Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/141/05. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The draft report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Nefyn Williams, Rhiannon Tudor Edwards and Joanna Charles’s posts are part funded and Noel Craine is employed by Public Health Wales. Jane Noyes received grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study and received other financial support for speaking at a Diabetes UK conference sponsored by Janssen-Cilag Ltd, AstraZeneca UK, Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd and Roche who may produce and distribute contraceptives to the target population of this systematic review outside the submitted work. Jo Rycroft-Malone is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) Board (commissioned research) and, since completing this research, she has been appointed director of the NIHR HS&DR programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Whitaker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The World Health Organization reports that there are 16 million births annually to mothers aged 15–19 years. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are a leading cause of death in this age group. Repeat pregnancy in adolescents is a significant public health concern across the world, since it frequently occurs in the context of economic constraints and poor maternal and child well-being. 1–3 Despite data from the UK that are consistent with a gradual decline in teenage conception rates, the UK continues to have one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in Western Europe. 4–6 Repeat pregnancies represent a considerable proportion of the overall rate of teenage pregnancy: one-fifth of births among girls under 18 years of age are estimated to result from repeat pregnancies7 and thus are a crucial focus for intervention. Around three-quarters of teenage pregnancies are unplanned with up to half resulting in abortion. 8 Within the UK, teenage pregnancy is strongly associated with social disadvantage. The social predictors of repeat adolescent pregnancy are varied and, previously, have been usefully grouped into predictors operating at individual, couple, family, community and social levels. 9 These predictors share much in common with those of first teenage pregnancies. ‘Unintended’ or ‘unplanned’ pregnancy have often been used as a proxy measure of poor sexual health. 10

Teenage pregnancies have a considerable impact on the individual well-being of teenage parents and their children. Inherent within the national strategy responses, and a range of other national policy documents addressing this issue, is the recognition that babies of teenage mothers have increased mortality in their first year and a significantly increased risk of living in poverty, poor achievement at school and being unemployed later in life,11 with substantial costs to society. Teenage pregnancies are a target for the England Teenage Pregnancy Strategy and their equivalents within the devolved governments of the UK. 8,12–14

Teenage pregnancy is associated with an almost threefold risk of preterm delivery and stillbirth. 1,15 Young mothers who have had repeat pregnancies are vulnerable to health risks associated with early childbearing,16,17 abortion outcomes and sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). 18 They also face a number of challenges, including interpersonal violence and abuse,19 inability to complete school and substance abuse. 17 This results in a significant socioeconomic cost to the adolescent, their families and societies at large. Societal costs result from the increased use of general and specialist health services for mother and child, programme implementation, educational and skills training for young mothers (and staff supporting them) to provide psychosocial and economic empowerment, welfare assistance for young mothers experiencing financial difficulties and lost tax revenues arising from reduced earnings. 20–24

Repeat pregnancy in adolescents is defined here as the incidence of two or more pregnancies before the age of 20 years. Defining ‘intended’ poses a challenge since this term is used inconsistently in the professional literature. For example, ‘intended’, ‘unintended’, ‘mistimed’, ‘wanted’, ‘unwanted’ and ‘planned’ are used interchangeably. A validated index has been developed to produce reliable estimates of intention in pregnancy, which also assesses if, or how, women’s accounts changed over time. 25 For this review, we have conceptualised unintendedness as a construct based on unwantedness and mistiming to mean any incidence of pregnancy when intention was not specifically stated. 26 We have included literature covering any repeat conception in young women that was not specifically planned. A woman’s perception of her pregnancy may change over time. The difference between an unintended conception and an unwanted child is not within the scope of this review. We have concentrated on interventions designed to reduce conceptions.

Description of the interventions

To address the short- and long-term consequences of unintended pregnancies for adolescents, their families and the society at large, various local and national public health programmes have been implemented for first-time pregnancies. It is not clear whether or not these interventions are effective at preventing repeat unintended pregnancies in teenagers. Such interventions may be population-based strategies or policies, or comprise simple interventions targeting specific groups, for example interventions may include contraception advice or provision, or complex interventions that include a combination of school- and community-based or targeted efforts. These interventions may, for example, be nurse-led interventions or occur in a group setting which includes peer support. The building blocks for these interventions could include, in differing combinations, elements of health education, skill building, contraception education and distribution, individual counselling, etc. Furthermore, they could be designed to increase adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes relating to the risk of unintended pregnancies and promote delaying the initiation of sexual intercourse and encourage the consistent use of birth control.

How the interventions might work

Interventions which have been shown to be effective at reducing first-time teenage pregnancies focused on sex education, skills training for jobs and personal development. 27–29 These complex interventions were intended to reduce teenage pregnancy by increasing self-confidence and work opportunities, combined with increasing access to contraception. With regard to repeat pregnancy, there is an additional concern for the well-being of a young mother’s other children. Therefore, complex interventions may aim to address parenting skills and a knowledge of child development, as well as meeting the goals and needs of the young mother.

Heller30 postulated that a multidimensional, theoretical model of adolescent pregnancy is conducive to the application of a preventative intervention research cycle to reduce the incidence of adolescent pregnancy. Other diverse theoretical models have been borrowed from different disciplines. Based on literature related to adolescent pregnancy, we have identified five candidate theories for consideration. These theories take differing, but not mutually exclusive, attitudes to the mechanisms and drivers at work: (1) social–cognitive–ecological theory; (2) developmental theories; (3) resilience theory; (4) recoil–rebound theory; and (5) resilience–recoil–rebound theory.

Social–cognitive–ecological theory

Social–cognitive–ecological theory31 addresses cultural norms, modelling and the concepts of self-efficacy and support. It is based on Bandura’s32 postulation that a person’s internalised standards for behaviour are developed from information conveyed by sources of social influence (parents, peers and characters portrayed in mass media) and their environment. For example, a young mother may desire a repeat pregnancy to seek a sense of fulfilment as a woman, to create a stable relationship with her partner or to improve connections within her family.

Developmental theories

Erikson33 posited that an adolescent has physical, cognitive, socioemotional and moral goals to accomplish during their transition to adulthood. Developmental theories described in repeat pregnancy literature address this transition. In addition, they address the management and perception of pregnancy by adolescents, and the relationship between risky sexual behaviour and pregnancy. These theories also examine the development of health promotion behaviours in families led by adolescent parents. 34

Resilience theory

The concept of resilience can be described as ‘the process of identifying or developing resources and strengths to flexibly manage stressors to gain a positive outcome, a sense of confidence or mastery, self-transcendence, and self-esteem’. 35 Adolescent resilience theory focuses particularly on the ‘assets and resources that enable some adolescents to overcome the negative effects of risk exposure’. 36

Recoil–rebound theory

The main focus of this theory is the parenting adolescent mother’s resilience, social influences, recoil (having a repeat adolescent pregnancy) and rebound (the use of contraception or abstinence to prevent a repeat adolescent pregnancy). 37

Resilience–recoil–rebound theory

This model, proposed by Porter and Holness,37,38 has four central concepts: the adolescent, pregnancy, recoil–rebound interactions and resilience. The external influences of family, peers, school, church and community, though incorporated, are not major concepts within this theory.

Why it is important to do this review

A Cochrane review27 on interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents reported 41 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and three mixed studies (individually and cluster randomised). The results showed that complex interventions, which were primarily a combination of educational and contraceptive interventions, lowered the rate of unintended pregnancy among adolescents.

The UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) characterised the necessity for this systematic review in its call for proposals as follows:

Numerous prevention strategies such as health education, skills-building and improving accessibility to contraceptives have been employed across the UK in an effort to prevent unintended teenage pregnancy.

Oringanje et al. (2009)27

The commissioners go on to characterise the question further: ‘. . . there is uncertainty regarding the effects of these interventions, and in many areas the problem persists despite co-ordinated efforts to halve the number of teenage pregnancies over recent years’. 27 They point out that ‘Some groups of adolescents are at risk of multiple unintended pregnancies and it is not known if specific interventions or approaches will help to reduce the risk of further pregnancies in girls who have already had one pregnancy’. 27

As well as considering the effectiveness of interventions, there are broader questions to answer such as values for money, acceptability of interventions and the facilitators of and barriers to uptake of intervention. In addition, consideration should be given to how specific interventions might work, under what circumstances and in which groups of teenagers.

Aims of the review: the hypotheses tested and the research questions

The overall aims of this review were to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for preventing repeat unintended pregnancies among adolescents, and to investigate the barriers to and facilitators of their implementation and uptake. Although these overall aims were broad, the focus was on the implementation of interventions.

The specific research objectives were to determine:

-

What factors characterise subgroups that are at greatest risk of repeat unintended pregnancies (i.e. what are the predictors of repeat unintended pregnancy)?

-

Which (elements of) interventions appear to be effective, how do they work, in what setting and for whom? (Conversely, why are they ineffective/why do they not work?)

-

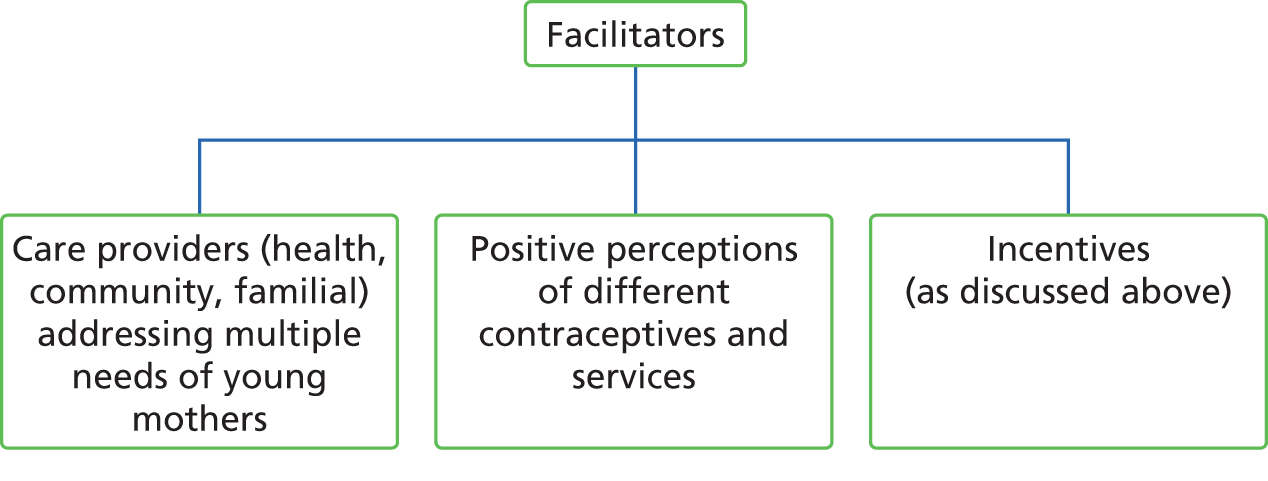

What are the barriers to and facilitators of the acceptability, uptake and implementation of interventions?

-

What is the relative cost-effectiveness of interventions?

Overall plan of the research

To address the complexity of the topic, a four-phase approach to the review was adopted:

-

Phase 1 We identified and filtered the literature by first applying inclusion/exclusion criteria then making a basic quality appraisal and a mapping of the literature types.

-

Phase 2 We prioritised and selected records for in-depth review and data extraction.

-

Phase 3 We synthesised the evidence according to study type and by using design-appropriate tools.

-

Phase 4 Finally, we gathered service user and stakeholder feedback and conducted an overarching narrative synthesis.

The map of these phases, evidence streams and methods of syntheses is fully described and illustrated in Chapter 3.

Structure of this report

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 fully describes all aspects of the search strategies, the sifting of evidence, the assessment of quality and the integration of the stakeholder’s consultation exercises. The methods employed for synthesising the different evidence streams are then discussed and, finally, details of the realist synthesis are given; this realist synthesis adds an extra dimension to the review by attempting to enable learning about the key contexts and mechanisms in order to provide a conceptual framework for the development of future interventions to prevent repeat teenage pregnancy. As the realist element is relatively unusual, we have detailed the rationale, methodology and approach in some detail.

Chapter 3, the results section, is divided into the results of the extractions and mapping exercises, including the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (see Figure 3), and the four basic review questions which address who is at risk, what is effective and cost-effective, and what are the barriers to and facilitators of implementation. We then report other outcomes of interest. The results we report here arise from both qualitative and qualitative evidence streams.

Chapter 4 brings a realist synthesis approach to bear on the evidence in order to draw out candidate theories of action of the interventions, and to identify barriers to and facilitators of intervention implementation.

In Chapter 5, the results reported in Chapter 4 are brought together in an overarching synthesis to enable the reader to see all the evidence summarised in matrix form.

In Chapter 6, the discussion and conclusions section, the findings are summarised. In addition, the review’s strengths and weaknesses are discussed, and the results are compared with existing literature before describing knowledge gaps, the implications for practice and policy, and identifying potential areas for future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes all aspects of the search strategies, the sifting of evidence, the assessment of quality and the integration of the stakeholder and service user consultation exercises. We then briefly discuss the methods employed for synthesising the different evidence streams. This is followed by an explanation of the realist synthesis, which adds an extra dimension to the review by attempting to enable learning about the key contexts and mechanisms in order to provide a conceptual framework for the development of future interventions to prevent repeat teenage pregnancy. As the realist element of this systematic review is relatively unusual, we have detailed the rationale, methodology and approach in some detail in this chapter.

