Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/403/90. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The draft report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Paton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus epidemiology and care in the UK

At the end of 2012 there were an estimated 100,000 people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the UK, of whom approximately 80% have been diagnosed and seen for HIV-related care. The annual number of new HIV diagnoses made in the UK continues to rise, with 6360 new cases in 2012,1 and as more people receive effective treatment the number of deaths continues to fall. Thus, the number of people receiving treatment and the already substantial burden on the NHS will continue for the foreseeable future. The cost of providing care and treatment to people living with HIV in the UK increased by about 600% from 1997 to 2010, when £762M was spent, mainly on antiretroviral therapy. 2

Principles of antiretroviral therapy

A range of drugs are available that are active in blocking the replication of HIV. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend a combination of two drug classes for the initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy (ART). 3,4 The principle of combining drugs with different mechanisms of action to increase potency and reduce the selection of drug-resistant mutants is common to the treatment of many infectious diseases. However, the need for combination therapy for HIV may be reduced after the initial period of treatment, once viral load (VL) has been suppressed and the risk of de novo resistance generation diminishes.

Recommendations for the threshold at which HIV treatment should be started differ internationally, with the current US treatment guidelines4 recommending starting all HIV-infected individuals on treatment, regardless of their cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell count, to reduce the risk of disease progression, and the UK guidelines3 recommending starting at a CD4 cell count of 350 cells/mm3. This is based predominantly on data from large cohorts which show that starting ART at CD4 cell counts of > 500 cells/mm3 was associated with slower HIV disease progression measured by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) events, HIV-associated mortality or all-cause mortality. 5,6 However, substantive evidence is now available from a large randomised controlled trial (RCT), the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) trial, that demonstrates that initiating ART at CD4 cell counts of > 500 cells/mm3 is of benefit. 7 Aside from potential benefits to the individual, early initiation of ART has been shown to effectively reduce HIV sexual transmission and may diminish population-level incidence of HIV infection. 8 Once started, treatment needs to be continued indefinitely – the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) trial showed inferior outcomes with treatment interruption, even at high CD4 cell counts. 9

As a result of the move towards extending therapy exposure (start earlier and continue indefinitely) is the realisation that patients are now facing the prospect of taking ART for decades. Maximising long-term durability, preserving a viable sequence of future drug options and minimising long-term side effects are becoming increasingly important considerations.

New strategic approaches

Much of the current pharmaceutical company-driven research as well as investigator-initiated research is now designed to look at switching drugs or compare regimens for toxicity or tolerability advantages. The search for cost-effective approaches to care, including ways of containing drug costs and approaches to simplify monitoring and follow-up, is also an important focus of current research.

The availability of effective and well-tolerated newer drug options that act on different targets, such as integrase inhibitors, has not only increased the treatment options available but also led to re-examination of the paradigm of care [treatment with triple therapy, consisting of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and a non-NRTI (NNRTI) or protease inhibitor (PI)] that has changed little in the last decade. The availability of more treatment options may have also allowed some flexibility to accept a small risk of treatment failure in a regimen that has fewer side effects or that effectively preserves long-term treatment options in the vast majority.

Thus, research into more innovative uses of current drugs, as well as ways of combining or sequencing drugs to maximise long-term outcomes (preserving viable treatment options, minimising toxicity, minimising cost), is increasingly important. Given that treatment interruption is not a sensible option, treatment simplification studies form an increasingly important aspect of the HIV treatment research agenda, not only for individual patients but also for health-care policy. 2,10,11 The most promising candidates for treatment simplification are undoubtedly the PIs.

Previous trials of protease inhibitor monotherapy

Protease inhibitors have very high antiviral activity, have the highest genetic barrier to resistance of all HIV drugs and are the only drugs that act at multiple steps of the HIV lifecycle, thus giving them the potential to be used alone as monotherapy. 12 A RCT that examined the use of PI monotherapy for treatment-naive patients showed clearly inferior performance, with the generation of substantial resistance. 13 However, other trials in which patients switch to PI monotherapy after achieving full VL suppression have been more successful. These trials have generally used lopinavir (LPV)/ritonavir and darunavir (DRV)/ritonavir monotherapy and have evaluated non-inferiority based on VL suppression in plasma at weeks 48 or 96 after switching from combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Results have been generally favourable, although several studies have failed to demonstrate non-inferiority compared with standard-of-care. Table 1 summarises the published RCTs on ritonavir-boosted PI monotherapy as a simplification strategy.

| Study | n (monotherapy vs. other) | Drug vs. comparator | Eligibility | End point | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arribas 2005,14 Pulido 2008,15,16 (OK study) | 21 vs. 21 | LPV/r vs. LPV/r plus two NRTIs | Experienced without PI failure VL < 50 copies/ml for > 6 months LPV/r plus two NRTIs for > 1 month |

VL < 500 copies/ml at week 48 (ITT, M or change = F) Failure = VL > 500 copies/ml × 2 that could not resuppress (< 50 copies/ml) with NRTIs |

No difference in virological suppression between arms at week 48 (81% and 95% in patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs respectively; p = 0.34) No major PI mutations were found even after 4 years’ follow-up |

| Pulido 2008,15 Arribas 200917 (OK04 study) | 103 vs. 102 | LPV/r vs. LPV/r plus two NRTIs | Experienced without PI failure VL < 50 copies/ml for > 6 months LPV/r plus two NRTIs for > 1 month |

VL < 500 copies/ml at week 48 (ITT, M or change = F) Failure = VL > 500 copies/ml × 2 that could not resuppress (< 50 copies/ml) with NRTIs |

No difference in virological suppression between arms by week 48 (94% and 90% in patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs respectively) with upper limit of 95% CI for difference of 3.4% Using < 50 copies/ml, 85% and 90% of patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs, respectively, had an undetectable VL at week 48 (p = 0.31; upper limit of 95% CI for difference of 14%) By week 96, 87% on monotherapy (n = 100) and 78% on triple therapy (n = 98; 95% CI –20% to +1.2%) showed effective virological suppression Using < 50 copies/ml, 77% and 78% of patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs, respectively, had an undetectable VL at week 96 |

| Nunes 200918 (KalMo study) | 30 vs. 30 | LPV/r vs. continued HAART | No history of VF VL < 80 copies/ml for > 6 months CD4 cell count of > 200 cells/mm3 |

VL < 80 copies/ml at week 96 (ITT, M = F) | No difference in virological suppression between arms by week 96 (80.0% and 86.6% in patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs respectively; p = 0.48) There was one virological failure (defined as a VL < 500 copies/ml) in each arm. No major PI mutations were found |

| Meynard 201019 (KALESOLO study) | 87 vs. 99 | LPV/r vs. continued HAART | Experienced VL < 50 copies/ml for ≥ 6 month |

VL < 50 copies/ml at week 48 | LPV/r monotherapy did not achieve non-inferiority vs. cART for maintaining plasma VL at < 50 copies/ml No major PI mutations were found |

| Gutmann 201020 (MOST study) | 29 vs. 31 | LPV/r vs. continued HAART | Experienced CD4 cell count of ≥ 100 cells/mm3 VL < 50 copies/ml for ≥ 6 months |

Treatment failure in the CNS or genital compartment (2 × VL > 400 copies/ml) | Trial ended prematurely when six patients on monotherapy demonstrated VF in plasma |

| Cahn 201121 | 41 vs. 39 | LPV/r vs. LPV/r plus two NRTIs | Experienced No history of VF HAART for ≥ 6 months VL < 50 copies/ml for ≥ 3 months |

VL < 200 copies/ml at day 360 | No difference in virological suppression between arms by day 360 (80% and 86.6% in patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs respectively; p = 0.611) Using < 50 copies/ml, 92% and 95% of patients on LPV/r monotherapy and LPV/r plus two NRTIs, respectively, had an undetectable VL at day 360 (p = 0.671) |

| Arribas 2010,22 Clumeck 2011,23 Arribas 201224 (MONET study) | 127 vs. 129 | DRV/r vs. DRV/r plus two NRTIs | Experienced HAART plus two NRTIs plus either NNRTI or PI at screening No previous use of DRV VL < 50 copies/ml for ≥ 6 months No previous VF |

Proportion with VL < 400 copies/ml at week 48 Treatment failure: 2 × VL > 50 copies/ml; discontinuation of randomised therapy (time to loss of virological response); stopping DRV/r or starting NRTIs in the monotherapy arm; or stopping NRTIs in the control arm (switches in NRTIs permitted) |

Non-inferiority demonstrated at week 48 in the per-protocol and ITT and by switch = failure analyses (86.2% vs. 87.8%, 84.3% vs. 85.3% and 93.5 vs. 95.1% in the monotherapy and triple therapy arms respectively) Non-inferiority not demonstrated at week 96 in ITT analysis 7/8 with detectable viraemia resuppressed with NRTI intensification 47 genotyped (20 in monotherapy arm): only one patient per arm had any evidence of genotypic resistance; both patients regained suppression without change in therapy By week 144, 69% and 75% of patients on monotherapy and triple therapy, respectively, had a VL of < 50 copies/ml (ITT switch = failure); these values were 84% and 83.5% if switches were not considered failures |

| Katlama 2010,25 Valantin 201226 (MONOI study) | 112 vs. 133 | DRV/r vs. DRV/r plus two NRTIs | Experienced DRV naive VL < 50 copies/ml at screening VL < 400 copies/ml for ≥ 18 months No PI failure CD4 cell count nadir of > 50 cells/mm3 All patients suppressed on DRV/r prior to randomisation |

Proportion with VL of < 400 copies/ml at week 48 Treatment failure: 2 × VL > 400 copies/ml; treatment modification; withdrawal |

Non-inferiority demonstrated at week 48 in the per-protocol analysis (94% and 99% of patients on DRV/r monotherapy and triple therapy, respectively, had undetectable VL; 90% CI for the difference –9.1 to 0.8%) Non-inferiority not demonstrated at week 48 in ITT analysis No resistance to PI emerged by week 48 No difference in virological suppression between arms by week 96 (88% and 84% in patients on DRV/r monotherapy and triple therapy respectively; p = 0.42) |

| Echeverria 201027 | 17 vs. 11 | SQV/r vs. continued HAART | Experienced VL < 50 copies/ml for ≥ 3 months No history of VF |

VF at week 48 | Only one patient from the SQV/r group experienced virological failure at week 48. A similar mean increase in CD4 cell count was observed in both groups at week 48 |

Small single-arm studies (n = 30–36) have explored ritonavir-boosted atazanavir simplification in patients effectively suppressed on cART, showing effective preservation of virological suppression in 64–80% of patients with no evidence of selection of PI-resistance mutations in those who developed VL rebound. 28–30

A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs identified 10 trials involving 1189 patients comparing three different PIs used as monotherapy against a standard regimen of a PI plus two NRTIs. 31 With the most conservative approach (VL < 50 copies/ml on two consecutive measurements), the risk ratios for effective viral suppression at 48 weeks for PI monotherapy compared with cART were 0.94 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.89 to 1.00] in the intention-to-treat analysis and 0.93 (95% CI 0.90 to 0.97) in the per-protocol analysis. Reintroduction of cART in 44 patients with virological failure led to de novo viral suppression in 93%.

Given the contradictory findings and the small size of the trials, PI monotherapy has not been widely adopted in HIV treatment guidelines. Only the European guidelines32 consider PI monotherapy an option and then only for selective patient groups.

Virological and resistance concerns over protease inhibitor monotherapy

A proportion of patients may not be able to maintain full viral suppression on PI monotherapy and, if not addressed, there is the theoretical risk that ongoing viral replication may lead to the selection of resistance mutations. However, the trials summarised in Table 1 as well as observational studies have shown that the selection of major PI mutations in patients with detectable viraemia while on PI monotherapy occurs only rarely. 33,34 In addition, complete concordance between circulating and cell-associated virus genotypes has been reported in patients on DRV monotherapy, with no major DRV-selected resistance mutations in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), offering additional reassurance that exposure to PI monotherapy, at least with DRV, may not compromise future antiretroviral treatment options. 35

Although resistance is rare, several studies have shown that some mutations at the gag cleavage site might reduce sensitivity to PI-based regimens. In the MONOI trial (n = 255),36 nine participants developed virological failure (defined as VL > 400 copies/ml in two consecutive samples) but major DRV-selected mutations could not be demonstrated in any of them using standard sequencing. However, by doing protease gene clonal analysis, the authors found that the virus of one of the nine patients with virological failure presented minority variants, with DRV resistance mutations at positions 32, 47 and 50 but no mutations in the gag region.

