Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 12/42/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Crathorne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Aim of the review

The aim of this assessment was to review and update research evidence as necessary to inform National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance to the NHS in England and Wales on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) for the treatment of cancer treatment-induced anaemia (CIA) (see Current service provision).

The previous guidance [technology appraisal (TA)1421] was primarily based on evidence presented to NICE in the assessment report by Wilson and colleagues. 2 We have incorporated relevant evidence presented in the previous report and report new evidence gathered since 2004.

Description of the health problem

Anaemia is defined as ‘a reduction of the haemoglobin (Hb) concentration, red blood cell (RBC) count, or packed cell volume below normal levels’ (p. v244). 3 A commonly used classification of anaemia according to Hb level is shown in Table 1. 3

| Severity | WHO, Hb level (g/dl) | NCI, Hb level (g/dl) |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 (WNL) | ≥ 11 | WNL |

| Grade 1 (mild) | 9.5–10.9 | > 10 WNL |

| Grade 2 (moderate) | 8.0–9.4 | 8–10 |

| Grade 3 (serious/adverse) | 6.5–7.9 | 6.5–7.9 |

| Grade 4 (life-threatening) | < 6.5 | < 6.5 |

It is the most frequent haematological manifestation in patients with cancer; > 50% of all cancer patients will be anaemic, regardless of the treatment received, and approximately 20% of all patients undergoing chemotherapy will require a red blood cell transfusion (RBCT). 4

The cause of anaemia is usually multifactorial and may be patient, disease or treatment related. 4 The haematological features in anaemic patients depend on the different types of malignant disease, stage and duration of the disease, the regimen and intensity of tumour therapy and possible intercurrent infections or surgical interventions. Tumour-associated factors, such as tumour bleeding, haemolysis and deficiency in folic acid and vitamin B12, can be acute or chronic. In the advanced stages of haematological malignancy, bone marrow involvement often leads to progressive anaemia. In addition, interaction between tumour cell populations and the immune system can lead to the release of cytokines, especially interferon-gamma, interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor. This disrupts endogenous erythropoietin synthesis in the kidney and suppresses differentiation of erythroid precursor cells in the bone marrow. As a result, patients with tumour anaemia may have relatively low levels of erythropoietin for the grade of anaemia observed. Moreover, activation of macrophages can lead to a shorter erythrocyte half-life and a decrease in iron utilisation.

Chemotherapy may cause both transient and sustained anaemia. 4 Mechanisms of drug-induced anaemia in patients with cancer include stem cell death, blockage or delay of haematopoietic factors, oxidant damage to mature haematopoietic cells, long-term myelodysplasia and immune-mediated haematopoietic cell destruction. 4 Patients treated with platinum-based regimens develop anaemia most often and frequently need transfusions. 4 As a consequence, dose-intensified regimens or shortened treatment intervals, as well as multimodal therapies, are associated with a higher degree of anaemia. 4 Anaemia can also compromise the effect of treatment because low tissue oxygenation is associated with a reduced sensitivity of tumours to radiation and some forms of chemotherapy, contributing to the progression of cancer and reduction in survival. 4

Among those patients with solid tumours, the incidence of anaemia is highest in patients with lung cancer (71%) or gynaecological cancer (65%); these patients have the highest frequency of anaemia and the highest rate of transfusion requirements. 4,5 The frequency of RBCT requirements in these patients varies from 47% to 100% depending on the cumulative dose of platinum chemotherapy received and other risk factors, for example age, disease stage and pretreatment Hb level. In haematological cancers, anaemia is an almost invariable feature of the disease. 4 In addition, some of the newer chemotherapeutic agents, such as taxanes or vinorelbine, are strongly myelosuppressive and frequently cause anaemia. 6

The clinical manifestation and severity of anaemia can vary considerably among individual patients. 4 Mild-to-moderate anaemia can typically cause such symptoms as headache, palpitations, tachycardia and shortness of breath. 4 Chronic anaemia can result in severe organ damage affecting the cardiovascular system, immune system, lungs, kidneys and the central nervous system. 4 In addition to physical symptoms, the subjective impact of cancer-related anaemia on quality of life, mental health and social activities may be substantial. 4 A common anaemia-related problem is fatigue, which impairs the patient’s ability to perform normal daily activities. 4

Relationship between cancer treatment-induced anaemia and survival

Although the evidence is uncertain, some researchers hypothesise that anaemia in cancer patients is associated with a worse prognosis. According to Bohlius and colleagues,7 one explanation may be that, as a result of a low Hb level, the tumour cells become hypoxic and are subsequently less sensitive to cytotoxic drugs, in particular oxygen-dependent chemotherapies. 8–10 Evidence for this, as reported in the study by Tonia and colleagues,11 exists in studies in which tumour control and overall survival (OS) are improved in solid tumour patients with better tumour oxygenation. 10,12 There is also the practical implication that severe anaemia may require a dose reduction or delay of chemotherapy, subsequently leading to a poorer outcome. It is therefore plausible that efforts taken to reduce anaemia may improve tumour response and OS. 7 That said, it should be noted that Hb levels elevated to > 14 g/dl in women and > 15 g/dl in men are undesirable and may lead to increased viscosity, impaired tumour oxygenation and thromboembolic events. 13

As an intervention used to increase Hb, and by association improve prognosis, some studies actually report a detrimental effect of ESAs on survival and tumour progression. 14–20 This effect is postulated to be caused by the presence of erythropoietin receptors on various cancers,21–25 whereby the endogenously produced or exogenously administered erythropoietin promotes the proliferation and survival of erythropoietin receptor-expressing cancer cells. 7 However, controversy about the functionality of these receptors remains26–30 and several studies show no effect on tumour progression for patients receiving ESAs. 17,31–33

It should be noted that the majority of the studies examined in the systematic reviews by Bohlius and colleagues7 and Tonia and colleagues11 used a wide range of administration frequencies and dosages of ESAs (generally exceeding the licence), which may result in an increase in adverse events (AEs) and mortality. This knowledge, along with the generally poor reporting and data omission on factors such as tumour stage and method of assessment, led to the conclusion by Tonia and colleagues11 that no clear evidence was found to either exclude or prove a tumour-promoting effect of ESAs.

Current management

Red blood cell transfusions

Anaemia in cancer patients can be treated with RBCTs, with 15% of people with solid tumours treated with RBCTs. 34

Different cut-off values are used for transfusions, depending on clinical symptoms and patient characteristics, with a Hb level of < 9 g/dl commonly used. 34 After administration of 1 unit of RBCs, the Hb level rises by 1 g/dl, with the lifespan of transfused RBCs being 100–110 days. Complications related to RBCT are procedural problems, iron overload, viral and bacterial infections and immune injury. 34

Erythropoietin-stimulating agents

Erythropoietin is an acidic glycoprotein hormone. Approximately 90% of the hormone is synthesised in the kidney and 10% is synthesised in the liver. Erythropoietin is responsible for regulating RBC production. Erythropoietin for clinical use is produced by recombinant DNA technology. 1

Exogenously administered erythropoietin is used to shorten the period of symptomatic anaemia in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. It is used in addition to, rather than as a complete replacement for, the existing treatments. Blood transfusion, in particular, may still be needed. 1

Marketing authorisations: haemoglobin levels

Initially, all ESAs were recommended for use at Hb levels of ≤ 11 g/dl, with target Hb levels not exceeding 13 g/dl. However, because of data showing a consistent, unexplained, excess mortality in cancer patients with anaemia treated with ESAs, a safety review of all available data on ESA treatment of patients with CIA was conducted in 2008 by the Pharmacovigilance Working Party at the request of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. As a result of this safety review, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) requested that the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPCs) for all ESAs be changed to highlight that ESAs should be used only if anaemia is associated with symptoms; to establish a uniform target Hb range for all ESAs; to mention the observed negative benefit risk balance in patients treated with high target Hb concentrations; and to include the relevant results of the trials triggering the safety review. SPCs for all ESAs were therefore revised in 2008 to decrease the Hb value for treatment initiation to ≤ 10 g/dl and to amend Hb treatment target values to 10–12 g/dl and Hb levels for stopping treatment to > 13 g/dl.

The EMA labels the use of ESAs as follows:

-

in patients treated with chemotherapy and with a Hb level of ≤ 10 g/dl, treatment with ESAs might be considered to increase Hb (to within the target range of 10–12 g/dl) or to prevent further decline in Hb

-

in patients not treated with chemotherapy, there is no indication for the use of ESAs and there might be an increased risk of death when ESAs are administered to a target Hb level of 12–14 g/dl

-

in patients with curative intent, ESAs should be used with caution.

These changes to the licence (Table 2) were introduced subsequent to the previous NICE appraisal.

| Pre 2008 | 2008 onwards |

|---|---|

|

|

Details of current licence recommendations are summarised in Table 3.

| Product characteristics | Epoetin alfa, epoetin zeta | Epoetin beta | Epoetin theta | Darbepoetin alfa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer (product) | Janssen-Cilag Ltd (Eprex®),35 Sandoz Ltd (Binocrit®),36 Hospira UK Ltd (Retacrit®)37 | Roche Products Ltd (NeoRecormon®)38 | Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Eporatio®)39 | Amgen Inc. (Aranesp®)40 |

| Marketing authorisation | Treatment of anaemia and reduction of RBCT requirements in adults receiving chemotherapy for solid tumours, malignant lymphoma or multiple myeloma, who are at risk of transfusion as assessed by their general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy) | Treatment of symptomatic anaemia in adults with non-myeloid malignancies receiving chemotherapy | ||

| Starting Hb level | ≤ 10 g/dl | ≤ 10 g/dl | ≤ 10 g/dl | ≤ 10 g/dl |

| Target Hb level | 10–12 g/dl | 10–12 g/dl | 10–12 g/dl | 10–12 g/dl |

| Initial treatment | 150 IU/kg SC TIW (or 450 IU/kg SC QW) | 150 IU/kg SC TIW (or 450 IU/kg SC QW) | 20,000 IU/QW | 2.25 µg/kg SC QW [or 500 µg (6.75 µg/kg) SC Q3W] |

| Dose increase | 4 weeks Hb increase < 1 g/dl and reticulocyte increase ≥ 40,000 cells/µl dose is doubled to 300 IU/kg TIW or 900 IU/kg QW | 300 IU/kg SC TIW | 4 weeks Hb increase < 1 g/dl dose is doubled to 40,000 IU/QW; if Hb increase insufficient at 8 weeks increase to 60,000 IU/QW | Not specified |

| Dose reduction | If Hb increases by ≥ 2 g/dl: 25–50%; if Hb > 12 g/dl: 25–50% | If Hb > 12 g/dl or increase is > 2 g/dl in 4 weeks: 25–50% | If Hb increases by ≥ 2 g/dl: 25–50%; if Hb ≥ 12 g/dl: 25–50% | |

| Dose withholding | If Hb > 13 g/dl, until 12 g/dl reinitiate at 25% lower dose | If Hb > 13 g/dl, until 12 g/dl reinitiate at 25% lower dose | If Hb > 13 g/dl, until 12 g/dl reinitiate at 25% lower dose | |

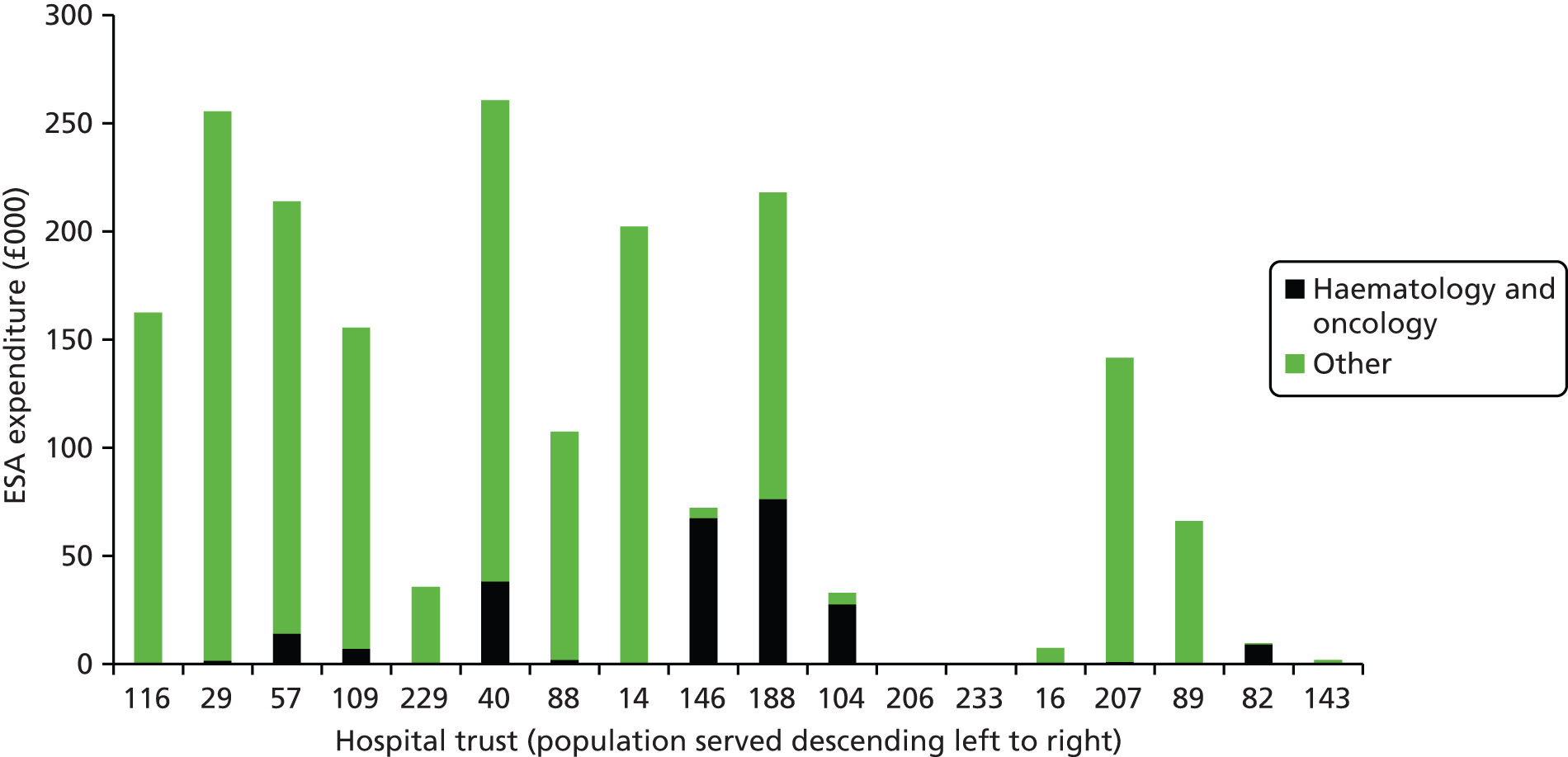

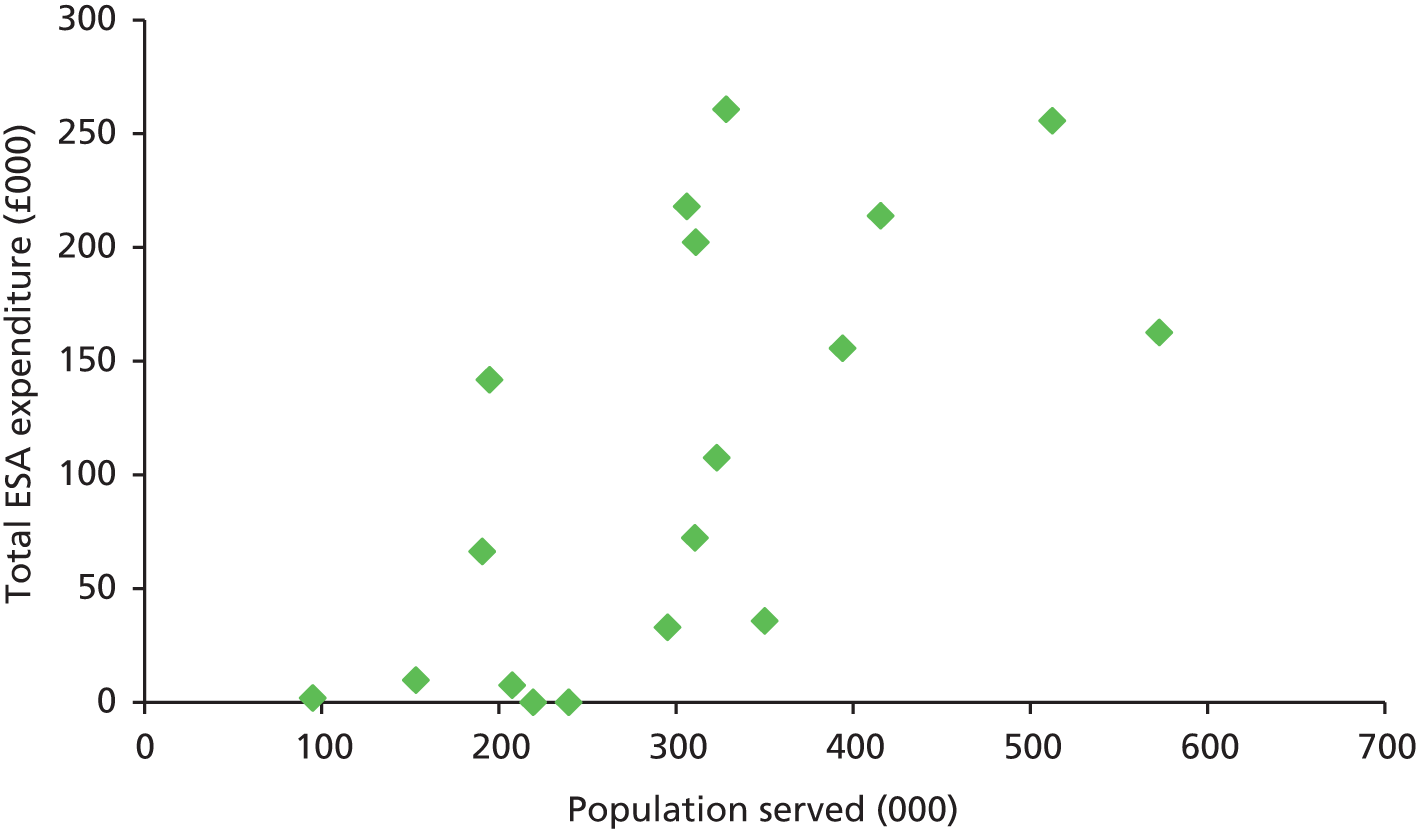

Current service provision

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance (TA142)1 currently recommends ESAs in combination with intravenous iron as an option for:

-

the management of CIA in women receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer who have symptomatic anaemia with a Hb level of ≤ 8 g/dl. The use of ESAs does not preclude the use of existing approaches to the management of anaemia, including blood transfusion when necessary

-

people who cannot be given blood transfusions and who have profound cancer treatment-related anaemia that is likely to have an impact on survival.

When indicated, the ESA used should be the one with the lowest acquisition cost.

Description of the technologies under assessment

Several short- and long-acting ESAs are available, including epoetin alfa, epoetin beta and darbepoetin beta. Since the last appraisal (2004) [the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) monograph relating to this was published in 20072], an additional two ESAs have become available: epoetin theta and epoetin zeta. All are administered by subcutaneous injection. This technology assessment report will consider six pharmaceutical interventions: epoetin alfa (Eprex®, Janssen-Cilag Ltd; Binocrit®, Sandoz Ltd), epoetin beta (NeoRecormon®, Roche Products Ltd), epoetin theta (Eporatio®, Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd), epoetin zeta (Retacrit®, Hospira UK Ltd) and darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp®, Amgen Inc.). 1 Two of the six ESAs, Binocrit and Retacrit, are biosimilars of epoetin alfa. A ‘biosimilar’ medicine is similar to a biological medicine (the ‘reference medicine’) that is already authorised in the European Union and contains a similar active substance to the reference medicine. The reference medicine for both Binocrit and Retacrit is Eprex/Erypo®, which contains epoetin alfa. Unlike generic medicines, biosimilars are similar but not identical to the original biological medicine. 41,42 Treatment recommendations according to licence are summarised for each pharmaceutical intervention in Table 3.

This NICE appraisal focuses on the treatment of CIA. As such, the appraisal does not cover all aspects of the licensed indications, such as the prevention of anaemia or the treatment of symptomatic anaemia as a result of chronic renal failure.

Clinical guidelines

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

In Europe, treatment guidelines for CIA have been formulated by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), who most recently updated its recommendations on the use of ESAs in September 2007. 41 In 2010, joint treatment guidelines were issued by American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology (ASCO/ASH). 42

The EORTC guidelines recommend that patients whose Hb level is < 9 g/dl should be assessed for the need for RBCT in addition to ESAs. 41 The joint ASCO/ASH guidelines suggest that RBCT is also an option for patients with CIA and a Hb level of < 10 g/dl, depending on the severity of the anaemia or clinical circumstances, and may also be warranted by clinical conditions in patients with a Hb level of ≥ 10 g/dl but < 12 g/dl. 42

Recommendations for ESA therapy for CIA are broadly similar between the EORTC guidelines and the joint ASCO/ASH guidelines, with small differences in the threshold for initiation of ESA therapy and variation in the wording related to Hb levels. 41,42

The EORTC guidelines41 emphasise that reducing the need for RBCT is a major goal of therapy in anaemic cancer patients and highlight that ESAs can achieve a sustained increase in Hb levels, unlike intermittent transfusions. The guidelines also state that there is no evidence that oral iron supplements increase the response to erythropoietic proteins, although there is evidence of a better response to erythropoietic proteins with intravenous iron.

British Columbia Cancer Agency

The British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) guidelines recommend treatment with ESAs for the treatment of CIA when the Hb level is 10 g/dl and there is a minimum of 2 months of planned chemotherapy. 43

The guidelines also state that the benefits of treatment must be weighed against the possible risks for individual patients: ESAs may increase the risk of death, serious cardiovascular events, thromboembolic events and stroke and they may shorten survival and/or increase the risk of tumour progression or recurrence, as shown in clinical trials in patients with breast, head and neck, lymphoid, cervical non-small-cell lung cancers and patients with active malignancies who are not treated with either chemotherapy or radiotherapy. 43

Existing evidence

Existing systematic reviews of effectiveness

There have been a number of well-conducted systematic reviews evaluating the effects of ESAs for treating CIA in cancer patients. We identified 11 systematic reviews (reported in 14 publications) that fulfilled the definition of a systematic review prespecified in the protocol; a summary of the eligible systematic reviews and a quality assessment [compared with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement44] is provided in Appendix 1.

