Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/70/01. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The draft report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Joanne Lord is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Nyssen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Therapeutic writing

Writing as a form of therapy to improve physical or mental health has a long history1 and is widely reported in psychology textbooks as being of therapeutic value. 2–5 It can take many formats including those from a psychotherapeutic background, such as therapeutic letter writing,6 specific controlled interventions, such as emotional disclosure/expressive writing,7 to more recent approaches, such as developmental creative writing8 and other epistolary approaches, such as blogging. 8 With the development of UK organisations such as Lapidus (Association for Literary Arts in Personal Development), dedicated to the promotion of therapeutic writing (TW) based on the premise that it has health benefits, and an increased interest in the potential of non-pharmacological adjunctive therapies, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of a variety of different approaches within this field. These include two main categories: written emotional disclosure [or emotional writing (EW)]9 and creative writing, such as poetry. 7 Other forms of creative writing include alpha writes/poems (a poetic device in which each successive line of the poem starts with the next letter of the alphabet, or a predetermined word or phrase written vertically down the page);10 writing from published poems/narratives; acrostics; and haiku poems (traditionally a haiku contains three lines of five, seven and then five syllables, making a total of 17 syllables; the tradition is modified so that no more than 17 syllables are arranged in no more than three lines, but the shorter the better);11 autobiographical writing (such as reflective diaries, journaling); descriptive writing; genre writing (e.g. fairy tales); free writing; short stories; drama or fictional narratives; unsent letters; diary/journaling; collaborative writing (workshops); writing accompanying other art forms; life writing or memoirs (such as reminiscence, life review); list writing; redrafting or sentence stems writing; scribing for others; writing from visual/sound stimuli (e.g. writing from mindfulness); writing from the senses; and writing in form and writing from music (as part of a music therapy). 10,12 Newer forms of writing include blogging or participating in web-based forums. 13,14

Dimensions of therapeutic writing

Within each type of TW there may be significant process variability, for example in the flexibility and number of topics; the dose (frequency and duration); group or individual delivery; computerised compared with handwritten exercises; participant recruitment; and financial compensation. However, a major distinction lies in whether the writing is facilitated or unfacilitated.

Facilitated therapeutic writing

Facilitated TW interventions, when a facilitator is present at some stage before or during the writing, might be delivered in many different ways and contexts: in a health-care centre, as part of a programme in a rehabilitation clinic or within a group of people with common or different chronic conditions, face to face or via the internet. People using these therapeutic tools may receive feedback from someone else, a health-care professional, a group of persons or not receive feedback at all. 10

Furthermore, the topic of the writing can be varied, from positive to negative expression of emotions through neutral topics (e.g. childhood/birth, life aims and goals, places, relationships). 10 TW can also be used in children, adolescents or adults and among different clients, such as the chronically ill (e.g. cancer, mental health problems, chronic infections) or healthy individuals, and assessed from different angles such as community carers, doctors and nurses, peer training, patient’s family and/or friends or the participant him/herself – the most usual perspective. 10

The writing event should not be considered as solely an isolated exercise but as a sequence of exercises, not necessarily all of which encompass a written component. As such, a common practice is that writing starts with (visual) stimuli12 or with mindfulness meditation in order to inspire people and to act as a form of distraction from reality. 15 The following examples of the work of facilitated writing practitioners in the UK exemplify the variety of this type of TW (Box 1).

Writing practitioner Carol Ross (CR) facilitates weekly TW groups for inpatients in mental health units in a UK NHS Foundation Trust. CR has developed her own practice, influenced by a number of published research studies, e.g. on positive writing; and by established therapies such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and narrative therapy.

A typical session lasts 60 minutes, attended by one to seven self-referred inpatients, and comprising 25 minutes of writing interventions (duration 5–15 minutes each) and 25 minutes of reading aloud and group discussion, with the remaining time being taken up with introductions, explanations and evaluation forms. Flexible writing interventions are used to allow tailoring of interventions for individuals and give patients some freedom to choose what they write. The writing practitioner writes and reads aloud what they have written with the group.

Many of the writing interventions CR uses in acute mental health settings, e.g. mindful writing, are aimed at calming the individual, decreasing anxiety, increasing mental focus and lifting mood. With some writing interventions, another effect is intended, e.g. broadening of cognitive focus, reframing, insight, improved self-expression.

CR’s TW toolbox includes mindful writing with either an external or internal focus; positive writing about the past, present and future; perspective shift writing, including unsent letters; and responding to published poems. The broadest range of TW is used in the general adult ward. In the older people’s assessment unit, some interventions are designed to trigger positive/neutral memories in a low pressure way (see Appendix 1, Table 75, illustrating the types of TW interventions used by CR).

In the PICU, the sessions are typically one to one or one to two, with individuals experiencing acute symptoms, e.g. of psychosis or mania. The PICU writing group is held in an open area so that patients who decline to do any writing, or even sit at the table, still sometimes take part in a brief conversation with the practitioner or other patients, and look at whatever prompt materials are on display, e.g. photographs or objects. Data from an internal audit suggest that the writing group contributes to a reduction in violent incidents in the PICU.

It will be seen that the practice described differs markedly from the unfacilitated EW method described by Pennebaker and Beall1 (see section below on EW), e.g. writing interventions are facilitated and take place in a group. Patients are also never directed to write about trauma.

Poetry therapy for people with mild mental health problems: Victoria FieldPoetry therapy practitioner Victoria Field (VF) facilitates a weekly Words for Wellbeing group in the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge in Canterbury (part of Kent Library Service), aimed at people with mild mental health problems, often as a result of LTCs. She ran a similar group for some years at Falmouth Health Centre, with referrals from GPs. VF qualified in 2005 as a Certified Poetry Therapist, with the NFBPT, which works with the therapeutic potential of both the receptive (reading and listening) and expressive (writing and sharing) aspects of writing. The practice can be adapted for individuals and non-writers but is always interactive for reasons outlined. 16 She is now approved as a Provisional Mentor–Supervisor for the NFBPT, training others in these techniques. The aims of the group are closely aligned with the NHS Wellbeing agenda. 17 A typical session lasts 2 hours, including a break, attended by anything from 2 to 18 people. An ideal group size is around 10, fewer when participants are more unwell or distressed. The group follows a set format, and this predictability is valued by attendees:

-

Reflective writing This is the activity closest to a written emotional disclosure type of intervention as described by Pennebaker and Beall. 1 However, it is firmly contained. Participants are invited to write for 6 minutes or so from a given prompt. This might be as simple as ‘I can see’ or ‘Here now’, or more elaborated, such as a list of statements, ‘Then I was, now I am’ or working with a metaphor, e.g. a colour or weather ‘Today I am’ or ‘Red is . . .’ This initial writing is intended to be private, although participants are invited to talk about what might have come up, and sometimes some wish to read.

-

The reading aloud of a poem Not necessarily literary, which VF has chosen for that week, followed by discussion of what it suggests.

-

Writing in response to the poem Again for a short period of 6/7 minutes, typically from a choice of prompts. The writing that emerges is often fully formed, powerful, satisfying to the writer and helpful for the listeners.

Writing and reading in this way offers a container for complex emotions, catharsis, pleasure, connection, validation, self-expression and mastery that may improve mood, decrease anxiety, allow reframing, insight and encourage a more nuanced approach to life. The group dynamic is also a powerful therapeutic tool (see Appendix 1, outlining VF’s professional perspective).

Write to life at Freedom from Torture: Sheila HaymanSheila Hayman is a member of Lapidus, and has run creative and therapeutic workshops for elderly day-care patients, detention centre visitors, children and the general public. However, her main work for the past 11 years has been with Write to Life, a unique therapeutic creative writing programme based at, and funded by, Freedom from Torture, the UK’s only national charity dedicated to the support and rehabilitation of torture survivors from around the world.

In 12 years, the group has grown to about 20 members, of whom a dozen regularly attend bi-weekly group workshops and individual one-to-one sessions. Members are referred, while still in clinical treatment, by the clinical key worker, and while they remain in treatment the group works closely with the clinician. However, as the group is open-ended, clients can stay as long as they like, and there are members who have been with the group for 6 years or more. This enables them to make huge strides in what they can achieve.

When they arrive, many are still very traumatised, unable to trust others or communicate freely, unable to talk about their past or present experiences or make friends. Over time, they make friends inside and outside the group, begin to enjoy not just writing but performing their work, and are enabled to address large gatherings of all sorts about the effects of torture, asylum and other aspects of their situation, as well as perform in public in plays and other events. They report improved sleep, reduced headaches and other sorts of pain, and most of all the reduction or even elimination of the flashbacks, nightmares and other symptoms of their post-traumatic condition.

The writing falls into two parts: the first is the public setting of the group, which is run by a group of volunteers who are professional writers rather than clinicians. This group writing sometimes focuses on matters of interest to the client base, such as journeys, poverty, or trust, but equally could be an exercise in literary criticism, or an invitation to reflect on living in London. It usually takes the form of a short exercise and discussion, followed by a longer piece of writing which members are invited to read out. Everybody has to write, but not everybody has to read out, as sometimes they find that the subject has unearthed things they prefer to keep private.

It is noticeable that the framework, often quite unguided as to the form of writing, enables group members to dig as deeply into their feelings, including bad ones, as they wish. Some people will always find a way of writing about the source of their pain, no matter how the exercise is framed. And that is how it should be. Others may want to be more structured, or literary, or metaphorical.

The strong feelings, and the personal exploration and laying of ghosts, are dealt with in the one-to-one element of the work. Usually, on the same day as the workshop, and purely for practicality, each group member is offered one-to-one sessions with one of the six writer/mentors. This is an opportunity to write about whatever they choose, and to dig as deeply as they wish into their past or present trauma. This writing may remain private, or be published, as they choose. Leaving the level of introspection up to them gives much more sense of control and safety, as reported by more than one group member, compared with their clinical therapy sessions, which may leave them distressed when they need to be okay for a meeting, or may make them jump with unexpected reactions.

Sometimes the writing seems to gloss over, or miss out, a crucial painful moment or event, and on these occasions the mentor, in consultation with the writer, may guide them to look again at that portion of the writing and fill in the missing emotion. This is why it’s important to collaborate with a clinician, at least in the early stages when clients are still raw and vulnerable. But in practice, our work, and, by their own account, that of our clinical colleagues, is often guided as much by instinct, common sense and experience, as any theory or training.

Perhaps the last thing to add is that clinicians at Freedom from Torture continue to send more clients than can be coped with, which is some vindication of the practice. As a bridge between intense therapy and the outside world, giving clients a skill they can take with them and a means of self-discovery, self-healing and personal growth, it seems, as the Hippocratic Oath puts it, to do no harm, and a great deal of good.

Unfacilitated emotional writing

Unfacilitated EW means writing, completed without any assistance, feedback, comment or any other form of support. Therefore, in the current review, an unfacilitated writing intervention has been defined as when a facilitator was simply not present in person during the writing exercise, as opposed to facilitated writing (described above). Typically, in unfacilitated writing interventions, participants are instructed to write for 15–30 minutes on 3 to 4 consecutive days (or at weekly intervals). Instructions on these unfacilitated writing assignments can be delivered in writing via leaflets, verbally over the telephone or even via video or the internet. Participants are asked to do their writing unassisted and alone at home or on their own in a given clinic or laboratory setting. In the most commonly evaluated form of unfacilitated EW, there is a single writing topic that can be chosen (usually disease or treatment focused), for which participants are directed to write emotionally and disclose about their deepest thoughts and feelings or about a self-selected trauma. Thereafter, either the writings may be collected by the practitioner without any feedback or the participant can simply decide what to do with the writing. Sometimes, practitioners provide participants the option to make telephone calls during the writing exercise should any concerns emerge; however, this action has not been considered as facilitation in this review.

The Pennebaker writing paradigm: expressive writing or written emotional disclosure

This is the most common form of unfacilitated EW. It is a technique whereby people are encouraged to write (or talk into a tape recorder) in private about a traumatic, stressful or upsetting event, usually from their recent or distant past. They write for 15–30 minutes typically for 3 or 4 days within a relatively short period of time, such as on consecutive days or within 2 weeks. The format has been relatively consistent since the earliest randomised controlled trials (RCTs),1,18 but more recent studies have varied the duration, number of sessions and topic of writing, including positive events and thoughts and feelings about illnesses. 19 RCTs of expressive/emotional writing have been conducted in a wide variety of participants, including healthy students, people undergoing psychological stressors, such as bereavement or being in a caregiving role, or in people with long-term physical conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and asthma. Variants of the technique include disclosure in front of a listener, who can be a confederate, a researcher or a doctor. For the purposes of this project, these activities are not considered to be EW and lie outside the scope of this review. The presence of a listener is likely to affect outcomes, as it potentially adds a counselling dimension.

Positive writing

Positive writing can be delivered either as part of a facilitated TW or unfacilitated EW intervention. The exercise involves writing about positive topics only, including positive emotions, typically for 20–30 minutes, three or four times per week if delivered as an unfacilitated EW intervention. Otherwise, the duration and length of the positive writing can be very varied when facilitated (see Appendix 1). Pennebaker et al. 19 found in a review published in 1997 that the description of positive emotions could predict improvements in health outcomes. Since then, researchers have studied the positive effects of the positive emotional disclosure, advocating that participants writing about the positive aspects of past traumas (benefit finding by describing any positive outcomes of the disease experience or treatment in detail) or simply about positive life events, could achieve comparable health improvements as those writing about past traumas. 20

Bibliotherapy

Although the above require the individual to write as part of therapy, other forms of therapy use existing texts. The most commonly encountered type of bibliotherapy, Reading Bibliotherapy, involves reading material specifically selected for its therapeutic potential for that person. 21 In the UK, Books on Prescription Schemes have been running in primary care for several years, and in 2013 a national scheme was launched in England by the Society of Chief Librarians and the Reading Agency. 22 Such reading bibliotherapy is not covered by this review.

In contrast, interactive bibliotherapy has been defined as the use of literature to bring about a therapeutic interaction between participant and facilitator. 21 The triad of participant, literature and therapist is viewed as critical. In fact, interactive bibliotherapy does not restrict itself to the written word: it can include the spoken word, for example in film or theatre but it must involve the coherent use of language. When interactive bibliotherapy uses poetry, it is synonymous with poetry therapy and they are both encompassed by the term biblio/poetry therapy. 21 Sometimes the literature involved in biblio/poetry therapy is new writing generated by the participants themselves. This type of creative writing biblio/poetry therapy is the principal form of facilitated TW included in this review and it is the form of TW used by the practitioner experts collaborating in the current systematic reviews (see Box 1, in which the TW expert practitioners describe their different facilitated biblio/poetry therapy practices).

Nonetheless, little has been published around all the different types of facilitated TW, and literature shows that the most evaluated form of TW is the EW intervention, described by Pennebaker and Beall1 Comprehensive research around the writing paradigm18,23–27 and narrative analysis within the health-care setting28–31 has been performed through the last decades.

Long-term conditions

The prevalence of long-term conditions (LTCs) increases with ageing populations. In 2002, the leading chronic diseases [cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes] were responsible for 29 million deaths worldwide. 32 According to the UK Department of Health (DH),33 more than 15 million people in England (including half of all those aged > 60 years) are living with at least one LTC, and the risk of death is particularly high in those with three or more conditions occurring concurrently. 34 LTCs also result in a huge burden on UK NHS resources. Although some are preventable, for most LTCs the only realistic management strategy is continuing care, as biological and psychosocial mechanisms regulating disease progression are not yet fully understood. As LTCs are difficult to improve, especially for elderly populations, health-care programmes, such as self-management support and patient education, often combined with structured clinical follow-up, have been suggested as a way to improve the quality of life (QoL) of such patients. 35 New therapeutic approaches, such as TW, have the potential to improve the QoL in people with LTCs.

Possible pathways linking memory, emotions and physical health

There are several potential ways that writing might impact on physical health. For example, cognitive restructuring or behavioural mechanisms (e.g. reflection on health behaviours) may lead to improvement in outcomes. However, many of the types of TW described above engage emotions and memories (both positive or negative) and there are physiological pathways linking memory, emotions, chronic stress and physical health.

Two interdependent memory systems are thought to be associated with remembering events in humans. 36 Episodic memory is linked to the hippocampus and this structure is vital for processing events that eventually become long-term memories. 37 Emotional memory is linked to the amygdala, part of the limbic system involved with emotions, in particular fear-related responses and general pleasant and unpleasant emotional processing. 38 Although the episodic and emotional memory systems are independent, they affect each other in a variety of ways. 36 Emotion enhances perception of, and attention to, the memory-provoking stimulus, as well as the long-term storage of the memory. 36 Episodic memory also influences emotional memory by, for example, causing the autonomic effects of emotional arousal (e.g. the sweaty palms and dry mouth) when remembering a past situation. 36

The limbic system has links with the cerebral cortex, the brainstem and the pituitary gland (part of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis). Parts of the cerebral cortex have a role in cognitive appraisal and the conscious awareness of emotional states, and can regulate amygdalar activity. 38 Through the brainstem, areas in the limbic system can control many internal conditions of the body, for example cardiovascular regulation. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is both responsive to psychological inputs and has significant influences on the immune system, which, in turn, influences physical health. 39 This pathway may be one of the ways chronic stress is linked to poor health. 39–42 It is therefore possible that a psychological intervention might improve aspects of physical health, and if modification of such pathways had even a small effect then this could have profound public health significance.

