Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/35/06. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The draft report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interest of authors

Phillip J Cowen has, in the last 3 years, been a paid member of an advisory board of Lundbeck. Nick Freemantle has received funding for research and consultancy from a variety of governmental, industrial, and charitable sources. Cormac J Sammon has received funding for research from Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics. Irene Petersen supervises a PhD student who is sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Irwin Nazareth is currently a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment commissioning board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Petersen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background, aims and objectives

Background

Onset of psychoses and psychotropic treatment

The onset of psychoses (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) in women usually occurs within childbearing age and long-term treatment is often required, including a mixture of psychotropic medication such as antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, for example valproate, lamotrigine and carbamazepine (see Table 1 for trade names and manufacturers). 1–6 In 2007 in the UK, women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia aged between 18 and 44 years received antipsychotic treatment for more than 50% of the time they were registered with a general practice. However, antipsychotics are being increasingly prescribed not just for schizophrenia, but also for bipolar disorder and severe depression. 2,7,8 A second UK study revealed that in 2009, 233 out of 682 (34%) women of childbearing age who had bipolar disorder received two or more prescriptions of valproate. 2 Atypical antipsychotics in combination with lithium are also often prescribed to women of this age group. 2,4

Pregnancy and psychotropic treatment dilemma

Although many women treated with psychotropic medication become pregnant or plan pregnancy,9–11 no psychotropic medication has been licenced for use in pregnancy. 12,13 This leaves women and their health-care professionals in a treatment dilemma as they need to balance the health of the women with that of the unborn child. 1,14–16 Advice on treatment varies across countries and in some instances standard psychiatric advice is that women should maintain pharmacological treatment across the perinatal period,17 however, some psychotropic medications are known to have teratogenic and adverse neurodevelopmental effects. 4,12,18 Thus, the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines12 for antenatal and postnatal mental health clearly state that valproate should not be offered for acute or long-term treatment of a mental health problem in women of childbearing potential. Likewise, the guidelines suggest that lithium should not be prescribed to women who are planning a pregnancy or who are pregnant, unless there has been a poor response to antipsychotic medication. 12 The evidence base for adverse effects of other psychotropic medications is sparse. Although antipsychotic drugs are often used in the treatment of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in pregnancy, several reviews conclude that there is a paucity of information on the risks and benefits of pharmacological treatment of psychoses in pregnancy in the absence of large and well-designed prospective studies. 1,14,17,19,20 This is further supported by a Cochrane review from 2004,21 updated in 2009,22 which concluded that no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to establish whether the benefits of taking antipsychotic drugs outweigh the risks for pregnant or postpartum women. Similarly, limited information is available for anticonvulsant mood stabilisers other than valproate,18 even though the prescribing of drugs such as lamotrigine has been on the rise for more than a decade.

In recognition of the lack of evidence on the risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in pregnancy and the difficulties encountered in evaluating this issue using a traditional RCT design, in 2001, the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned research utilising information derived from established databases. The commissioned call was titled ‘What are the risks and benefits of psychotropic drugs in women treated for psychosis who become pregnant?’ (HTA reference number 11/35/06). The ‘health technology’ to be evaluated in this call was psychotropic medications that included antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers prescribed to women with psychosis (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia or overlap syndromes) and whose symptoms are controlled on treatment and who become pregnant. The focus of the investigation was to compare the relative benefits and harms of these different drugs on the mother and the child, when prescribed both during pregnancy and when discontinued.

This project was hence designed in response to this commissioned call. We used data from two large UK clinical databases – The Health Improvement Network (THIN) and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) – to study ‘real-life’ prescribing of psychotropic medication just before, during and after pregnancy and to examine the absolute and relative risks of adverse maternal and child outcomes in women who use psychotropic medication in pregnancy.

Structure of the report

In this chapter of the report we include a description of the overall aim and the specific objectives. Chapter 2 then presents the overall methodology: the data sources, the development of the pregnancy cohorts and the linked mother–child cohorts, the study sample and target populations, and the ‘health technology’ (i.e. the psychotropic medications). This will be followed by the results of five descriptive studies in Chapter 3 with a focus on psychotropic drug utilisation, discontinuation and restarting of treatment. In Chapter 4 we report the results of a series of cohort studies that examine the absolute and relative risks of adverse maternal and child outcomes associated with psychotropic medication that emerged from the analyses of the data, followed by a synthesis and discussion of strength and limitations (see Chapter 5), conclusions and recommendations for future research (see Chapter 6) and a descriptive account of our work with patients and the public (see Chapter 7).

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of the project was to ascertain the risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in women treated for psychosis who become pregnant.

The specific objectives were to:

-

provide a descriptive account of psychotropic medication prescribed before pregnancy, during pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery in UK primary care from 1995 to 2012

-

identify risk factors predictive of discontinuation and restarting of lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilisers and antipsychotic medication

-

examine the extent to which pregnancy is a determinant for discontinuation of psychotropic medication

-

examine prevalence of records suggestive of adverse mental health, deterioration or relapse 18 months before and during the course of pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery

-

estimate absolute and relative risks of adverse maternal and child outcomes of psychotropic treatment in pregnancy.

Chapter 2 Methods

In this chapter we describe the data sources for the project (THIN and the CPRD) and how the pregnancy cohorts and mother–child cohorts were developed. We also describe our study samples and the ‘health technology’ under evaluation, that is, the psychotropic medication.

UK electronic primary care health records

We used data from two electronic health records data sources, THIN and the CPRD (formerly known as the General Practice Research Database). The Department of Primary Care and Population Health at University College London has a licence for full access to all of the THIN data. Hence, we used data from THIN to address four of our five objectives, but for our final objective (i.e. to calculate absolute and relative risks of adverse effects of discontinuation compared with continuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy on maternal and child outcomes) we supplemented our sample of pregnant women and their children in THIN with a sample of pregnant women who have been prescribed psychotropic medication either before and/or during pregnancy and their linked children from the CPRD in order to obtain a larger study sample. Below, we provide a description of the two data sources and information about how the cohorts of pregnant women and the linked mother–child cohort were derived.

The Health Improvement Network primary care database and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The Health Improvement Network and the CPRD are two large primary care databases that provide continuous anonymised longitudinal general practice data on patients’ clinical and prescribing records and include data from > 10% of the UK population, (www.csdmruk.imshealth.com/; www.cprd.com/intro.asp). Both databases collect data from general practices that use Vision computer software (In Practice Systems, London) (www.inps4.co.uk/vision) to manage patient consultations and health records. Diagnoses and symptoms are recorded by practice staff using Read codes, which is a hierarchical coding system including more than 100,000 codes. 23,24 Although the Read code system can be mapped to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), the Read codes also include a number of symptoms and administrative codes. 24 Information on weight, height, smoking habits, alcohol intake and illicit drug problems is also recorded as well as information on antenatal care and birth details, pregnancy outcomes and postnatal care. Prescriptions are issued electronically and directly recorded on the general practice computer systems and thus captured in specific therapy records that hold information on dates of prescription and generic names. Some information is also available on quantity and dosage, although this information is not always complete. In addition, the databases hold individual patient-level information about year of birth (month of birth for individuals < 15 years of age), date of registration, date of death and date of transfer out of the practice. There is also a household identifier, which is the same for individuals who are registered with the same practice and live in the same household. However, some household identifiers include more than one household. This may, for example, be the case where several people live in a block of flats (e.g. flat 2A, flat 2B). In THIN, social deprivation is recorded for each individual by quintiles of Townsend scores, based on information from the 2001 census25 In the CPRD, social deprivation information is available for practices that have signed up to their linkage scheme (www.cprd.com/recordLinkage/), but we did not have access to Townsend scores for this project from the CPRD.

Over 98% of the UK population are registered with a general practitioner (GP) (family doctor)26 and the databases are broadly representative of the UK population. 27,28 However, Blak et al. 27 demonstrated that THIN contains slightly more patients who lived in the most affluent areas (23.5% in THIN vs. 20% nationally). Although antenatal care is often shared between general practice staff and midwives, the GP remains responsible for women’s general medical care during pregnancy, including prescribing of medicines. Some women with psychosis also receive care from local NHS mental health trusts, but most mental health trusts have limited prescribing budgets; therefore, for most women, prescribing of psychotropic medication remains with GPs during pregnancy and hence this information is available in THIN and the CPRD.

Although computerisation of general practices started as early as the late 1980s, few practices used computers initially. It was, however, in the mid-1990s that an increasing number of general practices became fully computerised29 and in this study we utilised data from 1 January 1995, or when general practices met data quality standards. 28–30

Pregnancy cohort and mother–child cohorts

We created a cohort of pregnant women using data from THIN for the period 1 January 1995–31 December 2012. We subsequently linked the pregnant women’s clinical records to those of their children if they were registered with the same general practice. Details on how the cohort was created and the decisions that were made to identify a suitable cohort for further analysis are described below. We also describe how we linked mothers and children, and finally how we identified women receiving psychotropic treatments within these cohorts.

Pregnancy cohort

Our pregnancy cohort was based on the recorded date of delivery of the women, the postnatal care record, the first day of last menstrual periods (LMPs) and the estimated delivery dates (EDDs).

The Health Improvement Network includes records that are made as a part of clinical management in primary care; therefore, some pregnancy and antenatal records may not represent actual pregnancies, but they represent historical information. Furthermore, some pregnancies may result in early terminations (either selective or spontaneous abortions/miscarriages) and in these instances little information is recorded in the electronic health records, making it impossible to determine the start and duration of the pregnancy. We therefore derived a set of rules for the inclusion of pregnancies in our cohort. Every pregnancy was ascertained using two different types of information as follows:

-

LMP date

-

antenatal record

-

delivery record

-

postnatal care record

-

child whose GP record could be matched to the current pregnancy.

Further, we ensured that if we had information only on LMP and antenatal records, the latest antenatal record should be at least 105 days after the first date of the LMP (i.e. equivalent to 15 weeks’ gestation). Only a very small proportion (1%) of the pregnancy cohort was identified from LMP and antenatal records alone.

In total, we identified 495,953 pregnancies in 365,138 women who were permanently registered with one of the general practices that contributed data to THIN in the period between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2012. This cohort was used as the basis for selecting the target population for our examination of psychotropic medication prescribed before pregnancy, during pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery; changes in severity of illness during the course of pregnancy and in the period after delivery; and for assessing the absolute and relative risks of adverse maternal pregnancy outcomes.

Duration of pregnancy

In accordance with clinical practice in the UK, the first day of the LMP was considered as the start of pregnancy. As the clinical records do not always hold direct information about the pregnancy length, we estimated the duration of the pregnancy based on information on gestation and maturity of the fetus and/or baby as entered on the electronic record. For women where there was no information available on length of pregnancy or no indications that suggested a child was born pre or post term, we made the assumption that the pregnancy lasted the normal course of 280 days (40 weeks).

Linked mother–child cohorts

Pregnant women and their potential children were linked if they were both registered with the same general practice and shared the same family/household identifier. Furthermore, the date of delivery and the child’s month of birth were required to be near to each other (within 6 months) and the child should have been registered with the general practice within 6 months of birth.

We excluded mother–child pairs when several possible mothers could be linked to a child (< 0.2%). This could have occurred if two women from a block of flats (who would have shared the same household/family identifier) were pregnant at the same time. In cases where the child was registered with another general practice, linkage with the mother was not possible. This was also not done in instances where the mother and child moved to a different practice shortly after the birth of the child. We also excluded pregnancies from the mother–child cohort where there were two or more children associated with the same delivery.

We first identified mother–child pairs in THIN. They were combined with records from the CPRD and together used as the target populations to examine the absolute and relative risks of adverse effects of discontinuation compared with continuation of psychotropic medication on child outcomes.

Combining records from The Health Improvement Network and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

Inspired by previous research that utilised data from both THIN and the CPRD and demonstrated that combining clinical records from these two databases is feasible,31 we combined our cohorts derived from THIN with data from the CPRD, including pregnant women who have been prescribed psychotropic medication before and/or during pregnancy as well as a cohort of linked mother–child pairs.

We provide a brief description on how we combined the data from THIN and the CPRD, and the process used to remove records that were duplicated from those practices that contributed to both databases.

Although THIN and the CPRD receive raw data from general practices that use the Vision clinical software system, the two databases are structured in slightly different ways. The CPRD data were first reformatted such that the data structure was similar to that of THIN. We then derived a matching algorithm between the two databases based on patient registration data, medical records and patient demographics. As the two databases overlap at practice level, practices deemed to have a sufficient number of matching individuals were taken to be the same practice. THIN records for such practices were excluded and the CPRD records maintained for further analysis. Further details are provided in Appendix 1.

Study sample and target population

The target population for this project was women with psychosis (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or overlap syndromes) who are in receipt of antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, and who became pregnant. Some women receive psychotropic medication prior to formal diagnoses and others may never have a diagnosis of psychosis recorded in their electronic primary care health records. For antipsychotics and lithium, we therefore opted for the most sensitive approach and included all women who were treated with these medications prior to pregnancy in our studies, irrespective of whether or not they had a record of psychosis in their electronic health records. On the other hand, anticonvulsant mood stabilisers are prescribed for various indications. We therefore identified all women prescribed an anticonvulsant mood stabiliser, but for some analyses then limited our analyses to those with a history of psychosis (including bipolar disorder) or a recent record of depression (in the 3 years prior to the start of pregnancy).

Psychotropic medication

The ‘health technology’ under investigation in this project was (1) antipsychotics (atypical and typical); (2) lithium; or (3) anticonvulsant mood stabilisers. Table 1 provides a list of the generic names of each of the treatments.

| Antipsychotics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical | Atypical | Lithium | Anticonvulsant mood stabilisers |

| Asenapine (Sycrest®, Lundbeck) | Amisulpride (Solian®, Sanofi Synthelabo) | Lithium Camcolit®, Norgine; Li-Liquid®, Rosemont; Liskonum®, GSK; Litarex®, Dumex; Lithonate®, Approve Prescription Services; Phasal®, Lagap; Priadel®, Sanofi) | Carbamazepine (Arbil®, Ranbaxy; Carbagen®, Generics; Epimaz®, Ivax; Tegretol®, Novartis; Teril®; Timonil®, CP Pharmaceuticals) |

| Benperidol (Anquil®, Archimedes; Benquil®, Concord) | Aripiprazole (Abilify®, Otsuka) | Lamotrigine (Lamictal®, GSK) | |

| Chlorpromazine (Chloractil®, DDSA Pharmaceuticals; Largactil®, Sanofi-Aventis) | Clozapine (Clozaril®, Novartis; Denzapine®, Merz; Zaponex®, Ivax) | Sodium valproate (Epilim®, Sanofi-Aventis; Epilim Chrono®, Sanofi-Aventis; Episenta®, Desitin; Orlept®, Wockhardt) | |

| Chlorprothixene | Olanzapine (Zypadhera®, Lilly; Zyprexa®, Lilly) | Valproic acid (Convulex®, Pharmacia; Depakote®, Sanofi Synthelabo) | |

| Droperidol (Thalamonal®, Janssen; Droleptan®, Janssen-Cilag; Xomolix®, ProStrakan) | Paliperidone (Invega®, Janssen-Cilag; Xeplion®, Janssen) | Valproate semisodium (Convulex®, Pharmacia; Depakote®, Sanofi Synthelabo) | |

| Flupentixol (Depixol®, Lundbeck; Fluanxol®, Lundbeck) | Quetiapine (Atrolak®, Accord; Biquelle®, Aspire; Ebesque®, Ashbourne; Mintreleq®, CEB Pharma Ltd; Seotiapim®, Sandoz; Seroqul®, AstraZeneca; Sondate®, Teva; Zaluron®, Fontus) | ||

| Fluphenazine (Decazate®, Berk; Modecate®, Sanofi Synthelabo; Moditen®, Sanofi-Aventis; Motipress®, Sanofi Synthelabo; Motival®, Sanofi-Aventis) | Risperidone (Risperdal®, Janssen-Cilag) | ||

| Fluspirilene (Redeptin®, Fluspirilene) | |||

| Haloperidol (Dozic®, Rosemont; Fortunan®, Steinhard; Haldol®, Janssen-Cilag; Serenace®, Ivax) | |||

| Levomepromazine (Levinan®, Link; Nozinan®, Sanofi-Aventis) | |||

| Loxapine (Loxapac®, Wyeth) | |||

| Oxypertine (Integrin®, Sterling Winthrop) | |||

| Pericyazine (Neulactil®, JHC Healthcare) | |||

| Perphenazine (Fentazin®, Goldshield; Triptafen®, AMCo) | |||

| Pimozide (Orap®, Eumedica) | |||

| Pipotiazine (Piportil®, JHC Healthcare) | |||

| Promazine (Sparine®, Genus) | |||

| Remoxipride (Roxima®, AstraZeneca) | |||

| Sertindole (Serdolect®, Lundbeck) | |||

| Sulpiride (Dolmatil®, Sanofi-Aventis; Sulparex®, BMS; Sulpitil®, Pfizer; Sulpor®, Rosemont) | |||

| Thiopropazate | |||

| Thioproperazine | |||

| Thioridazine (Melleril®, Novartis; Rideril®, DDSA Pharmaceuticals) | |||

| Trifluoperazine (Stelazine®, Goldshield) | |||

| Trifluperidol (Triperidol®, Lagap) | |||

| Zotepine (Zolpetil®, Movianto) | |||

| Zuclopenthixol (Clopixol®, Lundbeck) | |||

We used all antipsychotics listed in the British National Formulary (BNF)32 chapter 4.2.1, except prochlorperazine, which is primarily prescribed for morning sickness in pregnancy (nausea gravidarum, emesis gravidarum). For anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, we focused on the three most commonly prescribed anticonvulsant mood stabilisers;33 lamotrigine, carbamazepine and valproate (sodium valproate, valproic acid and valproate semisodium) listed in the BNF chapter 4.8. For lithium, we included lithium carbonate and lithium citrate listed in the BNF chapter 4.2.3.

