Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/34/03. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Debi Bhattacharya reports funding from the University of East Anglia throughout the duration of the study. Clare F Aldus reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from the University of East Anglia. Garry Barton, Sathon Boonyaprapa, Richard Holland, Christina Jerosch-Herold, Charlotte Salter, Lee Shepstone, Steven Waton and David Wright report grants and personal fees from the University of East Anglia. Christine Bond reports non-financial support from the University of Aberdeen. Christine Walton reports grants and personal fees from NHS Anglia Commissioning Support Unit.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Bhattacharya et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Approximately 50% of patients do not take their prescribed medication as recommended by the prescriber,1 with researchers most commonly describing such behaviours as either unintentional or intentional. Unintentional non-adherence is not the result of any conscious decision by patients not to take their medication, and has been associated with impaired cognitive function and practical problems such as difficulty accessing medication from its packaging or swallowing the dosage form, while intentional non-adherence, a conscious decision to deviate from their prescribed regimen, is associated with patients’ beliefs and their experience of the medicine. As these definitions seem superficially distinct, it is argued that unintentional reasons, such as forgetting to take medication, may actually represent a subconscious decision to not prioritise medication taking and, therefore, is actually largely intentional in its origins. While intentional non-adherence is addressed through effective communication, psychological interventions and selecting therapies which are more patient acceptable, unintentional non-adherence requires interventions which act as memory cues or overcome physical barriers to medicine taking.

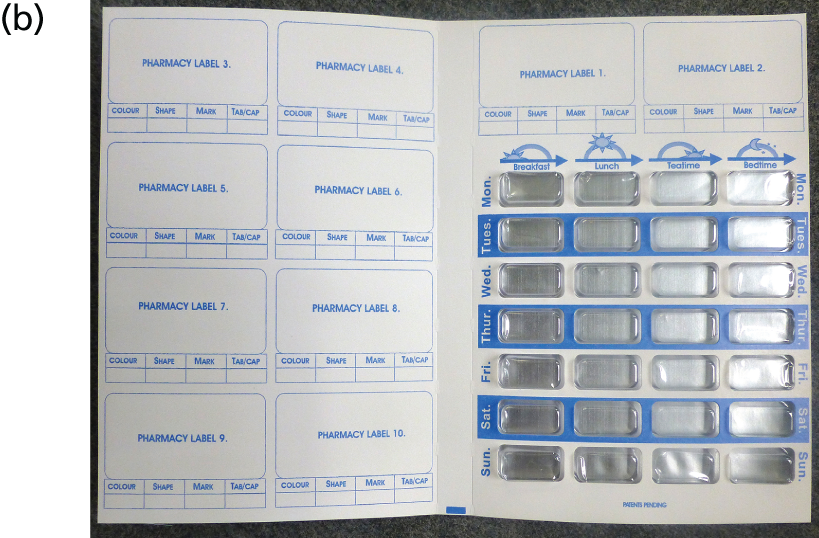

Medication organisation devices (MODs) are medical devices intended to address unintentional non-adherence1–3 by enabling patients to identify whether they have or have not taken their medicines and by enhancing the accessibility of the medicine. MODs are known by a wide range of terms, including monitored dosage system, multicompartment compliance aid and domiciliary dosage system (DDS), but all have similar design features. MODs comprise either a rigid pill box or semi-rigid blister pack, divided into days of the week, with several compartments per day to allow for the different timing of doses. Medicines are placed in the appropriate locations in the box or pack, which are clearly empty once the medicine has been removed. Figure 1 provides examples of MODs commonly used within the NHS in the UK. The Nomad Clear™ (Surgichem Ltd, Cheshire, UK) device has the 7 days of the week marked across the top with different dosage times down the left-hand side and therefore provides 1 week’s medication at a time. The Venalink™ (Venalink, Flintshire, UK) system, by contrast, provides the days of the week down the left-hand side and dosage times across the top.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of MODs commonly used in the UK. (a) Nomad Clear and Nomad Clear XL; and (b) Venalink.

It has been estimated that 100,000 people are currently using MODs in the UK3 to reduce unintentional non-adherence and, therefore, MODs potentially play an important role in ensuring that patients receive the full benefit from their medication. Non-adherence to prescribed therapy is one of the factors believed to contribute to decisions to transfer patients from their own homes into care homes. Consequently, MODs may additionally play a pivotal role in maintaining patients in their own home and prolonging their autonomy, which is in accordance with government targets to promote independence. 4

The national pharmacy contract provides for MODs supplied in accordance with the Equality Act. 5 In such cases, provision of medicines in MODs is deemed a reasonable adjustment for those individuals who, as a result of disability, are unable to safely take their medicines without such a device. Great variation in NHS funding of MOD provision exists, and in some localities MOD provision by pharmacists is commissioned using NHS funds, whereas in other localities where there are no such arrangements they are provided at the expense of the patient.

Despite the current disparity, existing evidence is insufficient to underpin the decision-making to either discontinue NHS funding of MODs or provide clear guidance to practitioners regarding their initiation. 6,7 The few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that have been conducted have been limited by small sample sizes or insufficient data to characterise the sample population or have focused on a specific disease area. It has been estimated that £23M is being spent annually on a non-evidence-based intervention. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, therefore, requested that a study be conducted to identify the most appropriate methodological approach to test the effect of MODs compared with usual packaging in older patients.

The absence of adequate large-scale studies means that there is a need to identify the most appropriate participants, to characterise participants, to select the most appropriate MOD and to define standard care and the intervention itself, while identifying and measuring the right outcomes, optimising recruitment and estimating variation in the primary outcome measure to power a definitive study. These different issues are, therefore, considered in turn.

Participant identification

A key consideration is to target patients who are unintentionally non-adherent. Considerable research has been conducted in order to establish the predictors of non-adherence and, while there is still much uncertainty, a positive association between magnitude of non-adherence and regimen complexity has been frequently reported. 8–12 Research suggests that older patients are prescribed an average of three regular medications; thus, a large proportion of the older population has at least one risk factor for non-adherence. It is, therefore, patients prescribed multiple medications who are at the greatest risk of non-adherence and to whom MODs are most frequently provided (Sharma S, Malik W, Shah A, Desborough J, Bhattacharya D, University of East Anglia, 2007, unpublished data).

Intentional non-adherence is associated with numerous factors such as beliefs about medicines13 and the quality of the patient–prescriber relationship. 14–16 The proportion of non-adherence that is attributable to intentional factors varies, usually ranging from 4% to 17%,15,17 but with figures as high as 37% reported in older people. 18 Owing to the high proportion of patients whose non-adherence is intentional, it is important that this behaviour is excluded from any trial involving MODs which is designed to address unintentional non-adherence. Furthermore, the provision of medicines in single compartments of an MOD makes differentiating between medications challenging for the patient, thereby reducing the ability of patients to choose which medications to take and not take. Such a situation may result in intentionally non-adherent patients omitting to take all medication stored in a MOD compartment. 15

Categorising non-adherence as intentional or unintentional can only be achieved by establishing the motivation for the deviation. A number of self-report tools have been developed to identify intentional non-adherence.

Therefore, this study proposed to identify the prevalence of intentional non-adherence in older people who are receiving polypharmacy regimes using a range of self-report tools, with a view to identifying a suitable tool and cut-off threshold to be used to exclude intentionally non-adherent participants from a definitive study.

Participant characterisation

Once an unintentionally non-adherent patient has been identified, reasons for his or her non-adherence need to be considered to ensure that these are taken into account when choosing a MOD and are also assessed as part of any evaluation to allow for confounding. 19 The most commonly reported factors that impair patients’ ability to adhere to their prescribed regimen are deficits of cognitive function, manual dexterity and visual acuity. 6 Although no clear relationship has been demonstrated between adherence and age, the prevalence of factors known to contribute to unintentional non-adherence increases as individuals age. An Australian survey of older patients (n = 120), with a mean age of 81.8 years, characterised participants in terms of cognitive function and visual acuity and then assessed ability to open a variety of commercially produced medication packaging. It was reported that 78.3% of participants were unable to open one or more of the medication packages in order to access the medication, with inability to access medication significantly associated with lower cognitive function and manual dexterity. 20 For trial purposes, the use of measures that can be replicated is necessary and, therefore, when available, the use of validated measures to test cognitive and functional ability is desirable.

Medication organisation device selection

In the absence of guidance, MODs are currently initiated to a wide range of patients with varying degrees of confusion. A survey of 10 purposively sampled pharmacists reported that eight would select a MOD without involving the patient in the decision-making and all pharmacists had a preferred MOD, thus suggesting that patient needs would not be the primary driver of MOD selection. 3 A larger survey of 105 pharmacists reported that pharmacists perceived that checking patients’ ability to use a MOD was the most important factor when considering whether or not to provide a patient with a MOD; however, it did not suggest that patients were actually being given a choice of MODs to select from.

Commercially available MODs are produced by different manufacturers and, consequently, vary considerably in terms of their size and method of medication access. 6 Systems used in pharmacies are sealed once the medication has been dispensed into them and are designed to be tamper evident. Some commercially available devices which are usually filled by the patient or carers, for example Dosett™ (Swereco, Stockholm, Sweden),21 are not funded by the NHS.

The ideal study, in line with best current practice, should allow participants to select the type of MOD they believe best meets their needs in discussion with the pharmacist.

Defining standard care

Medication organisation devices are heat-moulded (often) lidded plastic trays with wells, each sufficient in size to take multiple solid oral dose forms (SODFs) configured in four (labelled with times of the day) by seven (labelled with days of the week) format. They are intended to target unintentional non-adherence1–3 by providing medication in packaging which acts as a memory aid and which enhances accessibility for the patient. They come in a number of shapes and sizes and it was important to identify MODs acceptable to participants and to fit the NIHR research remit.

A number of factors have been cited as the rationale for MODs supporting adherence, including providing medicine storage which is easily accessible to the patient; reducing the complexity of adhering to a regimen; minimising dose amount and timing errors; and acting as a memory aid. A further benefit may be the weekly dispensing, which results in greater contact with the pharmacy team or a carer by virtue of the medication being supplied on a weekly rather than the more usual monthly basis. Research has demonstrated that reducing monitoring frequency from weekly to fortnightly reduces adherence to therapy and, therefore, it may follow that reducing medication supply frequency may have a similar effect. 22 It is possible that the beneficial effect thought to be associated with MODs could be obtained by dispensing medicine supplies in standard packaging (increasingly blister packs) and supplying at weekly intervals.

