Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/41/02. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in September 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Griffin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Management of hip pain in young adults

Until recently, the management of hip pain in young adults has been largely conservative. A minority of such patients had established osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, avascular necrosis or fractures, and their care sometimes included surgery. However, the majority had no specific diagnosis and received multidisciplinary non-operative care, provided by a combination of physiotherapists (probably the largest contribution), rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons, sport and exercise medicine physicians and general practitioners.

Femoroacetabular impingement

In the last few years there has been increasing recognition of the syndrome of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), which seems to account for a large proportion of the previously undiagnosed cases of hip pain in young adults. 1,2 Subtle deformities of the hip combine to cause impingement between femoral neck and anterior rim of the acetabulum, most often in flexion and internal rotation. 2 The deformities may include asphericity of the femoral head, widening of the femoral neck, overcoverage of the anterosuperior acetabular wall and abnormal version of the femur or acetabulum. 2 Excess contact forces between the proximal femur and the acetabular rim during terminal motion of the hip lead to lesions of acetabular labrum and the adjacent acetabular cartilage. 2 FAI seems to be associated with progressive articular degeneration of the acetabulum, usually starting from the anterosuperior rim and accelerating medially and posteriorly. 1–3

Open surgery for femoroacetabular impingement

In 2001, Ganz et al. 4 described a surgical technique to dislocate a hip joint without damaging the blood supply to the femoral head. This allowed the development of surgical techniques to correct the shape abnormalities of FAI. The technique involved a major operation, with a trochanteric osteotomy and a prolonged period on crutches. Ganz et al. 4 described a total of 213 surgical hip dislocations, in 164 cases of which the indication was FAI. Subsequently, there was a gradual development of interest in the international orthopaedic community in the problem of hip pain in young adults and an increasing recognition of FAI. Improved imaging, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance arthrography, allowed more confident diagnosis of FAI,5,6 and surgeons began to visit Ganz to learn the technique. Observational case series have been published describing good clinical results in terms of pain and function for surgical dislocation for FAI;7 however, only a few centres began to offer this treatment for patients, perhaps because the likely benefit, as perceived by surgeons and patients, was insufficient to justify the invasiveness and risks of such an extensive surgical procedure.

Arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement

Since the early 1990s there has been a slowly developing interest in arthroscopic surgery in the hip. Confined to just a few centres around the world, it seemed to be only rarely indicated and of doubtful clinical usefulness. In the early 2000s, a few surgeons, including one of the authors of this report (DG), began to explore the possibilities of arthroscopic surgery in the management of FAI. Since then, numerous authors have published observational case series reporting favourable outcomes in terms of pain and function for the arthroscopic management of FAI. 8–10 Overall, a recent systematic review of hip arthroscopy judged the evidence to support this treatment of FAI only as ‘fair’. 11 The feasibility team have conducted a Cochrane Review on surgery for the treatment of FAI and found no published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to help determine the efficacy and safety of surgery for FAI. 12 Four ongoing trials [including the Feasibility of Arthroscopic Surgery for Hip Impingement compared with Non-operative care (FASHIoN) study] were ongoing that when complete may be eligible for inclusion in the review and help determine the efficacy and safety of FAI surgery. The underlying message from systematic reviews is that better evidence for any sort of surgery is needed, ideally a well-designed RCT. With the majority of current literature focusing on the surgical management of FAI, there is little information about conservative (non-operative) treatment, which might form the natural comparator to surgery. 13

Likely difficulties in recruitment to a trial of treatment for femoroacetabular impingement

Pragmatic multicentre RCTs are acknowledged to be the best design for evaluating the effectiveness of health-care interventions as they provide robust evidence of effect, but they often encounter recruitment difficulties. 14–17 RCTs in surgery face particular challenges including that many surgeons have limited experience of RCTs, there are often learning curves for particular procedures, surgeons sometimes adopt idiosyncratic individual techniques, and the natural comparison might be a very different and more conservative type of management. 18,19 In order to participate in RCTs, all clinicians involved (surgeons and physiotherapists) need to accept at least collective uncertainty or equipoise between treatments, including the possibility that surgery is no more effective than best conservative care. For patients, the idea that there is uncertainty over the comparative effectiveness of surgical treatments and conservative care can be very difficult to accept. Lack of both clinician and patient equipoise could be major barriers to recruitment to a trial of surgery versus conservative care for FAI, especially as many patients may well feel that they have already had a period of conservative care. Trials comparing orthopaedic surgery with conservative care show widely varying recruitment rates.

-

A trial of surgery compared with conservative treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome found that 201 patients refused to enter any study and a further 207 refused to enter the trial but would enter an observational study. A total of 116 patients were randomised. Therefore, the recruitment rate for the trial was 22%. 20

-

A trial of vertebroplasty compared with conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures recruited 202 of 479 eligible patients (42%). 21

-

A trial of arthroscopic surgery compared with physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee recruited 188 patients out of 219 (86%). 22

Qualitative research methods can be used to understand recruitment difficulties and inform the development of strategies to improve recruitment to RCTs. 23–25 In the Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded ProtecT (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment) study, for example, the findings from an integrated qualitative study led to the rate of randomisation of eligible participants rising from 30% to 70% over a 12-month period. 23 The ProtecT trial was expected to be challenging for recruitment for reasons including strong treatment preferences by patients and clinicians. The qualitative research integrated within a feasibility study26 enabled a nuanced understanding of the recruitment process from the perspectives of potential participants, clinicians and triallists, including reasons for treatment preferences and unexpected misinterpretations of information. 23 Strategies were developed that led to improvements in levels of randomisation and informed consent. The research methods used in the ProtecT study were then developed into a complex recruitment intervention,27 which has been applied to several other RCTs in different contexts, leading to insights about recruitment issues and the development of targeted recruitment strategies. 24,25 This research is a major theme of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Collaboration and Innovation in Difficult and Complex Randomised Controlled Trials methodology hub, which specialises in working with RCTs likely to be challenging for recruitment, such as this study.

Purpose of this study

Theoretical arguments have been made that surgery for FAI may prevent the development of osteoarthritis,1,4 but there is little evidence for this. Surgery might be indicated to relieve symptoms, but an equally strong argument can be made that a well-constructed regime of conservative care will reduce the symptoms of FAI.

Femoroacetabular impingement surgery, including arthroscopic surgery, has evolved quickly, more quickly than our understanding of the natural history of FAI,28–30 so it is now not clear whether or not surgery offers real benefit over conservative care. A RCT of arthroscopic surgery compared with conservative care for FAI is appropriate, prompting interest from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme in funding such a trial.

However, this is a rapidly developing field, currently practised by relatively few surgeon innovators and specialists in conservative care; these groups may not be in equipoise, and this presents special problems in the performance of a trial. 18 In addition, patients are likely to have strong views about whether they would prefer surgical or conservative treatment, raising questions about their preparedness to be randomised.

The research question for this feasibility study was whether or not a substantive RCT of hip arthroscopy compared with conservative care for FAI could succeed and, if so, how best it might be designed. It included a pilot RCT to test the proposed processes of a substantive trial and, crucially, to estimate the rate of recruitment.

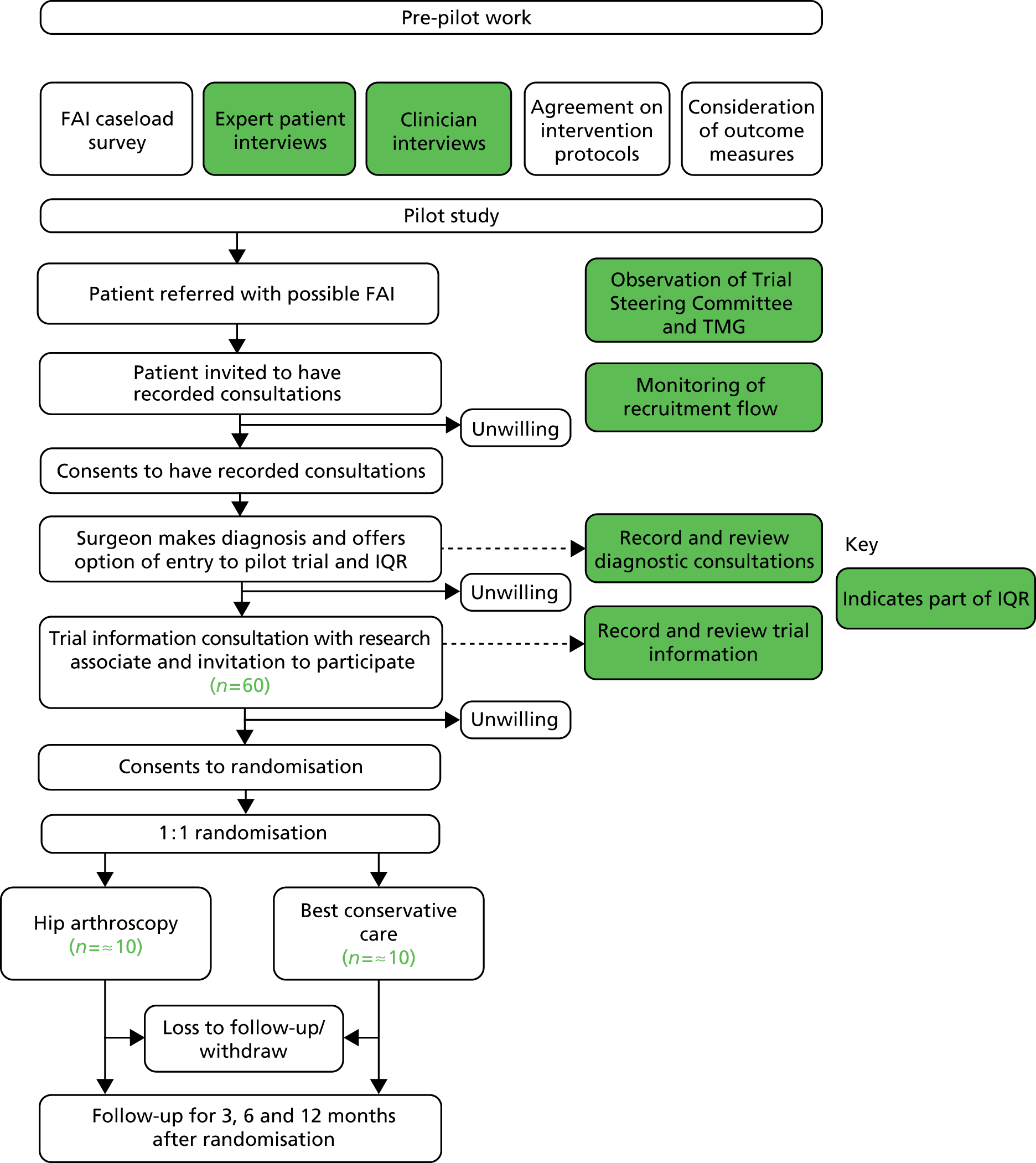

The research included several related studies, performed in two stages. Pre-pilot studies (see Chapter 2) estimated the number and distribution of patients available for a full trial in the UK, explored clinicians’ and patients’ attitudes towards a trial, developed a consensus among clinicians who manage patients with FAI for eligibility criteria, best conservative care and surgical protocols, examined possible outcome measures and estimated sample size for a full trial, and worked with patients to develop patient information for a trial. A pilot RCT (see Chapter 3) was then performed in order to estimate recruitment rates for a full trial. During the pilot RCT, an integrated qualitative study (see Chapter 4) of both patients and clinicians was performed to determine the barriers to, and develop solutions for, completing recruitment to a full RCT. The feasibility study design is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the feasibility study design.