Data analysis and statistical software

Data analysis conducted for each study is described in further detail in Chapters 3 and 4. Stata (version 13.1) (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all data management and analysis.

Ethics and scientific approvals

The scheme for THIN to obtain and provide anonymous patient data to researchers was approved by the NHS South-East Multicenter Research Ethics Committee in 2002. The CPRD has been granted Multiple Research Ethics Committee approval (05/MRE04/87) to undertake purely observational studies, with external data linkages, including Hospital Episode Statistics and Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data. The work of the CPRD is also covered by the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care – Ethics and Confidentiality Committee approval Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (a) 2012. Scientific approval for use of THIN data for this study was obtained from Cegedim Strategic Data Medical Research’s Scientific Review Committee (protocol number 13–059) and scientific approval for use of CPRD data was obtained from Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol number 14_087R).

Chapter 3 Psychotropic medication prescribed before pregnancy, during pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery

Introduction

In order to understand the risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in pregnancy, it is important to also have an overview of the utilisation of these medications before and during pregnancy. This has been the subject of a number of recent studies conducted in Europe and North America. 34–41 Epstein et al. 39 examined use of psychotropic medication using data from Tennessee Medicaid to conduct a retrospective cohort study of nearly 300,000 women enrolled in the database throughout pregnancy from 1985 to 2005. This study reported significant increases in the use of anticonvulsants among mothers with pain and other psychiatric disorders, but a decrease in the use of lithium and typical antipsychotics. 39 Two studies37,40 based on pharmacy dispensing data from the USA estimated the prevalence of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers and antipsychotics dispensed during pregnancy over the period 2001–7 from 11 US health plans participating in the Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Risk Evaluation Program involving 585,615 deliveries. One study37 reported a sharp increase in the use of atypical antipsychotics from 0.33% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29% to 0.37%)] in 2001 to 0.82% (95% CI 0.76% to 0.88%) in 2007, while the use of typical antipsychotics remained stable. The other study40 estimated that in 2001 there were 15.7 women receiving anticonvulsant mood stabilisers per 1000 deliveries in the USA, increasing to 21.9 per 1000 deliveries in 2007. A more recent study34 based on data from THIN demonstrated that for anticonvulsant mood stabilisers the overall prevalence of prescribing in pregnancy has remained at the same level, between 0.4% and 0.6% between 1994 and 2009; however, the prevalence of prescribing of individual types of anticonvulsants has changed over time with lamotrigine becoming increasingly common. 34

A study based on one of the UK primary care databases, the CPRD, including records from 1989 to 2010, found that among 420,000 pregnancies, treatment with antipsychotics (excluding prochlorperazine) followed a u-shaped pattern, with 0.15% of all women having a prescription in the 3 months before pregnancy, a decline during pregnancy (0.07–0.08% in the second and the third trimester) and an increase in the first 3 months after delivery, to 0.15%. 36 A dramatic decline in the dispensing of antipsychotics in the second and third trimester was also observed in the American dispensing data. 37 UK data suggest that the rate of discontinuation of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers depends on whether or not the woman has a record of epilepsy or bipolar disorder. 34 Thus, women with bipolar disorder were much more likely to discontinue treatment than women with epilepsy, although the medications were the same. 34 Petersen et al. 35 studied discontinuation of antidepressants in pregnancy and found that only 1060 (20%) out of 5229 women who were on antidepressant treatment 3 months before they became pregnant received further treatment after the first 6 weeks of their pregnancy (when the woman is likely to become aware of her pregnancy).

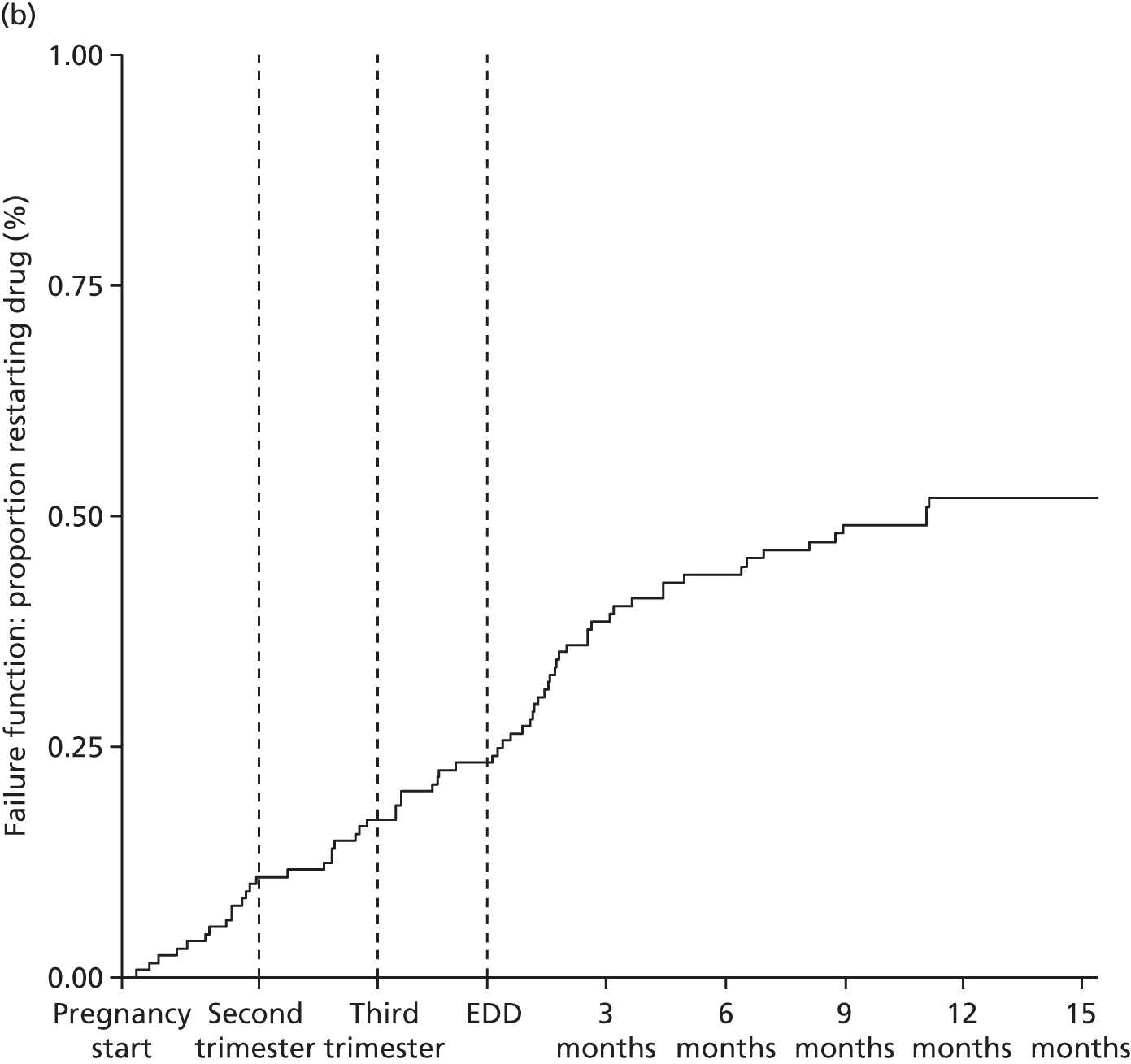

Limited information is available on the proportion of women who discontinued psychotropic medication just before or during pregnancy and who then restarted medication in either the course of being pregnant or in the post-partum period. However, studies on antidepressants indicate that reintroduction of antidepressant treatment in pregnancy is common. Cohen et al. 42 followed 54 non-depressed pregnant women who had discontinued antidepressant treatment around the time of conception. Of these women, 23 (42%) restarted antidepressant therapy during pregnancy, with nearly half of them (n = 11) doing so in the first trimester. Another study followed 70 women who discontinued antidepressants, and of these, 40 (57%) restarted treatment, almost half in the first trimester of pregnancy. 43 The major determinant of treatment reintroduction was relapse of the disorder, as noted from women who scored higher on depression and anxiety measures in cases where treatment was reintroduced. 39 Lithium and other mood stabilisers may on the other hand be introduced for preventative measures rather than to treat relapse. In fact, NICE guidance12 recommends that lithium may be stopped in early pregnancy, but reintroduced in the third trimester in the case of women at high risks of relapse.

Methods

Studies

We conducted five studies to evaluate utilisation and recording of mental health in primary care; these were (1) the prevalence, initiation and termination of prescribing of psychotropic medication at 6 months before pregnancy, during pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery; (2) the patterns of recording that indicate worsening of mental health at 18 months before pregnancy, during the course of pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery; (3) the time trends in prescribing of psychotropic medication around and during pregnancy over the calendar period 1995–2012; (4) the extent of discontinuation and factors associated with discontinuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy; and (5) the extent of restarting and factors associated with restarting psychotropic medication in pregnancy. Below we provide further details on each study in turn.

Study participants

We used data from women in the pregnancy cohort derived from THIN. As a minimum inclusion criterion, we required that women were registered with the practice throughout their pregnancy. For each of the individual studies, we introduced further inclusion criteria, detailed in the analysis section.

For the studies on discontinuation and restarting psychotropic medication, we randomly selected one pregnancy from the women who had records of more than one eligible pregnancy (antipsychotics, n = 19; lithium, n = 1; and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, n = 2). Pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or termination were excluded from all four studies as it was impossible to determine the start and end dates of these pregnancies.

Psychotropic medication, prescription intervals and dose

Most psychotropic prescribing occurred over monthly intervals. For > 98% of women prescribed antipsychotics in the year prior to pregnancy, the median gap between prescriptions was < 3 months (91 days) and similar patterns were observed for other psychotropic medication. We considered a new episode of treatment if a woman had not received psychotropic medication prescriptions in the past 3 months (91 days). Likewise, if a woman received no further prescriptions after 3 months, she was deemed to have discontinued an episode of treatment. The date of initiation was considered as the date the first prescription was issued for that episode. The date of termination was considered as the date of the last prescription issued in the episode.

For antipsychotics we also calculated the average daily dose during the period from 4–6 months before the start of pregnancy by dividing the total amount of drugs prescribed over the period by the expected total duration of the relevant prescriptions. Durations were estimated with the help of the enhanced dosage determination method developed by the University of Nottingham Division of Epidemiology and Public Health (further details can be obtained from the data providers of THIN, IMS Health). The mass of each antipsychotic drug was standardised into units of the defined daily dose (DDD) for maintenance treatment of psychosis. 44

Prevalence, initiation and termination of psychotropic treatment: study participants, outcomes and data analysis

Study participants

We included women from the pregnancy cohort who registered with their general practice in the relevant time periods.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were (1) prevalence of prescribing before pregnancy (6 months before), during pregnancy and after delivery [up to 15 months after delivery (approximately 24 months after conception)]; and (2) proportions of individuals who initiated, terminated or received isolated psychotropic prescriptions before and during pregnancy, and after delivery.

Data analysis

Prevalence

We provided estimates of the prevalence for each 3-month period (trimester in pregnancy) from 6 months prior to pregnancy to 15 months after delivery. Prevalence was estimated for each class of psychotropic medication as the number of women who received a prescription in the relevant time period (numerator), divided by the number of women in the cohort in the relevant time period (denominator). Women were included in the denominator for the prevalence estimates if they were registered with a practice for at least 1 day during the relevant period.

For antipsychotics and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers we further stratified the analyses according to treatment prescribed. For antipsychotics we stratified by typical and atypical antipsychotics, and for anticonvulsant mood stabilisers we stratified the analysis by lamotrigine, valproates and carbamazepine. We estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) for each 3-month period using the period from 1 to 3 months before pregnancy as a reference.

Multiple psychotropic medications

In order to gain a better understanding of drugs prescribed from the BNF chapter on the central nervous system, we explored prescription of multiple classes of drugs from antipsychotics (BNF chapter 4.2.1 and 4.2.2), lithium and anticonvulsants (BNF chapter 4.8.1), as well as antidepressants (BNF chapter 4.3), anxiolytics (BNF chapter 4.1.2) and hypnotics (BNF chapter 4.1.1). We estimated the number of women who were in receipt of more than one psychotropic medication in the 4–6 months before pregnancy.

Start and end of prescribing episodes and isolated prescriptions

For each 3-month period (trimester in pregnancy) we also estimated the number of individuals who started or ended a prescribing episode and the number of individuals who received an isolated prescription (no preceding or subsequent prescriptions within 91 days).

Patterns of recording that indicate worsening of mental health: 18 months before pregnancy, during the course of pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery

Study participants

We included women from the pregnancy cohort who registered with their general practice in the relevant time periods.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were records of suicide attempts, overdose and deliberate self-harm, hospital admissions, invoking under the Mental Health Act45 and entries of Read codes for psychosis, mania and hypomania. We combined the codes into three sets of outcomes: (1) suicide attempts, overdose or deliberate self-harm; (2) hospital admissions or examination under section under Mental Health Act; and (3) entries of psychosis, mania or hypomania.

Further details regarding the definition of outcomes and Read codes are provided in Appendix 1.

Data analysis

We provided estimates of the prevalence for each outcome group for each 3-month period (trimester in pregnancy) from 18 months prior to pregnancy to 15 months after delivery. Prevalence estimates were made for each of the three sets of outcomes by dividing the number of women who had a relevant record(s) (numerator) by the number of women who were registered with their general practice and thus in the cohort in the relevant time period (denominator). Women were included in the denominator for the prevalence estimates if they were registered with a practice for at least 1 day during the relevant period. They were included in the numerator if they had a least one Read code within the relevant record group. Some women may have contributed to several record groups.

The prevalence for each record group was plotted against time in relation to the pregnancy. We estimated PRs for each 3-month period using the period 1–3 months before pregnancy as a reference.

Time trends in prevalence of psychotropic medication treatment around and during pregnancy

Study participants

We included women from the pregnancy cohort who were registered with their general practice in the relevant time periods.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were annual prevalence of psychotropic treatment in (1) the 6 months before pregnancy; (2) pregnancy after the first 6 weeks of gestation (when the pregnancy is likely to be known); and (3) the first 6 months after delivery. Separate estimates were made for antipsychotics, anticonvulsant mood stabilisers and lithium. We provided the estimates by year of delivery for every 2-year period.

Data analysis

Prevalence was estimated as described in the previous section (see Patterns of recording that indicate worsening of mental health: 18 months before pregnancy, during the course of pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery). Estimates were made separately for the 6 months before pregnancy, during pregnancy (after the first 6 weeks of gestation) and in the first 6 months after delivery.

