Notes

Article history

This issue of Health Technology Assessment contains a project originally commissioned by the MRC but managed by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The EME programme was created as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) coordinated strategy for clinical trials. The EME programme is funded by the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the CSO in Scotland and NISCHR in Wales and the HSC R&D, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. It is managed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) based at the University of Southampton.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from the material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Featherstone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Stroke is the major cause of acquired adult physical disability and is responsible for 12% of all deaths in the UK. In Europe alone, there are approximately one million new cases of stroke a year. Atherosclerotic stenosis of the carotid artery is an important cause of stroke, which may be heralded by a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke, which recovers without causing serious disability. The risk of recurrent stroke in recently symptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis is as high as 28% over 2 years. The European Carotid Surgery Trial and the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) demonstrated that this risk was reduced significantly by carotid endarterectomy (CEA) compared with best medical treatment alone. 1–3 Carotid surgery has, therefore, become a standard treatment for these patients. However, the trials showed a significant risk of stroke or death resulting from surgery of between 6% and 8%. Surgery also caused significant morbidity from myocardial infarction (MI) during the general anaesthetic used in most centres and minor morbidity, including cranial nerve palsy and wound haematoma, from the incision.

The potential benefit of endovascular treatment (angioplasty with or without stenting) as an alternative to CEA was first highlighted by the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS). 4 This trial showed that endovascular treatment largely avoided the main complications of the endarterectomy incision (namely cranial nerve injury and severe haematoma). However, the rate of stroke or death within 30 days after treatment was high in both groups. Since completion of CAVATAS, stenting has largely replaced angioplasty, and stents and protection devices specifically designed for the carotid artery have been introduced.

At the time of the inception of the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS), stenting was a new method of treating carotid stenosis, which had evolved from the technique of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Stenting avoids some of the hazards of surgery and has become an established treatment for peripheral and coronary artery stenosis. Stenting is considered less invasive than CEA and has advantages in terms of patient comfort, because the procedure avoids an incision in the neck and is usually conducted under local anaesthesia. Hospital stay need only be for 24 hours after treatment if uncomplicated. When given the choice, stenting is preferred by many patients. However, stenting does not remove the atheromatous plaque, has not been shown to prevent stroke and might have an unacceptable incidence of restenosis.

Rationale

It would have been inappropriate to use the results of CAVATAS to propose the widespread introduction of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of carotid stenosis as an alternative to surgery, because the 95% confidence interval (CI) surrounding the 10% risk of any stroke within 30 days of treatment in the surgical and angioplasty groups was ± 5%. Nevertheless, the results supported the need for further randomised studies. The interventional technique used to treat carotid stenosis evolved during CAVATAS, from the use of simple inflatable balloon catheters at the beginning of the trial to the increasing use of stenting towards the end of the trial. Initially, stents were used only as a secondary procedure for inadequate results or complications of treatment after full balloon inflation. The desire to prevent these complications and superior early results in stented patients led to the increasing use of the technique of primary stenting, in which the intention is to deploy a stent in every patient before dilatation (but after pre dilatation if required to allow the atraumatic passage of the stent) of the artery. 5 Primary stenting is now accepted as best interventional practice6 and has become the radiological technique of choice for carotid stenosis, replacing balloon angioplasty. ICSS was initiated to provide randomised trial evidence on whether or not carotid artery stenting (CAS) was as effective as CEA in preventing recurrent stroke that is associated with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis.

Potential risks and benefits

Both surgical endarterectomy and stenting carry a risk of causing a stroke at the time of the treatment. Previous trials showed a significant risk of stroke or death at the time of surgery or stenting of between 6 and 10 in every 100 patients. However, patients were randomised to the study because the risk of strokes resulting from surgical or stenting treatment was believed to be less than leaving the carotid artery narrowing untreated. The majority of major strokes after carotid percutaneous transluminal angioplasty are the result of dissection of the carotid artery at the time of balloon inflation with subsequent thrombosis. It is believed that stenting is safer than simple balloon angioplasty because embolisation, dissection and closure of the carotid artery are less likely to occur. 5,6 The subgroup analysis of stented patients in CAVATAS was consistent with this suggestion. The adverse consequences of dissection are minimised because the stent maintains laminar flow across the stenosis and seals the site of dissection, preventing a free intimal flap. In addition, the stent mesh limits the size of any thrombus or atheromatous debris that may be dislodged from the plaque at the time of dilatation of the artery. Superior dilatation achieved by stenting compared with balloon angioplasty may also reduce the rate of stroke in the early post-treatment period. In the coronary circulation, stenting has been shown to produce superior outcomes compared with balloon angioplasty. 7,8 Individual case series suggested that carotid stenting has a similar rate of procedural stroke to that of carotid surgery. 5,6,9

Surgery also carries a risk of perioperative MI. Approximately 1 in 10 patients has temporary tongue or facial weakness as a result of cranial nerve palsy. A large blood clot (haematoma) may form at the site of incision, which may require removal. Surgery results in a permanent scar in the neck. Angiography and stenting may also result in bruising or haematoma at the site of injection (usually in the groin) and can cause temporary discomfort or pain in the neck. There is a small risk of allergic reactions to the contrast reagent used during angiography.

Although acceptable safety at the time of stenting had been suggested by the case series and registry data, at the time ICSS was initiated, stenting had not been subjected to a randomised trial in comparison with conventional surgical treatment and had not been demonstrated to prevent stroke, which is the aim of treatment. 10 Stenting does not remove the atheromatous plaque and stents may stimulate neointimal hyperplasia. In the long term, it is possible that the rate of restenosis would be greater after stenting than after carotid surgery, which could well result in an unacceptable rate of long-term stroke recurrence. There was, therefore, an important need to establish the efficacy of carotid stenting in comparison to surgery at a time when the technique was being widely introduced without adequate trial-based evidence for its safety and effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods

Objective

The objective of ICSS was to compare the risks, benefits and cost-effectiveness of a treatment policy of referral for carotid stenting compared with referral for carotid surgery.

Design

The ICSS was an international, multicentre, randomised controlled, open, prospective clinical trial comparing carotid surgery with carotid stenting. The trial was approved by the Northwest Multicentre Research Committee in the UK and by local ethics committees outside the UK. The full version of the protocol is available at www.cavatas.com. 11

Participants

Patients of either sex over the age of 40 years with symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis of the carotid artery were included in the trial. The consent form and patient information form are shown in Appendices 1 and 2, respectively. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined below.

Inclusion criteria

-

Symptomatic, extracranial, internal or bifurcation atheromatous carotid artery stenosis suitable for both stenting and surgery, and deemed by the randomising clinician to require treatment.

-

The severity of the stenosis of the randomised artery should be at least 50% (as measured by the NASCET method or non-invasive equivalent).

-

Symptoms must have occurred in the 12 months before randomisation. It was recommended that the time between symptoms and randomisation should be < 6 months, but patients with symptoms occurring between 6 months and 12 months could be included if the randomising physician considered that treatment was indicated.

-

The patient had to be clinically stable following their most recent symptoms attributable to the stenotic vessel.

-

Patients had to be willing to have either treatment, be able to provide informed consent and be willing to participate in follow-up.

-

Patients had to be able to undergo their allocated treatment as soon as possible after randomisation.

-

Any patient > 40 years of age could be included.

-

Patients could only be randomised if the investigator was uncertain which of the two treatments was best for that patient at that time.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients refusing either treatment.

-

Patients unable or unwilling to give informed consent.

-

Patients unwilling or unable to participate in follow-up for whatever reason.

-

Patients who had previously had a major stroke with no useful recovery of function within the territory of the treatable artery.

-

Patients with a stenosis that was known to be unsuitable for stenting prior to randomisation because of one or more of:

-

tortuous anatomy proximal or distal to the stenosis

-

presence of visible thrombus

-

proximal common carotid artery stenotic disease

-

pseudo-occlusion (‘string sign’).

-

-

Patients not suitable for surgery owing to anatomical factors (e.g. high stenosis, rigid neck).

-

Patients in whom it was planned to carry out coronary artery bypass grafting or other major surgery within 1 month of carotid stenting or endarterectomy.

-

Carotid stenosis caused by non-atherosclerotic disease (e.g. dissection, fibromuscular disease or neck radiotherapy).

-

Previous CEA or stenting in the randomised artery.

-

Patients in whom common carotid artery surgery was planned.

-

Patients medically not fit for surgery.

-

Patients who had a life expectancy of < 2 years owing to a pre-existing condition (e.g. cancer).

Interventions

Stenting protocol

Stenting was carried out as soon as possible after randomisation using percutaneous transluminal interventional techniques from the femoral, brachial or common carotid artery by a designated interventional consultant using an appropriate stent. A cerebral protection system was used whenever the operator thought that one could be safely deployed. Stents and other devices used in the trial had to be Conformité Européenne (CE) marked and approved by the steering committee.

Pre-medication was at the discretion of the interventionist, although the protocol recommended the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel as the antiplatelet regime of choice to cover the period of stenting and for a minimum of 4 weeks afterwards. Intra-procedural heparin was mandatory at a dose determined by the operator; post-procedural heparin could be given according to clinical requirements.

The trial protocol stated that atropine, or a similar agent, must be administered prior to stent deployment to counteract any effects on the carotid artery baroreceptors, which could lead to severe bradycardia or asystole.

Angiographic images showing the stenosis at its most severe prior to stenting and the same view and any other view that demonstrated the maximum residual stenosis after stenting were collected by the trial office.

Details of the procedure, including all periprocedural complications, drug therapy and devices used in the procedure, were reported on the stenting and cerebral protection technical data sheet which was returned to the trial central office.

Endarterectomy protocol

Endarterectomy was carried out as soon as possible after randomisation by a designated consultant surgeon. It was carried out using whichever procedures were standard at the individual centre, including the use of local or general anaesthesia, shunts or patches as required by the operating surgeon. Standard or eversion endarterectomy could be performed. Details of the procedure, including all periprocedural complications, drug therapy and type of endarterectomy performed, were reported on the surgery technical data sheet which was returned to the trial central office.

Approval of surgeons and interventionists, and credentialing of less-experienced operatives

An accreditation committee decided if surgeons and interventionists at enrolling centres had the appropriate experience and expertise to join the study. Surgeons and interventionists were expected to show a stroke and death rate within 30 days of treatment, consistent with the centres in the European Carotid Surgery Trial who had an average rate of 7.0% with a 95% CI of 5.8% to 8.3%. 1 Surgeons were expected to have performed a minimum of 50 carotid operations with a minimum annual rate of at least 10 cases per year. Interventionists were expected to have performed a minimum of 50 stenting procedures, of which at least 10 should have been in the carotid territory. Centres that had little or no experience of carotid stenting were allowed to join ICSS for a probationary period in order to gain the minimum experience of 10 carotid stenting procedures required to join the trial fully. Stenting procedures carried out during the probationary period were proctored by an experienced carotid interventionist appointed by the trial steering committee, until the proctor was satisfied that the interventionist(s) at the centre could satisfactorily carry out procedures unproctored. Probationary interventionists became fully enrolled in ICSS when the proctor was satisfied that the interventionist could perform procedures unsupervised and the interventionist had 10 or more successfully completed cases in the trial, with an acceptable complication rate.

Reporting of suspected problems with surgical or stenting techniques at individual centres

The database manager at the trial office monitored periprocedural outcome events, and if there were two consecutive deaths or three consecutive major events at a single centre within 30 days of treatment in the same arm of the study, then assessment of the events was triggered. A blinded assessment of the relevant outcome events was submitted by the central office to the chairman of the data monitoring committee who had the power to recommend further action, such as suspending randomisation at the centre. A cumulative major event or death rate of more than 10% over 20 cases would also trigger careful assessment of the relevant outcome events.

Data collected at baseline

Baseline data collected at randomisation included demographic data; existing medical risk factors; neurological symptoms and an assessment of disability using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS); current antiplatelet therapy and blood pressure; and films and reports of pre-randomisation brain imaging and the results of duplex ultrasound (DUS).

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed by a telephone call or fax to a computerised service provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Service Unit. It was stratified by centre with minimisation of the main risk factors and balanced between the arms. Patients who needed treatment of both carotid arteries could only be randomised for the carotid artery to be treated first. Two patients were randomised at the Service Unit by coin toss when the computerized service was not available.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up by a neurologist or a physician interested in stroke, who was not involved in the revascularisation procedure but who was not masked to group assignment, at the participating centres at 30 days after treatment, 6 months after randomisation and, then, annually after randomisation.

At each visit, levels of stroke-related disability were assessed using the mRS and any relevant outcome events notified to the central trial office. DUS examinations of the carotid arteries were carried out at each follow-up visit at centres with available facilities. Bilateral peak systolic and end diastolic velocities in the internal carotid artery and the peak systolic velocity in the common carotid artery were recorded. The data were collected on a follow-up form and an ultrasound report form (see Appendices 3 and 4), which were returned to the central trial office where the data were entered into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database. In addition to the clinical data, patients were asked to complete a EuroQol European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions – 3 level response (EQ-5D-3L™) questionnaire (see www.euroqol.com) to assess quality of life and health status at baseline, after stenting or surgery at 1 month, and then at 6-month and annual follow-up visits.

