Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/151/04. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in August 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Kaltenthaler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Historical perspective

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK provides guidance and advice to improve health and social care. NICE guidance contains evidence-based recommendations and includes technology appraisals (TAs), which are recommendations on the use of new and existing medicines and treatments within the NHS. The NICE single technology appraisal (STA) process is, in principle, undertaken for a single technology for a single indication, although more than one comparator may be included. The STA process began in 2005 and was introduced to enable the production of more rapid guidance than the existing NICE multiple technology appraisal (MTA) process so that new products could be approved as close to licensing as possible. Concerns were raised early on that although STAs resulted in more rapid guidance, there remained uncertainty concerning the extent to which STAs adequately addressed the specific decision problem under consideration. 1 There have been considerable changes to the STA process over time, such as the inclusion of scoping workshops, decision problem meetings, clarification letters and end-of-life criteria.

Previous research found the STA process to be slower than initially anticipated, primarily because of events outside NICE’s control,2 and that one-third of referred topics in the first 4 years of the STA process were either suspended or terminated. In their study comparing the NICE STA process with the Scottish Medicines Consortium process, Ford et al. 3 found that, overall, the STA process reduced the average time to publication compared with NICE MTAs (median 16.1 months compared with 22.8 months). However, for cancer medications, the STA process took longer than the MTA process (25.2 months compared with 20.0 months). Barham4 also found that STAs took longer than anticipated, particularly for cancer drugs. A more recent analysis by Casson et al. 5 found STAs to be significantly faster than MTAs for all conditions. NICE aims to issue guidance as close to marketing authorisation as is possible.

National Institute for Health Research single technology appraisal process

Table 1 shows a brief description of the STA process.

| STA process | Weeks (approximately) since process start |

|---|---|

| Scope developed, sent out for consultation, discussed at scoping workshop and final scope agreed | Draft scope in week 1, scoping workshop weeks 7–9 |

| Company discusses with NICE how the decision problem will be addressed | |

| Weeks (approximately) after decision problem meeting and invitations sent | |

| Company makes an evidence submission | 9 (received by ERG) |

| ERG report developed: 2 weeks into the process the clarification letter is sent to the company | 17 |

| First AC meeting to develop the ACD or FAD (if no ACD produced) | 21 |

| Second AC meeting to develop the FAD, if an ACD has been produced at earlier AC meetings | 29 |

| After close of appeal period, NICE publishes guidance | 38 |

The STA process is outlined in detail in NICE’s Guide to the Process of Technology Appraisal6 and includes the production of an evidence submission by the company producing the technology. The company submission (CS) to NICE forms the principal source of evidence for decision-making in the STA process. The company is expected to follow the decision-analytic approaches as described in the Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal7 and the submission is expected to contain an evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the technology. Evidence Review Groups (ERGs) are charged with the task of critically appraising the CS to identify strengths, weaknesses and gaps in the evidence presented. Assessment by the ERG is conducted over an 8-week period. Templates exist for both the CS and the ERG report. Early in the process a request for clarification, covering any issues that are unclear in the submission, is made to the company, which is then given an opportunity to respond. As part of the STA process, the ERGs also undertake exploratory analyses to explore uncertainties around the company’s model and the implications of these for decision-making. It is the responsibility of the ERG to determine what additional analyses are required and to undertake them. The ERG may also identify and correct technical or programming errors that are identified. This critical appraisal of the CS and additional work form the basis of the ERG’s report. The number and type of exploratory analyses undertaken varies between appraisals, but they can contribute important evidence for consideration by an Appraisal Committee (AC). These ERG reports are a central component of the evidence considered by the AC.

Little guidance is given to ERGs on how to produce their reports. Some assessment of process has been undertaken. For example, Wong et al. 8 assessed approaches used by ERGs to critically appraise search strategies within CSs. Previous research has highlighted issues with CSs that are particularly challenging to the ERGs. 9 Carroll et al. 10 suggested that company STA submissions could be improved if attention were paid to transparency in the reporting, conduct and justification of the review, and modelling processes and analyses, as well as greater robustness in the choice of data in the model and closer adherence to the scope or decision problem. Where this adherence is not possible, it was suggested that more detailed justification of the choice of evidence or data is required. Kaltenthaler et al. 11 also recommended the need for clear and transparent reporting of CSs, and for a clear and concise rationale for the synthesis of clinical data, the development of economic models and the assumptions used to develop models.

There are currently nine ERGs:

-

British Medical Journal (BMJ) Technology Assessment Group, BMJ Evidence Centre, BMJ Group

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and Centre for Health Economics (CHE), University of York

-

Health Economics Research Unit and Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen

-

Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd

-

Liverpool Reviews and Implementation Group (LRiG), University of Liverpool

-

Peninsula Technology Assessment Group, Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth

-

School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield

-

Southampton Health Technology Assessment Centre, University of Southampton

-

Warwick Evidence, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick.

An additional ERG, the West Midlands Health Technology Assessment Collaboration, undertook STAs during the period 2005–10.

The ERG report, together with other evidence, is considered by one of four NICE ACs. ACs can make four categories of recommendation: (1) recommended, (2) optimised (previously recommended under certain circumstances, e.g. to a subgroup within the licence), (3) only in research and (4) not recommended. Each appraisal may contain more than one recommendation. ‘Only in research’ recommendations are rare in any TA process. 12

A recommendation is considered provisional if the AC recommendation is not recommended, limitations are recommended on the use of the technology or the company is asked to provide further clarification of their evidence submission. If the recommendation is provisional, an appraisal consultation document (ACD) is produced. At this stage, a ‘minded no’ preliminary recommendation may be issued, requiring more information from companies before a final recommendation can be made. Following the publication of an ACD, companies may submit additional evidence, which may include a Patient Access Scheme (PAS) proposal, and the ERG may produce a report that assesses the impact of the PAS. A PAS may also be submitted earlier on in the STA process. The AC, as part of its deliberations, considers the PAS as part of the evidence for the appraisal.

The AC meets to consider the consultation comments received on the ACD and any additional evidence produced. The ERG may be asked to critique any new evidence from the company. Final recommendations are made in the form of the final appraisal determination (FAD). At the end of the appeal period, NICE guidance is produced.

Aims and objectives

This study was commissioned by NICE and aims to investigate how ERGs undertake exploratory analyses within the NICE STA process and how these analyses are used by the NICE ACs in their decision-making process. For the purpose of this research, an exploratory analysis is defined as any additional analysis generating an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and included in the ERG report section ‘Exploratory and sensitivity analyses undertaken by the ERG’. This is most commonly reported as Section 6 of an ERG report, if the suggested template is followed. This study aims to present an examination of the experiences and outcomes related to instances in which ERGs have conducted additional exploratory analysis and to examine what exploratory analysis have been done, and, where possible, why they were done and what the outcome of the analyses were in terms of how they were managed by the AC and used in the decision-making process. This is an under-researched area and this study was commissioned by NICE to develop understanding of this aspect of the STA process. This research is of interest to all key stakeholders in the STA process, including the ERGs, the pharmaceutical companies, AC members and NICE.

The study seeks to address the following objectives:

-

to identify ERG reports that contain exploratory analyses conducted by the ERG, as defined above

-

to identify ERG approaches to exploratory analyses of economic evidence submitted by companies for NICE STAs and to categorise these approaches by type of analysis performed

-

to identify data sources used for exploratory analyses undertaken by ERGs

-

to identify factors that influence or predict the extent of ERG exploratory analyses

-

to identify whether or not companies were provided with the opportunity to provide the analyses as part of the clarification stage

-

to identify situations in which a committee requested the ERG to conduct additional analyses

-

to make an assessment of the degree to which the exploratory analyses influenced a committee’s considerations and recommendations.

Chapter 2 Methods

This research was jointly undertaken by teams at ScHARR at the University of Sheffield and CRD and CHE at the University of York. The objectives addressed by this research were initially identified by NICE. A protocol was developed and peer reviewed and is available from the HTA website. 13 A content analysis of selected documents (documentary analysis) was undertaken to identify and extract relevant data, and narrative synthesis was used to rationalise and present these data.