Overall study design

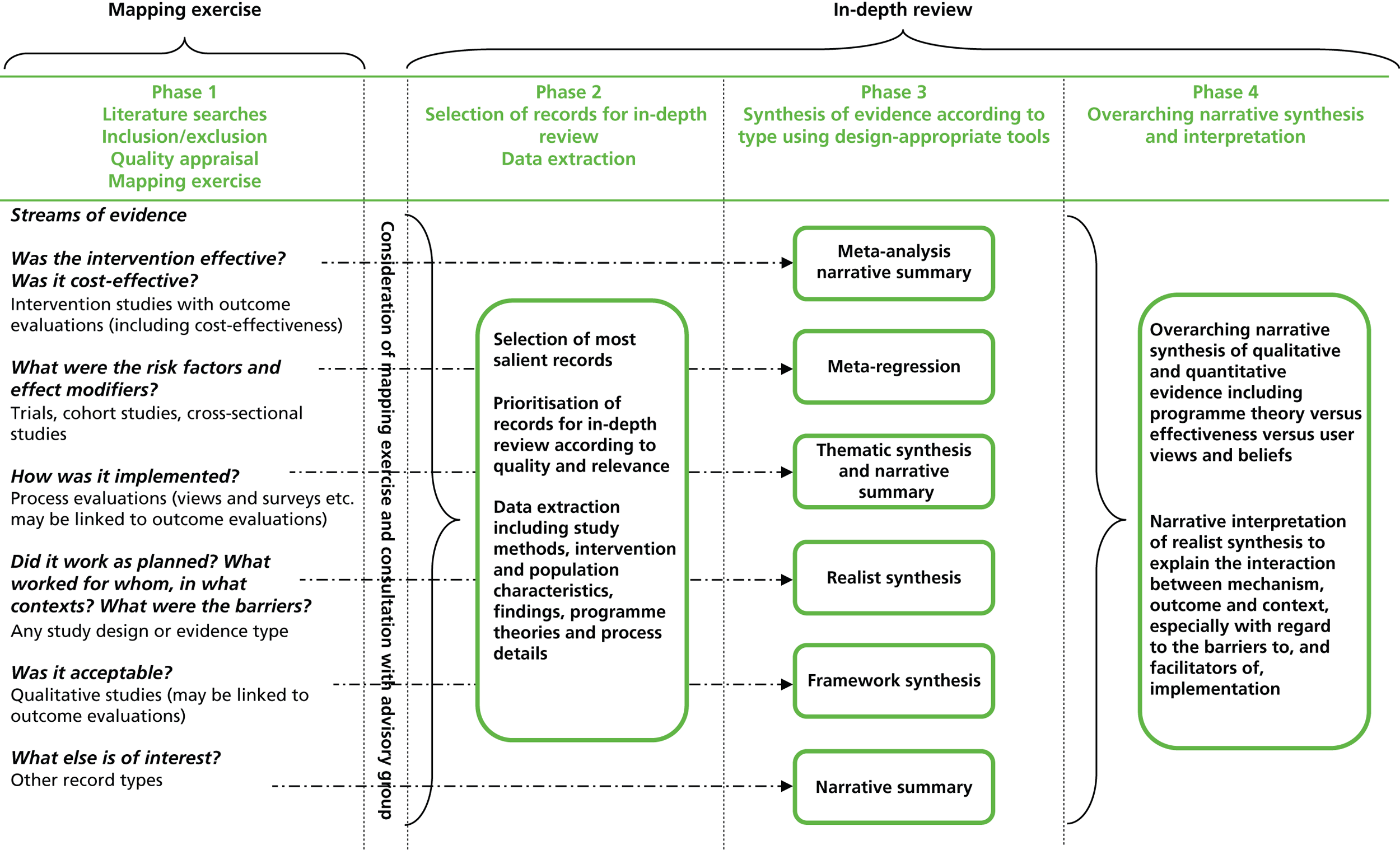

Initial scoping searches informed a tailored, four-phase approach to the review (Figure 1). For the overall framework of the mixed-methods review, we drew on the structured, phased, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) approach,39 and used their reviews of young people, pregnancy and social exclusion, and the barriers to and facilitators of children’s healthy eating as methodological exemplars. 40,41 After conducting extensive literature searches, screening the evidence against explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria and applying two initial screening criteria from our chosen quality appraisal tool, a mapping exercise was undertaken to organise and describe the evidence so as to give a clear picture of the body of research (phase 1). We presented the findings of our mapping exercise to our service provider consultation group; individual feedback regarding the focus of the in-depth review and possible gaps in the evidence were also presented.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of review methods.

After the mapping exercise, we prioritised and selected records for in-depth review and data extraction (phase 2) before synthesising the evidence according to study type and by using design-specific methods which we describe in more detail later in this chapter. Members of the review team presented preliminary findings at a second meeting of the service provider consultation group and subsequently to a group of young women who had experience of teenage pregnancy and early parenthood at meetings facilitated by Flying Start staff members (phase 3). Finally, we conducted an overarching narrative synthesis and interpreted the results (phase 4).

Stakeholder engagement

Members of our team were involved in co-ordinating a project (the Empower to Choose project) targeting repeat teenage conceptions, which is part of the Welsh Government’s Sexual Health and Wellbeing Action Plan12 aimed at reducing the rate of unwanted teenage pregnancies. The project included the implementation of an intervention to (1) increase education and raise awareness of the benefits of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in young women who present to services having conceived before their 18th birthday; and (2) provide a robust mechanism of referral to appropriate services for young women and capture patient-specific information that both supports individual patient care and allows audit of the number of looked-after children, the uptake of LARCs and pregnancy outcomes among this vulnerable group of young people. The work was guided by the Task and Finish Group, a group of practitioners, stakeholders, policy-makers and academics; Public Health Wales (PHW) co-ordinated this group and also facilitated the group engagement for this systematic review. The group also provided a route to engage with teenagers who had experienced pregnancy by utilising group members from two organisations that work with pregnant teenagers and young mothers: Barnardo’s Cymru (Cardiff, UK), which works with children, young people and families who are struggling to overcome the disadvantages caused by poverty, abuse and discrimination; and Flying Start (Swansea, UK), which is funded by the Welsh Government and brings together education, childcare, and health and social services to offer preventative interventions to improve outcomes for children. Both organisations work with pregnant teenagers and young mothers.

Literature searches

Databases searched

We conducted initial scoping searches to identify the volume and nature of the literature we were likely to encounter. Building on and revising those search strategies, we searched the major, relevant electronic databases (listed in Box 1) for published literature using strategies that combined thesaurus terms and keywords relating to pregnancy, termination of pregnancy (TOP) or parenthood with ‘adolescence’ and text word synonyms for ‘repeat’ or ‘subsequent’. These searches were conducted between May and July 2013 and updated in June 2014.

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations.

-

PsycINFO.

-

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature).

-

NHS EED (NHS Economic Evaluation Database).

-

EMBASE (Excerpta Medica database).

-

BNI (British Nursing Index).

-

ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center).

-

SocAbs (Sociological Abstracts).

-

DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects).

-

CDSR (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews).

-

HTA Database.

-

SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index).

-

ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts).

-

BiblioMap (the EPPI-Centre register of health promotion and public health research).

Design of search strategies

We used a search strategy developed and piloted in MEDLINE and subsequently modified for use in the other databases (full details of all the search strategies can be found in Appendix 1). Further modified versions of the same strategy were used to search the following databases for ‘grey’ literature: OpenGrey, Scopus, Scirus, Social Care Online, National Research Register, NIHR Clinical Research Network Portfolio and Index to THESES. To capture economic studies, we searched Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) and the American Economic Association’s electronic bibliography (EconLit). We applied an alternative search strategy specifically designed to capture the type of descriptive titles that are common in qualitative studies to the following selected databases: Sociological Abstracts (SocAbs), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), British Nursing Index (BNI) and the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). This strategy combined additional synonyms for ‘pregnancy’, ‘adolescence’ and ‘repeat’ with a brief qualitative filter comprising three broad free-text terms, ‘qualitative’, ‘findings’ and ‘interview$’, that has been shown to be as effective as a more complex one. 42,43

A number of systematic reviews related to teenage pregnancy have been published in the last two decades. The earliest we found in our scoping search was dated 1997. 44 Therefore, after allowing for an additional conservative margin, we limited our searches to 1995 onwards. We intended to conduct a separate sensitive search excluding the terms for second or subsequent pregnancies but including a filter for systematic reviews as a means of capturing relevant data from earlier studies; however, our expert panel advised us that social norms and behaviours relating to teenage motherhood have changed dramatically and that they considered evidence related to contraception more than 10 years old to be of limited relevance. Therefore, we omitted this additional search.

Owing to the dearth of UK literature identified in the database searches, we developed an additional strategy to identify UK grey literature using the search engine Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). This strategy comprised 24 search terms that were variations on ‘repeat’ or ‘second’ and ‘teenage’, ‘teenager’, ‘teenagers’, etc. and ‘pregnancy’ or ‘pregnancies’, each prefaced by the term ‘site: UK’. This search was conducted in January 2014.

In July 2014, we conducted repeat searches by (1) rerunning or updating the searches from all the relevant databases; (2) citation tracking the RCTs and systematic reviews identified during the course of our literature searches using ‘forward chaining’ and ‘backward chaining’ techniques;45 and (3) using the Google Scholar alert function to indicate any new trials on repeat adolescent pregnancy.

The issues surrounding implementation of interventions are a primary focus of this systematic review; qualitative and process evaluation evidence associated with trials is highly relevant, particularly to better understand the facilitators of and barriers to implementation. 46 Therefore, a key feature of our search strategy was to identify ‘evidence clusters’, that is studies that investigated the implementation or acceptability of interventions related to key RCTs. 47 These studies have the potential to indicate the effectiveness of an intervention as well as its acceptability to users and barriers to its implementation and uptake. However, we were unable to capitalise on the full potential of the approach as we wished to explore UK-relevant implementation issues, and all but one of the trials we identified were conducted in the USA and the other was conducted in Australia.

Finally, also in July 2014, we compiled a list of journals that had published the RCTs and the qualitative studies included in our review and compared this list with the Master List of hand-searched journals and conference proceedings (journals/conference proceedings being hand-searched by Cochrane Entities);48 we hand-searched the online indexes of 17 English-language journals that did not appear in this Master List from January 2010 (see Appendix 1). Because of time constraints and practical difficulties we did not search the index of one foreign language journal.

References were managed using EndNote bibliographic reference management software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and extracted data were organised in a database using Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant documents, which were retrieved and assessed according to the inclusion criteria described below (see Study inclusion criteria). Disagreements were resolved by discussion or, when necessary, by a third reviewer.

Stakeholder engagement exercises

Mapping exercise

In November 2013, we facilitated a meeting with a group of stakeholders, including public health, primary care, sexual health, obstetrics and midwifery representatives, as well as the full review team. A report of the meeting, including a list of those who attended, can be found in Appendix 2. We presented initial results from our mapping exercise to describe the scope of the literature we had identified and we conducted a workshop with three discussion groups which focused on linking the different topics to the group members’ experiences. We asked the subgroups at the meeting a range of questions; these are listed below:

-

How relevant is evidence from different settings and particularly from non-UK studies to your context?

-

What components of complex interventions do you consider to be most important in relation to reducing repeat pregnancies?

-

How relevant are other outcomes (health-related, social, educational, maternal or child-related, etc.) to repeat pregnancies?

-

Are repeat teenage pregnancies truly unintended? (What are the differences between unintended, unplanned and unwanted pregnancies?)

-

In your experience, what are the differences between the motivating factors for repeat teenage pregnancies and first teenage pregnancies?

-

Which intervention components best address the factors that motivate young women to have (or not to avoid having) a repeat pregnancy?

-

What are the barriers to and facilitators for accessing interventions?

-

What is the best way of packaging and presenting an intervention to teenage mothers to ensure maximum uptake (such as pregnancy spacing, making healthy choices, using contraception effectively, planning your future or others)?

-

How is the success of a programme best measured in monetary terms?

The meeting was concluded with feedback from the groups and discussion.

Presentation of preliminary findings and feedback exercise

In June 2014, a second meeting was facilitated as part of the work of the Task and Finish Group which co-ordinates the PHW response to teenage conceptions. Members of this group included public health, primary care, sexual health, obstetrics and midwifery representatives, as well as members of the review team. A report of the meeting, including an attendee list and comments made by stakeholders, can be found in Appendix 3.

We presented an overview of the study and progress to date, together with Phase 3 results from the quantitative and qualitative syntheses of the study, as well as preliminary findings from our realist synthesis, and invited feedback from the delegates.

We then presented the delegates with the following questions and received comments:

-

What do these findings mean to you within your work context?

-

Who do you think should hear these findings?

-

How do you think these findings should be delivered to these audiences to maximise uptake?

-

Is there a policy message?

-

Do these findings make sense to you?

-

How similar are they to the interventions you are delivering locally?

The findings from these meetings contributed to the realist synthesis (see Chapter 4) and informed the overarching synthesis (see Chapter 5).

Service user engagement

Two members of our team presented the findings of the review to a group of 17 young mothers, ranging in age from 15 to 22 years in April 2014. Flying Start helped us to organise and facilitate this meeting. Based on the evidence generated during the review, we sought opinions on the following three areas: (1) contraception, (2) psychosocial programmes and (3) barriers to and facilitators of the uptake of interventions. The findings were presented to the group through a range of person-centred activities. For example, to present the findings regarding contraception we used pictures of each contraceptive method on a flipchart with space to record summary points and keywords. The views expressed and the discussion that was stimulated are summarised in Appendix 4 and were used to inform both the realist synthesis and the narrative synthesis of this report.

Study selection

Study inclusion criteria

We included published studies from any country. Our search strategy was designed to capture published studies of any type, including trials of interventions, effectiveness studies, interrupted time series studies, cost-effectiveness studies, process evaluations, surveys and qualitative studies of participants’ views and experiences of interventions. We also considered relevant grey literature of any type, such as unpublished reports, service evaluations and theses, but limited this to UK-based literature so as to be applicable to the NHS and UK public health bodies. We set the earliest date for published work as 1995 and excluded any studies that reported data collected prior to 1990. We described the inclusion criteria using the patient intervention comparison outcome (PICO) framework. 49

Population

The population of interest comprised young women, aged ≤ 19 years at the time of conception, who had had at least one unintended pregnancy, whether the outcome was termination, miscarriage or delivery. If study populations were mixed, we included studies if at least 75% of the reported populations were young mothers in our target age group. 27

Interventions or phenomena of interest

We included studies of any intervention designed to reduce or delay repeat pregnancies (also referred to as ‘birth-spacing’ or ‘pregnancy-spacing’) in these young women, delivered in any educational, health-care or community setting. Interventions could have single or multiple components, and could be delivered to individuals or communities. We included studies designed to identify risk factors or subgroups at increased risk of repeat unintended pregnancy, or qualitative studies describing the experience of repeat teenage pregnancy if there was no actual intervention.

We included studies that identified barriers to and facilitators of the implementation and uptake of interventions, and explored the views of intervention recipients, providers and health professionals, particularly when information on whether or not the intervention was implemented and worked in the way intended was available. We looked for studies that could help us to identify programme theories and logic, and we looked for, and developed, candidate theories to explain why some young women have more than one unplanned pregnancy, in order to explain the relative success or failure of particular interventions. 50

Comparators

The comparators were no intervention, standard practice or an alternative intervention. Qualitative studies and studies containing epidemiological data suitable for contribution to risk factor assessment without a comparator were also included.

Outcomes

For this review, we selected studies that met the inclusion criteria irrespective of the results found. We focused on studies that reported on any primary or secondary outcomes of interest.

Primary outcomes

-

Effectiveness of interventions (reducing unintended teenage pregnancy).

-

Acceptability of interventions (the proportion of participants that reported the intervention was acceptable or, in the absence of this, the proportion of participants who were willing to be recruited into the study).

-

Uptake of the interventions (the proportion of participants who were recruited and received the intervention compared with those recruited).

Secondary outcomes

-

Reported changes in knowledge and attitudes about the risk of unintended pregnancies.

-

Age at initiation of sexual intercourse.

-

Use of birth control methods.

-

Abortion.