Chapter 2 Pre-pilot study

Objectives

The objectives of the pre-pilot study were to:

-

estimate the annual number of patients offered hip arthroscopy for FAI in the UK (see Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in the NHS in the UK: a workload survey)

-

explore clinicians’ (see Clinicians’ attitudes to randomisation of femoroacetabular impingement patients) and patients’ attitudes (see Develop eligibility criteria for a randomised controlled trial and design an operative protocol) to recruitment into a RCT of FAI treatments

-

develop a consensus for eligibility criteria for eligibility criteria, an operative care protocol and a best conservative care protocol among clinicians who manage patients with FAI (see Design of a best conservative care treatment protocol for femoroacetabular impingement and Possible outcome measures and sample size for a full randomised controlled trial)

-

consider possible outcome measures and estimate the sample size for a full trial (see Patients’ attitudes towards randomisation and design of patient information material for a randomised controlled trial)

-

develop trial procedures and patient information material to maximise recruitment rate to a RCT of arthrocopic surgery versus best conservative care for FAI section 2.7.

Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in the NHS in the UK: a workload survey

Introduction

The prevalence in the general population of symptomatic FAI (FAI hip shape morphology and concurrent hip symptoms) is not known. Similarly the proportion of these patients who require surgery is not known. The published literature has an overwhelming focus on the surgical management of FAI. 1,31,32 Obtaining an understanding of the amount of surgery that is being undertaken for FAI would help to understand the burden of symptomatic FAI and help to determine the likely pool of eligible patients for a RCT.

Objective

To estimate the frequency and types of FAI surgery being undertaken in the UK within the NHS.

Materials and methods

A list of all NHS hospital health boards and trusts within England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales was compiled using the NHS online resource: www.nhs.uk. All hospital trusts and health boards were contacted by telephone to determine if they had an orthopaedic service and within each orthopaedic service the number of orthopaedic departments that made up that service. Clinical directors for these departments/services were then contacted by letter requesting the names and contact details of all FAI surgeons within their department/service. Each FAI surgeon identified received a letter requesting the following workload data for the financial year 2011/12:

-

hip arthroscopies performed within the NHS over the last 12 months

-

number of hip arthroscopies performed for FAI within the NHS over the last 12 months

-

number of open surgical procedures performed for FAI within the NHS over the last 12 months.

Clinical directors and surgeons were contacted repeatedly by letter, e-mail and telephone and through their secretaries. When a consultant’s practice spanned less than 12 months, the results were not rescaled; instead, conservative estimates were obtained for the full 12 months by keeping case numbers the same, no matter the period of practice. When consultants provided a range, this was recorded and final calculations were made based on the lowest figure. Each surgeon returning data was assigned a postcode for their NHS practice and this was used to create a choropleth map of the workload data based on regions within the UK. Prevalence rates for surgery were then calculated for each region per 100,000 population using mid-2010 population estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). 33 Consultants who did not consider themselves as FAI specialty surgeons were removed from the database. Consultants who considered themselves to be FAI surgeons but were not currently performing this type of surgery within their NHS practice were kept on the database, with reasons for this recorded (e.g. no current funding for the procedure). Anyone who was considered a FAI surgeon but did not want to participate in the study was removed from the database. Data collection was undertaken over a 6-month period between May and October 2012.

In order to triangulate and validate the FAI surgical workload data obtained by survey, NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were obtained for procedures undertaken in 2011/12 using Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures-Fourth Edition (OPCS-4) codes within England. OPCS is a procedural classification for the coding of operations, procedures and interventions performed during inpatient stays, day case surgery and some outpatient attendances in the NHS. OPCS-4 is an alphanumeric nomenclature, with a four-character code system. The code system can also be combined to provide further detail. Specific procedure codes for FAI surgery have not yet been established.

In the absence of any established OPCS-4 codes for FAI surgery, the codes currently agreed and applied to FAI surgery within University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) were used: Z843, which represents surgery on the hip joint, combined with W844, endoscopic decompression of joint, or W802, open debridement of joint.

Validation of the HES data was undertaken using an independently locally collected database for FAI surgery at UHCW.

International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) version 21 for Windows was used for the statistical analysis. Summary statistics including mean [with confidence intervals (CIs)] and median (with interquartile ranges) values were reported for the data. Differences in workload data between arthroscopic and open surgery were analysed using a Student’s t-test. The level of statistical significance (p-value) was set at 0.05.

Results

There were a total of 193 NHS hospital health boards and trusts in the UK. Of these, 27 did not have an orthopaedic surgical department/service. A total of 2399 cases of surgery were undertaken for FAI over the 12 months. The breakdown of the workload data (both arthroscopic and open) for FAI surgeons who responded to the survey is shown in Table 1.

| Country | Hospital health boards and NHS trusts with a FAI surgeon | FAI surgeons | Surgeons not responding (%) | Hospital health board and NHS trusts with no funding for surgery | Open FAI surgery cases over 12 months | Arthroscopic FAI cases over 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 69 | 110 | 17 | 6 (8 surgeons) | 444 | 1791 |

| Scotland | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 62 |

| Wales | 2 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 55 |

| Northern Ireland | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 75 | 120 | 20 (17) | 8 | 491 | 1908 |

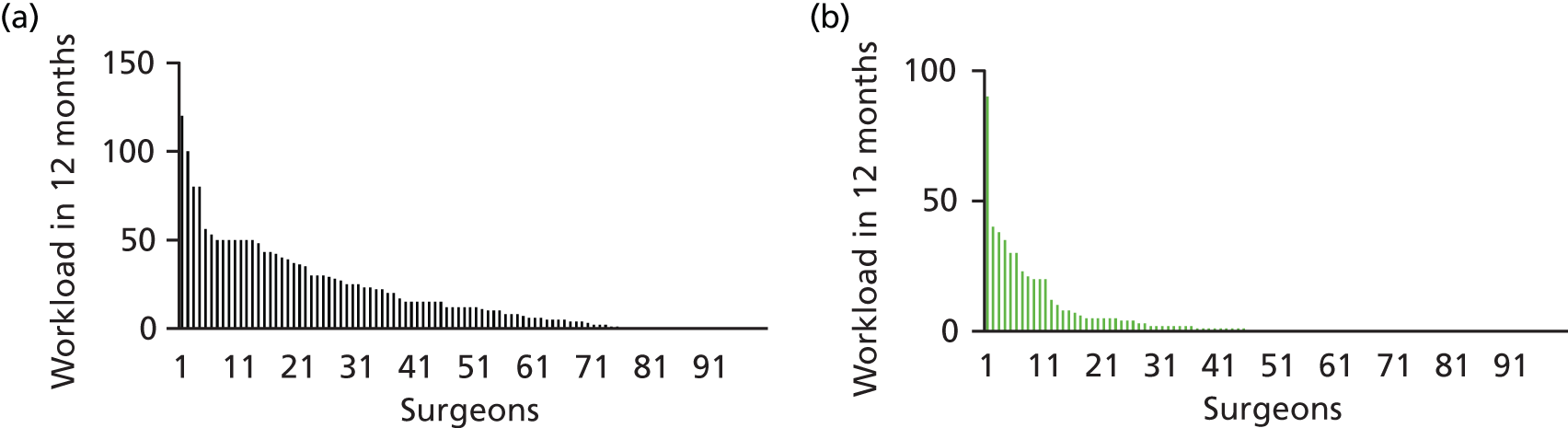

Of the 100 surgeons returning workload data, 25 did not perform any arthroscopic surgery over the 12-month period and 55 did not perform any open surgery over the 12-month period. The distributions of caseload by surgeon for open and arthroscopic surgery are shown in Figure 2 and the mean and median numbers of cases of FAI surgery per surgeon are shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

Distributions of caseload by surgeon for open and arthroscopic surgery. (a) Individual surgeon workload for FAI treated arthroscopically; and (b) individual surgeon workload for FAI treated with open surgery.

| Summary statistic | Arthroscopic FAI workload per surgeon | Open FAI per surgeon | Total FAI surgery workload per surgeon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | 19 (15 to 24) | 5 (7 to 3) | 24 (17 to 31) |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (0–30) | 0 (0–4) | 12 (0–34) |

