Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/53/06. The contractual start date was in February 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hywel Williams is Deputy Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme and chairperson of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. From 1 January 2016 he became Programme Director for the HTA programme. The NIHR HTA programme funded this study; however, Professor Williams was not involved in that funding decision.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by McMurran et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aims

The study aimed to determine if psychoeducation with problem-solving (PEPS) therapy in addition to usual treatment for people with personality disorder (PD) results in improved social functioning 72 weeks after randomisation (approximately 12 months after the end of treatment), compared with treatment as usual alone.

In addition, we intended to:

-

assess the costs and cost-effectiveness of PEPS therapy in addition to usual treatment compared with usual treatment alone

-

examine the effects on scheduled and unscheduled use of services

-

examine the effect on mood, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

-

evaluate referrers’ perceived effects of the intervention using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

-

evaluate participants’ perceived effects of the intervention in relation to the severity of the self-identified three most important problems

-

examine the process of change by testing the hypotheses:

-

that psychoeducation improves the therapeutic relationship

-

that social problem-solving therapy improves social problem-solving skills

-

-

conduct a qualitative investigation of the receipt of PEPS therapy in practice to identify the views of service users.

Scientific background

Personality disorder

Personality disorder is one of the most common mental health problems, and it is associated with substantial health-care costs. 1–3 Compared with those with no PD, people with PD show higher rates of premature mortality,4 greater engagement in health-compromising behaviours such as substance abuse,1 greater levels of general health problems5 and more use of health-care services. 6 PD is also associated with financial difficulties and problems maintaining jobs,5 marital dissatisfaction and intimate partner violence,7 crime8 and poor quality of life. 9 These matters make a strong case for treating people with PD.

Despite this, there is relatively little reliable evidence on the effectiveness of treatments for PD. Systematic reviews of all psychosocial treatments for PD identified only 27 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published up to 200610,11 and only a few trials have been published since then. 12,13 The majority of studies are underpowered and most related to one specific PD – borderline PD. Chambless and Hollon’s14 criterion for a treatment to be considered effective is that there should be at least two independent, well-conducted RCTs or single-case experiments. Only one therapy meets this criterion; dialectical behaviour therapy is more effective than usual treatment for reducing suicide attempts, service use and borderline symptomatology in borderline PD, although positive effects decay over time. 12 However, other cognitive and behavioural interventions are supported by single RCTs.

Many treatments for PD are intensive and of long duration, which limits the number of services that can be provided. Hence, the great majority of people who may benefit from psychological treatments do not receive them. Testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of shorter interventions is important if more people with PD are to be treated. Additionally, interventions that can be used with any PD have the potential to alleviate the burden on clinical services that can be created if specific types of PD need to be identified for treatment allocation, and if groups of service users with specific PDs need to be gathered for treatment to commence. In treating groups of people with mixed PDs, the treatment target necessarily needs to be a problem common to all.

One core feature of all PDs is the experience of problems with social and interpersonal functioning. 15–17 One relatively brief skills-training approach to improving problem-solving that has been evaluated specifically with people with borderline PD is the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) programme. 18 STEPPS is a 20-week group treatment programme for individuals with PD and others within that person’s system, such as family members, partners, friends and health-care professionals. STEPPS focuses on psychoeducation, emotion management training and behaviour management training. One RCT19 found that borderline symptoms were significantly more improved in those in a STEPPS group (n = 65) than in those who received treatment as usual (n = 59); however, this difference was no longer apparent at the 1-year follow-up. Improvements in secondary outcomes (including GAF, negative affectivity, depression, impulsiveness) and symptoms were also significantly greater for the STEPPS group post treatment but not at the 1-year follow-up. In another RCT,20 those who completed STEPPS (n = 33) were compared with those who received treatment as usual (n = 33), with no significant group differences in PD or other psychological symptoms at the 6-month follow-up, although the STEPPS group showed a significantly greater improvement in overall quality of life. There are clearly improvements to be made to problem-solving approaches for people with PD in terms of enhancing and sustaining outcomes and, as mentioned, offering a problem-solving approach to people with PDs other than borderline is a more practical prospect. Social problem-solving therapy is one viable and empirically supported alternative.

Social problem-solving therapy

Good social problem-solving is one component of social competence. 21,22 Social problem-solving is defined as ‘the self-directed cognitive-affective-behavioural process by which an individual attempts to identify or discover solutions to specific problems encountered in everyday living’23 (p.11). There is abundant evidence of an association between social problem-solving deficits and problems related to PD. 24–27 People with PD report less desirable scores on all scales of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory – Revised: Short Version (SPSI-R)28 compared with a sample of mature students,22 and people high on borderline traits show poorer social problem-solving abilities than those with lower borderline traits, particularly when experiencing negative emotions. 29 This information suggests that social problem-solving therapy may benefit people with PD.

Problem-solving therapy is suited to people with PD because the focus is on improving social functioning and reducing personal distress, which are considered to be of paramount importance in the treatment of PD. 30 The aim in problem-solving therapy is to help people to recognise their strengths and limitations, and to work with these to learn new skills that will enable them to cope more effectively with life’s problems. Problem-solving therapy works to decrease the person’s negative problem orientation and develop positive orientation, without which therapy is unlikely to be effective. 31

Engaging people with PD in treatment is a major challenge. 32,33 The social problem-solving approach enhances engagement by offering an accessible framework for change, supporting people in the experience of successful problem-solving and encouraging independence rather than reliance on therapy. Furthermore, the preliminary psychoeducation component of PEPS therapy aims to educate, build rapport and motivate people for problem-solving therapy. 34 PDs and their impact are discussed in a collaborative dialogue and problems that may be worked on in subsequent group sessions are identified. Psychoeducation has shown good effects with people with borderline PD, showing significantly greater declines in general impulsivity and the storminess of close relationships over 12 weeks than in those who did not receive psychoeducation. 35

Meta-analyses of problem-solving therapy outcome studies document its effectiveness for people with a wide range of mental health problems. 31,36,37 Detained PD offenders were identified as performing poorly in all aspects of social problem-solving compared with offenders with no PD and non-offenders. 38,39 A pilot study of a psychoeducational intervention aimed at clarifying the offenders’ PD diagnosis and identifying associated problems led to an increase in patients’ knowledge about PD and improved the therapeutic alliance. 34 A brief problem-solving therapy was evaluated with this client group, finding that social problem-solving abilities improved post therapy and that this improvement was sustained at a 6-month follow-up. 40 A social problem-solving intervention has also been evaluated with women in a secure setting, with improvements after treatment in risk and health,41 and with people at high risk of suicide, showing reduced suicidal ideation over those receiving treatment as usual. 42

Psychoeducation with problem-solving therapy

A combined PEPS therapy was evaluated with community adults with PD in a Phase 2 exploratory trial. 43 Overall, this sample had the lowest social problem-solving scores in comparison with mature students, prisoners and PD offenders. 44 At the end of treatment, compared with a wait-list control group, those treated with PEPS therapy showed better social functioning, as measured by the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ). 45 Analyses were conducted to examine the hypothesised mechanism of change, namely that improved social problem-solving leads to improved social functioning. 46 These analyses indicated that all aspects of social problem-solving improved over the course of PEPS therapy and, that controlling for baseline level of social functioning, the most important predictor of improvement in social functioning was a reduction in negative problem orientation (i.e. people felt less threatened by problems and more confident in their ability to solve problems). This exploratory study has been identified as important in four ways. 47,48 First, the intervention was brief and, hence, is likely to be more acceptable to patients and services. Second, PEPS therapy was delivered in clinical settings, hence its likely effectiveness in everyday practice was indicated. Third, PEPS therapy was offered to people with any PD or combination of PDs, so it was inclusive rather than exclusive. Finally, non-specialist staff delivered PEPS therapy; hence it would be possible to deliver it relatively cheaply. In addition, a Delphi study of patients’ views of PEPS therapy indicated that it was perceived as acceptable and useful. 49

Overall, PEPS therapy has the potential to contribute to the Department of Health’s agenda that PD should no longer be a diagnosis that excludes people from services. 50 It is an intervention in which staff can easily be trained and, thus, has the potential to make a significant contribution to building workforce capacity. 51 Here, we present the results of an adequately powered, multisite RCT.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The PEPS trial was a two-arm, parallel-group, pragmatic randomised controlled superiority trial comparing PEPS therapy plus treatment as usual with treatment as usual alone. Participants were individually randomised at a ratio of 1 : 1, and stratified by sex and centre.

