Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/63/03. The contractual start date was in August 2012. The draft report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Fortnum and Professor Taylor were co-authors on the previous Health Technology Assessment (HTA) publication reporting evaluation of the school entry hearing screen [Bamford J, Fortnum H, Bristow K, Smith J, Vamvakas G, Davies L, et al. Current practice, accuracy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the school entry hearing screen. Health Technol Assess 2007;11(32)]. Professor Taylor is chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research researcher-led panel, March 2014–February 2016 (appointment extended to February 2018), and a member from 2013. He is also a member of NIHR Priority Research Advisory Methodology Group (PRAMG), August 2015–present, is a core member of NIHR HTA Themed Call Board, 2012–present and is a member of the core group of methodological experts for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme, 2013–present.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Fortnum et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and main questions

Childhood hearing impairment and screening

Identification of permanent hearing impairment at the earliest possible age is crucial to maximise the development of speech and language and contribute to the best opportunities for educational achievement and quality of life. 1 Approximately 1 in every 1000 children born in the UK has a permanent bilateral hearing impairment of > 40 dB (average across four frequencies: 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) and a further 0.6 per 1000 has a unilateral impairment. 2 This equates to 800 children per year born with a permanent bilateral hearing impairment (moderate or greater) and 500 with a unilateral impairment. The introduction of the highly sensitive and specific Universal Newborn Hearing Screening (UNHS) programme has led to the identification of the vast majority of children born with a hearing impairment who undergo the screen. 3,4 However, not all children who will ultimately have a hearing impairment are identifiable at birth. Data published in 20015 reported an adjusted prevalence of permanent hearing impairment of > 40 dB (average of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) at age 3 years of 1.07 per 1000 and a prevalence for children aged 9–15 years of 2.05 per 1000. Thus, because of acquisition, progression or late onset of hearing impairment and/or geographical movement of families, there remain a significant number of children to be identified with a permanent hearing impairment after the newborn period. The onset of hearing impairment in children after the newborn period can occur at any time, which means there is no optimum time for a further universal hearing screen. The universal distraction hearing test, established in the UK in the 1950s and undertaken by health visitors at around 8 months of age, was abandoned following the introduction of UNHS, based on a lack of robust implementation and a low yield of cases. 6,7 Identification of hearing impairment in children in the time between the newborn period and school entry is achieved through parental and professional awareness and a close follow-up of children who pass the neonatal screen but are considered to be at risk. 8 A universal hearing screen when children start school, the school entry screening (SES) programme, was established in 1955 and remains in place in many parts of the UK. It is considered as a ‘back-stop’ screen to identify children as part of a ‘captive population’ at school entry. Note: SES always refers to the hearing screening in this report.

A number of studies and reviews2,9–12 have explored evidence for the value of the SES programme but without clear conclusions. Research has shown that the number of children identified by this screen around age 5 years (the yield) has decreased following the introduction of UNHS, and widespread development of a system that is responsive to professional and parental concerns at any age. 8,12 The SES programme is no longer universally applied. Bamford et al. 12 reported in 2007 that one in eight services had stopped offering the screen by 2005 and it is more likely that others have stopped since 2005 than that services have reinstated the screen. There are no guidelines on standard methodology nationally and procedures are variable. However, despite a lack of evidence of its value, many support its continuation as a ‘back-stop’ to identify an acknowledged small number of children who would otherwise not be identified with the consequent effect on their development of speech and language.

Childhood hearing impairment can be permanent (usually sensorineural although permanent conductive impairment also occurs) and will not improve, or transient (also referred to as conductive) and will usually fluctuate and can get better.

A sensorineural impairment occurs when the inner ear (cochlea) or auditory nerve does not function properly; this can be caused by many factors. As mentioned, the majority of children with sensorineural impairments will have been identified by the newborn screening programme. However, there is the possibility that a child has a progressive impairment that, at birth, was minimal and therefore enabled them to pass the newborn screen. It is also possible for a child to develop a sensorineural impairment. Sensorineural impairments are permanent and require management to ensure that the child has access to language; management is usually to fit children with hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Many more children will have a transient hearing impairment at some point in their childhood than will have a permanent impairment. A conductive loss occurs when there is a problem with the outer or middle ear, such as impacted wax in the ear canal or a build up of fluid in the middle ear [otitis media with effusion (OME), which usually is associated with colds and respiratory tract infections]. Conductive impairments are usually temporary, unless there is a malformation of the outer or middle ear, which can lead to a permanent impairment. Prevalence is greatest in the first year of life and again at around age 4–5 years. For children < 6 years, 80% will experience OME. 13,14 Most episodes of OME get better in a couple of months but a small proportion (3–4%) can be persistent and severe and lead to problems with behaviour, communication and progress at school. It is therefore important to identify those children with an ongoing problem, as their hearing impairment needs management to ensure that they can access spoken language clearly. The recommended management options are initially to watch and wait. Owing to the fact that the majority of these transient impairments will resolve spontaneously, most children will be observed for 3 months before any active management takes place, then the usual options are surgical insertion of grommets if the child’s hearing impairment meets national recognised criteria,15 or for them to be fitted with a hearing aid.

Some children with permanent sensorineural impairments may also have an additional transient conductive impairment that would require management.

Screening tests for hearing impairment identify any child who has a hearing impairment. The tests do not discriminate between a permanent impairment and a transient impairment. They are also able to identify a hearing impairment in one ear or in both ears. Thus, all children with a hearing impairment, whether permanent or transient, bilateral or unilateral, should be identified by the screening test if it is 100% sensitive.

Testing children between the ages of 4 and 6 years can be difficult. Most tests require the engagement of the child in a simple task, such as raising their hand or putting a ball on a stick. Some children may find it difficult to maintain their attention throughout the test and this can give rise to spurious results. It is important that the screener/tester has experience in working with children to enable them to identify when their attention could be affecting the results of the test and be able to change their own behaviour accordingly to engage with the child. At any age it is possible that some children may not be able to co-operate with the testing because of specific learning or behavioural needs.

The pure-tone screen (PTS) (Amplivox, Eynsham, UK) test involves placing headphones over the child’s ears and then presenting pure tones across the key frequencies for speech understanding (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz). The child needs to indicate by a simple action that they have heard a sound. The screen works on the basis that a child needs to hear two out of three presentations of each frequency at 20 dB hearing level (HL) in each ear to pass the screen.

The HearCheck (HC) screener (Siemens, Frimley, UK) is placed over the child’s ear and an automatic sequence of pure tones is played once at each of three levels at each of the frequencies 1 kHz (55 dB, 35 dB and 20 dB) and 3 kHz (75 dB, 55 dB, 35 dB), which is six tones in total. The child needs to indicate, usually by raising their hand that they have heard each tone.

Any child identified by a screening test as having a possible hearing impairment should be referred to audiology services, but many children at school entry have a transient conductive impairment and hence it is the case that many children referred will ultimately be found to have no permanent impairment.

The commonly used screening method of the PTS can identify all types of impairment. Specifically including tympanometry would indicate a problem with the middle ear, but only by including both air and bone conduction thresholds from pure-tone audiometry (PTA), masked where necessary, could a conductive impairment be indicated.

This is important because there are conflicting opinions on the target group of children to be identified by SES. Should it be designed to only identify children with a permanent impairment for whom intervention is a priority, or should it be designed to identify any impairment to ensure every child is assessed appropriately and intervention provided for all who would benefit, regardless of the permanence of the condition? For this report, in both the analyses of diagnostic accuracy in Chapter 3 and in the analyses of yield in Chapter 5, we have considered identification of any type of impairment as the outcome for assessing the screening tests or the screening programme as a whole.

Previous Health Technology Assessment study

A previous National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-commissioned study to evaluate SES by Bamford et al. 12 reported a survey of current practice, longitudinal data on yield, a systematic review of effectiveness of SES (which included a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of screening tests) and an economic model estimating cost-effectiveness. The 2007 HTA report12 concluded that there was insufficient good-quality data on which to base a decision about the value of SES following the introduction of UNHS. The executive summary of the report is included as Appendix 1.

However, the 2007 study did report longitudinal data from a single district in London which indicated a small but significant number of children with a permanent hearing impairment first identified via SES in that particular population,8 and national survey data which reported examples of children not identified by other methods.

One of the recommendations of the 2007 HTA report12 was the need for trials to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative approaches to the identification of a post-newborn screen for permanent hearing impairment. Studies concerned with the relative accuracy (in terms of sensitivity and specificity) of alternative screening tests are difficult to compare and are often flawed by differing referral criteria and differing case definitions. The 2007 HTA report12 identified 25 publications reporting studies of alternative screens or tests for screening at school entry. These data indicate that, using full PTA as the reference standard, the PTS test appears to have high sensitivity and high specificity for minimal, mild and greater hearing impairments – better than alternative tests for which evidence was identified. Spoken word tests were reported with acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity but are variable in their implementation. Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), tympanometry, acoustic reflectometry, parental questionnaires and otoscopy were reported with either variable or poor sensitivity and specificity. Only one study, published in 1980,16 has compared screening with no screening and the results were inconclusive.

Assessment of cost-effectiveness

In order to best provide a service for the identification of permanent childhood hearing impairment while making best use of scarce NHS resources, it is important to gather robust evidence to support particular cost-effective implementations of service delivery at times relevant to the aetiology of hearing impairment and the child’s development. There is no question that screening for hearing impairment at birth is efficient and cost-effective,3 but the value of any further universal screen remains uncertain. Aside from the minimal and very weak evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different implementations of SES reported by the 2007 HTA report12 we are not aware of literature on the resource implications of different implementations or different technologies. A version of the HC screener has been evaluated as a screening tool in children in only one published paper,17 but it did not report any resource use.

Study aims and objectives

The two overarching aims of this project were to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of hearing screening tests and to assess the cost-effectiveness of screening for hearing impairment at school entry. The specific research objectives of this project were:

-

To determine and compare the diagnostic accuracy of two screening methods used to identify hearing impairment at or around school entry. These are the widely established PTS (which is applied using headphones) and the HC screener, a hand-held PTS.

-

To investigate the impact of a potential false-negative result.

-

To update the 2007 HTA report12 systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of tests used for SES.

-

To assess the yield, referral age and route through assessment to intervention for childhood hearing impairment and measure the costs of referrals for a service that employs a routine SES programme and for a service that does not.

-

To determine the impact, both psychological and economic, on the child and the family of the child being referred for further assessment following the school entry hearing screen (both true and false positives).

-

To determine the resource costs in implementing either of the two alternative screening methods in primary schools and to elicit the views of the school nurses implementing the screening tests.

-

To refine an existing SES economic model (from the 2007 HTA report12) and to assess the cost-effectiveness of SES.

-

To provide estimates of the yield and nature of hearing impairment detected in a system with no SES system; the yield, consequences and costs of screen-positive individuals in a SES system; and the costs of setting up a SES system.

