Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/80/01. The contractual start date was in February 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All review authors have applied for and received competitive research grants. Carl J Heneghan reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the NIHR School of Primary Care, Wellcome Trust and the World Health Organization (WHO) during the conduct of the study, and has received expenses and payments for media work. In addition, he is an expert witness in an ongoing medical device legal case. He receives expenses for teaching evidence-based medicine and is paid for NHS general practitioner work in the out of hours service in Oxford. Tom Jefferson receives royalties from his books published by Blackwells and Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore, Rome. Tom Jefferson is occasionally interviewed by market research companies for anonymous interviews about Phase I or II pharmaceutical products. In 2011–13, Tom Jefferson acted as an expert witness in a labour case on influenza vaccines in health-care workers in Canada. In 1997–9, Tom Jefferson acted as a consultant for Roche, in 2001–2 for GlaxoSmithKline, and in 2003 for Sanofi-Synthelabo for pleconaril, which did not get approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Tom Jefferson was a consultant for IMS Health in 2013, and in 2014 was retained as a scientific adviser to a legal team acting on the drug Tamiflu (oseltamivir, Roche). In 2014–15, Tom Jefferson was a member of two advisory boards for Boerhinger and is in receipt of a Cochrane Methods Innovations Fund grant to develop guidance on the use of regulatory data in Cochrane reviews. Tom Jefferson has a potential financial conflict of interest in the investigation of the drug oseltamivir. Tom Jefferson is acting as an expert witness in a medicolegal negligence case involving the drug oseltamivir (Roche). Peter Doshi received €1500 (£1241; US$2052) from the European Respiratory Society in support of his travel to the society’s September 2012 annual congress in Vienna, where he gave an invited talk on oseltamivir. Peter Doshi is an associate editor of the British Medical Journal (BMJ). Peter Doshi gratefully acknowledges the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy for its funding support ($10,000) for a study to analyse written medical information regarding the possible harms of statins. Peter Doshi is also an unpaid member of the IMEDS steering committee at the Reagan–Udall Foundation for the FDA, which focuses on drug safety research. CDelM is the Co-ordinating Editor of the Acute Respiratory Infections Group of the Cochrane Collaboration. CDelM reports personal fees from Key Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of the study; grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), grants from NIHR (UK), personal fees from Elsevier and BMJ Books, from conference organisers for International Viral Infections Conference, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Key Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work. Rokuro Hama provided scientific opinions and expert testimony on 11 adverse reaction cases related to oseltamivir for the applications by their families for adverse reaction relief by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) and in the lawsuits for revocation of the PMDA’s decision concerning with these reactions. Most of the cases were reported in the International Journal of Research Studies in Management (2008:20:5–36). Rokuro Hama was an expert witness in the lawsuit on the adverse reaction of (death from) gefitinib against AstraZeneca and Japanese Minister of Health Labour and Welfare, and provided scientific opinions and expert testimony. He argued that gefitinib’s fatal toxicity was known before approval in Japan, as shown in ‘Gefitinib story’ (http://npojip.org/english/The-gefitinib-story.pdf) and in other articles (http://npojip.org/). Plaintiffs finally lost the case on 12 April 2013 at the Supreme Court of Japan. Rokuro Hama has received royalties from a published book.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Heneghan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and rationale

Since the mid-2000s the use of neuraminidase inhibitors (NIs) has been endorsed and billions of pounds have been spent stockpiling the two anti-influenza drugs oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, Roche) and zanamivir [Relenza®, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)] in preparation for an influenza pandemic. When the H1N1 pandemic emerged in 2009, the drugs were rolled out worldwide for the treatment and prevention of influenza and its complications. At that time, we were asked to conduct a systematic review for Cochrane to update evidence on their efficacy, during which it emerged that the validity of a key study underpinning the evidence on efficacy was unclear. After 3.5 years of making requests to the drug manufacturers, they provided us with full clinical study reports (CSRs).

Emergence of problems

The reasons for the stockpiling of oseltamivir and zanamivir are not well known, but the decision may be based on assumptions that the drugs would reduce hospital admissions and serious complications of influenza, such as pneumonia, by half and slow down the spread of the virus. 1–3 Some of these assumptions were supported by a peer-reviewed pooled analysis of 10 randomised trials of oseltamivir published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2003 by Kaiser et al. 4 This analysis seemed to be of high quality and formed a powerful scientific rationale for stockpiling,5 but during our review in 2009 it became apparent that the data underlying it were largely unpublished and inaccessible to independent scrutiny. Roche, the manufacturer of oseltamivir, funded the Kaiser review, employed some of its authors and had also sponsored the 10 trials. For 3.5 years Roche did not release the full CSRs despite a public pledge to do so made during the H1N1 ‘swine flu’ outbreak of 2009. 6,7

Research for our 2009 review also highlighted inconsistencies in decision-making. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which had access to the full CSRs, concluded on the product label that ‘Tamiflu has not been shown to prevent such complications [serious bacterial infections]’. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), which had only partial reports, and another prominent US agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), came to the exact opposite conclusion – all apparently based on the same trials. 8

Owing to the risk of reporting bias as a result of the large amounts of unpublished data there are uncertainties about the stated benefits of oseltamivir and about the conclusions of previous Cochrane reviews of NIs in adults and children. 9,10 To address this, we worked for 4 years to obtain full CSRs of the oseltamivir trial programme. CSRs are considered to be the most exhaustive summaries of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of drugs. They are usually composed of a main report of the trial (in introduction, methods, results and discussion style), with numerous appendices containing important supplementary data that are needed to understand and interpret the trial [e.g. protocol, protocol amendments, statistical analysis plan (SAP), blank case report forms (CRFs), certificates of analysis, randomisation list and informed consent forms]. 11 In the case of oseltamivir, CSRs were of a mean length of approximately 1300 pages (median around 900 pages). As a result of increasing availability, CSRs may in the future be incorporated into systematic reviews and other forms of evidence synthesis. 12,13

Rationale for this review

In the midst of the A/H1N1 influenza outbreak in June 2009, the Australian and UK governments commissioned an update of our long-standing Cochrane review on NIs for influenza in (otherwise) healthy adults (known as A047). At the time of publication of the 2009 update and its linked investigation by the British Medical Journal (BMJ), we underestimated the extent of the oseltamivir evidence development programme, expecting it to comprise around 36 trials, with only a proportion of these fitting our inclusion criteria. We were also unaware of the size and the level of detail that the CSRs contained.

Today, the obvious source of information on CSRs would be trial registries and company websites, but most trials of both NIs were carried out before inception or wide acceptance of centralised registries and company websites. In 2009–11, company websites did not, and still do not, have extensive lists of trials with downloadable CSRs. Many people had never heard of CSRs before media coverage of our work. We decided to construct our list by using multiple cross-referencing methods. We constructed a list beginning with clinical trials that were identified from previous review updates.

To ensure that the list did not include duplicate entries, we assigned to each trial a unique trial ID. ‘Author’ was insufficient to provide a unique trial ID, because different authors can be present across different versions of the same trial (i.e. the authors of CSRs can be different from publications arising from the same clinical trial).

Once we had as complete a list of trials as possible, we contacted manufacturers and sent them our draft list, asking them to check the accuracy and completeness of our list. Roche, GSK and BioCryst all did so, and informed us of additional trials.

We requested from Roche and GSK a series of regulatory documents under freedom of information (FOI) policies from both the FDA and the EMA. No substantial comments were made by Roche on the protocol of the Cochrane A159 review,14 which has been publicly available since December 2010.

Soon after the publication of the review, the BMJ agreed to publish our correspondence with Roche, GSK, EMA, CDC and World Health Organization (WHO), recording our attempts at retrieving the full reports without any conditions attached, and to understand the basis for promotion of the drugs (especially oseltamivir) by public health bodies. The correspondence (which is hundreds of pages long) formed the basis for what then became the BMJ Open Data Campaign and a stimulus for the later AllTrials campaign. Public exposure of this approach and considerable media coverage led to the unconditional release of 77 reports of oseltamivir of 82 studies sponsored by Roche and the equivalent of the 30 studies we had requested from GSK. For the full correspondence, see www.bmj.com/tamiflu and www.bmj.com/relenza. The reports (amounting to over 100,000 pages) are made available with this review for the first time at: https://datadryad.org/resource/doi:10.5061/dryad.77471/2, a positive step for open science. We have described the posting of these reports in a blog posting at: http://blog.datadryad.org/2014/04/17/tamiflu-data/, and a list of neuraminidase reviews, with peer review comments and responses relevant to review A159,14 is available at www.bmj.com/content/suppl/2014/04/09/bmj.g2545.DC1/jeft017746.ww8_default.pdf.

Before receiving the full reports, we resumed reviewing the remainder of the material that we had received in 2011. This mainly consisted of module 2s (Roche terminology for pre-study documents). Module 2s contained the information that was originally unavailable to us from Roche: study protocols with their amendments, randomisation lists, blank CRFs, certificates of analysis describing appearance and content of active and control capsules and, at times, SAPs. CRFs are containers for the rawest form of recorded data at the individual participant level.

While designing the tool to capture trial methods and assess bias, we also considered whether or not access to module 2 information (and later the full study reports) changed our perception of the trial and specifically our ‘risk-of-bias’ assessment. We found that access to what are supposed to be full study reports should provide clarity and remove the rationale for ‘unclear’ risk-of-bias judgements, and ideally remove the concept of risk leaving just ‘bias’, at least for certain study design elements, such as attrition bias. Either a design element introduces bias or it does not. In the case of the 15 full oseltamivir CSRs we reviewed when constructing our tool, only one report contained a protocol that predated the beginning of participant enrolment, only two reports had SAPs that clearly predated participants’ enrolment and three reports had clearly dated protocol amendments. No CSR reported a clear date of unblinding.

During the latter part of 2013, we received from the manufacturers tens of thousands of pages of full CSRs for both programmes combined.

These events form the basis for this review.

Aims and objectives

The main goals of the reviews included in this report were to:

-

describe the potential benefits and harms of NIs for influenza in all age groups by reviewing all CSRs of published and unpublished randomised, placebo-controlled trials and regulatory comments

-

determine the effect of oseltamivir on mortality in patients with 2009A/H1N1 influenza.

Research questions

The research questions addressed in this report are as follows:

-

What are the potential benefits and harms of NIs for the prevention and treatment of influenza in adults and children?

-

Does influenza virus-specific mechanism of action proposed by the producers fit the clinical evidence?

-

Does treatment with oseltamivir confer protection against mortality in patients with 2009A/H1N1 influenza?

Chapter 2 Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in adults and children

Abstract

Background

Neuraminidase inhibitors are stockpiled and recommended by public health agencies for treating and preventing seasonal and pandemic influenza. They are used clinically worldwide.

Objective

To describe the potential benefits and harms of NIs for influenza in all age groups by reviewing all CSRs of published and unpublished randomised, placebo-controlled trials and regulatory comments.

Search methods

We searched trial registries, electronic databases (to 22 July 2013) and regulatory archives, and corresponded with manufacturers to identify all trials. We also requested CSRs. We focused on the primary data sources of manufacturers but we checked that there were no published RCTs from non-manufacturer sources by running electronic searches in the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE, EMBASE.com, PubMed (not MEDLINE), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED).

Selection criteria

Randomised, placebo-controlled trials on adults and children with confirmed or suspected exposure to naturally occurring influenza.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted CSRs and assessed risk of bias using purpose-built instruments. We analysed the effects of zanamivir and oseltamivir on time to first alleviation of symptoms, influenza outcomes, complications, hospitalisations and adverse events in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. All trials were sponsored by the manufacturers.

Main results

We obtained 107 CSRs from the EMA, GSK and Roche. We accessed comments by the FDA, EMA and Japanese regulator. We included 53 trials in stage 1 (a judgement of appropriate study design) and 46 in stage 2 (formal analysis), including 20 oseltamivir (9623 participants) and 26 zanamivir trials (14,628 participants). Inadequate reporting put most of the zanamivir studies and half of the oseltamivir studies at a high risk of selection bias. There were inadequate measures in place to protect 11 studies of oseltamivir from performance bias due to non-identical presentation of placebo. Attrition bias was high across the oseltamivir studies and there was also evidence of selective reporting for both the zanamivir and oseltamivir studies. The placebo interventions in both sets of trials may have contained active substances.

