hospital), according to the study protocol, patients were offered ambulatory UDS if they had a normal result from standard multichannel UDS.

Assessment of protocol compliance

An assessment of compliance with the UDS SOP for the BUS and with GUP was performed on 64 (20%) of the first 302 UDS traces received at the study office, between May 2011 and May 2012.

An expert panel, comprising a consultant in urogynaecology and a urogynaecology research nurse from the lead centre, assessed the traces independently. They were blinded to the investigator’s UDS diagnosis, the UDS operator and centre providing the trace, to minimise any bias in the assessment. All participating sites were audited regarding the urodynamic technique used throughout the study.

Traces were randomly selected by the BUS trial co-ordinator from traces supplied by each of the recruiting hospitals, as suggested by the DMC. The expert panel rereviewed UDS traces they had undertaken (the lead centre recruited 37% of all participants into the BUS) but were not aware of which traces were from the lead centre.

Following review, the requirements of the UDS SOP were reiterated to recruiting centres via e-mails and a newsletter and also discussed at BUS training days, which were held 3 months and 15 months into the recruitment period. A total of 6 months after the initial audit, a second audit (June 2012 to December 2012) was performed on a further 60 traces.

Audit standards for urodynamic studies

The traces were reviewed to assess the presence of the following criteria:

-

adequate subtraction prior to filling cystometry (i.e. initially bladder and rectal catheters should be zero when open to atmosphere, at the level of upper symphysis)

-

sitting position during filling cystometry (recommended as per study protocol)

-

the cystometry filling rate was 100 ml/minute to begin with (then slowed as and if necessary)

-

a cough pre-void

-

a cough post void

-

presence of one cough per minute to assess ongoing adequate subtraction of intravesical and abdominal pressures.

In addition, agreement of initial diagnosis between study investigator and expert panel was assessed. The expert panel determined a diagnosis of USI, DO, low compliance, VD or normal, or combinations of these diagnoses.

Results

Between May 2011 and December 2012, a total of 124 UDS traces were reviewed against the UDS SOP criteria, Table 10 illustrates the result of the overall quality control check in UDS.

| Recommended actions in SOP | Audit May 2011 to May 2012 (%), n = 64 | Reaudit June 2012 to December 2012 (%), n = 60 |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate baseline zeroing pressures | 60 (93.7) | 57 (95) |