This study thus addressed the question of whether or not there should be a screening programme to identify permanent hearing impairment in children when they start primary school. It assessed if the cost of such a screen is appropriate for the outcomes achieved, that is, the number of children identified by this method compared with a system with no screen, which is responsive to parental or professional concern, along with comparisons of diagnostic accuracy of two different ways of doing the screen. Based on the findings, we make recommendations to contribute to decisions regarding the continued implementation of SES and the form that implementation should take.

Structure of the project and the report

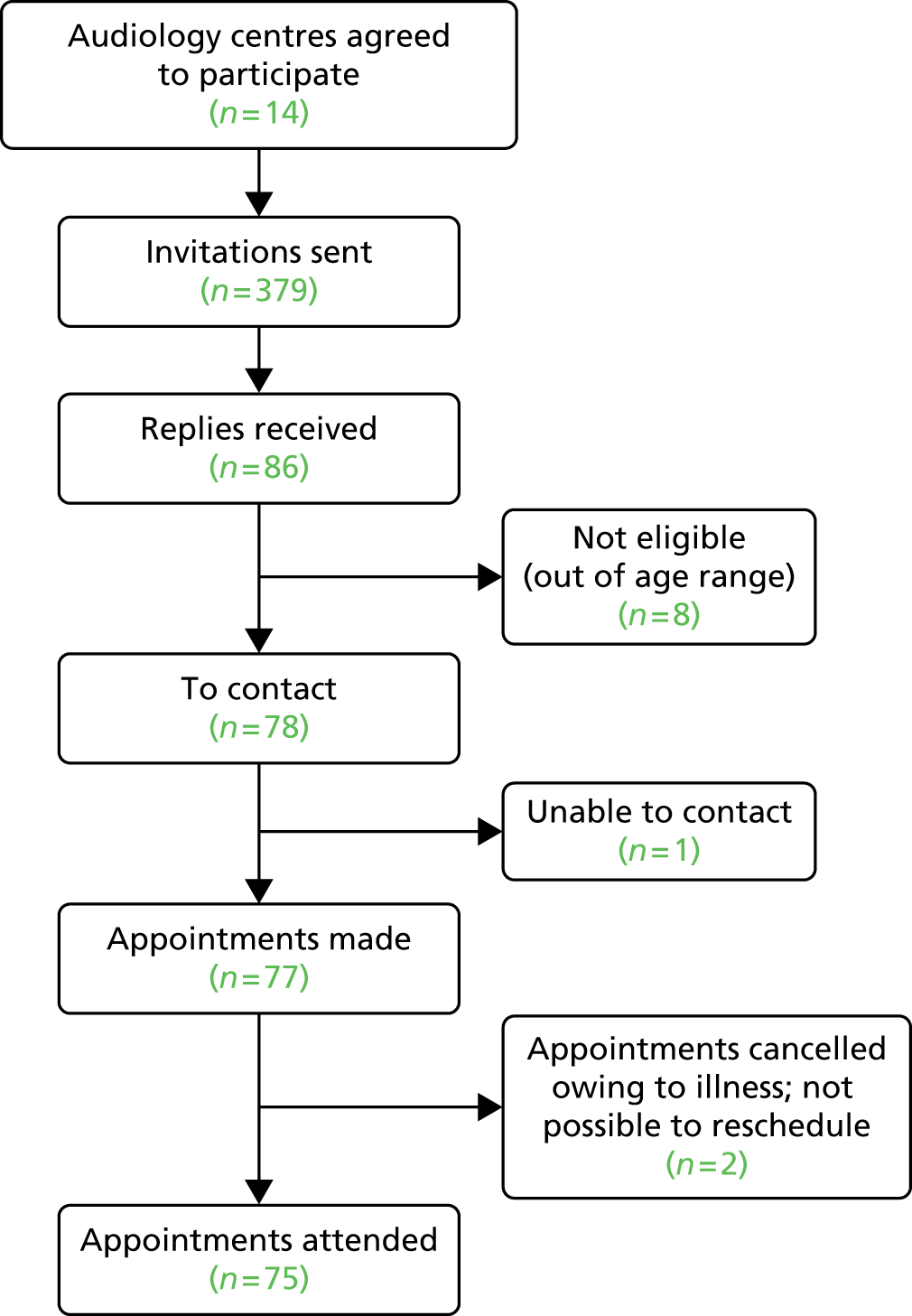

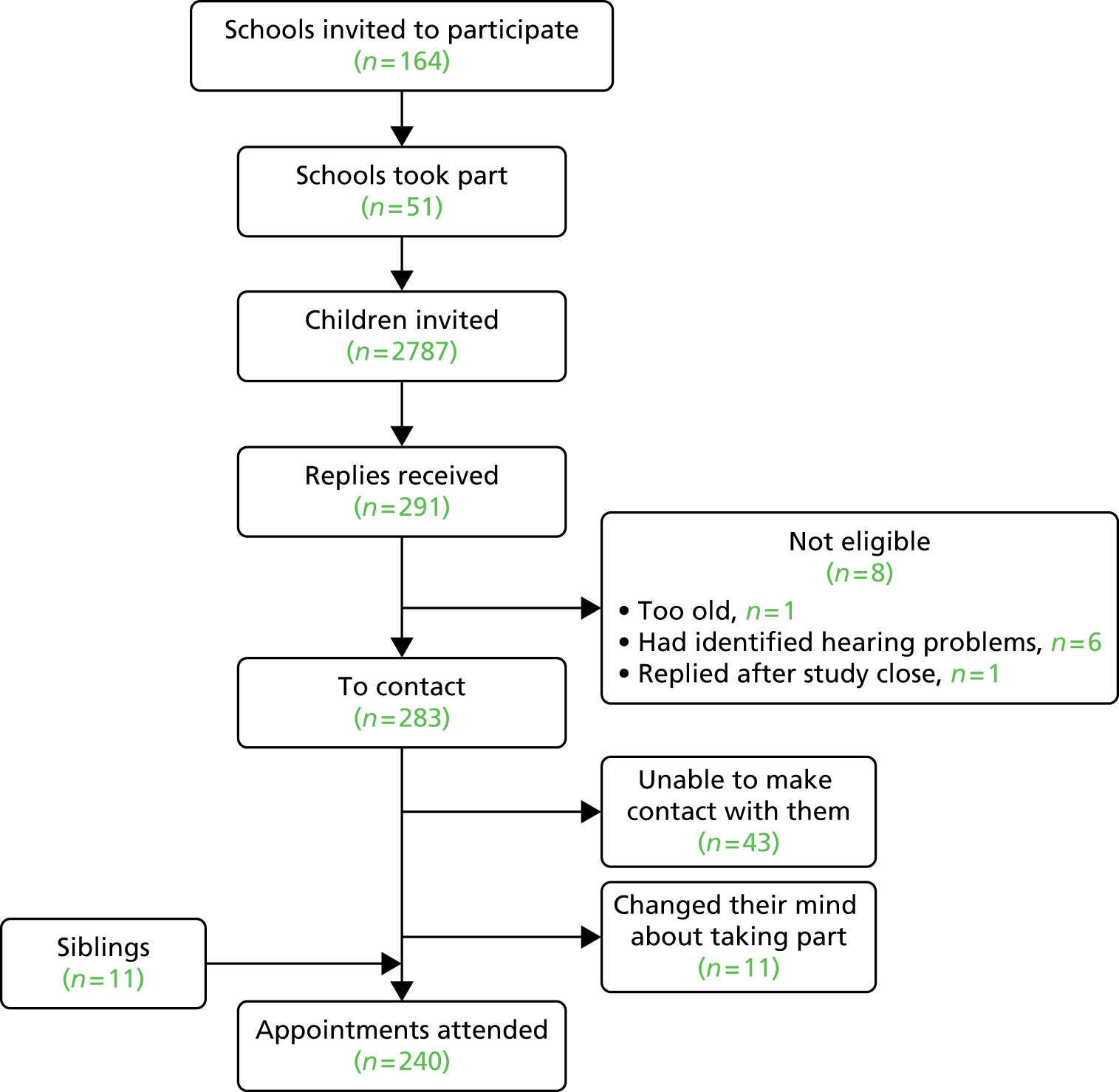

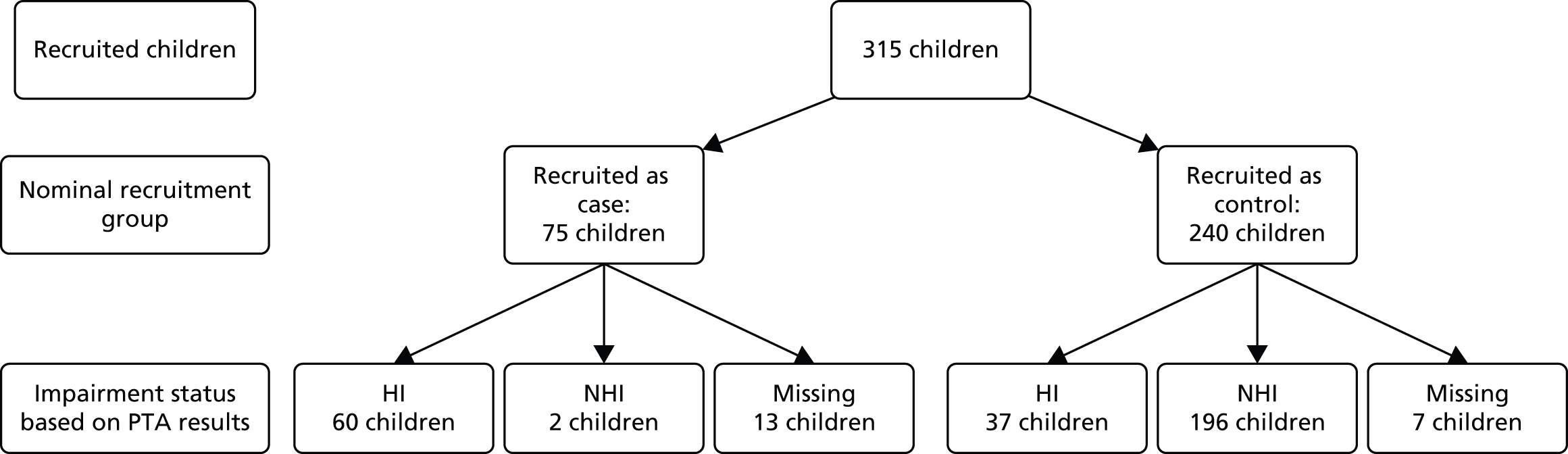

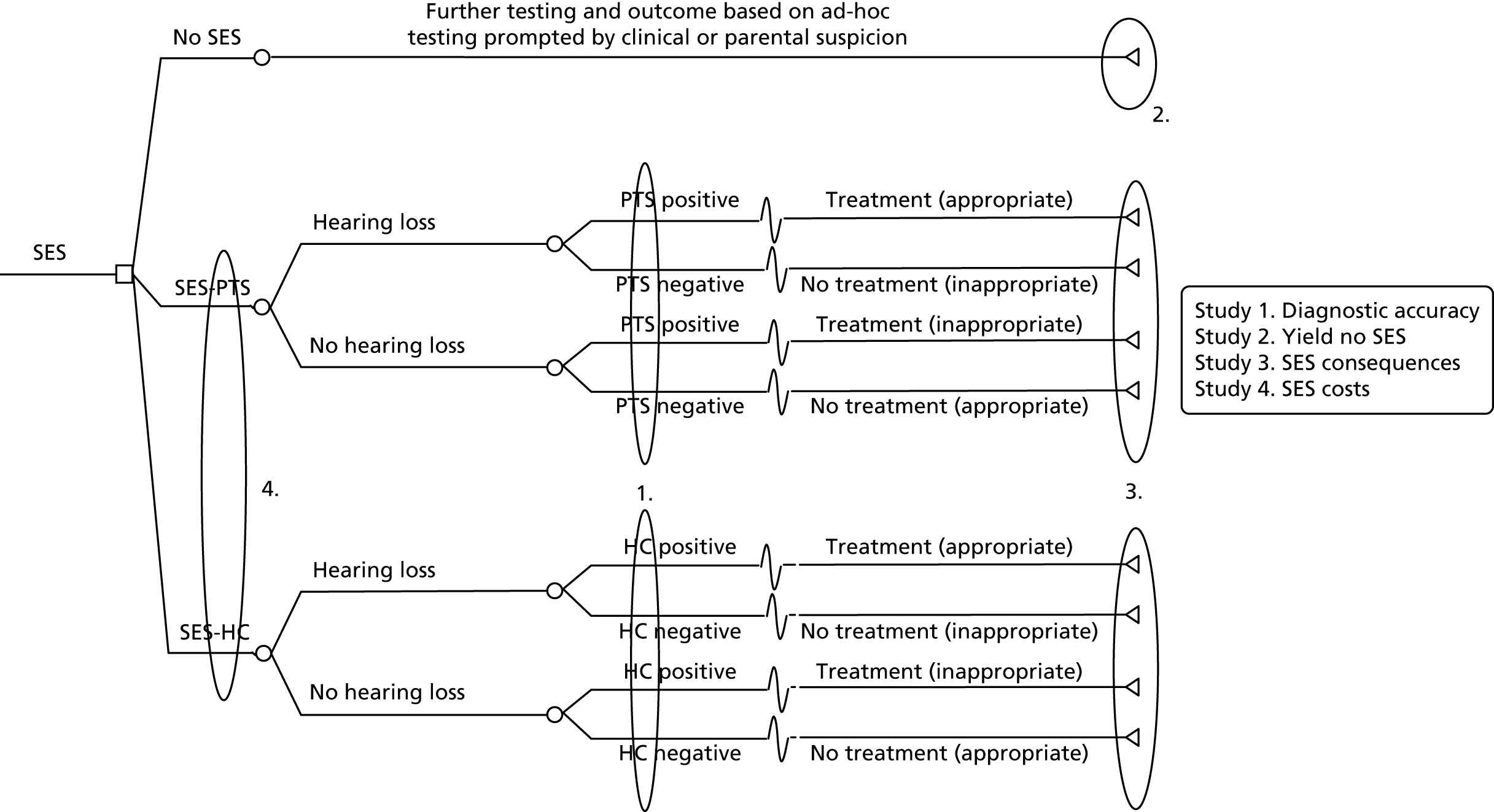

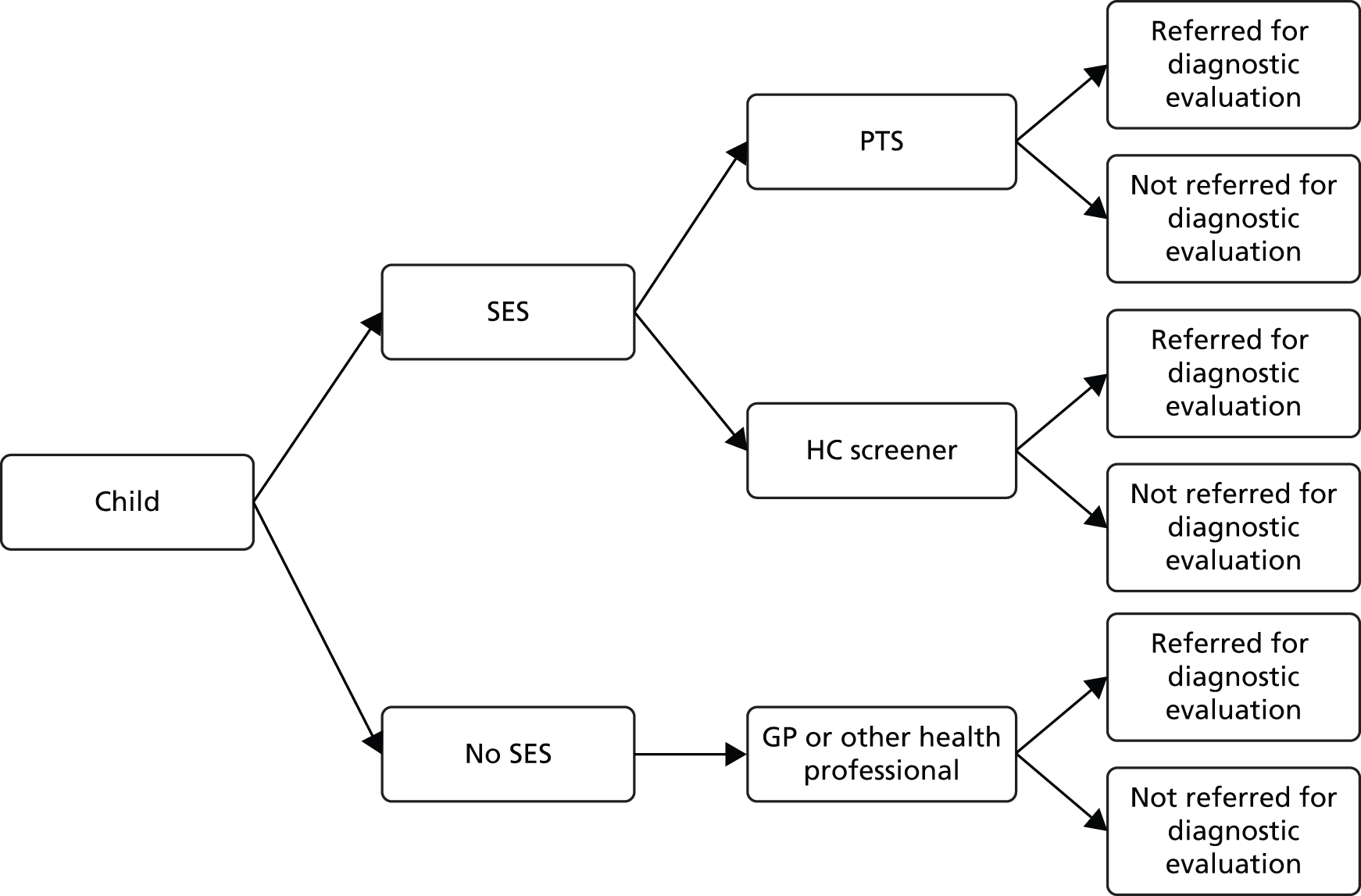

The project comprised four primary studies, a questionnaire survey and two systematic reviews. The planned participant flow for the four studies is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Planned participant flow.

Chapter 2 reports results from a systematic review undertaken to update the 2007 HTA report12 review of diagnostic accuracy of tests used for SES.

Chapter 3 reports results from the study that assessed the diagnostic accuracy of two methods of screening for the identification of hearing impairment for children aged 4–6 years. The PTS (four frequencies and one level) was compared with the HC screener (two frequencies and three levels) with respect to sensitivity and specificity.

Chapter 4 reports results from a systematic review of the issues around false negatives in screening for hearing impairment, and from the diagnostic accuracy study described above.

Chapter 5 reports and compares outcomes, including yield and age at referral, for an area where SES is in place (Nottingham) and an area where there has been no SES since 1997 (Cambridge).

Chapter 6 reports results from a questionnaire survey of parents of children referred to audiology services in Nottingham from SES. Data on parent experience are reported.

Chapter 7 reports results of a study of the practical implementation of the two screening tests in a primary school environment.

Chapter 8 reports results from the cost-effectiveness model of SES. Data from Chapters 3, 5, 6 and 7 informed the parameters in the model.

Finally, Chapter 9 summarises the discussion points from each part of the project and makes conclusions and recommendations.

Patient and public involvement