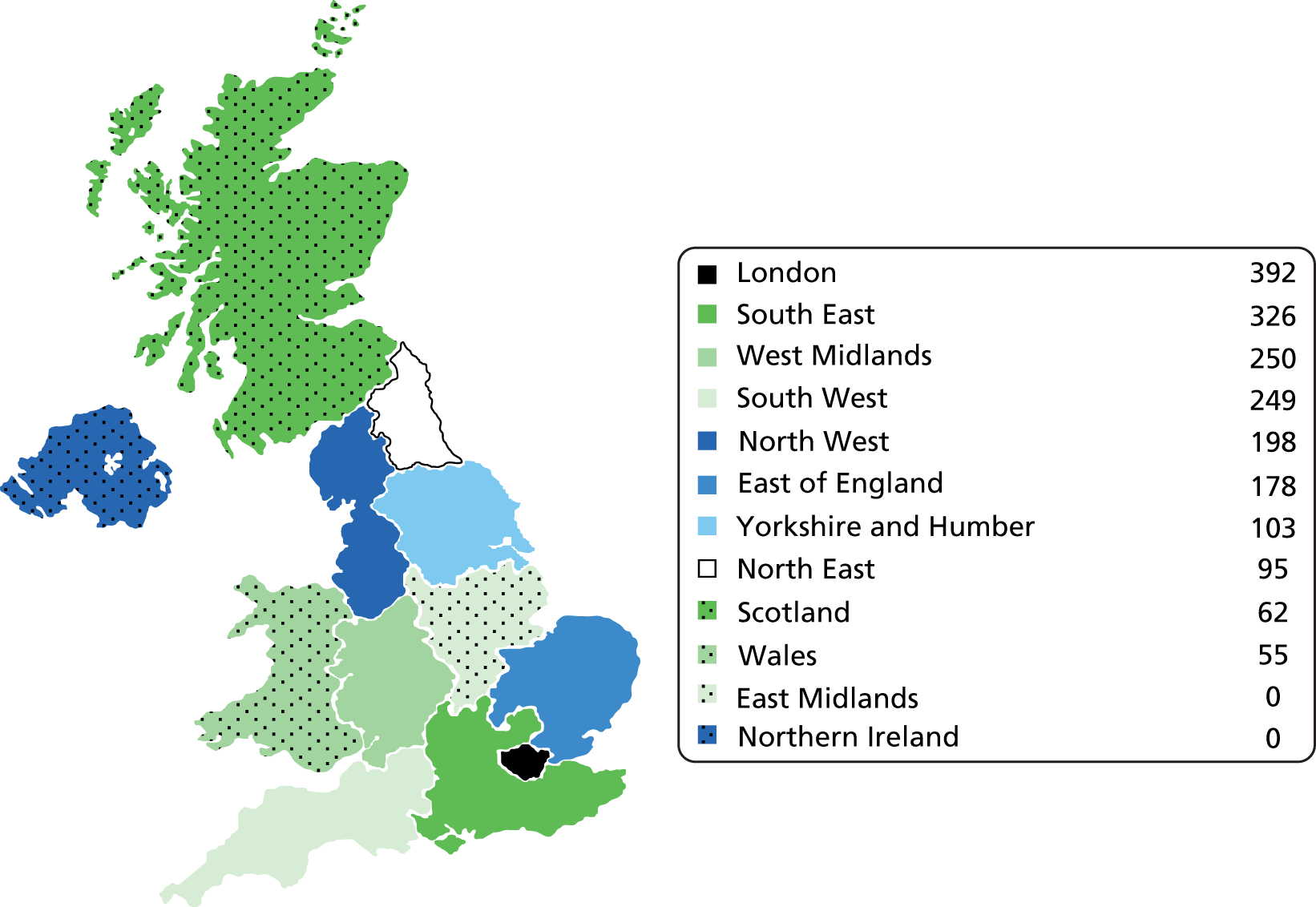

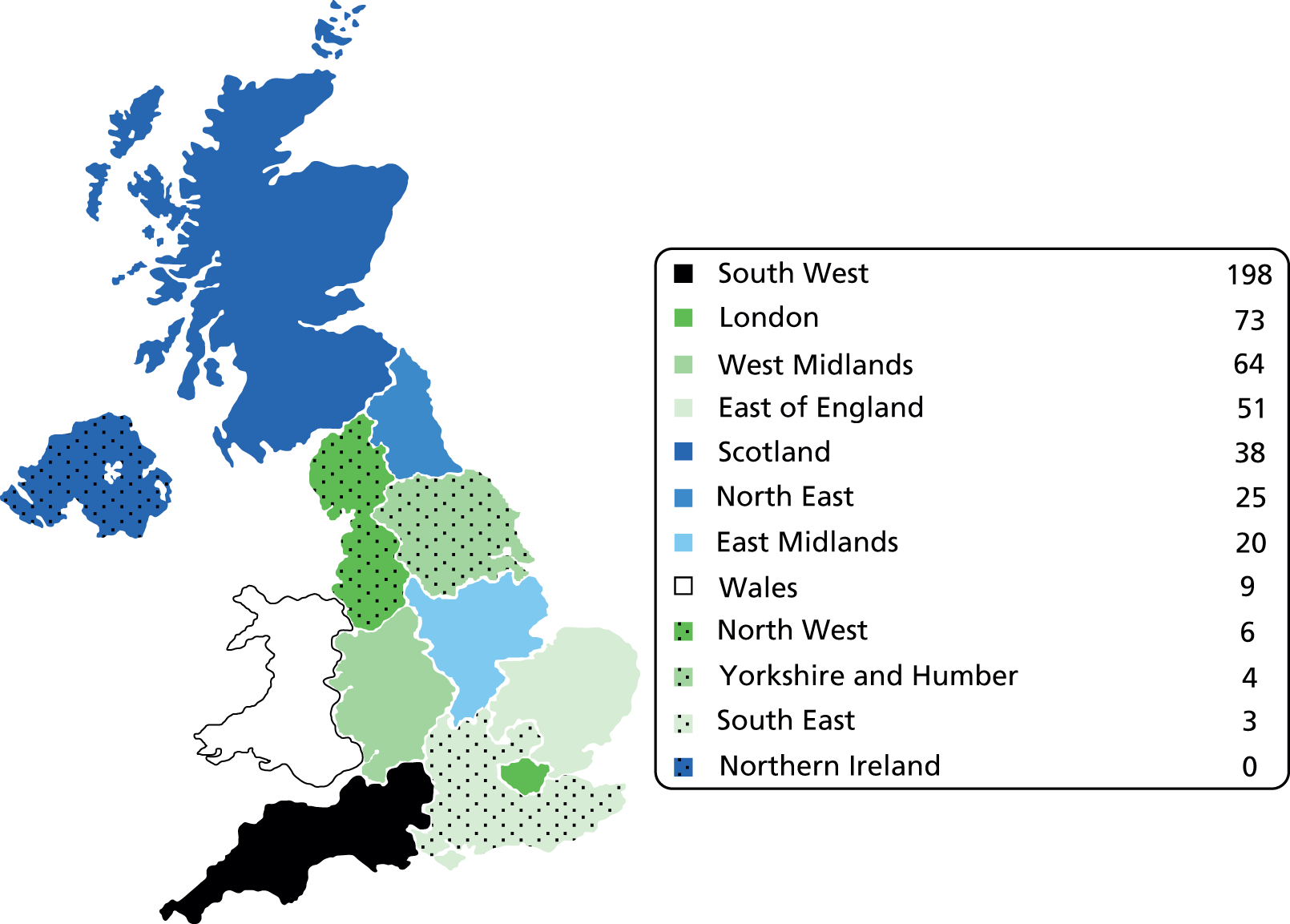

Each surgeon returning data was assigned a postcode for their NHS practice and this was used to create a choropleth map of the workload data based on regions within the UK. Figures 3 and 4 show the number of cases of FAI surgery performed by arthroscopic and open surgery, respectively, in regions of the UK.

FIGURE 3.

Choropleth map of arthroscopic surgery for FAI 2011/12. Number of cases of FAI surgery performed by arthroscopic surgery.

FIGURE 4.

Choropleth map of open surgery for FAI 2011/12. Number of cases of FAI surgery performed by open surgery.

Prevalence rates for FAI surgery using mid-2010 population estimates from the ONS33 are shown Table 3.

| Region | Mid-2010 population estimate33 | Arthroscopic FAI surgery cases | Arthroscopic FAI surgery per 100,000 population | Open FAI surgery cases | Open FAI surgery per 100,000 population | Total FAI workload per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 7,825,000 | 392 | 5.0 | 73 | 0.9 | 5.9 |

| South East | 8,523,000 | 326 | 3.8 | 3 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| West Midlands | 5,455,000 | 250 | 4.6 | 64 | 1.2 | 5.8 |

| South West | 5,274,000 | 249 | 4.7 | 198 | 3.8 | 8.5 |

| North West | 6,936,000 | 198 | 2.9 | 6 | 0.1 | 2.9 |

| East of England | 5,832,000 | 178 | 3.1 | 51 | 0.9 | 3.9 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 5,301,000 | 103 | 1.9 | 4 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| North East | 2,607,000 | 95 | 3.6 | 25 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Scotland | 5,222,000 | 62 | 1.2 | 38 | 0.7 | 1.9 |

| Wales | 3,006,000 | 55 | 1.8 | 9 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| East Midlands | 4,481,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Northern Ireland | 1,799,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 62,261,000 | 1908 | 3.1 | 491 | 0.8 | 3.9 |

Distribution of the numbers of cases per hospital trust is shown in Table 4, combining surgeons where they worked in the same trust.

| Summary statistic | FAI surgeons per hospital trust | Arthroscopy per hospital trust per 12 months | Arthroscopy for FAI per hospital trust per 12 months | Open surgery for FAI per hospital trust per 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.3 | 37.3 | 25.4 | 6.5 |

| 95% CI | 1.2 to 1.5 | 25.1 to 50.1 | 17.6 to 33.3 | 2.5 to 10.5 |

| Median | 1 | 22 | 12 | 0 |

| Interquartile range | 1 | 45 | 41 | 5 |

| Minimum and maximum | 1 and 4 | 0 and 352 | 0 and 149 | 0 and 132 |

Trusts with a workload of ≥ 10 hip arthroscopies for FAI per 12 months are summarised in Table 5.

| Hospital trust | Number of surgeons | Hip arthroscopy per 12 months | Hip arthroscopy for FAI per 12 months | Open surgery for FAI per 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frimley Park Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 159 | 149 | 1 |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ | 2 | 333 | 144 | 9 |

| Barts and The London NHS Trust | 3 | 50 | 140 | 30 |

| South West London Elective Orthopaedic Centre | 4 | 135 | 129 | 1 |

| Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust | 3 | 157 | 100 | 132 |

| Addenbrookes Hospital | 2 | 143 | 91 | 0 |

| The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital Birmingham | 2 | 135 | 90 | 15 |

| Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Hospital | 2 | 90 | 80 | 1 |

| South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 73 | 73 | 0 |

| Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 76 | 71 | 2 |

| Bangor Hospital | 3 | 59 | 55 | 9 |

| Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust | 1 | 53 | 53 | 1 |

| University College London Hospitals | 2 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Bolton NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 51 | 50 | 0 |

| Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust | 1 | 50 | 50 | 30 |

| South London Healthcare NHS Trust | 1 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust | 2 | 50 | 45 | 0 |

| Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 3 | 47 | 43 | 7 |

| Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 102 | 43 | 0 |

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | 1 | 48 | 42 | 0 |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 40 | 39 | 6 |

| Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 | 35 | 35 | 0 |

| Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 40 | 33 | 7 |

| Central Manchester University Hospitals | 1 | 40 | 30 | 0 |

| Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 30 | 25 | 0 |

| The Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS Trust | 1 | 25 | 25 | 5 |

| Royal Exeter and Devon | 1 | 28 | 23 | 0 |

| Weston Area Health NHS Trust | 1 | 352 | 23 | 4 |

| Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 22 | 22 | 5 |

| Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 | 22 | 22 | 0 |

| Southern General Hospital – Glasgow | 1 | 38 | 20 | 38 |

| University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Trust | 1 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 15 | 15 | 0 |

| Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | 1 | 40 | 15 | 1 |

| UHCW | 1 | 60 | 15 | 0 |

| Wirral University Teaching Hospital | 1 | 30 | 15 | 0 |

| Blackpool, Fylde and Wyre Hospitals | 1 | 31 | 12 | 0 |

| Luton and Dunstable Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 | 15 | 12 | 0 |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | 1 | 52 | 12 | 20 |

| Royal Surrey County NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| South Warwickshire Hospital | 1 | 18 | 12 | 0 |

| Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals | 1 | 29 | 10 | 4 |

| Poole Hospital | 1 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

From the initial survey there were 69 hospital trusts in England with at least one FAI surgeon. Of these 69 trusts, 53 had evidence of coded procedural activity from the HES data search. However, the data for both arthroscopic and open surgery were different by five or more procedures in 68 trusts when the two sources of data were compared. Local database results at UHCW showed that 12 arthroscopic and zero open surgeries were undertaken for FAI. The corresponding HES data reported 15 arthroscopic and more than one but fewer than five open surgeries for FAI.