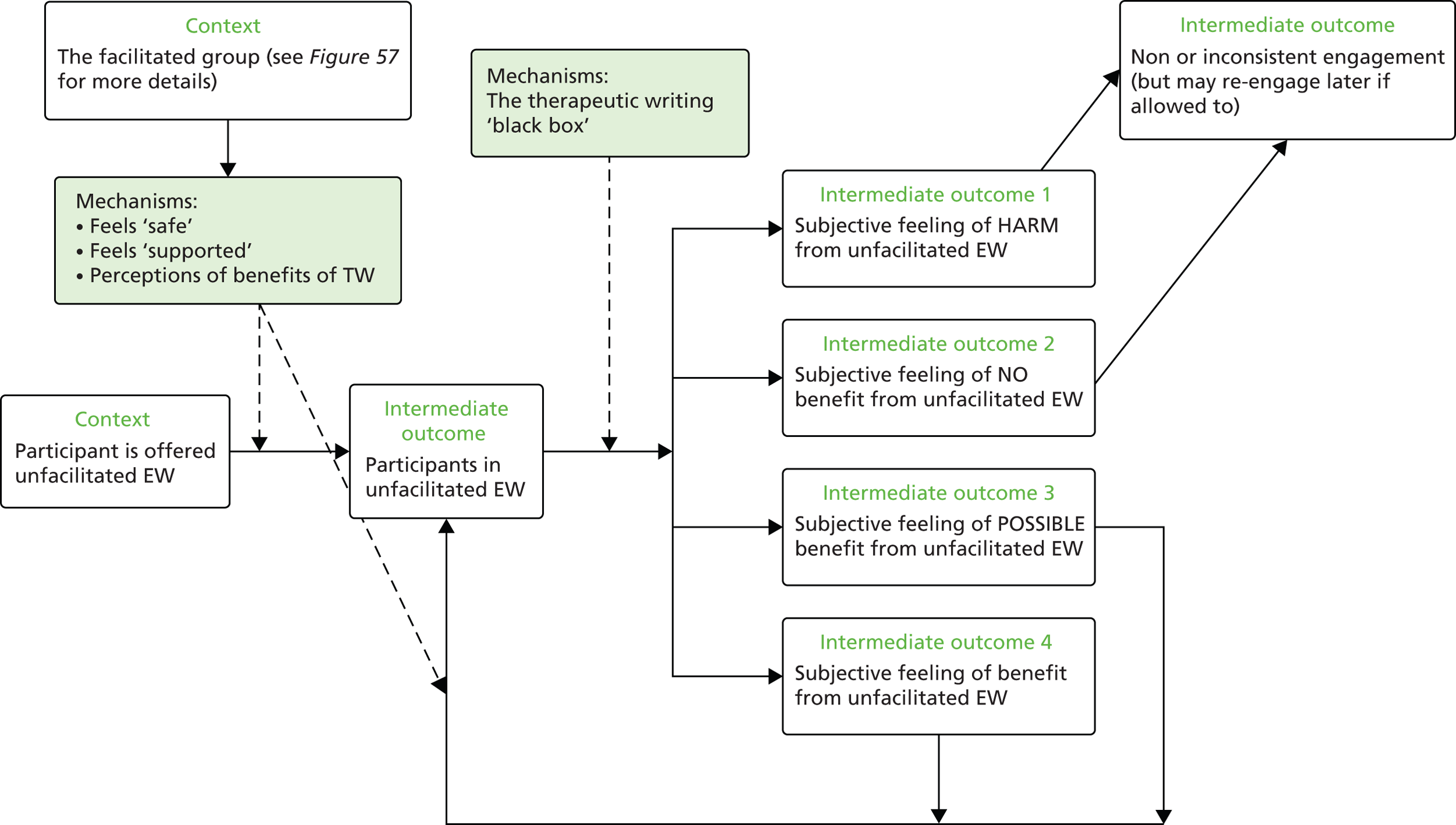

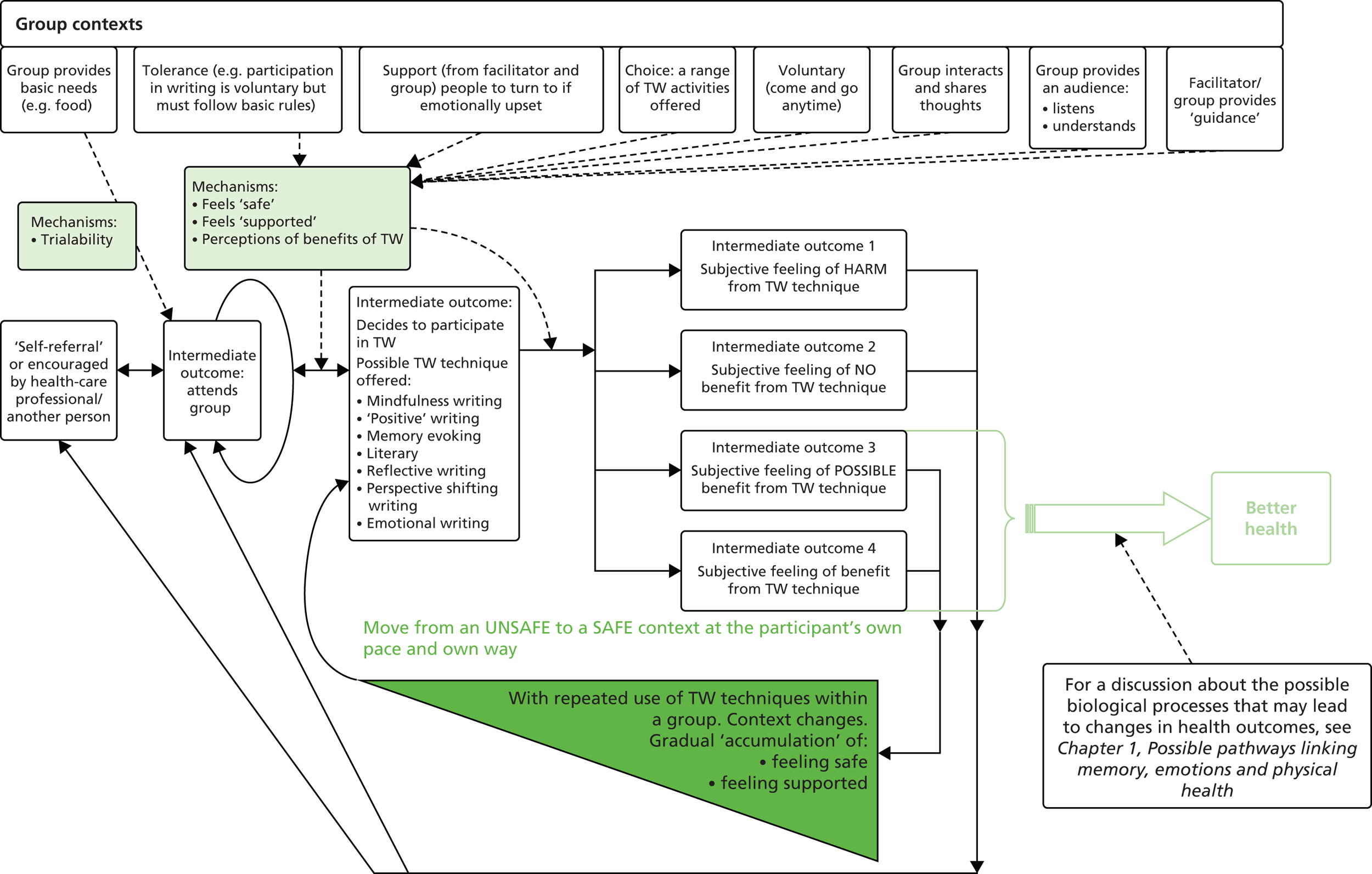

Realist synthesis

In this review, a conventional systematic review of the effectiveness of unfacilitated EW and facilitated TW was conducted, but, in addition, the findings of a realist synthesis are reported. Realist synthesis is a theory-driven interpretive approach to evidence synthesis. Rather than producing a judgement on whether (or not) an intervention works, realist syntheses attempt to explain outcome patterns in data using theory (or theories). It is particularly useful when interventions are complex and evidence is mixed or conflicting and provides little or no clues as to why the intervention worked or did not work when used in different contexts, by different stakeholders or when used for different purposes. 43

In brief, realist syntheses ask what works for whom in what circumstances, how and why? To do so, realist syntheses use a particular logic of analysis that deliberately breaks down how an outcome has arisen. An outcome is considered to have occurred because it is caused to do so by a causal process known as a mechanism. In addition, the contexts in which an outcome has occurred are also considered to be important as they cause mechanisms to be activated. This logic of analysis thus provides an approach for understanding how and why it is that context can influence outcomes. In summary, the realist logic of analysis used in a realist synthesis considers the interaction between context, mechanism and outcome (sometimes abbreviated as CMO). That is how particular contexts have triggered (or, conversely, interfered with) mechanisms to generate the observed outcomes. 43

To elaborate further, in order to understand how outcomes are generated, the roles of both external reality and human understanding and response need to be incorporated. Realism does this through the concept of mechanisms, whose precise definition is contested but for which a working definition is ‘. . . underlying entities, processes, or structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest.’44 Different contexts interact with different mechanisms to make particular outcomes more or less likely – hence, in general, a realist synthesis produces recommendations of the general format ‘In situations [X], complex intervention [Y], modified in this way and taking account of these contingencies, may be appropriate’. This approach, when done well, is widely recognised as a robust set of methods, which is particularly appropriate when seeking to explore the interaction between CMO in a complex intervention [e.g. see Berwick’s editorial explaining why experimental (RCT/meta-analysis) designs may need to be supplemented (or perhaps in some circumstances replaced) by realist studies aimed at elucidating CMOs]. 45

The philosophical basis underpinning a realist synthesis is realism. Realism assumes the existence of an external reality (a real world) but one that is filtered (i.e. perceived, interpreted and responded to) through human senses, volitions, language and culture. Such human processing initiates a constant process of self-generated change in all social institutions, a vital process that has to be accommodated in evaluating social programmes. In other words, the way individuals interpret and respond (or not) to the world around them has the potential to cause changes to this world around them. Such changes may then cause additional responses from individuals, potentially leading to a series of feedback loops. Within a realist synthesis, where possible, attempts are made to understand these feedback loops.

A realist approach is particularly useful for this project because TW is a complex intervention that could be useful in a variety of patient groups, and currently it is unclear whether it is effective for all or some, and how and why it might be effective.

Realist syntheses often use input from content experts to help develop the programme theories needed to explain how complex interventions work. In this project, input from practitioner experts was deliberately sought. During the second programme theory-building meeting with practitioner experts, they were asked for their feedback on what their views were on how TW was meant to work, for whom and why (see Chapter 5, Methods, for more details). Two practitioner experts [Carole Ross (CR) and Victoria Field (VF)] provided written responses (see Appendix 1, Tables 76 and 77, respectively) and have been included in this report as they provide an insight into how facilitated TW is used in the NHS and voluntary sector.

Previous systematic reviews on therapeutic writing in long-term conditions

There have been a number of systematic reviews on expressive writing,18,23,46,47 published in psychology journals, that have conducted meta-analyses according to normal practice in psychology, combining different types of participants and outcomes across different conditions, and using Cohen’s d or Hedges’ g statistics. Their results are difficult to interpret because effect sizes for specific populations and interventions are unclear. There have been three recent systematic reviews on TW in LTCs. One concerned post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) only and included five studies. 27 One of the included studies is on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) rather than TW,48 and another49 is a very small, non-randomised study with students. A second, unpublished systematic review was accessed via the internet. 26 This assessed TW for psychological morbidity in people with long-term physical conditions. The review included 14 RCTs and searches were conducted up to May 2011. It is unclear why this review did not include a number of potentially includable studies including Abel et al. 50 [human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)], Graham et al. 51 (chronic pain), Halpert et al. 52 [inflammatory bowel syndrome (irritable bowel syndrome, IBS)], Henry et al. 53 (breast cancer), Hughes54 (breast cancer), Kraaij et al. 55 (HIV), Petrie et al. 56 (HIV), Stark57 [fibromyalgia (FM)] and Theadom et al. 58 (asthma), as all of these studies measure psychological morbidity and were published before the search end date. It may be that they did not include some of these because of their definition of long-term physical conditions, as there is no uniform definition as yet. It is unclear how the results might have differed if some of these studies had been included. The third systematic review evaluated the impact of support on the effectiveness of written cognitive–behavioural self-help59 and thus was not really focused on TW per se. It included 38 studies, none of which are included in this project.

Hypotheses tested in the review (research questions)

Overall aims and objectives of this review

-

What are the different types of TW that have been evaluated in comparative studies? What are their defining characteristics? How are they delivered? What underlying theories have been proposed for their effect(s)?

-

What is the clinical effectiveness of the different types of TW for LTCs compared with no writing or other suitable comparators?

-

How is heterogeneity in results of empirical studies accounted for in terms of patient and/or contextual factors, and what are the potential mechanisms responsible for the success, failure or partial success of interventions (i.e. what works for whom in what circumstances and why)?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness or cost–consequences of one or more types of TW, in one or more representative LTCs, when there is sufficient information on the intervention, comparator and outcomes to conduct an economic evaluation?

Chapter 2 Systematic effectiveness review methods

Expert advisory group

We invited practitioner experts in the area of the TW who approached us following our contact with Lapidus and/or publicity following the awarding of the grant to contribute to the project. On invitation to join the project we were unaware of the techniques of TW that they were employing. Although they were all working in different fields, and with slightly different techniques and approaches, they were all practitioners of facilitated TW. Indeed, we were unable to identify any UK-based practitioners of clinically-based unfacilitated TW to invite to join us as advisors. However, one of our authors, CM, had previously conducted a trial of unfacilitated TW. 60 The practitioner experts were invited to collaborate during all phases of this project in the role of advisors, in order to inform our understanding of the range of TW interventions and to help reach consensus within the Steering Group Committee (SGC).

Search strategy

All electronic and hand-searches were conducted up to March 2013 by the lead researcher (OPN) in collaboration with a librarian (JB). A mapping search was performed in order to determine the extent of relevant literature (looking for both qualitative and quantitative studies). From the list of studies, appropriately includable studies for the systematic review were selected according to the selection criteria. A single electronic search was performed for both the mapping search and the systematic reviews of effectiveness and economic studies. A further search was conducted by CM in January 2015 to cover the 2 years since the previous search.

Search engines

Studies were systematically identified by searching a total of 22 electronic medical and psychological electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CAB Abstracts, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS), The British Library’s Electronic Table of Contents (Zetoc), Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Linguistics and Language Behaviour Abstracts, Periodicals Index Online, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for primary studies, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) for economic studies. Grey literature was searched because of the possibility that effect size estimates might have been overestimated owing to selective reporting bias and unpublished studies are known to be less likely to have statistically significant results compared with published studies. 61 Information on studies in progress and unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature was also sought by searching relevant databases including the Inside Conferences, Open System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, Dissertation Abstracts, Current Controlled Trials database and ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database, and The Campbell Library was searched for systematic reviews and economic evaluations. In addition, internet searches were also carried out using a specialist search gateway (OMNI), general search engine (Google) and a meta-search engine (ReadCube).The search was first conducted in Ovid for MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and then translated into the other databases. Similarly, the search in The Cochrane Library retrieved papers from the CDSR, Cochrane DARE and NHS EED.

The update searches (January 2015) included only the databases that had found all of the relevant citations in the previous search (i.e. MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Social SSCI, CINAHL and The Cochrane Library databases).

Additional searches and cross-referencing

Reference lists of included studies and previous reviews of emotional disclosure were screened. Experts in the area were contacted to identify additional unpublished literature. All studies previously included in former systematic reviews were searched for, screened against the inclusion criteria and considered for inclusion in current systematic review.

Search terms

Medical subject headings together with key words and controlled vocabulary were combined to capture two components of the review question: the populations and the interventions of interest. The search was limited to humans and there were no restrictions regarding the study design. The search terms used for each of the databases are listed in Appendix 3. In the update searches (January 2015) sensitive searches using very wide search terms (writing, writ*, etc.) were used in order to find all relevant studies that had been recently published.

The population of interest: long-term conditions

No definite list of LTCs was pre-established, as the potential range of diseases of interest was both extensive and diverse and made it difficult to create an exhaustive list. For the purposes of the search strategy and subsequent steps of the review, the UK DH definition of a LTC was adopted. 33 The definition states: ‘Long term conditions are those conditions that cannot, at present, be cured, but can be controlled by medication and other therapies. They include diabetes, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’. Where it was unclear whether or not a condition met criteria discussion was held with the SGC and consensus reached (Table 1, column 1).

| Included LTCs after executive decision | Excluded LTCs after executive decision | Included LTCs but analysed in separate groupa |

|---|---|---|

| Acquired brain injury | Acute stress | Addictive conditions (such as drug, alcohol dependence) |

| Anorexia | Alexythimia | Aphasia/agraphia |

| Body dysmorphia | Benign prostate enlargement/hypertrophy | Asperger’s syndrome |

| Bulimia | Bereavement | Bladder papilloma resection (low-grade non-invasive cancer) |

| Chronic pain (at least 3 months) | Body dissatisfaction | Cancers including those newly diagnosed |

| Cystic fibrosis | Child sex abuse | Learning disabilities |

| Deafness/blindness | Chronic dieters | |

| Eating disorders | Domestic violence | |

| High BP | EBV | |

| HIV | Lesbian/gay-related stress | |

| IBS | Mild traumatic brain injury | |

| Infertility | Obesity | |

| MI | Overweight | |

| Serious traumatic brain injury | People found to be at increased risk of developing a LTC | |

| Personality traits | ||

| Smoking | ||

| Unresolved grief |

For inclusion, populations had to have received a clinical diagnosis of the condition. In some studies participants had symptoms of LTCs (e.g. student populations) but no formal evidence of a clinical diagnosis and study participants did not report having been diagnosed with these conditions. For such studies the full text was scrutinised before making a decision regarding inclusion. The chronic conditions in these studies included anxiety, chronic stress, closed head injury, depression (usually stated as symptoms of depression), insomnia or poor sleep, migraine or tension headache, and suicidality.