We acknowledge the importance of the involvement of members of the public in all health research. This project evaluated a screening system for children and input from parents to the development and interpretation of the research question was very important. Recruiting such a person proved challenging, as parents have childcare responsibilities and/or employment considerations, which mean they have little time to spare and commit to a 2.5-year project. Having advertised and discussed the project with several parents, most of whom were unable to commit the time, we recruited the parent of a child who had experienced conductive hearing impairment during his early school years. This parent became a full member of the research team (JW).

He provided comments on research literature for parents, including the questionnaire used for the survey of parents of children referred to audiology services from SES. He also contributed to the development of methodology, offering advice on how to deal with lower-than-expected recruitment. He attended all the meetings of the research team, either in person or via the telephone, and contributed to discussions of the findings, presentation of results and development of recommendations. The project addressed various issues concerned with the identification of hearing impairment in children, and we recognise that individual parents may have experience of only one part of the service. Nonetheless, they bring the lay perspective to research design and, as an individual, represent other parents. To access input from a wider range of parents we recruited a representative from the National Deaf Children’s Society to the project steering group. Based on the guidelines issued by INVOLVE (the organisation funded by NIHR to support public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research) we provided reimbursement to the parent joining the research team for their input of an average of 1 day per month to advise the design and attend research meetings. In addition all travel costs were reimbursed.

Chapter 2 Update of the diagnostic accuracy systematic review

Introduction

This chapter presents an update of the systematic review of the diagnostic test accuracy undertaken in the 2007 HTA report. 12 That report identified 25 publications reporting studies of alternative screens or tests for screening at school entry, showing that, using full PTA as the reference standard, the PTS test appears to have high sensitivity and high specificity for minimal, mild and greater hearing impairments – better than alternative tests for which evidence was identified. Other tests (spoken word tests, OAEs, tympanometry, acoustic reflectometry, parental questionnaires and otoscopy) had either variable or poor sensitivity and specificity. Using additional evidence published since the 2007 HTA report, the aim of this update was to produce an updated summary of diagnostic test accuracy.

Objectives

To update the 2007 HTA report systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of tests used for SES. This work summarises the literature that has been published since the previous review and draws together the evidence from the previous review and the updated review.

