Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/66/01. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Little is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board, although he was not involved in the editorial processes for this report, and has provided consultancy work to Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Hay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Acute illness in young children is one of the most common reasons for consulting health care worldwide, and urinary tract infection (UTI) is an important cause of serious bacterial illness in children. 1 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a guideline on UTI in children in 2007. 2 This guideline emphasised the importance of prompt, microbiologically confirmed diagnosis and treatment of children, particularly in primary care where there is evidence that UTIs are missed. It also recommended a large prospective study to provide the diagnostic evidence needed to help primary care clinicians improve their recognition of children with UTI. 2

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme issued a commissioning brief (see Appendix 1) for such a study in 2008. Our four-centre consortium, led by the universities of Bristol and Cardiff, proposed the Diagnosis of Urinary Tract infection in Young children (DUTY) study with the aim of deriving and validating an algorithm for the diagnosis of UTI in children < 5 years old presenting to primary care with any acute (and largely undifferentiated) illness. We proposed a two-step algorithm, reflecting the two-step clinical process in the diagnosis of UTI: first to use symptoms and signs to help clinicians efficiently identify which young children should have their urine tested; and second to determine the added value of dipstick testing for determining which children warrant immediate antibiotic treatment.

We were particularly well placed to understand the challenges of conducting this study, with all the complexities of urine collection from acutely unwell children in the context of busy, UK primary care centres, as the Cardiff group, led by Dr Kathryn O’Brien, had been conducting a smaller study of similar design called ‘EURICA’ (The Epidemiology of URinary tract Infection in Children presenting with Acute illness in primary care) to establish the prevalence of UTI in pre-school children.

In this introductory chapter, we summarise the background leading to this study and describe the aims and objectives of the DUTY study.

Prevalence of urinary tract infection

It is important to know how often UTI is the cause of acute illness in children presenting in primary care in the UK as this will inform urine sampling strategies and influence levels of clinical suspicion among general practitioners (GPs).

There are wide variations in the reported rates of UTI in children depending on setting, inclusion criteria and microbiological laboratory test criteria. 3 Most studies report the rate of UTI as determined from laboratory samples which have been requested by clinicians who suspect UTI to be present. We cannot rely on urine sampling based on clinician suspicion to determine an accurate prevalence of UTI, as children with non-specific symptoms will be excluded from urine sampling.

Shaikh et al. published a review of the prevalence of UTI in children in 2008. 4 They included 14 studies of children < 2 years old and found a pooled prevalence of 7.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 5.5% to 8.4%]. Urine was collected using suprapubic aspiration (SPA), catheters or clean catch in the majority of studies. None used nappy pads and studies were excluded if > 25% of subjects with UTI had urine collected using bags. The review found a high degree of heterogeneity and a range in prevalence from 3.3% to 13.8%. The review included studies which had not systematically sampled urine from children, and two of the largest studies had included urine samples requested on the basis of clinician suspicion. 5,6

A more recent review (2012),7 of 21 studies, which included only studies where urine was systematically sampled (urine sampled from consecutive children from the study population rather than urine sampled according to clinician suspicion of UTI), found similar pooled prevalences to Shaikh et al. for UTI [7% for children < 3 months old (5.9% including only studies with more stringent UTI definitions); 8% for children up to 5 years old]. There was significant heterogeneity between studies. Furthermore, almost all of the studies were from the USA and included populations with very different ethnic makeups and levels of circumcision than the UK, both of which factors have been associated with UTI. 3,8 Most studies were from paediatric emergency departments and all excluded children without a fever (where fever was usually defined as > 38 °C). Therefore, these findings may not be generalisable to UK primary care. The EURICA study, conducted in UK general practice (n = 1003), with systematic urine sampling, found that 5.9% of children < 5 years presenting with an acute undifferentiated illness had UTI. 9

Importance of diagnosis

The accurate and timely diagnosis of UTI is important because appropriate treatment may alleviate short-term suffering and help to prevent longer-term adverse consequences such as renal scarring, impaired renal growth, recurrent pyelonephritis, impaired glomerular filtration, hypertension, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and pre-eclampsia. 10,11 Some recommendations advise prompt antibiotic treatment for symptoms suggestive of UTI in young children to prevent renal scarring. 2

That said, some childhood UTI may be self-limiting. Although there are no randomised placebo controlled trials of UTI in children, there is evidence in adults, and some indirect evidence in children, that some UTIs are self-limiting. 1,12,13 However, it is not clear which children have a self-limiting UTI, and, when they recover clinically, if they are still at risk of renal scarring and long-term complications. We do know that in half of adult women, bacteriuria persists following a symptomatic UTI if this is left untreated, even if their clinical symptoms have improved,14 and an experimental study in pigs found that renal scarring could occur even after symptomatic recovery. 15 In contrast to the guidelines for other self-limiting infections, those for UTI in children advocate its prompt microbiological diagnosis and treatment due to the association with long-term complications. 2

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the growth of significant bacteria [≥ 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per ml on culture of urine] in a patient with no symptoms. Although the population of interest for the DUTY study are acutely ill, and therefore not asymptomatic, it is possible that some of the children identified as having UTI due to a positive culture result could have asymptomatic bacteriuria with another coincidental illness. It is impossible to distinguish this case from a child with UTI because the presenting symptoms of UTI are often thought to be non-specific.

The significance and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in children remains controversial. Guidelines recommend that asymptomatic bacteriuria should not be treated in children. 2 However, this advice was based on a review of four studies, none of which included children < 4 years old. 2,16–19 A recent Cochrane review concluded that there were insufficient data to form reliable conclusions about the harms and benefits of treating covert bacteriuria in children. 20 A review in 1990 concluded that neonates and preschool children with asymptomatic bacteriuria should be treated. 21 We found only one study which followed up infants with asymptomatic bacteriuria for 6 years. None of the nine girls and 27 boys had renal damage on follow-up urography, although some developed pyelonephritis. 22 Numbers were small and some of the infants had received antibiotics for respiratory tract infections.

Several studies (most from the 1970s) have reported the prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in children. 23–31 Rates range from 0% to 1.8% for children < 5 years old, depending on sex and age. 7 NICE points out that children found to have asymptomatic bacteriuria on screening will include ‘those with no discernible history of UTI, some with a previous history of UTI, and some who have had symptomatic UTIs but have not been diagnosed’. 2 The authors of a Cochrane review of interventions for covert bacteriuria in children comment that some children identified with asymptomatic bacteriuria subsequently become symptomatic. 20

We considered these issues for the design of the DUTY study and concluded that we should only recruit children with constitutional or urinary symptoms associated with their acute illness, such that all children found to have significant bacteriuria with a uropathogenic organism would be considered to have a UTI.

Longer-term adverse consequences

There is evidence that UTI can lead to renal scarring. 2,32,33 A systematic review of the risk of renal scarring following first childhood UTI included 33 studies with a total of 4891 children. 33 The authors found that 57% had evidence of acute pyelonephritis (defect on early scans; based on 29 studies) and 18% had evidence of renal scarring (persistent defect on follow-up scans; based on 14 studies but this dropped to 15% when only the nine most recent studies were considered). However, there was significant heterogeneity between studies and children with UTI were not necessarily identified systematically. Although this systematic review represents the best available evidence, the finding that renal scarring occurs in 15–18% of children with UTI seems very high and may not be generalisable to a primary care population of children with UTI, if they had been identified through systematic urine sampling.

The risk of renal scarring following UTI seems to be greater in younger children, and renal scarring is uncommon over the age of 4 years. 2,32,34,35 It was previously thought that vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) had to be present for renal scarring to occur, but it is now accepted that renal scarring can occur, without VUR. 2,33,36,37

It is thought that renal scarring can be prevented if UTI is treated promptly with antibiotics,2 and there is some evidence that a delay in the treatment of acute UTI is more likely to result in renal scarring. 38–44

Renal scarring has been associated with long-term complications including renal failure [end-stage renal failure (ESRF)], hypertension and pre-eclampsia. 2,45–47 These are serious, chronic conditions responsible for significant morbidity and costs to the NHS. However, the evidence is weak and bias and/or confounding could be responsible for the observed associations. 47 A recent paper estimated the risk of ESRF following childhood UTI to be 0.1% but the authors suggest that this could be an underestimate. 46 The NICE guideline concludes that ‘there are no appropriate studies that accurately estimate the risks of long-term complications as a result of childhood UTI’, highlighting the need for a long-term cohort study. 2

Missed diagnosis

It is thought that many cases of UTI are currently being missed in primary care. 2 One UK-based randomised controlled trial (RCT), in which the intervention was a nurse-led clinic to facilitate urine collection and diagnosis, found a usual-care-arm diagnosis rate half that of the intervention group. 48 This study suggested that even more UTIs are missed in children < 1 year old and in children without specific urinary symptoms (up to 75%). 48

Frequency of paediatric urine sampling in primary care

The main barrier to diagnosing UTI is failure to request or obtain a urine sample. GPs may not request a urine sample if they do not suspect UTI, perhaps owing to non-specific symptoms or signs, or perhaps because they do not believe that UTI is sufficiently prevalent or likely in that child. Even if a urine sample is requested, it may not be obtained due to the practical difficulties of obtaining a urine sample from a young child. 49

An estimate of how often GPs obtain urine samples from acutely ill children consulting can be calculated from several studies published prior to the NICE guidelines. 2 Jadresic found that two urine samples per 100 registered children (< 2 years old) per year were sent to laboratories by GPs. 50 We know that children < 5 years old consult on average six times per year and that 87% of consultations are for acute illness. 51–53 This equates to urine being sampled in 0.4% of illness consultations in children < 2 years old. Another study in Wales gave a similar estimate, of 0.6% of illness consultations involving a urine sample. 54

The publication of the NICE guideline in 2007 may have raised the level of suspicion of UTI and urine sampling from acutely ill children. We estimated current levels of urine sampling from consultations with acutely ill children in Wales from Public Health Wales data. In 2012, 12,689 urine samples were received by microbiology laboratories from general practices in Wales for children < 5 years old (Dr Robin Howe, Consultant Microbiologist, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, 11 June 2013, personal communication). We do not know how many children were registered with practices in 2012, but from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2011 census there were 178,000 children < 5 years old living in Wales in 2011. 55 Assuming that all children were registered with practices; that numbers for 2012 were similar to 2011; that urine sampling reflected normal practice (some practices were participating in the DUTY study); that children consulted six times per year; and that 87% of consultations were for acute illness gives an estimate of urine sampled in 1.4% of acute illness consultations in children < 5 years old in Wales in 2012.

Unless GPs can target urine sampling extremely accurately, it is unlikely that such low levels of urine sampling will allow detection of the majority of UTIs.

Methods of urine sampling in primary care

There are five main methods of obtaining urine samples from children: SPA, catheter insertion, clean catch, nappy pad and bag collection. Owing to concerns about their invasive nature and the restrictions of time and space in the UK primary care setting, SPA and catheters are not recommended for use in UK primary care. 2 NICE suggest that samples should be collected using a method suitable for the age of the infant or child. 2 ‘Clean-catch’ samples are preferred, but urine collection pads are suggested if this is not possible.

Our HTA systematic review published in 2006 reviewed methods of urine sampling and included four studies in children < 5 years. 56 We have updated this systematic review for the DUTY study (see Appendix 2).

We found a further two primary studies, giving a total of six studies, that assessed urine sampling methods. 57–62 Two studies compared culture of urine bag specimens with culture of SPA samples. 57,59 One reported a sensitivity of 100% and the other of 50%; both studies found specificity to be around 90%. Two studies compared culture results from urine samples obtained by bag specimens with those obtained by catheter. 58,61 The appropriateness of a catheter specimen as the reference standard is questionable, meaning that these results are of limited value. One study compared culture of a nappy pad specimen with culture of SPA samples. This study reported a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94%, suggesting excellent agreement between the two sampling methods. 60

A recently published study assessed a device known as the ‘U-test’, which is a nappy pad incorporating a urine dipstick. 62 The accuracy results are, therefore, a combination of the nappy pad and the dipstick but show good accuracy with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 79%. However, these were compared with a reference standard consisting of a variety of urine collection methods (clean catch, bag, catheter or SPA) and the study had results available for only 25 participants.