The authors also discussed whether to consider some diagnosed conditions as LTCs, for example newly diagnosed cancer, or whether congenital conditions might be seen by some to reflect a continuum of normality (e.g. congenital deafness). It was decided to include these conditions but to analyse them separately. These are listed below (see Table 1, column 3).

It was decided to include all other cancer studies because patients may receive palliative care for prolonged periods, and terminally ill patients in hospices may still be receiving active treatment. Thus the distinction between active treatment and palliation might be difficult to distinguish and, furthermore, disease trajectories are not always predictable. There is a debate around whether or not obesity in the absence of any comorbidity is a disease;62 therefore, studies in people with uncomplicated overweight and obesity were excluded. Studies of addictive conditions (alcohol, smoking, illegal drugs, legal drugs) and learning disability were also included because the results could be useful to the NHS, although these might not meet the current definition of LTC. The following conditions were excluded:

-

personality traits, such as alexithymia, body dissatisfaction

-

people who had undergone stressful life events, such as bereavement, domestic violence, child sex abuse (unless PTSD diagnosed)

-

people found to be at increased risk of developing a LTC.

The intervention of interest: therapeutic writing

Prior to the drafting of the definitive list of search terms used to develop the search strategy, consensus within the SGC was reached on the relevant and appropriate terms related to TW interventions. The terms under debate had been identified as part of the mapping search. The aim was to capture the published literature related to the different types of TW interventions; therefore the main key terms referring to TW were defined, discussed, agreed and validated with the expert advice (Table 2, column 1).

| Terms considered | Terms not considered |

|---|---|

| Blogging | Bibliotherapy |

| Catharsis | Emotional announcement |

| Creative writing | Emotional perspective |

| Descriptive writing | Emotional revelation, revealment |

| Diary | e-therapy |

| EW | Internet writing |

| Epistolary writing | Moral disclosure |

| Experimental disclosure | Patient-reported outcomes writing |

| Expressive writing | Therapeutic (or therapy) disclosure |

| Forum | Truth disclosure |

| Handwriting | Wellness writing |

| Health status writing | Writing (or written) exercise |

| Journal, journaling | Written confession |

| Letter writing | Written divulgation |

| Life reminiscence | Written exposé |

| Life review | Written information |

| Life writing | Written material |

| Memoirs | Written/emotional betrayal |

| Narratives | Written/emotional declaration |

| Poetry, poem, poetic | |

| Reactive writing | |

| Reflective writing | |

| Sensitive writing | |

| Story writing | |

| Typing, keying | |

| Writing (as such) | |

| Writing as self-concealment | |

| Writing as self-disclosure | |

| Writing as self-help or self-management | |

| Writing for healing | |

| Writing therapy | |

| Writing to cure | |

| Writing workshop | |

| Written (Pennebaker) paradigm | |

| Written emotion | |

| written emotional disclosure | |

| written expression |

Some terms were not considered because:

-

they had been already identified with a more common synonym thought to be equivalent (e.g. writing for healing/writing to cure vs. wellness writing)

-

the focus of the writing was thought not to be therapeutic (e.g. written divulgation, written exposé or written material/information).

Selection of papers

Results from the electronic searches (titles and abstracts where available) were transferred into a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) following automatic de-duplication within the citation manager EndNote X 4.02 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and the manual removal of other duplicates.

Peer-reviewed articles and non-peer-reviewed papers (e.g. conference abstracts and dissertations) were then selected for potential inclusion in a two-stage process by one reviewer (OPN), with a random 10% selection of citations independently checked by a second reviewer (LB and CM). The two reviewers independently selected studies that met the predefined inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer or by the full team, depending on the complexity of the issues. When it was not possible to determine the study eligibility by title and abstract alone the full text was retrieved for assessment. Authors of conference abstracts were contacted for full articles.

During the selection of studies, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach was used. 63 A diagram was developed to show the numbers of studies in the different categories and the reasons for exclusion of full-text studies. Additionally, an expert in the field of TW was shown the list of included studies to check whether or not they believed that all relevant papers had been identified.

Inclusion criteria

Studies meeting the following inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review:

-

Studies assessing participants with at least one LTC as per DH definition. 33

-

Studies assessing any form of TW including emotional disclosure/expressive writing, poetry, diaries, etc., with inactive comparators or comparison groups thought to be inactive:

-

For example, if participants in the control arm were directed to write in a non-emotional way by using, for instance, neutral topics or by describing facts or how they managed their time. When the control group wrote about topics related to their illness or treatment, or when arousal of emotions might occur, these were not considered to be inactive controls and these studies were excluded. However, if descriptions of the comparators used were not provided, the paper was not be excluded on this basis alone.

-

-

Studies reporting any relevant clinical outcomes including both disease-specific outcomes and generic outcomes.

-

Outcomes related to physical (including physiological, haematological/immunological outcomes, pain, or disability), psychological, social and behavioural health. Performance, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as well as participant mental status, satisfaction and both intervention safety and compliance to treatment for the LTC, were of interest. Resource-use or cost data were also collected for economic consideration. Outcomes could be self-reported or evaluated by a clinician or a carer.

-

If the study could report relevant outcomes without reporting any usable numerical data. In this particular case, the authors were contacted for unpublished data.

-

-

Full versions of prospective randomised or non-randomised trials or observational studies having any form of comparison group including, for instance, RCTs/non-RCTs, cohort, case–control studies and economic evaluations.

Exclusion criteria

The following were excluded:

-

Studies including participants with acute conditions, stress, bereavement or any acute event.

-

Studies assessing any form of psychotherapy, counselling, talking to a listener, talking into a tape recorder, mobile phone or similar, where this was the primary mode of delivering the intervention, expressive drama, dance or film-making.

-

Any study that evaluated other people’s writing.

-

Any study that evaluated any type of writing as a diagnostic tool instead of as a therapeutic tool in the course of a disease treatment (e.g. patients with agraphia).

-

-

A comparative study with any active or probably active control including any form of TW or talking into a tape recorder or mobile telephone.

-

Studies assessing only intermediate physiological outcomes such as salivary cortisol, immune parameters not routinely measured in the management of LTCs or studies not reporting relevant numerical and usable data and/or where unpublished data could not be obtained.

-

Inappropriate study design for this review: single case reports, case series (as both have no comparator arm) and studies where results for intervention and control groups were not presented separately. Studies only available in brief abstract form.

Data collection

The forms used for the data extraction are shown in Appendix 4.

Data extraction methods

Study findings were extracted and entered into a spreadsheet by one reviewer (OPN) and checked by a second reviewer (CM, ST, AH, LS and LB) working independently. A purpose-built data extraction form (Excel) was developed and piloted prior to data collection. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. Missing information was obtained from investigators if it was crucial to subsequent analysis (this was not possible for the five studies identified in the updated search to January 2015). The software GetData Graph Digitizer version 2.26.0.20 (GETDATA Graph Digitizer, Moscow, Russia) was used when numerical data had to be derived from graphs. To avoid introducing bias, unpublished information was coded in the same fashion as published information.

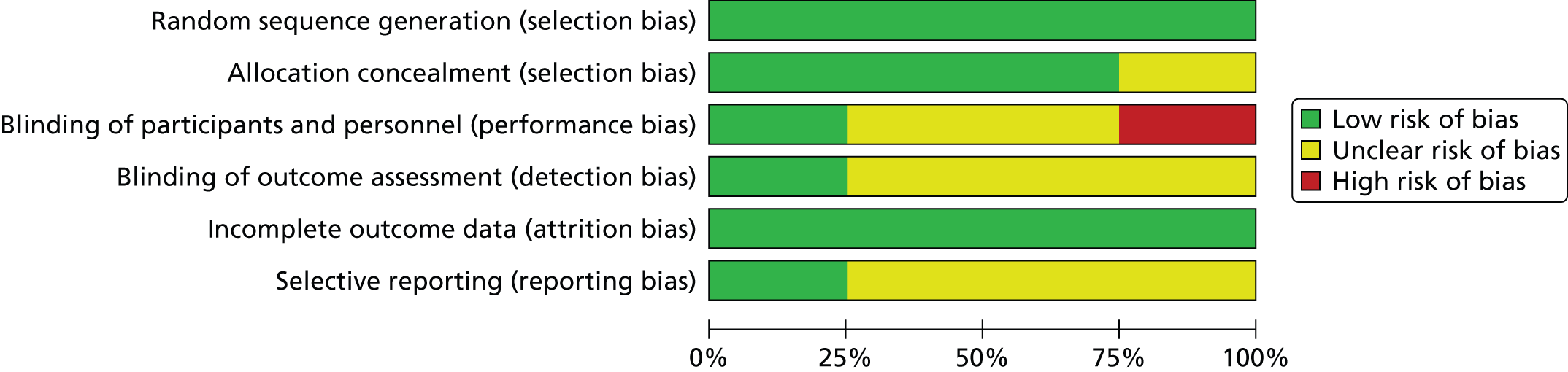

Quality assessment methods

Quality of studies was assessed based on accepted contemporary standards including the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for case–control studies. 64 The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool65 was used for RCTs and quasi-randomised trials. Risk of bias was qualified as high, low or unclear. The first assessment was performed by one reviewer (OPN) on all studies, with a second reviewer (CM, LB, LS, SJCT) independently checking each study.

Data analysis

Synthesis of data

In order to collate, combine and summarise the information from the included studies, narrative and quantitative (meta-analysis) approaches were undertaken. After all included studies were identified, the SGC discussed organisation of the data for analysis. It became clear that the studies fell into two distinct categories: those that were facilitated (such as interactive biblio/poetry therapy) and those that were not (such as unfacilitated TW models and its various elaborations). Discussion with our expert practitioners and consideration of the literature revealed that facilitated and unfacilitated writing interventions are fundamentally different. As explained by the practitioner experts, facilitated TW interventions consist of one or more interactive activities (including TW) between the group facilitator and participant, which allows a live, in-person communication and an element of quality control and tailoring. Usually, the facilitator is in the same room as the participant, and may help with any unexpected concern and/or guide the participant in the usual process of the intervention. For unfacilitated writing, studies were categorised by ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition) code according to the LTC assessed (see Chapter 3).

Analysis of studies

The numerical results from each of the included studies were checked to identify possible data entry problems. For each study, for continuous measures, either the mean and standard deviation (SD) at the various follow-ups, or any other statistic that could be used to calculate SD, such as the standard error (SE), were extracted for further analysis. For categorical measures, dichotomous or binary data, or counts and rates calculated from the number of events that each individual experienced, were collected.

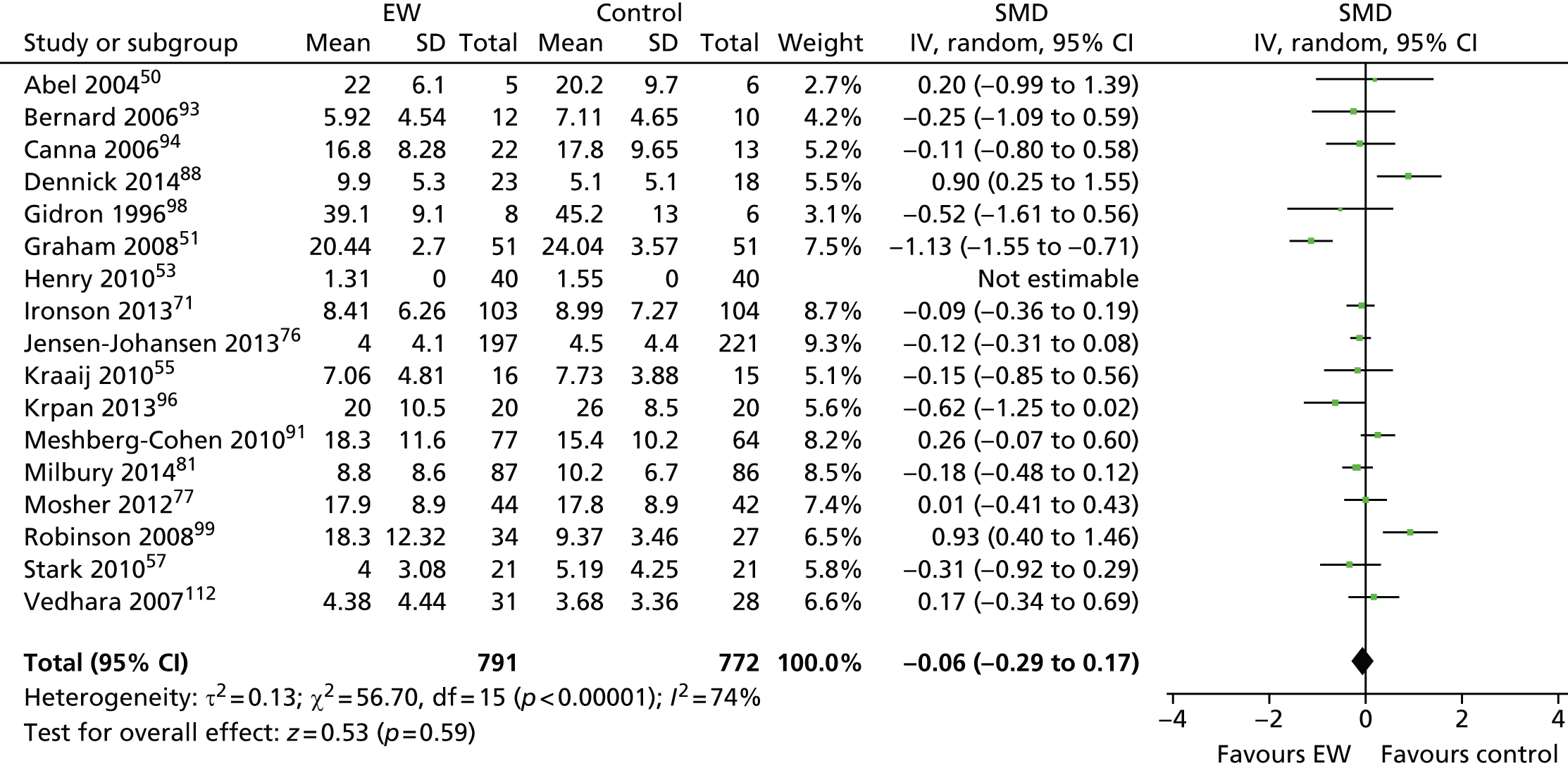

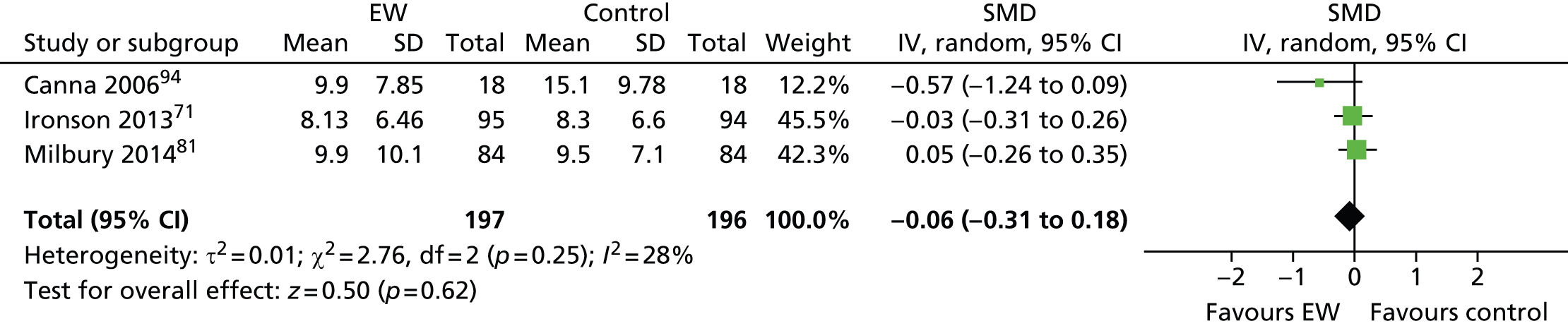

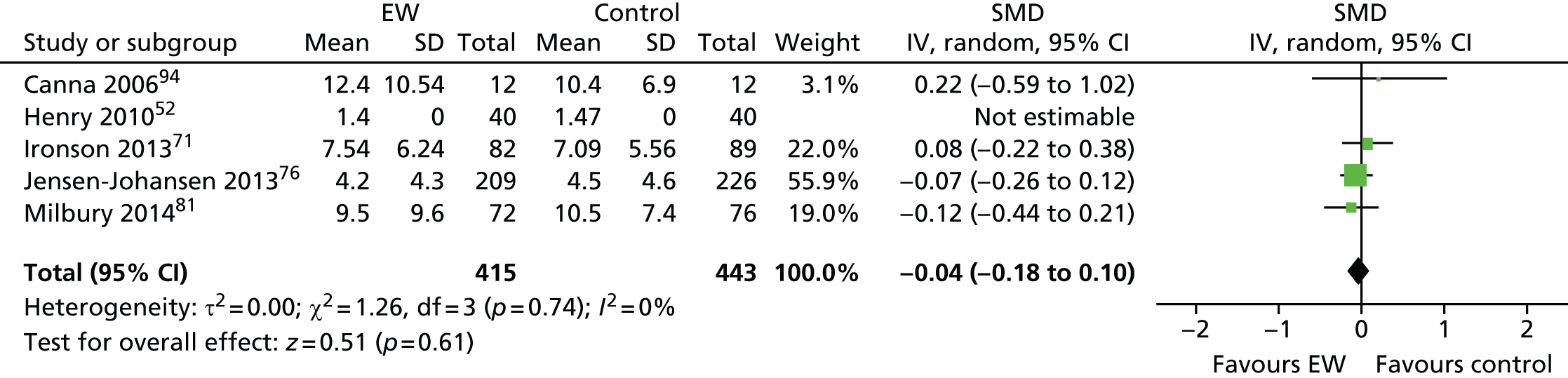

Meta-analyses

Pooled-effect estimations were conducted using the standard software package Review Manager 5.2.6 (RevMan 2012, The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Analyses were stratified according to the type of outcome measured. A comparison was performed when at least three studies used the same (or a similar) instrument to assess the same (or similar) aspects of a given outcome and when sufficient numerical data were reported. In the case of different follow-up periods, results were combined using threshold intervals of ‘immediate’, ‘short term’, ‘medium term’ and ‘long term’, as shown in Table 3.