Cochrane review

The Cochrane review by Tonia and colleagues11 was the most recent and authoritative review. The Cochrane review’s conclusions were that ESAs reduce the need for RBCTs but increase the risk for thromboembolic events and deaths. ESAs may improve quality of life but the effect of ESAs on tumour control is uncertain. The review concluded that ‘Further research is needed to clarify cellular and molecular mechanisms and pathways of the effects of ESAs on thrombogenesis and their potential effects on tumour growth (p. 2). 11

This was an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2004. 7 Searches were conducted in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, MEDLINE and other databases. Searches were carried out for the periods January 1985 to December 2001 for the first review, January 2002 to April 2005 for the first update and up to November 2011 for the most recent update. The authors of the review also contacted experts in the field and pharmaceutical companies [for access to individual patient data (IPD)]. Inclusion, quality assessment and data abstraction were undertaken in duplicate by several reviewers. Eligibility criteria are detailed and compared with those in the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG) review in Table 4. The Cochrane review differed from the PenTAG review in respect of the population (cancer-related anaemia vs. chemotherapy-induced anaemia) and the intervention [all ESAs irrespective of licence vs. ESAs within licence (defined based on start dose)].

| Criteria | Tonia and colleagues11 | Current systematic review |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients diagnosed with malignant disease (using clinical and histological/cytological criteria) and at risk of transfusion as assessed by their general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy). Excluded trials in which > 80% of participants were diagnosed with an acute leukaemia | Patients had to be receiving chemotherapy for solid tumours, malignant lymphoma, multiple myeloma or non-myeloid malignancies and at risk of transfusion as assessed by their general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy) |

| Intervention | ESAs to prevent or reduce anaemia, given singly or concomitantly with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or combination therapy | ESAsa to prevent or reduce anaemia, given concomitantly with chemotherapy |

| Dose: included studies or study arms with low doses | Dose: licensed dose defined by start dose even if it did not align with other criteria specified by the licence | |

| Comparator | Placebo or ‘no treatment’ was not required for inclusion but was considered in evaluating study quality | Placebo, standard care, no treatment/usual care |

| Outcomes | HaemR,b Hb change, RBCT, RBC units, OS, mortality, tumour response (CR), AEs, HRQoL | HaemR,b Hb change, RBCT, RBC units, OS, tumour response (CR), AEs, HRQoL |

| Study design | RCTs | RCTs, SRs of RCTsc |

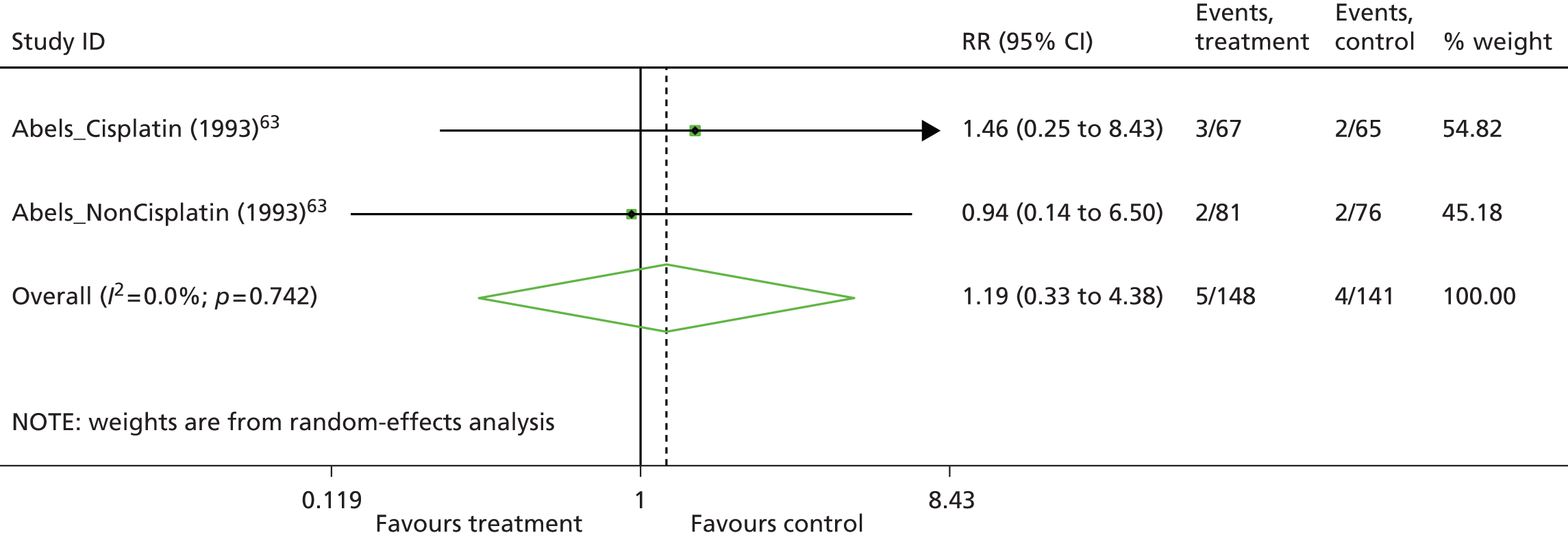

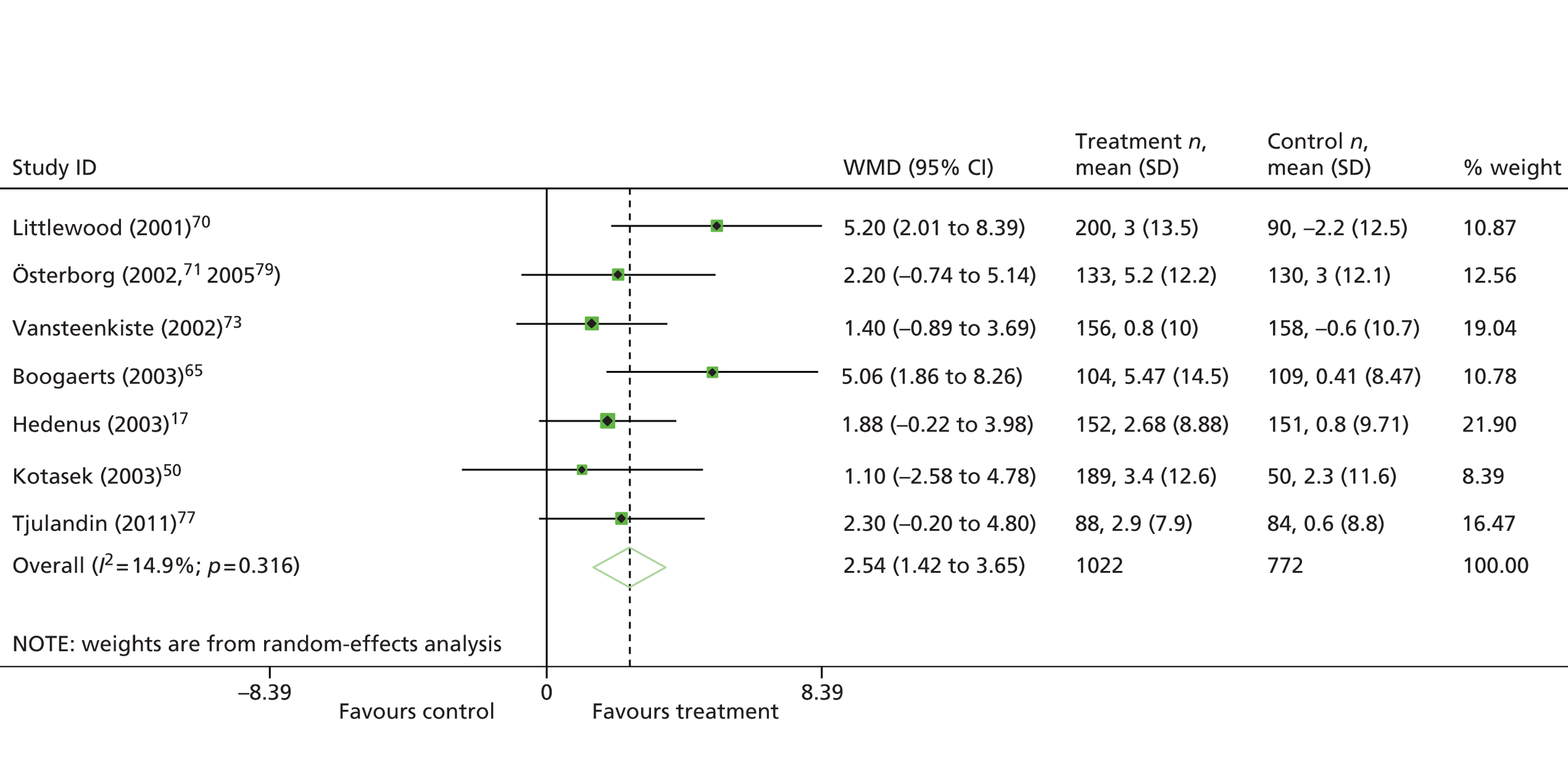

A total of 91 studies with 20,102 participants were included in the Cochrane review by Tonia and colleagues. 11 The results from the Cochrane review are summarised in Table 5 and compared with the results of the PenTAG HTA review throughout Chapter 3.

| Outcomes measured | Results |

|---|---|

| Anaemia-related outcomes | |

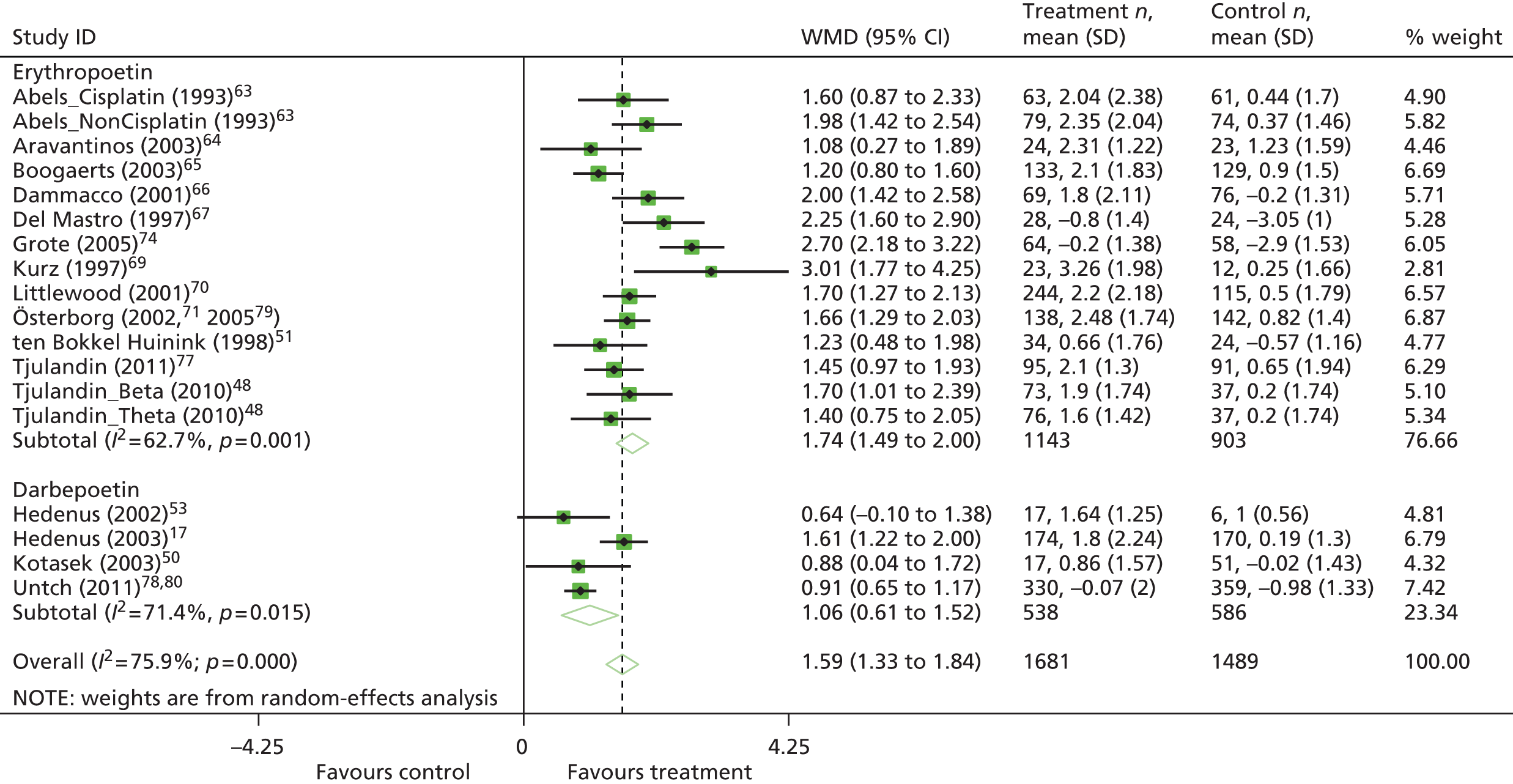

| Hb changea | WMD 1.57, 95% CI 1.51 to 1.62; χ2(het) = 564.37, df = 74; p < 0.001 75 trials, n = 11,609 |

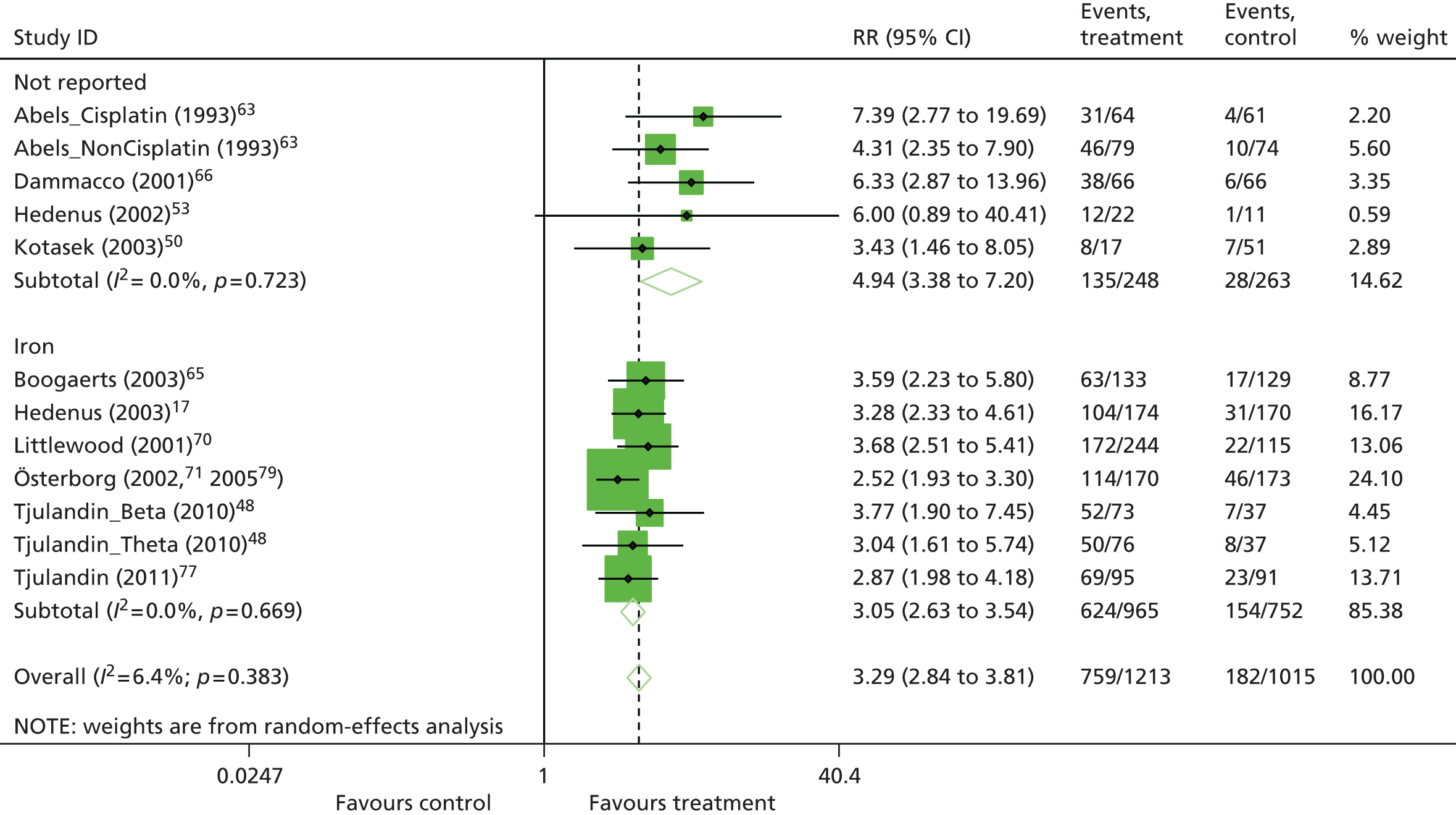

| HaemRb | RR 3.39, 95% CI 3.10 to 3.71; χ2(het) = 95.56, df = 45; p < 0.001 46 trials, n = 6413 |

| RBCT | RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.68; χ2(het) = 217.08, df = 87; p < 0.001 88 trials, n = 16,093 |

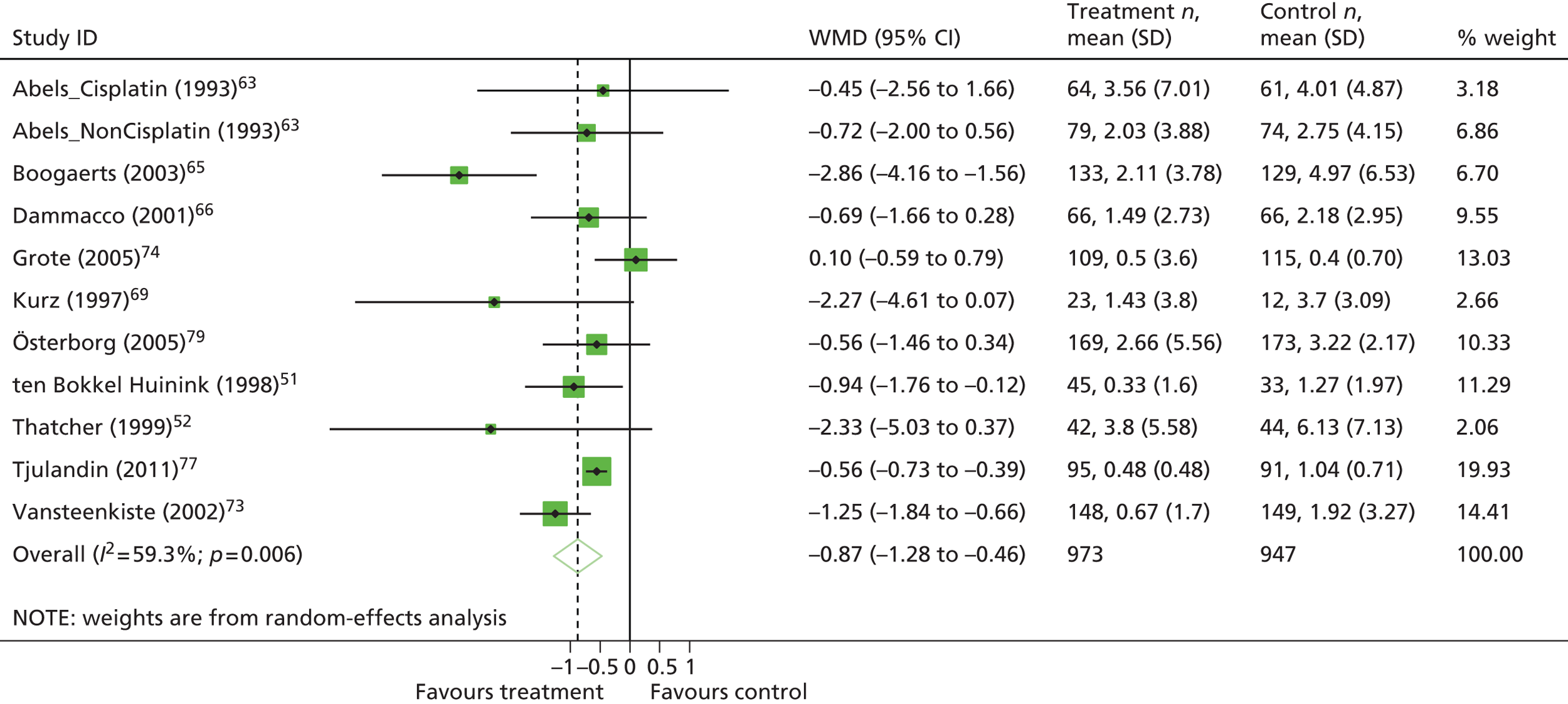

| Units transfused | WMD –0.98, 95% CI –1.17 to –0.78; χ2(het) = 34.52, df = 24; p = 0.080 25 trials, n = 4715 |

| Malignancy-related outcomes | |

| Tumour response | RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.06; χ2(het) = 16.10, df = 18; p = 0.59 19 trials, n = 5012 |

| OS | HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11; χ2(het) = 95.40, df = 75; p = 0.060 80 trials, n = 19,003 |

| Mortality | HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.29; χ2(het) = 59.49, df = 63; p = 0.600 64 trials, n = 14,179 |

| Safety-related outcomes | |

| Thromboembolic events | RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.74; χ2(het) = 34.99, df = 55; p = 0.980 60 trials, n = 15,498 |

| Hypertension | RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.56; χ2(het) = 26.87, df = 34; p = 0.800 35 trials, n = 7006 |

| Thrombocytopenia/haemorrhage | RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.42; χ2(het) = 14.50, df = 20; p = 0.800 21 trials, n = 4220 |

| Seizures | RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.41; χ2(het) = 6.19, df = 6; p = 0.400 7 trials, n = 2790 |

| Pruritus | RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.24; χ2(het) = 13.18, df = 15; p = 0.590 16 trials, n = 4346 |

| HRQoL-related outcomes | |

| FACT-F 13 items (score 0–52) | MD 2.08, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.72; χ2(het) = 36.48, df = 17; p = 0.004 18 trials, n = 4965 |

| Any subgroup effect | Yes: imputed vs. non-imputed data, baseline Hb level, type of anticancer therapy, duration of ESA treatment and ITT analysis |

Cochrane review: meta-analysis based on individual patient data

Another Cochrane review7 examined the effect of ESAs and identified factors that modify the effects of ESAs on OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and thromboembolic and cardiovascular events, as well as the need for transfusions and other important safety and efficacy outcomes in cancer patients. It concluded that ‘ESA treatment in cancer patients increased on study mortality and worsened OS. For patients undergoing chemotherapy the increase was less pronounced, but an adverse effect could not be excluded’ (p. 2).

The review was conducted in 2009. Searches were conducted in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and conference proceedings for eligible trials and manufacturers of ESAs were contacted to identify additional trials. The review included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing ESAs plus RBCT (as necessary) with RBCT (as necessary) alone to prevent or treat anaemia in adult or paediatric cancer patients with or without concurrent antineoplastic therapy. Inclusion, quality assessment and data abstraction were undertaken in duplicate by several reviewers. A meta-analysis of RCTs was conducted and patient-level data were obtained and analysed by independent statisticians.

A total of 13,933 cancer patients from 53 trials were analysed; 1530 patients died on study and 4993 died overall. ESAs increased on-study mortality [combined hazard ratio (cHR) 1.17; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.06 to 1.30] and worsened OS (cHR 1.06; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.12), with little heterogeneity between trials (I2 = 0%, p = 0.87, and I2 = 7.1%, p = 0.33 respectively). Thirty-eight trials enrolled 10,441 patients receiving chemotherapy (Table 6). The cHR for on-study mortality was 1.10 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.24) and that for OS was 1.04 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.11). There was little evidence of a difference between trials of patients receiving different cancer treatments (p-value for interaction = 0.42).

| Outcomes measured | Results |

|---|---|

| Malignancy-related outcomes | |

| OS | cHR 1.04, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.11 38 trials, n = 10,441 |

| On-study mortality | cHR 1.10, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.24 38 trials, n = 10,441 |

Previous Health Technology Assessment review

The previous HTA review (Wilson and colleagues2) informed NICE guidance (TA1421). It assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of epoetin alfa, epoetin beta and darbepoetin alfa in anaemia associated with cancer, especially that attributable to cancer treatment. The review concluded that ESAs are effective in improving the haematological response and reducing RBCT requirements, but that the effect on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is uncertain and the incidence of side effects and the effect on survival are highly uncertain. If there is no effect on survival it seems highly unlikely that ESAs would be considered a cost-effective use of health-care resources.

Using the Cochrane review45 published in 2004 as the start point, Wilson and colleagues2 conducted a systematic review of RCTs comparing ESAs with standard care. MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library and other databases were searched from 2000 (1996 in the case of darbepoetin alfa) to September 2004. Inclusion, quality assessment and data abstraction were undertaken in duplicate. Eligibility criteria are detailed and compared with those of the PenTAG review in Table 7. When possible, meta-analysis was employed. The economic assessment consisted of a systematic review of past economic evaluations, an assessment of economic models submitted by the manufacturers of the three ESAs and development of a new individual sampling model (see Chapter 4, Wilson and colleagues: summary).

| Eligibility criteria | Wilson and colleagues2 | Current systematic review |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients diagnosed with malignant disease (using clinical and histological/cytological criteria) and at risk of transfusion as assessed by the patient’s general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy) | Patients had to be receiving chemotherapy for solid tumours, malignant lymphoma, multiple myeloma or non-myeloid malignancies and be at risk of transfusion as assessed by the patient’s general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy) |

| Intervention | ESAs to prevent or reduce anaemia, given singly or concomitantly with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or combination therapy | ESAsa to prevent or reduce anaemia, given concomitantly with chemotherapy |

| Dose: included studies or study arms with low doses | Dose: licensed dose, defined by start dose, even if studies did not align with other criteria specified by the licence | |

| Comparator | Placebo or ‘no treatment’ was not required for inclusion but was considered in evaluating study quality | Placebo, standard care, no treatment/usual care |

| Outcomes | HaemR,b Hb change, RBCT, RBC units, OS, mortality, tumour response (CR), AEs, HRQoL | HaemR,b Hb change, RBCT, RBC units, OS, tumour response (CR), AEs, HRQoL |

| Study design | RCTs | RCTs, SRs of RCTsc |

A total of 46 RCTs were included in the review, 27 of which had been included in the Cochrane review. 7 All 46 studies compared ESA plus supportive care for anaemia (including transfusions) with supportive care for anaemia (including transfusions alone). Outcomes assessed were anaemia-related outcomes (haematological response, Hb change, RBCT requirements), malignancy-related outcomes (tumour response and OS), HRQoL and AEs.

Results from the previous HTA review2 (Table 8) are compared with the results of the PenTAG review throughout Chapter 3.

| Outcomes measured | Results |

|---|---|

| Anaemia-related outcomes | |

| Hb changea | WMD 1.63, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.80; χ2(het) = 23.74, df = 19; p = 0.21 10 trials, n = 1620 |

| HaemRb | RR 3.40, 95% CI 3.01 to 3.83; χ2(het) = 23.60, df = 32; p = 0.86 21 trials, n = 3740 |

| RBCT | RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.67; χ2(het) = 94.75, df = 48; p = 0.001 35 trials, n = 5564 |

| Units transfused | WMD –1.05, 95% CI –1.32 to –0.78; χ2(het) = 8.96, df = 16; p = 0.91 14 trials, n = 2353 |

| Malignancy-related outcomes | |

| Tumour response | RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.60; χ2(het) = NR; df = NR; p = NR 9 trials, n = 1260 |

| OS | HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.16; χ2(het) = 37.74, df = 27; p = 0.08 28 trials, n = 5308 |

| Mortality | NR |

| Safety-related outcomes | No safety-related meta-analysis |

| HRQoL-related outcomes | No HRQoL meta-analyses |

Key points

-

Anaemia is defined as a deficiency in RBCs. It is the most frequent haematological manifestation in patients with cancer; > 50% of all cancer patients will be anaemic, regardless of the treatment received, and approximately 20% of all patients undergoing chemotherapy will require a RBCT. The cause is multifactorial: patient, disease or treatment related.

-

Anaemia is associated with many symptoms, all of which affect quality of life. These symptoms include dizziness, shortness of breath on exertion, palpitations, headache and depression. Severe fatigue is probably the most commonly reported symptom and can lead to an inability to perform everyday tasks. However, fatigue in people with cancer can also have other causes, for example the disease itself, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, anxiety or depression.

-

Many people are anaemic when cancer is diagnosed, before any cancer treatment starts. The degree of anaemia caused by treatments such as chemotherapy often fluctuates depending on the nature of the treatment and the number of courses administered, but is typically at its worst 2–4 weeks after chemotherapy is given. Once cancer treatments are stopped, a period of ‘normalisation’ is likely, during which the Hb may return to pretreatment levels.

-

Options available for the management of CIA include adjustments to the cancer treatment regimen, iron supplementation and blood transfusion. The majority of people who become anaemic do not receive any treatment for their anaemia, but those who become moderately or severely anaemic are usually given blood transfusions. Complications related to RBCT include procedural problems, iron overload, viral and bacterial infections and immune injury.

-

Current evidence suggests that ESAs reduce the need for RBCT but increase the risk of thromboembolic events and death. There is suggestive evidence that ESAs may improve quality of life. Whether and how ESAs affect tumour control remains uncertain.