Although trials have usually shown very similar rates of VL suppression with PI monotherapy, there is a theoretical concern that there may be ongoing low-level HIV replication that could cause disease pathology. In both the MONET37 and MONOI38 trials no difference in the change from baseline of level of proviral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) (cellular integrated HIV-1 DNA) in PBMCs was observed between patients on DRV monotherapy and those on triple therapy. Furthermore, in an observational study,39 no difference in tonsil viral replication was observed between patients on NNRTI-based cART and patients on either DRV/r or LPV/r, but proviral DNA levels were found more frequently in patients on cART. Thus, there is no evidence for occult viral replication when patients have an undetectable VL on PI monotherapy.

Other concerns with protease inhibitor monotherapy

As a consequence of effective viral suppression, dementia and serious neurocognitive impairment that were frequently seen in patients with advanced HIV disease not receiving effective ART have become relatively rare in recent years. 40,41 Despite this, high rates of more subtle cognitive dysfunction in HIV-infected subjects are being increasingly described, with neurocognitive impairment rates approaching 50% in some cohorts. Several factors have been implicated in the evolution of neurocognitive impairment in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, including older age, a low nadir CD4 cell count, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection and possibly the use of antiretroviral regimens with poor central nervous system (CNS) penetration. 42 The penetration of PIs into the CNS is variable and generally inferior to that of the other main drug classes, thus raising the concern about the possibility of neurocognitive deterioration on PI monotherapy. Prior to this trial, this has not been systematically investigated with formal neurocognitive testing.

Data from RCTs have not shown consistent evidence for any excess risk of CNS adverse events (AEs) in patients on DRV and LPV monotherapy, although detectable HIV RNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of symptomatic patients has been reported. 43 The Monotherapy Switzerland/Thailand (MOST) trial20 was stopped prematurely when six patients on LPV/ritonivir monotherapy developed virological failure in peripheral blood. CSF samples were available for five of these patients and detectable VL was also confirmed in these. However, the results of the MOST trial are not in agreement with data generated in previous studies and, as the study was interrupted, its findings are difficult to interpret. 44 Furthermore, cross-sectional data showed that, compared with patients on cART, effectively suppressed patients on PI monotherapy did not show any higher rate of neurocognitive impairment. 45

Possible benefits of protease inhibitor monotherapy

Ritonavir-boosted PI monotherapy may reduce the risk of long-term toxicity associated with NRTIs and, in some cases, NNRTIs. In addition, PI monotherapy may possibly reduce the risk of long-term failure because of the high genetic barrier to resistance (compared with NRTIs and NNRTIs) and a better profile of preserved drug options for the future. Previous RCTs have not shown major differences in safety parameters between PI monotherapy and cART.

A further advantage is likely to be the reduction in treatment costs, although this may be offset by more frequent VL rebounds in patients on PI monotherapy leading to additional costs to health services. PI monotherapy as a strategy may be potentially cost saving if it can be implemented in a large group of patients on ART. 2

Rationale for this trial

The previous randomised trials of PI monotherapy summarised earlier have shown high rates of short-term VL suppression, sometimes meeting non-inferiority criteria, but have not been of sufficient size and duration to address definitively the effects on long-term drug resistance, clinical disease progression and drug toxicity in clinical practice. 17,24,25,31,46 This trial was designed to be different in a number of respects from the previously completed or ongoing pharma-sponsored studies:

-

Whereas other studies have examined the effect of PI monotherapy per se, this trial was designed to examine the effectiveness of a strategy that includes prompt switch back to standard-of-care when PI monotherapy does not maintain full virological suppression of < 50 copies/ml.

-

Whereas previous or ongoing studies were/are focused on specific PI drugs and specified comparator regimens, this trial allows drug selection according to patient/physician preference and selection or switching of PIs for maximising tolerability; it is therefore more relevant to clinical practice.

-

Whereas other studies were of relatively short duration (1–2 years), this trial set out to have a relatively long-term follow-up perod (up to 5 years), which is important for assessing long-term consequences of this strategy.

-

Whereas other studies have focused on short-term VL end points (reflecting their commercial origin and single drug focus), this trial has an end point of clinical drug resistance, chosen to be most relevant to the long-term goal of maintaining effective treatment regimens.

The Protease Inhibitor Monotherapy Versus Ongoing Triple Therapy (PIVOT) trial was designed as a pragmatic RCT to evaluate relevant long-term outcomes in patients following a PI monotherapy strategy in routine clinical care centres across the UK.

The main trial objectives were to:

-

determine whether or not a strategy of switching to PI monotherapy is non-inferior to continuing triple drug therapy (the standard-of-care) in terms of the proportion of patients who maintain all of their available drug treatment options after at least 3 years of follow-up

-

compare the safety and toxicity of PI monotherapy with those of standard-of-care triple therapy over 3–5 years

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of PI monotherapy after 3 years’ follow-up and to extrapolate to lifetime follow-up.

Chapter 2 Methods

This open-label randomised parallel-group trial (registered as ISRCTN04857074) was performed in 43 centres in the UK (sites listed in Acknowledgements).

Trial entry criteria

The trial enrolled HIV-positive adults aged > 18 years who had been on ART comprising two NRTIs and one NNRTI or one PI for at least 24 weeks with no change in the previous 12 weeks, who had a VL of < 50 copies/ml at and for at least 24 weeks before screening (one ‘blip’ to < 200 copies/ml allowed during this period if followed by two or more tests with a result of < 50 copies/ml), who had a CD4 cell count of > 100 cells/mm3 at screening and who were willing to continue with their current ART or change according to the randomised allocation. Exclusion criteria were known major PI resistance mutation(s) on previous resistance testing (if performed; not mandated), previous ART change for unsatisfactory virological response (change for toxicity prevention/management or convenience permitted), PI allergy, concomitant medication with PI interactions, current or anticipated requirement for radiotherapy or cytotoxic chemotherapy, treatment for acute opportunistic infection within the previous 3 months, current or planned pregnancy, active substance abuse or psychiatric illness (that would, in the opinion of the investigator, prevent compliance with the protocol or assessments), history of HIV encephalopathy with a current deficit of > 1 in any domain of the Neuropsychiatric AIDS Rating Scale (NARS),47,48 history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), 10-year absolute coronary heart disease risk of > 30% or risk of > 20% with diabetes or a family history of premature ischaemic heart disease/stroke,49 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, active/planned HCV treatment, hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen positive at screening or since HIV diagnosis (unless HBV DNA < 1000 copies/ml while off HBV-active drugs) or a fasting plasma glucose > 7.0 mmol/l at screening.

We chose to exclude patients with active substance use or psychiatric illness that was thought likely to prevent compliance with the protocol because we thought that it was paramount to conduct a definitive trial that answered the question of the risks for long-term treatment options arising from VL rebound and this would require very high levels of trial retention. We excluded patients with a high risk of CVD because of the concern that PIs may add to that risk, and it seemed inappropriate to randomise patients with CVD who were stable on relatively low-risk NNRTI-based regimens to a new regimen that might increase that risk. Most of the other inclusion and exclusion criteria are standard.

The protocol was approved by the Cambridgeshire 4 Research Ethics Committee and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Randomisation and treatment strategies

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio to maintain ongoing triple therapy (OT) or switch to ritonavir-boosted PI monotherapy (PI-mono). In the OT group, patients were managed using triple combination therapy regimens with changes allowed for toxicity, convenience or protocol-defined confirmed VL rebound (see Assessments). In the PI-mono arm, patients were switched to a single ritonavir-boosted PI (physician choice but ritonavir-boosted DRV 800 mg/100 mg once daily or ritonavir-boosted LPV 400 mg/100 mg twice daily were recommended). Patients switching from a NNRTI-based regimen continued on NRTIs for the first 2 weeks. PI substitution was allowed for toxicity or convenience. The strategy required prompt reintroduction of NRTIs (switch of PI to NNRTI discretionary) in the event of protocol-defined confirmed VL rebound (see Assessments), and patients were subsequently managed on combination therapy for the remainder of the trial. Subsequent switches for toxicity, convenience or VL failure were allowed, as for the OT group. The hypothesis was that PI-mono would be non-inferior to OT.

Randomisation was stratified by centre (nine groups) and baseline ART regimen (PI vs. NNRTI). The computer-generated, sequentially numbered randomisation list (permuted blocks of varying size) was preprepared by the trial statistician. Screening forms were faxed to a central trials unit, eligibility was confirmed and, on receipt of a baseline visit form, randomisation was performed by the trial manager who could access the next number but not the whole list.

Assessments

Study visits at baseline, weeks 4 and 8 (PI-mono only), week 12 and at every 12 weeks thereafter included assessment of clinical status, medication adherence (standardised questions), VL and CD4 cell count as well as safety blood tests (measured at the site laboratory). Visits at baseline, week 12, week 48 and every 48 weeks thereafter included additional assessments of 10-year CVD risk,49 neurocognitive function (described below), symptomatic peripheral neuropathy (Brief Peripheral Neuropathy Screen)50,51 and quality of life [self-completed Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV)]. 52

Neurocognitive testing was performed by designated research staff at each study site after receiving appropriate training by the co-ordinating centre. The training procedures included a face-to-face session, a training video and practice of the tests with at least five work colleagues before being allowed to assess study participants, followed by yearly revision. Five cognitive domains were explored with three different tests: verbal learning and memory were assessed using Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (HVLT-R),53 fine motor skills were assessed using the Grooved Pegboard Test54 and attention and executive function were assessed using Colour Trails Tests 1 and 2 respectively. 55 Test performance was considered invalid if participants decided to abandon the test before completion, if investigators failed to comply with standard procedures according to the instructions, or if the test was interrupted because of external factors. In addition, all scores were centrally monitored and extreme results were investigated and excluded if considered to be related to any of the situations listed above. Only participants with complete cognitive testing results available were included in the analyses. Raw scores for each cognitive test were transformed to z-scores using the manufacturers’ normative data53–55 adjusted for age (all tests) and years of education (Colour Trails Tests) by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation (SD) of test scores in reference populations. For the Grooved Pegboard Test the z-score was obtained by taking the average of the z-scores for the dominant and non-dominant hands. A summary score was then calculated for each patient by averaging the z-scores of the five tests [neurocognitive performance z-score 5 (NPZ-5)].

Clinical and laboratory events were classified by each site according to standard diagnostic criteria in the protocol [based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for AIDS;56 INSIGHT criteria for serious non-AIDS events;57 and Division of AIDS (DAIDS) criteria for AEs]58 and were reviewed by an independent physician at the trial co-ordinating centre. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. 59

If VL was detectable at ≥ 50 copies/ml at any visit, the test was repeated (on the same sample if available or on a fresh sample draw if not). If the VL was < 50 copies/ml, routine follow-up resumed; if the VL was ≥ 50 copies/ml, adherence counselling was performed and the patient returned for a confirmatory VL test at least 4 weeks from the date of the first sample. If the VL was < 50 copies/ml on the confirmatory test, routine follow-up resumed; if the VL was ≥ 50 copies/ml (i.e. third consecutive test) this met the protocol definition of confirmed VL rebound and the patient was required to change therapy and a repeat VL test was performed 4 weeks later.

Genotypic resistance testing was performed on all confirmed VL rebound samples and on rebound samples that did not meet this definition but preceded treatment switch. Genotypic testing was carried out at site laboratories and was repeated at the central laboratory if local sequencing was unsuccessful. Drug susceptibility prediction used the Stanford algorithm. 60 When resistance mutations were identified, comparison was made with any pre-trial genotypic testing reports.

The primary outcome was loss of future drug options, defined as new intermediate-/high-level resistance to one or more drugs in contemporary use to which the patient’s virus was considered to be sensitive at trial entry. Contemporary use was determined by current UK treatment guidelines,3 with saquinavir added as this was taken by some participants during the trial. Interim data were reviewed approximately annually by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC).