| Follow-up thresholdsa for meta-analysis, months | Equivalence, weeks | |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate | < 1 | < 4 |

| Short term | ≥ 1 and < 4 | ≥ 4 and < 17 |

| Medium term | ≥ 4 and < 8 | ≥ 17 and < 34 |

| Long term | ≥ 8 | ≥ 34 |

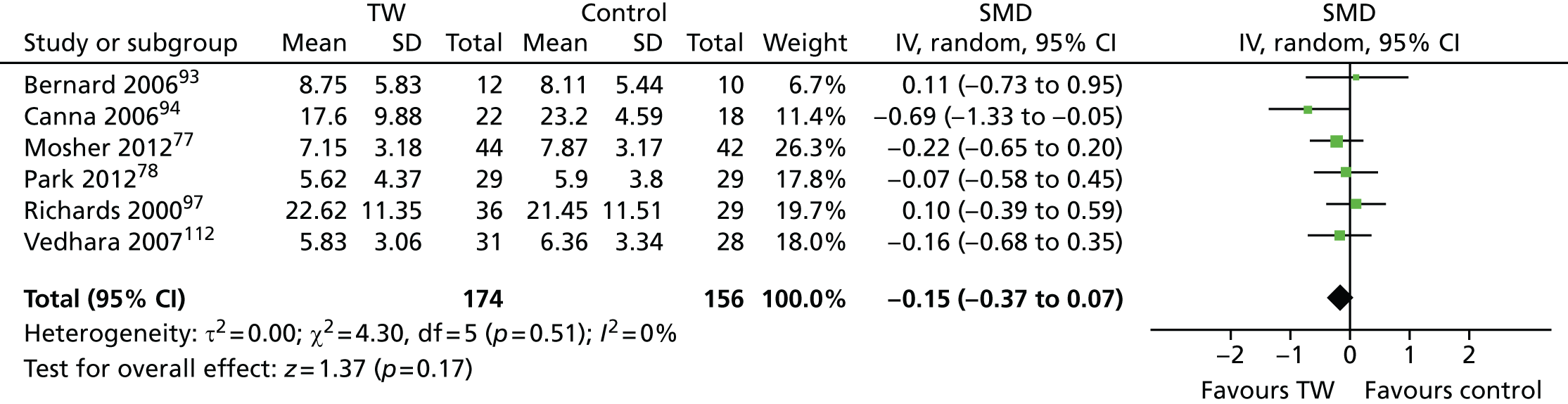

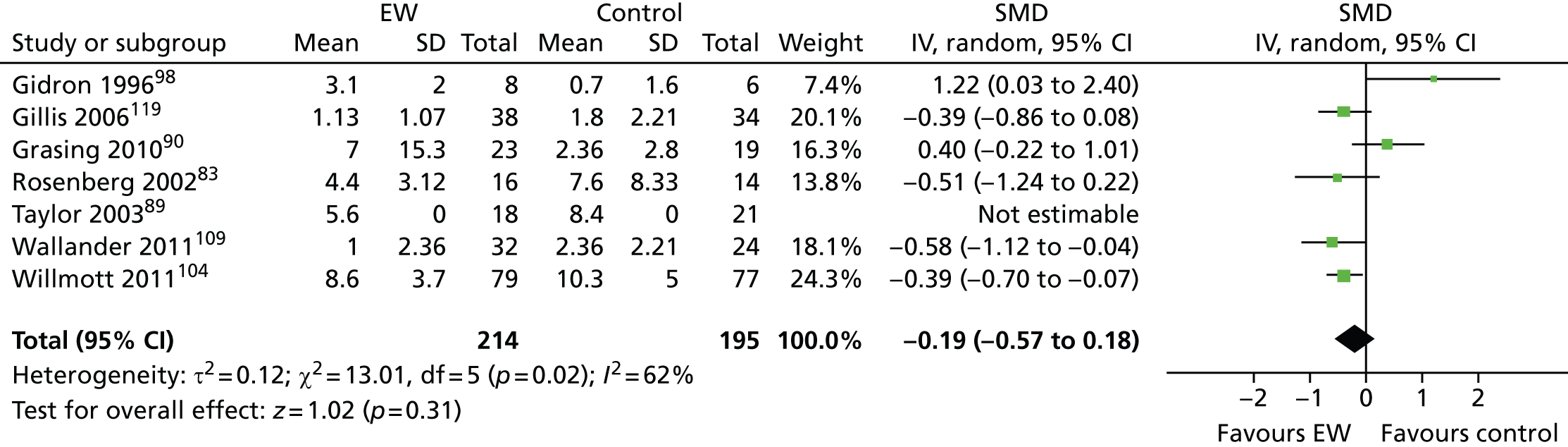

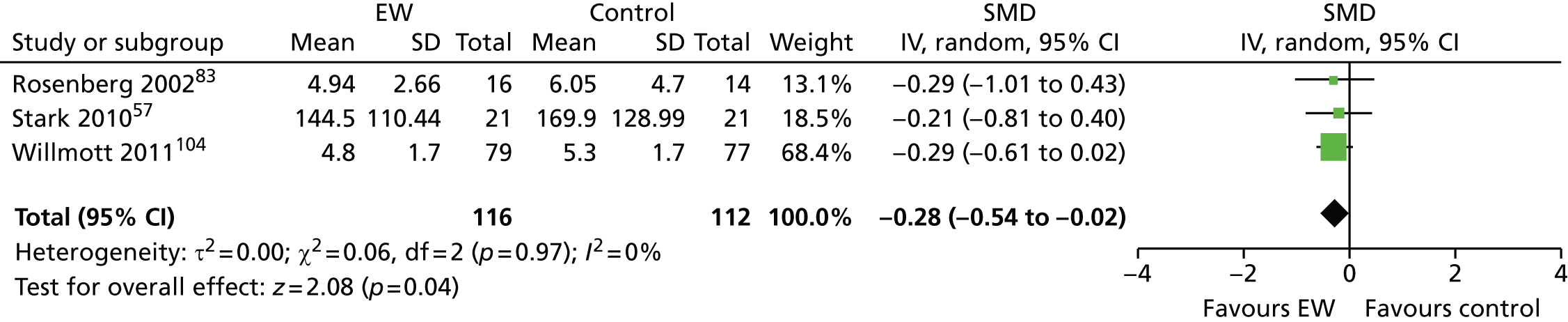

In cases where two studies reported short-term follow-up, and one study reported an immediate follow-up assessment, the studies were meta-analysed and combined into a short-term follow-up comparison. For continuous outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMDs) were used when outcomes were measured with different instruments. Random-effects models were used because of clinical heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity of results between studies was assessed using the I2-value. Conclusions regarding the estimates of effect sizes were interpreted cautiously if there was significant heterogeneity.

Unit of analysis issues

Only comparative studies were included. Participants were usually randomised to one group of two groups; however, some studies could compare one experimental TW intervention group against both a standard intervention (such as standard care) and one with placebo writing. Alternatively, two or more experimental interventions could be tested against a standard intervention (or with both a standard intervention and with placebo writing), giving a four-arm trial. There could be also trials with the same outcome assessed at different time points or just measured after the writing session or at the end of the treatment period.

For the systematic review, the interest lay only in the direct comparison between a TW intervention arm and an inactive comparator. If a trial had two intervention groups and two control groups, for meta-analysis the trial was treated as two separate trials one comparing, for instance, a more brief TW intervention against inactive comparator and one comparing a longer TW intervention against inactive comparator. Where there were two intervention groups and one control group, the TW intervention most widely used (i.e. the unfacilitated EW with the standard instructions was the one included in the meta-analysis).

Results across LTCs

Four analyses were performed:

-

physiological, disease-related and biomarker outcomes (results tabulated)

-

positive writing across LTCs (results tabulated)

-

depression (results tabulated and meta-analysed where possible)

-

anxiety (results tabulated and meta-analysed where possible).

Chapter 3 Systematic review results

Study selection

A total of 18,235 citations were initially retrieved from the searches in the different electronic databases. After removal of duplicates, 14,658 citations were initially screened. Based on the review of their corresponding titles and abstracts 14,374 records were excluded, while 284 full papers were marked for retrieval, either because they were potentially relevant or because insufficient information was reported in the title and abstract to make a final decision regarding inclusion in the systematic review. After screening the full papers, 64 publications relating to 64 unique studies were finally included in the systematic review: 58 from database searches and six from hand-searches. The duplicate checking of 10% of the titles and abstracts revealed no studies missed and excellent agreement on excluded studies. Therefore, no further checking was indicated.

All included studies were comparative studies evaluating a TW intervention in patients with different LTCs. A description of the process followed for the identification and selection of studies, and the number of studies identified through each step, is presented in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram. a, Final number of studies with no numerical results (after correspondence with authors); b, authors of the abstracts and ongoing studies were contacted to obtain a full-text version if available.

Included studies

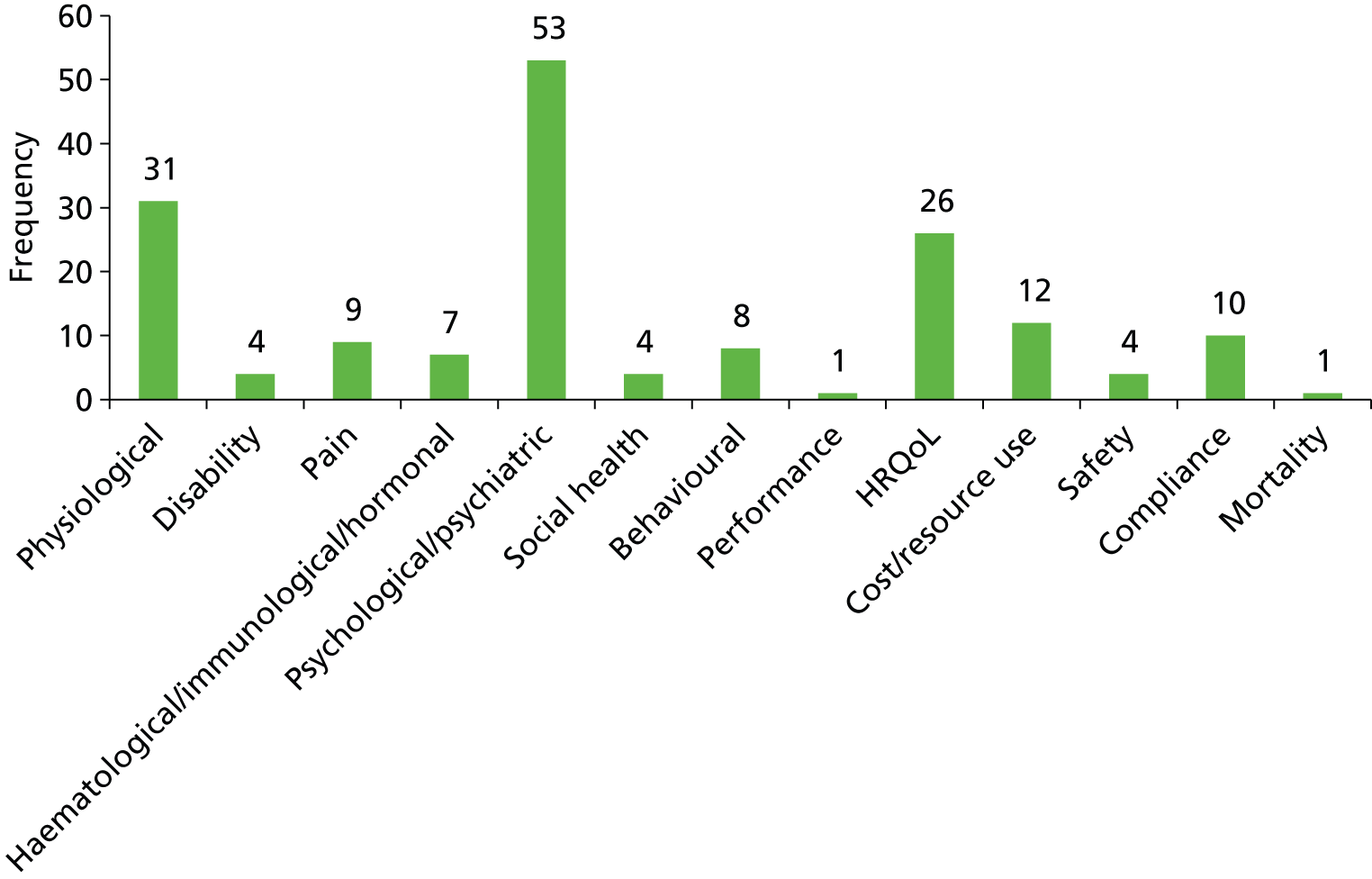

Details on the study design, participants’ chronic conditions, intervention types and processes, outcome measures, as well as the quality assessment of the included studies, are reported in Appendix 5. The number of studies categorised by ICD-10 code according to the LTC evaluated, together with the names of the studies in each category, are shown in Table 4. The number of studies published by year is shown in Figure 2, and the frequency of outcomes evaluated across the included studies is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Included studies by year of publication.

FIGURE 3.

Frequency of outcomes evaluated across the included studies.

| Condition | ICD-10 code | Number of unfacilitated EW studies (facilitated TW) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | B24 | 6 | Abel 2004,50 Ironson 2013,71 Kraaij 2010,55 Mann 2001,72 Petrie 2004,56 Wagner 201073 |

| Breast cancer | C50 | 8 | Craft 2013,74 Gellaitry 2010,75 Henry 2010,53 Hughes 2007,54 Jensen-Johansen 2013,76 Mosher 2012,77 Park 2012,78 Walker 199979 |

| Gynaecological and genitourinary cancers | C57, C61, C62, C64 | 5 (1) | Arden-Close 2013,80 Milbury 2014,81 Pauley 2011,82 (Rickett 201166), Rosenberg 2002,83 Zakowski 200484 |

| Other cancers | C80 | 2 | Cepeda 2008,85 Rini 201486 |

| Sickle cell disease | D57 | 1 | McElligott 200687 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | E11 | 1 | Dennick 201488 |

| Cystic fibrosis | E84 | 1 | Taylor 200389 |

| Dementia | F03 | (1) | (Hong 201167) |

| SUD | F14/F19 | 3 | Grasing 2010,90 Meshberg-Cohen 2010,91 Van Dam 201392 |

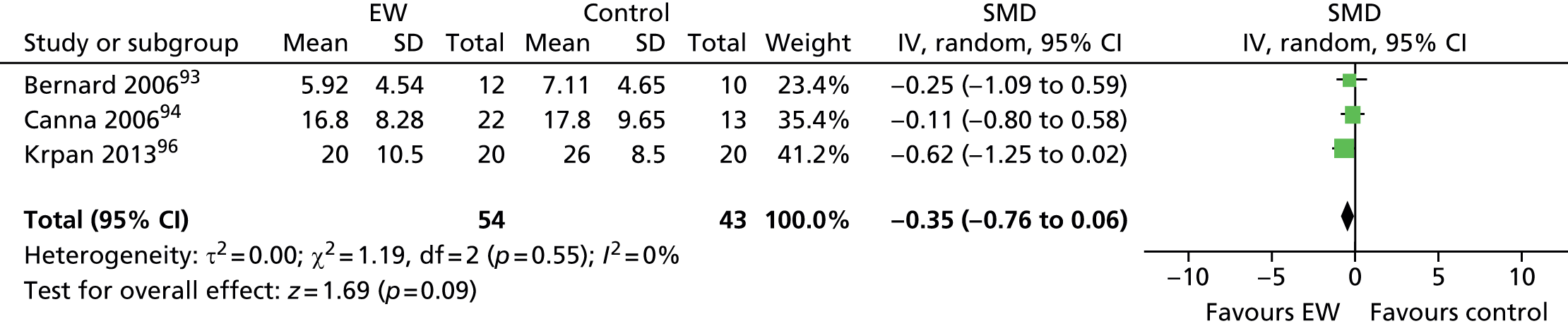

| Psychiatric disorders | F41–60 | 5 (1) | Bernard 2006,93 Canna 2006,94 (Golkaramnay 200768), Graf 2008,95 Krpan 2013,96 Richards 200097 |

| PTSD | F43 | 2 (2) | Gidron 1996,98 (Lange 200369), (Sloan 201270), Smyth 20089 |

| BN | F50 | 1 | Robinson 200899 |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | G12 | 1 | Averill 2013100 |

| Migraines and tension headaches | G43/G44 | 1 | D’Souza 2008101 |

| CVD | I51 | 3 | Bartasiuniene 2011,102 Hevey 2012,103 Willmott 2011104 |

| COPD and IPF | J44, J84 | 1 | Sharifabad 2010105 |

| Asthmaa | J45 | 4 | Harris 2005,106 aSmyth 1999,107 Theadom 2010,58 Warner 2006108 |

| IBS | K58 | 2 | Halpert 2010,52 Wallander 2011109 |

| Psoriasis | L40 | 3 | Paradisi 2010,110 Tabolli 2012,111 Vedhara 2007112 |

| Inflammatory arthropathiesa | M06/M45 | 6 | Broderick 2004,113 Hamilton-West 2007,114 Lumley 2011,115 Lumley 2014,116 aSmyth 1999,107 Wetherell 2005117 |

| FM and chronic pain | M79 | 4 | Broderick 2005,118 Gillis 2006,119 Graham 2008,51 Stark 201057 |

Regarding interventions, five used a facilitated type of TW66–70 and 59 studies71–119 used an unfacilitated type of EW therapy. Participants in the control groups were usually instructed to neutral writing; time-management writing; factual writing; non-writing; or waiting list. Most of the studies were published in the USA and, since 2008, the year with most studies published (n = 11) was 2010. Breast cancer and HIV were the most frequently evaluated conditions, followed by PTSD and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The outcomes most frequently evaluated were, in descending order, psychological, physiological and HRQoL.

