Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/52/03. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael G Mythen reports grants from Smiths Medical Endowment and Deltrex Medical, personal fees from Edward Lifesciences and Fresenius-Kabi for speaking, consultation or travel expenses, and personal fees from AQIX (start-up company with novel crystalloid solution – pre-clinical), patent pending for the QUENCH pump and patent issued for Gastrotim outside the submitted work. Ella Segaran reports grants from Abbott Nutrition to attend a UK Intensive Care conference outside the submitted work. Danielle E Bear reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Local Research Network, and personal fees/other support from Nestle Nutrition for speaker fees, Nutricia for speaker and consultancy fees plus payment of conference attendance, accommodation and travel expenses, Baxter for payment of course fees, travel and accommodation expenses and Corpak MedSystems UK for research support paid to Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, outside the submitted work. Geoff Bellingan reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research for Selective Decontamination of the Digestive tract in critically ill patients treated in Intensive Care Unit (The SuDDICU study) (09/01/13) during the trial.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Harvey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Malnutrition is a common problem in critically ill patients in UK NHS critical care units. 1 The consequences of malnutrition include vulnerability to complications, such as infection, which can lead to delays in recovery. Early nutritional support is therefore recommended for critically ill patients to address both deficiencies in nutritional state and related disorders in metabolism.

However, evidence is conflicting regarding the optimum route (parenteral or enteral) of delivery. 2–4 Meta-analyses of the trials comparing nutritional support via the enteral and parenteral route in critically ill patients have been published, but interpretation of their results is complicated by small sample size, poor methodological quality, select groups of critically ill patients studied, lack of standardised definitions for outcome measures and interventions combining more than one element of nutritional support, for example timing and route.

In 2003, Heyland et al. 2 reported no difference in mortality between patients given parenteral and enteral nutritional support, but enteral was associated with a significant reduction in infections. Safety, cost and feasibility led them to recommend enteral over parenteral in the critically ill adult patient. In 2004, Gramlich et al. 3 also found no difference in mortality but a significant reduction in infections with enteral nutrition (EN). 3 In addition, they reported no difference in length of unit stay or days on ventilation, but indicated that there were insufficient data to analyse these statistically. Using a different methodological approach to assessing quality of included studies (one less biased towards including the poorer-quality studies), Simpson and Doig,4 in 2005, found a significant reduction in mortality but a significant increase in infections with parenteral nutritional support compared with the enteral nutritional support. However, the significant mortality benefit with parenteral nutrition (PN) appeared to exist when compared with the provision of delayed, rather than early enteral nutritional support and thus this was not a like-for-like comparison. Similar time-based analyses for infections were not possible as a result of insufficient data.

All of the meta-analyses highlighted the problems of combining data from poor-quality studies conducted on heterogeneous patient populations (all were on select subgroups, such as head trauma, acute pancreatitis, etc.) plus variation in the timing of measurement of mortality and, perhaps more importantly, the nature and definitions for infections included and pooled (pneumonia, urinary tract, bacteraemia, wound, line sepsis, etc.). Owing to incomplete reporting, it was not possible to classify and combine infections based on risk of outcome (e.g. severe infection, moderate infection, subclinical infection).

The enteral route is the mainstay of nutritional support in critical care2,5,6 but it is frequently associated with gastrointestinal intolerance and underfeeding. 7,8 In contrast, the parenteral route though more invasive and expensive is more likely to secure delivery of the intended nutrition. 7 Historically, nutritional support via the parenteral route has been associated with more risks and complications (e.g. infectious complications) compared with the enteral route2–4 but recent improvements in the delivery, formulation and monitoring of PN justify further comparison and evaluation of these routes of nutritional support, particularly in the early phase of the illness. 9,10 Economic evidence surrounding the optimum route of delivery of nutritional support is largely based on evidence of effectiveness of questionable methodological quality and narrow focus on upfront acquisition costs, and full economic evaluation is lacking. 11

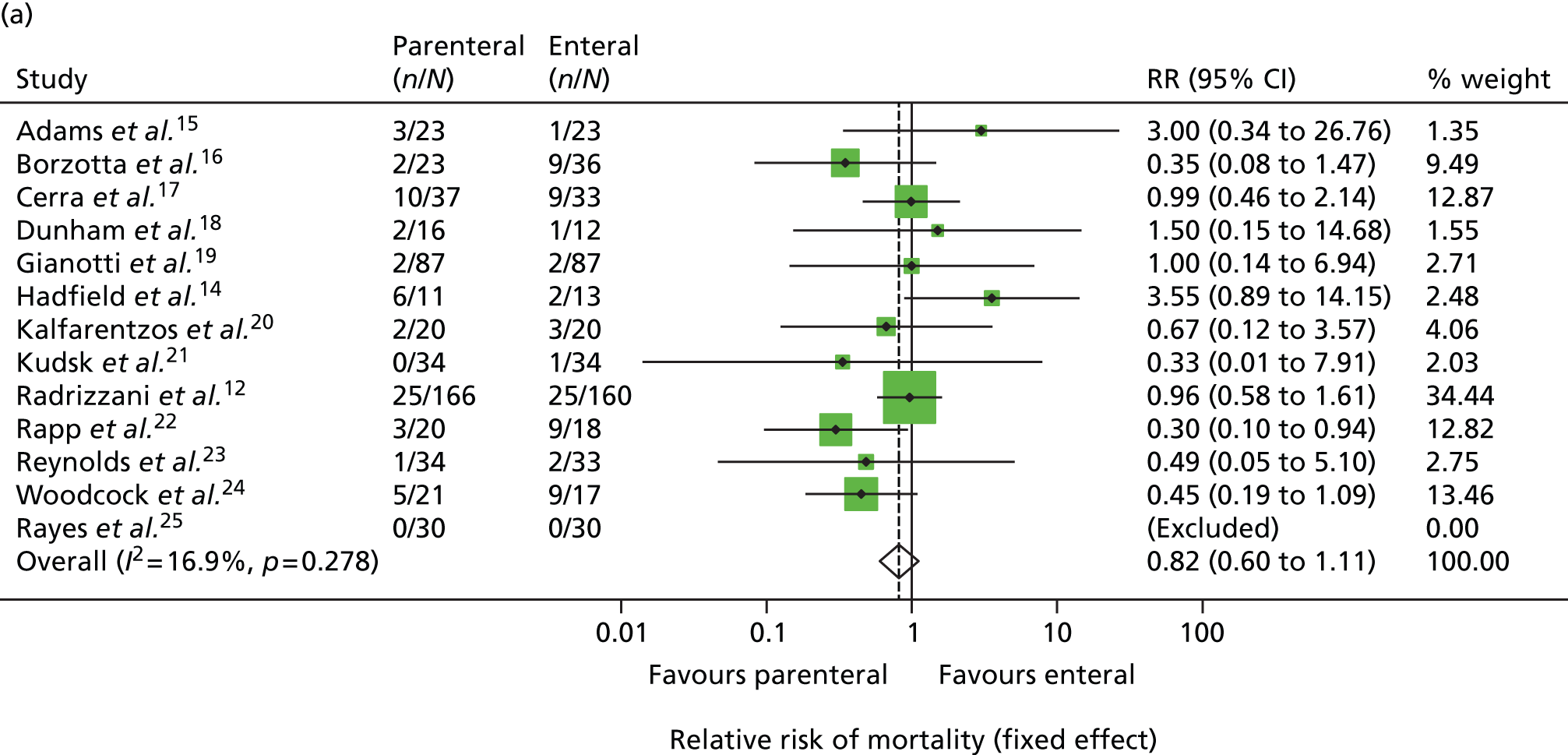

In view of this, in late 2007, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme put out a call for a large pragmatic randomised controlled trial to be conducted to determine the optimal route of delivery of early nutritional support in critically ill adults. In response to this call, in 2008, we updated the most recent systematic review by Simpson and Doig (see Figure 1). Highly sensitive search criteria identified a further 570 potentially relevant studies since May 2003. Following detailed review of these studies, one additional randomised controlled trial comparing PN and EN was identified. 12 This paper reported the full results of a trial previously identified by Simpson and Doig as having only interim results reported,13 but was excluded from their meta-analysis, as the enteral nutritional support arm included immune-enhancing supplements. As the use of immune-enhancing supplements was to be permitted in our study, we repeated the meta-analysis to include studies with supplementation of either arm. This resulted in the inclusion of this trial and one additional randomised controlled trial excluded from the Simpson and Doig meta-analysis on this criterion. 14 The results of the updated meta-analysis, including a total of 13 studies,12,14–25 indicated a non-significant survival benefit for parenteral support [relative risk 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60 to 1.11] but an increased risk of infection (relative risk 1.77, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.63) compared with enteral nutritional support (Figure 1). Consequently, parenteral nutritional support in the critical care unit remained controversial and no clear evidence existed as to the optimum route for delivery of early nutritional support to critically ill patients.

FIGURE 1.

Updated meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing PN with EN. (a) Relative risk of mortality; and (b) relative risk of infectious complications. RR, risk ratio. Based on the criteria of Simpson and Doig,4 updated to 24 January 2008, and with exclusion criteria relaxed to include trials that had been excluded previously because of the use of immune-enhancing supplements.

Aim

The aim of the CALORIES trial was to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early nutritional support in critically ill patients, delivered via the parenteral compared with the enteral route.

Objectives

Primary

The primary objectives of the CALORIES trial were to estimate the:

-

effect of early (defined as within 36 hours of the date/time of original critical care unit admission) nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with early nutritional support via the enteral route on all-cause mortality at 30 days, and

-

incremental cost-effectiveness of early nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with early nutritional support via the enteral route at 1 year.

Secondary

The secondary objectives of the CALORIES trial were to compare early nutritional support via the parenteral and enteral routes for:

-

duration of specific and overall organ support in the critical care unit

-

infectious and non-infectious complications in the critical care unit

-

duration of critical care unit and acute hospital length of stay

-

duration of survival at 90 days and at 1 year

-

mortality at discharge from the critical care unit and from acute hospital

-

mortality at 90 days and at 1 year

-

nutritional and health-related quality of life at 90 days and at 1 year

-

resource use and costs at 90 days and at 1 year, and

-

estimated lifetime incremental cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The CALORIES trial was a pragmatic, open, multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial with an integrated economic evaluation.

The trial was nested in the Case Mix Programme, the national clinical audit of adult general critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, established in 1995 and co-ordinated by Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) (Scotland has its own separate national clinical audit). 26 The Case Mix Programme is listed in the Department of Health’s ‘Quality Accounts’ for 2013–14 as a recognised national audit by the National Advisory Group for Clinical Audit and Enquiries.

Nesting the CALORIES trial in the Case Mix Programme ensured an efficient design (with respect to participating units and data collection) and facilitated efficient management of the study, including monitoring recruitment.

Research governance

The trial was sponsored by ICNARC and co-ordinated by the ICNARC Clinical Trials Unit (CTU).

An ethics application was submitted to the North West London Research Ethics Committee on 28 October 2010 and the CALORIES trial received a favourable opinion on 16 December 2010 (reference number: 10/H0722/78). The protocol is available via www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/.

To ensure transparency, the trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry on 25 March 2009. Registration was confirmed on 9 April 2009 (ISRCTN17386141).

The NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio details high-quality clinical research studies that are eligible for support from the NIHR CRN in England. The trial was adopted on to the NIHR CRN Portfolio on 24 March 2011 and was issued the NIHR CRN Portfolio number 10098.

Global NHS permissions were obtained from Central and East London Comprehensive Local Research Network (CLRN) on 10 March 2011 and local NHS permissions were obtained from each participating NHS trust. A clinical trial site agreement, based on the model agreement for non-commercial research in the health service, was signed by each participating NHS trust and the sponsor (ICNARC).

Following guidelines from the NIHR, a Trial Steering Committee (TSC), with a majority of independent members, was convened to oversee the trial on behalf of the funder (NIHR) and the sponsor (ICNARC). The TSC met at least annually during the trial and comprised an independent chairperson; independent lay members (representing patient perspectives); independent clinicians (specialising in critical care medicine); the chief investigator (KR); and the lead clinical investigator (MM) representing the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Additionally, an independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) was convened to monitor trial data and ensure the safety of trial participants. The DMEC met at least annually during the trial; it comprised two expert clinicians specialising in critical care medicine and was chaired by an experienced statistician.

Management of the trial

The trial manager was responsible for day-to-day management of the trial with support from the data manager, trial statistician and research assistant. The TMG, chaired by the ICNARC CTU manager (SH), was responsible for overseeing day-to-day management of the trial and comprised the chief investigator (KR), trial dietitians (DB, ES) and co-investigators (GB, RB, DH, RL and MM). The TMG met regularly throughout the trial to ensure adherence to the trial protocol and monitor the conduct and progress of the trial.

Network support

To maintain the profile of the trial, regular updates on trial progress were provided at quarterly meetings of the NIHR CRN Critical Care Specialty Group and at local CLRN meetings. In addition, updates were provided at national meetings, such as the Annual Meeting of the Case Mix Programme and the UK Critical Care Research Forum.

Design and development of the protocol

Clinicians – including doctors, nurses and dietitians, from NHS critical care units across the UK – were invited to a meeting in May 2010 to discuss the trial protocol. The purpose of the meeting was to provide a forum for clinicians who had expressed an interest in taking part in the trial to discuss the trial protocol in detail with the trial investigators. Following the meeting, minor changes were made to the trial protocol to ensure clarity.