Discussion

A minimum of 120 practising NHS FAI consultant surgeons collectively undertook at least 2399 FAI surgical procedures over a 12-month period. Of these, 1908 procedures (80%) were performed arthroscopically.

Although all health boards and trusts and corresponding clinical directors responded to our enquiries, it is possible that clinical directors are not always aware of all the expertise within their department. New FAI consultant surgeon appointments made after submission of data from the departmental clinical leads would not have been included in this data set, but the workload data for these surgeons are likely to be small given the short tenure and may already be accounted for in work being undertaken by existing surgeons.

The survey data rely heavily on surgeon recall, which is likely to have inaccuracies. However, the alternative of coded procedural data suffers from two major problems:

-

Coding of surgical procedures is known to be inaccurate. One study has reported accuracy of 47%. 34 The reason for this is that coding is frequently undertaken retrospectively by staff with no medical training and there are multiple ways of coding the same procedure. 34

-

Femoroacetabular impingement surgery has no specific procedural codes and is, therefore, coded using alternative combinations of the OPCS-4 coding system across NHS trusts.

For this reason, the HES data were used to triangulate/confirm locations of FAI surgery rather than provide any robust measure of the quantity of surgery.

Based on the ONS population data, the prevalence of surgery for FAI within the UK is 3.9 per 100,000. This figure represents a conservative estimate for prevalence of surgery for FAI within the UK because

-

a total of 20 (17%) surgeons did not provide data

-

the survey does not include surgery done outside the NHS.

In the absence of any formal operative coding for FAI, and with FAI surgical registries only recently commencing, this type of prevalence data has not been available to date through other sources. Although all health boards and trusts and corresponding clinical directors responded to our enquiries, it is possible that clinical directors are not always aware of all the expertise within their department. New FAI consultant surgeon appointments made after submission of data from the departmental clinical leads would not have been included in this data set; however, the workload of these surgeons is likely to be low given the short tenure and may all already be accounted for in work being undertaken by existing surgeons.

The results suggest the workload of FAI surgery is not spread evenly by region. There is a suggestion that more surgery is taking place in the South West, London and West Midlands regions per head of population, with marked variations in surgical workload across neighbouring regions, for example West Midlands and East Midlands (5.8 and 0.4 per 100,000, respectively). It is unlikely that these differences are due to regional variations in the prevalence of FAI; they and are more likely to represent regional variation in both surgical expertise and funding for FAI surgery. Surgical treatment of FAI is a relatively new and technically demanding procedure;35,36 therefore, the availability of surgeons with sufficient experience and expertise to undertake such surgery is likely to be limited. This is supported by the high workload among a small number of surgeons nationally. The data have highlighted marked regional variances in surgical workload and it is possible that some patients by the nature of their geography may not have easy access to the care that they would like.

The data presented provide epidemiological data on FAI surgery including those sites with a combined workload of 10 or more arthroscopic FAI procedures over 12 months. These sites may be particularly suited to become recruitment units for a RCT, provided the staff members involved in a RCT are in a position of equipoise.

The survey results provide a conservative estimate for both the number of FAI surgeons currently practising in the NHS and the prevalence of FAI surgery being undertaken. The results also highlight marked regional variances in surgical workload and it is possible that some patients by the nature of their geography may not have easy access to the care that they require. Finally, the results presented can be used to help plan a multicentre RCT based on the FAI surgical workload at each hospital trust.

Clinicians’ attitudes to randomisation of femoroacetabular impingement patients

Introduction

To participate in RCTs, clinicians need to accept at least collective uncertainty or equipoise between treatments, including the possibility that surgery does not work.

Objectives

To explore attitudes to randomisation of patients with FAI among a multidisciplinary sample of clinicians working in the centres performing hip arthroscopy.

Methods

We aimed to recruit a convenience sample of health-care professionals who have a special interest in hip conditions and were likely to see patients with FAI during their clinical practice. Semistructured interviews were carried out with a sample of orthopaedic surgeons, sport doctors and physiotherapists. To stimulate discussion, clinicians were provided with anonymous patient cases that cover the spectrum of patient presentations, including patient history (with duration of symptoms and previous treatments), examination findings and imaging (see Appendix 1). The clinicians were asked to ‘think aloud’ while considering the patient cases and the researcher used prompting questions to facilitate the clinician narrative of these processes. By introducing patient cases, we sought to deconstruct the cognitive processes involved when a clinician considers recruiting a patient to a clinical trial. This was done in order to elucidate the state of individual equipoise that may be influencing a recruitment decision (see Appendix 2).

The interviews were analysed thematically based on the Buckingham–Adams classification model of clinical decision-making. The analysis allowed to identify (1) relevant cues; (2) psychological representation of these clues (i.e. importance in diagnosis); (3) knowledge structures used (e.g. past clinical experience); (4) condition and treatment path inferences; and (5) potential outcomes associated with a particular treatment including introducing the trial. Key messages about what relevant cues to decision-making, information sources, clinical uncertainty and risks, and potential outcomes were considered by the clinicians were identified and discussed within the qualitative team. Recommendations about clinician recruitment and information provision for clinical teams involved in the trial were agreed and presented to the trial management team.

Results

A total of 28 clinicians were interviewed. Eighteen orthopaedic surgeons were identified from our workload survey (see Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in the NHS in the UK: a workload survey) as being high-volume arthroscopic FAI surgeons (> 20 procedures per year). Half of the physiotherapists (n = 6) were identified through a national survey (see Design of a best conservative care treatment protocol for femoroacetabular impingement), which requested the opinions of professionals who have a special interest in hip conditions. The other six physiotherapists and two sports physicians were interviewed when they attended a during an arthroscopic hip surgery conference. A detailed report of the recruitment processes and analysis of these interviews is presented in Appendix 3.

The results showed there was a lack of consensus about how best to treat FAI. The majority of clinicians accepted uncertainty between operative and non-operative treatments. Twenty-six clinicians (90%) believed that they were in equipoise and that a RCT was required to generate superior scientific evidence and guidelines for the care of patients with FAI. These were urgently needed, as they have witnessed increasing numbers of FAI patients in their routine practice. There were various statements supporting the trial; for example, a surgeon said:

The study is a very important one, it has not been done before and we need to do it to justify the role of surgery for this condition.

Surgeon 10

Despite this, five surgeons (36%) and two physiotherapists (10%) showed a lack of active clinical equipoise when faced with real-life case scenarios or discussing involvement with a pilot RCT. One surgeon has a fundamental disbelief in FAI, so that a trial of its treatment lacks relevance for them:

I’m not a massive believer that hip impingement exists, I think it’s over diagnosed.

Surgeon 3

Other clinicians are not in equipoise because they approach surgery for FAI with caution (n = 2); for example, a surgeon, referring to his practice, said:

I’m very careful that I counsel patients about the length of rehabilitation required after surgery, and that it’s definitely only for failure of conservative management.

Surgeon 6

Finally, some surgeons favoured surgery as the optimal treatment for FAI (n = 2), which is the case for the two physiotherapists who were not in equipoise; for example, one surgeon said:

I don’t believe there is any more a question of whether good surgery can relieve [FAI] symptoms.

Surgeon 9

There were seven surgeons who displayed both ‘theoretical’ and ‘active’ equipoise when assessing the case vignettes and these surgeons were invited to act as principal investigators (PIs) in the pilot RCT. Of these seven, there were three who were clearly of the strong belief that a RCT was the optimum solution to improving evidence and the remaining four were permissive.

A major concern for the surgeons (n = 10) was the duration of the trial, needing to balance sufficient length of follow-up to see changes with the potential for deterioration of a patient’s hip during conservative care; for example, one surgeon said:

The main concern with all of this is that if you’re delaying surgical treatment, are they going to progress essentially their arthritic symptoms or cartilage damage by introducing that delay.

Surgeon 13

They felt that the proposed duration of 12 months for the trial was pragmatic and, therefore, acceptable in this respect and would also be long enough to allow the patient to stabilise after either intervention. One surgeon indicated this agreement by saying ‘12 months may be a little long, but I can understand with what we are trying to come up’ (surgeon 11). The surgeons were anxious to know the mechanism by which the outcome of the trial would be assessed and were more comfortable with a patient-reported quality-of-life instrument rather than any other types of measure. All were familiar with and supported the use of either the Non-Arthritic Hip Score (NAHS) or the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33) as the primary outcome measure for a full trial.

The physiotherapists and sports physicians frequently mentioned two issues: (1) the need for more clarity of the eligibility criteria (i.e. patients who do not need surgery do not take part) and (2) the need for the new conservative care protocol to be more distinctive. For example, a physiotherapist said:

As long as conservative care is standardised and you’ve got a level of expertise by the people giving the conservative care, I think it is very valid.

Physiotherapist 5

The majority of clinicians that assumed patients would prefer surgery and were concerned about patient reactions to an invitation to participate in the study, which meant that patient expectations were not fulfilled. They also thought patient would respond negatively to being randomised. The following quotes illustrated these assumptions:

Patients get to the point where they’ve tried everything and sometimes they are looking for a surgical route, she had failed physiotherapy.