-

Childbirth.

-

Morbidity related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth.

-

Mortality related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth.

-

Sexually transmitted infections (including HIV).

-

Risky behaviours.

-

Abuse.

-

Validated quality-of-life indices.

The other phenomena of interest for the qualitative synthesis and realist review were the views and experiences of young women, families and professionals, and the identification of barriers to and facilitators of interventions relating to (1) acceptability, (2) uptake and (3) feasibility of implementation.

Study exclusion criteria

We did not exclude quantitative studies found in non-English-language publications; we used English-language abstracts, if available, to help decide whether or not they met our inclusion criteria and an online language translation service, Google Translate, to aid data extraction. Abstracts in which results could not be confirmed in subsequent publications were excluded. We found that translation software was adequate for the quantitative data extraction of baseline variables and outcome data but we were not confident of its reliability for the quality appraisal of studies; therefore, we asked a Spanish-speaking team member to appraise the quality of the foreign-language studies (which were published in Spanish and Portuguese).

A priori we had decided to exclude non-English-language qualitative studies if we had no native speakers available because of the complex nature of the linguistic validation of translations on such nuanced work. We did not, however, encounter any such papers so there was no loss of data.

We limited our searches for unpublished material to the UK to enhance the direct applicability of the results to the NHS and UK public health bodies. This judgement was supported by advice from the advisory group obtained during the stakeholder engagement exercise. Once studies found in the grey literature had met a very basic quality standard (see Quality appraisal section) they were included in the in-depth review and we incorporated further judgements about study quality when interpreting the evidence.

Data extraction

We created a bespoke set of data extraction forms to collect data from each study on the following: study characteristics (design, sample type, sample size, etc.); a description of the intervention or risk factors; the contextual factors in the study setting; the outcomes, including the costs of implementing the intervention; and programme theories or mechanisms described by the authors in the rationale behind the intervention or postulated in the explanation of the results. For quantitative studies, data extraction of study characteristics was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. The risk and outcome data were extracted independently by two reviewers and then compared; any disagreements were resolved by discussion and recourse to a third reviewer if necessary. Data extraction was performed on qualitative studies collaboratively by two reviewers.

Prioritising evidence for the in-depth review (further study inclusion criteria)

The review team, with advice from independent experts obtained during the stakeholder engagement exercises, prioritised the evidence for in-depth review. Beginning with evidence relating to primary outcomes and within each grouped set of data, we prioritised the best quality evidence of most relevance to address the research questions. In order to systematise this process we applied the completeness, accuracy, relevance and timeliness (CART) framework, whereby evidence is judged on the criteria of completeness, accuracy, relevance and timeliness. 51 We developed a protocol for applying CART criteria which can be found in Appendix 5. We screened all the studies using these criteria.

Study classification: Effective Practice and Organisation of Care classification

We classified all the quantitative papers using the flow chart shown in Appendix 6, in accordance with the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group’s non-randomised studies methods guidance on incorporating diverse types of evidence in a review (see Appendix 19). These guidelines classify the study designs to use for the evaluation of the effects of health-care interventions. If quantitative papers did not meet inclusion criteria for the quantitative effectiveness evaluation but did provide insights for either the qualitative or realist syntheses, they were transferred to that evidence stream for assessment. All studies that contained epidemiological data, no matter how they were classified according to EPOC criteria,52 were considered as part of the risk factor identification.