The MOD is, therefore, a two-component intervention: weekly supply and an aide-mémoire. Clearly, weekly supply in standard containers is cheaper than weekly supply in a MOD, and it is important to quantify the relative contribution of these two components of the intervention (the container and the dispensing frequency) to any observed improved adherence.

Outcomes

Adherence measurement

Studies of MODs have frequently focused on a specific disease, with a single therapeutic outcome or detection of particular chemicals in body fluids being used as a measure of adherence. Thus, little guidance is available to guide targeting of the wider population of patients for MODs in routine practice. Historically, direct measures of adherence, such as observation and detection of chemicals in bodily fluids, have been considered the gold standard. Observation clearly has significant cost implications for large-scale studies and is subject to the Hawthorne effect. Detection of chemicals in body fluids has the merit of being objective; however, it can be invasive and costly, and there remains the potential for patients to alter their medication-taking behaviour in the days prior to sample provision. Some of the disadvantages associated with observation as an adherence measure are exemplified by a trial which randomised patients to receive potassium supplementation or placebo tablets. 23 Measurement of urine potassium levels identified a reduction over time, which was most likely attributable to reduced patient compliance with 24-hour urine sample collection as the trial progressed; hence measured potassium levels were artificially low. The taking of blood samples would overcome the issues of patient compliance with inconvenient 24-hour urine samples; however, the acceptability to patients of frequent blood samples is even lower and has been demonstrated to adversely affect trial recruitment, with 52% of patients not consenting to trial participation, citing fear of phlebotomy. 24 An additional problem associated with such direct measures is intra- and interpatient variability in drug handling. This can be overcome to a certain extent by estimating individual variation in drug handling via repeated samples over a short period of time; however, this type of invasive assessment has low patient acceptability. Alternatively, Bayesian methodology can be used; however, this is complex and again provides only an estimate of variability.

The dosage unit count (DUC) is generally accepted as the pragmatic approach to adherence assessment. It is based on the assumption that, if the medication is not in the container, it has been taken by the patient. This is problematic when attempting to identify intentional non-adherence because patients may deliberately remove and discard tablets in order to disguise non-adherence. However, the assumption is valid if patients are predominantly unintentionally non-adherent. Previous research has demonstrated that use of the DUC method in the older patient population is feasible and acceptable. 15

More recently, electronic adherence monitoring (EAM) systems have enabled objective measurement of medication adherence that is less susceptible to the Hawthorne effect by virtue of being less intrusive and less conspicuous to the patient than direct adherence measures or DUC. The most widely used EAM system is the Medication Event Monitoring System™ (MWV Healthcare, Richmond, VA, USA). The Medication Event Monitoring System is a bottle thats cap contains a microprocessor that records the date and time of each bottle opening event; it has been widely used in clinical trials to assess medication adherence. 12,23,25,26 Trials have, therefore, generally approached objective adherence monitoring by decanting medication from usual packaging to the monitoring bottles. This has the limitation of not assessing adherence in a naturalistic setting, as usual dispensing is now routinely in manufacturer-issued blister packaging. A number of EAM systems are under development, and a 2-month pilot study (n = 52) of one EAM system to assess feasibility and acceptability for usual-care blister packaging reported promising results. Adherence data were obtained from 94.3% of participants and 67.4% of participants reported that they would consider using the EAM system for a long-term study. 27 Therefore, it was proposed that bespoke versions of an EAM system be evaluated to determine whether or not an EAM system can enable medication-taking events from MODs and ‘usual-care’ blister packs to be objectively and accurately recorded and compared.

Cost-effectiveness

In addition to assessing whether or not MOD provision affects adherence to medication regimes, it will be important to assess whether or not it confers health or economic benefits. Measures to detect changes in the utilisation of health or social services will be put in place and tested to determine utility for a definitive study.

Patient autonomy

In addition to the impact of MODs on adherence, it is important to establish patient acceptability. No studies have reported the impact of MODs on patient autonomy or ability to manage one’s own medication; however, there is anecdotal evidence of reduced autonomy, as patients are unable to differentiate one medication from another when medicines are packed in MODs and, therefore, cannot choose to omit a single type of medication if they so desire (e.g. to delay taking a diuretic when embarking on a long journey), sometimes resulting in the omission of all doses. 1 Conversely, patients may report that they feel enabled by feeling confident about managing their medication. A number of studies have explored patient autonomy with respect to medication taking in the context of describing the extent to which patients feel involved in the decision-making process. 28–30 However, exploration of whether or not patients feel as though they have some control over the medication-taking process is limited. Development of a tool to assess the impact of MODs on patients’ confidence in their ability to manage their own medication, on their satisfaction with their packaging and the service they receive was included. Carers and relatives are closely involved in the daily lives of older people with multiple comorbidities and, therefore, it is also important to assess the impact of providing MODs to older people on their carers or close relatives. An additional tool to determine carer perceptions of the impact of medicine packaging on patients’ confidence and their ability to manage their medicines and effects on the resource provided by carers and relatives was also included.

Patient medication administration errors

Studies evaluating patient medication administration errors have cited access to extra medication as a source of errors and, therefore, reducing the amount of medication to which a patient has access may also be a further source of error reduction. 31 For the duration of the study it was important for participants to have access only to the new stock of drugs supplied to them. Therefore, development of an appropriate process to ensure that errors in compliance could not be attributed to extra medication was included.

General dispensing and administration errors

The most substantial review to date of errors associated with MOD use was conducted in Australia; the Australian Incident Monitoring Study31 reported that 0.43% (52 out of 12,000) of medication-related errors were associated with MODs. In 26 cases, there was a problem with filling the MOD, such as wrong dose, dose omission or wrong medication. In 21 of these cases, nursing staff were responsible for the error, with the remainder being attributable to pharmacy staff or a carer. On 16 occasions problems using the MOD were cited as a reason for an error; however, the nature of these problems was not reported. Factors contributing to the reported problems included patient confusion/distraction and the MOD being inappropriate for the patient. 31 A further Australian audit32 of dispensing errors associated with 6972 dispensed MODs detected an error rate of 4.3%. 32

A 2007 UK evaluation of dispensing error rate associated with the pharmacy usual dispensing process33 reported 1.7% content errors out of 2859 dispensed items. Content errors were errors of omission, incorrect drug, incorrect strength, incorrect dosage form, added or missing dose units and expired medication. A similar US-based study conducted in 2003 reported an identical 1.7% error rate. 33 While general dispensing error rates are 1.7%, there are no UK data for MOD error rates and, therefore, it is necessary to record error rates for dispensing into both MODs and usual packaging.

In summary, comparative data in terms of error rate associated with MODs and usual dispensing are not available. Data regarding the incidence of dispensing errors associated with usual dispensing are available, but may not be generalisable to prescriptions assembled for an older population with more multiple items. A reasonable estimate of error rate requires a large sample size and significant resources. Within a relatively small-scale feasibility study it is, therefore, only appropriate to test tools designed to collect error data and to quantify and describe any identified errors.

Recruitment strategies

While recruitment via medical practice invitation letters is convenient in terms of research administration, response rates have historically been low, as the method requires the patient to be proactive in responding to a letter invitation – consent rates are frequently between 30% and 40%. 16,34 Waiting room recruitment by researcher, while more labour intensive, and thus costly, has yielded substantially higher response rates. 35–38 Identification of the most cost-effective approach to recruitment is, therefore, required within any feasibility study.

Summary

Despite the large amount of both NHS and private funds devoted to MODs, evidence of their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is limited, as indicated by a Department of Health-commissioned literature review conducted by Bhattacharya. 6 A 2006 Cochrane review7 concluded that MODs may improve adherence ‘with selected conditions examined to date’; however, further research is necessary to improve targeting. In order to achieve this, the impact of MODs on a more heterogeneous population needs to be established.

Preliminary work to determine the feasibility of conducting such a trial is required. An approach to measuring adherence which minimises the Hawthorne effect and which is discrete and compatible with both MODs and usual care needs to be identified from the potentially suitable EAM systems becoming available. The effect of MODs on patient autonomy requires consideration to ensure that the intervention is acceptable to patients. The potential for increasing dispensing errors because of the additional complexity of dispensing into MODs also requires consideration, as does the identification of the most appropriate method of recruitment. Finally, MODs are designed to address unintentional non-adherence and are a method for identifying and differentiating between different types of non-adherence requires development.

This feasibility study to determine the optimal design of a trial testing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MODs was carried out in two main phases. The first was the determination of optimal design features and identification of features that require testing for feasibility and acceptability. The second was the trial of this design and review of the procedures to further refine the trial design.

The initial RCT design was refined as a result of a systematic review and pre-trial focus groups. Post-trial focus groups of patient and health-care professional participants were used to further refine the design of the trial and to determine feasibility and acceptability. Findings and recommendations are presented in the following chapters.

Chapter 2 Systematic review

Rationale

The NIHR funded this feasibility study to design a definitive study to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MODs based, in part, on a recent systematic review conducted by Mahtani et al. in 2011. 39 The review concluded that findings from one favourable study are not sufficient to justify the allocation of NHS resources on MODs. In addition to this, the study focused on adherence rather than on the social and economic aspects important to the design of a definitive study. Therefore, under this study, the review was updated with respect not only to adherence but also to informing a definitive study with respect to key social and economic factors.

Objectives

The objectives of this systematic review were to identify and update the current evidence for the impact of MODs on adherence, health and humanistic and economic outcomes in patients self-administering prescribed medicines compared with usual packaging to inform a definitive study.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42011001718).

Article selection

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion when they met the following criteria.

Population

Patients, of any age, with any medical condition, in any setting and self-administering medication, where ‘self-administered’ is defined as medication taken by patients (with or without help from a carer) and where medical staff are not directly responsible for administration.

Interventions

Medication supplied in a MOD, packed by a health-care professional, a carer, the patient or a manufacturing company. MODs were defined as any container which permits patient or pharmacy placement of multiple solid oral dose medicines into wells arranged by time and/or date and with room for at least seven days’ medication.

