Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/38/01. The contractual start date was in October 2009. The draft report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Annemieke Hoek declares research awards from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ferring B.V. and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZoNMW), and personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, all unrelated to the PROMISE trial.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Coomarasamy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the physiological importance of progesterone in pregnancy, the individual and societal burdens of pregnancy loss, and the rationale to infer a role for progesterone in reducing the risk of miscarriage.

Existing knowledge

Progesterone in pregnancy

Progesterone is essential to achieve and maintain a healthy pregnancy. It is an endogenous hormone, secreted naturally by the corpus luteum (the remnants of the ovarian follicle that enclosed a developing ovum) during the second half of the menstrual cycle, and by the corpus luteum and placenta during early pregnancy. Progesterone prepares the tissue lining of the womb (endometrium) to allow implantation, and stimulates glands in the endometrium to secrete nutrients for the early embryo. During the first 8 weeks of pregnancy, progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum, but between 8 and 12 weeks the placenta takes over this role and maintains the pregnancy thereafter.

The importance of progesterone in pregnancy has prompted many clinicians to infer that progesterone deficiency may be aetiologically linked to recurrent miscarriage (RM), and that progesterone therapy in the first trimester of pregnancy may reduce the risk of miscarriage. In 2003 a Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline1 and a Cochrane review2 called for a definitive trial to test whether or not progesterone therapy in the first trimester could reduce the risk of miscarriage in women with a history of unexplained RM.

Burden of disease

Miscarriage is the commonest complication of pregnancy: one in six clinically recognised pregnancies ends in a miscarriage. 3 RM, the loss of three or more pregnancies, is a distinct clinical entity. The prevalence of RM (1%) is significantly higher than that expected by chance alone (0.4%). Even after comprehensive investigations, a cause for RM is identified in fewer than 50% of cases. 3 The majority of couples are, therefore, labelled as having unexplained RM.

Recurrent miscarriages affect over 6000 couples in the UK every year, and frequently result in substantial adverse physical and psychological consequences for women as well as impacting their families. For example, miscarriage has the potential to cause physical harm, including severe haemorrhage, infection, perforation of the womb during surgery for miscarriage and, rarely, maternal death. The eighth triennial Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths identified several women who had died from complications related to miscarriage. 4 Moreover, qualitative studies have shown the level of distress and the bereavement reaction associated with miscarriage to be equivalent to the impact of the stillbirth of a term baby. 3

Costs to the NHS

It is estimated that RM costs the NHS £28M per year. This value includes the costs of diagnosis (blood tests and ultrasonography), management of miscarriages (expectant, medical or surgical), investigations for causes of miscarriages (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome, parental karyotype and uterine cavity tests) and hospital inpatient costs. However, it does not include the management of the complications following treatment of miscarriages (such as uterine perforation, infection, bleeding or visceral damage) or any long-term health consequences of miscarriages or miscarriage management (including complications of intrauterine infections and adhesions). Thus, the true NHS perspective costs are likely to be higher than the estimated £28M per year. The societal costs, including days lost from work and out-of-pocket expenses for patients and partners, can be expected to be far greater.

Progesterone in clinical use for recurrent miscarriages

The PROMISE study was conceived to address the possibility that progesterone therapy in the first trimester of pregnancy may reduce the risk of RM. In 2007 we conducted a clinician survey in the UK (n = 114; response rate 102/114; 89.5%), and found that 2% (2/102) of clinicians use progesterone routinely and 3% (3/102) use it selectively in pregnant women with a history of RM. Over 95% (97/102) reported that they do not use progesterone for this indication and the vast majority of these (92/102; 90.2%) were willing to recruit to a trial evaluating the role of progesterone treatment for the prevention of RM.

We also carried out separate systematic reviews to examine (a) the effectiveness of progesterone in RM5 and (b) the safety of progesterone in pregnancy.

Effectiveness of progesterone in recurrent miscarriages

Two previously conducted systematic reviews2,6 had examined the role of progesterone therapy in RM, but, since these reviews were published and at the time of designing the PROMISE trial, new evidence7 had emerged. Therefore, we conducted a fresh systematic review with a meta-analysis.

We searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, ISI Web of Science Proceedings, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register, metaRegister of Controlled Trials database, MEDLINE and EMBASE resources, from database inception to January 2008, for the following search terms: (‘progesterone’ OR ‘progestagen’ OR ‘progestogen’ OR ‘progestin’ OR ‘progestational [hormone or agent] ‘ OR ‘progest$’). We considered outcomes of miscarriage (as defined by the primary authors), live birth, gestation at delivery, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

Four randomised trials7–10 were identified. There were 14 trials assessing the effects of progesterone in miscarriages including spontaneous (one-time) events2 but these trials should not be confused with trials assessing the effects of progesterone in RM. The quality of the four trials was poor (modified Jadad quality scores between 0/5 and 2/5; Table 1), and participant numbers were small even when the trials were combined in meta-analysis, with only 132 women actively treated with progestogens.

| Features | El-Zibdeh 20057 (n = 130) | Goldzieher 19648 (n = 18) | Levine 19649 (n = 30) | Swyer and Daley 195310 (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Unexplained RM (three consecutive miscarriages, and conditions such as antiphospholipid syndrome excluded) | Analysis restricted to those with a history of three or more miscarriages | History of three consecutive miscarriages | Analysis restricted to those with a history of three or more miscarriages |

| Intervention | Dydrogesterone 10 mg twice daily (oral) | Medroxyprogesterone 10 mg daily (oral) | Hydroxyprogesterone caproate 500 mg per week (intramuscular) | Progesterone pellets 6 × 25 mg inserted into gluteal muscle |

| Comparison | No treatment | Placebo | Placebo | No treatment |

| Duration of treatment | From diagnosis of pregnancy to 12 weeks | Unclear | Until miscarriage or 36 weeks | Unclear |

| Randomisation method | ‘Randomised’; method not given | ‘Sequentially numbered bottles’ | Alternation | Alternation |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Inadequate |

| Blinding | No | Double | Double | No |

| ITT analysis | Yes | Unreported | No | Unreported |

| Follow-up rates | 100% | 100% | 54% (26/56 excluded) | 100% |

| Jadad score | 0/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 |

Our review and a subsequent review conducted for Cochrane in 201311 found that all four trials showed a trend towards benefit of progesterone, but confidence intervals (CIs) were wide and differences were not statistically significant for all but one of the four trials. A meta-analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in miscarriages (odds ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.72; Figure 1). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity in the results (heterogeneity p-value 0.98).

FIGURE 1.

Meta-analysis of the four pre-existing trials of progestogen use in RM (outcome: miscarriage). df, degrees of freedom.

Although this evidence would be graded level 1a in the evidence hierarchy (because it is a systematic review of randomised trials), our survey of clinicians showed that it did not result in the use of progesterone for RM by clinical practitioners, owing to the weak methods and small sample sizes employed in the four published trials. One example of weak methodology was in lack of concealment, which has been shown to exaggerate effect sizes by up to 41%,12 although there is some evidence that this exaggeration may not be a concern when the outcome is objective. 13 Small sample sizes increase the likelihood of random error (generating the wide CIs in Figure 1). Nonetheless, the existing evidence presented a powerful reason to proceed with a trial of progesterone in RM, especially in consideration of the size of the effect observed and the low cost, widespread availability and convenience of the intervention, in addition to its safety profile.

Safety of progesterone supplementation in pregnancy

At the time of designing this study there was substantial evidence from in vitro fertilisation (IVF) practice that progestogen supplementation is safe to the mother and the fetus (at the proposed dose for the trial of 400 mg twice daily). 14–16

To further explore the question of safety, we conducted a review using the following search terms in MEDLINE (1966–2007) and EMBASE (1988–2007): (‘progesterone’ OR ‘progestational agents’ OR ‘progest$’) AND (‘adverse effects’ OR ‘complications’ OR ‘side effects’ OR ‘harm’) AND ‘pregnancy’. A systematic review of observational studies (both cohort and case–control studies) of first-trimester sex hormone exposure identified 14 studies, comprising 65,567 women. 17 The sex hormone in several of these studies was progestogens alone or with other steroids.

Most of the evidence in our review did not show harm, particularly any external genital malformation in the offspring, but one case–control study suggested an association between hypospadias and progestogen use. 18 Although findings from a case–control study represented weaker evidence than the better-quality evidence from larger cohort studies which did not substantiate this association, we decided to document all of the effects of progesterone in the PROMISE trial. More specifically, we decided to collect information about any neonatal genital abnormalities.

Meta-analyses of progesterone use in RM, in miscarriage2 and in the prevention of preterm birth19 did not identify any evidence of short-term safety concerns in women. However, it was not clear if these trials sought to document maternal side effects prospectively. In one study, intramuscular 17-OHP (hydroxyprogesterone) caused maternal adverse events (AEs) in 50% of women, largely due to injection site reactions. 20 This concern did not apply to the PROMISE trial, in which the route of administration was vaginal. Side effects were not reported in studies of vaginal progesterone in the context of prevention of preterm births. 21,22

Rationale

A trial of progesterone therapy in the treatment of unexplained RM was required for the following reasons:

-

The existing trials, although small and of poor quality, suggested a large benefit in a condition with substantial morbidity and costs.

-

A guideline by the RCOG and a Cochrane review called for a definitive trial to evaluate this research question. 12

-

Participants in two unpublished surveys [one of women with RM (n = 88) and the other of gynaecologists (n = 102) treating women with RM] demonstrated an interest in progesterone therapy and a willingness to participate in a potential trial (Arri Coomarasamy, University of Birmingham, 2008, unpublished data).

-

If proven to be effective, the intervention would represent a low-cost, safe and easily deliverable therapy.