Selection of single technology appraisals

The 100 most recently completed STAs (since 2009) for which guidance has been published were selected for inclusion in the analysis. It was considered among the team that 100 STAs represented the maximum number of appraisals that could be considered within the time and resource constraints of the project and that the 100 most recent appraisals would provide the most accurate reflection of current practice, as the process has changed substantially since the initial introduction of STAs in 2005. A list of the STAs included in this analysis is attached as Appendix 1.

All relevant documents for the 100 STAs were made available to the project team by NICE. The documents used in the data extraction were:

-

ERG reports (unredacted versions used by the ACs)

-

clarification letters and responses

-

the first ACD issued (subsequent ACDs were not considered)

-

the last FAD issued (where more than one FAD has been produced).

Information on the number of AC meetings for each STA was provided directly by NICE. The research required extraction of relevant data from more than 400 separate documents.

Data extraction

A sample data extraction template is attached as Appendix 2. The data extraction tool was formulated to extract relevant data to address the project objectives. 14 STA reports, clarification letters, ACDs and FADs all have a basic, standard structure, which facilitated data extraction. The ERG reports have a specific ‘Exploratory’ or ‘Additional analyses’ section, usually Section 6, from which the data on exploratory analyses were extracted. However, ERG reports and clarification letters and responses can vary greatly in their descriptions of analysis and level of detail. Pilot data extraction was initially undertaken by four extractors (AS, MH, SR and MR) on five STAs to develop and ensure the usability of the data extraction template. After modifications were made to the extraction form, a further pilot data extraction exercise was undertaken using three additional STAs in order to standardise extraction between the York and ScHARR teams. This process produced the final agreed data extraction tool (see Appendix 3). The final categories of exploratory analyses to be used in this study were created following this pilot process. They were based on discussions with the whole project team and an existing relevant, published taxonomy. 15 This approach was similar to framework analysis techniques for developing an a priori framework for coding qualitative data. 16 The categories were then defined in order to facilitate consistency of coding. The category ‘matters of judgement’ was originally composed of three more specific categories: (1) uncertainty and evidence variation, (2) alternative data and (3) ERG subjective judgement. However, it was found that the descriptions of the analyses in the reports were often inadequate for ensuring that the information was being interpreted and coded consistently into one of these categories. For this reason, a single, broader category of ‘matters of judgement’ was created. The final four agreed categories of exploratory analysis are listed below (Table 2). This simple scheme facilitated consistency of coding between data extractors.

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fixing errors | The ERG considered that something was unequivocally wrong in the company’s submitted model |

| Fixing violations | The ERG considered that the NICE reference case, scope or best practice had not been adhered to for one or more parameters or values, including missing out relevant comparators, and hence the model is not fit for purpose |

| Matters of judgement | The ERG did not consider that the submitted model was wrong as such, but amended the model by conducting an analysis (often a sensitivity or threshold analysis) to test uncertainties within the evidence or model, or because reasonable alternative assumptions could be applied. These could be hypothetical or based on alternative data in the published literature or provided by a company |

| ERG-preferred base case | The ERG conducted its own specific preferred base-case analysis. This might be the result of a series of exploratory analyses. This base case might still not be ideal from the ERG’s perspective |

The seven parts of the data extraction tool are outlined in Table 3.

| Section | Details of fields | Project objective |

|---|---|---|

| Basic characteristics |

|

4 |

| Company’s base-case ICER(s) |

|

4 |

| Number and type of exploratory analyses conducted by ERG |

|

1, 2, 3 |

| Clarification letter and responses |

|

5 |

| ACD |

|

7 |

| Additional work |

|

6 |

| FAD |

|

7 |

All data extractions were double-checked by two researchers: > 90% were double-checked by just two team members (DHM and PT) in order to enhance the consistency of extraction and interpretation. The York team extracted data from 24 STAs and the ScHARR team extracted data from 76 STAs. In order to reduce possible bias in extraction, the York team extracted data from all of the ScHARR ERG reports and the ScHARR team extracted data from all of the York CRD/CHE reports.

The level and type of detail provided in and across the ERG reports and clarification letters could be very different, which made data extraction time-consuming, difficult and, at times, a matter of interpretation. Despite efforts to simplify the data extraction and coding process (e.g. a small number of well-defined, mutually exclusive categories of analysis), data extractors sometimes had to exercise interpretation for some data, principally for whether exploratory analyses were prespecified or hinted at in clarification letters. This issue of interpretation also affected the actual number of exploratory analyses undertaken by an ERG and the influence of specific exploratory analyses on AC recommendations, in that in some instances multiple analyses might be counted separately and in other instances they may be lumped together as a single analysis. A typical example can found in the STA, Dabigatran Etexilate for the Prevention of Stroke and Systemic Embolism in Atrial Fibrillation (TA249). 17 In this case, the ERG conducted many exploratory analyses, generating a range of ICERs, including an ERG-preferred base-case ICER of £24,173 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). As part of these analyses, the ERG aimed to test the impact of applying three different, but equally justified, sources of cost data for international normalised ratio monitoring; this produced three only very slightly different ICERs. However, this was interpreted as only one exploratory analysis, although it might arguably have been interpreted as three separate analyses. This ERG report was considered to have a total of 14 exploratory analyses overall. In order to address issues of interpretation such as this, the mean number of exploratory analyses was calculated. The key data used in the synthesis were then reduced to whether a STA conducted more or fewer than the overall mean number of exploratory analyses, and whether just ‘one or more’ exploratory analyses were explicitly cited as having an influence on a recommendation. These arbitrary selections were made as a means of making the most of the data to address the objectives of the project.

Methods for analysis

A narrative synthesis was performed on the extracted data from the 100 ERG reports. 18 This involved summarising the key data through text and tables and then using narrative to highlight any potentially important patterns or relationships in the data. This approach was taken because the large number of reports and documents prevented meaningful, in-depth analysis of the text using qualitative methods, but the numbers were not large enough to permit meaningful statistical analysis of the data. The synthesis therefore described the incidence and frequency of exploratory analyses (objective 1); identified the types of exploratory analyses performed by ERGs, as well as their data sources, where appropriate (objectives 2 and 3); explored relationships between key variables and the presence and frequency of exploratory analyses (objective 4); described the role of exploratory analyses relating to the clarification process (objective 5) and additional analyses post ACD (objective 6); and assessed the possible influence of exploratory analyses on the recommendations of the ACs (objective 7). It was considered a priori that the disease area and a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY were the key variables most likely to predict the incidence and frequency of exploratory analyses. This was because of the known impact of disease area on other elements of STAs4 and the perceived importance of the £20,000 per QALY threshold for NICE decision-making. 19 An assessment was also made to identify any changes over time.

In conducting the synthesis, the following assumptions were made:

-

Every exploratory analysis had to have a separately reported ICER. If an analysis combined the results of two or more exploratory analyses to calculate the third ICER, then this was considered to be a further, separate analysis.

-

The ICER taken for comparison was for the technology against its principal comparator or in the principal scenario (its most likely use in clinical practice).

-

When the base-case or preferred ICER reported by the company, ACD or FAD was a range or multiple ICERs (e.g. for subgroups or scenarios), then the lowest ICER was used.

-

If the technology was considered to be a cost-effective use of NHS resources, then it was deemed to be so at a threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained.

-

If the ACD or FAD simply stated that the technology was ‘dominating’, then it was assumed that it was cost-effective at the threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained.

-

If the ACD or FAD simply stated that the technology was ‘dominated’, then it was assumed that it was not cost-effective at the threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained19 (although a technology could simply be dominated by a very cost-effective comparator).

-

The data on whether the analyses are mentioned by the ACD or FAD, or influenced their recommendation, relate to the exploratory analyses described in the ERG report or a specific addendum document (rather than any analyses conducted between the ACD and FAD).

-

If any work was conducted by a company between an ACD and a FAD, it was assumed that it was critiqued by the ERG as a standard procedure (explicit requests by an AC for an ERG to conduct such work were rarely recorded in the ACD).

-

Evidence of influence on a recommendation required a reference to an ERG’s exploratory analysis or its ICER.