-

Based on the previous assessment,2 NICE guidance (TA142)1 recommended the use of ESAs in combination with intravenous iron for the treatment of CIA in women with ovarian cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy with symptomatic anaemia (Hb ≤ 8 g/dl). The recommendation made in TA142 did not prohibit the use of other management strategies for the treatment of CIA, for example blood transfusion. 1 In addition, guidance set out in TA142 recommended ESAs in combination with intravenous iron for people with profound CIA who cannot be given blood transfusions. 1 The ESA with the lowest acquisition cost should be used. 1

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The purpose of this assessment was to review and update as necessary guidance to the NHS in England and Wales on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ESAs [epoetin alfa (Eprex and Binocrit), epoetin beta (NeoRecormon), epoetin theta (Eporatio), epoetin zeta (Retacrit) and darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp)] within their licensed indications for the treatment of CIA.

The project was undertaken based on a published scope46 and in accordance with a predefined protocol. There were no major departures from this protocol. The protocol stated that interventions would be evaluated in line with their UK marketing authorisations. However, as none of the included studies was completely aligned with the current licence we applied a definition of ‘within licence’, which was not predefined. Given the recent publication of the 2012 Cochrane review,11 which considered all ESAs, irrespective of their licence, ‘within licence’ was defined as a licensed starting dose, irrespective of how other licence criteria were dealt with.

Population

The population was people receiving chemotherapy for solid tumours, malignant lymphoma or multiple myeloma and people with non-myeloid malignancies at risk of transfusion as assessed by their general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy).

Haematological malignancy specifically refers to non-myeloid malignancy (chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease and multiple myeloma).

Interventions

The interventions considered were ESAs: epoetin alfa (Eprex and Binocrit), epoetin beta (NeoRecormon), epoetin theta (Eporatio), epoetin zeta (Retacrit) and darbepoietin alfa (Aranesp).

All interventions were considered according to their UK marketing authorisation with respect to the starting dose administered (see Table 3).

Comparators

The following comparators were considered:

-

best supportive care (including adjustment to the cancer treatment regimen, RBCT and iron supplementation)

-

one of the other interventions under consideration, provided it was used in line with its marketing authorisation.

Outcomes

Evidence in relation to the following kinds of outcomes were considered:

-

haematological response to treatment: defined as a transfusion-free increase in Hb of ≥ 2 g/dl or a haematocrit increase of 6 percentage points

-

need for blood transfusion after treatment: number of patients transfused and number of units transfused per patient

-

tumour response: time to cancer progression

-

OS

-

AEs of treatment: hypertension, rash/irritation, pruritus, mortality, thromboembolic events, seizure, haemorrhage/thrombocytopenia, fatigue, pure red cell aplasia (a note was made of other AEs described within the trial reports)

-

HRQoL: validated quality-of-life measures, for example the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Fatigue (FACT-F) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Anaemia (FACT-An), the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36).

Research question

This assessment addressed the following research question: ‘What is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ESAs (epoetin alfa, beta, theta and zeta and darbepoetin alfa) for treating CIA (including review of TA142)?’

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The review commissioned by NICE was to update the previous guidance (TA1421) based on the HTA review conducted by Wilson and colleagues. 2 The differences between the remit of the previous review and that of the current review are discussed in Chapter 1 (see Previous Health Technology Assessment review). The project was undertaken in accordance with a predefined protocol. There were no major departures from this protocol. The protocol stated that interventions would be evaluated in line with their UK marketing authorisations. However, as none of the included studies was completely aligned with the current licence we applied a definition of ‘within licence’, which was not predefined. Given the recent publication of the 2012 Cochrane review,11 which considered all ESAs irrespective of their licence, ‘within licence’ was defined as a licensed starting dose irrespective of how other licence criteria were dealt with.

A scoping search was undertaken to identify existing reviews and other background material. Among this literature two recent Cochrane reviews were identified that assessed the effectiveness of ESAs. 7,47

The aim was to systematically review the effectiveness of ESAs with regard to treating cancer treatment-related anaemia, their effects on patients regarding their underlying malignancy and survival and their effectiveness in improving quality of life and reducing the impact of AEs. Given the recent publication of the Cochrane review,11 the focus for this review was to identify and consider trials in which ESAs have been used in a manner consistent with or closest to their respective marketing authorisations (see Eligibility criteria, Dose).

Methods

Identification of studies

The search strategy was based on the strategy used in the previous multiple technology appraisal (MTA) on this topic by Wilson and colleagues. 2 It combined free-text and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms for epoetin (generic and brand names), cancer and anaemia (see Appendix 1). Search filters were applied to retrieve RCTs, cost-effectiveness studies and quality-of-life studies. The search terms and structure of the search were mainly the same as in the study by Wilson and colleagues,2 with additional search terms for epoetin theta, epoetin zeta and corresponding drug brand names. The search filters for RCTs, cost-effectiveness studies and quality-of-life studies were different from those used in Wilson and colleagues. 2 The filters were developed by an information specialist to ensure an appropriate balance of sensitivity and specificity. Changes to the previous MTA search strategy, including the filters, were made in MEDLINE and translated as appropriate for other databases. The MEDLINE randomised controlled trial (RCT) search strategy was checked by a clinical expert for inaccuracies and omissions relating to drug and cancer terms.

The databases were searched from the search end date of the previous MTA on this topic2 (search end date 2004). Although epoetin alfa (Binocrit), epoetin theta and epoetin zeta were not covered in the previous report, we believe that relevant interventional research is highly unlikely to have been published on these drugs before this date given that the drugs were launched in 2007 (Binocrit and epoetin zeta) and 2009 (epoetin theta). All searches were also limited to English-language papers, although some foreign-language papers would have been identified by virtue of being included in other systematic reviews.

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), The Cochrane Library including CENTRAL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the HTA database, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Office for Health Economics Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost), the British Nursing Index (ProQuest) and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (Ovid). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and EMA websites were also searched.

In addition, the following websites were searched for background information (all accessed 26 June 2015):

-

medical societies:

-

British Society for Haematology: www.b-s-h.org.uk/

-

Association of Cancer Physicians: www.cancerphysicians.org.uk/

-

ASH: www.hematology.org/

-

ASCO: www.asco.org/

-

Canadian Oncology Societies: www.cos.ca/

-

Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand: www.hsanz.org.au/

-

Clinical Oncology Society of Australia: www.cosa.org.au/

-

New Zealand Society for Oncology: www.nzsoncology.org.nz/

-

-

UK charities:

-

Cancer Research UK: www.cancerresearchuk.org/home/

-

Macmillan: www.macmillan.org.uk/

-

Marie Curie: www.mariecurie.org.uk/

-

-

non-UK charities:

-

American Cancer Society: www.cancer.org/

-

Canadian Cancer Society: www.cancer.ca/

-

Cancer Council Australia: www.cancer.org.au/

-

Cancer Society of New Zealand: www.cancernz.org.nz/

-

World Cancer Research Fund: www.wcrf-uk.org/.

-

The database search results were exported to, and deduplicated using, EndNote X5 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Deduplication was also performed using manual checking. The search strategies and the numbers of references retrieved for each database are detailed in Appendix 1. After the reviewers completed the screening process, the bibliographies of included papers were scrutinised for further potentially includable studies.

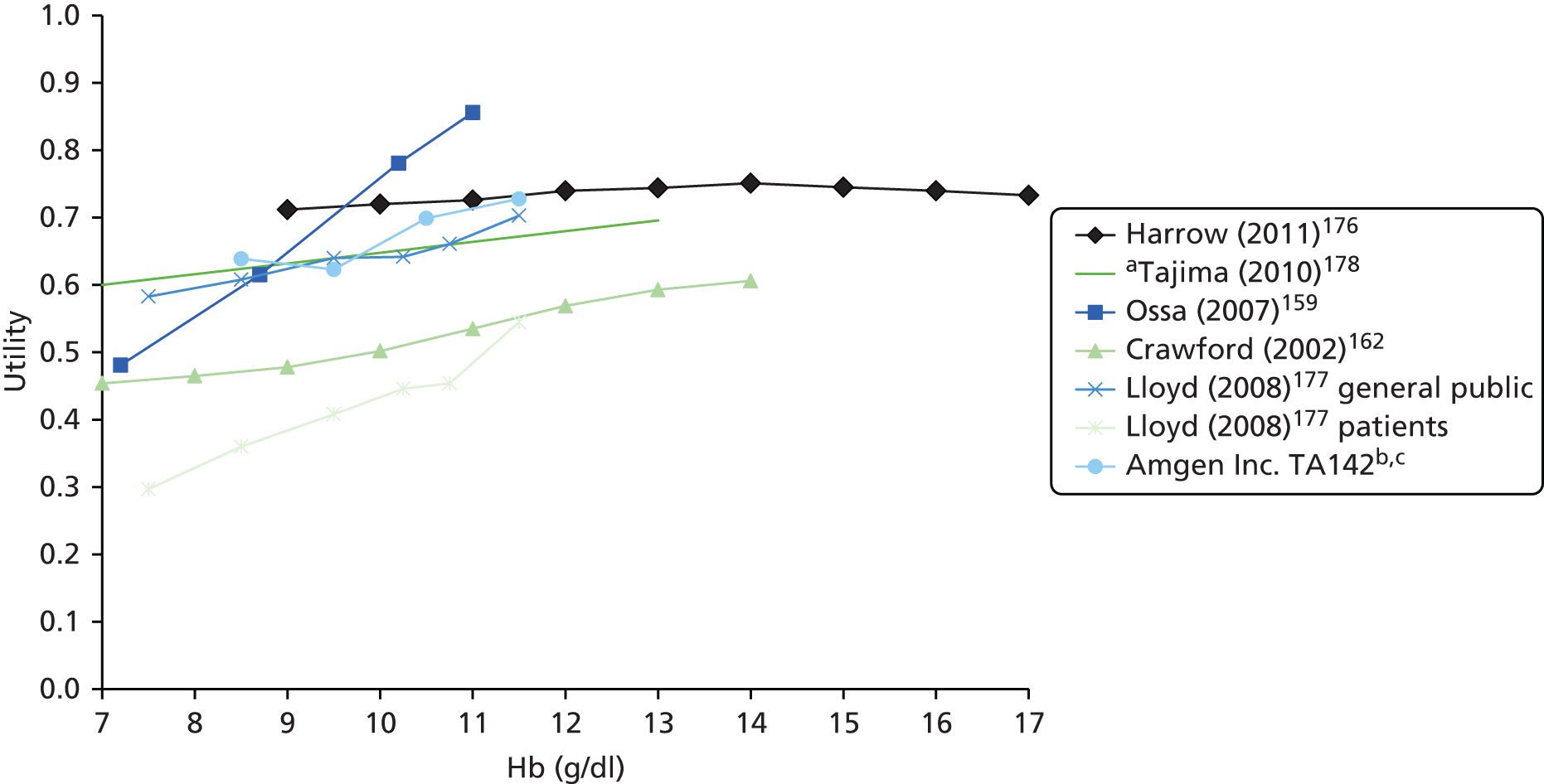

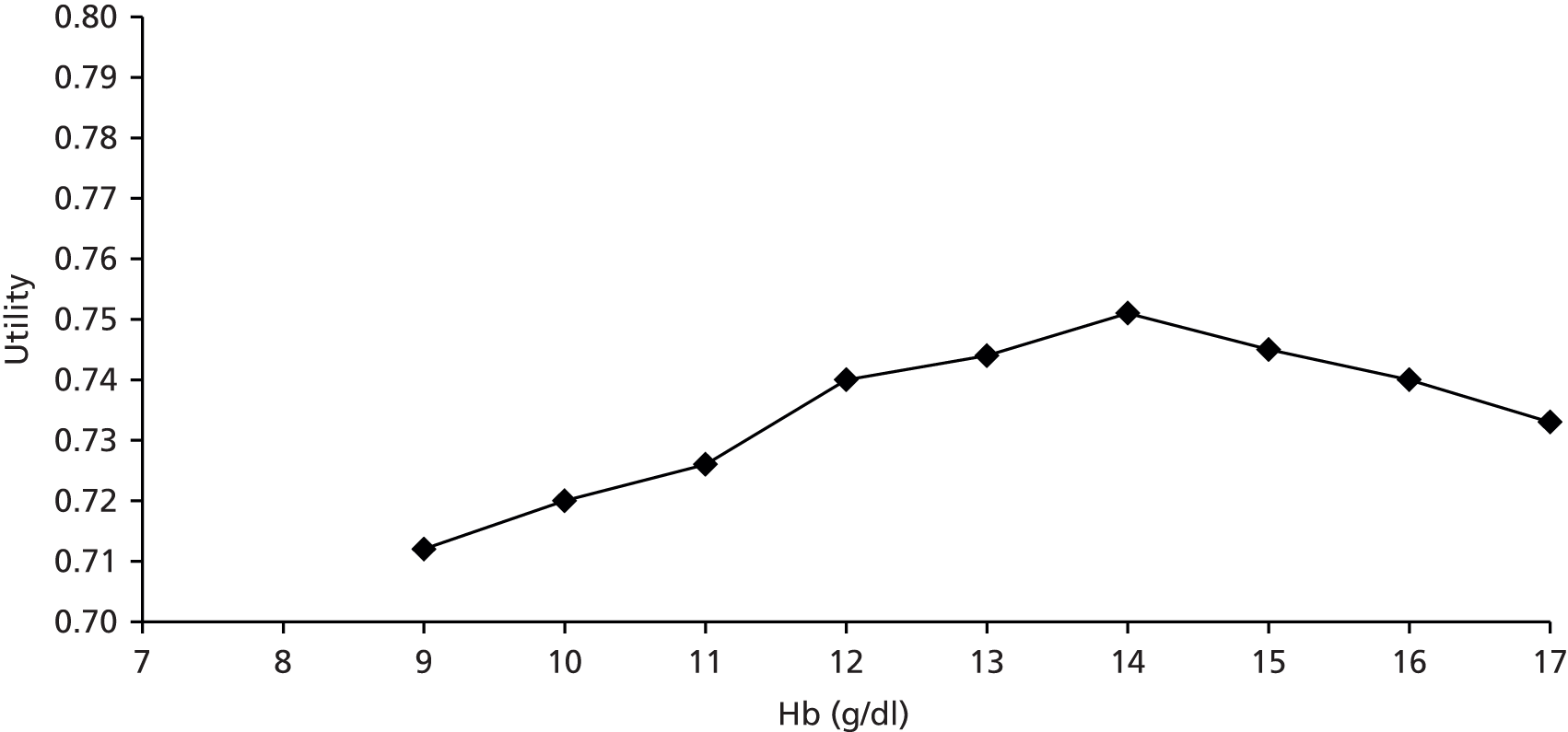

A supplementary search was carried out in MEDLINE (Ovid) to search for utilities as a function of Hb levels and for information on Hb levels after chemotherapy ends. A systematic search was not required for this part of the review and so the search strategy was limited to MEDLINE. These searches are detailed in Appendix 1.

Wilson and colleagues2

Studies included in the previous HTA review2 were screened against the inclusion criteria for the PenTAG review for includable studies.

Reference lists

Reference lists of included guidelines, systematic reviews and clinical trials were scrutinised for additional information.

Ongoing trials

A search for ongoing trials was also undertaken. Terms for the intervention (‘epoetin’ OR ‘darbepoetin’) and condition of interest (cancer* OR carcinoma* OR leukemia OR malignan* OR neoplasm* OR tumo?r OR myelo* OR lymphoma* OR oncolog* OR chemotherapy*) were used to search the trial registers ClinicalTrials.gov and Current Controlled Trials (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) for ongoing trials. Trials that did not relate to cancer-induced or chemotherapy-related anaemia were removed by hand sorting. Finally, duplicates, identified through their study identification numbers when possible, were removed. Searches were carried out on 28 August 2013.

Eligibility criteria

Study design

Only RCTs were included. Non-RCTs and quasi-randomised trials (such as when allocation is based on date of birth or day of month) were excluded.

Population

People receiving chemotherapy for solid tumours, malignant lymphoma or multiple myeloma and at risk of transfusion as assessed by their general status (e.g. cardiovascular status, pre-existing anaemia at the start of chemotherapy) and people with non-myeloid malignancies who are receiving chemotherapy were relevant to the scope of this review. There were no age restrictions; however, it is recognised that the licences for all of the interventions of interest do not cover the use of ESAs in children for this indication. Studies in which ESAs were given in the context of myeloablative chemotherapy ahead of bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation or for short-term preoperative treatment to correct anaemia or to support collection of autologous blood before cancer surgery were excluded.

Interventions

Studies evaluating the use of ESAs were included if ESAs were given to treat CIA. The ESAs of interest for this appraisal were epoetin alfa (Eprex and Binocrit), epoetin beta (NeoRecormen), epoetin theta (Eporatio), epoetin zeta (Retacrit) or darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp).

Concomitant anaemia therapy, such as iron or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) supplementation, was permitted, as was RBCT. However, G-CSF had to be administered to patients in both the treatment and the control arms.

Dose

For the main analysis for this systematic review, studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they evaluated a licensed (weight-based) starting dose, irrespective of how they dealt with other criteria stipulated by the licence (see Table 3).

With respect to European labelling, inclusion Hb levels ≤ 11 g/dl and > 11 g/dl and target Hb levels ≤ 13 g/dl and > 13 g/dl were considered in subgroup analyses; start dose plus an inclusion Hb level ≤ 11 g/dl and start dose plus an inclusion Hb level ≤ 11 g/dl plus a target Hb level ≤ 13 g/dl were also considered in post-hoc analyses.

Comparator

The main comparators of interest were placebo and best supportive care (including adjustment to the cancer treatment regimen, blood transfusion and iron supplementation). In addition, the comparator could be one of the other ESAs under consideration, provided that it was administered in line with the relevant marketing authorisation.

Outcomes

Outcomes sought from the studies fell into four categories: anaemia-related outcomes, malignancy-related outcomes, AE data and patient-specific outcomes such as quality-of-life outcomes and patient preferences:

-

Anaemia-related outcomes: haematological response to treatment (defined as a transfusion-free increase in Hb of ≥ 2 g/dl or a haematocrit increase of 6%), mean Hb change and RBCT requirements [including number of patients transfused, number of units transfused per patient and number of units transfused per average patient (i.e. including participants not requiring transfusion)].

-

Tumour response.

-

OS.

-

On-study mortality.

-

AEs: hypertension, rash/irritation, pruritus, mortality, thromboembolic events, seizure, haemorrhage/thrombocytopenia, fatigue and pure red cell aplasia. A note was made of other AEs described within the trial.

-

HRQoL: data on validated HRQoL measures was sought – anticipated HRQoL measures included Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) (including FACT-G, FACT-F and FACT-An) [see www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires (accessed July 2015)]. A note was made of any other HRQoL measure reported.

Selection of studies

Studies retrieved from the update searches were selected for inclusion according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria specified in Eligibility criteria. First, titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were screened for inclusion independently by four researchers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a fifth reviewer. Full texts of identified studies were obtained and screened in the same way. Abstract-only studies were included on the provision that sufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

In addition, studies included in the review conducted by Wilson and colleagues2 were screened for inclusion against the eligibility criteria for this review (see Chapter 1, Previous Health Technology Assessment review).

On completion of the first round of screening, eligible studies were then rescreened. For this stage, studies were eligible for inclusion in the review only if the ESA treatments evaluated were administered in accordance with their European marketing authorisations with respect to the starting dose, irrespective of how the study dealt with other criteria stipulated by the licence (see Table 3).

Data extraction and management

Included full papers were split between four reviewers for the purposes of data extraction using a standardised data extraction form. Data extraction was checked independently by another reviewer and discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of an additional review team member if necessary. Information extracted and tabulated included details of the study’s design and methodology, baseline characteristics of participants and results for the outcomes of interest (see Appendix 2).

If several publications were identified for one study, the data from the most recent publication were evaluated and these data were amended with information from other publications.

For studies comparing more than one experimental arm with one control arm, we assigned a separate reference for each study arm, using the author and publication year of the main publication and adding the suffixes a and b, etc. For example, the study by Tjulandin and colleagues48 compared two different experimental study arms with one control group. Because of this referencing system a study may appear more than twice in the list of included studies.

When there was incomplete information on key data, we referred to the 2012 Cochrane review. 11 For the Cochrane review the authors evaluated documents presented at the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) hearing at the US FDA held in May 2004, May 2007 and May 2008. These documents were reported to include briefing documents plus additional PowerPoint presentations prepared by medical review authors of the FDA, as well as documents and additional PowerPoint presentations prepared by the companies Roche, Johnson & Johnson and Amgen Inc.

Critical appraisal

The protocol stated that the Cochrane risk of bias tool would be used for quality appraisal; however, for consistency, assessments of study quality were performed using the same criteria as in the previous review. 2 The criteria used to critically appraise the included studies are summarised in Table 9. The results were tabulated and the relevant aspects described on the data extraction forms. Methodological notes were made for each included study on the data extraction forms, including the reviewer’s observations on sample size, power calculations, participant attrition, methods of data analysis and conflicts of interest. In addition, GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) analysis was carried out; the results are presented in Appendix 3.

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Treatment allocation | 1. Was allocation truly random? (Yes: random numbers, coin toss, shuffle, etc.; no: patient ID number, date of birth, alternate; unclear: if the method not stated) |

| 2. Was treatment allocation concealed? (Yes: central allocation at trial office/pharmacy, sequentially numbered coded vials, other methods in which the triallist allocating treatment could not be aware; inadequate: allocation was alternate or based on information known to the triallist; unclear: insufficient information given) | |

| Similarity of groups | 3. Were the patients’ characteristics at baseline similar in all groups? |

| Implementation of masking | 4. Was the treatment allocation masked from the participants? (either stated explicitly or an identical placebo used) |

| 5. Was the treatment allocation masked from clinicians? | |

| Completeness of trial | 6. Were the numbers of withdrawals, dropouts and those lost to follow-up in each group stated? |

| 7. Did the analysis include an ITT analysis or were < 10% of the study arm excluded? |