An economic analysis was conducted alongside the trial to determine the costs and cost-effectiveness of PEPS therapy compared with treatment as usual (see Chapter 5). In addition, a qualitative component sought to explore participants’ experiences of PEPS therapy and treatment as usual (see Chapter 6).

Study setting and participants

Study participants were recruited from three NHS trusts providing mental health services in central and north-west London, South Wales and the North-East of England.

We recruited participants from mental health services including community mental health teams (CMHTs), crisis resolution teams, primary care liaison teams, psychology services and on discharge from inpatient care.

Eligibility criteria

At the point of randomisation participants were required to have one or more PD, including a PD not otherwise specified, identified through the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) completed as part of the study-specific procedures at the screening visit. In addition, eligible participants were aged ≥ 18 years, living in the community (including residential or supported care settings) and proficient in spoken English and had capacity to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were a primary diagnosis of major functional psychosis, insufficient degree of literacy, comprehension or attention to be able to engage in trial therapy and assessments, engagement in a specific programme of psychological treatment for PD or likely to start such treatment during the trial period and participation in any other trial.

Identification of participants

Participants were identified by their mental health team. The initial approach about the study was made by a member of the potential participant’s mental health team, who sought verbal agreement from the potential participant to meet with the research team to discuss the study. Referral to the research team was made according to local procedures at each site.

All potential participants referred to the research team were recorded on the Participant Screening and Enrolment Log, whether or not they were enrolled in the trial.

Recruitment

Potential participants providing verbal agreement were referred to the research team who assessed eligibility according to the available clinical information, and invited potentially eligible participants to consider taking part in the trial. Potential participants were provided with written and verbal information about the trial and were given a minimum of 24 hours to consider whether or not to participate.

All participants joining the study provided written, informed consent. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. If participants declined to complete follow-up assessments when originally approached, the researcher sought verbal consent to contact them again at a later stage to see if they were willing to complete the assessments.

Recruitment strategy

The identification and recruitment of participants was actively managed at each site to reduce potential delays and group waiting times. Problem-solving group start dates were determined in advance, allowing a time-limited baseline and randomisation period to be specified, based on recommended minimum and maximum waiting times before commencement of treatment and between the individual and group components of PEPS therapy. The specifications were that psychoeducation should be completed a maximum of 4 weeks before the problem-solving group started. The maximum wait between randomisation and the group starting should be 10 weeks and the minimum should be 5 weeks. This enabled completion of the individual treatment sessions and first follow-up prior to the start of the problem-solving group.

Within each recruitment phase there was an approximate 5-week period within which baseline assessments and randomisation were completed for participants in a particular recruitment phase. Randomisation was completed as soon as possible after baseline assessments and in all cases this should have been done within 1 week.

A minimum starting group size of six was recommended. During the randomisation period, local teams aimed to randomise a minimum of 12 participants to ensure an adequate minimum starting group size. It was recommended that starting group sizes should generally be no more than 10 participants. However, local teams could use discretion in determining the appropriate group starting size according to local circumstances, current waiting times and recruitment rates.

Screening

To confirm eligibility for the trial the following screening measures were undertaken before randomisation:

-

The presence of PD was confirmed using the IPDE. 52 The IPDE is a 99-item, semistructured interview that allows both diagnostic and dimensional scores to be extracted for each PD according to either Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)53 or International Classification of Diseases54 criteria. DSM criteria were used in this trial. Each item is scored as the behaviour or trait being absent or normal (score 0), exaggerated or accentuated (score 1), or at the criterion level or pathological (score 2). Diagnostic scores were calculated in accordance with the scoring manual. A minimum of one ‘probable’ score on any diagnostic category including PD not otherwise specified was required to be eligible for the trial.

-

Adequate literacy was required to engage in trial therapies and assessments. In the majority of cases this was assessed by the investigator or authorised designee in conjunction with the participant’s usual-care team. Adequate literacy was determined in discussion with the participant and their clinical team, based on the ability to participate in the trial therapy and assessments. The Basic Skills Agency’s, Fast Track 20 Questions55 was available as an additional screening measure to aid assessment of literacy if required, but was not used. Study recommendations were that a score of ≥ 3 on the literacy component of the Fast Track 20 Questions indicated that additional consideration may be required, but did not prohibit further involvement in the trial. The final decision about inclusion or exclusion was made by the therapist in consultation with the referrer, the client and, if necessary, the site coinvestigator or site clinical supervisor.

Interventions

This was a two-arm trial comparing PEPS therapy in addition to treatment as usual with treatment as usual only.

Psychoeducation with problem-solving therapy

Psychoeducation with problem-solving therapy is a complex cognitive–behavioural intervention that integrates individual and group therapies. There are two distinct components – individual psychoeducation and group problem-solving therapy – with optional individual support sessions.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation consists of up to four sessions delivered by a mental health worker trained to administer the procedure. The number of sessions depends on the duration of sessions and the speed at which the participant can comfortably work through the session content. Although the guidance is to work in 1-hour sessions, some participants prefer to have longer and less frequent sessions to maintain the flow of the content.

The sessions are conducted as a one-to-one collaborative dialogue and are designed to fulfil both general and specific functions. In general, the aims are to build rapport with participants and enhance their motivation for the subsequent problem-solving therapy. This is done specifically by asking participants their views on how their personality leads to problems in interpersonal relationships and social functioning, introducing them to and discussing their PD diagnoses, and explaining how therapy can help people ameliorate their problems.

Interviewers follow a set procedure described in a facilitator’s manual (see Appendix 1). Participants are first asked about their understanding of personality and any personality-related problems that they experience in a brief interview consisting of six questions:

-

What does the word ‘personality’ mean to you?

-

Do you think your personality causes you problems? In what way?

-

Do you think your personality causes problems for other people? In what way?

-

Would you like to change the way you handle problems?

-

Some people are diagnosed as having a PD. Do you know what a PD is?

-

Have you ever been told you might have a PD?

Information on personality and PD is then provided, following an information sheet explaining the concept of personality in terms of it being the way people typically think, feel and behave, and PD being personality styles that persistently cause difficulties and distress. The suggestion that problem-solving therapy can help ameliorate problems is then introduced. Participants are asked to complete a checklist of what problems they experience in relation to their PD. The interviewer completes a checklist that takes the individual through their PD diagnoses, as identified prerandomisation using the IPDE,52 which is a structured clinical assessment. The interviewer and the participant discuss information about the individual’s personality problems from both perspectives. Participants are then guided to identify specific problems that they want to change, and prioritise those to be addressed in the subsequent problem-solving therapy sessions. The interviewer summarises the progress made in psychoeducation and logs the problems to be addressed in problem-solving therapy on a summary pro forma. This summary is used to convey the information to the problem-solving therapy facilitators. The content of psychoeducation is also summarised in a personalised booklet (see Appendix 2) that the participant is given to keep.