Patients were followed up to the end of the trial in 2011 (a maximum of 10 years after randomisation). Patients reaching their 5-year follow-up before the end of the trial were asked if they were willing to carry on with follow-up, in which case they continued with annual follow-up until the end of the trial.

Outcomes

The following events were collected and analysed as trial outcome events:

-

any stroke or death

-

TIA

-

MI within 30 days of treatment

-

cranial nerve palsy within 30 days of treatment

-

haematoma caused by treatment requiring surgery, transfusion or prolonging hospital stay

-

stenosis ≥ 70% or occlusion during follow-up

-

further treatment of the randomised artery by interventional radiology techniques or surgery after the initial attempt

-

quality of life, health status and health service costs.

Outcome events included in the safety analysis or primary outcome (stroke, MI within 30 days of treatment, death) were documented in detail by the investigating centre, censored after receipt at the central office to remove clues as to the treatment allocated, and then adjudicated by a neurologist at the central office and by an independent external neurologist. If the external neurologist’s adjudication differed from the central office, a third independent neurologist reviewed the event and the majority opinion prevailed. The major event and death forms are shown in Appendices 5 and 6.

Centres were asked to supply the following information for adjudication, whenever possible:

-

a report of the event using the standard trial case report form

-

a film copy of a computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scan as soon as possible after the event, together with a film copy of the pre-randomisation scan (if done) and a report of the event

-

copies of discharge summaries, death certificates and post-mortem results (if relevant).

Disability after stroke and cranial nerve palsy was assessed 30 days after treatment or at onset using the mRS. Duration of symptoms was recorded and outcome events were classified as disabling if the mRS score was 3 or more at 1 month. If the patient was not seen at exactly 30 days after onset of the event, the investigator was asked to estimate the 30-day mRS.

The degree of carotid stenosis during follow-up was determined in the study central office based on flow velocity data using pre-defined criteria,12 masked to treatment allocation and date of ultrasound follow-up. Results of carotid imaging studies ordered outside regular follow-up at the discretion of the treating clinicians (e.g. for recurrent symptoms) were also included. The main outcome event of the restenosis analysis was defined as any severe (≥ 70%) residual or recurrent stenosis, or occlusion of the carotid artery during follow-up. No correction was made for the presence of a stent when measuring stenosis severity.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted according to the statistical analysis plan for the short-term (safety) analysis or the long-term analysis (see Appendix 7), which provides a detailed and comprehensive description of the main, pre-planned analyses for the study. Analyses were performed with Stata statistical software version 12.1 or earlier (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), except for the MRI substudy and the study on the effect of white-matter lesions on periprocedural stroke, which used SPSS statistical software version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), respectively.

The main features of the analysis plan are summarised below.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is used to summarise representativeness of the study sample and patient throughput (see Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are presented by treatment group with continuous variables presented with means and standard error.

The analyses compare the treatment groups with respect to the length of time before treatment failure (i.e. occurrence of an outcome event) by means of the Mantel–Haenszel chi-squared test and Kaplan–Meier survival curves with a two-sided p-value of 0.05 (5% level) used to declare statistical significance with a 95% CI reported throughout. Secondary analyses compare the proportions of outcome events within 30 days of treatment. All analyses are adjusted for centre and pre-determined risk factors. Subgroup analyses examine risk factors for outcome events.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI with endarterectomy as the reference group using all available follow-up data. Log-rank tests were used to compare the two survival curves. Censoring was assumed to be non-informative.

As the restenosis outcome was interval-censored it was instead analysed using a generalised non-linear model which assumes proportional hazards and whose treatment effect parameter estimate can be interpreted as a log-HR. The treatment effect p-value for the restenosis outcome was calculated using a likelihood ratio test. Life-table analyses were used to estimate the cumulative incidences of restenosis at 1 year and 5 years after treatment.

Interaction tests were performed to investigate whether or not the relative treatment effect for the pre-defined primary long-term outcome, as well as for procedural stroke or death or ipsilateral stroke during follow-up, differed across various patient groups. Functional ability at the final follow-up or at death was compared between treatment groups across the entire range of the mRS at 1-year and 5-year follow-up using the permutation test described by Howard et al. 13 Drug treatments and blood pressure at 1-year and 5-year follow-up were compared using chi-squared tests and t-tests at each time point, respectively.

Sample size (original and revised)

At the commencement of recruitment in 2001 we planned to recruit 2000 patients, but this was revised shortly after the start of the trial in 2003 to 1500 in response to the initial funding period and taking into account the observed recruitment rate to that date. For 1500 patients, the 95% CI was the observed difference ± 3.0 percentage points for the outcome measure of 30-day stroke, MI and death rate and ± 3.3 percentage points for the outcome measure of death or disabling stroke over 3 years’ follow-up. The difference detectable with power 80% was 4.7 percentage points for 30-day outcome and 5.1 percentage points for survival free of disabling stroke. Similar differences were detectable for secondary outcomes. In 2007, the steering committee modified the protocol to emphasise that the sample size of 1500 patients should reflect only patients recruited at experienced centres, to ensure that the study would be adequately powered to compare outcomes of stenting performed by experienced interventionists with endarterectomy. An extension of funding was therefore obtained to allow the recruitment of a total of 1700 patients, anticipating that 200 of these would come from centres with probationary investigators.

Protocol amendments

The major amendments to the protocol during the course of the trial are detailed in Appendix 8. In brief, in addition to the modifications to the sample size described above, in 2003, clarification of the rules governing proctoring of probationary centres and the maximum permissible delays between symptoms and randomisation were added to the protocol. In 2007, an amendment was made to state that data from patients enrolled at probationary centres would be analysed separately from data from fully enrolled experienced centres. Subsequently, the steering committee decided after completion of recruitment and initial analysis of the results that the data from probationary and fully enrolled centres should be analysed together, because there was no significant difference in the results (indeed the results were slightly better at probationary centres).

The International Carotid Stenting Study–magnetic resonance imaging substudy: symptomatic and asymptomatic ischaemic and haemorrhagic brain injury following protected and unprotected stenting versus endarterectomy

Clinical follow-up of patients in ICSS was not masked to treatment allocation and, therefore, there was the possibility of potential bias in the ascertainment of non-disabling strokes. We therefore planned a substudy of ICSS at centres with sufficient neuroimaging facilities and capacity in which we would use multimodal MRI as an additional outcome measure of procedural cerebral ischaemia that could be analysed without knowledge of treatment allocation. We aimed to compare the risk of procedural ischaemia and persistent infarction on MRI between patients randomly allocated to receive stenting or endarterectomy. Moreover, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), a modern MRI technique, may show ischaemic lesions after carotid interventions even in patients who do not experience symptoms. 14 In previous studies, new ischaemic lesions on DWI were detected more frequently after stenting than after endarterectomy. 15–21 DWI lesions were also more frequent after unprotected stenting than after protected stenting. 22,23 However, selection bias and the use of historical controls might account for the observed differences in these non-randomised comparisons. In addition, it was not clear how ischaemic lesions on DWI relate to the risk of clinically apparent cerebrovascular events (stroke or TIA) associated with the intervention. Larger studies with randomised treatment allocation were needed to gain further insight into the significance of asymptomatic DWI lesions and their potential role as surrogate markers of treatment risk.

Cerebral protection devices are used in stenting with the aim of reducing the risk of plaque embolisation during the procedure. Recently completed randomised trials comparing the safety of stenting and endarterectomy yielded conflicting results. 24,25 Concern that stenting without cerebral protection might be associated with an increased risk of stroke led to the abandonment of unprotected procedures in one trial,25 but in another trial, there was no difference in the risk of stenting with and without protection. 24 Although clear evidence that cerebral protection enhances treatment safety is lacking,26 protection devices were widely used, significantly contributing to the cost of carotid stenting. We therefore planned to carry out an exploratory analysis of the MRI data to investigate the effect of cerebral protection devices on the risk of ischaemia associated with stenting.

Objectives

The primary objective of this substudy was to compare the risk of ischaemic brain injury assessed on MRI in patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis undergoing stenting in comparison to those undergoing endarterectomy.

Secondary objectives were: to assess the effect of protection devices on the risk of ischaemic brain injury associated with stenting; to compare the risk of haemorrhagic brain injury assessed on MRI in stenting compared with endarterectomy; and to gain further insight into the usefulness of ischaemic and haemorrhagic brain lesions on MRI as surrogate markers of the risk of carotid interventions.

The ICSS–MRI substudy was designed to allow a randomised comparison of the procedural risk of symptomatic and asymptomatic ischaemic and haemorrhagic brain injury visible on MRI between stenting and endarterectomy. The use of cerebral protection devices in patients undergoing stenting was not subject to randomisation in ICSS. However, the participating centres systematically used either protected or unprotected stenting. The risk of brain injury associated with either stenting technique could, therefore, be compared with a randomised control group of patients undergoing endarterectomy.

Outcome measures and analyses were defined as follows:

Primary outcome measure: rate of symptomatic and asymptomatic ischaemic brain injury detectable on MRI after endarterectomy and stenting.

Secondary analyses:

-

interaction between the use of protection devices and ischaemic brain injury in patients undergoing stenting

-

rate of symptomatic and asymptomatic haemorrhagic brain injury detectable on MRI after endarterectomy and stenting

-

relation of brain injury on MRI to risk of stroke during procedure and follow-up.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible to participate in the ICSS–MRI substudy if they were enrolled in the ICSS trial and separately provided written informed consent to undergo three MRI exams.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with contraindications to MRI (e.g. pacemakers, metallic implants and claustrophobia) were excluded from the ICSS–MRI substudy.

Magnetic resonance imaging protocol

Patients enrolled in the ICSS–MRI substudy had three MRI investigations, at 1–3 days before, 1–3 days after and 30 ± 3 days after the intervention. The following sequences were performed in all three investigations:

-

DWI to detect acute ischaemic brain injury associated with the procedure

-

gradient echo T2 star-weighted sequences to detect haemorrhagic brain injury associated with the procedure

-

T1-weighted, T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences were used to assess whether or not acute brain lesions detected on DWI after the procedure led to permanent scarring at 1 month.

Data acquisition

Baseline data (such as age, sex, medical risk factors, degree of carotid stenosis, etc.) were collected as part of ICSS. Two researchers, one a neurologist and one a neuroradiologist, with several years of experience in assessing brain scans in patients with cerebrovascular disease independently scored the presence, size and location (vascular territory) of ischaemic and haemorrhagic lesions on the MRI scans. A third experienced researcher reviewed the scans in case of disagreement. The scans were reported and scored blind to patient identifiers, treatment, date and time of the scans. Patients were clinically examined by a neurologist at the time of MRI examination and followed up after treatment as part of ICSS to determine outcome events, including TIA, stroke, MI and death.

Statistical analysis

The rates of ischaemic and haemorrhagic brain lesions were compared between patients undergoing endarterectomy and stenting using chi-squared tests2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Significance was declared at p < 0.05. Exploratory analyses were performed to test the interaction between the use of cerebral protection devices and the rate of DWI lesions after stenting.

Sample size calculation

Power calculations for this substudy were based on the primary outcome measure. The two largest series reported new ischaemic lesions on DWI after CEA in 17% and 34% of patients, respectively. 27,28 If a rate of new DWI lesions after endarterectomy of 25% is assumed, a total sample size of 200 patients would have a 90% power to detect a twofold increase in the DWI lesion rate associated with carotid stenting.

Effect of white-matter lesions on the risks of periprocedural stroke after carotid artery stenting versus endarterectomy

Leukoaraiosis was associated with a higher perioperative risk of stroke or death in patients assigned to CEA in the NASCET. 29 Patients with widespread white-matter changes allocated to the best medical management group also had an increased risk of stroke or death. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of white-matter lesions on the procedural risk of stroke and death in carotid stenting has hitherto not been investigated. We therefore investigated the effect of leukoaraiosis on the risk of procedural complications in a large group of patients with recently symptomatic carotid disease randomised in ICSS in a pre-specified analysis. 30 Brain imaging by CT or MRI was needed before revascularisation.

Methods

In this study of white-matter lesions, we included all patients enrolled in ICSS in whom copies of the baseline CT or MRI done before carotid stenting or endarterectomy were available. Patients were excluded if no baseline brain imaging was available or if the quality of the images was poor. Copies of baseline brain imaging were analysed by two investigators, one a neurology research fellow and one a neuroradiologist, who were both trained in the analysis of white-matter lesions and masked to treatment and clinical outcome, for the severity of white-matter lesions using the age-related white-matter changes (ARWMC) score. Differences were resolved by consensus. Patients were divided into two groups using the median ARWMC score. We analysed the risk of stroke within 30 days of revascularisation using a per-protocol analysis. A total of 1036 patients (536 randomly allocated to CAS, 500 to CEA) had baseline imaging available. The median ARWMC score was 7, and patients were dichotomised into those with a score of 7 or more and those with a score of < 7.

Cost–utility analysis of stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of symptomatic carotid stenosis

A cost–utility analysis with full incremental analysis was undertaken to compare the costs and outcomes associated with stenting and endarterectomy.