Comparator

Standard care and standard packaging only. No comparator is necessary for descriptive data regarding the number of errors, or the monetary or time costs associated with filling MODs.

Outcomes

Any of the following outcomes reported:

-

adherence to medicines (using only the objective adherence measures of adherence pill counts or electronic monitoring)

-

health outcomes

-

health-related quality of life

-

health or social care utilisation

-

dispensing or administration errors

-

prescribing or medicine supply, financial and staffing costs.

Study design

All study designs involving new data collection and analysis.

Mode of dissemination

No restrictions were applied. For example, conference abstracts and book chapters were eligible.

Exclusion criteria

-

Any MOD incorporating additional reminder systems, such as visual or auditory alarms, telephone or SMS messaging services, or provision of daily medication-taking ‘tick’ charts. Studies were not excluded if training in the use of the MOD was provided.

-

There was direct observation of medicine administration by a health-care professional.

-

A MOD was used as part of a complex intervention where the independent effect of the MOD on outcomes could not be isolated.

-

Language of publication is not English.

-

No novel empirical evidence is presented (i.e. review articles which do not collect new data).

Information sources

The following electronic databases were searched. Relevant reviews were identified in order to access their bibliographies (see the following for augmented searches).

-

The library of the Cochrane collaboration (www.thecochranelibrary.com) including the databases Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, HTA Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (searched from inception to 2012).

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid; searched from 1966 to 2012).

-

EMBASE (via Ovid; searched from 1980 to 2012).

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid; searched from 1874 to 2012).

-

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED; via Ovid; searched from 1985 to 2012).

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; via EBSCOhost; searched from 1982 to 2012).

-

Trials listed as complete in Current Controlled Trials (http://controlled-trials.com/; searched from inception to 2012).

-

York Centre for Review and Dissemination databases (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, NHS Economic Evaluation Database and the HTA database; www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/SearchPage.asp; searched from inception to 2012).

Search terms of medical subject headings, free text and trade names (see Appendix 1) were applied to title, abstract and whole text of articles within the Ovid search tool. For databases outside the Ovid platform, the same terms were utilised but with appropriate translation of syntax (truncation, wildcards, adjacency and Boolean operators). No restrictions were placed on year of publication and the full back-catalogues of the available databases were searched up to the end of 2012; the first search was run on 8 February 2012 and the search was updated on 11 January 2013.

In addition to formal searching of the above databases, searching was augmented via:

-

keyword searches in the Google Scholar™ search engine (http://scholar.google.com)

-

hand-searching of reference lists of included articles

-

hand-searching of identified review articles

-

hand-searching of reference lists of articles relevant to the project but excluded because of exclusion criteria (e.g. compared MODs to non-standard care, used additional interventions or measured adherence only via self-report)

-

personal communication with packaging companies

-

personal communication with research groups with an expertise in adherence.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of all identified articles were screened for relevance by two reviewers (CA, LC, EP or TB) with any disagreements resolved by discussion. When agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer moderated the final decision. Full-text articles were similarly screened by two reviewers (CA, EP or TB). In the case of articles identified as potentially relevant after full-text screening, data were independently extracted by two reviewers (EP and SW), with any differences resolved by discussion. Authors conducting the review were not blinded to any element of the identified articles.

Data collection process

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (EP and SW) using a standardised Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. Table 1 provides a summary of the data that were extracted to the spreadsheet.

| Data description | Data extracted |

|---|---|

| Generic items | Author names, year and place of publication |

| Design | Population, including sampling |

| Intervention and comparator descriptions | Outcomes and their measurement including cognitive function, manual dexterity or visual acuity |

| Quality | Cochrane risk of bias tool (see Risk of bias) |

Source of funding

Sources of funding were examined to identify any potential conflict of interest.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using items from the Cochrane risk of bias tool (randomisation procedure, concealment of allocation, blinding of assessors, blinding of treatment providers, whether or not attrition was variable between groups and how this was accounted for, whether or not all outcomes were reported, and whether or not there were any other clear threats to validity) as appropriate to the study design. When the study design did not permit randomisation or blinding of assessors, it was noted that such designs have greater risk of bias.

Summary measures

Meta-analysis was intended where measures were consistently reported across trials; however, owing to a lack of comparability, none was performed. Results are tabulated and described according to study outcomes.

Results

Study selection

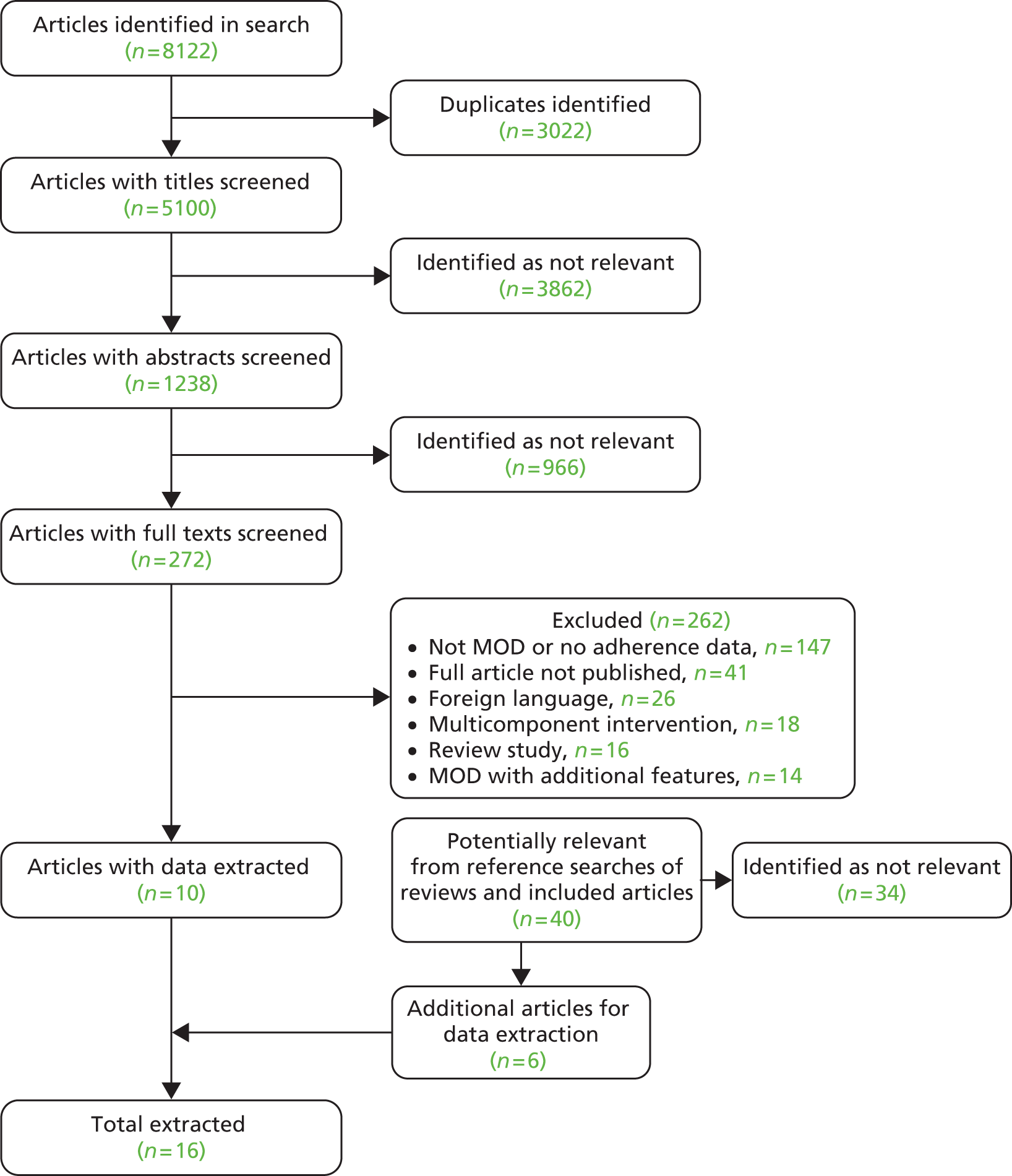

A total of 8122 studies were identified. After automatic removal of duplicates, 5100 articles were screened. Following this, 272 articles were retained for full-text screening. Three authors (CA, EP and TB) assessed these texts for eligibility and 10 articles were included. Screening of identified review articles and included articles, and those retrieved for detailed review, identified a further 40 potentially relevant studies, which yielded an additional six studies. A flow diagram summarising this process is detailed in Figure 2. No studies declared any conflict of interest.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of articles included in review.

Overview of studies

A summary of included studies is shown in Table 2. Of the 16 included studies, seven were undertaken in the USA, five in the UK and four in Australia and New Zealand. Six of the 10 non-US studies were identified via augmented searching, indicating a possible US bias in the availability of articles via academic databases.

| First author and year | Study design | Location | Condition | Setting | Average age (years) | Age range (years) | Type of MOD | Filler of MOD | Total n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker 198640 | RCT | USA | Hypertension | Hospital outpatient | – | – | Unsealed reusable MOD | Automatic device | 165 |

| aCarruthers 200832 | Audit | Australia | Mixed | Care home | – | – | Unsealed reusable MOD | Unclear | – |

| Crome 198241 | RCT | UK | Mixed | Hospital inpatient | 80.29 | 68–98 | Unsealed reusable MOD | Unclear | 78 |

| Feetam 198242 | Prospective | UK | Mental illness | Community | 42.40 | 18–68 | Sealed MOD | Unclear | 10 |

| Huang 20002 | RCT | USA | Vitamin supplementation | Community | 58.00 | – | Sealed MOD | Patient | 183 |

| Levings 199931 | Audit | Australia | Mixed | Community | 78.00 | – | Unclear | Unclear | –b |

| MacIntosh 200743 | RCT | Canada | Cancer | Hospital outpatient | 64.00 | 42–81 | Unclear | Researchers | 21 |

| McElnay 199244 | Cross-section | UK | None | Community | – | – | Sealed MOD | Pharmacists/pharmacy technicians | 6 |

| Petersen 200745 | Prospective | USA | HIV infection | Community | 44.00 | 38–49 | Unclear | Unclear | 269 |

| Rehder 198046 | RCT | USA | Hypertension | Hospital outpatient | 51.35 | 31–69 | Sealed MOD | Unclear | 50 |

| Roberts 200447 | Multiple | Australia | Mixed | Community | 76.80 | – | Mixed | Mixed | 353 |

| Ryan-Woolley 200548 | RCT | UK | Mixed | Care home | 78.80 | 67–92 | Sealed MOD | Unclear | 62 |

| Simmons 200049 | RCT | New Zealand | Diabetes mellitus | Community | 54.06 | – | Unsealed reusable MOD | Unclear | 68 |

| Skaer 199350 | RCT | USA | Hypertension | Pharmacy | 56.49 | – | 30-day tray | Unclear | 163 |

| Stewart 200151 | Cross-section | UK | Mixed | Community | – | – | Unclear | Nurses | 96 |

| Wong 198752 | RCT | USA | Mixed | Community | 79.00 | 66–90 | Unsealed reusable MOD | Unclear | 17 |

Eight studies were conducted in 2000 or later, and the majority were in domiciliary settings (n = 12). Seven studies did not target a specific illness and the remaining studies targeted hypertension,3 diabetes mellitus, mental health, cancer and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. One study44 examined the effect of MODs on dispensing procedures only. Nine studies were RCTs. Two studies were audits and so did not assess any adherence behaviour. 31,32 The combined population from all the studies was 1541.