Of the 64 included studies,9,51–58,66–119 599,51,54–58,66–68,71–77,79–86,88,89,91,93–119 were RCTs, and four52,78,87,92 were non-randomised studies. The remaining study53 was a matched case–control study. Among the 64 studies,9,51–58,66–119 one was written not in the English language but in Korean. 78 Smyth et al. 107 and D’Souza120 evaluated the effect of TW in two groups of patients with different conditions and reported relevant outcomes independently. Data were extracted on the most recent paper, or the most complete piece of information in the case of duplicates of an abstract and when the corresponding published article of a PhD thesis was retrieved. Fifty papers required correspondence with authors in order to get relevant unpublished information (or adequate data for meta-analysis purposes): 32 authors could be contacted and 14 provided the sought information. All 64 studies9,51–58,66–119 provided information (numerical data) relating to the efficacy and/or effectiveness of TW. Among those, numerical results were derived from graphs in nine studies. 51,53,56,70,85,103,110,114,121 Several studies under-reported the numerical data (e.g. reporting the mean with no measure of variability, such as the SD) or used different statistics [such as the median, together with confidence intervals (CIs) and/or ranges or the mean together with the SE] to report the results. All 64 studies9,51–58,66–119 were considered for the quantitative analysis and 35 were finally included in the meta-analyses.

Excluded studies

Abstracts and ongoing studies were excluded from the systematic review and have been listed separately with details of all excluded papers, with their reasons for exclusion (see Appendix 6, List of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion).

Nine studies evaluated TW but reported no numerical results for any of the outcomes measured and were therefore excluded from the systematic review, as they could not contribute to estimation of efficacy or effectiveness (see Appendix 6, List of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion).

Results of the different therapeutic writing interventions

This section is organised as follows:

-

facilitated writing (in one or more arms of the study)

-

unfacilitated writing (standard type) categorisated by ICD-10 code122

-

positive unfacilitated writing

-

summaries across different LTCs for:

-

physiological, disease-related and biomarker outcomes

-

depression

-

anxiety.

-

Most of the current published research focuses usually on unfacilitated EW for disease intervention types encompassing many variants. When a study had two groups of patients with different conditions, for example asthma and RA, results for each condition were reported under the separate ICD-10 codes where possible.

Facilitated therapeutic writing

Overview

There were five studies66–70 evaluating facilitated TW. A summary of their main characteristics is presented in Table 5.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | LTC | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golkaramnay 200768 | Germany | Matched case–control study | Mental health disorders | Group therapy through internet chat | No interventiona |

| Hong 201167 | Korea | RCT | Dementia (Alzheimer’s disease/vascular dementia/Parkinson’s disease) | Songwriting | Waiting list |

| Lange 200369 | The Netherlands | Non-randomised trial | PTSD | Interapy | Waiting list |

| Rickett 201166 | Australia | Non-randomised trial | Primarily cancer | Poetry writing programme/workshop | Waiting list |

| Sloan 201270 | USA | RCT | PTSD | Written exposure therapy | Waiting list |

All studies66–70 evaluated one facilitated intervention group against one control group. All studies66–70 were conducted in a different country. Two studies69,70 concerned PTSD and involved writing on trauma-related topics, but the remaining studies examined different conditions [dementia,67 mental health problems68 and serious physical illness66 (primarily cancer)]. Although grouped together here as facilitated TW, the interventions studied were all very different and the type and amount of level of facilitation (and indeed actual writing) varied greatly.

The studies conducted by Golkaramnay et al. 68 and Lange et al. 69 were internet based. Golkaramnay et al. 68 studied a chat room through which groups of participants recently discharged from psychiatric hospital communicated with each other in writing during weekly 90-minute sessions, guided by experienced group therapists who knew all of the participants beforehand. The intervention in Lange et al. 69 (Interapy) involved psychoeducation and 10 structured writing assignments over 5 weeks, delivered one to one via a website, with seven lots of feedback on the writing assignments from a therapist. Hong and Choi67 studied weekly group songwriting sessions in care home residents with dementia, but it is not clear how much actual writing was involved. Rickett et al. 66 examined the impact of eight weekly 2-hour facilitated poetry-writing workshops. The intervention in Sloan et al. 70 involved five 30-minute writing exercises with the first session preceded by some scripted psychoeducation delivered over 1 hour. The facilitation was limited to reading verbatim writing instructions at the start of the session and answering questions at the end.

The duration of the therapy sessions ranged from 45 minutes in Lange et al. 69 to 210 minutes in Sloan et al. 70 The duration of the intervention varied from five sessions in Sloan et al. 70 up to 16 weeks in Hong and Choi. 67

The outcomes evaluated in the studies with a facilitated intervention are reported in Table 6.

| First author, year | Emotional distress | Physical well-being | Life satisfaction | Cognitive functioning | Intrusions and avoidance | Symptomatic distress/physical symptoms | PTSD symptom severity | Health-care utilisation | Prior trauma exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golkaramnay 200768 | OQ-45.2 | GBB | FLZ | – | – | SCL-90-R (GSI) | – | LIFE | – |

| Hong 201167 | – | – | – | MMSE-K | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lange 200369 | – | – | – | – | IES | SCL-90 | – | – | – |

| Rickett 201166 | K-10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sloan 201270 | SAM | – | – | – | – | – | CAPS | – | TLEQa |

Physical symptoms were evaluated in two studies67,68 using the SCL-90-R (Symptom Checklist-90-Revised) although different subscales. The remaining studies66,69,70 evaluated different outcomes, although three studies assessed aspects of the participant’s emotional distress using different instruments [Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10), Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2)] with different scales and scoring systems.

