Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/69/05. The contractual start date was in June 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Panos Barlas received funding from training health professionals in acupuncture.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Foster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Pregnancy-related low back pain (with and without pelvic girdle pain)

Low back pain in pregnancy is defined as pain in the lower back, located above the lumbosacral junction, with or without radiation in the legs,1 although this is a narrower definition than that used in the general population,2 in which low back pain is usually defined as pain and discomfort localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain. Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) is musculoskeletal pain located within the pelvic area between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal folds, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints, that develops in relation to pregnancy. 3,4 The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with or separately from pain in the pubic symphysis.

Low back pain and PGP during pregnancy are common and, although they can occur separately, many women experience both. Although prevalence estimates vary between studies owing to different definitions and diagnostic criteria, low back pain is reported to affect between 45% and 75% of women at some stage during their pregnancy,5,6 with a point prevalence of approximately 34%. 6 Prevalence estimates for PGP range widely and include 20% overall,3 35% to 50% in early pregnancy and 60% to 70% in late pregnancy. 3,7,8 The pain increases with advancing pregnancy, is usually worse at night and interferes with sleep, daily activities and work. 7 It is a common reason for sick leave, with reports suggesting that 20–23% of women take sick leave because of their pain. 6,9 Studies have shown that pregnant women with back pain have lower quality of life than pregnant women without back pain. 10 Hence, low back pain and PGP in pregnancy negatively affect activities of daily life and quality of life during pregnancy and are an important health problem. Some have reported an increasing number of affected women requesting induction of labour or elective caesarean section before the recommended 39th week of gestation in order to achieve symptomatic relief. 11 Although longitudinal data are limited, it has been estimated that in 1 in 10 women the pain becomes long-lasting and disability persists after childbirth. 12,13 Pregnancy-related low back pain has been found to reduce soon after delivery but it improves in few women later than 6 months post partum. 14 By 2 years after giving birth, the prevalence of back pain has been reported to fall to the same level found pre pregnancy (18%).

A range of biomedical, psychological and social factors may be important predictors of non-recovery from low back pain in pregnancy, but in general these have not been well studied. Cohort studies15,16 suggest that predictors of poor recovery from symptoms post partum include older age, work dissatisfaction and the presence of combined low back pain and PGP in comparison with pain in either location alone. There is some evidence that women with combined pubic symphysis pain and bilateral posterior PGP in pregnancy have a slower recovery than those women with fewer pain locations12,16 and that women with a high number of other bodily pain sites are more likely to have high pain intensity scores and postpartum non-recovery. 17 Guidelines3 suggest risk factors for PGP include a previous history of low back pain and previous trauma to the pelvis. Studies of low back pain in general have shown the important role of psychosocial obstacles to recovery18,19 and there is some evidence that psychological factors such as a lack of belief in improvement,20 exaggerated negative thoughts or catastrophising about the pain, fear avoidance beliefs21 and distress (anxiety and depression) are also important predictors of poor outcome in women with pregnancy-related back pain. 8

Current clinical management

Women experiencing these problems most often report them to their midwives; for example, in an Australian study 71% reported their pain to their maternity carer,6 but it appears that few receive much in the way of treatment. Pierce et al. 6 found that only 25% of women received any treatment. There are no high-quality UK data that describe current treatment for pregnancy-related low back pain or PGP. It is most often accepted as a ‘normal’ discomfort of pregnancy6,11 with some suggesting this may be related to health professionals’ lack of knowledge about available treatments and fear of possible harmful effects of treatment on the developing fetus. 11 Women are encouraged to believe that their pain is temporary and self-limiting (which may not always be the case), a part of the normal aches and pains of pregnancy,11 and those involved in their care tend to give women information on how to self-manage7 through postural changes, adaptations in lifting techniques, simple exercises to try at home, rest, heat and cold therapy, supportive belts and pillows, massage and relaxation. Some women, however, do proceed to use a range of treatments, such as physiotherapy-led exercise, manual therapy, acupuncture, massage, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and mobility aids as well as safe pharmacological options (mostly paracetamol) and, much less commonly, epidural injections. 6,7,11 None of these treatment options has been well researched in women with pregnancy-related back pain.

Current NHS practice varies across services and geographical regions. Most women are not referred from their midwives or general practitioners (GPs) to other health professionals for treatment, but are advised to self-manage. The self-management advice tends to follow the guidance from national associations such as the National Childbirth Trust (www.nct.org.uk) or the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health (ACPWH; http://pogp.csp.org.uk/) and only the most severely affected women are referred to physiotherapists and receive individual assessment, advice or treatment. We estimate that approximately 10–20% of women are likely to be referred to see a NHS physiotherapist for help with severe back pain and/or PGP. In North Staffordshire, for example, 10% of women with back pain in pregnancy are referred by their midwife (and some cases by their GP), to women’s health physiotherapists, who invite them to a group advice and education session, and are offered individual care following the group session only if needed. The referral is left open for the duration of the pregnancy so that the woman can access further physiotherapy support if needed. In other services, physiotherapists offer individual assessment and individualised advice and treatment.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is based on needle stimulation of points on the surface of the body (acupuncture points) and originates from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). It encompasses a variety of different procedures and techniques but most often is based on penetrating the skin at anatomical points on the body with thin, solid, metallic needles that are manipulated manually or by electrical stimulation. Since its introduction to the West several hundred years ago, many different styles of acupuncture have developed, including Japanese meridian therapy, French energetic acupuncture, Korean constitutional acupuncture and Lemington five-element acupuncture. 22 Although similar to traditional acupuncture, these various styles have their own distinct characteristics. In the past several decades, new forms and styles of acupuncture have evolved, including ear (auricular), hand, foot and scalp acupuncture. As a result of advances in the understanding of the neurophysiology of pain and acupuncture, the boundary between acupuncture and conventional medicine is changing. For example, a simplified and more empirical Western approach to acupuncture of local dry needling at the site of pain or at points in the vicinity of pain, called trigger points, is popular among conventional health professionals (medical doctors and physiotherapists). Modern acupuncturists typically use a combination of both TCM meridian acupuncture points and non-meridial (or extrameridial) points. Once appropriate points are selected, the therapist inserts a needle into each point by gently tapping it into place and rotating it until the patient experiences a needle sensation or de-qi, usually described as a tingling, numbness or dull ache sensation. A typical session with acupuncture includes treatment with a varying number of needles (1–30) inserted and kept in place for 20–30 minutes, during which period the therapist may stimulate the needles by rotating or tapping them. Some therapists may also use electrical stimulation (in which an electrical stimulator is connected to the acupuncture needles), injection acupuncture (herbal extracts are injected into acupuncture points), heat lamps or moxibustion. Although the neurophysiological mechanisms of acupuncture are well established in research for experimental pain, the exact mechanisms underlying the action of acupuncture in clinical practice are still unclear. 23 In terms of Western scientific principles, it is uncertain how acupuncture may help musculoskeletal pain such as back pain in pregnancy. Current theories suggest that acupuncture may produce its effects through the nervous system by stimulating the production of biochemicals such as endorphins and other neurotransmitters that influence pain sensation; that acupuncture works through the gate control theory of pain, in which the sensory input is inhibited in the central nervous system by another type of input (the needle); or that the presence of a foreign substance (the needle) within the tissue of the body stimulates vascular and immunomodulatory factors such as mediators of inflammation. 22

The use of acupuncture for musculoskeletal problems appears to be increasing and acupuncture has been recommended within recent UK national guidelines for the management of persistent non-specific low back pain. 24 One of the few randomised trials conducted within the UK25 concluded that there was weak evidence of an effect of a short course of acupuncture on persistent non-specific low back pain (rather than back pain in pregnancy) at 12 months, but that at 24 months there was stronger evidence of a small benefit compared with usual GP care. The health economic analysis conducted alongside that trial26 concluded that acupuncture confers a modest health benefit for minor extra cost to the NHS. The most recent Cochrane Review of acupuncture for low back pain27 included 35 trials, but only three of these were of acute low back pain. Overall, no firm conclusions could be drawn but there was some evidence of short-term pain relief and functional improvement from acupuncture compared with no treatment or sham treatment. There was also some evidence that acupuncture, added to other conventional therapies, relieves pain and improves function better than conventional therapies alone.

A small number of trials have evaluated acupuncture for low back pain and PGP during pregnancy. 28–33 To date, two rigorously conducted systematic reviews have been published. 7,34 The first of these was a Cochrane Review of eight studies (1305 participants) testing the effects of adding various pregnancy-specific exercises, physiotherapy, acupuncture and pillows to standard pre-natal care. 7 That review found positive results for the additional benefit of strengthening exercises, pelvic tilt exercises and exercise in water for women with low back pain. Both acupuncture and stabilising exercises relieved PGP more than usual pre-natal care, and acupuncture provided more relief from evening pain than exercise. One study found that acupuncture was more effective than physiotherapy for pain reduction,28 although it was unclear if this was a result of the type of treatment delivery (acupuncture was individually delivered while the physiotherapy was delivered in groups). A further study showed that 60% of those who received acupuncture reported less intense pain, compared with 14% who had standard pre-natal care. 31 The second systematic review34 focused on randomised trials of needle acupuncture for back pain and PGP in pregnancy and included only three trials (448 women), all from Sweden. 28,31,32 The conclusions were similar to the Cochrane Review by Pennick and Young. 7 Overall, there was limited, though promising, evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture. Both systematic reviews highlighted the need for further high-quality trials given the weaknesses in the available evidence. Most previous trials have a moderate to high risk of bias, with unclear randomisation and allocation concealment and lack of full intention-to-treat analyses, and only one trial reported work outcomes, despite these clearly being an important outcome for both pregnant women and society more generally. The one trial with low risk of bias32 focused on Swedish women with PGP at 12–31 weeks’ gestation, and randomised them to standard treatment (information, advice about activities, a pelvic belt and a home exercise programme), standard treatment plus acupuncture (twice per week over 6 weeks using 10 local acupuncture points and seven extrasegmental points with the needles manipulated to evoke a de-qi sensation and left in situ for 30 minutes and stimulated every 10 minutes) or standard treatment plus stabilising exercise (individual stabilising exercises modified for pregnancy for a total of 6 hours over 6 weeks). Since the publication of the two systematic reviews in 2008, a small number of further studies were published. One small pilot study35 found auricular acupuncture to be more effective than either sham acupuncture or a waiting list control. Another further high-quality trial by Elden et al. 33 from Sweden compared standard treatment plus acupuncture with standard treatment plus sham (non-penetrating) acupuncture for women with PGP. In that trial, 12 acupuncture treatments were provided over 8 weeks and results showed no differences between groups on pain or sick leave, questioning the importance of needle penetration in the reported beneficial effects of acupuncture. The existing research clearly highlights the need for a high-quality randomised trial in the UK NHS setting, testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the addition of acupuncture to standard care (SC) for pregnant women with low back pain (with or without PGP). It also highlights the importance of including a sham or non-penetrating acupuncture intervention.