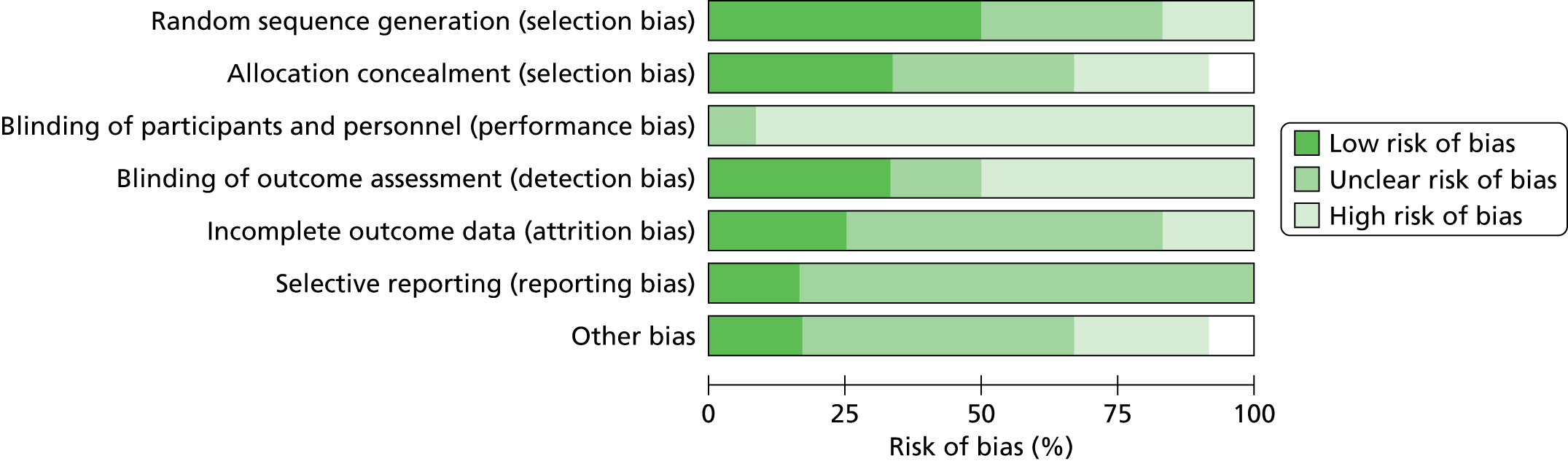

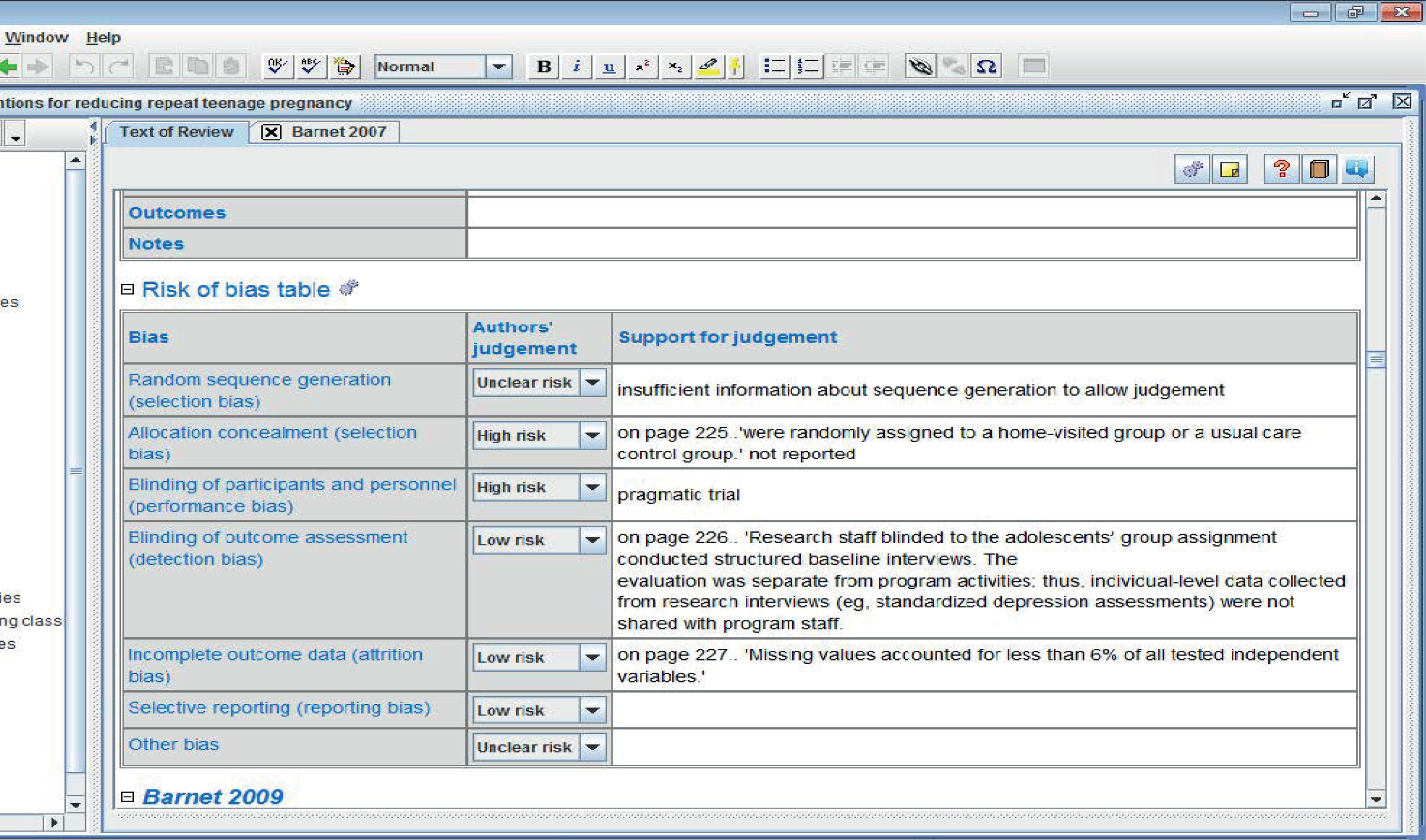

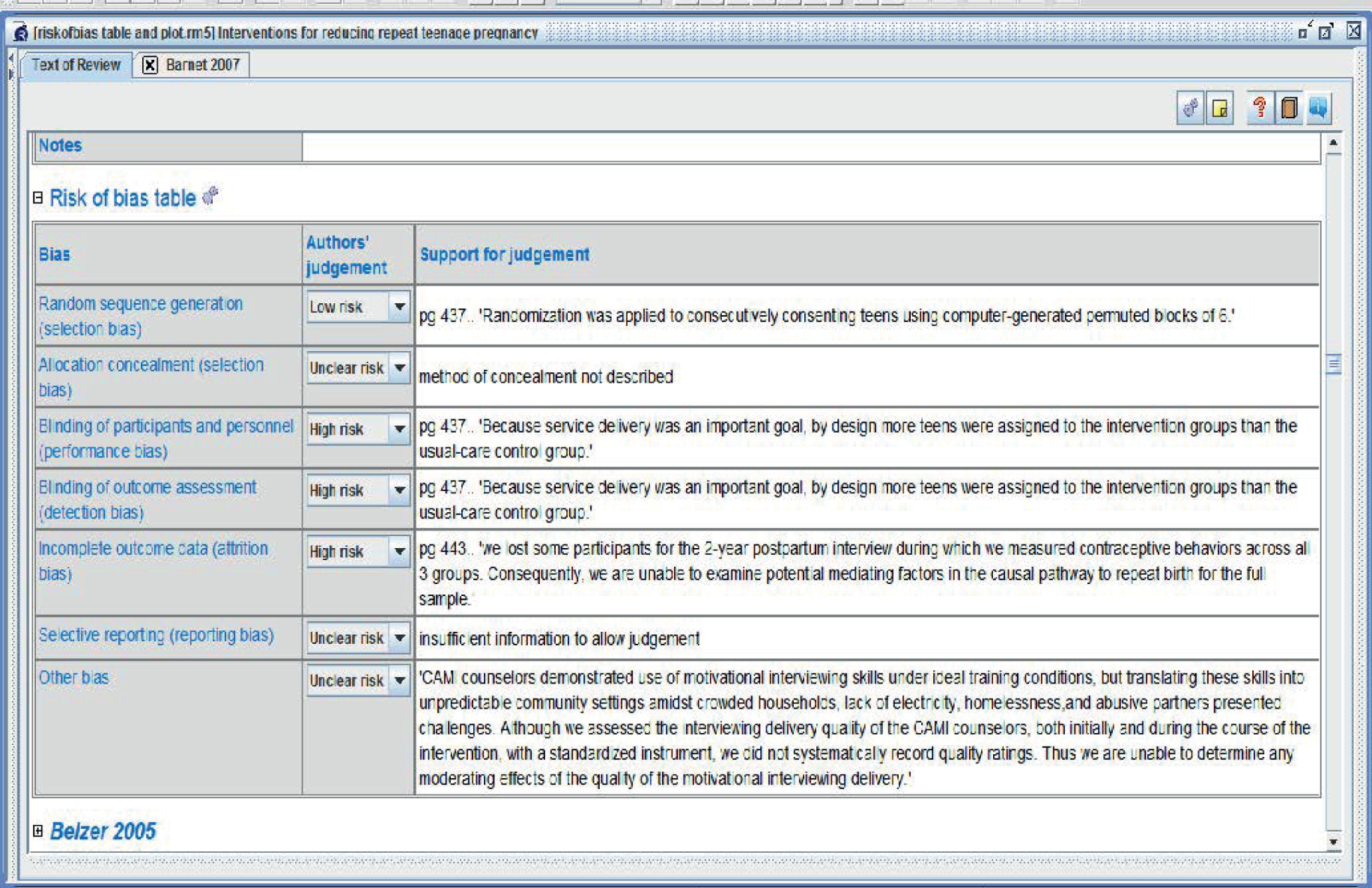

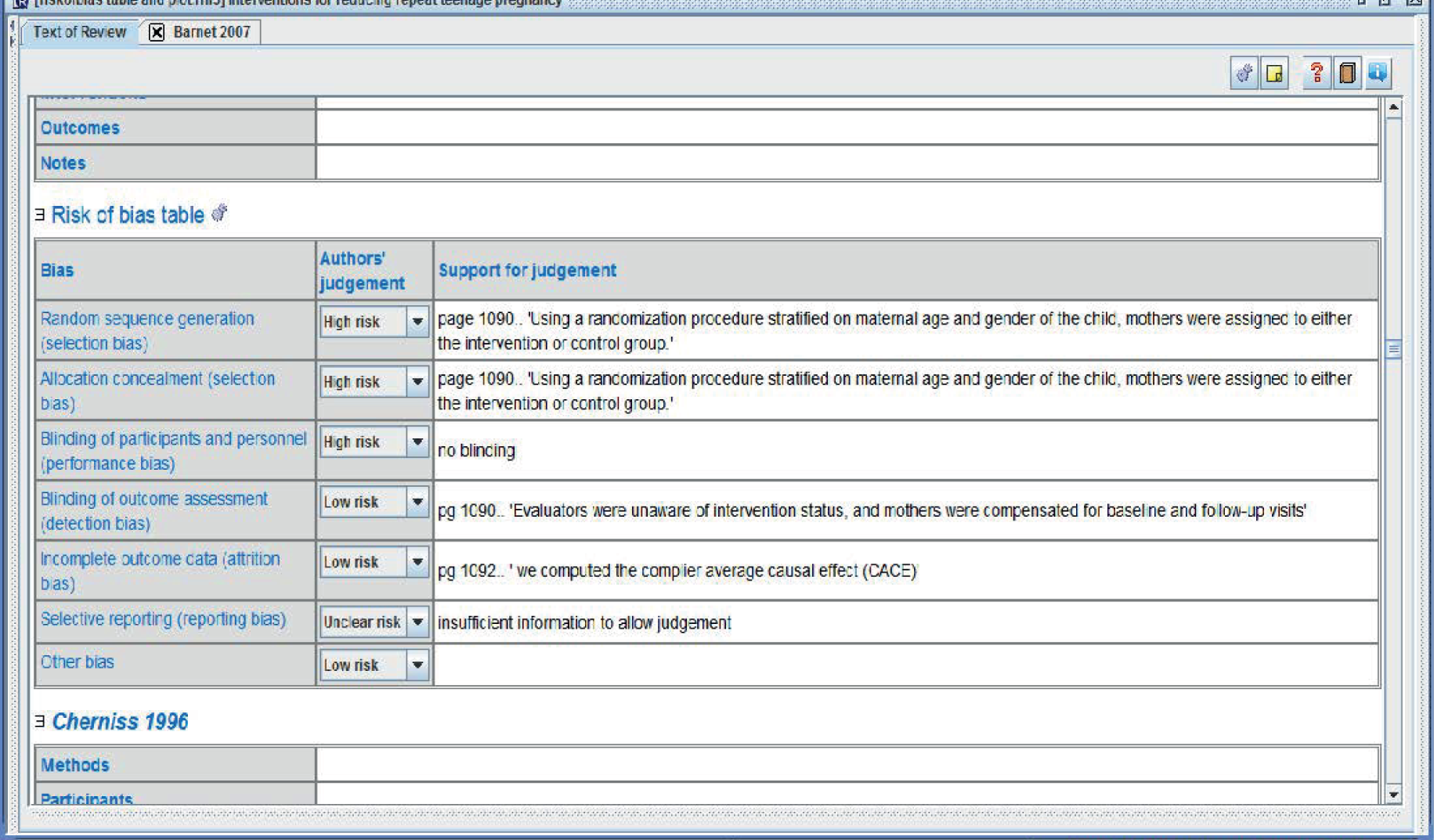

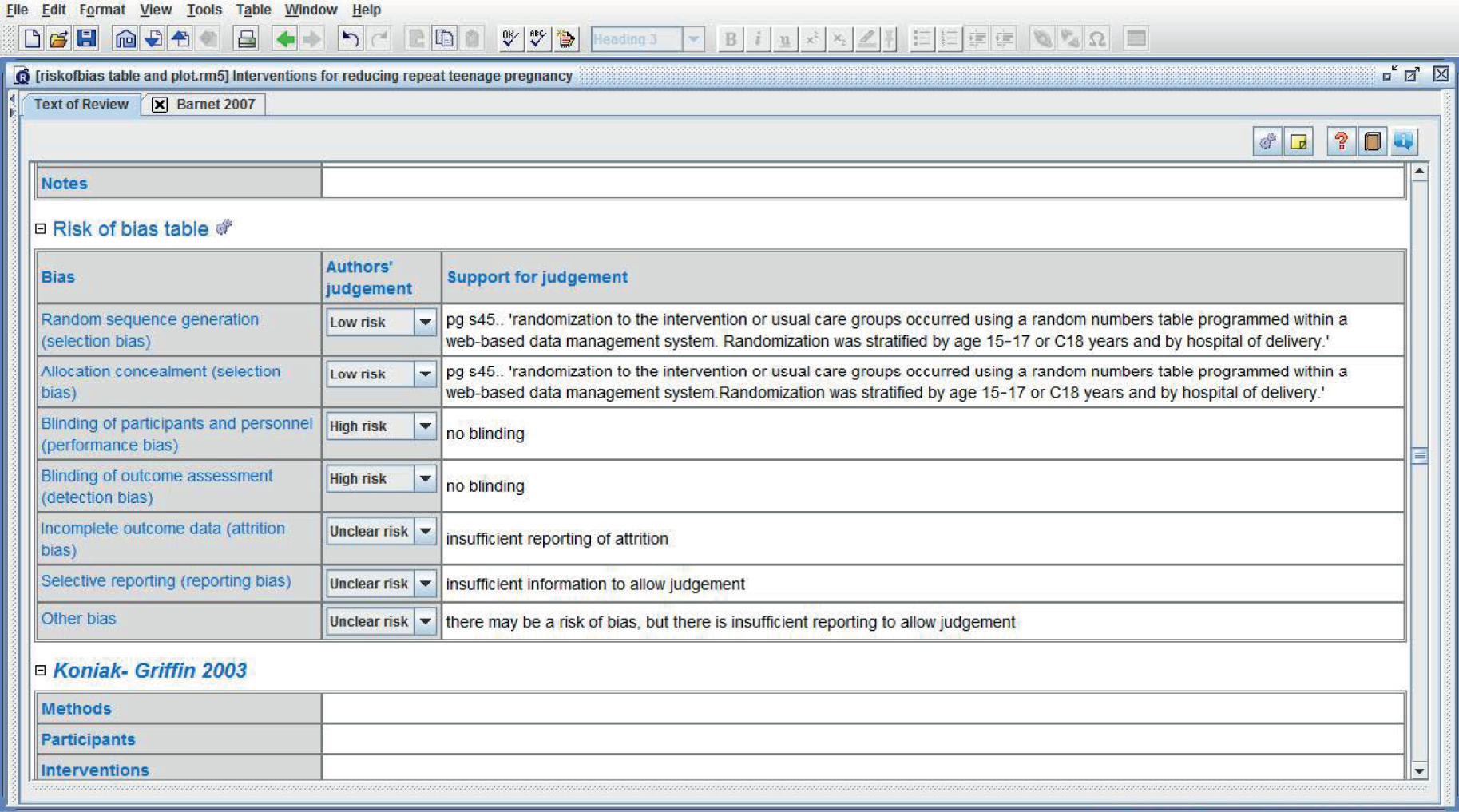

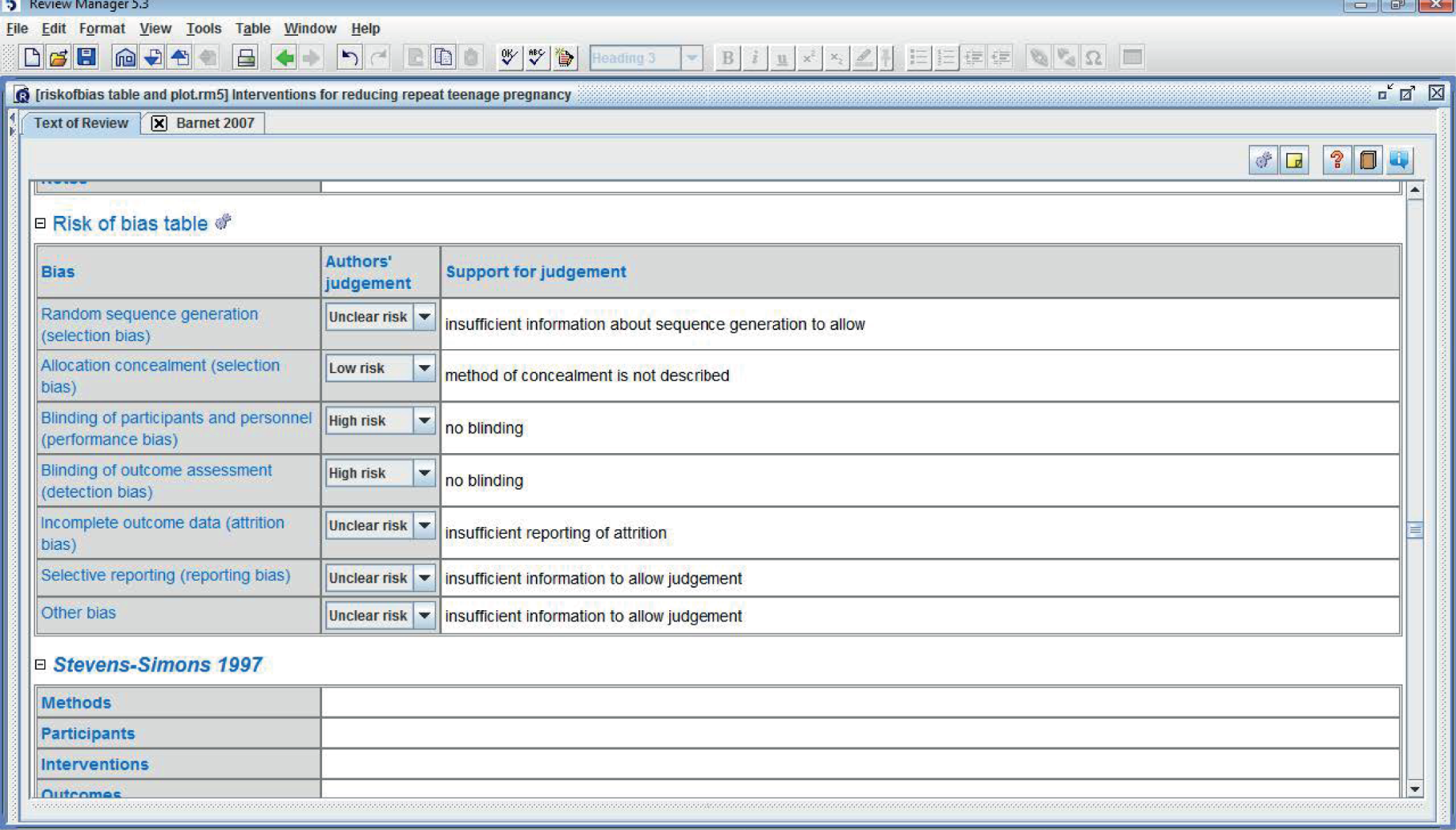

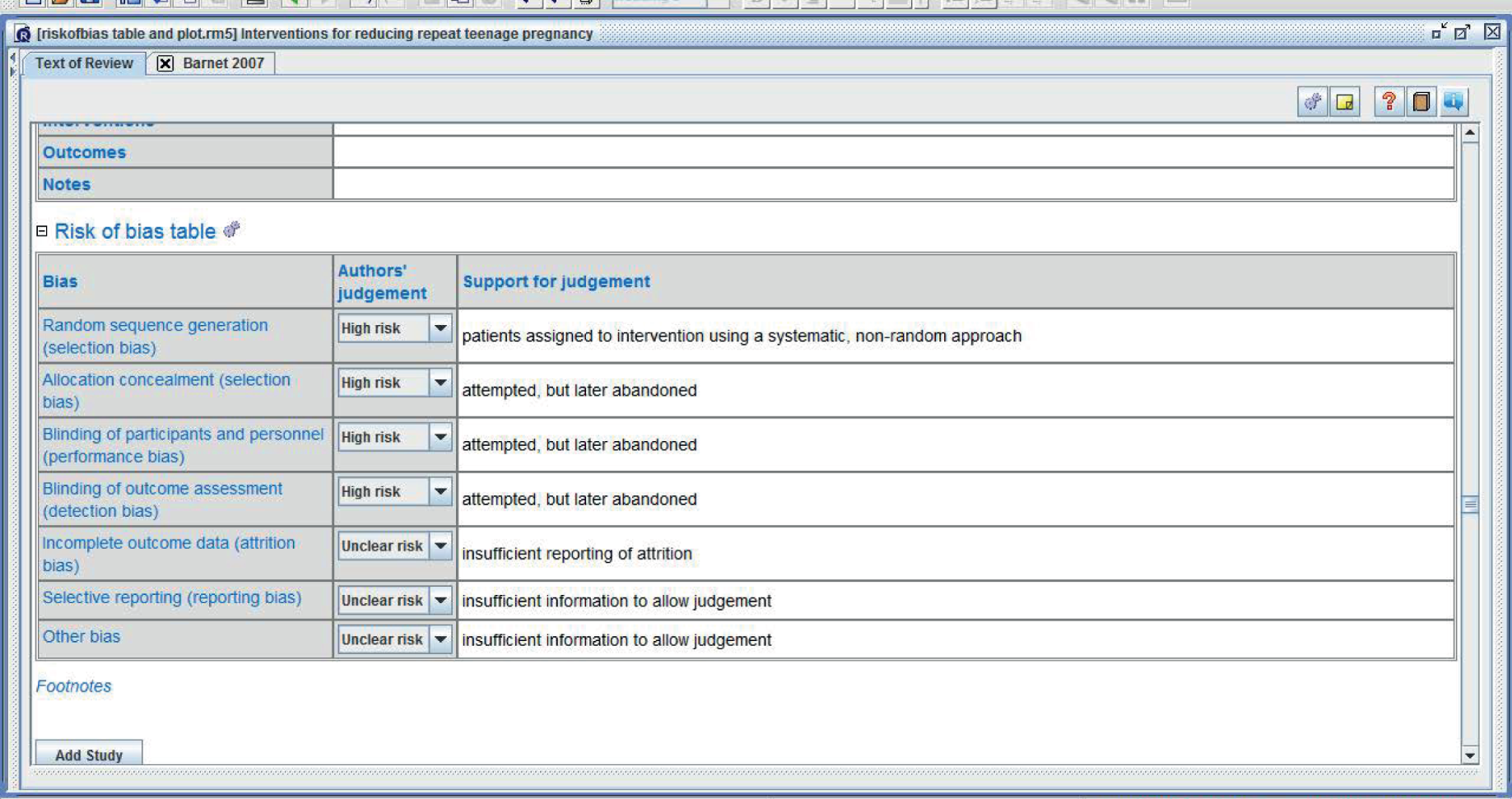

Quality appraisal

The protocol for part of this review is registered with Cochrane and we intend to be publish some of the findings as a Cochrane review. Therefore, RCTs and quasi-RCTs were assessed using Cochrane’s risk of bias tool. 53 We categorised and reported the overall risk of bias for each of the included trials as having:

-

a low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results) if all criteria were met

-

an unclear risk of bias (plausible bias that gives rise to some doubt about the results) if one or more criteria were deemed unclear

-

a high risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) if one or more criteria were not met.

The Cochrane risk of bias tool was supplemented by the mixed-methods appraisal tool (MMAT)54 (see Appendix 7 for mixed studies reviews). This MMAT has the advantage of incorporating the appraisal of several different study designs (qualitative, RCT, non-RCT, observational and mixed methods) using a single tool with a coherent range of quality criteria. 55

We slightly amended the published version of the MMAT54 for the qualitative studies by adding an alternative response, ‘somewhat’, for items that were partially described if we considered that either a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ response would be misleading. We used the MMAT assessment items relevant to the qualitative analysis as follows:

-

Are the sources of qualitative data (archives, documents, informants, observations) relevant to address the research question (objective)?