Problem-solving therapy

Problem-solving therapy is a 12-session manualised (see Appendix 3) group intervention designed to teach people a strategy for solving interpersonal problems. Problem-solving therapy is delivered by two mental health professionals trained to administer the therapy. The recommended starting group size was between 6 and 10 participants, but local sites were advised to use discretion so that when trial recruitment was slow, groups could start without undue delay; actual group sizes were between 5 and 12 participants. Sessions lasted approximately 2 hours, divided into 75 minutes of problem-solving work, a 15-minute break and 30 minutes of problem-solving work.

In each session, one participant worked through an actual problem that was identified in collaboration with one of the group facilitators prior to the group session. The problem selected could be an emotional or interpersonal problem, rather than a practical problem, and would be one that was current and important but not excessively distressing or unsuited to sharing in a time-limited group. Participants were then guided to learn the steps of the problem-solving process, based on the work of D’Zurilla and Nezu:56,57

-

orientation – identifying negative feelings and using these as a cue for initiating the problem-solving process

-

problem definition – defining their problem clearly and accurately, breaking down large problems into smaller, more manageable ones

-

goal-setting – setting specific goals for change

-

generating alternatives – generating solution options

-

decision-making – considering the consequences of each option to themself and others in both the short and the long term

-

action-planning – selecting potentially effective options and organising these into a means-end action plan.

Participants were then expected to implement the action plan and were offered optional fortnightly individual support sessions throughout the 12-week problem-solving group therapy to help with implementation. Progress with the action plan was reviewed in the next group session.

The problem-solving process is translated into colloquial questions, which are shown in Table 1, along with the formal stages of the process and the skills learned in each stage.

| Question | Stage | Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Feeling bad? | Orientation | Recognition and understanding of feelings countering impulsivity |

| What’s my problem? | Problem definition | Information gathering Assessing the quality and relevance of information Breaking down large problems |

| What do I want? | Goal-setting | Identification of needs Setting targets |

| What are my options? | Alternatives | Creative thinking |

| What’s my plan? | Decision-making | Challenging dysfunctional beliefs Challenging antisocial attitudes Anticipation of outcomes Forward planning |

| How did I do? | Evaluation | Recognise and reward success Recognise and address obstacles |

Throughout this process, attention was paid to improving optimism and hope for change, which is identified as of equal importance to problem-solving skills. This was done by helping participants experience success in problem-solving through guiding them through the problem-solving process, giving them support in their efforts to solve problems, identifying their strengths and highlighting problem-solving successes.

The process of problem-solving through addressing the key questions was recorded on a flip chart as the session progressed. The flip chart could be written by a group member or one of the facilitators, depending on the abilities of group members. This material was then transcribed to A4 sheets, which were given to the participant for his or her records, and a copy retained for the facilitators’ records. Individual support sessions of 1-hour duration were offered fortnightly to help the individual carry out problem-solving action plans. Additionally, participants were encouraged to work through problems independently outside sessions in order to generalise the new skills. A worksheet was provided to assist with independent working.

Problem-solving therapy was provided in mixed- or single-sex groups, depending on the stage of the trial (described in Changes to the intervention during the trial), the number and suitability of referrals received, and participant preference. Participants allocated to PEPS therapy were expected to attend every session, and regular attendance was encouraged in accordance with normal clinical practice. A record of attendance at sessions was maintained for all participants. Participants were not withdrawn from trial therapy for reasons of poor attendance. Owing to variable group attendance rates, a prespecified minimum attendance at group treatments was defined for participants to be considered to have received therapy per protocol. The agreed hypothesis was that attending ≥ 6 of the maximum 12 group sessions of problem-solving therapy would be associated with improved outcomes on the SFQ.

Changes to the intervention during the trial

Within the trial, problem-solving groups were originally intended to be single sex. This was to ensure consistency with the pilot study and in response to preferences expressed by service user representatives advising on the design of the study during protocol development. However, the requirement for single-sex groups was found to cause delays while awaiting the accrual of sufficient participants to form a group. This was a particular issue for male participants because fewer men were referred to the study.

After consulting with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), the study team took the decision to allow problem-solving therapy to be offered in mixed-sex groups. The reasons for this were:

-

Mixed-sex groups are routine practice in community-based clinical services already offering PEPS therapy.

-

Mixed-sex groups may help to reduce waiting times and delays between recruitment and randomisation.

-

Mixed-sex groups can provide clinical benefits (e.g. helping participants to address issues with relating to people of the opposite sex).

An amendment was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee to introduce this change in August 2011, approximately halfway through the recruitment period. Following implementation of this amendment, allocation to mixed- or single-sex groups was made in accordance with usual clinical practice, incorporating participant preference where possible.

Treatment as usual

Usual treatment was provided by participants’ usual-care teams in accordance with normal clinical practice. No restrictions were placed on access to other treatments during the trial period, although engagement in a specific programme of psychological treatment for PD was an exclusion criterion applied at the point of enrolment.

The original protocol included a standardised form of treatment as usual as the control. Shortly after the start of the recruitment period, it became apparent that there was substantial variability in the level and type of care provided to people with PD at each of the participating sites. Many potential participants were being assessed by mental health services and discharged without treatment. To exclude these people would seriously compromise recruitment to the trial. For this reason, the study team could not impose a standardised form of treatment as usual on the referring clinical services. The study team felt that this issue was likely to become more pressing as NHS cuts at the time caused CMHTs to reduce services. As a result, it was agreed that the trial should compare PEPS therapy with treatment as usual in whatever form that took, and the planned requirement for a standardised form of treatment as usual was removed from the protocol in August 2010. The standardised form of treatment as usual, outlined in the original protocol, was recommended as a minimum standard of care but this was not imposed on clinical services referring participants to the trial.

Treatment fidelity

Manualised assessment and treatments

The IPDE schedule, psychoeducation and problem-solving therapy are all comprehensively manualised.

Training and supervision

Therapists were qualified mental health nurses or psychology graduates with clinical experience. All IPDE assessors attended training in administering and scoring the structured interview from a qualified and highly experienced clinician and researcher. Each lead clinician who delivered psychoeducation and problem-solving therapy was trained to conduct the intervention. Problem-solving therapy groups were facilitated by two facilitators. Most cofacilitators also attended training in delivery of the intervention; however, on the rare occasions that this was not possible, groups could be cofacilitated by a facilitator who had not completed the training, provided that they were fully briefed by the lead therapist and were aware of the limitations of their involvement. A minimum of one fully trained and assessed facilitator was present at every group session.

Psychoeducation training was delivered after IPDE training and consisted of informing therapists of the rationale for psychoeducation, explaining the delivery mode of an educational dialogue and familiarising therapists with the materials and their sequence of delivery. Problem-solving therapy training consisted of 3 days in which groups of participants were given the theory, outcome evidence and role-play practice.

In each case (IPDE, psychoeducation and problem-solving), training followed an existing training protocol. Training was conducted centrally by experienced clinicians and researchers. After training, regular supervision was provided, both centrally and locally.

Competence checks

Audiotapes of treatment delivery were scrutinised by the trainers to ensure that each therapist was adhering to the treatment specification. Competence checklists were constructed for this assessment (see Appendices 4–6). These specified the key activities for conducting the IPDE and delivering psychoeducation and problem-solving sessions according to the intended treatment model. Cut-off scores for competence were agreed in advance and therapists were assessed for competence in delivering the treatment. None of the therapists failed to meet the competence criteria on any of the measures. Having assessed the therapists as competent to deliver the treatment according to the model and the protocol, no further checks were made. This was considered to reflect actual clinical practice in which staff are trained in a procedure and, if they meet the standards set by the trainers, they commence practice and the quality of their continued practice is monitored through supervision.