The NICE guidelines found ‘insufficient data to draw conclusions about urine collection bags and urine collection pads’ but advised that either is acceptable for UK primary care. 2 There have been only two studies published since these guidelines and these do not provide sufficiently strong data to change these conclusions, although the limited data suggest that pad specimens may be a more accurate method of urine collection than bag specimens. Furthermore, the pad sampling method has been shown to be more acceptable to parents than the bag method due to the problems of the bag adhesive irritating the child’s skin. 63 We prioritised clean-catch urine sampling where this was possible, and the use of nappy pad sampling where it was not, for the DUTY study.

Which children should have their urine sampled?

When faced with an acutely ill child, the clinician has several decisions to make to diagnose possible UTI:

-

Should a urine sample be obtained from the child?

-

If so, should the urine sample be tested with a dipstick?

-

Should the urine sample be sent to the laboratory for culture?

-

Should antibiotics be prescribed before the culture result is available?

-

Should antibiotics be prescribed once the culture result is available?

Identifying which pre-school children should be sampled in primary care is challenging, particularly in those < 2 years, because most are pre-verbal, symptoms and signs are usually non-specific, and obtaining uncontaminated samples is difficult. 2,49,64 NICE suggests that clinicians should test for UTI in children < 5 years with unexplained fever, vomiting, lethargy, irritability, poor feeding, abdominal pain, offensive urine, haematuria, frequency or dysuria. 2 However, they acknowledge a lack of evidence to support the diagnostic utility of these symptoms and signs, and uncertainty regarding the role of dipstick testing. 64

Existing evidence for the diagnostic value of symptoms and signs

We reviewed the evidence for the predictive values of clinical symptoms and signs for UTI in children (see updated systematic review in Appendix 2). We identified five primary studies (Craig et al. ,1 Gorelick and Shaw,65 Gorelick et al. ,66 Gauthier et al. 67 and O’Brien et al. 9) (n = 17,793) and one systematic review (eight primary studies)3 in children aged < 5 years old (n = 7892) that assessed clinical symptoms and signs. These were conducted mainly in hospital emergency departments; only one was conducted in general practice. 9 No individual or any combination of symptom(s) or sign(s) were sufficient to rule in a diagnosis of UTI, although some post-test probabilities (e.g. 25% for increased capillary refill time, no fluid intake and suprapubic tenderness) appear high enough to mandate urine testing and empirical treatment while awaiting culture confirmation.

The largest study, which included almost 16,000 children aged < 5 years presenting to the emergency department,1 derived a clinical prediction rule based on a combination of 27 symptoms and signs. The model was found to have an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.80 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.82). However, UTI was not identified through systematic urine sampling in this study, with urine cultures obtained in only 21% of children, calling into doubt the representativeness of this model to diagnose UTI.

The most representative primary care study to date (based in UK general practices with systematic urine sampling) also considered the predictive value of presenting symptoms and signs. 9 This study found younger age, urinary frequency and dysuria to be associated with UTI and found no association with fever or the presence of an alternative site of infection. However, the study was powered to determine UTI prevalence, not diagnostic accuracy, and this led to wide CIs around the diagnostic utility estimates.

Other risk factors

Age and sex

Previous studies have suggested that UTI is more common among males up until 3 to 6 months old. For children older than 12 months, UTI is more prevalent in females. 4,43

In our updated systematic review, we found that age < 3 months was a risk factor for UTI, irrespective of sex [likelihood ratio (LR) 3.9; 95% CI 3.2 to 4.8]. 68 The same study found a decreased likelihood of UTI in children aged > 3 years (LR 0.47; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.61). This study also found that being female increased the likelihood of UTI (LR 1.3; 95% CI 1.1 to 1.3) (see Appendix 2).

Circumcision status

Our review found consistent evidence that circumcision protected against UTI. The systematic review included in our review included six studies in boys aged < 24 months that assessed the association of circumcision and UTI, and reported a pooled LR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.63), suggesting that the likelihood of a UTI was lower in circumcised boys. 56 An additional study in boys aged 0–36 months supported this finding, although the CI was wide (LR 0.07; 95% CI 0.00 to 1.16). 67 It is worth recognising that many of the studies concerning UTI in children have been conducted in countries with much higher levels of circumcision than the UK. 7,69–71 The UK rate of circumcision is approximately 3%, compared with 80% in the USA. 72

Ethnicity

The systematic review included in our review included six studies that evaluated ethnicity in children aged < 24 months and found that non-black race increased the likelihood of UTI (LR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.8; systematic review of six studies)56 (see Appendix 2).

Past history of urinary tract infection

In our updated systematic review, we found that a prior history of UTI increased the risk of UTI, with a LR of 2.9 (95% CI 1.2 to 7.1) in children < 24 months old and a LR of 2.3 (95% CI 0.3 to 17.4) in children < 12 months old (see Appendix 2).

Summary of symptoms and signs

In our review we found that none of the risk factors, individually or in combination, was sufficient to rule in a diagnosis of UTI. Some combinations of symptoms, signs and proposed clinical prediction rules did reduce the probability of UTI below 2% and may be considered low enough to rule out UTI (see Appendix 2, Table 84). However, the studies on which these findings are based did not necessarily systematically sample urine, and were based on populations with a different ethnic mix and rate of circumcision from the UK and, therefore, may not be generalisable to UK general practice.

In the absence of accurate predictive symptoms and signs, a broad urine sampling strategy in children is advocated by NICE. 2 Others have also advocated urine ‘screening’ in some groups of children, for example in all febrile infants or broader urine sampling strategies in ill children. 70,73,74

A survey of 200 paediatricians in 1983 concerning the management of febrile infants found that all of the respondents felt that a UTI prevalence of 5% would warrant urine sampling in all; more than 80% felt that a prevalence of more than 3% would warrant urine sampling in all, and about half felt that a prevalence of between 1% and 3% would warrant sampling urine from all febrile children. 74

A recent retrospective study concluded that urine analysis should be added to the NICE ‘traffic light’ system for the detection of serious illness in febrile children < 5 years old. 73 This would require a large increase in urine sampling from acutely ill children.

Dipstick tests

Once a urine sample has been obtained, the clinician has the option of testing the urine sample with a urinary dipstick. The HTA-funded systematic review in 200656 found that urinary dipsticks were similar to the overall conclusions based on the updated review, that is that dipstick positive for both leucocyte esterase (LE) and nitrite is useful for ruling in a UTI and negative for both LE and nitrite is useful for ruling out a UTI. 56 NICE recommend only using dipsticks for diagnosis in children ≥ 3 years. They recommend that a urine sample should also be sent for culture in most cases (unless both LE and nitrite are negative on dipstick). 2 For children 3 years or older, and occasionally in younger children, NICE advise using a dipstick to help to target empirical antibiotics while waiting for urinary culture results. 2

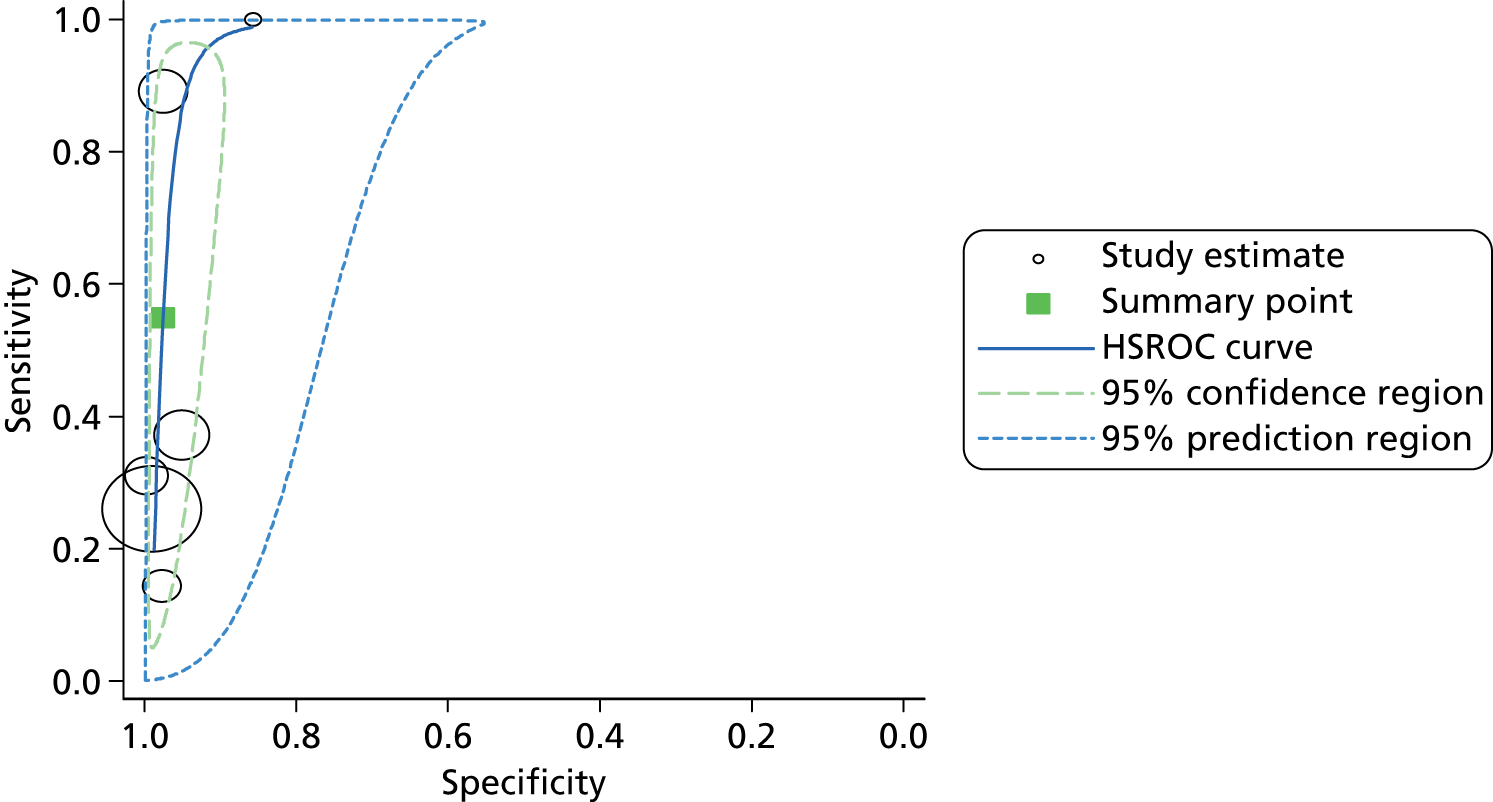

We have updated the 2006 systematic review for the DUTY study, which assessed the accuracy of dipstick testing for UTI in children (see Appendix 2). We found data from six primary studies57–62 (including those included in the HTA review) which assessed dipstick testing for LE and nitrite in children aged < 5 years. There was substantial heterogeneity across studies. Negative LRs were too heterogeneous to permit conclusions regarding the utility of LE or nitrite negative for ruling out a diagnosis of UTI, ranging from < 0.01 to 0.88 with a pooled estimate of 0.46 (95% CI 0.18 to 1.13). Positive LRs ranged from 6 to 108 with a pooled estimate of 22.8 (95% CI 11.1 to 46.5) suggesting that a dipstick positive for both LE and nitrite may be useful for ruling in a UTI. Positive LRs for the combination of LE or nitrite positive were also extremely heterogeneous, ranging from 1.8 to 73 with a pooled estimate of 10.5 (95% CI 3.4 to 32.2), making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the utility of this combination in ruling in a diagnosis of UTI. Negative LRs ranged from 0.16 to 0.32 with a pooled estimate of 0.22 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.30), suggesting that a dipstick negative for both nitrite and LE may be useful in ruling out a diagnosis of UTI.