-

Is the process for analysing qualitative data relevant to address the research question (objective)?

-

Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to the context, for example the setting, in which the data were collected?

-

Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to researchers’ influence, for example through their interactions with participants?

Pilot studies suggested that the MMAT54 was an efficient and reliable tool. However, it does not cover economic evaluations; therefore, for such evaluations, we used the Drummond checklist, which is recommended for economic studies56 (see Appendix 8).

Certainty of evidence

We used the accepted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the findings of reviews on effectiveness. 46 This is an overall quality of evidence rating which is combined to categorise the quality of evidence across outcomes as:

-

high, meaning that further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of the effect

-

moderate, meaning that further research is likely to have an important impact on the estimate of the effect and may change the estimate

-

low, meaning that further research is very likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of the effect and is likely to change the estimate

-

very low, meaning that any estimate of the effect is very uncertain.

However, the GRADE approach is not suitable for appraising the certainty of qualitative evidence; therefore, for qualitative evidence, we used the recently developed CerQual (certainty of the qualitative evidence) method47 to assess our level of certainty in the findings of the qualitative synthesis. Using the CerQual approach, our assessment of certainty was based on two factors: the methodological limitations of the individual studies contributing to a review finding and the coherence of each finding. Firstly, we agreed on a set of 25 findings statements that covered the main key findings of interest from the thematic synthesis. For each finding statement, we made a note of the studies that made a contribution to that finding. We agreed on how many studies made a contribution and the relevance of their context, and attributed an overall rating to the specific finding (high, medium or low) with a statement to explain the rating. We then looked at the quality of the studies (as assessed by the MMAT)54 contributing to the specific finding and attributed an overall rating (high, medium or low). However, the MMAT assessments were so adversely affected by poor reporting of the study methods that we also considered the extent to which the findings of each study were supported by extracts from the original data (i.e. the ‘thickness’ and ‘richness’ of the supporting data). The final rating was a combination of the two (high, medium or low) and we recorded a brief explanation.

Using the MMAT54 and based on the richness and thickness of the data, we deemed the qualitative studies to be of moderate to high quality. All of the qualitative studies supported their findings by quoting extracts from the data and, in several cases, there was evidence of in-depth engagement with participants resulting in particularly rich data sets. We considered whether or not findings were seen in more than one study and in more than one country and, in view of the limited geographical spread of the evidence (seven studies from the USA, two from the UK and one from Australia), whether or not it seemed plausible that they would be transferable between these contexts and to other comparable settings. Overall, our confidence in the certainty of findings was high (for 18 findings) to moderate (for four findings), with only three findings achieving low certainty because they were found in only one study and either the data supporting the finding was relatively weak or the finding itself was equivocal. A table summarising the qualitative findings and indicating the level of certainty for each finding, and a brief explanation of the assessment, can be found in Appendix 17.

Whether or not evidence from studies was included in the realist synthesis conceptual framework was based on an assessment of its relevancy and rigour. 57 Pawson58 stated that ‘Judgements about rigour are made not on the basis of pre-formulated checklists, but in relation to the precise usage of each fragment of evidence within the review’. Hence, pieces of evidence from the included studies were used to help us make sense of the programme theories we were exploring.

Mapping the evidence

We undertook a mapping exercise in accordance with the EPPI-Centre method. 40 We categorised the studies according to the study design or type of record (intervention study, process evaluation, qualitative study, report, etc.), the country, the health, educational or community setting in which the study took place, the topic or focus of the study/report, the population focus of the study/report and the study design. From the grouping exercise, we developed a descriptive map of the literature and used it to identify gaps in the identified research. The map also provided a basis for refining the scope of the review by aiding the advisory group at a meeting held late in Phase 1 to identify areas for in-depth focus.

Analysis and synthesis

The data that we considered in this review are diverse, and the data analysis and synthesis were complex. The choice of synthesis method depended on the questions addressed and the type of data included. Figure 1 illustrates the method of synthesis proposed for each evidence type.

Descriptive study summaries

We present the full findings of the data extraction exercise for studies included in the meta-analysis of RCTs and in the qualitative synthesis in a table of study characteristics (see Appendix 18). These include the study details, the setting, the population, the quality appraisal and the methods. We present sociodemographic characteristics known to be important from an equity perspective. For this process, the PROGRESS (place, race, occupation, gender, religion, education, socioeconomic status and social status) framework was utilised. 59 For the studies that were included in the risk factor analysis, a brief summary table containing the study type and PROGRESS data is included (see Appendix 19).