Amendments to the trial protocol

Following receipt of a favourable opinion of the trial protocol from the Research Ethics Committee on 16 December 2010, four substantial amendments were submitted and received favourable opinion. In summary, these were:

-

Amendment 1 (13 May 2011) – the personal/professional consultee consent form was replaced with a personal/professional consultee agreement form to clarify that consultees were being asked for agreement (not consent) for patients to participate in the trial according to the Mental Capacity Act (2005)27 and the National Research Ethics Service Guidance for Researchers & Reviewers. The patient information sheets (prospective and retrospective for the patient and for the personal/professional consultee) and consent forms (patient consent form and retrospective patient consent form) had minor administrative changes. A personal/professional consultee telephone agreement form was produced to ensure that, in the situation that a personal/professional consultee was contacted via the telephone for their opinion, this contact was documented. The trial protocol was amended to clarify the aim of the trial – to compare early nutritional support delivered via the parenteral with early nutritional support delivered via the enteral route – and to incorporate the most up-to-date version of the EuroQoL 5-dimension (5-level version) questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) to evaluate health-related quality of life at 90 days and at 1 year.

-

Amendment 2 (19 December 2011) – the letter to the patient’s general practitioner (GP) informing them of the patient’s participation in the trial was amended for use in cases when the patient was known to have died. The patient follow-up letters were amended to be specific to the follow-up time point, that is 90 days and 1 year post-randomisation, and minor semantic changes were made to the patient information sheets and consent/agreement forms.

-

Amendment 3 (4 October 2012) – following requests from research teams at sites, a CALORIES trial information leaflet for family and friends was produced. The leaflet was placed in the critical care unit relatives’ room, with the aim of providing relatives/friends of patients in critical care with a brief overview of the trial. The exclusion criterion ‘known to be participating in an interventional study’ was removed following review by the TMG; it was agreed that patients could be co-enrolled into two interventional studies if, after careful consideration, there were no concerns about patient safety, risk of biological interaction or the scientific integrity of the trial. Local principal investigators (PIs) were advised to contact the ICNARC CTU on a case-by-case basis to discuss co-enrolment of patients. In addition, minor semantic changes were made to the trial protocol and consent/consultee agreement forms.

-

Amendment 4 (23 October 2013) – a patient newsletter was added to the follow-up questionnaire pack that was sent to each patient at 90 days and 1 year post recruitment into the CALORIES trial.

NHS support costs

Trials in critical care are challenging and expensive to conduct. Unlike other areas of health care, such as oncology, recruitment cannot take place solely within usual office hours. Resources are needed to enable screening and recruitment 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Patients with a critical illness can be admitted to the critical care unit at any time of day or night, including weekends. Another challenge of critical care research is the informed consent process, which often has to be completed within a short time frame, as treatments are often time limited. Furthermore, critically ill patients usually lack the mental capacity to be able to provide informed consent prior to randomisation, in which case it is necessary to involve a personal or professional consultee in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act. 27 Senior, experienced staff are needed to be able to assess the patient’s mental capacity and to be able to effectively communicate information about the trial to the patient and/or their relatives in a stressful situation.

To this end, resources equivalent to 0.5 whole-time equivalent (WTE) band 7 research nurse, 0.1 WTE critical care consultant, 0.1 WTE band 7 dietitian and 1.4 hours per week of a band 6 pharmacist were successfully agreed with the lead CLRN on 21 June 2011.

Resources were based on an estimated 175 eligible admissions per unit per year, of whom approximately 60 would be recruited and 30 randomised to receive early nutritional support via the parenteral route. Using these recommendations, participating sites, assisted by the TMG, negotiated resources required locally for the trial with their respective research and development departments and CLRNs.

Patient and public involvement

Engagement with patients was vital to the successful conduct of the trial. The original study proposal was reviewed and endorsed by Patients on Intravenous and Nasogastric Nutritional Therapy support group. Two former critical care patients were independent members of the TSC and they provided input into the conduct of the trial, including reviewing literature to be given to patients and their families (e.g. patient information sheets and patient newsletters).

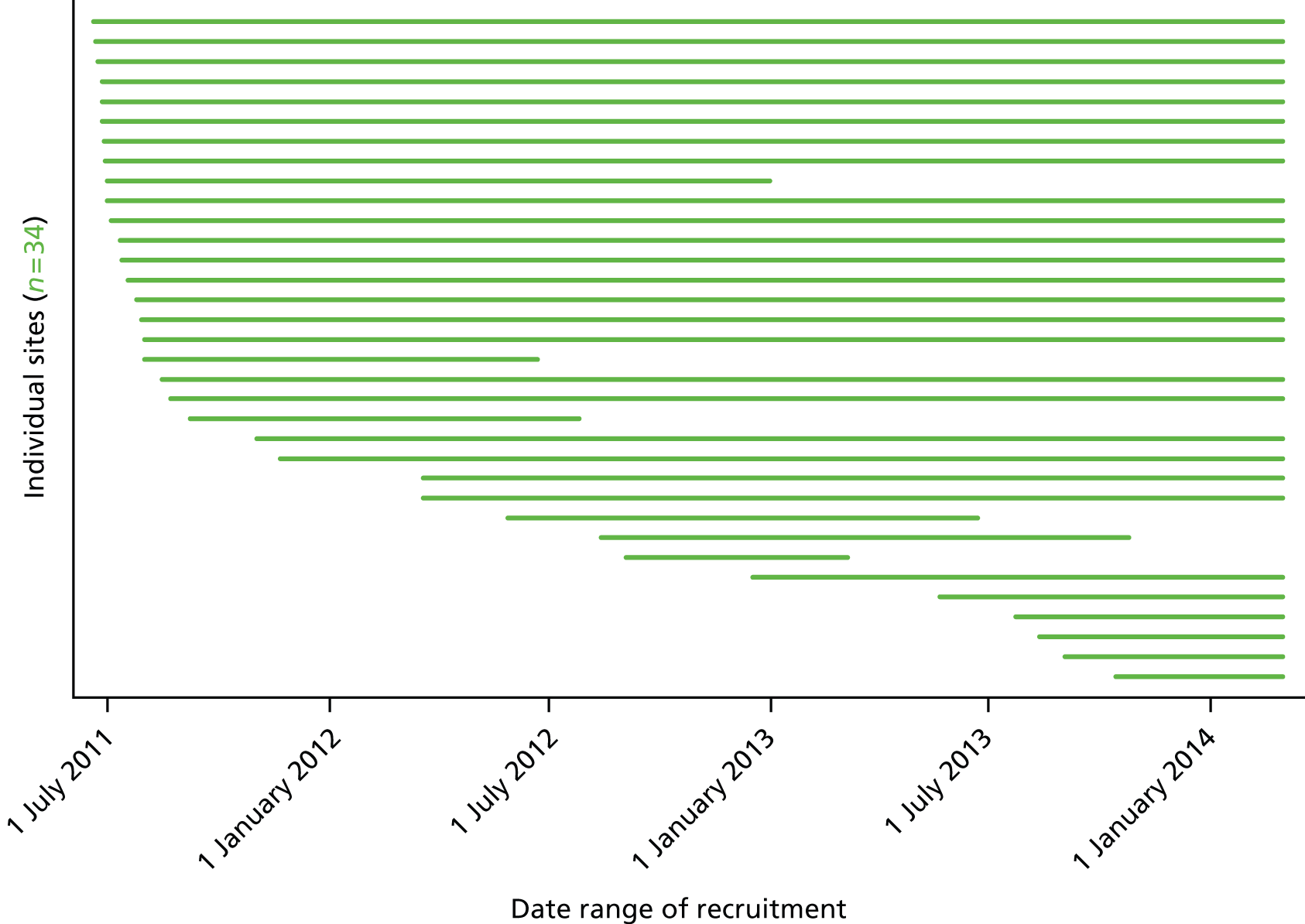

Participants: sites

The trial aimed to recruit a representative sample of at least 20 adult, general critical care units from the UK. Adult, general critical care units were defined as intensive care units (ICUs) or combined intensive care/high-dependency units. Stand-alone high-dependency units and specialist critical care units (e.g. neurosciences, cardiothoracic, etc.) were not eligible for participation in the trial. The criteria for inclusion were:

-

active participation in the Case Mix Programme – defined as submission of data no later than 6 weeks after the end of each quarter and returning corrected data validation reports no later than 6 weeks after receipt

-

pre-existing, established protocols for PN and EN reflecting mainstream practice (reviewed and approved by the TMG)

-

pre-existing implementation of bundles as promoted by the NHS (NHS Saving Lives: reducing infection, delivering clean and safe care – ‘High Impact Intervention No. 1: Central venous catheter’ and ‘High Impact Intervention No. 5: Ventilator’) to prevent the development of bloodstream infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia28,29

-

pre-existing prophylaxis protocol for the prevention of venous thromboembolism

-

glycaemic control protocol in line with international guidelines30

-

agreement to incorporate the CALORIES trial into routine unit practice, including prior agreement – from all consultants in the unit – to adhere to the patient’s randomly allocated route (parenteral or enteral route) for delivery of early nutritional support

-

agreement to recruit all eligible patients into the CALORIES trial and to maintain a screening log of eligible patients who were not randomised, and patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria but met one or more of the exclusion criteria

-

sign up from the unit clinical director, senior nurse manager, dietitian/clinical nutritionist and pharmacist, and

-

identification of a dedicated CALORIES trial research nurse.

All of the units actively participating in the Case Mix Programme were invited for expressions of interest to take part in the trial. In addition, the trial was promoted through presentations at relevant national meetings of professional organisations, such as the Intensive Care Society and at the UK Critical Care Research Forum.

A PI, who was responsible for the conduct of the trial locally, was identified at each participating site.

Site initiation

Site teams from all participating sites attended a site initiation meeting prior to the commencement of patient screening. Two site initiation meetings were held in London on 11 May 2011 and 8 June 2011, attended by staff from 22 critical care units. The purpose of these meetings was to present the background and rationale for the CALORIES trial and to discuss delivery of the protocol, including screening and recruiting patients, delivery of early nutritional support via the parenteral and enteral routes, data collection and validation, and safety monitoring. The operational challenges of conducting the trial at sites were discussed in detail, including strategies for ensuring effective communication within the critical care unit. The PI from each participating site was required to attend the meeting. If key research staff were unable to attend the meeting, or new staff came into post, additional site initiation meetings were conducted as required, either at sites or via teleconference. A standardised slide set from the site initiation meetings was circulated to facilitate internal training within a participating site.

Investigator site file

An investigator site file was provided to all participating sites. This contained all essential documents for the conduct of the trial and included the approved trial protocol; all relevant approvals (e.g. local NHS permissions); a signed copy of the clinical trial site agreement; the delegation of trial duties log; copies of the approved patient information sheets, patient consent form and personal/professional consultee agreement forms; and all standard operating procedures, for example for screening participants, for obtaining informed consent or consultee agreement, for randomising patients, for delivery of the intervention, and for collecting and entering data onto the secure, dedicated, electronic case report form. The site PI was responsible for maintaining the investigator site file. Responsible staff at sites were authorised to carry out trial duties (e.g. consenting, delivering the intervention) by the site PI on the delegation of trial duties log. This included a confirmation that the individual had been adequately training to carry out the specific duty.

Site management

Communication

The trial manager, with support from the data manager and research assistant, maintained close contact with the PI and trial team at participating sites by e-mail and telephone throughout the trial.

Teleconferences were held, initially every month then every 2 months, with trial teams at participating sites. The purpose of these was to provide updates on trial progress and to provide a forum for site teams to ask questions, discuss local barriers and challenges to the conduct of the trial, delivery of the intervention and to share successes and best practice. Notes, including ‘hints and tips’, from the teleconferences were distributed to all participating sites. The ICNARC CTU team facilitated further direct communication between sites via an e-mail forum for research nurses.

Teleconferences were also held with individual site teams, as required, to address site-specific issues in the conduct of the trial and/or to support training new staff.

Site monitoring visits

At least one routine monitoring visit was conducted at all participating sites during the trial. During the site visit, the investigator site file was checked for completeness, that is, that all essential documents were present; the patient consent forms and personal/professional consultee agreement forms were checked to ensure that the relevant correctly completed form was present for every patient recruited into the trial; and a random sample of patient case report forms were checked against the source data for accuracy and completeness. After the visit, the PI and site team were provided with a report summarising the documents that had been reviewed and actions required by the site team. The site PI was responsible for addressing the actions and reporting back to the ICNARC CTU. Additional visits were conducted on a risk-based approach, using recruitment rates, data quality and adherence to the protocol as central monitoring triggers.

Maintenance and motivation

During the trial, an e-mail was sent each month to site teams with an update on patient recruitment, and a newsletter was sent every quarter. These provided an opportunity to clarify any issues related to the conduct of the trial and to share ideas for maximising recruitment, as well as maintaining motivation and involvement through regular updates on progress.

To maintain the profile of the trial at participating sites, posters were displayed in staff areas and at relevant locations within the critical care unit, for example by the bedside or in EN and PN storage areas; pocket cards (summarising the eligibility criteria) and branded pens were distributed to staff; and certificates were given to clinical staff in recognition of their contribution to the trial.

Support

A 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, telephone support service was available to site teams for advice on screening and recruitment of patients and on delivery of the intervention. This ensured access to clinicians and dietitians for answering any queries on delivery of the intervention.