Overall, the data were too heterogeneous to draw firm conclusions regarding the accuracy of dipstick testing; however, the data suggest that a dipstick positive for both nitrite and LE may be useful for ruling in a diagnosis of UTI, while a dipstick negative for both nitrite and LE may be useful for ruling out a UTI. The NICE guidelines stated that ‘further investigation of LE and nitrite dipstick tests alone and in combination, stratified by age and method of urine collection, is required to determine their accuracy in diagnosing UTI.’2

Microbiological diagnosis of urinary tract infection in the laboratory

Bacteriuria threshold

Laboratory diagnosis of UTI is based on colony counts following culture, which reflect the concentration of organisms in urine and hence the likelihood that the bacteria grown arise from a UTI rather than contamination. The standard threshold for diagnosing UTI from culture of ≥ 105 CFU/ml was established by Kass over 50 years ago. 75 This was based on studies of adult women with acute pyelonephritis and asymptomatic women. Some have questioned if this threshold is appropriate for children,76,77 with most suggesting a lower threshold76–79 but one advocating an increase. 80 UTI is typically thought to be caused by a single organism present in a high concentration, usually ≥ 105 CFU/ml. 81 However, laboratory guidelines differ regarding the urine sampling method, nature and extent of bacterial growth required to confirm UTI. 82,83 For a clean-catch specimen in children, > 103 CFU/ml of a single species ‘may be diagnostic of UTI’; and a pure growth of between 104–105 CFU/ml is ‘indicative of UTI’. 82 Although usually a pure or predominant growth is required for the diagnosis of UTI, the growth of two organisms, each with a growth of ≥ 104 CFU/ml, would also be considered as positive by these guidelines. 82 NICE guidelines do not provide a definitive threshold for diagnosing UTI on culture but provide advice about the level of bacterial growth in relation to symptoms and signs. 2 Although NHS laboratories in the UK follow the UK Standards for Microbiological Investigation for the examination of urine, application of the method varies between laboratories.

Some secondary care studies have required two consecutive urine samples with significant bacteriuria to diagnose UTI. 84,85 It has been suggested that obtaining two samples from children in primary care would reduce the risk of false-positive results;80 however, it is unlikely that this would prove successful in primary care given the challenges and current low levels of urine sampling. It is also unclear if two samples would improve validity as there may be a greater number of false-negative results with this technique. Current guidelines advocate one sample. 2

Chapter 4 reports the DUTY study analyses used to determine the reference standard and bacteriuria threshold to be used for the development of the DUTY study diagnostic algorithm.

Culture techniques and uropathogenic organisms

Standard techniques for culturing urine vary but usually rely on either cystine-lactose-electrolyte-deficient (CLED) agar or, more recently, chromogenic agar. 83 No single medium is likely to support the growth of (and detection of) all possibly significant organisms; however, most organisms commonly associated with UTI are supported. Organisms less commonly associated with UTI may not grow at all or may grow at an insufficient rate to be detected, for example Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and the coagulase-negative staphylococci. 86 There is no definitive list of uropathogenic organisms and the distinction between uropathogenic and non-uropathogenic is not always clear. 82 Staphylococaus saprophyticus is commonly associated with UTI in females and growth is supported on the normal media used. Most studies report that most UTI is caused by Escherichia coli, both in adult and paediatric populations. 14 Enterobacteriaceae are usually considered to be uropathogens. 30,34–36,82,87 Non-enterobacteriaceae such as enterococci (Lancefield Streptococcus group B), coagulase-negative staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, S. saprophyticus and pseudomonads are also considered to be potentially significant isolates. 88 Colonies are counted following culture (for ‘between 18–24 hours’). However, reporting varies from laboratory to laboratory and often depends on the clinical information given on the clinical request form.

Contamination

It is recognised that difficulty in specimen collection and the interpretation of specimens potentially contaminated prior to culture, from skin, faeces and other sources may contribute to the misdiagnosis of UTI. 89–98 Overdiagnosing UTI can lead to unnecessary investigations and treatment, which entail risks of complications and psychological stress to the child and family. Discriminating between contamination with faecal organisms and potential UTI pathogens in the laboratory is difficult as the most common faecal organism and the most common pathogen causing UTI is E. coli, and high colony counts may be found in children without UTI.

Contamination rates in collection methods vary, as indeed do the definitions of contamination. Contamination rates range from 0% in clean catch to 48% of bag urines. 98 In a retrospective observational cohort study, contamination in clean catch, catheter specimen of urine and bag was 1%, 12% and 26%, respectively. 98 Definitions of contamination vary from single organism growth < 105 CFU/ml OR ≥ 2 organisms to ≥ 2 organisms present at ≥ 105 CFU/ml of urine. 89,91

In a US study, no institutional factors such as access to refrigeration were found to be associated with either low or high contamination rates. 99 Gender and diarrhoeal symptoms also had no association with higher contamination rates in children. 100 Perineal cleansing in female adults had no association with contamination rates, while urine contamination rates were higher in midstream urine collected from toilet-trained children when obtained without perineal/genital cleaning. 89,94 One of the only factors affecting contamination rates which has been published is changing nappy pads every 30 minutes. 91

Although contamination is generally considered to increase the probability of false-positive results, there is some suggestion that contaminated samples or samples with mixed growth may hide a true UTI, that is lead to false-negative results. 101,102

Economic considerations

Urinary tract infection is the fourth most common reason for prescribing antibiotics, accounting for approximately 8% of all antibacterial prescriptions. 103 While the unit costs of laboratory testing and antibiotic prescribing are relatively low,56 the economic implications of new clinical algorithms for urine sampling and testing may be substantial owing to (1) the large numbers of children who present with non-specific symptoms which might be caused by UTI; (2) the cost of subsequent diagnostic tests used to further evaluate children with recurrent/atypical UTI;2 (3) the substantial costs and impact on quality of life of a missed diagnosis that leads to rare but serious complications of UTI; and (4) the wider, long-term population impact of diagnostic algorithms on antibiotic prescribing and bacterial resistance. 104

The few economic evaluations of the diagnosis of UTI in young children have primarily aimed to identify the most cost-effective test or series of tests for diagnosing UTI, rather than address the important issue of exactly which children should be selected for urine sampling and testing in the first place. 2,5,6 There is limited economic evidence on which children should have a urine sample taken, by what sampling method, and which urinalysis tests should be used to guide initial treatment. Guidance is especially needed for children < 3 years of age for whom current NICE clinical guidelines are not based on evidence of cost-effectiveness. 3

Summary of DUTY study design

Summary of the research brief

The background given to the NIHR HTA research brief for improving the recognition of UTI in children in primary care (see Appendix 1) was summarised indicating the nature of the problem, that young children with UTI may present with non-specific symptoms such as poor feeding, vomiting, irritability, jaundice (in newborns) or fever alone, suggesting that a broader approach to testing may be appropriate. The research question that the commissioning brief proposed should be answered was: ‘Which clinical features of potential infection are useful in making a preliminary diagnosis of UTI in children < 2 years of age and indicate the need for a urine specimen to be taken?’

Summary of the justification for the DUTY study design

DUTY was a diagnostic cohort study, set up to systematically sample urine from acutely unwell children, with constitutional and/or urinary symptoms, in UK primary care in order to determine the diagnostic value of symptoms and signs for UTI. We proposed to develop and validate an algorithm in two steps: first, to use symptoms and signs to help clinicians to efficiently identify which young children should have their urine tested; and second, to determine the added value of dipstick testing. We included a health economic evaluation to determine the cost-effectiveness of the clinical algorithm compared with existing practice.

We recognised that the age at which children can verbalise their symptoms and achieve bladder control varies between children and that no single age < 5 years would adequately reflect this. We also knew that collecting urine samples from children under the age of 2 years would be challenging and that information from older pre-school children might still be valuable for younger pre-school children. We therefore proposed a study that recruited children up to but not including the age of 5 years.

Aim of the DUTY study

The aim of the DUTY study was to derive and validate an algorithm to improve the recognition of UTI in children < 5 years of age presenting to primary care with an acute illness. It was envisaged that the algorithm would be constructed to address two questions: (1) which children are at sufficient risk to warrant urine sampling; and (2) to determine the added value of point-of-care urine dipstick testing. The findings from these two stages would be combined to produce the overall algorithm.

Research objectives

The DUTY study’s ‘Detailed Project Description’ (the final protocol submitted with the final funding application) contained the following five research objectives:

-

To develop an algorithm that accurately identifies children presenting in primary care with an acute illness in whom a urine sample should be obtained, based on socio-demographic factors, medical history, symptoms and signs (see Chapter 5).

-

To assess whether dipstick urinalysis for nitrite, LE, protein, blood and glucose gives additional diagnostic information to objective (1) in the identification (ID) of urine samples that should be sent to the laboratory (see Chapter 5).