Fidelity checks

Treatment fidelity was assessed in three ways:

-

Measuring adherence to protocol implementation (e.g. frequency and duration of treatment sessions).

-

Assessing adherence to therapy, as specified in the treatment manual.

-

Clinical supervision.

Adherence to psychoeducation was self-rated by the therapist after the end of all psychoeducation sessions, using a standard protocol (see Appendix 7). Adherence to problem-solving group sessions was rated by experienced clinicians, based on a sample of audiorecorded sessions.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was social functioning as measured by the SFQ. 45 This is an 8-item self-report scale, on which each item is scored from 0 to 3. The total SFQ score ranges from 0 to 24. A reduction (i.e. an improvement) of ≥ 2 points on the SFQ at the 72-week follow-up was the specified clinically significant change.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes

-

Scheduled and unscheduled health-service use collected through a retrospective review of mental health service and general practitioner (GP) records.

-

Mood, measured by the HADS,58 a 14-item self-report questionnaire with scores in the range of 0 to 42, and on which higher scores are less desirable.

-

The referring clinician’s judgement of the participant’s overall level of psychosocial functioning assessed by the GAF. 53

-

The client’s assessment of severity, on a scale from not at all distressing (0) to very distressing (10), of the three problems they considered most important (three main problems).

Process measures

The following measures were intended as measures of the processes of change during PEPS therapy:

-

Therapeutic relationship was assessed using the Working Alliance Inventory – Short Revised (WAI-SR),59 a 12-item scale rated by both client and therapist to assess agreement on the tasks of therapy, agreement on the goals of therapy, and the bond between client and therapist, with a range of scores between 12 (poor) and 48 (good).

-

Social problem-solving abilities were measured by the SPSI-R,28 a 25-item self-report questionnaire that measures problem-solving orientations and styles, with five items in each of the five subscales: positive problem orientation, negative problem orientation, rational problem-solving, impulsivity/careless style and avoidance style. Effective social problem-solving is indicated by higher scores on positive problem orientation, rational problem-solving and the SPSI-R, and lower scores on negative problem orientation, impulsivity/careless style and avoidance style. A total social problem-solving score ranges from 0 to 25, in which a higher score is more desirable.

Health economic outcomes

Participants’ views and experiences

Qualitative semistructured interviews were completed with participants allocated to PEPS therapy after psychoeducation and after problem-solving therapy to seek participants’ views on treatment. Further interviews were completed with all participants after the final follow-up to seek participants’ views on the experiences of PEPS therapy and usual treatment.

Safety and tolerability measures

Adverse events occurring in trial participants were recorded and monitored. For the purposes of this trial, a recordable adverse event was defined as any of the following:

-

death for any reason

-

inpatient hospitalisation for any reason

-

any other serious, unexpected adverse event.

Adverse events were reported for all participants from consent to trial completion or early withdrawal from trial follow-up. If a participant withdrew from treatment but agreed to remain in trial follow-up, data collection, including adverse event reporting, continued in accordance with the protocol.

Premature withdrawal from the trial therapies or follow-up was reported, with reasons for withdrawal documented when these were given.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis

The analysis and reporting of the trial was in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 62–65 Analyses were detailed in a statistical analysis plan, which was finalised prior to completion of data collection and database lock. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical measures were used to examine the balance between the randomised arms at baseline.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis compared the mean SFQ score between PEPS and usual treatment at the 72-week postrandomisation follow-up, adjusted for baseline SFQ score and stratification variables (centre and sex), and implemented using maximum likelihood-based generalised linear modelling. The primary analysis compared individuals as randomised, regardless of treatment actually received or if 72-week follow-up SFQ data were observed (intention-to-treat principle). The effect is presented as an adjusted difference in means, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-value for the comparison.

Imputation of missing primary outcome data

The pattern of missing data was investigated by examining variables recorded at baseline that were associated with ‘missingness’ of SFQ score at the 72-week follow-up. Multiple imputation and analysis of multiple imputed data sets were conducted using ‘mi’ procedures in Stata. The imputation model contained site, age, sex, ethnicity, social status, PD category (simple or complex), SFQ at baseline and 24 weeks, baseline EQ-5D health state score, baseline HADS score, baseline SPSI-R score and baseline three main problems score, and 20 data sets were imputed.

Missing item data

For all outcomes that are a scale comprising a number of items, the following procedure was undertaken when > 0% and ≤ 15% of items were missing:

-

Step 1: calculate the scale mean for each participant (denoted by m1 for those with > 0% and ≤ 15% of items missing).

-

Step 2: calculate the mean of scale means for participants with complete scale data only (denoted by M1).

-

Step 3: calculate each item mean for all participants with observed data for that item (denoted by S1).

-

Step 4: for each item, calculate M1 – S1 (denoted by d).

-

Step 5: impute missing item data using m1 – d.

When > 15% of items were missing, the total scale score was regarded as missing and imputed using multiple imputation.

Clustering in psychoeducation with problem-solving arm

In this trial there were two potential sources of clustering in the PEPS arm only: by therapist in the first treatment phase and by the problem-solving therapy group in the second treatment phase. Data for the former were not available for some participants, or else treatment in the first phase was delivered by a single therapist per centre. Furthermore, any clustering effect was expected to be dominated by the latter. Therefore, we obtained clustered sandwich estimates of variance by specifying the ‘cluster’ option in all regression models, which relaxes the assumption that all observations are independent.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome:

-

Repeated the primary analysis with additional adjustment for any variables displaying marked imbalance between the arms at baseline.

-

Repeated the primary analysis restricted to those participants with observed primary outcome data at 72 weeks.

-

To examine treatment efficacy, complier average causal effect (CACE) estimates66 were calculated using instrumental variable regression methods for those participants in the PEPS arm who received the intervention in line with the treatment protocol. The definition of treatment received as per protocol was having completed psychoeducation according to the therapist assessment and attended a minimum of six of the group problem-solving sessions.

Subgroup analyses

Although no subgroup analyses were specified a priori, we conducted two exploratory subgroup analyses by including appropriate interaction terms in the regression model for the primary outcome. We investigated whether or not there was any evidence of differential effects of treatment on SFQ score at 72 weeks according to (1) study site (central and north-west London, South Wales and North-East England); (2) PD category (simple, complex); and (3) borderline PD diagnosis at baseline.

Secondary outcomes

Analysis of secondary outcomes was conducted using a similar approach as for the primary outcome, except that missing data were not imputed, and choice of regression model and presentation of the estimated between-group effect was dependent on outcome type (continuous, binary, ordinal, rate). We used proportional odds logistic regression for ordinal data and we checked the goodness-of-fit assumption for the Poisson regression analysis of count data using the Pearson test. Descriptive data are presented for each time point, but formal comparisons were only conducted for 72-week data. The exception to this is the SPSI-R total score, for which a repeated measures analysis was conducted including data at both the 24- and 72-weeks follow-up to examine whether any treatment effects were sustained or emerged later. This was tested formally with an interaction term between treatment group and time in the model, and in the absence of any evidence of a time effect, a repeated measures analysis generates an average effect size over the duration of follow-up.

Between-group differences in health-care service use and adverse events were estimated using binomial/Poisson regression modelling and allow for multiple events per individual.

Interim analysis

No formal interim analyses for effectiveness were planned or undertaken, however, unblinded data were periodically reviewed by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) during routine meetings.