Collaborators’ meeting

A collaborators’ meeting was held on 17 January 2013 to provide an update on trial progress, provide a forum for site teams and investigators to discuss operational challenges to the trial and identify possible solutions, and to share successes and best practice.

Participants: patients

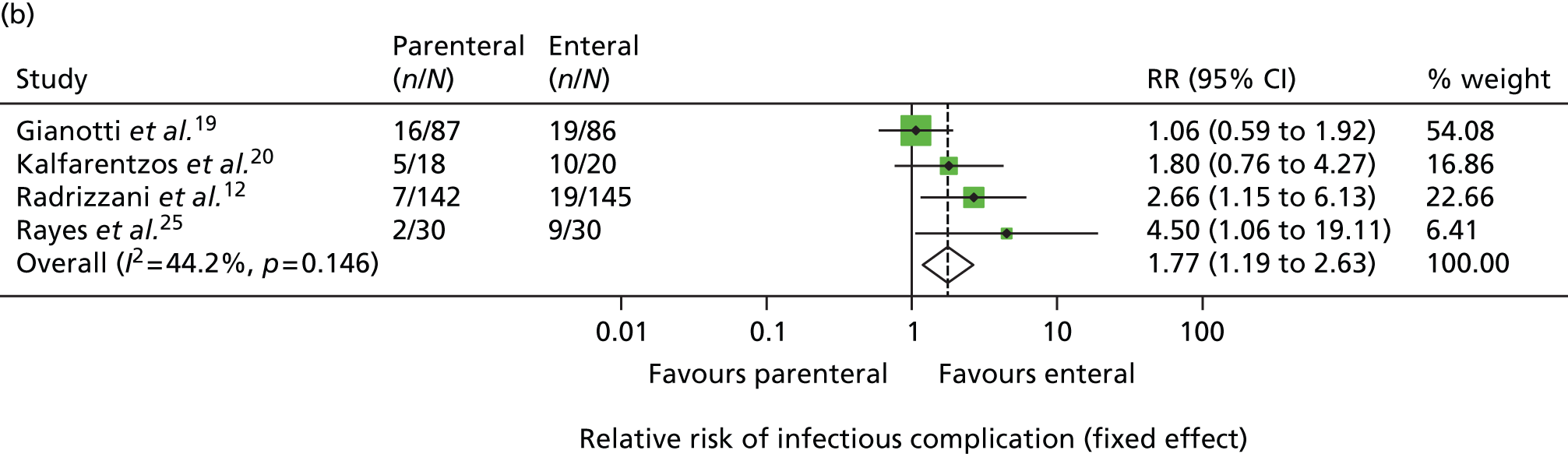

The trial procedures for recruitment and follow-up of patients are summarised in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of trial procedures for recruitment and follow-up of patients.

Eligibility

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the trial who, on admission (but within a time frame to obtain patient consent/consultee agreement, randomise and start nutritional support within 36 hours of the date/time of original critical care unit admission), were:

-

an adult (defined as age ≥ 18 years)

-

an unplanned admission (including planned admissions becoming unplanned, e.g. unexpected postoperative complications)

-

expected to receive nutritional support for ≥ 2 days in the critical care unit, and

-

not planned to be discharged within 3 days (defined by clinical judgement) from the critical care unit.

Patients were excluded from the trial if they met any of the following criteria:

-

had been in a critical care unit for > 36 hours (i.e. from the date/time of original critical care unit admission)

-

had been previously randomised into the CALORIES trial

-

had pre-existing contraindications to PN or EN

-

had received PN or EN within the 7 days prior to admission to the critical care unit

-

had been admitted with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy, needle/surgical jejunostomy or nasojejunal tube in situ

-

had been admitted to the critical care unit for treatment of thermal injury (burns)

-

had been admitted to the critical care unit for palliative care

-

their expected stay in the UK was < 6 months, or

-

known to be pregnant.

During the trial, on the advice of the Research Ethics Committee, patients who were known to have a pre-existing condition, such as dementia, which would have precluded them from providing informed consent at any point during the trial, were also excluded.

Screening and recruitment

Following attendance at a site initiation meeting, screening and recruitment was commenced at participating units once the clinical trial site agreement had been signed and all of the necessary approvals were in place.

To promote awareness of the trial and facilitate recruitment, posters providing information about the CALORIES trial were displayed in the critical care unit and in family/visitor waiting rooms.

Potentially eligible patients were identified and approached by authorised members of staff about taking part in the trial. Information about the trial was provided to the patient, which included the purpose of the trial, the consequences of taking part or not, data security and funding of the trial. This information was also provided in a patient information sheet (see Appendix 1), along with the name and contact details of the local PI, which was given to the patient to read before making their decision to take part, or not, in the trial.

If the patient lacked mental capacity (because of their acute illness) to understand the information about the trial then, in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act,27 a personal consultee, who could be a relative or close friend, was identified with whom to discuss the patient’s participation in the trial. If there was no personal consultee available then the patient was provided with a professional consultee, for example an independent mental capacity advocate appointed by the NHS hospital trust, with whom to discuss the patient’s participation in the trial. The personal/professional consultee was provided with the same information as for patients (see Appendix 1) along with an explanation that they were being asked for their agreement for the patient to take part in the trial. Patients and personal/professional consultees were provided with an opportunity to ask questions before being invited to sign the consent form or personal/professional consultee agreement form, as appropriate.

Informed consent

Staff members, who had received training on the background, rationale and purpose of the CALORIES trial, and on the principles of the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, were authorised by the PI to take informed consent from patients or informed agreement from a personal/professional consultee.

Once the staff member who was taking informed patient consent or consultee agreement was satisfied that the patient or personal/professional consultee had read and understood the patient information sheet, and that all of his/her questions about the trial had been answered, the patient or personal/professional consultee was invited to sign the patient consent form or personal/professional consultee agreement form, as appropriate.

For patients who had lacked mental capacity prior to randomisation, informed consent to continue participating in the trial was sought as soon as possible after the patient had regained mental capacity. If a patient did not regain mental capacity then, if possible, for patients entered via professional consultee agreement, agreement from a personal consultee was obtained for the patient to continue participating in the trial.

Randomisation and allocation procedure

Following informed consent from the patient or informed agreement from a personal/professional consultee, eligible patients were randomised via a central 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, telephone randomisation service hosted by Sealed Envelope Ltd. Patients were allocated, 1 : 1, to early nutritional support via either the parenteral route or the enteral route, by minimisation with a random component (each patient being allocated with 80% probability to the treatment group that would minimise imbalance). Minimisation was based on the following factors: site; age (< 65 years or ≥ 65 years); surgical status (surgery within 24 hours prior to unit admission or not); and malnutrition status (based on clinical judgement) (yes or no). A manual randomisation list (using permuted blocks, with block lengths of 4, 6 and 8) was prepared in advance of the trial by the trial statistician for use if the central telephone randomisation service was not available for any reason. Staff at participating sites were advised to call the 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, telephone support service if they experienced any problems with the central telephone randomisation service. Manual randomisation was carried out, as required, by the on-call member of the TMG. Details of any patients manually randomised were passed to the randomisation service for inclusion in the minimisation algorithm for subsequent allocations.

Screening log

To enable full and transparent reporting for the trial, brief details of all patients who met eligibility criteria or who met all of the inclusion criteria plus one or more of the exclusion criteria were recorded in the screening log. The reasons for eligible patients not being recruited were recorded, which included the patient declining the invitation to take part, the patient being excluded by the treating clinician, logistical reasons, etc. No patient identifiers were recorded in the screening log.

Treatment groups

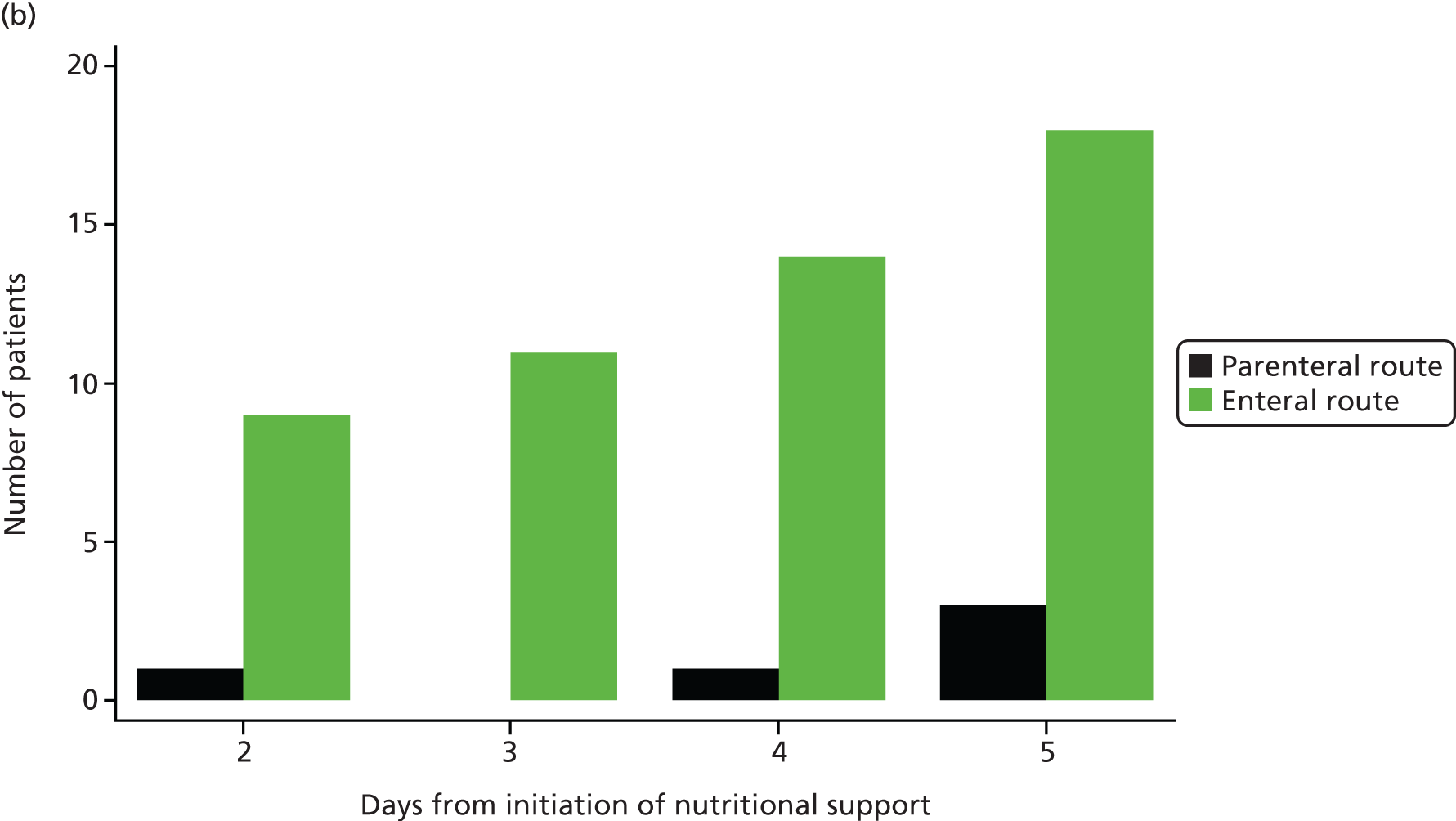

As a pragmatic trial, the CALORIES trial did not dictate the use of specific nutritional products or protocols for delivery of nutritional support via the parenteral and enteral routes. However, existing established protocols for delivery of PN and EN at participating units were reviewed and approved by the TMG to ensure that they fell within common boundaries.

Early nutritional support was delivered via either the parenteral or enteral route for the 5-day (120 hours) intervention period, unless the patient transitioned to exclusive oral feeding or was discharged from the critical care unit before this time. Patients were able to start oral feeding if clinically indicated during the 5 days.

Early nutritional support via the parenteral route

For patients who were randomised to early nutritional support via the parenteral route, a central venous catheter, with a dedicated lumen, was inserted and positioned in accordance with NHS guidelines. 28 Patients received a standard parenteral feed, obtained from the unit’s usual supplier and used within the licence indication, which contained between 1365 and 2540 total kcal/bag and between 7.2 and 16.0 g of nitrogen/bag. Unit staff aimed to feed patients to a target of 25 kcal/kg/day (based on actual body weight) within 48–72 hours of starting the feed. There was no specific target for the amount of nitrogen to be given. Enteral ‘trickle feeding’ (‘trophic feeding’) was not permitted for the 5-day (120 hours) intervention period.

Local unit policy and practice was followed for delivery of nutritional support via the parenteral route and included provision for:

-

ensuring that the patient received a nutritionally complete feed

-

inclusion of additional micronutrients (made under appropriate pharmaceutically controlled environmental conditions) if clinically indicated, and as prescribed by the clinician and/or dietitian in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines1

-

adjustment of total volume according to the patient’s fluid balance requirements

-

monitoring for specific nutritional-related complications

-

regular review of the patient for their ongoing nutritional support needs, and

-

energy requirements for patients with extremes of body mass index (BMI) (e.g. < 18.5 kg/m2 and > 30 kg/m2).