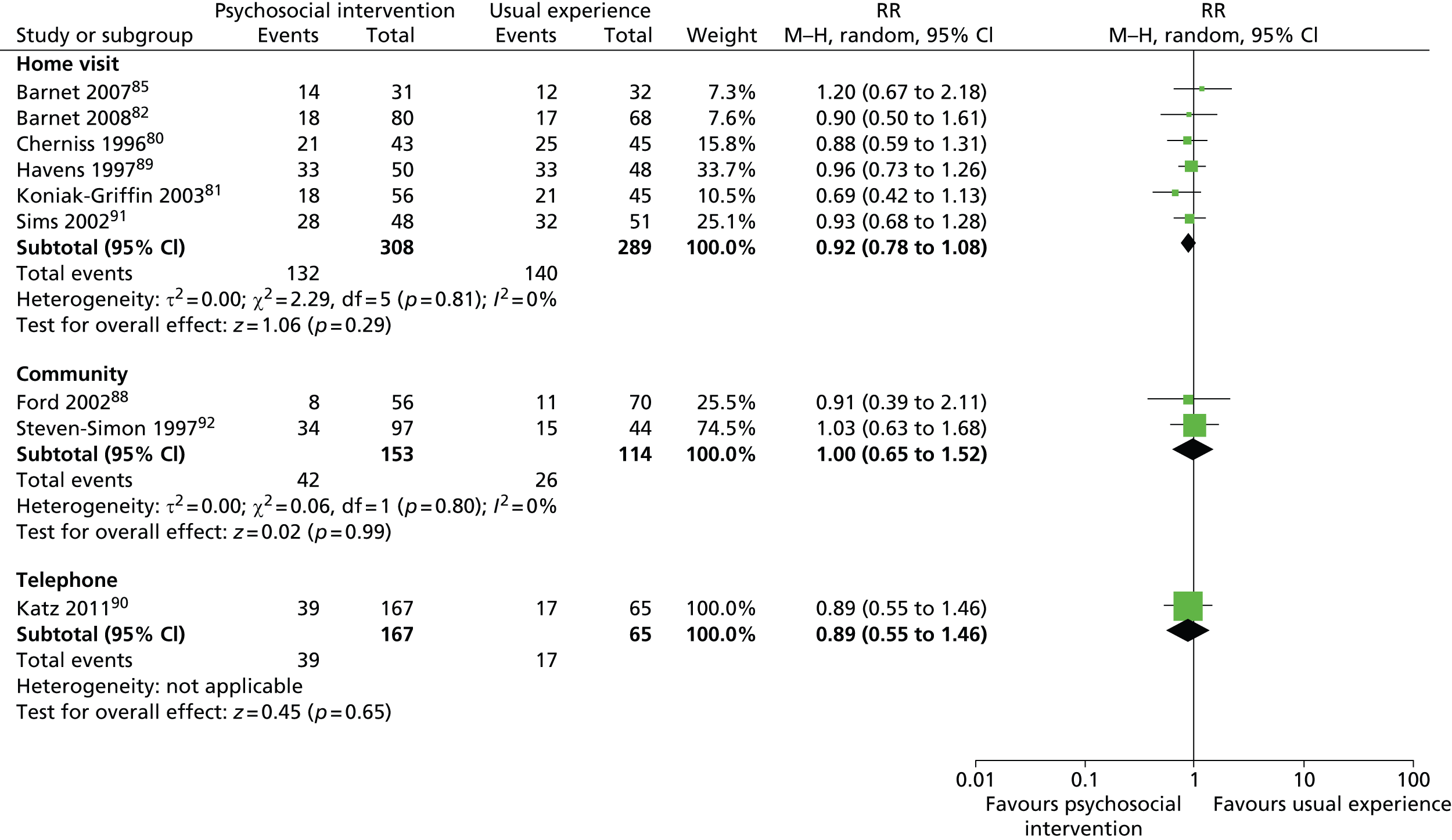

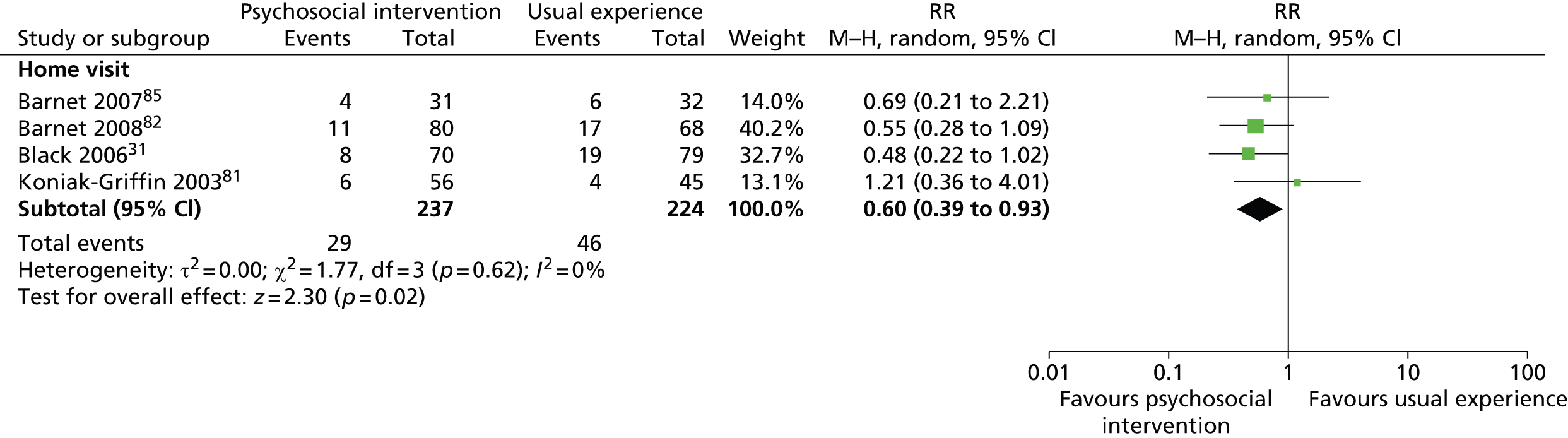

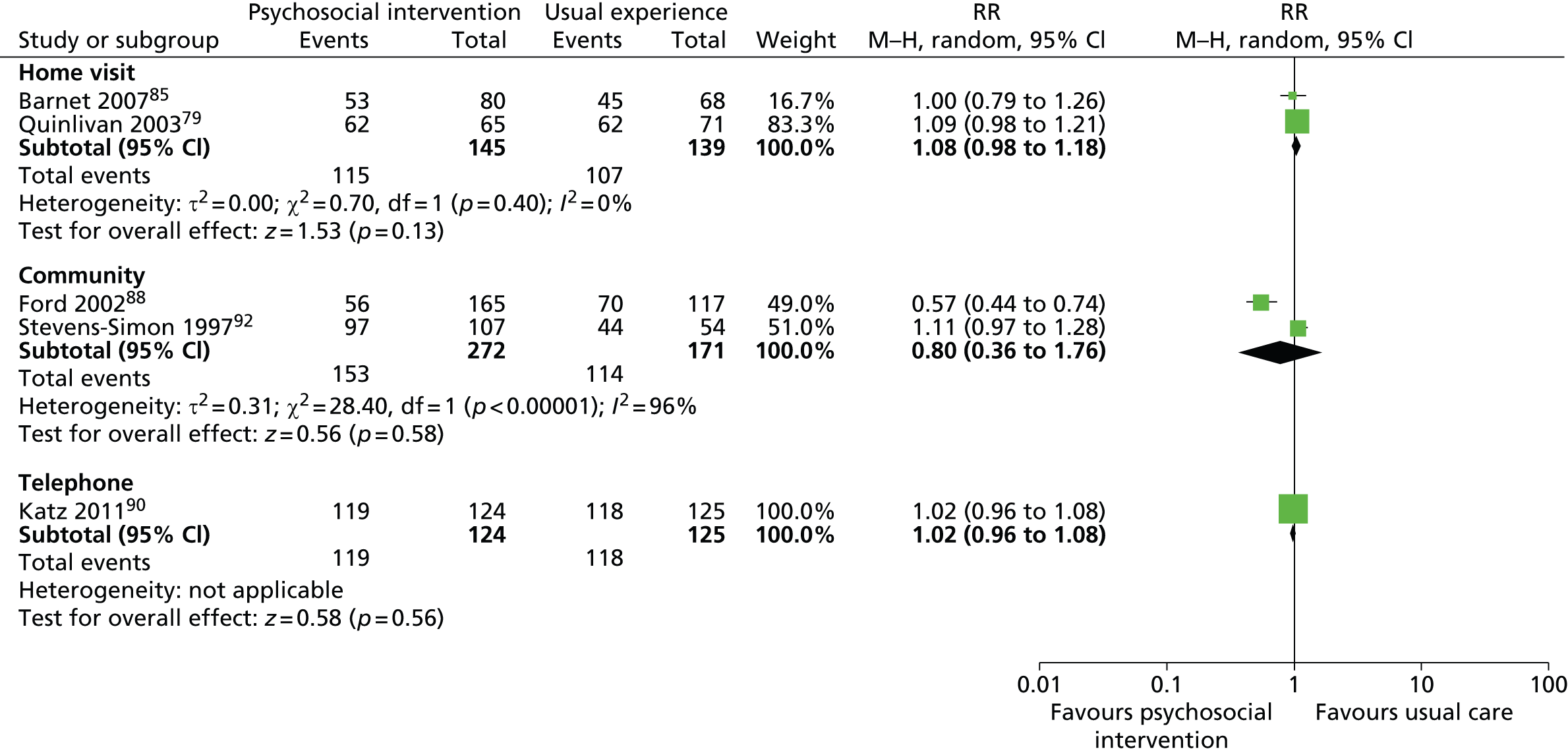

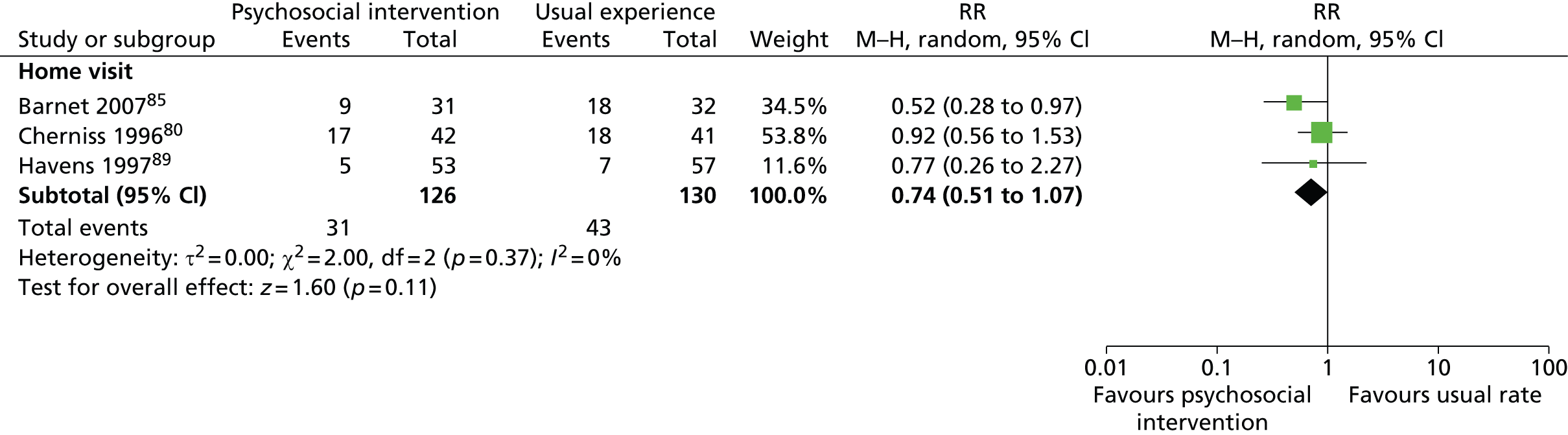

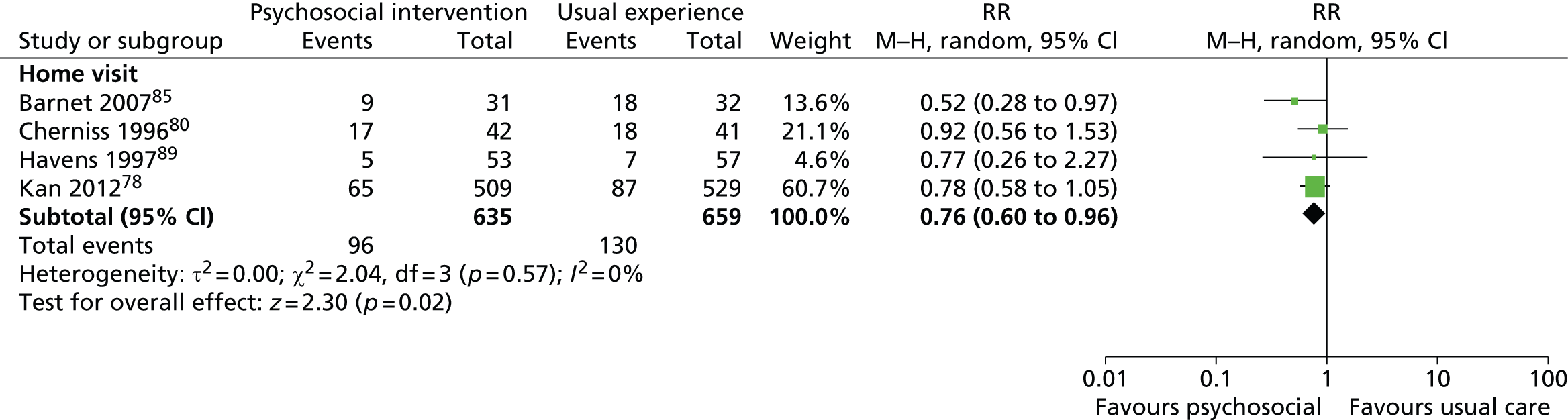

Quantitative meta-analysis

Measures of intervention effect

We have presented quantitative continuous outcomes using the original scales that were reported in each individual study. When appropriate, if the studies used different scales, we standardised the scores by dividing the estimated mean difference by its standard deviation (SD). Dichotomous outcome data were fitted with a random effects model using the Mantel–Haenszel test and presented as risk ratios (RRs). All outcome data were reported as effect sizes with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of assessment

In all studies, the unit of assessment was the individual.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed both clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by examining the characteristics of the studies, the similarity between the types of participants and the interventions, while statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2-statistic. We have reported statistical heterogeneity as important if it is at least moderate to substantial (I2 > 30%) and we have not pooled data when statistical heterogeneity was severe (I2 > 90%); if statistical heterogeneity (I2 between 60% and 90%) could be explained by clinical reasoning and a coherent argument made for combining the studies, the data were entered into a meta-analysis. After exploring the heterogeneity, if a coherent scientific argument could not be found, the study causing the heterogeneity was excluded and the analysis was repeated as a sensitivity analysis. If the heterogeneity was not adequately explained, the data were not pooled in a meta-analysis. In this case, or when only single outcomes were reported, we presented study findings in tables (see Appendix 19) and explored the relationships within and between studies in a narrative summary. 60

Assessment of reporting biases

We performed an assessment of reporting bias if we found an adequate number of studies (at least 10) by observing funnel plot asymmetry. 61 Possible sources of asymmetry were explored with an additional sensitivity analysis and the studies at greatest risk of bias removed. The most likely unbiased intervention effects are summarised in the meta-analyses (see Appendix 11 for judgements of risks of bias).

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing or unclear, we contacted the investigators of the primary research (see Appendix 9). After such correspondence, if the degree of imbalance in dropout between the groups was small and could be argued to be completely missing at random, data would have been re-analysed in accordance with a treatment-by-allocation principle62 whenever possible. However, in no case could this assumption be made so we used the available case population for meta-analyses.

Subgroup analysis and heterogeneity

Subgroups included and highlighted within the primary research as important confounders were used to identify risk factors as well as explain heterogeneity. The following were considered important factors with regard to exploring differences in intervention effectiveness: the age of the young mother; the deprivation index of the area of residence; the length of follow-up; a history of substance misuse; and looked-after children (or care leavers). However, none of these factors was found to be informative so no subgroup analyses were performed.

Certainty of the findings

After the primary analysis, the quality of the overall evidence for each outcome was judged using the GRADE approach (Guyatt et al. ). 46 In this approach, evidence from each outcome is initially rated as high if from randomised trials but its quality may then be ‘down-graded’ depending on the following factors:

-

limitations in study design or execution (risk of bias)

-

inconsistency of results (based on between-study heterogeneity)

-

indirectness of evidence (i.e. how closely the outcome measures, interventions and participants match those of interest)

-

imprecision (based on the CIs around the effect size)

-

publication bias.

GRADE profiler software was used to grade the evidence and generate evidence profile tables, which include a summary of the findings, number of participants in each group, the quality of the evidence for each outcome and an estimate of the magnitude of the effect. An example of GRADE profiles is shown in Appendix 10.