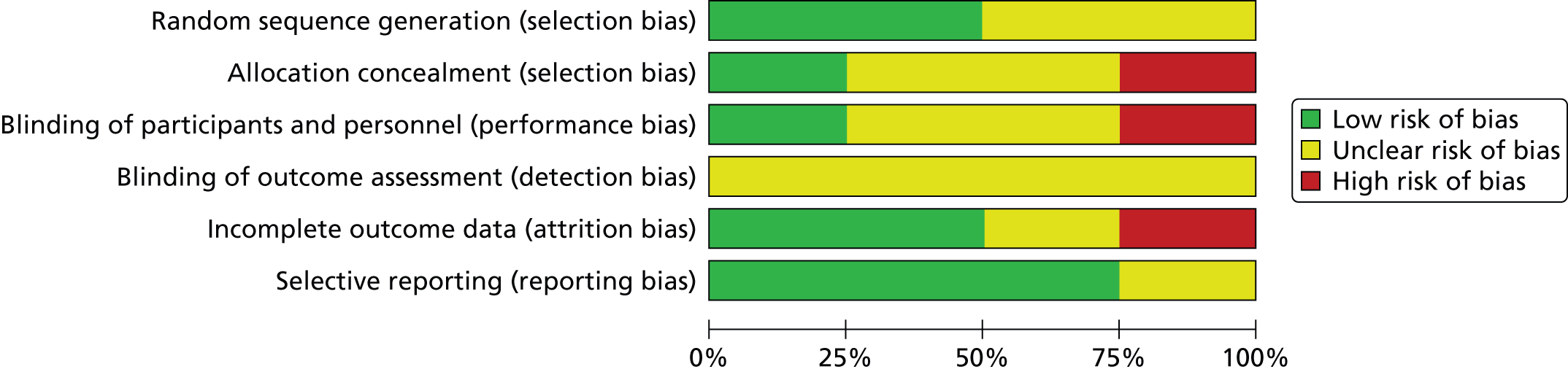

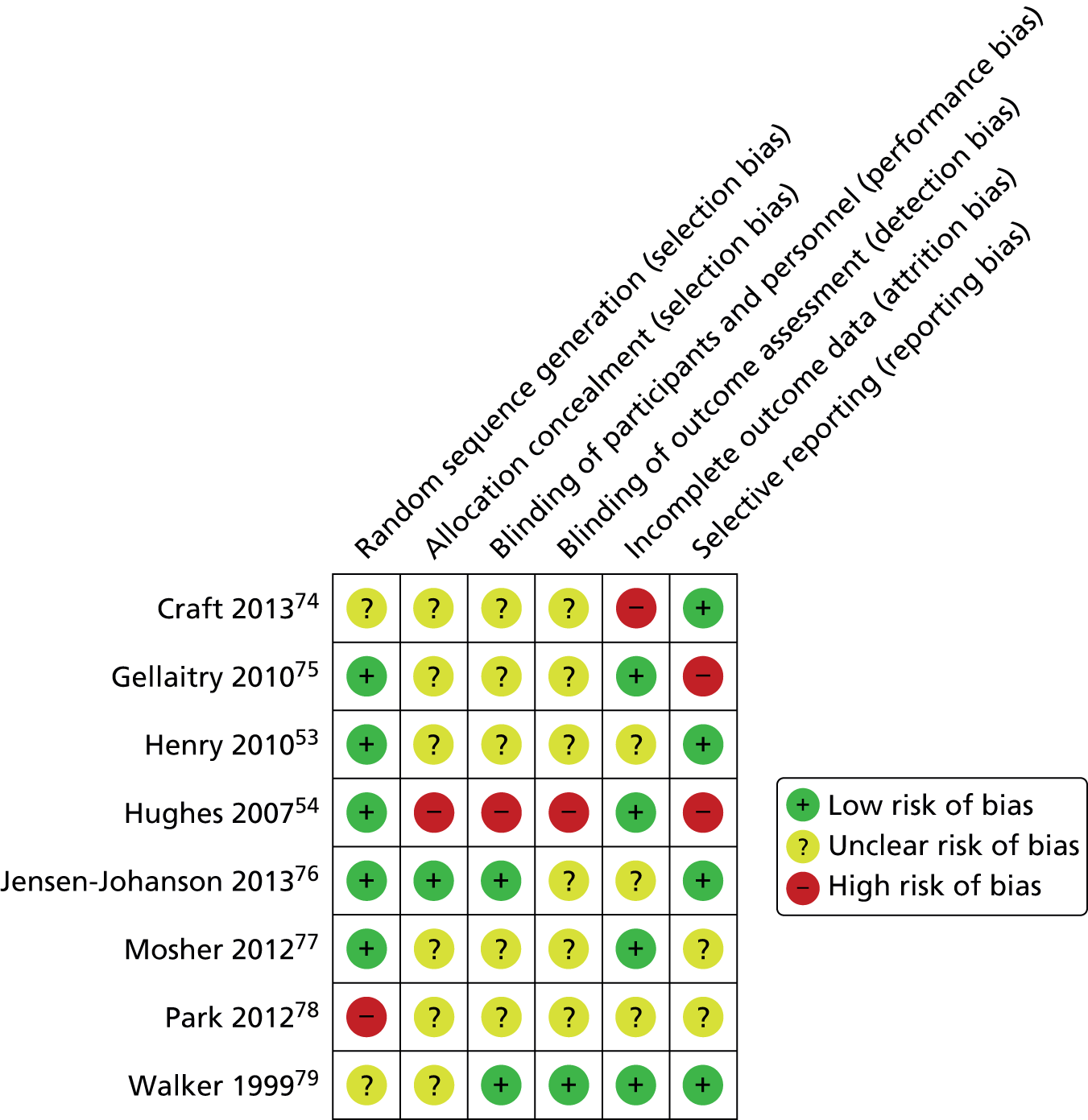

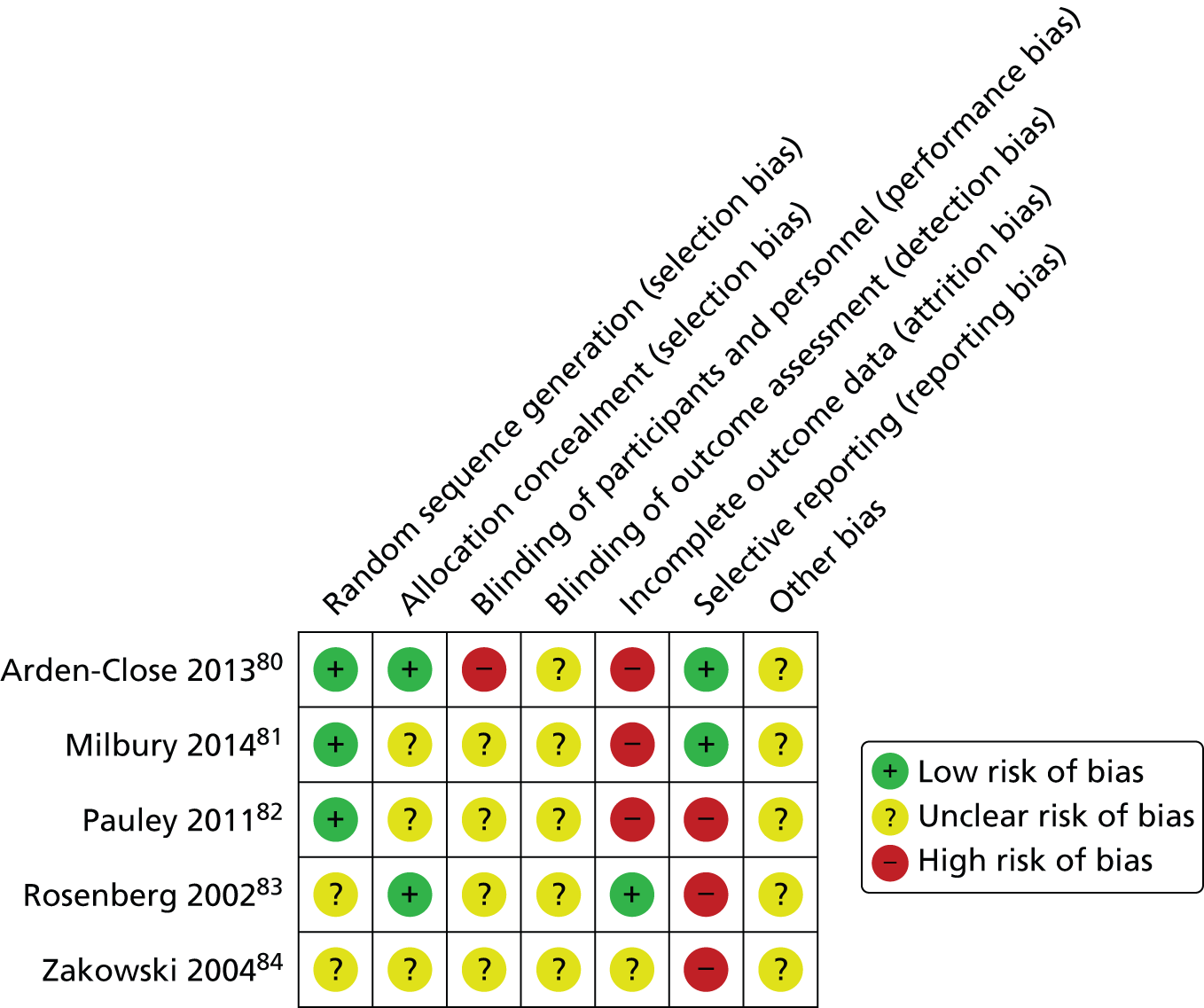

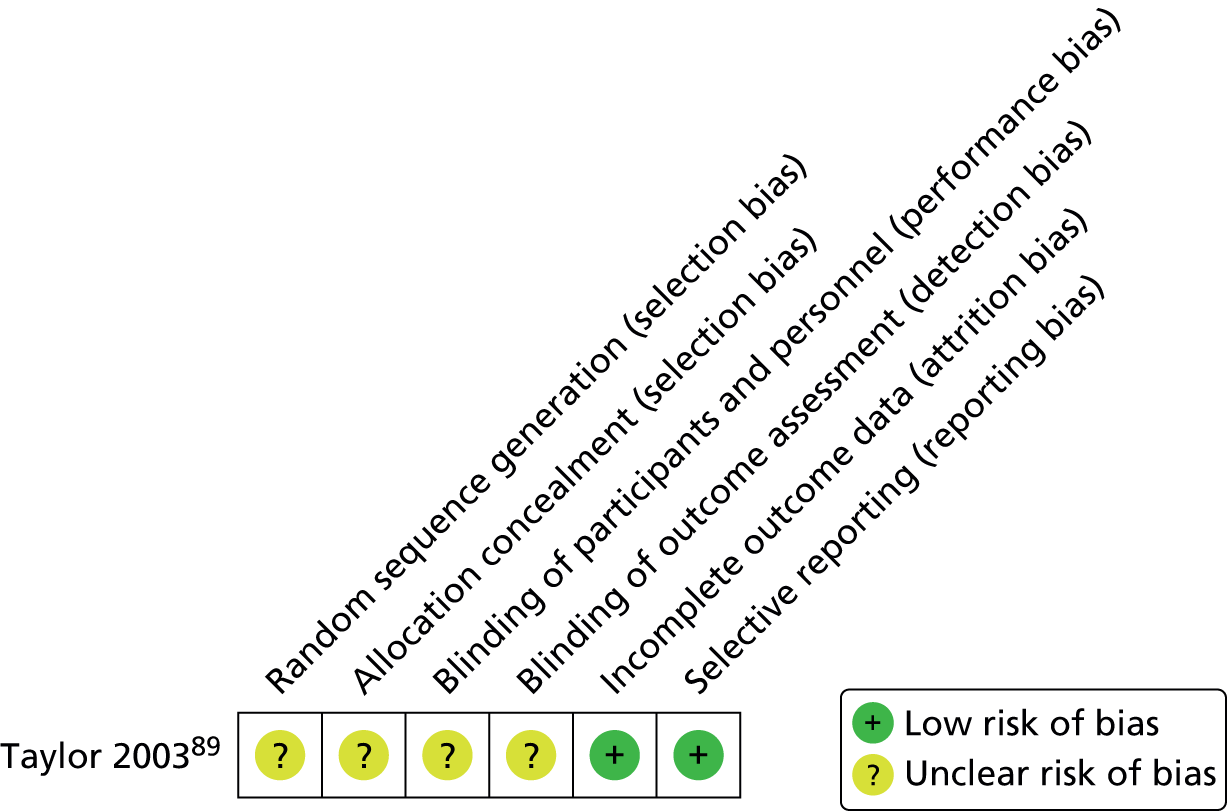

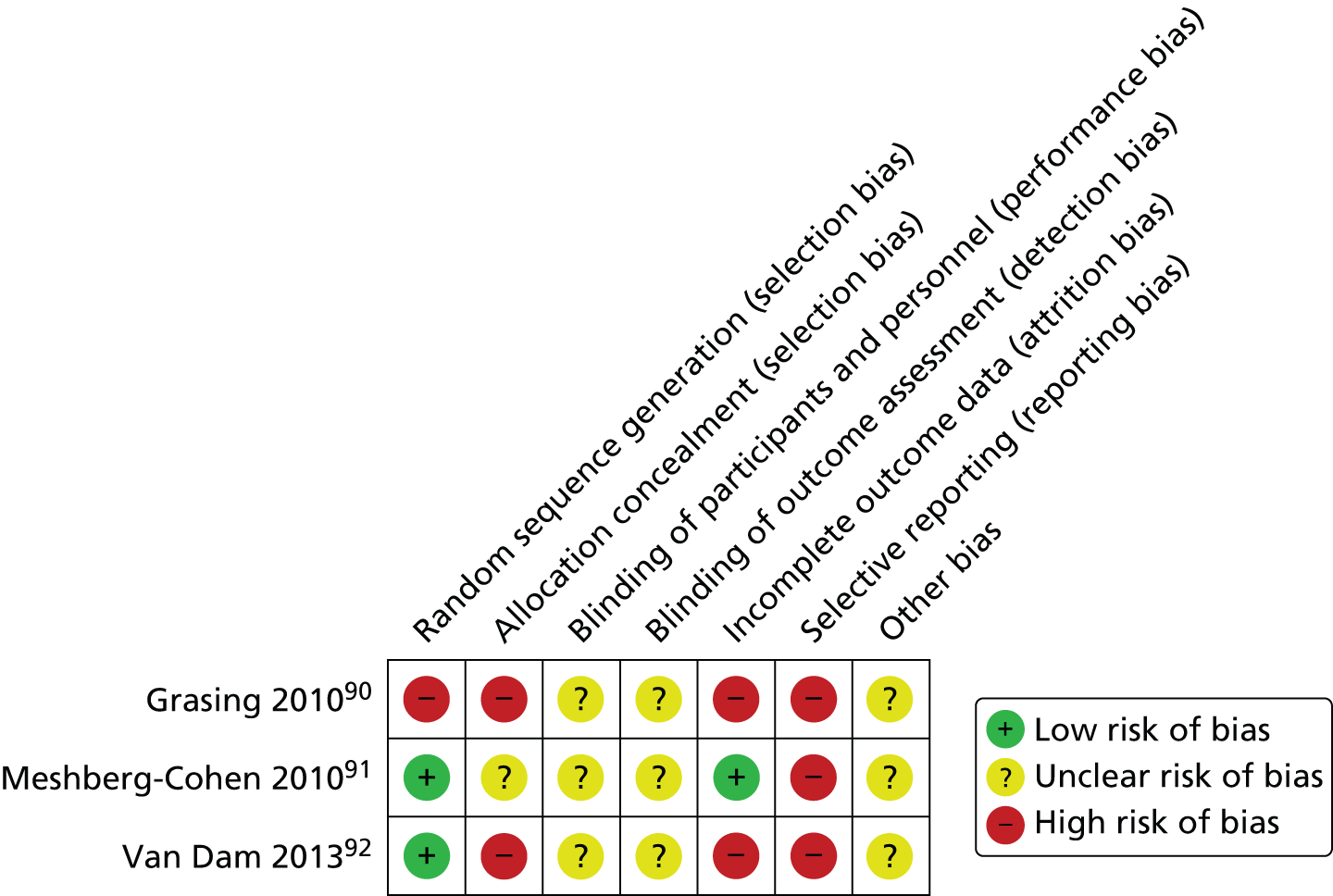

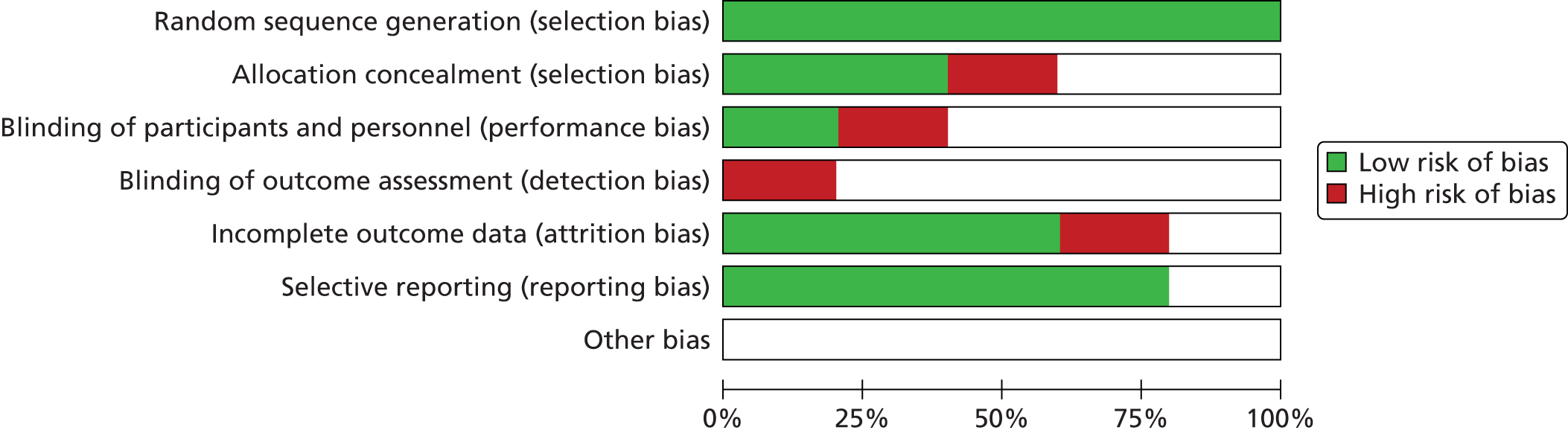

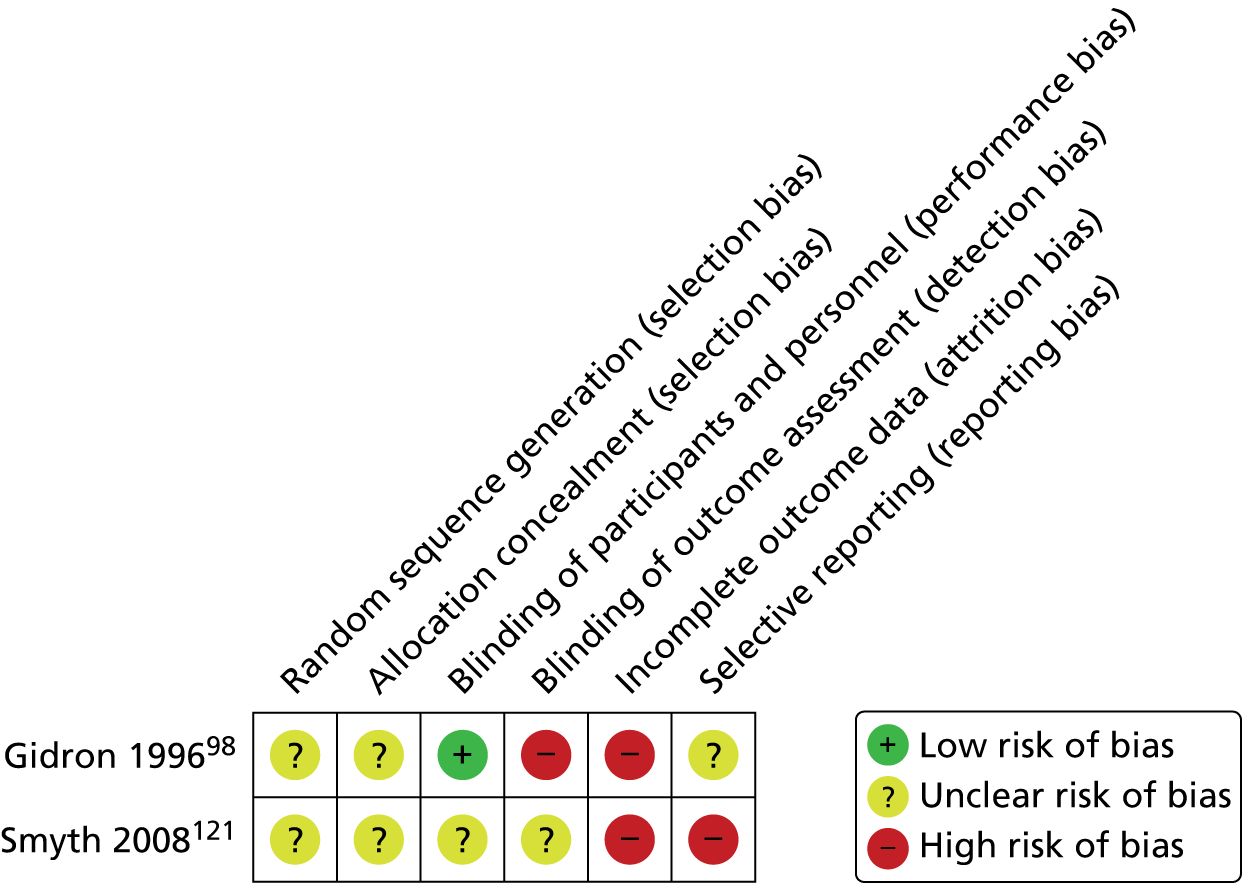

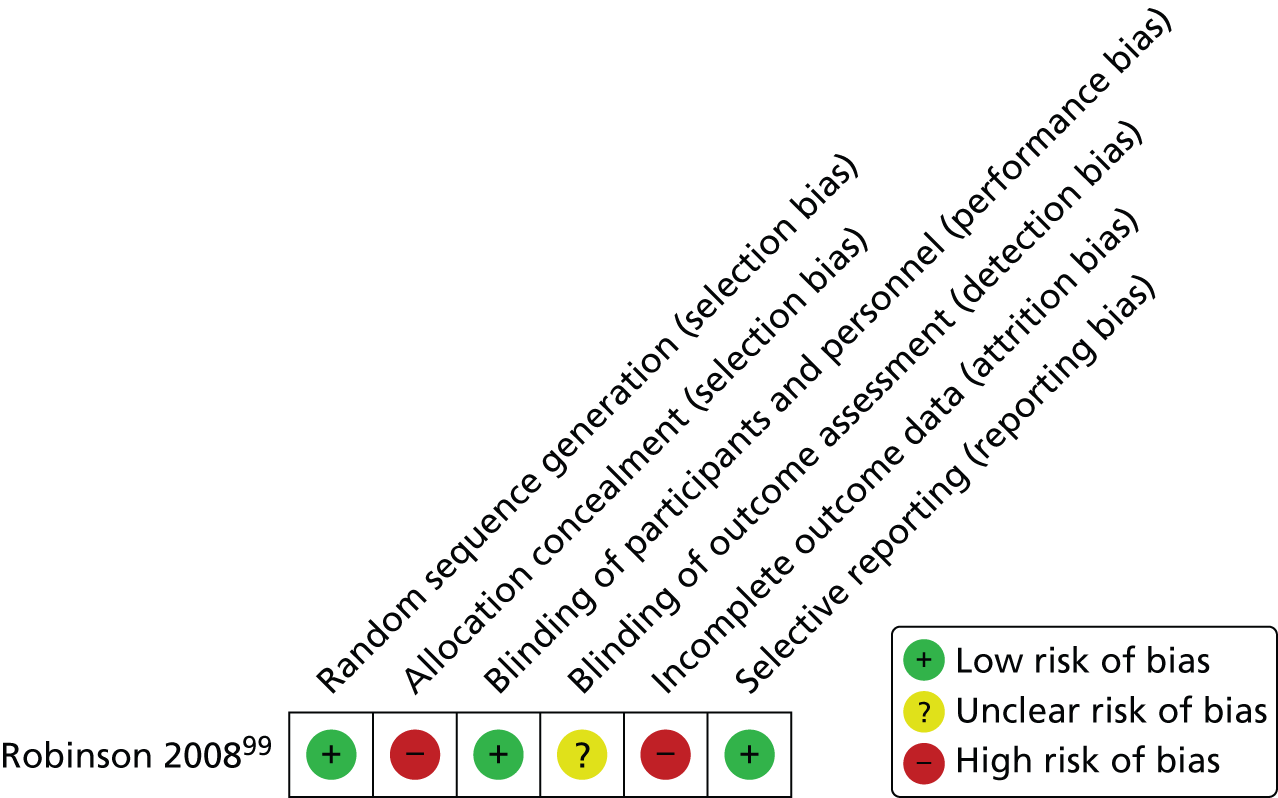

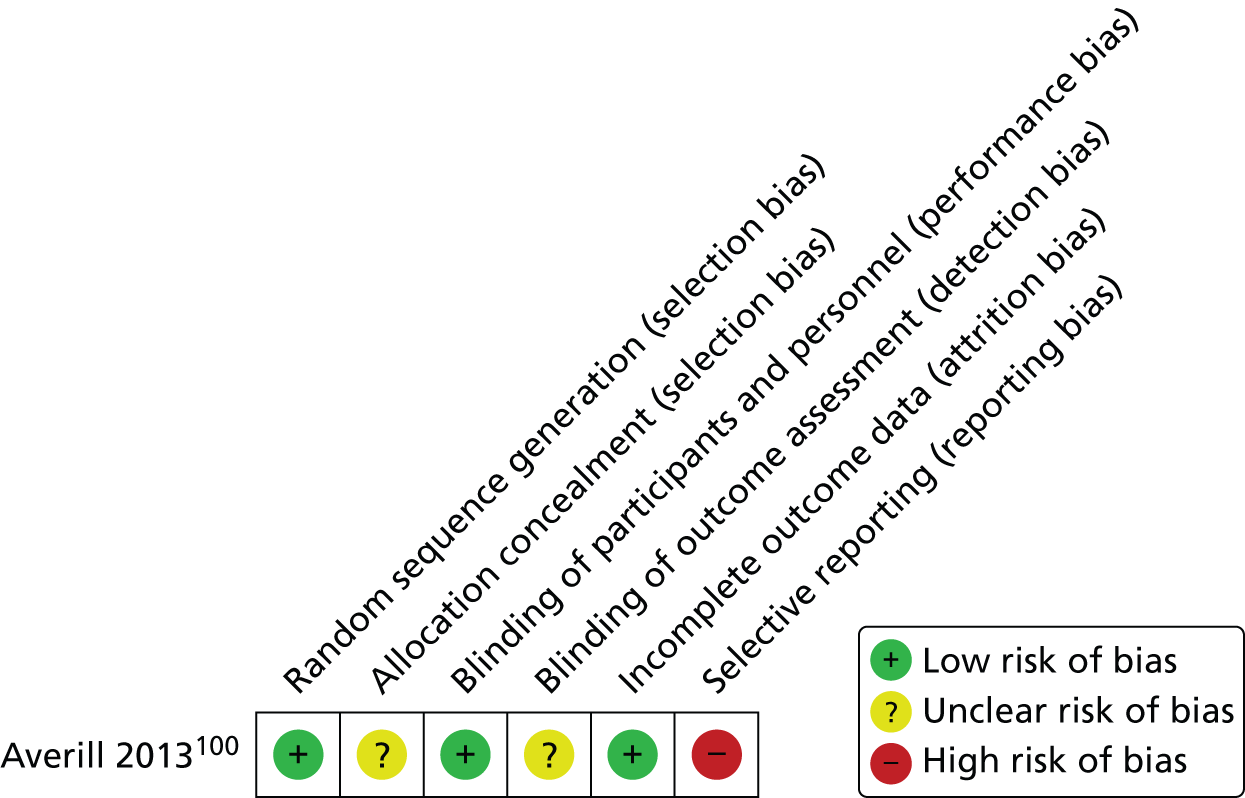

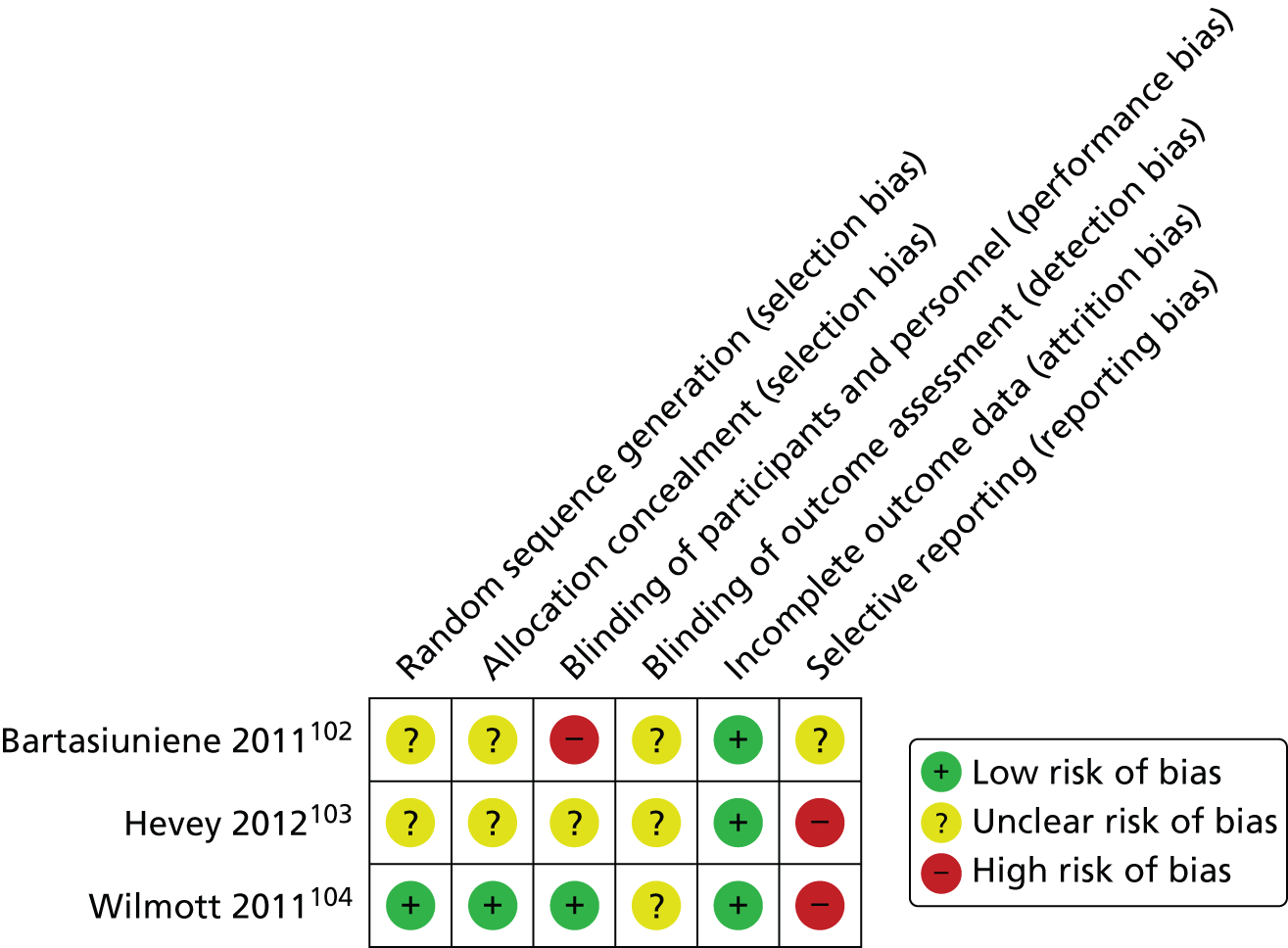

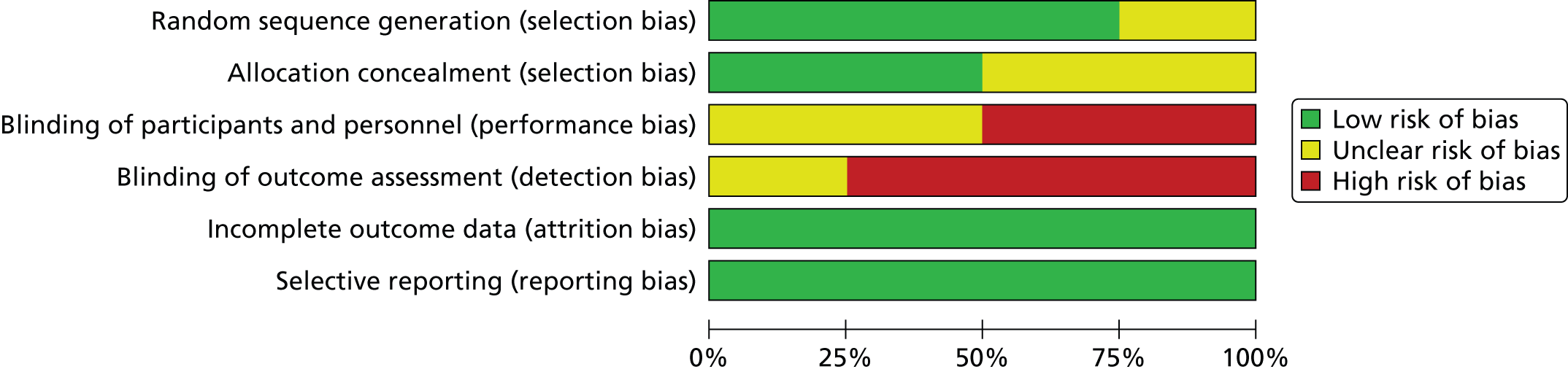

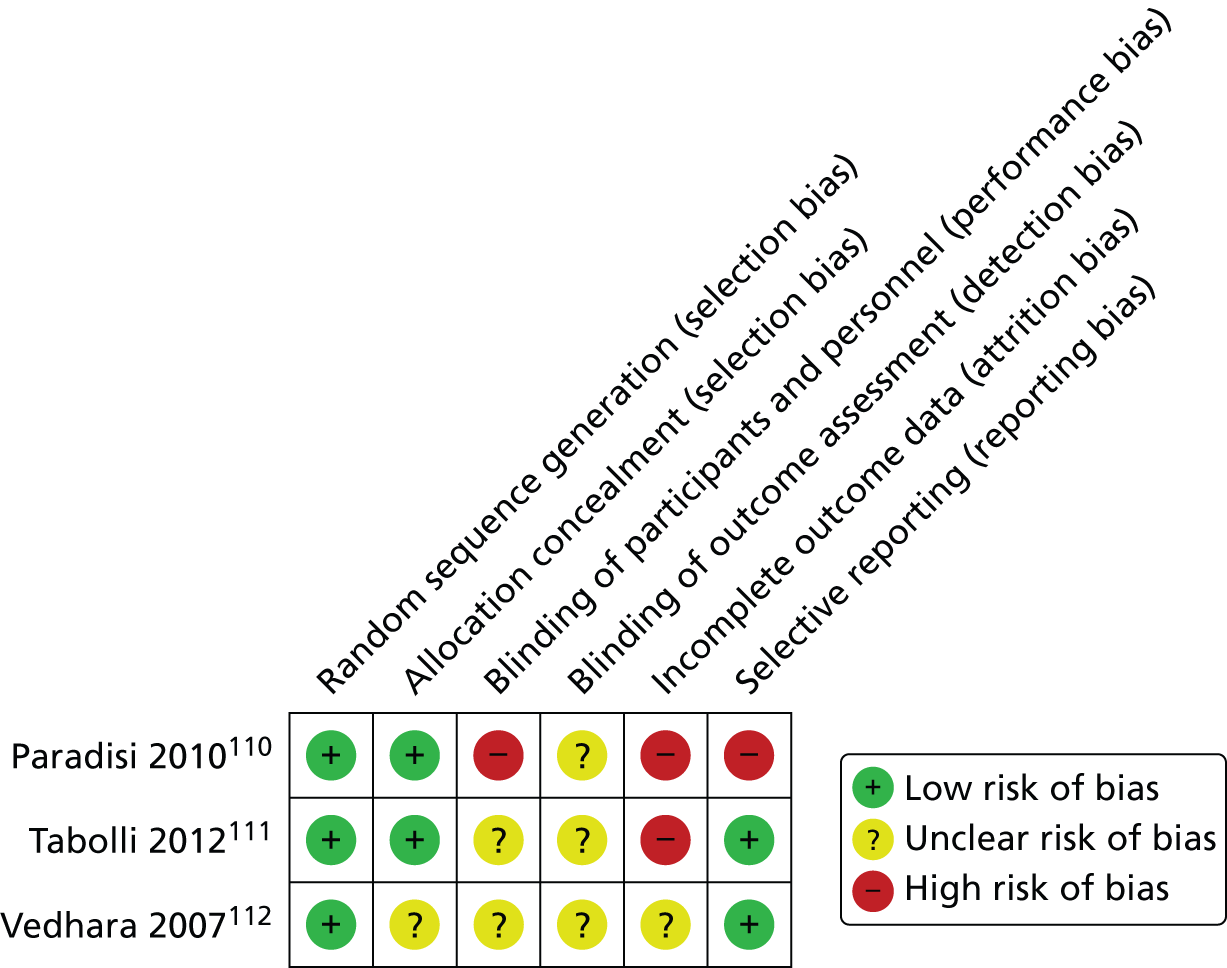

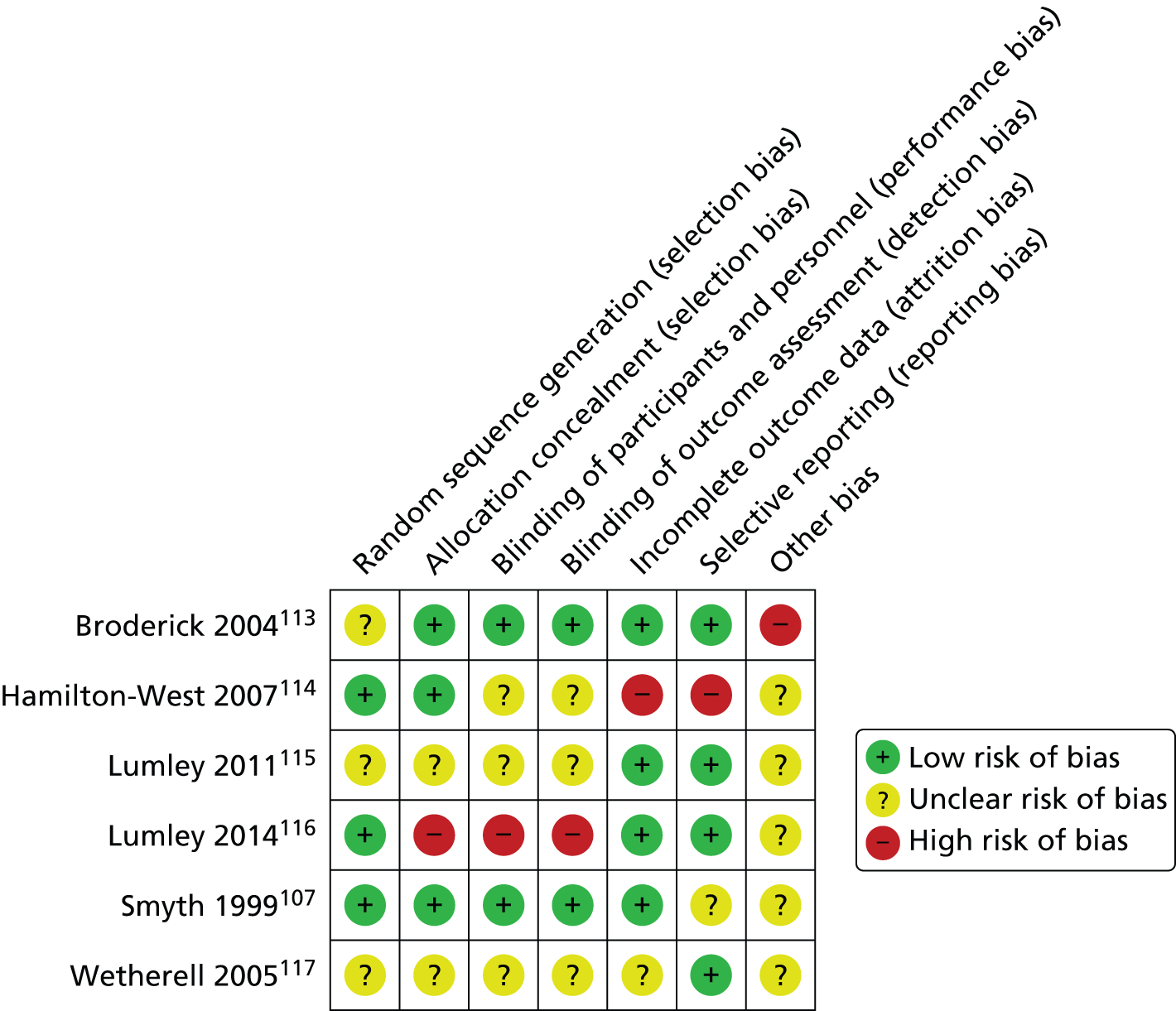

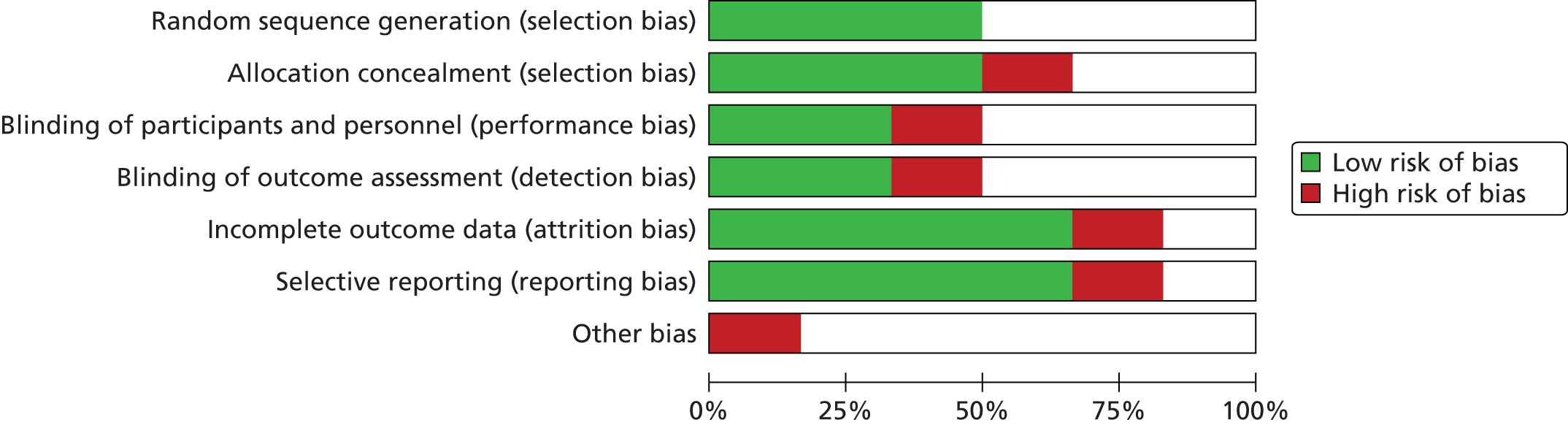

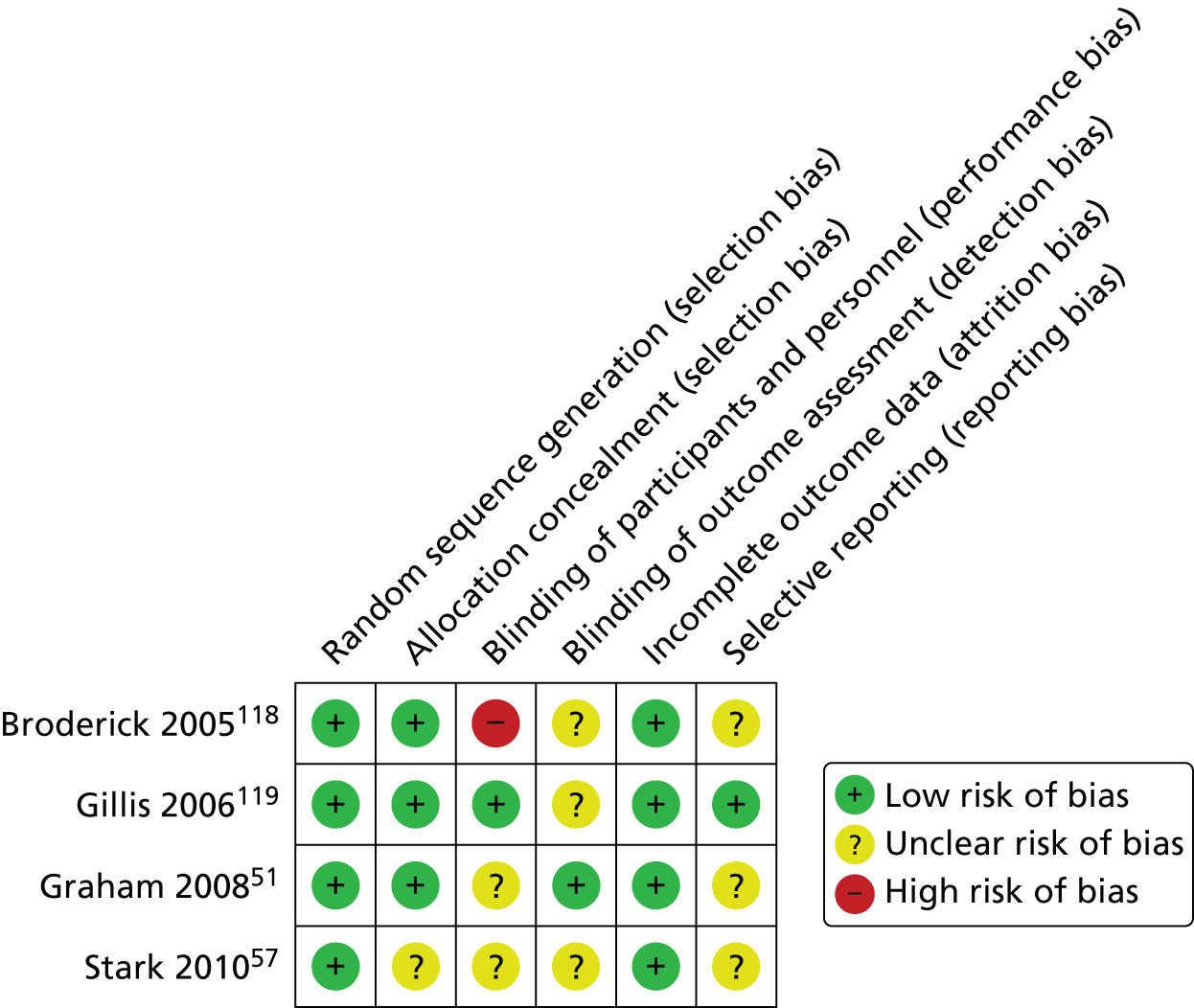

Quality of the included studies

A summary of the quality of the studies of facilitated TW is shown in Figures 4 and 5.

FIGURE 4.

Risk-of-bias summary in the studies of facilitated TW.

FIGURE 5.

Risk-of-bias graph in the studies of facilitated TW.

Golkaramnay et al. 68 was a matched case–control study; therefore, without allocation concealment (as it was not an RCT, it is not included in the risk-of-bias table). Participants and personnel were not blinded to the intervention performance. Blinding of the outcome assessment was unclear. The information related to the participation rates was unclear, thus the study was likely to introduce attrition bias. Similarity of groups at baseline was unclear. Selection was adequate, as the case definition and comparators were representative and comparable controls were selected from hospital records.

Two studies had allocation concealment. Hong and Choi67 may have introduced selection bias given the sequence generation was not concealed, whereas in Sloan et al. 70 randomisation was computerised and with allocation concealment. Selection bias was unclear in the remaining two studies. Participants and/or personnel masking was not performed in Hong and Choi,67 as opposed to Lange et al. ,69 in which masking was maintained at the intervention performance level. In the remaining studies, the information related to blinding was unclear. Rickett et al. 66 was the only study with a high risk of attrition bias. However, reporting bias was absent in all studies66,68–70 but Hong and Choi,67 in which it was assessed as unclear.

Numerical results

The numerical results reported in each of the five studies66–70 are summarised in Table 7.

| First author, year | Outcome measures | Follow-upa (weeks) | Facilitated intervention group | Control group | Author’s reported statistical significance (group-by-time interaction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n totalb | Final mean scorea | SDa | n totalb | Final mean scorea | SDa | ||||

| Golkaramnay 200768 | SCL-90-R | 52 | 97 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 104 | 0.86 | 0.68 | SS |

| OQ-45.2 | 52 | 97 | 56.12 | 23.35 | 104 | 65.83 | 27.96 | SS | |

| GBB | 52 | 97 | 19.60 | 13.90 | 97 | 24.68 | 14.82 | SS | |

| n of patients accessing psychotherapeutic care | 52 | 97 | 53.60% | NA | 94 | 62.80% | NA | NS | |

| n of patients who received medication | 52 | 97 | 55.90% | NA | 94 | 60.40% | NA | NS | |

| Hong 201167 | MMSE-K | Just after writing | 15 | 18.40 | 3.00 | 15 | 14.13 | 2.95 | SS |

| Lange 200369 | IES-I | Just after writing | 69 | 11.12 | 9.27 | 32 | 21.97 | 8.60 | SS |

| IES-I | 6 | 57 | 10.46 | 9.42 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| IES-Av | Just after writing | 69 | 6.17 | 7.14 | 32 | 17.28 | 8.29 | NS | |

| IES-Av | 6 | 57 | 5.70 | 7.51 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| SCL-90-D | Just after writing | 69 | 26.42 | 10.33 | 32 | 37.25 | 9.67 | SS | |

| SCL-90-D | 6 | 57 | 25.70 | 12.28 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| SCL-90-A | Just after writing | 69 | 15.32 | 5.65 | 32 | 20.41 | 7.38 | SS | |

| SCL-90-A | 6 | 57 | 14.84 | 7.33 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| SCL-90-S | Just after writing | 69 | 17.52 | 6.34 | 32 | 22.88 | 7.74 | SS | |

| SCL-90-S | 6 | 57 | 16.34 | 7.02 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| SCL-90-Sl pb | Just after writing | 69 | 5.80 | 2.96 | 32 | 5.50 | 2.40 | SS | |

| SCL-90-Sl pb | 6 | 57 | 5.18 | 2.79 | 32 | NRc | NRc | NA | |

| Rickett 201166 | K-10 | Just after writing | 14 | 4.30 | 0.62 | 14 | 3.90 | 0.77 | SS |

| Sloan 201270 | SAM | 6 | 22 | NRd | NRd | 24 | NRd | NRd | NA |