Time to first symptom alleviation

For the treatment of adults, oseltamivir reduced the time to first alleviation of symptoms by 16.8 hours [95% confidence interval (CI) 8.4 to 25.1 hours; p < 0.0001]. This represents a reduction in the time to first alleviation of symptoms from 7 to 6.3 days. There was no effect in asthmatic children, but in otherwise healthy children there was a reduction by a mean difference (MD) of 29 hours (95% CI 12 to 47 hours; p = 0.001). Zanamivir reduced the time to first alleviation of symptoms in adults by 0.60 days (95% CI 0.39 to 0.81 days; p < 0.00001), equating to a reduction in the mean duration of symptoms from 6.6 to 6.0 days. The effect in children was not significant. In subgroup analysis we found no evidence of a difference in treatment effect for zanamivir on time to first alleviation of symptoms in adults in the influenza-infected and non-influenza-infected subgroups (p = 0.53).

Hospitalisations

Treatment of adults with oseltamivir had no significant effect on hospitalisations [risk difference (RD) 0.15%, 95% CI –0.78% to 0.91%]. There was also no significant effect in children or in prophylaxis. Zanamivir hospitalisation data were unreported.

Serious influenza complications or those leading to study withdrawal

In adult treatment trials, oseltamivir did not significantly reduce those complications classified as serious or those that led to study withdrawal (RD 0.07%, 95% CI –0.78% to 0.44%), or in child treatment trials; neither did zanamivir in the treatment of adults or in prophylaxis. There were insufficient events to compare this outcome for oseltamivir in prophylaxis or zanamivir in the treatment of children.

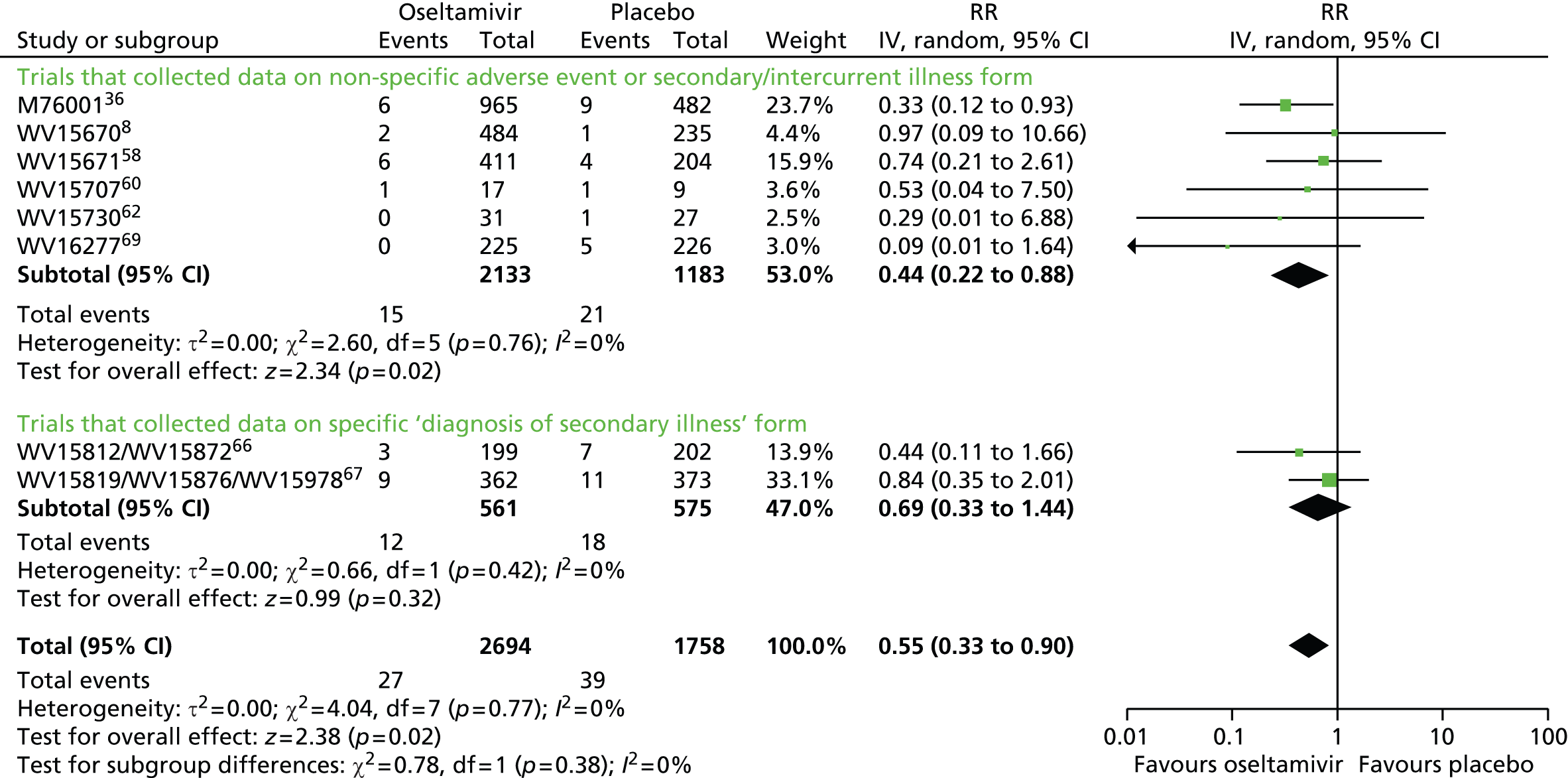

Pneumonia

Oseltamivir significantly reduced self-reported, investigator-mediated, unverified pneumonia [RD 1.00%, 95% CI 0.22% to 1.49%, number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) 100, 95% CI 67 to 451] in the treated population. The effect was not significant in the five trials that used a more detailed diagnostic form for pneumonia. There were no definitions of pneumonia (or other complications) in any trial. No oseltamivir treatment studies reported effects on radiologically confirmed pneumonia. There was no significant effect on unverified pneumonia in children. There was no significant effect of zanamivir on either self-reported or radiologically confirmed pneumonia. In prophylaxis, zanamivir significantly reduced the risk of self-reported, investigator-mediated, unverified pneumonia in adults (RD 0.32%, 95% CI 0.09% to 0.41%; NNTB 311, 95% CI 244 to 1086) but not oseltamivir.

Bronchitis, sinusitis and otitis media

Zanamivir significantly reduced the risk of bronchitis in adult treatment trials (RD 1.80%, 95% CI 0.65% to 2.80%; NNTB 56, 95% CI 36 to 155), but not oseltamivir. Neither NI significantly reduced the risk of otitis media and sinusitis in both adults and children.

Harms of treatment

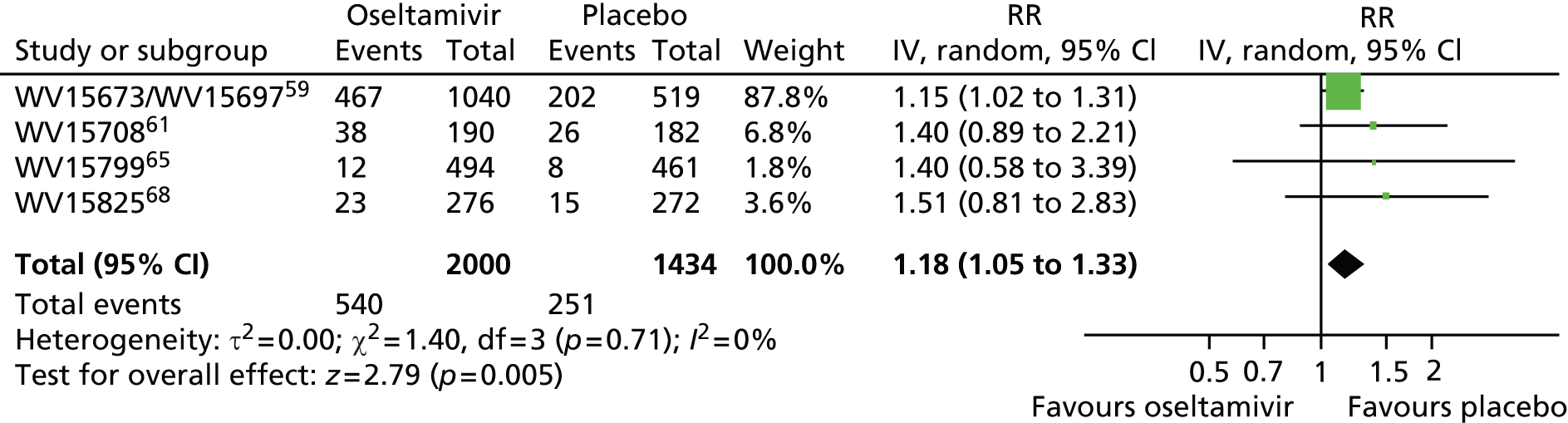

Oseltamivir in the treatment of adults increased the risk of nausea [RD 3.66%, 95% CI 0.90% to 7.39%; number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) 28, 95% CI 14 to 112] and vomiting (RD 4.56%, 95% CI 2.39% to 7.58%; NNTH 22, 95% CI 14 to 42). The proportion of participants with fourfold increases in antibody titre was significantly lower in the treated group than in the control group (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.97; I2 statistic = 0%) (5% absolute difference between arms). Oseltamivir significantly decreased the risk of diarrhoea (RD 2.33%, 95% CI 0.14% to 3.81%; NNTB 43, 95% CI 27 to 709) and cardiac events (RD 0.68%, 95% CI 0.04% to 1.0%; NNTB 148, 95% CI 101 to 2509) compared with placebo during the on-treatment period. There was a dose–response effect on psychiatric events in the two oseltamivir ‘pivotal’ treatment trials: WV15670 and WV15671, at 150 mg (standard dose) and 300 mg daily (high dose) (p = 0.038). In the treatment of children, oseltamivir induced vomiting (RD 5.34%, 95% CI 1.75% to 10.29%; NNTH 19, 95% CI 10 to 57). There was a significantly lower proportion of children on oseltamivir with a fourfold increase in antibodies (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.00; I2 statistic = 0%).

Prophylaxis

In prophylaxis trials, oseltamivir and zanamivir reduced the risk of symptomatic influenza in individuals (oseltamivir RD 3.05%, 95% CI 1.83% to 3.88%; NNTB 33, 95% CI 26 to 55; zanamivir RD 1.98%, 95% CI 0.98% to 2.54%; NNTB 51, 95% CI 40 to 103) and in households (oseltamivir RD 13.6%, 95% CI 9.52% to 15.47%; NNTB 7, 95% CI 6 to 11; zanamivir RD 14.84%, 95% CI 12.18% to 16.55%; NNTB 7, 95% CI 7 to 9). There was no significant effect on asymptomatic influenza (oseltamivir, RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.39 to 3.33; zanamivir RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.24). Non-influenza, influenza-like illness (ILI) could not be assessed as a result of data not being fully reported. In oseltamivir prophylaxis studies, psychiatric adverse events were increased in the combined on- and off-treatment periods (RD 1.06%, 95% CI 0.07% to 2.76%; NNTH 94, 95% CI 36 to 1538) in the study treatment population. While on treatment, oseltamivir increased the risk of headaches (RD 3.15%, 95% CI 0.88% to 5.78%; NNTH 32, 95% CI 18 to 115), renal events (RD 0.67%, 95% CI –0.01% to 2.93%; NNTH 150, NNTH 35 to NNTB > 1000) and nausea (RD 4.15%, 95% CI 0.86% to 9.51%; NNTH 25, 95% CI 11 to 116).

Authors’ conclusions

Oseltamivir and zanamivir have small, non-specific effects on reducing the time to alleviation of influenza symptoms in adults, but not in asthmatic children. Using either drug as prophylaxis reduces the risk of developing symptomatic influenza. Treatment trials with oseltamivir or zanamivir do not settle the question of whether or not the complications of influenza (such as pneumonia) are reduced, because of a lack of diagnostic definitions. The use of oseltamivir increases the risk of adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, psychiatric effects and renal events in adults and vomiting in children. The lower bioavailability may explain the lower toxicity of zanamivir compared with oseltamivir. The balance between benefits and harms should be considered when making decisions about use of both NIs for either the prophylaxis or treatment of influenza. The influenza virus-specific mechanism of action proposed by the manufacturers does not match the observed clinical evidence.

Background

This review (known as A159) reports our work using unpublished CSRs (see Appendix 1, Glossary) and regulatory documents containing comments and reviews to evaluate the safety and efficacy of NIs. We have called the body of clinical studies and regulatory comments ‘regulatory information’. For the history and evolution of the review, see Appendix 1.