The type and number of MODs assessed varied across studies. Unsealed reusable MODs were used in five studies40,42,49,52,54 and pre-sealed units were used in five studies;42,44,50 in five studies,31,43,45,50,51 the seal type was not specified. One study52 used multiple types of MODs.

Only one study used patient-filled MODs,2 although in Feetam and Kelly42 it was unclear who filled the MODs. In other studies, the units were filled before being supplied to the patient by researchers in one study,43 were filled by an automatic filling device in one study,40 were filled by community nurses in one study51 and were filled by unspecified professionals in the remaining studies. McElnay and Thompson44 timed the filling of MODs by five pharmacists and a pharmacy technician.

Figure 3 provides the number of studies published over each 5-year period. It can be seen that the frequency of relevant studies has dramatically increased over the past 10 years.

FIGURE 3.

Frequency of studies published per 5-year period.

Risk of bias

There was considerable risk of bias in many studies, which is summarised in Table 3. Only three of the nine RCT studies included information on randomisation,2,43,49 and none mentioned blinding. Other risks of bias identified included baseline differences between groups not accounted for in analysis,40,53 minimal participant information42,52 and minimal information on analysis. 42 Levings et al. 31 performed an audit of errors reported in the Australian Incident Monitoring Study and noted that some types of errors may be more likely to be reported than others (e.g. overdose). It is therefore difficult to determine whether or not the errors identified are representative of all errors. McElnay and Thompson44 determined the time taken to fill MODs, but they used fictional patients with only three medicines which may have led to an underestimation of the actual time required to fill.

| First author and year | Study design | Randomisation procedure | Concealment of allocation | Blinding of assessors | Blinding of treatment providers | Attrition addressed | All outcomes reported | Other risks of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker 198640 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ✗ | ? | ? | ✗ |

| Crome 198241 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

| Huang 20002 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ |

| MacIntosh 200743 | RCT | ✓ | ? | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

| Rehder 198046 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ |

| Ryan-Woolley 200548 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

| Simmons 200049 | RCT | ✓ | ? | ? | ✗ | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

| Skaer 199350 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ |

| Wong 198752 | RCT | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✗ | ? | ✗ |

| Carruthers 200832 | Audit | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ✓ |

| Feetam 198242 | Prospective | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ? | ✗ |

| Levings 199931 | Audit | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ? | ✗ |

| McElnay 199244 | Cross-section | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ✗ | ✗ |

| Petersen 200745 | Prospective | ✗ | ✗ | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

| Roberts 200453 | Mixed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ? | ✗ |

| Stewart 200151 | Cross-section | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ? | ✓ |

Effects of medication organisation devices

Medication adherence

Eight studies from seven papers estimated the effect of MODs on adherence. 40,41,43,45,46,52 Seven of these studies were RCTs. 2,40,41,43,46,52 These studies are presented in Table 4. All studies estimated adherence via pill count, with additional electronic monitoring for patients who were not using a MOD in one study. 45 Of the eight studies, four40,45,46,52 suggested improved adherence in the MOD group. Owing to overall heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was not possible.

| First author and year | Design | Adherence measure | Adherence MOD intervention (%) | MOD intervention, n | Adherence control (%) | Control, n | Adherence effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker 198640 | RCT | Per cent of sample taking > 80% of medicines | 84 | 86 | 75.3 | 85 | + ns |

| Crome 198241 | RCT | Per cent of doses missed | 26.1 | 40 | 26.2 | 38 | = |

| aHuang 2000a2 | RCT | Per cent of sample taking > 90% of medicines | 91 | 90 | 94 | 94 | = |

| aHuang 2000b2 | RCT | Per cent of sample taking > 90% of medicines | 87 | 148 | 93 | 149 | – |

| MacIntosh 200743 | RCT | Per cent of sample taking 100% of medicines | 81 | 21 | 86 | 21 | – |

| Petersen 200745 | Prospective | Difference in prescribed doses consumed | 4.1% improvement in adherence | – | – | – | +ss |

| Rehder 198046 | RCT | Per cent of sample taking > 95% of medicines | 89 | 25 | 47 | 25 | +ss |

| Wong 198752 | RCT | Per cent doses missed | 2.04 | 17 | 9.17 | 17 | +ss |

Becker et al. 40 found that 84% of participants took > 80% of their medicines when supplied with a foil-sealed blister pack MOD (time and day to take medicines on the back), compared with only 75.3% of participants without a MOD, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Petersen et al. 45 tracked a cohort of 269 HIV-infected patients between 1998 and 2005, of whom 163 were given a MOD according to clinical need. The effects of MODs on adherence were estimated via bootstrap sampling with double robust estimation to compensate for the lack of random allocation. MODs increased adherence by 4.1% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1% to 7.1%].

Rehder et al. ,46 in a study of patients with hypertension, showed that patients supplied with their medication in a Mediset™ MOD (Health Care Logistics, Circleville, OH, USA) were more adherent than those supplied with medication in a safety-capped vial. Of patients who received their medication in a Mediset™, 89% took more than 95% of their pills ,compared with 47% of those who received their medication in vials (the overall proportion of medicines taken was 95% compared with 87%, respectively).

In a crossover trial with older patients receiving either standard care or separate pre-sealed blister packs with doses required for each meal time (analogous to MODs), Wong and Norman52 found that patients in the blister group omitted to take fewer doses than in the usual-care group (2.04% with the MOD vs. 9.17% with standard care; p < 0.01).

Two studies found that the MOD had no effect on adherence. 2,41 In a study conducted by Crome et al. ,41 participants provided with medicines in weekly blister strips with the date and time for taking the dose on the back (C-Pak™, manufacturer information not available; analogous to a MOD) missed 26.1% of doses, compared with 26.2% of doses missed by participants receiving standard care.

Similarly, Huang2 found that participants taking vitamins from patient-filled MODs (one box/day) had a median adherence of 100% of pills taken in the MOD group (91% took > 90% of their medicines) and a median of 99% pills taken in the comparison group (94% took > 90% of their medicines). When they repeated this on a second cohort, median adherence was 99% for both groups but the proportion of patients achieving > 90% adherence was significantly lower in the MOD group than in the comparison group (87% vs. 93% respectively).

One other study also suggested poorer or equivalent adherence in the MOD group. In a study of patients taking capecitabine for breast or gastrointestinal cancer,43 adherence was generally high, with only 3 out of 24 of those in their first cycle and 4 out of 18 in their second cycle not 100% adherent. In a subsample of 21 participants taking part in a crossover design for a MOD (7-day container with exact doses for morning and evening) versus standard pill vials, a difference between groups of 81% in the MOD group versus 86% in the control group was not significant and amounted to only one participant not achieving perfect adherence in the MOD group (p = 1).

Health outcomes

Seven studies from six papers,40,45,46,49,53 including four RCTs,2,40,45,49,53 estimated the impact of MODs on health outcomes and are presented in Table 5. Three studies measured blood pressure changes,40,42,46 one vitamin serum levels,2 one viral load45 and one adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and patient function. 53

| First author and year | Design | Outcome measure | Change in outcome | MOD intervention, n | Control, n | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker 198640 | RCT | Diastolic BP | 1.45 | 86 | 85 | 0.259 |

| Huang 2000a2 | RCT | Change in vitamin C serum concentration | –0.9 | 90 | 94 | 0.47 |

| Change in vitamin E serum concentration | –2.4 | – | – | 0.06 | ||

| Huang 2000b2 | RCT | Change in vitamin E serum concentration | 0.9 | 148 | 149 | 0.53 |

| Petersen 200745 | Prospective | Viral load | 0.36 | – | – | < 0.05 |

| Rehder 198046 | RCT | Change in diastolic BP | 1 | 25 | 25 | > 0.05 |

| Change in systolic BP | Not reported | – | – | > 0.05 | ||

| Roberts 200453 | Mixed | Number of ADRs | Non-MOD group reported more ADRs (47.79%) than non-pharmacist supplied MOD group (43.24%) and pharmacist-supplied MOD group (32.56%) | – | – | 0.022 |

| OARS-IADL | Patients supplied with MODs by pharmacists had lower ability scores (10.25/14) than patients supplied by other health-care professionals (12.70/14) or not supplied with a MOD (12.34/14) | – | – | 0.001 | ||

| Simmons 200049 | RCT | Change in diastolic BP | –5.9 | 36 | 32 | 0.0041 |

| Change in systolic BP | –0.7 | – | – | 0.89 | ||

| Change in HbA1c | –1.0 | – | – | 0.026 |

Of the three studies measuring changes in blood pressure, only one suggested a positive impact. 40,46,49 Simmons et al. ,49 in a study of patients with diabetes mellitus, found a significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the MOD group compared with the standard care group. However, the reduction in systolic blood pressure was not significantly different between the groups. Becker et al. 40 did not find that use of a MOD impacted on diastolic blood pressure when change in blood pressure was controlled for baseline and pre-enrolment blood pressure measures, and age. Rehder et al. 46 did not report values for the impact of MODs on systolic blood pressure but noted that the difference was not statistically significant, and estimation of changes in diastolic blood pressure from graphical data showed an increase of 5 mmHg in the intervention group and 6 mmHg in the control group.