| SAM | 18 | 22 | NRd | NRd | 24 | NRd | NRd | NA | |

| SAM | 30 | 22 | NRd | NRd | 24 | NRd | NRd | NA | |

| CAPS | 6 | 22 | 19.30 | 22.23 | 24 | 73.68 | 35.43 | SS | |

| CAPS | 18 | 22 | 10.29 | 17.54 | 24 | 57.41 | 57.43 | SS | |

| CAPS | 30 | 22 | 10.46 | 17.54 | 24 | No follow-up at week 30 in control group | NA | ||

The follow-up assessment ranged from 5 weeks in Lange et al. 69 to 52 weeks in Golkaramnay et al. 92 In Sloan et al. ,70 data are available to only 18 weeks. Total sample sizes varied on each of the outcomes measured in Golkaramnay et al. ,68 in which initial total sample sizes were of 228 participants with a dropout rate of 10–15%. The remaining trials used intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. All of the studies66–69 reported final mean scores together with corresponding SDs, except Sloan et al. ,70 in which SEs were reported in a graph. All studies66–70 reported improvement in favour of the intervention group across all outcomes and follow-ups (except on health-care use outcomes in Golkaramnay et al. 68). It must be noted that three of the studies66,67,70 were very small. None of the studies evaluating facilitated TW interventions could be meta-analysed owing to lack of consistency in measurement and heterogeneity in interventions and participants.

Unfacilitated emotional writing by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition code

B24: human immunodeficiency virus

Overview

There were six studies50,55,56,71–73 evaluating unfacilitated EW in patients with HIV. A summary of main characteristics is presented in Table 8. All participants were diagnosed with HIV and were receiving active treatment at the time of the study. Some participants in Ironson et al. 71 also had PTSD (n = 85 men, n = 47 women).

| First author, year | Study design | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abel 200450 | RCT | Unfacilitated EW | Factual writing |

| Ironson 201371 | RCT | Unfacilitated EW | Factual writing |

| Kraaij 201055 | RCT | Computerised, structured, unfacilitated EW | Waiting list |

| Mann 200172 | RCT | Unfacilitated EW (positive writing) | Non-writing |

| Petrie 200456 | RCT | Unfacilitated EW | Time-management writing |

| Wagner 201073 | RCT | Unfacilitated EW | Factual and time-management writing |

Four studies were conducted in the USA,50,71–73 with Kraaij et al. 55 and Petrie et al. 56 conducted in the Netherlands and New Zealand, respectively. All studies50,56,71–73 except Kraaij et al. 55 had two groups and evaluated one EW intervention compared with one control. Kraaij et al. 55 also compared EW with a cognitive–behavioural self-help programme but this is not considered further here. Mann72 asked participants to write about a positive future with their HIV, in which they had to take only one tablet per day, and the remaining studies all explicitly involved standard EW writing. The studies by Abel et al. 50 and Kraaij et al. 55 used a disease-focus topic in the intervention arm, and the latter study was web based. The remaining studies56,71–73 used self-selected worst trauma for participants to write about. The length of the interventions varied across studies. In the studies by Abel et al. ,50 Petrie et al. 56 and Ironson et al. ,71 EW was conducted over 3 or 4 consecutive days, whereas in the remaining studies55,72,73 the writing exercises were distributed over 4 weeks (once or twice a week). Participants in the studies by Kraaij et al. ,55 Petrie et al. 56 and Wagner et al. 73 used computers or tablets to write, as opposed to the other studies in which EW was handwritten. Participants in the studies by Abel et al. ,50 Mann72 and Wagner et al. 73 were financially compensated for participation in the study.

The outcomes evaluated across the HIV studies of unfacilitated EW are reported in Table 9.

| First author, year | HIV-related physical symptoms | CD4+ count | VL | Psychosocial distress/perceived stress | Depression | Affects (mood states) | Optimism | Coherence | Stigma | QoL | Adherence and side effects | Resource use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel 200450 | – | – | – | – | CES-D | – | – | – | Stigma Scale and Disclosure Scale | SF-36 | – | – |