Sample size

The sample size calculation for the study was based on the primary hypothesis that those randomised to PEPS therapy in addition to usual treatment would have improved social functioning at 72 weeks after randomisation compared with those randomised to usual treatment only. We powered the trial to detect a difference of 2 points on the SFQ score (standardised effect size of 0.44). This is agreed to be a clinically significant and important difference. 67 We based our sample size estimate on a conservative (i.e. largest) estimate of standard deviation (SD) of 4.53 points.

To detect a difference in mean SFQ score of 2 points with a two-sided significance level of 1% and power of 80%, with equal allocation to two arms, would require 120 patients in each arm of the trial. In anticipation of a 30% loss to follow-up at 72 weeks after randomisation, we planned to randomise 340 participants (170 in each arm).

Randomisation

Following recruitment and completion of screening and baseline assessments, participants were randomly allocated to receive PEPS therapy in addition to usual treatment or usual treatment alone at a ratio of 1 : 1.

Randomisation was based on a computer-generated pseudo-random code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server. The randomisation was stratified by recruiting centre and sex. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until recruitment, data collection and all other trial-related assessments were complete.

The investigator, or an authorised designee, accessed the treatment allocation for each participant by means of a remote, internet-based randomisation system developed and maintained by the NCTU. Allocation was therefore fully concealed from recruiting staff.

Study procedures

Preparatory phase

Site initiation visits were completed prior to the start of recruitment to ensure that all site staff were trained in the protocol and study-specific procedures.

Visit schedule

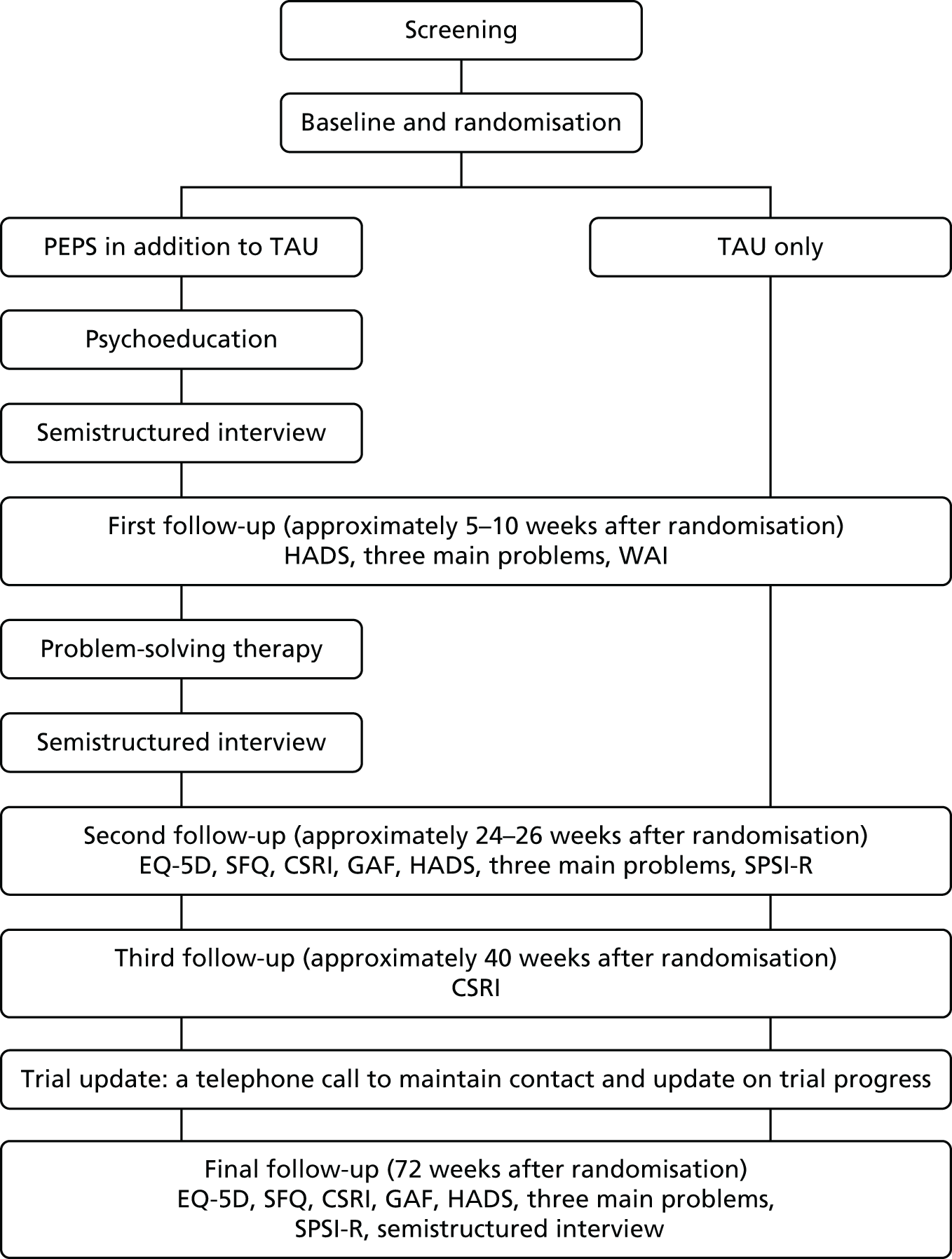

The duration of follow-up was 72 weeks post randomisation. The study schedule is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Schedule of visits. TAU, treatment as usual.

Data collection

Follow-up visits were completed in person or by telephone. To improve response rates at the final follow-up, the SFQ was posted to participants who could not be contacted by another means.

The majority of data were collected through the use of standardised, self-report assessment measures completed by participants during scheduled follow-up visits. Research staff involved in data collection were provided with guidance on the principles of standardised assessment and on the specific measures employed in the trial. Assessments were self-completed by participants or read aloud to participants by the researcher if required. In this case, questions were read out verbatim and were not reworded. No test feedback was given to participants.

The Service Use Record Check was completed by the research assistants after the final assessment measures had been collected. Service use data were collected from GP and mental health records retrospectively for the duration of the trial, according to a data collection manual that outlined procedures for accessing GP records, procedures for dealing with incomplete or inconsistent data, and definitions of key terms; standardised data collection forms were used (see Appendix 8).

Blinding

In pragmatic trials of this type, as in usual clinical practice, it is not possible to blind participants or clinicians to whether they are in the intervention or control arm of the trial; therefore, participants, mental health workers delivering the interventions and participants’ usual-care teams were aware of the treatment allocation. Most of the outcome data were obtained from self-report questionnaires from participants who were not blind to treatment allocation. However, outcome measures were administered by research assistants blinded to treatment allocation in order to reduce assessment bias as far as possible. Data analysts remained blinded to allocation during the study by having access to only aggregate data and no access to data that could reveal treatment arm, such as course attendance. Final analyses were conducted using treatment labels A/B, with allocation decodes released only after completion of analyses. Data that could reveal allocation were analysed following release of allocation decodes.

At the start of each follow-up, participants were reminded of the importance of not disclosing their treatment allocation to the research assistant using a suggested unblinding script (see Appendix 9). If the research assistant was inadvertently unblinded to treatment allocation before completing the final follow-up, a record of the incident of unblinding was made. Researchers also reported whether or not they were aware of the treatment allocation at the time of completing the primary end-point assessments. Owing to changes in personnel over the course of the trial, in some cases, end-point assessments were conducted by researchers who were not unblinded. A record was made of the blinding status of the researcher conducting the final follow-up data collection.

Payments to participants

Participants reaching the final follow-up were offered a non-contingent voucher payment in recognition of their contribution to the trial. Contact with the participant at the final follow-up was sufficient for provision of the voucher (i.e. payment was not contingent on completion of the final follow-up assessments). This voucher payment was introduced in an amendment in April 2013, approximately halfway through final follow-up completion.

