Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/55/33. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in January 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Bentley reports honoraria and travel subsistence from BioMarin to attend clinical advisory group in Berlin (April 2015) on respiratory management of mucoploysaccharoidoses. Anita K Simonds reports being on the steering committee of trial of adaptive servo ventilation in heart failure patients with predominant obstructive sleep apnoea (SERVE-HF). Chin Maguire reports grants from Motor Neuron Disease Association and non-financial support from Synapse Biomedical Inc. during the conduct of the study. Christopher J McDermott reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme, grants from the Motor Neurone Disease Association and non-financial support from Synapse Biomedical Inc. during the conduct of the study and separate to the Diaphragm Pacing in patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (DiPALS) trial. Lyn Taylor reports personal fees from PAREXEL International Corporation not associated with the DiPALS trial. Roger Leek reports membership of the Motor Neurone Disease Association. John Stradling reports personal fees from ResMed UK not associated with the DiPALS trial. Martin Turner reports grants from Medical Research Council, personal fees from Biogen Idec, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Neuraltus Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Ontario Brain Institute, personal fees from GLG Consulting and personal fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals not associated with the DiPALS trial. Richard W Orrell reports grants from the Motor Neurone Disease Association of England, Wales and Northern Ireland during the conduct of the study. Wisia Wedzicha reports grants from Johnson and Johnson, grants from Vifor Pharma, grants from Takeda, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Boehringer, personal fees from Takeda and personal fees from Vifor Pharma outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by McDermott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease with an annual incidence of 2–3 in 100,000 and a prevalence of 5–8 per 100,000. 1–3 Affected individuals experience increasing weakness affecting the limbs, speech and swallowing, and breathing. There is no cure for ALS and patients usually succumb to the illness within 2–3 years.

Management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Management is largely aimed at easing symptoms and supporting patients to maximise their function through a multidisciplinary approach. 4 One treatment, riluzole, can marginally slow down disease progression, prolonging survival, usually by around 3 months. 5,6 The exact mechanism by which riluzole affects the disease course is unclear, although it is known to modulate glutamate release, among other effects. However, the greatest impact on the disease course comes from the use of non-invasive ventilation (NIV). A randomised controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated an improvement in quality of life (QoL) and a median survival benefit of approximately 7 months (p = 0.006), in ALS patients using NIV who had good bulbar function. 7 NIV, however, is not without its problems, as some individuals are unable to tolerate it because of problems with claustrophobia and mask interface issues. Furthermore, there comes a point in the course of the disease when NIV is no longer effective.

Phrenic nerve stimulation, in which the diaphragm is stimulated into contracting, is a potential alternative or complementary method of providing respiratory support. The approach originated in patients with spinal cord injury, and historically it required direct phrenic nerve stimulation. The challenges with this approach have been the significant risk of iatrogenic phrenic nerve injury and, until recently, the need to undertake a thoracotomy. 8 More recently, phrenic nerve stimulation has been achieved using less invasive techniques. The NeuRX® RA/4 diaphragm pacing system (DPS)™ (Synapse Biomedical, Oberlin, OH, USA) is a four-channel percutaneous neuromuscular stimulation system. DPS has an advantage over the earlier direct approach, in that the stimulating electrodes can be inserted into the under-surface of the diaphragm using a minimally invasive laparoscopic technique. 9 The leads are then tunnelled to an exit site on the abdomen and an external stimulator delivers the stimulus pulses and provides respiratory timing. Initial experience with the NeuRX RA/4 DPS in the spinal cord injury population10 suggested diaphragm pacing (DP) could reduce time spent on mechanical ventilation. 11 The NeuRX RA/4 DPS is now licensed for use in spinal cord injury in many countries, including the USA, and within the European Union.

Evidence for diaphragm pacing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

To date, the evidence for DPS in the ALS population is limited to case series and one uncontrolled multicentre cohort study. Their findings are consistent with those from the spinal cord patient population, and highlighted the apparent simplicity and operative safety of the NeuRX RA/4 DPS. 7,10 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the NeuRX RA/4 DPS as a humanitarian-use device (HUD) in ALS following the submission of a humanitarian device exemption (HDE) application. The FDA summary of safety and probable benefit document (SSPB) summarises the evidence on which the HDE approval is based, which is largely on data from the aforementioned cohort study. 11 The main inclusion criteria for the study were patients with ALS with evidence of residual bilateral phrenic nerve function and a forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 85% at screening and above 45% at DPS implantation. The full data from this study, including baseline characteristics, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram, survival, etc., on the 144 patients enrolled have not yet been published. Of the 144, 106 were implanted with the NeuRX RA/4 DPS and survival data on 84 are presented in the SSPB. 11

Median survival data are reported as 39 months from ALS diagnosis and 19 months post implantation in the SSPB on 84 implanted patients. As the data are from a cohort study there is no randomised control population to compare survival with. Instead, a subgroup of the HUD patients (n = 43) was compared with a historical control group of NIV users. The DP HUD group patients demonstrated survival of 37.5 months from diagnosis, compared with 21.4 months from diagnosis for the historical NIV control group (p < 0.001).

Safety data have been published in the SSPB for 86 implanted patients from the cohort study. In these patients, there were no reported deaths and none who needed a tracheostomy with permanent ventilation within the 30-day postoperative period. Four serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported relating to implantation [capnothorax (n = 2), respiratory failure due to complications of surgery (n = 1) and serious anaesthetic reaction (n = 1)]. Therefore, the implantation procedure itself appeared to be relatively safe. Important adverse events (AEs) over the 12-month protocol reported were capnothoraces in 16 patients (19%), percutaneous site infection in eight patients (9%) and pacing-related discomfort, which was described as mild in 20 patients (23%) and moderate in two patients (2%). In the 86 patients implanted, there were no SAEs involving malfunctioning device components. There were 18 reports of anode malfunction in 18 patients (21%) and 44 reports of electrode malfunction in 28 patients (33%). Although there was relatively frequent electrode breakage, there was no need to reimplant any electrodes, as all occurred external to the body at the connector holder.

Following the HUD approval of the NeuRX RA/4 DPS for ALS, there has been increasing use of this therapeutic option worldwide. 12 The promising survival data, lack of apparent harm and absence of alternatives have made this an appealing option, especially among patients who are unable to tolerate NIV, who may account for up to 50% of patients with ALS. 2,3,13,14 The evidence base for the NeuRX RA/4 DPS for ALS is limited. Moreover, pacing is expensive and it is not known whether or not DPS would meet the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s threshold for cost-effective interventions for end-of-life care. At the time of conducting the Diaphragm Pacing in patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (DiPALS) trial, the cost of DPS and implantation procedures (the excess treatment costs) was approximately £16,500 per participant. Therefore, although the preliminary data are promising, DPS is unlikely to be widely introduced without robust, randomised evidence together with a formal analysis of cost-effectiveness. This was our motivation for undertaking the DiPALS trial.

Research objectives

The aim of this study was to perform a definitive RCT on the efficacy and safety of the NeuRX RA/4 DPS when used in addition to NIV, compared with standard care of NIV alone, in patients with ALS. Specifically, we wished to assess whether or not the use of DP in addition to NIV prolongs survival, and also to quantify its impact on:

-

QoL of the participant

-

QoL of the main carer

-

safety (AEs) and tolerability (withdrawal from treatment)

-

quality-adjusted life-years

-

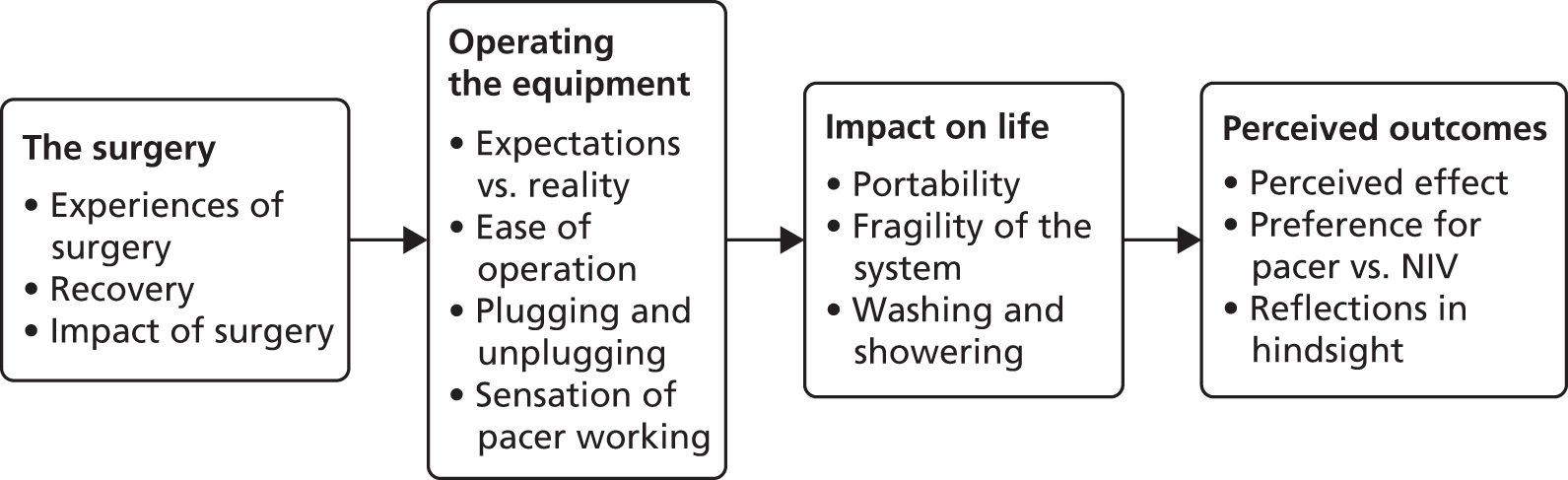

views and perceptions of patients and family carers regarding acceptability and impact on life.

Chapter 2 Methods

The original protocol for DiPALS was submitted to BMC Neurology15 and was published 8 months into the recruitment phase of the trial, prior to any analyses being performed. The methods described in this chapter are consistent with those as published and with the conduct of the trial in practice, but changes were made to the protocol over the course of the project. These are detailed at the end of this chapter, and tabulated in Appendix 1. None of the changes affected the conduct of the trial with respect to the intervention, the primary outcome measures or their statistical analyses.

This report has been prepared in accordance with the CONSORT statement (2010)16 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist and guide. 17

Trial design

The DiPALS trial was a multicentre, parallel-group, open-label RCT incorporating health economic analyses and a qualitative longitudinal substudy. The primary objective was to assess survival over the study duration of patients with ALS with respiratory failure, allocated to either standard care (NIV alone) or standard care (NIV) plus DPS using the NeuRX/4 DPS. Participants from seven UK hospitals were allocated to treatment using minimisation methods (see Appendices 2 and 3).

The trial was non-commercial, with input from Synapse Biomedical for quality assurance purposes, specifically for the training of surgeons and trial staff on implantation and technical aspects of the NeuRX/4 DPS.

Recruitment took place over 24 months (from December 2011 to December 2013).

Participants and eligibility criteria

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of ALS were identified and screened at participating sites or patient referral sites against the following eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Familial or sporadic ALS diagnosed as laboratory-supported probable, probable, or definite according to the World Federation of Neurology El Escorial criteria. 18

-

Stabilised on riluzole therapy for at least 30 days.

-

Respiratory insufficiency as determined by one or more of:

-

FVC < 75% predicted

-

supine vital capacity < 75% of sitting or standing vital capacity

-

sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP) < 65 cmH2O for men or 55 cmH2O for women in the presence of symptoms

-

SNIP < 40 cmH2O (see exclusion criterion 9).

-

partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) > 6 kPa (daytime) or PaCO2 > 6.5 kPa (overnight)

-

significant overnight O2 desaturation (> 5% of night with SpO2 < 90% during overnight oximetry).

-

-

Bilateral phrenic nerve function clinically acceptable as defined by either:

-

absence of paradoxical abdominal wall movement during a sniff manoeuvre (sharp inhalation through the nose) and recording < 10% decline of FVC when moving from sitting to supine position, or

-

on ultrasound: evidence of at least 1 cm of downward diaphragm movement independent of thoracic or abdominal wall movement during the patient performing a sniff manoeuvre.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Prior NIV prescription.

-

Pre-existing implanted electrical device such as pacemaker or cardiac defibrillator.

-

Underlying cardiac, pulmonary diseases or other disorders that would affect pulmonary tests independently of motor neurone disease/ALS (increased risk of general anaesthesia or adverse effect on survival over the course of the study).

-

Current pregnancy or breastfeeding.

-

Significant decision-making incapacity preventing informed consent by the subject because of a major mental disorder such as major depression, schizophrenia or dementia.

-

Marked obesity affecting surgical access to diaphragm or significant scoliosis/chest wall deformity.

-

The involvement in any respiratory trial that can influence the safety or outcome measures of this study within 3 months of the planned implantation of the device or during the year of follow-up.

-

Pre-existing diaphragm abnormality such as a hiatus hernia or paraoesophageal hernia of abdominal contents ascending into the thoracic cavity.

-

FVC < 50% predicted or SNIP < 30 cmH2O in patients unable to perform FVC (bulbar patients) (because of potential anaesthetic risk).

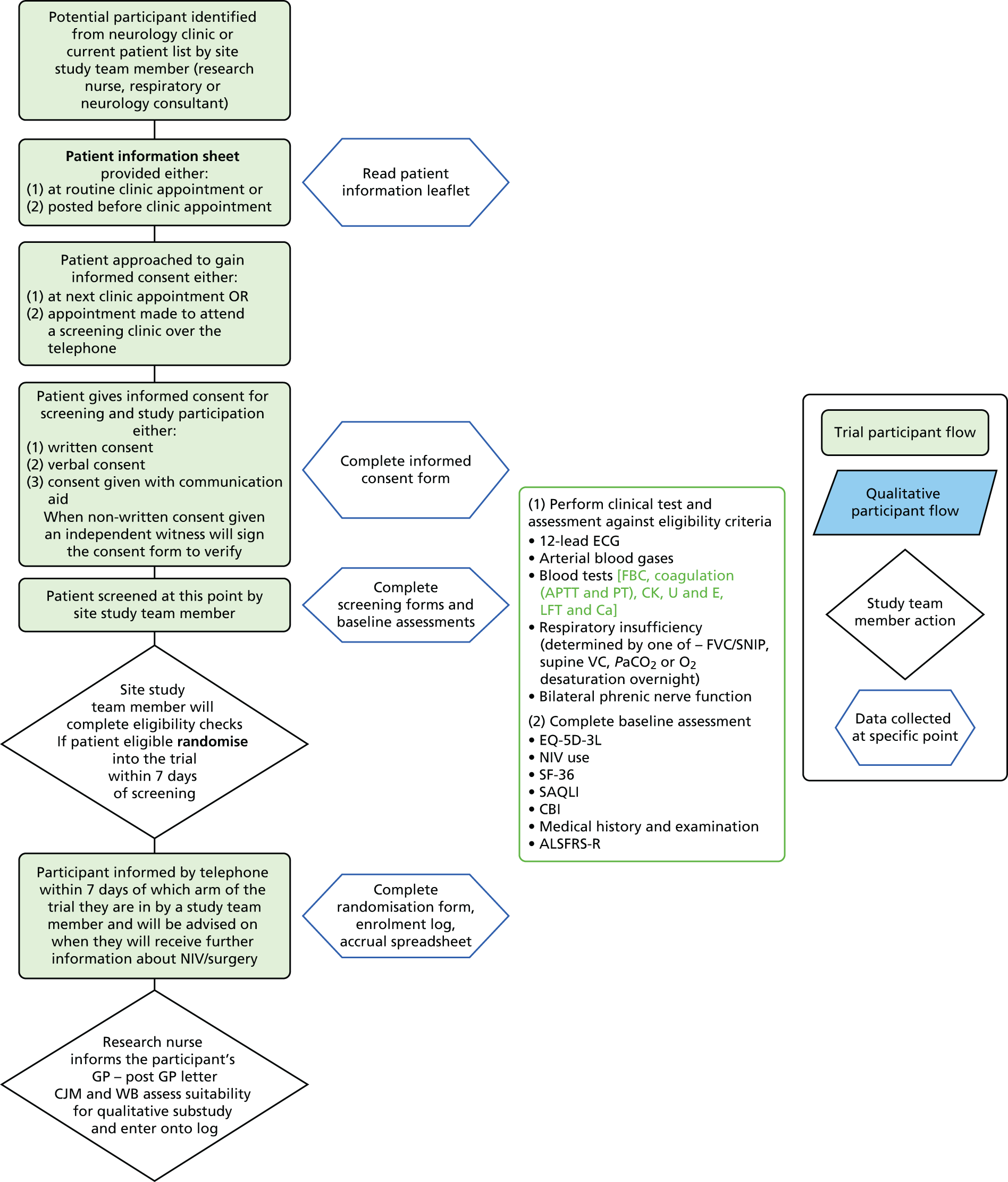

Participant identification

Potentially eligible patients were identified from NHS hospital clinics at lead research sites or participant identification centres by neurology or respiratory clinicians or a study research nurse (see Appendix 4).

All patients aged ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of ALS underwent a ‘prescreen’ whereby their last routine respiratory measure was checked to determine whether or not:

-

patients were ineligible because of poor respiratory criteria or other reason

-

patients were potentially eligible

-

patients may be eligible in the future as their respiratory measure was currently too good.

All those potentially eligible were approached at clinic to discuss the trial in detail. If they were identified from the clinic list prior to attendance the study information was sent to them by post.

Recruitment

Patients were approached by a member of the research team at sites when they attended routine clinic appointments. The study patient and carer information sheets formed a basis for a discussion with potential participants in clinics. Patients were given as long as they required to consider taking part in the trial, with further discussion by telephone or at another clinic offered. Informed consent was taken only if the researcher was satisfied that the patient fully understood the study procedures, was willing to undergo screening and participate in the trial, and was capable of giving full informed consent. Consent was obtained using participant and carer consent forms approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC), as either full written consent, verbal consent given or consent given via the use of a communication aid (for REC-approved patient information sheets see Appendices 5–8 and for REC-approved consent forms see Appendices 9–12). When non-written consent was obtained an independent witness was asked to sign the consent form to verify that consent was taken.

If participants were willing to provide reasons for declining participation in the trial, these were entered onto the screening log. Anonymised basic details (age, sex and reason for exclusion) were collected on all eligible patients to allow completion of the CONSORT flow chart.