Huang et al. 2 found that use of patient-filled MODs did not significantly affect serum vitamin C levels [mean reduction –0.9 mg/dl (95% CI –3.4 mg/dl to 1.6 mg/dl) in the Trial of Antioxidant Vitamins C and E (TRACE) cohort; mean increase 0.9 mg/dl (95% CI –2.0 mg/dl to 3.8 mg/dl) in the Vitamins, Teachers, and Longevity (VITAL) cohort] or serum vitamin E levels [mean reduction –2.4 mg/dl (95% CI –4.8 mg/dl to 0.00 mg/dl) in the TRACE study].

The study by Peterson et al. 45 in patients with HIV suggested the benefit of MODs, as indicated by a mean reduction of 0.36 log10 copies/ml (95% CI 0.09 to 0.63 log10 copies/ml) in the MOD group compared with the standard care and an odds ratio for the increase in the proportion of participants with a viral load below 400 copies/ml of 1.91 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.90).

The study by Roberts53 in older people also suggested that MODs provide benefit, especially when filled by pharmacists. Fewer ADRs were reported when pharmacist-filled MODs were used (32.56%, compared with 43.24% for non-pharmacist-filled MODs or 47.79% for no MODs). Participant ability was assessed using the Older Americans Resource Scale for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (OARS-IADL). Overall, these ratings were considered to be high in all groups on average, but patients who were supplied with a MOD by a pharmacist had significantly lower abilities scores with a mean [standard error (SE)] score of 10.45 (SE 0.24) out of 14, compared with 12.70 (SE 0.39) for patients who were supplied with a MOD by a non-pharmacist and 12.34 (SE 0.19) for patients who did not have a MOD. However, the direction of effect between MODs impacting on participant ability versus participant ability impacting on the decision to prescribe a MOD cannot be determined in this study.

Health-care utilisation

Table 6 summarises the studies examining the effects of MODs on health-care utilisation. It can be seen that this potential effect was explored in only three studies. 48,50,53

| Author and year | Design | Health-care utilisation measure | Health-care utilisation MOD | MOD intervention, n | Health-care utilisation control | Control, n | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts 200453 | Mixed | Number of different doctors visited regularly | 2.02 (pharmacist supplied), 2.91 (non-pharmacist supplied) | 209 | 2.41 | 144 | 0.012 |

| Number of doctors visited in last 2 months | 2.54 (pharmacist supplied), 2.05 (non-pharmacist supplied) | – | 3.05 | – | 0.03 | ||

| Number of hospital admissions (past 12 months) | 1.36 (pharmacist supplied), 0.56 (non-pharmacist supplied) | – | 0.78 | – | 0.001 | ||

| Per cent patients requiring hospitalisation in last 3 months | 59.54% (pharmacist supplied), 35.14% non-pharmacist supplied) | – | 35.14% | – | – | ||

| Ryan-Woolley 200548 | RCT | GP visits | 1.5 | 31 | 1.3 | 31 | 0.07 |

| Number of prescribed medicines | 4.2 | – | 4.8 | – | 0.024 | ||

| Skaer 199350 | RCT | Medicaid archive data of health-care spending per patient | –US$13.66 total spend per patient | 85 | – | 78 | > 0.05 |

Ryan-Woolley and Rees48 found that after 3 months the number of general practitioner (GP) visits was higher in the MOD group than in the standard care group [1.5 (range 1–3) vs. 1.3 (range 0–3) GP visits, respectively; p = 0.070], but that the mean number of medicines prescribed was lower [4.2 (range 2–9) vs. 4.8 (range 2–8 ) medicines per patient, respectively]. These values were more similar at baseline [4.5 (range 1–10) vs. 4.6 (range 1–9) medicines per patient, respectively].

Skaer et al. 50 found non-statistically significant reductions in physicians’ costs (–US$32.85), laboratory costs (–US$3.06) and hospital costs (–US$25.92), which led to provision of MODs resulting in a non-statistically significant reduction in overall costs of approximately US$13.66 per person.

Roberts53 found that the mean (SE) number of different doctors visited was lower in the group supplied with a pharmacist-filled MOD than in the group not supplied with a MOD [2.02 (SE 0.01) vs. 2.41 (SE 0.12) different doctors visited]. However, the number of different doctors visited by patients with non-pharmacist-supplied MODs was 2.91 (SE 0.22). Considering only the last 2 months of the study, the number of doctors visited was lower both for patients with pharmacist-supplied MODs [2.54 (SE 0.16)] and for those with non-pharmacist supplied MODs [2.05 (SE 0.33)] than for those without a MOD [3.05 (SE 0.22)]. Patients receiving MODs from their pharmacist required more hospitalisations [1.34 (SE 0.14)] than those receiving a non-pharmacist MOD [0.56 (SE 0.14)] or those without a MOD [0.78 (SE 0.11) ]. Similarly, the proportion of patients hospitalised was higher among those with a pharmacist MOD than among those not receiving a MOD or those receiving a non-pharmacist MOD (59.54% vs. 42.34% and 35.14%, respectively).

Dispensing errors

Only three studies investigated the frequency of dispensing errors. 31,32,53 There was little consistency of findings because of differences in definition and methods.

Carruthers et al. 32 found errors in 4.3% of Webster-paks™ audited by local health authority staff (297 errors in total from all audited 6972 packs). Of these, the most common reason was omission of a medicine (99 out of 297; 33.3%). Other reasons were supplying a discontinued medicine (37 out of 279), wrong strength (32 out of 297), incorrect instructions (32 out of 297), failure to deliver medicines (13 out of 297), wrong medicine (12 out of 297) and wrong label (7 out of 297). Errors occurred most commonly in pharmacies (125 out of 297).

In a smaller study of only 190 observations, and regardless of packer role (pharmacist, dispensary assistant or pre-registration pharmacy student), Roberts53 found a researcher-reported error rate for 44.7% of packs compared with only 5.7% when reported by staff. It was suggested that, when observed, the packers made more errors and also had a more stringent definition of errors. The most frequent causes were omission of medication (39%), adding extra tablets that had not been prescribed (24%) and placing tablets in the wrong compartment (12%). Higher error rates were associated with larger facilities, longer duration of time spent packing (r = 0.342; p = 0.004) and interruptions (r = –0.337; p = 0.003).

Finally, Levings et al. 31 audited the first 12,000 incidents reported in the Australian Incident Monitoring Study and identified 52 incidents involving MODs (referred to in their study as dosette boxes). Of these, 50% occurred during filling. There was no reported denominator to allow estimation of an error rate.

Supply procedures and costs

Four studies estimated the time taken to fill MODs,42,44,51,53 and two studied costs. 42,53

Feetam and Kelly42 found that a Medidos™ MOD (Allied Health, Perth, UK) took an average of 3 minutes to fill and 24 minutes to label.

In a simulated study involving five pharmacists and a pharmacy technician using medicines for five fictitious patients, McElnay and Thompson44 compared six different MODs for time to fill, user preferences and acceptability (Table 7). Extrapolated results suggest that an average time taken to fill a box would be 7 minutes per month (4 × 105 seconds) per patient, longer than for standard systems. The rank that pharmacists gave ‘ease of filling’ matched the ranking given for fill time.

| MOD device | Time to fill device, minutes : seconds (n = 6) | Perceived ease of filling (0–10) (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Dosette box | 1 : 45 | 8.3 |

| Medidosa | 2 : 52 | 7.8 |

| Medi-Wheela,b | 3 : 20 | 7.5 |

| Pill Millc,d | 2 : 27 | 5 |

| Superceld,e | 9 : 59 | 1.5 |

| MedSystem Week Pouchd,f | 2 : 48 | 7.7 |

Roberts et al. 53 identified that the time required to pack a MOD ranged from 3.2–8.6 minutes for large packing operations to 14–18.5 minutes for small packing operations. Time spent checking MODs ranged from 1.13–2.13 minutes for large operations to 3.01–8.61 minutes at small operations. Those filled using automated packing systems took less time to pack (0.99 minutes), while blister packs (3.34 minutes) and dosette boxes (10 minutes) took longer.

In a survey of 153 Scottish community nurses, 96 (63%) reported having experience of filling MODs. 51 The estimated average time for a nurse to fill one MOD was 34.2 minutes. The survey also identified concern at the impact of this workload on their schedules, lack of any formal training (most had received no training, 25% had received informal training) and lack of knowledge about which medicines could be placed in the devices. Nearly 60% of the nurses felt that pharmacists should fill the compliance devices.

Feetam and Kelly42 also estimated the cost of supplying Medidos MODs for 6 months to be 10 pence per week, compared with 21 pence per week for seven disposable bottles. Similarly, labelling was less expensive (1 pence vs. 4 pence), as was time spent labelling and filling (16 pence vs. 24 pence). Overall, this produced an estimated cost of 27 pence per week for a Medidos containing seven medicines, compared with 49 pence per week for seven pill bottles. Conversely, Roberts et al. 53 found that the annual cost of original packaging (US$942.73) was less than that of a MOD (US$1859.00 per year).

Quality of life and social services utilisation

No studies were identified which measured the impact of MODs on quality of life or social service utilisation.

Summary

Overall, the studies were of poor quality and used a wide range of MODs, populations/conditions and definitions and measures of adherence. No clear trend in any of the outcomes was observed. The reported information suggested that screening of patients to only include those demonstrating unintentional non-adherence was infrequent. For the outcomes of adherence, clinical improvement, health-care utilisation, processing time and costs, there were studies suggesting both that MODs were beneficial compared with standard care, and the converse. The review included studies published at any time, but the first studies identified were in the 1980s, and there was a possible indication of most activity between 2000 and 2008. No studies were identified with a publication date later than 2008.

The search terms were developed in order to identify MODs in the form of a container organising at least 7 days of medicines together. This, therefore, excluded systems which organise medicines into individual dosing times but do not arrange these into the days of the week as a fixed system. Systems such as individual plastic pouches each containing all of the medicines that are prescribed to be taken at the same time, such as the Unit Bag system1, were therefore excluded. This approach was adopted in order to minimise the heterogeneity of the intervention.