Physiotherapist 4

She’s going to be very unwilling not to have an operation, I would imagine.

Surgeon 3

Finally, clinicians reported potential regional sources of bias in the recruitment. For example, surgeons’ preferences for conservative or operative care could be at play. One surgeon said:

I think if it had been done 3–4 years ago, I think it would have been easier, it was less conviction and most surgeons that were doing it that it was the right thing to do.

Surgeon 14

Although another surgeon explained his own view as:

Of the majority of surgeons offering HA [hip arthroscopy] in the country, I see myself as being a little less invasive and more conservative [. . .] there are surgeons around the country who will operate in patients that I wouldn’t touch with a barge pole.

Surgeon 6

There are also perceived differences in physiotherapy provision. Clinicians reported their concern that local physiotherapy may not be of equal quality across the centres:

Are you suggesting a remote access physio who gives them a programme and liaises with the local physios? Because we don’t have specialist enthusiastic physios in our area which would be quite as knowledgeable as the ones you have in Coventry.

Surgeon 7

Discussion

Significant interest was evident in the clinical community for a RCT comparing hip arthroscopy and conservative care. Even though not all clinicians were in equipoise, almost all recognised uncertainty and felt that a RCT would help to guide their practice in future. Most surgeons were prepared to randomise patients.

The qualitative methods we described provided a novel approach to determining a more complete assessment of clinical uncertainty and equipoise. The results suggest that, while many clinicians might think they were in equipoise (theoretical equipoise) their actions and management decisions did not always support this position (active equipoise). It was likely that where there was a large discrepancy, recruitment of patients to a RCT was going to be challenging. Therefore, decisions about participating sites and PIs were informed by the results of this study. It also helped to provide guidance of study design features including follow-up duration, outcome measures and the need for distinctiveness of the best conventional care arm.

Develop eligibility criteria for a randomised controlled trial and design an operative protocol

Introduction

To date, no RCTs have been undertaken for FAI surgery and no previous eligibility criteria exist to guide a pilot. In addition, as a relatively new procedure, there are a variety of surgical techniques for arthroscopic FAI surgery and, therefore, it is necessary to develop and define a protocol of operative care in order to ensure that patients receive the same standard intervention and that the fidelity of this intervention can then be measured.

Objectives

-

Establish appropriate eligibility criteria for a RCT.

-

Establish a protocol of operative treatment for arthroscopic FAI surgery.

Methods

Researchers PW and DG developed draft eligibility criteria and an operative protocol based on their own experience of arthroscopic FAI surgery and available published literature. Sixteen hip arthroscopy surgeons, recognised as international experts in the field, were then individually invited to comment on these provisional documents. These surgeons were from the Multicenter Arthroscopy of the Hip Outcomes Research Network (MAHORN) (n = 12) and from a group who attended the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Research Symposium on Femoroacetabular Impingement in Chicago, IL, USA (n = 4). All surgeons approached agreed to participate. The feedback they provided was then used to modify the two documents. The eligibility criteria and protocol were recirculated to the 16 experts for further comment. The criteria and protocol were then discussed with a further sample of 14 UK specialist hip surgeons with experience of treating patients with FAI and likely collaborators for a full RCT. A final version of both documents was agreed and then used in the pilot RCT. The two documents continued to be evaluated in the light of feedback from the recruiting sites during the pilot RCT.

Results

The draft eligibility proposed that patients be included if:

-

they are aged 18–50 years

-

they have symptoms of hip pain: they may also have symptoms of clicking, catching or giving way

-

they show radiographic evidence of pincer- or cam-type FAI on plain radiographs and cross-sectional imaging37

-

the treating surgeon believes that they would benefit from arthroscopic FAI surgery

-

they are able to give written informed consent

-

they are able to participate fully in the interventions.

Patients would be excluded from participation in this study if:

-

they have previous significant hip pathology such as Perthes’ disease, slipped upper femoral epiphysis or avascular necrosis

-

they have had a previous hip injury such as acetabular fracture, hip dislocation or femoral neck fracture

-

they already have osteoarthritis, defined as Tönnis grade of > 1,38 or more than 2-mm loss of superior joint space width on anteroposterior pelvic radiograph8

-

there is evidence that the patient would be unable to participate fully in the interventions, adhere to trial procedures or complete questionnaires, such as cognitive impairment or intravenous drug abuse.

Initially, 11 out of the 16 surgeons agreed with these eligibility criteria. Others suggested the following modifications, which were agreed by the whole group:

-

Age range changed to include all patients ≥ 16 years. Some surgeons felt that patients between 16 and 18 years of age were an important part of their practice and that for these patients treatment effects would be similar to older adults. There was not thought to be any rationale for a maximum age limit; older patients may be, but need not necessarily be, excluded by the criterion ‘the treating surgeon believes that they would benefit from arthroscopic FAI surgery’.

-

Radiographic evidence of FAI was further defined to include an alpha angle of > 55 degrees or a lateral centre–edge (Wiberg) angle of > 40 degrees.

The draft operative protocol was:

-

general anaesthetic with muscle relaxation

-

supine or lateral patient positioning

-

operating table with facility for traction and allowing range of movement testing

-

arthroscopy of central compartment

-

arthroscopy of peripheral compartment working with one of the following: intact capsule, capsulotomy or capsulectomy

-

ability to undertake bony surgery to correct abnormalities on both the femoral head neck junction and acetabular side of the hip joint

-

ability to undertake soft tissue repair and/or debridement to the labrum and/or articular cartilage

-

ability to record with photos the intraoperative findings and solutions.

A total of 13 out of the 16 surgeons agreed with the draft operative protocol. Three surgeons proposed changes, which were agreed by the whole group:

-

the entire acetabular labrum should be examined

-

the entire articular surface should be examined

-

confirm that FAI has been relieved using either range of movement testing or an image intensifier

-

need to document intraoperative complication and their solutions.

Discussion

There was ready agreement on eligibility criteria for a trial, suggesting that surgeons have a clear idea who may benefit from hip arthroscopy for FAI. There was recognition that there are many subtleties of FAI morphology, but surgeons were happy to be pragmatic and ‘lump’ all of these into a single diagnosis. There may be differences in treatment effect according to type of FAI (some surgeons mentioned their sense that patients with cam-type FAI do better after surgery than those with pincer-type) and this raised the possibility of stratification or an a priori subgroup analysis in a full trial. These criteria define a generalisable sample representative of the patients currently receiving hip arthroscopy for FAI.

The operative protocol was broad enough to accommodate the variations of arthroscopic FAI surgical technique being used throughout the UK. However, the protocol retains the key steps regarded by the expert surgeons as essential to a successful hip arthroscopy for FAI.

We considered whether or not to protocolise the postoperative rehabilitation programme for the group randomised to surgery prior to the pilot trial. This is a pragmatic trial and we believe that the best option is for postoperative rehabilitation to reflect usual care as closely as possible. Postoperative rehabilitation varies, often from surgeon to surgeon and even within the same orthopaedic service. If we were to develop a postoperative rehabilitation programme that is similar to the personalised hip therapy (PHT) programme, this would change the question for the trial (and, therefore, it would no longer address the original commissioned call from the HTA programme). The question would then become ‘Does surgery provide additional benefit to a package of physiotherapy-led care?’ Our preference was to allow postoperative care to be offered as per usual practice for those randomised to surgery in the pilot trial and to measure that to allow for assessment of potential confounding.

Design of a best conservative care treatment protocol for femoroacetabular impingement

Introduction

Although conservative care is being used to treat patients with FAI,11 we had previously performed a systematic review that showed that detailed guidance and evidence on how this care should be delivered are not available. 13 This review suggested that non-operative care for FAI would typically be led by physiotherapists. Of 53 published articles, only four were empirical investigations of non-operative care for FAI and only one study39 provided both an experimental evaluation of treatment and an explicit description of the treatment protocol delivered by physiotherapists.

When there is a lack of evidence to guide care, it is appropriate to use a consensus-gathering approach in order to develop and rationalise best practice. 40 Murphy et al. 40 summarised three formal consensus-gathering techniques which have been used to guide health care in other subject areas:

-

Delphi method – involves participants receiving two, three or more sequential rounds of questionnaires and responding to ‘cues’, that is, statements that provoke decision-making based on responses from previous rounds. Results are aggregated and reviewed for agreement. 41

-

Nominal group technique (NGT) – involves a process of generating ideas which are then either accepted or rejected by group members. 42,43

-

Consensus Development Conference (CDC) – requires a group of individuals to attend a conference in which evidence is presented to them by experts. 44

Objectives

-

To develop a consensus on a best conservative care treatment protocol for patients with FAI that was both deliverable within the NHS and could be used within a RCT of best conservative care compared with hip arthroscopy surgery for FAI.

-

To agree, through patient involvement, the most appropriate name for the best conservative care treatment protocol.

Methods

The protocol proposed by Emara et al. 39 (Table 6) was used as the starting point for a best conservative care treatment protocol for FAI. This was developed using Delphi and NGT consensus-building methods, guided by available evidence and guidance from the MRC for developing a complex intervention. 45

| Initial assessment and treatment | Further assessment and treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 |

| Avoidance of excessive physical activity and anti-inflammatory drugs for 2 to 4 weeks | Physiotherapy for 2 to 3 weeks in the form of stretching exercises to improve hip external rotation and abduction in extension and flexion | Assessment of the normal range of hip internal rotation and flexion after the acute pain has subsided | Modification of activities of daily living predisposing to FAI (e.g. hip internal rotation associated with flexion and adduction) |

A core study group was formed to oversee the development, evaluate information gathered and provide a layer of NGT consensus to support the Delphi process. The core study group comprised two senior musculoskeletal physiotherapists with an interest in managing patients with FAI (David Robinson and Ivor Hughes), a senior academic research physiotherapist (NF) and an orthopaedic surgeon (PW).

When we began this study, we did not know which physiotherapists were directly involved in the management of patients with FAI, nor did we think it likely to be efficient to simply sample the physiotherapy profession in the UK at random. We therefore took a targeted approach to sampling, using networks of physiotherapists most likely to be involved in the management of this patient group. National advertisements were placed in the orthopaedic, rheumatology, pain and manual therapy electronic networks through the interactive, electronic Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) communication system in the UK (iCSP) and in the CSP’s Frontline magazine (twice-monthly magazine posted to approximately 52,000 CSP members in the UK). The adverts invited UK physiotherapists to help develop a consensus for a best conservative care treatment protocol for FAI. Electronic invitations were also sent to physiotherapists in the USA and Australia known to members of the core study group through previous collaborative work on FAI. To encourage a process of ‘snowball sampling’ within the international community, these therapists were encouraged to invite colleagues with experience and interest in managing FAI to join in the consensus development process.