Methods

Outcome measure

The outcome measure was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which combine length of life and quality of life; this is consistent with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations. Cost-effectiveness was expressed as incremental net monetary benefits (NMBs). The analysis took a UK NHS and personal social services (PSS) perspective. 31 Costs are calculated in 2013–14 Great British pounds. The time horizon was 5 years, which was long enough to reflect all important differences in costs or outcomes between the two treatments. An annual discount rate of 3.5% was applied to costs and outcomes. 31

Resource use and costs

For every patient we calculated the cost of the index procedure and the cost of follow-up using resource-use data collected prospectively in the trial. The former included surgeon and radiologist time; operating theatre time, including nursing staff, drugs, consumables and overheads; anaesthesia; materials and devices including stents, shunts, patches, cerebral protection devices, catheters, wires and sheaths; and length of hospital stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and inpatient ward. The latter included additional carotid artery procedures; complications within 30 days of index procedure (fatal and non-fatal MI, severe haematoma and disabling cranial nerve palsy); imaging tests; drug treatment; and non-disabling, disabling and fatal strokes.

Unit costs were obtained from published and local sources,32–35 inflated where appropriate32 and multiplied by resource use. Unit costs of surgeon, radiologist and operating theatre times were hourly costs applied to procedure durations collected during the trial. The choice of stents was at the discretion of the interventionist. In the base-case analysis each stent was assigned an acquisition cost of £840 based on the cost of the most commonly used stent, the Carotid WALLSTENT® (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) at the lead centre; this was varied in sensitivity analysis. Unit costs of hospital stays were daily costs applied to length-of-stay data collected in the trial. Length of stay on the ICU was not collected for individual patients, but mean values were collected by centre. From these data we assumed that where patients were admitted to the ICU post-operatively it was for 1 day. Unit costs of additional carotid artery procedures were assumed to be equal to the mean cost of the index procedures. Unit costs of drug treatment were monthly costs applied to treatment durations collected in the trial. Stroke events were recorded in the trial, but the costs of managing them were not. These were obtained from supplementary analyses of data from a contemporaneous UK population-based study of all strokes, the Oxford Vascular (OXVASC) study,36,37 which were used to predict care home and hospital care costs for each stroke patient as a function of their sex, age, disability before stroke, previous history of cardiovascular disease, initial stroke severity (non-disabling, disabling, fatal) and number of recurrent strokes (see Appendix 9).

Utilities and quality-adjusted life-years

Generic health status was described at baseline (randomisation), at 3 and 6 months, and at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years post-randomisation using the EQ-5D-3L descriptive system (see www.euroqol.com), containing five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, anxiety and depression) with three levels in each dimension. Each EQ-5D-3L health state can be converted into a single summary index (utility value) by applying a formula that attaches weights to each of the levels in each dimension based on valuations by general population samples. Given the perspective of our analysis, we used a value set for the UK population to calculate utility values at each time point for every participant. 38 Utility values of 1 represent full health, values of 0 are equivalent to death, negative values represent states worse than death. Patients who died were assigned a utility value of 0 at their date of death. A utility profile was constructed for every patient assuming a straight line relation between their utility values at each measurement point. QALYs for every patient from baseline to 5 years were calculated as the area under the utility profile.

Dealing with missing data

Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data for the following variables: cost of surgeon and radiologist time; cost of operating theatre time; cost of anaesthesia; cost of stents; cost of patches; cost of cerebral protection devices; cost of other materials used in stenting; cost of length of hospital stay; cost of non-fatal MI; cost of imaging tests; costs of drug treatment; cost of strokes; total cost; utility values at baseline, 3 months and 6 months post-randomisation, and 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years post-randomisation; and total QALYs. The cost variables were unit costs multiplied by resource use. Age, sex, study centre and treatment allocation were included in the imputation models as additional explanatory variables. We used multivariate normal regression to impute missing values and generated 20 imputed data sets. We repeated the multiple imputation several times using different random number seeds to investigate if the conclusions of the analysis changed.

Statistical methods

Mean costs, outcomes and NMBs were compared between all patients randomly assigned to stenting and to endarterectomy, irrespective of which treatment was administered and whether or not they received additional carotid artery procedures of either type. We calculated differences in mean costs and QALYs and incremental NMBs between groups. NMBs for stenting and endarterectomy were calculated as the mean QALYs per patient multiplied by the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY minus the mean cost per patient. Incremental NMBs were calculated as the difference in mean QALYs per patient with stenting versus endarterectomy multiplied by the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY minus the difference in mean cost per patient. We used the cost-effectiveness threshold range recommended by NICE of £20,000 to £30,00031 as the lower and upper limits of the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY. If the incremental NMB is positive (negative) then stenting (endarterectomy) was preferred on cost-effectiveness grounds. The QALYs gained were adjusted for age, sex, study centre and baseline utility values using regression analysis; the incremental costs were adjusted for age, sex and study centre. For each of the 20 imputed data sets we ran 1000 bootstrap replications and combined the results using equations described by Briggs et al. 39 to calculate standard errors around mean values accounting for uncertainty in the imputed values, the skewed nature of the cost data and utility values, and sampling variation. Standard errors were used to calculate 95% CIs around point estimates.

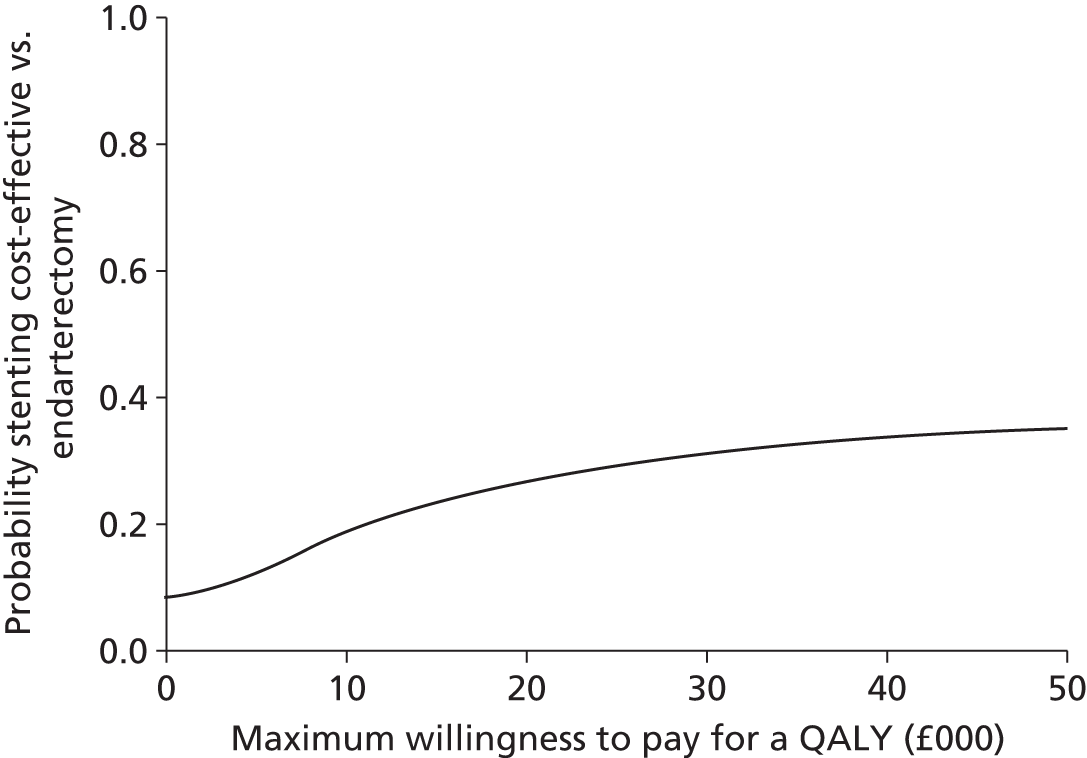

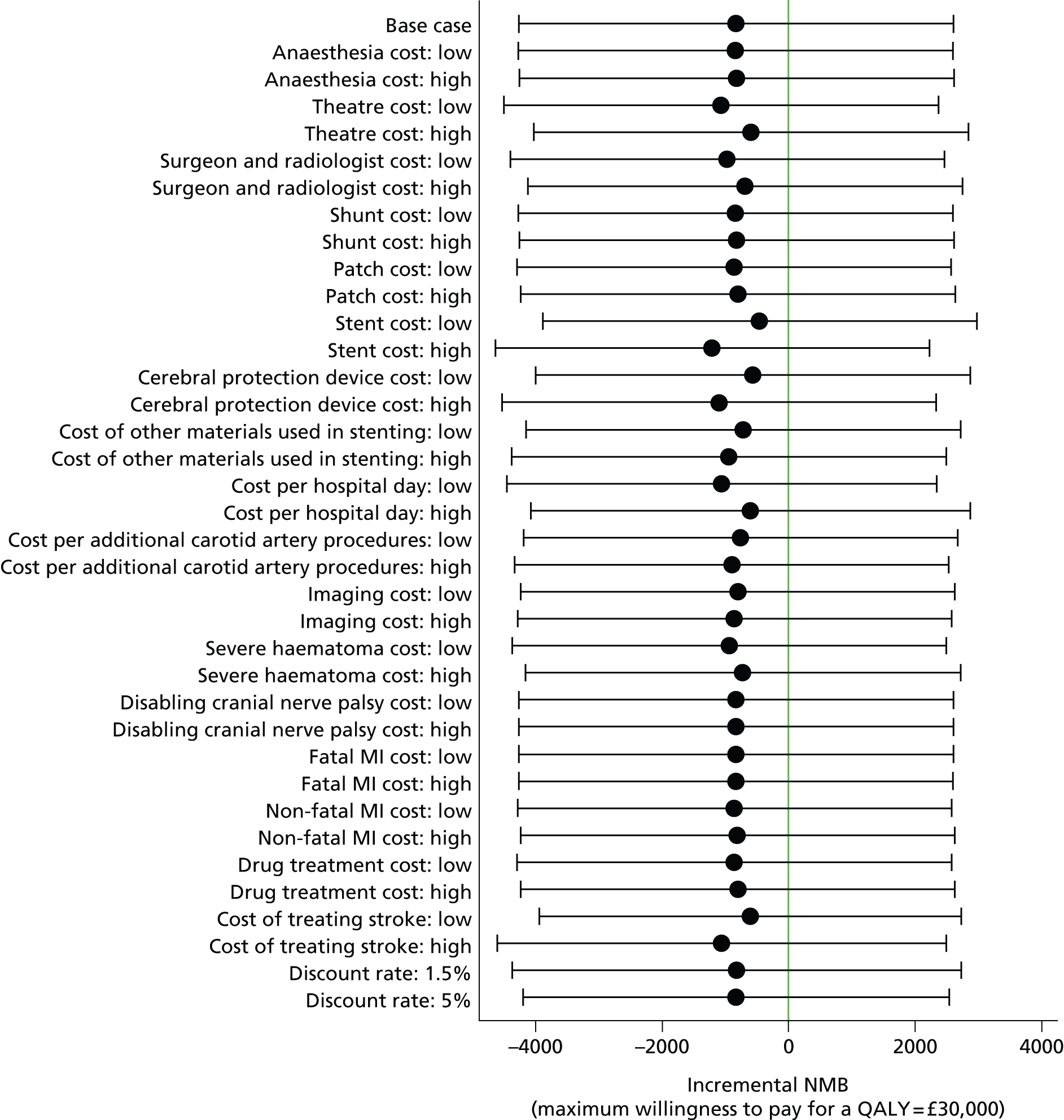

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve40 showing the probability that stenting was cost-effective compared with endarterectomy at a range of values for the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY was generated based on the proportion of the bootstrap replications across all 20 imputed data sets with positive incremental NMBs. 41 The probability that stenting was cost-effective at a maximum willingness to pay for a QALY of £20,000 and £30,000 was reported, based on the proportion of bootstrap replications with positive incremental NMBs at these values. We undertook further sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of uncertainty in the following components: no adjustment for age, sex, study centre and baseline utility values; complete-case analysis without imputing missing values; univariate analyses of high- and low-cost values (unit costs multiplied by resource use) for anaesthesia, operating theatre time, surgeon and radiologist time, shunts, patches, stents, cerebral protection devices, other materials used in stenting, length of hospital stay, additional carotid artery procedures, imaging, severe haematoma, disabling cranial nerve palsy, fatal and non-fatal MI, drug treatment, treating strokes (values per patient were recalculated to be 50% higher and 50% lower than the base case); and discount rate (1.5%, 5%). No significant interactions were found in any subgroup analyses of the primary outcomes in ICSS. In post-hoc subgroup analyses we calculated cost-effectiveness results separately by sex and age (≥ 70 years, < 70 years). We completed a Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement to ensure that the cost–utility analysis was reported appropriately (see Appendix 9).

Chapter 3 Results

The short-term and long-term outcomes of ICSS have been reported in the literature. 42,43

Recruitment

Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram of the flow of patients through the trial. Between May 2001 and October 2008, 1713 patients from 50 centres in the UK, mainland Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Canada were enrolled and randomised. The trial centres, together with the members of the trial committees, location of recruiting centres, number of patients recruited at each centre and the names of the investigators at each centre are detailed in Appendix 10. Three patients (two in the stenting group and one in the endarterectomy group) withdrew consent immediately after randomisation and were excluded from the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. In total, 1511 patients were enrolled at experienced centres and 202 at supervised probationary centres: 751 (88%) of 853 patients assigned to carotid stenting and 760 (89%) of 857 patients assigned to endarterectomy were randomised at centres classified as experienced. Most patients had their allocated treatment initiated (stenting group, n = 828; endarterectomy group, n = 821). Nine patients allocated to stenting crossed over to surgery without an attempt at the procedure and a further 16 had no attempted ipsilateral endarterectomy or stenting procedure (Figure 1). Fifteen patients allocated to endarterectomy crossed over to stenting without an attempt at endarterectomy and 21 had no attempted ipsilateral procedure.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for ICSS.

