Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/178/01. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The draft report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Aileen Clarke is Professor of Public Health and Health Services Research, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, UK, and the Warwick Medical School receive payment for this work. Aileen Clarke is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation editorial board. Ngianga-Bakwin Kandala and Aileen Clarke are also supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Auguste et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Overview

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Nearly one-third of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) [(Zopf 1883) Lehmann and Neumann 1896]; TB has an annual incidence of 9 million new cases and each year causes 2 million deaths annually worldwide. TB ranks as the second leading cause of death from an infectious disease. 1–3

In the UK, the prevalence of TB steadily decreased until the mid-1980s but has started to rise over the last 20 years, especially in ethnic minorities born in places with a high TB prevalence. 4,5 Between 1998 and 2009, annual TB notifications in the UK rose by 44%, from 6167 to 8900 cases. 4,6 Since 2005, this rate has remained high, leading to projections that in 2 years there will be more TB cases in the UK than in the USA,7 thereby posing a major public health challenge. The re-emergence has been largely driven by recently arriving immigrants in whom latent infection has been reactivated or who have acquired new infection as a result of their maintaining links with high-prevalence countries.

Aetiology and pathology of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis infection is transmitted to a healthy person through the air by inhaling respiratory fluids/sputum droplets containing MTB discharged by a person with active TB. The infected sputum droplets can dry and form into droplet nuclei, which can float in the air for a long period of time and penetrate the host. 8 TB can be transmitted through other routes including ingestion (e.g. from drinking unpasteurised cow’s milk)9 and inoculation (e.g. Prosector’s wart), although such cases are rare in the UK.

Once the bacteria are inhaled, the droplet nuclei travel through the mouth or nasal passages to the upper respiratory tract, bronchi and finally the alveoli of the lungs. The bacteria grow slowly and multiply in the alveoli over several weeks. Sometimes a small number of tubercle bacilli enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body such as to the bones, lymph nodes or brain. 8 In > 80% of cases the immune system kills and removes the bacteria from the body. 10 If the immune system does not kill the bacteria, macrophages within the immune system ingest and surround the tubercle bacilli within 2–8 weeks. The cells form a barrier shell that keeps the bacteria suppressed and under control, resulting in latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). Individuals with LTBI do not exhibit any clinical, radiological or bacteriological evidence of the pathogen. They are not infectious and may remain asymptomatic. 11 However, the latent infection may reactivate later in life, causing the individual to develop symptoms and become infectious. It has been estimated that people with LTBI are at 5–10% risk for developing active TB during their lifetime. 12,13 Therefore, this large pool of LTBI is an important reservoir of infection. 8,12

If the immune system cannot keep the bacteria suppressed or the barrier fails later, the bacilli begin to multiply and the individual develops active TB disease. Individuals who have active TB are infectious and each can spread MTB to up to 10–15 close contacts within a year. 14 The pathogen affects primarily the lungs (pulmonary TB) but can also involve other organs of the body (extrapulmonary TB). In the UK in 2012, pulmonary TB accounted for about 53% of all TB cases. 5

The period between infection and first signs of illness (incubation period) varies between 8 weeks and decades. The greatest chance of progressing to disease is within the first 2 years after infection, when approximately 50% of the 5–10% lifetime risk occurs. 15 The risk of infection and progression to active TB disease depends mostly on the host’s immune function as well as on the duration and proximity of exposure to a source afflicted with active MTB. 16 Therefore, certain population groups have a higher lifetime risk of developing TB. These vulnerable groups with low immunity and/or high exposure include long-term care facility workers, people born in or coming from countries with a high prevalence of TB, infants, children, those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), people with close contacts suspected of having active TB or those living in confined facilities (e.g. prison, homeless shelters). 5 These groups are particularly important as a reservoir of latent infection that could reactivate, and explain the trends observed for TB in the UK. 17

Active tuberculosis

When infection with MTB becomes active TB disease, the symptoms that occur are non-specific and depend on the site of TB infection. 18,19 Common signs and symptoms of active pulmonary TB may include a chronic cough for weeks or months accompanied by the coughing up of blood or blood-stricken mucus, pain in the chest, weight loss, intermittent fever and/or night sweats, poor appetite, chills, weakness or fatigue, and listlessness. 1,18,20 The clinical diagnosis of TB is based on TB-characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, chest radiography and microscopy of tissue biopsy or sputum samples. A definitive diagnosis of TB, however, is made through the identification of MTB in clinical samples (e.g. pus, tissue biopsy, sputum) using culture. 21,22 TB is difficult to culture and it takes several weeks to obtain a definitive result.

Tuberculosis is a curable disease; however, treatment is long and requires adherence, even through the side effects of treatment. 23 In the UK, most MTB infections are sensitive to the antibiotics used. 10 The routine management of active pulmonary TB includes a combination of antibiotics (e.g. isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) given over 6 months. 18 Although patients start to feel better after 2 months of treatment and are not infectious any longer, it is vital that they complete their treatment. 24,25 This ensures that the TB bacteria are completely killed off, preventing the return of symptoms and the risk of bacteria becoming drug resistant. Treatment of drug-resistant forms of TB is less effective, requires longer than 6 months and causes greater side effects. 10,26

Measurement of latent tuberculosis infection

Unfortunately, there is no diagnostic gold standard for the identification of individuals with LTBI. Instead, the available screening tests for LTBI provide an indirect assessment of the presence of LTBI by relying on a host’s immunological response to TB antigens. 27 In addition, none of the available LTBI tests can accurately differentiate between people with LTBI and people with active TB. 11

There are two types of commercially available tests used to identify LTBI in the UK: (1) the tuberculin skin test (TST) and (2) the interferon gamma (IFN-γ) release assays (IGRAs). 5 Until recently, the TST (introduced by Mantoux in 1907) has been the only standard test used for the identification of LTBI. 13 The administration of the TST involves an intradermal injection of purified protein derivative (PPD) in the forearm. The immune response (i.e. delayed hypersensitivity caused by T cells) to the TST is determined 48–72 hours after the injection by measuring the transverse diameter (in mm) of skin induration. 13,16 There is no international agreement on cut-off values for the definition of a positive tuberculin reaction. 12 The choice among commonly used cut-off values (e.g. a diameter of induration of ≥ 5 mm, ≥ 10 mm or ≥ 15 mm) depends on an individual’s risk factor profile for TB. Usually, a lower cut-off value of ≥ 5 mm is used for individuals at higher risk of TB (e.g. patients with organ transplants, immunocompromised patients, patients with HIV infection and those who have had recent contacts with an active TB patient) and a higher cut-off value of ≥ 10 mm is applied for individuals at lower risk of TB (e.g. high-risk racial minorities, children, recently arrived immigrants from high-prevalence countries and patients with diabetes, malignancies or renal failure). 16 The administration of the TST is relatively cheap and does not require a laboratory, but it does require a skilled operator.

Interferon gamma release assays have been recently developed as alternative screening tests for LTBI. There are two types of IGRA: QuantiFERON®-TB Gold-in-Tube (QFT-GIT) [old version: QuantiFERON®-TB Gold (QFT-G)] (Cellestis/Qiagen, Carnegie, Australia) and T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, UK). Both tests are commercially available in the UK. The QFT test is a whole-blood test based on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay whereas the T-SPOT. TB test uses peripheral blood mononuclear cells and is based on an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. 11 Both tests measure the cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell-released IFN-γ response to MTB-specific antigens [early secretion antigen target 6 (ESAT-6), culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) and tb7.7] in in vitro blood samples. 12,13,16

Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection

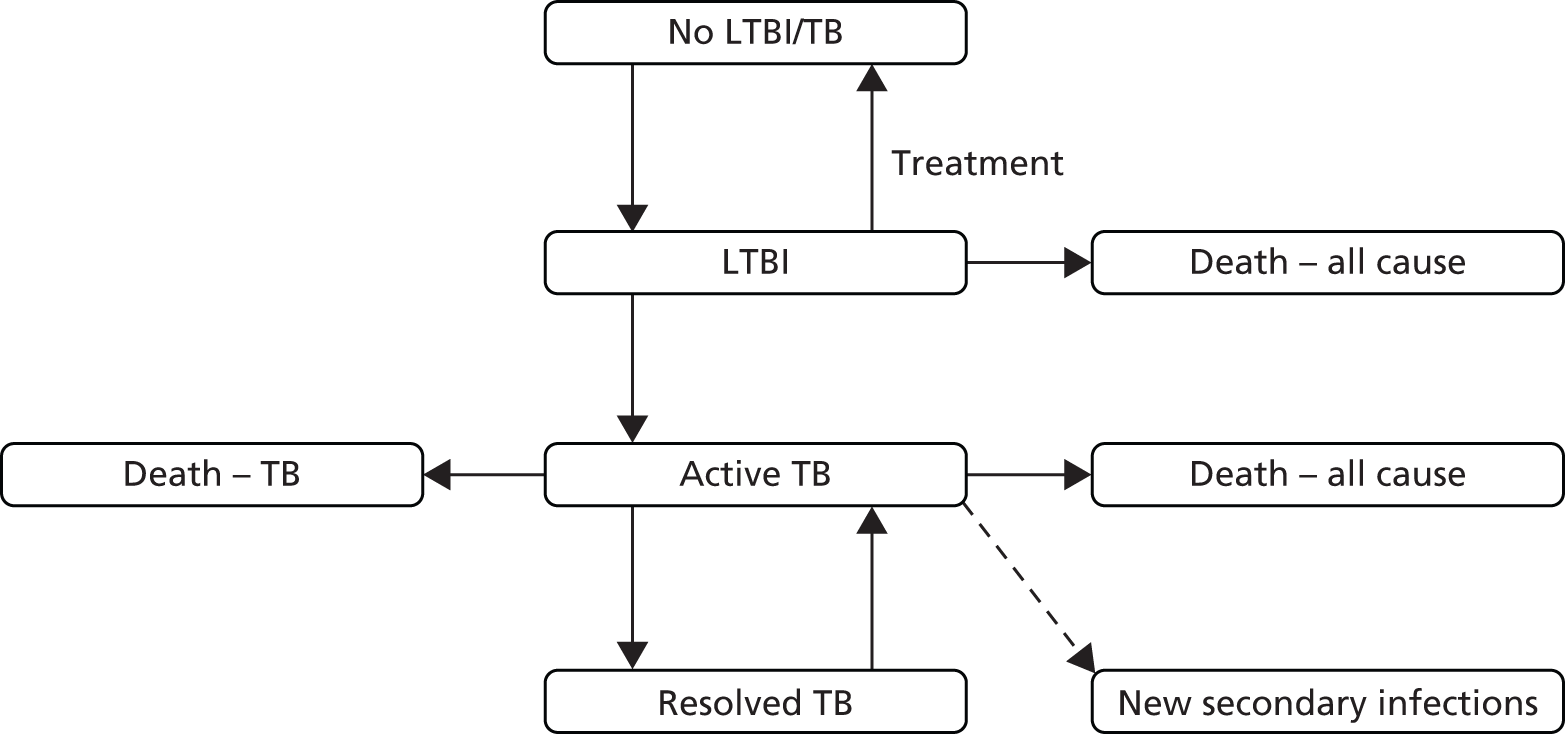

The aim of LTBI treatment is to prevent MTB bacteria from developing into active TB disease. Before treatment, all individuals found to have LTBI need to be tested for active TB. For individuals in whom active TB is ruled out, the prophylactic treatment of choice is isoniazid. For adults and children, the treatment should be given for between 3 and 6 months depending on the treatment regime. For individuals affected by HIV, treatment is given for 6 months. Rifampicin given for 4 months is the second-line treatment that can be used as an alternative in individuals who are resistant to isoniazid or at high risk of side effects from isoniazid. 16

Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology

All forms of active TB are legally notifiable by the physician making or suspecting the diagnosis under the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 198428 in England and Wales. It first became a statutory requirement to notify TB cases in 1913. Known as the Notifications of Infectious Diseases system, it continues to play a valuable role in the surveillance of TB; however, the information collected is limited and trends within subgroups of the population cannot be monitored. 29

In 1999, the Enhanced Tuberculosis Surveillance system was established to collect more detailed information on annual TB cases, including patient age, sex, ethnic group, country of birth, site of disease, NHS region and treatment outcomes. It has been reported that the Enhanced Tuberculosis Surveillance system reflects the true incidence of TB better than the Notifications of Infectious Diseases system as many measures are used to ensure that quality standards are met annually, thereby providing a corrected analysis of TB cases. 30 In 2012, completeness of data was 100% for mandatory fields and approximately 91% across other key fields for England and 89% for Wales. 5 This system provides the most comprehensive, timely and accurate information on active TB incidence in the UK29 and is therefore robust.

There is no national system that collects data for LTBI. For this reason there are no robust data for LTBI, although we can predict that for every person with active TB there are likely to be several with undiagnosed LTBI. Therefore, it seems reasonable to extrapolate from active TB and make the assumption that LTBI will follow a similar epidemiological pattern.

The rates of active TB peaked during the early 1900s with an annual incidence rate of approximately 320 per 100,000. The rate declined dramatically until at least 1987 to as low as 10.1 per 100,000 population per year. However, since the 1980s, the incidence rate began reversing and has reached highs of between 13.6 and 14.4 per 100,000 since 2005. 5 The most recent figures in 2012 report a total of 8751 active TB cases across the UK, giving an incidence rate of 13.9 per 100,000. 5 The burden of TB is highest in England, where in 2012 there were 8130 cases of active TB, a rate of 15.2 per 100,000; in Wales there were 136 active TB cases, a rate of 4.4 per 100,000. 5 Between 2010 and 2011, a total of 436 people died of TB in the UK. 5

Place of birth and ethnic minorities

The re-emergence of TB has been attributed to international migration, as recently arriving migrants have accounted for the majority of TB cases since 2000. In 2011 and 2012, foreign-born individuals accounted for 73% of reported TB cases. 5 It has been reported that there has been a 98% increase in the number of TB cases in individuals born overseas. 4,6,31 The rate of TB among the non-UK-born population is 80 per 100,000, which is almost 20 times the rate in the UK-born population. Almost half of the patients born outside the UK were diagnosed within 5 years of coming to the UK, with another 30% diagnosed within 2 years. 5 In total, 60% of foreign-born patients originated from South Asia, followed by 22% from sub-Saharan Africa. With respect to country of origin of foreign-born patients, the highest proportions are from India (31%), Pakistan (18%) and Somalia (6%). Similarly, a higher proportion of non-UK-born patients (> 50%) than UK-born patients (31%) present with extrapulmonary TB. 32

Among UK-born individuals, the highest rate of TB is found in ethnic minority groups. The largest proportions of cases are found in those of Indian (27%, 2296/8525), white (21%, 1814/8525) and Pakistani (17%, 1418/8525) ethnic origin. The highest rates of TB per 100,000 population are found in Indian, Pakistani and black ethnic groups (155, 132 and 97 per 100,000, respectively). 5 It has been indicated that recently arriving immigrants and ethnic minorities are vulnerable as a result of reactivation of latent infection once in the country or acquiring new infection as a result of their maintaining links with high-prevalence countries (e.g. they may visit rural Pakistan or they may have relatives from high-prevalence areas visit them). 33 In addition, having diabetes increases the likelihood of reactivation of TB, and diabetes is more common in individuals from South-East Asia, including the ethnic groups highlighted above. 34

Geographical difference

Since the establishment of the enhanced TB surveillance system, it has become clear that there is a drastic regional variation in the burden of TB. Active TB is highly concentrated in large cities, with London consistently accounting for the highest rates and sharpest increases since the early 1990s. In 2012, London accounted for almost 40% of all TB cases, with an annual rate of 41.8 per 100,000. London has the highest TB rate among all high-income European countries. 35,36 London is followed by the West Midlands, which accounts for 12% of the burden and has an annual rate of 19.3 per 100,000. 5 Both London and the West Midlands have high rates of immigration. 37

Within London there is great variation between boroughs. Twelve of the 33 local authorities have an annual incidence rate of 40 per 100,000. The boroughs with the highest annual incidence rates of TB are Newham (122 per 100,000) and Brent (100 per 100,000). However, other boroughs, such as Havering and Richmond-upon-Thames, have an annual incidence rate of < 10 per 100,000. 38 Similar to regional variation, borough variation within London may reflect demographic characteristics as Newham and Brent have some of the highest rates of immigrants and ethnic minorities. 39

A similar picture is seen in Birmingham. Annual incidence rates for Birmingham as a whole fluctuated between 33.7 and 44.8 cases per 100,000 between 2009 and 2013. In the fourth quarter of 2013, Sandwell and West Birmingham Clinical Commissioning Group had an annual incidence rate of 49.6 per 100,000 [95% confidence interval (CI) 43.5 per 100,000 to 56.4 per 100,000] whereas in Solihull it was 1.9 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.5 per 100,000 to 4.9 per 100,000). Again, this reflects the ethnic make-up of the areas [Helen Bagnall, Public Health England (PHE), West Midlands, May 2014, personal communication].

Age differences

The majority of patients with TB (60%) are aged between 15 and 44 years, followed by patients aged 45–64 years (21%) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (14%). The groups with the lowest rates of TB are those aged 5–14 years (3%) and those aged < 5 years (2%). Although children have a low burden of overall TB cases, once TB is transmitted to them they are more likely than adult hosts to develop active TB. Most cases in those aged 0–14 years are in the UK-born population from black African, Pakistani and white ethnic groups. 5

Immunosuppression and tuberculosis

In addition to young children, the risk of progression from LTBI to active TB is higher in people coinfected with HIV, patients immunocompromised because of comorbidity (e.g. diabetes, malignancy, renal disease) and/or people with long-term use of immunosuppressant medications [e.g. corticosteroids, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antagonists]. 11,16,40 Coinfection with HIV and TB has been internationally well documented. 41–43 In the UK there has been a decrease in the number of coinfected HIV–TB cases, from 9% of TB cases in 2003/4 to 3.6% of TB cases in 2013. 5 This has been in line with the general downward trends in HIV and TB in migrants from sub-Saharan Africa. 32

Social risk factors

There are defined social factors that contribute to the burden of TB in the UK. These social risk factors include homelessness (2.4%), a history of imprisonment (2.8%), and drug (2.8%) and alcohol (3.2%) misuse. 5 It is indicated that approximately 7.7% of TB cases present with at least one of these risk factors. These social risk factors are more common in UK-born (13.4%) than foreign-born (5.4%) cases. Within UK-born cases, almost half with at least one risk factor (46%) are from the white ethnic group. 5

Impact of the health problem

Significance for patients

For the 5–10% of patients who develop active TB, those with pulmonary TB can suffer extreme pain from the symptoms for weeks to months. 44 Similarly, extrapulmonary TB can result in serious complications for the bones, brain, liver, kidneys and heart. 44 Tissue damage can be permanent if TB is not treated early. 45 As a result of tissue damage, active TB can be fatal. In addition to the impact on physical functioning, active TB can also have psychosocial impacts, in particular from the isolation experienced during the treatment of TB. This can include anxiety, depression, disorientation, feelings of loss of control and mood swings. 46,47 A diagnosis of TB can also bring related stigma through which individuals face social and economic consequences. 48

Treatment of active TB causes many side effects depending on the regimen prescribed. Some symptoms are mild but other side effects can be serious and potentially life-threatening. These can include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, abdominal pain, lower chest pain or heartburn, skin rash, bleeding gums and nose, blurred vision, ringing sounds, hearing loss, peripheral neuropathy and hepatotoxicity. 16 Individuals on antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection may suffer more side effects with certain TB drugs. These side effects cause poor adherence to treatment. If treatment is incomplete, active TB is more likely to be complex and drug-resistant and result in the need for treatments with greater side effects. 16,49 To avoid the consequences of the disease and the side effects of treatment, it would be easier for patients to undergo LTBI treatment and prevent active disease.