-

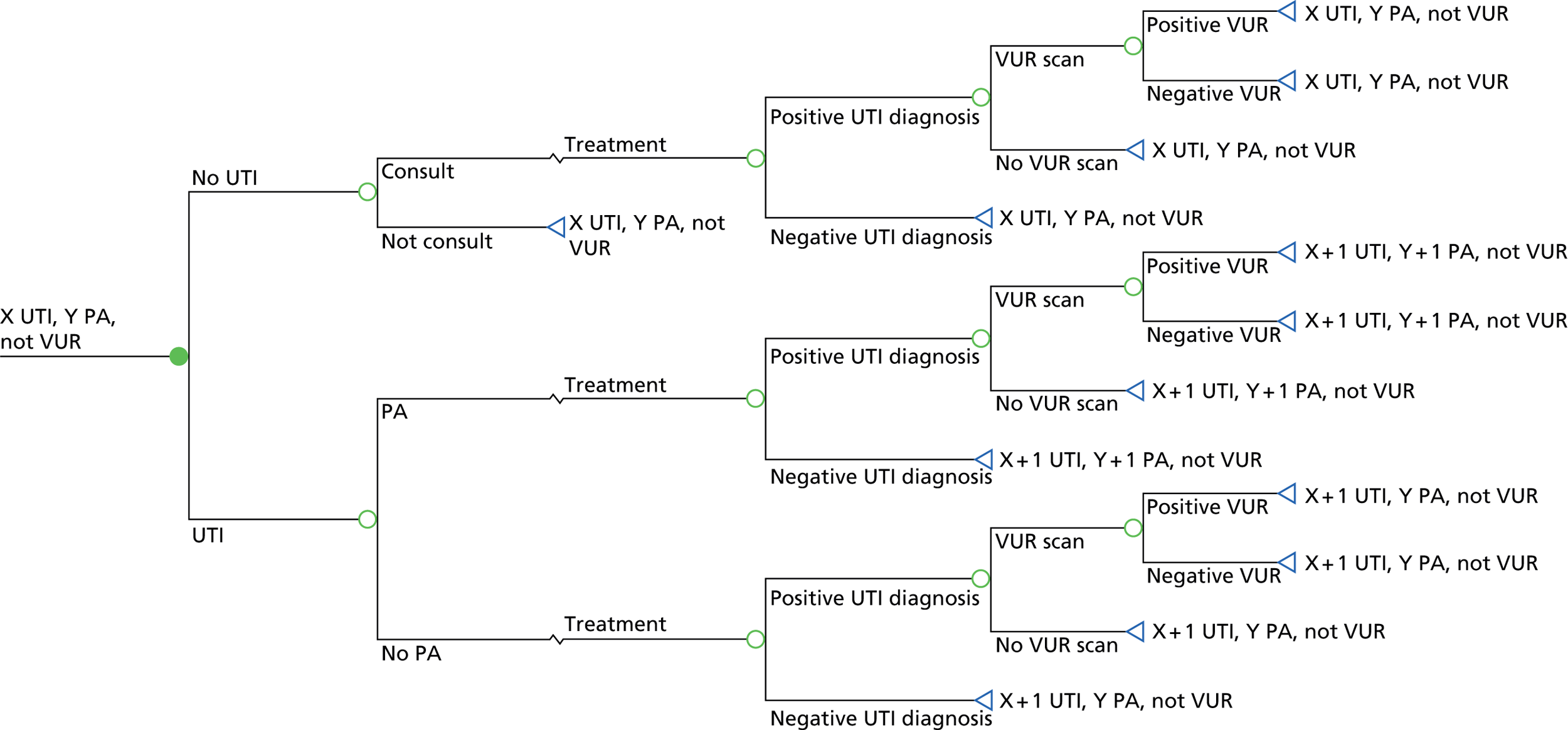

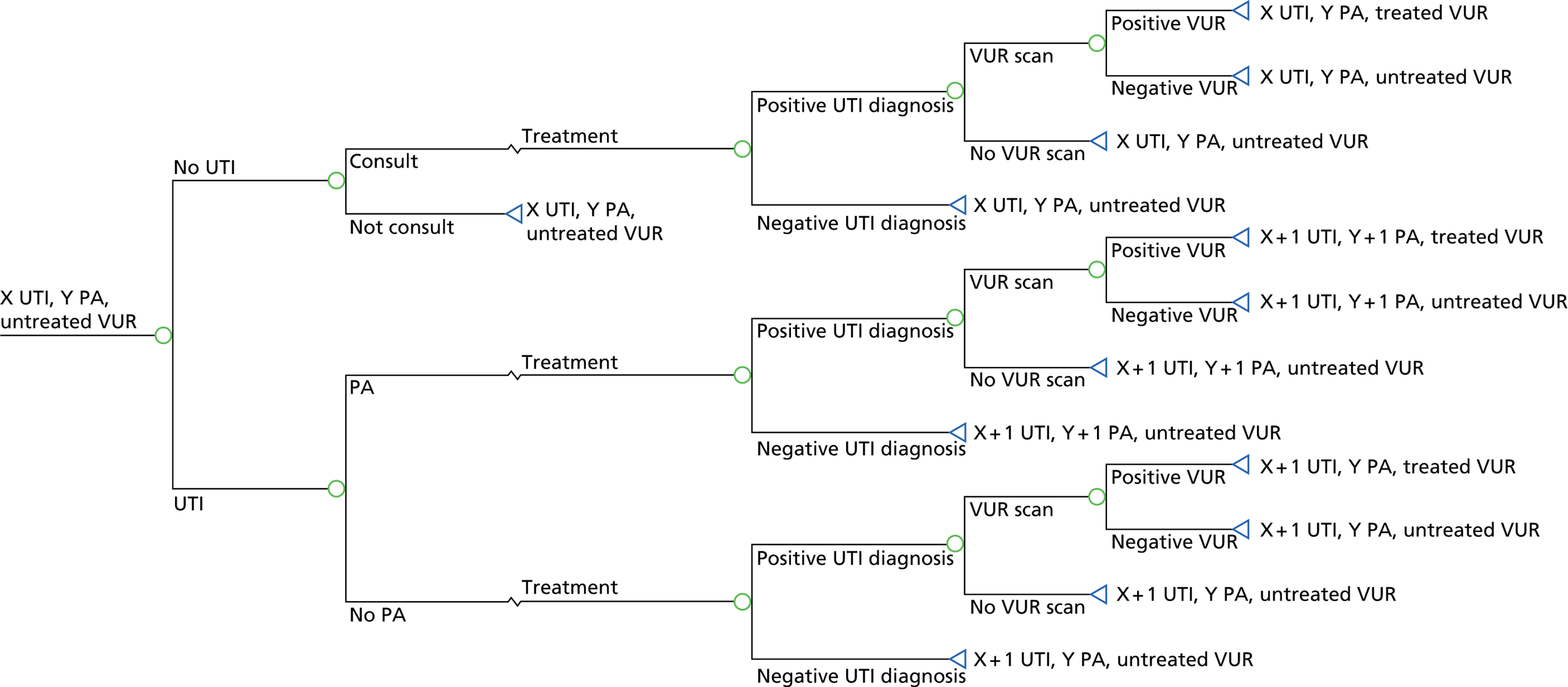

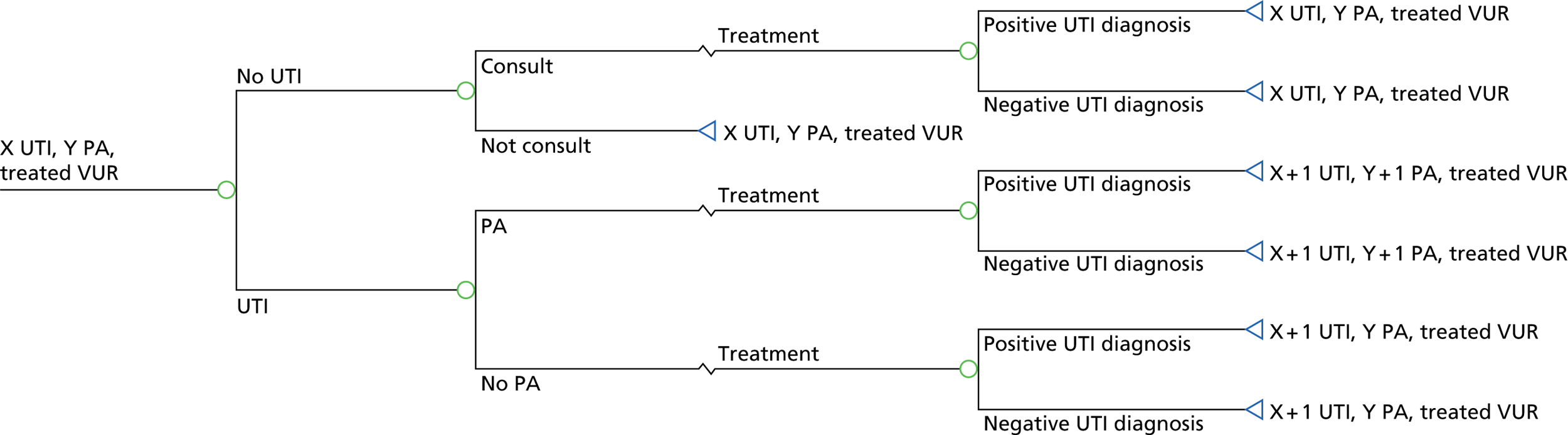

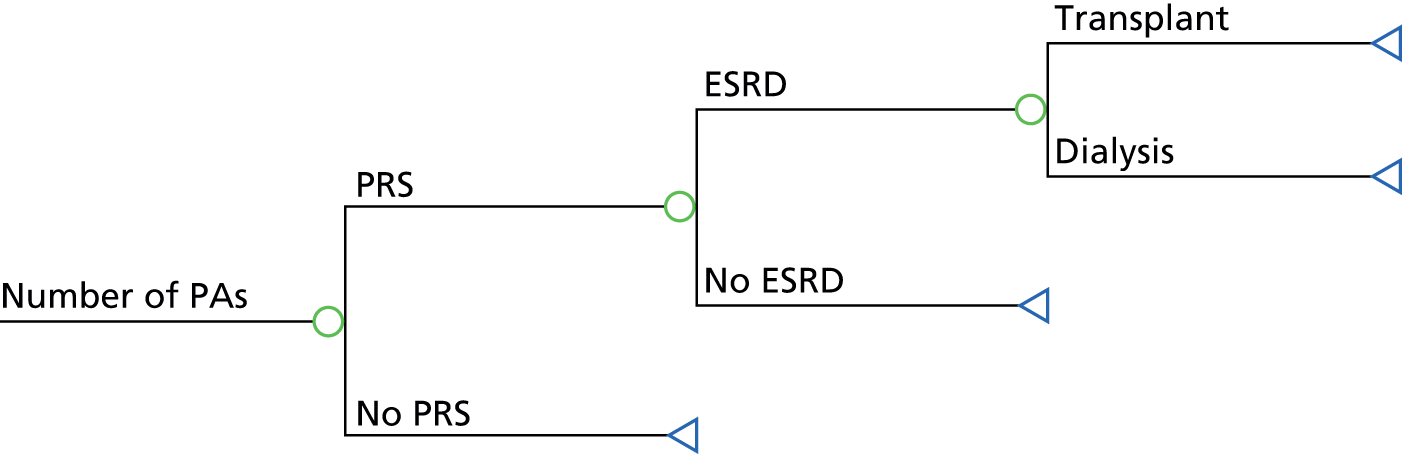

To model the cost-effectiveness (cost per correct diagnosis of UTI, cost per symptomatic day avoided and lifetime cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), including potential long-term complications of UTI) from NHS and societal perspectives of one or more diagnostic algorithm guided strategies (see Chapter 6).

-

To compare contamination rates for nappy pad versus clean-catch urine sampling methods (see Chapter 7).

-

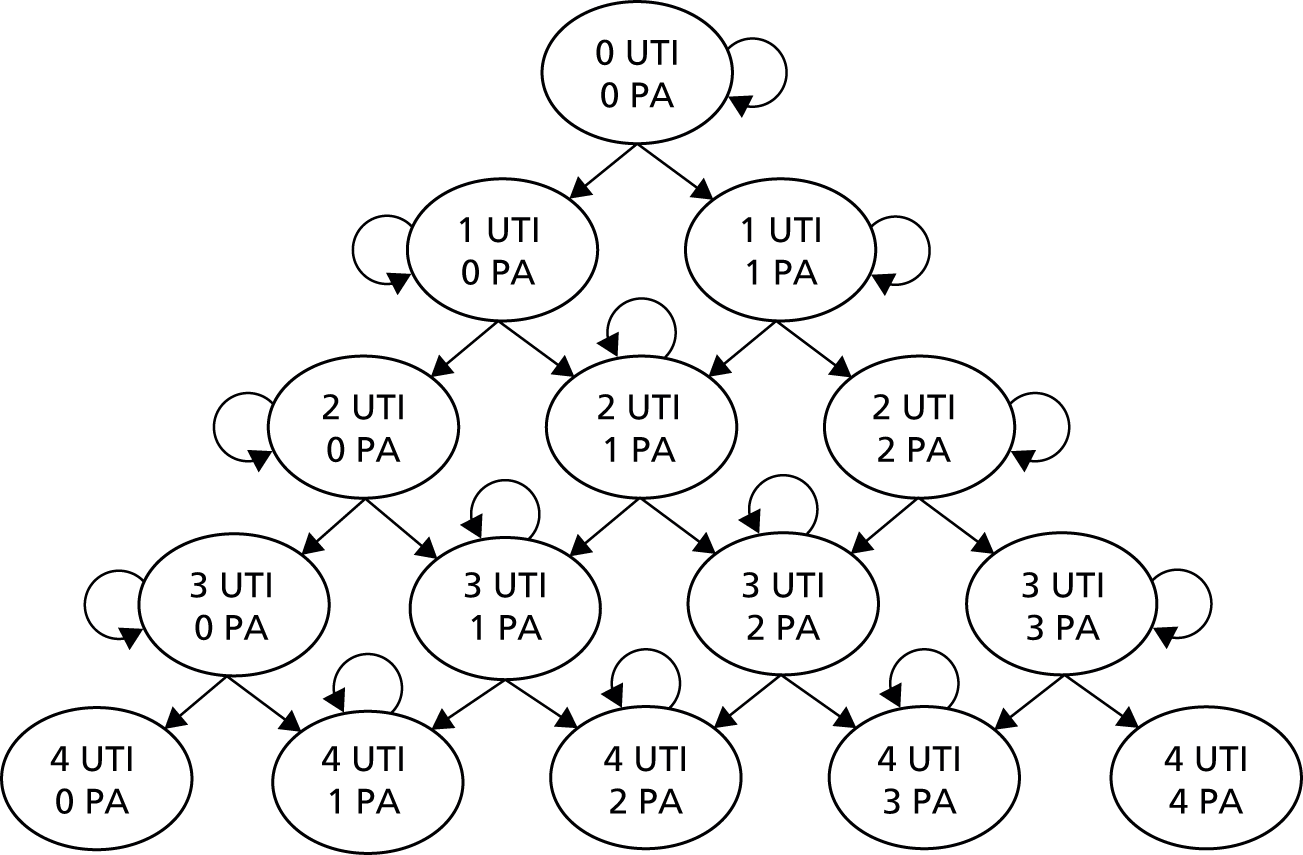

To explore the significance of two categories of positive urine culture (laboratory diagnosed UTI vs. asymptomatic bacteriuria/contamination) by (a) comparing the number of NHS contacts at 3 months in children with positive urine culture stratified at presentation by the responsible clinician’s assessment of possible UTI versus plausible alternative diagnosis, and (b) investigating for persisting bacteriuria in a second urine sample.

Changes to the original funding proposal

Planned change to age inclusion criterion

In response to reviewers’ comments (suggesting eligibility to < 4 years) to our detailed project description, and in communication with the HTA, we decided to increase eligibility to < 5 years. This was a pragmatic decision informed by early findings from the EURICA study (a similar study being conducted by the Cardiff members of the DUTY group) that showed higher recruitment, urine return rates and UTI prevalence in the ≥ 4 and < 5 years group and a judgement by the DUTY investigators that children ≥ 4 and < 5 years were often similar, with regard to development of language and bladder training skills, to children aged ≥ 3 and < 4 years.

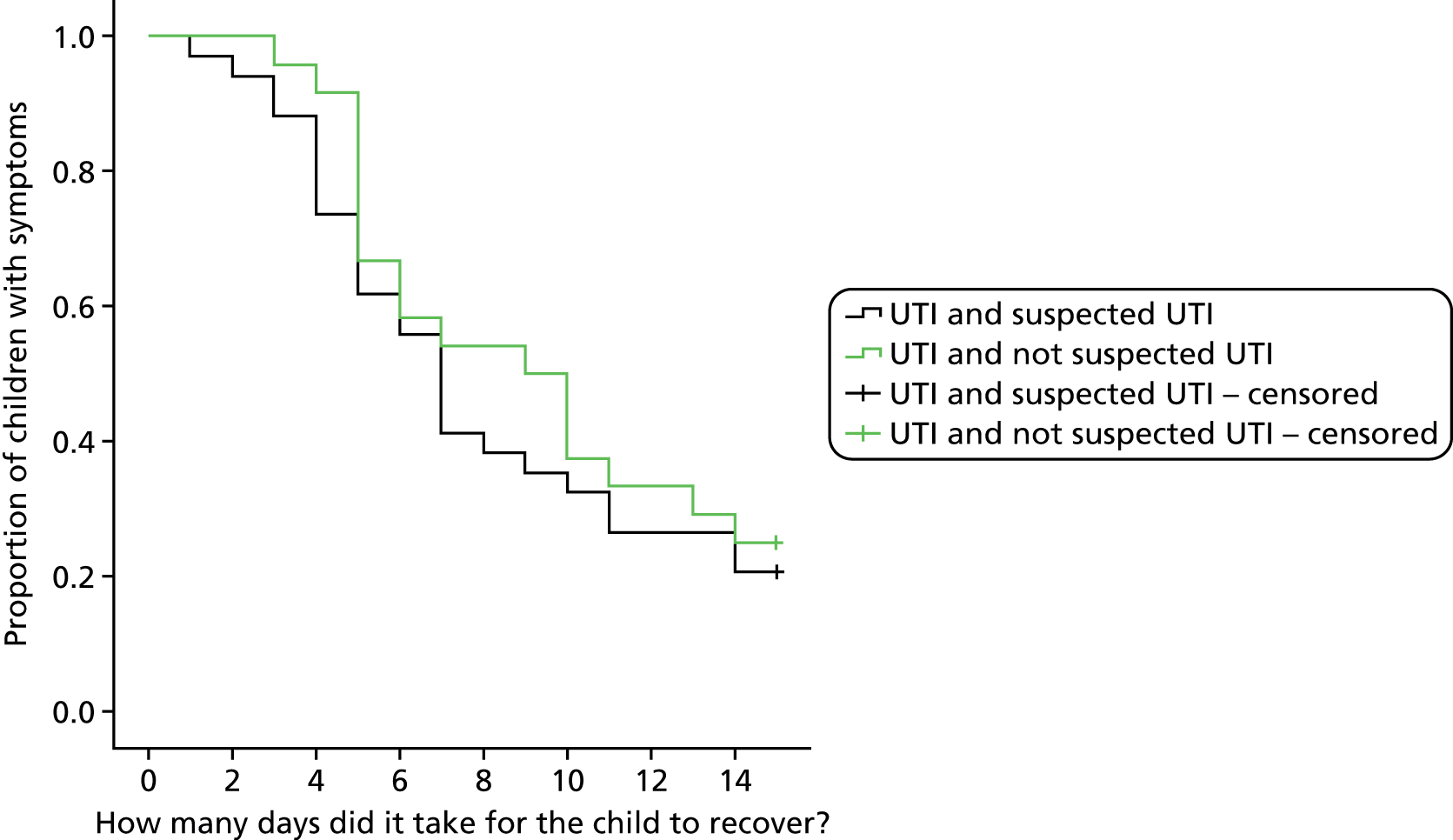

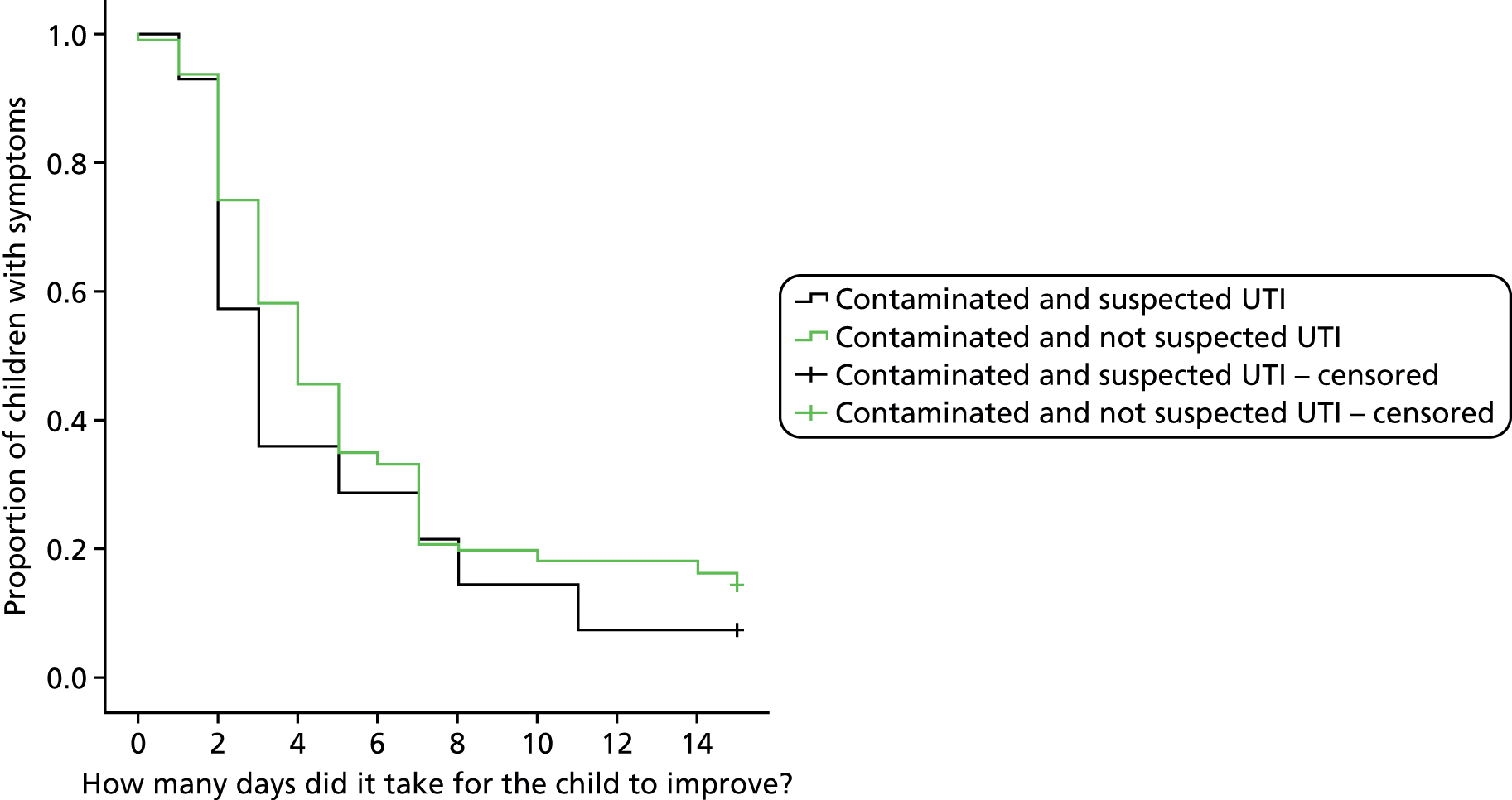

Planned change to research objective 5

The original funding proposal submitted to the HTA on 12 February 2009 contained five research objectives. The outcomes of the first four objectives are reported in this publication but the fifth was changed prior to publication of the final protocol105 (see Appendix 3). This was because the study eligibility criteria meant all children were unwell (or had urinary symptoms) thus making it difficult to determine asymptomatic bacteriuria as no children were asymptomatic. We therefore removed this as an objective and, instead, have undertaken exploratory analysis on the children who had positive or contaminated urine, investigating the impact of their clinician’s working diagnosis on symptom duration and number of NHS contacts at 43 months. These latter findings are reported in Chapter 7. We also decided that taking a second urine sample in this population would have been too large a logistic undertaking and that persistent bacteriuria was not the focus of the study.

Unanticipated changes to the validation process and reference standard

Our original intention had been to derive and externally validate the diagnostic algorithm, using an approximate 66/33 data split for derivation/validation and to analyse the clean-catch and nappy pad samples together. However, analyses reported in Chapter 4 suggested that the urine collection method was having a greater than anticipated effect on laboratory culture results. Therefore, and in consultation with a number of international experts, we decided to stratify algorithm development by the clean-catch and nappy pad collection method (approximately a 50/50 division of data) and to use bootstrapping to validate the algorithms. This decision was made for two reasons. First, the smaller than anticipated numbers of outcome events in the stratified analyses meant that analyses restricted to a development sample would have been underpowered and estimated coefficients imprecise. Second, our statistical advice was that the properties of a random split into development and validation samples could be mimicked by the bootstrap procedure that we adopted, and statistical overoptimism quantified using calibration slopes.

As it would better reflect day-to-day clinical practice, we originally intended to use ≥ 105 CFU/ml of a known uropathogen from the NHS laboratories as our reference standard. However, as the analyses presented in Chapter 4 show, there was greater than expected disagreement between local and research laboratories, with evidence that the research laboratory was both more reliable and more accurate than NHS laboratories. We therefore decided to use the research laboratory result as the reference standard.

Other changes from the detailed project description

Sample size

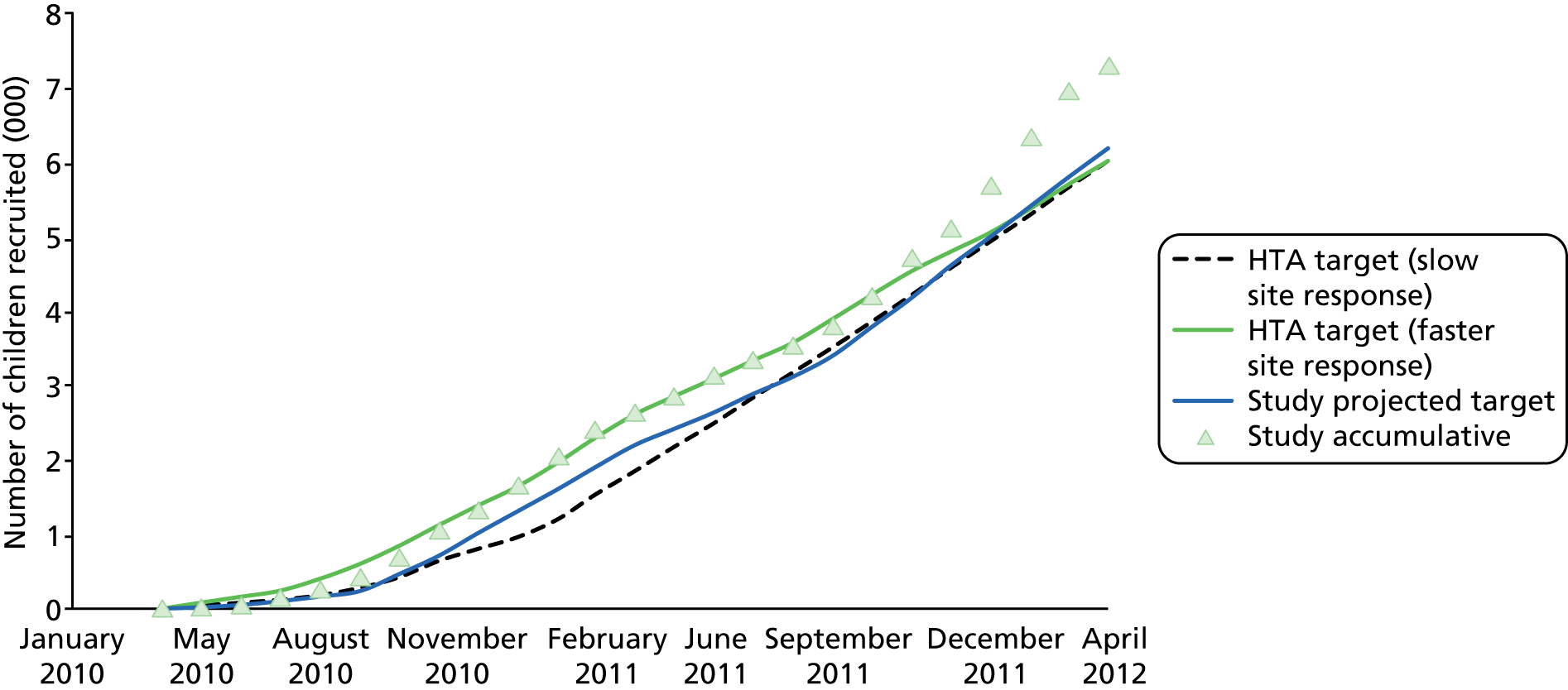

The original plan was to recruit 6000 children by end of April 2012. As this target was met early and the prevalence of UTI was lower than expected, we obtained ethical approval to continue recruiting until April 2012 even though this exceeded the original projected study requirement.

Investigation of UTI prevalence

In our protocol paper (see Appendix 3), we said that we would investigate factors influencing UTI prevalence. These results are reported in Chapter 7.

Chapter 2 Overall study methods

Summary of study design

DUTY was a 3-year multicentre, prospective diagnostic cohort study which aimed to recruit at least 6000 children aged before their fifth birthday, being assessed in primary care for an acute undifferentiated illness. Children were invited to participate when they presented to primary care acutely unwell (with non-traumatic aetiology) of ≤ 28 days’ duration. Urine samples were obtained from as many eligible, consented children as possible, and data were collected on medical history and presenting symptoms and signs. Urine samples were dipstick tested in primary care and sent for standard microbiological analysis, microscopy and culture at the primary care site’s usual local NHS microbiology laboratory, from here on referred to as the ‘local laboratory’.

In addition, and where sufficient urine volumes were available, a fraction of the urine sample was decanted and sent for parallel microbiological analysis at the study’s designated research laboratory in Cardiff [the Specialist Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Unit (SACU), Public Health Wales Microbiology Cardiff, University Hospital Wales], from here on referred to as the ‘research laboratory’. All children with culture positive urines and a random sample of children with urine culture results in other, non-positive categories were followed up by telephone to record symptom duration and health-care resource use at 14 days from recruitment, and through review of the child’s primary care medical notes at 3 months.

The primary outcome was a validated diagnostic algorithm using a reference standard derived from research laboratory results (see Chapter 4) of ≥ 105 CFU/ml of a single uropathogen (‘pure growth’) or ≥ 105 CFU/ml of a uropathogen with ≥ 3 log10 (1000-fold) difference between the growth of this and the next species (‘predominant growth’). We defined uropathogens as members of the Enterobacteriaceae group. We used logistic regression to identify the clinical factors (i.e. demographic, medical history, presenting symptoms and signs and urine dipstick analysis results) most strongly associated with a positive urine culture result to create a rule for use in clinical practice. An economic evaluation was conducted to compare the cost-effectiveness of the candidate prediction rules from the perspectives of families and the NHS.

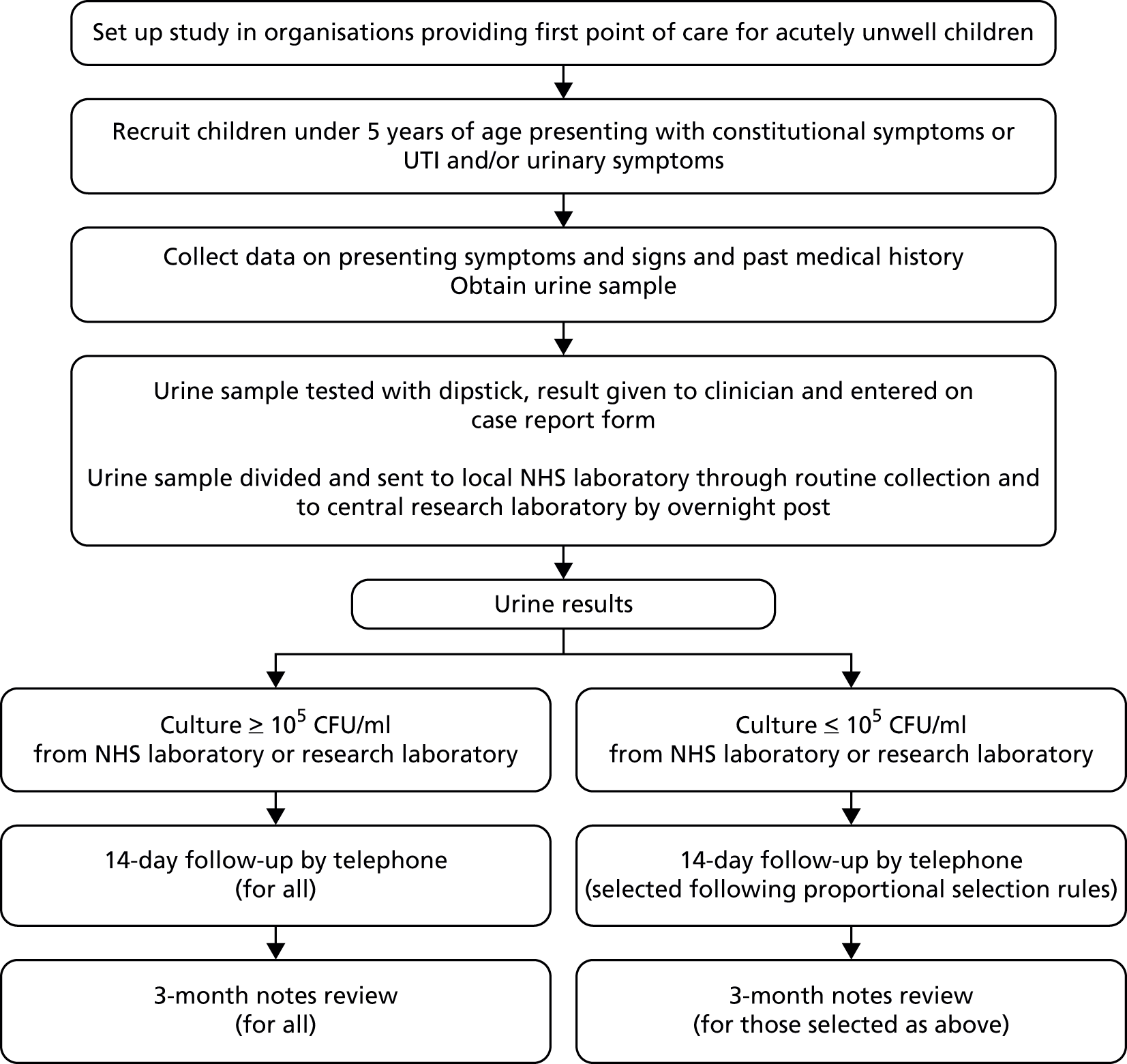

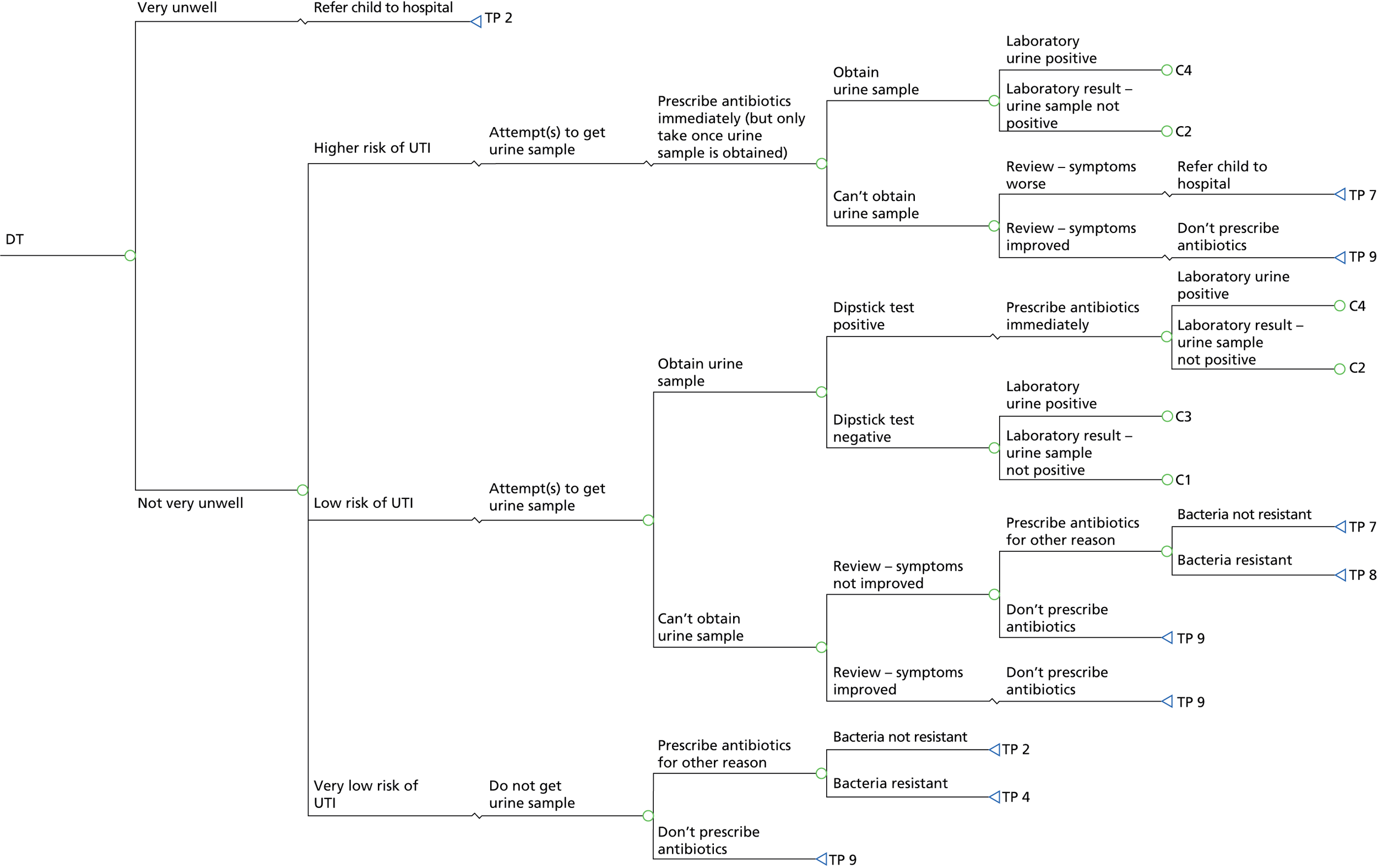

The study was sponsored by the University of Bristol and run jointly by Bristol and Cardiff University in collaboration with centres at Southampton University and King’s College London. The study is summarised in Figure 1.

Ethics and research and development approvals

Ethical approval for this multicentre study was given by a National Health Service (NHS) research ethics committee. The initial approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Southmead Research Ethics Committee on 9 December 2010, reference #09/H0102/64. NHS research and development (R&D) approval was also gained where the research was undertaken.

Parental contributions to the study

The study protocol, study documentation and procedures benefited significantly from feedback from parent groups and from continued engagement with parents both as formal advisors and as study participants. During study start-up, the parent members of the NIHR South West Medicines for Children Research Network were supplemented by additional parents, volunteering to serve on the Study Steering Committee and/or review and comment on study documents. This feedback informed, for example, our staffing structure (recruiting staff’s competence in working with children was considered absolutely essential) and methods for raising local awareness generally about what was considered a worthwhile and important study.

Once the study was under way, all questionnaires, processes and information (all formats) were reviewed and refined according to ongoing parental feedback about participation in the study.

Site recruitment

Recruitment period and locations

The study was open to participant recruitment from 7 April 2010 until 30 April 2012. Recruitment was implemented from four research centres at the universities of Bristol, Cardiff, Southampton and King’s College London. Each centre recruited children from primary care, defined as any NHS facility providing first-point-of-contact, face-to-face advice for parents of unwell children.

Selection of primary care sites

The majority of UK acute paediatric care is provided by GPs in primary care practices. To ensure we recruited to target, we estimated that we required between 80 and 100 primary care sites per centre, with each centre needing to contribute around 1500 children to achieve the study sample of 6000.

General practitioner practices were supplemented by NHS walk-in centres (WICs) and children’s emergency departments (CEDs). WICs manage large numbers of young children with acute, undifferentiated illnesses. For example, the South Bristol WIC estimated 2500 contacts for acute, non-traumatic, illnesses in children < 5 years old annually. Parents also use CEDs as a first point of contact for large numbers of acutely unwell children, particularly outside normal working hours. For example, > 5% of all attendances at UK CEDs are due to fever,106 which represents approximately 1400 children annually in each of Bristol, Cardiff and Southampton, and more in London. The majority of these are < 5 years old.

Site recruitment approach

In England and Wales, practice recruitment was supported by research staff from the primary care research network (PCRN) and the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research – Clinical Research Centre (NISCHR-CRC) Network.

General practitioner practices were invited to take part in the study either by letter or via a PCRN newsletter. Interested practices were contacted initially by e-mail to provide further information about the study and were followed up by telephone or face-to-face visit with the practice manager or lead research GP to discuss the study in more detail.

Working with the local research networks in both Wales and England provided the study team with the knowledge of which practices had experience of recruiting to studies within primary care and also highlighted practices to approach. The role of the local research networks is described below.

The role of the local research networks

Local research network support, primarily the PCRN and comprehensive local research networks (CLRNs) in England and, in Wales, NISCHR-CRC, was a decisive factor in enabling this study to recruit ahead of target. Collaboration with the local research networks provided the following benefits.

Advocacy and advice for general practitioner practice recruitment

Each study centre worked closely with local research networks to identify and recruit primary care sites to the study. This included attending research meetings, contributing to research network newsletters and bulletins, and working with the networks to approach appropriate sites to elicit expressions of interest.

Strategic advice for recruitment across the UK

Local research networks suggested the extension of recruitment to new areas of England. For example, PCRN South West supported the extension of DUTY study recruitment into the Peninsula area (Devon and Cornwall) to develop local research capacity and increase access to primary care portfolio studies, as well as boosting DUTY recruitment. In addition, the proactive support for the study provided by the Cumbria and Lancashire CLRN was a further significant boost to recruitment figures while enhancing the generalisability of the study findings by including more patients from rural rather than urban areas.

Support with gaining research and development approvals

For some local research network areas (e.g. Western, and the London networks) R&D approvals for recruitment in primary care (with the exception of CEDs in acute trusts) were granted at the level of the primary care trust (PCT). However, for some areas (e.g. Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria and Lancashire) site-specific approvals were required at the level of each GP practice. In these situations the local research network provided administrative time to support the completion of specific approvals for each of the numerous sites participating in the study.

Provision of research nurse resource

The DUTY study benefited from significant additional community research nurse (RN) capacity funded by the CLRNs, PCRNs and NISCHR-CRC. Dedicated sessions of nurse time were provided to support local primary care sites that did not have sufficient recruitment capacity in-house. Clinical staff recruiting to DUTY within the three active CEDs (the Bristol Children’s Hospital, the Evelina Children’s Hospital and Southampton Paediatric Accident & Emergency) were employed by the acute trusts and funded through the research networks or similar organisations.

Provision of training for recruiting staff

Local research networks not only provided facilities for DUTY researchers to train primary care-based recruiting staff, but offered ongoing training in good clinical practice and paediatric consent to clinicians and researchers involved in all aspects of the study.

Recruitment models

Primary care sites were offered two models of recruitment. The first was known as option 1, in which the majority of the recruitment procedures were undertaken by a RN or clinical studies officer (CSO) external to the primary care site, and funded by the DUTY study or the local PCRN, CLRN or NISCHR-CRC, to work with and recruit for the primary care site’s clinical team.

In option 2, recruitment was undertaken entirely ‘in-house’ by the primary care site’s practice team. The acute environment of CED and WIC recruitment meant that, for these settings, the option 1 model was the only viable model.

Study staff

The study grant provided full-time equivalent DUTY RN posts across all four study centres, which were supplemented by additional research staff (RN/CSOs) provided by local PCRNs and CLRNs (in England) and by NISCHR-CRC (in Wales).

Dedicated RNs/CSOs were available to provide external support for option 1 primary care sites, and to support autonomously recruiting option 2 sites through the provision of expert training, mentoring and problem-solving.

Site and staff training

The DUTY study team from each centre would meet with individual sites to explain the study and identify their working requirements and match this to the appropriate model of recruitment in order to meet both the study’s needs and those of each individual primary care site. The geographical area of the site was also taken into consideration. Rural practices were encouraged to adopt the option 2 approach, as it was impractical to use DUTY recruiters (RNs/CSOs).

DUTY recruiters were provided with study-specific training including paediatric informed consent, data confidentiality, data collection [using paper-based and electronic case report forms (CRFs)], collection of urine samples and safety reporting. Staff were encouraged to access PCRN or NISCHR-CRC’s informed consent and good clinical practice training days.

Sites were also offered practice-based training adjusted to meet their needs in order to tailor recruitment methods to the individual site. Reception staff were advised on how to introduce DUTY to parents of potential participants. Practice staff were trained on the method of processing the urine sample to send to local NHS and research laboratories and clinicians were provided guidance on informed paediatric consent. All staff involved with the study were provided training on data collection and CRF completion.

(Local) NHS laboratory recruitment

The participation of any primary care site in recruitment to the study depended on the support and participation of the local NHS microbiology laboratory to which the site routinely sent urine samples. In each area of recruitment, the local NHS laboratory was approached and service-level agreements put in place prior to involvement in the study. Key staff were provided with a study manual, essential documents and database instructions.

Training of staff was not required as they were only executing their normal routine procedures that were covered within the standard operating procedure (SOP) for their own laboratory. Laboratories were reimbursed with service support costs at a rate locally determined per sample processed.

Service support costs

Service support costs were provided by the local CLRNs for each centre in England and NISCHR-CRC in Wales. They were provided on a ‘per-patient’ basis for primary care sites and on a ‘per-sample’ basis for NHS microbiology laboratories.

For option 1 practices, which were supported by DUTY recruiters, the ‘per-patient’ reimbursement excluded activities undertaken by the DUTY recruiter (e.g. consent, CRF completion, urine sample management and online data entry). For option 2 practices, where all aspects of recruitment were undertaken by site staff, all recruitment activities were reimbursed. Payments were made only for children recruited with valid informed consent and without significant deviation from the study protocol.

To emphasise the importance of obtaining the urine sample in order to achieve the study’s primary outcome, service support reimbursements were linked to sites’ urine sample retrieval rates. Reimbursements of 100% were dependent on sites having a local laboratory urine sample retrieval rate of at least 90%, and a research sample dispatch rate of at least 85%. Practices that did not meet both of these thresholds were reimbursed only for those children in whom a urine sample was obtained.

For NHS microbiology laboratories, service support costs were reimbursed for all urine samples processed by the laboratory. The laboratory service support costs were based on a Department of Health-agreed cost for standard microscopy and culture, plus a component of administrative time for entering the urine culture results onto the DUTY study web-based database.

Participant selection

Eligibility criteria

The study inclusion criteria were designed to be as broad as possible. Children were eligible if they were aged before their fifth birthday and presented to primary care with a new acute illness episode of ≤ 28 days’ duration.

This illness needed to be associated with (1) at least one ‘constitutional’ symptom or sign identified by NICE2 as a potential marker for UTI – that is, fever, vomiting, lethargy/malaise, irritability, poor feeding and failure to thrive; and/or (2) at least one urinary symptom identified by NICE2 as a potential marker of UTI – that is, abdominal pain, jaundice (children < 3 months only), haematuria, offensive urine, cloudy urine, loin pain, frequency, apparent pain on passing urine and changes to continence.

Therefore, children consulting with other apparently obvious causes for their symptoms such as otitis media or bronchiolitis, as well as those with a history of previous UTI and known abnormalities of the urinary tract, learning difficulties, or reconsulting for an existing illness, were all included, as long as none of the exclusion criteria applied. Where possible, data were included for children recruited and immediately referred from primary care to secondary care. The eligibility criteria are summarised in Table 1. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria also made up the CRF section 1: screening form (see Appendix 4).

| Children only included if ALL criteria were met | Children were excluded if ANY criterion is met |

|---|---|

| Aged before their fifth birthday | Aged ≥ 5 years |

| Presenting at a participating NHS primary care site | Parents are unable or unwilling to assist with the study |

| Presenting with an acute (≤ 28 days) illness as the main reason for the parent to have requested an appointment | Illness longer than 28 days’ duration |

| Presenting with trauma as a predominant concern | |

| Presenting with at least one ‘constitutional’ symptom or sign identified by NICE2 as a potential marker for UTI – i.e. fever, vomiting, lethargy/malaise, irritability, poor feeding and failure to thrive and/or at least one urinary symptom identified by NICE2 as a potential marker of UTI – i.e. abdominal pain, jaundice (children < 3 months only), haematuria, offensive urine, cloudy urine, loin tenderness, frequency, apparent pain on passing urine and changes to continence | No urinary or constitutional symptoms as defined by NICE2 and listed in the left hand column |

| Known neurogenic (e.g. spina bifida) or surgically reconstructed bladder or urinary permanent or intermittent catheterisation (for whom different bacterial concentration cut points are used) | |

| Taking any antibiotics in the last 7 days | |

| Taking immunosuppressant medication (e.g. antirejection drugs, oral or intramuscular steroids or chemotherapy) | |

| Already recruited into the DUTY study | |

| Involved in current research or have recently (within 28 days) been involved in any research prior to recruitment | |

| There will be no recruitment to the study after the last NHS laboratory transport of the day has departed from that primary care site on Fridays | |

| For recruitment at A&E settings only: Children will not be eligible if their presentation at A&E is a direct result of GP referral (as they were then not acting as a first point of primary care contact) |

Widening participation

The study included parents who spoke non-English languages. Parent information sheets and consent forms were translated into other languages as required by participating GP practices (e.g. Welsh, Polish and Brazilian Portuguese). For languages less commonly spoken in the UK, particularly for those in which oral translation was more useful than written translation (e.g. Somali), translational services were accessed. Where possible, interpreters employed by recruiting primary care sites were used to support patient-clinician communications. When these services were not available, translational services were provided via Language Line (www.languageline.co.uk). In primary care sites in urban areas, the clinical care team often included a translator whose services were used when available.

Participant recruitment

The study recruitment process is summarised in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

DUTY study participant flow diagram (the numbers of children recruited are reported in Figure 4). Dashed line indicates that the parents can choose to participate either before or after the child sees the doctor/nurse.

The term ‘parent’ is used to refer to the person with legal responsibility for the child, but it also encompasses other carers (e.g. foster carers and legal guardians).

Registration and informed consent

All recruiting primary care sites displayed posters detailing the study in waiting areas. Parents and children were invited into the study in a number of ways:

-

Where possible, the study was mentioned to the parents of children < 5 years old by reception staff when they telephoned for an appointment or during telephone triage. In this instance, the parent was invited to come to the surgery 15 minutes early to receive further information from the RN/CSO.

-

Where the study was not raised at the time of making the appointment, parents of children already booked in were telephoned and advised about the study and invited to attend a little earlier.

-

If contact prior to attendance at the site was not possible, the parent was approached on arrival, given study information sheets and asked if they were happy to discuss participation with the RN/CSO.

-

Once the parent indicated that they were happy to discuss the study, the RN/CSO explained the study, answered any questions, ensuring that they fully understood the implications of participation, and checked the child’s eligibility.