| Filling in sitting position | 49 (76.5) | 38 (63.3) |

| Cystometry filling rate 100 ml/minute | 31 (48.4) | 43 (71.6) |

| Cough pre-void | 49 (70.3) | 60 (100) |

| Cough post void | 23 (35.9) | 45 (75) |

| Cough per minute | 49 (70.3) | 58 (96.6) |

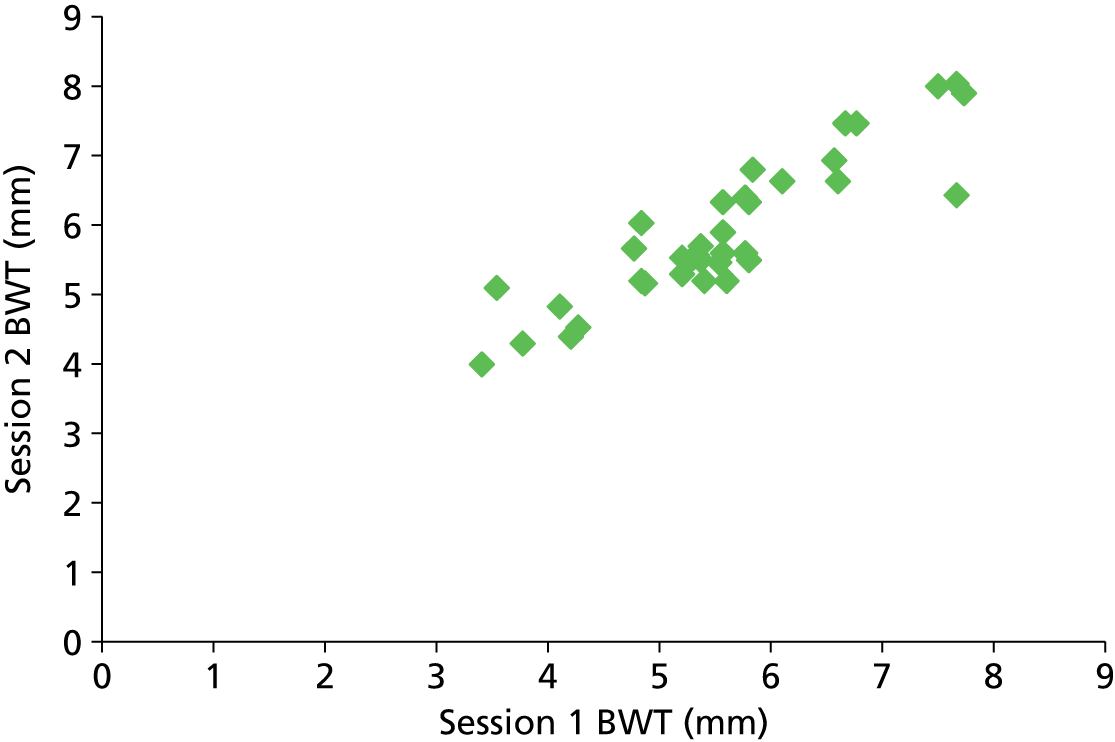