Description of the condition

Influenza is mostly a mild, self-limiting infection of the upper airways with local symptoms, including sniffles, nasal discharge, dry cough and sore throat, and systemic symptoms such as fever, headache, aches and pains, malaise and tiredness.

Occasionally, patients with influenza develop complications such as pneumonia, otitis media and dehydration or encephalopathy with or without liver failure, which may be due to the effects of the influenza virus itself or associated secondary bacterial infections and/or adverse effects of drugs such as antipyretics [including salicylates and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)]. 15

Influenza is not clinically distinguishable from ILI. 16 Epidemic influenza in humans is caused by influenza A and B viruses. Currently, influenza A/H1N1, influenza A/H3N2 and influenza B cause most influenza infections worldwide. 12

Description of the intervention

Neuraminidase inhibitors comprise inhaled zanamivir (Relenza®, GSK), oral oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, Gilead Sciences and F. Hoffman-La Roche), parenteral peramivir (Rapivab®, BioCryst Ltd), inhaled laninamivir (Inavir®, Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd)17 and others still under development. 18 The use of NIs has increased dramatically since the outbreak of A/H1N1 in April 2009, partly because of the rise in amantadine (Symmetrel®, Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc.)/rimantadine (Flumadine®, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc.) resistance and, in the early stages of the outbreak, the lack of a vaccine, which meant that NIs became a widespread public health intervention. WHO had previously encouraged member states to stockpile and gain experience of using NIs. 19–21

How the intervention might work

Although NIs may reduce the ability of the virus to penetrate the mucus in the very early stage of infection,6,22–24 their main mechanism of action is thought to lie in their ability to inhibit influenza viruses from exiting host cells. 23,25 The manufacturers state that oseltamivir does not prevent infection or affect antibody production,26 but it reduces symptom duration probably by reducing viral load, spread and release of cytokines,8,27 diminishing the chance of complications and interrupting person–person viral spread. Oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) is the prodrug of oseltamivir carboxylate, the effective form. Oseltamivir phosphate dissociates in the gastrointestinal tract to form oseltamivir, which is absorbed and metabolised into oseltamivir carboxylate by hepatic carboxylesterase. Oseltamivir may have a central depressant action15 and may also inhibit human sialidase,28 causing abnormal behaviour. Inhaled zanamivir reaches a far lower plasma concentration than its intravenous administration. 29

Any treatment that reduces the complications of influenza (e.g. pneumonia) and the excretion of the virus from infected people might be a useful public health measure to contain an epidemic by limiting the impact and spread of the virus. In addition to symptomatic treatment, prophylactic use for interrupting the spread of disease has informed pandemic planning over the past decade.

Why it is important to do this review

There are three major reasons for conducting this review, in addition to questions of efficacy associated with the clinical use of NIs for influenza:

-

Influenza antivirals are a commonly used and stockpiled drug against past and future pandemics on the basis of international and national recommendations. These recommendations are based on the claimed and assumed ability of the drug to reduce complications and transmission. 2,3 In theory, containing the spread of influenza allows time for an organised response with longer-term interventions (such as vaccines), which take time to produce. 3

-

The risk of reporting bias and publication bias leads to uncertainty about the effects of NIs and the results of previous Cochrane reviews of NIs in adults6,10,30,31 and children. 32

-

Oseltamivir is now on the list of WHO essential drugs. 33,34

Process

Review A159 is an amalgamation of two long-standing Cochrane reviews on the effects of NIs for influenza in healthy adults14 (also published in the BMJ31) and children,35 and it is based on the assessment of trials through their CSRs and other regulatory information; a decision we made after finding substantial reporting bias in the journal publications of the relevant trials.

For the full rationale for this process, see Appendix 1.

Examples of discrepancies and reporting bias

We identified that 60% (3145/5267) of patient data from randomised, placebo-controlled, Phase III treatment trials of oseltamivir have never been published. This includes M76001,36 the biggest treatment trial ever undertaken on oseltamivir (with just over 1400 people of all ages). Exclusion of unpublished data changed our previous findings regarding the ability of oseltamivir to reduce the complications of influenza. 8,31 In some cases, mistakes in the attribution of adverse events were discovered only through matching summary tables with individual participant listings. 37–39

A modified approach

We have modified the routine Cochrane processes to improve our previous methods, which we now consider to be inadequate. To resolve inconsistencies and under-reporting, we changed our approach by no longer including trial data as reported in papers published in biomedical journals. Instead, we treated CSRs as our basic unit of analysis. CSRs are often sent to national drug regulators, such as the FDA and the EMA (formerly the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products), which require far more stringent standards for completeness and accuracy of reporting than biomedical journals. Journal articles can be regarded as a very succinct synthesis of a CSR. In addition to seeking CSRs, we decided to read and review regulatory documentation. The FDA in particular (and the EMA to a far lesser extent) makes many of its scientific reviews available on its website. Unlike Cochrane review authors, regulators can have access to the whole data set and their comments can provide useful insight, helping to achieve a better understanding of trial programmes.

Clinical study reports generally remain hidden from public view and are not readily available for wider scientific scrutiny, despite the wealth of information that they contain for those willing and able to spend the time reading them and despite calls to make all relevant trial data public,11,40 as well as the known problems with reporting biases. 41,42

Implications

This modified approach to a Cochrane review aims to provide patients, clinicians and policy-makers with the most transparent and independent information possible about NIs for influenza. In addition, it should contribute to improving a European regulatory and pharmacovigilance legal framework, which commentators consider weak. 40,43 We believe that as NIs have become public health drugs, recommended and stockpiled globally, independent scrutiny of all of the evidence relating to harms and effects on complications is necessary to provide patients, policy-makers and physicians with a complete and unbiased view of their risks and benefits.

Implication for A/H1N1 (2009) influenza

In response to our 2010 review,14,31 some have argued that its findings cannot be applied to the 2009 A/H1N1, suggesting that it is a new virus and that, we thus need new evidence. 44–48 Novel A/H1N1 is a new strain of a subtype that has been circulating since 1977, but it also resembles the A/H1N1 strain that has been circulating since before 195749 or before the 1918 pandemic. 50 Influenza subtype A/H1N1 was indeed circulating at the time when the clinical trials, included in our previous reviews, were recruiting. In addition, oseltamivir and zanamivir were approved by regulators worldwide for the treatment and prevention of influenza types A and B, not specific subtypes or strains of influenza A and B. The expectation of regulatory approval is thus that the effects of these drugs demonstrated in clinical trials will apply to future strains of influenza A and B. Use of these drugs during the pandemic was not off-label. It was approved use on the assumption that the clinical trial evidence underpinning regulatory approval applied to novel A/H1N1. We reviewed the clinical trial evidence with the expectation that our results, similar to regulators, will apply to all influenza viruses.

Wider implications

The modified approach in this Cochrane review developed from the realisation that prior methods used to review NIs were inadequate. There is little reason to think that the lessons learned are limited to these particular drugs. 40,42,51–53 On this basis, our independent scrutiny, using all possible trial information, may inform both the wider debate on the adequacy of existing regulatory frameworks in the adoption of new drugs and the question of whether or not other systematic reviews should move to this new, more rigorous, approach, which focuses on trial programmes rather than single trials54,55 (see Appendix 1, Glossary). Although there is substantial evidence for the effects of reporting bias in estimates of effectiveness, less is known of its impact on the evidence of harms. 56 We decided to quantify the additional resources required to follow our modified methodological approach to assess the feasibility of other systematic reviews proceeding in a similar fashion.

Objective

To describe the potential benefits and harms of NIs for influenza in all age groups by reviewing all CSRs of published and unpublished randomised, placebo-controlled trials and regulatory comments.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included evidence from RCTs testing the effects of NIs for prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and treatment of influenza. Prophylaxis is the mode of use of NIs when there is expectation of possible near-future exposure to influenza.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is the use of NIs following probable exposure to influenza but before symptoms develop. Treatment is the use of NIs in persons showing probable signs of influenza.

Owing to discrepancies between published and unpublished reports of the same trials, we included only those trials for which we had unabridged CSRs (e.g. with consecutively numbered pages), even though they may be parts of CSRs (i.e. module 1 only) and information on reports of trials that were considered ‘pivotal’ (i.e. first- or second-line evidence to regulators in support of the registration application).

Types of participants

We included previously healthy people (children and adults). ‘Previously healthy’ includes people with chronic illness (such as asthma, diabetes, hypertension), but excludes people with illnesses with more significant effects on the immune system (such as malignancy or human immunodeficiency virus infection). We included only trials on people who were exposed to naturally occurring influenza with or without symptoms. We targeted the ITT and safety populations, as our prior review discovered compelling evidence that the intention-to-treat-influenza-infected (ITTI) subpopulation – the subpopulation deemed to be influenza-infected – was not balanced between treatment groups in the Roche oseltamivir trials. In addition, estimates from the ITT population will be more generalisable to clinical practice, where routine testing for influenza is not common in many countries (and even where it is used is of variable accuracy).

Types of interventions

Neuraminidase inhibitors administered by any route compared with placebo during the period in which medication was assumed and during the follow-up (on- and off-treatment) periods.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Symptom relief.

-

Hospitalisation and complications.

-

Harms.

-

Influenza (symptomatic and asymptomatic, always with laboratory confirmation) and ILI.

-

Hospitalisation and complications.

-

Interruption of transmission (in its two components, reduction of viral spread from index cases and prevention of onset of influenza in contacts).

-

Harms.

Secondary outcomes

-

Symptom relapse after finishing treatment.

-

Drug resistance.

-

Viral excretion.

-

Mortality.

-

Drug resistance.

-

Viral excretion.

-

Mortality.