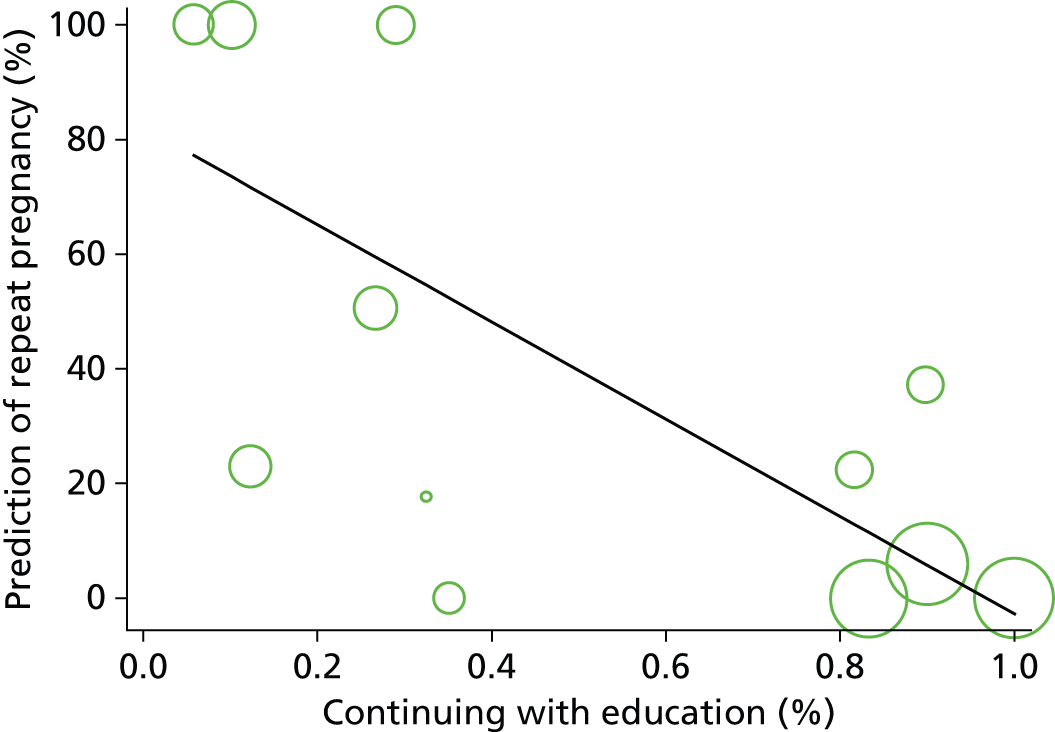

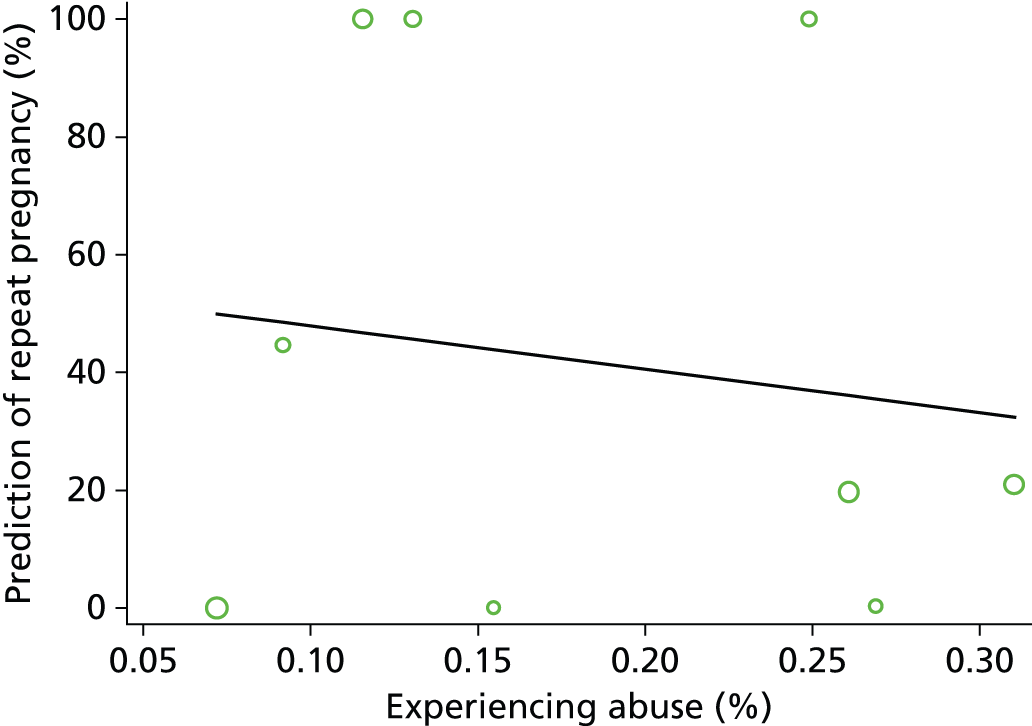

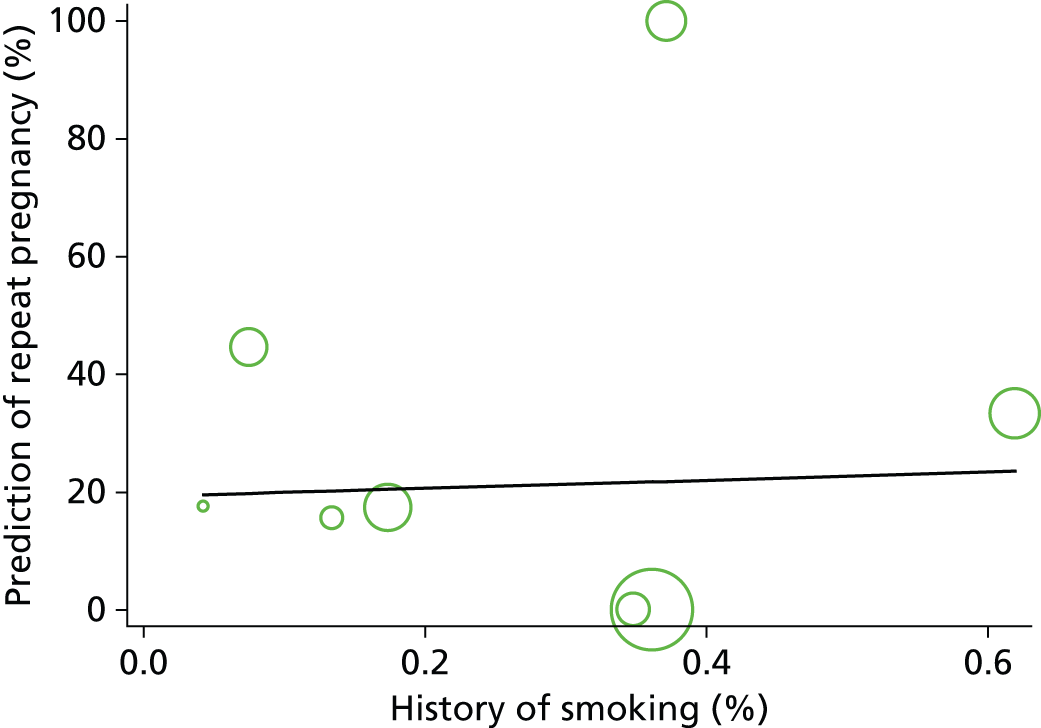

Investigation of risk factors using metaregression

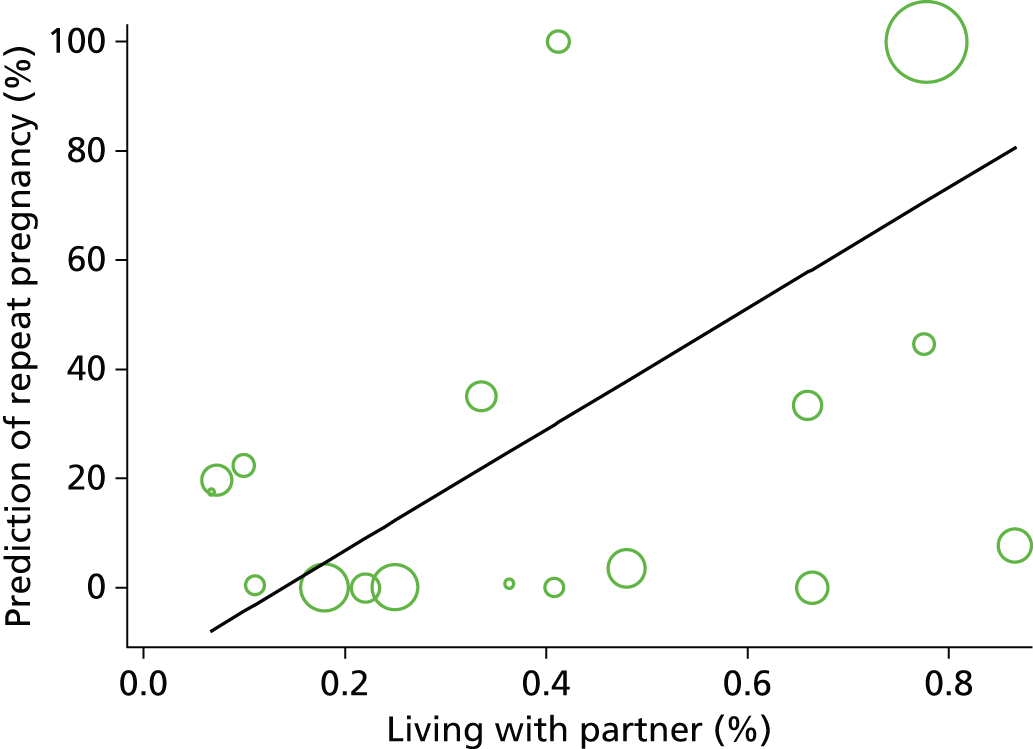

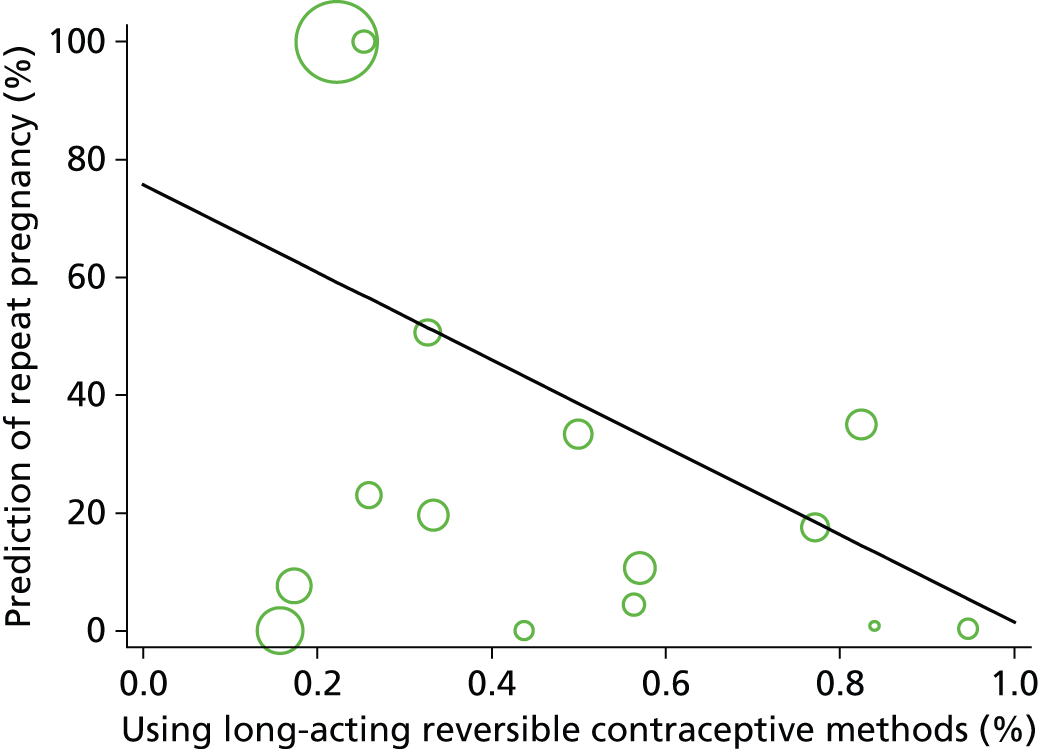

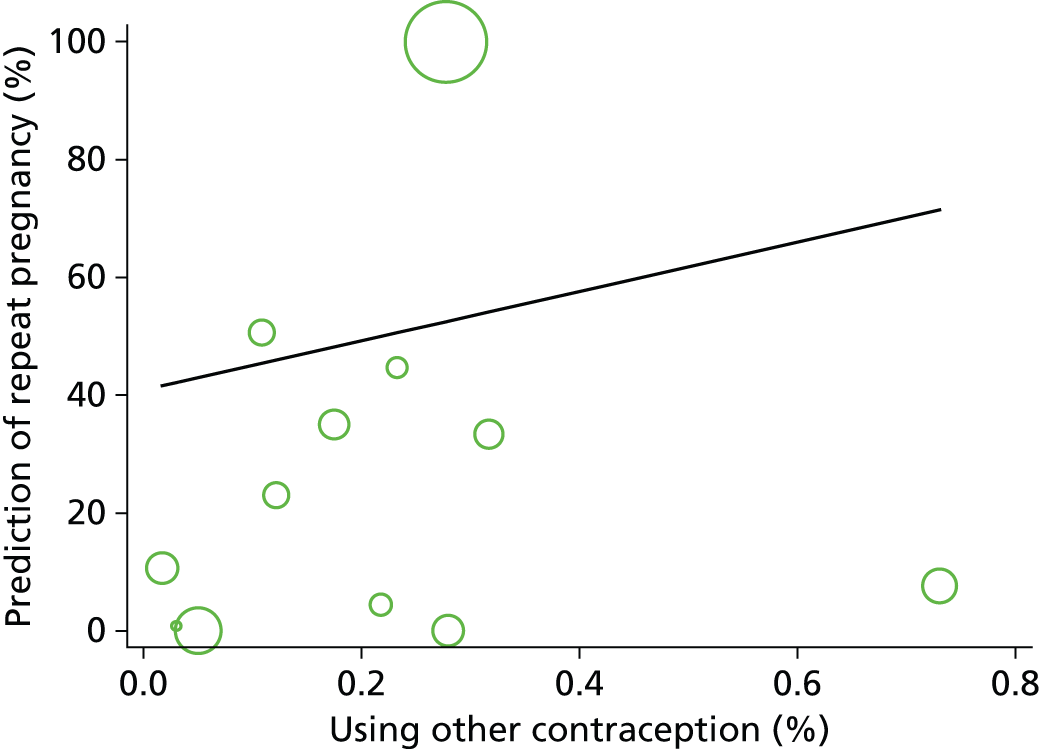

A key aim of the review was to search, identify and summarise the populations of young girls that are at greatest risk of repeat pregnancy (by, for example, considering income, social deprivation, ethnicity, degree of rurality, substance misuse, whether or not currently in care or care leavers, and those from vulnerable or at-risk communities). We expected that these factors would be considered and summarised as important confounding variables within RCTs, quasi-RCTs and cost–benefit analyses for studies investigating interventions to reduce repeat pregnancies. We also aimed to identify non-interventional studies that present epidemiological data (e.g. cohort studies, cross-sectional studies and policy documents) of effect modifiers associated with an increased risk of repeat pregnancy. We shortlisted possible risk factors from a review by Rigsby et al. 17 and added any risk factors which were supported by several studies. Data were extracted and summarised and, if possible (if 10 or more studies reported similar factors), presented in a metaregression summarising the standardised effectiveness by presenting the slope parameter, with the associated 95% CIs. Graphical representations of the metaregressions were plotted using the square root of the sample size for each of the studies.

Cost-effectiveness

We provide a narrative review of economic evaluations of interventions specifically designed to reduce the number of unintended repeat teenage conceptions. We planned to stratify any economic studies found by the public health lever mechanism used; examples of such mechanisms are government, statutory or legal mechanisms, public information mechanisms, school-based group or targeted interventions, and NHS- or charity-initiated mechanisms. We were particularly interested in the perspective of the analysis or the type of economic evaluation (e.g. cost analysis, cost–benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis or cost–utility analysis). We documented the way in which these studies attempted to overcome the methodological challenges specifically associated with these types of complex, preventative, behavioural change based interventions. 63–66 We planned to conduct a meta-analysis of the economic evidence (if the data were sufficiently homogeneous to allow it).

Qualitative studies

For qualitative studies, we developed, a priori, a coding framework adapted from the Support Unit for Research Evidence (SURE) framework67 for identifying factors affecting the implementation of a policy option (see Appendix 12), which was successfully used in a qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve child and maternal health. 47 Data were coded directly from the papers into the framework and thematic syntheses were conducted using a framework method developed by Ritchie and Spencer. 68

Surveys, process evaluations and other types of data

Data from surveys, process evaluations and other sources, such as reports, may be either semi-narrative or quantitative or both. Data were extracted to present evidence of acceptability and uptake of interventions, and were synthesised in a narrative summary and aggregated using thematic analysis. 69

Realist synthesis

We selected subsets of evidence and applied the principles of realist synthesis. 58,70,71 We identified explicit or implicit theories which postulate how an intervention has an underlying causal mechanism that works in a defined social context to result in a particular outcome. Such theories may also be used to explain the failure of an intervention. Additional theories were identified from the wider literature (e.g. policy documents), the advisory group members or personal contact with other experts in the field. Data synthesis involved individual reflection and team discussion in order to question the integrity of each theory, adjudicate between competing theories, consider the same theory in different settings and compare the particular theory with actual practice. 72 Coded data from the studies were then used to confirm, refute or refine the candidate theories. Thus, we attempted to explain which interventions work, for whom and under what circumstances.

Background

The study protocol73 outlines the plans to apply realist synthesis principles to the subsets of evidence that were included in the review, in order to provide an indication of the interventions’ causal mechanisms of action. Chapter 6 describes the findings, followed by implications for future intervention development and research.

Approach

A realist review adopts a theory-driven approach to evidence synthesis, which is underpinned by a realist philosophy of science and causality. 58,74 According to Pawson,58 any synthesis of evidence needs to investigate why and how interventions might work and in what contexts. The aim then is ‘to articulate underlying programme theories and then to interrogate the existing evidence to find out whether these theories are pertinent and productive.’58 In realism, theory is construed and framed in terms of a proposition about how and why interventions work (or not).

As this component was embedded in the broader evidence review and therefore not a full realist synthesis, we took the principles of realist synthesis and applied them in the interlinked stages described in the following sections.

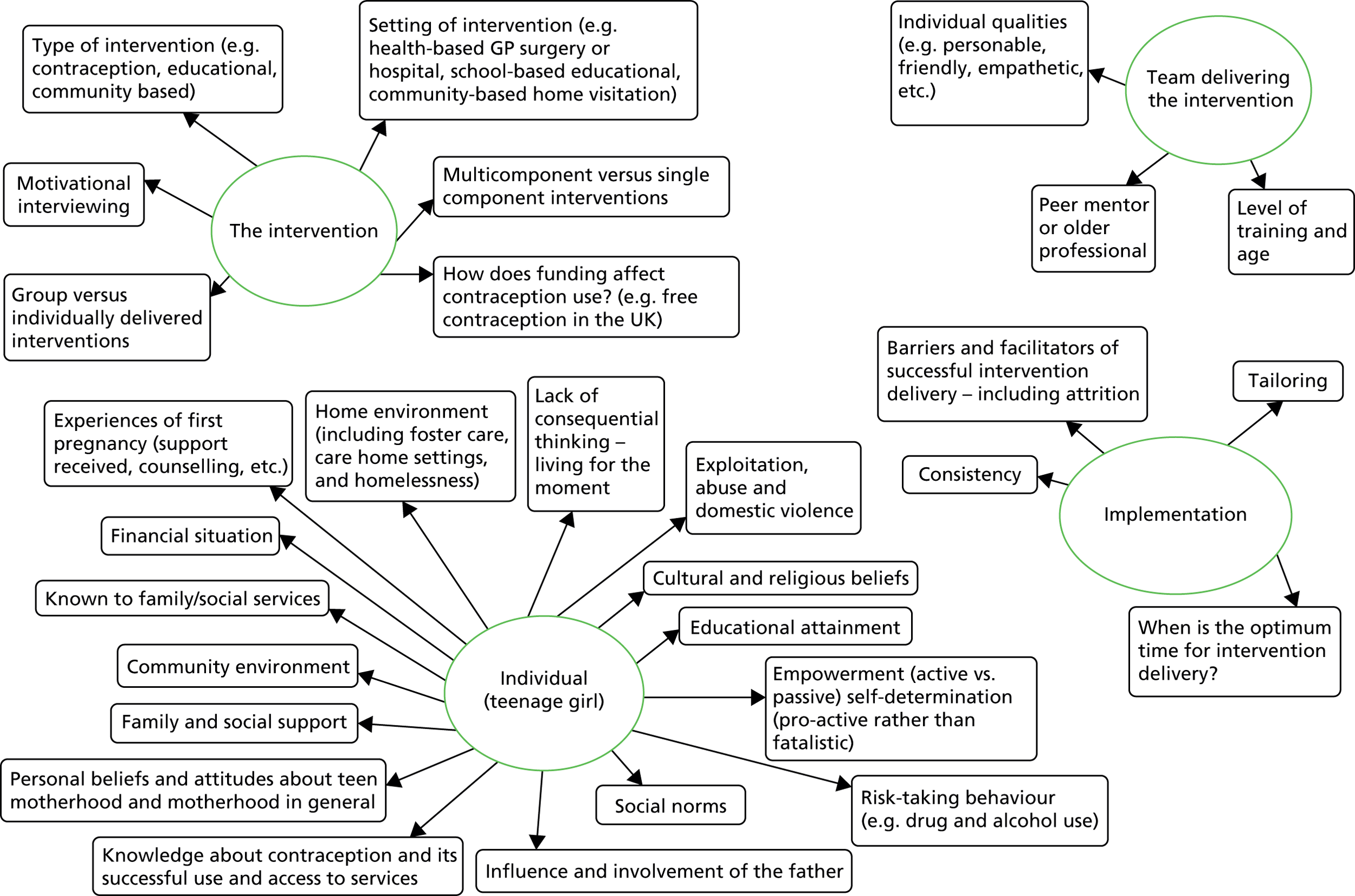

Identifying the territory

During the full screening of the papers for inclusion in the full review, the realist synthesis team met to map the conceptual and theoretical territory of the literature being retrieved (see Appendix 13). This involved a high-level theming process managed through deliberative processes, which were informed by the original brief, review questions, emerging evidence and other policy documents. This process resulted in a list of questions of interest that covered a number of different domains. At the individual level, the overarching question was ‘What factors predict repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?’ For example, family support, community, having an older boyfriend, and drug and alcohol abuse were considered as potential predictors of teenage pregnancy. Other questions resulting from this process were:

-

What personal factors (e.g. age, level of education, ethnicity, family support or peer influence) influence successful contraceptive use?

-

How does lack of knowledge affect repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How does social connectedness affect repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How do social, community and environmental factors influence repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How does living in an area of socioeconomic deprivation affect repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How can empowerment and realistic goal-setting facilitate interventions to reduce unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

What affects a girl’s motivation to prevent a repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

At an intervention level, the overarching question was ‘What factors facilitate intervention delivery?’ This question addressed, for example, which health professionals should deliver the intervention or the optimal time for delivering the intervention. Other questions included:

-

How do individual components of complex interventions impact on repeat unintended teenage pregnancy rates?

-

How do home visits as part of an intervention delay repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How can the delivery setting increase the success of an intervention?

-

When is the optimal time to deliver an intervention to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How can psychosocial models (e.g. Health Belief Model) be utilised in interventions to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

What are the barriers to successful contraception use?

-

How does mentoring and counselling from another teenager or peer counsellor reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How can tailoring be utilised in an intervention to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

How does funding affect contraception use?

-

What factors influence attrition in interventions delivered to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

Are multiple component interventions more effective than single component interventions at reducing repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

Are group delivered interventions more effective than individually delivered interventions at reducing repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

When considering the team delivering the intervention, the overarching question was ‘Who is the optimal practitioner to deliver an intervention to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?’ Other related questions are listed below:

-

What qualities does a practitioner need to have to deliver an intervention to reduce repeat unintended teenage pregnancy?

-

Are trained peer mentors more effective than older professional practitioners at delivering interventions to reduce unintended pregnancy?

Developing the conceptual platform for the review

Through further reading of the evidence that was emerging from the searching processes and a process of mapping, the realist review team constructed a series of conceptual maps that were linked to the questions outlined above. These maps represent the clustering of concepts, which, through further discussion and deliberation, were developed into four theory areas of interest for the realist review of evidence gathered. The theory elements identified are discussed in Chapter 3.

Stakeholder engagement

We had the opportunity to ‘test’ these theory areas with a group of stakeholders at the first stakeholder meeting (see Appendix 2). We gave the stakeholders an opportunity to add or amend the content of the theory areas through the use of an engaging process by which they could annotate the conceptual maps and provide a rationale for their suggestions. This resulted in some additions to the theory areas of connectedness and motivation.

Data extraction

The theory areas were made visible in the data extraction forms. We also developed a ‘crib sheet’ (see Appendix 13, Table 15) for the team to cross-reference as they were extracting data to act as an aide-memoire of the evidence they were searching for. The team met on a regular basis to discuss any further evidence they found in relation to the theory areas. As part of this process, the theory area ‘Targeting’ became ‘Tailoring’. ‘Setting/environment’ was spilt into evidence concerning the individual and evidence concerning the intervention. Two new areas were developed: ‘Other goals/aspirations’ and ‘Perceptions/ideas of parental responsibility’.

As extraction progressed, any new information found by the reviewers that did not fit into the theory headings was highlighted and given a new heading name, an explanation of what the theory area contained and keywords. As new theory areas emerged the ‘crib sheet’ was updated accordingly (see Appendix 13, Table 16).

Synthesis

Once the reviewers had completed their first and second extraction of assigned papers, they shared their summaries of the realist evidence. We used tables to state the author’s name, the verbatim extraction and the reviewer’s own commentary on the data. These commentaries were then pulled together into a single narrative for each theory area. We had an opportunity to present this emerging evidence at a further stakeholder group meeting (see Appendix 3). Summaries of the emerging evidence can be found in Appendix 13 (see Summary statements of emerging theory areas).

Summary of changes to protocol

We made the following minor changes to our protocol:

-

We added and developed the CART criteria to assess the completeness, accuracy, relevance and timeliness of studies to be included after the mapping exercise. This helped to focus our review aims.

-

We used only the Drummond checklist56 for economic studies, as the Phillips checklist75 was not needed.

-

We further refined the outcomes mentioned in the protocol to better reflect outcomes of our stakeholder consultations.

-

We used the SURE framework67 and realist synthesis instead of the Greenhalgh framework76 to map facilitators and barriers to intervention implementation, since we found it more appropriate for our review. Consequently, we made one minor addition to the methodological diagram.

-

We only formally translated RCTs and any study that we thought would make a significant contribution to the evidence, as Google Translate was sufficient for assessing the evidence and screening effectively.

-

We adopted EPOC criteria52 for defining quantitative evidence to ensure we included any studies yielding evidence of effect for inclusion in the sensitivity analysis, which was also an addition to the study protocol.

Chapter 3 Results

This section is divided into the results of the extractions and mapping exercises, including the PRISMA flow chart (see Figure 3), and the four basic review questions:

-

Who is at risk?

-

What is effective?

-

What is cost-effective?

-

What are the barriers to and facilitators of implementation?

We then report other outcomes of interest. The results we report here arise from both qualitative and qualitative evidence streams.

Search results

We identified 8668 study reports during the original search, and after deduplication and initial screening by title and abstract, 118 studies met our inclusion criteria for the mapping exercise. The vast majority of the studies in the mapping exercise (94 out of 118) were conducted in the USA, followed by eight in Brazil, seven in the UK, three in the Caribbean, two in Sweden, and one each in Mexico, South Africa, Taiwan and Australia. Fourteen of these studies were randomised trials, and the majority of studies were either set in health-care56 or community43 settings. The geographical diversity of these studies is illustrated in Figure 2, and study design and context are described in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Geographical spread of studies included in the mapping exercise.

| Characteristics | Number of studies (n = 118) |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| RCTs | 14 |

| Cohort studies | 40 |

| Case–control studies | 16 |

| Quasi-experimental studies | 3 |

| Mixed-methods studies | 2 |

| Process evaluations | 15 |

| Qualitative/views studies | 11 |

| Other report types | 17 |

| Intervention context | |

| Community | 43 |

| Health | 52 |

| Education | 4 |

| Multiple settings | 8 |

| Not reported | 11 |

After the mapping exercise, 70 studies met the CART criteria51 and were included in the in-depth review. Full details of these studies can be found in Appendix 15. Updated database searches, citation searches and hand-searching identified a further 5243 studies or reports which, after screening, resulted in additional seven included studies. The 77 included studies were: 14 RCTs, 10 qualitative studies and 53 other quantitative studies. Publication dates ranged from 1995 to 2014 and the studies had predominantly been carried out in the USA.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram

The PRISMA diagram77 (Figure 3) describes the full flow of studies through the filtering process to our final 77, including seven studies that were added as a result of the updated literature searches. Excluded studies and reasons for exclusions can be found in Appendix 16.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA diagram illustrating the sifting of evidence from discovery to inclusion in the review.

Content or intervention type

Interventions were predominantly of two types: (1) those that focused solely on promoting the uptake, or facilitating the timely postpartum uptake, of contraception, usually long-acting reversible methods delivered by injection, implant or intra-uterine devices, or oral contraception; and (2) complex interventions comprising various combinations of health, social and educational elements, one of which was usually a contraception regimen. Complex interventions often had multiple objectives which included promoting parenting skills and infant health and nutrition, as well as preventing repeat pregnancy. Specific components that we identified included:

-

Fertility health-related components:

-

pregnancy testing and maternity counselling

-

primary and preventative health-care services (including prenatal and postnatal care)

-

counselling and referral for family planning services

-

-

Sexual health education and guidance:

-

referral for screening and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS

-

educational services related to family life and problems associated with adolescent premarital sexual relations

-

-

Other maternal health components:

-

nutrition information and counselling

-

mental health services

-

-

Child health:

-

referral to appropriate paediatric care

-

-

Family support:

-

adoption counselling and referral services

-

addressing domestic violence and peer relationships

-

supportive counselling and social work services

-

-

General educational interventions:

-

Appropriate educational and vocational services including job skills training, tutoring and mentoring.

-

Overall summary of included studies and study quality

Studies used in the effectiveness evaluation

Using EPOC criteria,52 we identified 13 individual RCTs31,78–92 (one study reported in three papers82–84 and one in two papers85,86), one cluster RCT93 and two non-randomised trials94–96 (one of which was reported in two publications94,95) for potential inclusion in the meta-analysis. One of the ‘trials’78 was a meta-analysis of 12 smaller unpublished randomised and quasi-randomised trials and had an uncertain risk of bias; therefore, we did not include it in the primary analysis. As the non-randomised trials had a high risk of bias, we did not include them in the primary analysis either. 94–96 Therefore, we analysed 12 individually randomised trials31,79–81,85–92 in the principal analysis but have included the results obtained when the other four other studies were included as a sensitivity analysis. These studies were published between 1996 and 2012 (see Appendix 15).

Context/population

We used the PROGRESS framework to report on the sociodemographic characteristics. 59 All of the trials but one79 were based in the USA. The majority of the trials employed interventions for minority populations, for example African American, Hispanic and Latina American, and Pacific Islander populations. Three studies identified the socioeconomic status of the participants as ‘low’ or ‘poor’. 31,80,81

Interventions

The trials we included in the main analysis examined interventions that fell into two broad types: most were complex psychosocial programmes and one was a contraceptive programme. The psychosocial programmes offered an array of services, such as case management and referral; education about pregnancy, labour and delivery, contraception and infant health; child developmental training; contact facilitation with the health-care system; and individual counselling. These programmes were community based, or involved home visits or telephone counselling.

Studies used to identify risk factors

We used the criteria prescribed by EPOC52 to identify studies which reported on epidemiological risk factor data with a comparator. Thirty-four studies86,94,95,97–127 were used to identify risk factors in addition to the randomised trials discussed above. These 34 studies included 20 non-comparative studies,94,95,98–103,106,108,109,112–119,128 seven prospective cohort studies97,105,120–124 and eight retrospective cohort studies. 86,104,107,110,111,125–127

Qualitative studies

Ten studies published between 1998 and 2013 were included in the qualitative synthesis. 129–140 Two of the studies were reported in two papers, Clarke130,140 and Herrman. 132,133

Context/population

Participants in all 10 studies were pregnant or parenting teens. In one study, there was an additional group of teens who had had a recent abortion;137 in one study, parents or guardians of the teenage mothers were also recruited;129 and in two studies, key informants from health, community and educational organisations were included. 134,139 Seven studies were conducted in the USA,129,131–133,135,136,138,139 and the participants in five of these were predominantly of African-American and/or Hispanic ethnicity; in the remaining two US studies, the study participants were, in roughly equal proportions, white, African American or Asian/other. 131,139

Intervention/exposure

In one study, the participants were enrolled in a school-based intervention called the ‘Pregnancy free club’. In this intervention, public health nurses visited the school each day and delivered monthly pregnancy tests and surveys, health counselling and referral, and group health education classes. 136 In two studies, young mothers were participants in a mixed-methods observational study of African-American adolescent mothers’ contraceptive use and the risk of repeat pregnancy in the first postpartum year, known as the ‘Postpartum adolescent birth control study’. 135,138

Recruitment of participants

Participants in one study were recruited from a state supplemental nutritional programme for women, infants and children. 129 In another study, all participants were enrolled in high school and were receiving health care at an agency serving a low-income population and with specific expertise in caring for pregnant and parenting adolescents,131 and in two other studies participants were recruited from health, community, social service and educational agencies. 132,133,139 One study was carried out in Perth, Australia, where the participating teens were pregnant, parenting or had recently had an abortion. 137 One study focused on two study populations: (1) a group of teenage mothers of Caribbean ethnicity (from Barbados and Jamaica); and (2) a group of teenage mothers of various ethnicities (white, black, Asian and mixed race) in the UK. 130 For this latter study, we also included data relating to the London participants from the author’s doctoral thesis. 140 The final study was conducted in the UK and focused on abortion and repeat abortion. 134 A summary of the characteristics of included qualitative studies can be found in Appendix 18.

Quality appraisal of qualitative studies

We conducted quality appraisal using the appropriate questions for qualitative research in the MMAT. 54 We slightly amended the published version by adding an alternative response, ‘somewhat’, for items that were partially described, if we considered that either a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ response would be misleading.

The MMAT54 assessment items relevant to qualitative studies are:

-

Item 1 Are the sources of qualitative data (archives, documents, informants, observations) relevant to addressing the research question (objective)?

-

Item 2 Is the process for analysing qualitative data relevant to addressing the research question (objective)?

-

Item 3 Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to the context, for example the setting in which the data were collected?

-

Item 4 Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to researchers’ influence through, for example, their interactions with participants?

In keeping with the MMAT authors’ suggestion that ‘an overall quality score may be not informative (in comparison to a descriptive summary using MMAT criteria)’,54 we have not calculated an overall score but make the following observations: only two studies score ‘yes’ for all four items (Bull and Hogue;129 Hoggart et al. 134); one scores ‘yes’ for three items (Hellerstedt and Story131); and there was only one ‘no’ response among all the studies (item 4 in Lewis et al. 135). These observations are summarised in Table 2. The predomination of ‘somewhat’ and ‘cannot tell’ responses largely reflect deficiencies in reporting.

| Author and year | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bull, 1998129 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Clarke, 2010130 | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Cannot tell |

| Hellerstedt, 1998131 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell |

| Herrman, 2006,132 2007133 | Somewhat | Somewhat | Cannot tell | Somewhat |

| Hoggart, 2010134 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lewis, 2012135 | Yes | Yes | Somewhat | No |

| Schaffer, 2008136 | Somewhat | Somewhat | Cannot tell | Somewhat |

| Weston, 2012138 | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell |

| Wilson, 2011139 | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Cannot tell |

Economic findings

The search identified only one economic evaluation of an intervention for preventing repeat teenage pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis of two home-based computer-aided motivational interviewing interventions were compared with usual care based on findings from a linked RCT. 82–84 Key et al. 141 also proposed cost-savings from a secondary teenage pregnancy prevention intervention that included school-based social work services co-ordinated with comprehensive health care for teenage mothers and their children.

Realist synthesis

The realist evidence stream utilised evidence from all the study types listed previously. Additional evidence was drawn from non-comparison studies which comprised the rest of the studies identified by the searches and included, but not utilised, to date. Policy documents from the UK were also used to explore elements of the theory areas under investigation, applying the criteria of relevance and rigor. Two policy documents (Teenage Pregnancy Strategy: Beyond 2010, Department of Health;8 Reducing Teenage Pregnancy, NHS Scotland142) provided useful further evidence for the theory areas, and were thus included in the evidence base for the realist chapter.

Identified quantitative studies that were not synthesised in any ‘pooled’ analysis