However, the treatment of LTBI uses the same medication, with the same side effects, albeit usually for a shorter period of time. Adherence to treatment is likely to be a factor as taking medicines when you feel well is much harder than taking them when you feel unwell.

Significance for the NHS

The impact of TB as a health problem is extensive. As TB possesses the capacity to spread through the air to practically anyone it is a serious public health threat, although, in practice, infection beyond family members or close contacts is unusual. TB is on the increase in the UK and is decreasing in the USA. It has been estimated that in 2–5 years the burden of TB in the UK will be higher than that in the whole of the USA. 7 Furthermore, drug-resistant TB is increasing in the UK, which means that transmission of drug-resistant strains of TB may continue to increase and complicate the fight against TB.

The health-care costs associated with active TB include the costs of diagnosing and treating pulmonary TB, extrapulmonary TB, multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB. In the UK, the normal cost of treating a case of active TB is £5000 but the cost of treating multidrug-resistant TB is between £50,000 and £70,000 and the cost of treating extensively drug-resistant TB can be up to £100,000. 35,50 Using 2012 figures, we have estimated that annually TB treatment could cost approximately £50M. Given that LTBI represents a reservoir of potential TB disease, it is important to identify and, if appropriate, treat people with LTBI to reduce the spread and burden of TB disease. 13,18

Current service provision

Management of latent tuberculosis infection

The goal of screening for LTBI is to identify individuals who are at high risk of developing active TB who would potentially benefit from prophylactic treatment. In the UK, LTBI screening is recommended for contacts of patients diagnosed with active TB and recently arrived migrants. Contacts include household contacts defined as those who share a bedroom, kitchen, bathroom or sitting room with the index active TB case, as well as boyfriends or girlfriends and frequent visitors to the home. Workplace associates in close proximity to a patient for extended periods may be judged to be household contacts; however, the majority of workplace contacts are not screened. Casual contacts should be assessed only if the index case is particularly infectious or the contact case is at increased risk from infection. Nevertheless, all contacts should be offered information and advice about TB. Similar risk assessments take place in schools, nurseries, institutions such as prisons and hospitals, and for aircraft passengers, leading to screening of those perceived to be at risk. 10,51

Active case finding is recommended for migrants who have recently arrived in the UK from countries with a TB incidence of ≥ 40 per 100,000. 10 Identification of new migrants is recommended from port of arrival reports, new registrations with primary care, entry to education and links with statutory or voluntary groups working with new migrants. Health-care professionals responsible for new migrant screening are advised to co-ordinate a programme to detect and treat active and latent TB, provide the bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination when appropriate and provide relevant referrals and information. Commissioners, NHS employees and providers of TB services, and other statutory and voluntary organisations, are particularly advised to identify and manage TB in hard-to-reach groups such as the homeless, substance misusers, prisoners and vulnerable migrants. 52