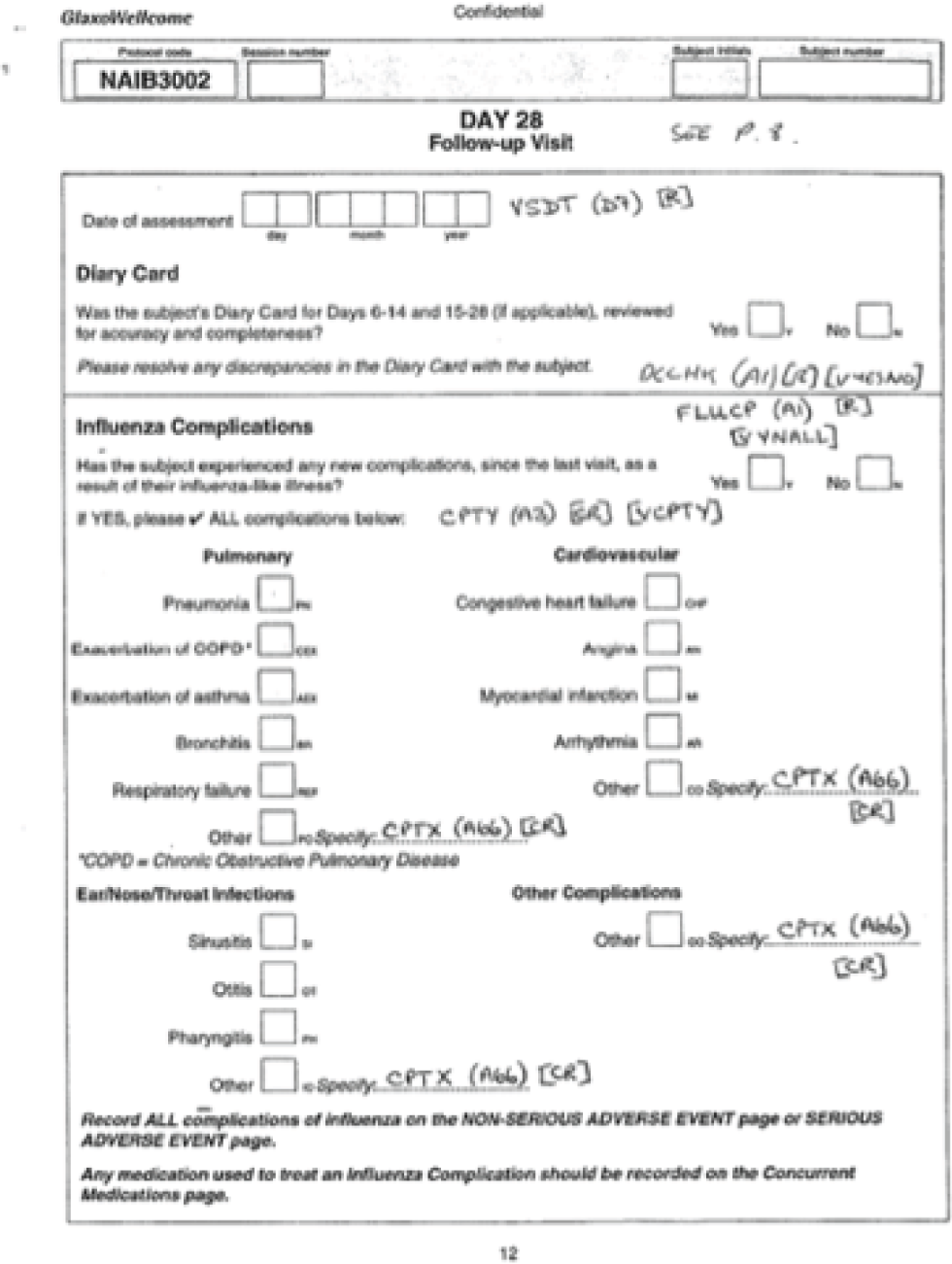

Although overall symptom reduction is well documented, our interest was particularly focused on complications and adverse events, as this is where evidence is currently scarce or inconclusive. 31,32 Our preliminary examination of some regulatory documents and some published versions of the studies had identified that some symptoms and sequelae of influenza (such as pneumonia) had been classified as either a ‘complication of influenza’ or as an ‘adverse event of the treatment’, or both. This is somewhat confusing and we intended to analyse ‘compliharms’ (see Appendix 1, Glossary) irrespective of the classification as a ‘complication of influenza’ or as an ‘adverse event of the treatment’ (see Appendix 2) in oseltamivir trials. Complications of particular interest included pneumonia, bronchitis, otitis media and sinusitis, as these were the secondary illnesses often collected in the Roche oseltamivir trials and we agreed that these events are clinically important. Initially, we constructed a table to illustrate the design methodology that was used for each complication by study (Table 1). The table included the following variables: definition of which events are termed complications; where complications are first defined in the CSR; diagnosis method; and availability of data. We then stratified our analysis by method of diagnosis with three possible criteria: (1) laboratory-confirmed diagnosis (e.g. based on radiologically or microbiologically confirmed evidence of infection); (2) clinical diagnosis without laboratory confirmation (diagnosed by a doctor after a clinical examination); and (3) other type of diagnosis, such as self-reported by patient. We conducted analysis of any complication (pneumonia, bronchitis, otitis media and sinusitis) that was classified as serious or led to study withdrawal.

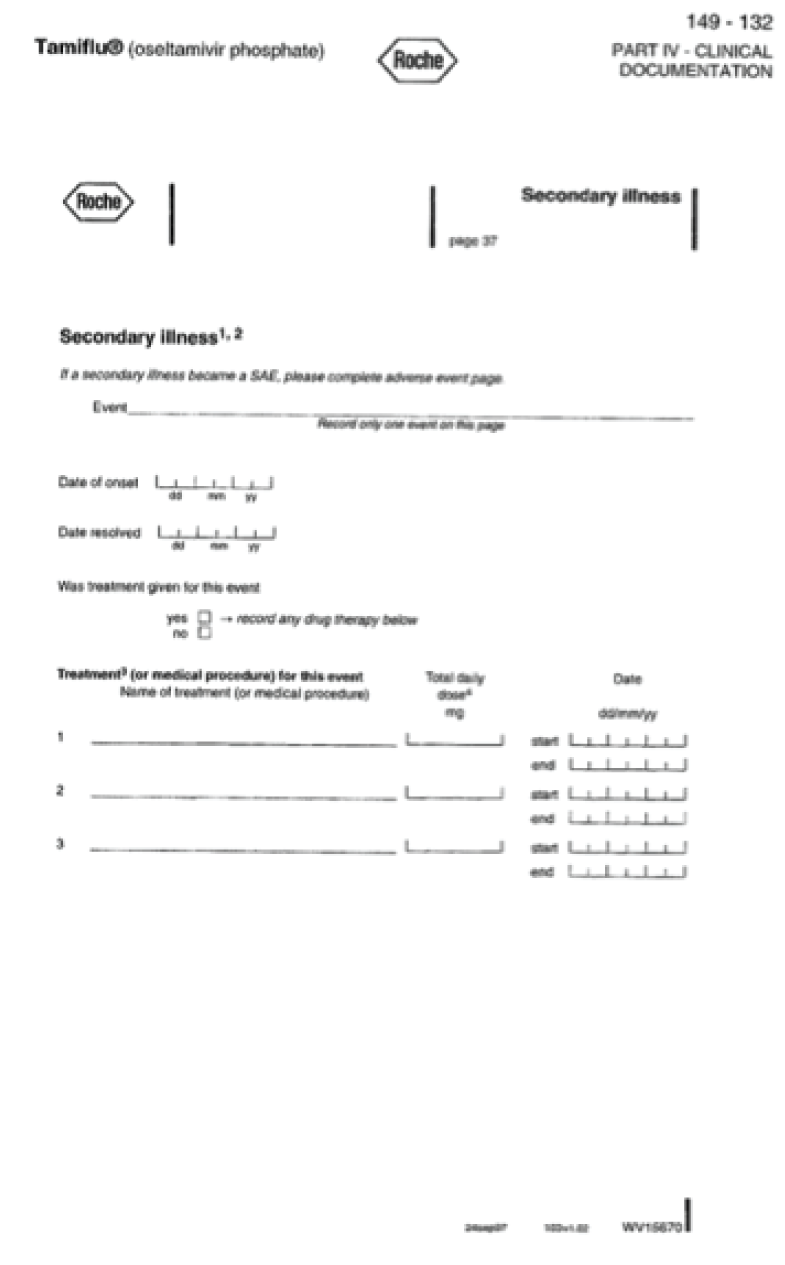

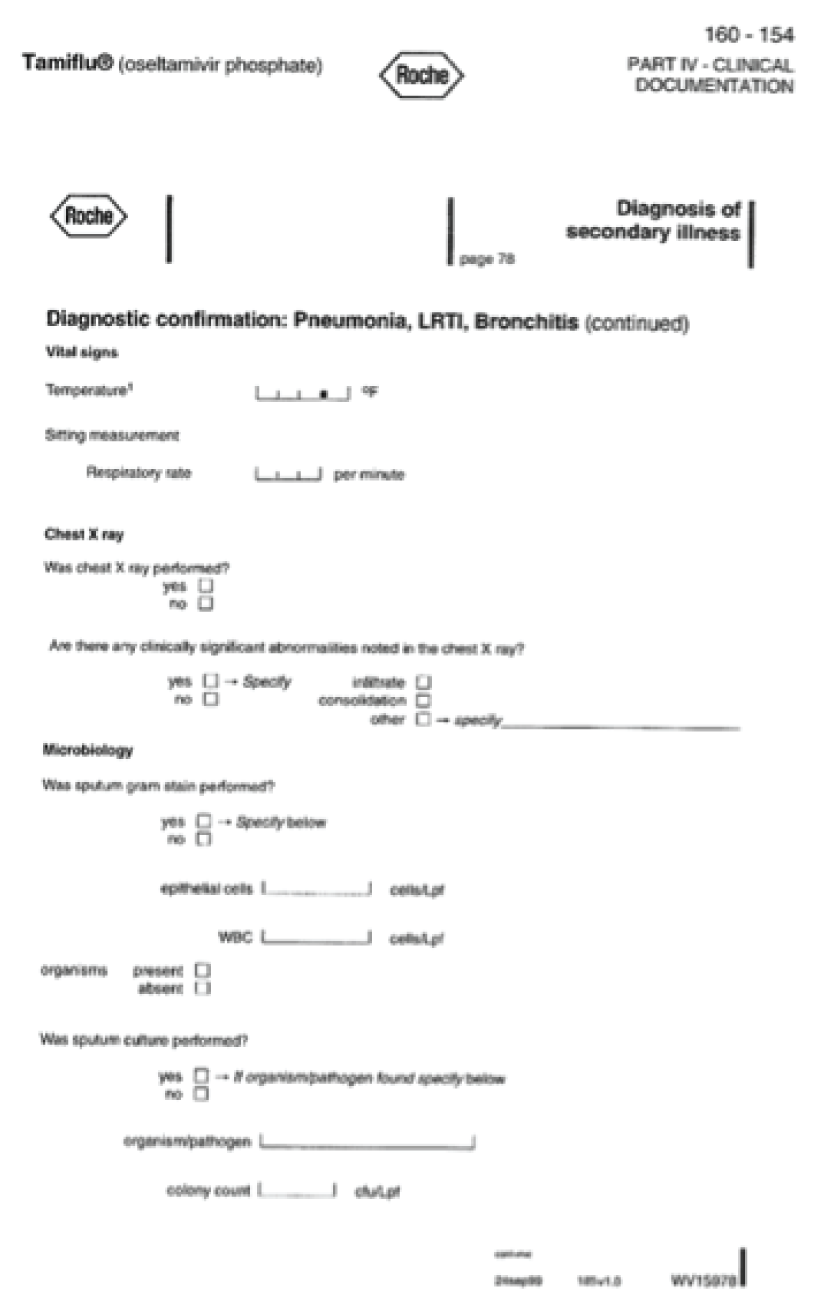

| Study | Where in CRF (PDF p. #) | Data captured | Person reporting (participant/investigator) | Where reported | Specific field for recording confirmatory assessment (e.g. CXR) | Confirmation (including Px) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M7600136 | 1167 | Yes/no answer to question: ‘Is this event a secondary illness related to influenza?’ Secondary illness is defined: sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, pneumonia plus other chest infections that are not diagnosed as bronchitis and/or pneumonia |

Investigator | In form for ‘Adverse events or intercurrent illness’ | No | Px |

| NV1687157 | 361, 389 | Form states: Have there been any changes in the patient’s health, including any new conditions or worsening of existing conditions since day 1 (please include secondary illnesses)? Yes/no: If ‘Yes’, please record the details on the ‘Adverse events or secondary illness’ form in the Additional Forms section of the CRF on p. 30.0. All serious adverse events must be reported within 1 working day of occurrence to Roche Page 30.0 of CRF (PDF p. 389) defines secondary illnesses as sinusitis, otitis media, bronchitis and pneumonia, and asks additional questions such as relationship to test drug and outcome, and leaves space for investigator’s comments on the adverse event |

Investigator | Secondary illness not listed as efficacy outcomes Recording of secondary illnesses was to occur in a form titled ‘Adverse event or secondary illness’ |

No | Px |

| WV156708 | 732, 754, 791, 832 | CRF (PDF p. 732) states: secondary illness reminder: has the patient reported any sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, other chest infection or pneumonia since baseline? Yes [ ] Complete secondary illness page (not the adverse event page) No [ ] Secondary illness page CRF (PDF p. 754) requests information on date of onset, date resolved, whether or not treatment was given and, if so, what treatment or medical procedures, total daily dose, and start/end date of treatment or medical procedure In addition, participants could fill in information related to a secondary illness in their diary card in the free-text box called ‘Notes’, which prompts participants: ‘Please can you record below any extra information about your flu which may be of interest to us, (for example: did your flu symptoms re-occur, and if so when?), and have you taken any other treatments? If so please record the treatment name and the dates you took it.’ (PDF p. 791) |

Participant, mediated through investigator | For investigators, on ‘Secondary illness’ form For participants, on ‘Notes’ section of diary card |

