Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/78/03. The contractual start date was in September 2008. The draft report began editorial review in December 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John G Williams was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board from 2008 to 2011 and the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Researcher-Led Board from 2009 to 2014.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Williams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and literature review

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic debilitating disease that affects about 150,000 people in the UK. 1,2 Some 25% of patients with UC present either for the first time or later, with acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASC) requiring hospital admission. 3 In patients with ASC, intravenous steroids are the first-line treatment. 4 However, about 30–40% of these patients are resistant to intensive steroid therapy. 5,6 Previously, colectomy was the only available option for these patients. 5 Although mortality following emergency colectomy has fallen over time, 10% of patients die within 3 months of surgery. 7

The use of intravenous or oral ciclosporin (Sandimmun® or Neoral®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd),8,9 a calcineurin inhibitor that selectively inhibits T-cell function, and infliximab (Remicade®, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd),10,11 a monoclonal antibody that targets tumour necrosis factor α, then offered hope for the treatment of steroid-resistant UC.

Several studies support the use of infliximab in patients with moderate or severe UC,12–15 especially steroid-resistant UC patients who do not tolerate ciclosporin. 12 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 infliximab studies found an average short-term response and remission of 68% and 40%, respectively, and an average long-term response and remission of 53% and 39%, respectively. 15 However, there are concerns about high rates of later relapses. 16,17 Two large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) also found highly significant improvements in total Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ)18 score and Short Form questionnaire-36 items physical and mental component scores19 for infliximab patients at 8 weeks when compared with placebo. 20 The current UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines allow the use of infliximab only when ciclosporin is contraindicated or as part of a research study. 21

Several studies support the use of ciclosporin as a safe and effective treatment for steroid-resistant UC,22–24 although it has been associated with side effects including dose-related toxicity23,25,26 and long-term failure. 23–25,27 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 ciclosporin studies reported a mean short-term response rate of 71%;28 one study reported that 65% of patients relapsed after 1 year and 90% after 3 years. 27 Another review of 32 studies reported a 51% short-term success rate. 29 However, the relevant Cochrane review concluded that there was limited evidence that ciclosporin was more effective than standard treatment for severe UC and that long-term benefits were unclear. 30 It also advocated research into the long-term effects of ciclosporin on quality of life (QoL) and its cost-effectiveness.

Review of literature

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, original studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses that compare ciclosporin and infliximab in the management of acute UC resistant to steroid therapy up to the 31 July 2014. We used the search terms: ‘ciclosporin’, ‘infliximab’, ‘ulcerative colitis’, ‘acute severe ulcerative colitis’ and ‘steroid resistant ulcerative colitis’. We included synonyms, different spellings and drug brand names in our search to identify all relevant articles. We used the electronic search strategies checklist of the Cochrane Collaboration. 31

We identified nine observational studies and one RCT32–41 that compared the efficacy and safety of ciclosporin with those of infliximab (Table 1). Although both ciclosporin and infliximab were effective in steroid-resistant UC, results did not agree which drug was better. 32–35 One small retrospective study34 of 38 patients with acute UC resistant to steroids showed a higher rate of colectomy in patients who received ciclosporin (63% and 68% at 3 and 12 months, respectively) than in those who received infliximab (21% and 37% at 3 and 12 months, respectively); there was no significant difference between groups in adverse events (AEs) or steroid dependence. A prospective study36 found the colectomy-free rate at discharge, and at 3 and 12 months from admission, was significantly higher in patients who had infliximab as a rescue therapy (n = 45) compared with those who had ciclosporin (n = 38). A minute retrospective study35 of two cohorts of patients (15 on ciclosporin and six on infliximab) showed a higher rate of colectomy and opportunistic infection in patients who received ciclosporin compared with those who received infliximab. A retrospective study of 49 patients on infliximab and 43 patients on ciclosporin showed that colectomy frequencies were significantly lower after rescue with ciclosporin than with infliximab, with no death or opportunistic infection. 32 Mocciaro et al. 33 retrospectively examined the outcomes of 30 patients who received ciclosporin and 30 patients who received infliximab for steroid-resistant acute UC and reported that the rate of colectomy at 12 months was 48% in the ciclosporin group compared with 17% in the infliximab group (p = 0.01); both drugs were equally safe without severe AEs. A recent UK inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) audit reported increased use of infliximab compared with ciclosporin in managing ASC; the clinical response rate was higher in patients who received infliximab. 42

| Study | Number of patients | Main outcomes reported | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laharie et al., 201241 |

|

Treatment failure: 60% with ciclosporin and 54% with infliximab (p = 0.52) SAEs: 16% with ciclosporin and 25% with infliximab Mucosal healing: 47% with ciclosporin and 45% with infliximab (p = 0.85) UK-IBDQ scores improved by 78 points with ciclosporin and 100 points with infliximab (p = 0.19) Colectomies: 17% in the ciclosporin and 21% in the infliximab group |

98 days |

| Leblanc et al., 201138 |

|

Colectomy rate: 54% in infliximab group and 67% in ciclosporin group Clinical remission: 25% in infliximab group and 14% in ciclosporin group AEs: 23% in infliximab group and 24% in ciclosporin group |

22 months |

| Mañosa et al., 200940 |

|

Six patients (37.5%) required colectomy and 19% of patients had SAEs | 195 days |

| Maser et al., 200837 |

|

Clinical remission: 40% in the infliximab-salvage group and 33% in the ciclosporin-salvage group The median duration of remission: 13.6 months in the infliximab-salvage group and 21.0 months in the ciclosporin-salvage group Colectomy rate: 40% in the infliximab group and 44% in the ciclosporin group SAEs: one in the infliximab group and two in the ciclosporin group |

Average duration of follow-up was 7.8 months for infliximab and 17.7 months for ciclosporin |

| Dean et al., 201234 |

|

Colectomy rate: 63% for ciclosporin and 21% for infliximab (p = 0.0094) at 3 months. By 12 months the rates were 68% and 37% for ciclosporin and infliximab, respectively (p = 0.06) Steroid dependence at 12 months was 50% for ciclosporin and 25% for infliximab (p = 0.36) There was no statistical difference in AEs between the two groups (p = 0.17) |

12 months |

| Chaparro et al., 201239 |

|

Colectomy rate was 30% SAE rate was 23% |

58 weeks |

| Croft et al., 201336 |

|

Colectomy rate: 44% for ciclosporin and 16% for infliximab at discharge (p = 0.006). At 3 months the colectomy rates were 47% vs. 24% (p = 0.04), and at 12 months colectomy rates were 58% vs. 35% (p = 0.04) for ciclosporin and infliximab, respectively | 12 months |

| Sjoberg et al., 201232 |

|

Colectomy rates: 5% vs. 27% at 15 days, 7% vs. 23% at 3 months and 23% vs. 43% at 12 months for ciclosporin and infliximab, respectively (p < 0.05) | 12 months |

| Mocciaro et al., 201233 |

|

Colectomy rates: 28.5% vs.17% (p = 0.25) at 3 months and 48% vs. 17% at 12 months (p = 0.007) for ciclosporin and infliximab, respectively The 1–2–3 year cumulative colectomy rates were 48%, 54%, 57% in the ciclosporin group and 17%, 23%, 27% in the infliximab group (p < 0.05) |

The mean follow-up was 74.7 months for ciclosporin and 33.6 months for infliximab |

| Daperno et al., 200435 |

|

Clinical remission: 53% in the ciclosporin group vs. 67% in the infliximab group Colectomy rates: 47% in the ciclosporin group vs. 33% in the infliximab group |

49 months |

Four studies37–40 explored the use of infliximab and ciclosporin as a second-line rescue therapy by crossing them over after failure of these agents as a first-line therapy. The studies concluded that the use of ciclosporin or infliximab as second-line rescue therapy induced remission in up to two-thirds of patients. 38 However, this remission was of limited duration, the rate of colectomy was around 40%, and the rate of serious adverse events (SAEs) ranged from 16% to 23%. 37–40

A recent meta-analysis of 321 patients in six retrospective cohort studies32–35,37,38 concluded that infliximab and ciclosporin are comparable when used as rescue therapy in acute severe steroid-refractory UC. However, the outcome measures were limited to colectomy rates, adverse drug reactions (ARs) and postoperative complications over 12 months. 43

Against this background of observational studies that compared these two drugs only indirectly, la Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives (GETAID) recently reported on the trial CycloSporine versus InFliximab (CySIF),41 the first head-to-head comparison of these two drugs. CySIF found no significant differences in ‘treatment failure’ within 98 days, defined as any of the following: (i) no clinical response after 7 days; (ii) no remission without steroids after 98 days; (iii) relapse between 7 and 98 days; (iv) SAE leading to treatment interruption; (v) colectomy; or (vi) death. However, CySIF recruited only 110 patients, followed them for only 98 days, reported no data on QoL and collected no data on costs or from participants.

The qualitative research reported in the literature on infliximab focuses on its role in treating rheumatoid arthritis. 44 There is no qualitative study that explores the use of ciclosporin in the treatment of acute UC. One qualitative study exploring patient and parent experiences of infliximab in paediatric gastroenterology, found favourable views of the drug when used in a hospital environment. 45 To our knowledge, no studies, qualitative or otherwise, have explored health professionals’ views of drug administration for treating steroid-resistant UC. This is disappointing as qualitative methods are well suited to investigate personal experience, individual perception and belief and meaning systems,46,47 enabling triallists to clarify patients’ and clinicians’ understandings of clinical practice and drug regimes. 48,49 Therefore, there is a need for a trial that also seeks the experiences and views of patients with acute UC about treatments and changes in health over time and of health-care professionals about ease of drug handling and drug preference.

Patients with UC incur substantial health-care costs over many years. As well as the direct costs of treatment by drug or surgery, UC patients consume a wide range of health-care resources including spells in hospital, attendances at emergency departments, outpatient visits, endoscopies and other investigations. Nevertheless, no study has assessed the cost-effectiveness of infliximab and ciclosporin in a head-to-head clinical trial. Instead, Markovian economic models have created hypothetical cohorts of patients with acute UC resistant to steroids to assess the cost-effectiveness of infliximab compared with ciclosporin and surgery. 50,51 These models used published evidence6,8,10,52 to extrapolate the costs and effects in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained by each drug. Although these models conclude that infliximab is a cost-effective treatment in comparison with ciclosporin and surgery, we need to interpret this claim with caution. Theoretical models cannot capture all aspects of disease progression and their costs; and require assumptions to replace unavailable primary data. Furthermore, they excluded patient mortality and side effects while assuming that infliximab had a better side effect profile and mortality rate than both ciclosporin and surgery. Therefore, direct comparison of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of infliximab and ciclosporin in patients with acute UC is essential.

In summary, infliximab and ciclosporin are often effective in the short term, but there is little long-term evidence about their relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The Evidence Review Group report commissioned by NICE concluded: ‘The results consistently indicate that the move from standard care to ciclosporin is highly cost-effective’. 53 Thus the policy issue is clear: should the NHS make a further move from ciclosporin to infliximab?

Hence we designed Comparison Of iNfliximab and ciclosporin in STeroid Resistant Ulcerative Colitis: pragmatic randomised Trial and economic evaluation (CONSTRUCT) to achieve a rigorous, comprehensive, long-term comparison of these drugs. In particular, during the trial we enhanced measurement of QoL and costs in four ways:

-

extending data collection for all trial participants, whenever recruited, until 28 February 2014

-

adding questionnaires at 18, 30 and 36 months to those at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months

-

adding four questionnaires following colectomy and any ensuing corrective surgery

-

planning to use the techniques of survival analysis and statistical imputation of missing values to impute costs and QoL for all CONSTRUCT participants who generate data on survival, colectomy or QoL after randomisation.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this trial was to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of infliximab and ciclosporin for patients with steroid-resistant UC over a period of up to 3 years.

Specific objectives were to:

-

compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after these two treatments

-

compare mortality, morbidity and disease activity between treatments

-

compare colectomy rates between treatments

-

compare cost-effectiveness of treatments in cost per QALY

-

investigate the views of patients about their health and treatments

-

investigate the views of health-care professionals about the treatments and their ease of administration.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

We conducted an open-label parallel-group, pragmatic randomised trial using mixed methods: quantitative (including health economics and routinely collected data) and qualitative. 54

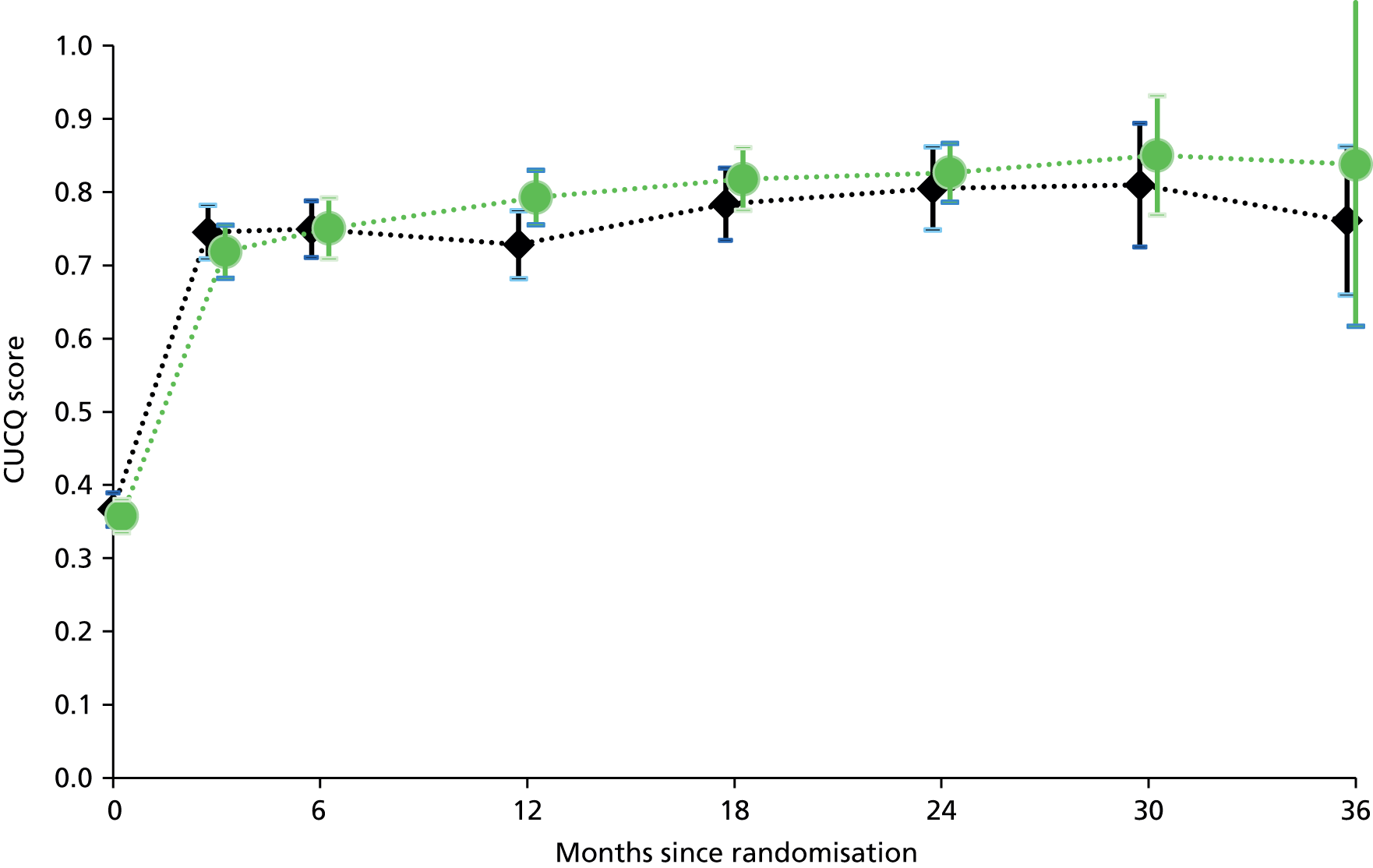

Our primary outcome measure was quality-adjusted survival (QAS)55 weighted by participants’ scores on the Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Questionnaire (CUCQ), our extension of the validated UK-IBDQ to include severe colitis and post-colectomy states. Secondary outcomes included two generic measures of QoL [European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)], emergency and planned colectomy rates, AEs and mortality.

We assessed the relative cost-effectiveness of the trial drugs through cost–utility analysis from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services, as recommended by NICE. 56 These analyses assessed differences between groups in total costs and QALYs.

Our qualitative studies aimed to enrich our quantitative results by exploring participants’ experiences of UC and the trial drugs, and their priorities for health and well-being. We also explored health-care professionals’ preferences between the trial drugs and their administration.

We used the Method for Aggregating The Reporting of Interventions in Complex Studies (MATRICS), which we had previously developed in another complex study, to integrate and compare the findings from the mixed methods used in CONSTRUCT. 57 We classified our outcomes into effects on participants; effects on gastroenterological services and professionals; and effects on the rest of the NHS and society. Using the MATRICS template, we combined all comparable findings into summary statements and highlighted where different methods resulted in inconsistent statements.

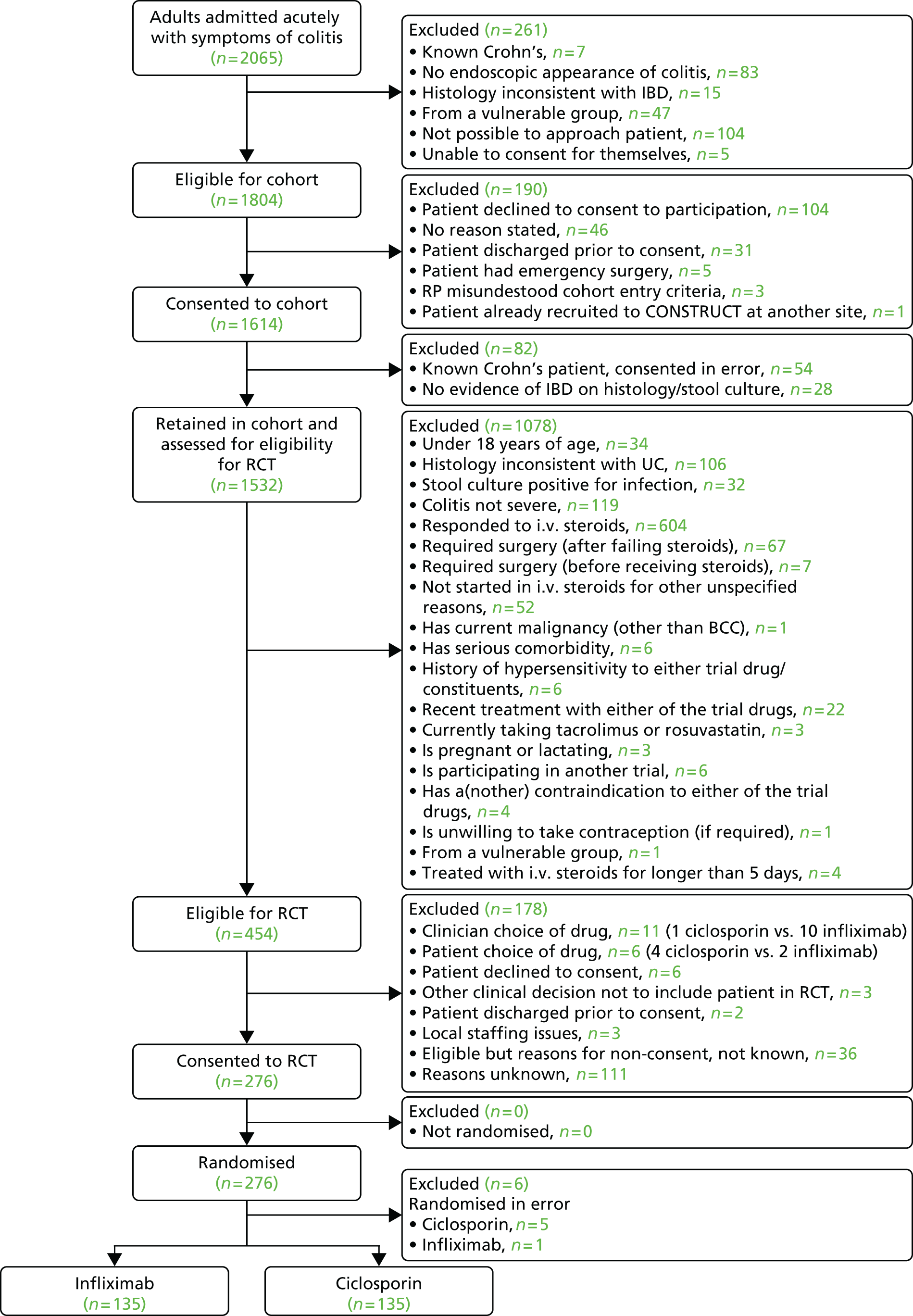

As we expected difficulty in recruiting acutely ill patients in hospital and completing their baseline data, we created a comprehensive cohort. We invited patients with known or suspected UC to join this cohort soon after admission. We explained that, if they had UC and did not respond to intravenous steroids, they might need other drug treatment; so, if they were suitable, we would invite them to further treatment as part of a clinical trial. To increase the chance of recruiting them, we collected their baseline data as soon as possible after they had consented.

From May 2010 until the end of February 2013 we recruited from the cohort to the trial those participants with UC who failed to respond to intravenous steroids over about 2–5 days, but did not then need surgery. After full written and oral explanation we invited participants who fulfilled the trial inclusion and exclusion criteria to consent to randomisation between infliximab and ciclosporin. Placebo controls would have been unethical, as these severely ill patients need treatment, as the NICE Evidence Review Group recognised. 53

We shall supplement our designed research data with routinely collected data held by the Health & Social Care Information Centre in England, the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage database in Wales, or the Health Informatics Centre in Scotland. As these data are not yet available for the full period of the trial, we shall analyse and report them in due course. We have consent from participants in both cohort and trial to access their routine data for 10 years from recruitment, and from trial participants to send them questionnaires over that period.

Recruitment

Trial sites

Via the British Society of Gastroenterology we asked consultant gastroenterologists to express interest in taking part in the study and to complete a questionnaire. We considered sites that had treated four or more patients with steroid-resistant UC in the previous 12 months to be eligible and invited them to seek local approval. As a result we initiated the trial in 67 NHS trusts or health boards, covering both teaching and district general hospitals in England, Scotland and Wales. We phased the initiation of these sites, reflecting the time needed to gain local research and development (R&D) approval.

Participants in cohort and trial

The target population for the cohort were inpatients with ASC, known or suspected, who were potentially eligible for the trial. The target population for the trial were cohort members who failed to respond to a course of about 2–5 days of intravenous steroid medication, but did not then need surgery. We invited eligible patients into the cohort as soon as feasible and into the trial once the clinical team had confirmed steroid resistance. The treatment of patients who did not consent to cohort or trial did not change in any way.

Participants in qualitative study

We used purposive quota sampling to identify 12 representative consenting participants from each arm of the trial for interview on two occasions (see Appendix 1). To include participants from sites starting later in the trial pro rata, we maintained a list of eligible participants.

We also interviewed principal investigators (PIs) and nurses responsible for administering and monitoring the drugs across the trial sites. We included both professions to explore drug administration, physical effects of both drugs on patients, personal preferences and their participation in CONSTRUCT. We used purposive sampling to recruit 12 PIs from three strata: sites that recruited well to cohort and trial; sites that recruited well to cohort but less well to trial; and sites that recruited poorly to both cohort and trial. However, we recruited all eight nurses from good recruiting sites as others would have little relevant experience of the trial drugs.

Informed consent

Patients eligible for the cohort received cohort participant information sheets (see Appendix 2) and oral explanation from consultant gastroenterologists or research professionals (usually research nurses); in response, patients gave written consent by signing and dating a cohort consent form (see Appendix 3). Cohort participants who became eligible for the trial received the patient information sheet (RCT) (see Appendix 4), and gave written consent by signing and dating a trial consent form (see Appendix 5). For both cohort and trial, those taking consent countersigned and dated the form to confirm that the participant had fully understood the nature of the study and had an opportunity to ask questions; they also put a copy of that consent in the participant’s medical record and gave another copy to the participant.

Research professionals could take consent to the cohort if authorised to do so on the site delegation log following appropriate training, including in good clinical practice (GCP). Although they could also explain the trial to cohort patients, responsibility for countersigning lay with the site PI or another doctor with delegated authority on the site delegation log. The trial consent form included consent to take part in qualitative interviews.

Withdrawal

The procedure for consenting participants stressed that they could withdraw from the cohort or trial whenever they wished without giving a reason and without affecting their care in any way. However, we documented any reasons given. Participants could stipulate the level of withdrawal: from the allocated treatment, from completion of further participant questionnaires, from consent to the use of any of their routine, or from any combination of these. We also encouraged site staff to trace participants lost to follow-up and document reasons when possible.

Between randomisation and the end of the trial, there were decisions to change allocated treatments, but these did not require withdrawal from this pragmatic trial. These included failure to respond to treatment with infliximab or ciclosporin, usually leading to surgical intervention.

Trial inclusion criteria

Patients admitted as emergency admissions with severe colitis (according to Truelove and Witts,4 a Mayo score of at least 2 on endoscopic finding or clinical judgement) who fail to respond to about 2–5 days of intravenous hydrocortisone therapy, who also had either:

-

histological diagnosis of UC in this episode

-

histological diagnosis of indeterminate colitis in this episode when clinical judgement (based on macroscopic appearance, disease distribution or previous history) suggested a diagnosis of UC rather than Crohn’s disease

-

symptoms typical of UC awaiting histology; or

-

history of UC confirmed histologically.

Trial exclusion criteria

-

Aged < 18 years of age on admission.

-

Histological diagnosis before randomisation inconsistent with UC.

-

Enteric infection confirmed before randomisation by stool microscopy, culture or histology (including Salmonella, Shigella, Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter and cytomegalovirus).

-

Vulnerable patient.

-

Unable to consent.

-

Positive pregnancy test or current lactation.

-

Woman of childbearing potential unwilling to use contraception during and for 6 months after treatment with infliximab in accordance with the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC).

-

Current malignancy, except basal cell carcinoma.

-

Serious comorbidity, including immunodeficiency, myocardial infarction within last month, moderate or severe heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV), acute stroke within last month, respiratory failure, renal failure, hepatic failure and active or suspected tuberculosis.

-

Other severe infections including sepsis, abscesses and opportunistic infections.

-

History of hypersensitivity to infliximab, ciclosporin or polyethoxylated oils (notably Sandimmun Concentrate for Solution for Infusion).

-

Current use of tacrolimus or rosuvastatin.

-

English not good in absence of local translator.

-

Need for emergency colectomy without further medical treatment.

-

Currently taking part in another clinical trial.

-

Treatment with either infliximab or ciclosporin in the 3 months before admission.

-

Any other contraindication to treatment with infliximab or ciclosporin.

Sample size and power

Our original target analysable sample size was 360 participants, based on a primary outcome of a change in HRQoL over 2 years. 54 However, in 2012 slower recruitment than predicted led us to seek agreement from the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to revise the primary outcome and reduce the analysable sample size to 250. We also proposed to analyse the area under the curve (AUC) of scores on the CUCQ collected every 6 months up to 3 years from randomisation; and to include participants who had undergone colectomy by developing and validating a post-colectomy extension to the CUCQ, which we termed the Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Questionnaire with post-colectomy extension (CUCQ+).

The changes required statistical imputation to exploit the resulting data set. As these techniques are difficult to incorporate into power calculations, we used a simpler calculation based on t-tests of mean CUCQ scores at 12 months. To detect an effect size of 0.35 in these scores with 80% power when using a 5% significance level, required that we analyse at least 250 trial participants. We used the techniques of statistical imputation applied successfully by the Cancer of the Oesophagous or Gastricus: New Assessment of the Technology of Endosonography58 and Folate Augmentation of Treatment – Evaluation of Depression (FolATED)59 trials to achieve an effective sample size of 250 for CONSTRUCT.

Randomisation

We allocated at random between infliximab or ciclosporin all participants who completed baseline assessment, met the trial inclusion criteria and gave informed consent. We used a password-protected website that accessed an adaptive algorithm to protect against subversion while ensuring that each trial arm was balanced by centre. 60 To validate each request for randomisation, the website asked:

-

for the participant’s trial number, and month and year of birth

-

for the name of person requesting randomisation (limited to those trained and authorised)

-

if consent had been given

-

if the participant had met the inclusion criteria

-

if the participant had none of the exclusion criteria

-

if the baseline questionnaire been completed.

If the responses to all four questions were ‘yes’, the website gave the name of the drug allocated to the participant and immediately confirmed the trial number and drug by e-mail, and recorded those on the randomisation database.

Hospital pharmacies at trial sites held the trial drugs. After each randomisation, the research staff confirmed study number and drug by fax to the relevant pharmacy who labelled the drug with the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials number, sponsor, participant’s trial number, name and address of supplier, dose and ‘For Clinical Trial Use Only’.

Blinding

As this was an open trial, there was no need for procedures to inform sites about allocated treatments. However, the chief investigator, trial methodologist, outcomes specialist, health economists and statisticians remained blind to them until the TSC and DMEC had reviewed and approved the analysis of the primary outcome.

Interventions

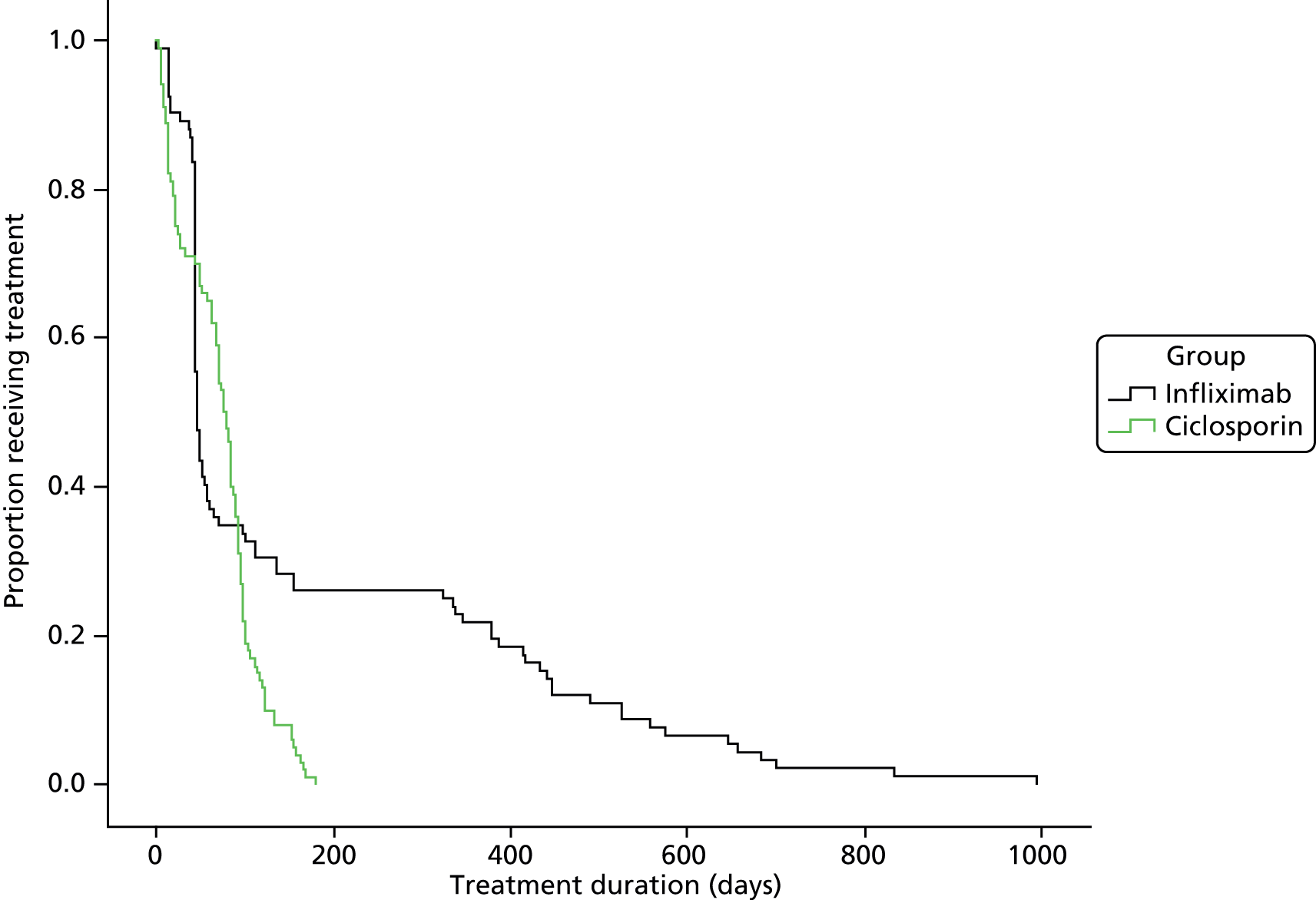

Participants randomised to infliximab received it as Remicade in 5-mg/kg intravenous infusions over 2 hours – forthwith, and at 2 and 6 weeks after the first infusion – in accordance with local prescribing guidelines.

Participants randomised to ciclosporin received it as Sandimmun by continuous infusion of 2 mg/kg/day. We asked sites to change the infusion every 6 hours, using non-polyvinyl chloride (PVC) bags and administration sets. Intravenous treatment continued for up to 7 days if successful. They switched participants responding to ciclosporin to twice-daily oral doses delivering 5.5 mg/kg/day, and adjusted doses to achieve trough ciclosporin concentration of 100–200 ng/ml. They measured whole-blood ciclosporin levels according to local practice, ideally 48 hours after oral therapy and then every 2 weeks. After 12 weeks, treatment was at the discretion of the participant’s consultant.

We asked centres to consult the SPC for Remicade or Sandimmun and oral ciclosporin (all available online) at the time of first prescription.

For both treatments we gave centres discretion to start azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine at therapeutic doses in week 4. We asked them to eliminate steroids by week 12 in participants who remained well, but to reinstate them in participants who became symptomatic. We also asked centres to give co-trimoxazole as prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly carinii) pneumonia in both groups.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the AUC of CUCQ scores. This is equivalent to QAS weighted by scores on the disease-specific CUCQ. We concurrently validated the CUCQ, which extends the validated UK-IBDQ61 to cover acute illness and colectomy.

Secondary outcomes

-

(a) Disease-specific QoL, measured by the CUCQ.

-

(b) and (c) Generic QoL, measured by the SF-12. 62

-

(d) Mortality.

-

(e) Colectomies, both emergency and planned.

-

(f) AEs.

-

(g) Readmissions, including those for causes other than UC.

-

(h) Malignancies.

-

(i) Serious infections.

-

(j) Renal disorders.

-

(k) Disease activity, using the criteria proposed by Truelove and Witts. 4

Economic outcomes

-

(l) NHS costs.

-

(m) HRQoL, measured by EQ-5D. 63

-

(n) Participants’ time off work.

Qualitative outcomes

-

(o) Participants’ views of their drugs and their consequences.

-

(p) Professional views of both drugs and their consequences.

Adverse events

Definitions

The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004: SI 2004/1031 describe thus:64

-

AE: any untoward medical occurrence in a subject to whom a medicinal product has been administered, including occurrences which are not necessarily caused by, or related to, that product.

-

AR: any untoward and unintended response to a medicinal product which is related to any dose administered to the subject.

-

Unexpected adverse reaction: an adverse reaction, the nature and severity of which is not consistent with the information in the SPC for the medicinal product.

-

SAE or serious adverse reaction (SAR) or suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR): any AE, adverse reaction or unexpected adverse reaction, respectively, that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; or

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

-

Causality

Causality is the degree to which an untoward medical occurrence can be attributed to the trial intervention rather than the underlying UC. We used the subjective scale: unrelated, unlikely to be related, possibly related, probably related or definitely related. We classed only the last three as ARs or SARs having a causal relationship. However, we did not class events caused by UC, notably worsening colitis or initial steroid resistance, as ARs. We reported SARs to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) annually.

Expectedness

We considered AEs, ARs, SAEs and SARs as ‘unexpected’ if their nature and severity was not consistent with the relevant SPC. Expected events included:

-

progression or exacerbation of the participant’s underlying UC, including clinical sequelae of progression, such as worsening diarrhoea or abdominal pain

-

medical or surgical procedures including surgery and endoscopy; however, we considered events that led to procedures and surgical sequelae, such as pleural effusion or small bowel obstruction, separately

-

conditions or symptoms present or detected before the first dose that did not worsen

-

recognised undesirable effects found in the current SPCs for Remicade, Sandimmun or Neoral; as SPCs updated regularly during the trial, we recommended that PIs consult the versions online.

Monitoring adverse events

In view of the extensive side effects of both trial drugs documented in their SPCs, and the many sequelae of disease progression, the protocol stipulated that we did not require expedited reporting of serious events from sites, unless they were unexpected, in which case we asked for notification within 24 hours.

We designed adverse event screening forms (AESFs) to enable local PIs to assess seriousness, causality and expectedness in a logical sequence (see Appendix 6). Sites sent AESFs, once countersigned by local PI or authorised person, securely via FaxPress to the trial office. The CONSTRUCT data manager was responsible for initial screening of AESFs, paying particular attention to completeness, raising queries with the local team and immediately notifying the chief investigator of events that might be classified as SUSARs. If uncertain, the chief investigator discussed them with the local PI before the final decision. We entered screened AESFs onto our Generic Clinical Information System (GeneCIS; version 10i, Swansea University, Swansea) and regularly checked that they were consistent with data on colectomies reported through case report forms (CRFs). Clinicians within the trial team reviewed the accumulating data on AEs, and commented on GeneCIS, if necessary after discussion with the local team.

At the end of the study, two clinicians in the trial team reviewed all SAEs to ensure consistency of interpretation in the final report, informed by data from sites on the duration of use of the drugs beyond the 3-month intervention period specified in the protocol. Once that period was complete, clinical management varied from participant to participant according to their progress and the clinical judgement of the local team. The reviewers also took the different pharmacokinetic profiles of the trial drugs into account because the bio-availability of ciclosporin is short-lived, whereas bio-availability of infliximab can persist until 6 months after the last infusion. With the exception of malignancy, therefore, we judged relatedness unlikely if the event occurred more than 1 month after ciclosporin, or more than 6 months after infliximab.

Problems caused by UC and the trial drugs may coincide in a single event. When an AESF documented a serious event, usually admission, and included more than one problem (e.g. abnormal liver and renal function tests), we used clinical judgement to decide which related to the drug and which was the prime cause of admission, and classified SAEs and reactions by body system.

Data collection

Baseline and follow-up data

At recruitment to cohort, we collected:

-

sociodemographic details: age, sex, ethnic group and truncated post codes, used to generate measures of social deprivation (Indices of Multiple Deprivation for England, Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, Carstairs Deprivation Scores for Scotland and Townsend scores for all three countries)

-

details of admission

-

disease history, including presenting complaint, time since first diagnosis and previous treatment, including any previous surgery, or biologic or steroid therapies

-

comorbidities, in particular cardiorespiratory, liver or renal disease, diabetes mellitus or hypertension

-

UC signs and symptoms, including duration of symptoms in current episode, stool frequency, blood pressure, pulse and temperature

-

current treatment, including type, dose and duration of steroid therapy

-

pathology results, including full blood count, inflammatory markers, liver and renal function tests, and total cholesterol

-

site and extent of disease according to Montreal classification of IBD65

-

histopathology results, including stool culture and histological diagnosis

-

family history of IBD

-

height, weight and smoking status.

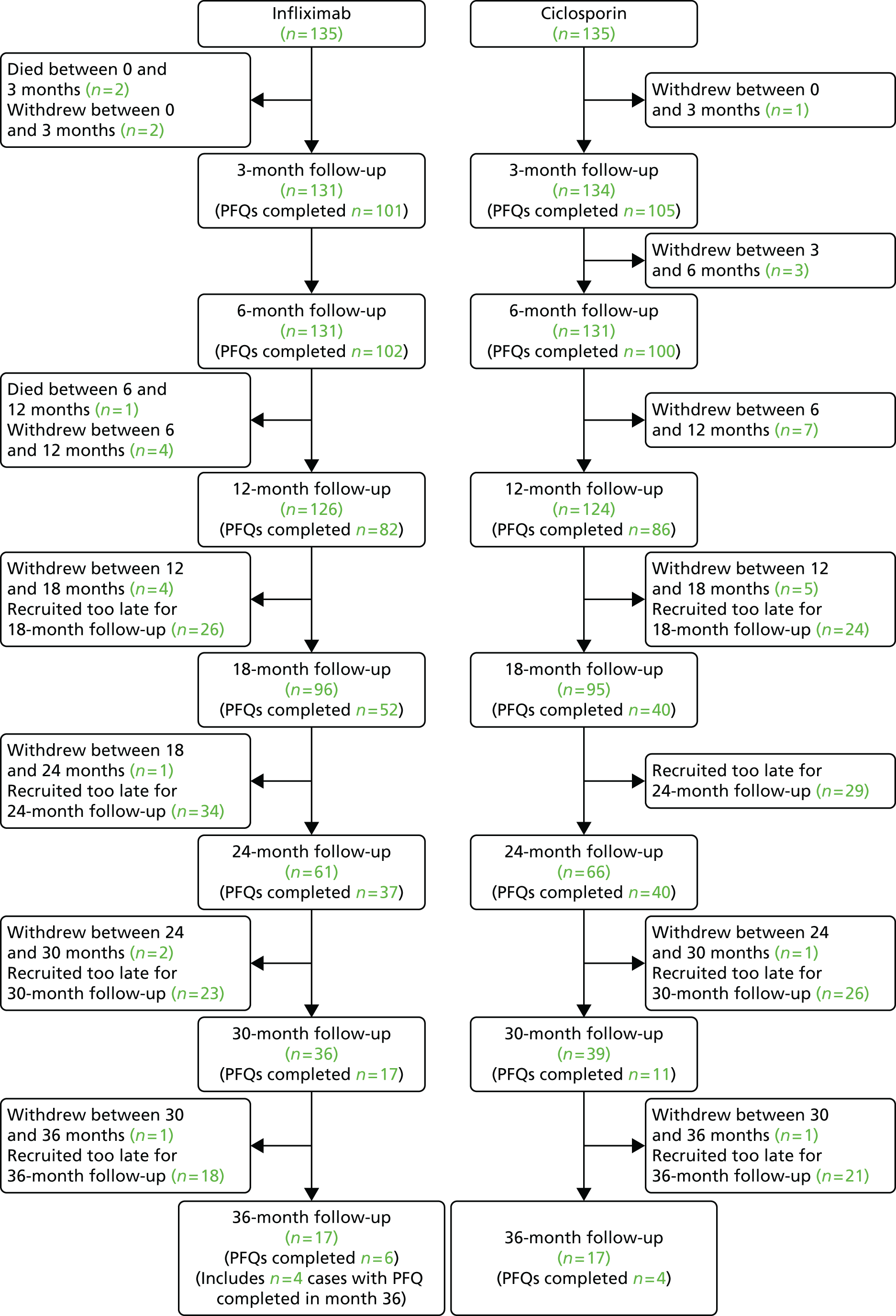

At 3 and 6 months after randomisation, and at 6-monthly intervals until 36 months, we collected clinical and resource-use data from participants’ records (see Appendix 7).

Process of data collection

Research staff at trial sites asked all trial participants to complete the Participant Baseline Questionnaire including the CUCQ, SF-12, EQ-5D and questions on primary care resource use (see Appendix 8); and the similar Participant Follow-up Questionnaire (PFQ) which also included questions about intercurrent events at 3, 6 and 12 months, and at 18, 24, 30 and 36 months if they reached these time points before March 2014 (see Appendix 9). Following admission a baseline CRF was completed by research staff to document demographic and clinical details (see Appendix 10).

We asked trial sites to arrange outpatient appointments to coincide with these times whenever compatible with routine clinical management. Local research staff posted PFQs to participants and asked them to bring completed questionnaires to clinics. Participants could either complete and return them by post or seek help at the clinic. We also asked sites to complete CRFs recording intercurrent events, secondary care resource use and drug treatment at these times, preferably at the outpatient appointments, or else from medical records (see Appendix 11).

The trial office sent Post-Colectomy Questionnaires (PCQs) and business reply envelopes to trial participants who underwent colectomy on discharge following surgery and at 4, 8 and 12 weeks thereafter (see Appendix 12). This PCQ included the CUCQ+, the post-colectomy version of the CUCQ and the EQ-5D.

Electronic data capture

We captured designed data on our existing GeneCIS, based on the Oracle(R) object-relational database management system (RDBMS version 10g, Oracle Corporation UK Ltd, Reading). The system is implemented in a three-tier architecture and remotely hosted in a professionally managed, secure environment. With support from local information technology departments, we provided access to hospital sites over the NHS N3 network.

We customised GeneCIS to support the trial following a detailed evaluation of requirements, including process mapping. The resulting electronic data capture structure reflected trial data requirements organised in a clinically logical manner. GeneCIS includes data validity controls, including predefined pick lists, and format and range constraints. We provided contextual guidance as help text and used system alerts to warn users when specific combinations of entered data affected eligibility, the potential for AEs or other important items.

Sites could choose either to enter data collection forms into GeneCIS locally or send completed forms by secure FaxPress to the trial office. Sixteen sites used local data entry; the rest faxed paper forms. The basic system and user interface were identical at sites and the trial office.

Data management and record keeping

All data acquisition, storage, transmission and use complied with the Data Protection Act. 66 The trial office recorded forms received on a bespoke Microsoft Access® 2007 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for tracking paperwork, and stored all forms in locked cabinets within a secure office with controlled access. We backed up GeneCIS and Access databases every day.

All GeneCIS users had role-based access to the system, including trial staff engaged in system configuration, data entry, helpdesk support or quality assurance. Those with authorised access to identifiable data did not contribute to analysis. Qualitative researchers had access to identifiable data to contact participants, but not to their clinical data. Trial sites had access only to identifiable data for their participants and could not view any other records.

We extracted data for analysis in pseudonymised form identified by participants’ trial numbers.

Data quality and information governance

We asked PIs to maintain site delegation logs authorising staff to perform defined tasks, to sign off any changes and to send them to the trial manager. When we updated trial documents including CRFs, we circulated new versions to sites with appropriate instructions. Sites replaced previous versions but retained them in trial site files.

We asked those making essential changes to data collected on paper to strike the original entry only once, insert the new data, and record the date and initials of the person responsible. GeneCIS maintained an electronic audit trail by annotating all data with the user, date and time of entry. It also checked data at entry, notably for correct format and within specified ranges. We subjected the resulting data to rigorous quality assurance, compared all anomalies with the paper source documents and consulted local staff when necessary.

We transcribed and reviewed interview data as soon as possible. We analysed the final transcripts without identifying patient, professional or hospital.

Routine data

Funded research data collection continued until March 2014. We plan to supplement the designed baseline data collected from cohort and trial participants with routinely collected data, including Hospital Episode Statistics (and the equivalent in Wales and Scotland), and mortality from the Office for National Statistics. We plan to continue follow-up for up to 10 years by linking routine mortality, inpatient and primary care data. Record linkage will use the existing facilities of the Farr Institute at Swansea University Medical School. Using these information sources, we plan to monitor all participants’ long-term outcomes, notably mortality, colectomies both emergency and elective, and major morbidity including hospitalisation and surgery, and thus most of their NHS costs. Hence we aim to achieve long-term follow-up of both trial participants and a large comprehensive cohort of patients with UC.

Qualitative methods

Trial participant interviews

To understand trial participants’ experiences and perceptions of treatment by infliximab, ciclosporin and surgery, we conducted telephone interviews at about 3 and 12 months after recruitment. We aimed to investigate their priorities for their health and well-being, and their perceptions of taking the drugs, side effects and response to treatment.

We first sought consent to interview when recruiting participants to the CONSTRUCT cohort. We sampled interviewees from those subsequently recruited to the trial. Hence they had all been admitted with ASC and received either infliximab or ciclosporin. We contacted those sampled following their first outpatient appointment after discharge, invited them to take part and arranged convenient 1-hour slots to enable them to talk freely without feeling rushed. As more than 50 trial sites across the UK contributed participants, interviews by telephone to participants’ homes enabled us to cover the trial population, minimise cost and ensure confidentiality.

Trained qualitative researchers used a semistructured approach to guide participants through the interview questions and give them the opportunity to develop their responses and raise issues that were important to them. The opening questions of the first interview schedule encouraged participants to think and talk about their health, what was important about it, and what good and bad health meant to them (see Appendix 13). More specific questions followed about their experiences of treatment, drug regimes and health care, and about their outcomes. We soon recognised that some participants had already required surgery for their colitis. We therefore adapted the interview schedule to capture the views of these participants (see Appendix 14).

At the end of each of these initial interviews, we asked participants to take part in a second interview about 12 months later to explore their subsequent experiences. For those, we used similar interview schedules but added questions, notably to explore changes in their health, in their opinions of treatment and in their interactions with health-care professionals (see Appendix 15). Again, we arranged convenient 1-hour slots for telephone interviews.

Health-care professional interviews

These aimed to gain insight into professional preferences between the two drugs and their personal contribution to the trial. Our specific objectives were to explore their views about:

-

administration of the two drugs, including ease of handling

-

effects of the drugs on health-care provision

-

personal preferences between the drugs

-

drug regulation and current policy

-

surgery for UC

-

equipoise in recruiting to the trial.

We therefore planned semistructured interviews lasting 30–40 minutes with flexibility for interviewees to expand on important issues and access their broad knowledge base. Our schedule covered interviewees’ beliefs and ways of working; aspects of drug provision that may affect preferences; their interaction with patients and others; and their contribution to the trial (see Appendices 16 and 17). We offered interviews face to face or over the telephone. We conducted separate interviews with consultants and nurses to provide a richer understanding of differences between professional groups. With participants’ consent we recorded and transcribed interviews for analysis.

Definition and validation of outcome measures

Background

We are entirely committed to the philosophy, expounded by NICE and implemented by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), that the ultimate criteria for interventions in health care are clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in improving the survival and QoL of patients over extended periods. Although we admire how the GETAID investigators implemented the CySIF trial with little funding, they recruited only 110 patients, followed them for only 98 days and reported only on ‘treatment failures’. This is not a good basis for NHS investment decisions worth hundreds of millions of pounds. Instead we chose QAS as our primary outcome and recruited enough participants to yield the power to discriminate between two contrasting drugs. That still left us with the task of developing and validating a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) applicable across the broad spectrum of disease severity within UC.

There are several disease-specific QoL measures for patients with IBD. 18,67–71 The most widely used is the McMaster Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire. 18,67,68,72,73 As it had not been validated for the UK, we previously conducted a development and validation study to anglicise it as the UK-IBDQ. 61 As this was a community study, however, we recognised in designing CONSTRUCT within acute care that, to avoid ceiling effects, we had to modify the UK-IBDQ by extending the range of responses for all items to include more severe replies; the number of items to include more questions addressing severe symptoms; and the frequency of administration in participants undergoing surgery. Furthermore, the UK-IBDQ has no questions about the impact on QoL of colectomy, which reportedly happens to 9–21% of those with UC. 74–76 We therefore derived from the UK-IBDQ a PROM for patients suffering from moderate to severe symptoms of Crohn’s or UC with or without stoma. We called this the CUCQ in its basic form, and the CUCQ plus stoma extension (CUCQ+) in its extended form. Preliminary validation of the CUCQ confirmed that it met essential psychometric criteria,77 with the result that the national IBD registry adopted it. Although we developed the CUCQ as a tool for both conditions, we validated it only on UC patients. As the development and concurrent validation of CUCQ and CUCQ+ underpin the primary analysis of CONSTRUCT, we now describe that validation.

Methods

We used the standard psychometric approach outlined by Streiner and Norman78 to develop and validate the CUCQ and CUCQ+ in three stages:

-

item generation

-

initial development in the CONSTRUCT cohort

-

definitive validation in the CONSTRUCT trial sample.

We used the 32 UK-IBDQ items [see Appendix 8, Section A: Crohn’s and Colitis Questionnaire (CCQ)], as the basis for developing the CUCQ and CUCQ+. We also reviewed the literature on PROMs in gastroenterology to identify additional items. After drafting the CUCQ and CUCQ+, we recruited an expert panel of gastroenterologists, outcome specialists, statisticians and patients to review the resulting questions and response options, and ensure they were appropriate for UC patients.

We piloted the draft questionnaires on a sample of 20 UC patients with or without stoma from Neath Port Talbot Hospital, Port Talbot, who were not participating in CONSTRUCT. We asked them to complete CUCQ or CUCQ+ as appropriate and added four supplementary questions:

-

Did you find any of the questions difficult to understand?

-

Was there any question you did not want to answer?

-

Was there any aspect of your bowel condition not covered by these questions?

-

Did you find any of these questions not applicable to you?

For our initial validation, we used patients recruited to the CONSTRUCT cohort but not the trial, who had therefore completed the CUCQ at baseline. Of the 32 CUCQ questions (see Appendix 18), six were not relevant to post-colectomy participants:

-

Q1: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you had loose or runny bowel movements?

-

Q2: On how many days in the last 2 weeks have you noticed blood in your stools?

-

Q6: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you opened your bowels more than three times a day?

-

Q9: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have your bowels opened accidentally?

-

Q24: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you wanted to go back to the toilet after you thought you had emptied your bowels?

-

Q26: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you had to rush to the toilet?

We therefore designed the CUCQ+ (see Appendix 9, For patients with stoma), with 10 stoma-specific questions replacing these six questions, making a total of 36 questions.

-

S1: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you been afraid that other people might hear your stoma?

-

S2: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you been worried that other people might smell your stools?

-

S3: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you been worried about possible leakage from your stoma bag?

-

S4: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you had problems with care for your stoma?

-

S5: On how many days over the last 2 weeks have you found the skin around your stoma irritated?

-

S6: In the last 2 weeks have you felt embarrassed because of your stoma?

-

S7: In the last 2 weeks have you felt less complete because of your stoma?

-

S8: In the last 2 weeks have you felt less attractive as a result of your stoma?

-

S9: In the last 2 weeks have you felt less feminine/masculine as a result of your stoma?

-

S10: In the last 2 weeks have you been dissatisfied with your body as a result of your stoma?

To calculate scores for participants who had not undergone surgery, we used the 32 CUCQ questions. For post-colectomy participants, we used the 10 stoma-specific questions and the 26 stoma-relevant CUCQ questions to calculate CUCQ+ scores. In analysing and validating both CUCQ and CUCQ+, we calculated scores as follows:

-

We scored questions with four responses as 0, 1, 2 or 3 in ascending severity.

-

We scored questions with responses between 0 and 14 days as the actual value.

-

We reversed the scoring of questions with wording in the reverse direction (Q7, Q22 and Q32) to code all questions in the same direction.

-

We rescaled questions between 0 and 1 by dividing actual responses by their maximum score (3 or 14).

-

We calculated CUCQ scores for non-colectomy participants, and CUCQ+ scores for post-colectomy participants, by summing all valid responses and dividing by the number of completed questions.

-

So the lower the CUCQ+ (or CUCQ score), the better the respondent’s health. In analysing the AUC, however, it is necessary to subtract the total CUCQ+ (or CUCQ) score from 1, so that higher scores show better health, consistent with both EQ-5D and SF-12.

However, we calculated CUCQ and CUCQ+ scores only when participants had responded to at least 75% of the questions – 24 out of 32 or 27 out of 36, respectively. If participants had completed fewer than 75% of questions, we treated the total CUCQ or CUCQ+ score as missing. To give equal weight to each question answered, our analysis plan used the original 32 CUCQ questions for non-colectomy participants and the 36 CUCQ+ questions for post-colectomy participants. To test the sensitivity of our findings to this simple approach, we repeated the analysis in two ways. First, we gave equal weight to core scores and stoma-specific scores, thus giving more weight to the latter. Second, we gave the stoma-specific scores 6 out of 26 of the weight given to core scores, as the original UK-IBDQ comprised 26 questions relevant to stomas and 6 questions inapplicable to stomas, thus giving less weight to stoma-specific scores.

Still following Streiner and Norman,78 we conducted initial psychometric development of the CUCQ on CONSTRUCT cohort patients (who had not had a colectomy):

-

We examined the 32 sets of response frequencies for floor or ceiling effects.

-

We calculated the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test to judge whether or not principal component analysis was appropriate.

-

We calculated Cronbach’s alpha (which should exceed 0.7 for good internal consistency).

-

We calculated item-total correlations for each question (which should exceed 0.2 for good homogeneity).

-

We undertook principal component analysis to assess the underlying structure; we considered factors important if their eigenvalues were clearly > 1, and individual questions as useful if their factor loadings exceeded 0.4.

-

We assessed the construct validity of the scale by examining the correlation between the CUCQ and two generic QoL questionnaires (EQ-5D and SF-12).

Then we undertook definitive validation of the CUCQ and CUCQ+ on the CONSTRUCT trial sample. First, we compared demographic characteristics of that sample with the cohort to ensure that they were similar. Then we analysed the trial sample in essentially the same psychometric way as the cohort, and tested whether or not the principal components arising from these two analyses were consistent. Finally, we repeated the principal component analysis of the trial sample after 12 months and tested whether or not principal components arising from the CUCQ for non-colectomy patients and those arising from the CUCQ+ for post-colectomy patients were consistent.

We also analysed reliability and responsiveness for the trial sample, initially combining CUCQ and CUCQ+ and then comparing them. We assessed test–retest reliability of the scales on participants who reported no change in their condition at successive assessments; we considered scales reproducible if intraclass correlation exceeded 0.75. We assessed responsiveness of the scales to change on participants who reported a change in their condition; we considered scales responsive if the responsiveness ratio exceeded 0.5.

Analysis

Clinical effectiveness

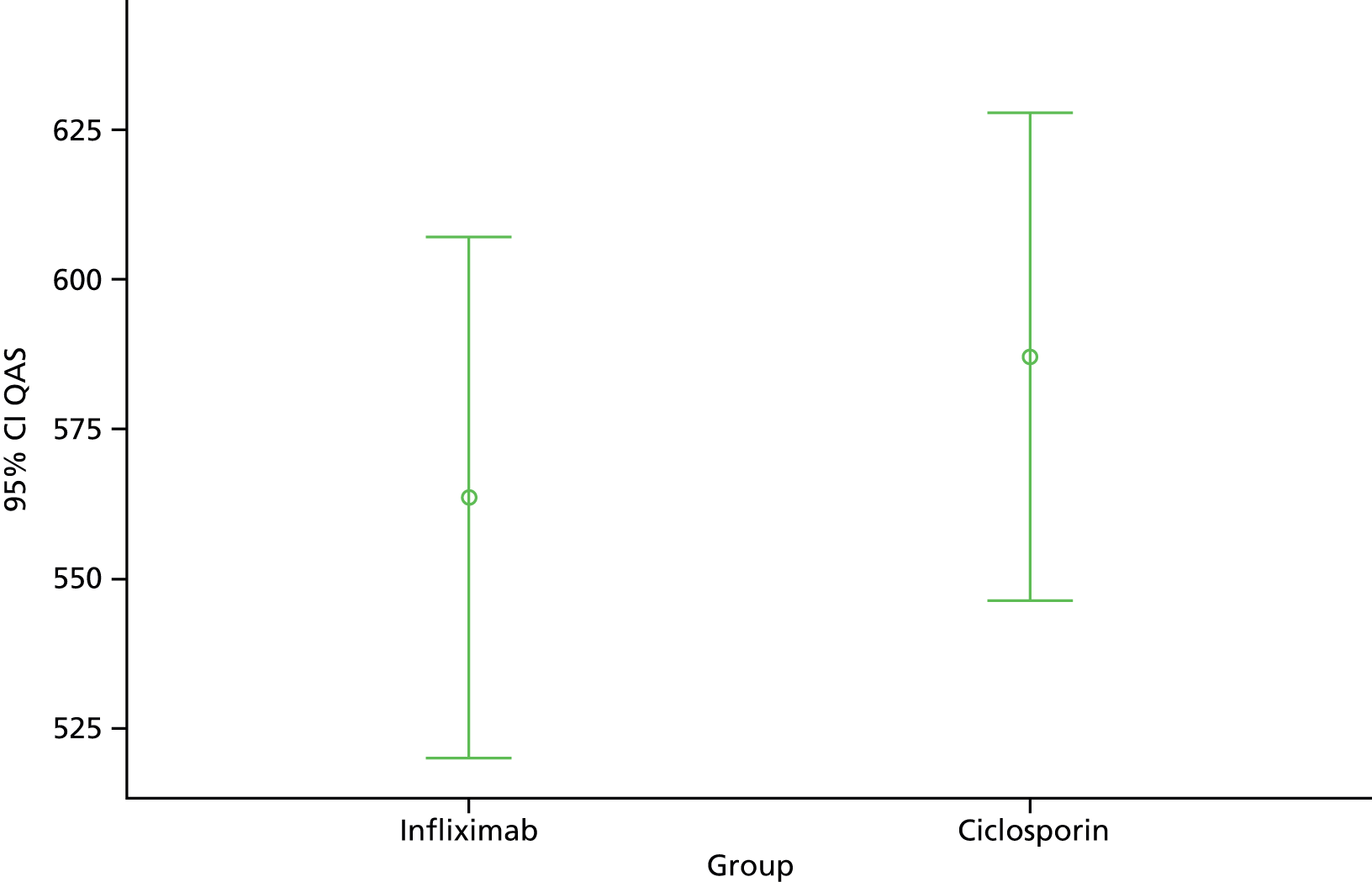

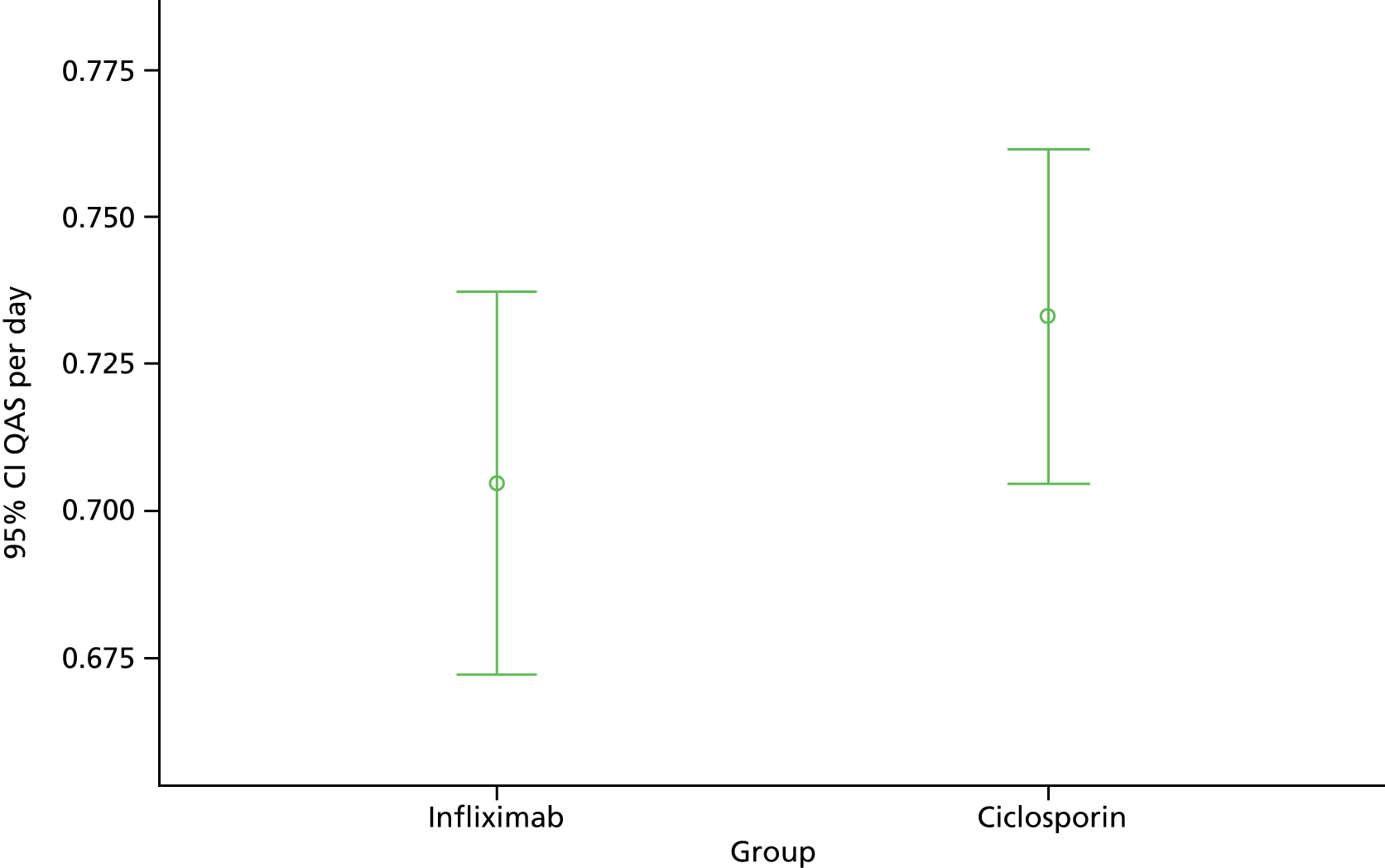

Primary analysis was by treatment allocated, reflecting the pragmatic nature of the trial design. Figure 1 illustrates the primary outcome measure – the AUC defined by CUCQ scores at baseline and all available time points before 31 March 2014 – also known as ‘QAS’. Within research into PROMs, there is a general convention that for generic PROMs ‘higher is better’ whereas for condition-specific PROMs ‘lower is better’. However, in order to be consistent with both EQ-5D and SF-12 we have subtracted calculated CUCQ scores from 1, so that higher is better.

FIGURE 1.

Primary outcome measure: area under the CUCQ curve.

We calculated this area by summing the areas of the component trapezia, thus assuming linearity between successive CUCQ scores, and setting the score at the end of follow-up equal to the last recorded score (last one carried forward). This method accommodates both missing values and extra values like those arising from PCQs.

The main analysis used a general linear model to estimate differences in QAS between groups, adjusting for covariates that may affect this measure, including trial site; data collected while assessing eligibility for cohort and trial, notably the sociodemographic variables age, gender, ethnic group, QoL, disease severity; current immunosuppressant therapy (using a binary indicator set equal to 1 for participants taking azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or methotrexate); and time in follow-up. We combined rare categories in factors like ethnic group, taking account only of observed numbers in each category and the coherence of new groupings.

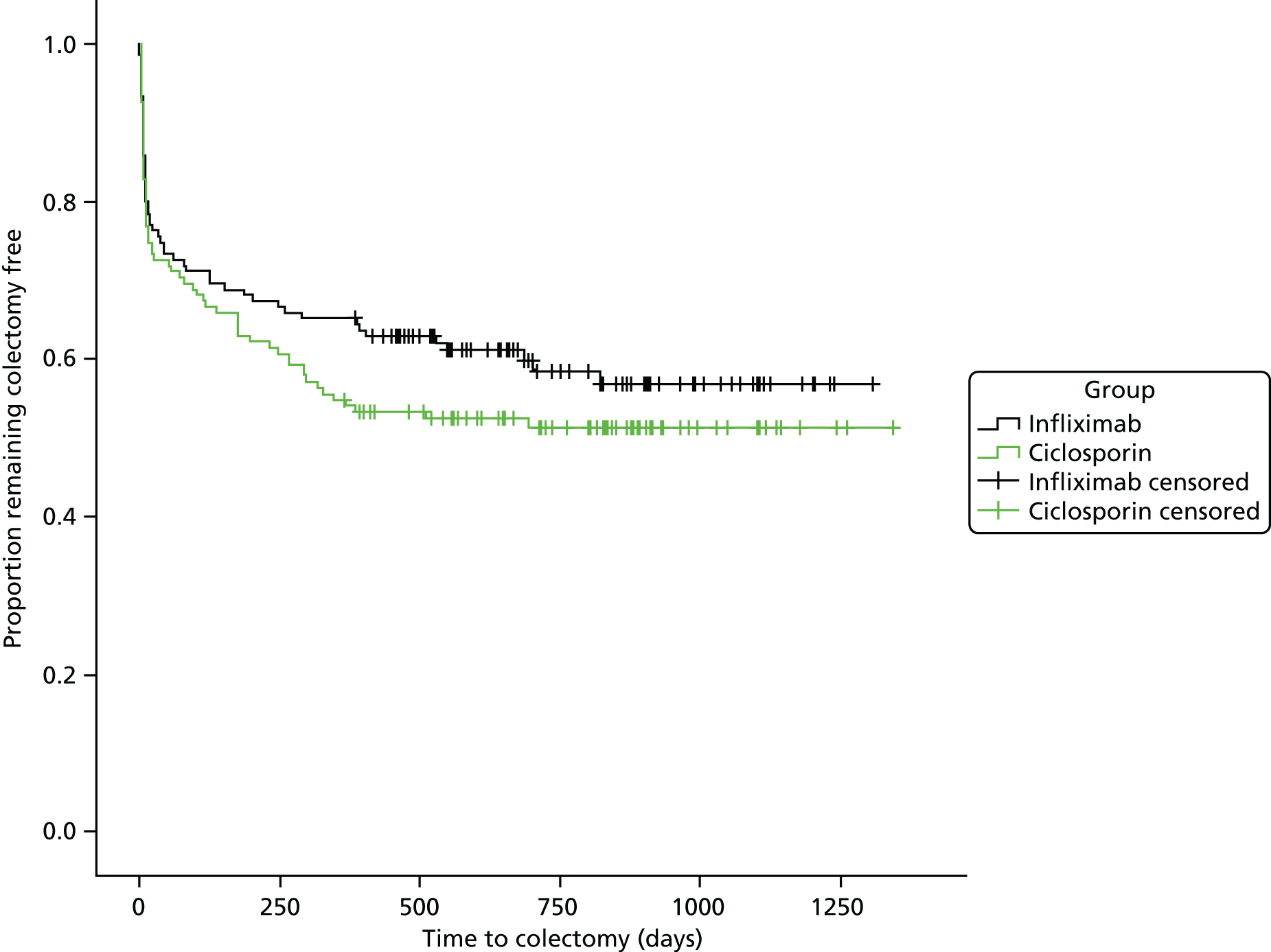

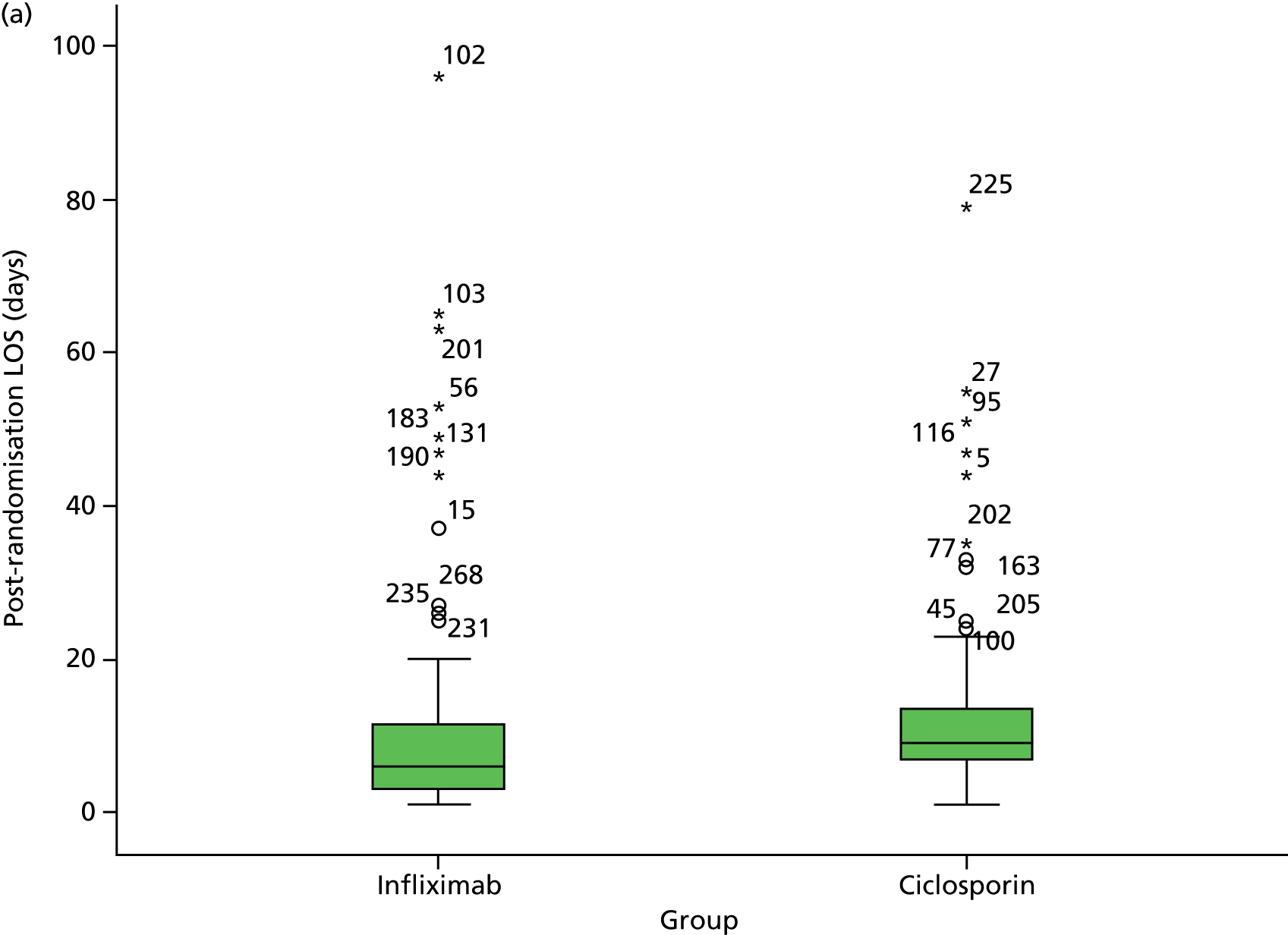

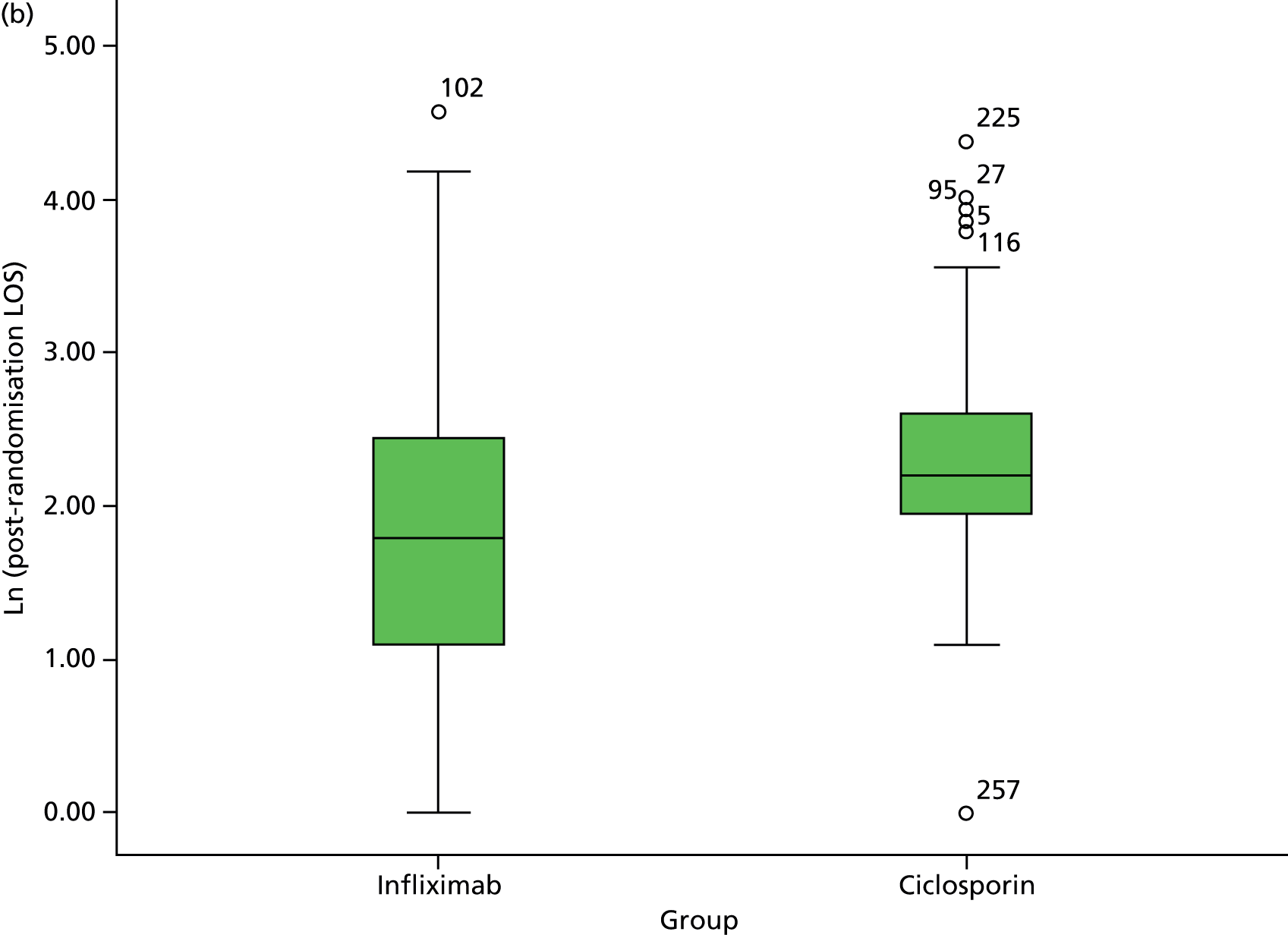

Secondary analyses adjusted for the same covariates as primary analysis and compared between groups: QAS per day (again using general linear models); QoL scores (using methods for repeated measures); proportion of participants undergoing colectomy (using binary logistic regression); time to colectomy (censored at the end of follow-up, and analysed by Cox regression); proportion of participants suffering one or more AEs (using binary logistic regression); and mortality.

We examined residual diagnostics in analyses that assume normality, with the options of data transformation and bootstrapping when residual distributions were markedly non-normal. We excluded identified outliers and reanalysed the revised data sets. We supplemented analyses by descriptive comparisons between groups in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, including estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), representing two-tailed tests at the 5% significance level.

Imputation of missing data

We used statistical imputation of censored and missing data to impute costs and QoL for all participants who generate data on survival, colectomy or QoL after randomisation. Thus we excluded participants without follow-up data, as calculation of QAS requires one or more CUCQ scores in follow-up.

None of the questionnaires has an official algorithm for imputing missing answers. So we imputed missing values within participant interviews using the Expectation Maximisation option in the Missing Value Analysis module within Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and calculated scores according to the instructions for the measure in question. When necessary we imputed missing scale and subscale scores by regression using the available values of that score at other times and the allocated treatment group. To avoid introducing outliers, we restricted imputed scores to the range observed for that measure in that group.

Cost-effectiveness

We collected data on NHS resource use from CRFs and PFQs completed at each follow-up time point, supplemented by data from other sources, notably, PCQs completed by patients undergoing colectomy, SAE forms and any relevant information provided by sites. Together CRFs covered resource use over the whole period during which participants were in the trial because each CRF recorded resource use since the previous CRF. To minimise recall bias, however, PFQs reported resource use over the previous 3 months. 79 This left gaps in the data, which we imputed. We estimated all costs in 2012–13 prices inflated when necessary using the NHS Pay and Prices Index. We applied a discount rate of 3.5% per annum to costs occurring beyond 12 months. We applied the same annual discount rate of 3.5% for QALYs beyond 12 months.

Participant Baseline Questionnaires recorded data on resource use in the 3 months before their consent for use as a covariate to account for any existing imbalances in resource use. As this resource use preceded randomisation, we did not include it in the costs analysed.

We based the cost of infusing ciclosporin (Sandimmun) on reported dose and duration in whole vials; and oral ciclosporin on reported dose and duration in whole dispensing packs (Table 2). We also added the cost of monitoring ciclosporin levels. We based the cost of infliximab (Remicade) on the reported dose in whole vials and, for infusions after the initial episode in hospital, we added the cost of admitting participants as day cases (£311).

| Drug | Dose | Unit cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Ciclosporin (Sandimmun) | 50 mg/ml, 1-ml ampoules | £1.94 |

| Oral ciclosporin | 100 mg, 30-capsule pack | |

| Neoral | £72.57 | |

| Deximune® (Dexcel Pharma Ltd) | £51.30 | |

| Capimune® (Mylan) | £51.30 | |

| Infliximab (Remicade) | 100-mg vial | £419.62 |

We also estimated the cost of preparing and delivering drug infusions from a questionnaire completed by 42 trial sites (81% of the 52 recruiting sites). For typical infusions they reported who mixes the infusion (nurse or pharmacist); the time taken to prepare the infusion; and the frequency of bag changes for ciclosporin participants. We multiplied by relevant unit costs:81 nurse £41 per hour; pharmacist £47 per hour; and £1.50 per infusion or bag change. For centres that did not respond to the questionnaire we imputed preparation and delivery costs by mean substitution.

Case report forms recorded data on hospital episodes, including the episode leading to recruitment. PFQs reported data on admissions to hospitals other than the trial site. To these we applied unit costs from either the 2012–13 Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) code FZ37 (non-elective episodes of inflamatory bowel disease without interventions, 19 years and over) or the HRG code FZ74 (non-elective episodes complex large intestine procedure, 19 years and over) and ‘complications and comorbidity’ (CC) codes based on participants’ length of stay in hospital (see Table 3). We costed days in hospital beyond the average for that HRG-CC at the published rate. For subsequent surgical procedures we used expert clinical opinion to identify the 2012–13 HRG code most appropriate to the information recorded as free text on the CRF, which often detailed specific procedures undertaken during each operation. Table 3 shows selected secondary procedures and their HRG codes, but not the many CC codes per HRG. Again, we used CC codes based on participants’ lengths of stay and costed excess days at published rates.

| HRG code | National average unit cost (£) | Average length of stay (days) | Cost per day (£) | Excess bed-day rate (£) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without surgerya | |||||

| Non-elective: IBD without interventions, 19 years and over (FZ37) | CC 0 | 1546 | 3.78 | 409 | 243 |

| CC 1–2 | 1692 | 4.39 | 385 | 237 | |

| CC 3–4 | 2218 | 5.62 | 395 | 230 | |

| CC 5+ | 12,630 | 7.82 | 336 | 229 | |

| With surgery (primary procedure)a | |||||

| Non-elective: complex large intestine procedure, 19 years and over (FZ74) | CC 0–2 | 5822 | 8.92 | 653 | 196 |

| CC 3–5 | 7573 | 12.60 | 601 | 162 | |

| CC 6–8 | 8623 | 17.21 | 501 | 390 | |

| CC 9+ | 10,136 | 19.93 | 509 | 229 | |

| With surgery (selected subsequent procedures)b | |||||

| Closure of stoma | FZ13 | Costs dependent on CC code | |||

| Ileoanal pouch | FZ69 | ||||

| Reversal of ileostomy | FZ83 | ||||

| Proctecomy, ileoanal pouch, loop ileostomy | FZ73 | ||||

| Completion proctectomy | FZ77 | ||||

Case report forms also recorded data on non-trial drugs administered to participants as inpatients. When the CRF did not record dose, we assumed that the participant had received the lowest dose recommended in the British National Formulary. 80 When the CRF did not record duration, we assumed that participants took any prescribed gastroenterology drugs throughout their hospital stay; we extended this rule to seven other drugs – alendronic acid, amlodipine, bisoprolol fumarate, clopidogrel, gliclazide, losartan potassium and rampiril. For all other inpatient drugs without specified duration we costed a single day’s dose. As we costed over 1800 drugs and formulations, we do not report them all here.

Participant Follow-up Questionnaires also reported data on non-trial drugs prescribed while participants were in the community. We costed these according to the dose and duration of treatment recommended by the British National Formulary in whole packs. Where duration was not recorded we assumed that the participant received a single pack.

Finally, PFQs reported on participants’ other encounters with the NHS, including general practitioners (GPs), nurses and other professionals at surgery, at home, in the community or by telephone; NHS Direct or NHS24; hospital emergency departments; and outpatient clinics (Table 4). Our main source of unit costs was Curtis,81 who included salaries and expenses, costs of training and qualifications, and capital and overhead costs.

| Resource | Details | Source | Unit cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS contacts | |||

| A&E visits | Treatments leading to admitted (not admitted) £146 (£112) | Curtis 201283 | 112.00 |

| Admitted nights | NIHR Clinical Research Network industry costing template | NIHR 201484 | 386.37 |

| Clinic visit | As outpatient appointment. Weighted average £135 (p. 107) | Curtis 201381 | 135.00 |

| Consultant: medical (p. 245) – per contract hour £139 | |||

| Clinic visit | Length of contact assumed same as GP (11.7 minutes) at £27.11 | Curtis 201381 | 27.11 |

| Telephone call | Length of telephone call assumed same as GP (7.1 minutes) at £16.45 | Curtis 201381 | 16.45 |

| Consultant: psychiatric (p. 246) – per contract hour £140 | |||

| Clinic visit | Length of contact assumed same as GP (11.7 minutes) at £27.29 | Curtis 201381 | 27.29 |

| Telephone call | Length of telephone call assumed same as GP (7.1 minutes) at £16.57 | Curtis 201381 | 16.57 |

| Consultant: surgical (p. 246) – per contract hour £140 | |||

| Clinic visit | Length of contact assumed same as GP (11.7 minutes) at £27.30 | Curtis 201381 | 27.30 |

| Dietitian | (p. 226) Hourly rate £35. Assumed session length same as GP practice nurse – 15.5 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 9.04 |

| GP (including travel, direct staff and qualification costs) (p. 191) | |||

| At practice | Per patient contact lasting 11.7 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 45.00 |

| Home visit | Per out of surgery visit lasting 23.4 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 114.00 |

| Telephone call | Per telephone consultation lasting 7.1 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 27.00 |

| Health visitor | |||

| Home visit | (p. 185) Per hour of home visiting – £71. Assumed length of visit same as GP home visit – 23.4 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 27.69 |

| Telephone call | (p. 185) Per hour of patient-related work – £59. Assumed length of telephone call same as GP practice nurse (6 minutes) | Curtis 201381 | 5.90 |

| Hospital (telephone call) | Assumed contact with clinical nurse specialist (p. 189) per hour of client contact – £90. Rate per 6 minutes’ telephone contact – £9 | Curtis 201381 | 9.00 |

| Midwife | (p. 186) Costed as nurse specialist (community) band 6 – £49 per hour. Length of contact assumed same as GP practice nurse – 15.5 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 12.66 |

| NHS Direct (telephone call) | Digitalhealth.net 201385 | 20.00 | |

| Nurse (GP practice) | GP practice nurse (p. 188) per hour of face-to-face contact rate – £52. Per average contact lasting 15.5 minutes – £13.43 | Curtis 201381 | 13.43 |

| Nurse (home visit) | Community nurse (including district nursing sister, district nurse) (p. 183) per hour of home visiting (including travel) – £70. Assumed length of home visit same as GP (23.4 minutes) – £27.30 | Curtis 201381 | 27.30 |

| Nurse specialist (p. 186) hourly rate £49 | |||

| Clinic visit | Assumed length of visit same as GP practice nurse – 15.5 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 12.66 |

| Home visit | Assumed length of visit same as GP home visit – 23.4 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 19.11 |

| Telephone call | Length of telephone call assumed as calls to hospital (6 minutes) at £4.90 | Curtis 201381 | 4.90 |

| Outpatient visit: gastroenterology | Service code 301 | Department of Health 201582 | 137.00 |

| Outpatient visit: general | Weighted average £135 (p. 107) | Curtis 201381 | 135.00 |

| Paramedic visit | Ambulance services – see, treat and refer (p. 107) | Curtis 201381 | 177.00 |

| Pharmacist | (p. 228) Per hour of direct clinical patient time – £94. Assumed length of session same as GP visit – 11.7 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 18.33 |

| Phlebotomist: | NHS Jobs (www.jobs.nhs.uk) specify that phlebotomists are clinical support workers with a salary between £14,000 and £22,000 p.a. | Curtis 201381 | 4.10 |

| Clinic visit | Clinical support worker (p. 237) hourly rate £21. Assumed length of contact same as GP visit – 11.7 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 4.10 |

| Home visit | Clinical support worker (community) (see p. 187) hourly rate – £30. Assumed length of contact same as GP home visit 23.4 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 11.70 |

| Physiotherapist | (p. 223) Hourly rate – £36. Assumed session length – 30 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 18.00 |

| Psychologist | (p. 179) Clinical psychologist – £134 per hour of client contact. Length of contact assumed same as GP practice nurse – 15.5 minutes | Curtis 201381 | 34.62 |

| Ultrasound | Less than 20 minutes | Department of Health 201582 | 51.00 |

| Walk-in centre | (p. 109) Walk-in services leading to not admitted | Digitalhealth.net 201385 | 41.00 |

| Tests and investigations | |||

| Ciclosporin levels | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 22.00 | |

| Abdominal X-ray | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 65.00 | |

| Barium enema | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 215.00 | |

| Barium follow through | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 350.00 | |

| Barium meal | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 175.00 | |

| Calcium and phosphate | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 4.10 | |

| Chest X-ray | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 50.00 | |

| Clotting profile | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 3.28 | |

| Colonoscopy with biopsy | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 827.00 | |

| Colonoscopy without biopsy | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 767.00 | |

| C-reactive protein | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 3.00 | |

| CT scan | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 475.24 | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 3.28 | |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 344.00 | |

| Full blood count | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 3.95 | |

| Liver function tests | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 4.45 | |

| MRI scan | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 574.91 | |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 610.00 | |

| Rigid sigmoidoscopy | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 210.11 | |

| Stool culture/testing | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 2.70 | |

| Thiopurine methyltransferase testing | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 31.70 | |

| Urea and electrolytes | Cardiff and Vale and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Boards | 3.65 | |

Case report forms also recorded data on the number and type of investigations undertaken. We estimated unit costs for these from two local but dissimilar trial sites – in Cardiff and Swansea (see Table 4). When participants died or withdrew further access to medical records, sites completed the next CRF from data available up to that time.

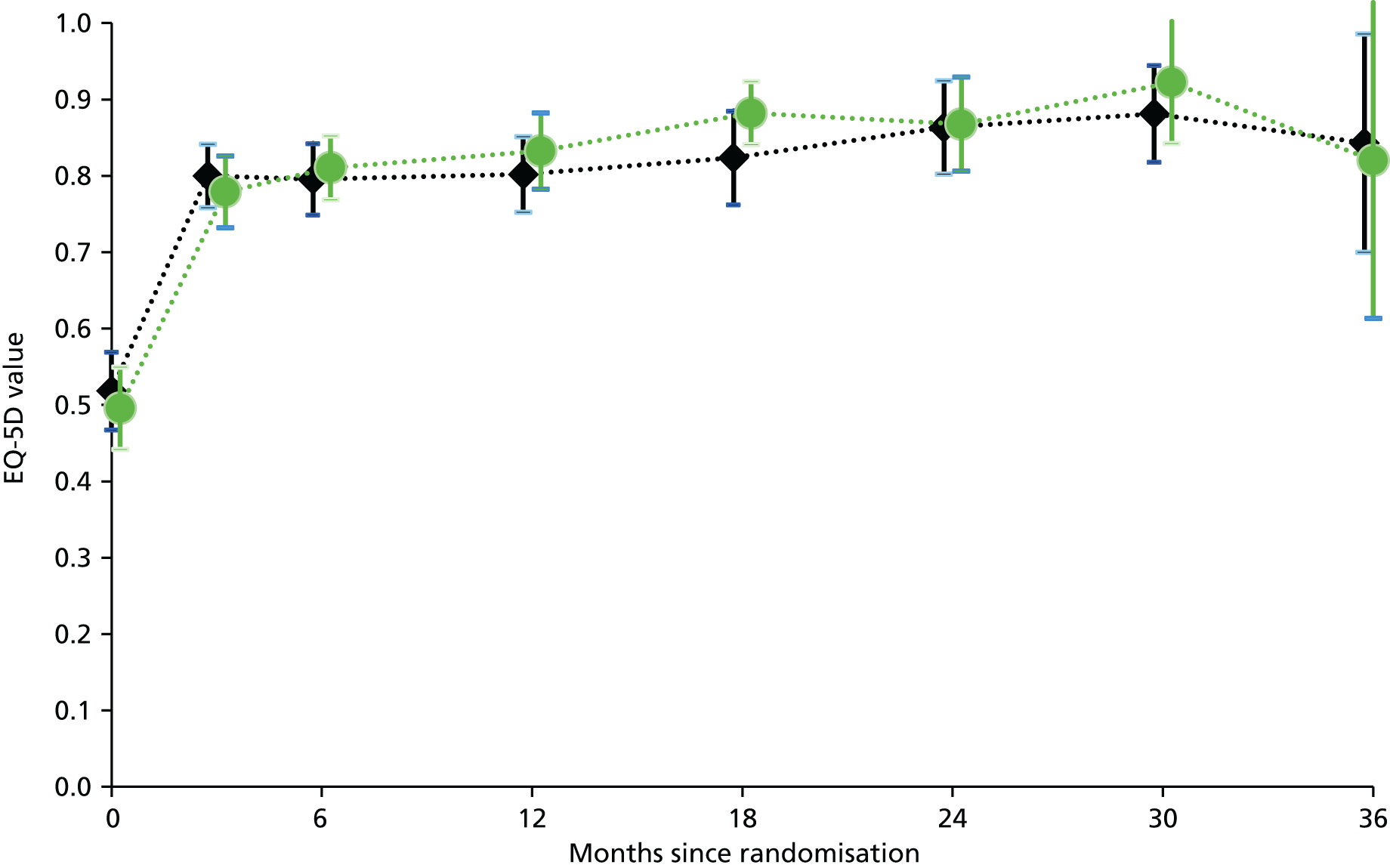

The primary outcome for economic analysis was QALYs estimated from the EQ-5D questionnaire within the PFQ administered at baseline and subsequent assessments. Participants who underwent colectomy also completed the EQ-5D within the PCQ at discharge from surgery and 4, 8 and 12 weeks thereafter. EQ-5D assesses HRQoL on five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression – using three levels for each dimension. We converted these to a single utility using the UK tariff. 86

We used the methods described above to impute missing data, which can happen in three ways:

-

CRF or PFQ received missing individual resource items

-

CRF or PFQ received but not covering the entire period since previous CRF; or

-

CRF or PFQ due but not received.

In these three scenarios we imputed thus:

-

We used age, gender, weight, ethnic group, smoking status and hospital data to impute missing items. If more than two were missing, we used mean regression imputation; as regression assumes normally distributed errors, we used log-transformation when the data broke this assumption.

-

We assumed that resource use varied linearly and therefore replaced missing data by the mean of the data available before and after, weighted if necessary.

-

After checking whether or not non-responders differed from responders in sociodemographic characteristics, we using the method described in (2).

-

Censoring data occurred because of the change to protocol which meant that not every participant could be followed up for the same length of time. We studied the mechanism of censoring87 on a range of variables including study arm. As these showed all censoring to be missing completely at random, no adjustments were made to resource data to account for any censoring effects.