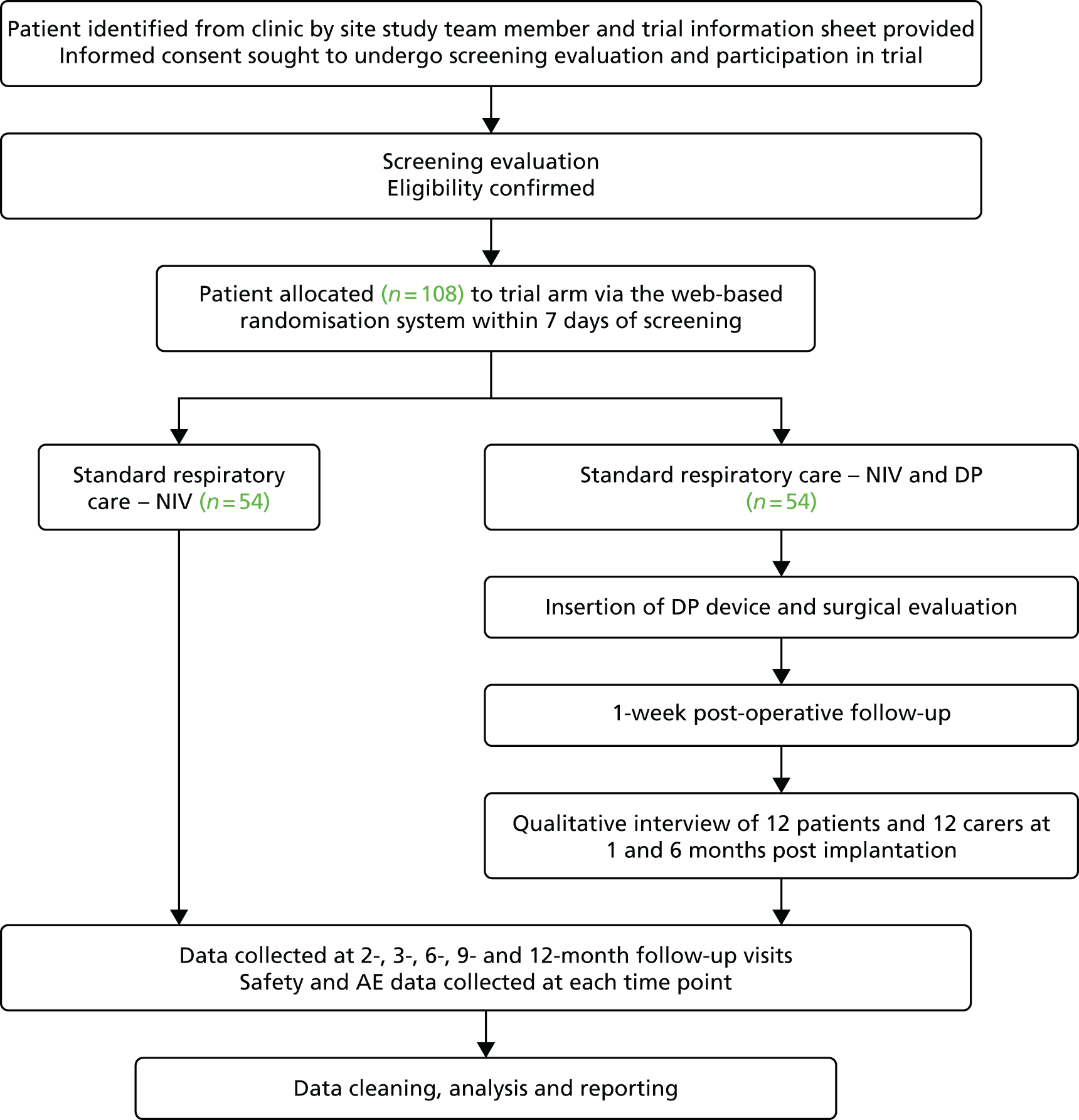

Participants were free to withdraw from the trial at any point without giving a reason, but data collected up to the point of study withdrawal were maintained and used in study analyses. Patients who asked to withdraw from treatment were encouraged to complete follow-up for QoL and safety to reduce attrition bias. All participants were followed up for survival until 12 months after the last participant was recruited, unless they specifically requested otherwise (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow diagram. a, At 9 months, only ED-5D-3L, DPS/NIV use, AEs and resource use collected. CBI, Caregiver Burden Inventory; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels; SAQLI, Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index questionnaire; SF-36, Short Form questionnaire-36 items.

Screening

Once patient consent had been confirmed, a member of the site study team initiated the screening process. Patient eligibility was assessed against both non-clinical and clinical criteria, and baseline assessments. Eligibility for the study was based on all the inclusion and none of the exclusion criteria being met. To confirm eligibility, a combination of techniques was used. Researchers checked medical notes/data to assess past medical history, current prescriptions and any other known information relating to eligibility criteria. At the screening visit, participants were asked to perform a respiratory test to determine their FVC or other measure. An assessment was made of the participant’s phrenic nerve function – a measure intended to ensure that, if the patient were randomised to DPS, it was likely that it would be possible to sufficiently stimulate the participant’s diaphragm once the system was fitted. All criteria were checked and signed off by the recruiting clinician. Once eligibility was established, participants were asked to complete baseline assessments and could proceed to randomisation and study procedures (see Figure 1).

Randomisation and blinding

Once eligibility had been confirmed and consent acquired, the participants were randomly allocated to a treatment group. The recruiting clinician accessed a centralised web-based randomisation system provided by the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) in partnership with a University of Sheffield wholly owned subsidiary software development company, epiGenesys. Sites were able to log on to the system using a site-specific username and password. Researchers were prompted to enter patient details (identification number, date of birth and the minimisation factors) and to confirm that consent and eligibility was complete. Following this, the randomisation system notified the user and the study manager of the treatment allocation. Patients were informed of their treatment allocation within 1 week of randomisation by telephone or letter.

The study was open label; it was not considered feasible to blind participants, carers or site staff as the study intervention involves a surgical procedure and ongoing use of an implanted medical device. A sham surgical procedure was considered but discounted as being an unnecessary burden to participants, given the objectivity of the primary outcome measure.

Patients were allocated their treatment (NIV alone or NIV plus DPS) by method of minimisation, using baseline bulbar function, baseline FVC, age and sex as the minimisation factors. Factors were categorised as follows: bulbar function (mild, moderate or severe); FVC (50–59%, 60–69% or ≥ 70%); age (≤ 39 years, 40–79 years or ≥ 80 years); and sex (male or female). The allocation incorporated a burn-in period of 10 participants (i.e. the first 10 participants were allocated using simple randomisation). Thereafter, allocation was performed using minimisation incorporating a random probability element of 80% into the allocation algorithm. That is each participant was allocated to the arm that reduced treatment imbalance with 80% probability and to the opposite arm with 20% probability.

The minimisation system was prepared by the study statistician; the study team did not have access to the allocation list in order to maintain allocation concealment. The study team and governance committees were blinded during the course of the study with the following exceptions: (1) the trial statistician and data management team had full access to unblinded outcome data; (2) the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) had access to unblinded summaries of outcome data; (3) site staff were aware of the treatment allocation of their own participants; and (4) the chief investigator, study manager and site monitor were aware of individual participants’ allocations and AEs but did not see unblinded comparative summaries. The trial unblinded statistician was responsible for providing the DMEC with the accumulating unblinded data summaries, but did not attend the closed meetings during which the DMEC reached its decisions.

The original analysis plan was signed off after recruitment start, by which point one participant had died. The updated analysis plan was written by the unblinded trial statistician and endorsed with minimal suggestions by the unblinded DMEC; all other reviewers and approvers did so blinded to outcome data.

Interventions

Participants were randomly allocated to receive either standard care (NIV) or standard care in addition to DPS using the NeuRX/4 DPS.

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation was initiated as per usual clinical practice at the study site after randomisation.

Diaphragm pacing system

The NeuRX DPS is licensed for use in patients with ALS (Conformité Européenne certificate number 518356). The FDA approved the device under HDE for patients with ALS who had stimulatable diaphragms and were experiencing chronic hypoventilation but who had not progressed to a FVC of < 45% of their predicted capacity.

The system is a four-channel intramuscular, motor point stimulation system. Intramuscular diaphragm electrodes are implanted laparoscopically into the diaphragm, with leads tunnelled to an exit site on the abdomen. The external part of the electrodes are connected to an external pulse generator (EPG), which is a small, white, portable box. A clinical station is used to programme each of the parameters (pulse frequency, pulse duration, inspiration time, pulse amplitude, pulse ramp and respiratory rate) on the EPG, which controls the stimulation delivered to the diaphragm via the implanted wires electrodes. The EPG provides repetitive electrical stimulation to the implanted electrodes allowing the diaphragm to contract in a manner that mimics breathing.

The Motor Neurone Disease Association provided funding for the purchasing of the NeuRX DPSs from the manufacturers of the device, Synapse Biomedical, which supplied them at reduced cost. The DPS system consists of components to both allow implantation of the electrodes into the diaphragm and its subsequent stimulation (Table 1).

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical station | Clinical station used to map the diaphragm during surgery (by surgeon) to find the point of maximal contraction. Enables programming of the EPG unit to adjust wire parameters at subsequent visits (by PI/research nurse) |

| Electrode delivery instrument | To enable surgical implantation of the device. Used during the laparoscopic procedure by surgeon |

| Clinical implantation kit | Electrodes and instruments required for implantation. Used in theatre by the surgeon |

| Patient kit | Includes EPG control unit and cables required for each patient. Used by PI/research nurse at sites |

Members of the surgical team were responsible for clinical implantation of the system (see Surgical implantation). Theatre staff processed the electrode delivery instrument to allow its use in theatre including sterilisation and maintenance. Local procedures at each hospital for implanting the device were followed in order to complete documentation to allow sites to receive the system. Hospital medical equipment departments checked equipment prior to use following local hospital procedures.

Surgical implantation

On randomisation, the research nurse made arrangements for the participant to have DPS fitted. The time elapsed between randomisation and surgery varied according to availability, but the protocol encouraged investigators to fit the DPS within 8 weeks of randomisation. Participants were booked for a preoperative assessment up to 1 week prior to the operation to ensure their respiratory criteria remained within the safe range (FVC ≥ 45% and SNIP ≥ 30 cmH2O) and to check they were otherwise able to undergo the procedure safely. The research nurse liaised with the trial manager, surgeons and anaesthetists and members of Synapse Biomedical to organise a theatre slot and medical equipment for the procedure. A member of Synapse Biomedical was present at each operation to provide verbal assistance to the surgeon including mapping the diaphragm and implantation of electrodes at the point of maximal stimulation, as per current standard practice. Synapse Biomedical technical staff received honorary contracts to attend each surgical procedure. Guidance was also provided by Synapse Biomedical in setting the DPS parameters postoperatively.

The clinicians performing the procedure in the treatment arm were experienced surgeons who received training in the DPS implantation technique and were competent to perform the procedure. The training process was straightforward as the technique is a modification of a standard abdominal laparoscopic procedure, and mirrored that employed in the previous DP cohort study. 11 Training was provided by a surgeon from Synapse Biomedical. Given the simplicity of the implantation of electrodes for an experienced laparoscopic surgeon, all surgeons were judged competent by Synapse Biomedical after observation of one implantation procedure. Again this reflects the training of surgeons in the previous multicentre cohort study. A single surgeon undertook procedures in six of the centres; the seventh (London) referred participants in the intervention arm to undergo surgery at the Oxford site. At all surgeries, Synapse Biomedical technical staff were present to advise on implantation.

During the implantation procedure, incisions of 0.5–1 inch long were made in the abdomen. More than one incision was made to enable instruments to be passed through the abdominal wall as per standard laparoscopic procedure.

The surgeon identified the best location to place the electrodes within the diaphragm. A probe was used to temporarily place an electrode on the surface of the diaphragm and to stimulate the diaphragm muscle at several locations. Once the best locations were identified, the probe was removed and two electrodes were placed in each side of the diaphragm muscle. The lead wires from these electrodes travelled under the skin to the abdominal wall. The wires were trimmed so that the ends sticking out of the skin were only 2–6 inches in length. A radiograph was taken following the surgery to check the position of the wires and to make sure that no air had travelled above the diaphragm and into the chest. At the end of surgery the clinical station read out was printed for surgical quality control, which displayed the functioning stimulus connection for each electrode wire.

An assessment of phrenic nerve function formed part of the screening procedures, as described in this section. The purpose of this was to assess whether or not there was enough residual phrenic nerve function to enable meaningful stimulation of the diaphragm with the NeuRX DPS. However, it is only at the time of the operation when it is possible to know for certain if the diaphragm is stimulatable. If during the implantation procedure the diaphragm was not stimulatable (no contraction observed during mapping), then the operation was stopped and the device was not inserted.

Evaluation of electrodes and diaphragm pacing system training

Evaluation of the electrodes and DPS was performed prior to discharge from hospital. A system check of the wires was completed. Using the clinical station electrode evaluation was performed, by adjusting individual stimulus parameters (pulse amplitude, width and frequency) to achieve a comfortable level of stimulation for the diaphragm conditioning sessions. During the initial stimulation period, the participant’s vital signs were monitored for any abnormalities. The patient was given a daily target for the number and length of DP sessions, which was recorded by the study team member in the patient diary for the patient to refer to at home.

Training of the participant and their caregiver took place prior to discharge. This included instruction in the care and use of the stimulator and data collection in the patient diary. Verbal and written instruction was provided in a patient/caregiver instruction manual.

Prior to discharge, the participant/or carer was required to show proficiency to the treating clinician in the following:

-

cleaning and care of skin, wires and exit site

-

care and use of the stimulator

-

attachment and detachment of all components

-

completion of patient diary.

It was accepted that initiation of pacing could be deferred until the 1-week postoperative appointment to allow patients to adjust to having the device fitted in the immediate postoperative period. This was to match practice at all sites, as it was recognised that this enables the patient to recover after their operation. Patients were able to turn the EPG control unit ‘on’ or ‘off’ after programming to provide an adequate stimulus. The initial target for pacing sessions for ALS patients was five times per day, with each session lasting at least 30 minutes. Patients were asked to build up to this target over the first month. In the second month, patients were required to gradually lengthen the training sessions. When pacing was being performed for 6–7 hours a day, patients were instructed to switch from pacing during the day to using the pacing device overnight while asleep. At this stage patients could additionally use the pacing device during the day if they felt it benefited them, but this was their decision. Patients were asked to continue to use their NIV as advised by their study doctor.

A patient diary was given to the participant (on NIV initiation) to take home to record the amount of time spent on DPS and/or NIV.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was overall survival.

Secondary outcomes

-

Quality-adjusted life-years, calculated from the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels (EQ-5D-3L) health utility questionnaire.

-

QoL, measured by the EQ-5D-3L, Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) and Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index questionnaire (SAQLI).

-

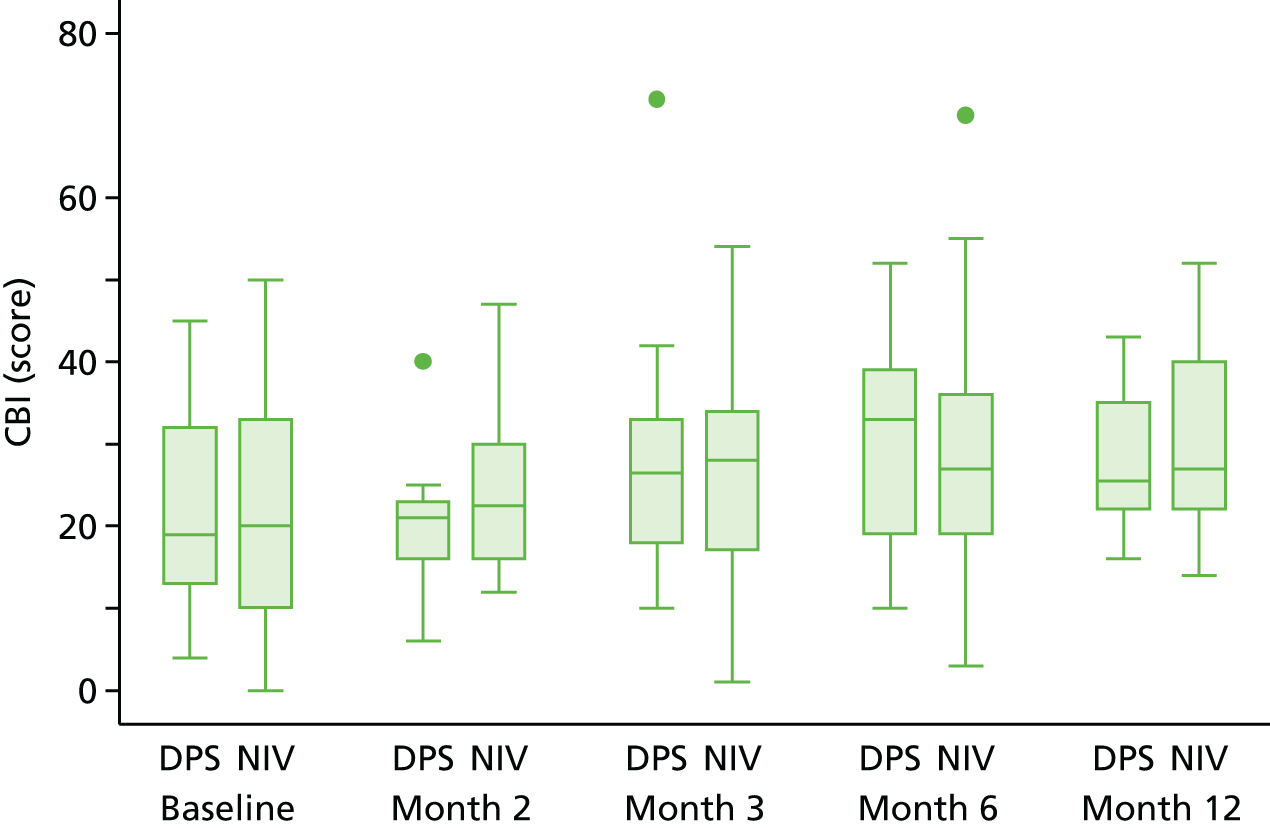

QoL of the main carer, measured by the EQ-5D-3L and Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI).

-

Safety and tolerability of the device.

-

Health economic objectives and resource use.

-

Perceptions of patients and carers regarding acceptability and impact of the device.

Initially, all of these outcome measures were assessed as per the original protocol; however, as a consequence of the trial’s early termination (see Chapter 3, Recruitment suspension), the above was amended. First, both the funder and sponsor agreed that given the substantial cost of the device and the apparent reduction in life-years in the pacing arm, the planned health economic analyses were now unnecessary. Second, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) requested widening the scope of the statistical analyses to address usage of both NIV and DPS in relation to survival.

We also reported tracheostomy-free survival (TFS), defined as the time from randomisation to either death or the placement of tracheostomy, whichever occurred first. Although not preplanned, this outcome was added to aid comparability with other studies that have reported TFS.