No | |

| WV1567158 | 740, 889, 1018 | CRF (PDF p. 740) states: Secondary illness reminder: Has the patient reported any sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, other chest infection or pneumonia since baseline? Yes [ ] Complete secondary illness page (not the adverse event page) No [ ] Secondary illness page CRF (PDF p. 889) requests information on date of onset, date resolved, whether or not treatment was given and, if so, what treatment or medical procedures, total daily dose and start/end date of treatment or medical procedure Secondary illnesses are listed as sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, pneumonia and other chest infections that are not diagnosed as bronchitis and/or pneumonia In addition, participants could fill in information related to a secondary illness in their diary card in the free-text box called ‘Notes’, which prompts participants: ‘Please can you record below any extra information about your flu which may be of interest to us, (for example: did your flu symptoms re-occur, and if so when?), and have you taken any other treatments? If so please record the treatment name and the dates you took it.’ (PDF p. 1018) |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Mentioned in module 1 and RAP, as tertiary outcomes not mentioned in protocol | No | Px |

| WV15673/WV1569759 | From 483 | No mention of pneumonia, secondary illness, complications in the CRFs | Unclear | Secondary illnesses not listed in protocol as end points. They are listed as safety end points in the RAP, which states that ‘pre-defined’ secondary illnesses were ‘sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, and other chest infections that are not diagnosed as bronchitis and/or pneumonia, plus recurrence of symptoms from the diary card once alleviation had occurred.’ (PDF p. 479) | ||

| WV1570760 | From 98 | Page 117: secondary illness reminder: Has the patient reported any sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, other chest infection or pneumonia since baseline? Yes [ ] Complete secondary illness page (not the adverse event page) No [ ] Page 131: diagnostic procedures 1. Were there any diagnostic procedures or tests carried out since day 1 as a result of influenza or secondary illness that were not scheduled as part of protocol? Yes Type of diagnostic procedure or test: 1. Chest X-rays 2. ECG 3. Bacterial culture 4. Bronchoscopy 5. Pulmonary function test 6. Viral culture (other than influenza) 7. Blood tests (other than antibody sample) 8 Other specify No Secondary illness p. CRF (PDF p. 158) requests information on date of onset, date resolved, whether or not treatment was given and, if so, what treatment or medical procedures, total daily dose and start/end date of treatment or medical procedure |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Mentioned in RAP as tertiary end points, pp. 57–8 | Yes | Px |

| WV1570861 | From 460 | Secondary illness reminder, p. 474: Has the patient reported any new episodes of sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, other chest infection or pneumonia since screening? Yes [ ] . . . Complete adverse event page No [ ] ‘Adverse events’ CRF collected data on date of onset, initial intensity, test drug adjustment, whether or not treatment was given (if so, what), most extreme intensity, relationship to test drug, outcome, whether or not it led to hospitalisation and a free-text line for recording ‘Comments on AE’ (e.g. PDF p. 479) |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Secondary illness not mentioned in protocol | No | Px |

| WV1573062 | From 340 | Secondary illness reminder: Has the patient reported any sinusitis, otitis, bronchitis, other chest infection or pneumonia since baseline? Yes [ ] . . . Complete secondary illness page (not the adverse event page) No [ ] The secondary illness page is descriptive of dates and Px |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Listed as tertiary end points in RAP, p. 297 | No | Px |

| WV1575863 | From 637 | Has the patient reported any new adverse events or symptoms (including intercurrent illnesses and secondary illnesses)? Yes [ ] record in the adverse events/intercurrent illness section of the case No [ ] report form Diagnostic confirmation of otitis media from p. 648 onwards |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Listed as secondary illnesses in core report modules 1 and 2, p. 36 | Yes | Px |

| WV15759/WV1587164 | From 665 | Has the subject reported any adverse events including secondary and intercurrent illnesses? | Participant, mediated through investigator | Secondary illnesses not mentioned in protocol, but secondary outcome in core report Note: worth looking at comparisons 1.49 to 1.51 in RM5. No effect but in bronchitis this study has a more conservative effect than NV16871, which has no definitions and no diagnostics |

Yes | Px |

| WV1579965 | From 642 | Secondary illness defined as in M76001.36 There is a generic physical examination form at p. 704, including ‘lungs’ normal/abnormal specify . . . . . At p. 709, has the patient reported any new AE, including intercurrent or secondary illnesses? Yes/no. If yes, record the adverse events/intercurrent illness section of the CRF (noted at p. 746 on the back of the CRF) with full history, physical examination and diagnostic work up questions for BRON ± PNUM ± LRTI ± SIN ± OM including questions about CXR, MRI, sputum, etc. |

Investigator | Proportion of contacts who are classified as having a secondary illness subsequent to a confirmed episode of influenza listed as tertiary end points | Yes | Px |

| WV15812/WV1587266 | From 285 | Has the patient reported any new adverse events or symptoms (including intercurrent illnesses and secondary illnesses)? Yes [ ] record in the adverse events/intercurrent illness section of the case No [ ] report form At pp. 450–74 is diagnosis of secondary illness page, which is very similar to the one at serial 10 Exhaustive list of diagnostic procedures |

Participant mediated through investigator | Listed as secondary tertiary in protocol at p. 252 | Yes | Px |

| WV15819/WV15978/WV1587667 | From 412 | Page 437 (adverse event reminder): Has the patient reported any new adverse events or symptoms (including intercurrent illnesses)? Yes [ ] record in the adverse events/intercurrent illness section of the case No [ ] report form In CRF p. 447 and p. 443, usual secondary illness reminder From p. 471, diagnosis of secondary illness. This is a one-page list of diagnostics similar to that at serial 10. The question is: ‘Were there any diagnostic procedures or tests carried out since day 1 as a result of influenza or secondary illness that were not scheduled as part of protocol?’ If yes, list per serial 10 From p. 486 is a list of diagnostic tests |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Secondary illness listed as secondary (required antibiotics) and tertiary outcomes in core report and as an addition in protocol amendment at p. 21 | Yes | Px |

| WV1582568 | From 389 | There is a usual note: please go to diagnosis of secondary illness at back of CRF, p. 487 Is this event a secondary illness related to influenza? Diagnosis of secondary illness From pp. 510–40 with exhaustive list of diagnostics as per serial 10 |

Participant, mediated through investigator | Secondary illness listed as secondary outcomes in protocol p. 346 Secondary illnesses recorded on ‘Adverse events’ CRF |

Yes | Px |

| WV1627769 | From 415 | Not found | Not found | Secondary illness not listed as efficacy outcomes |

In all cases of influenza complications reporting (pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis, otitis media) there is a variable degree of participant self-reporting, of investigator mediation (e.g. in writing down the details in the CRF) and lack of verification with investigations, such as culture or imaging. The ‘self-reported, investigator-mediated, unverified’ title is relevant to all complications but for brevity we use it as sparingly as possible.

For harms, we were limited by the frequency of occurrence of the adverse events collected in the trials. Consequently, we meta-analysed (1) all serious adverse events; (2) all adverse events leading to study withdrawal; (3) all withdrawals; (4) all adverse events within a CSR’s defined body system; and (5) a small group of common adverse events as defined in the FDA drug label for oseltamivir. There were too few events to meta-analyse: (1) deaths; (2) serious adverse events by body system; and (3) any events that had an overall incidence of < 0.5%. We did not meta-analyse outcomes with fewer than 10 events in total. We conducted analyses separately for on-treatment and off-treatment periods. However, in two cases for which (on-treatment) treatment effects were borderline statistically significant (prophylaxis with oseltamivir: renal body system on-treatment and psychiatric body system on-treatment), we conducted additional analysis combining on- and off-treatment periods to maximise statistical power. We conducted dose–response harms analysis for two treatment trials8,58 combined and one prophylaxis study,59 as these trials investigated the active agent at multiple doses. These studies8,58,59 included standard-dose and high-dose oseltamivir arms. For these analyses we used logistic regression, adjusting for study effects if appropriate (i.e. for the two treatment trials8,58) and testing for trend using a likelihood ratio test. We tested the hypothesis that increased dose of drug leads to increased incidence of adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

To identify trials in the manufacturer-funded clinical trial programmes for NIs, as well as non-manufacturer-funded clinical trials of NIs, we used a variety of methods that were applied to a variety of sources from the literature, manufacturers and regulatory bodies. These methods, as well as our methodology for identifying and obtaining relevant CSRs, are detailed in Appendices 1, 4 and 5.

Electronic searches

We used electronic searches to identify trials that were not identified by the methods outlined in Appendix 1, particularly for non-manufacturer-funded clinical trials (see Appendix 3 for details). For the 2012 review, we updated our searches of the electronic databases of published studies that were previously carried out for the Cochrane reviews on NIs in children35 and healthy adults,14 and then updated the searches again on 22 July 2013.

Searching other resources

For the description of our searches for regulatory information (FDA, EMA, Roche, GSK, the Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency), see Appendix 4.

Data collection and analysis

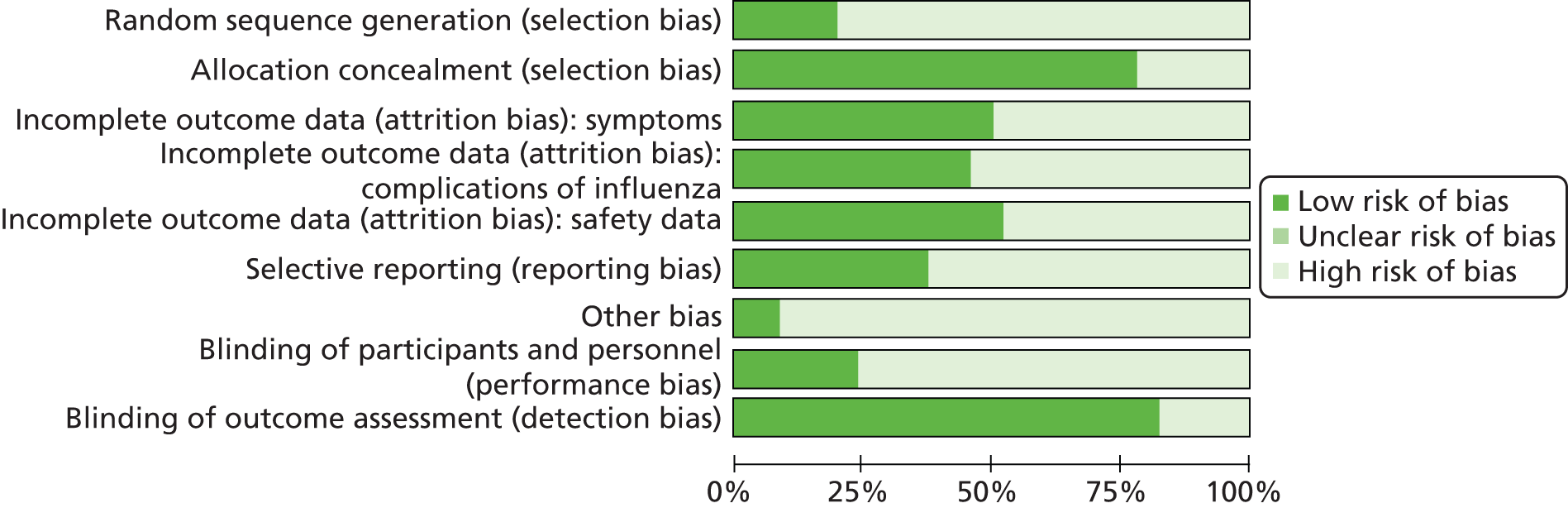

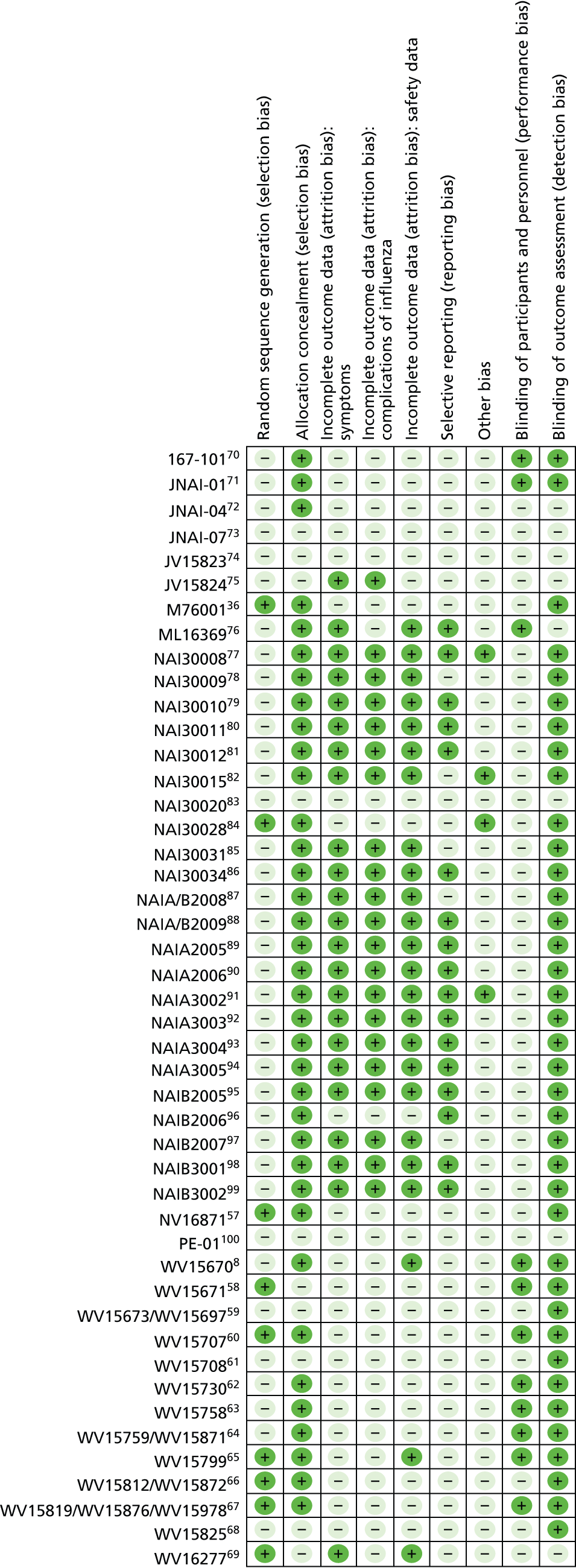

Collection and inventory of the evidence base was facilitated by the tools that were specifically developed for the review (see Appendix 5). The overall risk of bias is presented graphically in Figure 1 and summarised in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Risk-of-bias graph: review of authors’ judgements about each risk-of-bias item, presented as percentages across all included studies. ‘Other bias’ includes potentially active placebos.

FIGURE 2.

Risk-of-bias summary: review of authors’ judgements about each risk-of-bias item for each included study. ‘Other bias’ includes potentially active placebos. +, low risk of bias; –, high risk of bias.

Selection of studies

For this 2013 review, two authors (PD and TJ) reapplied the inclusion criteria for the oseltamivir CSRs and resolved disagreements by discussion. Two review authors (ES and IO) applied the criteria for the zanamivir CSRs, whereas one review author (CH) arbitrated.

For the procedures followed in the 2012 review, see Appendix 7.

Data extraction and management

The sizeable quantity of available data led us to subdivide the extraction, appraisal and analysis of the data into a two-stage exercise. In stage 1 we assessed the reliability and completeness of the identified trial data. We decided to include in stage 2 of the review (full analysis following standard Cochrane methods) only data that satisfied the following three criteria:

-

Completeness CSRs/unpublished reports include both identifiable CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement-specified methods to enable replication of the study. Identifiable CONSORT statement-specified results (primary outcomes, tables, appendices) must be available.

-

Internal consistency All parts (e.g. denominators) of the same CSRs/unpublished report are broadly consistent.

-

External consistency Consistency of data as reported in regulatory documents, other versions of the same CSRs/unpublished reports and other references, to be established by cross-checking.

This was a different approach to that used in the previous version of the current review,9 as we had only incomplete information at that time and applied only the second and third criteria.

Stage 1

For details of the use of the CONSORT-based extraction template and the assessment for stage 1 inclusion in the A159 review,9 see Appendix 5. In this review, assessment for inclusion in stage 1 was part of the inclusion procedure.

Stage 2

In stage 2, one review author extracted data and a second review author checked it. We extracted data on to standard forms, checked and recorded it.

Use of regulatory information

We used regulatory information to assess the possible correlation between citation frequency of oseltamivir treatment trials in the FDA regulatory documents and trial size.

Post-protocol analyses

After publication of the A159 protocol in December 2010, but before validation of our CONSORT-based extractions in the spring of 2011, we decided to carry out analyses (which we called post-protocol analyses) to test five null hypotheses that we had formulated while reading, summarising and reconstructing the CSRs. The hypotheses originated from our observations of discrepancies and other unexpected observations in the CSRs’ data, and were informed by reading regulatory information. Appendix 8 reports the rationale, methods to formulate and test, and the results of the hypotheses.

The hypotheses reflect the uncertainty prevailing in the evidence base at a time when full CSRs were not available for all studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Previous studies comparing regulatory with published or internal company sources of evidence have reported a variety of different biases that affect medical knowledge. 41,42,56,101 We will report in detail elsewhere our comments on using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool102 to appraise CSRs and for trial programmes, and our efforts to construct an instrument for assessing risk of bias in complete CSRs. A full description of the methods used to quantify biases will be published in another paper.

Measures of treatment effect

To estimate treatment effects we first calculated the risk ratios (RRs) and used the average (mean) control event rate and the pooled RRs reported in the figures to calculate the RDs. For consistency, we adopted this method for both the ‘Summary of findings’ tables and for the RDs reported in the text. For the analysis we chose to report the RRs, as they are more consistent across the studies, and we have reported the heterogeneity for the pooled RR. We reinterpreted the results using the RD, as this result is applicable to clinical decision-making. We calculated MDs for time to first alleviation of symptoms. For time to first alleviation of symptoms we also estimated the treatment effect as the percentage reduction in the average time to first alleviation of symptoms in the placebo group. Most zanamivir CSRs stated treatment effects only in terms of medians in each treatment group, as well as p-values from a hypothesis test comparing the time-to-event distributions. These data are insufficient for conducting a meta-analysis. However, often sufficient time-to-event data were reported to allow us to estimate restricted means and standard deviations. Restricted means are based on the maximum time reported where alleviation occurred. There were some patients for whom alleviation was censored at the maximum follow-up time; therefore, restricted means are underestimates of the true means. However, the proportion of patients who were censored was generally low and similar in both treatment arms, hence this limitation is unlikely to have led to bias. The length of follow-up varied across trials and this has led to high variation in the estimated means and standard deviations across trials.

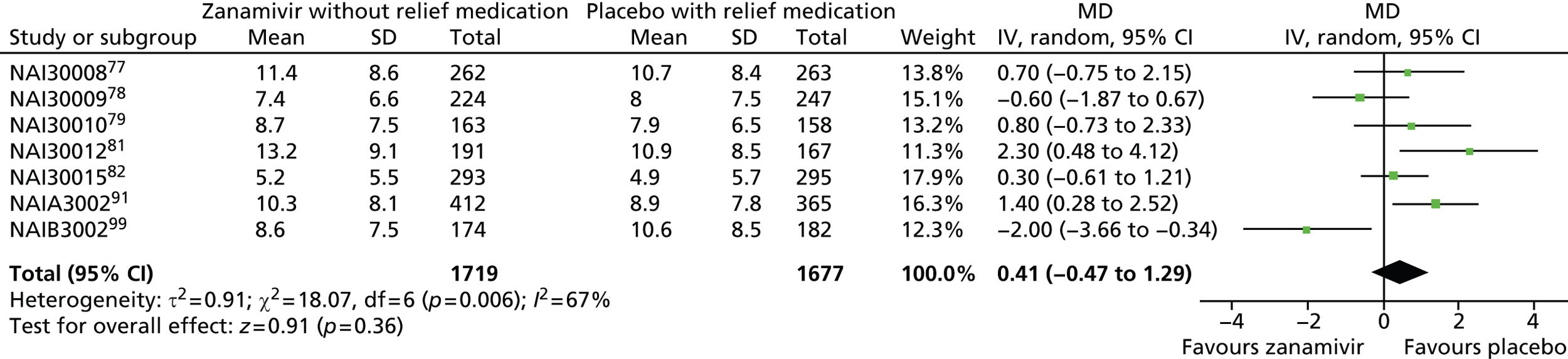

A post hoc analysis was undertaken after we discovered seven zanamivir trials that provided data on time to first alleviation of symptoms with and without relief medication. Each patient in the studies may or may not have taken relief medication [e.g. paracetamol (acetaminophen)] during the trial. Alleviation of symptoms may have occurred while the patient was taking relief medication and the ‘standard’ comparison was made using this scenario. However, an additional analysis used a stricter definition, for which alleviation of symptoms could be achieved only without the use of relief medication. For example, a patient may have achieved alleviation using relief medication after 5 days but took 7 days to achieve alleviation without the use of relief medication. The comparison we reported is for all patients for whom we used the stricter definition for the zanamivir group (alleviation without relief medication) and the less-strict definition for the placebo group (alleviation with relief medication).

We planned to use the tridimensional dose-relatedness, timing and patient susceptibility methodology to assess the likelihood of harms causality,103 but the quality of the data available did not allow for this.

Unit of analysis issues

Problems with unit of analysis are described in ‘Post-protocol hypotheses’ (see Appendix 8).

Dealing with missing data

We developed a comprehensive strategy for dealing with data that we know are missing at the trial level, that is, unpublished trials (see Search methods for identification of studies, above, and Appendices 1, 4 and 5) and unreliable published records, which are a very concentrated summary of CSRs. For example, in the oseltamivir trial programme, some trials’ CSRs (e.g. WP16263104) consist of 8545 pages. This has a 1000-fold greater length than its published version,105 which consists of seven pages. The purpose of this review is to provide as complete a picture as possible of trial programmes, without reliance on the published literature. Appendix 9 reports an example of the content of a typical Roche CSR.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used tau-squared (inverse variance method) and the I2 statistic to estimate between-study variance as measures of the level of statistical heterogeneity, and the chi-squared test to test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We carried out assessment of reporting biases (comparing CSR with the relevant publication) only in the first publication of A159. 106 For this version, as we had complete CSRs for the trial programmes of the two drugs, we expected to find all of the relevant information in these documents and adopted a binary assessment (high risk, low risk or unclear bias).

Data synthesis

We used the random-effects approach of DerSimonian and Laird107 based on MDs for analysis of time to first alleviation of symptoms. For all of the other outcomes we used the random-effects approach for binary data of DerSimonian and Laird107 where tau-squared was estimated using the inverse variance method.

Although overall symptom reduction is well documented, our interest was particularly focused on complications and adverse events, as this is where evidence is currently scarce or inconclusive. 31,32,35 Our preliminary examination of CSRs identified that some symptoms and sequelae of influenza (such as ‘pneumonia’) had been classified as either a ‘complication of influenza’ or as an ‘adverse event of the treatment’, or both. We called this somewhat confusing classification ‘compliharms’. We decided to deal with compliharms as follows. We identified complications of particular clinical interest as ‘pneumonia’, bronchitis, otitis media and sinusitis. We tabulated the type of data capture used for each complication (‘secondary illness’) by study, including the following variables: definition of what events are termed complications; which part of the CSR captured data on complications; who reported and captured the data; which diagnostic method was used; whether or not, and where, the diagnostic pathway was (usually a form); and whether or not prescriptions for treatment were captured. We then aimed to stratify our analysis by method of diagnosis with three possible criteria: (1) laboratory-confirmed diagnosis (e.g. based on radiologically or microbiologically confirmed evidence of infection); (2) clinical diagnosis without laboratory confirmation (diagnosed by a doctor/investigator after a clinical examination); and (3) other type of diagnosis, such as self-reported by patient. We also conducted analysis of any complication (such as ‘pneumonia’, bronchitis, otitis media and sinusitis) that was classified as serious or led to study withdrawal.

We tested the effects of oseltamivir in prophylaxis of influenza and ILI. However, the CSRs of prophylaxis trials do not define ILI but report eight different definitions for influenza with laboratory confirmation (see web extra influenza definitions, Appendix 11).

This is a complex and confusing set of definitions, in which, for example, the definition for upper respiratory tract infection with systemic disturbance is the same as one of the definitions for asymptomatic influenza. After discovering the absence of a definition for ILI, and the complex and confusing definitions for laboratory-confirmed influenza, we classified ILI as having two or more symptoms from the following: nasal congestion, headache, chills/sweats, sore throat, cough, fatigue, myalgia and fever. These were the symptoms reported in the efficacy listing of individual patients in module 3 of the prophylaxis trials CSRs.

In two oseltamivir treatment trials8,58 and one prophylaxis study59 there were three treatment arms comparing placebo, standard dose and high dose. For time to first alleviation of symptoms, we restricted comparison to placebo against standard dose (as this is how it was reported in the original report). However, for all other outcomes we combined the standard and high-dose treatment arms. There was little apparent difference in the incidence of outcomes between the standard- and high-dose arms, and combining the arms did not appear to cause heterogeneity. However, in two cases there was some evidence of a dose–response effect. These cases are described more fully below (see Results, Analysis of harms).

The majority of zanamivir trials compared placebo with inhaled zanamivir. However, some trials also included an intranasal zanamivir treatment arm and a combined arm of inhaled and intranasal treatment. The multiple zanamivir arms were generally combined for meta-analysis, as effects appeared similar and did not appear to cause heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated the robustness of complications outcomes using subgroup analysis by method of diagnosis. We investigated high estimates of heterogeneity, where possible, using subgroup analysis. For example, we conducted a subgroup analysis of time to first alleviation of symptoms in studies of oseltamivir treatment in children by partitioning studies into those of otherwise healthy children and those of children with chronic illness (asthma). Based on a referee’s comment, we conducted a subgroup analysis on time to first alleviation of symptoms by infection status for zanamivir. We could not do a similar analysis for oseltamivir because we did not have data on the non-influenza-infected patients, and we could not correctly identify the patients with influenza infection as a result of the effect of oseltamivir on antibodies.

In the trial programmes for both oseltamivir and zanamivir there was large variation in treatment effects for pneumonia across the populations studied (i.e. adults and children, as well as treatment and prophylaxis), hence we conducted a metaregression to investigate this heterogeneity. We included all of the studies that reported pneumonia (32 studies in total) and investigated the four binary factors: age group (adults vs. children), drug (oseltamivir vs. zanamivir): indication (treatment vs. prophylaxis) and method of diagnosis. For oseltamivir studies, the method of diagnosis was based on either data collected on non-specific adverse events or secondary/intercurrent illness forms, or data collected on specific ‘diagnosis of secondary illness’ forms that included objective criteria such as X-ray confirmation. For zanamivir, two trials included X-ray confirmation of pneumonia. We conducted the metaregression in Stata/SE, version 13 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using the metareg command. There were some studies where one treatment group had zero events, therefore we added 0.5 events to all treatment groups for all studies prior to analysis. The dependent variable in the regression was log-relative risk. A further post hoc analysis was undertaken after we discovered that seven trials provided data on time to first alleviation of symptoms with and without relief medication. Each patient in the studies may or may not have taken relief medication during the trial. Alleviation of symptoms may have occurred while the patient was taking relief medication, and the ‘standard’ comparison was made using this scenario. However, an additional analysis used a stricter definition, for which alleviation of symptoms could be achieved only without the use of relief medication. For example, a patient may have achieved alleviation using relief medication after 5 days but took 7 days to achieve alleviation without the use of relief medication. The comparison we reported is for all patients, for which we used the stricter definition for the zanamivir group (alleviation without relief medication) and the less strict definition for the placebo group (alleviation with relief medication).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses applicable to our post-protocol analyses have been covered above (see Methods). We used the fixed-effect method of Mantel and Haenszel as a sensitivity analysis to supplement our primary analyses using the random-effects method of DerSimonian and Laird. 107 Random-effects meta-analysis is known to be overly conservative with sparse data. Hence, we conducted sensitivity analysis using Peto’s method on two occasions for which we had sparse data and borderline statistically significant results (prophylaxis with oseltamivir: renal body system on-treatment and psychiatric body system on-treatment).

Results

Description of studies

We searched trial registries, electronic databases and regulatory archives, and corresponded with manufacturers to identify all trials and requested CSRs. Although this review focuses on the primary data sources of manufacturers, we checked that there were no published RCTs from non-manufacturer sources by running electronic searches in the following databases: CENTRAL 2013, Issue 6, limited to year published 2010–13 (20 search results); MEDLINE (January 2011 to July week 2, 2013) (56 search results) and MEDLINE (via Ovid) from 1 January 2011 to July week 2, 2013 (56 search results); EMBASE (January 2011 to July 2013) (90 search results) and EMBASE.com from 1 January 2011 to July 2013 (90 search results); and PubMed (not MEDLINE) with no date limit (21 records). We searched PubMed to identify publisher-submitted records that will never be indexed in MEDLINE and the most recently added records not yet indexed in MEDLINE. To identify reviews that may possibly have referenced further trials we searched DARE 2013, Issue 2 of 4 April (four search results); NHS EED, Issue 2 of 4 April 2013 (two search results); both resources parts of The Cochrane Library (accessed 22 July 2013); and HEED (searched 22 July 2013) (three search results).

Results of the search

Use of regulatory information

We were able to download 2673 pages from the FDA website. The table of contents (TOC) is provided in Tables 2–5. We used these pages to identify all of the trials that had been conducted within a drug’s trial programme. There was no correlation between citation frequency of oseltamivir treatment trials in the FDA regulatory documents and trial size. The biggest treatment trial36 is cited only four times in three documents, whereas other contemporary treatment trials are cited far more. 8,58,60,62,66 One trial,8 for example, is cited 46 times in the FDA documents. However, the combined enrolled denominator of the four treatment trials completed at the time8,58,60,62 was 1442, smaller than 1459. 36 This suggested that the FDA’s regulatory evaluation of Roche’s New Drug Application (NDA) was based predominantly on what Roche had presented to them as ‘pivotal’, or trials that best demonstrated the properties of oseltamivir, not the complete evidence base of all oseltamivir trials. One possible alternative explanation for this observation could have been the interval between trial completion, generation of the report and NDA submission. This explanation is supported by the relatively brief interval between completion of the M76001 trial36 (19 February 1999) and submission (on 30 April 1999) of NDA 021087 to the FDA. However, the core part of the submission (the clinical development programme) contains data from two (at the time of writing) ongoing trials. 66,67

| Mentioned study | File name | Pages on which study is mentioned (separated by commas) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 113502 | |||

| 113625 | |||

| 113678 | |||

| 114045 | |||

| NAI108166 | |||

| 105934 | |||

| NAI106784 | |||

| 107485 | |||

| 108127 | |||

| 112311 | |||

| 112312 | |||

| 113268 | |||

| GCP/95/045 | |||

| NAI10901 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin2.pdf | 15.15 | |

| NAI10902 | |||

| NAI3000877 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin2.pdf | 15 | Seven documents with 14 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin3.pdf | 13 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 19, 19, 20 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 1, 1, 3, 4, 4 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview9.pdf | 7.7 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/21036ltr.pdf | 2 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_MEDR.pdf | 33 | ||

| NAI3000978 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 1.2 | Seven documents with 110 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P1.pdf | 10, 10, 12, 13, 13, 14, 14, 17, 29, 42, 61, 62, 64, 64, 65, 65, 68 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P2.pdf | 33, 34, 36, 43, 43, 43, 43, 52, 52, 52, 53, 53, 56, 57 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 5, 5, 5, 6, 6, 8, 8 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_MEDR.pdf | 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 8, 9, 9, 10, 10, 11, 11, 11, 14, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 19, 19, 20, 20, 22, 23, 23, 23, 24, 24, 24, 25, 25, 25, 25, 25, 25, 26, 26, 26, 27, 27, 28, 28, 28, 29, 29, 31, 31, 31, 31 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_MICROBR.pdf | 3, 3, 4, 4, 4 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_STATR.pdf | 2, 2, 2, 4, 7, 12, 18, 18, 18, 19 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P1.pdf | 31.56 | One document with two instances | |

| NAI3001079 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 1.2 | Six documents with 65 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P1.pdf | 10, 12, 13, 14, 14, 15, 17, 62, 62, 62, 64 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P2.pdf | 34, 34, 36, 43, 53 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 5, 5, 6, 6 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_MEDR.pdf | 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 5, 18, 19, 21, 21, 22, 23, 23, 23, 23, 24, 25, 25, 25, 26, 26, 26, 26, 27, 27, 27, 28, 28, 29, 29, 29, 30, 31, 31, 31, 32 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_STATR.pdf | 2, 2, 13, 13, 13, 19 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 6 | One document with one instance | |

| NAI3001281 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 1 | One document with one instance |

| NAI3001582 | |||

| NAI3002083 | |||

| NAI3002884 | |||

| NAI3003486 | |||

| NAI40012 | |||

| NAIA1009 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P1.pdf | 56 | Four documents with 17 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P2.pdf | 1, 1, 1, 48, 49, 52 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 5, 5, 6 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_MEDR.pdf | 3, 3, 6, 7, 20, 31, 31 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview5.pdf | 18 | Five documents with five instances | |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview6.pdf | 9 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_ADMINCORRES_P2.pdf | 52 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 11 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_STATR.pdf | 2 | ||

| NAIA300291 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin1.pdf | 15 | Thirteen documents with 122 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin2.pdf | 6, 6, 7, 7, 14, 15, 22, 22, 23 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin3.pdf | 1, 4, 4, 12, 12, 12, 12, 17 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview1.pdf | 4, 14, 14, 14, 14, 14, 15, 15, 15, 15, 16 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview2.pdf | 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 8, 8, 9, 9, 9, 12, 12, 15, 16, 16, 16, 17 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview3.pdf | 5, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7, 7, 7, 8, 8, 9, 9, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 13, 14, 15, 15, 17, 18, 18, 19, 20, 21 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview4.pdf | 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 6 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview6.pdf | 4, 5, 10, 12 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 17 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 2, 2, 6, 6, 8, 8, 9, 10 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview9.pdf | 10 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-stats.pdf | 7 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/20000426_001/21–036-S001_RELENZA_BIOPHARMR.pdf | 5 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview1.pdf | 15 | One document with one instance | |

| NAIA300392 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 17, 17, 18 | Three documents with six instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 4.4 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview9.pdf | 22 | ||

| NAIA300493 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin3.pdf | 14 | Four documents with eight instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview6.pdf | 7 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 18, 18, 19 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview8.pdf | 4, 4, 4 | ||

| NAIA300594 | Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-admin3.pdf | 14 | Five documents with 12 instances |

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview1.pdf | 5 | ||

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview5.pdf | 12, 12, 12, 13, 14, 15, 15 | ||