Key methodological issues for the EASE Back study

Given the known limitations of previous trials of acupuncture, we followed published recommendations about methods and reporting trials of acupuncture,36 non-pharmacological interventions37 and sham interventions in trials of physical medicine and rehabilitation23 for our pilot trial. This was informed by the results of our pre-pilot work in phase 1 of the Evaluating Acupuncture and Standard carE for pregnant women with Back pain (EASE Back; a national survey and interviews) study and includes the rationale for acupuncture type, the details of the needling, the intervention protocol, other components of the treatment, practitioner background and experience, full details of the treatments, similar protocols for the true and sham acupuncture treatments and data on participants’ treatment preferences and expectations before they are randomised. There are several key methodological issues relevant to conducting trials of acupuncture (and, more broadly, non-pharmacological interventions for pain); these include sham treatment considerations, issues of blinding, safety, protocolising or standardising what is usually a highly individualised acupuncture treatment for the purposes of a trial and choosing the most appropriate package of SC for comparison. Each of these is discussed along with the implications for the EASE Back study.

Sham acupuncture

A key discussion in the existing research on acupuncture focuses on the challenge of adequate sham or placebo acupuncture treatments. 23 In fact, some believe that it is virtually impossible to construct a completely inert placebo that sufficiently mimics the insertion and manipulation of acupuncture needles; hence we use the term ‘sham’. The use of sham intervention helps to ensure participant blinding and reduces the risk of potential bias that can interfere with the observed outcomes. 23 We believe that any future large trial should include a treatment group that receives sham acupuncture to enable us to better understand the possible basis of acupuncture effects. Previous trials have used different methods of sham and there is little agreement on the best sham, given that some methods appear to induce physiological effects (e.g. inserting needles at non-acupuncture points or superficial needling at acupuncture points). 23 A perfect sham for acupuncture would induce the needle or de-qi sensation,23 but it is increasingly clear that inducing this needling sensation regardless of the stimulation point is associated with the physiological effects of acupuncture. A recent review38 concluded that the effect of acupuncture seems to be unrelated to the type of sham acupuncture used as control and that non-penetrating acupuncture shams are thought to be least likely to have physiological effects. We believe that using non-penetrating needles on a small number of the same acupuncture points that would be used for true acupuncture alongside the inclusion of acupuncture-naive participants are the best solutions to this challenge. Similar approaches have been used successfully in previous trials of acupuncture for musculoskeletal problems39 and pregnant women with PGP. 33 Thus, we included three treatment arms in the pilot EASE Back trial: SC, SC plus true acupuncture and SC plus sham acupuncture using non-penetrating needles. The use of sham in trials of acupuncture remains a matter of debate, and some may consider it an ethical dilemma. However, by ensuring that all our pilot trial participants received a package of SC, and that the acupuncture treatment (either true or non-penetrating) was in addition to this SC, we are confident that all participants received appropriate treatment for their pain.

Blinding

A further methodological challenge is the need to ensure adequate blinding: ideally, patients, therapists, outcome assessors and data analysts should be adequately blinded. In a trial of SC and acupuncture, clearly, the therapist cannot be blinded to treatment, but it is possible to blind acupuncture-naive patients to the type of acupuncture (true or non-penetrating), as well as those involved in collecting data and data analysis. Successful blinding has been achieved in a previous trial of acupuncture within the NHS39 and we incorporated this level of blinding into the EASE Back pilot trial. In particular, by gaining ethics approval to explain to potential participants that they would all receive SC and some would receive one of two forms of acupuncture, we were able to ensure that all participants expected to receive good treatment, thus maximising expectation and treatment credibility effects. We included measures of treatment preference and expectation in our pilot trial data set and captured information on treatment credibility at follow-up.

Safety/risks of acupuncture

Despite promising evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture for relief of back pain and PGP in pregnant women, some clinicians express concerns about safety. One concern is that acupuncture might induce pre-term labour, but available data show this not to be the case. The normal risk of pre-term labour (before 37 weeks’ gestation) is 7–10%. In one of the Swedish trials, Elden et al. 40 assessed the adverse effects of acupuncture on the pregnancy, mother, delivery and fetus/neonate. Acupuncture that may be considered strong was used and treatment was started in the second trimester of pregnancy. Adverse effects were recorded during treatment and throughout the pregnancy. The results showed that there were no serious adverse events (SAEs) after any of the treatments, in either babies or mothers. Minor adverse events were common in the acupuncture group, but women rated acupuncture favourably despite this. Therefore, acupuncture administered with a stimulation that may be considered strong led to minor adverse complaints from the mothers and had no observable severe adverse influences on the pregnancy, mother, delivery or fetus/neonate. In addition, acupuncture in early pregnancy (for nausea and vomiting) has been shown to be safe, with no adverse effects on perinatal outcome, congenital abnormalities, pregnancy complications and other infant outcomes. 41 In the wider literature, most side effects associated with acupuncture are minor and transient, such as dizziness/light-headedness and slight bleeding after the needles are removed. 42 Although there have been reports of fatal events following acupuncture (14 cases in a review of literature over the last 50 years),43 these appear to have been related to cases of clear malpractice and negligence (e.g. as described by Halvorsen et al. 44). In the UK, acupuncture training for health professionals, including physiotherapists, is set at a high level, and in trained hands acupuncture is a safe intervention. In our pilot trial in phase 2 of the EASE Back study, the participant information leaflet and consent procedures made the known risks clear and explained the frequency of these risks where these data were available while reassuring pregnant women that even strong acupuncture stimulation has been shown to have no adverse effects on the pregnancy, mother, delivery or developing baby. In addition, the trial design ensured that all women received SC and that acupuncture was in addition to this SC. Therefore, we did not withhold SC from any woman in the EASE Back trial.

Standardising acupuncture treatment for a randomised controlled trial

Since the location and manipulation of the needles in acupuncture are thought to be important in achieving successful outcomes, the therapist usually individualises the treatment for each patient in clinical practice. For the purposes of a trial, however, some degree of standardisation is needed in order to be able to describe the treatment that participants were expected to receive (the intervention protocol) and then to be able to judge whether or not patients received the treatment as expected (protocol adherence). Previous trials of acupuncture have been criticised for lack of clarity about the acupuncture intervention provided as well as for being overly prescriptive with the selection of acupuncture points and needle manipulation to the point that those using acupuncture in clinical practice do not feel that the acupuncture provided in the trial reflects their practice. We believe the best solution to this challenge, for the purposes of a randomised controlled trial (RCT), is to agree a semiflexible acupuncture protocol, in which therapists assess the individual patient’s pain type and location, they palpate for tender points and then they select points from a large number of points that have been agreed to be suitable for inclusion in the protocol (including acupuncture and tender points). This approach has been used successfully in previous trials33,39 ensuring that the acupuncture treatment is individualised, reflecting clinical practice, and that it can be amended over a course of treatment sessions but can also be clearly described in publications.

Copy of the Health Technology Assessment commissioning brief (Health Technology Assessment number 10/69/05)

Question: what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in pregnant women with back pain, in comparison to SC?

Technology: a 6-week acupuncture package, as may plausibly be delivered in the NHS.

Patient group: pregnant women with back pain (including women attending antenatal clinics and outpatients clinics because of back pain).

Control or comparator treatment: sham acupuncture.

Design: a feasibility study to assess the acceptability and design of a trial in the NHS. Methods are likely to include a survey of current practice and qualitative work with clinicians, patients and commissioners. Researchers should identify an appropriate acupuncture intervention and control. They should explore the merits of a sham acupuncture arm.

Important outcomes of main study: pain.

Other outcomes: adverse events, consumption of analgesics, obstetric outcomes, absence from work, functional status, health-related quality of life and cost-effectiveness.

Outcome of the feasibility study: outline plan for a randomised controlled study with evidence supporting its design and delivery.

Minimum duration of follow-up of main study: 6 months after delivery.

Appropriate standard care comparison

The choice of the comparison treatment in acupuncture trials is critically important. Previous trials that compare acupuncture with waiting list controls, ongoing stable medication or minimal care packages tend to show that acupuncture is superior, whereas those that compare acupuncture with more intensive or active interventions have tended to conclude that there are no differences between acupuncture and comparisons. 39 We wanted to include a SC comparison that accurately reflected what currently happens in the UK for pregnant women with low back pain. Thus, we followed the recommendations of Ee et al. 34 that some form of consensus about treatments for these women is essential to inform clinical trials. Although usual care differs in different services and geographical regions, our interview and survey results from the phase 1 pre-pilot work in the EASE Back study provide the most useful information on which to base a trial protocol for SC. These data ensured that the pilot trial protocol for SC reflected current care in the UK and thus is a fair comparison in the trial.