Follow-up visits

Follow-up visits were conducted at clinic (at 1 week and at 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months). Some questionnaires were completed via post/e-mail when participants were unable to come into clinic.

Data collection and management

Data collection forms

Data for all participants were captured on the following key sources:

-

screening log – prescreening details containing reasons for ineligibility or non-participation

-

participant and carer consent forms – informed consent

-

case report form – all other study forms including eligibility, baseline assessments, randomisation, surgery, follow-ups (at 1 week and at 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months) study completion (withdrawal), AEs/SAEs, concomitant medications and, unscheduled DPS visits

-

patient diary – DPS and/or NIV usage.

Database

Trial data were entered into a validated bespoke web-based database system (Prospect) managed by the Sheffield CTRU in partnership with a University of Sheffield wholly owned subsidiary software development company, epiGenesys. Prospect stores all data in a PostgreSQL 9.1 (open-source software from The PostgreSQL Global Development Group) database on virtual servers hosted by Corporate Information and Computing Services at the University of Sheffield. Prospect uses industry standard techniques to provide security, including password authentication and encryption using Secure Sockets Layer/Transport Layer Security. Access to Prospect was controlled by usernames and encrypted passwords, and a comprehensive privilege management feature was used to ensure that users had access to only the minimum number of data required to complete their tasks. An automated audit trail recorded when (and by which user) records were created, updated or deleted. Prospect provides validation and verification features which were used to monitor study data quality, in line with CTRU’s standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Methods used for treatment allocation, sequence concealment and blinding

Patients were allocated their treatment (NIV alone or NIV plus DPS) by a method of minimisation, using baseline bulbar function, baseline FVC, age and sex as the minimisation factors. Factors were categorised as follows: bulbar function (mild, moderate or severe); FVC (50–59%, 60–69% or ≥ 70%); age (≤ 39 years, 40–79 years or ≥ 80 years); and sex (male or female). The minimisation was non-deterministic and incorporated a burn-in period of 10 participants and a random probability element of 80% into the allocation algorithm. In other words, the first 10 participants were allocated using simple randomisation; thereafter, each participant was allocated to the arm that reduced treatment imbalance with 80% probability and to the opposite with 20% probability. A centralised, web-based randomisation system hosted by the CTRU was used to allocate treatment allocations. Sites were able to log on to the system using a site-specific username and password. Researchers were prompted to enter patient details (identification number, date of birth and the minimisation factors) and to confirm consent and eligibility were complete. Following this, the randomisation system notified the user and the study manager of the treatment allocation.

The study was open label: it was not considered feasible to blind participants, carers or site staff.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on log-rank test, using Simpson’s rule19 as implemented in Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to allow for the unequal length of follow-up. The study duration comprised an 18-month recruitment period and a 12-month follow-up period, giving a maximum follow-up of 30 months and a minimum of 12 months. Assuming control group survival proportions of 45%, 20% and 10% at the minimum, average and maximum follow-up times, respectively, a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.45 and an additional 10% loss to follow-up, a total of 108 patients (54 per group) were needed to ensure a power of 85% using a two-sided type I error of 5%. The control group figures were conservative estimates based on the sole RCT of NIV,1 which is now considered standard care in the UK. We estimated the sample size on a conservative (but clinically important) 1-year difference in survival of 45% versus 70%, which produced the estimated HR of 0.45. It was expected that complete survival data would be available on all participants recruited, based on previous experience in ALS trials. We did, however, allow for a 10% loss to follow-up in the sample size calculation.

With regard to QoL data, we expected a low level of missing data due to loss to follow-up. We reviewed the patients who were initiated on NIV between July 2008 and June 2009 and had maintained contact with 100% of those patients surviving at 12 months. The appointment of a research nurse at each study site enabled home visits to collect the QoL data when necessary.

Early stopping

No interim analyses or early stopping was foreseen. However, in December 2013 the DMEC recommended that recruitment to DiPALS should cease on safety grounds (discrepancy in survival between the two treatment arms), and a final decision to stop the trial was made in June 2014. The recommendations and actions taken are reported fully in results (see Chapter 3).

Statistical methods

Survival

The primary end point was overall survival, defined as the time from randomisation to death of any cause. Participants were followed up after the last participant’s last visit to determine their final status, and participants who remained alive were censored on the date last known to be alive. TFS was defined as the time from randomisation to either death or the placement of tracheostomy, whichever occurred first.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to visualise survival data and to derive summary statistics of median survival, interquartile range (IQR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The median survival was defined as the point the Kaplan–Meier curve first reached 0.5; if the survival curve did not drop this far, then the median survival is stated as ‘not reached’. The IQR and the CI for the median are defined analogously. Overall survival and TFS were compared between the groups using the log-rank test and modelled using Cox proportional hazards regression using the Efron adjustment for tied survival times and with the minimisation factors as covariates. The primary analysis was the Cox regression (i.e. adjusted) analysis. Pretrial modelling found Cox proportional hazards to be the best fit to previous data, but the Cox proportional hazards assumption was checked by adding time-dependent covariates and graphing scaled Schoenfeld residuals against time. 20 If Cox proportional hazards were found not to fit the data adequately, an accelerated failure time alternative was fitted and the adequacy of its fit assessed using Q–Q plots. 21 Finally, if this too did not fit, the non-parametric restricted mean survival analysis,22 derived from the area under the Kaplan–Meier survival curves, was used as the basis for summarising the treatment effect.

The overall survival was also reported as of the point at which the DMEC made the decision to (1) suspend the trial; and (2) terminate the trial with advice to stop pacing. In both of these additional analyses, participants who were randomised to pacing but did not receive it as a result of the DMEC decision (two patients) were excluded.

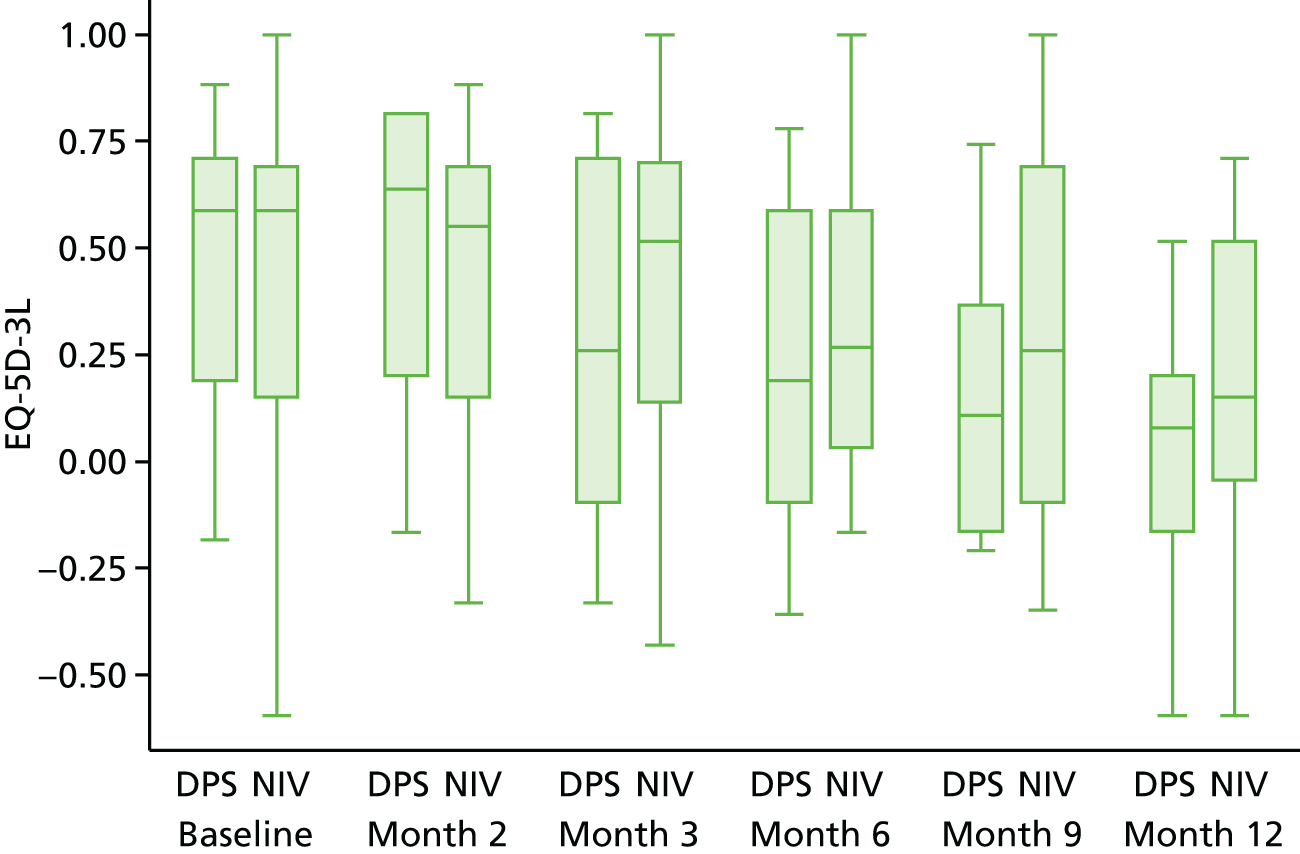

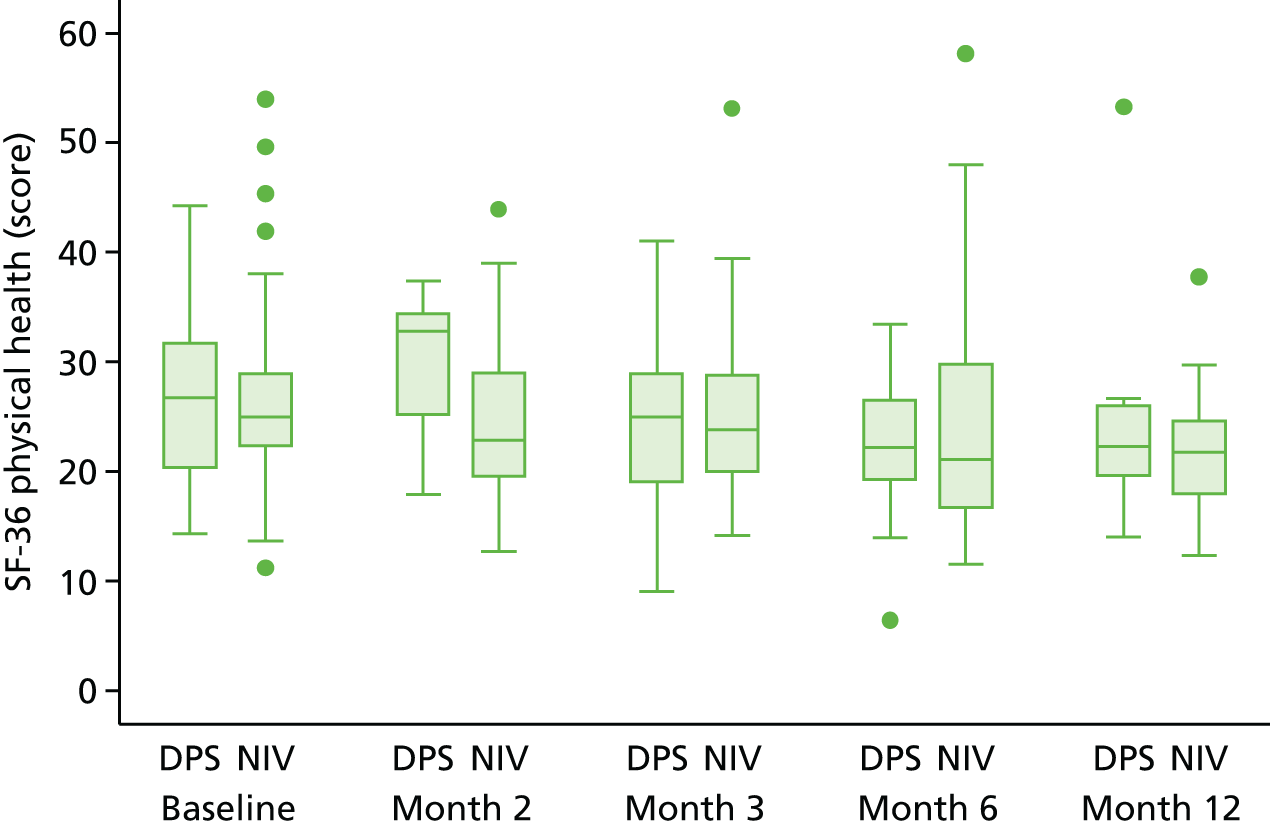

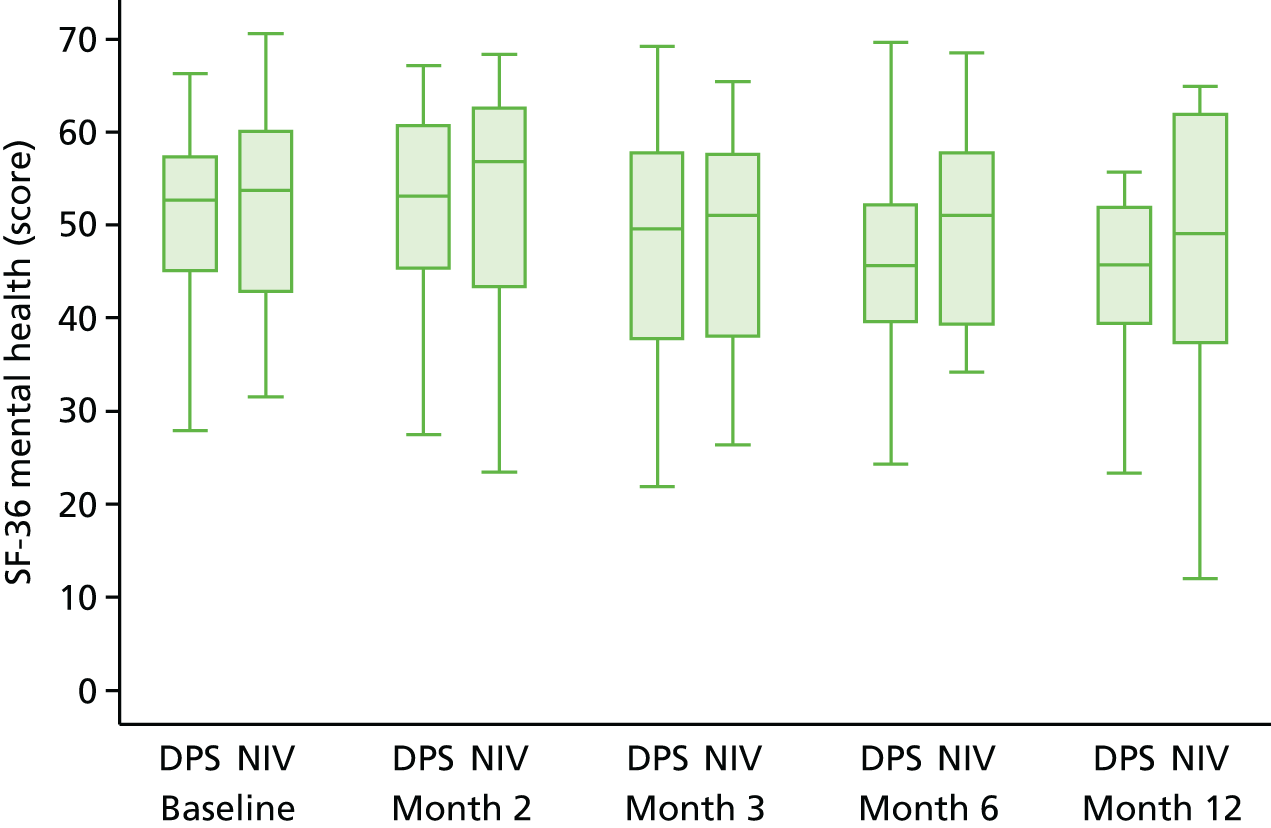

Quality of life

Quality of life was analysed both longitudinally (i.e. over the duration of the trial rather than at individual time points) and at the end of the study follow-up (12 months). Longitudinal analyses were performed using generalised least squares regression, with the baseline value and minimisation factors as covariates and the patient as a random intercept. End-of-study values were analysed using ordinary least squares regression, with the baseline value and minimisation factors as covariates. For each participant measure, a complete case analysis was followed by an analysis based on imputed data. First, in the case of participants for whom data for any visit were missing but data on either side were available (e.g. no month 2 data but baseline and month 3 data available), the value was imputed using the trapezoid rule. When absence of data persisted (e.g. because the participant withdrew from the study), the missing data were imputed using multiple imputation with chained estimation23 using Rubin’s rules and 50 imputations; the imputation model used the participant’s age, sex, rate of prerandomisation Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale – Revised (ALSFRS-R) score decline, FVC, treatment group and any data at other time points for the instrument. Missing data arising because of participant death were not imputed other than for EQ-5D-3L, as the primary objective was to assess QoL among participants while they remained alive. No attempt was made to impute missing data for the carer QoL.

The following QoL instruments and measures were collected for participants:

-

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels: health utility/tariff score and health status (‘thermometer scale’): the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire comprises six questions. Questions 1–5 are 3-point scales covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The responses to these questions map onto a health state in which 1 corresponds to perfect health and 0 to death. Negative values are possible; these are interpreted as a state worse than death. Question 6 is a standalone question that asks the participant to rate their overall state of health today on a continuous scale between 0 and 10.

-

Short Form questionnaire-36 items (version 1): aggregate physical health and aggregate mental health: the SF-36 was used to derive overall physical and mental health among the participants. Both scores are scaled such that the general population has a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with higher scores indicating a better QoL.