Secondary outcomes were the occurrence of serious drug or disease-related complications (death, serious AIDS-defining illness, serious non-AIDS-defining illness); the total number of grade 3 and 4 AEs; confirmed virological rebound (defined as above); CD4 cell count change from baseline; neurocognitive function change from baseline; cardiovascular risk change from baseline; and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) change from baseline (mental and physical health summary scores on the MOS-HIV questionnaire).

Additional specified safety outcomes included assessment of facial lipoatrophy, abdominal fat accumulation, peripheral neuropathy and eGFR.

Health-care costs were evaluated and a full health economic analysis performed as described in Chapter 4.

Sample size determination and statistical analysis

Assuming that 97% of patients in the OT group would maintain all future drug options (i.e. remain free of new resistance mutations) over 3 years,16,22,25 we estimated that approximately 280 patients per group would be required to demonstrate non-inferiority of PI-mono, defined by the upper limit of the 95% CI (two-sided) for the difference in the proportion of patients who maintain all future drug options over 3 years (OT – PI-mono) being < 10% with 85% power and allowing 10% loss to follow-up. The 10% non-inferiority margin was chosen based on US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance. 61,62

All comparisons were as randomised (intention to treat). Statistical tests presented are two-sided and test the null hypothesis of no difference between randomised groups. The absolute difference between the groups in the reduction of future drug options was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, with the 95% CI (two-sided) derived using bootstrap methods. The primary analysis included all new resistance mutations seen that conferred intermediate-/high-level drug resistance, but a sensitivity analysis was predefined in which loss of drug options was restricted to classes to which the patient was exposed during the trial (i.e. excluded mutations that were likely archived).

For secondary end points, binary outcome variables were compared between groups using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test and using logistic regression models for adjusted analyses; for continuous variables groups were compared using mean change from baseline and the t-test/linear regression [change was from baseline to the last available visit at which a measurement was performed or after week 144 (patients without such data were not included)]. Time-to-event outcomes were tested using a log-rank test. Poisson regression was used to compare incidence rates. Global tests of difference between randomised groups taking into account data at all follow-up time points were performed using generalised estimating equations (GEEs) (independent correlation structure, binomial or normal distribution as appropriate).

Patient and public involvement in the research

Given that this was a large UK-based trial looking at the long-term treatment of people living with HIV infection, it was considered critical from the outset to have involvement from the HIV community. An important consideration was that, in view of the cost-saving potential of the monotherapy approach, it was possible that the trial could at some stage be misrepresented as a cost-saving initiative and this perception might damage the trial. It was felt that engagement of the community was essential for maintaining the focus on the potential patient benefits, such as toxicity reduction, and ensuring that this message came across to the people in the trial as well as more broadly. The measures to engage the community are outlined briefly below.

The chief investigator approached the UK Community Advisory Board (UK-CAB), a network for community HIV treatment advocates, and asked for an opportunity to discuss the trial design at its meetings. He presented the trial design on two occasions and obtained useful feedback that resulted in a number of suggestions being incorporated in the final protocol (e.g. the suggestion to include therapeutic drug monitoring of PI levels at the first visit following randomisation in the PI-mono group).

At these meetings and in follow-up correspondence with UK-CAB, the chief investigator explained about the roles of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the IDMC and requested that UK-CAB provide a representative on each of these committees. A lay summary of the roles was produced as well as a description of the attributes that would be desired in those selected. UK-CAB organised an election process and a nominee for each of the two committees was selected.

The IDMC community representative attended all of the IDMC meetings and contributed to the discussion of the blinded data throughout the course of the trial.

The TSC community representative attended all of the TSC meetings and provided input into the final study protocol and all subsequent key decisions made during the course of the trial, including the approval of the study amendments, decisions on the viability of substudies, the decision to increase the sample size and include more sites in the UK and discussions around classification of end points in the final analysis. The TSC representative also fed back to the chief investigator any concerns that were circulating in the community or any community discussions (usually not directly related to the trial) about PI monotherapy that might impact on the trial and which needed to be addressed.

In parallel with engagement with UK-CAB and its nominated representatives, the trial team engaged with the African Eye Trust, a community group focused on the support of African HIV-positive patients, who represent a substantial proportion of the infected community in the UK. This community group organised workshops at regional sites that talked generally about clinical trials but which also specifically mentioned the PIVOT trial design and the opportunity that it presented for members of the community to participate in a trial. The trial was also featured in an article in the African Eye Voice magazine. Members of the African Eye Trust also helped patients who expressed an interest in the trial to understand the trial requirements and processes. This engagement likely contributed to the substantial representation of African patients in the trial (see Chapter 3), which is unusual for HIV trials conducted in the UK, Europe and North America, where enrolment tends to be dominated by white men who have sex with men.

Once the trial was complete, all participants were invited to hear about the results at a meeting that immediately followed (in the same afternoon) the results meeting for investigators. The study team, as well as several site investigators, were available to help patients interpret the findings and to answer questions about the study. This meeting was held before the formal release of the results at a major international HIV conference the following week. Participants provided very positive feedback and were highly appreciative of the opportunity to hear and discuss the results before their release at the conference.

Chapter 3 Results of the clinical trial

Trial recruitment

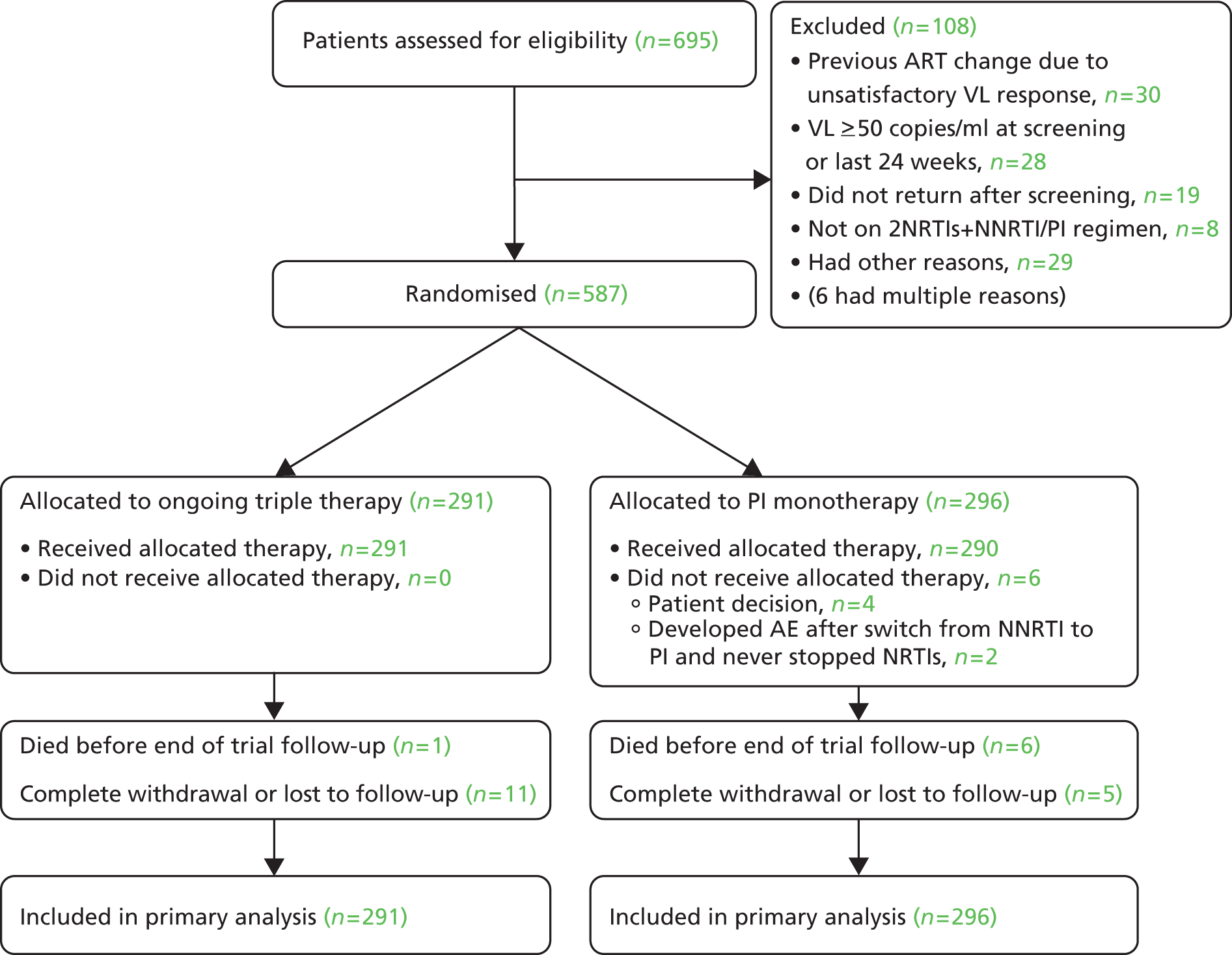

Recruitment to the trial commenced on 4 November 2008 with a target of 400 patients. In July 2009 the sample size was increased to 570 patients as emerging data from other studies22,25 indicated that event rates for the primary end point would likely be lower than first estimated. Recruitment ended on 28 July 2010 with 587 participants recruited from 43 sites across the UK (Figure 1). Study visits ended on 1 November 2013.

FIGURE 1.

Trial recruitment.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

Participant characteristics were similar between groups at baseline (Table 2). The median time on previous ART was 4 years and 53% were on a NNRTI-containing regimen at baseline.

| Characteristics | OT (n = 291) | PI-mono (n = 296) | Total (n = 587) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 43 (37–49) | 45 (39–50) | 44 (38–49) |

| Range | 23–75 | 23–67 | 23–75 |

| Mode of infection, n (%) | |||

| MSM | 175 (60) | 176 (59) | 351 (60) |

| Heterosexual | 108 (37) | 108 (36) | 216 (37) |

| Other | 8 (3) | 12 (4) | 20 (3) |

| Female, n (%) | 64 (22) | 73 (25) | 137 (23) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 206 (71) | 195 (66) | 401 (68) |

| Black | 73 (25) | 90 (30) | 163 (28) |

| Other | 12 (4) | 11 (4) | 23 (4) |

| HCV antibody positive, n (%) | 7 (2) | 14 (5) | 21 (4) |

| HIV disease status | |||

| Previous AIDS-defining illness, n (%) | 59 (20) | 57 (19) | 116 (20) |

| Nadir CD4 cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 181 (90–258) | 170 (80–239) | 178 (86–250) |

| Baseline CD4 cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 512 (386–658) | 516 (402–713) | 513 (392–682) |

| Baseline HIV VL undetectable, n (%) | 276 (95) | 279 (94) | 555 (95) |

| Duration of VL undetectable (months), median (IQR) | 36 (17–62) | 38 (22–66) | 37 (20–63) |

| ART history | |||

| Years since ART start, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.0–6.4) | 4.2 (2.4–6.9) | 4.0 (2.2–6.7) |

| Number of drugs ever received, median (IQR) | 5 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) |

| NNRTI at entry, n (%) | |||

| Any | 157 (54) | 157 (53) | 314 (53) |

| Efavirenz | 115 (40) | 115 (39) | 230 (39) |

| Nevirapine | 42 (14) | 39 (13) | 81 (14) |

| Etravirine | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| PI at entry, n (%) | |||

| Any | 134 (46) | 139 (47) | 273 (47) |

| Atazanavir | 59 (20) | 59 (20) | 118 (20) |

| LPV | 28 (10) | 49 (17) | 77 (13) |

| DRV | 24 (8) | 13 (4) | 37 (6) |

| Saquinavir | 16 (5) | 15 (5) | 31 (5) |

| Fosamprenavir | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 10 (2) |

| NRTIs at entry, n (%) | |||

| Any | 291 (100) | 296 (100) | 587 (100) |

| Emtricitabine/tenofovir | 190 (65) | 180 (61) | 370 (63) |

| Lamivudine/abacavir | 80 (27) | 82 (28) | 162 (28) |

| Other | 21 (7) | 34 (11) | 55 (9) |

Trial follow-up and withdrawal

The median duration of trial follow-up was 44 months (maximum 59 months); 1% died and 2.7% were withdrawn/lost to follow-up before the end of the trial (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Treatment and adherence

In the PI-mono group, the initial choice of PI was DRV (80%), LPV (14%) or another boosted PI (6%); 58% were still taking PI monotherapy at the end of the trial (23% reintroduced combination therapy for VL rebound, 4% reintroduced combination therapy for VL rebound not meeting protocol criteria, 5% reintroduced combination therapy for toxicity, 7% reintroduced combination therapy for other reasons/unknown and 2% never started monotherapy). Overall, 72% of follow-up time was spent on monotherapy. Self-reported adherence to study medication was high; across all visits, 93% of participants in the OT group and 92% of participants in the PI-mono group reported not missing any ART doses in the last 2 weeks (p = 0.51).