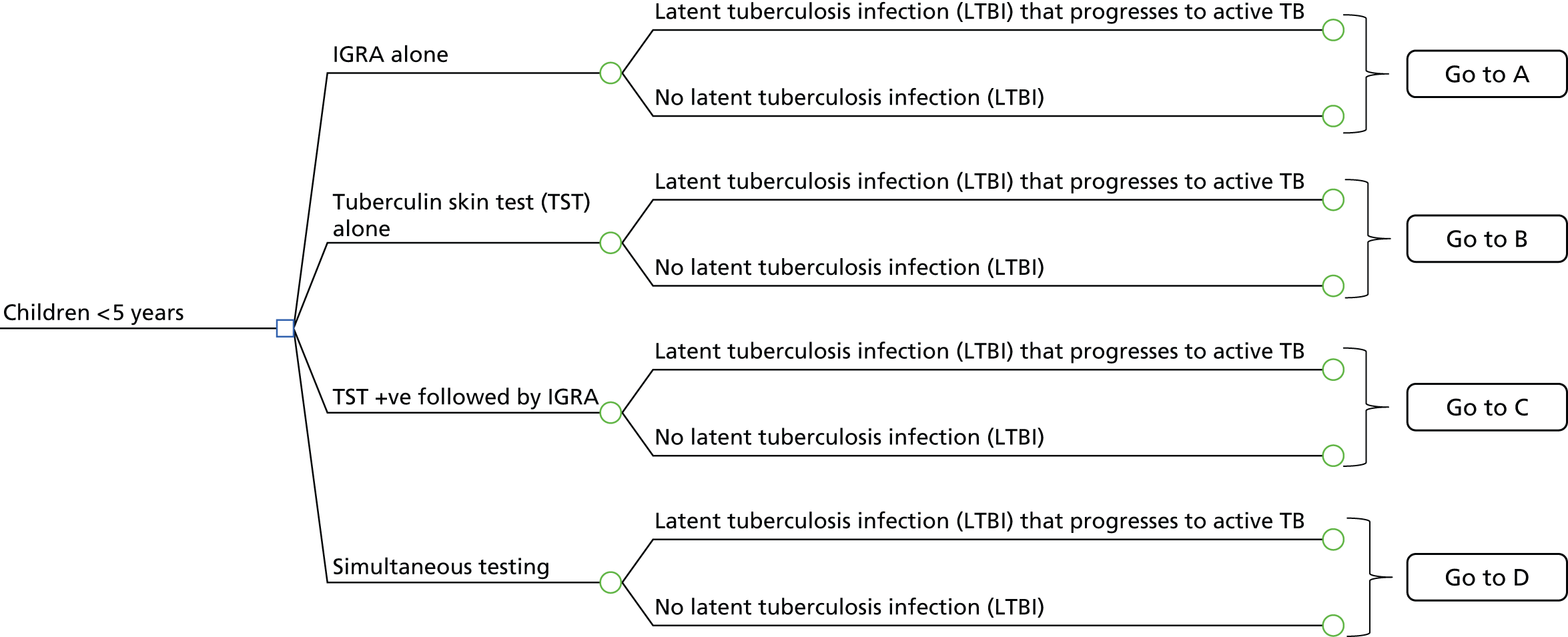

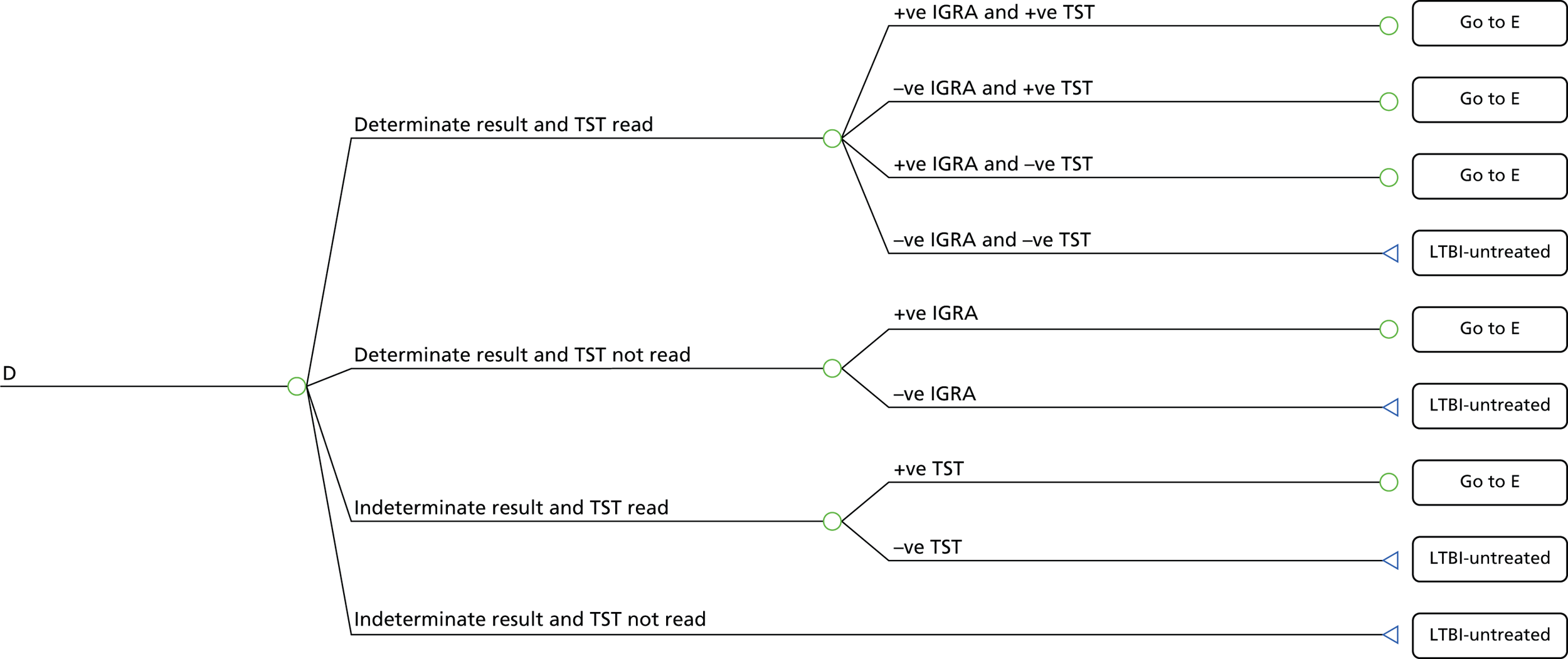

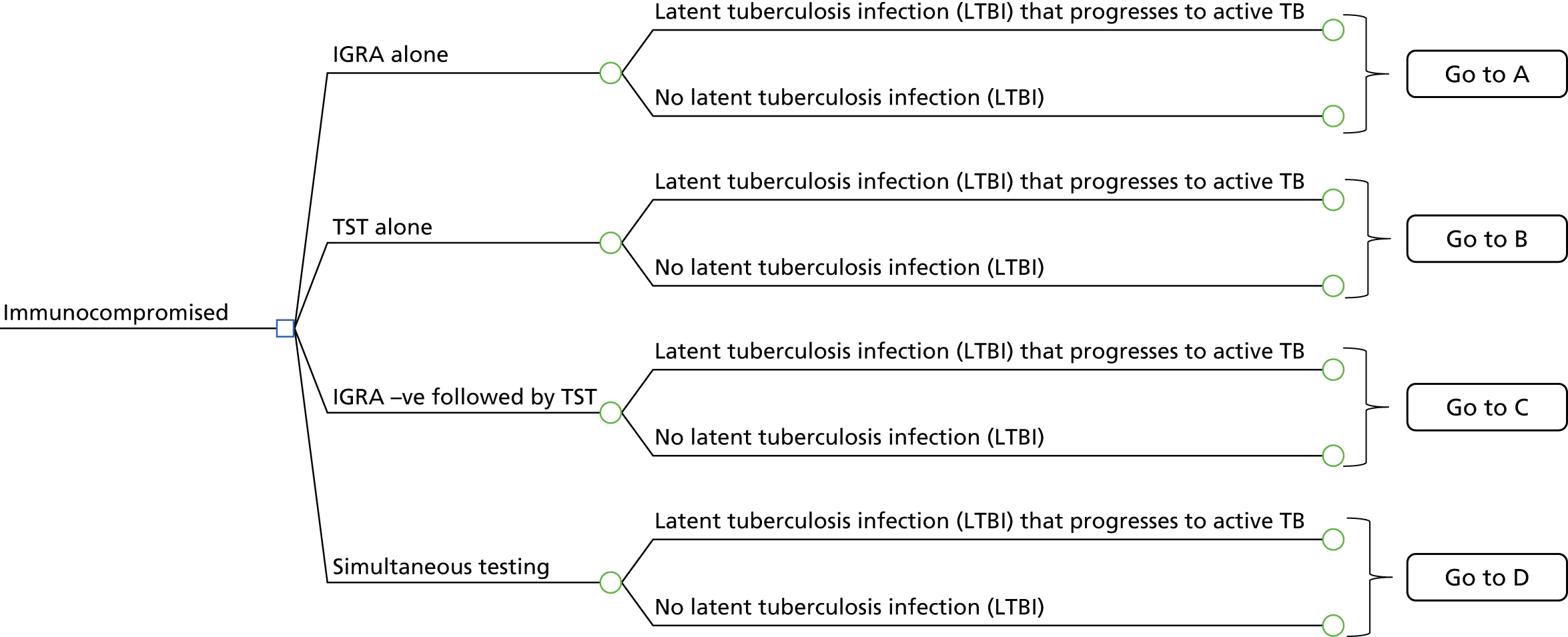

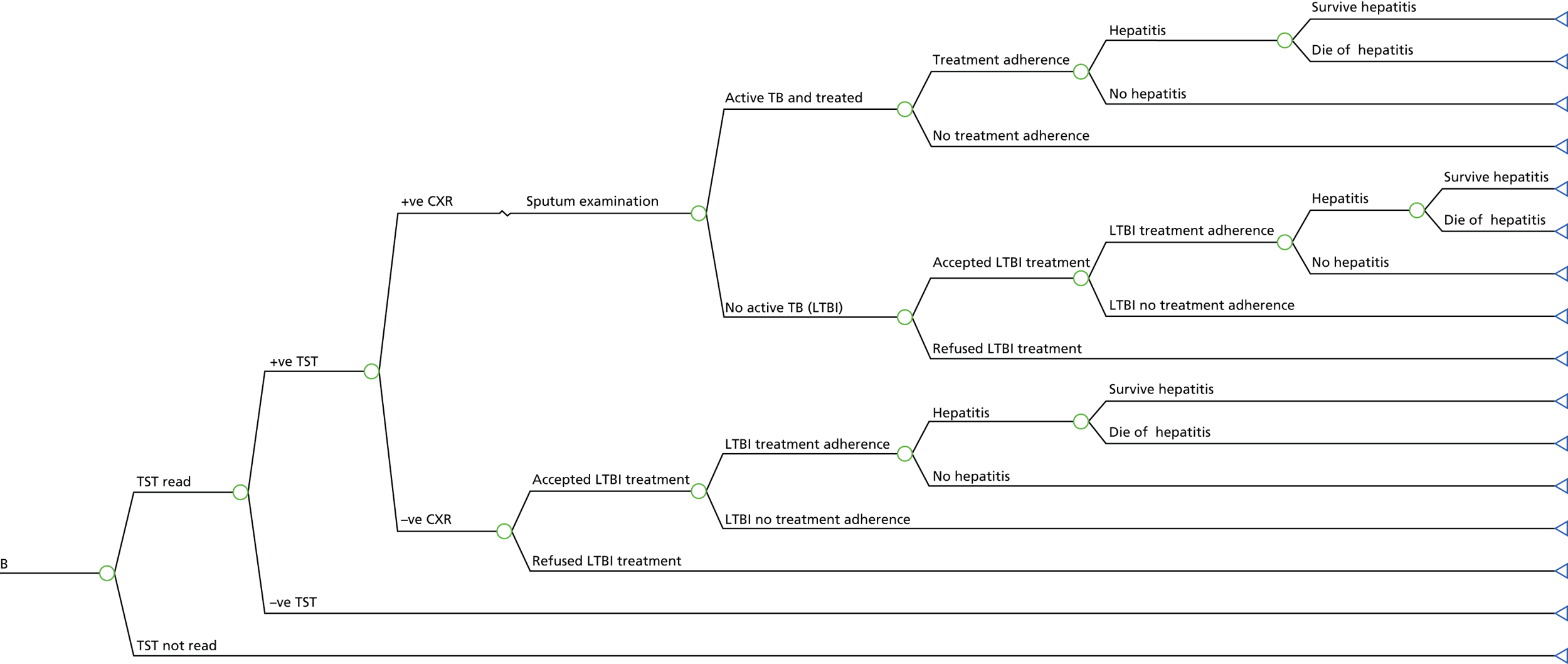

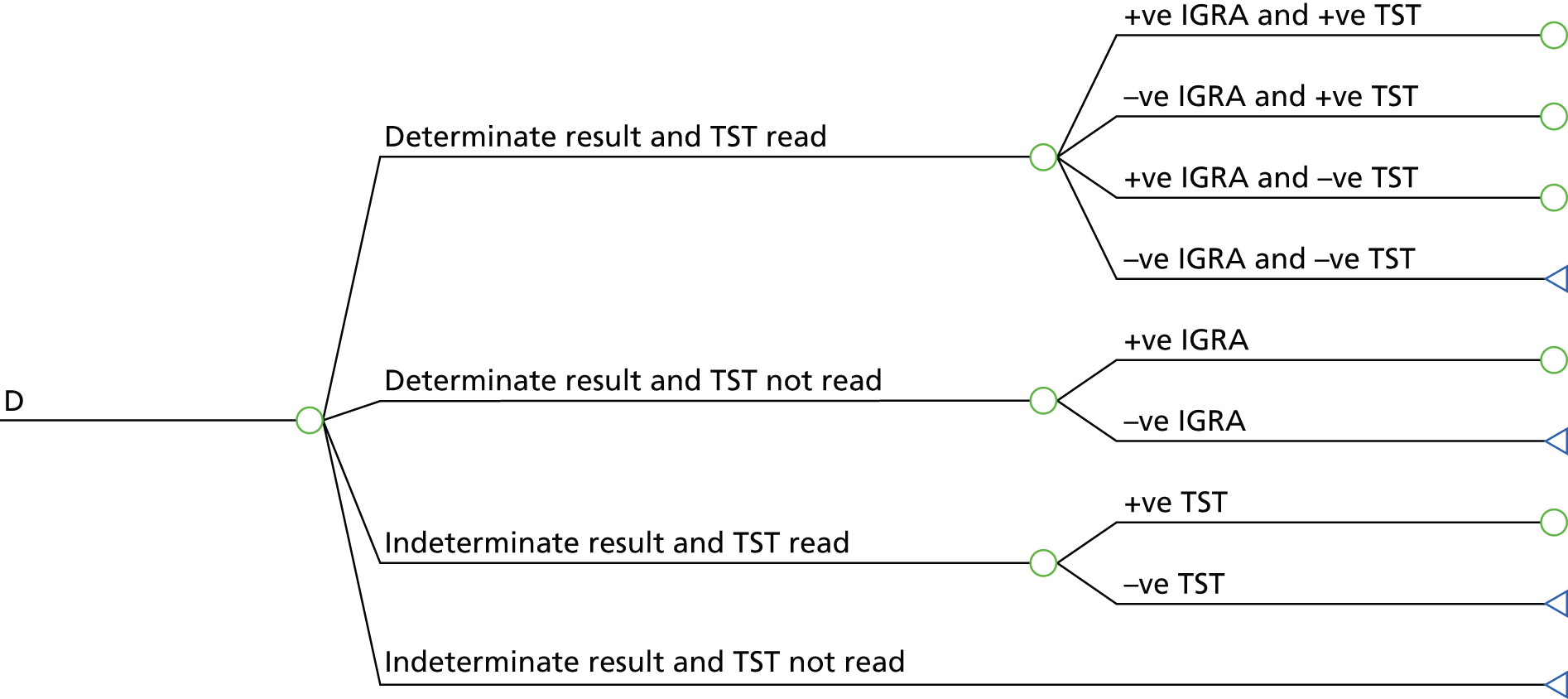

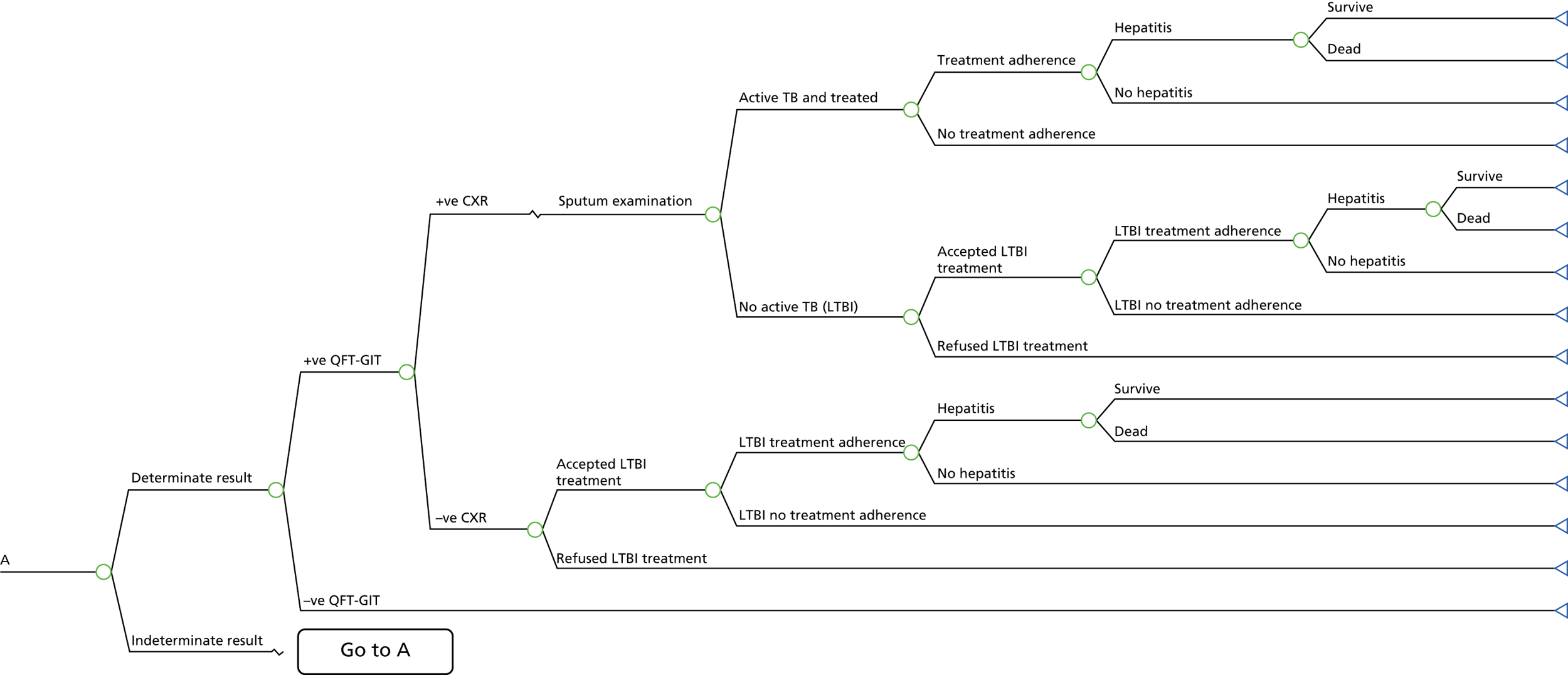

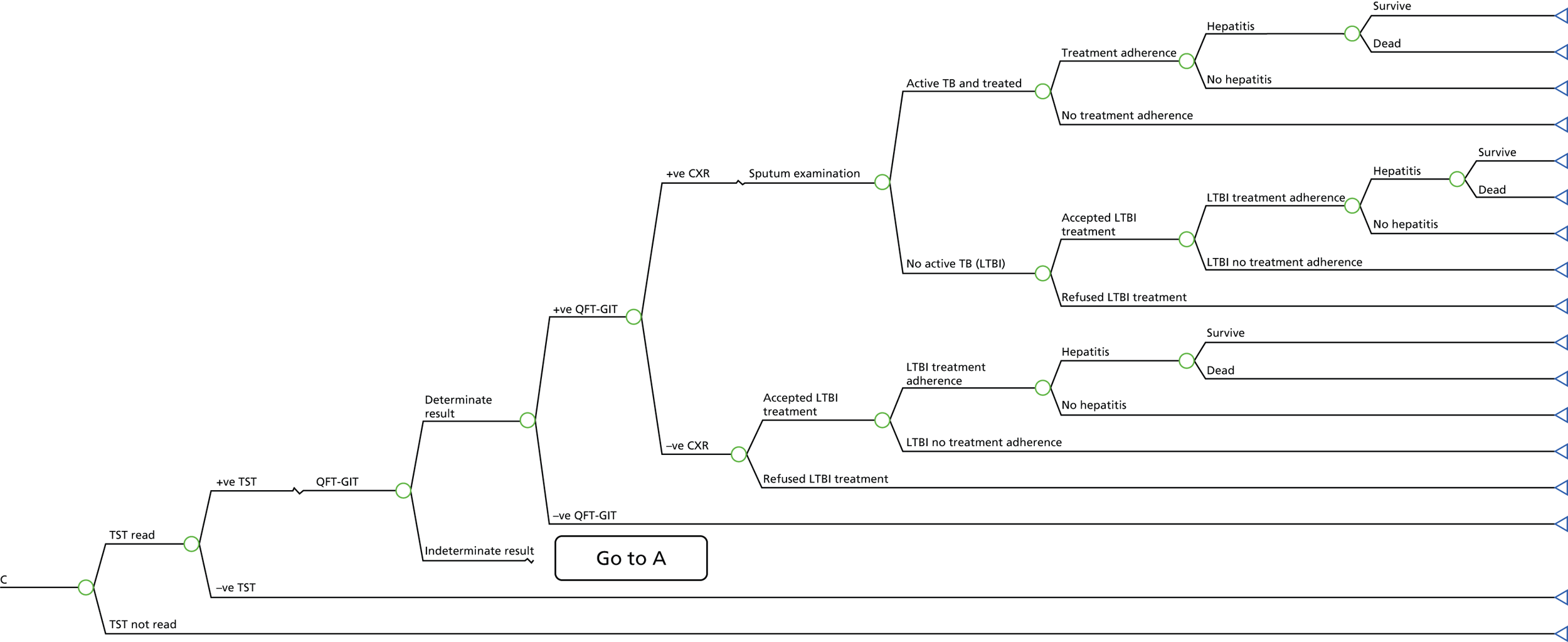

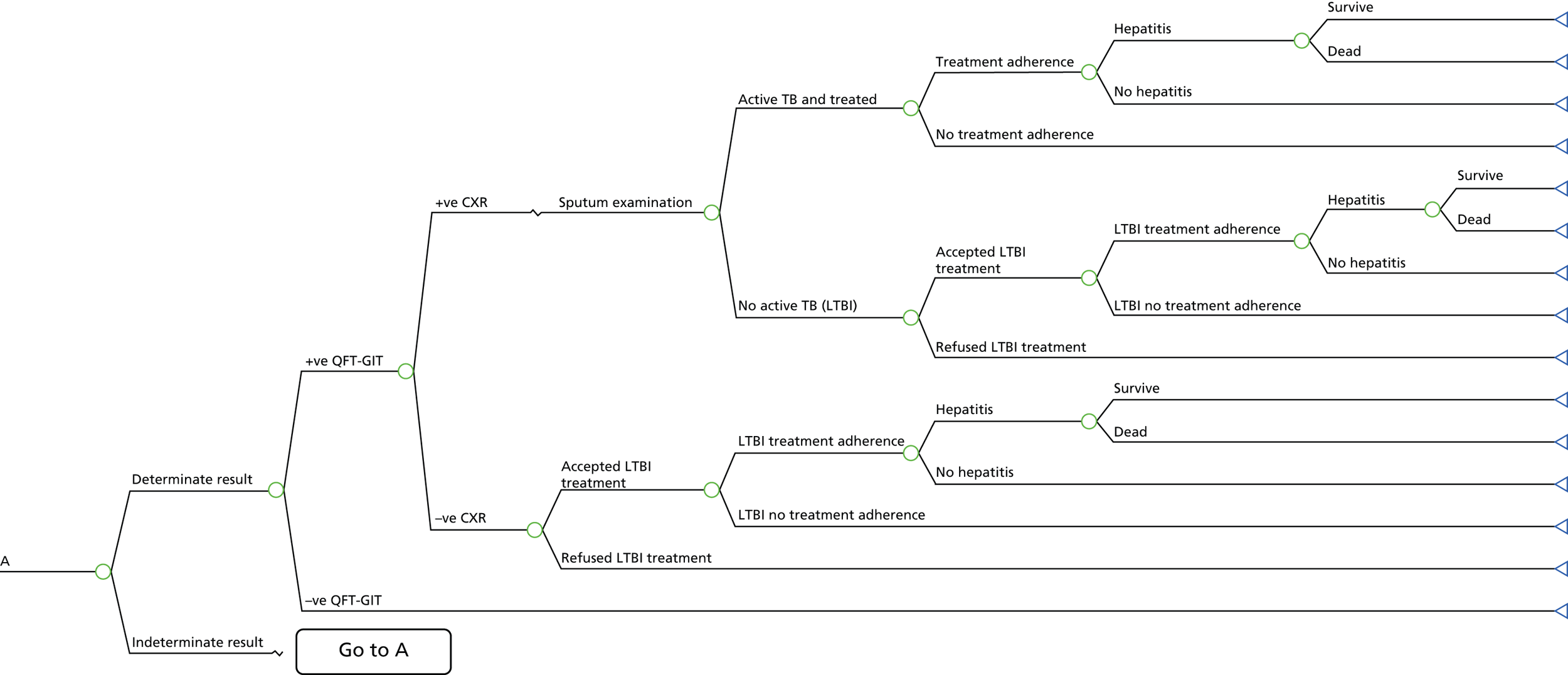

A simplified care pathway for LTBI screening derived from the National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions10,51 is presented in Figure 1 and further details about testing strategies for people being screened for LTBI are provided in Box 1.

-

Generally, individuals are tested for LTBI using TST (Mantoux), IGRA, both or a dual strategy of TST followed by IGRA. If the results are positive, individuals are assessed for active TB; if the results are positive they are treated for active TB and if they are negative they are then treated for LTBI. If the results for LTBI are negative the individual is offered a BCG vaccination if aged < 16 years or aged 16–35 years and from sub-Saharan Africa or from an area with an incidence of > 500 per 100,000. Individuals are given information and advice about TB. However, different testing and treatment pathways are recommended for different populations, including different age groups, new migrants and immunocompromised individuals. 10,51

-

TST is recommended for contacts aged > 5 years for the diagnosis of LTBI. IGRA is recommended for individuals whose TST shows positive results (≥ 5 mm diameter for those who have not been vaccinated with BCG and ≥ 15 mm diameter for those who have been vaccinated) or in people for whom TST would be less reliable, such as BCG-vaccinated people. Individuals with a positive IGRA or inconclusive TST are referred to specialist TB care. For contacts who are aged 2–5 years, a TST should be offered as the initial diagnostic test and, if the result if positive, taking BCG history into account, they should be referred to a TB specialist to exclude the possibility of active disease and to determine treatment, depending on the result. If the result of the TST is negative but the child is a contact of a person with sputum smear-positive disease, then an IGRA should be offered after 6 weeks alongside a repeat TST to increase sensitivity. 10,51

-

For child contacts of a person with sputum smear-positive disease aged 4 weeks to 2 years who have not been vaccinated, isoniazid should be started and a TST should be performed. If the TST is reported as positive, the child should be assessed for active TB and if active TB is excluded the child should then be offered full treatment for LTBI. If the TST is negative (< 5-mm induration), isoniazid should be continued for 6 weeks after which a repeat TST and IGRA should be performed. If repeat tests are negative, isoniazid should be stopped and BCG offered, whereas if either is positive active TB should be assessed and, if excluded, treatment for LTBI should be considered. For child contacts of a person with sputum smear-positive disease aged 4 weeks to 2 years who have been vaccinated, a TST should be performed and any positive results (≥ 15 mm) should be assessed for active TB. If active TB is excluded then a regimen of either 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid or 6 months of isoniazid should be given. If the TST is negative (< 15 mm) it should be performed again with an IGRA after 6 weeks. If both tests are negative no further action is needed. If either is positive, active TB has to be excluded and treatment for LTBI followed. 10,51

-

To diagnose LTBI in recently arriving migrants from high-incidence countries, for children aged 5–15 years a TST should be offered and if positive an IGRA should be performed. For individuals aged 16–35 years, either an IGRA alone or in a dual strategy with a TST should be offered. For those aged > 35 years, the individual risks and benefits of treatment should be considered before testing. For children aged < 5 years, a TST should be offered and if the initial test is positive taking BCG history into account then active TB disease should be excluded and LTBI treatment considered. 10,51

-

Regarding those who are immunocompromised, children should be referred to a TB specialist. For people with HIV infection and a CD4 count of < 200 cells/mm3 or between 200 and 500 cells/mm3, an IGRA should be offered with a concurrent TST. If either is positive, active TB should be ruled out before LTBI treatment is given. For other people who are immunocompromised, an IGRA should be offered alone or with a TST. 10,51

-

Once active TB has been excluded by chest radiography and examination, individuals should be offered treatment. Individuals aged ≥ 35 years without HIV infection should be assessed further and counselled about treatment because of the increasing risk of hepatotoxicity from medication. For those aged 16–35 years and not known to have HIV infection, treatment should include either 6 months of isoniazid or 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid. 10,51

-

Neonates who have been in close contact with people who have sputum smear-positive TB and who have not received at least 2 weeks of antiTB drug treatment should be started on isoniazid for 3 months and then a TST performed after 3 months of treatment. If the TST is positive, active TB should be assessed and, if found negative for active TB, isoniazid should be continued for a total of 6 months. If the TST is negative it should be repeated with an IGRA and if both are negative isoniazid should be stopped and BCG vaccination performed. In children aged > 2 years, 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid or 6 months of isoniazid should be given.

Current service cost

Estimates for the costs of diagnosing and treating LTBI have been provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (Table 1). These costs are based on NICE guidelines from 200651 and the partial update from 2011. 10 The costs shown include the unit costs of the disposables, the time to administer and read tests and the costs of collecting a blood sample per patient for the tests, calculated in 2011. The cost of chemoprophylaxis includes the cost of drugs, active TB tests, consultations and nurse visits, which were calculated in 2006. BCG costs are also from 2006. Compared with the cost of treating active TB (≥ £5000), diagnosing and treating LTBI per patient is less costly.

| Description | Test type | Unit cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of TST | – | 16.42 |

| Cost of IGRA | – | 30.34 |

| Household and other close contacts aged ≥ 5 years | TST | 16.42 |

| New entrants from high-incidence countries | ||

| Children aged < 5 years | TST | 16.42 |

| Children aged 5–15 years | TST | 16.42 |

| Adults aged 16–34 years | IGRA or dual | 30.34 or 46.76 |

| People aged > 35 years | Consider individual risk | |

| Household contacts aged 2–5 years | TST | 16.42 |

| IGRA if contact with a sputum smear-positive person and TST is negative | 30.34 | |

| Contacts aged ≥ 5 years – outbreak | IGRA | 30.34 |

| Immunocompromised HIV CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 | IGRA with concurrent TST | 46.76 |

| Immunocompromised HIV CD4 count 200–500 cells/mm3 | IGRA test or | 30.34 |

| IGRA with concurrent TST | 46.76 | |

| Cost of complete chemoprophylaxis treatment | – | 483.74 |

| BCG vaccination | – | 11.71 |

Variation in services and/or uncertainty about best practice

Limitations of latent tuberculosis infection screening tests

The main limitation of the TST is its inability to distinguish between reactions caused by MTB and those caused by BCG vaccination or non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). 11 The BCG vaccination is routinely used in countries with a high TB prevalence to prevent the spread of TB infection in infants and young children. The use of the TST test in such areas results in high false-positive rates. The boosting phenomenon, which occurs after repeated TSTs, may also lead to false positives, thereby limiting the specificity of the test. The TST has limited sensitivity when used in certain subpopulations (e.g. people with active TB, immunocompromised patients, the elderly and people with HIV infection, malnutrition or renal failure). The above-mentioned limitations are compounded by issues related to the interpretation of test results, which may independently influence false-positive and false-negative rates of the TST (e.g. different cut-off values, PPD dose). 12,13,16 Two health visits are required for the completion of the TST, which results in missed diagnoses in 10% of cases. 53 Measurement of the TST is also dependent on interobserver variability, which therefore requires adequate training to reduce variability. 54,55

Because the antigens in the IGRA tests are not present in the BCG vaccination and most NTM, the IGRAs are less influenced by previous BCG vaccinations and are less susceptible to false-positive NTM reactions, leading to higher specificity of these tests compared with the TST. 56 IGRAs also have the advantage of requiring a single patient visit rather than the sequential two-step testing required with the TST. Automated testing also means increasing the objectivity in the interpretation of test results. Finally, there is no influence from the boosting effect and so repeat screening is feasible. 57 The IGRAs, however, have their own limitations: specifically, they are more costly and labour intensive than the TST. Moreover, care in blood sampling is required and the time available for blood sample storage and analysis is restricted to 8–12 hours after collection. 12