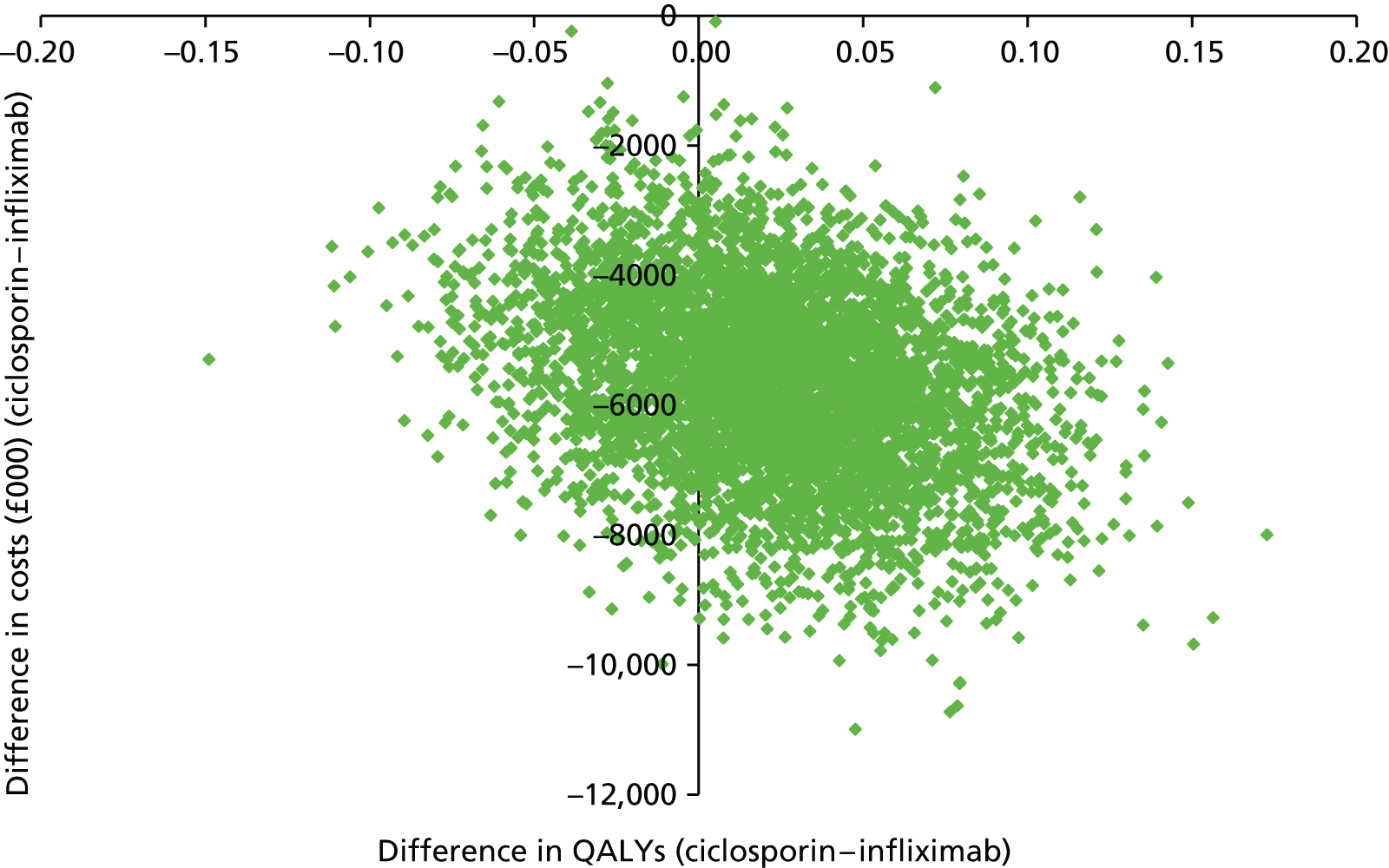

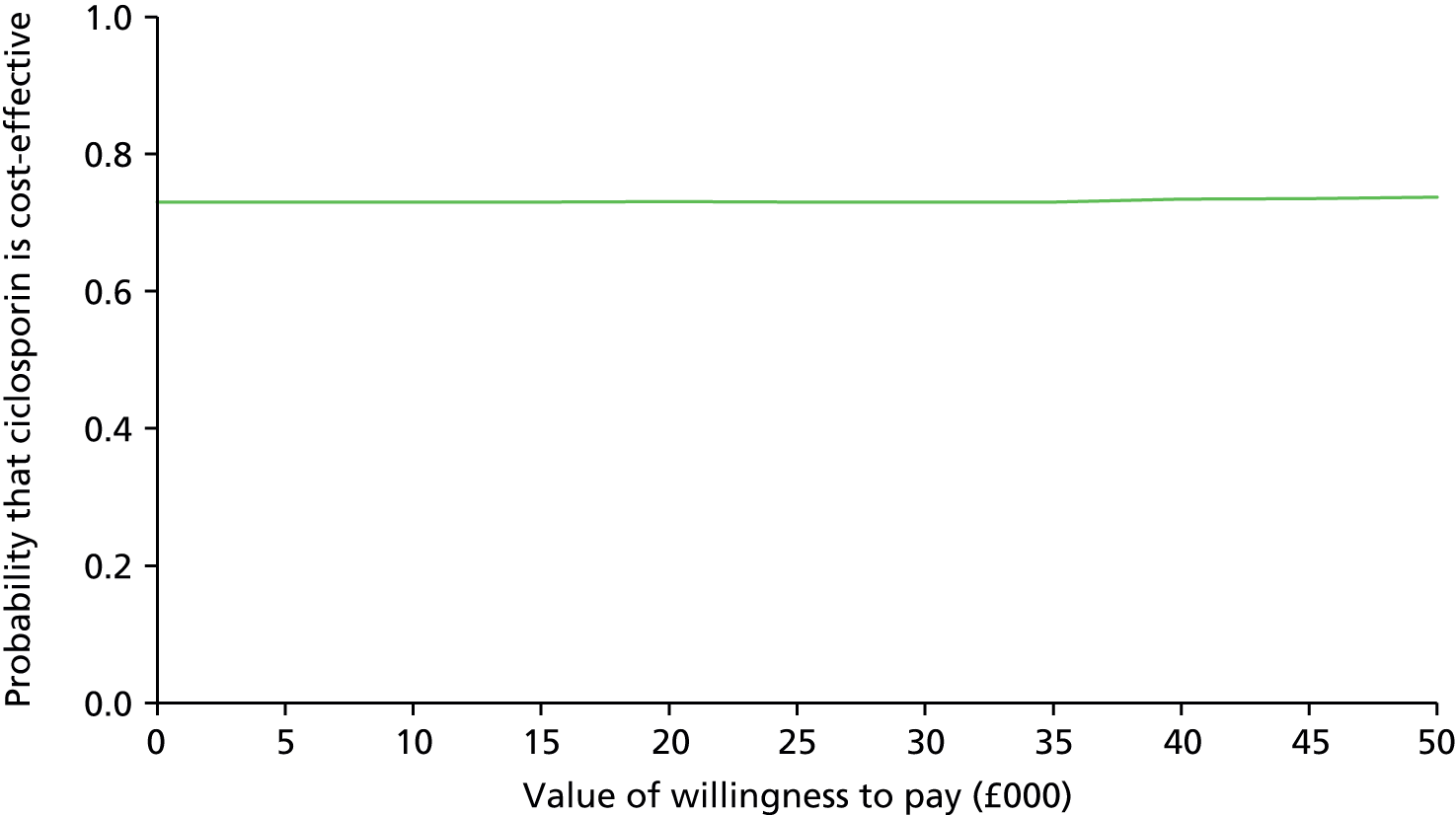

We estimated total costs by aggregating participants’ resource use. Although data collection for early participants could extend for 36 months, there were very few of these. Our primary analysis therefore compared costs and assessed cost-effectiveness over 30 months.

The calculation of the cost-effectiveness point estimate included all participants for whom we had EQ-5D data. In principle we aggregated their costs and QALYs over their (variable) periods in the study. To ensure that costs and QALYs covered the same periods, we compared the number of days covered by CRFs and PFQs. We fitted statistical models for NHS costs and QALYs using allocated drug, days since randomisation and the logarithm of those days as independent variables. We used the result coefficients to adjust NHS costs and QALYs to a period of 730 days.

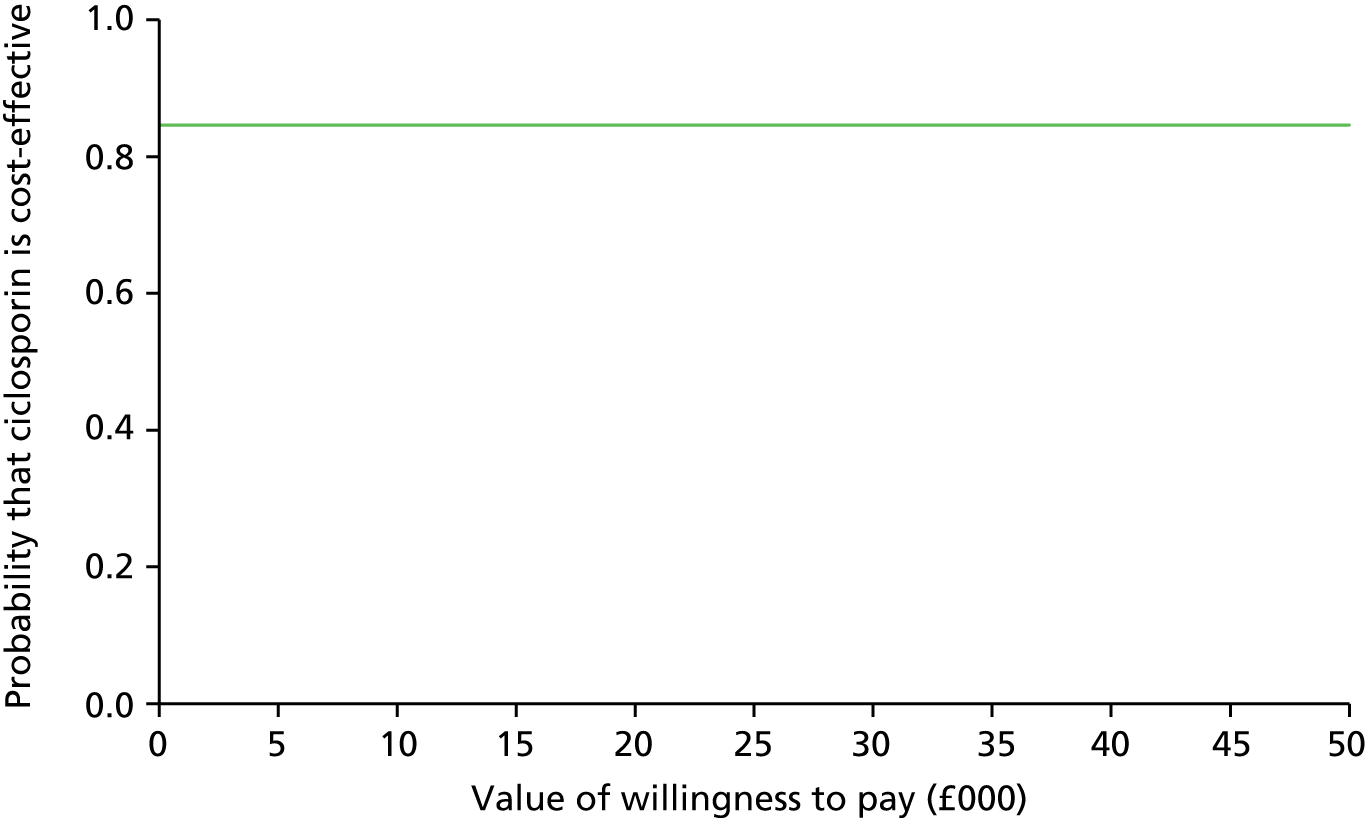

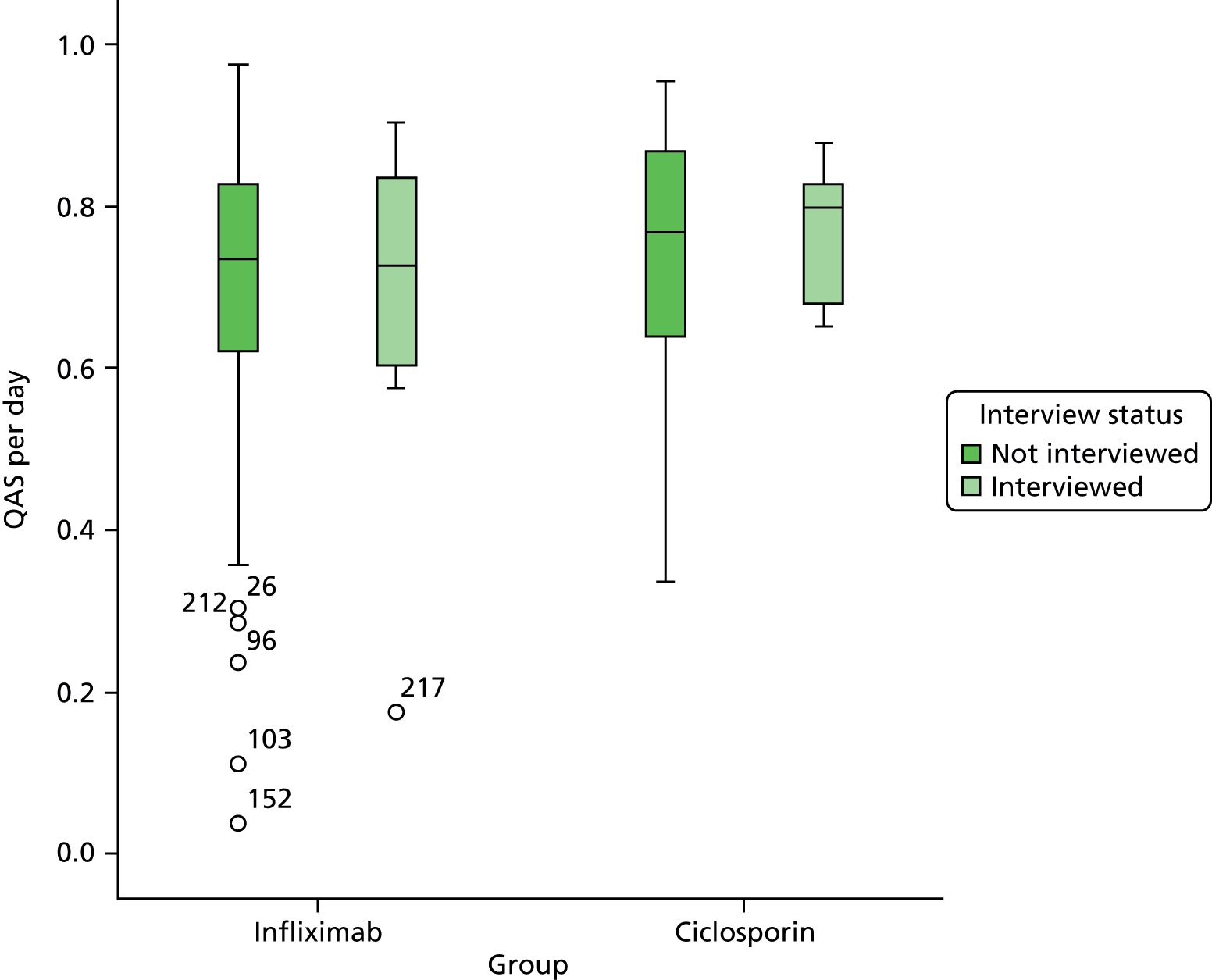

We undertook two contrasting sensitivity analyses: the first restricted analysis to 12 months, and thus analysed all 270 participants but none of their data beyond 12 months; the second restricted analysis to 24 months and those participants who took part for at least that duration.