Specific objectives

Primary objective

-

To test the hypothesis that, in women with unexplained RM, progesterone (400-mg vaginal capsules, twice daily), started as soon as possible after a positive urinary pregnancy test (and no later than 6 weeks of gestation) and continued to 12 weeks of gestation, compared with placebo, would increase live births beyond 24 completed weeks of pregnancy by at least 10%.

Secondary objectives

-

To test the hypothesis that progesterone would improve various pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (such as reduced miscarriage rates and improvements in survival at 28 days of neonatal life).

-

To test the hypothesis that progesterone, compared with placebo, would not incur serious adverse events (SAEs) in either the mother or the neonate (such as genital abnormalities in the neonate).

-

To explore differential or subgroup effects of progesterone in various prognostic subgroups, including subgroups of:

-

maternal age (≤ 35 years or > 35 years)

-

number of previous miscarriages (3 or ≥ 4)

-

presence or absence of polycystic ovaries.

-

-

To perform an economic evaluation for cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter reports the methods used to conduct the PROMISE trial. It describes the study design and protocol to progress potential participants from enrolment to completion of treatment, data analysis plans, quality assurance and governance.

Design

The PROMISE trial was conducted as a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international multicentre study, with health economic evaluation. Participants were randomised to receive progesterone or placebo in a 1 : 1 ratio.

Participants

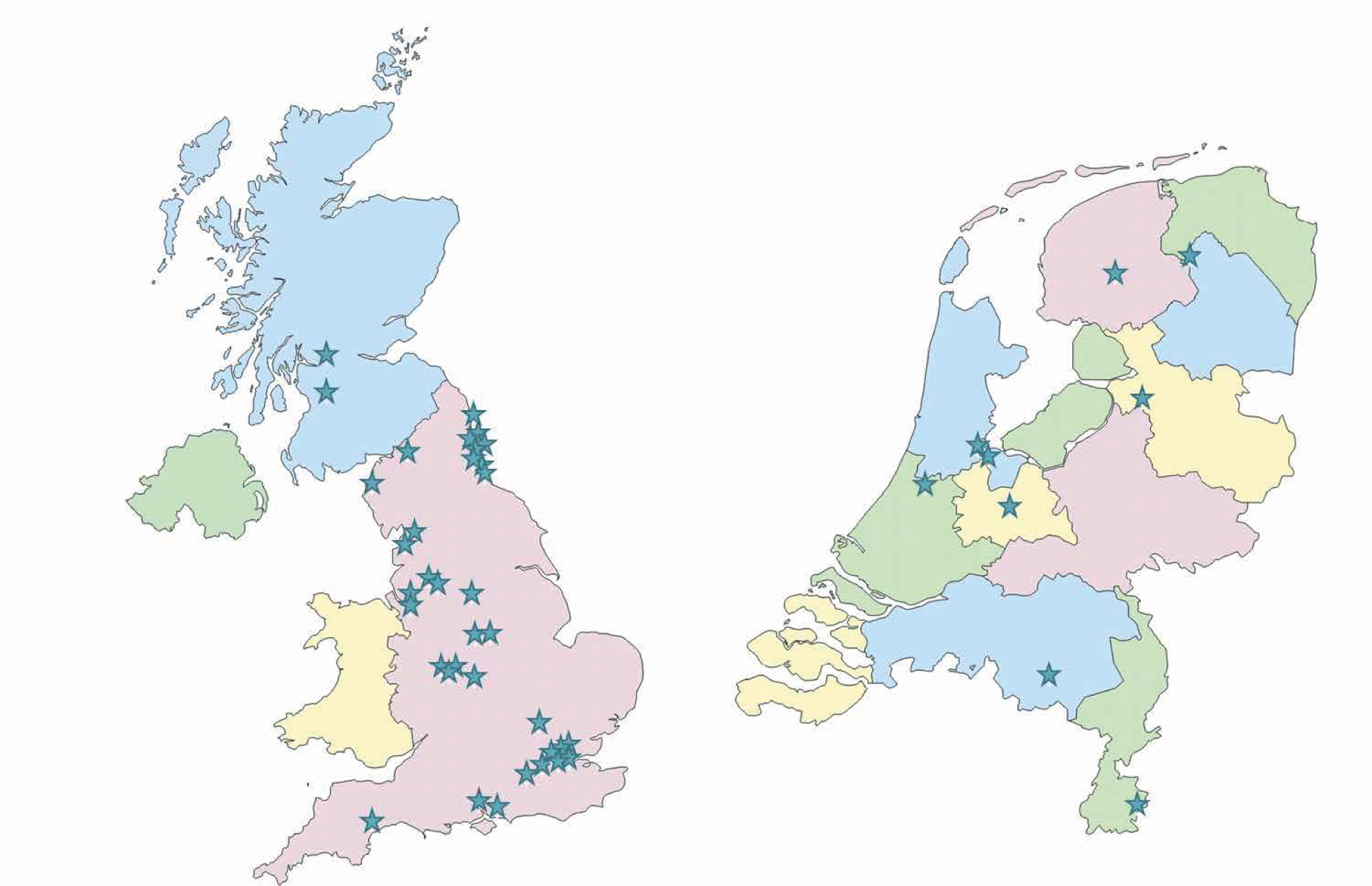

The participants in the PROMISE trial were recruited in hospital settings located across the UK (36 sites) and in the Netherlands (nine sites). These sites (Figure 2) included RM clinics and early pregnancy units in secondary or tertiary care hospitals.

All sites in the UK and the Netherlands with local investigators of appropriate capability and experience in conducting clinical trials were eligible to take part. Primary care settings were not utilised as either research sites or patient identification centres.

Participant eligibility for the trial was assessed according to the criteria listed below.

Inclusion criteria

In order to be eligible for the study, it was necessary for participants to meet all of the following criteria:

-

having a diagnosis of unexplained RM (three or more consecutive or non-consecutive first-trimester losses)

-

being aged 18–39 years at randomisation (the likelihood of miscarriages due to random chromosomal aberrations is higher in older women3,25 and such miscarriages are unlikely to be prevented by progesterone therapy)

-

trying to conceive naturally

-

willing and able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Participants could not be included in the study if any of the following criteria were applicable:

-

they were unable to conceive naturally (as confirmed by urinary pregnancy tests) within 1 year of recruitment or before the end of the randomisation period in the trial, whichever came earlier

-

they had antiphospholipid syndrome [lupus anticoagulant and/or anticardiolipin antibodies (immunoglobulin G or immunoglobulin M)]; other recognised thrombophilic conditions (testing according to usual clinic practice)

-

they had uterine cavity abnormalities (as assessed by ultrasound, hysterosonography, hysterosalpingogram or hysteroscopy)

-

they had abnormal parental karyotype

-

they had other identifiable causes of RM (tests initiated only if clinically indicated) such as diabetes, thyroid disease or systemic lupus erythematosus

-

they were on current heparin therapy

-

they had any contraindications to progesterone use (see the following section).

Contraindications to progesterone use

Women to whom any of the following applied were not eligible to take part in the trial:

-

they had a history of liver tumours

-

they had severe liver impairment

-

they had genital tract or breast cancer

-

they had severe arterial disease

-

they had undiagnosed vaginal bleeding

-

they had acute porphyria

-

they had a history during pregnancy of:

-

idiopathic jaundice

-

severe pruritus

-

pemphigoid gestationis

-

-

they were taking any of the following drugs, because these products interact with progesterone:

-

bromocriptine

-

cyclosporine

-

rifamycin

-

ketoconazole.

-

Recruitment

Potential participants were identified from dedicated RM clinics, or other hospital clinics in which the caseload included a substantial number of women with RM. Potential participants were identified and approached by clinic doctors, research nurses and midwives, after having received appropriate training relating to the trial. This training included the development of sensitivity in answering questions about the risks of pregnancy loss, and the importance of attention to early signs of possible miscarriage such as spotting or discharge.

The participant eligibility pathway to recruitment and randomisation is illustrated by Figure 3. Eligible women were given verbal and written explanations about the trial. They were informed clearly that participation in the trial was entirely voluntary, with the option of withdrawing at any stage, and that participation or non-participation would not affect their usual care. They were provided with a participant information sheet (PIS) (see Appendix 1). Eligible women were then given the opportunity to decide if they wished to participate, or if they needed more time to consider their decision, or if they did not wish to participate. In all three scenarios, the decision of the woman was respected. If a woman needed more time to consider her potential involvement, she was asked to call the research nurse or midwife when she had decided. If an undecided woman had not called within 14 days, the research nurse or midwife contacted her. If an initially undecided woman decided to participate later, the research nurse or midwife arranged a mutually convenient opportunity for the woman to be consented.