Monitoring of adverse events led to concern about the stenting results of two investigators at supervised centres. These investigators were stopped from treating further patients within the trial and their centres were suspended from randomisation. All the patients allocated to stenting (n = 11, five with disabling stroke or death) or endarterectomy during the same time period (n = 9, one with fatal stroke) at these centres were included in the analyses. One of the two centres subsequently restarted randomisation with a different investigator performing stenting.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Baseline patient characteristic | Stenting (n = 853) | Endarterectomy (n = 857) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 70 (9) | 70 (9) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 601 (70) | 606 (71) |

| Vascular risk factors | ||

| Treated hypertension, n (%) | 587 (69) | 596 (70) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 147 (24) | 146 (24) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 79 (12) | 78 (13) |

| Cardiac failure, n (%) | 23 (3) | 47 (5) |

| Angina in last 6 months, n (%) | 83 (10) | 77 (9) |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 151 (18) | 156 (18) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 109 (13) | 116 (14) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 57 (7) | 59 (7) |

| Other cardiac embolic source, n (%) | 19 (2) | 16 (2) |

| Diabetes mellitus, non-insulin dependent, n (%) | 134 (16) | 147 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus, insulin dependent, n (%) | 50 (6) | 41 (5) |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 139 (16) | 136 (16) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 205 (24) | 198 (23) |

| Ex-smoker, n (%) | 408 (48) | 424 (49) |

| Treated hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 522 (61) | 563 (66) |

| Total serum cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 4.8 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.3) |

| Degree of symptomatic carotid stenosis, n (%)a | ||

| 50–69% | 92 (11) | 76 (9) |

| 70–99% | 761 (89) | 781 (91) |

| Degree of contralateral carotid stenosis, n (%)a | ||

| < 50% | 565 (66) | 561 (65) |

| 50–69% | 128 (15) | 142 (17) |

| 70–99% | 105 (12) | 110 (13) |

| Occluded | 49 (6) | 37 (4) |

| Unknown | 6 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Most recent ipsilateral event, n (%)b | ||

| Ischaemic hemispheric stroke | 393 (46) | 376 (44) |

| TIA | 273 (32) | 303 (35) |

| Retinal infarction | 26 (3) | 23 (3) |

| Amaurosis fugax | 148 (17) | 142 (17) |

| Unknown | 13 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Event < 6 months prior to randomisation | 826 (97) | 816 (95) |

| Event 6–12 months prior to randomisationc | 27 (3) | 36 (4) |

| mRS at randomisation, n (%) | ||

| 0–2 | 756 (89) | 744 (87) |

| 3–5d | 81 (10) | 99 (12) |

Patient baseline characteristics (Table 1) and drug treatment during the trial (Table 2) were similar between the two treatment groups. At 1 year after randomisation, 97% of patients in both the stenting group and the endarterectomy group took any antiplatelet or anticoagulant; at 5 years, the percentages were 94% and 95% (Table 2). There were slightly more patients taking antihypertensive medications in the endarterectomy group at 1 year (71% vs. 75%; p = 0.088), but at 5 years the difference had reversed (83% vs. 76%; p = 0.017). However, this did not lead to any significant difference in systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between groups at either time point. The majority of patients were treated with lipid-lowering medications with no significant difference between the groups (82% of patients in the CAS group vs. 84% in the CEA group at 1 year, and 87% of patients in the CAS group vs. 86% in the CEA group at 5 years).

| Drug treatment and blood pressure | 1 year | 5 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stenting | Endarterectomy | Stenting | Endarterectomy | |

| Drug treatment (number of patients with data) | 714 | 751 | 343 | 329 |

| Any antiplatelet, n (%) | 668 (94) | 688 (92) | 303 (88) | 284 (86) |

| Aspirin alone, n (%) | 401 (56) | 413 (55) | 197 (57) | 169 (51) |

| Clopidogrel alone, n (%) | 79 (11) | 79 (11) | 40 (12) | 46 (14) |

| Dipyridamole + aspirin or clopidogrel, n (%) | 130 (18) | 154 (21) | 48 (14) | 48 (15) |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel, n (%) | 55 (8) | 34 (5) | 14 (4) | 17 (5) |

| Anticoagulation: vitamin K antagonists, n (%) | 36 (5)a | 57 (8)a | 23 (7) | 33 (10) |

| Other anticoagulation or antiplatelet, n (%) | 3 (0) | 10 (1) | 5 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Any anticoagulation or antiplatelet, n (%) | 696 (97) | 731 (97) | 322 (94) | 313 (95) |

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 510 (71) | 566 (75) | 286 (83)a | 250 (76)a |

| Lipid lowering, n (%) | 584 (82) | 629 (84) | 299 (87) | 282 (86) |

| Blood pressure (n patients with data) | 664b | 685b | 313b | 302b |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 147 (22)a | 144 (22)a | 142 (22) | 143 (23) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 79 (12)a | 78 (11)a | 77 (12) | 76 (12) |

Success of procedures and cross-overs

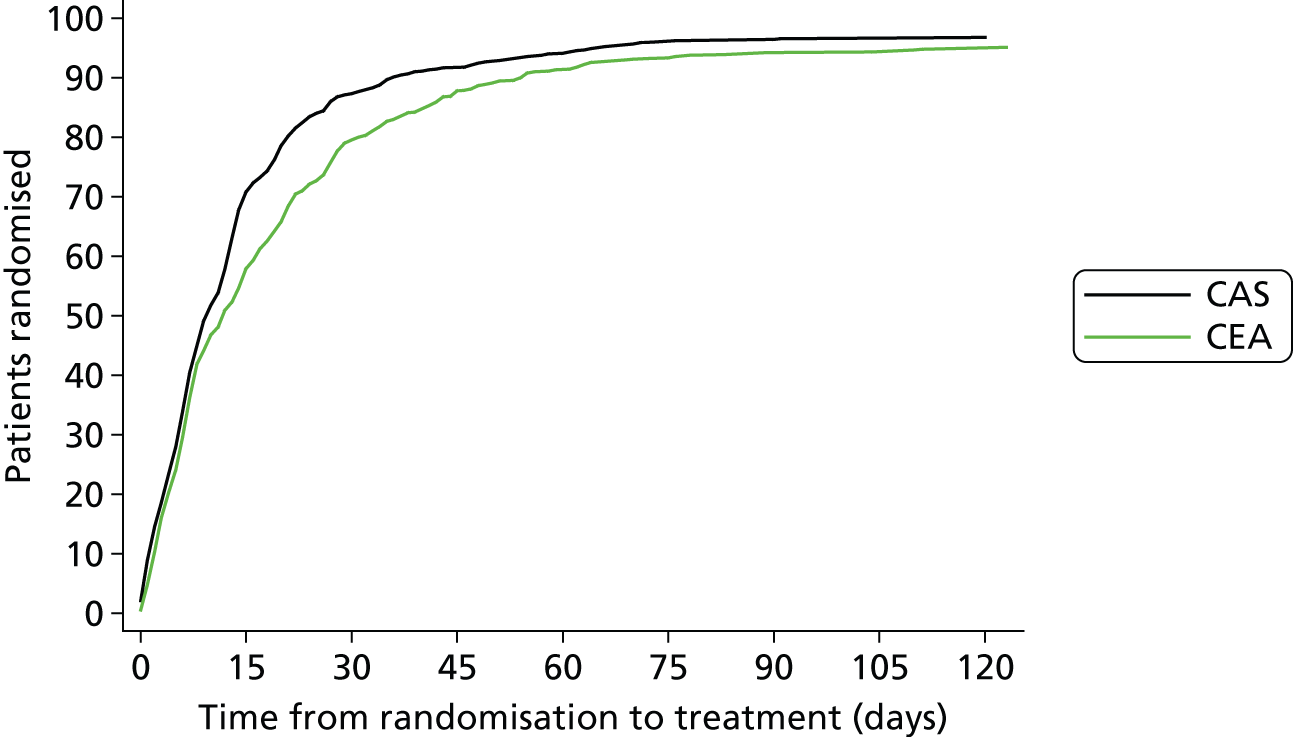

Figure 2 shows the delay from randomisation to first initiated ipsilateral treatment in the per-protocol analysis within the first 120 days after randomisation.

FIGURE 2.

Time between randomisation and treatment. Cumulative number of patients in whom allocated treatment was initiated per protocol plotted as a proportion (%) of the total number randomised in each treatment group (y-axis), against the delay in days between the dates of randomisation and treatment (x-axis). Only allocated per-protocol treatment dates were counted.

Median delay from randomisation to treatment was shorter in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group, as was the delay from most recent ipsilateral event to treatment (Table 3).

| Stenting (n = 828) | Endarterectomy (n = 821) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time from randomisation to treatment (days), median (IQR) | 9 (5–17) | 11 (5–24) | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 14 days, n (%) | 578 (70) | 469 (57) | |

| > 14 days, n (%) | 250 (30) | 352 (43) | |

| Time from most recent event to treatment (days), median (IQR) | 35 (15–82) | 40 (18–87) | 0.013 |

| ≤ 14 days, n (%) | 205 (25) | 151 (18) | |

| > 14 days, n (%) | 623 (75) | 668 (81) |

Of the 828 patients in whom stenting was initiated as allocated, 64 (8%) had their procedure aborted before the insertion of a stent (38 procedures were aborted because of difficulty gaining access to the stenosis; 15 were aborted because of the finding of an occluded artery, one patient had a fatal stroke, one patient had a fatal MI before completion of treatment, two had other medical complications, and further investigation in seven patients showed the artery to be < 50% stenosed). Of the 62 patients whose stenting procedure was aborted after initiation and who did not have a fatal event, 37 went on to have an ipsilateral endarterectomy, whereas 25 continued with best medical care only. Only two of the 821 patients whose allocated endarterectomy was initiated had their procedure aborted (one patient had an allergic reaction during general anaesthesia; the other became distressed and the endarterectomy had to be abandoned). Both patients subsequently had ipsilateral stenting.

The following stents were each used in 10% or more of the 764 patients in whom stents were inserted: Carotid WALLSTENT® (Boston Scientific), Precision (Cordis®, Freemont, CA, USA), and Protege™ (EV3®, Dublin, Ireland). The following were each used in < 10% of patients: Acculink (Guidant™, Santa Clara, CA, USA), XACT® (Abbott™, Santa Clara, CA, USA), S.M.A.R.T. ® (Cordis®, Miami Lakes, FL, USA), Cristallo Ideale (Invatec, Roncadelle, Brescia, Italy), Exponent (Medtronic®, Minneapolis, MN, USA), Next Stent (Boston Scientific). Protection devices were known to have been used in 593 (72%) of 828 patients. The following protection devices were each used in 10% or more of the patients in whom stenting was attempted: FilterWire EZ™ (Boston Scientific), ANGIOGUARD® (Cordis), SpiderFX™ (EV3) and Emboshield® (Abbott). A range of other protection devices were used in < 5% of patients. In 27 patients, it was not clear whether or not a protection device was used.