Early nutritional support via the enteral route

For patients who were randomised to early nutritional support via the enteral route, a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube was inserted and positioned in accordance with UK National Patient Safety Agency guidelines. 31,32 Patients received a standard enteral feed, obtained from the unit’s usual supplier, and used within the licence indication, which contained between 1365 and 2540 total kcal/day and between 7.2 and 16.0 g of nitrogen/day. There was no specific target for the amount of nitrogen to be given. Unit staff aimed to feed patients to a target of 25 kcal/kg/day (based on actual body weight) within 48–72 hours of starting the feed.

Local unit policy and practice was followed for delivery of nutritional support via the enteral route and included provision for:

-

ensuring that the patient received a nutritionally complete feed

-

adjustment of total volume according to the patient’s fluid balance requirements

-

monitoring for specific nutritional-related complications

-

regular review of patients for their ongoing nutritional support needs, and

-

energy requirements for patients with extremes of BMI (e.g. < 18.5 kg/m2 and > 30 kg/m2).

Outcome measures

The primary clinical effectiveness outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days following randomisation and the primary cost-effectiveness outcome was the incremental net benefit (INB) gained at 1 year following randomisation, at a willingness-to-pay of £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

The secondary outcomes were:

-

number of days alive and free from advanced respiratory support, advanced cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support and gastrointestinal support up to 30 days following randomisation

-

number of new, treated, confirmed or strongly suspected infectious complications, classified according to clinical diagnosis, which occurred in the critical care unit

-

non-infectious complications of episodes of hypoglycaemia, elevated levels of liver enzymes, nausea requiring treatment, abdominal distension and vomiting, collected through adverse event reporting up to 30 days following randomisation, and new or significantly worsened pressure ulcers while in the critical care unit

-

duration of critical care unit stay (from dates and times) and acute hospital length of stay (in whole days) following randomisation

-

duration of survival at 90 days and at 1 year following randomisation

-

all-cause mortality at discharge from the critical care unit and from the acute hospital

-

all-cause mortality at 90 days and at 1 year following randomisation

-

nutritional and health-related quality of life at 90 days and at 1 year following randomisation

-

resource use and costs at 90 days and at 1 year following randomisation, and

-

estimated lifetime incremental cost-effectiveness (INB).

Safety monitoring

Patients were monitored for adverse events occurring between randomisation and 30 days following randomisation. Specified adverse events were defined as follows:

-

abdominal distension was defined as any new, clinically significant change in appearance; abdominal distension was considered severe if there was an acute obstruction

-

abdominal pain was defined as any new episode of abdominal pain, localised to the abdomen and requiring more than just simple analgesia; abdominal pain was considered severe if it was not controlled with opiates

-

episodes of electrolyte disturbance were defined as any new, clinically significant electrolyte disturbance requiring active monitoring or treatment

-

haemopneumothorax was defined as any new haemopneumothorax requiring insertion of a chest drain

-

hepatomegaly was defined as any new or increased hepatomegaly on clinical examination

-

hyperosmolar syndrome was defined as any new, clinically significant osmolar gap requiring active monitoring or treatment

-

hypersensitivity reaction (anaphylactic reaction) was defined as any new anaphylactic reaction

-

episodes of hypoglycaemia were defined as any new episode of clinically significant hypoglycaemia requiring active monitoring or treatment

-

ischaemic bowel was defined as any new episode of ischaemic bowel inferred on radiology or diagnosed visually, for example during surgery or by endoscopy

-

jaundice was defined as any new, clinically significant jaundice requiring active monitoring or treatment

-

nausea requiring treatment was defined as any new episode of nausea requiring treatment with anti-emetic drugs

-

pneumothorax was defined as any new pneumothorax requiring insertion of a chest drain

-

raised levels of liver enzymes were defined as any new, clinically significant rise in liver enzyme levels requiring active monitoring or treatment

-

regurgitation/aspiration was defined as any episode of regurgitation/aspiration

-

vascular catheter-related infection was defined as any new vascular catheter-related infection for which a vascular catheter, such as a central venous catheter, was identified as the primary source of infection and associated with signs and symptoms of infection requiring antimicrobial drugs and/or removal of catheter, and

-

vomiting was identified as any episode of vomiting.

Unspecified adverse events were defined as an unfavourable symptom or disease that was temporally associated with the use of the trial treatments, whether or not it was related to the trial treatment, which was not deemed to be a direct result of the patient’s medical condition and/or standard critical care treatment.

All adverse events were recorded in the electronic case report form and reported, as part of routine reporting throughout the trial, to the DMEC and research ethics committee. Adverse events that were assessed to be serious (i.e. prolonging hospitalisation or resulting in persistent or significant disability/incapacity), life-threatening or fatal – collectively termed serious adverse events – were reported to the ICNARC CTU and reviewed by a clinical member of the TMG. Serious adverse events that were unspecified and considered to be possibly, probably or definitely related to the trial treatment were reported to the research ethics committee within 15 calendar days of the event being reported.

Data collection

A secure, dedicated electronic case report form, hosted by ICNARC, was set up to enable trial data to be entered by staff at participating sites. The electronic case report form was accessible only to authorised users and access was approved centrally by the trial manager, data manager or research assistant (after cross-checking the site delegation of trial duties log). Each individual was provided with a unique username and password and had access to data only for patients recruited at their site.

The data set for the CALORIES trial included the minimum data required to confirm patient eligibility, to describe the patient population, to monitor and describe delivery of the intervention, to assess primary and secondary outcomes and to enable linkage to the ICNARC Case Mix Programme (see Appendix 2). 26

Randomisation

Data were collected to enable the patient to be randomised, and included confirmation that the patient met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (see Appendix 2).

Baseline

The following data were collected at baseline to enable follow-up and to describe the patient population:

-

full name and address of the patient and their GP

-

date of birth

-

gender, and

-

raw physiology data to enable calculation of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (see Appendix 3). 33

Raw physiology data, to enable calculation of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation version II (APACHE II) and ICNARC scores and predicted risks of hospital death (see Appendix 3), were obtained from the Case Mix Programme Database. 34,35

Intervention period

Data were collected daily throughout the 5-day (120-hour) intervention period to monitor adherence to treatment allocation (early nutritional support via parenteral route or early nutritional support via enteral route) and to describe and cost delivery of early nutritional support via the parenteral and enteral routes. The data collected included:

-

nutritional support delivered during each calendar day, including mode of delivery of nutritional support, site of central venous catheter, site of enteral tube (nasogastric or nasojejunal), nutritional product type, volume of nutritional support delivered and any change to delivery of nutritional support

-

physiology, for example arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2), fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), blood pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, blood glucose, urine output, and

-

interventions, for example mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, systemic antibacterial drugs and/or antifungal drugs.

At critical care unit discharge

At the time of discharge from the critical care unit, the following data were collected:

-

route(s) of delivery of nutritional support in the critical care unit from day 7 following randomisation

-

interventions delivered in the critical care unit from day 7 following randomisation

-

new strongly suspected or confirmed infectious episodes, classified according to clinical diagnosis, which occurred in the critical care unit following randomisation

-

strongly suspected infection was defined as strongly suggestive evidence, for example evidence of gross purulence or evidence from radiological or other imaging techniques, and the commencement of antibacterials or antifungals for a suspected infection; strongly suggested evidence must have been documented in the case notes

-

confirmed infection was defined as laboratory/microbiological confirmation, including cultures, Gram stains and roentgenograms

-

-

organ support, as defined by the UK Department of Health Critical Care Minimum Dataset (CCMDS)36 (see Appendix 4) during the critical care unit stay, and

-

date and time of discharge from, or death in, the critical care unit.

At acute hospital discharge

At the time of discharge from the acute hospital, the following data were collected:

-

the locations of care during the patient’s stay in the acute hospital, for example critical care unit, ward

-

date that exclusive oral feeding commenced (if applicable) following the patient’s discharge from the critical care unit

-

date of discharge from, or death in, the acute hospital, and

-

discharge location, for example home, nursing home, other hospital.

At 30 days

All patients were followed up at 30 days following randomisation for the primary clinical effectiveness outcome (all-cause mortality) via the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) Data Linkage and Extract Service.

Longer-term follow-up

Following randomisation, a letter was sent to the patient’s GP informing them of the patient’s participation in the trial and a request for assistance with follow-up, if required. All patients who survived to leave hospital were followed up at 90 days for the secondary outcomes (all-cause mortality, duration of survival, health-related quality of life and resource use), and at 1 year for secondary outcomes (all-cause mortality, duration of survival, health-related quality of life and resource use) and to calculate the primary cost-effectiveness outcome (INB).

Data linkage with death registration

Follow-up of patients was carefully monitored to prevent any potential distress to those who care for the patient receiving a letter addressed to a deceased relative, partner or friend. The follow-up process started at 75 days for the 90-day follow-up and at 350 days for the 1-year follow-up to allow for the administrative processes. Each week a list of all patients who had been discharged alive from hospital and who were either 75 days or 350 days post-randomisation was sent to the HSCIC Data Linkage and Extract Service to confirm their mortality status. Patients indicated as having died were logged and the follow-up process ended.

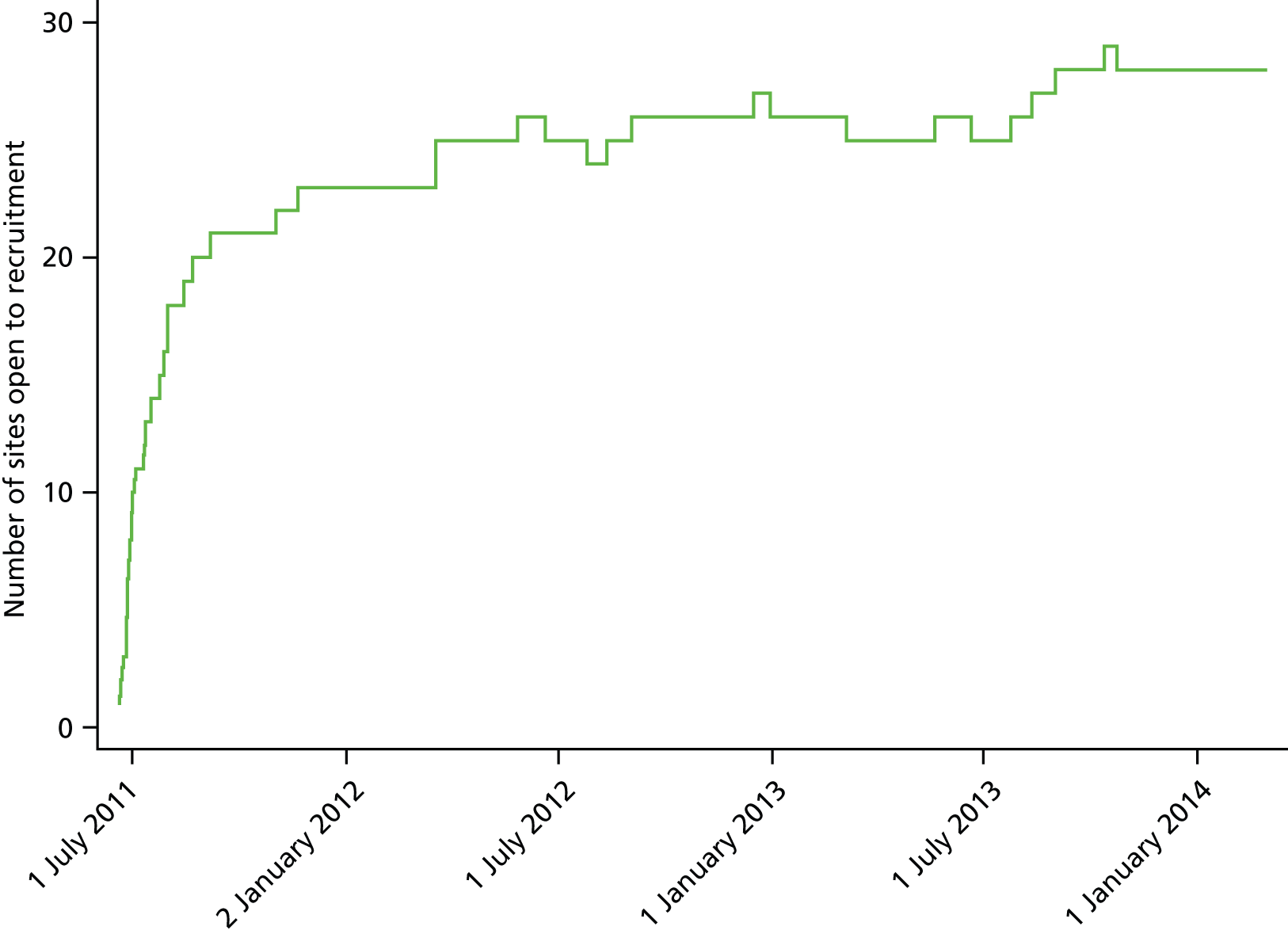

Follow-up procedure

Patients identified by the HSCIC Data Linkage and Extract Service as not having died started the follow-up process summarised in Figure 3. A questionnaire pack was sent from the ICNARC CTU, by post, to the patient. Following evidence-based practice for maximising responses to postal surveys,37 the questionnaire pack included a cover letter (see Appendix 5); the patient information sheet (see Appendix 1) or patient newsletter (which replaced the patient information sheet in November 2013); two questionnaires – the Health Questionnaire and the Health Services Questionnaire (see Appendix 6); a stamped-addressed return envelope; and a pen. The Health Questionnaire (see Appendix 6) included the required questions from the EQ-5D-5L to evaluate health-related quality of life38 and the Satisfaction with Food-related Life Questionnaire to evaluate the patient’s nutritional quality of life. 39 It is a measure of satisfaction developed by Grunert and the Food in Later Life team. The five items exhibit good reliability (as measured by Cronbach’s alpha), good temporal stability, convergent validity with two related measures, and construct validity as indicated by relationships with other indicators of quality of life. 39 The Health Services Questionnaire (see Appendix 6) included questions about the patient’s use of health services following discharge from the acute hospital and was used to cost subsequent use of health services. The cover of the questionnaires included a ‘do not wish to participate’ tick box.