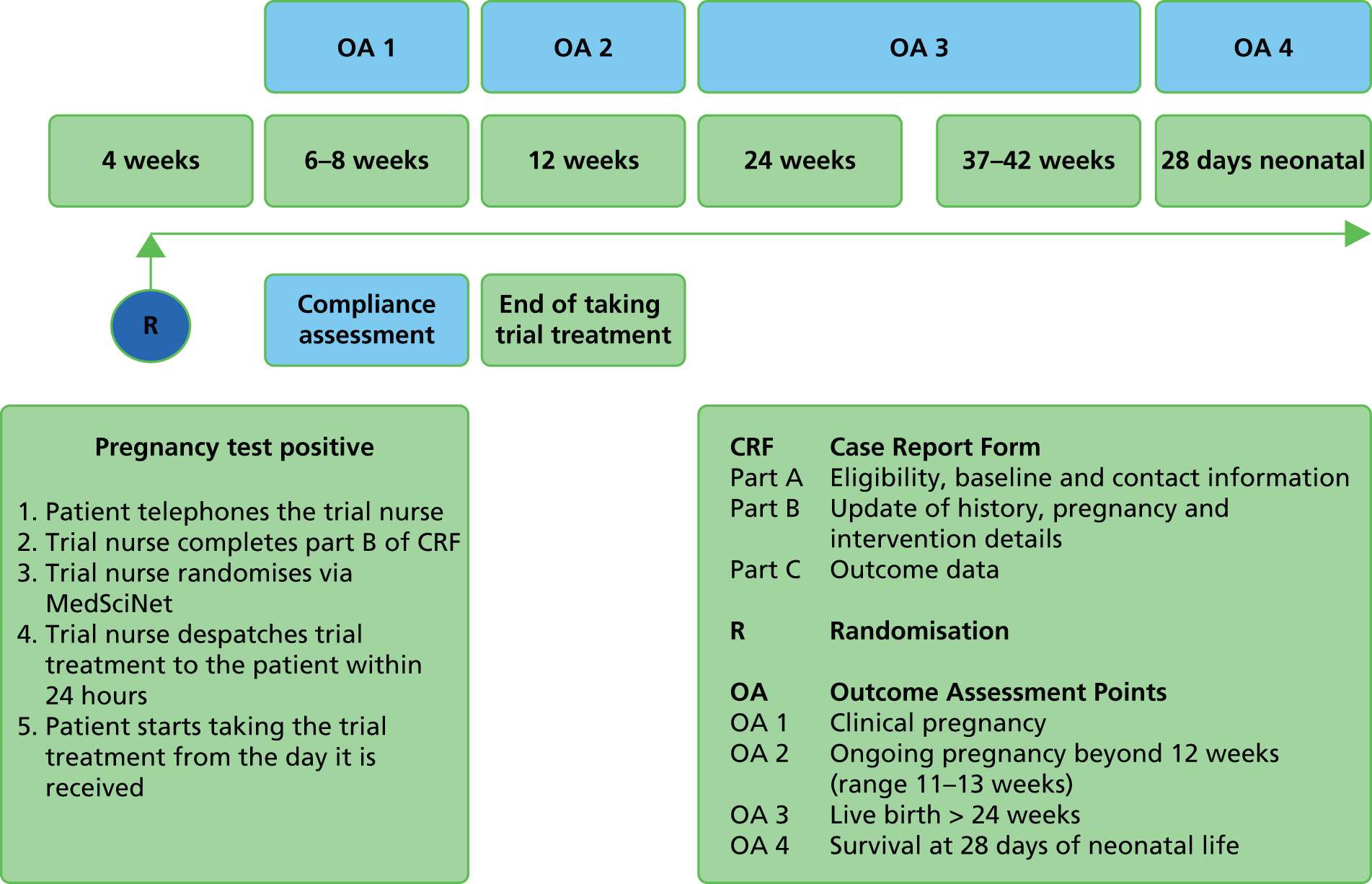

FIGURE 3.

Eligibility pathway to recruitment and randomisation. APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; CRF, case report form; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; M, miscarriage.

A written consent form (see Appendix 2) was provided to each woman who agreed to participate in the trial. The investigator and the participant both signed the consent form. The original copy was kept in the investigator site file, one copy was given to the participant and one copy was retained in the woman’s hospital records. Baseline demographic and medical data were collected, anonymised and stored in an electronic integrated trial management system (ITMS). Any identifying information was collected and stored in a password-protected local database on a secure computer with restricted access.

The first PROMISE participant was enrolled in June 2010 and randomised in October 2010. The last PROMISE participant was recruited and randomised in October 2013 (see Chapter 3, Recruitment).

Non-English speakers

We made provision for translation, if necessary, to communicate with non-English speakers and accommodate any special communications requirements of potential study participants. The PISs and consent forms (see Appendices 1 and 2) were translated from English into Dutch for use in the Netherlands.

Randomisation

Each woman consenting in advance of pregnancy was given instructions to notify the local research nurse or midwife by telephone as soon as she experienced a positive urinary pregnancy test. We expected most pre-consenting participants to notify us early in pregnancy, at approximately 4 weeks of gestation (4 weeks from their last menstrual period).

On receiving notification of pregnancy and confirming the woman’s willingness to participate in the trial (in either order of occurrence), the local research nurse or midwife reverified other aspects of eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, and obtained details of gestational age. Participants were randomised online to receive the trial intervention (either progesterone or placebo), via a purpose-designed ITMS. Each authorised member of the research team was provided with a unique username and password to the ITMS for this purpose. Online randomisation was available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, apart from during short periods of scheduled maintenance.

Sequence generation

Computer-generated random numbers were used, and participants were randomised online via a secure internet facility. This third-party independent ITMS was designed, developed and delivered by MedSciNet® (Stockholm, Sweden) according to standards of the International Organisation for Standardisation 9001:2000 and the requirements of the US Food and Drug Administration CFR21:11. 26

Participants were randomised to receive progesterone or placebo in a 1 : 1 ratio. A ‘minimisation’ procedure using a computer-based algorithm was used to avoid chance imbalances in important stratification variables. The stratification variables used for minimisation were as follows:

-

number of previous miscarriages (3 or > 3)

-

maternal age (≤ 35 or > 35 years)

-

polycystic ovaries or not

-

body mass index (BMI) (≤ 30.0 or > 30.0 kg/m2).

Allocation and minimisation

After all of the eligibility criteria and baseline data items were entered online, the ITMS generated a code number which took into account the minimisation variables recorded for the individual, and which was linked to a specific trial intervention pack. The code number was advised via e-mail to the local principal investigator (PI), the relevant trial pharmacist (see Distribution and Investigational medicinal product supply, Storage, dispensing and return) and the research nurse or midwife performing the randomisation.

Blinding

Participants, investigators, research nurses, midwives and other attending clinicians remained unaware of the trial drug allocation throughout the duration of the trial.

In the case of any SAE, the general recommendation was to initiate management and care of the participant as though the woman was taking progesterone. If the drug allocation was specifically requested to assist the medical management of a participant, clinicians could contact the trial manager or the trial co-ordinator for this purpose, 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (see Safety monitoring, Adverse events). Cases that were considered serious, unexpected and possibly, probably or definitely related to the trial intervention (see Appendix 3) were unblinded as appropriate. In any other circumstances, investigators and research nurses and midwives remained blind to drug allocation while the participant remained in the trial.

Distribution

On randomisation, the research nurse or midwife arranged the dispatch of a trial intervention pack to the local participating centre or the home address of the participant within 72 hours of receiving the telephone call informing of pregnancy. Nurses in the UK contacted the trial pharmacy at St Mary’s Hospital in London and nurses in the Netherlands contacted the trial pharmacy in Utrecht (see Investigational medicinal product supply, Storage, dispensing and return). Each trial intervention pack contained either progesterone or placebo.

Instructions to participants

The research nurse or midwife also provided the participant with instructions. In cases of delivery directly to the home address, the research nurse or midwife contacted the participant to ensure receipt and understanding of how to use the supplied capsules.

Each participant was expected to commence the trial intervention on the day it was received, and continue until it was finished, at around 12 completed weeks of gestation, unless the pregnancy ended before this time. The research nurse or midwife also telephoned each woman in the days immediately after the trial medicine was supplied, to ensure that the participant had started taking the medicine. In the event of the capsules being mislaid, the participant was instructed to telephone the research nurse or midwife, who would liaise with trial manager or the trial co-ordinator to arrange a further supply of the same type of intervention.

Each participant was asked for consent to notify the primary care provider (in the UK, the general practitioner) by letter that she was participating in the trial (see Appendix 4). Moreover, each participant was given a business card and a fridge magnet with contact details of local PROMISE investigators and the central Trial Co-ordinating Centre (TCC), to inform any directing clinicians, in case of potential drug interactions.

Interventions

Each participant in the PROMISE trial received either micronised progesterone or placebo capsules, to be administered vaginally. Both products were supplied by Besins Healthcare (Mountrouge, France), a global pharmaceutical company with a manufacturer’s licence for tablets and capsules, in compliance with good manufacturing practice standards27 and good clinical practice (GCP) requirements. 28,29

Progesterone capsules

The investigational medicinal product (IMP) was micronised progesterone at a dose of 400 mg (that is, two capsules of Utrogestan® 200 mg) taken vaginally twice daily (every morning and every evening) for the duration of treatment.

The anatomical therapeutic chemical classification code for the pharmacotherapeutic group of the IMP was G03D and the chemical abstract service number was 57-83-0. The product had all the properties of endogenous progesterone, with induction of a full secretory endometrium and in particular gestagenic, antiestrogenic, slightly antiandrogenic and antialdosterone effects.

Besins Healthcare held the manufacturing authorisation (France) for Utrogestan®, including for the indication of threatened miscarriage or prevention of habitual miscarriage due to luteal phase deficiency up until the 12th week of pregnancy.

Placebo capsules

Placebo capsules were vaginal capsules, composed of sunflower oil, soybean lecithin, gelatin, glycerol, titanium dioxide and purified water, encapsulated in the same form as the IMP, and identical in colour, shape and weight, for use in the control arm of the PROMISE trial. The dose, route and timing of administration were also identical to those in the active progesterone arm of the study.

Dose

The ideal dose of progesterone for the potential prevention of RM was unknown. The biologically effective dosage of micronised progesterone capsules ranged from 200 mg once daily to 400 mg twice daily according to the summary of product characteristics (SmPC)30 and the British National Formulary (BNF). 31 Our choice of 400 mg twice daily was made after a careful review of the existing literature and an extensive survey of clinicians in the UK (see Chapter 1, Existing knowledge, Progesterone in clinical use for recurrent miscarriages). We also reviewed other related evidence. For example, progesterone vaginal capsules are commonly used for luteal support in assisted conception at a treatment dose of 400 mg twice daily, with no specific safety concerns raised on this dose. 16,32

After evaluating the evidence, we considered the dosage of 400-mg vaginal progesterone twice daily to be an acceptable regimen to ensure a clinically effective dose, and to minimise the risk of a negative trial result from therapy with a suboptimal dose.