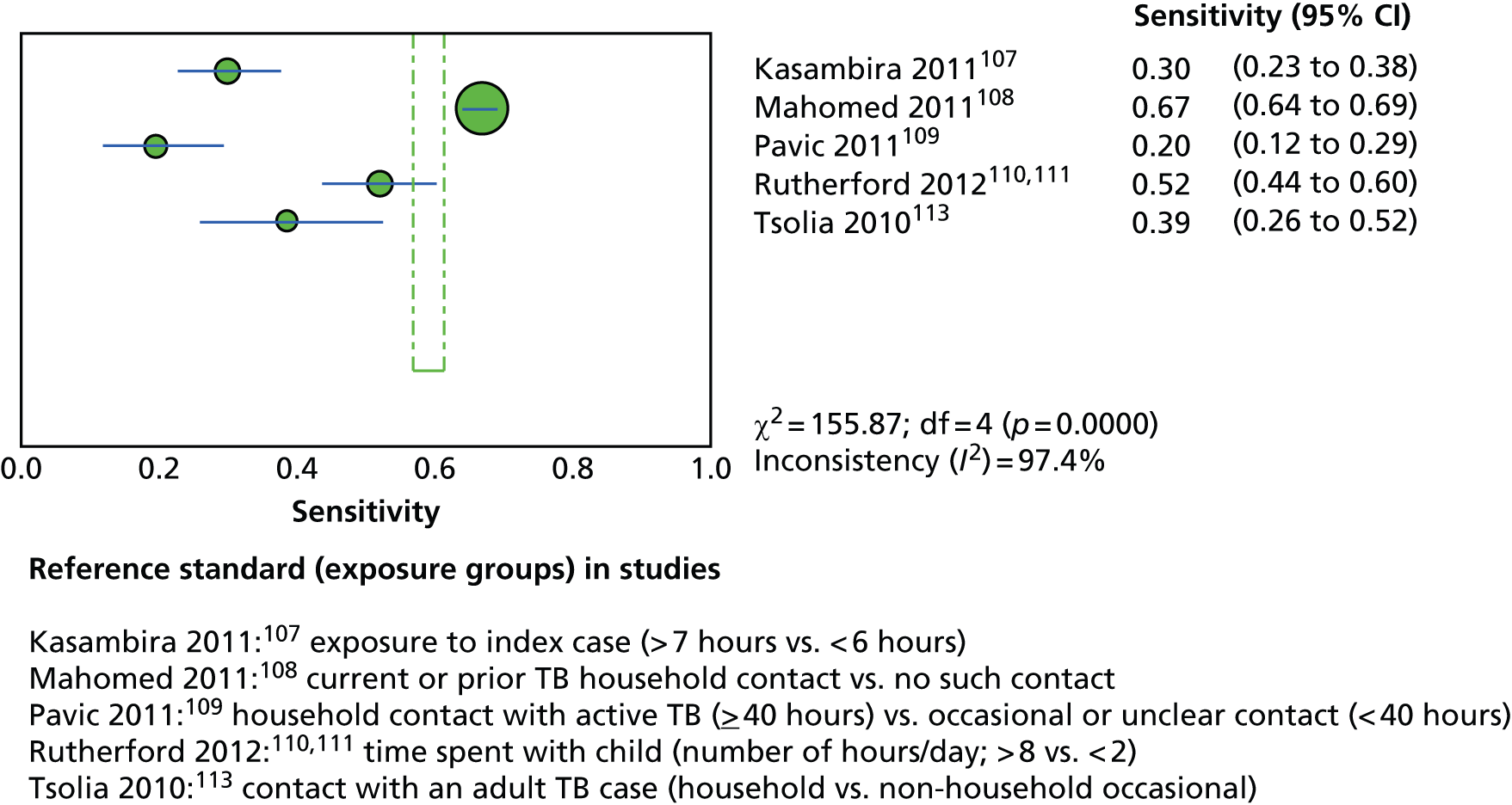

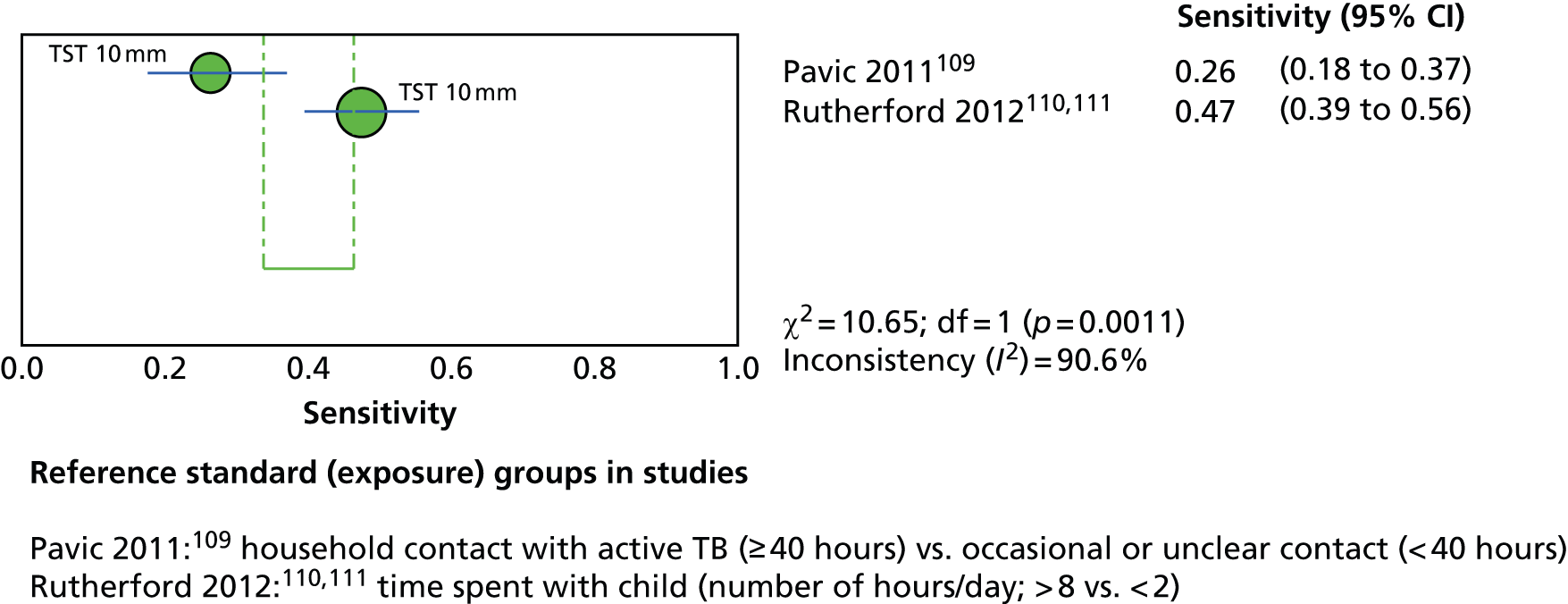

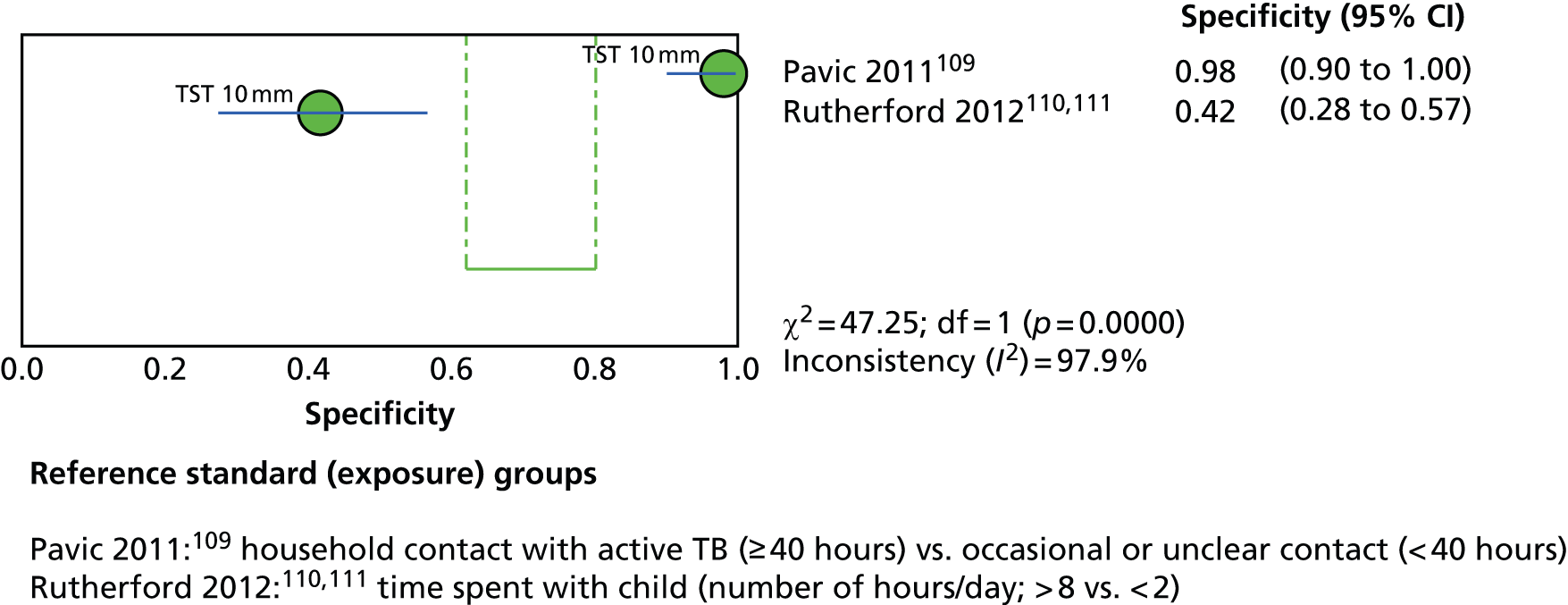

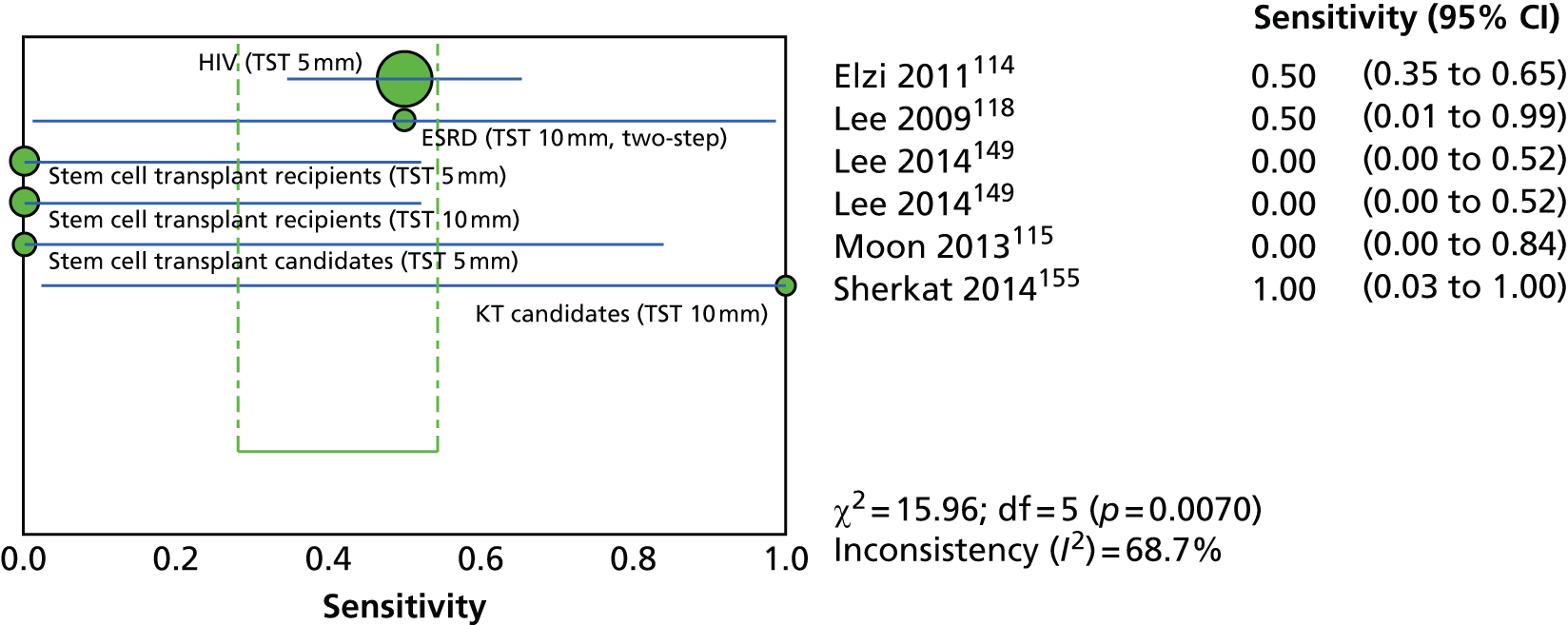

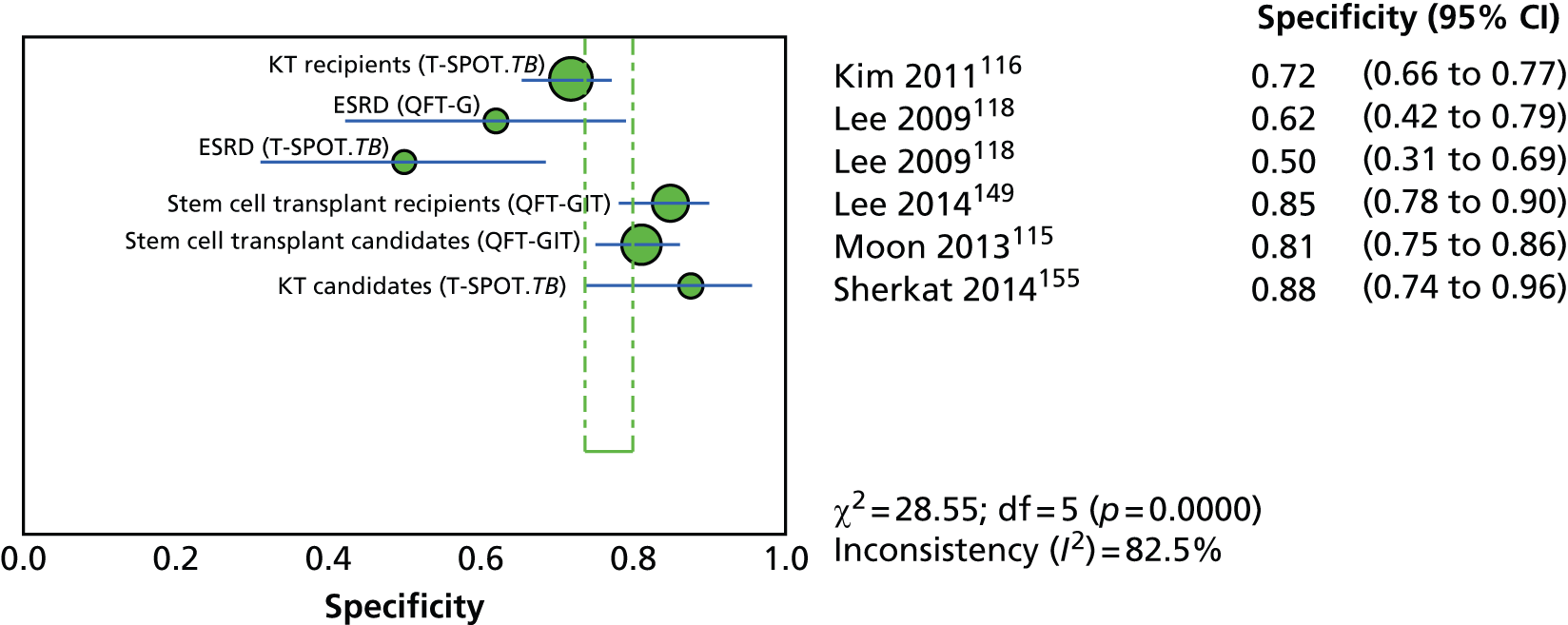

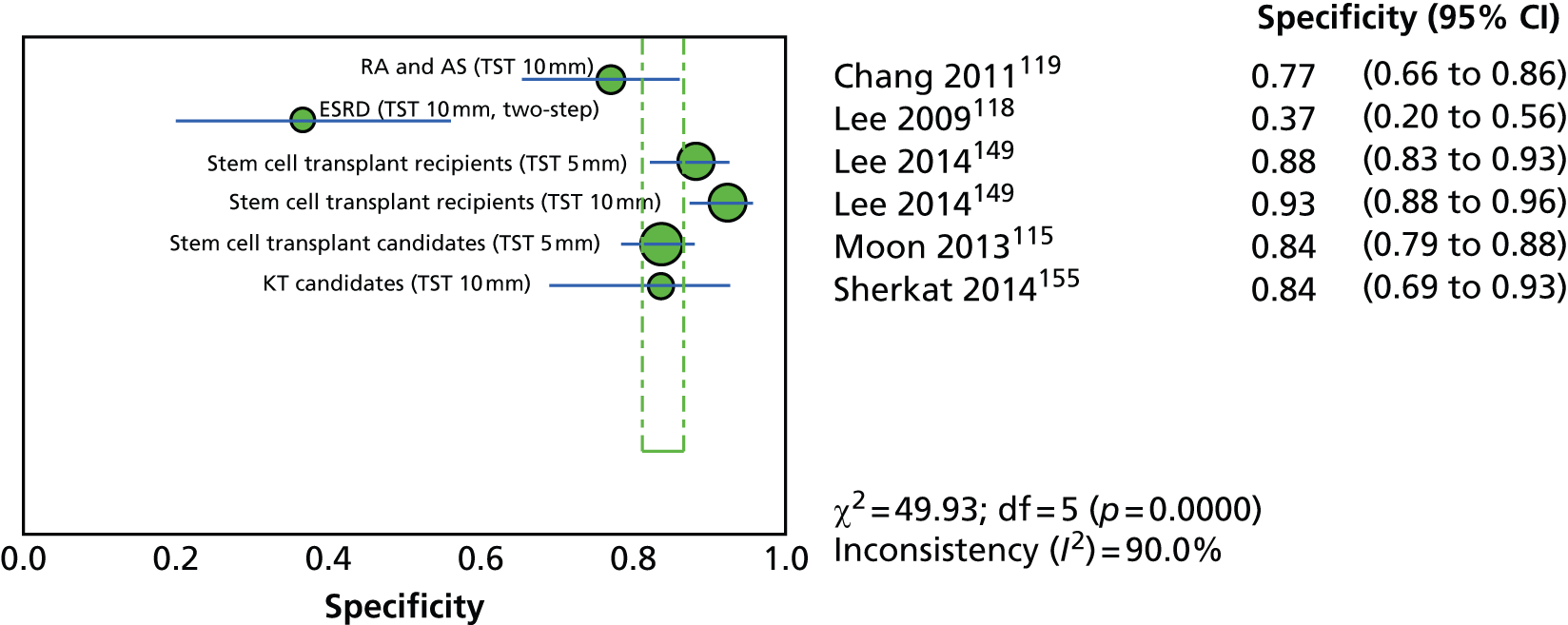

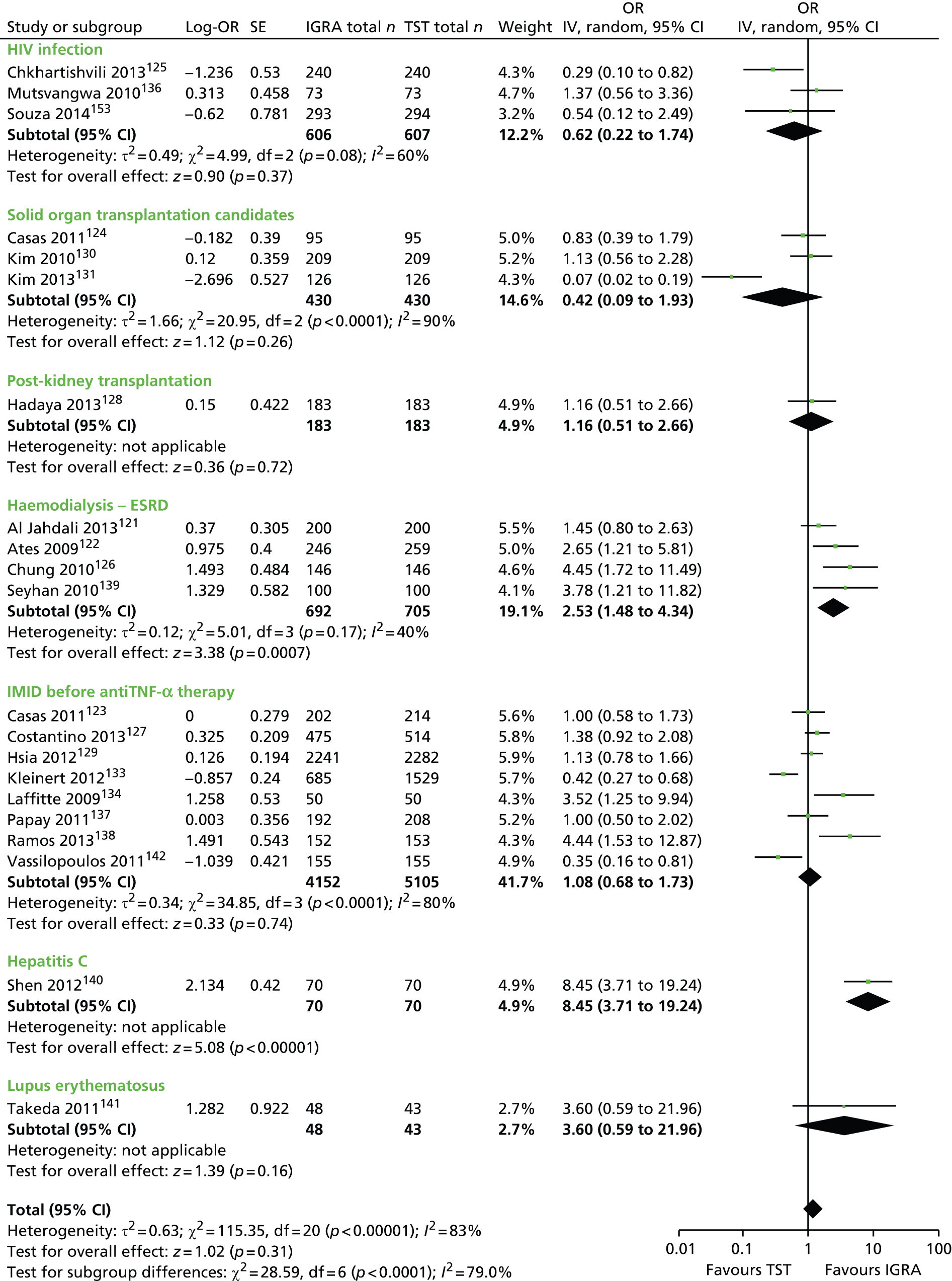

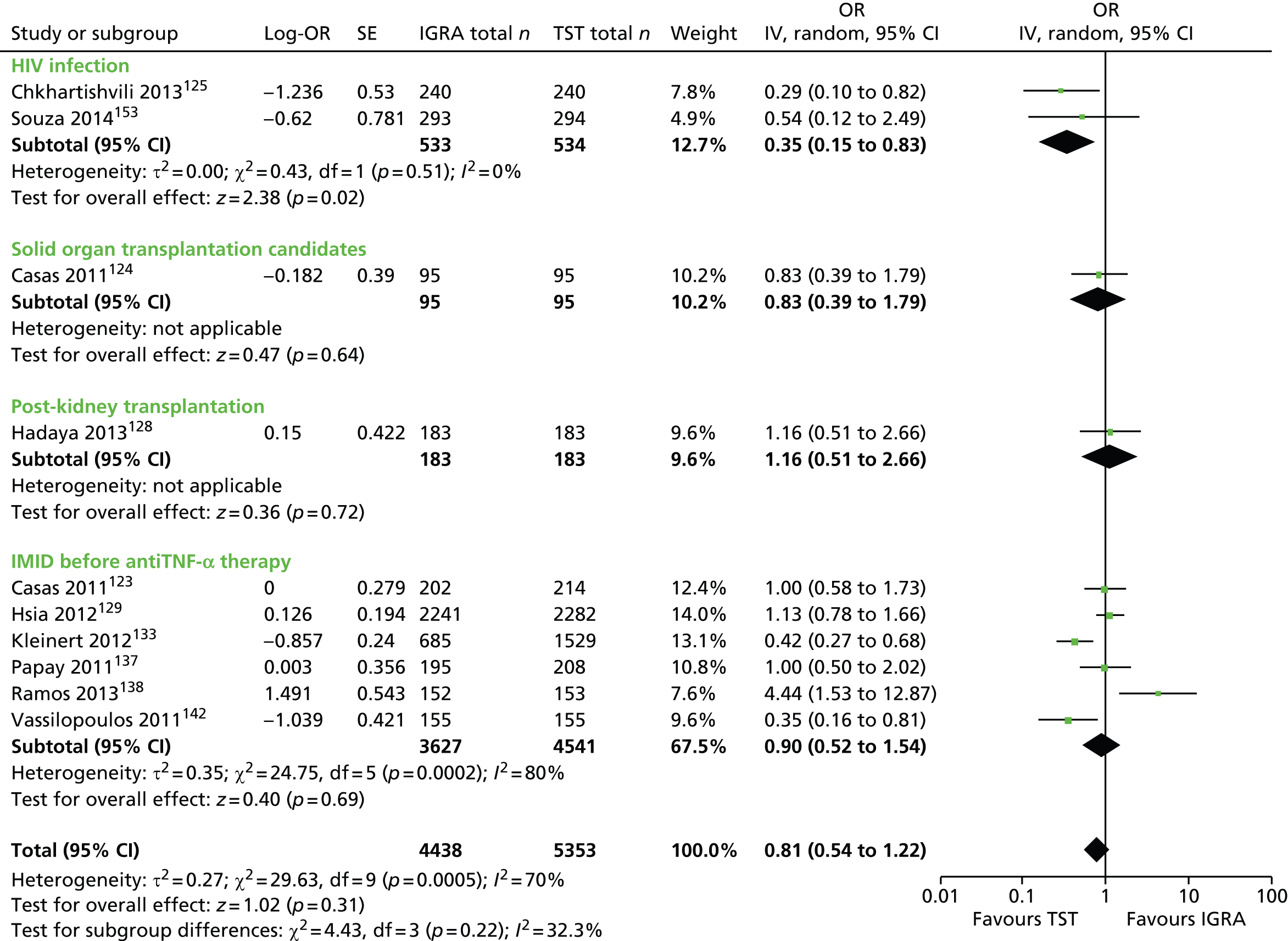

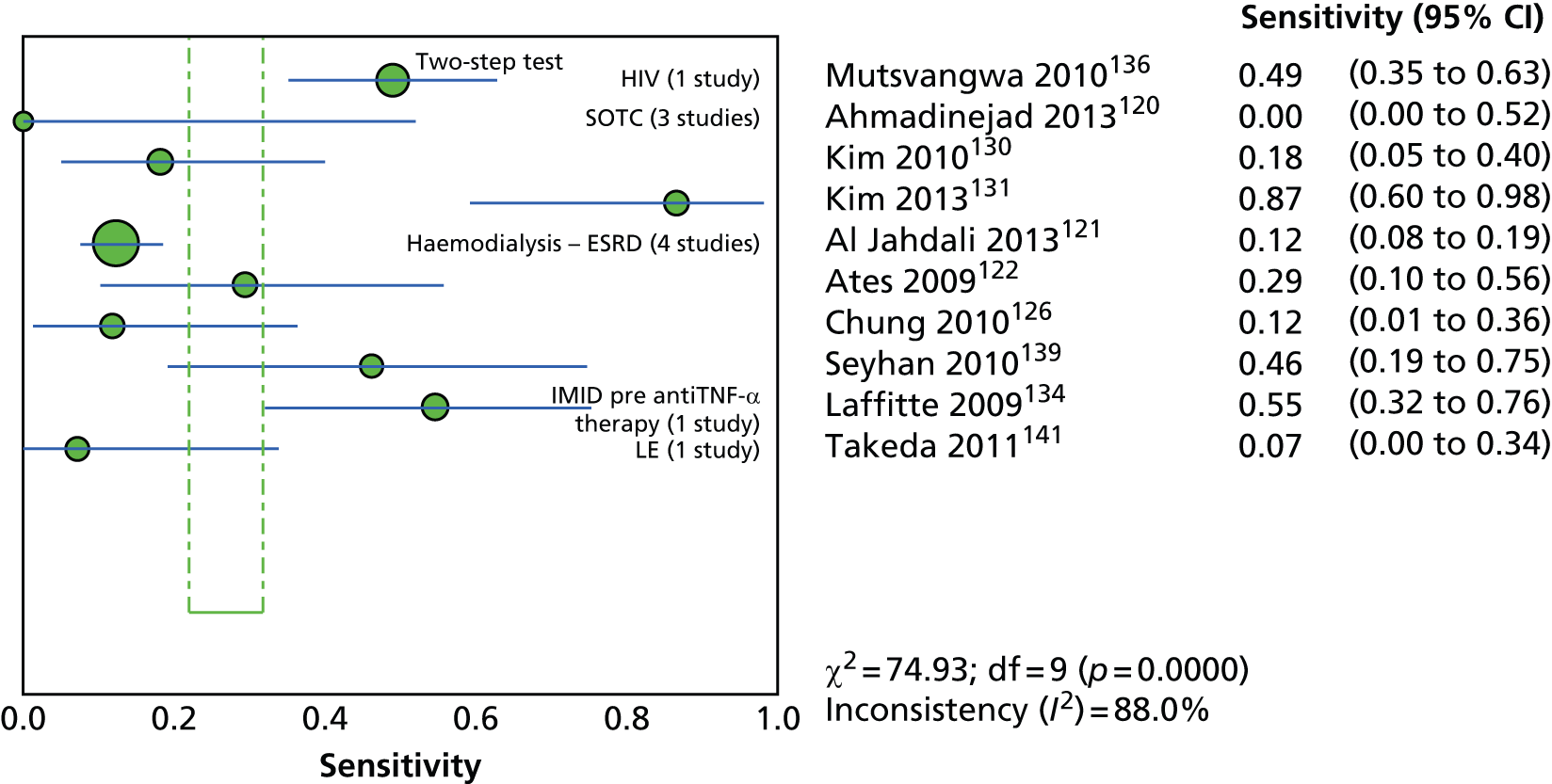

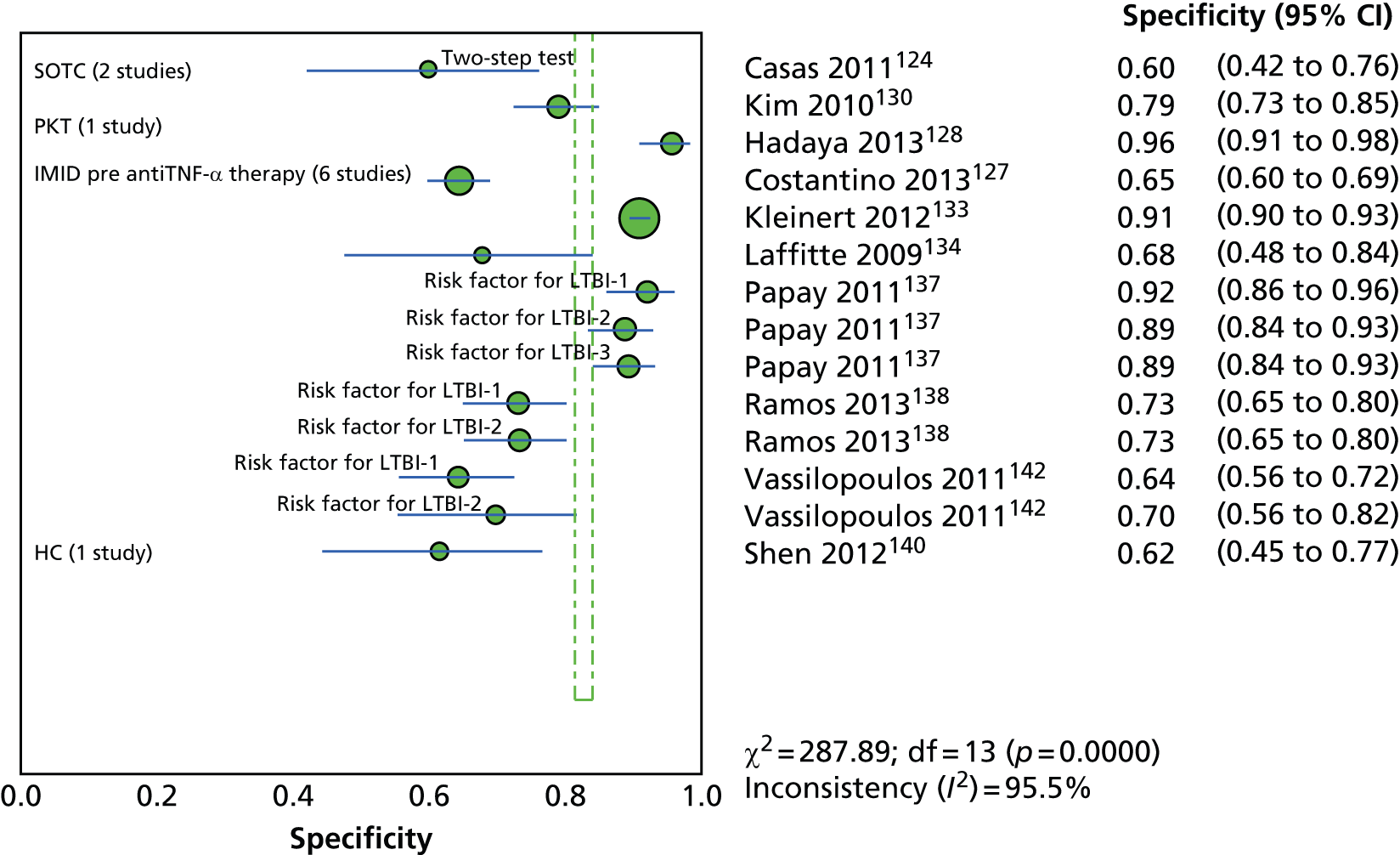

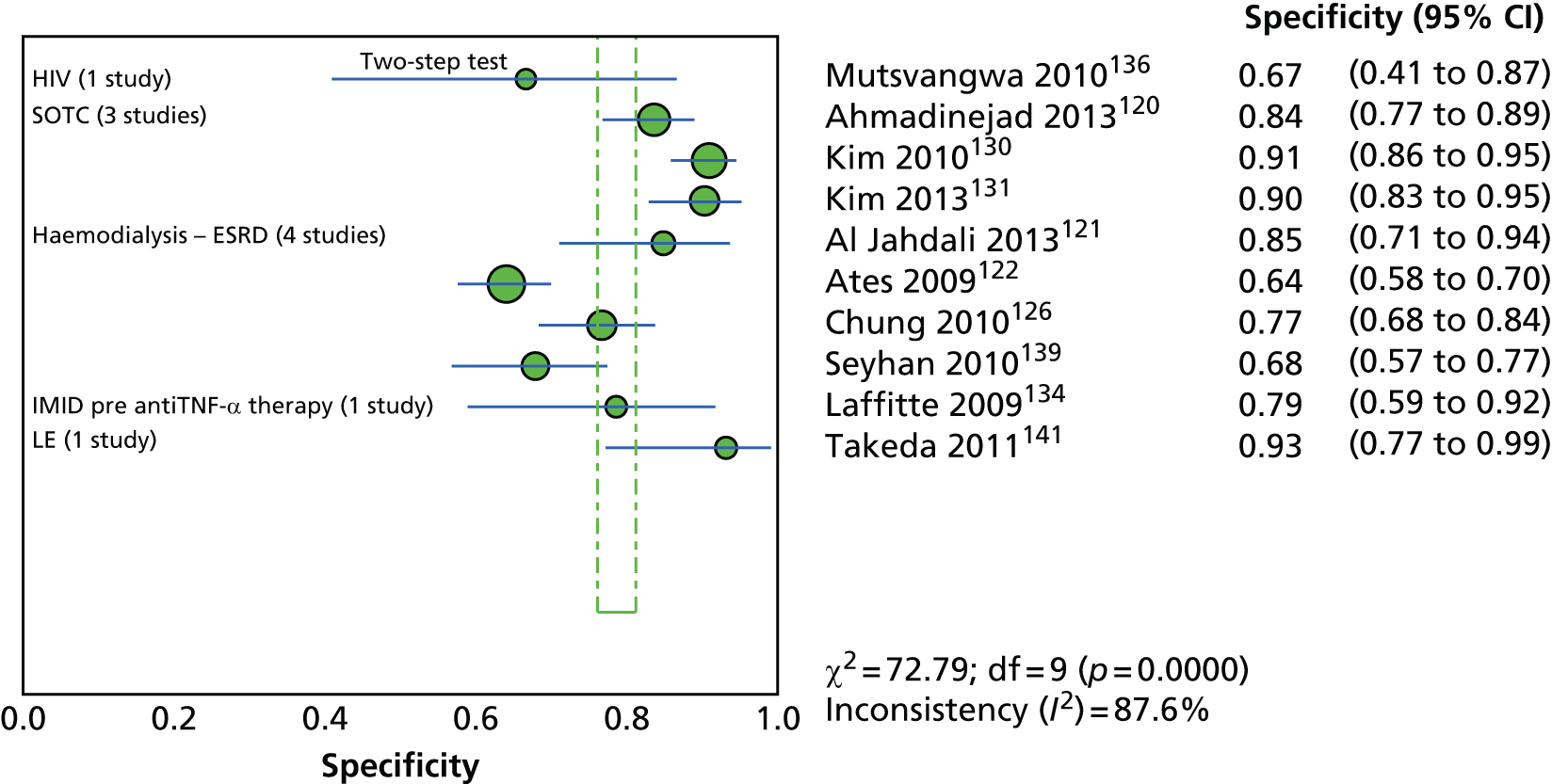

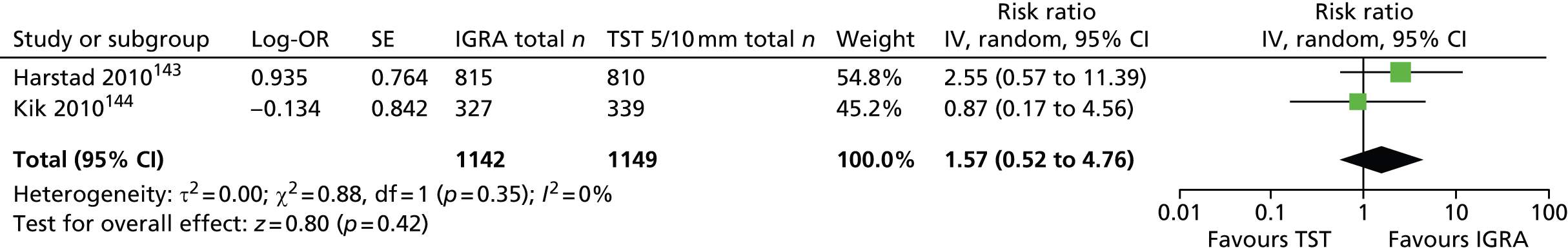

Diagnostic accuracy of latent tuberculosis infection tests

Since the introduction of IGRAs evidence on estimating and comparing the performance of the TST and IGRAs in people with LTBI has emerged; however, this assessment has been hampered by the absence of a gold standard for the diagnosis of LTBI, which would allow direct calculation of sensitivity and specificity for both types of tests. 11,12,18,40,57–59 Most studies have, instead, determined associations [e.g. diagnostic odds ratios (DORs) and other regression-based effect measures] between test results (i.e. TST or IGRAs) and surrogate measures of LTBI such as duration/proximity of exposure to a person with active TB or risk of development of active TB, or progression from LTBI to active TB [e.g. sensitivity, DORs, positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs), incidence rate ratios, cumulative incidence ratios (CIRs)]. 18,58,60 Some studies have assessed and compared the specificity of these tests in people at very low risk for MTB infection (e.g. healthy individuals, residents of low-incidence countries)57 or compared sensitivity in culture-confirmed individuals with active TB (taken as a surrogate reference standard for LTBI). 40,57,59 Using suboptimal reference standards for diagnostic accuracy testing can lead to an overestimation or underestimation of the true accuracy of a test. The degree of concordance (inter-rater or intrarater agreement, kappa statistic) and discordance between the results of the two tests (IGRAs and TST) has also been used. In general, both pooled sensitivity and specificity values of the IGRAs and the TST were similarly high in people who were not vaccinated with BCG (> 90%); however, the pooled specificity of the TST in BCG-vaccinated populations was much lower than that of IGRAs (about 56% vs. 96%). 11,53,57 In contrast, prospective longitudinal studies showed that neither the IGRAs nor the TST had a high prognostic value in predicting the risk of progression to active TB. 11,18

Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection

Once patients are diagnosed with LTBI using any of the available tests, there are claims of low adherence to chemotherapy treatment. 61 As a result of low adherence, an alternative therapy recommended in the USA62 has been implemented in some hospitals in the UK. It includes a new combination of isoniazid and a long-acting rifampicin called rifapentine given weekly for 12 weeks. Each of the 12 doses is directly observed being taken by a treatment supervisor. After LTBI is confirmed and active TB excluded, individuals are assessed for suitability for the rifapentine/isoniazid regimen. 61 Suitability is based on certain criteria including normal renal and liver function, aged ≥ 16 years, not pregnant, HIV-infected patients not on antiretroviral treatment, agreeable to direct observations and direct observations are feasible. If suitable, the regimen is prescribed and a TB specialist nurse sets up the direct observations. If it is not suitable other latent TB treatment is offered. This combination has been found to be as effective as the 9-month daily isoniazid regime used in the USA, with higher completion rates as only 12 doses are needed. 61

Relevant national guidelines including National Service Frameworks

The latest guidelines on the diagnosis, management and prevention of TB are available from NICE. There is a 2006 clinical guideline51 on the clinical diagnosis and management of TB and measures for its prevention and control, with a partial update in 2011,10 as well as 2012 public health guidance52 to identify and manage TB among hard-to-reach groups. The Department of Health has also published guidelines for the planning, commissioning and delivery of TB services,63 guidelines for testing health-care workers,64 a wider action plan for stopping TB in England65 and guidance for the prevention and control of HIV-related and drug-resistant TB. 66 Finally, the British Thoracic Society has published guidelines on the prevention, risk assessment and management of TB in adult patients with chronic kidney disease67 and in patients due to start antiTNF-α treatment,68 management of air travel passengers69 and management of opportunist mycobacterial infections. 70

Description of the technology under assessment

Summary of the intervention

As noted earlier, screening for LTBI is crucial to curb the re-emergence of TB as the majority of TB cases consist of latent TB that has been reactivated. 71 Testing and treating high-risk individuals for LTBI would not only prevent active TB illness for the individual but also would reduce the transmission of TB, thus reducing the pool of infection. 72

There is much interest in using IGRAs to identify individuals at high risk of LTBI because of the advantages that they have over the traditional TST, particularly that they require only one visit and that previous BCG status does not interfere with the results. For IGRAs to replace the TST in the current care pathway, they would have to show improved cost-effectiveness relative to the TST, although in the absence of a gold standard this is difficult. 73 Otherwise, IGRAs may have to be used as complementary tests to the TST, as is currently recommended in the national guidelines. 10

The results of an IGRA test depend on local arrangements but can be available within 1 week. 74 The TST takes 2–3 days as individuals must return to have the test read. 13,16 In combination, therefore, both tests take several days to be completed. IGRA testing comes at a higher cost than the TST and shifts the costs and labour from the clinic to the laboratory. 75 Both the TST and IGRAs require specific equipment either for administering the injection or taking a blood sample. In addition, IGRA testing requires advanced laboratory facilities. 75 Skilled personnel are needed to administer both tests and, in the case of the TST, are needed to read the result, whereas for IGRA testing laboratory personnel are needed to process the result. 73 In both cases patients follow a common pathway, with nurses providing patients with the result, following up patients for testing of active TB and offering treatment and advice. 10 IGRAs can be used in similar settings to the TST as long as there is access to a laboratory and pathways are negotiated so that samples can be analysed within 12 hours. 46

Screening tests for latent tuberculosis infection in special subgroups at risk

It has been suggested that screening tests applied to presumably healthy populations or those at low risk for progression to active TB may not be justified given the potential harms from unnecessary treatment. 16,76 It is also not feasible or cost-effective to universally screen the population as the administrative and clinical costs outweigh the benefits of identifying TB cases. 46 The benefits of screening for LTBI using these tests are likely to be maximal in individuals at high risk of contracting MTB (e.g. those recently arrived from countries with a high TB incidence, close contacts of those with active TB) and those with suspected LTBI who are at high risk of progression to active TB and complications associated with the infection (e.g. immunocompromised patients, young children). As these subgroups are at higher risk of developing active TB, it is of public health importance to identify LTBI in them.

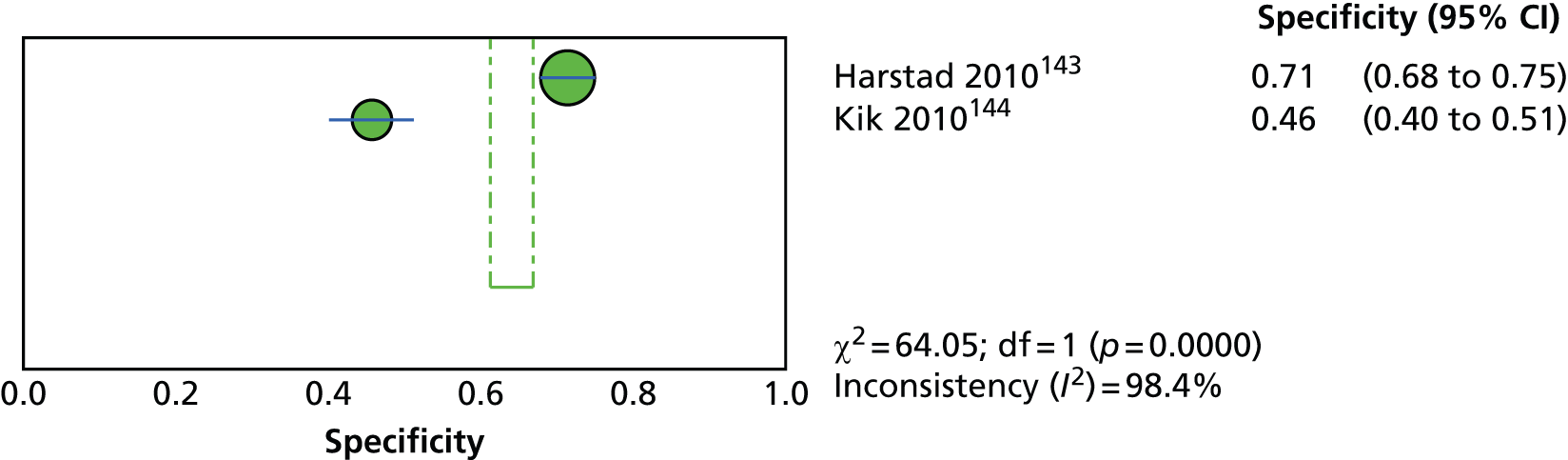

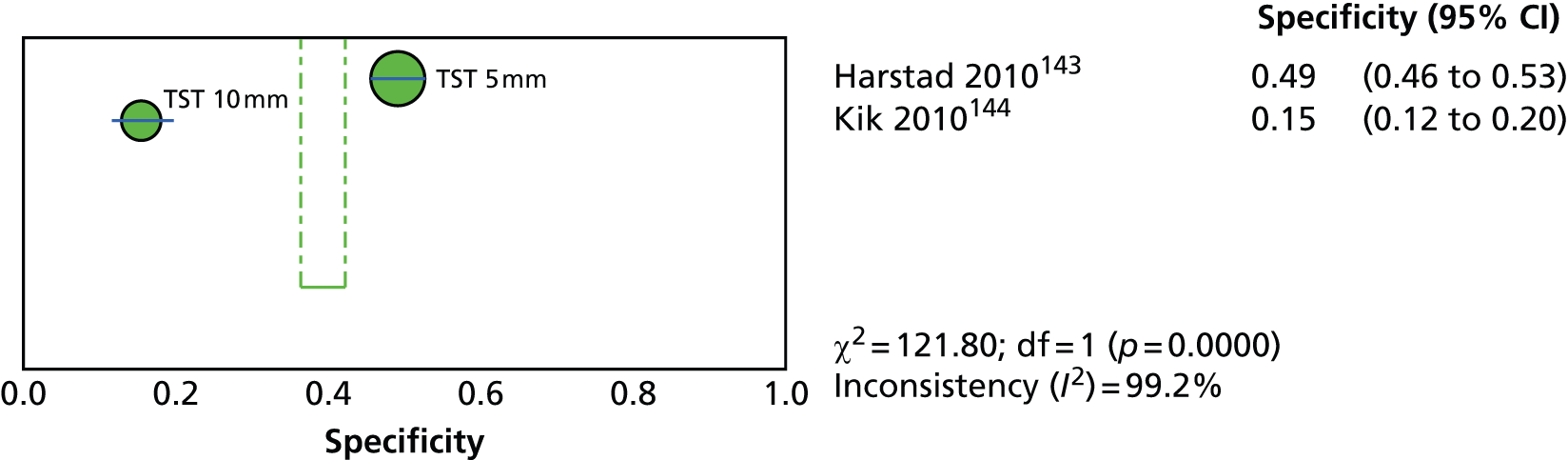

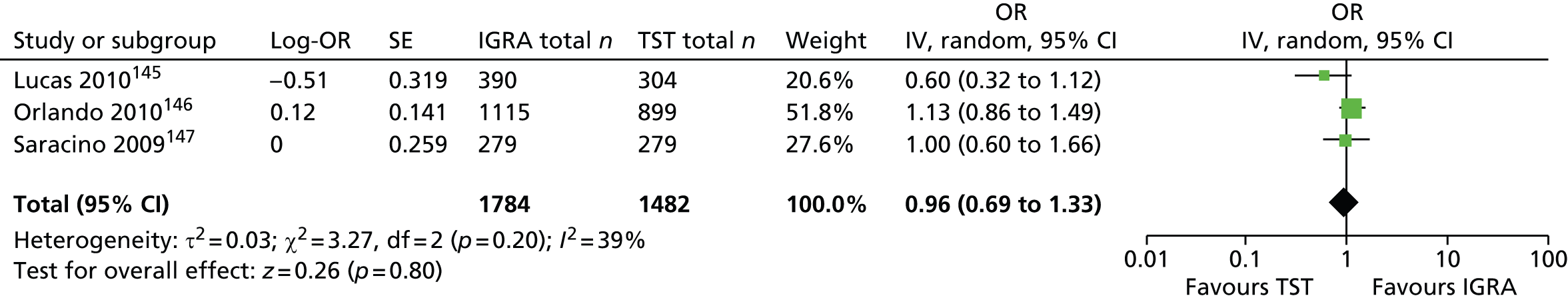

Studies comparing the TST and IGRAs for detecting LTBI in children have mostly demonstrated better specificity for IGRAs than the TST. 59 Sensitivity has been shown to be comparable between the TST and the IGRAs but to vary considerably between studies. Both specificity and sensitivity depend on an implied association between LTBI and exposure to TB (as a proxy for true-positive LTBI). The comparative evidence in immunocompromised people has been too scarce to draw definitive conclusions. One systematic review showed suboptimal but comparable performance between the TST and the IGRAs for identifying LTBI in HIV-infected patients. 40 In general, based on limited data, the accuracy indices for the TST and IGRAs in the subgroups of children and immunocompromised people have been shown to be suboptimal. However, the absence of a gold standard, small samples, indeterminate test results and heterogeneity between the studies make adequate comparisons between tests difficult. 11,16

One study has compared the TST and the two IGRAs (QFT-GIT and T-SPOT. TB) for detecting LTBI in migrants to the UK. 77 However, comparison of the tests was carried out only by evaluating the positive results of each, concordance between the tests and the factors associated with positivity. Yields of the test were computed at different incidence thresholds and the cost-effectiveness of the tests was estimated. The authors found that the TST was positive in 30.3% (53/175) of individuals who completed screening, QFT-GIT was positive in 16.6% (38/229) of individuals and T-SPOT. TB was positive in 22.5% (36/160) of individuals. The higher rate for the TST could be a result of the effect of BCG vaccination. Although NICE recommends that recently arriving migrants from countries with a TB incidence of ≥ 40 per 100,000 should be screened, the study found that this would require 97–99% of the cohort to be screened and would identify 98–100% of cases of LTBI whereas screening migrants from countries with an incidence of 150 per 100,000 would identify 49–71% of cases of LTBI but would require screening of only half of the cohort. The most cost-effective option was to screen recently arriving migrants from countries with a TB incidence of > 250 per 100,000 with one QFT-GIT test (£21,565.3 per case prevented) but, as this would miss many cases, screening recently arriving migrants from countries with a TB incidence of 150 per 100,000 was recommended as it was only slightly less cost-effective (£31,867 per case prevented) and would prevent an additional 7.8 cases of TB. This was confirmed in a previous study assessing groups of new migrants in the UK who should be screened for LTBI. 6 Despite these findings it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the accuracy of identifying LTBI in immigrants as no reference test was used for LTBI when comparing the tests.

New evidence is needed to determine the best approaches for identifying LTBI in all three groups of people (children, immunocompromised individuals and recently arrived immigrants from high-incidence countries). This will help in deciding whether IGRAs should replace or complement the TST and, if so, in which circumstances. There is an ongoing large multicentre cohort study assessing the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of IGRAs compared with the TST for predicting active TB in recently arrived migrants in the UK from high-incidence countries (> 40 per 100,000) and people who have been in contact with TB cases. In total, 10,000 participants (aged ≥ 16 years) will be recruited from 12 hospitals and general practitioner (GP) surgeries and followed up for 24 months; the results from this study will be available in 2017. 78

Current usage in the NHS

The UK National Screening Committee decided that TB screening should be organised locally rather than as a national programme. 79 Therefore, the implementation of NICE guidelines on LTBI testing using the TST and IGRAs has been very ad hoc across the NHS. In London, for example, it is reported that it has not been fully implemented and that current practice is not effective in detecting LTBI. 50

More recently, in March 2014, a tri-borough Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) report80 stated that ‘However, GP screening has to date been inconsistent and no clear assessment and patient pathway exists for latent TB’. Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland’s Tuberculosis Summary Needs Assessment from December 201381 mentions expanding numbers of cases of LTBI from IGRA testing but calls for a more systematic testing process for testing new entrants to make an impact on active TB cases. In addition, Kirklees’s JSNA82 mentions exploring funding to develop IGRA testing and Manchester City Council JSNA83 reports needing to improve LTBI screening.

Commissioners are currently looking at models for local service provision. This is in line with the suggested approach of TB control boards in the recent PHE consultation document Collaborative Tuberculosis Strategy for England 2014 to 2019. 7 There is not one agreed service model and PHE has recently sponsored several pilot projects, which are ongoing at present, looking at the feasibility of screening in different settings. These include the identification of eligible individuals from GP practice lists followed by an invitation for screening at the GP surgery by IGRA (Dr Huda Mohammed, PHE, West Midlands, 12 May 2014, personal communication) and a more innovative approach in which screening for LTBI was carried out using an IGRA at a college of further education among self-selected individuals taking part in English for Speakers of Other Languages classes following a campaign of education. 84 Neither of these studies has reported yet but they are expected to show positive result rates of between 17% and 20% (Dr Huda Mohammed, personal communication).

It is difficult to know how many GPs are identifying new entrants and organising testing for them or how many new entrants are contacting TB services directly for testing. The websites of several community TB85 teams list testing new entrants for LTBI as part of their remit and give a contact number or e-mail address. The Birmingham and Solihull Tuberculosis Service86 has a full page on its website with eligibility criteria for screening, whereas the Liverpool Community Health NHS Trust Tuberculosis Service87 excludes testing of new entrants who are students.

Taking the Coventry and Warwickshire area as a case study, the Meridian Practice in Coventry, a specialist service that cares for refugees and asylum seekers, offers IGRA testing to all registered patients (Najeeb Wai, practice manager, Meridian Practice, 8 July 2014, personal communication). The Coventry and Warwickshire Tuberculosis Service reports that it ‘indirectly tr[ies] to identify high TB risk individuals other than identified contacts and offer screening’ (Debbie Crisp, lead TB nurse specialist and primary care services for the Arden Community TB Service, 9 July 2014, personal communication). Apart from supporting the work at the Meridian Practice, it also supports the Warwickshire programme for looked-after children, which has an established TB screening programme incorporated into its medical review, and has plans to discuss the programme with the Coventry team. In addition, the Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership Trust commenced a TB screening programme for HIV-infected individuals in July 2013 and supports the LTBI treatment programme.

In summary, it is difficult to know how much awareness there is for LTBI screening in the primary care setting in the NHS. Pathways are not widely available, if they exist at all. Secondary care specialist services are more aware, but do not employ standard criteria for testing. There is great variability within the system. There is a clear need for new evidence to provide information on the most appropriate strategies available for identifying LTBI in the three subgroups of interest: children, immunocompromised individuals and recently arrived immigrants from high-incidence countries. This evidence will aid in the decision-making process on whether IGRAs should be used as a replacement or as an adjunct to the TST for the diagnosis of LTBI in these populations.

The next chapter discusses the decision problem and outlines the key clinical questions and objectives of this work.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Tuberculosis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The timely identification and prophylactic treatment of people with LTBI is of public health and clinical importance. Unfortunately, there is no diagnostic gold standard for the identification of individuals with LTBI who would benefit from such prophylactic treatment. Instead, the available screening tests provide indirect and imperfect assessment of the presence of LTBI. There are two types of tests used to identify LTBI in the UK: (1) the TST and (2) IGRAs.

In light of new evidence since 2009, this systematic review aimed to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening tests for LTBI (IGRAs and TST) in children, people who are immunocompromised or at risk from immunosuppression and recent arrivals from countries with a high incidence of TB. To do this we updated the searches since 2009 to identify relevant evidence and incorporate both pre- and post-2009 evidence into the analysis. This review also attempted to determine the most cost-effective approach for identifying LTBI.