-

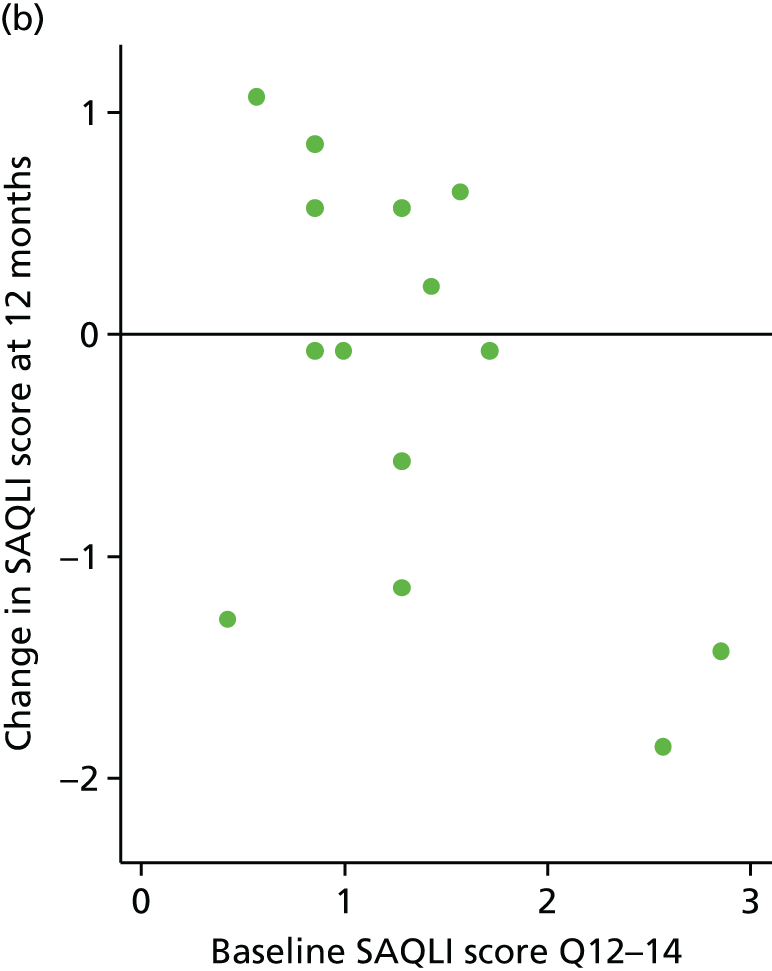

Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index questionnaire: the SAQLI is a single-domain questionnaire comprising 14 questions, each scored from 1 to 7: the SAQLI score is the average. When the questionnaire is incomplete (i.e. < 14 questions are answered), the overall score was defined as the average, provided at least half of the questions (7 of the 14) had been answered. Higher scores indicate a better QoL.

The following QoL instruments and measures were collected for carers:

-

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels: health utility/tariff score and health status (‘thermometer scale’): the questionnaire was identical to that provided to participants.

-

Caregiver Burden Inventory: the CBI is a one-domain questionnaire comprising 24 questions, each of which is scored from 0 to 4; the overall score is the total of these. Incomplete questionnaires are scaled up proportionate to the level of missing data unless 12 or fewer questions had been answered. Higher values indicate better QoL.

All questionnaires were completed at the screening visit and the at subsequent visits (2, 3, 6 and 12 months), the EQ-5D-3L (for participants and carer) was also completed at 9 months.

The analysis of EQ-5D-3L was conducted in two ways. First, an analysis of health status was conducted using data (possibly imputed) over the duration for which the participant was still alive. Second, the analysis was performed for all time points but with a score of 0 (which corresponding to a state of death) used following participant death. The two analyses answer different questions: the first is the health among survivors; and the second is the health of the population as a whole. The SF-36, SAQLI and CBI measures were analysed only for the duration in which the participant remained alive.

The EQ-5D-3L was further reported by subgroups (NIV tolerance and bulbar function). Testing for differential treatment effect between subgroups would necessitate a three-way interaction (treatment group × subgroup × time), which given the sample size would produce potentially unstable coefficients. Therefore, the focus here was on within-group summary statistics and graphical displays, separately by treatment group.

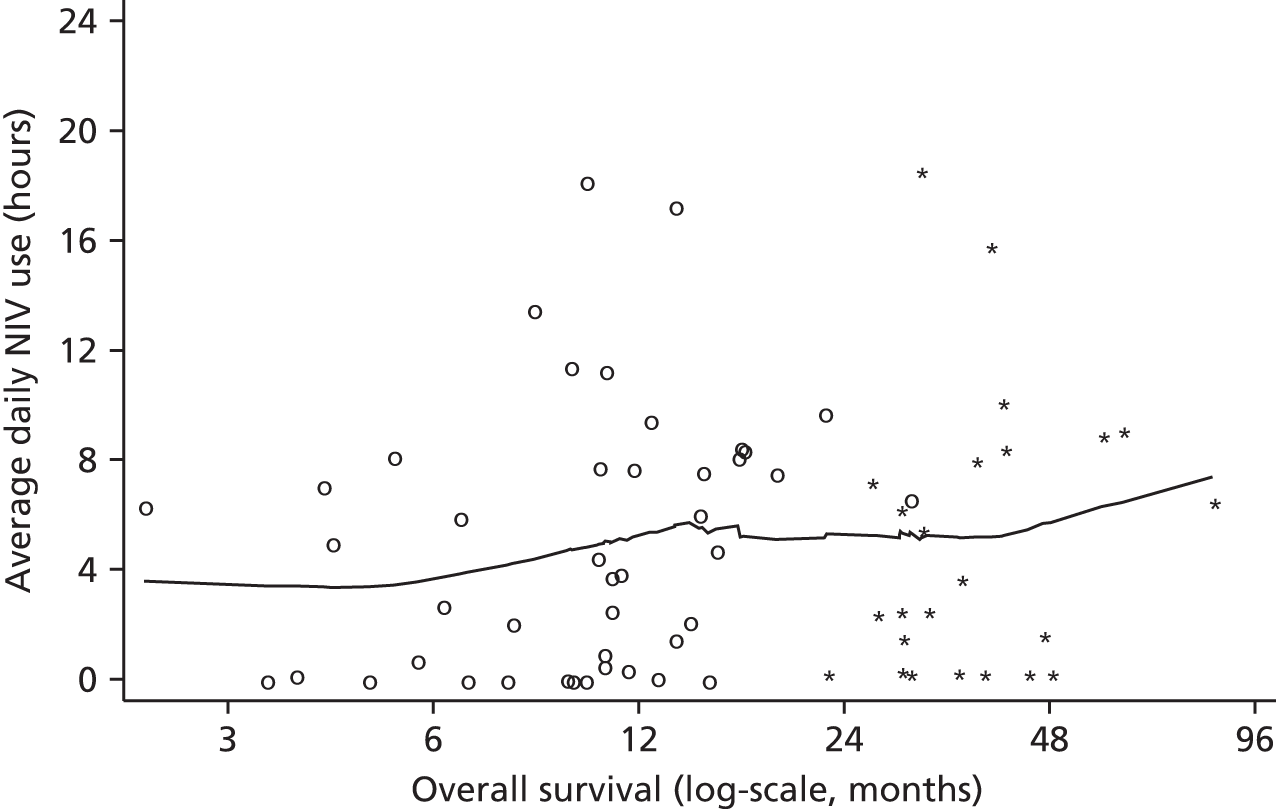

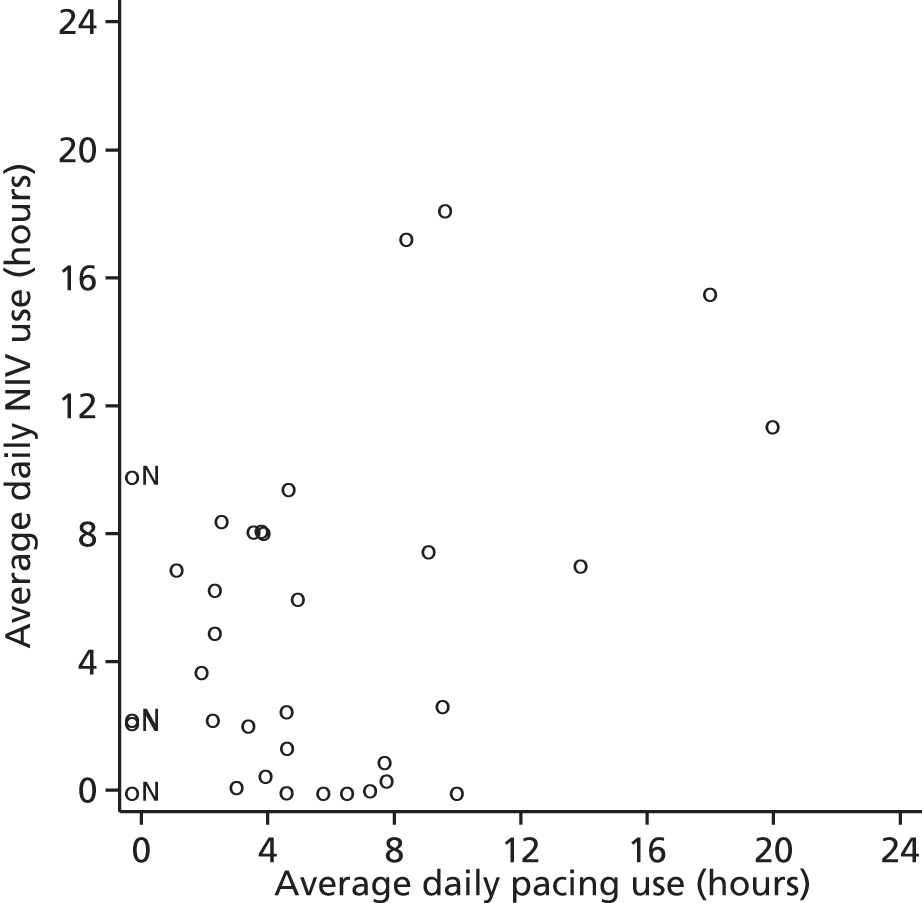

Non-invasive ventilation and diaphragm pacing usage

The original analyses of DPS and NIV usage were based primarily on diary data, augmented by participant recall at each visit when diary data were incomplete. Later on in the trial we were able to collect NIV usage data directly from the NIV machine itself, and this was the preferred source of average usage when available. Average NIV usage was defined as the average number of hours used from the date of NIV initiation onwards, and average DPS usage was defined as the average daily use from the date of procedure onwards.

The relationship between NIV and DPS usage by time point was also assessed. As the relationship between typical adherence (in hours) and survival was not expected to be linear, fractional polynomials were used to assess the fits of quadratic and other non-linear relationships. 24 Finally, usage was defined in categories. For NIV we followed the approach of Kleopa et al.,13 who characterised participants as non-adherent (typical usage < 1 hour per day), low-adherent (typical usage 1 to < 4 hours per day) and good adherence (typically ≥ 4 hours per day). Adherence to pacing was not categorised as (unlike NIV) normative data on optimal usage are not available, and also because of the small numbers within each category. Participants whose NIV or DPS adherence could not be determined based on the available data were excluded from these exploratory analyses.

Health resource use

Health resource use was summarised as the use of each of the following:

-

health service use – hospital admission, emergency department attendance, minor injury clinic or walk-in centre or general practitioner (GP)

-

respiratory device – cough assist machine, breath stacking, suction

-

health and social care – physiotherapist, occupational therapist, other

-

additional care/support – formal (e.g. home help) and informal (e.g. family/friends).