Route

An immunomodulatory effect of progesterone at the trophoblastic–decidual interface is the key presumed mechanism for preventing RM. 3,33–35 Our choice to use the vaginal route of administration was, therefore, rational to deliver a greater proportion of drug to the relevant site (the uterus) using the ‘first uterine pass’ effect. 36,37 Furthermore, studies that have used vaginal progesterone in the prevention of preterm birth have reported its effectiveness when given via this route. 19,21,22 For example, 14 out of 36 studies of second- and/or third-trimester progesterone to prevent preterm birth (identified by a recent systematic review) used vaginal progesterone, with significant improvements being observed for various clinical outcomes, confirming the biological effects of vaginal progesterone. 38

The acceptability and availability of interventional drugs were also important considerations supporting the vaginal route of drug delivery. Our discussions with consumer representatives confirmed that a vaginal formulation would be more acceptable to women than an intramuscular preparation. These findings were further supported by a study in which 12% of participants were unable to tolerate the intramuscular progesterone preparation and declined participation or withdrew from that trial. 20 Of those who did continue, 34% complained of localised soreness around the injection site. Finally, in our survey of women with RM conducted at St Mary’s Hospital and Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals in London, a very high acceptability of the vaginal route (81/88; 92%) was identified (Arri Coomarasamy, University of Birmingham, 2008, unpublished data).

The capsule formulation of the PROMISE trial is widely available in the UK and worldwide.

Timing

Treatment commenced as soon as possible after a positive pregnancy test and no later than 6 weeks of pregnancy, and continued until the gestational age of 12 weeks. Our rationale to discontinue the treatment at 12 weeks was that production of progesterone by the corpus luteum becomes less important than the placental production of progesterone after 12 weeks of gestation. Furthermore, in the only clinical trial of progesterone treatment for RM to have shown a statistically significant reduction in miscarriage rates, progesterone was given until 12 weeks of gestation (odds ratio 0.37, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.90). 7

Compliance assessment

Our previous experience of research and clinical care for women with RM demonstrated that they would be highly motivated and compliant with therapy advice. However, compliance in the PROMISE trial was evaluated by ‘pill-counting’.

Participants were asked to return completed, partially used and unused treatment packs to the trial centres. The research nurses and midwives at each study centre documented the capsules returned by each participant, while the trial pharmacists kept their own accountability logs.

In an effort to improve compliance, women who failed to return the blister packs from the previous 4 weeks, whether or not these were empty, using the envelope provided were contacted by the local research nurse or midwife by telephone or e-mail to be offered advice and support.

Non-compliance was defined as missing more than 20% of trial medicines for the gestational age at randomisation. Non-compliant participants were interviewed (face to face or via telephone) in an attempt to establish the reason(s) for their non-compliance.

Investigational medicinal product supply

Manufacture, packaging and labelling

All arrangements for trial drug supply, labelling, storage and preparation were undertaken as per the requirements of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. 39,40

Active (Utrogestan® vaginal 200 mg) and placebo capsules were manufactured and packaged (assembled) by Besins Healthcare, in compliance with good manufacturing practice (EU Directive 2003/94/EC)27 and GCP (Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC)28 requirements. Besins Healthcare also provided qualified person release of the trial drug under the requirements of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. 39,40

Each trial intervention pack contained the entire supply required for the treatment period of up to 8 weeks. As the treatment regimen was two Utrogestan® 200 mg or placebo capsules twice daily, the drug package for each participant contained 224 capsules: 2 (capsules) × 2 (twice daily) × 7 (7 days per week) × 8 (8 weeks) = 224.

The drug packages were labelled in compliance with the UK Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004,39,40 ensuring the protection of each participant, traceability and proper identification of the IMP and trial.

Storage, dispensing and return

At study initiation, supplies of progesterone and placebo capsules were delivered by Besins Healthcare to two study pharmacies, where the products were stored and whence they were dispensed to all participants.

The pharmacies were located at St Mary’s Hospital in London and the University Medical Centre of Utrecht. Both sites complied with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including (in the UK) the Duthie report41 and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britiain’s practice guidance on pharmacy services for clinical trials42 as well as the appropriate standard operating procedures of Imperial College London. 43

At the pharmacies, the PROMISE trial medications were stored separately from other stock, in areas with restricted access. Drugs expired or returned by participants were stored separately from unallocated trial medicines. Dispensing was undertaken against prescription forms, each entitled ‘The PROMISE trial, EudraCT Number 2009-011208-42’ and labelled with the name, date of birth and study identification number of the relevant participant and a unique code number provided by the ITMS for randomisation (see Randomisation, Allocation and minimisation). Each trial pharmacy kept detailed dispensing records including participant study numbers and names, code numbers, batch numbers, expiry dates, doses and dates of dispensing.

The trial co-ordinator monitored the quantity of supplies held by each dispensing pharmacy in comparison with the number and rate of randomisations undertaken, and liaised with Besins Healthcare to ensure adequate supplies of the IMP in the UK and the Netherlands.

Each participant in the PROMISE trial was provided with freepost envelopes to return the unused or used packets to the local study centre. All unused study drugs, including undispensed supplies and supplies returned by participants, were returned to the trial pharmacies for accountability and destruction. Both dispensing pharmacies were involved in the reconciliation of medicines returned by trial participants and the disposal of unused medication, in compliance with appropriate regulatory guidance.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Live birth beyond 24 completed weeks of gestation.

Secondary outcomes

-

Clinical pregnancy at 6–8 weeks (defined as the presence of a gestational sac, with or without a yolk sac or fetal pole).

-

Ongoing pregnancy at 12 weeks (range 11–13 weeks) (defined as the presence of a fetal heartbeat).

-

Miscarriage (defined as loss of pregnancy before 24 weeks of gestation).

-

Gestation at delivery.

-

Survival at 28 days of neonatal life.

-

Congenital anomalies, and specifically genital abnormalities.

Exploratory outcomes

-

Antenatal complications such as pre-eclampsia, small for gestational age (< 10th birthweight centile), preterm prelabour rupture of membranes and antepartum haemorrhage.

-

For live births at beyond 24 completed weeks of gestation: mode of delivery, birthweight, arterial and venous cord pH, APGAR (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration) score and resuscitation.

-

For neonates: surfactant use, ventilation support (days on intermittent positive pressure ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure and oxygen, and discharge on oxygen) and neonatal complications (such as infection, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotising enterocolitis, intraventricular haemorrhages and pneumothorax).

Resource use outcomes

The resource use data listed below were collected to estimate the costs associated with the provision of progesterone for RM:

-

antenatal, outpatient or emergency visits

-

inpatient admissions (nights in hospital)

-

maternal admissions to high-dependency units (HDUs) or intensive care units (ICUs) (nights)

-

neonatal admissions to special care baby units (SCBUs) or neonatal units (NNUs) (nights).

Future outcomes

Women were asked to consent for future evaluation of themselves and their child and the health records of both. Although long-term follow-up was outside the scope of the PROMISE trial, we recognised the value of data collected in this study to inform further studies on outcomes such as the composite end point of death or neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years of age, cognitive scale scores at 2 years of chronological age, and disability classified into domains according to professional consensus. The hospital number and (in the UK) NHS number of each baby within the PROMISE trial were recorded to facilitate future follow-up studies.

Outcome assessment

The ITMS was utilised to capture baseline and outcome data, for contemporaneous data cleaning, to produce reports for the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and to maintain an audit trail. Relevant trial data were transcribed directly into the ITMS. Source data comprised the research clinic notes, hospital notes, hand-held pregnancy notes, laboratory results and self-reports.

First outcome assessment (6–8 weeks of pregnancy)

The research nurse or midwife at each study site telephoned every participant at between 6 and 7 weeks of gestation, to ensure there were arrangements for an ultrasound appointment with her usual carers, before 8 weeks of gestation (Figure 4). If an appointment had not been booked, the research nurse or midwife assisted with booking. The research nurse or midwife telephoned each participant again between 3 and 5 days after the scheduled date of the ultrasound appointment, to obtain details of the observations of a gestational sac.

FIGURE 4.

Participant care pathway and outcome assessment.

Second outcome assessment (12 weeks of pregnancy)

The research nurse or midwife at each study site telephoned each participant between 10 and 12 weeks of gestation, to ensure there were arrangements for an ultrasound appointment with her usual carers, at between 12 and 14 weeks of gestation (see Figure 4). As previously, the research nurse or midwife assisted with booking an appointment if necessary, and telephoned the participant afterwards to obtain details of variables such as fetal heartbeat. The research nurse or midwife also recorded the expected date of delivery at this stage.

Third outcome assessment

The third outcome assessment was conducted at or after birth (see Figure 4). The research nurse or midwife at each study site telephoned every participant 2 weeks after the expected date of delivery to obtain pregnancy outcome data such as the mode of delivery, gestation, weight and APGAR score at birth. The ITMS generated automated prompts to alert the research nurse or midwife at the time of expected date of delivery. The research nurse or midwife also checked birth registers and inpatient records to track hospital admissions and pregnancy outcomes.

Fourth outcome assessment

The fourth and final outcome assessment was conducted to gather neonatal outcomes at 28 days after birth (see Figure 4). The research nurse or midwife at each study site telephoned every participant to obtain postnatal and neonatal outcome data including any nights of hospital admission or requirements for ventilation support, and complications such as early infection. The ITMS generated automated prompts to alert the research nurse or midwife at the appropriate time. Using the full repertoire of evidence-based methods to maximise data collection,44 the research nurse or midwife also checked birth registers and inpatient records to track hospital admissions and pregnancy outcomes.