Reimbursement of travel expenses incurred in relation to attendance at research appointments was offered, and travel expenses incurred by participants in conjunction with the treatments provided in the trial were paid in accordance with normal clinical practice at the local sites.

Patient and public involvement

Two service users were involved in the protocol development and in the preparation of the participant information sheet and consent form. Service user representatives on the Trial Management Group (TMG), TSC and DMEC contributed to the management and oversight of the trial.

Research governance

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. 68

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study, including amendments, was given by the South Wales Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/WSE03/48).

The final approved protocol was version 6.0, dated 3 April 2013. The original approved protocol was version 1.0, dated 18 September 2009. For a summary of amendments implemented during the trial see Appendix 10.

Oversight

A number of committees were assembled to ensure the proper management and conduct of the trial, and to uphold the safety and well-being of participants. The general purpose, responsibilities and structures of the committees were described in the protocol, with separate charters developed for the independent oversight committees.

The TMG comprised members of the study team and met regularly throughout the trial to oversee the day-to-day management of the trial. The TMG met approximately once a month for the duration of the trial, with meetings held face to face and by teleconference for those unable to attend in person. The TMG reviewed recruitment and data completion rates, as well as identifying and addressing any issues arising during the course of the trial.

Independent oversight of trial conduct was provided by the TSC and DMEC.

The independent TSC monitored, reviewed and supervised the progress of the trial. The TSC also monitored pooled data to consider safety and efficacy indications, and considered reports from the DMEC.

An independent DMEC was established, with access to unblinded data, to provide independent reviews and recommendations to the TSC regarding continuation of the study in light of potential treatment effect. The DMEC was advisory to the TSC. During routine conduct of the trial, the DMEC was the only group with access to unblinded data. The DMEC reviewed unblinded data at routine meetings held during the course of the trial. The data that were presented included listings of reported adverse events and reported hospitalisations collected from the CSRI.

For the schedule of meetings of the DMEC and TSC see Appendix 11.

Safety monitoring

Local procedures were implemented at each site to ensure adverse events were recognised and reported, including asking participants about adverse events during each contact and asking the participant’s clinical team to inform the site principal investigator if an adverse event was identified. The participant’s responsible clinician was also contacted by letter to request information on adverse events throughout the trial. In addition, in the event of loss to follow-up, the participant’s clinical team and/or GP were contacted to alert the responsible clinician to the participant’s loss to follow-up and to request information on any unreported adverse events to ensure that safety data remained accurate and up to date. All adverse events were reported to the trial co-ordinating centre within 24 hours of the study team becoming aware of them.

Adverse event reports were reviewed on receipt at the co-ordinating centre, and were assessed for relatedness and expectedness by the chief investigator in accordance with the National Research Ethics Service guidance on adverse event reporting in trials that do not include medicines. To guide this assessment, the adverse event form collected information on all possible and suspected causes identified from the available clinical information, including clinical notes and participant self-report. A categorical assessment of ‘relatedness to the trial’ was also made by the person reporting the event.

Adverse events were also classified by the person reporting them according to whether or not there were indications of ‘psychological antecedents’. Events that were deemed to have psychological antecedents were defined as mental health-related events. Mental health-related events were further categorised as follows:

-

self-harm, including drug or alcohol overdose

-

deterioration in mental health

-

suicidal ideation

-

suicide or attempted suicide

-

planned/respite hospital admission

-

other (specify).

The primary classification only was recorded. Adverse events were classified by the person reporting the event on the basis of the information available at the time (e.g. through participant self-report or clinical notes). For example, attempted suicide was recorded when this was the reason given by the participant, and it does not necessarily relate to the severity of harm caused or evidence of clear intent (i.e. events recorded as ‘attempted suicide’ are not necessarily life-threatening).

All adverse events were routinely reported to the Research Ethics Committee, DMEC and TSC as part of the regular reporting requirements. In addition, serious adverse events that were deemed to be both related to administration of any of the trial procedures and that were not identified as expected occurrences were subject to expedited reporting to the Research Ethics Committee, as required by the National Research Ethics Service guidance for studies that are not clinical trials of investigational medicinal products in the UK.

Chapter 3 Early stopping of recruitment and delivery of the trial intervention

The decision to stop recruitment and trial therapy

On 29 October 2012, following the fourth meeting of the DMEC, the DMEC chairperson wrote to the TSC notifying the TSC of a safety alert in the PEPS trial based on an untoward pattern of serious adverse events. The DMEC had done some investigations but had been unable to satisfy themselves of whether this finding might or might not have been treatment related. The DMEC recommended further investigations to clarify the safety and tolerability of the treatment and advised that randomisation to the trial be suspended until this had been further investigated. The DMEC did not recommend stopping the treatment of people currently in the trial, as they considered that the potential risks of harm in discontinuing treatment were not justified at that stage. Following subsequent correspondence and discussions between the two committees, during which the TSC reviewed the recommendations of the DMEC and the unblinded data on which they were based, the TSC agreed that a safety concern could not be ruled out, but made different recommendations to those advocated by the DMEC. The TSC communicated the following decisions to the chief investigator and trial co-ordinating centre in a letter dated 6 November 2012:

-

No further patients should be randomised into the PEPS trial.

-

Patients who were currently in treatment in the trial should no longer receive trial treatment within the parameters of the trial treatment protocol.

-

To fulfil the duty of care to patients who have completed the treatment phase of the trial the trial team should consider how to inform patients of the possibility of harm.

-

Trial data should continue to be collected and all patients followed up as per protocol.

A number of clinical concerns were raised by the PEPS trial team between 10 and 12 November 2012, and the study team felt that a challenge to the decision to stop trial treatment was warranted. In the absence of precedent in this situation, the following process was proposed by the trial co-ordinating centre and agreed by all parties, including the funder:

-

A joint meeting of TSC and trial team would be held.

-

The TSC would explain their decisions and rationale behind them.

-

The study team would present their concerns.

-

Chaired discussion between all parties.

-

The TSC would convene a closed meeting to consider the challenge and agree its response.

These discussions took place at a face-to-face meeting held on 15 November 2012. The meeting was hosted by the NCTU and chaired by a senior member of the NCTU, who was not otherwise involved in the trial. The closed TSC meeting was held on 19 November 2012. Immediately following this meeting, the TSC wrote to the study team to confirm the unanimous decision of the TSC to uphold its original decision. Following this confirmation, the study team took immediate steps to action the implementation plan that had been previously agreed during the meeting held on 15 November 2012 and in subsequent correspondence.

Stopping recruitment and trial therapy

On receipt of the notification of the initial decision from the TSC on 6 November 2012, the following interim actions were taken immediately by the chief investigator and trial co-ordinating centre:

-

The online randomisation system was suspended on 6 November 2012 to ensure that no further participants would be randomised.

-

The TMG, other coinvestigators, the trial funder and the trial sponsor were notified immediately.

-

A holding statement, approved by the TSC and sent on their behalf, was circulated to recruiting sites on 8 November 2012. Site principal investigators were asked to disseminate the holding statement to site staff and to stop any further recruitment of participants with immediate effect on 8 November 2012.

Delivery of the trial therapy was suspended where it was possible to do so without undue disruption (e.g. postponing appointments). At this stage, steps were not taken to permanently discontinue treatment or inform participants until the implications had been fully considered and a clinically appropriate action plan, with support and alternative treatment arrangements, was in place.

A brief search and consultation failed to find any previous examples of cessation of recruitment and treatment because of a safety alert in a trial of this type. Therefore, the process of stopping recruitment and delivery of trial therapy meant that additional, specific procedures were developed in collaboration between the TMG, TSC and NCTU with reference to clinical guidelines and accepted good practice. Regular communication was maintained during the planning and implementation to review progress and agree the next steps.