Rationale for the EASE Back study

A high-quality randomised trial in the NHS is needed to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding acupuncture to SC for pregnant women with low back pain (with and without PGP). Before such a large trial can be conducted, however, a feasibility and pilot study was commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to inform the design, recruitment, interventions and outcomes. A feasibility study is a research study carried out prior to a main study in order to answer the question ‘Can this study be done?’, and it is used to estimate important parameters needed to design the main study. 45 In the EASE Back study we wanted to find out whether or not pregnant women with low back pain would be willing to try acupuncture as a treatment and whether or not they had concerns about acupuncture or being involved in a trial. We also wanted to find out the likely proportions of eligible women from all of the pregnancies overseen by a large maternity centre and whether or not clinicians (community midwives and physiotherapists in particular) would be willing to recruit to, and treat, this patient population in a trial of acupuncture. We needed to test out all the processes of a future main trial and, therefore, the EASE Back study also involved a pilot RCT. A pilot study is a version of the main study run in miniature to test whether or not all the components of the main study can work together. 45 The EASE Back pilot RCT therefore tested the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the processes of identification of potentially eligible women, screening and recruitment, randomisation, training of participating research staff and physiotherapists, delivery of treatment, treatment fidelity and credibility of treatment. It allowed us to test whether or not pregnant women with back pain would be willing to be randomised, to test out the outcome measures that might be used in a future main trial, to explore the short-term effects of treatment on these outcomes, to determine short-term follow-up rate, to select a primary outcome measure for a future main trial and to estimate the sample size for a future main trial.

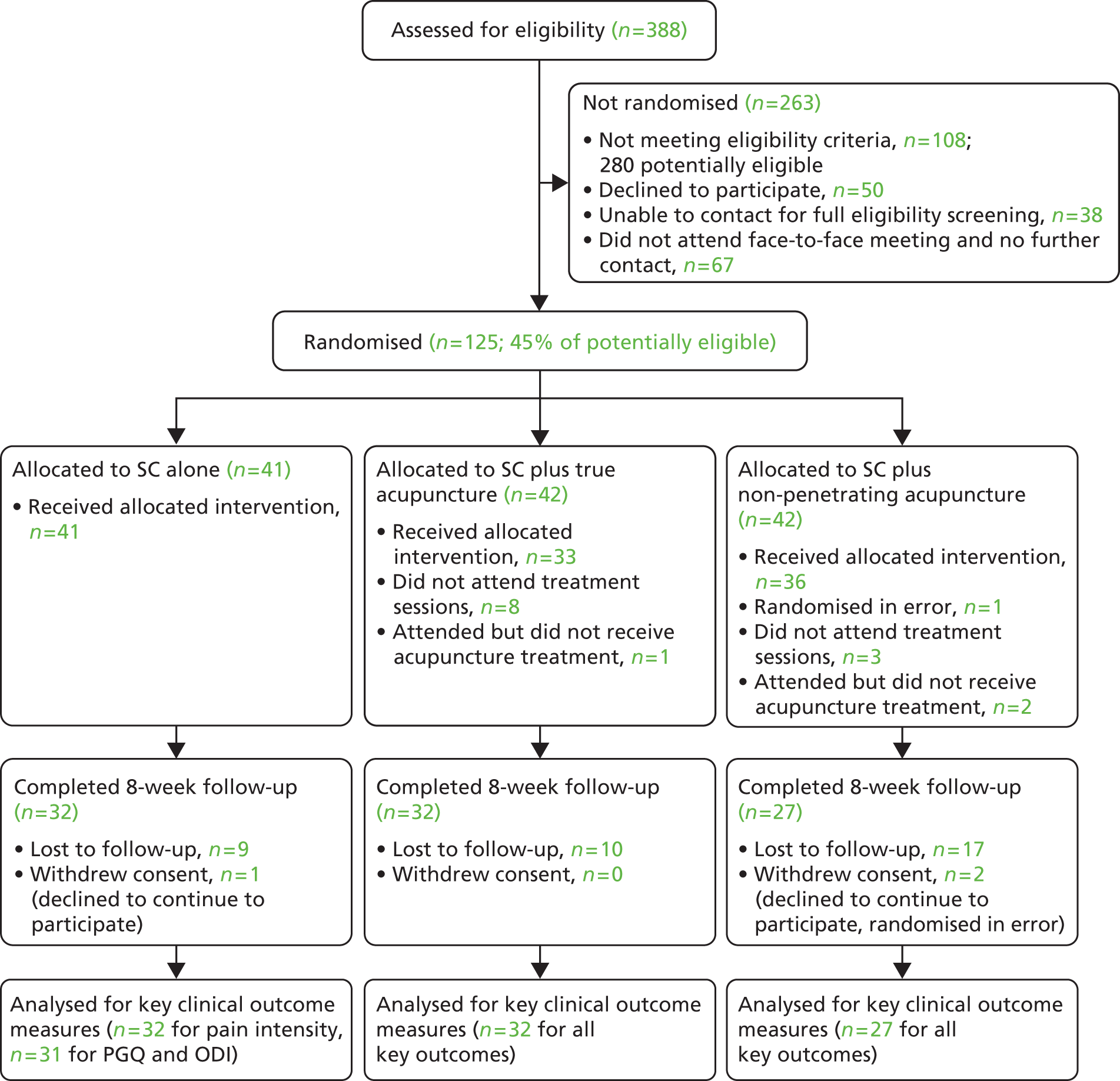

The EASE Back study was a mixed-methods feasibility and pilot study, designed in two phases over 24 months (June 2012 to May 2014), combining survey research (of current practice), qualitative research (focus groups and individual interviews) and a pilot randomised trial with pregnant women with back pain (with and without PGP) with short-term follow-up and audio-recordings of screening and consent meetings with a subsample of women. The results were shared at a dissemination event with stakeholders in May 2014 and consensus achieved about the feasibility and desirability of a main trial. Figure 1 provides a summary of the EASE Back study design.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the EASE Back study design. AACP, Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists; MIMDTP, McKenzie Institute of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy Practitioners; NP, non-penetrating.

Overall aim of the EASE Back study

The overall aim of the EASE Back study was to assess the feasibility of a future RCT to test the addition of acupuncture to SC in women with pregnancy-related low back pain.

Chapter 2 Phase 1 pre-pilot work

Objectives of phase 1 pre-pilot work

The specific objectives of phase 1 were to:

-

provide data on current UK SC and acupuncture treatment for low back pain in pregnant women

-

explore the views of pregnant women with back pain about the acceptability of the proposed interventions, the content and delivery of participant information, the outcomes most important to them and the most appropriate timing of outcome measurement

-

optimise trial information, recruitment and consent procedures by learning what works best from the perspectives of pregnant women with low back pain, midwives and physiotherapists

-

investigate the views of NHS health professionals regarding (1) the acceptability and feasibility of referring women with back pain in pregnancy to physiotherapists for acupuncture, (2) the proposed trial design and interventions and (3) ways in which to maximise recruitment and retention to a trial.

In order to address the above objectives, we used mixed research methods of a descriptive survey and qualitative interviews. Findings from the survey informed the semistructured interview schedule, and findings from both methods were integrated at the analysis stage to give additional validation. 46 The pre-pilot work in phase 1 was reviewed and approved by National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Greater Manchester North (ref. 12/NW/0227).

National survey of chartered physiotherapists

Methods

Design and setting

This was a national cross-sectional survey of national samples of physiotherapists working in the UK from June to July 2012. Consent of respondents was assumed if they completed and returned the questionnaire; therefore, written consent was not sought from each participant.

Survey sample and mailing

The inclusion criteria were physiotherapists who:

-

were members of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

-

had experience of treating women with pregnancy-related low back pain.

We randomly sampled from three professional networks of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Although the optimal approach to generate representative survey findings is to use a simple random sample, there is no comprehensive sampling frame for all UK-based physiotherapists available at the current time. The professional networks selected were those with interests relevant to low back pain, acupuncture and pregnancy/women’s health, with a total combined membership of around 7000 physiotherapists. This large sampling frame was required to access physiotherapists with a range of experience and clinical interests, to result in as generalisable a data set as possible about physiotherapy care for pregnancy-related back pain across the UK. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy is the predominant professional trade union and educational body for physiotherapists in the UK and has 30 affiliated professional networks, usually with a specific clinical or occupational interest, which members have the option of joining. It was not possible to target only those physiotherapists working in the NHS. Random samples of members of the three professional networks (total n = 1093) were mailed by the administrators of each network and two reminder mailings were subsequently sent to non-responders. The professional networks were chosen to include physiotherapists with a special interest in (1) women’s health (ACPWH), (2) acupuncture (the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists) and (3) musculoskeletal pain conditions (McKenzie Institute of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy Practitioners). An initial filter question identified those respondents who had never treated a pregnant woman with low back pain in pregnancy, and only respondents with experience of treating this patient group were included in the analysis.

As the aim of this survey was primarily descriptive, a formal sample size calculation was not carried out. Previous surveys of physiotherapists in the UK indicated a likely response rate of 55–60%47–49 and so we expected approximately 600–650 overall responses from the mailing of 1093. This sample size is sufficient to estimate the proportions of the key survey variables within less than a 5% margin of error with 95% confidence.

Survey questionnaire

A previous national survey questionnaire of physiotherapy practice for non-specific low back pain (not related to pregnancy) was adapted for use in this study. 48 The questionnaire captured information about respondents’ demographics and clinical practice including years in practice, practice setting, postgraduate training in musculoskeletal pain, women’s health and acupuncture as well as experience of managing women with pregnancy-related back pain. The questionnaire investigated current clinical care using a patient vignette of a specific, typical case developed from a real patient example following recommendations from other studies50–52 and was pilot tested with 18 physiotherapists. The patient vignette is reproduced below, whereas the full questionnaire is provided in Appendix 1. Respondents were asked how they would manage this woman, including likely treatment approaches, advice offered and number of treatment sessions provided. Specific questions on their use of acupuncture were also included.

We additionally asked the physiotherapists whether or not they routinely used specific advice or self-management leaflets in the management of pregnancy-related low back pain and PGP and, if so, to enclose a copy of the leaflet in their response to the survey. This resulted in the research team receiving examples of 37 different advice and self-management leaflets currently used by physiotherapists. These were used to help develop the self-management booklet used in the pilot RCT in phase 2 of the EASE Back study (see The development of a standard care protocol).

A 34-year-old woman was referred from her GP with symptoms of intermittent sharp pain at her lower thoracic and lumbar regions and reports that the symptoms began a few weeks ago. She is 24 weeks pregnant with her first child. She is in good general health and of normal weight for her height and has never had back pain before.