Continuity

From previous experience of research and clinical care for women with RM, we expected high rates of compliance with therapy advice. Moreover, the time interval between randomisation and final outcome assessment in the PROMISE trial was short (e.g. if delivery occurred at 40 weeks of gestation, the interval was 40 weeks), so we expected loss to follow-up to be minimal. Participants in the study continued to be managed by their clinical teams throughout their pregnancies, according to local protocols.

Withdrawal

Following discussion with the Trial Management Group (TMG), participants in the PROMISE trial could be withdrawn from trial treatment if it became medically necessary in the opinion of the investigator(s) or clinician(s) providing patient care. In the event of such premature treatment cessation, study nurses and midwives made every effort to obtain and record information about the reasons for discontinuation, and to follow up all safety and efficacy outcomes as appropriate.

Participants in the PROMISE trial could voluntarily decide to cease taking the study treatment at any time. If a participant did not return for a scheduled visit, attempts were made to contact her and (where possible) to review compliance and AEs. We documented the reason(s) for self-withdrawal where possible. Each woman remained able to change her mind about withdrawal, and reconsent to participate in the trial, at any time. Clear distinction was made between withdrawals from trial treatments while allowing further follow-up, and any participants who refused any follow-up. If a woman withdrew from taking the trial treatment but permitted further data collection, she was followed up and outcome assessments were undertaken for the remainder of the study.

If a participant explicitly withdrew consent to any further data recording, this decision was respected and recorded via the ITMS. All communications surrounding the withdrawal were noted in the study records and no further data were collected for such participants.

Concomitant non-trial treatments

Concomitant therapy was provided at the discretion of the care-providing clinicians, and all concomitant treatment and medications were documented via the ITMS. Post-randomisation use of heparin was discouraged unless there was a clear and recognised indication for it (heparin therapy at the time of randomisation made a woman ineligible to participate in the trial). Other than identified contraindicated drugs (see Participants, Exclusion criteria) and other progestogen preparations, the initiation of treatment for another indication did not necessitate withdrawal from the PROMISE study.

Safety monitoring

A review conducted in 2007, before the PROMISE trial commenced, showed no clear or consistent evidence of SAEs on the mother or the baby as a result of progesterone treatment during pregnancy (see Chapter 1, Existing knowledge, Progesterone in clinical use for recurrent miscarriages). Moreover, there is substantial evidence from other studies to indicate that progestogen supplementation at the dose administered in the PROMISE trial is safe to the mother and the fetus. 14–16

The SmPC for progesterone (vaginal capsules)30 states that ‘preclinical data revealed no special hazard for humans based on conventional studies of safety pharmacology and toxicity’ (© Datapharm).

Known side effects

The SmPC for progesterone (vaginal capsules)30 also states that ‘local intolerance (burning, pruritus or fatty discharge) has been observed during the different clinical trials and reported in the literature but incidences were extremely low’ (© Datapharm).

Overdose

The symptoms of progesterone overdose may include somnolence, dizziness and euphoria. In case of overdose, the care-providing clinicians of the PROMISE trial were prepared to undertake observation and reporting, and provide symptomatic and supportive measures, as required.

Dose modification for toxicity

The PROMISE trial included provision that, for participants experiencing non-serious side effects, the dosage could be reduced to 200 mg twice daily (one capsule in the morning and one at bedtime) at the discretion of the care-providing clinician, without unblinding treatment allocation (see the following section). The dose modification was noted on the case report form, along with the gestational age and the date on which such change was implemented.

Adverse events

The pharmacovigilance procedures of the PROMISE trial, including documentation, validation, evaluation and reporting, and responsibilities for the performance of these requirements, were based on the contemporaneously available literature to guide good practice. 28,45–47

Assessment

All of the trial participants were asked to report any hospitalisations, consultations with other medical practitioners, disability, incapacity or any other AEs to their local research team; if the local study nurse or midwife was unavailable for any reason, they were able to report the events to the trial manager or trial co-ordinator via telephone at any time. Moreover, at the time of each outcome assessment, investigators, research nurses and midwives at each study centre proactively asked each participant about any AEs in the preceding weeks. AEs were assessed by clinical investigators and further reported as appropriate, and in any case recorded in the ITMS for scheduled interim analyses to standard formats47 by the independent DMC. If a local clinical investigator was unavailable, initial AE reports without causality and expectedness assessment were submitted to the TCC by a health-care professional within 24 hours, and followed up by medical assessment as soon as possible thereafter, ideally within the following 24 hours.

Regardless of treatment allocation, the expectedness, seriousness and causality of AEs were assessed according to standardised definitions (see Appendix 3) as though the participant had received the active drug (progesterone).

Reporting

Adverse events were reported by local clinical investigators to the TCC, and thence to the sponsor (Imperial College London/Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Joint Research Compliance Office). The sponsor (or the chief investigator on behalf of the sponsor) reported to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The sponsor (or the trial co-ordinator on behalf of the sponsor) also reported to the Research Ethics Committee (REC), and equivalent bodies in the Netherlands, as appropriate. If information was incomplete at the time of initial reporting, or if the event was ongoing, local investigators forwarded follow-up information as soon as possible. If there was a difference between the expectedness, seriousness and causality assessments of the local investigator, the TCC and the sponsor, then the worst-case assessment was used for reporting.

Serious adverse events and serious adverse reactions were recorded on a purpose-designed SAE form and notified by local investigators to the TCC within 24 hours of the local investigators becoming aware of these events. Local investigators were responsible for additionally reporting SAEs to their host institutions, according to local regulations, and instituting supplementary investigations as appropriate based on clinical judgement of the causative factors. Any SAE or serious adverse reaction that was outstanding at the end of the trial treatment period was followed up at least until the final outcome was determined, even if this provision necessitated follow-up beyond 28 days postpartum. The TCC reported all SAEs to the independent DMC approximately 6-monthly. The DMC viewed data blinded to treatment, but was able to review unblinded data if necessary.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were unblinded, as appropriate, reviewed by the trial manager within 24 hours of reporting, and further reported to the MHRA and the REC, or the equivalent bodies in the Netherlands, by the TCC as soon as possible, and in any event within 15 days (or 7 days in the case of fatal or life-threatening SUSARs).

Unblinding

Unblinding was undertaken only in the event of a medical emergency requiring knowledge of the drug received. In the event that an investigator or the care-providing clinician required disclosure of the treatment allocation, the ITMS allowed the trial manager or the trial pharmacy to break the randomisation code. For this purpose, the TCC could be contacted between 09.00 and 16.00 every weekday; otherwise, the trial manager or designee could be contacted directly via a 24-hour trial mobile phone. The investigator or care-providing clinician communicating the alert was asked to provide the date of the requirement, the name of person requesting unblinding, the reason for unblinding and any other relevant information.

Sample size

The PROMISE trial investigators believed that it was important to ensure that the study was large enough to detect reliably moderate but clinically important treatment effects. Our calculations indicated that, to detect a minimally important difference (MID) of 10% in rates of live birth after at least 24 weeks (from 60% to 70%, odds ratio 1.56), for an alpha error rate of 5% and beta error rate of 20% (i.e. 80% power), it would be necessary to randomise 376 participants to the intervention arm and 376 participants to the control arm (752 participants in total). However, assuming and adjusting for a worst-case scenario of a loss to follow-up rate of 5%, the total number of participants required would be 790 (395 each in the progesterone and placebo arms). The sample size of the study was planned accordingly.

The MID of 10% was defined following consultations among health-care practitioners, patients and representatives of patient bodies. However, we noted that this difference was much smaller than that expected from the contemporaneously existing literature (see Chapter 1, Existing knowledge, Progesterone in clinical use for recurrent miscarriages), which showed that the odds of miscarriage could be more than halved with progesterone therapy (odds ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.72). Hence, assuming a conservative actual absolute difference of 15% in rates of live birth beyond 24 weeks, 790 participants (after accounting for 5% attrition) provided a power of 99%.

The 60% baseline (control) event rate was derived from a comprehensive audit carried out at the largest RM unit in the UK (St Mary’s Hospital in London) covering the period between 1998 and 2005, that showed the chances of live birth to be 61.8% (698/1129) after three miscarriages, 60.3% (350/580) after four miscarriages, 47.6% (109/229) after five miscarriages and 42.3% (82/194) after at least six miscarriages. However, because we had identified previously published evidence48 to suggest a higher control event rate, we performed a sensitivity analysis on the power calculations in which we assumed a higher control event rate of 70%. For a 10% absolute difference in rates of live birth after at least 24 weeks, and for an alpha error rate of 5%, 790 participants (after accounting for 5% attrition) gave a power of 89% (higher than 80% power when the control event rate was estimated to be 60%). We prudently adopted a lower control event rate for power calculation, to make provision for a worst-case scenario. All the power calculations noted above used two-sided binominal testing.

Statistical methods

Our data analysis plan was drawn up by the trial statistician and the study team, and approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and independent DMC prior to any analysis. The analysis was undertaken, using Stata® software, version 12 or later (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), based on treatment code and following the intention-to-treat principle. Only after the analysis was completed were the actual treatment arms corresponding to the treatment codes revealed. The components of analysis comprised (a) summarising baseline data, (b) intergroup comparisons, (c) subgroup analysis, and (d) adjustments and sensitivity analyses, such as to recognise the implications of missing data. The authors of this report had full access to all data collected in the study.