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy used and published in the 2007 HTA report on SES12 was reviewed and updated by an information specialist in the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group and re-run to identify studies published in the period January 2005 (search cut-off date of 2007 report, May 2005) to July 2014 (see Appendix 2). The following electronic databases were searched: The Cochrane Library (via Wiley) (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Science Citation Index (via Web of Science), Education Resources Information Center and ongoing trial databases (National Research Register, ClinicalTrials.gov and Research Findings Register).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical to those of the 2007 HTA report12 unless stated otherwise:

-

Study design: we included all primary diagnostic accuracy studies regardless of their specific design.

-

Population: we included children 4–6 years old. We excluded studies with a discrete age range that was completely outside our criteria (e.g. 1–3 years or 7–10 years). If a study included 4- to 6-year-old children but the age range was too wide (e.g. 6–19 years) and the results for different age categories were not reported separately, the study was also excluded from the review. We included, however, studies that at least partially covered but slightly exceeded the 4–6 years age range (e.g. 5–10 years) provided they met all other inclusion criteria. Whenever relevant and possible, the age of the included children is noted in the list of excluded full-text studies (see Appendix 2).

-

Screening tests or programmes: studies that evaluated one or more of the following hearing screening tests were included: sweep PTA, single-frequency PTA, transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE), distortion product otoacoustic emissions, questionnaires, otoadmittance tests, tympanometry, reflectometry and speech audiometry. (Note: sweep PTA and PTS are alternative terms for the same procedure. Where publications have used the term sweep PTA this description has been maintained.) Tests had to have been undertaken in either a primary school or the community [e.g. community clinic, family home or general practitioner (GP) surgery]. This could include hearing screening as a component of a multifaceted screen, such as a school entry medical examination.

-

Comparator: no hearing screening or hearing screening based on different tests or test protocols. We did not exclude studies without a comparator (studies that evaluated a single screening test) as long as they measured the performance of the evaluated test against an acceptable reference standard.

-

Reference standard: we included all studies that assessed the accuracy of the evaluated test(s) against a reference standard that included PTA.

-

Outcomes: the 2007 HTA review12 had a wider scope and also included studies that reported (1) the screen performance, that is, uptake (the number of children who actually received the screen) and yield (the number of cases identified); and (2) screen effectiveness, that is, language skills, health-related quality of life, communication skills, social interaction and educational performance. The current update focused on diagnostic accuracy only and included studies that reported the diagnostic accuracy of the evaluated test(s), regardless of whether or not the reported data were sufficient to reconstruct two-by-two table(s).

-

Language: no language restrictions were applied to the search and selection of studies.

Selection of studies and data extraction

After removing the duplicates, all records identified by the electronic searches were screened independently by two reviewers (HF and ZZ) at title and abstract level. Full-text copies were obtained for all publications identified as potentially relevant by at least one of the reviewers. Their suitability for inclusion in the review was assessed by one reviewer (ZZ) and checked by a second reviewer (CH) against the criteria specified above. Data were extracted from included studies by one reviewer (ZZ), entered into an Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and checked by a second reviewer (CH). Disagreements in the selection of studies and data extraction were resolved through discussion. Data were extracted from studies published in a language other than English with the help of a translator.

Assessment of the methodological quality

Although a new version of the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS) tool used in the 2007 HTA review12 is now available, the difference between the two versions is mainly in the structure and process of customising the tool and does not concern the contents of the actual checklist. 18,19 Therefore, we assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the original QUADAS checklist from the 2007 HTA review. This allowed for a direct comparison between the quality of the studies included in the 2007 report and in the current update. However, we provided more specific definitions of some QUADAS items that were not explicitly defined in the original checklist (see Appendix 2).

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Whenever possible, two-by-two tables were used to report the numbers of true-positive, false-positive, false-negative and true-negative results. The sensitivity and specificity of the index test (the test under evaluation) were calculated using The Cochrane Collaboration’s Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The same software was used to create forest plots of the paired sensitivity and specificity estimates and to plot the true-positive rate (sensitivity) versus the false-positive rate (1 - specificity) in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space. Heterogeneity was investigated visually by examining the forest plots and the ROC plot, and a decision was made whether or not to pool the results across studies. As standard funnel plots and tests for publication bias are not recommended in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy studies, we did not investigate publication bias. 20

Results

Search results and selection of studies

The electronic searches returned 892 papers after removal of duplicates. Screening at title or/and abstract level led to 39 citations being identified as potentially relevant. A further seven citations were found through hand-searching.

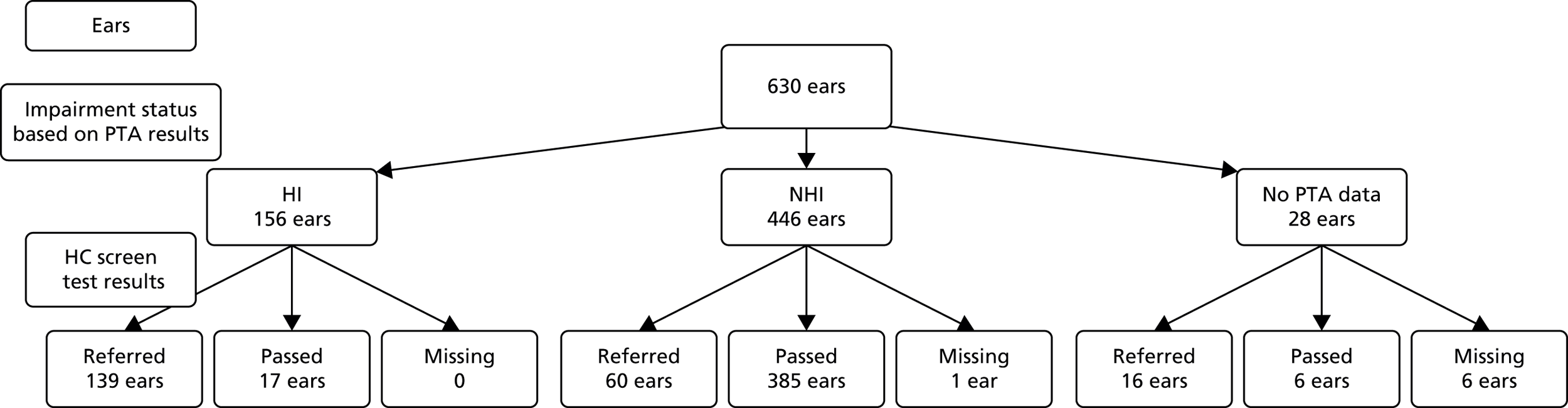

We obtained full-text copies of 45 of these studies and failed to obtain one. 21 After full-text evaluation 10 studies were selected for inclusion in the review. 17,22–30 Figure 2 details the selection process while the reasons for exclusion of full-text papers are given in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the selection process.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Briefly, 10 primary studies were included in this update. 17,22–30 One was published before 200524 but was included here as it had been missed by the original 2007 HTA report. 12 The other nine studies were published in the period 2005–2014. 17,22,23,25–30 Four of them were conducted in China22,23,27,30 and one in each of the following countries: Brazil,25 Greece,29 Japan,26 Kenya,24 the Philippines17 and the USA. 28

| Source and country | Sampling and inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Number of children (% male) | Mean age in years, (SD) or range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bu et al.,22 2005, China | Convenience sample of children grade 1–6 studying at one primary school | No exclusion criteria (except for a lack of consent) | 317 (49.5) | 9.43 (1.79) |

| Georgalas et al.,29 2008, Greece | Convenience sample of primary school children (6–12 years old) in one geographical area | No exclusion criteria (except for a lack of consent) | 86 (52.0) | 8.7 (2.0) |

| Gloria-Cruz et al.,17 2013, Philippines | Convenience sample of grade one elementary school children from three metropolitan schools | No exclusion criteria (except for a lack of consent) | 418 (56.9) | 8.6 (n/a) |

| Li et al.,23 2009, China | Convenience sample of children grade 1–6 studying at one rural school | No exclusion criteria (except for a lack of consent) | 154 (n/a) | 9.3 (1.7) |

| McPherson et al.,30 2010, China | Convenience sample of children 6–8 years old from a mainstream urban primary school | No exclusion criteria (except for a lack of consent) but no children with known cognitive or hearing impairments took part | 80 (62.5) | 7.04 (0.74) |

| Newton et al.,24 2001, Kenya | Convenience sample of children attending nursery schools and child health clinics in districts with audiologically trained ENT officers | No exclusion criteria | 735 (49.1) | 5.2 (n/a); range 2.21–7.5 |

| Samelli et al.,25 2011, Brazil | Convenience sample of children 2–10 years old living in an underserved metropolitan area with no UNHS | None specified | 214 (59.3) | Range 2–10 |

| Soares et al.,26 2014, Japan | Convenience sample of children 3–5 years old from a mainstream kindergarten (unclear if children from the nearby special school for hearing impaired children were also included in this age group) | Children unable to lie down still for several minutes (unable to complete procedure); lack of consent | 115 (n/a) | Range 3–5 |

| Wu et al., 2014,27 China | Random sample (5%, randomisation procedure not described) of 6288 eligible children enrolled from 41 kindergartens from a district area with a total of 106 kindergartens | Children who refused to participate or had learning disabilities | 312 (52.2) | 5.06 (0.72) |

| Yin et al., 2009,28 USA | Convenience sample of children 2–6 years old who are socioeconomically at risk (14% special education students) attending preschools in a large, urban, metropolitan school district | No exclusion criteria specified (except for the lack of consent) but no children previously identified with hearing impairment took part | 135 (n/a) | Range 2–6 |

| Source and country | Index test(s) | Setting (index test) | Test administrator (index test) | Cut-off (index test) | Reference standard | Setting (reference standard) | Test administrator (reference standard) | Definition of hearing impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bu et al., 2005,22 China | Questionnaire (CHQS) | Home | Parents/carers | No prespecified cut-off | Otoscopy, tympanometry and PTA | Same as TEOAE | Otolaryngologists, audiologists and nurses | Tympanogram type ‘B’ or an average threshold across four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) > 20 dB HL in either ear |

| TEOAE (Madsen Celesta 503 connected to a laptop) | School; quiet but not sound-treated room during normal attendance hours; ambient noise monitored | Otolaryngologists, audiologists and nurses | Pass: SNR values (an average of 1.5–4 kHz) of at least 3 dB and whole-wave reproducibility of at least 50% | |||||

| Georgalas et al.,29 2008, Greece | TEOAE (ILO 92 recorder). (Also, in combination with tympanometry but results not reported) | School; partially sound-proofed rooms | Otolaryngologists | Pass: if the TEOAE spectrum was recorded at least 3 dB above the noise floor and halfway across the frequency bands of 2–3 kHz and 3–4 kHz | Otoscopy, tympanometry and PTA | Same as for the index test | Same as for the index test | Average threshold > 25 dB across 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in either ear (> 30 dB also used but no full data reported) |