Her back pain presents as occasional sharp sensations at the lumbar/lower thoracic regions of her spine and seems to be unrelated to posture or activity. She also has some dull pain in the lower back region, which is more persistent but of lesser intensity than the sharp pain she occasionally experiences. Her symptoms are worse if she maintains a sitting posture for prolonged periods. She is reluctant to use any analgesic medication because of her pregnancy.

Upon examination there is no exacerbation with movement or any directional preference. She has normal range of movement and is moderately tender on the paraspinal muscles of her lower back. Straight-leg raise and slump tests are negative.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was primarily descriptive, using summary statistics to describe physiotherapists’ characteristics and provide data on current practice, including SC and their use of acupuncture. As treatment has been shown to differ across practice settings,53 treatment approaches used by respondents working in NHS and non-NHS settings were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared tests. This survey was not designed to test for differences between members of different professional networks. However, as the survey sample was not a simple random sample of physiotherapists in the UK, some exploratory comparisons between the professional networks were undertaken to explore any internetwork differences. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Response rate and characteristics of responders

Responses were received from 629 (58%) of those mailed. Of these, 499 had treated at least one woman with pregnancy-related low back pain and were included in the analysis. The demographic and practice characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. The respondents were very experienced (mean of 22 years in practice) and most were female. Respondents worked in a variety of settings: NHS only, non-NHS only or a combination of practice settings. Referrals of women with pregnancy-related back pain were received by respondents from a variety of other health-care practitioners and self-referral to physiotherapy by women themselves was also commonly reported. Approximately one-third of respondents reported seeing a pregnant woman with back pain at least once a month.

| Characteristic (denominator)a | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Years of experience (456) | 21.5 (mean) | 10.4 (SD) |

| Female (499) | 459 | 92.0 |

| Work setting (498) | ||

| Exclusively NHS | 201 | 40.4 |

| Exclusively non-NHS | 159 | 31.9 |

| Combination of NHS and non-NHS | 138 | 27.7 |

| Frequency of treating pregnant women with back pain (499) | ||

| Infrequent – at most one in last 6 months | 173 | 34.7 |

| Somewhat frequent – between two and five in last 6 months | 148 | 29.7 |

| Frequent – at least one per month | 70 | 14.0 |

| Very frequent – at least one per week | 108 | 21.6 |

| Referral sourceb (499) | ||

| Referral from GP | 347 | 69.5 |

| Referral from midwife | 241 | 48.3 |

| Self-referral | 240 | 48.1 |

| Referral from a physiotherapy colleague | 147 | 29.5 |

| Referral from obstetrician | 137 | 27.5 |

| Other | 38 | 7.6 |

| Trainingb | ||

| Specific postgraduate training in low back pain in general (491) | 444 | 89.0 |

| Specific postgraduate training in acupuncture (497) | 370 | 74.5 |

| Specific postgraduate training in women’s health (492) | 327 | 65.5 |

| Specific postgraduate training in low back pain in pregnancy (496) | 264 | 52.9 |

| Use of acupuncture in management of musculoskeletal pain (496) | 338 | 68.2 |

Standard care management

Standard care was explored by asking respondents to indicate the management options they would use for the typical patient described in the vignette. Most respondents (88%, n = 430) reported that they would be responsible for the care of such a patient, but 12% (n = 58) reported it was not their role and that this type of patient would be specifically referred to a women’s health specialist physiotherapist. A large majority of respondents (85%, n = 364) reported that they would manage this patient in one-to-one treatment sessions. The remainder reported that they would manage this patient as part of a group or class and that they would use one-to-one sessions for initial patient assessment only or only if required. This typical patient would be seen three or four times over a period of 3–6 weeks, although the episode would be left open for the duration of the pregnancy so that a woman could reconsult the physiotherapist if needed until after the birth of her baby. Table 2 summarises the episode of SC by physiotherapists.

| Characteristics of care (denominator)a | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of times patient typically seen (425) | ||

| Once | 51 | 12 |

| Twice | 103 | 24.2 |

| Three or four times | 205 | 48.2 |

| Five or more times | 66 | 15.5 |

| Time period over which patient would typically be treated (415) | ||

| 1–2 weeks | 79 | 19 |

| 3–6 weeks | 221 | 53.3 |

| 7–10 weeks | 70 | 16.9 |

| > 10 weeks | 45 | 10.8 |

| Typical episode of care (428) | ||

| Finished after treatment, re-referral required for further treatment | 27 | 6.3 |