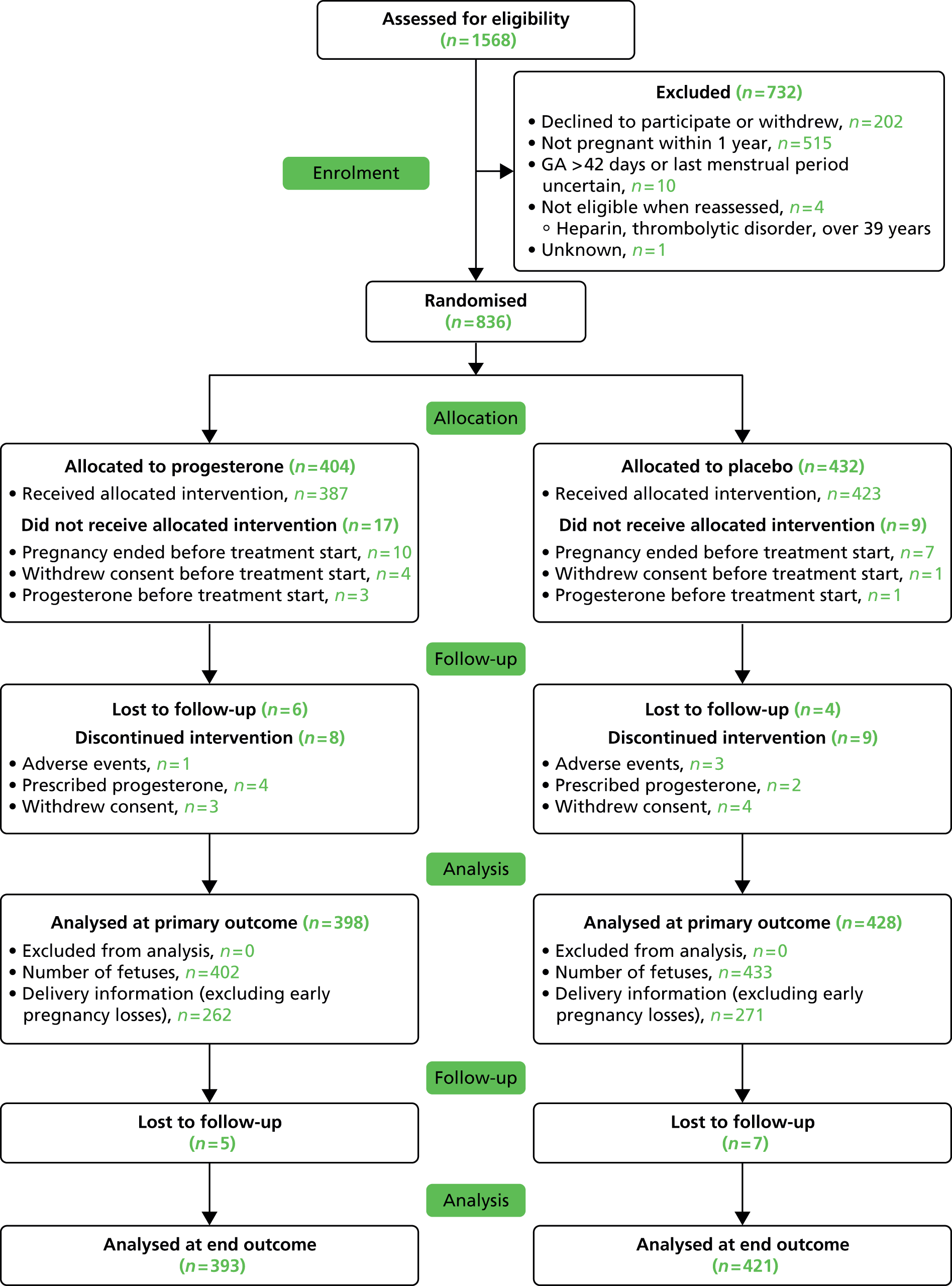

Summarising trial data

We planned to summarise the recruitment numbers, those lost to follow-up, protocol violations and other relevant data, using a Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. Baseline data and outcome data were separately summarised. For categorical data, we planned to provide proportions (or percentages). For continuous variables, we planned to examine the distribution of the observations and, if normally distributed, we planned to summarise them as means with standard deviations (SDs). If they were not normally distributed, we planned to report medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs); additionally, we planned to use geometric means and SDs for data where distributions appeared to be log-normal.

We planned to use diagnostic plots to assess the severity of deviations from normality, using log-transformations where necessary, assessing results as estimates with 95% CIs, and using bootstrapping with bias correction and acceleration where non-parametric methods were indicated.

Following previously published CONSORT recommendations,49–51 significance tests were not given between randomised treatment arms.

Intergroup comparisons

The primary analysis was undertaken on the basis of intention to treat. This approach was intended to avoid any potentially misleading artefacts of the study (such as non-random attrition). Every attempt was made to collect a complete data set about each pregnancy and women were encouraged to allow continued data collection even if withdrawing from trial treatment, because the exclusion of withdrawn participants from data analysis could bias results and reduce the power of the study to detect important differences. In particular, participants were followed up even after any protocol treatment deviation or violation. However, if a participant explicitly withdrew consent to any further data recording then all communications surrounding the withdrawal were noted and no further data were collected for such participants (see Outcomes, Withdrawal).

Participants were analysed according to the original randomised allocation, irrespective of compliance and crossovers. Binary regression with a log-link was used to assess relative risks (RRs) for the primary outcomes and for other binary outcomes such as clinical pregnancy at 6–8 weeks; ongoing pregnancy at 12 weeks (range 11–13 weeks), miscarriage rate and survival at 28 days of neonatal life, adjusting for minimisation variables.

Significance tests were, in general, carried out only for estimates of treatment effects, as separate tests for changes over time in the two groups might have resulted in entirely false and misleading conclusions about the differences between the groups when comparing p-values.

Notwithstanding our best efforts to collect a complete data set about each pregnancy, in a small number of cases it was not possible to determine the primary outcome of the study (see Chapter 3, Numbers analysed). We conducted an analysis whereby participants with missing primary outcome data were not included in the primary analysis. This presented a risk of bias, and secondary sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the possible impact of the risk, considering alternative assumptions both in favour and against the effect of the intervention. Other sensitivity analyses involved simulating missing responses using multiple imputation, using those baseline variables that are significantly related to the outcome as predictors.

Subgroup analysis

Three subgroup analyses were planned:

-

number of previous miscarriages (3 or ≥ 4)

-

maternal age (≤ 35 or > 35 years)

-

polycystic ovaries or not.

Subgroup analyses were conducted only for the primary end point, and multivariate logistic regression was used. In each case, a test for interaction was first used to determine whether or not treatment was particularly effective in individual subgroups; our performance of subgroup analyses was dependent on sufficient data. Because of the well-known risk of false positives, both main effects and tests for interaction were performed and assessed before we considered results for subgroups. In addition, post-hoc subgroup analysis was performed only for the purpose of hypothesis generation.

Adjustments and sensitivity analyses

The process of randomisation with minimisation is designed to result in comparison groups that are highly similar at baseline, even more so than would be expected by chance. However, if randomisation failed to achieve balanced groups, we planned linear or logistic regression to adjust for the imbalance. We planned to adjust for missing data using multiple imputation. In cases of difference, we planned to give greater weighting to the primary analysis of intergroup comparisons than to sensitivity analyses.

Interim analyses

Interim analyses of principal safety and effectiveness end points were conducted on behalf of the independent DMC. These were considered together with scheduled reports of SAEs. The trial statistician was unblinded to the level of groups ‘A’ and ‘B’. The meaning of ‘A’ and ‘B’ was made known to the DMC separately. The first interim analysis was undertaken after the primary outcome data became available for the first 100 participants, and thereafter at annual intervals.

We were prepared to consider early termination of the PROMISE trial in case of interim analyses showing overwhelming evidence of effectiveness or significant harm (see Termination). Effectiveness and futility criteria were defined by the DMC (see Governance, Trial oversight bodies) with regard to the Peto principle that a trial should be stopped only when there is overwhelming evidence against one treatment or another52,53 with a nominal interim alpha set at 0.001 using O’Brien and Fleming alpha spending rules. 54 Under these conditions, no adjustment to the overall level of significance was needed. 55,56

Long-term analyses

Although the development of the babies born to participants in the PROMISE trial was of interest to the investigators, this was outside the scope and time frame of the study. Nevertheless, we recognised the value of data collected in this study to inform further studies on outcomes such as the composite end point of death or neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years of age, cognitive scale scores at 2 years of chronological age, and disability classified into domains according to professional consensus. Women were asked to consent to future evaluation of themselves and their child and the health records of both, and could be traced through NHS Strategic Tracing Services. The hospital number and NHS number of each baby in the PROMISE trial were also recorded to facilitate future follow-up studies.