FIGURE 3.

Patient follow-up process at 90 days and at 1 year.

If no response was received after 2 weeks, a reminder letter was sent with another questionnaire pack. If no response was received after a further 2 weeks, the patient was telephoned, if contact details were available. Telephone calls were made at various times from Monday to Friday between 08.30 and 20.30 to maximise the chances of contacting the patient. Patients who were successfully contacted by telephone were asked if they had received the questionnaire pack and were invited to complete the questionnaires over the telephone, if it was convenient. In addition, patients were reminded about completing the questionnaire when they attended hospital follow-up appointments.

Follow-up ended on receipt of a completed (or blank) questionnaire; a questionnaire with a ticked ‘do not wish to participate’ box; notification to the ICNARC CTU by telephone or e-mail that the patient wished to withdraw from the trial; or if there was no response to telephone follow-up. For questionnaire packs returned indicating that the recipient was not known at the address, the contact details for the patient were checked with the recruiting hospital and/or GP.

For patients who were identified as either being a hospital inpatient, or resident in a care home or rehabilitation centre, the relevant institution was contacted to establish the status of the patient and the most appropriate way to proceed with follow-up. If the patient had mental capacity to consent but required assistance in reading and/or completing the questionnaire then health-care professionals usually assisted the patient. For patients who lacked mental capacity to consent, institutions advised on the most appropriate person to contact to complete the questionnaires.

If patients were identified as having no fixed abode but were registered with a GP or had regular contact with a homeless shelter then the questionnaire pack was sent to be passed (when appropriate) to them at their next appointment or visit.

Data linkage with the Case Mix Programme

Linkage of patient identifiable trial data to the Case Mix Programme Database provided information on the baseline characteristics of patients and subsequent admission to the critical care unit following discharge from the critical care unit.

Data for the Case Mix Programme are collected by trained data collectors to precise rules and definitions. The data then undergo extensive local and central validation for completeness, illogicalities and inconsistencies prior to pooling.

Data management

Data management was an ongoing process. Data entered by sites on to the electronic case report form were monitored and checked throughout the recruitment period to ensure that data were as complete and accurate as possible.

Two levels of data validation were incorporated into the electronic case report. The first was to prevent obviously erroneous data from being entered, for example entering a date of birth that occurred after the date of randomisation. The second level involved checks for data completeness and any unusual data entered, for example a physiological variable, such as blood pressure, which was outside of the predefined range. Site staff could generate data validation reports, listing all outstanding data queries, at any time via the electronic case report form. The site PI was responsible for ensuring that all of the data queries were resolved. Ongoing data entry and validation at sites was closely monitored by the data manager (JT) and any concerns were raised with the site PI.

The contact details for patients and their GPs (name and postal address) were checked weekly for completeness to avoid unnecessary delays in sending out questionnaire packs at 90 days and at 1 year.

Adherence to the trial protocol was closely monitored, including adherence to all elements of early nutritional support delivered via the parenteral and the enteral route. Any queries relating to adherence were generated in a separate monthly report, which was sent to the site PI. For each query, the PI was asked to explain the reason for any non-adherence to the protocol. If deemed necessary, a teleconference was arranged with the site to ensure that effective plans were put in place to improve future adherence.

Data received from completed Health and Health Services questionnaires were entered centrally into a secure database at the ICNARC CTU following a standard operating procedure. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or hospital staff members) were removed. All queries relating to data entry were reviewed by two members of the TMG (SH/BM) and any disagreement was reviewed and discussed with a third (KR).

To ensure that data were entered accurately, all questionnaire data entered into the database were cross-checked by a second member of the CTU team. Any errors that were found were logged and corrected on the database.

Sample size

Applying the trial entry criteria to over 500,000 admissions to adult, general critical care units in the Case Mix Programme Database, the 30-day mortality for unplanned, ventilated adult admissions staying ≥ 3 days was 32%. As the enteral route is the predominant choice for nutritional support, this mortality was used as the basis to estimate control group mortality.

A meta-analysis of existing randomised controlled trials of PN compared with EN indicated a potential relative risk reduction associated with PN of around 20% (see Figure 1). To have 90% power, with a type I error rate of 5% (two sided), to detect a 20% relative risk reduction (6.4% absolute risk reduction) from 32% in the enteral route group to 25.6% in the parenteral route group, requires a sample size of 1082 per treatment group (Stata/SE version 10.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). To allow 2% for crossover/protocol violation (in each direction) and 2% for loss to follow-up/withdrawal prior to 30 days (based on observed rates from the PAC-Man Study40), a sample size of 1200 per treatment group (2400 total) was required. No adjustment to the sample size calculation was made to account for subgroup analyses.

Interim analysis

Unblinded, comparative data on recruitment, withdrawal, adherence (to the allocated treatment) and serious adverse events were regularly reviewed by an independent DMEC.

Without specific analysis of the primary outcome, the DMEC reviewed data from the first 37 trial participants and continued to review data at least 6-monthly to assess potential safety issues and to review adherence. A single, planned, formal, interim analysis was performed at the point that 30-day outcome data for the first 1200 patients enrolled were available. A Haybittle–Peto stopping rule (p < 0.001) was used to guide recommendations for early termination as a result of harm. Following the planned interim analysis, the DMEC recommended that the trial continue with no changes.

Analysis principles

All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Patients were analysed according to the treatment group to which they were randomised, irrespective of whether or not the allocated treatment was received (i.e. regardless of whether they did or did not adhere to the allocated route). All tests were two-sided, with significance levels set at p < 0.05 and with no adjustment for multiplicity. All a priori subgroup analyses were carried out irrespective of whether or not there was strong evidence of a treatment effect associated with the primary outcome. As missing data for the clinical effectiveness primary outcome were anticipated to be minimal, a sensitivity approach was taken when the primary outcome was missing (see Secondary analyses of the primary outcome). Missing data for the cost-effectiveness analysis, as well as missing baseline data for adjusted analysis of clinical outcomes, were handled by multiple imputation.

Multiple imputation

Missing data in baseline covariates, resource use and health-related quality-of-life variables at 90 days and 1 year were handled with multivariate imputation by chained equations. 41 Under this approach, each variable was imputed conditional on fully observed baseline variables, such as age, sex, ICNARC Physiology Score, presence of cancer, length of stay in critical care and general medical wards, and all other imputed variables. When addressing the missing data, multiple imputation assumes that the data are missing at random, conditional on the observed data.

Patients who did not return or fully complete the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire administered at 90 days had their EQ-5D-5L utility scores imputed from those survivors who did fully complete the questionnaire. Similarly, for those eligible patients who did not return the Health Services Questionnaire, information on the use of outpatient services up to 90 days following randomisation was imputed from those patients who did complete this questionnaire. Health Services Questionnaire costs and quality-of-life end points were conditional on survival status; as such, the imputation was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, imputation models were specified for mortality at 90 days according to baseline covariates and auxiliary variables, including hospital length of stay of up to 90 days. In the second stage, for each of the imputed data sets from stage 1, imputation models were specified for Health Services Questionnaire costs and quality of life at 90 days for those patients who were missing these but were known to be alive at 90 days, or were predicted to be alive by the first stage imputation model.

Patients who did not return or fully complete the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire or the Health Services Questionnaire administered at 1 year also had their information imputed from those survivors who did fully complete the questionnaire, using a similar two-stage approach.

The resultant estimates were combined with Rubin’s rules, which recognise uncertainty both within and between imputations. 42 All multiple imputation models were implemented in the statistical package Stata/SE version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Statistical analysis: clinical effectiveness

Statistical analyses were conducted according to a pre-specified, published statistical analysis plan written prior to the interim analysis. 43 The final analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 13.0.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical data were summarised by treatment group. Statistical tests for differences between the groups were not reported, as these may be misleading. Discrete variables were summarised as numbers and percentages, which were calculated according to the number of patients for whom data were available; when values were missing, the denominator was reported. Continuous variables were summarised by standard measures of central tendency and dispersion, either mean and standard deviation (SD) and/or median and interquartile range (IQR) as specified below:

-

age, mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

sex, n (%)

-

severe comorbidities (as defined by APACHE II34), n (%):

-

severe liver condition

-

severe renal condition

-

severe respiratory condition

-

severe cardiovascular condition

-

immunocompromised

-

-

acute severity of illness:

-

surgical status – surgery within 24 hours prior to critical care unit admission, n (%)

-

ventilation status – mechanical ventilation at admission to the critical care unit, n (%)

-

malnourished – yes/no (based on clinical judgement), n (%)

-

actual/estimated BMI, mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

ulna length (cm), mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

mid-upper arm circumference (cm), mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

degree of malnutrition (high, BMI of < 18.5 kg/m2 or weight loss of > 10%; moderate, BMI of < 20 kg/m2 or weight loss of > 5%; no malnutrition) (based on NICE definitions1), n (%).

Adherence

Non-adherence with the allocated treatment was reported as the number and percentage of patients who:

-

did not receive any nutritional support

-

received first nutritional support via the opposite route to assigned

-

received initiation of nutritional support more than 36 hours after admission to critical care

-

received early nutritional support via assigned route and subsequently changed to opposite route during first 120 hours, or

-

received no nutritional support for at least a full 1-day period during the first 120 hours.