Each physiotherapist was given the first protocol39 with a questionnaire. The physiotherapists were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the proposed programme for the conservative treatment of FAI patients and, when appropriate, to provide comments and suggestions for improvement.

Results from the each round of Delphi consensus were tabulated by the core study group, and additional comments and treatment strategies suggested by the respondents were grouped into themes. An agreement level of ≥ 50% for this Delphi consensus technique was used. If no consensus was evident from the survey the core study group refined the protocol in light of the available feedback using a NGT-type approach. The refined protocol was then recirculated to the physiotherapists taking part in the Delphi consensus process and the cycle repeated until a consensus of ≥ 50% was achieved.

This protocol was then discussed with our panel of expert patients (described in section Patients’ attitudes towards randomisation and design of patient information material for a randomised controlled trial) in individual interviews. They expressed the view that the name ‘best conservative care’ did not fully express (to patients) the intent and content of the protocol. Previous qualitative research has highlighted the importance of naming treatments in order to improve uptake and compliance, in particular when being used in RCTs. 46 The expert panel was asked to suggest a suitable name for this best conservative care treatment protocol.

All physiotherapists identified as likely to be best conservative care providers in the pilot RCT were asked to detail exercises that would allow them to deliver the protocol. The exercises were then ranked and the most popular were included as a database resource (exercise template) to be used alongside the best conservative care protocol. In the early phases of recruitment to the RCT, a workshop (CDC methodology) was held among the physiotherapists delivering care, to refine the protocol. The physiotherapists attending the workshop were asked to share their experiences of delivering the protocol and make any suggestions for further amendments.

In the pilot RCT, all physiotherapists delivering the protocol were asked to complete case report forms for each patient. This included details about the number, nature and duration of the patient contact, and details of the exercises prescribed to each patient were recorded.

Results

Consensus development for the best conservative care protocol

In total, 36 physiotherapists responded and agreed to take part in the consensus process; 24 from the UK, 10 from USA and two from Australia. All were senior musculoskeletal physiotherapists who had previously managed patients with FAI. Details of the initial round of consensus development received from 36 physiotherapists are summarised in Tables 7 and 8.

| Agreement | Stages 1 and 2 of the Emara et al.39 protocol (initial assessment and treatment); level of agreement, n (%) | Stages 3 and 4 of the Emara et al.39 protocol (further assessment and treatment); level of agreement, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 16 (47) | 9 (25) |

| No | 7 | 6 |

| Unsure | 13 | 21 |

| Total | 36 | 36 |

| Stages | Additional themed comments made | Number of comments | Origin of comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial assessment and treatment (stages 1 and 2) | Core stability exercise and movement control | 21 | UK × 17, Australia × 2, USA × 2 |

| Muscle strengthening important | 7 | UK × 6, USA × 1 | |

| See patients more frequently/over a longer period | 5 | UK × 4, Australia × 1 | |

| Stretching exercise depending on what is limited | 4 | UK × 2, USA × 2 | |

| Soft tissue mobilisation to facilitate range of movement | 3 | UK × 2, USA × 1 | |

| Address flexion contractures | 2 | UK × 2 | |

| Massage to relieve tightness in hip muscles | 2 | UK × 1, Australia × 1 | |

| Avoid flexion stretching exercises during initial stages | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Internal rotation stretching when pain free | 1 | USA × 1 | |

| Gentle exercise to mobilise the joint in all directions | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Reduce overactive hamstring muscles | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Work on active abduction and external rotation | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Avoid excessive hip flexion | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| See patients less frequently | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Prolonged follow-up often needed | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Further assessment and treatment (stages 3 and 4) | Advice that cycling is acceptable with activity modification | 7 | UK × 6, Australia × 1 |

| Continue strengthening | 6 | UK × 6 | |

| Zigzag running no better than straight running | 4 | UK × 3, Australia × 1 | |

| Reassessment important | 2 | UK × 2 | |

| Using orthotics may help | 2 | UK × 2 | |

| Encourage hip capsule stretches | 2 | UK × 2 | |

| Stretches can be harmful | 2 | UK × 1, Australia × 1 | |

| Identify dysfunctional movement patterns to achieve long-term change | 2 | UK × 1, Australia × 1 | |

| More than twice-monthly supervision required | 2 | UK × 1, Australia × 1 | |

| Advice about lifestyle modification | 2 | UK × 1, USA × 1 | |

| Advice about alternative forms of exercise | 2 | UK × 1, Australia × 1 | |

| Advise to avoid deep squatting | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Advice on return to sport specific training | 1 | Australia × 1 | |

| Strengthening of internal and external rotators of hip | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Activity restriction on an individual basis | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Modification of running on an individual basis | 1 | UK × 1 | |

| Ensure activities can be undertaken with minimal adduction/Internal rotation | 1 | UK × 1 |

The level of agreement with the Emara et al. 39 protocol (initial protocol) among the 36 physiotherapists was below the 50% threshold that had been set for the Delphi consensus method. However, using the additional comments made by the physiotherapists, available evidence and established theory, two further protocols were developed independently by NF and PW and presented at a core study group meeting. Using the two independent protocols presented, the core study group derived a second protocol based on a majority within the group (NGT methodology).

The second protocol that the core study group formulated had four core components and four optional components, which are described below with a justification for including each component.

-

Core component 1: patient assessment. Both independently developed protocols featured this component. 39,47 Although not formally a treatment and as such not specifically mentioned in the questionnaire feedback received, the core study felt that this component should be explicitly included in the protocol, as it would underpin the remainder of the best conservative care treatment protocol.

-

Core component 2: patient education and advice. Both independently developed protocols featured this component. Thirteen comments from questionnaire respondents had suggested that physiotherapists should provide patient specific education about FAI including advice on lifestyle modification, how to do different forms of exercise and how to undertake common activities. Advice on activity modification was a feature of the published literature, including the Emara et al. protocol39 and Hunt et al. protocol,47 and the core study group felt that education and advice would be regarded as a core component of best practice among physiotherapists managing any painful musculoskeletal condition. Both lifestyle and activity modification draw on relevant theory in that behavioural modifications that might lead to reduced functional impingement should result in reduced symptoms. 3

-

Core component 3: help with pain relief. Both independently developed protocols featured this component. It is a feature of the published literature, including the Emara et al. 39 protocol, with which 44% of the physiotherapists agreed. 39,47 Analgesia is an established treatment for musculoskeletal pain. 48,49 Controlling musculoskeletal pain associated with FAI with analgesia therefore follows MRC guidance that treatment draw on relevant theory.

-

Core component 4: exercise-based hip programme. Both independently developed protocols featured this component. Thirty-seven additional comments from questionnaire respondents endorsed both hip-specific and more general exercises for managing patients with FAI. Of these, core or stability exercises were the most common (21 additional comments). The feedback suggested that the exercise programme should be individualised to the patient and progressed over time from core stability exercise and stretching to strengthening exercises. Exercise was a predominant feature of the Emara et al. 39 protocol and the other published literature for managing FAI non-operatively. 39,47,50 Exercise is an effective treatment for many other musculoskeletal pain problems51,52 and exercise-based programmes can produce similar improvements in symptoms to surgery. 53 Therefore, including an exercise-based hip regime to help manage the symptoms of FAI follows MRC guidance that treatment draw on relevant theory.

The core study group proposed the inclusion of optional components which could be undertaken in addition to the core components in order to individualise treatment, at the discretion of the physiotherapist delivering care.

-

Option 1: additional symptoms that patients with FAI may present with can also be treated.

-

Option 2: orthotics can be used to aid the treatment of biomechanical abnormalities.

-

Option 3: corticosteroid hip joint injection may be used for patients who cannot engage with ‘core’ treatment owing to acute pain symptoms.

-

Option 4: manual therapy – hip joint mobilisations may be added if appropriate, for example distraction and trigger point work.

The Emara et al. 39 protocol suggested that physiotherapy should be offered over a period of between 2 and 3 weeks. The initial round of physiotherapist responses suggested patients should be seen over a longer period and more frequently in order to provide best care. Currently within the NHS the average number of treatment sessions given by physiotherapist to musculoskeletal pain patients is between three and four face-to-face contacts. There is evidence to suggest that better outcomes are achieved from exercise-based regimes when they are supervised and the contact between the supervisor and patient is increased. 54,55 In order to allow more contact between therapists and their patients without increasing the burden of having to travel to clinic appointments, non-face-to-face contacts (e.g. telephone and e-mail) were also allowed in order to progress the exercise programme and to support patients in their adherence to the recommended exercises. The core study group suggested that the agreed protocol should be delivered over at least a 12-week period and a minimum of six treatment sessions (of which at least three should be face to face). The duration of care was both in keeping with established theory that suggests physiological changes in muscle occur after a 12-week programme of exercise. 56

The core study group agreed on the following protocol exclusions:

-

Painful hard end stretches were excluded. Although mentioned by only two physiotherapists in the initial questionnaire responses, there is some evidence in the literature to suggest that painful hard end stretches and forceful manual techniques in a restricted range of movement may be harmful. Therefore, although stretching was permitted, hard end of range stretches were excluded. 30

-

Group-based treatment was excluded in order to ensure care was individualised.

-

Care delivered by a technical or student instructor was excluded in order to ensure that care was delivered by qualified musculoskeletal physiotherapists.

The second protocol was distributed to the original group of 36 physiotherapists. Thirty-five (97%) responded, 30 (86%) agreed with the second protocol and provided no additional suggestions for change, and five disagreed with elements of the second protocol and made suggestions for change. These points were discussed among the core study group and the following changes were made:

-

Two optional booster sessions that could be delivered between 12 weeks and 6 months were added to a revised protocol. This was in response to concerns that the initial 12-week programme could prove to be insufficient to correct what is likely to be a significant chronic biomechanical dysfunction. Booster sessions would also help with adherence to the programme.

-

Taping techniques to help with postural modification/reminding were added to the protocol. Although mentioned by only one physiotherapist, it was noted that taping was a feature of the published literature. 13

Given the level of agreement (83%) achieved with the second protocol, the core study group decided to use the second protocol with the modifications discussed above for implementation in the RCT. This final protocol is shown in Box 1.

Four core components. Each patient should receive all four core components over at least a 12-week programme with at least six patient contacts (of which at least three are face-to-face contacts). Up to a further four ‘booster’ follow-ups can be arranged between 12 weeks and 6 months.