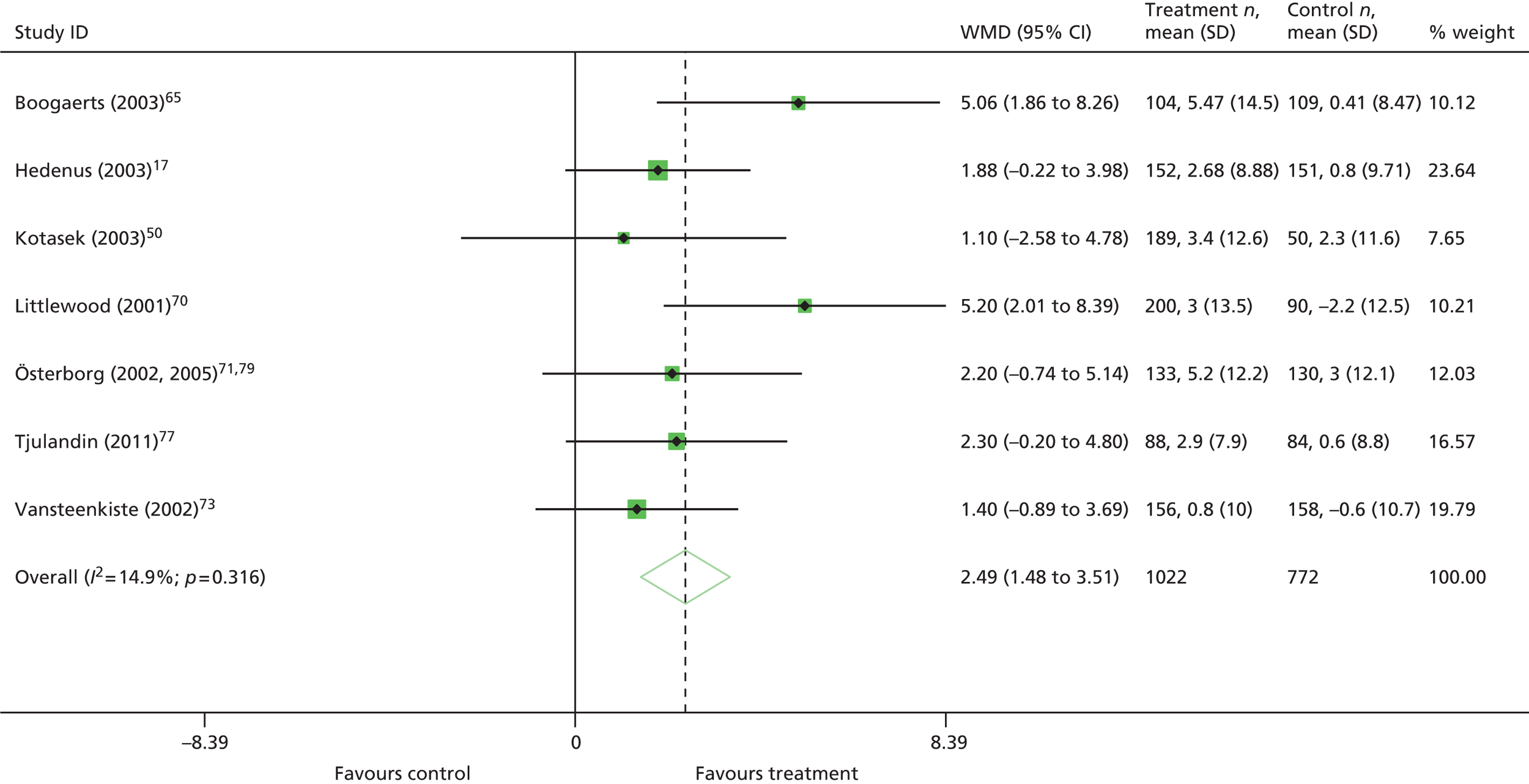

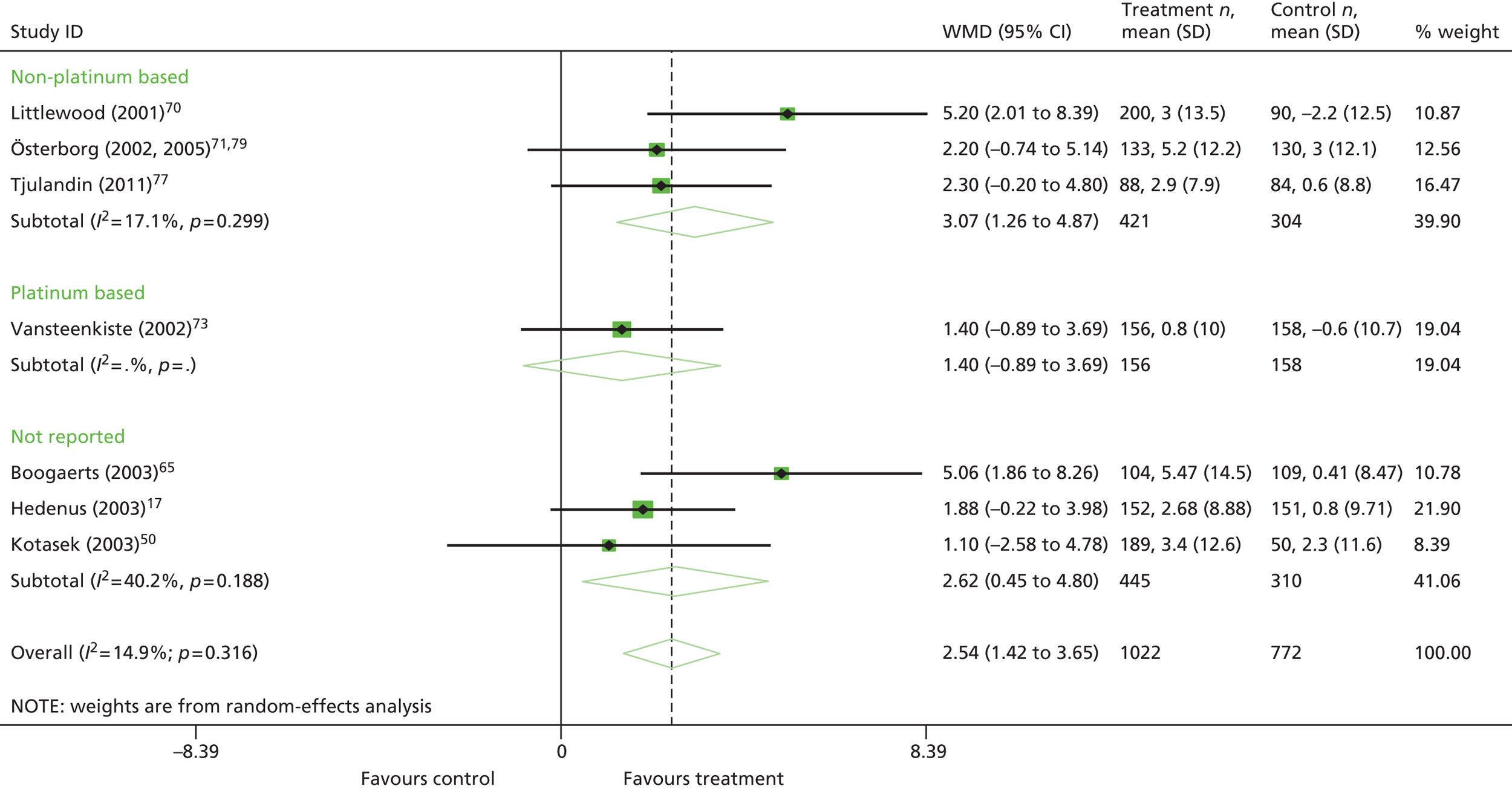

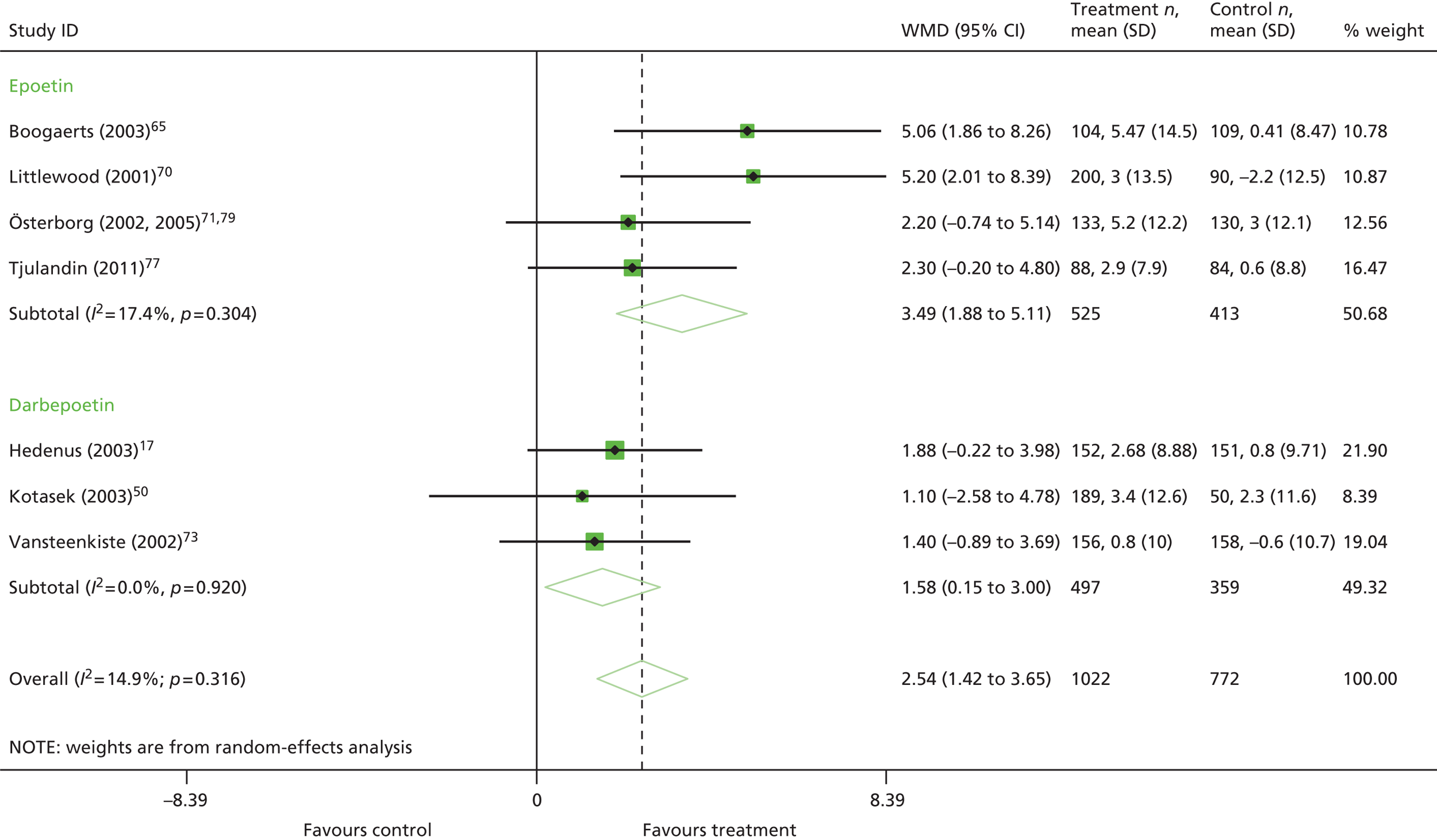

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

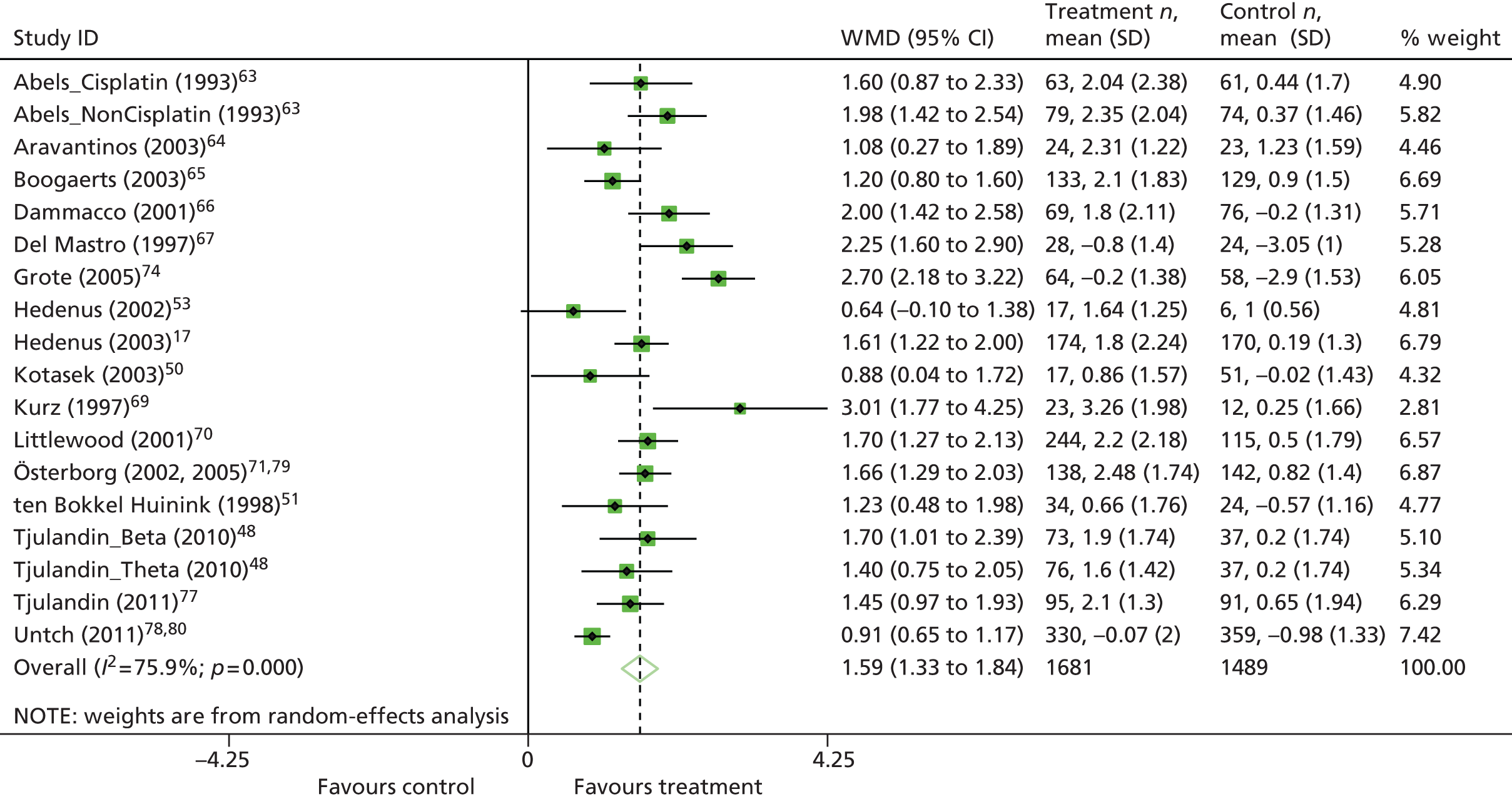

When data permitted, the results of individual studies were pooled using the methods described below.

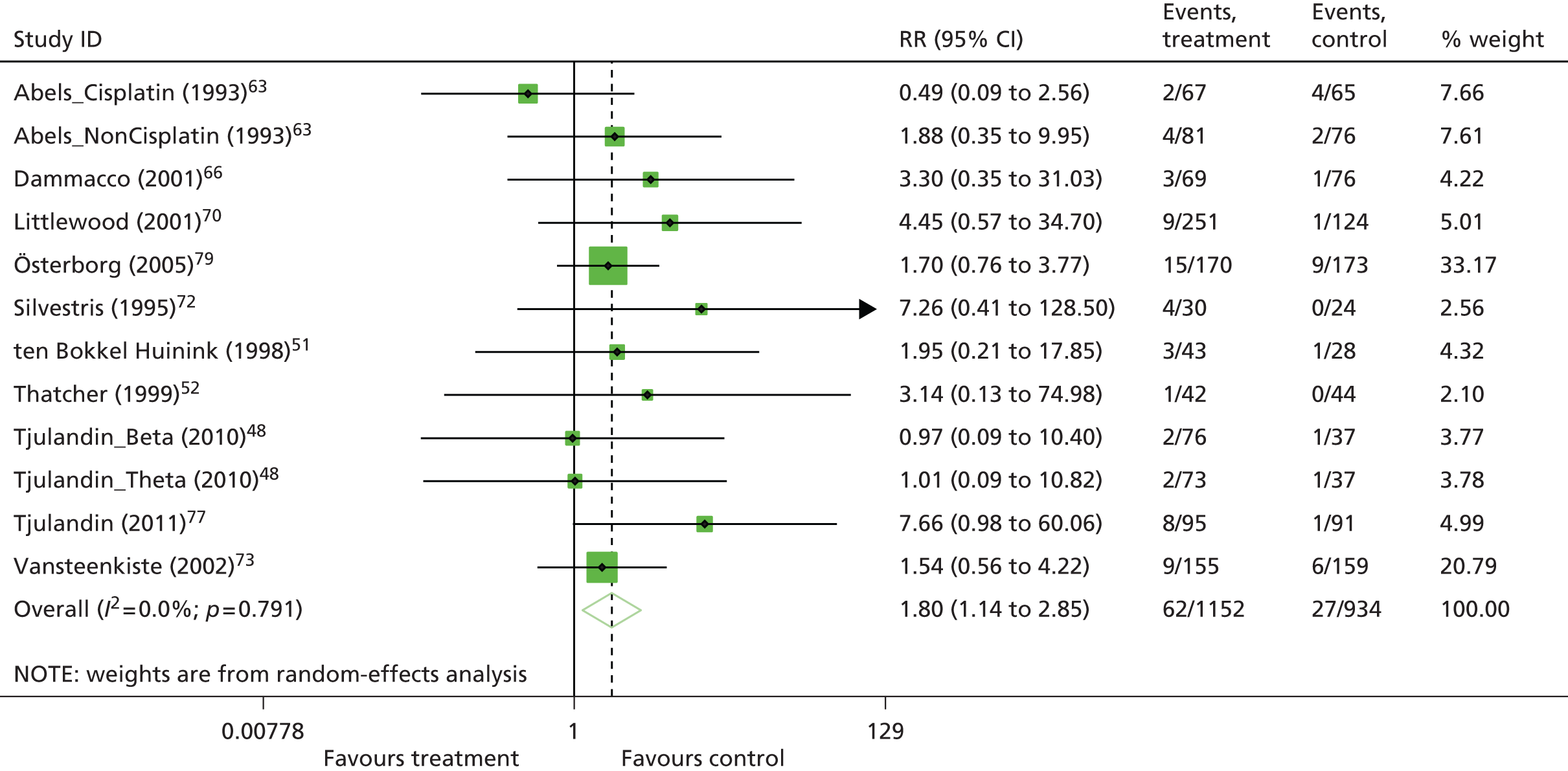

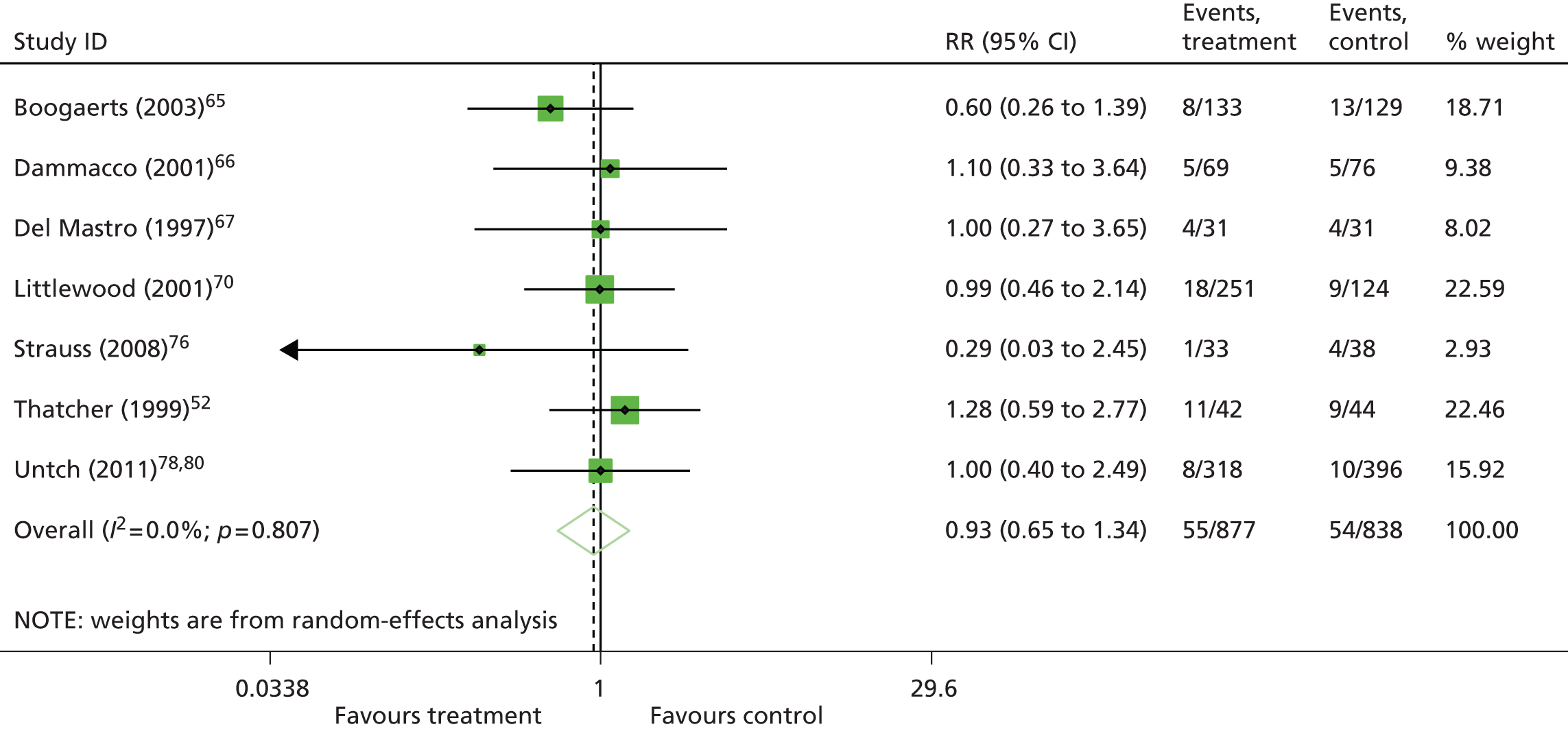

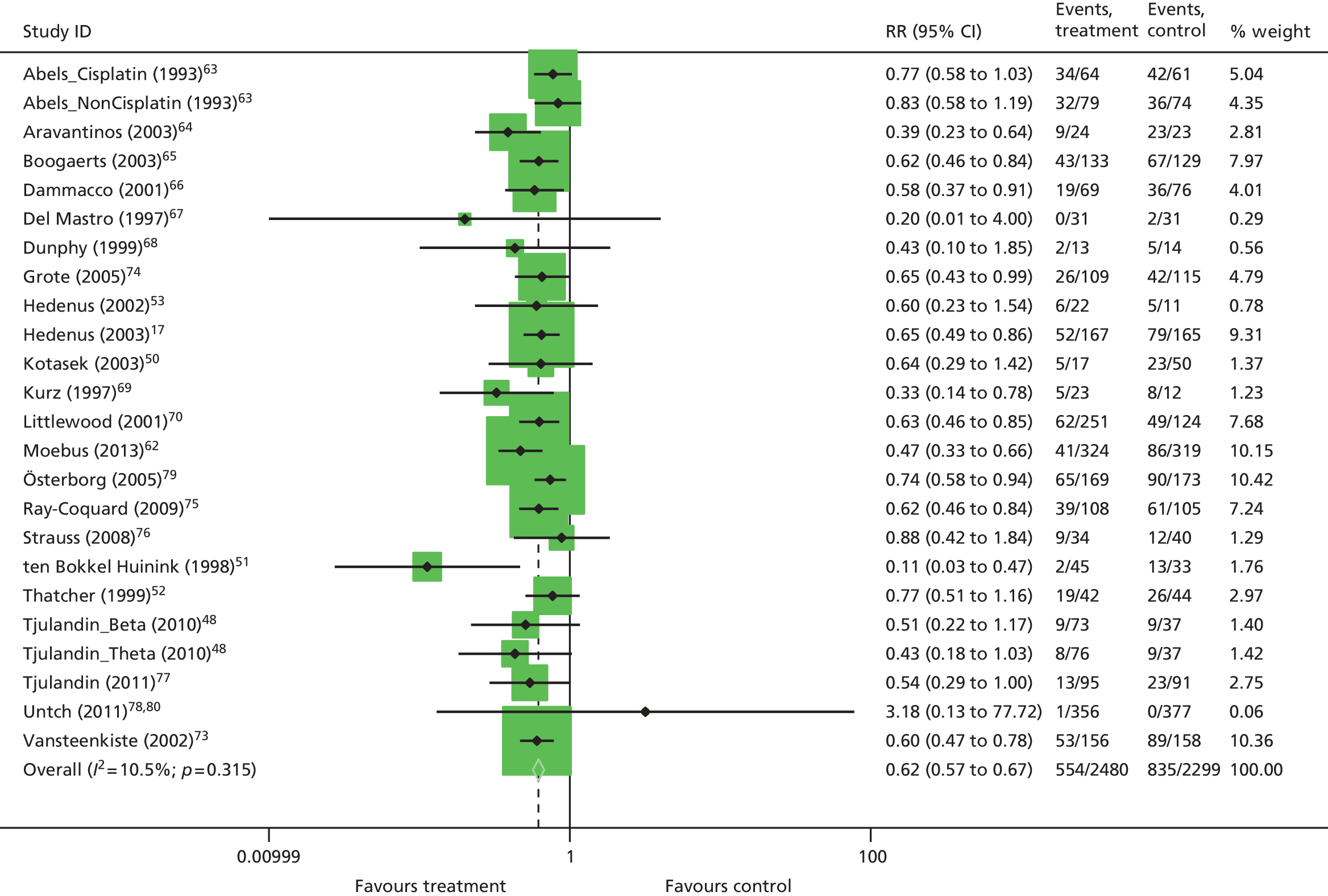

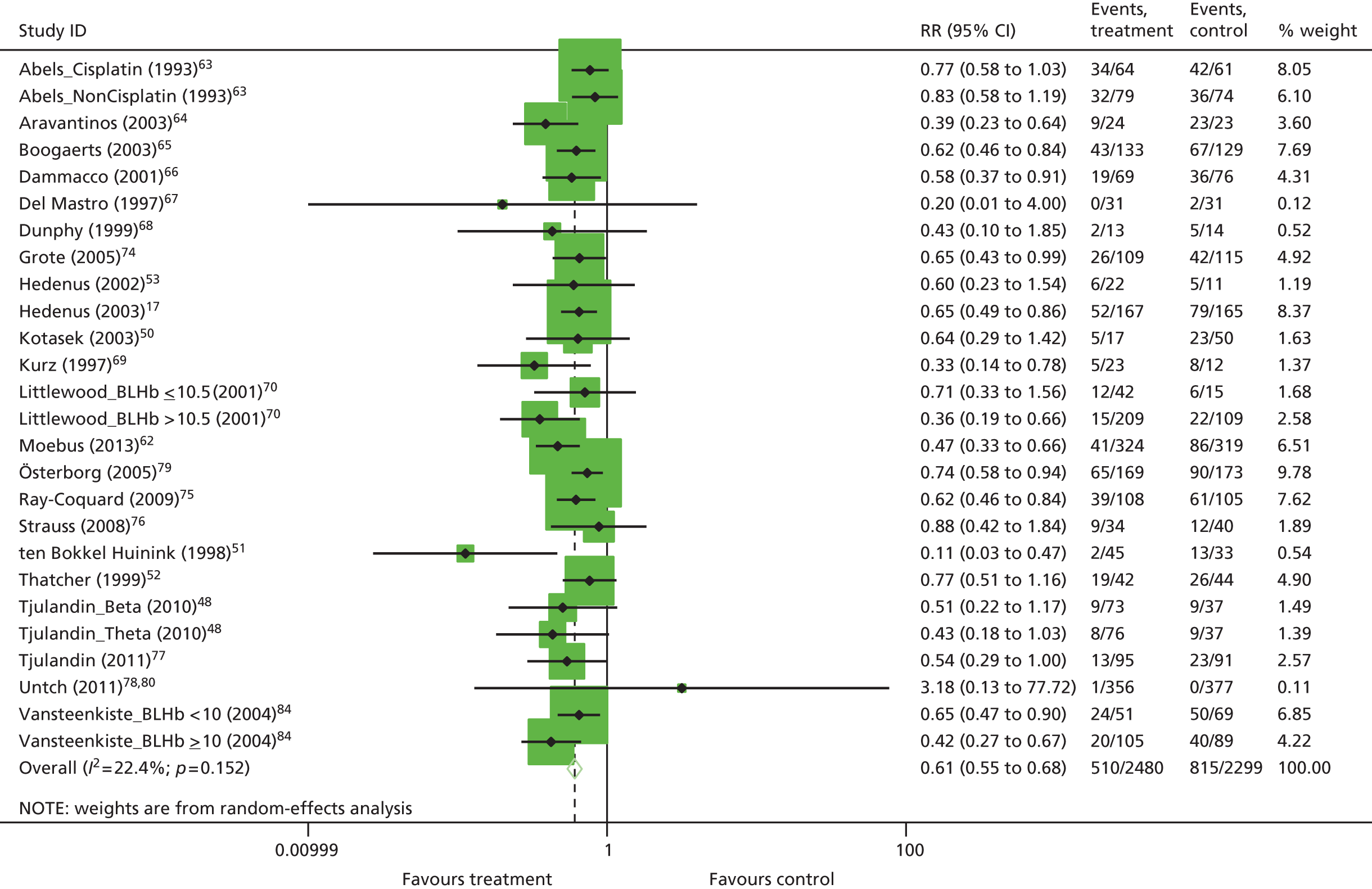

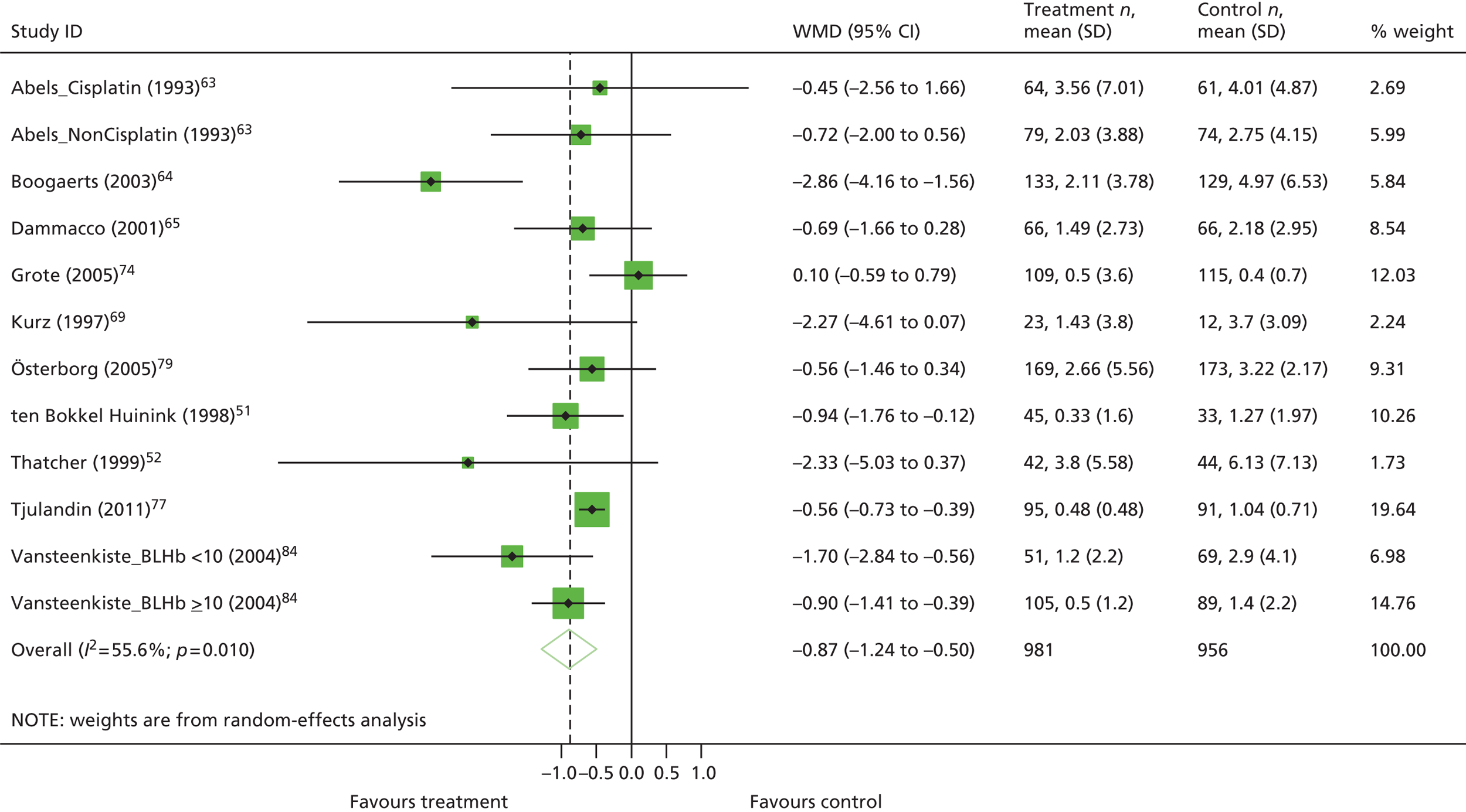

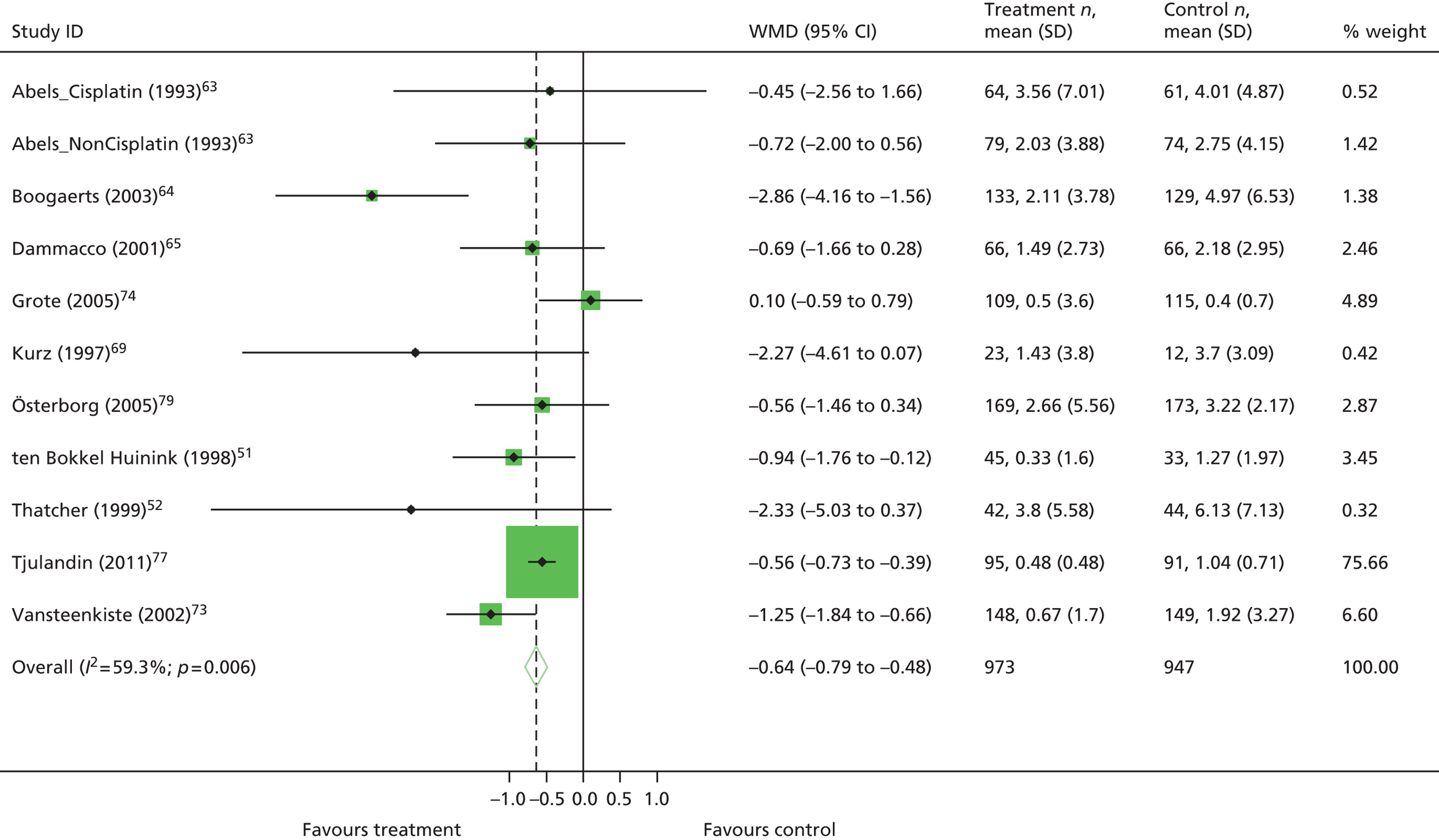

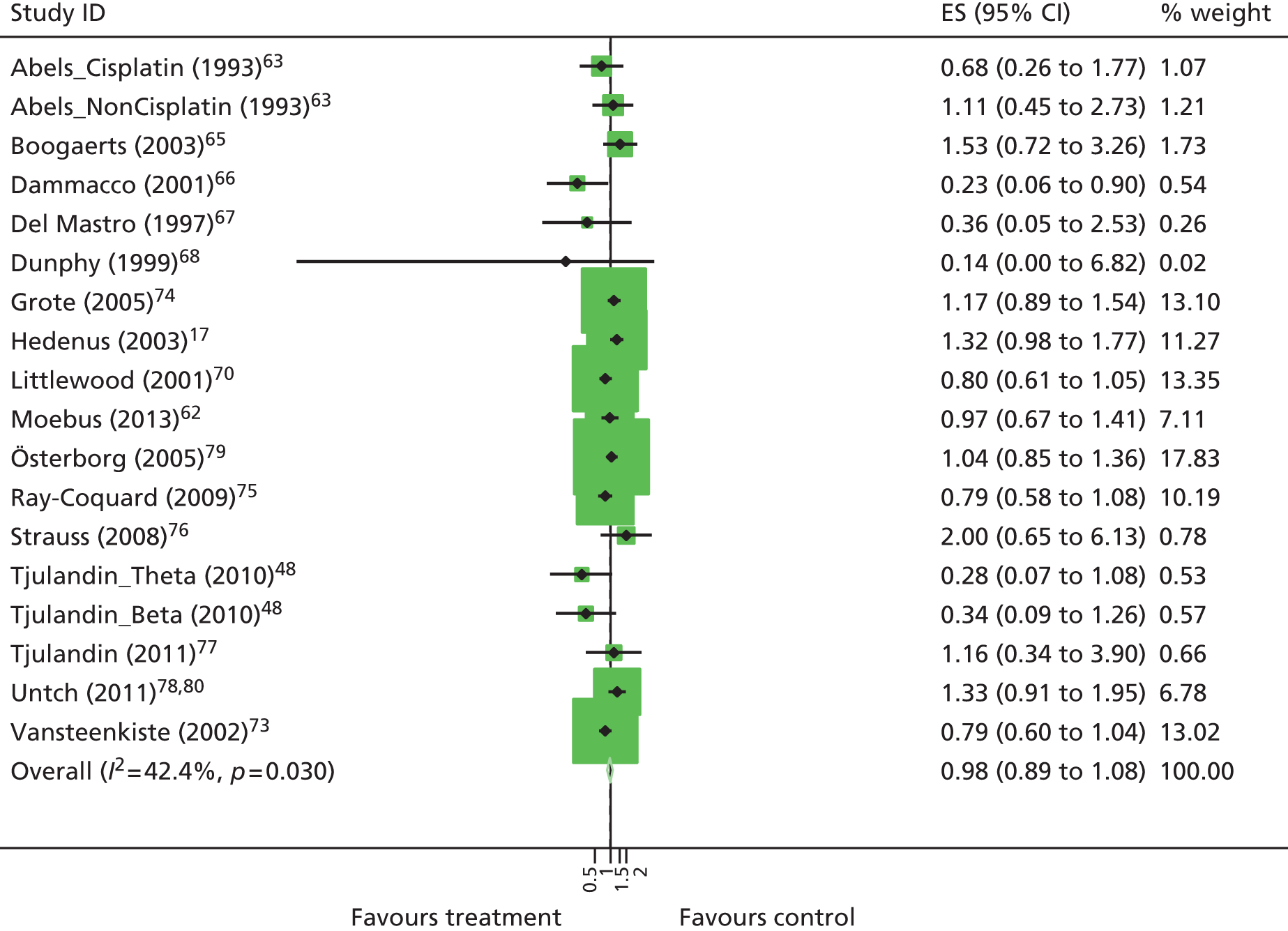

Because of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was assumed for all meta-analyses. For binary data, risk ratio (RR) was used as a measure of treatment effect and the DerSimonian–Laird method was used for pooling. For continuous data, standardised mean differences were calculated if the outcome was measured on the same scale in all trials. For HRQoL, only identical scales and subscales were combined in a given meta-analysis. For time-to-event data, that is, OS, data were extracted from the Cochrane review. 11 In the Cochrane review,11 hazard ratios (HRs) were based on IPD; when IPD were not available, HRs were calculated from published reports including secondary analyses, using methods reported in Parmar and colleagues,49 or binary mortality data. 11 Similarly, data from the Cochrane review11 were used for mean Hb change, transfusion requirement, mean units of blood transfused, complete tumour response, HRQoL and AEs if this information was not available in the published trial reports.

One study48 had two intervention arms that were separately compared with the control arm. To take account of the fact that some study-specific estimates would use the same control arm, the information was divided across the number of comparisons from the study. When pooling RRs, the number of events and the total sample size in the control arm were divided equally across the comparisons and, when pooling mean differences, the total sample size in the control arm was adjusted and divided equally across the comparisons. However, if only one experimental arm was eligible for the analysis,50–53 all participants assigned to the control arm were included.

The following prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted, if appropriate:

-

Hb level at study entry (< 10 g/dl vs. < 11 g/dl vs. < 12 g/dl vs. < 14.5 g/dl vs. not reported)

-

Hb inclusion criteria (≤ 11 g/dl vs. < 11 g/dl)

-

target Hb (≤ 12 g/dl and > 12 g/dl)

-

solid tumours compared with haematological malignancies (solid vs. haematological vs. mixed vs. not reported)

-

ovarian cancer compared with other cancers

-

type of chemotherapy treatment (platinum chemotherapy vs. non-platinum chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy plus radiotherapy vs. mixed chemotherapy vs. not reported)

-

short-lasting ESAs compared with long-lasting ESAs (erythopoietins vs. darbepoetin)

-

iron supplementation (iron supplementation given vs. no iron supplementation vs. iron handled differently in study arm vs. not reported)

-

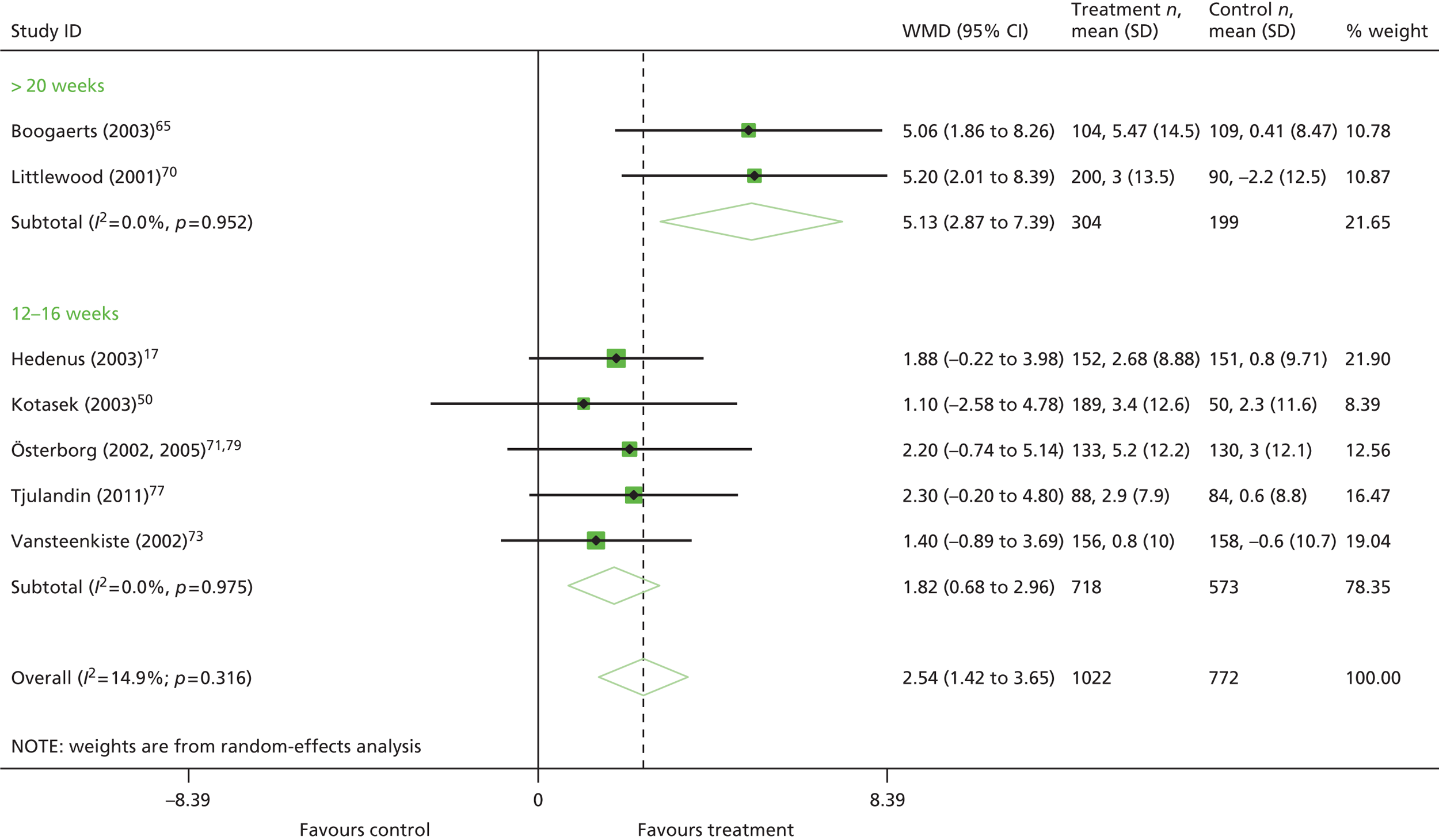

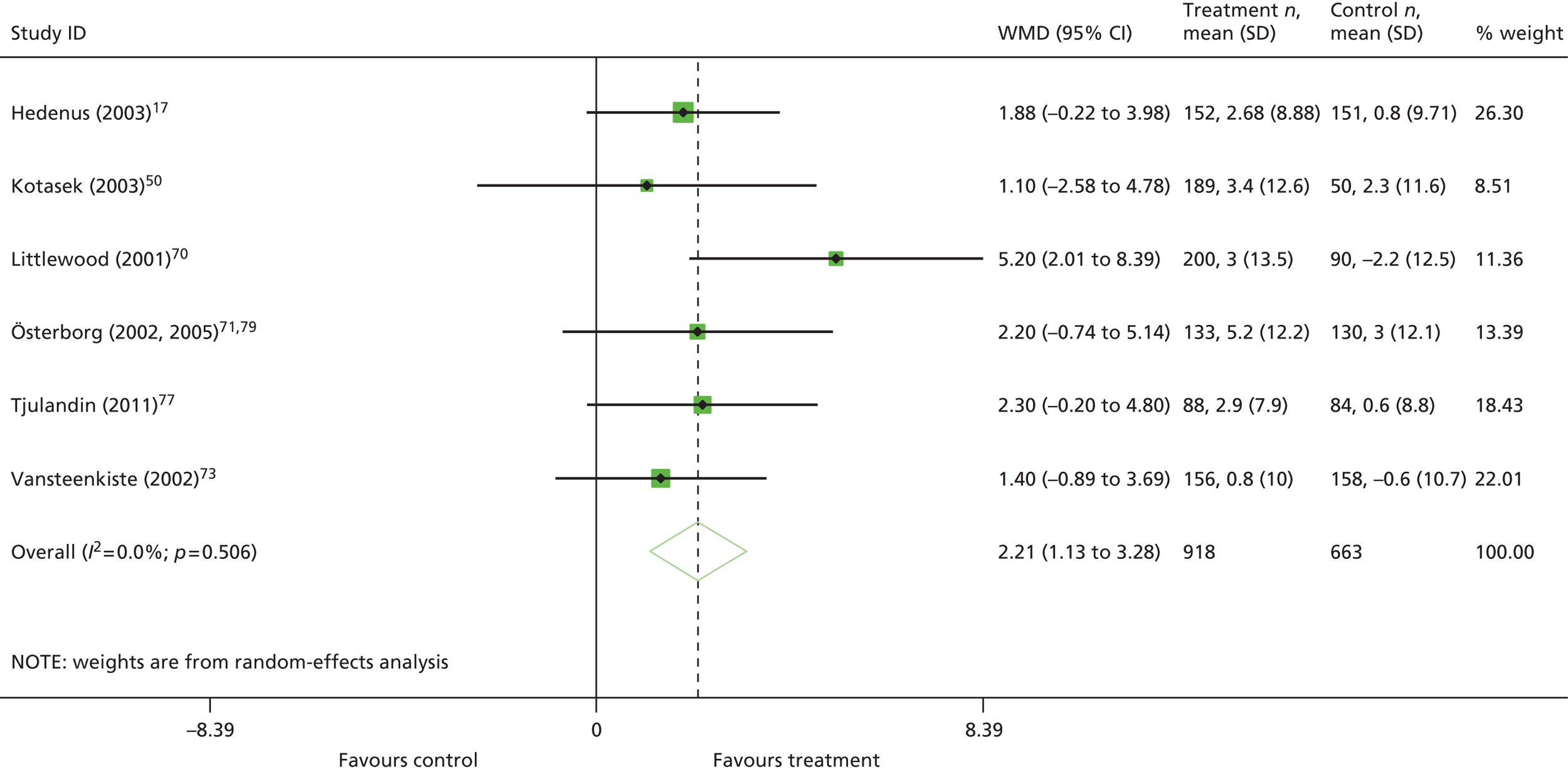

duration of ESA medication (6–9 weeks vs. 12–16 weeks vs. 17–20 weeks vs. > 20 weeks)

-

study design (placebo vs. standard care).

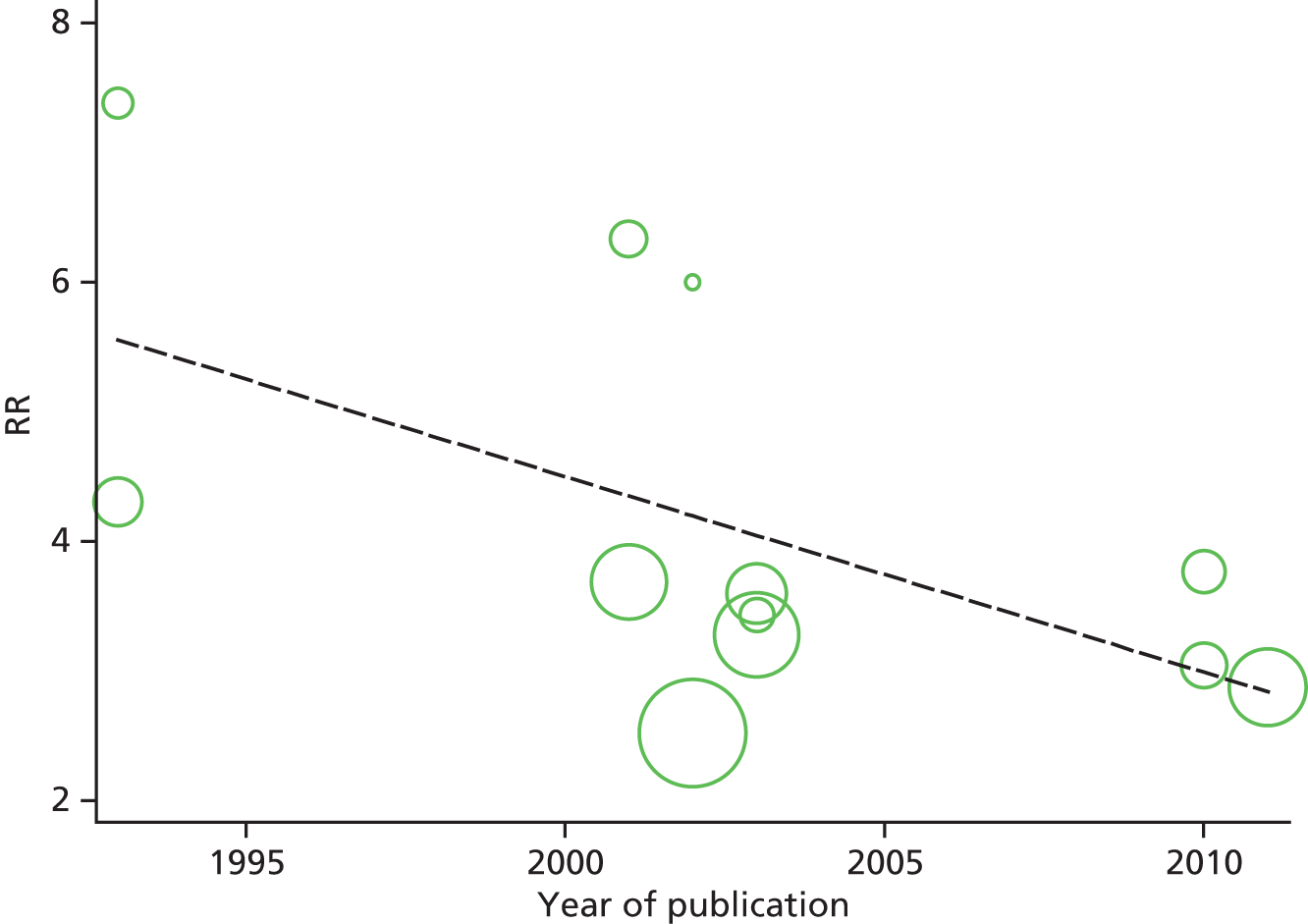

In addition, based on subgroup analyses, meta-regression models were conducted including random effects and a subgroup as a covariate to assess the effects of subgroups on the outcomes. These analyses were conducted if there was a sufficient number of studies in each subgroup. The DerSimonian–Laird method was used to estimate between-study variance in meta-regression. All covariates showing a significant effect (p < 0.05) in a univariate analysis were further considered in a model selection. However, these analyses should be interpreted with caution as they can be exploratory only and should be considered as hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing analyses. 54,55

We stated in the protocol that we would consider the use of iron supplementation plus ESAs; people with any type of cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy; people with head and neck malignancies; women with ovarian cancer; women with ovarian cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy; and people unable to receive blood transfusions.

All analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Sensitivity analysis

To allow comparison with the Cochrane review11 and with the previous HTA review,2 fixed-effects meta-analyses for the main analysis were also conducted.

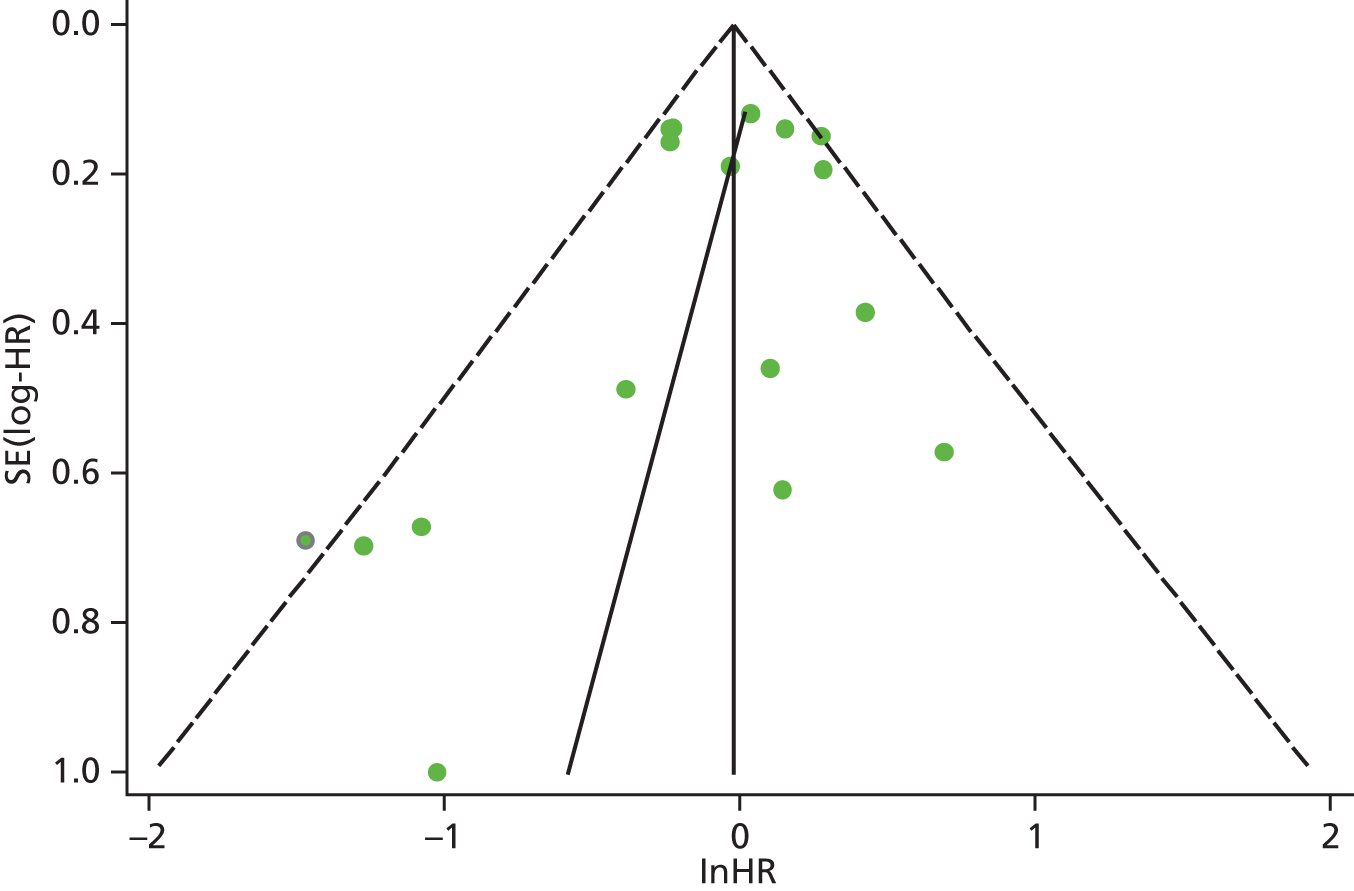

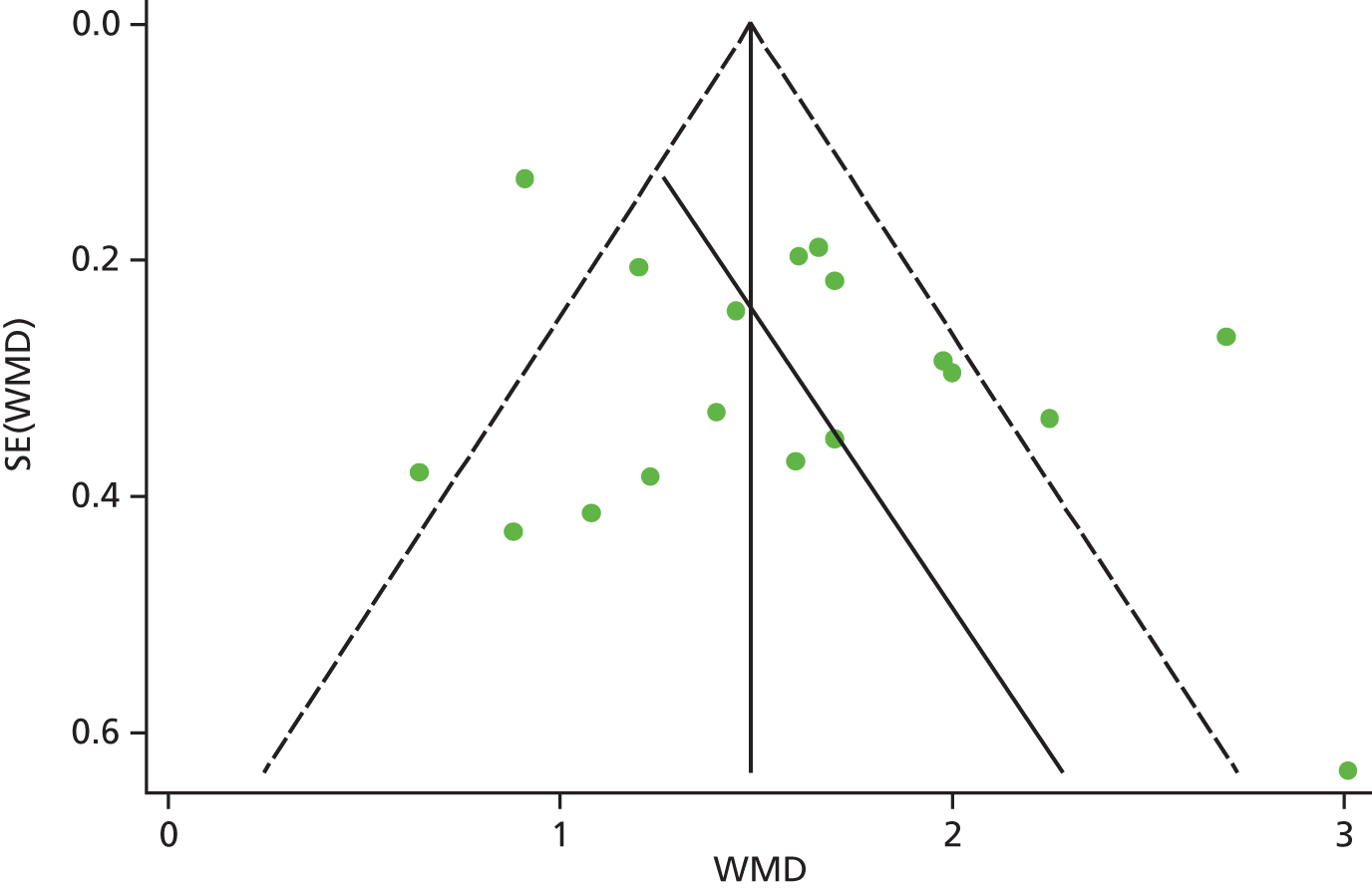

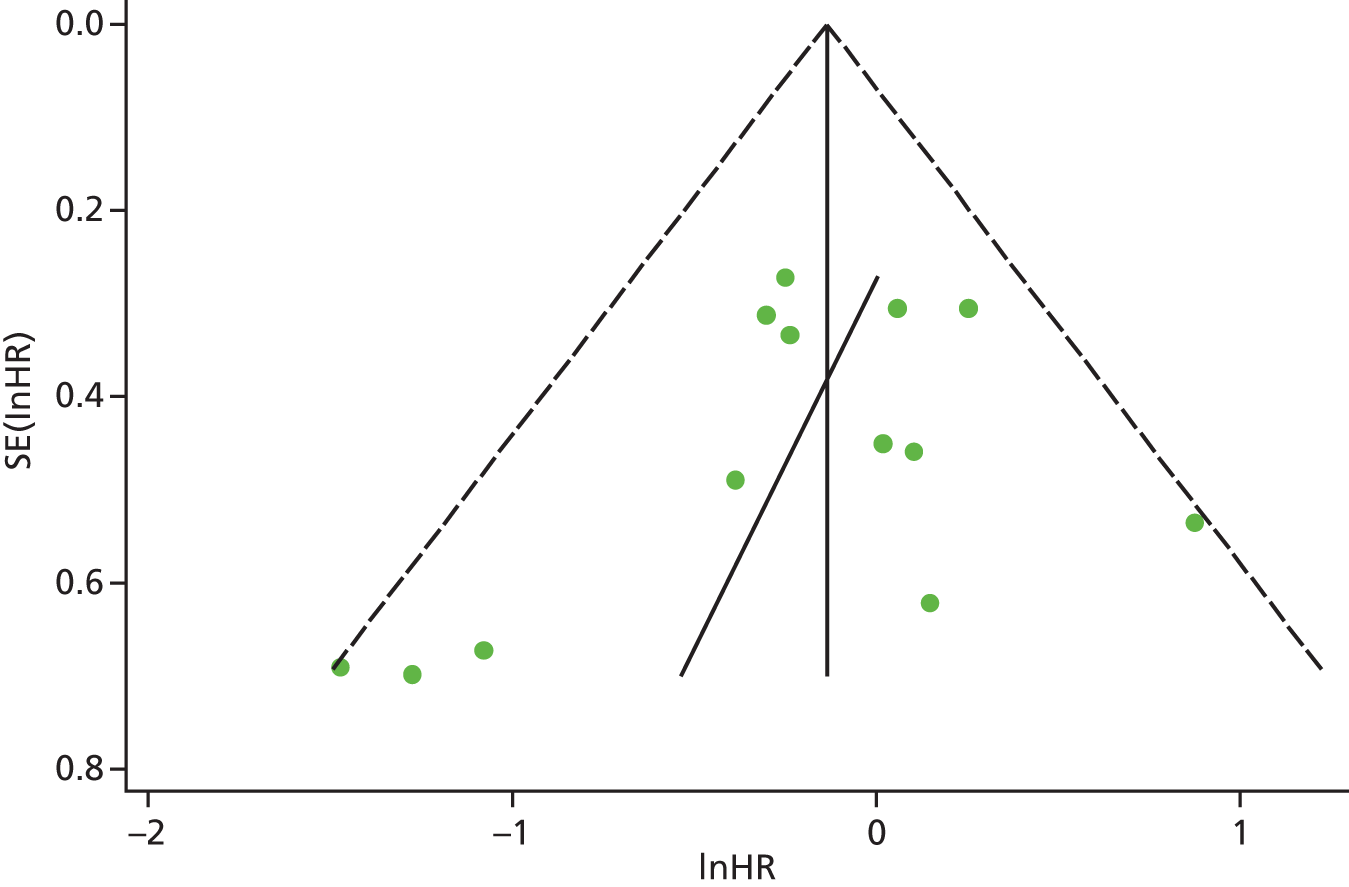

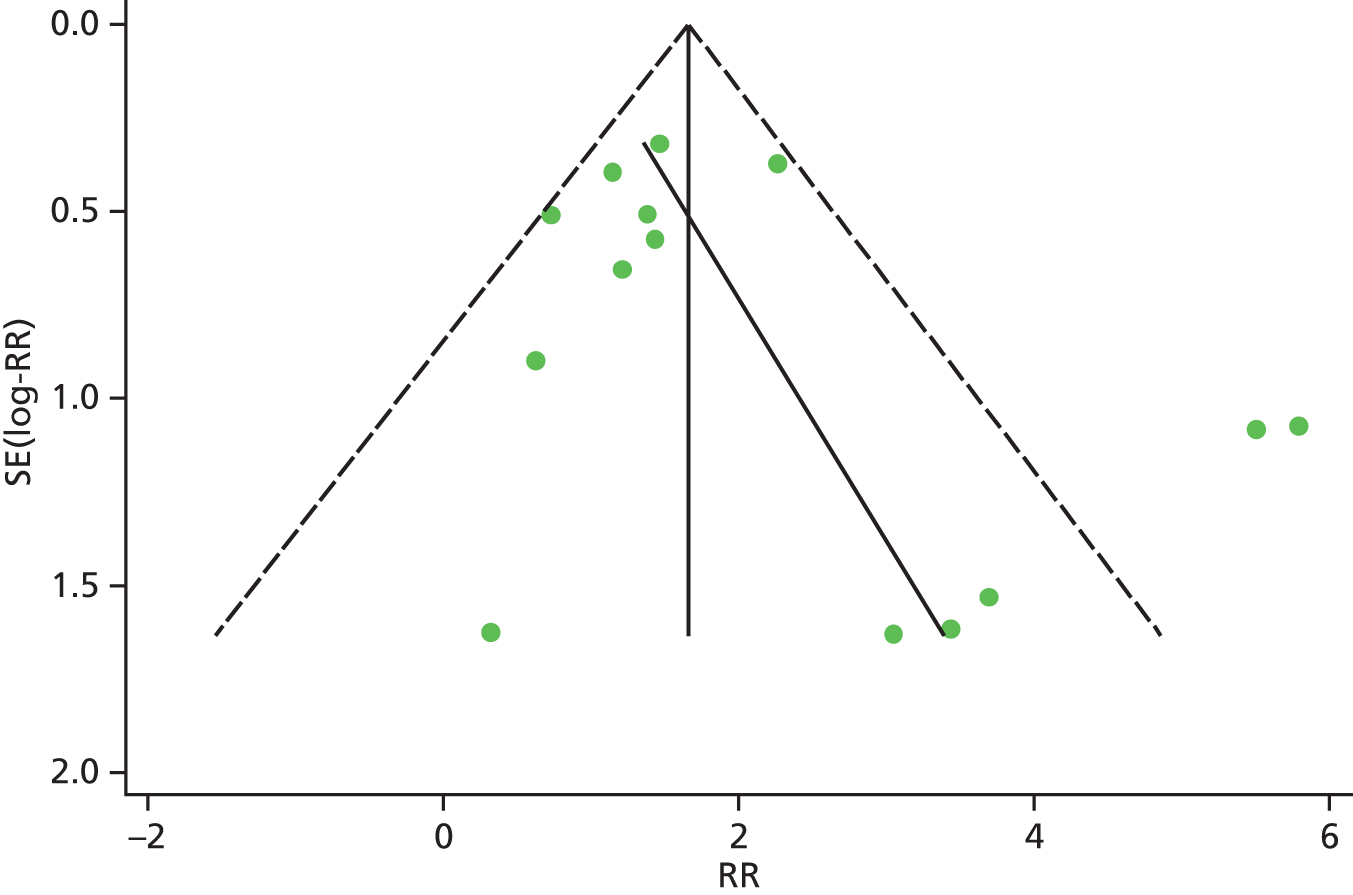

Assessment of bias

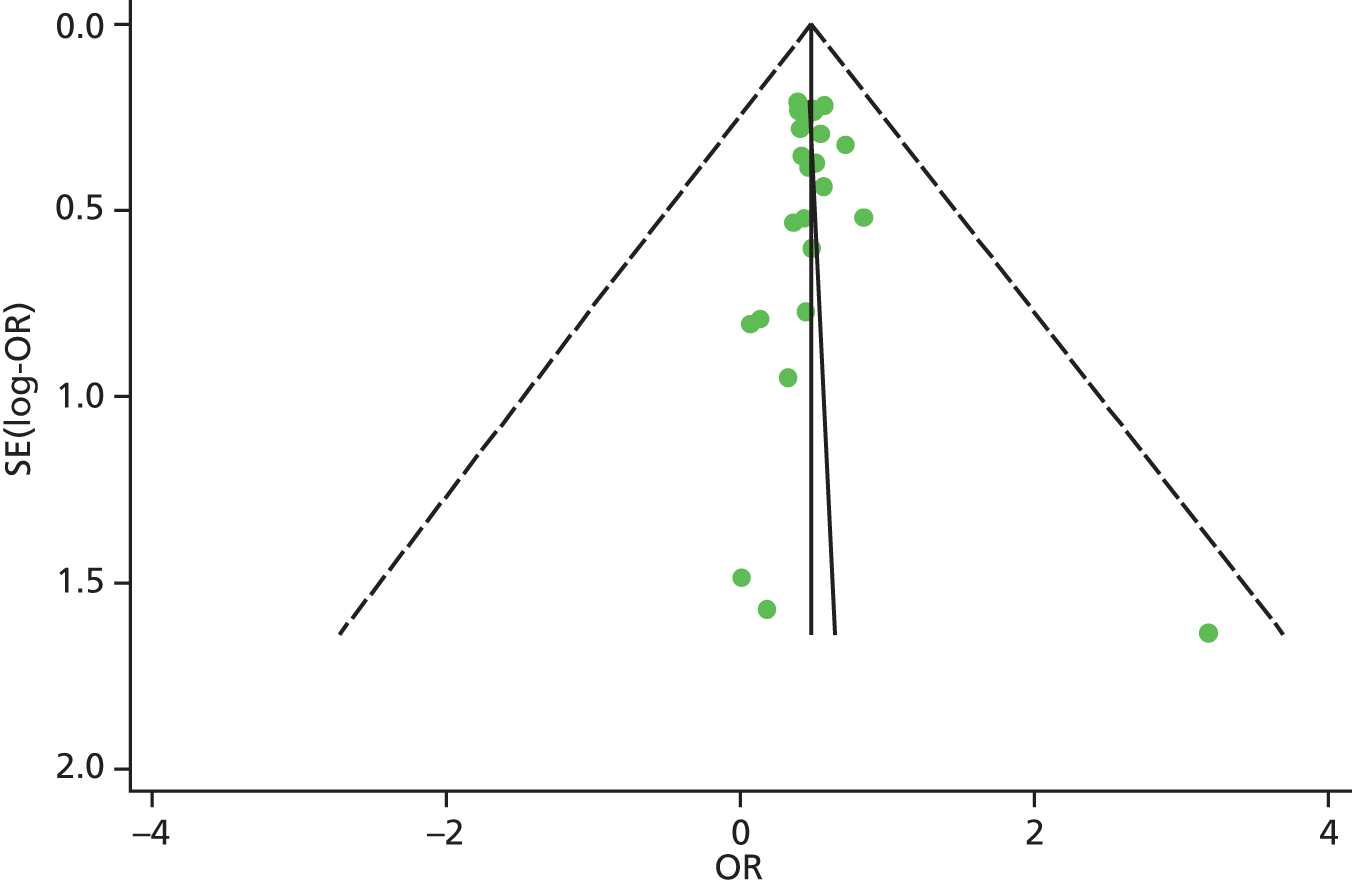

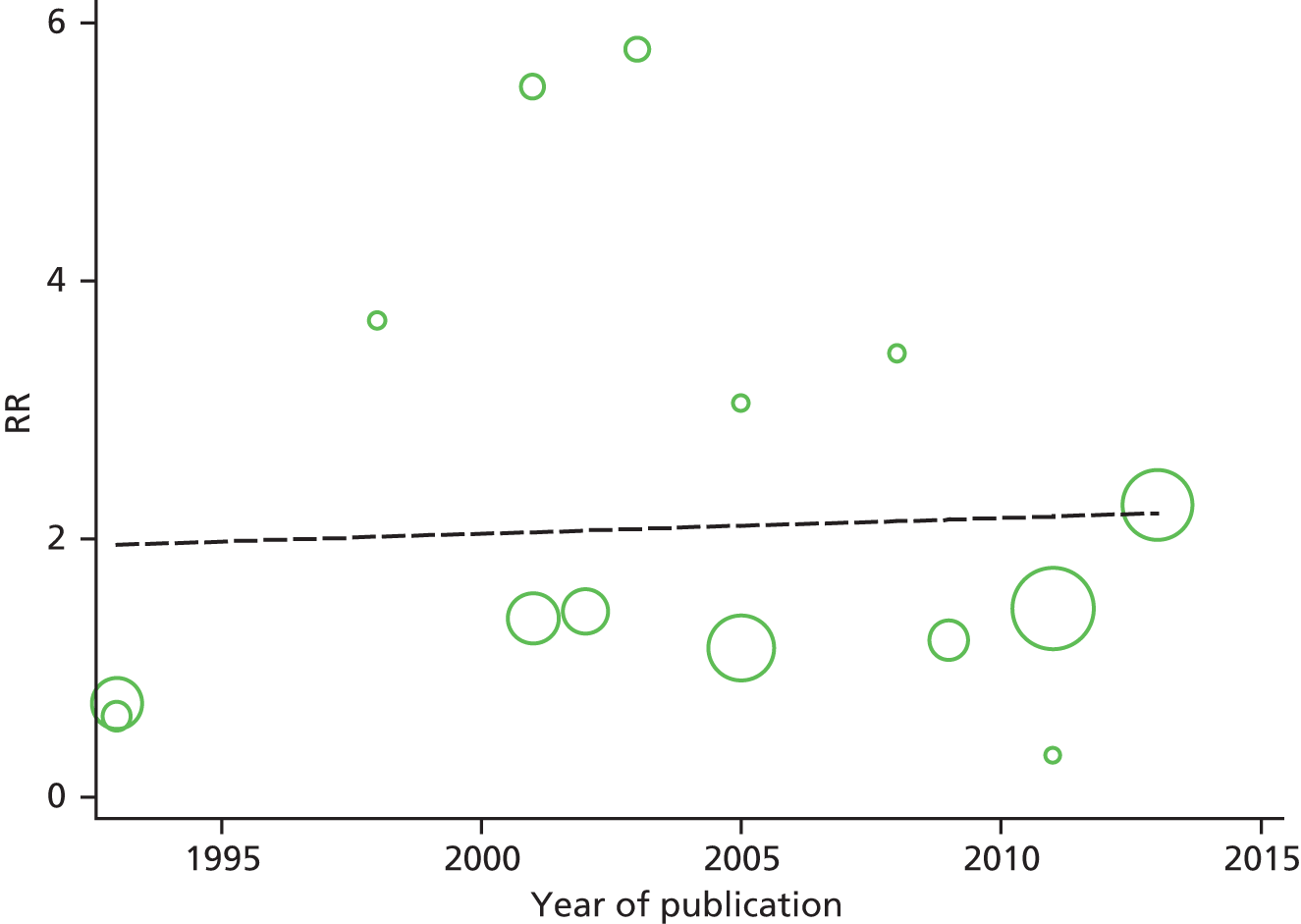

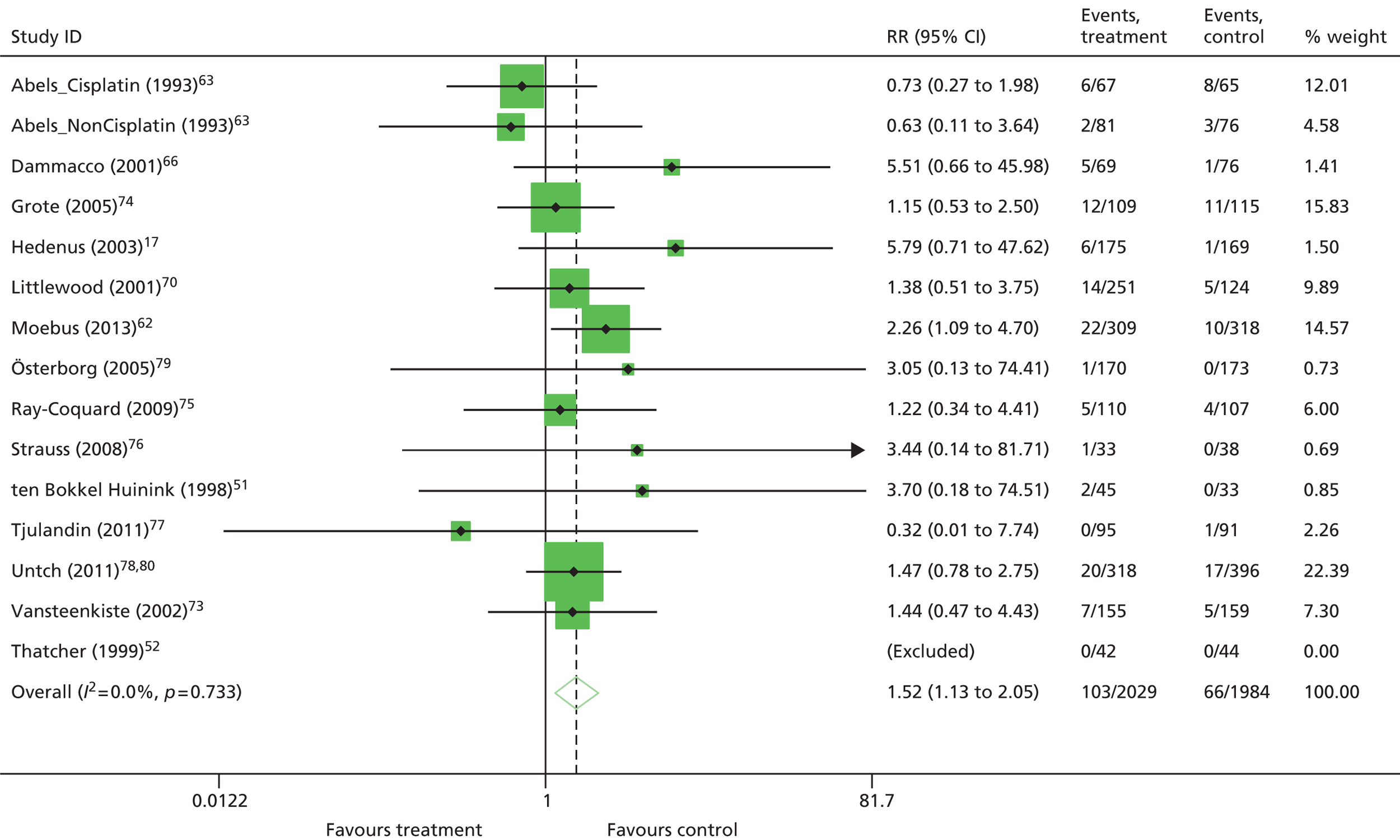

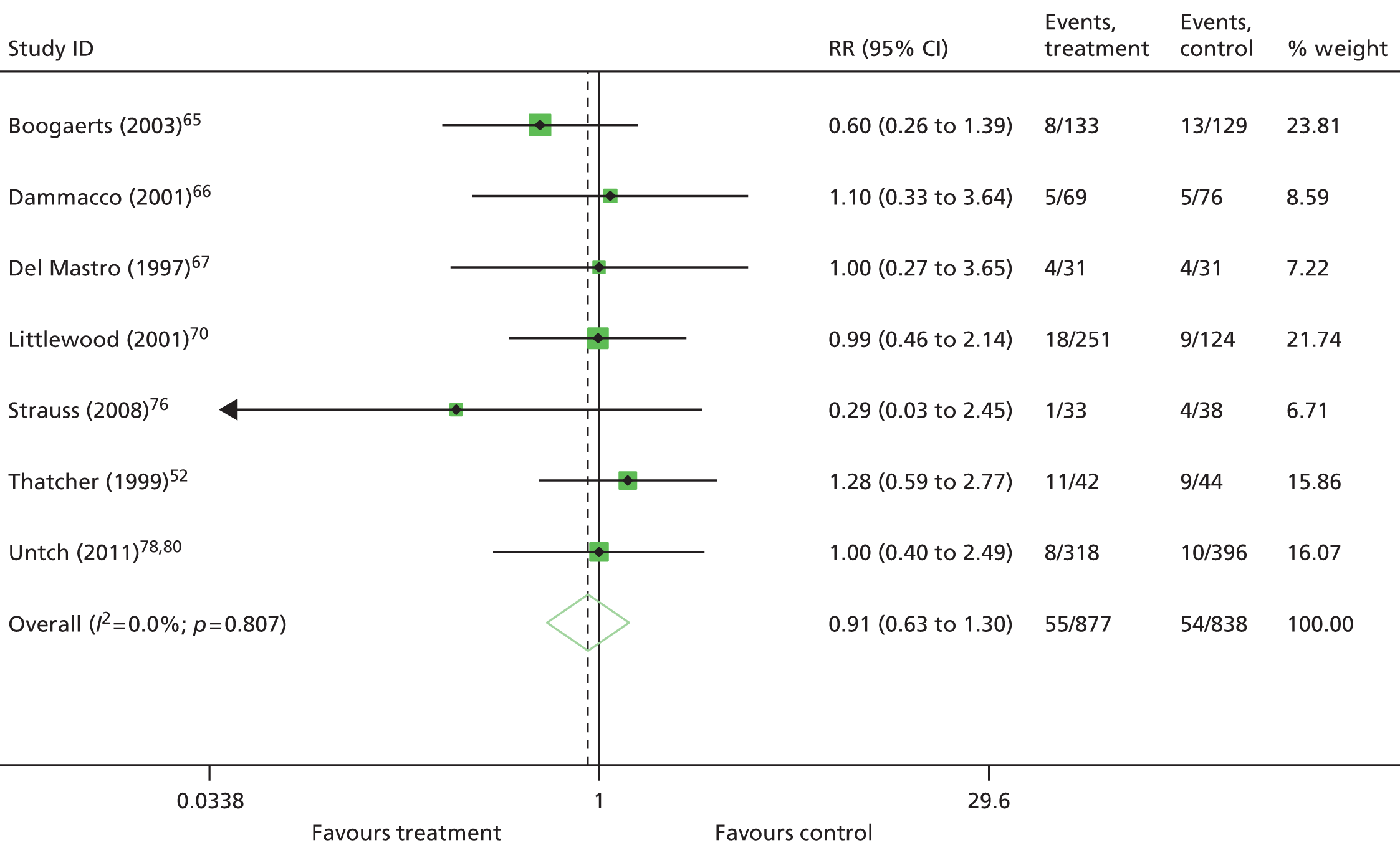

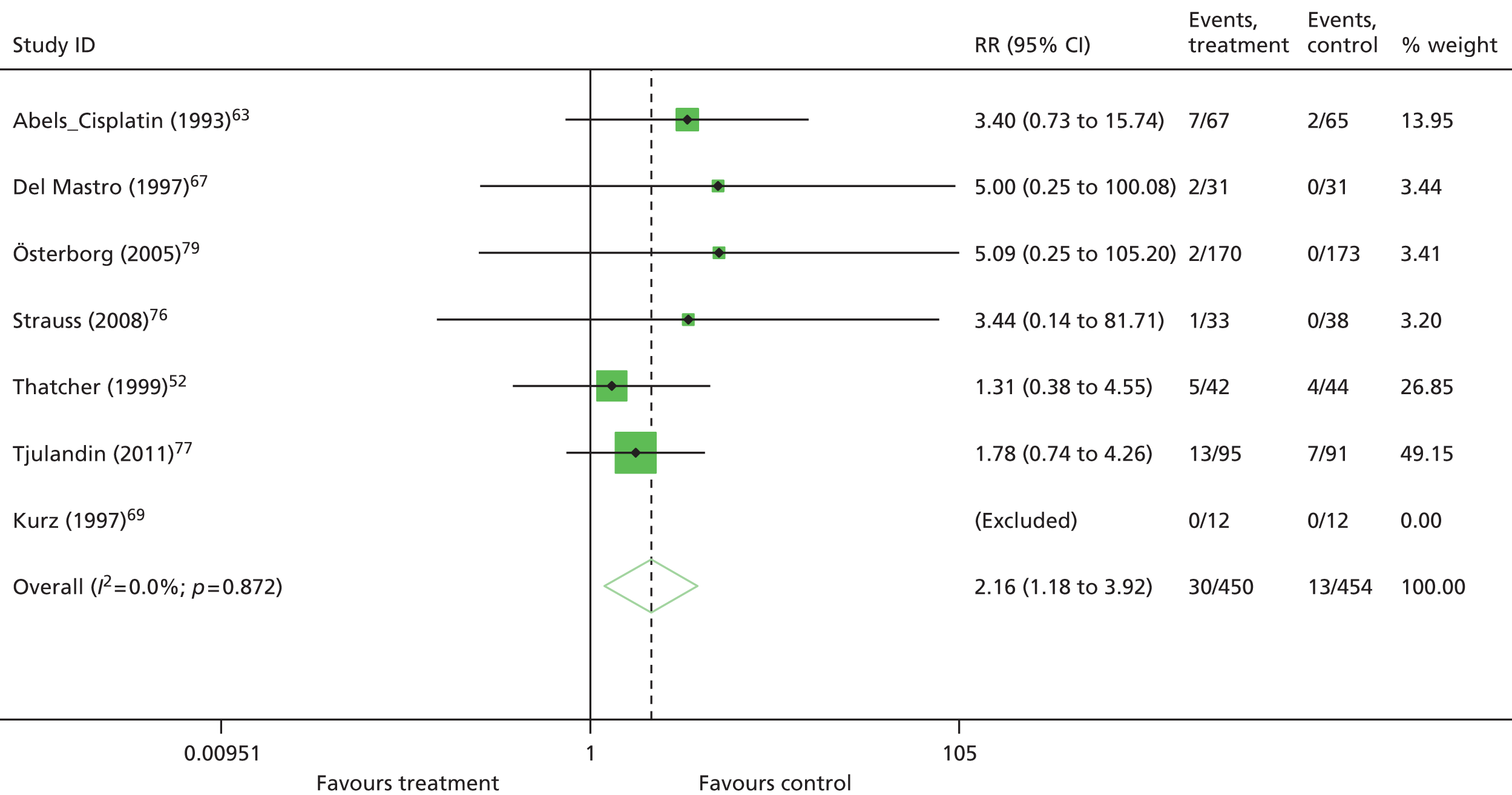

Identified research evidence was interpreted according to the assessment of methodological strengths and weaknesses and the possibility of potential biases. Publication bias for the main outcomes was assessed using funnel plots. The Egger test56 was used for continuous outcomes [mean difference, standard error (SE)] and the Harbord test57 was used for binary outcomes [odds ratio (OR), log SE]. However, it should be noted that these tests typically have low power to detect funnel plot asymmetry and so the possibility of publication bias existing in the meta-analysis cannot be excluded even if there is no statistically significant evidence of publication bias. In addition, meta-regression models including random effects and using publication year as a covariate to assess the effect of publication year on the considered outcome were conducted.

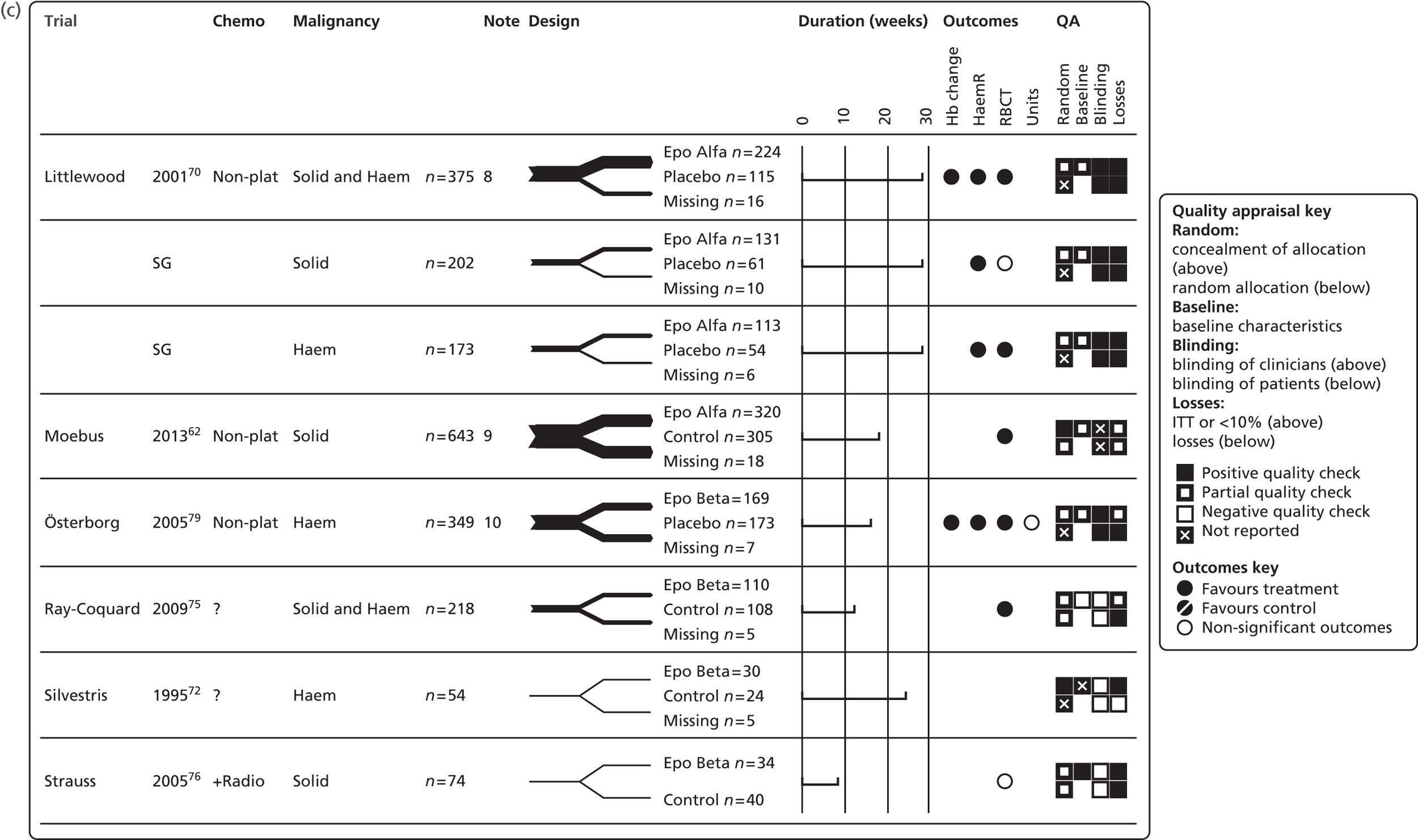

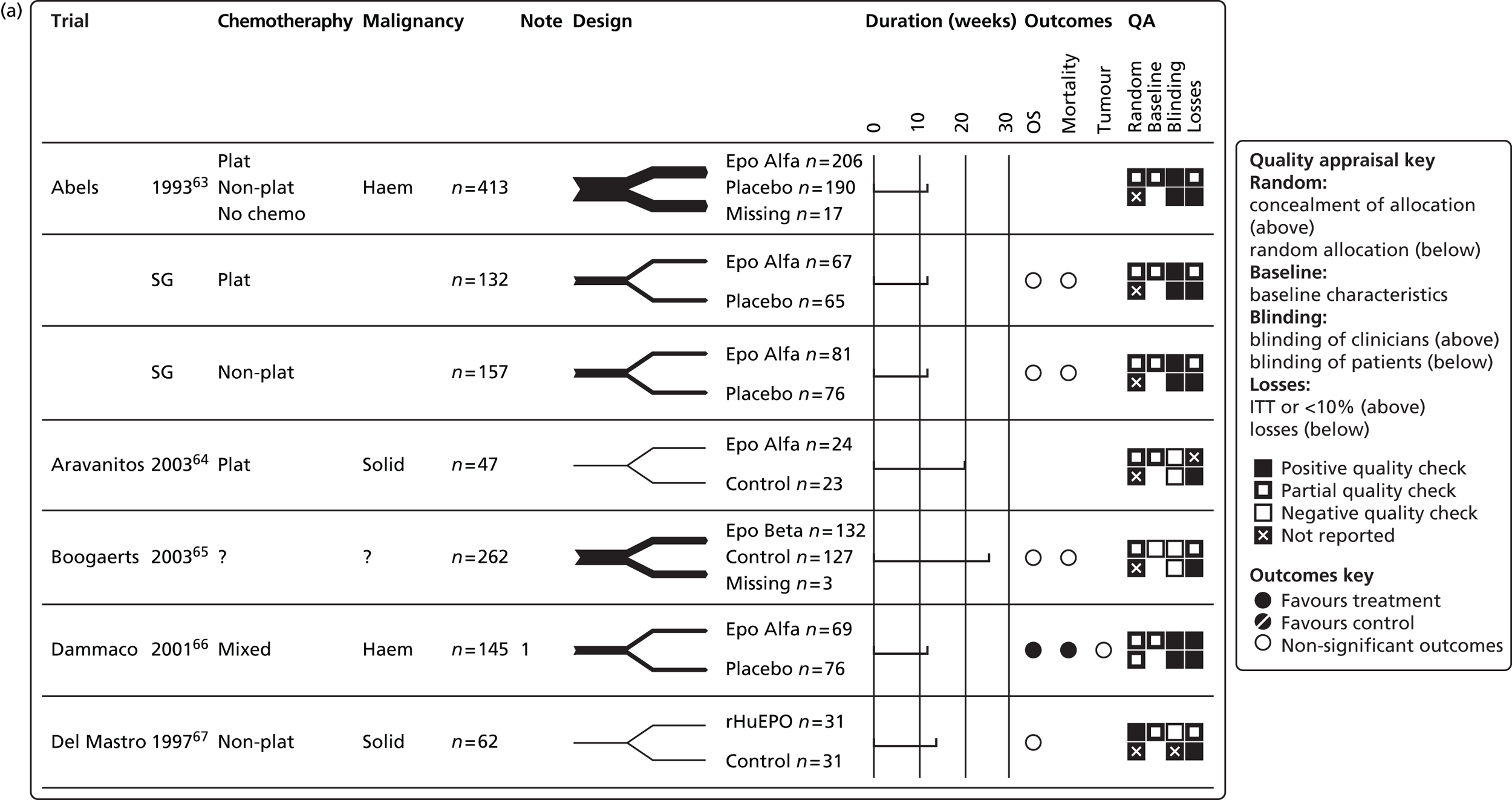

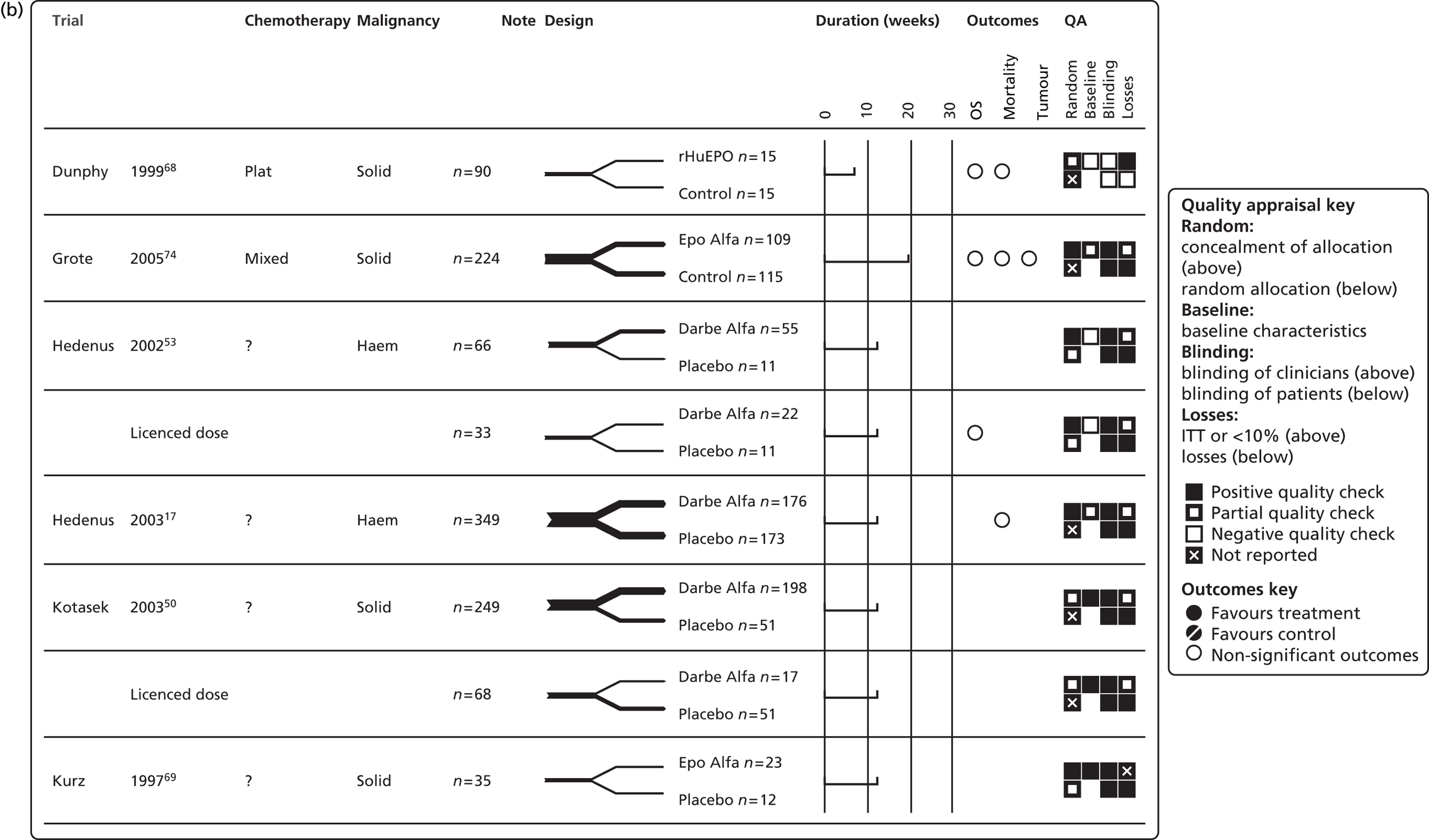

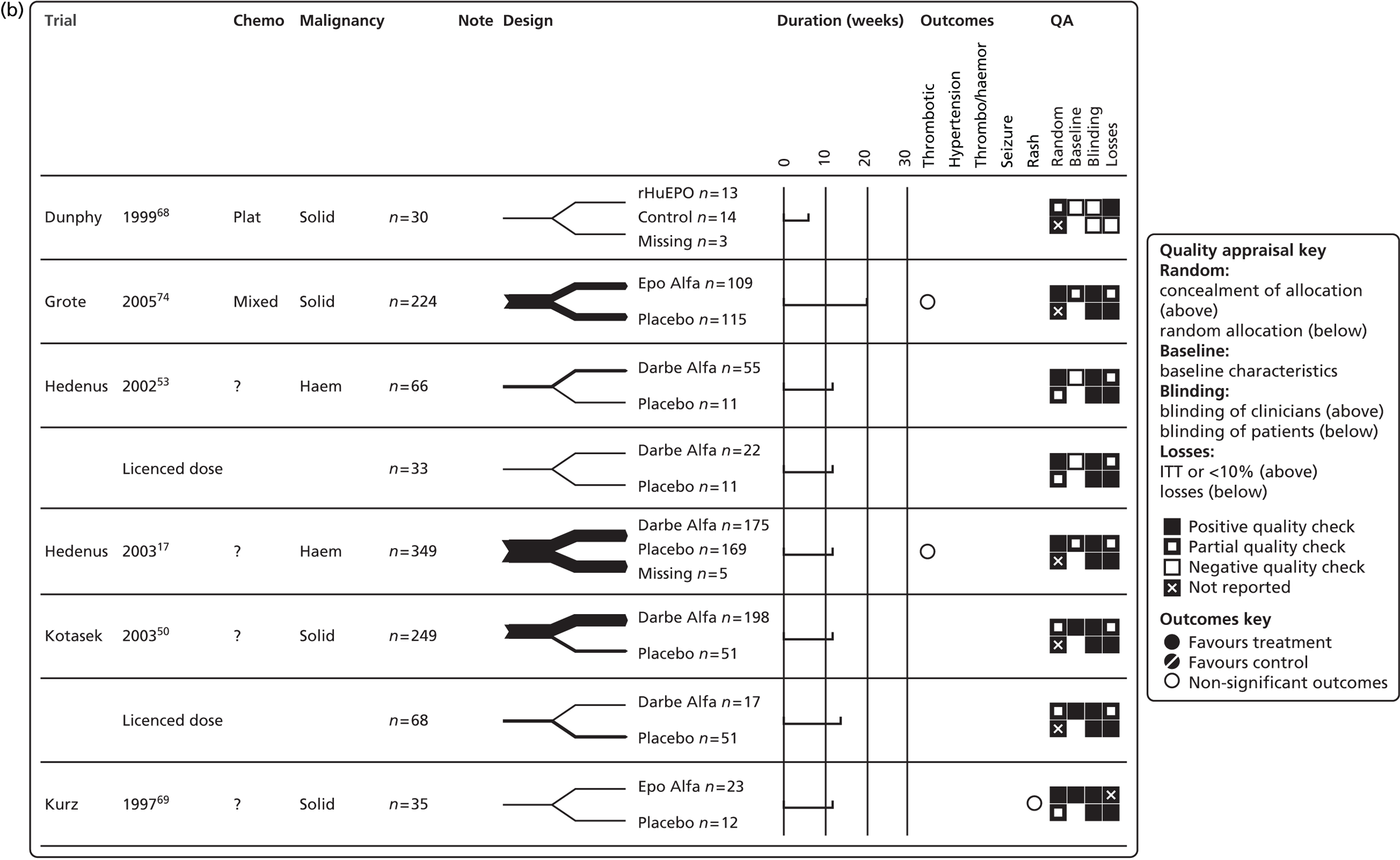

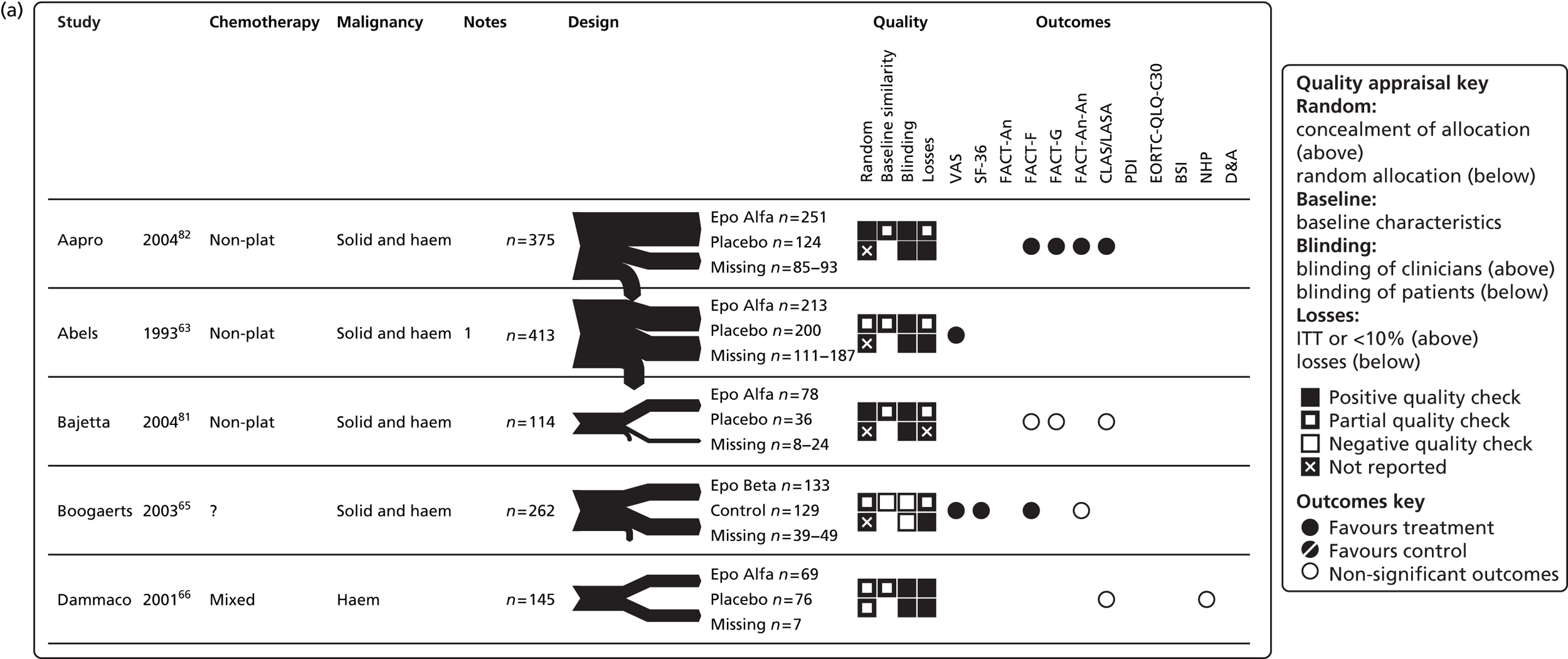

Graphical representation of summary trial information

We present a summary of information relating to each trial at the end of each comparison section using Graphical Overview for Evidence Reviews (Gofer) software (developed by Dr Will Stahl-Timmins at the University of Exeter Medical School in association with PenTAG and the European Centre for Environment and Human Health). These figures graphically represent the study design, study quality and results in a format that allows quick comparison between trials.

Note

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Results

Studies identified

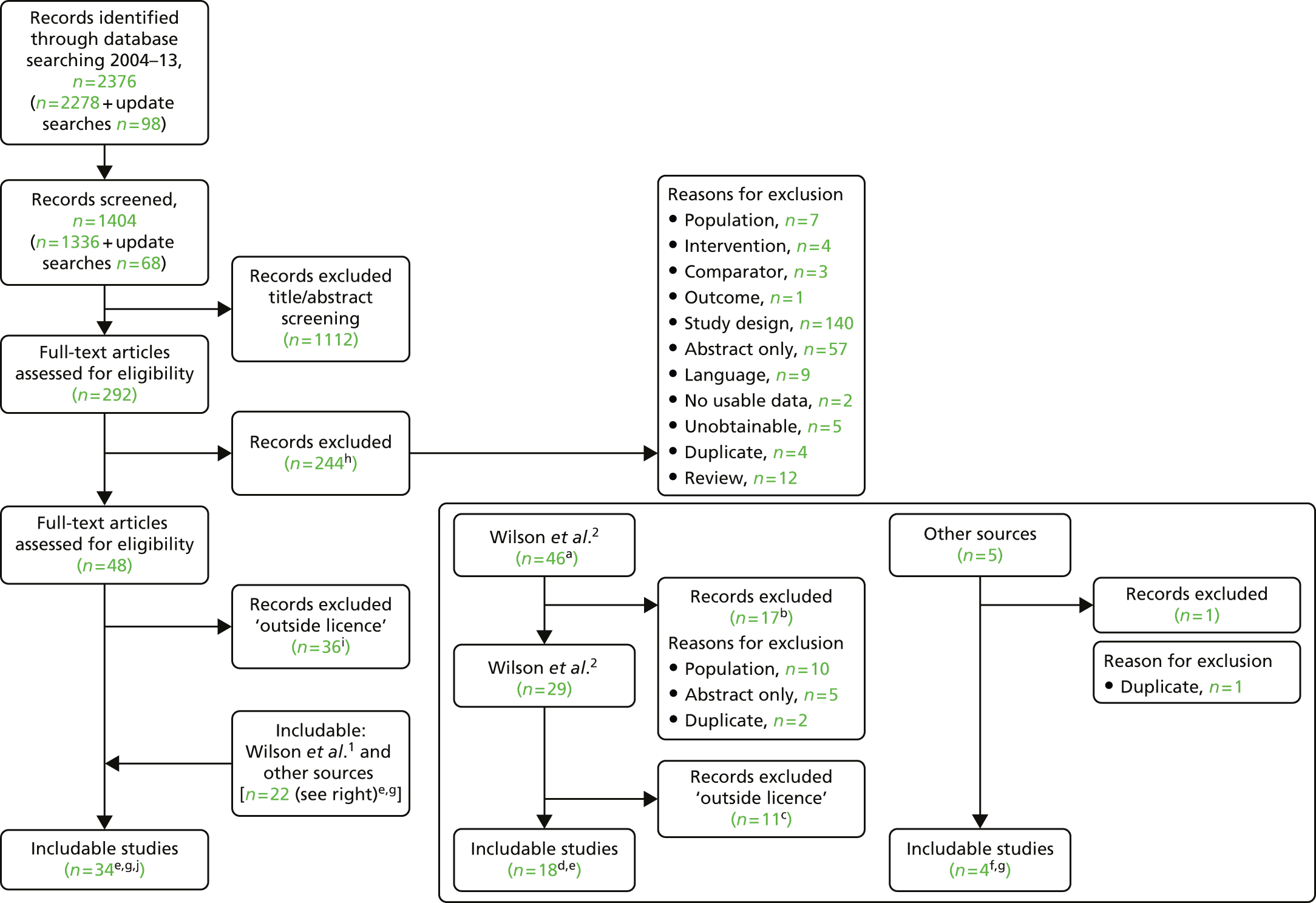

We screened the titles and abstracts of 1404 unique references identified by the PenTAG searches and additional sources and retrieved 292 papers for detailed consideration. Of these, 244 were excluded, five because they were unobtainable and 239 for other reasons (a list of these papers with reasons for their exclusion can be found in Appendix 4). Forty-eight studies met the prespecified criteria set out in the protocol and were considered eligible for inclusion. In assessing titles and abstracts, agreement between the two reviewers was good (κ = 0.693, 95% CI 0.648 to 0.738). At the full-text stage, agreement was substantial (κ = 0.792, 95% CI 0.705 to 0.879). At both stages, initial disagreements were easily resolved by consensus.

Twenty-nine studies from the previous HTA review2 were also considered eligible for inclusion in the update review. We also searched the citations of all of the includable studies and systematic reviews (including the 2012 Cochrane review;11 see Appendix 5). This process revealed an additional five primary studies. 58–62

In restricting eligibility to ESA treatments evaluated in accordance with their European marketing authorisation with respect to starting dose, 47 studies were excluded (a list of these studies together with the study characteristics can be found in Appendix 6). In total, 23 primary studies17,48,50–53,62–78 reported in 34 publications17,48,50–53,58–60,62–86 were judged to meet the inclusion criterion for the review (Table 10); study characteristics are summarised in Appendix 7. Primary studies are linked to multiple secondary publications, as shown in Appendix 8.

| Author, year | n | Agent | Control | Malignancy | Treatment | Outcomes | Multiple publications identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included studies from Wilson and colleagues2 meeting the inclusion criteria for the PenTAG review | |||||||

| Abels 199363 | 413a | Epoetin alfa | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: mixed | HaemR, Hb, HCT, RBCT, HRQoL,c AEc | Abels 1996,59 Case 1993,86 Henry 1994,85 Henry 199558 |

| Aravantinos 200364 | 47 | Epoetin alfa | Standard | Solid | Chemotherapy: platinum based | Hb, HCT, RBCT | NA |

| dBoogaerts 200365 | 262 | Epoetin beta | Standard | Solid and haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: NR | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL | NA |

| Dammacco 200166 | 145 | Epoetin alfa | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: mixede | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| Del Mastro 199767 | 62 | rHuEPOf | Standard | Solid (breast) | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| Dunphy 199968 | 30 | rHuEPOf | Standard | Solid (head and neck, lung) | Chemotherapy: mixed | Hb, RBCT | NA |

| Hedenus 200253 | 33g | Darbepoetin alfa | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: NR | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, AEs | NA |

| Hedenus 200317 | 349 | Darbepoetin alfa | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: NR | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, AEs, HRQoL | Littlewood 200683 |

| Kotasek 200350 | 249 | Darbepoetin alfa | Placebo | Solid | Chemotherapy: NR | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL | NA |

| Kurz 199769 | 35 | Epoetin alfa | Placebo | Solid (cervix, ovary, uterus) | Chemotherapy: mixed | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| Littlewood 200170 | 375 | Epoetin alfa | Placebo | Mixed | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | Aapro 2004,82 Bajetta 2004,81 Patrick 200360 |

| Österborg 200271 | 349 | Epoetin beta | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | Österborg 200579 |

| Silvestris 199572 | 54 | Epoetin alfa | Standard | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: NR | HaemR, Hb, AEs | NA |

| ten Bokkel Huinink 199851 | 122 | Epoetin beta | Standard | Solid (ovary) | Chemotherapy: platinum based | Hb, RBCT, AEs | NA |

| Thatcher 199952 | 130 | Epoetin alfa | Standard | Solid (SCLC) | Chemotherapy: mixed | Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| Vansteenkiste 200273 | 314 | Darbepoetin alfa | Placebo | Solid (lung) | Chemotherapy: platinum based | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AE, disease progression, survival | Vansteenkiste 200484 |

| PenTAG review update 2004 to July 2007 | |||||||

| Grote 200574 | 224 | Epoetin alfa | Placebo | Solid (SCLC) | Chemotherapy: mixed | Hb, RBCT, TR, survival, AEs | NA |

| Moebus 201362 | 643 | Epoetin alfa | Standard | Solid (breast) | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | Hb, RBCT, HRQoL,f survival, AEs | NA |

| Ray-Coquard 200975 | 218 | Epoetin alfa | Standard | Mixed | Chemotherapy: NR | RBCT, OS, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| Österborg 200579 | 349 | Epoetin beta | Placebo | Haematologicalb | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | HaemR, Hb, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | Österborg 200271 |

| Strauss 200876 | 74 | Epoetin beta | Standard | Solid (cervix) | Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | Hb, RBCT, TR, survival, AEs | NA |

| Tjulandin 201048 | 223 | Epoetin theta, epoetin beta | Placebo | Solid | Chemotherapy: platinum based | HaemR, RBCT, HRQoL,h AEs | NA |

| Tjulandin 201177 | 186 | Epoetin theta | Placebo | Mixed | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | HaemR, RBCT, HRQoL, AEs | NA |

| iUntch 201178 | 733 | Darbepoetin alfa | Standard | Solid (breast) | Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | Hb, pathological response, disease progression, survival, AEs | Untch 201180i |

Update searches were conducted on 2 December 2013 using the same methodology as described earlier. In total, 68 records were screened by two reviewers (LC and MH) and eight records were selected for full-text retrieval. No studies were judged eligible on full-text appraisal. A list of these papers with reasons for their exclusion can be found in Appendix 4.

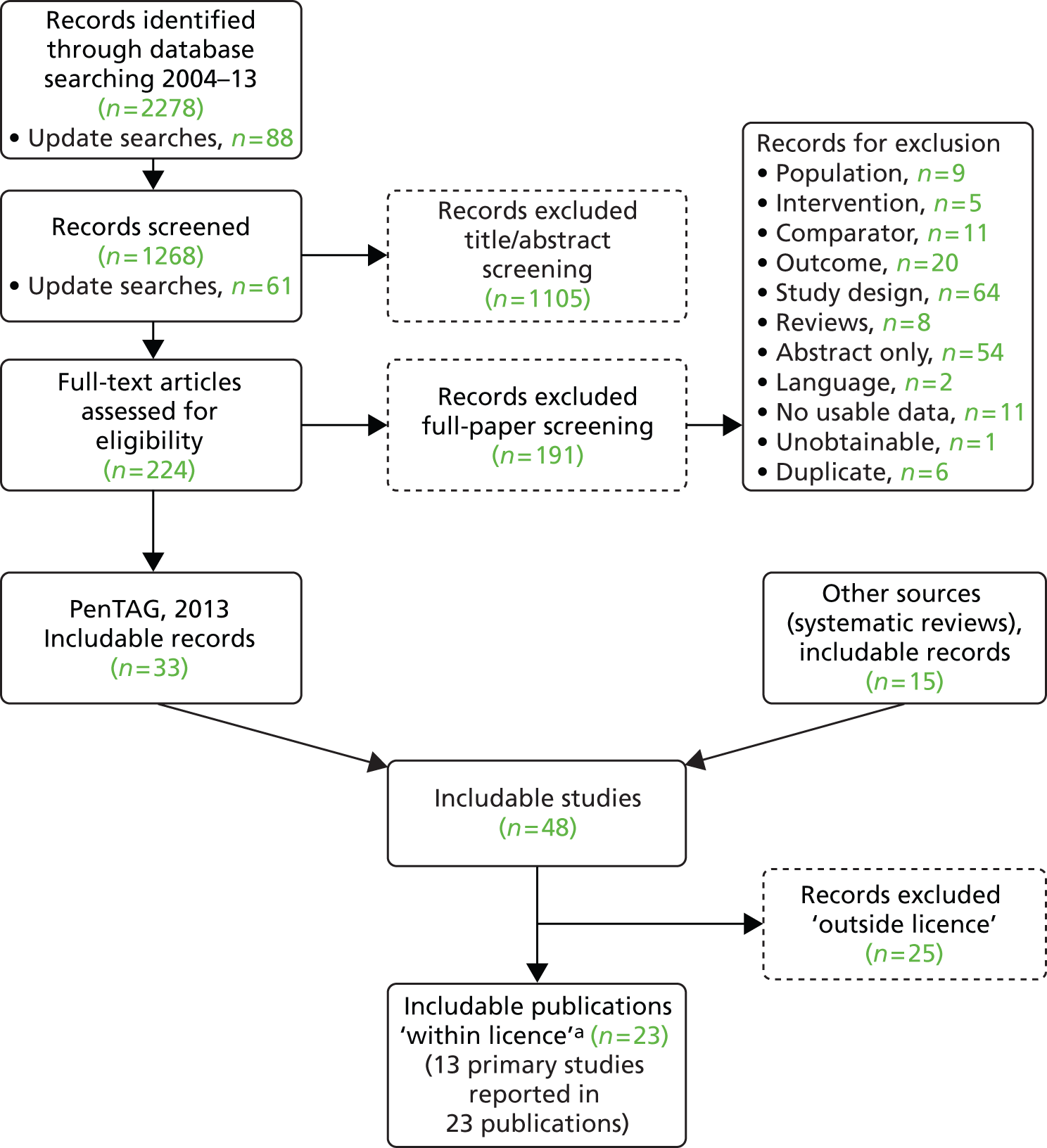

The process of identifying studies is illustrated in detail in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart: clinical effectiveness review. a, Number of included studies in the previous HTA review. 2 b, Excluded studies listed in Appendix 4 (see Wilson and colleagues2 excluded studies). c, Baseline characteristics for studies excluded on dose (‘outside of licence’, n = 11) are reported in Appendix 6. Note that, for four included trials50–53 that evaluated different ESA doses, only the within-license doses were included in the PenTAG review. As a result, the number of studies in the subsection of the table ‘Wilson and colleagues2’ is 15. d, Coiffier and colleagues87 was included in the review by Wilson and colleagues. 2 The full paper65 for this abstract was identified by citation chasing and included in the PenTAG review. e, Wilson and colleagues:2 16 primary trials17,50–53,63–73 reported in 18 publications. 17,50–53,58,63–73,86 f, Other sources: 11 systematic reviews2,7,11,41,88–94 reported in 12 publications. 2,7,11,41,88–95 g, Other sources: four studies59,60,62,85 were identified as eligible for inclusion. h, Excluded studies listed in Appendix 4 (see Clinical effectiveness review: excluded studies). i, Baseline characteristics for studies excluded on dose (‘outside of licence’, n = 36) are reported in Appendix 6. j, PenTAG searches 2004–13: seven primary trials48,74–78,80 reported in 12 publications. 48,74–84

Study characteristics

No head-to-head trials were identified in either the 2007 review2 or the update searches. One three-arm trial compared epoetin beta and epoetin theta with placebo;48 however, comparison was made only between each intervention and placebo. The majority of trials (> 50%) compared an ESA plus standard care with placebo plus standard care. Of these, four trials were identified in the update searches. 48,74,77,79 Of note, the Österborg and colleagues trial79 evaluated long-term survival for epoetin beta plus standard care compared with placebo plus standard care from the earlier 2002 RCT. 71 The remaining trials compared an ESA plus standard care with standard care alone. Of these, four trials (reported in five publications) were identified in the update searches. 62,75,76,78,80

Interventions and comparators

The following interventions were evaluated in the included studies: epoetin alfa, beta and theta and darbepoetin alfa (Table 11). In two of the included studies it was uncertain which ESA was evaluated [reported as recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO)],67,68 although it was assumed to be either epoetin alfa or epoetin beta based on the study dates and the doses evaluated. Of note, no studies of epoetin zeta met the eligibility criteria for this review (study design).

| Intervention | Number of studiesa | vs. placebo + SC | vs. SC alone | Total population,b n | Treated with ESA, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoetin alfac | 10c | 5 | 5c | 2284 | 1135 (56) |

| Epoetin betac | 4c,d | 1d | 3c | 768 | 382 (50) |

| Epoetin theta | 2d | 2d | 0 | 409 | 171 (42) |

| Epoetin zeta | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Darbepoetin alfa | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1678 | 727e (43) |

| rHuEPOf | 2 | – | 2 | 92 | 46 (50) |

| Total | 23d | 12d | 11 |

The ESA administration and dosing strategies varied considerably in the literature in terms of starting dose (fixed or weight based), trigger Hb level (the point below which ESAs should be administered, ≤ 10.0 g/dl), target Hb level (the point above which ESAs should be stopped or titrated, 10–12 g/dl), dose escalation (used if people do not achieve a haematological response within a specified time period), stopping rules for non-responders and duration of use following each chemotherapy session. These aspects will have an impact on clinical effectiveness. The majority (82%) of studies were initiated before the 2008 update of the SPCs and no studies were completely aligned with the UK marketing authorisation for these drugs in respect of these criteria (see Appendix 9).

This review focused only on those studies evaluating ESA treatment in accordance with UK marketing authorisations with respect to the starting dose (see Dose), irrespective of other aspects of the licence (e.g. starting or target Hb levels or stopping rules). For darbepoetin alfa, two studies50,53 were dose ranging studies and therefore evaluated doses under and over the current licence recommendations, and two studies51,52 included a second intervention group evaluating epoetin alfa at a start dose of 300 IU/kg. Only the licensed start doses from these studies were included in the PenTAG review. In addition, one study78,80 evaluated darbepoetin alfa at a dose of 4.5 µg/kg once every 2 weeks. This was considered to be within licence, as the equivalent dose per week (2.25 µg/kg) is a licensed dose.

Of note, none of the included studies evaluated ESAs entirely within the remit of their marketing authorisations, in particular with respect to trigger and target Hb levels and stopping rules, all of which were generally higher than specified in the licence. Appendix 9 provides a summary of the administration of ESAs within the included studies in relation to their respective licences. Two additional definitions of ‘within licence’ were considered in post-hoc analyses: (1) licensed start dose plus inclusion Hb level ≤ 11 g/dl and (2) licensed start dose plus inclusion Hb level ≤ 11 g/dl plus target Hb level ≤ 13 g/dl.

The majority of the trials gave ESA therapy over the course of the chemotherapy, with many continuing with ESA therapy for 4 weeks after chemotherapy, which is permissible within the licensed indications. The average time on erythropoietin treatment was 12 weeks, with trial duration clustering around 12–28 weeks. One study reported follow-up data. 79

Concomitant treatments

There were several possible concomitant treatments – G-CSF, iron supplementation and RBCT, with some protocols giving recommendations for when transfusions should be given (referred to in this review as transfusion triggers) (see Appendix 7). Two studies were identified in which G-CSF was given. In one study67 G-CSF was given at a dose of 5 µg/kg from day 4 until day 11 during the first five chemotherapy cycles, to allow accelerated chemotherapy. The second study75 stated that G-CSF could be used in primary or secondary prophylaxis as recommended by ASCO and French Federation of Cancer Centre guidelines. However, it was unclear whether G-CSF was administered to any of the study participants during the study period.

In the majority of studies (n = 1417,48,64,65,67–72,75–80) iron supplementation was given. Reporting of details in this respect varied. A fixed daily dose of oral iron (either 200 mg or 325 mg) for all patients was most common, although in a few studies administration of oral iron supplementation was dependent on transferrin saturation levels (i.e. ≤ 20% or < 10%); in one study70 daily oral iron supplementation was recommended, but if (during the study) transferrin saturation fell to ≤ 20% intravenous iron was recommended. In two studies that enrolled patients with a baseline transferrin saturation level of < 25%71,79 and < 20%,76 participants were given intravenous iron supplementation at a dose of 100 mg per week before the start of study treatment. In cases in which patients were contraindicated or the drug was not available, oral iron supplementation was administered. In one study69 intravenous iron supplementation was administered following each dose of chemotherapy, beginning with the next cycle. One trial was identified in which concomitant iron supplementation was given only to patients receiving an erythropoietin. 78,80 Several studies reported that iron supplementation was allowed during the study without specifying details or that iron supplementation was given at the investigators’ discretion. Nine studies did not report concomitant treatment and in two studies52,73 iron supplementation during the study period was not permitted.

Population characteristics

Population characteristics of the included trials are summarised in Tables 12 and 13; characteristics are described in more detail in Appendix 7.

| Malignancy | Mixed types | Specific malignancies |

|---|---|---|

| Solid tumours | Tjulandin 2010;48 Aravantinos 2003;64 Kotasek 2003;50 Dunphy 1999;68 Kurz 199769 | Moebus 201362 (breast); Untch 201178,80 (breast); Strauss 200876 (cervix); Grote 200574 (SCLC); Vansteenkiste 200273 (lung); Thatcher 199952 (SCLC); ten Bokkel Huinink 199851 (ovary); Del Mastro 199767 (breast) |

| Haematologicala | Hedenus 2003;17 Österborg 2002,71 bÖsterborg 2005;79 Hedenus 2002;53 Dammacco 200166 | Silvestris 199572 (MM) |

| Mixed solid and haematologicala | Tjulandin 2011;77 Ray-Coquard 2009;75 Boogaerts 2003;65 Littlewood 2001;70 cAbels 199363 |

| Malignancy | Trials |

|---|---|

| Chemotherapy: platinum based | Tjulandin 2010;48 Vansteenkiste 2002;73 Aravantinos 2003;64 aten Bokkel Huinink 1998;51 Abels 199363 |

| Chemotherapy: non-platinum based | Moebus 2013;62 Tjulandin 2011;77 Untch 2011;78,80 Österborg 2002,71 b2005;79 Littlewood 2001;70 aDel Mastro 1997;67 Abels 199363 |

| Chemotherapy: type unknown | Ray-Coquard 2009;75 Boogaerts 2003;65 Hedenus 2003;17 Kotasek 2003;50 Hedenus 2002;53 Silvestris 199572 |

| Mixed chemotherapy | Grote 2005;74 Dammacco 2001;66 Dunphy 1999;68 Thatcher 1999;52 Kurz 199769 |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | Strauss 200876 |

The age range of trial participants was 18–92 years. In the majority of included studies there was an equal distribution of men and women, with the obvious exception of trials whose populations had gynaecological and breast malignancies (within the breast malignancies group one patient was male70). However, in one study68 (head, neck and lung tumours) gender was not distributed equally between the two treatment groups; in the treatment arm 92% of participants were men, compared with an equal distribution of men and women in the control arm (50% each).

The studies included a variety of malignancies (see Table 12). Five trials included patients with a mix of solid tumours. 48,50,64,68,69 One of the retrospective analyses identified81 was a subgroup analysis of a breast cancer cohort enrolled in the study conducted by Littlewood and colleagues;70 however, the overall study was not powered to discriminate treatment differences within subgroups. Eight of the included studies concentrated on specific solid tumour types (breast n = 3;62,67,78,80 ovary n = 1;51 cervix n = 1;76 lung n = 352,73,74). Four studies included a mix of haematological malignancies (specifically haematological non-myeloid malignancies: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease and multiple myeloma);17,53,66,71,79 of these, one study was reported in two papers,71,79 with the later paper79 reporting long-term survival data from the earlier study. 71 One study focused on multiple myeloma. 72 Five studies included participants with a mix of solid and haematological malignancies. 63,65,70,75,77

Malignancy treatments consisted of chemotherapy (platinum based and non-platinum based) and chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. In four studies participants received platinum-based chemotherapy,48,51,64,73 in six studies participants were on non-platinum-based chemotherapy,62,67,70,71,77–80 in one study participants received platinum-based and non-platinum-based chemotherapy,63 in six studies participants were receiving chemotherapy but the type was unknown17,50,53,65,72,75 and in five studies participants were on mixed chemotherapy treatment. 52,66,68,69,74 Of the group of trials in which participants received mixed chemotherapy, two52,69 reported that the majority of participants received platinum-based chemotherapy (proportion not reported) and in one66 of the studies the majority of participants received non-platinum-based chemotherapy (proportion not reported). One trial involved participants on chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. 75

The majority of included studies specified the required baseline degree of anaemia in the eligibility criteria, with three studies not specifying this. The highest cut-off was a Hb level of ≤ 14.5 g/dl74 and the lowest was a Hb level of ≤ 8 g/dl. 72 Despite this, the mean/median Hb level at baseline ranged from 9.2 g/dl to 14.1 g/dl in the intervention group and from 9.1 g/dl to 14.1 g/dl in the control group.

Quality of the included studies

It was originally intended to use the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess study quality; however, all trials were assessed using the same quality assessment tool as in the previous HTA review. 2 Quality assessment criteria are presented in Table 9 and the study quality appraisal is presented in Table 14. However, there is some variation in the method of quality assessment between the previous review and the current review. In the current appraisal, only information published in the primary studies was considered when conducting the quality appraisal, whereas the previous HTA review also used quality assessment information published in the 2004 Cochrane review. 45 Cochrane review authors contacted the trial investigators to request missing data, including information on study conduct. In addition, we have access to new information from papers published after the inclusion date for the previous review. Only primary studies were appraised, with secondary analyses of previously published data not assessed. Similarly, if a trial was reported in multiple publications, only one quality assessment of the trial was conducted. In total, 23 trials were assessed,17,48,50–53,62,63–78 including eight trials not included in the previous HTA review. 2 In addition, GRADE analysis was carried out, with the results presented in Appendix 3.

| Author, year | Random allocation | Concealment of allocation | Baseline similarity | Patients blinded | Physicians blinded | Losses | ITT or < 10% dropout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abels 199363 | Uncleara | NR | Unclearb | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes |

| Aravantinos 200364 | Uncleara | NR | Unclearb | No | No | NR | Yes |

| Boogaerts 200365 | Uncleara | NR | No: previous chemotherapy, FACT-F | No | No | Partially | Yes |

| Dammacco 200166 | Uncleara | Unclearc | Unclearb | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, primary end point and HRQoL only |