Short-term outcomes

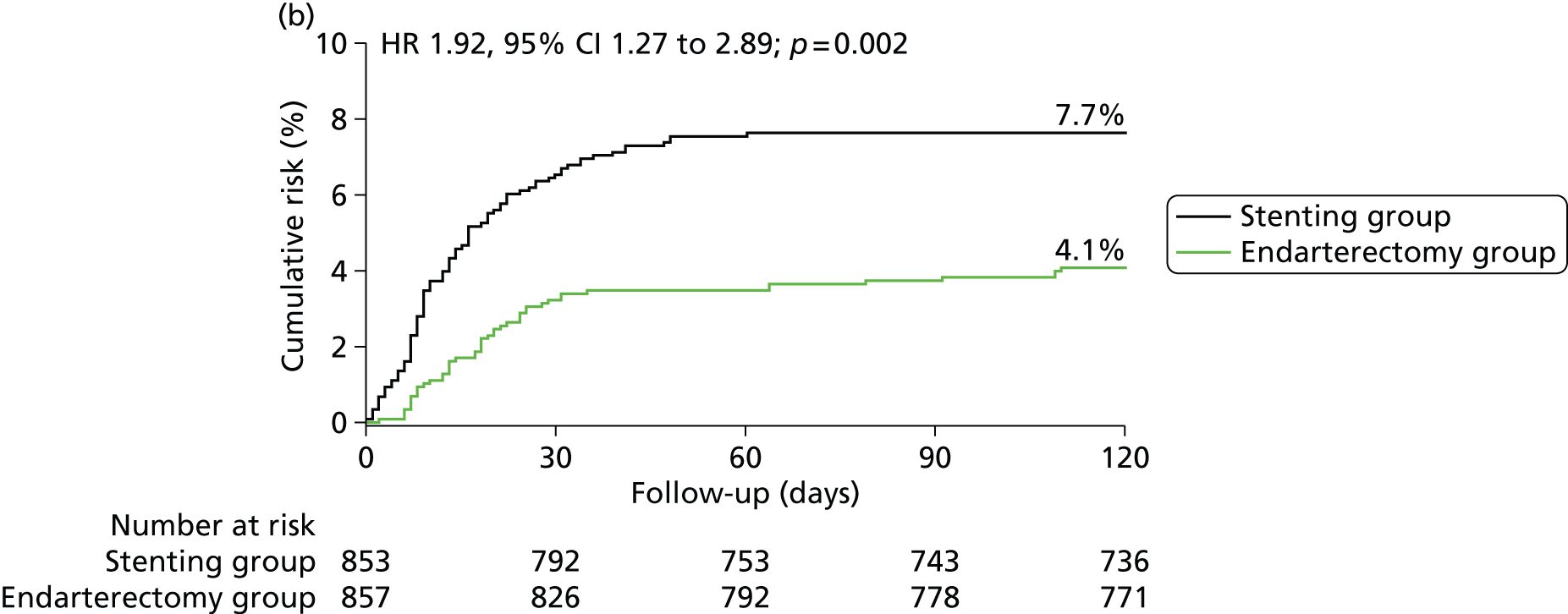

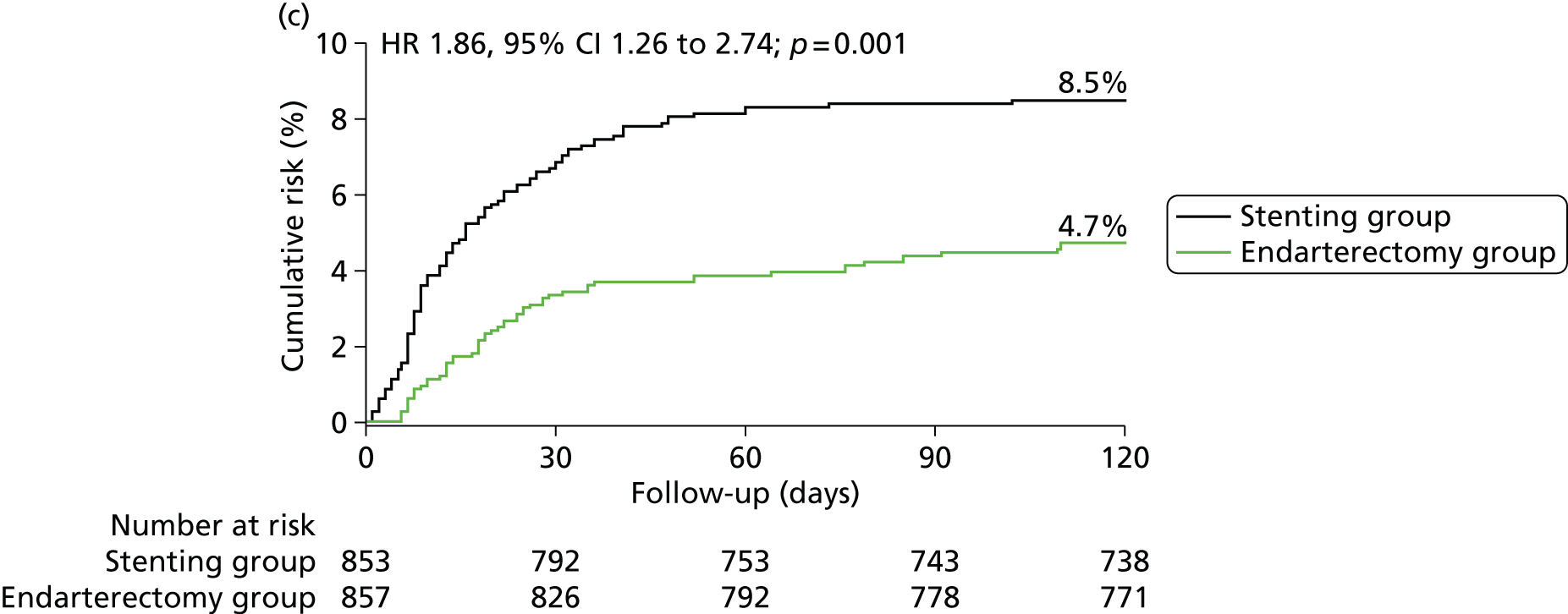

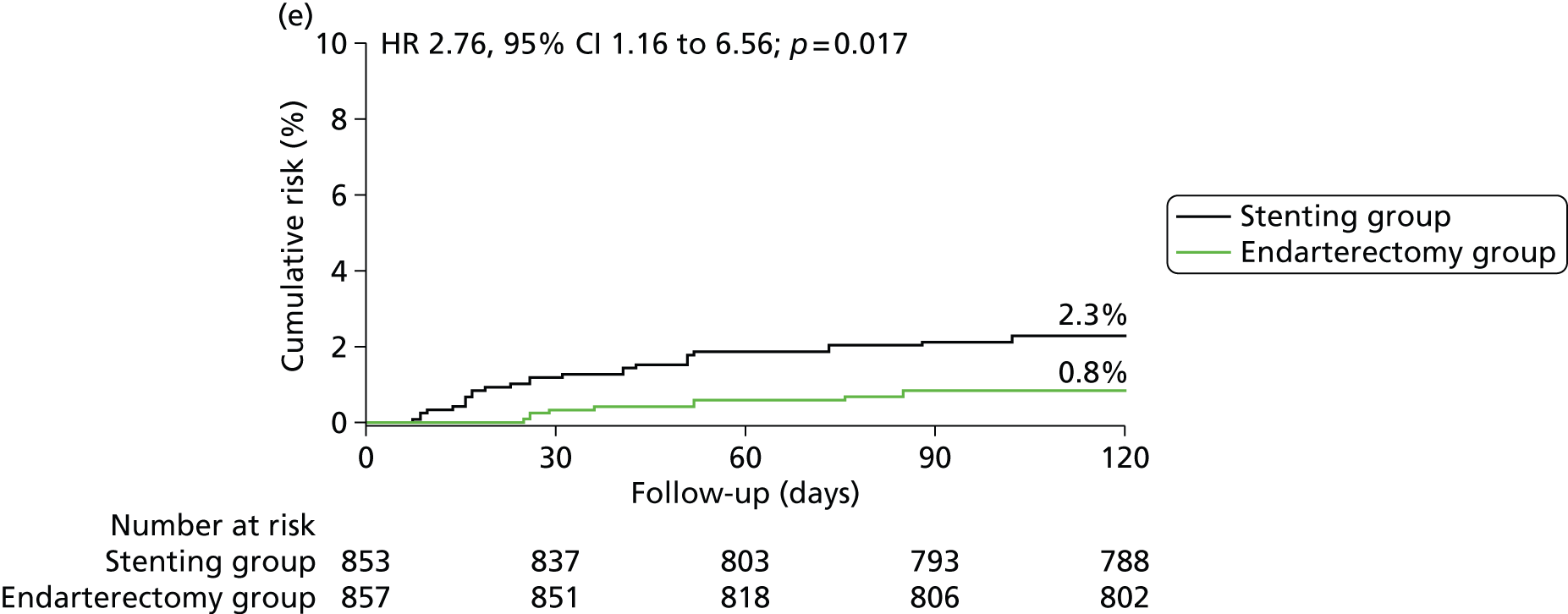

In the ITT analysis, between randomisation and 120 days, there was no significant difference in the rate of disabling stroke or death between groups (stenting group, 4.0% vs. endarterectomy group, 3.2%; Table 4). The risk of stroke, death or procedural MI 120 days after randomisation was significantly higher in patients in the stenting group than in patients in the endarterectomy group (8.5% vs. 5.1%), representing an estimated 120-day absolute risk difference of 3.3% (95% CI 0.9% to 5.7%) with a HR in favour of surgery of 1.69 (1.16 to 2.45, log-rank p-value = 0.006) (Figure 3 and Table 4).

FIGURE 3.

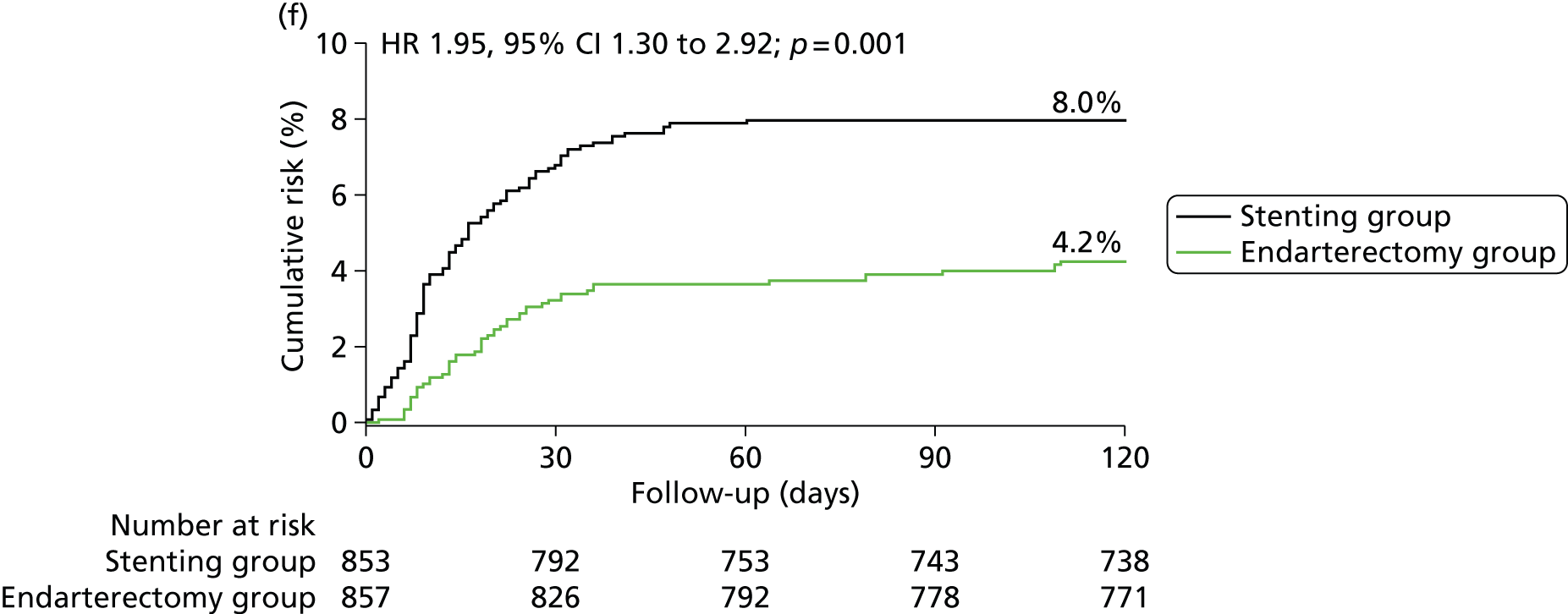

Kaplan–Meier estimates of cumulative incidence of main short-term outcome measures. Data are analysed by ITT. The numbers above the end of the lines are the incidence estimates at 120 days after randomisation. (a) Stroke, death or procedural MI (primary outcome measure); (b) any stroke; (c) stroke or death; (d) disabling stroke or death; (e) all-cause death and (f) any stroke or procedural death.

| Outcome measures | CAS N = 853, n (%) | CEA N = 857, n (%) | HR (95% CI) | RD (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main outcome | |||||

| Stroke, death or procedural MI | 72 (8.5) | 44 (5.2) | 1.69 (1.16 to 2.54) | 3.3 (0.9 to 5.7) | 0.006 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Any stroke | 65 (7.7) | 35 (4.1) | 1.92 (1.27 to 2.89) | 3.5 (1.3 to 5.8) | 0.002 |

| Any stroke or death | 72 (8.5) | 40 (4.7) | 1.86 (1.26 to 2.74) | 3.8 (1.4 to 6.1) | 0.001 |

| Any stroke or procedural death | 68 (8.0) | 36 (4.2) | 1.95 (1.30 to 2.92) | 3.8 (1.5 to 6.0) | 0.001 |

| Disabling stroke or death | 34 (4.0) | 27 (3.2) | 1.28 (0.77 to 2.11) | 0.8 (–0.9 to 2.6) | 0.34 |

| All-cause death | 19 (2.3) | 7 (0.8) | 2.76 (1.16 to 6.56) | 1.4 (0.3 to 2.6) | 0.017 |

Most outcome events, within 120 days of randomisation in the stent and endarterectomy groups occurred within 30 days of the first ipsilateral procedure (61 of 72 events vs. 31 of 44 events). A few events occurred after randomisation but before the date of treatment (two patients vs. one patient) in patients who had no attempted ipsilateral procedure (three patients vs. six patients), or more than 30 days after treatment but within 120 days of randomisation (six patients vs. six patients). Compared with endarterectomy, allocation to stenting had a greater 120-day risk of the outcome measures of any stroke, any stroke or death, any stroke or procedural death, and all-cause death (Table 4).

Most strokes within 120 days of randomisation were ipsilateral to the treated carotid artery and most were ischaemic (Table 5). There were very few haemorrhagic strokes, with only two patients in whom the cause of the stroke was uncertain.

| Outcome events | ITT analysis: events up to 120 days after randomisation, n (%) | Per-protocol analysis: events between 0 days and 30 days after treatment, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stenting, (N = 853) | Endarterectomy, (N = 857) | Stenting, (N = 828) | Endarterectomy, (N = 821) | |

| Any stroke | 65 (7.6)a | 35 (4.1) | 58 (7.0)a | 27 (3.3) |

| Ipsilateral stroke | 58 (6.8) | 30 (3.5) | 52 (6.3) | 25 (3.0) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 63 (7.4) | 28 (3.3) | 56 (6.8) | 21 (2.6) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.6) |

| Uncertain pathology | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Non-disabling stroke | 39 (4.6) | 14 (1.6) | 36 (4.6) | 11 (1.3) |

| Lasting < 7 days | 9 (1.1) | 5 (0.6) | 8 (1.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Lasting > 7 days | 31 (3.6)b | 9 (1.1)c | 29 (3.5)b | 6 (0.7)c |

| Disabling stroke | 17 (2.0)d | 20 (2.3) | 14 (1.7) | 14 (1.7) |

| Fatal stroke | 9 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 8 (1.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Procedural MI | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) |

| Non-fatal MI | 0 | 4 (0.5) | 0 | 5 (0.6)e |

| Fatal MI | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

| Non-stroke, non-MI death | 7 (0.8) | 5 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 1 (0.1)f | 45 (5.5) | 1 (1.0)f | 45 (5.5) |

| Disabling cranial nerve palsy | 1 (0.1)f | 1 (0.1) | 1 (1.0)f | 1 (0.1) |

| Haematoma | 31 (3.6) | 50 (5.8) | 30 (3.6) | 50 (6.0) |

| Severe haematomag | 9 (1.1) | 28 (3.3) | 8 (1.0) | 28 (3.4) |

The observed treatment effect was largely driven by the higher number of non-disabling strokes in the stenting group, most of which had symptoms lasting for more than 7 days. There was an excess of fatal strokes in the stenting group compared with the surgery group, but little difference in the number of patients with disabling stroke within 120 days of randomisation.

The per-protocol analysis included 1649 patients (stenting group, n = 828; endarterectomy group, n = 821). Results for 30-day procedural risk mirrored the results of the ITT analysis. Risk of stroke, death or procedural MI was higher in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group (30-day risk 7.4% vs. 4.0%) [risk difference (RD) 3.3%, 95% CI 1.1% to 5.6%; risk ratio (RR) 1.83, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.77; χ2 p = 0.003] (Table 6). Risk of any stroke or death up to 30 days after treatment remained significantly higher in patients in whom stenting was initiated than in patients with surgery initiated, but there was no significant difference in the risk of disabling stroke or death between treatment groups. There were more fatal strokes in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group (eight vs. three), but difference in the risk of death alone was no longer significant (see Table 5). Forty-three (74%) of 58 strokes in the stenting group and 12 (44%) of 27 strokes in the endarterectomy group occurred on the day of the procedure. There was no difference in the numbers of strokes occurring between day 2 and day 30 between the two treatments (15 vs. 15).

| Outcome measures | CAS N = 828, n (%) | CEA N = 821, n (%) | RR (95% CI) | RD (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main outcome | |||||

| Stroke, death or MI | 61 (7.4) | 33 (4.0) | 1.83 (1.21 to 2.77) | 3.3 (1.1 to 5.6) | 0.003 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Any stroke | 58 (7.0) | 27 (3.3) | 2.13 (1.36 to 3.33) | 3.7 (1.6 to 5.8) | 0.001 |

| Any stroke or death | 61 (7.4) | 28 (3.4) | 2.16 (1.40 to 3.34) | 4.0 (1.8 to 6.1) | 0.0004 |

| Disabling stroke or death | 26 (3.1) | 18 (2.2) | 1.43 (0.79 to 2.59) | 0.9 (–0.6 to 2.5) | 0.23 |

| Procedural death | 11b (1.3) | 4 (0.5) | 2.73 (0.87 to 8.53) | 0.8 (–0.1 to 1.8) | 0.072 |

Few procedural MIs were recorded (three in the stenting group, all of which were fatal, compared with five in the endarterectomy group). Cranial nerve palsies were almost completely avoided by stenting (RR 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.16; p < 0.0001) (see Table 5). The one cranial nerve palsy recorded in the stenting group occurred as a complication of an endarterectomy performed within 30 days of stenting. This patient and one additional patient in the endarterectomy group required percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding as a result of the cranial nerve palsies, which was classified as disabling. There were also fewer haematomas of any severity in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.93; p = 0.0197), and fewer severe haematomas requiring surgical intervention, blood transfusion or extended hospital stay (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.62; p = 0.0007) (see Table 5). A post-hoc sensitivity analysis was undertaken to examine if the results of the per-protocol analysis were affected by inclusion of patients in whom the allocated procedure was initiated but not completed. Exclusion of the 64 patients allocated to stenting and two patients allocated to endarterectomy in whom the procedures were aborted after initiation (i.e. including only patients in whom the allocated procedure was completed as planned) made little difference to the results (30-day risk of stroke, death or procedural MI of 7.6% in the stenting group vs. 4.0% in the endarterectomy group) (RD 3.6%, 95% CI 1.3% to 5.9%; RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.86; p = 0.002).

We undertook exploratory analyses of the composite outcome of stroke, death or procedural MI for pre-defined subgroups (Figure 4). These analyses suggested that carotid stenting might have a similar risk to endarterectomy in women, but that the intervention was more hazardous than endarterectomy in men. The difference was mainly caused by a higher risk of stroke, death or procedural MI in women assigned to endarterectomy than in men (7.6% vs. 4.2%). However, the difference between the HRs comparing the risk of stenting with endarterectomy in men and women only reached borderline significance (interaction p = 0.071). Stenting was more hazardous, and endarterectomy less hazardous, in patients not taking medication for hypertension at baseline than in patients taking medication for hypertension (see Figure 4). There was also a suggestion that patients who presented with multiple ipsilateral symptoms had a similar risk of stroke death, or procedural MI with stenting and endarterectomy. However, when compared with patients with only one event before randomisation, the difference in the HRs only reached borderline significance (interaction p = 0.055). There was no evidence that the relative increase in the hazard of an event in the stenting group compared with the endarterectomy group differed significantly across any other subgroups.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the short-term rate of stroke, death, or procedural myocardial infarction. Subgroups are defined according to baseline characteristics and analysed by intention to treat up to 120 days after randomisation, apart from time from event to treatment, which is analysed per protocol. p-values are associated with treatment-covariate interaction tests. a, Data are number of events of first stroke, death or procedural myocardial infarction within 120 days of randomisation/number of patients (Kaplan–Meier estimate at 120 days). b, Patients with missing information were excluded from the analysis. c, Time from the most recent ipsilateral event before randomisation to the date of treatment, analysed per protocol for 30-day procedural events only (results are relative risk and 95% CI at 30 days after treatment).

Duration of follow-up in the International Carotid Stenting Study

Figure 5 shows the number of patients remaining in follow-up in ICSS plotted against time from randomisation. Patients were followed up for a maximum of 10 years after randomisation with a median of 4.2 years and an interquartile range of 3.0–5.2 years. This amounted to 7355 patient-years of follow-up, without any difference between the two arms.

FIGURE 5.

Patients remaining in each arm of the study (per protocol) are plotted against year of follow-up. In total, there are 7354.45 patient-years of follow-up until time of last follow-up or death. CAS (n = 853): median follow-up = 4.2 years, interquartile range (IQR) 3.0–5.4 years (maximum = 10.0 years, 153 deaths); CEA (n = 857): median follow-up = 4.2 years, IQR 3.0–5.2 years (maximum = 9.6 years, 129 deaths).

Long-term primary and secondary outcomes

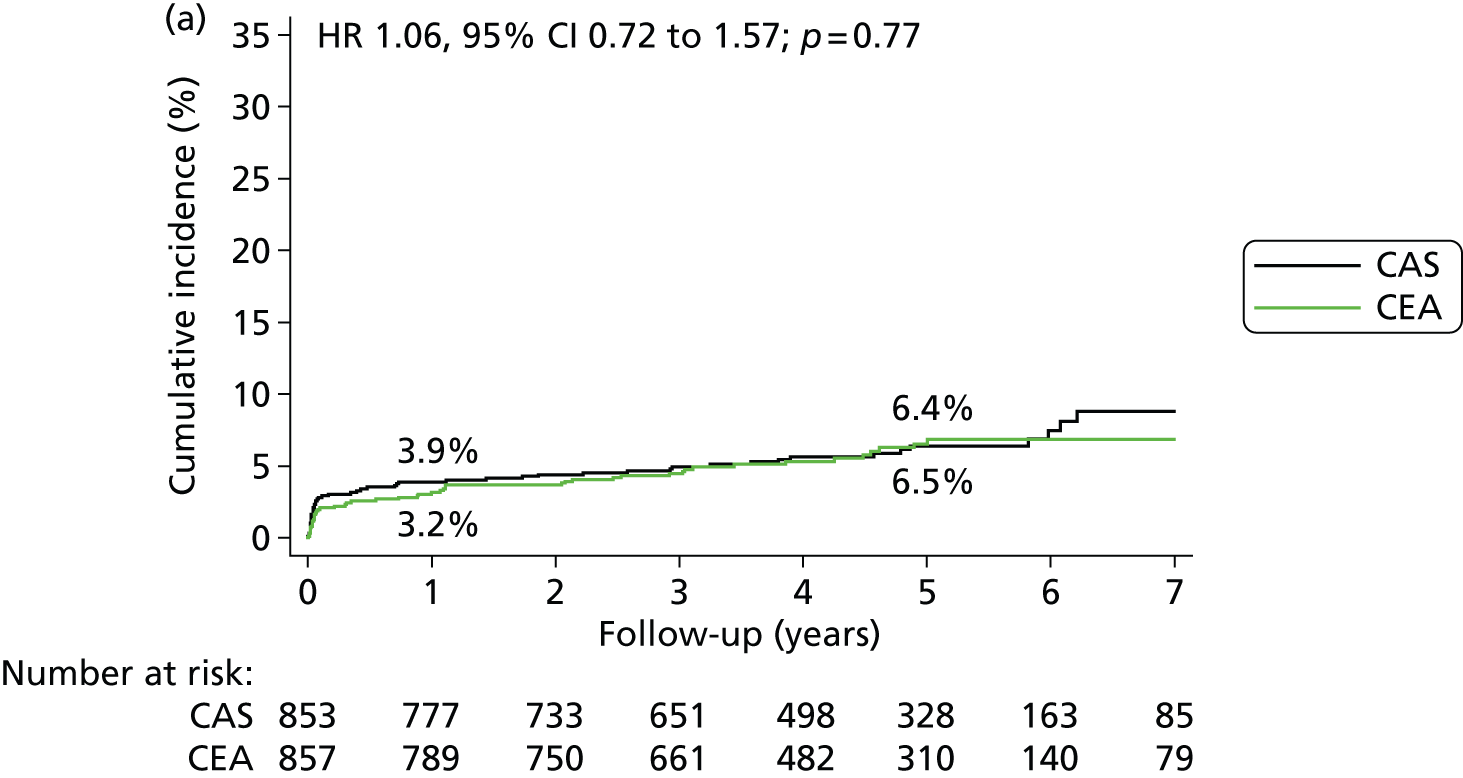

In the ITT analysis, the primary outcome event, fatal or disabling stroke between randomisation and the end of follow-up, occurred in 52 patients in the stenting group, corresponding to a cumulative 5-year risk of 6.4%, and in 49 patients in the endarterectomy group (5-year risk n, 6.5%), without any evidence for a difference in time to first occurrence of an event (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.57; p = 0.76) (Table 7 and Figure 6).

| Outcome events | Stenting (n = 853) | Endarterectomy (n = 857) | HRa (95% CI); p-value | Absolute risk difference, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n eventsa | Cumulative 1-year risk, % (SE) | Cumulative 5-year risk, % (SE) | n eventsa | Cumulative 1-year risk, % (SE) | Cumulative 5-year risk, % (SE) | At 1 year | At 5 years | ||

| Fatal or disabling stroke (primary outcome measure) | 52 | 3.9 (0.7) | 6.4 (0.9) | 49 | 3.2 (0.6) | 6.5 (1.0) | 1.06 (0.72 to 1.57); 0.77 | 0.7 (–1.0 to 2.5) | –0.2 (–2.8 to 2.5) |

| Any stroke | 119 | 9.5 (1.0) | 15.2 (1.4) | 72 | 5.1 (0.8) | 9.4 (1.1) | 1.71 (1.28 to 2.30); 0.0003 | 4.4 (1.9 to 6.9) | 5.8 (2.4 to 9.3) |