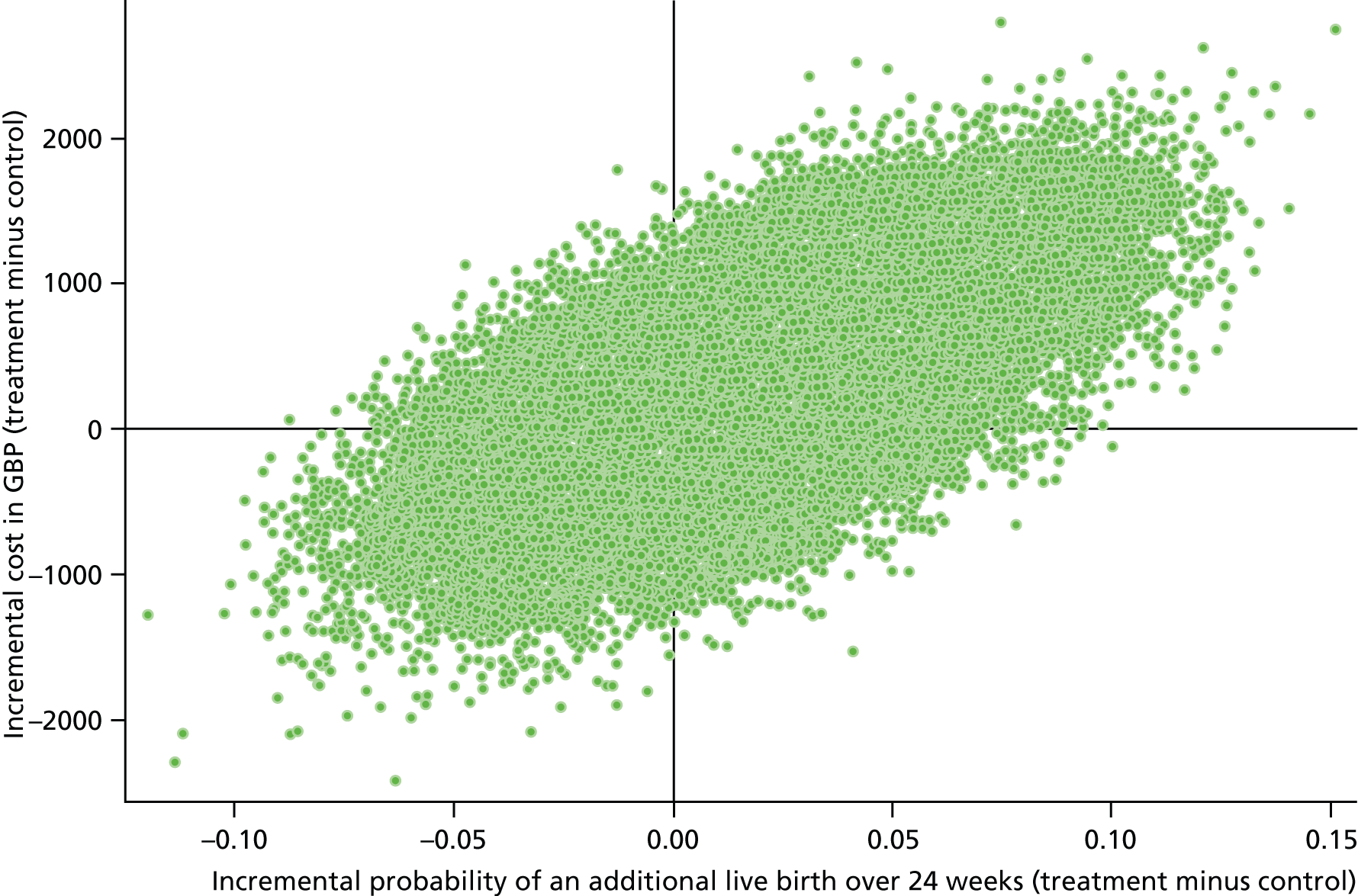

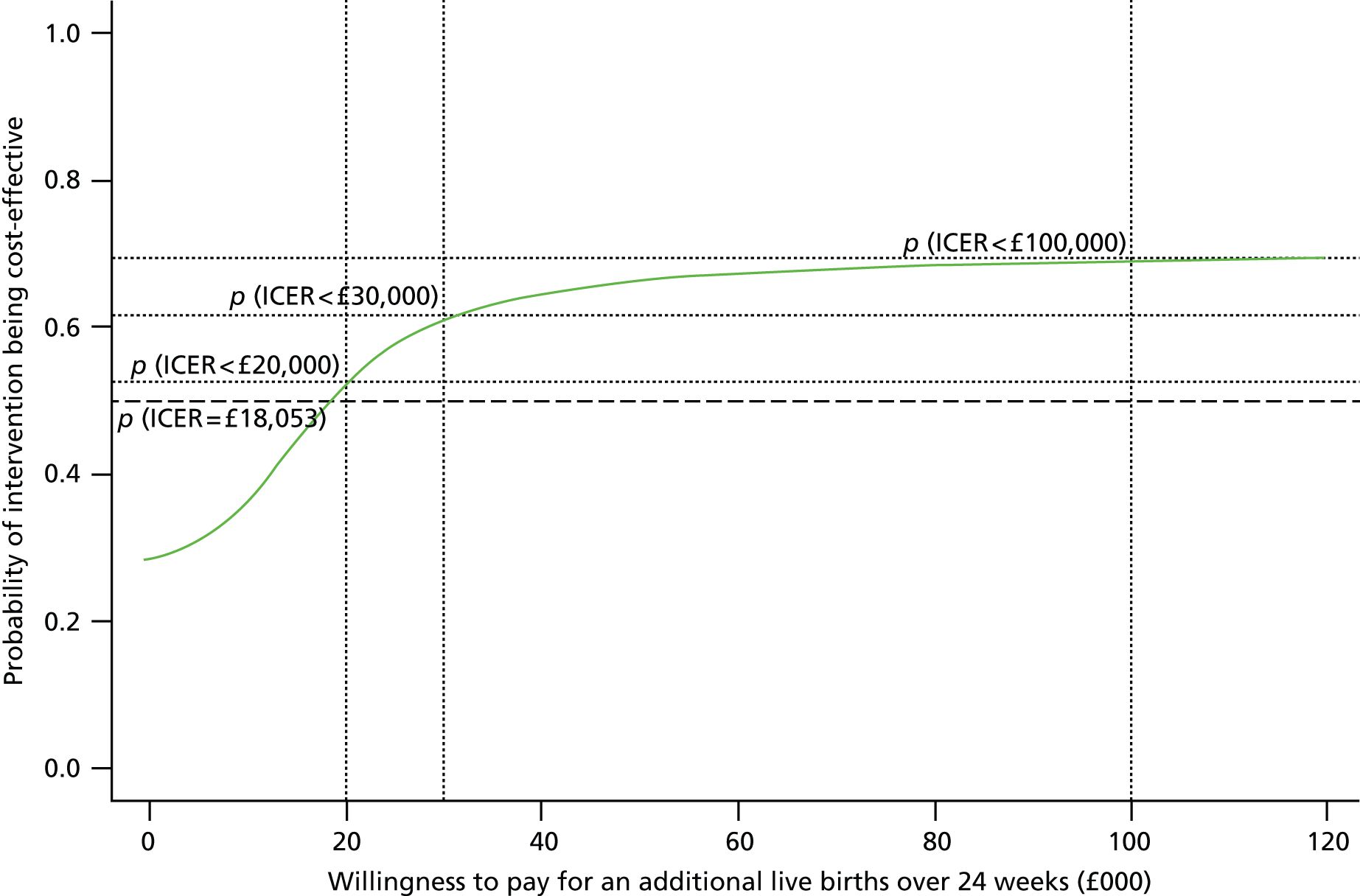

Health economic methods (see also Chapter 4)

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the PROMISE trial, pragmatically comparing the costs and consequences of treatment using progesterone versus those of usual care. To examine the effect of treatment of each woman (and baby) on health resource use, data were collected from enrolment until the trial end point (hospital discharge). The analysis considered the number of days that treatment was received and three categories of heath service resources [antenatal contacts, how the pregnancy ended (preterm pregnancy loss management or mode of delivery) and postnatal admissions]. This perspective assumed the most salient costs to be those accrued by perinatal services; the assumption was tested by model-based extrapolation and a sensitivity analysis.

The primary outcome of our economic analysis was incremental cost per additional live birth after at least 24 weeks of gestation, with data collected up to 28 days of neonatal life. In order to provide additional information about the wider resource implications to the NHS and longer-term implications to health status, a systematic search identified models employed previously in similar trial-based economic evaluations to extend the time horizon of the cost and generic health gains of the two arms of the PROMISE trial end point. Furthermore, strategies were identified to attribute variation relating to the surrogate outcome of intervention (gestational age) to estimate health-care costs and associated generic health gains in the longer term.

Data access and quality assurance

Data management

The trial was designed and conducted to meet the requirements of:

Information about participants in the PROMISE trial was collected directly from trial participants and hospital notes, and was considered confidential. The trial manager was responsible for overseeing data custody, but all of the staff involved in the study (clinical, academic and support personnel) shared the same duty of care to prevent any unauthorised disclosure of personal information. For this purpose, each trial participant was allocated a unique study number at recruitment, and all study documents used this reference as the identifier. Personal data and contact details were held in separate NHS or university password-protected databases at local sites (in compliance with local and national confidentiality and data protection standards), which were linked to the secure ITMS via the unique study number. All data were analysed and reported in summary format (individuals remaining unidentifiable).

Data were collected and stored on secure NHS or university computers. Access to data was restricted by usernames and passwords at two levels (to gain access to NHS and university computers and then to access the ITMS). Only when strictly necessary and after anonymisation were trial data encrypted and transmitted outside the NHS or university settings (e.g. to the DMC). No study data were retained in handheld media, laptops, personal computers or other similar media.

The online ITMS was maintained according to the security policies of the Women’s Health Unit of King’s College London. These policies included provision for password assignment, encryption, immediate back-up, off-site back-up and disaster recovery processes. Electronic data were backed up to both local and remote media in encrypted format every 24 hours. Paper-based data (such as signed consent forms) were kept in locked filing cabinets at each site.

The data generated during the trial were available for inspection on request by the participating physicians, representatives of the sponsor, the REC, host institutions and the regulatory authorities. These data-handling arrangements were clearly conveyed to participants in the PIS (see Appendix 1), and permission was obtained in the consent form (see Appendix 2).

On completion of data collection, the site files from each study centre were to be securely archived at the sites. Electronic study data remained securely stored within the ITMS. The trial master file was to be securely stored by the sponsor when all study activities were completed. In accordance with the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Amendment Regulations 2006 (sections 18 and 28),40 all the study data will remain securely stored for 25 years, to enable review, reappraisal and resolution of any queries or concerns and to facilitate further follow-up research. After this time the data will be securely destroyed.