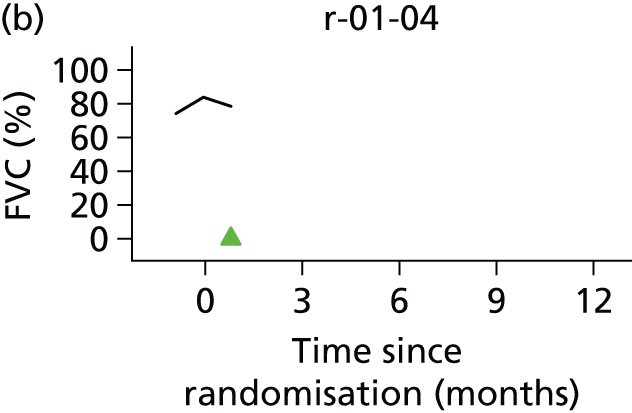

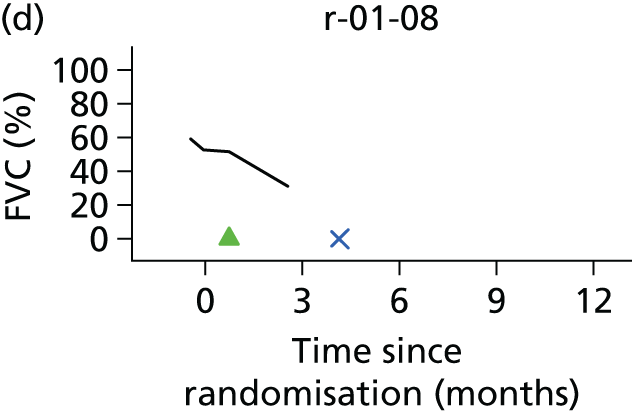

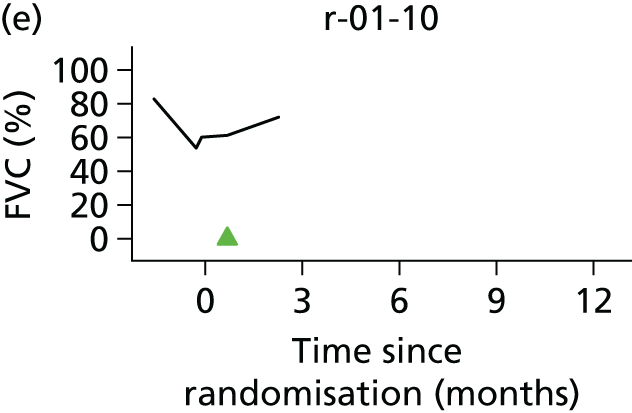

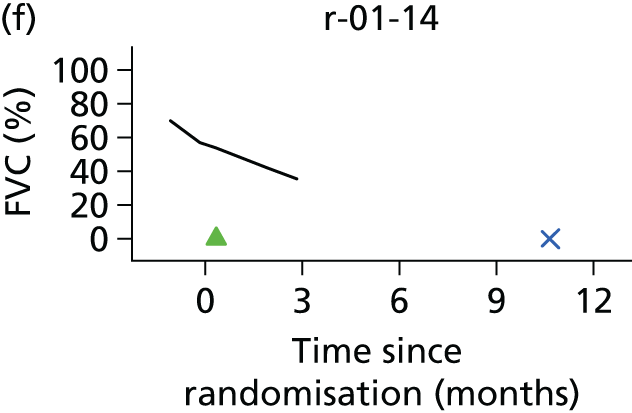

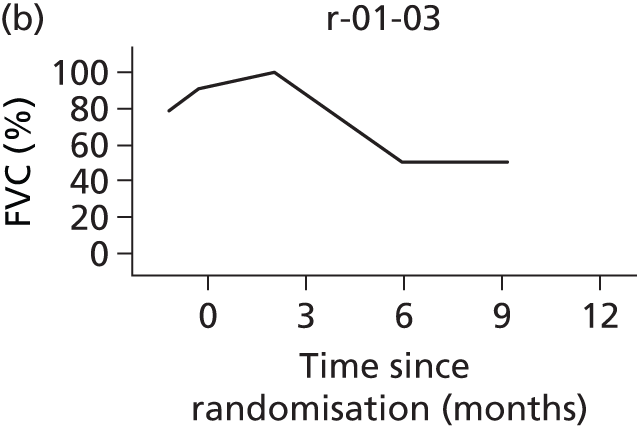

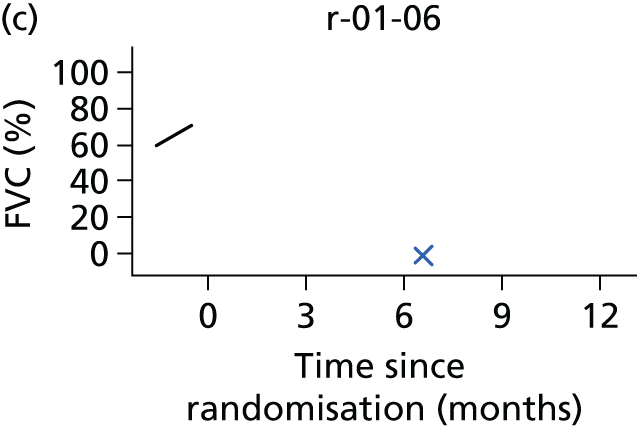

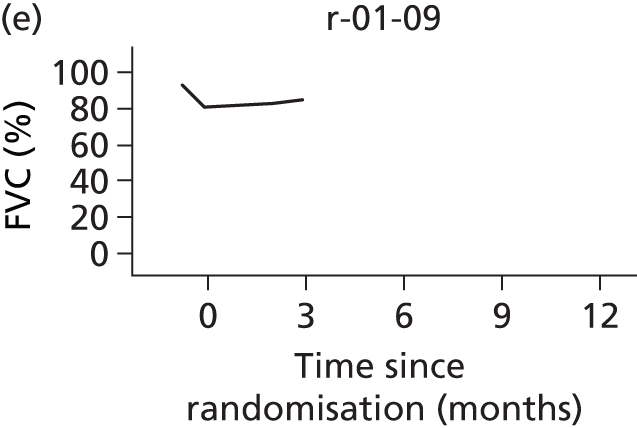

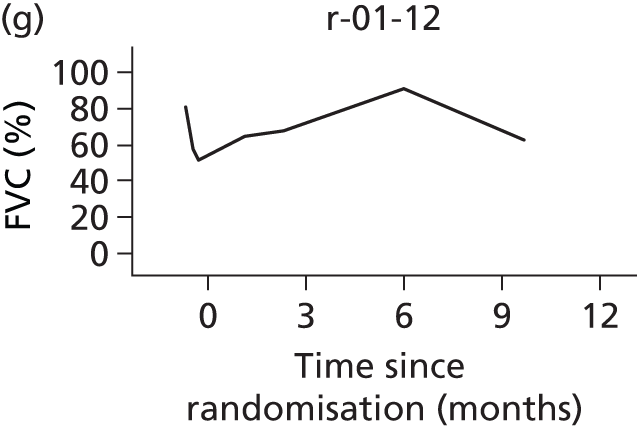

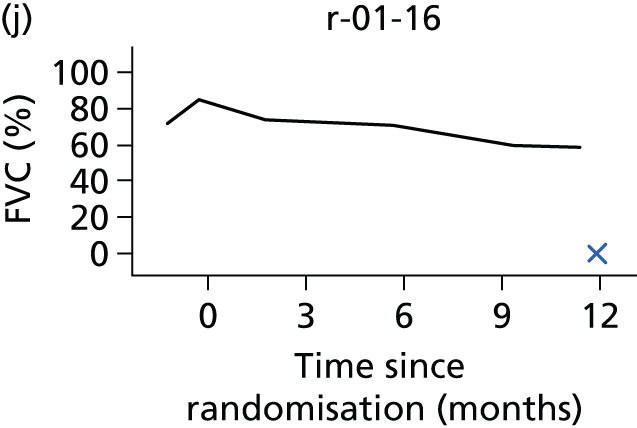

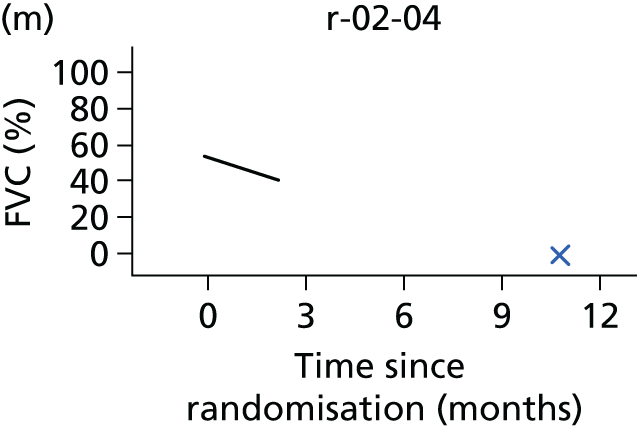

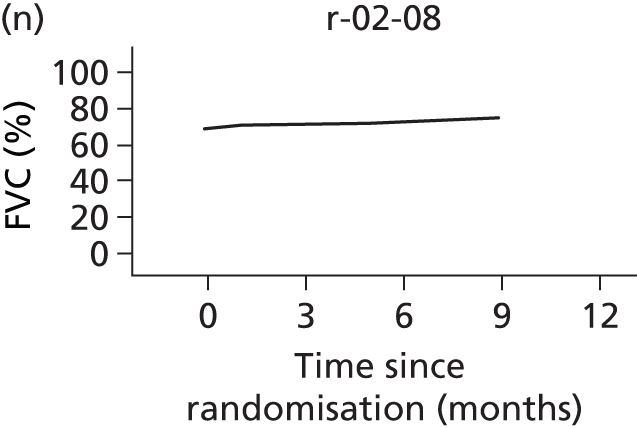

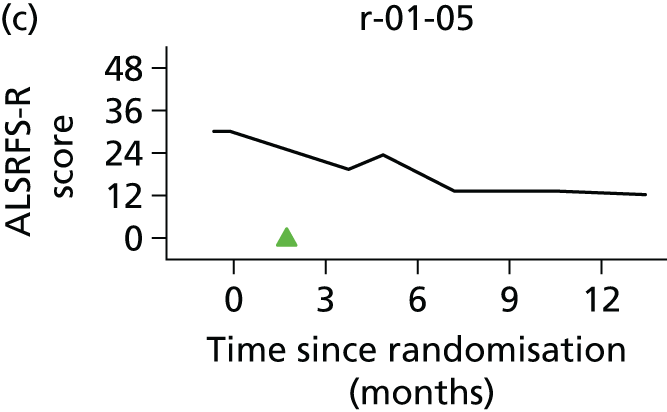

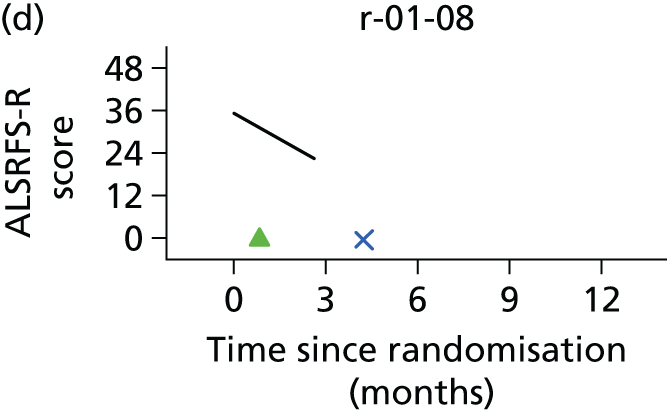

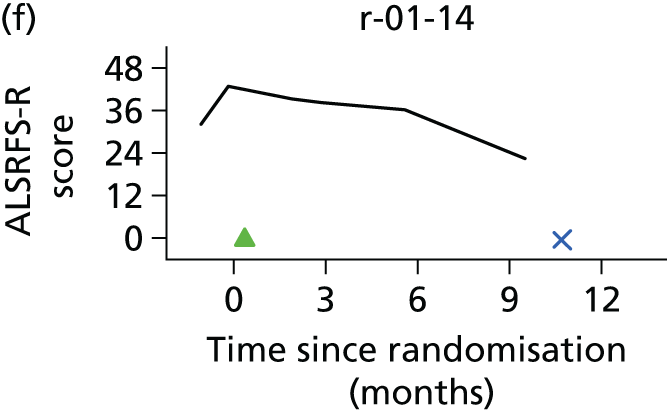

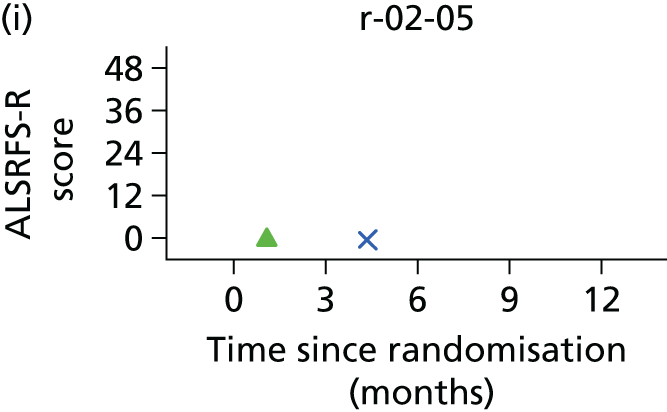

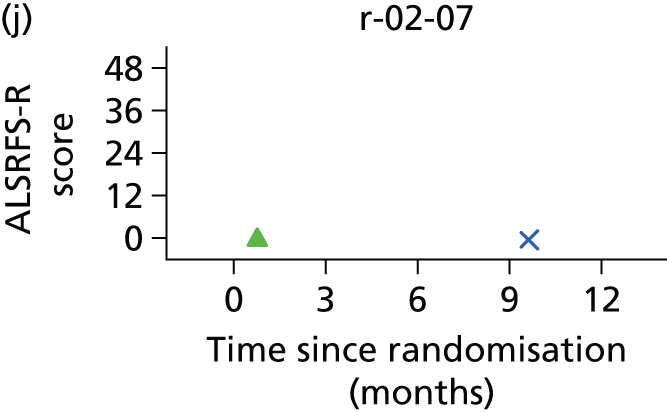

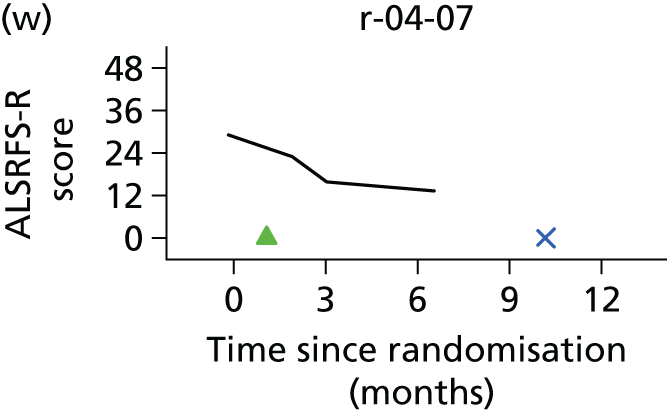

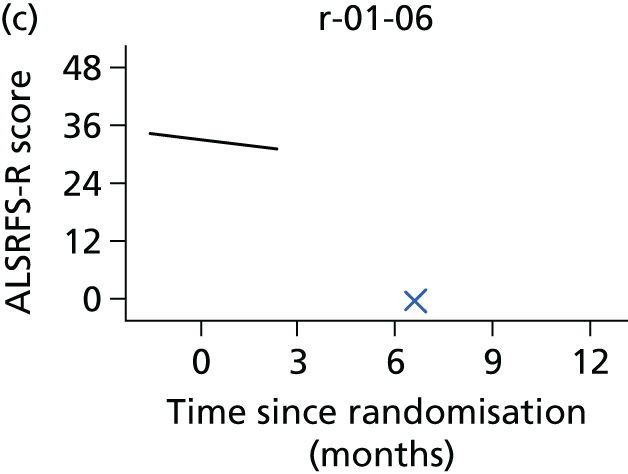

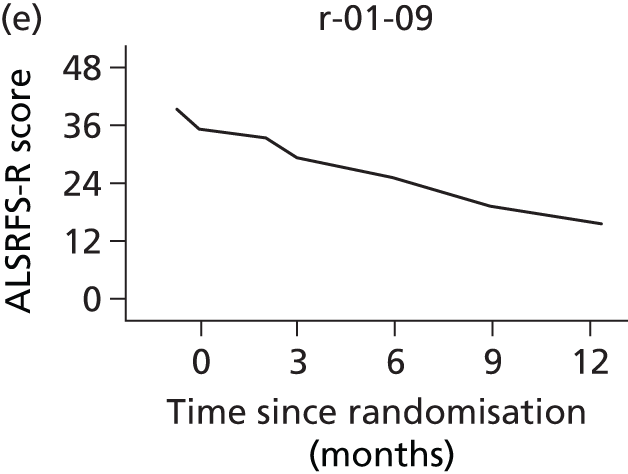

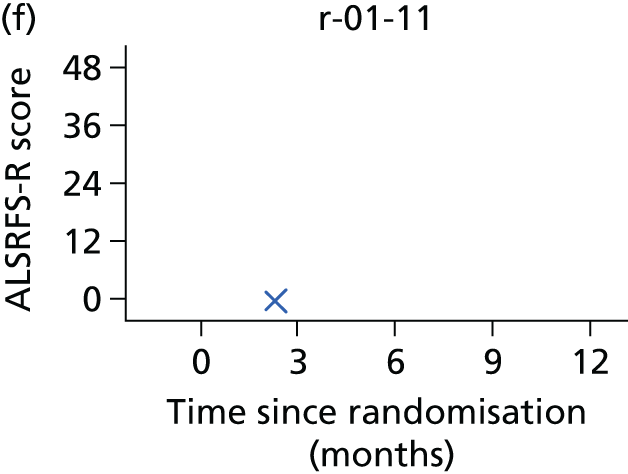

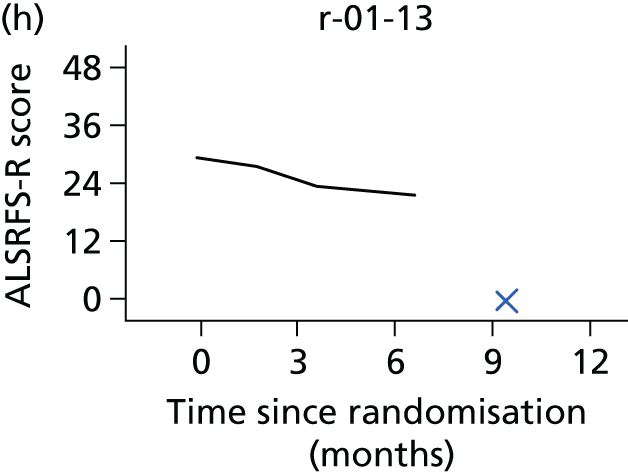

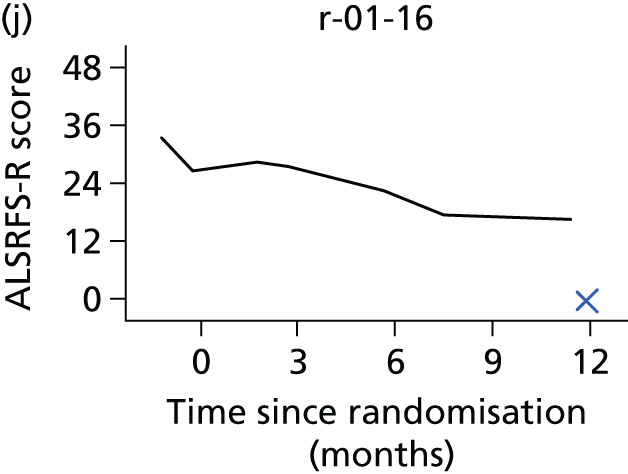

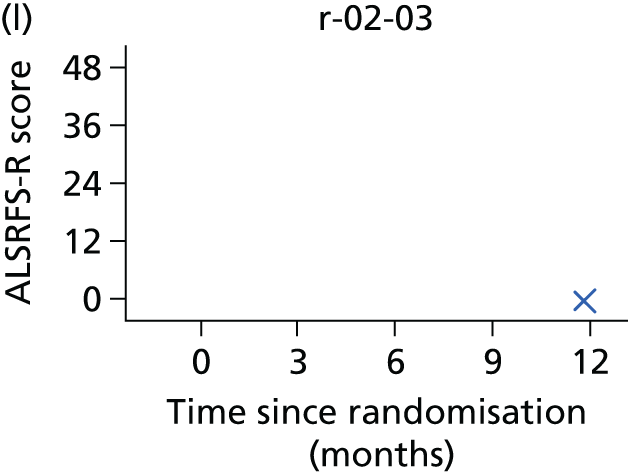

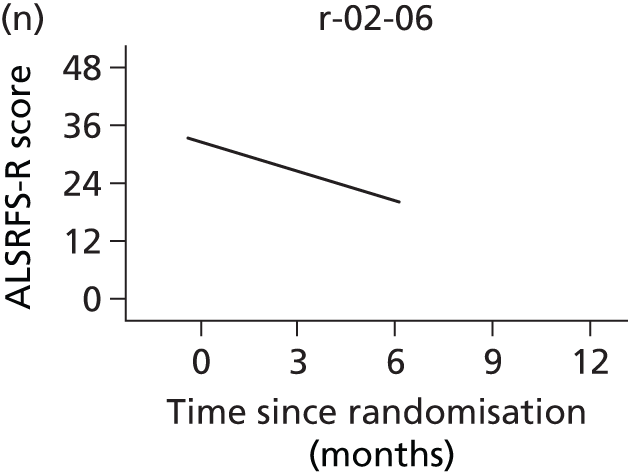

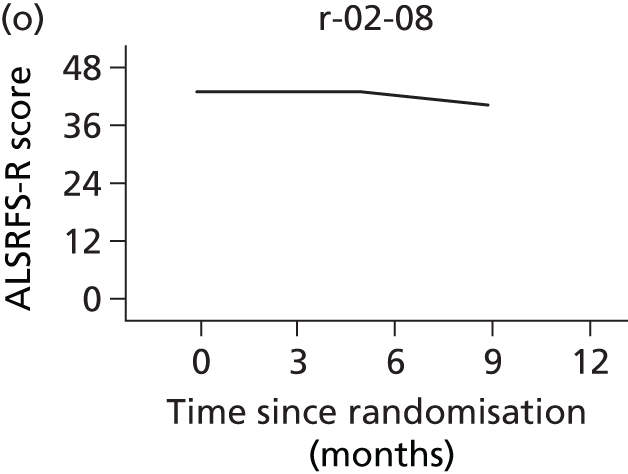

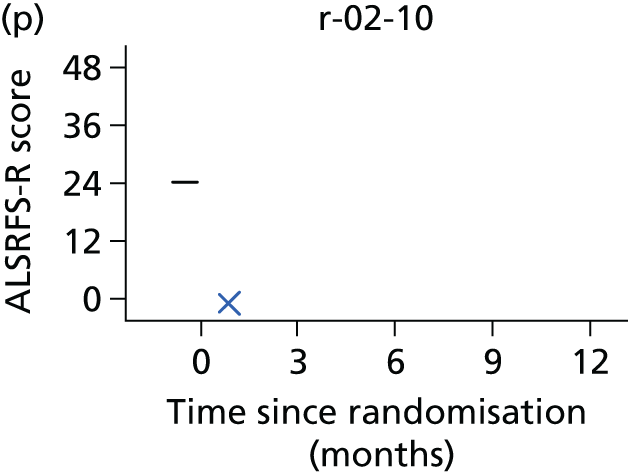

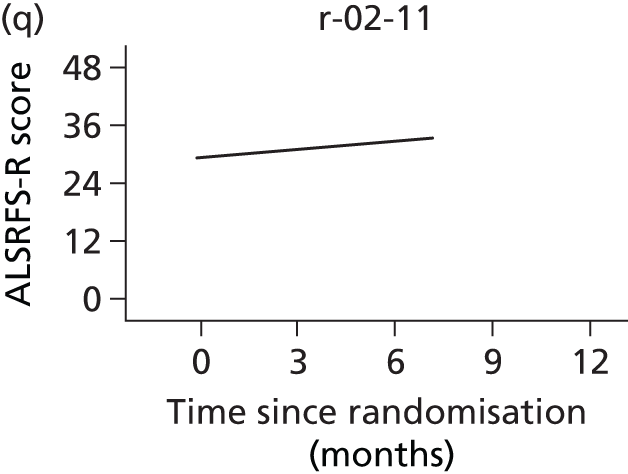

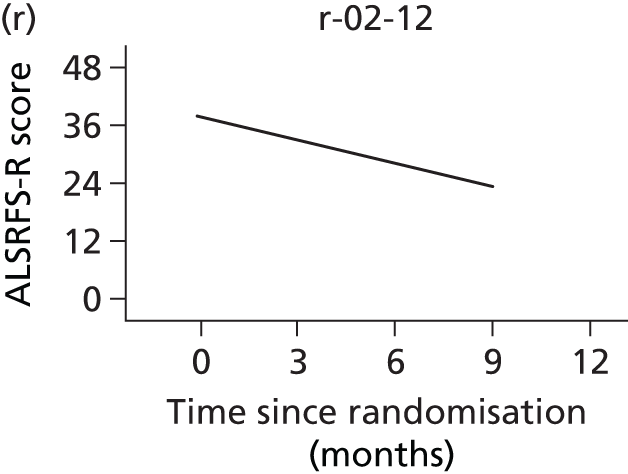

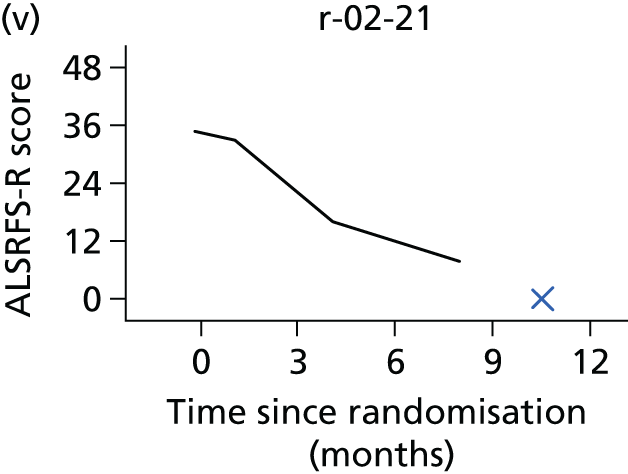

Additional outcomes: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale and respiratory function