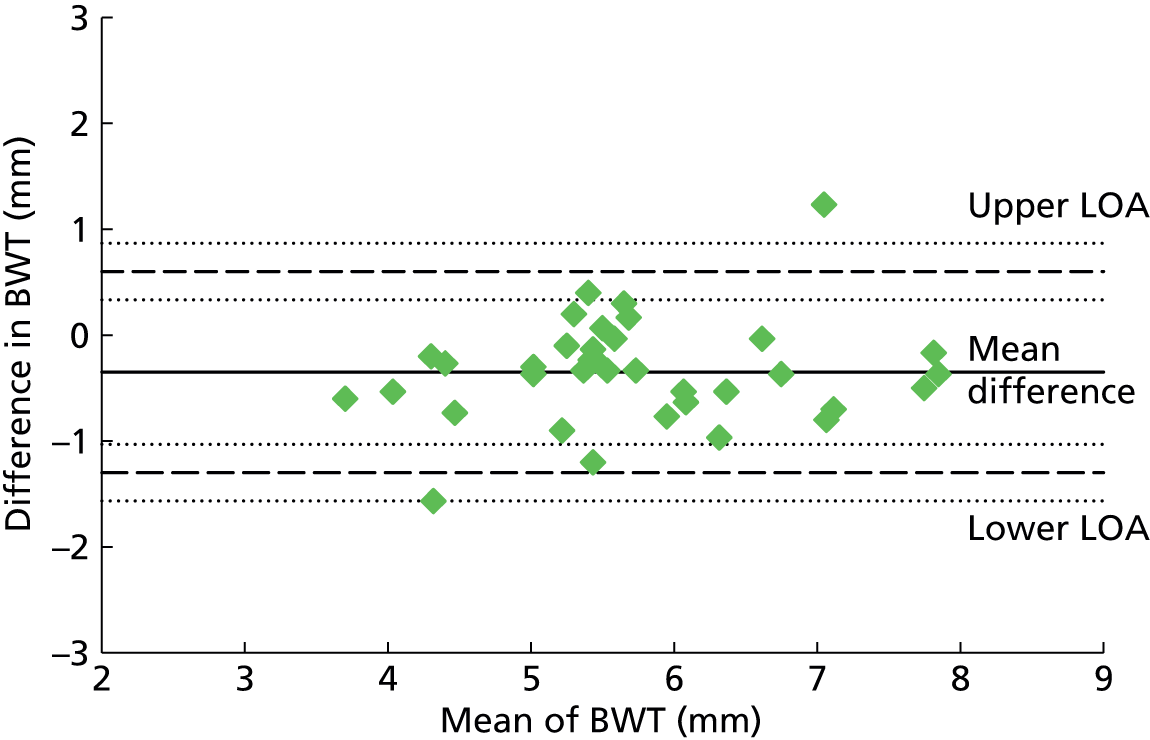

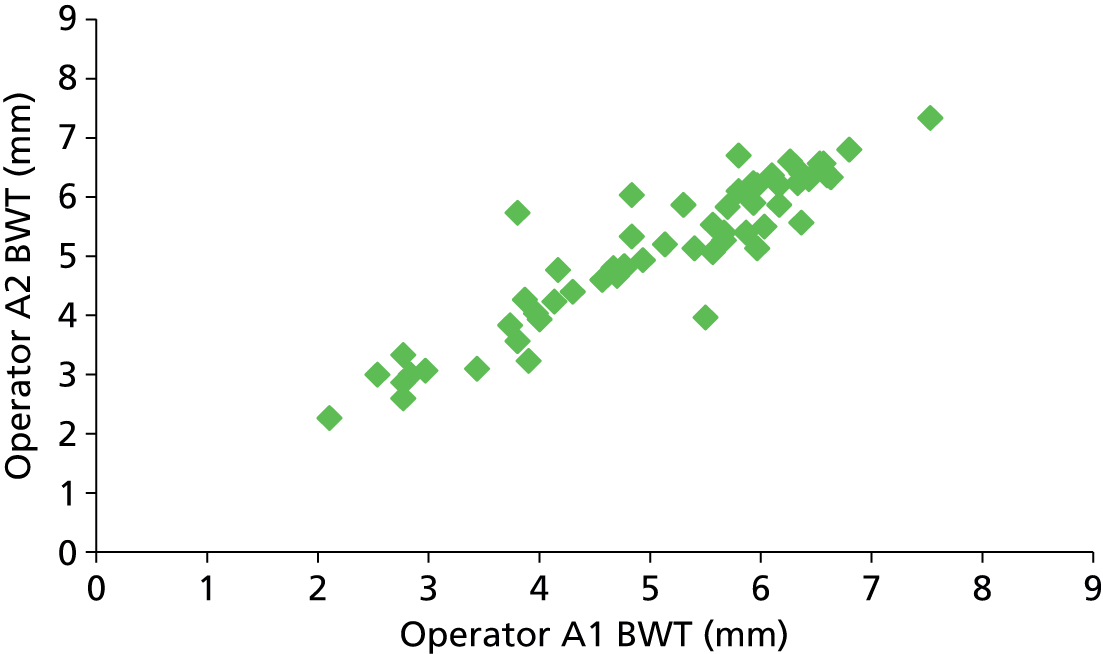

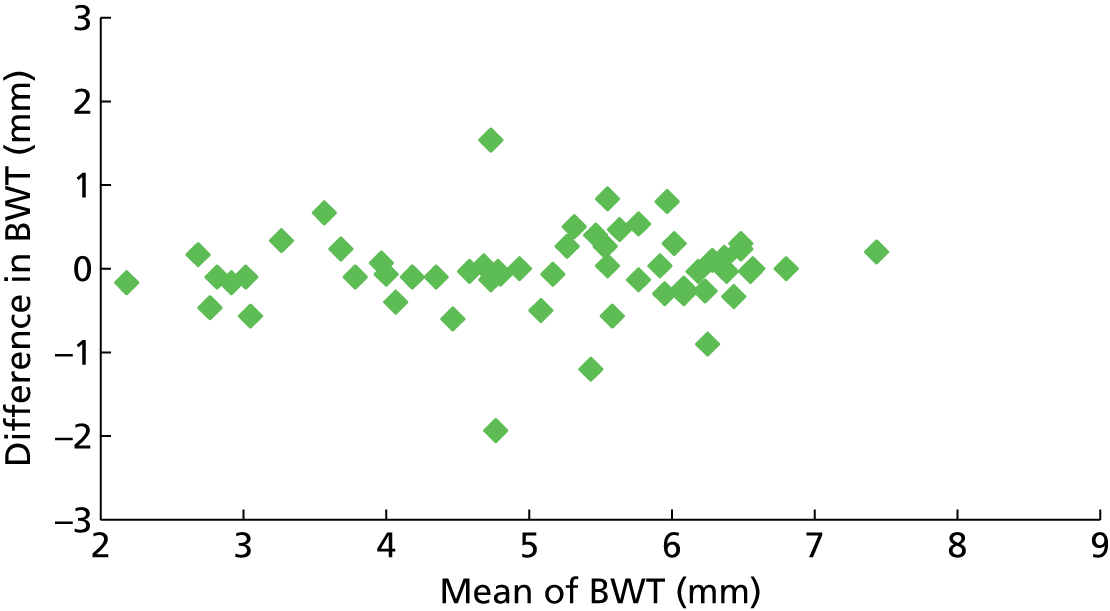