Data quality assurance

The PROMISE trial co-ordinator performed hospital site visits as part of trial monitoring activities (see Governance, Trial monitoring). This quality assurance activity occasionally involved source data verification. The research and development (R&D) departments of participating study centres also performed routine monitoring audits at least annually. The PROMISE trial was additionally selected for MHRA inspection at two locations (Liverpool Women’s Hospital and Luton and Dunstable Hospital).

The trial also adopted a centralised approach to monitoring data quality and compliance, using the ITMS.

Governance

At all times during the study, the PROMISE trial was conducted strictly in accordance with the most recent version of the authorised PROMISE trial protocol. The PROMISE trial protocol was developed in accordance with the ethical principles originating in the Declaration of Helsinki,60 the principles of GCP, the Medicines for Human Use Regulations 2004 and its subsequent amendments39,40 and the Department of Health’s 2005 Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. 61

Ethical implications

In designing the PROMISE trial and considering the ethical implications of the study, the issues indicated below were considered and resolved or safeguarded.

Administration of a drug without full knowledge of its effects (although the existing evidence suggested a large potential benefit)

Existing evidence suggested a potential benefit in reducing the risk of miscarriage but the clinical community was in equipoise (see Chapter 1, Existing knowledge, Progesterone for clinical use for recurrent miscarriages). There was overwhelming support for the study from clinicians, patients and representatives of patient bodies (see Chapter 1, Rationale).

Furthermore, we identified substantial evidence of the safety of progesterone in pregnancy (see Chapter 1, Existing knowledge, Progesterone for clinical use for recurrent miscarriages), from widespread use in pregnancy for other indications such as IVF practice16 and prevention of preterm birth. 19

Moreover, we put in place robust mechanisms to address potential AEs (see Safety monitoring, Adverse events), in an effort to minimise harm. Overall, the balance of potential benefit versus harm was felt to be ethically acceptable to proceed with the trial.

Potential for distress, discomfort and inconvenience to trial participants

During our interviews and consultations with patients and representatives of patient societies at the time of designing the trial, it emerged that any distress or discomfort to the participants would be limited, and of an acceptable level to most women. We also designed the study to reduce any potential inconvenience to the participants, and put in place accommodating provisions wherever possible.

Face-to-face interviews at the time of recruitment could prolong a hospital visit by approximately 30 minutes, but patients and patient society representatives felt that this delay was well within an acceptable time frame. Furthermore, although five or more telephone interviews could be viewed as intrusive, precautions were incorporated into the study protocol to minimise inconvenience to participants.

These precautions included:

-

enquiring at the beginning of the telephone call if it was a convenient time to conduct the interview and, if not, arranging to call at an alternative time

-

specifying the purpose and the expected duration of the call

-

not leaving any messages if the telephone was answered by an automated machine or anyone other than the index patient

-

not telephoning a participant at her place of work if this could be avoided.

Interestingly, most patients and patient society representatives welcomed the telephone calls because the research nurse or midwife was likely to be able to assist standard care (e.g. by helping to arrange ultrasound scans).

Ethical governance

Following a favourable opinion of the National Research Ethics Service via the West Midlands REC and before recruitment commenced at each participating centre, the TCC obtained favourable site-specific assessments and R&D approvals as required.

The PI of each participating study site was responsible for liaison with administrative and managerial representatives of the local institution, and obtaining any necessary permissions from trust authorities. On behalf of the local institution, the PI was also required to sign an Investigator’s Agreement in respect of accrual, compliance, GCP, confidentiality and publication. Deviations from the Investigator’s Agreement were monitored and remedial action taken as appropriate by the TMG.

In addition, and in compliance with the International Conference on the Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice, all institutions participating in the trial completed a delegation log and supplied this document to the TCC. The delegation log listed the responsibilities of each member of the local study team, and an up-to-date copy was stored in the site file at the institution and also at the TCC. A curriculum vitae of the PI, and confirmation of GCP training and honorary or substantive employment with the participating trust, was also verified by the trial manager and retained.

Clinical trial authorisation

Clinical trial authorisation for the PROMISE trial was obtained from the MHRA before recruitment started.

Changes to the protocol

It was agreed that if any amendments to the study protocol required regulatory approval (from the MHRA, REC or local R&D offices), these changes would not be instituted until the amendment had been reviewed and received favourable opinion from the relevant bodies. However, a protocol amendment intended to eliminate an apparent immediate hazard to participants would be implemented immediately, with notification and request for approval to the MHRA, REC and R&D offices as soon as possible.

There were no significant changes to the methods after trial commencement. All amendments to the study protocol were in the domain of clarifications to wording and intentions (see Appendix 5, Table 16).

Trial monitoring

The PROMISE trial was monitored according to the standard operating procedures of Imperial College London/Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Joint Research Compliance Office. 43

The purpose of monitoring was to:

-

protect the rights and well-being of trial participants

-

ensure that the reported trial data were accurate, complete and verifiable from source documents

-

ensure that the trial remained compliant with GCP and other regulatory and good practice guidance.

Participating centres were monitored by the TCC by checking incoming electronic forms for compliance with the protocol, consistency of data and missing data. The trial co-ordinator and trial manager remained in regular telephone or e-mail contact with centre personnel to check on progress and resolve any queries. In addition, periodic site monitoring was undertaken as required by the TCC or the sponsor to:

-

review understanding of the protocol and trial procedures by the trial staff

-

verify that the trial staff had access to the necessary documents

-

verify the existence of participants against clinic records and other sources

-

verify selected data items and SAEs recorded, compared with data in clinical records, to identify errors of omission as well as inaccuracies.

Monitoring visits were followed by a monitoring report, summarising the findings of the visit and recommending remedial actions as necessary. Investigator meetings were held at least annually for the purpose of learning, updating and sharing.

Trial oversight bodies

The PROMISE trial was overseen by the TMG, the DMC and the TSC (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Reporting relationships of trial oversight bodies. HTA, Health Technology Assessment; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research.

Trial Management Group

The TMG directed the management of the trial from the TCC, which was located in a secure office in the University of Birmingham. The TCC comprised the trial manager, trial co-ordinator and a research nurse, with support from the trial statistician, data manager, health economist and trial advisors. The day-to-day co-ordination of the trial was the responsibility of the trial manager (Professor Arri Coomarasamy) and the trial co-ordinator (Dr Ewa Truchanowicz), who maintained regular contact with local collaborators, research nurses and midwives at participating study sites. The trial manager and the trial co-ordinator reported to the TMG, and the TMG reported to the TSC (or directly to the DMC if necessary) any issues relating to the monitoring and auditing of the research (see Figure 5).

The TMG conducted meetings face to face or via teleconference, and action points were implemented via the TCC. The meetings were held on a weekly basis during the early stages of the trial, and regularly as required thereafter, but at least monthly. The TMG disseminated any relevant feedback to investigators and other stakeholders through various approaches, including investigator meetings.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC provided overall supervision of the trial, affording protection for participants by ensuring that it was conducted in accordance with International Conference on the Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and other relevant regulations. The TSC agreed and authorised the trial protocol and subsequent (minor) amendments (see Appendix 5, Table 16), and provided advice to investigators on all aspects of the trial. The role of the TSC also included reviewing recruitment, protocol deviations and recommendations from the DMC.

The TSC was chaired by an independent representative (Professor Siladitya Bhattacharya) and conducted meetings face to face or via teleconference on a 6-monthly basis, or more often if required.

Independent Data Monitoring Committee (see also Safety monitoring, Adverse events, and Statistical methods, Interim analyses)

The primary role of the PROMISE DMC consisted of periodic reviews of accruing data and assessments of safety, to make recommendations to the TSC about whether the trial should continue, or be modified or terminated. The DMC also reviewed interim analyses of major end points in addition to emerging data from other trials using progesterone in RM patients, to ensure that the continuation of the trial remained ethical.

The DMC additionally examined rates of recruitment, loss to follow-up, compliance and protocol violation data to ensure that the continuation of the trial was not futile.

The membership of the PROMISE DMC (chaired by Professor Jennifer Kurinczuk, and including Professor Javier Zamora and Professor Nick Raine-Fenning) was independent (none of the members had any financial or intellectual conflict of interest). The initiation meeting of the DMC, to review the study protocol and operating procedures, was conducted face to face and subsequent meetings were held either face to face or via teleconference.

Each DMC meeting comprised four consecutive components:

-

For DMC members only, to review rates of recruitment, baseline characteristics, effectiveness, safety, missing data and protocol violations; these data were prepared by the trial statistician, blinded to treatment allocation (identified only as ‘A’ and ‘B’).

-

For DMC members and the chairperson of the TSC, chief investigator, trial manager, sponsor or funder, as appropriate, to access relevant information.

-

For DMC members only, to review the issues arising from the open component above.

-

Discussions of the DMC with the chairperson of the TSC, the chief investigator and/or the trial manager, to convey the results and recommendations of the meeting.

The minutes from each open meeting were made available to all investigators and relevant stakeholders. The minutes from each closed meeting were archived by the DMC chairperson and the trial statistician.

Site responsibilities

To ensure the smooth running of the trial and to minimise the overall procedural workload, each participating centre designated appropriately trained and qualified local individuals to be responsible for the institutional co-ordination of clinical and administrative arrangements.

Local principal investigators

Each participating study centre nominated a local PI to oversee the conduct of PROMISE research at the particular institution. Each PI signed an Investigator’s Agreement to acknowledge these responsibilities, including:

-

adherence to the protocol of the trial

-

helping local colleagues to ensure that study participants received appropriate care throughout the period of research enrolment

-

protecting the integrity and confidentiality of clinical and other records generated by the research

-

reporting any failures in these respects, adverse drug reactions and other events or suspected misconduct through the appropriate systems.

Local nursing co-ordinators