Informing participants and clinicians of the trial changes

Everyone affected by the trial changes was provided with information by the research team. A written information sheet was provided. Participants who were ‘active’ in the trial (i.e. recently referred or in the treatment phase) were provided with additional information and support regarding their ongoing care. A separate, simplified version of the information sheet was available for participants in the follow-up period.

Clinical teams and referring clinicians were informed of the trial changes. They received the same information as participants, and were offered additional guidance on ‘frequently asked questions’ and sources of additional support and advice, should they be required to respond to queries or concerns from participants.

A letter was sent to the responsible clinician within mental health services and the GPs for all participants involved in the trial to inform them of the changes to the trial.

Participants and clinical teams were informed of the changes to the study as a matter of urgency. It was considered essential that all those affected by the changes were informed by the research team first, before this information was in the public domain.

The provision of information to people affected by the trial changes was completed on a staged basis so that the processes used and information provided could be informed by early feedback from participants and clinical teams. However, the process of informing people affected by the trial changes was time limited and all those affected by the changes were notified within a reasonable time scale. Whenever possible, this was within 4 weeks.

Updated consent

No further trial-specific procedures (e.g. continuation of the IPDE, sessions with a PEPS therapist or follow-up assessments) were completed with participants until they had been informed of the trial changes. Participants in the trial were asked to sign an updated consent form to confirm receipt of the new information and indicate their ongoing agreement to participate in the trial. Verbal consent was accepted for continuation of follow-up assessments completed by telephone, although written consent forms were also requested.

Issues relating to participants

When the decision to stop recruitment and delivery of the trial therapy was made, 306 participants had been randomised. The number of participants at each stage of the trial is shown in Table 2.

| Stage of the trial | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Randomised to PEPS therapy and active in the treatment phase of the trial | 19 |

| Randomised, active in follow-up | 210 |

| Randomised, completed trial follow-up | 54 |

| Randomised, withdrawn before completion | 23 |

| Active in screening phase | 38 |

| Referred but not yet started study-specific procedures | 42 |

Randomised to psychoeducation with problem-solving therapy and active in the treatment phase of the trial

Participants who had been randomised to receive PEPS therapy and were currently in the treatment phase of the trial were informed of the trial changes as soon as practically possible, and arrangements were made to ensure that the delivery of PEPS therapy was stopped in a clinically appropriate way. The TSC had confirmed that their recommendation to stop trial treatment did not advocate an abrupt stopping. Delivery of trial treatment in accordance with the protocol should cease; however, there was scope to meet with participants to explain the situation and to involve them in decisions about a structured and clinically appropriate end to trial treatment. What was clinically appropriate depended on the stage of PEPS therapy and the needs of individual participants. This was a clinical judgement made by the site principal investigator in consultation with clinicians involved in the trial, the participant’s usual clinical team and the participant, as appropriate. To underpin what was clinically appropriate we referred to national guidelines on treatment of PD. There are two National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the treatment and management of PD: one for borderline PD69 and one for antisocial PD. 70 Both emphasise the importance of endings and transitions. As a result, the study team identified a need to liaise with clinical teams to identify what support they could offer and how the investigators and trial therapists could assist.

Randomised, active in follow-up

Participants currently in follow-up were informed of the trial changes at their next scheduled follow-up appointment if this was due within 4 weeks. Participants were informed by letter before their next scheduled appointment, if this was necessary, to prevent an undue delay. Participants informed of the trial changes by letter were provided with contact details and invited to contact the study team should they have any queries or wish to discuss this further.

Active in screening phase

Participants who had not yet been randomised but were active in the screening phase of the trial were also informed promptly. Participants in the middle of the IPDE were given the choice to stop or continue this. Participants who completed the IPDE were offered feedback on the results of the IPDE, in accordance with the existing procedure for doing this at the end of the trial (this is distinct from the provision of psychoeducation).

Referred but not yet started study-specific procedures

There was a number of people who had not completed any study-specific procedures at the time of stopping, although some had given consent to join the trial. The research team contacted these people to thank them for their interest in the study and to inform them that recruitment to the trial had stopped.

Randomised, completed trial follow-up or withdrawn before completion

In addition, participants who were in follow-up and those who had completed their involvement with the trial (completed final follow-up or withdrew before completion) were informed and supported, as appropriate. Arrangements were made to contact participants who had completed their involvement in the trial and those who withdrew before completion. These participants were informed by letter and provided with a written information sheet.

The following people were not directly informed of the trial changes by the research team:

-

people who were referred to the PEPS trial, but were excluded before consent or declined to participate

-

participants who consented and withdrew before randomisation

-

participants who consented, but were not eligible for randomisation following screening.

Additional support for study staff

Study-wide guidance documents were prepared and maintained to ensure that everybody involved in informing participants and clinical teams, and responding to queries, including those responsible for staffing the trial helpline, had access to relevant written information to support them in this role.

Initially, local sites made arrangements for a limited local helpline to address queries and concerns from participants and clinical teams promptly. Arrangements for a trial-wide helpline were made, in the event that demand should exceed local capacity.

A press release was prepared and agreed by all parties so that a clear statement could be made in the event that the media picked up on the trial stoppage.

The national helpline and press statement were not used.

Documentation of the process

The process of informing participants and of stopping the delivery of PEPS therapy was clearly documented. Feedback given by participants was recorded to inform the ongoing process and ensure that lessons could be learned.

In addition to recording what information was provided and when, sites were also asked to document any questions, comments or concerns raised by participants and clinical teams, and to provide feedback to the trial co-ordinating centre on the issues raised.

Participants’ views on trial stoppage

Feedback was reviewed to identify learning points and enable reflection on the processes used in the trial and during implementation of the trial changes. 71 Specific feedback was received and documented from 37 participants from all trial stages. A number of recurring views were identified. Among the most frequently reported were that an initial increase in distress was expected when engaging in psychological therapies; stopping PEPS therapy led to a concern over the lack of alternative treatment options; that there were alternative interpretations of the finding that more adverse events were recorded in the PEPS group; and that therapy delivered within the trial could have been improved (e.g. needed to be longer). There were no complaints about how the trial changes were implemented.

Urgent safety measure

A substantial amendment (substantial amendment 08 dated 26 November 2012) sought retrospective approval from the Research Ethics Committee for implementation of the trial changes as an urgent safety measure. The procedure for informing participants and clinical teams, and supporting documents were submitted for ethical review and approval in parallel to implementation. Approval was received in December 2012.

Chapter 4 Results

Recruitment

Study recruitment commenced in August 2010. Between August 2010 and November 2012, 739 people were referred to the trial for assessment of eligibility. Of these, 444 people were initially assessed as eligible and provided consent to join the trial. The reasons for non-participation were not willing to provide consent (n = 113), not eligible (n = 49), unable to contact following referral to the trial (n = 106) and not recruited because of the early stoppage (n = 27). The reasons participants were deemed not eligible for enrolment are given in Table 3.

| Not eligible for enrolment in the trial | Total number of participants |

|---|---|

| Responsible clinician did not consider person had PD | 7 |

| Primary diagnosis of psychosis | 3 |

| Insufficient spoken English | 1 |

| Insufficient literacy, comprehension or attention | 3 |

| Receiving other psychological treatment for PD | 22 |

| Other | 13 |

| Total not eligible for enrolment in the trial | 49 |

One hundred and thirty-eight people provided consent to join the trial but withdrew or were excluded before randomisation. The reasons for withdrawal/exclusion before randomisation are presented in Table 4.

| Withdrawal/exclusion before randomisation | Total number of participants |

|---|---|

| PD diagnosis not confirmed by IPDE | 32 |

| Insufficient literacy identified at screening | 1 |

| Participant withdrew consent | 34 |

| Unable to contact | 23 |

| Early stopping of recruitment | 48 |

| Total withdrawn/excluded before randomisation | 138 |

Of the participants who consented but were not randomised, 67% were female and the average age was 38 years.