Patient education and advice-

Education about FAI and available treatments.

-

Advice about posture, gait and lifestyle behaviour modifications to try to avoid FAI. These may include measures to encourage posterior pelvic tilt (reduce pelvic inclination); positioning when sitting, standing, sit to stand; positioning when sleeping; positioning when running/cycling when relevant.

-

Advice about activities of daily living to try to avoid FAI (reducing/avoiding deep flexion, adduction and internal rotation of hip).

-

Advice about relative rest (for acute pain where patients cannot engage with their exercise-based personal hip programme) given that soft tissues take at least 8–10 weeks to heal. In particular, relative rest in a specific ROM when pain in that particular ROM is likely to represent ongoing inflammation and damage.

-

Specific activity/sport technique advice and modification. Examples include running with a broader base to encourage abduction, cycling with less internal rotation on pedals, skiing with skis further apart and using knee flexion more than hip flexion to lower centre of gravity.

-

History, which should include (although not exclusively) history of presenting complaint; relieving and aggravating factors; past medical history; medications; previous treatments tried; social history including occupation; and patients’ concerns/fears/beliefs, individual requirements and expectations.

-

Examination, which should include (although not exclusively) the pain-free and passive range of movement of the hip; strength of the hip; and the anterior impingement test.

-

Advice about anti-inflammatory medication for 2–4 weeks if not already tried and simple analgesics if the patient does not respond well to anti-inflammatory medication.

-

Engagement in, and adherence to, an exercise programme that has the key features of individualisation, progression and supervision.

-

A phased exercise programme that begins with muscle control work and progresses to stretching and strengthening with increasing ROM and resistance.

-

Muscle control/stability exercise (targeting pelvic and hip stabilisation, gluteal and abdominal muscles).

-

Strengthening/resistance exercise firstly in available range (pain-free ROM).

-

Stretching exercise to improve hip external rotation and abduction in extension and flexion (but not vigorous stretching – no painful hard end stretches). Other muscles to be targeted if relevant.

-

Exercise progression in terms of intensity and difficulty, gradually progressing to activity or sport-specific exercise when relevant.

-

A personalised and written exercise prescription that is progressed and revised over treatment sessions.

-

Encourage motivation and adherence through the use of a patient exercise diary to review progress.

-

Patients to have to access to simple exercise equipment (e.g. resistance bands, exercise balls and exercise mats).

-

Additional symptoms that patients with FAI may present with can also be treated as per the treating physiotherapists’ preferred methods.

-

Manual therapy: hip joint mobilisations (e.g. distraction and rigger point work).

-

Hip joint injection: for patients who cannot engage with ‘core’ treatment owing to acute symptoms. Maximum of one steroid hip injection.

-

Orthotics: patients can be assessed for biomechanical abnormalities and have these corrected (e.g. referral to a podiatrist for custom-made insoles).

-

Taping: taping techniques are permissible, for example taping the thigh into external rotation and abduction to help with postural modification/reminding.

-

Forceful manual techniques in restricted range of movement. No painful hard end of range stretches.

-

Group-based treatment.

-

Care delivered by a student or technical instructor.

ROM, range of motion.

Naming the best conservative care protocol

Eighteen expert patients participated in consideration of the best name for this protocol. They were asked to choose between four potential names which had been suggested by the core study group, with the option to suggest a different name if they wished to do so. Eight patients opted for the name ‘personalised hip therapy’, four patients voted for ‘personalised hip programme’, one patient preferred the name ‘focused hip therapy’ and three offered their own suggestions (including ‘conservative hip rehabilitation programme’ and the inclusion of the word ‘non-invasive’). ‘Conservative’ and ‘non-invasive’ were disregarded because they appeared to have a value attached to them; for example, the term ‘conservative’ could be confused with terms used in politics. The word ‘personalised’ was preferred for most people, as exemplified by this quote from a patient: ‘I said the last two [personalised hip treatment and PHT] because it makes it a personal issue for that person . . . going down a non-operative route would require different treatment for every different patient’ (patient 3). Patients preferred the word ‘therapy’ to indicate that there was an effort to ‘solve’ or ‘cure’ the condition as opposed to ‘programme’: ‘Therapy from a psychological point of view, people understand therapy [. . .] with regards to clinical treatment rather than a programme which can relate to anything in life’ (patient 13).

The name ‘personalised hip therapy’ appealed to and conveyed a positive message to patients. This name emphasises that the protocol is an active intervention that differs from other regimes patients may have previously tried. Patients said that these two elements were very important to patients who are experiencing FAI and considering treatment options.

Developing an exercise template and testing the protocol

Twelve physiotherapists were initially identified as likely to be providers of the best conservative care protocol during the pilot RCT in their hospitals. They suggested suitable exercises for core component 4 and the most popular 21 exercises are shown in Appendix 4.

A workshop (CDC-type methodology) was held after 42 patients were recruited to the RCT and 21 patients were allocated to and receiving the PHT protocol. Eight physiotherapists (out of 12 physiotherapists participating in the RCT) from seven recruiting centres attended the workshop to review the content and delivery of the protocol. Collectively, the physiotherapists were treating 18 patients within the RCT. The physiotherapists agreed that the protocol worked well but felt that they wanted to change the number of treatment sessions and the overall duration of the protocol, in order to ensure that they were able to deliver best care. As a result, one change was made to the protocol, which allowed a minimum of six and a maximum of 10 contacts over a 6-month period. In addition, the physiotherapists recommended that three further exercises should be added to the selection of 21 within the exercise template (see Appendix 4). The physiotherapists agreed that no further amendments would be needed to the protocol.

Discussion

Despite the increase in attention and recognition of FAI as a source of hip pain in young adults, there has been very little published information about appropriate conservative treatment approaches. Our aim was to develop an agreed high-quality best conservative care and physiotherapy-led treatment protocol for patients with FAI that could be used within a RCT. We combined results from a systematic review, Delphi consensus surveys with FAI physiotherapists, NGT consensus methodology, relevant literature on effective conservative care for other musculoskeletal pain conditions and the experiences of physiotherapists treating FAI patients within a RCT (CDC methodology), in order to develop the agreed treatment protocol, referred to as PHT.

In summary, PHT comprises four ‘core’ elements designed to be offered over a maximum of 6 months: (1) patient assessment; (2) patient education and advice; (3) help with pain relief; and (4) engagement with a supervised individualised exercise-based hip programme. A minimum of six and a maximum of 10 treatment contacts should be provided by the supervising physiotherapist over the 6-month period.

The protocol followed MRC guidance for the development of complex interventions and is based on theory when possible. 45 Research has already shown that exercise is an effective treatment for many types of musculoskeletal pain51,52 and has identified that exercise-based programmes can produce similar improvements in symptoms to surgery. 53 The PHT protocol provides guidance to other clinicians and researchers in an area where evidence and guidance are very limited.

Possible outcome measures and sample size for a full randomised controlled trial

A variety of outcome measures have been used to study patients with FAI, especially patient-reported hip-specific pain and function scales. Some, such as the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index57 and the Harris Hip Score,58 were intended for older patients with symptoms of severe arthritis and are most suitable to measure the effect of hip replacement surgery. These measures tend to exhibit ceiling effects and are not sensitive to change after treatment in patients with FAI. 58,59 A review of hip-specific patient-reported instruments for FAI18 recommended that newer instruments specifically designed for young adults might be used to measure primary outcome in studies for the effectiveness of treatment of FAI.

Non-Arthritic Hip Score is a self-administered instrument to measure hip-related pain and function in younger patients without arthritis. The score is valid compared with other measures of hip performance, internally consistent and reproducible. 60 However, it is not patient-derived, raising concern that it may not measure what is most important to patients.

The iHOT is a patient-derived, hip-specific, patient-reported instrument that measures health-related quality of life in young, active patients with hip disorders. 59 It was developed in a 5-year study by a large international collaboration of patients and clinicians led by MAHORN: an academic group of highly experienced hip arthroscopists closely associated with the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy (www.isha.net). It comprises 33 items, each measured on a visual analogue scale, to assess functional limitations, sports activities, job-related and emotional concerns. Importantly, these items were generated and refined by patients, reflecting their most important concerns. The instrument generates a single score in the range 0–100. People with no hip complaints usually score ≥ 95; a diverse international population of younger adults with a variety of hip pathologies had a mean score of 66 with a standard deviation (SD) of 19.3. iHOT-33 has been validated for use in patients with FAI and is sensitive to change after treatment for FAI. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) has been determined using an anchor and distribution-based approach in a group of 27 young active patients who were independent of the development population. Clinical change was determined using a global rating scale that asked patients whether their hip condition had improved, had deteriorated or had not changed since the previous assessment, using a single visual analogue scale. The MCID was 6.1 points. 61–63

The iHOT and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) have been adopted as the principal outcome measures by the UK Non-Arthritic Hip Registry. This registry is led by the British Hip Society (BHS); its use in all patients having arthroscopic FAI surgery is required by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 35