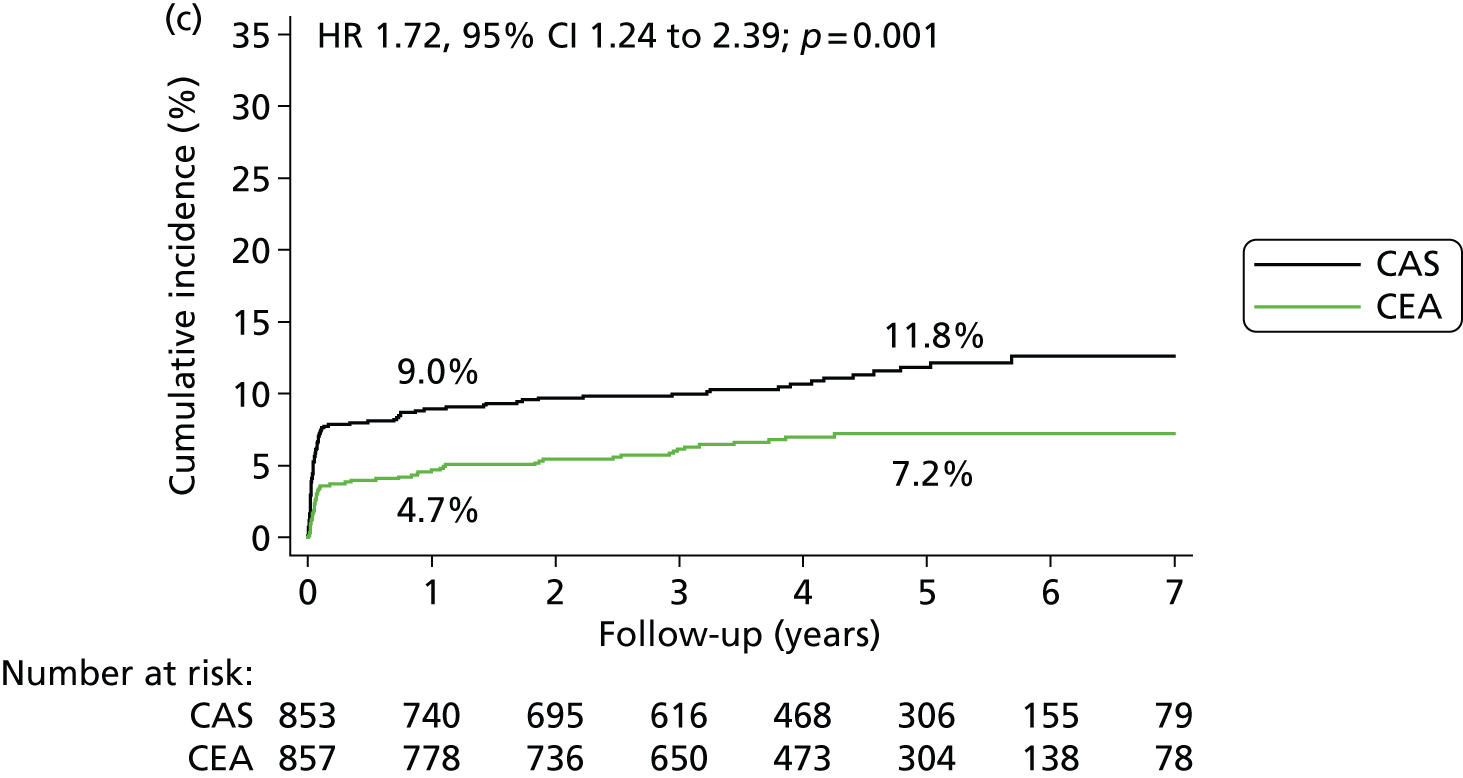

| Procedural stroke or death, or ipsilateral stroke during follow-up | 95 | 9.0 (1.0) | 11.8 (1.2) | 57 | 4.7 (0.7) | 7.2 (0.9) | 1.72 (1.24 to 2.39); 0.001 | 4.2 (1.9 to 6.6) | 4.6 (1.6 to 7.6) |

| All-cause death | 153 | 4.9 (0.7) | 17.4 (1.5) | 129 | 2.3 (0.5) | 17.2 (1.5) | 1.17 (0.92 to 1.48); 0.19 | 2.6 (0.8 to 4.4) | 0.2 (–4.0 to 4.4) |

FIGURE 6.

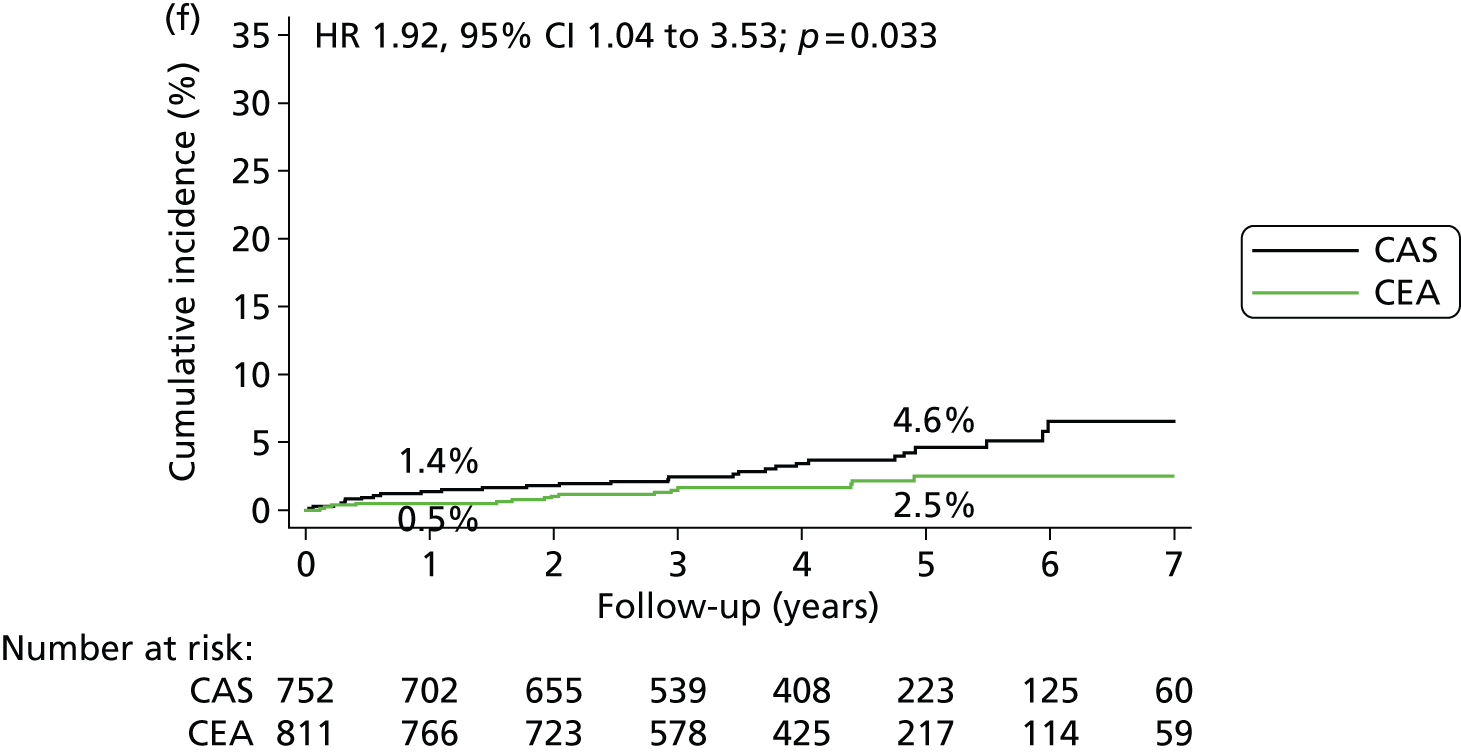

Kaplan–Meier estimates of cumulative incidence of major long-term outcome measures. (a) Fatal or disabling stroke; (b) any stroke; (c) procedural stroke or death, or ipsilateral stroke during follow up; (d) any stroke > 30 days after treatment; (e) ipsilateral stroke > 30 days after treatment; (f) contralateral carotid or vertebrobasilar stroke > 30 days after treatment; (g) ipsilateral carotid stenosis (≥ 70%) or occlusion during follow-up; and (h) all-cause death. Data were analysed by ITT from randomisation except for parts (d) to (f), which are analysed in the per-protocol population from 30 days post procedure, and part (g) which is analysed in the per-protocol population from treatment. The numbers on the lines are the estimated 1-year and 5-year cumulative incidences. The graphs have only been plotted to 7 years’ follow-up because the numbers with longer follow-up were < 100. However, the HRs were calculated using all relevant outcome events until the end of follow-up (maximum 10 years).

The following secondary outcome events occurred significantly more often in the stenting group in the ITT analysis between randomisation and the end of follow-up: any stroke (5-year risks 15.2% vs. 9.4%) (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.30; p = 0.0003); any stroke or death (27.5% vs. 22.6%) (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.63; p = 0.003); the combination of any procedural stroke, procedural death or ipsilateral stroke during follow-up (11.8% vs. 7.2%) (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.39; p = 0.001). There was no difference in all-cause mortality between treatment groups (17.4% vs. 17.2%) (HR 1.17, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.48; p = 0.19).

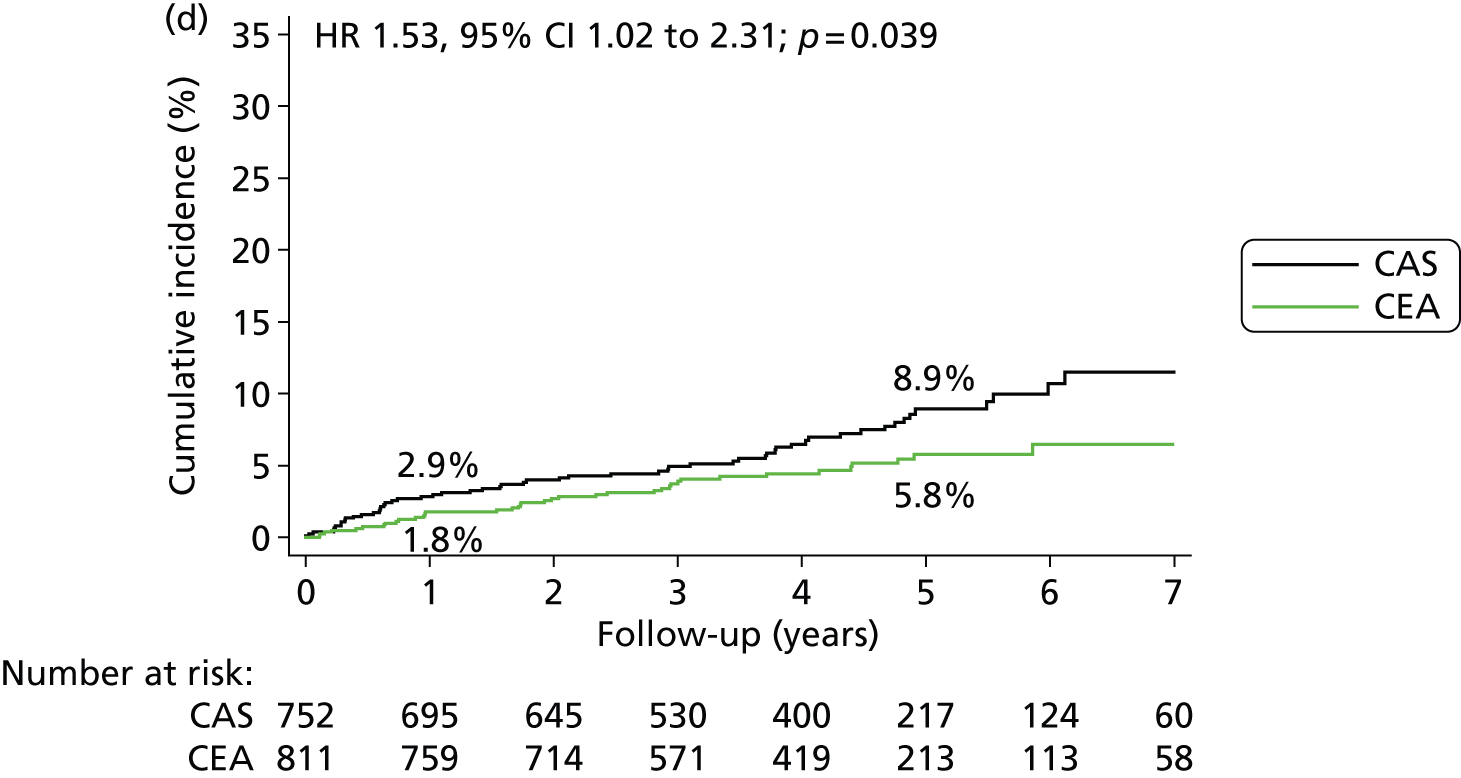

A total of 752 patients in the stenting group (88.2% of the ITT population) and 811 patients in the endarterectomy group (94.6%) were included in the per-protocol analysis of clinical outcome events. In the per-protocol analysis of events occurring more than 30 days after completed treatment up to the end of follow-up, there was no significant difference in the long-term risks of fatal and disabling stroke after stenting compared with endarterectomy (5-year risk 3.4% vs. 4.3%) (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.60; p = 0.78) (Table 8). There was also no significant difference in the rates of ipsilateral stroke in the territory of the treated carotid artery (4.7% vs. 3.4%) (HR 1.29, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.24; p = 0.36). However, stroke of any severity occurred more often after stenting (8.9% vs. 5.8%) (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.31; p = 0.039) (Figure 6 and Table 8). This difference was largely attributable to stroke occurring in the territory of the contralateral carotid artery or the vertebrobasilar circulation among patients treated with stents (5-year risks 4.6% vs. 2.5%) (HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.53; p = 0.033) and the majority were non-disabling.