Where possible, the RN/CSO recruited the participant while they were waiting to see the GP, in order that the participant was not delayed. However, if the participant’s appointment was at risk of being delayed, or it was more convenient for them, the RN/CSO offered to see them after their appointment or visit the parent and child later the same day at their home.

If the parent agreed for their child to participate, written informed consent was obtained from the parent. If the parent was not interested in hearing more about the study, no further approach was made.

In addition to the child being seen by the RN/CSO, they were seen by the child’s responsible clinician who managed the child according to their normal practice. The study CRF was then completed for all consented children by the RN/CSO and with clinical examination, diagnosis and management sections completed by the treating clinician (see Appendix 4).

Non-registration

Sites were asked to complete a screening log of all children whose parents were approached by the recruiting clinician and invited to participate in the study. Details were recorded such as their eligibility, whether consent was given or declined, and reason for declining to participate.

Urine sample collection

The collection of the urine sample was commenced as soon as possible and often while the RN/CSO completed the study CRF, with every effort made to obtain the urine sample while the child was at the recruiting site.

Rationale for urine collection methods

Suprapubic aspiration and ‘in-out’ catheterisation carry the lowest risk of contamination56 but are invasive and unacceptable to parents, and so are uncommon in UK primary care. They were, therefore, not appropriate or feasible for widespread use in the DUTY study. The risk of contamination is low with clean-voided midstream urine or ‘clean-catch’ samples compared with SPA samples. 2 However, obtaining clean-catch samples can be difficult for children in nappies, and parents find nappy pads or urine bags preferable. 63 Many parents prefer pads to bags as the bags have an adhesive strip that attaches to, and can irritate, the child’s skin. These may be suitable alternatives to SPA,2 but there are few data comparing ‘clean-catch’ with nappy pad samples. Thus, the preferred primary care method is the ‘clean catch’, and NICE recommend pad or bag when ‘clean catch’ is not possible. 2 Therefore, we followed the NICE recommendation for collecting urines, with clean catch being preferred to pads, and pads being preferred to bag.

Clean catch

The preferred method of ‘clean catch’ was used for children who were toilet trained or for whom the parent was happy to attempt collection. For the toilet-trained child, a small sterile bowl was used which could fit in a potty or which the parent could hold under the child while sitting on the toilet. For the child still in nappies, the parent first cleaned the nappy area, and then sat with the child on their knee with the bowl placed under the perineal area to collect the urine.

Nappy pad

As per NICE guidelines,2 ‘Newcastle nappy pads’ were used for children still in nappies whose parents did not think clean catch would be successful. First, the parent cleaned the nappy area using water or wipes (the wipes being supplied by the study). A nappy pad was inserted inside a clean nappy, and the nappy refastened. The nappy pad was removed as soon as the child urinated in order to reduce the risk of contamination. The perineum was recleaned and a fresh pad inserted every 30 minutes until micturition or immediately if the pad became contaminated with faeces. Once the child had urinated, and wearing disposable gloves, the RN/CSO removed the pad and urine was extracted into a sterile container as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bag urine collection

The child was cleaned in the nappy area by the parent using water or wipes. This was followed by careful drying with sterile towels to ensure that the bag stuck. The RN/CSO applied the bag in such a way to cover the child’s genitals. A nappy was then placed over the bag and checked after 30 minutes for urine. The urine was then decanted into a sterile container as per individual manufacturer’s instructions.

Collection of urine at home

If it was not possible to obtain a sample prior to the child leaving the primary care site, the parent was given the necessary equipment and advice on obtaining a urine sample at home. The parent was advised to store the sample in the fridge and return it to their primary care site as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours. The RN/CSO telephoned parents the next day to remind them to return the sample. Where feasible, the RN/CSO offered to collect the urine sample from the child’s home.

Maximising urine retrieval rates

Obtaining urine samples can be challenging, which is one of the reasons why urine samples are not currently routinely collected in primary care at a rate sufficient to avoid missed diagnoses. As a suboptimal rate of return of samples to the surgery by parents would have diminished power and increased risk of bias, a number of strategies were implemented to maximise retrieval rates. In addition to the role of the RN/CSO in following up parents whose child was not able to provide a sample during the recruitment visit, the data recorded in the study database were used to monitor the retrieval of urine specimens, allowing the research team to identify children for whom urine samples had not been provided, and therefore followed up with the recruiter. Additionally, primary care sites’ urine sample return rates were linked to the level of reimbursement via service support costs.

Urine dipstick methods

The RN/CSO tested the urine sample with a urine dipstick (Siemens Multistix® 8 SG, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Surrey, UK) provided by the study. The dipstick point-of-care test used tested for presence of blood, protein, glucose, ketones, nitrite and LE, and measured pH and specific gravity. A dipstick was placed in the urine as instructed, and results were interpreted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Urine collection information was collected in section 5 of the CRF (see Appendix 4). The time, the urine collection method and the dipstick test results (using the study-supplied Siemens Multistix® 8 SG) were also recorded in this section.

Dispatching urines to the laboratories

All urine samples, if sufficient quantity of urine was available, were divided into two fractions at the recruiting sites. The priority fraction was sent to the local NHS laboratory for routine diagnostic processing, and the second ‘research’ fraction to a research laboratory – the SACU, Public Health Wales Microbiology Laboratory, Cardiff – for more in-depth analysis. As only small volumes of urine (minimum 1 ml) were required for each laboratory, it was thought possible that most urine samples would be split into the two fractions.

The NHS ‘clinical’ fraction was placed in the urine specimen container stipulated by the site’s local NHS laboratory and labelled with the child’s unique DUTY study ID number on DUTY specific labels as provided in patient recruitment packs. Similar DUTY labels were adhered to specific DUTY microbiology requisition form and the sample sent to the local NHS laboratory using the site’s normal method of transport. Any samples returned to the site and not collected within 4 hours were refrigerated on site and processed within 36 hours. Clinicians received and acted on reports from their local laboratory as per usual clinical care. Research laboratory urine results were not routinely fed back to clinicians; this occurred only if a discrepancy was identified between local and research laboratory results.

The remaining portion of urine was decanted into a sterile container (Monovette®, Sarstedt AG & Co., Nümbrecht, Germany) containing boric acid. This was labelled with the child’s study ID number and sent by first-class Royal Mail using Post Office-approved Safeboxes™ to the research laboratory.

The urine sampling method, time of sample, time of dipstick test, results of dipstick and quantity of urine were recorded in section 5 of the CRF (see Appendix 4).

Study thank you vouchers

All parents received a £5 high street voucher from the RN/CSO as a ‘thank you’ token for their time in taking part in this first part of the study. A second £5 voucher was sent to those who were proportionally selected for follow-up at 14 days.

Data collection

The DUTY data collection process was complex and the CRF sections were developed with input from the study management group, which included primary care clinicians, consultant nephrologists, health economists, methodologists and statisticians.

To minimise human error, optimise the quality of data entry, and enable effective data collection from multiple sites across England and Wales, we developed a secure, web-based electronic data collection platform. Although this was our preferred data collection mechanism, it was supplemented by a parallel paper-based data collection system for clinicians not wishing to use web-based systems and to cover the event of internet failure. Unique study ID numbers were sequentially generated and used on pre-printed consent forms, paper CRFs, urine sample labels and microbiology requisition forms (for local NHS and research laboratories).

Clinical case report form

The purpose of the CRF was to capture children’s medical histories, examination findings and any known risk factors for UTI. It balanced the need to include as many of the known and potential features associated with UTI with the maximisation of speed and simplicity of completion.

DUTY index tests

Where available, the selection of index tests (the parent-reported symptoms, clinical signs and dipstick test results) was based on existing evidence. For example, at the time the CRF was developed, ethnicity,66 circumcision107 and a history of VUR108 were known to be associated with UTI in children. Moreover, the NICE clinical guideline2 on the diagnosis, treatment and long-term management of UTI in children had not long been published, and symptoms and signs were selected from these where evidence of diagnostic utility was available. Furthermore, DUTY was fortunate to be able to build on the experience of the EURICA study,109 and many of the EURICA symptoms and signs were considered for collection in DUTY.

Rationale for measuring symptom severity

We decided to measure not only the presence/absence of symptoms, but also their severity. We postulated that the presence of mild symptoms might not be as diagnostically important as severe symptoms. Therefore, parents were asked to rate all 30 symptoms as no problem/slight problem/moderate problem/severe problem, as well as giving a global rating of illness severity from ‘0’ to ‘10’.

Case report form summary

The CRF comprised five sections that facilitated data entry by different personnel so as to minimise the burden to busy health-care professionals meeting the demands of day-to-day clinical practice:

-

Eligibility screening and consent (to be completed by recruiting clinician within the recruitment interview with the parent).

-

Registration: background socioeconomic data included date of consultation, name, address, postcode, contact number/s, ethnicity, date of birth and sex. We also asked about the parent’s highest educational attainment level and their financial well-being to ascertain the financial burden on families, as postcode mapping may not address this at a household level.

-

Presenting symptoms and medical history included child’s presenting symptoms, ongoing health problems (such as asthma or heart disease), antenatal history (gestation at birth and the presence of urinary tract abnormalities on antenatal ultrasound), circumcision, previous UTI, and a sibling or parental history of UTI or other urinary tract diseases.

Medication history included recent and long-term use of medications (for chronic diseases). We were also interested in medicines that could predispose to UTI and these included the use of laxatives (as a proxy marker for constipation), salbutamol (which could relax bladder smooth muscle) and inhaled steroids (potential immune-suppressant). Toileting and hygiene behaviour was also included, as under- and overwashing and prolonged use of nappies/pull-ups have been postulated as risk factors for UTI. 2

-

Clinical examination and findings were measured using routine clinical method and included global clinician assessment of illness severity, the child’s vital signs and assessments of the child’s hydration, consciousness level, throat, ears, chest and abdomen.

Clinician working diagnosis and management included the clinician’s working diagnosis with an accompanying assessment of diagnostic certainty before and after seeing the dipstick urinalysis result.

Section 4 of the CRF also asked clinicians to report their subsequent management including the use of antibiotics and referral for secondary care assessment, and whether or not they would have requested a urine sample had the child not been entered into the DUTY study.

-

Urine collection and processing: urine sampling method (clean catch or nappy pad) and urinalysis results with date, time of testing, with a prompt to inform the responsible clinician of the dipstick result and confirmation that the sample had been sent to the local NHS and research laboratories. As one of the DUTY study aims was to assess the added diagnostic value of dipstick urinalysis (over and above the symptoms and signs), dipstick results were included in the CRF as an index test.

Patient follow-up

DUTY participants were proportionally selected for a follow-up interview at day 14 and medical notes review at 3 months post recruitment. The process by which children were selected and followed up is described below.

Telephone follow-up at day 14

At 14 days from the recruitment interview, study centre staff contacted parents of all children selected for follow-up according to the proportional selection rules (described in Table 2) to record symptom duration and health-care resource use during the 14-day period after recruitment. In older children (> 9 months), the interview also included a parent-completed questionnaire measuring child health-related quality of life (see Appendix 5). Owing to the young age of the participants, standard methods [e.g. European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)] for measuring health utilities were thought to be invalid. Instead, we used the TNO-AZL (Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research Academic Medical Centre) Preschool children Quality of Life (TAPQOL) questionnaire, completed at 14 days, to describe the health profiles of children with and without UTI. 110 TAPQOL measures parents’ perceptions of health across 12 domains (e.g. sleep, social functioning) and has been shown to be a reliable instrument for both infants and toddlers. 111 No mapping from TAPQOL responses to utility values exists, hence we used a proxy value from a condition (rotavirus) thought to have a similar health-related quality of life impact to UTI. The TAPQOL responses allowed us to validate this choice and make robust comparisons between the health-related quality of life of children with and without UTI.

| Category | Culture growth category | Definition | Laboratory | Proportion sampled, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ 105 CFU/ml | Pure or predominant species | BOTH NHS laboratory and research laboratory | 100 (all) |

| 2 | > 103 and < 105 CFU/ml | Pure or predominant species | Research laboratory | 20 |

| 3 | ≥ 105 CFU/ml | Two or more species | BOTH NHS laboratory and research laboratory | 20 |