An example of the data extracted for a single STA, and used in the synthesis, is reproduced in Appendix 3.

Chapter 3 Results

General overview

Between September 2009 and September 2014, 100 STAs were undertaken by NICE that resulted in the production of guidance and formed the basis for these analyses. In these 100 STAs, 40 different companies submitted documents as part of the NICE STA process. The companies who were involved with the largest number of submissions were Roche (n = 15), Novartis (n = 9), GlaxoSmithKline (n = 7), Bristol-Meyers Squibb (n = 7) and Bayer (n = 6). The majority of companies made only one or two submissions (Table 4).

| Company | Number of reports (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| 1. Alimera Sciences | 1 |

| 2. Alimta | 1 |

| 3. Allergan Ltd | 2 |

| 4. Amgen Inc. | 2 |

| 5. Astellas Pharma | 2 |

| 6. AstraZeneca | 4 |

| 7. Bayer Healthcare | 6 |

| 8. Biogen | 1 |

| 9. Boehringer Ingelheim | 3 |

| 10. Bristol-Meyers Squibb | 7 |

| 11. Celgene | 2 |

| 12. Cell Therapeutics Inc. | 1 |

| 13. Eli Lilly and Company | 5 |

| 14. Eliquis | 1 |

| 15. Eisai Co. Ltd | 1 |

| 16. Genzyme | 2 |

| 17. GlaxoSmithKline | 7 |

| 18. InterMune | 1 |

| 19. Janssen Pharmaceutica | 5 |

| 20. Laboratoires Servier | 1 |

| 21. Movetis | 1 |

| 22. MSD | 2 |

| 23. Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd | 1 |

| 24. Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd | 9 |

| 25. Novo Nordisk | 1 |

| 26. Otsuka Pharmaceutical | 2 |

| 27. Pfizer | 4 |

| 28. PharmaMar | 2 |

| 29. Pharmaxis | 1 |

| 30. Pierre Fabre | 1 |

| 31. Roche | 15 |

| 32. Sanofi-aventis | 3 |

| 33. Savient Pharmaceuticals Inc | 1 |

| 34. Schering-Plough | 2 |

| 35. Stelara | 1 |

| 36. Sucampo Pharma Europe | 1 |

| 37. Takeda UK Ltd | 2 |

| 38. The Medicines Company | 1 |

| 39. ThromboGenics | 1 |

| 40. UCB | 1 |

Ten ERGs conducted critical appraisals of these submissions. The principal ERGs were based at York CRD/CHE (18 reports), LRiG (17 reports), ScHARR (13 reports), Aberdeen (11 reports) and Southampton (10 reports). See Table 5 for the number of reports completed by each centre in this period.

| ERG | Number of reports (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Aberdeen | 11 |

| BMJ | 8 |

| Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd | 7 |

| LRiG | 17 |

| PenTAG | 4 |

| ScHARR | 13 |

| Southampton | 10 |

| Warwick | 5 |

| West Midlands | 7 |

| York CRD/CHE | 18 |

The principal disease areas covered by the STAs were cancer (44%), blood and the immune system (11%), cardiovascular conditions (10%) and musculoskeletal conditions (8%). The final scoping documents of the majority of the STAs (66%) included pre-specified subgroups. In 21% of the STAs, end-of-life criteria were considered by the AC (Tables 6 and 7).

| Disease area | Number of reports (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Blood and immune system | 11 |

| Cancer | 44 |

| Cardiovascular | 10 |

| Central nervous system | 4 |

| Digestive system | 2 |

| Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic | 4 |

| Eye | 7 |

| Infectious diseases | 2 |

| Mental health | 2 |

| Musculoskeletal | 8 |

| Respiratory | 3 |

| Therapeutic procedures | 2 |

| Urogenital | 1 |

| Prespecified subgroups and end-of-life criteria | Number of reportsa (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| With subgroups prespecified | 66 |

| With assessment for end-of-life criteria | 21 |

Finally, it should be noted that for 19 STAs (19%) no ACD was produced: decisions were simply recorded in the FAD. This means that some tables in the sections below do not report numbers for 100 STAs, but rather have a denominator of 81.

Exploratory analyses

Evidence Review Group reports that contain exploratory analyses

The vast majority (93%) of ERG reports for the STA process conducted and reported one or more exploratory analyses (Table 8): seven ERG reports did not contain any exploratory analysis that generated a new ICER. 20–26 In the 93 reports that did include an exploratory analysis, the number of analyses ranged from 1 to 29, with an approximate mean of 8.5 analyses per report and a median of 7.

| Exploratory analyses | Number |

|---|---|

| Proportion of reports with exploratory analyses | 93/100 (93%) |

| Proportion of reports without exploratory analyses | 7/100 (7%) |

| Number of exploratory analyses identified per report with analyses (mean) (number of exploratory analyses/number of reports with analyses) | 8.5 (798/93) |

| Number of exploratory analyses identified per report with analyses (range) | 1–29 |

Out of the 93 ERG reports with at least one exploratory analysis, a total of 40 (43%) included eight or more such analyses. For the 10 ERGs undertaking STAs, the mean number of exploratory analyses per report ranged from 2.3 (West Midlands) to 11.4 (ScHARR) (Table 9). It should be noted that no regression analyses were performed to explore the relationship between the mean number of analyses per report by ERG and other variables such as disease area and year, as well as other potentially influencing factors such as complexity and perceived quality of CSs, owing to the limitations of the data.

| ERG | Number of analyses/number of reports | Mean number of exploratory analyses per report |