| Ironson 201371 | Symptom checklist | Flow cytometry | Quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR | PTSDTOTa | HAM-D | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kraaij 201055 | – | – | – | – | HADS-D | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mann 200172 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LOT | – | – | – | Adherence and side effects due to HIV medicationb | – |

| Petrie 200456 | Self-rated health status | Flow cytometry | Quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR | PSSa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wagner 201073 | – | – | – | PSSa | – | PANAS-X(a) | HIV-OS | SOC | – | MOS-HIV | – | – |

Psychological outcomes (e.g. depression or mood) were the most commonly evaluated outcomes, together with physiological (e.g. HIV symptoms) and biological outcomes [e.g. viral load (VL) and cluster of differentiation antigen 4-positive lymphocyte cell count (CD4+ count)].

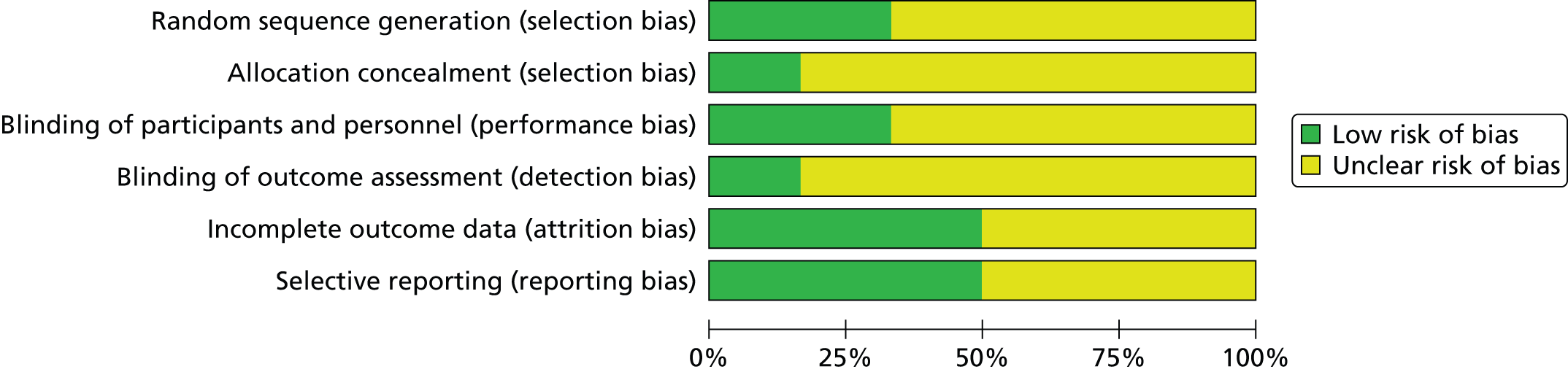

Quality assessment

A summary of the quality of the studies in HIV is shown in Figures 6 and 7. Two studies56,73 reported methods of randomisation. Allocation concealment was reported in only one study,56 and blinding was preserved in one other study. 50 The methods used were scarcely reported in almost all of the studies.

FIGURE 6.

Risk-of-bias summary in the HIV studies.

FIGURE 7.

Risk-of-bias graph in the HIV studies.

Numerical results

The numerical results reported in the HIV studies are summarised in Table 10. Follow-up assessments ranged from 2 weeks in Petrie et al. 56 to 52 weeks in Ironson et al. 71 Total sample sizes ranged from 11 participants in Abel et al. 50 to 212 participants in Ironson et al. 71 Petrie et al. 56 reported medians and SEs rather than means and SDs as in the other studies. Statistical significance of the follow-up results differences were not reported in the studies by Abel et al. ,50 Ironson et al. ,71 Mann,72 Petrie et al. 56 or Wagner et al. 73 The group-by-time interaction analysis in the Ironson et al. 71 and Kraaij et al. 55 studies was non-significant for the following outcomes: biomarkers, such as VL at long term only and CD4+ count at short, medium and long term, as well as depression [Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)] or social distress [The Davidson PTSD scale (PTSDTOT)]. However, in the Petrie et al. 56 study, the CD4+ count increased significantly in the EW group compared with control subjects when assessed at 26 weeks only.

| First author, year | Outcome measures | Follow-up (weeks) | Intervention group | Control group | Author’s reported statistical significance (group-by-time interaction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n totala | Final mean scoreb | SDb | n totala | Final mean scoreb | SDb | ||||

| Abel 200450 | Stigma Scale | 4.5 | 5 | 22.70 | 5.90 | 6 | 23.80 | 7.90 | NR |

| CES-D | 4.5 | 5 | 22.00 | 6.10 | 6 | 20.20 | 9.70 | NR | |

| SF-36 PCS | 4.5 | 5 | 525.00 | 141.10 | 6 | 610.00 | 277.00 | NR | |

| SF-36 MCS | 4.5 | 5 | 343.00 | 50.00 | 6 | 356.00 | 128.40 | NR | |

| Ironson 201371 | CD4+ count | 4 | 101 | 421.00 | 269.00 | 107 | 466.00 | 249.00 | NS |

| CD4+ count | 26 | 95 | 419.00 | 254.00 | 92 | 464.00 | 223.00 | NS | |

| CD4+ count | 52 | 78 | 429.00 | 251.00 | 87 | 491.00 | 302.00 | NS | |

| VL | 4 | 102 | 38,100.00 | 100.17 | 105 | 24,166.00 | 79,005.00 | NS | |

| VL | 26 | 96 | 47,406.00 | 114,877.00 | 89 | 28,743.00 | 94,105.00 | NS | |

| VL | 52 | 81 | 56,577.00 | 142,846.00 | 87 | 24,056.00 | 68,682.00 | NS | |

| HIV S-CL | 4 | 106 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 104 | 0.25 | 0.44 | NS | |

| HIV S-CL | 26 | > 93 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 94 | 0.27 | 0.45 | NS | |

| HIV S-CL | 52 | 81 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 88 | 0.26 | 0.44 | NS | |

| PTSDTOT | 4 | 104 | 20.63 | 23.72 | 108 | 23.84 | 21.93 | NS | |

| PTSDTOT | 26 | 94 | 17.66 | 20.13 | 96 | 19.83 | 21.73 | NS | |

| PTSDTOT | 52 | 82 | 18.08 | 20.41 | 91 | 17.89 | 22.42 | NS | |

| HAM-D | 4 | 103 | 8.41 | 6.26 | 104 | 8.99 | 7.27 | NS | |

| HAM-D | 26 | 95 | 8.13 | 6.46 | 94 | 8.30 | 6.60 | NS | |

| HAM-D | 52 | 82 | 7.54 | 6.24 | 89 | 7.09 | 5.56 | NS | |

| Kraaij 201055 | HADS-D | 4 | 16 | 7.06 | 4.81 | 15 | 7.73 | 3.88 | NS |

| Mann 200172 | LOT | 4 | 20 | 28.13 | 0.90 | 20 | 27.23 | 1.10 | NR |

| Adherence | 4 | 20 | 4.12 | 0.31 | 20 | 4.82 | 0.16 | NR | |