| Left open for duration of the pregnancy | 258 | 60.3 |

| Left open for a defined period after end of treatment | 66 | 15.4 |

| Other | 77 | 18.0 |

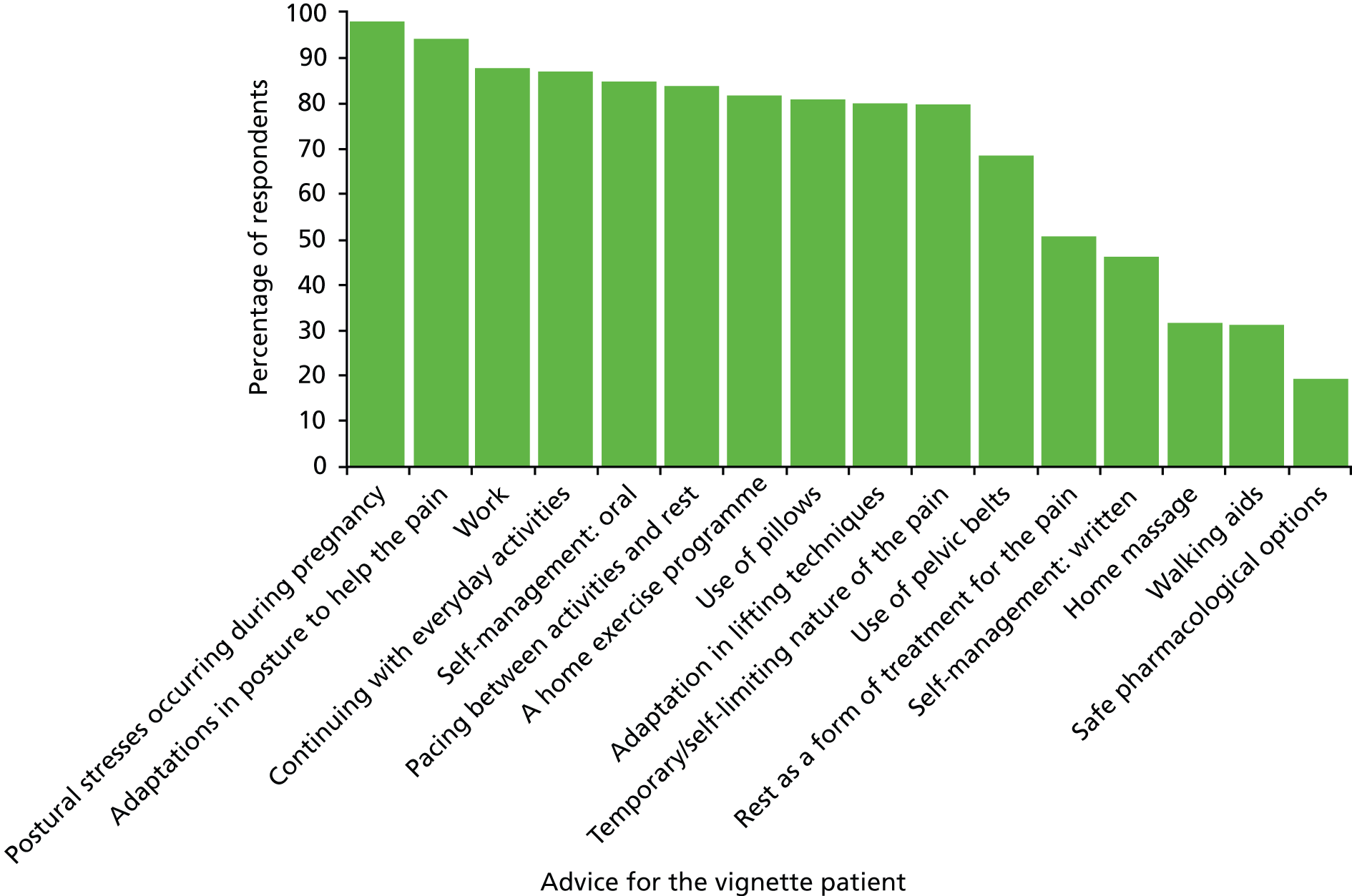

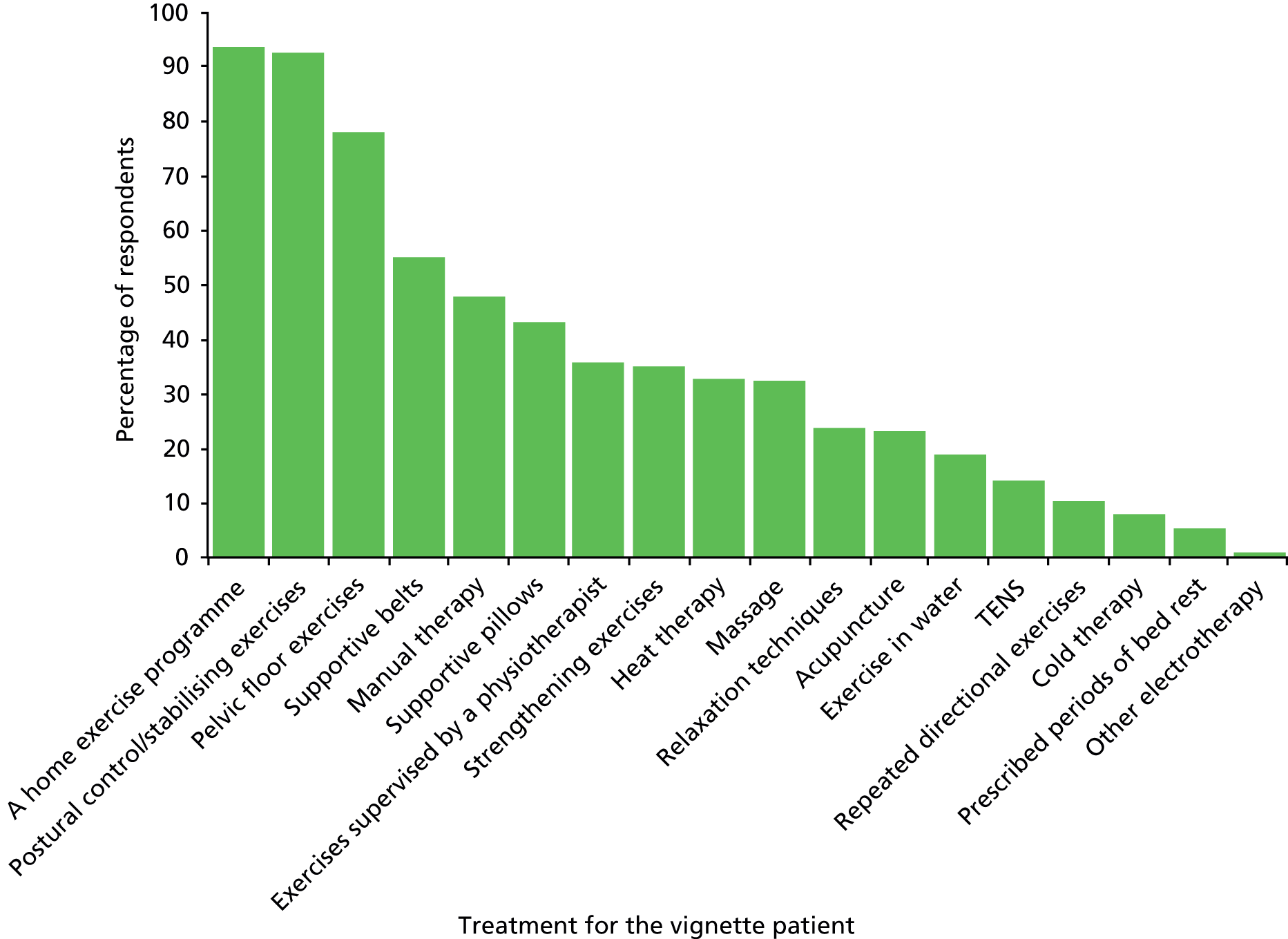

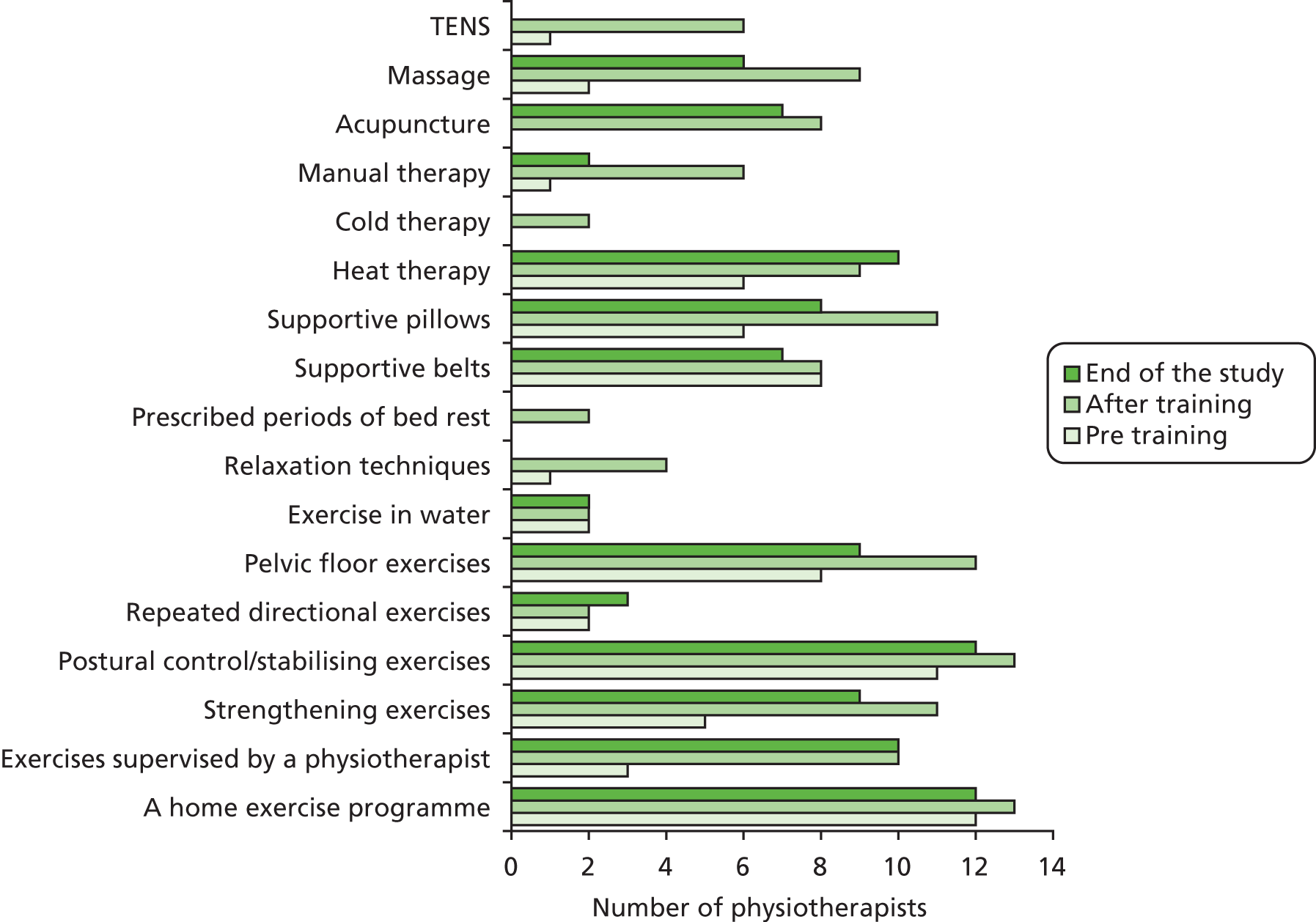

Many advice and treatment options were reported for the management of the typical patient described in the vignette, and combinations of advice and treatments were commonly reported. Advice on aspects of pregnancy, low back pain and activities of daily living was reported by the respondents and, although combinations of treatments were described in packages of care, most physiotherapists reported using exercise approaches to manage women with pregnancy-related low back pain (Figures 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Survey findings: advice for the vignette patient.

FIGURE 3.

Survey findings: treatment for the vignette patient.

Acupuncture management

Regarding use of acupuncture, of the 469 individuals who responded to this item, 68% (n = 338) reported that they used it in the management of patients with musculoskeletal conditions, including low back pain not related to pregnancy, whereas 37% (n = 126 of 337 responses to this question) reported that they used it to treat women with pregnancy-related low back pain. However, when asked about the treatment they would provide to the specific patient described in the vignette (430 responses), 24% (n = 101) reported that acupuncture would be part of their treatment. Respondents had a mean of 11 [standard deviation (SD) 6.2] years’ experience of using acupuncture in clinical practice. The majority of respondents (298 responses) used Western/medical acupuncture (71%, n = 212), 16% (n = 48) used TCM/traditional acupuncture and 11% (n = 32) used trigger point/myofascial acupuncture. Of 336 respondents completing details about acupuncture training, 37.5% had completed up to 80 hours of acupuncture training (the national minimum requirement for physiotherapists), 53% had completed more than 80 hours but less than 200 hours and 9.5% had completed a degree/diploma in acupuncture or equivalent.

If acupuncture was a treatment option selected by respondents for the vignette patient, further details about acupuncture management were requested in the questionnaire. The mean number of acupuncture points used in a treatment session was 7 (SD 2.6), with the needles being left in situ for a mean of 20 (SD 6.0) minutes, and 84% of respondents would elicit a de-qi needle sensation. The selection of acupuncture points varied considerably for the vignette patient, and the 10 most commonly reported local and distal acupuncture points are summarised in Table 3. Only two acupuncture points (BL25 and BL23) were reported by more than one-third of respondents. Of those using acupuncture in the treatment of pregnant women, 22 respondents (4%) reported they had observed some minor adverse effects during treatment. These included the patient feeling lightheaded/dizzy (n = 8) or fainting (n = 5), mild bruising at needle site (n = 3), worsening of symptoms (n = 3), vomiting (n = 2) and significant pain at a needle site (n = 1). One respondent reported that a patient she had treated with acupuncture miscarried the day after acupuncture treatment, but reported that the treatment was not thought to contribute to this.

| Acupuncture points | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Local acupuncture points (n = 93) | ||

| BL25 | 33 | 35.5 |

| BL23 | 31 | 33.3 |

| GB30 | 24 | 25.8 |

| BL26 | 22 | 23.7 |

| BL24 | 18 | 19.4 |

| BL28 | 13 | 14.0 |

| BL27 | 12 | 12.9 |

| HJJ | 10 | 10.8 |

| BL54 | 7 | 7.5 |

| BL22 | 7 | 7.5 |

| Distal acupuncture points (n = 81) | ||

| GB34 | 25 | 30.9 |

| LI4 | 20 | 24.7 |

| BL60 | 16 | 19.8 |

| LR3 | 16 | 19.8 |

| BL62 | 14 | 17.3 |

| ST36 | 13 | 16.0 |

| BL40 | 11 | 13.6 |

| GB41 | 7 | 8.6 |

| BL57 | 6 | 7.4 |

| SI3 | 5 | 6.2 |

Differences between respondents working in different practice settings (exclusively NHS or exclusively non-NHS) were few. However, those working exclusively in the NHS were more likely than those in non-NHS settings to report that they saw the patient only once or twice (52% compared with 17%). Conversely, physiotherapists reporting the most patient treatment visits (more than five) were more likely to be working in non-NHS settings (24%, compared with 7% in exclusively NHS settings). In addition, physiotherapists working in non-NHS settings more commonly than those working exclusively in NHS settings reported using treatment approaches that were classified as ‘hands-on’. Overall, the proportion of respondents who would offer the patient any hands-on treatment approaches was significantly higher among those who worked exclusively in non-NHS settings than among those working exclusively in NHS settings (Table 4). For example, of the 33% (101 out of 304) of respondents who would offer massage, 71 (70%) worked exclusively in non-NHS settings, compared with 30 (30%) who worked exclusively in the NHS.

| Treatment offered (total responses, n = 304) | Overall, n (%) | NHS, n (%) | Non-NHS, n (%) | Significancea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual therapy | 134 (44.1) | 53 (32.9) | 81 (56.6) | p < 0.001 |

| Acupuncture | 69 (22.7) | 23 (14.3) | 46 (32.2) | p < 0.001 |

| Massage | 101 (33.2) | 30 (18.6) | 71 (49.7) | p < 0.001 |

Differences between professional networks

Exercise was the most common treatment reported by respondents from all three professional networks. Data about the typical episode of care (number of treatment sessions, length of sessions, length of episode of care) were also similar across all networks. The one area in which reported practice differed between professional networks was in the use of acupuncture for the typical patient described in the vignette, with respondents from the acupuncture professional network (the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists) being more likely to report using acupuncture (43.9%) than those from either a general musculoskeletal (the McKenzie Institute of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy Practitioners; 9.0%) or a women’s health professional network (ACPWH; 6.2%).