| Outcome events | Stenting (n = 752) | Endarterectomy (n = 811) | Absolute risk difference, % (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n eventsa | Cumulative 1-year risk, % (SE)a | Cumulative 5-year risk, % (SE)a | n events | Cumulative 1-year risk, % (SE)a | Cumulative 5-year risk, % (SE)a | HRb (95% CI); p-value | At 1 year | At 5 years | |

| Fatal or disabling stroke | 24 | 0.9 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.8) | 27 | 1.4 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.9)a | 0.93 (0.53 to 1.60); 0.78 | –0.5 (–1.5 to 0.6) | –0.9 (–3.2 to 1.4) |

| Any stroke | 56 | 2.9 (0.6) | 8.9 (1.2) | 39 | 1.8 (0.5) | 5.8 (1.0) | 1.53 (1.02 to 2.31); 0.039 | 1.1 (–0.4 to 2.6) | 3.1 (0.0 to 6.2) |

| Ipsilateral carotid stroke | 28 | 1.4 (0.4) | 4.7 (0.9) | 23 | 1.1 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.8) | 1.29 (0.74 to 2.24); 0.36 | 0.2 (–0.9 to 1.3) | 1.2 (–1.1 to 3.6) |

| Contralateral carotid or vertebrobasilar stroke | 29 | 1.4 (0.4) | 4.6 (0.9) | 16 | 0.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.7) | 1.92 (1.04 to 3.53); 0.033 | 0.9 (–0.1 to 1.8) | 2.1 (–0.2 to 4.3) |

| Severe carotid restenosis (≥ 70%) or occlusion | 72/737 | 6.9 (1.0) | 10.8 (1.3) | 62/793 | 5.3 (0.8) | 8.6 (1.1) | 1.25 (0.89 to 1.75); 0.20 | 1.7 (–0.8 to 4.1) | 2.2 (–1.1 to 5.4) |

A total of 737 (98.0%) patients in the stenting group and 793 (97.8%) in the endarterectomy group were followed up with carotid ultrasound for a median of 4.0 years (interquartile range, 2.3–5.0 years) after treatment. There was no significant difference in long-term rates of severe carotid restenosis (≥ 70%) or occlusion, which occurred in 72 patients in the stenting group (5-year risk 10.8%) and in 62 patients in the endarterectomy group (5-year risk 8.6%) (HR 1.25, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.75; p = 0.20; see Table 8 and Figure 6).

Exploratory subgroup analyses showed no significant modification of the HR of the primary outcome event (Figure 7), nor of the combined outcome of procedural death or stroke, or non-procedural ipsilateral stroke by any of the evaluated variables (Figure 8).

FIGURE 7.

Hazard ratios of fatal or disabling stroke between randomisation and end of follow-up in various patient subgroups. Subgroups are defined according to baseline characteristics and analysed by ITT for all available follow-up, apart from time from event to procedure, which is analysed per protocol. P-values are associated with treatment–covariate interaction tests. a, Data are number of events of first fatal or disabling stroke/number of patients, and Kaplan–Meier estimate of cumulative risk at 5 years. Patients with missing information were excluded from the analysis. b, Time from most recent ipsilateral event before randomisation to the date of treatment, analysed per protocol from the time of procedure. All subgroups for analysis were pre-specified except for treated hyperlipidaemia which was added post hoc. AFX, amaurosis fugax.

FIGURE 8.

Hazard ratios of procedural stroke, death or ipsilateral stroke between randomisation and end of follow-up in various patient subgroups. Subgroups are defined according to baseline characteristics and analysed by ITT for all available follow-up, apart from time from event to procedure, which is analysed per protocol. P-values are associated with treatment–covariate interaction tests. a, Data are number of events of first ipsilateral stroke or procedural stroke or death/number of patients, and Kaplan–Meier estimate of cumulative risk at 5 years. Patients with missing information were excluded from the analysis. b, Time from most recent ipsilateral event before randomisation to the date of treatment, analysed per protocol from the time of procedure. AFX, amaurosis fugax.

Long-term functional outcome

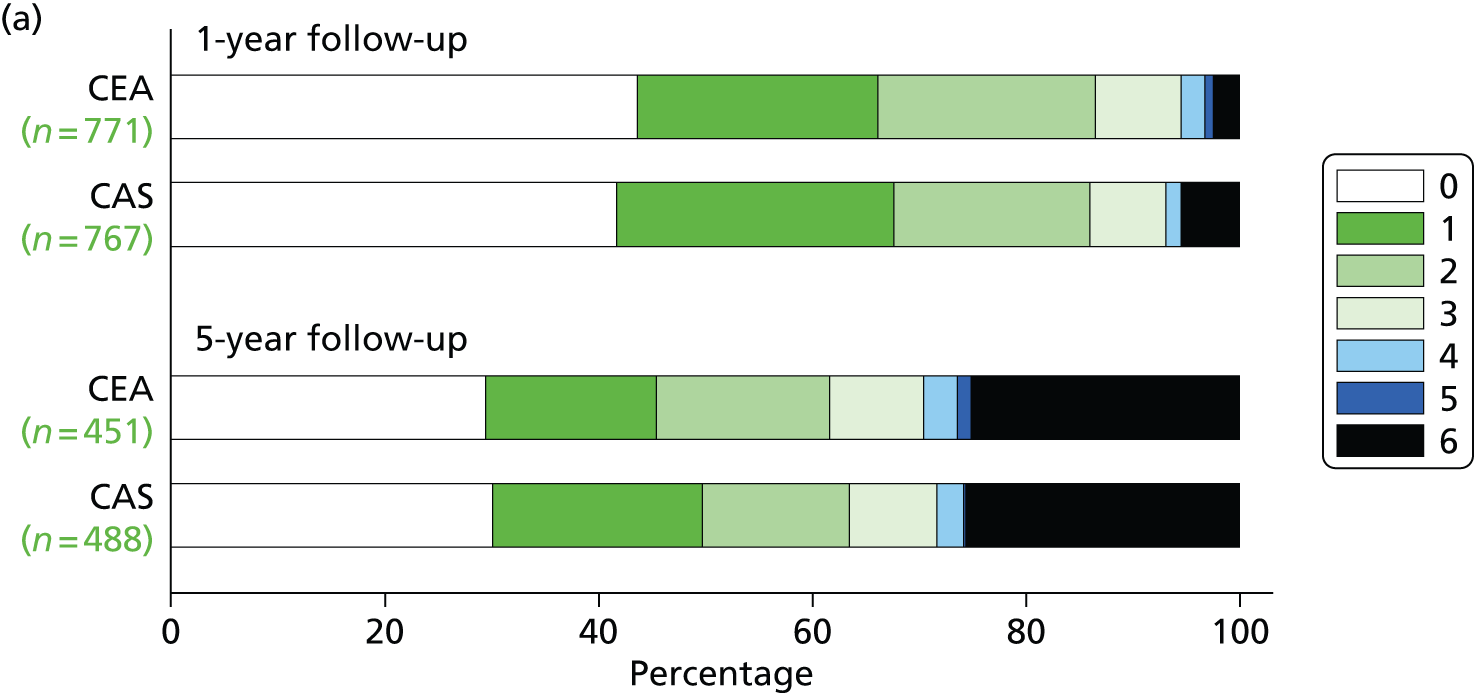

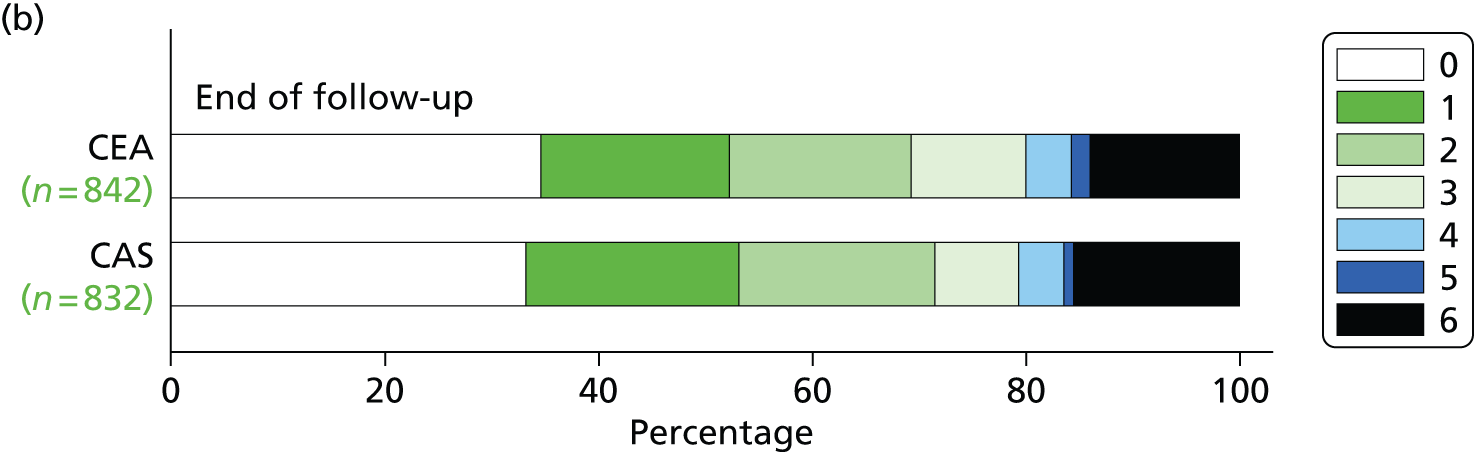

There was no difference in distribution of functional disability as measured by the mRS scores at the end of follow-up, nor was there any significant difference 1 or 5 years after randomisation (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

The distribution of scores on the mRS: (a) after 1-year and 5-year follow-up in patients allocated CAS or CEA using the Rankin scores in patients still surviving and in follow-up or who had died before at the indicated time points [permutation test comparing Rankin scores between the two groups at 1 year (unadjusted p = 0.70, adjusted for baseline mRS p = 0.11), at 5 years (unadjusted p = 0.54, adjusted for baseline mRS p = 0.98)13]; (b) at the last follow-up recorded for the patient, regardless of duration (unadjusted, p = 0.49; adjusted for baseline mRS score, p = 0.24).

Findings of the magnetic resonance imaging substudy

The MRI substudy has been previously published in detail. 44 A total of 231 patients (124 in the stenting group and 107 in the endarterectomy group) had MRI before and after treatment. Sixty-two (50%) of 124 patients in the stenting group and 18 (17%) of 107 patients in the endarterectomy group had at least one new DWI lesion detected on post-treatment scans done a median of 1 day after treatment [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 5.21, 95% CI 2.78 to 9.79; p < 0.0001]. At 1 month, there were changes on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences in 28 (33%) of 86 patients in the stenting group and six (8%) of 75 in the endarterectomy group (adjusted OR 5.93, 95% CI 2.25 to 15.62; p = 0.0003). In patients treated at a centre with a policy of using cerebral protection devices, 37 (73%) of 51 in the stenting group and eight (17%) of 46 in the endarterectomy group had at least one new DWI lesion on post-treatment scans (adjusted OR 12.20, 95% CI 4.53 to 32.84), whereas in those treated at a centre with a policy of unprotected stenting, 25 of 73 patients (34%) in the stenting group and 10 of 61 (16%) in the endarterectomy group had new lesions on DWI (adjusted OR 2.70, 95% CI 1.16 to 6.24; interaction p = 0.019).

Studies on the predictors of risk of individual procedures

Findings of study on the effect of white-matter lesions on the risk of periprocedural stroke

This analysis has been published in detail elsewhere. 30 Patients were divided into two groups using the median ARWMC. We analysed the risk of stroke within 30 days of revascularisation using a per-protocol analysis. A total of 1036 patients (536 randomly allocated to CAS, 500 to CEA) had baseline imaging available. Median ARWMC score was 7, and patients were dichotomised into those with a score of 7 or more and those with a score of < 7. In patients treated with CAS, those with an ARWMC score of 7 or more had an increased risk of stroke compared with those with a score of < 7 (HR for any stroke 2.76, 95% CI 1.17 to 6.51; p = 0.021; HR for non-disabling stroke 3.00, 95% CI 1.10 to 8.36; p = 0.031). However, we did not see a similar association in patients treated with CEA (HR for any stroke 1.18, 95% CI 0.40 to 3.55; p = 0.76; HR for disabling or fatal stroke 1.41, 95% CI 0.38 to 5.26; p = 0.607). Carotid artery stenting was associated with a higher risk of stroke compared with CEA in patients with an ARWMC score of 7 or more (HR for any stroke 2.98, 95% CI 1.29 to 6.93; p = 0.011; HR for non-disabling stroke 6.34, 95% CI 1.45 to 27.71; p = 0.014), but there was no risk difference in patients with an ARWMC score of < 7.

Findings of the analysis of the effect of baseline characteristics on the risk of stenting