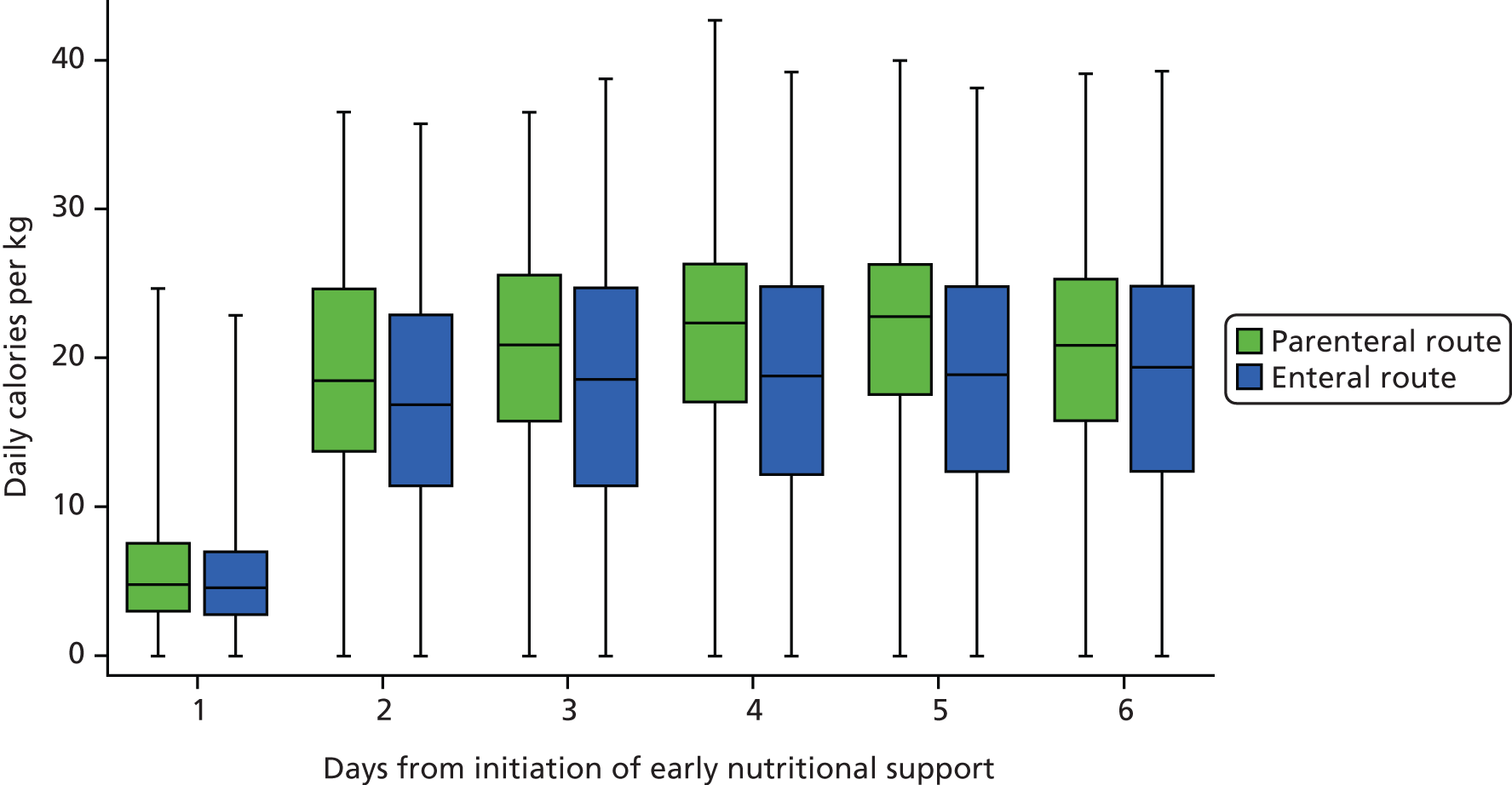

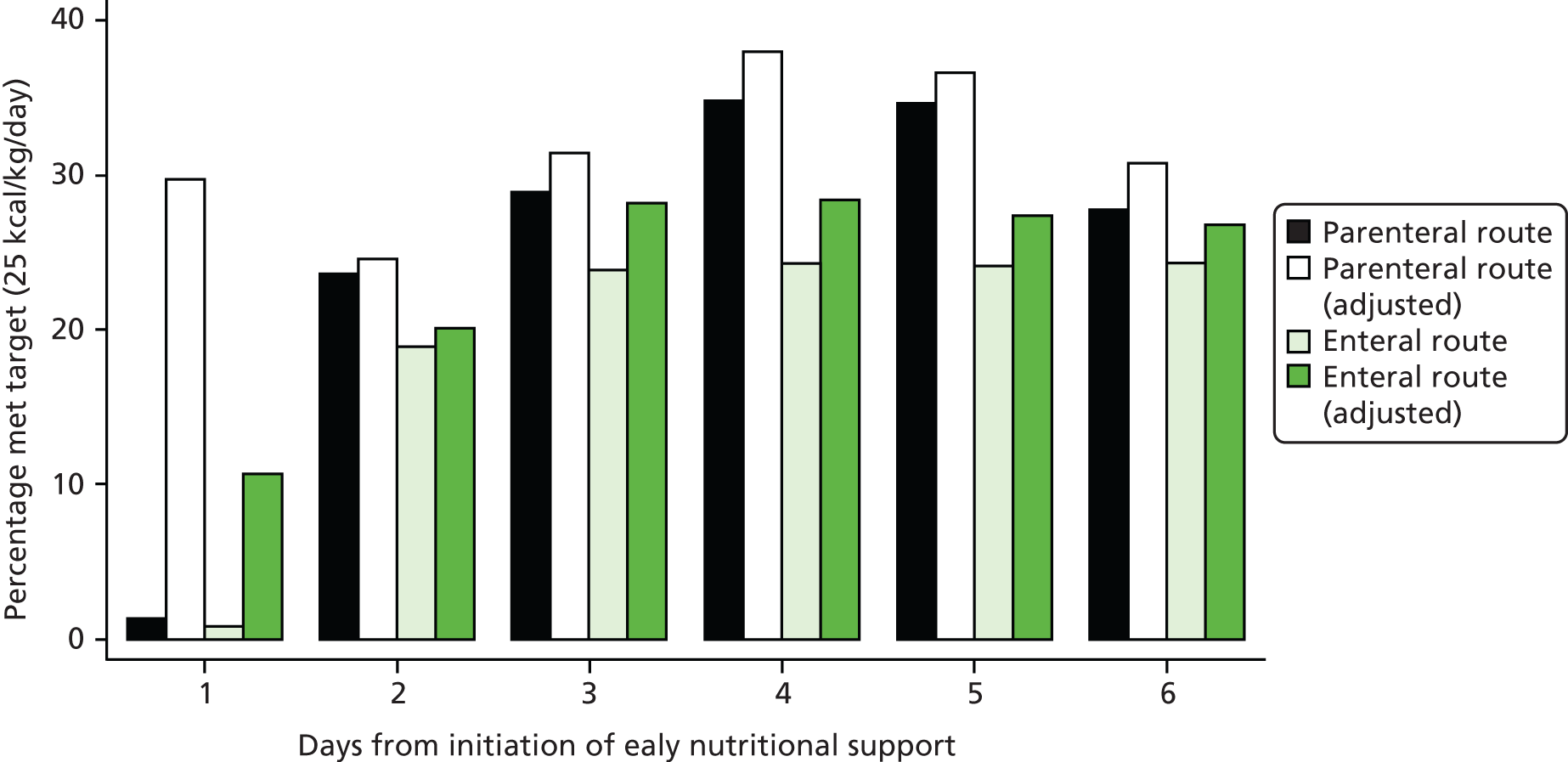

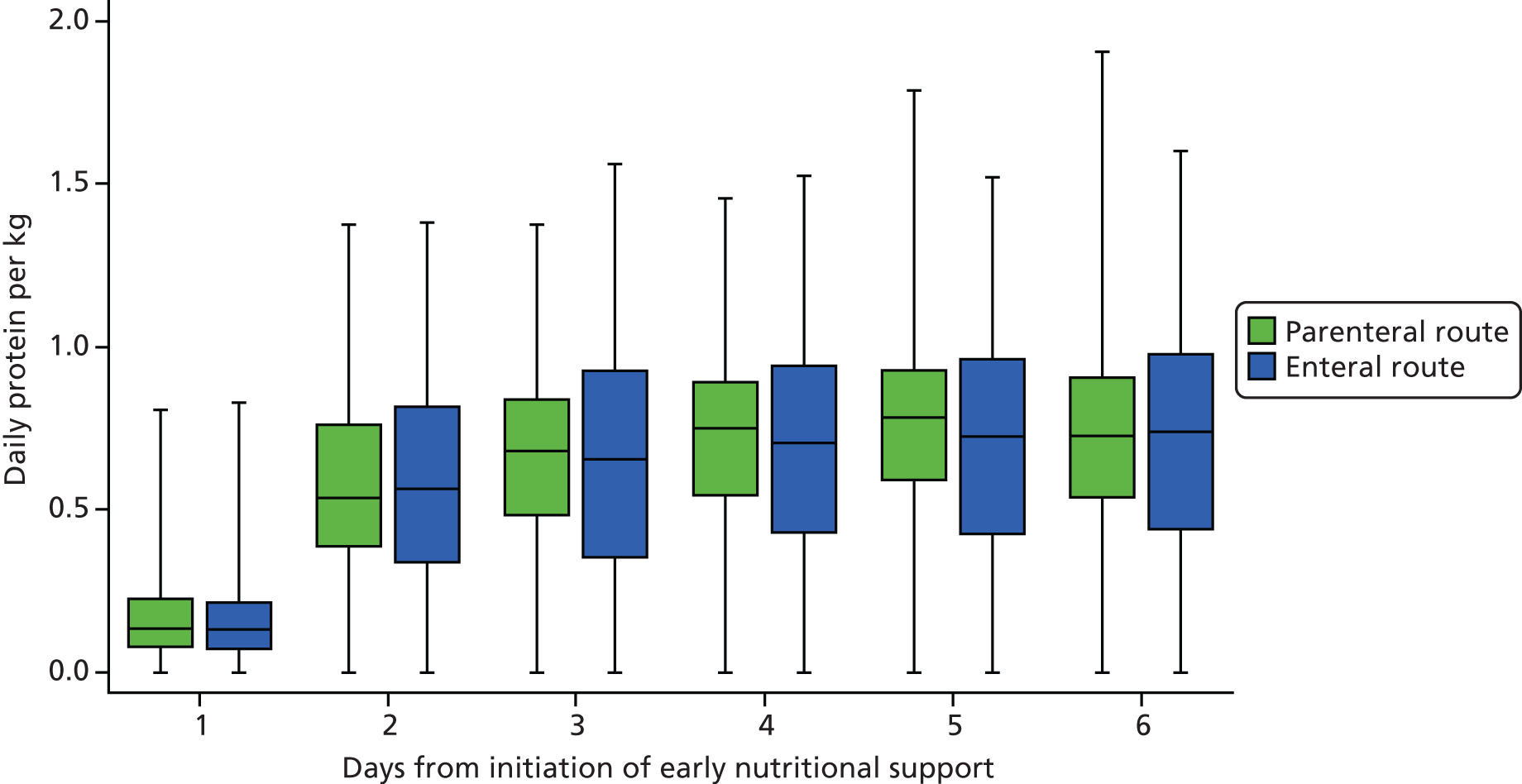

Delivery of care

Delivery of care was summarised by treatment group but not subjected to statistical testing. As with baseline characteristics, discrete variables were summarised as numbers and percentages. Percentages were calculated according to the number of patients for whom data were available; where values were missing, the denominator was reported. Continuous variables were summarised by mean (SD) and/or median (IQR), as specified below:

-

time from critical care unit admission to commencement of nutritional support (hours), median (IQR)

-

total calories and average calories per 24 hours received during intervention period (total calories and a breakdown of the total calories received via the enteral route, the parenteral route, intravenous (i.v.) glucose, propofol and oral feed), mean (SD)

-

total protein and average protein per 24 hours received during intervention period (total protein and a breakdown of the total protein received via the enteral and the parenteral route), mean (SD)

-

total gastric residual volume aspirated (ml) and average per 24 hours during intervention period, if fed via the enteral route, mean (SD)

-

total gastric residual volume replaced and average per 24 hours during intervention period, if fed via the enteral route, mean (SD)

-

patients receiving additives during intervention period (glutamine, selenium and fish oils), if fed via the parenteral route, n (%)

-

patients receiving prokinetics during intervention period, if fed via the enteral route, n (%)

-

patients receiving insulin, n (%), and total insulin received (IU), mean (SD), during intervention period

-

patients receiving vasoactive agents during intervention period, n (%)

-

incidence of diarrhoea and constipation, n (%)

-

time from randomisation to commencement of exclusive oral feeding (days), median (IQR)

-

daily SOFA score during the intervention period, median (IQR).

Primary outcome: clinical effectiveness

The number and percentage of deaths at 30 days following randomisation, due to any cause, were reported for each treatment group. The primary effect estimate was the relative risk of all-cause mortality at 30 days, reported with a 95% CI. The absolute risk reduction and 95% CI were also reported. Deaths at 30 days after randomisation were compared between the treatment groups, unadjusted, using Fisher’s exact test. A secondary analysis of the primary outcome, adjusted for baseline variables, was conducted using multilevel logistic regression. Baseline variables adjusted for in the multilevel logistic regression model were age, ICNARC Physiology Score, surgical status, degree of malnutrition and a site-level random effect. Baseline variables were selected for inclusion in the adjusted analysis a priori according to anticipated relationship with outcome. The results of the multilevel logistic regression model were reported as an adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI. The unadjusted odds ratio was presented for comparison.

Secondary outcomes: clinical effectiveness

The mean (SD) of the number of days alive and free from advanced respiratory support, advanced cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support and gastrointestinal support, as defined by the CCMDS36 (see Appendix 4), up to 30 days, within each treatment group, were reported. Patients who died within the first 30 days were assigned zero days alive and free of each organ support. Days of organ support were recorded only while the patient was in a critical care unit; any days outside of a critical care unit were assumed to be free of organ support. Differences between the treatment groups were tested using the t-test, using the non-parametric bootstrap to account for anticipated non-normality in the distributions. 44 A total of 1000 bootstrap replications were taken, stratified by treatment group, with bias-corrected and accelerated CIs reported.

The mean (SD) number of treated infectious complications per patient and the number and percentage of patients with each infectious complication (chest infection, central venous catheter infection, other vascular catheter-related infection, bloodstream infection, infective colitis, urinary tract infection, surgical site infection, other infectious complication) and each non-infectious complication (episodes of hypoglycaemia, elevated levels of liver enzymes, nausea requiring treatment, abdominal distension, vomiting, new or substantially worsened pressure ulcers) within each treatment group were reported. Infectious complications and pressure ulcers were assessed while the patient was in the critical care unit; all other non-infectious complications were collected through adverse event reporting up to 30 days following randomisation. Differences between the treatment groups were tested using the t-test for means and Fisher’s exact test for percentages.

The median (IQR) of the length of stay in critical care and in acute hospital were reported for each treatment group. Differences in length of stay between the treatment groups were tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, stratified by survival at critical care discharge and acute hospital discharge, respectively.

Kaplan–Meier curves by treatment group were plotted up to 90 days and 1 year after randomisation and compared using the log-rank test. An adjusted comparison was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model, which was adjusted for the same baseline variables as the primary outcome, including shared frailty within sites (gamma-distributed latent random effects). The appropriateness of the proportional hazards assumption was assessed graphically by plotting –log[−log(survival)] against log(time) within treatment groups. The number and percentage of deaths at critical care and acute hospital discharge, and by 90 days and 1 year post-randomisation, were reported for the treatment groups. Differences in all-cause mortality at each time point were compared, unadjusted, using Fisher’s exact test and, adjusted, using multilevel logistic regression, adjusted for the same baseline variables as the primary outcome.

Safety monitoring

The number and percentage of patients experiencing each serious adverse event (occurring between randomisation and 30 days) were reported for each treatment group. The total number of patients experiencing one or more serious adverse events was compared between treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test and summarised as a relative risk with 95% CI.