Participant flow

The CONSORT diagram in Figure 2 summarises the assessments completed at each time point.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT diagram. a, Not done is a combination of those participants who did respond to contact and those who chose not to attend the follow-up for that particular follow-up; b, two of the deaths occurred before and two after the trial was stopped.

Follow-up at 72 weeks after randomisation was completed for 62% and 73% in the usual treatment and PEPS arms, respectively. Follow-up rates for each time point by centre were as follows:

-

first follow-up: central and north-west London 75%, South Wales 89%, North-East England 80%

-

second follow-up: central and north-west London 61%, South Wales 73%, North-East England 74%

-

final follow-up: central and north-west London 66%, South Wales 76%, North-East England 62%.

The median (first quartile, third quartile) time between consent and randomisation was 6.1 (2.3, 11.9) weeks, and was 2.0 (1.0, 3.9) weeks between randomisation and first therapy session (PEPS only).

The mean times between randomisation and the first follow-up was 8.0 (SD 5.1) weeks, second follow-up was 28.8 (SD 6.9) weeks and final follow-up was 80.3 (SD 10.1) weeks.

Baseline characteristics of randomised participants

Table 5 summarises the randomised groups at baseline. Of the 306 participants, 230 (75%) were women and the mean age was 38.2 years (SD 10.9 years). The only variable with a notable imbalance between the arms at baseline was type of PD, with a greater proportion in the PEPS arm defined as complex (60% compared with 49% in the usual-treatment arm).

| Variable | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual treatment (n = 152) | PEPS (n = 154) | |

| Age at randomisation (years), mean (SD) | 37.8 (11.0) | 38.6 (10.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 115 (76) | 115 (75) |

| Male | 37 (24) | 39 (25) |

| Age left full-time education (years), mean (SD) | 16.9 (3.3) | 17.2 (3.7) |

| Highest educational attainment, n (%) | ||

| None | 29 (19) | 24 (16) |

| GCSE | 16 (10) | 22 (14) |

| A-level | 45 (30) | 35 (23) |

| Vocational | 10 (7) | 10 (7) |

| Degree | 32 (21) | 36 (23) |

| Other | 20 (13) | 25 (16) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 127 (83) | 129 (84) |

| Mixed | 9 (6) | 6 (4) |

| Black Caribbean | 6 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Black African | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Black other | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Asian Indian | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Asian other | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Other | 6 (4) | 12 (8) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | ||

| Never worked and long-term unemployed | 96 (63) | 105 (68) |

| Routine and manual occupations | 28 (18) | 20 (13) |

| Intermediate occupations | 13 (9) | 9 (6) |

| Managerial and professional occupations | 15 (10) | 20 (13) |

| IPDE type (definitive), n (%) | ||

| Paranoid | 16 (11) | 13 (8) |

| Schizoid | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Schizotypal | 0 | 0 |

| Antisocial | 31 (20) | 23 (15) |

| Borderline | 90 (59) | 93 (60) |

| Histrionic | 6 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Narcissistic | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Avoidant | 56 (37) | 57 (37) |

| Dependent | 7 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Obsessive–compulsive | 20 (13) | 14 (9) |

| PD not otherwise specified | 10 (7) | 14 (9) |

| PD,a n (%) | ||

| Simple PD | 77 (51) | 61 (40) |

| Complex PD | 75 (49) | 93 (60) |

Table 6 shows baseline demographic and outcome variables further categorised by follow-up at 72 weeks and trial arm. Participants who completed the trial were slightly older, more likely to be female and more likely to have never worked or be long-term unemployed. There was no strong suggestion that different types of participants were followed up in the two trial arms, although white participants were over-represented among completers in the usual-treatment arm, while those with PD classified as simple were over-represented among completers in the PEPS arm.

| Variable | Non-completer | Completera | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual treatment (n = 58) | PEPS (n = 41) | Usual treatment (n = 94) | PEPS (n = 113) | |

| Age at randomisation (years), mean (SD) | 36.2 (10.9) | 37.0 (11.3) | 38.9 (11.0) | 39.1 (10.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 38 (65) | 27 (66) | 77 (82) | 88 (78) |

| Male | 20 (35) | 14 (34) | 17 (18) | 25 (22) |

| Age left full time education (years), mean (SD) | 17.1 (3.8) | 16.4 (2.8) | 16.8 (2.9) | 17.5 (3.9) |

| Highest educational attainment, n (%) | ||||

| None | 11 (19) | 6 (15) | 18 (19) | 18 (16) |

| GCSE | 7 (12) | 4 (10) | 9 (10) | 18 (16) |

| A-level | 18 (31) | 12 (29) | 27 (29) | 23 (20) |

| Vocational | 5 (9) | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 8 (7) |

| Degree | 12 (20) | 8 (19) | 20 (21) | 28 (25) |

| Other | 5 (9) | 7 (17) | 15 (16) | 18 (16) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 44 (76) | 34 (83) | 83 (88) | 95 (84) |

| Mixed | 6 (11) | 4 (10) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Black Caribbean | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Black African | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Black other | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian Indian | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Asian other | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Other | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 4 (4) | 10 (9) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | ||||

| Never worked and long-term unemployed | 32 (55) | 27 (66) | 64 (68) | 78 (69) |

| Routine and manual occupations | 13 (23) | 4 (10) | 15 (16) | 16 (14) |

| Intermediate occupations | 7 (12) | 4 (10) | 6 (6) | 5 (4) |

| Managerial and professional occupations | 6 (10) | 6 (14) | 9 (10) | 14 (13) |

| PD, n (%) | ||||

| Simple PD | 28 (48) | 13 (32) | 49 (52) | 48 (42) |

| Complex PD | 30 (52) | 28 (68) | 45 (48) | 65 (58) |

| Baseline SFQ score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.9 (4.9) | 14.7 (4.1) | 14.0 (4.2) | 15.1 (4.0) |

| Median (first quartile, third quartile) | 15 (12, 19) | 14 (11, 18) | 14 (11, 17) | 15 (13, 18) |

| Baseline HADS score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.1 (8.1) | 28.6 (5.7) | 27.7 (7.3) | 27.0 (7.7) |

| Median (first quartile, third quartile) | 28.5 (21, 33) | 28 (24, 33) | 28 (23, 34) | 28 (23, 32) |

| Baseline EQ-5D health status score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.2 (23.9) | 44.3 (20.4) | 40.4 (23.5) | 44.6 (23.0) |

| Median (first quartile, third quartile) | 45 (25, 60) | 45 (30, 59) | 39.5 (20, 60) | 40 (30, 60) |

| Baseline SPSI-R score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (3.1) | 6.2 (3.1) | 6.9 (3.4) | 6.5 (3.0) |

| Median (first quartile, third quartile) | 6.2 (4.6, 8.6) | 6 (4.2, 8.2) | 7.2 (4.3, 9.1) | 6.6 (4.4, 8.6) |

| Baseline three-problem average score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.7 (1.1) | 9.0 (1.0) | 8.7 (1.1) | 8.6 (1.1) |

| Median (first quartile, third quartile) | 9 (8, 9.7) | 9 (8.7, 10) | 9 (8, 9.7) | 8.7 (8, 9.3) |

Duration of follow-up