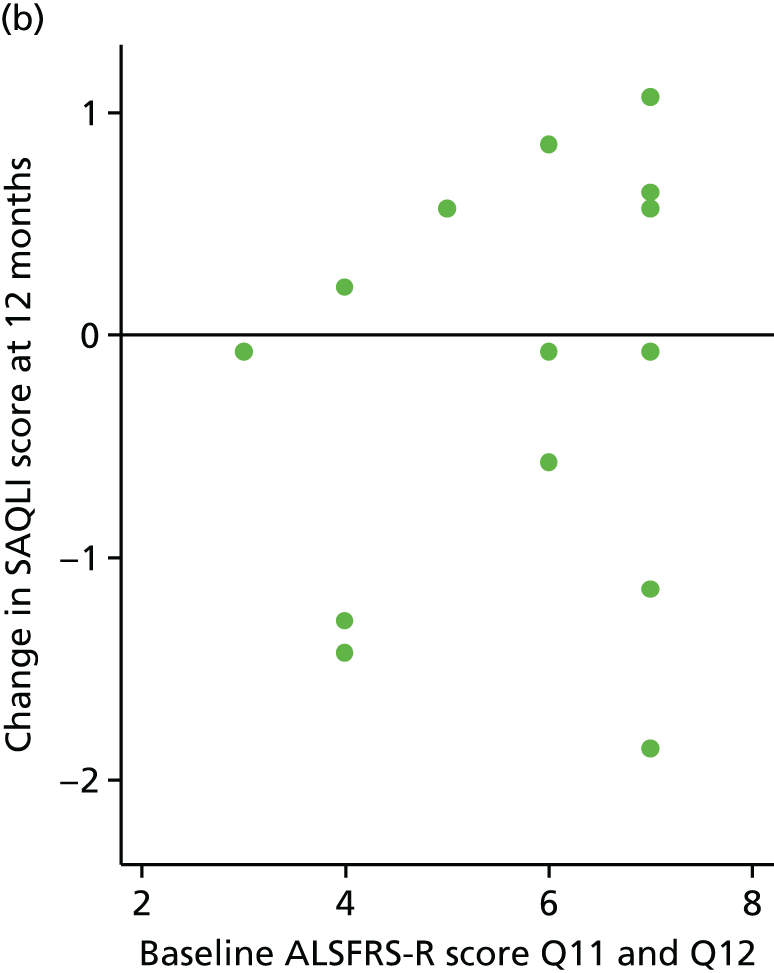

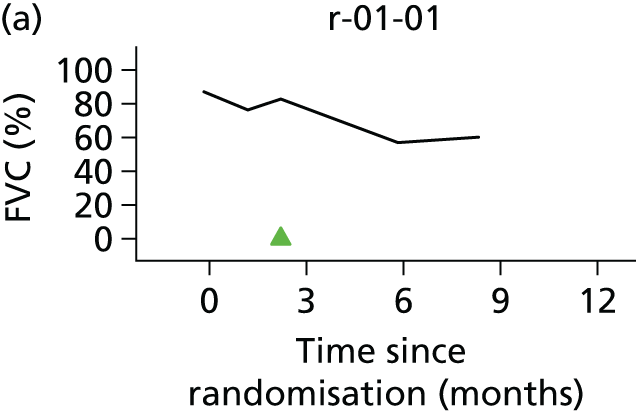

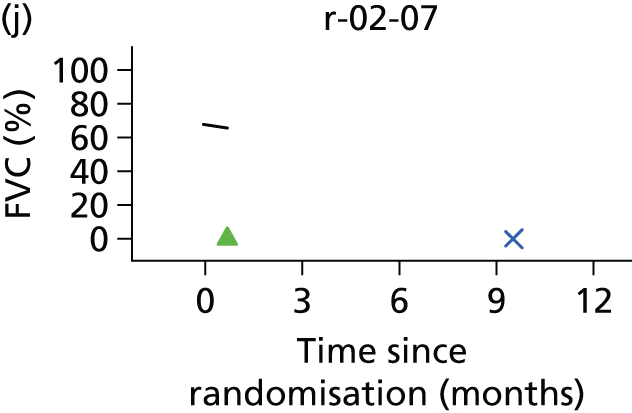

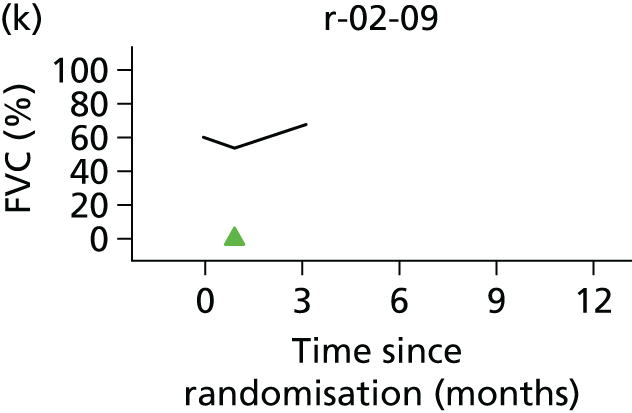

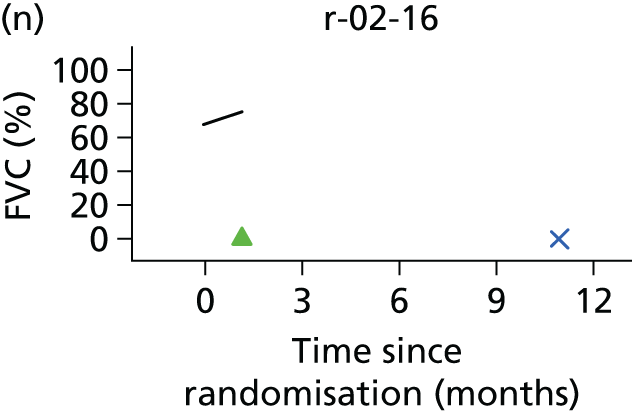

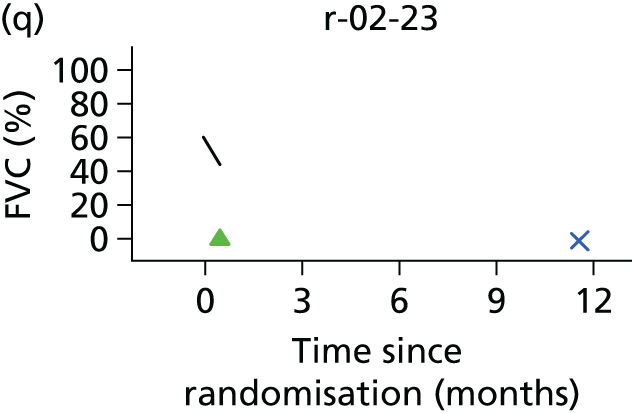

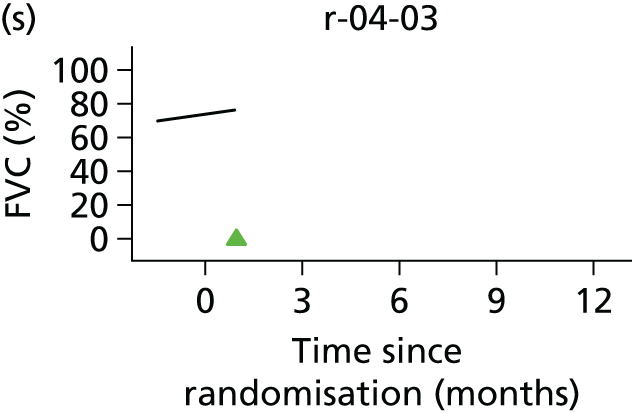

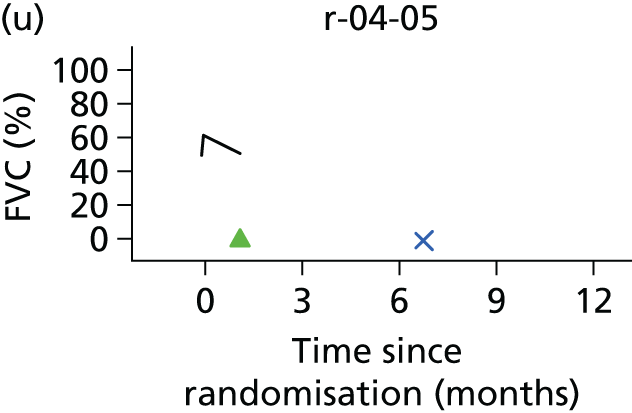

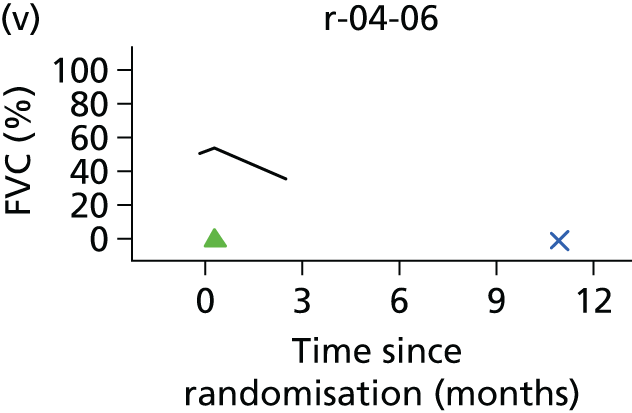

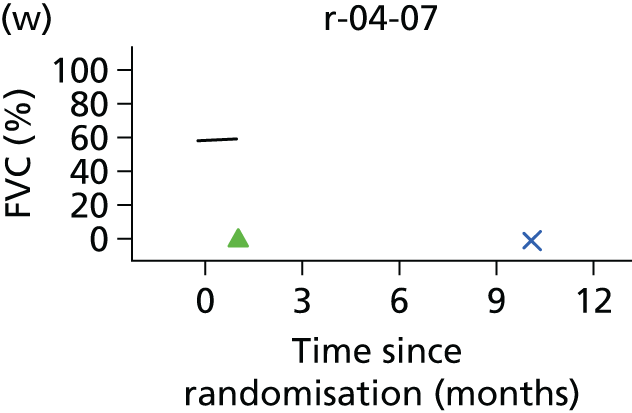

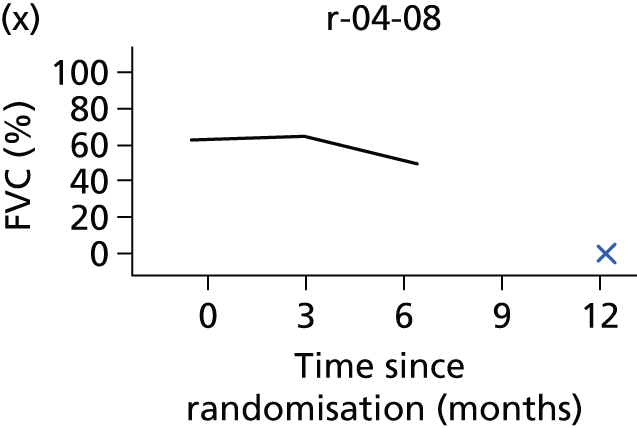

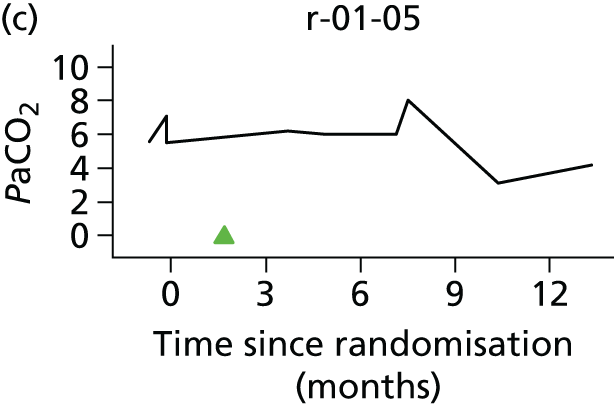

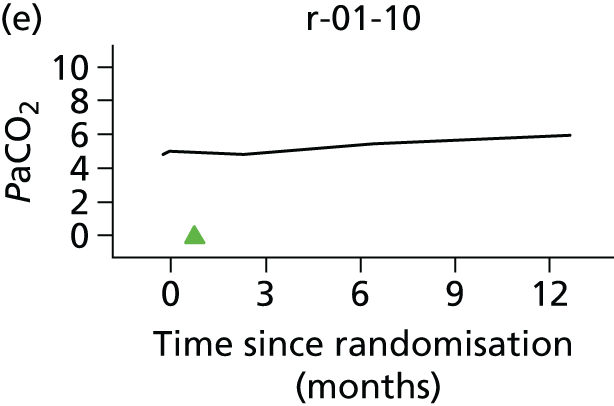

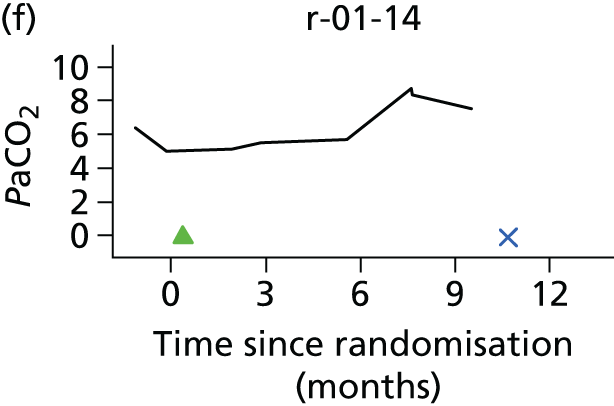

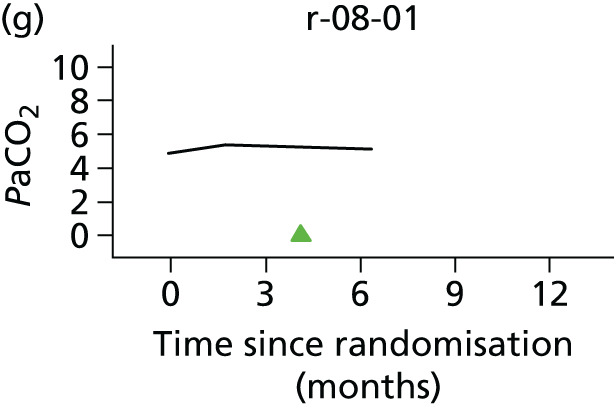

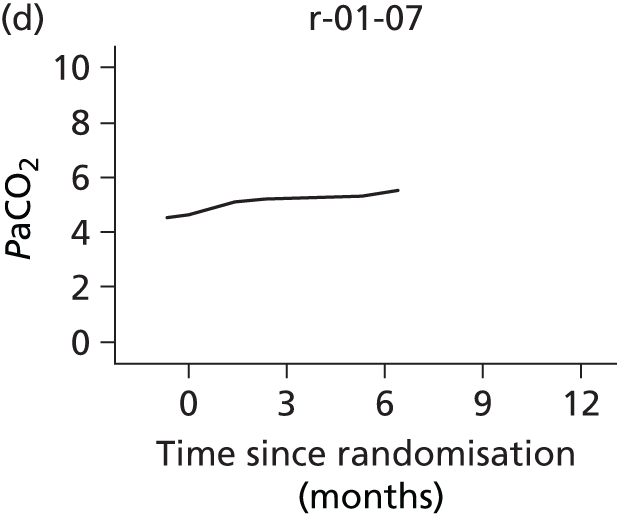

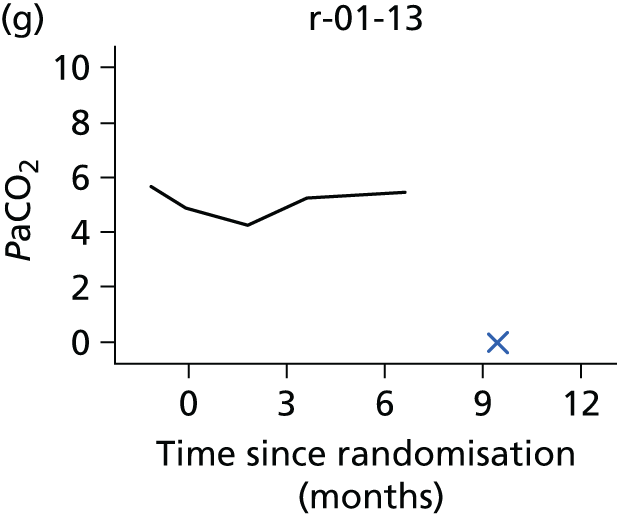

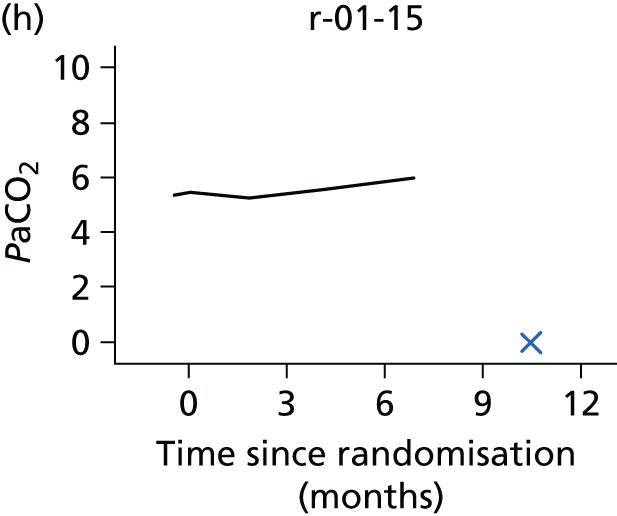

In the light of the early stopping, the TSC requested additional respiratory function data be collected to augment that which was already collected at baseline (and for DPS, immediately pre surgery). Specifically, we wished to assess (1) whether or not the groups were comparable at baseline; (2) whether or not decline among the NIV plus DPS group appeared more pronounced in the postsurgery period than in the NIV group; and (3) the trajectory across time in general to see if it offered any other clues with which to explain the findings. We were able to obtain data at some, but not all, sites for FVC, arterial carbon dioxide and ALSFRS-R.

Adverse events

Adverse events were coded by the chief investigator blind to the participant’s treatment group. AEs were summarised for each AE category and, overall, as the number and percentage of patients affected and as the number of events in total (as a patient may have more than one occurrence of the same AE). The summary was repeated for SAEs. All AEs that were adjudged related to pacing (either probably or definitely) are listed as recorded. Summaries are presented based on the randomised group (i.e. intention to treat), but any NIV plus DPS group AEs reported by non-implanted participants were highlighted.

General analysis considerations

All treatment comparisons use the NIV-only group as the reference (comparator); all statistical exploratory tests of main effects were two-tailed with α = 0.05; and all CIs were two-sided, with 95% intervals. A permutation test was used to confirm the p-value from the primary end point. 25 As interaction tests have low statistical power, consideration was given to p-values below 0.1 when testing interactions (treatment × centre and treatment × subgroups).