We accounted for variation in the denominator before and after pregnancy. Hence, for women to be included in the estimates for before pregnancy they had to be registered with their general practice for the 6 months before pregnancy. Likewise, women had to be registered for at least 6 months after pregnancy to be included in the estimates for after delivery.

Discontinuation and factors associated with discontinuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy

Study participants

This study included both a cohort of pregnant women and a comparison cohort of women who were not pregnant but who were prescribed psychotropic drugs, in order to examine the impact of pregnancy on discontinuation of these medications.

We included women from the pregnancy cohort and selected women who:

-

contributed data for at least 6 months before the pregnancy and throughout their pregnancy

-

received continuous psychotropic medication before they became pregnant, that is, women were selected if they received prescriptions between 4 and 6 months (inclusive) before they became pregnant

-

received at least one further prescription in the 3 months before the start of pregnancy.

Thus, we focused on women who received two or more prescriptions of psychotropic medication in the 6 months leading up to pregnancy.

We excluded women with a miscarriage, abortion or delivery in the 6 months prior to the start of their pregnancy since these women’s decisions about whether or not to discontinue medication might have been influenced by their previous pregnancy.

For the comparison cohort, we identified a cohort of twice as many women also in receipt of the relevant psychotropic prescriptions, but who were not pregnant for at least 12 months before and 24 months after a randomly selected index date. We stratified these groups such that the age distribution was similar in the pregnant and non-pregnant samples.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were (1) the time to last consecutive prescription of psychotropic medication in pregnancy; and (2) the factors associated with continuation of prescribed psychotropic medication in pregnant women. These included age, the average daily dosage (for antipsychotics), the length of time that the medication had been prescribed prior to pregnancy, prescription of other psychotropic medication (antidepressants, mood stabilisers or antipsychotics), records of illicit drug or alcohol problems, obesity, parity, social deprivation and ethnicity). While there is no direct measurement of severity of illness, the average daily dosage of antipsychotics and length of time the treatment had been prescribed prior to pregnancy may be indicative of the severity of illness.

Many other factors may impact on the decision to continue or discontinue psychotropic medication in pregnancy. We chose, however, to examine the variables described above, as they were available from primary care electronic health records.

Data analysis

We used Kaplan–Meier plots to examine time to last psychotropic prescription, and performed separate analyses for each class of psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers). We followed pregnant and non-pregnant women who were prescribed any of the three classes of psychotropic medication from 3 months before the pregnancy (or the index date for the non-pregnant women) and identified when they had their last consecutive prescription (identified as < 91 days after the previous prescription). We ended follow-up after 220 days (2 months before delivery). In the case of a premature delivery this was sooner than 220 days with follow-up ending at the time of delivery. Although we defined stopping psychotropic medication as the date of issue of the last prescription, we are aware that some women would have continued taking the drug beyond this point. The data were further stratified for atypical and typical antipsychotics and for different dosages of antipsychotics. In the case of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers the data were stratified by lamotrigine, carbamazepine and valproate and also by indication for prescription (i.e. distinctions were made between those who had an electronic health record of epilepsy, psychosis/depression or none of these).

In the pregnant cohort we examined whether or not continuation of antipsychotic and anticonvulsant mood stabiliser prescribing beyond 6 weeks of pregnancy was associated with the factors listed above using a Poisson regression model. We estimated the univariate relative risk ratios (RRRs) for each of the variables as well as the RRR adjusted for age and average daily dose. For antipsychotics we also examined if women switched between typical and atypical treatments.

For lithium we provided percentages and their CIs, but did not embark on further statistical analyses, as so few women received lithium prescriptions beyond 6 weeks of pregnancy.

Restarting and factors associated with restarting psychotropic medication in pregnancy

Study participants

In this study we began by using the same cohorts of women as used in the studies on discontinuation (see Chapter 3, Discontinuation and factors associated with discontinuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy), that is, women who were treated with psychotropic medication in the 6 months before they became pregnant. We then selected subsets of women who discontinued psychotropic treatments just before they reached 6 weeks of pregnancy.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were (1) time to first new psychotropic prescription; (2) the proportion of women who restarted psychotropic medication by 6 months after delivery; and (3) the factors/characteristics of the women associated with restarting of prescribed psychotropic medication. We included the following factors/characteristics: age, the average daily dosage (for antipsychotics), length of time the psychotropic medication had been prescribed prior to pregnancy and prescription of other psychotropic medication (antidepressants, mood stabilisers or antipsychotics).

Data analysis

We used Kaplan–Meier plots to examine time to renewal of prescribing the psychotropic prescriptions after the start of the pregnancy. Follow-up was censored at the earliest of the following: 15 months after delivery, 31 December 2012 or when the woman left the general practice. We conducted separate analyses for each class of psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers) and with antipsychotics we stratified our analyses for atypical and typical antipsychotics. For anticonvulsant mood stabilisers we performed the analysis for women who had a record of psychoses or depression.

We estimated the proportion with 95% CIs of women who had discontinued medication before 6 weeks of pregnancy and restarted treatment by 6 months after delivery. The characteristics of these women were tabulated and contrasted to women who had not restarted psychotropic medication by 6 months after delivery. For antipsychotics, we estimated the univariate RRRs for each of the variables as well as RRRs adjusted for age and average daily dose. For lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers we did not attempt further analysis, as the numbers were too small to produce meaningful results.

Changes to the protocol

We originally planned to undertake an evaluation of changes in severity of mental illness from the period commencing 18 months before the start of pregnancy up to 15 months after the delivery of the baby. This analysis was deemed infeasible, as it was not possible to ‘grade’ the severity of mental illness in an individual merely from their Read code entries. Instead we decided to explore how the entries varied more generally over this time period by choosing a number of outcomes suggestive of adverse mental health, deterioration or relapse and we then estimated 3-month (trimester in pregnancy) prevalence.

Results

Below we report the results on:

-

prevalence, initiation and termination of psychotropic treatment

-

patterns of recording that indicate worsening of mental health

-

time trends in prevalence of psychotropic treatment around and during pregnancy over the calendar period 1995–2012

-

discontinuation and factors associated with continuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy

-

restarting and factors associated with restarting psychotropic medication in pregnancy.

Prevalence, initiation and terminations of psychotropic treatment: 6 months before pregnancy, during pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery

Overall, 495,953 pregnancies were included in the study from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2012. Below we describe the results of our studies on the prevalence, initiation and termination of psychotropic treatment. Parts of this work have been published elsewhere. 46,47

Prevalence of psychotropic treatment before, during and after delivery

In the 1–3 months before the start of pregnancy 1051 out of 495,624 (0.21%) women were prescribed antipsychotics (Table 2), 78 out of 495,624 (0.015%) were prescribed lithium and 2046 out of 495,624 (0.41%) were prescribed anticonvulsant mood stabilisers (Table 3). Only 165 out of 52,998 (0.31%) of the women prescribed an anticonvulsant drug had a record of psychosis or depression (see Table 3).

| Prescribed antipsychotic | 4–6 months before pregnancy | 1–3 months before pregnancy | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | 1–3 months after delivery | 4–6 months after delivery | 7–9 months after delivery | 10–12 months after delivery | 13–15 months after delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any antipsychotic | 999 | 1051 | 992 | 554 | 509 | 987 | 1157 | 1127 | 1092 | 1065 |

| Any typical | 550 | 594 | 596 | 301 | 258 | 533 | 582 | 558 | 536 | 519 |

| Chlorpromazine | 120 | 134 | 185 | 110 | 81 | 114 | 117 | 109 | 98 | 101 |

| Trifluoperazine | 118 | 111 | 110 | 61 | 50 | 103 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 94 |

| Flupentixol | 112 | 125 | 86 | 28 | 15 | 108 | 123 | 123 | 115 | 130 |

| Promazine | 24 | 26 | 88 | 30 | 41 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 36 | 36 |

| Thioridazine | 96 | 97 | 52 | 20 | 17 | 83 | 114 | 97 | 89 | 77 |

| Haloperidol | 36 | 37 | 36 | 30 | 36 | 59 | 42 | 47 | 39 | 32 |

| Sulpiride | 15 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 33 | 24 | 23 | 17 |

| Pericyazine | 6 | 20 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 11 |

| Zuclopenthixol | 6 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| Fluphenazine | 15 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 17 | 13 | 14 |

| Perphenazine | 11 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 9 | 8 |

| Levomepromazine | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Droperidol | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Loxapine | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trifluperidol | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pimozide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pipotiazine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Paliperidone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Any atypical | 473 | 485 | 427 | 265 | 263 | 485 | 604 | 597 | 579 | 573 |

| Quetiapine | 173 | 200 | 171 | 113 | 112 | 177 | 209 | 211 | 209 | 214 |

| Olanzapine | 154 | 157 | 149 | 101 | 108 | 199 | 243 | 229 | 219 | 207 |

| Risperidone | 90 | 85 | 70 | 30 | 25 | 76 | 107 | 125 | 118 | 111 |

| Aripiprazole | 40 | 45 | 37 | 20 | 18 | 37 | 42 | 35 | 41 | 40 |

| Amisulpride | 21 | 17 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 28 | 19 | 17 | 19 |

| Clozapine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total pregnancies | 476,270 | 495,624 | 495,953 | 495,953 | 493,672 | 495,894 | 473,358 | 456,040 | 439,313 | 423,192 |

| Prescribed drug | 4–6 months before pregnancy | 1–3 months before pregnancy | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | 1–3 months after delivery | 4–6 months after delivery | 7–9 months after delivery | 10–12 months after delivery | 13–15 months after delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | 84 | 78 | 58 | 33 | 37 | 69 | 98 | 110 | 104 | 105 |

| Any of the three ACMS | 1991 | 2046 | 1991 | 1782 | 1741 | 1965 | 1957 | 1922 | 1862 | 1819 |

| Carbamazepine | 830 | 859 | 822 | 706 | 706 | 799 | 780 | 795 | 776 | 749 |

| Lamotrigine | 687 | 727 | 748 | 707 | 696 | 718 | 722 | 687 | 666 | 639 |

| Valproate | 629 | 607 | 556 | 472 | 436 | 562 | 577 | 555 | 545 | 556 |

| Total pregnancies | 476,270 | 495,624 | 495,953 | 495,953 | 493,672 | 495,894 | 473,358 | 456,040 | 439,313 | 423,192 |

| Women with a record of psychosis or depression | ||||||||||

| Any of the three ACMS | 160 | 165 | 135 | 57 | 55 | 121 | 151 | 159 | 149 | 152 |

| Carbamazepine | 77 | 82 | 65 | 23 | 26 | 59 | 61 | 68 | 61 | 53 |

| Valproate | 68 | 66 | 47 | 19 | 17 | 50 | 68 | 66 | 66 | 77 |

| Lamotrigine | 19 | 21 | 24 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 26 | 28 | 26 | 26 |

| Total pregnancies | 51,718 | 52,998 | 53,012 | 53,012 | 52,736 | 53,006 | 50,487 | 48,489 | 46,546 | 44,711 |

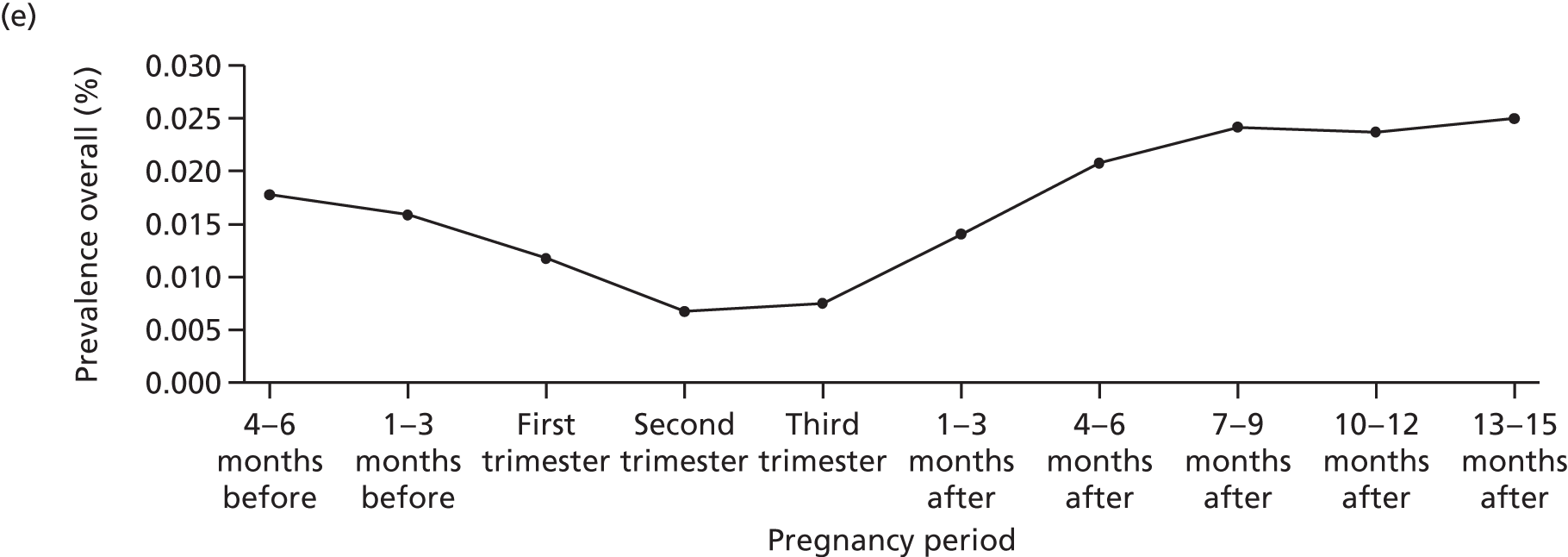

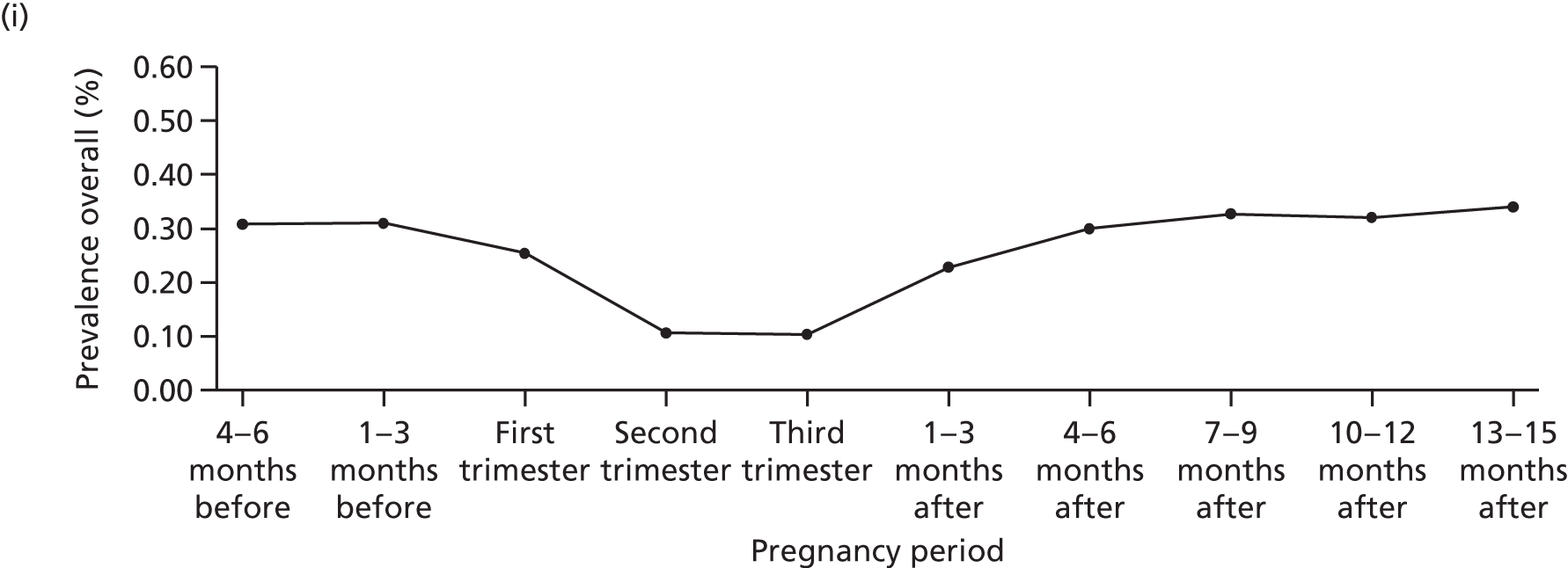

During pregnancy the prevalence of antipsychotics and lithium prescribing fell dramatically. Hence, 554 out of 495,953 (0.11%) were prescribed antipsychotics and 33 out of 495,953 (0.006%) lithium in the second trimester. The corresponding PRs of antipsychotics and lithium prescribing relative to the period from 1–3 months before pregnancy were 0.53 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.58) and 0.42 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.64), respectively (Table 4 and Figure 1). In the case of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers there was only a small decline in the prevalence of prescribing in pregnancy, 1782 out of 495,953 (0.36%) were prescribed in the second trimester and the PR was 0.87 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.93) (see Table 4 and Figure 1). In the case of those prescribed anticonvulsant mood stabilisers who had a record of psychosis or depression the level of prescribing in the second trimester fell dramatically, with 57 out of 53,012 (0.11%) being prescribed an anticonvulsant mood stabiliser in the second trimester. The PR in the second trimester was 0.35 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.47) (see Table 4 and Figure 1).

| Prescribed antipsychotic | 4–6 months before pregnancy | 1–3 months before pregnancy | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | 1–3 months after delivery | 4–6 months after delivery | 7–9 months after delivery | 10–12 months after delivery | 13–15 months after delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any antipsychotic | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | 1 | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.03) | 0.53 (0.47 to 0.58) | 0.49 (0.44 to 0.54) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) | 1.15 (1.06 to 1.25) | 1.17 (1.07 to 1.27) | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.28) | 1.19 (1.09 to 1.29) |

| Any typical | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08) | 1 | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.13) | 0.51 (0.44 to 0.58) | 0.44 (0.38 to 0.51) | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.01) | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.15) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.15) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) |

| Any atypical | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 1 | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.00) | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.64) | 0.54 (0.47 to 0.63) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) | 1.30 (1.16 to 1.47) | 1.34 (1.18 to 1.51) | 1.35 (1.19 to 1.52) | 1.38 (1.22 to 1.56) |

| Lithium | 1.12 (0.81 to 1.55) | 1 | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.06) | 0.42 (0.27 to 0.64) | 0.48 (0.31 to 0.71) | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.24) | 1.32 (0.97 to 1.79) | 1.53 (1.14 to 2.08) | 1.50 (1.11 to 2.04) | 1.58 (1.17 to 2.14) |

| Any of the three ACMS | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 1 | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.91) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) |

| Any of the three ACMS limited to women with SMI or recent depression | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.24) | 1 | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.03) | 0.35 (0.25 to 0.47) | 0.33 (0.24 to 0.46) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.93) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.21) | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.32) | 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | 1.09 (0.87 to 1.37) |

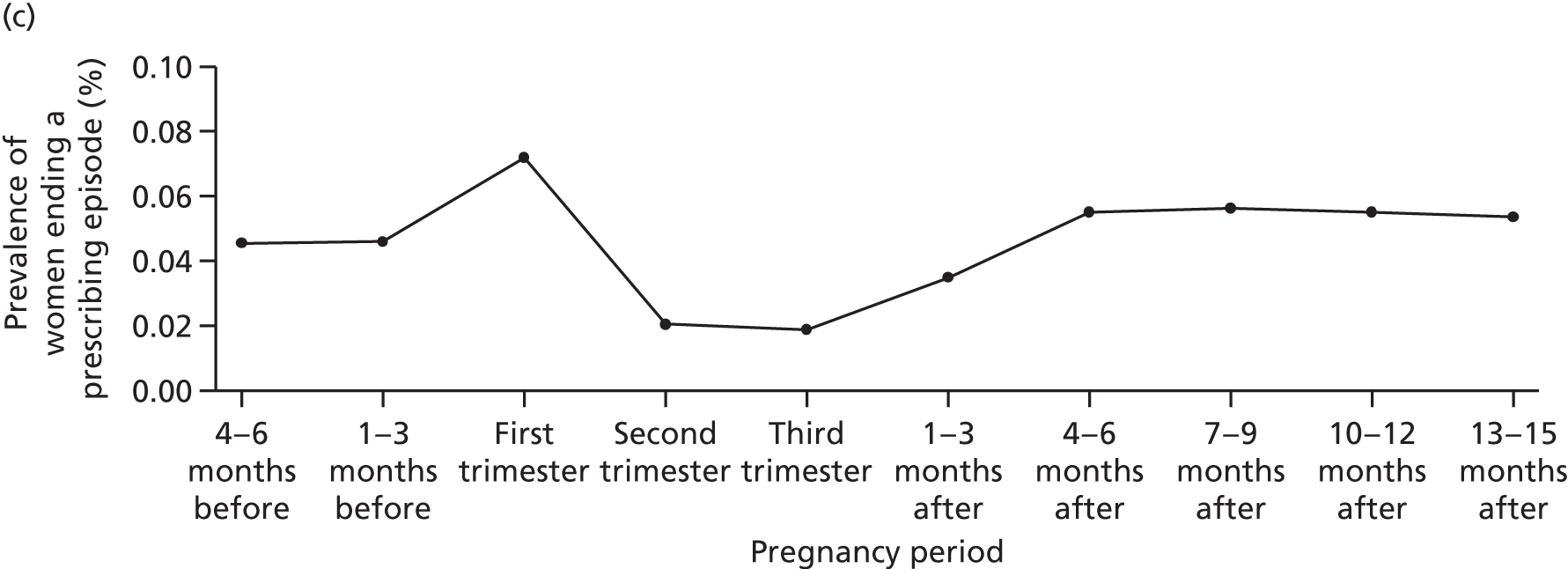

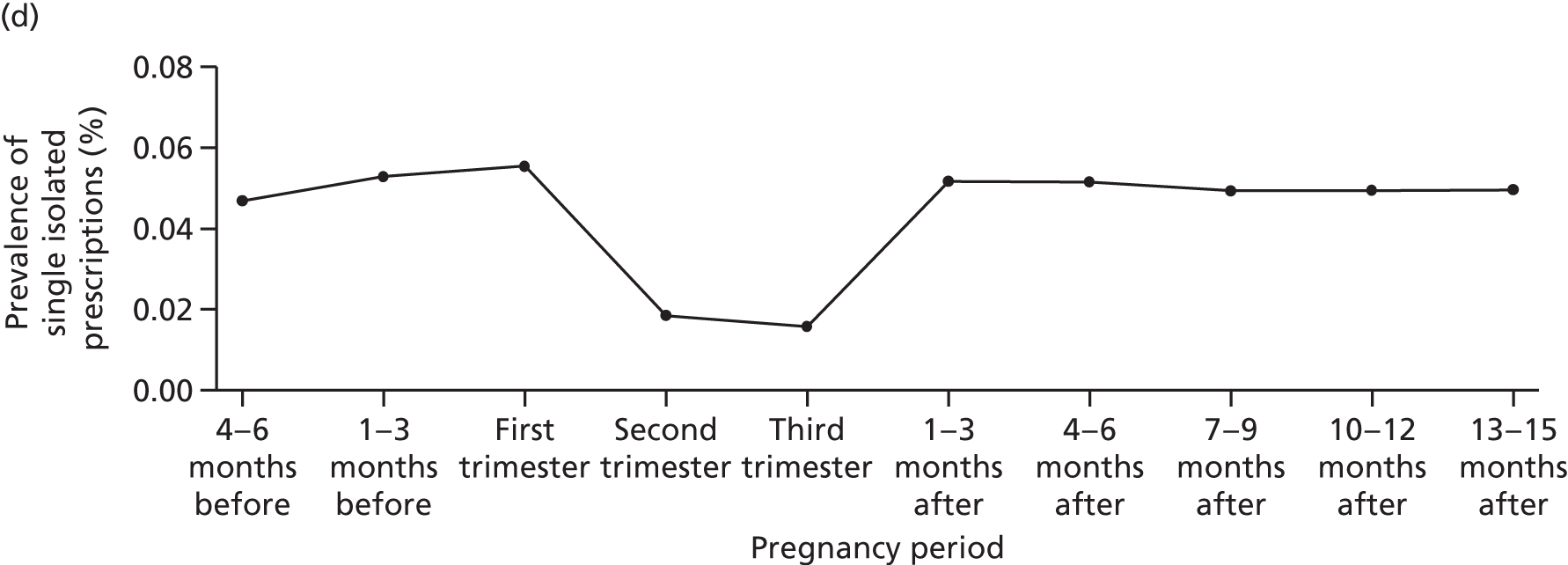

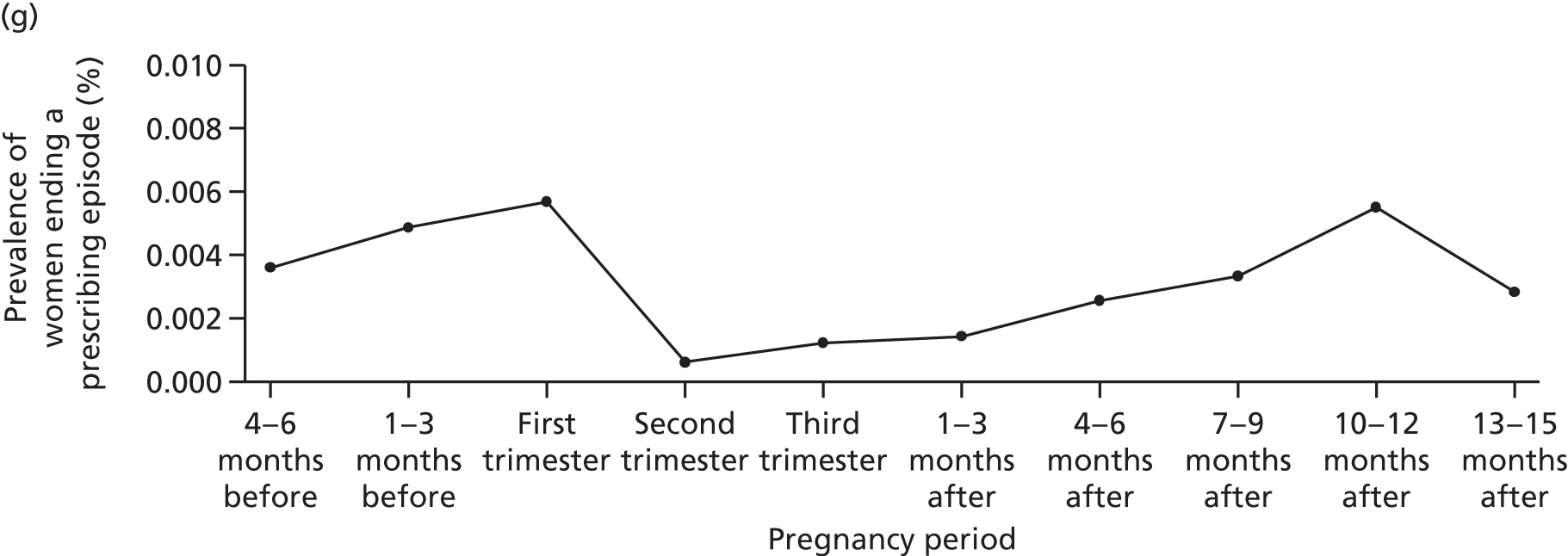

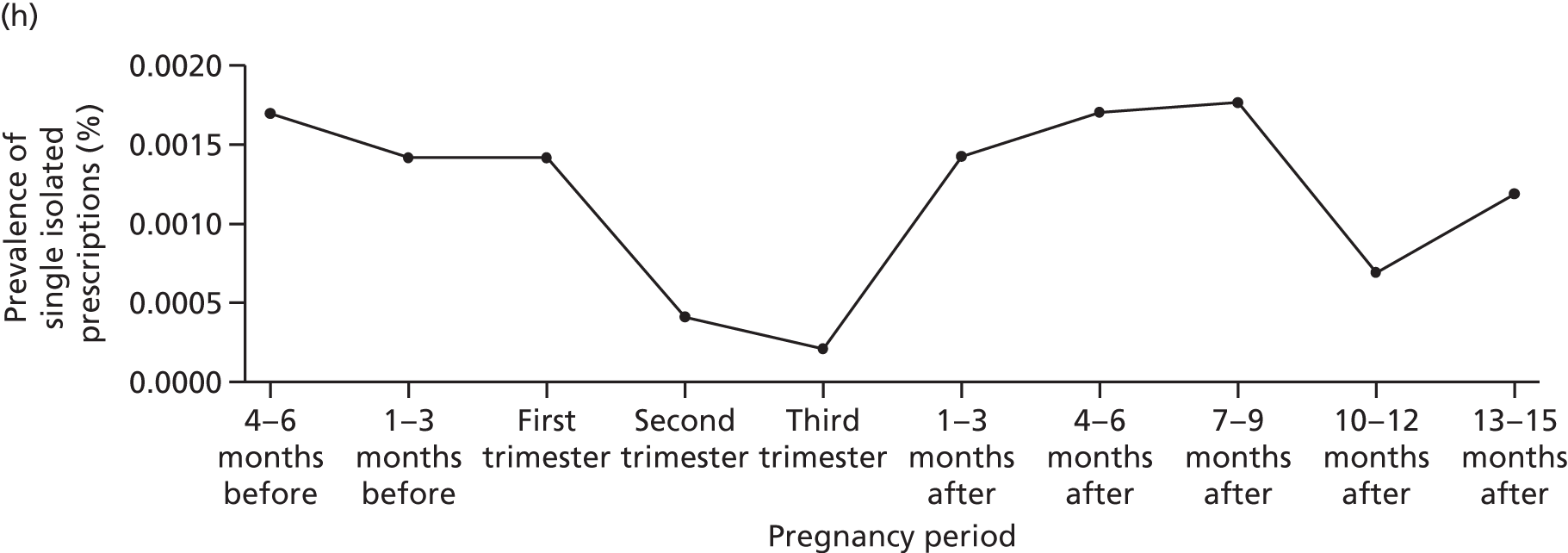

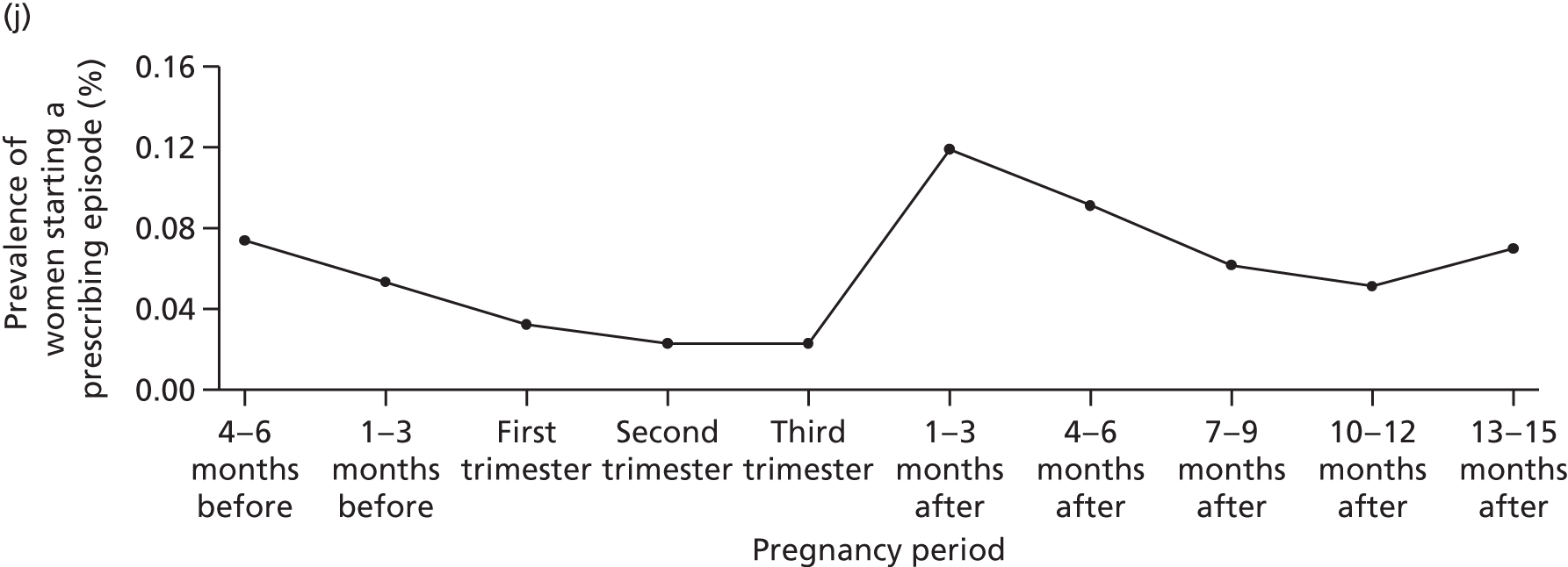

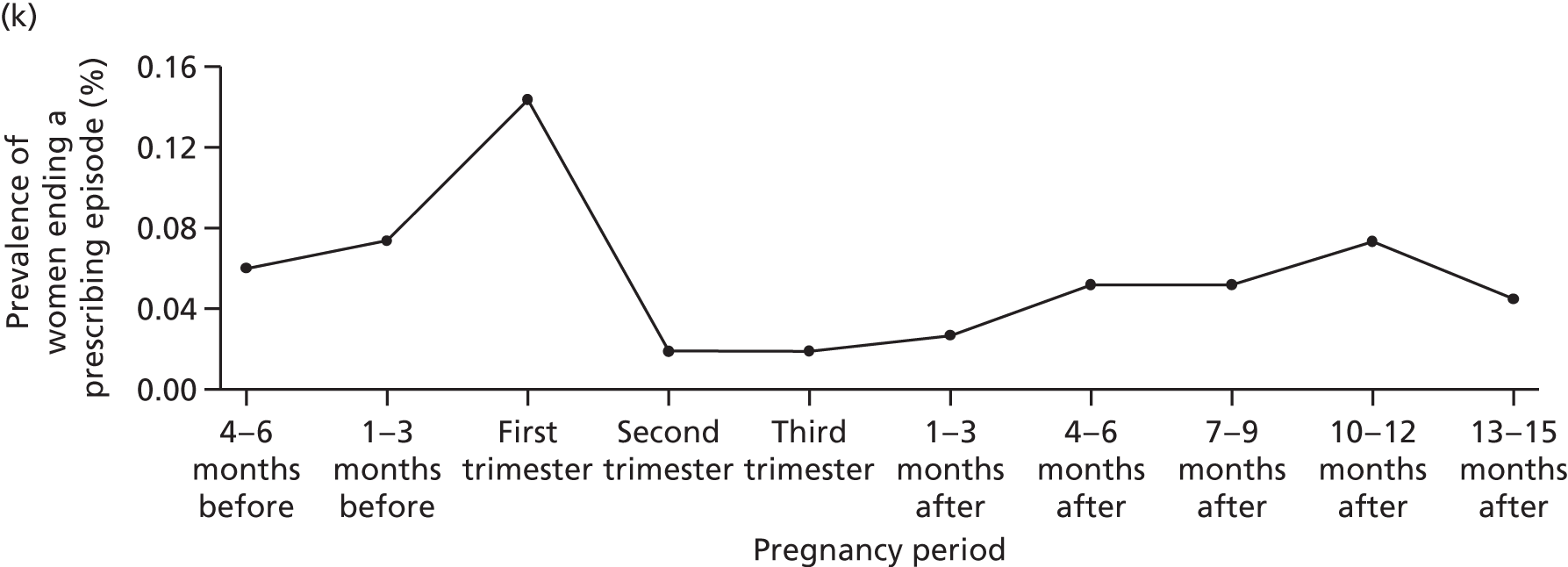

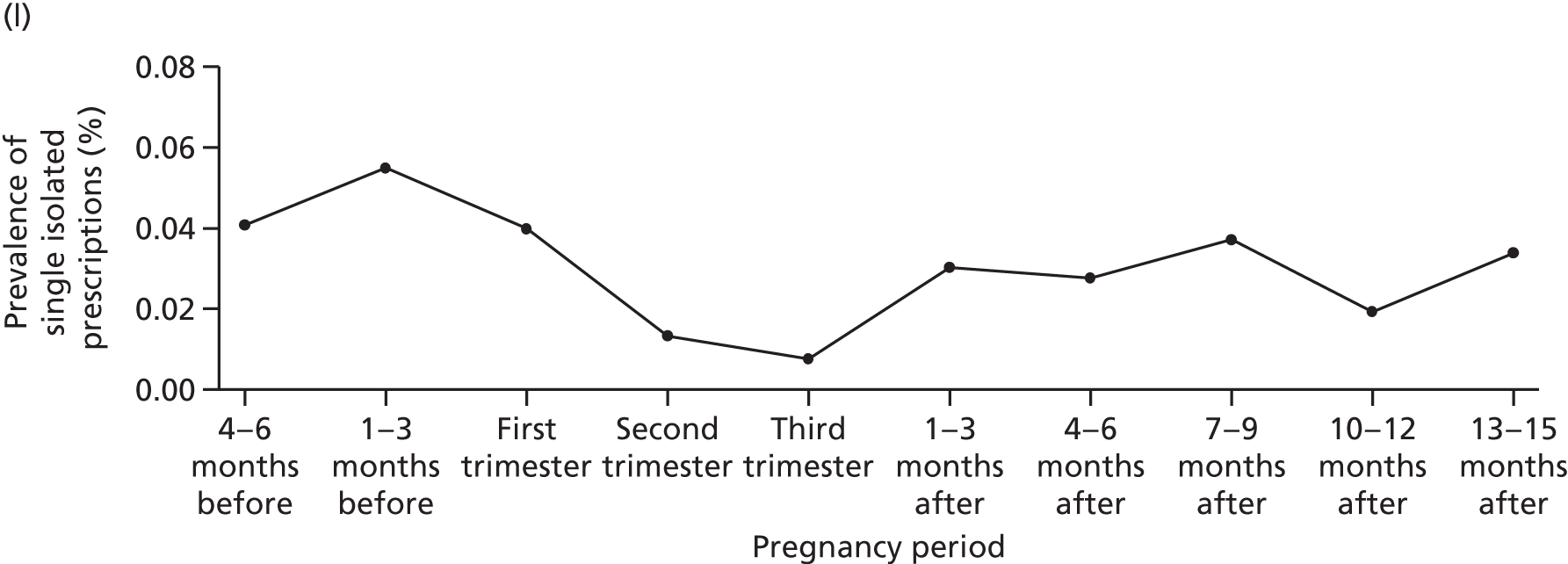

FIGURE 1.

Overall prevalence of antipsychotics (a–d), lithium (e–h) and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers (i–l) (women with a record of psychosis or depression) prescribing in the total pregnancy cohort along with levels of starting and ending a prescribing episode and single prescriptions.

For the period after delivery the prevalence of both antipsychotic and lithium treatment were higher in the period between 4 months and 15 months after delivery than before pregnancy. In the case of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers the prevalence after pregnancy remained similar to that before pregnancy irrespective of whether or not the sample was limited to women with psychoses or depression (see Table 4 and Figure 1). The three most commonly prescribed typical antipsychotics in pregnancy were chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine and flupentixol and for atypical antipsychotics, it was quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone (see Table 2). For anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, carbamazepine was primarily prescribed in pregnancy followed by lamotrigine and valproate (see Table 3), but this has changed over time, see Time trends in prevalence of psychotropic medication treatment around and during pregnancy over the calendar period 1995–2012.

Multiple psychotropic medications

Considering the six relevant classes of drugs [antipsychotics (BNF chapters 4.2.1 and 4.2.2); lithium and anticonvulsants (BNF chapter 4.8.1); antidepressants (BNF chapter 4.3); anxiolytics (BNF chapter 4.1.2) and hypnotics (BNF chapter 4.1.1)], in about 6% (28,305/495,953) of all pregnancies, the women received one class of psychotropic medication in the 4–6 months before they became pregnant, whereas < 1% received prescriptions from two to five classes (Table 5). The most typical combinations were antidepressants and hypnotics [1256 (0.25%)] and antidepressants and anxiolytics [906 (0.18%)]. Antipsychotics and antidepressants were prescribed in combination to 387 individuals, equivalent to 0.08% of the full pregnancy cohort, but to 38% (387/999) of the women prescribed antipsychotics 4–6 months before pregnancy. Anticonvulsant and antidepressants were prescribed to 317 (0.06%) of the full pregnancy cohort (Table 6), but to 16% (317/1991) of those who received anticonvulsant mood stabilisers 4–6 months before pregnancy.

| Number of drug categories | Frequency | Per centa |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 463,950 | 93.55 |

| 1 | 28,305 | 5.71 |

| 2 | 3156 | 0.64 |

| 3 | 456 | 0.09 |

| 4 | 73 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 13 | < 0.01 |

| Combination | Frequency | Per centa |

|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant and hypnotic | 1256 | 0.25 |

| Antidepressant and anxiolytic | 906 | 0.18 |

| Antipsychotic and antidepressant | 387 | 0.08 |

| Anticonvulsant and antidepressant | 317 | 0.06 |

| Antidepressant, anxiolytic and hypnotic | 187 | 0.04 |

| Anxiolytic and hypnotic | 122 | 0.02 |

| Antipsychotic, antidepressant and hypnotic | 80 | 0.02 |

| Antipsychotic, antidepressant and anxiolytic | 53 | 0.01 |

| Anticonvulsant and anxiolytic | 40 | 0.01 |

| Anticonvulsant, antidepressant and anxiolytic | 40 | 0.01 |

| Antipsychotic, antidepressant, anxiolytic and hypnotic | 35 | 0.01 |

| Antipsychotic, anticonvulsant and antidepressant | 34 | 0.01 |

Initiation of psychotropic treatment, termination of psychotropic treatment and isolated psychotropic prescriptions

Although very few women were prescribed a new episode of antipsychotics, lithium or anticonvulsant mood stabilisers immediately before and during pregnancy (see Figure 1), there was a sharp rise in the proportion of women initiating new episodes in the first 6 months after delivery (see Figure 1). In contrast, a large number of women terminated treatments before and during pregnancy. Thus, the highest proportion of women terminating treatments were found in the 1–3 months before pregnancy and during the first pregnancy trimester (see Figure 1).

In general there were few women who received a single isolated prescription of psychotropic medication and there were even fewer women who received such during the second and third pregnancy trimester (see Figure 1).

Patterns of recording that indicate worsening of mental health: 18 months before pregnancy, during the course of pregnancy and up to 15 months after delivery

Overall, 495,953 pregnancies were included in the study from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2012.

Below, we describe the annual prevalence of each of the three sets of outcomes: (1) suicide attempts, overdose or deliberate self-harm; (2) mental health hospital admission or examination in relation to the Mental Health Act;45 and (3) psychosis, mania or hypomania before, during and after delivery over the calendar period 1995–2012.

In general, relatively few women had any entries in their records that suggested deterioration or change of severity of mental illnesses in the period before and during pregnancy as well as after delivery (see Figure 2). The recording of suicide attempts, overdose or deliberate self-harm was relatively constant in the 18 months prior to pregnancy (Figure 2 and Table 7). During pregnancy the prevalence declined and relative to the period of 1–3 months before pregnancy the PR was 0.11 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.14) in the third trimester. It rose after pregnancy, but was still only half of what it was prior to pregnancy (see Table 7). The entries made of mental health hospital admissions or invoking of the Mental Health Act45 more than tripled just after delivery in comparison to the period of 1–3 months before pregnancy (PR 3.16, 95% CI 1.86 to 5.60) (see Table 7). Records of psychosis, mania or hypomania followed similar patterns with a doubling just after delivery in comparison to the 1–3 months before pregnancy (PR 2.02, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.69) (see Table 7).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence recording of (a) suicide attempts, overdose or self-harm; (b) mental health hospital admission; and (c) psychosis, mania or hypomania, from 18 months before the start of pregnancy up to 15 months after delivery.

| Prescribed antipsychotic | 4–6 months before pregnancy | 1–3 months before pregnancy | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | 1–3 months after delivery | 4–6 months after delivery | 7–9 months after delivery | 10–12 months after delivery | 13–15 months after delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide attempt, overdose or deliberate self-harm | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) | 1 | 0.50 (0.44 to 0.57) | 0.19 (0.15 to 0.23) | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.14) | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.36) | 0.43 (0.37 to 0.50) | 0.48 (0.42 to 0.55) | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.57) | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.63) |

| Hospital admissions or MHA examination | 1.53 (0.83 to 2.91) | 1 | 1.26 (0.66 to 2.44) | 0.79 (0.37 to 1.64) | 0.58 (0.25 to 1.28) | 3.16 (1.86 to 5.60) | 1.98 (1.11 to 3.66) | 1.26 (0.65 to 2.46) | 1.60 (0.86 to 3.05) | 1.79 (0.97 to 3.37) |

| Psychosis, mania or hypomania | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.46) | 1 | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.21) | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.79) | 0.53 (0.35 to 0.78) | 2.02 (1.53 to 2.69) | 1.38 (1.02 to 1.88) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.70) | 1.13 (0.81 to 1.56) | 0.74 (0.50 to 1.07) |

Time trends in prevalence of psychotropic medication treatment around and during pregnancy over the calendar period 1995–2012

Overall, 495,953 pregnancies were included in the study from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2012. Below we describe annual prevalence for each of the three classes of psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers) before, during and after delivery over the calendar period 1995–2012. The work on antipsychotics and lithium has been published in part elsewhere. 46,47

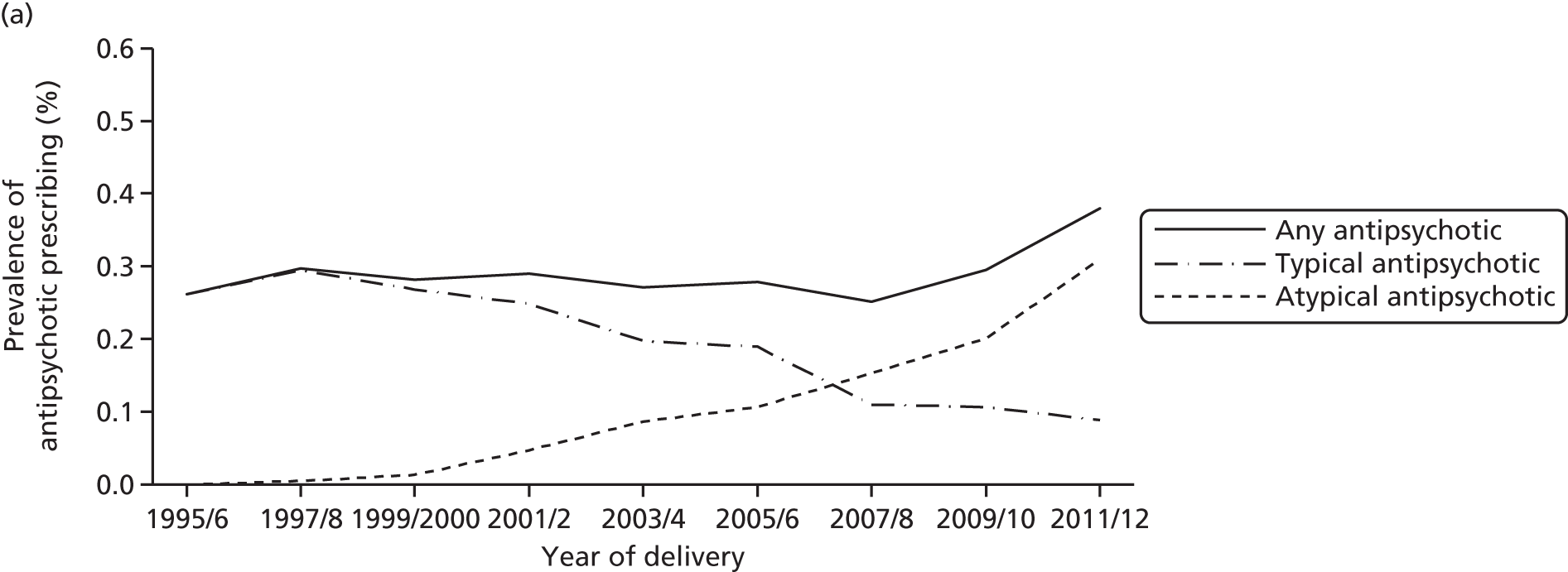

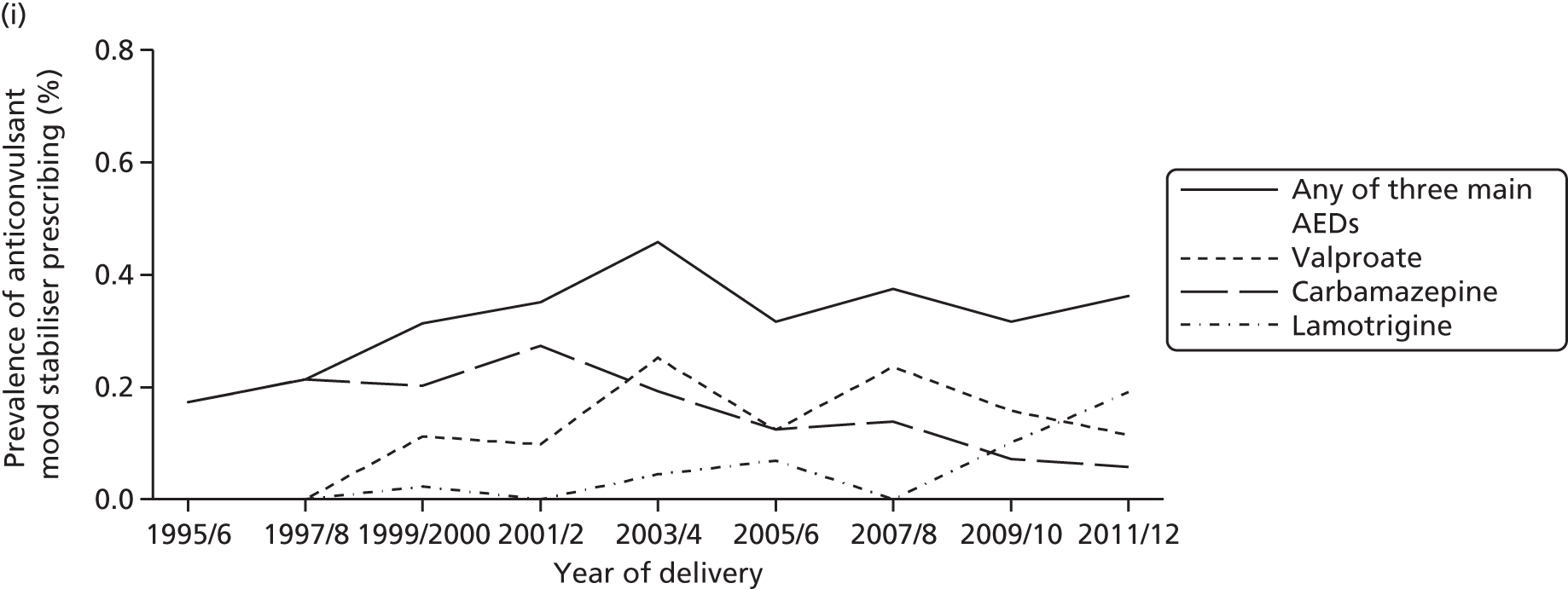

Overall, annual prescribing in the 6 months before pregnancy and during pregnancy of both antipsychotics and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers was relatively stable from 1995 to 2006, but increased from around 2007 (Figure 3). By 2011/12, just under 0.4% were prescribed antipsychotics in the 6 months before pregnancy and just under 0.3% received antipsychotic treatment in pregnancy by 2011/12, suggesting a more than 50% increase since 1995/6. For anticonvulsant mood stabilisers the prevalence figures for women with a record of psychoses or depression for 2011/12 were 0.6% before pregnancy, 0.26% during pregnancy and 0.36% after delivery. Hence the treatment prevalence has almost doubled since 1995/6 (see Figure 3).

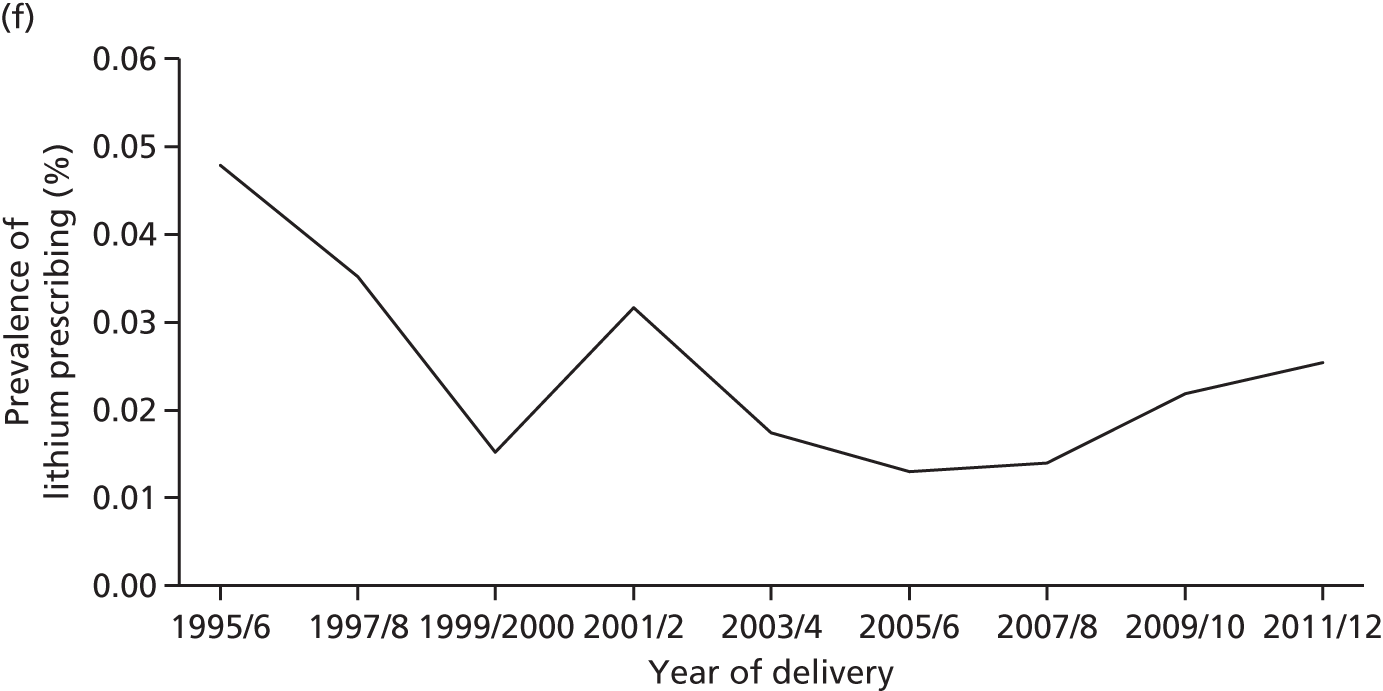

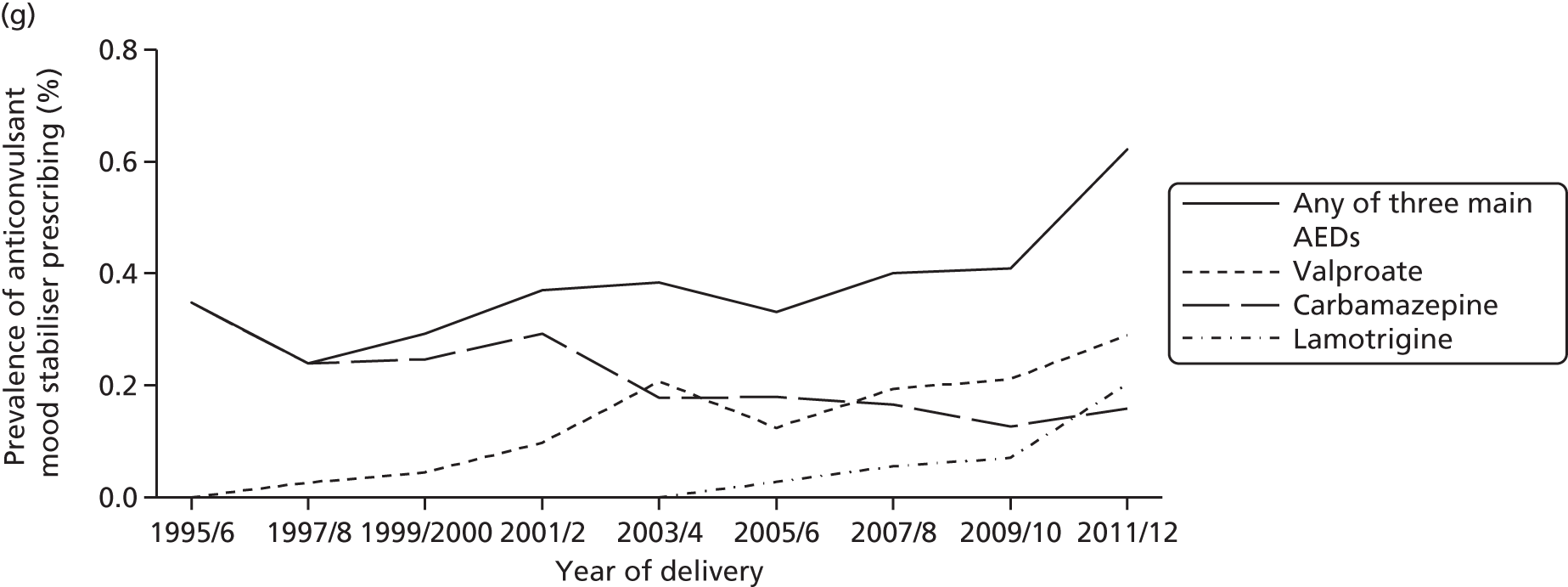

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of prescribing over calendar period 1995–2012. Prescribing of antipsychotics (a) in the 6 months before pregnancy; (b) during pregnancy; (c) 6 months after delivery; lithium (d) in the 6 months before pregnancy; (e) during pregnancy; (f) 6 months after delivery; anticonvulsant mood stabilisers (g) in the 6 months before pregnancy; (h) during pregnancy; and (i) 6 months after delivery.

Prescribing of typical antipsychotics has been declining since 1997/8, whereas prescribing of atypical antipsychotics has been increasing. Thus, atypical antipsychotics were more commonly prescribed before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after delivery after 2007/8 (see Figure 3). For anticonvulsant mood stabilisers, prescribing of carbamazepine has declined, whereas both valproate and lamotrigine have gradually increased before pregnancy (see Figure 3). By 2011/12, carbamazepine was superseded by lamotrigine before, during and after pregnancy and valproate was the most commonly prescribed anticonvulsant mood stabiliser before pregnancy (see Figure 3).

Lithium was rarely prescribed; before pregnancy the annual prevalence of lithium prescribing ranged between 0.01% and 0.03%, and during pregnancy between 0.003% and 0.018%. The annual prevalence in the 6 months after delivery declined from 0.048% in 1995/6 to 0.015 in 1999/2000 (see Figure 3).

Discontinuation and factors associated with continuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy

We identified 207 women receiving typical antipsychotics, 279 receiving atypical antipsychotics, 52 receiving lithium and 93 with a record of psychoses or depression receiving anticonvulsant mood stabilisers in the 4–6 months before the start of their pregnancy.

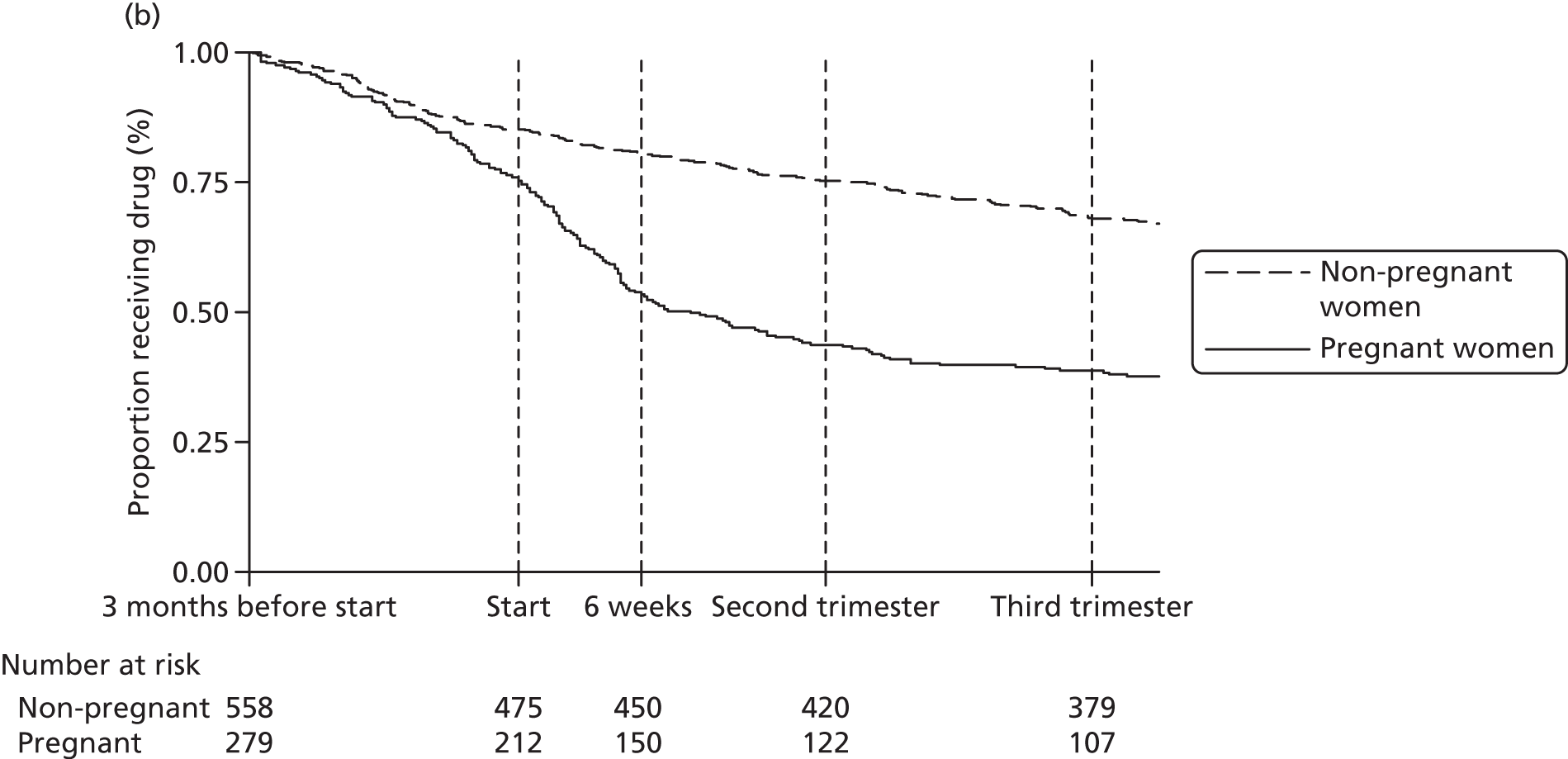

Although many women discontinued psychotropic medication either before or early in pregnancy the proportion varied between psychotropic treatments. Women prescribed atypical antipsychotics were least likely to discontinue treatment in pregnancy and 150 out of 279 (54%) received further prescriptions after 6 weeks of pregnancy (when the woman is likely to become aware of the pregnancy). In contrast, only 73 out of 207 (35%) women received further prescriptions of typical antipsychotics, 17 out of 52 (33%) lithium and 34 out of 93 (37%) anticonvulsant mood stabilisers after 6 weeks of pregnancy. By the start of the third trimester the figures were 107 out of 279 (38%) for atypical antipsychotics, 39 out of 207 (19%) for typical antipsychotics, 14 out of 52 (27%) for lithium and 13 out of 93 (14%) for anticonvulsant mood stabilisers.

We report below, additional results from studies on discontinuation of psychotropic medication in pregnancy and factors associated with continuation for each of the classes of psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilisers) Parts of this work have been published elsewhere. 46,47

Discontinuation of antipsychotics

Pregnant and non-pregnant women prescribed atypical antipsychotics discontinued at similar rates up to the start of pregnancy (or index date) (Figure 4). However, pregnant women were more likely to discontinue atypical antipsychotics than non-pregnant women (see Figure 4b).

FIGURE 4.

Discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs in pregnant and non-pregnant women by (a) typical; and (b) atypical antipsychotics.

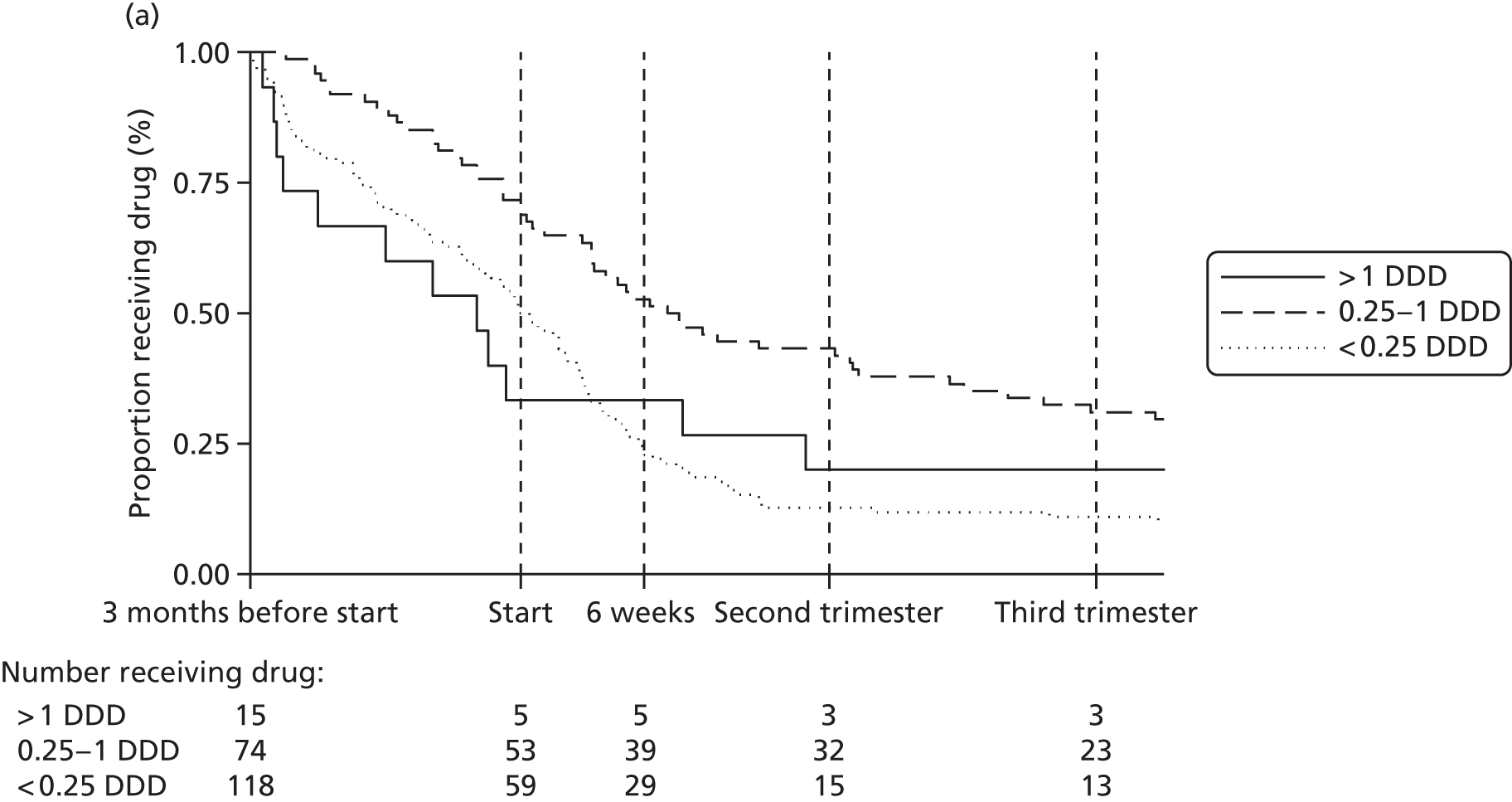

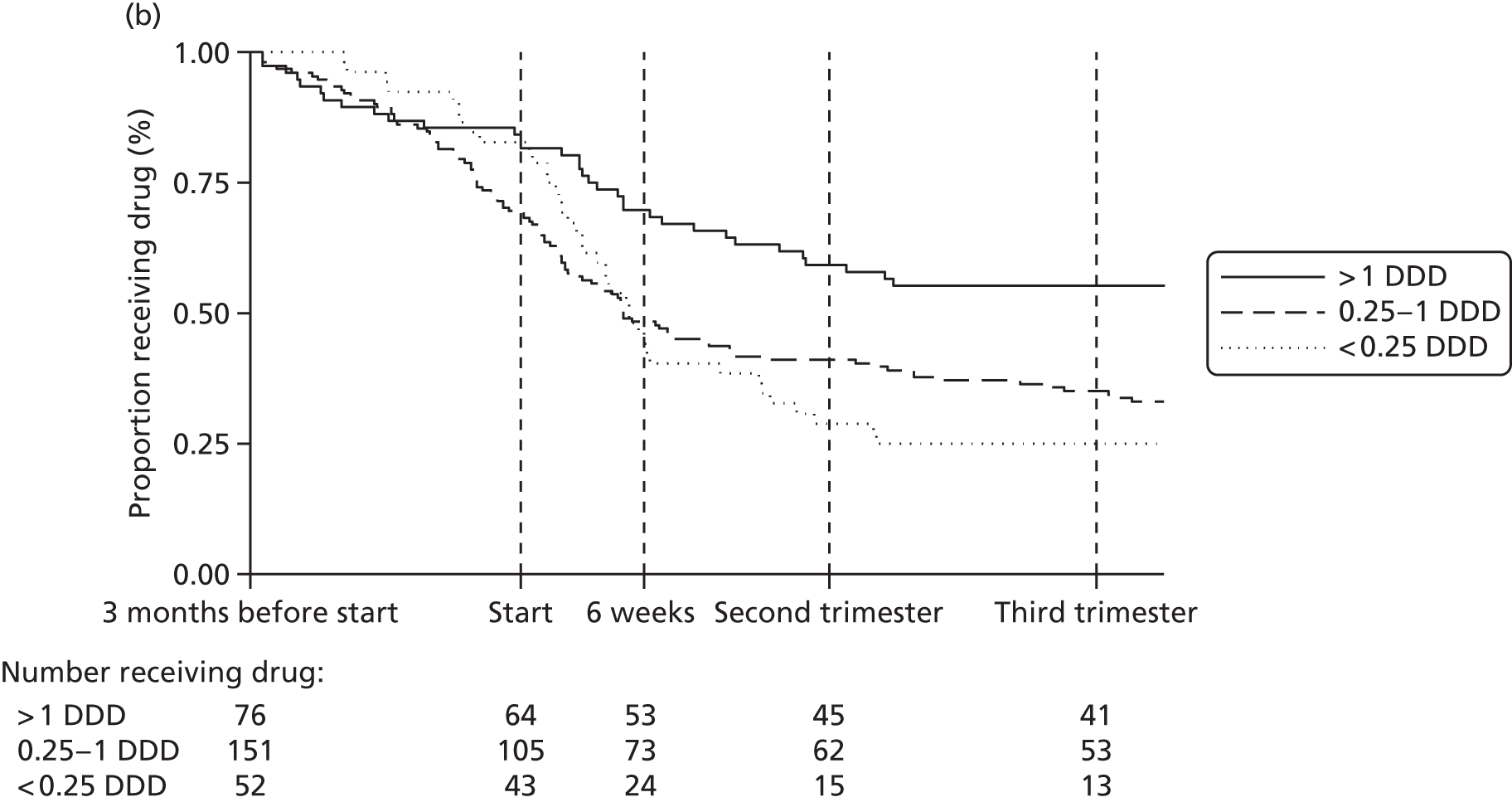

For women on typical antipsychotics there was a substantial difference in the rates of discontinuation between pregnant and non-pregnant women even before the pregnancy (see Figure 4a) and the gap became wider in early pregnancy (see Figure 4a). The comparisons with non-pregnant women, however, suggest that awareness of the pregnancy may not be the only reason for stopping antipsychotics. About 75% of non-pregnant women continued both typical and atypical antipsychotics throughout the follow-up period (see Figure 4).

The rates of discontinuation differed by dose and type of antipsychotics (Figure 5). Among women receiving prescriptions of less than one-quarter of the DDD of typical antipsychotics, only 29 out of 118 (25%) continued prescriptions after 6 weeks. For women on atypical antipsychotics the figure was 24 out of 52 (46%) after 6 weeks (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs in pregnant women, by dose, in women who were prescribed (a) typical; and (b) atypical antipsychotics.

Women on a high dose (DDD > 1) of typical antipsychotics were highly likely to discontinue prescriptions prior to pregnancy in contrast to women on a high dose (DDD > 1) of atypical antipsychotics (see Figure 5). Three out of 15 women on high dose typical antipsychotics were on depots prior to the start of pregnancy.

Factors associated with continuation of antipsychotics

Factors associated with continuation of receiving antipsychotic prescriptions beyond 6 weeks of pregnancy for typical antipsychotics included age and durations of treatment prior to pregnancy (Table 8). Those aged ≥ 35 years were more than three times as likely to continue treatment compared with those < 25 years [risk ratio (RR) 3.09, 95% CI 1.76 to 5.44]. The effect of age attenuated slightly after adjustment for dose. Likewise, those who had received continuous treatment for > 12 months prior to pregnancy were also more likely to continue treatment in pregnancy compared with those who had received < 6 months of continuous treatment prior to pregnancy (RR 3.12, 95% CI 1.97 to 4.95). This was still the case after adjustment for age and dose (RR 2.48, 95% CI 1.54 to 3.99). For atypical antipsychotics, length and dose of prior prescribing were also associated with continuation in pregnancy (Table 9). However, those aged 30–34 years were the most likely to continue prescriptions in pregnancy (see Table 9). For other factors examined (diagnosis of severe mental illnesses, also taking antidepressants and mood stabilisers, social deprivation, estimated parity, obesity, smoking, records of alcohol problems, illicit drug use and ethnicity) none of the adjusted effect sizes was larger than 1.67 or lower than 0.64 (see Tables 8 and 9).

| Factors | Typical antipsychotics (N = 207) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| RR | 95% CI | p-value | RR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Average daily dose (in units of DDD) | < 0.001 | 0.011 | |||||

| < 0.25 DDD | 118 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 0.25–1 DDD | 74 | 2.14 | 1.46 to 3.15 | 1.78 | 1.22 to 2.60 | ||

| > 1 DDD | 15 | 1.36 | 0.62 to 2.97 | 1.25 | 0.58 to 2.68 | ||

| Age band | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| < 25 years | 53 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 25–29 years | 42 | 1.49 | 0.74 to 2.99 | 1.34 | 0.68 to 2.62 | ||

| 30–34 years | 59 | 1.22 | 0.62 to 2.43 | 1.15 | 0.58 to 2.29 | ||

| ≥ 35 years | 53 | 3.09 | 1.76 to 5.44 | 2.60 | 1.47 to 4.59 | ||

| Continuous prior time on antipsychotics | < 0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| < 6 months | 98 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 6–12 months | 34 | 1.92 | 1.03 to 3.57 | 1.78 | 0.97 to 3.26 | ||

| > 12 months | 75 | 3.12 | 1.97 to 4.95 | 2.48 | 1.54 to 3.99 | ||

| SMI diagnosis code | 0.018 | 0.404 | |||||

| No | 160 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SMI diagnosis code | 47 | 1.57 | 1.08 to 2.27 | 1.17 | 0.81 to 1.71 | ||

| Also taking an antidepressant | 0.238 | 0.566 | |||||

| No | 66 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Taking an antidepressant | 141 | 0.80 | 0.55 to 1.16 | 0.90 | 0.64 to 1.28 | ||

| Also taking a mood stabiliser | 0.033 | 0.281 | |||||

| No | 191 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Taking a mood stabiliser | 16 | 1.68 | 1.04 to 2.71 | 1.31 | 0.80 to 2.12 | ||

| Townsend quintile | 0.562 | 0.440 | |||||

| 1 | 16 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 22 | 0.85 | 0.35 to 2.05 | 0.72 | 0.32 to 1.61 | ||

| 3 | 36 | 0.67 | 0.28 to 1.56 | 0.64 | 0.29 to 1.43 | ||

| 4 | 61 | 1.14 | 0.57 to 2.28 | 1.07 | 0.57 to 1.99 | ||

| 5 | 68 | 0.98 | 0.48 to 1.99 | 0.89 | 0.47 to 1.68 | ||

| Unrecorded | 4 | ||||||

| Estimated parity | 0.103 | 0.159 | |||||

| 0 | 84 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 | 57 | 1.47 | 0.91 to 2.40 | 1.34 | 0.87 to 2.08 | ||

| 2 | 44 | 1.82 | 1.13 to 2.93 | 1.65 | 1.06 to 2.57 | ||

| 3 or more | 22 | 1.39 | 0.72 to 2.69 | 1.52 | 0.80 to 2.90 | ||

| Obesity status | 0.771 | 0.759 | |||||

| Not obese | 186 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Obese | 21 | 1.09 | 0.61 to 1.95 | 1.09 | 0.63 to 1.90 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.912 | 0.602 | |||||

| Non-smoker | 106 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Smoker | 101 | 1.02 | 0.71 to 1.48 | 1.09 | 0.78 to 1.53 | ||

| Alcohol problems | 0.154 | 0.094 | |||||

| No | 191 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 1.47 | 0.87 to 2.50 | 1.59 | 0.92 to 2.75 | ||

| Illicit drug use | 0.941 | 0.866 | |||||

| No | 181 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 0.98 | 0.56 to 1.72 | 1.05 | 0.60 to 1.84 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Other | 204 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Black or minority ethnic | 3 | Could not be estimated – all three continue receiving prescriptions | |||||

| Factors | Atypical antipsychotics (N = 279) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| RR | 95% CI | p-value | RR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Average daily dose (in units of DDD) | 0.002 | 0.003 | |||||

| < 0.25 DDD | 52 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 0.25–1 DDD | 151 | 1.05 | 0.75 to 1.47 | 1.04 | 0.74 to 1.47 | ||

| > 1 DDD | 76 | 1.51 | 1.09 to 2.10 | 1.48 | 1.06 to 2.07 | ||

| Age band | 0.147 | 0.201 | |||||

| < 25 years | 53 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 25–29 years | 74 | 1.24 | 0.84 to 1.83 | 1.23 | 0.84 to 1.80 | ||

| 30–34 years | 82 | 1.50 | 1.04 to 2.15 | 1.45 | 1.02 to 2.08 | ||

| ≥ 35 years | 70 | 1.34 | 0.92 to 1.97 | 1.31 | 0.90 to 1.92 | ||

| Continuous prior time on antipsychotics | < 0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| < 6 months | 100 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 6–12 months | 53 | 1.34 | 0.93 to 1.93 | 1.34 | 0.93 to 1.94 | ||

| > 12 months | 126 | 1.78 | 1.34 to 2.35 | 1.67 | 1.27 to 2.21 | ||

| SMI diagnosis code | 0.005 | 0.073 | |||||

| No | 136 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SMI diagnosis code | 143 | 1.39 | 1.11 to 1.74 | 1.25 | 0.98 to 1.59 | ||

| Also taking an antidepressant | 0.097 | 0.402 | |||||

| No | 96 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Taking an antidepressant | 183 | 0.83 | 0.67 to 1.03 | 0.91 | 0.73 to 1.13 | ||

| Also taking a mood stabiliser | 0.098 | 0.574 | |||||

| No | 232 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Taking a mood stabiliser | 47 | 1.23 | 0.96 to 1.58 | 1.08 | 0.83 to 1.40 | ||

| Townsend quintile | 0.880 | 0.805 | |||||

| 1 | 26 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 32 | 1.10 | 0.70 to 1.74 | 1.07 | 0.68 to 1.67 | ||

| 3 | 52 | 0.93 | 0.59 to 1.45 | 0.87 | 0.56 to 1.35 | ||

| 4 | 72 | 0.93 | 0.61 to 1.42 | 0.87 | 0.57 to 1.33 | ||

| 5 | 85 | 1.03 | 0.69 to 1.54 | 0.94 | 0.63 to 1.41 | ||

| Unrecorded | 12 | ||||||

| Estimated parity | 0.474 | 0.511 | |||||

| 0 | 110 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 | 89 | 0.89 | 0.70 to 1.15 | 0.92 | 0.72 to 1.18 | ||

| 2 | 49 | 0.79 | 0.57 to 1.11 | 0.82 | 0.58 to 1.14 | ||

| 3 or more | 31 | 0.82 | 0.55 to 1.22 | 0.80 | 0.54 to 1.18 | ||

| Obesity status | 0.055 | 0.119 | |||||

| Not obese | 223 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Obese | 56 | 1.26 | 1.00 to 1.59 | 1.21 | 0.95 to 1.53 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.875 | 0.935 | |||||

| Non-smoker | 142 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Smoker | 137 | 0.98 | 0.79 to 1.22 | 0.99 | 0.80 to 1.23 | ||

| Alcohol problems | 0.595 | 0.385 | |||||

| No | 264 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 1.12 | 0.73 to 1.73 | 1.22 | 0.78 to 1.90 | ||

| Illicit drug use | 0.370 | 0.340 | |||||

| No | 246 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 33 | 1.15 | 0.85 to 1.55 | 1.16 | 0.85 to 1.58 | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.087 | 0.214 | |||||

| Other | 249 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Black or minority ethnic | 30 | 1.28 | 0.97 to 1.69 | 1.20 | 0.90 to 1.59 | ||

Switch between typical and atypical antipsychotic treatment

In general, few women switched between typical and atypical antipsychotic treatment just before or in pregnancy. Only 5 out of 207 (2.4%) women switched from typical to atypical antipsychotics and 9 out of 279 (3.2%) switched from atypical to typical antipsychotics. However, among the more frequently used antipsychotics, switching levels were high for two drugs: 12 out of 50 women (24.0%) switched from risperidone to another antipsychotic, while 9 out of 48 (18.8%) switched from trifluoperazine to another antipsychotic.

Discontinuation of lithium

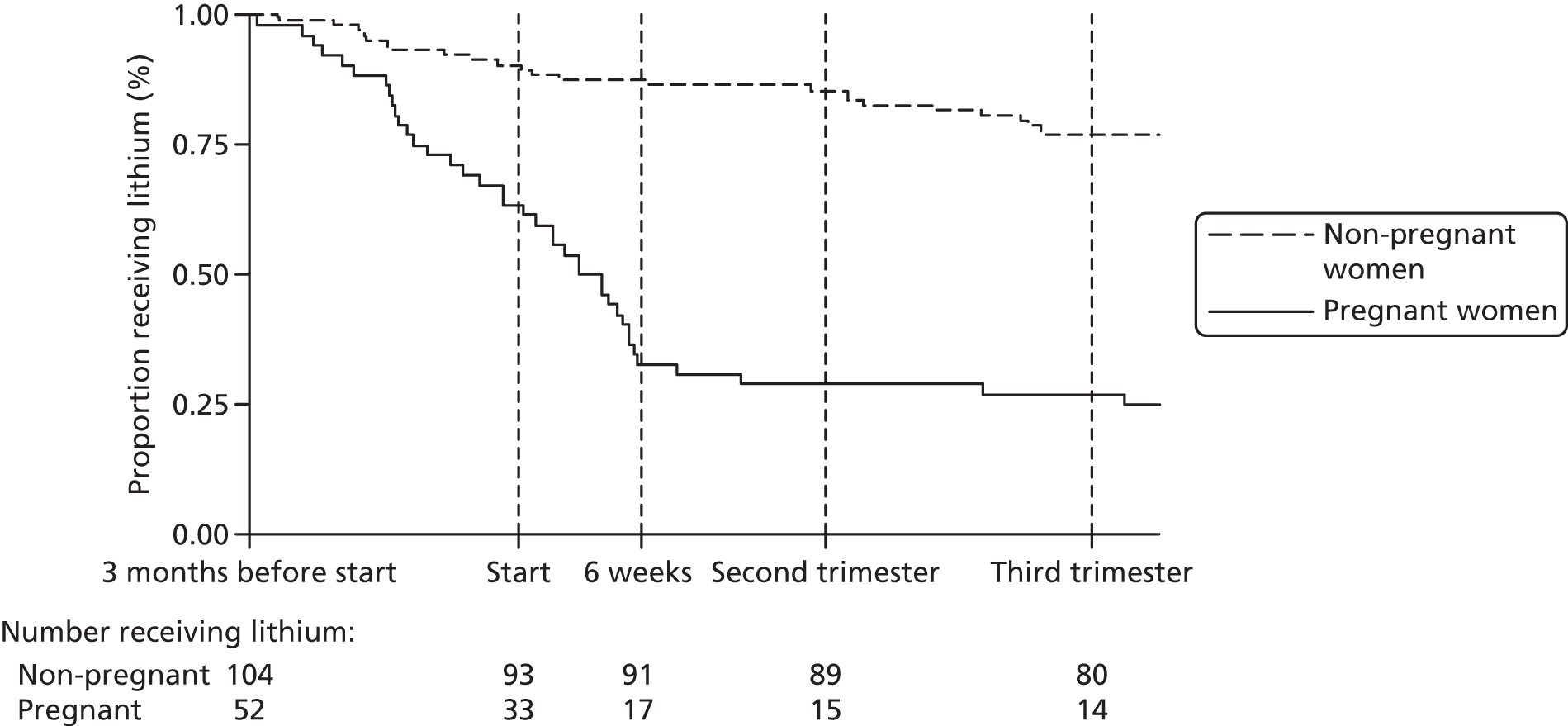

For lithium, there was a substantial difference in the rates of discontinuation between pregnant and non-pregnant women (Figure 6). Only 14 out of 52 (27%) continued lithium treatment after the start of the third trimester. Of the non-pregnant women, 80 out of 104 (77%) continued lithium treatment beyond this period (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Discontinuation of lithium in pregnant and non-pregnant women.

Factors associated with continuation of lithium

A greater proportion of those who continued lithium in pregnancy had been prescribed an antidepressant (47%) or antipsychotic (53%) in addition to lithium during the 4–6 months before pregnancy (compared with 34% prescribed antidepressants or antipsychotics in those who stopped). In addition, a greater proportion of those who continued lithium were having their first child (59% vs. 40%) or had been receiving continuous lithium prescriptions for < 6 months (47% vs. 31%). However, the small numbers of women involved mean that the CIs for these percentages are wide and generally overlap (Table 10).

| Factors | Stopped before 6 weeks (N = 35) | Continued beyond 6 weeks (N = 17) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Age band | ||||||

| < 25 years | 5 | 14.3 | 5.9 to 30.8 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| 25–29 years | 8 | 22.9 | 11.5 to 40.2 | 4 | 23.5 | 8.6 to 50.1 |

| 30–34 years | 10 | 28.6 | 15.7 to 46.2 | 7 | 41.2 | 20.2 to 66.0 |

| ≥ 35 years | 12 | 34.3 | 20.2 to 51.9 | 6 | 35.3 | 16.0 to 60.9 |

| Prior continuous time on lithium | ||||||

| < 6 months | 11 | 31.4 | 17.9 to 49.0 | 8 | 47.1 | 24.5 to 70.8 |

| 6–12 months | 6 | 17.1 | 7.7 to 34.0 | 2 | 11.8 | 2.7 to 38.8 |

| > 12 months | 18 | 51.4 | 34.7 to 67.8 | 7 | 41.2 | 20.2 to 66.0 |

| Estimated parity | ||||||

| 0 | 14 | 40.0 | 24.8 to 57.4 | 10 | 58.8 | 34.0 to 79.8 |

| 1 | 13 | 37.1 | 22.5 to 54.6 | 4 | 23.5 | 8.6 to 50.1 |

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 7.7 to 34.0 | 3 | 17.6 | 5.4 to 44.4 |

| 3 or more | 2 | 5.7 | 1.4 to 21.1 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| Also taking an antidepressant | 12 | 34.3 | 20.2 to 51.9 | 8 | 47.1 | 24.5 to 70.8 |

| Also taking an antipsychotic | 12 | 34.3 | 20.2 to 51.9 | 9 | 52.9 | 29.2 to 75.5 |

| Also taking an anticonvulsant | 6 | 17.1 | 7.7 to 34.0 | 3 | 17.6 | 5.4 to 44.4 |

Switch from lithium to antipsychotic treatment

Of the 39 women who discontinued lithium before the end of follow-up at 220 days, six received at least two prescriptions for an antipsychotic in the 91 days after lithium discontinuation. However, five of these were already receiving an antipsychotic prior to lithium discontinuation, so only one could be classed as having ‘switched’ treatment. We cannot exclude the possibility that some of the other five may have started a new antipsychotic while gradually tapering off lithium.

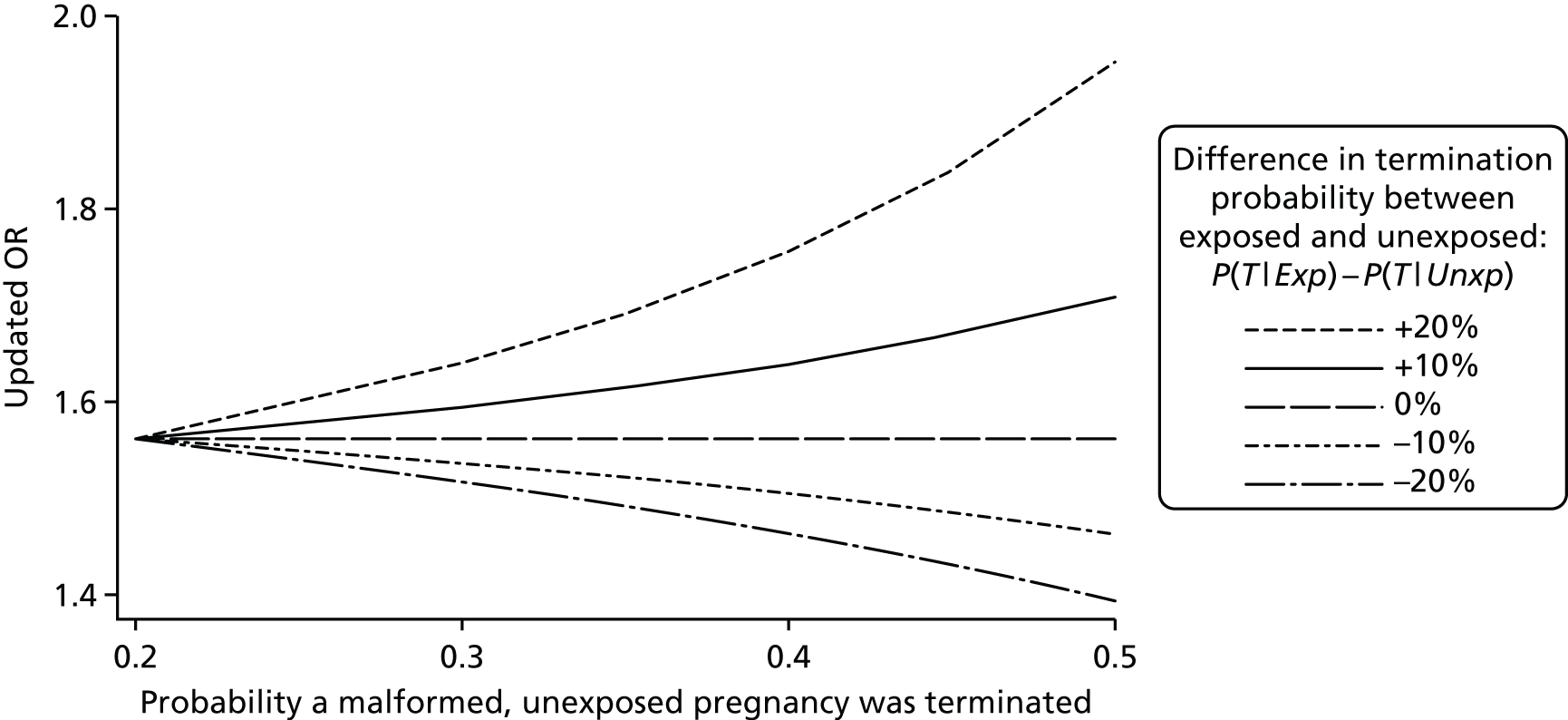

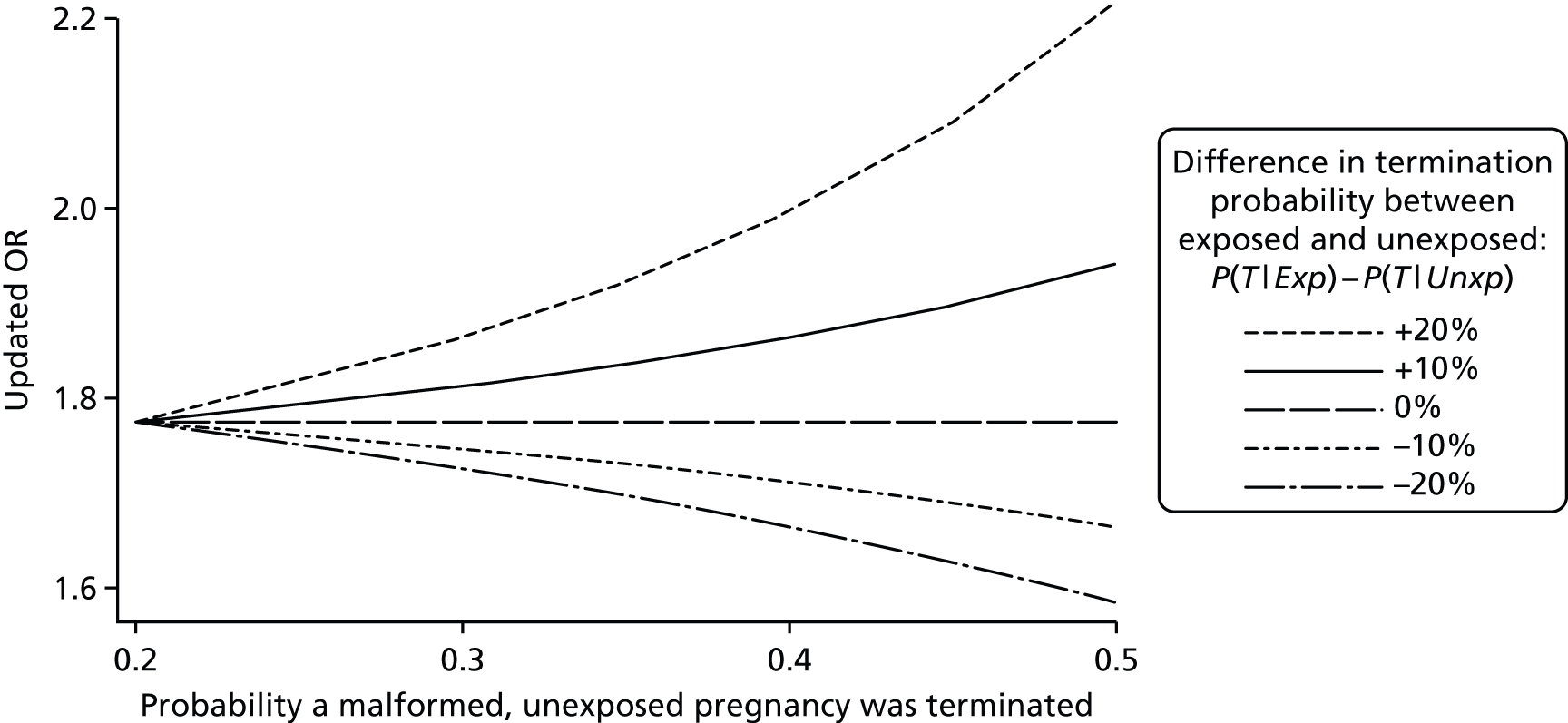

Discontinuation of anticonvulsant mood stabilisers