| Gloria-Cruz et al.,17 2013, Philippines | Audiometry (Siemens HC Navigator) | School; quiet but not sound-treated room; ambient noise monitored | Not specified but probably an audiologist | Pass: green light; refer: yellow or red light (separate results for red and yellow were also reported) | PTA | Same as for the index test | Audiologist | > 40 dB at 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 kHz in either ear |

| Li et al.23 2009, China | Questionnaire (CHQS-II) | Home | Parents/carers | No prespecified cut-off | Otoscopy, tympanometry and PTA | School; quiet but not sound-treated room during normal attendance hours; ambient noise monitored | Medical doctors and audiologists, under the supervision of an otolaryngologist | Evidence of OME or ‘B’-type tympanogram or threshold > 40 dB at 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 kHz in either ear |

| McPherson et al.,30 2010, China | Audiometry (Home Audiometer Software version 1.83) | School; quiet but not sound-treated room during non-attendance days; ambient noise monitored | Speech and hearing science undergraduates who had received 12 hours’ training | Refer: > 40 dB at 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 kHz in either ear; results also reported after excluding 0.5 kHz data | PTA | Same as for the index test | Same as for the index test (test administrators randomly assigned each time) | > 40 dB HL at 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 kHz in either ear |

| Newton et al.,24 2001, Kenya | Questionnaire | Home, nursery, child health clinic | Three modes: (1) a nursery teacher interviewing parents; (2) parents/carers; (3) a community nurse interviewing parents | Refer: one or more answers suggesting hearing impairment or uncertainty (question 5 excluded from analysis) | ENT examination including otoscopy and PTA | Quietest possible room (not sound treated); ambient noise measured whenever possible | ENT officers trained to perform PTA | Average threshold (0.5, 1 and 4 kHz) > 40 dB bilaterally |

| Samelli et al.,25 2011, Brazil | Questionnaire | Home, kindergarten, school or health unit | Evaluators (unspecified) | Refer: score ≥ 6 (ROC optimised); two additional cut-offs established to distinguish between conductive and sensorineural hearing impairment | Otoscopy, tympanometry and PTA | Sound-attenuated testing room | Evaluators (unspecified) | > 15 dB HL (0.25–8 kHz), tympanogram type B, C, As, or Ad and/or an absence of acoustic reflexes with one or both ears |

| Soares et al.,26 2014, Japan | AABR (MB11 BERA-phone®, MAICO Diagnostic GmbH, Berlin, Germany) | Kindergarten; quiet room (no further details); ambient noise monitored | Audiologist | Pass: a ‘pass’ line on the device’s graphic screen; refer: when 180 seconds elapsed without achieving pass line | PTA (preceded by ENT examination) | Same as for the index test | Audiologist from the institution in which the children belonged | > 25 dB HL at frequencies between 0.5 and 4 kHz |

| Wu et al.,27 2014, China | Audiometry (Smart Hearing) | School; quiet but not sound-treated room; ambient noise measured | Screening personnel (unspecified) who had some training | Refer: > 30 dB HL at 1, 2 and 4 kHz in either ear (plus children who failed the guidance stage) | Otoscopy, tympanometry, PTA (standard or play) and distortion product OAEs | Children’s Hearing and Speech Centre | Specialists at the centre (unspecified) | Hearing impairment: mild (26–40 dB HL), moderate (41–60 dB HL), severe (61–80 dB HL), or profound (> 80 dB HL) based on the average value of threshold at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz |

| Yin et al.,28 2009, USA | TEOAE (Otodynamics Echo Port ILO 288) | Preschool; quiet but not sound-treated room | Nurses and a paediatrician who had 1 hour of ‘hands-on’ training | Pass: automatically indicated when a TEOAE response was obtained for three of five frequency range with TEOAE being 5 dB above noise floor Refer: no TEOAE present or did not pass the required number of frequencies |

PTA | Unspecified | School audiologists | No response at any frequency (1, 2, 4 kHz) to 25 dB HL pure tone |

Although the majority of the included children were at or around school entry age, there was marked variability in terms of age range. Children’s age ranged from 225,28 to 13 years23 with the mean age ranging from 5.1 years [standard deviation (SD) 0.7 years]27 to 9.4 years (SD 1.8 years)22 (three studies25–27 did not report mean age and only gave age range as an inclusion criterion). The studies were relatively balanced in terms of participants’ gender, the proportion of males ranging from 48.4%26 to 62.5%30 (two papers23,28 did not report details). Apart from lack of consent, most studies did not specify any other exclusion criteria. One study26 excluded children who were unable to lie down still for several minutes, which was a necessary requirement for completing the screen procedure; one study27 excluded children with learning disabilities and two studies26,30 commented that no children with known cognitive or hearing impairments were included but it was unclear if this had been a prespecified exclusion criterion. Seven studies17,22–25,27,30 were conducted in countries without established UNHS.

Studies evaluated the performance of questionnaires (n = 4), audiometry (n = 3), TEOAE (n = 3) and automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) (n = 1). AABR is usually used to screen infants and was not listed in the initial inclusion criteria. However, we decided to include the study, as it evaluated, probably for the first time, the use of AABR in SES. Two studies22,23 evaluated different versions of the Chinese Hearing Questionnaire for School Children (CHQS). Only one study22 compared directly the performance of two different tests, a questionnaire and TEOAE, and one study29 evaluated a combination of TEOAE and tympanometry but did not report the results as adding tympanometry had not improved performance.

Questionnaires were completed by parents or carers in two studies,22,23 either by parents/carers or by teachers or community nurses interviewing parents (three different testing conditions) in one study24 and by unspecified evaluators in one study. 25 All other index tests were performed either by audiologists, otolaryngologists or other professional staff who had some preliminary training. With the exception of questionnaires, all other tests were performed at school or a community health centre in a quiet but not sound-treated room and the ambient noise level was monitored.

All studies except those evaluating questionnaires used a prespecified positivity threshold to define ‘pass’ and ‘refer’ outcomes. Data-driven selection of a threshold to achieve optimal performance (best sensitivity and/or best specificity) could lead to overly optimistic diagnostic accuracy estimates and the test is likely to perform worse when the same threshold is used in an independent sample of patients. 31

The reference standard was a combination of otoscopy, tympanometry and audiometry in four studies,22,23,25,29 otoscopy, tympanometry, audiometry and OAEs in one study,27 ear, nose and throat (ENT) examination including audiometry in two studies,24,26 and audiometry only in three studies. 17,28,30 The tests were performed by audiologists and otolaryngologists, usually in quiet but not sound-treated rooms with monitored ambient noise.

The mean prevalence of the target condition across all studies that reported outcomes at the level of the individual was 10.8% (SD 12.6%) and ranged from 0.7%28 to 46.7%. 25 The prevalence in the only study that reported ear-level outcomes was 4.8%. 17 These numbers should, however, be treated with caution, as the studies varied in their pass/refer criteria and included convenience samples drawn from populations likely to be different in terms of prevalence and spectrum of hearing impairments.

Methodological quality of included studies

The definitions of the assessment criteria are given in Appendix 2 and the results from the methodological quality assessment are summarised in Table 3. All studies had a prospective cross-sectional single-gate design. ‘Single-gate’ is a term introduced by Rutjes et al. 32 to describe diagnostic accuracy studies in which a single sample drawn from the target population receives the index test and the reference standard to allow calculation of the test’s sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, in ‘two-gate’ designs sensitivity and specificity are calculated separately based on two different samples of participants, that is, one with and one without the target condition. The two-gate design is prone to spectrum bias as the mix of participants in the two samples combined is unlikely to be representative of the target population. 32 Therefore, studies using a single-gate design are considered to be of better methodological quality.

| Study | Representative spectrum? | Selection criteria described? | Acceptable reference standard? | Acceptable time between tests? | Whole/random sample received the reference standard? | Same reference standard? | Reference standard and index test independent? | Index test described? | Reference standard described? | Blinded interpretation of index test? | Blinded interpretation of reference standard? | Same clinical data available as in practice? | Uninterpretable/intermediate results reported? | Withdrawals explained | Total score (number of ‘yes’) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Bu et al.,22 2005 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | 10 | Study 1 |

| Study 2 | Georgalas et al.,29 2008 | No | No | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | 8 | Study 2 |

| Study 3 | Gloria-Cruz et al.,17 2013 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | 11 | Study 3 |

| Study 4 | Li et al.,23 2009 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 | Study 4 |

| Study 5 | McPherson et al.,30 2010 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | 10 | Study 5 |

| Study 6 | Newton et al.,24 2001 | No | Yes | No | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 | Study 6 |

| Study 7 | Samelli et al.,25 2011 | No | No | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | 9 | Study 7 |

| Study 8 | Soares et al.,26 2014 | No | No | No | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | 7 | Study 8 |

| Study 9 | Wu et al.,27 2014 | No | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 | Study 9 |

| Study 10 | Yin et al.,28 2009 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 | Study 10 |

Although all included studies had a single-gate design, none of them included a representative sample of a relevant target population defined for the purpose of this review as 4- to 6-year-old children (± 1 year) at or around school entry stage who have no high-risk features (such as Down syndrome, cytomegalovirus infection or meningitis) and have been tested and found to have no hearing impairment at birth. Therefore, the studies are likely to suffer from a selection bias and to have limited applicability to the UK context because of the following methodological issues. First, some studies included children younger or older than the defined 4–6 years age range, which reflects, to some extent, the fact that school entry age varies across countries. Second, seven of the studies17,22–25,27,30 were conducted in countries without established UNHS, which is likely to impact on the prevalence and spectrum of hearing impairments in the included children. Third, most of the studies included small self-selected samples recruited from a single locality and, therefore, may not be representative, even when drawn from a relevant target population.

The execution of the index test(s) and the reference standard were reported in sufficient detail in the majority of the studies. In five studies,17,24,26,28,30 however, the reference standard was suboptimal and did not meet the quality criterion ‘PTA + tympanometry’. The time between the performance of the index test and the reference standard was < 1 month in four studies,17,22,23,30 was > 1 month in one study28 and was not reported in five studies. 24–27,29 Blinding of the index test evaluators to the results of the reference standard was not reported in three studies22,26,29 and blinding of the reference standard evaluators to the results of the index test was not reported in five studies. 22,23,26,27,29 Those criteria that were consistently met across the studies were questions 5–9 (see Appendix 2) concerning the application of the same reference standard to the whole or random sample, regardless of the index test result (verification bias); the independence of the reference standard from the index test (incorporation bias) and the description of index test and reference standard in sufficient detail to allow replication. According to the criteria for calculating a total quality score published in the 2007 HTA report,12 three studies25,26,29 were of ‘moderate’ quality (total score 7–9) and the remaining seven studies17,22–24,27,28,30 were of ‘good’ quality (total score of > 9).