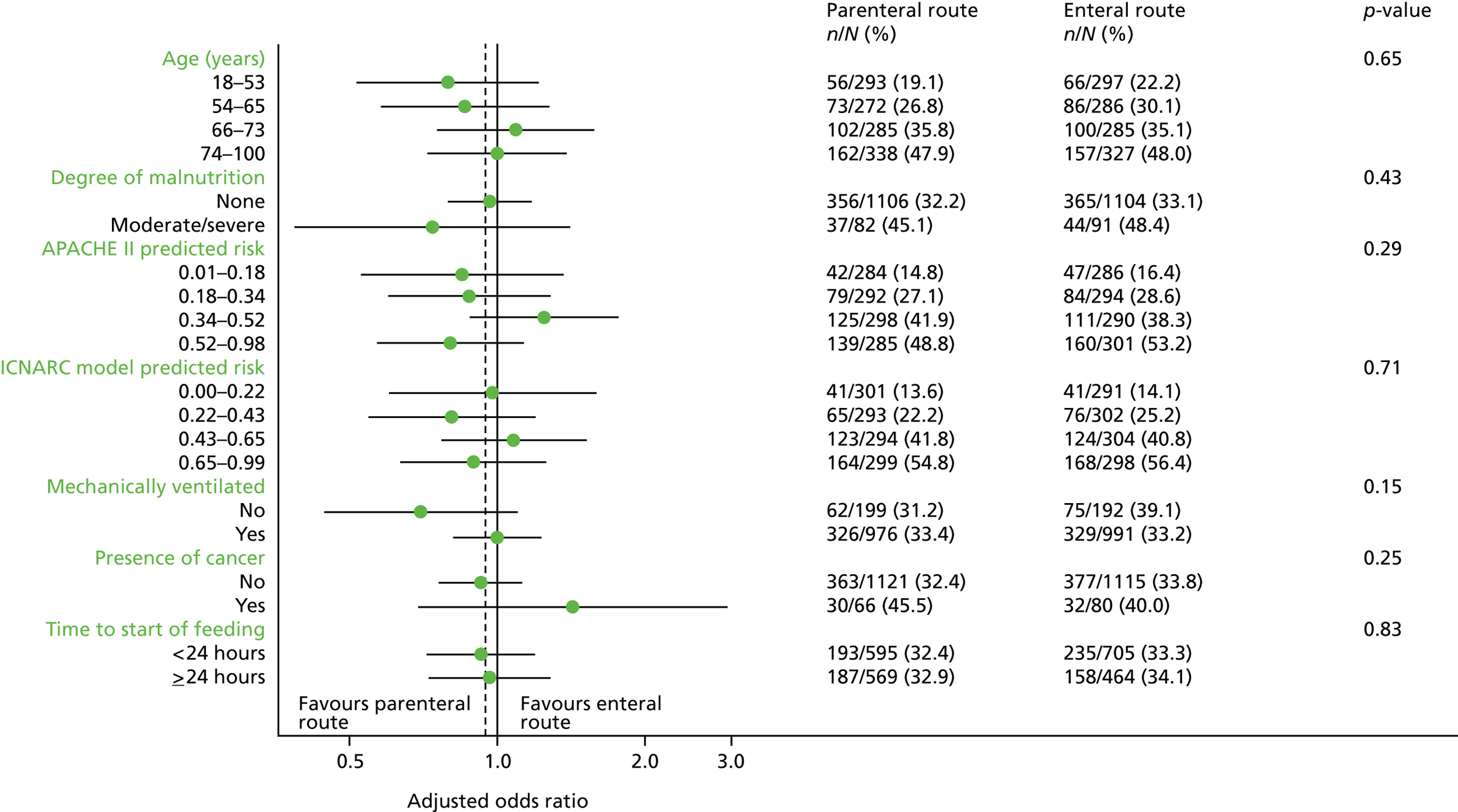

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome

Subgroup analyses were conducted to test for a difference in treatment effect according to pre-specified subgroups. Differences in the primary outcome (30-day mortality) were analysed by age (in quartiles), degree of malnutrition (high/moderate or none), acute severity of illness (APACHE II34 and ICNARC model35 predicted risk of mortality – in quartiles), mechanical ventilation at admission to the critical care unit, presence of cancer and time from critical care unit admission to commencement of nutritional support (< 24 hours vs. ≥ 24 hours).

These analyses tested for an interaction between the subgroup categories and the treatment group in multilevel logistic regression models, adjusted for the same baseline variables as used in the primary analysis.

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome

Sensitivity analyses for missing data in the primary outcome

As the number of missing data was anticipated to be minimal, a sensitivity approach was taken when the primary outcome variable was missing. The primary analysis was repeated once, assuming that all patients in the enteral route group with missing outcomes survived and all patients in the parenteral route group with missing outcomes did not survive. The analysis was then repeated again with the opposite assumptions. This approach gives the absolute range of how much the results could change if all of the data were complete.

Adherence-adjusted analysis

Although the intention-to-treat analysis provides the best estimate of the clinical effectiveness of early nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with the enteral route, it was also of interest to estimate what the efficacy of early nutritional support delivered via the parenteral route would be compared with the enteral route, if delivered as intended. In a randomised controlled trial, the allocated treatment can be used as an ‘instrumental variable’, that is, a variable associated with receipt of the intervention and associated with the outcome only through its association with the intervention. 45 This relationship enables us to estimate what the treatment effect would be for patients who are adherent to the protocol. The primary analysis was repeated adjusting for adherence using a structural mean model with an instrumental variable of allocated treatment, assuming a linear relationship between the degree of adherence (duration of allocated treatment received) and treatment effect. 46

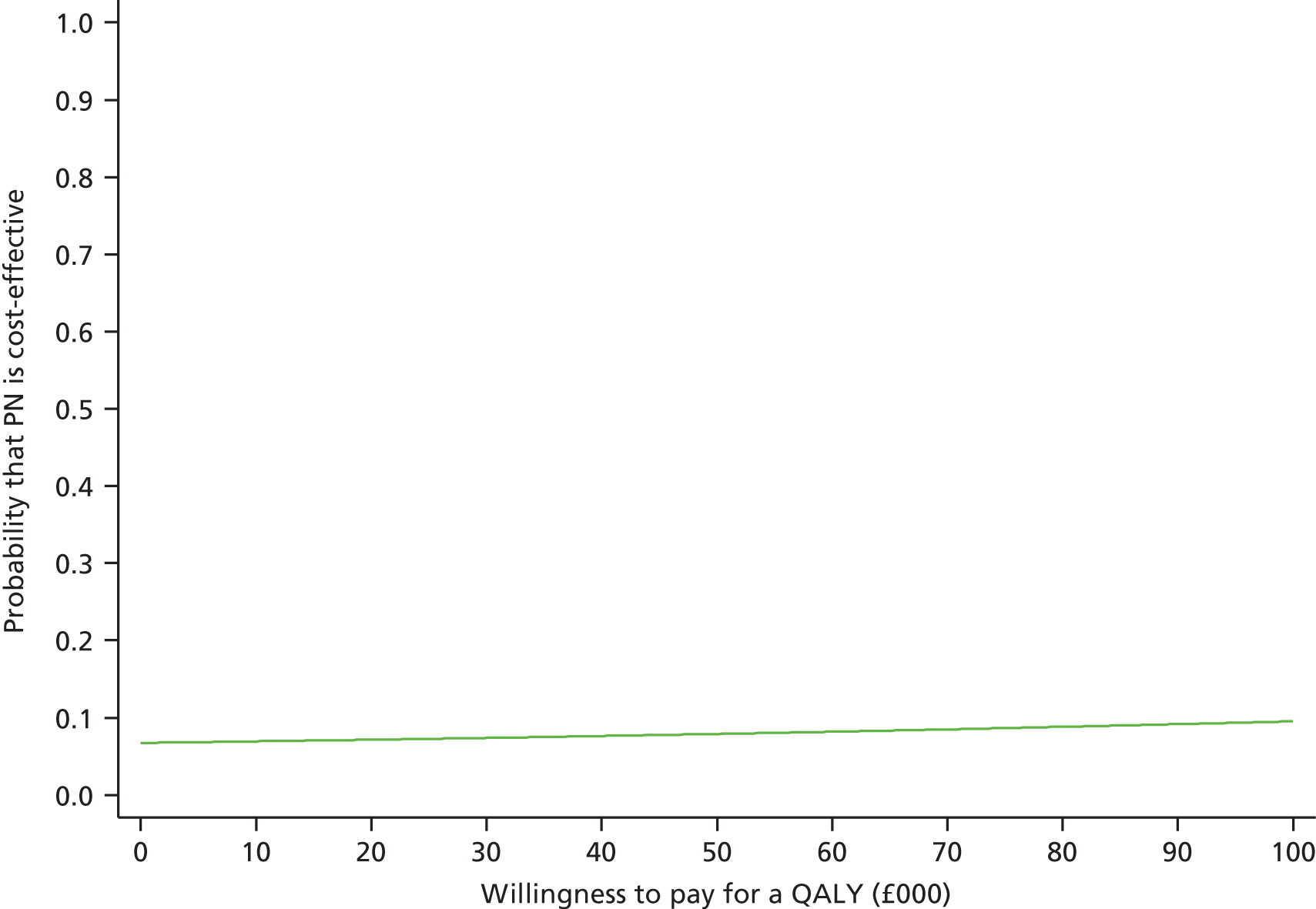

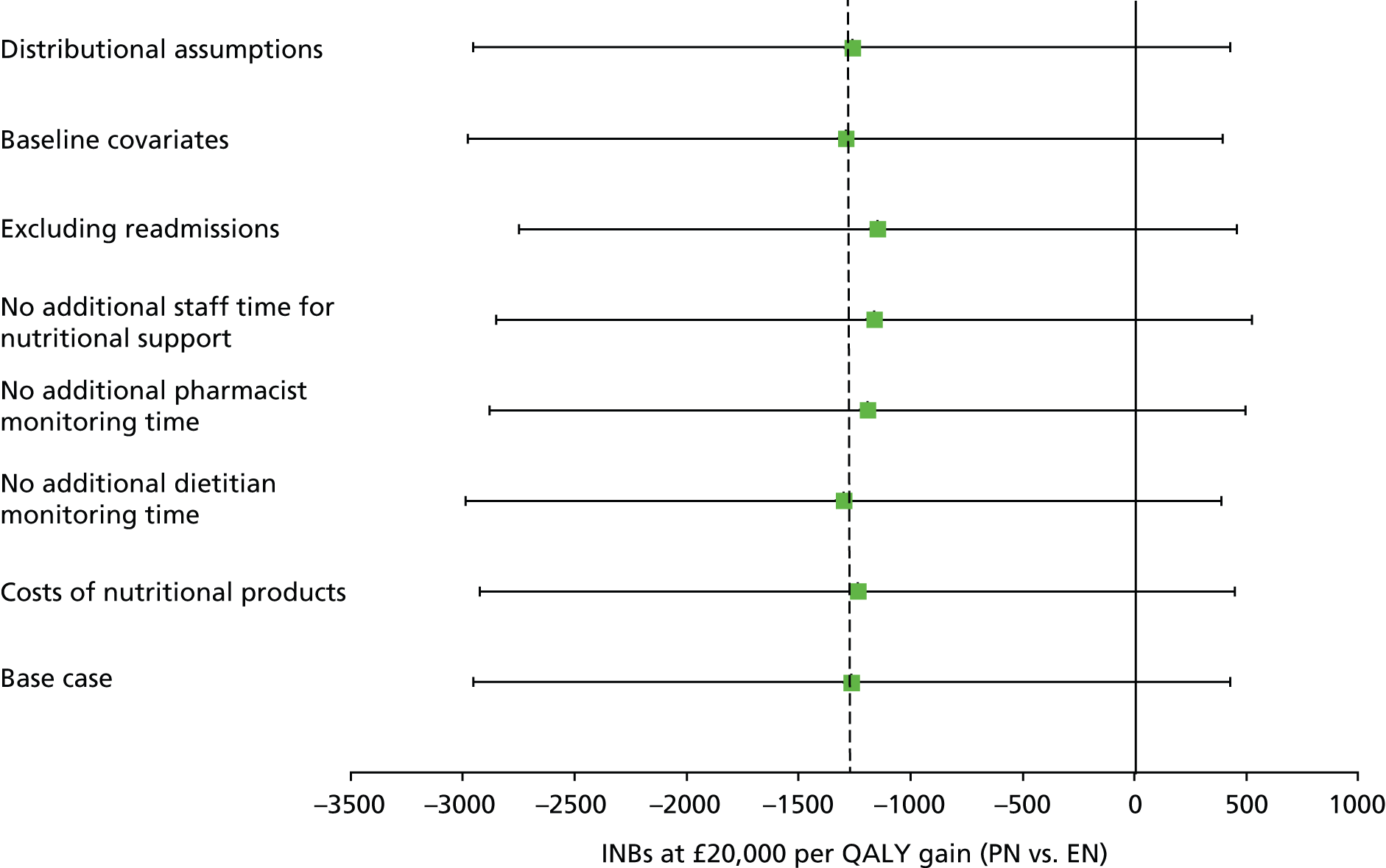

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A full cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken to assess which route of delivery for early nutritional support in critically ill adults, parenteral compared with enteral, was most cost-effective. This analysis assessed whether or not the additional intervention costs of early nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with the enteral route were justified by any subsequent reductions in morbidity costs and/or improvements in patient outcomes. The cost-effectiveness analysis was reported for three time periods: randomisation to 90 days; randomisation to 1 year; and lifetime. For each time period the cost-effectiveness analysis took a health and personal health services perspective,47 using information on health-related quality of life collected at 90 days and 1-year follow-up, combined with information on vital status, to report QALY. Each QALY was valued using the NICE-recommended threshold of willingness to pay for a QALY gain (£20,000),47 in conjunction with the costs of each strategy to report the incremental net monetary benefits (INBs) of early nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with early nutritional support via the enteral route, overall and for the same pre-specified subgroups as for the evaluation of clinical effectiveness (see Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome, below).

The primary objective of the cost-effectiveness analysis was to compare incremental cost-effectiveness at 1 year of early nutritional support via the parenteral route compared with the enteral route. The secondary objectives were to:

-

compare health-related quality of life at 90 days and 1 year between the treatment groups

-

compare resource use and costs at 90 days and 1 year between the treatment groups

-

estimate the lifetime incremental cost-effectiveness between the treatment groups.

The main assumptions of the cost-effectiveness analysis were subjected to extensive sensitivity analyses.

Resource use

The resource-use categories considered were chosen a priori, for which differences between the treatment groups were judged as being possible and likely to drive incremental costs, and were reported for each treatment group. Data for interventions, staff time and acute hospital stay for the index hospital admission were collected as part of the CALORIES trial data set. Readmissions to acute hospital including a critical care stay were identified from the Case Mix Programme Database. Readmission to acute hospital not involving critical care, as well as hospital outpatient and community services use, were collected as part of the Health Services Questionnaires completed at 90 days and 1 year.

Interventions

Use of nutritional feeding as a part of the CALORIES trial interventions in critical care unit has been considered in economic evaluation. For each patient, total volume of nutritional support delivered within the first six calendar days of nutritional support (encompassing the 120-hour intervention period) was calculated according to route of feeding and type of nutritional products. The use of alternative nutritional feeding due to crossover was included in the costing, which followed the intention-to-treat principle, as per the analysis of clinical effectiveness.

The use of i.v. glucose, propofol and insulin within the first six calendar days of nutritional support was recorded daily on the trial case report form for each patient. The trial case report form recorded daily volume and concentration of i.v. glucose and propofol, and total units (IU) of insulin. Use of propofol was recorded because of its relatively high calorie content.

Nutritional support from day 7 following initiation of nutritional support to discharge from the critical care unit was reported using trial case report form data. From calendar day 7 up to discharge from the critical care unit, trial case report forms recorded the date of each change of route of nutritional support, and these were aggregated to calculate the number of days each patient received nutritional support via each route. Costs of nutritional support from calendar day 7 up to discharge from critical care unit were calculated according to number of days of nutritional support via each route.

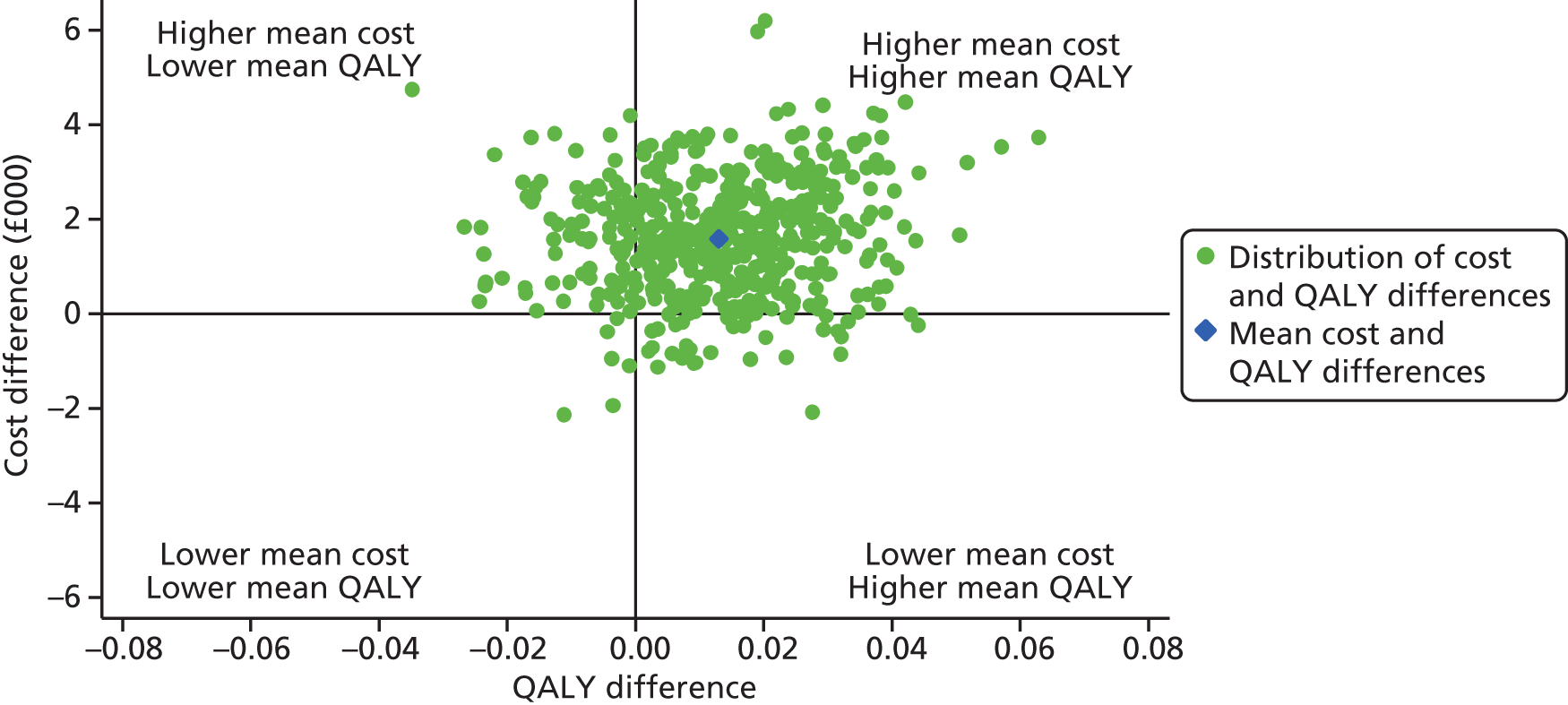

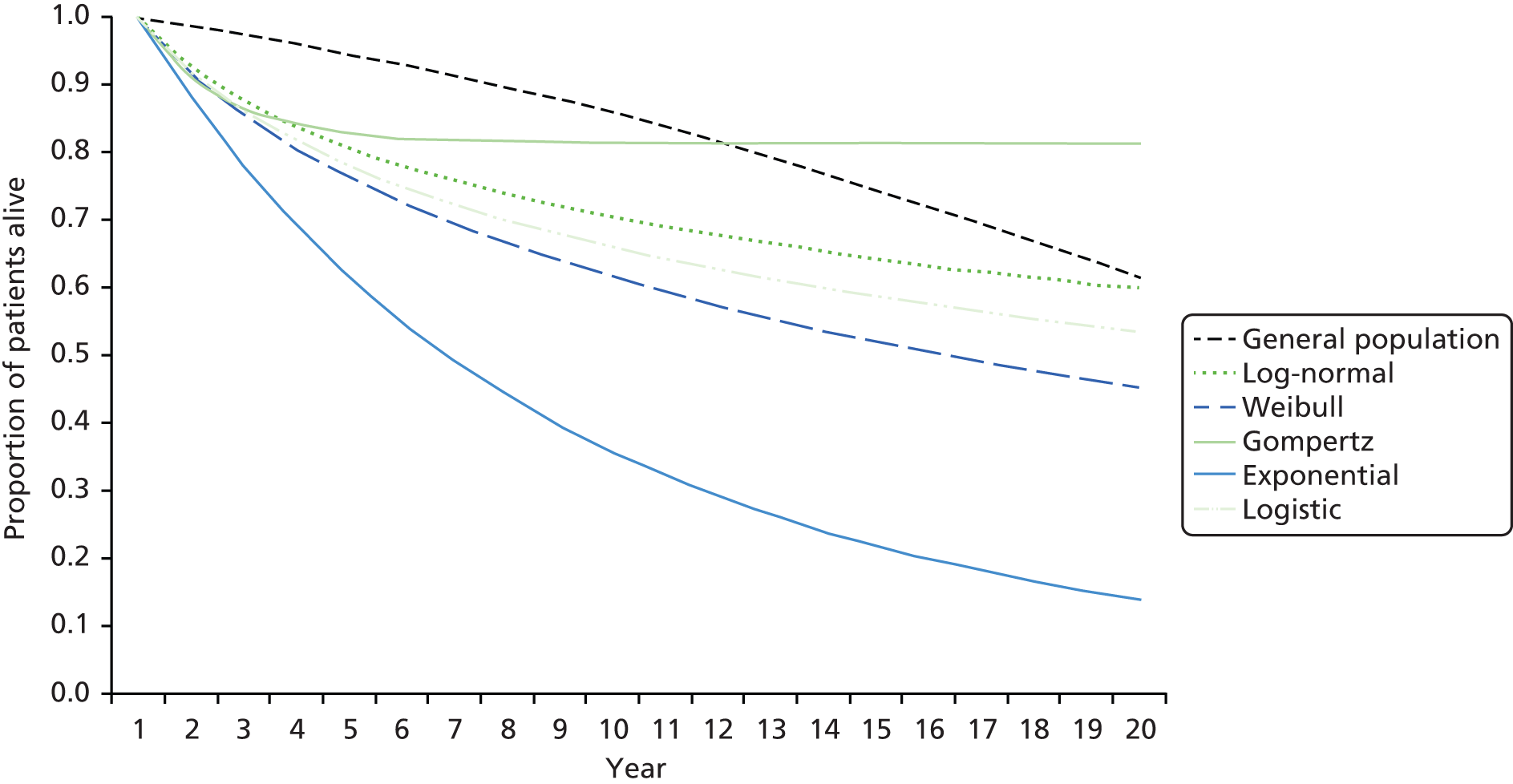

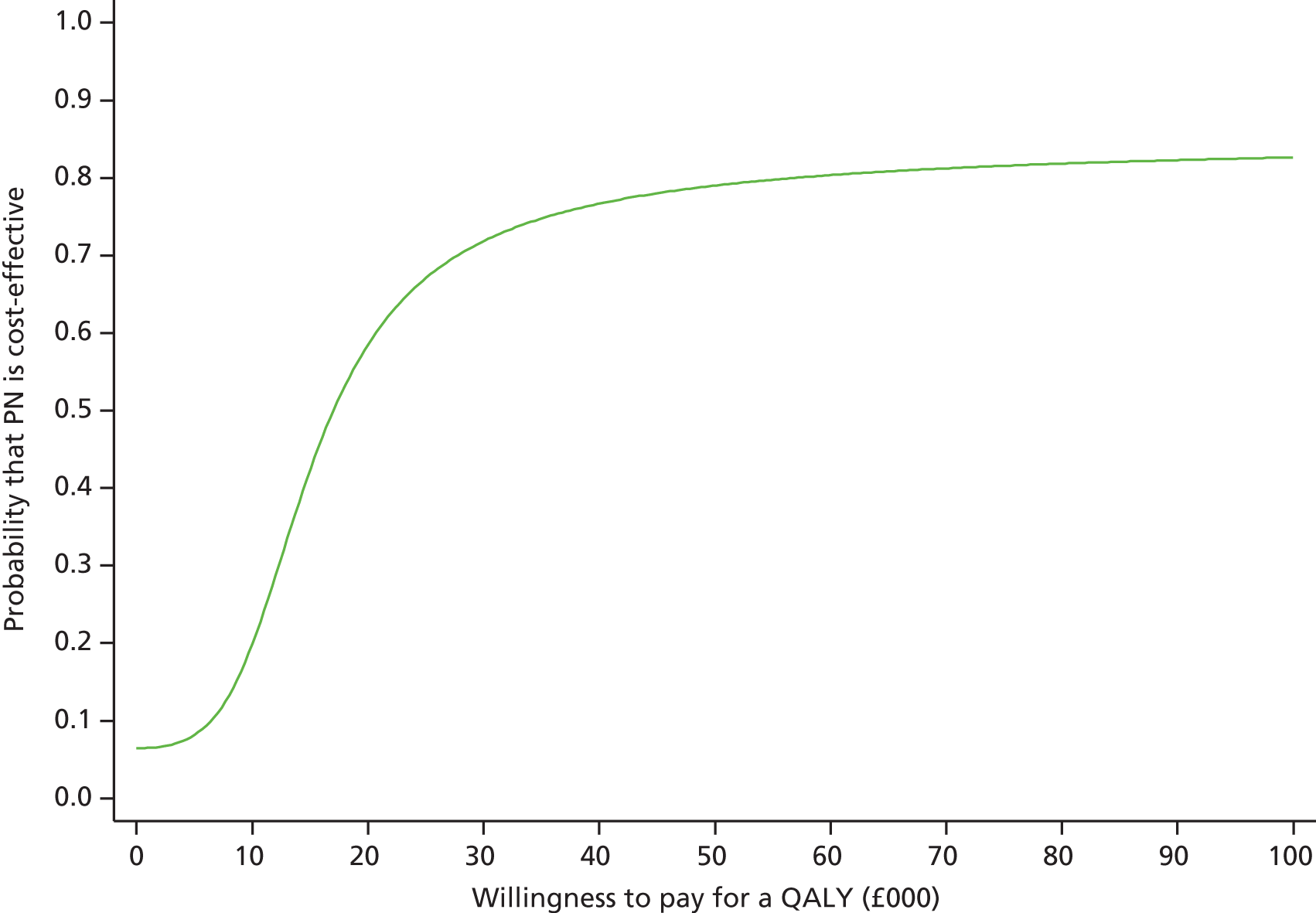

Staff time