These survey findings, particularly those from NHS-based clinicians, were used to help develop the treatment content and intervention protocols for the pilot EASE Back trial in phase 2 of the EASE Back study (see The development of a standard care protocol).

Qualitative focus groups and individual interviews

Methods

The qualitative research was guided by our initial research objectives but retained the flexibility to explore previously unforeseen avenues of enquiry. 54,55 Methods consisted of focus groups or individual interviews (in person or by telephone) with pregnant women, midwives and physiotherapists. Given that both health-care professionals56 and women57 can be difficult to engage in research, the offer of choice over interview format was pragmatic rather than methodological and intended to meet the needs of participants in terms of convenience. All participants were given full information about the study ahead of deciding to participate, with the option of focus groups or individual face-to-face or telephone interviews. The health-care practitioners were invited to complete a brief questionnaire to describe their qualifications and experience (see Appendix 2). Semistructured interview guides were developed from the research objectives and from the findings of the national survey. They focused on exploring the acceptability of acupuncture, the sort of information that might be required to reach a decision around participation in a trial, the most important outcomes and the most appropriate timing of outcome measures for the pilot trial. In addition, participants were also invited to talk about the care and support they considered available for this population (see Appendix 3 for copies of the topic guides). All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and the focus groups were facilitated by two members of the research team. Data collection was concurrent with all three sets of participants and ceased when data saturation was reached.

Interviews with pregnant women

For pregnant women, the original intention had been to hold a series of focus groups, offering individual interviews if these were more convenient. In the planned recruitment period for phase 1 of the study (June to September 2012) it was estimated that there might be as many as 600 pregnant women with low back pain under the care of the participating maternity hospital who could be invited to participate; however, owing to poor response to the invitation to participate in the interviews, we extended the recruitment phase by a further 2 months to November 2012. A convenience sampling strategy58 was adopted and any pregnant woman with back pain could either self-refer or agree for the health-care practitioner caring for her to pass on her contact details to the research team. A flyer and poster were designed outlining the study and providing contact details of the research team. In total, 3000 flyers and 100 posters were distributed through a variety of means: general maternity information packs when the woman first booked in with her community midwife; local antenatal clinics; community midwives giving the flyers directly to pregnant women under their care; and the women’s health physiotherapy service back class for pregnant women at the local hospital. In addition, an invitation to participate was also posted on internet sites [Mumsnet (www.mumsnet.com) and the Pelvic Pain Support Network (www.pelvicpain.org.uk)]. Contact was also made with the National Childbirth Trust (www.nct.org.uk) and the Pelvic Partnership (www.pelvicpartnership.org.uk), but administrative difficulties on the part of these organisations meant it was not possible for them to collaborate with the research team within the time frame of phase 1.

In total, 43 women gave consent to contact, which was attempted through telephone calls at differing times of the day, including in the evening, and a total of 18 women agreed to telephone interviews. On contact, if they were still willing to be interviewed, a convenient interview time was arranged. At that point, a letter confirming the interview arrangements, detailed information about the study and two copies of the consent form together with a stamped addressed envelope for the return of a signed copy of the consent form, were posted out. The information and consent form were discussed at the time of the interview and audio consent was also recorded then.

Interviews with midwives and physiotherapists

For the health professionals, a purposive sampling strategy was adopted to ensure a range of experience and perspectives. 59 Two teams of community midwives were approached, together with the group of research midwives working in the local maternity hospital who would be involved in recruiting women into the EASE Back pilot RCT. Physiotherapists from the local community musculoskeletal outpatient services and from the local hospital’s women’s health physiotherapy service were also invited to participate. In addition, a sample of those physiotherapists (n = 30) who consented to further contact on returned questionnaires from the national survey were also invited to take part. Owing to geographical spread and participant convenience, these individuals were also interviewed by telephone. The individual interviews took place after the focus groups with physiotherapists and, because of data saturation, were limited to three individuals. In total, 15 midwives and 21 physiotherapists took part, giving a total of 53 individuals interviewed in phase 1 (Table 5).

| Participants | Individual interviews (telephone) | Focus group interviews (face to face) |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | 17 participants | 0 focus groups |

| Midwives | 0 participants | 3 focus groups (2 with community midwives, 1 with research midwives), 15 participants in total (2 were maternity assistants) |

| Physiotherapists | 3 participants | 3 focus groups (2 with community physiotherapists, 1 with women’s health physiotherapists), 18 participants in total (1 was a physiotherapy technician) |

Analysis

An exploratory thematic analysis was adopted, within a constructivist grounded theory framework. Emergent findings were checked out in subsequent interviews across all three groups of participants in an iterative cycle. 60,61 All interviews were digitally recorded, lasted between 20 and 60 minutes and were transcribed in full. To preserve participants’ anonymity, all were given unique identification numbers. To maximise the benefits of the interdisciplinary research team, the interview coders brought differing disciplinary perspectives to bear on the qualitative data (BB, social science; PB, acupuncture; and JW, physiotherapy). To ensure intercoder reliability, each independently coded a random selection of interviews as part of agreeing the initial coding frame, which was then applied across the whole data set, checking for consistencies and confounding cases and for further refinements of the coding frame. The findings were then compared with those from the national survey to identify areas of corroboration and contradiction.

Results

Engagement in the interviews

Despite the many flyers, posters and efforts on the part of clinical staff to discuss the study with potentially eligible women, and extending the recruitment period by 2 months, only 43 women agreed to contact by (or contacted) the research team. Of these, two self-referred, two were referred by physiotherapists, three were referred by obstetricians and 20 were referred to the research team by community midwives. The remaining 16 were identified through members of the research team attending the back education class within the women’s health physiotherapy service in the local hospital. We received no responses to the online invitations to participate that had been posted on Mumsnet or the Pelvic Pain Support Network. There were also challenges in making contact with the 43 women and in setting up focus groups. On average, it took five telephone calls spread over different times of day, including the evenings, to make initial contact. Two women declined to be interviewed during their first telephone contact (one no longer had low back pain and the husband of the other was ill) and 22 women were not contactable despite the five contact attempts. The difficulties in contacting these women were discussed at the focus groups with midwives and physiotherapists. They expressed little surprise, which they attributed to a patient population struggling to cope with everyday life and, moreover, discussions suggested that travelling to a focus group meeting would be an additional and unacceptable burden for pregnant women. The decision to offer individual telephone interviews instead of focus groups was made. Eighteen women agreed to interview, one was unavailable at the agreed time, and so a total of 17 women were interviewed over the 6-month period from June to November 2012, representing 39% of those who consented to further contact.

Characteristics of participants

Despite the initial difficulties in contacting women, the interview sample of 17 women was diverse and sufficient for data saturation. The average age was 26 years, with a range from 22 to 34 years; gestation ranged from 15 to 39 weeks, with a mean of 32 weeks; and for eight women it was their first pregnancy. In terms of ethnicity, eight described themselves as English, five were ‘other British’, three were ‘other white’ and one was ‘African’. All were either married or living with a partner and employment included health professional and clerical worker.

Analysis of the midwives’ profiles questionnaires indicated that the average length of practice was 18 years, with the majority (n = 9) qualified for over 12 years. The least experienced person had been qualified for 3 years, and there were also two maternity assistants included in the focus groups. None reported any specific postgraduate training around the area of back pain in pregnancy. Six midwives reported that they saw pregnant women with back pain either very frequently (at least one per week) or frequently (at least one per month). Just one midwife reported seeing such patients infrequently (at most one in the last 6 months).

As with the midwives, the physiotherapists were experienced practitioners. Their average length of practice was 12 years, nine had been qualified for 12 years or more (one for 36 years) and the least experienced person had been qualified for over 3 years. Fourteen individuals had a Bachelor of Science in Physiotherapy, of whom one also had a Master of Science in Musculoskeletal Healthcare, one a Master of Science in Acupuncture, one an Advanced Critical Care Practitioner (ACCP) foundation qualification in acupuncture and one Higher National Diploma in Sports Science. Another person had a Diploma in Physiotherapy, two individuals reported themselves simply as members of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists (MCSP), and the final person was a physiotherapy technician with National Vocational Training Qualifications at Levels 1, 2 and 3. In terms of their contact with pregnant women, seven reported seeing such patients infrequently. All seven were community physiotherapists, and all apart from one reported that they had no specific postgraduate training in the topic of back pain in pregnancy. Unsurprisingly, the women’s health physiotherapists leading the hospital-based back class for pregnant women reported seeing such patients frequently. They identified that their education around treating pregnant women came from either in-house training or short (1-day) courses (the exact nature of these was not specified).

Key themes

We identified three main themes from the qualitative data in phase 1: the high burden of back pain in pregnancy and outcomes most important to women; the paucity of treatment options; and acupuncture as an acceptable intervention for women and midwives but generating concerns for many physiotherapists. Each of these main themes is presented briefly below with example quotations from the transcripts.

Theme 1: high burden of back pain in pregnancy and outcomes most important to women

During the interviews with these women a picture of the burden of low back pain in pregnancy and its often wide-ranging impact on daily life emerged strongly, corroborating the views of the midwives and physiotherapists, and highlighting the importance of flexibility in appointment times and treatment locations for the pilot RCT. The interview data highlighted the severely disabling effects of back pain during pregnancy, which can affect all aspects of life, ranging from sleep through to being unable to carry out basic activities of daily living. Many of the women reported considerable support from partners and family. However, there were also reports of serious misunderstandings in the workplace, arising from managers and/or colleagues seeing back pain as a normal part of pregnancy and expecting women to ‘just get on with it’, with resulting lack of support. For some, even attending routine antenatal appointments was difficult to negotiate with their workplace and, consequently, anything that might incur further time away from work was seen as challenging. This is particularly significant because many women reported needing to work as long as possible up to their due date, because of their maternity leave entitlement and for financial reasons. It was clear others in severe pain were unable to work or participate in social activities, with consequences for their mental well-being and relationships, as the following quote illustrates:

My mood at the moment is all over the place anyway [laughs], but it [the pain] affects you, because it does limit me, especially first thing in the morning when I’ve been in one position for a long period of time, it kind of freezes up. So in the morning when I get up, I kind of crawl out of bed rather than spring out of bed.

Individual interview: 56

The women interviewed did not expect to experience immediate pain relief with acupuncture but believed that it would take several treatments to make a difference. The severity of the pain and its impact on activities of daily life meant that they felt that it was unlikely the pain could be completely resolved but rather alleviation was seen as an acceptable outcome:

I know nothing can sort of get rid of my pain completely but perhaps just alleviate, you know, something to alleviate it for a little bit and enable me to sort of get around and move around a little bit more [yeah] you know? I think that would be a pretty good outcome really.

Individual interview: 156

Theme 2: the paucity of treatment options

The responses to the survey indicated that SC varied widely for this patient group. This variation in care and lack of effective treatment options were also reflected in the narratives from women and professionals. It was clear that the emphasis is on self-management strategies, with only the most severely affected women being referred to physiotherapists for individualised advice about posture, movement and gentle exercise. Both midwives and physiotherapists tended to view these women as ‘heart-sink’ patients for whom they could offer very little in the way of effective interventions, as this illustrates:

I think it’s one of the few types of patients that we won’t see more than once because you know that, physio-wise, there’s very little to offer. So it’s a case of give them what they need and leave them on hold for further appointments.

Community physiotherapists: group A, 48

Midwives and physiotherapists reported explaining the causes of back pain during pregnancy as a way of reassuring the women and, although they described offering advice, they felt that this amounted to ‘fobbing off’ their patients, expressing a lack of faith in the effectiveness of their suggestions. Moreover, the advice provided was clearly highly variable, indicating uncertainty among midwives and physiotherapists regarding the most appropriate forms of advice, and there clearly were no consistently used sources of advice in terms of either written leaflets or website resources. Examples of patient information leaflets (PILs) and websites recommended to women were collected from respondents to the national survey, and the 37 different leaflets returned underline the variation in current advice provided to these women. This reflects the uncertainty voiced by the professionals about what constitutes ‘the right advice’ for this group of patients. Most women were advised to try self-management techniques around posture, gentle exercise and pain relief medication. Women’s health physiotherapists reported favouring a ‘hands-off’ approach, with advice on posture, preparation for labour and delivery and feeding positions after delivery. They identified an important part of their role as providing reassurance. The uncertainty about what constituted ‘the right advice’ for this group of patients was reflected in the accounts of the women, who conveyed a sense of being left to ‘get on with it’, as this severely affected individual reported:

No, I refused to take that [co-codamol]. They did prescribe it in the end and I did take it home with me but I haven’t took any because I just don’t agree with that in pregnancy. And after that I was discharged because really there’s nothing you can do. They referred me to the physio back class that I went to, and every time I’ve seen my midwife, she gave me a little tip of how to get in and out of cars, and things like that. But I don’t really think it can be helped. I just think it’s one of them things you’ve got to deal with.

Individual interview: 75

Theme 3: acupuncture as an acceptable intervention for women and midwives, but generating concerns for many physiotherapists

Although some women did express the need for information and reassurance over safety of acupuncture and whether or not the positioning for acupuncture would require them to lie in positions that could exacerbate their pain, in the main women expressed little concern expressed about its use in pregnancy.

I think if people were telling me that it could help my back pain then I would pretty much do anything.

Individual interview: 149

I don’t know where they put the needles in pregnancy. If they were in my tummy I think I’d be a bit like, ‘mmm, not quite sure about that’.

Individual interview: 98

Midwives were generally in favour of the idea that acupuncture could be offered to women with pregnancy-related back pain and that it could offer a useful additional treatment option. They felt that many women would be interested in knowing more about acupuncture for their back pain, particularly those women who are severely affected, and who, they felt, would be willing to try it within the context of a trial. The midwives felt that pregnant women with back pain under their care would have few concerns about acupuncture and these would be most likely linked to the location of and sensations from the needles, as this focus group excerpt indicates:

[They’ll] want to know where you’re going to put the needles.

That’s the first thing I’d ask.

Yeah, and they’d want to know if it hurts.

Community midwives: group B, 373

Physiotherapists were also generally in favour of testing the additional benefit of acupuncture for this patient group in a trial because of the difficulties in treating the pain through other treatment methods.

I mean, it’s [acupuncture] very interesting because drugs do not seem to work for these women. You know, talking about sort of real heavy painkillers . . . We had a lady admitted last week and was immediately put on morphine, it didn’t touch her pain at all. And all that does then is make the baby sleepy, and the mum sleepy. So for some women it is very difficult pain to manage.

Women’s health physiotherapist group

However, the physiotherapists raised concerns about safety of acupuncture in pregnancy, given their previous acupuncture training during which they recalled they had been advised that acupuncture was contraindicated in pregnancy.

And again like the previous two people, I thought acupuncture was contraindicated, that was part of my training. And I wouldn’t have done it to a pregnant lower back pain patient.

Community physiotherapists: group B, 57

Such concerns included the general safety of acupuncture in pregnancy and the specific acupuncture points and techniques to be used, and these concerns were rooted in their lack of confidence and/or experience in caring for pregnant women, as this excerpt indicates:

With them being pregnant, you’re just so aware that they’re pregnant and you feel limited to what you can do because you don’t want to . . .

I think we’re just scared to hurt them, aren’t we?

Community physiotherapists: group A, 81

This fear was related to concerns over a perceived lack of adequate training, specifically in the application of acupuncture in pregnancy:

I don’t think I’ve got the training to do it. There might be other stuff out there, but I don’t feel that I’m well enough equipped to deliver other things.

Is that the same for everybody?

Yeah. I think because we don’t see them often enough, we don’t – there isn’t the training out there. We don’t know exactly . . .

Community physiotherapists: group A, 95

Such fears around possible harm to the mother and/or baby generated a culture of caution, underpinned by a fear of litigation. Although most physiotherapists shared these fears, the three who participated in individual interviews and who practised acupuncture with pregnant women held starkly contrasting views. They worked in NHS musculoskeletal outpatient departments in which acupuncture was available. One had been qualified for 11 years, one for 18 years and one for 28 years. They were confident about the safety and efficacy of acupuncture for this population and indeed considered it safer, in fact, than medication, as illustrated by this quotation:

I would use acupuncture as a first choice of treatment with pregnant ladies over medication because of the safety risks with medication. In fact, I find my pregnant patients respond better [to acupuncture] than perhaps my standard lower back pains.

Physiotherapists’ survey

These interview findings were pivotal in developing the content of the training and support programme offered to physiotherapists participating in the EASE Back pilot trial in phase 2.

In addition, both the midwife and physiotherapist interviews highlighted a number of issues around recruitment, including the importance of detailed patient information and reassurance (about the acupuncture needling, any known side effects on the baby, information about positioning during treatment), flexibility around time and location of treatments and generally minimising the research burden on participants. The fact that the issues emerging through the interviews and focus groups were consistent with some of the survey responses acted as a further form of validation. The qualitative results specifically about physiotherapists’ concerns in using acupuncture during pregnancy also help explain the practice patterns seen in the survey responses. The findings from the qualitative interviews were incorporated into the participant information leaflet, the recruitment methods, the selection of treatment sites, the treatment protocols and the outcomes for the EASE Back pilot trial in phase 2.

Implications for recruitment to the pilot randomised controlled trial

The challenges in recruiting pregnant women to participate in the phase 1 interviews made it clear that we needed to develop and test a range of approaches to identify and recruit eligible women for the pilot trial in phase 2. Originally the plan had been to raise awareness about the pilot trial by inserting a flyer within the booking information pack given when seen by their community midwives and for women with back pain in pregnancy to be given an information pack about the trial by their usual midwife. We tested these approaches in phase 1, and overall these approaches alone were not particularly successful in identifying suitable women who were willing to be involved in the interviews. Recruitment of this population to research in phase 1 was clearly challenging, and therefore we used the results of the interviews with pregnant women, midwives and physiotherapists as well as suggestions for additional recruitment methods from research midwives who had worked on other research studies with pregnant women in order to agree six methods with which to identify and recruit women to the pilot RCT in phase 2. While using six methods was complex for a pilot trial and we had not originally included these costs of some of these methods in the grant application, we were keen to test out the methods in order to identify a smaller set of methods that might work best for a future large trial. The details of the six methods are provided in the next chapter (see Chapter 3, Recruitment methods and procedures), but they included a brief questionnaire that screened for the presence of back pain and willingness to be contacted further among women attending their antenatal 20-week ultrasound scan appointment and a local awareness-raising campaign that included use of a study website, newspaper, radio and other local media in order to take the message about the study directly to local pregnant women who could then opt to self-refer to the research team for eligibility screening.

In addition, we had planned that research midwives would screen all women for eligibility in face-to-face information and consent meetings. Through discussions with the research midwives it was agreed that a much more efficient use of their time would be to conduct brief telephone screening first and invite only those who appeared potentially eligible to face-to-face meetings for full eligibility screening, informed consent and baseline data collection.

Specification of information and interventions for the pilot randomised controlled trial

The development of the participant information leaflet

In order for potential participants to be fully informed about what taking part in the pilot trial in phase 2 would involve, a detailed PIL was developed. The format and content of the PIL was both based on a best practice example provided within the good clinical practice and regulatory requirements for clinical trials and taken from the findings of the qualitative research in phase 1. Information was provided not only on the rationale of the study, why women were being invited to take part, what taking part would involve, issues around anonymity and confidentiality, payment and the funders of the study, but also on the acupuncture treatment. This specific information included the required positioning for treatment, the difference between acupuncture needles and other types of needles (e.g. those used to take blood), whether or not children were able to attend appointments, the ability to drive after treatment and the known risk of specific adverse events from acupuncture during pregnancy. The PIL was reviewed by patient representatives on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and amended following feedback. A copy of the PIL is in Appendix 4.

The development of a standard care protocol

Given the variation in SC for pregnancy-related back pain, we sought to use the results of the national survey and the qualitative interviews, along with available research evidence, to specify a SC intervention protocol for the pilot RCT. The protocol included a high-quality and comprehensive self-management booklet and, for those who needed it, an onward pathway to individualised assessment and treatment with an EASE Back study physiotherapist.

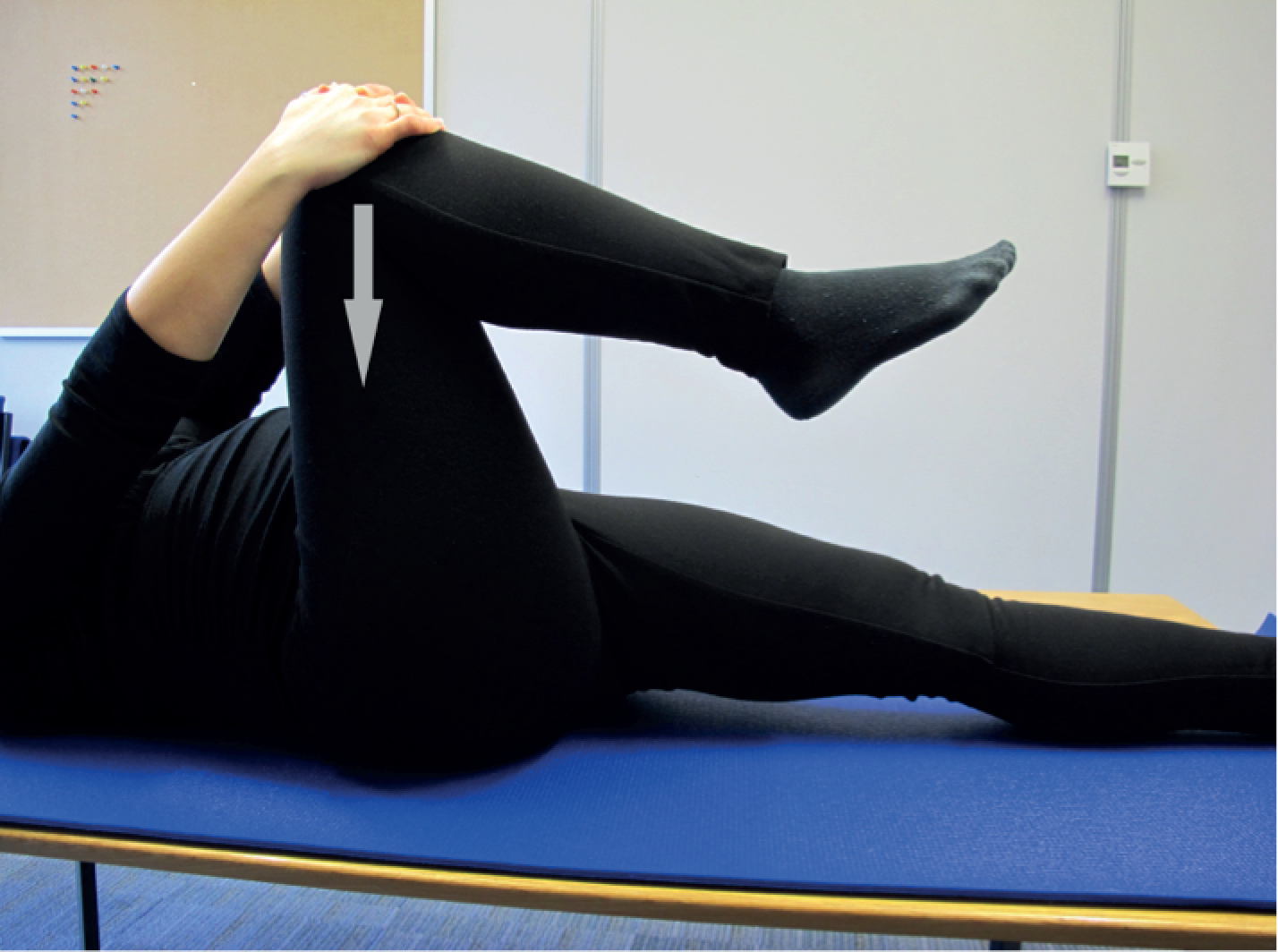

Self-management booklet

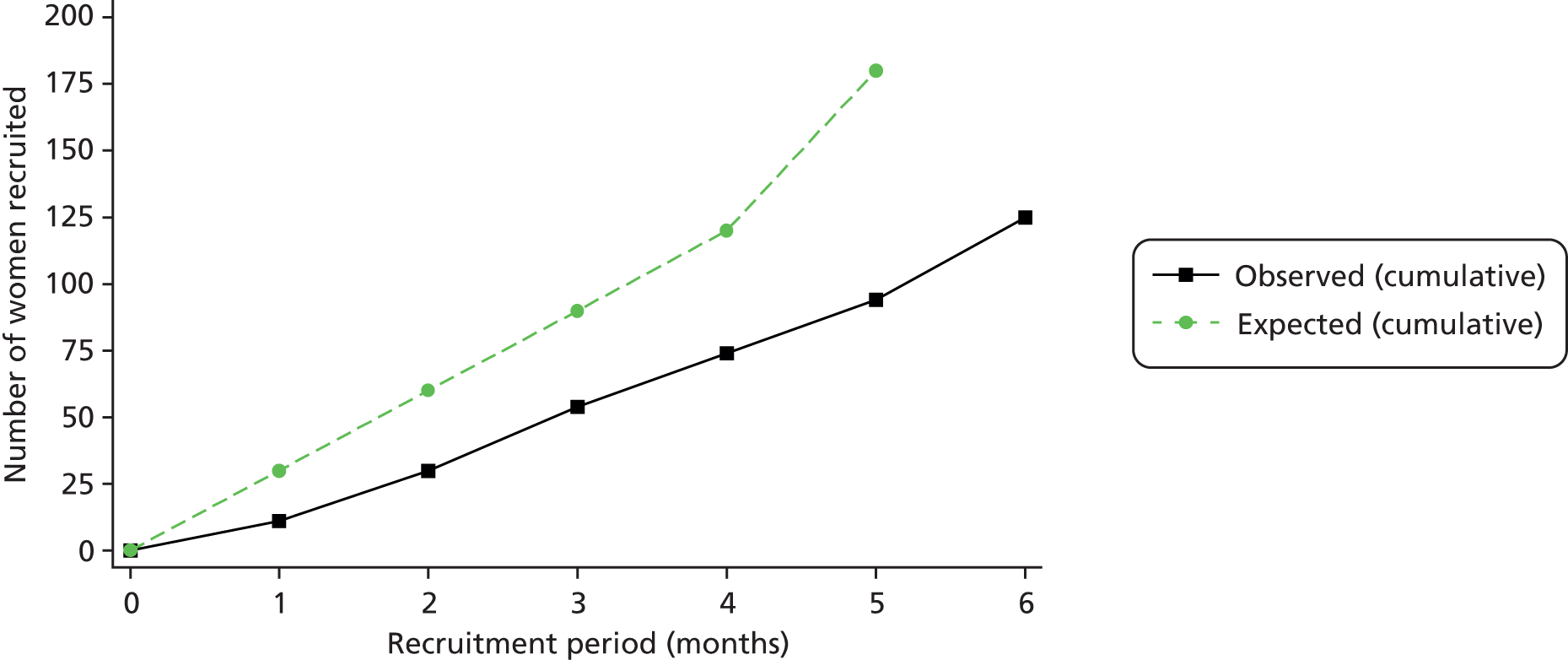

The national survey resulted in the research team receiving examples of 37 different advice and self-management leaflets currently used by physiotherapists across the UK. These were used to help develop the specific self-management booklet used in the pilot RCT. Other than the professionally produced leaflet Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain, published by the ACPWH, all others were examples of brief and inexpensive leaflets produced by individual NHS trusts or individual clinicians. It was clear that none was clearly fit for purpose for use in the EASE Back pilot RCT and, therefore, we developed the EASE Back: Managing Your Back and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy booklet specifically for use in phase 2. The available leaflets were reviewed for common themes and good examples of both content and layout, taking into account the issues raised by pregnant women, midwives and physiotherapists during the phase 1 pre-pilot work. We sought to develop a booklet that would be seen as more comprehensive than those available to date, that was produced in colour, of high quality, with clear photographs of real pregnant women (rather than diagrams only, as was the case in most of the available examples), divided into sections and with clear page numbers and handy hints boxes throughout. We also wanted the booklet to be of a size that women could fit into their handbag so that they could, if they wished, carry it around with them and thus refer to it during the day (most of the available examples were photocopied A4 sheets of paper). Working with the women’s health specialist physiotherapist at the participating hospital [University Hospital of North Staffordshire (UHNS)], who was also a member of the ACPWH, we developed sections for the booklet about the good prognosis of back pain in pregnancy, advice about appropriate self-management of back pain in pregnancy, including pacing between activities and rest, simple exercises to try at home, advice on adaptation in lifting techniques, tips about relieving postures for sitting, standing and sleeping, advice about work and continuing with everyday activities, the use of pelvic supports/belts and supportive pillows, and the use of simple and safe analgesics. We also included some self-management hints and tips, advice for labour and after the birth, a summary and useful websites.