The key clinical questions to be considered were:

-

Which diagnostic strategy is most clinically effective and cost-effective in accurately identifying LTBI in children?

-

Which diagnostic strategy is most clinically effective and cost-effective in accurately identifying LTBI in people who are immunocompromised or at risk of immunosuppression?

-

Which diagnostic strategy is most clinically effective and cost-effective in accurately identifying LTBI in people who are recent arrivals from countries with a high incidence of TB?

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness review methods

A protocol to which we adhered was developed for undertaking this systematic review of the clinical effectiveness literature. The presentation of our systematic review is in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Identification and selection of studies

Search strategy for clinical effectiveness

Scoping searches were undertaken to inform the development of the overall search strategy. An iterative procedure was used, with input from the searches and studies included in NICE clinical guideline 117 (CG117)10 and methods manuals. 88,89 The bibliographic database search strategies focused on the diagnosis of LTBI using IGRAs compared with other methods and were limited to articles in English that had been added to databases since searches for the equivalent questions in CG11710 were run (7–14 December 2009; see Appendix 1). The searches automatically picked up comparisons in performance between IGRAs and TSTs and therefore it was not necessary to search independently for comparator technologies (e.g. TSTs). The search strategies used in the major databases are provided in Appendix 2. Bibliographic database searches were undertaken on 9 and 10 April 2014 and were updated on 2 December 2014 using the same strategies. Supplementary searches were undertaken between 10 June 2014 and 5 August 2014 (see Appendix 2 for exact dates).

The search strategy included the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic bibliographic databases

-

contact with experts in the field

-

scrutiny of references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews

-

screening of manufacturers’ and other relevant websites.

The bibliographic databases searched were MEDLINE (Ovid); MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid); EMBASE (Ovid); The Cochrane Library incorporating the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and Health Technology Assessment database (Wiley); Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Web of Science); and Medion. ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) were searched for ongoing and recently completed trials.

Specific conference proceedings selected with input from a clinical expert were checked for the last 5 years. The online resources of relevant organisations were also searched. Further details of these searches are provided in Appendix 2.

Citation searches of included studies were undertaken using the Web of Science and Scopus citation search facilities. The reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were checked. Included papers were checked for errata using PubMed. Identified references were downloaded to bibliographic management software (EndNote X7; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

Inclusion and exclusion of studies

Inclusion criteria

Primary studies evaluating and comparing the head-to-head effectiveness of commercially available approaches/tests used for identifying people with LTBI:

-

IGRAs, for example:

-

QFT-GIT (old version: QFT-G)

-

T-SPOT. TB.

-

-

TST (i.e. Mantoux test).

Head-to-head studies involving a direct comparison between an IGRA and TST only were included.

Type and language of publication

-

Full-text reports published in English.

-

Abstracts (only if they were companion publications to full-text included studies).

Study design

-

Longitudinal studies (randomised controlled trials, retrospective or prospective cohort studies).

-

Cross-sectional or case–control studies.

Population

-

Children (both sexes, aged < 18 years, immunocompetent) (research question 1).

-

People (both sexes, any age) who were immunocompromised or at risk from immunosuppression (e.g. transplant recipients or those with HIV infection, renal disease, diabetes, liver disease, haematological disease, cancer or autoimmune disease or those who were on or about to start antiTNF-α treatment, steroids or ciclosporins) (research question 2).

-

People (both sexes, any age, immunocompetent) who had recently arrived from regions with a high incidence/prevalence of TB (countries/territories with an estimated incidence rate of ≥ 40 per 100,000, e.g. those in Africa, Central/South America, Eastern Europe and Asia) (research question 3).

Intervention

-

Two IGRAs (one- or two-step testing):

-

QFT-GIT (old version: QFT-G)

-

T-SPOT. TB.

-

Comparator

-

TST (Mantoux test) alone or plus IGRA (one- or two-step testing).

Construct validity measures (as a proxy for outcomes)

-

Progression to active TB.

-

Exposure to MTB defined by proximity, duration, geographical location or dose–response gradient.

-

People at low risk of MTB infection or healthy populations.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies not comparing IGRAs with the TST with regard to the prespecified construct validity (i.e. incidence of TB, exposure to MTB defined by proximity, duration, geographical location, dose–response gradient).

-

Studies not comparing the accuracy of tests (IGRAs with TSTs) in a head-to-head comparison to identify people with LTBI.

-

Studies (involving children, recently arrived immigrants or immunocompromised people) not reporting subgroup data separately for each relevant population.

-

Studies comparing the IGRAs with each other (e.g. QFT-G-IT vs. T-SPOT. TB) in identifying people with LTBI.

-

Studies applying non-commercial IGRAs, in-house IGRAs, older-generation IGRAs [e.g. PPD-based first-generation QuantiFERON-TB (QFT)] or tests unavailable in the UK.

-

Studies assessing the effects of TB treatment on IGRA/TST test results.

-

Studies evaluating and/or comparing the reproducibility (test and retest) of tests for identifying LTBI.

-

Studies not focusing specifically on LTBI [e.g. studies in which the presence of blood culture-positive TB (active TB) was used to estimate sensitivity – ‘active TB’ is assumed as the reference standard for the ‘true presence of LTBI’; however, given that active TB and LTBI are two clinically and immunologically distinct forms of TB, this assumption is problematic].

-

Studies using serial testing (e.g. health-care staff/students, military personnel or prisoners) of IGRAs (or TST) to detect LTBI.

-

Studies focusing on a specific biomarker (e.g. IFN-γ-inducible protein 10).

-

Systematic/narrative reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, case series, abstracts (see Type and language of publication), commentaries, letters or editorials.

Review outcomes

Diagnostic accuracy measures

-

Measures of association between test (IGRAs, TST) results and construct validity – I [i.e. prognostic value of tests in predicting the development/risk of active TB (sensitivity, specificity, false-negative and false-positive rates, PPVs and NPVs, incidence density rate ratios (IDRRs), CIRs].

-

Measures of association between test (IGRAs, TST) results and construct validity – II {i.e. exposure status/level with regard to MTB defined by proximity, length of time and type of contact and including the dose–response gradient if applicable [sensitivity, specificity, false-negative and false-positive rates, DORs, regression-based odds ratios (ORs) of test positivity]}.

-

Measures of association between test (IGRAs, TST) results and other construct(s) of validity – III [e.g. people at low risk for LTBI, e.g. healthy people, residents of low-incidence countries (specificity and false-positive rate)].

Measures of concordance and discordance

-

Agreement (inter-rater, intrarater) (kappa statistic, 95% CI).

-

Concordance between tests (%, 95% CI).

-

Discordance between tests (%, 95% CI).

Other outcomes

-

Dependence of test positivity (IGRAs, TST) on previous BCG vaccination.

-

Adverse events.

-

Likelihood of an indeterminate result.

-

Health-related quality of life.

Study selection strategy

Two independent reviewers screened all identified bibliographic records on title/abstract (screening level I) using a prespecified and piloted questionnaire form. Full-text reports of all potentially relevant records passing screening level I were then retrieved and independently reviewed using the same study eligibility criteria (screening level II). Any disagreements over inclusion/exclusion were resolved by discussion between two reviewers or by recourse to a third-party reviewer.

Data extraction strategy

Two reviewers independently extracted relevant data using an a priori defined pre-piloted data extraction sheet (see Appendix 3). Data extracted were cross-checked and any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third-party reviewer. Data extracted included information on the study [e.g. author, country, publication year, design, setting, sample size, follow-up duration, risk of bias (ROB) items such as blinding or incomplete outcome data], participants (e.g. age, sex, study eligibility criteria, comorbidities, BCG vaccination status/time, immune status), intervention/comparator tests (type of test/assay used for identification of LTBI, definition of positivity/negativity thresholds/cut-off values for each test, methods of laboratory analysis used for the derivation of test results, repeat testing), construct validity (e.g. definition of exposure to MTB in terms of proximity, length of time and/or type of contact; incidence of progression to active TB; timing of exposure to MTB/incidence of active TB; definition of low-risk populations; type of summary effect measures).

For individual studies, 2 × 2 contingency tables were constructed by cross-tabulating test results (separately for IGRAs and TST) with construct validity responses in relation to exposure level or incidence of progression to active TB. The proportions of subjects with positive and negative test results were extracted. For each test, all summary parameters of interest (see the list of outcomes) with corresponding measures of variability (95% CIs, p-values) were ascertained or calculated, if reported data permitted. A value of 0.5 was imputed for incidence studies with zero events for one of the compared tests to allow the calculation of CIRs and their ratios (R-CIRs). The R-CIRs were rendered indeterminate in the case of zero events in the 2 × 2 tables of both tests compared (no imputation was carried out). All relevant summary parameters were entered into the data extraction sheets and evidence and summary tables. Calculated parameters were marked as ‘calculated’.

Study quality assessment

The methodological quality of the incidence and exposure studies included in the current review was assessed using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool90 and a modified tool reported by Dinnes et al. ,44 respectively (see Appendix 4).

The QUIPS tool90 (also referred to as the ‘Methodology checklist: prognostic studies’, developed by Hayden et al. ,90 in the NICE Guidelines Manual89) was used to assess studies reporting the diagnostic performance/validation of tests (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, incidence density rate/CIRs, PPVs/NPVs, DORs, regression-based ORs). The QUIPS tool assesses the ROB in the six domains of patient selection/participation, study sample attrition, index test measurement, outcome/construct validity measurement, confounding and statistical analysis/outcome reporting. According to responses to prompting items, each of the six domains is rated as high, moderate or low ROB. The overall summary ROB rating for each study is then derived based on the domain-specific ROB ratings.

We used a modified tool reported by Dinnes et al. 44 to assess the quality of retrospective/cross-sectional studies reporting associations between test results and exposures. The QUIPS tool is not directly applicable to assessing the quality of retrospective/cross-sectional studies of association between test results and exposure because of the non-prognostic nature of their design (exposure is ascertained retrospectively, which is then correlated with test results). Appendix 4 outlines the criteria used to appraise these exposure studies. Each study was assessed for blinding of test results from exposure, description of index test and threshold (TST and IGRA), definition/description of exposure, completeness of verification of exposure and sample attrition. Each study was then awarded an overall quality score defined as:

-

low quality: studies with 0–2 satisfied (yes response) quality features

-

moderate quality: studies with three satisfied (yes response) quality features

-

high quality: studies with 4–5 satisfied (yes response) quality features.

Study quality was assessed independently by two reviewers (PS and KF). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer. The evidence across studies was summarised qualitatively using the overall ROB ratings (low, moderate, high).

Data synthesis and analysis

Given the absence of a gold standard for diagnosing LTBI, the performance of tests was compared using alternative methodologies that rely on validation of test results against predetermined validity constructs (i.e. proxies for a reference standard). Thus, our analyses focused on the following recommended approaches: (1) we evaluated and compared predictive values of IGRAs and the TST in relation to construct validity I (i.e. progression rate to active TB); (2) we evaluated and compared the degree of association/correlation of IGRA and TST results with construct validity II (i.e. exposure to MTB defined by proximity, duration or dose–response gradient); (3) we estimated and compared the specificity (or false positives) of IGRAs and the TST in relation to construct validity III (i.e. people at low risk of MTB or healthy populations); and (4) we measured the degree of concordance/discordance between IGRA and TST results. 44,91–94

For each index test (TST, IGRAs), if data permitted (either directly reported or, if not reported, calculated if possible), relevant statistical parameters of diagnostic test accuracy are presented per individual study. For statistics measuring agreement/disagreement between two tests, values for concordant (both tests positive or negative) and discordant (one test negative, the other test positive or vice versa) test results are presented or calculated if data permitted. Moreover, when possible, the likelihood of indeterminate test results was calculated.

The performance of the tests (in terms of diagnostic accuracy and concordance) was compared (e.g. IGRA vs. TST) using sensitivity, specificity, PPVs/NPVs, ratio of diagnostic odds ratios (R-DOR), ratio of incidence density rate ratios (R-IDRR) (or CIRs), regression-based ORs, kappa statistics, per cent discordance and likelihood of indeterminate test results. Note that, as there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of LTBI, specificity and sensitivity does not have the same meaning as in the conventional paradigm (i.e. against a gold standard) but reflects the performance of tests in relation to predetermined proxy constructs of validity (i.e. past exposure to TB or future progression to active TB).

The association between BCG vaccination and test performance in terms of specificity was explored by comparing false-positive rates (or odds of false positivity) of the TST and IGRAs in both BCG-vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals (i.e. dependence of false-positive rates on BCG vaccination status).

Summary measures of effectiveness (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, DOR, R-DOR, R-CIR) were pooled when deemed appropriate and feasible (based on the absence of clinical/methodological heterogeneity, the same cut-off values of a test or the absence of a test threshold effect on the DOR) using univariate95 and/or bivariate random-effects meta-analysis models. 19 The presence of heterogeneity across studies was determined using visual inspection of forest plots (of individual study ORs and R-DOR estimates and degree of overlap across 95% CIs) and chi-squared tests (two tailed, p ≤ 0.10). 96,97 A series of subgroup and sensitivity analyses (see below) was undertaken to explore potential reasons for statistical heterogeneity, if present. When pooling was not feasible, because of a lack of sufficient data or important clinical/statistical heterogeneity across studies (e.g. significant test threshold effect),98 the findings from individual studies were summarised qualitatively.

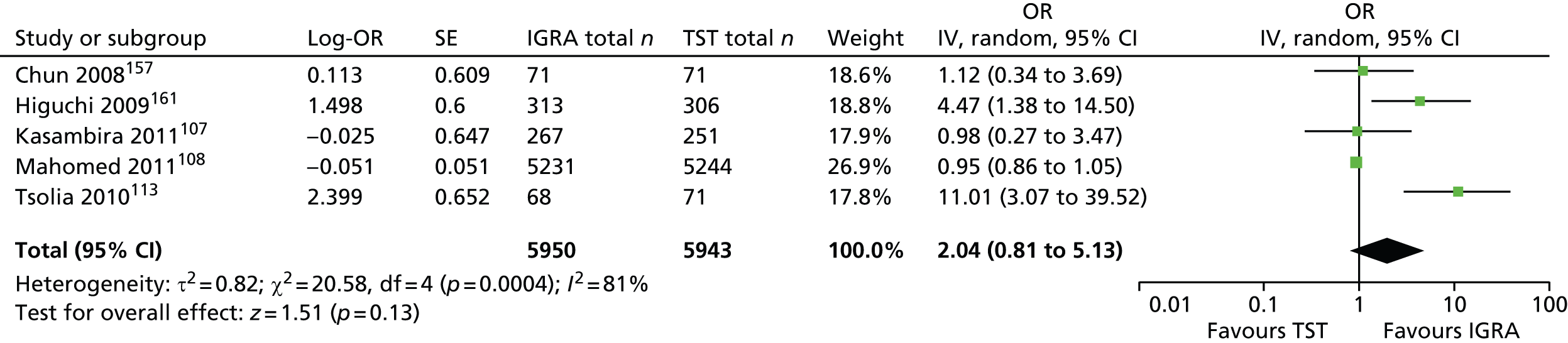

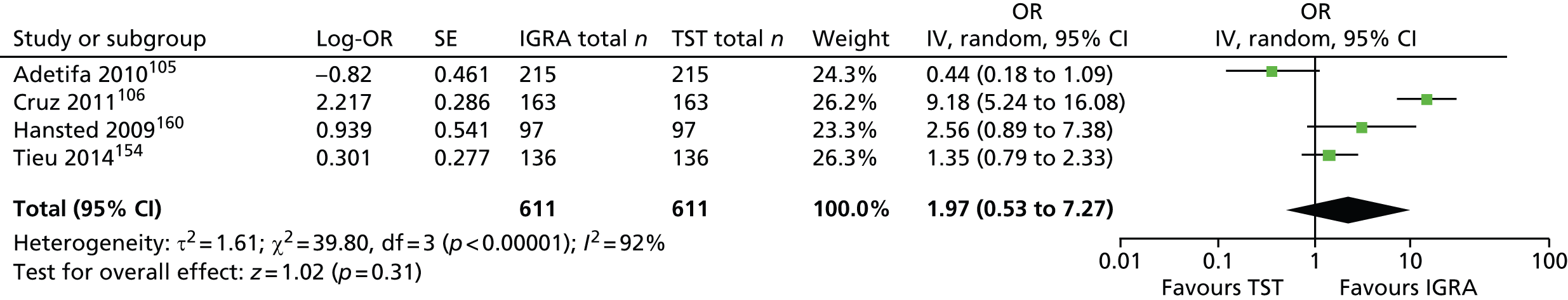

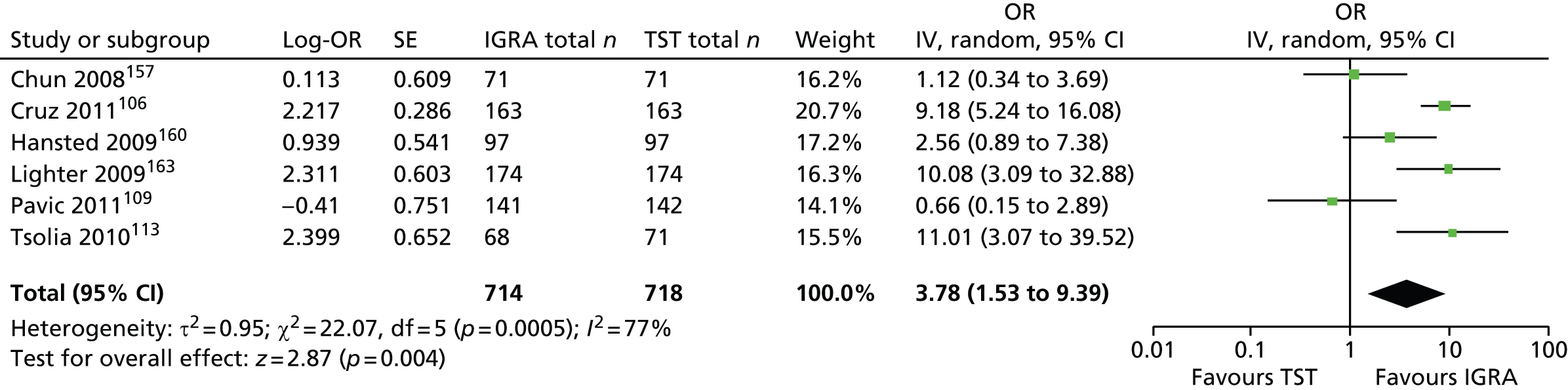

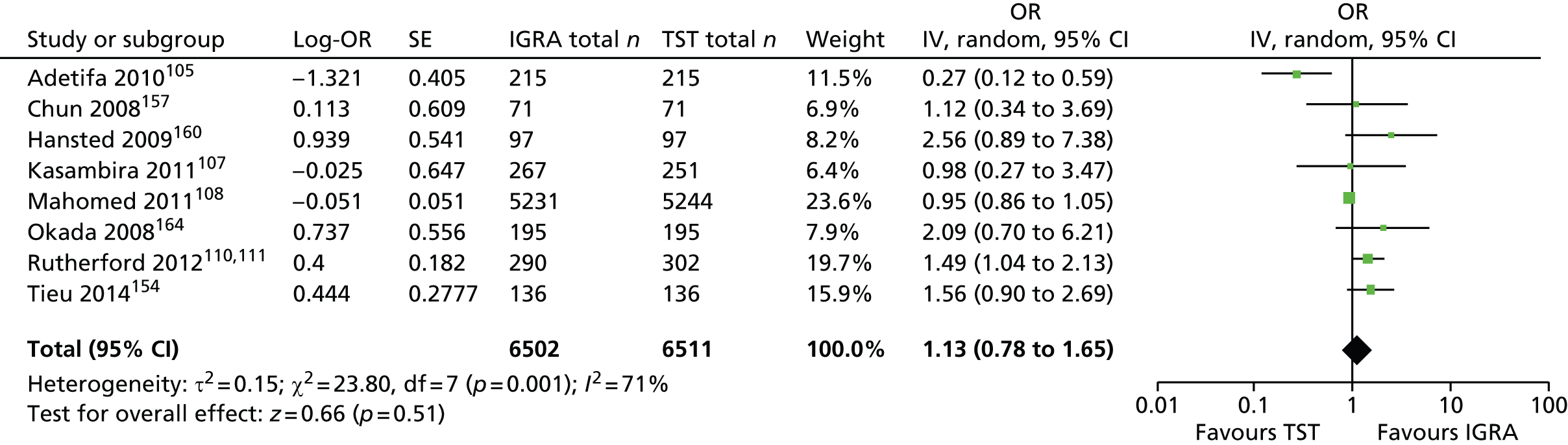

Data synthesis for the summary outcome measures is presented in evidence/summary tables and text overall and/or stratified by demographic characteristics (e.g. age), TST thresholds (≥ 5 mm, ≥ 10 mm, ≥ 15 mm), intervention (T-SPOT. TB vs. QFT) and prevalence/burden of TB in country of origin (high burden vs. low burden). 1 In addition, for people who were immunocompromised or at risk from immunosuppression (research question 2), when possible outcomes have been stratified by type of immunosuppression, use of immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. steroids, antiTNF-α treatment, antirheumatic drugs) and comorbidity condition (e.g. HIV infection, renal disease, diabetes, liver disease, haematological disease, cancer, autoimmune disease, transplant recipients).