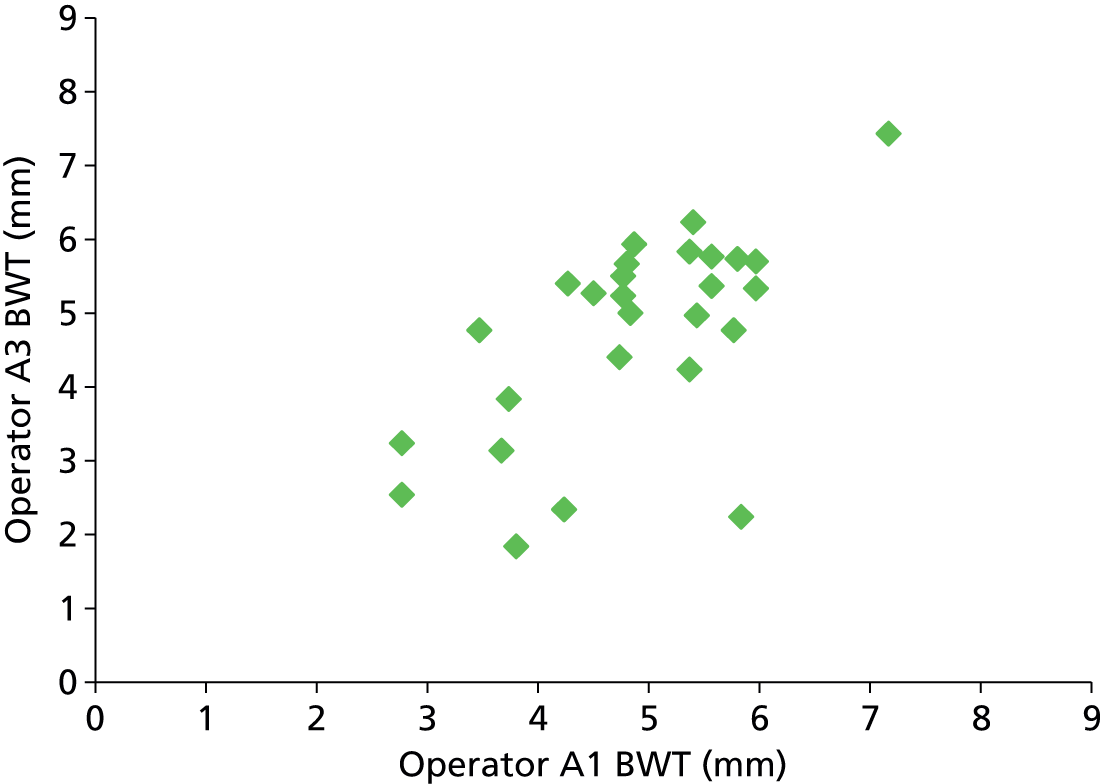

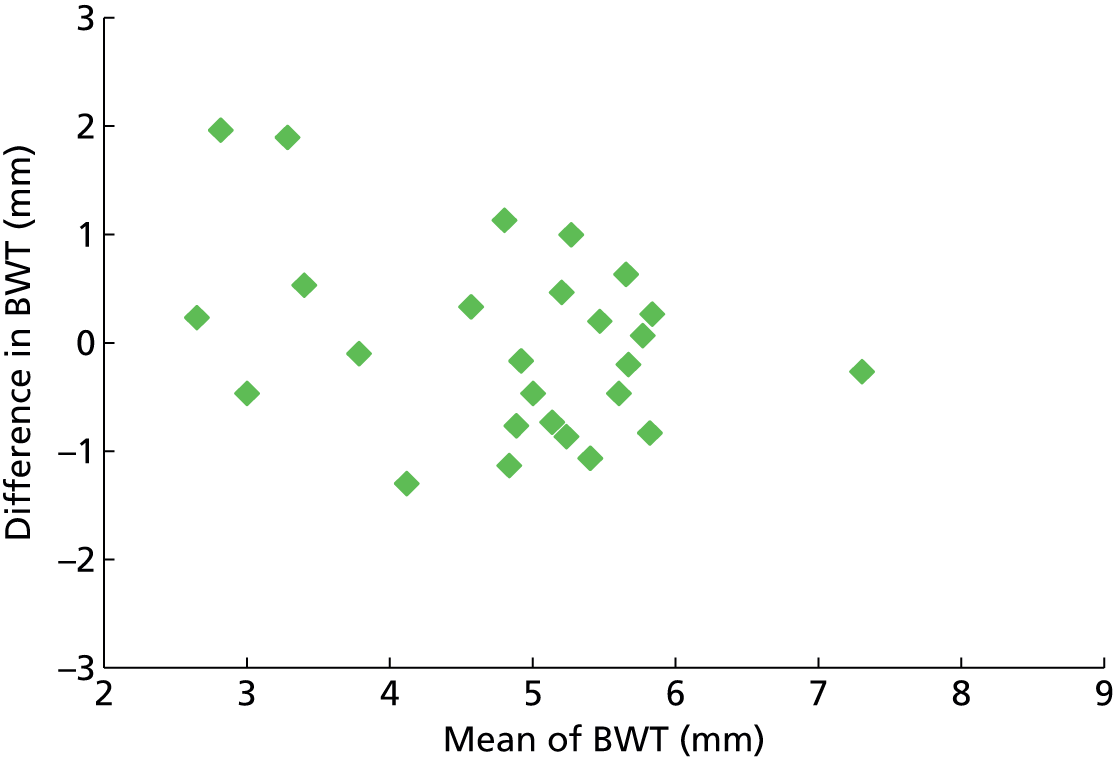

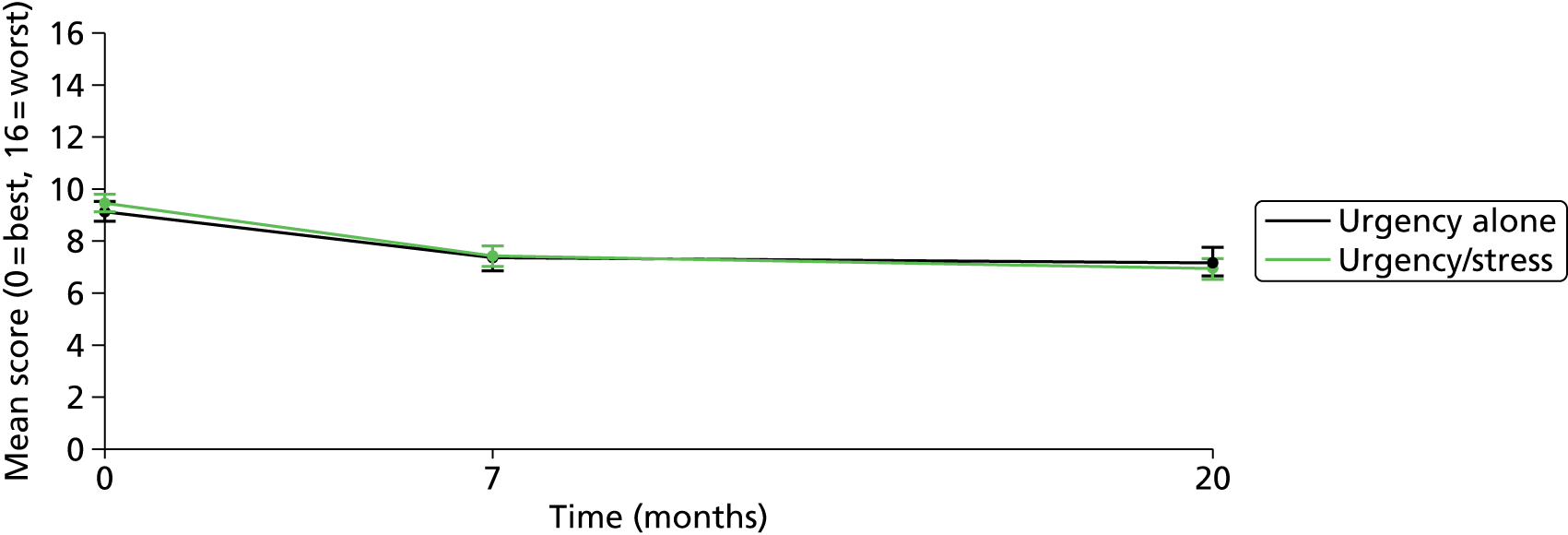

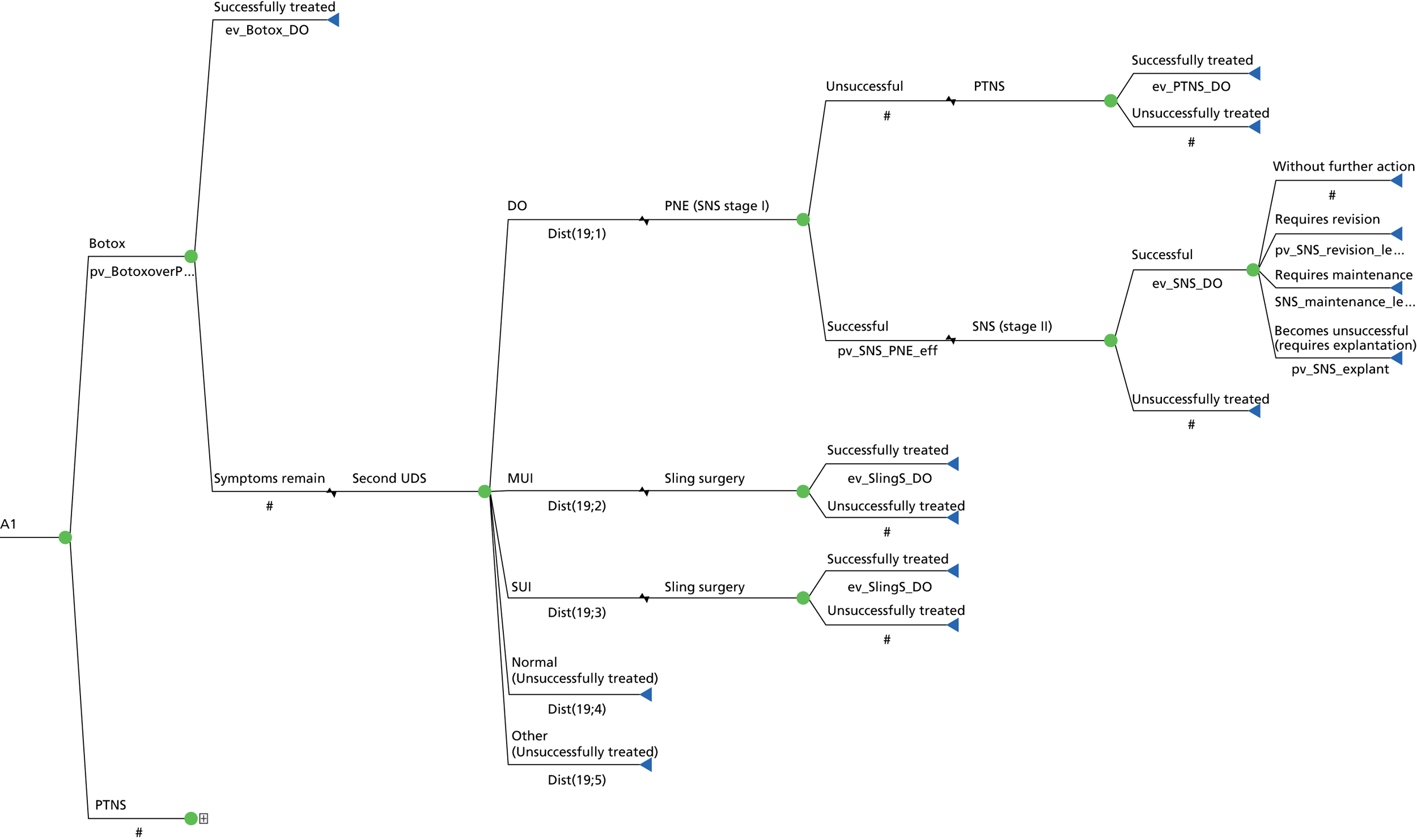

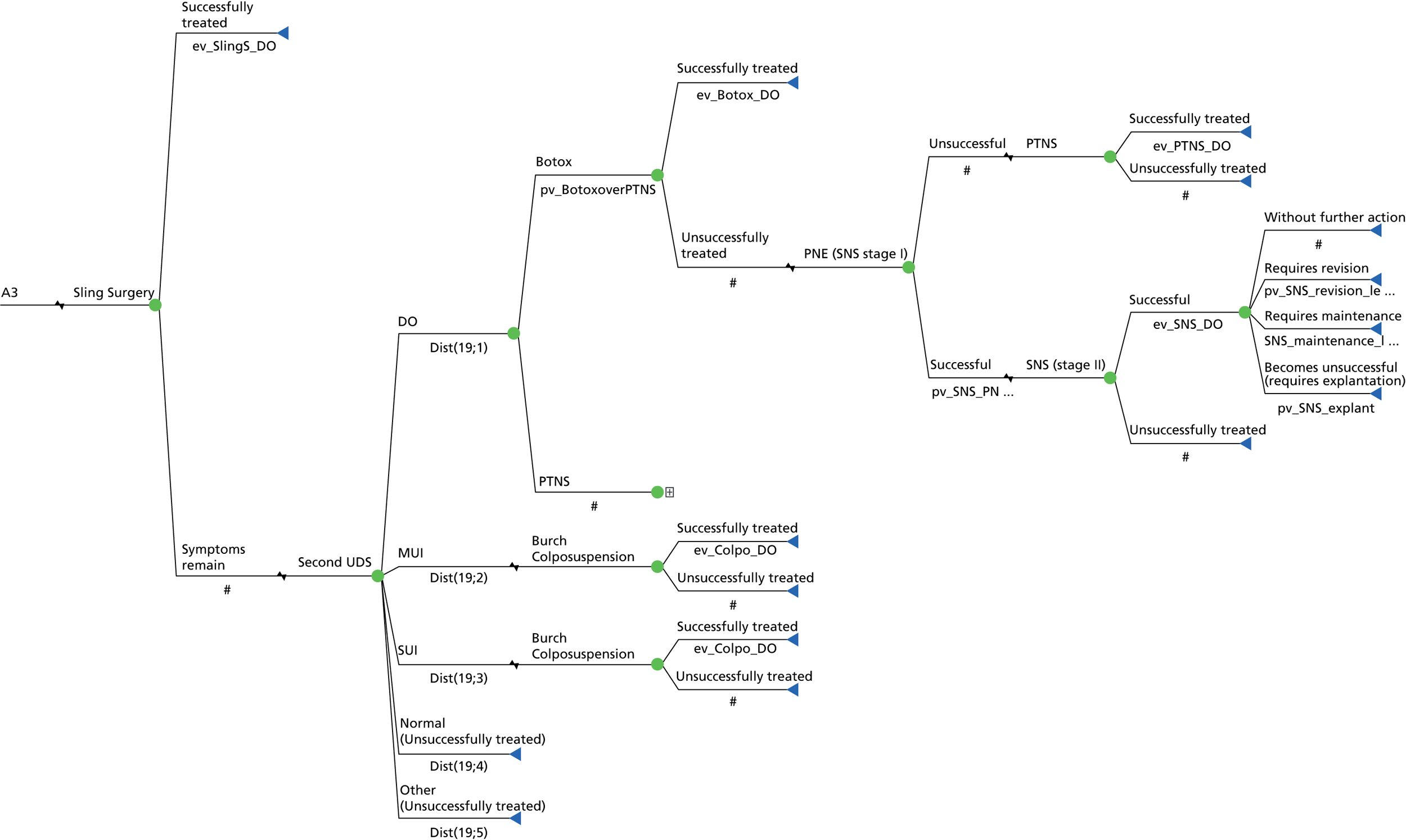

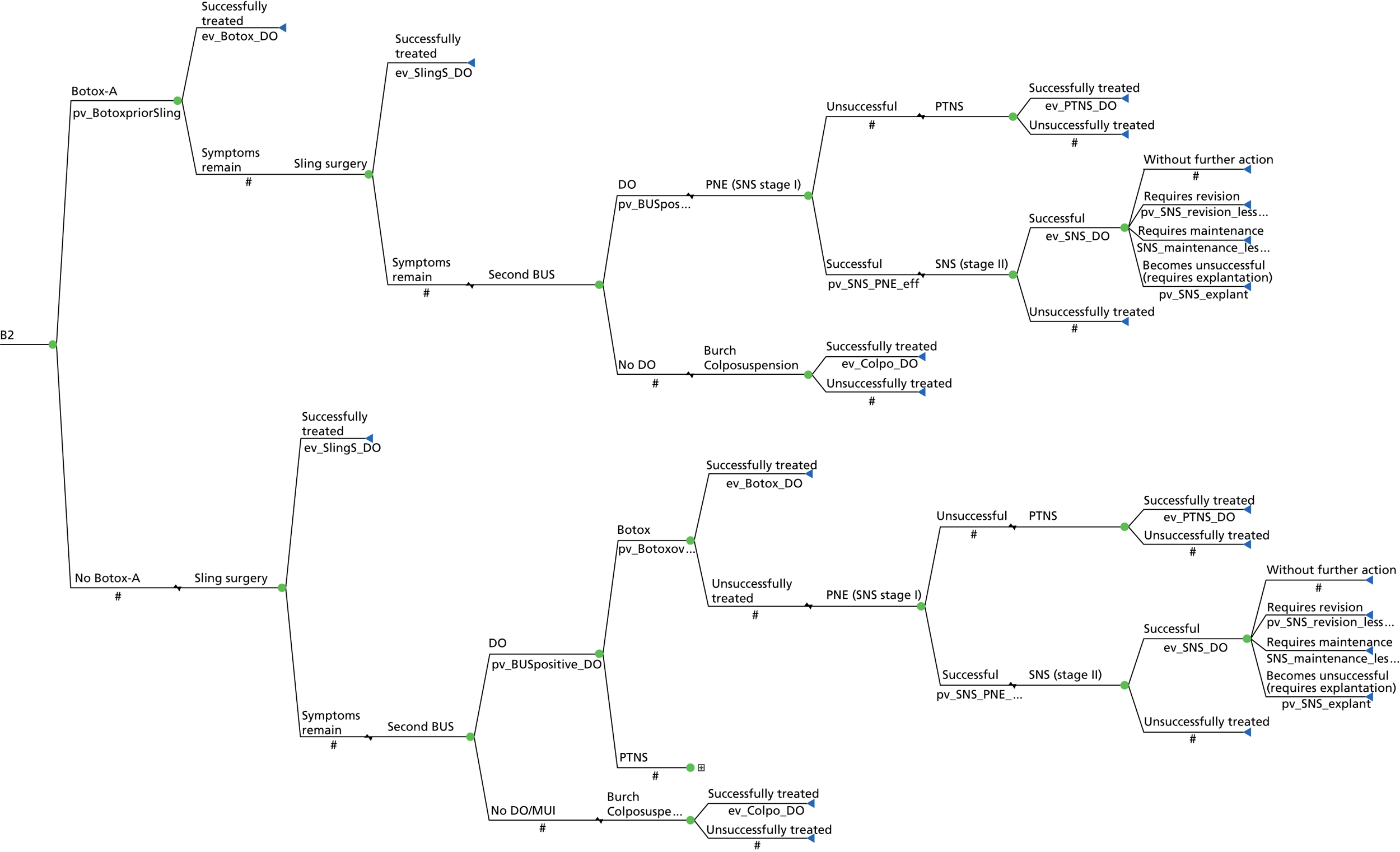

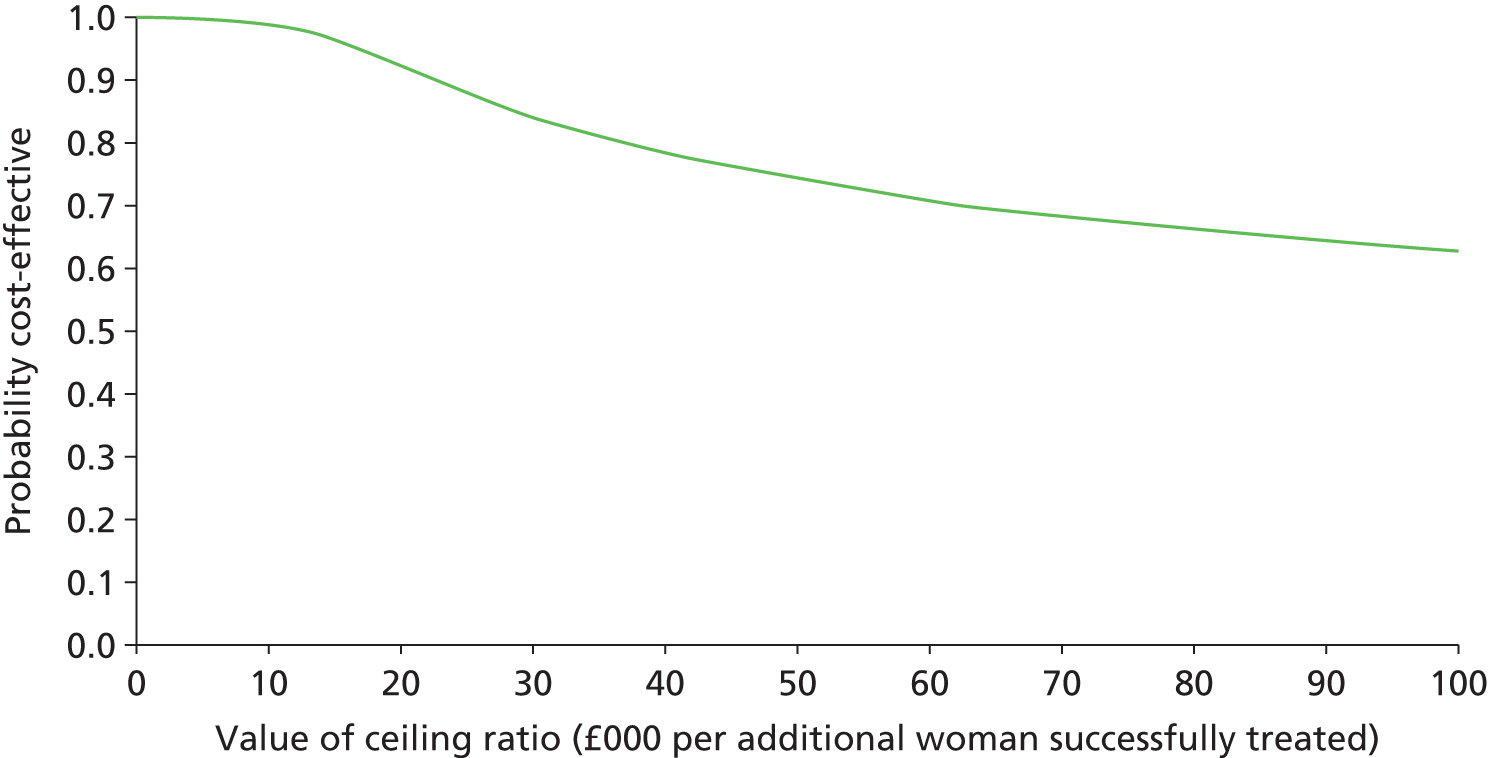

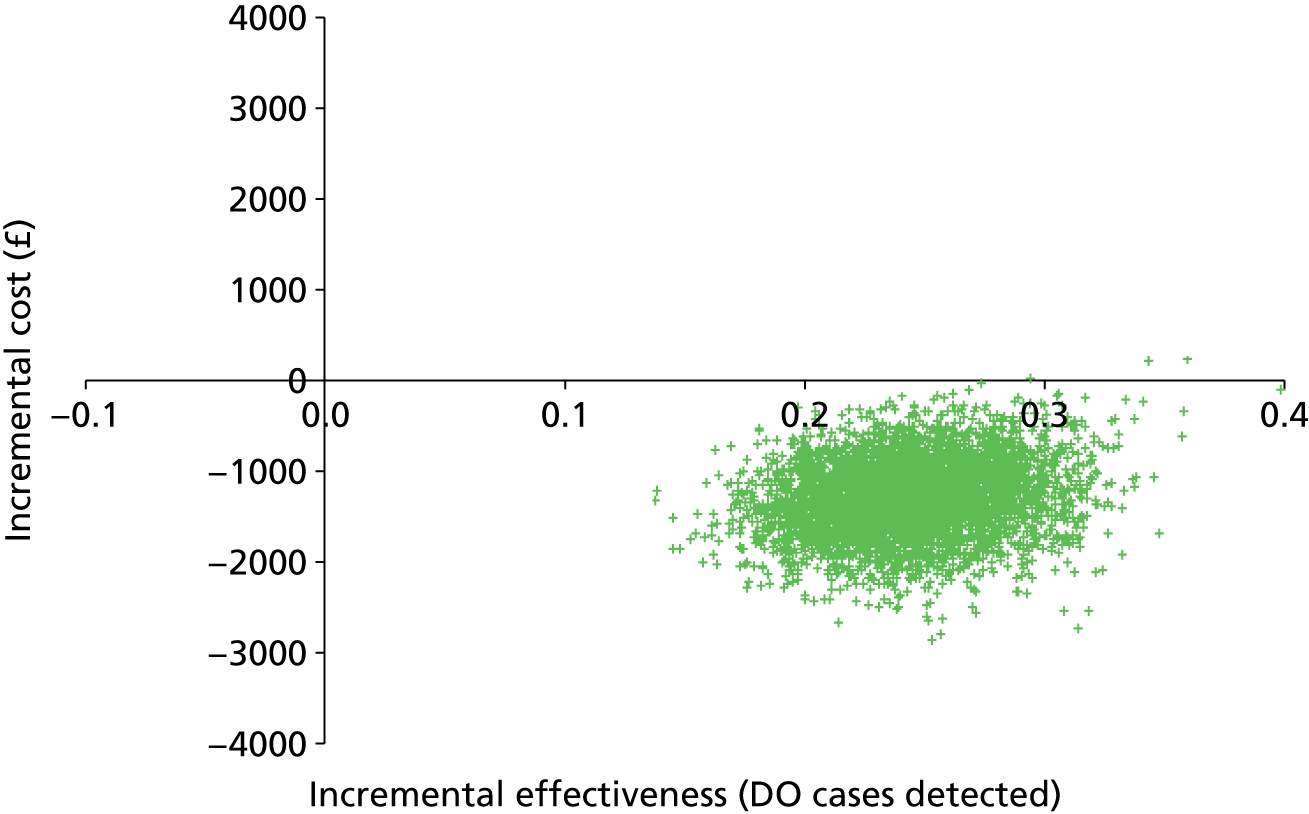

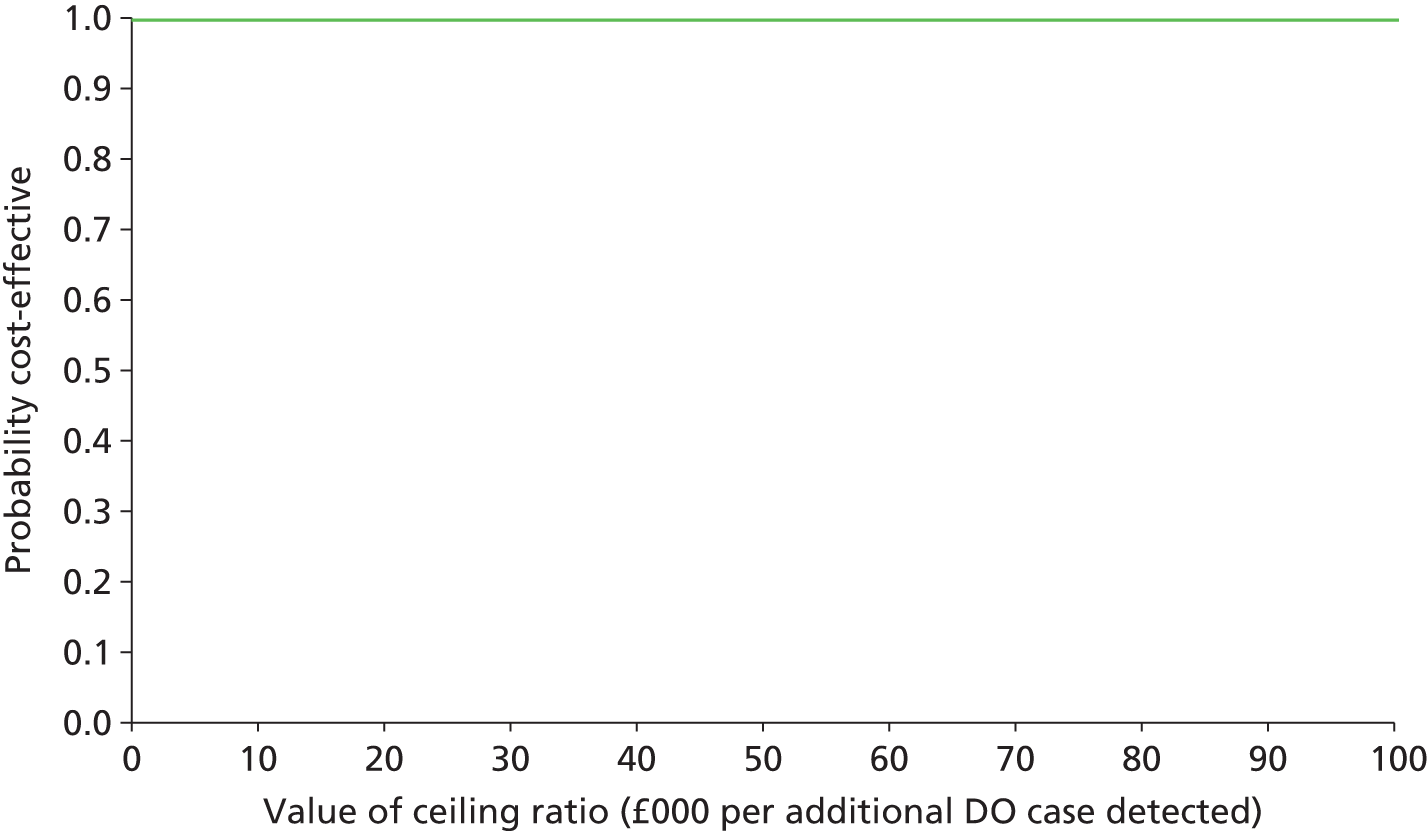

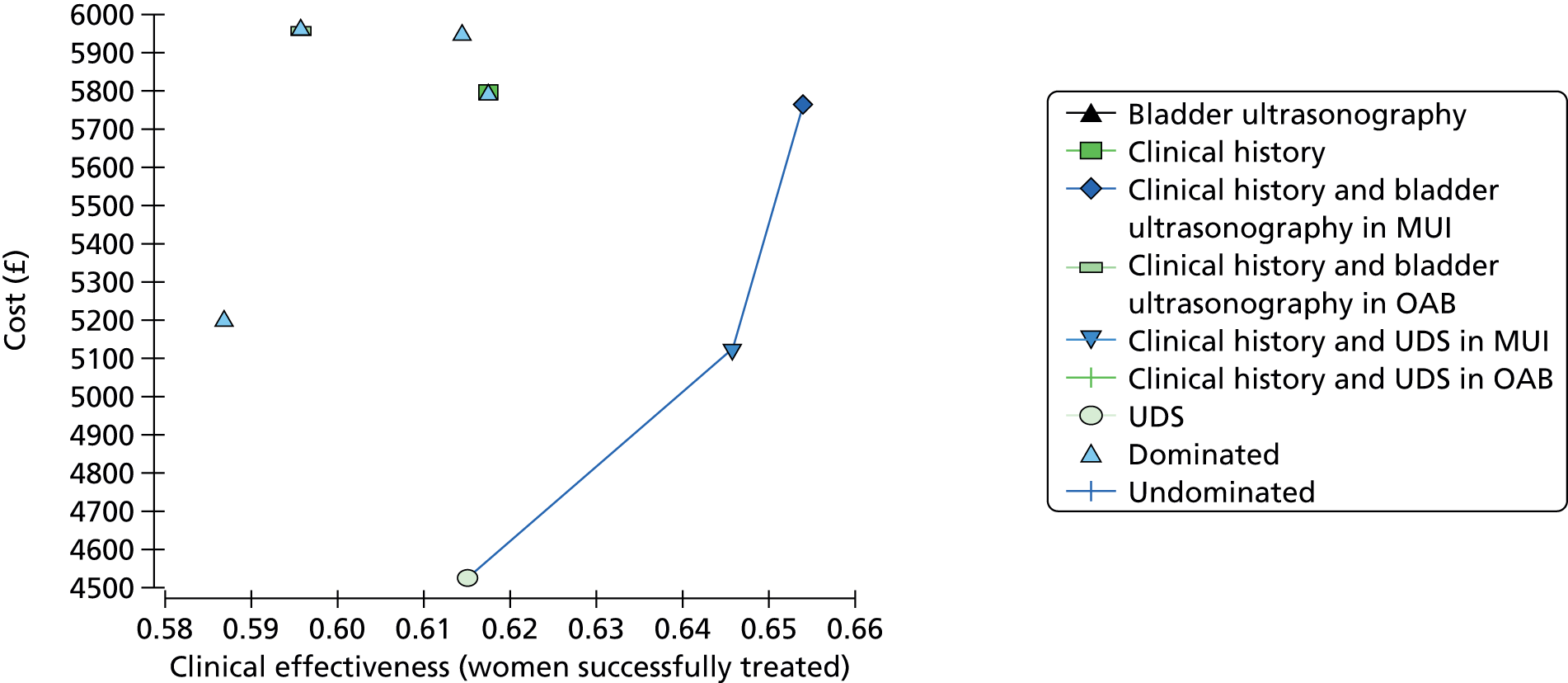

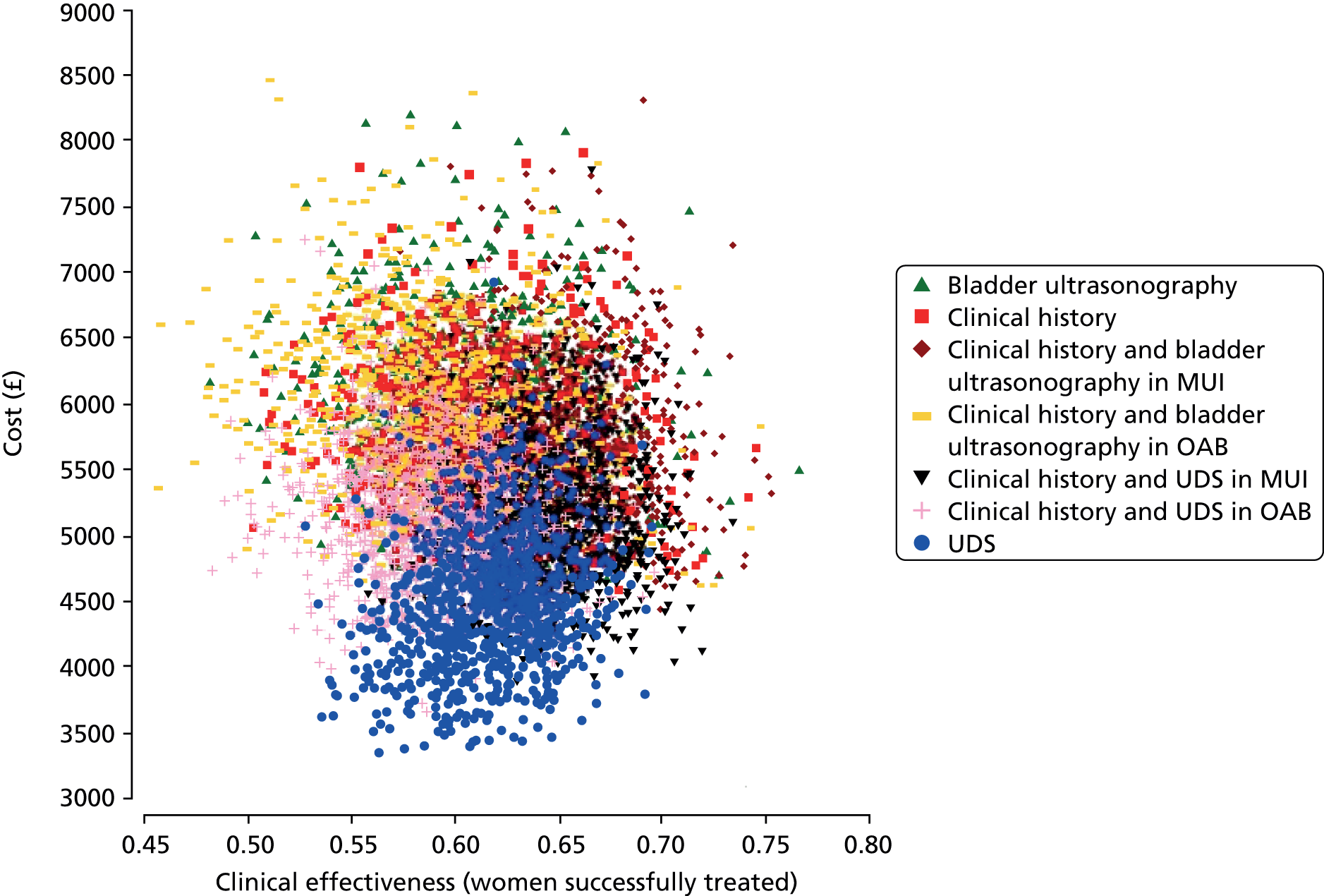

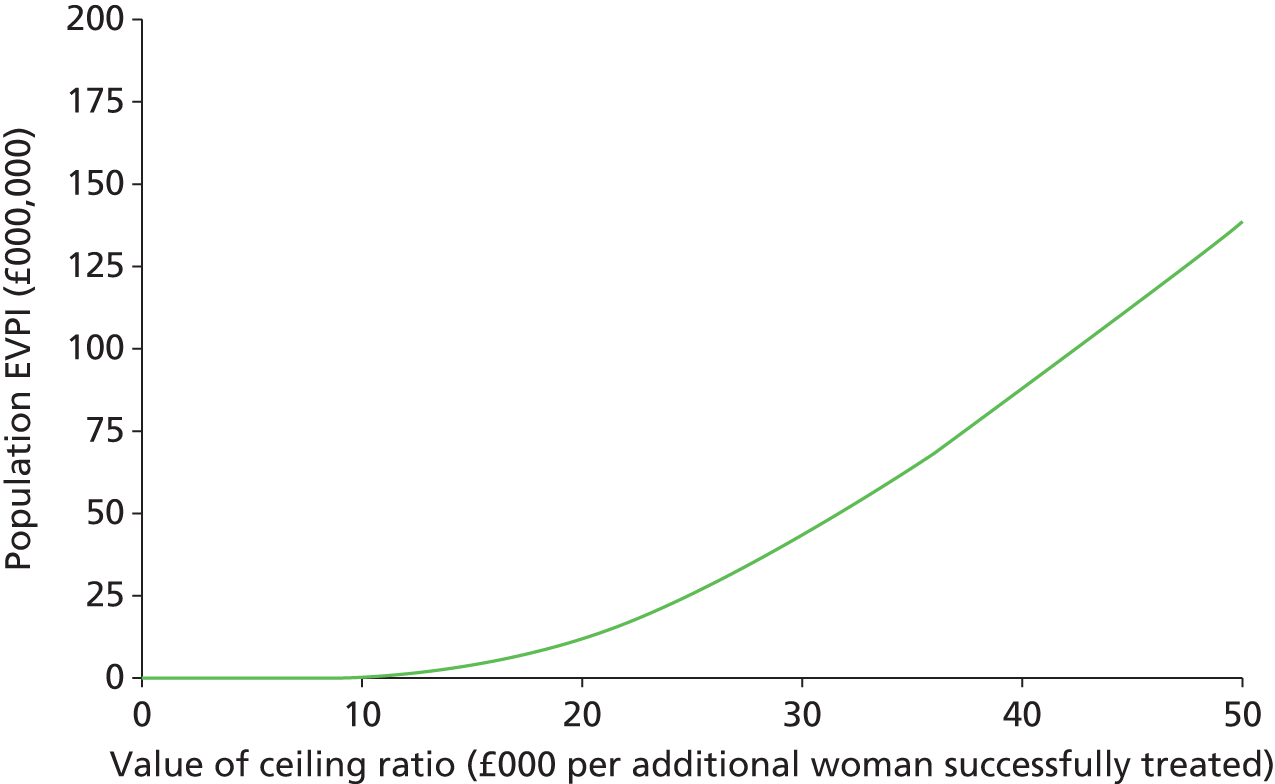

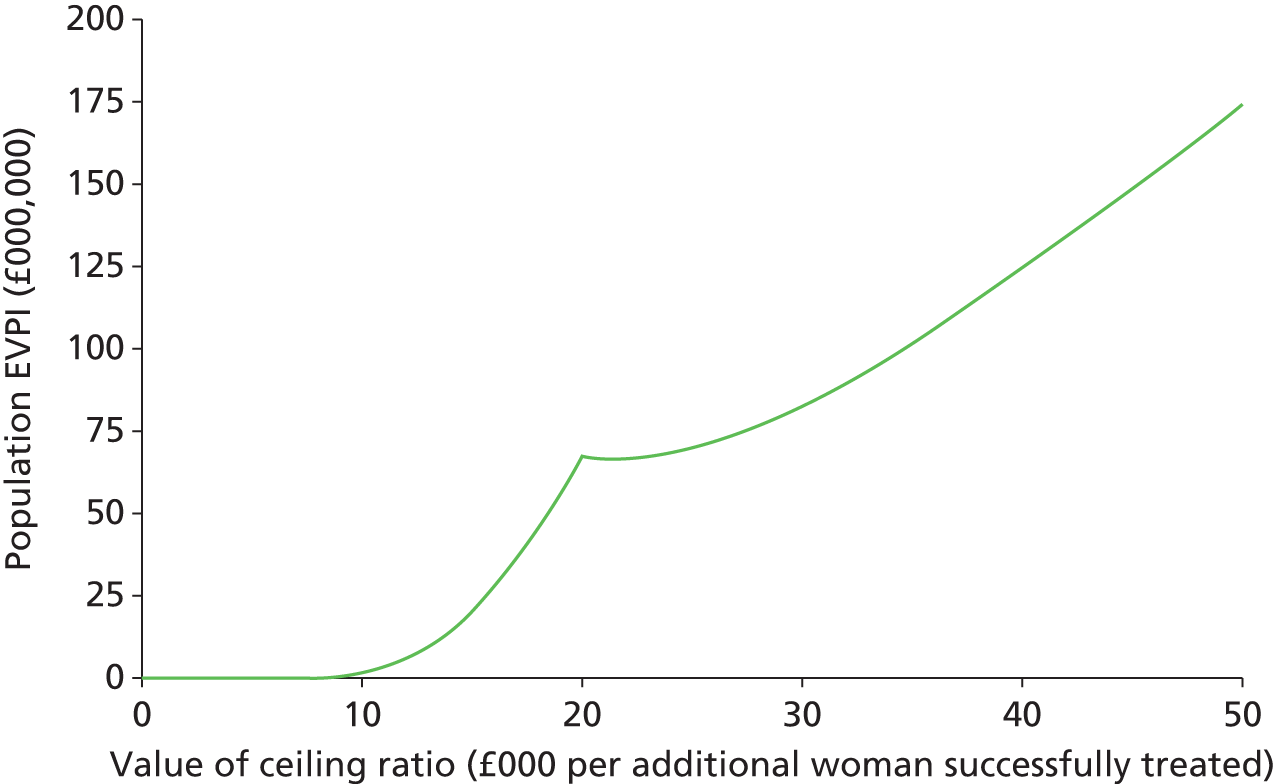

| Agreement between urodynamic diagnoses | 55 (85.9) | 57 (95) |