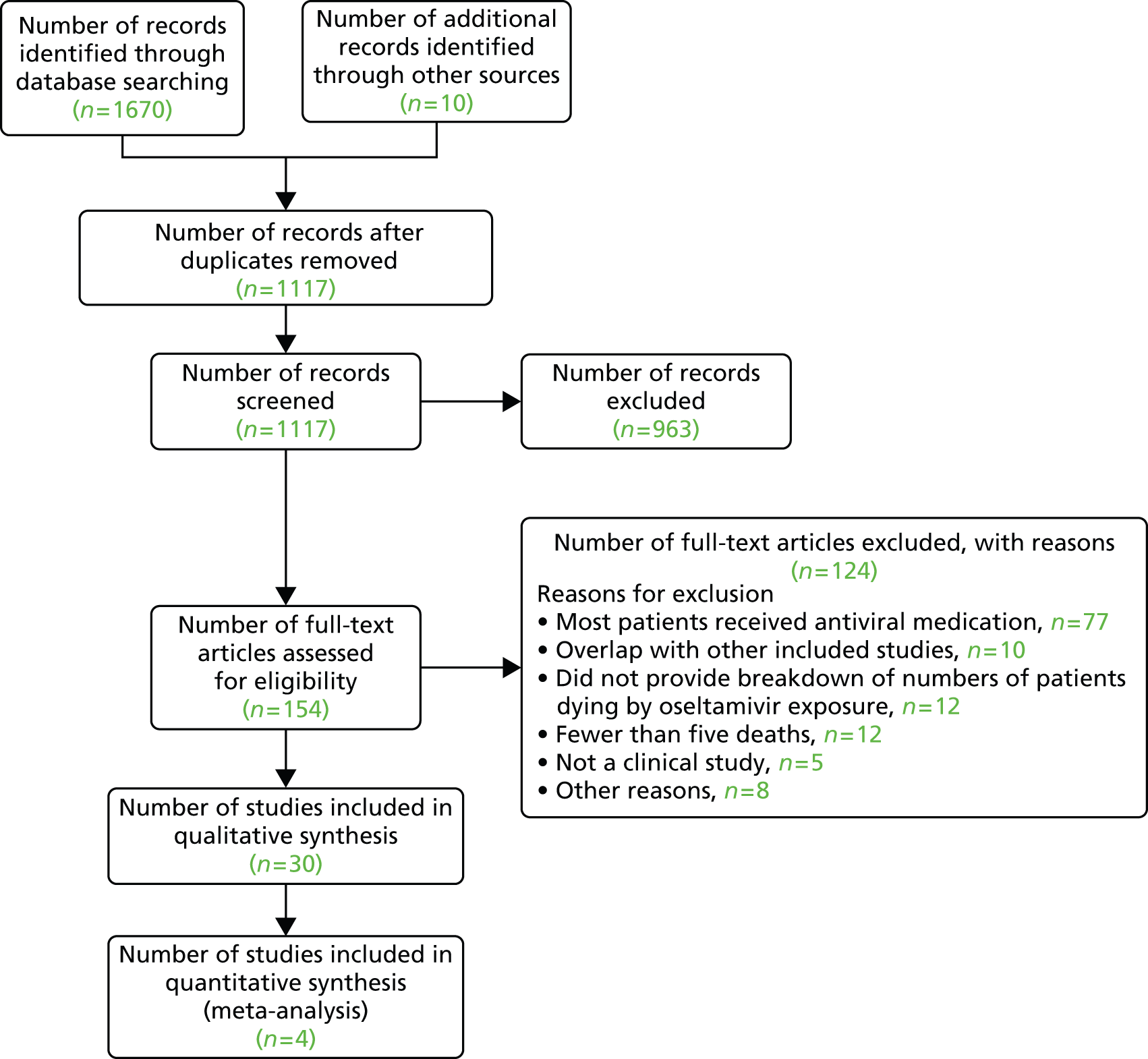

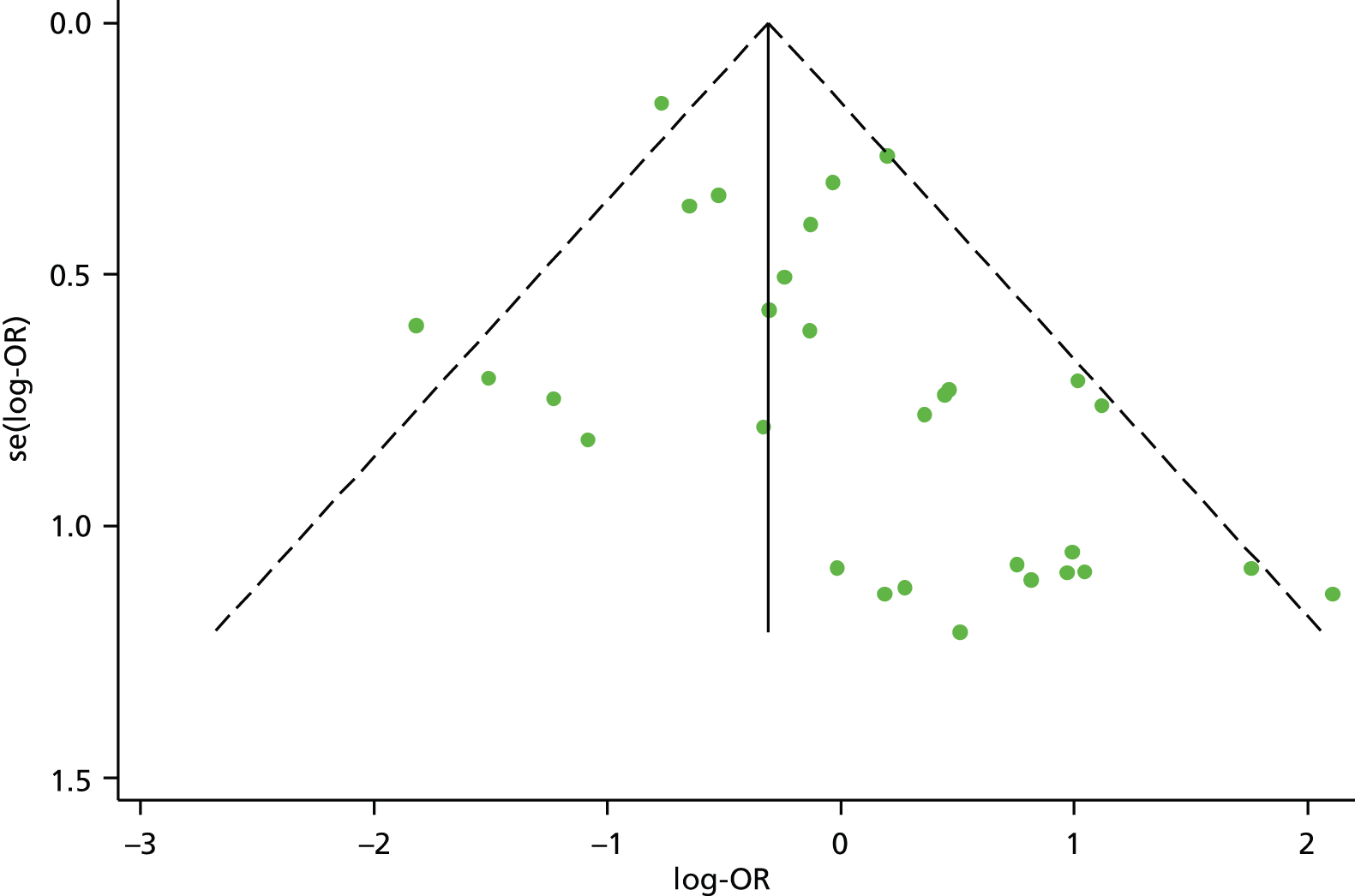

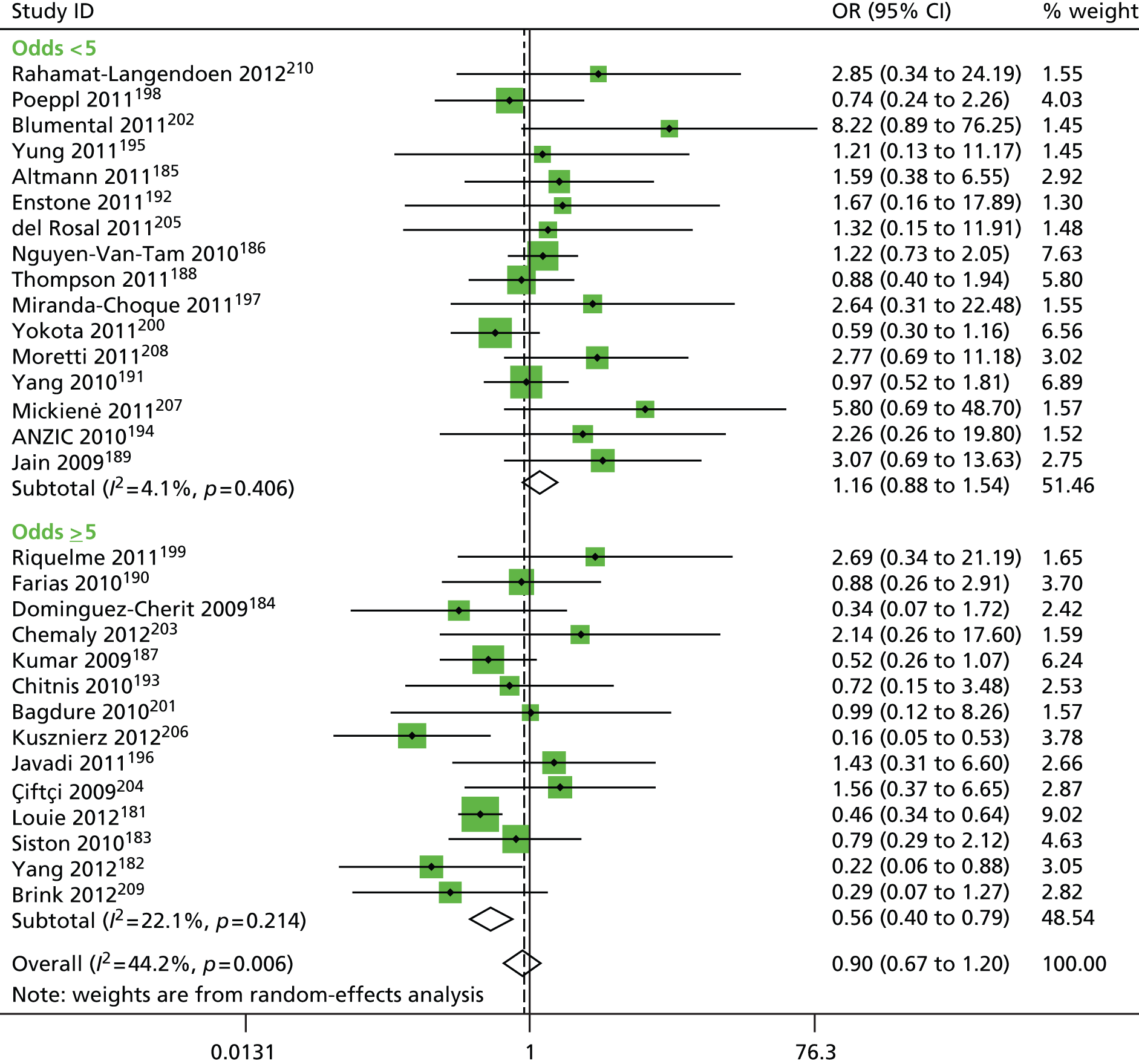

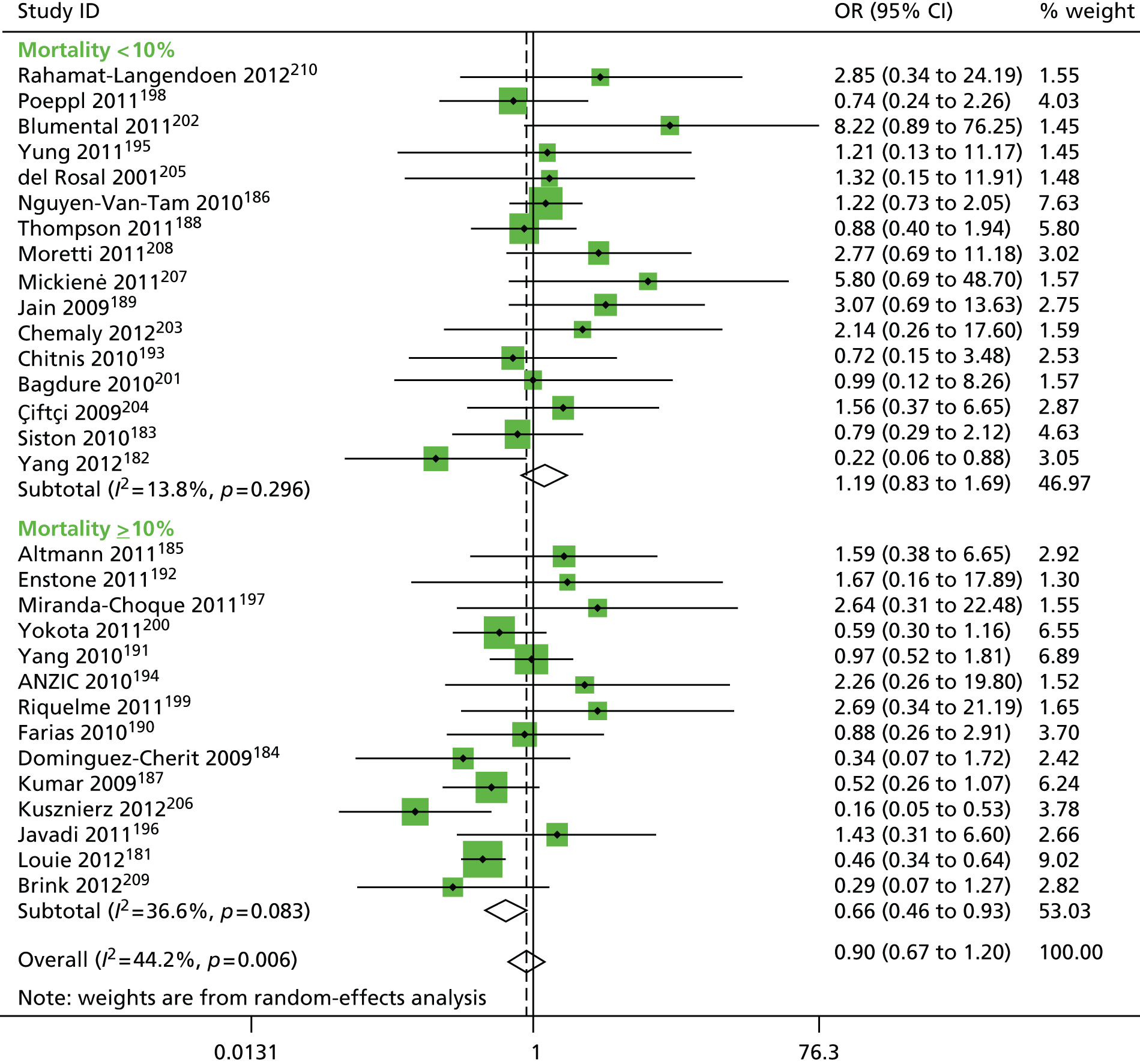

| Tamiflu and Relenza/Relenza/Relenza – NDA 021036/19990726_000/021036-medreview7.pdf | 14.15 | ||