As with any review, it is possible that relevant papers were not identified by our search strategy. However, the search terms were inclusive and applied to relevant databases, reference lists of retrieved papers were searched and hand-searching was undertaken. Contacting authors for additional information may have further enhanced the data presented.

With respect to the individual studies, the biggest limitation was study design and inadequate reporting of details to allow risk of bias to be fully assessed. In particular, without access to pre-study protocols it was impossible to determine whether or not studies reported all intended outcomes.

Chapter 3 The design phase

Introduction

Medical Research Council guidance for the development of complex interventions recommends that feasibility and pilot work is undertaken prior to embarking on a definitive study. 47 Feasibility studies are ‘pieces of research done before a main study and are used to estimate important parameters that are needed to design the main study’55 and are used to determine the acceptability of an intervention, measure demand for it, test its implementation and identify the most appropriate outcome measures with respect to sensitivity and practicability. 56 Feasibility studies are also used to determine the variance around the outcome measure to enable power calculations to be performed for the final definitive trial.

A review of the literature is now widely accepted as an essential component of studies to inform trial design. Systematic reviews offer the most rigorous methodological approach to identifying the existing literature through collating all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria. They use explicit and systematic methods to minimise bias in answering a specific research question. 57,58 Systematic reviews are, however, resource intensive, whereas literature reviews offer a more rapid appraisal of existing evidence and are appropriate for supplementing researcher expertise.

Although commonly associated with full trials, process evaluation is equally, if not more, important in a feasibility study, especially when there are many unknown and to-be-determined variables, contexts and design issues. In a feasibility study it is important to scrutinise and assess both the quantity and the quality of what is proposed. 59 Furthermore, qualitative research can be well utilised in order to assess many aspects of why, how and in what context a specific aspect of a trial, or potential trial, works. 60

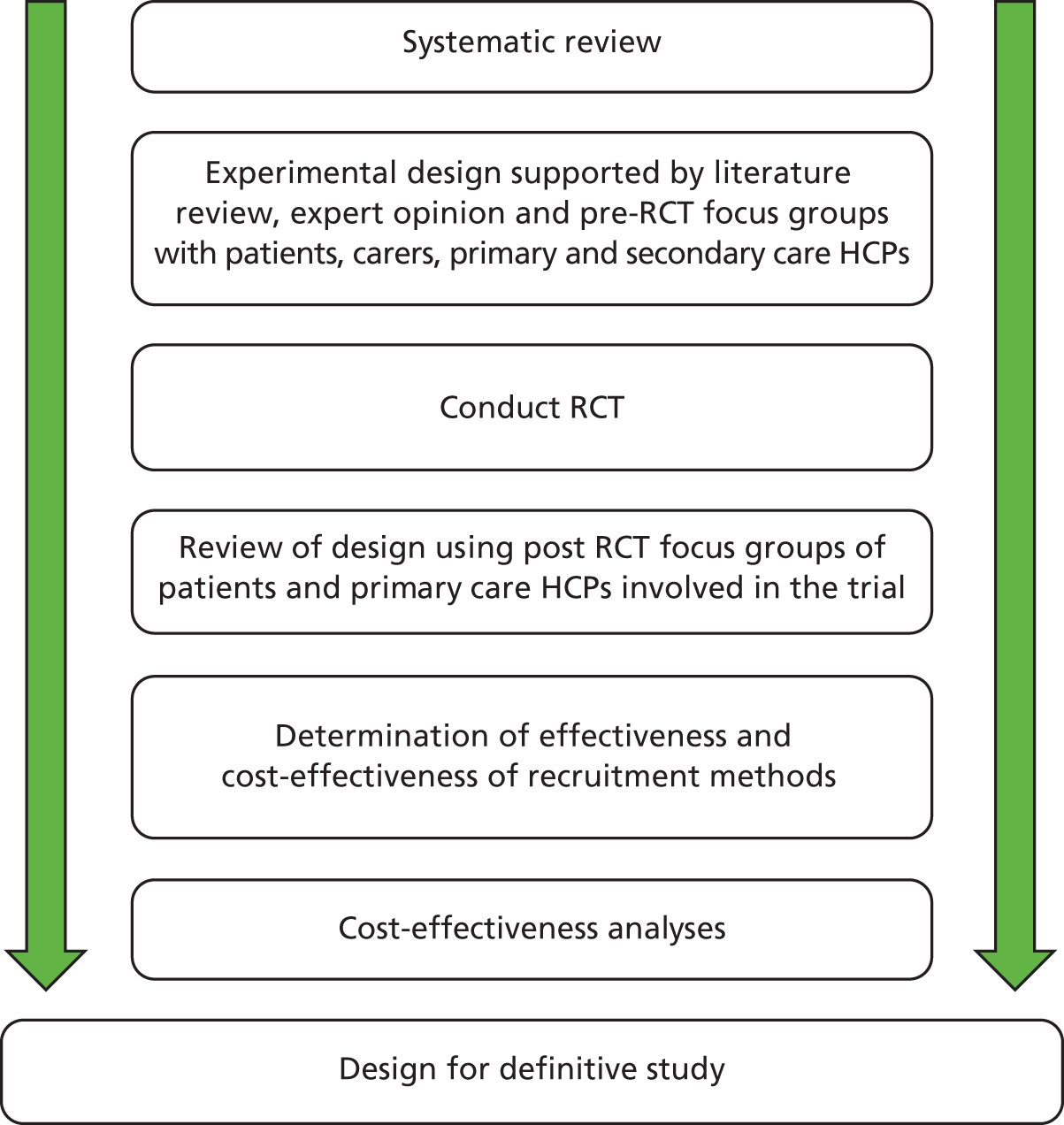

This project aimed to define the optimum design of a study to trial the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MODs. Mixed quantitative and qualitative methods were used to develop and evaluate the study design, as illustrated by Figure 4. The project comprised two phases:

-

Phase 1 – identifying the most appropriate design for a definitive study.

-

Phase 2 – investigating the acceptability of the design elements to trial participants and collaborators using focus groups comprising patients, carers and health-care professionals from both primary and secondary care sectors.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic illustrating the mixed-method design of the feasibility study. HCP, health-care professional.

Phase 1: literature review to inform trial design

Method

A review of peer-reviewed and grey literature using appropriate search terms to identify existing knowledge regarding the key design features was supplemented with expert opinion. The design elements investigated were identification of appropriate participants; characterisation of participants’ cognitive, manual and visual ability; selection of appropriate medication organisation devices; definition of standard care and the intervention; objective adherence monitoring; optimum recruitment strategies; and a suitable database.

Results

Identification of appropriate participants

The chief investigator (DB) had previously conducted a literature review regarding the characteristics of participants most likely to receive any benefit from a MOD, that is those patients at greatest risk of unintentional non-adherence. 6 The data from this literature review were used to generate the following initial parameters for participant identification and supplementary searches were used where necessary for further targeting.

Regimen complexity

Evidence suggests that patients who are prescribed multiple medications are at the greatest risk of non-adherence. Norfolk Medicines Support Service is a locally commissioned service which includes a patient home visit in order to establish the medicine-related support needs. The provision of a MOD is a frequently used intervention, and three was reported to be the minimum number of SODFs usually prescribed when a MOD is recommended, except when severe cognitive impairment has been identified.

Age

The funding brief for the study was to target older people. The National Service Framework for older people defines older people as aged ≥ 65 years. 4 However, UK wards specialising in medical care for older people and the British Geriatric Society use 75 years as the lower age boundary. 19

Unintentionally non-adherent

The MOD is intended to support unintentional non-adherence and thus it was essential to exclude patients at risk of intentional non-adherence. The literature review identified a number of self-report tools for identifying non-adherence; however, few provided sufficient information to distinguish between intentional and unintentional non-adherence. The four-item Medication Adherence Questionnaire is the most widely used self-report adherence measure, however, it demonstrates poor sensitivity and offers little information about the cause of non-adherence. 61

Members of the study team (DB and SW) had previously developed and tested a questionnaire designed to identify patients at risk of non-adherence. This questionnaire was informed by a meta-analysis of factors related to adherence conducted by SW. The key factors for intentional non-adherence identified were attitude towards prescribed therapy, patient–doctor relationship, risk-taking behaviour, perceived stress and mental well-being. 62 This questionnaire was a composite of validated tools and questions designed to capture the key factors.

Characterisation of participants’ cognitive, manual and visual ability

An Ovid MEDLINE title search using the terms ‘adherence + cognit*’ with no other limitations yielded 109 articles. Duplicate removal and title screening identified 23 relevant articles. Excluded articles were those describing cognitive therapy or adherence unrelated to medication taking, for example adherence to diet. Abstract and full-text searching resulted in exclusion of a further 10 articles as follows: not English language (n = 1), not cognitive impairment (n = 3), not primary research (n = 4) and children only (n = 2). The remaining 13 articles fell into two groups: multiple measures and single measures of cognitive function. Multiple measures, ranging from 4 to 19 items, to test a diverse range of cognitive abilities were used in eight articles. While these provide a detailed profile of a patient’s cognitive function, they present an excessive burden to the research participant, as this clinical level of detail is not required for the purposes of characterising a research participant. Single measures of cognitive function were used by the remaining five articles, the Dementia Rating Scale63 and the Trail Making Test64 were each used in one study, and three used the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). 65 The MMSE is an 11-item assessment scale scored out of 30. Traditionally, cognitive impairment is defined as a score of ≤ 23, at which the sensitivity is 83% and specificity 96%. 66

Discussions held with an expert in upper arm and hand function identified that manual dexterity is a composite of motor, sensory and visual skills. Commonly used tests of hand function with respect to medication adherence are the Purdue tests, grooved tests and nine-hole peg tests (9-HPTs). The Purdue pegboard is commonly used to assess the suitability of candidates for production line work when very high levels of dexterity are required in assembling fine components. This test was considered unsuitable in the context of personal pill taking. 67 The grooved pegboard test comprises metal pegs which are akin to small keys (30 mm long and 5 mm at their widest point) which must be rotated appropriately before insertion into keyhole-like depressions arranged in a 5 × 5 array. 68 The high visual requirement and very small pegs make this test unsuitable for the study population, as has been demonstrated by previous work in this area by Adams et al. 69 The 9-HPT comprises nine plastic dowels (each 6 mm in diameter), which are slotted into nine round holes arranged as a 3 × 3 array, and then removed from the holes. This test of finger dexterity has been described as particularly appropriate for use by the very old and very young and is also simple and quick to administer. 70 Additionally, the pegs for this test have a short axis that is very similar to those of tablets or capsules.