Analyses were by intention to treat, with preplanned secondary analyses of overall survival based on protocol adherence and NIV usage. Analyses were undertaken using Stata version 12.1 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Economic evaluation

Prior to the trial commencing, a modelling exercise was undertaken to assess the feasibility that pacing could be cost-effective at standard willingness-to-pay thresholds for end-of-life care. This modelling confirmed that pacing would be cost-effective if the trial were to demonstrate a treatment effect of similar magnitude as demonstrated by the SSPB cohort in comparison with historical data. A full cost–utility analysis was planned for this trial, but following the early termination of the trial the chief investigator and funder agreed that this was no longer necessary.

Research governance

Sponsorship

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust sponsored the trial (reference STH15625).

Oversight committees

Oversight committees were established to govern study conduct: Trial Management Group (TMG), TSC and DMEC. The trial was conducted in accordance with CTRU’s SOPs, with committees convening at appropriate intervals as dictated by both study requirements and SOPs (see Acknowledgements).

The TMG consisted of the chief (chairperson) and principal investigators (PIs) and key staff within the CTRU, and this committee met monthly via teleconference during trial recruitment and follow-up. An independent consultant neurologist chaired the TSC, other external members comprising a respiratory clinical expert, an independent statistician and two lay representative/patient and public involvement (PPI) members. All TSC members were appointed by the Health Technology Assessment programme. The DMEC consisted of an independent statistician, clinical neurologist (chairperson) and consultant neurologist. The TSC received formal recommendations from the DMEC.

Research Ethics Committee

Cambridge Central National Research Ethics Service committee (reference 11/EE/0026) approved the trial and all subsequent amendments.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

The intervention was used within its licence for intended use with appropriate Conformité Européenne mark documentation. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approval was not applicable.

Serious adverse events

Adverse events were reported in accordance with the CTRU’s AEs and SAEs SOP (PM004) and supplementary study-specific guidance approved by the sponsor.

Expected disease progression was specified in the protocol as an expected AE that did not need to be reported. Other expected AEs were listed with the requirement to report: chest infection requiring the use of antibiotics, an infection at the site where DPS was fitted and revision of the DPS.

Protocol non-compliances

Protocol non-compliances were reported in accordance with CTRU’s non-compliance SOP (PM011), but also additional study-specific guidance approved by the sponsor. Non-compliance categories were prespecified with the trial sponsor and are listed below. Major non-compliances were reported to the sponsor and immediate action taken; minor non-compliances were recorded by the CTRU and reported periodically to trial oversight committees and the sponsor.

Prespecified major non-compliances:

-

Participants found to be ineligible following randomisation.

-

Action: participant withdrawn.

-

-

Consent procedure or good clinical practice not followed correctly (e.g. patient not consented).

-

Action: participant reconsented.

-

Prespecified minor non-compliances:

-

completion of any baseline data post randomisation

-

minor errors on the consent form

-

patient did not receive allocated treatment

-

time-specific windows stated in the protocol missed (e.g. participant not randomised or informed of the arm allocated to within 7 days of screening).

Monitoring and reporting

The level and type of monitoring was informed by a risk assessment conducted during the set-up period of the study. A Data Monitoring and Management Plan and a Monitoring Plan were written and agreed with the sponsor prior to the start of trial recruitment. On-site and central data monitoring activities were completed to ensure participant safety, protocol compliance and data integrity.

Central monitoring

Data were centrally monitored based on parameters specified in the Data Monitoring and Management Plan. Checks included point of entry and post-entry validation checks and verification of data entry.

Site monitoring

The trial study manager completed a site initiation and training visit with research staff at sites prior to participant recruitment. Subsequent visits were conducted after sites had started recruitment to check the ongoing suitability of the site and to perform source data verification. Monitors checked data recorded on the case report form against medical records, discussed recruitment and issues with intervention delivery, SAEs/AEs, resolution of data queries and maintenance of the site file. A final closeout visit was performed at each site at the end of participant recruitment, scheduled once data collection was complete.

Monitoring issues were initially highlighted and discussed with sites, and remedial actions sent to the research nurse and PI. Any problem themes identified and specific issues with sites were discussed with the chief investigator and when required escalated to the sponsor, TSC and DMEC.

Reporting

The trial team were required to submit annual reports on trial progress, data completion rates, and safety and protocol compliance to the REC; and 6-monthly reports to the funding body.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

Details of substantial amendments submitted to the REC, which were important changes to trial methodology, are listed below.

November 2012: amendment 5 (minor)

Protocol version 3 specified that participant be initiated onto NIV (in both arms) within 1 to 2 weeks of randomisation. The protocol was amended to allow sites to initiate NIV as per usual clinical practice after the participants enrol onto the trial and not necessarily before DPS implantation. This distinction was necessary as, although participants were experiencing respiratory insufficiency based on their clinical assessments, clinicians wished to initiate NIV when participants were more symptomatic in line with their standard practice. The trial TSC were in agreement with this rationale. The protocol was also amended to allow DPS implantation to ideally occur within 8 weeks of randomisation based on the practical feasibility of getting participants into theatre.

June 2013: amendment 6 (substantial)

The protocol was clarified to state that blood gases were required only to assess PaCO2 levels (inclusion criteria 4e); if alternative respiratory measures were used for eligibility assessment, blood gases were not required. A member of Synapse Biomedical (manufacturers of the device) was present at each operation as stated in the protocol; however, as sites (surgeons, research nurses and clinicians) gained experience and became competent in the use of the device, it was felt appropriate that the protocol be amended. This change was also reflective of standard practice for having DPS fitted worldwide. The wording in the protocol was amended to:

A member of Synapse will attend each procedure until sites become competent with use of the device to manage patients independently. The local site PI will be responsible, after liaising with local site staff, deciding when site staff are competent in performing the intervention without any input from Synapse. The Surgeon at the site will self-certify their competency to perform the operation independently at this stage.

Although this change was approved by the REC, none of the surgeries was performed independently and a member of Synapse Biomedical was present at each operation to provide verbal assistance during the procedure. The protocol was amended to allow patients not to start pacing until the 1-week postoperative appointment to allow patients to adjust to having the device fitted in the immediate postoperative period and to ensure standardisation of the process across sites. This amendment also added both postal or e-mail options to optimise data collection when it was difficult for patients/carers to attend in person.

October 2013: amendment 7 (substantial)

The protocol was amended to allow respiratory tests up to 2 weeks pre consent to be used for eligibility assessment. This was felt an appropriate cut-off point to not overburden participants with repeat tests while still ensuring that respiratory function would not have significantly changed. As part of this amendment, the instructions on the participant diaries were changed and a newsletter template was approved to both provide more clarity on how to collect the data but also to emphasise the importance of doing so.

November 2013: amendment 8 (minor)

The previous protocol allowed self-reported NIV data to be collected from participants. As the study progressed, it was apparent that more detail was required to build a picture a more accurate picture of NIV use including NIV data collected directly from the NIV machines. The protocol was amended to allow NIV usage data from the machines to be collected.

January 2014: amendment 9 (substantial)

Following the DMEC’s recommendation to the TSC, recruitment into the trial was halted and participants randomised to DPS but who had not undergone surgical implantation were not to do so. Otherwise, participant follow-up was to continue as planned for those already in the trial.

June 2014: amendment 10 (substantial)

Researchers clarified the protocol to allow sites to initiate NIV post consent rather than post randomisation. As the screening process could take a few weeks, it was accepted that NIV could be initiated based on clinical need for participants in this period between consent and randomisation. The collection of routine respiratory and ALSFRS-R data was added to the protocol during the 12 months of participants’ involvement in the trial. This was to aid the analysis about the rate of participant deterioration over the course of the trial.

June 2014: amendment 11 (substantial)

Following unblinded data review on 23 June 2014, the DMEC recommended that participants in the pacing arm should be advised to discontinue using the DPS unless they specifically requested otherwise. All participants should remain under follow-up as scheduled. A specific SOP detailing discontinuation of DP at sites was written and submitted as part of the amendment, together with a GP letter and letters for participants still in the trial (one for each arm) to inform them of this decision and what to do next. Provision was made such that any participant wishing to continue using the DPS would be allowed to do so.

September 2014: amendment 12 (substantial)

A substantial amendment was submitted to allow central University of Sheffield researchers to interview site staff in relation to running the DiPALS trial locally. The interviews explored the experiences of the research staff recruiting participants, particularly with regard to the population (ALS participants at a later stage of disease); intervention (surgical intervention involving general anaesthesia, compliance with the intervention and standard care); and other barriers and facilitators to recruitment.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was sought throughout the trial. The Sheffield Motor Neurone Disease Research Advisory Group (SMNDRAG), an independent research advisory group, was approached and agreed to be involved at an early stage. The SMNDRAG was established in 2008 following the principles of INVOLVE. 26 The group comprises members of the public, including several carers of ALS patients, patients and other lay individuals who responded to the call for members. Research training is provided to all members of the public that volunteer for the SMNDRAG as part of their induction and ongoing support. The SMNDRAG has been a valuable part of the DiPALS trial, collaborating as part of the research team at all stages of the research process.

Proposal development

The SMNDRAG was consulted about the concept, research question and design at the proposal application stage. SMNDRAG members collaborated in writing the proposal, with particular input to the lay summary. They also suggested modifications to the protocol; an example of this was the addition of methods to capture carer experience, using both CBI and qualitative interviews.

During the trial

Following the funding decision, the SMNDRAG was involved during the development of the trial protocol and associated essential documents. Members were asked periodically to comment on key changes to participant materials when required.

Study oversight

A PPI member from the SMNDRAG was invited to attend the monthly TMGs for day-to-day running of the trial. The trial TSC had two independent members (PPI and lay person) to assist in governing trial conduct and provide advice from the patient/lay perspective.

Study dissemination

At the end of the study, the SMNDRAG members assisted in dissemination of the trial results through networks that have been established regionally and nationally, and in reviewing the plain English summary.

Chapter 3 Early stopping

Trial recruitment was stopped earlier than planned on safety grounds. The recommendations from the DMEC were accepted in full, and the subsequent changes to trial conduct and recruitment are detailed in this chapter.

Recruitment suspension

The fourth DMEC meeting was held on 16 December 2013. The ‘open’ part of the meeting discussed trial progress with both internal and external DMEC members. This was followed by a ‘closed’ meeting when the external, independent members reviewed unblinded safety data.

Following the closed meeting, the chairperson of the DMEC contacted the chief investigator on 18 December to recommend that the trial suspend recruitment temporarily based on safety grounds, citing a discrepancy in survival between the two arms. In doing so, the DMEC acknowledged that the sample size was relatively small (74 randomised, 24 deaths at the point of this recommendation), and that their decision would be reviewed as additional data became available.

The DMEC provided the following response:

The DMEC has reviewed the unblinded data on survival in the DiPALS study and the members of the Committee are unanimous in recommending that recruitment should cease as soon as practicable for reasons of safety, that monitoring of safety and survival should continue, and that the DMEC should review the updated survival data at the end of February 2014, and periodically thereafter.

Suspension of recruitment did not constitute an ‘urgent safety measure’.

In summary, the DMEC recommended that:

-

recruitment be suspended with immediate effect

-

implantation of new pacing devices be suspended

-

other aspects of the trial remain unaltered; in particular, patients in the pacing arm should be encouraged to continue using their device.

The CTRU suspended the online randomisation system on the same day to ensure that no further patients were recruited to the trial. The TMG (PIs, co-investigators, research nurses and relevant members of the CTRU) were all notified of this decision immediately (18 December 2013). All planned surgeries for the DPS were cancelled. The PIs and chief investigator discussed the key message to give to any concerned trial participants while still remaining blinded to the data.

The TSC convened on 20 December 2013 to discuss the implications of this decision and their concerns that the data had not been thoroughly scrutinised. These included the consideration of centre effects; the effect of patient withdrawal and non-implantation with the device; chance; and non-compliance with either NIV or DPS. A second unblinded report was produced and circulated to only the external, independent DMEC members that incorporated analyses to ensure all these issues were considered.

A joint TSC and DMEC meeting was held on 13 January 2014 to allow all members to present any remaining concerns before responding to the DMEC. The TSC and study team remained blinded to trial results. The DMEC upheld its initial decision by providing the following response to the additional data analyses:

The DiPALS DMEC members, having reviewed the updated unblinded report and having considered the points raised during discussion with the TSC, remain unanimous in their advice that recruitment into the DiPALS trial should cease, but that follow-up should continue. This advice is based on analysis of the primary end point (patient survival during the course of the trial). The DMEC considers that secondary analyses are unlikely to alter the safety concerns raised by the primary intention-to-treat analysis. The DMEC will be happy to consider further reports and to provide advice as required.

The TSC jointly agreed and communicated its agreement with the DMEC to suspend recruitment to the trial team late on 15 January 2014. The TSC requested that the DMEC continue to review unblinded data every 3 months to capture any further changes that would warrant discontinuation of the use of the DPS for participants in follow-up.

Informing the Research Ethics Committee

The acting trial manager informed the REC on 6 January 2014 of the initial decision to suspend recruitment, with a further notification to the REC on 15 January 2015 after the final TSC decision. A formal substantial amendment was submitted to the REC on 5 February 2014. A full account (see Recruitment suspension) was provided to the REC as part of the amendment. The sponsors of the trial (Sheffield Teaching Hospitals) approved the amendment, and sought direct assurance from the chairperson of the DMEC that participants already in the trial would continue to be followed up as per protocol, that is would continue to receive the intervention as prescribed. The CTRU informed the REC that as the central study team (chief investigator, and study and data managers) and all site study staff (PIs and research nurses) remain blinded to the data disclosed in the closed part of DMEC they would be unable to provide any further detail than that provided. The REC was asked to contact the chairperson of the DMEC for any further assurance regarding the decisions made.

As trial participants remained in follow-up and continued to receive the DPS intervention, they were not informed of the decision to halt recruitment of new participants into the trial.

Withdrawal of participants from diaphragm pacing system

The DMEC continued to review unblinded data and the next meeting was convened on 24 March 2014. The DMEC reviewed further deaths in each group and other safety and tolerability data. The DMEC requested that the chief investigator consider a pathway for formal participant withdrawal from the intervention, which would need to be ethically approved should this be required. Following this meeting there was no change in the study status.

The subsequent DMEC meeting was held on the 23 June 2014. The following recommendations were made by the DMEC after the closed session:

-

As the survival data suggest that DP poses an ongoing safety risk compared with standard care, in the interest of safety, DPS should be stopped in all participants using the approved process.

-

Participants, however, subject to consent, should continue to be followed up and data acquisition should continue until the planned end of the trial (December 2014).

The DMEC also wished to review the statistical analysis plan (see Appendix 13) prior to database lock and advised that the trial team (chief investigator, PIs and other central study staff) remain blinded to the data prior to final database lock and analysis. The DMEC advised that the study group inform the REC and discuss the withdrawal procedure with PIs and then withdraw patients as soon as practicably possible.

Formal stopping of recruitment

The recommendation to formally stop recruitment was made by the DMEC in June 2014. This time, its recommendations went further:

-

Participants in the pacing arm were to be informed of the concern and advised to cease use of their device forthwith (unless the patient and their clinician believed there were just grounds to do otherwise).

-

Trial follow-up was to continue until all participants had either died or completed the 12-month follow-up.

-

The TSC and trial team were to remain blind to the outcome data until this time.

Informing Research Ethics Committee, participants and investigators

The chief investigator and study manager drafted the following documentation to inform trial participants still in follow-up within the trial about the decision to stop pacing (see Appendices 14–17):

-

stop pacing participant letter – DPS arm

-

stop pacing participant letter – NIV arm

-

stop pacing GP letter – DPS arm

-

pacing discontinuation SOP.

A TMG meeting was held with study PIs the following day (24 June 2014) to review all drafted documents and agree the process. It is important to note that all the study team remained blinded to the data at this stage. Any modifications suggested to the process or documents were agreed at the meeting. Amended documents were submitted to the REC as part of a substantial amendment on 27 June 2014. Prior to this, the study manager sought confirmation about the nature of risk posed by the intervention; if there was an immediate risk, then urgent safety measures would be required. The DMEC confirmed that there was no evidence to suggest any immediate risk to participants in the DPS arm and, therefore, a more gradual approach was appropriate.

Research Ethics Committee approval was received on 4 July 2014. Individual research and development departments are required to approve a substantial amendment or raise no objections within 35 days of its valid receipt. Researchers did not wish to wait in order to implement this amendment and, therefore, the trial manager e-mailed, telephoned and spoke with each research and development department to approve the amendment to avert any delays in its implementation. The trial manager informed each PI and research nurse as soon as local approval was received. The chief investigator asked site PIs to use the approved documentation and process to directly inform participants of the study status and answer any questions that arose. The study manager asked to be notified of the status of each participant in the DPS arm after the conversation with the participant via the return of the participant discontinuation checklist.

The Motor Neurone Disease Association was informed of the advice to stop pacing. This was communicated to motor neurone disease patients via their website. The DiPALS trial website was updated to inform potential participants that the study was no longer in recruitment.