It was planned to conduct subgroup analysis according to BCG vaccination status, TST threshold (≥ 5 mm, ≥ 10 mm, ≥ 15 mm) and prevalence of TB in country of origin, if data permitted.

Calculations were performed using Meta-DiSc version 1.4 (Unit of Clinical Biostatistics, Ramón y Cajal Hospital, Madrid, Spain)99 and Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). 100

Overall quality of evidence

There is no formally accepted and validated approach for the assessment of the overall quality of evidence that would be appropriate to the type of evidence synthesised in this review. Work on the formulation of this approach is still ongoing [Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group; see www.gradeworkinggroup.org (accessed 15 December 2015)]. 101

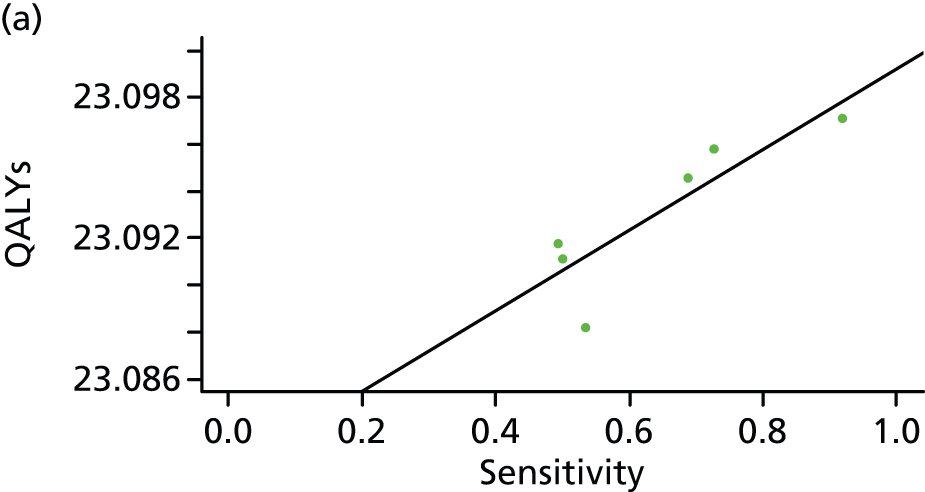

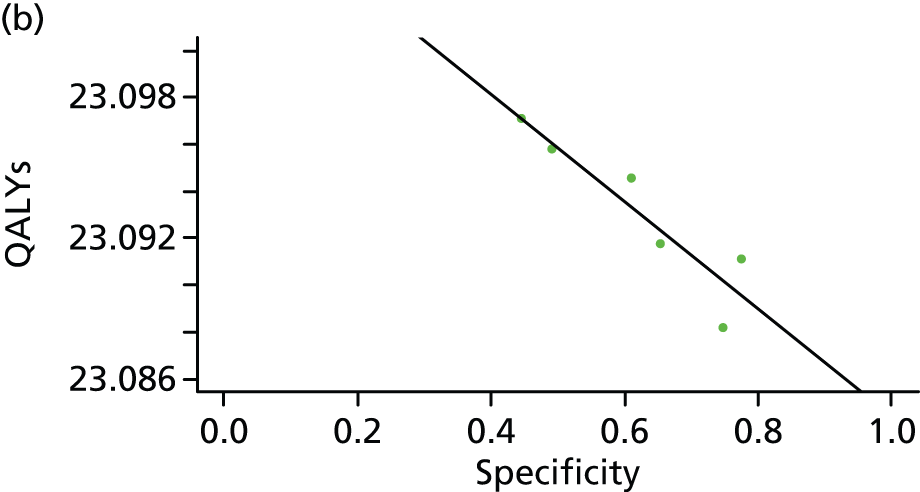

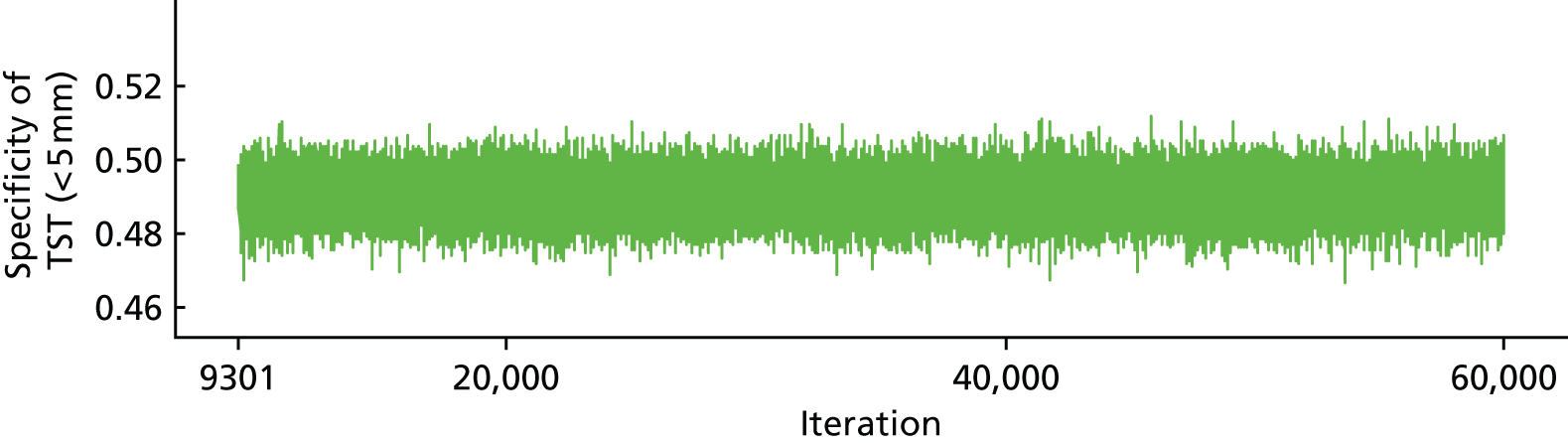

Derivation of summary measures of diagnostic accuracy

We used Bayesian meta-analysis to derive the sensitivity and specificity for various testing strategies for LTBI in the various population subcategories. The methods and results for this are reported in Chapter 6 [see Performance of screening texts (sensitivity and specificity)].

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness results

Number of studies identified

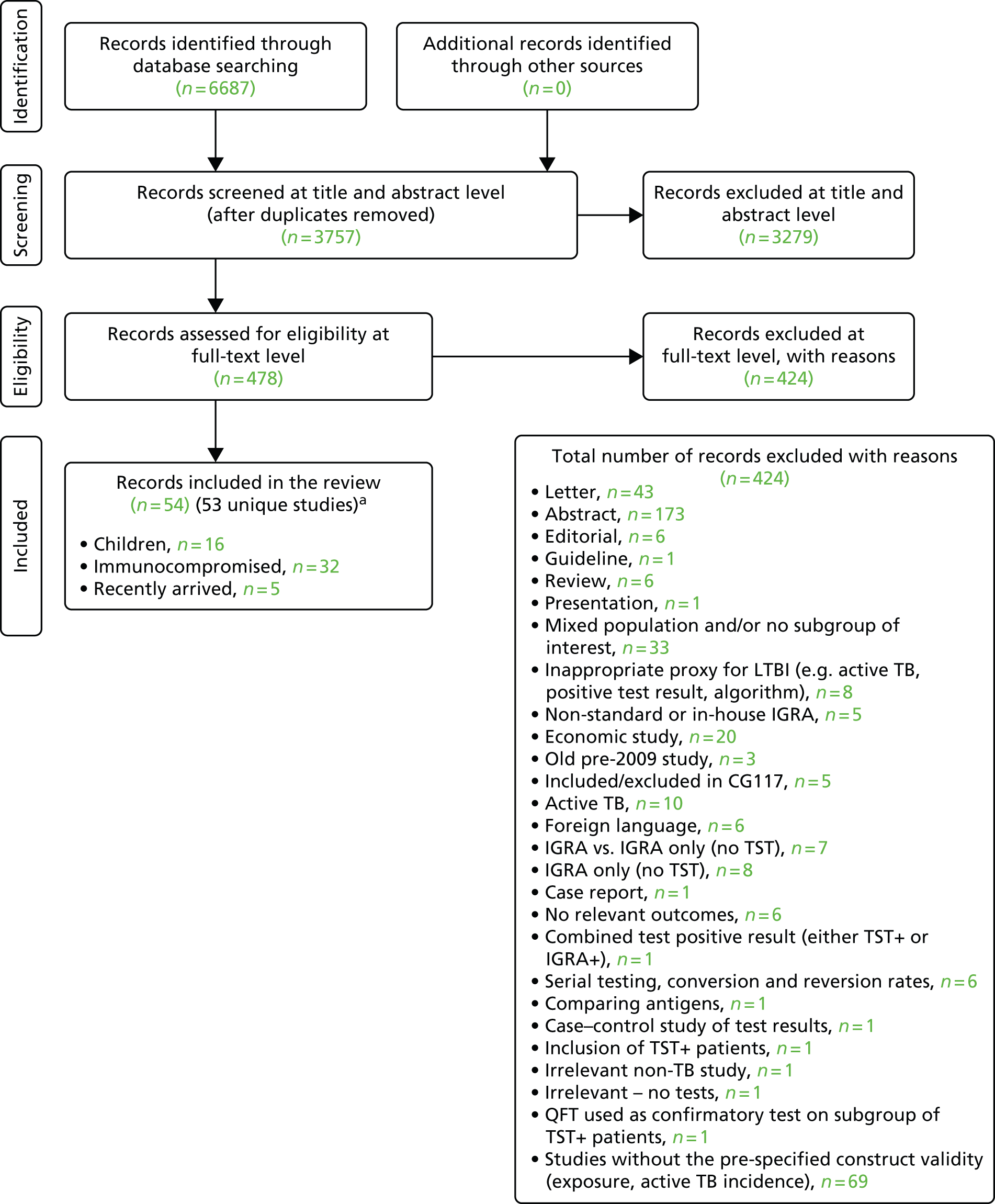

A total of 6687 bibliographic records were identified through electronic database searches. After removing duplicates, 3757 records were screened for inclusion. On the basis of title/abstract, 3279 records were excluded. The remaining 478 records were included for full-text screening. A further 424 records were excluded at the full-text stage. The remaining 54 records102–155 (53 unique studies) were considered relevant to the review since the previous NICE clinical guidance work in 2011 (CG117). 10 One study by Rutherford et al. 110,111 was presented in two publications. In addition, 37 studies156–192 from CG11710 were included in the current evidence synthesis (see Appendix 5). The study flow and the reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 2 and Appendix 6. A search for ongoing trials was undertaken in different databases (Clinical Trials.gov, WHO ICTRP) up to August 2014. A total of 50 ongoing trials were identified, of which 30 were excluded; the reasons for exclusion are presented in Appendix 7. Twenty ongoing trials were therefore considered relevant for inclusion in our review (see Appendix 8).

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses study flow diagram of studies identified since 2011. a, An additional 37 studies were included from CG117. 10

Description of included studies and synthesis

In the following sections we describe the baseline characteristics and study quality for the incidence and exposure studies of the three populations of interest: (1) children, (2) immunocompromised individuals and (3) those recently arrived from countries with a high TB incidence. Full data-extraction sheets including baseline characteristics for all recently identified studies since CG11710 are provided in Appendix 9. For each of the three populations we present the synthesis of the evidence in terms of the comparative performance of tests (diagnostic accuracy indices for identifying LTBI) and between-test concordance, discordance and agreement. Appendix 10 provides the incidence rates of TB for each included study since CG117. 10

Children and adolescents

Description of baseline characteristics

This section included 27 studies (28 publications102–113,148,150–152,154,156–166) in children and adolescents, of which 11 studies156–166 had already been reviewed in CG11710 (see Appendix 5). Our searches identified 16 additional studies (in 17 publications102–113,148,150–152,154), five102–104,150,152 of which investigated the incidence of active TB following testing for LTBI (incidence studies) and 11 of which (in 12 publications105–113,148,151,154) investigated levels of exposure in relation to LTBI test outcomes (exposure studies). Two publications110,111 reported data on the same population and were therefore considered as one study. See Appendix 9 for the full data-extraction sheets for all new included studies.

Incidence studies

Three102,104,152 of the five incidence studies included close contacts of TB cases and one study150 included only TST-positive (≥ 15 mm) children with no history of close contact with a TB case. Mahomed et al. 103 recruited low-risk high-school students in a high TB burden country, of whom 25% had current or past household contact with TB. Four studies were carried out in countries with TB vaccination: South Africa,104 Iran,103 Turkey150 and South Korea. 152 One study102 was carried out in Germany, in which only 35.7% of participants were BCG vaccinated. Four studies102–104,152 investigated the agreement of a QFT test with the TST. Four studies compared QFT-GIT with the TST in community settings102,103,150,152 whereas Noorbakhsh et al. 104 investigated the agreement between QFT-G and TST (≥ 10 mm) in a hospital setting. Follow-up to confirm active TB across the five studies ranged from 1 year104 to 3.8–4 years. 102,103 Table 2 provides further details on these studies.

| Study ID, country (burden) | Study aim, setting, design, follow-up duration and funding source | Method(s) of diagnosis of active TB | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Type and positivity threshold(s) of tests compared | Characteristics of study participants at baseline | Number of recruited and excluded study participants | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diel 2011,102 Germany (low) | Aim: to compare QFT-GIT with the TST in close contacts of patients with TB and evaluate progression to active TB for up to 4 years Setting: community-based contact study Design: prospective cohort study Follow-up: 2–4 years Funding source: NR (none of the authors had a financial relationship with a commercial entity that had an interest in the subject of this manuscript) |

CXR (and CT), identification of AFB in sputum samples by bronchoscopy or lavage of gastric secretions, conventional culture of MTB, nucleic acid amplification assays and/or histopathology, assessment of preceding clinical suspicion of TB. In culture-negative cases, and given a CXR consistent with TB, subsequent clinical and radiographic response to multidrug therapy over an appropriate time course (1–3 months) was considered sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of TB | Inclusion criteria: close contacts of smear-positive and subsequently culture-confirmed source MTB index cases; aggregate exposure time of the contact in the 3 months before the diagnosis of the respective index case (presumed period of infectiousness) > 40 hours indoors with shared air Exclusion criteria: contacts with an exposure time of < 40 hours to the source |

Type of tests: IGRA (QFT-GIT), TST Cut-off values/thresholds: IGRA: IFN-γ ≥ 0.35 IU/ml; TST: induration of > 5 mm or > 10 mm |

Mean (SD) age: 10.4 (4.3) years Female, n (%): NR Race/ethnicity, n (%): NR Geographical origin, n (%): Germany 84 (66.7) BCG vaccination, n (%): 45 (35.7) History of antiTB treatment, n (%): NR Total incidence of active TB, n/N (%): 6/104 (5.7) Chest radiography (yes/no): yes Clinical examination (yes/no): yes Morbidity, n (%): NR Comorbidity, n (%): NR |

Total number of recruited patients: 141; total number of excluded patients: 15 | Assessors of the TST were blinded to the QFT results and vice versa. Induration was read by trained and well-experienced public health nurses. If there was a borderline result (e.g. 5 mm exactly), a second reading was performed by a different nurse to verify the result. If there was disagreement, a third nurse read the TST and the consensus result was used |

| Mahomed 2011,103 South Africa (high) | Aim: to compare the predictive value of a baseline TST with that of the QFT-GIT for subsequent microbiologically confirmed TB disease among adolescents Setting: high school (TB vaccine trial site in the town of Worcester and surrounding villages; high burden of TB) Design: longitudinal cohort study Follow-up: 3.8 years Funding source: Aeras Global TB Vaccine Foundation with some support from the Gates Grand Challenge 6 and Gates Grand Challenge 12 grants for QFT testing |

Two sputum samples for smear microscopy on two separate occasions. If any single sputum sample was smear positive, a mycobacterial culture, chest radiography, and HIV test were performed | Inclusion criteria: adolescents aged 12–18 years Exclusion criteria: NR |

Type of tests: IGRA (QFT-GIT), TST Cut-off values/thresholds: IGRA: IFN-γ ≥ 0.35 IU/ml; TST: induration of ≥ 5 mm |

Mean (range or SD) age: NR Female, n (%): 2842 (54.2) Race/ethnicity, n (%): black 995 (19.0); mixed race: 3839 (73.2); Indian/white: 410 (7.8) BCG vaccination, n (%): yes 4917 (93.8); unknown 281 (5.4) History of antiTB treatment, n (%): NR Total incidence of active TB, n (%): 52 (1.0) Chest radiography (yes/no): yes Clinical examination (yes/no): yes Morbidity, n (%): NR Comorbidity, n (%): NR Type of during-study treatment, n (%): NR |

Total number of recruited patients: 6363; total number of excluded patients: 1119 | People with a recent household contact, TB-related symptoms, a positive TST of ≥ 10-mm induration or a positive QFT were referred for two sputum smears. If the results of either or both were sputum positive for AFB, the sputum samples were cultured and chest radiography and a HIV test were undertaken |