Test accuracy

Given the significant heterogeneity in the study characteristics and the reported test accuracy estimates (see Table 2 and Figure 3) we considered quantitative synthesis inappropriate and, instead, summarised the performance of different test types in tables and figures (Figures 3 and 4, and Table 4).

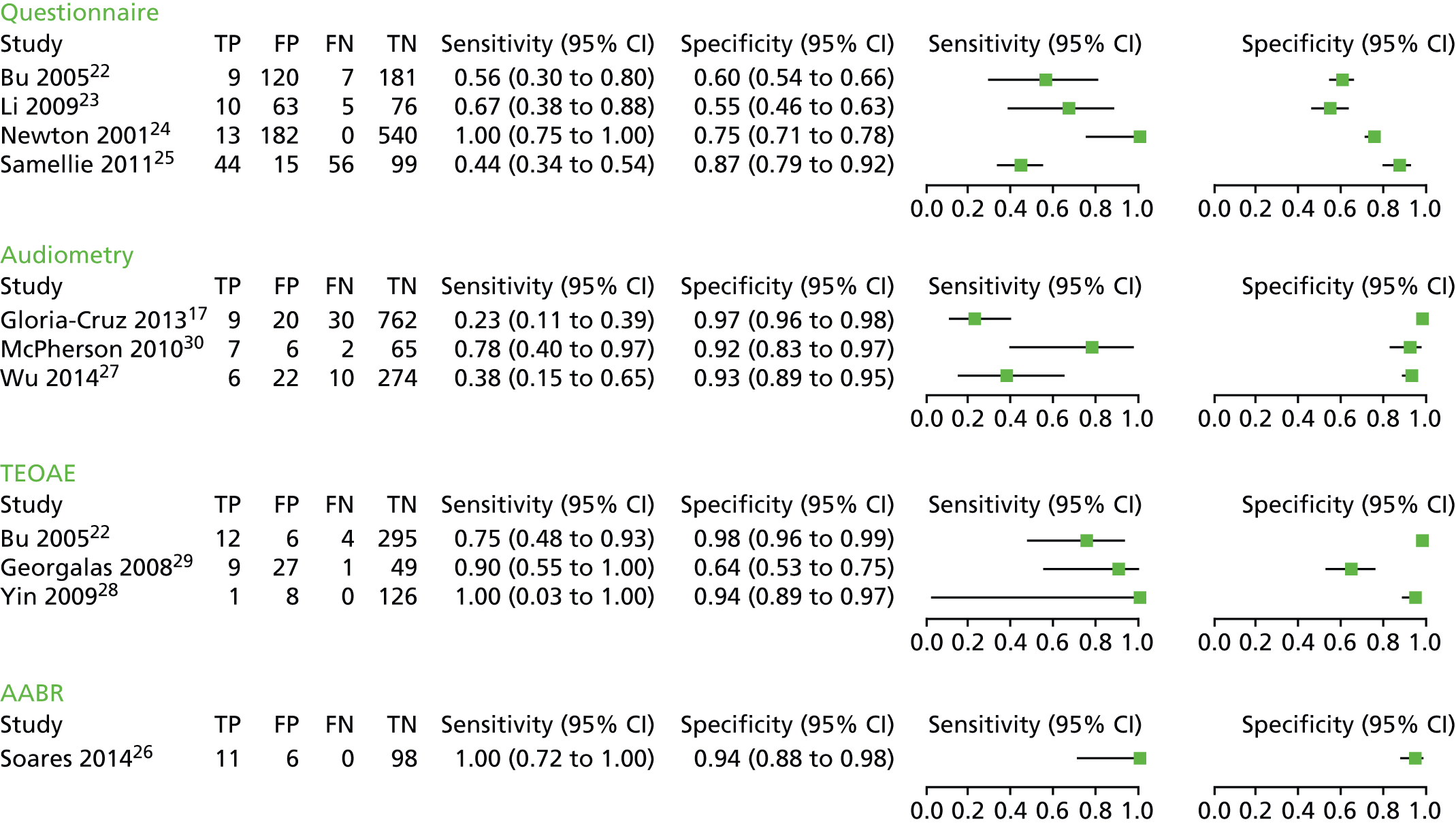

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of different types of hearing screening tests. Please note that the results for Bu et al. 22 are based on reading off the ROC plot in the paper and do not refer to a particular positivity threshold; the results for Li et al. 23 are based on ‘1+’ answers suggesting hearing impairment; and the results for McPherson et al. 30 are based on the data set that did not include results from 0.5 kHz. CI, confidence interval; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

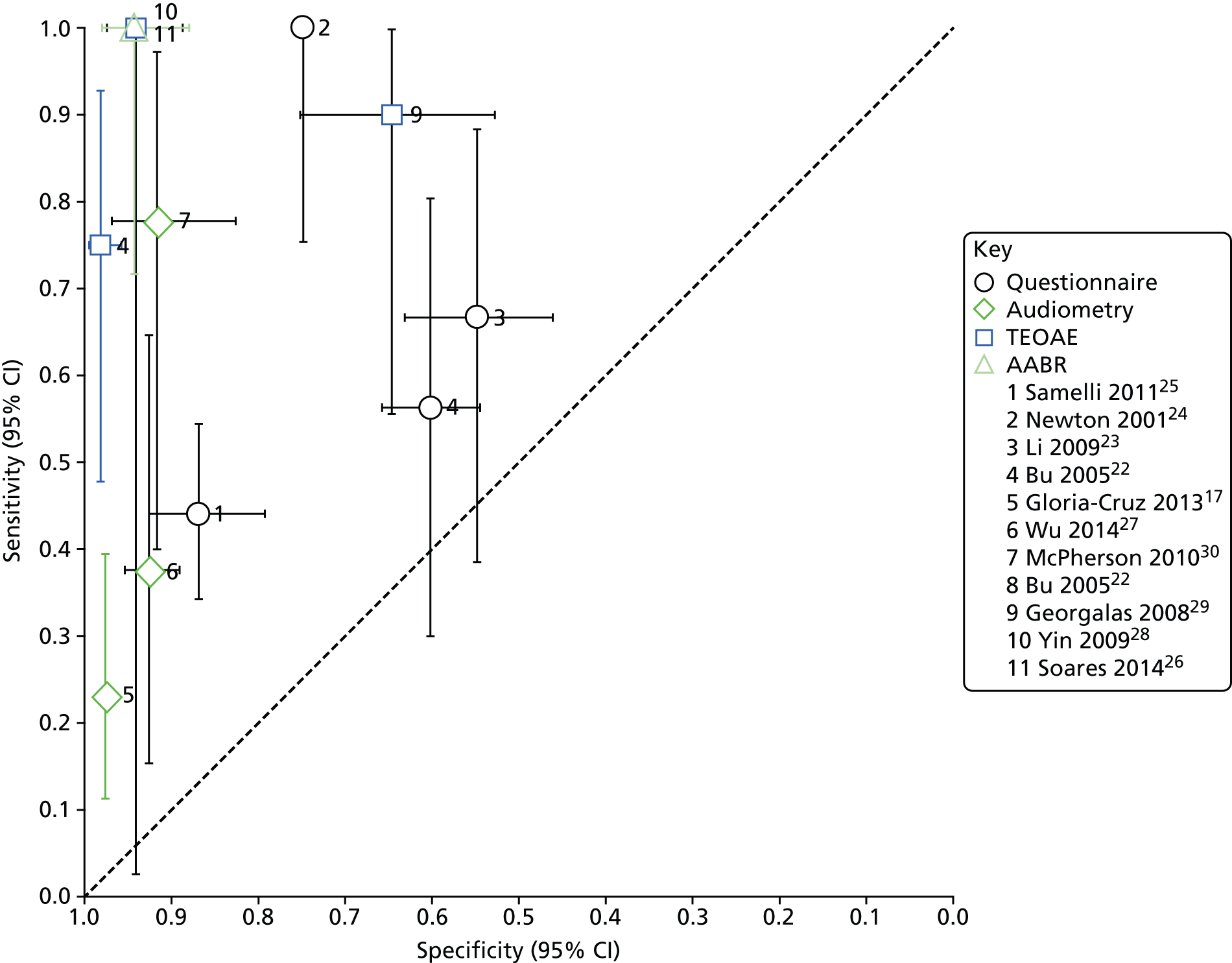

FIGURE 4.

Summary ROC plot of different hearing screening tests. Please note that the results for Bu et al. 22 are based on reading off the ROC plot in the paper and do not refer to a particular positivity threshold; the results for Li et al. 23 are based on ‘1+’ answers suggesting hearing impairment; and the results for McPherson et al. 30 are based on the data set that did not include results from 0.5 kHz. CI, confidence interval.

| Study and country | Index test cut-off | Total number | TP | FP | FN | TN | Prevalence % | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | Withdrawals and uninterpretable results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | ||||||||||

| Bu et al.,22 2005, China | Single questions | 317 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 5.05 | Range 7–42 | Range 76–99 | None reported; response rate to questionnaire was 61% |

| Unspecified cut-off (based on the ROC plot reported in the paper) | 317 | 9 | 120 | 7 | 181 | 5.05 | 56 (30 to 80) | 60 (54 to 66) | As above | |

| Li et al.23 2009, China | Scores of ≥ 1 to ≥ 5 | 154 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 9.74 | Range 0–67 | Range 55–100 | None reported; questionnaire’s response rate was 100% (after being distributed via students randomly selected by teachers) |

| Score of ≥ 1 | 154 | 10 | 63 | 5 | 76 | 9.74 | 0.67 (0.38 to 0.88) | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.63) | As above | |

| Newton et al.,24 2001, Kenya | Score of ≥ 1 (question 5 excluded) | 735 | 13 | 182 | 0 | 540 | 1.77 | 100 (75 to 100) | 75 (71 to 78) | Response rate to questionnaire was 88%; PTA could not be obtained for 22 children who were excluded from analysis |

| Samelli et al.,25 2011, Brazil | Score of ≥ 6 | 214 | 44 | 15 | 56 | 99 | 46.72 | 44 (34 to 54) | 87 (79 to 92) | None reported; response rate also not reported |

| Audiometry | ||||||||||

| Gloria-Cruz et al.,17 2013, Philippines | Pass: green; refer: yellow/red | 821 (ears) | 9 | 20 | 30 | 762 | 4.75 (ears) | 23 (11 to 39) | 97 (96 to 98) | 73% coverage of the entire population under study: 7 out of 418 children excluded as not available for testing; one child had only one ear tested |

| McPherson et al.,30 2010, China | > 40 dB any frequency | 80 | 10 | 35 | 0 | 35 | 12.5 | 100 (69 to 100) | 50 (38 to 62) | None reported; coverage of entitled children also not reported |

| > 40 dB, 0.5 kHz excluded | 80 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 65 | 11.25 | 78 (40 to 97) | 92 (83 to 97) | ||

| Wu et al.,27 2014, China | > 30 dB at 1, 2 or 4 kHz | 312 | 6 | 22 | 10 | 274 | 5.13 | 38 (15 to 65) | 93 (89 to 95) | 76 children refused to take part; eight children with learning disabilities were excluded |

| TEOAE | ||||||||||

| Bu et al.,22 2005, China | See Table 2 | 317 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 295 | 5.05 | 75 (48 to 93) | 98 (96 to 99) | As above |

| Georgalas et al.,29 2008, Greece | See Table 2 | 86 | 9 | 27 | 1 | 49 | 11.63 | 90 (55 to 100) | 64 (53 to 75) | 196 students enrolled but only 86 received PTA owing to financial constraints (selection criteria not clear) |

| Yin et al.,28 2009, USA | See Table 2 | 135 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 126 | 74 | 100 (3 to 100) | 94 (89 to 97) | 142 students enrolled in the diagnostic cohort of whom seven were excluded (two special education students refused TEOAE, three non-special education refused or were unable to do PTA, two students could not be tested using TEOAE owing to complete cerumen impaction) |

| AABR | ||||||||||

| Soares et al.,26 2014, Japan | n/a | 115 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 98 | 9.57 | 100 (72 to 100) | 94 (88 to 98) | 17 individuals (34 ears) excluded from the sample owing to failure to get good impedance or accurate PTA; and five ears (from the 163 included individuals) were also excluded |