Chapter 4 Trial results

Recruitment and participant flow

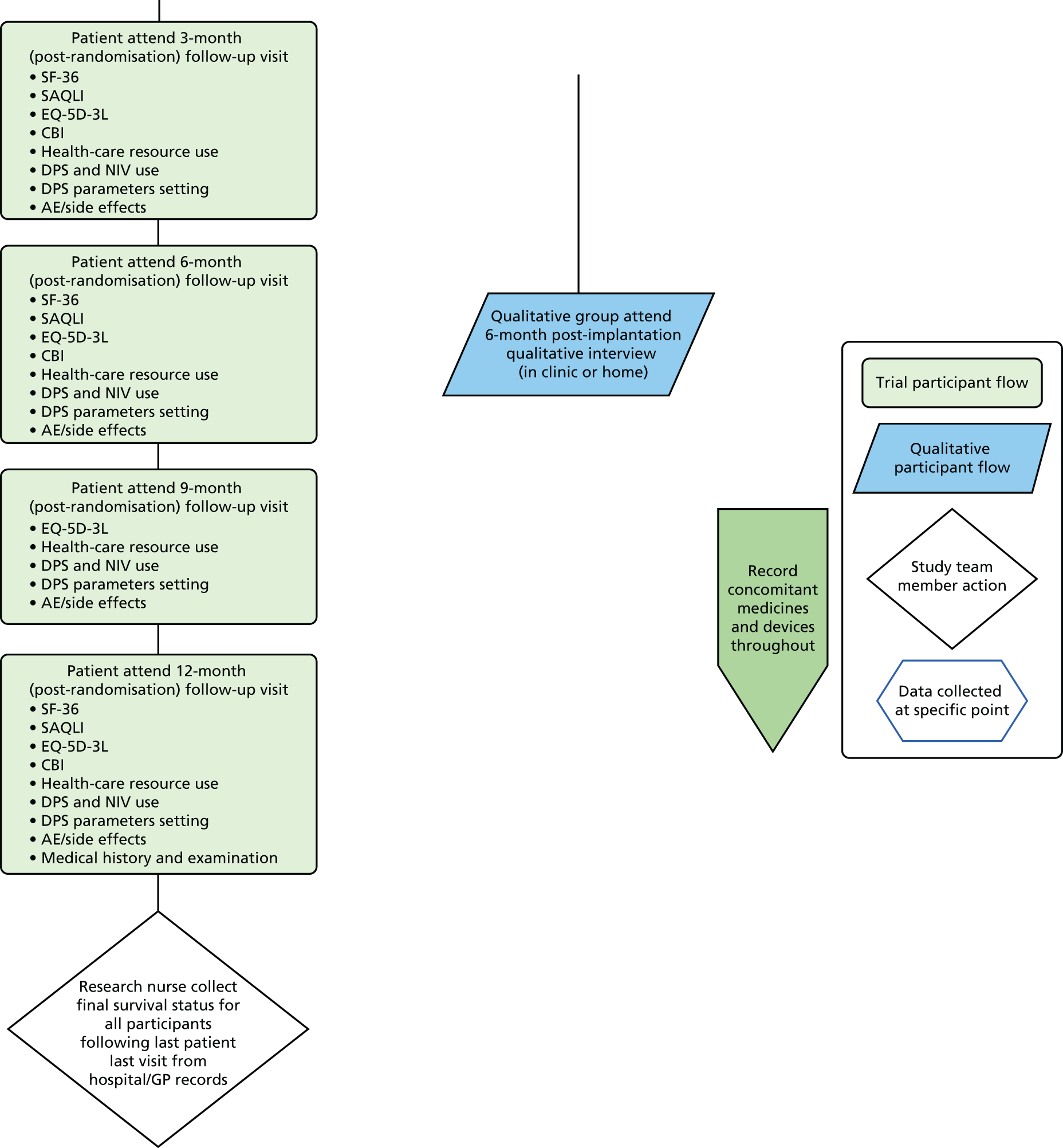

In total, 74 participants (37 per arm) were randomised between 5 December 2011 and 18 December 2013, when the DMEC recommended that recruitment cease. Study follow-up concluded in December 2014, by which time 47 patients had died; one patient was last followed up in August 2014, with the remaining 26 known to be alive in December 2014 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Trial profile (CONSORT diagram). MND, motor neurone disease; NK, not known.

Baseline data

A total of 74 participants were allocated (37 to each arm). The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. Participants were predominantly male with sporadic (usually limb) onset and with mild bulbar impairment (74%). Despite age being included as a minimisation factor, the NIV plus DPS arm was slightly older (average 60 vs. 54 years), a consequence of most participants falling into the middle category of age 40–79 years; this imbalance was addressed in all comparisons, however, as all prespecified analyses included age as a covariate (continuous, rather than the categorisation used for the purpose of minimisation).

| Variable | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| NIV plus DPS (N = 37) | NIV (N = 37) | |

| Centre, n (%) | ||

| Leeds | 2 (5) | 5 (14) |

| London | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Manchester | 6 (16) | 4 (11) |

| Newcastle | 6 (16) | 2 (5) |

| Oxford | 11 (30) | 13 (35) |

| Plymouth | 3 (8) | 3 (8) |

| Sheffield | 8 (22) | 9 (24) |

| Age (years)a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 60 (9.7) | 54 (12.0) |

| Median (range) | 61 (34–83) | 53 (23–76) |

| Trial subgroup, n (%) | ||

| < 40 years | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| 40–79 years | 35 (95) | 34 (92) |

| ≥ 80 years | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Sex, n (%)a | ||

| Male | 29 (78) | 29 (78) |

| Female | 8 (22) | 8 (22) |

| Bulbar score (%)a | ||

| Mild (9–12) | 26 (70) | 29 (78) |

| Moderate (5–8) | 8 (22) | 6 (16) |

| Severe (0–4) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) |

| FVC (%)a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 66.1 (12.3) | 64.6 (12.1) |

| Median (range) | 62.5 (51–105) | 62.5 (42–97) |

| Trial subgroup, n (%) | ||

| 50–59% | 13 (35) | 16 (43) |

| 60–69% | 12 (32) | 10 (27) |

| ≥ 70% | 11 (30) | 10 (27) |

| Missingb | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| ALS onset type, n (%) | ||

| Sporadic | 34 (92) | 35 (95) |

| Familial | 3 (8) | 2 (5) |

| ALS onset site, n (%) | ||

| Limb | 26 (70) | 28 (76) |

| Bulbar | 10 (27) | 6 (16) |

| Respiratory | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Mixed | 0 | 2 (5) |

| ALS diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Clinically definite | 26 (70) | 22 (59) |

| Clinically probable | 7 (19) | 9 (24) |

| Clinically probable, laboratory supported | 4 (11) | 6 (16) |

| Time from symptom onset to randomisation (months) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 22 (18) | 22 (15) |

| Median (range) | 17 (4–89) | 18 (3–66) |

| Trial subgroup, n (%) | ||

| < 12 months | 12 (32) | 14 (38) |

| 12–24 months | 14 (38) | 12 (32) |

| ≥ 24 months | 11 (30) | 11 (30) |

| ALSFRS-R score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.9 (7.4) | 33.7 (6.5) |

| Median (range) | 33 (21–46) | 35 (21–46) |

| Rate of ALSFRS-R score decline/monthc | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.99 (0.68) | 0.94 (0.71) |

| Median (range) | 0.80 (0.02–2.92) | 0.92 (0.20–3.72) |

Primary outcome (overall survival)

Primary overall survival analyses

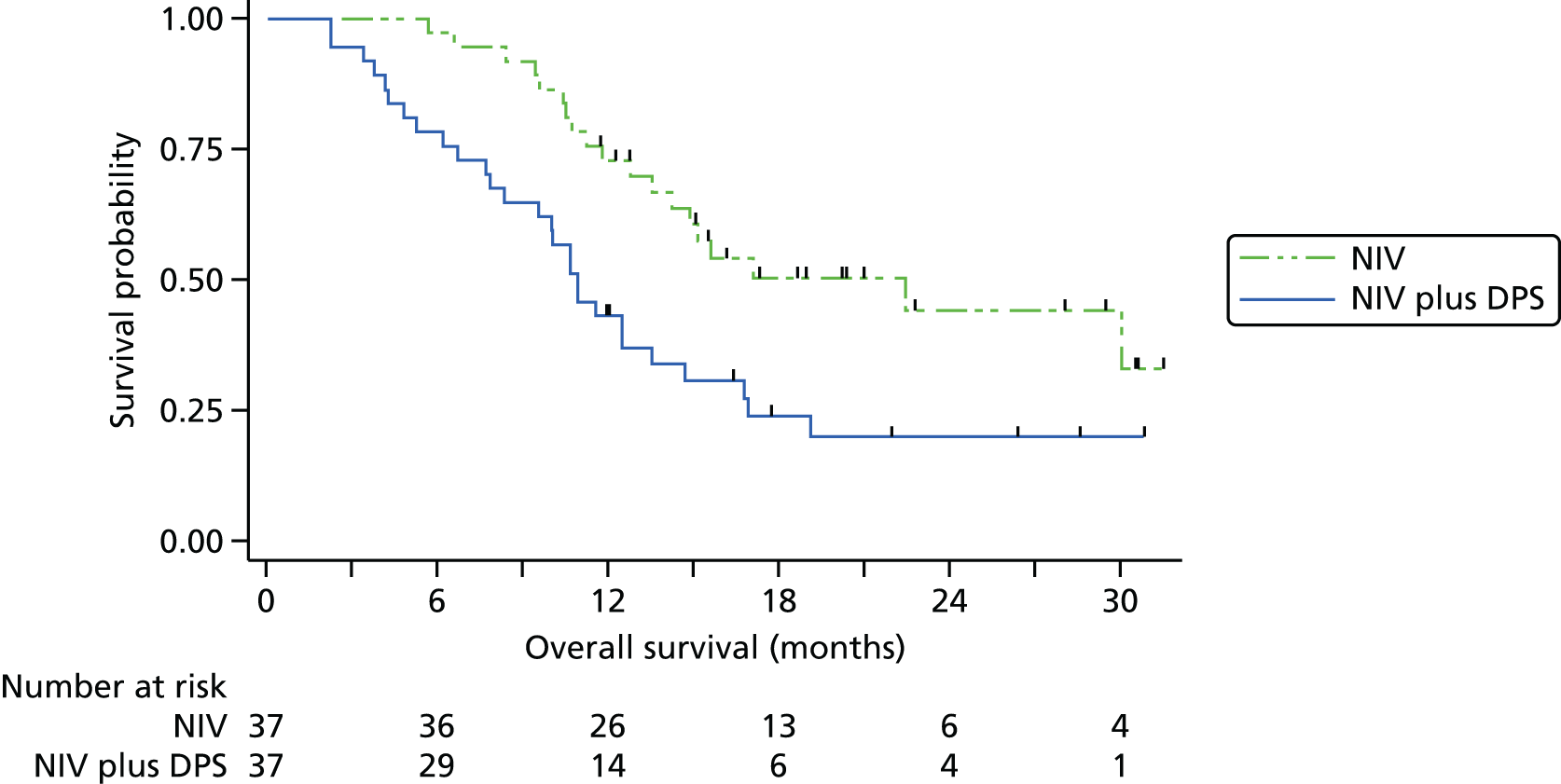

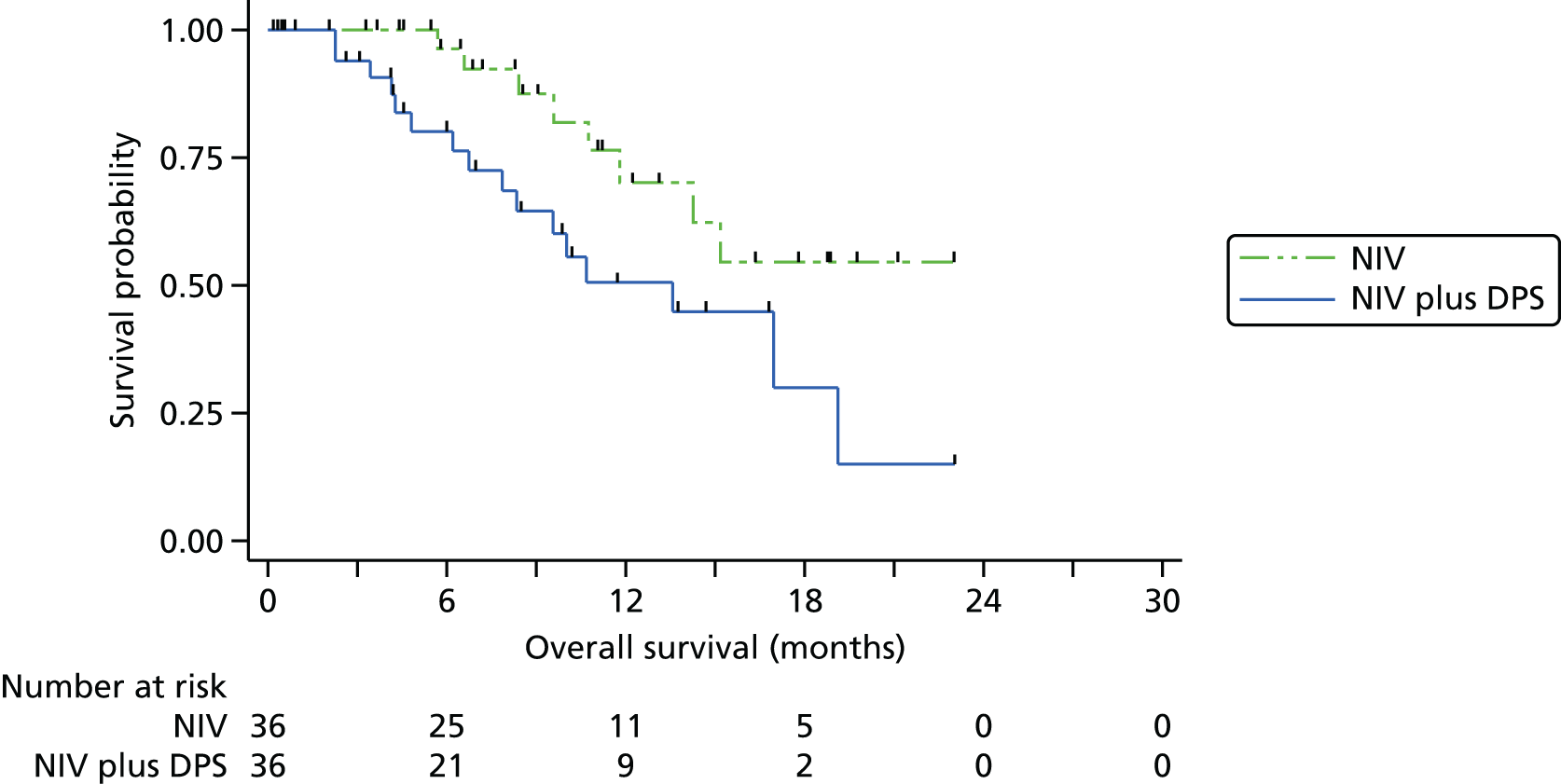

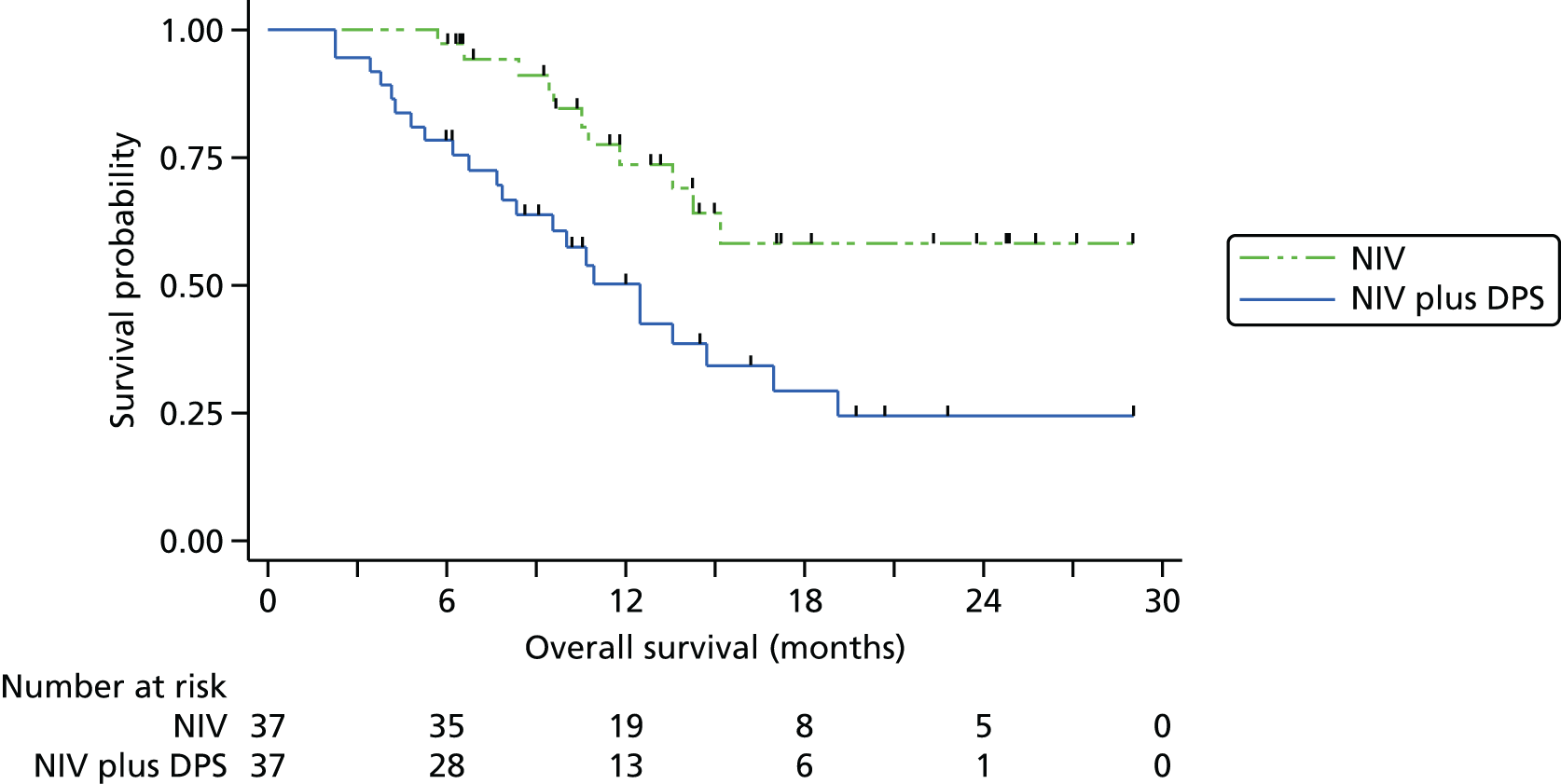

The Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival is presented in Figure 3. The median survival was 11.0 months (95% CI 8.3 to 13.6 months) in the pacing arm and 22.5 months in the control arm. As the upper bound of the Kaplan–Meier survival curve never reached 50%, the upper limit of the 95% CI is unknown: the lower bound is 13.6 months. The HR (adjusting for minimisation covariates) was 2.27 (95% CI 1.22 to 4.25; p = 0.01), indicating the risk of death at any point in time was higher in the NIV plus pacing arm than in the control arm. A permutation test approach, as recommended by Scott et al. ,25 produced a p-value of 0.013 confirming the statistical significance of this difference.

FIGURE 3.

Overall survival.

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the consistency of findings to different covariates and to different models. First, we allowed for between-site differences via a stratified log-rank test in which the strata comprised the seven hospitals. The findings from doing this were not materially changed. There was, however, evidence of non-proportionality of the hazards of the two groups, as detected by the Grambsch–Therneau test20 for the correlation between residuals and time (ρ = –0.31; p = 0.03). In other words, although overall NIV plus DPS was associated with a twofold increase in hazard, the impact was greater in early months and smaller among longer-term survivors. Two alternative modelling approaches were fitted: first, an accelerated failure time model (in which the time, rather than hazard, is modelled); and, second, a non-parametric restricted mean survival time, in which the difference in mean survival is estimated based on the area between the Kaplan–Meier curves. 22 The findings from the sensitivity analyses analysis are presented in Table 3. Overall, the magnitude of the survival deficit in the NIV plus DPS group was remarkably consistent, with survivorship always significantly lower in the NIV plus DPS group.

| Method of analysis | Trial arm | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIV plus DPS | NIV | |||

| Cox proportional hazards regression | Deaths per person-year follow-up | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |