Notes

Article history

This issue of Health Technology Assessment contains a project originally commissioned by the MRC but managed by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The EME programme was created as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) coordinated strategy for clinical trials. The EME programme is funded by the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the CSO in Scotland and NISCHR in Wales and the HSC R&D, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. It is managed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) based at the University of Southampton.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from the material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David A Richards receives funding support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. Simon Gilbody was a NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board member during the conduct of this study (tenure 23 June 2008 to 30 September 2014). Glyn Lewis is currently a NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board member. Peter Bower reports personal fees from the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Richards et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter utilises material from three1–3 of the four Open Access articles previously published by the research team in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licences (CC BY 2.0, CC BY 3.0 and CC BY 4.0).

Depression

Depression results in substantial disability and is recognised as a major health problem; it is currently the second largest cause of global disability. 4 Around 350 million people are impacted by depression across the world and each year up to 5.8% of men and 9.5% of women will suffer from an episode of depression. 5 Depression has a very significant impact on physical health, occupational functioning and the social lives of sufferers. 6 Often anxiety is also present, causing further disability. 7

Depression is the acknowledged reason for two-thirds of all suicides. 8 The nature of depression is that it can frequently be chronic, with regular bouts of relapse and subsequent new episodes. After one depressive episode, around 50% of people will experience additional episodes. The risk of subsequent relapse is 70% after a second bout of depression and as much as 90% following three or more episodes. 9 Among other diagnostic criteria, depressive symptomatology incorporates depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, insomnia or sleeping too much and fatigue or loss of energy. 10

Although effective pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression are available, people are often treated with a less than optimal programme. Internationally, there is often poor patient adherence to pharmacological treatment11 and further problems caused by organisational barriers between generalists and specialist mental health professionals. 12,13 There is often very limited support for primary care doctors when treating participants with both psychosocial interventions and pharmacological methods. Such support may be critical given that, in systems such as that in the UK and elsewhere, the general practitioner (GP) is the sole responsible medical clinician for 90–95% of patients. 14

Collaborative care

In a previous systematic review of 36 studies testing organisational interventions,15 it was concluded that guidelines, practitioner education and other simple interventions were not effective in studies attempting to improve the management of depression. However, there is better evidence for the role of organisational interventions in improving the management of a range of chronic conditions generally. Organisational strategies have been used in the management of depression, including ‘collaborative care’. This is a complex intervention developed in the USA that has been supported by previous reviews. Collaborative care has been identified as the most effective of the range of organisational approaches studied. 15–20

Collaborative care incorporates a multiprofessional approach to patient care; a structured management plan; scheduled patient follow-ups; and enhanced interprofessional communication. 21 In practice, this is achieved by the introduction of a care manager into primary care, responsible for delivering care to depressed patients under supervision from a professionally qualified mental health specialist and for liaising between primary care clinicians and specialists. Care management has been described as a health worker taking responsibility for proactively following up a patient, assessing patient adherence to psychological and pharmacological treatments, monitoring patient progress, taking action when treatment is unsuccessful and delivering psychological support. 18 Care managers work closely with the primary care provider (who retains overall clinical responsibility) and can receive regular supervision from a mental health specialist. 15,22 The specific disciplines vary by country context but can include counsellors, paraprofessionals or nurses as care managers, and psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health nurses acting in the specialist role.

Systematic reviews23,24 demonstrate that collaborative care improves depression outcomes, with some studies showing benefit for up to 5 years. Before developing the CollAborative DEpression Trial (CADET), our 2006 systematic review24 of 28 collaborative care studies showed collaborative care to be effective [standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.17 to –0.32]. The I2 estimates of inconsistency were 80% for antidepressant use and 54% for depressive outcomes. In metaregression analyses three intervention content variables predicted improvement in depressive symptoms, recruitment by systematic identification (p = 0.061), care managers having a specific mental health background (p = 0.004) and provision of regular supervision for care managers (p = 0.033), which reduced the overall heterogeneity (I2) from 54% to 48% for systematic identification, 43% for case manager background and 49% for supervision.

More recently (after the initiation of the CADET trial) we have undertaken a Cochrane review. 23 Our new analyses show greater improvement in depression outcomes for adults with depression treated with the collaborative care model compared with usual care in the short term (0–6 months) [SMD –0.34, 95% CI –0.41 to –0.27; relative risk (RR) 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43], medium term (7–12 months) (SMD –0.28, 95% CI –0.41 to –0.15; RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48) and long term (13–24 months) (SMD –0.35, 95% CI –0.46 to –0.24; RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.41). However, these significant benefits were not demonstrated into the very long term (≥ 25 months) (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27). In metaregression of this significantly larger study data set (n = 79) collaborative care that included psychological interventions predicted improvement in depression (beta-coefficient 20.11, 95% CI 20.01 to 20.20; p = 0.03). These new data include the results of our CADET trial along with another nine UK studies and a greatly expanded study data set. We include them here for completeness and refer to them further in the discussion.

In 2008, at the commencement of the CADET trial, collaborative care had generally been developed and tested in the USA within managed health-care settings. It is possible that the overall effectiveness of collaborative care programmes might vary when it is implemented and evaluated in non-US settings. In other areas of mental health care results from US-developed organisational interventions have not generalised outside the original health-care context. 25 For collaborative care, there was some supportive evidence from other contexts, including the developing world,26,27 but prior to the CADET trial there has been uncertainty around the standardised effect size in UK trials (SMD 0.24, 95% CI –0.060 to 0.547) and elsewhere. 24 These limited non-US data and the relatively small effect size in trials of patients with depression alone led the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)28 to issue a research recommendation that ‘The efficacy of organisational interventions, such as chronic disease management programmes or other programmes of enhanced care for depression, should be tested in large-scale multicentre trials in the NHS’ (research recommendation 5.6.8.1, p. 103). This provided us with the rationale to undertake a fully powered UK evaluation of collaborative care.

Development of the CollAborative DEpression Trial

In published studies there is considerable between-study heterogeneity in terms of the duration and intensity of collaborative care and the training and background of care managers. Therefore, to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of collaborative care in the UK, we conducted a series of Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded preparatory studies. We wished to develop an intervention in anticipation of a fully powered randomised controlled trial. We carefully developed our collaborative care intervention to be applicable outside the USA, in health-care systems with a well-developed primary care sector. 29–31

In our Phase II testing of this intervention,30 we found preliminary evidence that collaborative care adapted to the UK was acceptable to patients and clinicians and may be effective outside the USA, but that a cluster randomised controlled trial was required to guard against potential contamination between trial arms. We amended the clinical protocol studied in our pilot trial to take account of acceptability data in our qualitative interviews and designed a cluster randomised controlled trial of sufficient power to detect clinically meaningful and achievable differences between collaborative care and usual care. We now report the results of this pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial1 to determine whether or not collaborative care is more clinically effective and cost-effective than usual care in the management of patients with moderate to severe depression. This report is divided into chapters detailing the methods and results of our primary clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness questions followed by similar chapters for our process evaluation. We have undertaken an additional long-term follow-up of clinical outcomes and report this in a separate chapter. Finally, we conclude with a discussion chapter summarising our results and considering their implications for the management of depression.

Chapter 2 Trial methods

This chapter utilises material from three1–3 of the four Open Access articles previously published by the research team in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licences (CC BY 2.0, CC BY 3.0 and CC BY 4.0).

Research question

Is collaborative care more clinically effective and cost-effective than usual care in the management of participants with moderate to severe depression in UK primary care?

Study design

The CADET trial was a multicentre, two-group, cluster randomised controlled trial with allocation of general practice clusters to two trial arms: collaborative care (experimental group) or usual care (GP management). We chose a cluster design given that our Phase II trial30 described in the previous chapter demonstrated that a participant-randomised trial of collaborative care could be vulnerable to contamination and open to type II error, underestimating the true effect size of the intervention through potential intervention ‘leakage’.

Patient and public involvement

We involved patient and public representatives at all stages of the project. A patient and public involvement (PPI) advisor (CM) was a trial applicant, investigator and full member of the Trial Management Group (TMG). He attended all meetings of the TMG and advised on patient-facing materials including ethics materials and participant therapeutic manuals and on the conduct of the trial including project management, questionnaire development, data collection and project dissemination. There were two PPI representatives on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), one from a depression consumer advocacy group and another with lived experience of depression. Both provided important checks and balances as part of the independent TSC oversight of the trial.

In addition, the trial was initially co-ordinated from the Mood Disorders Centre at the University of Exeter and latterly from the University of Exeter’s Medical School. Both the Mood Disorders Centre and the Medical School operate within a culture of PPI, guided by published theories of participation, empowerment and engagement, through the Mood Disorders Centre’s 20-strong Lived Experience Group and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) CLAHRC (Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) for the South West’s patient involvement group PenPIG (Peninsula Public Involvement Group).

Setting and participants

We recruited participants between June 2009 and January 2011 from the electronic case records of primary care general practices in three UK sites: Bristol, London and Greater Manchester.

Inclusion criteria

Our eligibility criteria were as follows:

-

Adults aged ≥ 18 years meeting International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) criteria for a depressive episode. 32 Diagnosis was determined by research personnel interviewing potential participants using the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R),33 a computerised interview schedule that establishes the nature and severity of neurotic symptoms and identifies a categorical diagnosis of mild, moderate or severe depression.

-

Newly identified as depressed, including those with or without previous episodes; in treatment for an existing diagnosis of depression but not responding; suffering from peri- or postnatal depression; or suffering with comorbid physical illness or comorbid psychological disorders such as anxiety.

-

People were eligible to participate whether or not they were in receipt of antidepressant medication in line with the pragmatic nature of this trial and to reflect usual primary care management of depression in the UK.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded people for whom there was a sufficiently severe risk of suicide that they required immediate specialist mental health crisis management; those with type I and type II bipolar disorder; those with psychosis; those with depression that was associated with a recent bereavement; those with an alcohol or drug abuse primary presenting problem; and those who, at the time of interview, were receiving specialist mental health treatment for their depression, including psychotherapy.

Randomisation

We randomly allocated primary care practices to either collaborative care or treatment as usual as they were recruited into the trial. We minimised randomisation within our three sites using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) rank,34 the number of GPs and practice size.

Allocation concealment

We concealed the allocation sequence from the researchers as they recruited practices by ensuring that researchers were unaware of prior allocations or the allocation sequence. Randomisation was undertaken by the trial statistician using Minim (www.sghms.ac.uk/depts/phs/guide/randser.htm). 35 We managed participant identification and the trial databases through our partnership with the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU), who undertook these functions remotely from the trial team and trial statistician.

Blinding

In this type of trial, in which interventions are complex and clearly different from each other, it is not possible to blind participants, care managers or GPs and so our procedures focused on helping to keep research workers blind to participant allocation and protecting the study against assessment interpretation bias through the use of self-report measures. Our research workers were blinded to practice allocation. To help control for the effect of any potential unblinding after research workers assessed and confirmed that people were eligible for the trial, they then collected participant outcomes as self-report measures.

After assessments had been completed, research workers recorded participants’ data on a remote, web-based system. This database, administered by PenCTU, allocated each participant an identification number and, if in a collaborative care cluster practice, automatically advised the relevant care manager to contact the participant. The system also automatically communicated with each participant’s GP by letter.

Recruitment

Potential participants were identified by clinical studies officers (CSOs) or practice staff from July 2009 to January 2011. These workers searched the computerised records of participating practices over a 19-month period, looking for records of people with at least one identification code for depression recorded against their name by their GP in the previous 4 weeks. We searched for those codes most widely used by GPs to classify participants as depressed.

The lists of people generated by the searches were screened by GPs to remove the names of anyone whom GPs knew would not meet our inclusion criteria or who would be excluded at interview. Staff then sought permission from potentially eligible people for researchers to contact them. Potentially eligible people were sent an information sheet and reply slip in the post. Practice staff or CSOs followed up this letter by telephone after 1 week.

Those who gave research interview consent were contacted by a researcher trained in the specific interview procedures by study investigators and an interview was organised at the convenience of the participant. Interviews took place either in their home or at their GP practice no earlier than 48 hours after they had received the trial information letter. The first part of the research interview consisted of the researcher outlining the trial in detail and answering questions. Once the potential participants were fully briefed and willing to enter the trial, researchers asked them to fill in and sign the trial consent form, following which the diagnostic component of the baseline interview was undertaken.

If the diagnostic component of the baseline interview – the CIS-R33 – confirmed that a potentially eligible person met our depression diagnostic inclusion criteria, he or she was included as a participant in the trial, the research interview proceeded and a full baseline data set was taken.

Intervention and comparator groups

Intervention: collaborative care

Our experimental intervention was collaborative care. As detailed earlier, the specific components of the intervention had been developed, tested and amended in our earlier trial and process evaluation. 30 Care managers in three UK sites provided the intervention under supervision from specialists in mental health care. A copy of the complete clinical protocol is provided in Appendix 1. A summary of the collaborative care protocol is given in the following sections.

Care management

All participants received usual care from their GP. Collaborative care consisted of 6–12 contacts between the care manager and the trial participant, with contacts spanning a period of no more than 14 weeks. The initial appointment was of 30–40 minutes’ duration and was conducted in a face-to-face manner. Subsequent appointments were undertaken on the telephone and were of 15–20 minutes’ duration. Although most follow-on appointments were by telephone, care managers could arrange to meet the participant face-to-face if either party thought that this was desirable. Routinely, however, the telephone was the preferred contact medium for the majority of follow-on appointments.

Although the frequency of contacts was determined by a participant’s needs, in our protocol we suggested that contacts should be undertaken weekly during the first month or so of care management. We recommended that fortnightly appointments could be arranged after this. Once again, we designed our protocol to be sufficiently flexible to permit more frequent sessions if either party regarded this as important, given the progress of the participant or his or her clinical presentation. We recommended short frequent sessions to care managers as opposed to lengthy appointments on a less frequent basis. We asked care managers to be flexible with appointment schedules to permit sessions to be delivered outside usual 0900–1800 working hours, but our expectation was that the majority of sessions would occur during these hours. We advised care managers to try many times to contact participants if they did not manage to get through on the telephone at first. This is an important component of collaborative care protocols worldwide, because many people with depression avoid contact with other people because of their mood state, with social avoidance being a common symptom.

During appointments, care managers would:

-

assess participants’ views about psychological and medication treatments

-

negotiate a treatment programme that was acceptable to participants

-

help participants with their management of any prescribed antidepressants

-

support participants to use behavioural activation, a brief low-intensity psychosocial treatment for depression

-

provide advice on relapse prevention.

Symptom assessment

Care managers conducted a symptom assessment every time they had a session with a participant, whether face to face or by telephone. They used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)36 to evaluate and record common symptoms of depression and then engaged participants in a discussion regarding these symptoms. We chose the HADS so as not to use the same measure [the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)37] as our primary research outcome measure. Care managers also conducted a risk assessment to assess the level of risk to self and others for each participant. These assessments were undertaken at the beginning of each appointment.

Medication management

We instructed care managers to help participants engage appropriately with any medicines that they had been prescribed for their depression. Each participant’s GP remained the responsible medical practitioner in terms of medication prescription but the care manager helped participants understand the reason for their prescription, reinforced information from their GP and problem solved any difficulties that participants had in tolerating their medicines.

Behavioural activation

Behavioural activation is a psychological treatment with good evidence that it is as effective as cognitive–behavioural therapy in depression. 38 Behavioural activation is a brief psychological treatment that helps people interrupt patterns of avoidance that maintain depression. Behavioural activation assists people to increase their levels of activity to help them experience more examples of situations likely to lead to a positive mood. Behavioural activation was suitable for care managers to use given its simplicity and brevity and had been tested previously in our pilot work. We provided participants with support information prepared by the trial team. In summary, participants were supported through a self-guided behavioural activation treatment programme that helped them to increase the frequency and range of activities in their day-to-day lives.

Communicating with general practitioners

We outlined three levels of care manager contact with GPs:

-

Level 1. Care managers communicated a brief statement of the participant’s main problem and treatment plan to the GP after the first treatment session, using a structure outlined in our protocol. If participants were progressing satisfactorily and/or willing to engage in the treatment plan, routine records of each contact were recorded.

-

Level 2. If participants were not progressing satisfactorily, or they wanted to change their pharmacological treatment regime, the case manager could alert their GP as required. In these instances care managers could inform the GP about changes that may need to be made to the treatment plan. Care managers could also let the GP know if a participant had been advised to make an appointment with his or her GP.

-

Level 3. We instructed care managers to contact GPs in person directly or by telephone should there be an urgent need to do so. Circumstances requiring level 3 contact included a participant experiencing intolerable medication side effects, a substantial worsening in a participant’s mental health or a participant being at acute risk to self or others.

Care managers

Care managers were existing NHS mental health workers working in a primary care environment. They had been previously trained as paraprofessional mental health workers. They continued to treat patients in their existing NHS role, undertaking care management of CADET participants alongside their NHS caseload. Care managers were supervised each week by specialist mental health workers including clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, academic GPs with a special interest in mental health or senior nurse psychotherapists. Every CADET participant was discussed at least once a month. Discussions were organised using a bespoke computerised patient case management information system [PC-MIS (see www.pc-mis.co.uk; accessed 17 November 2015)]. PC-MIS includes automated alerts so that supervisors and care managers are informed of their supervision discussion schedules automatically, including algorithms driven by routine outcome measures that identify participants not responding to treatment.

Specialist mental health worker members of the investigator team trained care managers using a 5-day collaborative care instruction programme. The training consisted of protocol instruction, modelling and treatment session role play. All components of the collaborative care protocol were included in the programme. This included the initial contact, subsequent appointments, telephone working, GP liaison and supervision. The training instructed care managers on both specific case management skills such as participant education, medication support and behavioural activation and non-specific factors necessary to develop therapeutic engagement.

Each care manager received a handbook to accompany the training programme (see Appendix 1). The handbook included a collaborative care management session-by-session guide and participant information materials on depression, medication and behavioural activation. The handbook contained all of the worksheets and diaries that care managers were to use in supporting participants with their collaborative care activity programme. It also included information on, and examples of, how care managers should communicate with GPs and provided worksheets to help them prepare case materials for supervision discussions.

Supervision

Specialist mental health professionals – psychiatrists and psychological therapists (RA, JC, LG, DK, KL and SP) – supervised the care managers. Supervisors helped and supported care managers through discussion with them about participant progress. Care managers discussed participant symptom levels, treatment plans and their own care management activities. In this, they were prompted by alerts on PC-MIS. In addition to routinely triggered discussions they were also able to bring any problems experienced in managing specific cases to supervision. Supervisors assisted care managers with any communications that they needed to have with GPs, for example communicating medication advice for individual participants. Supervisors undertook sessions with care managers over the telephone, either on an individual basis or in groups on a weekly basis. At each supervision session the following cases were reviewed:

-

all new participants

-

participants who had reached a scheduled supervision review point after being in the trial for 4, 8 or 12 weeks

-

participants who were not improving as expected, for example when an adequate trial of antidepressant medication was not having a therapeutic effect or when participants were not benefiting from or engaging in the behavioural activation programme

-

overdue participants; that is, when the care manager had not been able to make contact with a participant as previously arranged

-

any other participants requiring discussion and/or an overview of current caseloads.

Supervision was principally informed by ratings collected from participants using the HADS, assessments of participant risk to self and others, details of participant concordance with treatment plans and discussions of care management strategies. Supervision focused care managers’ attention on their overall decision-making for individual participants while also helping them practice care management principles for their whole caseload.

Control condition: usual care

General practitioners provided control participants with care that reflected their standard practice. For control participants this included antidepressant therapy and/or referral to specialist mental health care. Given that the CADET trial was a pragmatic trial, we did not specify any clinical protocols for usual care. However, we did measure the components of usual care received by participants.

Outcomes

Primary clinical outcome

The primary clinical outcome was depression severity at 4 months’ follow-up using the PHQ-9. 37

Secondary clinical outcomes

Secondary outcomes were the PHQ-9 at 12 months, quality of life [Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)39], worry and anxiety [General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)40] at 4 and 12 months, health state values (health-related quality of life) [European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)41,42] at 4 and 12 months and participant satisfaction [Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8)43] at 4 months.

Demographic data on sex, age, ethnic origin, education level, employment, marital status, presence or absence of antidepressant treatment, previous history of depression, severity of depression, any secondary diagnoses of an anxiety disorder and any participant self-reported long-standing physical illness were also collected at baseline.

Economic outcomes

The health economic end point was the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) at 12 months. We used the recommended area under the curve approach for assessing repeated measures. 44,45 Resource use pertaining to the collaborative care intervention as delivered by care managers and supervisors in the trial was collected directly from our trial and case records. These data included care manager and specialist supervision contact time. Participant-level health and social care resource use data, information on informal care from friends/relatives and other participant costs (e.g. over-the-counter costs, one-off participant costs) were collected at the 4-month and 12-month follow-up points using a self-report format with assistance from interviewers. These same data were collected at baseline using the same self-report data collection approach, asking participants to report their resource use during the 6-month period prior to the baseline assessment. Given the difficulties in collecting data on medication use using the self-report format we did not include medication use in the estimates of health and social care resource use. However, data are reported on the proportion of participants on antidepressant medications at baseline and 12 months’ follow-up.

Although all baseline interview data were collected during a face-to-face interview, we were more flexible with our follow-up assessments. We used face-to-face, telephone or postal methods of data collection in accordance with participants’ wishes and to maximise data collection. For resource use data we used face-to-face or telephone methods of data collection, all using an interviewer-assisted self-report format.

Sample size

The CADET trial was powered at 90% (alpha = 0.05) to detect an effect size of 0.4. This effect size is regarded as a clinically meaningful difference between interventions of this type. 46 The proposed effect size was also within the 95% CI of the effect that we had predicted following our analysis of our feasibility and pilot study. 30 This study had shown a potential effect size of 0.63 with a 95% CI from 0.18 to 1.07. However, an effect size of 0.4 is greater than that in the meta-analysis results of trials published at the time that we were commissioned to undertake the CADET trial (effect size 0.25, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.32). 24

In a two-arm randomised controlled trial in which participants are the unit of randomisation, we would have required 132 participants per group to detect a difference of 0.4 between groups. However, cluster randomisation produces a design effect and inflates the required sample size. In our trial, we planned for 12 participants in each primary care cluster and we used data from our pilot study30 to estimate the intracluster correlation (ICC) as 0.06. The design effect was calculated as 1.65 and we estimated our required sample size without any attrition to be 440. We estimated that the CADET trial might suffer from around 20% participant attrition at our primary end point. In this scenario, to be able to follow up 440 participants, we planned to randomly allocate 550 participants across the trial arms. To deliver this target we decided to recruit 48 practices with up to 14 participants per practice, given that our recruitment rate would not be exactly even between practices.

Statistical methods and analyses

Clinical outcomes

All of our analyses for all of our outcomes used the intention-to-treat principle. We reported all outcomes according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 47 We analysed all data in Stata 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). We wrote, and agreed with the TSC, an a priori analysis plan. We used ordinary least squares or logistic regression, allowing for clustering by use of robust standard errors, to analyse outcomes at 4 and 12 months. We adjusted at the cluster level for minimisation variables and site and at the individual level for age and, when appropriate, the baseline measurement of the variable. We undertook sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of missing data. We estimated this by chained regression equations multiple imputation48 using all available scale clinical scores, age, sex, practice variables, site and treatment group.

Standardised effect sizes for our outcome variables were calculated by taking the mean difference between the intervention group and the control group and dividing the difference by the pooled standard deviation (SD). We also calculated the degree of clustering within our participant clusters by GP practice. We have reported these as ICC coefficients.

We wanted to ensure that our results could be easily interpreted from a clinical perspective and compared with existing published studies. Therefore, using the baseline SD for all participants, we calculated rates of ‘recovery’ and ‘response’. These commonly used metrics can help service commissioners, managers, clinicians and patients translate continuous outcome variables into a meaningful clinical figure. The rate of recovery can be regarded as the proportion of participants with a PHQ-9 score of ≤ 9 at the end of the trial whereas the response rate can be regarded as a ≥ 50% reduction in scores from baseline. Finally, to further aid interpretation the numbers needed to treat were deduced from the inverse of the absolute risk reduction adjusted for clustering by practice.

Economic outcomes

In our economic evaluation we undertook our economic analyses from the UK NHS and Personal Social Services perspective (third-party payer perspective). We also undertook a sensitivity analysis using the broader participant and carer perspective. We estimated the costs associated with health and social care service use and the additional cost of the delivery of the collaborative care intervention and estimated QALYs.

Data on resource use were combined with published unit costs to estimate the mean cost per participant. We used nationally available data sources, in UK pounds sterling at 2011 costs (Table 1), adjusted for inflation when necessary, to compute health-care resource values from unit costs. To estimate the intervention cost for collaborative care, we based our calculations on costs for UK NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) Band 5 staff. We chose a unit cost of £65 per hour for patient contact time,49 a rate equivalent to that for a qualified mental health nurse. All staff cost components are included in this unit cost, for example telephone and travel time, including an allowance of contact time to non-contact time of 1 : 0.89. 49 Supervision costs were calculated by selecting the full costs for specialist mental health professionals at NHS AfC Band 8a49 from a unit cost of £135 per hour for clinical supervisors. QALYs were estimated over the 12-month follow-up period using the EQ-5D trial data, applying UK tariffs obtained from a UK general population survey to value the EQ-5D health states. 53

| Resource item | Unit cost (£)a | Source | Basis of estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP (surgery/practice) | 36.00 | Curtis49 | GP appointment/surgery; based on costing at 11.7 minutes |

| GP (home) | 121.00 | Curtis49 | |

| Practice nurse (surgery) | 15.00 | Curtis49 | Assuming average contact time of 15.5 minutes and using hourly rate for nurse contact time |

| Practice nurse (home) | 30.00 | Curtis49 | Assuming average contact time of 25 minutes and using hourly rate for nurse contact time |

| Walk-in centre (appointment) | 41.00 | Curtis49 | Walk-in service (not admitted) |

| Counsellor | 60.00 | Curtis49 | Per consultation |

| Mental health worker | 76.00 | Curtis49 | Mental health nurse, £76 per 1-hour contact (assumed 1 hour) |

| Social worker/care manager | 212.00 | Curtis49 | Per 1-hour contact (assumed 1 hour) |

| Home help/care worker | 18.00 | Curtis49 | Per weekday hour |

| Occupational therapist | 82.00 | Curtis49 | Community-based occupational therapist per 1 hour of client contact (assumed 1 hour) |

| Voluntary group (e.g. Mind) | 21.73 | Curtis50 | Cost per user session, voluntary/non-profit organisation (£21 per session in 2010) |

| Acute psychiatric ward (bed-day) | 312.00 | Curtis49 | Cost per bed-day |

| Long-stay ward (bed-day) | 222.52 | Curtis50 | Cost per bed-day (£215 in 2010) |

| General medical ward (bed-day) | 321.00 | Curtis49 | Weighted average of all adult mental health inpatient days |

| Accident and emergency (contact) | 106.00 | Curtis49 | Contact, not admitted |

| Day hospital (day) | 126.00 | Curtis49 | Cost per day, weighted average of all adult attendances |

| Psychiatrist (outpatient contact) | 161.38 | bDepartment of Health51 | 2008–9 cost per consultation (£155; code MHOPFUA2) |

| Psychologist (outpatient contact) | 135.00 | Curtis49 | Cost per contact hour (assumed 1 hour) |

| Community psychiatric nurse/care co-ordinator (outpatient contact) | 76.00 | Curtis49 | Mental health nurse, £76 per 1-hour contact (assumed 1 hour) |

| Other outpatient contact | 143.00 | Curtis49 | Outpatient consultant services, weighted average |

| Day care centre (community services/social care) | 34.00 | Curtis49 | Cost per user session |

| Drop-in club (community services/social care) | 34.00 | Curtis49 | Assume the same cost as day care centre, cost per user session |

| Help from friends/relatives | 18.00 | Curtis49 | Use cost per hour, based on unit cost for home help/care worker |

| Lost work (day) (friends/relatives) | 99.6 | ONS52 | Based on median gross weekly earnings in 2011 for full-time employees of £498 |

| Travel cost per mile (participant’s own car) | 0.44 | Estimate of reclaim/expense rate (running cost per mile) |

We estimated mean costs and QALYs for our primary economic evaluation by treatment allocation. We used covariates that were prespecified for age (at the individual level) and deprivation (IMD), site and practice size (at the cluster level). A multilevel regression model (Stata, xtmixed) was used for the primary analyses. This took into account the hierarchical (clustered) nature of the data, presenting the ICC for the main analyses. We undertook data analyses using generalised linear modelling, with appropriate family and link components to account for the non-normally distributed nature of cost data. Analyses were undertaken in Stata 12.

We conducted a number of sensitivity analyses for areas of uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness analyses:

-

We considered the effect of missing data, estimated by multiple imputation (Stata MI command, with 25 replicated data sets), using all available data on the target variable together with covariates for individual and cluster variables used in the base-case regression analyses. 54

-

We undertook analyses using a broader analytical perspective, including estimated costs for informal care and participant out-of pocket expenses.

-

We analysed data for a scenario using trial data from the SF-36 to estimate QALYs using the Short Form questionnaire-6 dimensions (SF-6D),55 which presents tariffs obtained from a UK general population survey to value health states as an alternative QALY outcome measure.

-

We considered uncertainty in the intervention costs.

-

We analysed a scenario in which one participant, with an extremely high level of self-reported resource use, was excluded, as this potentially offers a more likely and policy-relevant estimate of cost-effectiveness.

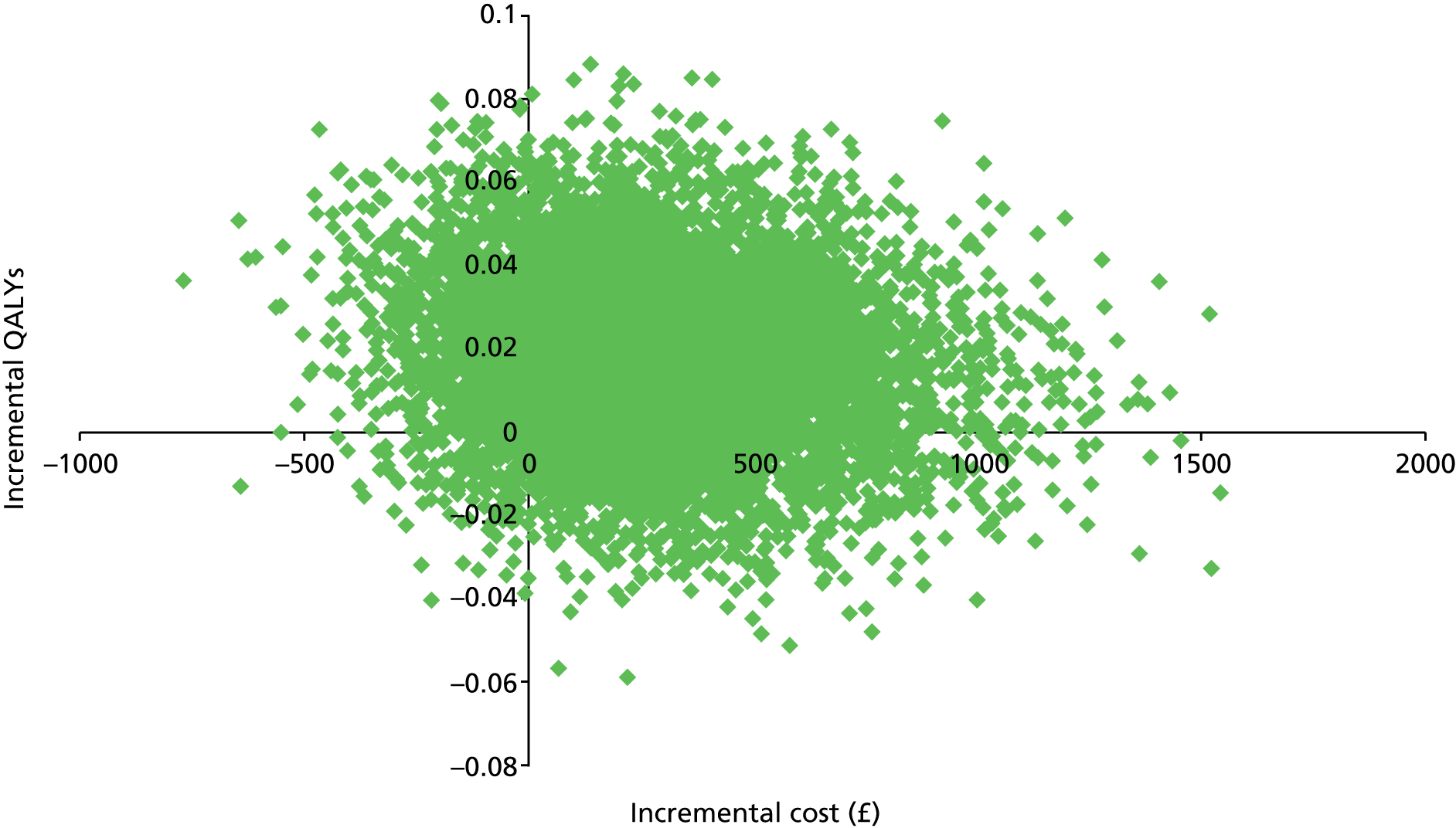

We combined estimates of incremental costs and incremental benefits to present incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), allowing decision-makers to assess value for money using the cost per QALY estimates [ICER = (CostCC – CostTAU)/(QALYCC – QALYTAU), where CC represents collaborative care and TAU represents treatment as usual]. We used the NICE threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY,56,57 that is the expected payer willingness to pay per unit of additional outcome, to assess the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care, with ICERs below these values regarded as cost-effective. We used the non-parametric bootstrap approach,58 with 10,000 replications, to estimate 95% CIs around estimated cost differences and QALY differences to address uncertainty. To present the level of uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness estimates we used the cost-effectiveness plane to present combinations of incremental cost and incremental QALY data from bootstrap replicates and used the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) with the ‘net benefit statistic’ [net monetary benefit = (incremental QALYs × willingness to pay per QALY) – incremental cost)]59,60 to present the probability that the intervention is cost-effective (i.e. incremental net benefit statistic is 0) against a range of potential cost-effectiveness thresholds.

Participant consent and ethical approval

We were granted ethical approval by the NHS Health Research Authority, National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee South West (NRES/07/H1208/60). We ensured that informed consent was gathered from participants before they undertook any engagement with the study, including data collection and treatment allocation and receipt. In detail, the process was as follows.

First, potential participants had to indicate their potential interest in the trial. They then consented to a researcher-led discussion. Everyone who reached this stage was sent the full participant information sheet by a member of the CADET research team and an appointment was also made. At the initial appointment the trial was explained in detail by the research interviewer, who also answered potential participant questions.

We informed all potential trial participants that being consented into the trial would not replace or adversely affect usual care delivered by their GP. All interviewees were told that they could avail themselves of other services or treatments and that they could withdraw from the trial without incurring any penalty to their health or treatment choices. Having considered these facts and agreed to trial participation, we asked potential trial participants to sign a formal consent form. All of our researchers undertaking this consent process were trained and supervised by the CADET investigator team.

Chapter 3 Results of the clinical and economic analyses

This chapter utilises material from two2,3 of the four Open Access articles previously published by the research team in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licences (CC BY 3.0 and CC BY 4.0).

Participant flow and retention

Allocation of practices

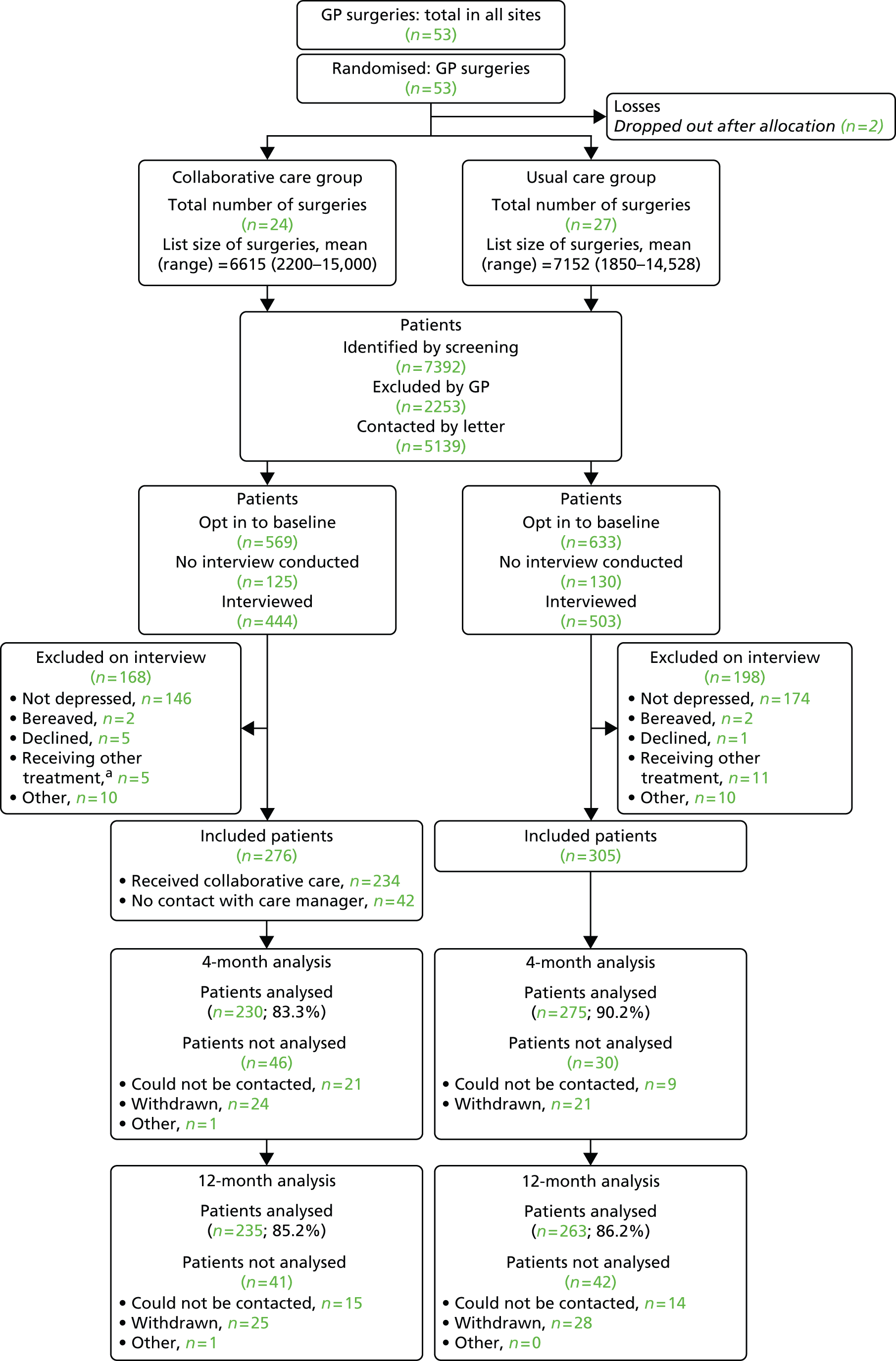

In total, 53 practices were randomised, two of which dropped out after allocation (Figure 1). These practices were removed from the minimisation schedule and their data did not influence later allocations. During recruitment, we found that the cut-off adopted for the IMD had been set far too high, with all practices so far recruited being below the cut-off. We changed this cut-off to one close to the median of practices so far recruited, retaining allocations so far. One practice was found to have been mistakenly recorded in the wrong geographical area; it was moved to the correct group, retaining its allocation. Of the remaining 51 practices, two did not recruit any participants.

FIGURE 1.

Trial CONSORT diagram. a, The number of patients in the collaborative care group who were excluded on interview because they were receiving treatment from secondary care or ‘another mental health provider’ (n = 5) includes one participant who was initially allocated in error and who was subsequently excluded.

Tables 2 and 3 show the geographical distribution of practices and minimisation variables (IMD, number of GPs and number of registered patients per practice), respectively, by intervention group. There was a wide range for all three practice characteristics.

| Site | Collaborative care | Usual care | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Manchester | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Bristol | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| London | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| Total | 24 | 27 | 51 |

| Variable | Group | Number of practices | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMD | Collaborative care | 24 | 9210 | 7416 | 317 | 27,365 |

| Usual care | 27 | 8449 | 6012 | 265 | 19,536 | |

| Total | 51 | 8807 | 6651 | 265 | 27,365 | |

| Number of GPs (whole-time equivalents) | Collaborative care | 24 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| Usual care | 27 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 7.8 | |

| Total | 51 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 10.0 | |

| Number of patients | Collaborative care | 24 | 6615 | 3282 | 2200 | 15,000 |

| Usual care | 27 | 7152 | 3781 | 1850 | 14,528 | |

| Total | 51 | 6899 | 3530 | 1850 | 15,000 |

Participant recruitment

The mean number of participants recruited for the remaining 49 practice clusters was 11.9 (SD 3.9, range 4 to 20). We recruited 581 participants in total and followed up 505 (87%) and 498 (86%) at 4 and 12 months, respectively. The CONSORT diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants through the trial.

Baseline characteristics of participants

The mean age of participants was 44.8 years (SD 13.3) and 72% were women. Fewer than half (44%) of participants were in full- or part-time paid employment. More than half (56%) of the participants fulfilled ICD-10 criteria for a moderately severe depressive episode, with a further 30% meeting criteria for severe depression and 14% meeting criteria for mild depression and 73% of all participants having had depression in the past (Table 4). Almost all (98%) participants had a secondary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, the most common being generalised anxiety disorder. Almost two-thirds of participants (64%) reported a long-standing physical illness (e.g. diabetes, asthma, heart disease). At baseline, 83% of participants had been prescribed antidepressant drugs by their primary care doctor.

| Characteristic | Collaborative care (n = 276) | Usual care (n = 305) | Total (n = 581) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP practices by centre, n | |||

| Bristol | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| London | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| Greater Manchester | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Minimisation variables, mean (SD) | |||

| IMD | 9210 (7416) | 8449 (6012) | 8807 (6651) |

| Number of GPs | 3.8 (2.0) | 4.0 (1.9) | 3.9 (1.9) |

| Number of patients | 6615 (3282) | 7152 (3781) | 6899 (3530) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 202 (73.2) | 216 (70.8) | 418 (71.9) |

| Male | 74 (26.8) | 89 (29.2) | 163 (28.1) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.0 (13.2) | 44.5 (13.4) | 44.8 (13.3) |

| Range | 18 to 82 | 17 to 79 | 17 to 82 |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| White British | 233 (84.4) | 261 (85.6) | 494 (85.0) |

| Other | 43 (15.6) | 44 (14.4) | 87 (15.0) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| None | 54 (19.6) | 74 (24.3) | 128 (22.0) |

| GCSE/O-level | 65 (23.6) | 81 (26.6) | 146 (25.1) |

| Post GCSE/O-level | 84 (30.4) | 79 (25.9) | 163 (28.1) |

| Degree or higher | 49 (17.8) | 53 (17.4) | 102 (17.6) |

| Other or don’t know | 24 (8.7) | 18 (5.9) | 42 (7.2) |

| Employment, n (%)a | |||

| Employed/self-employed | 130 (47.4) | 122 (40.0) | 252 (43.5) |

| Not working | 144 (52.6) | 183 (60.0) | 327 (56.5) |

| Married/cohabiting, n (%) | 127 (46.0) | 114 (37.4) | 241 (41.5) |

| Prescribed antidepressants, n (%) | 231 (83.7) | 249 (81.6) | 480 (82.6) |

| CIS-R score, mean (SD) | 28.8 (9.3) | 30.3 (8.9) | 29.6 (9.1) |

| ICD-10 diagnosis, n (%)b | |||

| Mild | 42 (15.2) | 41 (13.4) | 83 (14.3) |

| Moderate | 156 (56.5) | 167 (54.8) | 323 (55.7) |

| Severe | 78 (28.3) | 96 (31.5) | 174 (30.0) |

| Previous history of depression, n (%) | 202 (73.2) | 220 (72.1) | 422 (72.6) |

| Secondary diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Any anxiety disorder | 269 (97.5) | 301 (98.7) | 570 (98.1) |

| Long-standing physical illness | 171 (62.0) | 199 (65.2) | 370 (63.7) |

| Baseline outcomes, mean (SD) | |||

| PHQ-9 score | 17.4 (5.2) | 18.1 (5.0) | 17.8 (5.1) |

| GAD-7 score | 12.9 (5.3) | 13.6 (4.7) | 13.3 (5.0) |

| SF-36 MCS score | 23.2 (10.4) | 22.3 (10.3) | 22.7 (10.3) |

| SF-36 PCS score | 44.8 (12.4) | 44.5 (12.3) | 44.6 (12.3) |

| EQ-5D score | 0.50 (0.29) | 0.46 (0.31) | 0.48 (0.30) |

| SF-6D score | 0.54 (0.08) | 0.54 (0.09) | 0.54 (0.08) |

The distribution of PHQ-9 scores at baseline was negatively skewed, with the majority of scores being in the higher part of the range. The mean PHQ-9 score overall was 17.8 (SD 5.1), with the usual care group having a slightly higher average score than the collaborative care group (18.1 vs. 17.4 respectively) (Figure 2 and see Table 2). All subjects were selected for the trial using a different measure of depression (CIS-R) from that used in the analysis to avoid problems of regression towards the mean. Low scores represent random variation because of measurement error.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of PHQ-9 scores at baseline.

Delivery and receipt of the intervention

A total of 10 care managers provided collaborative care for 276 participants. The mean number of participants managed per care manager was 27.6 (SD 16.42, range 4 to 46).

Patients received a mean of 5.6 (SD 4.01, range 0 to 15) sessions with their care manager. Forty-two (15.2%) participants did not attend any sessions with their care manager, 213 (77.2%) had two or more contacts and 171 (62.0%) had four or more contacts. The mean total time in collaborative care was 3.03 hours (SD 2.18 hours) over a period of 12 weeks (SD 7.75 weeks). For those participants who attended at least one session, the mean duration of the sessions was 34.5 minutes (SD 8.2 minutes). Most participants in both collaborative care and usual care remained on antidepressant medication (74.8% vs. 73.8% at 4 months; 69.7% vs. 69.2% at 12 months).

The mean number of collaborative care sessions per participant in which medication was discussed was 3.2 (SD 3.43, range 0–13). The mean number of sessions incorporating behavioural activation was 5.4 (SD 3.4, range 0–13). The mean number of face-to-face contacts per participant was 1.17 (SD 0.92, range 0–6). The mean number of telephone contacts was 5.3 (SD 3.5, range 0–14).

We collected 220 supervision records reporting a mean supervision time of 35 minutes per week, with six participants discussed on average per session. Participants were discussed in an average of three supervisory sessions over the course of their intervention, at 6 minutes per participant per session. Care managers, therefore, received the intended level of supervision and number of sessions, with the number of participants discussed being dependent on the caseload of individual care managers.

Primary outcome: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 at 4 months

The primary and secondary outcomes at 4 and 12 months are presented in Table 5 and data on recovery, response and numbers needed to treat are presented in Table 6. With regard to the primary outcome (PHQ-9 at 4 months) we found a significant effect of collaborative care. The estimated mean depression score was 1.33 PHQ-9 points lower (95% CI –2.31 to –0.35; p = 0.009) for participants receiving collaborative care than for participants receiving usual care after adjustment for baseline depression. More participants receiving collaborative care than those receiving usual care met criteria for recovery [odds ratio (OR) 1.67, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.29; number needed to treat 8.4] and response (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.58; number needed to treat 7.8).

| Outcome | Collaborative care | Usual care | Adjusted difference | 95% CI | p-value | Effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||

| PHQ-9 score at baseline | 276 | 17.4 | 5.2 | 305 | 18.1 | 5.0 | ||||

| PHQ-9 score at 4 monthsa | 230 | 11.1 | 7.3 | 275 | 12.7 | 6.8 | –1.33 | –2.31 to –0.35 | 0.009 | 0.26 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| PHQ-9 score at 12 months | 235 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 263 | 11.7 | 6.8 | –1.36 | –2.64 to –0.07 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| GAD-7 score at baseline | 276 | 12.9 | 5.3 | 305 | 13.6 | 4.7 | ||||

| GAD-7 score at 4 months | 228 | 9.1 | 6.8 | 273 | 9.8 | 5.8 | –0.39 | –1.30 to 0.53 | 0.4 | 0.08 |

| GAD-7 score at 12 months | 227 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 253 | 9.1 | 6.2 | –1.09 | –2.21 to 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| SF-36 MCS score at baseline | 276 | 23.2 | 10.4 | 305 | 22.3 | 10.3 | ||||

| SF-36 MCS score at 4 months | 227 | 34.6 | 15.4 | 268 | 30.7 | 13.7 | 3.4 | 1.1 to 5.7 | 0.005 | 0.33 |

| SF-36 MCS score at 12 months | 223 | 36.4 | 15.0 | 249 | 33.4 | 14.5 | 2.5 | –0.6 to 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.24 |

| SF-36 PCS score at baseline | 276 | 44.8 | 12.4 | 305 | 44.5 | 12.3 | ||||

| SF-36 PCS score at 4 months | 227 | 45.8 | 13.2 | 268 | 45.6 | 13.8 | –0.05 | –1.67 to 1.56 | 0.9 | –0.004 |

| SF-36 PCS score at 12 months | 223 | 46.1 | 13.2 | 249 | 44.9 | 13.3 | –0.93 | –0.93 to 3.01 | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| CSQ-8 score at 4 months | 232 | 25.3 | 5.8 | 269 | 22.1 | 6.2 | 3.13 | 1.87 to 4.39 | < 0.001 | 0.52 |

| Collaborative care | Usual care | ORa | 95% CIb | p-valueb | Number needed to treatc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Recovered/responded, n (%) | n | Recovered/responded, n (%) | |||||

| Recoveryd | ||||||||

| 4 months | 230e | 108 (47.0) | 275 | 96 (34.9) | 1.67 | 1.22 to 2.29 | 0.001 | 8.4 |

| 12 months | 235 | 131 (55.7) | 263 | 106 (40.3) | 1.88 | 1.28 to 2.75 | 0.001 | 6.5 |

| Responsef | ||||||||

| 4 months | 230e | 99 (43.0) | 275 | 83 (30.2) | 1.77 | 1.22 to 2.58 | 0.003 | 7.8 |

| 12 months | 235 | 115 (48.9) | 263 | 93 (35.4) | 1.73 | 1.22 to 2.44 | 0.002 | 7.3 |

Secondary outcomes

Depression at 12 months

At 12 months’ follow-up, PHQ-9 data were available for 498 participants, 86% of those recruited (see Table 5). There was a significant effect of collaborative care on depression at 12 months. The mean PHQ-9 score was 1.36 points lower (95% CI –2.64 to –0.07; p = 0.04) in participants receiving collaborative care than in those receiving usual care (standardised effect size 0.28, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.52). More participants in collaborative care than in usual care met criteria for recovery (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.75; number needed to treat 6.5) and response (OR 1.73, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.44; number needed to treat 7.3) (see Table 6).

Anxiety

We found no significant effect of collaborative care on anxiety at 4 months, as measured by the GAD-7 (see Table 5). The adjusted difference between the groups in the anxiety score at 4 months was 0.39 (95% CI –1.30 to 0.53; p = 0.4). At 12 months there was also no significant effect of collaborative care on anxiety. The adjusted difference between the groups in the anxiety score at 12 months was 1.09 (95% CI –2.21 to 0.03; p = 0.06).

Quality of life

Mental health

We found a highly significant effect of collaborative care on the mental component summary (MCS) score of the SF-36 at 4 months, with the mean score higher by 3.4 T-score points (95% CI 1.1 to 5.7 T-score points; p = 0.005) in the collaborative care group. This corresponds to an effect size of 0.33 SD (95% CI 0.11 to 0.56 SD). At 12 months this effect was no longer significant (mean difference 2.5 T-score points, 95% CI −0.6 to 5.5 T-score points; p = 0.1).

Physical health

We found no significant effect of collaborative care on the quality of physical health at 4 months, as measured by the SF-36. The difference between the groups in the physical component summary (PCS) score of the SF-36 was 0.05 T-score points (95% CI –1.67 to 1.56; p = 0.9). The same was true at 12 months, with a difference in PCS T-score points between the groups of 1.04 (95% CI −0.93 to 3.01; p = 0.3).

Table 7 shows the adjusted effect of collaborative care on each SF-36 subscale at 4 months. Four of the subscales indicated significant benefits of collaborative care: mental health, role limitations (emotional) and vitality of the mental components and general health of the physical components. Although not significant, the other element of the mental dimension, social functioning, showed a small estimated benefit, too.

| Subscale | Coefficient | Robust standard error | t | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0.038 | 0.078 | 0.49 | 0.6 | −0.119 to 0.194 |

| Role limitations, physical | 0.065 | 0.096 | 0.68 | 0.5 | −0.128 to 0.258 |

| Bodily pain | −0.021 | 0.095 | −0.22 | 0.8 | −0.211 to 0.170 |

| General health perceptions | 0.271 | 0.071 | 3.81 | < 0.001 | 0.128 to 0.415 |

| Social functioning | 0.157 | 0.114 | 1.37 | 0.2 | −0.074 to 0.387 |

| Mental health | 0.289 | 0.103 | 2.79 | 0.007 | 0.081 to 0.497 |

| Role limitations, emotional | 0.264 | 0.100 | 2.63 | 0.01 | 0.062 to 0.465 |

| Vitality | 0.337 | 0.097 | 3.48 | 0.001 | 0.142 to 0.531 |

Client satisfaction at 4 months

We found a highly significant effect of collaborative care on client satisfaction (see Table 5). The adjusted difference between the groups in satisfaction score at 4 months was 3.13 (95% CI 1.87 to 4.39; p < 0.001). The estimated effect size for the CSQ-8 was 0.52 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.73). This has been calculated slightly differently from the effect sizes for the PHQ-9, GAD-7 and SF-36 because there is no baseline SD. The crude SD within intervention groups for all participants at 4 months was used.

Missing data

In Table 8 we present the results after multiple imputation for the effect of collaborative care at 4 and 12 months on the main scales used, which also shows the results of the analyses using the available data, which were reported in the preceding sections. The imputed estimates are very similar to the available data estimates and so we can conclude that for all of these analyses the effects of collaborative care are little affected by missing data. The lower GAD-7 anxiety score at 12 months in the collaborative care group, which is not significant in the available data analysis, is just statistically significant in this simulation. However, the difference in the p-value (0.06 or 0.05) is very small.

| Scale | Data | Coefficient | Robust standard error | t | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score at 4 months | Imputed | −1.31 | 0.53 | −2.49 | 0.02 | −2.37 to −0.26 |

| Available data | −1.33 | 0.49 | −2.72 | 0.009 | −2.31 to −0.35 | |

| PHQ-9 score at 12 months | Imputed | −1.29 | 0.62 | −2.08 | 0.04 | −2.54 to −0.04 |

| Available data | −1.36 | 0.64 | −2.13 | 0.04 | −2.64 to −0.07 | |

| GAD-7 score at 4 months | Imputed | −0.37 | 0.45 | −0.82 | 0.4 | −1.27 to 0.53 |

| Available data | −0.39 | 0.45 | −0.85 | 0.4 | −1.30 to 0.53 | |

| GAD-7 score at 12 months | Imputed | −1.07 | 0.52 | −2.04 | 0.05 | −2.12 to −0.01 |

| Available data | −1.09 | 0.56 | −1.95 | 0.06 | −2.21 to 0.03 | |

| SF-36 PCS score at 4 months | Imputed | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 1.0 | −1.53 to 1.59 |

| Available data | −0.05 | 0.80 | −0.07 | 0.9 | −1.67 to 1.56 | |

| SF-36 PCS score at 12 months | Imputed | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 0.3 | −0.84 to 2.80 |

| Available data | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.3 | −0.93 to 3.01 | |

| SF-36 MCS score at 4 months | Imputed | 3.6 | 1.2 | 3.13 | 0.003 | 1.3 to 6.0 |

| Available data | 3.4 | 1.2 | 2.97 | 0.005 | 1.1 to 5.7 | |

| SF-36 MCS score at 12 months | Imputed | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.86 | 0.07 | −0.2 to 5.4 |

| Available data | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.60 | 0.1 | −0.1 to 5.5 | |

| CSQ-8 score at 4 months | Imputed | 3.20 | 0.61 | 5.23 | < 0.001 | 1.97 to 4.44 |

| Available data | 3.13 | 0.63 | 4.98 | < 0.001 | 1.87 to 4.39 |

Missing data were related to intervention group. Table 9 shows missing PHQ-9 data at 4 months and 12 months by intervention group. At 4 months, missing data were significantly more likely in the collaborative care group. At 12 months the difference between the groups was much smaller and not significant. As far as we can tell, this difference in missingness at 4 months does not produce a difference in the outcome variables between the two groups and does not explain the observed lower PHQ-9 score in the collaborative care group. This difference persists at 12 months, when the difference in missingness is much smaller.

| Time point of missing PHQ-9 data | Intervention group, n (%) | OR for missing data in collaborative care group | p-value (robust standard error) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care | Usual care | |||

| 4 months | 46 (16.7) | 30 (9.8) | 1.83 | 0.03 |

| 12 months | 41 (14.9) | 42 (13.8) | 1.09 | 0.7 |

Results of the economic analyses

Our estimated mean cost per participant for the delivery of the collaborative care intervention was £272.50. This cost estimate includes care manager costs at £232 and clinical supervision costs of £40.50. Our probabilistic analyses used to explore uncertainty around the main cost component, drawing from the distribution of contact time for care managers, showed that in 95% of simulations (cost estimates) the estimated cost of collaborative care was between £101 and £592 per participant (median £249 per participant).

NHS and social care resource use and costs

We found no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in use of resources prior to the baseline assessment. Table 10 presents resource use over the 12-month follow-up period and Table 11 presents the costs associated with the resource use over the 12-month follow-up period. Table 12 presents cost data by category with comparison by treatment group. We found a broadly similar pattern of resource use across groups, with estimated mean costs of NHS and social care (third-party payer perspective), excluding the collaborative care intervention, of £1571 and £1614 for usual care and collaborative care participants respectively. After adjustment for baseline costs and individual and cluster covariates the cost difference was not statistically significant, with wide CIs. When including the cost of the collaborative care intervention, the mean total NHS and social care costs were £1571 and £1887 for usual care and collaborative care participants, respectively, but, similarly, after adjustment the cost difference of £271 was not statistically significant. Excluding the intervention cost, the one area of substantial cost difference between groups was for hospital stay, with a mean cost difference of £161 (regression-adjusted estimate). This estimated difference in hospital costs was driven by one participant in the collaborative care group who reported an acute psychiatric hospital stay of 100 days. When we excluded this participant from the analyses, the cost difference for hospital stay was adjusted to £34.27 (95% CI –£119 to £189) and the related differences in NHS and social care costs, without collaborative care costs and with collaborative care costs, were adjusted to –£209 (lower cost for collaborative care) and £63 (additional cost for collaborative care), respectively.

| Resource item | Usual care (n = 305) | Collaborative care (n = 276) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) [range] | n | Mean (SD) [range] | |

| Primary/community care (contacts) | ||||

| GP (surgery/practice) | 244 | 8.21 (6.69) [0–56] | 217 | 7.77 (6.78) [0–45] |

| GP (home) | 247 | 0.12 (0.80) [0–11] | 218 | 0.05 (0.27) [0–3] |

| Nurse (surgery/practice) | 247 | 1.77 (3.08) [0–24] | 215 | 1.68 (3.10) [0–32] |

| Nurse (home) | 247 | 0.06 (0.46) [0–4] | 218 | 0.05 (0.45) [0–6] |

| Walk-in centre | 247 | 0.32 (0.87) [0–8] | 217 | 0.31 (0.86) [0–5] |

| Counsellor | 246 | 3.58 (11.26) [0–116] | 212 | 2.67 (7.21) [0–48] |

| Mental health worker | 247 | 0.58 (3.51) [0–50] | 215 | 0.79 (3.72) [0–36] |

| Social worker | 247 | 0.34 (1.79) [0–14] | 218 | 0.58 (3.94) [0–33] |

| Home help/care worker | 247 | 4.35 (47.27) [0–722] | 218 | 1.24 (15.07) [0–220] |

| Occupational therapist | 247 | 0.22 (0.98) [0–9] | 218 | 0.13 (0.61) [0–5] |

| Voluntary group | 247 | 0.94 (5.80) [0–64] | 218 | 0.22 (1.39) [0–16] |

| Secondary care | ||||

| Hospital admissions, n | 247 | 34 | 218 | 28 |

| Acute psychiatric ward (days) | 247 | – | 218 | 0.78 (11.51) [0–170]a |

| Psychiatric rehabilitation ward (days) | 247 | – | 218 | – |

| Long-stay ward (days) | 247 | 0.06 (0.94) [0–15] | 218 | – |

| Psychiatric ICU ward (days) | 247 | – | 218 | – |

| General medical ward (days) | 247 | 0.48 (2.02) [0–21] | 217 | 0.42 (1.67) [0–12] |

| Other hospital ward (days) | 247 | 0.28 (1.58) [0–17] | 218 | 0.39 (2.12) [0–24] |

| Accident and emergency (attendance) | 247 | 0.40 (0.93) [0–7] | 218 | 0.34 (0.76) [0–5] |

| Day hospital (attendance) | 247 | 0.60 (2.22) [0–24] | 218 | 0.36 (1.19) [0–12] |

| Outpatient appointment | 247 | 2.62 (5.60) [0–58] | 217 | 2.63 (5.63) [0–65] |

| Social care (contact/session) | ||||

| Used day care services (%)b | 247 | 3/2 | 218 | 4/3 |

| Day care centre | 247 | 0.28 (4.54) [0–70] | 218 | 0.07 (1.08) [0–16] |

| Drop-in club | 247 | 0.56 (5.26) [0–70] | 218 | 0.12 (1.40) [0–20] |

| Day care other | 247 | 0.39 (2.85) [0–28] | 217 | 0.65 (5.67) [0–74] |

| Informal care from friends/relatives | ||||

| Had help/care from friends/relatives (%)b | 45/48 | 38/35 | ||

| Hours per week help from friends/relativesc | 230 | 6.11 (15.44) [0–112] | 209 | 3.95 (10.11) [0–104] |

| Report time off work for friends/relatives (%)b | 7/9 | 7/10 | ||

| Days off work lost by friends/relatives | 246 | 4.05 (29.14) [0–360] | 217 | 1.65 (11.28) [0–144] |

| Participant other costs | ||||

| OTC cost (£) | 246 | 28.40 (57.90) [0–429]d | 215 | 40.31 (68.61) [0–507]d |

| Travel costs (£) | 246 | 10.98 (30.30) [0–320] | 216 | 14.33 (37.57) [0–202] |

| Own car travel (miles) | 246 | 26.12 (77.68) [0–600] | 214 | 31.53 (138.95) [0–1862] |

| Other ‘one-off’ costs (£) | 246 | 35.77 (144.35) [0–1569] | 218 | 51.58 (213.53) [0–1998] |

| Resource item | Usual care (n = 305) | Collaborative care (n = 276) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) (£) | n | Mean (SD) (£) | |

| Primary/community care | ||||

| GP (surgery/practice) | 244 | 295.52 (241) | 217 | 279.76 (243) |

| GP (home) | 247 | 14.21 (97) | 218 | 5.55 (32) |

| Nurse (surgery/practice) | 247 | 26.54 (46) | 215 | 25.19 (46) |

| Nurse (home) | 247 | 1.94 (14) | 218 | 1.38 (13) |

| Walk-in centre (attendance) | 247 | 13.28 (35) | 217 | 12.66 (35) |

| Counsellor | 246 | 214.63 (676) | 212 | 160.47 (433) |

| Mental health worker | 247 | 44 (267) | 215 | 59.74 (283) |

| Social worker | 247 | 72.10 (379) | 218 | 122.53 (835) |

| Home help/care worker | 247 | 78.27 (851) | 218 | 22.38 (271) |

| Occupational therapist | 247 | 18.26 (80) | 218 | 10.53 (50) |

| Voluntary group | 247 | 20.50 (126) | 218 | 4.88 (30) |

| Secondary care | ||||

| Acute psychiatric ward | 247 | 0 | 218 | 243.30 (3,592) |

| Psychiatric rehabilitation ward | 247 | 0 | 218 | 0 |

| Long-stay ward | 247 | 13.51 (212) | 218 | 0 |

| Psychiatric ICU ward | 247 | 0 | 218 | 0 |

| General medical ward | 247 | 154.65 (649) | 217 | 134.61 (535) |

| Other hospital ward/stay | 247 | 90.97 (507) | 218 | 123.69 (682) |

| Accident and emergency | 247 | 43.06 (99) | 218 | 36.47 (81) |

| Day hospital | 247 | 74.99 (280) | 218 | 45.08 (150) |

| Outpatient appointment, psychiatrist | 247 | 26.79 (148) | 217 | 43.88 (170) |

| Outpatient appointment, psychologist | 247 | 25.14 (313) | 217 | 25.51 (296) |

| Outpatient appointment, community psychiatric nurse | 247 | 8.92 (67) | 217 | 12.61 (166) |

| Outpatient appointment, other | 246 | 306.93 (588) | 215 | 285.34 (498) |

| Social care | ||||

| Day care centre | 247 | 9.64 (151) | 218 | 2.50 (37) |

| Drop-in club | 247 | 19.13 (179) | 218 | 4.06 (48) |

| Day care other | 247 | 13.35 (97) | 217 | 22.09 (193) |

| Informal care from friends/relatives | ||||

| Help from friends/relatives | 230 | 5714.73 (14,455) | 209 | 3698.50 (9462) |

| Days off work lost by friends/relatives | 246 | 403.26 (2902) | 217 | 164.78 (1123) |

| Participant other costs | ||||

| OTC costs (£) | 246 | 28.40 (58) | 215 | 40.31 (69) |

| Travel costs (£) | 246 | 10.98 (30) | 216 | 14.33 (38) |

| Own car travel | 246 | 11.75 (35) | 214 | 14.19 (63) |

| ‘One-off’ costs (£) | 246 | 35.77 (144) | 218 | 51.58 (213) |

| Resource item | Usual care (n = 305) | Collaborative care (n = 276) | Difference, no adjustment (£) | Difference, adjusted for baseline and participant/cluster covariates,a mean (95% CI)b (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) (£) | n | Mean (SD) (£) | |||

| Primary and community services/care | 243 | 801.49 (1476.98) | 208 | 715.86 (1220.06) | –85.63 | –116.48 (–341.06 to 110.91) |

| Secondary care: hospital stay | 247 | 259.14 (835.40) | 217 | 402.65 (2282.88) | 143.51 | 160.92 (–70.81 to 481.70) |

| Secondary care: outpatient care | 246 | 368.03 (781.43) | 215 | 368.09 (692.60) | 0.06 | –30.68 (–148.85 to 111.70) |

| Secondary care: day hospital | 247 | 74.99 (280.31) | 218 | 45.08 (149.65) | –29.91 | –14.52 (–50–13 to 17.94) |

| Accident and emergency | 247 | 42.06 (98.66) | 218 | 36.47 (80.51) | –5.59 | –5.87 (–22.39 to 9.99) |

| Day services and care | 247 | 42.12 (334.85) | 217 | 28.67 (203.43) | –13.45 | 1.83 (–38.51 to 41.01) |

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services (excluding collaborative care) | 242 | 1570.70 (2441.55) | 205 | 1614.32 (3714.49) | 43.62 | 1.78 (–454.82 to 640.81) |

| Collaborative care | – | 272.50 | 272.50 | – | ||

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services | 242 | 1570.70 (2441.55) | 205 | 1886.82 (3714.49) | 316.12 | 270.72 (–202.98 to 886.04)c |

| Patient personal costs (OTC costs/medications and travel costs plus patient ‘one-off’ costs) | 244 | 86.64 (175.50) | 211 | 120.79 (260.37) | 34.15 | 24.95 (–12.41 to 65.61) |

| Informal care costs | 230 | 5714.73 (14,455.18) | 209 | 3698.50 (9642.61) | –2016.23 | –1114.13 (–3366.09 to 1117.32) |

| Total costs (NHS and patient/related costs) | 223 | 7010.59 (13,492.42) | 195 | 5764.48 (10,796.40) | –1246.11 | –312.83 (–2339.92 to 2035.27)c |

Broader participant-level and social costs

In Tables 10 and 11 we report resource use and cost estimates associated with informal care from friends and/or relatives and other participant out-of-pocket expenses. Our findings show that informal care costs, when estimated using a shadow price for informal care (an estimate of £18 per hour; see Table 1), represented the largest resource and cost burden associated with participants’ depression. Participants in the usual care group reported a high use of informal care, which resulted in a higher mean (SD) cost estimate over 12 months of £5715 (£14,455); this compared with £3699 (£9462) in the collaborative care group. However, there is wide variation in the self-report data as shown by the large SDs. When adjusting for baseline costs and other covariates the difference in estimated cost for informal care was –£1114 (95% CI –£3366 to £1117), with lower costs for the collaborative care group and, therefore lower total costs for the collaborative care group (see Table 12).

Quality-adjusted life-years

In Table 13 we report data on health state values for the EQ-5D and SF-6D and the estimated QALY values over the 12-month follow-up period. When adjusted for baseline and for individual and cluster covariates we found a difference of 0.02 QALYs (95% CI –0.02 to 0.06 QALYs) over 12 months for the EQ-5D and 0.017 QALYs (95% CI 0.000 to 0.032 QALYs) for the SF-6D. Both measures show a QALY gain for collaborative care, although the EQ-5D difference is not statistically significant.

| Resource item | Usual care (n = 305) | Collaborative care (n = 276) | Difference, no adjustment | Difference, adjusted for baseline and participant/cluster covariates,a mean (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) [range] | n | Mean (SD) [range] | |||

| EQ-5D: baseline | 305 | 0.464 (0.313) [–0.29 to 1.00] | 276 | 0.504 (0.288) [–0.349 to 1.00] | 0.040 | |

| EQ-5D: 4 months | 273 | 0.557 (0.331) [–0.239 to 1.00] | 228 | 0.599 (0.341) [–0.484 to 1.00] | 0.042 | |

| EQ-5D: 12 months | 254 | 0.593 (0.338) [–0.349 to 1.00] | 227 | 0.650 (0.317) [–0.484 to 1.00] | 0.057 | |

| EQ-5D: QALYs (12 months) | 248 | 0.554 (0.286) [–0.27 to 0.97] | 218 | 0.605 (0.261) [–0.29 to 0.97] | 0.051b | 0.019 (–0.019 to 0.06)c |

| SF-6D: baseline | 303 | 0.538 (0.86) [0.30 to 0.77] | 274 | 0.540 (0.83) [0.30 to 0.82] | 0.002 | |

| SF-6D: 4 months | 269 | 0.597 (0.126) [0.30 to 1.00] | 227 | 0.614 (0.140) [0.32 to 1.00] | 0.017 | |

| SF-6D 12 months | 250 | 0.605 (0.131) [0.30 to 1.00] | 223 | 0.634 (0.144) [0.30 to 1.00] | 0.029b | |

| SF-6D: QALYs (12 months) | 241 | 0.591 (0.109) [0.30 to 0.90] | 211 | 0.609 (0.114) [0.35 to 0.91] | 0.018 | 0.0168 (0.000 to 0.032) |

Cost-effectiveness analyses

In Table 14 we present estimates of cost per QALY, based on participants with data on costs and outcomes at follow-up. The base-case cost per QALY for collaborative care was £14,248, adopting a NHS and social care perspective, with uncertainty around this estimate illustrated in Figure 3 (cost-effectiveness plane) and Figure 4 (CEACs). The probability that collaborative care is cost-effective compared with treatment as usual is 0.58 at a willingness to pay of £20,000 per QALY and 0.65 at a willingness to pay of £30,000 per QALY.

| Scenario/analysis | Difference, adjusted for baseline and participant/cluster covariates,a mean (95% CI) | ICER, cost (£) per QALY | Probability collaborative care cost-effective at WTPb per QALY gained of | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| £20,000 per QALY | £30,000 per QALY | |||

| Base case | ||||

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services costs (£) | 270.72 (–202.98 to 886.04) | |||

| EQ-5D: QALYs (12 months) | 0.019 (–0.019 to 0.06) | 14,248 | 0.58 | 0.65 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||

| 1. Base-case cost-effectiveness analysis with multiple imputation of missing data | ||||

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services costs (£) | 292.08 (–216.88 to 801.04) | |||

| EQ-5D: QALYs (12 months) | 0.017 (–0.020 to 0.054) | 17.490 | NA | NA |

| 2. Cost-effectiveness analysis using SF-6D QALY data | ||||

| SF-6D: QALYs (12 months) | 0.0168 (0.000 to 0.032) | 16,114 | 0.57 | 0.72 |

| 3. Cost-effectiveness analysis when excluding one high-cost participant | ||||

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services costs (£) | 63.34 (–295.98 to 422.67) | |||