Parental questionnaires

Four studies22–25 reported the diagnostic accuracy of questionnaires, two of which evaluated different versions of the same tool (CHQS). 22,23 All questionnaires had been independently validated and the authors reported satisfactory reliability. None of the studies used a prespecified positivity threshold, which means that the reported diagnostic accuracy might be exaggerated. The two studies evaluating CHQS reported results from a range of different scores23 or a range of sensitivity and specificity values obtained for different individual questions and combinations. 22 The results included in the forest plot and the ROC curve plot (see Figures 3 and 4) for these two studies correspond to positivity thresholds that resulted in the best overall performance: a total score of > 1 for the study by Li et al. ,23 and sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 60% read-off the ROC plot in the paper for the study by Bu et al. 22

Across all studies, sensitivity ranged from 44% to 100% and specificity from 55% to 87% (see Figure 3). The ROC plot in Figure 4 clearly shows that the performance of the questionnaires was poor, with three of the studies,22,23,25 close to the line of no effect (the dotted diagonal line), which indicates accuracy no better than expected due to chance. Only the study conducted by Newton et al. 24 showed relatively good overall accuracy with excellent sensitivity (100%) and moderate specificity (75%). However, the definition of hearing impairment in this study was bilateral hearing impairment of > 40 dB and three of the four children with unilateral hearing impairment of > 40 dB were missed by the questionnaire. Including these children in the analysis brings the sensitivity down to 82% while specificity remains the same (75%).

Audiometry

The diagnostic accuracy of audiometry was evaluated in three studies: two evaluated computer-based audiometers27,30 and one a hand-held device. 17 Sensitivity ranged from 23% to 78% and specificity from 92% to 97% (see Figure 3). McPherson et al. 30 reported two sets of results – before and after excluding the data for 0.5 kHz – which they considered problematic owing to possible interference from ambient noise. With the 0.5 kHz data included, sensitivity was 100% and specificity was 50%; excluding 0.5 kHz data led to a marked decrease in sensitivity (78%) and increase in specificity (92%). The forest plot and the ROC plot (see Figures 3 and 4) show that, based on the studies included here, portable audiometry tools have much better and more consistent specificity, but variable sensitivity, noting, however, that there is a considerable difference between the technologies evaluated, particularly between the computer-based audiometers and the hand-held HC screening device.

Transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions

Three studies22,28,29 evaluated the accuracy of TEOAE, one of which compared its performance with that of a questionnaire (see Figures 3 and 4). 22 Sensitivity ranged from 75% to 100% and specificity from 64% to 98%. However, the sensitivity estimate reported by Yin et al. 28 had a very wide confidence interval (CI) (3% to 100%), indicating considerable statistical uncertainty. The comparative study found that the diagnostic accuracy of TEOAE was superior to that of the questionnaire with sensitivity of 75% versus 56% and specificity of 98% versus 60%. The sensitivity estimates of the two tests, however, had overlapping CIs, suggesting that the result might be due to chance rather than real superiority.

Automated auditory brainstem response

Only one study26 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of AABR as a screening test for school entry children. This study was conducted in Japan, included children 3–5 years old and the evaluated device, MB11 BERA-phone® (MAICO Diagnostic GmbH, Berlin, Germany), was operated by an audiologist. The study had the lowest quality score of all included studies (see Table 3) because of a failure to provide a clear description of the selection process and to report important aspects of the study design, such as time between index test and reference standard, blinding and availability of clinical data to test administrators. The test showed very high performance with 100% sensitivity and 94% specificity but the sensitivity estimate had a relatively wide 95% CI (72% to 100%) owing to a small sample size and a low event rate.

Discussion

Summary of the findings from the 2007 Health Technology Assessment report

The 2007 HTA report12 included 25 primary studies reporting the performance of a wide range of hearing screening tests, including parental questionnaires, impedance audiometry/tympanometry, spoken word tests, otoscopy, audiometry, TEOAE and other tests and combinations of tests. The overall conclusion was that evidence was of unacceptable variability in terms of methodological quality and study characteristics and, as a result, drawing strong conclusions about the performance of different tests was not possible.

With those caveats taken into account and including only the subset of studies that used PTA as a reference standard, the findings from the 2007 HTA report suggested that: sweep PTA had high sensitivity and specificity; spoken word tests had acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity; TEOAE had high specificity but somewhat lower sensitivity; tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry had variable sensitivity and specificity; parental questionnaires and otoscopy had poor sensitivity and specificity; and there was insufficient evidence to comment on the accuracy of combinations of tests (p. 48).

Combining the results from the 2007 Health Technology Assessment report and the current update

The studies identified in the current update provide additional test accuracy data for the following three categories of tests evaluated in the original HTA review: parental questionnaires, sweep PTA tests and TEOAE. Below we discuss the combined evidence from the two sets of studies for each category of tests.

Parental questionnaires

In the 2007 HTA report12 three studies33–35 examined the accuracy of parental questionnaires and reported sensitivities ranging from 34% to 71% and specificities ranging from 52% to 95%. In the update we included four studies22–25 evaluating questionnaires that reported sensitivities and specificities in the range of 44–100% and 55–87%, respectively (Table 5). As none of them used a prespecified positivity threshold, the reported test accuracy estimates are likely to be overoptimistic and the performance of the evaluated questionnaires worse when applied in practice. The study by Newton et al. 24 reported very high sensitivity but the definition of hearing impairment was very restrictive and may not be appropriate for most circumstances. Taking into account the methodological limitations of the studies and the marked heterogeneity in their results, the combined evidence from the original 2007 HTA report and the current update suggest that, on the whole, parental questionnaires have poor diagnostic accuracy and may not be suitable for mass screening, especially in the context of established UNHS and sensitised educational and health-care systems.

| Report | Study | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current update | Bu et al., 200522 | 56 (30 to 80) | 60 (54 to 66) |

| Li et al., 200923 | 67 (38 to 88) | 55 (46 to 63) | |

| Newton et al., 200124 | 100 (75 to 100) | 75 (71 to 78) | |

| Samelli et al., 201125 | 44 (34 to 54) | 87 (79 to 92) | |

| 2007 HTA report12 | Gomes and Lichtig, 200533 | 71 (n/a) | 64 (n/a) |

| Olusanya, 200134 | 34 (n/a) | 95 (n/a) | |

| Hammond et al., 199735 | 56 (n/a) | 52 (n/a) |

Audiometry-based tests

Five evaluations reported in four studies36–39 included in the original 2007 HTA report and three17,27,30 in the current update evaluated the accuracy of audiometry-based tests. The original five studies, all assessing pure-tone sweep devices, reported sensitivities ranging from 86% to 100% and specificities from 65% to 99%. The three studies in the update reported sensitivities in the range of 23% to 78% and specificities 92% to 97% (Table 6). McPherson et al. ,30 achieved high specificity (92%) only after the results from the 0.5 kHz frequency were excluded from the analysis. This was a post-hoc decision made to reduce the interference from background noise. With this caveat noted, the new studies reported higher and more consistent specificity but lower and widely varying sensitivity estimates compared with the original studies. When combined, the results from the two sets of studies are more difficult to interpret, as there is a marked heterogeneity in both sensitivity and specificity. However, given the gap of > 10 years between the two sets of studies and the technical differences between the evaluated devices, it might be more reasonable to interpret the results from the new studies separately instead of combining them with those from the 2007 HTA review. 12

| Report | Study | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current update | Gloria-Cruz et al., 201317 | 23 (11 to 39) | 97 (96 to 98) |

| McPherson et al., 201030 | 78 (40 to 97)a | 92 (83 to 97) | |

| Wu et al., 201427 | 38 (15 to 65) | 93 (89 to 95) | |

| 2007 HTA report12 | Sabo et al., 200036 | 87 (n/a) | 80 (n/a) |

| Orlando and Frank, 198737 | Range 82–100b | Range 65–90b | |

| Orlando and Frank, 198737 | Range 91–100b | Range 97–98b | |

| FitzZaland and Zink, 198438 | 93 (n/a) | 99 (n/a) | |

| Holtby et al., 199739 | 86 (n/a) | 70 (n/a) |

Transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions

Only two of the studies included in the original 2007 HTA report12 evaluated the accuracy of TEOAE. 36,40 The first reported sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 91%, and the second one reported sensitivities ranging from 67% to 100% and specificities from 80% to 98% depending on the ‘refer’ criterion used. In comparison, three studies22,28,29 were included in the current update, reporting sensitivities from 75% to 100% and specificities from 64% to 98%. Table 7 illustrates the heterogeneity in the results. Although the new studies reported higher sensitivities, the CIs were very wide, indicating considerable statistical uncertainty. With the exception of Georgalas et al. 29 the specificity estimates across all studies were higher and more consistent, suggesting a relatively low false-positive rate. We could not identify obvious reasons for the low specificity reported by Georgalas et al. 29 However, this was a small, poorly reported study with considerable methodological limitations (total quality score = 8) and its results should be interpreted with caution.

| Report | Study | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current update | Bu et al., 200522 | 75 (48 to 93) | 98 (96 to 99) |

| Georgalas et al., 200829 | 90 (55 to 100) | 64 (53 to 75) | |

| Yin et al., 200928 | 100 (3 to 100) | 94 (89 to 97) | |

| 2007 HTA report12 | Sabo et al., 200036 | 63 (n/a) | 91 (n/a) |

| Nozza et al., 199740 | 67–100 (n/a) | 80–98 (n/a) |

Other tests

None of the studies included in the original HTA report assessed the accuracy of AABR and none of the studies included in the update assessed the accuracy of spoken word tests, otoscopy, the audiometric Rinne test and reflectometry. Although one study29 evaluated the accuracy of tympanometry in combination with TEOAE it reported results only for TEOAE as adding tympanometry had failed to improve performance.

Conclusion

This updated review confirms the conclusion from the 2007 HTA report12 that, because of a marked variability in the design, methodological quality and the results of the existing studies, it is not possible to draw strong conclusions about the performance of individual test types for use in SES.

Moreover, there were significant differences in the technical characteristics of some of the evaluated devices even when they belonged to the same screening modality (e.g. in the audiometry-based category there were two computer-based devices, one of which involves joysticks, etc., to help children respond, whereas the third one was a hand-held device). This is not surprising given that the studies included in the 2007 HTA and the current update span a period of 30 years. Interpreting their results together, even in the context of a narrative synthesis, requires careful consideration of the differences between the evaluated tests, which, in some cases, might be too great to justify such an approach. Combining the results from more modern devices with those from older ones and making general conclusions based on all the studies included in a particular category may be inappropriate. The performance of currently available tests is of interest to policy-makers.

With these caveats in mind, the findings from the current update, interpreted in the context of the 2007 HTA report,12 could be summarised as follows:

-

We were able to identify a limited number of studies that provided additional diagnostic accuracy data for only the following categories of hearing screening tests: parental questionnaires, audiometry-based tests, TEOAE and AABR. No studies evaluating AABR were included in the 2007 HTA report. 12

-

Questionnaires had the poorest diagnostic accuracy compared with all other tests. The only study that directly compared a questionnaire with another test (TEOAE) supported this finding. 22

-

Audiometry-based tests had high specificity but variable sensitivity.

-

Studies evaluating TEOAE reported variable sensitivity with wide CIs, whereas specificity estimates were relatively high and more consistent (with the exception of one study). 29

-

The study evaluating AABR reported high sensitivity and specificity.

The majority of the studies were conducted in countries without an established UNHS system and with variable health-care arrangements and, therefore, the reported results may have limited applicability to the UK context characterised with a well-established UNHS system, sensitised educational system and highly accessible and responsive health care.

Chapter 3 Diagnostic accuracy of the pure-tone screen and HearCheck screener for identifying hearing impairment in school children

Introduction

In the survey of practice reported in the 2007 HTA report12 the test used for the hearing screen was in all cases the PTS but there was a wide variety of implementations of this, with different frequencies, pass criteria and retest protocols. Studies concerned with the relative accuracy (in terms of sensitivity and specificity) of alternative screening tests are difficult to compare and often flawed by their use of different referral criteria and case definitions. As reviewed in Chapter 2, the 2007 HTA report12 identified 25 publications reporting comparative trials of alternative screens or tests for screening at school entry. Most studies were undertaken in populations where the prevalence of undetected hearing impairment was considerably greater than that likely to be encountered in a system where a UNHS programme has been introduced. These published data indicate that, using full PTA as the reference standard, the PTS test appears to have high sensitivity and high specificity for minimal, mild and greater hearing impairments; better than alternative tests for which evidence was identified. Spoken word tests were reported with acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity but are variable in their implementation. OAEs, tympanometry, acoustic reflectometry, parental questionnaires and otoscopy were reported, with either variable or poor accuracy.

A new device, the HC screener, came onto the market in 2005 as a tool for screening for hearing impairment in adults in a general practice setting. It is hand held and has an automatic presentation of a series of tones at two frequencies and three levels: 1 kHz at 55, 35 and 20 dB HL, and 3 kHz at 75, 55 and 35 dB HL. It has potential to be a quicker test in the school setting but it has not previously been assessed as a tool for screening in children.

Objectives

In this chapter we use a two-gate case–control design32 to:

-

estimate the diagnostic accuracy of the PTS and HC tests for discriminating between children with a hearing impairment (of any type) and children with no hearing impairment, using PTA results as the reference standard

-

compare the diagnostic accuracy between the PTS and HC methods.

Measures of diagnostic accuracy are reported at the level of the ear and at the level of the child. From the outset we considered the ear-level analysis to be primary to the objectives addressed in this chapter because it directly addresses the question of the accuracy of the tests for discriminating between hearing and impaired ears. The child-level accuracy estimates are more relevant, however, for informing the refinement of the existing economic model of the benefits of a SES programme, reported in Chapter 8.

Methods

Design

This study used a directly comparative two-gate (‘case–control’) design,32 with separate sources (gates) used to recruit those with the target condition (hearing impairment – cases) and those without (no hearing impairment – controls). Case children were recruited through audiology services in England whereas the control children were recruited largely from Nottinghamshire primary schools. The implications of this are discussed later in this chapter (see Discussion).

Recruitment

Cases were children aged 4–6 years recruited between February 2013 and August 2014 who were identified by collaborating audiology services [in Nottingham, Sheffield, Leicester (City and County), Chesterfield, Derby, Mansfield, Lincoln, Birmingham, Huntingdon, Bradford, Rotherham and Doncaster] and who had permanent sensorineural or conductive hearing impairment averaged across the four frequencies 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz, either bilaterally (average of 20–60 dB HL) or unilaterally (any level ≥ 20 dB HL). The senior paediatric audiologist in each centre drew up a list of all children meeting the definition criteria. Audiologists were given stamped envelopes to address and post to potential participants and agreed together with the researchers when to send the letters. Each identified family was sent a letter on behalf of the research team inviting them to take part in the study, together with information about the study. Children were not invited to take part if they were unwell such that their illness would affect the results of the tests or if the responsible audiologist felt it would be inappropriate or cause added unnecessary burden (e.g. seriously or terminally ill family member). Parents willing to take part replied directly to the research team. Eligible children for whom agreement was provided to take part were invited to undergo the two screening tests, either in their own homes, or at Nottingham Hearing Biomedical Research Unit (NHBRU), depending on their preference. Researchers sent holding letters if necessary for children < 4 years old, explaining that an appointment would be made for them after their fourth birthday. The reference standard definition of hearing impairment was based on PTA results, thus case children were also excluded if there was no record of a PTA in the previous 12 months or planned for the following 3 months, and if the family was unwilling to travel to their local service or to Nottingham to undergo the assessment.

Control children, defined as having no previously identified hearing impairment, were recruited from the Foundation Year and Year 1 of schools in the Nottingham area, between February 2013 and June 2014. The study researchers provided a letter of invitation and information pack for the school to distribute to all parents of children in the aforementioned year groups; invitation methods were agreed with the school. Children for whom agreement to take part was provided were invited to undergo the two screening tests and a PTA at NHBRU. Children needed to have the PTA measured in a soundproofed room, and hence the option to have the screening test at home was not possible.

To help ensure that the cases and controls were representative of the sources from which they were drawn, the audiologists and researchers were advised to not just pick those whom they thought might be easy to test. For all children the invitation pack contained an invitation letter, a one-page summary information sheet, a pictorial information sheet for the children and a pre-paid return envelope. Full participant information sheets were sent to the parent (either via e-mail or post) once an appointment was made (see Appendix 3) (the full sheet was originally included in the invitation pack, but a revision was made in December 2013, to be less overwhelming for the parent and to save paper).

Parents of all children involved were offered the opportunity to receive a short summary of the findings at the end of the study. A £20 book token (revised from £10 after 7 months of recruitment in an attempt to improve recruitment) was given to each child as a thank you for his/her time and inconvenience. Travel expenses to NHBRU were reimbursed in line with University of Nottingham standard policy. Schools that participated in the recruitment of control children were entered into a prize draw with a chance to win £100.

Assessment

Once a reply slip was received, the researcher contacted the parent (via telephone, e-mail or letter) to make an appointment either at NHBRU (case and control children) or at their home (case children only). They were also asked about access issues or translator needs. Parents were usually reminded about the appointment by telephone or e-mail on the day prior to the appointment. After case children had their appointment, the researcher phoned the audiologist, asking them to post their most recent PTA results to NHBRU. This could be a PTA measured in the previous 12 months or one that is scheduled to be measured in the following 3 months.

For all appointments the researcher checked that the parent had all the study information, explained what would happen at the appointment and how that fitted into the project, and answered any questions they might have. The consent form was explained and written consent obtained. The researcher emphasised that participation was voluntary and consent regarding the child’s participation in the project could be withdrawn at any time without penalty or affecting the quality or quantity of the child’s future medical care, or loss of benefits to which the child and his/her family was otherwise entitled. It was explained that in the event of withdrawal, their data collected so far could not be erased and that consent would be sought to use the data in the final analyses where appropriate. The informed consent form was signed and dated by the parent or legal guardian and researcher before the child entered the study – usually at the start of the screening appointment. Copies of the consent form were kept by the parent or legal guardian, the researchers, and, for case children only, in the child’s hospital records (see Appendix 3).

Data collection was planned prospectively in advance of administering the tests and reference standard to the children. Background details [visit date, school for control children, hospital for case children, date of birth, postcode, background sound level, gender, ethnicity, medical conditions on the day (including respiratory infections)] were recorded on the case report form (CRF) and testing was then administered.

The audiometer (used for the PTS testing for all children and for the PTA for control children) and HC device were checked each day, by listening to the tones at the testing frequencies, to ensure they were audible. Valid calibration was undertaken in the previous 12 months for the audiometer and sound level meter and in the previous 3 years for the HC screener according to manufacturers’ recommendations. Headphones were cleaned with a disinfectant wipe before each child was tested and new disposable cups were used for the HC screener. Items likely to cause noise (e.g. mobile phones, washing machines, televisions) were turned off where possible, and the level of background noise was measured with a sound level meter. Although, for control children, the door of the room in which the two screening tests were conducted was left open, and sometimes siblings were present, the ambient noise conditions were much quieter than rooms that are usually available in schools for conducting the hearing screen. For case children, where the screens were conducted at home, attempts were made to minimise the noise levels.

The researchers were trained in administering the PTA and PTS tests by the audiologists in the Children’s Hearing Assessment Centre (CHAC) in Nottingham, using a mixture of observation, practice with children and feedback. Further familiarisation with the equipment and procedures was gained by testing staff from the research department.

The order of administering the two screening tests and which researcher undertook them were each determined by separate lists based on computer-generated simple (unrestricted) random numbers. Each test was administered to both ears. For case children, one researcher performed the PTS and another researcher performed the HC screen. For control children, one researcher carried out both the screening tests and then another researcher performed the PTA measurement. An effort was made to blind the second researcher to the results of the first test(s) by asking them to leave the room. The PTA result for case children obtained from their audiologist (measured within 12 months before or 3 months after the study visit) was examined only after the result of the screening tests were known.

Screening tests

Pure-tone screen