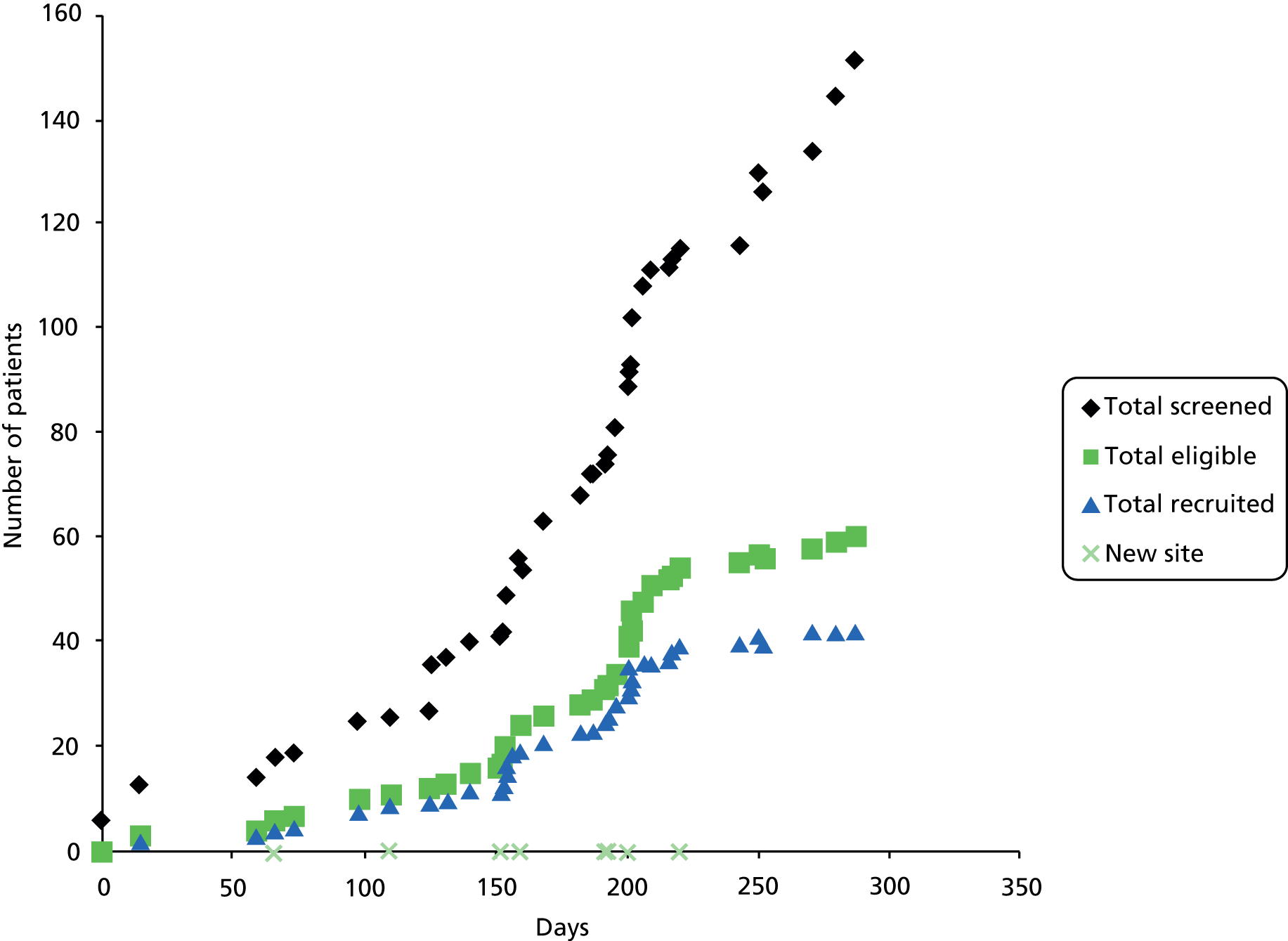

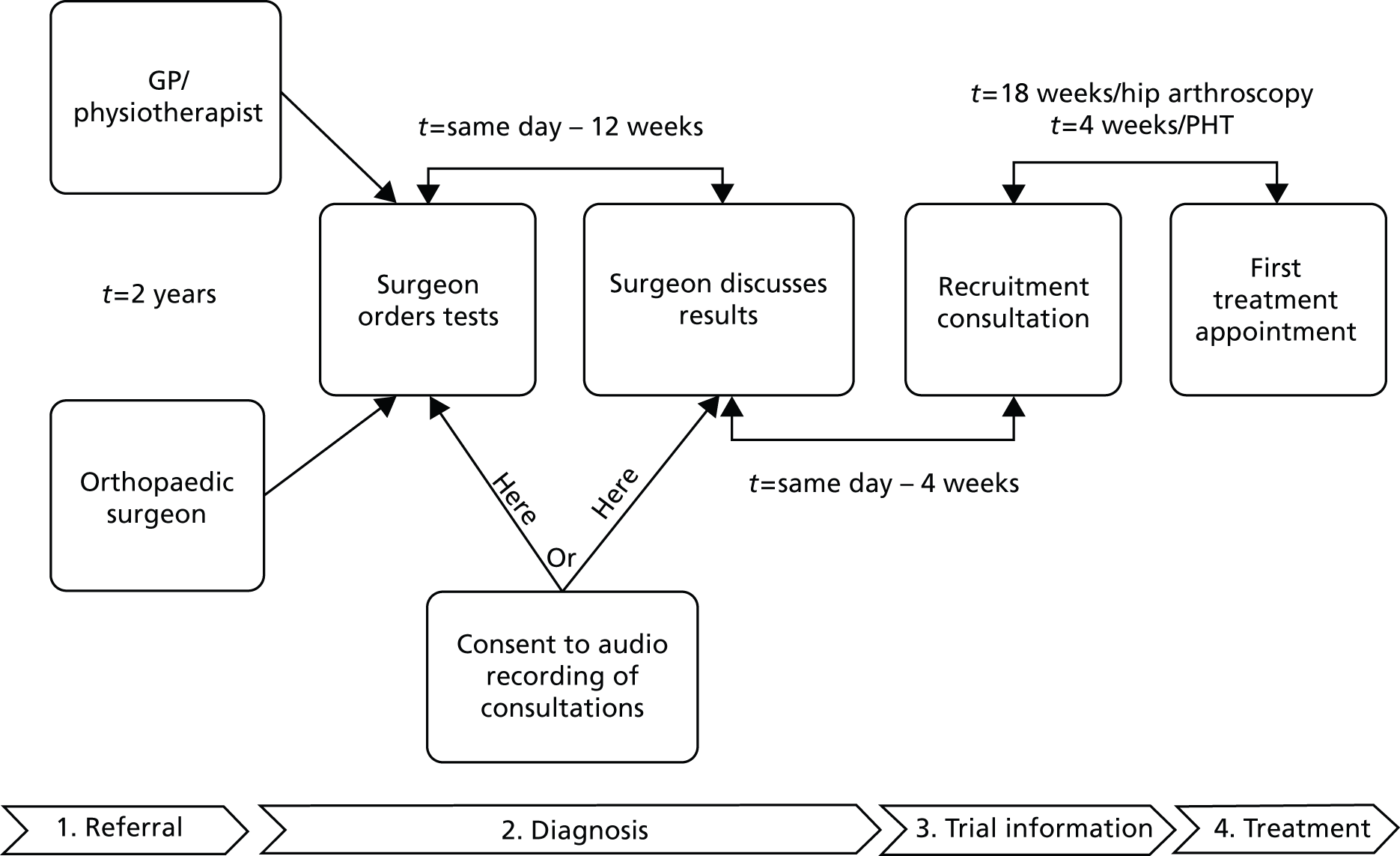

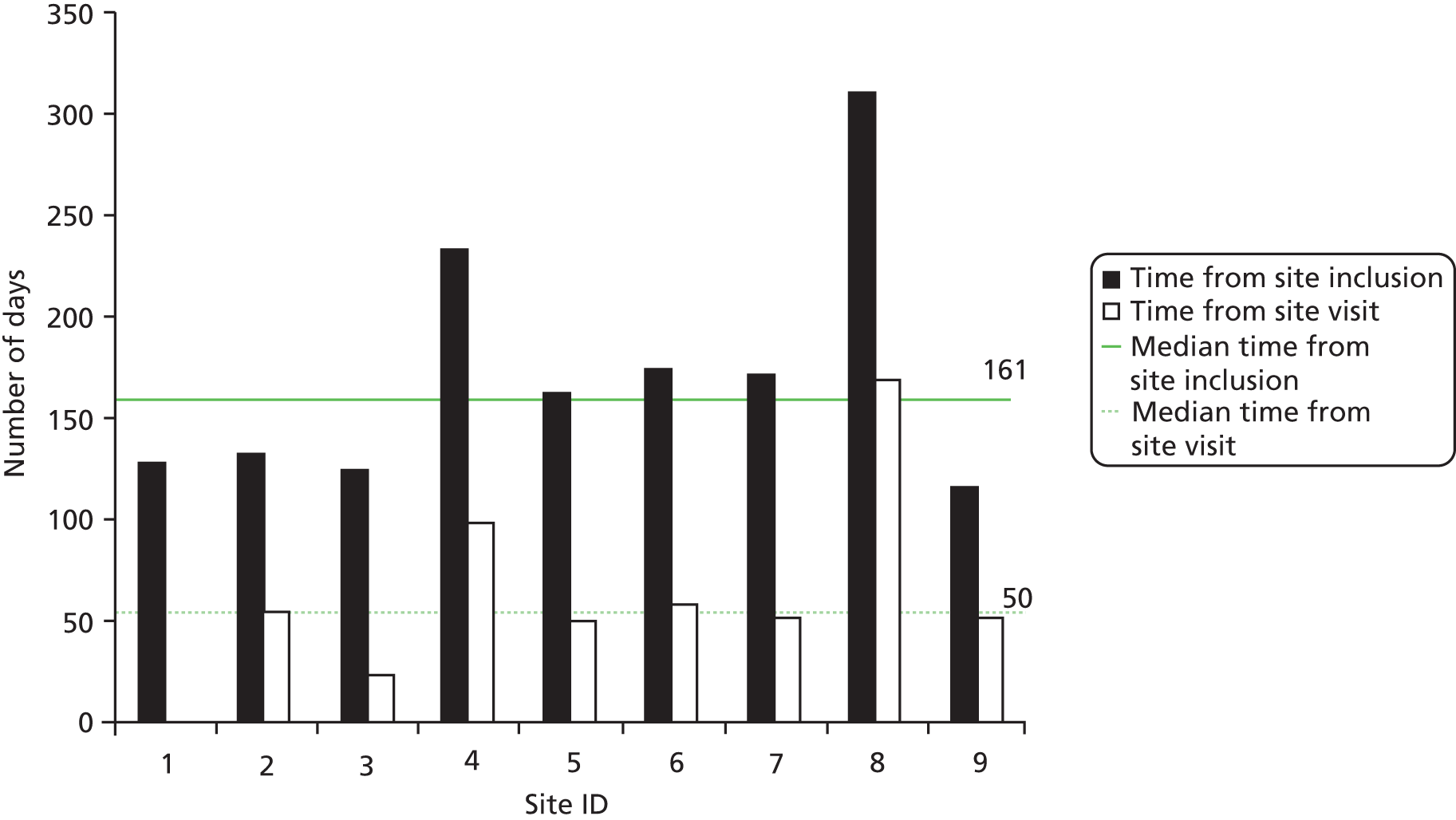

In our pilot RCT (see Chapter 3), we tested both NAHS and iHOT-33 as potential primary outcome measures and found both to be easy to use and acceptable to patients. We asked surgeons for their preference during our interviews with PIs, and all felt that either would be satisfactory; three suggested that the use of iHOT in the national Non-Arthritic Hip Registry made this preferable. The extensive patient involvement in item generation, the availability of an independently determined MCID and the use of iHOT as the principal outcome measure for the UK Non-Arthritic Hip Registry lead us to suggest iHOT-33 as the most appropriate primary outcome measure for a full trial.