Virological rebound and resuppression

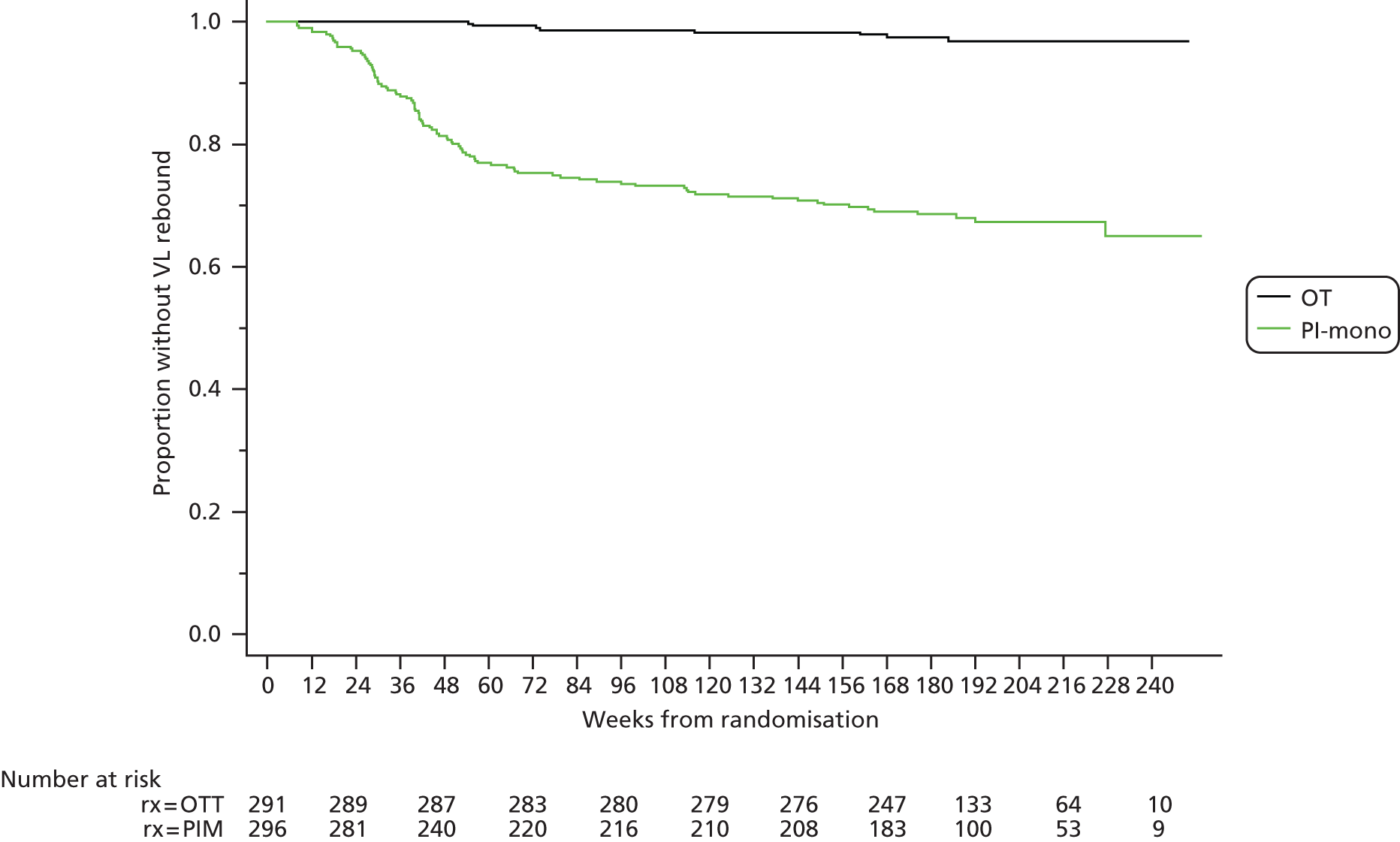

One or more episodes of confirmed VL rebound were observed in eight patients (Kaplan–Meier estimate 3.2%) in the OT group and 95 patients (35.0%) in the PI-mono group (absolute risk difference 31.8%, 95% CI 24.6% to 39.0%; p < 0.001). The rate of rebound while on monotherapy was highest in the first year (24 per 100 person-years vs. 6 per 100 person-years thereafter; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Time to virological rebound.

There was no difference in the rate of rebound by PI in the PI-mono group [14 (95% CI 11 to 17), 8 (95% CI 4 to 17) and 12 (95% CI 5 to 27) rebounds per 100 person-years for DRV, LPV, and other PIs respectively; p = 0.52 for overall comparison between groups]. The median peak VL at first episode of rebound on monotherapy was 526 copies/ml; of the 91 patients with subsequent VL tests, 22 (24%) resuppressed spontaneously and 69 (76%) resuppressed a median of 3.5 weeks after changing ART.

Figure 4 shows the time to first VL below 50 copies/ml (mid-point between the last test with a VL above 50 copies/ml and the first test with a VL below 50 copies/ml) for patients at the time of first rebound who were taking PI monotherapy. Outcomes by type of treatment switch are shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 4.

Time to VL resuppression following change of ART in the PI-mono group.

FIGURE 5.

Outcome of VL rebound episodes in the PI-mono group.

Resistance and loss of future drug options

The proportion of patients with loss of future drug options at 3 years, the primary outcome, was 0.7% in the OT group and 2.1% in the PI-mono group [difference 1.4% (–0.4% to +3.4%); non-inferiority criterion met; Table 3]. PI-mono was also non-inferior in prespecified secondary analyses including the loss of drug options during the full trial follow-up period and excluding loss of options attributed to mutations likely to be archived (as described in the following paragraph).

| Loss of future drug optionsa | OTb | PI-monob | PI-mono – OTc |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 36 months, n (%) | 21,2 (0.7) | 65–10 (2.1) | 1.4% (−0.4% to 3.4%) |

| At the end of the trial, n (%) | 41–4 (1.8) | 65–10 (2.1) | 0.2% (−2.5% to 2.6%) |

| At the end of the trial, limited to drug classes given during the trial (excluding likely archived resistance), n (%) | 31–3 (1.5) | 35–7 (1.0) | −0.4% (−2.1% to 1.4%) |

One participant on atazanavir monotherapy developed the I50L mutation (as a mixture with wild type), conferring high-level atazanavir resistance. An isolated L90M mutation was detected in two patients on DRV monotherapy; both resuppressed with the reintroduction of NRTIs. This mutation, possibly archived, does not affect DRV sensitivity but confers resistance to saquinavir and thus met the end point definition. NRTI or NNRTI mutations were detected in three patients in the PI-mono group, likely archived from previous treatment. In the OT group, three patients had loss of future drug options to drug classes that they were taking and one, taking a PI-based regimen, had NNRTI mutations that were likely archived (Tables 3 and 4).

| Patient | Cumulative ART exposure before trial entry | Time of resistance test (trial week)b | Cumulative ART exposure during the trialc | VL (copies/ml) at time of resistance test | Drug-resistance mutations presentd | Drugs with reduced susceptibilitye | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRTI, NNRTI | PI | NRTI, NNRTI,II | PI | RT | PRO | NRTI | NNRTI | PI | |||

| OT group | |||||||||||

| 1 | ZDV, 3TC, NVP, ABC | ATV | –89 | – | – | – | 118I, 179D | – | – | – | – |

| 70 | ABC, 3TC | ATV | 33,300 | 118I, 179D, 184V | 84V | 3TCH, FTCH | – | SQVH, TPVI, ATVI, FPVH | |||

| 185 | TDF, FTC, RAL (3TC, ABC) | DRV (ATV) | 4100 | 118I, 179D | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2 | d4T, TDF, EFV, FTC | DRV | –286 | – | – | – | – | 71V | – | – | – |

| 193 | TDF, FTC, RPV | (DRV) | 1500 | 100I, 103N, 184V | 71V | 3TCH, FTCH | NVPH, EFVH, ETVI, RPVI | – | |||

| 3 | ddI, 3TC, EFV, FTC, TDF | 161 | TDF, FTC, ETV (EFV, NVP) | (DRV) | 60 | 138A, 184V/I | – | 3TCH, FTCH | – | – | |

| 167 | TDF, FTC, ETV (EFV, NVP) | (DRV) | 5400 | 65R, 138A, 181C, 184V/I, 221Y, 230L | – | 3TCH, FTCH, ABCH, TDFI | NVPH, EFVH, ETVH, RPVH | – | |||

| 4 | 3TC, ABC | LPV, SQV | –179 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 51 | TDF, FTC | DRV | 2300 | 106A | – | – | NVPH, EFVI | – | |||

| PI-mono group | |||||||||||

| 5 | FTC, TDF, EFV | – | –165 | – | – | – | – | 71T | – | – | – |

| 48 | – | ATV | 23,400 | – | 20T, 50L/I, 71T | – | – | ATVH | |||

| 57 | – | ATV | 3300 | – | 20T, 71T | – | – | – | |||

| 61 | – | ATV | 2400 | – | 71T | – | – | – | |||

| 6 | ZDV, 3TC, ABC, EFV | LPV | 155 | – | DRV | 200 | – | 90M | – | – | SQVI |

| 7 | FTC, TDF, EFV | – | 73 | – | DRV | 300 | – | 71I, 90M | – | – | SQVI |

| 8 | 3TC, ABC, EFV | – | 82 | – | DRV | < 20 | 103N | – | – | NVPH, EFVH | – |

| 9 | ZDV, 3TC, FTC, TDF, NVP | SQV | –290 | – | – | – | – | 11I | – | – | – |

| 83 | – | DRV | 1100 | 103N | – | – | NVPH, EFVH | – | |||

| 10 | ZDV, 3TC | LPV | 17 | – | DRV | 300 | 41L, 215D | – | ZDVI | – | – |

Serious drug- or disease-related complications

There were no differences in serious drug- or disease-related complications (death, AIDS-defining illness, serious non-AIDS-defining illness) (Tables 5–7). Causes of death (one in the OT group, six in the PI-mono group) were diverse and none was considered to be related to the treatment strategy (see Table 6).