Visual skills required for successfully taking medication are those related to near vision only. Expert advice indicated that the test should assign a text size threshold at habitual visual acuity, that is in usual lighting conditions, at usual distance and using usual visual aids and that reading ability need not be assessed. Bailey–Lovie reading cards fulfil this requirement. 71

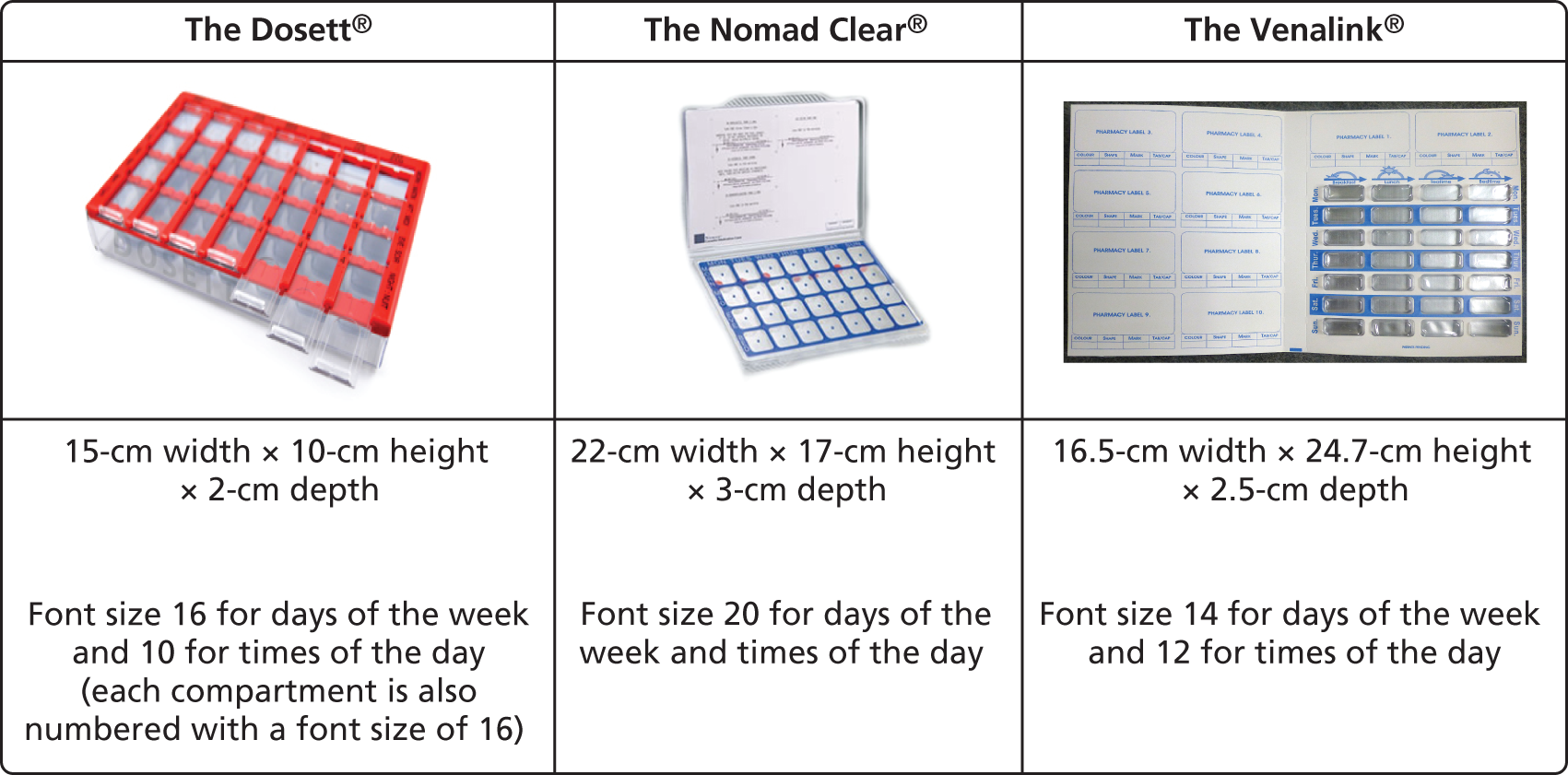

Selection of appropriate medication organisation devices

A survey of pharmacies to establish the MODs that are supplied had previously been undertaken by DB. This identified three MODs most frequently used: dosette boxes, Nomad Clear and Venalink. Figure 5 provides the specification for each of these. The dossette box, although frequently recommended by pharmacies, does not conform to recommendations for MOD characteristics as it is not a sealed unit; thus, medicines dispensed into the MOD are not protected from water vapour and atmospheric gases. 72 This means that medicines dispensed in the MOD are at increased risk of degradation. The Nomad Clear and Venalink are both sealed containers and thus afford greater protection to the medication. Furthermore, it is recommended that MODs should have tamper-evident seals, which dosette boxes do not have.

FIGURE 5.

Medication organisation devices.

Nomad Clear is a lidded, clear rigid plastic tray of pre-formed compartments. It is cold sealed using a flat plastic adhesive film through which pills are accessed. The film is labelled with days of the week and times of the day and is perforated at the perimeter of each compartment to facilitate ease of access. Nomad Clear XL™ (Surgichem Ltd, Cheshire, UK) is identical to Nomad Clear but, having larger compartments, is better suited to those prescribed more medicines. The Venalin is a cold-sealed device which closely represents blister packaging. It comprises a non-rigid plastic tray into which pills are dispensed. This non-rigid tray is then inserted into a cardboard wallet labelled with days of the week and times of the day and sealed using an opaque adhesive cover.

Defining standard care and the intervention

Expertise within the research team was used to define standard care and the intervention. Prescription medication packaging of solid oral dose medications in the UK is largely 28-dosage units labelled with the days of the week.

Research has demonstrated that reducing monitoring frequency from weekly to fortnightly reduces adherence to therapy and, therefore, it may follow that reducing medication supply frequency may have a similar effect. 22 It is possible that the beneficial effect seen with MODs could be obtained by dispensing medicine supplies in standard packaging (increasingly blister packs) and supplying at weekly intervals.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure, as stipulated by the funding agreement, was EAM. EAM overcomes the problem of self-presentation bias which is associated with self-reported adherence. EAM may, however, be susceptible to reactivity bias as the device used for EAM acts as a constant reminder of trial participation and thus may alter usual patient medication-taking behaviour, resulting in artificially inflated adherence. 73,74

Broad-ranging web-based searches were carried out to identify candidate objective adherence monitoring technology and manufacturers were approached to determine whether or not they could supply suitable technology for these purposes.

These searches identified that technological advances mean that it is now possible to objectively measure adherence. This type of monitoring is less susceptible to the Hawthorne effect by virtue of being less intrusive and less conspicuous to the patient than direct adherence measures or DUCs. Electronic medication monitoring systems were initially developed as bottle-based systems containing a switch and data logger in the cap. Such electronic medication monitoring systems have been widely used in clinical trials to assess medication adherence. 11,24–26 The data logger records the date and time of each bottle opening event. However, usual dispensing is now generally in manufacturer issued packaging which is in blister pack form. Trials have, therefore, generally approached this issue by decanting medication from usual packaging into the monitoring bottles. This has the limitation of not assessing adherence in a naturalistic setting.

Similar technological principles have been applied to blister packs; however, there is a further challenge to then translate this to electronic monitoring of manufacturer supplied blister packaging. There is no standardisation to the size and shape of solid oral dosage forms; thus, there is a huge array of different-sized and -shaped packaging.

The main requirements of an electronic monitoring system are that it is discrete, accurate and robust, and consistent for both MODs and usual-care blister packaging; in addition, the comparator must look and feel like usual care and the intervention should provide a good approximation of the intervention as it would in a real setting.

A number of potential candidate technologies were identified for EAM of usual packaging and three organisations were approached for information or to supply devices for the project [Med-ic MMD Solution™, Qolpac b.v. NL and Future Technology (UK)].

Qolpac b.v. (NL) provides electronics-based e-health solutions. Its Objective Therapy Compliance Monitoring (OtCM™, Qolpac, NL, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) system is a powered, single-circuit and resistor-based system printed using silver or copper ink onto a clear plastic sticky-backed film which records each time a blister seal is broken, assuming that this equates to ingestion. Data are downloaded to computer software which records the blister position and time it was broken to within 10 seconds of the actual time. Figure 6 shows a representation of the Qolpac b.v. OtCM system.

FIGURE 6.

Representation of an EAM system for blister packs.

Future Technology (UK) Ltd (Banbury, Oxfordshire, UK) has recently developed SMARTpack™, which is similar to the Qolpac product in design and data produced but uses mobile phone technology to transfer data from a logging device to a remote server.

GP Solutions (UK) Ltd supplied the E-wallet™ (Manchester, UK): a system that enables medication-taking events from blister packs and MODs to be recorded in the same manner as the previous two systems. Further details of the systems are presented in Tables 8 and 9 and in Appendix 2.

| Characteristic | Qolpac b.v. NL, OtCM | Future Technology (UK) Ltd, SMARTpack | GP Solutions UK Ltd, E-wallet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Discrete unit for which the patients’ usual pill pack is overlaid with a flex-circuit (flexible self-adhesive film on which circuit is printed) and a small additional unit measuring approximately 40 mm × 40 mm × 4 mm attached directly to the pill pack comprising power source, data logger and magnetic circuit connection to measure adherence | Unit dose or multidose blister sealed directly with a flex-circuit. The blister is inserted into a lightweight plastic holder that contains a power source, data logger, multipin circuit connection unit and messaging system to measure adherence. The messaging system can be GPRS using mobile phone technology or NFC | Bespoke blister packs overlaid with flex-circuit to which a monitoring unit measuring approximately 40 mm × 40 mm × 4 mm comprising power source, data logger and multipin circuit connection unit are attached. The whole package is housed within a cardboard outer to measure adherence |

| Recyclability | EAM unit designed to be reused | EAM unit designed to be reused | EAM not designed to be reused |

| Software | Appropriate software in place | Appropriate software in place | Appropriate software in place |

| Date | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pill count | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pack temperature | No | Yes | Yes |

| Adherence | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Data | |||

| Monitored | Resistivity at 30-second intervals | Circuit integrity at 30-second intervals | Circuit integrity at 30-second intervals |

| Stored | Data logger within EAM unit | Data logger within EAM unit | Data logger within EAM unit |

| Captured | NFC/scan | GPRS/NFC/scan | NFC/scan |

| Design principle | Qolpac b.v. NL, OtCM | Future Technology UK Ltd, SMARTpack | GP Solutions UK Ltd, E-wallet |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOD design | Under development | Prototype | 1 × commercial model |

| Blister pack design | Under development | Under development | 4 × commercial models |

| In-house evaluation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| In-house evaluation blister pack | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| In-house validation MOD | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| In-house validation blister pack | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Multisite validation MOD | No | No | No |

| Multisite validation blister pack | No | No | No |

| Advantages/limitations |

|

|

|

All systems require precision-designed detection circuits which fit discretely to the surface of the blister pack. Each blister pack requires a slightly different design to ensure accurate recording of pill-taking events, that is if the circuitry does not cross the pill position then the removal of a pill will not be recorded. For a study of one medication, such systems are relatively cost-effective; however, in the case of studies involving multiple different medicines, each with individually shaped packaging, the cost of developing a detection circuit bespoke for each different type of medication would be prohibitive.

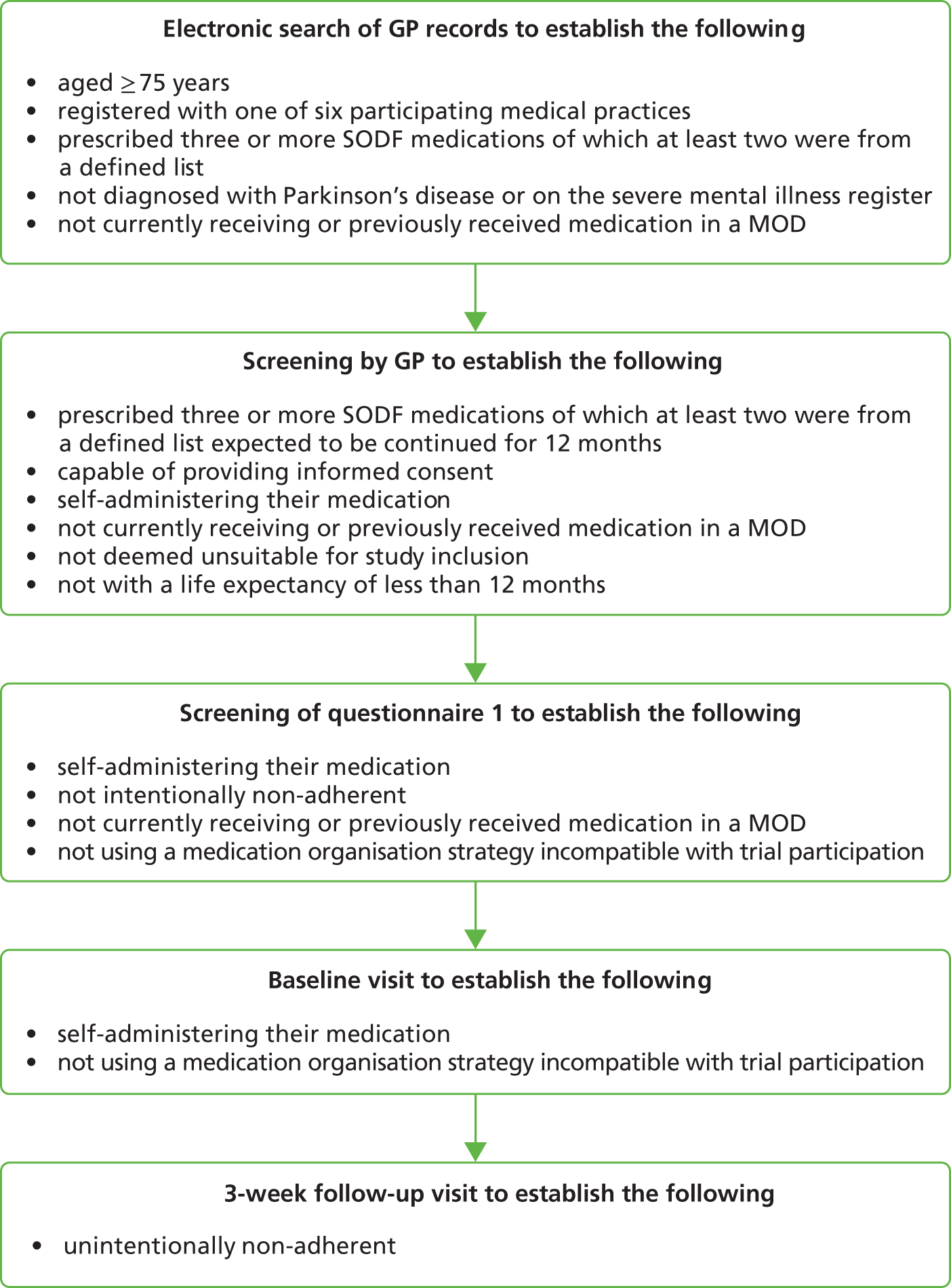

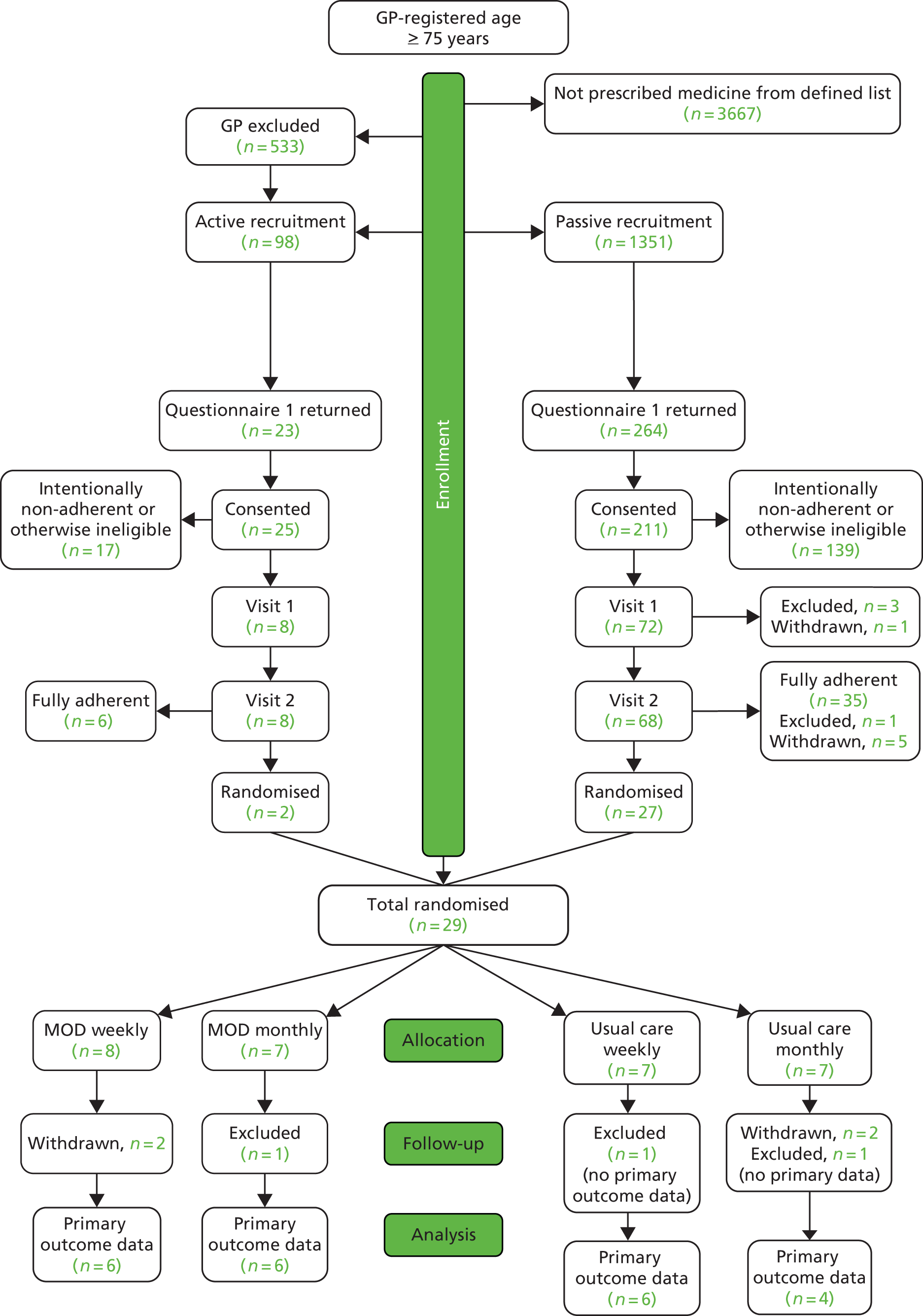

A 2-month pilot study (n = 52) of this technology to assess feasibility and acceptability reported promising results. Adherence data were obtained from 94.3% of participants, and 67.4% of participants reported that they would consider using the electronic monitoring system for a long-term study. 27 The original protocol for the pilot RCT set out to include adults aged ≥ 75 years if they were prescribed three or more SODF medications which were expected to be continued for 12 months, were registered with one of six participating medical practices and an associated pharmacy and were capable of providing informed consent. However, owing to technical difficulties with the supply of a suitable EAM system, the eligibility criteria were revised. The EAM systems were not universal and because of cost restrictions could be developed for only a limited range of pack sizes. Therefore, eligibility criteria were relaxed to enable adults aged ≥ 75 years who were taking three or more SODFs to be recruited. At least two of the participants’ medications needed to be from a defined list of 11 medications sourced from one supplier and identified by study GPs as those most commonly taken by patients in the over-75-years age group to enable electronic monitoring of adherence to at least two medicines.