|---|---|---|

| ScHARR | 148/13 | 11.4 |

| BMJ | 83/8 | 10.4 |

| CRD | 173/18 | 9.6 |

| PenTAG | 38/4 | 9.5 |

| Southampton | 91/10 | 9.1 |

| Warwick | 44/5 | 8.8 |

| Aberdeen | 72/11 | 6.5 |

| LRiG | 96/17 | 5.6 |

| Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd | 37/7 | 5.3 |

| West Midlands | 16/7 | 2.3 |

| Total and mean | 798/100 | 8 |

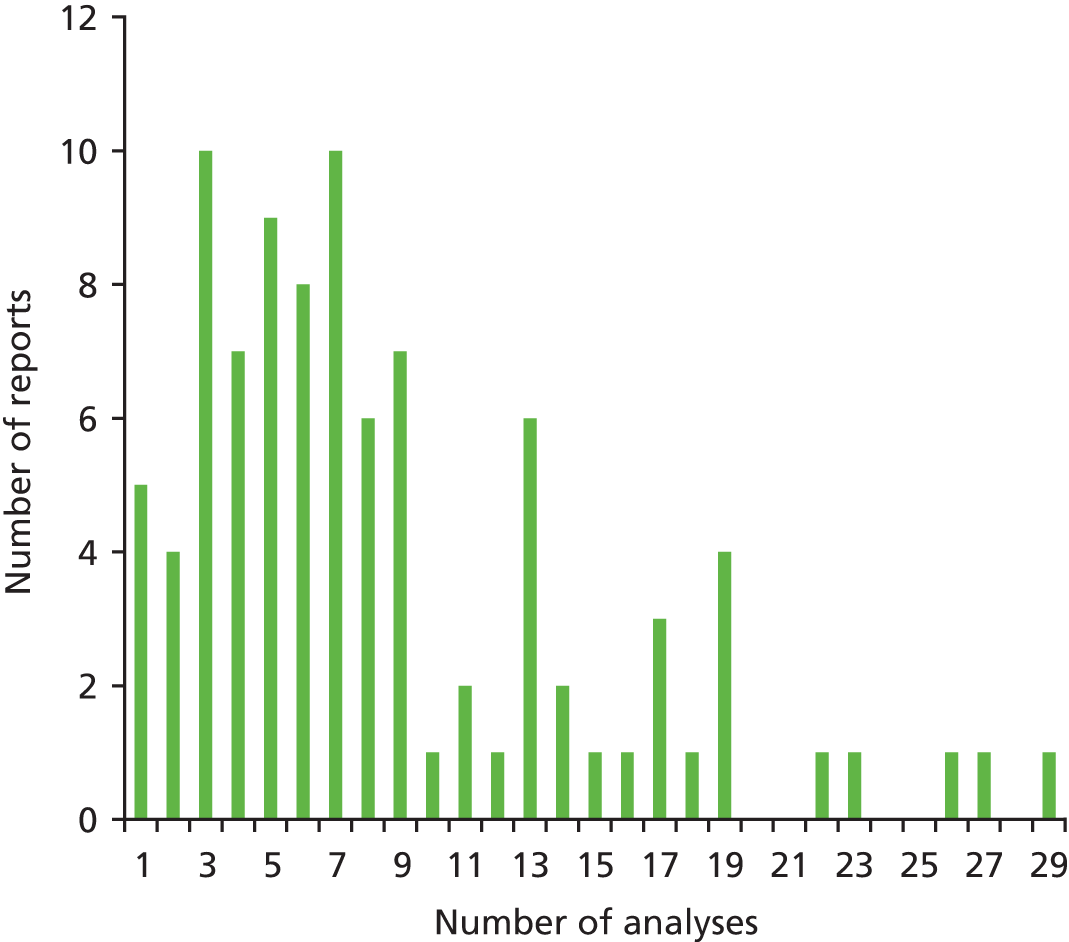

It is clear from the histogram (Figure 1) that the vast majority of ERG reports conducted nine or fewer analyses. Ten reports contained three or seven analyses, nine reports contained five analyses and six reports contained eight analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of exploratory analyses.

Categories of Evidence Review Group approaches to exploratory analyses of economic evidence

For the 93 ERG reports that generated at least one exploratory analysis, the type of analysis that appeared in the largest proportion of reports was the category of ‘matters of judgement’; that is, the ERG considered there to be uncertainty or possible variation regarding the evidence used to populate the model. At least one such exploratory analysis was conducted in 89% of ERG reports. As a category of exploratory analysis, the calculation of a new base case by an ERG appeared in more ERG reports (48%) than analyses which were concerned with either fixing outright errors in the submitted models (35%) or fixing violations (18%) (Table 10).

| Category | Number of reports (%) (n = 93) |

|---|---|

| Matters of judgement | 83 (89) |

| ERG base-case/preferred analysis | 45 (48) |

| Fixing errors | 33 (35) |

| Fixing violations | 17 (18) |

Some examples of each of the categories are illustrated below based on extracts of text included in ERG reports.

Matters of judgement

Section 6.1 and 6.3: Opinion sought by the ERG suggested that it is far from certain that denosumab will be administered in a primary care setting, and so some analysis was undertaken based on assumptions that denosumab, zoledronate and ibandronate are administered entirely in a secondary care setting. . . . Tables xxx have been provided to show how the ICERs for denosumab change by subgroup using full secondary care costing assumptions for administration of denosumab and all the secondary comparators

TA20429

Sections 6.4.2 and 6.4.3: The ERG noted in its critique of the manufacturer’s submission that some of the assumptions in relation to treatment initiation and monitoring costs were not considered to be sufficiently justified. The ERG examined a scenario which assumed that all treatments (as opposed to just dronedarone) could be initiated in an outpatient setting. The resulting effect on the ICERs was marginal and the overall conclusions on cost-effectiveness is not altered. . . . The ERG expressed some concern that the utility values applied in the economic model potentially imply a higher estimate of quality of life than that expected from the general UK population. In an attempt to address this issue, the ERG adjusted the constant value of the regression model used to estimate utility values to ensure that the values applied in the model do not exceed those of the general population. The adjustment was made to the regression constant such that the utility value estimated for a 70 year old AF [atrial fibrillation] male without any symptoms was reduced from 0.918 to 0.78, with the same adjustment applied throughout the model for all patients. The ERG recognises that this is not the most appropriate way to change the utility values but without access to the individual patient level data of the AFTER study this was the best that the ERG could do to take account of the manufacturer’s potentially overly optimistic estimates of overall QALYs. Table xxx presents the ICERs for the base case populations incorporating the adjustment in HRQoL [health-related quality of life]. The implications for the cost-effectiveness results were limited.

TA19730

Section 4.2.5: Pioglitazone costs

ISD Scotland prescription data notes the following balance between the three doses of pioglitazone in the year to December 2010 . . . Ignoring the 15mg dose still suggests that a significant proportion of patients may not titrate up to the maximum 45 mg. Given a rough balance of 60:40 for 30mg: 45 mg would imply an average annual cost for pioglitazone of £487 compared to the £516 of the base case: a reduction of £29. Over the initial 5 years of the modelling, on the basis of a discounted survival of 4.548 years in the pioglitazone arm this would be anticipated to reduce the pioglitazone total discounted costs by £130. In itself, this would only worsen the cost effectiveness estimate for once-weekly exenatide compared to pioglitazone from the £8,624 per QALY of the base case to £9,357 per QALY.

TA24831

Evidence Review Group base-case/preferred analysis

Section 5.5.3: New model results were generated by the ERG to take account of each of the issues previously identified (sections 5.5.2 and 5.5.3 above); the separate effect of each change is shown in the upper section of Table xxx compared to the manufacturer’s submitted base case analysis. The most influential amendments are the removal of a limit on the number of cycles of treatment any patient could receive, and substitution of utility values based on the incidence of AEs [adverse events] reported in the JMEN trial. The combined effect of these changes is to increase the incremental cost attributable to use of pemetrexed by 35% as well as reducing the incremental QALYs gained by 2%, so that the ICER increases from £33,732 to £47,239 per QALY gained.

TA19032

Fixing errors

Section 5.5.3: A continuity correction is applied to models where a quantity is estimated at fixed time points, but the entity of interest (e.g. cost or survival) is accrued over the period between the fixed points. Relying only on values at either of the fixed points defining an interval may lead to systematic over or under-estimation. . . . The correct approach is to use the area under the curve (AUC) from the trial analysis unaltered, and then calculate ‘mid-cycle’ corrected estimates for the remainder of the model duration derived from a parametric model. When this approach is applied to the manufacturer’s base case, the incremental utility gain is reduced by 3.5%, and the ICER correspondingly increased to £34,860 per QALY gained.

TA19032

Section 5.3.3: A minor error has been detected in calculating the proportion of patients assumed to receive docetaxel and erlotinib in second-line therapy. When this is corrected the ICER for the manufacturer’s base case rises slightly to £33,817 per QALY gained.

TA19032

Fixing violations

Addendum: Can an indication of the cost effectiveness of the first-line aripiprazole strategy compared with a first-line risperidone strategy be provided using the estimated costs for risperidone (for adolescent schizophrenia) and the manufacturer’s economic model? These issues were identified as important by NICE as risperidone is generally reported as the current standard first line treatment in adolescent schizophrenia, while the manufacturer’s economic model includes olanzapine as the main comparator (due to inadequacies in the evidence base, discussed in the MS [manufacturer’s submission] and the ERG report). Other comparators in the NICE scope were not modelled here. A limitation of this modelling is that data on risperidone is from one RCT [randomised controlled trial] only, not based on evidence from a systematic review.

TA21333 (e.g. failure to consider a key comparator in the scope)

Section 5.3.3: Post progression costs and utilities are calculated in the submitted model by apportioning the overall mean survival between maintenance, second-line CTX [chemotherapy], BSC [best supportive care] and terminal care phases. Since apportioning is carried out on the basis of discounted overall survival estimates, and the costs are then discounted again, the post progression costs are double discounted in the model. In addition, the estimation of QALYs relies on the same discounted survival values and were similarly double discounted, so that incremental utilities are also affected. The net consequence of correcting this error in the manufacturer’s base case is to increase incremental costs by a small amount (for BSC costs only), but to increase incremental QALYs by about 5.5%, so that the ICER falls to £32,091 per QALY gained.

TA19032 (a base-case error)

Sources of evidence

It was difficult to ascertain the exact proportion of exploratory analyses that sourced data and to identify those sources, but it was apparent that published literature, rather than the company or clinical experts, was the principal source of data used by the ERGs, where a particular source was specified. Extractors categorised particular sources of alternative data used for exploratory analyses in a total of 86 reports (Table 11).

| Source of data for exploratory analyses | Apparent sources of data for exploratory analyses (n = 86) |

|---|---|

| Literature | 69 (80%) |

| Manufacturer | 33 (38%) |

| Clinical advisors | 15 (17%) |

| Other | 41 (48%) |

| Unclear | 8 (9%) |

Factors that might influence or predict the presence of Evidence Review Group exploratory analyses

As noted above, this study aimed to test the possible influence of disease area, a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained and changes over time as the factors most likely to predict the presence and numbers of exploratory analyses.

Disease area

Only five disease areas were the subjects of seven or more STAs. In this group, the blood and immune system had the highest proportion of its STAs, with eight or more exploratory analyses (64%), and cancer, the indication with the highest number of STAs, had the lowest (38%). However, the numbers were generally too small to suggest that disease area might predict a higher than average number of exploratory analyses (Table 12).

| Disease area | Number of reports with exploratory analyses (%) (n = 93) | Number of reports with eight or more exploratory (%) analyses |

|---|---|---|

| Blood and immune system | 11 (12) | 7/11 (64) |

| Cancer | 40 (43) | 15/40 (38) |

| Cardiovascular | 9 (10) | 4/9 (40) |

| Central nervous system | 4 (4) | 2/4 (50) |

| Digestive system | 2 (2) | 0/2 (0) |

| Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic | 3 (4) | 1/3 (25) |

| Eye | 7 (8) | 4/7 (57) |

| Infectious diseases | 2 (2) | 1/2 (50) |

| Mental health | 2 (2) | 1/2 (50) |

| Musculoskeletal | 7 (8) | 4/7 (50) |

| Respiratory | 3 (3) | 0/3 (0) |

| Therapeutic procedures | 2 (2) | 1/2 (50) |

| Urogenital | 1 (1) | 0/1 (0) |

Company’s base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio and the cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained

Of the 93 companies’ submissions that attracted one or more exploratory analyses by an ERG, the proportion submitting base-case ICERs that were cost-effective at the threshold of £20,000 per QALY was almost the same as the proportion at or above this threshold. The likelihood of an ERG performing eight or more exploratory analyses was not affected by the ICER: the proportion of reports that did so was approximately the same (41% and 45%) (Table 13).

| ICER | Number of reports with one or more exploratory analyses |

|---|---|

| ≤ £20,000 per QALY gained | 44/93 (47%) |

| > £20,000 per QALY gained | 49/93 (53%) |

| Number of reports with eight or more exploratory analyses | |

| ≤ £20,000 per QALY gained | 18/44 (41%) |

| > £20,000 per QALY gained | 22/49 (45%) |

It is therefore the case that the presence of exploratory analyses, or of eight or more exploratory analyses, is not obviously predicted either by the disease area covered by the STA or by a company’s base-case ICER being less or more than the lower end of the cost-effectiveness threshold of < £20,000 per QALY.

Other factors that might determine the presence of exploratory analyses

The absence of exploratory analyses, or the presence of a relatively low number, could be caused by many factors. It could be that the submitted model was considered fit for purpose (e.g. TA267:22 ERG report, section 5.3, 122: ‘The ERG was satisfied with the estimates obtained from the manufacturer’s model. Moreover, the sensitivity and subgroup analyses carried out by the manufacturer provided sufficient assessment of any areas of uncertainty’). Equally, it could be caused by the submitted model being perceived to be flawed to such a degree that additional analyses using the model and its data were deemed to offer no value for decision-making (TA310:23 Section 6: ‘In view of the serious nature of the major issues identified by the ERG, no attempt has been made to quantify the combined effect on the ICER per QALY gained of correcting the minor issues identified below. The ERG takes the view that to do so would give misleading credibility to the manufacturer’s ICERs per QALY gained. Instead, the minor issues are described and the ERG’s preferred input values have been presented to allow comparison with those used by the manufacturer.’).

The proportion of ERG reports with eight or more analyses appears to be relatively stable over time (from 2011 to 2014 the proportion of these as a percentage of all STAs in 1 year was always between 38% and 45%), which suggests that there have not been any particular developments that appear to influence the frequency of exploratory analyses (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Single technology appraisals over time and proportions with eight or more exploratory analyses.

Relationship between clarification requests, Evidence Review Group critiques and exploratory analyses

After a company makes a submission, the ERG has only 2 weeks to read the submission and to request clarification or data from the company. The data presented here consider whether or not any of the exploratory analyses conducted by the ERG were specifically requested from the company but were not provided; were requested but could not be completed by the company for a particular reason; were based on data that were requested by the ERG in the clarification letter; or were ‘hinted at’ in the clarification process (Table 14).

| Clarification letter information | Proportion of clarification-letter-based analyses |

|---|---|

| Proportion of reports with exploratory analyses that performed at least one exploratory analysis that was covered in the clarification letter | 65/93 (70%) |

| Clarification letter-based analyses as a proportion of the total exploratory analyses within these 65 reports | 287/653 (44%) |

| Clarification letter-based analyses as a proportion of the total exploratory analyses within all 93 reports | 287/798 (36%) |

The relationship between an exploratory analysis and a request made in a clarification letter was rarely very clear and might consist of little more than an analysis on an issue raised in the letter, without being directly based on that request. It is clear, however, that, even with such possible indirect associations between requests and the ERGs’ exploratory analyses, the majority of exploratory analyses performed by ERGs (64%) were conducted for reasons other than the failure of the company to perform a specific, requested analysis; rather, because the ERG identified other issues with the model, including any which they had not had time to explore fully within the 2-week time frame for clarification.

It is also clear that almost every exploratory analysis performed was the result of an issue raised by an ERG in its specific critiques of the submitted economic evaluation, usually in the chapter of the ERG report preceding the section given over to the exploratory analyses. Examples of ERG reports that do not justify their exploratory analyses in this way are very rare. For example, in TA196,34 the exploratory analysis undertaken was to set the recurrence-free survival utility parameter equal to values of 0.95 and 0.90. This does not appear to be mentioned or hinted at in the ERG’s critical appraisal.

Appraisal Committees and additional analyses

The majority of STAs involved additional work being performed between the production of the ACD and the FAD. However, it was rare for the ACD to mention a request for an ERG to conduct further specific analyses or critical appraisal. Where this did occur, it usually took place before the ACD. For example:

ERG Addendum: SHTAC were requested to provide additional analyses for the STA of aripiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents (aged 15-17 years).

TA21333

ERG Addendum: This document provides further comment from the ERG regarding the indirect comparisons of erlotinib and gefitinib presented by the manufacturer in the MS [manufacturer’s submission]. It is provided in response to a NICE request arising from the pre-meeting briefing discussions.

TA25835

It was more often the case that the ACD would request additional work from a company. For example:

ACD, 4.10: The Committee concluded that it was difficult to establish the most plausible ICER for this treatment because sensitivity analyses to capture all preferred assumptions were not available. However, the Committee concluded that the ICER may be within the range that is consistent with an appropriate use of NHS resources. Therefore, because of these uncertainties, the Committee expects the manufacturer to respond to this appraisal consultation document by addressing the remaining uncertainties and by providing a revised cost-effectiveness analysis . . .

TA22636

ACD, 4.21: In summary, the Appraisal Committee could not assess whether gefitinib is a cost-effective treatment option because it did not have sufficient information to assess the most plausible ICER for gefitinib compared with standard platinum combination therapy or with pemetrexed and cisplatin. Therefore the Appraisal Committee is minded not to recommend gefitinb for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC [non-small-cell lung cancer]. It is recommending that clarification should be sought from the manufacturer, including analyses that use alternative survival extrapolations and application of hazard ratios, amended first-line chemotherapy costs and chemotherapy cycles, alternative prevalence rates of EGFR-TK [epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase] mutations and alternative assumptions about the cost of the EGFR-TK mutation tests.

TA19237

However, it was most often the case for there to be no specific request at all, but for a company to conduct additional work or resubmit with a PAS in response to a negative recommendation in the ACD (Table 15). It is often apparent in the FAD that this work was completed and also submitted for appraisal by the ERG or the NICE Decision Support Unit.

| Details of STAs with ACDs | Proportion satisfying criteria (%) |

|---|---|

| Proportion of STAs with additional work between the first ACDa and the FAD | 60/81 (71) |

| Proportion of these STAs with a no or minded no recommendation in the ACD | 58/60 (97) |

| Proportion of these STAs with an unspecified ICER in the ACD | 20/60 (33) |

| Proportion of these STAs with a preferred ICER ≥ £20,000 per QALY gained in the ACD | 38/60 (63) |

| Proportion of these STAs with a preferred ICER < £20,000 per QALY gained in the ACD | 2b/60 (3) |

However, it should be noted that 19 out of 100 STAs did not produce an ACD; in these instances a FAD was issued without the prior publication of an ACD. In all 19 of these FADs, the technology received a positive recommendation. In the vast majority of these STAs, the company’s ICER in its original submission was cost-effective at the threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained (15/19, 79%). These STAs also have a smaller proportion of ERG reports (32%) with eight or more exploratory analyses than does the sample as a whole (42%) (Table 16).

| Details of STAs without an ACD | Number of STAs (%) (n = 19) |

|---|---|

| Proportion of these STAs with a company ICER of ≤ £20,000 | 15 (79) |

| Proportion of these STAs with eight or more exploratory analyses | 6 (32) |

| Proportion of these STAs with a positive recommendation in the FAD | 19a (100) |

Table 17 shows the source of the ICERs preferred by the ACs as stated in the ACDs and FADs from the STAs included in this analysis. Often more than one preferred ICER was presented in the documents. The source of the preferred ICER was not always clear in the ACD and FAD. Of the 81 STAs with ACDs, for the majority of cases either there was no preferred ICER (38%) or the ICERs presented by the ERG were preferred by the AC (36%). In the 100 FADs, 27% of the preferred ICERs were from the ERG and 23% were from the company. The number of preferred ICERs including both company and ERG increased from 7 (9%) at the ACD to 17 (17%) at the FAD. It should be noted that in 7 of the 100 STAs no ERG exploratory analyses were undertaken.

| ERG | Company | Both ERG and company | No preferred ICER | Unclear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACD (n = 81) | ||||

| 29 (36%) | 9 (11%) | 7 (9%) | 31 (38%) | 5 (6%) |

| FAD (n = 100) | ||||

| 27 (27%) | 23 (23%) | 17 (17%) | 24 (24%) | 9 (9%) |

Influence of the exploratory analyses on Appraisal Committees’ considerations and recommendations

Of the 100 STAs, 76 had one or more exploratory analysis performed by the ERG and also had an ACD. In all but two of these STAs, the ACD made mention of at least one ERG exploratory analysis, and in a large majority (72%) at least one such analysis appeared to influence the ACD recommendation (Table 18).

| Type of recommendation | Number of reports (%) |

|---|---|

| ACD | |

| ACD mentions one or more exploratory analysis | 74/76 (97) |

| ACD recommendation is clearly influenced by one or more of the mentioned exploratory analyses | 55/76 (72) |

| FAD | |

| FAD mentions one or more exploratory analysis | 87/93 (94) |

| FAD recommendation is clearly influenced by one or more of the mentioned exploratory analyses | 44/93 (47) |

All 100 STAs produced a FAD and 93 also had at least one exploratory analysis. Eighty-seven of these 93 FADs (94%) mentioned one or more of the original exploratory analyses from the ERG reports, but only 47% of STAs had final recommendations that appeared to be influenced by at least one of the exploratory analyses.

A full list summary of the ACD and FAD decisions is given in Table 19. Technologies received positive recommendations in < 18% of ACDs but subsequently received positive recommendations in 72% of FADs.

| Decision | Number of reports (%) |

|---|---|

| ACD (n = 81) | |

| Recommended | 10 (13) |

| Optimised | 4 (5) |

| Minded no | 19 (23) |

| No | 48 (59) |

| FAD (n = 100) | |

| Recommended | 51 (51) |

| Optimised | 21 (21) |

| No | 28 (28) |

It is worthy of note that almost half (48%) of the STAs that had an ACD that reported a recommendation of no, only in research or minded no had moved to an outright recommendation or optimised recommendation in the FAD. Only one-third of STAs did not see a positive recommendation (Table 20).

| ACD to FAD recommendation | Number of reports (%) (n = 81) |

|---|---|

| No or minded no to recommended (including optimised) | 39 (48) |

| No change positive recommendation (including from optimised to full recommendation) | 14 (17) |

| No change negative recommendation | 28 (35) |

The ERG exploratory analyses apparently influenced the recommendation in a smaller proportion of FADs (47%) than ACDs (72%). This can be explained by taking into account the work conducted between the ACD and the FAD, reported in the section Appraisal Committees and additional analyses.

Patient Access Schemes

A total of 40 of the 100 STAs involved the submission of a PAS either as part of the original submission or after the first ACD. The influence of the PAS on the final recommendations, when submitted as part of the original appraisal, is unclear (Table 21). Almost half of companies that submitted a PAS did so from the start of the process (17/40). Seven of the submissions did not have an ACD and received a positive recommendation at the FAD. Of the remaining STAs, similar numbers received positive and negative recommendations in the FAD.

| Number of STAs with a PAS | Change from ACD no to FAD positive recommendation | Change from ACD minded no to FAD positive recommendation | No change positive recommendation (no ACD) | No change negative recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17/40 | 3/17 | 3/17 | 7/17 | 4/17 |

However, when a PAS was submitted after the production of the ACD, it led to a positive change in recommendation in 65% (15/23) of STAs (Table 22). This compares with 70% (7/10) when the PAS was submitted as part of the original submission. The likelihood of a final negative recommendation appeared to be slightly lower (24% vs. 35%) when a PAS was submitted as part of the original submission.

| Number of STAs with a PAS | Change from ACD no to FAD positive recommendation | Change from ACD minded no to FAD positive recommendation | No change negative recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23/40 | 11/23 | 4/23 | 8/23 |

It is apparent that the ERG exploratory analyses are highly influential in the ACD but are necessarily superseded by the additional work of companies and ERGs later, after the ACD, especially with a PAS. However, Table 18 also suggests that the recommendations of almost half of the FADs (44%) were apparently still influenced to some degree by one or more of the exploratory analyses performed by ERGs in the earlier stages of the appraisal process and the ACD comments and recommendation will naturally have influenced the FAD also.

A summary of decisions and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios

The perceived cost-effectiveness or otherwise of a technology is often considered to play a key role in decisions. For this reason, a summary of the ICERs submitted by companies, and the preferred ICERs of ACs, as outlined in the ACD and FAD, is tabulated below. It is apparent how many technologies appear to be cost-effective at a threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained in the original CSs (Table 23), and how few maintain that level of cost-effectiveness after appraisal and the production of the ACD.

| Company base-case ICER to ACD-preferred ICER | Number (%) of reports (n = 81) |

|---|---|

| No change (≤ £20,000) | 9 (11) |

| From ≤ £20,000 to > £20,000 | 4 (5) |

| From ≤ £20,000 to ‘no preferred’ or ‘no plausible ICER’ | 20 (25) |

| From ≥ £20,000 to ‘no preferred’ or ‘no plausible ICER’ | 13 (16) |

| No change (> £20,000) | 35 (43) |

The majority of ACDs record preferred or most plausible ICERs of > £20,000 per QALY gained or state that there is no plausible ICER owing to uncertainties within the evidence and model (Table 24).

| ACD finding | Number (%) of reports (n = 81) |

|---|---|

| With preferred ICER of ≤ £20,000 per QALY gained | 9 (11) |

| With preferred ICER of > £20,000 per QALY gained | 39 (48) |

| AC unable to specify a preferred ICER | 33 (41) |

By the production of the FAD, 37% of the STAs had achieved a preferred ICER at this level and 43% of the technologies were deemed to be cost-effective at a threshold of less than £30,000 per QALY (Table 25).

| FAD finding | Number of reports (n = 100) | Proportion (%) of recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| With preferred ICER of ≤ £20,000a | 37 | 37/37 (100) |

| With preferred ICER of £20,000–30,000 | 6 | 6/6 (100) |

| With preferred ICER of > £30,000 | 36 | 17/36 (47) |

| AC did not specify a preferred ICERb | 21 | 12/21 (57) |

All 43 STAs with a FAD-preferred ICER of < £30,000 per QALY gained received positive recommendations, as did a further 29 in which the FAD did not specify a preferred ICER or reported one that was > £30,000 per QALY, yet the technology was still considered a cost-effective use of NHS resources. Therefore, 40% (29/72) of recommendations were for technologies with an ICER that fell outside the perceived threshold of cost-effectiveness, and only 8 of these 29 took end-of-life criteria into account. However, it is noteworthy that 90% (19/21) of STAs that took into account end-of-life criteria (see Table 7) resulted in a FAD with an unspecified ICER or one in excess of £30,000 per QALY.

The ICERs preferred by ACs were, therefore, often higher than the base-case ICER submitted by a company, principally as a result of the exploratory analyses of an ERG. However, it is not the case that these ERG analyses always generated a single, higher ICER than that submitted by the company. The analyses would most often generate a number of different ICERs, with the aim of testing the findings of the submission and providing useful information for the committees based on different thresholds or scenarios. A typical example can be found in one STA, Dabigatran Etexilate for the Prevention of Stroke and Systemic Embolism in Atrial Fibrillation (TA249). 17 The CS reported a base-case ICER of £7940 per QALY for dabigatran 150 mg versus its principal comparator, warfarin. The ERG conducted 14 exploratory analyses generating a range of ICERs, including an ERG-preferred base-case ICER of £24,173 per QALY. The conclusion of the first AC was that the preferred ICER was between £6300 and £24,000 per QALY and the final decision was that the most plausible ICER was < £20,000 per QALY. The company’s ICER was, therefore, relevant and exploratory analyses generated the highest ICER, but the final decision was made based on consideration of the range of ICERs.

Chapter 4 Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Over 400 documents were analysed from the 100 STAs included in this analysis. The ERGs performed at least one exploratory analysis in 93% of all STAs (objective 1). An ERG’s judgement relating to perceived uncertainties or possible variation in the evidence base and model was the type of exploratory analysis appearing in the largest proportion of ERG reports (objective 2). Where alternative data for an exploratory analysis were identified, published literature such as trial evidence was the most frequent source (objective 3).

As demonstrated by the frequency, number and type of analyses performed, ERG exploratory analyses were not simply conducted to generate a single, alternative ICER, but rather presented a number of scenario analyses, presumably with the intention of allowing an AC to decide which ICER they preferred. The aim was to ensure that the AC had sufficient information in order to reach a decision. Where it was deemed that the company had not provided this, it was the ERG who was responsible for undertaking what they determined to be the most appropriate exploratory analyses. In essence, ERGs plug the gaps in the evidence. They play in important role in reducing the uncertainty associated with the AC decision-making process through their critical appraisal of the CS and undertaking exploratory analyses. Not only do they test the company model, they aim to anticipate what information the AC will need in order to make their decisions.

The incidence and frequency of ERG exploratory analyses do not appear to be related to any developments in the process between 2009 and 2014, the disease area covered by the STA or the company’s base-case ICER. There is no clear pattern to the presence or frequency of these analyses, although there does appear to be a pattern in the mean number of analyses by ERG (objective 4). However, this association has not been tested in a regression analysis to confirm whether or not the ERG centre is an independent predictor of the number and extent of exploratory analyses. It might be affected by many variables, such as disease area and year, as well as the complexity and perceived quality of CSs. Therefore, this finding should be interpreted with caution and more research is needed to determine the relationship between ERG and the number and extent of exploratory analyses. The number of exploratory analyses undertaken may also vary according to the skills, experience and judgments of the ERGs and that of individuals within the ERGs. This issue was not explored within this study.

The numbers of STAs undertaken by individual companies was small. Companies do not always produce their submissions ‘in-house’ and may commission health economics consultancy organisations to produce their submissions. This issue was not addressed in this study.

Fewer than half of the exploratory analyses were requested or hinted at in the clarification letters submitted to companies (objective 5). This may be because of the clarification letter being submitted so early on in the process that the ERG had not had time to develop a full understanding of the model and what information may be needed. However, it was rare for an exploratory analysis not to be justified in a preceding chapter of the ERG report in the critique of the submitted model.

For the majority (71%) of STAs, additional work was submitted by the company and ERG between the ACD and the FAD. The ACD for almost all (97%) of these particular STAs made a ‘no’ or ‘minded no’ recommendation (objective 6). Approximately one-fifth of STAs did not produce an ACD; a large majority of these STAs had a company ICER that was cost-effective at the threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained and all received a positive recommendation in the FAD and required fewer exploratory analyses than the sample as a whole.

At least one of the exploratory analyses conducted and reported by an ERG is mentioned in 97% of ACDs and had a clear influence on more than two-thirds of ACD recommendations. The influence of these exploratory analyses is reduced in the FAD, although they still had a direct influence on the final recommendations in almost half of STAs. The preferred ICERs reported in ACDs were 36% from ERGs, 11% from companies and 9% from both. This changed at the FAD, where the preferred ICERs were 27% from ERGs, 23% from companies and 17% from both. The findings of work conducted by the company and ERG between the ACD and the FAD appear to reduce the influence of the original ERG exploratory analyses on the final recommendation, although the original analyses help to shape the ACs preferred assumptions and inform further work (objective 7).

It cannot be assumed that the number of exploratory analyses is an indicator of the quality of a CS. As stated above, with reference to STAs with no such analyses, this absence might be as a result of a model being deemed by the ERG to be of either very good quality or very poor quality. If a model is considered to be of very poor quality, the ERG may decide that it is pointless to undertake any exploratory analyses at all. The type of analysis is more informative regarding quality. Analyses that are categorised as matters of judgement might indicate an ERG exploring multiple scenarios relevant to an otherwise essentially sound model and submission. This represented the principal type of analysis in this sample of STAs: 89% of ERG reports with analyses contained at least one such analysis (see Table 10). However, if the ERG is conducting analyses to fix errors or violations then this suggests that there were issues with the perceived quality of the submitted model. In this sample, ERGs conducted at least one such analysis, respectively, in 35% and 18% of STAs.

Strengths and limitations of the assessment

A strength of this research is that this was an analysis of the most recent 100 STAs, which offers a good summary of current and recent practice. The development of a simple coding scheme, the extensive piloting of the data extraction tool and the double-checking of all key data across the 100 STAs by at least two experienced cost-effectiveness modellers reduced the likelihood of inconsistency and inaccuracy in the data. In addition, the method of synthesis was principally descriptive, which reduces the likelihood of overstating relationships in the data, and a reductive approach was taken to managing data that might be affected by interpretation or by poor reporting in the original documents.

There are, however, some limitations in this research. The descriptions of analyses undertaken were often highly specific to a particular STA and could be inconsistent across ERG reports and, thus, difficult to interpret. The source of ICERs cited in ACDs and FADs could also be unclear or open to interpretation. There are inherent weaknesses in using documentary analysis in that the researcher is able to analyse only what has been reported. The level and type of detail provided in and across the ERG reports and clarification letters could be very different, which made data extraction time-consuming, difficult and, at times, a matter of interpretation. Documents varied greatly in their description of analysis and the level of detail presented. Despite efforts to simplify the data extraction and coding process, data extractors sometimes had to exercise interpretation for some data. It was often difficult to understand from the documents alone the decision-making process that was being undertaken. In addition, the data did not permit a deeper exploration of the nuances and complexities within the types of analyses (e.g. using the fields types of models and nature of the implementation of the exploratory analysis, including data sources).

Data extraction was undertaken by only two research teams, who between them had undertaken nearly one-third of the STAs. Although this introduced a potential source of bias, it was overcome to some extent by having neither team extract data from their own reports. In addition, the inside knowledge obtained from working on so many STAs was crucially important in interpreting the data.

It was not possible to report reliably exactly what proportion of the 100s of exploratory analyses was actually mentioned in ACDs or FADs, or influenced their recommendations, and so this has been reduced simply to whether ‘one or more’ exploratory analyses were mentioned or had an influence in any particular STA. When grouping reports by disease area or ICER or numbers of exploratory analyses, the numbers were too small to evaluate relationships in the data using basic statistical tests in a meaningful manner. Further exploration, for example by assessing more STAs, might be able to determine whether or not disease area is a predictor not only of the number of analyses but also of the type of analysis undertaken. These limitations suggest that only cautious conclusions should be drawn from the evidence, especially concerning the generalisability of any findings.

Chapter 5 Recommendations

From the available evidence, it is not possible to specify the most useful type of ERG exploratory analysis, or the optimal number of analyses, for any particular STA, so ERGs can only continue to follow current approaches, unless there are changes to the time frame or quality and breadth of the models submitted by companies. It is important to recognise that exploratory analyses introduce greater transparency into the evidence presented to the AC, providing a range of options from which the Committee can decide which judgements it considers most reasonable. As such, the inclusion of exploratory analyses in the STA process must be encouraged.

Any recommendations generated from this research are best developed in conjunction with all key stakeholders including companies, NICE and the ERGs. The following are suggested recommendations for consideration:

-

The ERGs spend a considerable amount of time identifying errors, inconsistencies and testing assumptions in company models. In some instances the company provides verification of the model already. However, where this is not the case, companies may wish to further explore the value of additional peer review processes to identify such errors before submission.

-

Unequivocal errors in the CS could be listed and dealt with in a separate section of the ERG report, distinct from other exploratory analyses undertaken by the ERG. The results from the correction of these errors and no other changes could be presented in this section. If possible, these can be rechecked by the company and agreement reached on the correct company ICER.

-

Where possible, companies should be asked at clarification letter stage to undertake exploratory analyses identified as potentially important by the ERG and NICE at this early stage. However, the ERG would still be required to undertake further exploratory analyses that are identified after the clarification letter stage.

-

We recommend that a common terminology be used to describe the types of issues identified within STA models and to describe the types of exploratory analyses undertaken by the ERGs. The taxonomy used in this report may provide a useful starting point for ensuring consistency in the use of such terminology.

Chapter 6 Conclusions

Implications for service provision

The exploratory analyses undertaken by the ERGs appear to plug some of the gaps in the evidence received from CSs, reduce uncertainty and support AC decision-making. They frequently influence both ACD and FAD recommendations. Therefore, the use of ERG reports in the STA process appears to be highly effective, in that all relevant information needed to reduce uncertainty is presented to the AC in a timely and transparent manner, although the process can be resource- and time-intensive. It is often only by the ERGs undertaking exploratory analyses that uncertainties in the evidence base are addressed and ACs have enough evidence to make decisions on technologies. The number and extent of exploratory analyses undertaken appear to be consistent over time and across disease areas. ERGs frequently conduct exploratory analyses to test or use more appropriate parameters in the economic evaluations submitted by companies as part of the STA process. ERG analyses are often highly influential in the first recommendations of ACs. Their influence might then be superseded by later work (though they necessarily do indirectly impact on the work conducted between an ACD and a FAD), but might still have an influence on a recommendation in as many as half of all FADs. The provision of a longer period of reflection for ERGs to identify all the possible issues or uncertainties with submitted evaluations might permit the development of more comprehensive clarification letters and allow companies to perform more of the required additional analyses.

Suggested research priorities

Future research priorities include:

-

Undertaking a more in-depth analysis of how ERGs make decisions regarding which exploratory analyses should be undertaken. This could take the form of a prospective qualitative study of a limited number of STAs.

-

Qualitative research with ACs members to determine when and which type of exploratory analyses are most useful in their decision-making so that energies can be focused on these analyses.

-

In-depth analysis of the category of ‘matters of judgement’. This could be done by prospectively categorising the nature of the implementation of any exploratory analysis and the data sources used, for example whether an analysis was based on different but equally valid assumptions or different but equally valid sources of data. More in-depth analysis could be undertaken to explore how the presence and extent of the exploratory analyses may vary according to the skills, experience and judgments of the ERGs.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to our project advisors for providing support and advice for this report:

-

Nwamaka Umeweni, Technical Adviser, TAs, NICE

-

Meindert Boysen, Programme Director, Technology Appraisals, PAS Liaison Unit and Highly Specialised Technologies.

We would like to thank the following for reviewing the draft report:

-

Dr Hazel Squires (Senior Research Fellow), ScHARR, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

-

Professor Rumona Dickson (Professor of Health Services Research), LRiG, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.

Thanks also to Gill Rooney (ScHARR, University of Sheffield) for providing project management and administration support.

Contributions of authors

Eva Kaltenthaler led the project, developed the protocol and undertook data extraction.

Christopher Carroll developed the protocol and undertook data extraction and data analysis.

Daniel Hill-McManus undertook data extraction and data checking.

Alison Scope developed the protocol and undertook data extraction.

Michael Holmes developed the protocol and undertook data extraction.

Stephen Rice developed the protocol and undertook data extraction and data checking.

Micah Rose developed the protocol and undertook data extraction and data checking.

Paul Tappenden developed the protocol and undertook data checking.

Nerys Woolacott developed the protocol.

All members of the project team contributed to the writing of the report.

Data sharing statement

Non-confidential data used in this report can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Kaltenthaler E, Tappenden P, Booth A, Akehurst R. Comparing methods for full versus single technology appraisal: a case study of docetaxel and paclitaxel for early breast cancer. Health Policy 2008;87:389-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.02.007.

- Kaltenthaler E, Papaioannou D, Boland A, Dickson R. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence single technology appraisal process: lessons from the first 4 years. Value Health 2011;14:1158-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.007.

- Ford JA, Waugh N, Sharma P, Sculpher M, Walker A. NICE guidance: a comparative study of the introduction of the single technology appraisal process and comparison with guidance from Scottish Medicines Consortium. BMJ Open 2012;2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000671.

- Barham L. Single technology appraisals by NICE: are they delivering faster guidance to the NHS?. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:1037-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/0019053-200826120-00006.

- Casson SG, Ruiz FJ, Miners A. How long has NICE taken to produce Technology Appraisal guidance? A retrospective study to estimate predictors of time to guidance. BMJ Open 2013;3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001870.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guide to the Processes of Technology Appraisal 2014. www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg19/chapter/foreword (accessed 4 August 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal 2013 2013. www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf (accessed 4 August 2015).

- Wong R, Paisley S, Carroll C. Assessing searches in NICE single technology appraisals: practice and checklist. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2013;29:315-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0266462313000330.

- Kaltenthaler E, Boland A, Carroll C, Dickson R, Fitzgerald P, Papaioannou D. Evidence Review Group approaches to the critical appraisal of manufacturer submissions for the NICE STA process: a mapping study and thematic analysis. Health Technol Assess 2011;15. http://dx.doi.org/10.3310/hta15220.

- Carroll C, Kaltenthaler E, Fitzgerald P, Boland A, Dickson R. A thematic analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of manufacturers’ submissions to the NICE Single Technology Assessment (STA) process. Health Policy 2011;102:136-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.06.002.

- Kaltenthaler EC, Dickson R, Boland A, Carroll C, Fitzgerald P, Papaioannou D, et al. A qualitative study of manufacturers’ submissions to the UK NICE single technology appraisal process. BMJ Open 2012;2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000562.

- Longworth L, Youn J, Bojke L, Palmer S, Griffin S, Spackman E, et al. When does NICE recommend the use of health technologies within a programme of evidence development? A systematic review of NICE guidance. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:137-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40273-012-0013-6.

- National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre . HTA Reference No. 14 151 04 Exploratory Analyses in the NICE STA Process n.d. www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/130181/PRO-14-151-04.pdf (accessed 4 August 2015).

- Appleton JV, Cowley S. Analysing clinical practice guidelines. A method of documentary analysis. J Adv Nurs 1997;25:1008-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251008.x.

- Tappenden P, Chilcott JB. Avoiding and identifying errors and other threats to the credibility of health economic models. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:967-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0186-2.