| Serious drug- or disease-related complications | OTa (n = 291) | PI-monoa (n = 296) | Difference (95% CI) (%)b | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 8 (2.8) | 15 (5.1) | 2.3 (–0.8 to 5.4) | 0.15 |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (2) | 1.7 (–0.3 to 3.6) | 0.12 |

| AIDS-defining event, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.0 (–1.3 to 1.3) | 1 |

| Serious non-AIDS-defining event, n (%) | 7 (2.4) | 12 (4.1) | 1.6 (–1.2 to 4.5) | 0.26 |

| Patient (group) | Cause of death (week of presentation of terminal condition) | Clinical history and risk factors | HIV disease status from trial entry to presentation of terminal condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (OT) | Metastatic adenocarcinoma, probable lung origin (week 20) | 58-year-old male; 40 pack per year history of smoking; presented with a right thigh mass; mediastinal and adrenal mass on CT | CD4 525 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL suppressed from randomisation to presentation of the terminal condition |

| 2 (PI-mono) | Trauma, presumed suicide (week 17) | 47-year-old male; no history of depression | CD4 215 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL suppressed from randomisation to death |

| 3 (PI-mono) | Pulmonary embolism (week 51) | 40-year-old female; hospitalisation for encephalitis (weeks 40–50); pulmonary embolism secondary to deep-vein thrombosis | CD4 333 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL rebound week 36 because of non-adherence; resuppressed partially with reintroduction of combination therapy |

| 4 (PI-mono) | Breast carcinoma, recurrent (week 7) | 54-year-old female; angiosarcoma of the breast 2 years before study entry treated by mastectomy | CD4 550 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL suppressed from randomisation to presentation of the terminal condition |

| 5 (PI-mono) | Small-cell lung carcinoma (week 178) | 59-year-old male; smoker for 30 years; presented with headache; lung mass on CT, biopsy showed small-cell carcinoma of the lung | CD4 208 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL suppressed from randomisation to presentation of the terminal condition |

| 6 (PI-mono) | Glioblastoma (week 66) | 61-year-old male; non-smoker; presented with headache at week 66; brain mass on CT, biopsy showed high-grade glioblastoma | CD4 468 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL rebound weeks 25–32 (< 300 copies/ml). Resuppressed with addition of TDF/FTC thereafter |

| 7 (PI-mono) | Anal carcinoma (week 80) | 56-year-old male; smoker; anal mass detected; biopsy showed squamous cell carcinoma | CD4 319 cells/mm2 at baseline; VL rebound weeks 24–43 (max. 815 copies/ml). Resuppressed with addition of TDF/FTC thereafter |

| Event | OT (n = 291) | PI-mono (n = 296) |

|---|---|---|

| Serious AIDS-defining events | ||

| AIDS encephalopathy | 1 | |

| Cytomegalovirus colitis | 1 | |

| Serious non-AIDS-defining events | ||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | |

| Facial wasting | 1 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | |

| Renal failure | 1 | |

| Malignancy | 5 | 10 |

| Anal squamous cell carcinoma | 1a | |

| CNS (glioblastoma) | 1a | |

| Hodgkin’s disease | 1 | |

| Lung (small-cell carcinoma) | 1a | |

| Metastatic carcinoma (angiosarcoma, unknown primary) | 1a | 1a |

| Prostate cancer | 2 | 1 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 | |

| Skin carcinoma (variousb) | 1 | 4 |

Serious adverse events and grade 3/4 clinical events

The number of serious adverse events (SAEs) overall and by category and the number of SAEs that were considered to be related to ART did not differ between the groups (Tables 8–10). However, there were fewer total grade 3 or 4 AEs in the PI-mono group (see Table 8), the difference reflecting fewer laboratory events (Table 11).

| Event | OTa (n = 291) | PI-monoa (n = 296) | Difference (95% CI) (%)b | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAE, n (%) | 45 (15) | 56 (19) | 3.5 (–2.6 to 9.6) | 0.27 |

| Grade 3/4 AE, n (%) | 159 (55) | 137 (46) | –8.4 (–16.4 to –0.3) | 0.043 |

| Event | OT (n = 291)a | PI-mono (n = 296)a |

|---|---|---|

| Total events | 61 | 75 |

| Death | 1 | 6 |

| Life-threatening | 4 | 2 |

| Caused/prolonged hospitalisation | 58 | 67 |

| Disability/incapacity | 0 | 2 |

| Congenital anomaly/birth defect | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 4 | 5 |

| Event | OT (n = 291)a | PI-mono (n = 296)a | Difference (95% CI) (%) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.0) | –1.0 (–3.2 to 1.1) | 0.34 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | ||

| SAE | 2 | 0 | ||

| Grade 3/4 AE | 3 | 3 | ||

| SAE plus grade 3/4 AE | 1 | 0 |

| Event | OT (n = 291)a | PI-mono (n = 296)a | Difference (95% CI) (%)b | p-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical events | ||||

| Total | 49 (17) [78] | 65 (22) [91] | 5.1 (–1.3 to 11.5) | 0.12 |

| Cardiovascular | 8 (3) [11] | 7 (2) [7] | –0.4 (–2.9 to 2.2) | 0.77 |

| Respiratory | 5 (2) [5] | 11 (4) [11] | 2.0 (–0.6 to 4.6) | 0.14 |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 (4) [15] | 7 (2) [8] | –1.8 (–4.6 to 1.1) | 0.23 |

| Hepatic | 2 (1) [2] | 3 (1) [3] | 0.3 (–1.4 to 2.1) | 1.00 |

| Renald | 2 (1) [2] | 3 (1) [3] | 0.3 (–1.4 to 2.1) | 1.00 |

| CNSe | 9 (3) [10] | 17 (6) [20] | 2.7 (–0.7 to 6.0) | 0.12 |

| Skin | 7 (2) [7] | 9 (3) [9] | 0.6 (–2.0 to 3.3) | 0.64 |

| Other | 20 (7) [26] | 24 (8) [30] | 1.2 (–3.0 to 5.5) | 0.57 |

| Laboratory events | ||||

| Total | 131 (45) [158] | 97 (33) [117] | –12.2 (–20.1 to –4.4) | 0.002 |

| Phosphate decreased | 73 (25) | 37 (13) | –12.6 (–18.8 to –6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin increased | 44 (15) | 21 (7) | –8.0 (–13.1 to –3.0) | 0.002 |

| Lipids increased | 22 (8) | 39 (13) | 5.6 (0.7 to 10.5) | 0.026 |

| Haematological | 8 (3) | 5 (2) | –1.1 (–3.4 to 1.3) | 0.38 |

| Other | 7 (2) | 11 (4) | 1.3 (–1.5 to 4.1) | 0.36 |

Renal toxicity

Fewer patients in the PI-mono group experienced an eGFR of < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2 during follow-up (Table 12) and there was a trend towards a reduced decline in eGFR in the PI-mono group (Figure 6), although the difference at the end of the trial was marginal (see Table 12). There was no evidence of serious clinical consequences: the only case of end-stage renal failure occurred in the PI-mono group in a patient with pre-existing chronic renal impairment at trial entry.

| Outcome | OT (n = 291) | PI-mono (n = 296) | Difference (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated GFR < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2, n/N (%)b | 28/290 (10) | 15/296 (5) | –4.6% (–8.8% to –0.4%) | 0.033 |

| Mean change (ml/minute/1.73 m2), mean (SE) | –5.13 ± 0.67 | –3.83 ± 0.66 | 1.30 (–0.55 to 3.15) | 0.09 |

FIGURE 6.

Absolute eGFR over time.

Differences in the numbers ever having an eGFR of < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2 as well as in the mean change from baseline were similar when values were calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault equation64 instead of the CKD-EPI formula. 59

Fewer patients in the PI-mono group experienced a phosphate level of < 0.65 mmol/l (p < 0.001; see Table 11). Patients allocated to the OT group had on average slightly lower serum phosphate levels over the whole follow-up period than patients allocated to the PI-mono group (unadjusted GEE for global difference in mean change, p = 0.017; Figure 7). There was, however, no significant difference in mean change from baseline to the last available visit, with measurement at or after week 144 (difference PI-mono – OT adjusted for baseline value: +0.02 mmol/l, 95% CI –0.01 to +0.05; t-test p = 0.48).

FIGURE 7.

Absolute plasma phosphate levels over time.

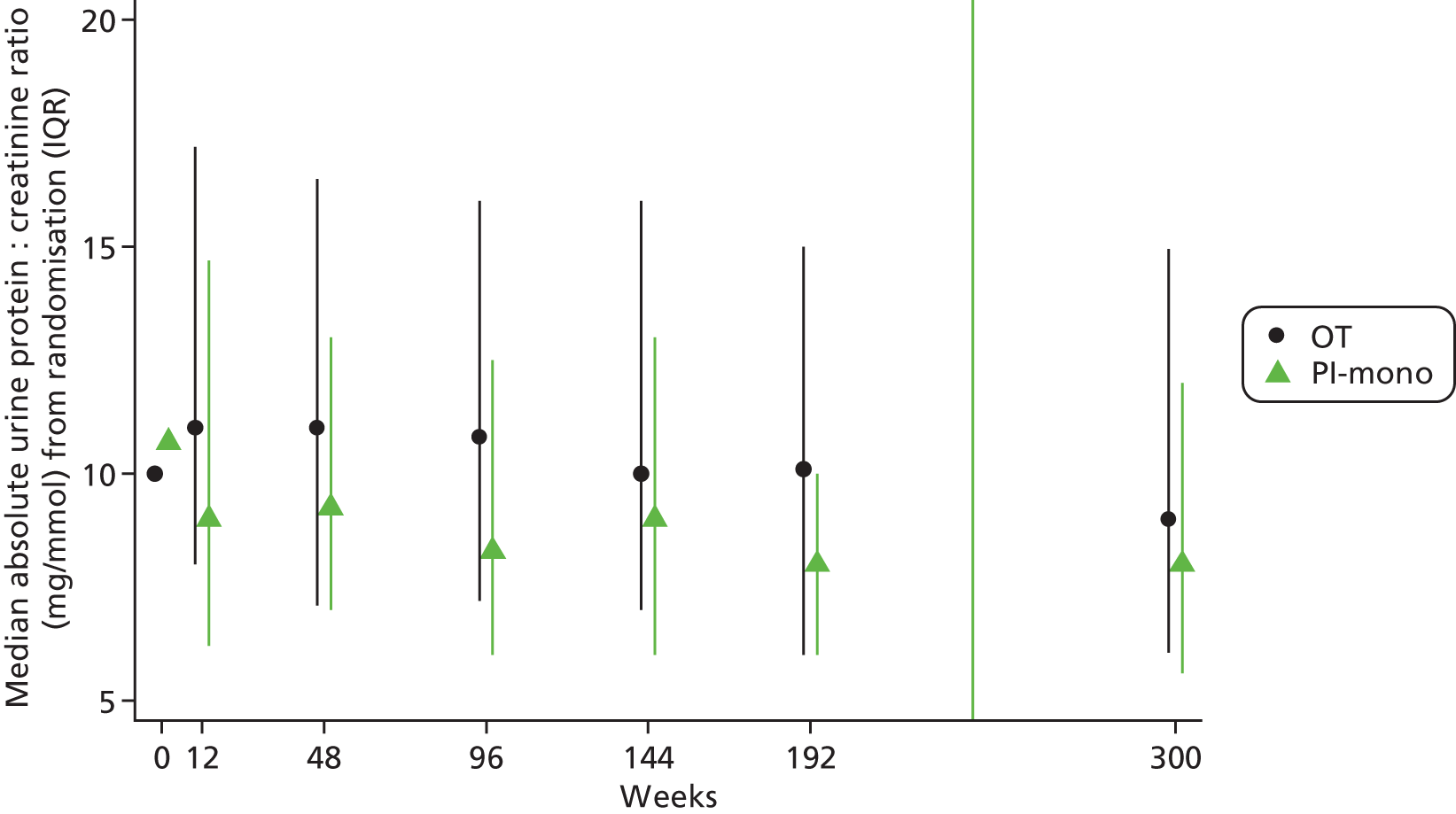

Patients allocated to the OT group had on average a slightly higher urine protein–creatinine ratio over the whole follow-up period than patients allocated to the PI-mono group (unadjusted GEE for global difference in mean change after log10 transformation, p = 0.021; Figure 8). Patients in the OT group also had a larger urine protein–creatinine ratio at the last available visit with measurement at or after week 144 (p = 0.026).

FIGURE 8.

Absolute urine protein–creatinine ratio over time. IQR, interquartile range.

In total, 65/271 (24%) in the OT group and 42/270 (16%) in the PI-mono group, respectively, ever had a urine protein–creatinine ratio of > 200 mg/g (difference –8.4%, 95% CI –15.1% to –1.8%; p = 0.014), including single increased values (cut-off not prespecified).

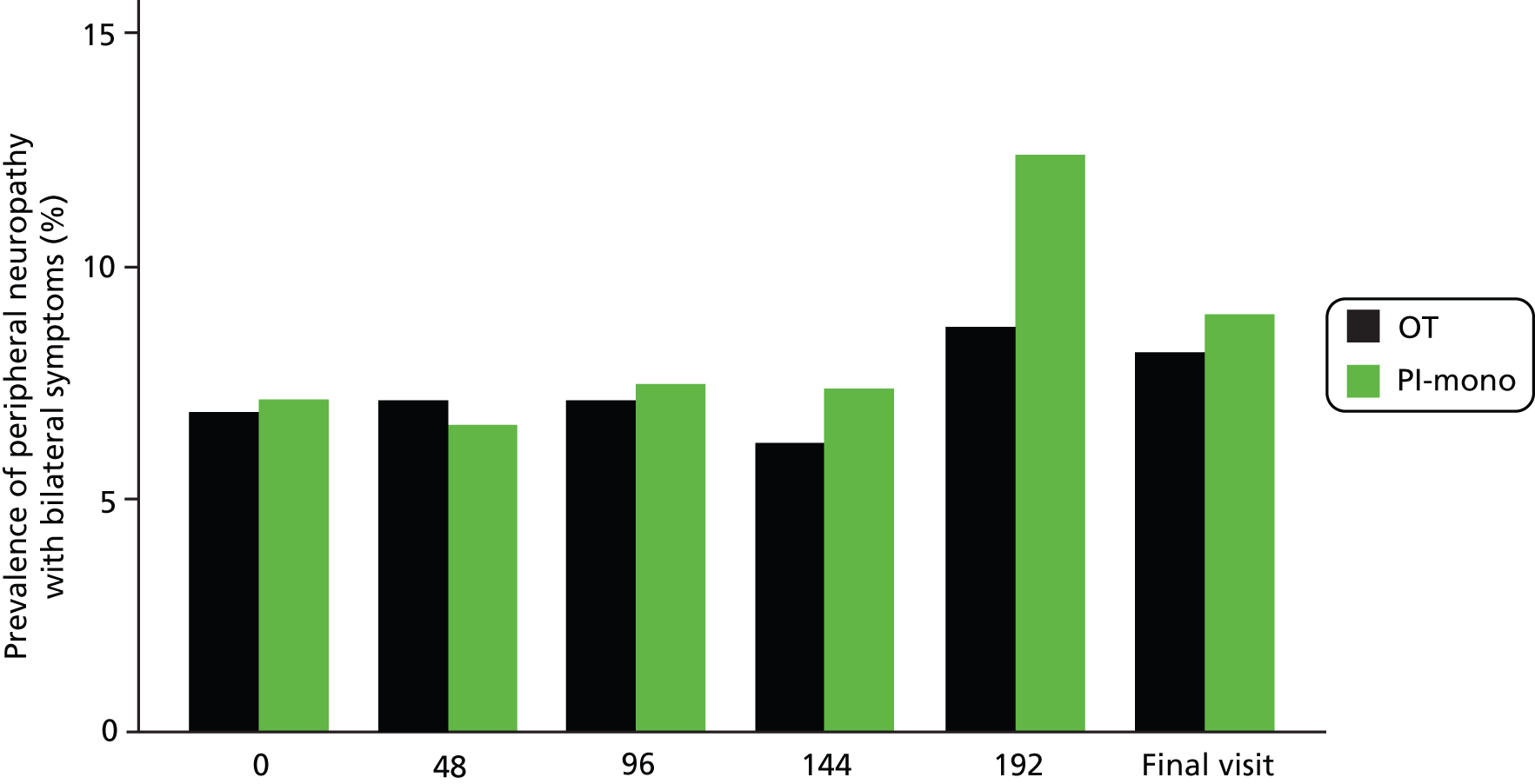

Peripheral neuropathy and lipodystrophy

Proportions of patients with symptomatic peripheral neuropathy, facial lipoatrophy and abdominal fat accumulation did not differ between the groups during follow-up (Table 13 and Figure 9).

| Outcome | OT (n = 291) | PI-mono (n = 296) | Difference (95% CI) (%)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic peripheral neuropathy, n/N (%)b | 44/283 (15.5) | 46/289 (15.9) | 0.4 (–5.6 to 6.3) | 0.90 |

| Facial lipoatrophy, n/N (%)c | 23/282 (8.2) | 35/289 (12.1) | 4.0 (–1.0 to 8.9) | 0.12 |

| Abdominal fat accumulation, n/N (%)d | 47/274 (17.2) | 57/277 (20.6) | 3.4 (–3.1 to 10.0) | 0.30 |

FIGURE 9.

Symptomatic peripheral neuropathy prevalence over time.

Cardiovascular disease risk

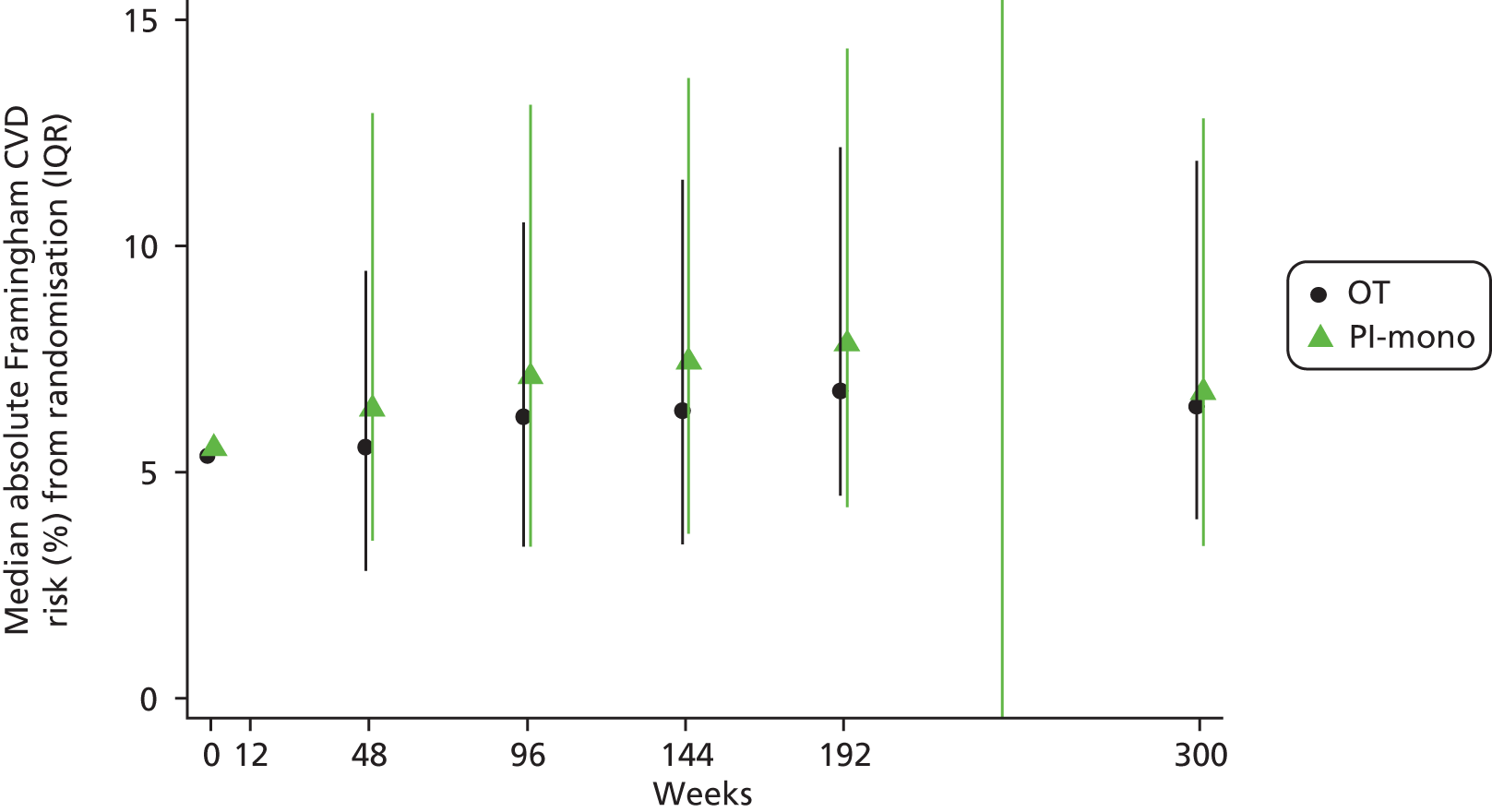

There was no difference in Framingham risk score65 between the groups over the whole follow-up period (unadjusted GEE for global difference in mean change, p = 0.56) (Figure 10). The mean [standard error (SE)] change in risk score for a CVD event over the next 10 years, from baseline to the last available visit, with measurement at or after week 144, was +1.3% (0.3%) and +1.6% (0.3%) in the OT and PI-mono groups, respectively; the difference between the groups adjusted for baseline values was 0.3% (95% CI –0.6% to 1.1%; t-test p = 0.52). In total, 9/281 (3%) in the OT group and 16/288 (6%) in the PI-mono group, respectively, ever newly had a CVD risk of > 30% after baseline (difference 2.4%, 95% CI –1.0% to 5.7%; p = 0.17).

FIGURE 10.

Absolute CVD risk over time (estimated using the Framingham equation).

CD4 cell count change

There was no difference in CD4 cell count between groups over the whole follow-up period (unadjusted GEE for global difference in mean change, p = 0.91) (Figure 11). Mean (SE) change from baseline to the last available visit, with measurement at or after week 144, was +93 (10) cells/mm3 in the OT group and +109 (9) cells/mm3 in the PI-mono group; the difference between the groups adjusted for baseline values was +16 (95% CI –11 to +42) cells/mm3 (t-test p = 0.30).

FIGURE 11.

Absolute CD4 cell count over time.

Neurocognitive function

There was no difference between the groups in the change in mean NPZ-5 score on the neurocognitive function tests (Figures 12 and 13). The mean (SE) change from baseline to the last available visit, with measurement at or after week 144, was +0.53 ± 0.04 and +0.52 ± 0.04 in the OT and PI-mono groups, respectively; the difference between the groups adjusted for baseline value was –0.01 (95% CI –0.11 to 0.09; t-test p = 0.94).

FIGURE 12.

Absolute NPZ-5 score over time.

FIGURE 13.

Change in NPZ-5 score from baseline.

Quality of life

Changes in the mental and physical health summary scores from baseline to the last study visit were calculated from the responses on the MOS-HIV questionnaire, with imputation of missing data on individual subscales. Changes from baseline were relatively small in both groups and there was no significant difference between the groups (Table 14).

| Quality of life, summary score | OT (n = 291) | PI-mono (n = 296) | Difference (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health, mean change | –0.75 ± 0.57 | –1.82 ± 0.54 | –1.07 (–2.61 to 0.47) | 0.17 |

| Physical health, mean change | –0.76 ± 0.53 | –1.17 ± 0.46 | –0.41 (–1.79 to 0.98) | 0.56 |

Chapter 4 Health economics analysis

Outline of the analysis

The objective of the health economics analysis was to investigate the cost-effectiveness of the strategy of switching to PI monotherapy compared with continuing triple therapy in HIV-1-infected patients. The cost-effectiveness analysis considered costs from a NHS perspective (2012 GBP) and health outcomes in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each treatment group from the PIVOT trial. The base-case analysis was a within-trial analysis and had a 3-year (156-week) time horizon. Secondary analyses modelled lifetime costs and outcomes. All analyses were performed using individual patient-level data on resource use and HRQoL from the PIVOT trial. Table 15 provides a description of the data collected for the economic evaluation.

| Category | Description of data collected | Time points |

|---|---|---|

| HRQoL | The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions 3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) health questionnaire | Baseline and every 12 weeks |

| ART drug costs | Generic names of ART drugs used as well as dosage, quantity and duration of usage | Every 12 weeks |

| Cost of visits to HIV clinics | Scheduled visits to HIV clinics every 12 weeks in the PI-mono group and an additional scheduled appointment within the first 12 weeks after initiation of monotherapy (frequency considered necessary for routine clinical care on monotherapy) | Every 12 weeks |

| Scheduled visits every 24 weeks in the OT group (frequency considered necessary for routine clinical care on triple therapy) | ||

| Additional unscheduled visits for both groups | ||

| Includes the cost of usual laboratory tests and additional resistance tests in the PI-mono group | ||

| Cost of hospital services | Visits to non-HIV outpatient clinics or accident and emergency departments | Every 12 weeks |

| Inpatient admissions, including length of stay and reason for admission | ||

| Primary care costs | Visits to general practitioners | Every 12 weeks |

| Trial protocol-driven costs | Measurement of PI concentration in the PI-mono group, required by the trial protocol | Every 12 weeks |

| Visits to HIV clinics that are not expected to be part of routine clinical practice, required by the trial protocol | ||

| Neurocognitive testing, required by the trial protocol | ||

| Cost of concomitant drugs | Generic names of cholesterol-lowering agents used as well as dosage, quantity and duration of usage | Every 12 weeks |

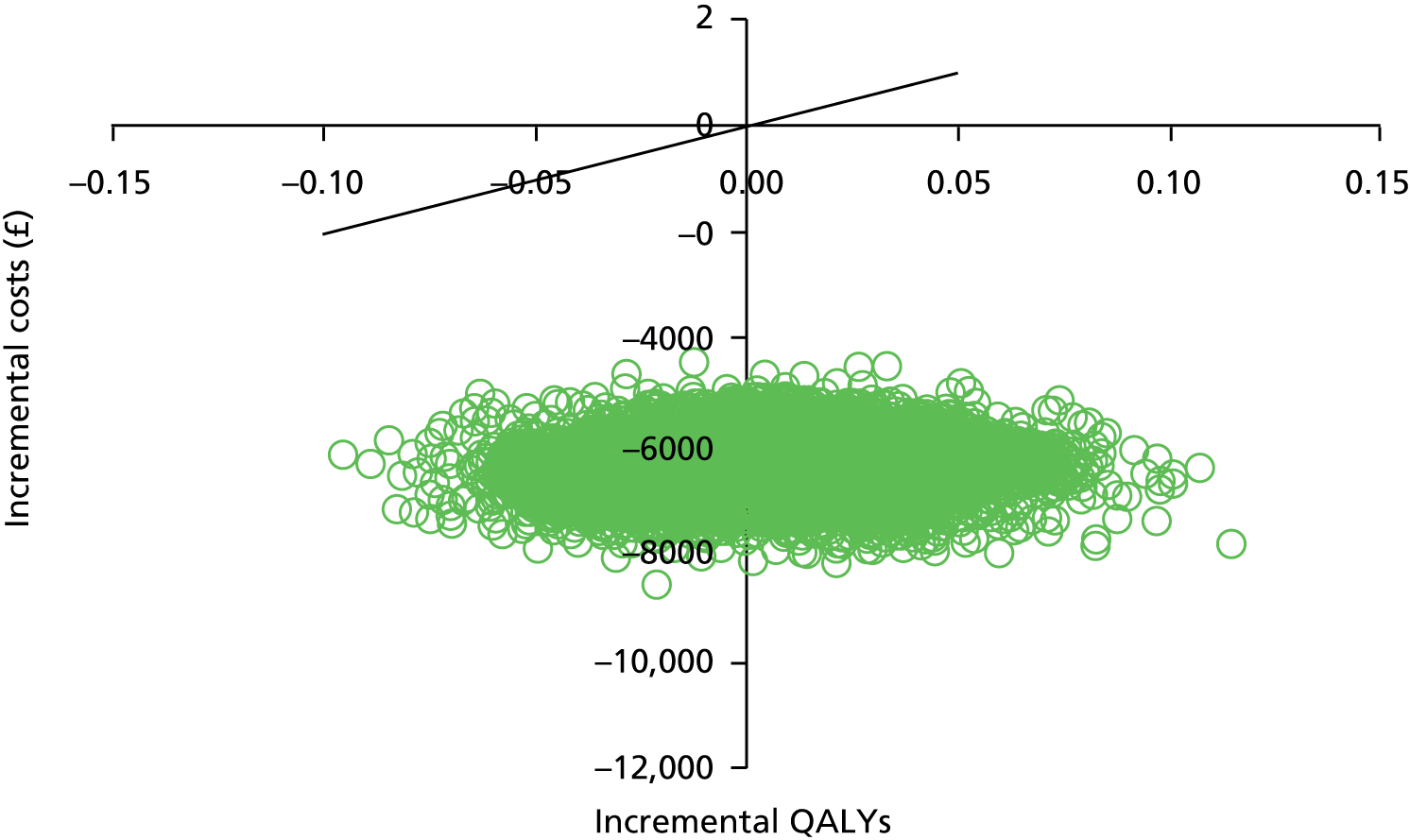

Missing data on costs and QALYs were handled using multiple imputation (MI) and regression analysis was used to adjust for baseline covariates. When one option generated additional mean QALYs at a higher mean cost, comparative results were presented as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) by dividing the difference in mean costs by the difference in mean QALYs. 66 The cost-effectiveness of PI-mono was assessed by comparing ICERs to the cost-effectiveness threshold range of £20,000–30,000 per QALY defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 67 All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. All costs and QALYs accrued beyond the first year were discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%. 67

Health-care resource usage

Data on resource use were collected at scheduled visits every 12 weeks. In addition to the scheduled visits every 12 weeks, which patients in both trial arms attended, two additional visits were scheduled at weeks 4 and 8 for the PI-mono group. The recording of resource use was based on patients’ recollections since the last visit. As patients were asked to recall their use of health-care resources since the last visit it was assumed that visits that followed one or more omitted visits captured all of the use since the last recorded visit. The use of the following types of resources was recorded: ART use, HIV clinic visits, visits to accident and emergency or non-HIV outpatient clinics, general practitioner (GP) visits, hospital inpatient stays and use of concomitant drugs. The use of ART was recorded by clinical staff, whereas the length of any interruptions in ART treatment was based on the patients’ own recollections. Concomitant drugs included all cholesterol-lowering agents as the use of these was expected to differ a priori. 68 The patients attending the scheduled visit at week 4 post randomisation were assumed to have their PI drug concentration measured, as per protocol. No further PI drug concentration measurements were assumed to be performed. No attempts were made to distinguish visits that were HIV related from those that were not. In both groups the costs of all visits were included in the calculations. The total resource consumption among the complete cases is summarised in Table 16 along with the corresponding unit costs.

| Resource type | PI-mono (n = 266) | OT (n = 254) | Unit cost and sourcea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Used by, n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Used by, n (%) | ||

| ART drug use at the 3-year follow-up visit | |||||||

| Monotherapy | 162 (60.9) | 4 (1.6) | Various69,70 | ||||

| Any triple therapy use | 104 (39.1) | 250 (98.4) | Various69,70 | ||||

| No use | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | £0 | ||||

| Routine HIV clinic visits | 16.60 (3.74) | 15 (4) | 266 (100) | 8.31 (3.9) | 7 (3) | 254 (100) | PI-mono: £411.81;71,[CA] OT: £40471 |

| Primary care | |||||||

| GP visits | 6.24 (6.16) | 5 (7) | 244 (91.7) | 6.06 (6.06) | 4.75 (6) | 234 (92.1) | £5372 |

| Hospital services | |||||||

| Outpatient clinic or A&E visits | 3.7 (5.39) | 2 (5) | 188 (70.7) | 4.49 (7.19) | 2 (4) | 194 (76.4) | £106.2071 |

| Inpatient admissions | 0.368 (0.83) | 0 (0) | 60 (22.6) | 0.311 (0.79) | 0 (0) | 50 (19.7) | Various71 |

| Trial protocol-driven resource use | |||||||

| Neurocognitive testing | 3.81 (0.56) | 4 (0) | 265 (99.6) | 3.82 (0.58) | 4 (0) | 252 (99.2) | £32.9472–75 |

| PI drug concentration measurements | 0.974 (0.16) | 1 (0) | 259 (97.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | £60CA |

| Non-routine HIV clinic visits | 0.98 (0.24) | 1 (0) | 255 (95.9) | 6.69 (0.67) | 7 (0) | 254 (100) | PIM: £411.81;71,[CA] OT: £40471 |

| Concomitant drug use at the 3-year follow-up visit | |||||||

| Cholesterol-lowering agents | 59 (22.2) | 35 (13.8) | Various70 | ||||

Costs

Resource use estimates were obtained from the PIVOT trial and unit costs were obtained from routinely published national cost sources: the British National Formulary (BNF),70 the Department of Health’s Commercial Medicines Unit’s Electronic Market Information Tool,69 the Personal Social Services Research Unit report on the unit costs of health and social care72 and NHS reference costs71 (see Table 16). All analyses assume that no costs of ART drugs are incurred in periods of interrupted treatment. Furthermore, potential ART drug waste from switching drug combinations before a package had been finished was not registered and therefore not estimated. All six categories of health-care resources consumed were included in the base-case analysis of costs accrued within 3 years. As such, the base case also includes the resource use that could mainly be attributed to the trial protocol (see Table 16).

Quality-adjusted life-years

The QALY is a generic measure of health that combines effects of interventions on both life expectancy and HRQoL and their side-effects and is defined as a year lived with full health. 66 To calculate the total QALYs gained per patient the length of life was weighted by the HRQoL. During the PIVOT trial, HRQoL was measured at baseline and at each scheduled follow-up visit using the three-level version of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-3L). 76 Responses were converted into the EQ-5D-3L index score using weights based on the UK value set. 77

Missing data

Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to handle missing data on costs and outcomes. 78–80 The use of MI requires a less strong assumption regarding the missingness mechanism than the assumption needed to perform complete-case analysis. When complete-case analysis is performed in the presence of missing data it is assumed that there is no underlying relationship between missing values and any observed or unobserved variables; that is, that values are missing completely at random. 81 In contrast, MI requires that missing data can be assumed to be missing at random conditional on values of observed variables but not on any unobserved variables. 81 As such, missing data were handled using MI. A total of 20 imputations (m = 20) was performed as previous research suggested that m = 20 would improve efficiency in the presence of 10–30% missing data. 82 The model imputed HRQoL scores, ART drug costs, primary care costs, secondary care costs, the cost of HIV clinic visits and the cost of concomitant drug use at each 12-week time point. To further inform the imputation model the following auxiliary variables were included: age, gender, ethnic origin, baseline CD4 cell count, history of diabetes, smoking status, history of coronary artery disease, years of education, years since diagnosis, number of days off work between each time point and an indicator of whether patients were receiving a NNRTI-based or a PI-based regimen prior to randomisation. The imputation model performed predictive mean matching to handle the bounded and skewed nature of costs and HRQoL scores. In predictive mean matching the specified covariates are used to estimate a predictive model but, instead of replacing missing values with the model-predicted values, the nearest observed value is used to fill the missing value. By applying predictive mean matching, predictions that lie outside the bounds of each variable were avoided. 83 However, the distribution of imputed values will often closely match that of the observed values. Following the use of MI to generate estimates that replace missing values, the uncertainty of these values is incorporated in the estimation of mean costs and QALYs using a method commonly known as Rubin’s rule. 84

Regression analyses of costs and quality-adjusted life-years

Regression methods were used to obtain the incremental estimates of costs and QALYs between treatment groups while adjusting for the baseline characteristics that were selected a priori. A generalised linear model (GLM) was chosen as it offers a flexible framework to handle adjustment for baseline covariates when the distribution of the dependent variable is right skewed. 85 However, QALYs are usually left skewed. 86 Therefore, to be able to adjust the QALYs gained for baseline covariates, the QALY decrement was estimated. The QALY decrement is defined as the maximum QALYs that could possibly be accrued within the time frame minus the actual QALYs gained. Because the distribution of QALYs was left skewed, the distribution of QALY decrements was right skewed. Hence the GLM for right-skewed (gamma) distributions was a good match for both cost regressions and regressions of QALY decrements. An identity link function was applied to assume an additive effect of covariates on costs and QALY decrements. 85 Costs and QALY decrements were adjusted for the following baseline covariates: age, gender, ethnic origin, time since HIV diagnosis, history of diabetes, smoking status, history of coronary artery disease and CD4 cell count. In the regression of QALY decrements, the baseline HRQoL score was also included, as failure to do so may bias estimates in the presence of an imbalance in baseline HRQoL score between the treatment groups. 87 Regression analysis and MI of missing values was conducted in Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Scenario analyses

Several scenario analyses were conducted to assess the impact of uncertainty on the cost-effectiveness results and to strengthen the external validity of the results; these are summarised in Table 17.

| Scenario | Element | Base case | Variation for the sensitivity analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costs | All unit costs for ART drugs were drawn from the Department of Health Commercial Medicines Unit’s Electronic Market Information Tool69 and the BNF70 | 1a: 10% reduction in all ART drug costs |

| 1b: 20% reduction in all ART drug costs | |||

| 1c: 30% reduction in all ART drug costs | |||

| 1d: 40% reduction in all ART drug costs | |||

| 1e: 30% reduction in ART drug costs for the OT group and 10% reduction in the PI-mono group | |||

| 1f: Estimated reductions obtained from personal communication with HIV pharmacist | |||

| 2 | Costs | All cost categories included | The costs that were deemed attributable to the trial protocol were excluded |

| 3 | Missing data | Data assumed to be missing at random; analysis therefore conducted on imputed data | Data assumed to be missing completely at random; analysis therefore conducted on the complete-case data |

| 4 | Mortality | All patients included | The six patients who died within 3 years were excluded from the analysis |

Scenarios 1a–f were constructed to incorporate potential reductions in the price of ARTs. Scenarios 1a–d assumed 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% reductions in the price of all ARTs respectively. Scenario 1e assumed a 10% reduction in the price of ART drugs in the PI-mono group and a 30% reduction in the price of ART drugs in the OT group. This scenario was constructed to explore the impact that generic versions of frequently used triple therapy drugs could be speculated to have on the cost-effectiveness of PI-mono compared with OT. Scenario 1f applied information about the current prices being paid, which was obtained through clinical advice with a HIV pharmacist in a major NHS trust.

In scenario 2 the costs of trial protocol-driven resource consumption were excluded as they might not be a part of routine clinical practice. PI monotherapy patients may need a stricter monitoring regimen than patients on triple therapy to ensure that combination therapy can be reintroduced promptly if a VL rebound occurs. The base case assumes that both PI-mono patients and OT patients attend scheduled HIV clinic visits every 12 weeks. Although this is considered reasonable in a routine clinical setting for PI monotherapy patients, it would be considered excessive for patients on triple therapy. Patients on triple therapy may only routinely attend scheduled HIV clinic visits every 24 weeks and the additional visits which the OT patients were subject to during the PIVOT trial were therefore considered to incur trial protocol-driven costs. This means that the trial protocol-driven consumption of health-care resources is higher in the OT group than in the PI-mono group. In scenario 2, these trial protocol-driven costs are excluded to assess the cost-effectiveness of PI monotherapy in a routine clinical setting. Hence scenario 2 assumes that PI-mono patients attend the HIV clinic every 12 weeks, whereas OT patients attend every 24 weeks. Furthermore, neurocognitive testing and PI drug concentration measurements conducted for the trial were excluded entirely.

In scenario 3 a complete-case analysis was performed to assess the impact of MI on the estimate of incremental costs and QALYs. GLM regression was also used in the complete-case analysis to adjust for baseline covariates. However, in the complete-case analysis QALY decrements could not be adjusted for history of diabetes and history of coronary artery disease because none of the complete cases was characterised by these at baseline. This was not considered to be a major issue as the restricted model for QALY decrements in the complete-case analysis was nested in the full model.

Scenario 4 addressed the within-trial mortality. The patients who died within 3 years (described in Chapter 3) were excluded from the analysis as it was considered unlikely that within-trial mortality was caused by treatment allocation. In total, six patients were removed from the data set after MI was performed. GLM regression of costs and QALY decrements was then performed using the remaining 291 PI-mono patients and 290 OT patients.

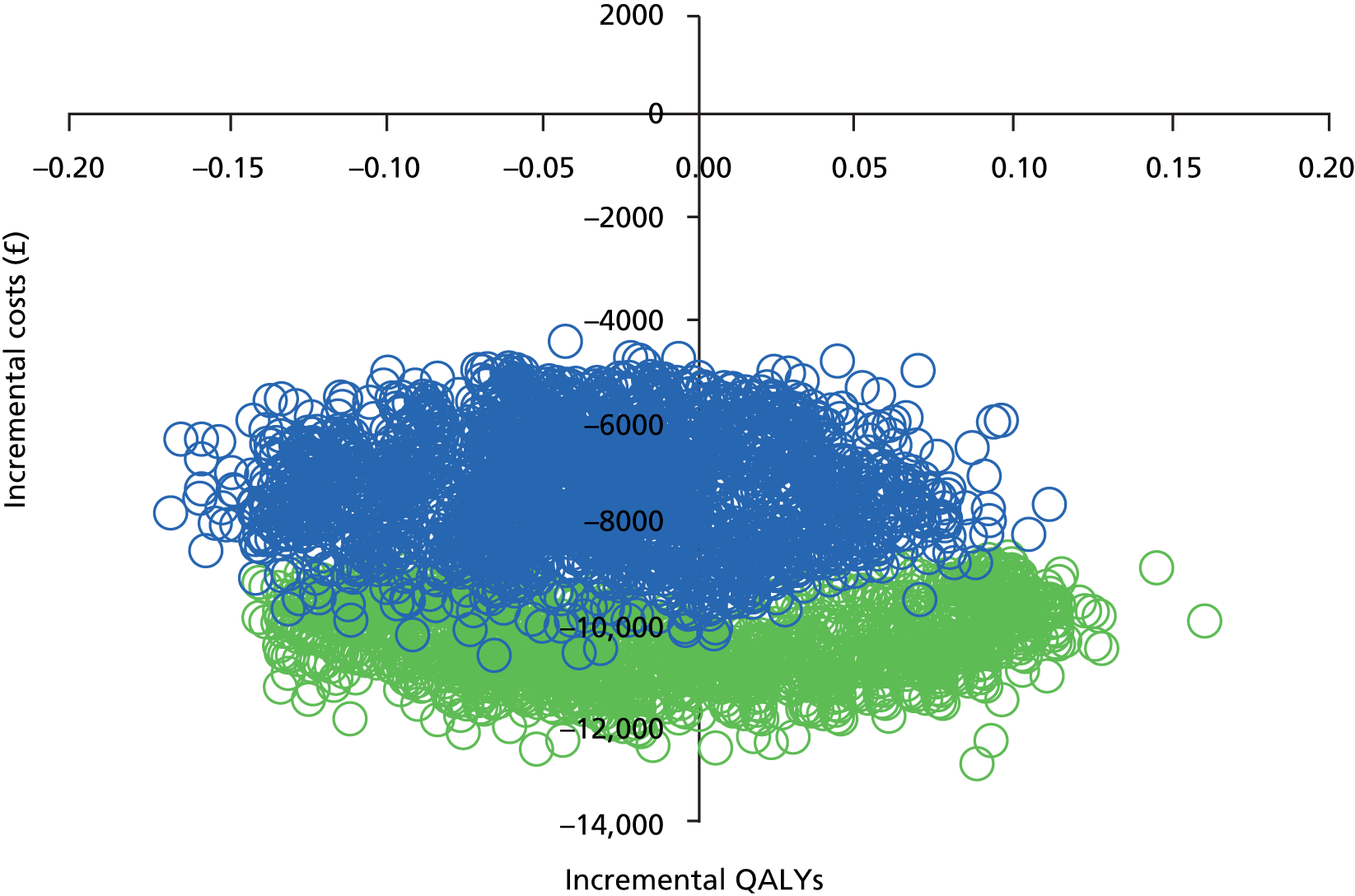

Subgroup analysis

In the PIVOT trial the randomisation of patients was stratified by whether ART treatment before randomisation was a PI-based or a NNRTI regimen. The stratification was carried out to ensure that equal numbers of patients from each stratum were randomised to each of the treatment groups because previous treatment was expected to impact on the success of the PI-mono strategy. This expected heterogeneity in treatment success is also likely to impact on costs and QALYs. Therefore, an exploratory subgroup analysis was conducted to investigate whether previous treatment regimen could be identified as a source of heterogeneity. 88 The subgroup analysis was performed by adding the previous regimen (PI based or NNRTI based) as a covariate and adding an interaction term between allocated treatment group (PI-mono or OT) and previous treatment regimen in regression models for costs and QALYs. As such, the subgroup analysis assumes that the impact of other covariates is independent of previous treatment.

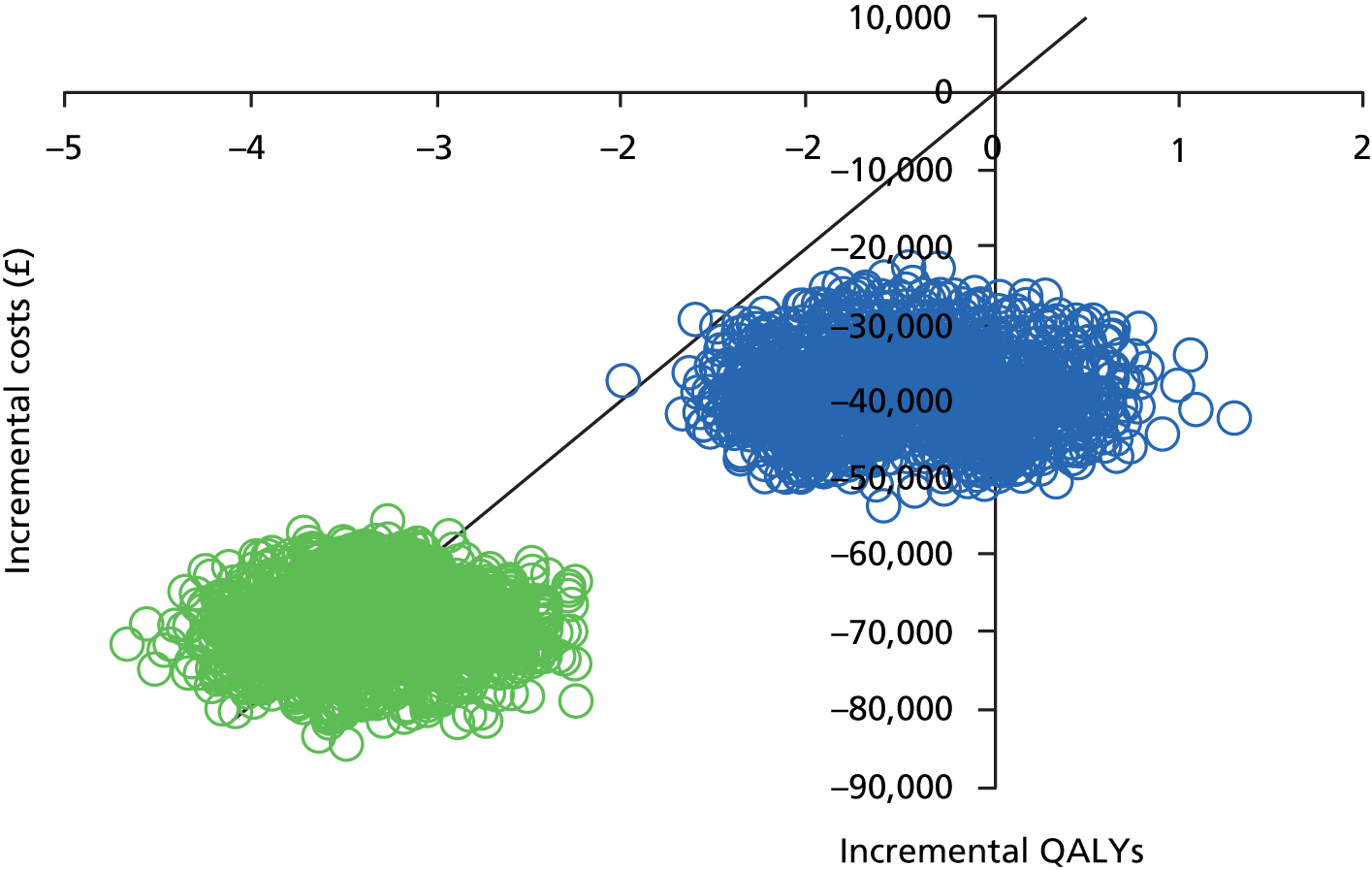

Modelling lifetime costs and quality-adjusted life-years

The validity of the base case within the trial analysis for assessing cost-effectiveness relies on the assumption that no differences in costs or QALYs between the treatment groups persist beyond the trial follow-up period. As this can be considered a strong assumption, exploratory extrapolation was performed to assess the impact of differences persisting beyond the trial period. Two scenarios, A and B, were considered to model the future costs and QALYs by treatment group.